Title: Home Life in Tokyo

Author: Jukichi Inouye

Release date: July 19, 2021 [eBook #65870]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Ronald Grenier (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/University of Toronto Library.)

BY

JUKICHI INOUYE

WITH

NUMEROUS

ILLUSTRATIONS

TOKYO

1910

PRINTED BY

THE TOKYO PRINTING COMPANY LTD.

The object of the present work is to give a concise account of the life we lead at home in Tokyo. I am aware that there are already many excellent works on Japan which may be read with great profit; but as their authors are most of them Europeans or Americans, and naturally look at Japanese life and civilisation from an occidental point of view, it occurred to me that notwithstanding the superabundance of books on Japan, a description of Japanese life by a native of the country might not be without interest. I believe it is the first time that such a task has been undertaken by a Japanese, for works in English which I have so far seen written by my countrymen treat of abstruse subjects and do not deign to touch upon such homely matters as are here dealt with.

The information I have endeavoured to convey in these pages is open, I fear, to the charge of scrappiness. It is unavoidable from the very nature of the work, the purpose of which is to select from the wealth of material in hand such matters as are likely to interest the general reader. I make no pretension to completeness or comprehensiveness of treatment.

I may also explain that I have confined myself in these pages to the depiction of life in Tokyo. To attempt to include the various customs that prevail in other parts of the country would to difficult and tedious. I felt that it would add materially to clearness and simplicity if I localised my observations; and it was only natural that Tokyo the capital should be selected for the purpose.

Finally, I would point out that I have made no distinction in the grammatical number of the Japanese words used in this book. It may at times puzzle the reader to find the same words occur, as in Japanese, in both the singular and the plural; but to the Japanese ear the addition of the English plural suffix seems to impair the euphony of Japanese speech.

JUKICHI INOUYE.

Tokyo, Japan,

September. 1910.

{i}

CHAPTER I.

Tokyo the Capital.

The youngest of the capitals—Yedo—The feudal government—Prosperity of Yedo—Its population—The military class—The Restoration—The new government—National reorganisation—Centralisation—Local government—Tokyo the leader of other cities—Struggle between Old and New Japan—The last stronghold of Old Japan.

CHAPTER II.

The Streets of Tokyo.

The area and population of Tokyo—Impression of greater populousness—Street improvements—Narrow streets—Shops and sidewalks—Road-making—Dusty roads—Lamps and street repairs—Drainage—Street-names—House-numbers—Incongruities.

CHAPTER III.

Houses: Exterior.

Name-plates—Block-buildings—Gates—The exposure of houses—Fires—House-breaking—Japanese houses in summer and winter—Storms and earthquakes—House-building—The carpenter—The garden.

CHAPTER IV.

Houses: Interior.

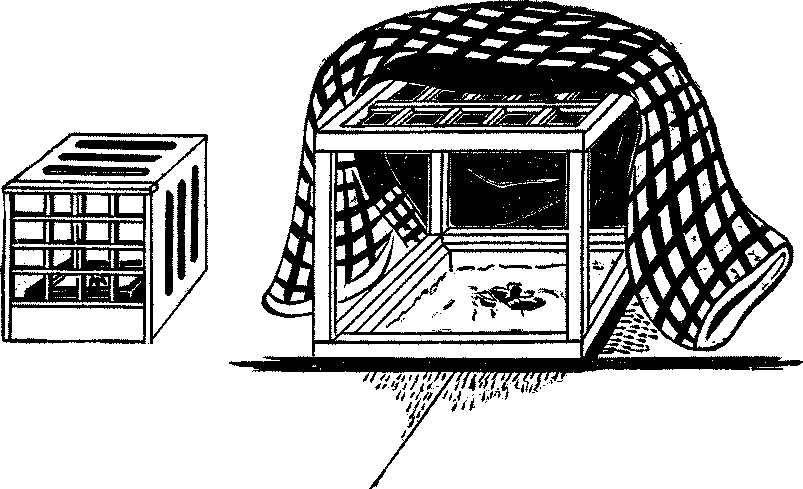

The sizes of rooms—The absence of furniture—Sliding-doors—Verandahs—Tenement and other small houses—Middle-sized dwellings—The porch and anteroom—The parlour—Parlour furniture—The sitting-room—Closets and cupboards—Bed-rooms—The dining-room—Chests of drawers and trunks—The toilet-room—The library—The bath-room—Foot-warmers.

{ii}

CHAPTER V.

Meals.

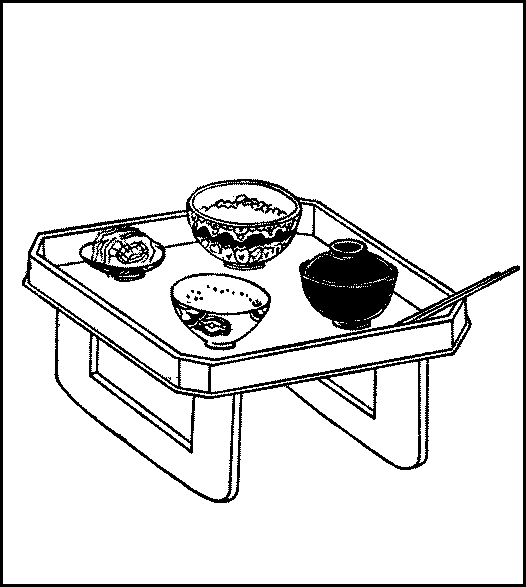

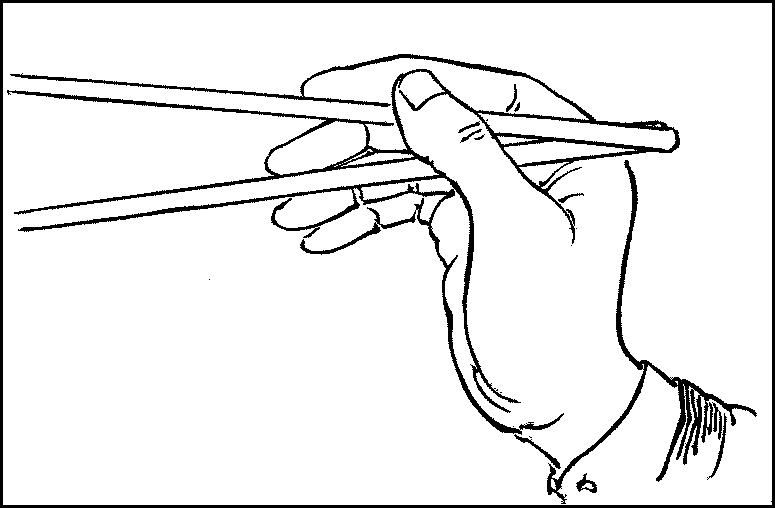

Rice—Sake—Wheat and barley—Soy sauce—Mirin—Rice-cooking—Soap—Pickled vegetables—Meal trays—Chopsticks—Breakfast—Clearing and washing—The kitchen—The little hearth—Pots and pans—Other utensils—Boxes and casks—Shelves—The sink and water-supply—The midday meal—The evening meal—Sake-drinking.

CHAPTER VI.

Food.

Japanese diet—Vegetables—Sea-weeds and flowers—Fish—Shell-fish—Crabs and other molluscs—Fowl—Meat—Prepared food—Peculiarities of food—Fruits—The bever—Baked potatoes and cracknel—Confectionery—Reasons for its abundance—Sponge-cake—Glutinous rice and red bean—Kinds of confectionery—Sugar in Japanese confectionery.

CHAPTER VII.

Male Dress.

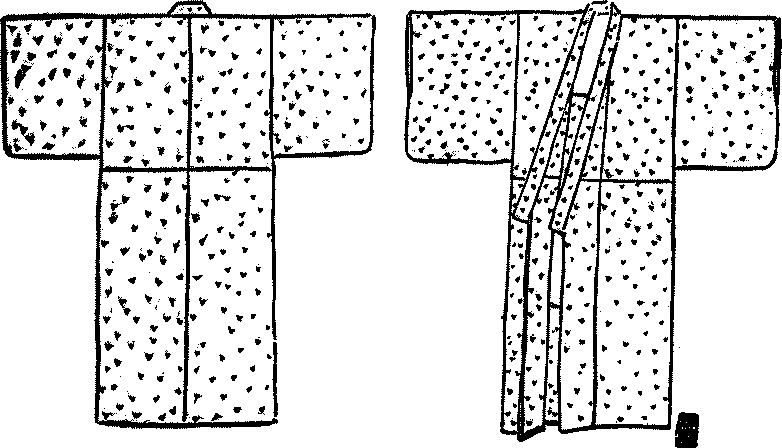

Japanese and foreign dress—Progress in the latter—Japanese clothes indispensable—Kimono—Cutting out—Making of an unlined dress—Short measure—Extra-sized dresses—Yukata—The lined kimono—The wadded kimono—Under-dress—Underwear—Obi—Haori—The crest—The uncrested haori—Hakama—Socks—How to dress Wearing of socks.

CHAPTER VIII.

Female Dress.

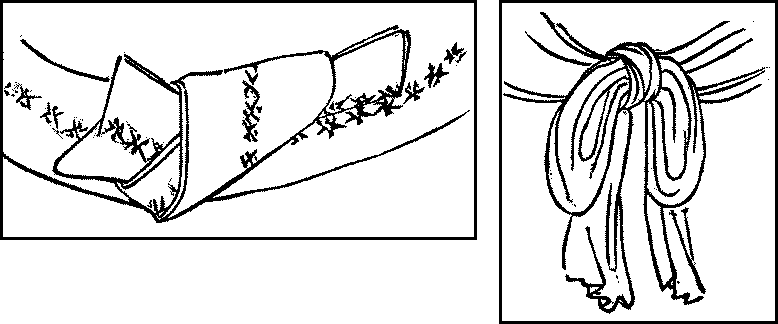

Attempts at Europeanisation—Difference between Japanese and foreign dresses—Expense and inconvenience of foreign dresses—Japanese dresses not to be discarded—How the female dress differs from the male—Underwear and over-band—Haori—Hakama—Obi—How to tie it—The dress-obi—The formal dress—Home-wear—Working clothes—The sameness of form—The girl’s dress—Dress and age.

CHAPTER IX.

Toilet.

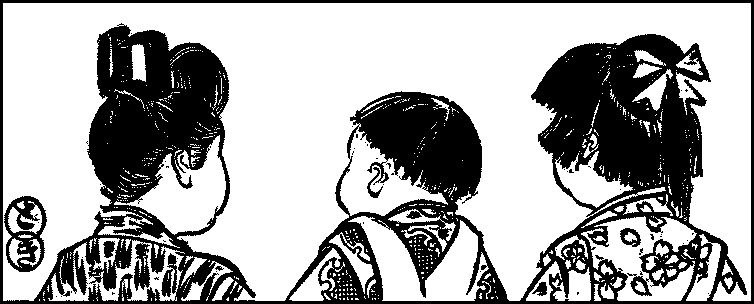

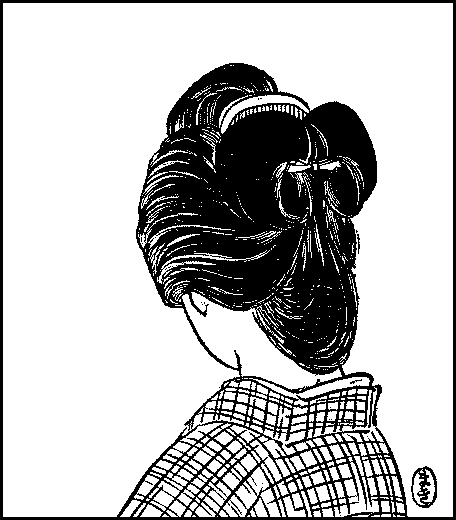

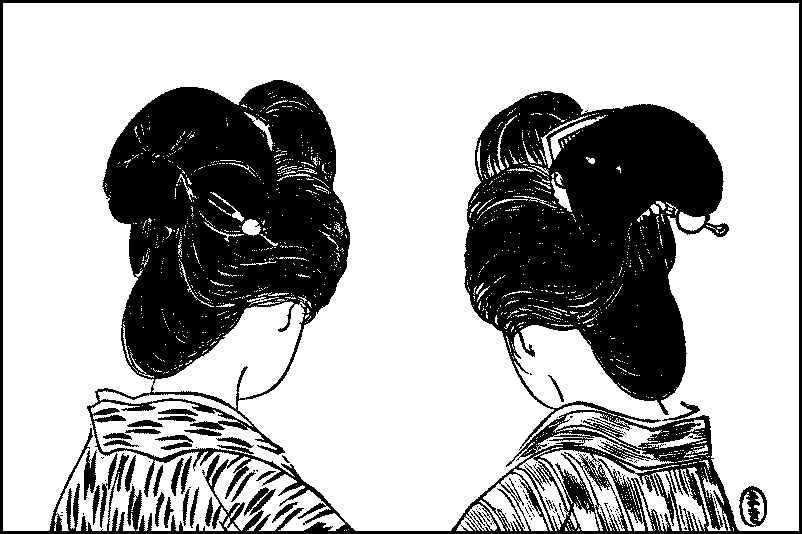

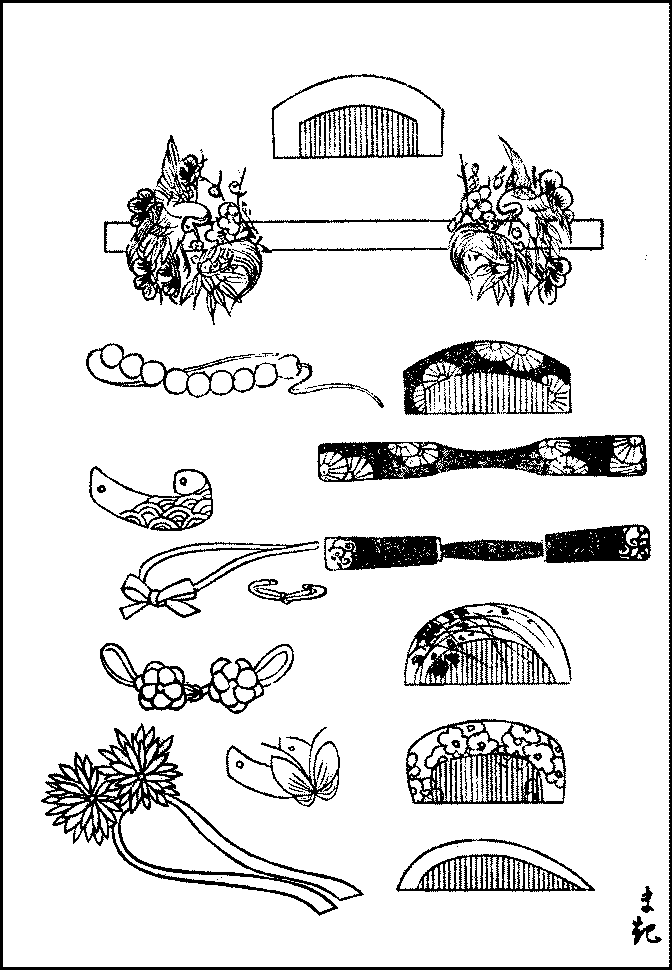

Queues—Hair-cutting—Moustaches and beards—Shaving—Women’s coiffure—Children’s hair—“Inverted maidenhair”—Shimada—“Rounded chignon”—Other forms—The lightest coiffure—Bars—Combs—Ornaments round the chignon—Hair-pins—The hair-dresser—The kind of hair esteemed—Lots of complexion—Girls painted—Women’s paint—Blackening of teeth—Shaving of eyebrows—Washing the face—Looking-glasses.

{iii}

CHAPTER X.

Outdoor Gear.

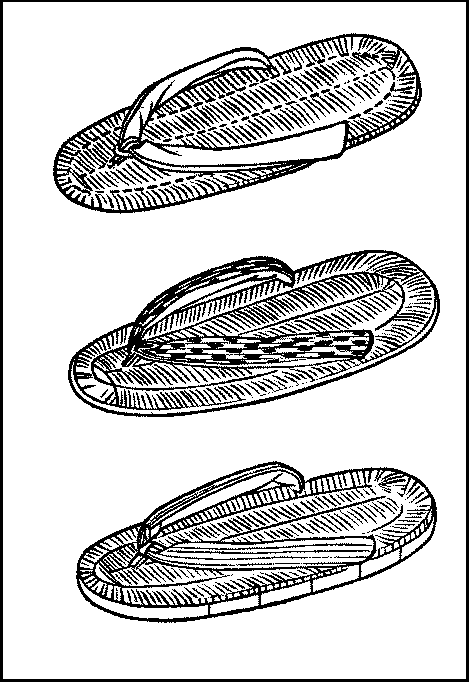

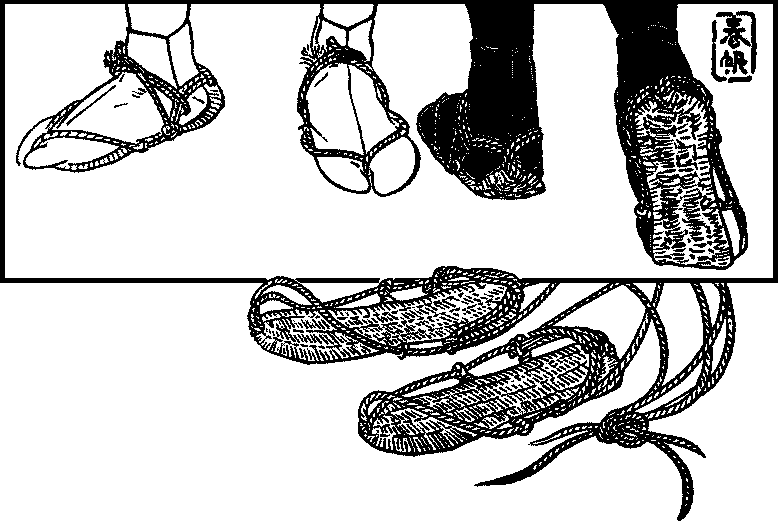

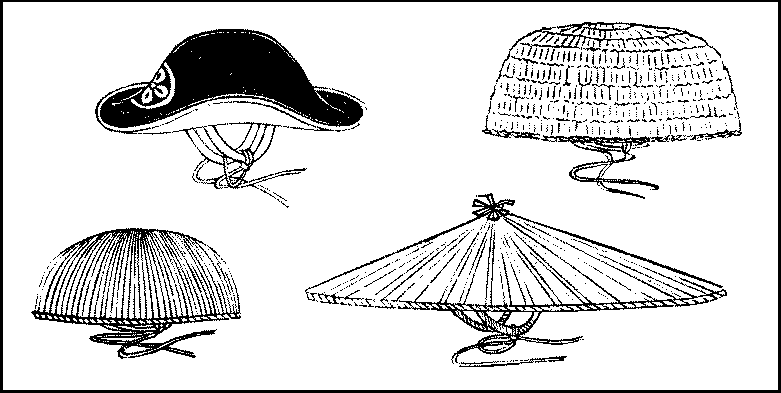

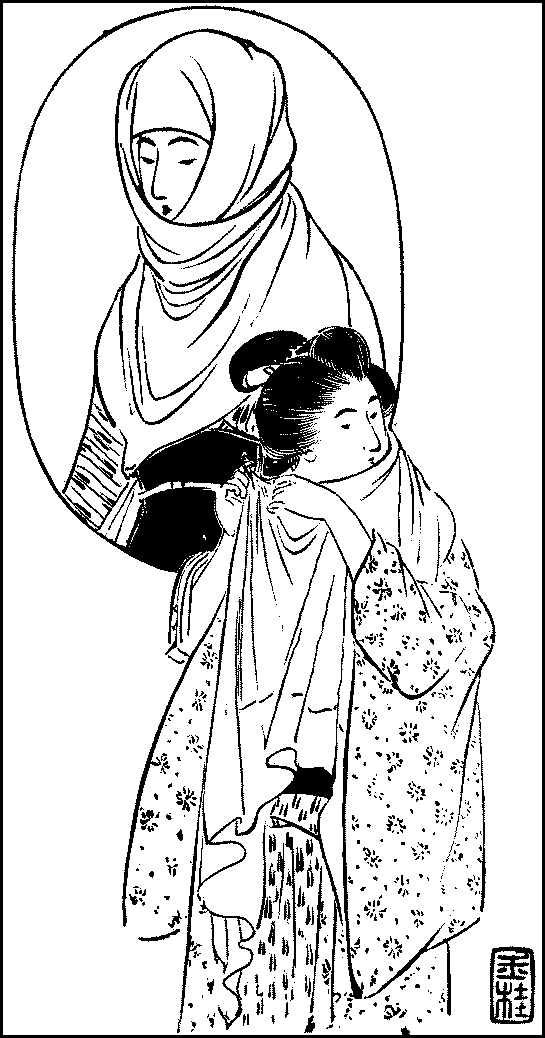

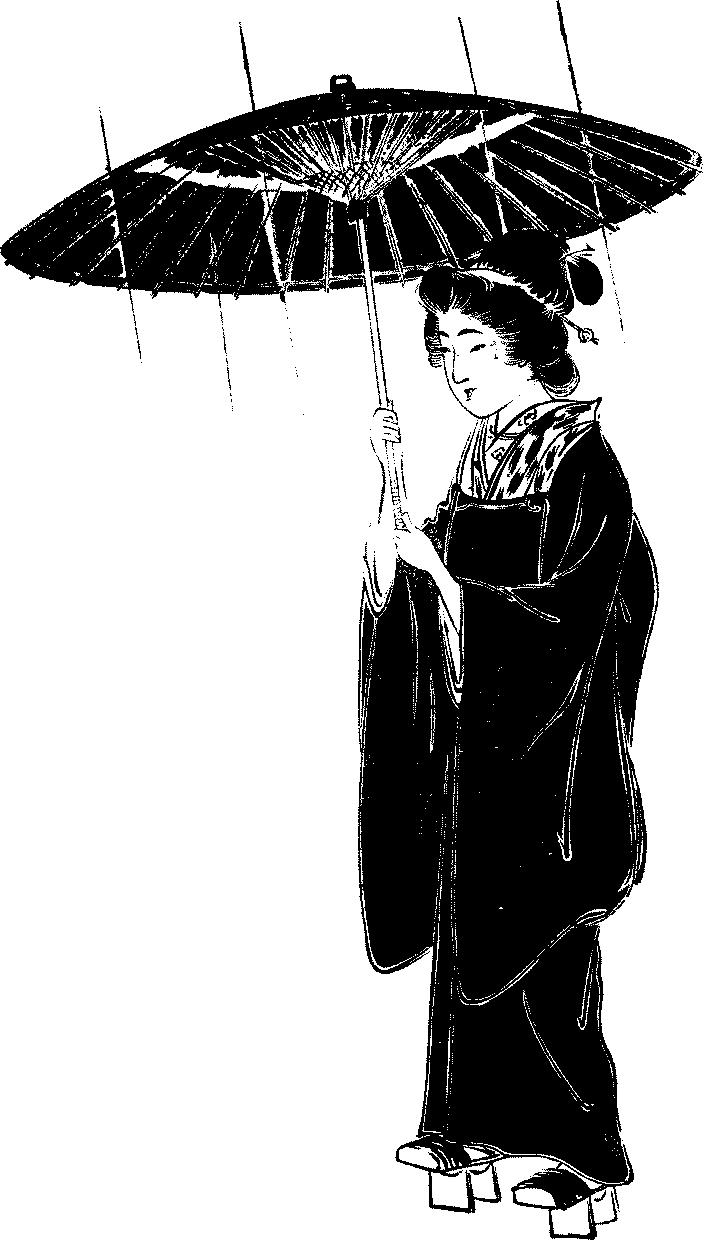

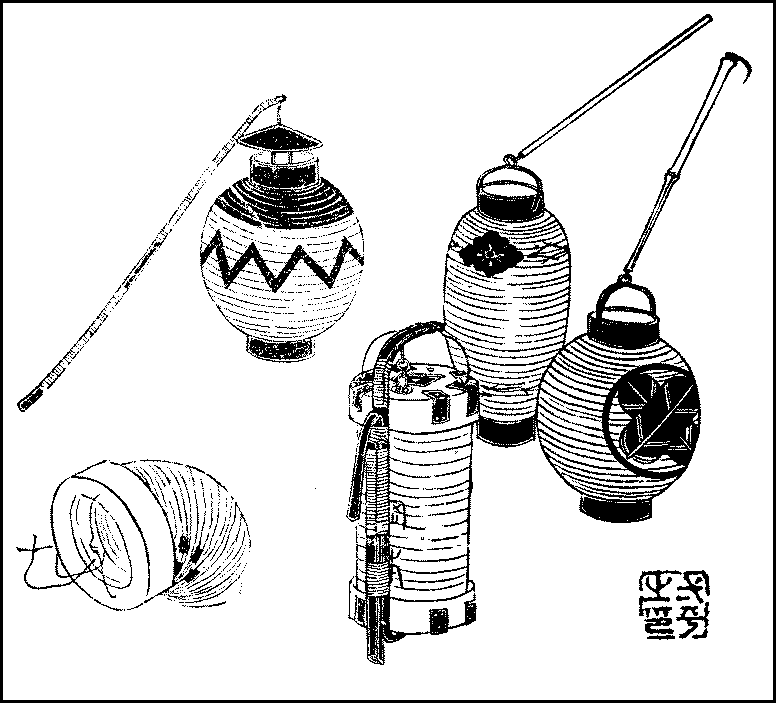

Boots and shoes versus clogs and sandals—Inconvenience of foreign footgear—Shoes and boots at private houses—Clogs and sandals able to hold their own—How clogs are made—Plain clogs—Matted clogs—Sandals—Straw sandals—Headgear—Woman’s hood—Overcoats and overdresses—Common umbrellas—Better descriptions of umbrellas—Lanterns—Better kinds of lanterns.

CHAPTER XI.

Daily Life.

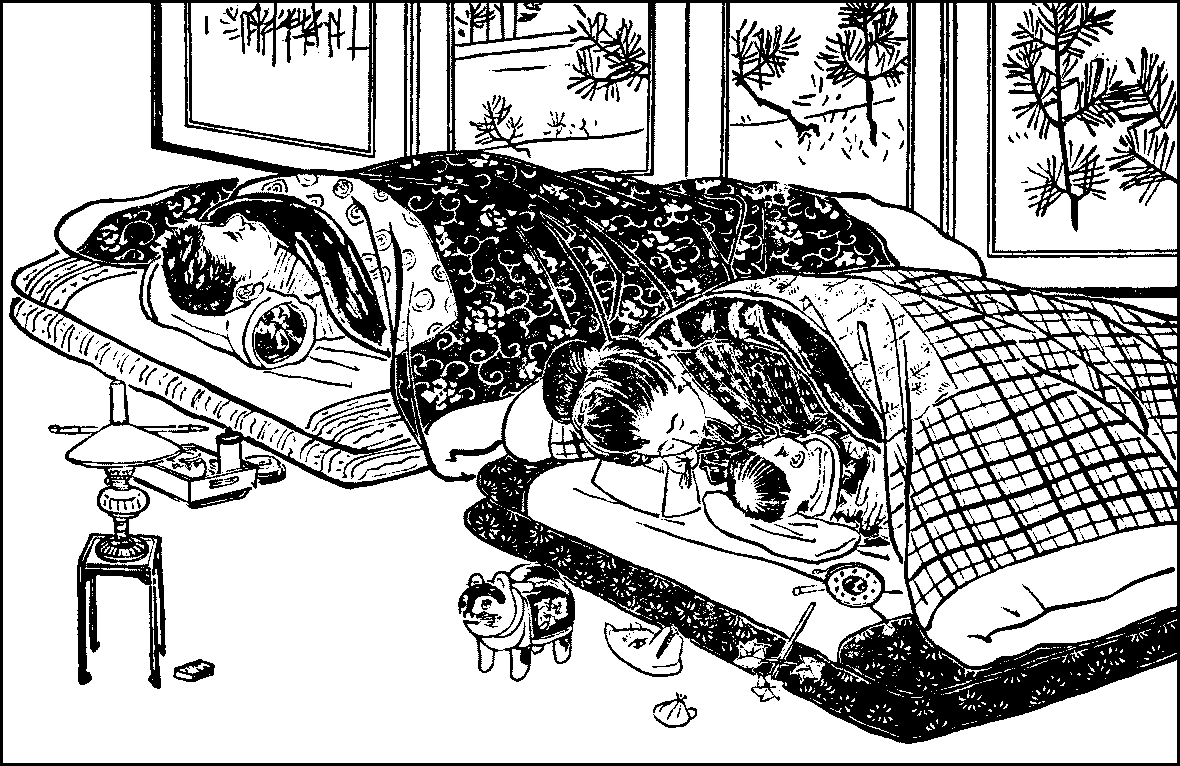

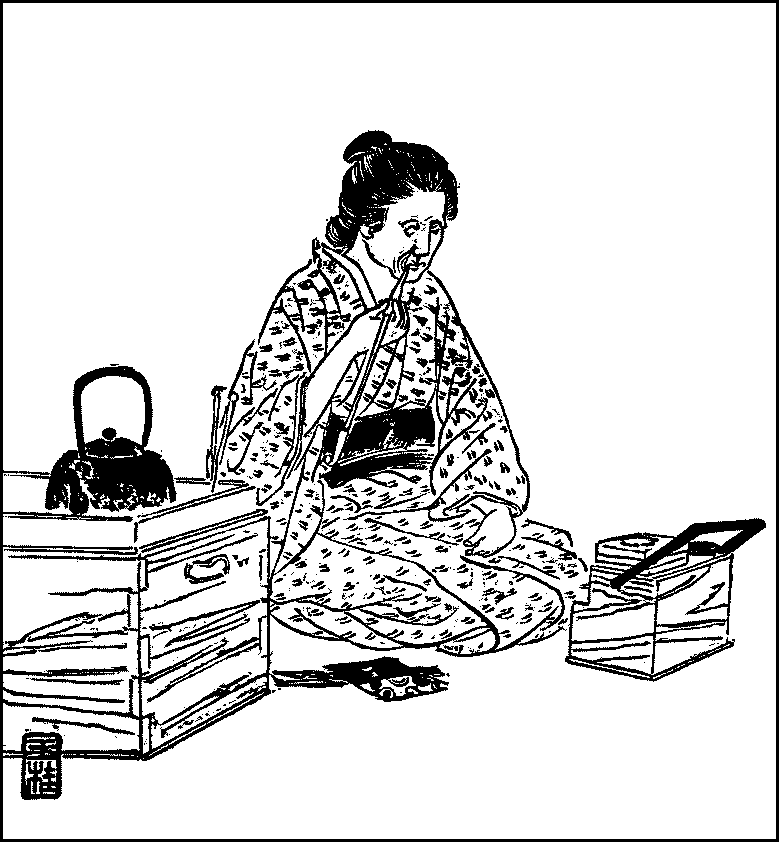

Busy life at home—Discomforts of early morning—Ablutions—Off to school and office—Smoking—Giving orders—Morning work—Washing—Needlework—The work-box—Japanese way of sewing—Ironing—Remaking clothes—Home duties—Bath—Evening—Early hours.

CHAPTER XII.

Servants.

The servant question—Holidays—Hours of rest—Incessant work—Servants trusted—Relations with their mistresses—Decrease of mutual confidence—Life in the kitchen—Servants’ character—Whence they are recruited—Register-offices—The cook—The housemaid—The lady’s maid—Other female servants—The jinrikisha-man—The student house-boy.

CHAPTER XIII.

Manners.

Decline of etiquette—Politeness and self-restraint—“Swear-words”—Honorifics—Squatting—Kissing—Calls made and received—Rules for behaviour in company—Inconsiderate visitors—Woman’s reserve before strangers—Hospitality—Reticence on family matters.

CHAPTER XIV.

Marriage.

Girls and marriage—Young men—The marriage ceremony—Match-making—Betrothal—The bride’s property—Wedding decorations—The nuptials—Wedding supper—Congratulations—Post-nuptial parties—Japanese style of engagement—The advantages of the go-between system—The go-between as the woman’s deputy—The go-between as mediator—Marriage a civil contract in Japan—No honeymoon—The Japanese attitude towards marriage.

{iv}

CHAPTER XV.

Family Relations.

The family the unit of society—Adoption—The wife’s family relations—The father—Retirement—The retired father—The mother-in-law—A strong-willed daughter-in-law—Tender relations—Domestic discord—Sisters-in-law—Brothers-in-law—The wife usually forewarned—The husband also handicapped—His burdens—Old Japan’s ideas of wifely duties—The Japanese wife’s qualities—Petticoat government—The wife’s influence.

CHAPTER XVI.

Divorce.

Frequency of divorces—The new Civil Code on marriage and divorce—Conditions of a valid marriage—Invalid marriages—Cohabitation—The wife’s legal position—Her separate property—The rights of the head of the family—Care of the wife’s property—Forms of divorce—Grounds for divorce—Custody of children—No damages against the co-respondent—Breaches of promise of marriage—Few mercenary marriages—Widow-hunting also rare.

CHAPTER XVII.

Children.

Child-life—Love of children—Desire for them—Child-birth—After-birth—Early days—The baby’s food—The “first-eating”—Superstitions connected with infancy—Carrying of babies—Teething—Visits to the local shrine—Toddling—Weaning—The kindergarten and primary school—The girls’ high school—The middle school—The popularity of middle schools—Hitting—Exercises and diversions—Collections.

CHAPTER XVIII.

Funeral.

Unlucky ages—The Japanese cycle—Celebration of ages—Respect for old age—Death—Preparations for the funeral—The wake—The coffin and bier—The funeral procession—The funeral service—Cremation—Gathering the bones—The grave—Prayers for the dead—Return presents—Memorial services—The Shinto funeral.

CHAPTER XIX.

Accomplishments.

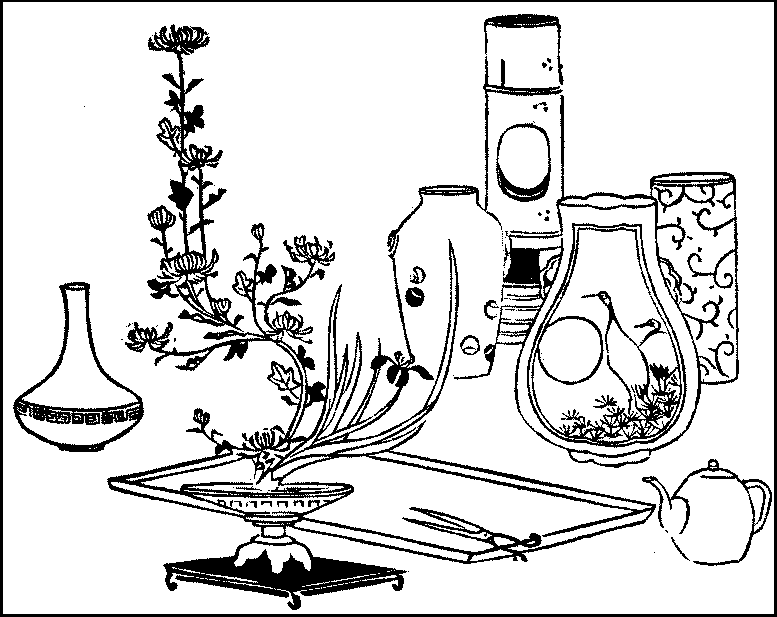

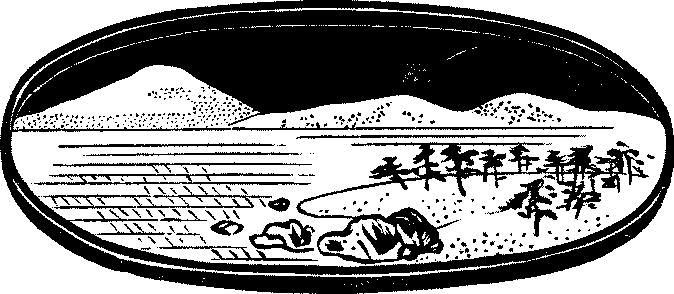

Composition—The writing-table—Odes—Songs—The haiku—Chinese poetry—Tea-ceremony—Its complexity—Its utility to women—The flower arrangement—The underlying idea—Its extensive application—The principle of the arrangement—Manipulation{v} of the stalks—Drawing water—Vases—Tray-landscapes—The koto—The samisen—Its form—Its scale—How to play it—The crudity of Japanese music—Its unemotional character.

CHAPTER XX.

Public Amusements.

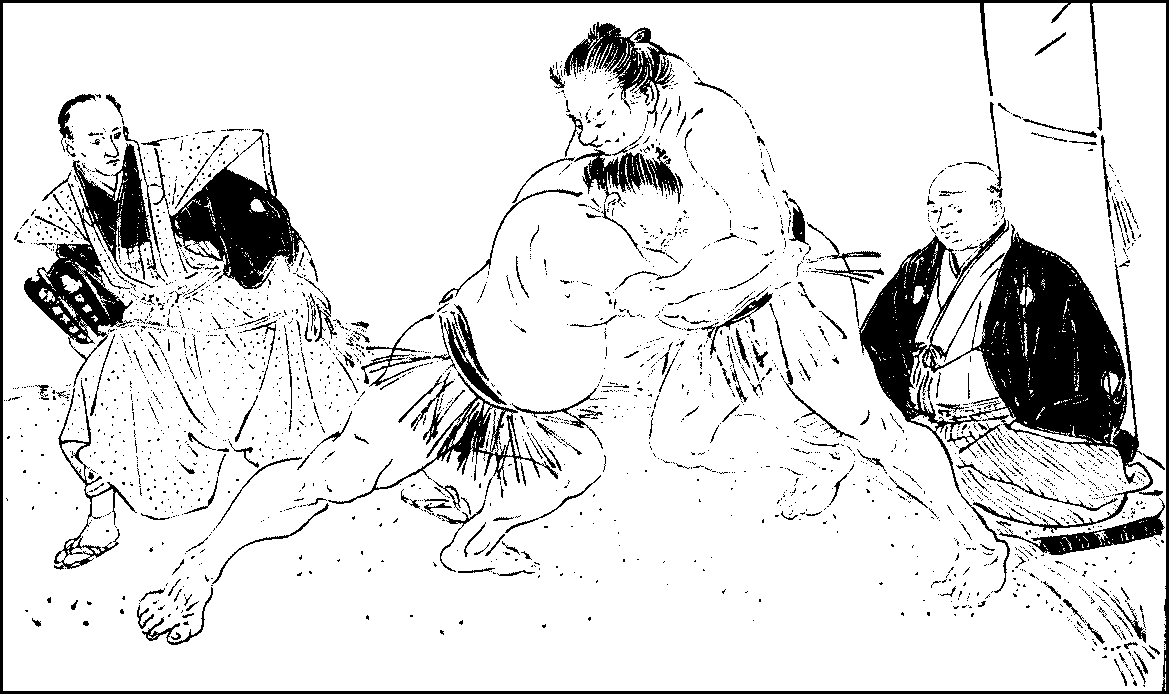

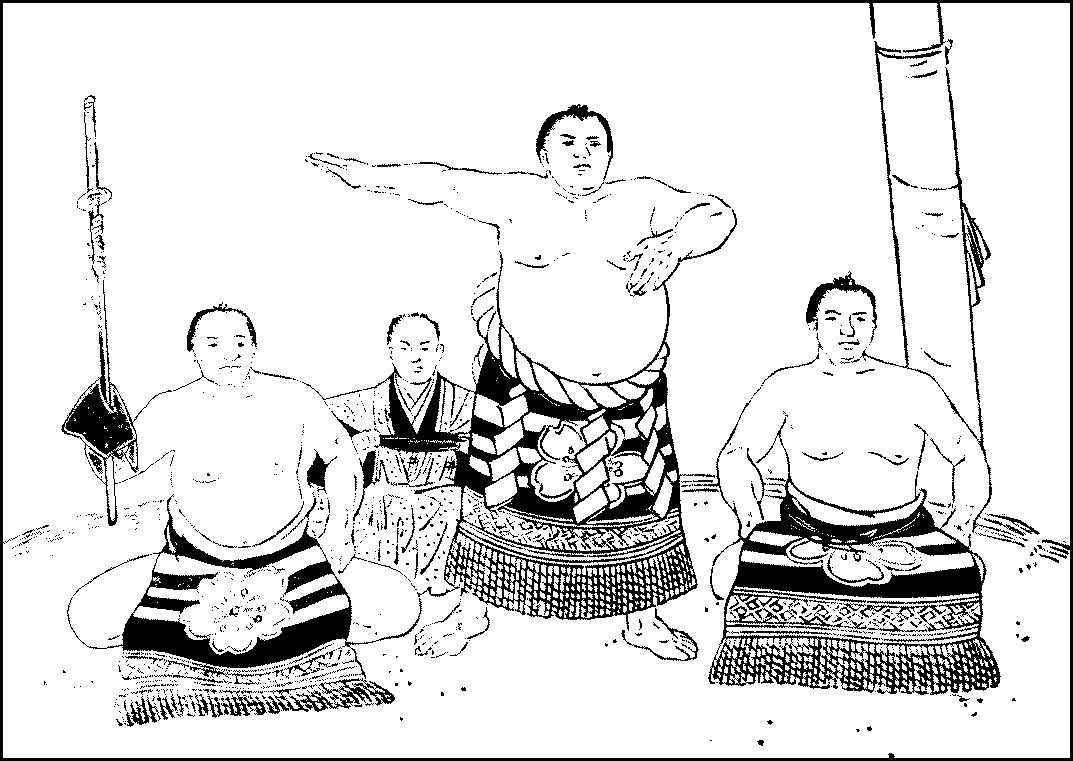

Pleasures—No-performance—Playgoing—The theatre—Japanese dramas—Gidayu-plays—Actors—A new school of actors—Actresses—Wrestling—Wrestlers—The wrestling booth—The wrestler’s apparel—The Ekoin matches—The umpire—The rules of the ring—The match-days—The story-tellers’ hall—Entertainment at the hall.

CHAPTER XXI.

Feasts and Festivities.

Festivities in the old days—The New Year’s Day—The New Year’s dreams—January—February—The Feast of Dolls—The Equinoctial day—Plum-blossoms—Cherry-blossoms—The flower season—Peach-blossoms—Tree-peonies and wistarias—The Feast of Flags—The Fête of the Yasukuni Shrine—Other fêtes—The Feasts of Tanabata and Lanterns—The river season—Moon-viewing—The Seven Herbs of Autumn—October—The Emperor’s Birthday—Chrysanthemums and maple-leaves—The end of the year.

CHAPTER XXII.

Sports and Games.

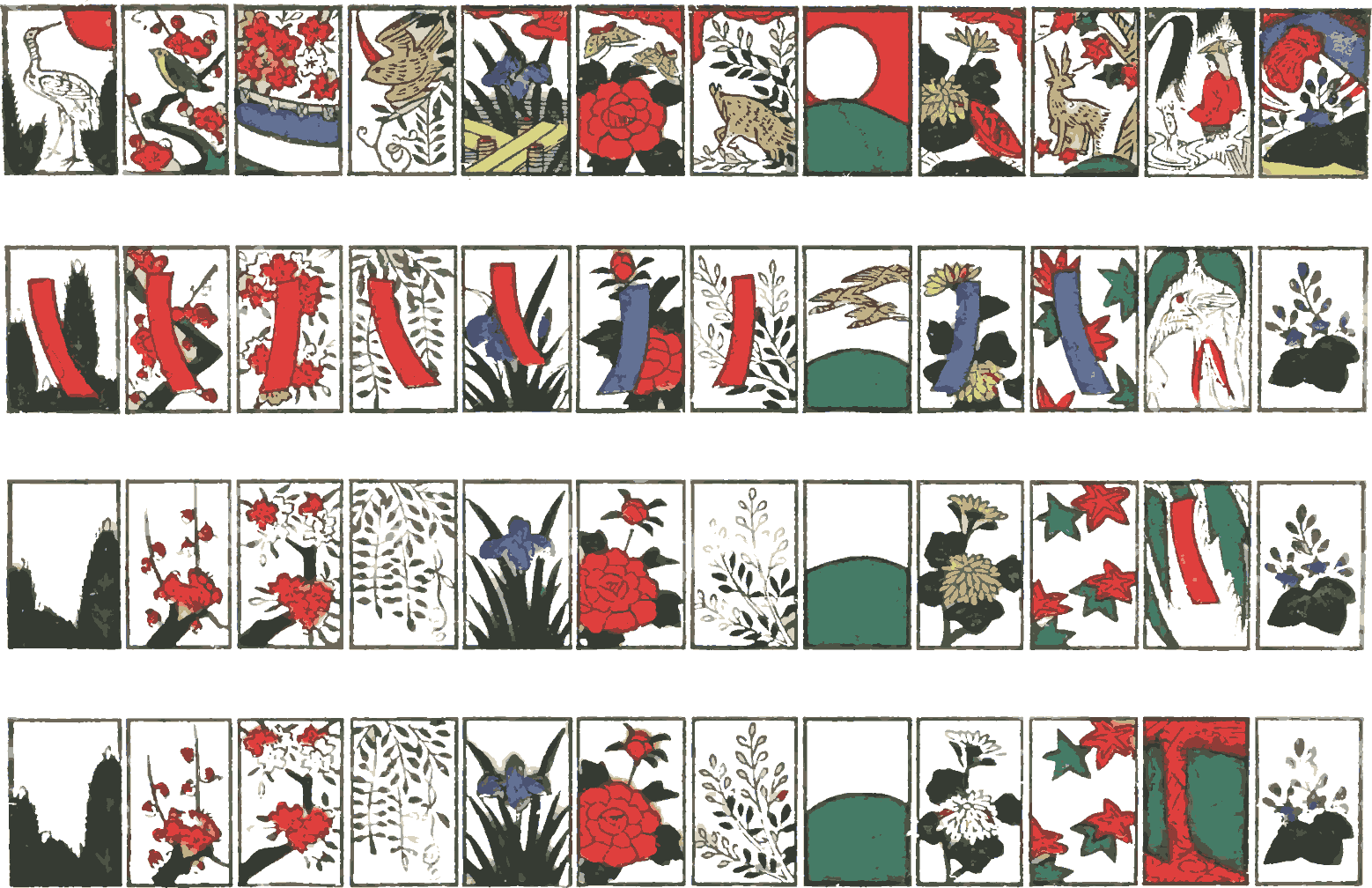

Hunting—Horse-racing—Fishing—Outdoor games—Billiards—Sugoroku—Iroha-cards—Ode-cards—Ken—Japanese chess—The moves—Use of prisoners—The game of go—Its principle—Camps—Counting—“Flowers-cards”—Players—How to play—Claims for hands—Claims for combinations made—Reckoning.

{vi}

| The Seven Herbs of Autumn | Frontispiece. | |

| Page. | ||

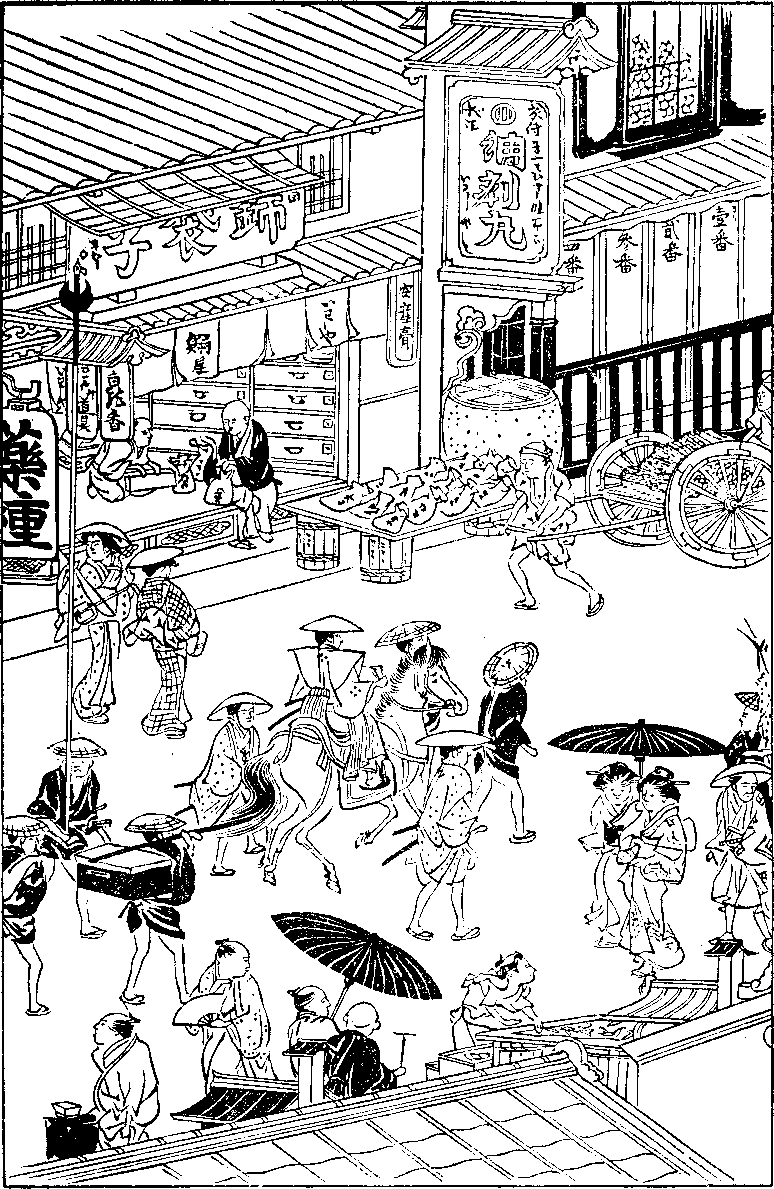

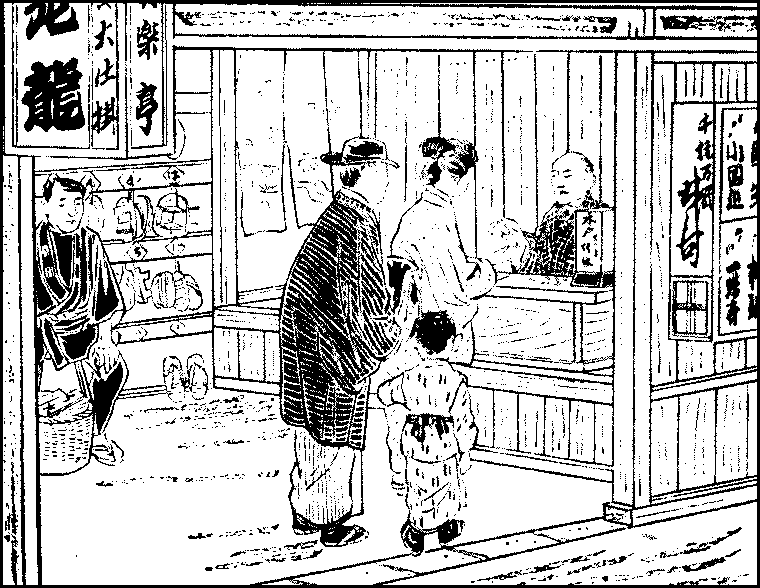

| A Street in Yedo (From a picture by Settan, 1783–1843) | 13 | |

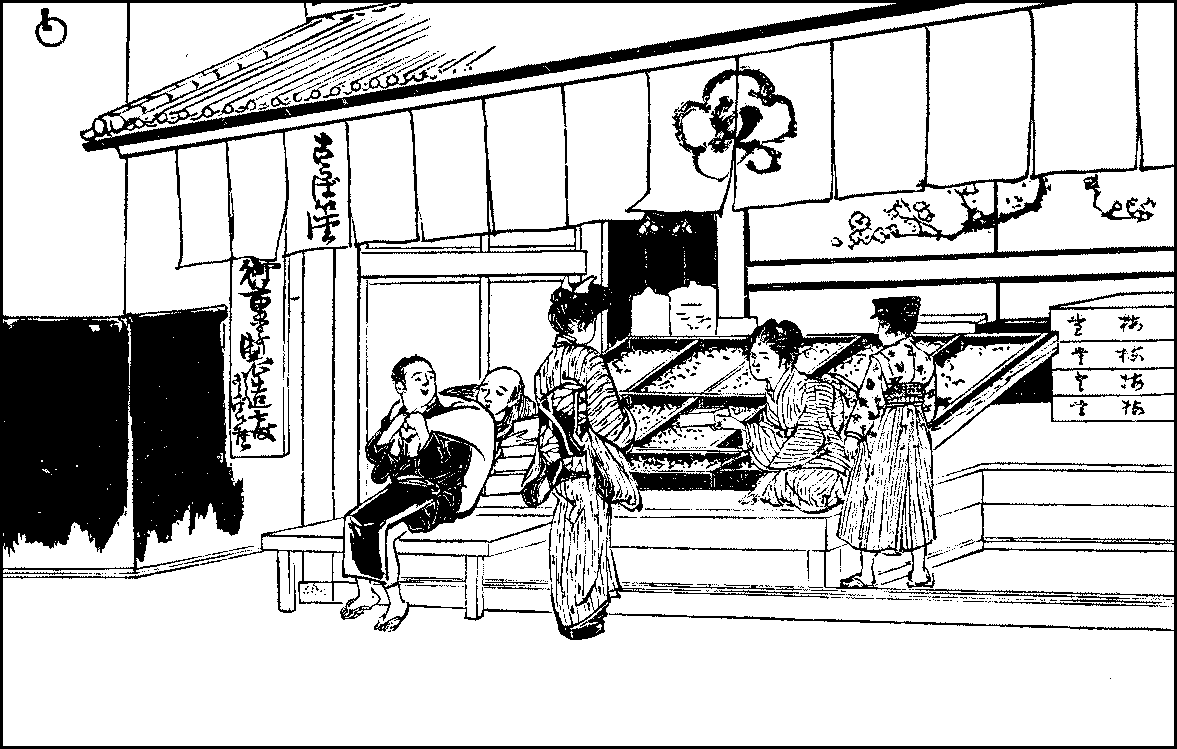

| A Shop in Tokyo | 18 | |

| In the Slums | 25 | |

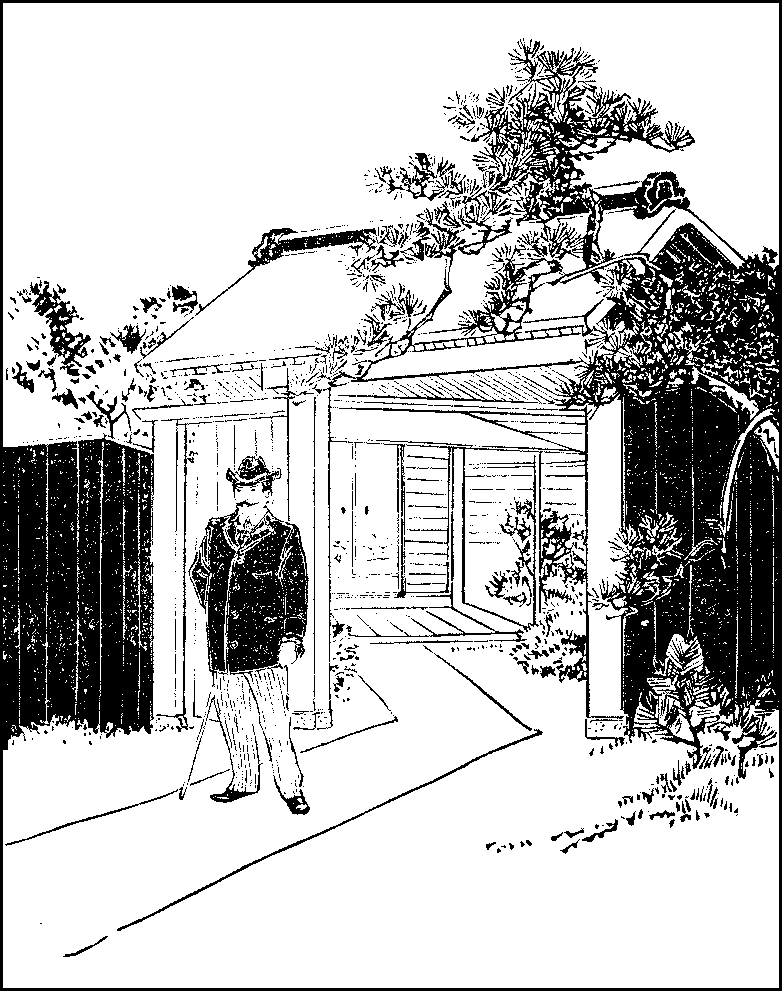

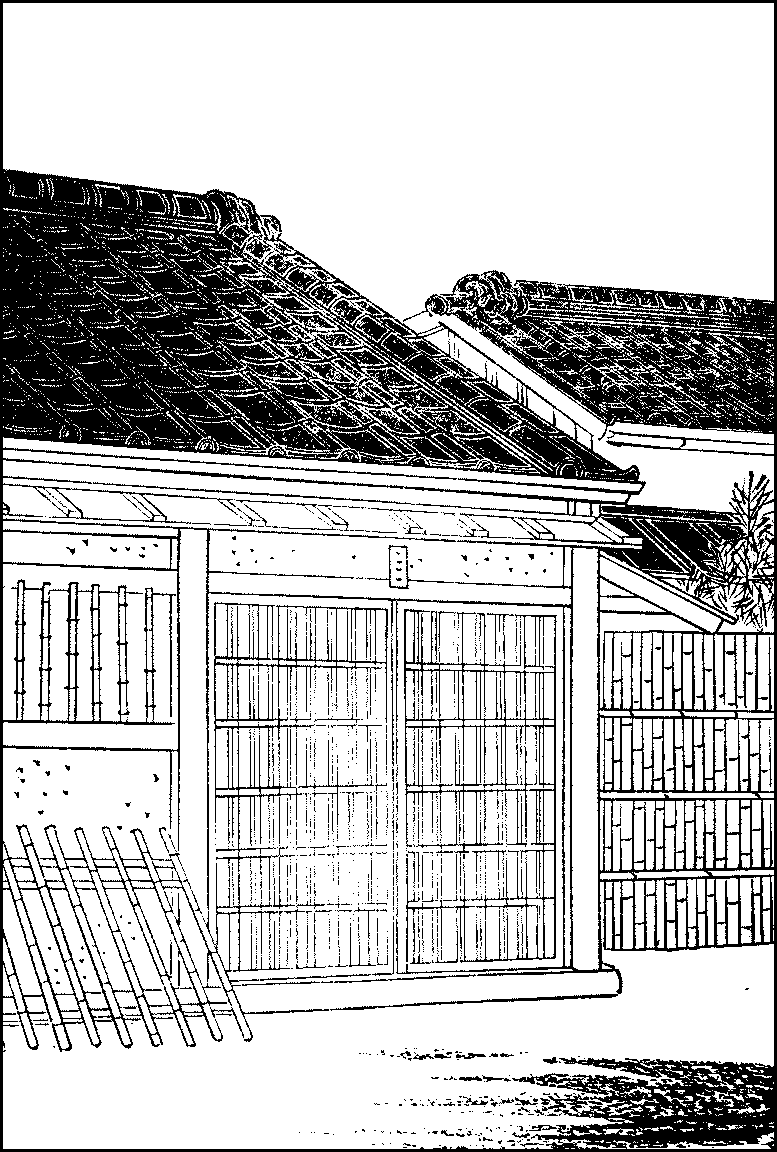

| A House and a Gate | 27 | |

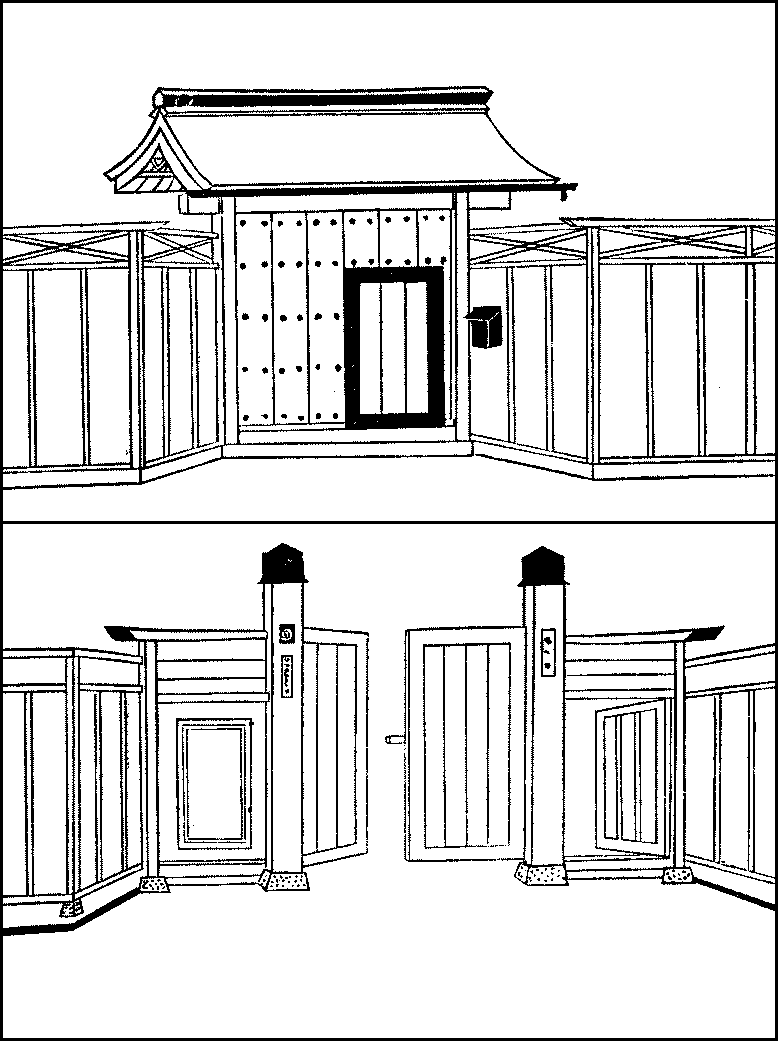

| A Roofed and a Pair Gate | 29 | |

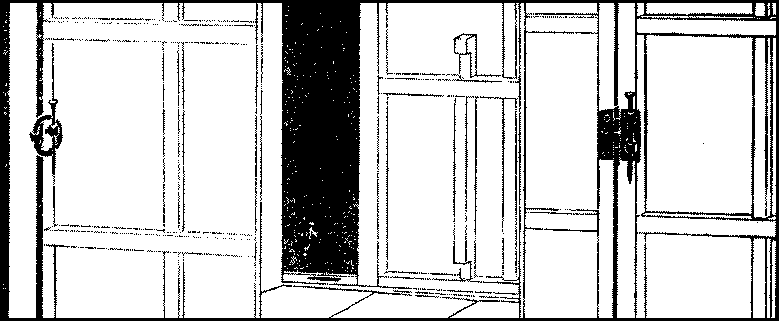

| Door-fastenings | 32 | |

| A House without a Gate | 36 | |

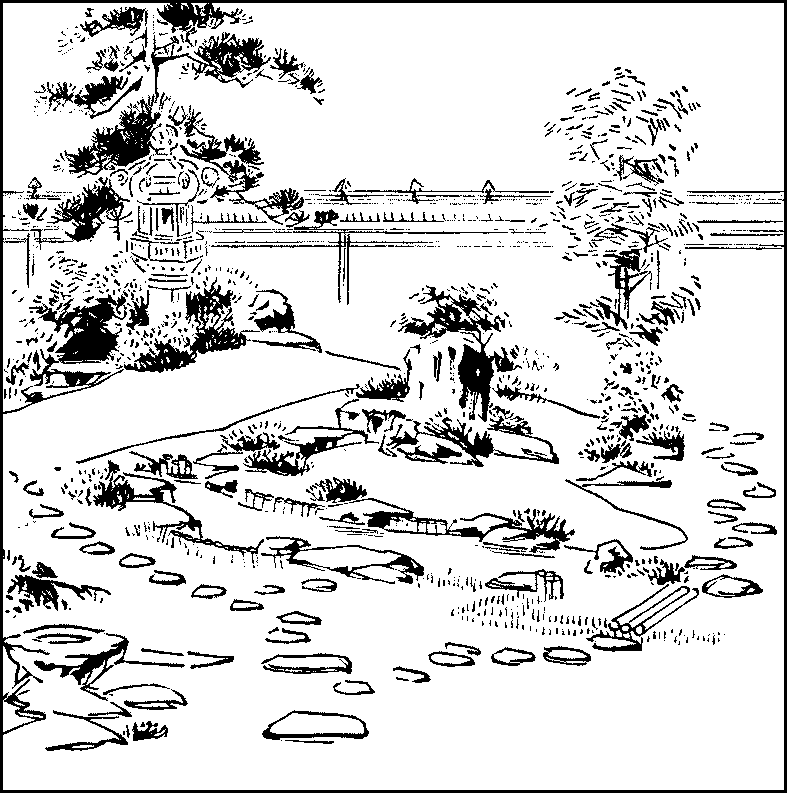

| A Garden | 38 | |

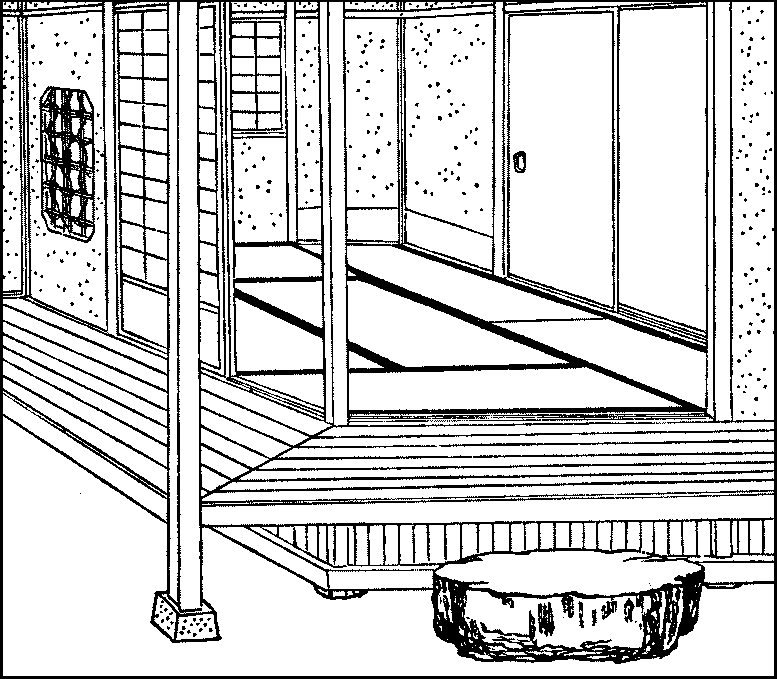

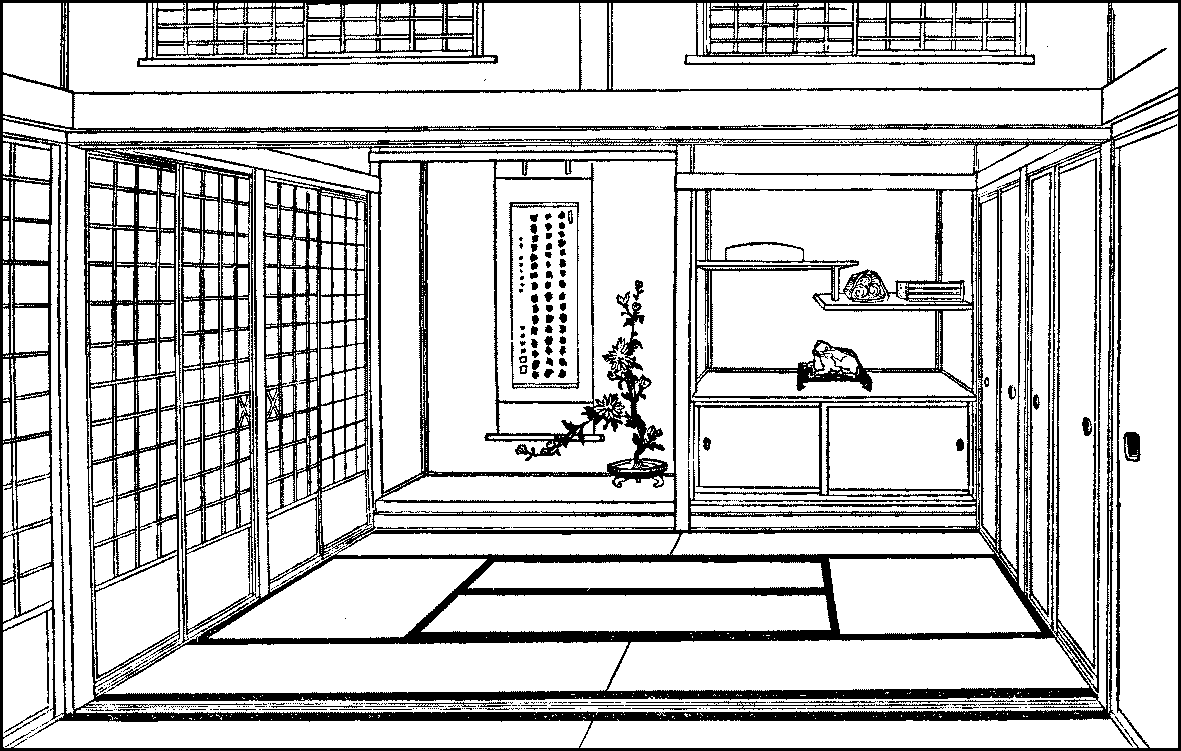

| A Six-matted Room and Verandah | 41 | |

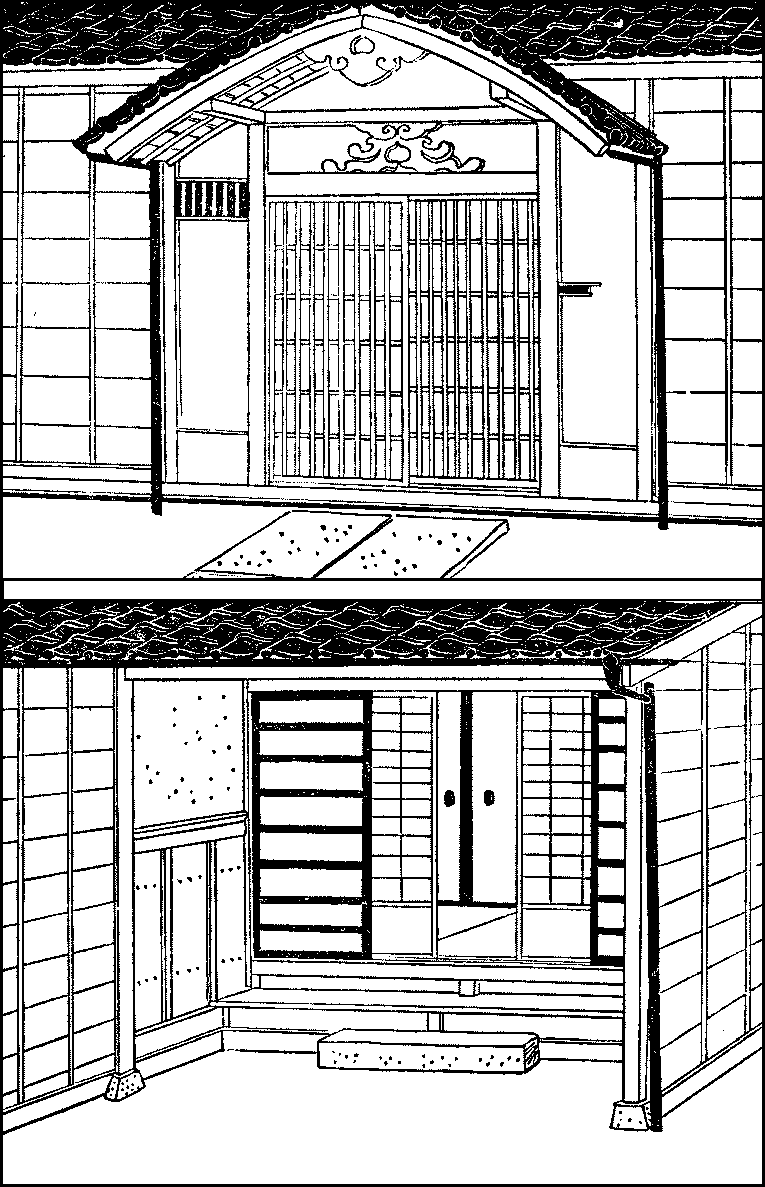

| The Porch, open and latticed | 45 | |

| An Eight-matted Parlour | 47 | |

| A Visitor | 49 | |

| A Sitting-room | 50 | |

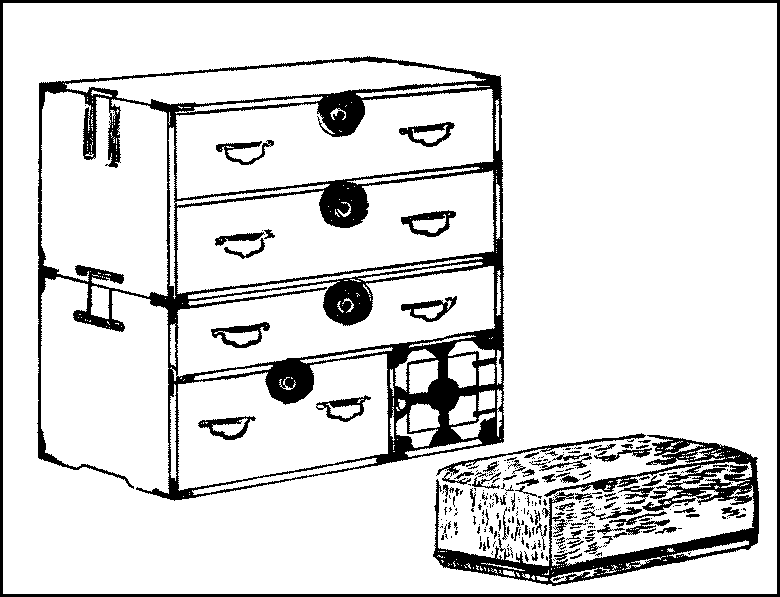

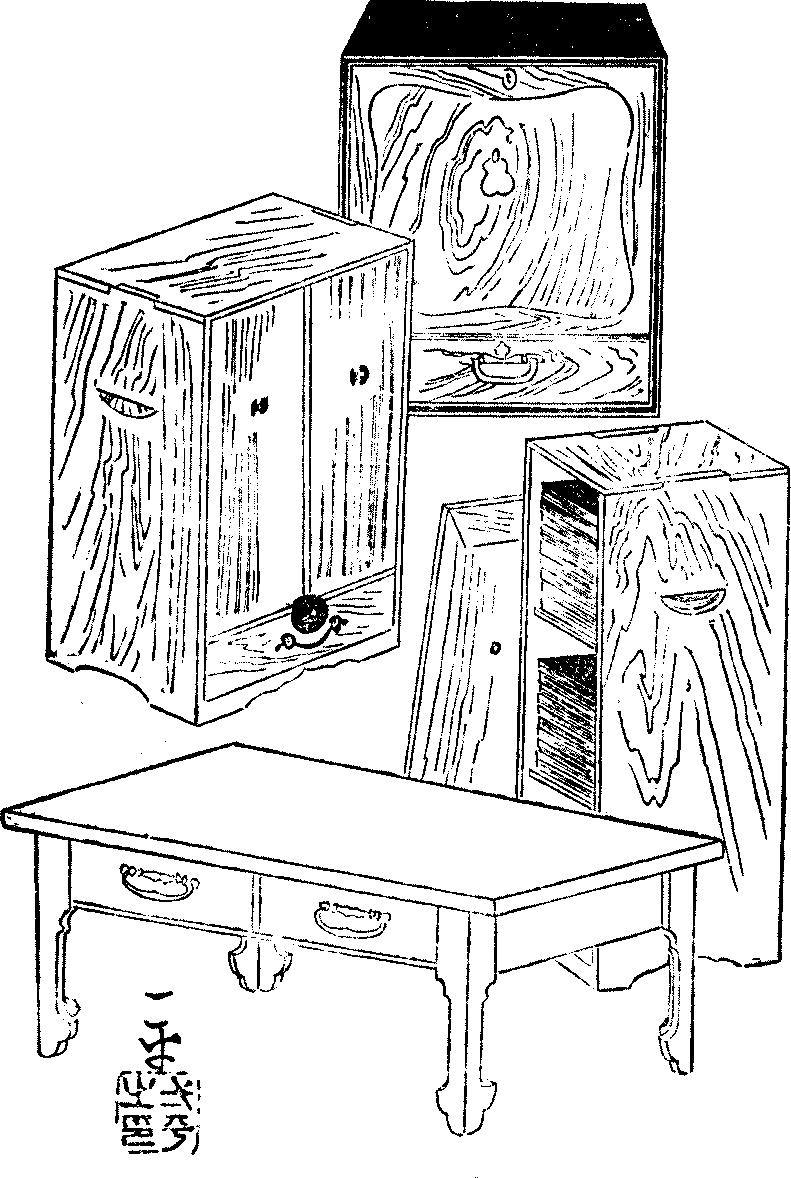

| A Chest of Drawers and a Trunk | 52 | |

| Foot-warmers | 55 | |

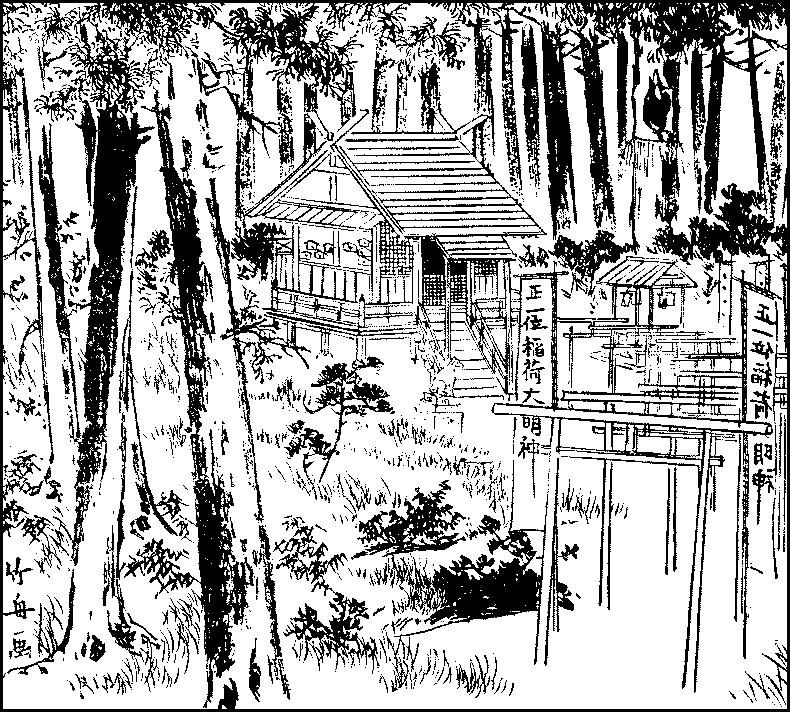

| A Shrine of the Rice-god | 57 | |

| A Meal-tray | 60 | |

| How to hold Chopsticks | 61 | |

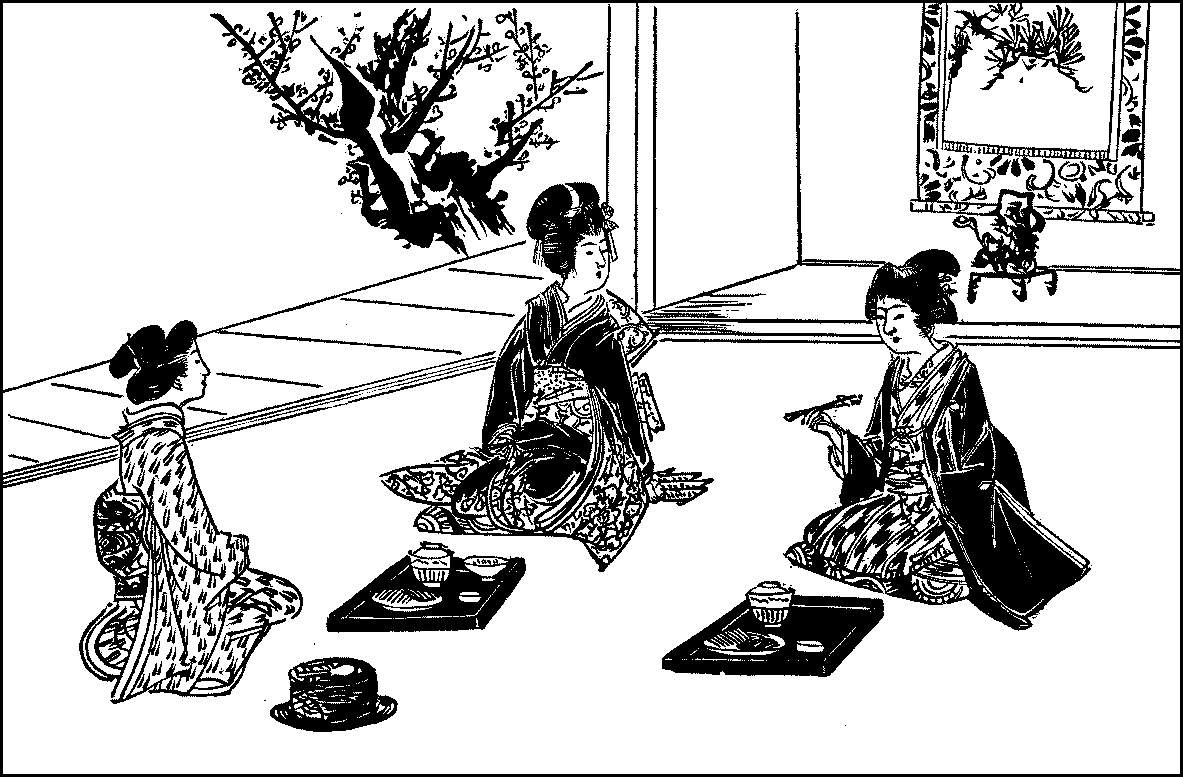

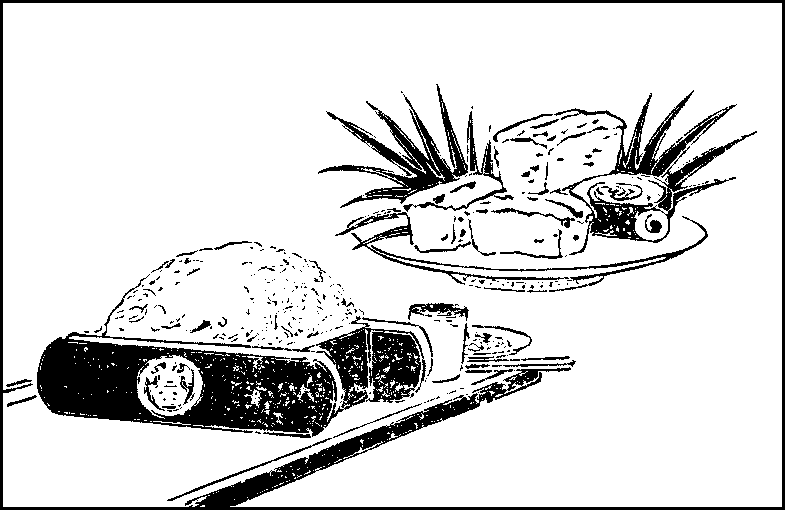

| A Meal | 63 | |

| The Kitchen | 65 | |

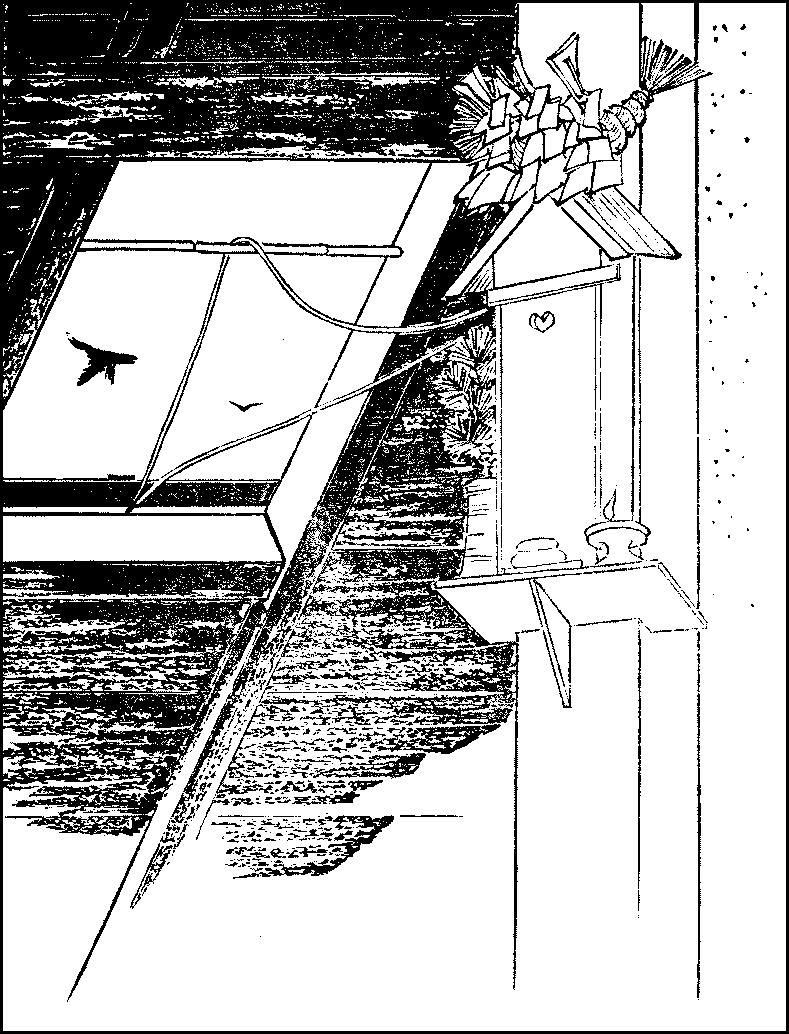

| A Skylight and the Kitchen-god | 67 | |

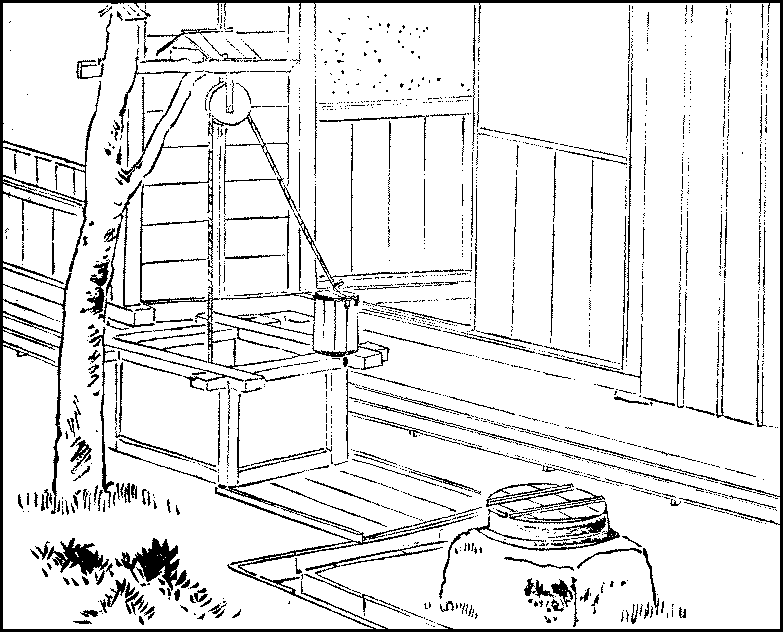

| A Well | 69 | |

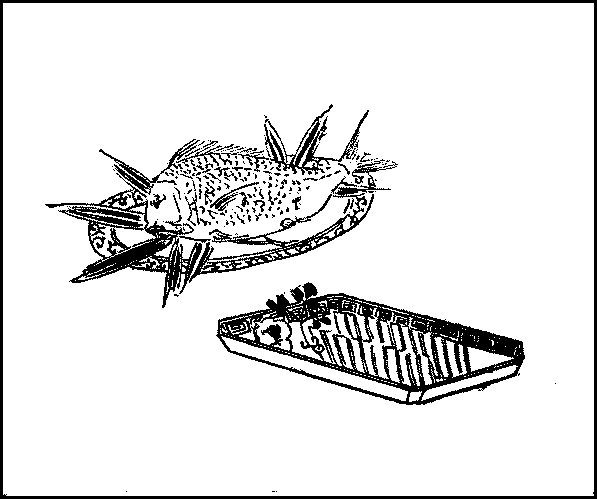

| Raw Fish, whole and sliced | 72 | |

| Sushi and Soba | 77 | |

| A Box of Sponge-cake | 79 | |

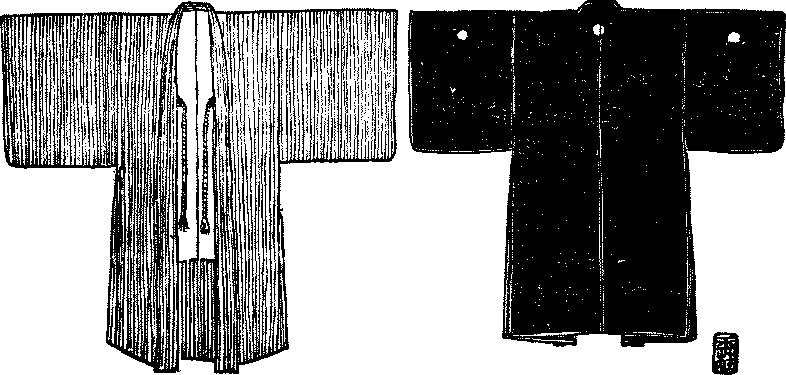

| The Kimono, rear and front view | 86 | |

| The Obi, square and plain | 88 | |

| The Haori | 89 | |

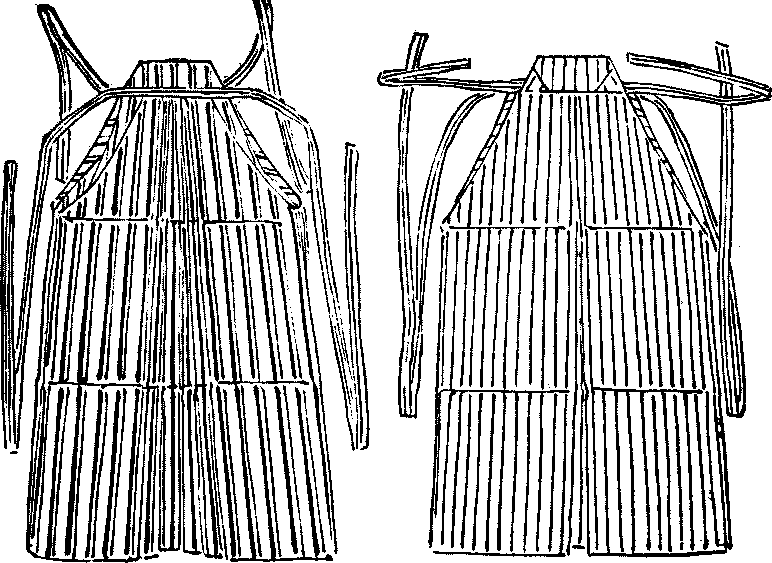

| The Hakama | 91 | |

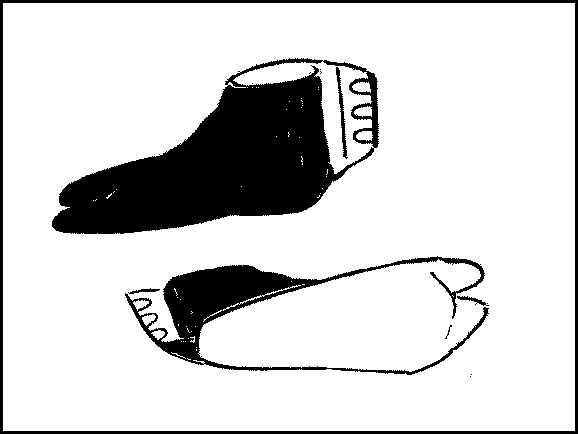

| Socks | 92 | |

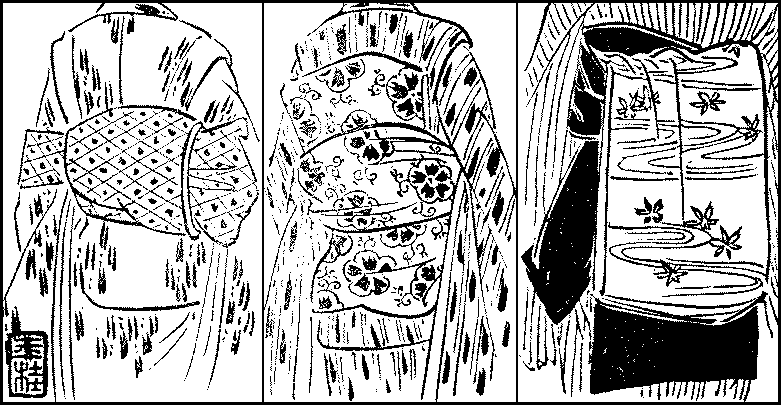

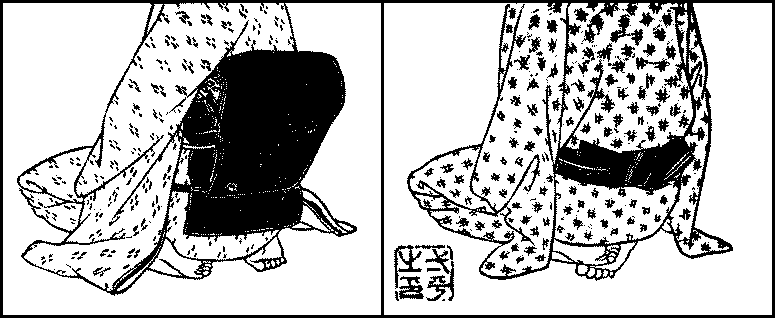

| The Obi for ordinary wear | 98 | |

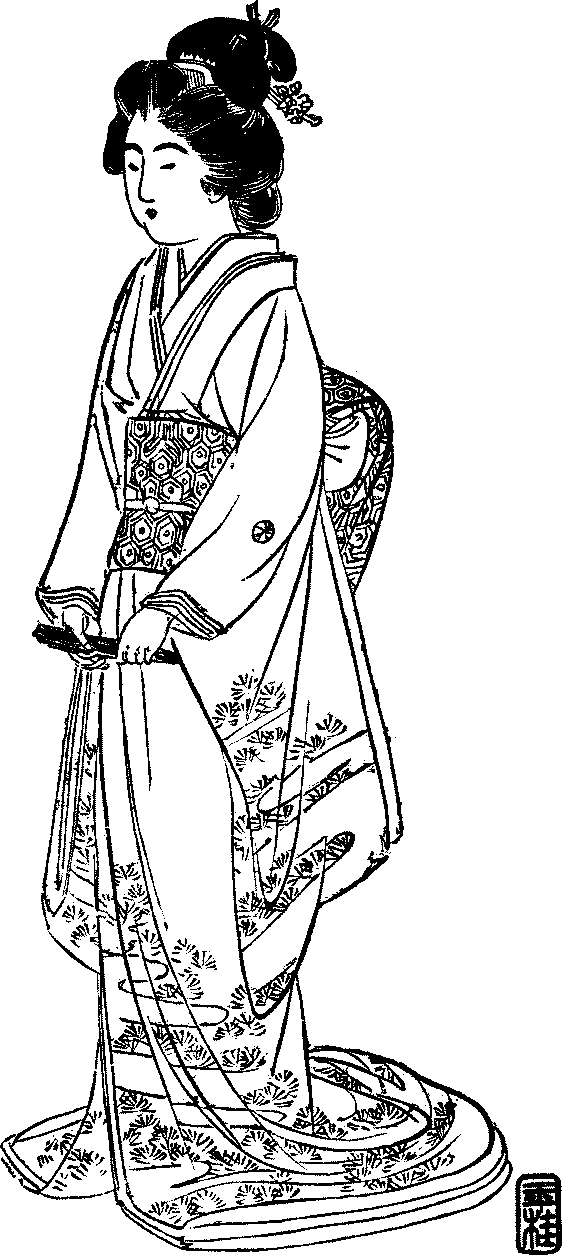

| The Dress-obi | 100 | |

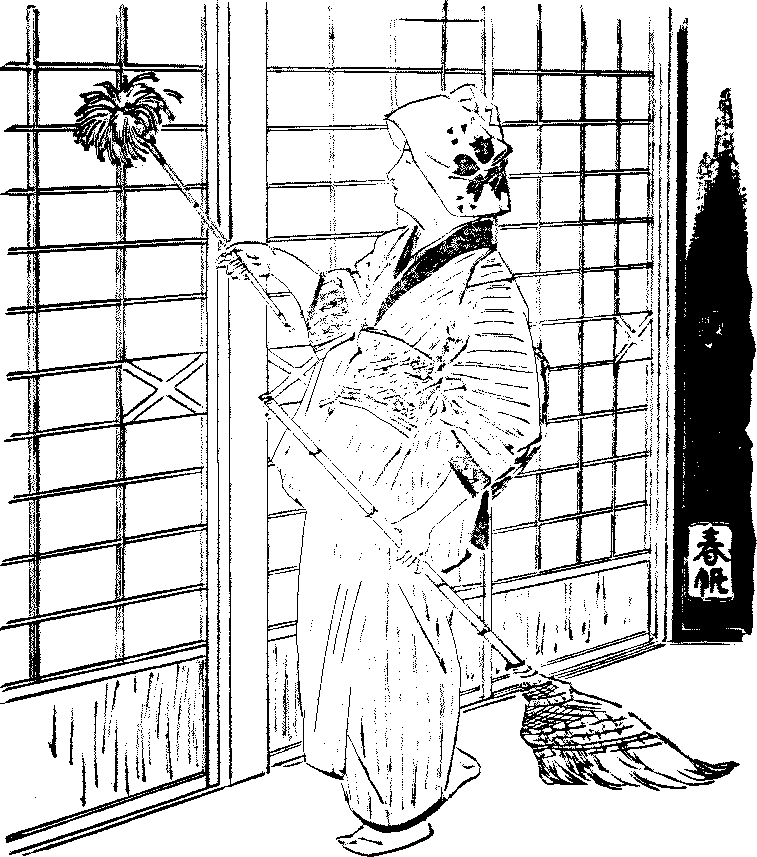

| A Servant with Tucked Sleeves | 102 | |

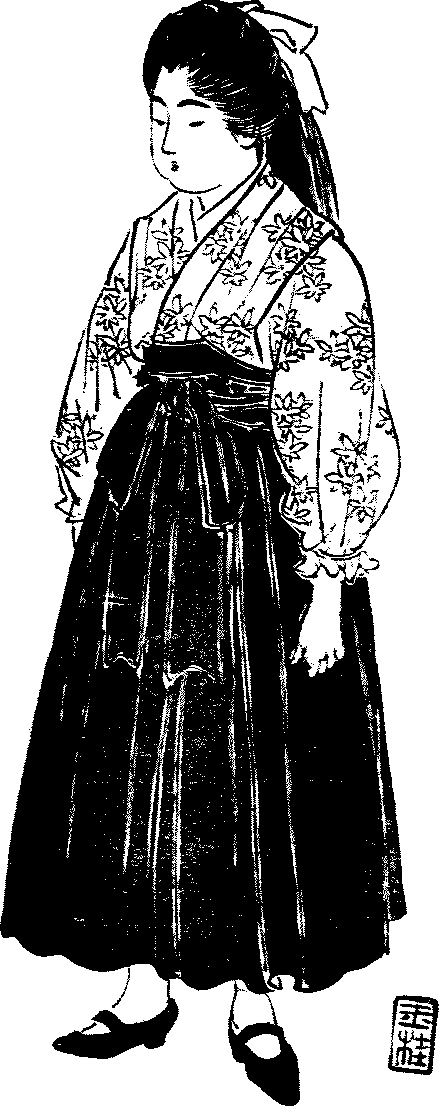

| The Reformed Dress | 103 | |

| A Young Lady dressed for a Visit | 105 | |

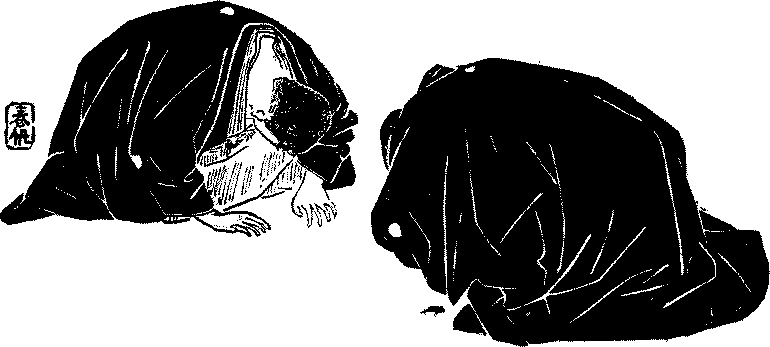

| Queues | 108 | |

| The “203-metre Hill” and “Penthouse” | 109 | |

| Young Girls’ Hair | 110 | |

| The “Inverted Maidenhair” | 111 | |

| The Shimada and “Rounded Chignon” | 112 | |

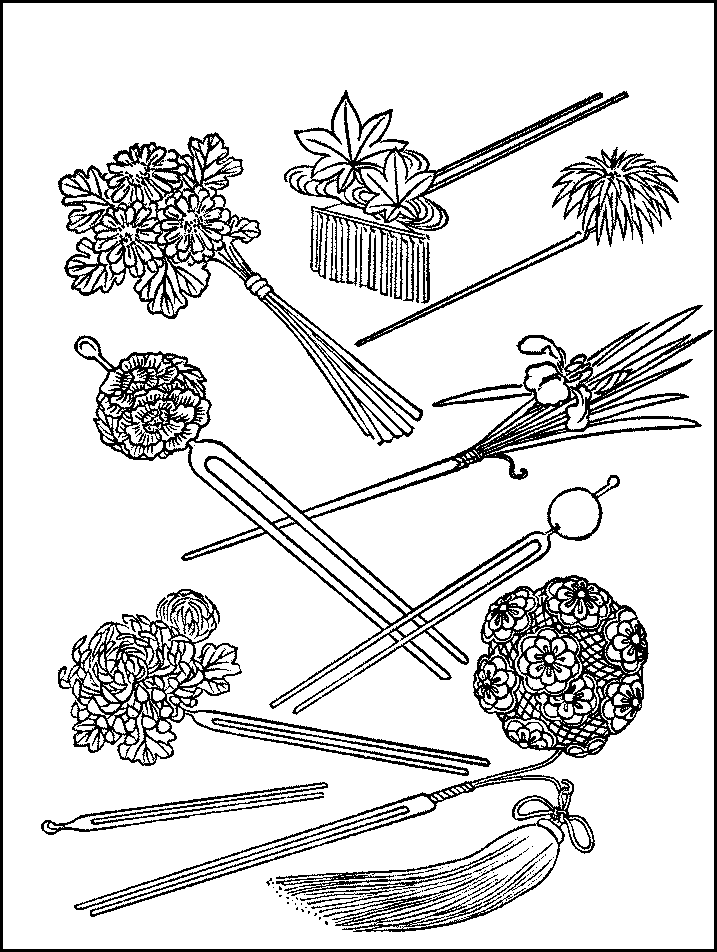

| Bars, Combs, and Bands | 114 | |

| Ornamental Hair-pins | 116 | |

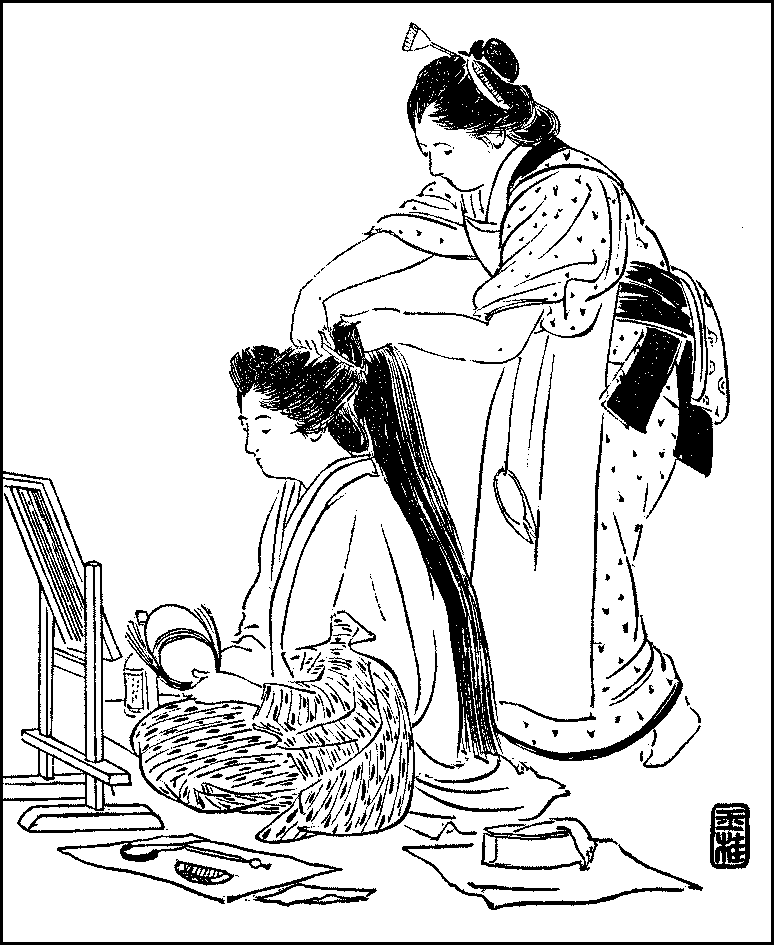

| The Hair-dresser | 117 | |

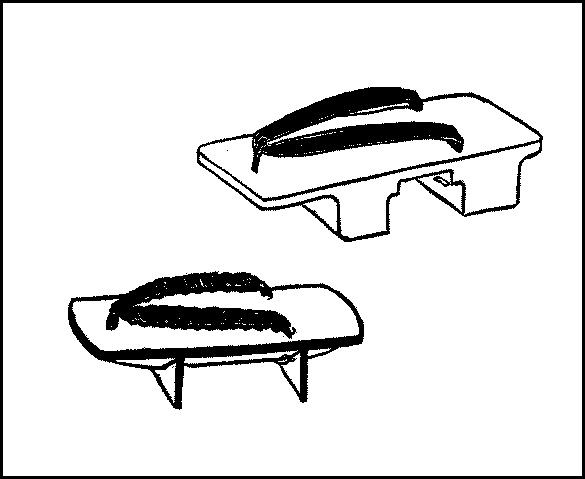

| Plain Clogs | 124 | |

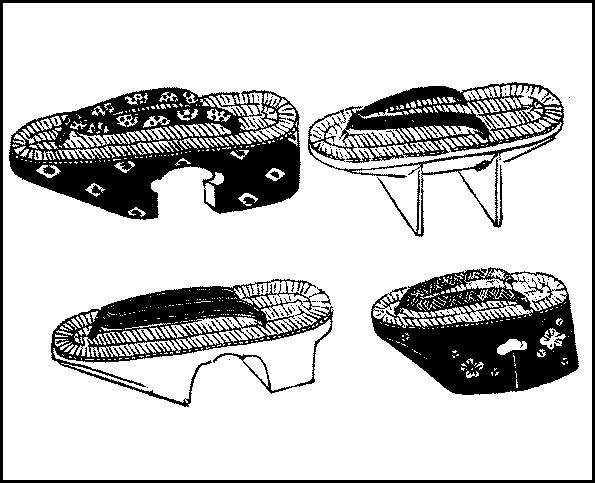

| Matted Clogs | 126 | |

| Matted Sandals | 127 | |

| Straw sandals | 128 | |

| Old Headgear | 129 | |

| A Hood | 130 | |

| An Overdress | 132 | |

| Lanterns | 134 | |

| The Family in Bed | 137 | |

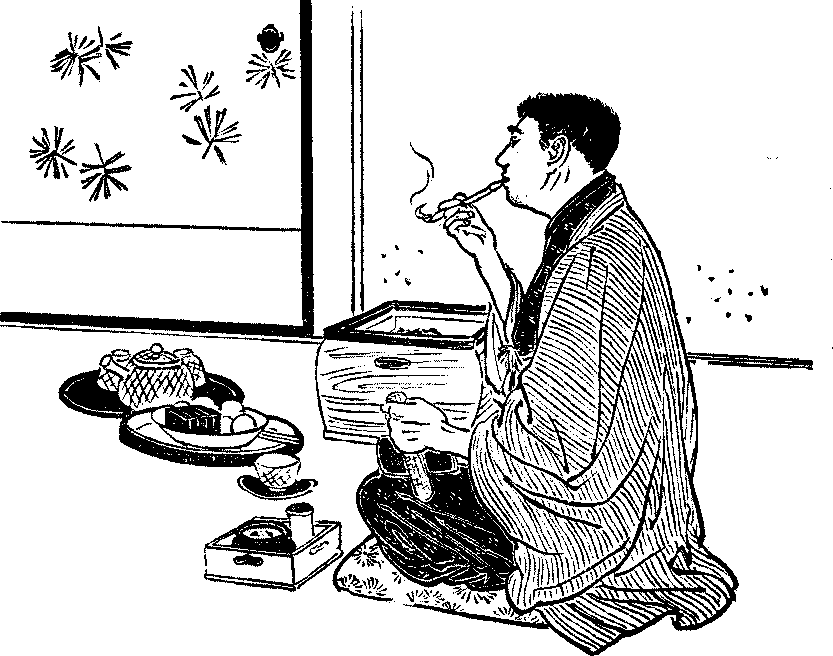

| A Woman smoking | 141 | |

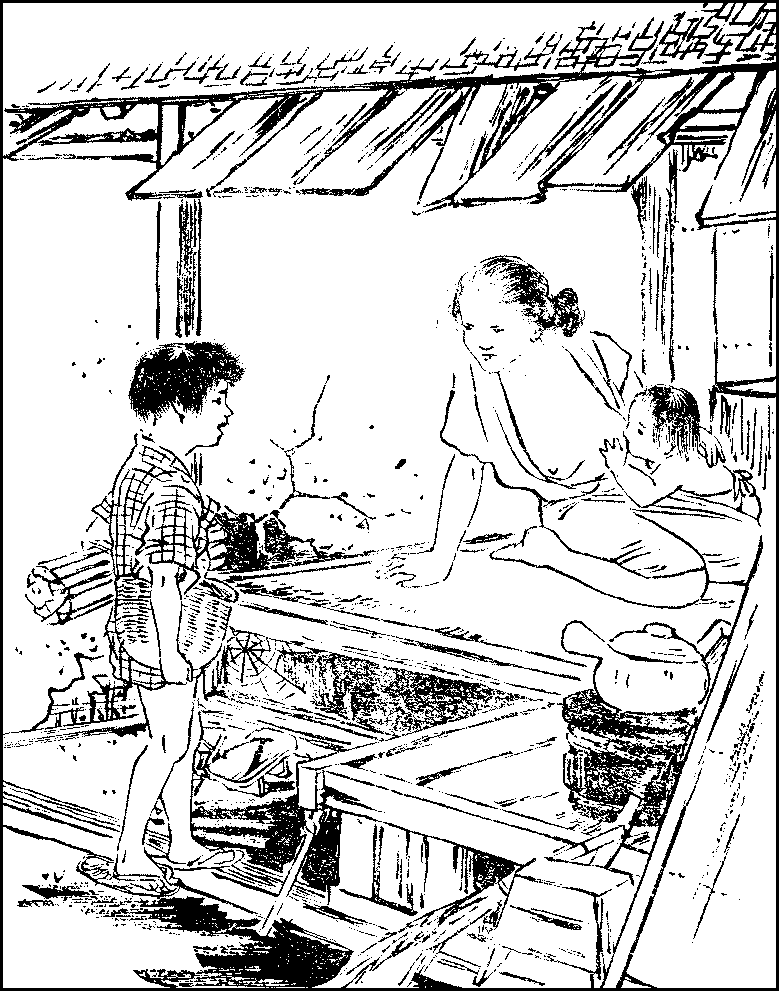

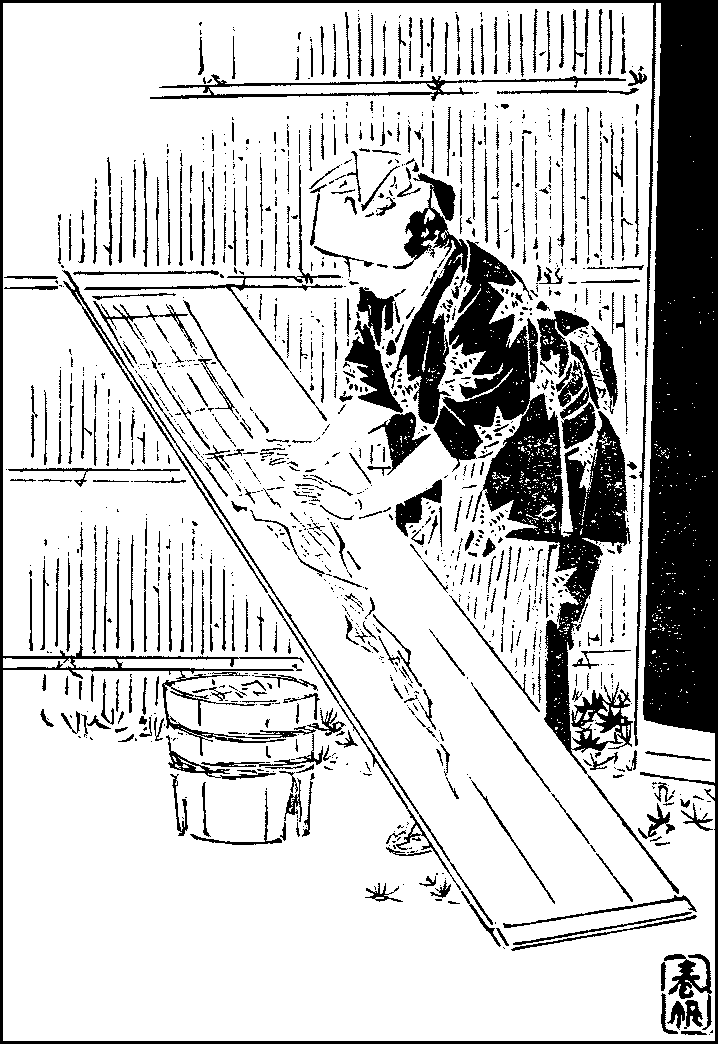

| The Starching-board | 143 | |

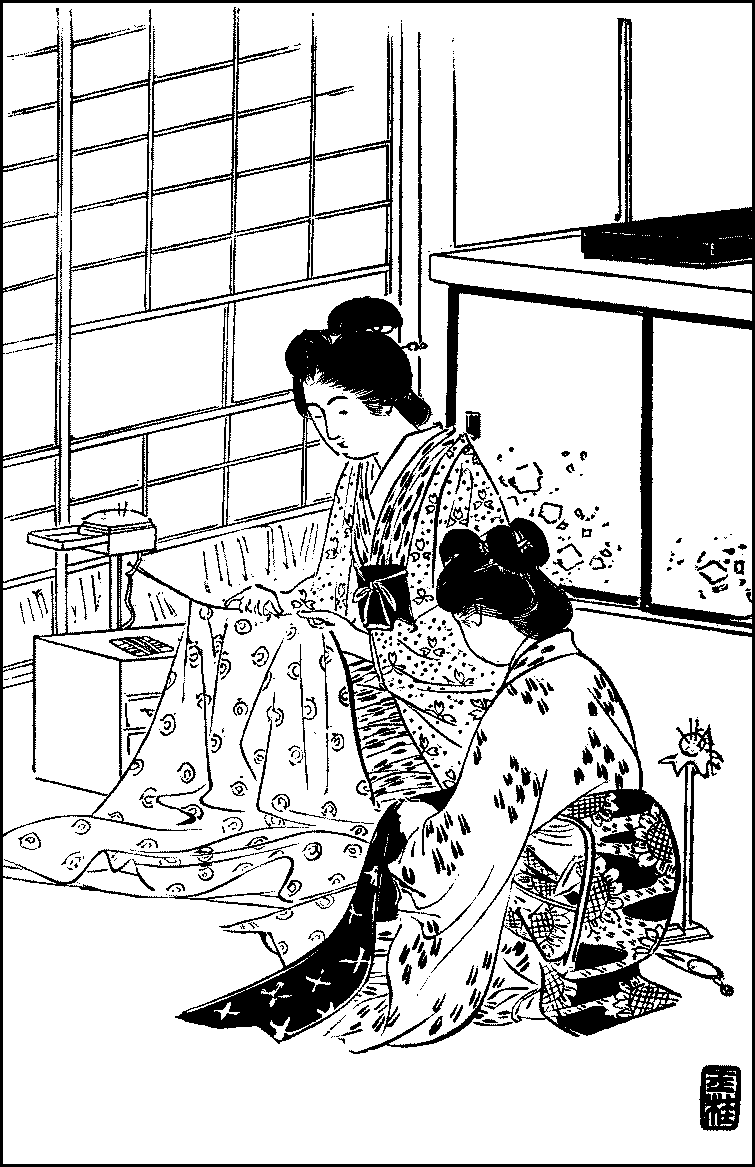

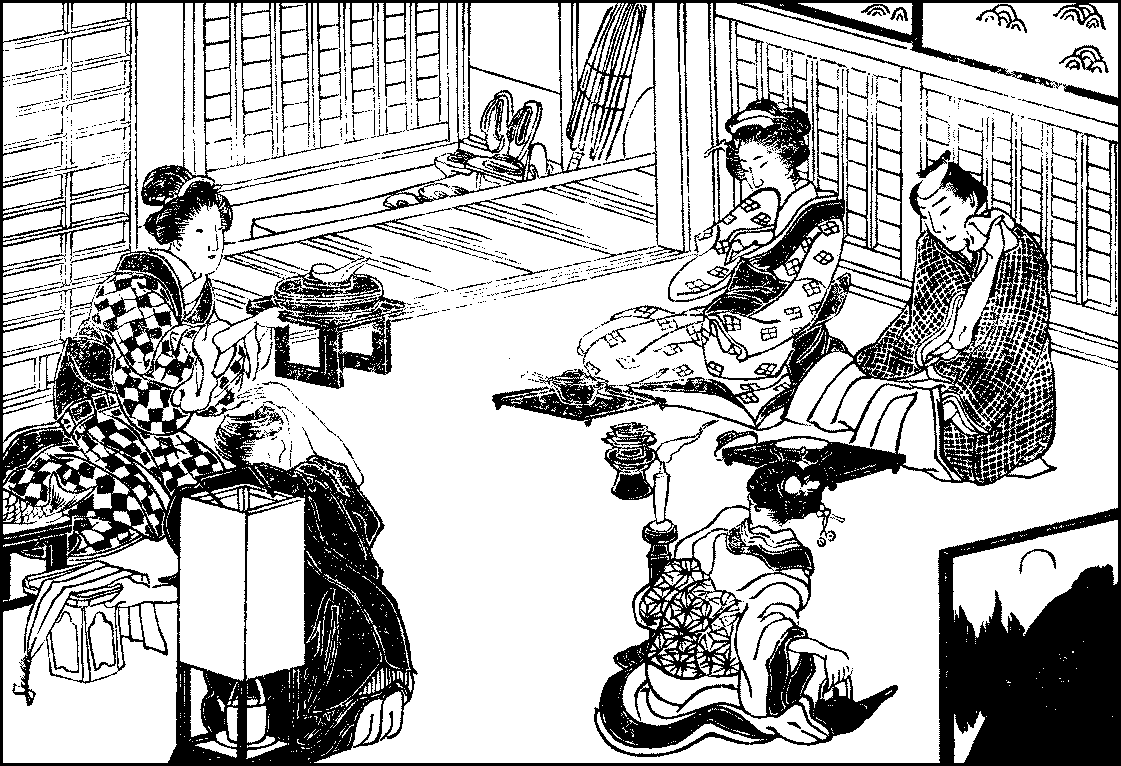

| Needlework | 146 | |

| The Servant at the Sliding-door | 152 | |

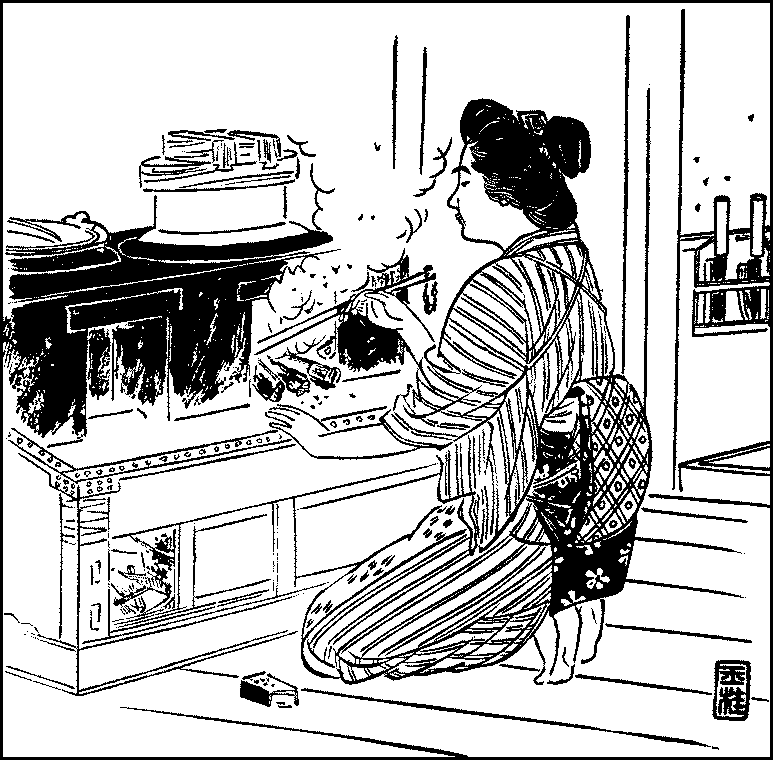

| Cooking Rice | 158 | |

| The Housemaid at work | 160 | |

| The House-boy | 162 | |

| Bowing | 168 | |

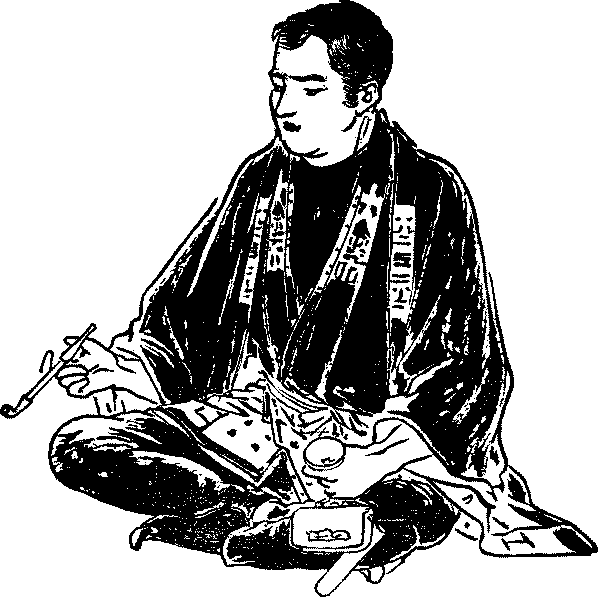

| Sitting with Crossed Legs | 169 | |

| Squatting | 170 | |

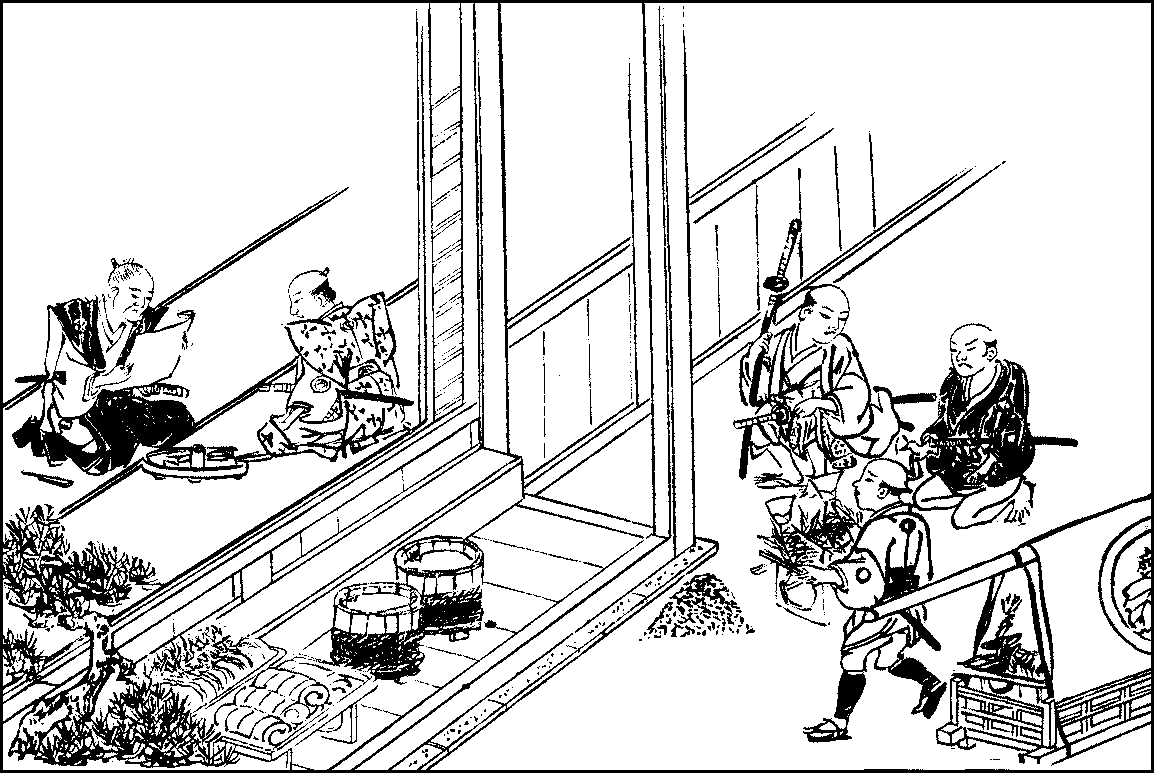

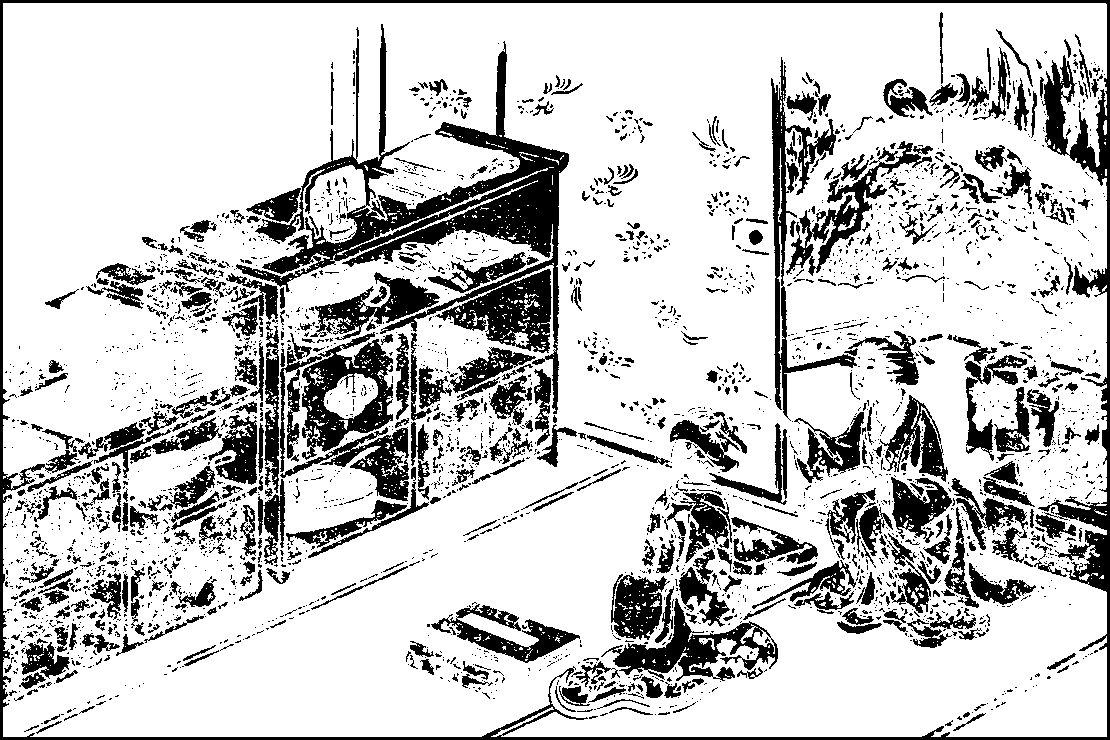

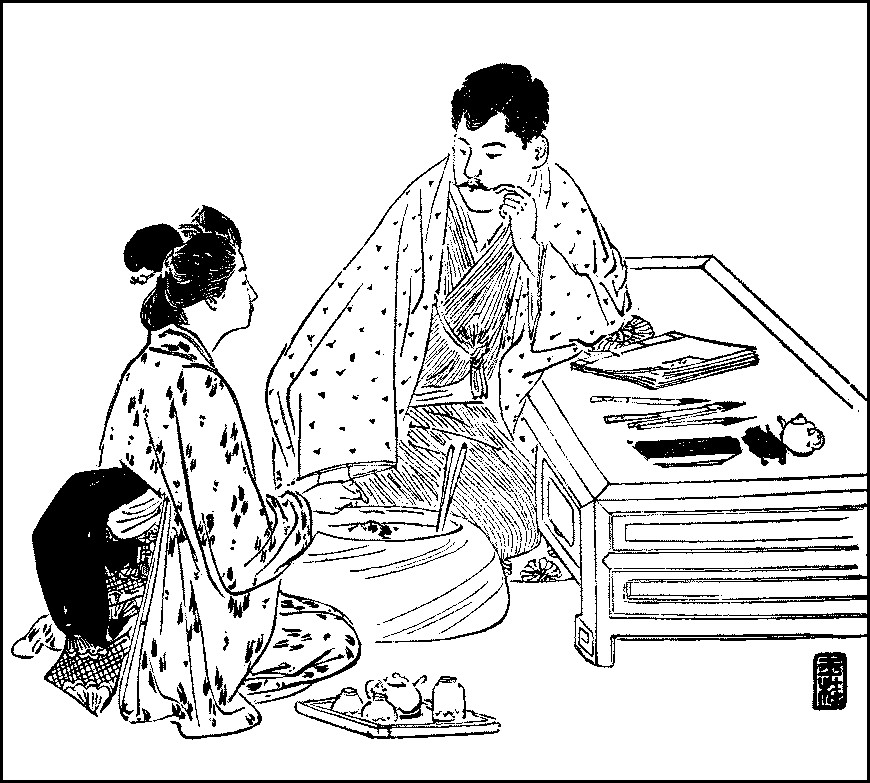

| Betrothal Presents (From a picture by Sukenobu, 1678–1751) | 178 | |

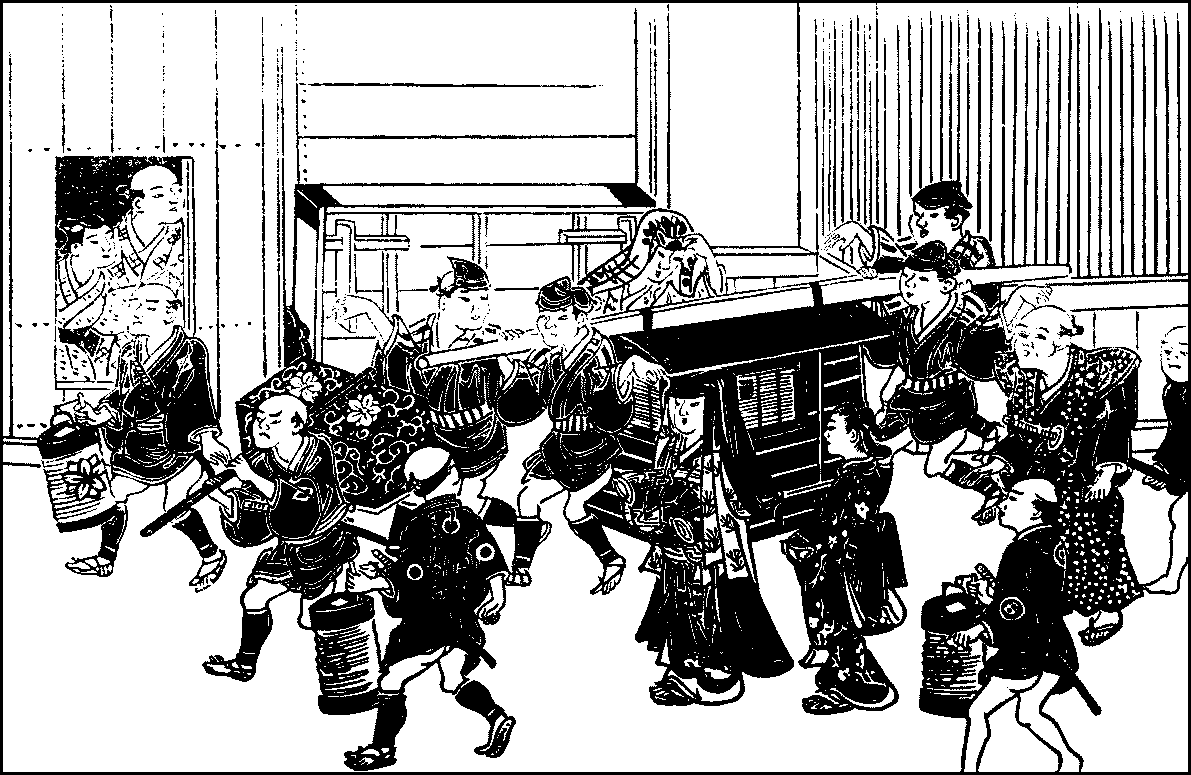

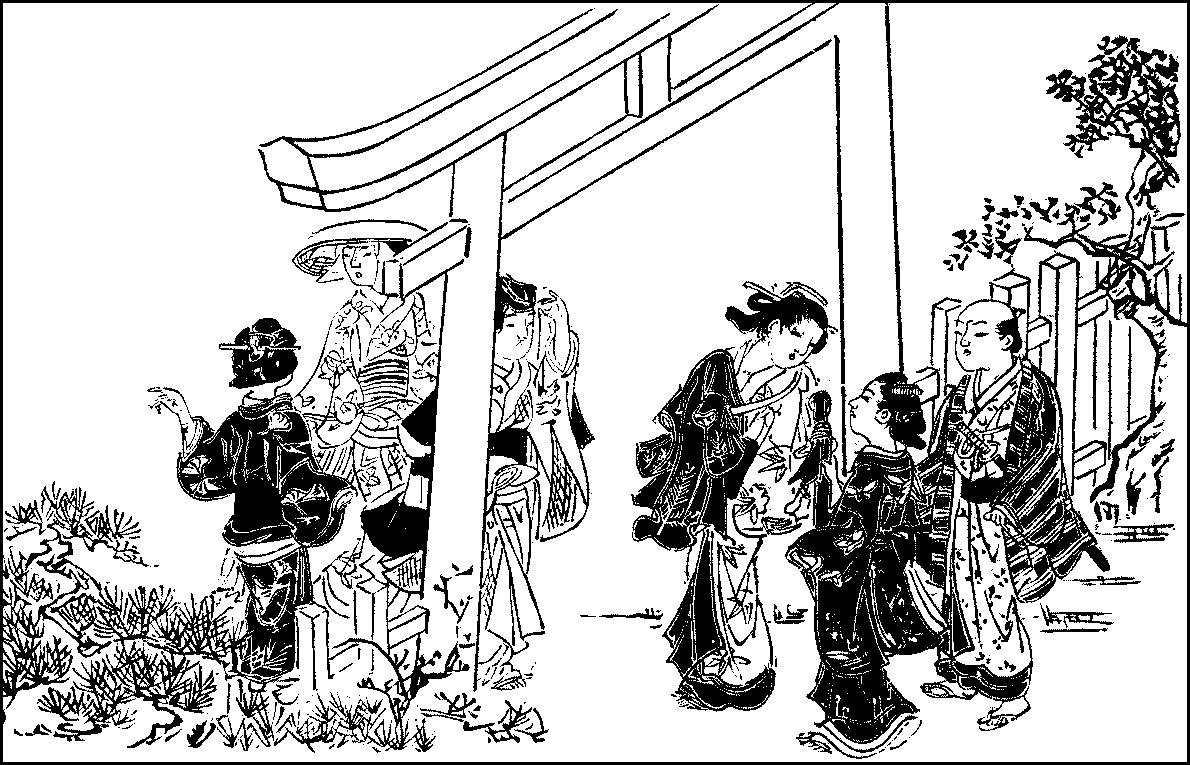

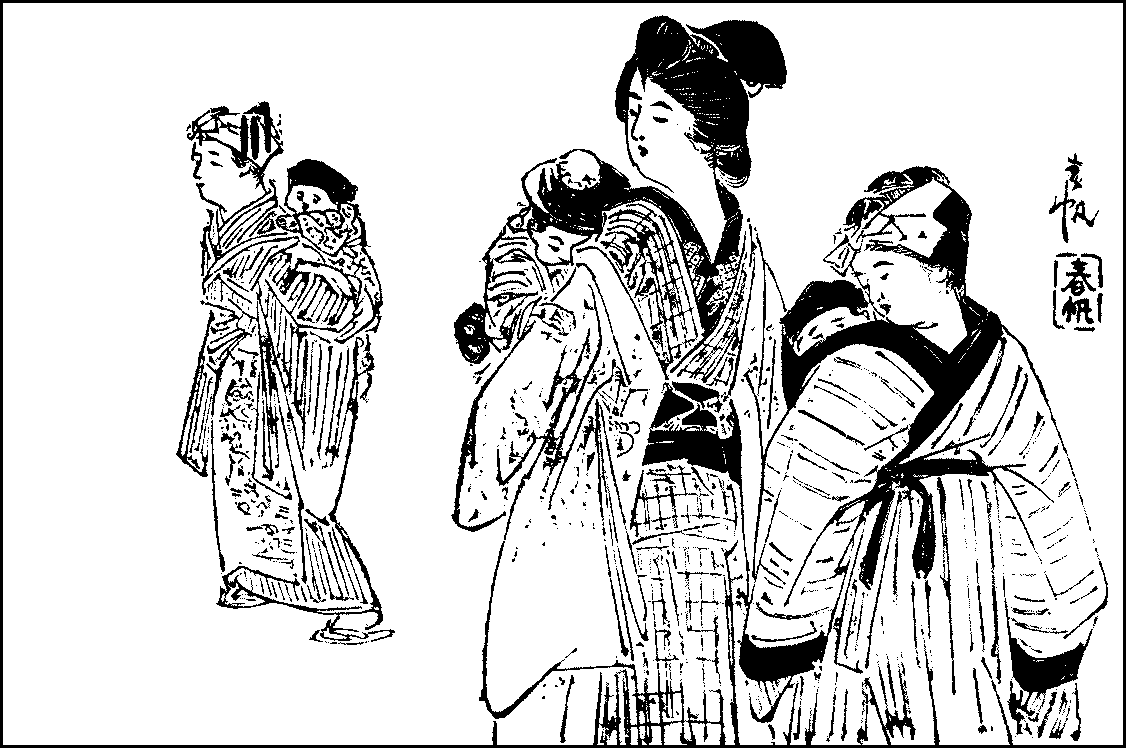

| The Bridal Procession (From a picture by Sukenobu) | 180 | |

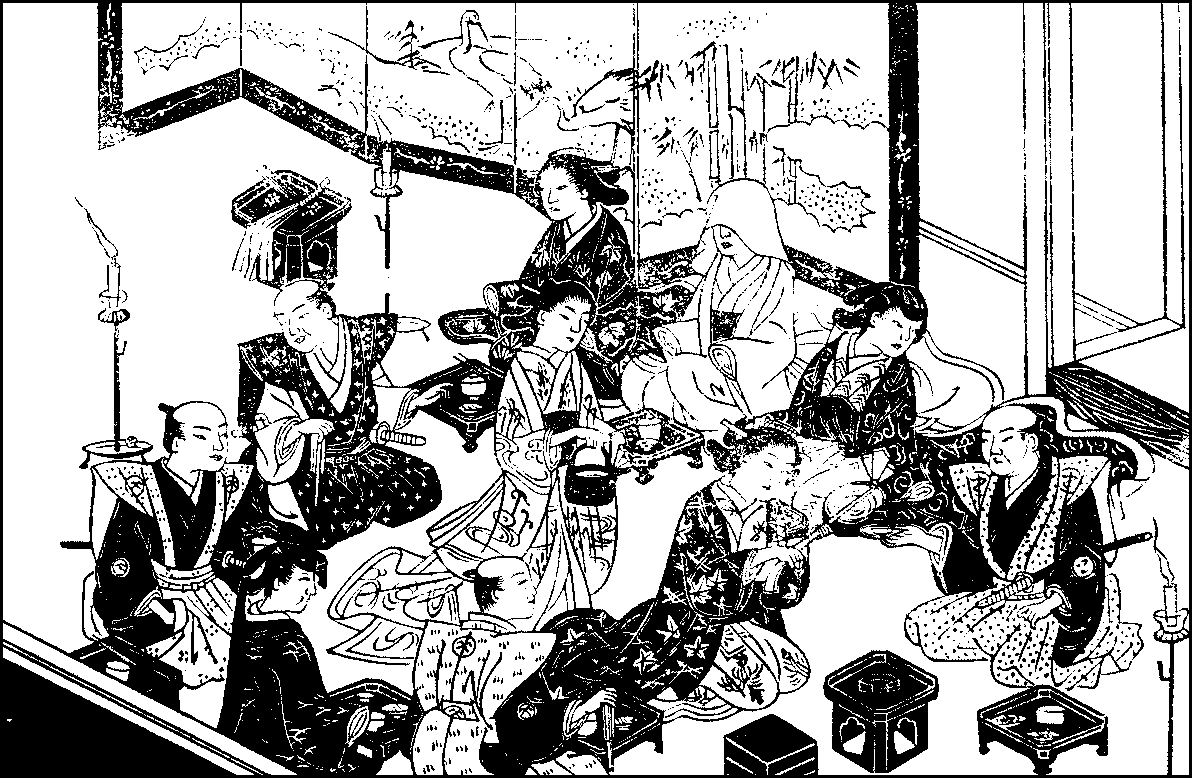

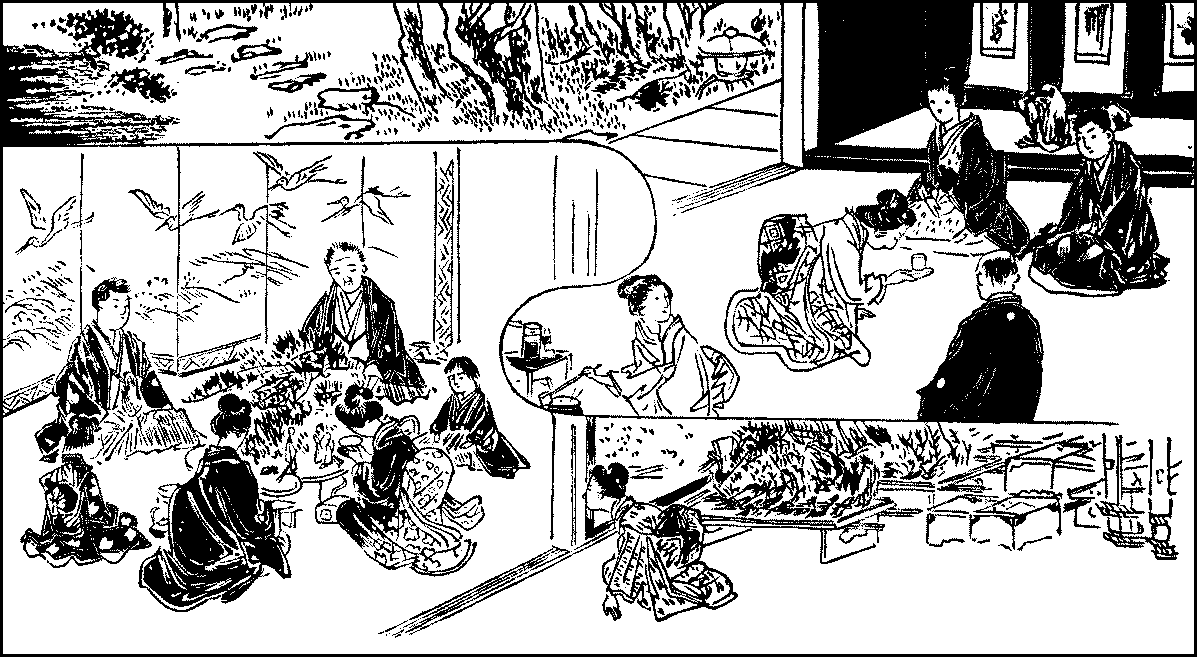

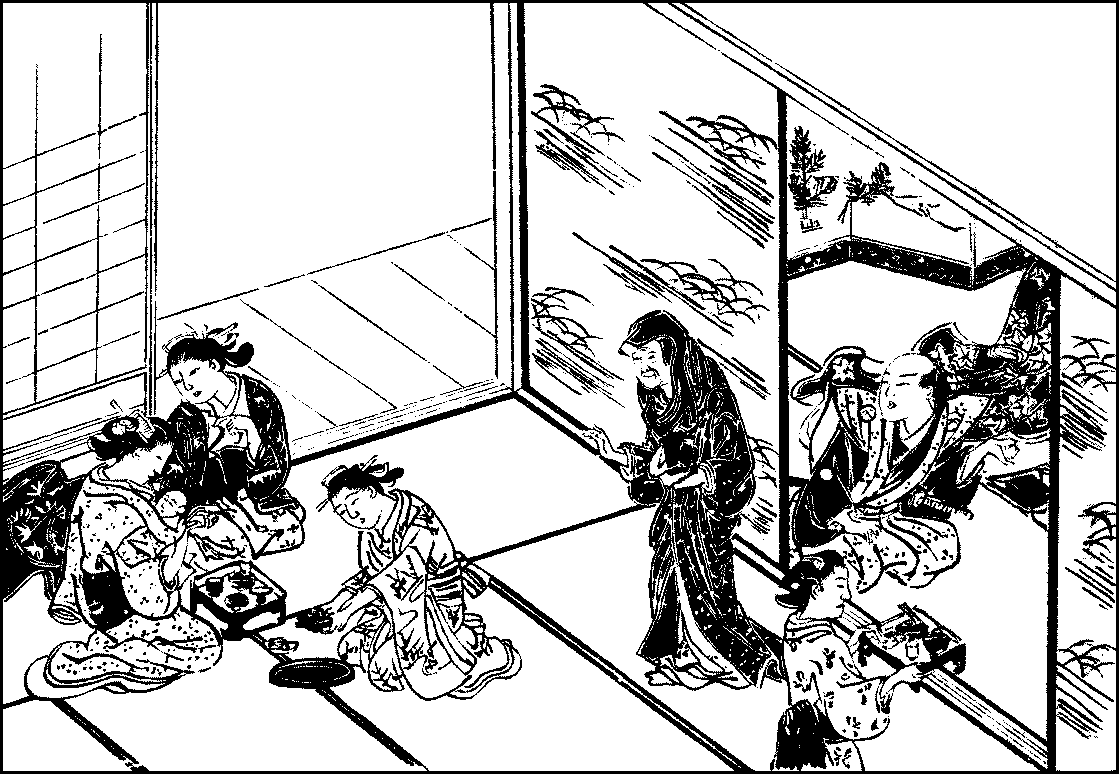

| The Wedding Party (From a picture by Sukenobu) | 182 | |

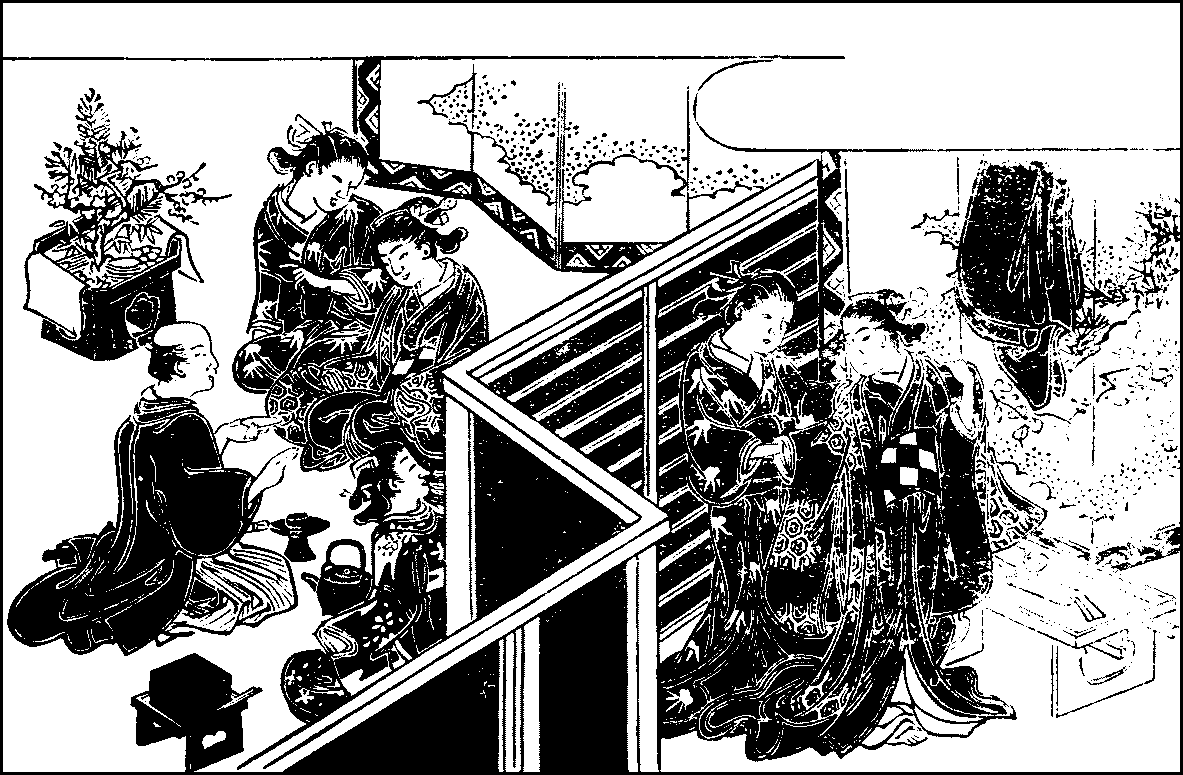

| The Exchange of Cups (From a picture by Sukenobu) | 184 | |

| The Bride’s Cabinets (From a picture by Sukenobu){vii} | 186 | |

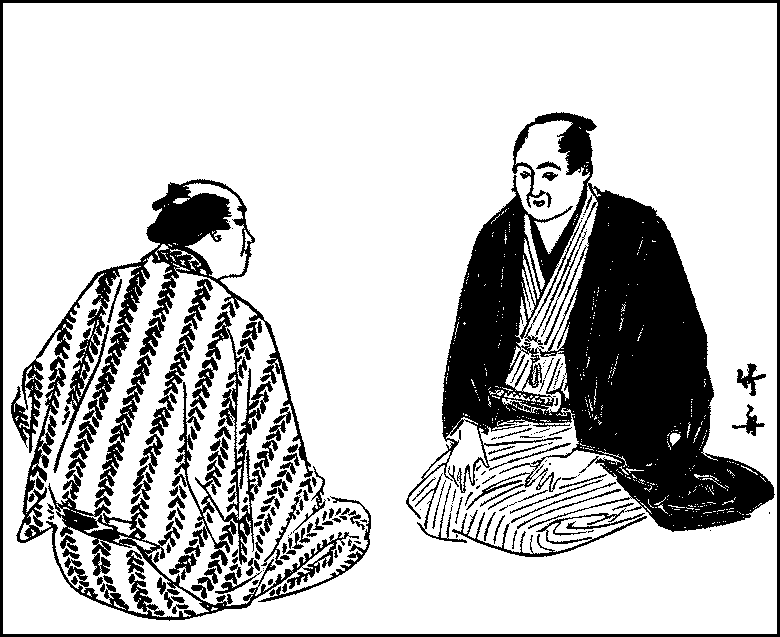

| The First Meeting and Wedding at the Present Time | 188 | |

| A Daimyo’s Wedding | 190 | |

| A Lower-class Wedding | 192 | |

| Husband and Wife | 196 | |

| A Domestic Quarrel and Reconciliation | 199 | |

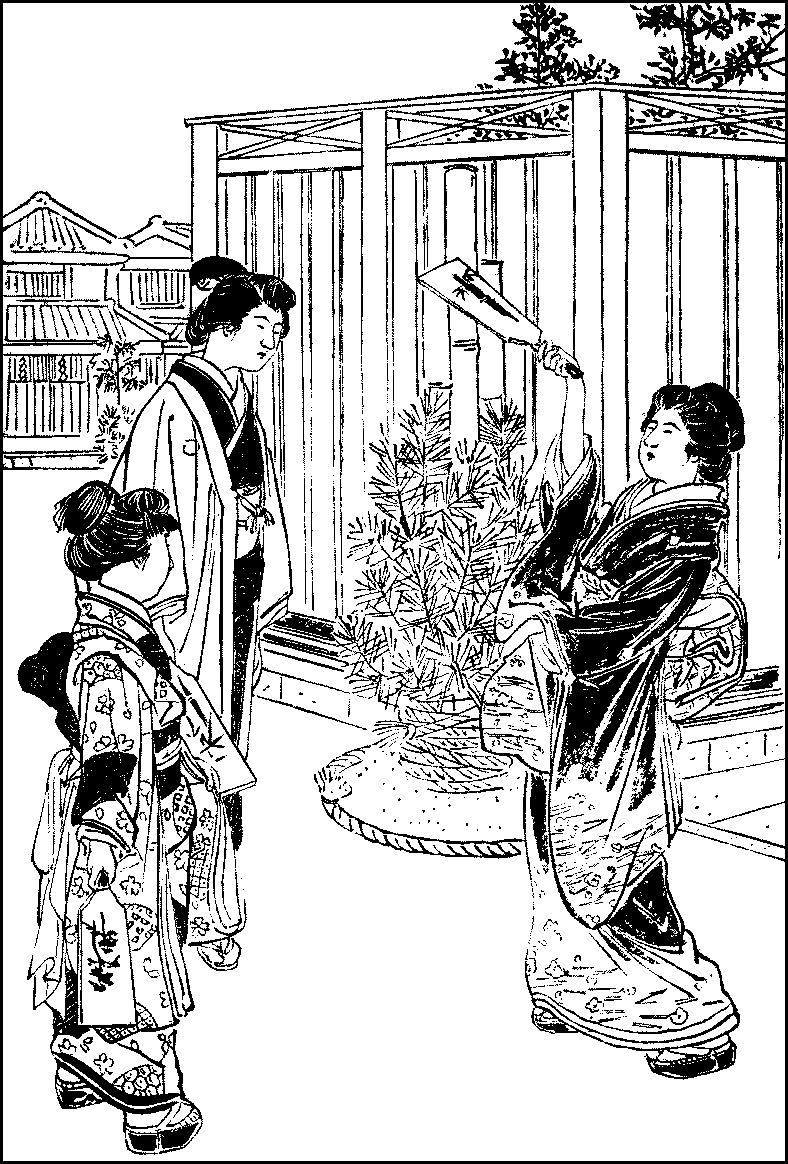

| The First Visit to the Local Shrine (From a picture by Sukenobu) | 222 | |

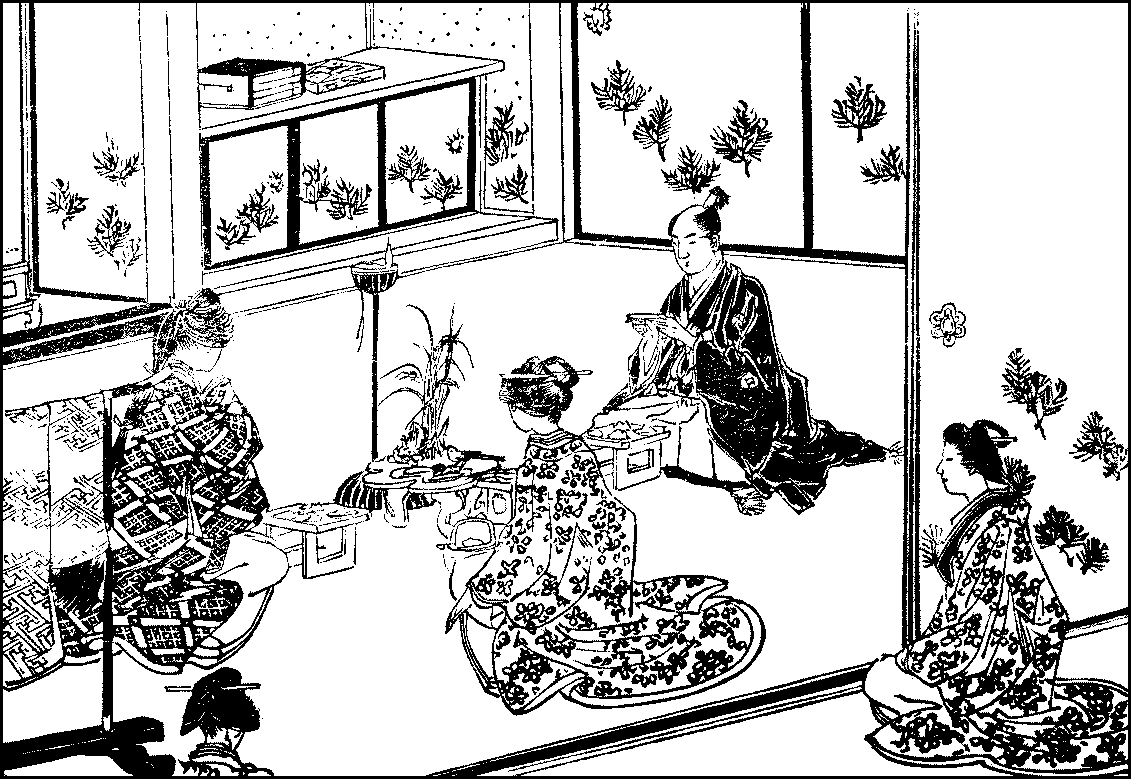

| The “First-eating” (From a picture by Sukenobu) | 224 | |

| Carrying Children | 227 | |

| Fencing | 233 | |

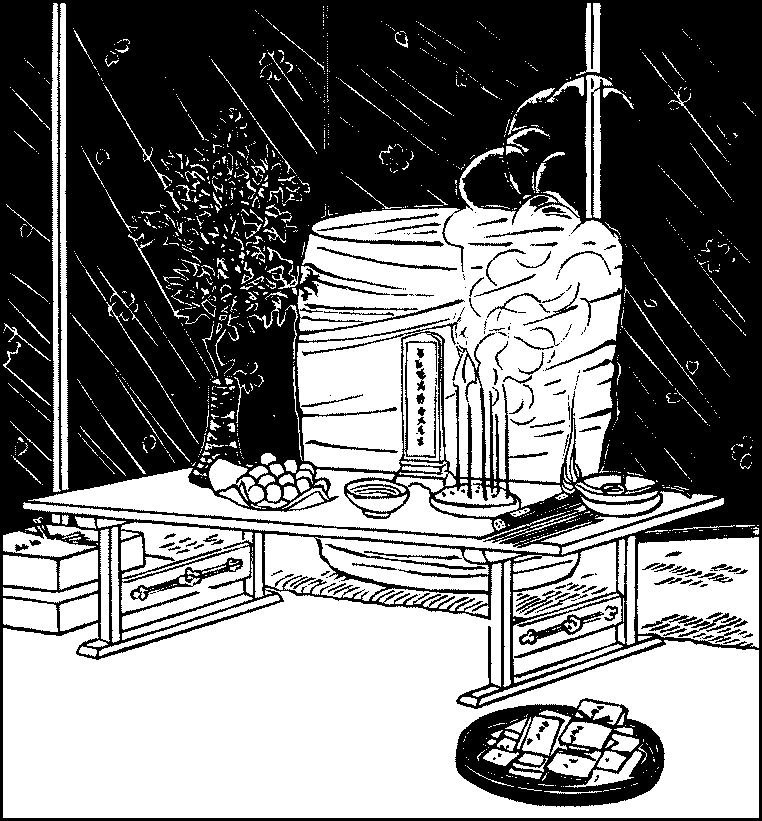

| Offerings before a Coffin | 238 | |

| Coffins and an Urn | 241 | |

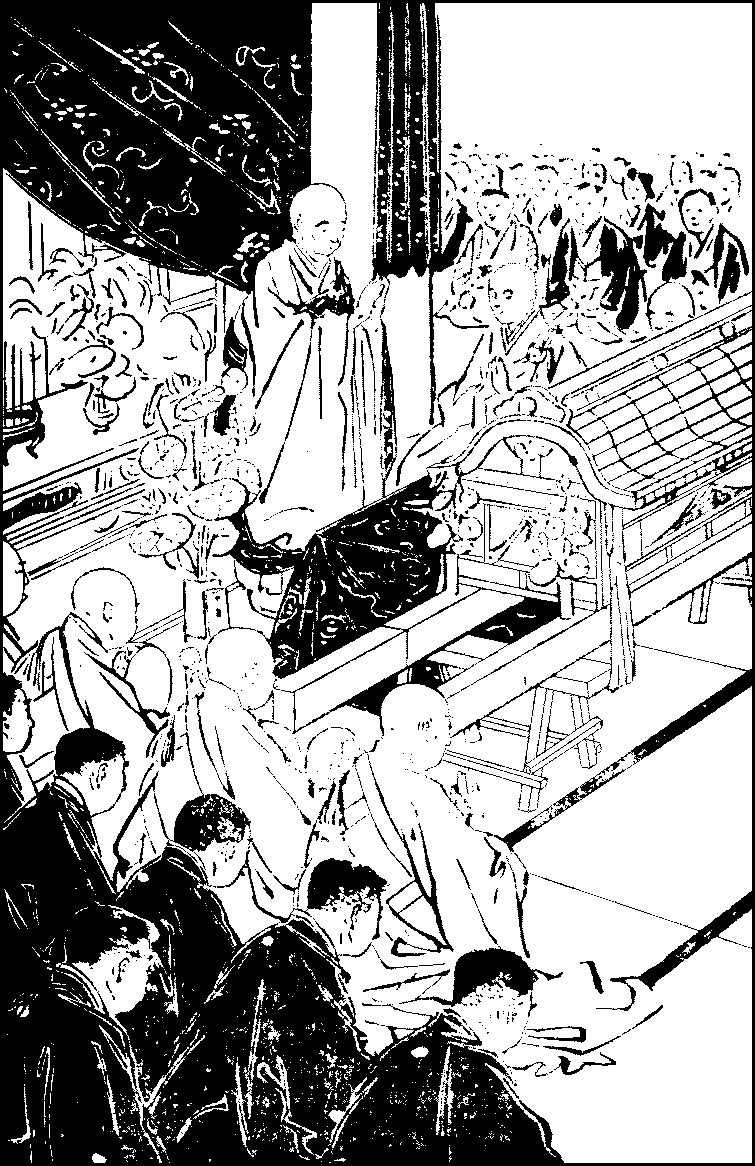

| A Buddhist Funeral Service | 242–3 | |

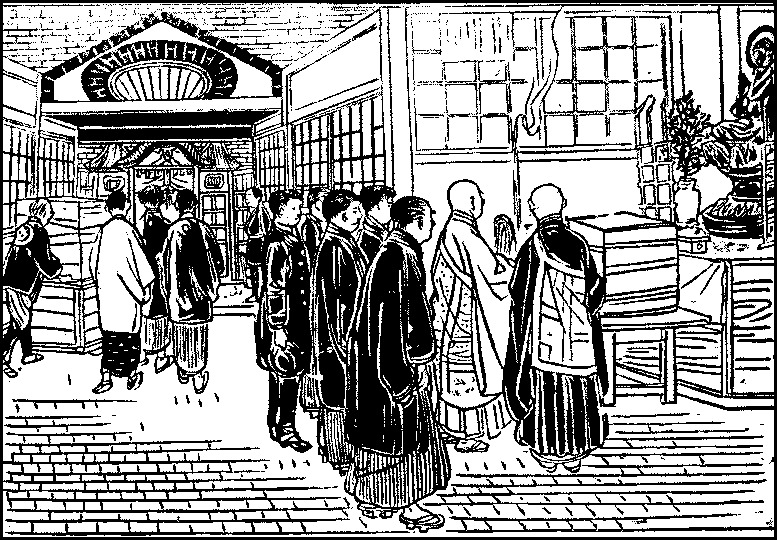

| Service at the Temple | 245 | |

| At the Crematory | 246 | |

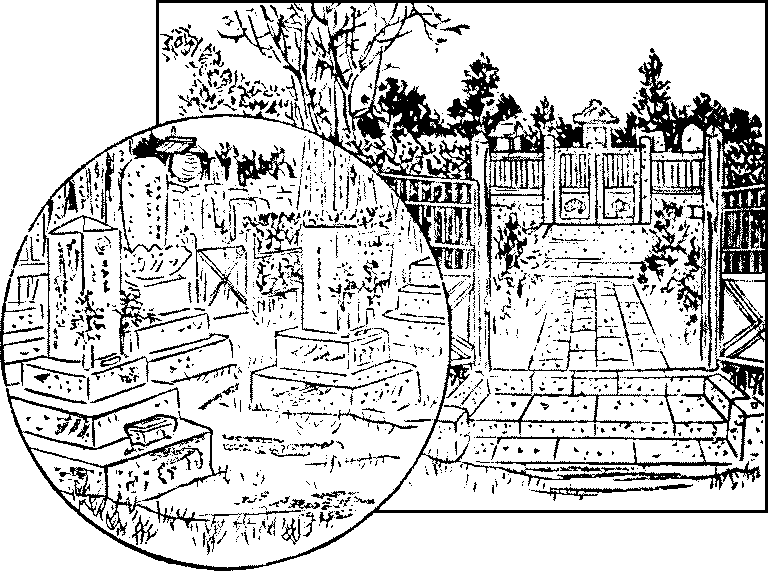

| Graves | 247 | |

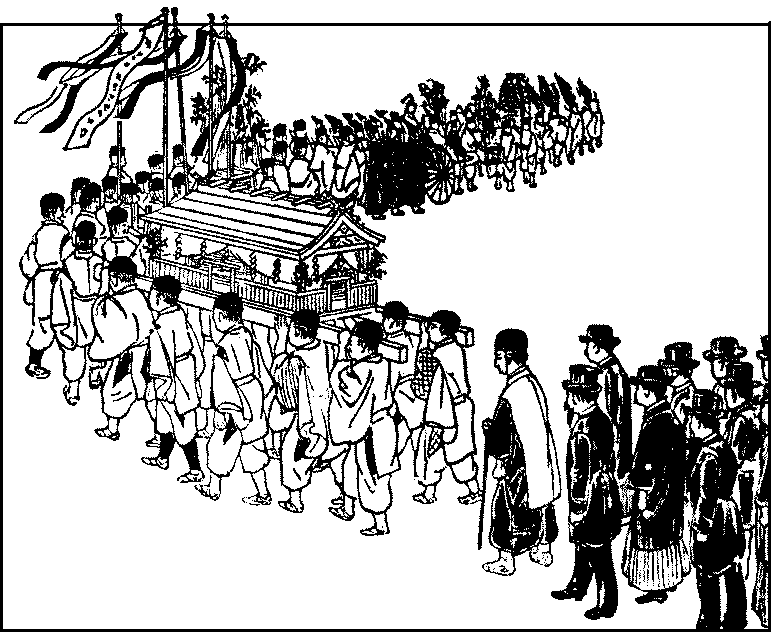

| A Shinto Funeral Procession | 249 | |

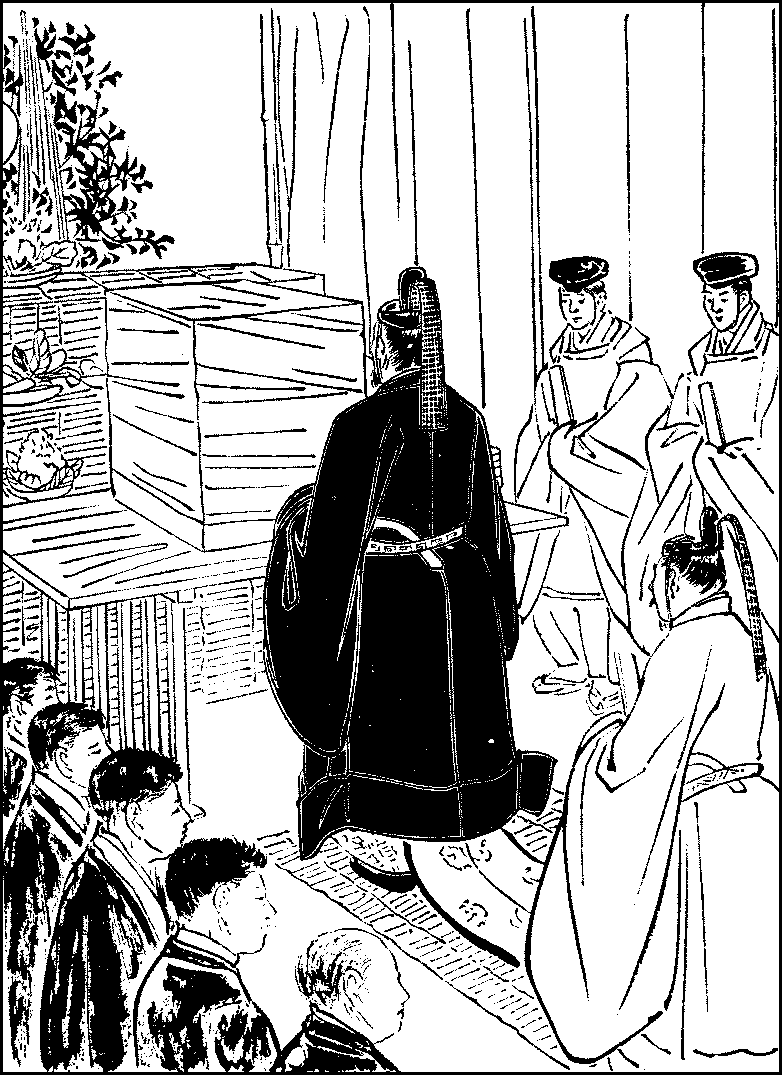

| A Shinto Funeral Service | 250 | |

| A Writing-table and Book-cases | 253 | |

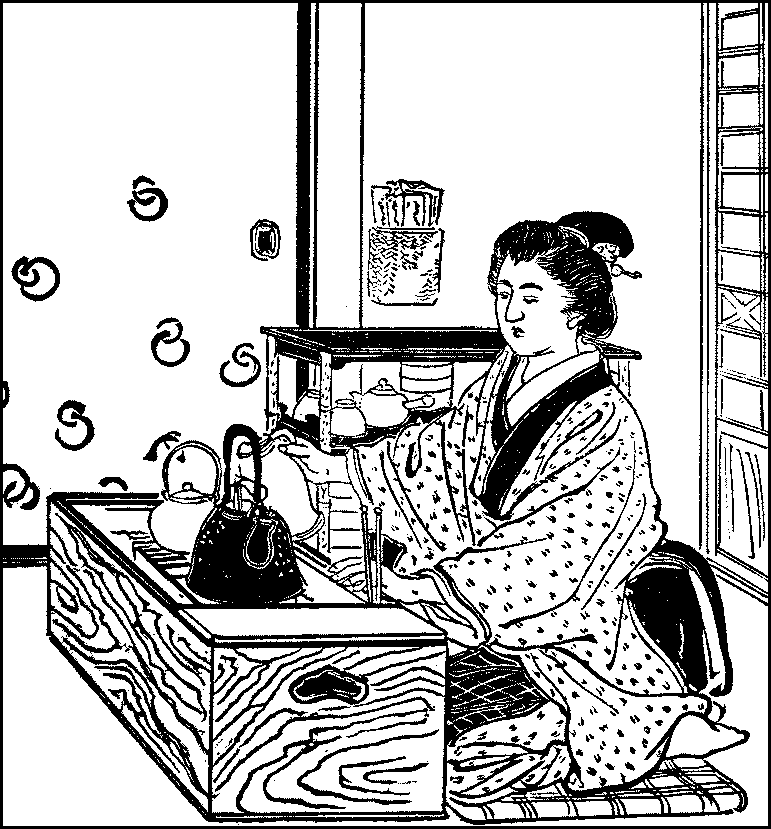

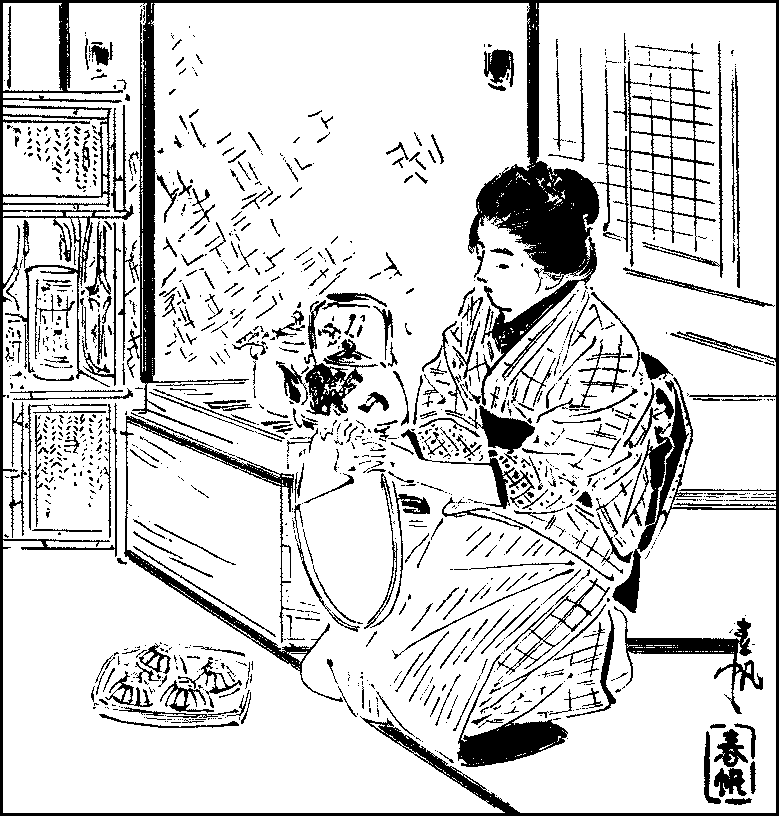

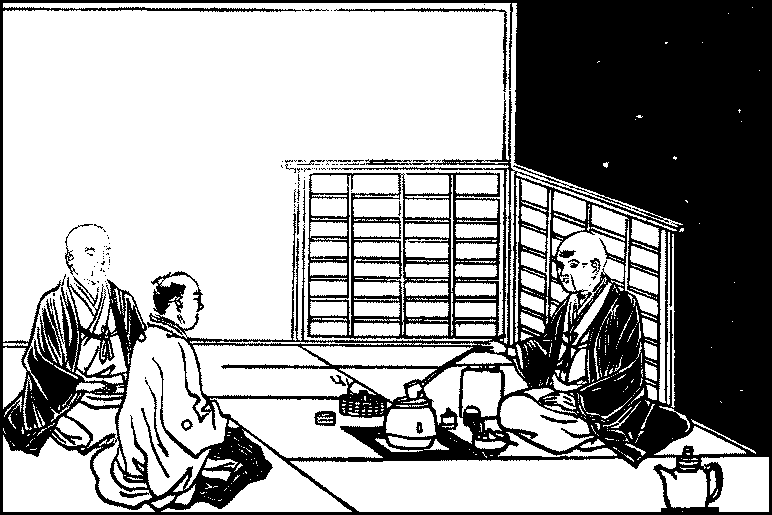

| Tea-making | 260 | |

| Flower-vases | 262 | |

| A Tray-landscape | 264 | |

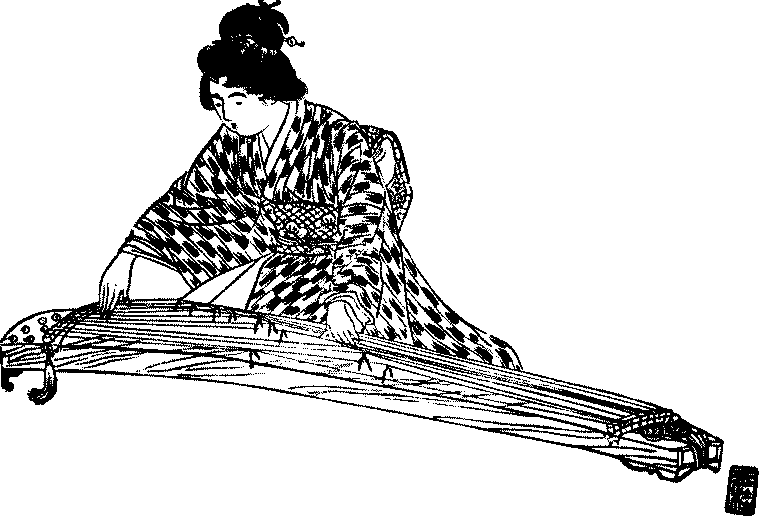

| The Koto | 265 | |

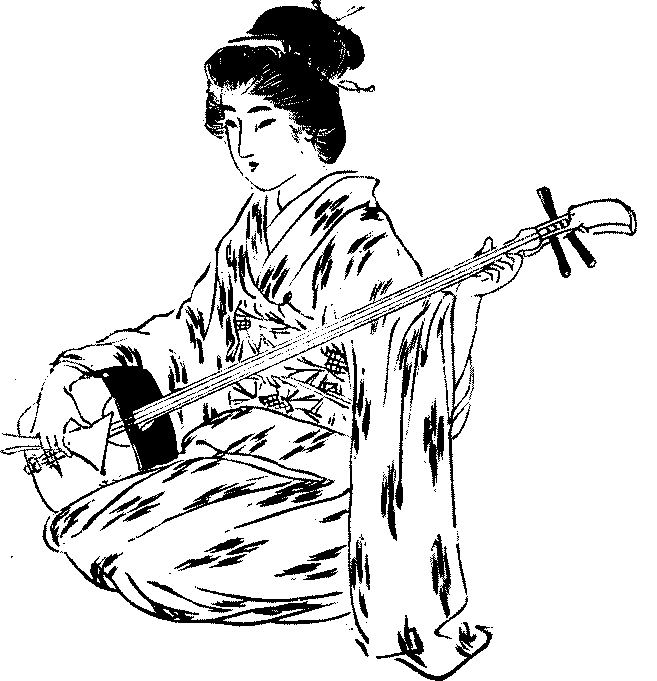

| The Samisen | 267 | |

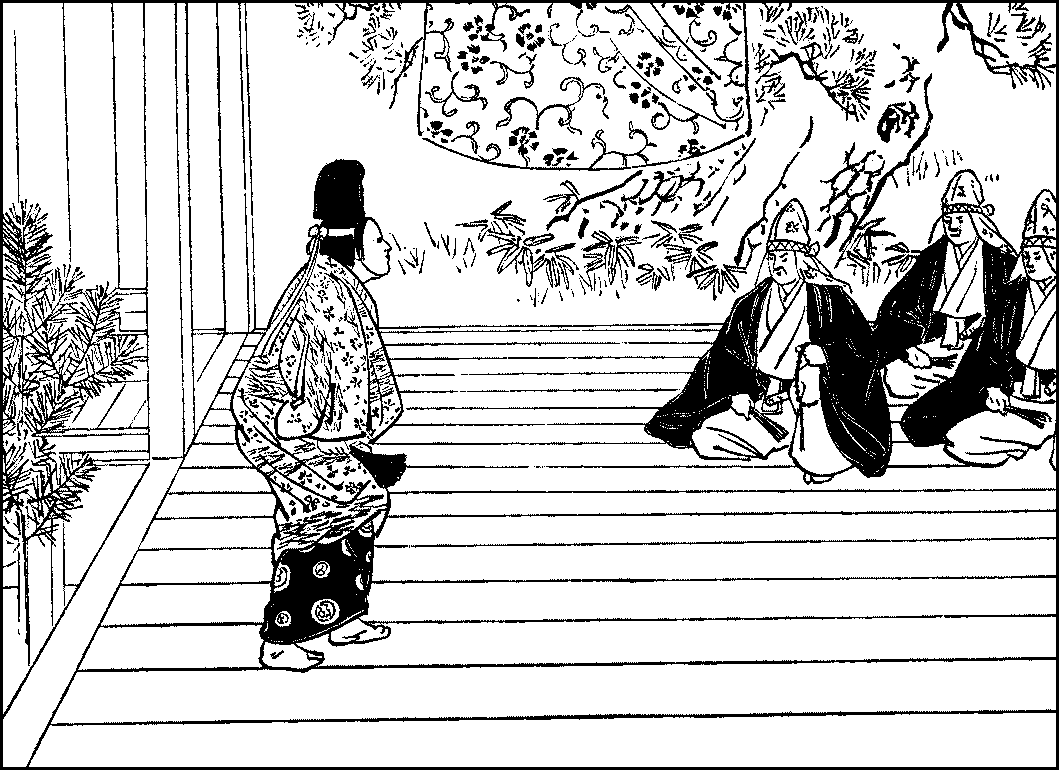

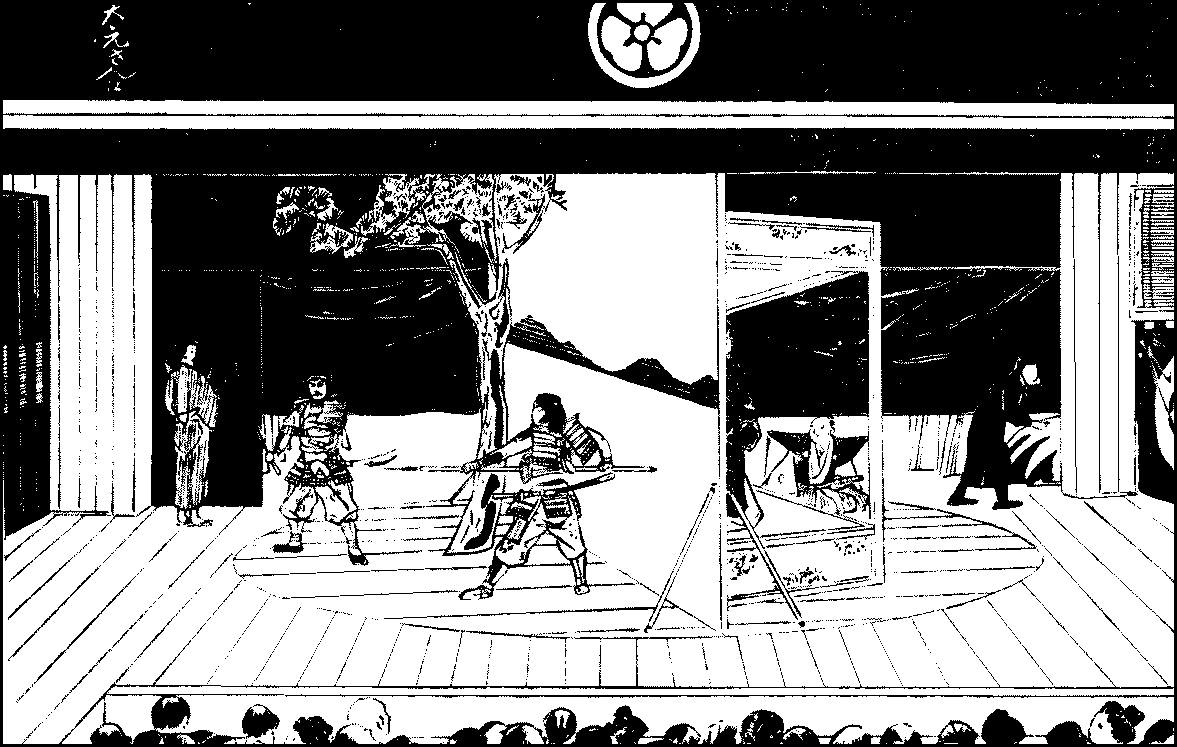

| A No-dance | 270 | |

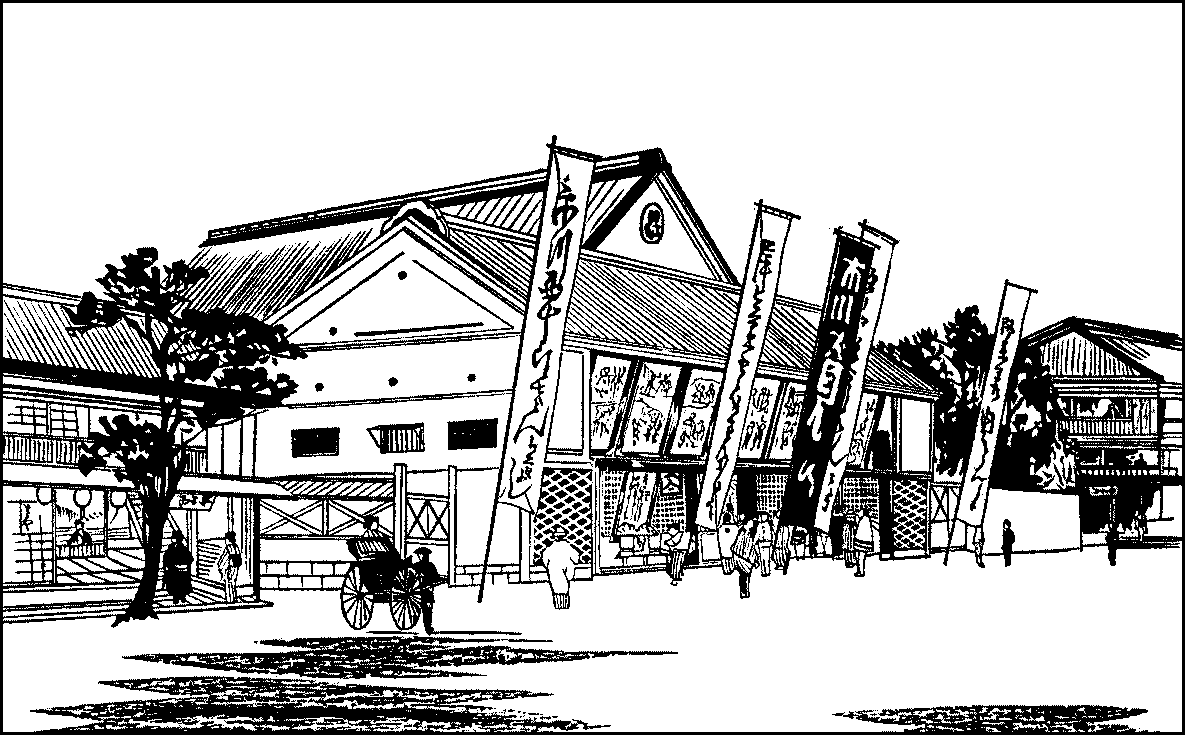

| The Entrance of a Theatre | 272 | |

| The Stage and Entrance-passage | 273 | |

| The Revolving-stage | 275 | |

| A Wrestling-match | 279 | |

| The Champion’s Appearance in the Ring | 281 | |

| The Entrance of a Story-tellers’ Hall | 283 | |

| A Story-teller on the Platform | 285 | |

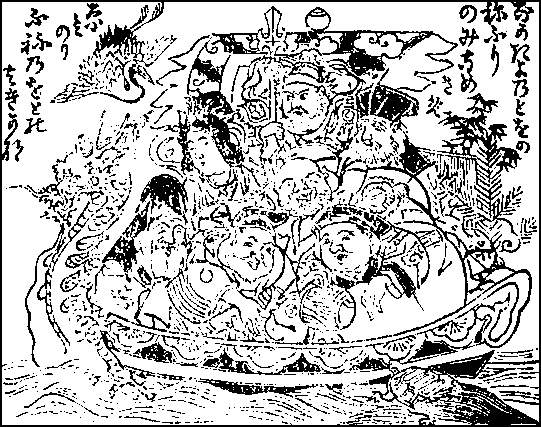

| The Treasure-ship | 289 | |

| The New Year’s Decorations | 290 | |

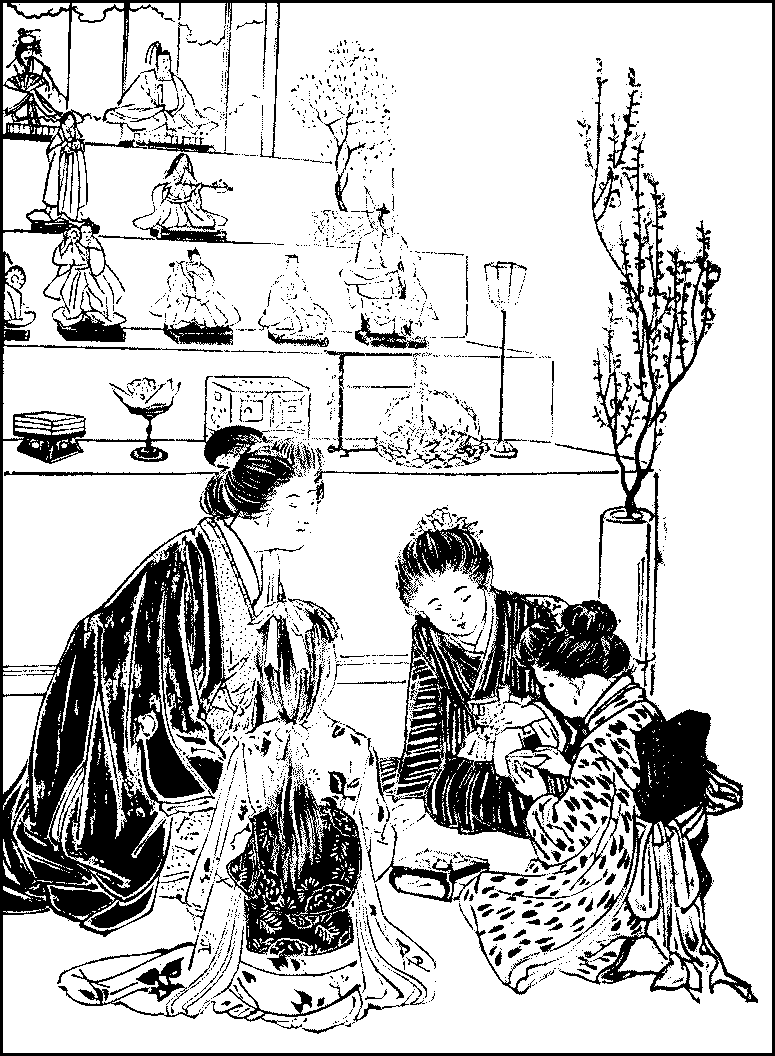

| The Feast of Dolls | 293 | |

| Cherry-flowers at Mukojima | 295 | |

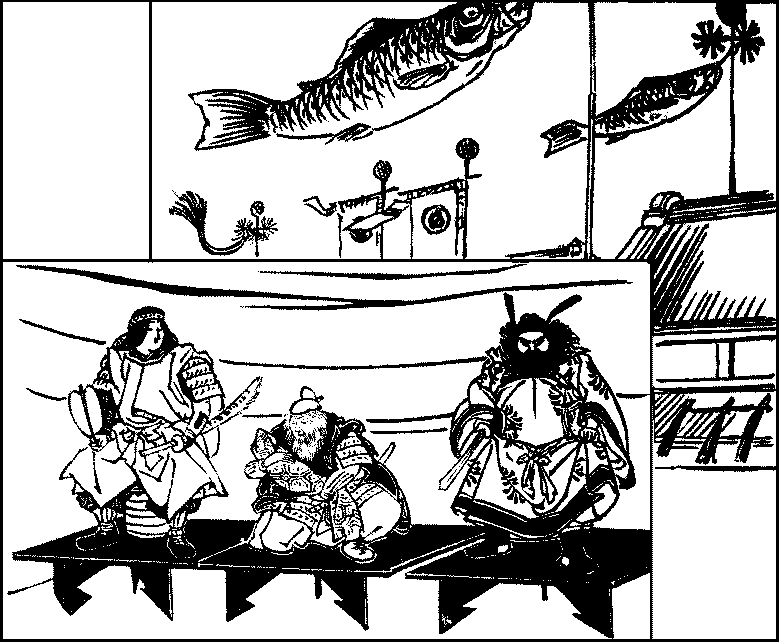

| The Feast of Flags | 298 | |

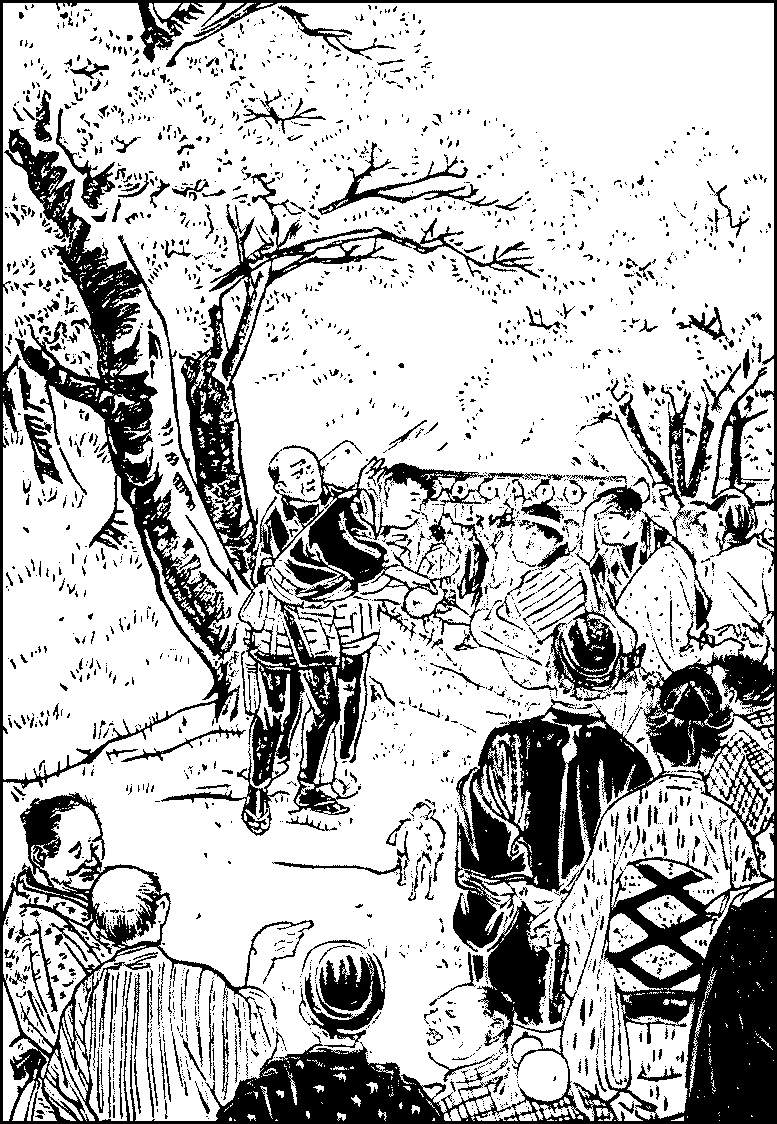

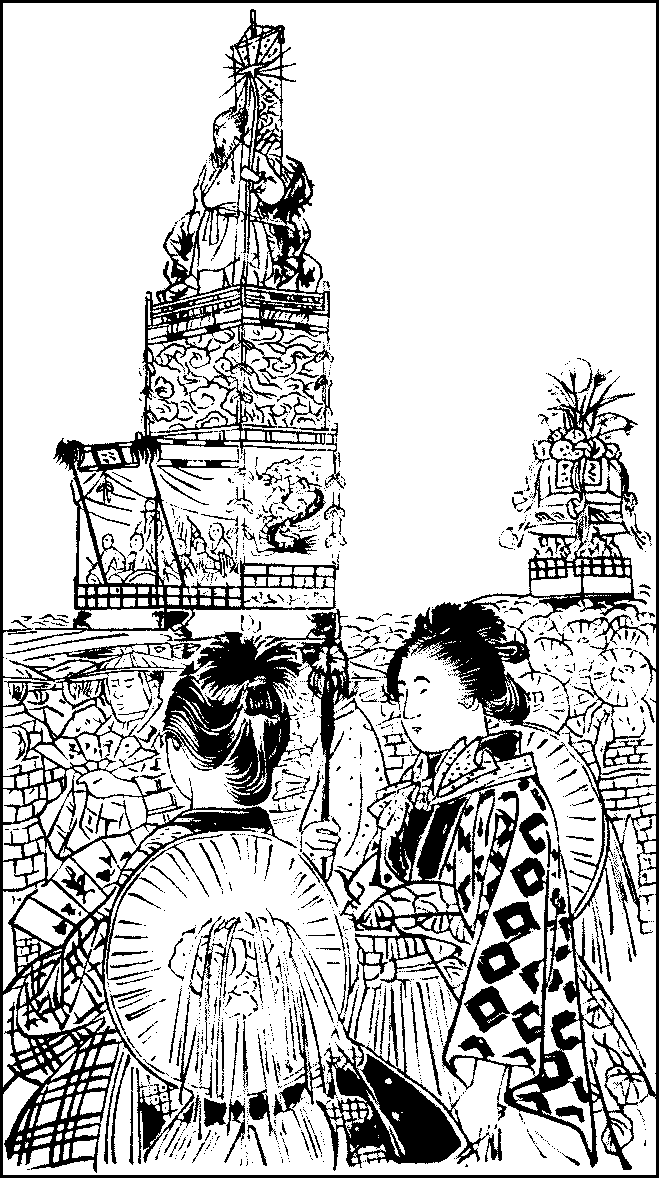

| The Fête of Sanno | 299 | |

| The Feast of Lanterns | 301 | |

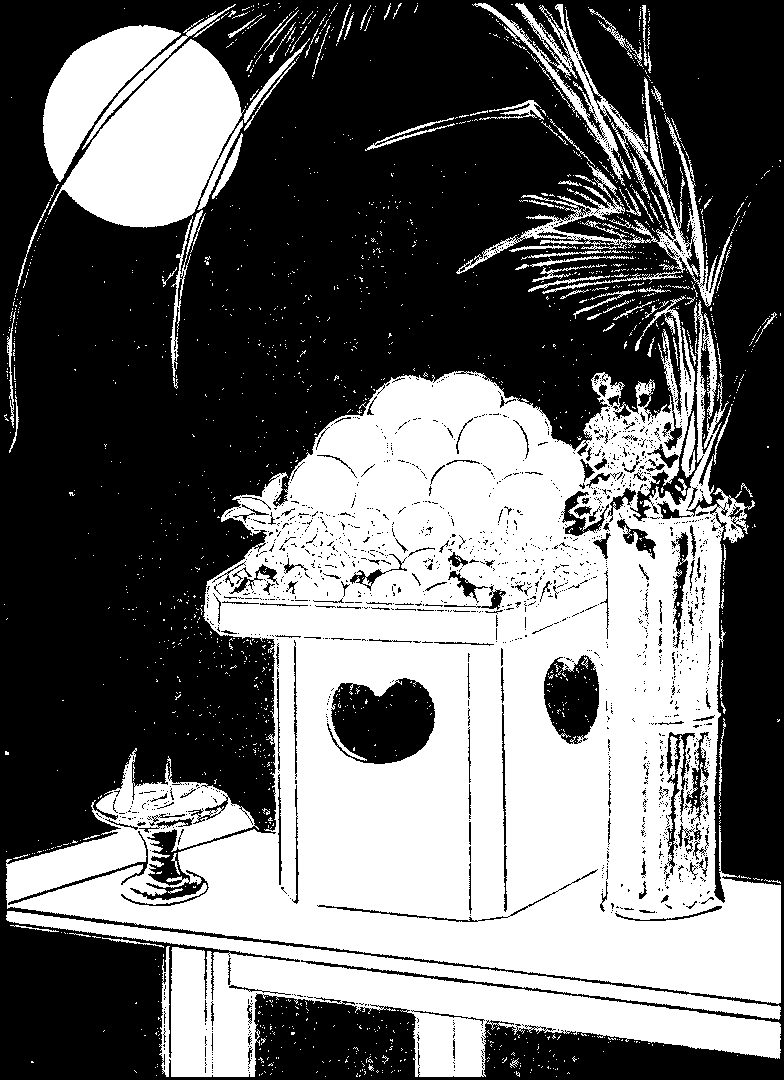

| Offerings to the Full Moon | 303 | |

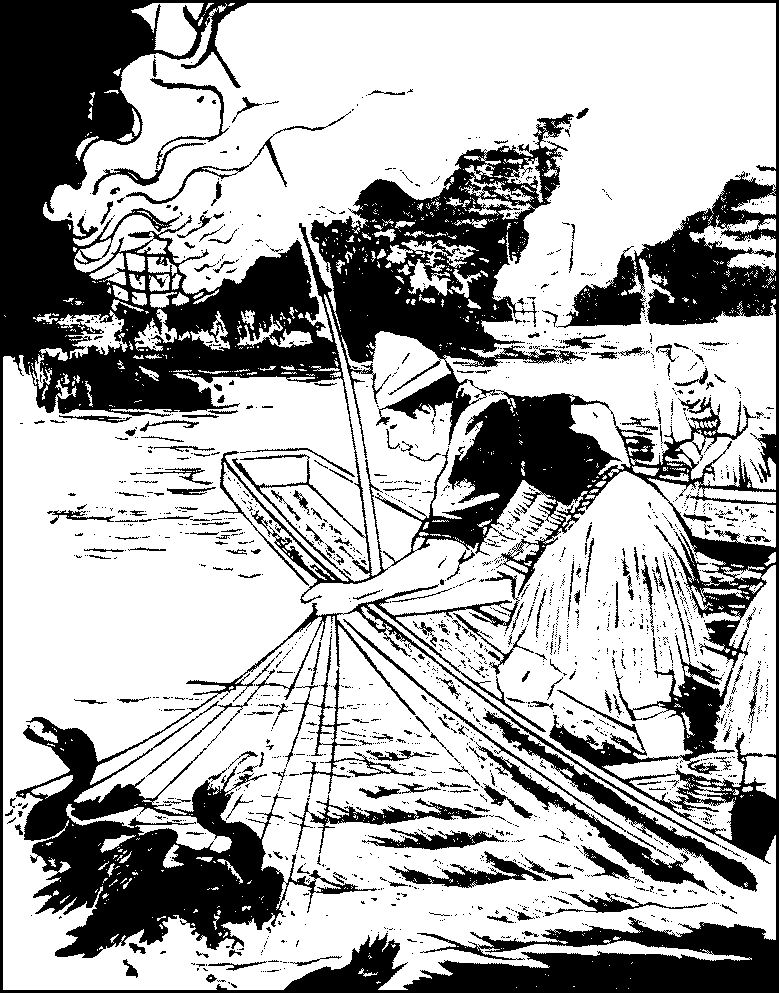

| Cormorant-fishing | 307 | |

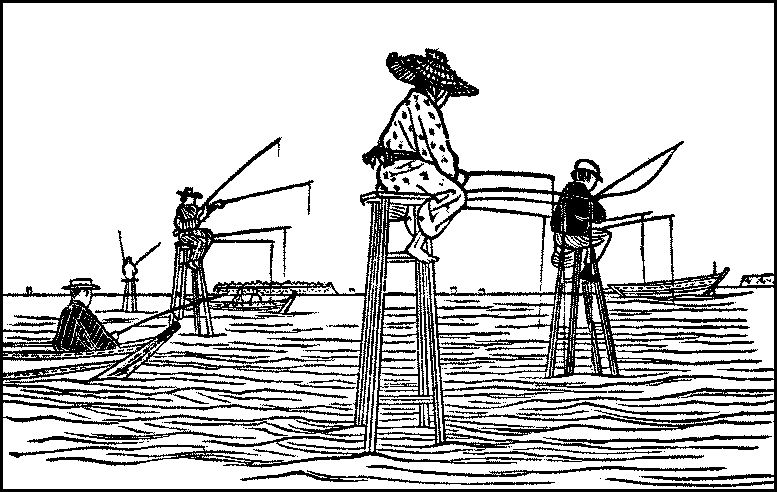

| Angling-stools | 308 | |

| Sugoroku | 309 | |

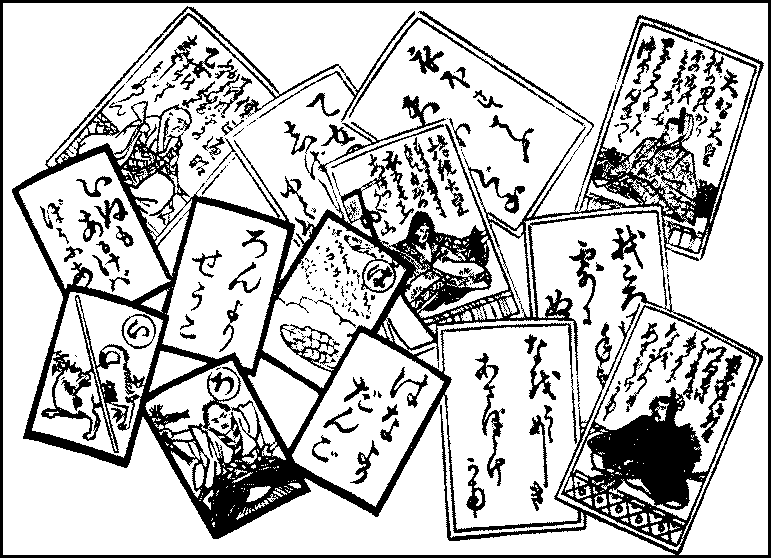

| Iroha and Ode-Cards | 311 | |

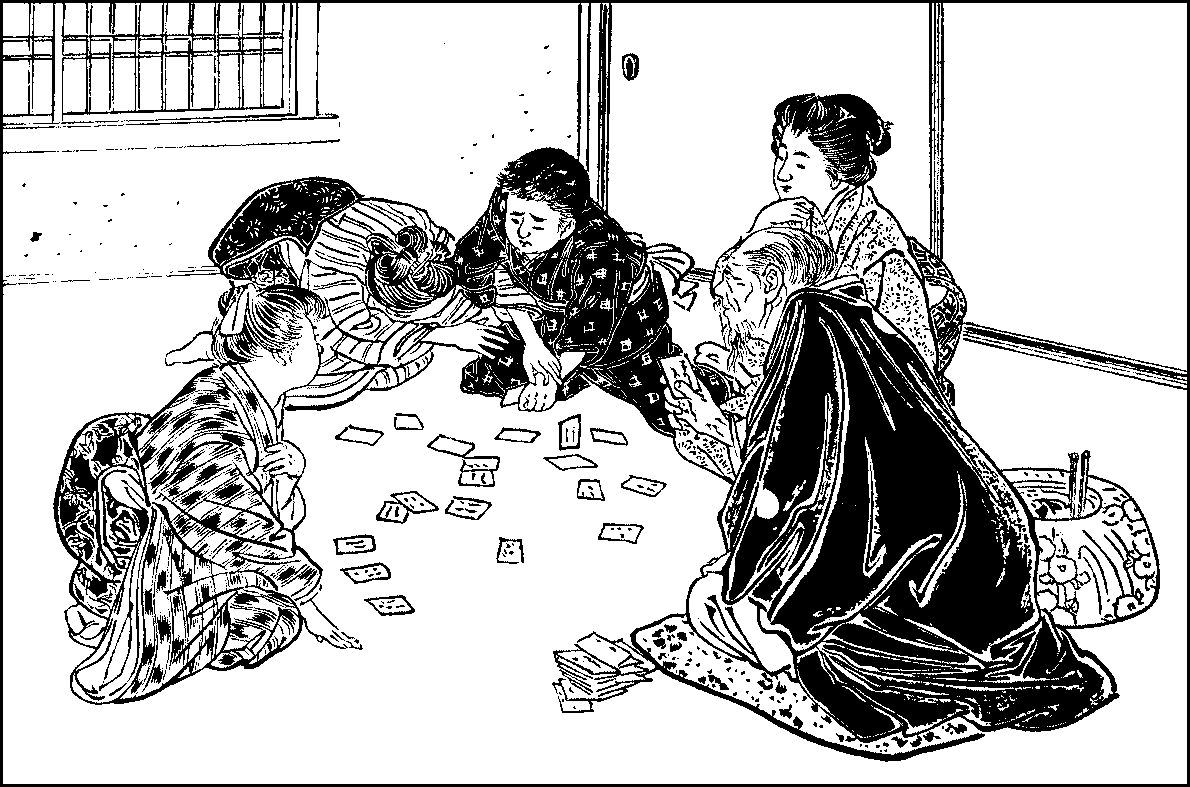

| Playing Ode-cards | 312 | |

| The Game of Ken | 315 | |

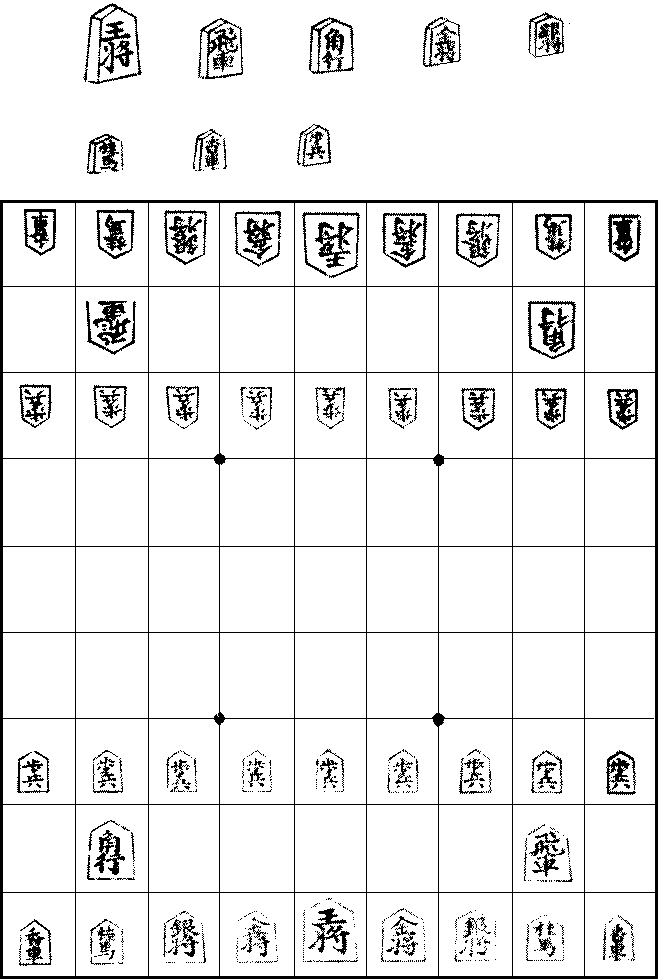

| Japanese Chess | 317 | |

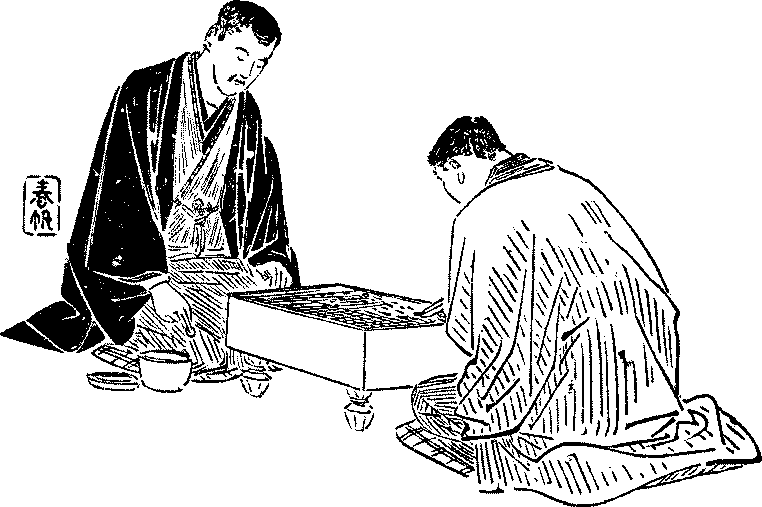

| The Game of Go | 318 | |

| “Flower-cards” | 321 | |

{1}

The youngest of the capitals—Yedo—The feudal government—Prosperity of Yedo—Its population—The military class—The Restoration—The new government—National reorganisation—Centralisation—Local government—Tokyo the leader of other cities—Struggle between Old and New Japan—The last stronghold of Old Japan.

TOKYO is the youngest of the great capitals of the world, for it was only in 1868 that the present Emperor of Japan left the old city where his ancestors had for centuries lived in seclusion and made the Shogun’s stronghold his new home and seat of government. It was a politic move; because though the Shogun had already resigned his office and surrendered the absolute authority he had exercised in the government of the country, there were still many among his followers who were unwilling to give up their hereditary offices. Had the Emperor then remained in Kyoto and there established his government, it would have been comparatively easy for these discontented partisans of the Shogun to foment an insurrection in the largest city of the Empire, which might assume serious proportions before it could be quelled, especially in those days when the means of communication and transportation were yet very primitive. Hence, it was decided to remove the central government to the possible hot-bed of disaffection and, by the strong arm of the newly-constituted administration, to nip in the bud all signs of rebellion. And so the Emperor and his Court forsook the city which had been the nominal capital for a thousand years and took up their abode in the great military centre which was known as Yedo; but when the Emperor arrived at the old{2} castle of the Shogun, he gave it the name of Tokyo, or the Eastern Capital, to distinguish it from the late capital, Kyoto, which is on that account also spoken of by the people as Saikyo, or the Western Capital.

But Yedo itself was not very old. Towards the close of the fifteenth century, a renowned warrior, Ota Dokan by name, built a little castle in the village of Yedo. Not long after his death, his family became extinct and others succeeded to the lordship of the little castle. A century later, Tokugawa Iyeyasu, one of the most powerful daimyo, or territorial lords, at the time, became master of the Eight Provinces east of the Hakone Mountains and was on the point of establishing his government at Kamakura, the capital of the first line of Shogun, when he was persuaded by his suzerain, the Taiko Hideyoshi, who is best known to history for his invasion of Korea, to set up his headquarters at Dokan’s castle-town which possessed great strategic advantages over Kamakura. Accordingly, in 1590, Iyeyasu came to the village of Yedo and saw that the castle could be developed into a formidable fortress. At once he set to work rebuilding it on a gigantic scale. Bounded on the north and west by a low line of hills, on the south by the Bay of Yedo, and on the east by marshes, it was in those days of bows and arrows and hand-to-hand fights almost impregnable. Behind the hills lay the wide plain of Musashino, across which no enemy could approach unobserved, while it was equally difficult to make a sudden attack upon the castle from the sea or over the marshes. The castle covered upwards of five hundred acres within its inner walls. The swamp was reclaimed, and merchants, artisans, priests, and men of other crafts and professions were induced by liberal offers to settle in the new city. The reclaimed land soon became the principal merchant quarter.

In 1603, Iyeyasu became Shogun, or military suzerain of the country. The Shogun was appointed by the Emperor, who delegated to him the civil and military government of the land. The Emperor made the appointment nominally of his own will; but in reality he was compelled to confer the title on the most powerful of his subjects. It was to Iyeyasu but a confirmation of the{3} influence he already wielded as the most formidable of all the territorial barons. And thus fortified by the Imperial nomination, he began at once to take measures for the general pacification of the country which had for years been plunged in a terrible civil war. His first step was to consolidate his power; and it was done with such success that the Shogunate remained in his family for two hundred and sixty-five years. This predominance of his family was in a great measure due to his skill in providing against those evils which had wrecked former lines of Shogun. All these dynasties had fallen through coalitions of powerful daimyo in different parts of the country and the consequent inability to cope with insurrections which broke out simultaneously in various quarters. To prevent such coalitions Iyeyasu created small fiefs around the territories of great daimyo and gave them to his own adherents, who acted as spies upon these daimyo and frustrated any attempts they might make at conspiracy. The territories along the great highway between Yedo and Kyoto he also apportioned among his followers, so that he had always a ready access to the Emperor’s city and could without difficulty control every movement of the Imperial Court. Another plan he formed towards the same end, though it was not actually carried out until the time of his grandson. This was the compulsory residence of the daimyo in Yedo for a certain term every other year; the time for reaching and leaving the city was fixed for each daimyo by the Shogun’s government. Their wives, with rare exceptions, remained permanently in Yedo and were practically hostages at the Shogun’s court.

The effect of this last measure was the increased prosperity of Yedo. All the daimyo were compelled to keep a house in the city. They built most of their palaces around the castle, and in the same enclosures were erected numerous houses for their retainers. Many daimyo had one or more mansions in the suburbs, not a few of which were noted for their size and their beautiful grounds. The most celebrated of these mansions is now the Imperial Arsenal, the garden of which is one of the sights of Tokyo; and another forms a part of the Palace of the Crown Prince and is also the place where the Imperial chrysanthemum party is given every{4} autumn. The building of the daimyo’s mansions, the number of these lords being at the time about two hundred and fifty, naturally attracted merchants, artisans, and other classes of people from all parts of the country. And Yedo rose before long to be the most flourishing city in Japan. It set the example to all the other cities of the Empire, for the daimyo copied in their own castle-towns all that they found to their taste during their forced sojourn in Yedo. This leading position which the Shogun’s city held in the feudal days has been retained even in an increased measure by the capital of New Japan.

Some idea of the prosperity of Yedo may be formed from the fabulous accounts of its wealth current among the country-people, who believed that in the main streets of the city land was worth its weight in gold. But a more definite proof is to be found in the computations which were made from time to time with respect to its population. Estimates based upon official records in the early years of the Shogunate are very incomplete. Thus, we are told that there were in 1634, 35,419 citizen householders and twenty-three years later, as many as 68,051, which would give a citizen population, at the rate of 4.2 persons per household, of 148,719 and 285,814 respectively, an increase which is obviously too great for so short an interval. The first trustworthy computation is probably that for the year 1721, when the citizens and their families were said to aggregate about half a million and the military class, with their servants, were put at a little over a quarter of a million. Priests, street-vendors, and beggars with whom the city swarmed did not most likely fall much below fifty thousand, so that we may without any great error take the total population at eight hundred thousand. More than a century later, in 1843, that is, a few years before the outbreak of the dissensions which finally broke up the feudal government, the total population was calculated from similar sources at 1,300,000, of which 300,000 or nearly one quarter, belonged to the military class. Old European travellers put the population of Yedo at various figures ranging from a million and a half to three millions, but the above computation is probably as near the truth as we can hope to get; and in view of the fact that{5} Yedo was a dozen years later torn by factions and was practically in a state of civil war, we may safely conclude that its population never exceeded that calculated for the year 1843.

In the above-mentioned estimate the military population of Yedo is put at 300,000. It was computed in the following manner:—There were in the country two hundred and sixty-seven daimyo, every one of whom had two or more mansions in Yedo. The total number of their retainers and servants, with their families, in fact, of all who depended for their subsistence upon these barons, was calculated at over 137,000. The immediate feudatories of the Shogun who all lived in Yedo, numbered 22,000; and they, with their families and servants, made up 160,000. From these figures the great influence wielded by the samurai in Yedo may be readily inferred.

Though Yedo thus prospered and the Shogun’s rule there seemed firmly established while thousands of samurai were ready to lay down their lives for his welfare, contentment was far from universal in the country. Some of the great daimyo whose ancestors had submitted to Iyeyasu only because of his overwhelming power, would have gladly raised the standard against his descendants if they had seen any chance of success; they knew that two centuries and a half of peace had enervated the Shogun’s court and luxurious habits corrupted his government and that it would not be a difficult task to crush him if they could form a coalition against him. But as yet they did not know whom to trust among their fellow-daimyo, and discontent smouldered ready to burst out at the first opportunity.

And that opportunity came in good time. The arrival of Commodore Perry’s squadron and the subsequent conclusion of treaties by the Shogun with the foreign powers are matters of history. Centuries of isolation had lured the nation into the belief that it could for ever remain free from all contact with the outside world; the treaties, therefore, came upon it as a rude awakening from its long-cherished dream, and the possible consequences of the opening of the country to foreign trade and intercourse naturally aroused all its fears. A strong agitation arose in denunciation of the{6} Shogun’s act to which the Emperor’s sanction had not yet been given, and when orders came from Kyoto to abrogate the new treaties, the enemies of the Yedo government saw their opportunity; they turned to the sovereign who lived hidden from public gaze in his palace and knew that the salvation of their country could be brought only by the Emperor coming to his own again and assuming the direct government of his people. Leaders among these loyalists were the clans of Satsuma and Choshu, two of the most powerful in Japan, which were later joined by those of Hizen and Tosa, and many others. The Shogun did his utmost to suppress these risings; but being at length convinced, by his utter failure, of his own powerlessness, he resigned his office in 1867 and restored the reins of government into the hands of his sovereign.

The Emperor thereupon made Yedo his capital and to it flocked the men who had helped to overthrow the Shogun’s government. The small bands of the latter’s adherents who still offered resistance were soon overcome. The national government was reorganised by men from the loyal clans. Though the Shogun had been denounced for his friendly attitude towards foreigners, the new government was even more cordially disposed towards them. The truth is that though the Shogun’s enemies were at first all for the expulsion of foreigners out of the country, wiser heads among them soon came to understand that it would not be possible to get rid of these unwelcome visitors and return to the old state of isolation. This conviction was especially brought home to the great clans of Satsuma and Choshu when Kagoshima, the chief town of the former, and Shimonoseki, the seaport of the latter, were bombarded for outrages upon Europeans, one by a British fleet in 1863 and the other by combined squadrons of Great Britain, France, Holland, and the United States in the following year; and they saw that the only way for their country to preserve her independence and secure a footing in the comity of nations was to be as strong as those powers and advance in that path of civilisation which had given them such a commanding position in the world. But so long as the Shogunate stood, they let the anti-foreign agitation take its course; when, however, it fell and the way was{7} cleared for a reorganised government, they set to remodelling it on western lines. Then commenced that process of national renovation which has astonished the world.

With the fall of the Shogunate and the reorganisation of the national government the feudal system was doomed; for such a programme as Japan had already sketched out for herself was incompatible with that medieval form of government. This fact was soon recognised by the daimyo of Satsuma and Choshu, who offered in 1868 to surrender their fiefs; the generous offer was gladly accepted and their example was followed by all the other daimyo. But for the time the ex-daimyo were all appointed governors of their respective fiefs so that they might aid in bringing their former subjects to a full sense of the new condition of things. Three years later, in 1871, the clans were abolished and the whole country was divided into prefectures. The daimyo and their retainers received government bonds in commutation of the incomes they had thitherto derived from their fiefs. The substitution of prefectures for clans was made with the object of breaking up the clan bias which was prejudicial to national unity and of giving the central government a more complete control over the provinces by the appointment to prefectural offices of high officials from Tokyo. For to prevent disaffection or crush open revolt in the provinces, it was necessary to centralise as much as possible the government of the country; and with all its precautions, the new government had to cope with several little uprisings, culminating in the Satsuma rebellion which spread over a greater part of the island of Kyushu and taxed its resources to the utmost. But when this was quelled, the country enjoyed absolute peace; no internal disorder has since taken place with the sole exception of a small local trouble in 1884.

The result of this centralisation was that Tokyo became the centre of the whole national life. Men seeking office hurried to it; students entered its schools; the trades and professions seemed to thrive only in the capital. The measures which the government took at the time tended still further to make Tokyo attractive. For the Restoration and the consequent national reorganisation were for the{8} most part the work of the military class, or rather of the samurai of a few clans under the guidance of a small group of leaders. The country bowed to the inevitable; but the people had little or no voice in the matter. Whatever drastic measures the government might take, the nation at large could not at a word of command throw off the immemorial traditions in which it had been brought up; it failed to realise the drift of the new policy its leaders were entering upon. Consequently, the first and most important duty of the government was to guide its people in the path it had taken. New laws were published with minute instructions; schools of all kinds were established on the western plan, the higher colleges being located in Tokyo; model government factories were built in the environs of the city; in short, nothing that a paternal government could do was omitted to take the people by the leading-strings. The higher schools were soon filled; their graduates found ready employment. The country was ruled by a huge army of officials, who, taking as they did the place of the old samurai in the popular estimation, commanded respect and deference often out of proportion to the importance of their posts, which, with the comparatively high salaries they enjoyed in those days, made government service the most attractive of all occupations. In fact, in the early days, Tokyo may be said to have derived its enhanced prosperity from the superabundance of officials. Then too, men of the legal, medical, and other professions all opened practice in Tokyo; only in recent years when every rank has been overcrowded in the city, have they sought fresh fields in the provinces.

It was not long, however, before the evils of excessive centralisation began to make themselves felt; and when the task of national reorganisation was fairly complete, steps were taken towards decentralisation. Prefectural assemblies were opened in 1881 as a preliminary measure to the establishment of the national assembly. In 1888, local self-government was granted to provincial cities, towns, and villages, and everything was done to promote local prosperity. The close of the year 1890 saw the opening of the national diet. The war with China in 1894–5 and that with Russia{9} ten years later brought on in either case a sudden activity in all departments of commerce and industry and gave a great impetus to railway enterprise. Many bogus companies, it is true, were formed at the same time, and their collapse was a serious set-back to the national economy. But the undoubted increase of commercial and industrial enterprises has served to relieve the pressure of population upon Tokyo. Osaka, for instance, which has for centuries been a great commercial centre, has within the last few years become as great a centre of industry, with a population exceeding a million. Kyoto, the old capital, remains somnolent; but Nagoya and the trade-ports of Kobe and Yokohama are forging ahead. In short, though Tokyo, as the capital, will probably remain the largest city in the Empire, it cannot be denied that it is not now so far in advance of the rest as it was a few years ago. This rise of great provincial cities is a necessary result of the growth of manufacturing industries which are bound, if the country is to prosper, to take the place of agriculture, which is too limited in its scope in a country of such a moderate extent as Japan. It is indeed but a repetition of the rise of the great provincial towns like Birmingham, Sheffield, and Manchester in England in the last century.

Still Tokyo must take the lead in all that pertains to the adoption of western civilisation. Osaka and other manufacturing cities will develop the inevitable but unwelcome phases of western industrialism. Already the labour problem looms before us, and the government must before long legislate on the question. There are also signs of socialistic agitation. But these questions do not affect Tokyo so seriously as other cities, for the factories on its outskirts are comparatively few and the land is too valuable for residential purposes to be occupied by manufactories.

Tokyo will remain what it has always been, the home of the best classes in every department of national life. It will always indicate the high-water mark of oriental culture and occidental influence. Here, as nowhere else, will be seen that antagonism of the two, the pressure of western customs and ways of life following on the heels of the sciences and practical knowledge we are eagerly imbibing from the West and the resistance of oriental traditions and{10} usages, which refuse to admit a tittle more than is absolutely necessary to bring the country to a material and intellectual equality with the foremost nations of the world. To those who look below the surface nothing is more interesting in viewing the progress of Japan than this combination of radicalism and conservatism. The Japanese, for all his apparent love of innovation, still retains that stolid self-satisfaction usually associated with the oriental mind, though it is no rarer in the West. He has long recognised that his country must advance along the lines taken at the Restoration, but he would have the development take place without the sacrifice of the national characteristics which have marked his countrymen from time immemorial. The agitation which was set up some twenty years ago for the preservation of these characteristics by those who feared the mania for everything European which was then at its height would result in the obliteration of the qualities which have kept Japan in full vitality through the centuries, still finds an echo in his heart. The threatened sudden metamorphosis of those days was but a passing whim; the change is now slower and more subtle, and it is hard to mark the exact line at which the encroaching tide of European civilisation shall be made to stop. But the Japanese feels that the line must be drawn somewhere. The problem is certainly difficult to solve. It appears hardly possible to reap the fruits of the material and intellectual progress of the West and yet to shut out the moral and religious sources of that progress; but for all that, it would be premature to pronounce it impossible. For we have already done what seemed at first beyond the verge of possibility. Who, for instance, of the thousands who nightly thronged to the Savoy Theatre to laugh over the famous Gilbert and Sullivan opera, would have thought at the time that a few years thence their country would form a treaty of alliance with the land of Koko, Yum-yum, and Nankipoo? They would have flouted the very idea; but that alliance is generally regarded as a natural outcome of the recent course of events in the Ear East. Would it be, we wonder, a much harder task to discriminate the elements of European civilisation?

There are of course people who find their account in advocating{11} the rapid adoption of everything European; but their utmost efforts notwithstanding, there is one citadel which will long resist their attacks and remain almost as purely Japanese as in the days of their forefathers. That impregnable citadel is the home; woman is in Japan as elsewhere the greatest conservative element of national life, and within her sphere of influence tradition reigns as supreme as ever. Globe-trotters who advise their friends to visit this country with as little delay as possible for fear that in a few years Old Japan would cease to be, do not reckon with our domestic life. Japanese women are as a class gentle, pliant, and docile; and these qualities stand them in good stead at home. Whether it be that they manage with all their demureness to twist their lords round their little fingers or that the latter are afraid that any change in home life would develop a new revolting woman who would refuse to be as submissive as they are at present, the fact remains that with the mass of the nation there has been little change in the conditions of domestic life. And what these conditions are and how little the influx of new ideas has affected the home of Old Japan, it is the object of the following chapters to relate.

{12}

The area and population of Tokyo—Impression of greater populousness—Street improvements—Narrow streets—Shops and sidewalks—Road-making—Dusty roads—Lamps and street repairs—Drainage—Street-names—House-numbers—Incongruities.

THE area of Tokyo is not so great as is generally supposed. The people of Yedo used to say that their city was ten miles square; but the extreme length, from north-east to south-west, of Tokyo which does not differ materially in its limits from the old city, is no more than eight miles. The actual area is only 18,482 acres, or nearly twenty-nine square miles. The population fell with the decline of the feudal government and was under a million in the early days of the new regime. The registered population returned to one million in 1884. The municipal census which was taken for the first time on the first of October, 1908, gave the settled population as 1,622,856, composed of 872,550 males and 750,306 females, and the number of families as 377,493. This took no account of the floating population which probably exceeds a hundred thousand; there is also a large population, not less than a quarter of a million, which the rise of rents and the facilities of electric-tramway communication have sent outside the administrative limits of the municipality; it forms, properly-speaking, a part of the population of the city.

Tokyo is therefore a great city; but the stranger who visits its streets for the first time usually gets an impression of an even greater populousness. For the streets are always in the evening teeming with young children; they are not gutter-snipes, but children of respectable parents, small tradesmen or private persons of slender means, who let them run about on the public road rather than romp in their narrow dwellings. But it is not the children alone{14} who think they have a greater right of way over the roads than the public: for on summer evenings especially, men and women turn out of doors and walk about or sit on benches outside their houses. Shops are completely open and reveal the rooms within, so that whole families may be seen from the streets; and as most houses are of only one or two stories, people live for the most part on the ground-floor. Even in private residences of some pretensions, the thin wooden walls allow voices to be easily heard on warm days when the rooms are kept open. So that from the people he sees crowding the houses and the noises he hears on all sides, the stranger is often deceived into giving the city credit for a larger population than it actually possesses.

The streets themselves are worth notice. If the foreigner who comes to Japan expects to see in such a great capital the asphalt carriageway and paved sidewalk of his native country, he will be sadly disappointed, for Tokyo, with all its multitudinous thoroughfares, cannot boast even the boulevards and avenues of a European provincial town. In spite of the efforts of the Tokyo municipality, the streets are still narrow. Their total length is about six hundred miles, with a width ranging from one yard to fifty, the average being nine yards. It was decided twenty years ago to widen some three hundred miles of these roads, giving the largest a width of forty yards for carriageway with a footway on either side of six yards, and the smallest a carriageway of twelve yards and a footway one yard wide. The work is to be accomplished in ninety years. Improvements to this end are slowly going on. The fact is that the City Fathers missed a great opportunity in the early years of the new regime when, upon the desertion of the residences of the daimyo and other feudatories after the fall of the Shogunate, land could have been purchased for a song, for it went begging in the heart of the city at less than thirty yen an acre. Those who were wise enough to buy it have made big fortunes, for the same land now sells for a hundred thousand yen or more per acre. Now, however, the municipality cannot command sufficient funds to purchase the land needed for improvements along the streets proposed, but buys it up only when it is absolutely necessary to relieve the congestion{15} of traffic; and elsewhere it waits patiently until a fire burns down the streets and clears the required space for it as, in that case, it will not have to give any compensation for the removal of the houses.

In the old days, the narrowness of the streets did not interfere with such traffic as was then carried on. The daimyo and others of high rank rode in palanquins, and officials went about on horseback; but the rest of the world walked. The citizens were not allowed to make use of other legs than their own. Those who had to go about much put on cheap straw sandals, which were thrown away at the end of their journey, so that they did not give a thought to the width or the state of the road as they had in any case to wash their feet afterwards; while others, of the common people, were, if they met a daimyo’s procession, thrust to the wall or oftener into the ditch, and they too cared as little for the width of the thoroughfare. And when a samurai met another in a narrow lane, it was by no means rare, if their sword-scabbards touched in passing, for an altercation to arise and be followed by bloodshed; but as brawls were in their way, they did not trouble themselves about the widening of the road. Pedestrians, moreover, could always pick their way in any street, and if they saw coming towards them a daimyo’s retinue or a company of swash-bucklers, they usually turned into a side-street. To the happy horsemen and palanquin-riders the size of a street was a matter of absolute indifference, for if those on shanks’ mare got in their way, it was their lookout. But luckily for these walkers there was little else for them to dodge, for vehicles were comparatively few. The only objects on wheels were handcarts and waggons drawn by horses or oxen. These waggons came from the country with bags of rice, fuel, and other necessaries, and were used, not for their speed which was a snail’s pace, but for their carrying power.

In these latter days, however, things have materially changed. Men to-day would be put to the blush by the hale old survivors of those pedestrian times, for they have gone to the other extreme. The conveniences of the jinrikisha, or two-wheeled vehicles drawn by men, and latterly of electric tramways have sapped all energy out of them, and we hear little nowadays of walking feats. There{16} were in 1900 forty-six thousand jinrikisha in Tokyo; but the electric cars, which began to run a few years later, are driving them out of the city, for they are now less than one-half of that number. Still, the pedestrian has need to keep a good lookout on the road, for where, in the absence of footways, men, women, children, vehicles, and horses move about in an inextricable jumble, it is a matter for wonder that accidents are not more frequent. Besides the jinrikisha and electric cars, there are thousands of handcarts, some drawn by coolies and carrying objects of every description from household articles to stones for road-making and trees for gardens, and others drawn by milkmen with their milk-cans, by apprentices with their masters’ wares, by pedlars with various assortments to attract the housewife’s eye, or by farm-boys with vegetables fresh from the field. There are but a thousand waggons drawn by horses or oxen in Tokyo; but as there are twice as many more in the surrounding country, they are very much in evidence in the city since they make their presence unpleasantly obtrusive in narrow streets. These waggons, however, move slowly and give one time to get out of their way. In this respect they are better to meet than the carriages which drive on indifferent to the width of the road; in narrow streets the latter are preceded by grooms who hustle all loiterers out of the way. They are only less eagerly shunned than the motor-cars and the files of handcarts which move leisurely along with pink flags marked “ammunition” from the Imperial arsenal.

But the Ishmael of the streets of Tokyo was until lately the bicycle. A few years ago there were six thousand of these machines in the city; they were patronised by shop-apprentices who, with large bundles on their backs, scorched through crowded streets careless of accidents to themselves or others. These apprentices were therefore in the policeman’s black books; nor did the jinrikisha-man look upon them with any favour, for he regarded bicycling as an innovation intended to defraud him of his fares. But his hostility against the bicycle melted away when he was confronted by the electric car which has proved itself the most formidable of his foes. The bicycle, too, has suffered an eclipse;{17} for apprentices and others of its patrons find it more expensive to keep it in repair than to travel by the car at the cost of a penny per trip. The motor-car also made its debut a few years back and the dust it raises and the smell of petrol it leaves in its track have brought upon it the anathema of all pedestrians; and though the police regulations prohibit a motor-car from traversing streets less than twelve yards wide, it runs merrily through lanes and small side-streets. It sometimes charges into shops and makes havoc among their merchandise. The pranks it plays in the hands of unskilful chauffeurs are not likely to lessen its unpopularity.

What with carriages, jinrikisha, waggons, handcarts, and bicycles jostling one another and men, women, and children threading their way through the labyrinth or fleeing before motor or electric cars, the more frequented streets of Tokyo present a confused mass of traffic; but in respect of actual numbers they are really less crowded than western streets of similar importance. The busy appearance is mostly due to the absence of sidewalks, and the bustle is increased by the wayfarers having to run to and fro to get out of the way of the vehicles. In streets provided with sidewalks one would expect less confusion; but as a matter of fact, people are so used to walking among vehicles of all sorts that they prefer sauntering on the carriageway to quietly pacing the sidewalks; and it is no uncommon experience to meet a company walking abreast in the middle of the road and dodging carriages while the sidewalks are almost deserted.

Sidewalks are not likely to gain in popularity until improvements are made in the arrangements of shops. There are no streets in Tokyo which are known as fashionable afternoon resorts, because the shops are so constructed that one cannot stop before them without being accosted by the squatting salesmen. Only in a few main streets are there regular rows of shops with show-windows against which one could press one’s nose to look at the wares exhibited or peer beyond at the shop-girls at the counter; but then business is not done in Japan over the counter, nor do shop-girls hide their charms behind a window, for the shops are open to the street and the show-girls, or “signboard-girls” as we call them, squat{19} at the edge visible to all passers-by and are as distinctive a feature of the shop as the signboard itself. The goods are exhibited on the floor in glass cases or in piles, a custom which is not commendable when pastry or confectionery is on sale, for standing as it does on the south-eastern end of the great plain of Musashino, Tokyo is a very windy city, and the thick clouds of fine dust raised by the wind on fair days cover every article exposed and penetrate through the joints of glass cases, so that in Tokyo a man who is fond of confectionery must expect to eat his pound of dirt not within a lifetime, but often in a few weeks. If one stops for a moment to look at the wares, he is bidden at once to sit on the floor and examine other articles which would be brought out for his inspection, whereupon he has either to accept the invitation or move on. One seldom cares therefore to loiter in the street. The only shops that are often crowded by loiterers are the booksellers’ and cheap-picture dealers’.

But even more unpleasant than the narrowness of the streets is the state in which many of them are to be found. In a few streets the roadway has been dug up and pyramidal stones have been laid on the bed with the points up; they are then covered with earth and broken stone and finished with a top-dressing of gravel. They are not, however, rolled as steam-rollers have only lately made their appearance in Tokyo; sometimes small stone-rollers, about two feet in diameter, are drawn over the metal by a dozen coolies, but the work is inefficient as the pressure of such toy rollers is too slight to make any sensible impression. For the most part, therefore, newly-made roads are left to be levelled with the beetle-crushers of the long-suffering public. The municipality finds it the cheapest way. This is bad enough on the gravelled road, but the tortures it inflicts on men and beasts of burden, to say nothing of the rapid wear and tear of vehicles, are indescribable when the thoroughfare is repaired in the orthodox style. Whenever the road wants mending, cartloads of pebbles are, according to this method, brought from the beds of the rivers in the neighbourhood of Tokyo and scattered over the highway. They are laid evenly, but not levelled or rolled. The public press them down as they walk with their clogs, sandals, or boots; immediately any part is embedded in the{20} soil, that path alone is used till it is beaten flat, so that one often sees a narrow path meandering in a wide stone-covered road, along which all traffic is carried on and the rest of the road is practically unused. When this path is beaten in and becomes hollow, more cartloads of pebbles are thrown upon it and the public recommence their patient task of road-levelling. But fortunately for them, they are materially aided in this benevolent work by the solstitial rains, which when they come down in torrents, soon bury the stones in the clayey soil, and for the nonce the people walk over it rejoicing until the municipality sets them a new task; or the rains have done their work but too well and the poor pedestrians find themselves wading through quagmire.

Indeed, quagmire is what we find in many streets after rain; for the supply of rubble is necessarily limited as it comes mostly from the rivers in and about the city, and consequently a majority of roads are left uncared for. These, after a heavy rain, are covered with a thick coating of mud, which when the sun has dried it, leaves behind deep ruts, making the roads more unpleasant to walk on than when covered with pebbles. In midsummer when the ridges of these ruts have been pulverised and blown in all directions so that one appears to be walking on sand, the roads are watered twice or more every day. The watering is done on high roads by coolies with small hand-drays out of which water is sprinkled spasmodically, and as the men stop from time to time to take breath, there are on many spots pools of water in which one can soil one’s footgear as effectually as on the rainiest day. But worse still is the watering done by private persons on the part of the road facing their dwellings. These merely ladle the water from their pails and sprinkle it in splashes, leaving in the middle of the street puddles for children to make mud-cakes in. In short, the great objection to the way in which the streets are watered in Tokyo is that it is too much for laying the dust, but not enough for flushing the roadway.

The pedestrian has therefore to be very careful in selecting the part of the road to walk on in both wet and fine weather. This is not very difficult in the daytime; but at night, especially when there is no moon, the task is hard to accomplish with success;{21} for rarely are street lamps set up at the public expense, and in most streets the inhabitants have lamps for their own convenience over their front doors or gates; but the light of these lamps is very meagre as they are naturally not intended to guide the stray wayfarer over the road. But even these are of some service in streets of shops where the front doors are ranged pretty closely together; in roads, however, where there are only private houses, the gates being far apart, the lights are also at some distance from each other and the passenger has mostly to trust to his luck to keep himself clean. That luck, however, deserts him at times, for the repairs which the roads seem to undergo in every part of the city are astonishingly frequent. It is not the mere mending that is the cause of the trouble, but the constant pulling up of the roads for laying or repairing gas-pipes, water-pipes, and what not that so often brings one to an impasse. As, moreover, the authorities work independently of one another, a road which has been dug up for one purpose and filled in again, may be pulled up for another. Matters are not likely to improve in the near future, for before long the telegraph and telephone authorities must have a hand in digging up the road; at present the wires are overhead, but the poles are already overweighted and cannot be loaded much more without serious danger to traffic. Electric-light wires are equally menacing; and the situation is only aggravated where the electric cars run through crowded streets of the business quarters.

The wretched state of the roads after rain is undoubtedly due to imperfect drainage. The cross-section of the roads has little or no curvature or gradient, and the gutters, where they have been made, do not drain off and are only receptacles for muddy stagnant water. They are occasionally cleaned by heaping the mire on the roadside. And yet, curious to state, in spite of these insanitary methods, the rate of mortality in Tokyo is not so high as might be expected. It varies from twenty to twenty-five per thousand on the registered population and therefore must be less when the floating population is taken into account. It shows that Tokyo is not an unhealthy city, and when the municipality has carried out the plan it has made for a drainage system, the Japanese{22} capital will probably compare favourably with most other great cities of the world.

There is one peculiarity about the streets of Tokyo which deserves mention, that is, the way they are named. Of course every thoroughfare has a name given to it; but it differs from streets in other countries in that name being the designation, not of the thoroughfare itself, but of the section or piece of land through which it runs. Thus, two or more thoroughfares which run through the same section are known by the same name; in a large section there may be a dozen streets running in all directions and bearing the same name. When a road runs on the boundary of two sections, the opposite sides would be known by different names, and a man walking in the middle of such a road would be perambulating two streets at one and the same time. Some of the larger sections, if regularly built, are divided on the main road into subsections by streets crossing them; but irregular streets are arbitrarily subdivided so that it is often very hard to find one’s way through them. As many sections are full of tortuous streets with turnings and alleys, the numbering of houses in a section is often complicated, and one seldom knows where the numbers begin or end. Frequently consecutive numbers are to be found in entirely different directions and in hunting up a number, one has to traverse the length and breadth of the section before one comes upon it.

The numbering of houses is further complicated by the fact that the same number is given often to dozens, and sometimes to hundreds, of houses. The explanation is that the numbering first took place while the great daimyo’s mansions were still standing; and when they were pulled down and cut up into smaller lots, these lots retained the same numbers. There are in Tokyo at least two of these great estates which have been divided into nearly a thousand house-lots. It is indeed hard to see how these houses could be renumbered, because in that case every division of an estate would necessitate the renumbering of the whole street, which, in a city like Tokyo where the sizes of houses are constantly changing, would be simply intolerable. Besides these divisions of mansions, we must take into account the frequency of fires.{23} Changes take place not seldom after a fire in the number of houses in a street, and it would of course be impracticable to renumber the whole street whenever a portion of it is burnt down. Sometimes an additional designation, usually a second set of numbers, is given to a group of houses with the same street-number; but fancy names, such as are common in the suburbs of London, are hardly ever given to dwelling-houses. It may therefore be imagined that it is no light task to look up a friend in an unfamiliar quarter.

The stranger, then, who visits the streets of Tokyo will find much to arouse his curiosity in the open, windowless shops, the jinrikisha, the native dresses of men and women, the throngs of hawkers, and the ceaseless din of traffic; and at the same time, as he comes to Japan usually in search of the quaint and bizarre, he will perhaps be disappointed when he sees the countless overhead wires, the electric trams, omnibuses, and bicycles, European clothes of all shades and descriptions, and other encroachments of western civilisation, which he had hoped to leave behind him and which somewhat shock his artistic sense in their new surroundings. But these inæsthetic innovations he must put up with, for they are typical of the present stage of Japanese civilisation, and nowhere else are they more marked than in Tokyo. The herculean task Japan has set herself leaves her little leisure to consider its artistic effects; she is too much in earnest to waste a thought on the awkward cut of the habiliments she is donning; and only when she has so adapted herself as to fit them exactly, will she turn her attention to their frills and trimmings.

{24}

Name-plates—Block-buildings—Gates—The exposure of houses—Fires—House-breaking—Japanese houses in summer and winter—Storms and earthquakes—House-building—The carpenter—The garden.

WE have already said that the complicated way of numbering streets and the inclusion of a large group of buildings in one number make it hard to find any particular house. They necessitate a dreary going to and fro through a series of thoroughfares, which is very trying to one’s temper and would in most cases oblige one after a long search to give it up altogether, were it not for the circumstance that not only shops and private offices, but also nearly every private house, has a name-plate nailed over the front door or on the gate-post. If, therefore, we can, in the course of our wanderings through a street, alight upon the right number, we can generally find the house, provided there are not too many with the same number. The name-plate has usually inscribed on it the number of the house and the name of its occupant, and his title if he is a peer. Besides the name-plate, there is on the gate-post the brass-badge of the insurance company if the house has been insured, to enable the company’s private firemen to identify the house and give necessary assistance in case of a fire in the neighbourhood. The gate-post has also the telephone-number placarded in large figures for the telephone-rate collector’s convenience.

Shops and most mercantile offices open directly upon the street; but with respect to private houses there is no definite rule. Cheap houses are built in long blocks; of these the worst description is to be found in back courts; they are of one story, or if of two stories, the second has a very low ceiling. They are usually in a dilapidated condition and propped up on all sides; they are in{25} fact our slums. The smallest of these houses is only twelve feet by nine. A block may be made up of a dozen such houses, six on either side with a wall running through the middle from end to end. It is a peculiarity of our tenement houses which have to be low on account of the frequency of earthquakes that they are thus divided vertically into narrow compartments and differ in this respect{26} from the many-storied houses in the West, which are divided horizontally and occupied in flats. While the ground-rent is still comparatively low, this habitation in transverse sections, so to speak, is feasible for the poor; but even now, as the rent is steadily rising in all quarters, the tendency is to drive these humble dwellers outside the city limits. As it is, only in the poorer districts are these miserable houses to be seen; for in the busier quarters the ground-rent is already too high for them. But buildings in blocks are not all of the poorest kind, though it must be admitted that dwelling in a “long building,” as a block of this description is called, implies on the face of it life on a humble scale. In the old times well-to-do retainers, who had large houses of their own in the country, lived when in Yedo in the “long buildings” surrounding their lord’s mansion. Small shops are also built in blocks.

Though many private houses in the business quarters have no gates, those of any pretensions in the residential districts where land is naturally cheaper, are mostly provided with them. It is not usual for professionals in humbler walks of life and for artisans to live within a gate; but officials and others of some social standing prefer to have one to their houses. Sometimes there is a single gate to a large compound with a number of small houses in it; in such a case the gate-post is studded with name-plates. Gates, too, vary in size and form. The most modest are no more than low wicker-gates which can be jumped over and offer no bar to intrusion. Others are of the same make, but stand higher so that the interior can be seen only through cracks. But the most common consist of two square posts with hinged doors which meet in the middle and are kept shut by a cross-bar passing through clamps on them. These gates may be of the cheapest kind of wood, such as cryptomeria, or may be massive and of hard wood. Another common kind has a roof over it with a single door which is hinged on one post and fastened on to the other and provided with a small sliding-door for daily use. The larger pair gates have also small side-doors for use at night when they are themselves shut.

After entering by the gate, we come to the porch; the distance{27} between them varies with the size and exposure of the house. It is not true, as has been said by some writers on Japan, that in our houses the parlour and the garden invariably occupy the rear while the kitchen is in front. Their position depends upon the exposure of the house. No people short of savages probably lead a more{28} open-air life than we do in our wooden houses. Our paper sliding-doors, which are our only protection against wind and cold in winter, admit both light and air; and we provide personally against the cold by wearing wadded clothing and huddling over braziers, while in summer all the sliding-doors are often removed to let the cool breeze blow through the house. It becomes, then, an important matter in building or selecting a house to see that its principal rooms are so arranged as to get the warm rays of the sun in winter and the cool breezes in summer. As both these are to be obtained from the south, the principal rooms are made to expose their open side to that direction. In winter the exposure of these rooms makes a vast difference in the consumption of charcoal as the sun shining through the open side warms the rooms more thoroughly than the braziers can do. Next to the south, the east is the favourite direction, as the east wind coming over the Pacific Ocean is milder than the north or west. The west wind, crossing as it does the snowy ridges of Central Japan, is cold in winter while the piercing rays of the westering sun make the rooms intolerably hot in summer; and the north wind is cold in winter and in summer breezes seldom come from that direction. In short, then, the principal rooms face the south, if possible, or south-east, or sometimes the east. As the garden is naturally in front of the principal rooms, its position depends upon theirs, and it is made to lie, if possible, on the south side of the house. If the gate is on the north side of the premises, it is close to the house; but if it is on the south side, the garden intervenes. It should, however, be stated that some people purposely make their principal room face north; their reason is that if the garden lay south of the house, the trees and plants in it would display their north or rear side to those within, and they are therefore willing to put up with the cold blasts from the north for the pleasure of looking at the front and sunny side of their plants.

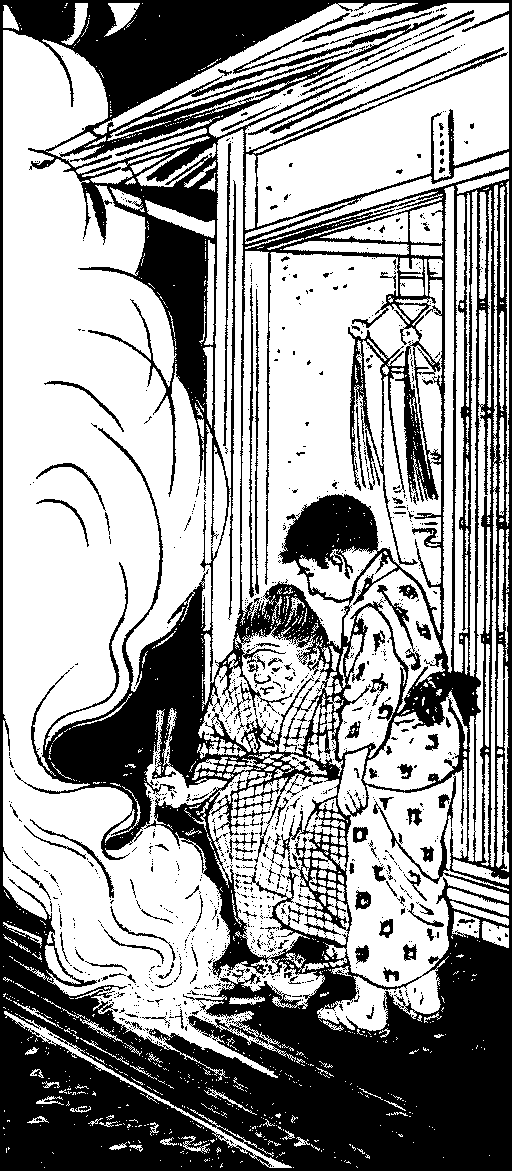

Most houses in Japan are made of wood. In Tokyo only a little over one-eighth of the houses are made of other materials, that is, of brick, stone, or plaster, so that the capital may be said to be a city of wooden houses. It is therefore, needless to add,{29} often ravaged by fire. In old Yedo fires were known as the “Flowers of Yedo,” being as much among the great sights of the city as the cherry-blossoms on the south-east bank of the River Sumida, the morning-glories of Iriya, or the chrysanthemums of Dangozaka, for which Tokyo is still noted. Under the feudal{30} government occurred several fires which burnt down tens of thousands of houses, and even under the new regime disastrous fires are not unknown. On two occasions, in 1879 and 1881, over ten thousand houses were destroyed; but the last great conflagration took place in 1892 when four thousand buildings were devoured by the flames. Since then, though fires have been frequent enough, their ravages have been more limited, thanks to a more efficient system of fire-brigades and plentiful supply of water. During the last few years the average number of houses annually destroyed has been about seven hundred, which cover an area of seven and a half acres; and as the total area of buildings in Tokyo is three thousand seven hundred acres, the fires destroy every year one five-hundredth part of the city. The actual loss of property is not so great as might at first sight be supposed; for it is a notorious fact that houses in Tokyo are not so carefully constructed as in Kyoto and other cities, and the greater risks from fire incurred in the capital discourage the building of costly houses unless they are to stand on extensive grounds. Formerly it was calculated that the average life of a house was about thirty years; but now the lesser frequency of fires would give them a much longer lease. This is comforting to house-owners; but it must be confessed that wooden houses more than thirty years old are not pleasant to live in. The timber, unless extremely well-seasoned, becomes warped and the pillars of the house get out of the perpendicular, with the result that the sliding-doors refuse to close flat upon them but leave a space at the top or bottom through which the cold wind whistles at will in winter. This is the case even with carefully-built houses, while in others the defects are still more glaring. The jerry-builder’s hand is conspicuous in most houses to let, and the rent is high compared with the cost of construction. The landlords protest that they have to charge a high rent as whole blocks may be swept away in one night through malice or stupidity. And there is something to be said for their argument, especially as fire insurance is still far from universal, for it is strange when one comes to think of it that there are not more destructive fires. It is so easy to burn down a wooden house. A rag soaked with kerosene is enough{31} to destroy any number of houses and is the favourite means with incendiaries who hope to steal household goods which are brought out in confusion into the street whenever there is a fire in the neighbourhood. Besides, a slight act of carelessness or neglect may lead to a terrible conflagration; a candle left too near a paper sliding-door was the origin of the great fire of 1892 already mentioned. Similarly, a kerosene lamp or a brazier overturned, a pinch of lighted tobacco or an unextinguished cigar-end, an over-heated stove or a piece of red-hot charcoal dropped on the floor, these are among the commonest causes of fires; and even the cheap Japanese matches, of which as the splints are not dipped in paraffin, at least half a dozen are needed to light a cigarette in the open air, are responsible for as many fires every year. Since such slight accidents may at any time lead to great disasters, the inhabitants, as they go to bed, are never sure, especially in crowded quarters, of still having a roof over their heads next morning. They may be aroused from their slumbers by the dreaded triple peal of the alarm-bell and find the neighbouring street or next door wrapped in flames, and just manage to run out of their houses with nothing but the clothes on their backs. We are, however, so used to the fire-alarm that if the peals are double to indicate that the fire is in the next district, we only get out of bed to look at it from idle curiosity and turn in again unless our house is leeward of the burning district or we have to run to the assistance of a friend there; and if the bell gives only single peals, which signify that at least one district intervenes between the burning street and the fire-lookout, we turn in our beds and perhaps picture to ourselves the lively time they must be having in that street. A fire is, on account of its uncertainty and suddenness, only less feared than an earthquake, and the general feeling among the citizens is that of insecurity.

There is, however, still another element of insecurity in wooden houses. House-breaking is by no means difficult in Tokyo. In the daytime the front entrance is generally closed with sliding-doors which can, however, be gently opened and entered without attracting notice unless some one happens to be in an adjoining{32} room. The kitchen door is usually kept open, and it is quite easy to sneak into the kitchen and make away with food or utensils. Tradesmen, rag-merchants, and hawkers come into the kitchen to ask for orders, to buy waste-paper or broken crockery, or to sell their wares, so that there is nothing unusual in finding strange men on the premises. Sometimes these hawkers are really burglars in disguise come to reconnoitre the house with a view to paying it a nocturnal visit. At night, of course, the house is shut and the doors are bolted or fastened with a ring and staple, but very seldom locked or chained. As the doors are nothing more than wooden frames with horizontal cross-bars, on which boards less than a quarter of an inch thick are nailed, it would not be difficult to cut a hole with a chisel large enough for the hand to reach the bolt or the staple or to clear the whole space between the cross-bars for the body to pass through. But quieter methods are generally preferred. Single burglars usually come in by the skylight, closed at night by a small sliding-door, which does duty as chimney in the kitchen, or crawl under the floor which is some two feet from the ground, by tearing away the boarding under the verandah and come up by carefully removing the loose plank of the floor, under which fuel is kept in the kitchen. If the burglars are in a gang, they naturally come in more boldly than these kitchen sneaks. Once inside, the thief has the run of the house as all the rooms{33} communicate by sliding-doors and are never locked, and the whole household is at his mercy. Since, then, houses are so easy of entry, it might be supposed that burglaries are very frequent in Tokyo; that such is not the case is probably due to the somewhat primitive methods pursued by these gentry and to the effective detective system of the police authorities. The strict police registration of every inhabitant and the easy access of all the rooms in a house make concealment very difficult, and the criminal is readily shadowed as he wanders from place to place throughout the Empire.

To this general insecurity from fire and burglary all wooden houses are subject; but if we take into consideration the actual number of homes which fall victims to them, we are compelled to conclude that though the feeling of insecurity may always be present, the chances of its being realised are somewhat remote, so that it is not so bad as it looks in these respects to live in the wooden houses of Tokyo. Fires are most frequent in winter from braziers being then in use and kerosene lamps being in requisition for longer hours every evening, and burglaries, too, increase in the same season from the sufferings of the poor being intensified. But in the summer heat the Japanese house is extremely pleasant. The whole house is open and lets the cool breeze blow from end to end; bamboo screens are hung in front of the verandah where it is exposed to the burning rays of the sun. On the second story we sit in thin cotton garments and feel the breeze all over the body, and look down upon the landscape garden before us or beyond at the peerless Mount Fuji on the south-west or at Mount Tsukuba on the northern edge of the Musashino plain. It is especially enjoyable when fresh from a hot bath, we squat or loll on the mats, fan in hand, and engage in desultory talk or in a quiet game until the sun sinks and wine and fish are brought before us. The Japanese house is an ideal summer villa when we can rest ourselves from the heat and dust of the busy city. But in the city itself it is far otherwise. The dust blows in with every gust, and the house, to be properly kept, must be swept several times a day. The narrowness of the streets and lowness of the ceilings give the{34} shops in crowded quarters insufficient light, though more than enough of dusty air. But in winter we feel the inadequacy of wooden houses; it is next to impossible to keep out the cold effectually; a room never gets thoroughly warmed. The wind blows in through the crevices of the sliding-doors, for the edges on which these doors meet are flat and never dovetailed. The paper of the doors is porous, and through its pores the air gets in; there is certainly this to be said for it that in a Japanese room one need never fear asphyxiation, however much charcoal may be burning in the braziers. These braziers are for warming the hands and the face if one crouches over them; but for the body, we get the warmth from the abundance of wadded clothing. We can therefore keep fairly warm if we merely sit on the mats; but directly we move or stand up, the cold attacks us. Most Japanese are, however, used from childhood to these cold rooms and do not feel the chill. Many of them think nothing of sitting for hours in a cold draught.

A Japanese wooden house looks pretty when new; but after some years when the outside is weather-beaten, the pillars begin to warp and the walls to crumble, its charms, too, are on the wane. A well-built house may be comfortable for twenty or at most thirty years, after which it is uninhabitable without considerable repairs. The few private houses which still remain that were built before the Restoration are at best rain-proof, and afford little protection against wind. There are certainly public buildings, such as shrines and temples, which have survived many centuries and are not unfrequently picturesque as they peer through their groves; but a close inspection would soon reveal the repairs they have undergone, pillars repainted, roofs retiled, gable-ends regilt, and the interior generally renovated. There is wanting in Japanese dwelling-houses that poetical charm which age lends to brick and stone buildings in the West with their dark-stained casements and ivy-mantled walls; and time which mellows and imparts a deeper hue to stone dry-rots wood and saps it of its strength, and long before storms make any impression upon brick, the frame-house falls to the ground. But in Japan it is not merely wind and rain{35} that houses have to contend against; the earthquake is the foe that makes them to totter. Every earthquake, by shaking them up, tends to loosen the joints and disturb the equilibrium of the building; and as a good many such shocks, about a hundred and fifty, occur in the course of a year, their combined effect is by no means negligible. Houses have therefore to be built with the possible effects of earthquakes in view.