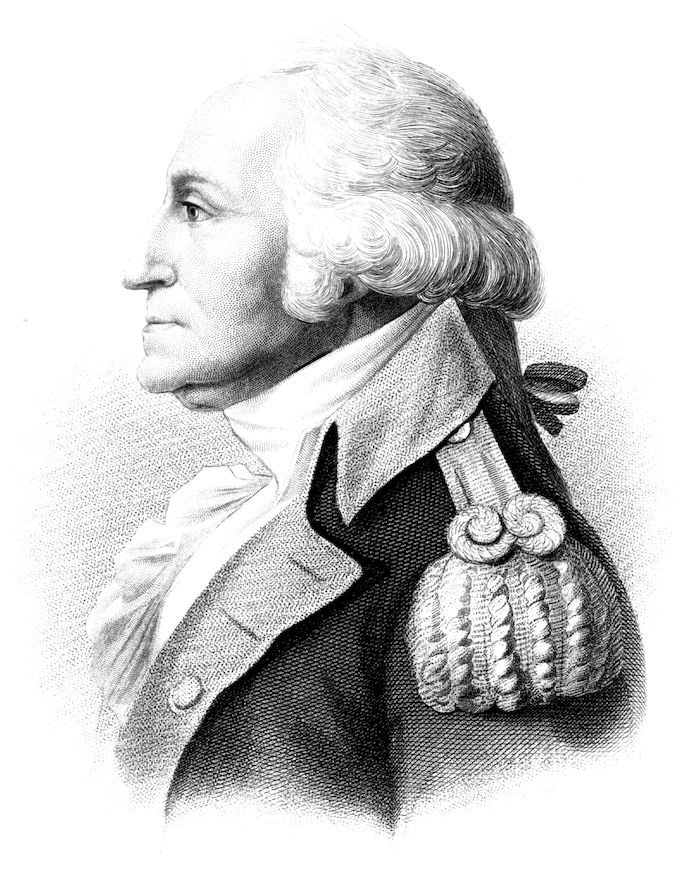

WASHINGTON

From the St Memin Crayon in possession of J. Carson Brevoort Esq.

Title: Washington the Soldier

Author: Henry B. Carrington

Release date: May 19, 2021 [eBook #65380]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Richard Tonsing and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Since the first appearance of this volume, during the winter of 1898–9, the author has considerately regarded all letters and literary comments received by him, as well as other recent works upon the life and times of Washington. His original purpose to treat his subject judicially, regardless of unverified tradition, has been confirmed.

Washington’s sublime conception of America, noticed in Chapter XXXVI., foreshadowed “a stupendous fabric of freedom and empire, on the broad basis of Independency,” through which the “poor and oppressed of all races and religions” might find encouragement and solace.

The war with Spain has made both a moral and physical impress upon the judgment and conscience of the entire world. Unqualified by a single disaster on land or sea, and never diverted from humane and honorable methods, it illustrates the intelligent patriotism and exhaustless resources of our country, and a nearer realization of Washington’s prayer for America.

Looking to the general trend of Washington’s military career, it is emphasized, throughout the volume, that the moral, religious, and patriotic motives that energized his life and shaped his character were so absolutely interwoven with the fibre of his professional experiences, that vithe soul of the Man magnified the greatness of the Soldier.

In connection with Washington’s relations to General Braddock, mentioned in the First Chapter, it is worthy of permanent record that Virginia would not sanction, nor would Washington accept assignment, except as Chief of Staff. He was not a simple Aid-de-Camp, but of recognized and responsible military merit.

The text of this volume, completed in the spring of 1898 and not since modified, requires a different Preface from that first prepared. The events of another war introduce applications of military principles which have special interest. This is the more significant because modern appliances have been developed with startling rapidity, while general legislation and the organization of troops, both regular and volunteer, have been very similar to those of the times of Washington, and of later American wars.

His letters, his orders, his trials, his experiences; the diversities of judgment between civilians and military men; between military men of natural aptitudes and those of merely professional or accidental training, as well as the diversities of personal and local interest, indicate the value of Washington’s example and the character of his time. Hardly a single experience in his career has not been realized by officers and men in these latter days.

A very decided impression, however, has obtained among educated men, including those of the military profession, that Washington had neither the troops, resources, and knowledge, nor the broad range of field service which have characterized modern warfare, and therefore lacked material elements which develop the typical soldier. But more recent military operations upon an extensive scale, especially those of the Franco-Prussian War, and the American Civil War of 1861–1865, have supplied material for better appreciation of the principles that were viiiinvolved in the campaigns of the War for American Independence, as compared with those of Napoleon, Wellington, Marlborough, Frederick, Hannibal, and Cæsar.

With full allowance for changes in army and battle formation, tactical action and armament, as well as greater facilities for the transportation of troops and army supplies, it remains true that the relative effect of all these changes upon success in war upon a grand scale, has not been the modification of those principles of military science which have shaped battle action and the general conduct of war, from the earliest period of authentic military history. The formal “Maxims of Napoleon” were largely derived from his careful study of the campaigns of Frederick, Hannibal, and Cæsar; and these, with the principles involved, had specific and sometimes literal illustration in the eventful operations of the armies of the Hebrew Commonwealth. As a matter of fact, those early Hebrew experiences were nearly as potential in shaping the methods of modern generals, as their civil code became the formative factor in all later civil codes, preëminently those of the English Common Law. The very best civil, police, and criminal regulations of modern enactment hold closely to Hebrew antecedents. And in military lines, the organization of regiments by companies, and the combinations of regiments as brigades, divisions and corps, still rest largely upon the same decimal basis; and neither the Roman legion nor the Grecian phalanx improved upon that basis. Even the Hebrew militia, or reserves, had such well-established comprehension of the contingency of the entire nation being called to the field, or subjected to draft, that as late as the advent of Christ, when he ordered the multitudes to be seated upon the grass for refreshment, “they seated themselves in companies of hundreds and fifties.” The sanitary and police regulations of their camps have never ixbeen surpassed, nor their provision for the cleanliness, health, and comfort of the rank and file. From earliest childhood they were instructed in their national history and its glorious achievements, and the whole people rejoiced in the gallant conduct of any.

Changes in arms, and especially in projectiles, only induced modified tactical formation and corresponding movements. The division of armies into a right, centre, and left, with a well-armed and well-trained reserve, was illustrated in their earliest battle record. The latest modern formation, which makes of the regiment, by its three battalion formation, a miniature brigade, is chiefly designed to give greater individual value to the soldier, and not subject compact masses to the destructive sweep of modern missiles. It also makes the force more mobile, as well as more comprehensive of territory within its range of fire. All this, however, is matter of detail and not of substance, in the scientific conduct of campaigns during a protracted and widely extended series of operations in the field.

Military science itself is but the art of employing force to vindicate, or execute, authority. To meet an emergency adequately, wisely, and successfully, is the expressive logic of personal, municipal, and military action. The brain power is banded to various shaftings, and the mental processes may differ by virtue of different applications; but the prime activities are the same. In military studies, as in all collegiate or social preparation, the soldier, the lawyer, or the scientist, must be in the man, and not the necessary product of a certificate or a diploma. The simplest possible definition of a few terms in military use will elucidate the narrative as its events develop the War for American Independence, under the direction of Washington as Commander-in-Chief.

Six cardinal principles are thus stated:

xI. Strategy.—To secure those combinations which will ensure the highest possible advantage in the employment of military force.

Note.—The strategical principles which controlled the Revolutionary campaigns, as defined in Chapter X. had their correspondence in 1861–1865, when the Federal right zone, or belt of war, was beyond the Mississippi River, and the left zone between the Alleghany Mountains and the Atlantic Ocean. The Confederate forces, with base at Richmond, commanded an interior line westward, so that the same troops could be alternatively used against the Federal right, left, and centre, while the latter must make a long détour to support its advance southward from the Ohio River. Federal superiority on sea and river largely contributed to success. American sea-control in 1898, so suddenly and completely secured, was practically omnipotent in the war with Spain. The navy, was a substantially equipped force at the start. The army, had largely to be created, when instantly needed, to meet the naval advance. Legislation also favored the navy by giving to the commander-in-chief the services of eminent retired veterans as an advisory board, while excluding military men of recent active duty from similar advisory and administrative service.

II. Grand Tactics.—To handle that force in the field.

Note.—See Chapter XVII., where the Battle of Brandywine, through the disorder of Sullivan’s Division, unaccustomed to act as a Division, or as a part of a consolidated Grand Division or Corps, exactly fulfilled the conditions which made the first Battle of Bull Run disastrous to the American Federal Army in 1861. Subsequent skeleton drills below Arlington Heights, were designed to quicken the proficiency of fresh troops, in the alignments, wheelings, and turns, so indispensable to concert in action upon an extensive scale. In 1898 the fresh troops were largely from militia organizations which had been trained in regimental movements. School battalions and the military exercises of many benevolent societies had also been conducive to readiness for tactical instruction. The large Camps of Instruction were also indispensably needed. Here again, time was an exacting master of the situation.

III. Logistics.—The practical art of bringing armies, fully equipped, to the battlefield.

xiNote.—In America where the standing army has been of only nominal strength, although well officered; and where militia are the main reliance in time of war; and where varied State systems rival those of Washington’s painful experience, the principle of Logistics, with its departments of transportation and infinite varieties of supply, is vital to wholesome and economic success. The war with Spain which commenced April 21, 1898, illustrated this principle to an extent never before realized in the world’s history. Familiarity with details, on so vast a scale of physical and financial activity, was impossible, even if every officer of the regular army had been assigned to executive duty. The education and versatile capacity of the American citizen had to be utilized. Their experience furnished object lessons for all future time.

IV. Engineering.—The application of mathematics and mechanics to the maintenance or reduction of fortified places; the interposition or removal of artificial obstructions to the passage of an army; and the erection of suitable works for the defence of territory or troops.

Note.—The invention and development of machinery and the marvellous range of mechanical art, through chemical, electrical, and other superhuman agencies, afforded the American Government an immediate opportunity to supplement its Engineer Corps in 1898, with skilled auxiliaries. In fact, the structure of American society and the trend of American thought and enterprise, invariably demand the best results. What is mechanically necessary, will be invented, if not at hand. That is good engineering.

V. Minor Tactics.—The instruction of the soldier, individually and en masse, in the details of military drill, the use of his weapon, and the perfection of discipline.

Note.—Washington never lost sight of the set-up of the individual soldier, as the best dependence in the hour of battle. Self-reliance, obedience to orders, and confidence in success, were enjoined as the conditions of success. His system of competitive marksmanship, of rifle ranges, and burden tests, was initiated early in his career, and was conspicuously enjoined before Brooklyn, and elsewhere, during the war.

The American soldier of 1898 became invincible, man for man, because of his intelligent response to individual discipline and drill. Failure in either, whether of officer or soldier, shaped character and xiiresult. As with the ancient Hebrew, citizenship meant knowledge of organic law and obedience to its behests. Every individual, therefore, when charged with the central electric force, became a relay battery, to conserve, intensify, and distribute that force.

VI. Statesmanship in War.—This is illustrated by the suggestion of Christ, that “a king going to war with another king would sit down first and count the cost, whether he would be able with ten thousand to meet him that cometh against him with twenty thousand.”

Note.—American statesmanship in 1898, exacted other appliances than those of immediately available physical force. The costly and insufferable relations of the Spanish West Indies to the United States, had become pestilential. No self-respecting nation, elsewhere, would have as long withheld the only remedy. Cuba was dying to be free. Spain, unwilling, or unable, to grant an honorable and complete autonomy to her despairing subjects, precipitated war with the United States. The momentum of a supreme moral force in behalf of humanity at large, so energized the entire American people that every ordinary unpreparedness failed to lessen the effectiveness of the stroke.

It was both statesmanship and strategy, to strike so suddenly that neither climatic changes, indigenous diseases, nor tropical cyclones, could gain opportunity to do their mischief. When these supposed allies of Spain were brushed aside, as powerless to stay the advance of American arms in behalf of starving thousands, and a fortunate occasion was snatched, just in time for victory, it proved to be such an achievement as Washington would have pronounced a direct manifestation of Divine favor.

But the character of Washington as a soldier is not to be determined by the numerical strength of the armies engaged in single battles, nor by the resources and geographical conditions of later times. The same general principles have ever obtained, and ever will control human judgment. Transportation and intercommunication are relative; and the slow mails and travel of Revolutionary times, alike affected both armies, with no partial benefit or injury to either. The British had better communication by water, but not by land; with the disadvantage xiiiof campaigning through an unknown and intricate country, peopled by their enemies, whenever not covered by the guns of their fleet. The American expedition to Cuba in 1898 had not only the support of invincible fleets, but the native population were to be the auxiliaries, as well as the beneficiaries of the mighty movement.

Baron Jomini, in his elaborate history of the campaigns of Napoleon, analyzes that general’s success over his more experienced opponents, upon the basis of his observance or neglect of the military principles already outlined. The dash and vigor of his first Italian campaign were indeed characteristic of a young soldier impatient of the habitually tardy deliberations of the old-school movements. Napoleon discounted time by action. He benumbed his adversary by the suddenness and ferocity of his stroke. But never, even in that wonderful campaign, did Napoleon strike more suddenly and effectively, than did Washington on Christmas night, 1776, at Trenton. And Napoleon’s following up blow was not more emphatic, in its results, than was Washington’s attack upon Princeton, a week later, when the British army already regarded his capture as a simple morning privilege. Such inspirations of military prescience belong to every age; and often they shorten wars by their determining value.

As a sound basis for a right estimate of Washington’s military career, and to avoid tedious episodes respecting the acts and methods of many generals who were associated with him at the commencement of the Revolutionary War, a brief synopsis of the career of each will find early notice. The dramatis personæ of the Revolutionary drama are thus made the group of which he is to be the centre; and his current orders, correspondence, and criticisms of their conduct, will furnish his valuation of the character and services of each. The single fact, xivthat no general officer of the first appointments actively shared in the immediate siege of Yorktown, adds interest to this advance outline of their personal history.

For the same purpose, and as a logical predicate for his early comprehension of the real issues involved in a contest with Great Britain, an outline of events which preceded hostilities is introduced, embracing, however, only those Colonial antecedents which became emotional factors in forming his character and energizing his life as a soldier.

The maps, which illustrate only the immediate campaigns of Washington, or related territory which required his supervision, are reduced from those used in “Battle Maps and Charts of the American Revolution.” The map entitled “Operations near New York,” was the first one drafted, at Tarrytown, New York. In 1847, it was approved by Washington Irving, then completing his Life of Washington, and his judgment determined the plan of the future work. All of the maps, however, before engravure, had the minute examination and approval of Benson J. Lossing. The present volume owes its preparation to the personal request of the late Robert C. Winthrop, of Massachusetts, made shortly before his decease, and is completed, with ever-present appreciation of his aid and his friendship.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Early Aptitudes for Success | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The Ferment of American Liberty | 10 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Outbreak of Repressed Liberty | 20 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Armed America needs a Soldier | 31 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Washington in Command | 41 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| British Canada enters the Field of Action | 50 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Howe succeeds Gates.—Closing Scenes of 1775 | 58 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| America against Britain.—Boston taken | 68 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Systematic War with Britain begun | 82 |

| xviCHAPTER X. | |

| Britain against America.—Howe invades New York | 93 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Battle of Long Island | 101 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Washington in New York | 114 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Washington tenders, and Howe declines, Battle.—Harlem Heights and White Plains | 125 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The First New Jersey Campaign.—Trenton | 134 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| The First New Jersey Campaign developed.—Princeton | 150 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| The American Base of Operations established.—The Second New Jersey Campaign | 160 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| British Invasion from Canada.—Operations along the Hudson | 171 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Pennsylvania invaded.—Battle of Brandywine | 181 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Washington resumes the Offensive.—Battle of Germantown | 192 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Jealousy and Greed defeated.—Valley Forge | 198 |

| xviiCHAPTER XXI. | |

| Philadelphia and Valley Forge in Winter, 1778 | 210 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| From Valley Forge to White Plains again.—Battle of Monmouth | 221 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| The Alliance with France takes effect.—Siege of Newport | 238 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Minor Events and Grave Conditions, 1779 | 246 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Minor Operations of 1779 continued.—Stony Point taken.—New England relieved | 255 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| Shifting Scenes.—Temper of the People.—Savannah | 263 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| The Eventful Year 1780.—New Jersey once more invaded | 269 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| Battle of Springfield.—Rochambeau.—Arnold.—Gates | 282 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| A Bird’s-eye View of the Theatre of War | 294 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| The Soldier tried.—American Mutiny.—Foreign Judgment.—Arnold’s Depredations | 304 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| The Southern Campaign, 1781, outlined.—Cowpens.—Guilford Court-house.—Eutaw Springs | 312 |

| xviiiCHAPTER XXXII. | |

| Lafayette in Pursuit of Arnold.—The End in Sight.—Arnold in the British Army | 323 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| New York and Yorktown threatened.—Cornwallis inclosed by Lafayette | 333 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| British Captains outgeneraled.—Washington joins Lafayette | 344 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| The Alliance with France vindicated.—Washington’s Magnanimity.—His Benediction | 352 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

| Washington’s Prediction realized.—The Attitude of America pronounced | 366 |

| Appendix A.—American Army, by States | 377 |

| Appendix B.—American Navy and its Career | 378 |

| Appendix C.—Comparisons with Later Wars | 380 |

| Appendix D.—British Army, at Various Dates | 383 |

| Appendix E.—Organization of Burgoyne’s Army | 387 |

| Appendix F.—Organization of Cornwallis’s Army | 388 |

| Appendix G.—Notes of Lee’s Court-martial | 389 |

| Glossary of Military Terms | 393 |

| Chronological and Biographical Index | 397 |

| ILLUSTRATIONS. | ||

|---|---|---|

| PAGE | ||

| Washington | Frontispiece. | |

| [Hall’s engraving from the St. Memin crayon.] | ||

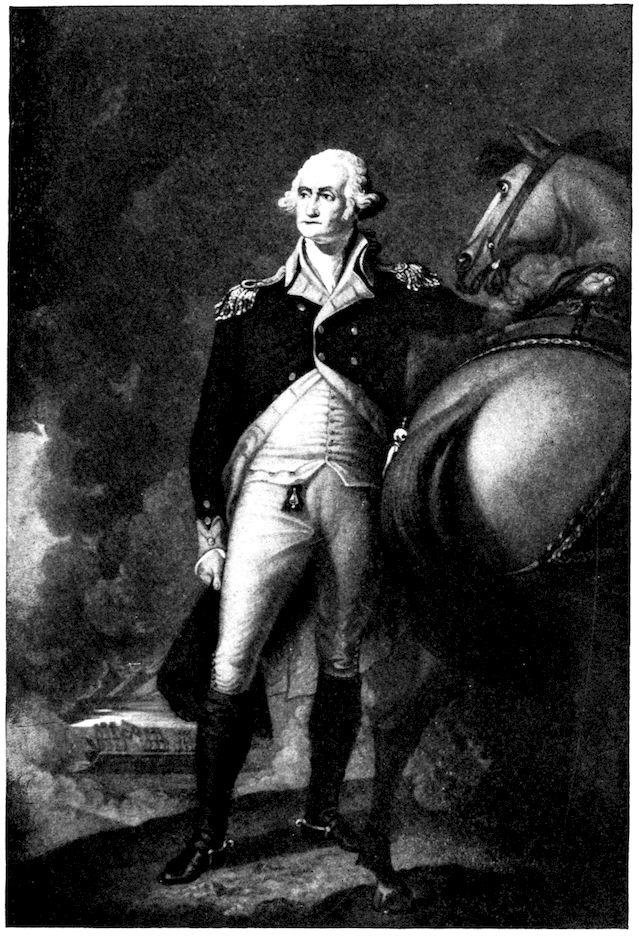

| Washington at Four Periods of his Military Career | 40 | |

| [From etching, after Hall’s Sons’ group.] | ||

| Washington at Boston | 80 | |

| [From Stuart’s painting, in Faneuil Hall, Boston.] | ||

| Washington before Trenton | 143 | |

| [From Dael’s painting.] | ||

| Washington in his Room at Valley Forge | 207 | |

| [From the painting by Scheuster.] | ||

| MAPS. | ||

| I. | —Outline of the Atlantic Coast | 1 |

| II. | —Boston and Vicinity | 69 |

| III. | —Battle of Long Island | 105 |

| IV. | —Operations near New York | 125 |

| V. | —Capture of Fort Washington | 132 |

| VI. | —Trenton and Vicinity | 144 |

| VII. | —Battle of Trenton: Battle of Princeton | 151 |

| VIII. | —Operations in New Jersey | 161 |

| IX. | —Attack of Forts Clinton and Montgomery | 179 |

| X. | —Battle of Brandywine | 186 |

| XI. | —Battle of Germantown | 196 |

| xxXII. | —Operations on the Delaware | 202 |

| XIII. | —Operations near Philadelphia | 204 |

| XIV. | —Encampment at Valley Forge | 211 |

| XV. | —Battle of Monmouth | 224 |

| XVI. | —Outline Map of Hudson River | 255 |

| XVII. | —Battle of Springfield: Operations from Staten Island | 283 |

| XVIII. | —Lafayette in Virginia | 339 |

| XIX. | —Operations in Chesapeake Bay | 355 |

| XX. | —Siege of Yorktown | 357 |

The boyhood and youth of George Washington were singularly in harmony with those aptitudes and tastes that shaped his entire life. He was not quite eight years of age when his elder brother, Lawrence, fourteen years his senior, returned from England where he had been carefully educated, and where he had developed military tastes that were hereditary in the family. Lawrence secured a captain’s commission in a freshly organized regiment, and engaged in service in the West Indies, with distinguished credit. His letters, counsels, and example inspired the younger brother with similar zeal. Irving says that “all his amusements took a military turn. He made soldiers of his school-mates. They had their mimic parades, reviews, and sham-fights. A boy named William Bustle, was sometimes his competitor, but George was commander-in-chief of the school.”

His business aptitudes were equally exact, methodical, and promising. Besides fanciful caligraphy, which appeared in manuscript school-books, wherein he executed profiles of his school-mates, with a flourish of the pen, as well as nondescript birds, Irving states that “before he 2was thirteen years of age, he had copied into a volume, forms of all kinds of mercantile and legal papers: bills of exchange, notes of hand, deeds, bonds, and the like.” “This self-tuition gave him throughout life a lawyer’s skill in drafting documents, and a merchant’s exactness in keeping accounts, so that all the concerns of his various estates, his dealings with his domestic stewards and foreign agents, his accounts with government, and all his financial transactions, are, to this day, monuments of his method and unwearied accuracy.”

Even as a boy, his frame had been large and powerful, and he is described by Captain Mercer “as straight as an Indian, measuring six feet and two inches in his stockings, and weighing one hundred and seventy-five pounds, when he took his seat in the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1759. His head is well shaped though not large, but is gracefully poised on a superb neck, with a large and straight rather than a prominent nose; blue-gray penetrating eyes, which were widely separated and overhung by heavy brows. A pleasing, benevolent, though a commanding countenance, dark-brown hair, features regular and placid, with all the muscles under perfect control, with a mouth large, and generally firmly closed,” complete the picture. The bust by Houdon at the Capitol of Virginia, and the famous St. Memin crayon, fully accord with this description of Washington.

His training and surroundings alike ministered to his natural conceptions of a useful and busy life. In the midst of abundant game, he became proficient in its pursuit. Living where special pride was taken in the cultivation of good stock, and where nearly all travel and neighborly visitation was upon horseback, he learned the value of a good horse, and was always well mounted. Competition in saddle exercise was, therefore, one of the most pleasing and constant entertainments of himself and 3companions, and in its enjoyment, and in many festive tournaments that revived something of the olden-time chivalry of knighthood, Washington was not only proficient, but foremost in excellence of attainment.

Rustic recreations such as quoits, vaulting, wrestling, leaping, the foot-race, hunting and fishing, were parts of his daily experience, and thoroughly in the spirit of the Old Dominion home life of the well-bred gentleman. The gallantry of the times and the social amenities of that section of the country were specially adapted to his temperament, so that in these, also, he took the palm of recognized merit. The lance and the sword, and every accomplishment of mimic warfare in the scale of heraldic observance, usual at that period, were parts of his panoply, to be enjoyed with keenest relish, until his name became synonymous with success in all for which he seriously struggled. Tradition does not exaggerate the historic record of his proficiency in these manly sports.

Frank by nature, although self-contained and somewhat reticent in expression; unsuspicious of others, but ever ready to help the deserving needy, or the unfortunate competitor who vainly struggled for other sympathy, he became the natural umpire, at the diverting recreations of his times, and commanded a respectful confidence far beyond that of others of similar age and position in society. With all this, a sense of justice and a right appreciation of the merit of others, even of rivals, were so conspicuous in daily intercourse with a large circle of familiar acquaintances, whether of influential families or those of a more humble sphere of life, that he ever bent gracefully to honor the deserving, while never obsequious to gain the favor of any.

Living in the midst of slave labor, and himself a slaveholder, he was humane, considerate, and impartial. Toward his superiors in age or in position, he was uniformly 4courteous, without jealousy or envy, but unconsciously carried himself with so much of benignity and grace, that his most familiar mates paid him the deference which marked the demeanor of all who, in later years, recognized his exalted preferment and his natural sphere of command. The instincts of a perfect gentleman were so radicated in his person and deportment, that he moved from stage to stage, along life’s ascent, as naturally as the sun rises to its zenith with ever increasing brightness and force.

All these characteristics, so happily blended, imparted to his choice of a future career its natural direction and character. Living near the coast and in frequent contact with representatives of the British navy, he became impressed by the strong conviction that its service offered the best avenue to the enjoyment of his natural tastes, as well as the most promising field for their fruitful exercise. The berth of midshipman, with its prospects of preferment and travel, fell within his reach and acceptance. Every available opportunity was sought, through books of history and travel and acquaintance with men of the naval profession, to anticipate its duties and requirements. It was Washington’s first disappointment in life of which there is record, that his mother did not share his ardent devotion for the sea and maritime adventure. At the age of eleven he lost his father, Augustine Washington, but the estate was ample for all purposes of Virginia hospitality and home comfort, and he felt that he could be spared as well as his brother Lawrence. With all the intensity of his high aspiration and all the vigor of his earnest and almost passionate will, he sought to win his mother’s assent to his plans; and then, with filial reverence and a full, gracious submission, he bent to her wishes and surrendered his choice. That was Washington’s first victory; and similar 5self-mastery, under obligation to country, became the secret of his imperial success. Irving relates that his mother’s favorite volume was Sir Matthew Hale’s Contemplations, moral and divine; and that “the admirable maxims therein contained, sank deep into the mind of George, and doubtless had a great influence in forming his character. That volume, ever cherished, and bearing his mother’s name, Mary Washington, may still be seen in the archives of Mount Vernon.”

But Washington’s tastes had become so settled, that he followed the general trend of mathematical and military study, until he became so well qualified as a civil engineer, that at the age of sixteen, one year after abandoning the navy as his profession, he was intrusted with important land surveys, by Lord Fairfax; and at the age of nineteen was appointed Military Inspector, with the rank of Major. In 1752 he became the Adjutant-General of Virginia. Having been born on the twenty-second day of February (February 11th, Old Style) he was only twenty years of age when this great responsibility was intrusted to his charge.

The period was one of grave concern to the people of Virginia, especially as the encroachments of the French on the western frontier, and the hostilities of several Indian tribes, had imperilled all border settlements; while the British government was not prepared to furnish a sufficient military force to meet impending emergencies. As soon as Washington entered upon the duties of his office, he made a systematic organization of the militia his first duty. A plan was formulated, having special reference to frontier service. His journals and the old Colonial records indicate the minuteness with which this undertaking was carried into effect. His entire subsequent career is punctuated by characteristics drawn from this experience. Rifle practice, feats of horsemanship, 6signalling, restrictions of diet, adjustments for the transportation of troops and supplies with the least possible encumbrance; road and bridge building, the care of powder and the casting of bullets, were parts of this system. These were accompanied by regulations requiring an exact itinerary of every march, which were filed for reference, in order to secure the quickest access to every frontier post. The duties and responsibilities of scouts sent in advance of troops, were carefully defined. The passage of rivers, the felling of trees for breastworks, stockades, and block-houses, and methods of crossing swamps, by corduroy adjustments, entered into the instruction of the Virginia militia.

At this juncture it seemed advisable, in the opinion of Governor Dinwiddie, to secure, if practicable, a better and an honorable understanding with the French commanders who had established posts at the west. The Indians were hostile to all advances of both British and French settlement. There was an indication that the French were making friendly overtures to the savages, with view to an alliance against the English. In 1753 Washington was sent as Special Commissioner, for the purpose indicated. The journey through a country infested with hostile tribes was a remarkable episode in the life of the young soldier, and was conducted amid hardships that seem, through his faithful diary, to have been the incidents of some strangely thrilling fiction rather than the literal narrative, modestly given, of personal experience. During the journey, full of risks and rare deliverances from savage foes, swollen streams, ice, snow, and tempest, his keen discernment was quick to mark the forks of the Alleghany and Monongahela rivers as the proper site for a permanent post, to control that region and the tributary waters of the Ohio, which united there. He was courteously received by St. Pierre, the French 7commandant, but failed to secure the recognition of English rights along the Ohio. But Washington’s notes of the winter’s expedition critically record the military features of the section traversed by him, and forecast the peculiar skill with which he accomplished so much in later years, with the small force at his disposal.

In 1754 he was promoted as Colonel and placed in command of the entire Virginia militia. Already, the Ohio Company had selected the forks of the river for a trading-post and commenced a stockade fort for their defence. The details of Washington’s march to support these pioneers, the establishment and history of Fort Necessity, are matters of history.

Upon assuming command of the Virginia militia, Washington decided that a more flexible system than that of the European government of troops, was indispensable to success in fighting the combined French and Indian forces, then assuming the aggressive against the border settlements. Thrown into intimate association with General Braddock and assigned to duty as his aid-de-camp and guide, he endeavored to explain to that officer the unwisdom of his assertion that the very appearance of British regulars in imposing array, would vanquish the wild warriors of thicket and woods, without battle. The profitless campaign and needless fate of Braddock are familiar; but Washington gained credit both at home and abroad, youthful as he was, for that sagacity, practical wisdom, knowledge of human nature, and courage, which ever characterized his life.

During these marchings and inspections he caused all trees which were so near to a post as to shelter an advancing enemy, to be felled. The militia were scattered over an extensive range of wild country, in small detachments, and he was charged with the defence of more than four hundred miles of frontier, with an available 8force of only one thousand men. He at once initiated a system of sharp-shooters for each post. Ranges were established, so that fire would not be wasted upon assailants before they came within effective distance. When he resumed command, after returning from the Braddock campaign, he endeavored to reorganize the militia upon a new basis. This reorganization drew from his fertile brain some military maxims for camp and field service which were in harmony with the writings of the best military authors of that period, and his study of available military works was exact, unremitting, and never forgotten. Even during the active life of the Revolutionary period, he secured from New York various military and other volumes for study, especially including Marshal Turenne’s Works, which Greene had mastered before the war began.

Washington resigned his commission in 1756; married Mrs. Martha Custis, Jan. 6, 1759; was elected member of the Virginia House of Burgesses the same year, and was appointed Commissioner to settle military accounts in 1765. In the discharge of this trust he manifested that accuracy of detail and that exactness of system in business concerns which have their best illustration in the minute record of his expenses during the Revolutionary War, in which every purchase made for the government or the army, even to a few horse-shoe nails, is accurately stated.

Neither Cæsar’s Commentaries, nor the personal record of any other historical character, more strikingly illustrate an ever-present sense of responsibility to conscience and to country, for trusts reposed, than does that of Washington, whether incurred in camp or in the whirl and crash of battle. Baron Jomini says: “A great soldier must have a physical courage which takes no account of obstacles; and a high moral courage capable 9of great resolution.” There have been youth, like Hannibal, whose earliest nourishment was a taste of vengeance against his country’s foes, and others have imbibed, as did the ancient Hebrew, abnormal strength to hate their enemies while doing battle; but if the character of Washington be justly delineated, he was, through every refined and lofty channel, prepared, by early aptitudes and training, to honor his chosen profession, with no abatement of aught that dignifies character, and rounds out in harmonious completeness the qualities of a consummate statesman and a great soldier.

In 1755, four military expeditions were planned by the Colonies: one against the French in Nova Scotia; one against Crown Point; one against Fort Niagara, and the fourth, that of Braddock, against the French posts along the Ohio river.

In 1758, additional expeditions were undertaken, the first against Louisburg, the second against Ticonderoga, and the third against Fort Du Quesne. Washington led the advance in the third, a successful attack, Nov. 25, 1758, thereby securing peace with the Indians on the border, and making the fort itself more memorable by changing its name to that of Fort Pitt (now Pittsburgh) in memory of William Pitt (Lord Chatham), the eminent British statesman, and the enthusiastic friend of America.

In 1759, Quebec was captured by the combined British and Colonial forces, and the tragic death of the two commanders, Wolfe and Montcalm, made the closing hours of the siege the last opportunity of their heroic valor. With the capture of Montreal in 1760, Canada came wholly under British control. In view of those campaigns, it was not strange that so many Colonial participants readily found places in the Continental Army at the commencement of the war for American Independence, and subsequently urged the acquisition of posts on the northern border with so much pertinacity and confidence.

11In 1761, Spain joined France against Great Britain, but failed of substantial gain through that alliance, because the British fleets were able to master the West India possessions of Spain, and even to capture the city of Havana itself.

In 1763, a treaty was effected at Paris, which terminated these protracted inter-Colonial wars, so that the thirteen American colonies were finally relieved from the vexations and costly burdens of aiding the British crown to hold within its grasp so many and so widely separated portions of the American continent. In the ultimate settlement with Spain, England exchanged Havana for Florida; and France, with the exception of the city of New Orleans and its immediate vicinity, retired behind the Mississippi river, retaining, as a shelter for her fisheries, only the Canadian islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon, which are still French possessions.

In view of the constantly increasing imposition of taxes upon the Colonies by the mother country, in order to maintain her frequent wars with European rivals, by land and sea, a convention was held at New York on the seventh day of October, 1765, called a Colonial Congress, “to consult as to their relations to England, and provide for their common safety.” Nine colonies were represented, and three others either ratified the action of the convention, or declared their sympathy with its general recommendations and plans. The very brief advance notice of the assembling of delegates, partly accounts for the failure of North Carolina, Virginia, New Hampshire, and Georgia, to be represented. But that convention made a formal “Declaration of Rights,” especially protesting that “their own representatives alone had the right to tax them,” and “their own juries to try them.”

As an illustration of the fact, that the suggestion of 12some common bond to unite the Colonies for general defence was not due to the agencies which immediately precipitated the American Revolution, it is to be noticed that as early as 1607, William Penn urged the union of the Colonies in some mutually related common support. The Six Nations (Indian), whom the British courted as allies against the French, and later, against their own blood, had already reached a substantial Union among themselves, under the name of the Iroquois Confederacy; and it is a historical fact of great interest, that their constitutional league for mutual support against a common enemy, while reserving absolute independence in every local function or franchise, challenged the appreciative indorsement of Thomas Jefferson when he entered upon the preparation of a Constitution for the United States of America.

And in 1722, Daniel Coxe, of New Jersey, suggested a practical union of the Colonies for the consolidation of interests common to each. In 1754, when the British government formally advised the Colonies to secure the friendship of the Six Nations against the French, Benjamin Franklin prepared a form for such union. Delegates from New England, as well as from New York, Pennsylvania, and Maryland, met at Albany on the fourth of July, 1754, the very day of the surrender of Fort Necessity to the French, for consideration of the suggested plan. The King’s council rejected it, because it conceded too much independence of action to the people of the Colonies, and the Colonies refused to accept its provisions, because it left too much authority with the King.

Ten years later, when the Colonies had been freed from the necessity of sacrificing men and money to support the British authority against French, Spanish, and Indian antagonists, the poverty of the British treasury drove George Grenville, then Prime Minister, to a system of 13revenue from America, through the imposition of duties upon Colonial imports. In 1755 followed the famous Stamp Act. Its passage by Parliament was resisted by statesmen of clear foresight, with sound convictions of the injustice of taxing their brethren in America who had no representatives in either House of Parliament; but in vain, and this explosive bomb was hurled across the sea. Franklin, then in London, thus wrote to Charles Thompson, who afterwards became secretary of the Colonial Congress: “The sun of Liberty has set. The American people must light the torch of industry and economy.” To this Thompson replied: “Be assured that we shall light torches of quite another sort.”

The explosion of this missile, charged with death to every noble incentive to true loyalty to the mother country, dropped its inflammatory contents everywhere along the American coast. The Assembly of Virginia was first to meet, and its youngest member, Patrick Henry, in spite of shouts of “Treason,” pressed appropriate legislation to enactment. Massachusetts, unadvised of the action of Virginia, with equal spontaneity, took formal action, inviting the Colonies to send delegates to a Congress in New York, there to consider the grave issues that confronted the immediate future. South Carolina was the first to respond. When Governor Tryon, of North Carolina, afterwards the famous Governor of New York, asked Colonel (afterwards General) Ashe, Speaker of the North Carolina Assembly, what the House would do with the Stamp Act, he replied, “We will resist its execution to the death.”

On the seventh of October the Congress assembled and solemnly asserted, as had a former convention, that “their own representatives alone had the right to tax them,” and “their own juries to try them.” Throughout the coast line of towns and cities, interrupted business, 14muffled and tolling bells, flags at half-mast, and every possible sign of stern indignation and deep distress, indicated the resisting force which was gathering volume to hurl a responsive missile into the very council chamber of King George himself.

“Sons of Liberty” organized in force, but secretly; arming themselves for the contingency of open conflict. Merchants refused to import British goods. Societies of the learned professions and of all grades of citizenship agreed to dispense with all luxuries of English production or import. Under the powerful and magnetic sway of Pitt and Burke, this Act was repealed in 1766; but even this repeal was accompanied by a “Declaratory Act,” which reserved for the Crown “the right to bind the Colonies, in all cases whatsoever.”

Pending all these fermentations of the spirit of liberty, George Washington, of Virginia, was among the first to recognize the coming of a conflict in which the Colonial troops would no longer be a convenient auxiliary to British regulars, in a common cause, but would confront them in a life or death struggle, for rights which had been guaranteed by Magna Charta, and had become the vested inheritance of the American people. Suddenly, as if to impress its power more heavily upon the restless and overwrought Colonists, Parliament required them to furnish quarters and subsistence for the garrisons of towns and cities. In 1768, two regiments arrived at Boston, ostensibly to “preserve the public peace,” but, primarily, to enforce the revenue measures of Parliament.

In 1769, Parliament requested the King to “instruct the Governor of Massachusetts” to “forward to England for trial, upon charges of high treason,” several prominent citizens of that colony “who had been guilty of denouncing Parliamentary action.” The protests of the Provincial 15Assemblies of Virginia and North Carolina against the removal of their citizens, for trial elsewhere, were answered by the dissolution of those bodies by their respective royal governors. On the fifth day of May, 1769, Lord North, who had become Prime Minister, proposed to abolish all duties, except upon tea. Later, in 1770, occurred the “Boston Massacre,” which is ever recalled to mind by a monument upon the Boston Common, in honor of the victims. In 1773 “Committees of Correspondence” were selected by most of the Colonies, for advising the people of all sections, whenever current events seemed to endanger the public weal. One writer said of this state of affairs: “Common origin, a common language, and common sufferings had already established between the Colonies a union of feeling and interest; and now, common dangers drew them together more closely.”

But the tax upon tea had been retained, as the expression of the reserved right to tax at will, under the weak assumption that the Colonists would accept this single tax and pay a willing consideration for the use of tea in their social and domestic life. The shrewd and patriotic citizens, however boyish it may have seemed to many, found a way out of the apparent dilemma, and on the night of December 16, 1773, the celebrated Boston Tea Party gave an entertainment, using three hundred and fifty-two chests of tea for the festive occasion, and Boston Harbor for the mixing caldron.

In 1774, the “Boston Port Bill” was passed, nullifying material provisions of the Massachusetts Charter, prohibiting intercourse with Boston by sea, and substituting Salem for the port of entry and as the seat of government for the Province. It is to be noticed, concerning the various methods whereby the Crown approached the Colonies, in the attempt to subordinate all rights to the 16royal will, that Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut, until 1692, were charter governments, whereby laws were framed and executed by the freemen of each colony. The proprietary governments were Pennsylvania with Maryland, and at first New York, New Jersey, and the Carolinas. In all of these, the proprietors, under certain restrictions, established and conducted their own systems of rule. There were also the royal governments, those of New Hampshire, Virginia, Georgia, and afterwards Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and the Carolinas. In these, appointments of the chief officers pertained to the Crown.

At the crisis noticed, General Gage had been appointed Governor of Massachusetts Colony, as well as commander-in-chief, and four additional regiments had been despatched to his support. But Salem declined to avail herself of the proffered boon of exceptional franchises, and the House of Burgesses of Virginia ordered that “the day when the Boston Port Bill was to go into effect should be observed as a day of fasting, humiliation, and prayer.”

The Provincial Assembly did indeed meet at Salem, but solemnly resolved that it was expedient, at once, to call a General Congress of all the Colonies, to meet the unexpected disfranchisement of the people, and appointed five delegates to attend such Congress. All the Colonies except Georgia, whose governor prevented the election of delegates, were represented.

This body, known in history as the First Continental Congress, assembled in Carpenter’s Hall, Philadelphia, on the fifth day of September, 1774. Peyton Randolph, of Virginia, was elected president, and Charles Thompson, of Pennsylvania, was elected secretary. Among the representative men who took part in its solemn deliberations must be named Samuel Adams and John Adams, of 17Massachusetts; Philip Livingstone and John Jay, of New York; John Dickinson, of Pennsylvania; Christopher Gadsden and John Rutledge, of South Carolina; Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee, and George Washington, of Virginia.

During an address by Lord Chatham before the British House of Lords, he expressed his opinion of the men who thus boldly asserted their inalienable rights as Englishmen against the usurping mandates of the Crown, in these words: “History, my lords, has been my favorite study; and in the celebrated writers of antiquity have I often admired the patriotism of Greece and Rome; but, my lords, I must declare and avow, that in the master states of the world, I know not the people, or senate, who, in such a complication of difficult circumstances, can stand in preference to the delegates of America assembled in General Congress at Philadelphia.” This body resolved to support Massachusetts in resistance to the offensive Acts of Parliament; made a second “Declaration of Rights,” and advised an American association for non-intercourse with England. It also prepared another petition to the King, as well as an address to the people of Great Britain and Canada, and then provided for another Congress, to be assembled the succeeding May. During its sessions, the Massachusetts Assembly also convened and resolved itself into a Provincial Congress, electing John Hancock as president, and proceeded to authorize a body of militia, subject to instant call, and therefore to be designated as “Minute Men.” A Committee of Safety was appointed to administer public affairs during the recess of the Congress. When Captain Robert Mackenzie, of Washington’s old regiment, intimated that Massachusetts was rebellious, and sought independence, Washington used this unequivocal language in reply: “If the ministry are determined to push 18matters to extremity, I add, as my opinion, that more blood will be spilled than history has ever furnished instances of, in the annals of North America; and such a vital wound will be given to the peace of this great country, as time itself cannot cure, or eradicate the remembrance of.”

Early in 1775 Parliament rejected a “Conciliatory Bill,” which had been introduced by Lord Chatham, and passed an Act in special restraint of New England trade, which forbade even fishing on the banks of Newfoundland. New York, North Carolina, and Georgia were excepted, in the imposition of restrictions upon trade in the middle and southern Colonies, in order by a marked distinction between Colonies, to conserve certain aristocratic influences, and promote dissension among the people; but all such transparent devices failed to subdue the patriotic sentiment which had already become universal in its expression.

At that juncture the English people themselves did not apprehend rightly the merits of the dawning struggle, nor resent the imposition by Parliament, of unjust, unequal, and unconstitutional laws upon their brethren in America. Dr. Franklin thus described their servile attitude toward the Crown: “Every man in England seems to consider himself as a piece of a sovereign; seems to jostle himself into the throne with the King; and talks of ‘our subjects in the Colonies.’”

The ferment of patriotic sentiment was deep, subtle, intense, and ready for deliverance. The sovereignty of the British crown and the divine rights of man were to be subjected to the stern arbitrament of battle. One had fleets, armies, wealth, prestige, and power, unsustained by the principles of genuine liberty which had distinguished the British Constitution above all other modern systems of governmental control; while the scattered 19two millions of earnest, patriotic Englishmen across the sea, who, from their first landing upon the shores of the New World had honored every principle which could impart dignity and empire to their mother country, were to balance the scale of determining war by the weight of loyalty to conscience and to God.

British authority, which ought to have gladly welcomed and honored the prodigious elasticity, energy, and growth of its American dependencies, as the future glory and invincible ally of her advancing empire, was deliberately arming to convert a natural filial relation into one of slavery. The legacies of British law and the liberties of English subjects, which the Crown did not dare to infringe at home, had been lodged in the hearts of her American sons and daughters, until resistance to a royal decree had become impossible under any reasonable system of paternal care and treatment. Colonial sacrifices during Indian wars had been cheerfully borne, and free-will offerings of person and property had been rendered without stint, upon every demand. But it seemed to be impossible for George the Third and his chosen advisers to comprehend in its full significance, the momentous fact, that English will was as strong and stubborn in the child as in the parent.

Lord Chatham said that “it would be found impossible for freemen in England to wish to see three millions of Englishmen slaves in America.”

Respecting the attempted seizure of arms rightly in the hands of the people, that precipitated the “skirmish,” as the British defined it, which occurred at Lexington on the nineteenth day of April, 1775, Lord Dartmouth said: “The effect of General Gage’s attempt at Concord will be fatal.”

21Granville Sharpe, of the Ordnance Department, resigned rather than forward military stores to America.

Admiral Keppel formally requested not to be employed against America.

Lord Effingham resigned, when advised that his regiment had been ordered to America.

John Wesley, who had visited America many years before with his brother, and understood the character of the Colonists, at once recalled the appeal once made to the British government by General Gage during November, 1774, when he “was confident, that, to begin with, an army of twenty thousand men would, in the end, save Great Britain both blood and treasure,” and declared, “Neither twenty thousand, forty thousand, nor sixty thousand can end the dawning struggle.”

During the summer of 1774 militia companies had been rapidly organized throughout the Colonies. New England especially had been so actively associated with all military operations during the preceding French and Indian wars, that her people more readily assumed the attitude of armed preparation for the eventualities of open conflict.

Virginia had experienced similar conditions on a less extended and protracted basis. The action of the First Continental Congress on the fifth day of September, 1774, when, upon notice that Gage had fortified Boston, it made an unequivocal declaration of its sympathy with the people of Boston and of Massachusetts, changed the character of the struggle from that of a local incident, to one that demanded organized, deliberate, and general resistance.

Notwithstanding the slow course of mail communications between the widely separated Colonies north and south, the deportment of the British Colonial governors had been so uniformly oppressive and exacting, that the people, everywhere, like tinder, were ready for the first flying spark. A report became current during September, 22after the forced removal of powder from Cambridge and Charlestown, that Boston had been attacked. One writer has stated, that, “within thirty-six hours, nearly thirty thousand men were under arms.” This burst of patriotic feeling, this mighty frenzy over unrighteous interference with vested rights, made a profound impression upon the Continental Congress, then in session at Philadelphia, and aroused in the mind of Washington, then a delegate from Virginia, the most intense anxiety lest the urgency of the approaching crisis should find the people unprepared to take up the gage of battle, and fight with the hope of success. All this simply indicated the depth and breadth of the eager sentiment which actually panted for armed expression.

The conflict between British troops and armed citizens at Lexington had already assumed the characteristics of a battle, and, as such, had a more significant import than many more pronounced engagements in the world’s history. The numbers engaged were few, but the men who ventured to face British regulars on that occasion were but the thin skirmish line in advance of the swelling thousands that awaited the call “To arms.”

Massachusetts understood the immediate demand, having now drawn the fire of the hitherto discreet adversary, and promptly declared that the necessities of the hour required from New England the immediate service of thirty thousand men, assuming as her proportionate part a force of thirteen thousand six hundred. This was on the twenty-second day of April, while many timid souls and some social aristocrats were still painfully worrying themselves as to who was to blame for anybody’s being shot on either side.

On the twenty-fifth day of April, Rhode Island devoted fifteen hundred men to the service, as her contribution to “An Army of Observation” about Boston.

23On the following day, the twenty-sixth, Connecticut tendered her proportion of two thousand men.

Each Colonial detachment went up to Boston as a separate army, with independent organization and responsibility. The food, as well as the powder and ball of each, was distinct, and they had little in common except the purpose which impelled them to concentrate for a combined opposition to the armed aggressions of the Crown. And yet, this mass of assembling freemen was not without experience, or experienced leaders. The early wars had been largely fought by Provincial troops, side by side with British regulars, so that the general conduct of armies and of campaigns had become familiar to New England men, and many veteran soldiers were prompt to volunteer service. Lapse of time, increased age, absorption in farming or other civil pursuits, had not wholly effaced from the minds of retired veterans the memory of former experience in the field. If some did not realize the expectations of the people and of Congress, the promptness with which they responded to the call was no less worthy.

Massachusetts selected, for the immediate command of her forces, Artemas Ward, who had served under Abercrombie, with John Thomas, another veteran, as Lieutenant-General; and as Engineer-in-Chief, Richard Gridley, who had, both as engineer and soldier, earned a deserved reputation for skill, courage, and energy.

Connecticut sent Israel Putnam, who had been inured to exposure and hardship in the old French War, and in the West Indies. Gen. Daniel Wooster accompanied him, and he was a veteran of the first expedition to Louisburg thirty years before, and had served both as Colonel and Brigadier-General in the later French War. Gen. Joseph Spencer also came from Connecticut.

Rhode Island intrusted the command of her troops to 24Nathaniel Greene, then but thirty-four years of age, with Varnum, Hitchcock, and Church, as subordinates.

New Hampshire furnished John Stark, also a veteran of former service; and both Pomeroy and Prescott, who soon took active part in the operations about Boston, had participated in Canadian campaigns.

These, and others, assembled in council, for consideration of the great interests which they had been summoned to protect by force of arms. At this solemn juncture of affairs, the youngest of their number, Nathaniel Greene, whose subsequent career became so significant a factor in that of Washington the Soldier, submitted to his associates certain propositions which he affirmed to be indispensable conditions of success in a war against the British crown. These propositions read to-day, as if, like utterances of the old Hebrew prophets, they had been inspired rules for assured victory. And, one hundred years later, when the American Civil War unfolded its vast operations and tasked to the utmost all sections to meet their respective shares in the contest, the same propositions had to be incorporated into practical legislation before any substantial results were achieved on either side.

It is a historical fact that the failures and successes of the War of American Independence fluctuated in favor of success, from year to year, exactly in proportion to the faithfulness with which these propositions were illustrated in the management and conduct of the successive campaigns.

The propositions read as follows:

I. That there be one Commander-in-Chief.

II. That the army should be enlisted for the war.

III. That a system of bounties should be ordained which would provide for the families of soldiers absent in the field.

25IV. That the troops should serve wherever required throughout the Colonies.

V. That funds should be borrowed equal to the demands of the war and for the complete equipment and support of the army.

VI. That Independence should be declared at once, and every resource of every Colony be pledged to its support.

In estimating the character of Washington the Soldier, and accepting these propositions as sound, it is of interest to be introduced to their author.

The youthful tastes and pursuits of Nathaniel Greene, of Rhode Island, those which shaped his subsequent life and controlled many battle issues, were as marked as were those of Washington. Unlike his great captain, he had neither wealth, social position, nor family antecedents to inspire military endeavor. A Quaker youth, at fourteen years of age he saved time from his blacksmith’s forge, and by its light mastered geometry and Euclid. Providence threw in his way Ezra Stiles, then President of Yale College, and Lindley Murray, the grammarian, and each of them became his fast friend and adviser.

Before the war began, he had carefully studied “Cæsar’s Commentaries,” Marshal Turenne’s Works, “Sharpe’s Military Guide,” “Blackstone’s Commentaries,” “Jacobs’ Law Dictionary,” “Watts’ Logic,” “Locke on the Human Understanding,” “Ferguson on Civil Society,” Swift’s Works, and other models of a similar class of literature and general science.

In 1773, he visited Connecticut, attended several of its militia “trainings,” and studied their methods of instruction and drill. In 1774, he visited Boston, to examine minutely the drill, quarters, and commissary arrangements of the British regular troops. Incidentally, he met one evening, at a retired tavern on India wharf, a British sergeant who had deserted. He persuaded him 26to accompany him back to Rhode Island, where he made him drill-instructor of the “Kentish Guards,” a company with which Greene was identified. Such was the proficiency in arms, deportment, and general drill realized by this company, through their joint effort, that more than thirty of the members became commissioned officers in the subsequent war.

The character of the men of that period, as in the American Civil War, supplied the military service with soldiers of the best intelligence and of superior physical capacities. Very much of the energy and success which attended the progress of the American army was traceable to these qualities, as contrasted with those of the British recruits and the Hessian drafted men.

Greene himself, unconsciously but certainly, was preparing himself and his comrades for the impending struggle which already cast its shadow over the outward conditions of peace. Modest, faithful, dignified, undaunted by rebuffs or failure, and as a rule, equable, self-sacrificing, truthful, and honest, he possessed much of that simple grandeur of character which characterized George H. Thomas and Robert E. Lee, of the American conflict, 1861–5. His patriotism, as he announced his propositions to the officers assembled before Cambridge, was like that of Patrick Henry, of Virginia, who shortly after made this personal declaration: “Landmarks and boundaries are thrown down; distinctions between Virginians, Pennsylvanians, New Yorkers, and New Englanders are no more;” adding, “I am not a Virginian, but an American.”

By the middle of June, and before the Battle of Bunker Hill (Breed’s Hill), the Colonies were substantially united for war. During the previous month of March, Richard Henry Lee had introduced for adoption by the second Virginia Convention, a resolution that “the Colony be 27immediately put in a state of defence,” and advocated the immediate reorganization, arming, and discipline of the militia.

A hush of eager expectancy and an almost breathless waiting for some mysterious summons to real battle, seemed to pervade both north and south alike, when a glow in the east indicated the signal waited for, and even prayed for. The very winds of heaven seemed to bear the sound and flame of the first conflict in arms. In six days it reached Maryland. Intermediate Colonies, in turn, had responded to the summons, “To arms.” Greene’s Kentish Guards started for Boston, at the next break of day. The citizens of Rhode Island caught his inspiration, took possession of more than forty British cannon, and asserted their right and purpose to control all Colonial stores.

New York organized a Committee of Public Safety,—first of a hundred, and then of a thousand,—of her representative men, as a solid guaranty of her ardent sympathy with the opening struggle, declaring that “all the horrors of civil war could not enforce her submission to the acts of the British crown.” The Custom-house and the City Hall were seized by the patriots. Arming and drilling were immediate; and even by candle-light and until late hours, every night, impassioned groups of boys, as well as men, rehearsed to eager listeners the story of the first blood shed at Concord and Lexington; and strong men exchanged vows of companionship in arms, whatever might betide. Lawyers and ministers, doctors and teachers, merchants and artisans, laborers and seamen, mingled together as one in spirit and one in action. An “Association for the defence of Colonial Rights” was formed, and on the twenty-second of May the Colonial Assembly was succeeded by a Provincial Congress, and the new order of government went into full effect.

In New Jersey, the people, no less prompt, practical, 28and earnest, seized one hundred thousand dollars belonging to the Provincial treasury, and devoted it to raising troops for defending the liberties of the people.

The news reached Philadelphia on the twenty-fourth of April, and there, also, was no rest, until action took emphatic form. Prominent men, as in New York, eagerly tendered service and accepted command, so that on the first day of May the Pennsylvania Assembly made an appropriation of money to raise troops. Benjamin Franklin, but just returned from England, was made chairman of a Committee of Safety, and the whole city was aroused in hearty support of the common cause. The very Tory families which afterwards ministered to General Howe’s wants, and flattered Benedict Arnold by their courtesies, did not venture to stem the patriotic sentiment of the hour.

Virginia caught the flying spark. No flint was needed to fire the waiting tinder there. Lord Dunmore had already sent the powder of the Colony on board a vessel in the harbor. Patrick Henry quickly gathered the militia in force, to board the vessel and seize the powder. By way of compromise, the powder was paid for, but Henry was denounced as a “traitor.” The excitement was not abated, but intensified by this action, until Lord Dunmore, terrified, and powerless to stem the surging wave of patriotic passion, took refuge upon the man-of-war Fowey, then in the York river.

The Governor of North Carolina, as early as April, had quarrelled with the people of that Colony, in his effort to prevent the organization of a Provincial Congress. But so soon as the news was received from Boston of the opening struggle, the Congress assembled. Detached meetings were everywhere held in its support, and from all sides one sentiment was voiced, and this was its utterance: “The cause of Boston is the cause of all. Our 29destinies are indissolubly connected with those of our eastern fellow-citizens. We must either submit to the impositions which an unprincipled and unrepresented Parliament may impose, or support our brethren who have been doomed to sustain the first shock of Parliamentary power; which, if successful there, will ultimately overwhelm all, in one common calamity.” Conformable to these principles, a Convention assembled at Charlotte, Mecklenburg County, on the twentieth of May, 1775, and unanimously adopted the Instrument, ever since known as The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence.

In South Carolina, on the twenty-first day of April, a secret committee of the people, appointed for the purpose, forcibly entered the Colonial magazine and carried away eight hundred stands of arms and two hundred cutlasses. Thomas Corbett, a member of this committee, secured and opened a royal package just from England, containing orders to governors of each of the southern Colonies to “seize all arms and powder.” These were forwarded to the Continental Congress. Another despatch, dated at “Palace of Whitehall, December 23d,” stated that “seven regiments were in readiness to proceed to the southern Colonies; first to North Carolina, thence to Virginia, or South Carolina, as circumstances should point out.” These intercepted orders contained an “Act of Parliament, forbidding the exportation of arms to the Colonies,” and stimulated the zeal of the patriots to secure all within their reach. Twenty days later, the tidings from the north reached Charleston, adding fuel to the flame of the previous outbreak.

At Savannah, Ga., six members of the “Council of Safety” broke open the public magazine, before receipt of news from the north, seized the public powder and bore it away for further use. Governor Wright addressed a letter to General Gage at Boston, asking for troops, 30“to awe the people.” This was intercepted, and through a counterfeit signature General Gage was advised, “that the people were coming to some order, and there would be no occasion for sending troops.”

Such is the briefest possible outline of the condition of public sentiment throughout the country, of which Washington was well advised, so far as the Committee of the Continental Congress, of which he was a member, could gather the facts at that time.

Meanwhile, Boston was surrounded by nearly twenty thousand Minute Men. These Minute Men made persistent pressure upon every artery through which food could flow to relieve the hungry garrison within the British lines.

Neither was the excitement limited to the immediate surroundings. Ethan Allen, who had migrated from Connecticut to Vermont, led less than a hundred of “Green Mountain Boys,” as they were styled, to Ticonderoga, which he captured on the tenth of May. Benedict Arnold, of New Haven, with forty of the company then and still known as the Governor’s Guards, rushed to Boston without waiting for orders, and then to Lake Champlain, hoping to raise an army on the way. Although anticipated by Ethan Allen in the capture of Ticonderoga, he pushed forward toward Crown Point and St. John’s, captured and abandoned the latter, organized a small naval force, and with extraordinary skill defeated the British vessels and materially retarded the advance of the British flotilla and British troops from the north.

These feverish dashes upon frontier posts were significant of the general temper of the people, their desire to secure arms and military supplies supposed to be in those forts, and indicated their conviction that the chief danger to New England was through an invasion from Canada. But the absorbing cause of concern was the deliverance of Boston from English control.

The Second Continental Congress convened on the tenth day of May, 1775. On the same day, Ethan Allen captured Ticonderoga, also securing two hundred cannon which were afterwards used in the siege of Boston. Prompt measures were at once taken by Congress for the purchase and manufacture of both cannon and powder. The emission of two millions of Spanish milled dollars was authorized, and twelve Colonies were pledged for the redemption of Bills of Credit, then directed to be issued. At the later, September, session, the Georgia delegates took their seats, and made the action of the Colonies unanimous.

A formal system of “Rules and Articles of War” was adopted, and provision was made for organizing a military force fully adequate to meet such additional troops as England might despatch to the support of General Gage. Further than this, all proposed enforcement by the British crown of the offensive Acts of Parliament, was declared to be “unconstitutional, oppressive, and cruel.”

Meanwhile, the various New England armies were scattered in separate groups, or cantonments, about the City of Boston, with all the daily incidents of petty warfare which attach to opposing armies within striking distance, when battle action has not yet reached its desirable opportunity. And yet, a state of war had been so far 32recognized that an exchange of prisoners was effected as early as the sixth day of June. General Howe made the first move toward open hostilities by a tender of pardon to all offenders against the Crown except Samuel Adams and John Hancock; and followed up this ostentatious and absurd proclamation by a formal declaration of Martial Law.

The Continental Congress as promptly responded, by adopting the militia about Boston, as “The American Continental Army.”

On the fourteenth day of June, a Light Infantry organization of expert riflemen was authorized, and its companies were assigned to various Colonies for enlistment and immediate detail for service about Boston.

On the fifteenth day of June, 1775, Congress authorized the appointment, and then appointed George Washington, of Virginia, as “Commander-in-Chief of the forces raised, or to be raised, in defence of American Liberties.” On presenting their commission to Washington it was accompanied by a copy of a Resolution unanimously adopted by that body, “That they would maintain and assist him, and adhere to him, with their lives and fortunes, in the cause of American Liberty.”

It is certain from the events above outlined, which preceded the Revolutionary struggle, that when Washington received this spontaneous and unanimous appointment, he understood definitely that the Colonies were substantially united in the prosecution of war, at whatever cost of men and money; that military men of early service and large experience could be placed in the field; that the cause was one of intrinsic right; and that the best intellects, as well as the most patriotic statesmen, of all sections, were ready, unreservedly, to submit their destinies to the fate of the impending struggle. He had been upon committees on the State of Public Affairs; was 33constantly consulted as to developments, at home and abroad; was familiar with the dissensions among British statesmen; and had substantial reasons for that sublime faith in ultimate victory which never for one hour failed him in the darkness of the protracted struggle. He also understood that not statesmen alone, preëminently Lord Dartmouth, but the best soldiers of Great Britain had regarded the military occupation of Boston, where the Revolutionary sentiment was most pronounced, and the population more dense as well as more enlightened, to be a grave military as well as political error. And yet, as the issue had been forced, it must be met as proffered; and the one immediate and paramount objective must be the expulsion of the British garrison and the deliverance of Boston. It will appear, however, as the narrative develops its incidents, that he never lost sight of the exposed sea-coast cities to the southward, nor of that royalist element which so largely controlled certain aristocratic portions of New York, New Jersey, and the southern cities, which largely depended upon trade with Great Britain and the West Indies for their independent fortunes and their right royal style of living. Neither did he fail to realize that delay in the siege of Boston, however unavoidable, was dangerous to the rapid prosecution of general war upon a truly military plan of speedy accomplishment.

His first duty was therefore with his immediate command, and the hour had arrived for the consolidation of the various Colonial armies into one compact, disciplined, and effective force, to battle with the best troops of Great Britain which now garrisoned Boston and controlled its waters.