Title: Life in Canada

Author: Thomas Conant

Release date: July 3, 2021 [eBook #65750]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

by

Thomas Conant,

Author of “Upper Canada Sketches.”

Toronto

William Briggs

1903

Entered according to Act of the Parliament of Canada, in the year one thousand nine hundred and three, by Thomas Conant, at the Department of Agriculture.

“If a book comes from the heart, it will contrive to reach other hearts; all art and author’s craft are of small account to that.”

In the following pages will be found some contributions towards the history of Canada and of the manners and customs of its inhabitants during the hundred years beginning October 5th, 1792. On that date my ancestor, Roger Conant, a graduate of Yale University, and a Massachusetts landowner, set foot on Canadian soil as a United Empire Loyalist. From him and from his descendants—handed down from father to son—there have come to me certain historical particulars which I regard as a trust and which I herewith give to the public. I am of the opinion that it is in such plain and unvarnished statements that future historians of our country will find their best materials, and I therefore feel constrained to do my share towards the task of supplying them.

The population of Canada is but five and one-third millions, but who can tell what it will be in a few decades? We may be sure that when our population rivals that of the United States to-day, and when our{vi} numerous seats of learning have duly leavened the mass of our people, any reliable particulars as to the early history of our country will be most eagerly sought for.

As a native resident of the premier Province of Ontario, where my ancestors from Roger Conant onwards also spent their lives, I have naturally dealt chiefly with affairs and happenings in what has hitherto been the most important province of the Dominion, and which possesses at least half of the inhabitants of the entire country. But I have not the slightest desire to detract from the merits and historical interest of the other provinces.

Thomas Conant.

Oshawa, January, 1903.{vii}

| CHAPTER I | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

| Roger Conant—His position in Massachusetts—Remained in the United States two years without being molested—Atrocities committed by “Butler’s Rangers”—Comes to Upper Canada—Received by Governor Simcoe—Takes up land at Darlington—Becomes a fur trader—His life as a settler—Other members of the Conant family | 13 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Colonel Talbot—His slanderous utterances with regard to Canadians—The beaver—Salmon in Canadian streams—U. E. Loyalists have to take the oath of allegiance—Titles of land in Canada—Clergy Reserve lands—University of Toronto lands—Canada Company lands | 27 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The War of 1812—Canadian feeling with regard to it—Intolerance of the Family Compact—Roger Conant arrested and fined—March of Defenders to York—Roger Conant hides his specie—A song about the war—Indian robbers foiled—The siege of Detroit—American prisoners sent to Quebec—Feeding them on the way—Attempt on the life of Colonel Scott of the U. S. Army—Funeral of Brock—American forces appear off York—Blowing up of the fort—Burning of the Don bridge—Peace at last | 37 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Wolves in Upper Canada—Adventure of Thomas Conant—A grabbing land-surveyor—Canadian graveyards beside the {viii}lake—Millerism in Upper Canada—Mormonism | 60 |

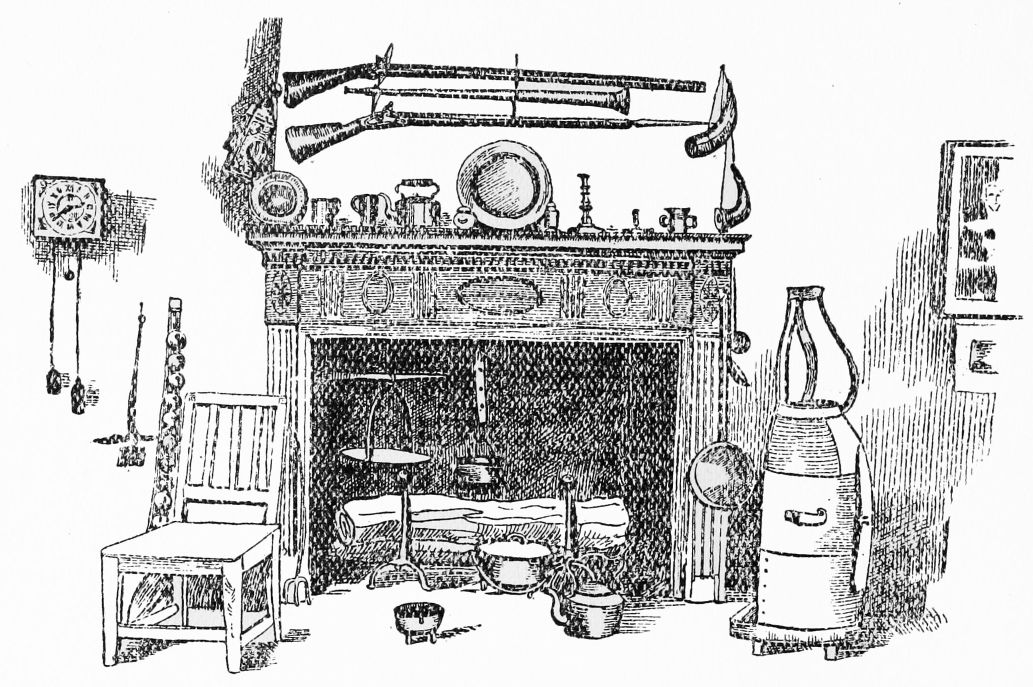

| CHAPTER V | |

| Abolition of slavery in Canada—Log-houses, their fireplaces and cooking apparatus—Difficulty experienced by settlers in obtaining money—Grants to U. E. Loyalists—First grist mill—Indians—Use of whiskey—Belief in witchcraft—Buffalo in Ontario | 72 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| A manufactory of base coin in the Province of Quebec—A clever penman—Incident at a trial—The gang of forgers broken up—“Stump-tail money”—Calves or land? Ashbridge’s hotel, Toronto—Attempted robbery by Indians—The shooting of an Indian dog and the consequences | 87 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| The Canadian Revolution of 1837-38—Causes that led to it—Searching of Daniel Conant’s house—Tyrannous misrule of the Family Compact—A fugitive farmer—A visitor from the United States in danger—Daniel Conant a large vessel owner—Assists seventy patriots to escape—Linus Wilson Miller—His trial and sentence—State prisoners sent to Van Diemen’s Land | 97 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Building a dock at Whitby—Daniel Conant becomes security—Water communication—Some of the old steamboats—Captain Kerr—His commanding methods—Captain Schofield—Crossing the Atlantic—Trials of emigrants—Death of a Scotch emigrant | 114 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Maple sugar making—The Indian method—“Sugaring-off”—The toothsome “wax”—A yearly season of pleasure | 122 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Winter in Ontario—Flax-working in the old time—Social gatherings—The churches are centres of attraction—Winter marriages—Common schools—Wintry aspect of {ix}Lake Ontario | 129 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| The coming of spring—Fishing by torch-light—Sudden beauty of the springtime—Seeding—Foul weeds—Hospitality of Ontario farmers | 136 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Ontario in June—Snake fences—Road-work—Alsike clover fields—A natural grazing country—Barley and marrowfat peas—Ontario in July—Barley in full head—Ontario is a garden—Lake Ontario surpasses Lake Geneva or Lake Leman—Summer delights—Fair complexions of the people—Approach of the autumnal season—Luxuriant orchards | 145 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| Some natural history notes—Our feathered pets—“The poor Canada bird”—The Canadian mocking-bird—The black squirrel—The red squirrel—The katydid and cricket—A rural graveyard—The whip-poor-will—The golden plover—The large Canada owl—The crows’ congress—The heron—The water-hen | 159 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Lake Ontario—Weather observations with regard to it—Area and depth—No underground passage for its waters—Daily horizon of the author—A sunrise described—Telegraph poles an eye-sore—The pleasing exceeds the ugly | 170 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| Getting hold of an Ontario farm—How a man without capital may succeed—Superiority of farming to a mechanical trade—A man with $10,000 can have more enjoyment in Ontario than anywhere else—Comparison with other countries—Small amount of waste land in Ontario—The help of the farmer’s wife—“Where are your peasants?”—Independence of the Ontario farmer—Complaints of emigrants unfounded—An example of success | 180 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| Unfinished character of many things on this continent—Old Country roads—Differing aspects of farms—Moving from the old log-house to the palatial residence—Landlord and tenant should make their own bargains—Depletion of {x}timber reserves | 201 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| Book farmers and their ways—Some Englishmen lack adaptiveness—Doctoring sick sheep by the book—Failures in farming—Young Englishmen sent out to try life in Canada—The sporting farmer—The hunting farmer—The country school-teacher | 208 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| Horse-dealing transactions—A typical horse-deal—“Splitting the difference”—The horse-trading conscience—A gathering at a funeral—Another type of farmer—The sordid life that drives the boys away | 219 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| City and country life compared—No aristocracy in Canada—Long winter evenings—Social evenings—The bashful swain—Popular literature of the day—A comfortable winter day at home—Young farmers who have inherited property—Difficulty of obtaining female help—Farmers trying town life—Universality of the love of country life—Bismarck—Theocritus—Cato—Hesiod—Homer—Changes in town values—A speculation in lard | 227 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| Instances of success in Ontario—A thrifty wood-chopper turns cattle dealer—Possesses land and money—Two brothers from Ireland; their mercantile success—The record of thirty years—Another instance—A travelling dealer turns farmer—Instance of a thriving Scotsman—The way to meet trouble—The fate of Shylocks and their descendants | 244 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| Manitoba and Ontario compared—Some instances from real life—Ontario compared with Michigan—With Germany—“Canada as a winter resort”—Inexpediency of ice-palaces and the like—Untruthful to represent this as a land of winter—Grant Allen’s strictures on Canada refuted—Lavish use of food by Ontario people—The delightful climate of {xi}Ontario | 255 |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| Criticisms by foreign authors—How Canada is regarded in other countries—Passports—“Only a Colonist”—Virchow’s unwelcome inference—Canadians are too modest—Imperfect guide-books—A reciprocity treaty wanted | 268 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| Few positions for young Canadians of ambition—American consulships—Bayard Taylor—S. S. Cox—Canadian High Commissioner—Desirability of men of elevated life—Necessity for developing a Canadian national spirit | 277 |

| CHAPTER XXIV | |

| A retrospect—Canada’s heroes—The places of their deeds should be marked—Canada a young sleeping giant—Abundance of our resources—Pulpwood for the world—Nickel—History of our early days will be valued | 286 |

Roger Conant—His position in Massachusetts—Remained in the United States two years without being molested—Atrocities committed by “Butler’s Rangers”—Comes to Upper Canada—Received by Governor Simcoe—Takes up land at Darlington—Becomes a fur trader—His life as a settler—Other members of the Conant family.

The author’s great-grandfather, Roger Conant, was born at Bridgewater, Massachusetts, on June 22nd, 1748. He was a direct descendant (sixth generation) from Roger Conant the Pilgrim, and founder of the Conant family in America, who came to Salem, Massachusetts, in the second ship, the Ann—the Mayflower being the first—in 1623, and became the first Governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony under the British Crown. He was graduated in Arts and law at Yale University in 1765. At the time of the outbreak of the Revolution in 1776 he was twenty-eight years old. His capacity and business ability may be judged from the facts that he owned no fewer than 13,000 acres of land in New England, and that when he came to Canada he brought with him £5,000{14} in British gold. He appears to have been a man of keen judgment, of quiet manners, not given to random talking, of great personal strength, and highly acceptable to his neighbors. In after days, when he had to do his share toward subduing the Canadian forest, they tell of him sinking his axe up to the eye at every stroke in the beech or maple. The record is that he could chop, split and pile a full cord of wood in an hour.

Although he became a United Empire Loyalist and ultimately came to Canada, leaving his 13,000 acres behind him in Massachusetts, for which neither he nor his descendants ever received a cent, Roger Conant’s decision to emigrate was not taken at once. The Revolution broke out in 1776, but he did not remove from his home until 1778. Even then he does not appear to have been subjected to the annoyances and persecution which some have attributed to the disaffected colonists. What the author has to say on this point comes from Roger Conant’s own lips, and has been handed down from father to son. He has, therefore, no choice in a work of this kind but to give it as it came to him. It has been the rule among many persons who claim New England origin to paint very dark pictures of the treatment their forefathers received at the hands of those who joined the colonists in revolt from the British Crown. For instance, words like the following were used soon after the thirteen colonies were accorded their independence and became the United States:

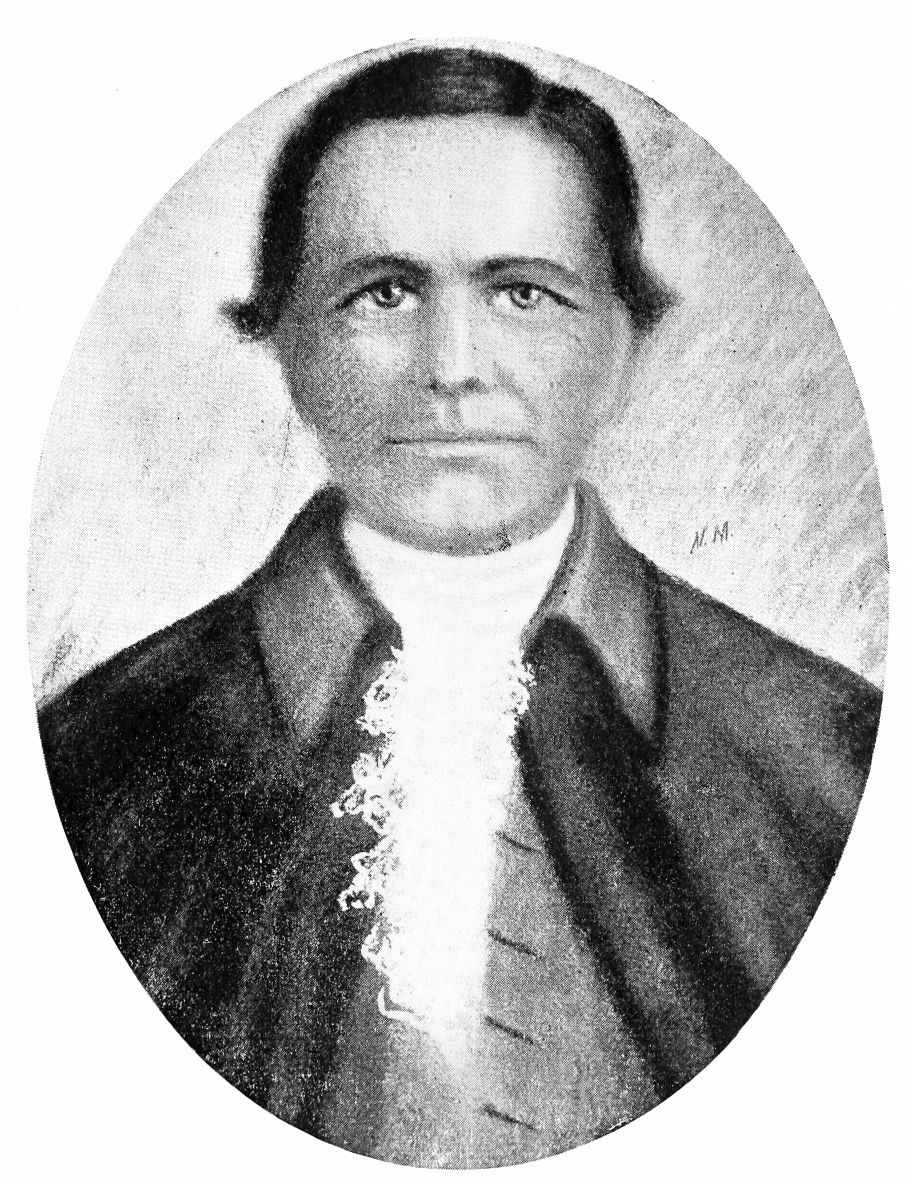

ROGER CONANT.

Born at Bridgewater, Mass., June 22, 1748.

Graduated at Yale University in Arts and law, 1765.

Came to Darlington, Upper Canada, a U. E. L., 1792.

Died in Darlington, June 21, 1821.

“Did it serve any good end to endeavor to hinder Tories from getting tenants or to prevent persons who owed them from paying honest debts? On whose cheek should have been the blush of shame when the habitation of the aged and feeble Foster was sacked and he had no shelter but the woods; when Williams, as infirm as he, was seized at night and dragged away for miles and smoked in a room with fastened doors and closed chimney-top? What father who doubted whether to join or fly, determined to abide the issue in the land of his birth because foul words were spoken to his daughters, or because they were pelted when riding or when moving in the innocent dance? Is there cause to wonder that some who still live should yet say of their own or their fathers’ treatment that persecution made half of the King’s friends?”

Roger Conant, however, during the two years he remained at Bridgewater after the breaking out of the Revolution, was free from these disagreeable experiences. He frequently reiterated that such instances as those of Foster and Williams were very rare, and maintained that those who were subject to harsh treatment were those who made themselves particularly obnoxious to their neighbors who were in favor of the Revolution. Persons who were blatant and offensive in their words, continually boasting their British citizenship and that nobody dare molest them—in a word, as we say, a century and a quarter after the struggle, forever carrying a chip on the shoulder and daring anybody to knock it off—naturally rendered themselves objects of dislike. It must be borne in mind that, right or wrong, the entire community were almost a unit in their contention for separation from Great Britain. Yet Roger Conant, who did not take up arms with the patriots, was not molested. His{16} oft-repeated testimony was that no one in New England need have been molested on account of his political opinions.

As a matter of fact, he frequently averred that he made a mistake when he left New England and came to the wilds of Canada. To the latest day of his life he regretted the change, and said that he should have remained and joined the patriots; that the New Englanders who were accused of such savage actions towards loyalists were not bad people, but that on the contrary they were the very best America then had—kind, cultivated and considerate. Nor was he alone in this conviction. He was fond of comparing notes with other United Empire Loyalists with whom from time to time he met. He was always glad to meet those who had come to Canada from the revolted colonies. And he again and again averred that their opinion tallied with his own, viz., that they were mistaken and foolish in coming away. He entertained no feelings of animosity against the new government who appropriated his 13,000 acres. Neither does the author. Such feelings were and are reserved for Lord North, whose short-sightedness and obstinacy were the immediate cause of the war. A man who could say that “he would whip the colonists into subjection” deserves the universal contempt of mankind, especially when it is remembered that at the very moment of his outbreak of ungoverned and arbitrary temper the colonists were only waiting for an opportunity to consummate an entente cordiale with the Mother Country, and to return to former good feeling and peace.{17}

On the other hand, Roger Conant had that to tell regarding some of the British forces which does not form pleasant reading, but which the author feels impelled to set down in order to present a faithful picture of Great Britain’s stupendous folly, viz., her war with the American colonies in 1776. The first body of irregular troops of any sort that he saw who were fighting for the King were Butler’s Rangers, which body, to his astonishment, he found in northern New York State when wending his way to Upper Canada. For some time he tarried in the district where this force was carrying on its operations. It would seem as if the very spirit of the evil one had taken possession of these men. Acts of arson by which the unfortunate settler lost his log cabin, the only shelter for his wife and little ones from the inclemency of a northern winter, were too common to remark. Murder and rapine were acts of everyday occurrence. Manifestly these atrocious guerillas could not remain in the neighborhood that witnessed their crimes. They found their way in various directions to places where they hoped to evade the tale of their villany. In after years one of these very men wandered to Upper Canada, and, as it happened, hired himself to Roger Conant to work about the latter’s homestead at Darlington. An occasion came when this man, who was very reticent, had partaken too freely of liquor, so that his tongue was loosed, and in an unbroken flow of words he unfolded a boastful narrative of the horrid deeds of himself and his companions of{18} Butler’s Rangers. One day, he said, they entered a log-house in the forest in New York State, and quickly murdered the mother and her two children. They were about applying the torch to the dwelling, when he discovered an infant asleep, covered with an old coverlet, in the corner of an adjoining bedroom. He drew the baby forth, when one of the Rangers, not quite lost to all sense of humanity, begged him to spare the child, “because,” as he said, “it can do no harm.” With a drunken, leering boast he declared he would not, “for,” said he, as he dashed its head against the stone jamb of the open fireplace, “Nits make lice, and I won’t save it.”

It is no wonder that Roger Conant said that many times his heart failed him when these terrible acts of Butler’s Rangers were being perpetrated, and that he felt sorry even then, when in New York State and on his way to Upper Canada, that he had not remained in Massachusetts and joined the patriots. It is to be remembered that these persons were burnt out, murdered, and their women outraged, simply because they thought Britain bore too heavily on them, and that reforms were needed in the colonies. Nor could these acts in even the smallest degree assist the cause of Britain from a military point of view.

On October 5th, 1792, Roger Conant crossed the Niagara River on a flat-bottomed scow ferry, and landed at Newark, then the capital of Upper Canada. Governor Simcoe, who had only been sworn in as Governor a few days previously, came to the wharfside

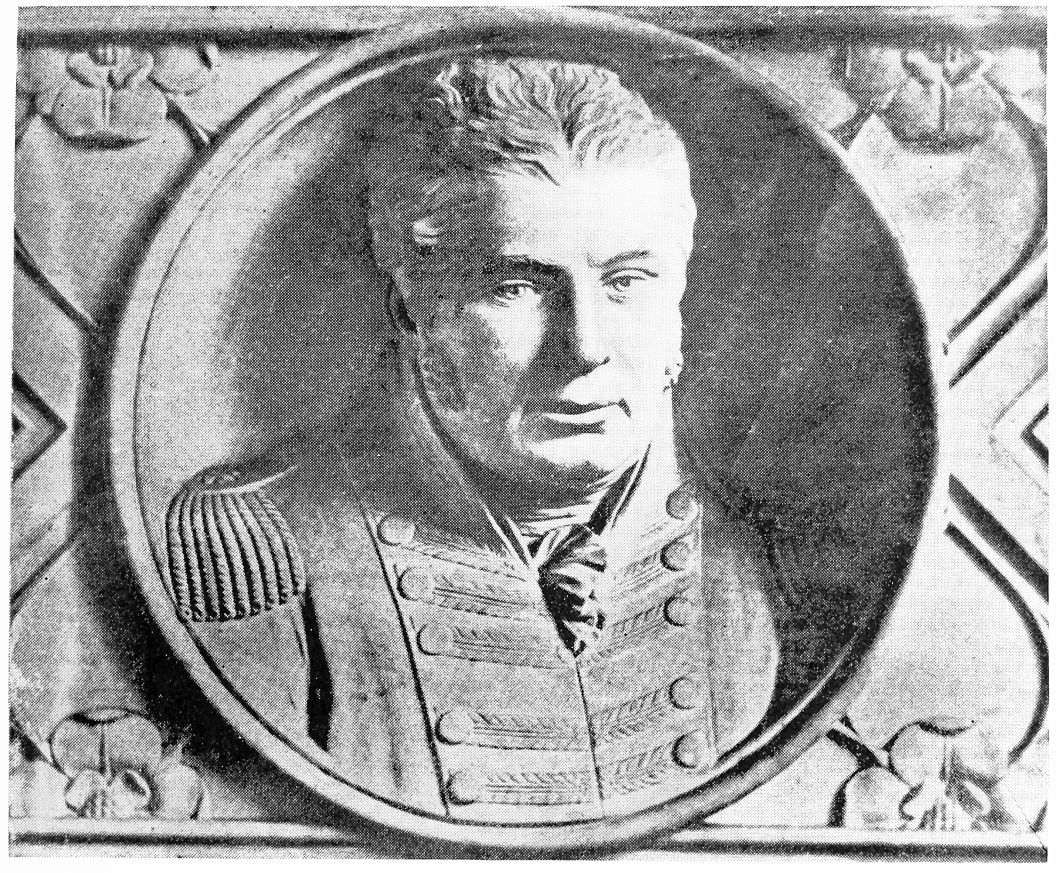

GOVERNOR SIMCOE.

(From the tomb in Exeter Cathedral, England.)

(By permission from the J. Ross Robertson collection.)

to meet the incoming emigrant, who, with his wife and children, his waggons and his household stuff, had come to make his future home in Upper Canada.

“Where do you wish to go?” said the Governor.

“I think of following the north shore of the lake eastward till I find a suitable place to settle in, sir.”

“But the land up there is not surveyed yet. Should you not prefer to go up to Lake Simcoe? That is where I would like to see you take up your abode.”

But Roger Conant shook his head. He had made up his mind to go to the north shore of the lake, eastward, and there he ultimately went. When Governor Simcoe found that he was determined, he told him that when he had fixed on a location he was to blaze the limits of the farm on the lake shore he would like to have. When the survey was completed, he, the Governor, would see that he got his patents for the area so blazed. And in justice to the Governor, the author is pleased here to set down that he faithfully kept his word. The patents for the land blazed by Roger were duly and faithfully made out. But the author must express strong disapproval of his ancestor’s ultra modesty in not blazing at least a township in Durham County to compensate him and his heirs for the 13,000 acres which he had lost in Massachusetts.

Roger blazed but some 800 acres. For one thing, blazing involved a large amount of very heavy work. The intervening trees of the unbroken forest had to{20} be cut away. A straight line must be made out from blaze to blaze. Besides, the emigrant to those silent and pathless forests appears to have had small thought of any future value of the land thus acquired, and as he would have said, colloquially, he was not disposed to bother with blazing over eight hundred acres.

Realizing the difficulty the incomer would have in getting across the fords at the head of Lake Ontario, between Niagara and Hamilton, Governor Simcoe sent his aide-de-camp to pilot the cavalcade. No waggon road had been constructed along the shore. But the sand was the only obstruction, and after several days’ travel he arrived at Darlington, where was the unbroken forest, diversified only by the many streams and rivers of undulating central Canada. It was a fine landscape that lay around the emigrant, with the divine impress still upon it. The red man had not changed its original features. He had contented himself with the results of the chase among the sombre shades of the forest, or, floating upon the pure blue waters in his birch-bark canoe, he took of the myriads upon myriads of the finny tribe from the cool depths below.

The whites had only just begun to obtain a livelihood in the broad land. Not more than 12,000 persons of European descent then dwelt in all Upper Canada, now forming the peerless Province of Ontario, with its 3,000,000 of inhabitants. Roger Conant had chosen a beautiful location, and here with a valiant heart he started to hew out a home for himself and his family. Although he had brought to this prov{21}ince from Massachusetts £5,000 in British gold, he was unable at the first to make any use of it, simply because there were no neighbors to do business with, and manifestly no trade requirements.[A] But we find him, about the year 1798, becoming a fur trader with the Indians. He invested some of his money in the Durham boats of that day, which were used to ascend the St. Lawrence River from Montreal, being pulled up the rapids of that mighty river by ropes in the hands of men on shore. Canals, as we have them now around the rapids, were not then even thought of. Nor was the Rideau Canal, making the long detour by Ottawa, which did so much afterwards to develop the western part of the province. With capital, and possessing the basis of all wealth robust health, Roger Conant pursued the fur trade with the Indians to its utmost possibility. Disposing of the goods he brought from Montreal in his Durham boats, he accumulated, by barter, large quantities of furs. To Montreal in turn he took his bundles of furs, and gold came to him in abundance, so that he rapidly accumulated a considerable fortune. While doing so, and pursuing his trading with the red men, his home life was not neglected. Rude though his log-house beside the salmon stream at Darlington was, it was spacious and comfortable, and in its day might even be termed a hall. It had the charm of a fine situation, and it had Lake Ontario for its adjacent prospect. Conant had brought a few books from his Massachusetts home{22} at Bridgewater, and while he conned these ever so faithfully over and over again, the great book of nature was always spread before him in the surpassingly beautiful landscape that included the shimmering waters of the lake, the grass lands upon the beaver meadow at the mouth of the salmon stream, and the golden grain in the small clearings which he had so far been able to wrest from the dark, tall, prolific forest of beech, maple and birch, with an occasional large pine, that extended right down to the shingle of the beach. Of his sons it may be said that, although capable men, they were handicapped in the race with the incoming tide of settlers so soon to come to the neighborhood of that rude home at Darlington, in the county of Durham, Upper Canada. They were at a grievous disadvantage because of their lack of education. Education could not be obtained in Ontario in the early days of the nineteenth century. There were no schools, and had there been schools there would have been no pupils. Consequently we find Roger’s sons possessing grand physical health, and pursuing the vigorous life of that day, with but little education. They felled the forest, and obtained from the soil the crops that in its virginity it is always ready to give. Eliphalet, who was only a very small boy when his father brought him from Massachusetts, attended to the business affairs of the family as his father got older, and we find him making, after Roger Conant’s death, a declaration as to his father’s will, in which he states that he is especially cognizant that the will should be so and so. That instrument was{23} admitted as a will by the court of that day, 1821, the date of Roger’s death. To us such proceedings seem crude, particularly as the document referred to conveyed an estate of great value.

With regard to this will a singular circumstance must be noted. Roger died a very large real estate owner. This part of his possessions is duly scheduled. But of his hoard of gold no mention is made. The author’s paternal uncle, David Annis, who lived with the family till his death in 1861, frequently said in the author’s hearing—it was a statement made many times—that Roger Conant had gold and buried it. Why he did so is a mystery. It is also certain that no one has yet unearthed that gold. On the farm at Darlington on which he resided, a few days before his death he took a large family iron bake-kettle, and after placing therein his gold he buried it on the bank of the salmon stream of which mention has already been made. The bake-kettle was missed from its accustomed position by the open fireplace, but search failed to reveal its whereabouts. Thereafter, and many times since, persons with various amalgams and with divining rods and sticks have searched for this buried treasure, but always in vain.

Of Eliphalet, the son, who did the business of the family, being the elder son, all trace is lost, and there is no one known to-day who claims descent from him.

Abel, another son, had an immense tract of land in Scarborough, on the Danforth Road, near the Presbyterian Centennial Church of that township. His son, Roger, left a most respectable and interesting{24} family in Michigan, of whom the best known and most intelligent is Mrs. Elizabeth West, of Port Huron, in that State. It does not appear that Abel Conant ever disposed of his Scarborough estate by deed or by will, but simply lost it, so lightly in those days did the inhabitants value accumulated properties.

Barnabas, another son of Roger, disappeared, and all trace of him is lost. Jeremiah—still another son—died about 1854 in Michigan. Of him, also, nothing is known. Lastly Thomas, the youngest son—grandfather of the author—as will be seen later in this volume, was assassinated when a young man during the Canadian Revolution of 1837-8.

Roger Conant’s daughter, Rhoda, became the wife of Levi Annis. From this union sprang a numerous and most progressive family, who are to-day, with their descendants, among the foremost of our land.

Polly, another daughter, married John Pickel and left a small family, descendants of which still reside in Darlington in the vicinity of the ancestral home.

It will be noted as a singular fact that even the most ordinary emigrants from Great Britain, seeking a home here in those early days, were in some respects better equipped than the sons of Roger Conant, with their prospect of becoming heirs of large property. For, coming from Great Britain, the land of schools, the poor emigrant generally possessed a fair education, which the young Conants did not. Also, they had, besides, the prime idea of gaining a home in the new land and keeping it. Not so the Conant sons, who so easily secured an abundance from the ple{25}thoric returns of the virgin soil of that day. Books were denied them. Of the diversions of society, the theatre or the lecture room, they knew nothing. Consequently they found their own crude diversions as they could. “Little” or “Muddy” York, the nucleus of Toronto, began to become a settlement, and to that hamlet they easily wended their way to find relief from the humdrum life among the forests at home. It is told that frequently, when they were short of cash, they would drive a bunch of cattle from their father’s herd to York and sell them, spending the proceeds in riding and driving about the town. That in itself is not very much to remark, seeing that they were the sons of a rich man, and their doings were no more than compatible with their conceded station in life. And so far as is known in an age when everybody consumed more or less spirituous liquors in Upper Canada, the Conant sons were not particularly remarkable either for their partaking or their abstemiousness. Their loss of properties cannot be attributed to their convivial habits, but rather to a want of appreciation of their possessions.

Daniel Conant, the author’s father, unmistakably inherited the vim and push of his grandfather, Roger. Thus we find him as a young man owning fleets of ships on the Great Lakes, as well as being a lumber producer and dealer in that commodity second to none of his day.[B] It may be observed, in passing, that Roger Conant during the whole of his life never seemed to care for office. Offices were many times{26} offered to him by the British Government, but he steadily refused, and died without ever having tasted their sweets. His own business was far sweeter to him, and he was far more successful in it than he could have been in office. His grandson, Daniel, had this family trait. He did not spend an hour in seeking preferments, and office to him had no allurements. His education was meagre. It was, however, sufficient to enable him to do an enormous business. He not only amassed wealth, but by his efforts in moving his ships and pursuing his business generally, he did much for the good of his native province, and for his neighbors. While his lumber commanded a ready sale in the United States markets, it was also used very largely in building homes for the settlers in his locality. The poor came to him as to a friend, and never came in vain. At his burial in 1879 hundreds of poor men, as well as their more fortunate neighbors, followed his bier to the grave. Perhaps no more striking token of the regard in which he was held by the poor can be cited, and the author glories in this tribute to his memory by the meek and lowly.

Colonel Talbot—His slanderous utterances with regard to Canadians—The beaver—Salmon in Canadian streams—U. E. Loyalists have to take the oath of allegiance—Titles of land in Canada—Clergy Reserve lands—University of Toronto lands—Canada Company lands.

Thomas Talbot, to whom the Government gave—presumably for settlement—518,000 acres near London, Ont., began to reside on the tract soon after the emigrant whose fortunes we are following arrived in Upper Canada, in 1792. Talbot had previously been Secretary to Governor Simcoe, and was consequently stationed at Newark, the capital, where the settlers were seen as they came into the country from the United States. Why so great a grant was made to him is inexplicable. But it was nevertheless made, and the author proposes to tell how he repaid it. He appeared all the time he was alive, and living in Upper Canada, to thoroughly despise us. Among the other utterances which he sent from Canada to Great Britain was that concerning the origin of Canadians, and although his words are calumniatory, we must have them, for he incorporated them in his book about Canada. Thus he speaks of us: “Most Canadians are descended from private soldiers or{28} settlers, or the illegitimate offspring of some gentlemen or their servants.” He penned these words somewhere about the year 1800. They cannot refer to persons of United States origin—the incomers from the thirteen revolted colonies, which were now independent—because these were not born in Canada. He must therefore have referred to those Canadians and their descendants who were living in Canada in 1792, when he was the Secretary of Governor Simcoe. It is not within the province of the author to defend from Talbot’s calumnies that portion of our fellow-Canadian subjects. His calumny is foul, mean, untrue, and very unjust. Of New England origin himself, the author leaves this insult to be avenged by the pen of some fellow-Canadian who claims descent from old Canadians who were in the country when the war of the Revolution was about closing. So foul an aspersion should never have been passed over in silence.

The foregoing is, however, by the way. We are pursuing the fortunes of Roger Conant, and we find him from 1792 to 1812 struggling among the forest{29} trees to gain a livelihood, or his labors on land occasionally diversified by his work on the lake, the waters of which, perhaps, yielded the most easily obtainable food. Mention has been made of the beaver meadow, and at this date the settler would often come across the traces of this industrious animal. The beaver is the typical unit or emblem of the furs of Canada. All other values of furs were made by comparison with the value of a beaver skin. In intelligence the beaver surpasses any of the fur-bearing animals. In the quality of his workmanship he is the mechanic of the animal tribe, and easily and far-away outstrips all his fellow-brutes, domestic or wild. He can fell a tree in any desired direction, and within half a foot of the spot on which he requires it to fall. One beaver is always on guard and vigilant while the others work. A single blow of the tail of the watching beaver upon the water will cause every other of his fellows to plump into the water and disappear. To carry earth to their dam they place it upon their broad, flat tails and draw it to the spot. While his home is always in close proximity of water he is sometimes caught on land, while proceeding from one body of water to another. Should you meet him thus at disadvantage upon the land, he does not even attempt to run away, nor to defend himself, for he well knows that both attempts would be utterly useless. Another defence is his; he appeals to one’s sympathy by crying—crying indeed so very naturally, while big tears roll from his eyes, with so close an imitation of the human, that it startles even the hunter himself. Many a beaver has been{30} magnanimously given his life out of pure sympathy for the poor defenceless brute when caught at an unfair advantage away from his habitable element of water.

Salt-water salmon, too, swarmed at that date in our Canadian streams in countless myriads. In the month of November of each year they ascended the streams for spawning, after which they were seen no more until the summer of the following year. While we have no positive evidence that they return to the salt water, we know they must do so, because they are so very different from land-locked salmon or ouananiche. They were never caught in Lake Ontario after spawning in the streams in November, until June of the next year. Nor were they found above Niagara Falls, being unable to ascend that mighty cataract. Roger Conant said that his first food in Upper Canada came from the salmon taken in the creek beside his hastily built log-house. To help to realize how plentiful these fish were at the annual spawning time, we may adduce Roger Conant’s endeavor to paddle his canoe across the stream in Port Oshawa in 1805, when the salmon partly raised his boat out of the water, and were so close together that it was difficult for him to get his paddle below the surface. A farm of 150 acres on the Lake Ontario shore, that he acquired just previous to the War of 1812, he paid for by sending salmon in barrels to the United States ports, where they brought a fair cash price. Increasing population, no close seasons by law, nor any restrictions whatever, have been the causes which have resulted in almost destroying

these kings of fish that once came in uncountable swarms.

It will be gathered that up to the War of 1812, the settler, homely clad, axe in hand, subdued the forest, and spent happy, even if wearisome, days, with his dog generally as his only companion. It was during these years that he exhibited that skill in wielding the axe of which mention has been made. To-day, our few remaining woods being more open, and the timber being smaller, such feats would be impossible.

The first beginnings of public utilities were being made. Roads were being cut out of the forest. Some of these grew into forest again so little were they used.

In the last chapter it was noted that Roger Conant lost all his lands in New England by expropriation after the war of 1776. On arriving in Upper Canada he felt the great necessity of bestirring himself to make a fortune again here. Side by side with his clearing operations he carried on his fur-trading, and soon his desires in regard to wealth were gratified, but he never reconciled himself to being so far from his Alma Mater, Yale University (New Haven, Conn.), from which he had been graduated (in Arts and Law) in 1765.

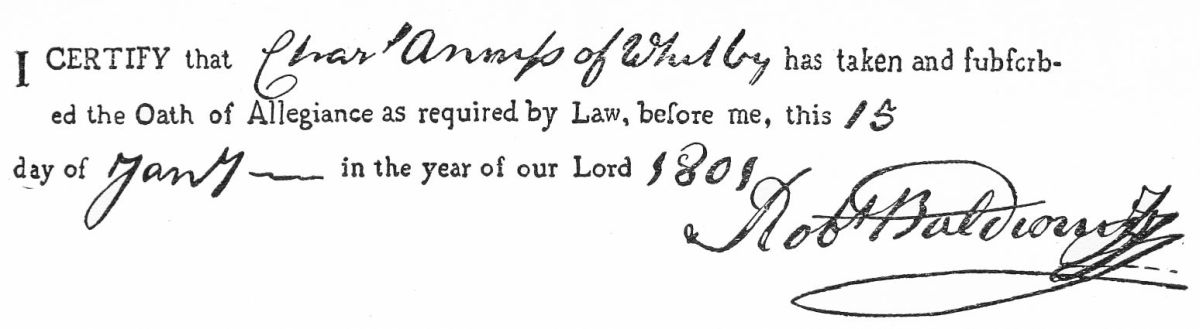

Notwithstanding all the sacrifices made by the United Empire Loyalists to maintain British connections, many of them were asked to take the oath of allegiance on reaching their respective localities when they sought to make their home in Canada. Annexed is a photographic document of evidence,{32} being a copy of the certificate of the oath of allegiance taken by one of the author’s relatives before the famed Robert Baldwin. One of the very earliest court summonses of Upper Canada is also reproduced (page 35) and it will be found very interesting. The reader will notice the absence of all printing on this document.

Obviously the title to all lands in Canada, after the conquest of 1759, and not previously granted by the king of France, was vested in the British Crown. There were a few lots of land so granted by the king of France in Upper Canada, but only a few. In Quebec, or Lower Canada, much of the land had already been so granted along the St. Lawrence River. These grants had, as a matter of course, to be respected by Great Britain. The French grants in Upper Canada were only a few along the Detroit River and at the extreme western boundary of the province. The easy accessibility of the lands by water will no doubt account for these grants having been located so remote from all neighbors, the nearest being those in Lower Canada from whence these grants came. Certain lands were also set apart for the Protestant clergy, viz., one-seventh of all lands granted. After a time, instead of taking the one-seventh of each lot granted, they were all added together and formed a whole lot—the “Clergy Reserve” lands, which became afterwards such a bone of contention. In these deeds gold and silver is reserved for the Crown. All white pine trees, too, are reserved, because naval officers had passed along the shore of{33}

FAC-SIMILE OF CERTIFICATE OF OATH OF ALLEGIANCE.

I CERTIFY that [signature] has taken and subscrbed the Oath of Allegiance as required by Law, before me, this 15 day of Jan___ in the year of our Lord 1801 [signature]]

Lake Ontario, about the time of the war of the Revolution, and saw the magnificent white pines. These officers were all searching for suitable trees to make masts for the Royal navy, and here they found them; hence the reservation of these trees in all Crown deeds. All deeds of realty to-day in Upper Canada make the same reservations, viz., “Subject nevertheless to the reservations, limitations and provisions expressed in the original grant thereof from the Crown.”

In Australia and New Zealand the governments make reservations so very binding that they can resume possession of lands at any time, as the author found when travelling there in 1898. Our antipodes have not deeds in fee simple as we have. No instance has ever been known in the locality of middle Ontario, in which the author’s home is, and that of his forefathers since 1792, of the Crown ever exercising its right to make use of the reservations.

Time-honored big wax seals were attached to all Crown grants. These seals were quite four inches in diameter, one-third of an inch thick, and secured to the parchment by a ribbon, while the Royal coat-of-arms was impressed on either side of the seal. To the honor and respect of the Crown, be it said, its treatment of the struggling settler was always generous and fair.

The Clergy Reserve lands, which, we have seen, were set apart, soon began to command purchasers, being mainly along the waters of Lake Ontario, as were the other patented lands. In the Act creating{35}

the Clergy Reserve Trust, gold and silver were reserved, but not white pine, because there simply was none there to reserve.

The University of Toronto received odd lots here and there in Upper Canada for its support. This created another source from which tithes came. There were no reservations in the University deeds of 1866. They cited the Act which gave the University these lands.

Lastly came the Canada Company, the last remaining source of tithes. While the Crown, the Clergy Reserves and the University of Toronto were always fair and considerate to the settler, this company always demanded its full “pound of flesh,” and got it, too. It may be observed that the arrangements with regard to these deeds were made by the Imperial Government at home wholly. We were not consulted. By virtue of the Canada Company’s grant, thousands and thousands of acres of lands in Upper Canada were withheld from settlement for many years. To-day the grievance has passed, because they have next to no lands remaining. Perhaps, as Upper Canada has nearly three millions of population now (from 12,000 in 1792), we ought not to grieve. It did us harm, it is true, but it was no doubt unthinkingly originated in London, in 1826, and without sufficient consideration.{37}

The War of 1812—Canadian feeling with regard to it—Intolerance of the Family Compact—Roger Conant arrested and fined—March of defenders to York—Roger Conant hides his specie—A song about the war—Indian robbers foiled—The siege of Detroit—American prisoners sent to Quebec—Feeding them on the way—Attempt on the life of Colonel Scott of the U. S. army—Funeral of Brock—American forces appear off York—Blowing up of the fort—Burning of the Don bridge—Peace at last.

In twenty years from the time Governor Simcoe established his capital at Newark, on the Niagara River, after being sworn in as Governor of western Canada (his incumbency being the real commencement of the settlement of Upper Canada), began the War of 1812 between Great Britain and the United States. Our peaceably disposed and struggling Canadians, trying to subdue the forest and to procure a livelihood, were horrified to have a war on their hands. They could ill afford to leave their small clearings in the forest, where they garnered their small crops, to go and fight. Not one of them, however, for a single moment thought of aiding the United States or of remaining neutral. Canada was their home, and Canada they would defend. From 12,000 in 1792 in Upper Canada, 40,000 were now within its{38} boundaries, endeavoring to make homes for themselves. We have the fact plainly told that, although at least one-third of all the inhabitants in 1812 were born in the United States, or were descendants of those who were born there, not one of them swerved in his loyalty to Canada, his adopted country. This is saying a very great deal, for it was in no sense Canada’s quarrel with the United States. If Great Britain chose to overhaul United States merchantmen for deserting from the Royal navy, it is certain that Canada could not be held responsible for any such high-handed act. Canadians generally at the breaking out of the war, whether of United States origin or from the British Isles direct, felt that Great Britain had been very assertive towards the United States, and had also been rather inclined to be exacting. Such was the feeling generally. No one, however, for a moment wavered. All were loyal and all obeyed the summons to join the militia and begin active service. Britain’s quarrel with the United States, in obedience to the mandate of some Cabinet Ministers safely ensconced in their sumptuous offices in London, worked incalculable hardships to the struggling settlers in the depths of our Canadian forests.

To vividly realize how very intolerant of any discussion of public matters of that day the Family Compact was, a personal narrative will be found interesting. Roger Conant, one day in the autumn, went from his home in Darlington to York. He had been requisitioned by the British officers just out from England (and whom he respected) to take an ox-cart{39}

load of war material along the Lake Ontario shore to York. Now at home, his neighbors being very sparse, he had but few opportunities to converse and compare opinions about the war. Once at York the desired opportunity came. When sitting at a hotel fire, with a number of civilians about, opinions were quite freely expressed by those present. Roger Conant remarked that he was sorry for the war, and that although he would fight for Britain and Canada, he felt that Britain should arrange the differences with the United States and not drag Canada into a war in which she had not the least interest. He further remarked to the assembled civilians about the fire, that he thought Britain, too, very arbitrary in searching vessels of the United States indiscriminately and taking seamen from them without knowing them to be deserters from the British navy. Some one of the assembly quickly reported that remark to the commandant of the fort at York. Roger was arrested in an almost incredibly short time, brought before a court-martial next morning and fined eighty pounds (Halifax), being about $320 of our money. Hard as this was, he paid the fine, held his peace, and went off home, until called to serve in the ranks, which he did duly and faithfully. Family Compact rule was answerable for such treatment, as it certainly was for the responsibility for the Revolution which followed in 1837. To the honor of Roger Conant be it always said, however, that he turned out, donning his best suit, and made for the nearest commanding officer. No settler ever refused to turn out, although when

once turned out, they seemed so ludicrously weak that they felt themselves only a handful. There were a few British soldiers in red coats, but the defenders that made their way to York along the shores of Lake Ontario were a motley throng. There was no pretence at uniforms, nor was there indeed during the war, or very little of it. Let us realize if we can that these poor fellows had to walk along the lake shore. Here and there only were roads to be found cut out of the dense dark forest and back from the lake shore. Very few were fortunate enough to possess boats or canoes in which to row or paddle to York. Some, however, were able to adopt this mode of transit, and thereby hangs a tale. On one occasion a party of militiamen, accompanied by one or two soldiers—among them a drummer—were to be seen with their boats ashore, one of their craft being turned bottom upwards, and having the carcase of a fine porker “spread-eagled,” as sailors say, on either side of the keel. It appears that on their way to York the party had “commandeered” a pig they had come across, and being sharply pursued by its owner, they had taken this means of concealing their booty. No one thought of pulling the boat out of the water and turning it up to find the pig. At the same time they had requisitioned a fine fat goose, wrung its neck, and were carrying it away. In this case, with the pursuers at heel, the task of hiding the loot had fallen to the drummer. He speedily arranged matters by unheading his drum and placing the coveted bird inside, and the story goes that on the favorable oppor{42}tunity arriving, both pig and goose formed the basis of an excellent feast on the lake shore, in which, if tradition is to be believed, one officer, at least, joined with considerable readiness.

Roger joined the rank and file of the militia, but afterwards, having blooded and fleet saddle-horses in his stables on Lake Ontario shore in Darlington, the commanding officers employed him as a despatch bearer. In turn in the militia and then as despatch bearer, when nothing seemed doing, his time was fully occupied at the business of war. He was then sixty-two years of age, but so pressed were the authorities for men, that age did not debar from service, but physical inability only.

Having accumulated wealth both in lands and specie, Roger’s first thought, on the breaking out of war, was for the safety of his specie. Mounting his best saddle-horse he rode some thirty miles west from his home in Darlington to Levi Annis’s, his brother-in-law, in Scarborough, in order that this relative might become his banker, for in those days there were no banks, and people had to hide their money. Entering his brother-in-law’s log-house, he removed a large pine knot from one of the logs forming the house wall. He placed his gold and silver within the cavity, and the knot was again inserted and all made smooth. Levi Annis gave no sign, and no one that came to the inn ever suspected the presence of this hoard of wealth. But when the war was over, Roger Conant again visited Levi Annis in Scarborough. Three years had passed away since, in his presence,{43}

the treasure had been inserted in the wall. In his presence also the pine knot was now removed, and the bullion—about $16,000 in value—was drawn forth intact.

Among the records that have come down to the author from Roger Conant, and along with fragmentary papers left by him, by Levi Annis, David Annis, and Moode Farewell, various scraps of songs of the time 1812 to 1815 are garnered. Perhaps the song of the greatest merit and widest celebrity was “The Noble Lads of Canada,” the beginning of which was:

It is just as well for the present generation to know this jingle, absurd as it may be. There were many verses in it, but all much to the same tenor, and while they pleased Canadians who sang the song, they were certainly harmless, and to-day we can afford to laugh at them. It is so very ridiculous to think of our handful of men going over to the United States and “pulling their dwellings down.” Our defence at home was quite another matter, but we are proud of it nevertheless. Human nature is much the same here as elsewhere, and was also in 1812-15. Thus{45} would the author illustrate how he applies the inference; there were over a half of the inhabitants who came directly from the British Isles, or were descended from those who came. The greater part of the settlers were poor. Generally the U. E. Loyalists and their descendants were fairly well-to-do. If not well-to-do they were far better off than the others. Consequently some mean-spirited among the settlers from Britain or their descendants, who were so poor, would depreciate the U. E. Loyalists if possible. Roger Conant said that one envious neighbor set the Indians upon him, during a lull in the war, while he was at home, by telling them he was a Yankee, and that they might rob him if they chose. For the object of plunder, they came upon him because he had an abundance of stock, the best in the land, as well as goods of various sorts for Indian fur trading, while his money, as we have seen, was safely banked in a pine log in Scarborough. One night there came to his home in Darlington, in the year 1812, a single Indian who asked to rest before the open fire for the night. Permission was given, and he squatted before the blazing wood fire of logs. On watching him closely, a knife was seen to be up his sleeve of buckskin, but not a word was spoken of the discovery. Shortly another Indian came in and squatted beside the first on the floor, and in utter silence. Now came a third Indian, who, in his turn, crouched with the two former ones.

No doubt now remained in Roger Conant’s mind as to their purpose, and he roused himself to the{46} occasion. They meant robbery, and murder, if necessary, to accomplish it. An axe at hand being always ready, he seized it, and drew back to the rifle hanging upon the wall, never absent therefrom unless in actual use. His family he sent out to the nearest neighbors, a mile away, along the lake shore.

“None of you stir. If you do, I’ll kill the first one who gets up. Stay just where you are until daylight.”

And now a squaw came in and sat beside the three crouching bucks, and cried softly. Very generally Indian squaws’ voices are soft, and naturally their crying would be soft, as was this squaw’s. Entreating with her crying, she began to beg for the release of the Indians, assuring the vigilant custodian “that they no longer meditated injury, nor theft, but would go away if they could be released.”

In this manner, with their nerves at high tension, the night passed, and not until the light of the next day did the guard dare to release his Indian prisoners. Then, one by one only, he allowed them to walk out of doors. It is very probable that this was an extreme case, but it occurred just as narrated. Not again during the war was Roger Conant molested by the Indians.

Not yet had the first year of the war (1812) dragged its slow length along. About the Niagara River the fighting had been most active at all points. Rumors of the clash of arms came from the West to those in central Upper Canada. General Hull thought himself secure at Detroit with a broad and deep river rolling between him and his opponents in Canada. Neither

depth of river nor width, however, kept our men away from Detroit. No Canadian can contemplate this exploit of our arms without a swelling of pride. Detroit became ours on the 15th of August, 1812, when General Hull surrendered the whole command of 2,500 men, without terms, and Michigan was our lawful conquest. Immediately on the surrender of so many men to us, it became a serious question what to do with so many prisoners of war. We possessed no place in Upper Canada where they could be securely kept, and at old Quebec only could we depend upon them being safely retained. Consequently to Quebec they were sent. They were sent thither in boats and canoes in which they assisted in rowing and paddling. In this manner they went to Quebec, and were apparently well content with their lot. So very meagre, however, were our resources that we could not furnish boats for all of them, and many were compelled to walk along the lake shore. They were fed at various places along the route, among others at Farewell’s tavern, near Oshawa, an engraving of which as it stands now is given on opposite page. From the author’s tales of his forbears he gets the story of these prisoners coming to their home to be fed. Guards, indeed, they had, but they outnumbered them ten to one, and even more, simply because we had not the men to guard them. From what can be learned, however, none ran away.

Coming to the Conant family homestead to be fed, without warning, a big pot of potatoes was quickly boiled. A churning of butter fortunately had been{48} done that day, just previous to their coming, and a ham, it so happened, had been boiled the day preceding. All was set before them, and copious draughts of buttermilk were supplied. Guards and prisoners fared alike. There were no evidences of ill-feeling or rancor, but good nature and good humor prevailed, even if some shielded ministers in far-away London at that day forced the combat upon them.

Perhaps the most curious and picturesque instance of the fighting in and about this part of Canada was the taking of General Scott a prisoner at Queenston, and the occurrences subsequent to his capture. It seems that General Scott had been particularly active all day during the engagement of October 13th, 1812. Being a large man, and dressed in a showy blue uniform, although not then so high in rank as he afterwards became, he gained the attention of the Indians in our army. Nothing came of that immediately, but near evening his part of the United States forces were surrounded, and Colonel Scott (as he then was) was compelled to surrender. On the final conclusion of the day’s engagement, General Brock having been killed early in the day, he was invited to dine with General Sheaffe, then commanding our forces. Our prisoner, Colonel Scott, had given his parole not to attempt to escape, until regularly exchanged, so it was quite in order for him to accept the general’s invitation to dine. Just as they were in the act of sitting down at the table an orderly came to the diningroom, and said some Indian chiefs were at the door{49} and wished to see Colonel Scott. Excusing himself, the Colonel went to the door, and in the narrow front hall met three Indians, fully armed and in all proper Indian war-paint and feathers. One Indian then asked Colonel Scott where he was wounded. When Scott replied that he had not been wounded, the questioning Indian said he had fired at him twelve times in succession, and with good aim, and that he never missed. Presuming on Colonel Scott’s good-nature, he took hold of his shoulder, as if to turn him around for the purpose of finding the wounds. “Hands off,” Scott said, “you shoot like a squaw.” Without more ado or warning the three Indians drew their tomahawks and knives, and essayed to attack the Colonel, although then a prisoner of war. As they were in the narrow hall, the plucky United States prisoner could not effectually use his sword arm for his defence, and his life was consequently in danger. But he backed them by quick thrusts of the sword out of the door, where he had more room for the play of his weapon, and then stood at bay. It was indeed a fight to the death, and even so good a swordsman as Colonel Scott must have succumbed, had not the guard of our army, seeing at a glance what was up, rushed to Scott’s rescue and helped him to drive the Indians off.

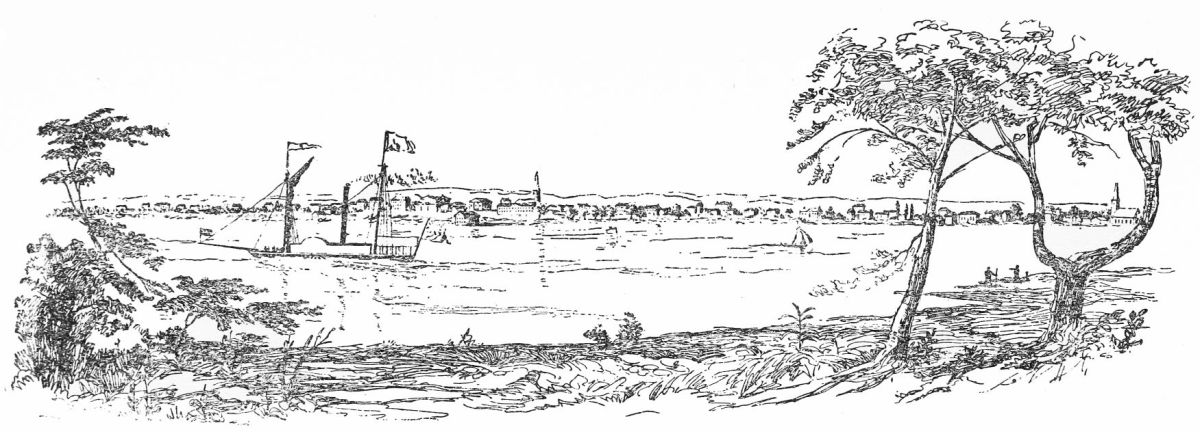

Not many days after this unseemly encounter, Colonel Scott was brought to York in one of the small gunboats which we had then on Lake Ontario for the defence of the lake ports. These boats, it is true, were not very elegant in their lines, nor were they formid{50}ably armed. All haste had been made to construct them; only a few weeks before the timber of which they were constructed was growing in the parent trees. Green timber and lumber, as any one will know, must make a very indifferent boat, and not a lasting one. It is a fact, nevertheless, that the single swivel gun which each boat carried did good service when called upon and was no mean antagonist. Be that as it may, we should not look in contempt on these mean gunboats, or compare them with the monster fighting ships of this day. These were the ships our fathers used, and the people of the United States also, and well they served their day. An engraving of York at this early day will be found on the opposite page, the little town which has become imperial and palatial Toronto, with more than a fifth of a million of people, and the change has been wrought in eighty-nine years.

Following, however, the fortunes of Colonel Scott until he came to Quebec, we shall find him a prisoner in the cabin of a large ship lying at anchor at the foot of the cliff on which that ancient city stands. Not among a lot of other prisoners from the United States do we find the Colonel on this ship—for there were many of them on board—but aft in the cabin with the officers. One day his quick ear heard the prisoners being interrogated on deck. With a few eager strides he ascends the cabin steps and is on deck. He finds many of the United States prisoners drawn up in line and an officer questioning them. Those who showed by the burr on their tongues to be unmistakably of Irish or Scotch origin were{51}

VIEW OF YORK. FROM THE OLDEST EXTANT ENGRAVING.

(By permission from the J. Ross Robertson collection.)

called out and sent away to an adjoining man-of-war, there to serve in the Royal Navy, although protesting they were American citizens.

Five of those in the line Colonel Scott heard called, and saw them sent away.

“Silence!” he cried. “Men, not another word out of you. Don’t let them catch you by the tongue”; and every man’s mouth closed like a trap.

It was Britain’s old contention, “Once a British subject, always a British subject,” and no latitude was allowed for transference of citizenship to the United States with residence in that country. To-day we never cease to wonder that Great Britain could be so impolitic as to take such a high-handed course. Time, however, has changed all that, and a war such as that of 1812 will never again stain the escutcheons of Great Britain, Canada or the United States.

Very soon after this Colonel Scott was exchanged, and quickly shook the dust of Canada from his feet and found his way back to the United States.

Let us turn to a little pleasanter phase of this early stage of the war. General Brock, as before mentioned, was killed early in the day at the battle of Queenston, on October 13th, 1812. That his high character and bravery were not overestimated the sequel will show. Thompson, who fought on our side, and who wrote of the war in 1832, being an eye-witness, says he was held in such high esteem, even by the enemy, that “during the movement of the funeral procession of that brave man, from Queens{53}ton to Fort Niagara, a distance of seven miles, minute guns were fired at every American post on that part of the line, and even the appearance of hostilities was suspended.” From some relative of the author who fought on our side the word has come down to him, that the Americans fired on their side of the Niagara River an answering shot for every one our men fired, all the time they were marching the seven miles down the river in the funeral procession. And the relative in the ranks added that every voice was hushed, not a word was spoken, grief was apparent in every man’s face, and every one seemed sorry because we had such a war on hand, and because we were engaged in the business of war with our kinsmen.

And now the second year of the war had come with its attendant vicissitudes and dangers.

Very few of the militia had been allowed to leave the ranks during the past winter, for an attack was expected just as soon as the ice should break up in the bays on Lake Ontario. In the early spring of 1813 the ice seems to have left the bays very early, for on April 26th the American forces were enabled to appear off York, in gun-boats and transports, and eager for the fray. Now, it has always been asserted that Great Britain availed herself of all the savages she could get, both in the War of 1812, as well as in the War of the Revolution in 1776. In a measure only is this true. We see them, however, at this time helping to oppose the landing of the Americans at York on April 26th, 1813. If the author speaks in{54} positive terms he hopes to be forgiven, for his forbear, Roger Conant, was there, musket in hand, and by his own lips has given the record which by natural descent has come down to the author. He said Indians were placed along the lake bank, one Indian between two white men, to repel the advance of the Americans from their boats on landing. That is to say, two white men were supposed to be able to keep one Indian up to his duty. But they couldn’t do it, for when the Americans really did land, and began the attack, many of the Indians got up and fled back from the shore of the lake to the forest beyond. And it is further told to the author by the same descent of lip service, that some of our militiamen were so incensed at the Indians for running away that they turned their muskets around from the Americans and fired at the fleeing Indians. Very probably their aim was faulty, for so far as is known no Indians fell, and more than likely our men did not aim to kill.

The result of the landing of the American forces we all know only too well, for our few men could not stay the hands of the assailants, who landed at will, and took possession of the country about. Near where the monument of the old French fort is, in the Industrial Fair grounds, near also to the York Pioneers’ log cabin, was the scene of this Indian running and the American landing. On the next day we find the Americans advancing upon the old fort to the east of the scene of the landing place. For a time, we know, our men made a stand for{55} defence around and about that old fort. It is not at all probable we could have held it permanently, for the Americans outnumbered us, and were just as brave as our men were when at their best. Just how it was done my ancestor did not seem to know, but the word somehow, by very low whispers or signs, was passed around that the fort would be blown up, and that it was better to get out. Such a word came to Roger Conant, as he always stoutly maintained, and, acting upon it, in the very nick of time, he dropped out of the fort, when it blew up and killed so many Americans. He said that to his startled vision the air appeared full of burnt and scorched fragments of human bodies, and that they fell about him in a horrifying manner.[C] It is not in the province of the author to express an opinion as to the expediency of this act, but it was done no doubt for the best, and we to-day find no fault with our general in command who gave that terrible order.

Yet York and its neighborhood were still at the mercy of the American conquering army, and General Sheaffe began to think intently of his own safety. Mounting his horse he rides eastward, down King{56} Street towards Kingston, and leaves his troops to follow more leisurely on foot. It is twelve miles from Toronto to Scarborough, where Levi Annis lived at his hotel. His testimony was that General Sheaffe appeared before his hotel door with his horse quite done up, and covered with foam. On going to the door and asking as to the trouble, General Sheaffe explained to Levi Annis that he had ridden from York, without drawing rein, and that it was most important that the Americans should not catch him. There certainly is room for excuse for General Sheaffe at this juncture, although Levi Annis was naturally much astonished at the state of nervousness in which he saw him. We must not forget that the General had only 1,500 men, all told, with which he had to defend all Upper Canada, and with this very small support no doubt he felt as he said, “that it was most important that he should not be captured.” Just as quickly as possible after the blowing up of the fort, some 150 men of the British regulars and Canadian militia got together and made their way to Kingston. At this time the first Don bridge had been built. It was of logs, mainly pine, which were cut near to the last approach to the bridge. A considerable causeway extended over the mud flats, on the east side, to the span of the bridge proper. It was very crude, and had been built in 1800 without the aid of experienced men or mechanics. It stood well enough, nevertheless, and did its work well, until that memorable day when our men retreated over it and burnt it as they went—April 27th, 1813. It was done as a

precautionary measure in order to impede the progress of the victorious Americans, should they choose to follow in pursuit.

To those who did military service in this war 200 acres of the public lands were due. Roger Conant did not receive his 200 acres, although most justly entitled to them. To know the cause why he did not receive his land grant it will be necessary to go back a little. After the conquest of Canada and the Treaty of Paris (in 1763) which followed, some British officers were given appointments and places in Canada—no doubt to provide for them. When Upper Canada was made a separate province in 1791, more of these officials were given places. These persons seemed to have nothing in common with the people. On the contrary they seemed to seek to rule and get good livings out of them, and essayed to keep their places, becoming in time the Family Compact. It was their acts and those of their successors that caused the outbreak in 1837 which led to the Canadian Revolution. To these pampered office-holders it did not appear that the U. E. Loyalists, who had made most magnificent sacrifices for our country, were worthy of even civil treatment. So to Roger Conant they never gave the military land grant, and this treatment was meted out to most of the U. E. Loyalists who so faithfully served through that most unfortunate and deplorable war.

Peace! peace! Peace tardily came at last in 1814, the Treaty of Ghent having been signed on the 24th day of that year. The author realizes that, to-day,{58} Canadians in their well-appointed and refined homes fail to enter into the feelings of our forefathers whose hearts leaped for joy as they thanked the great God for that inestimable blessing of peace. Fond mothers told it to the infants at the breast as they bounced them aloft and reiterated again and again, “Peace, darling, peace!” The gray-haired sire, whose days were numbered, dropped unchecked, unbidden tears of joy, silently and without a voice, as he too thanked his Maker again and again for that peace between neighbors and kindred that never should have been broken. No more would the neighborless settler fear peril as the darkening shadows of evening came about his log cabin in the great forest, or dread that before the light of another dawn armed foemen might come and take him prisoner, and drive his wife and little ones into an inclement winter night by the application of the torch. Strong men grasped each others’ hands, and shook, and bawled themselves hoarse in simple exuberance of spirits, and in the intensest feeling of thankfulness that peace had come to them once again. Nor was this outburst of feeling mere exultation over the Americans. All felt that we had honorably acquitted ourselves in a military point of view, but the Americans at the same time had fought with valor, and we really had not much to taunt them with.

It would perhaps be superfluous to record many of the particular charges which our people laid at the door of the Americans during the war. It is in evidence equally that the Americans laid quite as{59} many sins to our people for their acts, while making forays on United States soil. So far as one may judge there is not any preponderating weight of evidence for either side. It is true we do accuse the Americans of burning the public buildings in York after the taking of the place, when the fort blew up on April 27th, 1813. The author is inclined to think that the Americans should not have applied the torch. On the other hand, we blew up the fort and utterly destroyed many hundreds of Americans in an instant, including their general.

The testimony of the great General Sherman, who, in 1865, marched with an army of 70,000 men through Georgia, Alabama, the Carolinas and Virginia, destroying everything in a belt fifty miles wide, and than whom no one was better qualified to judge, was this: “War is hell.” It would have been futile for our people to expect humane war. There are no recriminations to make. In closing the records of the War of 1812 let us realize with our forefathers that peace, blessed peace, came to them and has ever since been with us. God be thanked.{60}

Wolves in Upper Canada—Adventure of Thomas Conant—A grabbing land-surveyor—Canadian graveyards beside the lake—Millerism in Upper Canada—Mormonism.

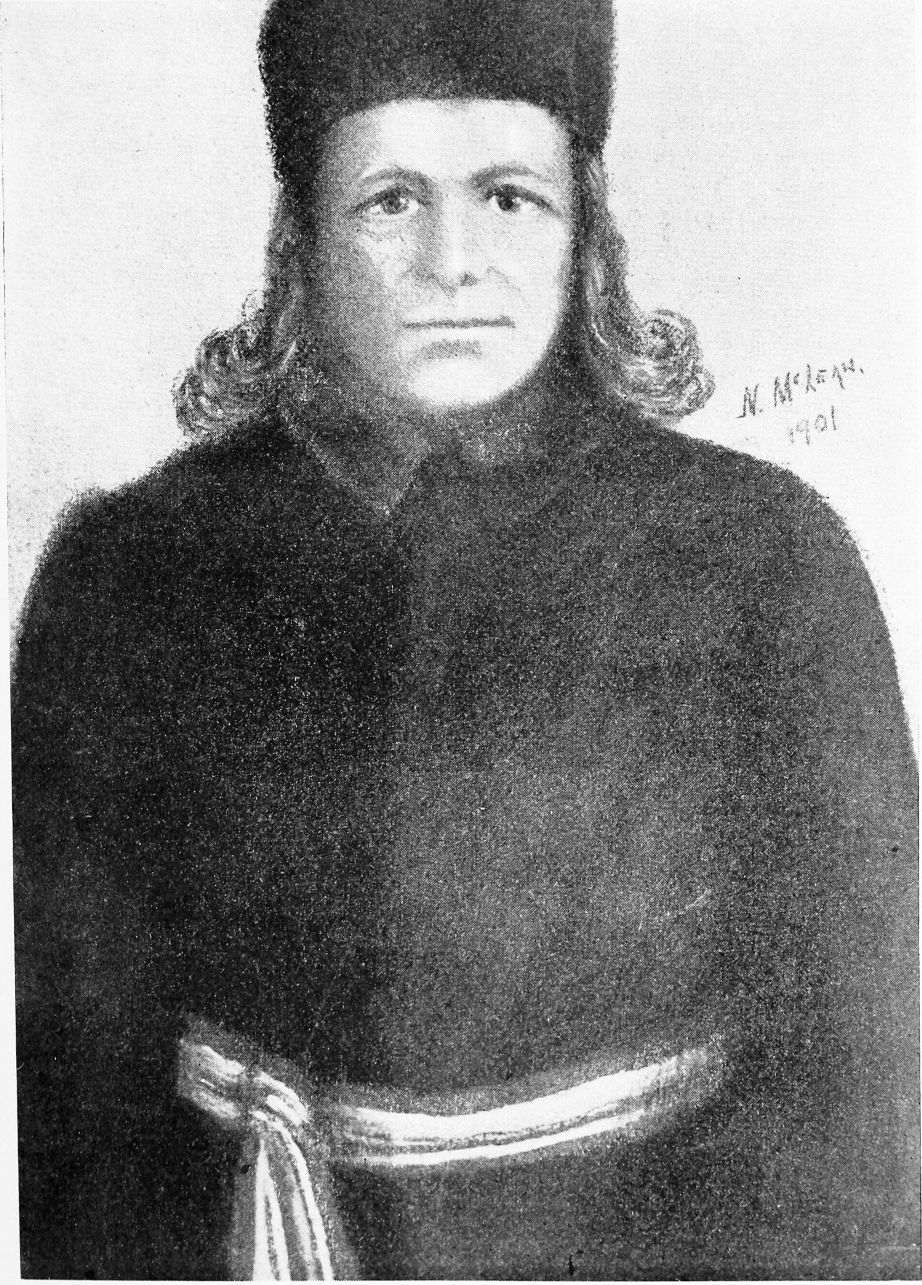

Turning to ordinary affairs, we find that at this date our Government helped the settler to exterminate wolves by paying a bounty of about $6 for each wolf head produced before a magistrate. In reference to these ferocious animals, once so plentiful in Canada, an anecdote of the author’s grandfather will be found both interesting and instructive, giving us a true glimpse of the county in 1806. Thomas Conant, whose portrait is found on opposite page, and who was assassinated during the Canadian Revolution on February 15th, 1838 (vide “Upper Canada Sketches,” by the author), lived in Darlington, Durham County, Upper Canada. In the fall of 1806 he was “keeping company” with a young woman, who lived some three miles back from Lake Ontario, his home being on the shore of that great lake. Clearings or openings in the forest were at this time mostly along the lake shore. Consequently, to pay his respects to the young woman, he had to pass through some forest and clearings in succession. It was in November of that year. Snow had not yet fallen, but the ground

THOMAS CONANT.

Was born at Bridgewater, Mass., in 1782; came to Darlington, Canada, with his father, Roger Conant, in 1792. On February 15th, 1838, during the Canadian Revolution, he was foully massacred by one Cummings (in Darlington), a despatch bearer, of Port Hope, Ont. The assassin was applauded for the act by the Family Compact.

was frozen. Tarrying until midnight at the home of the object of his affections, he left, alone and unarmed, to walk the three intervening miles to his home. Getting over about one-half the distance, he heard the distant baying of wolves. Fear would, it may be supposed, lend speed to his feet, but thinking rightly that he could not outstrip the wolf on foot, he walked quietly along, watching for a convenient tree for climbing. In a very few minutes the wolves were upon him, in full cry, eyes protruding, tongues lolling, and ready to devour him. A near-by beech tree, which his arms could encircle, furnished him with the means of escape. He climbed, and climbed, while the wolves surrounded him and watched his every motion, never ceasing their dismal howls the live-long night. Thus he kept his lonely vigil. To lose his hold for a single second meant instant death. Great, however, as was the tension upon his strained muscles, they held on. Morn tardily came at last, and with its first peep the wolves left him and were seen no more. When they were really gone, he said he for the first time began looking about him, and found, with all his climbing, he had ascended a very few feet from the ground, and but just out of reach of the wolves’ jaws as they made frantic jumps to reach him. We may, however, be safe in assuming that the scare and involuntary vigil did not do him much harm, for in the March following (1807) he married the girl he went to visit that night, and made no complaints of having been maltreated by wolves.{62}

In dismissing Thomas Conant at this time, the author digresses to say that he was born in the United States, and was only a small lad when Roger Conant, his father, brought him here. He was a generous, industrious citizen, and was always noted for being one of the best natured men in Canada, and possessed ability of a very high order. He was liked universally by all who knew him, and he pursued the ordinary avocations of life, such as Canadians then pursued, up to the time of his assassination (as before mentioned) during the Canadian Revolution, on February 15th, 1838. He went down to the grave from the stroke of a sword, wielded by a dragoon, and without any provocation other than accusing the dragoon of being drunk, as he was and had been many times previously when on duty as despatch bearer. But such was the state of affairs in Canada in 1837-8 that no investigation was held, nor was the murderer ever punished even in the mildest degree. The author asks the reader’s indulgence when he says he is very certain that only his grandfather’s (Thomas Conant) untimely death prevented him from leaving a name after him high up in Canadian annals, for he was a man of grand physique (6 feet 2 inches in height) and of commanding talents. He had a well-balanced mind and had wealth at his command.

Surveyors were now at work plotting out the townships, and settlers were coming very rapidly to occupy the lands which were surveyed. Readers will bear in mind that the Family Compact was still in full power.{63} All grants for lands had to come through them. A story of a famous old land surveyor is in order in this place. He had been surveying for many seasons, and, about quarterly, came to York to make his reports and show the plots of the new townships laid out. It so happened that an uncle of the author’s was chain-bearer (whose office Fenimore Cooper, the novelist, has immortalized) to this long-winded surveyor. At the time of his service as chain-bearer this uncle was only a lusty young man, and was not supposed to know the very first elements of surveying. Among other things it was his duty to erect the tent for the nightly bivouac, and make a fire at the tent mouth. Before the dancing, fitful flames, lights and shadows in the forest primeval, he nightly sat with the lordly surveyor, and saw him prepare rude maps of the past day’s work. And, without any sort of knowledge of surveying, he saw him just touch a parallelogram here and there (which would represent 100 acres) with the point of his red pencil; but ever so light was the touch. Night after night he saw dots go down on the parallelograms, and when the quiver was full of sheets of survey, to York he went with the surveyor, to report at the Crown Lands office. He said that in the office he noticed the officials in charge scanning very intently for the red but faint dots. We all now know the result: friends of the government officials had secured hundreds and hundreds of acres of the best lands in the region surveyed, while the surveyor became a mighty land-owner of most choice lands, and died a very, very wealthy man. As may be sur{64}mised, he had marked the choicest 100-acre lots with faint red dots, and he and the officials grabbed the very choicest lands in that surveyor’s district. Should a would-be purchaser ask for any certain lot, he was put off for a day in order that they might see in the surveyor’s map if it really was a choice one, as they surmised, since he asked to buy it, in which case some friend immediately entered for it, and consequently that choice lot the settler could not purchase. Using a fictitious name to illustrate, it is said, and truly, too, that Peter Russell, Governor, deeded to Peter Russell, Esquire, many choice lots of 100 acres each of the public domain in Canada, in the days of the Family Compact. But here one can justly remark that the eternal fitness of things comes pretty nearly correct after all, for, although that surveyor was fabulously wealthy, none of the property to-day is in any of his descendants’ possession, nor are there offspring of any of the Family Compact with enough pelf to-day, severally or collectively, to cause any comment. “The mills of the gods grind slowly, but they grind exceeding small,” in Canada just as they did in Greece and Rome in days of yore.

This travesty of the conveying of public lands was one very just cause of complaint on behalf of the people, and the refusal of the authorities to correct it helped materially to cause the Canadian Revolution of 1837-38.