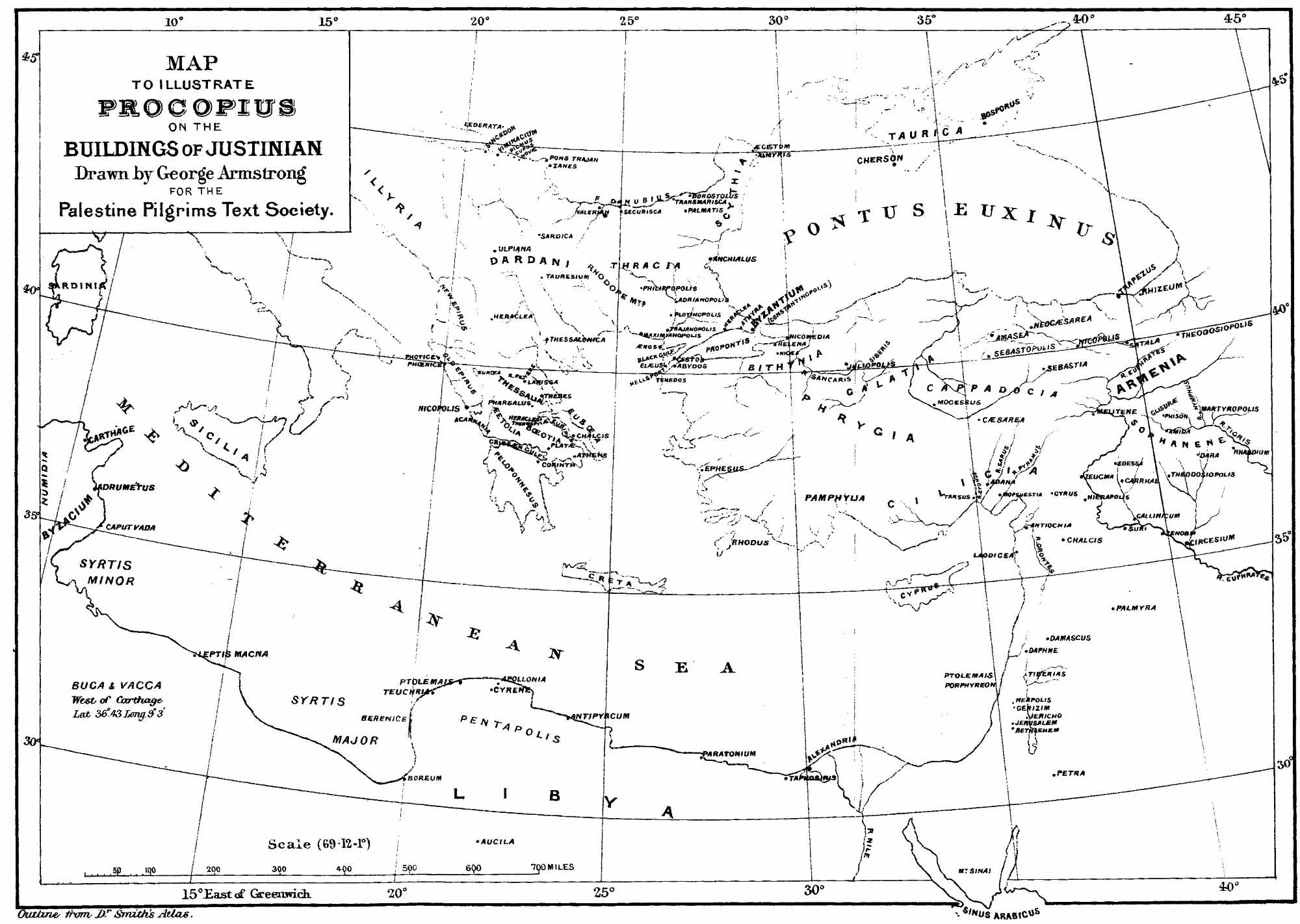

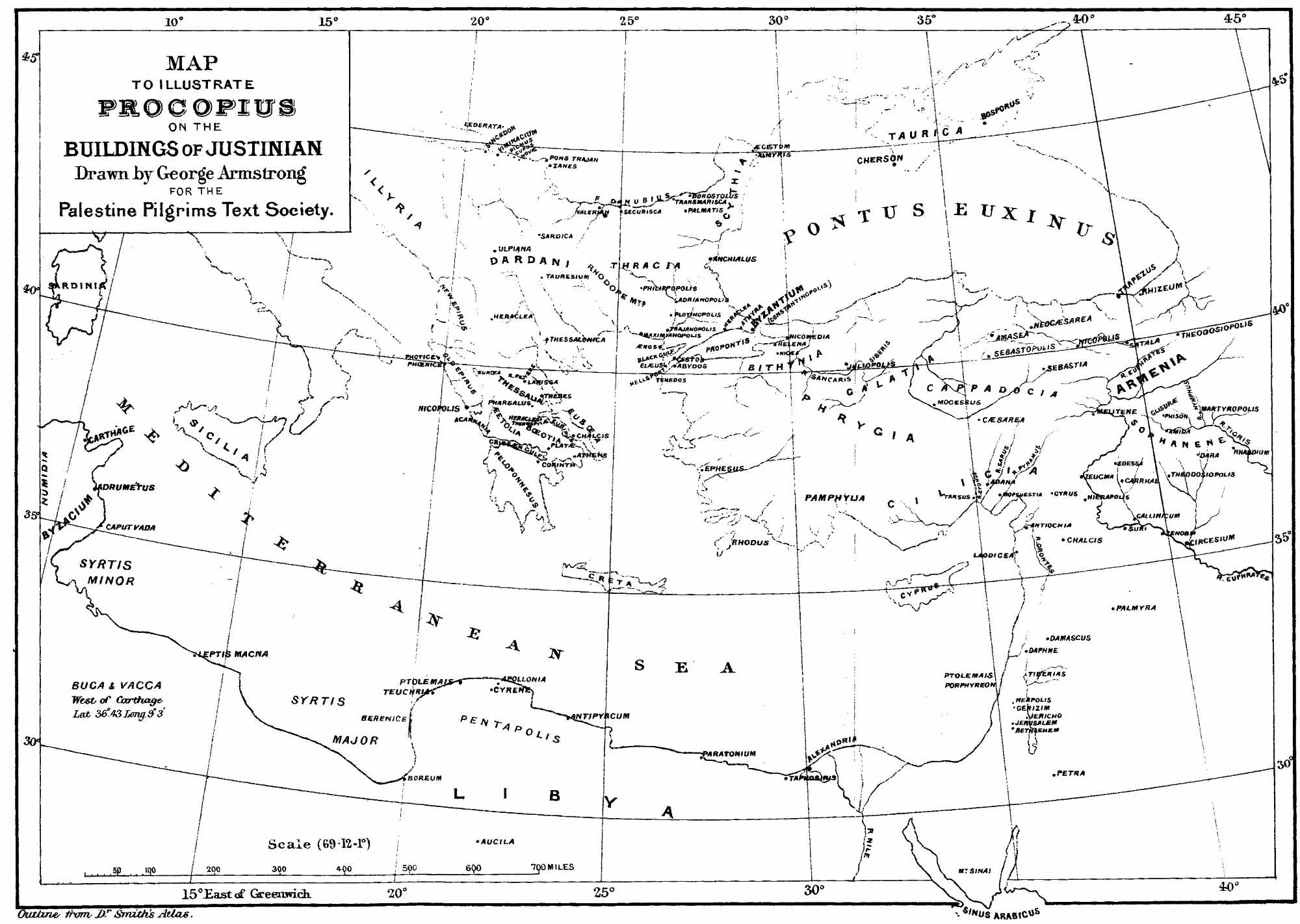

Drawn by George Armstrong FOR THE Palestine Pilgrims Text Society.

Outline from Dr. Smith’s Atlas.

Title: Of the Buildings of Justinian

Author: Procopius

Annotator: T. Hayter Lewis

Sir Charles William Wilson

Translator: Aubrey Stewart

Release date: May 21, 2021 [eBook #65404]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Turgut Dincer, Les Galloway and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Obvious typographical errors have been silently corrected. Variations in hyphenation, spelling and punctuation remain unchanged.

The table of contents was added by the transcriber

The cover was prepared by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

iii

Palestine Pilgrims’ Text Society.

OF THE

BY

PROCOPIUS

(Circ. 560 A.D.).

Translated by

AUBREY STEWART, M.A.,

LATE FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE,

AND ANNOTATED BY

COL. SIR C. W. WILSON, R.E., K.C.M.G., F.R.S.,

AND

PROF. HAYTER LEWIS, F.S.A.

LONDON:

1. ADAM STREET, ADELPHI.

1888.

Procopius was born at Cæsarea in Palestine, early in the sixth or at the end of the fifth century. He made his way, an adventurer, to Constantinople, where he began as an advocate and Professor of Rhetoric. He had the good fortune to be recommended to Belisarius, who appointed him one of his secretaries. In that capacity Procopius accompanied the general in his expedition to the East, A.D. 528, and in that against the Vandals, A.D. 533. The successful prosecution of the war enriched Belisarius to such an extent that he was enabled to maintain a retinue of 7000 men, of whom Procopius seems to have been one of the most trusted, since we find him appointed Commissary General in the Italian war. On his return to Constantinople, he was decorated with one of the innumerable titles of the Byzantine Court, and entered into the Senate. In the year 562 he was made Prefect of Constantinople, and is supposed to have died in 565—the same year as his former patron Belisarius.

His works are (1) the Histories (ἱστορίαι) in eight books, namely, two on the Persian War (408-553), two on the War with the Vandals (395-545), and four on the Wars with the Goths, bringing the History down to the year 553. iv (2) The six books on the Buildings of Justinian, and (3) the Anecdota, or Secret History—a work which has always been attributed to him.

The ‘Histories’ appeared first in Latin, 1470, the translator being Leonardo Bruni d’Arezzo (Leonardo Aretino), who, believing his own MS. to be the only one in existence, gave himself out for the author. They were first published in Greek, at Augsburg, 1607: but the ‘Buildings’ had already appeared at Basle, 1531.

The ‘Secret History’ was first published, with a translation into Latin, at Lyons in 1623. The ‘Histories’ and the ‘Anecdota’ have been translated into French. An English translation of the ‘Secret History’ was published in 1674. No other part of Procopius has, until now, been translated.

The following version of the ‘De Ædificiis’ has been specially made for the Pilgrims’ Text Society, by Aubrey Stewart (late Fellow of Trinity, Cambridge), who has added the valuable notes marked (S.). The notes marked (L.), chiefly archæological, have been supplied by Professor Hayter Lewis, and those marked (W.), chiefly topographical, by Colonel Sir C. W. Wilson, the Director of the Society.

The illustrations of St. Sophia are taken from the magnificent work by Salzenberg, published at Berlin.

Those from Texier and Pullan are taken by the kind permission of Mr. Pullan from their work on ‘Byzantine Architecture.’

In the investigation of the antiquities of Palestine, the name of Justinian, as associated with them, comes forward as often as that of Constantine or Herod.

From Bethlehem to Damascus—from the sea-coast to v far beyond the Jordan—there are few places of note in which some remains, dating from his era, do not exist, or in which, at the least, some records of his works are not left in the history of his time. To him Mount Sinai owes the Church of the Holy Virgin.

At Bethlehem he is said to have enlarged, if not rebuilt, the great Basilica.

At Gerizim the mountain still bears on its summit the remains of the church which he there constructed, and Tiberias is still surrounded, in part, by the walls raised by him.

He is known to have constructed a large church to the Virgin on the Mount of Olives, and several other churches in and about Jerusalem, the grandest of which is described to have been an architectural gem, was in the Harem area itself.

Besides these, which are definitely recorded to have been his work, he is supposed by some of the best authorities to have erected the Golden Gate and the Double Gate; and of late years it has been contended that the Sakhrah itself was constructed by him as it now exists.

But there is scarcely one of these edifices, where remains of them exist or are supposed so to do, which has not been the subject of controversy, the authorship of the Sakhrah (taking that as an instance) having been assigned, by various persons who would usually be considered as authorities on the subject, to the Romans under Constantine, to the Byzantines under Justinian, and to the Arabs under Abd-el-Melek.

It becomes, therefore, important to have a clear record as to what Justinian did, not only in Palestine but in vi other countries, so as to be able to judge to some extent, by well-authenticated examples, of the founders of those edifices whose history is involved in doubt.

Of the writers who can give us this record, none has such authority as Procopius, or gives so much detailed information; and he has, for that reason, been largely quoted by Gibbon and by well-nigh every other writer on Byzantine history; and he gives such definite information as to the dates of many of Justinian’s buildings which remain to us, as to form a standard by which to recognise the general characteristics in outline and detail adopted by his architects in his greatest works, and which characterize the style now well known as Byzantine.

Its first and greatest example is St. Sofia at Constantinople, which is, perhaps, the boldest instance of a sudden change in almost every respect, whether of plan, elevation, or detail, which is known in architecture.

Before its construction, the ground-plan of well-nigh every building known to Western architects had defined the plan of all above it.

The columns in the apse of the Basilica, or church, carried galleries or other erections above it, of varied design, but in the same straight or curved lines as those beneath them.

The lines of the dome (except in slightly exceptional cases, such as the ruin known as the Temple of Minerva Medica at Rome, or the Temple of the Winds at Athens) were carried up on the distinct lines of the lower walls.

The capitals of the columns in the works of the ancient Greeks or Romans were in each building carved on the same design; and however beautiful each might be, vii the eye would see but one form of the Doric, Ionic, or Corinthian, through the whole range of a colonnade.

The Byzantines changed all that.

The great dome of St. Sophia (the boldest piece of novel construction ever, perhaps, attempted) forms the crown of a building quite original in plan; and this dome is placed, not as that of the Roman Pantheon, low down on thick walls of its own form, but suspended high above all the roof around it, on four arches, which spring from detached piers, the keystone alone of each arch giving a direct support to the dome; in every other part it overhangs the void in the boldest manner.

The circular work between these arches is carried in a manner which is comparatively easy to imitate now; but the rude and often picturesque results of attempts at imitation in mediæval times, more especially in the South of France, show how difficult the work was found to be at the outset.

Earthquake and faults of construction occasioned the rebuilding of the great dome; but it still crowns, after a trial of more than 1,300 years, one of the most beautiful buildings in existence.

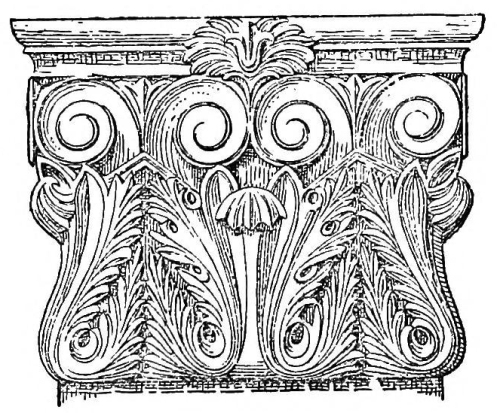

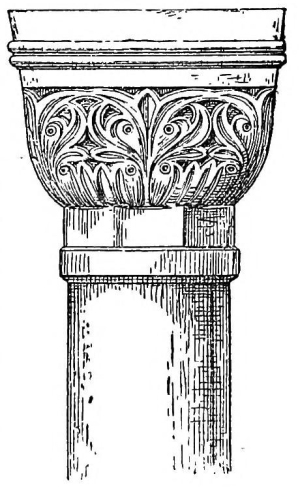

Then the capitals of the columns, whose general outlines bear few traces of the ancient orders, were often carved each in a different manner, and, though harmonizing with each other in general outline, could bear separate scrutiny, and show each a special motive and design.

The carving of these capitals, and of the other beautiful scroll-work and foliage which decorate the walls of St. Sophia, has come down to us through the Normans, and is quite peculiar.

viii

It had none of the soft, round forms which the Romans loved, but is cut in a sharp, crisp, and somewhat stiff style, casting distinctly marked and sharp shadows, and the eyes of the foliage and other well-marked parts are emphasized by being deeply drilled in. Many of the Byzantine characteristics had been, to a large extent, foreshadowed in Eastern buildings, even at so early a time as the Assyrian bas-reliefs; but it is to Byzantine architects, under the fostering care of Justinian, that we owe the picturesque changes and details of that style, the Byzantine, which takes its name from his capital and is, to a large extent, identified with himself.

All the drawings have been made for this volume by Mr. George Armstrong, formerly on the Survey Party under Captain Conder and Captain Kitchener.

(L.)

ix

| PAGE | |

| MAP ILLUSTRATING PROCOPIUS | Frontispiece |

| PLAN OF CONSTANTINOPLE | 1 |

| CHURCH OF ST. SOPHIA | 5 |

| DETAILS OF CAPITALS, ETC., OF ST. SOPHIA | 7 |

| SECTION OF ST. SOPHIA | 9 |

| SS. SERGIUS AND BACCHUS, CHURCH OF | 19 |

| FORTIFICATIONS AT DARA | 42 |

| CASTLE AND COLUMNS OF EDESSA | 60 |

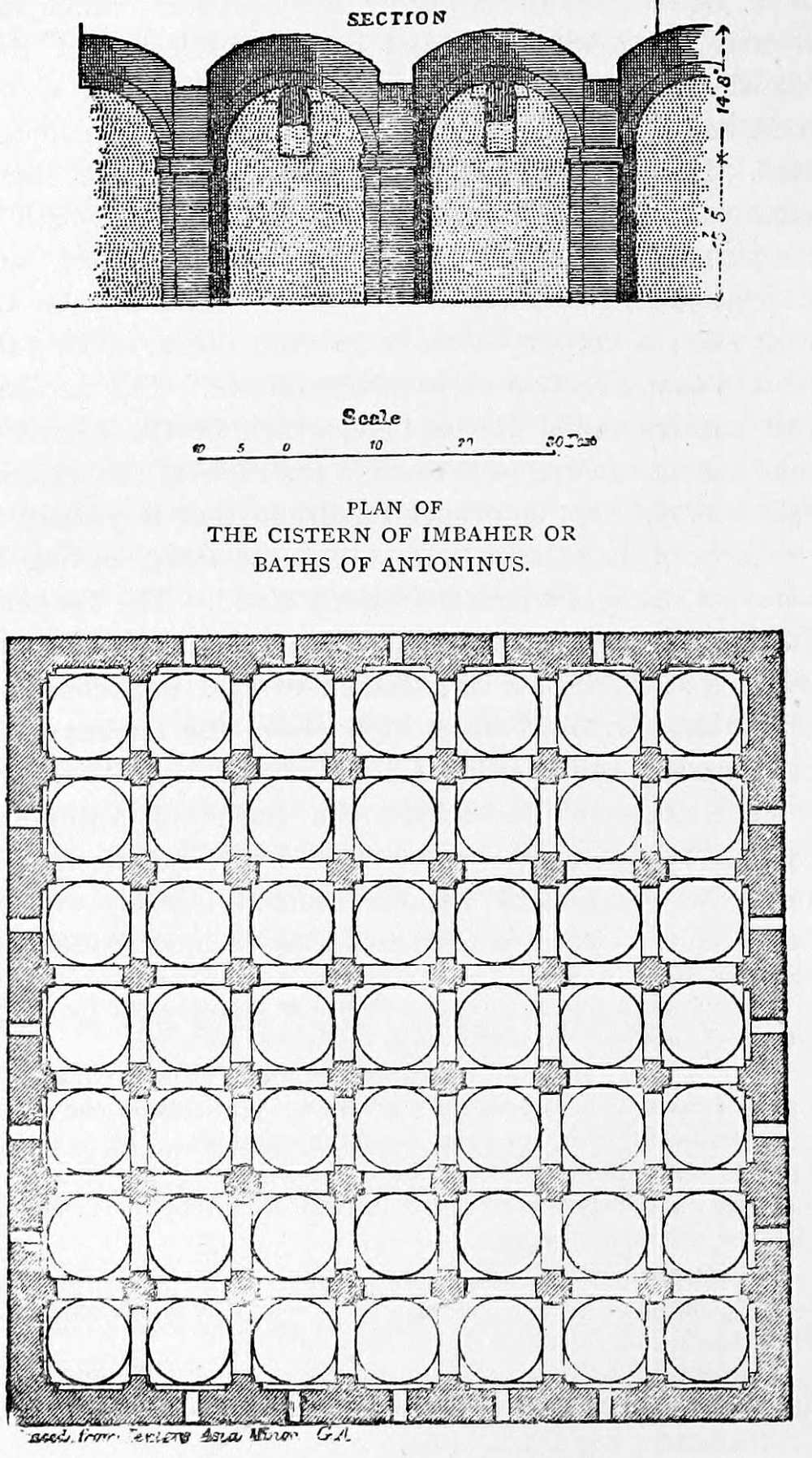

| CISTERN OF IMBAHER OR BATHS OF ANTONINUS | 132 |

| BRIDGE ACROSS THE RIVER SANGARIS | 133 |

| ES SAKHRA (DOME OF THE ROCK) | 139 |

| EL AKSA | 140 |

| CHURCH ON MOUNT GERIZIM | 144 |

| CHURCH AT BETHLEHEM | 148 |

| CHURCH OF MAGNE KAHIREH | 160 |

1

I have not begun this work through any desire to make a display of my own virtue, or trusting to my powers of language, or wishing to gain credit by my knowledge of the places described, for I had nothing to encourage me to undertake so bold a project. But I have often reflected on the great blessings which countries derive from history, which transmits to posterity the remembrance of our ancestors, and opposes the efforts of time to cover them with oblivion; which always encourages virtue in its readers by its praise, and deters them from vice by its blame, and in this way destroys its power. All we need study then is to make clear what has been done, and by whom of mankind it was done; and this, I imagine, is not impossible even for the weakest and feeblest writer; besides this, the writing of history enables subjects who have been kindly treated by their rulers, to express their gratitude, and to make a more than adequate return, seeing that they only for a time enjoy the goodness of their princes, while they render their virtues immortal in the memory of their descendants, many of whom in this 2 very way have been led by the glory of their ancestors to a love of virtue, and have been probably preserved from a dissolute course of life by the dread of disgrace. I will shortly explain my object in making these prefatory remarks.

The Emperor Justinian was born in our time,[1] and succeeding to the throne when the state was decayed, added greatly to its extent and glory by driving out from it the barbarians, who for so long a time had forced their way into it, as I have briefly narrated in my ‘History of the Wars.’ They say that Themistocles, the son of Neocles, prided himself on his power of making a small state great, but our Emperor has the power of adding other states to his own, for he has annexed to the Roman Empire many other states which at his accession were independent, and has founded innumerable cities which had no previous existence. As for religion, which he found uncertain and torn by various heresies, he destroyed everything which could lead to error, and securely established the true faith upon one solid foundation. Moreover, finding the laws obscure through their unnecessary multitude, and confused by their conflict with one another, he firmly established them by reducing the number of those which were unnecessary, and in the case of those that were contradictory, by confirming the better ones. He forgave of his own accord those who plotted against him, 3 and, by loading with wealth those who were in want, and relieving them from the misfortunes which had afflicted them, he rendered the empire stable and its members happy. By increasing his armies he strengthened the Roman Empire, which lay everywhere exposed to the attacks of barbarians, and fortified its entire frontier by building strong places. Of his other acts the greater part have been described by me in other works, but his great achievements in building are set forth in this book. We learn from tradition that Cyrus the Persian was a great king, and the chief founder of the empire of his countrymen; but whether he had any resemblance to that Cyrus who is described by Xenophon the Athenian in his Cyropædia, I have no means of telling, for possibly the art of the writer has given some embellishments to his achievements; while as for our present Emperor Justinian (whom I think one may rightly call a king by nature, since, as Homer says, he is as gentle as a father), if one accurately considers his empire, one will regard that of Cyrus as mere child’s play.[2] The proof of this will be that the empire, as I just now said, has been more than doubled by him, both in extent and in power; whilst his royal clemency is proved by the fact that those who wickedly plotted against his life, although they were clearly convicted, not only are alive and in possession of their property at the present day, but even command Roman armies, and have been promoted to the consular dignity. Now, as I said before, we must turn our attention to the buildings of this monarch, lest posterity, beholding the enormous size and number of them, should deny their being the work of one man; for the works of many men of former times, not being confirmed by history, have 4 been disbelieved through their own excessive greatness. As is natural, the foundation of all my account will be the buildings in Byzantium, for, as the old proverb has it, when we begin a work we ought to put a brilliant frontispiece to it.

5

I. The lowest dregs of the people in Byzantium once assailed the Emperor Justinian in the rebellion called Nika, which I have clearly described in my ‘History of the Wars.’ To prove that it was not merely against the Emperor, but no less against God that they took up arms, they ventured to burn the church of the Christians. (This church the people of Byzantium call Sophia, i.e., Σοφία—Wisdom; a name most worthy of God.) God permitted them to effect this crime, knowing how great the beauty of this church would be when restored. Thus the church was entirely reduced to ashes; but the Emperor Justinian not long afterwards adorned it in such a fashion, that if anyone had asked the Christians in former times if they wished their church to be destroyed and thus restored, showing them the appearance of the church which we now see, I think it probable that they would have prayed that they might as soon as possible behold their church destroyed, in order that it might be turned into its present form. The Emperor, regardless of expense of all kinds, pressed on its restoration, and collected together all the workmen from every land, Anthemius of Tralles,[3] 6 by far the most celebrated architect, not only of his own but of all former times, carried out the King’s zealous intentions, organized the labours of the workmen, and prepared models of the future construction. Associated with him was another architect named Isidorus, a Milesian by birth, a man of intelligence, and worthy to carry out the plans of the Emperor Justinian. It is, indeed, a proof of the esteem with which God regarded the Emperor, that He furnished him with men who would be so useful in effecting his designs, and we are compelled to admire the intelligence of the Emperor, in being able to choose the most suitable of mankind to carry out the noblest of his works.

The church consequently presented a most glorious spectacle, extraordinary to those who beheld it, and altogether incredible to those who are told of it. In height it rises to the very heavens, and overtops the neighbouring buildings like a ship anchored among them: it rises above the rest of the city, which it adorns, while it forms a part of it, and it is one of its beauties that being a part of the city, and growing out of it, it stands so high above it, that from it the whole city can be beheld as from a watch-tower. Its length and breadth are so judiciously arranged that it appears to be both long and wide without being disproportioned. It is distinguished by indescribable beauty, for it excels both in its size and in the harmony of its proportion, having no part excessive and none deficient; being more magnificent than ordinary buildings, and much more elegant than those which are out of proportion. It is singularly full of light and sunshine; you would declare that the place is not lighted by the sun from without, but that the rays are produced within itself, such an abundance of light is poured into this church. Now the front of the church (that is to say the part towards the rising 7 sun, where the sacred mysteries are performed in honour of God) is built as follows. The building rises from the ground, not in a straight line, but set back somewhat obliquely, and retreating in the middle into the form of a half-circle, a form which those who are learned in these matters call semi-cylindrical, rising perpendicularly. The upper part of this work ends in the fourth part of a sphere, and above it another crescent-shaped structure is raised upon the adjacent parts of the building, admirable for its beauty, but causing terror by the apparent weakness of its construction; for it appears not to rest upon a secure foundation, but to hang dangerously over the heads of those within, although it is really supported with especial firmness and safety. On each side of these there are columns standing 8 upon the floor, which themselves also are not placed in a straight line, but arranged with an inward curve of semicircular shape, one beyond another, like the dancers in a chorus. These columns support above them a crescent-shaped structure. Opposite this east wall is built another wall containing the entrances, and upon either side of it also stand columns with stonework above them in a half-circle exactly like those previously described. In the midst of the church are four masses of stone called piers, two on the north and two on the south side, opposite and equal to one another, having four columns in the central space between each. These piers are composed of large stones fitted together, the stones being carefully selected and cleverly jointed into one another by the masons, reaching to a great height. Looking at them you would compare them to perpendicular cliffs. Upon these four arches rise in a quadrilateral form. The extremities of these arches join one another in pairs, and rest at their ends upon these piers, while the other part of them rise to a great height, and are suspended in the air. Two of these arches, that is, those towards the rising and the setting sun, are constructed over the empty air, but the remainder have under them some stonework, with small columns. Now above these arches is raised a circular building of a spherical form through which the light of day first shines; for the building, I imagine, overtops the whole country, and has small openings left on purpose, so that the places where these intervals in the construction occur may serve for conductors of light. Thus far I imagine the building is not incapable of being described, even by a weak and feeble tongue. As the arches are arranged in a quadrangular figure, the stonework between them takes the shape of a triangle; the lower angle of each triangle, 9 being compressed between the shoulders of the arches, is slender, while the upper part becomes wider as it rises in the space between them, and ends against the circle which rises from thence, forming there its remaining angles. A spherical-shaped dome standing upon this circle makes it exceedingly beautiful; from the lightness of the building it does not appear to rest upon a solid foundation, but to cover the place beneath as though it were suspended from heaven by the fabled golden chain. All these parts surprisingly joined to one another in the air, suspended one from another, and resting only on that which is next to them, form the work into one admirably harmonious whole, which spectators do not care to dwell upon for long in the mass, as each individual part attracts the eye and turns it to itself. The sight causes men to constantly change their point of view, and the spectator can nowhere point to any part which he admires more than the rest, but having viewed the art which appears everywhere, men contract their eyebrows as they look at each point, and are unable to comprehend such workmanship, but always depart thence stupified through their incapacity to comprehend it. So much for this.

The Emperor Justinian and the architects Anthemius and Isidorus used many devices to construct so lofty a church with security. One alone of these I will at this present time explain, by which a man may form some opinion of the strength of the whole work; as for the others, I am not able to discover them all, and find it impossible to explain them in words. It is as follows:—The piers[4] of 10 which I just now spoke are not constructed in the same manner as the rest of the building, but in this fashion: they consist of quadrangular courses of stones, rough by nature, but made smooth by art; of these stones, those which make the projecting angles of the pier are cut angularly, while those which go in the middle parts of the sides are cut square. They are fastened together not with what is called unslaked lime, not with bitumen, the boast of Semiramis at Babylon, nor anything of the kind, but with lead, which is poured between the interstices, and which, pervading the whole structure, has sunk into the joints of the stones, and binds them together; this is how they are built. Let us now proceed to describe the remaining parts of the church. The entire ceiling is covered with pure gold, which adds glory to its beauty, though the rays of light reflected upon the gold from the marble surpass it in beauty; there are two porticos on each side, which do not in any way dwarf the size of the church, but add to its width. In length they reach quite to the ends, but in height they fall short of it; these also have a domed ceiling and are adorned with gold. Of these two porticos, the one is set apart for male, and the other for female worshippers; there is no variety in them, nor do they differ in any respect from one another, but their very equality and similarity add to the beauty of the church. Who could describe the galleries[5] of the portion set apart for women, or the numerous porticos and cloistered courts 11 with which the church is surrounded? who could tell of the beauty of the columns and marbles with which the church is adorned? one would think that one had come upon a meadow full of flowers in bloom: who would not admire the purple tints of some and the green of others, the glowing red and glittering white, and those, too, which nature, like a painter, has marked with the strongest contrasts of colour? Whoever enters there to worship perceives at once that it is not by any human strength or skill, but by the favour of God that this work has been perfected; his mind rises sublime to commune with God, feeling that He cannot be far off, but must especially love to dwell in the place which He has chosen; and this takes place not only when a man sees it for the first time, but it always makes the same impression upon him, as though he had never beheld it before. No one ever became weary of this spectacle, but those who are in the Church delight in what they see, and, when they leave it, magnify it in their talk about it; moreover, it is impossible accurately to describe the treasure of gold and silver plate and gems, which the Emperor Justinian has presented to it; but by the description of one of them, I leave the rest to be inferred. That part of the church which is especially sacred, and where the priests alone are allowed to enter, which is called the Sanctuary, contains forty thousand pounds’ weight of silver!

The above is an account, written in the most abridged and cursory manner, describing in the fewest possible words the most admirable structure of the church at Constantinople which is called the Great Church, built by the Emperor Justinian, who did not merely supply the funds for it, but assisted it by the labour and powers of his mind, as I will now explain. Of the two arches which I 12 lately mentioned (the architects call them ‘lori’[6]), that one which stands towards the east had been built up on each side, but had not altogether been completed in the middle, where it was still imperfect; now the piers upon which the building rested, unable to support the weight which was put upon them, somehow all at once split open, and seemed as though before long they would fall to pieces. Upon this Anthemius and Isidorus, terrified at what had taken place, referred the matter to the Emperor, losing all confidence in their own skill. He at once, I know not by what impulse, but probably inspired by heaven, for he is not an architect, ordered them to carry round this arch; for it, said he, resting upon itself, will no longer need the piers below. Now if this story were unsupported by witnesses, I am well assured that it would seem to be written in order to flatter, and to be quite incredible; but as there are many witnesses now alive of what then took place, I shall not hesitate to finish it. The workmen performed his bidding, the arch was safely suspended, and proved by experiment the truth of his conception. So much then for this part of the building; now with regard to the other arches, those looking to the south and to the north, the following incidents took place. When the arches called ‘lori’ were raised aloft during the building of the church, everything below them laboured under their 13 weight, and the columns which are placed there shed little scales, as though they had been planed. Alarmed at this, the architects again referred the matter to the Emperor, who devised the following plan. He ordered the upper part of the work that was giving way, where it touched the arches, to be taken down for the present, and to be replaced long afterwards when the damp had thoroughly left the fabric. This was done, and the building has stood safely afterwards, so that the structure as it were bears witness to the Emperor.

II. In front of the Senate House there is an open place which the people of Constantinople call the Augustæum: in it there are not less than seven courses of stone in a quadrangular form, arranged like steps, each one so much less in extent than that which is below, that each one of the stones projects sufficiently for the men who frequent that place to sit upon them as upon steps. From the topmost course a column rises to a great height—not a monolith, but composed of stones of a considerable periphery, which are cut square, and are fitted into one another by the skill of the masons. The finest brass, cast into panels and garlands, surrounds these stones on every side, binding them firmly together, while it covers them with ornament, and in all parts, especially at the capital and the base, imitates the form of the column. This brass is in colour paler than unalloyed gold; and its value is not much short of its own weight in silver. On the summit of the column there stands an enormous horse, with his face turned towards the east—a noble sight. He appears to be walking, and proceeding swiftly forwards; he raises his left fore-foot as though to tread upon the earth before him, while the other rests upon the stone beneath it, as though it would make the next step, while he places his 14 hind feet together, so that they may be ready when he bids them move. Upon this horse sits a colossal brass figure of the Emperor, habited as Achilles, for so his costume is called; he wears hunting-shoes, and his ankles are not covered by his greaves. He wears a corslet like an ancient hero, his head is covered by a helmet which seems to nod, and a plume glitters upon it. A poet would say that it was that ‘star of the dog-days’ mentioned in Homer.[7] He looks towards the east, directing his course, I imagine, against the Persians; in his left hand he holds a globe, by which the sculptor signifies that all lands and seas are subject to him. He holds no sword or spear, or any other weapon, but a cross stands upon the globe, through which he has obtained his empire and victory in war; he stretches forward his right hand towards the east, and spreading out his fingers seems to bid the barbarians in that quarter to remain at home and come no further. This is the appearance of the statue.

The Church of Irene,[8] which was next to the great 15 church, and was burnt down together with it, was rebuilt on a large scale by the Emperor Justinian—a church scarcely second to any in Byzantium except that of Sophia. There was between these two churches a hospice for the relief of destitute persons and those in the last extremity of disease, suffering in body as well as in fortune, which was built in former times by a God-fearing man named Sampson. This also did not remain unscathed by the insurgents, but perished in the fire, together with the two neighbouring churches. The Emperor Justinian rebuilt it in a more magnificent fashion, and with a much greater number of rooms, and he has also endowed it with a great annual revenue, in order that the sufferings of more unfortunate men may be relieved in it for the future. Insatiate as he was in his love for God, he built two other hospices opposite to this, in what are called the houses of Isidorus and Arcadius, being assisted in these pious works by the Empress Theodora. As for all the other churches which this Emperor raised in honour of Christ, they are so many in number and so great in size that it is impossible to describe them in detail, for no power of words nor one’s whole life would suffice to collect and to recite the list of their several names: let this much suffice.

III. We must begin with the churches of the Virgin Mary, for it is understood that this is the wish of the Emperor himself, and the true method of description distinctly points out that from God we ought to proceed to the Mother of God. The Emperor Justinian built in all parts of the Roman empire many churches dedicated to the Virgin, so magnificent and large, and constructed with such a lavish expenditure of money, that a person beholding any one of them singly would imagine it to have been his only work, and that he had spent the whole period of his reign in adorning it alone. For the present, as I said 16 before, I shall describe the churches in Byzantium. One of the churches of the Virgin[9] was built by him outside the walls, in a place named Blachernæ (for he must be credited with the pious foundations of Justin, his uncle, since he administered his kingdom at his own discretion). This church is near the sea-shore, of great sanctity and magnificence; it is long, yet its width is well proportioned to its length, and above and below it is supported and rests on nothing less than sections of Parian marble which stand in the form of columns. These columns are arranged in a straight line in all parts of the church except in the middle, where they are set back. Those who enter this church especially admire its lofty and at the same time secure construction, and its splendid yet not meretricious beauty.

He built another church in her honour in the place which is called the Fountain, where there is a thick grove of cypress trees, a meadow whose rich earth blooms with flowers, a garden abounding in fruit, a fountain which noiselessly pours forth a quiet and sweet stream of water, in short where all the surroundings beseem a sacred place. Such is the country around the church; but as for the church itself, it is not easy to describe it in fitting words, to form an idea of it in the mind, or to express it in language; let it suffice for me to say thus much of it, that in beauty and size it surpasses most other churches. Both these churches are built outside the city walls, the one at the place where the wall starts from the sea-shore, 17 the latter close to what is called the Golden Gate, which is near the further end of the fortifications, in order that both of them might form impregnable defences for the city walls. Besides these, in the temple of Hera, now called the Hiereum, he erected a church in honour of the Virgin, which cannot easily be described.

In that part of the city which is called Deuteron[10] he built a noble and admirable church in honour of St. Anne, whom some think to have been the mother of the Virgin, and the grandmother of Christ; for God, in choosing to become man, subjected Himself to having grand-parents and a genealogy on His mother’s side like a man. Not very far from this church, in the last street of the city, there is a fine church built in honour of the martyr Zoe.

He found the church of the Archangel Michael[11] at Byzantium small, very dark, and quite unworthy of being dedicated to the archangel, having been built by one Senator, a patrician in former times, and in shape very like a small bedroom in a poor man’s house. Wherefore he razed it entirely to the ground, that no part of its former unseemliness might be left, and rebuilding it of a goodly size, in the manner which we now see, changed it into a building 18 of wonderful beauty. This church is of a quadrangular form, its length apparently not greatly exceeding its width; of its sides, that which looks towards the east has at its extremities a thick wall constructed of a great mass of stones, but in the middle is set back, forming a recess, on each side of which the roof is supported by columns of variegated stone. The opposite wall, that towards the west, is pierced with doors opening into the church.

IV. His faith in the Apostles of Christ is testified in the following manner: In the first place he built the Church to SS. Peter and Paul, which did not exist before in Byzantium, close to the King’s palace, which was formerly called by the name of Hormisdas.[12] This was once his own private house; and when he became Emperor of the Romans, he made it look worthy of a palace by the magnificence of its buildings, and joined it to the other imperial apartments. Here also he built another church dedicated to the glorious saints Sergius and Bacchus,[13] and 19 afterwards another church standing obliquely to it. These two churches stand, not facing one another, but obliquely towards one another, joined together, and vying one with another. They have a common entrance, are equal to one another in all respects, are surrounded by a boundary wall, and neither of them exceeds the other or falls short of it, either in beauty, size, or any other respect; for each alike reflects the rays of the sun from its polished marble, and is alike covered with lavish gilding and 20 adorned with offerings; in one respect alone they differ, that the length of one is straight, whereas the columns of the other for the most part stand in a semicircle. They both have one portico at their vestibule, which from its great length is called Narthex.[14] The whole vestibule, the court, the inner doors from the court and the neighbourhood of the palace are alike common to both, and both these churches are so admirable that they form a great ornament to the entire city, and especially to the palace.

After this, out of his exceeding great reverence for all the Apostles,[15] he did as follows. In ancient times there was one church at Byzantium dedicated to all the Apostles, but through length of time it had become ruinous, and seemed not likely to stand much longer. Justinian took this entirely down, and was careful not only to rebuild it, but to render it more admirable both in size and beauty; he carried out his intention in the following manner. Two lines were drawn in the form of a cross, joining one another in the middle, the upright one pointing to the rising and setting sun, and the other cross line towards the north and the south wind. These were surrounded by a circuit of walls, 21 and within by columns placed both above and below; at the crossing of the two straight lines, that is, about the middle point of them, there is a place set apart, which may not be entered except by the priests, and which is consequently termed the Sanctuary. The transepts which lie on each side of this, about the cross line, are of equal length; but that part of the upright line towards the setting sun is built so much longer than the other part as to form the figure of the cross. That part of the roof which is above the Sanctuary is constructed like the middle part of the Church of Sophia, except that it yields to it in size; for the four arches are suspended and connected with one another in the same fashion, the circular building standing above them is pierced with windows, and the spherical dome which overarches it seems to be suspended in the air, and not to stand upon a firm base, although it is perfectly secure. In this manner the middle part of the roof is built: now the roof over the four limbs of the church is constructed of the same size as that which I have described over the middle, with this one exception, that the wall underneath the spherical part is not pierced with windows. When he had completed the building of this Sanctuary, the Apostles made it evident to all that they were pleased and thoroughly delighted with the honour paid them by the Emperor; for the bodies of the Apostles Andrew, Luke, and Timothy, which had before this been invisible and altogether unknown, were then made manifest to all men, signifying, I imagine, that they did not reject the faith of the Emperor, but permitted him openly to behold them, to approach and to touch them, that he might gain from them assistance and security for his life. This was discovered in the following manner.

The Emperor Constantine built this church in the 22 name and in honour of the Apostles, making a decree that there should be a sepulchre there for himself, and for those who should rule after him, women as well as men; which is observed even to the present day. Here also the body of the father of Constantine was laid; but he did not in any way hint that the bodies of the Apostles were there, nor did there appear to be any place set apart for the bodies of saints. When, however, the Emperor Justinian was rebuilding this church, the workmen dug up the whole foundation, lest any unseemly thing should be left in it. They saw there three neglected wooden coffins, which declared by inscriptions upon them that they contained the bodies of the Apostles Andrew, Luke, and Timothy, which the Emperor and all Christian men beheld with the greatest delight. A solemn procession and public festival was ordered, and, after the customary rites had been performed in their honour, the coffins were covered up, and again placed in the ground. The place was not left unmarked or uncared for, but was reverently dedicated to the bodies of the Apostles. In return for the respect paid them by the Emperor, the Apostles, as I said before, made themselves manifest to all men; for, under a religious prince, the host of heaven do not hold themselves aloof from the affairs of men, but love to mingle with them, and rejoice in intercourse with mankind.

Who could be silent about the Church of Acacius,[16] which, being ruinous, he pulled down and built up again from its very foundations, adding wonderfully to its size? 23 It rests on all sides upon brilliantly white columns, and its floor is covered with similar marble, from which so bright a light is reflected as to make one imagine that the whole church is covered with snow. Two porticos stand in front of it, the one supported on columns, and the other looking towards the forum. I was within a little of omitting to mention the church which was dedicated to St. Plato the Martyr,[17] a truly worthy and noble building, not far from the forum, which is named after the Emperor Constantine; and likewise the church dedicated to the Martyr Mocius,[18] which is the largest of all these churches. Besides this, there is the Church of the Martyr Thyssus, and the Church of St. Theodorus,[19] standing outside the city in the place which is called Rhesias, and the Church of the Martyr Thecla, which is near the harbour named after Julian, and that of St. Theodota in the suburb which is called Hebdomon. All these were built from their foundations by this Emperor during the reign of his uncle Justin, and are not easy to describe in words, while it is impossible to admire them sufficiently when beholding them. My narrative is now attracted to the Church of St. Agathonicus,[20] and I am forced to mention it, 24 though I have no longer voice nor words befitting such a work: let it be sufficient for me to have said thus much of it; I will leave the description of its beauty and sumptuousness in all respects to others to whom the subject is fresh, and who are not wearied out by their labours.

V. Finding other churches in what is called the Anaplus, and along the coast of the opposite continent, which were not worthy to be dedicated to any of the saints, as also round the gulf which the natives call Ceras,[21] after the name of Ceroessa, the mother of Byzans, who was the founder of the city, he showed a royal munificence in all of them, as I will presently prove, having first said a few words about the glory which the sea adds to Byzantium.

The prosperity of Byzantium is increased by the sea which enfolds it, contracting itself into straits, and connecting itself with the ocean, thus rendering the city remarkably beautiful, and affording a safe protection in its harbours to seafarers, so as to cause it to be well supplied with provisions and abounding with all necessaries; for the two seas which are on either side of it, that is to say the Ægean and that which is called the Euxine, which meet at the east part of the city and dash together as they mingle their waves, separate the continent by their currents, and add to the beauty of the city while they surround it. It is, therefore, encompassed by three straits connected with one another, arranged so as to minister both to its elegance and its convenience, all of them most charming for sailing on, lovely to look at, and exceedingly safe for anchorage. The middle one of them, 25 which leads from the Euxine Sea, makes straight for the city as though to adorn it. Upon either side of it lie the several continents, between whose shores it is confined, and seems to foam proudly with its waves because it passes over both Asia and Europe in order to reach the city; you would think that you beheld a river flowing towards you with a gentle current. That which is on the left hand of it rests on either side upon widely extended shores, and displays the groves, the lovely meadows, and all the other charms of the opposite continent in full view of the city. As it makes its way onward towards the south, receding as far as possible from Asia, it becomes wider; but even then its waves continue to encircle the city as far as the setting of the sun. The third arm of the sea joins the first one upon the right hand, starting from the place called Sycæ,[22] and washes the greater part of the northern shore of the city, ending in a bay. Thus the sea encircles the city like a crown, the interval consisting of the land lying between it in sufficient quantity to form a clasp for the crown of waters. This gulf is always calm, and never crested into waves, as though a barrier were placed there to the billows, and all storms were shut out from thence, through reverence for the city. Whenever strong winds and gales fall upon these seas and this strait, ships, when they once reach the entrance of this gulf, run the rest of their voyage unguided, and make the shore at random; for the gulf extends for a distance of more than forty stadia in circumference, and the whole of it is a harbour, so that when a ship is moored there the stern rests on the sea and the bows on the land, as though the two elements contended with one another to see which of them could be of the greatest service to the city.

VI. Such is the appearance of this gulf; but the Emperor 26 Justinian rendered it more lovely by the beauty of the buildings with which he surrounded it; for on the left side of it, he, to speak briefly, altered the Church of St. Laurentius the Martyr, which formerly was without windows and very dark,[23] into the appearance which it now presents; and in front of it he built the Church of the Virgin, in the place which is called Blachernæ, as I described a little above. Behind it he built a new church to SS. Priscus and Nicolaus, renewing the whole building. This is an especially favourite resort of the people of Byzantium, partly from their respect and reverence for the saints, which were their countrymen, and partly to enjoy the beauty of the situation of the church; for the Emperor drove back the waves of the sea, and laid the foundations as far among the billows as possible. At the upper part of the gulf, in a very steep and precipitous place, there was an ancient Church of SS. Cosmas and Damianus; where once these saints appeared on a sudden to the Emperor as he lay grievously sick and apparently at the point of death, given up by his physicians, and already reckoned as dead, and miraculously made him whole. In order to repay their goodness, as far as a mortal man may do, he entirely altered and renewed the former building, which was unseemly and humble, and not worthy to be dedicated to such great saints, adorned the new church with beauty and size and brilliant light, and gave it many other things which it did not formerly possess. When men are suffering from diseases beyond the reach of physicians, and despair of human aid, they resort to the only hope which is left to them, and sail through this gulf in boats to this church. As soon as they begin their voyage they see this church 27 standing as though on a lofty citadel, made beautiful by the gratitude of the Emperor, and affording them hope that they too may partake of the benefits which flow from thence.

On the opposite side of the gulf the Emperor built a church which did not exist before, quite close to the shore of the gulf, and dedicated it to the Martyr Anthimus. The base of this temple, laved by the gentle wash of the sea, is most picturesque; for no lofty billows dash against its stones, nor does the wave resound like that of the open sea, or burst into masses of foam, but gently glides up to the land, silently laps against it, and quietly retreats. Beyond this is a level and very smooth court, adorned all round with marble columns, and rendered beautiful by its view of the sea. Next to this is a portico, beyond which rises the church, of a quadrangular form, adorned with beautiful marble and gildings. Its length only exceeds its breadth far enough to give room for the sanctuary, in which the sacred mysteries are performed, on the side which is turned towards the rising sun; such is the description of it.

VII. Beyond this, at the very mouth of the gulf, stands the Church of the Martyr Irene,[24] which the Emperor has so magnificently constructed that I could not competently describe it; for, contending with the sea in his desire to beautify the gulf, he has built these churches as though he were placing gems upon a necklace; however, since I have mentioned this Church of Irene, it will not be foreign to my purpose to describe what took place there. Here, from ancient times, rested the remains of no fewer 28 than forty saints, who were Roman soldiers, and were enrolled in the twelfth legion, which formerly was stationed in the city of Melitene, in Armenia; now, when the masons dug in the place which I just spoke of, they found a chest with an inscription stating that it contained the remains of these men. This chest, which had been forgotten, was at that time purposely brought to light by God, both with the object of proving to all men with how great joy He received the gifts of the Emperor, and also in order to reward his good works by the bestowal of a still greater favour; for the Emperor Justinian was in ill-health, and a large collection of humours in his knee caused him great pain. His illness arose from his own fault; for during all the days which precede the Paschal Feast, and are called fast-days, he practised a severe abstinence, unfit not only for a prince, but even for a man who took no part in political matters. He used to pass two days entirely without food, and that, too, although he rose from his bed at early dawn to watch over the State, whose business he ever transacted, both by actions and words, early in the morning, at midday, and at night with equal zeal; for though he would retire to rest late at night, he would almost immediately arise, as though disliking his bed. Whenever he did take nourishment, he refrained from wine, bread, and all other food, eating only herbs, and those wild ones which had been for a long time pickled in salt and vinegar, whilst water was his only drink. Yet he never ate to repletion even of these; but whenever he dined, he would merely taste this food, and then push it away, never eating sufficient. From this regimen his disease gathered strength, defying the efforts of physicians, and for a long time the Emperor suffered from these pains. During this time, hearing of the discovery of the relics, he disregarded human art, and 29 commended himself to them, deriving health from his faith in them, and finding healing in his bitterest need from his true faith; for as soon as the priests placed the paten upon his knee, the disease at once vanished—forced out of a body dedicated to God. Not wishing that this matter should be disputed, God displayed a great sign as a testimony to this miracle. Oil suddenly poured forth from the holy relics, overflowed the chest, and besprinkled the feet and the purple garment of the Emperor. Wherefore his tunic, thus saturated, is preserved in the palace as a testimony of what then took place, and for the healing of those who in future time may suffer from incurable disorders.

VIII. Thus did the Emperor Justinian adorn the gulf which is called the Horn; he also added great beauty to the shores of the other two straits, of which I lately made mention, in the following manner. There were two churches dedicated to St. Michael the Archangel, opposite to one another, on either side of the strait, the one in the place called Anaplus[25] on the left hand as one sails into the Euxine Sea, and the other on the opposite shore. This place was called Pröochthus by the ancients—I suppose because it projects a long way from that shore—and is now called Brochi, the ignorance of the inhabitants having in process of time corrupted the name. The priests of these two churches, perceiving that they were dilapidated by age, and fearing that they might presently fall down upon them, besought the Emperor to restore them both to their former condition; for in his reign it was not possible for a church either to be built, or to be restored when ruined, except from the royal treasury, and that not only in Byzantium, but also everywhere throughout the Roman Empire. The Emperor, as soon as he 30 obtained this opportunity, demolished both of them to the foundation, that no part of their former unseemliness might be left. He rebuilt the one in Anaplus[26] in the following manner. He formed the shore into a curve within a mole of stone, which he erected as a protection to the harbour, and changed the sea-beach into the appearance of a market; for the sea, which is there very smooth, exchanges its produce with the land, and sea-faring merchants, mooring their barques alongside the mole, exchange the merchandise from their decks for the produce of the country. Beyond this sea-side market stands forth the vestibule of the church, whose marble vies in colour with ripe fruit and snow. Those who take their walks in this quarter are charmed with the beauty of the stone, are delighted with the view of the sea, and are refreshed with the breezes from the water and the hills which rise upon the land. A circular portico surrounds the church on all sides except the east. In the midst of it stands the church, adorned with marble of various colours. Above it is suspended a domed roof. Who, after viewing it, could speak worthily of the lofty porticoes, of the buildings within, of the grace of the marble with which the walls and foundations are everywhere encrusted? In addition to all this, a great quantity of gold is everywhere spread over the church, as though it grew upon it. In describing this, I have also described the Church of St. John the Baptist,[27] which the Emperor 31Justinian lately erected in his honour in the place called Hebdomon; for both the two churches are very like each other, except only that the Church of the Baptist does not happen to stand by the sea-shore.

The Church of the Archangel, in the place called Anaplus, is built in the above manner; now upon the opposite shore there is a place at a little distance from the sea, which is level, and raised high upon a mass of stones. Here has been built a church in honour of the Archangel, of exceeding beauty, of the largest size, and in costliness worthy of being dedicated to the Archangel Michael by the Emperor Justinian. Not far from this church, he restored a church of the Virgin, which had fallen into ruins long before, whose magnificence it would take long to examine and to express in words; but here a long-expected part of our history finds its place.

IX. Upon this shore there stood from ancient times a beautiful palace: the whole of this the Emperor Justinian dedicated to God, exchanging present enjoyment for the reward of his piety hereafter, in the following manner. There were at Byzantium a number of women who were prostituted in a brothel, not willingly, but compelled to exercise their profession; for under pressure of poverty they were compelled by the procurer who kept them to 32 act in this manner, and to offer themselves to unknown and casual passers-by. There was here from ancient times a guild of brothel-keepers, who not only carried on their profession in this building, but publicly bought their victims in the market, and forced them into an unchaste life. However, the Emperor Justinian and the Empress Theodora, who performed all their works of piety in common, devised the following scheme. They cleansed the State from the pollution of these brothels, drove out the procurers, and set free these women who had been driven to evil courses by their poverty, providing them with a sufficient maintenance, and enabling them to live chaste as well as free. This was arranged in the following manner: they changed the palace, which stood on the right hand as one sails into the Euxine Sea, into a magnificent convent, to serve as a refuge for women who had repented of their former life, in order that there spending their lives in devotion to God, and in continual works of piety, they might wash away the sins of their former life of shame; wherefore this dwelling of these women is called from their work by the name of the Penitentiary. The princes endowed this convent with large revenues, and furnished it with many buildings of exceeding great beauty and costliness for the comfort of these women, so that none of them might be forced by any circumstances to relax their practice of chastity. So much then for this part of the subject.

As one sails from this place towards the Euxine Sea, there is a lofty promontory jutting out from the shore of the strait, upon which stood a Church of the Martyr St. Pantelëemon,[28] which, having been originally carelessly built, and having been much ruined by lapse of time, was taken 33 down by the Emperor Justinian, who built the church which now stands there with the greatest magnificence, and both preserved the honour due to the martyr and added beauty to the strait by building on each side of it the churches which I have mentioned. Beyond this church, in a place which is called Argyronium, there was, in old times, a hospital for poor men afflicted with incurable diseases, which having in the course of time fallen into the last stage of decay, he most zealously restored, to serve as a refuge for those who were thus afflicted. Near this place there is a district by the sea-side called Mochadius, which is also called Hieron. Here he built a temple in honour of the Archangel of remarkable splendour, and in no respect inferior to those Churches of the Archangel, of which I spoke just now. He also built a church dedicated to St. Tryphon the Martyr, decorated with much labour and time to an indescribable pitch of beauty, in that street of the city which is called by the name of ‘The Stork.’ Furthermore, he built a church in the Hebdomon, in honour of the martyrs Menas[29] and Menæsus; and finding that the Church of St. Ias the Martyr, which is on the left hand as one enters the Golden Gate, was in ruins, he restored it with a lavish expenditure. This is what was done by the Emperor Justinian in connection with the churches in Byzantium; but to describe all his works throughout the entire Roman Empire in detail, is a difficult task, and altogether impossible to express in words, but, whenever I shall have to make mention of the name of any city or district, I shall take the opportunity of describing the churches in it.

X. The above were the works of the Emperor Justinian 34 upon the churches of Constantinople and its suburbs; but as to the other buildings constructed by him, it would not be easy to mention them all. However, to sum up matters, he rebuilt and much improved in beauty the largest and most considerable part both of the city and of the palace, which had been burned down and levelled with the ground. It appears unnecessary for me to enter into particulars on this subject at present, since it has all been minutely described in my ‘History of the Wars.’ For the present I shall only say this much, that the vestibule of the palace and that which is called Chalce, as far as what is known as the House of Ares, and outside the palace the public baths of Zeuxippus,[30] and the great porticoes and all the buildings on either hand, as far as the forum of Constantine, are the works of this Emperor. In addition to these, he restored and added great magnificence to the house named after Hormisdas, which stands close to the palace, rendering it worthy of the palace, to which he joined it, and thereby rendered it much more roomy and worthy of admiration on that side.

In front of the palace there is a forum surrounded with columns. The Byzantines call this forum the Augustæum. I mentioned it in a former part of this work, when, after describing the Church of St. Sophia, I spoke of the brazen statue of the Emperor, which stands upon a very lofty column of stones as a memorial of that work. On the eastern side of this forum stands the Senate House, which baffles description by its costliness and entire arrangement, and which was the work of the Emperor Justinian. Here at the beginning of every year the Roman Senate holds an annual festival, according to the custom of the State. 35 Six columns stand in front of it, two of them having between them that wall of the Senate House which looks towards the west, while the four others stand a little beyond it. These columns are all white in colour, and in size, I imagine, are the largest columns in the whole world. They form a portico covered by a circular dome-shaped roof. The upper parts of this portico are all adorned with marble equal in beauty to that of the columns, and are wonderfully ornamented with a number of statues standing on the roof.

Not far from this forum stands the Emperor’s palace, which, as I have said before, was almost entirely rebuilt by the Emperor Justinian. To describe it all in words is impossible, but it will suffice for future generations to know that it was all the work of this Emperor. As, according to the proverb, we know the lion by his claw, so my readers will learn the magnificence of this palace from the entrance-hall. This entrance-hall is the building called Chalce; its four walls stand in a quadrangular form, and are very lofty; they are equal to one another in all respects, except that those on the north and south sides are a little shorter than the others. In each angle of them stands a pier of very well-wrought stone, reaching from the floor to the summit of the wall, quadrangular in form and joining the wall on one of its sides: they do not in any way destroy the beauty of the place, but even add ornament to it by the symmetry of their position. Above them are suspended eight arches, four of which support the roof, which rises above the whole work in a spherical form, whilst the others, two of which rest on the neighbouring wall towards the south and two towards the north, support the arched roof which is suspended over those spaces. The entire ceiling is decorated with paintings, not formed of melted wax poured upon it, 36 but composed of tiny stones adorned with all manner of colours, imitating human figures and everything else in nature. I will now describe the subjects of these paintings. Upon either side are wars and battles, and the capture of numberless cities, some in Italy, and some in Libya. Here the Emperor Justinian conquers by his General Belisarius; and here the General returns to the Emperor, bringing with him his entire army unscathed, and offers to him the spoils of victory, kings, and kingdoms, and all that is most valued among men. In the midst stand the Emperor and the Empress Theodora, both of them seeming to rejoice and hold high festival in honour of their victory over the kings of the Vandals and the Goths, who approach them as prisoners of war led in triumph. Around them stands the Senate of Rome, all in festal array, which is shown in the mosaic by the joy which appears on their countenances; they swell with pride and smile upon the Emperor, offering him honours as though to a demi-god, after his magnificent achievements. The whole interior, not only the upright parts, but also the floor itself, is encrusted with beautiful marbles, reaching up to the mosaics of the ceiling. Of these marbles, some are of a Spartan stone equal to emerald, while some resemble a flame of fire; the greater part of them are white, yet not a plain white, but ornamented with wavy lines of dark blue.[31] So much for this building.

XI. As one sails from the Propontis towards the eastern part of the city, there is a public bath on the left hand which is called the Baths of Arcadius, and which forms an 37 ornament to the city of Constantinople, great as it is. Here our Emperor constructed a court standing outside the city, intended as a promenade for the inhabitants, and a mooring-place for those who sail past it. This court is lighted by the sun when rising, but is conveniently shaded when he proceeds towards the west. Round it the sea flows quietly with a gentle stream, coming like a river from the main sea, so that those who are taking their walks in it are able to converse with those who are sailing; for the sea reaches up to the basement of the court with great depth, navigable for ships, and by its remarkable calm enables those on the water and on the land to converse with one another. Such is the side of the court which looks upon the sea, adorned with the view over it, and refreshed with the gentle breezes from it. Its basement, its columns, and its entablature are all covered with marble of great beauty, whose colour is of a most brilliant white, which glitters magnificently in the rays of the sun; moreover, many statues adorn it, some of brass and some of marble, composing a sight well worth mention; one would conjecture that they were the work of Phidias the Athenian, of Lysippus of Sicyon, or of Praxiteles. Here also is a statue of the Empress Theodora on a column, which was erected in her honour by the city as an offering of gratitude for this court. The face of the statue is beautiful, but falls short of the beauty of the Empress, since it is utterly impossible for any mere human workmen to express her loveliness, or to imitate it in a statue; the column is of porphyry, and clearly shows by its magnificent appearance that it carries the Empress, before one sees the statue.

I will now explain the Emperor’s works to afford an abundant supply of water to the city. In summer-time the imperial city used for the most part to suffer from 38 scarcity of water, although at other seasons it had sufficient; for at that time, in consequence of the drought, the fountains flowed less plenteously than at other seasons, and supplied the aqueducts of the city very sparingly. Wherefore the Emperor devised the following plan. In the Portico of the Emperor, where the advocates, and magistrates, and other persons connected with the law transact business, there is a very lofty court of great length and width, quadrangular in shape, and surrounded with columns, which is not constructed upon an earthen foundation, but upon the rock itself. Four porticos surround this court, one upon each side of it. The Emperor Justinian excavated one of these porticos, that upon the south side, to a great depth, and stored up there the superfluity of water from the other seasons for use in summer. These cisterns receive the overflow from the aqueducts, when they are too full of water, giving them a place to overflow into, and afford a supply in time of need when water becomes scarce. Thus did the Emperor Justinian arrange that the people of Byzantium should not want for sweet water.

He also built new palaces elsewhere, one in the Heræum,[32] which is now called the Hiereum, and in the place called Jucundiana. I am unable to describe either the magnificence or exquisite workmanship, or the size of these palaces in a manner worthy of the subject. Suffice it to say that these palaces stand there, and were built in the presence and according to the plans of Justinian, who disregarded nothing except expense, which was so large that the mind is unable to grasp it. Here also he con 39structed a sheltered harbour, which did not exist before. Finding that the shore was exposed on both sides to the winds and the violence of the waves, he arranged a place of refuge for mariners in the following manner: he constructed what are called chests, of countless number and of great size, flung them into the sea on each side of the beach in an oblique direction, and by continually placing fresh layers in order upon the others, formed two walls in the sea opposite to one another, reaching from the depths below to the surface of the water on which the ships sail; upon this he flung rough stones, which when struck by the waves break their force, so that when a strong wind blows in the winter season, everything between these walls remains calm, an interval being left between them to serve as an entrance for ships into the harbour. Here also he built the churches which I formerly mentioned, and also porticos, market-places, public baths, and everything else of that sort; so that this palace in no respect falls short of that within the city. He also built another harbour on the opposite continent, in the place which is called after the name of Eutropius, not very far from the Heræum, constructed in the same manner as that which I mentioned above.

The above are, described as briefly as possible, the works of the Emperor Justinian in the imperial city. I will now describe the only thing which remains. Since the Emperor dwells here, a multitude of men of all nations comes into the city from all the world, in consequence of the vast extent of the empire, each one of them led thither either by business, by hope, or by chance, many of whom, whose affairs at home have fallen into disorder, come with the intention of offering some petition to the Emperor. These persons, forced to dwell in the city on account of some present or threatened misfortune, in addition to their other 40 trouble are also in want of lodging, being unable to pay for a dwelling-place during their stay in the city. This source of misery was removed from them by the Emperor Justinian and the Empress Theodora, who built very large hospices as places of refuge in time of need for such unfortunate persons as these, close to the sea, in the place which is called the Stadium, I suppose because in former times it was used for public games.

Note.—For the interesting church of the Chora, see Appendix.

I. The new churches which the Emperor Justinian built in Constantinople and its suburbs, the churches which were ruinous through age, and which he restored, and all the other buildings which he erected there, are described in my previous book; it remains that we should proceed to the fortresses with which he encircled the frontier of the Roman territory. This subject requires great labour, and indeed is almost impossible to describe; we are not about to describe the Pyramids, that celebrated work of the Kings of Egypt, in which labour was wasted on a useless freak, but all the strong places by means of which our Emperor preserved the empire, and so fortified it as to render vain any attempt of the barbarians against the Romans. I think I should do well to start from the Median frontier.

When the Medes retired from the country of the Romans, restoring to them the city of Amida,[33] as has been narrated in my ‘History of the Wars,’ the Emperor Anastasius took great pains to build a wall round an, at that time, unimportant village named Dara, which he observed was situated near the Persian frontier, and to form it into a 41 city which would act as a bulwark against the enemy. Since, however, by the terms of the treaty formerly made by the Emperor Theodosius with the Persians, it was forbidden that either party should build any new fortress on their own ground in the neighbourhood of the frontier, the Persians urged that this was forbidden by the articles of the peace, and hindered the work with all their power, although their attention was diverted from it by their war with the Huns. The Romans, perceiving that on account of this war they were unprepared, pushed on their building all the more vigorously, being eager to finish the work before the enemy should bring their war against the Huns to a close and march against themselves. Being alarmed through their suspicions of the enemy, and constantly expecting an attack, they did not construct their building carefully, but the quickness of building into which they were forced by their excessive hurry prevented their work being secure; for speed and safety are never wont to go together, nor is swiftness often accompanied by accuracy. They therefore built the city-walls in this hurried fashion, not making a wall which would defy the enemy, but raising it barely to the necessary height; nor did they even place the stones in their right positions or arrange them in due order, or fill the interstices with mortar. In a short time, therefore, since the towers, through their insecure construction, were far from being able to withstand snow and hot sun, most of them fell into ruins. Thus was the first wall built round the city of Dara.[34]

42

It occurred to the Emperor Justinian that the Persians would not, as far as lay in their power, permit this Roman fortress to stand threatening them, but that they would march against it with their entire force, and use every device to assault its walls on equal terms; and that a number of elephants would accompany them, bearing wooden towers upon their backs, which towers instead of 43 foundations would rest upon the elephants, who—and this was the worst of all—could manœuvre round the city at the pleasure of the enemy, and carry a wall which could be moved whithersoever its masters might think fit; and the enemy, mounted upon these towers, would shoot down upon the heads of the Romans within the walls, and assail them from above; they would also pile up mounds of earth against the walls, and bring up to them all the machines used in sieges; while if any misfortune should befall the city of Dara, which was an outwork of the entire Roman Empire and a standing menace to the enemy’s country, the evil would not rest there, but the whole state would be endangered to a great extent. Moved by these considerations he determined to fortify the place in a manner worthy of its value.

In the first place,[35] therefore, since the wall was, as I have described, very low, and therefore easily assailable, he rendered it inaccessible and altogether impregnable. He placed stones which so contracted the original battlements as only to leave small traces of them, like windows, allowing just so much opening to them as a hand could be passed through, so that passages were left through which arrows could be shot against the assailants. Above these he built a wall to a height of about thirty feet, not making the wall of the same thickness all the way to the top, lest the foundations should be over-weighted by the mass above, and the whole work be ruined; but he surrounded the upper part with a course of stones, and built a portico extending round the entire circuit of the walls, 44 above which he placed the battlements, so that the wall was throughout constructed of two stories, and the towers of three stories, which could be manned by the defenders to repel the attacks of the enemy; for over the middle of the towers he constructed a vaulted roof, and again built new battlements above it, thus making them into a fortification consisting of three stories.

After this, though he saw, as I have said before, that many of the towers had after a short time fallen into ruin, yet he was not able to take them down, because the enemy were always close at hand, watching their opportunity, and always trying to find some unprotected part of the fortifications. He therefore devised the following plan: he left these towers where they were, and outside of each of them he constructed another building with great skill, in a quadrangular form, well and securely built. In the same manner he securely protected the ruinous parts of the walls with a second wall. One of these towers, which was called the Watchtower, he seized an opportunity of demolishing, rebuilt it securely, and everywhere removed all fear of want of strength from the walls. He wisely built the outside part of the wall to a sufficient height, in due proportion; outside of it he dug a ditch, not in the way in which men usually make one, but in a small space, and in a different fashion. With what object he did this, I will now explain.

The greater part of the walls are inaccessible to besiegers, because they do not stand upon level ground, nor in such a manner as would favour an attack, but upon high precipitous rocks where it would not be possible to undermine them, or to make any assault upon them; but upon the side turned towards the south, the ground, which is soft and earthy and easily dug, renders the city assailable. Here, therefore, he dug a crescent-shaped 45 ditch, deep and wide, and reaching to a considerable distance. Each end of this ditch joined the city wall, and by filling it with water he rendered it altogether impassable to the enemy. On the inner side of it he built a second wall, upon which during a siege the Roman soldiers keep guard, without fear for the walls themselves and for the other outwork which stands before the city. Between the city wall and this outwork, opposite the gate which leads towards Ammodius, there was a great mound, from which the enemy were able to drive mines towards the city unperceived. This he entirely removed, and levelled the spot, so as to put it out of the enemy’s power to assault the place from thence.

II. Thus did Justinian fortify this stronghold;[36] he also constructed reservoirs of water between the city walls and the outwork, and very close to the Church of St. Bartholomew the Apostle, on the west side. A river runs from the suburb called Corde, distant about two miles from the city. Upon either side of it rise two exceedingly rugged 46 mountains. Between the slopes of these mountains the river runs as far as the city, and since it flows at the foot of them, it is not possible for an enemy to divert or meddle with its stream, for they cannot force it out of the hollow ground. It is directed into the city in the following manner. The inhabitants have built a great channel leading to the walls, the mouth of which is closed with numerous thick bars of iron, some upright and some placed crosswise, so as to enable the water to enter the city, without injury to the strength of its fortifications. Thus the river enters the city, and after having filled these reservoirs, and been led hither and thither at the pleasure of the inhabitants, passes into another part of the city, where there is an outfall constructed for it in the same way as its entrance. The river in its progress through the flat country made the city in former times easy to be besieged, for it was not difficult for an enemy to encamp there, because water was plentiful. The Emperor Justinian considered this state of things, and tried to find some remedy for it; God, however, assisted him in his difficulty, took the matter into His own hands, and without delay ensured the safety of the city. This took place in the following manner.