Title: Spruce Tree House Trail Guide: Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado

Creator: Mesa Verde Museum Association

United States. National Park Service

Release date: July 17, 2021 [eBook #65858]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

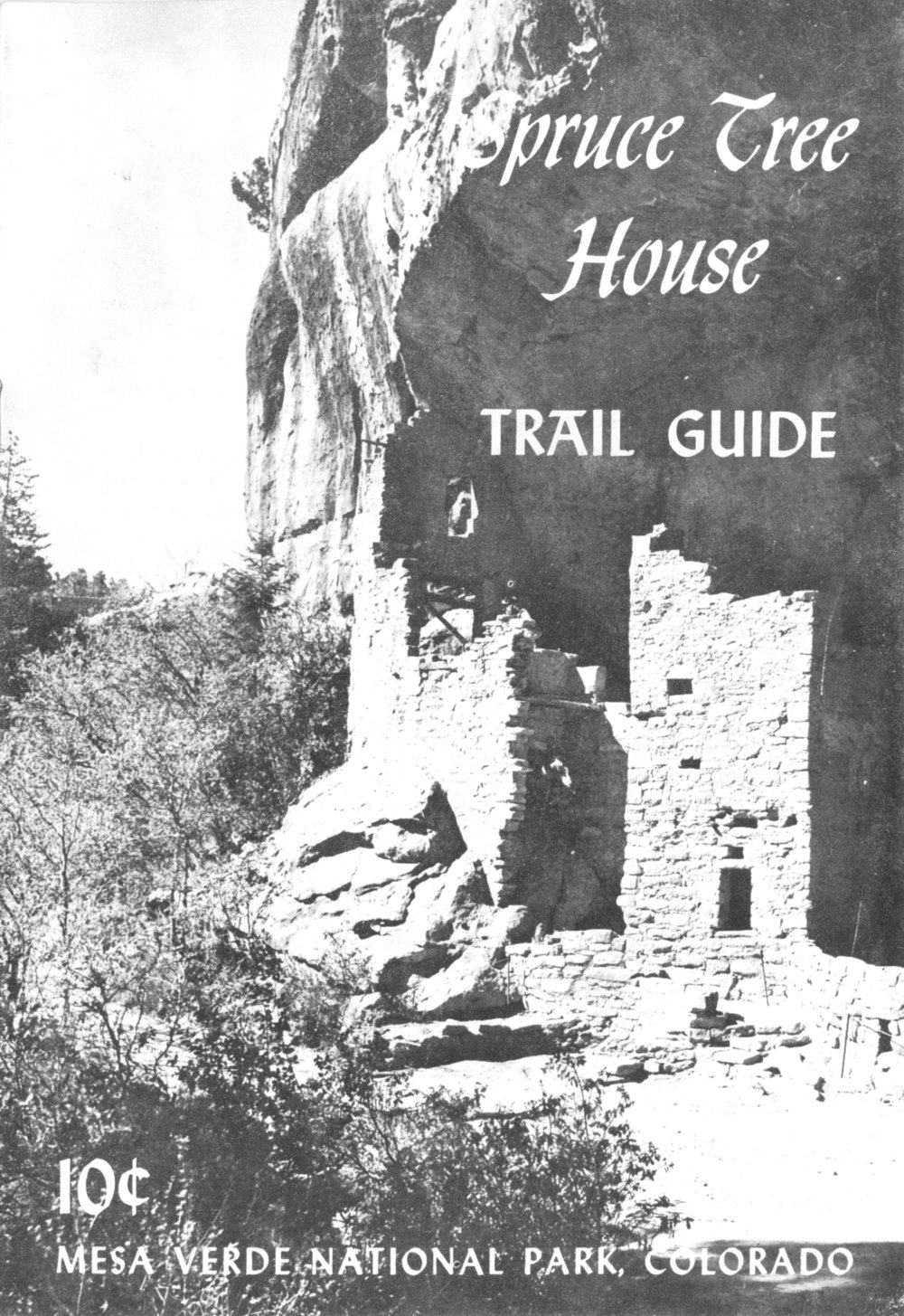

MESA VERDE NATIONAL PARK, COLORADO

10¢

* * * * * * * *

This guide booklet has been prepared to help you enjoy one of the larger cliff dwellings in Mesa Verde National Park. The numbered stations along the front of the dwelling are points of interest which are explained by the numbered paragraphs and illustrations in this booklet.

You are welcome to use this booklet. Please place it in the box at the other end of the ruin as you leave. If you wish to purchase the booklet, please drop 10 cents in the coin box.

Please do not climb or stand on the walls or crawl through any of the doorways.

* * * * * * * *

COVER: North end of Spruce Tree House.

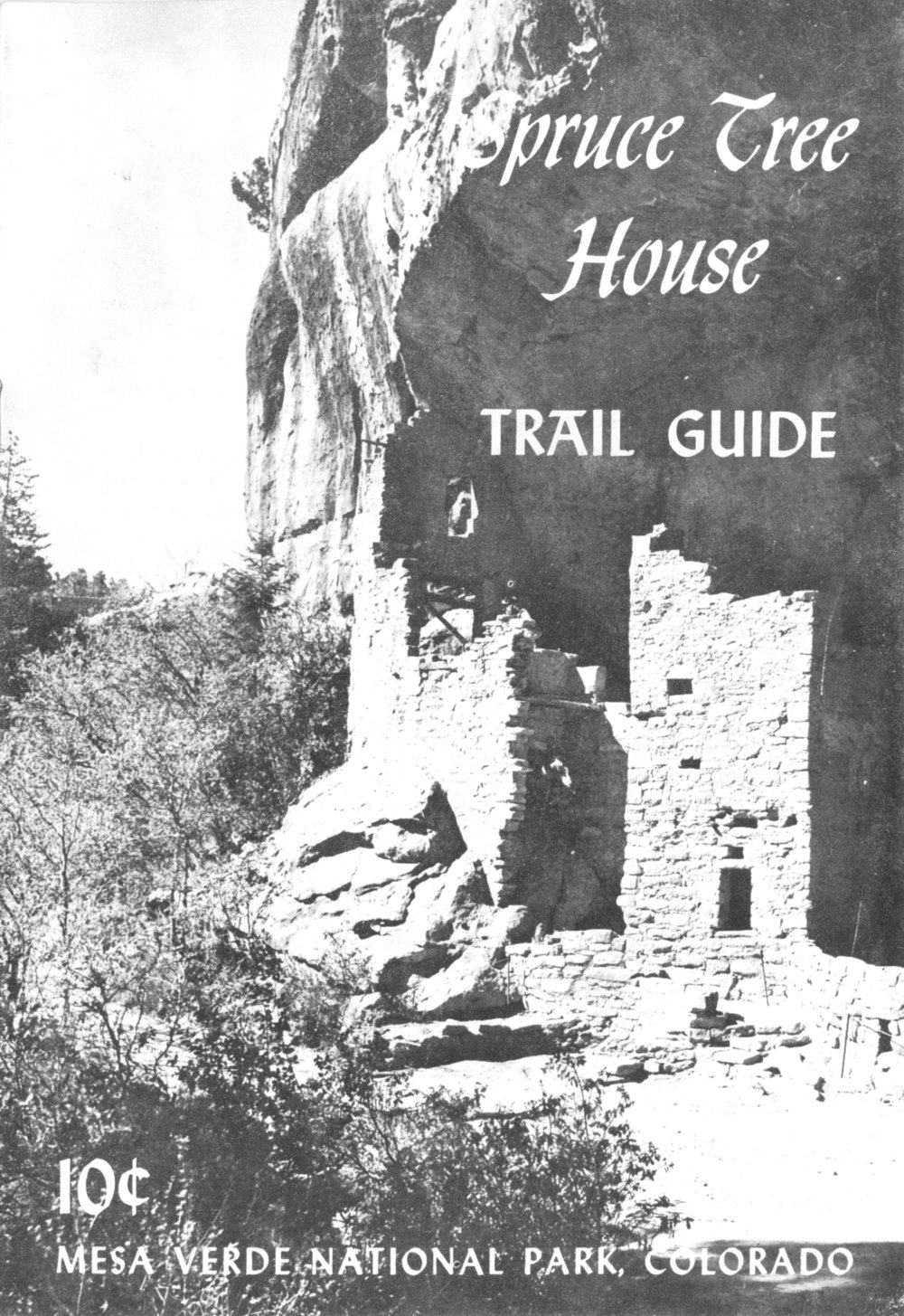

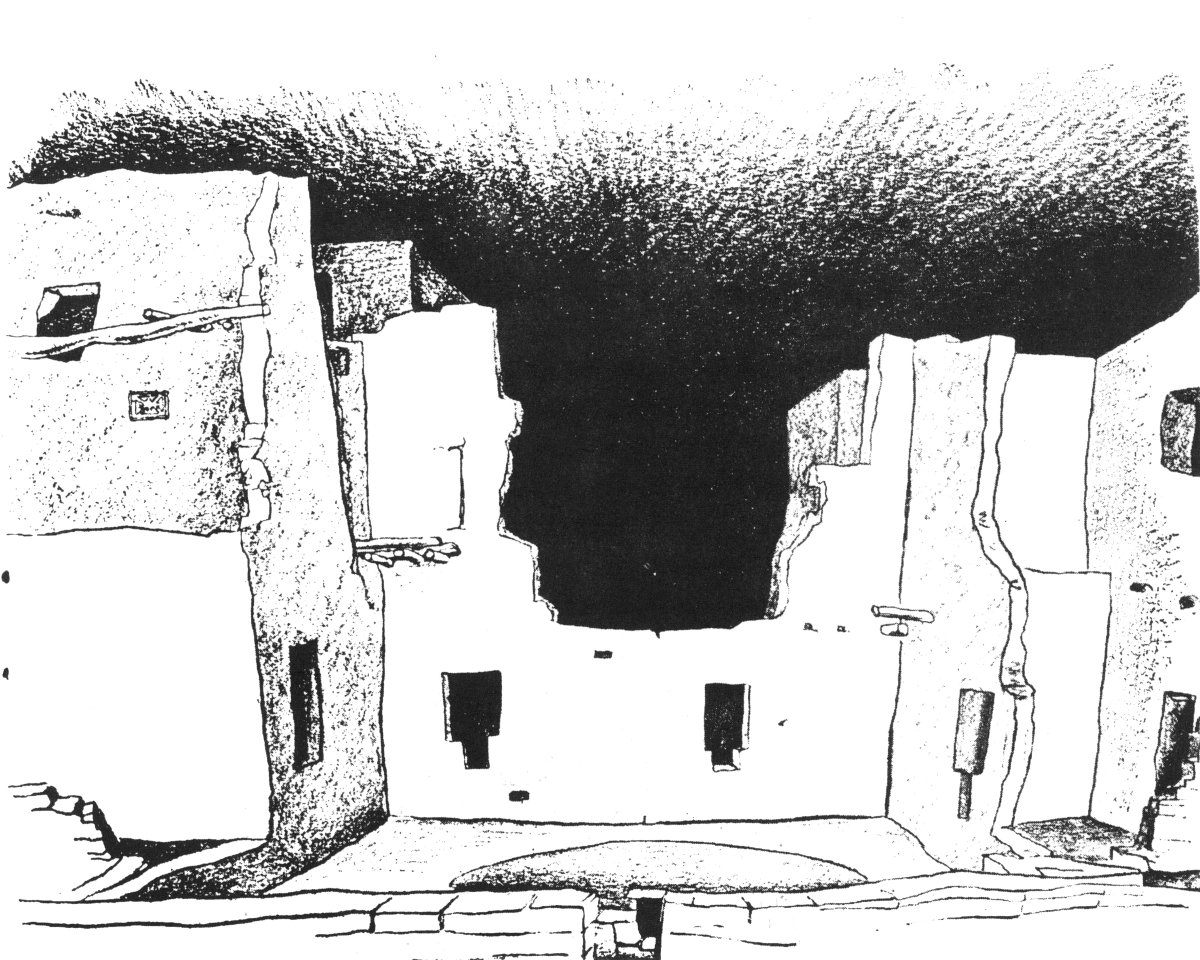

Spruce Tree House from the south end.

Spruce Tree House is the third largest cliff dwelling in Mesa Verde National Park. It is built in a natural cave 216 feet in length, 89 feet in greatest depth, and 60 feet in greatest height. The complete dwelling contained about 114 rooms. Most of these were living rooms, but there were many storerooms and 8 ceremonial rooms. It is thought that between 200 and 250 people may have lived in this cliff house at one time. It was occupied from about A.D. 1200 to, or shortly before, A.D. 1300.

The First Court

Spruce Tree House is typical of the larger cliff dwellings found in the Mesa Verde. It consists of several groups or blocks of rooms around open courts. Within each court is an underground ceremonial room called a kiva (Key-vah). Originally, there were flat roofs on these kivas. These roofs formed the courtyard floor and provided work space for daily activities. The rooms around the court were used primarily for sleeping and storage and for shelter against the cold of winter.

The rooms are generally small, averaging 6 by 8 feet and 5½ feet high. Floors and roofs of the second and third stories were made of large poles covered with smaller sticks, then bark or grass, and a thick layer of clay. A few of the rooms had fireplaces but most were without interior light or heat. Probably one family occupied a room.

Compare the picture of the First Court with the dwelling to locate the following:

A. These are unshaped building stones. Most of the 3 building blocks used in the dwelling were carefully shaped by the Indians before they were set in place. The walls were built of stone with adobe clay as mortar, much as we would build with brick. When a wall was finished, it was often coated with a layer of clay plaster.

B. These were storage rooms.

C. Each room had individual doorways such as these.

D. Some rooms had ventilation openings or “windows” like this one.

In the corner of the court to your left are corn grinding bins. Women knelt with their heels against the wall and ground corn, dried nuts, berries and roots on the large flat stone, the metate, with the small hand stone, the mano.

The circular room directly ahead of you is one of two found in this dwelling. Circular rooms were not common but they have been found in several ruins.

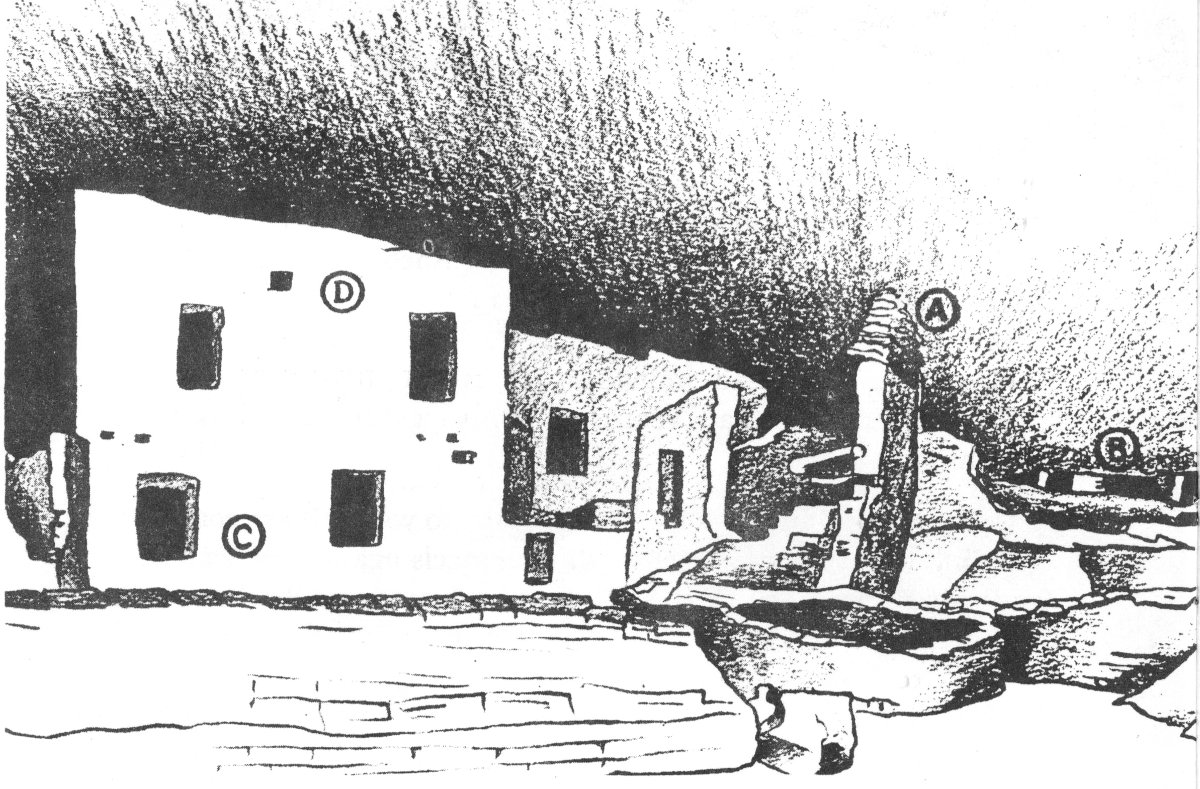

The Second Court. Main street section.

Note the passageway or “street” which provided access to rooms at the back of the cave in this part of the dwelling.

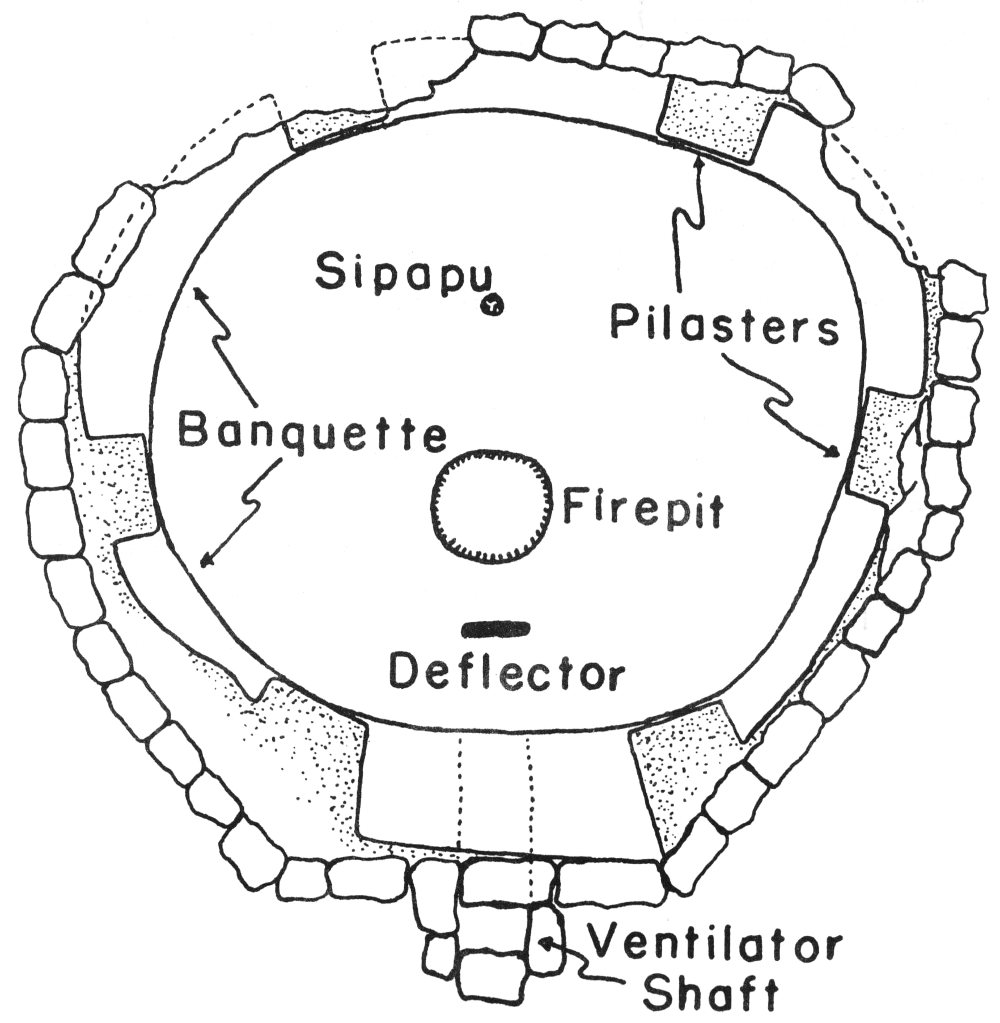

Ground plan of a kiva.

Step into the courtyard and look into the kiva. The name kiva is a modern Hopi Indian word meaning ceremonial room. Judging by present day Pueblo Indian custom, generally only men would be members of kiva societies which performed religious ceremonies for bringing rain, good crops and general well-being to the village. Women undoubtedly assisted in some ceremonies. When no rituals were being held, the kiva probably was used as a clubroom and workroom by men.

The ventilator shaft brought fresh air into the kiva. The deflector was a baffle to keep the air from blowing directly across the firepit in the floor. The fire provided light and warmth. The sipapu (see-pah-pooh) was a symbolic opening 5 from the underworld of the gods and spirits. The bench, or banquette, was a shelf or storage space. The pilasters, of which there are generally six, were roof supports. Entrance to the kiva was by means of a ladder through a hatchway in the roof.

If you want to go into a kiva, climb down the ladder in front of the next courtyard. Notice the cribbed roof. This is a restoration copied from originals found in place in other ruins.

Behind the rooms in this part of the dwelling is a large enclosed area which was used as a trash room. The villagers also kept some of their domesticated turkeys penned up in it. The main village trash dump was the talus slope on which you are now standing.

The black stain on the cave roof is smoke.

Notice the wall decorations on the second floor room to the left. It was made by plastering colored clay on the walls. Many rooms were once decorated inside like this one.

The Third Court

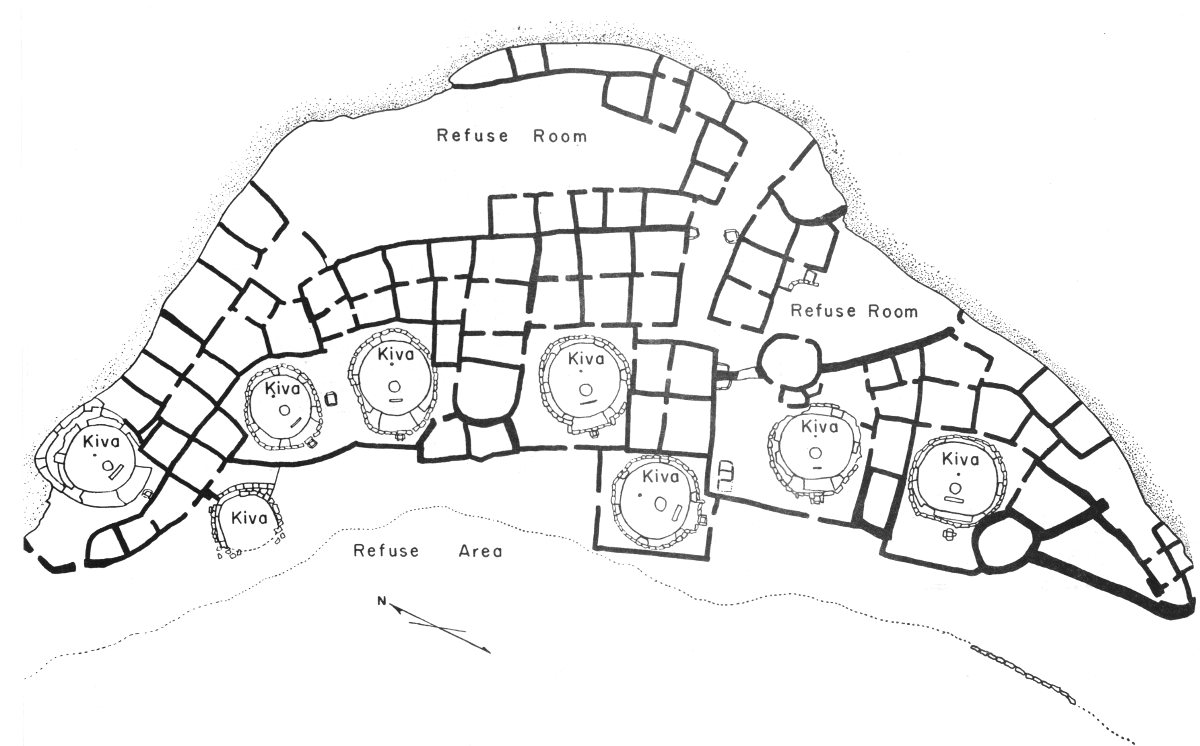

Ground plan of Spruce Tree House

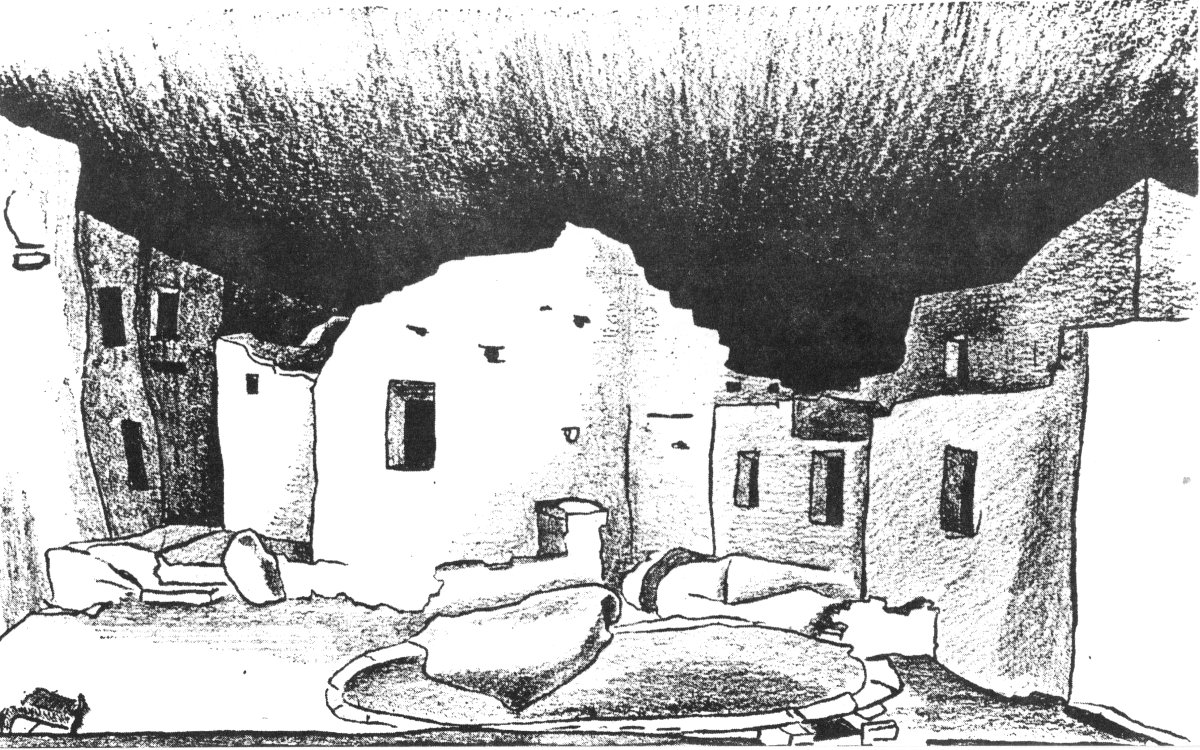

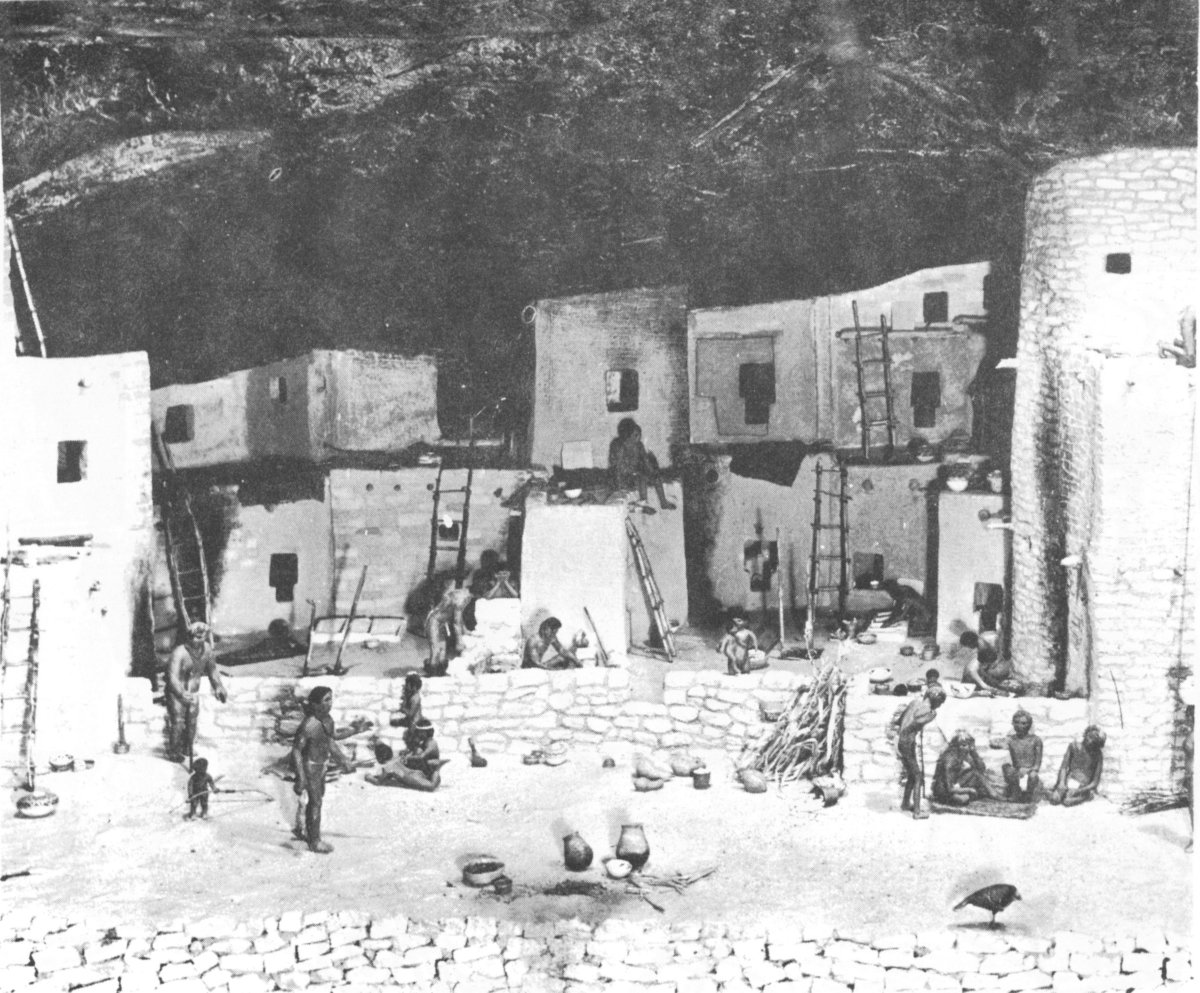

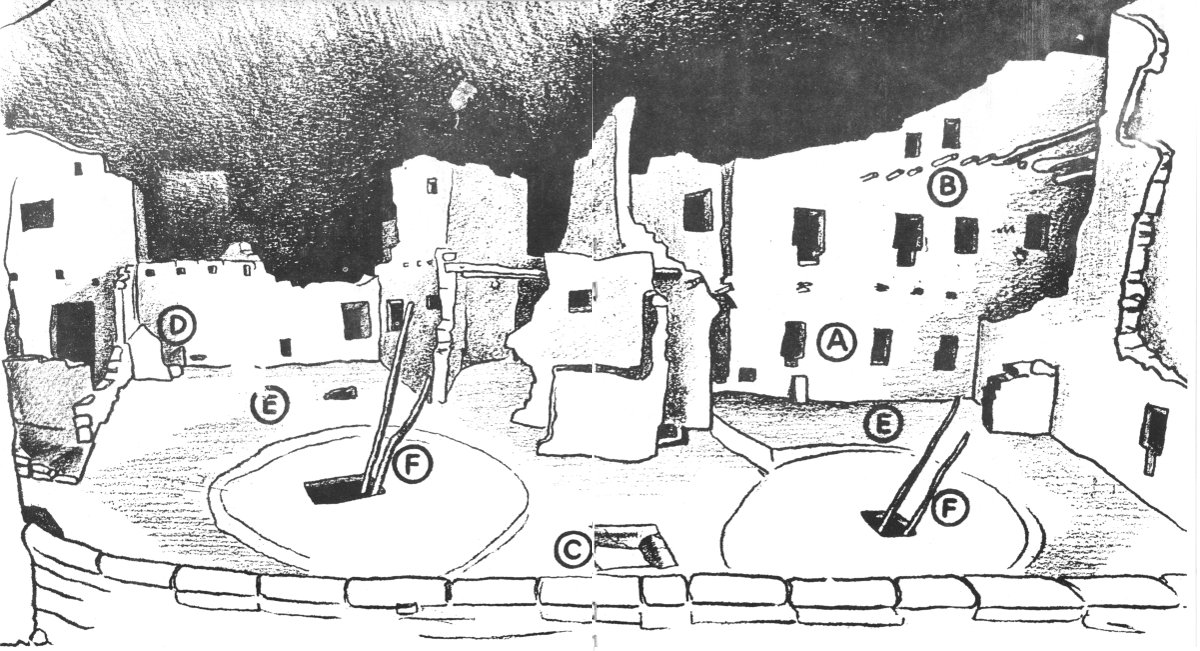

Spruce Tree House about A.D. 1260. (Museum diorama)

Spruce Tree House 700 years ago was a thriving village. If you could have visited it you would have seen women busily cooking over firepits in the courtyards, others grinding corn, weaving baskets or making pottery. Men who were not tending their mesa-top fields might have been building a new room, making or mending their tools or performing an age-old ceremony in one of the kivas. You would have seen children playing and old people resting against the low wall across the front of the dwelling as they basked in the warm sun dreaming of their younger days. There would also be dogs and turkeys wandering through the village and picking over the trash dump for bits to eat. Unfortunately, this all came to an end shortly before A.D. 1300.

Compare the illustration with the dwelling to locate the following:

A. These are doorways. Some are T-shaped, some are rectangular, but we don’t know why the two types. Notice that some of the doorways were closed with stone slabs.

B. These original timbers supported a balcony as well as the floors in the rooms. Balconies made it easy to get into the upper rooms. Balconies and rooftops were reached by ladders.

C. Most of the cooking was done outside in the courtyards over firepits like this one. Very few of the rooms had firepits in them.

D. This was a storage bin made of sandstone slabs.

E. The courtyard was the scene of most of the daily activities—grinding corn, preparing food, making tools, pottery, etc.

F. The ladders lead to kivas beneath the courtyard. These ladders and kiva roofs have been restored.

Spruce Tree House from the north end

The cliff dwelling was named Spruce Tree House by the ranchers who first discovered it in 1888. A large tree which they misidentified as a spruce tree was found growing against the cliff right in front of the dwelling. It is said that the men first entered the ruin by climbing down this tree.

This is a good place to take a picture.

IF YOU HAVE NOT PURCHASED THIS BOOKLET PLEASE LEAVE IT IN THE BOX BY THE TRAIL AS YOU LEAVE.

IF YOU WOULD LIKE TO KEEP IT, PLEASE DROP 10 CENTS IN THE COIN BOX.

Thank you.

Spruce Tree House is the third largest cliff dwelling in Mesa Verde National Park. It is located in Spruce Tree Canyon, a branch of the much larger Navajo Canyon. The cave, which is really a very large overhang, was formed by flaking or spalling of the cliff above a small seep-spring, and by freezing and thawing during the winter. There is no evidence that the Indians tried to shape or enlarge the caves; to do so would have been a tremendous task with their primitive tools.

Spruce Tree House was an Indian village and, like towns and villages today, it was not all built at one time; rather, it grew section by section over a period of years. Sometime around A.D. 1200 a group of Indians—perhaps related families—moved into the cave and built the first units. Each unit consisted of living and storage rooms clustered about an open court which contained a kiva. The courtyard and kiva probably served as a center for the social and religious activities of the group. New units were added to the structure as other families moved into the village. When people needed more space, they added new rooms alongside, in front, in back, or on top of the existing rooms. Shortly before A.D. 1300 when the Indians finally abandoned Spruce Tree House, the village contained 114 rooms.

The ground plan on Page 6 shows the arrangement of the rooms. Most of these were in double rows within the cave; in some places there were three rows. The interior rooms, dark and poorly ventilated, were probably used for storage. The central portion of the structure was built three stories high and reached the cave ceiling; most of the buildings, however, were only two stories in height.

To us these small rooms seem cramped, cold, and dark—quite unsuitable as living spaces. But these people probably spent little time inside the rooms, using them mainly for protection against the cold, for sleeping, and for storage. Most of the time they were probably out in the courtyards or on the flat rooftops working or carrying on other daily activities.

It is unlikely that all 114 rooms in Spruce Tree House were in use at the same time. New rooms were built as older ones fell into decay; smaller rooms were probably vacated for larger ones as the number of villagers increased. A conservative guess sets 200 to 250 as the largest number of people who lived in Spruce Tree House at any one time.

The Indians of the Mesa Verde, like their neighbors in the surrounding areas, were dry-farmers—depending upon rainfall to water their crops. In the fields on the mesa tops they grew corn, beans and several varieties of squash. The rainfall probably averaged about 18 inches a year, just as it does now, which is more than sufficient for dry-farming. The Indians supplemented their diet with wild roots, nuts and berries as well as with meat from large and small game animals.

The period of the cliff dwellings is known as the Classic Period and marks the climax of Pueblo culture in this region. The Mesa Verde people made beautiful pottery and decorated it elaborately with geometric and animal figures in black on a white or light-gray background. They also made cotton cloth which they often decorated with colored designs. Their masonry was of exceptional quality with the building blocks beautifully shaped and carefully laid in clay mortar.

The Classic Period came to an end shortly before A.D. 1300 when the Indians abandoned their homes in the Mesa Verde and moved away. We can only guess the reasons for such a move. One suggestion is that the great drouth, which lasted from A.D. 1276 to A.D. 1299, caused them to leave. Another suggestion is that this was a period of strife either between the villages themselves or between these village people and nomadic groups moving into the area. Whatever the reasons, the cliff dwellings of the Mesa Verde were empty by A.D. 1300.

It was a rancher from Mancos, named Richard Wetherill, who first discovered Spruce Tree House—on December 18, 1888. He and his brother-in-law, Charley Mason, also discovered Cliff Palace that same day. The men had been looking for lost cattle when they first saw the cliff ruins.

Spruce Tree ruin before excavation.

And the ruin after excavation and stabilization.

In 1906 Mesa Verde was set aside as a National Park by Act of Congress to protect and preserve these dwellings of the prehistoric Indians. In 1908 Dr. Jesse Walter Fewkes of the Smithsonian Institution excavated Spruce Tree House. He removed the debris of fallen walls and collapsed roofs and stabilized the dwellings more or less as you see them now. It has been necessary, of course, to further stabilize the walls from time to time, but aside from minor repairs and the roofing of the three kivas, the dwelling is original work done by the Indians some 700 to 800 years ago.

The dating of Spruce Tree House and other ruins in the Mesa Verde has been done by the study of tree-rings from original roofing timbers. If you are interested in how archæologists determine the dates, see the exhibit on tree-ring dating in the museum.

This trail guide booklet is not a government publication and is not included in your fee to enter Mesa Verde National Park. It is published and sold by the Mesa Verde Museum Association, a non-profit organization, whose aims are to help in the understanding and interpretation of the park story. Your comments and suggestions concerning this booklet will be appreciated.

If you are interested in the work of the National Park Service, and in the cause of conservation in general, you can give active expression of this interest, and lend support by alining yourself with one of the numerous conservation organizations which act as spokesman for those who wish our scenic and historic heritage to be kept unimpaired “for the enjoyment of future generations.”

Names and addresses of conservation organizations may be obtained at the Information Desk.

MISSION 66 is a 10 year development program, now in progress, to enable the National Park Service to help you to enjoy and to understand the parks and monuments, and at the same time, to preserve their scenic and scientific values for your children and for future generations.

The books and cards described below are published by the Mesa Verde Museum Association, a non-profit organization. All proceeds are used to further research and interpretation in the Mesa Verde. You can purchase these items at the sales or information desks in the Museum lobby or order them from the association, Box 38, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado. On mail orders, please include 10 cents postage for each publication.

INDIANS OF THE MESA VERDE, by Don Watson

This 188 page book with 17 pages of pictures deals with the customs, ceremonies and daily lives of the Indians who lived in the cliff dwellings. The origin of the American Indian and the archeology of the Mesa Verde are also explained. $1.00

CLIFF DWELLINGS OF THE MESA VERDE, by Don Watson

This 9 × 12 inch, 52 page picture book of the Mesa Verde ruins deals with the discovery of the cliff dwellings, their early exploration, architectural details and the reasons why they were built. You can buy the two books described above as a set for $1.75. $1.00

THE MESA VERDE STORY, as told by the Mesa Verde Museum Dioramas.

Large color prints of the five dioramas which picture the development of the Mesa Verde people. Complete descriptive text on the back of each card. The Fifth Diorama is a scale model of Spruce Tree House. $ .50

The Mesa Verde Museum Association offers a number of publications for sale which deal with the archeology, ethnology and natural history of the Four Corners region and the Southwest, as well as selected children’s books. A descriptive list of publications may be obtained at the museum desk or by writing the association.

This booklet is published by the

MESA VERDE MUSEUM ASSOCIATION

Published in cooperation with

The National Park Service