Title: The art of music. Vol. 01 (of 14)

The pre-Classic periods

Editor: Daniel Gregory Mason

Author of introduction, etc.: C. Hubert H. Parry

Editor: Leland Hall

Edward Burlingame Hill

César Saerchinger

Release date: June 21, 2021 [eBook #65658]

Language: English

Credits: Andrés V. Galia, Jude Eylander for the music archives and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTES

In the plain text version Italic text is denoted by _underscores_. The sign ^ represents a superscript; thus e^ represents the lower case letter e written immediately above the previous character.

Most of the Greek words included in the original work have been transliterated to the Latin alphabet. The only exception has been the words belonging to the song Prayer to the Muse. The transliterated Greek words have been signaled in the text with the sign [Greek: text transliterated].

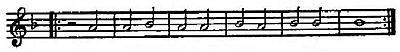

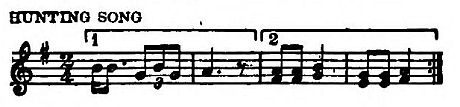

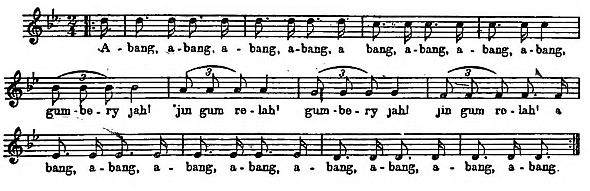

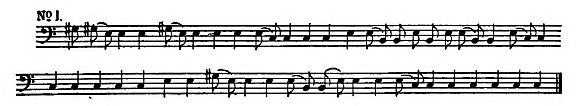

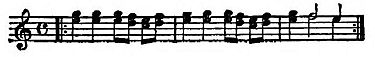

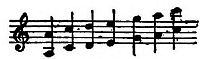

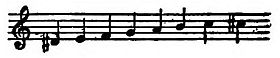

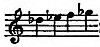

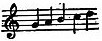

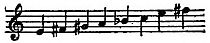

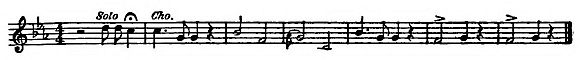

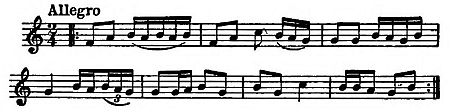

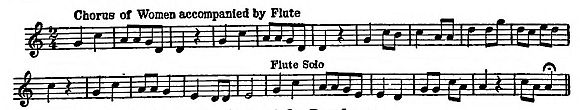

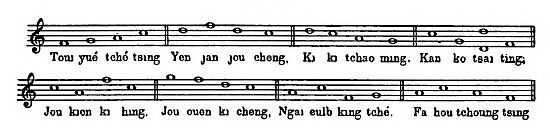

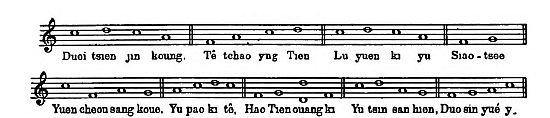

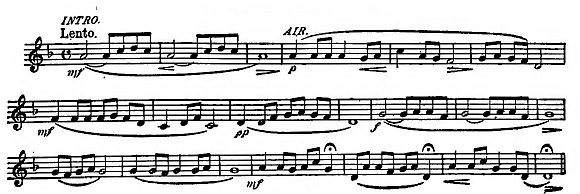

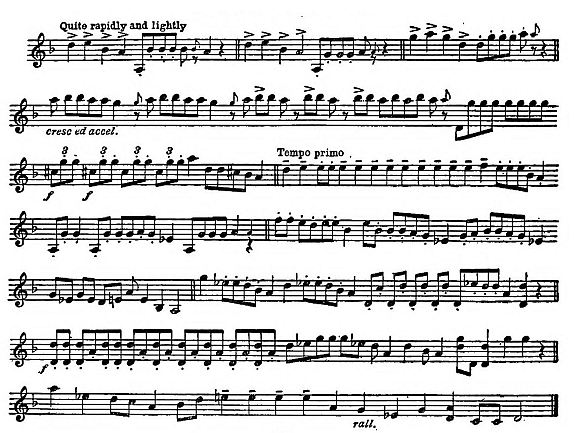

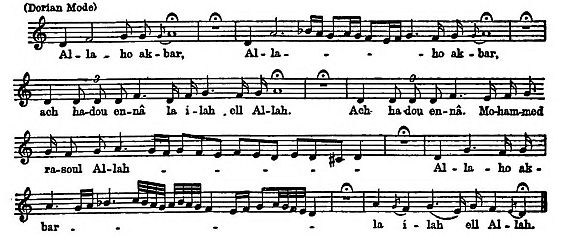

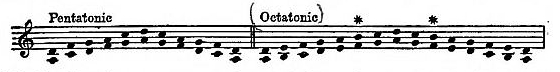

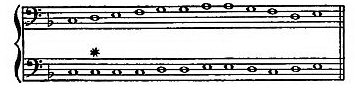

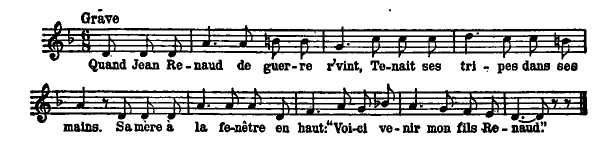

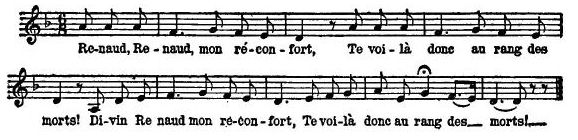

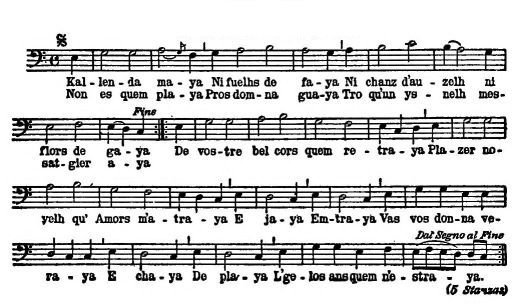

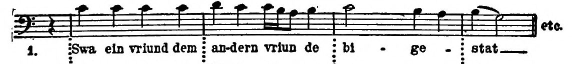

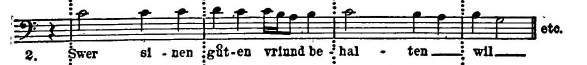

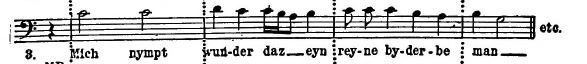

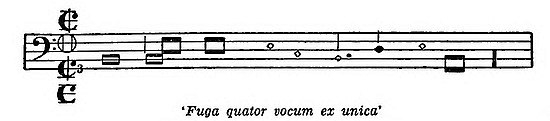

The musical files for the musical examples discussed in the book have been provided by Jude Eylander. Those examples can be heard by clicking on the [Listen] tab. This is only possible in the HTML version of the book. The scores that appear in the original book have been included as images.

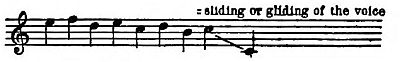

In the plain text version there are some musical signs that cannot be reproduced. They are indicated in the text with the label [music sign]. Those music signs are included as images in the HTML version of the work.

In some cases the scores that were used to generate the music files differ slightly from the original scores. Those differences are due to modifications that were made during the process of creating the musical archives. These scores are included as png images, and can be seen by clicking on the [PNG] tag in the HTML version of the book.

Obvious punctuation and other printing errors have been corrected.

Some of the tables and diagrams presented in the plain text version have been modified from their original lay-out to avoid unsupported display. The original layout of those tables and diagrams are available in the HTML version where they have been included as images.

The book cover has been modified by the Transcriber and is included in the public domain.

THE ART OF MUSIC

The Art of Music

A Comprehensive Library of Information

for Music Lovers and Musicians

Editor-in-Chief

DANIEL GREGORY MASON

Columbia University

Associate Editors

EDWARD B. HILL LELAND HALL

Harvard University Past Professor, Univ. of Wisconsin

Managing Editor

CÉSAR SAERCHINGER

Modern Music Society of New York

In Fourteen Volumes

Profusely Illustrated

NEW YORK

THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC

1915

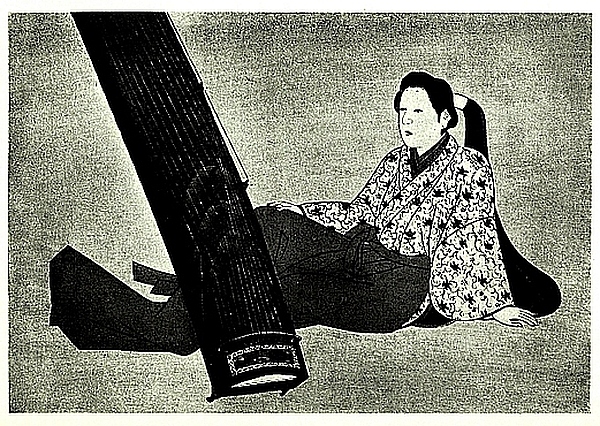

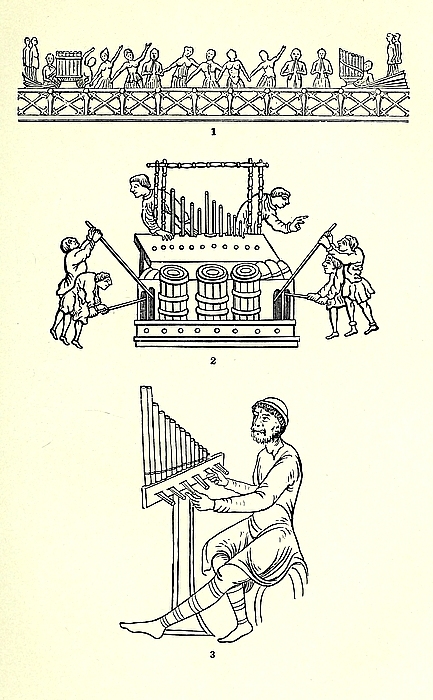

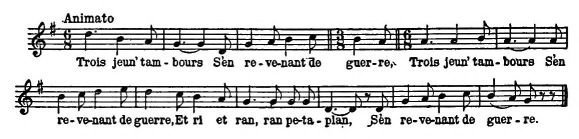

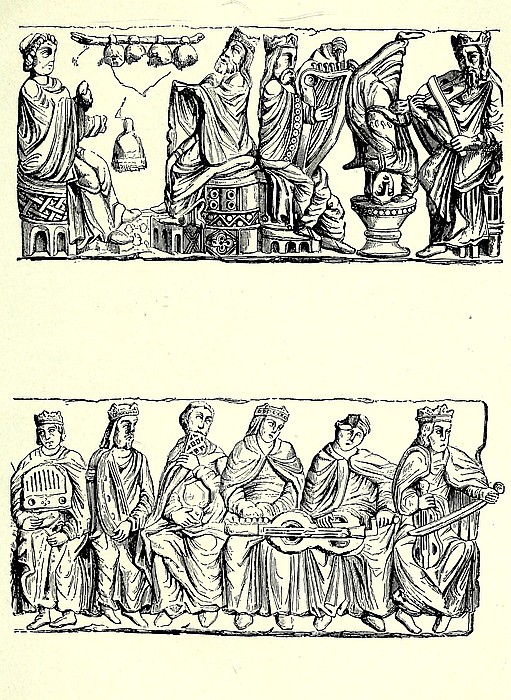

From the Breviary of King René,

a 15th century manuscript in the Bibliothèque

de l’Arsenal.

Department Editors:

LELAND HALL

AND

CÉSAR SAERCHINGER

Introduction by

C. HUBERT H. PARRY, Mus. Doc.

Director Royal College of Music, London.

Formerly Professor of Music, University of Oxford, etc.

BOOK I

THE PRE-CLASSIC PERIODS

NEW YORK

THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC

Copyright, 1915, by

THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC, Inc.

[All Rights Reserved]

CONTENTS OF THE SERIES

Volume I. Narrative History of Music—Book I: The Pre-Classic Periods.

Introduction by Sir C. Hubert H. Parry, Mus. Doc., Director of the Royal College of Music, London.

Volume II. Narrative History of Music—Book II: Classicism and Romanticism.

Introduction by Leland Hall, Past Professor of Musical History, University of Wisconsin.

Volume III. Narrative History of Music—Book III: Modern Music.

Introduction by Edward Burlingame Hill, Instructor in the History of Music, Harvard University.

Volume IV. Music in America.

Introduction by Arthur Farwell, Associate Editor, ‘Musical America.’

Volume V. The Voice and Vocal Music.

Introduction by David Bispham, LL.D.

Volume VI. Choral and Church Music.

Introduction by Sir Edward Elgar, O.M.

Volume VII. Pianoforte and Chamber Music.

Introduction by Claude Debussy.

Volume VIII. The Orchestra and Orchestral Music.

Introduction by Dr. Richard Strauss.

Volume IX. The Opera.

Introduction by Alfred Hertz, Conductor, Metropolitan Opera House, New York.

Volume X. The Dance.

Introduction by Anna Pavlowa, of the Imperial Russian Ballet.

Volume XI. Dictionary of Musicians and General Index.

Volume XII. Dictionary of Music and General Index.

Volume XIII. Musical Examples.

Volume XIV. Modern Musical Examples.

THE ART OF MUSIC

So many and varied are the paths of musical enjoyment and profit opened out in the following pages, so different and sometimes so conflicting are the types of art represented there, that the timid or inexperienced reader may well pause at the threshold, afraid of wholly losing his way in such a labyrinth. He may hesitate to trust himself in so unfamiliar a landscape without first seeing some sort of small-scale plan of the ground, which, omitting the confusing details, shows in bold relief only the larger and essential divisions—the ‘lay of the land.’ Such a plan it is the object of this introduction to furnish.

Of the two most general types of reader, the professional musician and the amateur or lover of music, the first is least in need of such assistance. His keen interest in his specialty will naturally determine the order of his reading; he will look first for all he can find about that, and later work out from that centre in various directions, and meanwhile the plan peculiar to this work of assembling all information on a given subject contained in any of the volumes under a name or subject word in the index volume will make this process as systematic and economical of time as it is fascinating to intellectual curiosity. Thus the index volume will serve as a sort of central rotunda, so to speak, making each room in this house of information accessible from every other, and it will matter little at what point we enter. The singer may go in by Volume V, the pianist by Volume VII, the organist by Volume VI: all will eventually penetrate the entire edifice.

It is, then, the music lover unfamiliar with all musical technique, and quite unspecialized in his interest, who most needs the help that these preliminary suggestions may offer. The kind of help he will want will depend, of course, on what it is he chiefly wishes to gain by his reading. Now we shall probably not go far wrong in saying that such a reader will desire, first, that general knowledge of the most important schools and the greatest individuals of music history which is not only a powerful aid to the enjoyment of music, but is nowadays coming to be considered an essential part of a liberal education. Secondly, he will wish to gain sufficient familiarity with music itself, and sufficient understanding of the instruments by which it is produced and the ways in which they influence its structure and style, to afford him the basis for sound discrimination between good, bad, and indifferent music, to develop, in short, his taste. In the third place, he will justly consider that, however abstruse and involved the theory of music may be, its fundamental principles are nevertheless accessible to the layman, and that familiarity with such principles, especially those of musical structure, affording as it will an insight into the way music is put together, is an invaluable aid to that sympathetic understanding of it which comes only to the alert and attentive listener. In a word, the music lover will demand of his reading that it instruct him historically, that it refine his taste by developing his sense of style, and that it intensify his enjoyment by showing him how to listen.

Glancing now at the table of contents, we shall see that ‘The Art of Music’ naturally divides itself into three portions, each especially suited to subserve one of these three needs of the reader. The first four volumes, historical in character, are primarily instructive. Volumes V to IX, inclusive, deal with the practical side of the art—what is sometimes called ‘applied music’—and in describing the chief media by which it is produced, such as the voice, the organ, the piano, the string quartet, the orchestra, provide general notions of what is appropriate to each. The short essays on harmony and on form in Volume XII, and many passages of explanation of similar matters scattered through all the volumes, will acquaint the student with the fundamental principles of musical theory and the standard types of musical structure, thus affording him valuable aid to appreciative listening. The three portions of the work, historical, practical, and theoretical, are finally correlated and unified by Volumes XI and XII, the Dictionary and Index, and illustrated by the musical examples in Volumes XIII and XIV.

Let us examine a little more closely the ground covered by each of these three general sections, one after another, not yet in detail—that will come only with the actual reading—but with the idea rather of getting a bird’s-eye view of the whole field in its salient masses and divisions.

The history of music is like that of other arts in being divided into schools or epochs. These are of course to a certain extent arbitrary and artificial—marked off by critics for convenience of classification—and a composer may belong to two or more schools, as Beethoven, for example, is both ‘classical’ and ‘romantic,’ without being any more aware of it than we are when our train crosses the line, say, from New York State into Massachusetts. But they are also in part natural and real, because any fruitful idea in art—such as the ‘impressionistic’ idea of light in painting, for instance—is so much greater than any one man’s capacity to grasp it that a whole generation or more of artists is needed to develop its possibilities. Such a group of artists forms what we call a ‘school’ or ‘period,’ beginning usually with pioneers whose work is crude but novel, continuing with countless workers, most of whom are after a short time completely forgotten, and culminating with one or two greatly endowed masters who gather up all the best achievements of the school in their own work and stands for posterity as its figure-heads, or in some cases engulf it entirely in their colossal shadows. Pioneers, journeymen, geniuses—that is the list of characters in the drama we call an artistic school.

If we try to outline in the roughest way the half dozen or so most important schools we can find in the entire history of music we shall get something like the following. After the long groping among the rudiments that went on through Greek and early Christian times there emerged during the middle ages a type of ecclesiastical music which, after a development of several centuries, culminated in the work of Orlando de Lasso (1520-1594), Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1524-1594), and others. This music is as primitive, archaic, and severe to our ears as the early Flemish religious pictures are to our eyes. It can be described chiefly in negatives. It did not employ instruments, but only voices in the chorus. It had no regular time-measure, but wandered on with as little definiteness of rhythm as the Latin prose to which it was set. It employed no grating harsh combinations of tones (‘dissonances’) such as make our music so stirring to the emotions, partly because they are difficult for voices, partly because the science of harmony was in its infancy, partly because the kind of expression it aimed at was that of religious peace. Each group of voices had its own melody to carry, and as there were sometimes as many as sixteen groups an extraordinarily complex web of voices or ‘parts’ was developed, to which is due the name of polyphonic (many-voiced) applied to this school. Unsuited as it is to the restless temper of the modern man, it often attained within its own limits an exquisite beauty.

With the application of this general type of art, the polyphonic, to instruments, especially the organ, new developments supervened. Dissonances were perfectly easy, and most effective, on the organ, that would have been impossible for voices. Definite metre and rhythm were gradually introduced. Above all, the many melodies of the older style to some extent gave way to the massive detached chords more suitable to the organ (because the player could grasp them by handfuls instead of having to make his fingers play hide and seek among the keys), and thus was born another great type of style, the ‘homophonic’ (one main melody, accompanied by chords rather than by other melodies). At the same time the intellectual interest was vastly increased by the use of more and more definite and recognizable bits of melody, happily called the ‘subjects’ or ‘themes’ of the composition, which could be developed and marshalled just as a writer develops and marshals his thoughts. The fugue is the arch type of this kind of composition, with its style partly polyphonic and partly homophonic, its deep thoughtfulness, its ingenuity, and its surprising variety and depth of emotional expression. Its supreme master was Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750).

Despite the mixture of styles in the fugue, however, the preponderant element was still the basket-like texture of winding melodies suitable especially to voices—hence it was only in the suite, a type which developed at the same time and of which also Bach was one of the supreme masters, that the homophonic style suitable to instruments was freely worked out. Instruments mark the rhythm much more strongly than voices, so that all sorts of dance movements are particularly appropriate for them. When the rhythm is so marked, comparatively short phrases of tune stand out sharply and balance each other like the verses in a couplet of poetry. Composers soon found out how further to group these phrases in definite parts or sections, so contrasted that the whole of the short piece or ‘movement’ presented a perfectly clear, sharp impression, had a definite beginning, middle, and end—a clear scheme of form. This clearness of impression was enhanced by making only one line of melody—the ‘tune’ or ‘air,’ as we say—prominent, either subordinating all the others or doing away with them entirely in favor of an accompaniment of detached chords such as we find in a modern waltz or march. The suite, then, as it is found in its golden age, the eighteenth century, is a series of short dance tunes of strongly marked rhythm, precise in phraseology and concise in form, in the homophonic style. Among its masters may be mentioned, besides the German Bach, Couperin and Rameau in France, Corelli (violin) and Scarlatti (harpsichord) in Italy, and Handel in England.

Closely allied with the suite, indeed an offshoot from it, is the sonata, originally any piece for instruments (from sonare, to sound or play) as distinguished from a cantata for voices (from cantare, to sing). The old sonatas are essentially suites. But the generation after Bach’s, of which one of his own sons, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, was a guiding spirit, hit upon one of those apparently simple but immensely fruitful ideas out of which whole schools are made. It was this: Instead of coming to a stop as soon as you have outlined a single musical idea or ‘theme,’ and then merely repeating or slightly elaborating it, as was done in all the movements of the typical suite, why not embrace in the span of your thought two contrasting ideas,[1] so characterized and arranged that each should serve as the effective foil of the other? Once this notion of making a piece of music out of two contrasting themes was tried out in practice it proved to have endless potentialities. In the two hundred years that have elapsed since C. P. E. Bach’s birth in 1714 its possibilities have not been exhausted; it has shown an elasticity which has enabled it to serve equally for the embodiment of such different ideas as those of Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Tschaikowsky, Brahms; it has been applied to all branches of instrumental music, extending its sway quickly from the ‘sonata,’ specifically so called, for one, two or three instruments, to the quartet, quintet, etc., for a group, to the concerto for a soloist with orchestral accompaniment, and to the overture and the symphony for full orchestra.

The purest examples of the application of this scheme to orchestral music are to be found in the first movements of the symphonies of Joseph Haydn (1732-1809), of W. A. Mozart (1756-1791), and above all of Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1821), the genius in whom the classical symphony culminated. The method adopted in such movements, of which the opening allegro of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony may stand as an unsurpassable model, was, first, to present two strongly individual and contrasting musical ideas (‘themes’), the first usually more vigorous in character, the second more tender and appealing; second, to let these thoughts germinate or develop in such a way as to bring clearly forth what was at first latent in them; and, finally, to draw together the threads and complete the musical action by a restatement of the root ideas in something like their original form. The variety, the power, the subtlety, the unfailing instinct for beauty, with which Beethoven worked out the almost limitless possibilities of such a scheme can hardly be realized even dimly save by a loving study of his masterpieces, phrase by phrase, almost note by note. His symphonies are like Greek statues of the great period in their infinite variety, their perfect unity. It may seriously be doubted whether music can ever a second time attain the harmony of all its elements that it found in this supreme master—that which one of his critics has happily termed ‘the perfect balance of expression and design.’

Certain it is that immediately after him, in large measure as a result of his own example, it took a pronounced turn toward picturesqueness, toward highly personal expression, toward all that is conveniently summed up in the vague word Romanticism. Just what romanticism means it is easier to suggest by examples than to define in general terms. Franz Schubert (1797-1828), emphasizing the lyric element in orchestral music, so that his symphonies have almost the personal expressiveness of songs, is romantic. Robert Schumann (1810-1856), with his vivid short piano pieces bearing such suggestive titles as ‘Soaring,’ ‘Whims,’ ‘In the Night,’ ‘Why,’ and with his musical portraits of friends, his quotations from his own works, and other ingenious devices for stimulating our imaginations, literary and pictorial as well as musical, is romantic. Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) is romantic with his orchestral canvases of the Hebrides islands bathed in sunshine and clamored over by sea-birds, and of the delicate dances of Shakespeare’s fairies in the ‘Mid-summer Night’s Dream’; and romantic is Frédéric Chopin (1809-1849), with his nocturnes and preludes. The composers of the romantic period, in fact, embodied in the types of design they inherited from Beethoven (but practised, as a rule, with far less mastery than he) a sort of poetic suggestion of all kinds of things outside of music. Their art is essentially an art of suggestion; and, while its purely musical beauty is often great, they wish us not to rest content with the music for itself, but to regard it as a symbol of something beyond.

Once composers had begun to label, so to speak, the musical expressiveness which the classicists preferred to leave free to act upon each hearer according to his temperament and associations, certain especially literary minds among them, notably Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) and Franz Liszt (1811-1886), naturally felt impelled to carry the process a step further, to amplify and edit the label into complete ‘directions for using.’ Such ‘directions for using’ are called ‘programs,’ and the school which affects them is named ‘programmistic,’ or, by analogy with a similar school in literature, ‘realistic.’ Your typical programmist, such as Berlioz, is not satisfied with the romanticist’s mere suggestion of a subject; he demands in advance a complete bill of fare of his musical feast. When Beethoven, a classicist, deals with a human emotion—love, for instance, as in the Fifth Symphony—he aims merely to stimulate in us the most general feeling and let each of us interpret for himself; when a romanticist like Tschaikowsky writes almost equally beautiful love music he gives a fillip to our imagination by naming it an overture to ‘Romeo and Juliet’; but when Berlioz conceives his Symphonie Fantastique he must have his lover killed on the guillotine—he must even hear the knife fall. Such a theory of musical æsthetics is evidently highly dangerous, since it tends to bind shackles on the free movement of the music, and also to distract the hearer’s attention from the music to something far less vital. Nevertheless in the hands of Richard Strauss in our own day (born 1864), who seems to be the genius in which this school is to culminate, it has led to remarkable results.

We have now reviewed in highly summary fashion some of the chief schools, with their most representative masters, that may be noted in a bird’s-eye view of the history of instrumental music. As for the other [Pg xi] great branch of the art, music associated with literature, and especially its most important manifestation, the opera, classification according to artistic principles is both more difficult and less necessary, since the opera can very well be studied by countries rather than by schools. The reader will at any rate find in his study of opera that one or two clear conceptions of the national or racial character of the three peoples who have done the most important work in the operatic field, the Italians, the French, and the Germans, will help him more than æsthetic standards difficult to apply to an æsthetic hybrid which is neither drama nor music. Thus the Italian sensuousness has been both the blessing and the curse of opera in Italy: the blessing by keeping it simple and tuneful, as in so much of Rossini (1792-1868), Bellini (1802-1835), Donizetti (1798-1848), the early Verdi (1813-1901), and even such moderns as Mascagni and Leoncavallo; the curse of opening the door to all sorts of absurdities on the dramatic side, and to the abuse of the power of the singers in meaningless virtuosity. Again, the keen dramatic sense of the French has helped to minimize such absurdities in works produced by their composers or at their national opera house under their national influence, as for instance those of Gluck (1714-1787), Cherubini (1760-1842), Meyerbeer (1791-1864), and others. Finally the warmth of sentiment of the Germans, their unrivalled faculty for getting at the emotional essence of a situation and expressing it in music, must be accorded a large part in the power of the romantic operas of the German Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826) and the music dramas of Richard Wagner (1813-1883). In revenge the Teutonic deficiency of dramatic sense and tolerance of tedium are to some extent accountable for those long stagnations of the action in the Wagnerian dramas which the most ardent admirers of Wagner the musician no longer deny.

In all this historical study of the earlier volumes of ‘The Art of Music’ the reader will be primarily in quest of information, his interest will be that of the scientist in facts. Even here, however, he will soon find himself discriminating the good from the bad, or from the less good, setting up standards of comparison, in a word, mingling with his purely scientific interest in facts an artistic interest in values. In all periods he will find the great man distinguished from the little by nobility, depth, and variety of thought, and by purity of style. In all ages he will discover hosts of mediocrities for one genius. He will realize that there were as many routinists in the polyphonic school, as many dry-as-dusts in the classic, as many sentimentalists in the romantic, as there are uninspired scene-painters among the programmists. He will remark what may be called the double paradox of art: first, that cheap decorativeness, empty display of merely technical skill, ‘splurge’ of all sorts, while often making music popular in its own day, has always killed it early for posterity, as for example in the case of the over-ornamented arias of Italian opera or the equally over-ornamented piano pieces of Thalberg and other early nineteenth century pianists; second, that simplicity, directness, sincerity are always at first ignored or misunderstood, and only gradually take the supreme place which belongs to them, as we see in studying such otherwise dissimilar artists as Gluck, Mozart, Beethoven, Schumann, Wagner, Brahms, Franck. Such observations open up the path to a true, independent, and unconventional estimate of artistic values, to the development of real taste.

It is especially in amplifying, clarifying, and solidifying this taste that the second group of volumes, dealing with the media of musical production, will be useful to the unprofessional reader. A knowledge of the construction of instruments and of the style appropriate to each, as determined by its peculiarities and exemplified [Pg xiii] in its literature, is a great aid both to the appreciation of excellence and to the detection of shoddiness. A simple example will make this clear. Every one who has watched a pianist play a waltz knows how appropriate and convenient for the piano is that kind of accompaniment which has been called the ‘dum-dum-dum’—where the left hand first sounds the bass and then strikes twice a chord completing the harmony and at the same time marking the rhythm. This is an excellent piano device, because it does these three needful things in the simplest possible way. What shall we say, however, when laziness or incompetence, writing a waltz for orchestra, borrows this piano device without change, as it does constantly in the popular music of the day? Evidently enough, what was well fitted to the piano is ridiculous for an orchestra: for here it gives the bass instruments a series of detached notes without coherence or interest, and condemns the unfortunate players who provide the middle parts to repeat an endless ‘dum-dum, dum-dum’ which outrages all musical instinct.

Or, again, we sometimes hear piano pieces in which the harmonies are arranged in solid chords, as in the hymn-tune familiar in the protestant church. Why the effect should be so singularly vapid we do not know until we think of the peculiarities of the instruments involved. Voices, especially in large groups, as in congregational singing, move slowly, sustain well, and show their quality best when disposed in broad masses. Hence the appropriateness to them of these deliberate chords. But the piano, on the contrary, sustains very poorly, achieves fullness of volume only by means of rapid utterance, and is in short at its very worst in the hymn-tune style. Piano tone requires to be split up into many facets, to be carved, so to speak; but vocal tone is like those substances, such as colored marble, which show their texture best in the block. Recently[Pg xiv] there has been much controversy as to the appropriateness of organ transcriptions of orchestral works. No doubt the organ can render the notes of a symphony quite as well as the poor overworked piano, but a rudimentary knowledge of the mechanism of the organ will show us where lies its special capacity—in the sustaining and rolling up of great masses of tone, and not at all in that more intimate expressiveness through swelling and fading and through accent in which the violin is peerless. The organ is magnificent in a Bach fugue, unsatisfactory in a Beethoven symphony, ridiculous in a popular dance. Thus on all sides we see that style depends on the medium, and that a sensitive taste will no more detach a musical figure from its appropriate setting than it will transfer the costume of the logging-camp to the drawing-room, or vice versa.

What makes all study of this kind particularly necessary to the would-be intelligent music-lover of to-day is that our generation seems to be going through a period of unusual confusion in all matters of taste. Whether it be that our resources have accumulated faster than our powers of assimilation could develop, or that popular education, while increasing the amount of musical enjoyment, has lowered its quality, or that the ever-present commercialism has betrayed us—whatever be the causes, it is certain that almost all our standards have suffered from a false liberalism, that we have lost old lines and boundaries without getting anything to put in their place, and that much as we may boast of no longer starving our artistic instincts as did our puritan forefathers, we do not yet discriminatingly nourish them, but rather overeat ourselves sick. There is hardly any branch of music where this tendency to excess may not be discovered. The modern conception of the piano, for instance, as a rival of the orchestra in richness, variety, and power of sound has adulterated piano style in many respects. It has led directly to ‘un[Pg xv]grateful’ writing for the piano by composers, to pounding and other exaggerations by players. There are few musicians nowadays who show the fine self-control that made Schumann and Chopin models of how the piano should be treated. The rare intuition of Debussy in this respect is one of the true justifications of a vogue not perhaps altogether free from faddism.

In chamber music, notably the string quartet, where delicateness of sonority is even more vital to the style, since it is the condition of the clearness of the individual voices, and cannot be departed from without an immediate coarsening of the texture, there is the same tendency to imitate the orchestra. One hears many modern quartets in which all four instruments keep restlessly sawing away, often on two strings at once, as if they were taking part in a hurdle race or a debating society, rather than in a work of art. Special effects like harmonics and the use of the mute, appropriate enough in solos and at long intervals, are grossly abused. In striving to be something beyond its frame this most exquisite combination of four musical personalities loses all its intimateness, all its charm. Even orchestral music itself does not escape these perversions. There is a distinct cult at the present day, especially in France, for playing at concerts music originally written to accompany pantomimes or ballets, and even for composing pieces intended for concert according to the processes suitable for such illustrative music—with highly spiced sonorous effects, schemes of structure based on dramatic action, and little or no purely musical interest. Indeed, all thoughtful observers must sometimes ask themselves if this universal tendency to force things out of their natural fields, to make them do not what they can do best, but what they are least expected to do, is not a symptom of a grave disorder of our æsthetic sense, a preference of novelty to beauty, a debased fondness for the queer, an invasion of art by[Pg xvi] that low curiosity which draws a street crowd around any one who will stand on his head, or wear his clothes wrong side before. The reader genuinely fond of music will be glad to combat this tendency to the best of his power, and to that end will inform himself of those peculiarities of instruments by which appropriateness of style is so largely determined.

What the average reader can get from his study of the theoretical portions of ‘The Art of Music’ will depend largely on his instinctive sense of the larger bearing of technical facts. Studied with pedantic insistence of detail harmony is a dry subject; studied with an imagination eager for the light it throws on general æsthetic questions it proves unexpectedly illuminating. Harmony describes the material available to the musician; it is, we might say, the dictionary from which each composer chooses the words he needs to express his thought; and to study it is therefore for the lover of music much what it is for the lover of literature to study the vocabularies of his favorite authors—the derivations of the words, their ancient associations, the flavors which cling about them. Just as Sir Thomas Browne has his special words, noble-sounding, many-syllabled, and his special forms of sentence that roll grandly off the tongue, and as Keats finds in the same English a completely different instrument, capable of romantic utterance and full of elusive suggestion: so the harmony of Bach is not the harmony of Schumann, although it is made out of the same notes and even many of the same chords. Indeed, the very same chord is not the same in effect, in style, when used in the context of two composers, or even of one composer in two different moods; a chord is a chameleon that takes the color of its surroundings. How full of sadness, of infinite resignation, is the first B flat chord in the Adagio of the Ninth Symphony! How the very same B flat chord pulsates with energy in the Allegro of the [Pg xvii] Fourth! The study of the action and reaction of harmony and style is a fascinating one, in spite of its difficulty—one on which books might be written, as many have been on the choice of words in literature.

Easier, however, and much more directly helpful to appreciation, is the study of the chief principles of musical form or structure, as they affect, not the composer, but the listener. As one going into a foreign country provides himself with some guidance as to the main things he is going to see there, so the music lover to whom symphonic music remains to some degree a foreign region likes to find out before he hears it what he is to listen for. That knowledge in detail will be found in the essay on musical form in Volume XII. Here it is our business, as before, avoiding detail, to get such a bird’s-eye view as may be possible of the most general facts of musical form. Especially agreeable and useful would it be if we could show that, in music as elsewhere, form and formalism are two essentially different things, and that while formalism is the conventionalizing and stiffening that indicate lowered vitality or incipient death in a work of art, form [Pg xviii] is the necessary shape it takes because it is alive. The formless is not yet alive; the formal is dying or dead; only the formed truly lives. Therefore musical form is quite simple and natural, like the branching of trees or the crystallizing of salts, and the study of it is based on observation and common sense, and strives to determine how sounds have to be ordered to become intelligible.

Essentially there are but three processes concerned in musical construction—the announcement or exposition of the themes, their elaboration or development, and their recapitulation. These processes are the natural outcome of quite simple psychological facts, and are duplicated in literature and other arts. The announcement of a theme is the preliminary statement, [Pg xix] made as simple and as brief as possible, of the thought with which the composer proposes to occupy himself. For the listener, it is the presentation of a bit of melody of a particular rhythmic profile which he remembers by this profile, this characteristic combination of long and short, accented and unaccented notes, just as he remembers a person by the shape of his face. Careful attention to the main themes of a composition is of vital importance to appreciation, since the themes are the actors of the musical drama, and all the action is really only the working out of their latent characteristics.

This is what we mean by development. In no music worthy of the name is development an artificial, intellectual process; it is simply the germination of the theme-seeds. As it results, however, in constantly increasing complexity, it would quickly confuse the listener were it not judiciously combined with simple [Pg xx] repetitions of the original ideas, serving both to mark the completion of one cycle of development and sometimes to initiate a new one. The recapitulations insure the unity of the impression as a whole made by the work of art; the developments give it the richness and variety inseparable from all life.

The many special musical forms of which the student will read are merely so many clearly defined combinations of these three processes. Thus in the minuet, for example, a comparatively primitive form, there is one theme, expounded, developed, and recapitulated, and [Pg xxii] in the second part called trio, a second theme treated exactly the same way. In the ‘Song form’ so called, used for slow movements of sonatas and symphonies, there is usually an exposition of a theme, a slight development, and an ornamented or otherwise varied repetition; then, without any complete stop, a contrasting theme, treated much the same way; finally, a return of the main theme, either treated as at first or somewhat [Pg xxiii] more briefly. Sometimes there is a short coda (concluding section) with further slight development of one or both themes.

The sonata form, as we have already seen, is distinguished from both these more rudimentary types by having two themes of almost equal importance—sometimes three. These contrast with each other in expression, rhythm, and what is called ‘key.’ Their development is extended and occupies the entire middle part [Pg xxiv] of the piece. They are regularly recapitulated much as at first, but now both in the same ‘key,’ and may be followed by a coda, which with Beethoven assumes sometimes almost the importance of a second development. In the rondo there is a constant alternation between a main theme and other secondary themes or sections of development.

Thus in all the special forms we find but different applications of the three fundamental processes of exposition, development, and recapitulation, much as all plants go through the necessary cycle of seeding, growth, and blossoming. The more the music of the [Pg xxv] great symphonic masters is studied the more marvellous will the reader find the mingling of ingenuity and simplicity with which they know how to marshal their thoughts. Such study makes listening no longer a passive or even wearisome process, but the most fascinating reliving of a spiritual life as many-sided, as infinitely various, as filled with beauty, as that of Nature herself.

Daniel Gregory Mason.

June, 1914.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] To be exact Emanuel Bach was not responsible for the idea of contrast, which was a principle developed by the so-called Mannheim school, whose leader was Johann Stamitz. But with Bach the two separate sections of the ‘Exposition’ first become distinct.

A NARRATIVE HISTORY OF MUSIC

BOOK I

A NARRATIVE HISTORY OF MUSIC

INTRODUCTION

Musical art is the idealized art of the inner man as distinguished from the arts of painting and sculpture and their like which are the idealized expression of what is outside him. It is the result of the urgent impulses of certain peculiarly constituted human beings to express things which move them in ways which are favorable to permanence; which permanence proves attainable only through the controlling influence of the instinct for order.

The instinct for order and the impulse to gratify it in all directions seem to be present in all unperverted human beings; which is obviously the consequence of the fact that it has always ministered to the preservation of those who possessed it. The primitive savage who kept his weapons in some kind of orderly fashion, and knew where to lay his hands on them when wanted, easily survived the disorderly savage who could not find them soon enough to prevent being exterminated. The primitive savage who could dispose his means of existence in an orderly fashion was more likely to survive the savage who had no proper place for anything; and there were thousands of other ways in which this instinct favored its possessor; and favored him more and more as social and anti-social conditions progressed in complexity. Looked at from another point of view, that of experience, the lack of the sense of order betokens low mental power; and the possession of it in higher and higher degrees is a token of higher and higher capacities of mind.

The sense of order is the basis of organization; and out of organization comes permanence. The more perfect the organization the more lasting is the thing organized. What is well built is well organized for its purpose, and stands fast. What is ill built is badly organized for its purpose, and tumbles down. And so it is with a work of literature. It cannot be said that a noble thought ill-presented will soon be forgotten; but its being ill-presented makes it obscure. And it must be admitted that fascination is added to the utterance of a great thought by the perfect clearness and nicety with which it is expressed. The presentation is in that sense admirably organized and the mind welcomes it, and returns to it frequently with delight; whereas if it is clumsily expressed it gives the mind unnecessary trouble to understand what it means, and then there is a feeling of distaste and annoyance which prejudices the welcome that the great thought merits.

So it is with a work of art. Clumsiness and incoherence of structure beget discomfort, however great the intentions. Imperfections which may not be noticed at first grow more and more oppressive, till they become unbearable, and at last mankind is impelled to regard the good intentions as little better than opportunities wasted.

It may be justly argued that such imperfections are inevitable not only because art represents human efforts but because organization takes centuries to effect. It is also true that certain types of imperfection are pathetically attractive and afford a kind of interest in themselves where they suggest the kind of human condition and effort which is characteristic of the time and circumstances in which any individual work of art was produced. But in such case it is necessary that the motive shall be honorable. After ages will never be able to regard the deficiencies in modern church and chapel architecture, stained glass windows, modern tombstones and suburban villa residences with anything but disgust. Putting such aberrations aside for the present, it is pleasant to realize that one of the privileges of an instinct for style is to be able to recognize the stage of organization which has been reached, both in diction and structure, by the qualities of any work of art, and to locate the type of organization and balance its proportionate relation to what is expressed, and, more subtly still, to discern even the intention. Men who have any artistic instinct estimate the quality of a work of art by such an adjustment. They feel its nobility if it has any, even though the standard of organization is low, by estimating the quality of the thought in connection with the inevitable limitations of the means of expression. A work of art may inspire constant delight even though its form be obvious and its details crude, if the methods employed are sincere efforts to express with the best means available an inspiring idea. Limitations do not necessarily imply false construction. There is this to be remembered: that the progress of thought and the progress of organization proceed together and that a thought which clearly belongs to several generations ago will not be as complex or have to cover so much ground as the thought of later times of equal status; and that the limitation of the means of organization of the time to which the thought belongs will therefore be adequate and congenial to that thought, whereas, if a composer or artist use only the resources of diction and design of two hundred years ago to express a modern thought, the deficiency of the organization becomes at once apparent.

It is worth while to observe parenthetically that in primitive stages of art men did not attempt organization in order to give permanence to their artistic products. Their attitude was that of the unconscious child, and they merely sought to gratify their instinct for order, and arrived at the principle of organization in the process. So the beginnings of art were the direct result of the inevitable processes of the universe. Men found out the relation of organization to permanence long afterward, when they developed the capacity to analyze and consider what they were doing.

Mankind, like the individual, passes through three stages in his manner of producing and doing things. The first is unconscious and spontaneous, the second is self-critical, analytical, and self-conscious; and the third is the synthesis which comes of the recovery of spontaneity with all the advantages of the absorption of right principles of action. In the products of the first stage people delight in spite of crudity and clumsiness because they are fervent, genuine, essentially human. The products of the second are often ineffectual, occasionally suggestive, and for the most part more historically than humanly interesting. It is in the last phase that the greatest works of musical art are produced; and it is in such works of art that the approximation to perfection may be found, in which there is no part which has not some relation to every other part; nothing which does not minister to the fullness with which the inner idea of the artist is expressed; in which every curve of melody, every progression of harmony, every modulation, every rhythmic group, every climax and relaxation of stress, every shade of color, and every part of the inner texture at once ministers to coherent and cogent expression and at the same time fulfills its function in the general scheme of design or organization. From mere elementary orderliness art has progressed in such things to the very highest manifestations of the subtlest and most perfect organization which the human mind is capable of achieving. But it must be admitted that such an ideal is only reached in very rare cases, by masters whose complete absorption in the work of artistic creation is undisturbed by distracting influences; who can maintain their concentration through a prolonged and coherent effort; and who have the gift to apply their faculties and successfully call upon their minds to provide exactly the right methods and procedures whenever required, and at the same time to hold everything balanced by the requirements of proportionate relation which is indispensable to true artistic organization.

It is to such perfection that all true artists aspire, and it is only those who are absolutely true to themselves who can even approximate to it. In days when commercialism is rampant and the favor of such as are totally ignorant of the most elementary artistic principles is held to be the criterion of artistic worth, it practically becomes impossible.

There are two phases of organization. The first is the organization of terms, signs, methods, materials, some of which must be found before art begins, but most of which are found as it evolves. The second phase is the organization of the individual works of art. The parallel that springs to mind at the moment is the organization of units and supplies of an army, on the one hand, and, on the other, the organization of the campaign and the engagements for which the forces and their needs were organized. Upon the former kind of organization it is not necessary to dwell. It is an obvious necessity of art. But, though part of it, it does not illustrate or affect the quality of the art products except in a purely elementary and mechanical sense. Of the latter kind, which manifests itself inevitably in varying degrees in every musical work from the cheapest popular song to the highest instrumental symphony, it must be admitted that it is worth while to have some little understanding; especially of the relations to one another of the various branches and factors in the artistic scheme which the study of such things in detail is apt to miss.

At the outset the curious anomaly may be admitted that expression and organization appear to be antagonistic. This is only one way of recognizing that art, like everything else, is achieved by the accommodation of opposites. The very idea of human feeling being expressed in preconceived set terms sounds so preposterous as to be almost repugnant. Yet if it is not expressed in set terms how should it maintain its hold upon the mind? We know by experience that human feeling upsets organization (as, for instance, in the confusion of rhythm into which highly emotional performers and singers are driven), and that organization stifles human feeling (as, for instance, in the empty, inadequate words that are stuffed into poetry to make rhymes, and the ridiculous shams that are stuffed in architecture as in music to make a pattern complete). But, as a matter of fact, though language also might be described as antagonistic to feeling, yet feeling cannot definitely be conveyed to other beings without being formalized into words, and the words arranged according to the recognized rules of prosody. And, as a matter of experience, when language has become, as it does, a spontaneous means of expressing feeling, it very often intensifies the feelings that it is used to express. Many men are more excited by their own violent language than by the motives which caused them to give vent to it. So in art some men only begin to find out how strong their feelings are when they try to put them into shape. The mere fact of organizing effective climaxes according to settled principles causes them to believe in deep-set passion which they would not otherwise have suspected in themselves. Oratory is never in itself a proof of greatness or even sincerity of soul.

So it cannot be maintained that the appearance of antagonism is fully borne out by experience. But what is evident is that the human element represents instability and the constructive element stability; and the adjustment of the two keeps art alive. All art that has life in it must be in unstable equilibrium, for, indeed, all thought whatever induces instability. Stable equilibrium, if such a thing could be conceivable, is merely abeyance of activity. As a matter of fact there is no part of the universe which is in stable equilibrium, art as little as the rest of it. Art is, in the widest sense, man’s highest expression of the Spirit of the Universe; that is of the effects which are produced in his inner man by his personal experiences in it and his cogitations about it, and art’s life is governed by the same laws. In the universe all things seem to tend toward stable equilibrium, and yet of necessity when it seems to be approached some new direction of force disturbs it and sets up new systems of motions which may last for ages. So in art there has been a tendency to deal with the claims of feeling and the claims of form at different times. At certain periods in art’s history the human element predominated and the claims of organization were either ignored or overlooked. The result was incoherence, and the need of more circumspect procedure gave organization an excessive spell of attention. Convention then took the place of realities and art became the playground of ingenious dry-as-dusts, till the human element again asserted its claims and progress swayed in the direction of instability again; and so the great rhythm was maintained.

But it would be absurd to pretend that the alternation proceeded regularly without yielding to external influences. The direction which art took was often influenced by social conditions external to itself. A chance whiff of fashion or a wave of impulse in favor of intellectual subtleties would naturally cause a phase[Pg xxix] of art in which human feeling would be crowded out by superfluity of organizing ingenuity. A state of society in which a few people enjoyed the results of their ancestors having annexed all the material advantages of the world and regarded the rest of humanity as merely provided by Providence to minister to their vanities, would be peculiarly favorable to the exuberance of conventional pattern-making and elegant futilities; while the successful overthrow of such a poisonous tradition and the general acceptance of the widest claims of humanity to common justice naturally brought an overwhelming impulse of human feeling into play. But the apparent derangement of the ebb and flow was not actually destructive of the principle, but only affected the length of the periods and the extent of the one influence on the other.

As a rule the instinctive discernment of humanity was so far just that it is far more easy to point to periods when human feeling predominated than to those when the organizing instinct predominated. This was natural because all artistic beings are, as far as the impulse is concerned, at the outset bent upon expressing feelings of some sort. Even those who have more aptitude for technical efficiency than mind are not actually aiming at producing supernaturally correct grammatical exercises. They are always much offended if such a thing is suggested. The unsophisticated lovers of music who have no technical knowledge to speak of are always concerned with the human side of it, they are moved by the sound, the color, the rhythm, the character of the melody, and, as far as they can get at it, by the idea the composer wants to express. It lies with the unsophisticated to maintain the claims of that side of art, as Wagner suggested when he said that he made his works for the not-musicians.

The fully instructed are inevitably inclined to over[Pg xxx]estimate mere workmanship. The wonder that is inspired by supremely masterly organization impels experts to be carried away by their admiration of it; and, moreover, it is practicable to discuss that aspect of art fully and clearly, whereas language is not apt to discuss the meaning and spirit of musical art, for the obvious reason that it is the business of music to express things that are beyond the reach of words. And it is pathetic to think how many thousands of people who have musical insight, and are really moved and inspired by it, are, through their very conscientious desire to understand it, misled into supposing that organization and dexterous use of the methods of art are the things that are of highest importance. This has been the bane of the greater part of theoretic writing about art and is the thing which arouses rebellion in ardent and aspiring minds against the stress that is laid on principles of form and grammatical orthodoxies. To such dispositions it seems preposterous to devote so much attention to the organization and to take so little count of the thing organized; and their antagonism is indeed very serviceable. For, however ridiculous the results their ardor often produces, they do help to keep art alive and to prevent its being stifled by conventions. And they do maintain the necessary protest against the paralyzing theory that has at times been propounded, that art is merely a special manifestation of clever mechanical ingenuity. Coherent organization is indeed a necessary condition of art, but the thing organized is of the foremost importance. The idea comes first and the organization is secondary. Yet the one is futile without the other; the idea cannot be conveyed without the organization, but organization without something to organize is mere superfluity. The idea without organization is mere incoherence; mere organization without meaning is empty puzzle making. Neither by itself has any claim to be distinguished as art.

The ways in which a work of art can be organized are practically innumerable; but in musical art they all have the simple structural basis of a departure from a given point to a point or many points of contrast and back home again. The infinite number of varieties depends on the manner in which the central point is established, and how the departure from it is made; how the contrasting middle portion is organized, and how the return home is established. The evolution of principles of form consists in the elaboration of the main divisions into subordinate contrasts, contrasts to contrasts, inner organic procedures, devices of structure which are linked and superimposed on one another, in which the steps that lead away from the main centre are successively distributed in subtle gradations, all of which are available to make the adaptation to the idea more perfect. The story of the evolution is perspicuously clear, as the vast amount of devoted and, latterly, intelligent labor which has been expended upon collecting folk-songs and specimens of quasi-musical phrases of savages has completed the story from the first appearance of the desire for some kind of orderliness up to the portentous elaborations of European music of the present day.

The way complication has been built upon complication may be easily grasped by observing the successive stages of art for which organization had to be provided. At first it had only to serve for a single melodic line; then, in the period of ecclesiastical choral music, for two or more combined melodic lines; then composers combined more and more melodic lines as they found out how it could be done, and this caused their minds to be almost monopolized by what may be called linear organization, which is a systematized relation of melodic parts which are quasi independent, but knit into unity by their subjection to the rules of melodic scales, which were called modes. The highest[Pg xxxii] outcome of long and concentrated thought in this direction was the type of organization known as the fugue, which is a linear principle of organization vitalized by the systematic distribution of recognizable melodic phrases. Fugue was the first form in which the musical idea was the most prominent factor in organization, and in the hands of genuine composers was developed to a high degree of perfection. But it left almost unrealized the problem of organization which dawned upon men’s minds as necessary when they began to feel the harmonies which were the result of combined melodious parts as entities in themselves. This problem was dealt with in the period when men devoted themselves to the classification of harmonies in key systems, which gave every harmony a definite function in artistic organization; and the capacity of the human mind was developed till it could recognize one succession of harmonies as representing one key centre and another succession of harmonies as representing another key centre, and this made an orderly succession of key centres the new basis of organization. Then the human mind grew to be able to discern these principles of order when composers dispensed with the sounding of the concrete harmonies and only represented them by ornamental procedures; through which the trained mind can perceive and infer the groups of harmonic successions which are implied and recognize the respective keys to which they belong. Complication yet further expanded the basis of organization as composers approached what may be called the extreme of sophistication, which became attainable by a reversion to the linear system, in which harmony was again suffused by polyphonic methods, and the individual notes of the ornamental formulas themselves are made to represent centres of activity and have their own harmonization; which harmonization subsists in spite of its apparent clashing with the harmonization of other ornamental notes, which the mind is able to endure because it intellectually segregates the notes which represent different systems and allots them to their respective centres and so keeps them apart from one another. The superimposition of device upon device is like a perpetual budding from a germ cell, with the additional analogy to things physical, that each generation is always consistent in its characteristics and identifiable. The quickness of the human mind at grasping the especial type of organization which it has to accept, in order to follow the idea of the composer, is one of its most extraordinary capacities; as is the development of the art which enables the adequately equipped composer to be sure that his most subtle sophistications are sure to meet with understanding from the auditors who are equally well equipped. When an ignoramus looks at a full score of any big modern work and sees there the hundreds of notes that are to be sounded in a few seconds, and sounded also for the fraction of a second and no more, most of which are not harmony notes but only suggest them by the way they are grouped, and yet convey to the qualified auditor a perfect sense of orderliness and coherence, it will either give him the sense of the amazing development of art and of human capacity to follow what is offered to it as art, or incredulity, in accordance with his temperamental bias.

But it has to be remembered that, in order to find any method of organization serviceable, the auditor must have gone through some of the steps which enable him to follow the procedure. It is here that certain perplexing incapacities will find their explanation. It frequently happens that a person of considerable musical culture is amazed to find that some passage which he regards as one of the noblest and most moving in the whole range of art leaves the majority of average audiences entirely blank and unmoved—and this[Pg xxxiv] may happen with people who are constantly hearing music. It happens most frequently when a person who cultivates late phases of instrumental music is brought into contact with the finest choral music of the sixteenth century. The meaning and purpose of the several motions have not come under his attention and he has no clue whatever to the scheme of organization. The contempt with which the complacent classicist of the sonata period looked down upon the form of the fugue was owing to musicians having broken altogether for the time with organization of the fugal type and having become incapable of listening to and understanding the motions of two or three independent parts at once. For here it will be as well to observe that every step in the building up of art by the addition of notes to a scale, of new chords which were devised, and of methods and devices of all sorts had special functions when they were invented, just as much as every conceivable feature in architecture had a function. But mankind always forgot the original meaning very soon and applied the various features to other purposes, most of which were quite without meaning and merely served for barren show. And it is this forgetfulness which makes so many people totally indifferent to the finest artistic achievements. They are expressed in a language they do not understand.

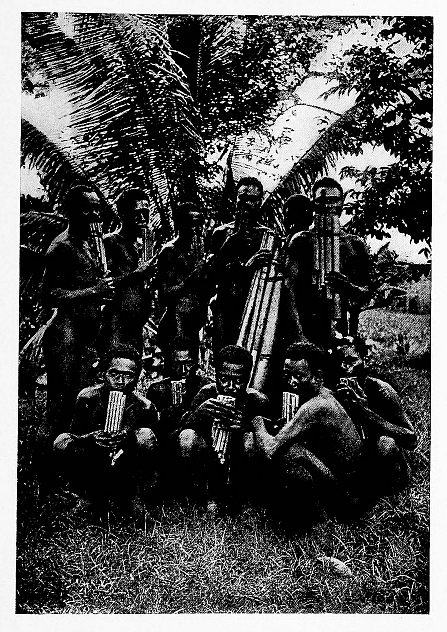

It must be obvious that there is a very close connection between the type and complexity of organization and the standard of mental development of those for whom it is devised. The study of folk-music and the music of primitive savages is very enlightening in this respect; especially in respect of the organization, which is based in great part on musical phrases. As might be naturally supposed the earliest sign of awakening intelligence is found in mere reiteration of some melodic or rhythmic formula. This is essentially the primitive savage type and is met with in extraordinary per[Pg xxxv]sistency under varied conditions. It is a most remarkable fact that such undisguised reiteration is a conspicuous feature of the music of relatively undeveloped races in the present day, who have adopted the advanced methods of modern music with remarkable success. It is the more curious as the composers of the more developed races do not resort to such naïve reiteration except as a basis for presenting a phrase or passage in different lights by variation. And with the undeveloped races their reversion to a primitive practice, especially at points of great excitement, is an unconscious admission of the nearness of their temperamental average to that of their primitive ancestry. As a principle mere reiteration is hardly worthy of the name of organization, it might rather be called a preliminary procedure, or a means of keeping things going. It does not imply any mental development, it only implies some kind of definition and capacity of recognition. The first step toward real organization comes when a phrase or short passage of melody is alternated with another which serves as a contrast with it, and returns again to the first phrase to give the sense of completeness. Yet even such a simple principle of orderliness needed considerable progress in mental grasp before it could be attained. It might perhaps be regarded as the significant feature which distinguishes folk-music from savage music. Folk-music is indeed a very considerable advance on the music of primitive savages, and it shows the growth of power to attain to real orderliness, as the basis of art, by the employment of simple and clear forms of organization, which are evolved quite irrespective of any collusion or imitation between the races that resorted to it. As folk-music is always melodic it did not admit of great variety of elaboration in the organization of the tunes, yet there was sufficient to illustrate the average disposition toward intellectuality of the races which the[Pg xxxvi] songs represent. Races which are notable for the quickness of their intelligence and their delight in the exercise of it show it in the closeness and interest of the structure of their folk-music, as is the case with Scotch tunes, and those whom imagination, feeling, or sentiment are specially liable to dominate are represented by forms which are vaguer and less elaborately organized. On the side of character, also, it is parenthetically observable that folk tunes reflect the temperamental qualities of the races and localities to which they belong most truthfully—such as the vivacity and love of orderly design of the French, the pathos and pugnacity of the Irish, the sober simplicity and deliberation of the English, the sentimental reflectiveness of Germans, the spasmodic vehemence of Hungarians, and the love of elaborate ornamentation of Orientals. Slavonic folk-music is also most characteristic, but it is most difficult to define. It has in most cases a flavor of the playful unconsciousness of youth, simplicity of structure and a kind of pathetic gaiety. This close connection between a race or a geographical attitude of mind and its folk-music is really a foretaste of the connection which persisted throughout the whole story of art’s evolution. A people’s music so accurately represents its temperamental qualities that, if there was any doubt about a race’s character, the music they favor would solve it. In folk-music the element of rhythm figures very considerably; and, as it is a subject about which a great deal of confusion of mind seems to exist, it is advisable to give a little attention to it. It is a defining and vitalizing influence of the highest importance; for it is only through rhythm that the individual factors of organization become identifiable. It is through the grouping of beats into two, three, four, five, six, and so on that the nuclei which are the basis of organization are grouped into coherent and distinguishable factors. Inasmuch as a note is nothing by itself, and only becomes something when it has relation to another note, and, as these notes must succeed one another in time, it is necessary to have some means of defining the respective lengths of time which are to be relatively allotted to the respective notes; and rhythm is the process by which the progress of sounds in time is marked off and organized. Without it there would be mere vagueness and confusion.

This is the aspect of rhythm from the point of view of organization. That was not its object in the beginning, but to minister to expression of feeling. All people who have not attained to an advanced stage of culture and intelligence delight in rhythm; and the sphere it occupies in folk-music is enlightening; for its preponderance varies considerably. In some folk-music it is always conspicuous, as in Hungarian and French folk-music; in some it is only moderately apparent and rarely aggressive, except when the words associated with it imply vigorous action, as in English and German folk-music. There are obvious implications which are suggested by the fact. The aggressively rhythmic music shows a predisposition for instrumental music, and the less rhythmic for vocal music. The former represents the music of action and the latter the music of inner feeling. The former secular feeling and the latter serious feeling associated with religion of some sort.

Rhythm suggests bodily activity. Its essential function is to represent the expression of feelings by motions of the body, arms, legs, or any part that can move freely. This is verified by the fact that rhythmic music impels people to join in with hands and feet, and this is also the underlying basis of dance music; for the object of dance music is to inspire people to rhythmic activity, and its connection with expression is verified by the fact that so much dance music, even in the earliest times, has been mimetic. The position of rhythm in artistic music is strange, for it is undeniable that the preponderant impulse of serious composers is to hide it away in sophistications. Indeed, for many centuries it was, possibly unconsciously, kept at bay. Pure unsophisticated rhythm belongs to the primitives. It is not the form of expression congenial to self-respecting and developed races when they are taking anything serious in hand. This is partly because it does, as above remarked, represent physical expression, which is not the type to which intellectual people are prone. Developed minds want to convince by argument; primitive people by force. Moreover, rhythm is not progressive. In its direct forms it is probably much as it was with the cave dwellers. Its limitations are obvious; and its simple forms are indicative of a primitive state in those that use it.

As a matter of fact, it seems to be the ingrained impulse of composers whose feeling for their art is highly developed to disguise it, as though the frank use of it was commonplace and cheap. What appears to be progress in rhythm is indeed not in rhythm itself, but in that very sophistication. It is like the sophistication of metre in the blank verse of Shakespeare or Milton, or even in the lyric poetry of Shelley and Keats and later poets, which makes English lyrics so difficult for inefficient and unliterary composers to set. The parallel in poetry and verse is complete. For the jog-trot of those indifferent poets who make an appeal to the undeveloped minds of the herd is poetry of a low order, just as is the rhythmic commonplace of cheap-minded composers.

The higher type of composer deals with rhythm as with everything else. He uses the simple basis of a definite rhythm to build upon it something interesting. What would be commonplace and familiar is made worthy of the name of art by its presentation in rela[Pg xxxix]tion to other rhythms, or in combination with an independent grouping of strong and weak beats which gives it new significance. Such sophistication of rhythm was very difficult in the times when music was confined to one melodic part. But it became easy when choral music developed into contrapuntal treatment of melodic voice parts, and it attained in later days to the highest pitch of interest when the harmonic style was reinfused with polyphonic methods, and full opportunities were afforded for combining different rhythms at once, and ordinary rhythms in one part could be made quite interesting or amusing through their association with other parts which are purposely at variance with the essential rhythm. By such procedure composers succeeded in avoiding the use of common property and could enjoy the inestimable services of rhythm as a vitalizer and a definer without condescending from their high estate. The reticence of the higher type of composer in the matter of rhythm, and his tendency to refrain from such undisguised relaxation, is curiously confirmed by the history of sacred music. It is a very singular fact that, in the long period of over five centuries, during which church music was developed from the most primitive conditions till it manifested such wonderful perfection of spirit and workmanship at the end of the sixteenth century, composers, guided by instinct rather than conscious reasoning, always endeavored to suppress or hide the sense of rhythm. As music began to grow from the doubling of plain-song at the intervals of fifths and fourths and octaves (which was so convenient to the different calibres of the voices which had to sing it), by filling in the steps between one principal note and another with shorter notes, and so developed primitive counterpoint, composers soon began to aim at giving the effect of independence to human voices by making them move at different times and in different directions; by mak[Pg xl]ing use of syncopations, suspensions, dotted notes that overlapped one another, and all such procedures as obscured the rhythmic element. And even when, owing to special circumstances, they were driven to make parts move simultaneously, as in later harmonic procedure, they made the chords halt and move again, and even occasionally drop the principal accent, to obviate the sense of rhythmic lilt—as may be observed in some of the hymn tunes of Orlando Gibbons, which have had to be altered and made quite commonplace in modern times to suit the mechanical habits of modern congregations.

This curious persistence may be explained by the fact that devotional feeling is not demonstrative. Western people in really devotional frame of mind do not gesticulate or fling their arms and legs about to express their feelings, but are bowed down in spiritual ecstasy. The music was the true expression of the spirit; and, till secular music began to react upon religious music after the beginning of the seventeenth century, the music of the services of the church might fairly be described as anti-rhythmic. And it still remains a fact that whenever rhythm makes its appearance prominently in music which purports to be devotional it is a proof of its insincerity. But there are always many things which concur in achieving a big result, and it must be admitted that conjoined with the instinct which avoided rhythm in religious music was the fact that all the early religious music was essentially vocal; and vocal music in its purest simplicity is comparatively unrhythmic. It learnt definite and consistent rhythm from instrumental music when that came to be cultivated with vigor from the beginning of the seventeenth century onward. It is true that dance music was sung, and that the Balletti of such a delightful composer as Morley have wonderful rhythmic verve; but such compositions represent the time when musical[Pg xli] expansion was moving strongly in a secular direction and instruments were beginning to exert their influence. The greater madrigals of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries still illustrate the inherent peculiarity of pure choral music and give ample proofs of the composers’ endeavors to disguise the rhythmic element and represent the underlying principle of the grouping of strong and weak beats without adopting obvious rhythmic organization. Instrumental music, on the other hand, inevitably implies rhythm. In its most primitive phases it was probably nothing but rhythm, and that rhythm of a perfectly frank and undisguised description. In its early artistic, phases it was generally full of rhythmic life without obtruding the rhythm as a special means of appeal to the audience, as is the case in modern popular music. The deeply ingrained habits of counterpoint which still persisted in the eighteenth century made even suites of dance tunes so full of texture in detail that the rhythm was rather the basis of the definition of pulses than a factor in the effect. If the story of modern music were followed up with special reference to rhythm it would be found that the aim of all composers who took their art seriously has been to avoid the commonplaces and to sophisticate rhythm in such a way as to make it serve as an additional source of expression, instead of a mere mechanical incitement to movement. The increase of orchestral instruments offered ample opportunities to sophisticate rhythms in a manner analogous to the charming effects of early choral music, in which syncopation and cross-rhythms add a genuine interest to the fundamental rhythm and seem to play with the hearers by making them feel that one rhythm is superimposed on another. Even in actual modern dance tunes of the best kind the impulse to add something independent to the fundamental rhythm is found in such devices as tying over the[Pg xlii] last note of a group of three in a valse to the strong beat of the succeeding rhythmic group, while the essential rhythm is maintained by the bass or other instruments of the accompaniment, and composers have even successfully devised such attractive ingenuities as the effect of three long beats being superimposed on two groups of the three lesser beats of the established rhythm. The well-known combination in Mozart’s Don Giovanni of a minuet and a valse each in triple time and a country dance in 4/4 time is one of the most ingenious illustrations of such combined rhythms. The essential basis of all such devices is the sophistication of the obvious, which is the natural impulse of every true composer.