Title: The Death of Captain Wells

Author: Allan H. Dougall

Creator: Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen County

Release date: July 21, 2021 [eBook #65890]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Captain William Wells

Prepared by the Staff of the

Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen County

1954

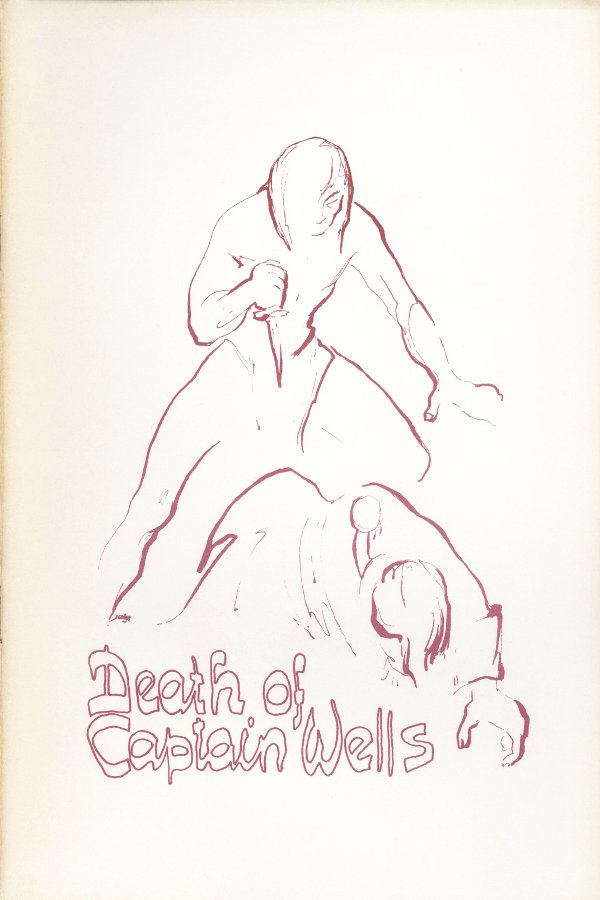

One of a historical series, this pamphlet is published under the direction of the governing Boards of the Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen County.

BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF THE SCHOOL CITY OF FORT WAYNE

PUBLIC LIBRARY BOARD FOR ALLEN COUNTY

The members of this Board include the members of the Board of Trustees of the School City of Fort Wayne (with the same officers) together with the following citizens chosen from Allen County outside the corporate City of Fort Wayne.

The character of William Wells remains an enigma, for his life has long been obscured by conflicting accounts of his role in Indian affairs. At one time, William Henry Harrison, governor of the Indiana Territory, thought him untrustworthy and believed that he should be removed from his position as Indian agent. Wells often appeared to his contemporaries as a turncoat and a traitor to his own people because of his sympathy with the red men. Other accounts, chiefly by his military associates, are earnest tributes to his strength and valor. Captain Allan H. Dougall, author of the following article, considered Wells only a “celebrated Indian fighter.”

Captain Dougall relates the death of Wells at the Massacre of Fort Dearborn, on the site of the present city of Chicago. His account first appeared in the FORT WAYNE DAILY GAZETTE, December 18, 1887. The Boards and the Staff of the Public Library of Fort Wayne and Allen County reprint the item in the hope that it will interest and inform local readers. Grammar, spelling, and punctuation have been changed to conform to current usage.

In July, 1812, Captain Nathan Heald, then in command of Fort Dearborn, notified General William Hull that he was being surrounded by a furious band of Indians who were in communication with Tecumseh; Heald desired aid immediately. General Hull sent an express to Fort Wayne to speed the immediate relief of Captain Heald and his command. Hearing of the proposed expedition, Captain William Wells volunteered to go to the relief of Captain Heald and to act as escort for the soldiers. His offer was accepted; on August 3, 1812, he set out with thirty hand-picked Miami warriors, who were friendly, fully equipped, and full of hope and courage.

Wells had been stolen by the Miami when he was a boy of twelve; soon afterward he was adopted by Little Turtle, their great chief. He served with the Indians at the outbreak of hostilities in 1790 and was present at the defeat of St. Clair near Fort Recovery, Ohio. It is said, however, that he then began to realize that he was fighting against his own kindred, and he soon resolved to leave the Indians. Therefore, he asked Little Turtle to accompany him east of Fort Wayne to a point on the Maumee known as the “Big Elm.” When the two had reached this spot, Wells said: “Father, we have long been friends; I now leave you to go to my own people. We will be friends until the sun reaches the midday height. From that time we will be enemies. If you want to kill me then, you may. If I want to kill you, I may.” He then crossed the Maumee River and set out for General Wayne’s army. Sometime after reaching Wayne, he was made captain of a company of scouts. Later he settled north of the St. Mary’s River on a farm which is still known as Wells Reserve. At this time he served as Indian agent and as justice of the peace. Wells also rendered valuable services to General Harrison, governor of the territory.

“...we have long been friends...”

Nothing unusual occurred on the journey of Captain Wells to Fort Dearborn with his Miami warriors. He arrived safely on the evening of August 12, but he was too late to have any influence on the question of the evacuation of the fort. Captain Heald had already determined to follow out General Hull’s instructions by agreeing to deliver the fort and its contents to the Indians. The supplies of muskets, ammunition, and whisky were very large; and it appears that Captain Heald had thought of leaving them as they were. On learning this, Captain Wells told him that it was madness to hand over these supplies, which would only serve to excite the already infuriated Indians. In this opinion, Captain Wells was ably supported by John Kinzie and some of the junior officers, who prevailed on Captain Heald to destroy the supplies. Accordingly, on the night of the thirteenth, he caused all surplus ammunition and arms to be destroyed and all the whisky to be thrown into Lake Michigan. In the afternoon of the fourteenth, a council was held between the whites and the Indians, at which the Potawatomi professed to be highly indignant at the destruction of the whisky and ammunition; they made numerous threats which plainly showed their murderous intentions.

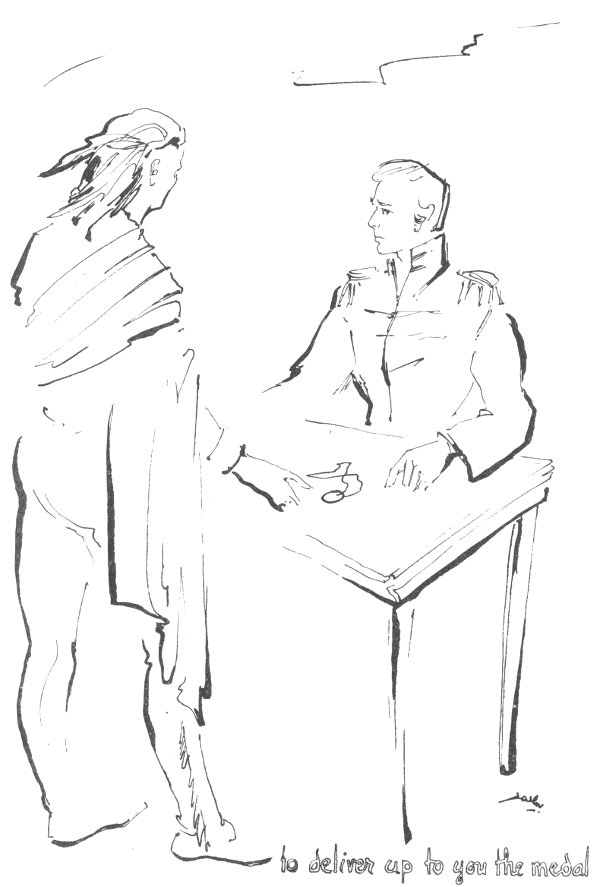

Black Partridge, who was one of the most influential of the Potawatomi chiefs, had been friendly to the whites since the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, when he had received a medal from General Wayne. In the evening Black Partridge came to the fort and entered Captain Heald’s headquarters. “Father,” he said, “I come to deliver up to you the medal I wear. It was given me by the Americans, and I have long worn it as a token of mutual friendship. But now our young men are resolved to imbrue their hands with the blood of the whites, and I cannot restrain them. I will not wear a token of peace when I am compelled to act as an enemy.”

As the number of Indians about the fort was constantly increasing, Captain Heald at last decided to evacuate the fort, which he should have done before. On the morning of August 15, 1812, the troops commenced to move out of the fort; by some strange and weird choice of the drum major, a dead march was played as they marched.

to deliver up to you the medal

They advanced along the lake shore, keeping near the water east of the sand hills and banks; these elevations partially screened them from view. The group had not proceeded far, when to their surprise the five hundred Potawatomi who had volunteered as an escort suddenly filed to the right and rapidly disappeared among the sand hills. As soon as the Indians were out of sight on the west side of the hills, they crouched down to hide their movements and ran ahead some distance to form an ambuscade. Then they awaited the coming of the troops. Riding ahead, Captain Wells had observed their movements; with his experience he knew immediately that the party would be attacked. He returned to the troops, dismounted, assembled the soldiers, and marched them forward. When the little band had reached a point about one and a half miles from the fort, the Indians opened fire on them. The company of soldiers charged up the bank and over the sand hills, firing as they advanced, while the Indians returned the fire with deadly effect from their sheltered position. As soon as the fighting commenced, the friendly Miami who had come from Fort Wayne and had stood by their adopted brother, Captain Wells, and their white allies, deserted them and took no part in the fight. Captains Wells and Heald and their small body of troops, fighting against fearful odds, succeeded in dislodging the enemy from their sheltered position; but the Indians were so numerous that part of them were able to outflank the soldiers and to take possession of their horses and baggage.

During the fight a young Indian crept up to the baggage wagon, which contained twelve children, and tomahawked and scalped all of its occupants. Captain Wells, after fighting desperately, was surrounded and stabbed in the back. His body was horribly mangled; his head was cut off, and his heart was cut out and eaten by the savages. They thought that some of the brave captain’s courage and skill would thus be imparted to them. He was indeed a fearless officer and a celebrated Indian fighter, but the odds against him had been too great. Fifty-two whites were killed, including twenty-six soldiers, twelve militiamen, two women, and twelve children.

Captain Heald ordered a retreat and withdrew the small remnant of his command. A parley ensued, and Heald surrendered on the condition that lives be spared. The soldiers then marched back to the fort, which was immediately plundered and burned by the Indians.

It is sentimental nonsense to attribute the massacre 8 to the failure of Captain Heald to act promptly at the time of the evacuation. The experiences and records of those who lived with and had dealings with Indians show beyond all doubt that as a race they are treacherous by nature. The more the government and individuals do for them, the more treacherous and unreliable they become.

CAPTAIN ALLAN H. DOUGALL

FORT WAYNE DAILY GAZETTE, December 18, 1887