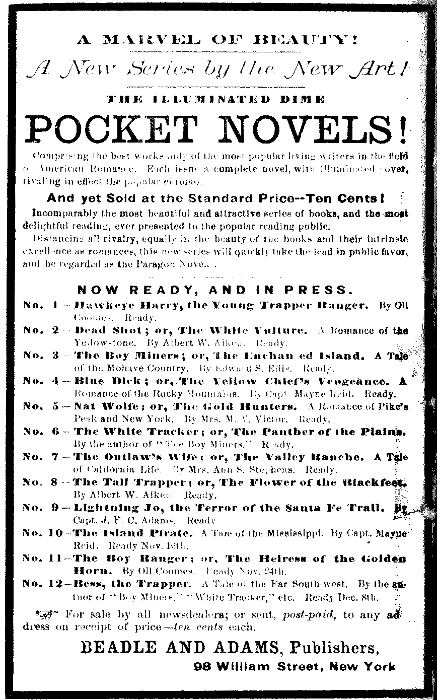

Title: Lightning Jo, the Terror of the Santa Fe Trail: A Tale of the Present Day

Author: Edward Sylvester Ellis

Release date: June 1, 2021 [eBook #65487]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: David Edwards, Martin Pettit and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (Northern Illinois University Digital Library at http://digital.lib.niu.edu/)

Transcriber’s Note:

Obvious typographic errors have been corrected.

THE TERROR OF THE SANTA FE TRAIL.

A TALE OF THE PRESENT DAY.

BY CAPT. J. F. C. ADAMS.

NEW YORK:

BEADLE AND ADAMS, PUBLISHERS,

98 WILLIAM STREET.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1874, by

BEADLE AND ADAMS,

In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

(P. N. No. 9.)

LIGHTNING JO,

THE TERROR OF THE SANTA FE TRAIL.

“To the Commandant at Fort Adams:

“For God’s sake send us help at once. We have been fighting the Comanches for two days; half our men are killed and wounded, and we can not hold out much longer. But we have women and children with us, and we shall fight to the last and die game. Send help without an hour’s delay, or it’s all up.

J. T. Shields.”

Covered with dust, and reeking with sweat, with bloody nostril and dilated eye, the black mustang thundered up to the gate of the fort, staggered as if drunken, and then with a wheezing moan, shivered from nose to hoof, and with an awful cry, like that of a dying person, his flanks heaved and he dropped dead to the ground, his lithe, sinewy rider leaping from the saddle, just in time to escape being crushed to death.

Scarcely less frightful and alarming was the appearance of the horseman, so covered with dust and grime, that no one could tell whether he was Indian, African or Caucasian; but, whoever he was, he showed that he was alive to the situation, by running straight through the gate of the stockades, into the parade-ground, where, pausing in a bewildered sort of way, he glanced hurriedly around, and then shouted:

“Where’s the commandant? Quick! some one tell me!”

Colonel Greaves chanced to be standing at that moment in converse with a couple of his officers, and upon hearing the cry, he moved toward the stranger with a rapid tread, but with a certain dignified deliberation that always marked his[Pg 10] movements. Knowing him to be the man for whom he was searching, the messenger did not wait for him to approach, but fairly bounded toward him, and thrusting a piece of dirty paper, scrawled over with lead pencil, looked imploringly in his face, while he read the words given above.

And as the colonel read, his brows knitted and his face paled. He felt the urgency of that despairing appeal, and he saw the almost utter impossibility of complying with it.

“When was this written?” he asked, of the dust-begrimed courier.

“At daybreak this morning,” was the prompt reply.

“How far away are your friends?”

“Forty miles as the crow flies, and I have never drawn rein since my horse started, till he fell dead just outside the gate.”

“How many men are there in this fix?”

“There were twenty men, and a dozen women and children. When I left, about half that number were alive, and whether any are still living, God only knows, I don’t.”

“I hope it is not as bad as that,” said the colonel, again glancing at the paper, and involuntarily sighing, for despite his schooling upon the frontier, he felt keenly the anguish of this wail, that was borne to him across the sad prairie. “Not as bad as that, I trust; for if they have held out two days, we may hope that they are able to hold out still longer. But how is it that you succeeded in reaching us, when they could not?”

Feeling that some explanation was expected of him, the messenger spoke hurriedly, but as calmly as possible:

“Twenty of us were conveying a party of women and children—the families of merchants and officers at Santa Fe—through the Indian country, on our way to that city, when the Comanches came down on us, in a swarm of hundreds, and finding there was no escaping a fight, we ran our wagons in a circle, shut the women and horses inside, and then it seemed as if hell was let loose upon us. Yelling, shouting, screeching, charging was kept up all that day into the night. We picked off the red devils with every shot, but the more we killed the thicker they came, seeming to spring up from the very ground, until the prairie was covered with them[Pg 11] At night we had a little rest, and we thought perhaps they would draw off and let us alone. Why they didn’t make a charge upon our camp that night, I can not tell; but they only sent a few stray shots, more than one of which was fatal, and at daylight the fun began again, and never stopped till the sun went down, when there wasn’t much of a pause then. That was yesterday, and we had it all through the night, and since we halted the day before yesterday, there hasn’t been a drop of water for horse, man, woman or child, so that you can see what an awful strait they are in.”

By this time quite a group had gathered about the messenger, enchained by the thrilling tale he told, the truth of which was so eloquently attested by his manner and appearance.

“But you haven’t told us how you got here,” reminded the colonel, as the man paused for a moment. “You have succeeded at least in insuring your safety.”

“We made up our minds about midnight last night that something of the kind had to be done, as it was our only hope. Two of our men tried to steal through, crawling on hands and knees, but both were caught within a hundred yards of the camp—one shot dead, and the other so badly tomahawked, that he died within an hour of getting back to us. So I told Shields to let me have his mustang, which is the fleetest creature on the plains, and I would either get through or do as the others did. So, just about daybreak, I crammed that slip of paper in the side of my shoe, stretched out flat on the mustang’s back and give him the word. Away he went like a thunderbolt, with the rifles cracking all about my ears, and the Comanche thundering down upon me like so many bloodhounds. I fell more than one bullet in my legs, and I knew the horse was hurt pretty bad—it didn’t hinder his going, and the noble fellow kept straight along till he brought me here. But you act as if you didn’t know me.”

“Know you?” repeated the amazed colonel. “I never saw you before.”

The powdered, begrimed face was seen to expand into something like a grin, and raising his hand, the courier literally scraped the dust from his cheeks and eyebrows, and then, as he removed his hat, a general exclamation of amazement escaped all.

“Jim Gibbons! is it you?” called out the commandant, as he recognized a man who had been employed at his fort a year before. “I thought your voice had a familiar sound, but then your own mother would not have recognized you.”

“But come,” added Gibbons, moving about uneasily, “we’ll talk over this matter some other time. I’ve brought you the message, colonel,” he added, making a graceful military salute. “I had heard in St. Louis that you had been sent to another command, else I would have known whom to ask for. Now, can you help us or not?”

The officer folded his arms behind his back and walked slowly over the parade-ground, signifying by a nod of his head, that Gibbons should do the same.

“I must help you,” he said, in a low voice; “such a call as that can not pass unheeded. But, Jim, you see my fix. We ought to have a full regiment to garrison this fort, and the Government allows me but six hundred. Two hundred of these men are on a scout up toward the mountains, and won’t be in till dark. Do you know there is some reason to fear an attack upon the fort, from a combination of several tribes under the direction of the infernal Comanche, Swico-Cheque?”

“Why he is at the head of the devils that have our friends walled in. I know him too well, and have seen him a dozen times, circling around on his horse, yelling like a thousand panthers, and tiring about a dozen shots a minute. I have fired at him five or six times, but never grazed him once.”

“Well, I think it is more than likely that we shall have an[Pg 13] attack from him. Now, you know something of life on the plains; tell me how many men you need to bring your friends into the fort.”

“We ought to have a hundred, at the least.”

“You ought to have five hundred at the smallest calculation. I tell you the Indians in this part of the country are among the best fighters and hunters in the world, and if I send a hundred men out into the country, where they are sure to come against old Swico and his band, the chances are that they will all be served as were Colonel Fetterman’s men at Fort Phil Kearney, a month or two ago. You know that over a hundred of them went out, and never a one was ever seen alive again.”

“But, if I understand that matter right,” replied Gibbons, who was becoming impatient and uneasy at the delay, “these men were entrapped and massacred; I don’t think there is any likelihood of that in our case. But, colonel, pardon me; I wish to know your decision, either one way or the other, at once. If you conclude that you can not spare a hundred men to go forty miles away to help this party, then let me have a fresh horse. I will return, sail in and go under with the rest.”

And Gibbons attested the earnestness of what he said, by starting to move away; but Colonel Greaves caught his arm.

“Hold on! you shall have the men you need. I have been trying ever since I heard your story to decide whether I ought to risk the safety of a hundred men to save one-tenth that number; but I can’t think. It seems to me that I hear the wailing cry of those women and children coming over the prairie, and if I should turn my back upon them, their voices and moans would follow me ever afterward in my waking and sleeping hours. Yes, Jim, you shall have the hundred men. I will lead them myself, and we will make hot work in that gulch before we get through.”

The colonel, having made his decision, did not hesitate for a moment. Turning sharply upon his heel, he beckoned to the adjutant, and gave him peremptory orders to make ready a hundred men for a scout into the Indian country. They were to be armed with rifle, revolver and cavalry swords, and to be mounted on the best horses at the fort.

As he turned about to say a few words to Gibbons, he saw the tears making furrows down his grimy cheeks. He attempted to speak, but for a few seconds was unable to articulate. Taking the hand of the colonel, he finally said, in a choking voice:

“I thank you, colonel, and God grant that this may not be too late. Oh, if you could have seen those pleading faces of the women, those cries of the helpless children for one swallow of water, the dead bodies of the men, that we had drawn in behind the wagons out of reach of the red-skins, and the screeching devils all around, you would send your whole garrison to their rescue. Where is Lightning Jo?”

“He went out with the scouting party this morning, and that is what caused me to hesitate about sending the company to the help of your friends. I always feel tolerably comfortable when I know that he is at the head of the men.”

While the bustle of hurried preparation was going on within the fort, Gibbons accompanied the colonel to his lodgings, where he washed the dust from his person, partook of water and refreshments and explained more in detail the particulars of the misfortune of his friends. He was equally desirous that the wonderful scout, Lightning Jo, should lead the partly, as he was a host of himself, and having lived from earliest childhood in the south-west, he was as thorough an Indian as the great chieftain, Swico-Cheque himself, and the daring Comanches held him in greater terror than any other living personage.

But the case was one that admitted of no delay—even if it was certain that Jo would be in at the end of an hour. Half that time might decide the fate of the little Spartan band struggling so bravely in Dead Man’s Gulch, and the release of the beleaguered ones was now the question above all others.

It required but a very short time for the party to complete their preparations. Out of the seemingly inextricable confusion of stamping horses, and men running hither and thither, all at once appeared full one hundred men, mounted, armed and officered precisely as they had been directed.

An orderly stood holding the horse of Colonel Greaves,[Pg 15] until he was ready to mount, while another was at Gibbons’ disposal.

The next moment the two latter had leaped into their saddles, and placing themselves at the head of the cavalcade, rode out of the stockade upon the open prairie, which had scarcely been done, when a new and most gratifying surprise awaited them. The march was instantly halted, and the face of Colonel Greaves and of Gibbons lit up with pleasure.

That which arrested the attention of the company riding out of the stockade of Fort Adams, was the sight of another party of horsemen coming through a range of hills about half a mile distant, one glance only being sufficient to identify them as the scouts already referred to as being under the guidance and leadership of the great western celebrity, Lightning Jo.

“Now, that’s what I call lucky,” exclaimed Colonel Greaves. “Jo is the very man of all others that we need.”

The horsemen rode down the declivity at an easy gallop, and shortly reined up in front of the stockade, with a graceful salute, and an action that indicated that he awaited the commands of his superior officer.

The scouts, or hunters, had turned their time to good account, as was shown by a number of buffalo carcasses, or rather the choice portions of such, supported across the saddles of their animals; the appearance of the beasts, too, indicated that many of them had been subjected to the hardest kind of riding.

A few words explained to Lightning Jo the business about to be undertaken, and he at once assumed his position as leader of the company that had just prepared to start, the colonel withdrawing into the fort again, where it was his manifest duty to remain, while the desperate attempt to [Pg 16]relieve the beleaguered party in Dead Man’s Gulch was being made.

The scout did not take a fresh horse, and when pressed to do so, he declared that his mustang was as capable of a fifty mile tramp, as he was upon the morning he started upon the hunt from which he had just returned.

“Come, boys! business is business,” said he, in his crisp, sharp tone, as his steed carried him by one or two bounds to the head of the cavalcade he was to lead. “Come, Gibbons, keep yer place alongside me, and yer can explain as we ride along.”

And as the company of brave men gallop to the southward on their errand of mercy, each man a hero, and all with set teeth and an unalterable determination in their hearts to do all that mortal man could do to save the despairing little band that had sent its wail of anguish across the prairie, we will improve the occasion by glancing at the remarkable man who acted as their leader.

Lightning Jo had gained his appellation from the wonderful quickness of his movements, and his almost miraculous skill as a scout. His celerity of movement was incredible, while his equally astonishing strength excited the wonder of the most famous bordermen of the day. It was a well established fact that Lightning Jo, a couple of years before, at Fort Laramie, had been forced into a personal encounter with a badgering pugilist, who was on his return to the States from California, and who had the reputation of being one of the most scientific hitters that had ever entered the prize ring, and who on the occasion referred to was so completely polished off by Jo, that he lay a month at the fort before he recovered from his injuries.

It was said, and there was every reason to believe it, that he was capable of running miles with the speed of the swiftest mustang of the prairie; that he had traversed the Llano Estacado back and forth, times without number, on foot, passing through the very heart of the Comanche country, without any attempt to disguise himself, or conceal his identity in any way; and yet there was not a mark upon his person to attest the dangers through which he had passed scathless and unharmed.

His horsemanship was perfect in its way, and no living Comanche—the most wonderful riders on the Western Continent—had been known to exceed, and very few to equal him. For the amusement of those gathered at some of the posts which he had visited, he had ridden his mustang at full speed and bare back, throwing himself from one side to the other, and firing from beneath the neck or belly of the animal, picking up his hat from the earth when galloping, at the same headlong rate, striking a match upon a stone on the ground and carrying the blaze lighted in his hand. He had thrown the lasso, with such skill, as to catch the hoof of the plunging buffalo, and then by a flirt of the rope, flung the kicking brute flat upon his side, as the daring rider thundered past, and slapped his hat in the eyes of the terrified animal. He could fling the coil with the unerring certainty of a rifle shot, and would manipulate the rope into as many fantastical convolutions as a Chinese conjurer.

His prowess with the rifle was equally marked, and the tales of his achievements with his favorite weapon were so incredible in many instances, that we would not be believed were we to repeat them. He carried a long, murderous-looking weapon, the mountings of which were of solid silver, and had been presented to him by one of his many friends, whom he had been the instrument of saving.

At the home of his old mother at Santa Fe—the only living relative he had upon earth—he had rifles, swords, guns and every manner of weapon, of the most costly and valuable nature, that had been given him by grateful friends. His revered parent during his absence was literally overwhelmed with attentions and kindnesses by virtue of her relationship to Lightning Jo, the scout and guide who had proved such a blessing to the settlers of, and travelers through the West.

The hero was about thirty years of age, slim and tall to attenuation, with high cheek-bones, eyes of midnight blackness that snapped fire when he was roused, and long hair, as stiff, wiry and black as the tail of his mustang. His countenance was swarthy, and with a little “touching up” he might have deceived Swico himself into the belief that he was one of his own warriors. This was the more easy as Jo spoke the Comanche tongue with the fluency of a genuine member[Pg 18] of that warlike tribe; but he scorned such suggestions when made to him, declaring that he was able to take care of himself anywhere and in any crowd, no matter who were his friends or who were his enemies, an assertion which no one cared to dispute in a practical way.

Looking at his profile as he rode along over the prairie at a sweeping gallop, it would have been seen that his nose was large, thin and sharp, the chin rather prominent, and the lips thin. The mouth was rather large, and the upper lip shaded by a thin, silky mustache of the same jetty hue as his eyes. The rest of his face was totally devoid of beard, except a little furze in front of his ears. He had never used the razor, nor did he expect to do so.

Of course he sat his horse like a centaur, and, as he rode along, those keen, restless eyes of his wandered and roved from side to side, almost unconsciously on his part, as he was ever on the alert for the first appearance of danger. Such in brief were a few of the noticeable points of the great scout, Lightning Jo, who was a leader of the party of rescue, and who is to play such a prominent part in the thrilling events we are about to narrate.

As he rode beside Gibbons, whose anxiety was of the most intense character, and who could not avoid giving frequent expression to it, the scout at length said:

“Just stop that ’ere fretting of yours, now, Gib; ’cause it don’t pay; don’t you see we’re all stretching out on that ’ere forty miles, just as fast as horse-flesh kin stand it? Wal, that being so, where’s the use of fuming?”

“I know, Jo, but how can a person help it when he knows not whether his friends are dead or alive? There is philosophy in your advice about whining and complaining, and it reminds me of one of the members of the party—a young lady, whose disposition had something heavenly in it.”

“Who was she?” asked the scout, in an indifferent way.

“Her name, I believe, was Manning—Lizzie Manning—”

“What!” exclaimed Lightning Jo, almost bounding from his saddle, “is she there, in that infarnal place? How in the name of Heaven did she get there?”

“She was one of the party that left St. Louis, and of course shared our dangers the same as all.”

“The sweetest, purtiest, best little piece of calico that has been heard,” repeated the scout to himself. “God save her, for she’s worth all the rest. Come, boys,” he called out to those behind him, “ride your hosses as you never rid ’em afore. I’d dash through fire, water, smoke, brimstone and blazes, to save that gal!”

Leaving Lightning Jo and his party riding at a tremendous rate over the prairie to the rescue of the sorely beleaguered company in Dead Man’s Gulch, we must precede him for awhile to that terrible spot, where one of the most dreadful tragedies of the many there enacted was going on.

The party, numbering over thirty, two-thirds of whom were hardened, bronzed hunters, had been driven tumultuously into the place by the sudden appearance of the notorious Swico-Cheque and his band, where they had barely time to throw their men and horses into the roughest attitude of defense, when they were called upon to fight the screeching Comanches, in one of the most murderous and desperate hand-to-hand encounters in which they had ever been engaged.

Our readers have already learned, from the hurried words of Gibbons, something of the experience of the beleaguered whites during the two days and nights immediately following the halt, and preceding his own departure, and it is not our purpose to weary them and harrow their feelings by a recital of the horrible incidents of that stubborn fight.

When Jim Gibbons, hugging the neck of his mustang, dashed at full speed through the lines of the Comanches, he left behind him ten able-bodied men, or, more properly, ten who were still able to load, aim and fire their rifles. More than that number lay scattered around, among the wagons, on the ground, in every position, killed by the bullets of the wonderful red riders and riflemen.

The wagons, as is the practice at such times, had been run together into an irregular circle, one being placed in the center (as the safest spot), into which the women and children were tumbled, and where, for the time, they were safe from the bullets that were rattling like sleet around them, and striking down their brave defenders upon every hand.

This done, the men devoted themselves to keeping back the swarming devils, that made a perfect realization of pandemonium as they circled about the doomed band.

In what way Dead Man’s Gulch gained its name no one can tell with any certainty, but most probably from the number of massacres and deaths that had taken place within its horrid precincts. It was simply a hollow, somewhat resembling the dried-up bed of a small lake, and, instead of being properly a gulch, was more like a basin, so that to enter it from any direction, one was compelled to descend quite a slope.

The trail which the party were following led directly through the center of this place, it being by far the most feasible route, in spite of the ascent and descent, on account of the broken nature of the country both to the north and south.

Dead Man’s Gulch, occupying an area of several acres, was strewn and covered with bones, as if indeed it were the site of some ancient catacomb, that had been rent in twain by some convulsion of nature.

A slight examination would have shown that these bones were those of horses and human beings, telling in most eloquent language to the beleaguered whites that the fate which threatened them was that which had overtaken many a one before them.

Dead Man’s Gulch indeed was a favorite point of the Comanches, who were always roving the prairies in search of such bands as these, and it was consequently well known and dreaded by all who were compelled to make the journey; and the scene to which we now direct the attention of the reader was, as we have shown, a repetition of what had been enacted there time and again without number.

The first day’s fight was especially destructive upon the horses, it being found almost impossible to shelter them from the aim of the Comanches. As a consequence, the second[Pg 21] morning found but few of these indispensable requisites in a journey of this kind. Those that had escaped, however, were secured and sheltered in such a way as to keep them from the other bullets that endeavored to seek them out.

Captain Shields, a sturdy borderer, and a man who had crossed the plains a score of times, suspected from the first that the only possible hope for his company was for some one to get through the Comanche lines to Fort Adams, and that was the reason why he so carefully protected the two or three remaining mustangs from death.

This, as a matter of course, was the last desperate resort, and was only to be attempted when it was absolutely certain that nothing else could avail.

His first hope was that by a determined and deadly resistance he could convince the red-skins that it would not pay to keep up the contest, for the warlike Comanches have the reputation of possessing discretion as well as bravery; but, in the present case, they certainly were warranted in concluding they had the game in their own hands, and, despite the murderous replies of the whites, they refused to be driven away, and kept up a dropping fire, circling round and round the hills above, and preventing any attempts of the whites to move out.

For some time Captain Shields and his men fired from behind their horses and wagons, but they soon improved on this, and taking their positions in the wagons themselves, found that they were quite well able to pick off their assailants, while they were tolerably well protected from the return fire, the red-skins being compelled to fire more at random.

And lying in this posture, they were compelled to see the remaining horses shot down, excepting the single one upon which Jim Gibbons made his escape.

And thus the fight—of itself one of the most bitter and sanguinary among the thousand and one of the West—raged, and as it raged there were exhibited some of the most daring performances upon both sides, and among them all was no loftier nor higher-souled courage than that of our heroine—the young and beautiful Lizzie Manning of Santa Fe.

The sun was past the meridian, when the hundred men, under the command of Lightning Jo, left Fort Adams and struck off in almost a due southerly direction.

It required sharp riding to reach Dead Man’s Gulch by nightfall; but all had strong hopes of doing so, as it was summertime, and a goodly number of hours yet remained at their command, while their mustangs were toughened and fleet, and they were now put to the full test of their endurance.

Lightning Jo knew very well the location of the fatal gulch, and although he did not say as much, yet he had very little hope of reaching it in time to be of any earthly use to the poor wretches cramped up there and fighting so desperately for life.

Swico could not fail to know the meaning of the flight of Gibbons through his lines. He must know that he was making all haste to Fort Adams for succor, and that, if he did not speedily complete the awful business he had taken in hand, without much longer delay, the chances were that he would be disputed and compelled to fight a third party.

The prairie continued quite level, with dry grass that did not prevent a cloud of dust arising from the hoofs of the horses. The plain was broken here and there by ridges and hills, some of the latter of considerable elevation. Between these the rescuing parties were compelled frequently to pass, some of them being so close together that the thought of an ambuscade was instantly suggested to the mind of every one.

But Jo was not the man to go it blind into any contrivance that the red-skins might set to entrap him, and his practiced eye made certain that all was right before he exposed his brave men to such danger.

He was rather expecting some flank movement upon the[Pg 23] part of his old enemy, but he was disposed to believe that, whatever plan he adopted, he would not “try it on” until the whites reached the vicinity of Dead Man’s Gulch.

“Mebbe he’s got things fixed to tumble us in there too,” he thought to himself; “and mebbe ef he has, he’ll find his flint will miss fire.”

The company galloped steadily forward until something like three-fourths of the distance was passed, and the sun was low in the west. They were riding along at the same rattling pace, all on the alert for signs of their enemies, and they were just “rising” a swell of moderate elevation, flanked on both sides by still higher hills, when the peremptory voice of Lightning Jo was heard, ordering a halt.

The command was obeyed with extraordinary precision, and every man knew as if by instinct that trouble was at hand. Naturally enough their eyes were turned toward the hills, as if expecting to see a band of Comanches swarming down upon them, and in imagination they heard the bloodcurdling yells, as they poured tumultuously over the elevations, exulting in the work of death at their hands.

But all was still, nor could they detect any thing to warrant fear, although the manner of Lightning Jo indicated clearly that such was the case.

He did not keep them long in suspense.

“Some of the Comanches are there,” remarked Lightning Jo, in his offhand manner; “whether old Swico himself is among ’em or not, I can’t say till I go forward and find out. Keep your guns and pistols ready, for there may be a thousand of ’em down on ye afore ye know it.”

And with this parting salutation, or rather warning, the scout started his horse on a gallop, straight toward the rise, as though he purposed to ride directly between the hills already mentioned. But seemingly on the very point of entering, he turned his mustang sharply to one side, and instead of passing between, circled around the hill upon his right.

All this time he sat as erect and proud in his saddle as though he were approaching the stockade of the fort, which he had made his head-quarters for so many years.

The cavalrymen, as a matter of course, scrutinized his movements with the intensest interest.

“How easy for a stray shot to tumble him out of his saddle!” was the reflection of nearly every one watching the daring soldier.

This action of Lightning Jo speedily carried him over a portion of the ridge, and out of sight of the horsemen, who could only surmise what was going on beyond.

But the sharp, pistol-like crack of a rifle, within five minutes of the time he had vanished from view, proved that the fears of Lightning Joe were well founded, and that the drama had already opened in dead earnest.

Indeed it had. The scout had detected all-convincing signs of the presence of his old enemies upon the hill, and the simple artifice of turning aside, at the last moment, had given him the advantage of flanking his foes, and coming upon them from altogether an unexpected quarter.

As he passed over the ridge, Jo saw about twenty Comanche Indians sitting quietly upon their horses, and in a position that indicated that they were composedly expecting the appearance of their prey from another quarter. Instead of turning to flee, the scout saluted them in his customary manner by bringing up his rifle, and boring a hole through the skull of one of the astonished red-skins, before the rest really suspected what was going on.

“Tahoo—oo!” called out Jo, as he witnessed the success of his shot, and he followed it up with another yell that was peculiarly his own, and which was so impossible of imitation that he was known by it from Arizona to Mexico.

The Comanches were not men of wood to sit still upon their animals, and remain targets for one of the most skillful riflemen living.

Identifying their assailant by means of his yell, they instantly scattered, as if a bombshell had landed among them, and they scampered down the other side of an adjoining hill, and out of sight of Jo, carrying their fallen comrade with them.

This, it would seem, ought to have satisfied the scout, but it did not. He suspected that a larger party of Indians was in the neighborhood, and determined to make sure before returning to his men.

The actions of the Comanches seemed to indicate that they[Pg 25] were about making an attempt to surround him, and he made ready to guard against it.

“Let ’em surround me! I feel wolfish to-day, and I think it’ll do me good to let off some of my extra steam among ’em.”

He gazed furtively over his shoulder, nevertheless, for he had no wish to be taken off his guard, in such a desperate encounter as this was certain to prove, in case a collision occurred.

His mustang stepped very carefully, with his head raised and his ears pricked, for he fully felt the delicacy of the situation, and knew that at any moment they were liable to be enveloped by a horde of their enemies.

The sagacity of the horse was the first to give notice of the approach of danger. He was stepping stealthily along, his senses on the alert, when he suddenly paused, with a slight whinny.

At the same instant, Lightning Jo caught a peculiar sound, as if made by the grating of a horse’s hoof upon the gravel, and he turned his head with the quickness of lightning.

There they were, sure enough!

Yes; Lightning Jo found that the Comanches were coming, and at a rather rapid rate, too. There was no flinging himself over the side of his mustang and making him a shield against the blows of the red-skins, for the latter were on every side of him. The fact was they had recognized that peculiar yell of his, and hastily laid their plans to make him prisoner.

But Jo wasn’t made a prisoner yet, by a long shot, and finding that he was at a disadvantage on the back of his steed, he quietly slipped off; looping his rifle by a contrivance of his own to his side, he whipped out a couple of revolvers, one in either hand, and the fun began on the instant.

It wasn’t the way of Jo to await the opening of a game like this, but to open it himself, and the instant he could cock the handy little weapons, he began popping away right and left, the astounded Comanches going down like ten-pins before the savage “bull-dogs,” who had a way of biting every time they gave utterance to a bark. But there were but ten such “bites” available, and carefully as the scout husbanded his ammunition, the barrels were speedily emptied without any sensible diminution of his peril.

There was no one Comanche, nor no single half-dozen of them, that would have believed it possible to secure possession of Lightning Jo, and so they went into the scrimmage in such overwhelming numbers that escape upon his part looked impossible. By the time the barrels of his revolvers were emptied there were fully fifty Indians surrounding him. Nearly, if not quite all of them, were mounted, and they were not the men to show mercy to such a character as Lightning Jo, who had worked more mischief against the tribe than any dozen frontiersmen with whom they had exchanged shots.

Had this indomitable scout been alone upon the prairie his lighting would undoubtedly have been of the most terrific nature, and he would have died, like Colonel Crockett at the Alamo, with an “army of dead” about him; but with all of Jo’s wonderful prowess, he saw that the assistance of his friends was needed, and without any hesitation he gave utterance to his “call,” which reached the ears of his listening cavalrymen, who were equally prompt in responding to the cry.

But the time that must elapse between the call and the arrival of reinforcements, short as it was, was all sufficient for the Comanches to encompass the death of a dozen antagonists, unless they were checked by a most stubborn and skillful resistance.

And just that resistance and that fight now took place.

Instead of clubbing his rifle and using the weapon in that shape, as almost any man would have done, Jo now had recourse to that wonderful science in which he was such an adept, demonstrating that to such a man there is no weapon at his command like the naked fist.

It was a treat to see him use his powers, and had he only possessed a rock or wall to back against, so as to prevent an insidious approach from behind, he could have kept off the Comanche nation, so long as they lunged up to him in such a blind, headlong fashion as the present.

The posture taken by Lightning Jo was according to the latest “rules of the London prize ring,” and consisted in having his arms up in front of him, the left slightly in advance, while he balanced himself upon his left foot, so poised that he was “firm on his pins,” or ready to leap backward or forward, as necessity demanded.

The foremost Comanche, who had dismounted, was almost up to Jo, when he thought somebody’s mustang had kicked him fairly in the face, and he made three back summersets before he could put the brake on. And then, just as he was getting up, he was knocked down again by a couple of his comrades going over him, and then, as those arms began working like piston-rods, and with a velocity a hundred times as great, the cracking of heads was something like the going off of a pack of Chinese crackers ignited together.

Heads were down and heels up, as the red-skins leaped from the backs of their animals and charged in upon the scout, who, as cool as when partaking of a leisurely meal, allowed every one to come just within reach of his iron knuckles, when he let drive like a cannon shot.

Finding that it was impossible to take him afoot, several of the red-skins attempted to ride him down; but there was something in his appearance as he thus acted on the defensive that prevented them from approaching too close, just as the bravest horse will recoil from the bear when he faces about.

Then, too, as it became apparent that there was no capturing the scout in front, the Indians exerted themselves to the utmost to steal around in his rear, and to fling him to the ground. This kept things lively for the time, and the way Lightning Jo spun around and danced upon his legs, striking incessantly, and occasionally putting in a terrific kick now and then, was a marvel in itself.

Now he seemed to be down and out of sight, but the next instant he popped up from some other point, and sent in a volley of blows with the same lightning-like force and skill.[Pg 28] The Indian that clutched at him and was certain he had got him, clutched the empty air, and did get, along the head, in such a way that he ever after held him in the most vivid remembrance.

All this was thrilling and, in a certain sense, amusing; but after all, despite the extraordinary skill and quickness displayed by the scout, it could not really extricate him from the difficulty. A man has but two arms with which to guard himself, and when he is pressed from every point, with an increasing pressure, no human being can keep such a swarm at a distance. He is like the man set upon by thousands of rats.

Furthermore, although Jo knew that his friends were making all haste to his rescue, yet he saw things could not remain as they were even until then.

He therefore determined to make a desperate attempt to break through the surrounding lines.

In the awful sufferings to which communities and companies are sometimes doomed, it is often found that the most delicate and refined females display the greatest fortitude and the truest heroism. When the terrible calamity came upon Captain Shields and his party, it was generally supposed that the first to succumb, from sheer terror alone, would be the frail, blue-eyed, laughing Lizzie Manning, whose gentleness of heart, and mirthful ways, had won the affections of all, before the journey from St. Louis was fairly begun.

There was a blanching of the damask cheek, a faint scream of fear, when the half naked Comanches suddenly burst forth to view, and sent in their first volley, and she scrambled nimbly into the “fort,” as the refuge wagon was termed, thoughtful enough, however, to be the very last one to enter. By the time she had taken her place upon the straw-covered floor upon the bottom, her courage had returned to her, or[Pg 29] more properly speaking, she rose to the situation, and displayed a lofty courage and a rare good sense that excited the wonder and compelled the admiration of all.

By her aid, the screaming, terrified children were speedily quieted, and the scarcely less frantic mothers were made to realize that their own safety lay in retaining their self possession, and keeping themselves and their children out of range of the rifle-balls that were clipping the canvas covering of the wagon, and burying themselves in the planking all about them. By this means something like order was obtained in the crowded little party, and they had nothing to do but to watch furtively the fighting going on all around them, to look at the horrid Comanches circling back and forth, with wonderful contortions upon their horses, to see their frightful grimaces, and the flash of their rifles almost in their very faces, as they seemed to be rushing down as if about to overwhelm and crush the little party out of existence.

It was a thrilling sight that they looked upon, as they saw these Indians pitching headlong from their saddles; but their hearts were wrung with anguish as they saw more than one of their own number fall, some at full length beneath the wagons, and others among the floundering horses, where their deaths were frequently hastened by the hoofs of the frantic animals.

Suddenly Lizzie Manning sprung from the wagon, and heedless of the hurtling bullets, started to run across the open space inclosed by the irregular circle of wagons. She had taken but a few steps, when a young man dashed out from the rear of one of the lumbering wagons, and excitedly waved her back.

“For Heaven’s sake, Lizzie, back this instant!” he called out, walking rapidly toward her in his anxiety; “it is sure death to advance. Wait not a second!”

She paused, as if the voice had a familiar sound, and stared in a bewildered way at the speaker, a fine, manly-looking young fellow, whose hair was blown about his face, and whose pale countenance and flashing eyes showed that he appreciated the danger, and had the courage not to flinch before it.

Only for a moment did the young maiden pause, and then[Pg 30] (only a few feet separating them, as he had continued advancing from the first) she pointed to the prostrate figure of a man beneath the wagons.

“There is Harrison, who has been so kind to me, ever since we started—he fell just now, and stretched out his arms for help. I must go to him.”

“He is past all help,” said the man, solemnly, “and you will only lose your own life if you venture near him, for he took one of the most dangerous posts of all.”

“Nevertheless, he may be alive, and I may be of help to him.”

And as she spoke, the maiden hurried on to where the prostrate and now silent figure of one of her defenders lay. The distance was short, but as Egbert Rodman had declared, it was encompassed with death; and for one moment he meditated seizing the arm of the girl, and compelling her by main force to return to the shelter of the wagon; but something in her manner and appearance restrained him; and, forgetful of his own peril, he gazed with an awed feeling, as he would have watched the tread of an angel upon this sinful earth of ours.

With a somewhat rapid tread, but without any undue haste, and certainly without any fear, Lizzie advanced straight to the wagon where the poor fellow lay, flat upon his back, and directly between the wheels, motionless and with one knee drawn up, as if asleep.

Kneeling down she took the hand still warm in her own, and with the other brushed back the dank hair from the forehead of the man, and asked, in that wonderfully sweet voice of hers:

“Oh, Mr. Harrison, is there nothing I can do for you?”

He opened his eyes, and looked at her with a dim wildness, his face ashy pale, and then something like a smile lit up his ghastly features, as he pointed to his breast.

“My wife—my babe—darling Nelly—”

She understood him, and drew from his breast-pocket a photograph of his wife—with a rosy-cheeked, smiling cherub of a little girl, laughing beside her knee.

“Tell them—my last thoughts—my last prayers were of them—” he stammered.

“I will—I will,” said the girl. “Is there nothing more I can do—?”

He made an effort to speak, but the words were choked in their utterance, and with his eyes fixed upon hers, he died without a struggle.

But that one soulful, grateful look of those dark eyes, as they faded out in death, amply repaid the brave-hearted Lizzie Manning for the noble deed she had done, and she rose to her feet, glad that she had heeded the mute call of the dying man, who could have scarcely hoped, at such a time and under such circumstances, any heed would have been paid to it, unless it were the mocking taunts of the merciless Comanches.

In the mean time, the battle was raging with infernal hotness. All of Captain Shields’ party were unerring marksmen, and they were so accustomed to the most desperate contests with the red-skins, that despite the terrible strait in which they were placed, they preserved their coolness and equipoise like true veterans, and loaded and fired with such rapid sureness, that to this alone may be attributed the severe check, which kept the Comanches from making an overwhelming charge, that would have carried every thing before them.

The first night passed with little disturbance, as we have already shown, and the second day the battle was renewed and kept up with scarcely an intermission until nightfall.

This day, especially the latter portion, was very warm, and the suffering of the little band was terrible—so much so that many of the living envied the dead, who had been so speedily released from their distress. The thirst felt by all was a perpetual torment, from which there was scarcely the slightest relief. Many of the men, despite the great danger, dug into the ground, until the damp soil was reached, which they[Pg 32] scooped up and placed in their mouths as a slight assuagement of their anguish.

The females stood the trial like martyrs, for their own greatest suffering was that of seeing the half-dozen moaning children piteously begging for water, when there was none to give them.

The history of the world has proven that men will run any risk, no matter what, for the sake of satisfying the maddening thirst, that threatens to drive them raving wild; and, it was this that was the cause of one of the most daring deeds ever recorded, upon the part of young Egbert Rodman.

The Comanches could not but be aware of this fearful distress of the whites, and with a fiendish malignity, characteristic of the Indian race, just at nightfall, when the Dead Man’s Gulch was bathed in mellow twilight, one of the red-skins was seen to leap off his mustang and walk toward the encampment, with a large tin canteen in his hand—a relic undoubtedly of some massacre of United States soldiers.

There was a lull in the firing at this moment, and the whites, at a loss to understand the meaning of the proceeding, stealthily peered out from their coverts in the wagons, to learn what new trick was on the tapis.

It looked as if he were going to summon them to surrender, or call for a parley, as he walked straight forward until he was within a hundred feet of the nearest wagon, when he paused and held up the canteen before him, contorting his face into the most grotesque grimaces, and shaking the vessel in front and over his head.

The stillness at this moment was so profound, that more than one distinctly heard the gurgle of water in the vessel, and, if any doubt remained of the red-skin’s purpose, it was dissipated by his calling out, in broken English:

“Yengese—come—muchee drink—hab muchee drink—”

These words were scarcely uttered, when crack, crack went two rifles almost simultaneously, and the foolhardy wretch made a scrambling leap, and his taunting words ended in a wild howl, as he fell prostrate across the can, that he had brandished so tormentingly in the faces of the sufferers.

It is strange that such a dog should not have known the risk he ran in making such a taunt.

The Indian had scarcely fallen when several of his comrades started down the declivity to bring away his body. At the same moment, Egbert Rodman, who was in one of the wagons, sprung out, and was seen to run at full speed in the direction of the fallen man.

“Come back! come back! or you’re a dead man!” shouted Captain Shields, divining his purpose on the instant.

But the young man’s lips were set, and he was determined upon possessing that canteen, if it were within the range of human possibility. He saw a horde of Comanches swarming down the gulch on a full run, screeching like demons, and evidently certain of securing the daring Yengee, whose torturing thirst had stolen away his senses.

But Egbert was not to be deterred by any such appalling danger as this. Now that he had undertaken the desperate task, nothing but death should turn him aside!

In far less time than it requires to be narrated, he had sped over the intervening ground, and was at the prostrate figure. He was fleet of foot, and he ran as he never ran before, reaching it, however, only a few seconds in advance of the rescuing Comanches, one of whom actually fired and missed him, when scarcely a rod in advance.

One tremendous jerk of his arm, and Egbert threw the dead Indian off the canteen, and catching it up in his hand, he turned about and started at the same headlong speed for the encampment, clinging to the vessel as if it was his own life; but the Comanches were all about him, and it looked as if it was all up, when he whipped out his only weapon—his revolver, and blazed away right and left in their very faces. At the same instant the whites opened fire, and made such havoc, that in the confusion Egbert made a dash, and sped like a reindeer for the wagons, and leaped in behind them with the canteen and the water and himself intact.

Then a shout went up from within the little band, and making his way to the central wagon, Egbert first furnished the moaning children with several swallows of the delicious—(oh, how delicious!) fluid, no argument inducing Lizzie Manning to take a drop, until all her companions had first done so.

Then the brave fellow made his way from man to man,[Pg 34] every one partaking of the soul-reviving cold water, whose delicious taste could not have been approached by the “nectar of the gods.”

All drank moderately, for they knew that Egbert was to come last, and nothing could induce one to cut his allowance short; and so he let several swallows gurgle down his parched throat, when he carried the remainder to the women’s wagon, and placing it in the hands of Lizzie, said:

“Keep it for the poor suffering little ones and for yourselves! We are hardy men, and can stand thirst better than they, and know how to chew our bullets, when we have nothing else!”

With many a fervent blessing upon the noble fellow’s head, the canteen was accepted and preserved as he requested.

The second night the moon, that rode high on the sky, enabled the little party of white men in Dead Man’s Gulch to detect the Comanches as they prowled about, and our friends proved their vigilance by picking off every one who thus exposed himself to their deadly rifles.

For the first half of the night little rest was obtained by either side—the spitting shots continuing with a rapidity, and in such numbers, as sometimes to resemble platoon firing—but, shortly past the turn of night, the Comanches seemed to grow weary of the incessant din, and being a fair target for the whites so long as they remained on the hill, where they were brought in fair relief against the sky, they assumed safer positions, and for a long time perfect silence remained.

By this time, despite the respite afforded by the captured canteen, the condition of the party was as desperate as it could be. Although the whites had been very careful in exposing themselves to the aim of the Comanches, yet so deadly had it been that there were now only ten men left, [Pg 35]including Gibbons. Shortly after midnight two of these made the attempt to steal through the environing lines, and both lost their lives, in the manner recorded elsewhere. This left but eight able-bodied men to continue the defense, and Gibbons began arranging his flight with Shields, they keeping it a secret from the rest, as it was feared that there would be a strife as to who should go, every one being anxious to get out of such a hell as Dead Man’s Gulch by any means, so long as a suitable pretext could be found.

But one horse was left unharmed. The others were dead, stretched in different places around the open space, and, under the warm sun, an odor of the most offensive character was beginning to rise from them. Worse still, there were men here and there, and some of them in wagons, to whom the right of sepulture could not be given; and they lay, with dark, discolored faces, staring up to the sky, happier than were those who were left behind to struggle and fight on, only to die at last a still more dreadful death then had come to them.

All was still, and in the large wagons, devoted to the shelter of the women and children, the latter were sound asleep, as were most of the former. Lizzie Manning had endeavored to inspire hope in the despairing ones around her, and was now sitting, with folded hands, upon a blanket, her shawl gathered over her shoulders, and in that attitude was awaiting sleep, when she heard a faint footstep near her, and turning her head, descried the figure of Egbert Rodman advancing, with a hesitating step, in that direction, his actions indicating that he felt considerable doubt as to the propriety of that which he was doing.

Believing that he was seeking an opportunity to say something to her, Lizzie spoke to him in a low, reassuring voice.

“Well, Egbert, is it I that you wish to see? If so, come nearer, where your voice will not be so likely to be heard.”

“I was wondering whether you were asleep or not,” he replied, making his way to the rear of the wagon, where her face could be seen looking encouragingly out upon him. “There is no fighting going on at present; it won’t do for one to go to sleep, and I was thinking that possibly you might be awake, and with no ability to close your eyes in[Pg 36] slumber. But, if you have, don’t fail to say so, and I will wait until to-morrow, or until there is a more favorable opportunity.”

“You need not leave, Egbert,” said she. “I did not sleep a single minute last night, nor can I do so to-night. I am glad that you have come, that we may have a chat with each other, without disturbing any one else. Somehow or other, I feel a strong conviction that this is the last night that will be spent in the gulch.”

Egbert had thought the same for hours, but he had kept his premonitions to himself, and it cut him to the heart when the gentle and ordinarily light-hearted girl spoke of it in such positive and hopeless tones.

Yet nothing was to be gained by denying the existence of such a desperate strait.

“It does look so, indeed,” he replied, in a low voice, as he leaned against the wagon in such a posture that his head was brought close to hers. “It is not likely that any diversion will be created in our favor, and we can not keep up a successful resistance much longer. Our numbers are getting too small.”

“I hope they will end this struggle by firing into and killing us all together,” returned Lizzie, in her sad, sweet tones, and her heart gave a great throb as she reflected upon the fate of falling into the hands of these tiger-like Comanches. “Do you not think they will do so, Egbert?”

He could not answer in the affirmative, so he did the best thing possible, making answer:

“You know that we shall keep up the fighting as long as any of us are left. When our men become so scarce, or are nearly all gone, the women can take their places, and thus compel the death which I know would be welcome to all.”

“Well, Egbert,” said she, in tones of Christian resignation, “it is only a step between this and the other life. Father and mother and sisters and brothers will mourn when they learn of the death that Lizzie died, but then she has only gone on before—just ahead of them.”

“Yes,” replied the young lover, who felt soothed, albeit saddened, by the words of the sweet girl. Reaching up his hand, he took hers, and with a solemn, sacred feeling, said:

“I suppose, Lizzie, now that we stand in the presence of death, you will permit me to declare how I loved you the first time I saw you in St. Louis, and how that love has increased and deepened with every hour since, until I feel now, like the romantic cavaliers of old, that it is sweet to stand here, and to die, knowing that I die defending your honor and your life. Lizzie, my own dearest one, you have all my heart. None who have seen you can fail to respect your sweetness of character, and the veriest slave was never held a more helpless captive by his task-master than I am by you. It would be idle for me to expect any thing like a similar emotion upon your part, but I am sure you will not be offended at what I have said. Tell me that.”

“No; I am not—”

Egbert fell her hand tremble in his own, and a strange yearning came over him to hear what she had checked herself in saying. Could it be that she felt in any degree the same emotion that penetrated his whole being? No, impossible; and yet what meant this trembling, this agitation, this excitement?

But she said not the words he was so anxious to hear, and they talked awhile longer upon the desperate situation, and then, kissing the dear hand that he had fondled and held imprisoned in his own, he bade her good-night, and returned to his post of duty.

All through this singular fight, Lightning Jo had kept within reach of his mustang, which occasionally put in a kick now and then, in the hope that he might be turned to account; but the tumult and uproar became so terrific, that he finally became panic-stricken, and with a whinny of the wildest terror, he made a plunge among the scarcely-less excited animals, when his furious struggles added to the fearful [Pg 38]uproar, which was already sufficient to drive an ordinary man out of his senses.

Lightning Jo, as we have said, knew that his friends were coming over the hills at the topmost bent of their speed; but the flight of his horse, and the rapid closing in of the Comanches, made further delay fatal, and with the promptness that was a peculiar characteristic of the man, he grasped his loaded rifle in his hands, and made his desperate struggle for freedom.

This was simply an attempt to dodge beneath the horses’ bellies out beyond them, where he knew his own fleetness could be depended on to carry him safely into the company of his own men.

And now began a most extraordinary performance, and an exhibition of Lightning Jo’s miraculous quickness of movement was given, such as would seem incredible in a description like ours. He was walled in on every hand by the swarming Comanches, but by the matchless use of his tremendous arms, he kept back the scores from entangling him in their embrace; until, all at once, he was seen to make a leap upward, directly over the shoulders of those immediately surrounding, and he shot beneath the belly of the nearest mustang like a whizzing rocket.

And, as he did so, he gave utterance to that strange yell of his, like the yelping prairie-dog, whose bark is cut short, as he plunges headlong into his hole, by the sudden whisking of his head out of sight.

The Comanches who caught the dissolving view of the scout, made a desperate struggle to capture him, and those who were still mounted, and saw him leaping beneath their animals, turned them aside, and cut, slashed and thrust at him in the most spiteful fashion, while others sprung off their horses, and did their utmost to intercept and cut him off, or to trip him to the earth, or to disable him in some way that would prevent his succeeding in his threatened escape from their clutches.

It would be a vain attempt to follow his movements in the way of description, when the eye itself was unable to do so; and, despite the astonishing celerity of the Comanches, whose nimbleness of movement is proverbial in the West, they[Pg 39] were completely baffled in every effort they made to entrap him.

Here, there, everywhere, he was seen, shooting out sometimes from between a horse’s legs, and then was in another place before the animal could resent the shock given him—in front—in the rear—leaping to one side—backward—forward—and threw the whole troop into confusion—every now and then giving utterance to that indescribable yell, so that the red-skins were actually in chase of that—and all the time steadily approaching the outer circle of mustangs, and ever keeping in mind the proper direction for him to follow, to meet the much-needed soldiers.

And all this took place in one-tenth the time required in our references. The bewildering dodging and doubling of Lightning Jo continued until he shot from beneath the last horse, and then with a triumphant screech, he sped away like a terrified antelope.

Hitherto the efforts of the Comanches had been directed toward capturing the redoubtable scout, and they soon dashed their animals after him on a full run, in the hope of riding him down before he could reach the assistance which they knew was so close at hand.

It proved closer indeed than they suspected; for they had hardly started upon the fierce pursuit when a rattling discharge of rifles rose above the din and confusion, just as the whole company of United States cavalry thundered over the ridge, and came down upon them like the sweep of a tornado that carries every thing before it.

There were a few exchanges of shots, and then the Comanches would have excited the admiration of a troop of Centaurs by their display of horsemanship. Speeding forward like a whirlwind, the shock of the opposing bodies seemed certain to be like that of an earthquake; but, at the very instant of striking, every Indian shied off, either to the right or the left, and by a quick, rapid circle of their well trained animals, they shot away beyond reach of harm from cavalry, and skurried away over the hills and ridges, disappearing from view with the same astonishing quickness, that made successful pursuit out of the question.

Driven away in this unceremonious fashion, the Comanches[Pg 40] were compelled to leave their dead upon the field—the wounded managing to take care of themselves, and to get out of harm’s way, ere the cavalry could swoop down upon them. The fashion of giving quarter, in the contests between the Indians and white men, has never been very popular, and at the present day, it may be considered practically obsolete, so that the Comanches displayed only ordinary discretion in “getting up and getting”—if we may be permitted to use the expressive language of the West itself, in referring to an engagement of this kind.

Accustomed as were these men to the exhibitions of the wonderful powers of Lightning Jo, they were astounded at the exhibition of their own eyes, of the deeds he had done during the few minutes that he had engaged in the encounter with the red-skins. The troop gathered around the battlefield, and were commenting in their characteristic manner upon his exploits, when the scout himself, seeing his mustang near at hand, made haste to secure him, and leaping upon his back, he lost no time in placing himself at their lead, and turning his face toward Dead Man’s Gulch, he said, in his sharp, peremptory way, when thoroughly in earnest:

“Come, boys, we have lost too much time. We must git there afore dark, if we git there at all.”

Gibbons, the messenger, placed himself beside him, and, as soon as they were fairly under way, Jo remarked to him:

“I hardly know what to make of it. Old Swico is not with them skunks, and I am disappointed. It has a bad look.”

“Why so?” inquired his comrade, who was partly prepared for the answer.

“I ain’t sartin—but it looks to me as if the business is finished down at the Gulch.”

“Then why should not the chief, released from there, be here with his men?” continued Gibbons.

“This is only a part of his men; there wa’n’t many Comanches among the hills. I think the old dog sent them off on purpose to bother us and keep us back as much as they could.”

“While Swico and the others have taken another direction?”

“Exactly, and carried the women and children with them; and if so, we might as well turn back to Fort Adams ag’in.”

But the scout, as he uttered these chilling words, set his teeth, and rode his mustang harder than ever toward Dead Man’s Gulch.

The wagon containing the females and the children was that which carried the provisions—the others being piled up with the luggage belonging to the different members of the party, and which they had formed into rude barricades from which they fired out, with such deadly effect, upon the Comanches, who, from the nature of the case, were unable to make any kind of approach without exposing themselves to that same unerring fire.

One of the men, at stated periods, visited the provision wagon, and brought forth lunch for his comrades, who felt no suffering in that respect—their great trial being the lack of water. But for the providential supply, secured in the manner already narrated, human endurance would not have permitted the whites to have held out longer than the beginning of this terrible, and what was destined to prove the last, day—the one following the departure of Gibbons, the messenger, for Fort Adams.

It should be made clear at this point also that, of the half-dozen women, and the same number of children, not one had husband, or father, or blood-relative among the defenders, so that, while their situation could scarcely have been more trying, it was deprived of the poignant anguish of seeing the members of their own household shot down in cold blood before their eyes.

No pen can depict the gratitude and love they felt for these men, who, it may be said, were giving up their lives to[Pg 42] protect them; for, at the first appearance of the dreaded Comanches, every one of them could have secured their safety by dashing away at full speed, upon their fleet-footed mustangs, and leaving the helpless ones to their fate.

But of such a fashion is not the Western borderer, who will go to certain death, rather than prove false to those who have been intrusted to his care. The party had been sent to St. Louis, under an agreement to bring this little company to their homes in Santa Fe, on their return from an excursion to the Eastern States, and there was not one of them who would have dared to ride into the beautiful Mexican town with the tidings that they had perished, and he had lived to tell the tale. Far better, a thousand times, that their bones should be left to bleach upon the prairie, rather than they should live to be forever disgraced and dishonored, and to carry an accusing conscience with them for the remainder of their days.

The children, during the first twenty four hours, probably suffered the most, in their cramped, constrained position, being compelled to remain within the wagon, lest, if they exposed themselves by appearing upon the ground, they should be slain by the Comanches, who availed themselves of every opportunity to retaliate upon the whites.

After it became pretty certain that Jim Gibbons had penetrated and passed through the Comanche lines, Captain Shields prepared for a deadly charge from their enemies, and from his place in his vehicle he called to the others to make ready also.

The men thus talked with each other, while their faces were mutually invisible; but the little circle permitted the freest intercommunication. His advice was followed, and every rifle loaded and kept ready to be discharged at an instant’s warning.

It was terribly annoying to feel, at a juncture like this, that they must husband their fire on account of the failing supply of ammunition, and at the same time manage the business in such a way that the Comanches themselves should not be permitted to discover the appalling truth.

“Don’t fire too often,” called the captain, in his cautious way, “and when you do make sure that you let daylight[Pg 43] through one of the red devils. I think they will open on us in some way, and very soon, too.”

It seemed strange that the uproar and tumult which had marked the flight of Gibbons should be succeeded in its turn by such a profound silence as now rested upon the gulch. From the place where our friends crouched not a single Comanche could be seen, nor could their location be detected by the slightest sound.

From far away on the prairie came the faint sound of a rifle—but in the immediate vicinity all was still.

Captain Shields was of the opinion that Swico, the chief, had gathered his warriors around him, just outside the gulch, and was holding a consultation as to what was the best to be done, as it was now as good as certain that, before the dawn of another day, a heavy force of cavalry would be down upon them.

There were some who really believed that the Comanches would now draw off and disappear altogether from the place where they had suffered such a terrible repulse; but for this very reason, the experienced frontiersman, Captain Shields, was certain that the contrary would prove to be the case. The incitement of revenge would prompt them rather to make the most desperate charges and the most furious assaults upon the little Spartan band.

And while the old hunter lay upon his face in the wagon, stealthily peering out, and listening for the first approach of his foes, he coolly calculated the chances of the day.

“Six of us left, and we average three rifles apiece—to say nothing of revolvers that are scattered all among the boys. We can load and fire these, perhaps four or five times apiece—not oftener, certainly—that is, if we can only get the opportunity to load and fire them. After that— Well, everybody has got to die some time.”

At this, he stealthily moved around, and peered out at the wagon containing the helpless ones, and he muttered:

“All seems to be quiet there, and I guess none of them have been reached by these bullets whizzing all about them, which may be either good or bad fortune.”

Then as he resumed his position of guard, he cleared his vision with his hand, and added:

“It’s mighty rough on them. We men are always expecting such things, and are sort of ready for it; but for helpless women and children— Helloa! what in the name of Heaven can that be?”

Captain Shields might well give utterance to this exclamation, for just then his eyes were greeted with the most singular sight he had ever seen in all his life. He rubbed his eyes and stared, and finally turned to young Egbert Rodman, who just then crawled into the wagon.

“If I was a drinking man,” said he, “I would swear that I had the jim-jams sure. Look out the wagon, Rodman, and tell me whether you see any thing unusual, or different from what we have been accustomed to look upon for the last day or two.”

The young man did as requested, and the exclamation that escaped him convinced the somewhat nervous officer that his head was still level, and his brain was playing no fantastic freak with him.

The sight which greeted their eyes, and so excited their wonder, came first in the shape of a horse, which, walking slowly forward, steadily loomed up to view, until it stood directly on the border of the gulch, where, at a hundred yards distant, and with the clear sunlight bathing him, every outline was distinctly visible.

But it was not the horse, but that which was upon it, that so excited the wonder and speculations of those who saw him. Close scrutiny gave it the appearance of an animal standing upon all-fours upon the back of the horse, like Barnum’s trained goat Alexis. It was, however, three times the size of that sagacious creature, and an Indian blanket was thrown over it, so that little more than the general outlines could be discerned.

This enveloping blanket reached to the neck of the “what[Pg 45] is it?” leaving the head entirely exposed. This was round, and bullet-shaped, and moved in that restless, nervous way peculiar to animals. It seemed as black as coal, and resembled the head of one of those giant gorillas which Du Chaillu ran against in the wilds of Central Africa.

A strange chill crept over the two men, as they felt that this animal was looking steadily down upon the encampment, as if meditating a charge upon it, and only waiting to select the most vulnerable point.

The steed supporting this nondescript stood neither directly facing nor broadside toward the whites—but in such a position that their view could not have been better. The horse remained as stationary and motionless as if he were an image carved in bronze.

No other living creature being in sight, the eyes of the little band of defenders in Dead Man’s Gulch were speedily fixed upon this strange phenomenon, and its movements were watched with an intensity of interest which it would be hard to describe.

“It is some Comanche deviltry,” was the remark of Egbert Rodman, after he had surveyed the object for several minutes. “They have grown tired of running against our bullets, and are about to try some other means.”

“But what sort of means is that?” asked the captain, who beyond question was a little nervous over what he saw.

“That is rather hard to tell, until we have some more developments; but you know that the red-skins, from their earliest history, have been noted for their ingenious tricks, by which they have outwitted their foes, and you may depend upon it that this is one of their contrivances, although I must say that I do not see the necessity for any such labored attempts as that, when they have every thing their own way; and, if they would only make a united and determined charge, we should all go under to a dead certainly.”

Captain Shields, however, like many of the bravest men, was superstitious, and he was inclined to believe that there was something supernatural in the appearance of this thing, and, although he hesitated to say so, yet he looked upon it as having a most direful significance concerning himself and his friends.

Still the horse remained perfectly motionless, and the quadruped, with the blanket thrown over his back, was steadily gazing down upon them, from his perch upon the back of another quadruped.

The profound stillness that then reigned over the prairie and in Dead Man’s Gulch was rather deepened by the sound of the faintest, most distant report of a gun that seemed to have come from some point miles and miles away, in the direction of Fort Adams, proving plainly that the pursuit of the flying messenger was not yet given over.

Egbert Rodman concluded that there was a very easy and speedy way of settling the business of convincing the awed captain that there was nothing possessed by this curious animal that was not the common possession of his race. As he stood, partly turned toward him, he could not have desired a better target for a carefully aimed rifle, and he determined to tumble him from the back of the horse, and thus put a speedy end to that bugbear of the captain’s.

Without saying a word as to his intentions, he carefully thrust the muzzle of his rifle through the aperture in the canvas of the wagon, and sighted at about where he supposed the seat of life to be. He held his aim only long enough to make certain, and then pulled the trigger and looked out to see the “what is it?” pitch to the ground, and reveal his particular identity in his death-struggles before their eyes.

But what did he see? The creature, standing in precisely the same posture, and looking steadily down upon them, as unmoved as though such a thing as a gun had never been invented.

But Egbert, although very much astounded, was not yet prepared to admit that the nondescript was impregnable against a good Springfield rifle, even if those about him were under a superstitious spell.

And so, with the same steadiness of eye and nerve, he reached out and took a second rifle from beside him, and shoved this through the “port hole.”

The same unexceptionable target remained, and he resolved that this time there should be no failure. He was a good marksman, and he made certain aim, while more than one breathlessly watched the result.

The same as before! Not a sign of the thing being harmed in the least!

“Shoot no more!” said Captain Shields, in an awed voice, “there is nothing mortal about it! It is sent to warn us of what is so close at hand!”

When Egbert Rodman fired and missed the second time at the apparition at the top of the gulch, his emotions were certainly of the most uncomfortable kind.

He was now certain that in both instances he had hit it fairly and plumbly in the very point aimed at, and it was equally certain that he had not harmed it in any way.

The mustang did not stir an inch, nor did any movement upon the part of its strange rider indicate that he or it was sensible of the slightest disturbance from the two bullets that had been aimed at its life. Clearly then it was useless to waste any more precious ammunition upon it, when it was simply throwing it away.