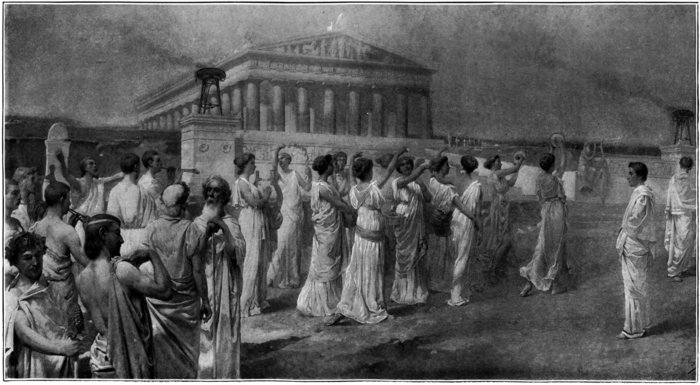

AN ANTIQUE FÊTE.

From the Painting in the Salon by P. L. Vagnier.

Title: The Girl's Own Paper, Vol. XX, No. 993, January 7, 1899

Author: Various

Release date: August 21, 2021 [eBook #66099]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Susan Skinner, Chris Curnow, Pamela Patten and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

AN ANTIQUE FÊTE.

From the Painting in the Salon by P. L. Vagnier.

{225}

Vol. XX.—No. 993.]

[Price One Penny.

JANUARY 7, 1899.

[Transcriber’s Note: This Table of Contents was not present in the original.]

SELF-CULTURE FOR GIRLS.

CHRONICLES OF AN ANGLO-CALIFORNIAN RANCH.

ART IN THE HOUSE.

VARIETIES.

“OUR HERO.”

SONG.

THE RULING PASSION.

ABOUT PEGGY SAVILLE.

ALL ABOUT OATMEAL.

ANSWERS TO CORRESPONDENTS.

ASPIRATION.

All rights reserved.]

There is, perhaps, no word in the present day which has been more frequently used and abused than “culture.” It has come so readily to the lips of modern prophets, that it has acquired a secondary and ironical significance. Some of our readers may have seen a clever University parody (on the Heathen Chinee) describing the encounter of two undergraduates in the streets of Oxford. One, in faultless attire, replies proudly to the other’s inquiry where he is going—

“I am bound for some tea and tall culture.”

{226}

He is, in fact, on the way to a meeting of the Browning Society, and when a Don hurries up to tell him the society has suddenly collapsed, great is the lamentation!

Probably the society in question deserved no satire at all; but there is a sort of “culture for culture’s sake” which does deserve to be held up to ridicule.

We find nothing to laugh at, however, but a very real pathos, in the letters that are reaching us literally from all quarters of the globe; and we long to help the writers, as well as those who have similar needs and longings unexpressed. “How can I attain self-culture?” is the question asked in varying terms, but with the same refrain.

Girls, after schooldays are past, wake up to find themselves in a region of vast, dimly-perceived possibilities:

“Moving about in worlds not realised.”

More to be pitied is the lot of those who have not had any schooldays at all worth speaking of, and who are awaking to their own mental poverty—poverty, while there is wealth all about them which they cannot make their own. Their case is like that of the heir to some vast estates, who cannot enjoy them, because he cannot prove his title.

What, then, is this much talked-of culture?

There are several things which it is not.

To begin with, it is not a superficial smattering of certain accomplishments.

It is not a general readiness to talk about the reviews one has read of new books.

It is not the varnish acquired from associating day by day with well-educated and urbane people.

It is not development to an enormous extent in one direction only.

It is not attending one course of University Extension Lectures.

It is not the knack of cramming for examinations, and of passing them with éclat.

All these elements may enter into culture, but they are not culture itself.

It is a harder matter to define culture than to say what it is not. As we write these words, our eye falls on the saying of a well-known prelate, reported in the Times of the day: “General culture—another name for sympathetic interest in the world of human intelligence.” This sounds rather highflown and difficult, but we may add three more definitions—

“Culture is a study of perfection.”—Matthew Arnold.

“Culture is the passion for sweetness and light, and (what is more) the passion for making them prevail.”—Matthew Arnold.

“Culture is the process by which a man becomes all that he was created capable of being.”—Carlyle.

The third of these is, perhaps, the best working definition of culture, for it shows its real importance and significance, and also makes it simpler to understand.

Look at a neglected garden. The grass is long and rank; the beds are a mere tangle of weeds and of straggling flowers that have run to seed, or deteriorated in size and sweetness until they can hardly be called flowers at all. It is a wilderness.

The garden is taken in hand and cultivated, not by a mechanical ignorant gardener, but by someone who understands the capacities of the soil, and knows what will do well and repay his care. See the transformation in time to come! There is everything by turn that is beautiful in its season; the lovely herbaceous border, the standard rose-trees, the sheltered bed of lilies of the valley, the peaches on the warm southern wall, the ferns waving in feathery profusion in the cool corner near the well—all that the garden can produce for delight to the eye or for food is there. The ground is not given over exclusively to one flower, one vegetable; it is not stocked mechanically for the summer with geraniums and calceolarias; but it is, as we say in homely parlance, “made the most of” in every particular, and is a delight to behold.

This may seem a simple illustration, and we are writing not for the erudite, but for the simple reader. The man or woman of culture is the man or woman whose nature has been cultivated in such a way as to develop all its capabilities in the best possible direction; whose education has been adapted skilfully to taste and capacity, and who has been taught the art of self-instruction.

It is hardly necessary to urge the value of this “cultivation.” “Cultivation is as necessary to the mind as food to the body,” said a wise man, and this is gradually coming to be believed. Culture is something more by far than mere instruction, though instruction is a means by which it may be attained. Bearing in mind our simile of the garden, we are led on from one thought to another.

It was a very wise man indeed who pointed out that, even as ground will produce something, “herbs or weeds,” the mind will not remain empty if it is not cultivated; it tends to become full of silly or ignorant thoughts like “an unweeded garden.”

Again, in a well-ordered, cultivated plot of ground we have what is useful as well as what is lovely. In culture, not only the acquirement of “useful knowledge” plays a part, but the storing of the mind with what is beautiful, the development of taste in all directions.

In brief, a woman of real culture is the woman who makes you instinctively feel, when in her company, that she is just what she was meant to be; harmoniously developed in accordance with her natural capacity. There is nothing startling about her paraded attainments. The extreme simplicity of a person of true culture is one of the most marked traits, and the chief point that distinguishes spurious from real culture is that the former is inclined to “tall talk” and the latter is not.

Charles Dickens can still make us smile at his caricature of an American L. L. (literary lady) and her remarks on her introduction to some great personage. She immediately begins—

“Mind and matter glide swift into the vortex of Immensity. Howls the sublime, and softly sleeps the calm Ideal in the whispering chambers of Imagination. To hear it, sweet it is. But then outlaughs the stern philosopher and saith to the Grotesque: ‘What ho; arrest for me that Agency! Go, bring it here!’ And so the vision fadeth.”

The woman of culture does not attempt fine talking, and it is only gradually that her power and charm dawn upon her companion. “It is proof of a high culture to say the greatest matters in the simplest way.”

In the same manner simplicity is a proof of high breeding. The people who are “somebody” are, as a rule, easy to “get on” with. It is the rich “parvenue” who is disconcerting, and who tries to drag into her conversation the names of great people or great doings that will impress her companion.

When we observe this sort of thing in a woman, we always know she is not “to the manner born.” So when we hear people declare, “I am afraid of So-and-so because she is so clever,” we feel that, if there is ground for their fear, there is something defective in the clever one’s culture.

Why should Culture be Desired?

It opens the eye and ear to the beauty and greatness of the world, revealing wonders that could not otherwise be understood, and bringing with it a wealth of happiness; and more, it gives an understanding of life in its due proportion. The woman of culture is not the woman who objects to perform necessary tasks at a pinch because they are “menial,” or takes offence at imaginary slights, or is for ever fussing about her domestic duties and her servants, or gets up little quarrels and “storms in a teacup” generally, or delights in ill-natured gossip. She sees how ineffably small such things are, and she sees them in this light because she has the width of vision which enables her to discern the meaning of life as a whole. Those whose eyes have once been opened to the beauty and pathos that lie around their path, even in the common round of daily duty, do not notice the dust that clings to their shoes.

Sympathy is an accompaniment of true culture; the sympathy that comes of understanding. Ignorant people are very often hard just because of ignorance. They cannot in the least enter into the feelings of others, nor do they understand that there is a world beyond their own miserable little enclosure.

For instance, what a puzzle a clever, sensitive, imaginative child is to people of contented matter-of-fact stupidity! One need not think of Maggie and Mrs. Tulliver, or Aurora Leigh and her aunt, to illustrate this—there are plenty of examples from real life.

The girl does not take to sewing and the baking of bread and puddings; she is always wanting to get hold of a book—never so happy as when she is reading. Or the boy is always poring over the mysteries of fern and flower—never so happy as when he is afoot to secure some fresh specimen. People of culture would foresee that the one may be a student, the other a botanist, in days to come, and, while of course insisting that practical duty is not selfishly overlooked, they would try to give scope for the individual taste. People without culture would set the whole thing down as laziness and vagabond trifling and “shirking,” to be severely repressed. Sympathetic insight is one of the most valuable attributes of culture; valuable all through life, especially when dealing with others.

But we can imagine that the reader may be thinking rather hopelessly, “It is not necessary to preach to me on the advantages of culture; I am fully convinced of them; but all you say makes me hopeless of ever attaining such a degree of perfection. In fact, I can see culture is not for me at all, and I must just go on as I am.”

The dictionary definition of culture is “the application of labour, or other means, to improve good qualities, or growth.” This does not sound quite like the other definitions, and a great deal of confusion has been caused by people forgetting that the word “culture” is used for two things—the “process” of cultivation, and the “result” of that process. Now it is quite true that “culture,” in the last and highest sense, is not within the reach of all our readers; but surely there is no reader who would say she cannot “apply labour or other means” to improve her intelligence, be it in ever so small a degree. It is better to cultivate a garden ever so little than to leave it a wilderness.

Culture, looked upon as a process, may begin and go on almost indefinitely. Goethe well says—

“Woe to every sort of culture which destroys the most effectual means of all true culture, and directs us to the end, instead of rendering us happy on the way.”

In other words, it is foolish to strain miserably after “culture for culture’s sake,” endeavouring to reach an impossible goal, and feeling discontented and wretched because it is too remote. The wise way is to do the best one can with the opportunities that lie within reach. Every girl who reads these pages can do something to render herself a little nearer her ideal of “culture,” and in the subsequent papers we shall try to show her how she can best succeed.

Lily Watson.

(To be continued.)

{227}

By MARGARET INNES.

OUR CHOICE OF LAND FOR LEMONS—THE PLANTING OF THE TREES—OUR REMOVAL TO THE BARN.

Meanwhile we were furiously busy at the old search again. We were able to get more and fresh details about the whole business from a source which we knew to be perfectly reliable; and as these facts were encouraging, we picked up heart again. The whole surrounding neighbourhood was driven over, generally with a pick and shovel in the buggy with which to make careful examination of the depth and kind of soil.

There were plenty of ready-made ranches for sale, but they were never just what we wanted. So we resolved that if we bought anything, it should be untouched, uncleared land, on some of the foothills where we could get a broad and sweeping view of the splendid ranges of mountains. We would make our own ranch, planned after our own tastes, and, above all, we would build our own house.

We had determined to plant lemons. They seemed to us to have many advantages over other fruits. The land which will produce fine lemons must necessarily be limited in area; it must be high enough to escape the frost. Lemons do not need the great heat which is needed to ripen oranges. They are gathered all the year round and will keep. Deciduous fruit ripens all at one time, and has to be gathered and sold at once, which makes it necessary to engage outside labour. As all wages are very high, this is a heavy expense. Even if the fruit is dried, as in the case of peaches, pears, prunes, apples, etc., for winter use, considerable work is involved, and as far as we can learn, yields only a small profit for this extra trouble. Lemons too, in America, are a daily necessity, not a luxury. Everyone uses them, and the drinking saloons alone require a constant supply.

These were the principal reasons which decided our choice, and at last, after a whole year’s uncertainty, we found land in a position that we liked—good rich land, lying high, and in a most beautiful position, with a splendid view of the distant mountains, the tops of five ranges standing up, one behind the other, and the different distances marked with exquisite softness of colouring.

It was situated about fourteen miles from San Miguel, not out of reach of the cool breeze which blows from the sea all day and every day during the summer.

We went many times to examine it, and finally the great decision was taken to buy thirty acres. At that time we found we could buy in this neighbourhood first-class citrus land, with water, at about one hundred dollars the acre. We knew there was no good land to be had for less. As a matter of fact, however, the first cost of land and water bears but a small proportion to the whole cost of the ranch up to the point of yielding returns.

After our long time of anxious indecision, it was a relief to have something settled about the future, and to plan and work for the new home, although I must confess that, as long as no definite steps had been taken, I was conscious of a hope buried deep down out of sight, that it might be proved wisest for us to return to the dear old country. The home-sickness was such a hunger and pain.

It was the month of June when we bought our land, and we were anxious to plant as many trees as possible without delay, for the later the summer, the drier the ground. Spring is, of course, the best time for planting, when the earth is in beautiful condition after the winter rains. But to wait till next spring seemed too great a loss of time. We were very proud of ourselves that we managed to get five hundred beautiful little lemon-trees planted before the end of July.

Considering that the ground had to be cleared of brush and sumac and sage, then ploughed, and the water-pipes laid from the main in such a manner as to reach all over the ranch, and the position of the trees carefully measured (this last all the more difficult in our case, because the ground is up and down hill)—considering all this hard work, we had a right to some self-satisfaction.

We were able to find a competent ranchman who lived quite conveniently near, for, until we had time to build, there was nowhere for him to sleep on the ranch, although, in some cases, the conveniences for these men are of the roughest. We heard from one man that, when he arrived at a new place and asked where he was to sleep, the “boss” stared at him a moment, then, giving a comprehensive glance round his enormous tract of land, said, “Well, if you can’t find a place to suit you in seven thousand acres, I guess I can’t help you!” However, I do not vouch for the truth of this, although sleeping out-of-doors in the summer months in this beautiful climate is no hardship.

During this busy time, my husband and eldest boy drove out constantly to the ranch for a stay of three or four days at a time, returning home for a short rest at the little house in San Miguel, then back again to the hard work of planting, etc. On these expeditions they started always very early in the morning, and took with them provisions and various odds and ends to give them some comfort in the tent in which they slept.

We were feeling the urgent necessity for carrying through some plan that would enable us to settle at the ranch altogether with as little delay as possible. So we decided to have our barn built first and to live in this till the house should be finished. This we carried out, and it saved us much loss of time and vexation, both in building the house and in working the ranch.

It was an exciting moment when the day arrived for us to move from our little house at San Miguel to the barn at the ranch. A removal is a very different matter in this far-away corner from the same thing in any more settled part of the world. Looking back to the old life in the beloved old country, I find I have an almost sentimental regard for the strong, well-trained men who come and help so splendidly at such times. Here, where the rule of life is to help yourself in everything, one has to be thankful for the most casual, untrained assistance—very little of that too, and at a price that would make one open one’s eyes at home.

We had two large waggons coupled together, the one behind being called a trailer, with six horses to pull the load; and our luggage, which included a large iron cooking-stove and a grand piano, was packed into these in a most casual fashion. They looked very top heavy when ready to start, and we knew the road to be terribly rough, full of “chuck holes” and sudden lumps. However, we waved the men a cheery farewell as they lumbered off, and then turned to gather up the numberless forgotten odds and ends and to pack them into the “Surrey,” which stood waiting for us.

It looked like part of a gipsy procession when we had finished, and we rejoiced that our boys had gone with the waggons, for there seemed absolutely no room for anybody inside the “Surrey.” Nevertheless, we wedged ourselves in somehow, my husband and I and the “coloured lady” whom I was taking out as cook, also two small dogs that had been added to the family. Then we also lumbered off, leaving with rather mixed feelings the little house where we had done our first housekeeping in California.

About a month before this, after many experiments with horses we had bought a pair of greys, and now drove them out to the ranch, where they were to plough and cultivate and to serve as carriage horses when needed.

The ordinary ranch horse is of a lighter build than his cousin the English farm horse, having a strong dash of broncho mixed with his peasant blood, which makes him rather lively and very tough.

Ours were called Dan and Joe. Joe was very gentle and willing, and Dan, who for some years had worked constantly with him, traded on his goodness and left always the greatest strain of everything to him. However, generally they ran along together at a good pace and gave no trouble.

This day we were obliged to go more slowly, as the “Surrey” was so heavily laden, and the rough country roads bumped and lurched us about so violently that it was difficult to keep ourselves and our bundles from being shot into the air. With all our care, a large and tempting piece of cheese, which had been added to the provisions as an afterthought, disappeared, and we spent some valuable time in turning back to hunt for it.

We were anxious to reach the ranch as long before sunset as possible, for we knew it would not be easy work to get our little family settled in the barn.

(To be continued.)

{228}

How to Stencil in Oil Colours.

Ordinary tube colours should be used for stencilling on your furniture mixed with a little copal varnish and slightly thinned with turps. Driers are put up in tubes under the names of sacrum or sugar of lead, and it is as well to mix a little with your colours as it makes them dry off quickly. The white should be mixed up in a batch with the varnish, driers and turps, and be of the consistency of thick cream. Your tinting colours should be squeezed out on your palette so that you can readily mix up your tones.

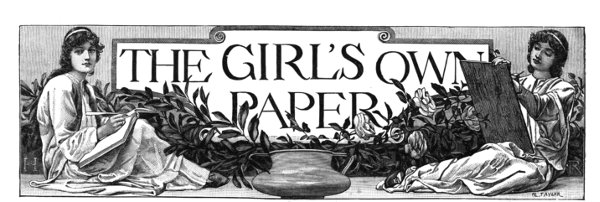

Fig. 1.—Panel of corner cupboard decorated in stencilling. The centre panel is founded on the iris, with the daisy at base.

Stencil brushes are round and short in the hair, so that they present a flat surface on the stencil. You require three or four, two about an inch in diameter, one five-eighths and one three-eighths or a quarter of an inch. Two or three small flat hog brushes for touching in ties and putting in particular parts of a stencil should be handy. We will begin with the stiles of the door of chiffonier, which is decorated with the ornamental stencil B, Fig. 1 in first article. We put the corners in first and this corner I cut separately as I could not fit in the stencil I was using. Having done this see how your other stencil will work out, for it does not look workmanlike to start at the top and find that you have to end it with a different spacing to what you started with. If you begin in the centre of each stile and work to the corners you will obtain a symmetrical result. Always remember to space out any part of your work which is conspicuous, so that the stencil seems to just fit in the space as though it were cut specially for it. I find it a good plan to have some pins handy, and just tap in a couple, one at each end of the stencil, to keep it from shifting while you rub on the colour. Both your hands are then at liberty. Or you can get a friend to hold the plate down on the wood, but the pinning does almost better. If you shift the stencil before you have knocked out the impression you will not get a sharp result.

Having tinted your white to the desired tone spread a little of the colour on to your palette and knock your stencil brush on to this colour a few times, so that the brush takes up some of the colour, then begin by gently knocking the brush on to the wood over the cut-out portions until you have completely covered them with colour. Don’t try to do this too quickly. Proceed gently, getting the colour out of your brush by degrees, and take up the colour from the palette in the same gentle manner. The reason for this caution is that if you take up too much colour at a time in your brush and knock it violently on the stencil plate, you will find when you lift up the same that the impression, instead of being sharp will be blobby at the edges through the colour having worked under the stencil.

The art of stencilling is in getting sharp, clean impressions, and this can only come of care and taking time. On no account get the colour too thin. It should be of such a consistency as will enable you to knock it out of the brush with slight exertion. If too stodgy thin it with a drop or two of turps and linseed oil, and then mix with palette knife, but on no account get turps into the stencil brush or you will get very bad impressions, for the colour is sure then to run under the stencil. Therefore again I say, don’t hurry.

I have said nothing yet as to the tones of colour to be used. This is a matter of taste, and is a most difficult subject to write about. Two artists will use the same colours, and yet one with an eye for colour will give us beautiful harmonies, and the other one wanting this delicacy of perception will give us crudity. Form in your mind some tone of colour suggested, say, by the warm mellow colours of autumn, the soberer russet and greys of the winter, or the light, fresh, delicate tints of spring, and carry these suggestions out in your decoration. The corner cupboard, Fig. 1, we might tint in the russet tones, and you will find that such colours as raw sienna, raw umber, yellow ochre, terra verte, burnt sienna, chromes Nos. 1 and 2, Prussian blue, French ultramarine, and light red will supply you with a very varied palette. White tinted with yellow ochre, raw sienna or raw umber are all good tones for stencilling in, and each of them can be mixed or toned with one of the others. The addition of terra verte or Prussian blue will give you soft tones of green. By using such a yellow as ochre to make greens you obtain softer, quieter tones than if you used chromes. Suppose you have small quantities of the above three tints mixed on your palette, you can take a little of one in your brush and knock that out on the stencil, and then a little of the next tint and knock that out, and so on with the third. In this way you get a variety of tints in the stencilled border and yet a certain “tone” will run all through, which gives one a sense of harmony, and at the same time variety, and so lessens the hard mechanical look which stencilling in just one colour is apt to give. Then, too, when you have knocked out one impression before lifting off the stencil, you can take one of the hog hair brushes or the smallest stencil brush and put in the body and the portion of the wings around it of the butterflies B in the corner cupboard, Fig. 1, in a little darker colour, say more raw umber or sienna. It is very little more trouble and greatly adds to the general effect to give these accents. The idea is to make the butterflies come off the web, so keep the web lighter and the insects darker.{229} In the border B, Fig. 1, in first article the flowers might be touched in to bring them off the lines of the background.

The pattern on the spaces surrounding the door A, Fig. 1, can still be in the same tones, varied as I have suggested, but the panels of the doors being themselves more naturalesque, might be a little more positive in colouring, i.e., the leaves and grass can be put in, in quiet, soft tones of green, while the flowers could be in lemon chrome and white or bluish purple made of rose madder and French blue or Indian red and Prussian blue lightened with white, but don’t make the colouring too bright, so that it is in too strong contrast to the stiles. Greens made of blue and chrome are much cruder than if you use yellow ochre or raw sienna. Going back now to the colouring of the chiffonier Fig. 1 (p. 13) in first article. The plinth or bottom D can be in low-toned greens, not too dark but darker than the leaves in the panels, while the daisies can be in grey made of white, raw umber, and a touch of blue, with centres in yellow. Stencil the flowers first and then with a small brush put in the yellow centres. A slight touch of pink at the edges of the daisies might look well, effected by using a small hog brush and a little rose madder. The leaves around the column keep in the quiet greens used in plinth D. The back of the upper part of chiffonier, Fig. 2, with its shelf can be treated like the panels in colouring, and the festoon above the shelf can have the flowers in the grey and the leaves in russet not too dark, and the ribbon in pale blue. As you have a white surface to decorate, be careful not to get your colouring too strong. Use plenty of white with all your colours, for you will find that delicate tones are much pleasanter to live with than heavy ones. A little of the pure colours from the tubes will tint a lot of white, so the colours will not be a great expense. Buy the flake white in half-pound tubes for cheapness.

In arranging stencils act somewhat on the plan I have observed, which is to keep the more naturalesque stencils for such places as panels or other flat, broad surfaces, and as a framing to them the more ornamental patterns, to contrast with the natural ones. The butterfly border on the stiles of the corner cupboard B, Fig. 1, is a good foil to the iris panel, just as the border B, Fig. 1, is a good foil to the daisy panel in the chiffonier.

The conventional grass seemed a suitable pattern for the plinth, and such a purely ornamental design as a festoon not inappropriate to the shaped top.

I have mentioned before that great variety can be obtained by combining portions of different stencils. The plinth D, Fig. 1, of chiffonier, for instance, is a combination of two, the flowers being from one and the grass itself from another. The butterfly and sprig running border, Fig. 1, in second article, I have shown in variation, and the border in corner cupboard, A, Fig. 1, is made by taking the sprig portion only and putting the root in between each impression. When you want only a portion of a stencil cover over the rest with paper, so that you do not get an impression of a part you do not require.

Some colours are very fugitive such as indigo, crimson lake, yellow lake, etc.; but the colours I have mentioned may be relied upon for permanency.

When the stencilling is thoroughly dry it will preserve the work to give it a coat of white hard varnish. Apply this freely with a flat hog brush (or regular varnish brush), seeing that you miss no portion of the surface. Keep it from the dust until dry and you will have a pretty and useful article of furniture. Of course you may have some other article to do up than the chiffonier I have sketched, which I took simply because it was to my hand, but you can easily apply these hints to your own necessities.

When your stencils are done with you wash them thoroughly in turpentine, both back and front, and dry them and put them away, keeping them flat.

While you are using your stencils wipe the back after each impression, so that if any colour has worked there you can remove it. Have an old board and some newspaper to lay the stencil on when you clean it.

With the batch of stencils given with these articles endless variations and combinations are possible. Many of the patterns too could be easily adapted for needlework; in fact, you have only to lightly stencil your material in water colour and work over the impressions. Use Chinese white if a dark textile, and lamp black and Chinese white if a light one.

Though I have advised white paint for these two articles of furniture, there is no reason why you shouldn’t try dark ones. Stencilling is very effective on dark paint, and a cabinet or cupboard painted a dark brownish green would look well with stencilling in shades of old gold. To get a rich colour the final coat must have very little white with it. For a brownish green use burnt sienna, black, deep chrome, and touch of Prussian blue, with only enough white to make it light enough.

Fred Miller.

How to Get On.

When Lord Esher took leave of the Bench and Bar recently, he made a noteworthy utterance, which has an interest for all young people, even though they are not lawyers or ever likely to be.

This eminent judge, who has sat on the judicial bench with great distinction for twenty-nine years, told his hearers that resoluteness of purpose had been the secret of his success.

“What I will say to all of you,” he remarked, “is this. I became a judge because I had made up my mind and will, from the beginning, that I would be a judge. Do not suppose I had no checks, and that there were not occasional times when it appeared that one was being passed over. I said, ‘Never mind the checks; I will go on, and I will get to the top, if it is possible to do it!’ I recommend that to you all.”

Such is Fame.

The great Napoleon, more than a year after he had become Emperor, tried to find out if there was anyone in France who had never heard of him.

It was not long before he discovered a wood-cutter at Montmartre within the walls of Paris, to whom the name of Napoleon was quite unknown, and, more than that, the man was ignorant of the Revolution and had no knowledge of the fact that Louis XVI. was dead.

Another anecdote showing equally well that the trumpet of fame does not reach the ears of everybody was told by Mr. Roebuck in the course of a speech made at Salisbury in 1852. He told his audience that when he mentioned the recent death of the Duke of Wellington to a “shrewd Hampshire labourer,” the man replied—

“I be very sorry for he. But who was he?”

Kindness and Courage.

A Real Friend.—Account her your real friend who desires your good rather than your good-will.

Answer to Triple Acrostic (p. 63).

(Extra Christmas Part.)

| 1. | E | ver | G | ree | N |

| 2. | L | E | A | ||

| 3. | I | st | H | mi | A |

| 4. | S | ol | A | nu | M |

| 5. | H | u | Z | z | A |

| 6. | A | nd | I | ro | N |

Elisha—Gehazi—Naaman. {230}

By AGNES GIBERNE, Author of “Sun, Moon and Stars,” “The Girl at the Dower House,” etc.

FROM OVER THE WATER.

Lucille, turning to go, made a little sign to Roy to follow her. Ivor opened the door, moving mechanically, as if his mind were far away; and Roy, with a show of reluctance, went in her rear.

“But, Mademoiselle, I want to know about them all at home. Molly most! And Den can tell me.”

“Yes; soon. But would you not leave Monsieur to read his letter in peace? Would not that be kind?”

“Are you more sorry for Den than for the rest of us?” demanded Roy, his frank grey eyes looking Lucille in the face somewhat laughingly. The question took her by surprise; and afterwards she recurred to it, wondering at the boy’s unconscious penetration. At the moment she met his glance readily enough.

“I do not know. I am sorry for you all. But Captain Ivor—yes, perhaps most. I am not sure. He is more changed by his imprisonment than any. Cannot you perceive? Mais non—you are a boy—you do not look.”

“I do, though,” protested the injured Roy. “That was why I wouldn’t go on playing chess. And then for you to say that I don’t look. But I can’t see that Den is changed—not a scrap. What do you mean? He’s the best old fellow that ever lived—just as he always was, you know.”

“Old!” repeated Lucille, with a lifting of her eyebrows.

“O, that’s only—that means nothing. At least, it means that I like him better than anybody else—except Molly. No, he isn’t old really, of course—he was twenty-five his last birthday.” Roy laughed to himself.

“Something that you find amusing, Roy!”

“It’s only the letter. Do you know, that’s from the girl he is going to marry some day. It’s from Polly.”

“Oui.” Lucille had already conjectured as much. “Mademoiselle Pol-ly. C’est un peu drôle, ce nom-là.”

“But ’tis not Mademoiselle Po-lee. ’Tis just Polly. You do say names so drolly—so French! Den says I’m not to cure you of talking as you do, because ’tis pretty. But her name really and truly isn’t Polly. She is Mary Keene—only no one ever calls her Mary.”

“Mademoiselle Marie Keene—ah, oui. And is this Mademoiselle Keene pretty—gentille?”

“I should just think she was. The prettiest girl that ever was,” declared Roy. “Though I like Molly best, you know, and she’s not pretty. But Polly’s nice, too. May I go back now? Den has had lots of time.”

“I would wait—ten minutes—why not? You have not yet unpacked for monsieur.”

Roy murmured one impatient “Bother! Plague take it!” and then his face cleared, and he complied. Ivor did not know how much he owed to Lucille, in being thus left to the undisturbed enjoyment of his letter.

He forgot all about both Lucille and Roy, when once he had it in possession. The very touch of that thick paper, with its red seals, did him good. As he unfolded it, the weight on his brain lessened, and sight became more clear. If Polly only wrote to say that she was growing tired of waiting and could not promise to wait indefinitely, still even that would be better than not hearing at all—even to know the worst at once would be better than absolute uncertainty. And meanwhile it was her own handwriting.

There was one sheet, square-shaped, written well over. Polly’s letter came first, and another from somebody else followed it. Ivor did not trouble himself as to the authorship of the second, till he had read through the first. He scarcely vouchsafed it a glance.

The early part of Polly’s effusion, which bore a date many weeks old, was written in a strain of studied archness and badinage, such as in those days was greatly affected by young ladies. Towards the end a little peep into Polly’s heart was permitted. She had apparently just received one of Ivor’s many epistles, the greater number of which never reached their destination.

“Bath. November 7, 1803.

“My dear Captain Ivor,—So you consider that I have been too slow in writing to you, and you make complaint that I leave you too long without Letters. But how know you that I have not sent at least one for every single one of yours to me? In truth, I cannot boast of any vast correspondence on your side, my dear Sir, since the letter which is now arriv’d is but the second in——O in quite an interminable length of time. And were it not that I have an exceeding Aversion to the writing of Letters, as indeed you ought to be aware, since I am sure I have told you as much, I might feel Regrets at hearing so seldom—but that it means the less toil on my part, you understand. If it were not that in your last you give a delicate hint that Silence on my part might be construed to mean something of the Nature of Indifference, why even now I should be greatly disposed to indulge my Dislike to driving the Quill, and wait till another day.

“But since doubtless you will expect to hear, and since we never may know which letters have gone astray, I will so far overcome my inclinations—or my disinclinations—as to sit down and endeavour to entertain you with the best of Bath News.

“My letter which was writ from Sandgate you have, I trust, already received, and thus you know all about the scare which took place, when the French fleet was descried by somebody of not very good sight—or so I suppose!—and when signals went wrong, and the Soldiers and Sea-fencibles and Volunteers were all called out, and when General Moore galloped the whole distance from Dungeness Point to be in time, and when Mrs. Bryce’s heart failed her. But not Polly’s, Captain Ivor—of that you may be sure! For Polly is to be one day the wife of a soldier! And also Polly knew that, if she were to be taken prisoner, as Mrs. Bryce dolefully foretold, why—why—that might mean that she could hope to be sent to where Somebody is, whom she would not be greatly sorry to see once again.

“Mrs. Bryce insisted on coming hither in hot haste, lest Napoleon should please to land at Sandgate, where General Moore waited to receive him; and now she is in doubt what to do next, since some think London is the safer place to be in. But General Moore does not now think that Napoleon will make any effort till spring, since any day winter storms in the Channel may begin; and Jack scorns the notion that, when he does come, he will ever advance beyond the sea-beach. ’Tis said that, if Mr. Pitt comes into power again, he will speedily start some new ideas for our Preservation; and my Grandmamma says, therefore, that we may not start any new expenses till we know to what length Taxation will allow us to run. But for which I wanted much a new frock.

“Last week I was in Bristol for three days, with our Grandmother’s old friends, Mr. and Mrs. Graham. I was asked to a dance with them, and I went, but without the smallest idea of dancing, having been assured that beaux were scarce, and strangers seldom asked. So I determined to enjoy seeing others more fortunate, and to pass a quiet stupid evening, meditating on an absent Somebody—can you by any possibility guess Whom, my dear Sir?

“But matters turned out otherwise. I had entered the room only a few minutes, when a most genteel handsome young Man advanced, and with such sort of speeches as you all make solicited the honour of my hand. To tell you the honest and plain truth, I had seen him before, and I therefore graciously assented. I left the ladies that accompanied me—Mrs. Graham and Mrs. Graham’s sister—to look out for themselves; and I began thereupon to enjoy myself. Now, if you want to know his name, you must wait till I choose to tell you. He contributed to my passing a very agreeable evening; and so far I am obliged to him, for he knew many who were present, and he took good care that I should be in no lack of partners; but whether I ever see him again does not seem to be of any sort of consequence. Everyone was astonished at my great good luck in dancing, for the Gentlemen were, as usual, idle. There were some sad Coxcombs present, I regret to say, who found it too much exertion even to come forward and shawl a lady, when she was departing. But I forget—I am writing to one who knows not the meaning of the word ‘trouble,’ and who{231} would never leave any woman, not if she were the least Bewitching of her Sex, to stand neglected, if he could put matters right. So you see, my dear Sir, what my opinion of you is.

“Having related thus much, I really am bound to go farther, and to inform you that the young man’s name was Albert Peirce, that he is a nephew of the good Admiral, that he is an officer in His Majesty’s Army, and that I saw him at Sandgate, the evening before our great scare about the Invasion. After all his civilities in the way of getting me Partners, he also handed me down to the vastly elegant Supper, which was provided; and by that time, there’s no doubt, I needed it.

“You may perhaps be thinking that I do very well without you, on the whole; yet I cannot say that I do not miss my absent friend. Indeed I do, and my Spirits are lower since you went away. ’Tis said too that my Roses are much diminished, and that I must e’en take to the use of Painting and Cosmetics, if I would preserve my charms; but this, I confess, I am loath to do. So come home again, my dear Denham, I entreat of you, as soon as ever you may, for in truth I am longing to see you again. Is there no Exchange of Prisoners ever to be brought about by the two Governments? The present state of things is sad and dolorous for so many. I think of sending this letter to your old address in Paris, in a cover addressed to M. de Bertrand, who so kindly took in Roy, when he had the Small-pox. It appears that few letters which are posted, arrive safely; and ’tis at least worth while to try this mode. And now I must write no more, for my Grandmother craves a part of the sheet for a letter on her own behalf, that she may give suitable particulars about Molly, who begs me to send her Duty to her Parents, and her Love to Roy. I have begged only that the Letter may be writ to yourself, that so the whole sheet may be yours.

“So at present no more, from

“Yours faithfully and Till Death,

“Polly Keene.”

Denham held the signature to his lips. Would he ever again be tempted to doubt sweet Polly’s constancy?

The letter following, on the last page, was much shorter and different in style. Mrs. Fairbank wrote—

“My dear Captain Ivor,—I am desirous to let Colonel Baron and his wife know that Molly is in good health, and Behaves herself as she ought. I have therefore requested the use of one page in Polly’s letter, since she assures me that she has nought else to say that is of great Importance. You will doutless kindly give my message to Colonel and Mrs. Baron.

“I am greatly Indebted to Colonel Baron for the money which has been sent to me by his Bankers regularly, in conformity with his orders given many months ago. Expenses are increasingly heavy, as Prices continue steadily to arise, in consequence of the long-continued Wars; and I shou’d find it tru’ly difficult to manage, as things are now, but for his Seasonable and generous Help. I am thankful to have it in my power to do all that is needed for Molly, and the help to myself is not small. Bread and every necessary are rising.

“Molly has a Governess who comes in every day; and I am pleased to be able to report that she makes good advance in her Study’s, as much as one cou’d expect. The young Governess is of French Extraction, her father having lost his life in the French Revolution, and her mother having fled with this daughter to England. She will therefore be able to impart to Molly the correct Pronunciation of French terms, which few Britishers manage to Acquire. Molly is growing fast, and though she will never be handsome, she is gaining a Pleasing expression of countenance; her manners are Genteel; and she behaves with Candour and Propriety.

“Serious fears have been Entertain’d of a French Invasion of this Country, but I trust, thro’ the Mercy of God, that the danger is averted for this autumn. Mr. and Mrs. Bryce have fled to Bath for greater Safety, in accordance with my Advice; and indeed I was heartily glad when Polly had left Sandgate. If the french Army shou’d land, and shou’d advance to Lonn, God forbid they shou’d molest the good Citizens, who I hope will be enabled to drive the french by thousands into old Thames.[1] People seem now, however, greatly to relax in their fears.

“You will dou’tless be glad to hear that Polly is well, though she has not quite her usual bloom. Indeed, I am convinc’d that she has suffered greatly from your prolonged Absence, although, having a high Spirit, she does not readily betray her feelings.

“Believe me, my dear Sir,

“Yours sincerely,

“C. Fairbank.”

“Den, is it from Polly?” cried Roy, bursting into the room.

“Yes. And Molly is quite well, and sends you her love. Come, we must tell your mother that I have heard.”

“I’ve done your unpacking. Mademoiselle wouldn’t let me stay. She said I ought to leave you to read your letter in peace.”

“Rather hard upon you, eh?” suggested Ivor. “Come along!” and Roy, forgetting all else, sent a shout in advance to prepare his mother for what was coming.

They had to make the most of this letter. None could guess how long a time might pass before they would hear again. Every detail was eagerly dwelt upon, and on the whole Polly’s report was counted satisfactory. Naturally it awoke fresh memories, fresh regrets, fresh longings; yet Denham at least seemed the better for his “medicine.” The look of weight and strain was gone from his face next morning, and he appeared to be in much his usual spirits, when he proposed a walk with Roy to explore the neighbourhood. He and the Colonel had just returned from appel; all détenus and prisoners having at stated intervals to report themselves at the maison de ville.

“Will you have to sign your names every day?” Mrs. Baron asked, on hearing particulars.

“At present, no. Den and I and a few others are excused from doing so more often than once in five days. But the greater number have to show themselves every day—unless they can send a medical certificate, forbidding them to go out, on account of illness.”

“Remedy worse than disease,” murmured Ivor.

“And if one stays away, without sending such a certificate, the gendarmes promptly make their appearance, expecting a fee for the trouble.”

“How much?”

“Three francs—so I am told.”

“What a shame!”

“General Roussel does not seem to be a bad sort of fellow. Civil enough. But they mean to be strict.”

“Good many escapes of late, sir.”

“Why, Den—escapes when they’ve given their parole!” cried Roy.

“No; only when they have not given their parole. That makes all the difference.”

“And may you and papa go wherever you like?”

“Within stiff limits. Five miles from the town—no more without leave.”

“I foresee that we shall have to pay pretty liberally for that leave,” added the Colonel.

“Did you see many friends there, George?”

“A good many coming and going. All of course who were at Fontainebleau are here, and numbers from Valenciennes and Brussels. We came across Mr. Kinsland, and General Cunningham and Welby, Greville, Franklyn and others.”

“Den, I say, do come along,” urged Roy, who had already been for a run, but who greatly preferred a companion.

“All right—if you don’t mind paying a call by the way.”

Roy declared himself ready for anything, and they went first toward the lower part of the town, on a level with the river. Roy, full as usual of ideas and talk, poured out for his companion’s edification some items of information, which he had gained from Mademoiselle de St. Roques.

“She says Verdun is an awfully old place—goes back to almost the days of Charlemagne. When did Charlemagne live? And only a little while ago it was a French border town—frontier town, I mean—but it isn’t now, because Napoleon has conquered such a lot of Europe. And do you know, the Prussians took it from France only just a few years ago, after quite a short siege. And the French Governor killed himself.”

“Saved Napoleon the trouble, I suppose.”

“Does Napoleon kill his generals when they are beaten? Oh, let’s go up on the ramparts! Look, there are trees all along, just like a boulevard. Mademoiselle says the ramparts are three miles long. Are they, do you think? What is the business you have to do on the way? Are you going to see somebody?”

(To be continued.)

{232}

THE LESSON.

{233}

By L. G. MOBERLY.

Among the crowd in the top gallery at St. James’s Hall was one very remarkable figure who was an object of speculation to most of his fellow-listeners at the Monday Popular Concerts. He was a regular and unfailing attendant for many, many years, but not very long ago he disappeared suddenly in the middle of the season, and his place knew him no more.

He was an old man, apparently between seventy and eighty, very tall, thin almost to emaciation, with a magnificent head, white hair that was still thick and rather long, a short white beard and moustache, a fine straight nose, and very sad, kindly grey eyes. His hands, though old and shrunken, with their veins standing out in relief, were well shaped, and still had the trained, capable look that only those people possess who, having been taught to use and develop the muscles of their hands while young, keep them in constant use and practice afterwards.

That he was very poor was certain, for year by year he appeared in the same clothes. A very old, threadbare, but well-brushed Inverness cape, a white woollen comforter, and a soft felt hat that had once been black, but was now of the indescribable greenish-brown tint that black hats assume in their last stages of existence. He also wore grey cloth gloves and carried a thick blackthorn walking-stick with a knob handle.

He came alone to the concerts and sat on the extreme right-hand of the gallery, close against the wall, in the third row from the front. Sometimes he was joined by a young man, who was the only person he was ever seen to converse with at length, though he would answer politely any chance question about the music or the artists, on both of which subjects he appeared to have considerable knowledge.

His English was perfect and fluent, but the impression prevailed in the gallery that he was foreign.

One Monday evening a few years ago he came to the gallery at seven o’clock and took his usual place. It happened to be the first appearance of Joachim that season, and it was not unreasonable to suppose that there might be a crowd. The old gentleman looked round anxiously as each new-comer opened the door, fearing evidently that some stranger would take the seat next him. His fears, however, were vain ones on that night, and at about twenty minutes before eight, looking round as the door opened, his face lighted up with joy as his friend, a rather good-looking, dark young man, pushed his way across the gallery to his side.

“Dear Professor Crowitzski,” he said affectionately, “I am sorry to be so late. I knew you would be anxious, but I have come straight from Grignoletti’s house in the Avenue Road.”

“My dear boy—my dear boy,” returned the old man tremulously, “I have been anxious about you for several reasons. I have thought much about your interview with Grignoletti and its possible result, and I also began to fear you would not get here in time to hear the Brahms Sextett, which is placed first upon the programme to-night. I would not have you miss it if you could possibly help it; you should hear Brahms as often as you can. Do not neglect the other masters of course. Hear and study the works of all; but especially those of that great trinity, Bach, Beethoven, Brahms. Now, however, tell me about yourself. Did Grignoletti hold out any hope to you?”

“Indeed he did,” said the young man, “almost too much, for I do not quite see how the hope is to be realised. He spoke in high terms of my voice, said I had a career before{234} me, and advised my entering the Royal Academy at once, saying he should not let me study with anyone but himself.”

“That is a high compliment,” said the Professor. “Grignoletti is the finest teacher of singing in London. Moreover, he is a true artist and an honest man. He will say nothing to you he does not mean. But tell me what difficulties stand in your way.”

Herbert Maxwell sighed. It was so hard to see the bright pathway of his highest wishes shining in the distance, and to realise that between him and the beginning of it lay a dark stream that could only be crossed by means of golden stepping-stones.

“I’m afraid money is the chief difficulty,” he said rather sadly. “The Academy fees are ten pounds a term. The half-term examination is next Monday, and I have not the means of raising five pounds. You know my mother and I depend entirely on my weekly wage, and it is not a very large one.”

“I know—I know,” replied the old man; “but supposing this amount could be found, how would you support your mother and yourself when you give up your present work? If you mean to adopt singing as your profession, you must give your whole time to the study of music.”

“It was in that matter that Grignoletti showed himself so very kind,” said Herbert. “He asked me how I lived, and promised, if I were admitted to the Academy, he would find work for me by which I could earn at least as much as I do now, and which would also increase my musical knowledge. He——”

A sudden storm of applause interrupted him, in which he joined vigorously, as Joachim, followed by the other artists, emerged from the curious little well at the end of the platform, where those of the players and singers who are not performing assemble to listen to those who are, sitting on the stairs or on the settee just inside.

Nothing more was said by the old Professor or Herbert himself on the subject of his musical education. The concert absorbed them both entirely, and in the intervals between each item on the programme no other subject was discussed by them but the music and the performers.

It was a shorter concert than usual, and as they were slowly making for the door with the rest of the crowd, the old man said to his young friend, “Can you come home with me to-night, my dear boy? I have something more to say to you, and I cannot say it here. I do not think it will make you very late.”

“I shall be very glad to,” replied Herbert, “and very glad to hear anything from you. You are the only person in the world to whom I can go for advice about music. It is very good of you to take so much interest in me.”

At Piccadilly Circus they got into that red omnibus which is affectionately called by those who use it constantly “The Kennington Lobster,” and travelled over Westminster Bridge some little distance down the wide Kennington Road.

“Green Street,” said the Professor after a time, and the conductor stopped the omnibus almost immediately.

They got down and turned into a little street on the right-hand of the main road; one of those streets still to be found here and there in some of the older parts of London, though they are fast being swept away by the remorseless builder to make room for the huge piles of model dwellings that are springing up on every side.

It was a narrow street of small but still respectable-looking houses, not detached. Each had a tiny square of garden in front of its one window, and a path of flagstones led from the gate to the front door.

The old man stopped at No. 9, opened the door with a latch-key, and led the way up a narrow staircase to the second floor.

“Wait a moment till we have a light,” he said; “you may fall over something in my tiny room.”

It was a tiny room indeed that Herbert found himself in when the Professor had lighted the lamp, and, as might have been expected, not a luxurious one; but it was as neatly arranged as a ship’s cabin, and everything was scrupulously clean.

On one side of the room stood a very narrow bed covered with a patchwork quilt, at its foot a tiny square washstand of painted deal. An old-fashioned mahogany chest of drawers piled high with books, a small deal table in the middle of the room, an old stuffed chair by the fireplace, and a low wooden one by the head of the bed completed the tale of furniture, with the exception of—a piano!

It was of the small, old-fashioned, cottage kind, with a square lid and faded green silk fluting for its front. It looked thin and worn like its master; but there it was. It proved, too, that its owner must be a musician, for there was nothing on the top of it. There was not much room anywhere, save on the little table, to put anything down; but the Professor would have been horrified at the idea of using the piano as a resting-place for anything. He would not even let Herbert put his hat on it.

“I should like to hear you sing,” he said, going to a large square pile of something by the piano covered with an old cloth. “Do you know the ‘Elijah’?” He lifted the cloth as he spoke and disclosed a quantity of music; sheet music, loose and bound, and scores of many famous works—all old, all worn, but still his treasures. He picked out a vocal score of the “Elijah” and put it on the piano desk.

“Yes,” said Herbert. “Shall I try ‘If with all your hearts’?”

The old man nodded with a smile, and, sitting down on the crazy music stool, laid his aged hands upon the aged keys.

It needed but two bars to show Herbert that his old friend was a real artist. The piano’s tone was like a tone ghost; but it was in perfect tune. The Professor saw to that himself. And his touch seemed so to caress the yellow keys that they gave him the very best they still had in them.

As the song proceeded, the old gentleman smiled and nodded gently to himself, as if he, too, were pleased and satisfied with what he heard. He had good reason. Herbert’s voice was of that rare delicious quality given perhaps to one singer in a generation. Full, rich, intensely sympathetic, without a trace of that metallic hardness in the upper notes so often found in tenor voices. He sang the great solo with the utmost simplicity, but with a beauty of expression that would have gone straight to the heart of any audience, musical or unmusical.

“My boy, you have a gift—a great gift,” said the Professor solemnly at the end. “See that you use it well. You may, if you choose, be one of the singers of the world; but it will mean more than three years at the Academy, and then to sing at ballad concerts. Aim at the highest, and make up your mind that it must be your life work. You must let me help you put your foot on the lowest rung of the ladder. You can climb yourself afterwards.”

He went to the bed and drew from underneath it a small old-fashioned box covered with skin with the hair on and studded with brass nails. This he unlocked, and took from it a small yellow canvas bag.

“I have here,” he said, “a kind of nest egg which I have managed to put by from time to time out of my little income. It is the exact sum you need just now, and you must pay your first fees with it.”

“My dear Professor,” stammered Herbert, completely taken aback, “indeed, I cannot! I should never forgive myself for taking money that you might possibly want for all sorts of things before I had a chance of paying it back again!”

“Nonsense!” replied the old man, rather sternly. “You must take it! I will have it so. I should never forgive myself if I allowed your young life and precious talent to be wasted because you were in want of what I had lying idle! You can repay me some day when you can spare it.”

“But what will you do in the meantime?” asked the young man rather diffidently, for he felt a delicacy about inquiring too closely into the old man’s circumstances.

“My dividend falls due to-morrow,” was the reply. “There is not the smallest reason for your refusing to take this. Go home to your mother, tell her everything is decided, and take care of your voice for the next week. Shall you be at the concert next Monday? Perhaps not, if you are kept late at your work. If I do not see you there, will you come here the next day and tell me about it all?”

His young friend promised this gladly; and in order to cut short his expressions of thanks, the Professor took up the lamp and lighted him downstairs, giving him a last warning against taking cold or overtiring his throat as he let him out.

“He is a good boy,” he said to himself as he went back to his little room. “I am very glad I was able to do it. It is for the young ones to carry on the world. We old ones who have served our time must stand by and encourage the others.”

He set about preparing his frugal supper—a small loaf and a pennyworth of milk, which he took from a cupboard in one corner of the room. He put the milk into a tiny tin saucepan, and, as of course there was no fire in the grate, he lighted a little spirit lamp, set the saucepan over the flame, and sat down to watch till it boiled.

His mind was still running on Herbert Maxwell and his probable career, and from that it wandered back to his own young days. Gradually he seemed to live through the whole of his past life. He recalled the early home life in the comfortable house at Clapham; his kind Polish parents who had been driven like so many others from their own country; his childish passion for music which had caused him so often to be laughed at by his English schoolfellows, and the decision of his parents that he should adopt it as a profession. Then came those happy student days at Leipzig, with the growing consciousness of his own powers and the encouragement of his teachers and fellow students, his début at the Gewandhaus, with the applause and laurel wreaths, succeeded by his first concert tour in Germany. He remembered his return home, to his parents’ joy, and his success in London as a player and teacher, with constant tours on the Continent, during one of which he met that lovely girl he afterwards wooed and won, to spend those few happy years with him till her sudden death abroad.

Then followed a ghastly blank, with isolated memories of being in some great building with many other people, who were all waited on by kindly men and sweet-faced women, and he could remember the feeling of having been ill and not knowing how. Till one day, when he had grown stronger, the knowledge came to him that, for a time, his mind had left him.

He vividly recalled his return to England, to find himself forgotten and eclipsed by{235} others who had sprung to fame during his long absence, his failure to obtain either engagements or pupils, and, finally, the collapse of the bank in which almost all his savings had been placed.

At this point, as if in sympathy with his thoughts, the spirit-lamp went out with a little “fuff,” and the milk, which was on the verge of boiling over, collapsed too.

This recalled him from his sad memories, and he tried, as he ate his bread and milk, to put them out of his mind and to think of the pleasanter events of the evening—of the fine concert, how splendidly Joachim played, and of his young friend, whose mother would be so glad at her boy’s good fortune.

But he could not rid himself of them, and even through the night his broken sleep was haunted by harassing dreams and vague feelings of some impending evil.

(To be concluded.)

By JESSIE MANSERGH (Mrs. G. de Horne Vaizey), Author of “Sisters Three,” etc.

obert did not make his appearance next morning, and his absence seemed to give fresh ground for the expectation that Lady Darcy would drive over with him in the afternoon and pay a call at the vicarage.

Mrs. Asplin gathered what branches of russet leaves still remained in the garden and placed them in bowls in the drawing-room, with a few precious chrysanthemums peeping out here and there; laid out her very best tea cloth and d’Oyleys, and sent the girls upstairs to change their well-worn school dresses for something fresher and smarter.

“And you, Peggy dear—you will put on your pretty red, of course!” she said, standing still, with a bundle of branches in her arms, and looking with a kindly glance at the pale face which had somehow lost its sunny expression during the last two days.

Peggy hesitated and pursed up her lips.

“Why ‘of course,’ Mrs. Asplin? I never change my dress until evening. Why need I do it to-day just because some strangers may call whom I have never seen before?”

It was the first time that the girl had objected to do what she was told, and Mrs. Asplin was both surprised and hurt by her tone in which she spoke—a good deal puzzled too, for Peggy was by no means indifferent to pretty frocks, and as a rule fond of inventing excuses to wear her best clothes. Why, then, should she choose this afternoon of all others to refuse so simple a request? Just for a moment she felt tempted to make a sharp reply, and then tenderness for the girl whose mother was so far away took the place of the passing irritation, and she determined to try a gentler method.

“There is not the slightest necessity, dear,” she said quietly. “I asked only because the red dress suits you so well, and it would have been a pleasure to me to see you looking your best. But you are very nice and neat as you are. You need not change unless you like.”

She turned to leave the room as she finished speaking; but before she had reached the door, Peggy was by her side, holding out her hands to take possession of twigs and branches.

“Let me take them to the kitchen, please! Do let me help you!” she said quickly, and just for a moment a little hand rested on her arm with a spasmodic pressure. That was all, but it was enough. There was no need of a formal apology. Mrs. Asplin understood all the unspoken love and penitence which was expressed in that simple action, and beamed with her brightest smile.

“Thank you, my lassie, please do! I’m glad to avoid going near the kitchen again, for when cook once gets hold of me, I can never get away. She tells me the family history of all her relations, and indeed it’s very depressing, it is” (with a relapse into her merry Irish accent), “for they are subject to the most terrible afflictions! I’ve had one dose of it to-day, and I don’t want another!”

Peggy laughed and carried off her bundle, lingered in the kitchen just long enough to remind the cook that “Apple Charlotte served with cream” was a seasonable pudding at the fall of the year, and then went upstairs to put on the red dress, and relieve her feelings by making grimaces at herself in the glass as she fastened the buttons.

At four o’clock the patter of horses’ feet came from below, doors opened and shut, and there was a sound of voices in the hall. The visitors had arrived!

Peggy pressed her lips together and bent doggedly over her writing. She had not progressed with her work as well as she had hoped during Rob’s absence, for her thoughts had been running on other subjects, and she had made mistake after mistake. She must try to finish one batch at least to show him on his return. Unless she was especially sent for she would not go downstairs; but before ten minutes had passed, Mellicent was tapping at the door and whispering eager sentences through the keyhole.

“Peggy, quick! They’ve come! Rosalind’s here! You’re to come down! Quick! Hurry up!”

“All right, my dear, keep calm! You will have a fit if you excite yourself like this!” said Peggy coolly.

The summons had come and could not be disregarded, and on the whole she was not sorry. The meeting was bound to take place sooner or later, and, in spite of her affectation of indifference, she was really consumed with curiosity to know what Rosalind was like. She had no intention of hurrying, however, but lingered over the arrangement of her papers until Mellicent had trotted downstairs again and the coast was clear. Then she sauntered after her with leisurely dignity, opened the drawing-room door, and gave a swift glance round.

Lady Darcy sat talking to Mrs. Asplin a few yards away in such a position that she faced the doorway. She looked up as Peggy entered and swept her eyes curiously over the girl’s figure. She looked older than she had done from across the church the day before, and her face had a bored expression, but, if possible, she was even more elegant in her attire. It seemed quite extraordinary to see such a fine lady sitting on that well-worn sofa, instead of the sober figure of the Vicar’s wife.

Peggy flashed a look from one to the other—from the silk dress to the serge, from the beautiful weary face to the cheery loving smile—and came to the conclusion that, for some mysterious reason, Mrs. Asplin was a happier woman than the wife of the great Lord Darcy.

The two ladies stopped talking and looked expectantly towards her.

“Come in, dear! This is our new pupil, Lady Darcy, for whom you were asking. You have heard of her——”

“From Robert. Oh, yes, frequently! I was especially anxious to see Robert’s little friend. How do you do, dear? Let me see! What is your funny little name? Molly—Dolly—something like that I think—I forget for the moment!”

“Mariquita Saville!” quoth Peggy blandly. She was consumed with regret that she had no second name to add to the number of syllables, but she did her best with those she possessed, rolling them out in her very best manner and with a stately condescension which made Lady Darcy smile for the first time since she entered the room.

{236}

“Oh—h!” The lips parted to show a gleam of regular white teeth. “That’s it, is it? Well, I am very pleased to make your acquaintance, Mariquita. I hope we shall see a great deal of you while we are here. You must go and make friends with Rosalind—my daughter. She is longing to know you.”

“Yes, go and make friends with Rosalind, Peggy dear! She was asking for you,” said Mrs. Asplin kindly, and as the girl walked away the two ladies exchanged smiling glances.

“Amusing! Such grand little manners! Evidently a character.”

“Oh, quite! Peggy is nothing if not original. She is a dear, good girl, but quite too funny in her ways. She is really the incarnation of mischief, and keeps me on tenter-hooks from morning until night, but from her manner you would think she was a model of propriety. Nothing delights her so much as to get hold of a new word or a high-sounding phrase.”

“But what a relief to have someone out of the ordinary run! There are so many bores in the world, it is quite refreshing to meet with a little originality. Dear Mrs. Asplin, you really must tell me how you manage to look so happy and cheerful in this dead-alive place? I am desolate at the idea of staying here all winter. What in the world do you find to do?”

Mrs. Asplin laughed.

“Indeed, that’s not the trouble at all; the question is how to find time to get through the day’s duties! It’s a rush from morning till night, and when evening comes I am delighted to settle down in an easy-chair with a nice book to read. One has no chance of feeling dull in a house full of young people.”

“Ah, you are so good and clever, you get through so much. I want to ask your help in half-a-dozen ways. If we are to settle down here for some months there are so many arrangements to make. Now tell me, what would you do in this case?” The two ladies settled down to a discussion on domestic matters, while Peggy crossed the room to the corner where Rosalind Darcy sat in state, holding her court with Esther and Mellicent as attendant slaves. She wore the same grey dress in which she had appeared in church the day before, but the jacket was thrown open and displayed a distractingly dainty blouse, all pink chiffon, and frills, and ruffles of lace. Her gloves lay in her lap, and the celebrated diamond ring flashed in the firelight as she held out her hand to meet Peggy’s.

“How do you do? So glad to see you! I’ve heard of you often. You are the little girl who is my bwothar’s fwiend.” She pronounced the letter “r” as if it had been “w,” and the “er” in brother as if it had been “ah,” and spoke with a languid society drawl, more befitting a woman of thirty than a schoolgirl of fifteen.

Peggy stood motionless and looked her over, from the crown of her hat to the tip of the little trim shoe, with an expression of icy displeasure.

“Oh dear me, no,” she said quietly, “you mistake the situation. You put it the wrong way about. Your brother is the big boy whom I have allowed to become a friend of mine!”

Esther and Mellicent gasped with amazement, while Rosalind gave a trill of laughter, and threw up her pretty white hands.

“She’s wexed!” she cried. “She’s wexed, because I called her little! I’m wewwy sowwy, but I weally can’t help it, don’t you know. It’s the twuth! You are a whole head smaller than I am.” She threw back her chin, and looked over Peggy’s head with a smile of triumph. “There, look at that, and I’m not a year older. I call you wewwy small indeed for your age.”

“I’m thankful to hear it! I admire small women,” said Peggy promptly, seating herself on a corner of the window seat, and staring critically at the tall figure of the visitor. She would have been delighted if she could have persuaded herself that her height was awkward and ungainly, but such an effort was beyond imagination. Rosalind was startlingly and wonderfully pretty; she had never seen anyone in real life who was in the least like her. Her eyes were a deep, dark blue, with curling dark lashes, her face was a delicate oval, and the pink and white colouring, and flowing golden locks gave her the appearance of a princess in a fairy tale, rather than an ordinary flesh and blood maiden. Peggy looked from her to Mellicent who was considered quite a beauty among her companions, and oh dear me! how plain, and fat, and prosaic she appeared when viewed side by side with this radiant vision! Esther stood the comparison better, for though her long face had no pretensions to beauty, it was thoughtful and interesting in expression. There was no question which was most charming to look at; but if it had come to a choice of a companion, an intelligent observer would certainly have decided in favour of the Vicar’s daughter. Esther’s face was particularly grave at this moment, and her eyes met Peggy’s with a reproachful glance. What was the matter with the girl this afternoon? Why did she take up everything that Rosalind said in that hasty, cantankerous manner? Here was an annoying thing—to have just given an enthusiastic account of the brightness and amicability of a new companion, and then to have that companion come into the room only to make snappish remarks, and look as cross and ill-natured as a bear! She turned in an apologetic fashion to Rosalind, and tried to resume the conversation at the point where it had been interrupted by Peggy’s entrance.

“And I was saying, we have ever so many new things to show you—presents, you know, and things of that kind. The last is the nicest of all; a really good, big camera with which we can take proper photographs. Mrs. Saville—Peggy’s mother—gave it to us before she left. It was a present to the schoolroom, so it belongs equally to us all, and we have such fun with it. We are beginning to do some good things now, but at first they were too funny for anything. There is one of father where his boots are twice as large as his head, and another of mother where her face has run, and is about a yard long, and yet it is so like her! We laughed till we cried over it, and father has locked it away in his desk. He says he will keep it to look at when he is low-spirited.”

Rosalind gave a shrug to her shapely shoulders.

“It would not cheer me up to see a cawicature of myself! I don’t think I shall sit to you for my portrait, if that is the sort of thing you do, but you shall show me all your failures. It will amuse me. You will have to come up and see me vewwy often this winter, for I shall be so dull. We have been abroad for the last four years, and England seems so dark and dweawy. Last winter we were at Cairo. We lived in a big hotel, and there was something going on almost every night. I was not out, of course, but I was allowed to go into the room for an hour after dinner, and to dance with the gentlemen in mother’s set. And we went up the Nile in a steamer, and dwove about every afternoon, paying calls, and shopping in the bazaars. It never rains in Cairo and the sun is always shining. It seems so wonderful! Just like a place in a fairy tale.” She looked at Peggy as she spoke, and that young person smiled with an air of elegant condescension.

“It would do so to you. Naturally it would. When one has been born in the East, and lived there the greater part of one’s life, it seems natural enough, but the trippers from England who just come out for a few months’ visit are always astonished. It used to amuse us so much to hear their remarks!”

Rosalind stared and flushed with displeasure. She was accustomed to have her remarks treated with respect, and the tone of superiority was a new and unpleasing experience.

“You were born in the East?”

“Certainly I was!”

“Where, may I ask?”

“In India—in Calcutta, where my father’s regiment was stationed.”