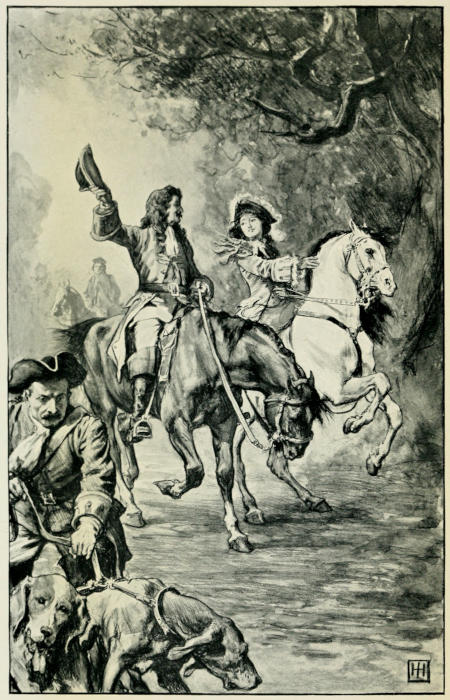

“CARESSING HER HORSE WITH ONE HAND.”

(Page 35.)

Title: Cerise: A Tale of the Last Century

Author: G. J. Whyte-Melville

Illustrator: G. P. Jacomb Hood

Release date: June 15, 2021 [eBook #65619]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Suzanne Shell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (https://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Cerise, by G. J. (George John) Whyte-Melville, Illustrated by G. P. Jacomb-Hood

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/cu31924013570126 |

Cerise

Cerise

A Tale of the Last Century

By

G. J. Whyte-Melville

Author of “Market Harborough,” “Katerfelto,”

“Satanella,” etc., etc.

Illustrated

by

G. P. Jacomb-Hood

London

Ward, Lock & Co., Limited

New York and Melbourne.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | The Daisy-Chain | 9 |

| II. | The Montmirails | 17 |

| III. | Monsieur l’Abbé | 25 |

| IV. | Tantara! | 34 |

| V. | The Usher of the Black Rod | 44 |

| VI. | A Jesuit’s Task | 51 |

| VII. | St. Mark’s Balsam | 59 |

| VIII. | The Grey Musketeers | 68 |

| IX. | Eugène Beaudésir | 76 |

| X. | The Boudoir of Madame | 86 |

| XI. | What the Serpent Said | 94 |

| XII. | Out-manœuvred | 105 |

| XIII. | The Mother of Satan | 113 |

| XIV. | The Débonnaire | 122 |

| XV. | The Masked Ball | 132 |

| XVI. | Raising the Devil | 144 |

| XVII. | A Quiet Supper | 151 |

| XVIII. | Baiting the Trap | 160 |

| XIX. | Mater Pulchrâ, Filia Pulchrior | 167 |

| XX. | A General Rendezvous | 177 |

| XXI. | The Fox and Fiddle | 185 |

| XXII. | Three Strands of a Yarn | 193 |

| XXIII. | The Parlour-Lodger | 202 |

| XXIV. | A Volunteer | 210 |

| XXV. | Three Pressed Men | 218 |

| XXVI. | “Yo-heave-yo!” | 227 |

| XXVII. | ‘The Bashful Maid’ | 235 |

| XXVIII. | Dirty Weather | 244[8] |

| XXIX. | Port Welcome | 250 |

| XXX. | Montmirail West | 259 |

| XXXI. | Black, but Comely | 272 |

| XXXII. | A Wise Child | 277 |

| XXXIII. | Jack Aground | 286 |

| XXXIV. | Jack Afloat | 294 |

| XXXV. | Besieged | 301 |

| XXXVI. | At Bay | 309 |

| XXXVII. | Just in Time | 317 |

| XXXVIII. | Mère avant tout | 326 |

| XXXIX. | All Adrift | 335 |

| XL. | Homeward Bound | 341 |

| XLI. | Lady Hamilton | 351 |

| XLII. | The Desire of the Moth | 360 |

| XLIII. | For the Star | 370 |

| XLIV. | “Box it About” | 379 |

| XLV. | The Little Rift | 389 |

| XLVI. | The Music Mute | 399 |

| XLVII. | The “Hamilton Arms” | 408 |

| XLVIII. | Pressure | 419 |

| XLIX. | Poor Emerald | 429 |

| L. | Captain Bold | 441 |

| LI. | Sir Marmaduke | 448 |

| LII. | The Bowl on the Bias | 458 |

| LIII. | Fair Fighting | 466 |

| LIV. | Friends in Need | 475 |

| LV. | Forewarned | 486 |

| LVI. | Forearmed | 494 |

| LVII. | An Addled Egg | 503 |

| LVIII. | Horns and Hoofs | 511 |

| LIX. | A Substitute | 518 |

| LX. | Solace | 529 |

In the gardens of Versailles, as everywhere else within the freezing influence of the Grand Monarque, nature herself seemed to accept the situation, and succumbed inevitably under the chain of order and courtly etiquette. The grass grew, indeed, and the Great Waters played, but the former was rigorously limited to certain mathematical patches, and permitted only to obtain an established length, while the latter threw their diamond showers against the sky with the regular and oppressive monotony of clockwork. The avenues stretched away straight and stiff like rows of lately-built houses; the shrubs stood hard and defiant as the white statues with which they alternated, and the very sunshine off the blinding gravel glared and scorched as if its duty were but to mark a march of dazzling hours on square stone dials for the kings of France.

Down in Touraine the woods were sleeping, hushed, and peaceful in the glowing summer’s day, sighing, as it were, and stirring in their repose, while the breeze crept through their shadows, and quivered in their outskirts, ere it passed on to cool the peasant’s brow, toiling contented in his clearing, with blue home-spun garb, white teeth, and honest sunburnt face.

Far off in Normandy, sleek of skin and rich of colour, cows were ruminating knee-deep in pasturage; hedges were[10] loaded with wild flowers, thickets dark with rank luxuriance of growth, while fresh streams, over which the blue kingfisher flitted like a dragon-fly, rippled merrily down towards the sea. Through teeming orchards, between waving cornfields, past convent-walls grown over with woodbine and lilac and laburnum, under stately churches, rearing Gothic spires, delicate as needlework, to heaven, and bringing with them a cool current of air, a sense of freedom and refreshment as they hurried past. Nay, even where the ripening sun beat fiercely on the vineyards, terraced tier upon tier, to concentrate his rays—where Macon and Côte-d’Or were already tinged with the first faint blush of their coming vintage, even amidst the grape-rows so orderly planted and so carefully trained, buxom peasant-girls could gather posies of wild flowers for their raven hair, to make their black eyes sparkle with merrier glances, and their dusky cheeks mantle in rich carnation, type of southern blood dancing through their veins.

But Versailles was not France, and at Versailles nothing seemed free but the birds and the children.

One of the alleys, commanded from the king’s private apartments, was thickly crowded with loungers. Courtiers in silk stockings, laced coats, and embroidered waistcoats reaching to their thighs, wearing diamond hilts on their rapiers, and diamond buckles in their shoes, could not move a step without apology for catching in the spreading skirts of magnificent ladies—magnificent, be it understood, in gorgeousness of apparel rather than in beauty of face or symmetry of figure. The former, indeed, whatever might be its natural advantages, was usually coated with paint and spotted with patches, while the latter was so disguised by voluminous robes, looped-up skirts, falling laces, and such outworks and appendages, not to mention a superstructure of hair, ribbon, and other materials, towering so high above the head as to place a short woman’s face somewhere about the middle of her whole altitude, that it must have been difficult even for the maid who dressed her to identify, in one of these imposing triumphs of art, the slender and insignificant little framework upon which the whole fabric had been raised. Devotion in woman is never more sublime than when sustaining the torture of dress.

It was all artificial together. Not a word was spoken but might have been overheard with entire satisfaction by the unseen sovereign who set the whole pageant in motion. Not a gesture but was restrained by the consciousness of supervision. Not a sentiment broached but had for its object the greater glorification of a little old man, feeble and worn-out, eating iced fruit and sweetmeats in a closet opening from a formal, heavily-furnished, over-gilded saloon, that commanded the broad gravel-walk on which the courtiers passed to and fro in a shifting, sparkling throng. If a compliment was paid by grinning gallant to simpering dame, it was offered and accepted with a sidelong glance from each towards the palace windows. If a countess whispered scandal to a duchess behind her fan, the grateful dish was sauced and flavoured for the master’s palate, to whom it would be offered by the listener on the first opportunity. Marshals of a hundred fights tapped their jewelled snuff-boxes to inhale a pinch of the King’s Mixture. Blooming beauties, whose every breath was fragrance, steeped their gossamer handkerchiefs in no other perfume than an extract from orange-flowers, called Bouquet du Roi.

For Louis the Fourteenth, if he might believe his household, Time was to stand still, and the Seasons brought no change. “I am the same age as everybody else,” said a courtier of seventy to his Majesty at sixty-five. “The rain of Marly does not wet one,” urged another, as an excuse for not covering his head in a shower while walking with the king. By such gross flattery was that sovereign to be duped, who believed himself a match for the whole of Europe in perceptive wisdom and diplomatic finesse.

But though powdered heads were bowing, and laced hats waving, and brocades ruffling in the great walk, swallows skimmed and darted through the shades of a green alley behind the nearest fountain, and a little girl was sitting on the grass, making daisy-chains as busily as if there were no other interest, no other occupation at Court or in the world.

Her flapping hat was thrown aside, and her head bent studiously over her work, so that the brown curls, silken and rich and thick, as a girl’s curls should be, hid all of her face but a little soft white brow. Her dimpled arms and hands moved nimbly about her task, and a pair of sturdy,[12] well-turned legs were stuck out straight before her, as if she had established herself in her present position with a resolution not to stir till she had completed the long snowy chain that festooned already for several yards across the turf. She had just glanced in extreme content at its progress without raising her head, when a spaniel scoured by, followed at speed by a young gentleman in a page’s dress, who, skimming the level with his toe, in all the impetuous haste of boyhood, caught the great work round his ankles, and tore it into a dozen fragments as he passed.

The little girl looked up in consternation, having duly arranged her face for a howl; but she controlled her feelings, partly in surprise, partly in bashfulness, partly perhaps in gratification at the very obvious approval with which the aggressor regarded that face, while, stopping short, he begged “Mademoiselle’s pardon” with all the grand manner of the Court grafted on the natural politeness of France.

It was indeed a very pretty, and, more, a very lovable little face, with its large innocent blue eyes, its delicate peach-like cheeks, and a pair of curling ruddy lips, that, combined with her own infantine pronunciation of her baptismal name Thérèse, had already obtained for the child the familiar appellation of “Cerise.”

“Pardon, mademoiselle!” repeated the page, colouring boy-like to his temples—“Pardon! I was running so fast; I was in such a hurry—I am so awkward. I will pick you a hatful more daisies—and—and I can get you a large slice of cake this evening when the king goes out of the little supper-room to the music-hall.”

“Mademoiselle” thus adjured, rose to her full stature of some forty inches, and spreading her short stiff skirt around her with great care, replied by a stately reverence that would have done credit to an empress. Notwithstanding her dignity, however, she cast a wistful look at the broken daisy-chain, while her little red lips quivered as if a burst of tears was not far off.

The boy was down on his knees in an instant, gathering handfuls of the simple flowers, and flinging them impetuously into his hat. It was obvious that this young gentleman possessed already considerable energy of character, and judging from the flash of his bold dark eyes, a determined[13] will of his own. His figure, though as yet unformed, was lithe, erect, and active, while his noble bearing denoted self-reliance beyond his years, and a reckless, confident disposition, such as a true pedagogue would have longed and failed to check with the high hand of coercion. In a few minutes he had collected daisies enough to fill his laced hat to the rims, and flinging himself on the turf, began stringing them together with his strong, well-shaped, sunburnt fingers. The little girl, much consoled, had reseated herself as before. It was delightful to see the chain thus lengthening by fathoms at a time, and this new friend seemed to enter heart and soul into the important work. Active sympathy soon finds its way to a child’s heart; she nestled up to his side, and shaking her curls back, looked confidingly in his face.

“I like you,” said the little woman, honestly, and without reserve. “You are good—you are polite—you make daisy-chains as well as mamma. My name’s Cerise. What’s your name?”

The page smiled, and with the smile his whole countenance grew handsome. In repose, his face was simply that of a well-looking youth enough, with a bold, saucy expression and hardy sunburned features; but when he smiled, a physiognomist watching the change would have pronounced, “That boy must be like his mother, and his mother must have been beautiful!”

“Cerise,” repeated the lad. “What a pretty name! Mine is not a pretty name. Boys don’t have pretty names. My name’s George—George Hamilton. You mustn’t call me Hamilton. I am never called anything but George at Court. I’m not big enough to be a soldier yet, but I am page to Louis le Grand!”

The child opened her eyes very wide, and stared over her new friend’s head at a gentleman who was listening attentively to their conversation, with his hat in his hand, and an expression of considerable amusement pervading his old, worn, melancholy face.

This gentleman had stolen round the corner of the alley, treading softly on the turf, and might have been watching the children for some minutes unperceived. He was a small, shrunken, but well-made person, with a symmetrical leg[14] and foot, the arched instep of the latter increased by the high heels of his diamond-buckled shoes. His dress in those days of splendour was plain almost to affectation; it consisted of a full-skirted, light-brown coat, ornamented only with a few gold buttons; breeches of the same colour, and a red satin waistcoat embroidered at the edges, the whole suit relieved by the cordon bleu which was worn outside. The hat he dangled in his pale, thin, unringed hand was trimmed with Spanish point, and had a plume of white feathers. His face was long, and bore a solemn, saddened expression, the more remarkable for the rapidity with which, as at present, it succeeded a transient gleam of mirth. Notwithstanding all its advantages of dress and manner, notwithstanding jewelled buckles, and point lace, and full flowing periwig, the figure now standing over the two children, in sad contrast to their rich flow of youth and health, was that of a worn-out, decrepid old man, fast approaching, though not yet actually touching, the brink of his grave.

The smile, however, came over his wrinkled face once more as the child looked shyly up, gathering her daisy-chain distrustfully into her lap. Then he stooped to stroke her brown curls with his white wasted hand.

“Your name is Thérèse,” said he gravely. “Mamma calls you Cerise, because you are such a round, ruddy little thing. Mamma is waiting in the painted saloon for the king’s dinner. You may look at him eating it, if your bonne takes you home past the square table in the middle window opposite the Great Fountain. She is to come for you in a quarter of an hour. You see I know all about it, little one.”

Cerise stared in utter consternation, but at the first sound of that voice the boy had started to his feet, blushing furiously, and catching up his hat, to upset an avalanche of daisies in the action, stood swinging it in his hand, bolt upright like a soldier who springs to “attention” under the eye of his officer. The old gentleman’s face had resumed its sad expression, but he drew up his feeble figure with dignity, and motioned the lad, who already nearly equalled him in height, a little further back. George obeyed instinctively, and Cerise, still sitting on the grass, with the daisy-chain in her lap, looked from one to the other in a state of utter bewilderment.

“Don’t be frightened, little one,” continued the old gentleman, caressingly. “Come and play in these gardens whenever you like. Tell Le Notre to give you prettier flowers than these to make chains of, and when you get older, try to leave off turning the heads of my pages with your brown curls and cherry lips. As for you, sir,” he added, facing round upon George, “I have seldom seen any of you so innocently employed. Take care of this pretty little girl till her bonne comes to fetch her, and show them both the place from whence they can see the king at dinner. How does the king dine to-day, sir? and when?” he concluded, in a sharper and sterner tone. George was equal to the occasion.

“There is no council to-day, sire,” he answered, without hesitation. “His Majesty has ordered ‘The Little Service’[1] this morning, and will dine in seventeen minutes exactly, for I hear the Grey Musketeers already relieving guard in the Front Court.”

“Go, sir,” exclaimed the old gentleman, in great good-humour. “You have learnt your duty better than I expected. I think I may trust you with the care of this pretty child. Few pages know anything of etiquette or the necessary routine of a Court. I am satisfied with you. Do you understand?”

The boy’s cheeks flushed once more, as he bowed low and stood silent, whilst the old gentleman passed on. The latter, however, had not gone half-a-dozen paces ere he turned back, and again addressed the younger of the children.

“Do not forget, little one, to ask Le Notre for any flowers you want, and—and—if you think of it, tell mamma you met the honest bourgeois who owns these gardens, and that he knew you, and knew your name, and knew how old you were, and, I dare say, little one, you are surprised the bourgeois should know so much!”

That Cerise was surprised admitted of small doubt. She had scarcely found her voice ere the old gentleman turned out of the alley and disappeared. Then she looked at her companion, whose cheeks were still glowing with excitement, and presently burst into a peal of childish laughter.

“What a funny old man!” cried Cerise, clapping her[16] hands; “and I am to have as many flowers as I like—what a funny old man!”

“Hush, mademoiselle,” answered the boy, gravely, as though his own dignity had received a hurt, “you must not speak like that. It is very rude. It is very wrong. If a man were to say such things it should cost him his life.”

Cerise opened her blue eyes wider than ever.

“Wrong!” she repeated, “rude! what have I done? who is it, then?”

“It is the King!” answered the boy, proudly. “It is Louis le Grand!”

Ladies first. Let us identify the pretty little girl in the gardens of Versailles, who answered to the name of Cerise, before we account for the presence of George Hamilton the page.

It is a thing well understood—it is an arrangement universally conceded in France—that marriages should be contracted on principles of practical utility, rather than on the vague assumption of a romantic and unsuitable preference. It was therefore with tranquil acquiescence, and feelings perfectly under control, that Thérèse de la Fierté, daughter of a line of dukes, found herself taken out of a convent and wedded to a chivalrous veteran, who could scarcely stand long enough at the altar, upon his well-shaped but infirm old legs, to make the necessary responses for the conversion of the beautiful brunette over against him into Madame la Marquise de Montmirail. The bridegroom was indeed infinitely more agitated than the bride. He had conducted several campaigns; he was a Marshal of France; he had even been married before, to a remarkably plain person, who adored him; he had undergone the necessary course of gallantry inflicted on men of his station at the Court and in the society to which he belonged; nevertheless, as he said to himself, he felt like a recruit in his first “affair” when he encountered the plunging fire of those black eyes, raking him front, and flanks, and centre, from under the bridal wreath and its drooping white lace veil.

Thérèse had indeed, in right of her mother, large black eyes as well as large West Indian possessions; and her[18] light-haired rivals were good enough to attribute the rich radiance of her beauty to a stain of negro blood somewhere far back in that mother’s race.

Nevertheless, the old Marquis de Montmirail was really over head and ears in love with his brilliant bride. That he should have indulged her in every whim and every folly was but reasonably to be expected, but that she should always have shown for him the warm affection of a wife, tempered by the deference and respect of a daughter, is only another instance, added to the long score on record of woman’s sympathy and right feeling when treated with gentleness and consideration.

Not even at Court did Madame de Montmirail give a single opportunity to the thousand tongues of scandal during her husband’s lifetime; she was indeed notorious for sustaining the elaborate homage and tedious admiration of majesty itself, without betraying, by the flutter of an eyelash, that ambition was roused or vanity gratified during the ordeal. It seemed that she cared but for three people in the world. The chivalrous old wreck who had married her, and who was soon compelled to move about in a wheeled chair; the lovely little daughter born of their union, who inherited much of her mother’s effective beauty with the traditional grace and delicate complexion of the handsome Montmirails, a combination that had helped to distinguish her by the appropriate name of Cerise, and the young Abbé Malletort, a distant cousin of her own, as remarkable for shrewd intellect and utter want of sentiment as for symmetry of figure and signal ugliness of face. The Grand Monarque was not famous for consideration towards the nobles of his household. Long after the Marquis de Montmirail had commenced taking exercise on his own account in a chair, the king commanded his attendance at a shooting-party, kept him standing for three-quarters of an hour on damp grass, under heavy rain, and dismissed him with a pompous compliment, and an attack of gout driven upwards into the region of the stomach. The old courtier knew he had got his death-blow. The old soldier faced it like an officer of France. He sent for Madame la Marquise, and complimented her on her coiffure before proceeding to business. He apologised for the pains that took off his attention at intervals, and[19] bowed her out of the room, more than once, when the paroxysms became unbearable. The Marquise never went further than the door, where she fell on her knees in the passage and wept. He explained clearly enough how he had bequeathed to her all that was left of his dilapidated estates. Then he sent his duty to the king, observing that “He had served his Majesty under fire often, but never under water till now. He feared it was the last occasion of presenting his homage to his sovereign.” And so, asking for Cerise, who was brought in by her weeping mother, died brave and tranquil, with his arm round his child and a gold snuff-box in his hand.

Ladies cannot be expected to sorrow as inconsolably for a mate of seventy as for one of seven-and-twenty, but the Marquise de Montmirail grieved very honestly, nevertheless, and mourned during the prescribed period, with perhaps even more circumspection than had she lost a lover as well as, or instead of, a husband. Wagers were laid at Court that she would marry again within a year; yet the year passed by and Madame had not so much as seen anybody but her child and its bonne. Even Malletort was excluded from her society, and that versatile ecclesiastic, though pluming himself on his knowledge of human nature, including its most inexplicable half, was obliged to confess he was at a loss!

“Peste!” he would observe, taking a pinch of snuff, and flicking the particles delicately off his ruffles, “was not the sphinx a woman? At least down to the waist. So, I perceive, is the Marquise. What would you have? There is a clue to every labyrinth, but it is not always worth while to puzzle it out!”

After a time, when the established period for seclusion had expired, the widow, more beautiful than ever, made her appearance once more at Court. That she loved admiration there could not now be the slightest doubt, and the self-denial became at length apparent with which she had declined it during her husband’s lifetime, that she might not wring his kind old heart. So, in all societies—at balls, at promenades, at concerts—at solemn attendances on the king, at tedious receptions of princes and princesses, dukes and duchesses, sons and daughters of majesty, legitimate[20] or otherwise—she accepted homage with avidity, and returned compliment for compliment, and gallantry for gallantry, with a coquetry perfectly irresistible. But this was all: the first step was fatal taken by an admirer across that scarce perceptible boundary which divides the gold and silver grounds, the gaudy flower-beds of flattery from the sweet wild violet banks of love. The first tremble of interest in his voice, the first quiver of diffidence in his glance, was the signal for dismissal.

Madame de Montmirail knew neither pity nor remorse. She had the softest eyes, the smoothest skin, the sweetest voice in the bounds of France, but her heart was declared by all to be harder than the very diamonds that became her so well. Nor, though she seldom missed a chance of securing smiles and compliments, did she seem inclined to afford opportunity for advances of a more positive kind. Cerise was usually in her arms, or on her lap; and suitors of every time must have been constrained to admit that there is no duenna like a daughter. Besides, the child’s beauty was of a nature so different from her mother’s, that the most accomplished coxcomb found it difficult to word his admiration of mademoiselle so as to infer a yet stronger approval of madame herself. The slightest blunder, too, was as surely made public as it was quickly detected. The Marquise never denied herself or her friends an opportunity for a laugh, and her sarcasm was appropriate as pitiless; so to become a declared admirer of Madame de Montmirail required a good deal of that courage which is best conveyed by the word sang-froid.

And even for those reckless spirits, who neither feared the mother’s wit nor respected the daughter’s presence, there was yet another difficulty to encounter in the person of the child’s bonne, a middle-aged quadroon to whom Cerise was ardently attached, and who never left her mistress’s side when not employed in dressing or undressing her charge. This faithful retainer, originally a slave on the La-Fierté estates, had passed—with lands, goods, and chattels—into the possession of the Marquise after the death of her mother, the duchess, who was said to have a black drop of blood in her veins, and immediately transferred her fidelity and affections to her present owner. She was a large, strong[21] woman, with the remains of great beauty. Her age might be anything under fifty; and she was known at Court as “The Mother of Satan,” a title she accepted with considerable gratification, and much preferred to the sweeter-sounding name of Célandine, by which she was called on the West Indian estate and in the family of her proprietors.

Notwithstanding her good looks, there was something about Célandine that made her an object of dread to her fellow-servants, whether slaves or free. The woman’s manner was scowling and suspicious, she suffered from long fits of despondency; she muttered and gesticulated to herself; she walked about during the night, when the rest of the household were in bed. Altogether she gave occasion, by her behaviour, to those detractors who affirmed that, whether his mother or not, there was no doubt she was a faithful worshipper of Satan.

In the island whence she came, and among the kindred people who had brought with them from Africa their native barbarism and superstitions, the dark rites of Obi were still sedulously cultivated, as the magic power of its votaries was implicitly believed. The three-fourths of white blood in the veins of Célandine had not prevented her, so they said, from becoming a priestess of that foul order; and the price paid for her impious exaltation was differently estimated, according to the colour of those who discussed the revolting and mysterious question, even amongst the French domestics of Madame de Montmirail, and in so practical an age as the beginning of the eighteenth century. The quadroon, finding herself shunned by her equals, was drawn all the closer to her mistress and her little charge.

Such was the woman who pushed her way undaunted through the crowd of courtiers now thronging the Grand Alley at Versailles, eliciting no small share of attention by the gorgeousness of her costume; the scarlet shawl she had bound like a turban round her head, the profusion of gold ornaments that serpentined about her neck and arms, together with the glaring pattern of white and orange conspicuous on her dress, till she reached the secluded corner where Cerise was sitting with her broken daisy-chain and her attendant page, as she had been left by the king.

The quadroon’s whole countenance brightened into beauty[22] when she approached her darling, and the child bounding up to meet her, ran into her arms with a cry of delight that showed their attachment was mutual. George, extremely proud of his commission, volunteered to guide them to the spot whence, as directed, they could witness the progress of the king’s dinner, and the strangely-matched trio proceeded through the now decreasing crowd, to all appearance perfectly satisfied with each other.

They had already taken up their position opposite the window which his Majesty had indicated, and were in full enjoyment of the thrilling spectacle he had promised them, namely, a little old man in a wig, served by half-a-dozen servants at once, and eating to repletion, when Cerise, who clung to Célandine’s hand, hid her face in the bonne’s gown, to avoid the gaze of two gentlemen who were staring at her with every mark of approval. “What is it, my cherished one?” said the quadroon, in tender accents. “Who dares frighten my darling?” But the fierce voice changed into coaxing tones when the bonne recognised a familiar face in one of her charge’s unwelcome admirers.

“Why, it’s Monsieur l’Abbé! Surely you know Monsieur l’Abbé! Come, be a good child, then; make Monsieur l’Abbé a reverence, and wish him good-day!”

But Cerise persistently declined any friendly overtures whatever to Monsieur l’Abbé; hanging her head and turning her toes in most restively; so the three passed on to witness the process of eating as performed by Louis le Grand; and Monsieur l’Abbé, crumpling his extremely plain features into a sneer, observed his companion, “It is droll enough, Florian, children never take to me, though I make my way as well as another with grown-up people. They seem to mistrust me from the first. Can it be because I am so very ugly?”

The other smiled deprecatingly. “Good looks,” said he, “have nothing to do with it. Children are like their elders—they hate intellect because they fear it. Oh, Malletort! had I the beauty of Absalom, I would give it all willingly to possess your opportunities and your powers of using them!”

“Thank you,” replied Malletort, looking gratified in spite of himself at the compliment, but perhaps envying[23] in his secret heart the outward advantages which his friend seemed so little to appreciate.

Florian de St. Croix, just on the verge of manhood, was as handsome a youth as might be met with amongst the thousand candidates for the priesthood, of whom he was one of the most sanguine and enthusiastic. Not even the extreme plainness of his dress, appropriate to the sacred calling he was about to enter—not even his close-cut hair and pallid hue, result of deep thought and severe application—could diminish the beauty of his flashing eyes, his clear-cut features, and high, intellectual forehead, that denoted ideality and self-sacrifice as surely as the sweet womanly mouth betrayed infirmity of purpose and fatal subservience to the affections. His frame, though slender, was extremely wiry and muscular; cast, too, in the mould of an Apollo. No wonder there was a shadow of something like jealousy on his companion’s shrewd, ugly face, while he regarded one so superior in external advantages to himself.

The Abbé Malletort was singular in this respect. He possessed the rare faculty of appreciating events and individuals at their real value. He boasted that he had no prejudices, and especially prided himself on the accuracy with which he predicted the actions of his fellow-creatures by the judgment he had formed of their characters. He made no allowance for failure, as he gave no credit to success. Men, with him, were capable or useless only as they conquered or yielded in the great struggle of life. Systems proved good or bad simply according to their results. The Abbé professed to have no partialities, no feelings, no veneration, and no affections. He had entered the Church as a mere matter of calculation and convenience. Its prizes, like those of the army, were open to intellect and courage. If the priest’s outward conduct demanded more of moderation and self-restraint, on the other hand the fasts and vigils of Rome were less easily enforced than the half-rations of a march or the night-watches of an outpost.

Moreover, the tonsure in those days might be clipped (not close enough to draw attention) from a skull that roofed the teeming brain of a politician; and, indeed, the Church of Rome not only permitted but encouraged the assumption of secular power by her votaries, so that the most important[24] and lucrative posts of the empire were as open to Abbé and Cardinal as to a Colonel of the Body-guard or a Marshal of France; while the soldier’s training fitted him far less than the priest’s to countermine the subtleties of diplomacy or unravel the intricacies of finance. There remained, then, but the vow of celibacy to swallow, and, in truth, the vow of celibacy suited Malletort admirably well. Notwithstanding his ugly face, he was an especial favourite with women, on whom his ready wit, his polished manners, and, above all, his imperturbable coolness, made a pleasing impression. They liked him none the less that his reputed hardness of heart and injustice towards themselves were proverbial. While, as for his plain features, why, to quote the words of Ninon de l’Enclos, who ought to have been a good judge in such matters, “A man’s want of beauty is of small account if he be not deficient in other amiable qualities, for there is no conquest without the affections, and what mole can be so blind as a woman in love?”

The crowd had passed on to witness the king’s dinner, now in full progress, and the two soberly-clad friends found themselves the only occupants of the gardens. Side by side they took their seats on a bench under a row of lime-trees, and continued the conversation which had originated in little Cerise and her childish beauty.

“It is a face as God made it,” said Florian, his boyish features lighting up with enthusiasm. “Children are surely nearer Heaven than ourselves. What a pity to think that they should grow into the painted, patched, powdered hypocrites, of whom so many have passed by us even now.”

“Beautifully dressed, however,” answered his worldly senior, placidly indifferent, as usual, to all that did not concern his own immediate comfort. “If there were no women, Florian, there would be no children, I conclude. Both seem necessary evils. You, I observe, prefer the lesser. As for being near Heaven, that, I imagine, is a mere question of altitude. The musketeer over there is at least a couple of inches nearer it than either of us. What matter? It will make little difference eventually to any one of the three.”

Florian looked as if he did not understand. Indeed, the Abbé’s manner preserved a puzzling uncertainty between jest and earnest. He took a pinch of snuff, too, with the air of a man who had thoroughly exhausted the question. But his companion, still harping on the beauty of the child, continued their conversation.

“Is she not a cousin of yours, this little angel? I know you are akin to that beautiful Marquise, her mother. Oh,[26] Malletort, what advantages you possess, and how unconscious you seem of them!”

“Advantages!” repeated the Abbé, musing. “Well, perhaps you are right. Handsome women are the court-cards of the game, if a man knows how to play them. It is a grand game, too, and the stakes are well worth winning. Yet I sometimes think if I had foreseen in time how entirely you must devote body and soul to play it, I might never have sat down at all. I could almost envy a boy, like that merry page who passed us with my baby-cousin—a boy, whose only thought or care is to spend the time gaily now, and wear a sword as soon as his beard is grown hereafter.”

“The boy will carry a sword fairly enough,” answered Florian; “for he looks like a little adventurer already. Who is he? I have remarked him amongst the others for a certain bold bearing, that experience and sorrow alone will, I fear, be able to tame.”

“It will take a good deal of both to tame any of that family,” answered Malletort; “and this young game-chick will no doubt prove himself of the same feather as the rest of the brood when his spurs are grown. He’s a Hamilton, Florian; a Hamilton from the other side of the water, with a cross of the wildest blood in France or Europe in his veins. You believe the old monkish chronicles—I don’t. They will tell you that boy’s direct ancestor went up the breach at Acre in front of Cœur de Lion—an Englishman of the true pig-headed type, who had sense enough, however, to hate his vassal ever after for being a bigger fool than himself. On the mother’s side he comes of a race that can boast all its sons brave, and its daughters—well, its daughters—very much the same as other people’s daughters. The result of so much fighting and gasconading being, simply, that the elder branch of the family is sadly impoverished, while the younger is irretrievably ruined.”

“And this lad?” asked Florian, interested in the boy, perhaps because the page’s character was in some respects so completely the reverse of his own.

“Is of the younger branch,” continued Malletort, “and given over body and soul to the cause of this miserable family, whose head died, not half-a-dozen years ago, under[27] the shadow of our grand and gracious monarch, a victim to prejudice and indigestion. Well, these younger Hamiltons have always made it their boast that they grudged neither blood nor treasure for the Stuarts; and the Stuarts, I need hardly tell you, Florian, for you read your breviary, requited them as men must expect to be requited who put their trust in princes—particularly of that dynasty. The elder branch wisely took the oaths of allegiance, for the ingratitude of a reigning house is less hopeless than that of a dethroned family. I believe any one of them would be glad to accept office under the gracious and extremely ungraceful lady who fills the British throne, established, as I understand she is, on so broad a basis, there is but little room for a consort. They are scarce likely to obtain their wish. The younger branch would scout the idea, enveloped, one and all, in an atmosphere of prejudice truly insular, which ignorant people call loyalty. This boy’s great-grandfather died in a battle fought by Charles I., at a place with an unpronounceable name, in the province of ‘Yorkshires.’ His grandfather was shot by a platoon of musketeers in his own courtyard, under an order signed by the judicious Cromwell; and his father was drowned here, in the channel, carrying despatches for his king, as he persisted in calling him, under the respectable disguise of a smuggler. I believe this boy was with him at the time. I know when first he came to Court, people pretended that although so young he was an accomplished sailor; and I remember his hands were hard and dirty, and he always seemed to smell of tar. I will own that now, for a page, he is clean, polished, and well dressed.”

Florian’s dark eyes kindled.

“You interest me,” said he; “I love to hear of loyalty. It is the reflection of religion upon earth.”

“Precisely,” replied the other. “A shadow of the unsubstantial. Well, all his line are loyal enough, and I doubt not the boy has been brought up to believe that in the world there are men, women, and Stuarts. The fact of his being page here, I confess, puzzles me. Lord Stair protested against it, I know, but the king would not listen, and used his own wise discretion, consenting, however, that the lad should drop his family name and be called simply—George. So George fulfils the destiny of a page, whatever that may[28] be—as gaudy, as troublesome, and to all appearance as useless an item in creation as the dragon-fly.”

“And has the child no relations?” asked Florian; “no friends, nobody to whom he belongs? What a position; what a fate; what a cruel isolation!”

“He is indeed in that enviable situation which I cannot agree with you in thinking merits one grain of pity. You and I, Florian, with our education and in our career, should, of all people, best appreciate the advantages of perfect freedom from those trammels which old women of both sexes call the domestic affections.”

“So young, so hopeful, so spirited,” continued Florian, speaking rather to himself than his informant, “and to have no mother!”

“But he had a mother, I tell you,” replied Malletort, “only she died of a broken heart, as women always do when a little energy is required to repair their broken fortunes. Our mother, my son,” he proceeded, still in the same half-mocking, half-impressive tone, “our mother is the Church. She provides for us carefully during life, and when we die in her embrace, at least affords us decent burial and prayers for our welfare hereafter. I tell you, Florian, she is the most thoughtful as she is the most indulgent of mothers. She offers us opportunity for distinction, or allows us shelter and repose according as our ambition soars to heaven, or limits itself, as I confess mine does, to the affairs of earth. Who shall be found exalted above their kind in the next world? (I speak as I am taught)—Priests. Who fill the high places in this? (I speak as I learn)—Priests. The king’s wisest councillors, his ablest financiers, are men of the sober garment and the shaven crown; nay, judging from the simplicity of his habits, and the austerity of his demeanour, I cannot but think that the bravest marshal in our armies is only a priest in disguise.”

“There are but two careers worthy of a life-sacrifice,” observed Florian, his countenance glowing with enthusiasm, “and glory is the aim of each. But who would compare the soldier of France with the soldier of Rome?—the banner of the Bourbon with the cross of Calvary? How much less noble is it to serve earth than heaven?”

Malletort looked in his young friend’s face as if he thought such exalted sentiments could not possibly be real, and shrewdly suspected him of covert sarcasm or jest; but Florian’s open brow admitted of no misconstruction, and the elder man’s features gradually relaxed into the quiet expression of amusement, not devoid of pity, with which a professor in the swimmer’s art, for instance, watches the floundering struggles of a neophyte.

“You are right,” said he, calmly and after a pause; “ours is incomparably the better profession of the two, and the safer. We risk less, no doubt, and gain more. Persecution, in civilised countries at least, is happily all the other way. It is extremely profitable to be saints, and there is no call for us to become martyrs. I think, Florian, we have every reason to be satisfied with our bargain. Why, the very ties we sever, the earthly affections we resign, are, to my mind, but so many more enforced advantages, for which we cannot be too thankful.”

“There would be no merit were there no effort,” answered the other. “No self-denial were there nothing to give up; but with us it is different. I am proud to think we do resign, and cheerfully, all that gives warmth and colouring to the hard outlines of an earthly life. Is it nothing to forego the triumphs of the camp, the bright pageantry, the graceful luxuries of the Court? Is it nothing to place yourself at once above and outside the pale of those sympathies which form the very existence of your fellow-men? More than all, is it nothing, Malletort,”—the young man hesitated, blushed, and cast his eyes down—“is it nothing to trample out of your heart, passions, affections—call them what you will—that seem the very mainspring of your being? Is it nothing to deny yourself at once and for ever the solace of woman’s companionship and the rapture of woman’s love?”

“You declaim well,” replied Malletort, not affecting to conceal that he was amused, “and your arguments would have even more weight were it not that you are so palpably in earnest. This of itself infers error. You will observe, my dear Florian, as a general rule, that the reasoner’s convictions are strong in direct proportion to the weakness of his arguments. But let us go a little deeper into this[30] question of celibacy. Let us strip it of its conventional treatment, its supposed injustice, its apparent romance. To what does it amount? That a priest must not marry—good. I repeat, so much the better for the priest. What is marriage in the abstract?—The union of persons for the continuation of the species in separate and distinct races. What is it in the ideal?—The union of souls by an unphilosophical and impossible fusion of identity, which happily the personality of every human being forbids to exist. What is it in reality?—A fetter of oppressive weight and inconvenient fabric, only rendered supportable from the deadening influence of habit, combined with its general adoption by mankind. Look around you into families and observe for yourself how it works. The woman has discovered all her husband’s evil qualities, of which she does not fail to remind him; and were she a reflective being, which admits of argument, would wonder hourly how she could ever have endured such a mass of imperfections. The man bows his head and shrugs his shoulders in callous indifference, scorning to analyse the disagreeable question, but clear only of one thing—that if he were free, no consideration would induce him to place his neck again beneath the same yoke. Another—perhaps! The same—never! Both have discovered a dissimilarity in tastes, habits, and opinions, so remarkable that it seems scarcely possible that it should be fortuitous. To neither does it occur that each was once the very reflection of the other, in thought, word, and deed; and that a blessing pronounced by a priest—a few years, nay a few months, of unrestricted companionship—have wrought the miraculous change. Sometimes there are quarrels, scenes, tears, reproaches, recriminations. More often, coldness, self-restraint, inward scorn, and the forbearance of a repressed disgust. Then is the separation most complete of all. Their bodies preserve to each other the outward forms of an armed and enforced neutrality, but their souls are so far asunder that perhaps, of all in the universe, this pair alone could, under no circumstances, come together again.”

“Sacrilege!” broke in Florian, indignantly. “What you say is sacrilege against our very nature! You speak[31] of marriage as if it must be the grave of Love. But at least Love has lived. At least the angel has descended and been seen of men, even though he touched the mountain only to spring upward on his flight again towards the skies. He who has really loved, happily or unhappily, married or alone, is for that love ever after a wiser, a nobler, and a better man.”

“Not if he should happen to love a Frenchwoman,” observed the other, taking a pinch of snuff. “Thus much I will not scruple to say for my countrywomen: their coquetries are enough to drive an honest man mad. With regard to less civilised nations (mind, I speak not from personal experience so much as observation of my kind), I admit that for a time, at least, the delusion may possess a charm, though the loss must in all cases far exceed the gain. Set your affections on a German, for instance, and observe carefully, for the experiment is curious, if a dinner with the idol does not so disgust you that not a remnant of worship is left to be swept away by supper-time. A Pole is simply a beautiful barbarian, with more clothing but less manner than an Indian squaw. An Italian deafens you with her shrill voice, pokes your eye out with her fingers, and betrays your inmost secrets to her director, if indeed she does not prefer him to you in every respect. An Englishwoman, handsome, blonde, silent, and retiring, keeps you months in uncertainty while you woo, and when won, believes she has a right to possess you body and soul, and becomes, from a sheer sentiment of appropriation, the most exacting of wives and the most disobliging of mistresses. To make love to a Spaniard is a delicate phrase for paying court to a tigress. Beautiful, fierce, impulsive—with one leap she is in your arms—and then for a word, a look, she will stab you, herself, a rival, perhaps all three, without hesitation or remorse. Caramba! she considers it a compliment no doubt! Yet I tell you, Florian, were I willing to submit to such weaknesses, I had rather love any one of these, or all of them at once for that matter, than attach myself to a Frenchwoman.”

Florian opened his dark eyes wide. This was new ground to the young student. These were questions more interesting than the principles of Aristotle or the[32] experiences of the Saints. He was penetrated, too, with that strange admiration which the young entertain for familiarity with evil in their elders. The other scanned him with half-pitying interest; broke a branch from the fragrant lime-tree under which they sat, and proceeded to elucidate his theory.

“With all other women,” said Malletort, “you have indeed a thousand rivals to out-do; still you know their numbers and can calculate their resources; but with the Frenchwoman, in addition to these, you have yet another, who changes and multiplies himself day by day—who assumes a thousand Protean forms, and against whom you cannot employ the most efficient weapons—such as vanity, gaiety, and love of dissipation, by which the others are to be subdued. This enemy is dress—King Chiffon is the absolute monarch of these realms. Your mistress is gay when you are sad, sarcastic when you are plaintive, reserved when you are adventurous. All this is a matter of course; but as Monsieur Vauban told the king the other day in these gardens, ‘no fortress is stronger than its weakest place,’ and every citadel may be carried by a coup de main, or reduced by the slower process of blockade. But here you have a stronghold within a stronghold; a reserve that can neither be tampered with in secret nor attacked openly; in brief a rival who owns this incalculable advantage, that in all situations and under all circumstances he occupies the first place in your mistress’s thoughts. Bah!” concluded the Abbé, throwing from him the branch which he had stripped of leaves and blossoms, with a gesture that seemed thus to dismiss the subject once for all; “put a Frenchwoman into what position you will, her sympathies indeed may be with her lover, but her first consideration is for her dress!”

As the Abbé spoke he observed a group of four persons passing the front of the palace, under the windows of the king’s dining-saloon. It consisted of little Cerise, her mother, Célandine, and the page. They were laughing and chatting gaily, George apparently taking his leave of the other three. Florian observed a shadow cross the Abbé’s face, that disappeared, however, from those obedient features quickly as it came; and at the same moment the[33] Marquise passed her hand caressingly over the boy’s dark curls, while he bent low before her, and seemed to do homage to her beauty in the act of bidding her a courteous farewell.

Year by year a certain stag had been growing fatter and fatter in the deep glades and quiet woodlands that surrounded Fontainebleau. He was but a pricket when Cerise made her daisy-chain in the gardens of Versailles, but each succeeding summer he had rubbed the velvet off another point on his antlers, and in all the king’s chase was no finer head than he carried the day he was to die. Brow, bay, and tray, twelve in all, with three in a cup at the summits, had been the result of some half-score years passed in the security and shelter of a royal forest; nor was the lapse of time which had thus brought head and haunch to perfection without its effect upon those for whose pastime the noble beast must fall.

Imagine, then, a glowing afternoon, the second week in August. Not a cloud in the sky, a sun almost tropical in its power, but a pure clear air that fanned the brow wherever the forest opened into glades, and filled the broad nostrils of a dozen large, deep-chested, rich-coloured stag-hounds, snuffing and questing busily down a track of arid grass that seemed to have checked their steady, well-considered unrelenting chase, and brought their wondrous instinct to a fault. One rider alone watched their efforts with a preoccupied air, yet with the ready glance of an old sportsman. He had apparently reached his point of observation before the hounds themselves, and far in advance of the rest of the chase. His close-fitting blue riding-coat, trimmed with gold-lace and turned back with scarlet facings, called a “just au corps,” denoted that he was a courtier; but the keen eye, the erect figure, the stateliness, even stiffness of[35] his bearing, smacked of the old soldier, more, the old soldier of France, perhaps the most professional veteran in the world.

He was not so engrossed with his own thoughts, however, but that his eye gleamed with pleasure when a tan-coloured sage, intent on business, threw a square sagacious head into the air, proclaiming in full deep notes his discovery of the line, and solemn conviction that he was right. The horseman swore a good round garrison oath, and cheered the hound lustily. A cry of tuneful tongues pealed out to swell the harmony. A burst of music from a distant glade announced that the stag had passed yet farther on. A couple of royal foresters, in blue and red, arrived on foot, breathless, with fresh hounds struggling in the leash; and a lady on a Spanish barb, attended by a plainly-dressed ecclesiastic, came cantering down the glade to rein up at the veteran’s side, with a smile of greeting on her face.

“Well met, Monsieur le Prince, once more,” said she, flashing a look from her dark eyes, under which, old as he was, he lowered his own. “Always the same—always successful. In the Court—in the camp—in the ball-room—in the field—if you seek the Prince-Marshal, look in the most forward post, and you will find him.”

She owed him some reparation for having driven him from her side in a fit of ill-humour half an hour before, and this was her way of making amends.

“I have won posts in my time, madame,” said the old soldier, an expression of displeasure settling once more on his high worn features, “and held them, too, without dishonour. It is perhaps no disgrace to be worsted by a woman, but it is humiliating and unpleasant all the same.”

“Dishonour and disgrace are words that can never be coupled with the name of Chateau-Guerrand,” returned the lady, smiling sweetly in his face, a process that appeared to mollify him considerably. Then she completed his subjection by caressing her horse with one hand, while she reined him in so sharply with the other, that he rose on his hind-legs as if to rear straight on end.

“You are a hard mistress, madame,” said the gentleman, looking at the beautiful barb chafing and curveting to its bit.

“It is only to show I am mistress,” she answered in a low voice, that seemed to finish the business, for turning to her attendant cavalier, who had remained discreetly in the background, she signed to him that he might come up and break the tête-à-tête, while she added gaily—

“I am as fond of hunting as you are, prince. Hark! The stag is still forward. Our poor horses are dying with impatience. Let us gallop on together.”

The Marquise de Montmirail had considerably altered in character since she tended the infirmities of her poor old husband, or sat in widow’s garments with her pretty child on her knee. A few years at the Court of France had brought to the surface all the evil of her character, and seemed to have stifled in her everything that was good. She had lost the advantage of her daughter’s companionship, for Cerise (and in this perhaps the Marquise was right) had been removed to a distance from the Court and capital, to bloom into womanhood in the healthier atmosphere of a provincial convent. She missed her darling sadly, no doubt, and for the first year or two contented herself with the gaieties and distractions common to her companions. She encouraged no lover, properly so called, and had seldom fewer than three admirers at a time. Nor had the king of late taken special notice of her; so she was only hated by the other Court ladies with the due hatred to which she was entitled from her wealth, beauty, and attractions.

After a while, however, she put in for universal dominion, and then of course the outcry raised against her was loud and long sustained. She heeded it little; nay, she seemed to like it, and bandied sarcasms with her own sex as joyously, to all appearance, as she exchanged compliments with the other.

She never faltered. She never committed herself. She stood on the brink, and never turned giddy nor lost her presence of mind. What she required, it seemed, what she could not live without, was influence, more or less, but the stronger the better, over every male creature that crossed her path. When this was gained, she had done with them unless they were celebrities, or sufficiently frivolous to be as variable as herself. In either of such cases she took considerable pains to secure the empire she had won. What[37] she liked best was to elicit an offer of marriage. She was supposed to have refused more men, and of more different ranks, than any woman in France. For bachelor or widower who came within the sphere of her influence there was no escape. Sooner or later he must blunder into the net, and the longer he fought the more complete and humiliating was his eventual defeat. “Nothing,” said the Abbé Malletort, “nothing but the certainty of the king’s unacknowledged marriage to Madame de Maintenon prevented his cousin from obtaining and refusing an offer of the crown of France.”

She was beautiful, too, no doubt, which made it so much worse—beautiful both with the beauty of the intellect and the senses. Not strictly by any rules of art, but from grace of outline, richness of colouring, and glowing radiance of health. She had all the ways, too, of acknowledged beauty; and even people who did not care for her were obliged to admit she possessed that strange, indefinite, inexplicable charm which every man finds in the woman he loves.

The poor Prince-Marshal, Hector de Chateau-Guerrand, had undergone the baptism of fire at sixteen, had fought his duels, drank his Burgundy, and lost an estate at lansquenet in a night before he was twenty. Since then he had commanded the Musketeers of the Guard—divisions of the great king’s troops—more than once a French army in the field. It was hard to be a woman’s puppet at sixty—with wrinkles and rheumatism, and failing health, with every pleasure palling, and every pain enhanced. Well, as he said himself, “le cœur ne vieillit jamais!” There is no fool like an old one. The Prince-Marshal, for that was the title by which he was best known, had never been ardently attached to anybody but himself till now. We need not envy him his condition.

“Let us gallop on together,” said the Marquise; but ere they could put their horses in motion a yeoman-pricker, armed to the teeth, rode rapidly by, and they waited until his Majesty should have passed. Their patience was not tried for long. While a fresh burst of horns announced another view of the quarry further on, the king’s little calèche turned the corner of the alley at speed, and was pulled up with considerable dexterity, that its occupant might[38] listen for a moment to determine on his future course. Louis sat by himself in a light, narrow carriage, constructed to hold but one person. He was drawn by four cream-coloured horses, small, well-bred, and active. A child of some ten years of age acted postilion to the leaders, but the king’s own hand drove the pair at wheel, and guided them with all the skill and address of his early manhood.

Nevertheless, he looked very old and feeble when he returned the obeisance of the Prince-Marshal and his fair companion. Always punctiliously polite, Louis lifted his hat to salute the Marquise, but his chin soon sank back on his chest, and the momentary gleam died out in his dull and weary eyes.

It was obvious his health was failing day by day; he was now nearly seventy-seven years of age, and the end could not be far off. As he passed on, an armed escort followed at a few paces distance. It was headed by a young officer of the Grey Musketeers, who saluted the Prince-Marshal with considerable deference, and catching the eye of the Marquise, half halted his horse; and then, as if thinking better of it, urged him on again, the colour rising visibly in his brown handsome face.

The phenomenon of a musketeer blushing was not likely to be lost on so keen an observer as Madame de Montmirail, particularly when the musketeer was young, handsome, and an excellent horseman.

“Who is that on guard?” said she, carelessly of course, because she really wanted to know. “A captain of the Grey Musketeers evidently. And yet I do not remember to have seen his face at Court before.”

Now it was not to be expected that a Marshal of France should show interest, at a moment’s notice, in so inferior an official as a mere captain of musketeers, more particularly when riding with a “ladye-love” nearly thirty years younger than himself, and of an age far more suitable to the good-looking gentleman about whom she made inquiries. Nevertheless, the Prince had no objection to enter on any subject redounding to his own glorification, particularly in war, and it so happened that the officer in question had served as his aide-de-camp in an affair that won him a Marshal’s baton;[39] so he reduced his horse’s pace forthwith, and plunged into the tempting subject.

“A fine young man, madame,” said the Prince-Marshal, like a generous old soldier as he was, “and a promising officer as ever I had the training of. He was with me while a mere cadet in that business when I effected my junction with Vendôme at Villa-Viciosa, and I sent him with despatches from Brighuega right through Staremberg’s uhlans, who ought to have cut him into mince-meat. Even Vendôme thanked him in person, and told me himself I must apply for the brave child’s promotion.”

Like other ladies, the Marquise suffered her attention to wander considerably from these campaigning reminiscences. She roused herself, however, enough to answer, not very pertinently—

“What an odious man the Duke is, and how hideous. Generally drunk, besides, and always disagreeable!”

The Prince-Marshal looked a little put out, but he did not for this allow himself to be diverted from his subject.

“A very fortunate soldier, madame,” he replied, pompously; “perhaps more fortunate than really deserving. Nevertheless, in war as in love, merit is of less importance than success. His Majesty thought well to place the Duke over the head of officers whose experience was greater, and their services more distinguished. It is not for me to offer an opinion. I serve France, madame, and you,” he added, with a smile, not too unguarded, because some of his teeth were gone, “I am proud to offer my homage to both.”

The Marquise moved her horse impatiently. The subject did not seem to amuse her, but the Prince-Marshal had got on a favourite theme, and was not going to abandon it without a struggle.

“I do not think, madame,” he proceeded, laying his hand confidentially on the barb’s crest—“I do not think I have ever explained to you in detail the strategical reasons of my forced march on Villa-Viciosa in order to co-operate with Vendôme. I have been blamed in military circles for evacuating Brighuega after taking it, and abandoning the position I held at the bridge the day before the action, which I had caused to be strengthened during the night. Now there is much to be urged on both sides regarding this movement,[40] and I will endeavour to make clear to you the arguments for and against the tactics I thought it my duty to adopt. In the first place, you must bear in mind that the enemy’s change of front on the previous morning, which was unexpected by us, and for which Staremberg had six cogent reasons, being as follows―”

The Marquise looked round to her other cavalier in despair; but no assistance was to be expected from the cynical Abbé—for it was Malletort in attendance, as usual, on his cousin.

The Prince-Marshal was, doubtless, about to recount the dispositions and manœuvres of three armies seriatim, with his own advice and opinions thereon, when relief came to his listener from a quarter in which she least expected it.

She was preparing herself to endure for the hundredth time the oft-told tale, when her horse started, snorted, trembled violently, and attempted to wheel round. In another instant an animal half as big as itself leaped leisurely into the glade, and went lurching down the dry sunny vista as if in utter disregard and contempt of its pursuers.

The stag had been turned back at several points by the horns of the foresters, who thus melodiously greeted every appearance of their quarry. He was beginning to think some distant refuge would be safer and more agreeable; also his instinct told him that the scent would improve while he grew warmer, and that his noisy pursuers would track him more and more unerringly as the sun went down.

Already he felt the inconvenience of those fat haunches and that broad russet back he carried so magnificently; already he heard the deep-mouthed chorus chiming nearer and nearer, full, musical, and measured, like a death-bell.

“En avant!” exclaimed Madame de Montmirail, as the stag, swerving from a stray hound, stretched into an honest, undisguised gallop down the glade, followed by the straggler at its utmost speed, labouring, over-paced, distressed, but rolling on, mute, resolute, and faithful to the line. The love of rapid motion, inseparable from health, energy, and high spirits, was strong in the Marquise. Her barb, in virtue of his blood, possessed pace and endurance; his mistress called on him to prove both, while she sped along on the line of[41] chase, accompanied by several of the hounds, as they straggled up in twos and threes, and followed by most of the equestrians.

Thus they reached the verge of the forest, and here stood the king’s calèche drawn up, his Majesty signing to them feebly yet earnestly that the stag was away over the plain.

Great was now the confusion at so exciting and so unexpected an event. The foresters, with but little breath to spare, managed to raise a final flourish on their horns. The yeoman-prickers spurred their horses with a vigour more energetic than judicious; the hounds, collecting as it seemed from every quarter of the forest, were already stringing, one after another, over the dusty plain. The king, too feeble to continue the chase, yet anxious to know its result, whispered a few words to his officer of the guard, and the Musketeer, starting like an arrow from a bow, sped away after the hounds with some half-dozen of the keenest equestrians, amongst whom were the Marquise and the Prince-Marshal. Many of the courtiers, including the Abbé, seemed to think it disloyal thus to turn their backs on his Majesty, and gathered into a cluster to watch with interjections of interest and delight the pageant of the fast-receding chase. The far horizon was bounded by another range of woods, and that shelter the stag seemed resolved to reach. The intervening ground was a vast undulating plain, crossed apparently by no obstacles to hounds or horsemen, and varied only by a few lines of poplars and a paved high-road to the nearest market-town.

The stag then made direct for this road, but long ere he could reach it, the chase had become so severe that many of the hounds dropped off one by one; and of the horses, only those ridden by the Marquise, the Prince-Marshal, and the Grey Musketeer, were able to keep up the appearance of a gallop.

Presently these successful riders drew near enough to distinguish clearly the object of their pursuit. The Musketeer was in advance of the others, who galloped on abreast, every nerve at its highest strain, and too preoccupied to speak a syllable.

Suddenly a dip in the ground hid the stag from sight;[42] then he appeared again on the opposite rise, looking darker, larger, and fresher than before.

The Musketeer turned round and pointed towards the hollow in front. In a few more strides his followers perceived a fringe of alders serpentining between the two declivities. Madame de Montmirail’s dark eyes flashed, and she urged her barb to yet greater exertions.

The Musketeer sat back in his saddle, and seemed to collect his horse’s energies for an effort. There was an increase of speed, a spring, a stagger, and he was over the rivulet that stole deep and cool and shining between the alders.

The Marquise followed his horse’s footmarks to an inch, and though the barb threw his head up wildly, and galloped furiously at it, he too cleared the chasm and reached the other side in safety.

The Prince-Marshal’s old blood was warmed up now, and he flew along, feeling as he used in the days of the duels, and the Burgundy, and the lansquenet. He shouted and spurred his steed, urging it with hand and voice and leg, but the highly-broken and well-trained animal felt its powers failing, and persistently declined to attempt the feat it had seen the others accomplish; so the Prince-Marshal was forced to discontinue the chase and remain on the safe side of the rubicon, whence he turned his horse unwillingly homewards, heated, angry, and swearing many strange oaths in different languages.

Meanwhile the other two galloped on, the Marquise, though she spared no effort, finding herself unable to overtake the captain of Grey Musketeers.

All at once he stopped short at a clump of willows, through which the chase had disappeared, and jumping off his horse, left the panting beast to its own devices. When she reached the trees, and looked down into the hollow below, she perceived the stag up to its chest in a bright, shallow pool, at bay, and surrounded by the eager though exhausted hounds.

The Musketeer had drawn his couteau de chasse, and was already knee-deep in the water, but hearing her approach, turned back, and, taking his hat off, with a low obeisance, offered her the handle of his weapon.

It was the customary form when a lady happened to be present on such an occasion, though, as now, the compliment was almost always declined.

He had scarcely gone in and given the coup de grace, which he did like an accomplished sportsman, before some of the yeomen-prickers and other attendants came up, so that the disembowelling and other obsequies were performed with proper ceremony. Long, however, ere these had been concluded the Marquise was riding her tired horse slowly homeward through the still, sweet autumn evening, not the least disturbed that she had lost the Abbé and the rest of her escort, but ruminating, pleasantly and languidly, as her blood cooled down, on the excitement of the chase and the events of the day.

She watched the sunset reddening and fading on the distant woods; the haze of twilight gradually softening, and blurring and veiling the surrounding landscape; the curved edge of the young moon peering over the trees, and the evening-star hanging, like a golden lamp, against the purple curtain of the sky.

With head bent down, loose reins, and tired hands resting on her lap, Madame de Montmirail pondered on many matters as the night began to fall.

She wondered at the Abbé’s want of enterprise, at the Prince-Marshal’s activity—if the first could have yet reached home, and whether the second, with his rheumatism, was not likely to spend a night in the woods.

She wondered at the provoking cynicism of the one and the extraordinary depressive powers possessed by the other; more than all, how she could for so long have supported the attentions of both.

She wondered what would have happened if the barb had fallen short at his leap; whether the Musketeer would have stopped in his headlong course to pity and tend her, and rest her head upon his knee, inclining to the belief that he would have been very glad to have the opportunity.

Then she wondered what it was about this man’s face that haunted her memory, and where she could have seen those bold keen eyes before.

For the courtiers of Louis le Grand there was no such thing as hunger or thirst, want of appetite, heat, cold, lassitude, depression, or fatigue. If he chose they should accompany him on long journeys, in crowded carriages, over bad roads, they were expected, nevertheless, to appear fresh, well-dressed, exuberant in spirits, inclined to eat or content to starve, unconscious of sun and wind; above all, ready to agree with his Majesty upon every subject at a moment’s notice. Ladies enjoyed in this respect no advantage over gentlemen. Though a fair amazon had been hunting the stag all day, she would be required to appear just the same in grand Court toilet at night; to take her place at lansquenet; to be present at the royal concerts, twenty fiddles playing a heavy opera of Cavalli right through; or, perhaps, only to assist in lining the great gallery, which the king traversed on his way to supper. Everything must yield to the lightest whim of royalty, and no more characteristic reply was ever made to the arbitrary descendant of St. Louis than that of the eccentric Cardinal Bonzi, to whom the king complained one day at dinner that he had no teeth. “Teeth, sire!” replied the astute churchman, showing, while he spoke, a strong, even well-polished row of his own. “Why, who has any teeth?”

His Majesty, however, like mortals of inferior rank, did not touch on the accomplishment of his seventy-seventh year without sustaining many of the complaints and inconveniences of old age. For some time past not only had his teeth failed, but his digestion, despite of the regimen of iced[45] fruits and sweetmeats, on which he was put by his physician Fagon, became unequal to its task. Everybody but himself and his doctor perceived the rapidity with which a change was approaching. In vain they swaddled him up in feather-pillows at night, to draw the gout from him through the pores of his skin; in vain they administered sage, veronica, cassia, and Jesuit-bark between meals, while they limited his potations to a little weak Burgundy and water, thereby affording some amusement to those present from the wry faces made by foreign lords and grandees who were curious to taste the king’s beverage. In vain they made him begin dinner with mulberries, and melons, and rotten figs, and strong soups, and salads. There is but one remedy for old age, and it is only to be found in the pharmacopœia, at the last chapter of the book. To that remedy the king was fast approaching—and yet hunting, fiddling, dining, promenades, concerts, and the whole round of empty Court gaiety went on all the same.

The Marquise de Montmirail returned to her apartments at the palace with but little time to spare. It wanted but one hour from the king’s supper, and she must attend with the other ladies of the Court, punctual as clockwork, directly the folding-doors opened into the gallery, and his Majesty, in an enormous wig, should totter in at one end to totter out again at the other. Nevertheless, a good deal of decoration can be done in sixty minutes, when a lady, young and beautiful, is assisted by an attendant whose taste becomes chastened and her activity quickened by the superintendence of four distinct toilets every day. So the Marquise and Célandine between them had put the finishing touches to their great work within the appointed time. The former was going through a gratifying revision of the whole at her looking-glass, and the latter was applying to her mistress’s handkerchief that perfume of orange-flowers which alone his Majesty could endure, when a loud knocking at the outer door of the apartment suspended the operations of each, bringing an additional colour to the Marquise’s cheek, and a cloud of displeasure on the quadroon’s brow.

“See what it is Célandine,” said the former, calmly, wondering in her heart, though it seemed absurd, whether[46] this disturbance could relate in any manner to the previous events of the day.

“It is the Abbé, I’ll be bound,” muttered Célandine, proceeding to do as she was bid; adding, sulkily, though below her breath, “He might knock there till his knuckles were sore if I was mistress instead of maid!”

It was the Abbé, sure enough, in plain attire, as became his profession; but with an expression of hope and elation on his brow which even his perfect self-command seemed unable to conceal.

“Pardon, madame!” said he, standing, hat in hand, on the threshold; “I was in attendance to conduct you to the gallery, as usual, when the intelligence that reached me, and, indeed, the confusion I myself witnessed, induced me to take the liberty of waiting on you at once.”

“No great liberty,” answered the Marquise, smiling, “seeing that I must have encountered you, at any rate, within three paces of my door. But what is this alarming news, my cousin, that agitates even your imperturbable front? Nothing wrong with the barb, I hope!”

“Not so bad as that, madame,” replied the Abbé, who was rapidly recovering his calmness. “It is only a matter affecting his Majesty. I have just learned the king is taken seriously ill. Fagon crossed the courtyard five minutes ago. Worse than that, Père Tellier has been sent for.”

“Père Tellier!” repeated the Marquise. “The king’s confessor! Then the attack is dangerous?”