Title: The Story of the Sun: New York, 1833-1918

Author: Frank Michael O'Brien

Author of introduction, etc.: Edward Page Mitchell

Release date: July 18, 2021 [eBook #65868]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: deaurider, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Transcriber's Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

Sun

Sun

THE STORY OF

The  Sun.

Sun.

NEW YORK, 1833–1918

BY

FRANK M. O’BRIEN

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY EDWARD

PAGE MITCHELL, EDITOR OF “THE

SUN”—ILLUSTRATIONS AND FACSIMILES

NEW YORK: GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

Copyright, 1918,

By George H. Doran Company

Copyright, 1917, 1918, The Frank A. Munsey Company

Copyright, 1918, The Sun Printing and Publishing Association

Printed in the United States of America

TO

FRANK A. MUNSEY

It is truer, perhaps, of a newspaper than of most other complex things in the world that the whole may be greater than the sum of all its parts. In any daily paper worth a moment’s consideration the least fancifully inclined observer will discern an individuality apart from and in a degree independent of the dozens or hundreds or thousands of personal values entering at a given time into the composite of its grey pages.

This entity of the institution, as distinguished from the human beings actually engaged in carrying it on, this fact of the newspaper’s possession of a separate countenance, a spirit or soul differentiating it from all others of its kind, is recognised either consciously or unconsciously by both the more or less unimportant workers who help to make it and by their silent partners who support it by buying and reading it. Its loyal friends and intelligent critics outside the establishment, the Old Subscriber and the Constant Reader, form the habit of attributing to the newspaper, as to an individual, qualities and powers beneficent or maleficent or merely foolish, according to their mood or digestion. They credit it with traits of character quite as distinct as belong to any man or woman of their acquaintance. They personify it, moreover, without much knowledge, if any, of the people directing and producing it; and, often and naturally, without any particularviii concern about who and what these people may be.

On their own side, the makers of the paper are accustomed to individualise it as vividly as a crew does the ship. They know better than anybody else not only how far each personal factor, each element of the composite, is modified and influenced in its workings by the other personal factors associated in the production, but also the extent to which all the personal units are influenced and modified by something not listed in the office directory or visible upon the payroll; something that was there before they came and will be there after they go.

Of course, that which has given persistent idiosyncrasy to a newspaper like the Sun, for example, is accumulated tradition. That which has made the whole count for more than the sum total of its parts, in the Sun’s case as in the case of its esteemed contemporaries, is the heritage of method and expedient, the increment of standardised skill and localised imagination contributed through many years to the fund of the paper by the forgotten worker as well as by the remembered.

The manner of growth of the great newspaper’s well-defined and continuous character, distinguishing it from all the rest of the offspring of the printing press, a development sometimes not radically affected by changes of personnel, of ownership, of exterior conditions and fashions set by the popular taste, is a subject over which journalistic metaphysics might easily exert itself to the verge of boredom. Fortunately there has been found a much better way to deal with the attractive theme.

The Sun is eighty-five years old as this book goes to press. In telling its intimate story, from the September Tuesday which saw the beginning of Mr. Day’s intrepid and epochal experiment, throughout the daysix of the Beaches, of Dana, of Laffan, and of Reick to the time of Mr. Munsey’s purchase of the property in the summer of 1916, Mr. O’Brien has done what has never been undertaken before, so far as is known to the writer of this introduction, for any newspaper with a career of considerable span.

There have been general histories of Journalism, presenting casually the main facts of evolution and progress in the special instance. There have been satisfactory narratives of journalistic episodes, reasonably accurate accounts of certain aspects or dynastic periods of newspaper experience, excellent portrait biographies or autobiographies of journalists of genius and high achievement, with the eminent man usually in strong light in the foreground and his newspaper seldom nearer than the middle distance. But here, probably for the first time in literature of this sort, we have a real biography of a newspaper itself, covering the whole range of its existence, exhibiting every function of its organism, illustrating every quality that has been conspicuous in the successive stages of its growth. The Sun is the hero of Mr. O’Brien’s “Story of the Sun.” The human participants figure in their incidental relation to the main thread of its life and activities. They do their parts, big or little, as they pass in interesting procession. When they have done their parts they disappear, as in real life, and the story goes on, just as the Sun has gone on, without them except as they may have left their personal impress on the newspaper’s structure or its superficial decoration.

During no small part of its four score and five years of intelligent interest in the world’s thoughts and doings it has been the Sun’s fortune to be regarded as in a somewhat exceptional sense the newspaper man’s newspaper. If in truth it has merited in any degreex this peculiar distinction in the eyes of its professional brethren it must have been by reason of originality of initiative and soundness of method; perhaps by a chronic indifference to those ancient conventions of news importance or of editorial phraseology which, when systematically observed, are apt to result in a pale, dull, or even stupid uniformity of product. Mr. Dana wrote more than half a century ago to one of his associates, “Your articles have stirred up the animals, which you as well as I recognise as one of the great ends of life.” Sometimes he borrowed Titania’s wand; sometimes he used a red hot poker. Not only in that great editor’s time but also in the time of his predecessors and successors the Sun has held it to be a duty and a joy to assist to the best of its ability in the discouragement of anything like lethargy in the menagerie. Perhaps, again, that was one of the things that helped to make it the newspaper man’s newspaper.

However this may be, it seems certain that to the students of the theory and practice of journalism, now happily so numerous in the land, the chronicler of one highly individual newspaper’s deeds and ways is affording an object lesson of practical value, a textbook of technical usefulness, as well as a store of authoritative history, entertaining anecdote, and suggestive professional information. And a much wider audience than is made up of newspaper workers present or to come will find that the story of a newspaper which Mr. O’Brien has told with wit and knowledge in the pages that follow becomes naturally and inevitably a swift and charming picture of the town in which that newspaper is published throughout the period of its service to that town—the most interesting period in the existence of the most interesting city of the world.

It is a fine thing for the Sun, by all who have workedxi for it in its own spirit beloved, I believe, like a creature of flesh and blood and living intelligence and human virtues and failings, that through Mr. Munsey’s wish it should have found in a son of its own schooling a biographer and interpreter so sympathetically responsive to its best traditions.

Edward P. Mitchell.

| CHAPTER I | |

| SUNRISE AT 222 WILLIAM STREET | |

| PAGE | |

| Benjamin H. Day, with No Capital Except Youth and Courage, Establishes the First Permanent Penny Newspaper.—The Curious First Number Entirely His Own Work | 21 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| THE FIELD OF THE LITTLE “SUN” | |

| A Very Small Metropolis Which Day and His Partner, Wisner, Awoke by Printing Small Human Pieces About Small Human Beings and Having Boys Cry the Paper | 31 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| RICHARD ADAMS LOCKE’S MOON HOAX | |

| A Magnificent Fake Which Deceived Two Continents, Brought to “The Sun” the Largest Circulation in the World and, in Poe’s Opinion, Established Penny Papers | 64xiv |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| DAY FINDS A RIVAL IN BENNETT | |

| The Success of “The Sun” Leads to the Founding of The “Herald.”—Enterprises and Quarrels of a Furious Young Journalism.—The Picturesque Webb.—Maria Monk | 103 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| NEW YORK LIFE IN THE THIRTIES | |

| A Sprightly City Which Daily Bought Thirty Thousand copies of “The Sun.”—The Rush to Start Penny Papers.—Day Sells “The Sun” for Forty Thousand Dollars | 121 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| MOSES Y. BEACH’S ERA OF HUSTLE | |

| “The Sun” Uses Albany Steamboats, Horse Expresses, Trotting Teams, Pigeons, and the Telegraph to Get News.—Poe’s Famous Balloon Hoax and the Case of Mary Rodgers | 139 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| “THE SUN” IN THE MEXICAN WAR | |

| Moses Y. Beach as an Emissary of President Polk.—The Associated Press Founded in the Office of “The Sun.”—Ben Day’s Brother-in-Law Retires with a Small Fortune | 164xv |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| “THE SUN” DURING THE CIVIL WAR | |

| One of the Few Entirely Loyal Newspapers of New York.—Its Brief Ownership by a Religious Coterie.—It Returns to the Possession of M. S. Beach, Who Sells It to Dana | 172 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| THE EARLIER CAREER OF DANA | |

| His Life at Brook Farm and His Tribune Experience.—His Break with Greeley, His Civil War Services and His Chicago Disappointment.—His Purchase of “The Sun” | 202 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| DANA: HIS “SUN” AND ITS CITY | |

| The Period of the Great Personal Journalists.—Dana’s Avoidance of Rules and Musty Newspaper Conventions.—His Choice of Men and His Broad Definition of News | 233 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| DANA, AS MITCHELL SAW HIM | |

| A Picture of the Room Where One Man Ruled for Thirty Years.—The Democratic Ways of a Newspaper Autocrat.—W. O. Bartlett, Pike, and His Other Early Associates | 247xvi |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| DANA’S FIRST BIG NEWS MEN | |

| Amos J. Cummings, Dr. Wood, and John B. Bogart.—The Lively Days of Tweedism.—Elihu Root as a Dramatic Critic.—The Birth and Popularity of “The Sun’s” Cat | 262 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| DANA’S FAMOUS RIVALS PASS | |

| The Deaths of Raymond, Bennett, and Greeley Leave Him the Dominant Figure of the American Newspaper Field.—Dana’s Dream of a Paper Without Advertisements | 293 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| “THE SUN” AND THE GRANT SCANDALS | |

| Dana’s Relentless Fight Against the Whisky Ring, the Crédit Mobilier, “Addition, Division, and Silence,” the Safe Burglary Conspiracy and the Boss Shepherd Scandal | 304 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| “THE SUN” AND “HUMAN INTEREST” | |

| Something About Everything, for Everybody.—A Wonderful Four-Page Paper.—A Comparison of the Styles of “Sun” Reporters in Three Periods Twenty Years Apart | 313xvii |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| “SUN” REPORTERS AND THEIR WORK | |

| Cummings, Ralph, W. J. Chamberlin, Brisbane, Riggs, Dieuaide, Spears, O. K. Davis, Irwin, Adams, Denison, Wood, O’Malley, Hill, Cronyn.—Spanish War Work | 328 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| SOME GENIUS IN AN OLD ROOM | |

| Lord, Managing Editor for Thirty-Two Years.—Clarke, Magician of the Copy Desk.—Ethics, Fair Play and Democracy.—“The Evening Sun” and Those Who Make It | 369 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| THE FINEST SIDE OF “THE SUN” | |

| Literary Associations of an Editorial Department That Has Encouraged and Attracted Men of Imagination and Talent.—Mitchell, Hazeltine, Church, and Their Colleagues | 402 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| “THE SUN” AND YELLOW JOURNALISM | |

| The Coming and Going of a Newspaper Disease.—Dana’s Attitude Toward President Cleveland.—Dana’s Death.—Ownerships of Paul Dana, Laffan, Reick, and Munsey | 413 |

| Bibliography | 435 |

| Chronology | 437 |

| Index | 439 |

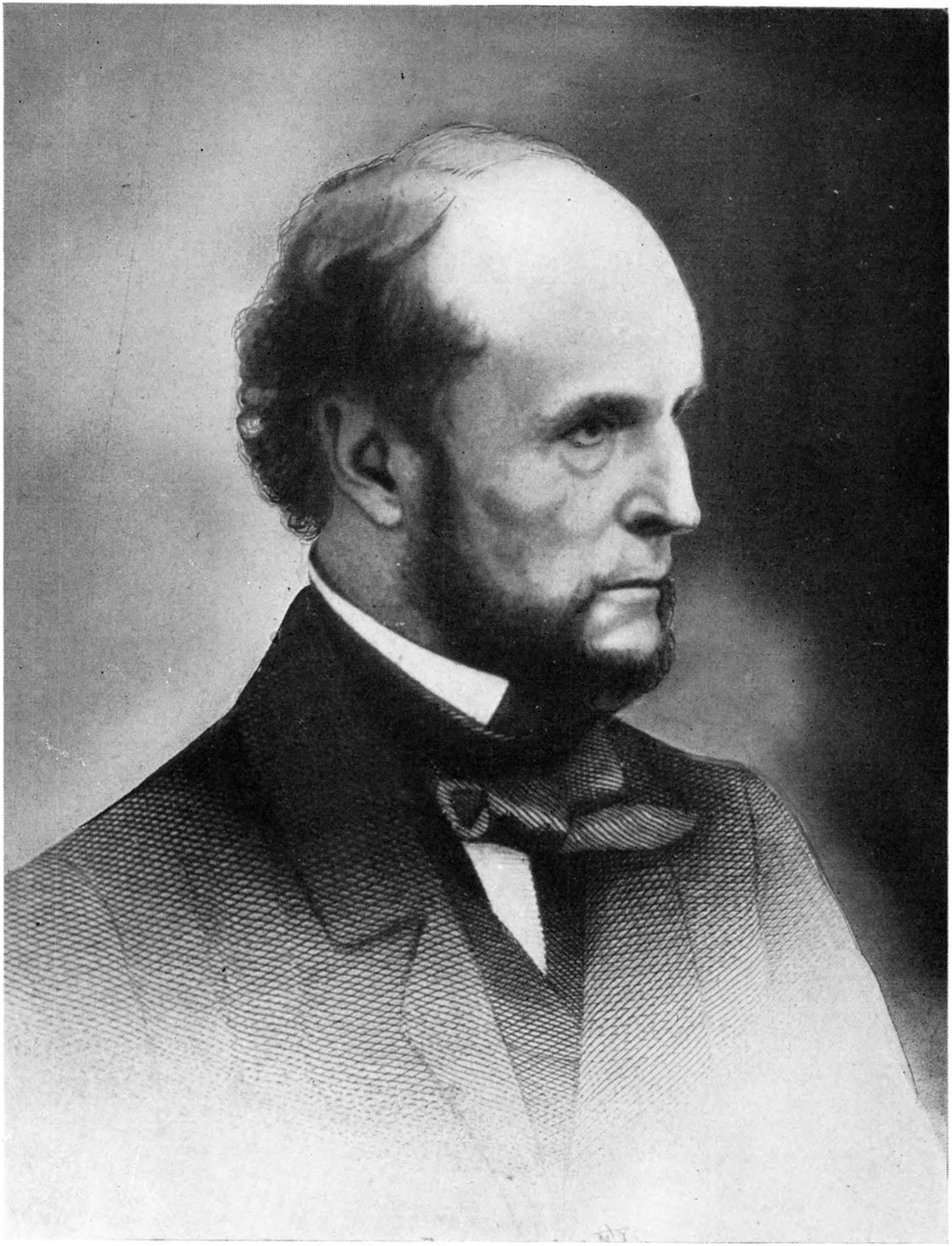

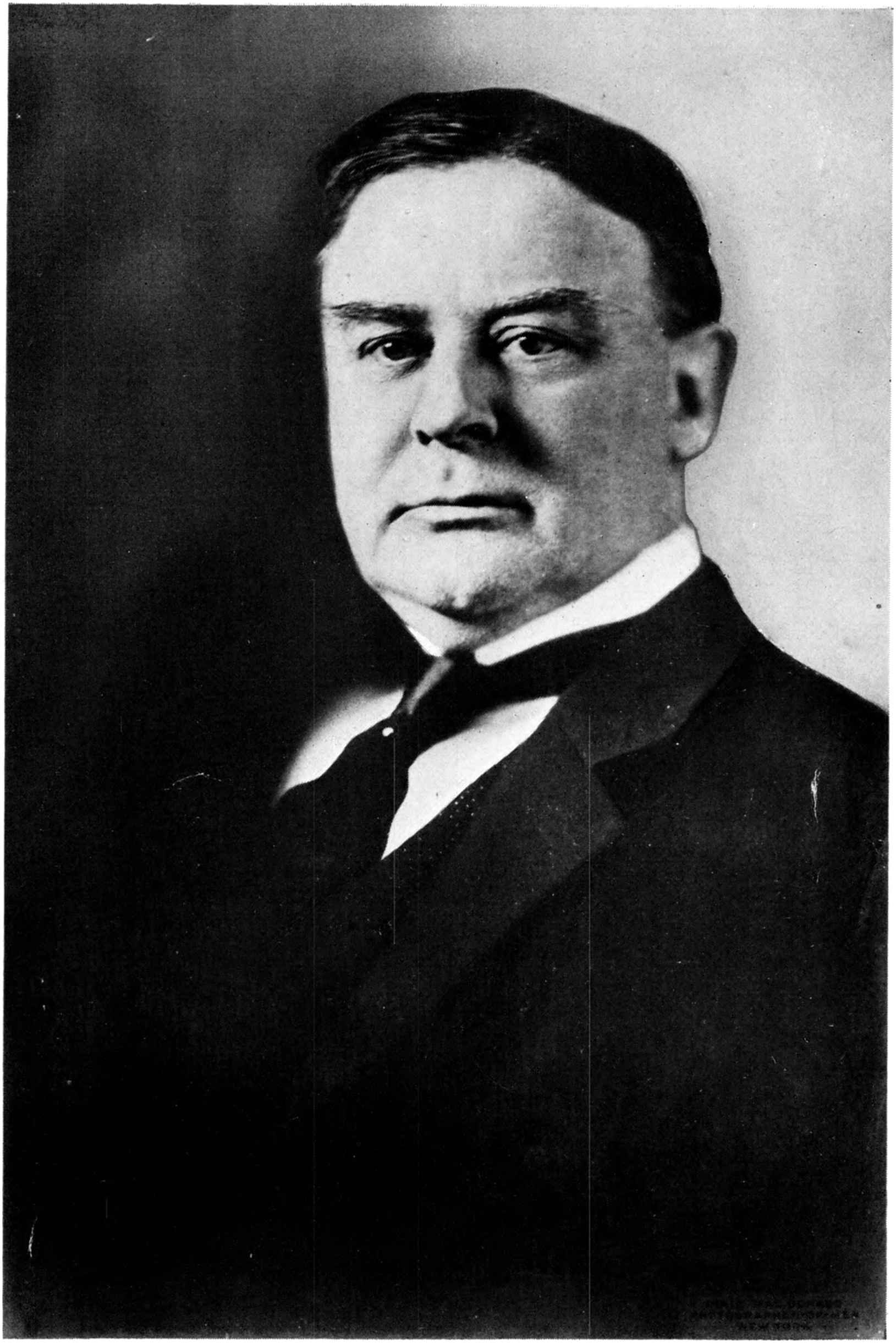

| BENJAMIN H. DAY, FOUNDER OF “THE SUN” | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| BENJAMIN H. DAY, A BUST | 22 |

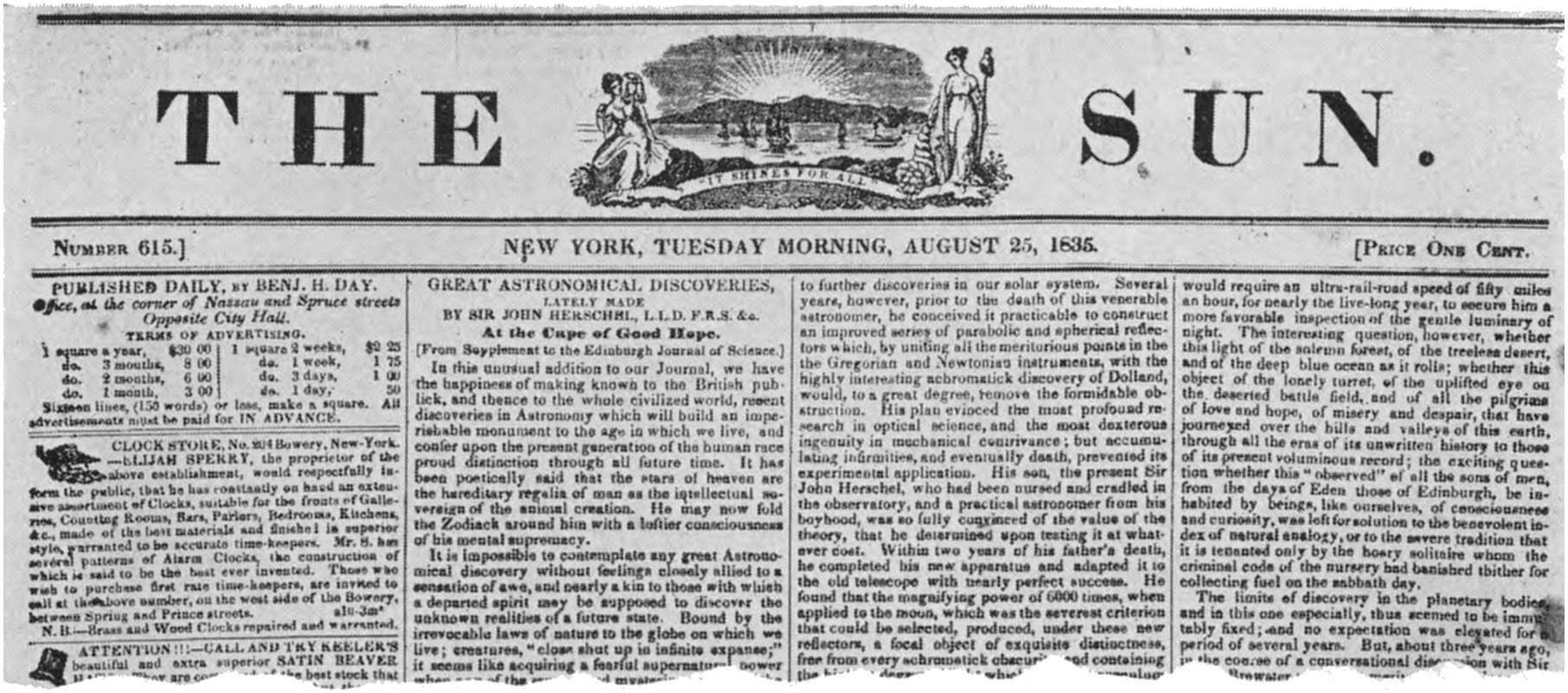

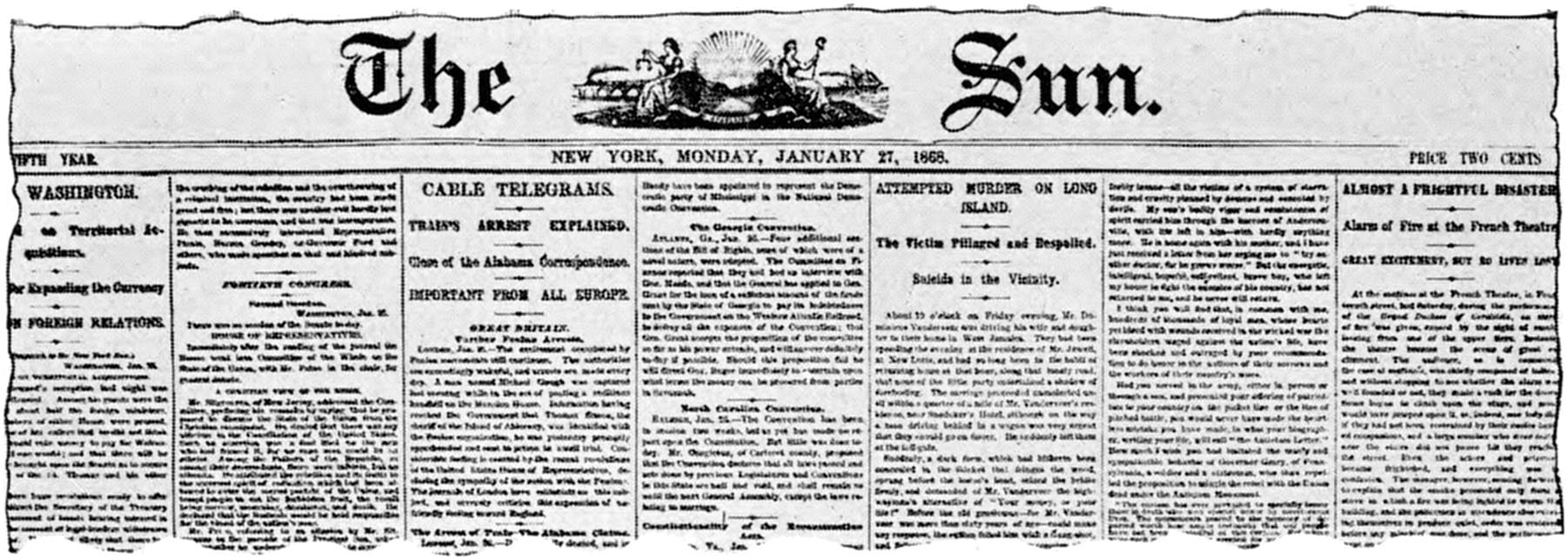

| THE FIRST ISSUE OF “THE SUN” | 28 |

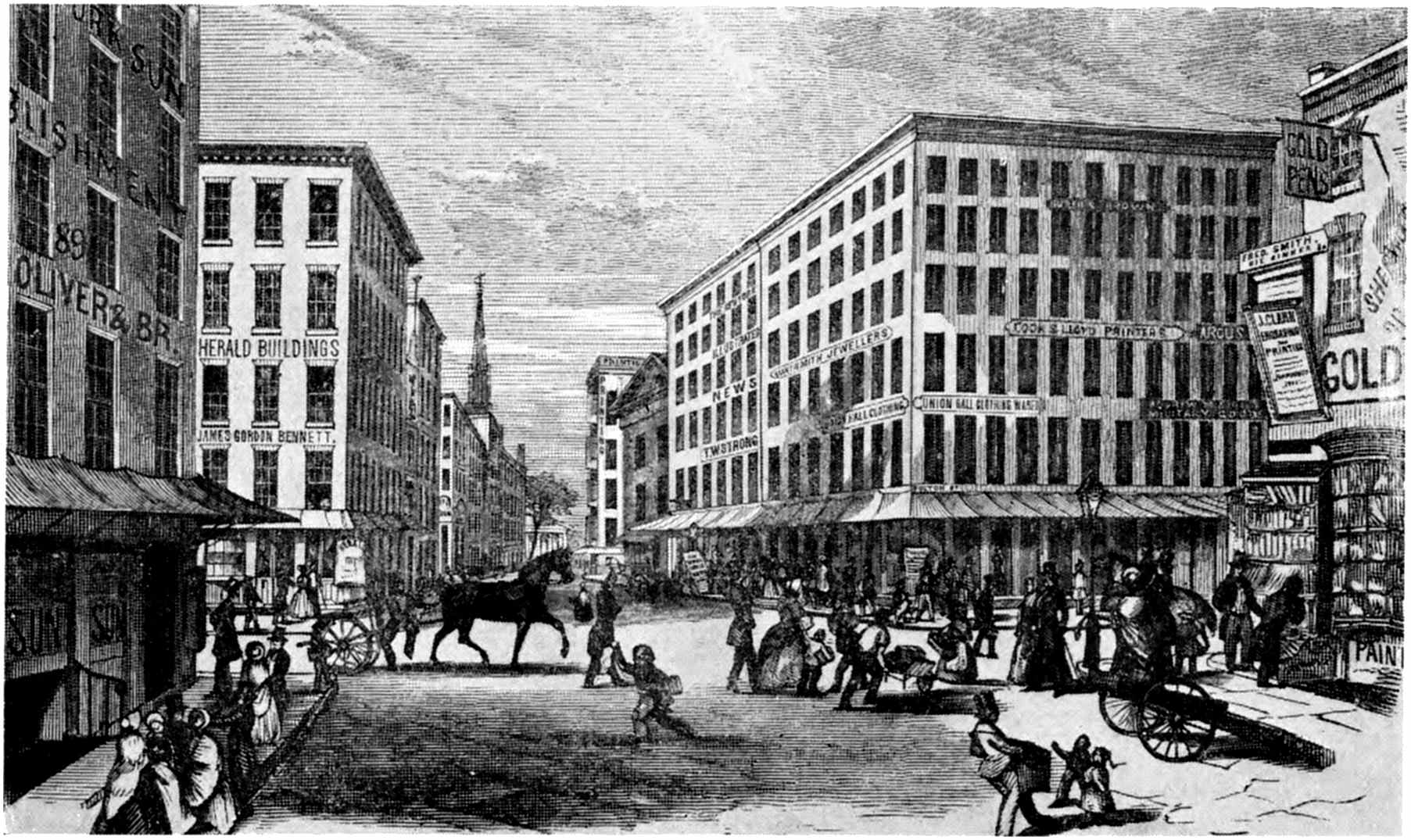

| THE FIRST HOME OF “THE SUN” | 34 |

| THE SECOND HOME OF “THE SUN” | 34 |

| BARNEY WILLIAMS, THE FIRST NEWSBOY | 50 |

| RICHARD ADAMS LOCKE, AUTHOR OF THE MOON HOAX | 68 |

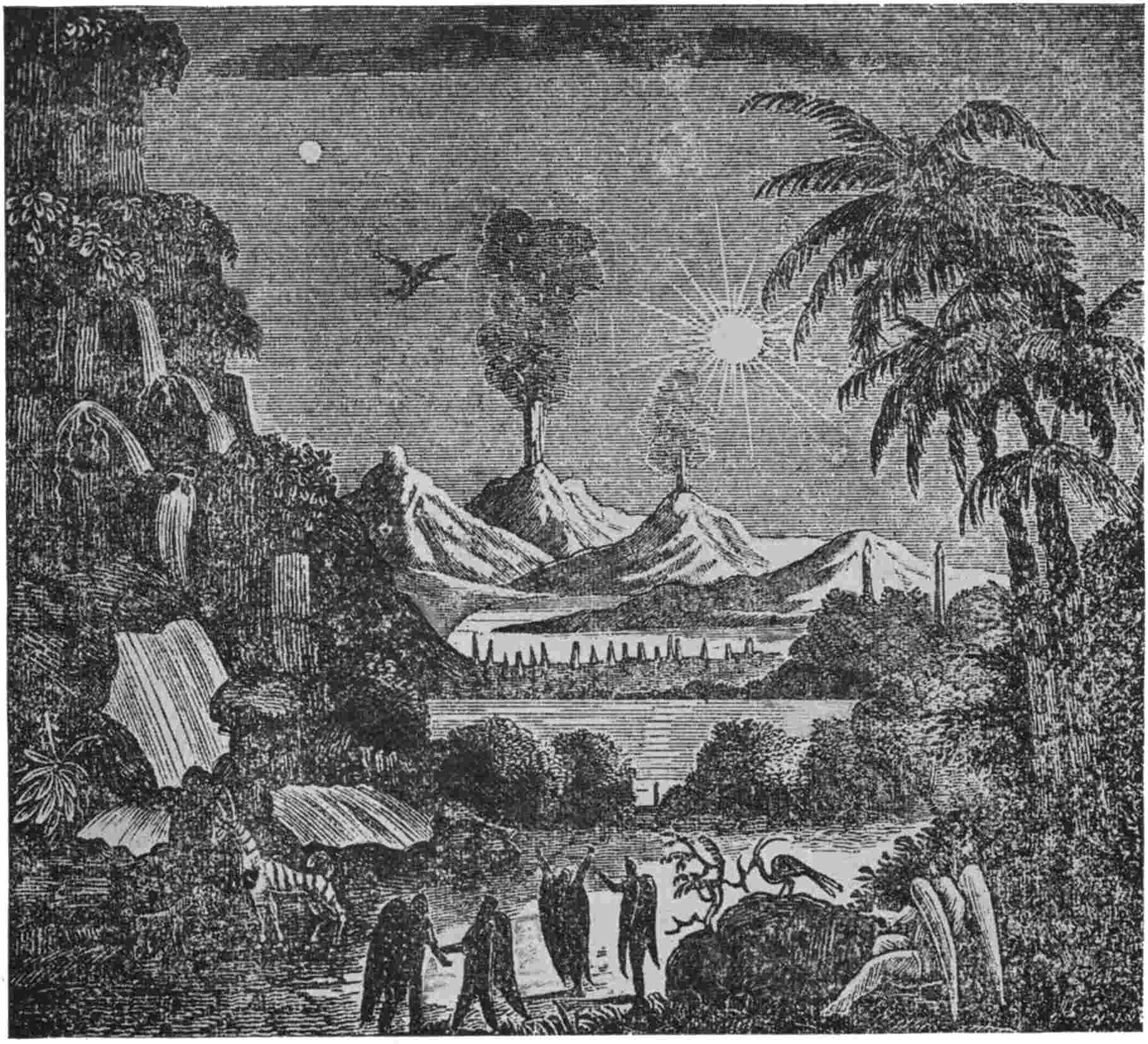

| THE FIRST INSTALMENT OF THE MOON HOAX | 96 |

| A MOON SCENE, FROM LOCKE’S GREAT DECEPTION | 96 |

| MOSES YALE BEACH, SECOND OWNER OF “THE SUN” | 124 |

| AN EXTRA OF “THE SUN” | 136 |

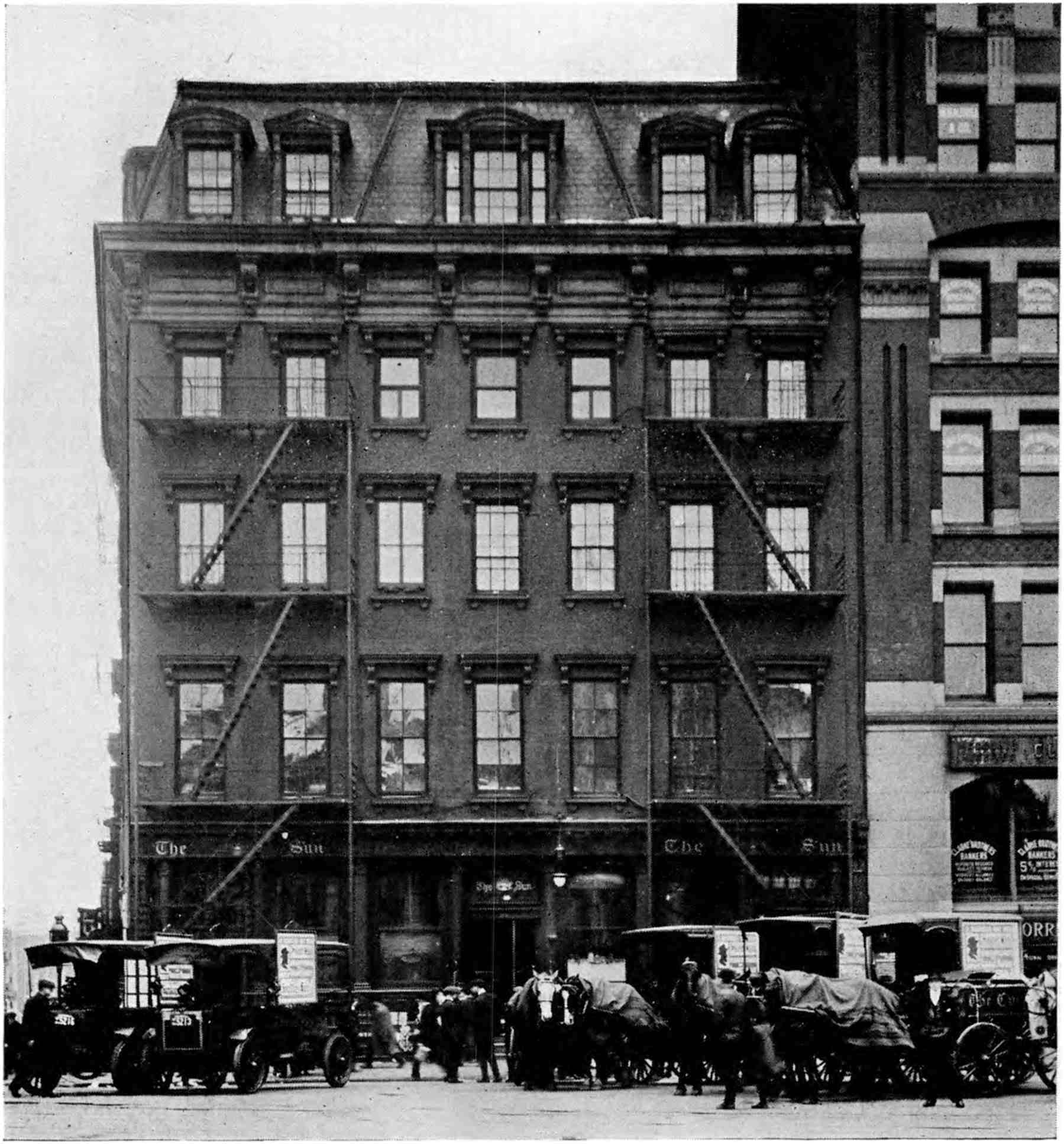

| THE THIRD HOME OF “THE SUN” | 136 |

| MOSES SPERRY BEACH | 166 |

| ALFRED ELY BEACH | 170 |

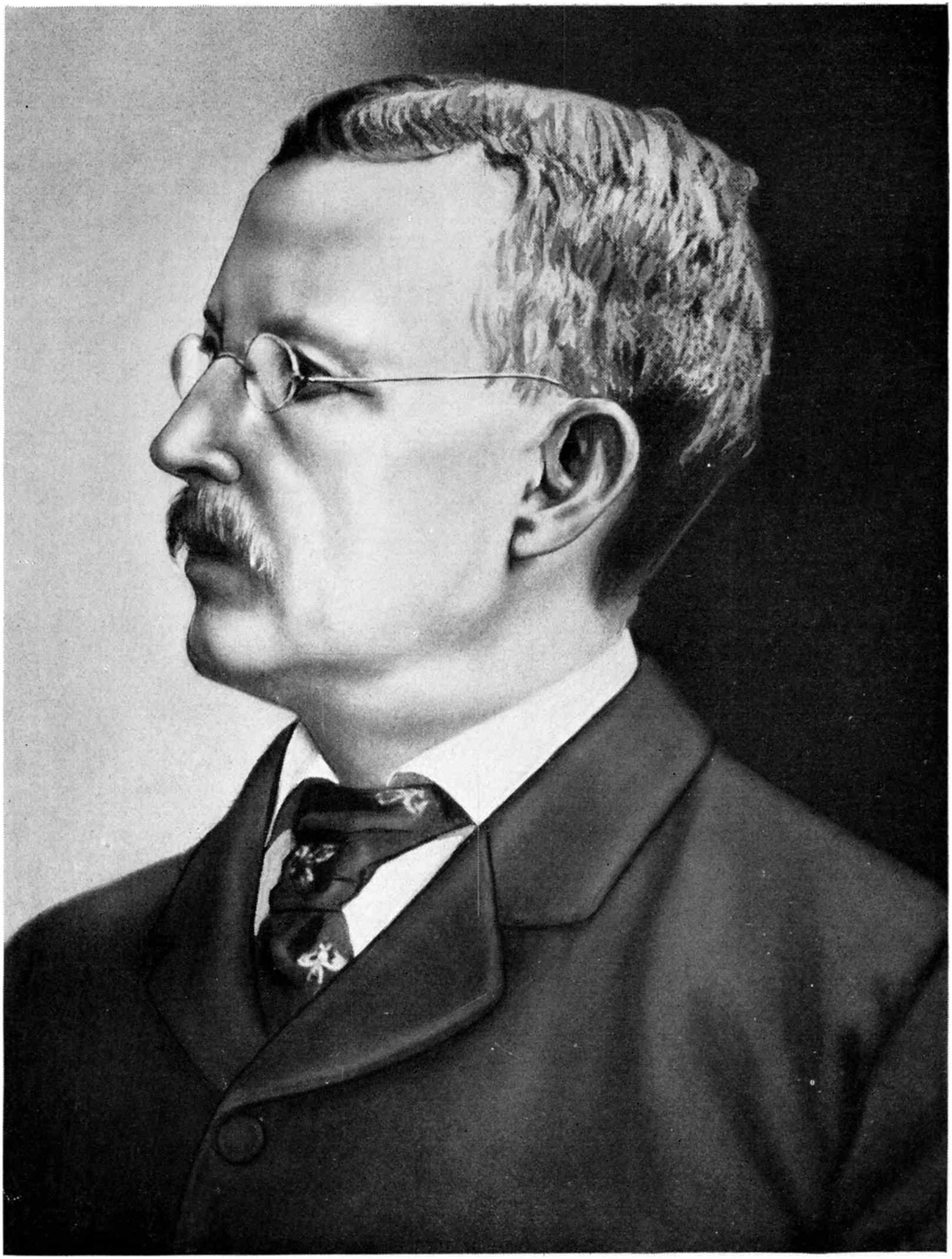

| CHARLES A. DANA AT THIRTY-EIGHT | 204 |

| MR. DANA AT FIFTY | 224 |

| THE FIRST NUMBER OF “THE SUN” UNDER DANA | 236 |

| THE HOME OF “THE SUN” FROM 1868 TO 1915 | 236 |

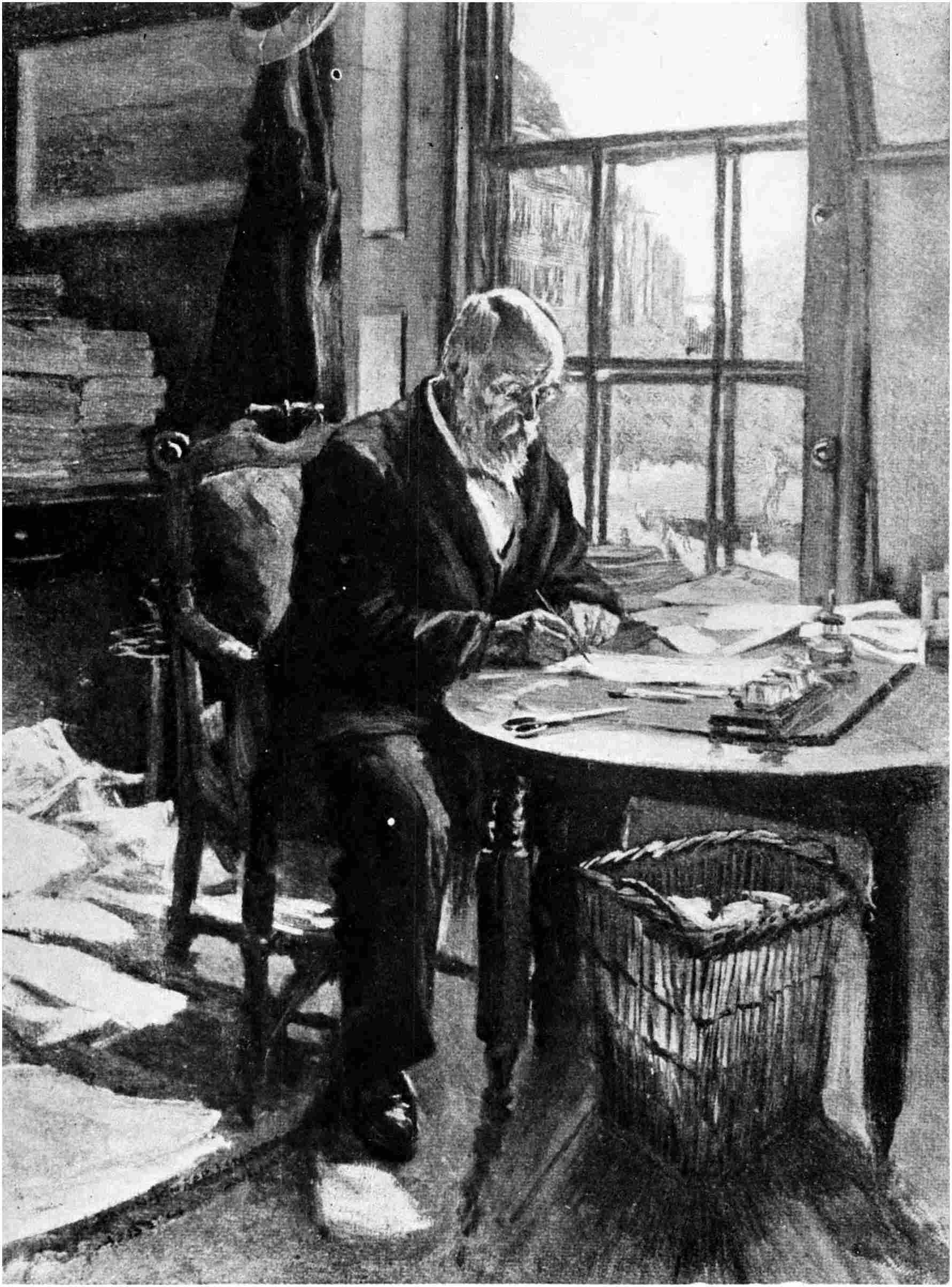

| MR. DANA IN HIS OFFICE | 248 |

| JOSEPH PULITZER | 258 |

| ELIHU ROOT | 258 |

| JUDGE WILLARD BARTLETT | 258 |

| MR. DANA AT SEVENTY | 270 |

| AMOS JAY CUMMINGS | 280 |

| DANIEL F. KELLOGG | 290 |

| AMOS B. STILLMAN | 290 |

| JOHN B. BOGART | 290xx |

| JAMES GORDON BENNETT, SR. | 300 |

| HORACE GREELEY | 300 |

| HENRY J. RAYMOND | 300 |

| JULIAN RALPH | 316 |

| ARTHUR BRISBANE | 330 |

| EDWARD G. RIGGS | 350 |

| CHESTER SANDERS LORD | 370 |

| SELAH MERRILL CLARKE | 380 |

| SAMUEL A. WOOD | 390 |

| OSCAR KING DAVIS | 390 |

| THOMAS M. DIEUAIDE | 390 |

| SAMUEL HOPKINS ADAMS | 390 |

| WILL IRWIN | 398 |

| FRANK WARD O’MALLEY | 398 |

| EDWIN C. HILL | 398 |

| PAUL DANA | 404 |

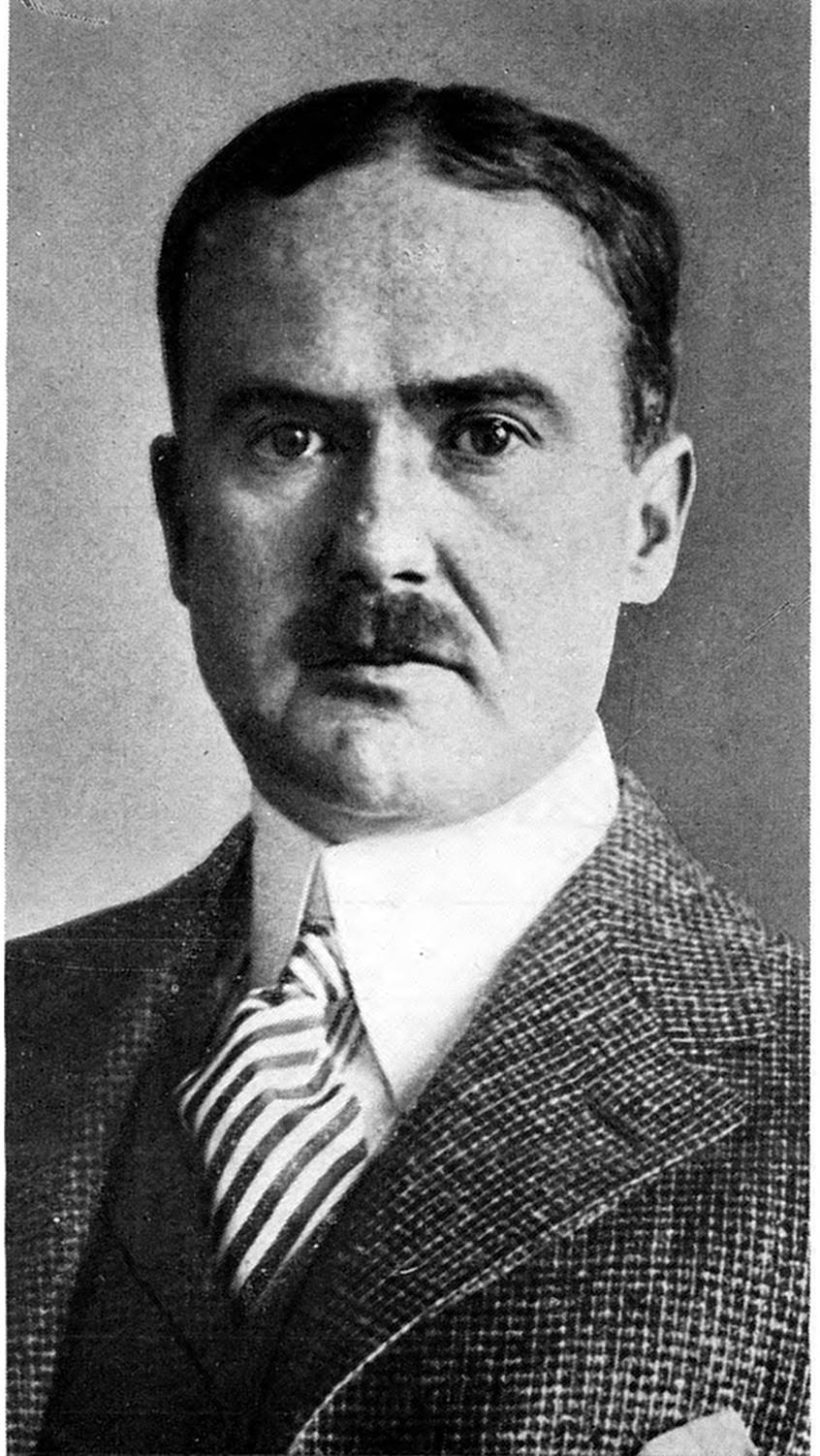

| WILLIAM M. LAFFAN | 410 |

| WILLIAM C. REICK | 416 |

| FRANK A. MUNSEY | 422 |

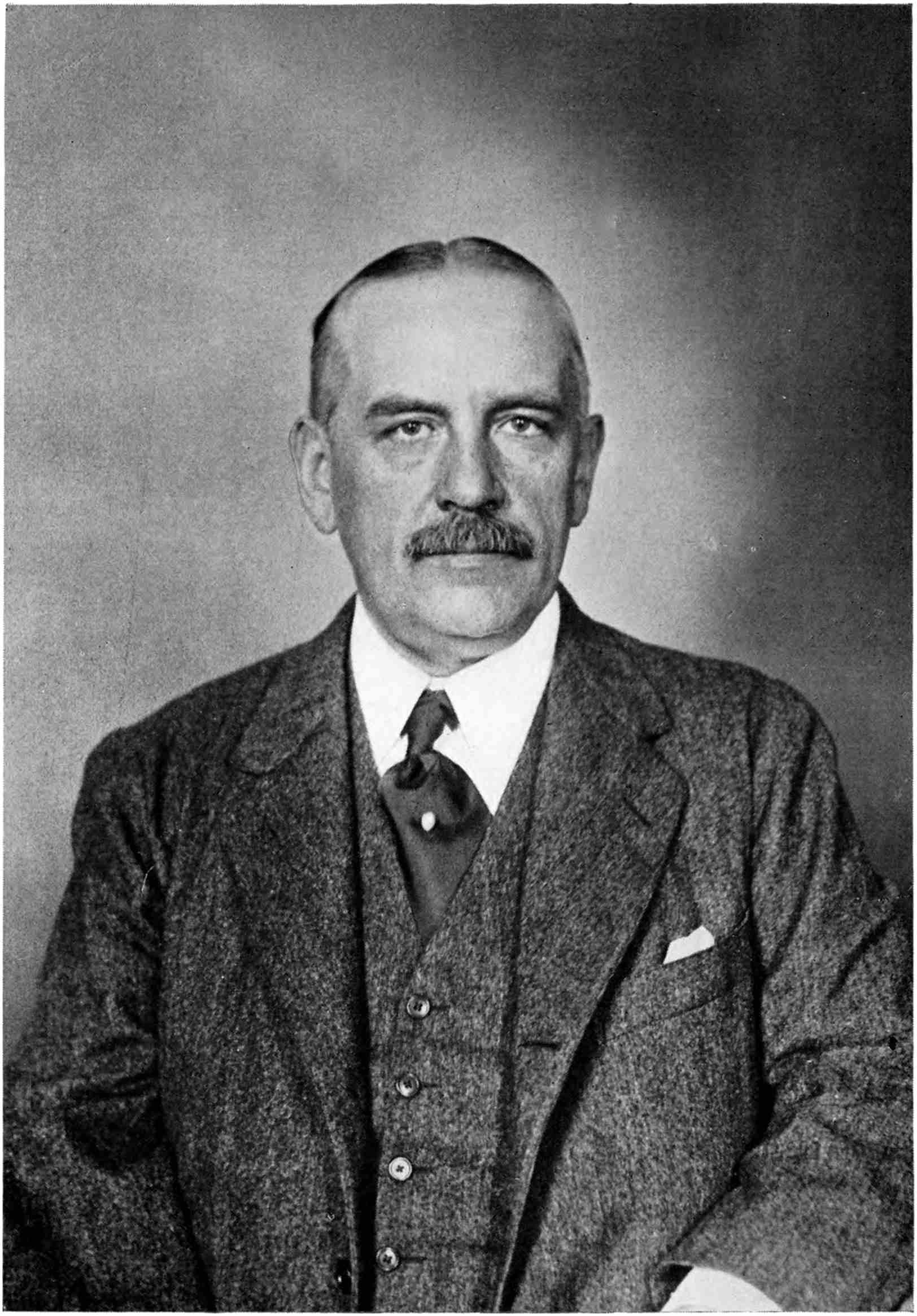

| EDWARD PAGE MITCHELL | 430 |

21

Benjamin H. Day, with No Capital Except Youth and Courage, Establishes the First Permanent Penny Newspaper.—The Curious First Number Entirely His Own Work.

In the early thirties of last century the only newspapers in the city of New York were six-cent journals whose reading-matter was adapted to the politics of men, and whose only appeal to women was their size, perfectly suited to deep pantry-shelves.

Dave Ramsey, a compositor on one of these sixpennies, the Journal of Commerce, had an obsession. It was that a penny paper, to be called the Sun, would be a success in a city full of persons whose interest was in humanity in general, rather than in politics, and whose pantry-shelves were of negligible width. Why his mind fastened on the Sun as the name of this child of his vision is not known; perhaps it was because there was a daily in London bearing that title. It was a short name, easily written, easily spoken, easily remembered.

Benjamin H. Day, another printer, worked beside Dave Ramsey in 1830. Ramsey reiterated his idea to his neighbour so often that Day came to believe in it, although it is doubtful whether he had the great faith that possessed Ramsey. Now that due credit has been given to Ramsey for the idea of the penny Sun, he22 passes out of the record, for he never attempted to put his project into execution.

Nor was Day’s enthusiasm for a penny Sun so big that he plunged into it at once. He was a business man rather than a visionary. With the savings from his wages as a compositor he went into the job-printing business in a small way. He still met his old chums and still talked of the Sun, but it is likely that he never would have come to start it if it had not been for the cholera.

There was an epidemic of this plague in New York in 1832. It killed more than thirty-five hundred people in that year, and added to the depression of business already caused by financial disturbances and a wretched banking system. The job-printing trade suffered with other industries, and Day decided that he needed a newspaper—not to reform, not to uplift, not to arouse, but to push the printing business of Benjamin H. Day. Incidentally he might add lustre to the fame of the President, Andrew Jackson, or uphold the hands of the mayor of New York, Gideon Lee; but his prime purpose was to get the work of printing handbills for John Smith, the grocer, or letter-heads for Richard Robinson, the dealer in hay. Incidentally he might become rich and powerful, but for the time being he needed work at his trade.

Ben Day was only twenty-three years old. He was the son of Henry Day, a hatter of West Springfield, Massachusetts, and Mary Ely Day; and sixth in descent from his first American ancestor, Robert Day. Shortly after the establishment of the Springfield Republican by Samuel Bowles, in 1824, young Day went into the office of that paper, then a weekly, to learn the printer’s trade. That was two years before the birth of the second and greater Samuel Bowles, who was later to23 make the Republican, as a daily, one of the greatest of American newspapers.

BENJAMIN H. DAY

A Bust in the Possession of Mrs. Florence A. Snyder, Summit, N. J.

Day learned well his trade from Sam Bowles. When he was twenty, and a first-class compositor, he went to New York, and worked at the case in the offices of the Evening Post and the Commercial Advertiser. He married, when he was twenty-one, Miss Eveline Shepard. At the time of the Sun’s founding Mr. Day lived, with his wife and their infant son, Henry, at 75 Duane Street, only a few blocks from the newspaper offices.

Day was a good-looking young man with a round, calm, resolute face. He possessed health, industry, and character. Also he had courage, for a man with a family was taking no small risk in launching, without capital, a paper to be sold at one cent.

The idea of a penny paper was not new. In Philadelphia, the Cent had had a brief, inglorious existence. In Boston, the Bostonian had failed to attract the cultured readers of the modern Athens. Eight months before Day’s hour arrived the Morning Post had braved it in New York, selling first at two cents and later at one cent, but even with Horace Greeley as one of the founders it lasted only three weeks.

When Ben Day sounded his friends, particularly the printers, as to their opinion of his project, they cited the doleful fate of the other penny journals. He drew, or had designed, a head-line for the Sun that was to be, and took it about to his cronies. A. S. Abell, a printer on the Mercantile Advertiser, poked the most fun at him. A penny paper, indeed! But this same Abell lived to stop scoffing, to found another Sun—this one in Baltimore—and to buy a half-million-dollar estate out of the profits of it. He was the second beneficiary of the penny Sun idea.

William M. Swain, another journeyman printer, also24 made light of Day’s ambition. He lived to be Day’s foreman, and later to own the Philadelphia Public Ledger. He told Day that the penny Sun would ruin him. As Day had not much enthusiasm at the outset, surely his friends did not add to it, unless by kindling his stubbornness.

As for capital, he had none at all, in the money sense. He did have a printing-press, hardly improved from the machine of Benjamin Franklin’s day, some job-paper, and plenty of type. The press would throw off two hundred impressions an hour at full speed, man power. He hired a room, twelve by sixteen feet, in the building at 222 William Street. That building was still there, in the shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge approach, when the Sun celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in 1883; but a modern six-story envelope factory is on the site to-day.

There is no question as to the general authorship of the first paper. Day was proprietor, publisher, editor, chief pressman, and mailing-clerk. He was not a lazy man. He stayed up all the night before that fateful Tuesday, September 3, 1833, setting with his own hands some advertisements that were regularly appearing in the six-cent papers, for he wanted to make a show of prosperity.

He also wrote, or clipped from some out-of-town newspaper, a poem that would fill nearly a column. He rewrote news items from the West and South—some of them not more than a month old. As for the snappy local news of the day, he bought, in the small hours of that Tuesday morning, a copy of the Courier and Enquirer, the livest of the six-cent papers, took it to the single room in William Street, clipped out or rewrote the police-court items, and set them up himself. A boy, whose name is unknown to fame, assisted him at devil’s work. A journeyman printer, Parmlee, helped25 with the press when the last quoin had been made tight in the fourth and last of the little pages.

The sun was well up in the sky before its namesake of New York came slowly, hesitatingly, almost sadly, up over the horizon of journalism—never to set! In the years to follow, the Sun was to have changes in ownership, in policy, in size, and in style, but no week-day was to come when it could not shine. Of all the morning newspapers printed in New York on that 3rd of September, 1833, there is only one other—the Journal of Commerce—left.

But young Mr. Day, wiping the ink from his hands at noon, and waiting in doubt to see whether the public would buy the thousand Suns he had printed, could not foresee this. Neither could he know that, by this humble effort to exalt his printing business, he had driven a knife into the sclerotic heart of ancient journalism. The sixpenny papers were to laugh at this tiny intruder—to laugh and laugh, and to die.

The size of the first Sun was eleven and one-quarter by eight inches, not a great deal bigger than a sheet of commercial letter paper, and considerably less than one-quarter the size of a page of the Sun of to-day. Compared with the first Sun, the present newspaper is about sixteen times larger. The type was a good, plain face of agate, with some verse on the last page in nonpareil.

An almost perfect reprint of the first Sun was issued as a supplement to the paper on its twentieth birthday, in 1853, and again—to the number of about one hundred and sixty thousand copies—on its fiftieth birthday, in 1883. Many of the persons who treasure the replicas of 1883 believe them to be original first numbers, as they were not labelled “Presented gratuitously to the subscribers of the Sun,” as was the issue of 1853. Hardly a month passes by but the Sun receives one of26 them from some proud owner. It is easy, however, to tell the reprint from the original, for Mr. Day in his haste committed an error at the masthead of the editorial or second page of the first number. The date-line there reads “September 3, 1832,” while in the reprints it is “September 3, 1833,” as it should have been, but wasn’t, in the original. And there are minor typographical differences, invisible to the layman.

Of the thousand, or fewer, copies of the first Sun, only five are known to exist—one in the bound file of the Sun’s first year, held jealously in the Sun’s safe; one in the private library of the editor of the Sun, Edward Page Mitchell; one in the Public Library at Fifth Avenue and Forty-second Street, New York; and two in the library of the American Type Founders Company, Jersey City.

There were three columns on each of the four pages. At the top of the first column on the front page was a modest announcement of the Sun’s ambitions:

The object of this paper is to lay before the public, at a price within the means of every one, ALL THE NEWS OF THE DAY, and at the same time afford an advantageous medium for advertising.

It was added that the subscription in advance was three dollars a year, and that yearly advertisers were to be accommodated with ten lines every day for thirty dollars per annum—ten cents a day, or one cent a line. That was the old fashion of advertising. The friendly merchant bought thirty dollars’ worth of space, say in December, and inserted an advertisement of his fur coats or snow-shovels. The same advertisement might be in the paper the following July, for the newspapers made no effort to coordinate the needs of the seller27 and the buyer. So long as the merchant kept his name regularly in print, he felt that was enough.

The leading article on the first page was a semi-humorous story about an Irish captain and his duels. It was flanked by a piece of reprint concerning microscopic carved toys. There was a paragraph about a Vermont boy so addicted to whistling that he fell ill of it. Mr. Day’s apprentice may have needed this warning.

The front-page advertising, culled from other newspapers and printed for effect, consisted of the notices of steamship sailings. In one of these Commodore Vanderbilt offered to carry passengers from New York to Hartford, by daylight, for one dollar, on his splendid low-pressure steamboat Water Witch. Cornelius Vanderbilt was then thirty-nine years old, and had made the boat line between New York and New Brunswick, New Jersey, pay him forty thousand dollars a year. When the Sun started, the commodore was at the height of his activity, and he stuck to the water for thirty years afterward, until he had accumulated something like forty million dollars.

E. K. Collins had not yet established his famous Dramatic line of clipper-ships between New York and Liverpool, but he advertised the “very fast sailing coppered ship Nashville for New Orleans.” He was only thirty then.

Cooks were advertised for by private families living in Broadway, near Canal Street—pretty far up-town to live at that day—and in Temple Street, near Liberty, pretty far down-town now.

On the second page was a bit of real news, the melancholy suicide of a young Bostonian of “engaging manners and amiable disposition,” in Webb’s Congress Hall, a hotel. There were also two local anecdotes; a paragraph to the effect that “the city is nearly full of28 strangers from all parts of this country and Europe”; nine police-court items, nearly all concerning trivial assaults; news of murders committed in Florida, at Easton, Pennsylvania, and at Columbus, Ohio; a report of an earthquake at Charlottesville, Virginia, and a few lines of stray news from Mexico.

The third page had the arrivals and clearances at the port of New York, a joke about the cholera in New Orleans, a line to say that the same disease had appeared in the City of Mexico, an item about an insurrection in the Ohio penitentiary, a marriage announcement, a death notice, some ship and auction advertisements, and the offer of a reward of one thousand dollars for the recovery of thirteen thousand six hundred dollars stolen from the mail stage between Boston and Lynn and the arrest of the thieves.

The last page carried a poem, “A Noon Scene,” but the atmosphere was of the Elysian Fields over in Hoboken rather than of midday in the city. When Day scissored it, probably he did so with the idea that it would fill a column. Another good filler was the bank-note table, copied from a six-cent contemporary. The quotations indicated that not much of the bank currency of the day was accepted at par.

The rest of the page was filled with borrowed advertising. The Globe Insurance Company, of which John Jacob Astor was a director, announced that it had a capital of a million dollars. The North River Insurance Company, whose directorate included William B. Astor, declared its willingness to insure against fire and against “loss or damage by inland navigation.” At that time the boilers of river steamboats had an unpleasant trick of blowing up; hence Commodore Vanderbilt’s mention of the low pressure of the Water Witch. John A. Dix, then Secretary of State of the State of29 New York, and later to be the hero of the “shoot him on the spot” order, advertised an election. Castleton House Academy, on Staten Island, offered to teach and board young gentlemen at twenty-five dollars a quarter.

Such was the first Sun. Part of it was stale news, rewritten. Part was borrowed advertising. It is doubtful whether even the police-court items were original, although they were the most human things in the issue, the most likely to appeal to the readers whom Day hoped to reach—people to whom the purchase of a paper at six cents was impossible, and to whom windy, monotonous political discussions were a bore.

In those early thirties, daily journalism had not advanced very far. Men were willing, but means and methods were weak. The first English daily was the Courrant, issued in 1702. The Orange Postman, put out the following year, was the first penny paper. The London Times was not started until 1785. It was the first English paper to use a steam press, as the Sun was the first American paper.

The first American daily was the Pennsylvania Packet, called later the General Advertiser, begun in Philadelphia in 1784. It died in 1837. Of the existing New York papers only the Globe dates back to the eighteenth century, having been founded in 1797 as the Commercial Advertiser. Next to it in age is the Evening Post, started in 1801.

The weakness of the early dailies was largely due to the fact that their publishers looked almost entirely to advertising for the support of the papers. On the other hand, the editors were politicians or highbrows who thought more of a speech by Lord Piccadilly on empire than of a good street tragedy; more of an essay by Lady Geraldine Glue than of a first-class report of a kidnapping.

30

Another great obstacle to success—one for which neither editor nor publisher was responsible—was the lack of facilities for the transmission of news. Fulton launched the Clermont twenty-six years before Day launched the Sun, but even in Day’s time steamships were nothing to brag of, and the first of them was yet to cross the Atlantic. When the Sun was born, the most important railroad in America was thirty-four miles long, from Bordentown to South Amboy, New Jersey. There was no telegraph, and the mails were of pre-historic slowness.

It was hard to get out a successful daily newspaper without daily news. A weekly would have sufficed for the information that came in, by sailing ship and stage, from Europe and Washington and Boston. Ben Day was the first man to reconcile himself to an almost impossible situation. He did so by the simple method of using what news was nearest at hand—the incidental happenings of New York life. In this way he solved his own problem and the people’s, for they found that the local items in the Sun were just what they wanted, while the price of the paper suited them well.

31

A Very Small Metropolis Which Day and His Partner, Wisner, Awoke by Printing Small Human Pieces About Small Human Beings and Having Boys Cry the Paper.

How far could the little Sun hope to cast its beam in a stodgy if not naughty world? The circulation of all the dailies in New York at the time was less than thirty thousand. The seven morning and four evening papers, all sold at six cents a copy, shared the field thus:

MORNING PAPERS

| Morning Courier and New York Enquirer | 4,500 |

| Democratic Chronicle | 4,000 |

| New York Standard | 2,400 |

| New York Journal of Commerce | 2,300 |

| New York Gazette and General Advertiser | 1,500 |

| New York Daily Advertiser | 1,400 |

| Mercantile Advertiser and New York Advocate | 1,200 |

EVENING PAPERS

| Evening Post | 3,000 |

| Evening Star | 2,500 |

| New York Commercial Advertiser | 2,100 |

| New York American | 1,600 |

| Total | 26,500 |

New York was the American metropolis, but it was of about the present size of Indianapolis or Seattle. Of32 its quarter of a million population, only eight or ten thousand lived above Twenty-third Street. Washington Square, now the residence district farthest down-town, had just been adopted as a park; before that it had been the Potter’s Field. In 1833 rich New Yorkers were putting up some fine residences there—of which a good many still stand. Sixth Street had had its name changed to Waverley Place in honor of Walter Scott, recently dead, the literary king of the day.

Wall Street was already the financial centre, with its Merchants’ Exchange, banks, brokers, and insurance companies. Canal Street was pretty well filled with retail stores. Third Avenue had been macadamized from the Bowery to Harlem. The down-town streets were paved, and some were lighted with gas at seven dollars a thousand cubic feet.

Columbia College, in the square bounded by Murray, Barclay, Church, and Chapel Streets, had a hundred students; now it has more than a hundred hundred. James Kent was professor of law in the Columbia of that day, and Charles Anthon was professor of Greek and Latin. A rival seat of learning, the University of the City of New York, chartered two years earlier, was temporarily housed at 12 Chambers Street, with a certain Samuel F. B. Morse as professor of sculpture and painting. There were twelve schools, harbouring six thousand pupils, whose welfare was guarded by the Public School Society of New York, Lindley Murray secretary. The National Academy of Design, incorporated five years before, guided the budding artist in Clinton Hall, and Mr. Morse was its president, while it had for its professor of mythology one William Cullen Bryant.

Albert Gallatin was president of the National Bank, at 13 Wall Street. Often at the end of his day’s work33 he would walk around to the small shop in William Street where his young friend Delmonico, the confectioner, was trying to interest the gourmets of the city in his French cooking. Gideon Lee, besides being mayor, was president of the Leather Manufacturers’ Bank at 334 Pearl Street. He was the last mayor of New York to be appointed by the common council, for Dix’s advertisement in the first Sun called an election by which the people of the city gained the right to elect a mayor by popular vote.

A list of the solid citizens of the New York of that year would include Peter Schermerhorn, Nicholas Fish, Robert Lenox, Sheppard Knapp, Samuel Swartwout, Henry Beekman, Henry Delafield, John Mason, William Paulding, David S. Kennedy, Jacob Lorillard, David Lydig, Seth Grosvenor, Elisha Riggs, John Delafield, Peter A. Jay, C. V. S. Roosevelt, Robert Ray, Preserved Fish, Morris Ketchum, Rufus Prime, Philip Hone, William Vail, Gilbert Coutant, and Mortimer Livingston.

These men and their fellows ran the banks and the big business of that day. They read the six-cent papers, mostly those which warned the public that Andrew Jackson was driving the country to the devil. It would be years before the Sun would bring the light of common, everyday things into their dignified lives—if it ever did so. Day, the printer, did not look to them to read his paper, although he hoped for some small part of their advertising. It is likely that one of the Gouverneurs—Samuel L.—read the early Sun, but he was postmaster, and it was his duty to examine new and therefore suspicionable publications.

Incidentally, Postmaster Gouverneur had one clerk to sort all the mail that came into the city from the rest of the world. It was a small New York upon which the timid Sun cast its still smaller beams. The mass of the34 people had not been interested in newspapers, because the newspapers brought nothing into their lives but the drone of American and foreign politics. A majority of them were in sympathy with Tammany Hall, particularly since 1821, when the property qualification was removed from the franchise through Democratic effort.

New York had literary publications other than the six-cent papers. The Knickerbocker Magazine was founded in January of 1833, with Charles Hoffman, assistant editor of the American Magazine, as editor. Among the contributors engaged were William Cullen Bryant and James K. Paulding. The subscription-list, it was proudly announced, had no fewer than eight hundred names on it. The Mechanics’ Magazine, the Sporting Magazine, the American Ploughboy, the Journal of Public Morals, and the Youth’s Temperance Lecturer were among the periodicals that contended for public favour.

Bryant was a busy man, for he was the chief editor of the Evening Post as well as a magazine contributor and a teacher. Fame had come to him early, for “Thanatopsis” was published when he was twenty-three, and “To a Water-fowl” appeared a year later, in 1818. Now, in his thirties, he was no longer the delicate youth, the dreamy poet. One April day in 1831 Bryant and William L. Stone, one of the editors of the Commercial Advertiser, had a rare fight in front of the City Hall, the poet beginning it with a cowskin whip swung at Stone’s head, and the spectators ending it after Stone had seized the whip. These two were editors of sixpenny “respectables.”

THE FIRST HOME OF “THE SUN,” 222 WILLIAM STREET

(Under the Arrow)

THE SECOND HOME OF “THE SUN”

Nassau Street, from Frankfort to Spruce, in the Early Forties. “The Sun’s” Second Home Is Shown at the Right End of the Block. The Tammany Hall Building Became “The Sun’s” Fourth Home in 1868.

Irving and Cooper, Bryant and Halleck, Nathaniel P. Willis and George P. Morris were the largest figures of intellectual New York. In 1833 Irving returned from Europe after a visit that had lasted seventeen years.35 He was then fifty, and had written his best books. Cooper, half a dozen years younger, had long since basked in the glory that came to him with the publication of “The Spy,” “The Pilot,” and “The Last of the Mohicans.” He and Irving were guests at every cultured function.

Prescott was finishing his first work, “The History of Ferdinand and Isabella.” Bancroft was beginning his “History of the United States.” George Ticknor had written his “Life of Lafayette.” Hawthorne had published only “Fanshawe” and some of the “Twice Told Tales.” Poe was struggling along in Baltimore. Holmes, a medical student, had written a few poems. Dr. John William Draper, later to write his great “History of the Intellectual Development of Europe,” arrived from Liverpool that year to make New York his home.

Longfellow was professor of modern languages at Bowdoin, and unknown to fame as a poet. Whittier had written “Legends of New England” and “Moll Pitcher.” Emerson was in England. Richard Henry Dana and Motley were at Harvard. Thoreau was helping his father to make lead-pencils. Parkman, Lowell, and Herman Melville were schoolboys.

Away off in Buffalo was a boy of fourteen who clerked in his uncle’s general store by day, selling steel traps to Seneca braves, and by night read Latin, Greek, poetry, history, and the speeches of Andrew Jackson. His name was Charles Anderson Dana.

The leading newspaperman of the day in New York was James Watson Webb, a son of the General Webb who held the Bible upon which Washington took the oath of office as first President. J. Watson Webb had been in the army and, as a journalist, was never for peace at any price. He united the Morning Courier36 and the Enquirer, and established a daily horse express between New York and Washington, which is said to have cost seventy-five hundred dollars a month, in order to get news from Congress and the White House twenty-four hours before his rivals.

Webb was famed as a fighter. He had a row with Duff Green in Washington in 1830. In January, 1836, he thrashed James Gordon Bennett in Wall Street. He incited a mob to drive Wood, a singer, from the stage of the Park Theater. In 1838 he sent a challenge to Representative Cilley, of Maine, a classmate of Longfellow and Hawthorne at Bowdoin. Cilley refused to fight, on the ground that he had made no personal reflections on Webb’s character; whereupon Representative Graves, of Kentucky, who carried the card for Webb, challenged Cilley for himself, as was the custom. They fought with rifles on the Annapolis Road, and Cilley was killed at the third shot.

In 1842 Webb fought a duel with Representative Marshall, of Kentucky, and not only was wounded, but on his return to New York was sentenced to two years in prison “for leaving the State with the intention of giving or receiving a challenge.” At the end of two weeks, however, he was pardoned.

Having deserted Jackson and become a Whig, Webb continued to own and edit the Courier and Enquirer until 1861, when it was merged with the World. His quarrels, all of political origin, brought prestige to his paper. Ben Day had no duelling-pistols. His only chance to advertise the Sun was by its own light and its popular price.

Beyond Webb, Day had no lively journalist with whom to contend at the outset, and Webb probably did not dream that the Sun would be worthy of a joust. Perhaps fortunately for Day, Horace Greeley had just37 failed in his attempt to run a one-cent paper. This was the Morning Post, which Greeley started in January, 1833, with Francis V. Story, a fellow printer, as his partner, and with a capital of one hundred and fifty dollars. It ran for three weeks only.

Greeley and Story still had some type, bought on credit, and they issued a tri-weekly, the Constitutionalist, which, in spite of its dignified title, was the avowed organ of the lotteries. Its columns contained the following card:

Greeley & Story, No. 54 Liberty Street, New York, respectfully solicit the patronage of the public to their business of letterpress printing, particularly lottery-printing, such as schemes, periodicals, and so forth, which will be executed on favorable terms.

It must be remembered that at that time lotteries were not under a cloud. There were in New York forty-five lottery offices, licensed at two hundred and fifty dollars apiece annually, and the proceeds were divided between the public schools and a home for deaf-mutes. That was the last year of legalized lotteries. After they disappeared Greeley started the New Yorker, the best literary weekly of its time. It was not until April, 1841, that he founded the Tribune.

Doubtless there were many young New Yorkers of that period who would have made bang-up reporters, but apparently, until Day’s time, with few exceptions they did not work on morning newspapers. One exception was James Gordon Bennett, whose work for Webb on the Courier and Enquirer helped to make it the leading American paper.

Nathaniel P. Willis and George P. Morris would probably have been good reporters, for they knew New York and had excellent styles, but they insisted on being38 poets. With Morris it was not a hollow vocation, for the author of “Woodman, Spare That Tree,” could always get fifty dollars for a song. He and Willis ran the Mirror and later the New Mirror, and wrote verse and other fanciful stuff by the bushel. Philip Hone would have been the best reporter in New York, as his diary reveals, but he was of the aristocracy, and he seems to have scorned newspapermen, particularly Webb and Bennett.

But somehow, by that chance which seemed to smile on the Sun, Ben Day got clever reporters. He wanted one to do the police-court work, for he saw, from the first day of the paper, that that was the kind of stuff that his readers devoured. To them the details of a beating administered by James Hawkins to his wife were of more import than Jackson’s assaults on the United States Bank.

When George W. Wisner, a young printer who was out of work, applied to the Sun for a job, Day told him that he would give him four dollars a week if he would get up early every day and attend the police-court, which held its sessions from 4 A.M. on. The people of the city were quite as human then as they are to-day. Unregenerate mortals got drunk and fought in the streets. Others stole shoes. The worst of all beat their wives. Wisner was to be the Balzac of the daybreak court in a year when Balzac himself was writing his “Droll Stories.”

The second issue of the Sun continued the typographical error of the day before. The year in the date-line of the second page was “1832.” The big news in this paper was under date of Plymouth, England, August 1, and it told of the capture of Lisbon by Admiral Napier on the 25th of July. Day—or perhaps it was Wisner—wrote an editorial article about it:

39

To us as Americans there can be little of interest in the triumph of one member of a royal family of Europe over another; and although we can but rejoice at the downfall of the modern Nero who so lately filled the Portuguese throne, yet if rumor speak the truth the victorious Pedro is no better than he should be.

The editor lamented the general lack of news:

With the exception of the interesting news from Portugal there appears to be very little worthy of note. Nullification has blown over; the President’s tour has terminated; Black Hawk has gone home; the new race for President is not yet commenced, and everything seems settled down into a calm. Dull times, these, for us newspaper-makers. We wish the President or Major Downing or some other distinguished individual would happen along again and afford us material for a daily article. Or even if the sea-serpent would be so kind as to pay us a visit, we should be extremely obliged to him and would honor his snakeship with a most tremendous puff.

Theatrical advertising appeared in this number, the Park Theater announcing the comedy of “Rip Van Winkle,” as redramatized by Mr. Hackett, who played Rip. Mr. Gale was playing “Mazeppa” at the Bowery. Perhaps these advertisements were borrowed from a six-cent paper, but there was one “help wanted” advertisement that was not borrowed. It was the upshot of Day’s own idea, destined to bring another revolution in newspaper methods:

TO THE UNEMPLOYED—A number of steady men can find employment by vending this paper. A liberal discount is allowed to those who buy to sell again.

Before that day there had been no newsboys; no papers were sold in the streets. The big, blanket political40 organs that masqueraded as newspapers were either sold over the counter or delivered by carriers to the homes of the subscribers. Most of the publishers considered it undignified even to angle for new subscribers, and one of them boasted that his great circulation of perhaps two thousand had come unsolicited.

The first unemployed person to apply for a job selling Suns in the streets was a ten-year-old-boy, Bernard Flaherty, born in Cork. Years afterward two continents knew him as Barney Williams, Irish comedian, hero of “The Emerald Ring,” and “The Connie Soogah,” and at one time manager of Wallack’s old Broadway Theatre.

When Day got some regular subscribers, he sent carriers on routes. He charged them sixty-seven cents a hundred, cash, or seventy-five cents on credit. The first of these carriers was Sam Messenger, who delivered the Sun in the Fulton Market district, and who later became a rich livery-stable keeper. Live lads like these, carrying out Day’s idea, wrought the greatest change in journalism that ever had been made, for they brought the paper to the people, something that could not be accomplished by the six-cent sheets with their lofty notions and comparatively high prices.

On the third day of the Sun’s life, with Wisner at the pen and Barney Flaherty “hollering” in the startled streets, the editor again expressed, this time more positively, his yearning that something would happen:

We newspaper people thrive best on the calamities of others. Give us one of your real Moscow fires, or your Waterloo battle-fields; let a Napoleon be dashing with his legions through the world, overturning the thrones of a thousand years and deluging the world with blood and tears; and then we of the types are in our glory.

41

The yearner had to wait thirty years for another Waterloo, but he got his “real Moscow fire” in about two years, and so close that it singed his eyebrows.

Lacking a Napoleon to exalt or denounce, Mr. Day used a bit of that same page for the publication of homelier news for the people:

The following are the drawn numbers of the New York consolidated lotteries of yesterday afternoon:

62 6 59 46 61 34 65 37 8 42

So Horace Greeley and his partner, with their tri-weekly paper, could not have been keeping all of the lottery patronage away from the Sun.

Over in the police column Mr. Wisner was supplying gems like the following:

A complaint was made by several persons who “thought it no sin to step to the notes of a sweet violin” and gathered under a window in Chatham Street, where a little girl was playing on a violin, when they were showered from a window above with the contents of a dye-pot or something of like nature. They were directed to ascertain their showerer.

The big story on the first page of the fourth issue of the Sun was a conversation between Envy and Candor in regard to the beauties of a Miss H., perhaps a fictitious person. But on the second page, at the head of the editorial column, was a real editorial article approving the course of the British government in freeing the slaves in the West Indies:

We supposed that the eyes of men were but half open to this case. We imagined that the slave would have to toil on for years and purchase what in justice was already his own. We did not once dream that light had so far progressed as to prepare the British nation42 for the colossal stride in justice and humanity and benevolence which they are about to make. The abolition of West Indian slavery will form a brilliant era in the annals of the world. It will circle with a halo of imperishable glory the brows of the transcendent spirits who wield the present destinies of the British Empire.

Would to Heaven that the honor of leading the way in this godlike enterprise had been reserved to our own country! But as the opportunity for this is passed, we trust we shall at least avoid the everlasting disgrace of long refusing to imitate so bright and glorious an example.

Thus the Sun came out for the freedom of the slave twenty-eight years before that freedom was to be accomplished in the United States through war. The Sun was the Sun of Day, but the hand was the hand of Wisner. That young man was an Abolitionist before the word was coined.

“Wisner was a pretty smart young fellow,” said Mr. Day nearly fifty years afterward, “but he and I never agreed. I was rather Democratic in my notions. Wisner, whenever he got a chance, was always sticking in his damned little Abolitionist articles.”

There is little doubt that Wisner wrote the article facing the Sun against slavery while he was waiting for something to turn up in the police-court. Then he went to the office, set up the article, as well as his piece about the arrest of Eliza Barry, of Bayard Street, for stealing a wash-tub, and put the type in the form. Considering that Wisner got four dollars a week for his break-o’-day work, he made a very good morning of that; and it is worthy of record that the next day’s Sun did not repudiate his assault on human servitude, although on September 10 Mr. Day printed an editorial grieving over the existence of slavery, but hitting at the methods of the Abolitionists.

43

These early issues were full of lively little “sunny” pieces, for instance:

Passing by the Beekman Street church early this morning, we discovered a milkman replenishing his lacteous cargo with Adam’s ale. We took the liberty to ask him, “Friend, why do ye do thus?” He replied, “None of your business”; and we passed on, determined to report him to the Grahamites.

A poem on Burns, by Halleck—perhaps reprinted from one of the author’s published volumes of verse—added literary tone to that morning’s Sun.

In the next issue was some verse by Willis, beginning:

Then, and for some years afterward, the Sun exhibited a special aversion to alcohol in text and head-lines. “Cursed Effects of Rum!” was one of its favourite head-lines.

The Sun was a week old before it contained dramatic criticism, its first subject in that field being the appearance of Mr. and Mrs. Wood at the Park Theatre in “Cinderella,” a comic opera. The paper’s first animal story was printed on September 12, recording the fact that on the previous Sunday about sixty wild pigeons stayed in a tree at the Battery nearly half an hour.

On September 14 the Sun printed its first illustration—a two-column cut of “Herschel’s Forty-Feet Telescope.” This was Sir W. Herschel, then dead some ten years, and the telescope was on his grounds at Slough, near Windsor, England. Another knighted Herschel with another telescope in a far land was to play a big part in the fortunes of the Sun, but that comes later. In the issue with the cut of the telescope was a paragraph44 about a rumour that Fanny Kemble, who had just captivated American theatregoers, had been married to Pierce Butler, of Philadelphia—as, indeed, she had.

Broadway seems to have had its lure as early as 1833, for in the Sun of September 17, on the first page, is a plaint by “Citizen”:

They talk of the pleasures of the country, but would to God I had never been persuaded to leave the labor of the city for such woful pleasures. Oh, Broadway, Broadway! In an evil hour did I forsake thee for verdant walks and flowery landscapes and that there tiresome piece of made water. What walk is so agreeable as a walk through the streets of New York? What landscape more flowery than those of the print-shops? And what water was made by man equal to the Hudson?

This was followed by uplifting little essays on “Suicide” and “Robespierre.” The chief news of the day—that John Quincy Adams had accepted a nomination from the Anti-Masons—was on an inside page. What was possibly of more interest to the readers, it was announced that thereafter a ton of coal would be two thousand pounds instead of twenty-two hundred and forty—Lackawanna, broken and sifted, six dollars and fifty cents a ton.

On Saturday, September 21, when it was only eighteen days old, the Sun adopted a new head-line. The letters remained the same, but the eagle device of the first issue was supplanted by the solar orb rising over hills and sea. This design was used only until December 2, when its place was taken by a third emblem—a printing-press shedding symbolical effulgence upon the earth.

The Sun’s first book-notice appeared on September 23, when it acknowledged the sixtieth volume of the45 “Family Library” (Harpers), this being a biography of Charlemagne by G. P. R. James. “It treats of a most important period in the history of France.” The Sun had little space then for book-reviews or politics. Of its attitude toward the great financial fight then being waged, this lone paragraph gives a good view:

The Globe of Monday contains in six columns the reasons which prompted the President to remove the public deposits from the United States Bank, which were read to his assembled cabinet on the 18th instant.

Nicholas Biddle and his friends could fill other papers with arguments, but the Sun kept its space for police items, stories of authenticated ghosts, and yarns about the late Emperor Napoleon. The removal of William J. Duane as Secretary of the Treasury got two lines on a page where a big shark caught off Barnstable got three lines, and the feeding of the anaconda at the American Museum a quarter of a column. Miss Susan Allen, who bought a cigar on Broadway and was arrested when she smoked it while she danced in the street, was featured more prominently than the expected visit to New York of Mr. Henry Clay, after whom millions of cigars were to be named. For the satisfaction of universal curiosity it must be reported that Miss Allen was discharged.

On October 1 of that same year—1833—the Sun came out for better fire-fighting apparatus, urging that the engines should be drawn by horses, as in London. In the same issue it assailed the gambling-house in Park Row, and scorned the allegation of Colonel Hamilton, a British traveller, that the tooth-brush was unknown in America. Slowly the paper was getting better, printing more local news; and it could afford to, for the penny46 Sun idea had taken hold of New York, and the sales were larger every week.

Wisner was stretching the police-court pieces out to nearly two columns. Now and then, perhaps when Mr. Day was away fishing, the reporter would slip in an Abolition paragraph or a gloomy poem on the horrors of slavery. But he was so valuable that, while his chief did not raise his salary of four dollars a week, he offered him half the paper, the same to be paid for out of the profits. And so, in January of 1834, Wisner became a half-owner of the Sun. Benton, another Sun printer, also wanted an interest, and left when he could not get it.

Before it was two months old the Sun had begun to take an interest in aeronautics. It printed a full column, October 16, 1833, on the subject of Durant’s balloon ascensions, and quoted Napoleon as saying that the only insurmountable difficulty of the balloon in war was the impossibility of guiding its course. “This difficulty Dr. Durant is now endeavoring to obviate.” And the Sun added:

May we not therefore look to the time, in perspective, when our atmosphere will be traversed with as much facility as our waters?

In the issue of October 17 a skit, possibly by Mr. Day himself, gave a picture of the trials of an editor of the period:

SCENE—An editor’s closet—editor solus.

“Well, a pretty day’s work of it I shall make. News, I have nothing—politics, stale, flat, and unprofitable—miscellany, enough of it—miscellany bills payable, and a miscellaneous list of subscribers with tastes as miscellaneous as the tongues of Babel. Ha! Footsteps!47 Drop the first person singular and don the plural. WE must now play the editor.”

(Enter Devil)—“Copy, sir!”

(Enter A.)—“I missed my paper this morning, sir, I don’t want to take it—”

(Enter B.)—“There is a letter ‘o’ turned upside down in my advertisement this morning, sir! I—I—”

(Enter C.)—“You didn’t notice my new work, my treatise on a flea, this morning, sir! You have no literary taste! Sir—”

(Enter D.)—“Sir, your boy don’t leave my paper, sir—I live in a blind alley; you turn out of —— Street to the right—then take a left-hand turn—then to the right again—then go under an arch—then over a kennel—then jump a ten-foot fence—then enter a door—then climb five pair of stairs—turn fourteen corners—and you can’t miss my door. I want your boy to leave my paper first—it’s only a mile out of his way—if he don’t, I’ll stop—”

(Enter E.)—“Sir, you have abused my friend; the article against Mr. —— as a candidate is intolerable—it is scandalous—I’ll stop my paper—I’ll cane you—I’ll—”

(Enter F.)—“Mr. Editor, you are mealy-mouthed, you lack independence, your remarks upon Mr. ——, the candidate for Congress, are too tame. If you don’t put it on harder I’ll stop my—”

(Enter G.)—“Your remarks upon profane swearing are personal, d——n you, sir, you mean me—before I’ll patronize you longer I’ll see you in ——”

(Enter H.)—“Mr. ——, we are very sorry you do not say more against the growing sin of profanity. Unless you put your veto on it more decidedly, no man of correct moral principles will give you his patronage—I, for one—”

(Enter I.)—“Bad luck to the dirty sowl of him, where does he keep himself? By the powers, I’ll strike him if I can get at his carcass, and I’ll kick him anyhow! Why do you fill your paper with dirty lies about Irishmen at all?”

48

(Enter J.)—“Why don’t you give us more anecdotes and sich, Irish stories and them things—I don’t like the long speeches—I—”

(Devil)—“Copy, sir!”

The day after this evidence of unrest appeared the Sun printed, perhaps with a view to making all manner of citizens gnash their teeth, a few extracts from the narrative of Colonel Hamilton, “the British traveler in America”:

In America there are no bells and no chambermaids.

I have heard, since my arrival in America, the toast of “a bloody war in Europe” drank with enthusiasm.

The whole population of the Southern and Western States are uniformly armed with daggers.

At present an American might study every book within the limits of the Union and still be regarded in many parts of Europe, especially in Germany, as a man comparatively ignorant.

The editorial suggested that the colonel “had better look wild for the lake that burns with fire and brimstone.”

The union printers were lively even in the first days of the Sun, which announced, on October 21, 1833, that the Journal of Commerce paid its journeymen only ten dollars a week, and added:

The proprietors of other morning papers cheerfully pay twelve dollars. Therefore, the office of the Journal of Commerce is what printers term a rat office—and the term “rat,” with the followers of the same profession with Faust, Franklin, and Stanhope, is a most odious term.

The “pork-barrel” was foreshadowed in an item printed when the Sun was just a month old:

49

At the close of the present year the Treasury of the nation will contain twelve million dollars. This rich and increasing revenue will probably be a bone of contention at the next session of Congress.

At the end of its first month the Sun was getting more and more advertising. Its news was lively enough, considering the times. Rum, the cholera in Mexico, assassinations in the South, the police-court, the tour of Henry Clay, and poems by Walter Scott were its long suit. The circulation of the little paper was now about twelve hundred copies, and the future seemed promising, even if Mr. Day did print, at suspiciously frequent intervals, articles inveighing against the debtor’s-prison law.

The Astor House—now half a ruin—was at first to be called the Park Hotel, for the Sun of October 29, 1833, announced editorially:

THE PARK HOTEL—Mr. W. B. Astor gives notice that he will receive proposals for building the long-contemplated hotel in Broadway, between Barclay and Vesey Streets.

An advertisement which the Sun saw fit to notice editorially was inserted by a young man in search of a wife—“a young woman who understands the use of the needle, and who is willing to be industrious.” The editorial comment was:

The advertisement was handed to us by a respectable-looking young man, and of course we could not refuse to publish it—though if we were in want of a wife we think we should take a different course to obtain one.

Sometimes the police items, flecked with poetry, and presumably written by Wisner, were tantalizingly reticent, as:

50

Maria Jones was accused of stealing clothing, and committed. Certain affairs were developed of rather a singular and comical nature in relation to her.

Nothing more than that. Perhaps Wisner rather enjoyed being questioned by admiring friends when he went to dinner at the American House that day.

Bright as the police reporter was, the ship-news man of that day lacked snap. The arrival from Europe of James Fenimore Cooper, who could have told the Sun more foreign news than it had ever printed, was disposed of in twelve words. But it must be remembered that the interview was then unknown. The only way to get anything out of a citizen was to enrage him, whereupon he would write a letter. But the Sun did say, a couple of days later, that Cooper’s newest novel, “The Headsman,” was being sold in London at seven dollars and fifty cents a copy—no doubt in the old-fashioned English form, three volumes at half a guinea each.

The Sun blew its own horn for the first time on November 9, 1833:

Its success is now beyond question, and it has exceeded the most sanguine anticipations of its publishers in its circulation and advertising patronage. Scarcely two months has it existed in the typographical firmament, and it has a daily circulation of upward of two thousand copies, besides a steadily increasing advertising patronage. Although of a character (we hope) deserving the encouragement of all classes of society, it is more especially valuable to those who cannot well afford to incur the expense of subscribing to a “blanket sheet” and paying ten dollars per annum.

In conclusion we may be permitted to remark that the penny press, by diffusing useful knowledge among the operative classes of society, is effecting the march of51 intelligence to a greater degree than any other mode of instruction.

The same article called attention to the fact that the “penny” papers of England were really two-cent papers. The Sun’s price had been announced as “one penny” on the earliest numbers, but on October 8, when it was a little more than a month old, the legend was changed to read “Price one cent.”

BARNEY WILLIAMS, THE COMEDIAN, WHO WAS THE FIRST NEWSBOY OF “THE SUN”

The Sun ran its first serial in the third month of its existence. This was “The Life of Davy Crockett,” dictated or authorized by the frontiersman himself. It must have been a relief to the readers to get away from the usual dull reprint from foreign papers that had been filling the Sun’s first page. In those days the first pages were always the dullest, but Crockett’s lively stories about bear-hunts enlivened the Sun.

Other celebrities were often mentioned. Aaron Burr, now old and feeble, was writing his memoirs. Martin Van Buren had taken lodgings at the City Hotel. The Siamese Twins were arrested in the South for beating a man. “Mr. Clay arrived in town last evening and attended the new opera.” This was “Fra Diavolo,” in which Mr. and Mrs. Wood sang at the Park Theatre. “It is said that Dom Pedro has dared his brother Miguel to single combat, which has been refused.” A week later the Sun gloated over the fact that Pedro—Pedro I of Brazil, who was invading Portugal on behalf of his daughter, Maria da Gloria—had routed the usurper Miguel’s army.

On December 5, 1833, the Sun printed the longest news piece it had ever put in type—the message of President Jackson to the Congress. This took up three of the four pages, and crowded out nearly all the advertising.

52

On December 17, in the fourth month of its life, the Sun announced that it had procured “a machine press, on which one thousand impressions can be taken in an hour. The daily circulation is now nearly FOUR THOUSAND.” It was a happy Christmas for Day and Wisner. The Sun surely was shining!

The paper retained its original size and shape during the whole of 1834, and rarely printed more than four pages. As it grew older, it printed more and more local items and developed greater interest in local affairs. The first page was taken up with advertising and reprint. A State election might have taken place the day before, but on page 1 the Sun worshippers looked for a bit of fiction or history. What were the fortunes of William L. Marcy as compared to a two-column thriller, “The Idiot’s Revenge,” or “Captain Chicken and Gentle Sophia”?

The head-lines were all small, and most of them italics. Here are samples:

INGRATITUDE OF A CAT.

PERSONALITY OF NAPOLEON.

WONDERFUL ANTICS OF FLEAS.

BROUGHT TO IT BY RUM.

The news paragraphs were sometimes models of condensation:

PICKPOCKETS—On Friday night a Gentleman lost $100 at the Opera and then $25 at Tammany Hall.

The Hon. Daniel Webster will leave town this morning for Washington.

John Baker, the person whom we reported a short time since as being brought before the police for stealing a ham, died suddenly in his cell in Bellevue in the greatest agony—an awful warning to drunkards.

53

James G. Bennett has become sole proprietor and editor of the Philadelphia Courier.

Colonel Crockett, it is expected, will visit the Bowery Theater this evening.

RUMOR—It was rumored in Washington on the 6th that a duel would take place the next day between two members of the House.

SUDDEN DEATH—Ann McDonough, of Washington Street, attempted to drink a pint of rum on a wager, on Wednesday afternoon last. Before it was half swallowed Ann was a corpse. Served her right!

Bayington, the murderer, we learn by a contemporary, was formerly employed in this city on the Journal of Commerce. No wonder he came to an untimely fate.

DUEL—We understand that a duel was fought at Hoboken on Friday morning last between a gentleman of Canada and a French gentleman of this city, in which the latter was wounded. The parties should be arrested.

LAMENTABLE DEATH—The camelopard shipped at Calcutta for New York died the day after it was embarked. “We could have better spared a better” crittur, as Shakespeare doesn’t say.

The Sun, although read largely by Jacksonians, did not take the side of any political party. It favoured national and State economy and city cleanliness. It dismissed the New York Legislature of 1834 thus:

The Legislature of this State closed its arduous duties yesterday. It has increased the number of our banks and fixed a heavy load of debt upon posterity.

Nothing more. If the readers wanted more they could fly to the ample bosoms of the sixpennies; but54 apparently they were satisfied, for in April of 1834 the Sun’s circulation reached eight thousand, and Colonel Webb, of the Courier and Enquirer, was bemoaning the success of “penny trash.” The Sun replied to him by saying that the public had been “imposed upon by ten-dollar trash long enough.” The Journal of Commerce also slanged the Sun, which promptly announced that the Journal was conducted by “a company of rich, aristocratical men,” and that it would take sides with any party to gain a subscriber.

The influence of Partner Wisner, the Abolitionist, was evident in many pages of the Sun. On June 23, 1834, it printed a piece about Martin Palmer, who was “pelted down with stones in Wall Street on suspicion of being a runaway slave,” and paid its respects to Boudinot, a Southerner in New York who was reputed to be a tracker of runaways. It was he who had set the crowd after the black:

The man who will do this will do anything; he would dance on his mother’s grave; he would invade the sacred precincts of the tomb and rob a corpse of its winding-sheet; he has no SOUL. It is said that this useless fellow is about to commence a suit against us for a libel. Try it, Mr. Boudinot!

During the anti-abolition riots of that year the Sun took a firm stand against the disturbers, although there is little doubt that many of them were its own readers.

The paper made a vigorous little crusade against the evils of the Bridewell in City Hall Park, where dozens of wretches suffered in the filth of the debtors’ prison. The Sun was a live wire when the cholera re-appeared, and it put to rout the sixpenny papers which tried to make out that the disease was not cholera, but “summer complaint.” Incidentally, the advertising55 columns of that day, in nearly all the papers were filled with patent “cholera cures.”

The Sun had an eye for urban refinement, too, and begged the aldermen to see to it that pigs were prevented from roaming in City Hall Park. In the matter of silver forks, then a novelty, it was more conservative, as the following paragraph, printed in November, 1834, would indicate:

EXTREME NICETY—The author of the “Book of Etiquette,” recently printed in London, says: “Silver forks are now common at every respectable table, and for my part I cannot see how it is possible to eat a dinner comfortably without them.” The booby ought to be compelled to cut his beefsteak with a piece of old barrel-hoop on a wooden trencher.

Not even abolition or etiquette, however, could sidetrack the Sun’s interest in animals. In one issue it dismissed the adjournment of Congress in three words and, just below, ran this item:

THE ANACONDA—Most of those who have seen the beautiful serpent at Peale’s Museum will recollect that in the snug quarters allotted to him there are two blankets, on one of which he lies, and the other is covered over him in cold weather. Strange to say that on Monday night, after Mr. Peale had fed the serpent with a chicken, according to custom, the serpent took it into his head to swallow one of the blankets, which is a seven-quarter one, and this blanket he has now in his stomach. The proprietor feels much anxiety.

Almost every newspaper editor in that era had a theatre feud at one day or another. The Sun’s quarrel was with Farren, the manager of the Bowery, where Forrest was playing. So the Sun said:

56

DAMN THE YANKEES—We are informed by a correspondent (though we have not seen the announcement ourselves) that Farren, the chap who damned the Yankees so lustily the other day, and who is now under bonds for a gross outrage on a respectable butcher near the Bowery Theater, is intending to make his appearance on the Bowery stage THIS EVENING!

Five hundred citizens gathered at the theatre that night, waited until nine o’clock, and then charged through the doors, breaking up the performance of “Metamora.” The Sun described it:

The supernumeraries scud from behind the scenes like quails—the stock actors’ teeth chattered—Oceana looked imploringly at the good-for-nothing Yankees—Nahmeeoke trembled—Guy of Godalwin turned on his heel, and Metamora coolly shouldered his tomahawk and walked off the stage.

The management announced that Farren was discharged. The mayor of New York and Edwin Forrest made conciliatory speeches, and the crowd went away.

The attacks of Colonel Stone, editor of the six-cent Commercial, aroused the Sun to retaliate in kind. A column about the colonel ended thus:

He was then again cowskinned by Mr. Bryant of the Post, and was most unpoetically flogged near the American Hotel. He has always been the slave of avarice, cowardice, and meanness.... The next time he sees fit to attack the penny press we hope he will confine himself to facts.

A month later the Sun went after Colonel Stone again:

The colonel ... for the sake of an additional glass of wine and a couple of real Spanish cigars, did actually57 perpetrate a most excellent and true article, the first we have seen of his for a long time past. Now we have serious thoughts that the colonel will yet become quite a decent fellow, and may ultimately ascend, after a long course of training, to a level with the penny dailies which have soared so far above him in the heavens of veracity.

It must be said of Colonel Stone that he was a man of literary and political attainments. He was editor of the Commercial Advertiser for more than twenty years.

The colonel did not reform to the Sun’s liking at once, but the feud lessened, and presently it was the Transcript—a penny paper which sprang up when the Sun’s success was assured—to which the Sun took its biggest cudgels. One of the Transcript’s editors, it said, had passed a bogus three-dollar bill on the Bank of Troy. Another walked “on both sides of the street, like a twopenny postman,” while a third “spent his money at a theatre with females,” while his family was in want. But, added the Sun, “we never let personalities creep in.”

The New York Times—not the present Times—had also started up, and it dared to boast of a circulation “greater than any in the city except the Courier.” Said the Sun:

If the daily circulation of the Sun be not larger than that of the Times and Courier both, then may we be hung up by the ears and flogged to death with a rattle-snake’s skin.

The Sun took no risk in this. By November of 1834 its circulation was above ten thousand. On December 3 it published the President’s message in full and circulated fifteen thousand copies. At the beginning of58 1835 it announced a new press—a Napier, built by R. Hoe & Co.—new type, and a bigger paper, circulating twenty thousand. The print paper was to cost four-fifths of a cent a copy, but the Sun was getting lots of advertising. With the increase in size, that New Year’s Day, the Sun adopted the motto, “It Shines for All.” which it is still using to-day. This motto doubtless was suggested by the sign of the famous Rising Sun Tavern, or Howard’s Inn, which then stood at the junction of Bedford and Jamaica turnpikes, in East New York. The sign, which was in front of the tavern as early as 1776, was supported on posts near the road and bore a rude picture of a rising sun and the motto which Day adopted.

In the same month—January, 1835—the bigger and better Sun printed its first real sports story. The sporting editor, who very likely was also the police reporter and perhaps Partner Wisner as well, heard that there was to be a fight in the fields near Hoboken between Williamson, of Philadelphia, and Phelan, of New York. He crossed the ferry, hired a saddle-horse in Hoboken, and galloped to the ringside. It was bare knuckles, London rules, and only thirty seconds’ interval between rounds:

At the end of three minutes Williamson fell. (Cheers and cries of “Fair Play!”) After breathing half a minute, they went at it again, and Phelan was knocked down. (Cheers and cries of “Give it to him!”) In three minutes more Williamson fell, and the adjoining woods echoed back the shouts of the spectators.

The match lasted seventy-two minutes and ended in the defeat of Williamson. The Sun’s report contained no sporting slang, and the reporter did not seem to like pugilism:

59

And this is what is called “sports of the ring!” We can cheerfully encourage foot-races or any other humane and reasonable amusement, but the Lord deliver us from the “ring.”

The following day the Sun denounced prize-fighting as “a European practice, better fitted for the morally and physically oppressed classes of London than the enlightened republican citizens of New York.”

As prosperity came, the news columns improved. The sensational was not the only pabulum fed to the reader. Beside the story of a duel between two midshipmen he would find a review of the Burr autobiography, just out. Gossip about Fanny Kemble’s quarrel with her father—the Sun was vexed with the actress because she said that New York audiences were made up of butchers—would appear next to a staid report of the doings of Congress. The attacks on Rum continued, and the Sun was quick to oppose the proposed “licensing of houses of prostitution and billiard-rooms.”