![[Image of the book's cover unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: Wildwood Ways

Author: Winthrop Packard

Release date: August 23, 2021 [eBook #66113]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Emmanuel Ackerman, Steve Mattern, Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

|

List of Illustrations (etext transcriber's note) |

WILDWOOD WAYS

BY

WINTHROP PACKARD

AUTHOR OF “WILD PASTURES”

BOSTON

SMALL, MAYNARD AND COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1909

By Small, Maynard and Company

(INCORPORATED)

Entered at Stationers’ Hall

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U.S.A.

The author wishes to express his thanks to the “Boston Transcript” for permission to reprint in this volume matter which was originally contributed to its columns.

TO-DAY came with a flashing sun that looked through crystal-clear atmosphere into the eyes of a keen northwest wind that had dried up all of November’s fog and left no trace of moisture to hold its keenness and touch you with its chill. It was one of those days when the cart road from the north side to the south side of a pine wood leads you from early December straight to early May. On the one side is a nipping and eager air; on the other sunny softness and a smell of spring. It is more than that difference of a hundred miles in latitude which market gardeners say exists between the north and south side of a board fence. It is like having thousand{4} league boots and passing from Labrador to Louisiana at a stride.

On the north side of a strip of woodland which borders the boggy outlet to Ponkapoag Pond lies a great mowing field, and here among the sere stubble I stand in the pale shadow of deciduous trees and face the wind coming over the rolling uplands as it might come across Arctic barrens, singing down upon the northerly outposts of the timber line. On the south side the muskrat teepees rise from blue water at the bog edge like peaks of Teneriffe from the sunny seas that border the Canary Isles. Such contrasts you may find on many an early December day, when walking in the rarefied brightness of the open air is like moving about in the heart of a diamond.

Yet even the big mowing field shows unmistakable signs of having been{5} snugged down for the winter. Here and there a tree, still afloat in its brown undulating ocean, seems to be scudding for the shelter of the forest under bare poles, while the stout white oaks lie to near the coast under double-reefed courses, the brown leaf-sails still holding to the lower yards while all the spars above have been blown bare. The woodchuck paths, that not long ago led from one clover patch to another and then on to well-hidden holes, lie pale and untravelled, while their fat owners are snugged down below in warm burrows with their noses folded in under their forepaws. Tradition has it that they will wake in a warm spell in midwinter and peer out of their burrows to see what the prospect of spring may be. Hence, the second of February is not only Candlemas day, but ground-hog day in rural tradition, the{6} day on which the woodchuck is fabled to appear at the mouth of his underground retreat and look for weather signs, but I don’t know anyone who has ever seen him do it. You may often find skunk tracks in the snow or mud during a good midwinter thaw, but I have never seen those of the woodchuck then, and I am quite confident that he stays snugged down the winter through.

Scattered here and there about the borders of the field are groups of dwarf goldenrod still in full leaf and flower, so far as form goes. The crowded terminal panicles of bloom bend gracefully towards earth like stout ostrich plumes, and I think they are more beautiful in the feathery russet of crowded seed-masses than they were in their September finery of golden yellow. Their stems are lined with leaves still, but these have{7} lost their sombre green to put on the color of deep seal brown. It is as if they had donned their sealskin cloaks for winter wear.

But all these clumps are doubly protected in another way, not for their own sake, for they are but dead stems, but for the birds, who will need their seeds when the snows later in the month shall have covered the ground far out of their reach. All the autumn the winds have been whirling dry leaves back and forth, and each clump has trapped them cunningly till the slender stems that might otherwise be buried and broken by the snow are reënforced on all sides by elastic leaves that will hold them bravely up. Here is an open larder, a free-lunch counter for the goldfinches and chickadees of next January. Here they may glean and glean again, for except they{8} be plucked by eager beaks some of these seeds will not let go their grip on the receptacles till spring rains loosen them and the ground is fit for their sowing.

Everywhere in wood and pasture the numbers of seeds of plants and trees that are thus held waiting the winter gleaners are incomputable; nor will these need to seek them on the plant itself, for little by little as the winter winds come and go they will loose their hold and scatter themselves about as we scatter crumbs for the snow-birds and sparrows. Here are the birches, for instance, holding fast still to their wealth. If bursting spring buds could be gray-brown in color instead of sage-green we well might think the trees had another almanac than our own and that with them it was late April, for wherever the trees are silhouetted against the light we{9} see every twig decorated with new life. It is new life, indeed, but not that of spring leaves. Every tree has a thousand cones, and every cone is packed with tiny seeds about a central core of stiff fibre that is like a fine wire.

Holding the seeds tight in their places are little flat scales, having an outline like that of a conventionalized fleur-de-lis or somewhat like tiny flying birds. The whole is so keyed by the tip that as they hang head down it is possible to dislodge only the topmost scales and seeds. A very vigorous shake of the tree sends a cloud of these flying, but when you look at the tree you find that not a thousandth part of its store has been dispensed. When the midwinter snows lie deep all about, the paymaster wind will requisition these stores as needed for the tiny creatures of the wood and scatter{10} them wide on the white surface, till it will look as if spiced by the confectioner, so well does the forest take care of its own. The Lady Amina of the Arabian tale picking single grains of rice at the banquet might not seem to dine more daintily. The spring will be near at hand when the last of these birch seeds will have been dispensed. Thus innumerable graneries are stored the woodland and pasture through, so lightly locked that all may pilfer, and so abundantly filled, pressed down and running over that there shall be no lack in either quantity or variety.

Far other and stranger forms of winter-guarding forethought are to be seen all about the big mowing field and in the coppices that divide it from the open marsh and the pond shore, if we will but look for them. In many places{11} has witchery been at work as well as forethought, and strange and unaccountable things have been brought to pass that tiny creatures may be kept safe until spring. Here and there among the goldenrod stems you find one that is swollen to the size of a hickory nut, a smooth globe which is merely the stem expanded from the diameter of a toothpick to three-quarters of an inch. When I split this bulb with my knife I find it made up of tough pith shot through with the growing fibres of the plant, but having a tiny hollow in the centre.

Here, snugly ensconced and safe from all the cold and storms, is a lazy creature so fat that he looks like a globular ball of white wax. Only when I poke him does he squirm, and I can see his mouth move in protest. His fairy language is too fine for my ear, tuned to the rough{12} accents of the great world, but if I am any judge of countenances he is saying: “Why, damme, sir! how dare you intrude on my privacy!”

After all he has a right to be indignant, for I have not only wrecked his winter home, but turned him out, unclothed and unprotected, to die in the first nip of the shrewish wind. Unmolested he would have leisurely enlarged his pith hall by eating away its substance and in the spring have bored himself a cunning hole whence he might emerge, spread tiny wings and enjoy the sunshine and soft air of summer. His own transformations from egg to grub, from grub to gall-fly, are curious enough; yet stranger yet and far more savoring of magic is the growth of his winter home. By what hocus-pocus the mother that laid him there made the slender stem of the{13} goldenrod grow about him this luxurious home, is known only to herself and her kindred, and until I learn to hear and translate the language which the grub used in swearing at me when I broke into his home, it is probable that I shall still remain ignorant.

But let us leave Labrador and let ourselves loose upon Louisiana, for we may do it in five minutes. The oaks and the pines, the maples, the birches and the shrubs of the close-set thickets which guard the bog edge, I know not what straining and restraining power they have upon this keen wind, but when it has filtered through them it has lost its shrewishness and, meeting the warm embrace of the low hung sun, bears aromas of spring. It is as if wood violets had shot his garments full of tiny odors of April as he traversed the wood, or per{14}haps the perpetual magic of life which seems to well up from swampy woodland had seized upon him as it seizes upon all that passes and made him the bearer of its potency. Across the bog to the pond outlet, through this spring-soft atmosphere lies a slender road, lined with thickets, where I do not wonder the Callosamia promethia, the spice-bush silk-moth, likes to spin his own winter snuggery and dangle in the soft air till the real spring taps at his silken doorway and soft rains lift the latch and let him out.

Not far away, among the leaves that lie ankle deep among the shrubbery that skirts the hickories and oaks, are the cocoons of Actias luna; among them, shed from the oaks, are those of Telia Polyphemus, and if I seek, it is not difficult to find the big pouch where Samia{15} cecropia waits for the same call. Some May evening there shall be a brave awakening in the glades and on the borders of the bog. It shall be as if the tans and pinky purples and rose and yellow of the finest autumn leaves took wing again in the spring twilight and floated about at will owing nothing to the winds, and then the luna moth, the fairy queen of dusk, all clad in daintiest green trimmed with ermine and seal and ostrich plumes, shall come among them and reign by right of such beauty as the night rarely sees, all this sprung from the papery cocoons swung in the roadside bushes or tumbled neglectfully among the shifting autumn leaves in the tangle at the roots of the wild smilax.

Here is magic for you, indeed, of the kind that the parlor magician is wont to supply; frail and beautiful things grown{16} at a breath, almost, from obscure and trivial sources. Yet I seem to find a more potent if less spectacular witchery in what has been done to the willows that here and there grow in the thicket that borders the slender bog road. Some winged sprite has touched their branch tips with fairy wand and whispered a potent word to them, and the willows have obeyed and grown cones! These are an inch or more in length and as perfect with scales as those of the pines up in the wood. But there are no seeds of willow life in them. Instead there is at the core an orange-yellow, minute grub, the larva of a fly that stung the willow tip last spring and, stinging it, laid her egg therein.

That the egg should become a grub and that later the grub in turn should become a fly is nothing in the way of{17} magic, or that it should fatten in the meanwhile on willow fibre. The necromancy comes in the fact that every willow tip that is made the home of this grub should thenceforth forsake all its recognized methods of growth and produce a cone for the harboring of the grub during the winter’s cold. There are many varieties of these gall-producing insects. The oaks still hold spherical attachments to their leaves, produced in the same way. Look among your small fruits and you will find the blackberry stems swollen and tuberculous from a similar cause, and full of squirming life. It is all necromancy out of the same book, the book of the witchery of insects that makes human life and growth seem absurdly simple by comparison. The snugging down of the open world in preparation for winter is full of such tales, and he who runs{18} through the wood on such a day in December may read them.

Standing in the spring-like warmth at the pond outlet and looking down the line where bog meets water I can count the dark peaks of the muskrat teepees, receding like a coast range toward the other shore. The muskrats have built higher than common this year, because, I fancy, they expect much water, having had it low all summer and fall. Some of them are half as high as I am and must have cost tremendous labor in tearing out the marsh roots and sods and collecting them thus in pyramidal form. Their roads run hither and yon across the bog and are so well travelled that the travellers must be numerous as well as active. They have laid in a store of lily roots and sweet-flag for the winter, and their underwater entrances lead upward to{19} quarters that are dry and snug. Here they are as secure from frost as was the white grub that I hewed from his pith hall in the goldenrod stem. When the ice is thick all about, their house will be as hard of outside wall as if built of black adamant yet their water-entrance will be free, beneath the ice, and they will go to and fro by it, seeking supplies or perhaps making friendly calls.

All the morning the marsh grass billowed and the water sparkled, one to another, about their houses, and if you listened to the grass you might hear its fine little sibilant song, a soft susurrus of words whose only consonant is s, set to a sleepy swing. It is a song that seems to harmonize with the fine tan tones of the bog as they fade into silvery white where the sun reflects from smooth spears. Over on the distant hillside the{20} pines, navy blue under cloud shadows, hummed in the wind like bassoons; distant and muted cornets sang clear in the maples, and all about the feathery heads of the olive swamp cedars you caught the faint shrilling of fifes if you would but listen intently. Now and then the glocken-spiel tinkled in mellow yellow notes among the dry reeds on the marge, but these echoed but familiar runes. The tan-white bog grass that is so wild it never heard the swish of scythe, sang, soft and sibilant, an elfin song of the lonely and untamed.

With the singing of the wind into the tender spring of the south side the day grew cold with clouds. The sky was no longer softly blue, but gray and chilling, the pond lost its sparkle and grew purple and numb with cold, and all among the bare limbs you heard the song of the{21} promise of snow. But the clouds stopped at a definite line in the west and at setting the sun dropped below this and sent a golden flood rolling through the trees that mark the boundary between field and pond, lighting up all the bog with glory and gilding the muskrat teepees and the tall bog grass and the distant trees across the water till all the sere and withered leaves were bathed in serenity, as softly and serenely bright as if the golden age had come to us all. In this wise the crystal day, with its sheltered exultation of spring and its gray promise of winter’s snow all fused into one golden delight of sunset glory, marched on over the western hills trailing paths of gilded shadow behind it along which one walked the homeward way as if into the perfect day.

THE lonesomest spot in all the pasture, the one which the winter has made most vacant of all, is the corner where hangs the great gray nest of the white-faced hornets. Its door stands hospitably open but it is no longer thronged with burly burghers roaring to and fro on business that cannot wait. It was wide enough for half a dozen to go and come at the same time, yet they used to jostle one another continually in this entrance, so great was the throng of workers and so vigorous the energy that burbled within them. While the warm sun of an August day shines a white-faced hornet is as full of pent forces, striving continually to{26} burst him, as a steam fire-engine is when the city is going up in flame and smoke and the fire chief is shouting orders through the megaphone and the engineer is jumping her for the honor of the department and the safety of the community. He burbles and bumps and buzzes and bursts, almost, in just the same way.

It is no wonder that people misunderstand such roaring energy, driving home sometimes too fine a point, and speak of Vespa maculata and his near of kin the yellow jackets, and even the polite and retiring common black wasp, with dislike. In this the genial Ettrick Shepherd, high priest of the good will of the open world, does him, I think, much wrong. “O’ a’ God’s creatures the wasp,” he says, “is the only one that is eternally out of temper. There’s nae sic thing as pleasing him.{27}”

This opinion is so universal that there is little use in trying to controvert it, and yet these white-faced hornets which I have known, if not closely, at least on terms of neighborliness, do not seem to merit this opprobrium. That they are hasty I do not deny. They certainly brook no interference with their right to a home and the bringing up of the family. But I do not call that a sign of ill temper; I think it is patriotism.

Probably the trouble with most of us is that we have happened to come into quite literal contact with white-face after the fashion of one of the early explorers of the country about Massachusetts Bay. Obadiah Turner, the English explorer and journalist, thus chronicles the adventure in the quaint phraseology of the year 1629.

“Ye godlie and prudent captain of ye{28} occasion did, for a time, sit on ye stumpe in pleasante moode. Presentlie all were hurried together in great alarum to witness ye strange doing of ye goode olde man. Uttering a lustie screme he bounded from ye stumpe and they, coming upp, did descrie him jumping aboute in ye oddest manner. And he did lykwise puff and blow his mouthe and roll uppe his eyes in ye most distressful waye.

“All were greatlie moved and did loudlie beg of him to advertise them whereof he was afflicted in so sore a manner, and presentlie, he pointing to his foreheade, they did spy there a small red spot and swelling. Then did they begin to think yt what had happened to him was this, yt some pestigeous scorpion or flying devil had bitten him. Presentlie ye paine much abating he saide yt as he sat on ye stumpe he did spye upon ye{29} branch of a tree what to him seemed a large fruite, ye like of wch he had never before seen, being much in size and shape like ye heade of a man, and having a gray rinde, wch as he deemed, betokened ripenesse. There being so manie new and luscious fruites discovered in this fayer lande none coulde know ye whole of them. And, he said, his eyes did much rejoice at ye sight.

“Seizing a stone he hurled ye same thereat, thinking to bring yt to ye grounde. But not taking faire aime he onlie hit ye branch whereon hung ye fruit. Ye jarr was not enow to shake down ye same but there issued from yt, as from a nest, divers little winged scorpions, mch in size like ye large fenn flies on ye marshe landes of olde England. And one of them, bounding against hys forehead did give in an instant a most{30} terrible stinge, whereof came ye horrible paine and agonie of wch he cried out.”

Let go on the even tenor of his home-building and home-keeping way, white-face is another creature. One of his kind used to make trips to and from my tent all one summer, and we got to be good neighbors. At first I viewed him with distrust and was inclined to do him harm, but he dodged my blow and without deigning to notice it landed plump on a house-fly that was rubbing his forelegs together in congratulatory manner on the tent roof. He had been mingling with germs of superior standing, without doubt, this house-fly, but his happiness over the success of the event was of brief duration. There came from his wings just one tenuous screech of alarm followed by an ominous silence of as brief duration. Then came the deep roar{31} of the hornet’s propellers as he rounded the curve through the tent door and gave her full-speed ahead on the home road. An hour later he was with me again, had captured another fly almost immediately, and was off. He came again, many times a day, and day after day, till I began to know him well and follow his flights with the interest of an old friend.

He never bothered me or anyone else. He had no time for men; the capture of house-flies was his vocation and it demanded all his energy and attention. In fact that he might succeed it was necessary that he should put his whole soul into earnest endeavor, for he was not particularly well equipped for his work. He had neither speed nor agility as compared with his quarry, and if house-flies can hear and know what is after them, the{32} roar of his machinery, even at slowest speed, must have given them ample warning. It was like a freighter seeking to capture torpedo boats. They could turn in a circle of a third the radius of his and could fly three miles to his one, yet he was never a minute in getting one.

I think they simply took him for an enlarged edition of their own kind and never knew the difference until his mandibles gripped them. He used to go bumbling and butting about the tent in a near-sighted excitement that was humorous to the onlooker. He didn’t know a fly from a hole in the tentpole, and there was a tack in the ridgepole whose head he captured in exultation and let go in a sort of slow wonder every time he came in. He got to know me as part of the scenery and didn’t mind lighting on top of my head in his quest, and he never thought of{33} stinging me. I timed his visits one sunny, still day and found that he arrived once in forty seconds. But this was only under most favorable weather conditions. A cloud over the sun delayed him and in wet weather he was never to be seen.

His method with the fly in hand was direct and effective. The first buzz was followed by the snip-snip of his shear-like maxillaries. You could hear the sound and immediately see the gauzy wings flutter slowly to the tent floor. If the fly kicked much his legs went in the same way. Then white-face took a firmer grip on his prize and was off with him to the nest. The bee line is spoken of as a model of mathematical directness, but the laden bee seeking the hive makes no straighter course than did my hornet to his nest in the berry bush down in the pasture.{34}

Flies were plentiful and, knowing how many hornets there are in a nest, I expected at first that he would bring companions and perhaps overwhelm my hospitality with mere numbers, but he did nothing of the kind. I have an idea that he was detailed to the fly catching work just as other workers were busy gathering nectar and honey dew for the young and others still were nest and comb building. Later in the summer another did come, but I am convinced that he happened on the other’s game preserve by accident and was not invited. The two between them must have captured thousands of flies and carried them off alive to their nest.

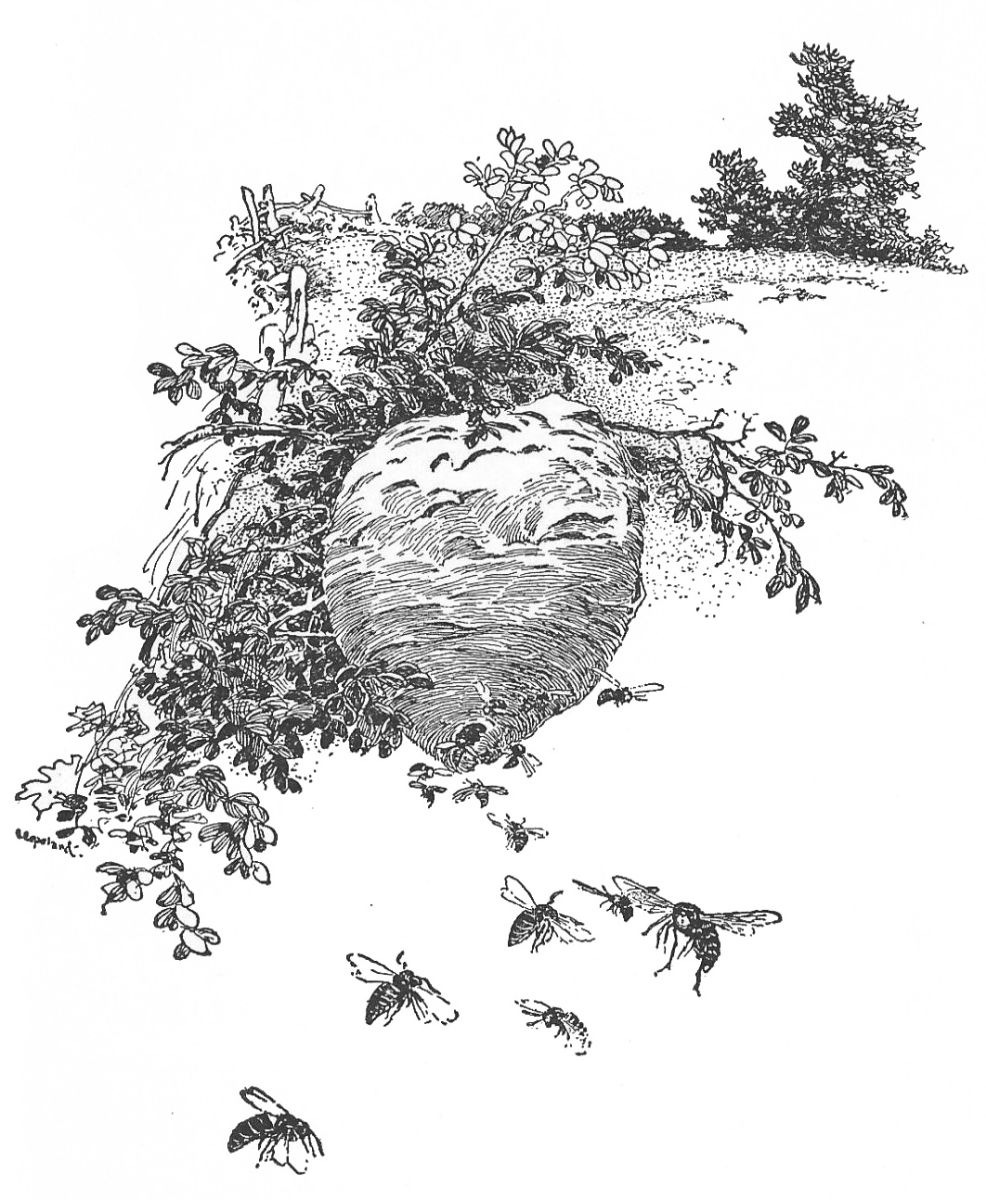

Thus their paper fort, hung from the twigs of a blueberry bush, had by September grown to the dimensions of a water-bucket and contained a prodigious

Their paper fort had by September grown to the dimensions of a water-bucket and contained a prodigious swarm of valiant fighters

swarm of valiant fighters and mighty laborers, so much will persistent labor, even by near-sighted, dunder-headed hornets, accomplish. I say near-sighted, for the two specimens of Vespa maculata who used to hunt flies in my tent were certainly that. I say also dunder-headed, for if not that they would have learned eventually the location of that tack head and ceased to capture it. Barring these failings, no doubt congenital, I know of no pasture people who show greater virtues or more of them than the white-faced hornets.

The weak beginnings of their great community home in the berry bush were made in early May when a single lean and hungry queen mother crept from a crevice in the heart of a great hollow chestnut where she had survived the winter. She sunned herself for a time at the opening,{36} then began eagerly chewing fibre from a gray and bare dead limb near by. She chewed this and when it was softened to a pulp she flew straight to the berry bush and began her long summer’s work. Laboring patiently she made and brought enough of the paper pulp moistened with her own saliva to form a nest half the size of an egg containing just a few cells in a single comb that was horizontal and opened downward. In these she laid an egg each, worker’s eggs.

Always the first brood is of workers only, and it would seem that the mother hornet is able by some strange necromancy to lay an egg which shall produce, as she wills, a worker, a drone or another queen, for the hornet hive, like that of the honey-bee, has the three varieties. While these eggs hatch she completes the nest and then begins feeding the funny{37} little white maggots which hang head down in the cells, stuck to the top by a sort of glue which was deposited with the egg.

Honey and pollen is the food which the youngsters receive, varied as they grow up with a meat hash of insects caught by the mother and chewed fine. Soon they fill the cells, stop eating, and spin for themselves a sort of silk night shirt and a cap with which they close the mouth of the cell. Here they remain quiet for a few days, changing from grub to winged creature as does a butterfly during the chrysalis stage of its existence.

Those were busy days for the queen mother, for she had the work and the care of the whole wee hive on her hands, and she showed herself capable not only of doing her own feminine part in the hive economy, but that of half a dozen work{38}ers as well, making paper, doing construction work, finding and bringing honey and pollen and insects for the food of the young grubs, and finally helping them cut away the seals to the cells and grasping the young hornets in her mandibles and hauling them out of their comb.

These young hornets washed their faces, cleaned their antennæ, ate one more free meal and set to work. Thereafter the queen mother, having reared her retinue, worked no more, but kept the hive and produced worker eggs as new cells were provided for them, now and then perhaps feeding the children when the workers were busiest.

The first care of the new-born workers was to clean out the once used cells and to build new ones. But there was no room for new comb within the thin paper{39} envelope which the mother had built as a first hive. They therefore cut this away, chewing it to pulp again, and building new cells with a larger covering all about them. Then below the first comb they hung a second by paper columns so that there was space for them to pass between the two, standing on top of one comb while they fed the young hanging head down in the comb above.

They also added cells to the sides of the old comb, making it much wider. The first little round egg-shaped nest was all of one color, a soft gray, but the new additions are apt to be lighter or darker in color, according to the idiosyncrasies of the individual worker. Some indeed have a faint touch of brown when newly added to the structure though these soon fade, yet you may recognize always the dividing line between one horne{40}t’s work and another’s by the difference in shade.

Thus the work went on during the summer, more cells being added to the existing combs, new combs being hung below, and always the surrounding envelope being cut away and replaced to accommodate the internal growth. Late August saw the last additions made. The hive then roared with life. The summer had been a good one and food was plentiful. Under the bounty of fierce summer heat and ample food the workers had developed a new faculty.

I have given them the masculine pronoun in speaking of them, for they certainly seemed to deserve it. Surely only males could be at once so sharp and so blunt, so burly, so strenuous and so devoid of interest in anything but their work. Yet it is a fact that in August{41} some of the workers began to lay eggs, and if the old proverb that “Like produces like” holds good they still deserve the masculine pronoun, for these eggs produced only males.

At the same time the queen began to lay eggs which were destined to produce other queens. How all this could have been known about beforehand it is hard to tell, but such must have been the fact, for the cells in which these eggs were to be laid were made larger than the others as the greater size of males and females requires.

Thus the climax of the work of the great paper hive was reached. The new queens had been safely reared and had reached maturity when the first chill days of autumn came. These days brought rain, and the change from bustling life to silence was most startling. Almost in{42} a day the hive was deserted. It was as if the entire colony had swarmed, and so they had, but not as a hive of bees swarms. They had left the old home never to return, but not as a colony seeking a new land in which to prosper. The first chill of autumn laid the cold hand of death on their busy life. They went away as individuals and stopped, numbed with cold, wherever the chill caught them.

Where they went it is hard to say, but one hornet or a thousand crawling into a crevice to escape the cold is easily lost in the great world of out-of-doors. No worker survives the winter. I think the intensity of their labors during the summer, the continued use of that energy that bubbles within them all summer long, exhausts them and they succumb easily, worked out. With the young queens it is different. Their work is yet{43} to come, and the strong young life within them gives them vitality to endure the winter, though seemingly frozen stiff in their crevices. Yet only a few of these come through in safety. If the queens of one hive all built next year, the pasture would be a far too busy place for mere man to visit.

It is just as well as it is, yet I am glad that each year sees at least one queen white-face pulp-making in the May sun. Pasture life without her uproarious progeny would lack spice. The great gray nest is pathetic in its emptiness, and I am glad to forget it and its bustling throng, remembering only the one busy worker that used to come into the tent and, having caught his fly, hang head downward from ridge-pole or canvas-edge by one hind foot while all his other feet were busy holding his lamb for the shearing.

TOWARD midnight the pond fell asleep. All day long it had frolicked with the boisterous north wind, pretending to frown and turn black in the face when the cold shoulders of the gale bore down upon its surface, dimpling as the pressure left it and sparkling in brilliant glee as the low hung sun laughed across its ruffles. The wind went down with the sun, as north winds often do, and left a clear mirror stretching from shore to shore, and reflecting the cold yellow of the winter twilight.

As this chill twilight iced into the frozen purple of dusk, tremulous stars quivered into being out of the violet blackness of space. The nebular hypoth{48}esis is born again in the heavens each still winter night. It must have slipped thence into the mind of Kant as he stood in the growing dusk of some German December watching the violet-gray frost vapors of the frozen sky condense into the liquid radiance of early starlight, then tremble again into the crystalline glints of unknown suns whirling in majestic array through the full night along the myriad miles of interstellar space.

Standing on the water’s edge on such a night you realize that you are the very centre of a vast scintillating universe, for the stars shine with equal glory beneath your feet and above your head. The earth is forgotten. It has become transparent, and where before sunset gray sand lay beneath a half-inch of water at your toe-tips, you now gaze downward through infinite space to the nadir,{49} the unchartered, unfathomable distance checked off every thousand million miles or so by unnamed constellations that blur into a milky way beneath your feet. The pond is very deep on still winter nights.

If you will take canoe and glide out into the centre the illusion is complete. There is no more earth nor do the waters under the earth remain; you float in the void of space with the Pleiades for your nearest neighbor and the pole star your only surety. In such situations only can you feel the full loom of the universe. The molecular theory is there stated with yourself as the one molecule at the centre of incomputability. It is a relief to shatter all this with a stroke of the paddle, shivering all the lower half of your incomputable universe into a quivering chaos, and as the shore looms black and uncertain in the bitter chill it is never{50}theless good to see, for it is the homely earth coming back to you. You have had your last canoe trip of the year, but it has carried you far.

No wonder that on such a night the pond, falling asleep for the long winter, dreams. A little after midnight it stirred uneasily in its sleep and a faint quiver ran across its surface. A laggard puff of the north wind that, straggling, had itself fallen asleep in the pine wood and waked again, was now hastening to catch up. The surface water had been below the freezing point for some time and with the slight wakening the dreams began to write themselves all along as if the little puff of wind were a pencil that drew the unformulated thoughts in ice crystals. Water lying absolutely still will often do this. Its temperature may go some degrees below the freezing point{51} and it will still be unchanged. Stir it faintly and the ice crystals grow across it at the touch.

Strange to tell, too, the pond’s dreams at first were not of the vast universe that lay hollowed out beneath the sky and was repeated to the eye in its clear depths. Its dreams were of earth and warmth, of vaporous days and humid nights when never a frost chill touched its surface the long year through, and the record the little wind wrote in the ice crystals was of the growth of fern frond and palm and prehistoric plant life that grew in tropic luxuriance in the days when the pond was young.

These first bold, free-hand sketches touched crystal to crystal and joined, embossing a strange network of arabesques, plants drawn faithfully, animals of the coal age sketched in and suggested only,{52} while all among the figures great and small was the plaided level of open water. This solidified, dreamless, about and under the decorations, and the pond was frozen in from shore to shore. Thus I found it the next morning, level and black under one of those sunrises which seem to shatter the great crystal of the still atmosphere into prisms. The cold has been frozen out of the sky, and in its place remains some strange vivific principle which is like an essence of immortality.

New ice thus formed has a wonderful strength in proportion to its thickness. It is by no means smooth, however. The embossing of the reproductions of these pond dreams of fern and palm and plesiosaurus makes hubbles under your steel as you glide over it, though little you care for that on your first skate of the{53} year. The embossing it is, I think, that largely gives it its strength, and though it may crack and sag beneath you as you strike out, you know that its black texture is made up of interlacing crystals that slip by one another in the bending, but take a new grip and hold until your weight fairly tears them apart.

The small boy knows this instinctively and applies it as he successfully runs “teetley-bendoes” to the amazement and terror of the uninitiated grown-ups. If you have the heart of the small boy still, though with an added hundred pounds in weight, you may yet dare as he does and add to the exhilaration born of the wine-sweet air the spice of audacity. An inch or so of transparent ice lies between you and a ducking among the fishes which dart through the clear depths, fleeing before the under water roar of your ad{54}vance, for the cracks, starting beneath your feet and flashing in rainbow progress before you and to the right and left, send wild vibrations whooping and whanging through the ice all over the pond. Now the visible bottom drops away beneath you to an opaqueness that gives you a delicious little sudden gasp of fear, for you realize the depth into which you might sink; again it rises to meet you and here you may bear down and gain added impetus, for you know that the ice will be thicker in shallow water.

So you go on, and ever on. It is not wise to retrace your strokes, for those ice crystals that gave to let you through and then gripped one another again to hold you up may not withstand a second impact; nor is it wise to stop. Mass and motion have given you momentum and{55} you have acquired some of the obscure stability of the gyroscope. You tend to stay on your plane of motion, though the ice itself has strength to hold only part of your weight. Thus the wild duck, threshing the air with mighty strokes, glides over it, held up by the same obscure force. The ice has no time to break and let you through. You are over it and onto another bit of uncracked surface before it can let go.

The day warmed a little with a clear sun but the frost that night bit deep again and the next morning the ice had nearly doubled in thickness and would not crack under any strain which my weight could put upon it. A second freezing, even though both be thin, gives a stronger ice than a single freezing of equal depth, just as the English bowmaker of the old days used to glue to{56}gether a strip of lancewood and a strip of yew, or even two strips of the same wood, thus making a far stiffer bow than one made of a single piece of equivalent dimensions.

This ice was much smoother too. That evaporation which is steadily going on from the surface of ice even in the coldest weather, the crystals passing to vapor without the intervening stage of water, had worn off the embossing. The ice instead of being black was gray with countless air bubbles all through its texture. You will always find these after a day’s clear sun on a first freezing. I fancy the ice crystals make minute burning glasses under the sun’s rays and thus cause tiny meltings within its own bulk, the steam of the fusing making the bubbles; or it may be that the air with which the north wind of two days before{57} had been saturating the water was thus escaping from solution.

It was midday of this second day of skating weather before I reached the pond. The sky was overcast, the wind piped shrill again, and there were snow-squalls about. The pond was empty and lone. I thought no living creature there beside myself, and it was only at the second call of a familiar voice that I believed I heard it. Then, indeed, I stopped and listened up the wind. It came again, a wild and lonely whistle that was half a shout, beginning on the fifth of the scale, sliding to the top of the octave, and then to a third above, and I heard it with amazement. The pond was firmly covered with young ice. Why should a loon be sitting out on it and hooting to me?

There was silence for a space while I{58} looked in vain, for the first flakes of a snow-squall were whitening the air and had made the distant shore indistinct. Then it spoke again, almost confidentially, that still lonely but more pleasing whinny, a sort of “Who-who-who-who” that is like a tremulous question, weird laughter, or a note of pain as best fits the mind of the listener. The voice came from the geographical centre of the pond’s loneliness, the one point where a wild bird like the loon, obliged to make a stand, would find himself farthest from all frequented shores. I skated up the wind in that direction, but the snow blew in my eyes and I could see but little.

Suddenly right in front of me there was a wild yell of dismay, despair and defiance all mingled in a single loon note, but so clearly expressed that you could not fail to recognize them, then a quick{59} splash, and I had almost skated into a hole in the ice, perhaps some ten feet across.

Then I knew what had happened. A loon, wing-tipped by some poor marksman, had dropped into the pond before the freeze. He could dive and swim, no doubt, as well as ever but could not leave the water. When the pond began to freeze he did the only thing possible in his losing fight. That was to seek the loneliest spot in the surface and keep an opening in the ice when it began to form. I could see the fifteen-foot circle which had been his haven for the first night and day. Then with the second freezing night he had been obliged to shorten this. Two feet and a half of new ice showed his inner line of defence rimmed accurately within the greater circle and showing much splashing where he had, I{60} thought, breasted it desperately all the long night in his brave fight to keep it open.

How long without human intervention he might brave the elements and keep his narrowing circle unfrozen would of course depend on the weather. If it did not come on too severe he might live on there till his wing healed and by a miracle win again to flight and safety. The cold would not trouble him nor the icy water. The loon winters anywhere from southern Massachusetts south and, strong and well, has no fear of winter. But there entered into this the human equation. The next man along would likely go home and get a shotgun.

As I noted all this a head appeared above the water in the pool. There was another shriek of alarm and it vanished in a flash and a splash. It was forty sec{61}onds by my watch before the bird appeared again. This time he rose almost fully to the surface and sounded a war cry, then dove again and was under for seventy seconds. And so as long as I stood my distance motionless he came and went, never above water for more than a few seconds, varying in length of time that he stayed below from half a minute to a minute and a quarter, and never going below without sounding the eerie heartbreak of his call.

Then I skated away to get my camera and was gone three-quarters of an hour. Returning I saw him in the distance, for the snow had almost passed. He saw me too and dived. Gliding up I knelt at the very edge of the hole and was fixing the camera when he came up. He sat level on the surface for a second, seemingly not noticing me. Then, warned by{62} a motion that I made in trying to adjust the focus, he sounded a wild and plaintive call that seemed to have in it mingled fear and defiance, heartbreak and triumph, and plunged beneath the surface with a vigor and decision that sent him far beneath the ice, his great webbed feet driving him with great jumps, as a frog swims.

I saw him shoot away from the hole, trailing bubbles. I waited kneeling, watch in hand and thumb on bulb, a minute, two minutes, three, five, ten. The snow shut in again thick, the north wind sang a plaintive dirge and I realized that the picture would never be taken. Instead I was kneeling at the deathbed of a wild Northern spirit that perhaps deliberately took that way of ending the unequal struggle.

The loon knows not the land. Even{63} his nest he builds on the water’s edge and clambers awkwardly to it with wings and bill as well as feet. The air and water are his home, the water far more than the air, and he knows the underwater world as well as he does the surface. I shall never know whether my loon went so far in his flight beneath the ice that he failed to find his way back, or whether his strength gave out. Knowing his untamed and fearless spirit I am inclined to believe that he deliberately elected to die at home, in the cool depths that he loved rather than come back to his poor refuge in the narrowing ice circle and face that strange creature that knelt at the edge.

THE spring of this, our new year of 1909, is set by the wise makers of calendars to begin at the vernal equinox, say the twenty-first of March, but the weatherwise know that on that date eastern Massachusetts is still in the thrall of winter, and spring, as they see it, is not due till a month later.

Yet they are both wrong, and we need but go into the woods now to prove it. The spring in fact is already here. The new life in which it is to express itself in a thousand forms is already growing and much of it had its beginning in late August or early September of last year. The wind out of the north may retard it indeed, but it needs but a touch of the{68} south wind to start it in motion again, and the deep snows that are yet to come and bury it so that the waves of arctic atmosphere that may roll over its head for weeks will never be able to touch it are a help.

Many a hardy little spring plant blooms first, not in April as we are apt to think, but more likely in January, though it may be two feet deep beneath the snow and ice and unseen by any living creature. To go no farther than my own garden, I have known a late January thaw, rapidly carrying off deep snow, to reveal the “ladies’ delights” in bloom beneath an overarching crust of ice. The warm snow blankets had effectually insulated the autumn grown buds from the zero temperature two feet above, and the warmth of the earth beneath had not only passed through the frost but melted{69} a little cavern beneath the snow, and there the hardy plants had responded to the impulse of the spring that was already with them.

In this wise the chickweed blooms the year round though rarely are circumstances such that we note it in the winter months. Now and then the hepatica opens shy blue eyes beneath the enfolding snow and it is common in times of open weather in midwinter to read newspaper reports of the blooming of dandelions in December, or January. These are just as much in bloom on other winters but the snow covers them from sight and it takes a thaw which sweeps the ground clear of snow to reveal them.

It is good now and then to get a green Christmas such as we have just had, for in it we may go forth into the fields and realize that the spring has not retreated{70} to the Bahamas, but merely to the subsoil, whence it slips, full of warmth and thrill, on any sunshiny day. If we will but seek the right places we need not search long to find April all about us, though they may be cutting ten-inch ice on the pond and winter overcoats be the prevailing wear.

To-day I found young and thrifty plants, green and succulent, of two varieties of fern that are not common in my neighborhood and that I had never suspected in that location. I had passed them amid the universal green of summer without noticing them, but now their color stood out among the prevailing browns and grays as vividly as yellow blossoms do in a June meadow.

Yet I sought the greater ferns of my acquaintance in vain in many an accustomed place. Down by the fountain{71} head is a spot where the black muck, cushioned with yielding sphagnum, slopes gently upward to firmer ground beneath the maples till these give way to the birches on the drier hillside. Here the ostrich fern waved its seven-foot fronds in feathery beauty amid the musky twilight of the swamp all summer long.

It was as if giants, playing battledore, had driven a hundred green shuttlecocks to land in the woodcock-haunted shelter. The tangle of their fronds was chin high and you smashed your way through their woody stipes with difficulty, so strong and thick were they. Now they have vanished and scarcely a trace of their presence remains. Brown and brittle stalks rise a little from the earth here and there, and if you search among fallen leaves you may find the ends of their rootstalks with the growth for next year{72} coiled in compact bundles there, ready to unfold.

From these rootstalks spring in all directions slender underground runners whence will grow new plants. But none of this is visible. The only reminder of that once luxurious thicket is the brittle, brown stalks that still, here and there, protrude from the fallen leaves.

It is difficult to see where they all went, but there is something savoring of the supernatural about ferns, anyway. Shakspeare says: “We have the receipt of fern-seed; we walk invisible.” For men to use this receipt the seed must be garnered on St. John’s eve in a white napkin with such and such incantations properly recited. The Struthiopteris germanica had plenty of fern-seed on St. John’s eve. It must have used the old-time incantations with success, for all the{73} giant shuttlecocks that thronged the swale with a close-set tangle of feathery green have vanished.

I sought another moist and shady woodland where all the early spring the ground was a warm pinky brown with the fuzz of uncurling fiddle heads, and later the brown, leaf-carpeted earth was hidden in a delicate lace patterned of the young fronds of the cinnamon and the interrupted fern. To this woodland came the yellow-warblers for the soft fuzz for use in nest building, it compacting readily into a felt-like mass that is at once yielding and durable. The cinnamon fern when it has reached any size has an underground stump that is as woody and tough almost as that of a tree. Its strong fronds are next to those of the ostrich-fern in the woody vigor of their stipes. Surely these might have lasted.{74} Yet not one form of fern life was visible in this once thronged wood. Like the ostrich ferns they had poured their own fern-seed on their heads and whispered the correct incantation at the coming of the first chill wind. I am inclined to think it all happened in a jiffy, when happen it did, for I have been back and forth through that part of the wood all the fall and I cannot recall the day on which they were first missing. It seems as if I would have noticed their gradual crumbling and decay.

The same is true of the clumps of Osmunda regalis that grew here and there along the pond shore. Rightly named “regalis” they stood in royal beauty four or five feet tall and leaning over the water’s edge admired the bipinnate grace of their fronds, while the tallest stalks bore aloft the clusters of spore cases that{75} looked like long spikes of plumed flowers. No wonder the plant which is common to England also drew the notice of Wordsworth, who refers to it as—

Flowering fern it is rightly named, too, but it had flowered and gone, and I found of all its regal beauty but a single stalk with brown spore-cases held rigidly aloft among a tangle of brown leaves and bog grass.

Then I looked for the sensitive fern. This with its slender, creeping rootstock sending up single fronds is less woody than any of the others and I began to suspect that it would have disappeared utterly. So the sterile fronds had.{76} There was no trace of them in spots that in summer were a perfect tangle. But this was not true of the fertile stalks. Here and there these, like the one of the royal fern, stood erect and bore their close-lipped spore cases, seal-brown and stiff, high above dead leaves and other decay of fragile annuals.

All this made a disheartening fern chase, and I turned to the steep side of the hemlock-shaded northern hill, sure of one hardy variety that would have no use for invisibility, however chill the north wind might blow. No smile of direct sunlight ever touches this hill. It is set so steep that only the mid-summer midday sun overtops its slant and this the dense hemlock foliage shuts out. No woodland grasses grow in its dense shadow and only here and there the partridge berry and the pyrola creep down a little from{77} the top of the ridge where some sunlight slips in. Yet in its densest part the Christmas fern revels and throws up fronds that seem to catch some of their dark beauty from the deep green twilight of the place. In the spring these stand in varying degrees of erectness, but autumn seems to bring a change in the cellular structure of the lower part of the stipe and weaken it so that the fronds fall flat upon the earth. They lose none of their firm texture or color, however, and be the temperature ever so low or the snow ever so deep they undergo no further change till the next spring fronds are well under way. Sometimes even in mid-summer you may find the fronds of the year before, somewhat fungi-encumbered and darkened with age, but still green.

No other fern grows in the denser{78} portions of this hemlock twilight, though the Christmas fern clings close to it, and does not spread to the more open glades on other portions of the hill. Another northern hill of similar steepness but shaded by an old growth of pines through which certain sunlight filters during most of the day has specimens of the Polystichum acrostichoides growing only in its most sheltered nooks from which they do not seem to spread even to the brighter spots near by on the same declivity. Hence I infer that the plant prefers the twilight, and does not thrive in even occasional sunlight.

Just at the base of this second hill, however, where cool springs begin to bubble forth in the mottled shadow, I caught a gleam of a lighter, lovelier green that was like a dapple of sunlight on clumps of Christmas ferns, and I came{79} near passing it by for that. Then, because I had never seen this fern growing in a dapple of sunlight, I went to it and found that I had chanced upon a group of the spinulose wood fern. The plumose fronds showed no more winter effects than did those of the Christmas ferns. The keen frosts had not shrivelled them, nor was there any hint of the brown that might come with the ripening of leaves or the departure of sap.

Like the other ferns they had suffered a failing of tissues near the base of the stipe, but pinnules, midribs and rachis were as softly, radiantly green as they had been under the full warmth of the summer sun. Owing to this failure of tissues in the stipe they lay flat to the ground, but they were still beautiful, perhaps more so than they had been when they stood more erect in summer, and{80} were obscured and hidden by the other green things of the wood. I know I tramped within a few feet of them again and again last summer without noticing them, yet to-day they caught my eye a long way off, and held it in admiration even after a long and close inspection.

Farther down in the very swamp, laid flat along the sphagnum and oftentimes frozen to it, were fronds of the crested shield-fern and the patches of these tolled me far from my find and it was only on coming back for another look that I discovered the prettiest thing about it. That was, near by and half sheltered by tips of the elder fronds, young plants of the same variety, just advancing from the prothallus stage and having one or two miniature fronds like those of the parent plant but not more than two or three inches long.{81}

These looked so tiny as compared with the mature ferns, but were so erect and confident, so fresh and green and very much alive though the temperature about them night after night had been far below freezing and their roots then stood in ice, that it was worth a journey, just to look at them. How their tender tissues had stood the temperature of ten above zero that had surrounded them a few nights before is more than I can answer. The faintest touch of frost kills the fronds of the great seemingly tough cinnamon and ostrich ferns. Yet these dainty little plants of Nephrodium spinulosum with their miniature fronds of tender lacework had not even wilted or cowered before deep and continued cold as had the stalks of their elders of the same species, but stood erect, nonchalant and seemingly eagerly growing still.{82}

We may say if we will that it is all a part of that magic of youth that makes a million miracles each spring but that does not explain it. Why should these be so strong and full of life when the fronds of the hay-scented fern, for instance, have been shrivelled to dry and crumbling brown fragments under the same conditions? I cannot answer this either.

Last of all I thought of the polypodys that grow in the rock crevices all down along the glen, and went to see how they fared. It has been a hard year for these little fellows. There must have been weeks at a time during the scorching days of the long summer’s drought that their roots, clinging precariously in rock crevices and dependent for moisture wholly on rain and dew, were dry to the tips. The very heat of the rock itself{83} under the blister of the sun would not only evaporate all moisture, but would so remain in the rock all night as to prevent any dew from condensing on it.

I had seen the polypodys at midday curled up on themselves seemingly nothing but dried tissues that could never be again infused with the breath of green life. Yet, let there come but the briefest of showers and you would see them uncurl, lift their fronds to the breeze, and go on as cheerily as their lower level neighbors the lady-ferns whose pinnules flashed in the drip of the splashing stream and whose roots bathed in the shallows.

The summer must have weakened them. Were they the sort to shrivel at the touch of the freezing wind and vanish into the fern-seed magic of invisibility? Not they. The slender crevice of black dirt in which their roots grow was black{84} adamant with frost, but the polypodys swayed in the biting wind as jauntily as they had in the soft airs of summer and were as green and unharmed by the winter thus far as the Christmas ferns had been.

While I gazed at them, admiring their toughness and courage, my eye caught a bit of greenery on the rock high above and I had found the second unexpected fern of my winter day’s hunt, for there from a crevice dripped the rounded, finely crenate, dark green pinnæ of Asplenium trichomanes, the maidenhair spleenwort.

Many a day during the summer had I sat on that ledge, listening to the prattle of the brook down the glen and watching the demoiselle flies flit coquettishly up and down stream while the dragonflies with masculine directness darted hither{85} and thither. The polypodys must have often dropped their fern-seed on my head, but the magic that they invoked with it must have been of the sort that made not me, but the little fern above invisible, for it remained for this winter day of a green Christmas week to show me its fragile beauty still green and undisturbed in the winter weather. No other evidence was needed, nor could I have any so good, to prove that spring is indeed here before the winter comes, and though the cold and snow may retard they cannot prevent it from reaching the full beauty and climax of maturity.

TOWARD morning the south rain, whose downpour was the climax of the January thaw, ceased, and in the warm silence that followed Great Blue Hill seemed like a gigantic puffball growing out of the moist twilight into the dryer upper atmosphere of dawn. Standing on its rounded dome you had a singular sense of being swung with it upward and eastward to meet the light. At such times the whirling of the earth on its axis is so very real that one wonders that the ancients did not discover it long before they did. Surely their mountaineers must have known.

After a little the battlemented donjon{90} of the observatory looms clear and you begin to notice other details of the gray earth beneath your feet. The south wind has brought and left with you for a brief space the atmosphere of the Bermudas, and you need only the joyous hubbub of bird songs to think it June instead of January. Instead there is a breathless silence that is like resignation and a portent all in one. Breathing this soft air in the golden glow of daybreak it seems as if there could never be such things as zero temperature and northwest gales; but the whole top of the hill keeps silence. It knows.

As the day grows brighter you can see the little scrub-oaks that make the summit plateau their home crouch and settle themselves together for the endurance test which is their winter lot. They have opened their hearts to the south rain{91} while it lasted, but they know what to expect the moment it is gone. They studied the weather from Blue Hill summit long before the observatory was thought of.

All trees love the hill, but few can endure its winter rigors. You can see where the hickories and red cedars have swarmed up the steep from all sides, and as you note how the scrub-oaks compact themselves you will see also the cedars holding the rim of rock as did that thin red line of Scottish Highlanders at Inkermann, all dwarfed and crippled with the struggle till they seem far different trees from the debonair slim and sprightly red cedars of the alluvial plain. You can fairly see them clench their teeth and hang on.

Yet they love the rocks that they have gripped for some hundreds of years, and{92} nothing but death will part them. There are red cedars growing out of the gray granite near the southern rim of Blue Hill that I believe were there when Bartholomew Gosnold stepped ashore, the first Englishman to set foot on the soil of Massachusetts. No such age belongs to the hickories that have managed to get head and shoulders above the rim of the plateau, yet they too have lost their slender straightness. The cold and the summit winds have pressed them back upon themselves till they are stubby, big-headed dwarfs.

Of how the other trees climb the hill we shall learn more if we begin at the bottom, and we could have no better day in which to look them up than this, for the south rain has swept the ground bare of all snow and left us for a space this temperature of the Carolinas rather than{93} that of Labrador, which is our usual portion in January. Indeed, from the sunny plain which stretches from the southern base of the rock declivity you can see where even tender and jocund plants once began the climb most jauntily.

Stalwart yellow gerardias, six feet tall some of them, grow in the rich black mould that makes steps upward through the rock jumble. From August till the frost caught them they scattered sunshine all along beneath the hickories and chestnuts, maples and white oaks, tipping it out of golden bowls to be shattered into the mists of goldenrod blooms that followed after. These gerardias, though dry and dead, stand now, and will stand despite gales and snow all winter long, boldly lifting brown seed pods aloft, pods that grin in the teeth of bitter gales and send their chaffy seeds floating up the{94} slope to plant the sunshine banner a little farther aloft for next year. Many centuries they have been at it, but few of them have climbed far, yet they so love the hill that they cling tenaciously to the ground they have gained and seem to grow more vigorously there than on less rugged soil.

The roughest ledges of the hill jut boldly to the southward, showing gray granite shoulders to the sun and making this side almost a sheer rock precipice. Yet here the Highlander cedars have chosen to make their climb in battalions, plaiding the gray surface with russet brown and olive green, clinging tenaciously by toe-tips where it would seem as if only air-plants might find nourishment. No other trees dare the bare granite steep, though hickories flank the cedars wherever the slopes of the ridge{95} have crumbled a little and given a better foothold of black soil.

Strange to say, the purple wood-grass that surely loves sandy plains best has sent little scouting parties up with the hickories, and here and there occupies tiny plateaus among the ledges well up toward the ridge, often rimmed round with the purplish green of the mountain cranberry. At the bottom of the gullies the maples began the climb, but they did not last long. Red and white oaks have won farther up, but stopped invariably before the summit of the gully was reached.

From the beautiful Eliot Memorial Bridge, near the eastern limits of the summit plateau of Blue Hill, you catch a wonderful glimpse southeasterly right down a narrow ravine to a wider valley, and thence down again to a glow of white{96} ice which is Houghton’s Pond. The bare trees no longer hide one another and you see where they made a flank movement in force for the summit, swarming over the wider upland valley, and narrowing to a wild charge of great chestnuts up the gully. These chestnuts do not seem to stand rooted. They sway this way and that and seem to hurrah and wave flags in the wild excitement of a desperate and hopeful venture. They are motionless, of course, but they have all the semblance of splendid action that genius has given to sculpture, and they add romance to the most picturesque spot on the range. Yet never a chestnut top is lifted above the ridge which tops the gully. To it they came in all the fine enthusiasm of a well-planned and concerted advance, but stopped so suddenly that you see them in splendid action still, as if with one foot{97} in the air for the step that should take them above the ridge.

The north wind of the ages has stopped them right there where their tops are just far enough above the level of the ridge edge to be safe from it. You see them best by climbing down the little gully among evergreen wood ferns which grow in the rich, moist soil among the rocks, the only touches of green unless you happen upon some polypodys seemingly growing out of the rock itself.

Right among the chestnuts the semblance changes again with the harlequin-like magic of the woods. The big trees are no longer fixed in the attitude of desperate charge upon a rampart, as you saw them from above. Among them they seem to be tipsy bacchanals who have chosen the little secluded glen for a place of revelry, and are reeling about it like clumsy{98} woodsmen in a big-footed dance. A chestnut tree standing by itself on a plain is as stately and dignified as a village patriarch. Grouped together in level, rich woodland, chestnuts are prim and almost lady-like. Why these particular trees in the little glen at the east side of Blue Hill summit should skip about in clumsy riot is more than I can tell, but they certainly seem to do it, and I am not the only one who has seen it and been shocked by it.

Right near by is a company of schoolgirl beeches, very straight and slim and fair-skinned and pale. These have drawn together in a shivering group and show every symptom of feminine dignity, very young and quite outraged. They whisper and draw themselves up to the full tenuity of their height and you can hear the dry snip of indignation in their voices long{99} before you reach them. No doubt they thought to have the glen all to themselves for a proper picnic with prunes and pickles, and here are these great fellows thus misbehaving! It is a shame and the park police should put a stop to it. The beeches are so frosty in their indignant withdrawal that the icy whispering of their dry leaves sounds like fast falling sleet. Slip among them when you are next on the hill, shut your eyes and listen. The day may be as sunny and warm as a winter day can be, but you will think you hear the snow falling fast and will be sorry you have not brought your fur muffler.

As for the chestnuts, I suspect they drank mountain dew at the illicit still just below the gully. Surely no springs should have a license to do business among the hilltops of this granite range.{100} Yet they well up freely among the lesser spurs that lie between Great Blue and Hancock, and their moisture, drawn from cool depths to little ponds where the southern sun shines in and the north and west winds are held back by granite ridges, make rallying places for all kinds of wood and pasture people that have yearned for mountain heights, but could not stand the rigors of the summits. There are three of these little ponds on the heights of the range almost within a stone’s throw of one another. It may be that the seepage from surrounding ledges accounts for their flow of water, but I am more inclined to think that cracks in the backbone of the hills let the water flow up from subterranean depths. The margins of two of them are the happy home of greenbrier which grows in tropical luxuriance all about, so binding the{101} bushes together with its spiny twine that it is almost impossible to pass through them to the water. Button-ball and high-bush blueberry grow with it and hold out their branches for its smilax-like decoration, and the solemn and secretive witch-hazel stalks meditatively about wherever the overhead foliage is dense enough to make the mysterious twilight that it best loves. It strolls up the gully beneath the shade of the chestnuts and you can but fancy it smiling sardonically at their revelry and the prim indignation of the schoolgirl beeches. Here and there swamp maples, strangely out of place on hilltops, glow gray in the dusk as you stand below them, or blush red in the clear sun as you look at their branch tips from the cliffs. It is a picturesque little three-spurred peak lying here between Great Blue and Hancock so shel{102}tered and warm in the midday sun that it is only by watching the sky that you know it is winter, though the ice is white and strong on the little ponds.

I think you can get the best view of all of Great Blue Hill from the summit of the lesser hill beyond the spurs and ponds and south of Hancock, just overhanging Houghton’s Pond. There you see the forest-clad slope sweep grandly up to form this broad upland valley, wrinkle a bit with the folds where lie the three little ponds, then rise again most majestically all along the steep side of the hill. At this time of year it is one broad, majestic mass of the warm gray of bare tree trunks in which rock ridges stand indistinct in purer color, while here and there clustering twig masses purple it. You can see the black shadows in the face of the cliff where stands the little glen in{103} which the chestnuts disport, and down near the highest of the three ponds is a beautiful little splash of white all flushed with pink. This marks the location of a group of young birches, the only ones I find on the heights of the range.

Midday had passed and with it the genial warmth that the south wind had brought us. Instead romping northern breezes had a tang in them and torn clouds sailed swiftly into view over the summit of Great Blue, rushing deep blue shadows across the warm grays of the landscape. The age-old battle of sun and wind was going on on every summit of the range. Climbing the southerly slope of Hancock it was hard to believe it winter. You got either season on the summit plateau according to the nook you chose, but standing on the rim of the precipice, which faces north you had no doubts.{104} From your feet to the foot of the hill in this direction it was winter indeed. Yet here was the greenest spot in the whole range. Scrambling perilously down the face of the cliff I touched rich green vegetation with either hand and stood amid luxuriance at the bottom. For here you are at the meeting place of ferns.

Little sunshine reaches the face of this cliff in the high noon of a midsummer day. No direct ray touches it all winter long, yet in the chill twilight the polypodys swarm all along the summit of the ridge and drip and dance down and stretch out their hands to neighbor ferns that climb cheerily to meet them out of the moist shadows below. These are the evergreen wood ferns. In the rich black frozen earth of the lower woodland they grow in profusion. On the rocky acclivity they hold each coign of vantage and{105} splash the plaid of gray rock and brown leaves with their rich green. Where cliff meets rock jumble the two draw together and fraternize, and the polypodys come farther off the cliff than I have often seen them, and the wood ferns grow in slenderer crevices of the bare rock than anywhere else that I know.

The sun was gone from all the little ravines on the way back from Hancock to Great Blue, and the chill of the fern-festooned shadow of the cliff that I had just left seemed to go with me all along. It was especially dark and chill in the little gully and I reached the summit of the big hill too late to find the sun. There, where daybreak had breathed of spring, nightfall shivered in the bite of winter winds. A million electric glints splintered the purple dusk to northward, but there was no warmth in them even{106} when they fused into the glow of the great city. With the shadow of night the cruel grip of winter had shut down on the hilltop and I knew again, as I had known in the golden glow of the morning, that it was midwinter. The dwarfed and storm-toughened shrubs seemed to crouch a little closer to the adamantine earth, and their frost-stiffened twigs sang in the bitter north wind. I felt the chill in my own marrow and eagerly tramped the ringing granite toward home.{107}

IT seems to be our lot this winter to have April continually smiling up in the face of January. Again and again the north wind has come down upon us and set his adamantine face against all such folly. The turf has become flint; the ice has been eight inches thick on pond and placid stream, and the very next morning, maybe, the soft air has breathed of spring, and bluebirds have twittered deprecatingly as if glad to be here, but altogether ashamed to be found so out of season. As a matter of fact, of course, some bluebirds winter with us, but they don’t warble “cheerily O” in the teeth of the north winds. On those days you must seek them in the cuddly seclusion{110} of dense evergreens, more than likely among close-set cedars where the blue cedar-berries are still sweet and plenty. But we have had many days in this January of 1909 when the bluebirds have had a right to feel called to at least take a hurried glimpse at the bird boxes or the holes in the old apple trees, just as people take a flying trip to the summer cottage on a warm Sunday; they know they can’t stay, but it is delightful to just look it over and plan.

I think the crows, though they are tough old winter residents, have something of the same impulse to plan nests and make eyes and cooing conversation, one to another. To-day I heard, in the pine treetops of a little pasture wood where several pair nest every year, the unmistakable note. In that great song of Solomon which the whole out-door{111} world will chorus in the full tide of spring the crows have the bass part, no doubt, but they sing it none the less musically. It is surprising what a croak can become, between lovers.

I saw them slip away silently and shamefacedly as I approached, and I knew them for callow youngsters, high-school age, let us say, to whom shy love-making is never quite out of season. But they got their come-uppance the moment they sailed out of the grove, for their appearance was greeted with a wild and raucous chorus of crow ha-ha-ha’s. High in the air, flapping round and round in silence above the pines, a half dozen riotous youngsters of their own age had been observing them, chuckling no doubt and winking to one another, and now that the culprits were driven out into the open where all could see{112} them the chorus of jeers knew no bounds. It was as unmistakable as the caressing tone, this jeering laughter. You had but to hear it to know very well what they were saying. The crow language has but one word, which in type is caw. But their inflections and tone qualities are such that it is easy to make it express the whole diatonic scale of primitive emotion.

Many of our summer birds whose winter range barely includes us seem to be more than usually prevalent this winter. It may be that the mild season has to do with this, but it is equally probable that a plenitude of food is more directly responsible. Seed-eating birds are particularly in luck this year. I do not know of a winter when the birch trees have fruited so plentifully, nor have I noticed so many flocks of song sparrows{113} as this year. I find them twittering happily along through the wood, hanging in quite unsparrow-like attitudes from slender birch twigs, busy robbing the pendant cones of their tiny seeds. In the summer you know the song sparrow as a very erect bird. He sits on some topmost twig of cedar or berry bush and pours forth quite the cheeriest and sweetest home song of the pasture land. Or perchance he flies, and the usual short and oft-repeated refrain seems to be broken up by flutter of his wings into a longer, softer, and more varied song that has less of challenge and more of sweet content in it. In his winter notes, which are really nothing but a cheery twittering, I always think I hear something of the mellow singing quality of this song of the wing.

To-day I saw a sharp-shinned hawk,{114} hunting noiselessly, no doubt for these same sparrows. He flitted among the treetops like a nervous flash of slaty gray, and was gone so quickly that had I not heard the welt of his wing tips on the resisting air as he turned a sharp corner I should never have seen him. Most of our hawks, though well known to take an occasional chicken, are mouse and grasshopper eaters. The sharp-shinned is the real chicken hawk, for he eats more birds than anything else, though the small songsters of the thicket form the greater part of his diet. I have rarely seen him here in winter, though his summer nest is common in the deep woods, with its cream-buff eggs heavily blotched with chocolate brown. Just as the plenitude of food of their kind kept the song sparrows with us to enjoy the mild weather, so I think the multitude{115} of song sparrows and other succulent titbits made the sharp-shinned hawk willing to winter where he had summered.