Title: The Pioneer Home

Author: Anonymous

Release date: April 26, 2021 [eBook #65168]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

THIS HOME OF AN OHIO PIONEER IS DEDICATED TO THE EARLY SETTLERS OF THE MIAMI VALLEY. THROUGH COURAGE, TOIL AND PERSEVERANCE, THEY OVERCAME HARDSHIP AND DANGER, AND BROUGHT CIVILIZATION TO THE WILDERNESS.

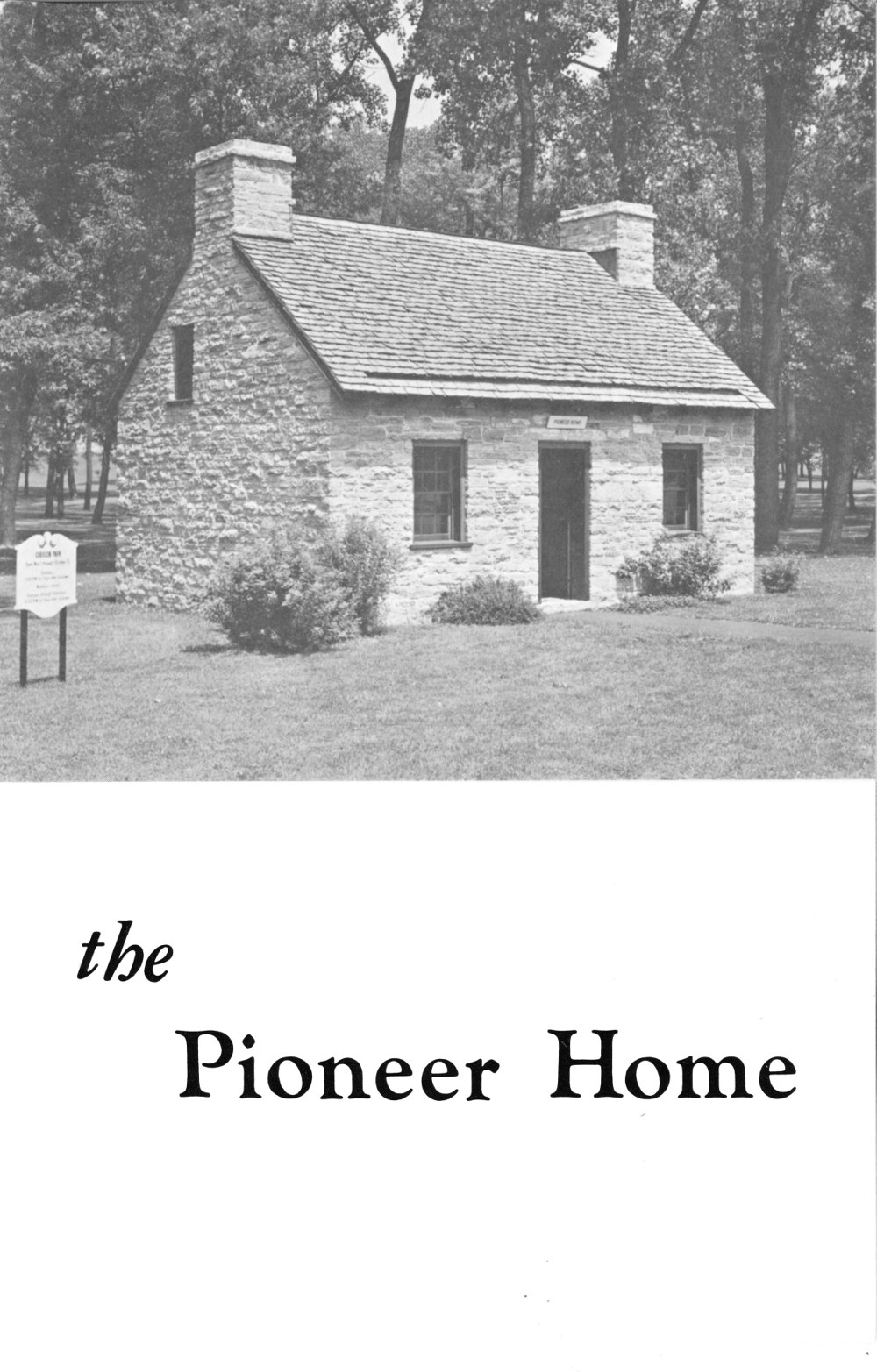

The Pioneer Home, which serves as an Information Center for Carillon Park, is believed to have been built about 1815.

It was originally located in Washington Township about five miles southwest of Centerville on Social Row Road, about halfway between Sheehan Road and Yankee Street. In the spring of 1953 it was torn down and moved to Carillon Park, where it was rebuilt, using the original stones and timbers.

Abstract records in the Court House show that the 20-acre plot on which this house was originally located was sold by Abner and Patsy Garrard on February 14, 1815, to William Morris and his wife. The purchase price was $140. Later records show that the Morrises sold the property on September 18, 1838, for $753. The difference in the purchase and selling prices was the largest in over 50 years and indicates that the house was built sometime during that 23-year period.

Since 1858 the property has had a number of owners, including an Elizabeth Morris, who bought it in 1856 and lived there for 30 years. Whether she was related to the builder of the house is not known. In 1896 the property was purchased by Mr. and Mrs. Hugh E. Brunk, who lived in the house until 1907.

Most houses built in the early 1800’s were made of logs and chinked with plaster made of lime and sand. This house was built of a good 2 quality white limestone, the reason probably being that stone was easier to obtain than logs in this particular location, because a stone quarry was located scarcely a quarter-mile away. The old quarry, near Sheehan Road, long since has been abandoned.

The stone walls of the house were about 18 inches thick and the inside surface of these walls was plastered. The whole interior of the downstairs rooms, except the floors, was whitewashed. The interior dimensions of the lower floor are 15 by 23 feet.

Floor joists, rafters, and shingle laths were all hand hewn from white oak. Examination of the floor joists disclosed that four of them had been split from the same log. All wooden trim and the door and window frames were of black walnut. In the period when this house was built, the use of this kind of wood was not at all uncommon even in barns.

The floor boards were about one and a quarter inches thick and were of beech and walnut. There is no ridge pole to support the roof, but the rafters are notched and put together with wooden pins. The split shingles were of oak. In the work of reconstruction, all of the stone used is the original stone except the floor, which formerly was of wood. The ceiling beams, attic flooring, rafters and most of the shingle laths are originals. The remaining woodwork which was in bad condition has been replaced but the original details of design and construction have been carefully reproduced.

The fireplace chimneys are a part of the end walls. This style of architecture shows the Moravian influence, the Moravians being a religious sect who came to Ohio mostly from North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Georgia.

Wooden partitions at one time divided the lower floor into three rooms: two tiny bedrooms and the living room. Because they made the rooms so small, these partitions were not included when the house was rebuilt.

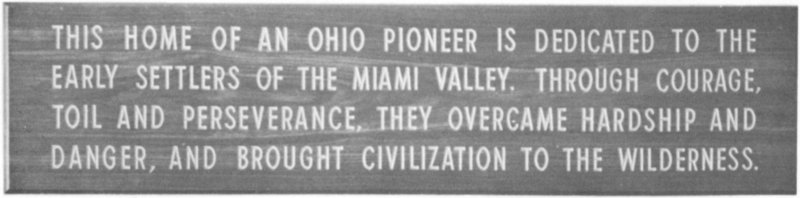

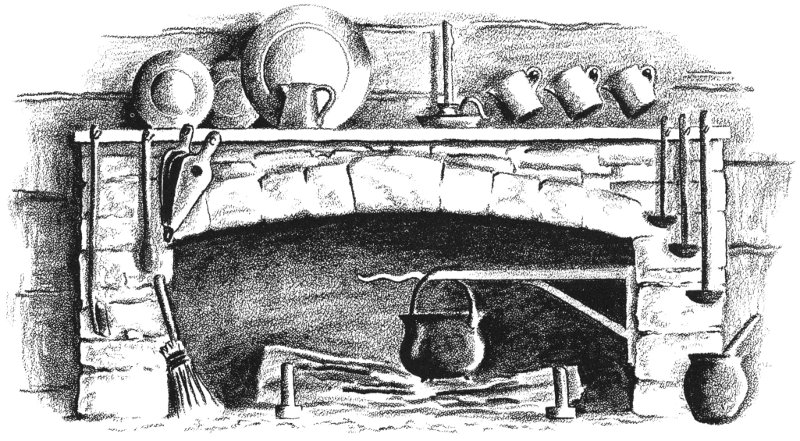

Each room had its own fireplace. The large one was used for cooking and for heating the combination kitchen and living room. The two smaller fireplaces were in the bedrooms. They were connected to a single chimney and have been omitted.

The large fireplace was the center of activity for the household. Every morning a large log would be brought in and placed on the embers left from the fire of the night before. This log would be big enough to last 3 the day, and smaller sticks and logs would be put in front of it. If no coals survived from the night before, the fire had to be lighted by sparks from flint and steel, which was always a tedious task, or coals might be borrowed from a neighbor. This was seldom necessary because most families took care not to let their fires go out.

Hinged to the side of the big fireplace was a crane with pot hooks or “trammels” on which cooking utensils were hung. Its deep pit provided storage for wood ashes so necessary to the pioneer for the making of lye used in making soap and hominy. Nearby was the inevitable bellows—known in those days as “belluses”—and the hearth brush.

Cooking over an open fireplace was difficult, but many housewives became very proficient at it, and meat cooked in this way had a flavor unexcelled by any mode of cooking today.

The big fireplace also had its disadvantages. With the first frost, flies were likely to swarm down through the chimney and into the room.

On one side of the fireplace was a built-in cupboard where cooking utensils and dishes were kept. The plates and bowls usually were made of wood or pewter, and the knives, forks and spoons of horn. Also in the cupboard might be found a bread basket, dough trough, candle-stick molds, a bootjack, and a box of sand used to polish the pewter ware.

On the other side of the fireplace was a steep staircase leading to the attic and typical of those found in small houses of the period.

Nearby, perhaps over the fireplace, were suspended a flint-lock musket and powder horn. Hanging from the ceiling of the room might be a warming pan, raccoon skins, fox pelts, slabs of bacon and venison, chains of sausages, and strings of dried apples and red peppers. And on a convenient shelf was the family Bible, the leather cover of which was used—without any disrespect intended—by the man of the house for stropping his straight-edge razor.

The attic of the house was floored with rough boards but was otherwise unfurnished. It had been used as a bedroom, and imagination can conjure the image of a small, wide-eyed boy lying on a pallet of rustling corn husks, listening to the wind rattle the shingles and dodging an occasional drop of rain which seeped through. Perhaps it wasn’t always 4 imagination when he heard the howl of wolves or the yell of a passing Indian. A portion of the attic floor has been cut away so visitors may see the original rafters and shingle strips.

Fireplace

About the time the Pioneer Home was built, carpenter work was relatively expensive. Dormer windows containing 12 panes of glass cost $12; door frames were 8c a linear foot and window frames 16c. Panel doors were priced at 75c per panel. This partially explains why the windows were few and small. Another reason, of course, was the difficulty of heating the house adequately in the winter. It was also very difficult to transport large panes of glass over rough roads from the East.

The house at one time had a partial basement with dirt floor, but it had no porches. At a later date a wooden lean-to was added at the rear but it has long since disappeared. This addition housed a bedroom and kitchen.

In the yard behind the house there was probably an outdoor fire pit with a large iron kettle suspended above it. This kettle was used for making soap, lard, and apple butter, and on wash days for boiling clothes. There was also a smokehouse and tobacco-drying and stripping shed.

Also just outside the back door was a rough wooden water bench on which were a wooden basin, a gourd dipper, and soap made of grease, ashes and sand.

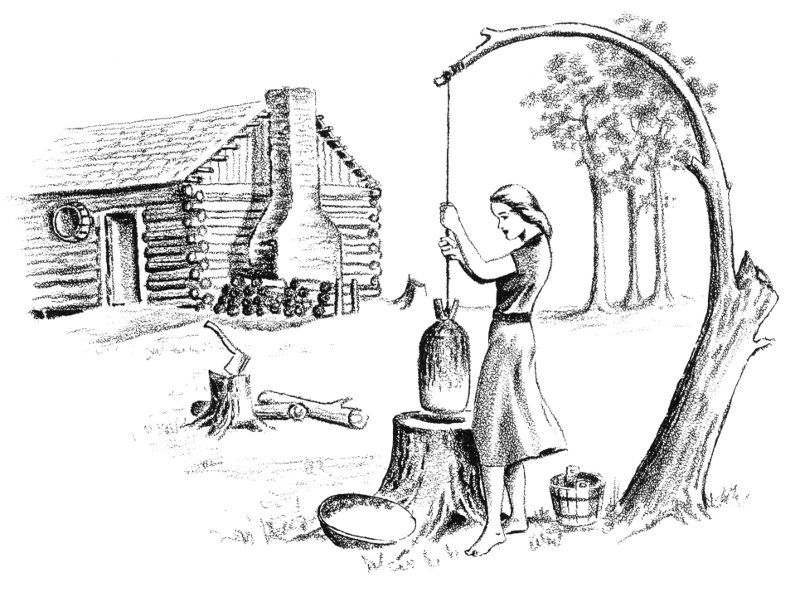

As was the practice in those days, the house was located on the bank of a small stream, a tributary of Hole’s Creek. Near this stream, a well was dug and a well-sweep erected for lowering the oaken bucket into the well.

This Pioneer Home was placed in Carillon Park to show the people 5 of this generation how their forefathers lived. The purpose of this book, too, is to describe the hardships overcome by the pioneers who braved the unknown wilderness to help carve the destiny that we, as Americans, enjoy today.

Of William Morris and his wife, little is known. But much is known of the era in which they lived.

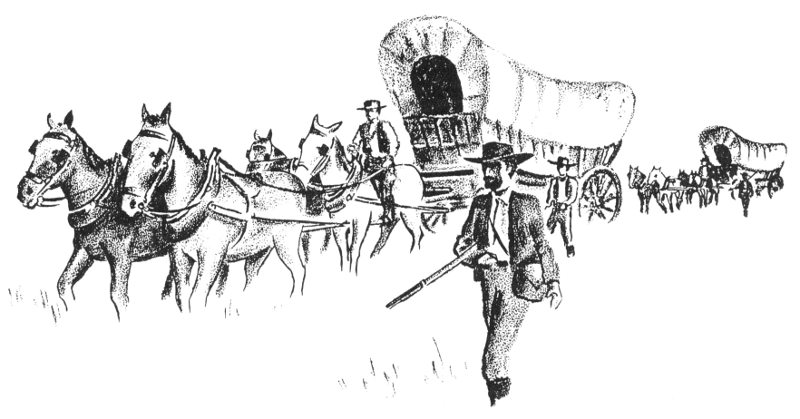

Most of the early pioneers who came to the Miami Valley trekked westward over the rough mountain trails to Pittsburgh and then sailed down the Ohio River. A few more hardy souls came overland all the way.

These settlers were attracted to the Valley by descriptions of this “fabulous” land where the earth needed “only to be tickled with the hoe to laugh with the harvest.”

The trip westward was both expensive and uncomfortable. Household goods and supplies were loaded in “road wagons” and the wife and children clambered on top of the load. The man of the family and the larger boys usually rode horses.

As many as six horses were used to pull the lumbering wagons over the steep mountain trails, and often it was necessary to stop during the ascent to rest the horses. At these times large rocks were placed behind the wheels to keep the wagons from rolling backward. The deep mud of the valleys was almost as difficult to overcome.

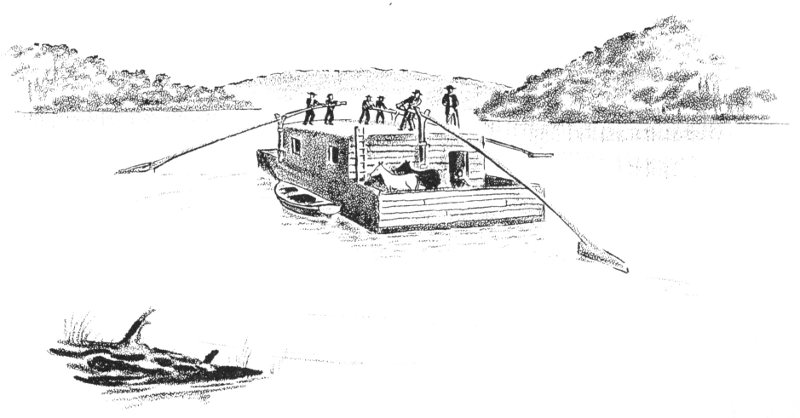

It was a relief indeed when the Alleghenies had been crossed and the family safely transferred to the “broad horn” river boat. The journey downstream was more serene, but was long and tiring. However, there was always something new to be seen around the next bend of the river and always stories to listen to ... stories of singing fish, of wild Indian raids, and of the fine town of Losantiville, the early name for Cincinnati. The entire journey from Pittsburgh to Cincinnati required about six weeks. The trip from Cincinnati to Dayton was usually made by wagon, although some boats were “poled” up the Miami River at a speed of about eight miles a day.

Essential to the pioneer of the early American frontier was a dependable rifle to provide food and protection for his family. This “Kentucky Rifle,” a muzzle loader which used percussion caps, was fashioned about 1830 by a Pennsylvania gunsmith for Jacob Deeds, great-grandfather of Colonel E. A. Deeds whose grandfather, Andrew Deeds, brought it to Ohio in 1850. This rifle is a later version of the flintlock rifle which made possible settlement of the dark, lonely and often dangerous forests that once covered most of Ohio. It now is mounted on the wall of the Pioneer Home.

It was in February, 1796, that the first surveying party came to what is now Washington Township—the township in which the old stone house was located. That was less than a year after Daniel Cooper came from Cincinnati and laid out the town of Dayton.

The surveying group was made up of Aaron Nutt, Benjamin Robbins, and Benjamin Archer. They pitched camp near what is now Centerville, but were quick to move a couple of miles northeast when they discovered signs of recent occupation of the site by Indians.

Although there were a few Indian raids in Montgomery County during its earliest years, most of the Indians were peaceful except when drunk. The major losses caused by them were through thievery of horses and other livestock.

The three surveyors drew cuts for choice of lands and then returned to Kentucky. The next spring Robbins returned with his wife and children. They built a log cabin on a half-section of land west of the site of Centerville. Nutt and Archer returned two years later.

One of the best-known early settlers was Dr. John Hole, who moved to the area from New Jersey in 1797. He located three and a half miles northwest of the site of Centerville on a stream which he named Silver Creek. Because of his prominence in the community, the stream became 7 known as Hole’s Creek, and so it is named today. Dr. Hole erected a log cabin with a clapboard roof and a “cat and clay chimney,” made of sticks and clay. He later put up two sawmills. Being the only doctor in that part of the Valley, Dr. Hole served patients ten and twelve miles away.

Washington Township was organized in 1803, the same year Ohio became a state and two years before Dayton was incorporated. It was named in honor of General George Washington, for many of the early settlers were formerly Revolutionary War soldiers. In the first election in that year the township—then considerably larger than it is now—cast 95 votes for governor.

The first church meeting in the area was held in 1799, but the first church building was not occupied until four years later. It was called the Sugar Creek Baptist Church. One of its early members and workers was Abner Garrard, owner of the land on which the stone house later was built. The first minister of the church was the Rev. Charles McDaniel, who sometimes rode 30 miles to preach at some remote settlement. He was paid only what his congregations desired to give him.

Because there were no traveled roads through the forests, trails leading to the church were blazed on trees extending as far as five miles.

There were three small settlements in the township in those early days: Centerville, near the center of the township; Woodburn to the northwest, and Stringtown to the southeast.

No one was very rich or very poor in those days, and everyone worked. Of all living creatures, wrote Benjamin Franklin, quoting an old Negro 8 saying, only the hog doesn’t work: “He eat, he drink, he walk about, he go to sleep when he please, he live like a gentleman.”

It was true. The hogs roamed the forests at will, fattening on nuts, but the horses and oxen and humans worked!

There was grain to be planted, but there were none except hand-wrought plows, made from jack-oak sticks shaped and sharpened as best they could be and more than often drawn by a team of slow-moving oxen broken to the yoke. A few years later this primitive plow was improved by being tipped with an iron point. The axe was often used to break the ground for planting, and seed was dropped in by hand. There were no barns, so the newly cut unthreshed grain was stacked in the fields. It was threshed with flails or tramped out under animals’ hooves. Corn was gathered, husked, and shelled by hand, and potatoes were dug with a sturdy pointed stick.

The tilled land was used as much as possible. It was not unusual for a flax patch to be sowed in March, harvested in June, and then planted with potatoes.

Life in the early 1800’s was not all work, however, and sometimes pleasure was combined with the chores that had to be done.

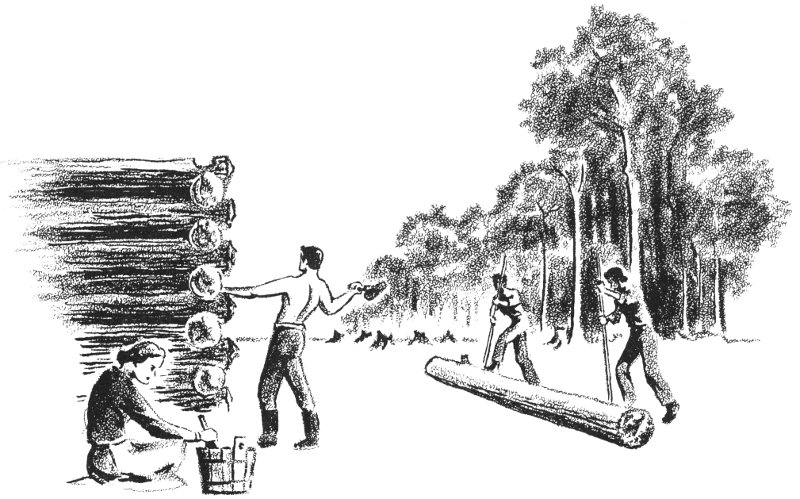

Erecting a cabin called for a log rolling or house raising party. The men of the community assembled and then divided into small groups: one group to fell the trees, another to drive the horses and drag the logs to the site, another to shape the logs, another to saddle and notch the corner logs and put them in place, and another to chink the cracks between the logs. Thus, a cabin usually was erected in a single day, and the work was accompanied by much merriment, usually ending with a party in the new house that night.

Husking bees also enabled the young people to combine work with pleasure. The work was accompanied by songs and stories, and occasional squeals of laughter when one of the boys husked a red ear of corn, for that entitled him to kiss the nearest girl. In the evening, supper was served and it was followed by a dance and perhaps an opportunity for couples to walk home by moonlight.

Bees or “frolics” also were held for reaping, sewing, quilting, flax-scutching, and many other occasions.

There also was the more enjoyable work of making cider or maple sugar, and the excitement of smoking a bee tree to obtain the honey inside.

Sleighing was a popular pastime in the winter. The young people bundled themselves in warm clothing, placed bags of hot sand at their feet, pulled bear skin robes over their knees and then set out with many a laugh and song. On a crisp, clear night the sleighbells and the singing could be heard from several miles distant.

The biggest social events of the day were the weddings. Often they occurred at noon, to be followed by an afternoon of merry-making, a big supper for the whole wedding party, and a dance in the evening. The most popular dances were jigs, four-handed reels, double shuffles, and scamper-downs.

The parents often helped their children start married life by giving them a cow, ewe, or sow, a saddle, spinning wheel, kitchen utensils, or a feather bed.

A bride with an embroidered muslin gown for the wedding was considered fortunate, indeed. Usually the women of the day wore clothing made of “linsey.” This was made of linen and wool, often in plaids and stripes. The men wore buckskin breeches, coonskin caps, and crude leather shoes, boots, or moccasins. In summer they sometimes went barefoot, except when they went into the forests. Men, women, boys and girls often wore a loose outer jacket called a “wamus.”

Much of the cloth for clothing was made from flax or wool grown by the settlers. Most of the housewives had spinning wheels, but only a few had looms, for they were expensive and skill was required to operate them. The weaving would be done for a fee by those who owned looms. Walnut hulls were crushed and used for dye. Buttons were often made of thread, and needles and pins were scarce and expensive.

The first store in Washington Township was established by Aaron Nutt, Sr., in what is now Centerville. He took a flatboat load of produce to Baltimore, sold it, and invested the money in a horse, a cart, and a load of drygoods, which he brought overland to Ohio.

Cash was scarce and much of the trading was on a barter basis. To buy items such as tea, coffee, leather, lead, powder, and iron, required either money or certain items which were considered of cash value—linen cloth, feathers, beeswax, and deerskins.

Here are some examples of prices charged in 1815: linsey $1 per yard; cambric $2.25 per yard; darning needles 6¼c each; lead pencils 31c; nutmegs 18c each; pewter dish $2.25; tea $2.50 per pound; 8-penny 11 nails 21c per pound; calico 87½c per yard; salt $13 per 100 pounds; flour $1.50 per barrel; wheat 25c per bushel; oats 10c per bushel.

Because of the high prices of coffee and tea, many housewives served “flour chocolate,” a beverage made from corn, wheat and rye, or tea made from spices, sassafras or sage. The housewife had to pulverize her own spices, powder the salt, roast and grind the coffee, and make her own yeast and soap.

Although some of the non-essentials were high in price, no one lacked for food. Nearly every household had at least one cow, some chickens, and some pigs. In 1810, records show that beef could be bought for 3c a pound and pork for 3½c. Chickens were worth 75c a dozen and potatoes 25c a bushel.

Wild turkeys, pheasants, rabbits, squirrels, ducks, geese, and deer abounded in the forests. There was plenty of corn for hoe cakes, hominy and mush; beans; blackberries; grapes; nuts; honey; and maple sap for sugar.

For breakfast the man of the house might find on his table ham, eggs, corn pone and fried potatoes, in addition to the standard dish, mush and milk. For a variation, or if meats were not handy, hominy and mush might be cooked in sweetened water with bear oil or grease from fried meat added. For supper he might have wild turkey, smoked sausage or venison, cheese, peaches or pears, and vegetables. Once a 12 week in most households the supper consisted of “pot luck,” made of meat and various vegetables, cooked together in one big pot.

In almost every house there was a store of cider, brandy, rum or whiskey, but the men seldom overindulged except at weddings and funerals. It was not uncommon at such affairs for an argument to ensue and end in a fist fight.

Schools followed the establishment of churches in the township. The school building was a log cabin with a fireplace at one end, and it often was erected in a single day. Desks were made of puncheons and seats of flattened saplings. The children usually wrote with pens made of goose quills, for pencils were too scarce and too expensive. Ink was made from maple bark and copperas.

The school curriculum was confined to the “three R’s”: reading, ’riting, and ’rithmetic, and no high standards were required of the teachers. More often than not, the teacher was selected because of his or her physical inability to do other work rather than an ability to teach. Each patron paid his proportionate share of the cost of operating the school, even to the point of boarding the teacher for a certain length of time. The unfortunate teacher, like the pauper, was looked upon as a person merely to be tolerated. All that was expected of the pupils was the ability to write legibly, to read the Bible or an almanac, and to compute the value of a load of produce.

Mail deliveries in the rural areas were unknown, but a post office was established in Dayton in 1804, and by 1810 mail was being brought from Cincinnati by horseback once a week.

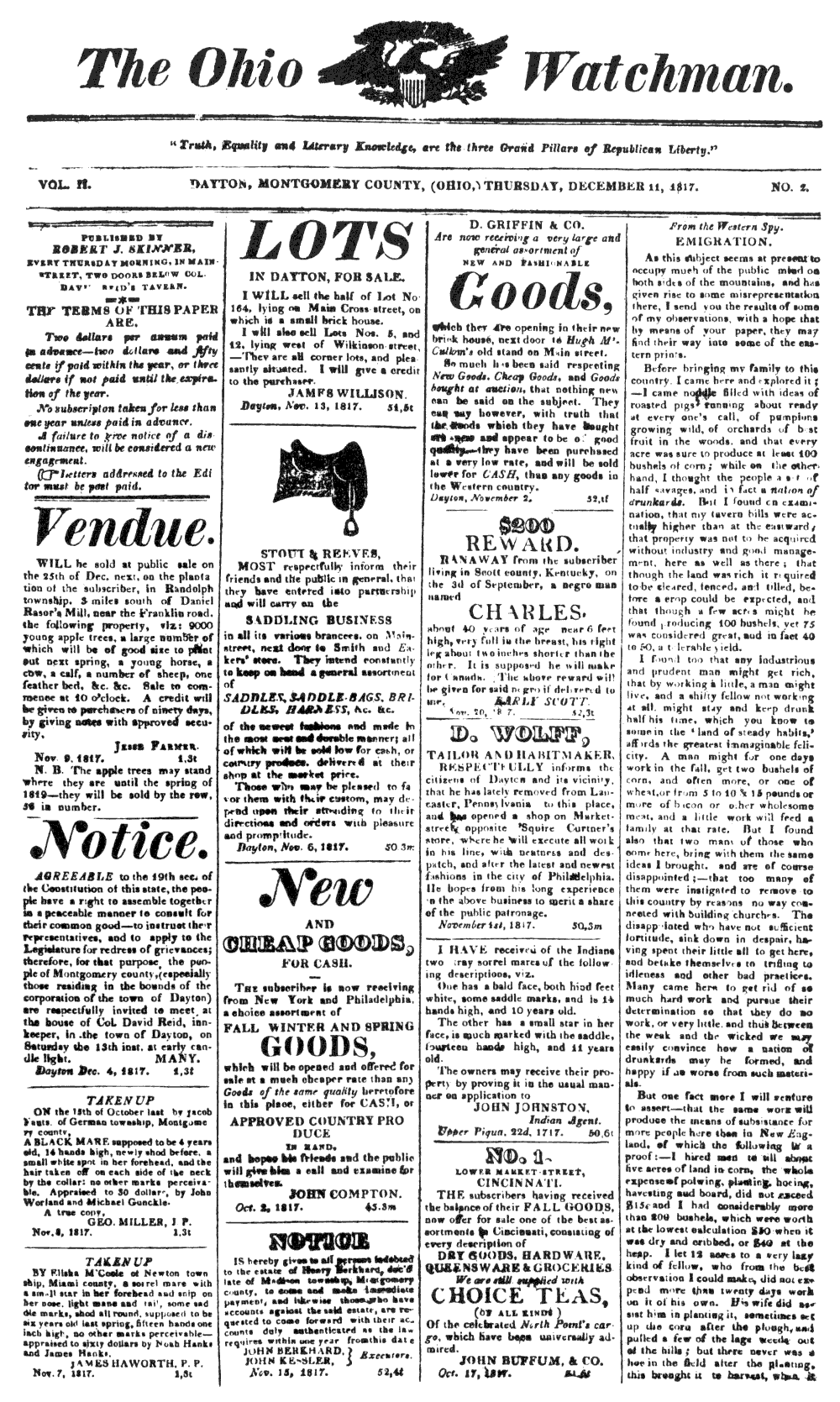

The township people seldom had an opportunity to see a newspaper, and it was a treat, indeed, when a copy of “The Ohio Watchman,” a 12- x 20-inch paper printed in Dayton, fell into their hands. Often the paper would be passed along from home to home many weeks after its date of printing.

In these crude surroundings our forefathers lived. They built their cabins amid mud, stumps, poison ivy, mosquitoes, rattlesnakes, wolves, and wildcats.

It was in this environment that babies were born and grew to healthy adulthood, although they entered this world without benefit of sanitary facilities and hospitals, and often even without the presence of a doctor or midwife.

To imagine that wilderness civilization—without telephones, electricity, bathrooms, furnaces, automobiles, trains, airplanes, radio, and television—is difficult. But it is even more difficult to comprehend that these improvements date back only a few short years to the lifetimes of our own grandparents.

But amid the physical changes, one thing has not changed: the spirit that conquered the wilderness. Thanks to that spirit, even greater advancements, no doubt, are ahead.

And through those years to come, the Pioneer Home in Carillon Park will remain as a symbol of hardships overcome, of progress through work, of the strength of character that has built our America.

“Truth, Equality and Literary Knowledge, are the three Grand Pillars of Republican Liberty.”

VOL. II. NO. 2.

DAYTON, MONTGOMERY COUNTY, (OHIO,) THURSDAY, DECEMBER 11, 1817.

PUBLISHED BY

ROBERT J. SKINNER,

EVERY THURSDAY MORNING, IN MAIN

STREET, TWO DOORS BELOW COL.

DAVID REID’S TAVERN.

THE TERMS OF THIS PAPER ARE.

Two dollars per annum paid in advance—two dollars and fifty cents if paid within the year, or three dollars if not paid until the expiration of the year.

No subscription taken for less than one year unless paid in advance.

A failure to give notice of a discontinuance, will be considered a new engagement.

☞Letters addressed to the Editor must be post paid.

Will be sold at public sale on the 25th of Dec. next on the plantation of the subscriber, in Randolph township, 3 miles south of Daniel Rasor’s Mill, near the Franklin road, the following property, viz: 9000 young apple trees, a large number of which will be of good size to plant out next spring, a young horse, a cow, a calf, a number of sheep, one feather bed, &c. &c. Sale to commence at 10 o’clock. A credit will be given to purchasers of ninety days, by giving notes with approved security.

Jesse Farmer. Nov. 9, 1817 1,3t

N. B. The apple trees may stand where they are until the spring of 1819—they will sold by the row, 56 in number.

AGREEABLE to the 19th sec. of the Constitution of this state, the people have a right to assemble together in a peaceable manner to consult for their common good—to instruct their representatives, and to apply to the Legislature for redress of grievances; therefore, for that purpose the people of Montgomery county, (especially those residing in the bounds of the corporation of the town of Dayton) are respectfully invited to meet at the house of Col. David Reid, innkeeper, in the town of Dayton, on Saturday the 13th inst. at early candle light.

MANY. Dayton Dec. 4, 1817. 1,3t

ON the 15th of October last by Jacob Yants of German township, Montgomery county.

A BLACK MARE supposed to be 4 years old, 14 hands high, newly shod before, a small white spot in her forehead, and the hair taken off on each side of the neck by the collar: no other marks perceivable. Appraised to 30 dollars by John Worland and Michael Gunckle.

A true copy,

GEO. MILLER, J P. Nov. 8, 1817. 1,3t

BY Elisha M’Coole of Newton township, Miami county, a sorrel mare with a small star in her forehead and snip on her nose, light mane and tail, some saddle marks, shod all round, supposed to be six years old last spring, fifteen hands one inch high, no other marks perceivable—appraised to sixty dollars by Noah Hanks and James Hanks.

JAMES HAWORTH, P. P. Nov. 7, 1817. 1,3t

I WILL sell the half of Lot No. 164, lying on Main Cross street, on which is a small brick house.

I will also sell Lots Nos. 5, and 12, lying west of Wilkinson street,—They are all corner lots, and pleasantly situated. I will give a credit to the purchaser.

JAMES WILLISON. Dayton, Nov. 13, 1817. 51,5t

MOST respectfully inform their friends and the public in general, that they have entered into partnership and will carry on the

SADDLING BUSINESS

in all its various branches, on Main-street, next door to Smith and Eaker’s store. They intend constantly to keep on hand a general assortment of

SADDLES, SADDLE-BAGS, BRIDLES, HARNESS, &c. &c.

of the newest fashions and made in the most neat and durable manner; all of which will be sold low for cash, or country produce, delivered at their shop at the market price.

Those who may be pleased to favor them with their custom, may depend upon their attending to their directions and orders with pleasure and promptitude.

Dayton, Nov. 6, 1817. 50,3m

The subscriber is now receiving from New York and Philadelphia, a choice assortment of

FALL WINTER AND SPRING

GOODS,

which will be opened and offered for sale at a much cheaper rate than any Goods of the same quality heretofore in this place, either for CASH, or

APPROVED COUNTRY PRODUCE IN HAND,

and hopes his friends and the public will give him a call and examine for themselves.

JOHN COMPTON. Oct. 2, 1817. 45,3m

IS hereby given to all persons indebted to the estate of Henry Berkhard, dec’d late of Madison township, Montgomery county, to come and make immediate payment, and likewise those who have accounts against the said estate, are required to come forward with their accounts duly authenticated as the law requires within one year from this date.

JOHN BERKHARD, JOHN KESSLER, Executors. Nov 15, 1817. 52,4t

Are now receiving a very large and general assortment of

NEW AND FASHIONABLE

Goods,

which they are opening in their new brick house, next door to Hugh M’Cullom’s old stand on Main street.

So much has been said respecting New Goods, Cheap Goods, and Goods bought at auction, that nothing new can be said on the subject. They can say however, with truth that the goods which they have bought are new and appear to be of good quality—they have been purchased at a very low rate, and will be sold lower for CASH, than any goods in the Western country.

Dayton, November 2. 52,tf

RANAWAY from the subscriber living in Scott county, Kentucky, on the 3d of September, a negro man named

CHARLES,

about 40 years of age, near 6 feet high, very full in the breast, his right leg about two inches shorter that the other. It is supposed he will make for Canada. The above reward will be given for said negro if delivered to me.

EARLY SCOTT Nov. 20, 1817. 52,3t

RESPECTFULLY informs the citizens of Dayton and its vicinity that he has lately removed from Lancaster, Pennsylvania to this place, and has opened a shop on Market-street, opposite Squire Curtner’s store, where he will execute all work in his line, with neatness and despatch, and after the latest and newest fashions in the city of Philadelphia. He hopes from his long experience in the above business to merit a share of the public patronage. November 1st, 1817. 50,3m

I HAVE received of the Indians two stray sorrel mares of the following descriptions, viz.

One has a bald face, both hind feet white, some saddle marks, and is 14 hands high, and 10 years old.

The other has a small star in her face, is much marked with the saddle, fourteen hands high, and 11 years old.

The owners may receive their property by proving it in the usual manner on application to

JOHN JOHNSTON, Indian Agent. Upper Piqua, 22d, 1817. 50,6t

THE subscribers having received the balance of their FALL GOODS, now offer for sale one of the best assortments in Cincinnati, consisting of every description of

DRY GOODS, HARDWARE, QUEENSWARE & GROCERIES.

We are still supplied with

CHOICE TEAS,

(OF ALL KINDS)

Of the celebrated North Point’s cargo, which have been universally admired.

JOHN BUFFUM, & CO. Oct. 17, 1817. 51,6t

As this subject seems at present to occupy much of the public mind on both sides of the mountains, and has given rise to some misrepresentation there, I send you the results of some of my observations, with a hope that by means of your paper, they may find their way into some of the eastern prints.

Before bringing my family to this country, I came here and explored it.—I came noddle filled with ideas of roasted pigs running about ready at every one’s call, of pumpions growing wild, of orchards of best fruit in the woods, and that every acre was sure to produce at least 100 bushels of corn; while on the other hand, I thought the people a of half savages, and in fact a nation of drunkards. But I found on examination, that my tavern bills were actually higher than at the eastward, that property was not to be acquired without industry and good management, here as well as there; that though the land was rich it required to be cleared, fenced, and tilled, before a crop could be expected, and that though a few acres might be found, producing 100 bushels, yet 75 was considered great, and in fact 40 to 50, a tolerable yield.

I found too that any industrious and prudent man might get rich, that by working a little, a man might live, and a shifty fellow not working at all, might stay and keep drunk half his time, which you know to some in the ‘land of steady habits,’ affords the greatest imaginable felicity. A man might for one days work in the fall, get two bushels of corn, and often more, or one of wheat, or from 5 to 10 & 15 pounds or more of bacon or other wholesome meat, and a little work will feed a family at that rate. But I found also that two many of those who come here, bring with them the same ideas I brought, and are of course disappointed;—that too many of them were instigated to remove to this country by reasons no way connected with building churches. The disappointed who have not sufficient fortitude, sink down in despair, having spent their little all to get here, and betake themselves to trifling in idleness and other bad practices. Many came here to get rid of so much hard work and pursue their determination so that they do no work, or very little and thus between the weak and the wicked we may easily convince how a nation of drunkards may be formed, and happy if no worse from such materials.

But one fact more I will venture to assert—that the same work will produce the means of subsistence for more people here then in New England, of which the following is a proof:—I hired men to till about five acres of land in corn, the whole expense of plowing, planting, hoeing, harvesting and board, did not exceed $15, and I had considerably more than 200 bushels, which were worth at the lowest calculations $50 when it was dry and cribbed, or $40 at the heap. I let 12 acres to a very lazy kind of fellow, who from the best observation I could make, did not expend more than twenty days work on it of this own. His wife did assist him in planting it, sometimes set up the corn after the plough, and pulled a few of the large weeds out of the hills; but there never was a hoe in the field after the planting. This brought in to harvest, which is....

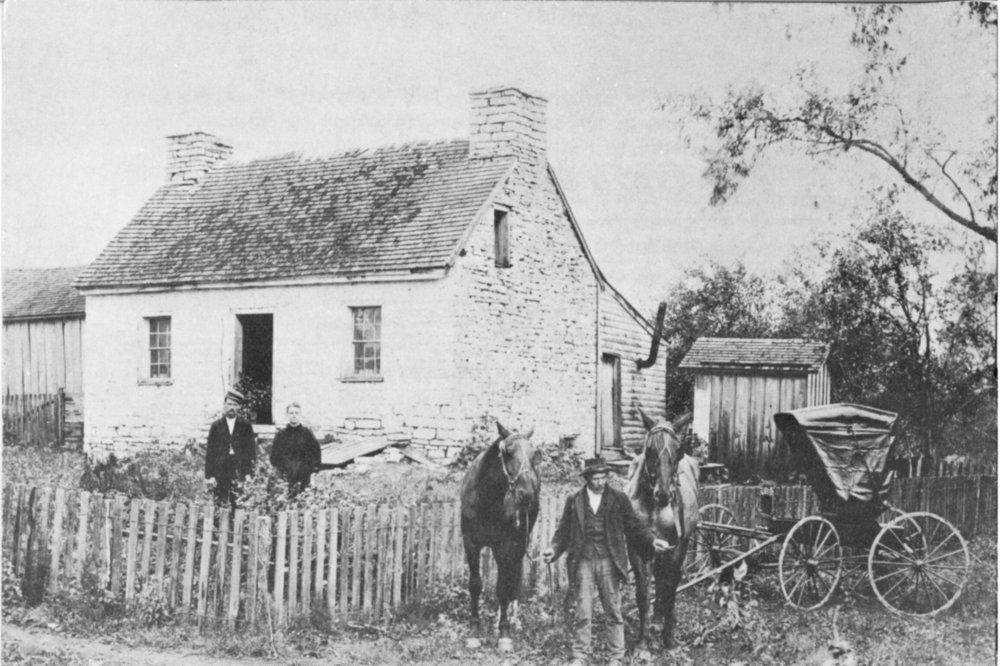

The Pioneer Home as it appeared in October, 1898. The couple shown in the yard are Mr. and Mrs. Hugh Elva Brunk and the man holding the team of horses is Andrew Beltz. This picture was borrowed from Mrs. Cora Brunk of Springboro, Ohio, who once lived in the stone house.

CARILLON PARK

DAYTON, OHIO

One of a series of Carillon Park booklets.

Price ten cents.

AS 107

H1WW

PRINTED IN U.S.A.