![[Image of the book's cover unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: Drawings in pen & pencil from Dürer's day to ours, with notes and appreciations

Author: George Sheringham

Editor: C. Geoffrey Holme

Release date: July 14, 2021 [eBook #65836]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

|

(In certain versions of this etext [in certain browsers] clicking on the image will bring up a larger version.) (etext transcriber's note) |

EDITED BY GEOFFREY HOLME

LONDON: THE STUDIO, Lᵀᴰ 44 LEICESTER SQUARE, W.C.2

MCMXXII

In the original circular relating to this volume it was announced that Mr. Malcolm C. Salaman would contribute the letterpress. The Editor desires to express his sincere regret that, owing to serious indisposition, Mr. Salaman has been unable to fulfil this intention.

The Editor wishes to acknowledge his indebtedness to the following owners who have kindly lent drawings for reproduction in this volume: Messrs. Ernest Brown and Phillips (The Leicester Galleries), Mr. William Burrell, Lt.-Col. Pepys Cockerell, Mr. Campbell Dodgson, C.B.E., Mr. Charles Emanuel, Mr. William Foster, Mrs. G. R. Halkett, Mr. Harold Hartley, Mr. Francis Harvey, Mr. C. C. Hoyer-Millar, Mr. J. B. Manson, Mr. A. P. Oppé, Monsieur Ed. Sagot, Mr. Edward J. Shaw, J.P., Monsieur Simonson, Mr. G. Bellingham Smith, Mr. Roland P. Stone, Mr. D. Croal Thomson, Mr. Charles Mallord Turner and Sir Robert Woods, M.P. Also to Messrs. William Marchant & Co. (The Goupil Gallery), Mr. T. Corsan Morton, Mr. E. A. Taylor and Mr. Lockett H. Thomson for the valuable assistance they have rendered in various ways; and to Messrs. G. Bell & Sons, Messrs. Chapman & Hall, Messrs. Charles Chenil & Co., Messrs. J. M. Dent & Sons, Mr. William Heinemann, and the Proprietors of La Gazette du Bon Ton, Punch and The Sketch for permission to reproduce drawings of which they possess the copyrights.{v}{iv}

| “Notes and Appreciations.” By George Sheringham | 1 |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | |

| Albano, Francesco. Pen Drawing. Photo, Anderson | 58 |

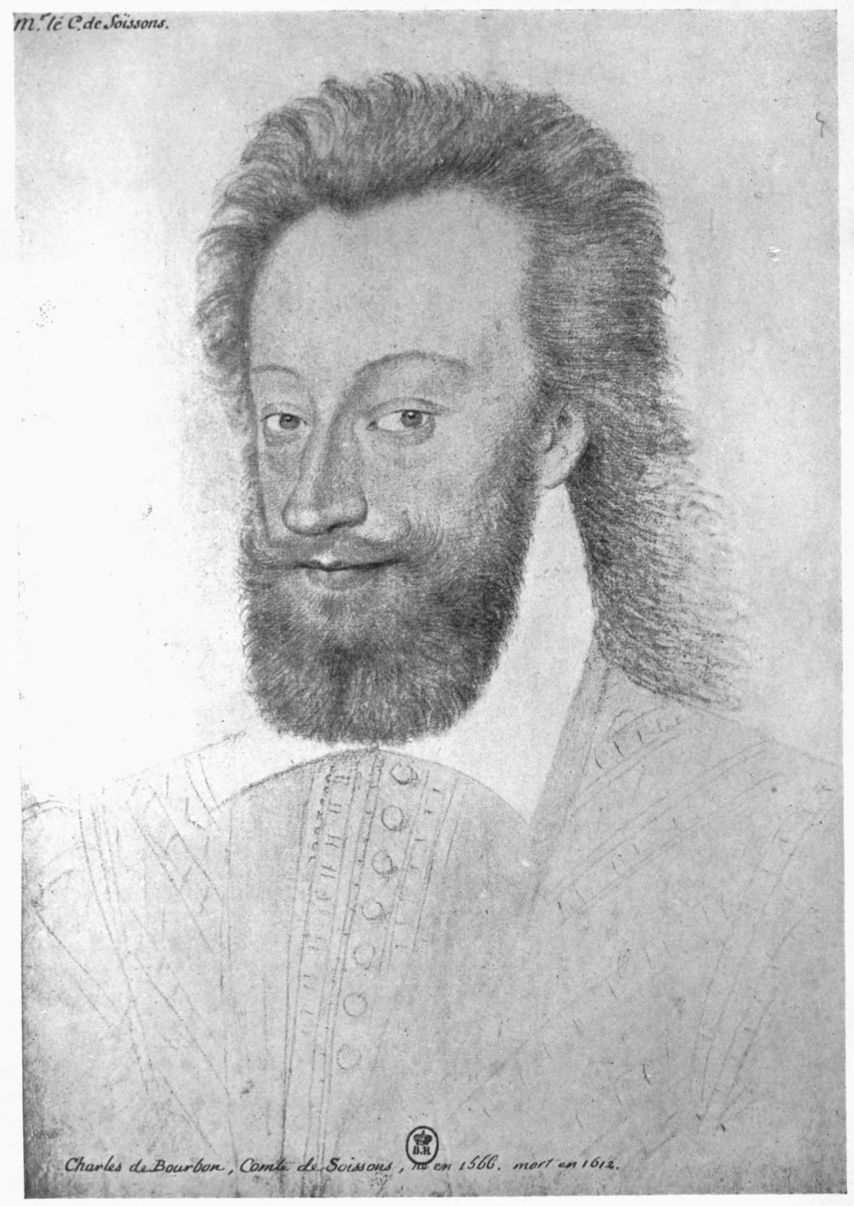

| Artist Unknown. Drawing in Pencil and Chalks. Photo, Giraudon | 72 |

| Barbieri, Giovanni Francesco. (See Guercino) | |

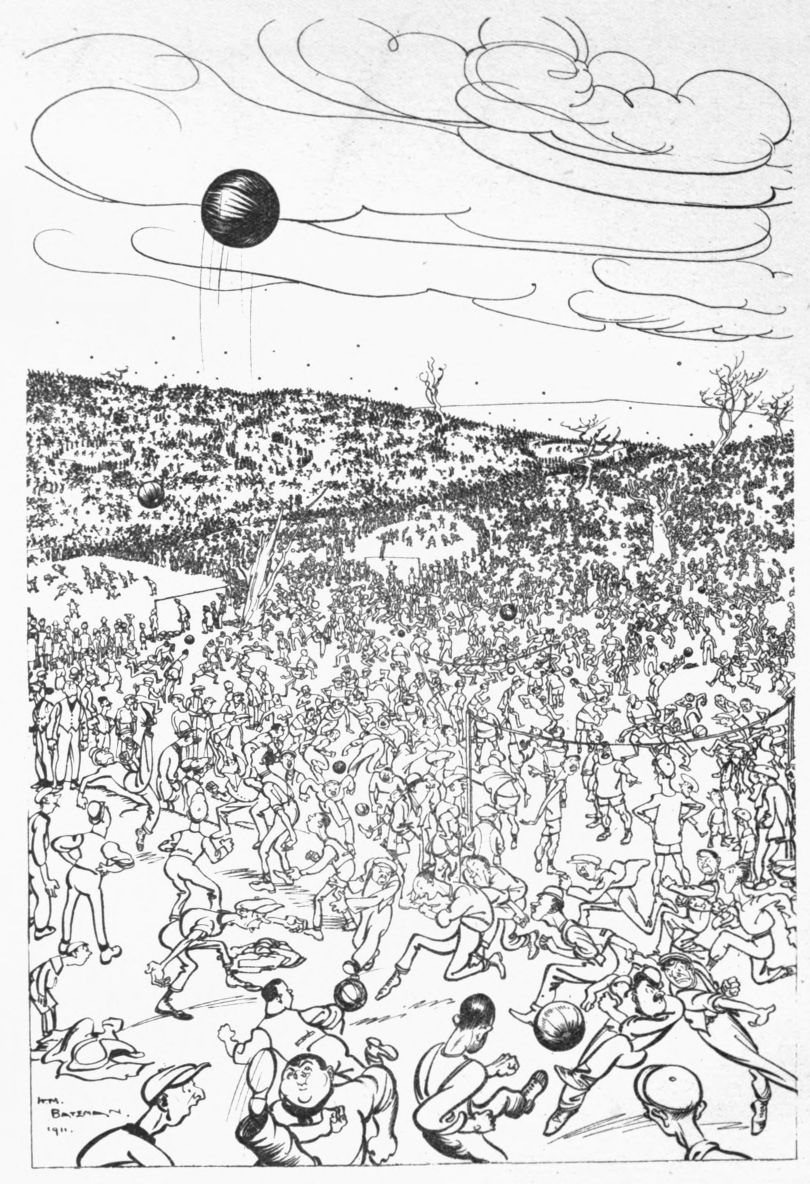

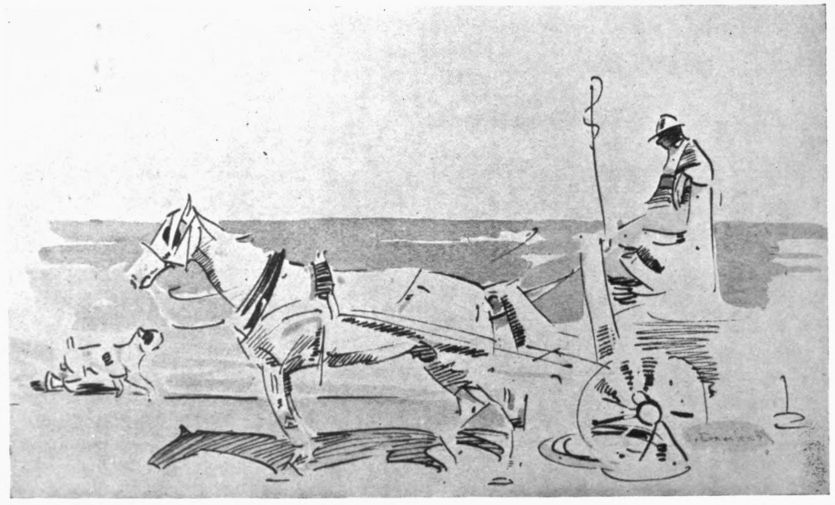

| Bateman, H. M. An Open Space (pen) | 140 |

| Beardsley, Aubrey. John Bull (pen) | 120 |

| ““Pen Drawing | 121 |

| Béjot, Eugène. Le Quai de Paris à Rouen | 178 |

| Belcher, George. Drawing in pencil and wash | 141 |

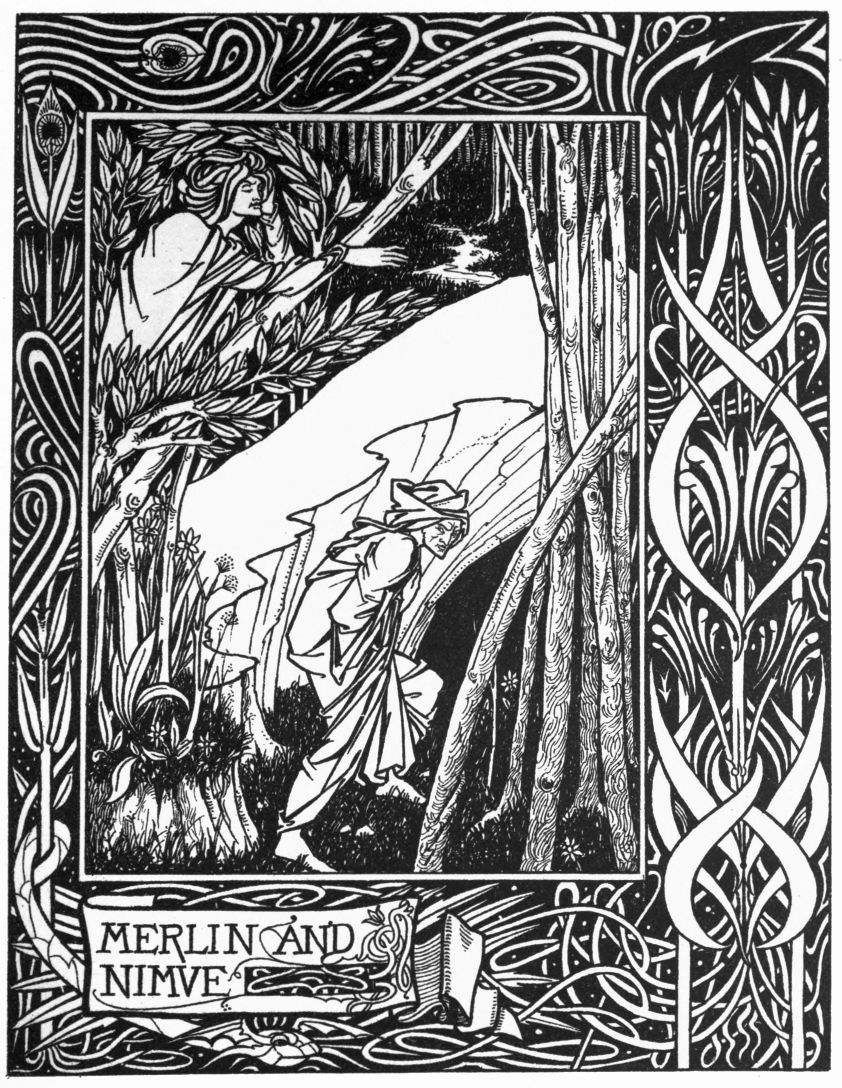

| Bell, R. Anning, R.A., R.W.S. Pen Drawing | 164 |

| Bellini, Gentile. The Turk (pen). Photo, Anderson | 40 |

| ““The Turkish Lady (pen). Photo, Anderson | 41 |

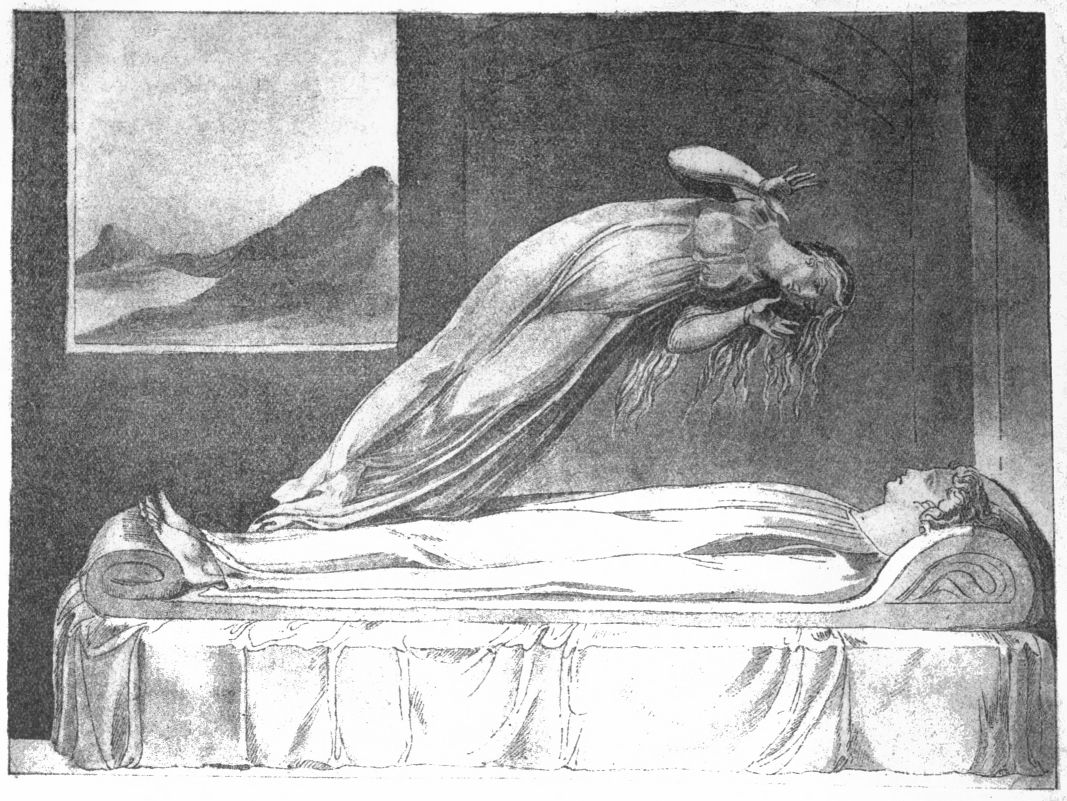

| Blake, William. The Soul hovering over the Body (pen and wash) | 119 |

| Blampied, E., R.E. The Sick Mother (pen) | 147 |

| Bone, Muirhead. Front of the Quirinal Palace, Rome (pencil) | 160 |

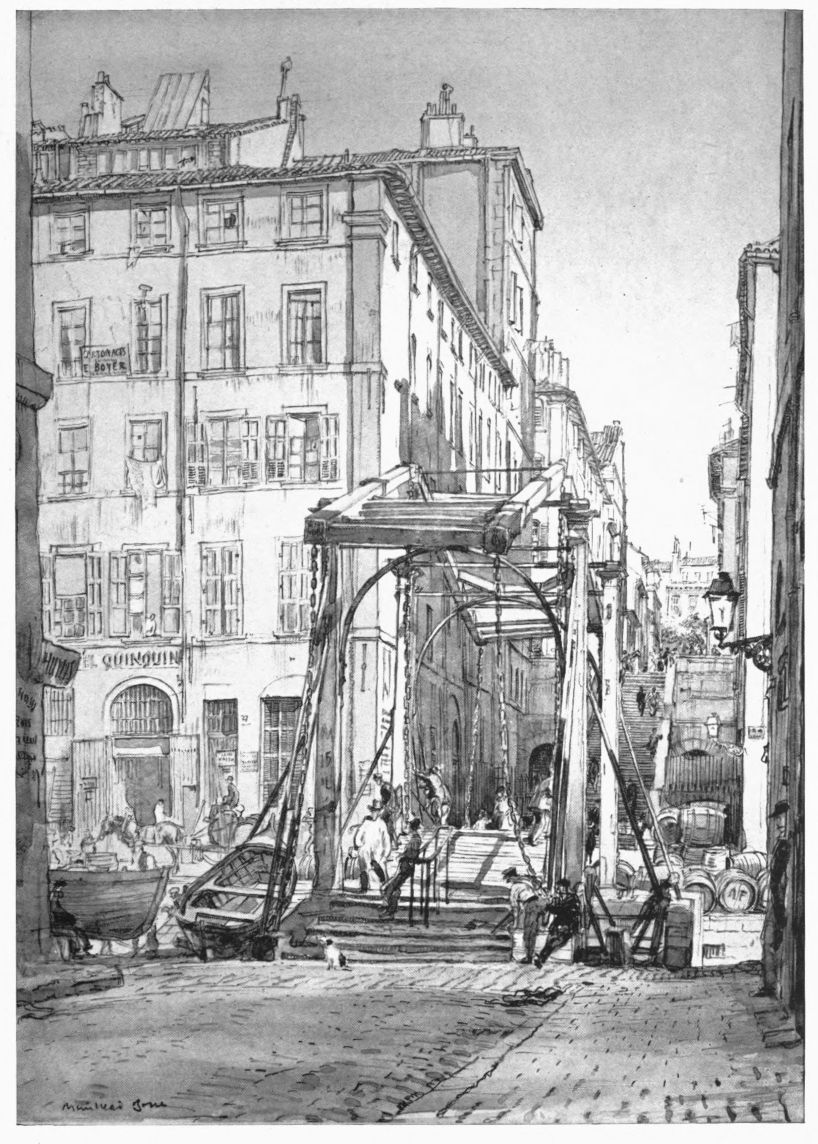

| ““Quai du Canal, Marseilles (pencil) | 161 |

| Botticelli, Sandro. Abundance (pen and pencil) | 47 |

| Boutet de Monvel, Bernard. Venus et l’Amour (pen) | 182 |

| ““““ Pen Drawing | 183 |

| Brangwyn, Frank, R.A. The Steam Hammer (pen and chalk) | 139 |

| Burne-Jones, Bart., Sir Edward. Seven Works of Mercy (pencil) | 126 |

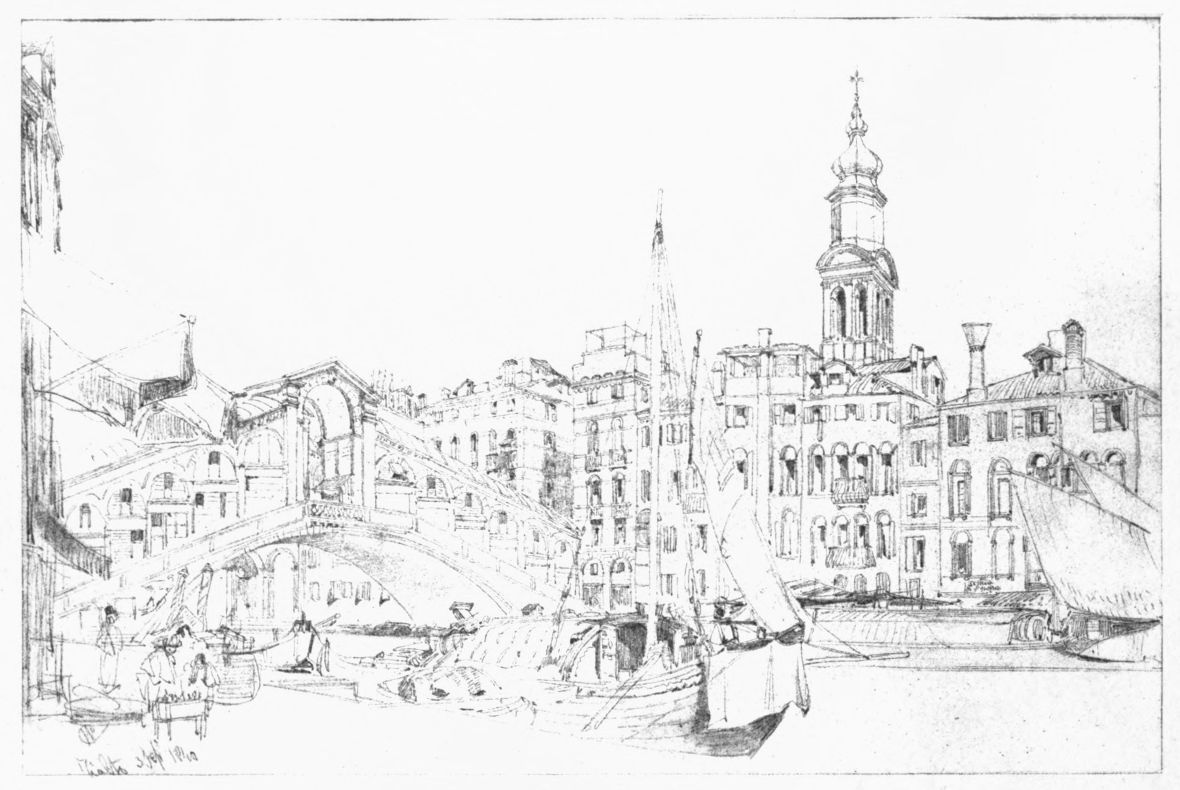

| Callow, William, R.W.S. The Rialto, Venice (pencil) | 132 |

| Canaletto. Pen Drawing. Photo, Mansell | 76 |

| Carlègle, E. Pen Drawing | 184 |

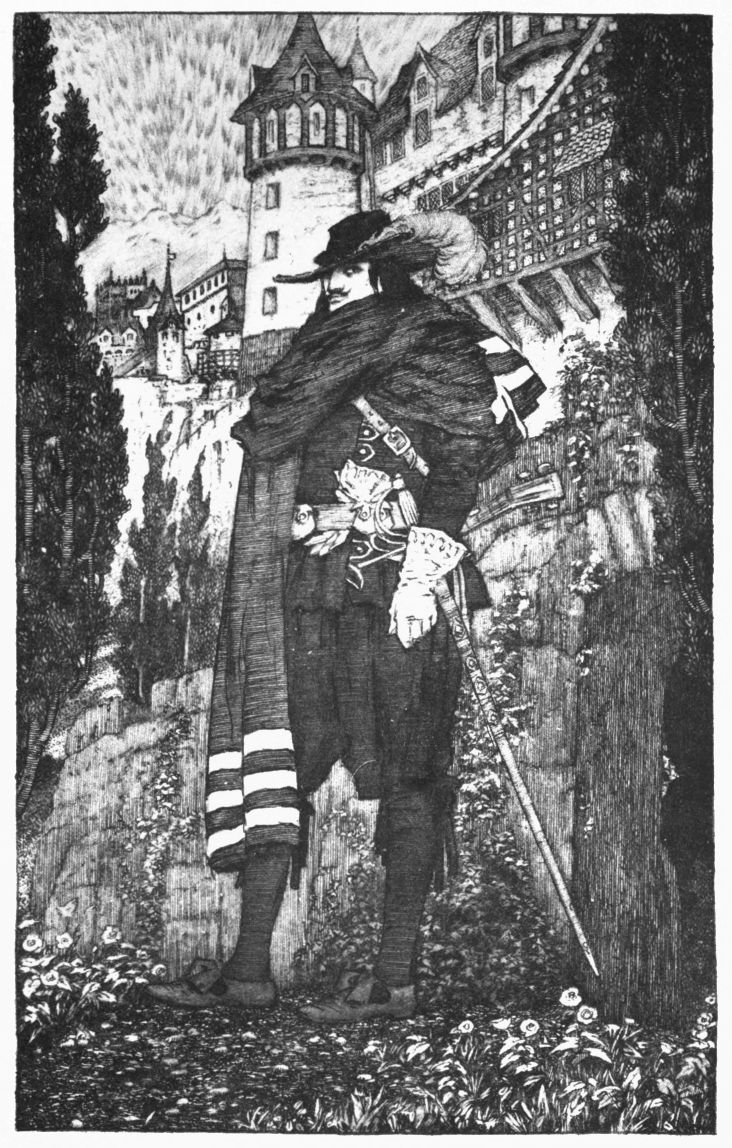

| Clarke, Harry. Pen Drawing | 151 |

| Claude Lorrain. Pen Drawing | 71 |

| Constable, John, R.A. Salisbury (pencil) | 85 |

| Correggio. The dead Christ carried off by Angels (pen). Photo, Brogi | 31 |

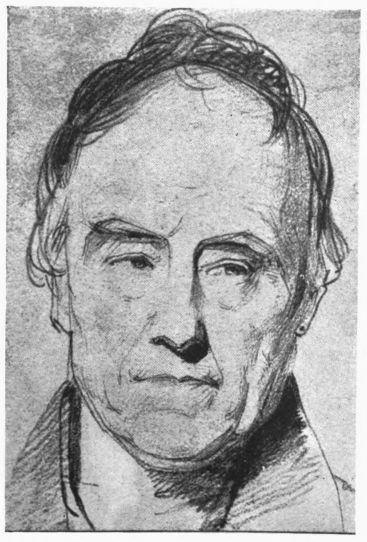

| Cosway, Richard, R.A. Henry (pencil and chalk) | 83 |

| Cotman, John Sell. On the Yare (pencil) | 86 |

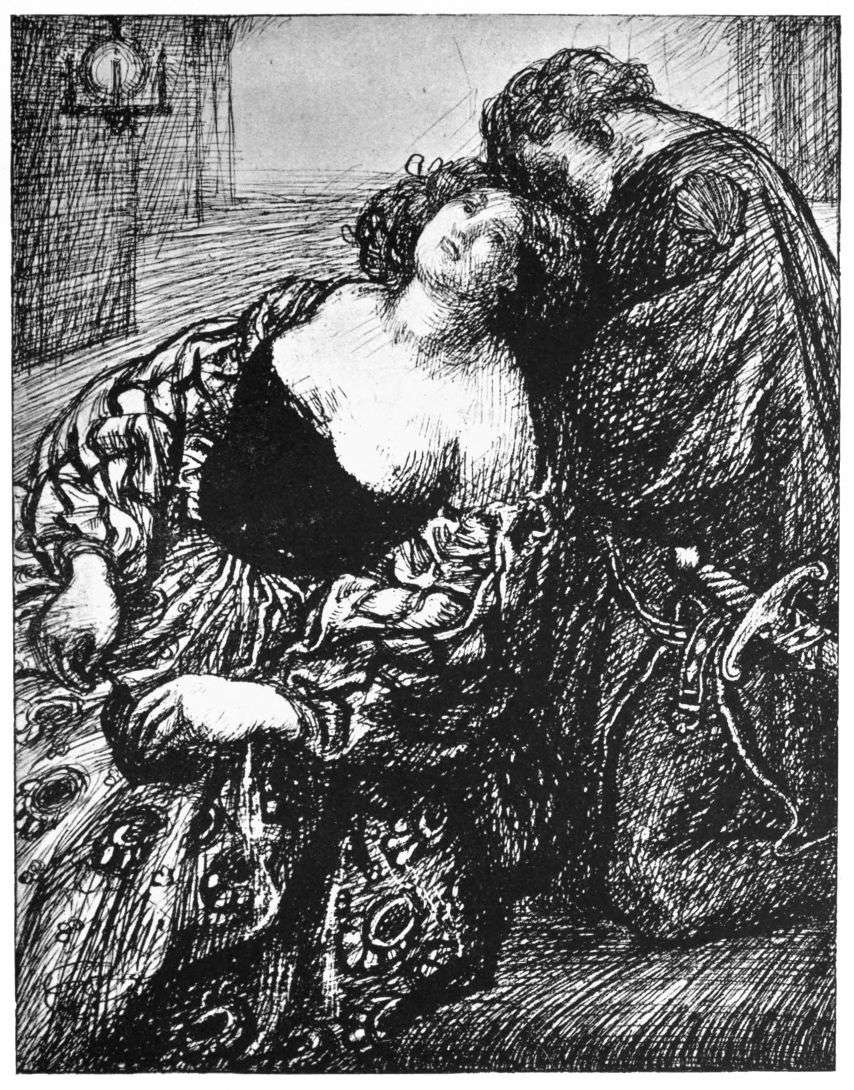

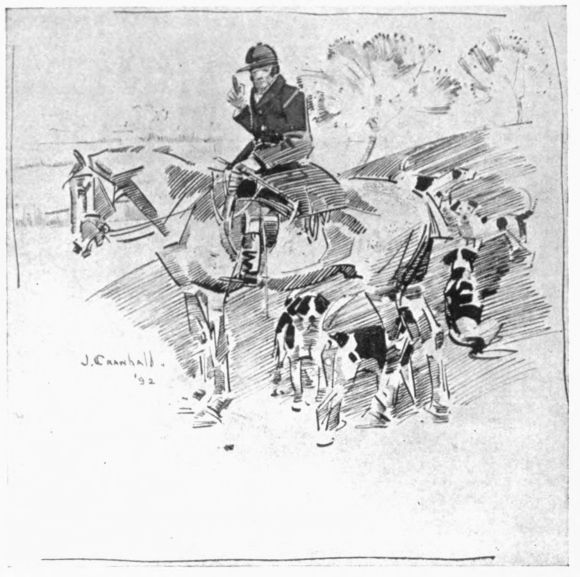

| Crawhall, Joseph. Pen Drawings | 166 |

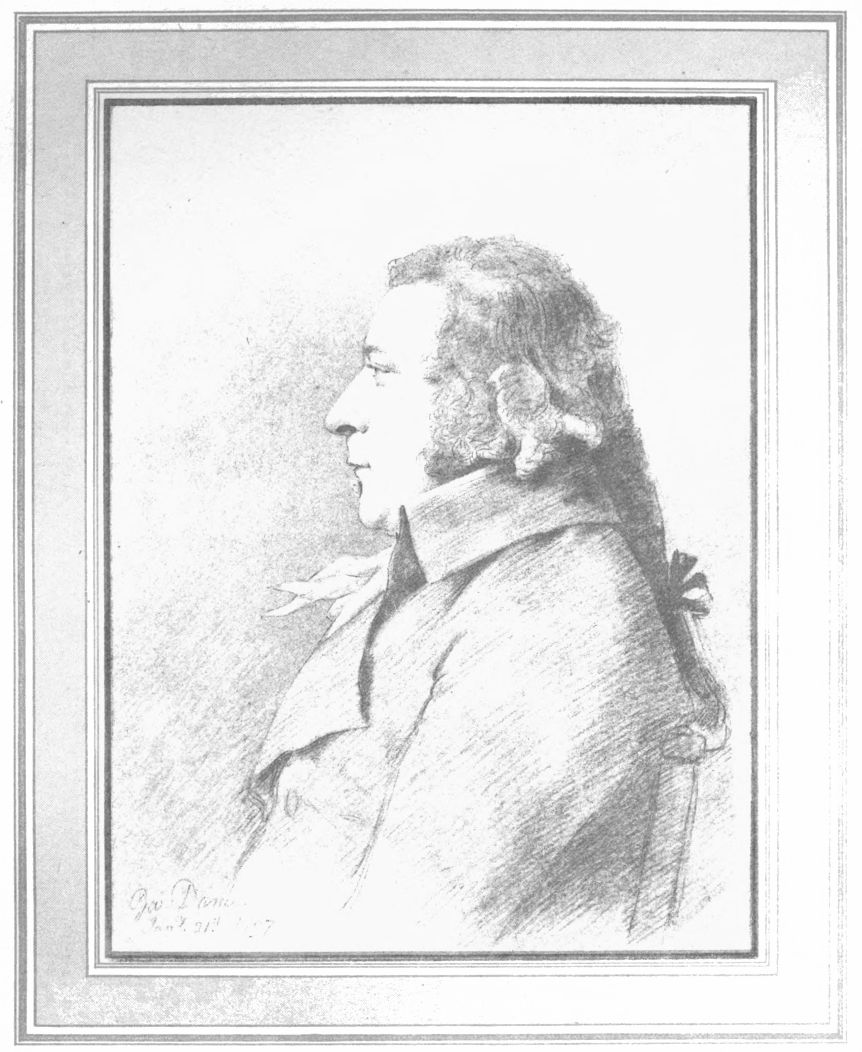

| Dance, George, R.A. Parke, Musician (pencil) | 87 |

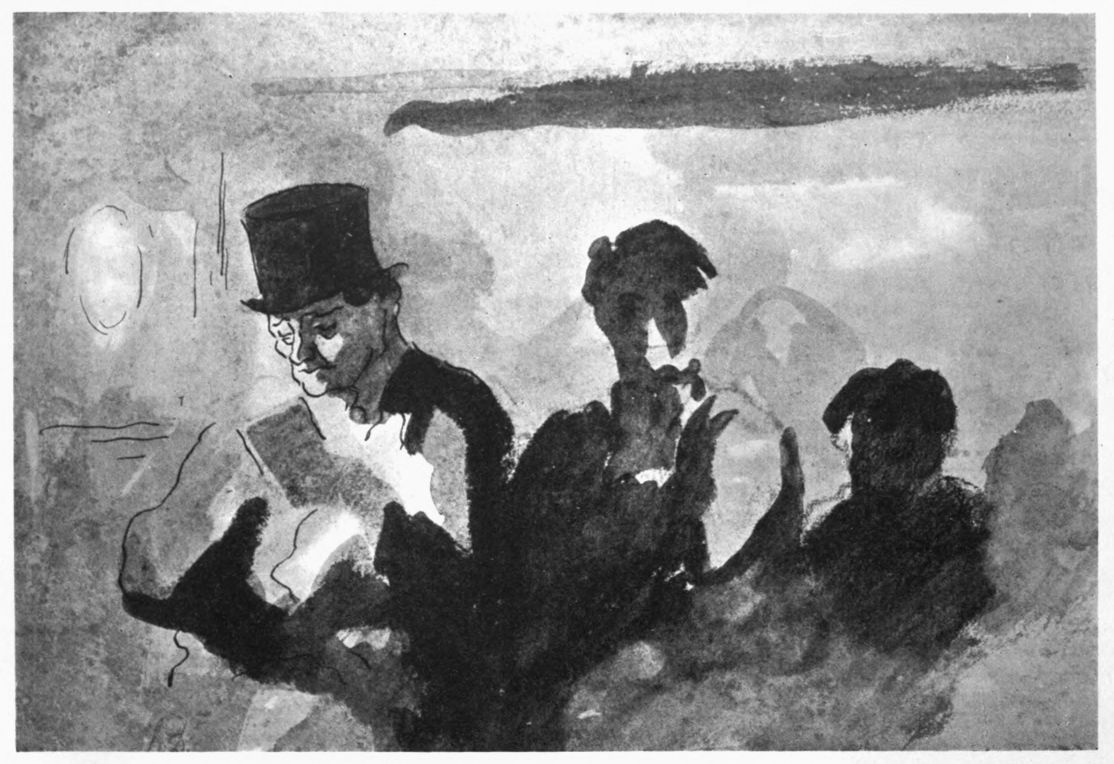

| Daumier, Honoré. En Troisième (pen and wash) | 98 |

| ““Les Trois Connaisseurs (pen and wash) | 99 |

| Dulac, Edmund. Pencil Study | 170 |

| Du Maurier, George. Pen Drawing | 113 |

| Dürer, Albrecht. A Courier (pen). Photo, Anderson | 25 |

| ““The Rhinoceros (pen). Photo, Anderson | 26 |

| ““The Procession to Calvary (pen). Photo, Brogi | 27 |

| ““Praying Hands (pen). Photo, Mansell | 28 |

| Emanuel, Frank L. Pencil Drawing | 138 |

| Fisher, A. Hugh, A.R.E. Pencil Drawing | 143 |

| Flint, W. Russell, R.W.S. Women quarrelling (pencil) | 134 |

| Forain, J. L. Pen Drawing | 174 |

| Foster, Birket, R.W.S. Pen Drawing | 92 |

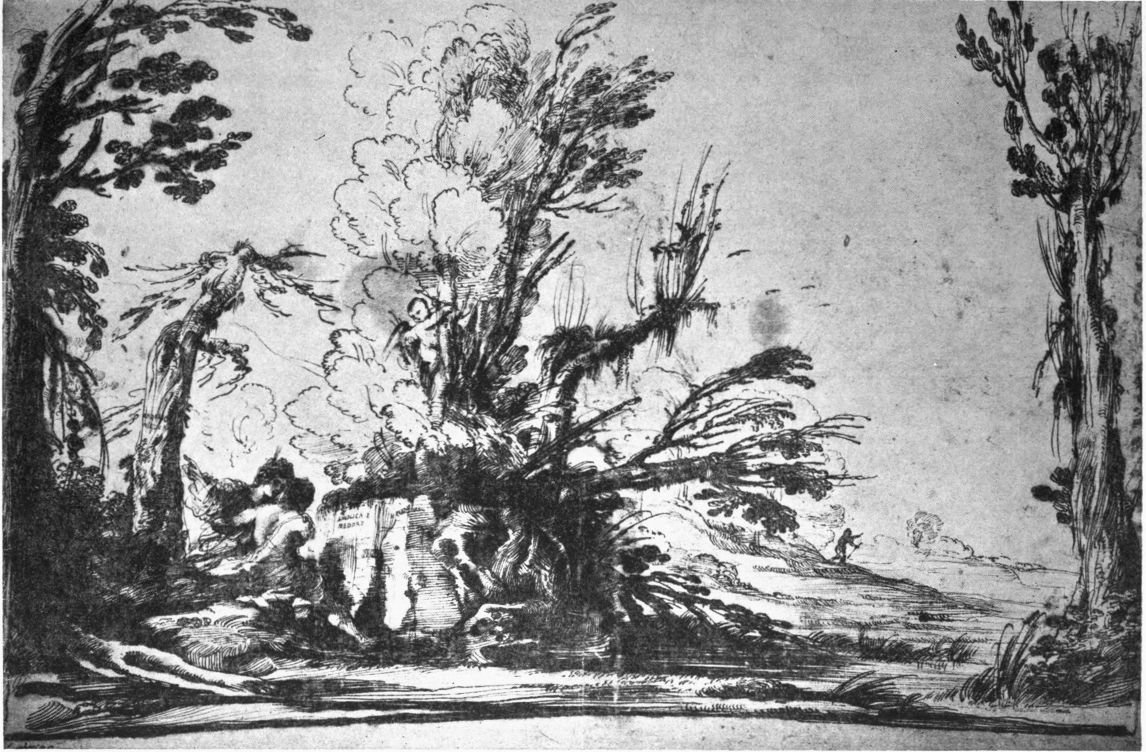

| Fragonard, J. H. Cupids playing around a fallen Hermes (pen) | 79 |

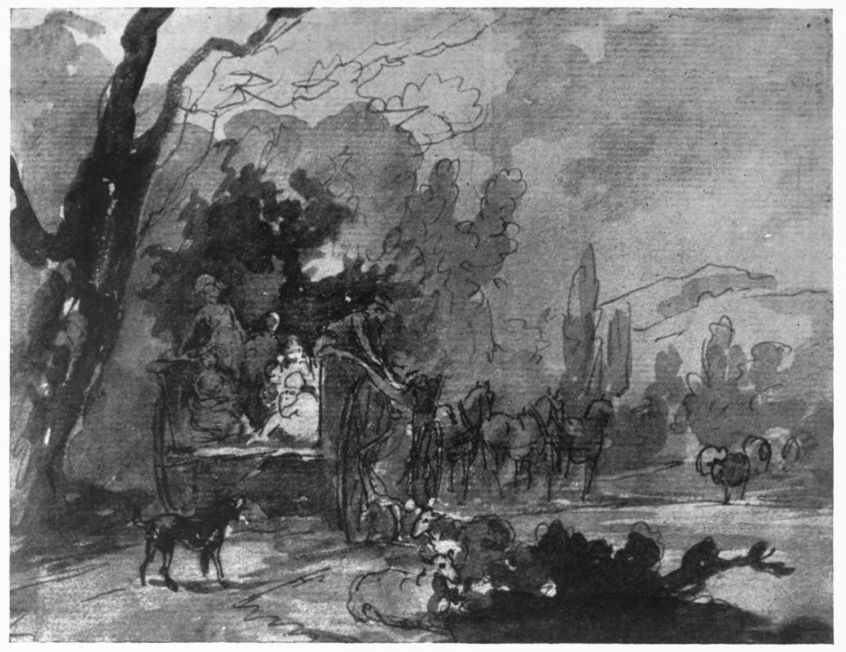

| Gainsborough, Thomas, R.A. The Harvest Wagon (pen). Photo, Mansell | 82 |

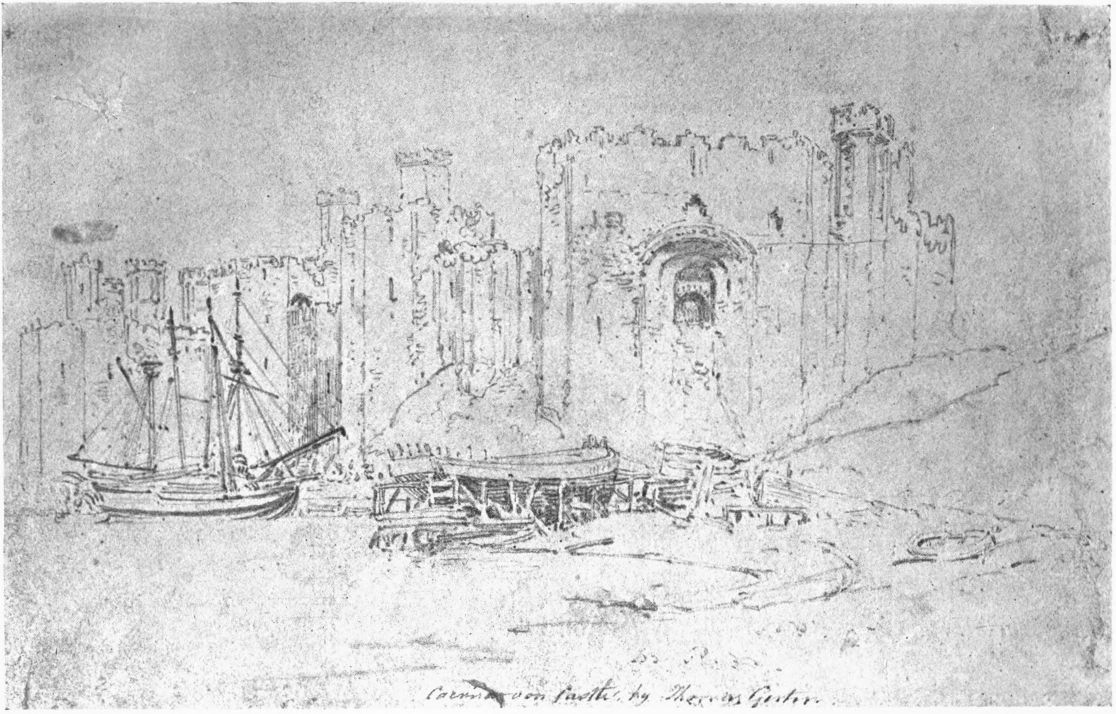

| Girtin, Thomas. Carnarvon Castle (pencil) | 89 |

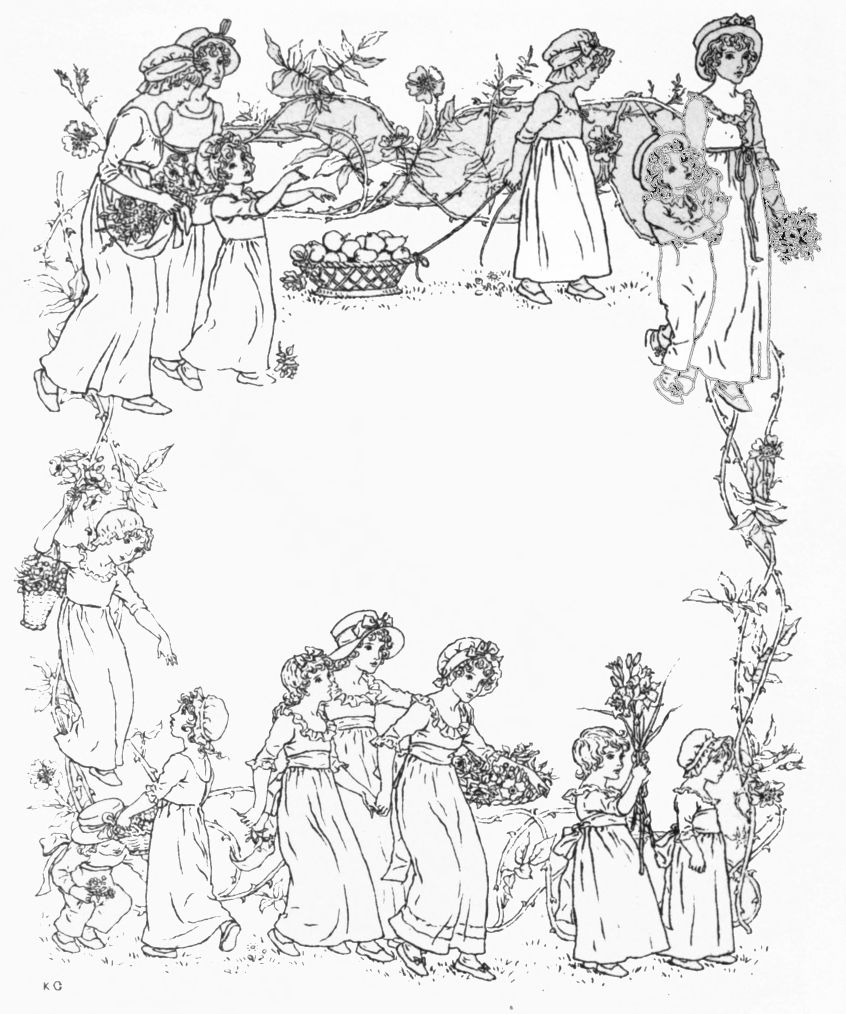

| Greenaway, Kate. Pen Drawing | 116 |

| Griggs, F. L. Pen Drawing | 165 |

| Guardi, Francesco. Venice (pen) | 77 |

| Guercino, Il. Pen Drawing. Photo, Anderson | 57 |

| Hill, Adrian. Folkestone (pencil) | 137 |

| Hill, Vernon. A Sleeper (pencil) | 158 |

| Holbein, Hans. The Family of Sir Thomas More (pen) | 29 |

| Houghton, A. Boyd. Pen Drawing | 111 |

| Hubbard, E. Hesketh. S. Anne’s Gate, Salisbury (pencil) | 154 |

| Hughes, Arthur. Unseen (pen) | 118 |

| Ingres, J. A. D. Madame Gatteaux (pencil). Photo, Mansell | 95 |

| ““Paganini (pencil) | 96 |

| ““C. R. Cockerell (pencil) | 97 |

| Jones, Sydney R. Near Chesham, Bucks. (pen) | 157 |

| Jouas, C. Drawing in pencil and coloured chalks | 175 |

| Keene, Charles. Pen Drawings | 105 to 109 |

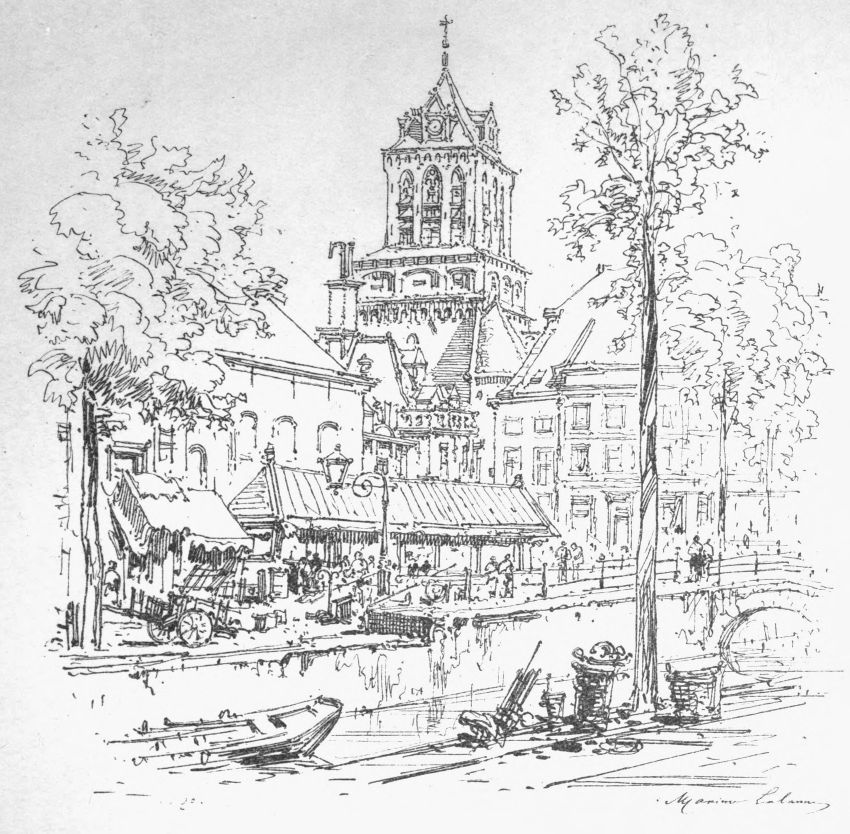

| Lalanne, Maxime. Delft (pen) | 171 |

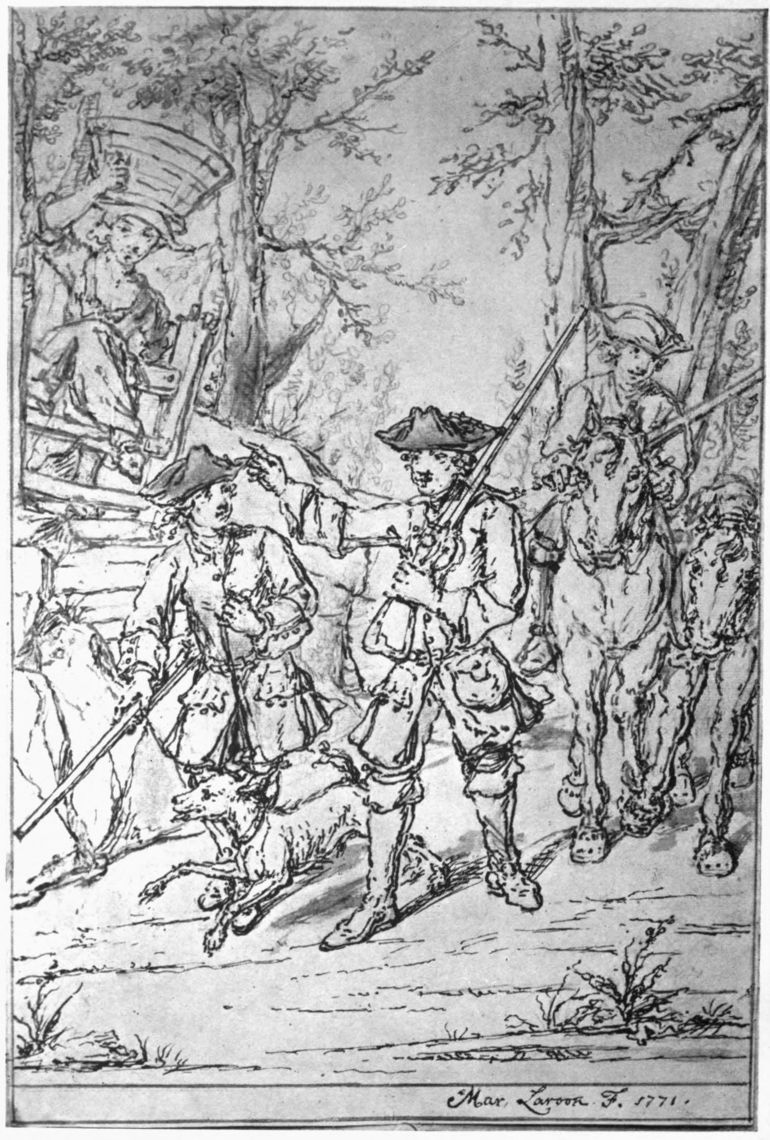

| Laroon, Marcellus. A Hunting Party (pen and pencil) | 78 |

| Lawrence, Sir Thomas, P.R.A. Lady Mary Fitzgerald (pencil) | 93 |

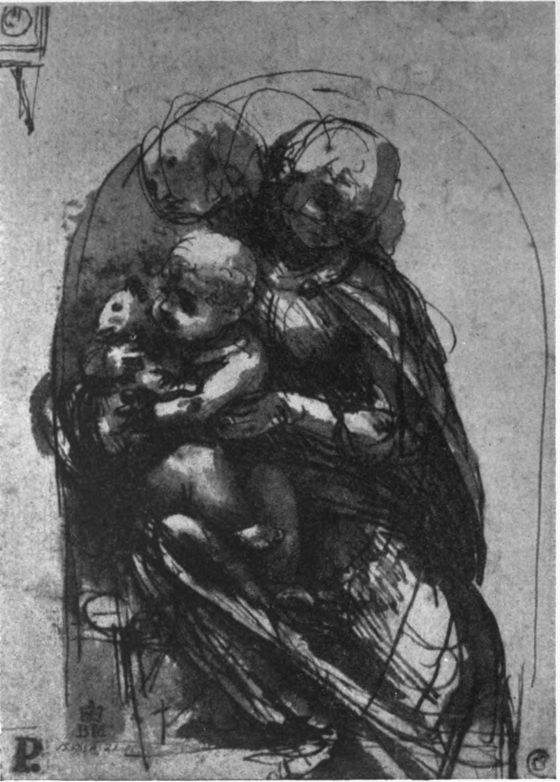

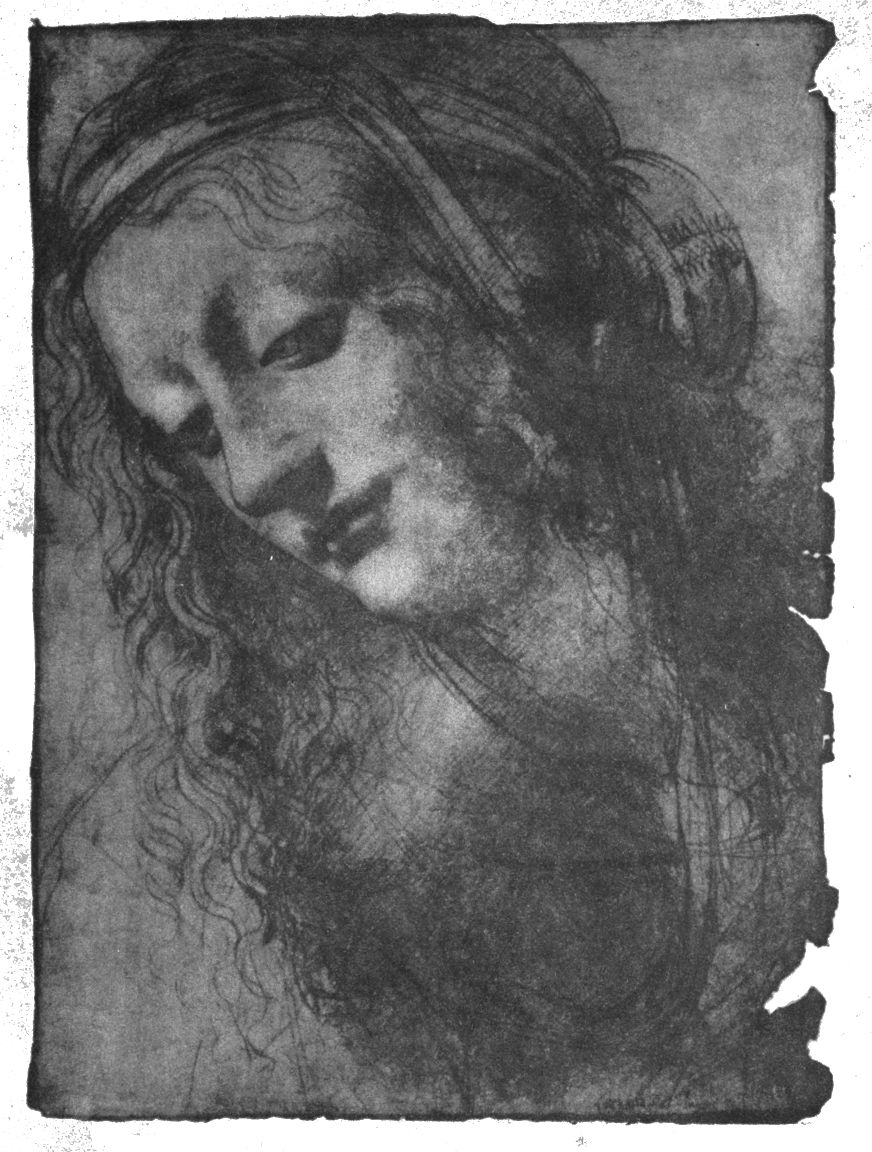

| Leonardo da Vinci. Pen Studies. Photos, Anderson and Brogi | 32 |

| “““Head of an Old Man (pencil) | 33 |

| “““Madonna and Child (pen). Photo, Anderson | 34 |

| “““Head of a Young Woman (pen). Photo, Braun & Co. | 35 |

| Lepère, A. Le Vieux Menton (pen) | 176 |

| ““Crèvecœur (pen) | 177 |

| Lhermitte, L. Pen Drawing | 146 |

| Mahoney, James. Pen Drawing | 110 |

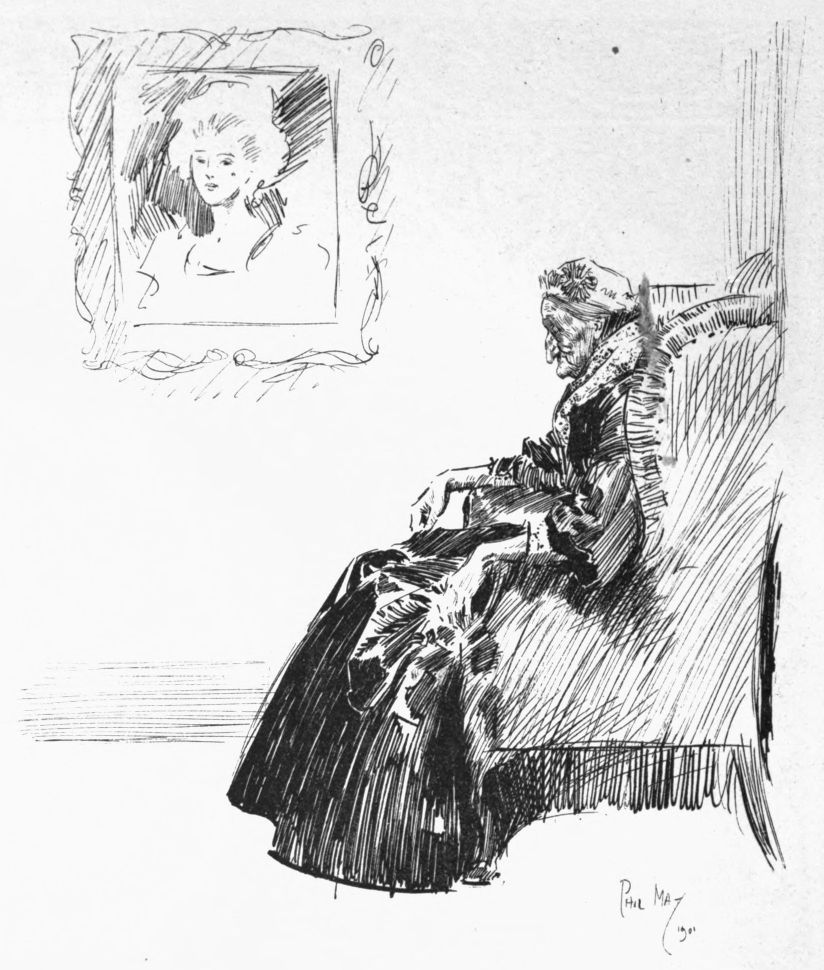

| May, Phil. A Portrait of her Grandmother (pen) | 122 |

| ““Drawing in pencil and chalk | 123 |

| McBey, James. The Stranded Barge (pen) | 167 |

| Meryon, Charles. Pencil Drawing | 101 |

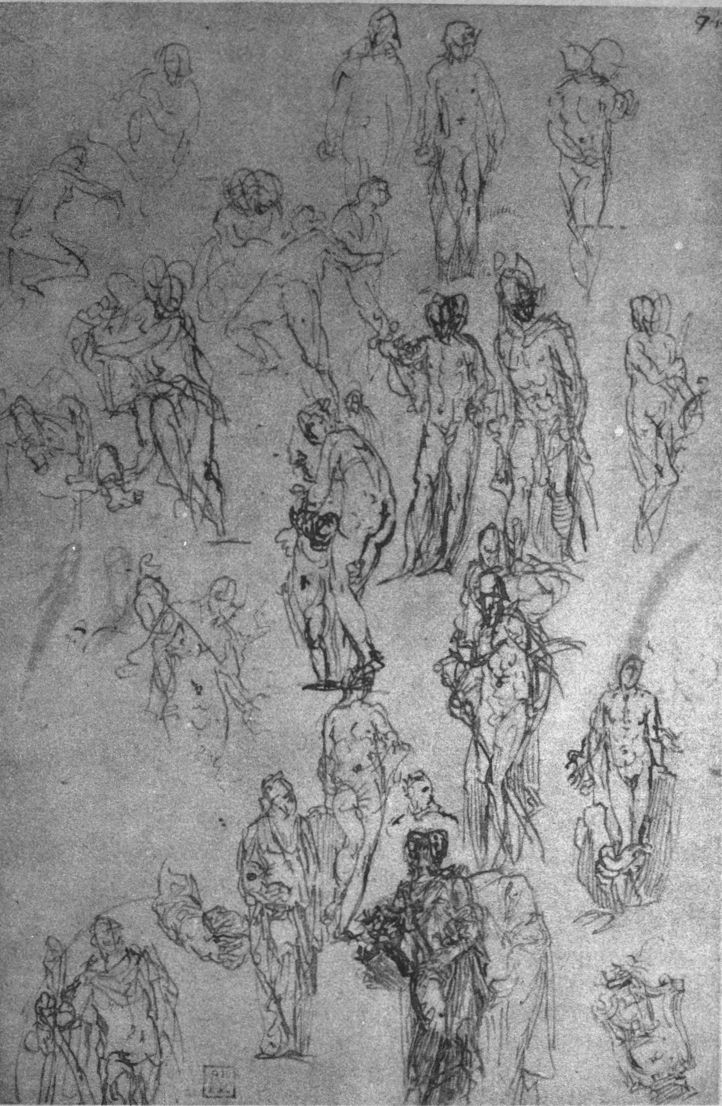

| Michelangelo. Pen Drawings. Photo, Anderson | 42, 43, 46 |

| “Pen Drawing | 45 |

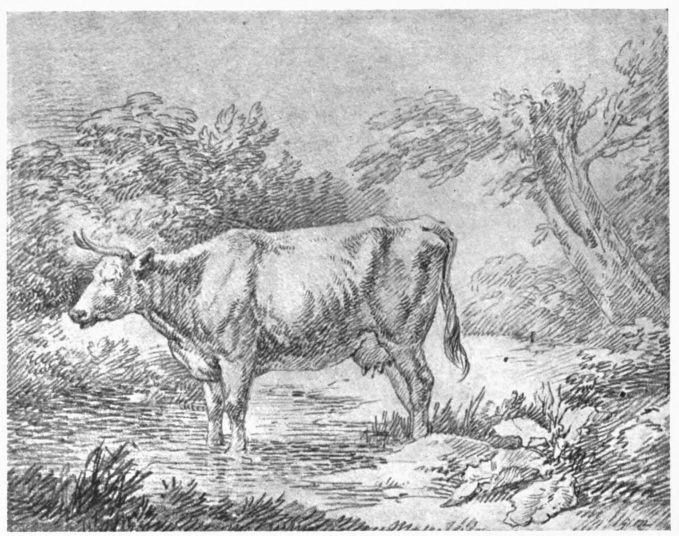

| Morland, George. Pencil Drawing | 86 |

| New, Edmund H. Grasmere Church (pencil) | 152 |

| North, J. W., R.A. The Gamekeeper’s Cottage (pen) | 117 |

| Orpen, Sir William, R.A. Mother and Child (pencil) | 148 |

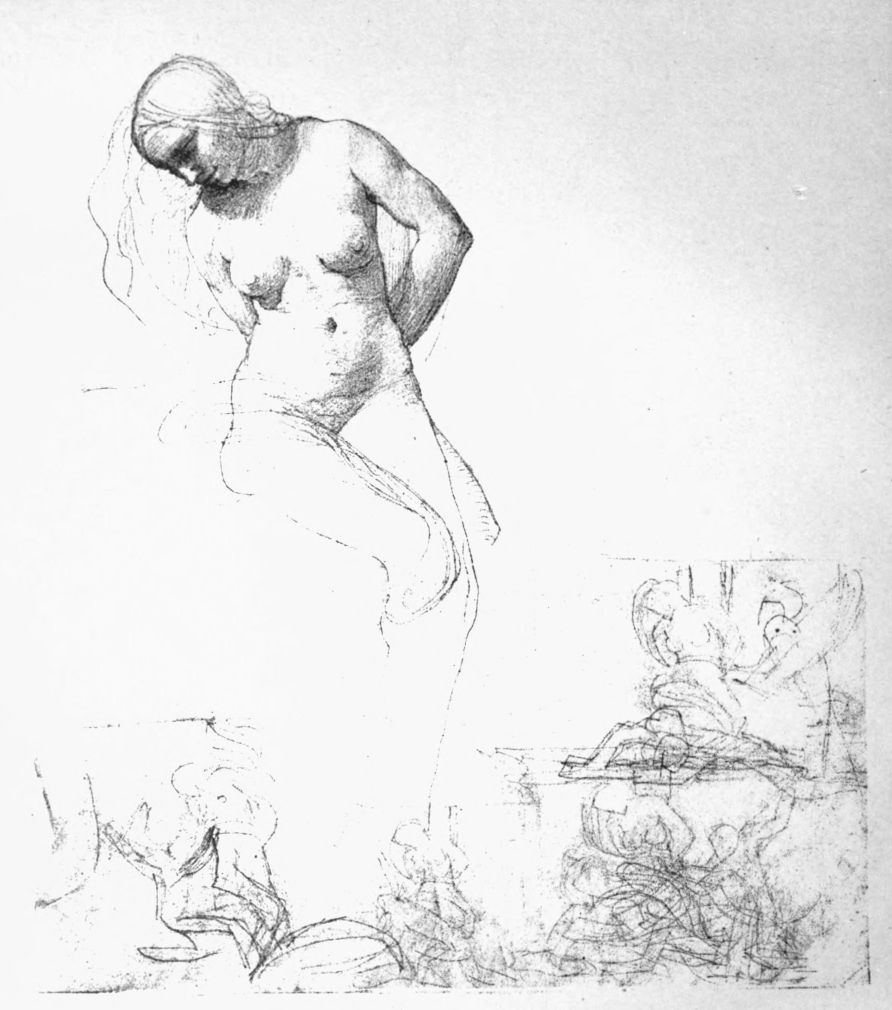

| “““After Bathing | 149 |

| Ospovat, Henry. “Life might last! We can but try” (pen) | 163 |

| Ostade, Adriaen van. Tavern Scene (pen) | 68 |

| Parmigianino. Pen Drawing. Photo, Brogi | 75 |

| Partridge, Bernard. Place du Pillori, Pont-Audemer (pen) | 133 |

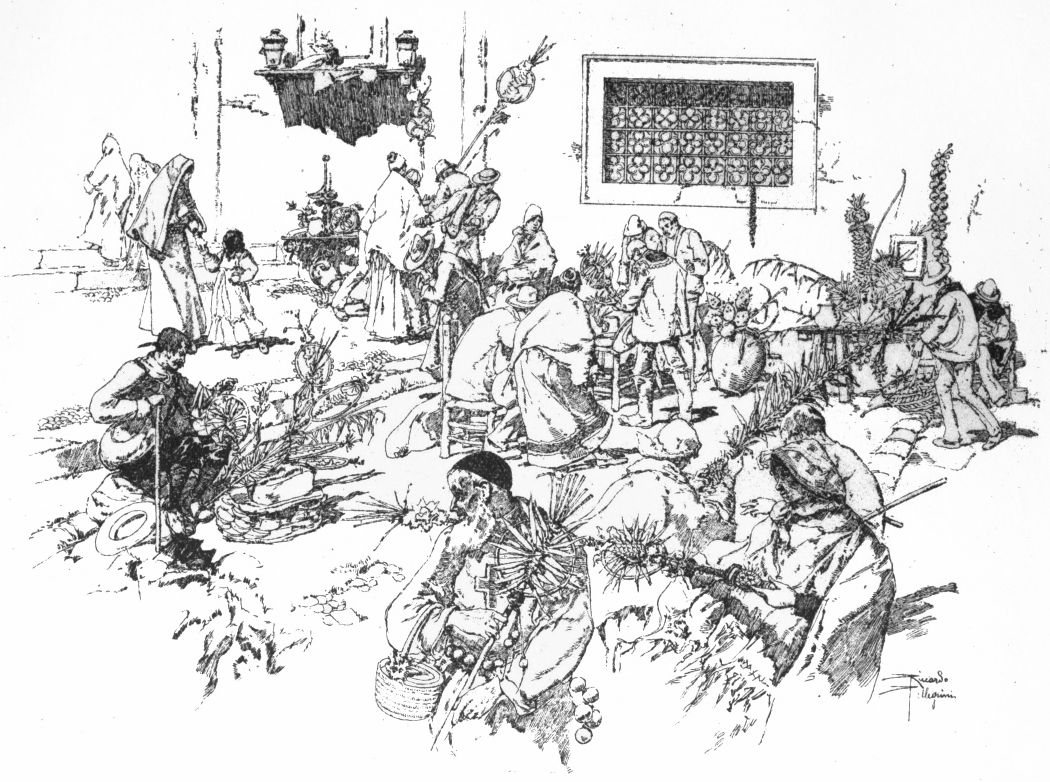

| Pellegrini, Riccardo. Palm Sunday in Italy (pen) | 125 |

| Peruzzi, Baldassare. Pen Drawing. Photo, Anderson | 37 |

| Philpot, Glyn W., A.R.A. Pencil Study | 168 |

| Pinturicchio, Bernardino. Young Woman with Basket (pen) Photo, Brogi | 31 |

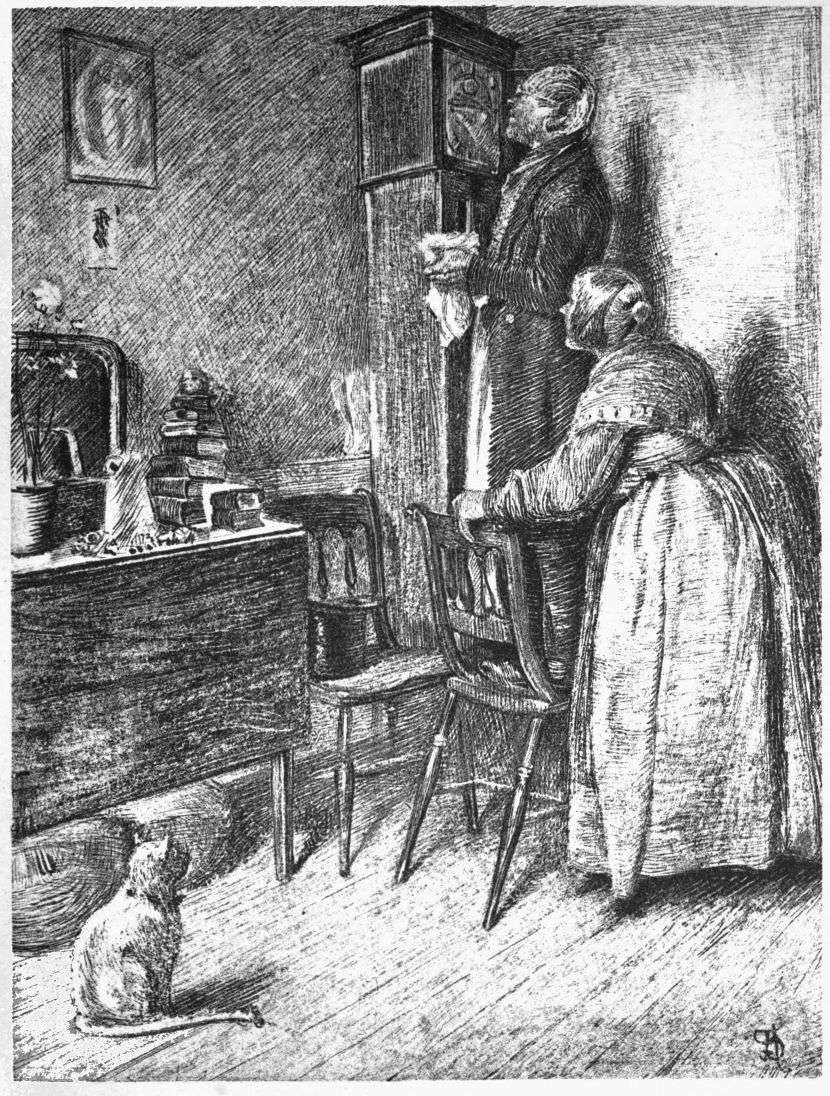

| Pinwell, C. J. The Old Couple and the Clock (pencil) | 115 |

| Poulbot, F. Pen Drawing | 181 |

| Poussin, Nicolas. Pen Drawing | 70 |

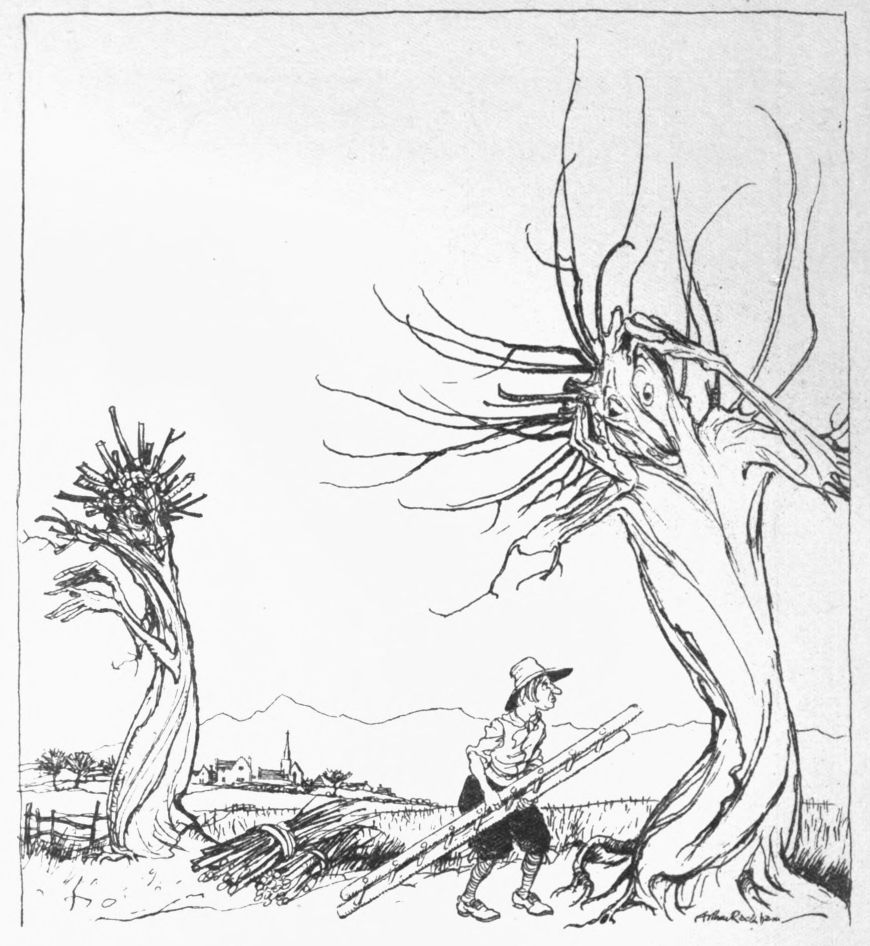

| Rackham, Arthur, R.W.S. Pen Drawing | 150 |

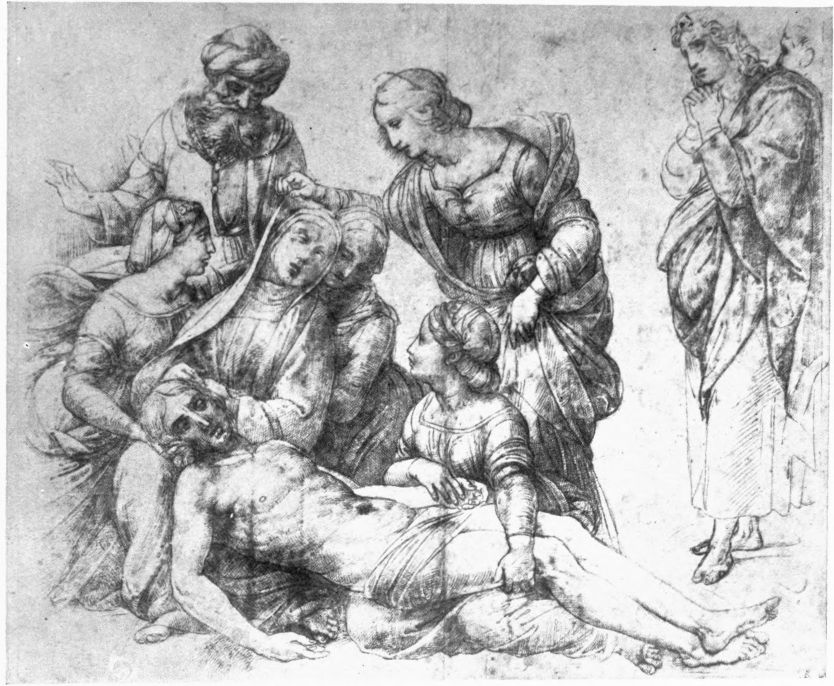

| Raphael. Pen Drawings. Photo, Anderson | 49, 53 |

| “La Vierge (pen). Photo, Mansell | 50 |

| “Pen Study. Photo, Mansell | 51 |

| Raphael, School of. Pen Drawing. Photo, Anderson | 54 |

| Rembrandt. Lot and his Family leaving Sodom (pen). Photo, Anderson | 61 |

| Rembrandt. Saskia (pen) | 63 |

| “Old Cottages (pen) | 64 |

| “Pen Drawing | 64 |

| “Judas restoring the Price of his Betrayal (pen). Photo, Braun & Co. | 65 |

| Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. Pencil Drawing | 127 |

| Roubille, A. Pen Drawing | 179 |

| Russell, Walter W., A.R.A. Pencil Study | 159 |

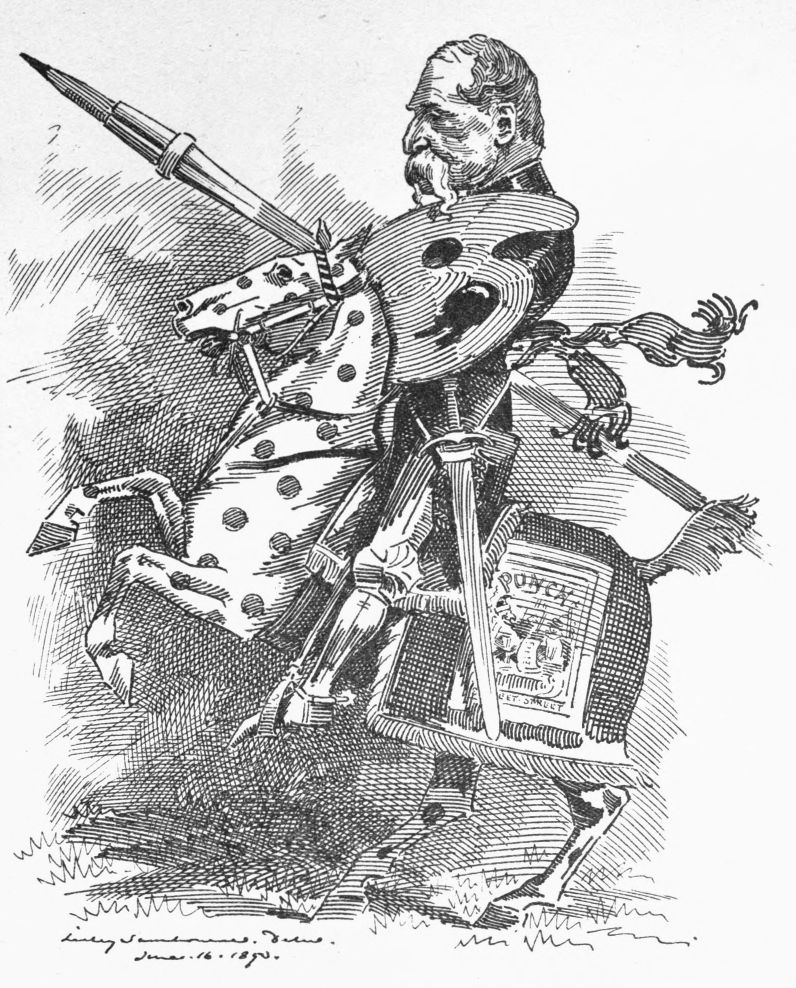

| Sambourne, Linley. The Black-and-White Knight (pen) | 131 |

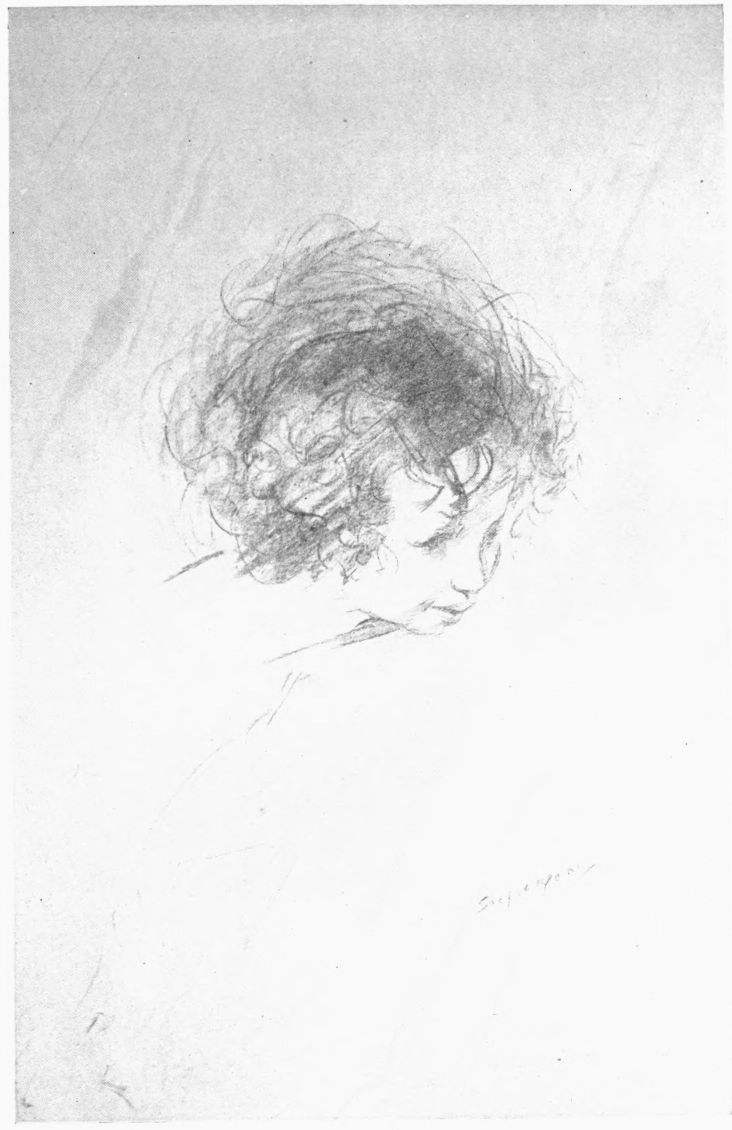

| Shepperson, Claude A., A.R.A., A.R.W.S. The Child (pencil) | 135 |

| Sime, S. H. Pen Drawing | 155 |

| Spurrier, Steven. Pencil Study | 144 |

| Steinlen, T. A. Les Bûcherons (pen) | 172 |

| ““Laveuses | 173 |

| Stevens, Alfred. Pencil Study | 102 |

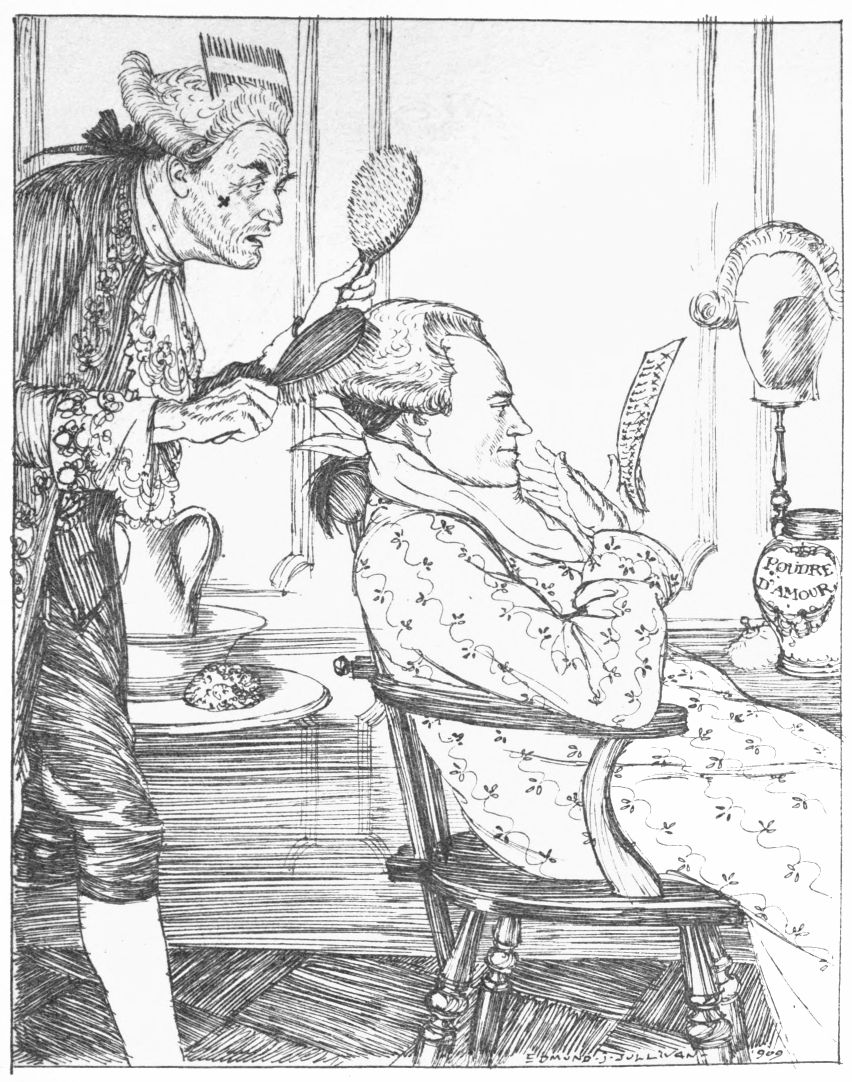

| Sullivan, Edmund J., A.R.W.S. Robespierre’s List (pen) | 145 |

| Tenniel, Sir John. “What’s this?” said the Lion (pencil) | 128 |

| ““Three little Men (pencil) | 128 |

| Tiepolo, G. B. Faun and Nymph (pen) | 73 |

| Tintoretto. Pen Drawing. Photo, Brogi | 59 |

| Titian. Pen Drawings | 38, 39 |

| Tonks, Henry. Pencil Study | 169 |

| Turner, J. M. W., R.A. Carew Castle Mill (pencil) | 90 |

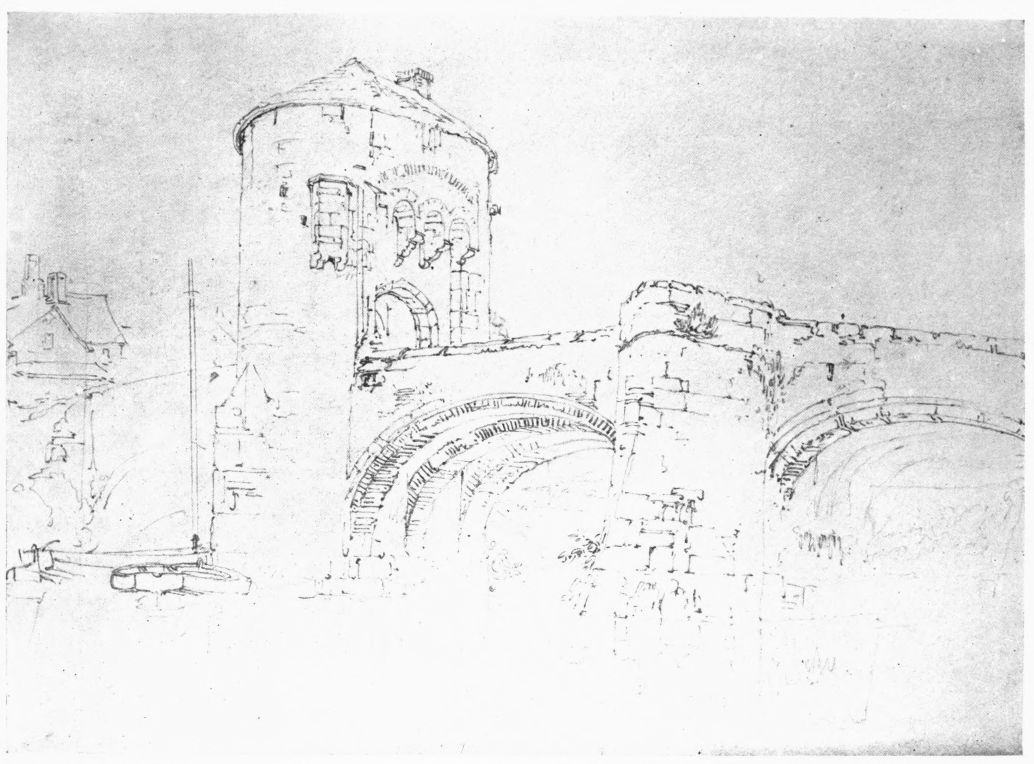

| “““Monow Bridge, Monmouth (pencil) | 91 |

| Velasquez. Philip IV (pen) | 60 |

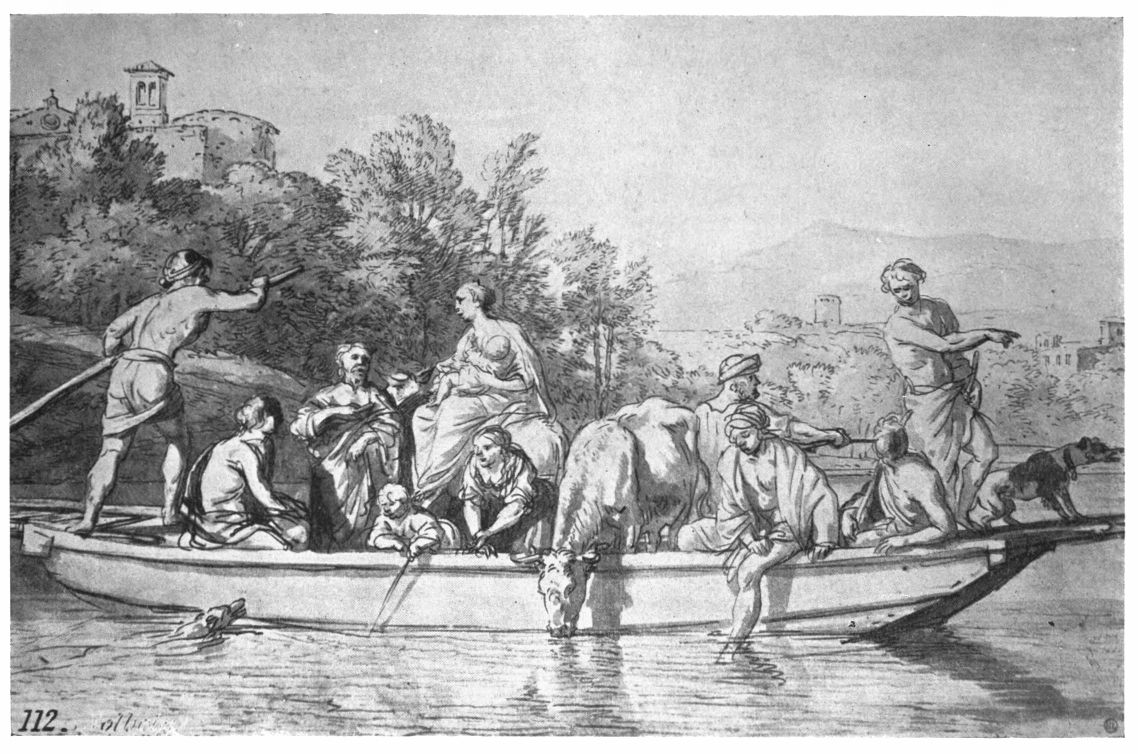

| Velde, Adriaen van de. Le Passage du Bac (pen). Photo, Mansell | 69 |

| Veronese, Paolo. Pen Studies | 55 |

| Verpilleux, E. Pencil Drawing | 153 |

| Vinci, Leonardo da. (See Leonardo). | |

| Visscher, Cornelis. Portrait Study in pencil | 67 |

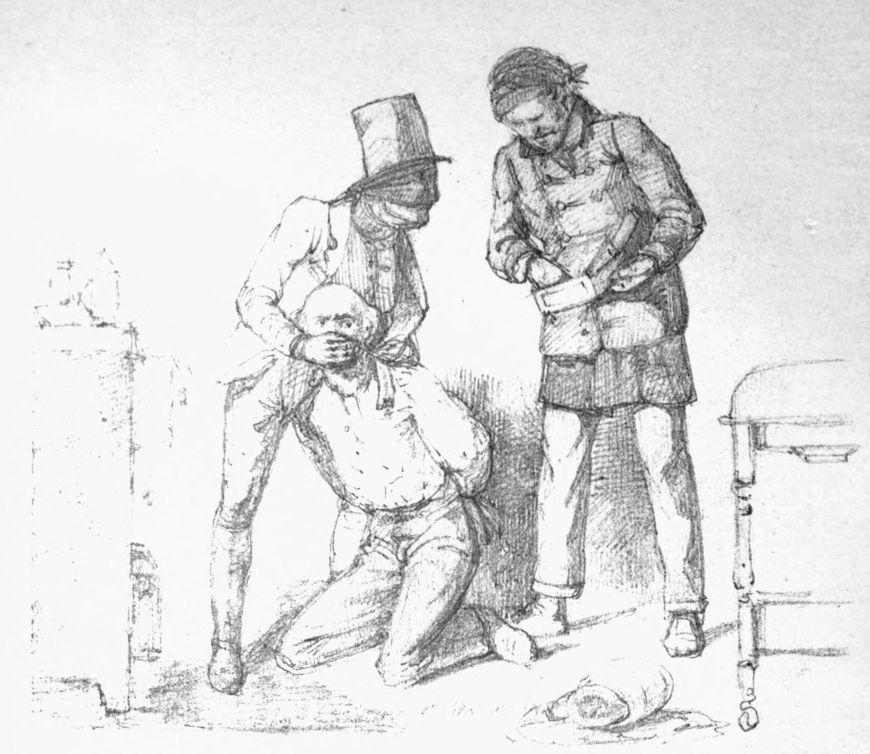

| Walker, Fred, A.R.A. A Dark Deed (pencil) | 112 |

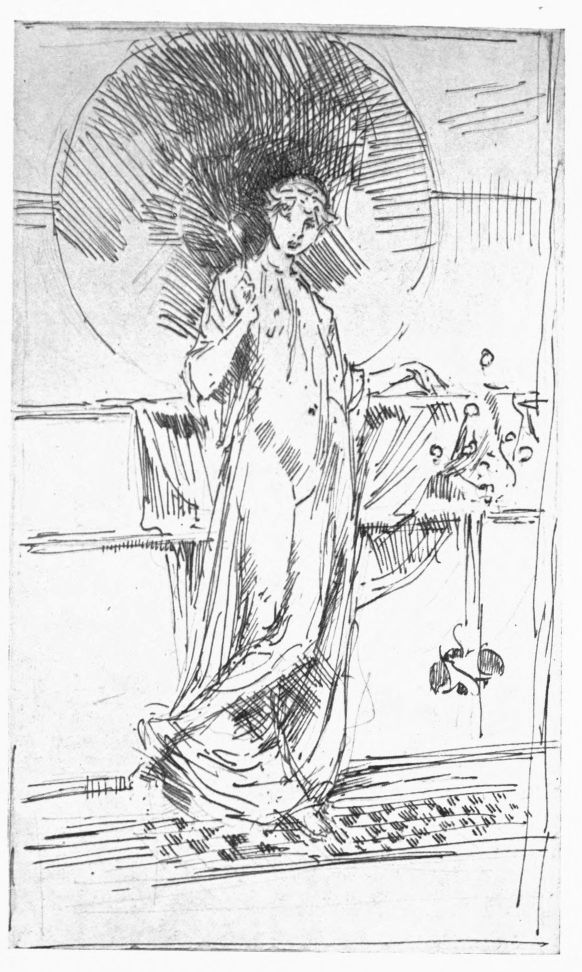

| Whistler, J. McNeill. Girl with Parasol (pen) | 129 |

| Wilkie, Sir David, R.A. The Mail Coach (pen) | 103 |

| Winterhalter, Franz Xaver. Portrait Studies in pencil | 81 |

Printed by Herbert Relach, Ltd., 19-24, Floral Street, Covent Garden, London, W.C.2.{1}

DRAWING is a thing to be looked at and not written about. Pages and

pages written about it will not make a good drawing bad nor a bad

drawing good; nor will they, unfortunately, really equip and instruct

anyone to know the one from the other—should he happen to lack that

subtle sense whereby such things are known; for the reason why one

drawing is justly ranked as a masterpiece while another is thrown away

lies hidden on the plane of our more transcendental perceptions—such,

for example, as the sense whereby we know whether a note is in tune or

out of tune; and further: whether a musical composition is base in its

gesture or great. At present the majority of people lack these senses

but, due to a guiding justice, this fact rarely if ever prevents the

artist who has achieved something great from receiving, though it may

have been long retarded, his full meed of praise eventually. That the

praise is so often belated and the appreciation of an artist retarded

until, for him, it has lost its savour is due to many causes: so long as

the competitive and childish habit persists—of awarding the palm of

greatness to one man’s work by the simple expedient of simultaneously

condemning someone else’s—narrowness and prejudice will continue to

trouble the artist. It should surely not be difficult to realize that

the world of art—like the Kingdom of Heaven—has many mansions, and

that, though both have their “housing problems,” still—in both there is

room for many.

DRAWING is a thing to be looked at and not written about. Pages and

pages written about it will not make a good drawing bad nor a bad

drawing good; nor will they, unfortunately, really equip and instruct

anyone to know the one from the other—should he happen to lack that

subtle sense whereby such things are known; for the reason why one

drawing is justly ranked as a masterpiece while another is thrown away

lies hidden on the plane of our more transcendental perceptions—such,

for example, as the sense whereby we know whether a note is in tune or

out of tune; and further: whether a musical composition is base in its

gesture or great. At present the majority of people lack these senses

but, due to a guiding justice, this fact rarely if ever prevents the

artist who has achieved something great from receiving, though it may

have been long retarded, his full meed of praise eventually. That the

praise is so often belated and the appreciation of an artist retarded

until, for him, it has lost its savour is due to many causes: so long as

the competitive and childish habit persists—of awarding the palm of

greatness to one man’s work by the simple expedient of simultaneously

condemning someone else’s—narrowness and prejudice will continue to

trouble the artist. It should surely not be difficult to realize that

the world of art—like the Kingdom of Heaven—has many mansions, and

that, though both have their “housing problems,” still—in both there is

room for many.

In life the “housing problem” for the artists is acute and vexed—they have to scramble for a place and, in the scramble, if some are unduly praised far more are unduly blamed. Death seems to be the only arbiter of justice for them. In the struggle for recognition none are more unscrupulous and narrow than the artists themselves; with the instinct of self-preservation strongly developed in them they, metaphorically, deal what they hope will be death-blows at all who stand in their way. It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for an artist to be a just critic of his contemporaries. The truth of this assertion is easily tested: ask an artist his opinion of a mixed dozen of old masters—he will have words of praise for all of them and his comparisons will be just and true. Then ask him his opinion of a dozen of the leading artists of his own day—he will not have words of praise for more than two; and if by chance he should still be a student in the schools he will find himself only able to praise one of them; and the remarks he will make about the others will be in questionable taste! Even our most revered old masters gave way to this human weakness. For instance, Michelangelo treated Leonardo as though he held him in profound contempt; especially in a little matter connected with the casting of a bronze. In fact—each paid the other the compliment of jealousy.{2}

The deplorable battle that had to be waged before Whistler’s genius could be accepted is also a good example. In the very forefront of the fight rode Whistler shamelessly wounding, for the sake of his own aggrandizement, his opponents, who were really his brother artists. Viewed at this distance of time it looks a dirty business, and several good artists are only now healing of their wounds. He is forgiven of course, firstly because he was a genius of a high order and secondly because of his wit and the irresistible style with which he handled his weapons; and thirdly because he was, of course, most venomously attacked on all sides himself. It was the power of Whistler’s caustic wit that caused the prestige of our leading art society to become so undermined that, until quite recently, many of our greatest living artists could not face the ignominy of exhibiting there; and to this day one still meets with the bashful student who has to deny himself any visits to its exhibitions!

Fenollosa says: “Art is the power of the imagination to transform materials—to transfigure them—and the history of Art should be the history of this power rather than the history of the materials through which it works.” In the limited size of this book neither the one nor the other history is attempted of European pen and pencil art. Had either been intended the English draughtsmen could not so preponderate in it. That they do so is due to the fact that the book is intended primarily for the English public, and is published in the hope that it may help somewhat to stimulate its appreciation of what its own artists have done and are doing, and what the great masters did in the past.

Drawings have this great advantage—that they convey their meaning instantly. They tell their story more swiftly than a telegraph-form, whereas ideas on a printed page have to be assimilated in the usual processional order. So whoever looks through this collection of drawings with intelligent interest must be rewarded with a share in the vision of many great men on a great variety of subjects. And whether he is conscious of the process or not he must retain some memory of each; perhaps—with luck and other qualities—a very clear memory. For it is a gain, a privilege and a delight to be able to assimilate in an instant the fine idea of a great artist. Surely, too, it must give to the reader a momentary feeling of freedom from the shackles of space and time. My point is that it would take the briefest writer many pages to present to the student of psychology the personality and character of, say, the Earl of Surrey, as they are conveyed to him by Holbein’s drawing—in one coup d’œil. And it would be indeed a long book that gave him as adequate a presentment (as do these drawings) of a hundred different persons, places and incidents by a hundred different writers. For in this book are drawings that will teach{3} him to see like gods, like super-men, like birds, like swashbucklers, and even to see with the eyes of little old ladies. And Michelangelo, in return for a glance, will give him his great conception, and Mr. Bateman will crack ten jokes with him in as many seconds.

But it takes two to establish a work of art—the artist and the other man; and even then the other man can only take from it what he can put into it: Mr. Bateman’s jokes fall flat if the other man has no sense of humour. Michelangelo has no message for the man entirely unfamiliar with fine ideas. The artist can but launch his work of art on the world and hope that the other man will recognize it.

Such diversity of presentment as the collection of drawings in this book gives should do something to inculcate a more catholic appreciation of art than one finds in that unpleasant being—“the average man.” It is the critic’s business to educate the public to that catholicity of appreciation, but unfortunately he may delight in doing the opposite: too often Ruskin’s eloquent writings did but beautifully express his bigoted prejudices. His eloquence succeeded in foisting upon the public as masterpieces—meriting comparison with the works of Titian and Tintoretto—certain banal, third-rate Victorian water-colours. And he is committed to a description of Canaletto as a base painter—because Canaletto painted into a picture what Ruskin considered an unworthy artifice. The critical faculty is to a considerable extent intuitive and sub-conscious, and therefore to concentrate only along a special line of thought is the worst possible training for a critic. However, the English people, having ceased to rely so completely on John Ruskin to do their thinking for them, and growing suspicious of the carping of that most irascible critic have, among other things, discovered the splendid sincerity of Canaletto for themselves. Let us hope that they had the generosity, in embracing Canaletto, to do so without discarding someone else of equal value; but, as a rule, immobile minds cannot take in a new thought without first ejecting some other:—our grandfathers worshipped at Raphael’s shrine; our fathers at Turner’s and we—losing interest in both—have “discovered” Velasquez; the talk in the schools and coteries is of Leonardo and Uccello while Rubens, too, is forgotten or disapproved. Cannot Uccello be great without the depreciation of Raphael! Or must partisan hero-worship be carried on about art in the same spirit as the butcher-boys of rival firms wear light or dark blue ribbons on one special day in the spring!

Surely the real value of art in this world lies in its diversity and infinite variety. The artist’s principal function in the community is that he teaches it to see. This is the great man’s final achievement. So that men who come after him say: “Ah, it was Rembrandt who taught us how glorious a thing is light”; “it was Whistler who showed us the mystery of the evening and the beauty of the Thames”; “Turner who{4} gave us sunsets and Velasquez who taught us the marvel of our physical vision and showed us the very air we breathe.” As each new artist reaches the height of his art our horizon should grow wider and the vision of the world more rich. The new generations are going to teach us the beauty of our back streets and gasometers. Good luck to them, for when they have done it our dullest walks will have a zest!

But Art cannot be of the most truly vital and evolutionary kind unless it is born of national inspiration and has its roots in the social and spiritual life of a people—growing in response to their conscious need and desire for it. We adulate the great Italian artists instead of paying our homage to the Italian people for producing them—as they undoubtedly did, by desiring them; for art was not only a joy to their kings and prelates but a spiritual need to themselves. In such an atmosphere great men were bound to arise to give form to the ideals and emotions of the nation. Other countries have in equal degree made this demand at certain periods of their history; to mention the more obvious—Egypt, Persia, Greece, China, France, Japan. And in answer—great men have arisen to express what were really national ideals in concrete form. The demands of a king and his court may produce a Velasquez; the desire of a city may produce a Watteau or a Sargent; but only the desire of a nation can produce a great school in art.

Religion once held the artist as her most valuable ally and was, invariably, the source of his inspiration in all the greatest masterpieces he gave the world in all branches: whether in architecture, sculpture, painting, or in the lesser arts of carving, illuminating, embroidery, jewellery. For art has ever reached its high-water mark in the expression of religious ideals or in ministering to the needs of a religious civilization: the temples of Egypt, Greece and Ancient India; the paintings of the great schools of Italy, China, Flanders and Japan; the sculptures of the Parthenon and the Renaissance; and even the ju-jus of Africa and Australasia (about the virtues of which Chelsea mimics the adulations of Paris) were one and all oblations to the gods. But Religion in a frenzy of madness drove the artist from her sanctuaries and has not yet admitted the disastrous results of her crime. And all over the world—in the East as well as in the West—the artist has now retaliated and has gone elsewhere for his inspiration (and, incidentally, has turned, for the most part, for his appreciation to the race who are still forbidden by the sacred tenets of their faith to make to themselves “any graven image”). And art is now only the demand of the few.

At this particular point in history—a fact that should give us to think—the peoples of all the world are very far from clamouring to see their ideals given form through art. That many of them have ideals and can formulate their desires this generation has had ample proof; as for in{5}stance it had of the English—in the war. But the English have given innumerable proofs, too, that the desire of the mass of this people does not tend towards the arts—for however many great painters the English have produced the fact remains that our only national art—except perhaps the school of Reynolds and a tradition of landscape painting—is, still, literature; as it always has been. It is nothing to us that a national memorial is not conceived on nearly such large or costly lines as are our drapery stores. This causes us no concern whatever; we get what we want—economy of public money; and what we deserve—unworthy memorials. To the present-day public the function of the artist is of small importance—his work is there to amuse us, to flatter our vanity, to decorate our hideous houses (with which we are well content) and, when he is dead, to afford us the mild excitement of a little speculative buying. With such a point of view we can produce no great school in art. Nothing can change us except we change ourselves. Gallant attempts to change us have been made by individuals: Ruskin, in proclaiming one of the world’s great painters, sought to instil some fire of art into our flaccid hearts—and what happened? We pretended to desire great things; we became sentimental about the “beauties of nature” and our insincere desires produced a school of hucksters—who profaned the work of their master and sullied the beauties of nature.

Where a country has no national art the message of its great men, when they come, has to be completed just so far as they can take it in their own lifetime; for it is carried no further by those who follow them; whereas, when art is national, all its forms “interact. From the building of a great temple to the outline of a bowl which the potter turns upon his wheel, all effort is transfused with a single style,” and the message of a great man may take centuries to achieve its completion and fullness in a progressive unfoldment in evolution.

So many of the greatest drawings of the old masters were done in chalk that it is sometimes difficult to find examples executed in pen or pencil that will bring their work within the scope of this book; but in the Family of Thomas More we have an example of Holbein’s pen drawing which could not be better for our purpose. It is obviously the carefully thought out design for a painting of considerable size and, like all Holbein’s portraits, is a most intimate and searching study of psychology. Composition drawings (and this one is a good example) are among the most valuable to us of all works of art. Valuable because the composition sketches of a great man are generally pure inspiration throughout. In them he has worked too rapidly to be conscious of his method—he has been as unconscious as a writer is of his hand-writing. Napoleon said:{6}

“Inspiration is the instantaneous solution of a long meditated problem”; what more perfect description could one have of a composition sketch, for the artist does, as a rule, meditate a problem for a long time but the moment he finds the solution he sets down his idea with the greatest zest seizing the first thing to hand—generally a pen or a pencil. Moreover, in the first rapid sketch that records his inspiration his mental vision is clear; the interruptions—inevitable in the slow process of painting a picture—having not yet occurred.

This book abounds with examples of sketches done in this way. They may have been done thus, only as a means to an end, but that end is often more nearly reached in the “instantaneous solution” than in the finished picture that follows—though we may prize this for many other qualities.

Rembrandt above all others delighted in setting down his ideas in this way; and there are still in existence nearly nine hundred of these vital drawings of his. I think I shall not be contradicted when I say that the method by which these Rembrandt sketches were produced defies analysis: they are not outline drawings, nor are they drawings of light (like Daumier’s sketches), they are a kind of pictorial calligraphy—as Sir Charles Holmes once pointed out—closely allied to the Japanese method of brush drawing, though they are infinitely more varied and are not a set of symbols constantly rearranged and adjusted for each new problem; as is often the case in Japanese drawings; and also in the case of our modern illustrators—who serve up again and again a few threadbare receipts for hats, boots, facial expressions and so forth. With these draughtsmen the line has all the hardness that one would expect from the use of a metal point; the quill pen is incomparably a more sympathetic instrument than the metal pen, and it is to be hoped that, as methods of reproduction improve (and they are improving) draughtsmen will again take to using the quill.

Rembrandt has shown us that the quill or reed pen can give a more flexible line than any other instrument or medium (except perhaps a brush) that the artist has at his disposal. Even chalk has not quite the same possibilities in this particular respect, because the point is continually crumbling as it is worn away, and the pencil—so suitable for crisp or delicate work—cannot be used for emphatic statement without the risk of happening upon that heavy quality that is so unpleasant.

It is at about this stage that I feel some sort of an essay on drawings and drawing in general is expected of me. However, as I do not expect it of myself it is not likely to happen; and he who does must, I fear, be disappointed. I hold the opinion, as I have already said, that a drawing is a thing to be looked at and not written about and I therefore content myself with the simple statement that a drawing is a symbolic arrangement{7} of marks made by an intelligent person with a pointed instrument on a more or less plain surface. Now, though these three essentials—the symbology, the arrangement and the intelligence of the person—may all be excellent, the question of whether he may claim to be really a draughtsman or why and when he may not be allowed any such claim will ultimately always be decided by the quality of the marks; in a drawing these are more usually curved lines; but to decide whether they have the right quality or the wrong quality is a matter most subtle, eclectic and erudite.

In Manchester, and the north of England generally, business men call an artist’s personal style in drawing and design “his handwriting.” And indeed the phrase has a nice aptness, for the quality of a man’s line in pen or pencil work is as personal to himself and as unlike another’s as is his calligraphy—and, like it, may charm or offend us. However—no one ever has had any doubt about the charm and rightness of the quality of Holbein’s lines.... “These are no imitations of classic suggestion but a new creation on parallel lines ... there are men who can create with the same naïveté and beauty as the Ionians. And let it be noted, too, that these curves ... are the farthest removed in all art from the insipidity of the Renaissance flourishes, which we sometimes teach as a poisonous miasma in our art schools. These are curves of extreme tension, as of substances pulled out lengthwise with force that has found its utmost resistance, lines of strain, long cool curves of vital springing, that bear the strength of their intrinsic unity in their rhythms.” So wrote Ernest Fenollosa—one of the few great writers on art. He was not writing about Holbein, but how well he might have been! What an admirable commentary it makes on the drawings of this master draughtsman—“curves of extreme tension ... cool curves of vital springing.” ... Look at the drawings of the Duchess of Suffolk; Thomas Watt; Bishop Fisher or the Family of Thomas More (reproduced here, p. 29) or any other portrait drawing by Holbein and I think it cannot but be agreed that it is a perfect description of that most difficult thing to describe—Holbein’s line. It must be admitted that Holbein as a decorator seems to have been a different being—“Renaissance flourishes” were then his stock in trade; they sprout from every available excrescence. But most fortunately, in his portraits, he had no use for the flourish; and here we are only concerned with his portrait drawings.

One cannot study Michelangelo without realizing or at any rate suspecting that all presentment of psychology essentially depends upon proportions, subtly observed; and though one cannot expect a master in an art school to allow his pupils to draw the model in inaccurate proportions as a general rule he might, one thinks, occasionally with advantage—say one day a week—order them to decide in their minds first what{8} type, psychologically, they most wish to suggest by the human figure and to think out, then, what proportions would best convey the idea of it—deliberately falsifying, where necessary, the proportions of the model to achieve their purpose. The proportions in a Michelangelo drawing are not, accurately, those in a human figure. But, by a general concensus of opinion, they are accepted as suggesting a psychology more divine than human. This then must have been Michelangelo’s intention. How did he do it. If we cannot learn the secret by studying his drawings we have little else to help us except the following cryptic receipt, that legend tells us came from him, and which has still remained undeciphered—“a figure should be pyramidal, serpentine, and multiplied by one two and three.” Is there any connection between it and the occultists’ formula—“the one becomes two, the two three, and the three seven,” and their axiom that “Seven is the perfect Number”?

The principle of selecting deliberately where the proportions shall be inaccurate to observed fact, for the purpose of suggesting a desired type, is not unlike the principle that Rodin used to convey the idea of action in a figure:—he taught that movement could best be suggested by including in the pose at least two more or less instantaneous positions or movements which could not, accurately, occur simultaneously in a human figure.

That standard of excellence in art—that a picture or statue should “be true to life”—has befogged too many of us. Art is in its essence and in its finality—artificial. And proficiency is nothing if the obvious, the non-essential and the trivial have been relied on to convey the artist’s idea.

Reproductions of Michelangelo’s and Holbein’s finest drawings are usually hung in most art schools—as examples of how to draw I suppose. But, with curious inconsistency, the masters teach their students to do it by a system of straight-line-scaffolding known as blocking in; a method that has never been used by any of the greater draughtsmen, but which was, I believe, imported from Paris in the ’seventies or ’eighties; as an antidote, no doubt, to the “poisonous miasma” that Fenollosa condemns! However, competent draughtsmen are, of course, produced by art schools here, as in other countries in considerable numbers, but it is scarcely a debatable point that what modern art most lacks is tradition. Present day conditions make the old system of apprenticeship almost impossible—students are too numerous and the artists too varied and contradictory in their opinions for any workable system of apprenticeship to continue. The few attempts that are made in this direction usually come to an unsatisfactory end. And so tradition is dead or lost. The system as it was practised in the days of the Renaissance—in conserving tradition—was of immense value to the continuous progress of art; but in these days the student is thrust from the art school into the world to make his way{9}—as innocent of traditions as a newly-hatched sparrow is of feathers. He is equipped with the experience and opinions of his fellow students and the maxims that are the stock in trade of the professional art-master; who—though he is sometimes a real teacher and even an inspired and inspiring teacher—is far more often merely an artist earning his living by instructing his pupils in a system that he has himself evolved, and which he is quite unable to demonstrate has ever been used by any great draughtsman or painter.

To quote an example—no doubt an extreme case but a fairly typical one—the student will be shown, as I have already said, a fine Holbein drawing, and urged to emulate and study it with the closest attention; but to do so he is given a blunt stick of charcoal and a piece of white machine-made paper and initiated into a system of indicating measurements and directions with heavy black lines. It is implied that all the great masters began their careers by working in this way though, for obvious reasons, no proof of this can ever be produced. It is further implied that if he will apply himself to the art-master’s method with real zeal he will in time be able to produce drawings like Holbein, Ingres or Leonardo. If the student is a natural draughtsman he invariably breaks away from the art school’s set of rules; and the master generally has wit enough to let him go his own way. But the others—well the others generally learn later in life with some bitterness how they have been duped; unless they have had the good fortune to be the pupils of Mr. Walter Sickert or Professor Tonks—who both really have traditions from the old masters.

It would be wiser and better that the proprietors and governors of most of our art schools should say frankly—“we cannot teach drawing as the great draughtsmen were taught, we teach a fairly serviceable method of drawing which it must be clearly understood is intended to be painted over.” However—their system of teaching drawing seems to be much sounder than their system of teaching painting.

At this point I want to say too, that though the word “rhythm” is often uttered in the schools very little that is useful or illuminating is taught there about this most subtle and essential quality in art. Essential in drawing, in line, in spacing, in chiaroscuro and in composition. It is always present in the work of the greater masters. Curiously enough, too, it is often the one quality that causes a lesser man to hold rank among them. A drawing can hardly be stated by one line, usually it needs many, and rhythm is the principle whereby the draughtsman can make a number of complex statements in a drawing synthetically an harmonious whole. It is by rhythm that every line is related to every other line: they have the same relation to each other on the paper as dancers have one to another in a ballet. When a ballet—such as The Humorous Ladies—has been danced to its conclusion, though there may{10} have been many movements, each and all were in sympathy with each other and with the main theme.

Rhythm is, I think, the secret of the charm or power in the work of artists as widely different as M. Leon Bakst, Lovat Fraser and Claude Shepperson.

The modern art school seems to be a sort of clearing house for the elimination of the student who thinks the life of an artist more attractive than—say—life in an office. This type predominates in practically all art schools. He (or she) is intensely serious about being an artist, but is not seriously interested in art. After a period more or less prolonged, this kind of neophyte discovers that the work of an artist is not materially assisted by sombrero hats, flowing ties, bobbed hair, corduroy trousers, fancy-dress dances, views about free love, all night discussions about ethics—and so on, one need not continue the familiar list. Having, I say, discovered that the most assiduous cultivation of these exciting manners and customs does not constitute the life of an artist this neophyte drops out of the race, as far as the art world is concerned, and disappears. Years of hard work and perhaps actual privation were not in his contract with the Muse, at least—he did not notice the clause! If that hard-work business was the game then no candle was worth it! Is there any harm done. As far as the unserious student is concerned, I suppose there may have been some good, but his effect on the art school is wholly bad. It makes anything approaching to the old system of apprenticeship impossible; and we have any number of proofs that this old system was the right one.

Whether art is national or personal in its message there is no doubt that its artists are a peculiar people; they consist of two kinds (but many sects): one—the craftsman—has a mission to create exquisite things and the other has a mission to see exquisitely and to teach others to see exquisitely too. It is not possible to predict what new thing the craftsman will next make beautiful or what new thing the artist will next interpret as beautiful. They are inspired by a spirit that bloweth where it listeth. How great the power of this spirit in us still is is proved by the astonishing number of unlovely things that have been lately revealed to the world as beautiful, through the mysterious alchemic process of this spirit of vision working in the artist. But the spirit of inspiration did not always work thus. Some centuries ago—when we had not so long emerged from Greek thought and the influence of Plato—the process was almost the reverse. It required that the artist should first see beautifully on the plane of ideas some mental conception and then give it birth in a material form. In those days the æsthetic sense was the guiding intelligence that moulded man’s civilization and environment. In other words art produced the environment that produced the artist. Communing with the spirit, the artist, looking inward and not out, sought his sub{11}ject in his own mind or soul; and only through his art did it become an objective reality for others. But now, to-day, the æsthetic principle no longer moulds our civilization; has but a negligible influence even on our thought and no effect upon the practical affairs of life. We train our workers to live and labour without a knowledge even that such principles exist or that in past ages such ideas controlled the growth of nations.

That era is now closed, for “no phase or school of art in human society, however beautiful, but contains within itself the germs of its own destruction.” From the beauty of the past comes the grim battle-field of to-day—where we wage our keen struggle for existence. Governments cannot be taking architecture seriously when they are too out-at-elbows to find housing accommodation for their populations—even in thea meanest huts. And so it follows that their smaller buildings—such as their post-offices, labour exchange bureaus, etcetera—are quite unashamedly practical; in the most commonplace sense. Meanly designed and economically executed to the lowest contractor’s tender, ignoring even the simple, strong beauty that can be achieved merely by mechanical efficiency (except recently in a few local housing schemes) they hedge us about on all sides against the old æsthetic sense. Dimly we are aware that we have lost that guiding intelligence—the spirit of art—that lighted the path for our forefathers; and shamelessly we ignore all the wealth of tradition we inherited from the preceding eras of their greatness.

And the artist—has lost his inner vision. And in his place a new one has been evolved; one who is equal to the task that we have set him: he paints—not ideas but—life as he finds it; he paints experiences; he records emotions; if he receives a visual shock—he cannot make enough haste to do a picture recording it; for to him it is a psychological experience and therefore supremely worth recording. We here set him about with evils and surround him with the sordid and ostentatious; the spirit working in him by a new alchemy has called evil good; what will happen to the world if he should forget and call good evil! Let us hope rather that the spirit of vision—guiding him now to look outward on the visible world for his subject—will inspire him to penetrate the darkness of the æsthetic desert we have set about him; and that—again communing with the spirit—he will give us—not, as before, ideals from his own mental psychology but—see for us and reveal to us finely the mass-psychology of mankind. But it is not possible to prophesy what the art of the future may be that mankind of the future will approve.

France has now no national art—save her sense of humour (and we all know to what she turns infallibly for stimulation in that!) but she does know a great man when she produces one; nor does she confound him{12} with a lesser artist, however much excitement she may indulge in in making a passing fashion of the latter: her pride in Puvis de Chavannes does not waver. She has recently had some men of genius, and they are typically French, but can we accept them as having founded a national art in France? No—for we experience the fact that the truths that Cézanne, Van Gogh and Gauguin came to teach are no truer for restatement by their disciples, nor have they been further illuminated for us by the endless repetitions of their personal conventions. But the astonishing fact is now being daily insisted upon by some among us that the art of these Frenchmen is national to England!

England once came near to having a national art—in the school of Reynolds, Gainsborough, Romney and Lawrence. At any rate their work, reproduced in coloured-engravings by men almost their equal, did reach the people in response to their demand for it and so became at least a national tradition; brilliant but all short-lived.

Ultimately it is the love of the people that alike crowns the king or acclaims the artist, and until this happens no artist can be sure of a prominent rank among the great; however much seeming popularity he may enjoy in his lifetime. But there are reasons why an artist is sometimes not given the rank he deserves until long after he should be—apart from those supplied by the uncatholic point of view engendered in the people by lack of education and the jealousy engendered in his contemporary artists by their struggle for recognition. For instance—he may complete very little work; or else his work may not be seen or known except to a few private collectors and dealers, who are wisely but selfishly exploiting it commercially; thus the recognition of his work by the public may be retarded, for the simple fact that it does not know of its existence: as in the case of Joseph Crawhall, who, when his work is known, will undoubtedly be given the high rank he deserves and become as famous to the public as he is now to the collector. I do not hesitate to prophesy this in spite of the fact that I once heard one of our best known critics state with considerable fervour that he wished Crawhall had destroyed all he had ever done instead of only what he did destroy (probably nearly or quite half his work).

An artist as a rule lives by selling his work and though the fact that works of art are articles of commerce may delay or accelerate the verdict on him it will not ultimately affect it. These things are on the knees of the gods; for though he, in his lifetime, may receive from educated people a concensus of approval, posterity may yet reverse the judgment. He may have been approved because his work was bought, and his work may have been bought for much the same reason that some persons back horses. In fact there is a certain resemblance between the two. In the{13} art world, as on the race-course, the favourites are obvious and expensive; and, to continue the analogy, outsiders have a most unexpected way of turning out to be winners. But here the analogy must end—for a dead artist may be a little gold-mine whereas a dead racehorse is merely cat’s-meat. Michelangelo is still a winner: it is interesting to know that reproductions of his drawings are, to-day, sold in far larger numbers than are the reproductions of any other man. To the student of drawing he is still a god and, because of his superhuman ability to draw, he lives in the student’s mind in a divine halo.

With regard to works of art considered as speculative investments I offer the following advice: be sure you know a good drawing when you see one, and buy a man’s drawings when he is young. To wait until he has proved himself as a painter before accepting him as a draughtsman is, economically, a bad principle. He—the now arrived painter—will multiply the original price of his early drawings by twenty and pocket his just but belated reward. Belated, because it would have been far more valuable to him in the early days of his career to have sold the same drawings for smaller sums when, probably, money was hard to come by and may have meant much in the completion of his training. And the drawings will probably be as good as any he will ever do; for, later in life, when drawing is practised with a view to painting, the results are generally more summary and, though frequently more masterly, they seldom have quite the same sincerity as those done early in life, when—as a rule forbidden by his teacher to paint—he will put into his drawings the whole of his best endeavour and aim at creating a drawing that shall be a complete work of art in itself; with the result that these early productions are often “arrived” works of art, with a special beauty and interest of their own, even before he has emerged from the student stage himself.

There are many instances of this among the old and modern masters. Among the latter there is Mr. Augustus John, who, while still at the Slade School, produced drawings that proved him to be a great draughtsman; and though his recent drawings may be the product of maturity—they may be finger-posts, as it were, to new and original fields of art—they have demonstrated the fact no more forcibly than did his early work.

Certain collectors, of course, have been fully alive to this point about the work of young artists, and those who acquired some of the early drawings of our greater men a few years ago must now be congratulating themselves on their discernment; also on their astuteness—for they probably acquired these masterpieces for absurdly small sums.

It is the public rather than the collector who has been slow to realize the decorative value and charm of drawings. Is it confusing them with the large, bloodless engravings of the Victorian dining-room? If so, it is a pity; for drawings are a most fitting form of wall decoration for small{14} rooms: in their slight suggestion of subtle colour they harmonize admirably with plain distemper walls—decorating without being obtrusive—they take their place quietly in the scheme of the room.

But to return to the old masters.... Dürer’s work is essentially and typically German, and reveals the old German spirit at its best—as it was in its romantic age before Luther. To study Dürer’s drawings is to become convinced of the truth of mediæval legend: mystical symbology—in passing through the crucible of his mind—issues thence established as historic fact; and it would be as true to say of him that historic fact—passing through the same crucible—becomes mystically symbolic. In everything he did one feels that the primary interest of each drawing for him lay always in a metaphysical, religious or philosophical idea. In all of them there is what Whistler condemned as out of place, in a picture, and called, “the literary quality.” If Taine, the Frenchman, be right, he puts Whistler’s argument out of court; for Taine is convinced that the artist’s whole raison d’être and mission is to present and interpret to the people in a simple language that they can understand the philosophical and other ideas they desire but cannot formulate for themselves. Under the old spirit of art the artist undoubtedly did recognize this as his mission, whereas to-day he often contents himself—like the modern playwright—by presenting the people with problems, in the hope perhaps that they will supply him with the solutions at which he has not yet himself arrived; and by believing that the intellectual exercise involved may be as educative for them as were the methods of the earlier masters. At any rate Dürer’s works stand as a formidable monument to the rightness of Taine’s theory. Certainly in the art of illustrating ideas it would be difficult to find anyone to surpass Dürer; or to surpass him in his fine sense of how to decorate a page. But throughout his work one feels a lack of any sense of humour; and also, perhaps of spontaneity. If genius is an infinite capacity for taking pains—then Dürer was a genius. In all his work there is an immense sincerity; and this carries him to great heights in some of his religious drawings—for instance in that superb wood-cut of his of Christ praying in the Garden of Gethsemane.

It would be misleading to say that there was much in common in the outlook of Dürer and Leonardo and yet I am tempted to point out that there was a certain similarity, in spite of the fact that the vision of the latter was infinitely more gracious; at any rate they both included caricature and architectural draughtsmanship among their arts; and both were interested in mathematics and science.

What a strange race of supermen might be evolved if science and art could combine to give birth to a progeny in which the essence of both were equally mingled. Once upon a time by some miracle of the Gods{15} and Muses such essences were so mingled, and a son was brought to birth whose doings were an astonishment and delight to his contemporaries and whose work was a record and proof of the success of the experiment. But the experiment was not repeated, and one may hazard a guess which Muse it was said “A most successful and unexpected result; add the data to the sum of human knowledge and let us proceed to the next experiment on our schedule!”

And the most artistic of scholars and the most scholastic of artists remains a lonely figure, for whom we can find no comparison: a fascinating enigma for the race.

He not only astounded and delighted his contemporaries but each succeeding generation; nor have we yet measured the extent of the knowledge materialized in the work of Leonardo da Vinci.

The creative artist is not satisfied with an intellectual grasp of a truth, for his aim must always be to translate abstract ideas into form; to clothe his thought in a visible or aural body. To the mind of the scholar, though, he must appear a most practical, almost utilitarian being—one who does not regard the acquirement of knowledge as an end sufficient in itself! Leonardo da Vinci combined in his personality the genius of both types. His scientific drawings are full of the finest æsthetic feeling; his æsthetic drawings are a marvel to the scientist. He had a passionate love of research, and the fact that he left so few completed paintings must be attributed to his having devoted so much of his energy to research. He did, however, leave great numbers of drawings that, by common consent, are ranked among the greatest achievements in art. They are the unique records of one of the noblest minds the race has produced—that of a supreme master of creative art.

I always think of Daumier as of a man going through the dark and crowded streets of a city holding a lighted lamp and thrusting it into dusty corners. And of him shaking with Gargantuan laughter—while he watches the antics of the strange people he discovers—and penetrating with a glance to the very depths of their pathetic and ridiculous souls. But while his pencil mocks them his great heart loves them!

I have heard it asserted that Daumier drew like a sculptor, but I think it would be nearer the truth to say that in his finest drawings he is concerned first and last and all the time with light. For him this was scarcely a limitation: the light rays are gathered by the point of his pencil and fixed—by some alchemic process of his will on the paper—to glow there for our satisfaction as long as his drawings endure. Whereas, in a sculptor’s drawings, light is but a means to an end (he would carve the paper if he could!) he throws lines like measuring cords round the form—each a statement of some measurement of contour—and having established in this way a mass, he is able to take from it the elevation of{16} all subsidiary and related forms with, one might say, his mental calipers. A process of drawing widely different from that practised by Daumier.

One cannot help feeling that, to this aristocrat of French artists, a display of emotions in a drawing would have been a most unclassic and plebeian sign of weakness. And one seems to know that in Ingres’ art of pure unemotional drawing—his eye measured, his brain commanded, his hand obeyed and the pencil glided from one position to the next by the most direct path, a curve so slight as to be almost straight; leaving its grey immaculate line to prove its absolute obedience to the draughtsman’s will ... and so the drawing would grow without an unnecessary stroke or a correction; simply the unfoldment of a preconception carried out according to plan and justly recording his penetrating analysis of a subject.

The guiding star and strength of Ingres’ genius was his conviction that he could not err.

M. Anatole France tells a characteristic story of an encounter with Ingres in his own youth:—he was at the opera one evening, the house was full and not an empty seat was to be seen. Suddenly an impressive looking stranger stepped up to him and said “Young man, give me your seat—I am Monsieur Ingres.”

How consistent the great man was! From his earliest youth he appears to have never doubted himself or his work; there was calm assurance in everything he did.

Elsewhere in these notes I have referred to the fact that artists often do their finest drawings early in life, and here we happen on one of the young men of whom I wrote: Ingres did some of his finest drawings twenty or thirty years before he painted his most famous pictures. That marvellous drawing—The Stamaty Family—is dated 1818, and the Lady with Sunshade—as perfect a portrait drawing as could well be imagined—was done in 1813; and many fine drawings earlier still; whereas his famous picture La Source was painted in 1856, and many of his best known pictures were done in the period between 1840 and 1866.

Cotman is another man of whom one feels tempted to say—in studying his work—that one cannot see any signs in it that he ever mistrusted the rightness of his aims and methods. It is customary to write of Cotman’s life as both unhappy and unsuccessful, but instead it should be borne in mind that he did have success of the best kind—he was immensely successful in painting what he wanted to paint; and no artist can have a success more dear to him than that. His methods were most consistent, and so it is probable that—disgusted with a world that only required his services as a drawing-master—he pursued his own way and managed to be as happy as any other genius in the practice of his art.{17}

Until very recently his name was generally mentioned with three or four of his contemporary water-colour painters—as though there were not much to choose between the batch; but gradually the weight of public opinion is proclaiming the conviction that Cotman was a head and shoulders above the group with which he has been catalogued; and year by year the appreciation of his work grows in volume. His position, however, is still not recognized as, I am convinced, it will be in a few years time. His method of painting was so widely different to Turner’s that the public and the critics—dazzled by the sunsets of “our greatest painter”—have been slow indeed to recognize the originality and distinction of Cotman’s genius. As a draughtsman of landscapes he excelled in lyrical beauty and perfection of technical accomplishment; but his paintings should be studied with his drawings, for it is in these that he showed his real originality—producing paintings that are comparable, as decorations, with the prints of the greater Japanese wood-engravers; and at a time, it should be remembered, when these prints were unknown in Europe.

“He became a sort of household word”—so wrote Mr. Robert Ross in his readable little book on Beardsley.

A description of Beardsley’s reputation more wide of the mark I cannot imagine. Beardsley is really one of England’s “skeletons in the cupboard.” The average Englishman is somewhat ashamed of Beardsley as a fellow countryman, he feels there has been some mistake—the fellow ought to have been a Czecho-Slovac! To think that the year 1872 (a most respectable year!) should have brought to light this utterly un-English phenomenon is not pleasing to him. I have seen more than one young English student embarrassed and somewhat annoyed when an enthusiastic Frenchman has congratulated him on being a compatriot of that “great genius Aubrey Beardsley.” All the world over Beardsley is still “caviare to the general” and particularly to the English general. He is acceptable enough when his ideas are popularized by other artists: throughout France and America whole schools of present day illustrators are founded on his work; and he is rightly acknowledged as the “old master” of mechanical line engraving. He was the first artist to understand really and utilize to the full the possibilities of this process of reproduction; and—as so often happens with the first man to use a process intelligently—he carried it further and found it less restricting than any who have followed him.

Beardsley had an immense power of technical invention—like Hokusai, he was able to bring any subject of his choice within the scope of his convention, and to render it in a way that was perfect for the process by which his work was to be reproduced.

There is an ironical beauty in everything he ever did, and his com{18}positions—regarded as an adjustment of spaces—are more consistently original and daring than those of any other Western artist, old or modern; only in the East can we find his equal in this particular expression of creative art.

The shock that Beardsley gave to British feelings was, I fancy, due far more to the intrinsic originality of his compositions than to the “nautiness,” imagined or real, in his drawings, about which we have heard so much. It is surely a case of honi soit qui mal y pense, for there is nothing in the books of drawings by Aubrey Beardsley that are published in this country that could offend a school miss.

Mr. G. K. Chesterton’s Father Brown says in one of his adventures “Its the wrong shape in the abstract. Don’t you ever feel that about Eastern art? The colours are intoxicatingly lovely; but the shapes are mean and bad—deliberately mean and bad. I have seen wicked things in a Turkey carpet.” Well, Father Brown’s remark is illuminating, for not only are there wicked shapes in Turkey carpets but, however “beautifully seen” the rest of a Beardsley drawing is, the drawing of the faces in it is often deliberately mean and bad. But I think, also, that it would have been more just of Father Brown to have completed his remark with the “finish” that “is an added truth” by saying that he had never seen a wicked shape in a Persian carpet. This generalization about Eastern art and “the wrong shape in the abstract” makes one fear that perhaps the champion of Mr. Bateman might be no friend to Beardsley; and I regret to think that Mr. Chesterton might not champion Eastern shapes; or Beardsley—though I can understand his not doing so: I venerate him as the British lion and therefore it seems but natural that he should wage perpetual war against the unicorn—and doubtless he might regard Beardsley as a fabulous beast. The British feeling is strong about shapes—an Englishman likes to recognize a shape instantly; should he fail to do so he really is extremely uncomfortable and affronted and will, as often as not, turn on the creator of the “wrong shape” and accuse him of ungentlemanly conduct.

At any rate the British public has always accepted as final Mr. Punch’s opinion on matters of humour. He has given it an almost unbroken tradition—which is more than can be said of any other institution of English art—and it is grateful. When he imported from Australia the brilliant draughtsman Phil May it took the newcomer to its bosom without any hesitation—and he has nestled there ever since. But the artworld—so-called—though on quite good terms with Mr. Punch does not always accept his opinion unquestioned: it has been known to make invidious comparisons between his paper and Jugend or Le Rire, and has even gone so far as to attempt wit at his expense; as in the case of the gentleman who said Punch is “written by Mr. Pickwick, for Mr. Pick{19}wick about Mr. Pickwick”—which was rude and surely lacking in the deference due to our elderly purveyor of humour! However, in the matter of Phil May, Mr. Punch scored handsomely, and persons, even with the highest brows, have accepted his drawings con amore.

Phil May’s drawings look the most spontaneous things imaginable—and no doubt this is true of their humour—but his method of drawing was an elaborate process of elimination. The execution of a rather finished pencil drawing was the first stage of his work—in this he elaborated all the characteristics that his keen eye and ready humour had observed—and the final stage was calligraphic in character and displayed his genius for simplification. With a few deft strokes of the pen—disposed with an almost uncanny knowledge of essentials—he made what appeared to be—when the careful pencil work was rubbed out—a most spontaneous sketch. In truth, it was no such thing, but an intellectual exercise in the eclectic art of elimination arrived at by means exactly opposite to those usually employed by artists who seek spontaneity in their work. Phil May understood the English people and they understood Phil May. His humour synchronized with the public of his day—as did the work of Rowlandson in another age and probably, like his, it will be prized as a record of a period, as well as for its intrinsic value as the work of a most original draughtsman.

The witty line is most often the brief line, but though Phil May’s line was not always a brief one it never failed to be a witty one.

The Englishman has probably the finest collection of drawings that has ever been brought together in one place. It is housed in an excellent museum built for its accommodation and placed in charge of the finest experts that can be found. It is further ordained that if the Englishman wishes to inspect his treasures he shall do so in the greatest possible comfort. No guest of a Sultan could look at his host’s collection of, let us say, Persian miniatures, in more luxury than can the-man-in-the-street look at his own collection of drawings in the Print Room of the British Museum; patient and courteous persons wait on his every whim; and expert opinion, should he require it, is imparted to him without a smile or hint of impatience at his ignorance. In short, everything is done to coax him to a study of his collections except one thing—and that is to inform him that he possesses these treasures.

I think the attention of the Trustees of the British and other Museums might be drawn to the fact that the-man-in-the-street cannot know about his priceless possessions unless someone informs him. The assumption that the information is imparted to him in early youth by his parents is erroneous. He may well live and die, and frequently does, without knowing what the words Print Room stand for. The question of how to inform him if he does not know might be left in the hands of{20} one who is an expert in the art of reaching his intelligence. True, the notice boards of our Museums might then assume a somewhat jaunty air, offensive to the grave habitués—this is what might greet them and what they might not like: “Come where it’s always bright! Free! Now showing all day in the Print Room. The finest collection of drawings in the world: Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci, supported by an allstar company of draughtsmen! Central heating! Perfect ventilation!” But the habitués would doubtless come back to their haunts after a few days’ disgusted abstention from their habits and—what is more important—the-man-in-the-street would now be the-man-in-the-Print-Room.

I am aware that the subject I am required to write about is Pen and Pencil Drawings, and I have faith that I shall come to it but—being filled with a desire to write about chalk drawings, charcoal drawings, paintings, the-man-in-the-street, and all manner of things relevant and irrelevant—I need to remind myself of it. Even then I may come to my subject by a route not unlike that taken by Mr. William Caine in his essay on Cats: he began, he continued and he went on to the end in an unbroken eulogy on dogs and their admirable qualities viewed from all angles, and then summed up and dismissed his subject for ever with this line: “Cats have none of these characteristics.”

I shall, then, continue my aberrant course with the remark that I am constantly struck by the fact, in most exhibitions, that in half the pictures there either the subject is too small to deserve a picture or the picture is too large for its subject. The first is an error of taste and the second an error of scale.

The pleasure we derive from a sense of the fitness and rightness of the scale of a picture may be only common-sense but it is certainly lacking in many painters, especially in the average painter of modern “exhibition pictures.” In these so often there are great spaces of merely tinted canvas which serve no really useful or legitimate purpose; and do not even contribute to the scheme of the picture as a decoration. Sometimes, possibly, this coloured canvas may suggest a sense of space and bigness but it is a rather obvious expedient and it fails to be impressive if one compares it with the sense of spaciousness that has been conveyed to one often by a few square inches of paper in a drawing. Fortunately, as a rule, big pictures nowadays are generally painted for exhibitions—just as fat-stock is reared to be shown at a particular agricultural show: the show over—the fat-stock is hastily conveyed to the nearest butcher. But the fate of the big picture is rather mysterious and I will not suggest what I think really happens to it, for after all I may be quite wrong. Certainly in France though, where the output of big pictures is double or treble that of this country, their post-exhibition fate is fairly obvious: the great majority of French houses are incapable of accommodating these Salon triumphs, and it is the rarest thing to find one of these huge canvases in the houses{21} of the rich and ostentatious bourgeois. Happily for the draughtsman he is not tempted to work on the heroic scale so that—when the swing of the pendulum may have placed his work temporarily or permanently out of fashion—his work can usually be accommodated in a portfolio; for the size of a drawing is generally regulated by the medium employed. However, as genius may ignore custom, habit and even existing rules of good taste, someone—with a right to the title—may come along and do silverpoint drawings on ten-foot sheets of paper—just as a famous modern etcher is doing plates of a size absolutely forbidden by the professors, and yet everyone—except a few contemporary etchers—admits them to be masterly.

The official picture could and should be a human document, but this it can hardly be if all humorous side-lights are rigidly excluded in it—however serious the affairs it purports to present. The old masters knew human nature, therefore in their paintings of ceremonial affairs they did not forget to touch delicately on its weaknesses, even sometimes accenting these as comic-relief. Though I would not be so rash as to suggest the desirability of comic-relief in our official pictures, I am tempted to think that relief of some kind would be well received.

Another point about the official picture is that it is generally very large and is, as a rule, about the dullest product of the brush; for the average modern painter when called upon to perform in this way generally becomes simply overwhelmed with deep seriousness. He designs his picture in the most pompous and formal manner and produces results either boring or unintentionally funny, which latter is perhaps the more tolerable.

Not so with Sir William Orpen—his keen sense of humour is apparent in all his work, whether he is painting tone studies of mirrors at Versailles or drawing his friends on the rocky coasts of Ireland. It is one of the many charms that delight us in his work and does not detract an iota from its distinction and importance. Some of his exquisite drawings are reproduced here, and though the full purity of the line cannot be retained in reproduction they are some of the perfect things in this book.

It is a relief to find oneself thinking in terms of “perfection” about the work of any man so modern as Sir William Orpen. Because, of course, where the modern draughtsman and painter—as is so commonly the case—despises his materials and scorns technique it is impossible for one to do so. The mind—which is so much the product of the senses—must know distaste where the senses are repelled. One may forgive him because of other merits in his work, but the merits have to be rather splendid to cover sufficiently such sins. To Whistler and the stylists who have followed him much of their inspiration must have come from the materials of their craft. One is grateful that they grasped this truth that{22}

the English Pre-Raphaelites also missed—that rare and delicious qualities in the handling of a medium best present to the mind rare and beautiful qualities in nature. In this sense Mr. Philpot is essentially a stylist—one feels that to him the intrinsic beauties of his medium form an appreciable amount of his inspiration: that—quite literally—common oils and varnishes can be blended to a golden elixir for his use. For the materials of his craft are for the artist what he chooses to make them: a piece of red chalk in one man’s hand is a lump of hardened mud, conveniently sharpened to a point for making marks on paper, while, to another, it is a precious substance mined from the earth in some distant country and prepared with infinite care, and he knows that one touch of it on a paper—most carefully chosen—can be the basis of a delicious colour-harmony; that ink can flow from a reed pen in a line straight and true or run its course with subtle modulations—as a little stream flows from the hills.

A lead pencil after all can be only the bitten stump on the office boy’s desk—an instrument for unseemly writings or obscene scrawlings; or it can be a cunningly wrought stick of plumbago encased in a scented cylinder of cedar—such a thing as Leonardo would have loved. Is not the artist capable of an alchemy that can change dross to gold!

The rewards of the successful artist are many and varied, but the most coveted, surely—and the least often secured—is the reward of international fame. The list is not long of the English artists who have achieved it—indeed it is unjustly short. The English are, themselves, always generous in their acceptance of foreign artists—even to the neglect of their own; in this they are unlike other nations, particularly the French who, though slow to acclaim foreign artists, are loud-voiced in praise of their own home-grown products. But Mr. Brangwyn’s name, in spite of this, stands high in Europe. It would scarcely be an exaggeration to say that his work stands for English contemporary painting half the world over.

An artist who is painting for an international public distributed in all parts of the world is not likely to bother himself with artistic party-politics, and it is noticeable that Mr. Brangwyn does not move with the ebb and flow of opinion in London. He is not a fashionable painter and is not ever likely to be. In another age his art might have produced a new school.

There have, it might be said, been two Rubens in the history of European art. The first was Peter Paul and the second—Brangwyn.

Rubens (Peter Paul) has been out of fashion since Mr. Sickert made Tottenham Court Road delightful by teaching us how they paint in Paris, but Venice seems more interested in how Mr. Brangwyn paints in London.{23}

Fine draughtsman as Mr. Brangwyn is, his drawings always remind us that he is a painter, and a decorative painter. Curiously enough though, they scarcely suggest a reserve of strength, in fact on the contrary, for everything that Mr. Brangwyn has to say is stated—whether in painting or drawing—with the utmost energy and vigour of his capacity. He gives generously, freely, without stint from a full brush—he draws from the shoulder as it were; and that his aim is the decoration of large spaces in architectural settings is always apparent in his work; and that this is its usual destiny should be remembered when his drawings are being studied. It is through the medium of his drawings and sketches that we have, in these days, to study Mr. Brangwyn’s art, for the large decorations—destined for public buildings in other countries—on which he is constantly engaged, leave England (as a rule) without being exhibited. Doubtless we can add this loss to our list of grudges against the officials of the painting world, for the public have long ago realized the importance of Mr. Brangwyn’s position and are justly proud of him. The psychological interest of his figures is of a basic and standard kind and generally full of suggestion of forms personal to his own art.

The difficulty with Mr. Bateman is to take him seriously. Really he is a most serious phenomenon—and yet the bare mention of his name sets us chuckling in happy reminiscence and digging each other in the ribs in cheery anticipation of jokes yet unborn.

It would be doing him but scant justice, really, if we were to give him some honorary degree—called him Dr. Bateman and sat him in a “chair” at one of the Universities as Professor of human psychology. Instead we just go on buying any paper that he happens to be drawing for—and laughing. But the day may come when he might turn round on us, wearied of our interminable cackling, and say “Cry you devils, cry!” and then we shall be sorry—but we shall cry all right: a few little adjustments of that subtle line of his and the humour we value so highly would become tragedy.

In England there seems to be a curious tradition that a drawing becomes funny if it has a funny story printed underneath it; that the expression on one face in a group of persons if slightly ludicrous makes a drawing humorous. In a Bateman drawing the drawing is the humour and the humour is the drawing. Everything is in the same terms throughout. His very line seems to have a risible ripple in it, for his humour is the real thing—not irony or satire but the essential spiritual faculty of perceiving the incongruous wherever it occurs. He has a host of imitators, abroad as well as in this home circle of islands, but they are sheep in wolves’ clothing and the joke is not in them—they satirise the already ridiculous.