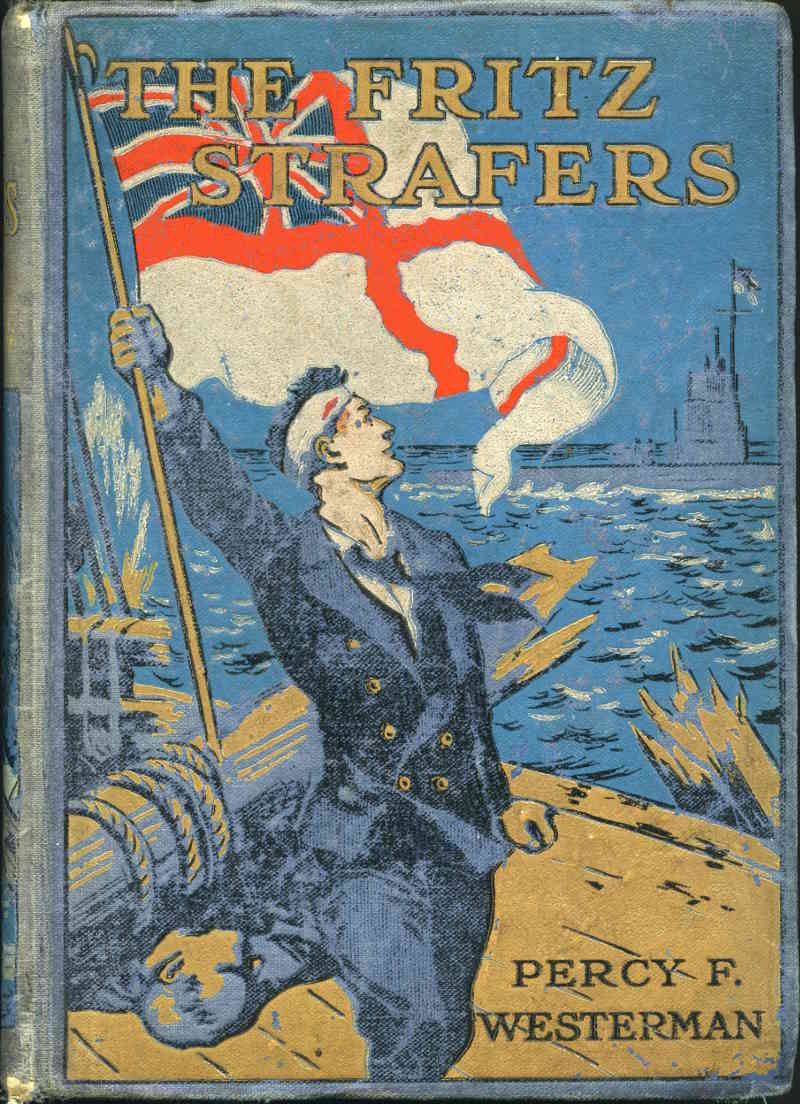

{Illustration: cover}

Title: The Fritz Strafers: A Story of the Great War

Author: Percy F. Westerman

Illustrator: Stanley L. Wood

Release date: May 5, 2021 [eBook #65262]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: R.G.P.M. van Giesen. Thank you, Pierre and Sasha!

| CHAPTER. | PAGE | |

| I. | "Coming Events..." | 13 |

| II. | The Danger Signal | 23 |

| III. | The Ober-Leutnant's Jaunt | 34 |

| IV. | Foiled | 45 |

| V. | The Pursuit | 54 |

| VI. | Von Loringhoven Learns News | 62 |

| VII. | Bruno's Escapade | 75 |

| VIII. | Torpedoed | 86 |

| IX. | The Skipper of the "Guiding Star" | 95 |

| X. | The Blimp to the Rescue | 106 |

| XI. | The Strafing of U 254 | 118 |

| XII. | Prisoners of War | 127 |

| XIII. | The End of the "Tantalus" | 135 |

| XIV. | A Chance Shot | 143 |

| XV. | Laid by the Heels | 158 |

| XVI. | The Struggle in the Lonely Cottage | 168 |

| XVII. | The Burning Munition Ship | 176 |

| XVIII. | The Fugitive | 189 |

| XIX. | Billy's Flying-Boat | 201 |

| XX. | Rammed | 210 |

| XXI. | The Last Voyage of s.s. "Andromeda" | 221 |

| XXII. | Farrar's First Bag | 233 |

| XXIII. | The Storm | 246 |

| XXIV. | The Sinking Transport | 254 |

| XXV. | Holcombe's Surprise | 262 |

| XXVI. | A Fight to a Finish | 276 |

| XXVII. | In The Hands of the Huns | 291 |

| XXVIII. | "A Second Kopenick Hoax" | 304 |

| XXIX. | A Surprise | 313 |

| XXX. | Comrades in a Strange Land | 326 |

| XXXI. | A Dash for Freedom | 337 |

| XXXII. | Touch and Go | 352 |

| XXXIII. | The Great Strafe | 366 |

| XXXIV. | And Last | 376 |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | |

|---|---|

| "Defiantly displayed the Emblem of Freedom" | Frontispiece |

| Facing page | |

| "A Couple of Bluejackets Burst through the Undergrowth" | 52 |

| "Seizing Farrar, began to haul him out of the Cottage, despite a Strenuous Resistance" | 172 |

| "'Good Heavens! It's Old Slogger!'" | 324 |

"QUITE right for once, Moke. Young brothers are unmitigated nuisances," declared Hugh Holcombe. "If I hadn't been such a silly owl to let my young brother try his luck with my motor-bike, I wouldn't be sitting here in this muggy carriage. Any sign of Slogger yet?"

The youth addressed as Moke thrust his bulky head and shoulders out of the open window and made a deliberate survey of the road that ran steadily down the hillside until it merged into the station yard of the little town of Lynbury.

It was a case of somewhat regrettable inadvertence when fifteen years previously Sylvester's parents had had him christened in the name of Anthony Alexander; for when, in due course, the lad entered Claverdon College the fellows, the moment they saw his initials painted boldly upon his trunk and tuck-box, dubbed him "Moke," and the name stuck like tar.

He did not resent it, which showed tact. In fact, he rather rejoiced in the nickname. It harmonised with his slow, plodding, deliberate ways. Imprimis, he was a swot; modern languages were his forte, although he was no mean classical scholar for his age. Anything of a mechanical nature failed to interest him. He knew a motor-bike when he saw one, but that was all. Ask him "how it worked"—a question to which his companion would reply by a fusillade of highly technical explanations—and he was "bowled middle stump."

Hugh Holcombe was cast in a different mould. Except in point of age there was little in common between the two lads. Holcombe was tall for his age, and possessed the appearance of a budding athlete. Although in mufti—he was spending the last week of the Christmas vacation with an uncle at Southsea before rejoining Osborne College—there was a certain self-assurance that the natural outcome of a training that inspires manliness, self-reliance, and courage from the first moment that an embryo Nelson sets foot in the cradle of the Royal Navy.

And the still absent Slogger——?

Slogger must wait until he enters this narrative. Sufficient to say that the three lads—as yet mere strands in the vast fabric of Empire—were to make their mark in the titanic struggle that was to convulse the whole world, each working in a different manner to one and the same just purpose.

It was in those halcyon, far-off days preceding the fateful 4th day of August 1914. To be more precise, it was January of the preceding year. Little did hundreds, nay thousands, of doting parents then imagine that on land and sea, in the air and in the waters under the earth, would their sons risk, and often give their young lives, for King, Country, and Freedom's Cause.

"Not the suspicion of a sign," replied Sylvester to his companion's inquiry. "He'll miss the train if he doesn't buck up. Here's the guard toddling along the platform."

"Hope that silly cuckoo of a Slogger won't miss it!" exclaimed Holcombe, resting his hands on the Moke's back and peering through the narrow space betwixt the latter's broad shoulders and the top of the carriage window. "He promised he'd bring an accumulator along with him, and I want to have some fun with the beastly thing during the next few days."

It was nearly eight o'clock in the morning. The sun was on the point of rising, while over the town the retreating shadow of night still contended with the grey dawn of another day. Passengers in twos and threes, most of them carrying luggage, were hurrying towards the station in the knowledge that the 8 a.m., although it was usually later in starting, sometimes did steam out at five minutes to the hour. Still no signs of Slogger.

"Dash it all, the train's starting!" exclaimed the Moke, as a cloud of white vapour drifted from under the carriages.

"Not much," corrected Holcombe. "It's only the steam from the heating apparatus. The guard isn't ready yet."

He indicated the venerable official on whom under Providence depended the safety and welfare of such of His Majesty's lieges who adventured themselves upon the Lynbury and Marshton Branch Line. Usually the guard would walk along the platform, exchanging scraps of conversation with his patrons, most of whom he knew by name, but on this occasion he was seated on a large wicker hamper and was studiously and laboriously writing in a note-book.

Curiosity was one of the Moke's failings, in that he was unable to restrain an outward display of a desire for knowledge. The mere fact that the guard was seated within four yards of the carriage-window and yet failed to exchange the usual pleasantries with the hefty youth wearing the Claverdon College cap rather puzzled him.

"Hullo, guard!"

At this greeting the official raised his eyes, looked at Sylvester for a brief instant and resumed his absorbing task. It was too much for the Moke's curiosity.

"Hullo, guard!" he repeated. "You look busy."

It was just what the guard was waiting for. Slowly and deliberately he rose and walked up to the carriage window.

"I am, young gentleman," he replied. "I'm looking up the names of those passengers who remembered me last Christmas."

Holcombe chuckled audibly. His companion, striving to hide his confusion, fumbled in his pocket.

"Sorry, guard——" he began.

"Quite all right, sir," interposed the guard, waving aside the proffered sixpence. "I take the will for the deed. When you come to Lynbury as a member of the Diplomatic Corpse (the guard knew Moke's ambitions, although his rendering of the title of that branch of the Civil Service was a trifle gruesome and wide of the mark), an' you, young gentleman (indicating Holcombe), as a full-blown captain, then perhaps, if I'm still here to see you, I'll drink your health in a bottle of Kentish-brewed ale—best in the world, bar none."

He pulled out and consulted a large silver watch.

"Time we're off, young gents," he announced, as the clanging of the station bell resounded along the now almost deserted platform.

"Slogger's missed it," declared Holcombe as the whistle blew.

With a jerk the little train started on its five-mile journey. Already the last carriage was half way down the platform when a loud shout of "Stand-back, sir!" attracted the two lads' attention.

The next instant the door was thrown open, and with an easy movement the missing Slogger swung himself into the compartment and waved a friendly salute to the baffled porter who had vainly attempted to detain him.

"By Jove, Slogger!" exclaimed Hoke, "you've cut it fine. Incurring penalties, too, under the company's bye-laws."

"P'r'aps," rejoined the unruffled arrival. "What's more to the point, I've caught the train—see? Oh, by the by, Holcombe, here's that blessed accumulator I promised you. 'Fraid I've spilt some of the acid, but that can't be helped. Had to shove it in my pocket when I sprinted."

Holcombe took the proffered gift and, reluctantly sacrificing an advertisement paper from a recently purchased motor-journal, carefully wiped off the residue of the spilt acid, while Slogger, perfunctorily turning the lining of his pocket inside out and shaking it against the sill of the window, dismissed from his mind the possibilities of the corrosive action on his clothes.

Nigel Farrar, otherwise Slogger, was a tall, broad-shouldered youth of sixteen. His nom-de-guerre was singularly appropriate, as indeed most nicknames bestowed by one's chums in a public school usually are. He won it on the cricket field; upheld it in every sport and game in which he took part. His remark to the Moke was characteristic of his thoroughly practical manner. To attain a desired end he would, even at his present age, "force his way through a hedge of hide-bound regulations." It was on this account, and to a certain extent because he did not shine at studious work, that he did not wear a prefect's badge on his cap, although by far and away the most athletic youth at Claverdon.

Farrar and Holcombe were similar in more than one respect. Both were physically and morally strong; both were deeply interested in things mechanical and practical. They were typical examples of the modern boy. Even at an early age fairy tales would have "bored them stiff." Show them an exact model of an intricate piece of machinery they would probably pronounce it to be ripping, and almost in the same breath put forth sound theories as to how the mechanism actuated. But Farrar was rather inclined to be what is popularly described as "slap-dash." With him everything had to be done in a violent hurry, while Holcombe was slow and precise in his movements, although far in advance of the painstaking Moke, who stood an excellent chance of passing the "Civil Service Higher" provided he could speed up sufficiently to get his examination questions answered within the specified time limit.

As the train rattled and jolted on its journey the three travellers fell to discussing the still remote summer holidays.

"I'm off to Germany," announced the Moke. "The governor takes me every year, you know."

"You'll be nabbed one of these fine days, my festive, and clapped into a German prison," declared the naval cadet with the air of a man who enjoys the confidence of High Officialdom and is actually in the know.

"What for?" inquired Sylvester. "I don't run up against regulations every time I get the chance, either here or abroad," he added. "I'm not like Slogger, you know."

"Thanks for small mercies," rejoined Farrar. "As a matter of fact, Holcombe, my governor talks of taking the yacht to the Baltic. How about it? Like to come along too. Spiffing rag we can have."

"Thanks, no," replied Holcombe ungraciously. "When war with Germany breaks out I want to have a look in. It's on the cards that the Dartmouth cadets will be embarked for duty with the fleet if there's a scrap, and by that time I hope I'll have passed through Osborne."

"There'll be no war with Germany," declared the Moke with a firm conviction based upon his father's views upon the subject. "Germany is our very best friend at the present day."

"A good many fools think that," said Holcombe bluntly. "Those are the fellows who would barter our naval supremacy for the sake of a paltry six or eight millions a year."

"You talk as if you were a millionaire yourself," remarked Sylvester, with thinly veiled sarcasm. "Of course the navy's your firm that is to be. You're only a cadet yet, Holcombe, an' don't you forget it. What's the use of an expensive navy when disputes can be settled by arbitration?"

"Arbitration!" snorted Slogger. "What's the use of arbitration? It's all right for little nations when the big ones are on the spot to keep order. I guess Holcombe's right. There'll be a most unholy scrap some day between England and Germany, and we'll all have to chip in—every man-jack of us."

"Think so?" inquired Holcombe with professional jealousy. "The navy'll manage the business properly, and you civilian chaps can stop at home and thank your lucky stars there is a navy."

"Of course we'll return grateful thanks," agreed Farrar; "but all the same, the navy won't be able to see the business through without the assistance of the Naval Reserve and all that jolly crowd, you know. So it's just possible, my dear Holcombe, that you and I may be in the same scrap. Before that comes off I want to work in that trip to the Baltic this summer, so don't induce the Government to declare war just at present, will you, old sport?"

Half seriously, half in jest, the trio continued the discussion, unconscious of the fact that the subject was the shadow cast by coming events.

A LONG and crowded train stood in Poldene Station prior to setting out upon the last stages of its journey from London to the Trecurnow Naval Base.

It was late in the autumn of 1917, and well into the fourth year of the titanic struggle that will go down to posterity as The Great War.

Save for a few aged male porters, half a dozen women of a type evolved by war-time conditions ("porteresses," a commander called them when hailing for some one to shift his gear from a taxi to the luggage-van), and a few keenly interested Devonshire children, the platform was devoid of the civilian element; but from one end to the other of the cambered expanse of asphalt pavement the down platform was teeming with officers and bluejackets, all only too glad to have the opportunity of stretching their stiff limbs after long and tedious hours of confinement in the train. Men whose moustaches were enough to proclaim them as members of the R.N.R. mingled with the clean-shaven or beardless stalwarts of the pukka navy, while others in salt-stained blue jerseys and sea-boots, hardy fishermen in pre-war days, were now about to fish for deadly catches—drifting mines.

Outside the open door of a carriage, almost at the end of the train, stood two officers. One was a medium-size, dark-featured man whose rank, as denoted by the strip of purple between the gold rings on his cuffs, was that of engineer-lieutenant. The other, a tall, powerfully-built youth—for he was not yet out of his teens—sported the uniform of a sub-lieutenant of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve.

"It's a great wheeze—absolutely," declared the engineer-lieutenant, who was explaining a technical matter in detail to his deeply interested companion. "The double-cam action to the interrupted thread is some scheme, what? You follow me?"

"It certainly ought to put the wind up Fritz," admitted the sub. "But there's one point that I haven't yet got the hang of. The sighting arrangements may be all very well, but how about refraction?"

"We make due allowance, my festive," replied the engineer-lieutenant. "You see—hullo, you're not smoking!"

"Quite correct," agreed the junior officer. "Quite correct, Tommy. Matter of fact, like a blamed idiot I left my pouch in the smoking-room and never found it out until I arrived at the station. Too late to buy any off the stalls, you know."

"Cigarette?" The engineer-lieutenant's silver cigarette-case was proffered with the utmost alacrity. "You don't smoke 'em as a rule, I know, but in the harrowing circumstances——"

"Thanks," exclaimed his companion. Then deftly tearing the paper he roiled the liberated weed between the palms of his hands and filled his pipe.

"Rather unorthodox, what?" queried the engineer-lieutenant, smiling at the sight of a fellow ramming choice Egyptian cigarette tobacco into a briar.

"Possibly," admitted the other. "The main thing is that I've filled my pipe."

He struck a match, effectually shielding the light by his hands after the manner of men accustomed to do so in the teeth of a gale. "Now to return to earth once more."

"Slogger, by all that's wonderful!" exclaimed a crisp, full-toned voice. "What is dear old Slogger doing down in this part of the country?"

"Cadging tobacco," replied the R.N.V.R. man. "Also looking after the welfare and morals of a party of bluejackets. Bless my soul, Holcombe, this is great. Let me see—three years, isn't it, since we knocked up against each other?"

"Three years and two months," admitted Sub-Lieutenant Holcombe. "I saw your appointment announced and meant to write to you. Somehow I didn't. Why? Ask me another. I can't tell you. What's your ship?"

"The 'Tantalus,'" replied Farrar. "We're just off on convoy duties to the West Indies. Oh, by the way, let me introduce you to Tommy."

"Too late, old bird," exclaimed Holcombe, shaking hands with the engineer-lieutenant. "Tommy was in his last term at Osborne when I joined. D'ye remember that topping rag we had at Cowes, Tommy? Of course you do. An' I hear you dropped in for a chunk of kudos in the Jutland scrap?"

"Oh, dry up, do!" protested the modest hero. "What's your packet?"

"The 'Antipas,'" replied Holcombe. "Just commissioning."

"New destroyer, isn't she?" inquired Farrar.

"Yes; the old boat of that name piled herself on the rocks on the East Coast. We've got a topping skipper—Tressidar's his name. We're off Fritz-hunting in the Irish Sea, I hear. Not quite so exciting as the North Sea, perhaps, but I've had enough of the Auldhaig Flotilla Patrol for the present, thank you. Hullo, who's the Brass Hat?"

He indicated a tall, florid-featured Staff Officer in the uniform of a major who was striding between the press of bluejackets in the direction of the rear portion of the train. By his side walked a huge St. Bernard dog, muzzled and held by a massive steel chain.

"Hanged if I know," replied Farrar. "I didn't see him at Paddington, but that's not saying much. Suppose he's giving an eye to those Tommies in the fore-part of this packet. Fine dog, anyhow."

Orders were shouted along the platform. Rapidly the navy folk boarded the train until the major stood almost alone in the resplendent glory of his immaculate uniform.

"Guard!" he exclaimed peremptorily. "I want to accompany this brute in your compartment. He doesn't like a crowd, but he's quite safe when I'm with him."

"Very good, sir," replied the guard, touching his cap. "We're just off, sir."

"Wonder who the Brass Hat is?" reiterated Holcombe. "Did you notice that he didn't seem at all keen on salute-hunting? Kept well this end of the platform, and didn't have a pal to speak to. Well, if he is a hermit, he'll have solitude and repose in the luggage van. Dashed fine dog," he added in endorsement of his chum's declaration. "Advantage of having a Service chap for a master: no jolly worry about feeding the brute."

For some minutes silence reigned. The officers in the compartment were studiously watching the unsurpassable Devon scenery as the train swept through the coombes of the shire of the Sea Kings.

"Wonder when we'll see this sight again?" remarked Farrar. "Dash it all, I love the sea as a brother, but I'm jolly glad to get a sniff of the land after days and weeks of steady steaming. That's where you destroyer fellows score: a week or ten days is your limit."

Holcombe smiled.

"Think yourself jolly lucky, my festive volunteer," he rejoined. "You've generally dry decks, plenty of room to move about, and enough variety of companionship to save you from quarrelling with your messmates through sheer boredom. Try a destroyer for a change, and then see if you are of the same opinion. By the by," he added, "heard anything of the Moke?"

"Sylvester? Rather!" replied Farrar. "He's a prisoner in Hunland. Collared at Mayence when war broke out. Last I heard of him was that he was at Ruhleben."

"Poor bounder!" muttered Holcombe. "Was his governor collared too?"

"No; the Moke appears to have done rather a smart thing," answered Farrar. "He had a pal with him, it appeared, and the pal was taken queer and had to go to hospital. Sylvester had good reasons for supposing there was trouble ahead on the political horizon, so he bundled his parent down to Basle and made him promise to stop there until he heard from him. Meanwhile the Moke goes back to Mayence and stands by his chum, knowing that there was a thousand chances to one that he would be detained—and he was."

"Sort of Pythias and Damon, eh?" remarked the engineer-lieutenant.

"Sporty of him," added Holcombe. "Hullo, this looks a bit rotten. We're running into a fog."

The train was nearing a lofty double-spanned bridge across a wide river. The hitherto double track had merged into a single one, as the railway swept through a deep cutting on to the embankment that formed the approach to the main structure. Patches of mist were drifting slowly down the river, and although it was possible to see from shore to shore, the low-lying valley was blotted out by the rolling billows of vapour.

A great-coated sentry pacing resolutely up and down was a silent testimony to the importance of the bridge, and to the vigilance of the authorities, while a little way from the embankment could be seen a "blockhouse" outside of which other members of the guard were "standing easy."

Half way across the bridge the train pulled up. Immediately windows were opened and the long line of carriage windows were blocked with the faces of the curious bluejackets, the men taking advantage of the stop to engage in a cross-fire of chaff with the occupants of the adjoining carriages.

Ten minutes passed, but the train gave no sign of moving. Once or twice the driver blew an impatient blast, but the distant signal stood resolutely at danger.

"Nice old biff if the train did happen to jump the rails just here," remarked the engineer-lieutenant.

"Shut up, Tommy!" exclaimed Farrar. "You're making Holcombe jumpy."

"Stow it, Slogger!" protested the sub of the 'Antipas.' "I'm only going to have a look out. Here, I say; cast your eye this way."

"Periscope on the port bow, eh?" inquired Tommy facetiously, as the two men made their way to the window. "Gangway there, Holcombe. You ask us to admire something, and at the same time you block the view with your hulking carcase. I say, something fishy—what?"

Lying on the permanent way, almost abreast the front part of the guard's van, was a small leather suit-case, to the handle of which was attached a thin cord. Evidently some one had an object in wanting to dispose of the case, for an endeavour had apparently been made to swing it under the carriage; but, the cord breaking, the attempt had been frustrated.

"Jolly queer," agreed Farrar. "If any one wanted to get rid of the thing why didn't he heave it over the bridge? Here's the guard. We'll call his attention to it.... Suppose it's all right?"

The guard came hurrying along the permanent way. He had been conferring with the engine-driver as to the probable reason for the delay and had come to the decision to allow the train to proceed at a slow pace as far as the next station—a distance of about a quarter of a mile beyond the bridge—since it was impossible for a train coming in the opposite direction to enter the "block sector" at which the signal was at danger.

"Don't know how it came there, sir," declared the guard, when the derelict bag was brought to his notice. "It certainly wasn't there when I went by five minutes ago. Sure it's not your property, gentlemen?"

He spoke after the manner of a long-suffering official who ofttimes has been the victim of a practical joke on the part of facetious passengers.

"Not ours," replied Farrar. "Perhaps the driver's dropped his war-bonus?"

"Most-like the Army gent with the dog has got rid of some surplus rations, sir," countered the guard.

"Quite possible," agreed the engineer "luff" with a grin. "You ask him."

The guard clambered on the footboard and swung himself through the open doorway of the van. In five seconds he was back again.

"He's not there, sir," he reported, "and the dog neither. You didn't by any chance see him go along the permanent way?"

The three officers descended. Owing to the fact that the train was standing in a curve only two carriages were visible from where they stood. From the nearmost one an engineer-commander and a gunnery lieutenant were watching the proceedings with bored interest.

"Going to give the train a friendly leg-up, Tommy?" inquired the engineer-commander.

"We've found some one's kit, sir," replied the young officer, picking up the case and fumbling with the lock.

"Hold on!" exclaimed Holcombe warningly. "This isn't quite all jonnick to my fancy."

"What are you fellows doing?" asked the "gunnery-jack." "Shove the stuff in the scran-bag and don't keep the train waiting all day."

Holcombe took the bag from the engineer sub's hands and made his way to the carriage occupied by the last speaker.

"What do you make of this, sir?" he inquired. "We fancy it belonged to a Staff Officer—the one with a St. Bernard, you may remember—and he's left the train since we've been here."

The lieutenant examined the exterior of the derelict with rapidly increasing interest.

"Hang it all!" he exclaimed; "I'll take all responsibility. Here goes."

And with a powerful heave he hurled the bag over the edge of the bridge.

Seven seconds later a terrific crash rent the air. The pungent fumes of acrid-smelling smoke eddied between the lattice-work girders.

"Thought as much," remarked the lieutenant with a cheerful grin on his bronzed features. "Yankee troop train due about now, eh? Only waiting until we were clear of the bridge? Lucky for us we are over the centre of the span, or that stuff might have given the piers a nasty jar. Staff Officer, you said?"

"Yes, sir," replied Holcombe.

"Beat up a dozen hands," continued the lieutenant briskly. "I'll bear the brunt if they are left behind. We'll see if we can run this mysterious Brass Hat to earth. I say, Curtis," he added, turning to the engineer-commander, "he's had at least five minutes' start. Bet you a box of De Reszke's we catch the chap within an hour."

"Done," replied the other.

MIDNIGHT, somewhere off the North Cornish coast. To be more accurate, the position was, according to observations made by Ober-leutnant Otto von Loringhoven commanding H.I.M. unterseeboot 254, was Hatstone Point south-south-east 1/4 east, and Polgereen Point south by west 1/4 west. The rugged coast was all but hidden in the low-lying mist, only the loftier headlands being visible against the starlit sky. There was little or no wind, but shorewards a continual rumble betokened the presence of ground-swell—the "fag-end" of enormous waves generated hundreds of miles away in the vast Atlantic.

U 254 was proceeding dead slow towards the shore. The steady beat of her muffled exhausts was only just audible above the lap of the water against her blunt bows and the ripple in the wake of her triple propellers.

The ober-leutnant was standing on a raised platform that surrounded the elongated conning-tower. He was a tall, heavily built man—massive-looking in his long double-breasted coat and sea-boots. On his head he wore a black sou'-wester that, with the turned-up collar of his greatcoat and the dark muffler round his neck, left only a small portion of his face exposed: pale pasty features, shaggy beetling brows, small beady eyes, a large nose, flattened at the tip, and a loose mouth partly hidden by a closely trimmed moustache.

Close behind him stood the unter-leutnant, Hans Kuhlberg, a typical, loose-limbed, weak-chinned Prussian. No further description of this young swashbuckler is necessary. A British schoolboy was once asked by an examiner to describe the manners and customs of a certain savage tribe of Central Africa. His reply, "Manners none; customs beastly," would be equally applicable to Hans Kuhlberg.

A quartermaster at the steering-wheel on deck and a couple of hands using the lead-line were the only members of the piratical Hun crew visible; the others, eighty worthy upholders of the debased cult of German sea-power, were stowed away within the three hundred feet of steel hull.

"Report when you find fifty metres," ordered von Loringhoven for the twentieth time, addressing the leadsmen in harsh yet restrained tones, for acting under instructions they refrained from announcing the "cast" lest the sound of their voices would carry to the ears of an alert British patrol-boat's crew.

"Are you really going ashore, Herr Kapitan?" asked the unter-leutnant, who was vigorously engaged in chewing an apple—part of the spoils from a captured topsail schooner that had been sunk off Lundy a couple of days previously.

"I said so, Hans," replied von Loringhoven, "and I mean to go. Himmel! A little less noise with your throat. One would think you were drinking soup."

"Sorry, Herr Kapitan," exclaimed Hans Kuhlberg humbly. "It is a juicy—and I forgot."

U 254 was having a "day off." It was not her fault but her misfortune. Eighteen hours earlier she had approached a possible victim—a large cargo boat lying at anchor off Cardiff. Von Loringhoven was quite under the impression that the outlines of a destroyer showing up against her side was mere camouflage; but when the shadow became substance in the form of a very aggressive unit of the British Navy, U 254 was only too glad to dive. Even then it was a very narrow shave, for a four-inch shell whistled within a few inches of the periscopes. For the time being von Loringhoven prudently decided to keep away from the recognised trade routes and find a less unhealthy spot in order to charge batteries. Closing with the Cornish coast the ober-leutnant took it into his head to have a jaunt ashore on English soil.

"Fifty metres, Herr Kapitan, and a sandy bottom," reported the leadsman.

"Good!" ejaculated von Loringhoven. "See that the collapsible boat is launched, Kuhlberg. I am leaving you in charge. Keep awash, unless you sight anything of a suspicious nature, until dawn. Then rest on the bottom. At one o'clock—twenty-five hours from now—send a boat for me. Is there anything you want me to bring back?"

"Tobacco and cigarettes, Herr Kapitan," replied the unter-leutnant. "These English are swine, but they manage to get excellent tobacco. I was in hopes that when we sent that Dutch vessel to the bottom we might find good tobacco, but, ach! the stuff we found was intolerable."

His superior officer laughed.

"There is a box of cigars in my cabin," he remarked. "Mind they don't turn your head. I go and change in order to meet Englishmen as one of themselves."

Von Loringhoven disappeared below, to return in a quarter of an hour's time dressed in civilian clothes.

"Is it wise, Herr Kapitan?" asked Kuhlberg. "Your get-up is superb; yet, if you should be detected, you will be shot as a spy."

"I doubt it," rejoined the ober-leutnant. "These English are not thorough like us. They would hesitate before condemning to death a German naval officer; rather they would make much of him. An account of his adventures would appear in the British newspapers.... Nevertheless, don't think, Kuhlberg, that I want to desert you indefinitely. It is only for a few hours. Boat ready?" he inquired, dropping his bantering tone.

With muffled oars the boat approached the shore, von Loringhoven handling the yoke-lines with the air of a man who is well acquainted with his surroundings. Less than four years previously he had spent a month in North Cornwall, ostensibly to indulge in "surf-bathing." There was hardly a cove betwixt Hartland Point and St. Ives that he had not explored, aiding his trained memory by means of photographic and business-like sketches.

"Lay on your oars!" ordered the ober-leutnant, as the boat glided under the overhanging cliffs of a bold headland.

Von Loringhoven produced a powerful pair of Zeiss binoculars from his coat pocket, and focussed them upon a ledge of rocks that formed a breakwater, partly natural, partly artificial, to a tidal harbour.

"H'm," he muttered. "I thought so. They have patrols out. No matter, I must take the Fisherman's Stairs. Give way gently, men."

Protected by an outlying ledge the cove for which the boat was making was uninfluenced by the sullen ground swell. Noiselessly and unseen von Loringhoven stepped ashore, gave a few whispered instructions to the coxswain, and sent the boat back to the lurking submarine.

The ober-leutnant waited until the faint plash of the oars failed to reach his ears, then treading softly he made his way over the rough slippery causeway along the base of the cliffs. At intervals he stopped to listen intently, but only the low rumble of the surf and the occasional call of a belated sea-bird broke the silence.

It required a considerable amount of nerve to ascend or descend Fishermen's Stairs, even in broad daylight. The darkness, doubtless, modified much of the forbidding appearance of the precipitous way, but on the other hand it seemed to hide many of the otherwise visible dangers.

Von Loringhoven counted the steps as he climbed. He knew the exact number, unless, since his last visit, a landslide had altered the natural features of the place. Once he muttered a curse as his feet slipped, yet, hardly deigning to make use of the rusty iron chain that served as a rough handrail, he gained the summit of the cliffs.

Perfectly aware of the regulations that no unauthorised person must use the cliff-path between sunset and sunrise, the ober-leutnant proceeded cautiously until he gained a narrow lane leading towards the little town. Here, throwing off his secretive manner, he started off at a brisk walk until he reached a row of semi-detached villas on fairly lofty ground overlooking the harbour.

Noisily opening the gate of one of the houses von Loringhoven strode up the path with deliberate footsteps. A timorous step would, he argued with himself, give rise to suspicion. At the front door he knocked loudly and waited.

Although the heavy dark curtains over the upstairs windows allowed no strong beam of light to penetrate von Loringhoven knew by the metallic click of a switch that the electric light had just been put on. Then came the shuffling noise of slippered feet descending the stairs and the unbolting of the door.

"Hullo, Tom!" exclaimed von Loringhoven, as the door was thrown open, revealing in the faint starlight the tall, burly figure of a man in a long dressing jacket.

"Hullo, James!" was the equally boisterous reply. "You're late. Missed the last train, eh? Come in."

These histrionic greetings completed, the occupier closed the door and switched on the light, and the ober-leutnant was ushered into a well-furnished room opening out of the hall.

"You risked it, then," remarked the ober-leutnant's companion, speaking in German. "I am not surprised, von Loringhoven. Karl told me.... Business brisk?"

Ernst von Gobendorff, German by birth and upbringing, but, unfortunately, Anglo-Saxon in appearance, was one of the vast Hun espionage organisation now admitted by the most sceptical to flourish on British soil. With Teutonic thoroughness, and hitherto without the crass blundering that has oft-times wrecked the deep-laid plans of kultur, von Gobendorff had gained a high position in the ranks of the Kaiser's emissaries in hostile lands. He, like many others, was paid by results, although he drew a small fixed salary from his Hunnish paymasters. For the last eighteen months Cornwall had been the scene of his labours, most of his work consisting of transmitting information of the movements of shipping to the U-boat commanders operating off the coast. He looked English; he spoke English with a faultless Midland accent; he had an English registration card, which, though easy to obtain, is generally sufficient to satisfy the curiosity of the average county policeman. Under the assumed name of Thomas Middlecrease, and posing as a commercial traveller to a London house, he "worked" the length and breadth of the Delectable Duchy with a zeal that was the envy and admiration of genuine Knights of the Road.

Von Gobendorff was not merely a spy: he was a desperado, whenever opportunity occurred, under the distinguished patronage of the German High Command. His system of communicating with Berlin was so skilfully manipulated that unless all telegraphic and mail dispatches between Great Britain and neutral countries were suspended, he could rely upon his reports reaching the Admiralty-strasse within forty-eight hours.

"Business," replied von Loringhoven, leaning back in a lounge chair and thrusting his feet close to an electric radiator—"business is as usual. And yours?"

"Rather slack of late," admitted von Gobendorff. "However, I am expecting a coup. How is your brother, the Zeppelin commander?"

The ober-leutnant shrugged his shoulders.

"Julius burnt his fingers when he kidnapped von Eitelwurmer by mistake," he replied. "You may hear of him again, as I believe there is to be another intensity on the part of our aerial cruisers. By the by, how is von Eitelwurmer?"

"Ask me another question, Otto," replied the spy. "All I know is that he's dead; an accident, according to a North Country paper. I did not think it prudent to make further inquiries."

"At any rate," remarked von Loringhoven, "he did something to the honour and glory of the Fatherland. But what is this coup to which you referred?"

"I hear on excellent authority that a train load of American troops—curse them!—leaves Trecurnow to-morrow; or rather, I should say, to-day," said von Gobendorff, glancing at the clock.

The ober-leutnant nodded thoughtfully.

"Fairly safe?" he queried. "Well, I'll ask no more questions on that subject. You must be tired, and to do one's work properly rest is essential. I'm going to be your guest, von Gobendorff, for just about twenty-four hours, but in the circumstances I will excuse your absence. By the by, you'll be returning about six, I hope? Dine with me at the Imperial Hotel. I suppose," he added reminiscently, "that the food is not quite so good nor so plentiful as when last I visited Cornwall?"

"There is a difference," replied von Gobendorff, "but nothing like to the extent we Germans hoped. This starving-out campaign seems to hang fire."

"Our U-boats will bring England to her knees yet," declared the ober-leutnant. "They say these English never know when they are beaten, but they'll find out soon."

"One might also say that they never know when they are winning," added the spy. "Much as I hate to have to say it I must admire the matter-of-fact way in which these English take ill-news."

"They get plenty of that," retorted von Loringhoven ironically. "Every week, and down go twenty merchant ships. How long can England stand that?"

"And how many of our unterseebooten vanish while doing the good work?" asked von Gobendorff. "I am afraid, von Loringhoven, that even you cannot answer the question. It is these Englanders' mule-headed contempt for frightfulness that is making Germany's task doubly—nay, trebly hard. But we must argue no longer, Otto," he added, seeing indications of a rising temper in his guest. "We'll go to bed. I will be off before you are up, so, until to-night at the Imperial Hotel, auf Wiedersehen."

ERNST VON GOBENDORFF was up betimes. A forty or fifty miles' railway journey was before him. Until he was within a short distance of Poldene Station he did not consider it prudent to assume his disguise.

He knew that the great Poldene Bridge was closely guarded both by land and water. To attempt to approach would be courting suspicion, even if he appeared in a military officer's uniform. He knew that he could board a "Service" train at Poldene, but here again the difficulty arose as to how he could obtain the privacy necessary for the ultimate attainment of his designs.

The spy alighted at a small station midway between the town and the bridge. He had had a first-class carriage to himself, and the fact that he had entered it as a well-groomed civilian and had left the train dressed in the uniform of a major of the Intelligence Staff passed unnoticed.

His next step was to make for an isolated cottage standing on high ground overlooking the river. Three small boys, sauntering along the leafy lane, turned and gazed at the khaki-clad man. It was mere curiosity. They would have stared at any stranger, whether in uniform or otherwise, but von Gobendorff's lowering brows betokened intense annoyance. It meant that he had to walk past his immediate objective and return when the youngsters were at a safe distance.

A little farther down the lane a middle-aged man in worn fustian clothes was ambling along. Seeing the supposed major approach the fellow stopped, and, pulling out a clasp knife, began to cut hazel switches from the hedge. By this time von Gobendorff was within ten paces of him, and the man resumed his walk with three wands in his hand.

Von Gobendorff seemingly paid little or no attention, but, shifting his suit-case from his right hand to his left, he struck his heel lightly with his malacca cane—thrice, in a most casual way.

"Have you been to the cottage, Herr von Gobendorff?" asked the man in German. "I had to go down to the river, but I hoped to be back before you arrived."

"It matters little," replied the spy. "Have you arranged about a dog?"

"A huge beast," was the reply. "Terrifying in appearance, but he's muzzled and chained."

"It is well," rejoined von Gobendorff. "Now listen carefully. I don't want this business bungled. You say you can get across to the signal-post without being seen from the signal-box, and you know what to do?"

"Yes," was the reply. "All that is necessary is to remove a bolt from the rod, and the signal-arm, being weighted, will rise to the danger position."

"Quite so," agreed von Gobendorff; "but the point is this: can you lower the arm again? The train must be delayed for not longer than five minutes—less if possible. I will place the explosive between the rails. It has a six-minute fuse, so there is little margin. I don't want to be blown up with a crowd of Englishmen."

"I understand," replied the other. "But will six minutes be enough?"

"Enough and no more," rejoined the spy. "The moment the down train crosses the bridge and gains the double-track the American troop train, which will have to wait for it, will start again. Once over the bridge it will not matter whether the engine is over the point of detonation, for the whole structure will collapse and the train with it. Now, fetch me the dog."

The huge St. Bernard showed neither enthusiasm nor mistrust at the sight of its new master. It suffered itself to be taken away on the lead, and, as previously related, the pseudo major and his canine companion contrived to board the guard's van of the Service down train to Trecurnow.

In spite of his steady nerves von Gobendorff's pulse quickened as the train came to a standstill on the centre of the lofty bridge. As he expected, the guard's attention was directed towards the signal set at danger. What was better still, the man alighted and walked along the permanent way.

The spy waited until he saw the guard returning. Five minutes had almost elapsed, but the signal had not dropped. Von Gobendorff was confronted by two alternatives: either to set the fuse in action and drop the explosive under the carriage before the guard returned, or else wait until the line was reported clear. He chose the former, relying implicitly upon his assistant's ability to lower the signal-arm.

Therein he made a grievous error, for the bolt, in being released from the operating rods of the signal, took it into its head to jerk itself out of the man's grasp, rolling down the embankment and choosing a secure retreat under the roots of a thick thorn-bush. The wrench which von Gobendorff's accomplice employed was too massive to be used as a temporary bolt, and in the absence of anything suitable it was impossible to pull down the arm to the safety position. The train beginning to move towards the fellow's scene of action warned him that it was unhealthy to linger longer, so taking to his heels he bolted.

Meanwhile the spy cautiously lowered the explosive out of the window, intending to swing it under the carriage, but forgetting that the dog's chain was padlocked round his own wrist von Gobendorff was unpleasantly surprised when the St. Bernard shook his massive head. The sudden jolt had the result of jerking the cord out of the spy's hand, and the leather case dropped upon the permanent way in full view of the occupants of the two adjoining carriages.

Von Gobendorff made no effort to retrieve his dangerous property. It was high time that he put a safe distance between him and the explosive, for the fuse had now been active for two minutes and the signal-arm still remained at danger.

Uttering maledictions upon himself for not having unlocked the dog's chain from his wrist the spy drew the key from his pocket. To his dismay the key failed to open the padlock, while an attempt to unfasten the rusty spring-hook that fastened the chain to the animal's collar was equally fruitless.

Once again the Teutonic love of detail had over-reached itself. Von Gobendorff had arranged everything to the minutest point, but there was a slight flaw in the operations and it led to failure.

Followed by the St. Bernard the spy leapt from the van and, taking advantage of the fact that the attention of the spectators at the window was centred upon the still obstinately fixed signal, was soon lost in the drifting mist that, fortunately for him, was rising over the eastern end of the bridge.

Knowing that there was a sentry posted on the embankment von Gobendorff advanced boldly, trusting to his disguise to enable him to pass. In this he was quite successful, for the man, on seeing the "Brass Hat" approach, stood still to the salute, the pseudo major returning the compliment in correct military style.

Once clear of the sentry von Gobendorff scrambled down the embankment and made towards the well-wooded country at high speed. With luck he hoped to cover half a mile before the expected explosion occurred; even then his margin of safety was perilously small.

Suddenly the deep boom of a heavy explosion rent the air. Instinctively the spy stopped and listened intently; but no crash of falling girders and masonry, nor the cries of hundreds of men hurtling to their doom, followed the initial roar.

Conscious of failure von Gobendorff broke into a string of oaths as he resumed his flight. The dog was beginning to become a hindrance, for hitherto it had followed well; but now it showed a strong disinclination to be urged at a rapid pace at the end of a chain.

Pulling out a revolver the spy eyed the animal with the intention of trusting to a bullet to sever the recalcitrant chain. At the sight of the weapon the St. Bernard's misgivings were roused, for with a deep growl the powerful brute backed, tugging viciously at the restraining links. Too late the spy thought of unbuckling the massive metal collar, for a warning growl from the muzzled brute let him know very effectively that the St. Bernard's motto was "Noli me tangere." One of the links snapped, and the dog sat down on its haunches while the spy retreated for several feet before subsiding upon the gnarled, and exposed root of a large tree.

Regaining his feet von Gobendorff took to his heels, wrapping the severed portion of the padlocked chain round his wrist as he ran. Before he had gone very far the St. Bernard came bounding to his side.

"Go back, you brute!" exclaimed the spy apprehensively. "Go home!"

Somewhat to his surprise the animal turned tail and ambled off. Just then came the sound of voices. Already his pursuers were on his trail.

Then the unpleasant thought occurred to him that perhaps the dog might be pressed into the service of the men on his track. He wished that he had risked the sound of a revolver shot and had put a bullet through the creature's brain. He had no love for man's best friend; in his youth he had been systematically cruel to animals, and the instinct still lingered. At the best he regarded a dog simply as a slave—an instrument: When no longer of use to him he would not have the slightest compunction in taking its life. It was only fear of discovery that stayed his hand.

Von Gobendorff was a fair athlete. He was especially good at long-distance running, and as he ran with his elbows pressed to his sides his footsteps made hardly any noise. He recognised the fact that it was necessary to avoid stepping on the dried twigs that lay athwart the path or to plunge recklessly through the brushwood.

Presently he came to a fairly wide brook. He hailed the sight with delight. For one thing the water would slake his thirst; for another he could throw the dog off the scent (supposing the animal turned against its temporary master) by wading up-stream.

Before he had waded ten yards he heard sounds of his pursuers coming straight ahead as well as on his left. It was an ominous sign, for they had evidently made their way through the wood on a broad front, and some had out-distanced the rest.

Ahead was a thick clump of willows, the thickly leafed branches trailing in the limpid water. For this cover the spy made, bending low to avoid the trailing boughs. Suddenly he stepped into a deep hole. Immersed to his neck he regained his footing; steadying himself against the force of the stream by grasping a bough.

Nearer and nearer came the sound of his pursuers' footsteps, till a couple of bluejackets burst through the undergrowth and pulled up on the bank within twenty feet of the fugitive.

"S'elp me!" exclaimed one, pointing straight in the direction of the immersed spy. "If that ain't just the bloomin' place for that cove to hide. Come on, mate, let's see what's doin'."

"TALLY-HO!" shouted Sub-Lieutenant Farrar, as the party of bluejackets, headed by the four officers, raced along the permanent way, followed by a running fire of chaff and caustic comment from their envious fellow-passengers. It would have wanted but half a word from the gunnery-lieutenant to have emptied the train, for, with inexplicable intuition, every man knew that the fortunate party was in pursuit of some desperado who had done his level best to blow up the bridge.

"A sovereign for the man who captures the fellow," announced the gunnery-lieutenant; then, remembering that he had not so much as set eyes on a coin of that denomination for the last three years, he modified his offer. "Dash it all, a pound note I mean!"

The astonished sentry at the approach to the bridge could only volunteer the information that a Staff major, accompanied by a large dog, had passed by a short time before. Alarmed at the explosion the rest of the guard had turned out, and upon a description of the suspect being given, then they, too, joined in the pursuit.

"He's made for that wood for a dead cert., sir," remarked Holcombe, as a partial lifting of the mist revealed the nearmost trees of a dense plantation.

"More'n likely," agreed the gunnery-lieutenant. "Three of you men make your way round to the right, and three to the left. You'll be on the other side before we can push our way through. The others extend in open order, and keep your weather eye lifting."

"These trees could give shelter to a full company," observed Holcombe, as the two subs found themselves in the dense undergrowth. "There's one thing—that dog can't climb a tree."

"He'd probably cast off the tow-line and abandon the brute," said Farrar. "If I had the ordering of the business I'd make for the nearest telegraph office and wire instructions for every Brass Hat within ten miles to be arrested on suspicion."

"Just the sort of thing you would do, Slogger, my festive bird," replied Holcombe. "Imagine twenty or thirty Staff officers being laid by the heels until they could establish their identity."

"It would be drastic but efficacious," grunted Farrar, as he pushed aside a sapling that had just hit him in the face.

"Unless the fellow's shed his gorgeous khaki and red plumage," added his companion. "Look out! don't lose touch with those bluejackets on your right."

He indicated two able seamen who, country born and bred before they elected to serve His Majesty upon the high seas, were entering upon the pursuit with the eagerness of a couple of trained pointers; while the additional inducement of "arf a quid apiece"—they had struck a bargain to share the proceeds, if won—had whetted their zeal to the uttermost.

"We're on his track, sir," declared one of the men, stooping and picking up a polished bit of metal. "'E's dropped a link of that dawg's chain. An' see, sir, 'ere's footprints, quite new-like."

For fifty yards the marks of the fugitive's boots were followed. From the fact that they were the imprints of the toes only, it showed that the man had been running. Then the trail was lost on hard ground.

"We'll pick them up again up-along," declared the second bluejacket optimistically, as he gave a quick glance at the bark of every tree he passed to detect, if possible, the abrasions caused by the foot gear of a climbing man.

A thick clump of prickly undergrowth offered no serious obstacle to the two A.B.'s. Farrar and Holcombe thought better of it, considering the present-day prices of uniform, and made a detour. By the time they resumed their former direction the bluejackets were fifty yards ahead.

Presently the men came to a dead stop on the edge of a brook.

"S'elp me!" exclaimed one. "If that ain't just the bloomin' place for that cove to hide. Come on, mate, let's see what's doin'."

"Right-o," assented the other. "But look out for holes. There usually are some under willows such as that. Let's get up-stream a bit afore we cross. 'Tain't no use getting wet up to your neck when you need only wet your beetle-crushers."

Before these good intentions could be carried out the shrill blast of a whistle echoed through the wood, while the gunnery-lieutenant's voice gave the order, "Retire on your supports."

"Guess Gunnery Jack imagines we're on a bloomin' field day," grumbled one of the bluejackets, and, although he wistfully eyed the suspicious willow, he hastened to obey orders.

A petty officer hurried between the undergrowth, hot and panting with his exertions.

"He's collared," he announced. "They're bringing him to the guard-room up on the bridge."

"Who's the lucky blighter?" inquired one of the disappointed twain.

"Mike O' Milligan," was the reply. "He put the kybosh on the Tin Hat before he had time to look round."

"Then the spy is feeling sorry for himself," remarked Farrar, who had overheard the conversation. "O' Milligan is the champion heavyweight boxer of the old 'Tantalus,' and there are a few nimble lads with the gloves in our ship's company."

"The blighter gets no pity from me," declared Holcombe. "I remember a yarn my skipper told—— Hullo! here's the dog."

The St. Bernard, with a couple of feet of chain trailing from its collar, bolted straight up to the two subs. Giving Holcombe a preliminary sniff the animal turned its attention to Farrar, thrusting its muzzled head against his hands.

"The poor beast is horribly thirsty," he remarked. "I'll take his muzzle off."

"Better be careful," cautioned Holcombe. "Hanged if I'd like to feel those teeth."

"You see," rejoined Farrar, and bending over the animal he unloosened the tightly fitting strap that secured the muzzle.

The dog barked joyously and, wagging his tail, followed his benefactor to the stream, where it drank "enough water to float a t.b.d.," according to Holcombe.

Suddenly the dog stood with its body quivering with excitement and its eyes fixed upon some object on the opposite bank. Then it gave vent to a low, deep growl as the willow branches rustled audibly.

"What's up, old boy?" asked Farrar. "He's spotted something," he added, addressing his companion.

"A water rat, most likely," rejoined Holcombe casually. "Come on; if we want to see anything of the prisoner we'd better crowd on all sail."

"And the dog?"

"Bring him along, too; he's apparently taken a fancy to you, Slogger. Keep him as a mascot. We have a bulldog, a Persian kitten, and a mongoose already given us for the 'Antipas.' 'Sides, there's heaps of room on board your packet."

The St. Bernard offered no objection to the decision; in fact, he signified his approbation by means of a succession of deep-throated barks when Farrar called him to heel. Then as docilely as a pet lamb the newly acquired mascot followed the two subs out of the wood.

Already the captive had been carried to the guard-room. The gunnery-lieutenant and Engineer-Commander Curtis were within, while the bluejackets, drawn up a short distance from the entrance, were standing at ease.

"Well done, O' Milligan!" exclaimed Farrar, for the pugilistic A.B. was in the sub's watch-bill. "How did you manage to nab the fellow?"

"Sure, sorr," said the Irishman, "Oi saw him trapesin' along the path, so Oi goes up to him. 'Now, be jabbers,' sez Oi, 'are you for comin' aisy an' quiet, or am Oi to dot you one?' 'The divil!' sez he. 'Sure,' sez Oi. 'There's nothin' loike bein' straightforward. Between you an' me an' gatepost, the Huns an' the Ould Gintleman are loike Murphy's pigs you can't tell any difference.' Wid that he tries the high hand—sort o' 'Haw-haw, d'ye know who Oi am, my man?' As if by bein' consaited he hoped to get to wind'ard of Mike Milligan. 'Come on, you Hun,' sez Oi, an' makes to grab his arm. Arrah! He swore loike a haythen an' tried to break away, so Oi just hit 'im on the point of his chin an' down he wint."

"And he hasn't recovered yet, sir," added another bluejacket. "O' Milligan did his job properly."

At that moment the gunnery-lieutenant, accompanied by the engineer-commander and the sergeant of the guard, came out of the building.

"Party—'shun!" ordered the former. "By the right—double."

The engine was whistling peremptorily. Disregarding the eager inquiries of his brother officers in the carriage the gunnery-lieutenant ordered his men to board the train, which, during the pursuit of the miscreant, had moved on sufficiently to enable the American troop train to pass.

As Farrar and Holcombe, accompanied by the St. Bernard, were about to enter the carriage the gunnery-lieutenant called them aside.

"Don't say too much about the business," he cautioned them. "We've made a deuce of a blunder, and I expect there'll be a holy terror of a row up-topsides. The unlucky bounder laid out by one of the bluejackets was a genuine major; both the sergeant and the corporal of the guard were certain on that point. It is an unfortunate coincidence, and what is worse the fellow we went after has got away. Whether they catch him or not rests with the military and the civil police. We did what we could, and did it jolly badly."

"After all," remarked Farrar when the two chums were once more seated in the compartment, "my way, although drastic, would have been better than this fiasco; and I guess that poor blighter of a major would think so too if he had the choice between a punch on the jaw from a champion boxer or spending a couple of hours under escort with a dozen other Brass Hats to keep him company."

"It was a bit of excitement, if nothing else," said Holcombe.

"And I've found a jolly fine dog," added the R.N.V.R. sub, patting the huge animal's head. "I'll call him Bruno... and I don't think we'll need this again."

And he hurled the dog's muzzle out of the window.

AT a quarter to six Ober-Leutnant Otto von Loringhoven strolled into the lounge of the Imperial Hotel and, ringing for the waiter, booked two seats at a table for dinner. This done he carefully selected a choice cigar and ensconced himself in a large easy-chair. Ostensibly interested in the pages of a newspaper he was furtively taking stock of the other occupants of the lounge.

Von Loringhoven had had a really enjoyable day. He had done his level best to banish from his mind all thoughts of his dangerous and degraded profession. He appreciated the short respite from the mental and physical strain of commanding a U-boat. Until the evening he would take a well-earned holiday.

Accordingly he had made a few purchases in the little town of articles that were not readily obtainable by the simple expedient of looting a captured merchantman. Then, in possession of a small flask and a packet of sandwiches, he struck inland towards the wild and unfrequented moors.

Once or twice during the day he thought of von Gobendorff, and wondered whether his attempt had met with success. Not that he evinced any great concern over the business. The spy had not taken him into his confidence sufficiently to explain the details of his proposed attempt upon the troop train. There was once the haunting suspicion that should von Gobendorff be caught the consequences might be rather awkward for the ober-leutnant. Von Loringhoven had little faith in his fellow-countrymen; he would not be greatly surprised if the spy, in an endeavour to mitigate his deserved punishment, would give information to the British authorities to the effect that a German submarine commander was at large on Cornish soil.

Early in the afternoon von Loringhoven began to make his way back to the town. Taking a footpath he passed close to half a dozen German prisoners-of-war engaged in agricultural work.

In broken German he addressed one of them, inquiring whether the fellow would take the opportunity of escaping should such a chance occur. The broad-shouldered Bavarian shook his head emphatically. "No," he replied. "Why should I? We are well fed. After eighteen months on scanty rations in the hell of Ypres a man would be a fool to wish to go back over there."

The ober-leutnant resumed his walk, pondering over his compatriot's words. There were evidences in plenty that the German theory, that six months of unrestricted U-boat warfare would bring England to the verge of starvation, was very wide of the mark; and the prisoner's tacit assertion that he preferred to live and eat in England to fighting and semi-starvation for the sake of the Fatherland was striking evidence that the German submarine campaign was a failure in spite of its unprecedented savagery and frightfulness.

Before proceeding to the hotel von Loringhoven bought a paper. If he bought it with the idea of gleaning any important information he was grievously mistaken. The war news was confined to a few brief communiqués. The rest of the columns were taken up with local and county topics unconnected with the war, a number of advertisements, and a few carefully worded announcements of deaths in action of Cornishmen.

Long before the ober-leutnant had finished his cigar a fresh-complexioned, round-faced subaltern entered the room and, spotting a brother officer, began a conversation in tones loud enough to enable von Loringhoven to follow every word.

"I say," he remarked. "Have you heard anything about the attempt to blow up Poldene Bridge?"

"My sergeant said something to me about it," replied the other. "I didn't pay much attention to him, as he's a regular old woman for getting hold of cock-and-bull yarns."

"It's right enough," persisted the first speaker. "There was an explosion while the Navy Special was hung up on the bridge. Signals tampered with, I understand. No damage done, but evidently the fellow or fellows on the job knew what they were about, for a troop train filled with Yankees was due to cross almost at the same time. It's a mystery to me how these Huns get to know of the movements of transport and troop trains. All the week American transports are to be diverted from Liverpool to Trecurnow, as those rotten U-boats have been reported in force off the Antrim coast."

After talking on several other subjects one of the subalterns inquired, "Heard anything of your young brother recently? Dick, I mean. He was in the 'Calyranda' when she struck a mine, I believe?"

"Yes, he's appointed to the 'Tantalus.' She's leaving Trecurnow on Thursday for Hampton Roads."

"Escorting duties?"

"On the return voyage—yes. Outward bound they're taking a number of big pots to attend an Allied conference at Washington, I understand. At any rate, young Dick has to get a new mess-jacket. Thought he'd be able to do without that luxury until after the war. ...Oh, by the way, here's news. I was lunching yesterday with my cousin—you know, the lieutenant-colonel who won the D.S.O.—and he happened to mention——"

Von Loringhoven listened intently, smiling grimly behind his newspaper. From the tittle-tattle of a raw subaltern he was gleaning more intelligence than he could from a dozen journals, for the youngster seemed to take a special delight in letting the other guests know that he was in close touch with the Powers that Be.

From time to time the ober-leutnant glanced at the clock. It was now twenty minutes to seven. Von Gobendorff was considerably overdue, and von Loringhoven was feeling hungry.

"My friend is apparently unable to be present," he said to the head waiter. "You can serve me now. I suppose as a dinner for two has been ordered I must pay for both?"

"That is the rule of the hotel, sir," replied the man.

"And in that case I presume I can have a double allowance?"

The waiter shook his head and winked solemnly.

"Can't be done, sir," he replied. "'Gainst regulations. You'll pay for two dinners, I admit, sir; that's your misfortune."

"Then I suppose the extra meal will be wasted?"

"A drop in the ocean of waste, sir, I assure you," said the man confidentially. "Tons of waste down this part of the country. Take petrol, for example. I've a motor-bike of my own and can't use it, although half a gallon of petrol a week would be as much as I want. And yet the coastguards, when hundreds of cans were washed ashore along the coast, were told to wrench off the brass caps of the tins—useful for munitions, I suppose, sir—and chuck petrol and cans back into the sea. And I paid my licence to the end of the year."

"Hard lines," remarked the ober-leutnant. "But the nation's at war, you know."

"Quite true, sir," replied the man. "I wouldn't mind making sacrifices if I knew all the petrol was going to naval and military use—tanks and patrol boats and the like—but waste like I've been telling you makes me a bit up the pole. Ah, sir, you needn't worry about that second dinner, for here's Mr. Middlecrease."

The waiter hurried off, while von Gobendorff, well-groomed and debonair, greeted the ober-leutnant.

"Sorry I'm so infernally late, Smith," he exclaimed. "Must blame the trains. Missed my connection at Okehampton, don't you know."

The two Germans sat down to their belated meal, talking the while on commonplace topics.

They certainly made a faux pas in the way they gulped down their soup, but the rest of the diners, although they exchanged sympathetic glances, had never had the misfortune to visit German "bads" in pre-war days; otherwise they might have "smelt a rat."

Von Loringhoven paid the bill and carefully placed the receipt in his pocket-book. "It will be a souvenir of a pleasant evening," he remarked to his companion. "A certificate to the effect that I have invaded England, hein?"

It was close on nine o'clock when von Loringhoven accompanied the spy to his home. Once in von Gobendorff's study, with a thick curtain drawn over the door, the latter unburdened himself.

"Ach!" he exclaimed, stretching his limbs and yawning prodigiously; "I have had a nasty time, Otto. Often I thought I would have to forego this pleasurable evening in exchange for a prison cell."

"You bungled, then?"

"Perhaps. It was hardly my fault. I am inclined to blame Schranz. I deposited the explosive all right, but the signal did not fall within the prearranged limit. Consequently I had either to make a bolt for safety or stay where I was and get blown up. I chose the first alternative."

"And the explosion?"

"It came off," replied the spy. "Somehow the bridge was not destroyed. Why I know not. Then I was hotly pursued. That fool of a dog—I had taken the precaution of having one sent from London—nearly put me away, but just as I had given myself up as lost the men in pursuit were recalled. Then at the first opportunity I discarded my disguise—I was wearing two suits of clothes: a good tip, Otto, unless you happen to be wearing a military or naval uniform under your civilian's dress. Himmel! it was decidedly unpleasant in those saturated clothes, for I had been standing up to my neck in water for nearly twenty minutes."

"It was a wonder that your wet clothes did not give you away," remarked von Loringhoven.

"They certainly gave me a cold," admitted the spy, suppressing a sneeze. "You should have seen me, Otto, stripped to the skin in a secluded hollow, and wringing out my garments one by one. It was a chilly business donning the damp things, but I walked briskly over the moors until the wind dried them to a state of comparative respectability. Then I struck the high road towards Poldene station. There were patrols and police out, but they never suspected me, as I was proceeding towards the scene of my frustrated attempt. And here I am. Well, have you picked up any information?"

The ober-leutnant shook his head. He was too wily a bird to impart an important piece of news even to a compatriot, so the matter of the date of departure of the "Tantalus" was withheld.

"No," he replied. "I have been having a rest, that is all. I go back to my work with renewed zest. I drink, von Gobendorff, to the confusion of England. Hoch, hoch, hoch!"

At half-past ten the ober-leutnant left the house, declining the spy's offer to accompany him part of the way. Without encountering a single person, for he knew the actual times at which the cliff patrol passed, he gained the little cove. By the luminous hands of his watch he had nearly an hour to wait, and waiting in the darkness, with only the sullen thresh of the surf and the eerie cries of innumerable seabirds to break the silence, was tedious, especially as he dared not smoke.

Presently, above the noise of nature's handiwork, came the bass hum of an aerial propeller. The ober-leutnant gazed upwards between the narrow walls of the rocky inlet.

"Too slow for a seaplane or a flying-boat," he muttered. "It must be one of those infernal coastal airships. Himmel! I hope she hasn't any suspicions of U 254 lying off the shore. I've waited quite long enough to my liking. Ach, there she is. I thought so."

At an altitude of less than two hundred feet above the summit of the cliffs the "Blimp" glided serenely, the suspended chassis being invisible against the greater bulk of the grey envelope that showed darkly against the starlit sky.

The airship was flying against the wind, and was proceeding at a rate not exceeding fifteen miles an hour "over the ground"—the ground in this instance being the sea. At that comparatively slow speed she appeared to the watcher in the depths of the cove to be almost stationary, and the sight filled him with misgivings.

Suddenly a searchlight flashed from the vigilant guardian of the coast, stabbing the darkness with a broad blade of silvery radiance. Instinctively von Loringhoven averted his face. He could see the grotesquely foreshortened shadow of himself cast upon the rocks. He wondered whether an alert observer had him "fixed" with his powerful night-glasses. He was afraid to move lest his action would satisfy any lurking doubt in the mind of the watchers above. Supposing the Blimp sent a signal to the nearest coastguard station, reporting a suspicious character in the cove?

All these thoughts flashed through the ober-leutnant's brain in less than twenty seconds. Then the penetrating beam swung like a giant pendulum, sweeping every square yard of sea within an arc of two miles' radius.

The ray ceased its movements and was directed upon a dark object lying at a distance of less than five cables' lengths from the shore. Von Loringhoven's breath came in short gasps. Momentarily he expected to see the flash of a gun or hear the sharp explosion of compressed air that would send an aerial torpedo on its death-dealing errand.

By degrees the ober-leutnant's eyes grew accustomed to the glare, and he made the discovery that the object was a two-masted fishingboat that, having been unable to reach harbour before "official sunset," was endeavouring to make port and risk divers pains and penalties for being under way during prohibited hours.

Down swept the airship, her searchlight relentlessly focussed upon the delinquent, until the officer in charge of the Blimp was able to discover the registered number of the boat and shout by means of a megaphone a promise that the master of the fishing-boat would be "hauled over the coals" at no very distant date.

This duty performed the airship rose and, turning, travelled "down wind" at high speed, whereat von Loringhoven heaved a deep sigh of genuine relief.

The hour of midnight passed and the ober-leutnant still waited. He was beginning to think that he was marooned on hostile ground and that the submarine had met with misfortune, when a dark shape glided round the rocks at the entrance to the cove.

"You are late!" exclaimed von Loringhoven hastily, as the coxswain of U 254's canvas boat brought the frail cockleshell alongside the rough jetty.

"It was a cursed English airship that detained us, Herr Kapitan," replied the man. "We had to submerge. We thought we were detected; only, it seems, it was a fishing craft that occupied the airship's attention."

Not another word did von Loringhoven speak until he gained the U-boat's deck.

"How stand the accumulators, Herr Kuhlberg; and what petrol have we on board?"

The unter-leutnant gave the required information.

"Just enough to take us home, Herr Kapitan," he added tentatively, for the prolonged cruise—already U 254's time limit was exceeded—was jarring his nerves very badly.

"Perhaps," rejoined von Loringhoven, with a sneer. "Meanwhile we are going to lie off the Scillies until the end of the week, so reconcile yourself to that, my friend."

"You have heard something, then, Herr Kapitan?" asked the unter-leutnant eagerly, his despondency departing at the prospect of doing a great deed—torpedoing a huge unarmed liner, perhaps.

"I have," replied von Loringhoven. "The English cruiser 'Tantalus' leaves Trecurnow on Thursday with a number of delegates for a conference at New York. The 'Tantalus' is, of course, armed, and, as you know, English gunners shoot straight. How does that suit you?"

Hans Kuhlberg's attempt to put a brave face upon the matter was a failure. His superior officer smiled disdainfully, for there was no love lost between the two.

"I am going to turn in now," he added. "You know the course; keep her at that until you sight Godrevy Light and then inform me."

AT eight o'clock on the following Thursday morning H.M.S. "Tantalus" cast off from her moorings in Trecurnow Roads and stood down Channel.

She was an armoured cruiser of an obsolescent type, and although not powerful enough to be of material use to the Grand Fleet, was admirably adapted to the work allotted to her—ocean patrolling and escorting transports to and from overseas. Since the outbreak of war her steaming mileage worked out at a little over 200,000 miles, or roughly eight times the circumference of the earth. During this stupendous task her engines had given hardly any trouble, and never once had had a serious breakdown—a feat that was rendered possible solely to the unremitting care and attention of her engineering officers and ratings. Sixteen years previously her contract speed was twenty-five knots; and when occasion required her "black squad" could whack her up to her original form.

On either side of the cruiser a long, lean destroyer kept station, for the "Tantalus" was to be escorted through the danger zone. Waspish little motor patrol boats, too, were dashing and circling around her, their task being to put the wind up any lurking U-boat that was bold enough to risk being rammed or blown up by depth charges by the attendant destroyers.

"Mornin', Slogger, old bird," exclaimed a voice. "Looking for your friend, Holcombe?"

Farrar, whose turn it was to be Duty Sub of the Watch, was levelling his glass at one of the destroyers. Upon hearing himself familiarly addressed—for the nickname of schooldays still stuck—he turned and placed the telescope under his arm.

"Mornin', Banger," he replied. "No; I knew it was no use looking for Holcombe on that packet. The 'Antipas' is of a later type; besides, she's not completed commissioning yet. How's that dog of mine behaving?"