![[Image of the book's cover unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: Treatise on landscape painting in water-colours by David Cox

Author: David Cox

Author of introduction, etc.: A. L. Baldry

Editor: C. Geoffrey Holme

Release date: July 31, 2021 [eBook #65962]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

| (In certain versions of this etext [in certain browsers] clicking on the image will bring up a larger version.) | ||

| (etext transcriber's note) | ||

| —— | ||

| FOREWORD BY A. L. BALDRY | ||

| A TREATISE ON LANDSCAPE PAINTING and EFFECT IN WATER COLOURS | ||

| TO THE PUBLIC | ||

| ADVERTISEMENT | ||

| GENERAL OBSERVATIONS ON LANDSCAPE PAINTING | ||

| ON OUTLINE | ||

| ON LIGHT AND SHADE, AND EFFECT | ||

| METHOD OF LAYING ON THE TINTS | ||

| ON COLOURING | ||

| TEMPLE OF FANCY | ||

| —— | ||

| Plate: | I. | STUDIES. |

| II. | STUDY. | |

| III. | STUDY. | |

| IV. | STUDY. | |

| V. | STUDY. | |

| VI. | NEAR KNOWLE, WARWICKSHIRE. | |

| VII. | NEAR BROMLEY, KENT. | |

| VIII. | STUDIES. | |

| IX. | DINAS MAWDDWY, NORTH WALES. | |

| X. | NEAR BIRMINGHAM. | |

| XI. | NEAR HAMPTON-IN-ARDEN, WARWICKSHIRE. | |

| XII. | NORTH WALES. | |

| XIII. | NEAR LEICESTER. | |

| XIV. | NEAR LLANFAIR, NORTH WALES. | |

| XV. | NEAR LLANFAIR, NORTH WALES. | |

| XVI. | ON BROMLEY HILL, KENT. | |

| XVII. | ON DULWICH COMMON, SURREY. | |

| XVIII. | DOLBADARN TOWER, NORTH WALES. | |

| XIX. | LLANFAIR CHURCH, NORTH WALES. | |

| XX. | STUDY. | |

| XXI. | STUDY. | |

| XXII. | BIRCH. | |

| XXIII. | ELM. | |

| XXIV. | POLLARD WILLOW. | |

| XXV. | OAK. | |

| XXVI. | BEECH. | |

| XXVII. | ASH. | |

| XXVIII. | ASTON HILL, NEAR BIRMINGHAM. | |

| XXIX. | BRIDGNORTH BRIDGE, SHROPSHIRE. | |

| XXX. | PART OF KENILWORTH CASTLE. | |

| XXXI. | HAMPTON-IN-ARDEN, WARWICKSHIRE. | |

| XXXII. | NEAR LLANFAIR, NORTH WALES. | |

| XXXIII. | NO. 1., 2. | |

| XXXIV. | NO. 3., 4. | |

| XXXV. | NO. 1., 2. | |

| XXXVI. | STUDIES. | |

| XXXVII. | OLD BUILDINGS, HASTINGS. | |

| XXXVIII. | OLD BUILDINGS, LAMBETH. | |

| XXXIX. | MORNING—VIEW OF WINDSOR CASTLE. | |

| XL. | EVENING—VIEW OF CONWAY CASTLE. | |

| XLI. | HAZY MORNING. | |

| XLII. | MID-DAY. | |

| XLIII. | A HEATH—CLOUDY EFFECT. | |

| XLIV. | SNOWDON, NORTH WALES. | |

| XLV. | COTTAGE NEAR NORTH FLEET, KENT. | |

| XLVI. | LANE AT EDGBASTON, NEAR BIRMINGHAM. | |

| XLVII. | AN EFFECT AFTER A STORM—VIEW ON THE COAST NEAR HARLECH, NORTH WALES. | |

| XLVIII. | TRANSIENT EFFECT—VIEW IN BATTERSEA MARSH. | |

| XLIX. | DOLBADARN TOWER, LLANBERIS LAKE, NORTH WALES. | |

| L. | PONT ABERGLASLYN, NORTH WALES. | |

| LI. | HASTINGS FISHING-BOATS RETURNING ON THE APPROACH OF A STORM. | |

| LII. | SHEEP-SHEARING—A VIEW IN SURREY. | |

| LIII. | MORNING—FISH-MARKET ON THE BEACH, HASTINGS. | |

| LIV. | TWILIGHT—WARWICK CASTLE. | |

| LV. | MORNING—ETON COLLEGE. | |

| LVI. | NOON—LLANELLTYD VALE, NORTH WALES. | |

| LVII. | PART OF BATTLE ABBEY | |

| LVIII. | VIEW IN SURREY | |

| LIX. | EFFECT, MORNING | |

| LX. | EFFECT, MID-DAY | |

| LXI. | EVENING. VIEW OF WINDSOR CASTLE | |

| LXII. | TWILIGHT. VIEW OF HARLECH CASTLE NORTH WALES | |

| LXIII. | WIND | |

| LXIV. | RAIN | |

| LXV. | CALM. HASTINGS FISHING-BOATS | |

| LXVII. | CLOUDY EFFECT. DISTANT VIEW OF CARNARVON CASTLE | |

| LXVIII. | MISTY MORNING | |

| LXIX. | AFTERNOON EFFECT. VIEW IN SURREY | |

| LXX. | RAINBOW EFFECT. WESTMINSTER ABBEY, FROM BATTERSEA MARSH | |

| LXXI. | MOONLIGHT EFFECT. VIEW ON THE THAMES | |

| LXXII. | SNOW SCENE. VIEW IN SUSSEX | |

WITH A FOREWORD

BY A. L. BALDRY

EDITED BY GEOFFREY HOLME

LONDON: THE STUDIO, Ltd., 44 LEICESTER SQ., W.C. 2

MCMXXII

When an artist is beyond question a master of his craft it is always particularly interesting to hear what he has to say about the principles by which his art is controlled and the methods he employs in his practice. It is, of course, in his work, in the things he creates, that he gives the complete expression of his convictions and that the full product of his experience is embodied, but by the aid of words he is able not only to declare the intention by which his expression has been directed but also to explain the technical processes which have enabled him to arrive at his results. His creed, once set down in writing, is made permanently available for the guidance of all who study his work and seek to realise his purpose; the statement of his methods becomes an enduring record to which those who come after him can refer when they wish to understand the manner of his production.

In this way, indeed, the educational value of the master’s precepts is maintained indefinitely. Even after his personal and living influence has been withdrawn his authority persists and his teaching remains active, because in all its essentials it is still within the student’s reach. Fashions in art may vary from time to time, but its fundamental principles do not change and the exposition of these principles which has served one generation is just as helpful to another.

Therefore, such a book as this “Treatise on Landscape Painting and Effect in Water Colours, from the first rudiments to the finished picture,” by David Cox, deserves as ready an acceptance to-day as it received when it was first published more than a century ago. David Cox is justly counted among the greater British masters—that can scarcely be disputed—he was also a teacher of very wide experience and he knew well how to enable others to profit by the knowledge he had accumulated. It was the fruit of this experience that he gathered in his “Treatise,” and it was in response to a demand from the people who were best able to judge the quality of his teaching that he undertook the preparation of the book. “The urgent and repeated solicitations of many of his pupils,” he says in his foreword, “have induced the author of this work to submit to the public those results which are the result of many years’ study, and which may guide the student in the selection of appropriate effects of nature, adapted to the different characters of landscape composition.”

That in referring to “urgent and repeated solicitations” he was not using a mere figure of speech is likely enough, for in those days plenty of people wanted to be taught and the master who knew his business was very much in request. Drawing and water-colour painting were reckoned as elegant accomplishments which formed a necessary part of a{2} polite education, and there was not only a host of amateurs who were ready to learn but a number of professional students as well with a real desire to become proficient in a new and attractive form of practice in which art patrons and collectors were showing themselves to be much interested. The official type of art school with which we are familiar to-day was almost non-existent—or at all events there were few such places available for the amateur—so the private teacher had to supply the deficiency and to assume a position of considerable responsibility. However, it cannot be disputed that he filled this position in a way that brought him credit and that what he had to do was done with marked efficiency.

Certainly, the students then had privileges which we to-day can justly envy. They were extraordinarily fortunate in their teachers, for they were able to obtain instruction from some of the greatest masters whom this country has produced. Turner, De Wint, Cotman and David Cox, and many other men of distinction who were their contemporaries were actively engaged in teaching during some part of their lives and by their genius and experience they raised greatly the standard of popular taste and fostered a feeling for art in social circles. Moreover, by their practice and precept they developed the new art of painting in water colours from a tentative and timid form of expression into something splendidly robust and full of brilliant possibilities.

It may, perhaps, seem a matter for regret that an artist of rare capacities, like David Cox, should have apparently wasted in the drudgery of teaching so much of the time which he might have employed to advantage in following his profession as a painter. But by his work as a drawing-master he not only created a public which learned eventually to show an effective appreciation of his productions, but he also helped on a movement which was of benefit to others as well as himself. If the art in which he excelled had been taught only by the less competent men it would scarcely have secured so quickly such a large measure of recognition; it was the ability of the teachers to prove how great were its possibilities that ensured its acceptance and established its authority.

Still, it must be admitted that many of these men whom we now rank as masters became teachers from necessity rather than choice. At the end of the eighteenth century it was often difficult for a young artist to earn a living; pictures fetched low prices and the demand for them was uncertain, so he had to seek out other sources of income. Teaching, badly paid as it was, was a very real help and the man who could secure a good connection in schools and among private pupils was able to maintain himself while he was waiting to find buyers for his works. If the patrons{3} failed to appear he remained a teacher to the end of his days, counting himself fortunate if he was able to hold his own against the competition of younger men who were ready to oust him from his place.

David Cox was decidedly one of those who were forced into teaching by circumstances, for he was born of humble parents and had from early life to make his way in the world by his own exertions. He had during his childhood some small amount of art training and when he was barely seventeen he began to work as a scene-painter, first in Birmingham, where he was born, and afterwards in London. But even then he was a serious student of nature with ambitions to become a landscape painter, and soon after he came to London he took the opportunity to get some lessons from John Varley in water-colour painting. In this new art he made such satisfactory progress that he gave up his theatrical work, devoting himself, instead, to landscape painting and teaching. Even then he was only twenty-two and he had still much to learn to fit himself for the career on which he was entering; but so assiduous was he in his study of nature and so consistent in his effort to acquire a full command of technical processes that he was able at the age of thirty—in 1813—to secure election as a member of the Society of Painters in Water Colours. This election can be taken as evidence that he was already regarded by his fellow-artists as a man of some distinction in his profession. But the same year brought other evidences of his growing success, for it saw his appointment as drawing-master in the Military Academy at Farnham, and also the issue of the first parts of his “Treatise on Landscape Painting,” in which he was able to talk about the “repeated solicitations” of his pupils and to imply that his position as a teacher was one which justified him in speaking with authority about matters of technical practice.

Yet, with what he might regard as a fairly established place in the world he was by no means relieved from his struggles for existence. He had advanced, it is true, beyond the stage when he was glad to get a couple of guineas a dozen for the drawings which he sold to dealers, but his smaller works still fetched only a few shillings and a large one not more than five or six pounds. It was necessary for him to work very hard and to practise the strictest economy to maintain himself and his wife and child, and it was impossible for him to do without the earnings which teaching brought him. It was probably for this reason that in 1814, when he gave up his post at the Military Academy because he felt the work there to be unsuited to him, he left London and settled in Hereford, where teaching engagements in schools and private families were plentiful and where he was able to take in pupil-boarders.{4}

At Hereford he remained for nearly fourteen years, but he visited London annually and he made periodical sketching excursions to different parts of the British Isles and occasionally abroad. Eventually he returned to London and lived at Kennington until 1841, when he moved once again, this time to Harbourne, a suburb of his native town, Birmingham, where he died in 1859. Slowly but surely he built up his reputation, more slowly still he increased his income and added to his savings, but it was not until his final departure from London that he was able to free himself from his responsibilities as a teacher and to devote the whole of his energies to painting.

Indeed, the move to Harbourne was made partly to obtain leisure for practice in oil painting, as he had conceived a somewhat sudden desire to acquire a mastery of that medium. He had used oils many years before, but for sketches rather than finished pictures; the ambition to achieve more in this direction came to him about 1839, when he made the acquaintance of W. J. Muller and watched that extraordinarily skillful painter at work. Cox, who was then a man of fifty-six, became a sort of pupil of the younger artist and accepted hints from him with characteristic humility—he is reported to have said on one occasion during a technical demonstration, “You see, Mr. Muller, I can’t paint.”

However, if such a remark were justifiable in 1839, it was certainly subject to considerable modification very few years later, for Cox, once started in the right direction, developed quickly into an oil painter of unquestionable distinction. He never, perhaps, reached quite the same degree of proficiency which he had attained in water colours, but he did work which was worthy of him and he added many fine canvases to the series which generation by generation has been built up by the masters of British landscape. Fortunately, he did not devote the whole of his time to pursuit of new methods, indeed, to this final period of his life belong some of the greatest of his water-colour paintings—possibly practice with oils heightened his keenness of vision and increased the strength with which he handled the more delicate medium, and no doubt freedom from distractions enabled him to work more deliberately and with closer concentration.

If Cox’s career is judged by the conventional money standard it would be scarcely possible to say that he achieved success, for at no time were his earnings large—he is said to have only once received £100 for a picture—and the small competence which he amassed in his later years would have seemed merely poverty to anyone less modest and simple-minded. But if he is measured by the true standard, of accomplishment, he can be reckoned as successful in the highest degree. His paintings{5} are distinguished by an exquisite perception of the great facts of nature and by a consistent significance of interpretation, they have a most attractive individuality, and their technical mastery is exceptionally convincing—they put him definitely among the leaders of the British school. As a teacher he had a wide and wholesome influence because he sought to impress upon his pupils his own sincere belief that nature is and always must be the right source of an artist’s inspiration, and because he tried to make them devout and serious students like himself.

It was essentially from the standpoint of the landscape painter that he approached his teaching. His “Treatise” was intended to guide the student “in the selection of appropriate effects of nature,” or in other words, to point the way to a proper understanding of nature’s subtleties. Cox did not believe in an easy and convenient formula; he did not use one himself and he had no wish to impose it upon others. In this his attitude was partly temperamental and partly, no doubt, due to the fact that, unlike many of his contemporaries, he did not spend his earlier years in learning the conventions of the topographical draughtsman—he was a translator and an interpreter, not merely a copyist, and although his interpretation was eminently a true one, its truth appeared in his realisation of the great fundamentals, not in the laborious statement of local trivialities. He expressed this himself on one occasion when the committee of the Water-Colour Society had complained that some paintings of his were “too rough”—he wrote, “They forget that these are the work of the mind, which I consider very far before portraits of places.”

This faith that painting should be the work of the mind, and of a mind so stored with impressions of nature that it would be able infallibly to recognise what was the way in which each aspect of nature should be treated, is very clearly demonstrated in his “Treatise.” Read between the lines of its practical advice the book, indeed, is an eloquent assertion of a master’s creed, and as such it is instructive not only to the student who wishes to profit by its technical hints but also to the judges of art who are anxious to appreciate the principles of which David Cox and his greater contemporaries were masterly exponents.

There is much in the text that explains these principles and defines the manner in which they should be applied. For instance, when Cox dwells upon “the necessity of becoming thoroughly acquainted with, and of obtaining a proper feeling of, the subject,” and when he says that “the picture should be complete and perfect in the mind before it is even traced upon the canvas,” he is simply advocating that first and most vital essential in all artistic effort, accurate and intelligent observation.{6}

Again, when he insists that “in the selection of a subject from nature the student should ever keep in view the principal object which induced him to make the sketch,” and adds that “the prominence of this leading feature in the piece should be duly supported throughout; the character of the picture should be derived from it; every other subject introduced should be subservient to it; and the attraction of the one should be the attraction of the whole,” he is only pointing out the necessity for orderly and logical design. His arguments, too, that the sentiment of the subject should be reflected in the manner of its treatment, that “such force and expression should be displayed as would render the effect, at the first glance, intelligible to the observer,” and that the right relation should be scrupulously maintained between the leading object in the composition and the less prominent accessories, are wholly inspired by the belief that a sense of balance and proportion are as indispensable to the student as the power to see and to think about what he sees.

Further, what he has to say about the need for exactness in the preparatory stages of a painting is most significant, as it shows how much importance he attached to systematic accomplishment and steady progression from one stage of the work to another. But here also the foundation must be observation—the student “must possess a clear conception of his subject” because upon that depends the perfection of his outline, and “it will be necessary for him to be particular in his designation of the outline” because only in that way will he be able to proceed to his own satisfaction and convey a definite and correct idea to the observer. Cox very rightly claims that “he who devotes his time to the completion of a perfect outline, when he has gained this point, has more than half finished his piece: while the author of a slovenly outline creates for himself an infinity of trouble, in order to avoid additional errors in the colouring of his subjects: and after all his efforts, finds it impossible to produce a picture perfect in any one part,” and he adds some valuable suggestions as to the way in which this perfect outline—by which he means simply certainty and expressiveness of draughtsmanship—should be obtained. Always, however, he asserts that the way to success lies only through persistent endeavour and unfailing consistency of purpose—“if the mind be fixed and sincere in pursuit of the art, difficulties will be easily surmountable: they will rather quicken than damp the desire for improvement,” and “the accomplishment of one task will only give additional stimulus for the performance of another” are essential articles in the creed which he professed and practised throughout his life.

In fact, he regarded art as the intellectual result of a visual exercise and to obtain this result he prescribed a rigorous discipline. His teaching is{7} all the more worthy of attention now because it provides an antidote to the sloppy conventionalism which is poisoning much of the art of to-day. There were no affectations about David Cox, and the poses of our modern artists of the “advanced” school would have seemed to him particularly offensive. Yet, he was himself a pioneer, and in some ways a rebel; but in breaking new ground he was seeking to make progress by overcoming the difficulties of art and his rebellion was against limitations which he knew to be unreasonable. His book is proof enough that he would have had no sympathy with reactionaries who make a pretence of primitive simplicity so that they can shirk the labour of learning their craft; and all that he has included in it shows that to him that art only was right which was earnest, sincere, and honest, and unquestioning in its worship of nature.

WITH

EXAMPLES

IN

Outline, Effect, and Colouring.

————

BY

D A V I D C O X.

————

LONDON:

Printed for and published by S. and J. FULLER, at the Temple of Fancy, RATHBONE PLACE;

And sold by Messrs. Longman, Hurst, Bees, Orme, and Brown; Sherwood, Neely, and Jones; and Gale and Curtis, Paternoster-Row, Ackermann, Strand,

and by all Booksellers in Town and Country.

1813.

PRICE 7s. 6d.

Facsimile of the cover of the original edition, published in 1813

{10}

In an age when the patronage extended to the Fine Arts bears a full proportion to the growing expansion of the human mind, and when our National Taste is no longer put out to nurse, an apology for the publication of a new Work, tending to the still more complete elucidation of principles not yet perfectly understood, and giving greater facilities to the labours of the young Artist, will scarcely be considered necessary. If an excuse were sought for, however, the Publishers would confidently point to the acknowledged eminence of the Author of the production which they have the honour to propose to the notice of the world; to the new and interesting principles which it will develope; and to the extent and excellence of the examples with which it will abound. To an enlightened and liberal public, possessing ability to discriminate, and spirit to reward talent, it is unnecessary to urge any additional claims to their attention and support.

The abilities of Mr. Cox, as a Painter in Water Colours, have been long established; and his knowledge of Effect is equal to that of any Artist of which the age can boast. His Pencil Drawings are of the boldest style; and the Etchings, in imitation of Lead Pencil and Chalk, which will be found amongst the examples appended to this Work, will be marked by a peculiar character of fidelity, and derive an additional value from the circumstance of their being executed by himself.—In the first of these Sketches, the most simple principles of the Art will be exposed; and the advancement of the young Student will be accomplished by their gradual progression to subjects more interesting in their detail, and of greater difficulty in their execution.

In the progress of the Work, the Author will introduce a variety of imitations of his Drawings, in Sepia and Colours, from all the most striking Effects in Nature; the Plates from which will be executed by the first Aquatinta Engraver in London; and the subjects appropriated to this department of the Work will be so selected, as to display an unusual variety of the most picturesque Scenes in England and Wales.

The diversity and character of these Examples, combined with the sound and simple instruction which will be found in these Numbers, will render it a most desirable object of study, not only to the fashionable Amateur, but to the young Artist whose disposition and ambition urge him on in pursuit of professional eminence. All speculative and uncertain theories will be cast aside, to make room for tried rules and solid principles; the object of the whole being gradually to conduct the Student, by the most direct paths, to the highest point of practical excellence: and the Proprietors feel the most confident anticipations of the brilliant success which will crown this Undertaking, from the consciousness that a Work, better qualified to establish those ends which it professes to keep in view, is not to be found amongst the productions of contemporary genius.{11}

The urgent and repeated solicitations of many of his Pupils have induced the author of this Work to submit to the Public those remarks which are the result of many years’ study, and which may guide the Student in the selection of appropriate effects of Nature, adapted to the different characters of Landscape composition.

In his choice of the examples to elucidate these Observations, he has been guided by a wish to lay before the Learner, as far as the limits of the Work would admit of such illustrations, some of the most striking effects, where incident combines with Nature to give expression and vigour to each scene. A more satisfactory elucidation of this rule will be afforded in the examples appended to the subsequent pages.

The principal art of Landscape Painting consists in conveying to the mind the most forcible effect which can be produced from the various classes of scenery; which possesses the power of exciting an interest superior to that resulting from any other effect; and which can only be obtained by a most judicious selection of particular tints, and a skilful arrangement and application of them to differences in time, seasons, and situation. This is the grand principle on which pictorial excellence hinges; as many pleasing objects, the combination of which renders a piece perfect, are frequently passed over by an observer, because the whole of the composition is not under the influence of a suitable effect. Thus, a Cottage or a Village scene requires a soft and simple admixture of tones, calculated to produce pleasure without astonishment; awakening all the delightful sensations of the bosom, without trenching on the nobler provinces of feeling. On the contrary, the structures of greatness and antiquity should be marked by a character of awful sublimity, suited to the dignity of the subject; indenting on the mind a reverential and permanent impression, and giving, at once, a corresponding and unequivocal grandeur to the picture. In the language of the pencil, as{12} well as of the pen, sublime ideas are expressed by lofty and obscure images; such as in pictures, objects of fine majestic forms, lofty towers, mountains, lakes margined with stately trees, rugged rocks, and clouds rolling their shadowy forms in broad masses over the scene. Much depends upon the classification of the objects, which should wear a magnificent uniformity; and much on the colouring, the tones of which should be deep and impressive.

In the selection of a subject from Nature, the Student should ever keep in view the principal object which induced him to make the sketch: whether it be mountains, castle, groupes of trees, corn-field, river scene, or any other object, the prominence of this leading feature in the piece should be duly supported throughout; the character of the picture should be derived from it; every other subject introduced should be subservient to it; and the attraction of the one, should be the attraction of the whole. The union of too great a variety of parts tends to destroy, or at least to weaken the predominance of that which ought to be the principal in the composition; and which the Student, when he comes to the colouring, should be careful to characterise, by throwing upon it the strongest light. In his attention to this rule, however, the Student must be particular not to fall into the opposite extreme, by suffering the leading object of his composition so fully to engross his attention as to render him neglectful of the inferior parts. Because they are not to be exalted into principals, it does not follow that they are to be degraded into superfluities.

All the lights in a picture should be composed of warm tints, except they fall on a glossy or reflective surface; such as laurel leaves, glazed utensils, etc., which should be cool, and the lights small, to give them a sparkling appearance: but care must be taken not to introduce a cold colour in the principal light, which, as already mentioned, should be thrown upon the leading feature of a picture, as it conduces to destroy the breadth that should be preserved; while on the contrary, the opposition or proximity of a cool to a warm colour assists greatly in giving brilliancy to the lights. If the picture, for instance, should have a cool sky, the landscape ought to be principally composed of warm tints; as contrast of this description tends to the essential improvement of the general effect.

All objects which are not in character with the scene should be most carefully avoided, as the introduction of any unnecessary object is sure to be attended with injurious consequences. This must prove the necessity of becoming thoroughly acquainted with, and obtaining a proper feeling{13} of, the subject. The picture should be complete and perfect in the mind, before it is even traced upon the canvas. Such force and expression should be displayed, as would render the effect, at the first glance, intelligible to the observer. Merely to paint, is not enough; for where no interest is felt, nothing can be more natural than that none should be conveyed.

Finally, it may be observed, that it is only by a due attention to each distinct part, and by a skilful combination of all, that the whole can be effective and delightful.

The young draftsman who is ambitious of future eminence must be close in his attention to those minute points which, skilfully combined, constitute the excellence of the painter. In the outset, it will be necessary for him to be particular in his designation of the Outline, for the perfection of which, he must possess a clear conception of his subject; otherwise, be his genius what it may, he will wander wildly, without either promoting his own satisfaction, or conveying a definite or correct idea to the observer. Too little attention has generally been paid to this point, by Students: they are too apt to appear disconcerted and discouraged, when the task wears a complexion of difficulty.

A clear and decided Outline possesses a manifest superiority over an imperfect or undecided one, inasmuch as it renders unnecessary those continual references to Nature or to copy, which must be had recourse to, where the Outline is defective. He who devotes his time to the completion of a perfect Outline, when he has gained this point, has more than half finished his piece; while the author of a slovenly Outline creates for himself an infinity of trouble, in order to evade additional errors in the colouring of his subjects; and after all his efforts, finds it impossible to produce a picture perfect in any one part. To attain proficiency in the art of pencilling, the Student is recommended to practise Drawing from the casts of the antique, by which study he will acquire a growing facility in the designation of fine forms, as well as a more correct and decided mode of outlining. The Pupil will also find his progress greatly accelerated by the dedication of his leisure moments to copying objects of still life—a practice which will be found replete with advantage, when he studies combinations of subjects for compositions of landscape scenery.

In tracing the distinct objects of a landscape, it is recommended to attend more particularly to the general forms than to detail: for example, in{14} sketching a mountain, it will be sufficient to describe the extreme Outline, without descending to the diversified and numerous ridges which may appear; for although these uneven divisions arrest the attention of the Student, when engaged in tracing the particular form of the eminence, they are lost to the eye which embraces, at one view, the whole of the scene. A greater degree of minuteness, however, ought to be observed in the Outline of the fore-ground of a picture, where the features of the object assume a more specific appearance, shewing decided forms, and obtruding all their diversities of shape upon the view. To obtain excellence in this respect, it will be necessary to make correct drawings from Nature, of weeds, plants, bark of trees, and such objects as usually constitute the foreground of a landscape.

The Student must first commence with perpendicular, horizontal, and diagonal lines, to give the hand that freedom and certainty which are necessary. The Drawing must be strongly marked in the shade and foreground of the subject, but more delicately in the lighter parts, and as the distance gradually increases. Due attention to this cannot fail to give the true spirit and perspective. The Plates of this Work should be copied in regular succession, and any bad line that may be made should be entirely expunged; for all effort to rectify, by retouching, will only give the piece a scratched and indecisive appearance, and consequently will cause confusion and mistakes in the colouring.

Any little failure must not be made the source of discouragement; and in case the Student should not have succeeded altogether so well as could be wished, in the first attempt, he ought by all means to persevere until completely successful; carefully endeavouring, in his renewed efforts, to avoid the same errors. This mode will assuredly be followed with far greater improvement than can possibly attend hasty transitions from one subject to another, without producing perfection in either.

The best and surest method of obtaining instruction from the Works of others is not so much by copying them, as by drawing the same subjects from Nature immediately after a critical examination of them, while they are fresh in the memory. Thus they are seen through the same medium, and imitated upon the same principles, without preventing the introduction of sufficient alterations to give originality of manner, or incurring the risk of being degraded into a mere imitator.

If the mind be fixed and sincere in pursuit of the Art, difficulties will be easily surmountable: they will rather quicken than damp the desire for improvement; for it is only where talent is required that Genius can be{15} active. The accomplishment of one task will only give additional stimulus for the performance of another. Increasing pleasure will naturally flow from progressive improvement. The mind will ever be busily and pleasingly employed; for “the effect of every object that meets a Painter’s eye may give him a lesson.”

It is here that the Art begins to display its varied and inexhaustible beauties, and to reward the patient and improving Student. The outline being completed in the manner prescribed by the foregoing instructions, Light and Shade, and Effect, should be studied in sepia or Indian ink, by which a clearer conception of each will be acquired than if practised in colours; the variety of the latter tending to perplex the mind, and to divert it from the main object. Colouring is a distinct and subsequent branch, and is only to be learnt by long and minute observation of the diversified tints and hues of Nature. The principle of Light and Shade, on the contrary, is established by theory. This subject has already been so admirably treated on, that it will be impossible to give a better insight into it than is contained in the following passages extracted from a celebrated Work.

“Shadow is a diminution of light occasioned by the interposition of some opake body, which receiving and intercepting the light that should be cast on the plane it is placed on, there gives a shadow of its own form: for light being of a communicative nature, diffuses itself on every thing not hid from it, particularly on every thing that is plain and smooth; but where there happens the least elevation, a shadow is produced which exhibits the figure of the illumined part on the plane.

“The diversity of luminaries occasions a difference of shadows; for if the body that illumines be larger than the body illumined, the shadow will be less than the body. If they be equal, the shadow will be equal to the illumined; and if the luminary be less than the object, the shadow will be continually enlarging as it goes farther off.

“From what has been observed we draw this conclusion: that the same object may project shadows of different forms, though still illumined on the same side; the sun giving one form, the torch or lamp another.

“The sun always makes its shadow equal to the object; that is, projects it parallel-wise. It is certainly of consequence to observe these rules precisely, and not take the rules for candles, lamps, and the like, in lieu thereof.{16}

“The shadow of objects given by a torch or lamp is not projected in parallels, but in rays proceeding from a centre: whence the shadow is never equal to the object, but always larger; and grows larger as it recedes further.

“To find a shadow, two things are supposed, viz., light and body. Light, though quite contrary to shadow, is yet what gives it its being; as the body, or object, is what gives its form and figure. To conceive the nature of shadows more clearly, and render the practice more easy, it must be observed, that there are two points to be made use of: one of them, the foot of the light, which is always taken on the plane the object is placed upon; the other, the luminous body;—the rule being common to the sun, torch, etc., with this difference, that the sun’s shadow is projected in parallels, and that of the torch in rays, from the centre, as before mentioned. But as all objects on earth are so small in comparison of the sun, the diminution of their shadows is imperceptible to the eye, which sees them all equal, neither broader nor narrower than the object that forms them. On this account, all the shadows caused by the sun are made in parallels.

“To find the shadow of any object whatever opposed to the sun, a line must be drawn from the top of the luminary, perpendicular to the plane where the foot of the luminary is to be taken; and from this, an occult line to be drawn through one of the angles of the plane of the object; and another, from the sun to the same angle. The intersection of the two lines will express how far the shadow is to go. All the other lines must be drawn parallel hereto.

“All given shadows must appear darker than that part of the object not illumined, for this reason—those parts of objects not illumined receive the reflection of the brightness around them; while the shadow given can receive no reflection but from the object in shade.”

Having thus given the origin of Light and Shade, it will be necessary next to proceed to give some idea of the various effects of Nature, and the class of scenery suitable to each effect; as the great merit of a picture depends on the most appropriate Effect given to each scene.

Abrupt and irregular lines are productive of a grand or stormy Effect; while serenity is the result of even and horizontal lines, where no roughness or intersections appear, to invade the mild harmony of beauty.

Morning Effect, for instance, may be displayed in any composition the form and character of which are pleasing to the eye—where the pendent forms of trees, combined with other objects, communicate to the mind a{17} delightful impression; and a similar observation will hold good with respect to Mid-day, which may be produced in various situations: but owing to the great glare of light in such Effects, hay-fields, corn-fields, or any busy scene on rivers, etc., are suitable for the Effect, and as regards Evening and Twilight. Such Effects being calculated to convey to the mind impressions of grandeur, the composition should be studied, to produce such an Effect; and the Colouring ought to be perfectly in unison with the peaceful repose or the gloomy majesty which controls the scene.

A flat country, on the marshy banks of a winding river, should be seen beneath a grey, clouded sky. The transient effect adapted to such a landscape is produced by the fleeting lights of the sunbeams, struggling, between the interstices of the blowing clouds. The old Pollard Willow is strictly characteristic of this scene, being indigenous to countries of this description; and its situation in the landscape might be such, as to carry the eye through all the various meanderings of the stream.

In landscapes which may have been selected solely with a view to the display of some particular object, and which are low, and, on the whole, less prolific in interest, and less gratifying to the eye, than others might have been, an additional feature of interest should be thrown into the sky, to aid, by the contrast it would afford, the effect of the whole, which otherwise might appear unsatisfactory; taking care, at the same time, not to invade or to injure the prominent character of the picture. On the other hand, however, where the scene itself is naturally full of interest, the picture will of course admit of a less beautiful and imposing; sky: although in this case, as in the former, due attention should be paid, to support the character of the whole. At the same time it ought to be fully explained, that these observations must be understood as by no means intended to confine the exertions of the Student entirely to the particular subjects which have been chosen for illustration in the various Effects of this Work; as it will be obvious, in drawing from Nature, the Student will find subjects very different, equally adapted to this purpose; and in his selections from the objects which may present themselves to his notice, he will of course find, in his own taste, a guide which will be more or less correct, in proportion as he has cultivated and refined it.

It will be necessary that the Pupil should be provided with good hair pencils, sepia or Indian ink, and saucers to mix each separate shade in; also paper strained upon a proper drawing-board.{18}

The outline being made very correct, the Pupil will mix up three or four different shades, according to the number of distances there may be in the copy, and carefully match them to each, commencing with the sky, and keeping the drawing-board a good deal sloped, which will assist the tint to follow the pencil in the part where he is at work. He will also be particularly careful always to lay it on clear to the outline. After he has gone over the sky, in all the principal parts, sufficient to produce the effect, he will next proceed to lay in all the shades, or masses of shadow, which usually form the general effect of the composition; beginning always with the third distance in the landscape; afterwards the second or middle distance; and then working the fore-ground in the same way. It ought to be observed as an invariable rule, that the pencil should be tolerably full of colour, in order that it may float, which will give clearness to the work. After having gone over the whole in the shadows, the Learner will mix a tint something lighter than each shadow, which must be used upon the lights in blending the dark into the lights, such as in fractured stone, brick, broken plaister, etc., and in those parts of trees where it is required to break the shadows into the light branches by small touches; which will give a finish to the appearance of the drawing, and soften or blend together any parts which may appear too abrupt. In the finishing, a dark shade should be mixed up, with which those parts in the shadows which require to be marked out in the outline may be finished up; and a proper depth should be given to the dark parts: but care should be taken not to use this dark tint in any bright light, as it would render the part harsh, and unpleasant to the eye.

It must be observed, that in putting on all tints or shadows the Student must accustom himself to working with his board straight before him; and in laying on his tints, must be particularly careful to begin by laying them close to the outline, and not by repeated touches, or dragging the pencil backward and forward in a timid manner, without any decided method—a fault that is chiefly owing to the outline not being made correct; for where the Pupil has made a correct and decided outline, all timidity vanishes, and he will work with spirit and freedom. The reverse is the cause of so many failures in the commencement of the Art.

The effect having been studied in Sepia or Indian ink, in the Colouring of his subject the young Student should be particularly attentive to the adaptation of his colours to the composition and effect of the piece. In{19} Morning and Evening effects we naturally look towards the light which at those periods of the day is marked by a mild beauty which gratifies and attracts, yet divested of that dazzling noontide effulgence which weakens and repulses, the eye. Those objects which are seen against the strongest light must wear a neutral tint, which may be termed negative harmony; for were they to be garbed in the rich and full-dress liveries of Nature, the influence of the lustres behind them would in a great measure be rendered nugatory, and the effect weak and full of error: on the contrary, in the representation of broad sunshine or mid-day, those parts of the piece which are visited by, but not seen against, strong lights, will admit of a rich and beautiful harmony of colour, without doing violence to truth, or infringing on the economy of Nature; and this may be called positive harmony, or a picture of colour.

Every tint should be laid on with clearness and decision, so that the object may receive its proper tone at the first touch of the hair pencil; nor is less skill required in the choice and appropriation of the colours, which should be diversified as much as is consistent with the unison necessary to the production of harmony. Objects which are exposed to the light require a higher finish and more glowing warmth of colour than those which are shrouded in shade; while the minutest parts of the former ought to be touched with the utmost care, so as to render visible and striking all that the broad and bright radiance of the sun may be supposed to develope. The latter will admit of a less laboured and less perfect delineation. In the lights of a picture, attention to this rule is indispensable, where it is necessary to distinguish, with so much correctness of detail, those very objects which in shadow would permit that intimacy of union which would almost make them appear as one.

The light aerial tints should be laid on the remotest parts of a picture, gradually brightening into more rich and decided tones as they approach the nearer and more prominent objects; taking care to preserve the same atmosphere throughout the picture.{20}

PLATE LVII

PART OF BATTLE ABBEY

This subject is selected, as being the most simple, both in its design and colouring, that could well have been fixed upon: still, however, it will be necessary to give a description of the tints used, viz.—The sky is coloured with indigo alone; the clouds with indigo mixed with light red; the distance, indigo finished with the same colour, and a little lake; the building is washed over with indigo, light red, and a little gamboge; and the shadowed parts of it with indigo and lake, finished with Vandyke brown and a little indigo. The greens in the foreground are composed of indigo, burnt sienna, and gamboge, finished with Vandyke brown.

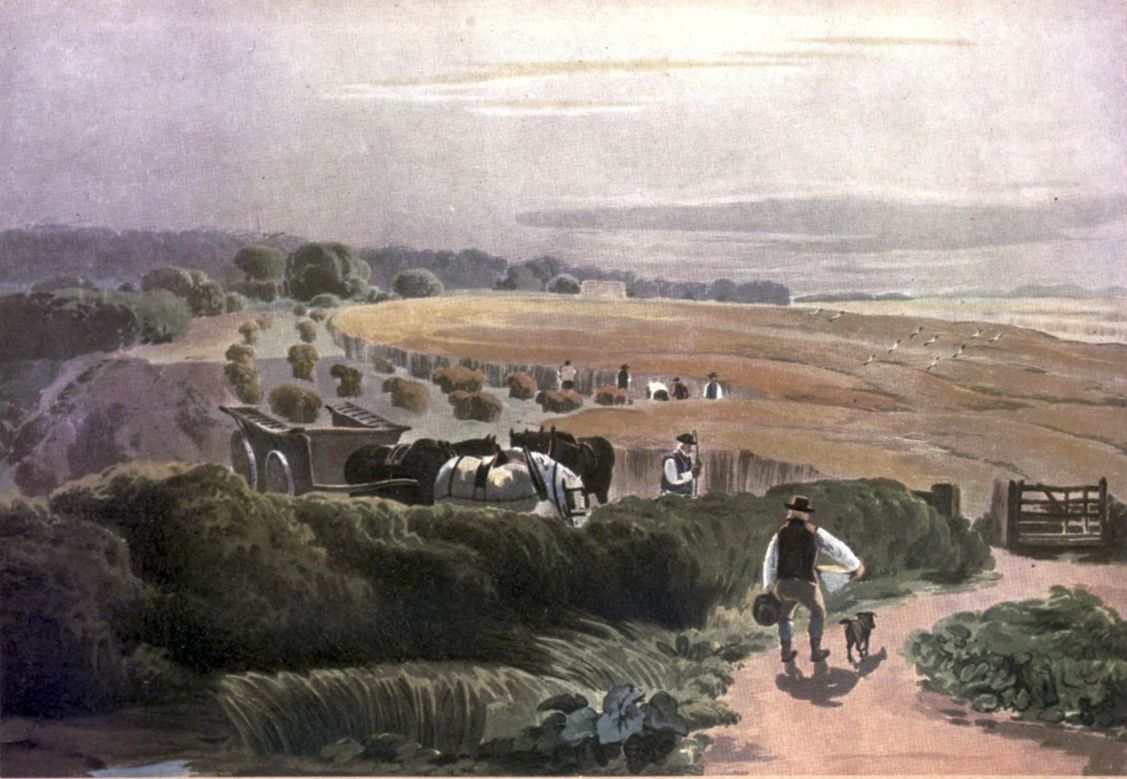

PLATE LVIII

VIEW IN SURREY

Is intended as a contrast to the foregoing Plate, producing, by the effect of a dark sky, a strong light upon the principal object. The colours for the sky are composed of indigo, lake, and ivory black; the distance, indigo finished with the same colour and a little lake. That part of the cottage where the light is strongly reflected, is yellow ochre, with a little burnt sienna mixed in the richer tones; the roof is black and lake, with a little burnt sienna, finished with the same; the shadows and the grey tint upon the timber, indigo and Indian red; the road, with indigo and Indian red also, which is finished with Vandyke brown and lake. The greens for the bank and the bushes are indigo, burnt sienna, and gamboge, completed with indigo and brown pink, and a few touches of Vandyke brown.

PLATE LIX

EFFECT, MORNING

Morning Effect should be produced by sparkling and catching lights. A scene on the banks of a river is here intended to produce the effect, while the clear reflection of the different objects in the water gives stillness to the scene; and the people crossing in the ferry-boat to market is an incident which materially tends to stamp the character and elucidate the effect of the picture. The sky tints are composed of indigo, lake, and a little gamboge, gradually softened in with light ochre towards the horizon; the upper part of the sky is finished with a little ultramarine; the water washed in with the same tints as the lower part of the sky; the distance, indigo and a little light red; the trees and bank, in the second distance, indigo and Indian red, re-touched in the lights with light ochre and gamboge; the shadows upon the house, indigo and Indian red; the light side, light ochre; the foreground trees, bank, and weeds are worked in with a grey composed of indigo, Indian red, and brown pink, finished with the same three colours, preserving some quite white for the sparkling lights, which are to be carefully filled up with gamboge and indigo; the bark of the trees, indigo and Indian red; the whole of the foreground finished with indigo and burnt sienna, heightened up with Vandyke brown.

PLATE LX

EFFECT, MID-DAY

As the light is required to be broad, an open scene appears well calculated to produce the effect; and a Corn-field is made choice of. The colours for the sky are indigo and lake; the foliage in the distance, indigo and Indian red; the corn-field, yellow ochre, finished with yellow ochre and Vandyke brown; the bushes in front, indigo, Indian red, and brown pink; the road, light red; the foreground finished with Vandyke brown.

PLATE LXI

EVENING. VIEW OF WINDSOR CASTLE

The upper part of the sky is coloured with indigo, lake, and a little gamboge, gradually softened in with light ochre as it descends, and toward the horizon with light red. The Castle is laid in with a warm tint of indigo and light red, then shaded lightly with indigo and lake. The different greens in the woods are composed of indigo, burnt sienna, and gamboge, varied as required; the shadows in the nearer parts, indigo and burnt sienna; the water with the same colours. The trees in the foreground are indigo and burnt sienna, and the finishing touches with Vandyke brown. The whole of the foreground and wood glazed with brown pink.

PLATE LXII

TWILIGHT. VIEW OF HARLECH CASTLE NORTH WALES

The grey tint in the sky is composed with indigo and Indian red, and the horizon is coloured with light ochre; the distant mountains with indigo, finished with the same, mixed with lake, and a little Venetian red on the light sides; the nearer mountains, indigo, lake, and Venetian red; the Castle, with the same; the rocks and foreground, lake, ivory, black and burnt sienna; the greens, burnt sienna, gamboge, and indigo; the trees, indigo and burnt sienna, heightened with spirited touches of Vandyke brown.

PLATE LXIII

WIND

The general tone of colour is a silvery grey, upon which the effect of the piece most materially depends; the sky, indigo and Indian red throughout, with a little warm tint upon the edges of the clouds; the distance, indigo, gradually adding Indian red towards the middle and foreground; the Mill, with the same colour, glazed lightly with Vandyke brown; the heath, indigo and burnt sienna, with clear touches of lake and a very little indigo for the bloom of the wild flowers, etc., finished with Vandyke brown.

PLATE LXIV

RAIN

The clouds, indigo and Indian red, finished with indigo and lake, and a few touches of light red, subdued with a little indigo on the edges of the clouds; the distance, with the same grey colour as the clouds; the bright greens, burnt sienna, indigo, and gamboge, glazed with Vandyke brown; the gipsey tents are lightly coloured with lake and a little black, and varied with a few clear tints.

PLATE LXV

CALM. HASTINGS FISHING-BOATS

The blue sky is coloured with indigo and a little lake; the clouds, with indigo and Indian red; the sea, indigo, gamboge, and a little lake; the boats, sails, etc., with a grey tint of indigo and Indian red mixed, glazed with Vandyke brown and burnt sienna; the figures shaded with the same grey as the boats, and coloured as may be required.

PLATE LXVI

STORM. VIEW NEAR HASTINGS

The colour of the clouds is composed with indigo, lake, and black; the warmer parts, indigo and light red; the sea, indigo and Vandyke brown; the rocks laid in with indigo and Indian red, and enriched with tints of lake, Vandyke brown, and burnt sienna, finished with a few decided touches of Vandyke brown.

PLATE LXVII

CLOUDY EFFECT. DISTANT VIEW OF CARNARVON CASTLE

A mixture of indigo, lake, and black for the clouds; distance with indigo and lake; and the middle distance, indigo, lake, and brown pink; the rocks and foreground are shaded with lake and black; the lights varied with a little yellow ochre, also with indigo and lake mixed; the green, indigo and burnt sienna, glazed with brown pink.

PLATE LXVIII

MISTY MORNING

The sky is laid in with indigo and Indian red, softened with light ochre toward the horizon; the whole of the trees, water, bank, etc., are first worked in with a tint composed of indigo, Indian red, and a little brown pink, afterwards glazed with brown pink, indigo, and burnt sienna, as the warmth or coldness of the objects may require.

PLATE LXIX

AFTERNOON EFFECT. VIEW IN SURREY

The warm tint in the sky is composed with indigo, light red, and yellow ochre, adding more ochre towards the sun; the clouds, indigo and Indian red, tinged with a little yellow ochre; the whole of the landscape laid in with indigo, Indian red, and brown pink, and glazed with brown pink, Vandyke brown, and indigo; the sheep, shaded with indigo and light red mixed, and tinted with light ochre.

PLATE LXX

RAINBOW EFFECT. WESTMINSTER ABBEY, FROM BATTERSEA MARSH

The sky with indigo, lake, and gamboge, taking care to soften the edges of the rainbow with clear water; and when perfectly dry, colour the outer extremity of the rainbow with red; then soften in with it a yellow, which will produce an intermediate tint of orange. While the yellow is wet, run in a blue, which will give a green between the two colours; and under the blue, a little lake must be softened in. The tints upon the bushes on the opposite side of the water are varied with gamboge, burnt sienna, and indigo; the water, the same tint as the sky; the barge, lake and black, finished with Vandyke brown.

PLATE LXXI

MOONLIGHT EFFECT. VIEW ON THE THAMES

The blue in the sky with indigo and lake, subdued with a little gamboge; the clouds tinted with light red and indigo mixed; the distance, water, trees, etc., worked in with a grey composed of indigo, lake, and gamboge, and glazed with brown pink; the barge, with a clear tint of lake and black, glazed with Vandyke brown, finished with a few smart touches of the same.

PLATE LXXII

SNOW SCENE. VIEW IN SUSSEX

The sky is first coloured with indigo and Indian red; afterwards, in parts, with indigo alone. The whole of the landscape is shaded with indigo and Indian red, finished with Vandyke brown and brown pink; the sheep, with a warm grey of indigo and light red, tinted with yellow ochre.

FOOTNOTES:

[A] Reprinted from the cover of the original edition, published in 1813

[B] Reprinted from the original edition, published in 1813

[C] Reprinted from the cover of the original edition, published in 1813