Title: Secret History of To-day: Being Revelations of a Diplomatic Spy

Author: Allen Upward

Illustrator: W. Dewar

Release date: August 30, 2021 [eBook #66181]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: D A Alexander, John Campbell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by University of California libraries)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the book. There are only two in this book.

Obvious typographical errors and punctuation errors have been corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within the text and consultation of external sources.

Except for those changes noted below, all misspellings in the text, and inconsistent or archaic usage, have been retained.

Pg vi: ‘William II.’ replaced by ‘Wilhelm II.’.

Pg vii: page no. ‘256’ replaced by ‘254’, and ‘258’ replaced by ‘256’.

Pg 188: ‘William II.’ replaced by ‘Wilhelm II.’.

Pg 303: ‘Guiseppe Sarto’ replaced by ‘Giuseppe Sarto’.

“The Kaiser was attired in his most magnificent costume, wearing the famous winged helmet on his head, and surrounded by a galaxy of ministers and great officers, all arrayed in the utmost military splendour.”

Being Revelations of a Diplomatic Spy

By

Allen Upward

Author of “Secrets of the Courts of Europe”

“Treason,” etc.

Illustrated

G. P. Putnam’s Sons

New York and London

The Knickerbocker Press

1904

[Pg iii]

| I | |

| PAGE | |

| THE TELEGRAM WHICH BEGAN THE BOER WAR | 1 |

| II | |

| THE BLOWING UP OF THE ‘MAINE’ | 31 |

| III | |

| THE MYSTERY OF CAPTAIN DREYFUS | 56 |

| IV | |

| WHAT WAS BEHIND THE TSAR’S PEACE RESCRIPT | 91 |

| V | |

| WHO REALLY KILLED KING HUMBERT | 120 |

| VI | |

| THE PERIL OF NORWAY | 146 |

| VII[iv] | |

| THE RUSE OF THE DOWAGER EMPRESS | 170 |

| VIII | |

| THE ABDICATION OF FRANCIS-JOSEPH | 191 |

| IX | |

| THE DEATH OF QUEEN DRAGA | 217 |

| X | |

| THE POLICY OF EDWARD VII | 242 |

| XI | |

| THE HUMBERT MILLIONS | 264 |

| XII | |

| THE BLACK POPE | 288 |

[v]

| PAGE | ||

| “The Kaiser was attired in his most magnificent costume, wearing the famous winged helmet on his head, and surrounded by a galaxy of ministers and great officers, all arrayed in the utmost military splendour.” | ||

| Frontispiece | ||

| “A glance at the cheval glass showed me a stiff, well set-up Prussian official.” | 10 | |

| “‘I have sent for you, in two words, to find out for me the authorship of this telegram,’ the Kaiser said.” | 12 | |

| “‘My God!’ he cried out. ‘Who has done this? I shall be ruined!’” | 22 | |

| “‘We shall find out whether he is a priest,’ was the retort.” | 46 | |

| “She would talk about her convent.” | 48 | |

| “‘Father Kehler has been good enough to visit a poor sailor who is lying sick on board,’ he said, in a tone evidently meant to rebuke my impertinence.” | 50 | |

| “‘As to that—impossible!’ he exclaimed with vigour. ‘That is our secret—ours, you understand.’” | 62 | |

| “‘Am I under arrest too?’ Prince Pierre demanded with some indignation.” | 72 | |

| “The Tsar now interposed in a tone of more authority than I had ventured to hope for. ‘Do you suggest, M. V——, that the whole staff of the French army are engaged in a conspiracy to forge documents?’” | 88 | |

| [vi] “‘Your Majesty must judge me by what I have done already. Two days ago you had never heard my name. Now I am here, alone with you, with a loaded revolver in my pocket.’ The Sultan started violently.” | 98 | |

| “It was a singular scene, as I stood there laying down pile after pile of greasy ten-thousand-rouble notes on a richly inlaid table.” | 106 | |

| “There at my feet, along the widening valley, lay a double line of rails, and all across the level space stretched low banks and ditches—the lines of a vast encampment, capable of accommodating half a million men.” | 116 | |

| “I walked past him without a word.” | 126 | |

| “‘I am not under anybody’s orders,’ I said, rising to my feet.” | 130 | |

| “‘You are free,’ he said briefly. ‘The right man has been arrested, too late.’” | 144 | |

| “‘Let me see your warrant,’ I said.” | 158 | |

| “He bent forward to listen, and as he did so I launched my clenched fist at his right temple with my full force.” | 164 | |

| “I watched the brave monarch read it through from beginning to end without one manifestation of dismay.” | 168 | |

| “Finally he turned his back without a word, and rushed from the room.” | 176 | |

| “ Wilhelm II. strode to me, seized me by the shoulders, and thrust me out of the room.” | 188 | |

| “‘Will you permit me to ask you,’ he said politely, ‘if you have ever done any business on behalf of the Emperor of Austria-Hungary?’” | 192 | |

| “The Emperor could not repress a slight start.” | 198 | |

| “I rode right over him.” | 212 | |

| [vii] “I took out my loaded revolver, cocked it, and advanced to the threshold.” | 232 | |

| “Queen Draga cast herself on the inanimate form on the bed, concealed the face in her arms, and allowed herself to be stabbed by a dozen bayonets.” | 240 | |

| “‘V——!’ he exclaimed, drawing back as if he had been stung.” | 250 | |

| “‘Arrest that man!’ the Kaiser commanded, without giving him time to speak.” | 254 | |

| “‘Now,’ said the Kaiser, stepping close to my side, ‘tell me the truth—the real truth, mind—and I will spare your life.’” | 256 | |

| “‘I am going to ask you to undertake a service of an unusual kind.’” | 266 | |

| “My visitor started as she heard her name, and threw up her veil with a gesture of astonishment and indignation.” | 274 | |

| “I was stopped at the barricade by a pompous sergeant of police.” | 280 | |

| “The chief detective came close up to me, put his mouth to my ear, and whispered, ‘Le drapeau blanc!’” | 284 | |

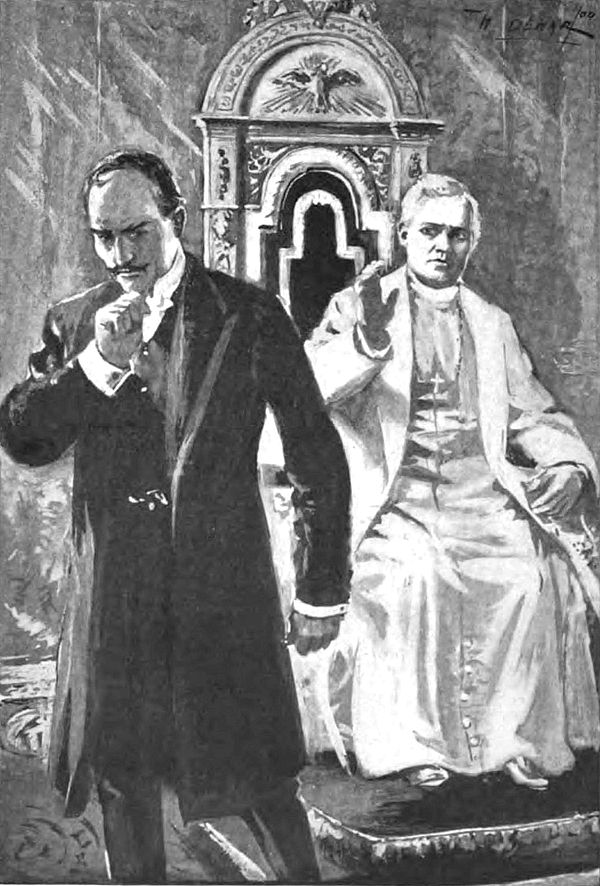

| “I found the Cardinal absorbed in the inspection of his newly arrived treasures.” | 296 | |

| “Saddened and subdued, I quitted the audience chamber of Pius X.” | 306 | |

| “‘I can only render one more service to your Majesty, and that is to advise you to make your peace with the Black Pope.’” | 308 |

[Pg 1]

The initials under which I write these confessions are not those of my real name, which I could not disclose without exposing myself to the revenge of formidable enemies. As it is, I run a very great risk in making revelations which affect some of the most powerful personages now living; and it is only by the exercise of the utmost discretion that I can hope to avoid giving offence in quarters in which the slightest disrespect is apt to have serious consequences.

If I should be found to err on the side of frankness, I can only plead in excuse that I have never yet betrayed the confidence placed in me by the various Governments and illustrious families which have employed me from time to time. The late Prince Bismarck once honoured me by saying: ‘To tell secrets to Monsieur V—— is like putting them into a strong box, with the certainty that they will not come out again until one wants them to.’

[2]

In these reminiscences it is my object to recount some of the services I have rendered to civilisation in the course of my career, while abstaining as far as possible from compromising exalted individuals or embittering international relations.

That I am not a man who opens his mouth rashly may be gathered from the fact that, although at any time during the long struggle between Briton and Boer for the mastery in South Africa, I might have completely changed the situation with a word, that word was not uttered while a single Boer remained under arms.

In order to explain how I came to be concerned in this affair, I had better begin by giving a few particulars about myself, and the almost unique position which I hold among the secret service bureaus of Europe and America.

By birth I am a citizen of the United States of America, being the son of a Polish father, exiled on account of his political opinions, and a French mother. From my childhood I showed an extraordinary aptitude for languages, so that there is now scarcely a civilised country outside Portugal and Scandinavia in which I am not able to converse with the natives in their own tongue. At the same time, I was possessed, ever since I can remember, with a passion for intrigue and mystery. The romances of Gaboriau were the favourite reading[3] of my boyhood, and it was my ambition to become a famous detective, the Vidocq of America.

Fired by these visions, I ran away from the insurance office in which my parents had placed me, when I was little more than sixteen, and applied for admission to the ranks of the famous Pinkerton Police. Although my youth was against me, my phenomenal command of languages turned the scale in my favour, and I was given a trial.

Very soon I had opportunities of distinguishing myself in more than one mission to Europe, on the track of absconding criminals; and in this way I earned the favourable notice of the heads of the detective police in London, Paris, Berlin, and other capitals.

At length, finding that I possessed unique qualifications for the work of an international secret agent, I decided to quit the Pinkerton service, and set up for myself, making my headquarters in Paris. From that day to this I have had no cause to repent of my audacity. I have been employed at one time or another by nearly every Government in the world, and my clients have included nearly every crowned head, from the late Queen Victoria to the Dowager Empress of China. I have been sent for on the same day by the Ambassadors of two hostile Powers, each of which desired to employ me against the other.

[4]

On one occasion I acted on behalf of a famous German Chancellor against his then master, and on another on behalf of the Emperor against his Chancellor; and neither had cause to complain of my fidelity. I have been instrumental in freeing a Queen renowned for her beauty from the persecution of a blackmailer set on by a foreign court; and I have more than once detected and defeated the plots of anarchists for the assassination of their rulers.

In this way it has come about that I enjoy the friendship and confidence of many illustrious personages, whose names would excite envy were I at liberty to mention them in these pages; and that few events of any magnitude happen in any part of the globe without my being in some measure concerned in them.

Often, when some great affair has been proceeding, I have felt myself as occupying the position of the stage manager, who looks on from the wings, directing the entrances and exits of the gorgeously dressed performers who engross the attention and applause of the ignorant spectators on the other side of the footlights.

The true story of the famous telegram which may be said to have rendered the South African War inevitable is one which strikingly illustrates the[5] extent to which the public may be deceived about the most important transactions of contemporary history.

Every one is familiar with the situation created by that celebrated despatch. For some time previously all England, and, in fact, all Europe, had been agitated by the intelligence that Johannesburg was on the eve of insurrection, that the Boers were drawing their forces together about the doomed city, that Dr. Jameson had dashed across the frontier with five hundred followers in a mad attempt to come to the aid of the threatened Outlanders, and that his action had been formally disavowed by the British Government.

Close on the heels of these tidings came the memorable day on which London was cast into gloom by long streams of placards issuing from the newspaper offices bearing the dismal legend, ‘Jameson Beaten and a Prisoner!’

While the populace were yet reeling under the blow, divided between distress at this humiliation for the British flag, and indignation at the criminal recklessness which had staked the country’s honour on a gambler’s throw, there came the portentous news that the head of the great German Empire, the grandson of Queen Victoria, had sent a public message of congratulation to the Boer President, rejoicing with him in the face of the world over an[6] event which every Englishman felt as a national disaster.

That hour registered the doom of the Pretorian Government. Jameson was scornfully forgotten. The British people, as proud as it is generous, made up its mind that the forbearance so long extended to a vassal of its own, could no longer be shown with honour to the protégé of a mighty European Power.

On the very day on which this celebrated despatch appeared as the chief item of news in all the newspapers of the world, I received an urgent cipher message from the Director of the Imperial Secret Service, Herr Finkelstein, demanding my presence in Berlin.

My headquarters, as I have said, are in Paris, and fortunately I was disengaged when the summons arrived. I had merely to dictate a few dozen wires to my staff, while my valet was strapping up the portmanteau which always stands ready packed in my dressing-room, and to look out my German passport—for I have a separate one for every important nationality—and in an hour or two I was seated in the Berlin express, speeding towards the frontier.

From the bunch of papers which my attentive secretary had thrust into the carriage, I learned something of the effect which the German Emperor’s[7] interference in the affairs of South Africa had produced on the public mind in England. It was evident that the Islanders were strongly roused, and were preparing to pick up the gage of battle which had been thrown down. No sooner had I reached German territory than I found evidences of an even greater excitement. The whole nation seemed to have rallied round the Kaiser, and to be ready to back up his words with martial deeds.

By this time I had little doubt that I had been sent for in connection with the outbreak of hostile feeling between the two Powers. But it was impossible for me to anticipate the actual nature of the task which awaited me.

On reaching Berlin I was met by a private emissary of Finkelstein’s, who hurried me off to the Director’s private house. The first words with which he greeted me convinced me that the business I had come about was of no ordinary kind.

‘Do not sit down,’ he said to me, as I was about to drop into a chair, after shaking hands with him. ‘I must ask you to come to my dressing-room at once, where you will transform yourself as quickly as possible into an officer of the Berlin Police. The moment that is done, I am to conduct you to the Palace, where his Majesty will see you alone.’

As I followed the Director into the dressing-room, where I found a uniform suit laid out ready for my[8] wearing, I naturally asked: ‘Can you tell me what this is about?’

Finkelstein shook his head with a mysterious air.

‘The Kaiser has told me nothing. But he warned me very strictly not to let a single creature in Berlin know of your arrival, and from that fact I have naturally drawn certain conclusions.’

I gazed at Finkelstein with some suspicion. We were good friends, having worked together on more than one occasion, and I knew he would have no wish to keep me in the dark. On the other hand, if he had been instructed to do so, I knew he would not hesitate to lie to me. The secret service has its code of honour, like other professions, and fidelity to one’s employer comes before friendship.

Keeping my eye fixed on him, I observed carelessly—

‘You will tell me just as much or as little as you think fit, my dear Finkelstein. On my part I shall, of course, exercise a similar discretion after his Imperial Majesty has given me my instructions.’

As I expected, the bait took. Curiosity is the besetting weakness of a secret service officer, and the Berlin Director was no exception to the rule. Putting on his most confidential manner, he at once replied—

‘My dear V——, if you and I do not trust each other, whom can we trust? Rest assured that my[9] confidence in you has no reserves. I have spoken the bare truth in saying that the Kaiser has given me no indication of his object in sending for you. But the fact that he has ordered me to take these precautions to conceal the fact of your arrival in Berlin tells me plainly that there is a person whom he wishes to keep in ignorance; and that person can only be——’

‘The Chancellor?’ I threw in, as my companion hesitated.

Finkelstein nodded.

‘You consider, perhaps, that it is against the Chancellor that I am to be employed?’ I went on.

‘It looks like it,’ was the cautious answer.

‘And the reason why this task is not placed in your hands?’

‘Is because I am a native of Hanover, and the Kaiser regards me rather as a public official than as a personal servant of his own dynasty,’ said Finkelstein.

‘In other words, he regards you as a creature of the Chancellor’s,’ I commented bluntly.

The Director made a pleasing and ingenious attempt to blush.

‘I can only affirm to you, on my sacred word of honour, that his Majesty has no cause to trust me any less than if I were a Prussian,’ he declared. ‘And I shall take it as a personal kindness if you[10] will endeavour to convince the Kaiser of my loyalty.’

‘I will take care that he knows your sentiments,’ I answered, with an ambiguity which Finkelstein fortunately did not remark.

By this time I had completed my transformation. A glance at the cheval glass showed me a stiff, well-set-up Prussian official, exhaling the very atmosphere of Junkerdom and sauerkraut. I gave the signal to depart, and we were quickly driving up the Unter den Linden on our way to the Imperial Palace.

‘Announce to his Majesty—the Herr Director Finkelstein and the Herr Inspector Vehm,’ my companion said to the doorkeeper.

A servant, who had evidently received special instructions, stepped forward.

‘The Herr Inspector is to be taken to his Majesty at once,’ he said firmly.

Finkelstein bit his lip as he unwillingly turned to re-enter his carriage. I followed the lackey into the private cabinet of the monarch who had just found himself the centre of an international cyclone.

“A glance at the cheval glass showed me a stiff, well set-up Prussian official.”

Wilhelm II. received me cordially. It was not the first time we had met. About the time of his ascending the throne I had been the means of inflicting on him a defeat which a smaller man would have found [11]it hard to forgive. Fortunately, the German Kaiser was of metal sterling enough to recognise merit even in an enemy, and to realise that my fidelity to my then employer was the best guarantee that I should be equally faithful to himself, if it fell to my lot to serve him.

‘What has Finkelstein told you?’ was the Emperor’s first question, after he had graciously invited me to sit down.

‘Only that he was able to tell me nothing, sire.’

The Emperor gave me a suspicious glance.

‘He appeared to regret that your Majesty had not given him your confidence,’ I added, choosing my words warily. ‘He assured me that you might rely on his entire devotion, as much so as if he were a native of your hereditary States.’

‘And what do you say as to that?’ demanded the Kaiser, with a piercing look.

‘I think that your Majesty cannot be too careful whom you trust.’

Wilhelm II. allowed himself to smile gravely.

‘I see, Monsieur V——, that you are a prudent man. If Herr Finkelstein wishes to convince me of his loyalty to the Hohenzollerns, he cannot begin better than by renouncing the pension which he continues to draw secretly from the Duke of ——.’ His Majesty pronounced the name by which a well-known dispossessed sovereign goes in his exile.

[12]

Familiar as I long have been with instances of perfidy in others, I could not restrain an exclamation of astonishment at this revelation of Finkelstein’s double dealing. The Kaiser continued—

‘After that you will not be surprised if I caution you particularly against letting Herr Finkelstein know anything of the object of the inquiry I wish you to undertake.’

I bowed respectfully, and waited with some impatience to learn the true nature of my mission.

‘I could not receive you here without taking some one into the secret of your employment,’ the Kaiser went on to explain; ‘and I chose Finkelstein in order to give the affair as much as possible the aspect of a private and domestic matter. In reality the task I have to set you is one of the most grave in which you have ever been engaged.’

The Kaiser took one of the Berlin papers of the day before, which was lying on the desk in front of him, and pointed to a column in which was set out in conspicuous type the telegram which had convulsed Europe and Africa, and had already caused Lord Salisbury to issue orders for the mobilisation of his Flying Squadron.

‘I have sent for you, in two words, to find out for me the authorship of this telegram,’ the Kaiser said.

“‘I have sent for you, in two words, to find out for me the authorship of this telegram,’ the Kaiser said.”

Notwithstanding my long training in the most [13]tortuous paths of secret intrigue, I was fairly taken aback by this announcement.

‘That telegram!’ I could only exclaim. ‘The one which your Majesty addressed to President Kruger!’

‘I never sent it,’ Wilhelm II. declared gravely. ‘It is a forgery pure and simple.’

For a moment I sat still in my chair, almost unable to think.

‘But what——? But who——?’ I articulated, struggling with my bewilderment.

‘That is what you have got to find out for me,’ was the answer. ‘Let me tell you all I know. The first intimation I had of the existence of such a thing was the sight of it in the Press. I sent instantly for the Chancellor, who came here wearing a reproachful expression, and evidently prepared to complain bitterly of my having taken such a step without previously informing him. When I told him that the whole thing was an impudent fabrication, he could scarcely believe his ears. In fact, for some time I believe he was inclined to consider my repudiation of it as a mere official denial.’

I ventured to raise my eyes to his Majesty’s as I observed—

‘Your Majesty has taken no steps to make your repudiation public?’

The Kaiser gave an angry frown.

‘That is the serious part of the affair,’ he answered.[14] ‘Kruger, in his eagerness to proclaim to the world that I was on his side, had sent copies of this infamous production to every newspaper in the two hemispheres before it reached my eyes. At the moment when I first saw it, it had already been read and commented upon all round the globe. The British newspapers were already threatening war, and my own people had been excited to a pitch of enthusiasm such as no other act of mine has ever called forth. You see the position I was placed in. If I were now to disavow this forgery, my disavowal would be received everywhere with the same scepticism as was felt even by my own Chancellor. The British would triumph over me, and my own subjects would never forgive me for what they would regard as a surrender to British threats.’

I sat silent. I realised the full difficulty of the Kaiser’s position. He was committed in spite of himself to the act of some impostor, whose real motives were yet to be discovered, but who had already succeeded in bringing the two greatest Powers of Europe to the verge of war.

‘Before I can undo the mischief which has been done,’ the Emperor proceeded, ‘I must first of all ascertain from what quarter this forgery emanated. When I have obtained that information, backed by clear and convincing proofs, it may be possible for[15] me to satisfy the British Government that they and I have been the victims of a conspiracy. If you can succeed in furnishing me with those proofs, it shall be the best day’s work you ever did in your life.’

I listened carefully to these words, scrutinising them for any trace of a double meaning. It was impossible for me to dismiss entirely from my mind that suspicion which the story told by Wilhelm II. was naturally calculated to excite. I asked myself whether the Kaiser was really in earnest, or whether he was not inviting me, in a delicate fashion, to extricate him from the consequences of his own rashness, by putting together some fictitious account of the origin of the telegram, which might impose on Lord Salisbury.

It was clearly necessary, however, for me to appear to be convinced.

‘May I ask if your Majesty’s suspicions point in any particular direction?’ I asked, trying to feel my way cautiously. ‘The President of the Boers is perhaps——’

The Kaiser interrupted me.

‘I do not think Kruger would dare to provoke me by such a trick. He would know that he would be the first to suffer when it was found out. No, I am convinced that we must look nearer home for the traitor.’

[16]

Something in the Emperor’s tone struck me as significant.

‘If you could give me any indication of the person——’ I ventured to throw out.

His Majesty looked at me fixedly as he answered—

‘Does it not occur to you, Monsieur V——, that there is in my Empire a powerful family, the heads of which seem at one time to have cherished the notion that the Hohenzollerns could not reign without them, a family which aspired to play the same part in modern Germany which was played by the Mayors of the Palace in the Empire of the Merovingians?’

‘You allude, sire, without doubt, to the Bismarcks?’

‘My grandfather was forced into war with the French by a forged telegram. There would be nothing surprising in an attempt from the same quarter to force me into a war with England.’

I had no answer to make to such reasoning. Daring as such a manœuvre might appear, it was absurd, in the face of historical facts, to pronounce it improbable.

After a minute spent in considering the situation, I turned to the question of how the fraud might have been carried out.

It was quite clear to me that such a message could not have gone over the ordinary wires. The[17] despatches of Emperors are not, as a rule, handed in over the counter of a post-office, like a telegram from a husband announcing that he is prevented from dining at home. I asked the Kaiser to explain to me the system pursued with regard to Imperial messages.

‘That is a matter about which you will be able to learn more from the Chancellor than from me,’ was the answer. ‘Foreign despatches go through the Chancellery, and there is a staff of telegraphists there to deal with them. The wire goes direct to the Central Telegraph Office, I believe, from which it would, of course, find its way to the Cable Company.’

‘Then this fabrication must have been sent from the Chancellery in the first instance?’ I inquired. ‘It could not have been received at the Central Office from an outside source?’

‘Impossible. They would not dare to transmit a message in my name which had not reached them through one of the authorised channels.’

This was the reply I had expected. But I did not fail to mark the admission that there was more than one channel through which the forgery might have come. I was quick to ask—

‘Is there not some other source from which this telegram may have reached them besides the Chancellery? Your Majesty, no doubt, has a private wire from the Palace.’

[18]

The Kaiser looked a little put out.

‘That is so, of course,’ he conceded. ‘But that wire is used only for my personal messages, and those of the Imperial family.’

‘Still, a message received over this wire, and couched in your name, would be accepted at the Central Office, would it not?’ I persisted.

‘Undoubtedly. But the Palace operator, a man who works under the eye of my secretary, would not dare to play me such a trick, which, he would be aware, must be detected immediately. Take my advice, Monsieur V——, waste no time over side paths, but go direct to the Chancellor, and commence your perquisitions among his staff.’

I bowed respectfully, as though accepting this plan of campaign. But, as I withdrew from the Emperor’s cabinet, the doubt pressed more strongly than ever upon my mind whether I was not being asked to play a part. I half expected to find everything prepared for me at the Chancellery, prearranged clues leading to the detection of a culprit who would recite a confession which had been put into his mouth beforehand.

I was perfectly willing to perform my part in the comedy in a manner satisfactory to my employer, but all the same I meant to keep my eyes open, and not to let myself be the victim of a deception intended for English consumption.

[19]

In this mood I presented myself before the Chancellor. As soon as the Imperial autograph introducing me had met his eye, his Excellency threw aside, or pretended to throw aside, all reserve.

‘I am delighted to find the Emperor has placed this business in your hands, Monsieur V——,’ he said obligingly. ‘Your reputation is well known to me, and I am convinced that you will be perfectly discreet. The Emperor is, of course, thoroughly taken aback by the results of his unfortunate impulse, and wishes to relieve himself of the responsibility he has incurred. In that I am quite willing to help him, but not at my own expense, you understand.’

I murmured something about the Bismarcks. His Excellency gave a smile of contempt.

‘All that is absurd,’ he rapped out. ‘The Emperor is quite foolish about that family, which possesses no more influence to-day than any Pomeranian squire. No, if his Majesty wants a victim he ought to be content with one of his own staff. I refuse to allow the Imperial Chancellery to be discredited in the eyes of Europe.’

This reception, so unlike what I had anticipated, made me begin to think that my inquiry would have to be serious. After a little further conversation with the Chancellor I decided to go to work regularly,[20] beginning by tracing the Imperial telegram back from the Central Office.

The Chancellor readily furnished me with the necessary authority to produce to the Director of the Telegraph Service, to whom I had merely to explain that I had been instructed to verify the exact wording of the now famous despatch.

It is unnecessary for me to detail my interview with this functionary, whose share in the business was purely formal. Suffice it that within a quarter of an hour after entering his office, I came out with the all-important information that the congratulation to Mr. Kruger had come direct from the Imperial Palace, over the Kaiser’s private wire.

By this time it was clear to me that either Wilhelm II. was playing a very complicated game indeed with me, or he really was the victim of one of the most audacious coups in history. My interest in the investigation was strongly roused, as I made my way to the Palace for the second time that day, bent upon a meeting with the telegraphist by whose agency, it now appeared, the war-making despatch had come over the wires.

My recent audience in the Imperial cabinet had invested me with authority in the eyes of the household, and I had no difficulty in getting a footman to conduct me to the operator’s room, which was situated at the far end of the corridor which[21] I had previously passed through on my way to the Kaiser.

The room being empty on my arrival, I dismissed the footman in search of the operator, who, he informed me, would most probably be found with the private secretary to the Emperor.

The moment I found myself alone I stepped up to the apparatus. I am an expert telegraphist, and the machine speedily clicked off the following despatch—

‘To the German Ambassador, London.—See Lord Salisbury privately, at once, and inform him British Government entirely deceived as to my sentiments. Proofs will be sent to you shortly.—Wilhelm, Kaiser.’

I had hardly taken my fingers off the instrument when the door opened and the operator walked in.

Herr Zeiss—I heard this name at the Central Office—appeared to me to be a simple-minded man, more likely to be the victim of a conspiracy than himself a conspirator. I thought it my best plan to assume an air of omniscience at the outset.

‘How is this, sir!’ I demanded with some sternness. ‘Do your instructions permit you to leave this instrument unguarded for any person who pleases to send his own messages over the Emperor’s private wire?’

The telegraphist stared at me with a mixture of surprise and alarm.

[22]

‘I don’t know who has authorised you, Herr Inspector——’ he began, when I cut him short.

‘Am I to go to his Majesty, and ask him if you have permission to leave this room when you please, without taking any precautions against the unauthorised use of the wire?’

Herr Zeiss quickly changed his tone.

‘That is not a thing of which I am ever guilty,’ he protested.

‘You have been guilty of it just now,’ I retorted.

‘I have not been away two minutes. No one could have taken advantage of my absence.’

‘Nevertheless, advantage has been taken of your absence.’

‘I don’t believe it!’

‘Ask the Central Office to repeat the message you have just sent them, then.’

Casting a frightened look at me, the man complied. I have seldom seen an expression of deeper astonishment and terror on a man’s face than that which marked the unfortunate operator’s as my despatch came back to him, word after word, ending with the Imperial signature.

‘My God!’ he cried out. ‘Who has done this? I shall be ruined!’

‘Whether you are ruined or not depends entirely on yourself,’ I said sharply. ‘It is in my power to save you, but only upon one condition.’

[23]

“‘My God!’ he cried out. ‘Who has done this? I shall be ruined.’”

Herr Zeiss turned on me a gaze of mute appeal.

‘You must tell me the exact truth,’ I proceeded, ‘and you must tell me everything. How often have you left this room without taking precautions against the misuse of the wire in your absence during the last two days?’

Zeiss considered for a moment. Then his face brightened up.

‘Not once, I can assure you positively of that, Herr Inspector.’

This answer, given so confidently, came as a severe check to me. I looked at the man sternly, as I responded, with assumed confidence—

‘And I am positive that you are mistaken. An unauthorised use has been made of this wire, and I am determined to know by whom.’

The operator’s face fell once more. He appeared to me to be honestly at a loss.

‘Come,’ I put in, ‘think again. Begin by recalling any occasions on which you have been called away hurriedly, and have perhaps omitted to lock the door.’

‘But there has been no such occasion. I swear to you that I have not once left this room without taking ample precautions.’

I fancied I discerned a touch of hesitation, rather in the operator’s tone than in his actual words.

‘Speak more plainly,’ I said. ‘What do you mean by precautions?’

[24]

‘Either the door was locked, or else——’ This time the hesitation was palpable.

‘Or else what?’

‘It was left in the charge of a trustworthy person.’

‘And that trustworthy person, who was he?’ I found it hard to suppress all signs of excitement as I put this question.

‘The gentleman who will shortly be my brother-in-law.’

‘Ah! Perhaps this gentleman is an employee in the same department as yourself?’

‘Not at all,’ Zeiss protested earnestly. ‘He is a teacher in the Military College. He knows nothing of telegraphy; in fact, he has sometimes asked me questions on the subject which have convinced me that he is quite a fool where electricity is concerned.’

‘Indeed! And the name of this foolish person, if you please?’

‘Herr Severinski.’

‘A Pole!’ I exclaimed.

‘No, a Russian. He was exiled to Siberia on account of his political opinions, but escaped. He teaches Russian in the college.’

‘How did he come to be left in charge of this room?’

‘He called here the day before yesterday, in the[25] evening, to speak to me about his marriage with my sister. They have been engaged for some time, you must know. While he was here I received a note from my sister herself, pressing me to come and speak to her at once outside the Palace. I went, leaving my brother-in-law to wait here during my absence. My sister, I found, merely wished to urge me not to object to any proposal made by her betrothed. On my return I found Severinski yawning and apparently bored to death in my absence. I asked him, and he assured me no one had come near the room while I was away.’

I could scarcely resist smiling as the whole intrigue, so simple, and yet so consummately successful, lay bared to my perception. My whole anxiety now was to keep the worthy but stupid Zeiss ignorant of the transaction in which he had been an unwitting accomplice.

I brought him away from the Palace with me, so as to leave him no opportunity of warning Severinski, and we proceeded together to the Russian’s quarters. I flatter myself that the professor of the Military College was not a little disconcerted when he saw his dupe followed into the room by an Inspector of the Berlin Police.

I explained my position in such a manner as to let Severinski see that I knew everything, without enlightening the other man.

[26]

‘The day before yesterday Herr Zeiss left you alone in his room in the Palace. You took the opportunity to send a telegram, the terms of which are known to me, over the Emperor’s private wire. For this offence you and he are liable to severe punishment. What I now have to propose to you is to make a confession which will have the effect of exonerating every one except yourself. If you do this, I think I can promise you that you shall suffer no penalty beyond, of course, the loss of your post in the Military College.’

Severinski gave me a glance of intelligence.

‘You do not require me to denounce anybody else?’ he inquired significantly.

‘I do not require you to confess what is obvious to every one,’ I returned with equal significance.

Poor Zeiss followed this exchange with an air of bewilderment. It was evident that the discovery of the other’s guilt had caused a shock to his confiding nature, and he was still trying to reconcile the Russian’s prompt surrender to me with his previous stupidity on questions of electrical science, when I summarily dismissed him from further share in the interview.

As soon as we were by ourselves Severinski spoke out boldly enough.

‘I am quite willing to give you a statement that I sent the telegram. But I am not going to tell you[27] anything more. You must know that I am an Anarchist.’

I waved my hand scornfully.

‘If I consent to your suppressing the truth, Professor Severinski, it does not follow that I am willing to listen to absurd fictions. Be good enough to write out and sign a circumstantial account of your own part in this clumsy plot, and I will undertake that you shall not pass to-night in prison.’

The Russian had the sense to do what he was told without further parley. I got from him more than I expected. He consented to put in writing that it was after his betrothal to Fraulein Zeiss that he had been solicited to make use of his connection with the Kaiser’s private telegraphist, and he stated the amount of the bribe, a very heavy one, paid him for his services in sending the Imperial congratulations to the President of the Transvaal. We became so friendly over the discussion that Severinski, who was bursting with vanity over his success, wanted me at last to let him tell me too much. I was obliged to order him to be silent.

‘If you tell me that you are an agent of a certain great Power, I must repeat what you say to the Kaiser. Then one of two things will happen. Either your Government will avow your action, in which[28] case you will be hanged as a spy, or it will disavow you, in which case you will pass the rest of your life in prison as a criminal lunatic.’

This menace had all the effect which I could have desired, and I was satisfied that the Russian would now hold his tongue.

Bidding him a cordial farewell—for I confess the fellow’s audacity had inspired me with some admiration—I hastened back to the Palace, to lay the results of my investigations before Wilhelm II.

‘Your Majesty has been victimised by a secret agent whose employers are interested in bringing about a feeling of ill-will, if not an actual war, between Germany and Great Britain. The day before yesterday this agent, whose name is Severinski, and who is employed to teach Russian’—Wilhelm II. started—‘in the Berlin Military College, visited your private telegraphist in the room at the end of this corridor. He had previously contrived that the telegraphist should be called away during his visit, and he took advantage of this absence to send the message which has caused so much trouble.’

The Kaiser made no reply until he had finished reading the proofs I laid before him.

‘And you did not ask this Severinski by whom he was set on?’ demanded his Majesty, giving me a keen glance.

[29]

‘I did not know whether you would wish me to do so,’ I answered respectfully.

‘You were right, a thousand times right,’ exclaimed the Emperor. ‘As long as they are in doubt whether I know it is they who have played me this trick, I have the advantage of them, and they will keep silence for their own sakes.’ He paused in deep consideration for a minute, then he looked up quickly. ‘All this time I must not forget the English. Tell me, Monsieur V——, are you personally known to Lord Salisbury?’

‘I have that honour, sire. On one occasion——’

‘Enough! There is not a moment to lose. You will leave Berlin by the first train, and proceed straight to the Ambassador’s house in London. He will take you round to the Prime Minister, and you will offer him the proofs which you have just offered me, explaining at the same time that the excited state of public feeling in both countries makes it impossible for me to take any open action in the matter.’

I bowed and moved towards the door.

‘I will wire to the Ambassador to expect you,’ called out the Kaiser.

‘Pardon me, your Majesty has done so already.’

‘How?’

‘I also passed five minutes alone in the room of Herr Zeiss,’ I explained.

[30]

In the years which have elapsed since this celebrated episode, Wilhelm II. has left no means untried to convince the British people of his friendly sentiments towards them. It is as a service to his Imperial Majesty, though without authority from him, that I now venture to lift the veil from the most astounding transaction in the annals of even Muscovite diplomacy.

[31]

Although the revelations which have been made already in the British House of Commons have thrown some light on the international intrigues which complicated the progress of the Cuban War, the tragic event which caused the United States to draw the sword against Spain has remained a profound mystery to the present hour.

The truth concerning the destruction of the United States warship Maine, in the roadstead of Havana, is known fully to only two persons now alive. One of these two has taken the vow of perpetual silence in the monastery of La Trappe, and his name is already forgotten by the world.

I shall cause some surprise, perhaps, when I venture to assert that had I left my hotel ten minutes earlier on a certain memorable night in the year 1898, the Spanish flag might still be flying over the citadel of Havana.

The extraordinary adventure which I am going to relate had its starting-point in Paris, which is, to a[32] large extent, the clearing-house of international politics—the diplomatic exchange where the representatives of the Powers meet, and sound each other’s minds. For this reason the highest post in the diplomatic service of every country is still the Paris Embassy, although France itself scarcely ranks to-day as a Power of the first magnitude.

It is Paris, as every one is aware, which was the scene of the long negotiation between the representatives of the Cuban insurgents and the Government of Madrid on the question of the terms to be granted by Spain to her discontented colony. In this negotiation it is equally well known that the Cuban delegates received the moral support of the United States; but it is not generally known that the Spanish Government acted throughout in consultation with most of the European Powers.

I was looking on at the negotiation without any very great interest, sharing, as I did, in the general impression that Spain would give way before long, when I was surprised one morning by receiving a visit from a very remarkable character.

Ludwig Kehler was a Bavarian, who had begun life as a candidate for the priesthood. A disgraceful affair, the particulars of which I had never learned, had caused his dismissal from the seminary, and, after drifting about the world for a time, and mixing in very shady company, he[33] suddenly appeared in Berlin in the character of a police agent.

The exact nature of the services which he rendered to the police was a mystery, but I had formed the theory that he was employed as a spy on the German Catholics, whose attachment to the House of Hohenzollern has always been suspected in Berlin.

The presence of this man in Paris was in itself an unusual event. It did not occur to me to connect it with the Spanish-American question, and that for a very simple reason. Germany is the one country in Europe which has never possessed a foot of soil in the New World. Spain, Portugal, England, France, and even Holland and Denmark have planted their flags across the Atlantic, but the German Michael has been content to remain at home while his neighbours were colonising the globe.

I received Kehler coldly. My acquaintance with him was a purely professional one, and he was a man whom I profoundly distrusted.

As soon as I could do so, without positive rudeness, I invited him to explain the object of his visit.

‘It is of a confidential nature,’ prefaced the Bavarian. ‘May I assure myself that our conversation will remain a secret between us two?’

I bowed gravely.

‘That is always understood, where I am concerned.[34] A man who desires to be trusted must begin by establishing a reputation for secrecy.’

Kehler contented himself with this assurance, dry as it was.

‘I thank you, Monsieur V——. Your reputation is so well established that I had no intention except to ask whether you were willing to receive the proposals I have come to make?’

‘Proceed, Herr Kehler, if you will be so good.’

‘You have learnt, no doubt, that the Spanish Government has made up its mind to concede the terms demanded on behalf of the Cubans by the United States?’

Although I was not aware that things had reached this point, I did not allow Kehler to see that he had given me any information.

‘By this act,’ he continued, ‘the Americans have, in fact, declared that no European Power has any right to enter their hemisphere without their permission.’

‘All that is well known, Herr Kehler.’

‘The question then arises whether the European Powers will allow themselves to be driven out, one by one, or whether, by a bold combination, they will reduce the United States to some respect for the law of nations.’

‘Such a combination would be inopportune at this moment, because the British would stand aloof.’

[35]

‘Because they look upon the struggle as one between Spaniard and Cuban,’ Kehler rejoined quickly. ‘But let us suppose there to be a war, in which the United States was engaged against Spain?’

‘You have just said there will be no such war.’

‘A war is always possible, provided those interested in bringing it about are not too scrupulous.’

This sinister language at length convinced me that the Bavarian had not come to see me for nothing. I decided to draw him out.

‘Provided such a war actually commenced, I agree that some combination on behalf of Spain might be possible,’ I murmured, as though reviewing the situation in my mind. ‘But where is the Government sufficiently in earnest to undertake so terrible a responsibility?’

‘It is that Government,’ Kehler responded, ‘which sees its subjects departing in greater numbers every year, but which looks around in vain for some unoccupied region towards which to direct the stream of emigration.’

‘You mean Germany?’

‘We look around us,’ he continued, scarcely noticing my interruption, ‘and we see all the continents staked out in advance by other Powers: Asia by England and Russia, Africa by England and France, North America by England and the United[36] States, Australia by England alone. There remains only South America, in the possession of weak Latin races, unable to make use of their advantages, but who are protected in their decay by the bullies of Washington.’

‘A war in which the United States found itself fully occupied would be a fine opportunity for the German Michael to plant his standard in Brazil or the Argentine, I understand.’

Kehler looked at me earnestly.

‘The man who undertook the task of making such a war inevitable, without compromising exalted personages, would be no loser,’ he remarked significantly.

I looked back at the Bavarian before demanding—

‘Have you any definite scheme to put before me?’

‘Until I know that you accept,’ he demurred.

‘I do not know that you are accredited,’ I reminded him.

‘What authority do you require?’

‘The Imperial autograph simply.’

‘Impossible.’

‘I am accustomed to be trusted by my employers,’ I returned decidedly. ‘I cannot act under any other conditions.’

‘That is final?’

‘It is final.’

[37]

‘Then I am afraid I can only ask you to forget that I have occupied so much of your time.’

I allowed Kehler to rise and take his departure without making the least sign. The moment he was out of hearing I sprang to the telephone and rang up the agent of the Sugar Trust.

Herr Kehler’s refusal to produce the guarantee for which I asked convinced me that he contemplated some action of a character doubtful, to say the least, if not criminal.

It would have been useless for me to communicate my suspicions to the American Minister in Paris. The diplomacy of the United States, blunt and self-reliant, takes little account of the subterranean intrigue which pervades European politics. But the Government of Washington was not the only factor concerned. As Europe is beginning to learn, the Union is a federation, not so much of those geographical divisions which are painted in different colours on the map, and called States, but of those vast organisations of capital which control the American electoral system, and fill the Senate with their delegates. Nebraska, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Illinois—these are merely names for school children; the Silver Ring, the Steel Trust, the Cotton Trust, the Pork Trust—such are the true American Powers.

During the whole of the Cuban negotiation the[38] Sugar and Tobacco Trusts had been represented in Paris by agents whose object it was to avert an annexation of Cuba by the United States, an act which would, of course, mean the free admission of Cuban sugar and tobacco into the markets. Adonijah B. Stearine, the Sugar Agent, was a shrewd man, and I had no doubt I should find him a ready listener to what I had to say.

Within an hour of Kehler’s departure, Mr. Stearine was seated in my office. I had to pick my words carefully not to break the promise of secrecy into which I had been beguiled.

‘I have just seen a secret agent who wanted me to help him in some trick to force on a war between the States and Spain.’

Stearine rolled his eyes and whistled thoughtfully.

‘Who sent him?’

‘I can’t say. He refused to disclose his principal, and so I would have nothing to do with him.’

The Sugar Agent pursed up his lips, and frowned.

‘I guess this is a dodge of Bugg’s,’ he muttered.

‘What Bugg?’

‘You don’t say you haven’t heard of Bugg—Milk W. Bugg, the Pork Trust’s man over here? I reckon Bugg is the smartest man in Chicago, and Chicago is the smartest town in the States, and the States is the smartest country on earth; so there you are.’

[39]

‘The man who came to me is a German,’ I hinted.

‘Bugg’s smartness,’ was the comment.

‘He wanted me to think he came from Berlin.’

‘Bugg is real smart,’ breathed Mr. Stearine with admiration.

It was evident that the agent of the Sugar Trust was unable to see past the figure of his rival, which filled up his mental horizon. I did not consider it worth while to argue the point.

‘The question is, Do you want this to be stopped?’ I said.

Stearine looked at me with something like surprise.

‘Think you can?’ he questioned briefly.

‘I know the man who is at work. I can shadow him and find out what he is doing.’

‘You will have to be almighty quick about it,’ retorted the other. ‘When did this man get away!’

‘Only an hour ago,’

Mr. Stearine gazed at me with a disconcerting scrutiny. Then he remarked slowly and emphatically—

‘If this is Bugg’s game, and you have given him an hour’s start, I calculate he will be opening a store in Havana this day six months.’

The Pork Trust, it was clear, had everything to gain by a war by which the Sugar Trust had everything[40] to lose. But, in spite of Mr. Stearine’s confident assurances, I continued to have my own opinion about the power behind Herr Kehler.

‘Do you want me to act?’ I demanded briefly.

‘I want you to take a hand—yes.’ The Sugar Agent took out his pocket-book, and counted out bills to the amount of ten thousand dollars. ‘You can play up to that,’ he added, ‘and then you can let me know how the game stands. I guess I shall buy Pork Consols.’

With this discouraging observation, Stearine left.

It did not take me long to decide on my plans. As it was not likely that Kehler was apprehensive of being watched, it would be an easy task to trace him, and I at once gave orders to my staff to that effect, with the result that I learned in a few hours that the Bavarian had put up at the Hotel des Deux Aigles, and was leaving by the Sud Express for Madrid.

I now decided on one of the boldest and most effective strokes in my repertory. I went openly to the station, took my own ticket, and entered the compartment of the sleeping-car in which Kehler had booked his own place.

The real astonishment of the Bavarian at seeing me I met with an affectation of moderate surprise on my own part.

‘So you are going with me?’ I observed.

[41]

‘With you!’ Kehler exclaimed.

‘It appears so. No doubt you have been instructed?’

Kehler denied it energetically.

‘But you refused to participate in a certain design,’ he reminded me.

‘I laid down certain conditions, which you declined to fulfil, but which have since been complied with by your principal.’

The Bavarian was thunderstruck. I relied upon his having reported his failure to whomever it was that had sent him to me; and there was nothing impossible in the suggestion that I had in consequence been approached directly.

‘You have credentials, I suppose?’ he asked.

I nodded carelessly.

‘You will convince me, perhaps?’ he persisted.

‘Are you authorised to convince me?’ was my retort.

‘You know it—no.’

I shrugged my shoulders and remained silent.

So commenced the most extraordinary journey I have ever taken, a journey which was destined to end only at Havana. Across France and Spain and the Atlantic Ocean we travelled side by side, each unwilling to lose sight of the other; I, resolved to find out and if possible thwart the designs of my companion; Kehler, unable to determine whether I[42] was an opponent, a rival, or a spy set over him by those on whose behalf he was engaged.

On the frontier, at Hendaye, a despatch was handed in to me through the carriage window. It was from Stearine, and contained these words, whose terrible significance I was designed to learn later—

‘United States warship Maine arrived harbour Havana.’

The agent of the Sugar Trust had been too careful to say more. But it was clear that he regarded this event as a move in the game played by the great exporting Trusts.

From the moment of our arrival in Madrid I was no longer able to keep a close watch on Kehler, though by a sort of tacit agreement we stayed at the same hotel. I found out that he was paying visits to the Provincials of the Jesuit and Franciscan Orders, and had been admitted as a visitor to one or two convents, and for a time I was tempted to relax my suspicions, and to think that the Bavarian was engaged in some Catholic espionage. These doubts were suddenly dissipated by my meeting him one day in the courtyard of the hotel attired in the habit of a priest—the dress of which he had been deprived on account of his youthful misconduct.

I could not doubt that this dress was a mere disguise, and that it had been assumed for a political purpose. I went up to him and whispered—

[43]

‘Do we still recognise each other, or do you prefer that we meet as strangers?’

‘As fellow-travellers simply, I should prefer,’ he responded.

The next day he had disappeared from the hotel. I set the agencies at my command to work, and learned without much difficulty that passages had been reserved for the false priest and a Sister of Mercy travelling under his protection, on board a Spanish steamer sailing from Cadiz to Havana.

Needless to add, I was on board the same steamer when she quitted her moorings and breasted the waves of the open sea. During the voyage I had many opportunities of watching Kehler and his companion, who were constantly together, holding long private conversations in retired corners of the vessel. The nun, who was presented to me as Sister Marie-Joseph, was a pale, delicate-looking girl of about twenty, with that abstracted look in her eyes which betokens a mind wavering between earnestness and hallucination.

Dimly, and through clouds of uncertainty, I began to perceive that Kehler had ransacked the convents of Madrid for a suitable instrument, and that he was hard at work hypnotising the unfortunate girl’s mind, so as to prepare it for any suggestion he might have to make.

Before we reached Cuba I contrived to speak to[44] the Sister apart. I found her reserved and distrustful of a heretic, as she had evidently been told to consider me. On my satisfying her that I had been brought up a Catholic, she became slightly more communicative, and revealed a disposition singularly sincere and devoted, but almost morbid in its detestation of Protestantism. She betrayed a feeling of horror at the idea of American domination in the Catholic island of Cuba, and it was in vain that I represented to her the generous tolerance accorded to our religion in the United States.

I did not dare to ask her the subject of her conferences with Kehler. To have hinted at the Bavarian’s true character would have been simply to forfeit her confidence in myself. I decided to reserve my efforts in this direction until our arrival in Havana, where I did not doubt that I should be able to find some responsible ecclesiastic who would undertake the investigation of Kehler’s antecedents.

In the meantime I could only wait and watch. I was painfully impressed by the steady growth of the false priest’s influence over his victim, who seemed at last to respond to his least word or gesture. I had before me the spectacle of a possible Teresa or Elizabeth being gradually transformed into a Ravaillac by the dexterous touches of a rascally police agent.

As soon as we entered the harbour Kehler and[45] his companion got ready to disembark. I noticed that at this moment they were separated, the Sister going ashore by herself with a large basket trunk, while her protector followed at some distance behind.

They met again at the hotel, to which I had accompanied the man. By this time I had forced a certain degree of acquaintance on the couple, though I was unable to interrupt the intimacy of their private intercourse. I arranged to secure a room next to that of the Sister, and I observed with some surprise that Herr Kehler was lodged in another wing of the building.

By a coincidence we found the hotel full of naval officers from the Maine, who had chosen it for their headquarters while on shore. Instead of disconcerting Kehler, this circumstance appeared to give him every satisfaction.

He went out of his way to show civility to the Americans, and rapidly became intimate with several of them. Sister Marie-Joseph, on the other hand, held sullenly aloof, scarcely able to repress some signs of the abhorrence which the sight of the heretics inspired.

The visit of the Maine was understood to be a pacific one. It was a demonstration to the world that the relations between the United States and Spain continued to be those of perfect friendship, and that the former Power was inspired by[46] peaceful motives in seeking to bring about an understanding between the belligerent Cubans and the mother-country.

Nevertheless it was an imprudent act to send a man-of-war, flying the Stars and Stripes, into the harbour of a place swarming with fanatical Spaniards, furious at the interference of another Power between them and their revolted subjects. It was, in fact, a provocation, and it was not surprising that the astute agent of the Sugar Trust had seen in this proceeding the work of those commercial powers whose interest lay in the direction of a rupture.

Faithful to my preconceived intention, I took an early opportunity of waiting upon a high Church functionary in the city, to warn him of the true character of the Bavarian.

The reception I met with was a cold one, however. Monsignor X—— allowed me to see that he considered me an officious person.

‘May I ask what is your interest in all this?’ he demanded, as soon as I had made my statement.

‘I represent the Sugar Trust,’ I told him.

‘The Sugar Trust?’

‘The manufacturers of sugar in the United States, who fear the competition of cane sugar, and are therefore opposed to the annexation of Cuba, which would involve free trade with the island,’ I explained.

[47]

“‘We shall find out whether he is a priest,’ was the retort.”

‘And you suggest that this Father Kehler——?’

‘Herr Kehler,’ I corrected. ‘This man is no more a priest than I am. He is believed to be the agent of a Chicago Trust, which desires to see Cuba brought within the Union.’

‘We shall find out whether he is a priest,’ was the retort. ‘Before he can say Mass in this diocese he will have to apply for permission, and to show his ordination papers.’

‘But if he does not wish to say Mass? If he merely confines himself to directing the Sister whom he has conducted here?’

‘In that case we cannot interfere. We have no more proof that she is a Sister than that he is a priest?’

I gave Monsignor X—— an indignant look, which he bore with coolness.

‘Besides, what is it that you apprehend?’ he asked. ‘One cannot deal with imaginary dangers.’

‘I am sure that these two persons are bent on some desperate enterprise—that their presence in Havana bodes no good to the cause of peace,’ was all I could find to say.

The ecclesiastic made a scornful gesture.

‘It appears to me that this is a matter which concerns the police,’ he said, in a tone which signified that the interview was at an end.

I returned to my quarters, realising to the full[48] the difficulty of any effective action. To go to the police would be merely to invite a repetition of the snub which I had just received from the ecclesiastical authority. I could only rely on my own resources.

I sent a wire to Stearine: ‘War agent here as priest, accompanied by nun,’ and waited. It was just possible that Stearine might have connections through which those who had power in the Church at Havana might be influenced, in which case I had no doubt that Monsignor X—— would very quickly become interested in the doings of ‘Father’ Kehler.

I can hardly tell what it was precisely that I expected to happen. I had some idea of an assassination, possibly of the captain of the Maine, or perhaps of the American Consul, by Sister Marie-Joseph.

Day by day I perceived the unhappy girl becoming more and more wrought up to the pitch of enthusiasm necessary for the perpetration of some hideous deed, like that of Charlotte Corday, or Judith. Curiously enough, the poor Sister showed an inclination for my society, perhaps because I was a familiar face. She would sit beside me in the drawing-room of the hotel and talk about her convent, in which she had been educated and passed most of her life.

“She would talk about her convent.”

I learned that she was of a noble family, rendered poor by the ravages committed in the course of the [49]Cuban insurrection, a fact which may have helped to exasperate her spirit. But I sought in vain to draw her into any confidences on the subject of her mission to Havana. The moment I touched on that topic she became dumb, and made an excuse to leave me.

During the next few days I observed the intimacy between Kehler and the American officers becoming closer. The German could speak English fluently, and this circumstance naturally recommended him as a companion in a place where Spanish and French are almost the only languages known to the inhabitants. There was a young lieutenant, or sub-lieutenant, in particular, who was constantly in Kehler’s company, viewing the sights of the town, or smoking with him on the hotel verandah. Suspecting that my man had some object in cultivating this lieutenant, I endeavoured to make his acquaintance myself, only to find my advances rebuffed in a manner which showed me plainly that Kehler had been at work disparaging me beforehand.

One day as I was standing on the verandah I noticed the pair come out of the hotel together, and turn in the direction of the harbour. I followed at a discreet distance, and saw the officer conduct Kehler into a boat, manned by sailors from the Maine, in which they pulled off to the ship. I stood watching, and at the end of about an hour I[50] saw them coming back, the face of the false priest wearing a serious expression.

I took advantage of my acquaintance with him to meet the pair as they landed, and accost them carelessly.

‘You have been to have a look over the ship?’ I threw out.

Kehler tried to pass on with a careless nod, but the lieutenant, less discreet, drew himself up with a severe glance at me.

‘Father Kehler has been good enough to visit a poor sailor who is lying sick on board,’ he said, in a tone evidently meant to rebuke my impertinence.

I bowed with assumed respect. But as they went on their way I experienced a sensation of alarm. The pretext which had imposed on the officer was transparent enough as far as I was concerned. I realised that Kehler was steadily pursuing some well-thought-out design, and that he had contrived this visit to the man-of-war with some dark purpose which it was my business to discover.

I determined at length, since Kehler’s friend was so strongly prejudiced, to seek out some other officer, preferably the commander, and take him into my full confidence. Unhappily events marched too swiftly for me. That very evening it was already too late.

“‘Father Kehler has been good enough to visit a poor sailor who is lying sick on board,’ he said, in a tone evidently meant to rebuke my impertinence.”

Passing through the entrance hall on my way [51]upstairs to dress for dinner, I was struck by the sight of the basket-trunk belonging to Sister Marie-Joseph standing strapped-up, ready to go away. At the foot of the staircase I encountered the Sister herself, evidently prepared for departure.

She appeared pleased to have the opportunity of bidding me farewell.

‘I shall not forget you where I am going,’ she said with a mournful smile, as she extended her hand.

‘May one inquire where that will be?’ I ventured to ask.

She shook her head.

‘It is an affair of duty. I am going a very long way, and you will never see me again.’

‘And Father Kehler,’ I forced myself to say, ‘does he accompany you?’

A momentary expression of repugnance, almost of loathing, flashed out on her pale face.

‘No, no! The padre has done his part in conducting me so far, and finding me the situation of which I was in search. I have parted with him now, and we have nothing more to do with one another.’

This answer relieved my mind of a burden. I came hastily to the conclusion that Kehler, finding himself able to carry out his projects without assistance, had decided to dispense with an embarrassing[52] ally, and I was glad to think that this poor girl would be delivered from his evil influence.

What blindness are we capable of towards those very things which seem the clearest to our after-recollections!

I took the precaution to ascertain at the bureau that Kehler was still staying on in the hotel, and I came down to dinner with a light heart.

A number of the American officers were dining in the hotel that night. There appeared to be a sort of entertainment going forward, in which some Spanish officers from the garrison were fraternising with them.

Kehler, deprived of the company of his lieutenant, sat at a small table by himself, and I noticed that he was drinking heavily, while his flushed face and inflamed eyes showed him to be labouring with an excitement which I ascribed to the influence of the wine.

I sat down at another table, and busied myself with efforts to disentangle the threads of the intrigue which was being woven around me. I cast a thought or two after the poor girl, with whom I had been so strangely associated.

Absorbed in these thoughts, I did not mark the evening advancing, when I was gradually aroused by the breaking up of the military party. The lieutenant, who had shown so strong a dislike for me,[53] rose from his seat and came my way, taking a Spanish officer by the arm.

As they approached, I perceived from his gait that the American had been affected by the healths he had been drinking. I saw him point me out to his companion as they approached, and he muttered something in the other’s ear, which caused the Spaniard to turn on me a glance of grave disgust.

Stung by this insufferable insolence, I sprang to my feet, and placed myself in front of the lieutenant.

‘Have you anything to say to me, sir?’ I said sternly.

‘Nothing. I do not talk with spies,’ was the coarse retort.

‘But you take them on board the ship it is your duty to guard,’ I returned fiercely, carried out of myself.

The lieutenant drew back, amazed.

‘I have taken a worthy priest to console a dying man—one of his own faith,’ he stammered out.

‘A German police agent, disguised as a priest, I suppose you mean. The spy Kehler?’

He began to tremble violently. ‘But the Sister! The nurse!’

‘Sister Marie-Joseph! What do you mean?’

‘She is on board now, nursing O’Callaghan.’

It was my turn to utter an oath of consternation.

[54]

‘Come with me. Take me on board instantly, or take me to your commander.’

‘We will go on board,’ said the sobered lieutenant.

Glancing round as I followed him out I saw that Kehler had disappeared. Quickening our steps by a common instinct, the lieutenant and I almost ran down to the water’s edge.

‘Thank God!’ burst from his lips as we came in sight of the majestic vessel lying peacefully at her anchors in the calm waters of the bay, her spars and turrets outlined against the clear, starlit sky, and only a few twinkling lights betraying the presence of the two hundred men who slept below her decks. The same instant there was a spout of fire, a cloud of wreck and dust mounted to heaven, and a thunderous boom stunned our ears, and sent the waters of the bay dashing up at our feet.

The Maine had broken like a bubble. I saw all in a flash—in some dark way that will never now be revealed Sister Marie-Joseph had blown up the Maine. Kehler had succeeded—I had failed.

It has not been easy for me to write the story of what I regard as the greatest failure of my career. My mistake was the initial one of refusing to purchase Kehler’s confidences, by the expedient of pledging myself to assist his enterprise.

Immediately the intelligence of the disaster reached Europe Stearine sent me a cable peremptorily enjoining[55] silence. That injunction I consider has now lost its force through three circumstances, the lapse of time, the death in action of Lieutenant ——, and the living suicide of the arch-criminal, haunted by the horror of his own deed, in the deathlike cloisters of La Trappe.

[56]

Every one must feel that the last word has not been said on that extraordinary transaction which convulsed France, and shocked Europe, during the close of the nineteenth century, under the name of the Dreyfus Case.

It is true that no effort has been spared by the Government of the Republic to put an end to an agitation which threatened to develop into a civil war. A general amnesty has been proclaimed; the courts of law have been forbidden to entertain any proceedings involving the guilt or innocence of Captain Dreyfus, his accusers or his partisans, and the French press has been appealed to, in the name of patriotism, to close its columns to all further discussion of the dangerous topic.

Such an attitude, adopted in order to save France from disruption, is not without a certain dignity; but it is at the same time terribly unjust. It is as if France had repeated to the victim of the Devil’s Isle[57] the memorable words—‘It is better that one man should die for the people.’

The one person in Europe who is completely ignorant of the true motives underlying this grim tragedy is without doubt Dreyfus himself. That taciturn, commonplace figure, suddenly elevated into the position of criminal, martyr, and hero, was merely the shuttlecock driven through the air by unseen hands. Even if he was guilty of writing the celebrated bordereau—a question which the Court of Rennes decided in the affirmative—he must have done it by the order of others, given for reasons which he did not comprehend.

It will be remembered that before and during the second trial of Dreyfus, the strongest efforts were put forth on his behalf by three foreign Powers—those composing the Triple Alliance. The German, Austrian, and Italian military attachés, breaking through the etiquette of their position, disclaimed, each on his personal word of honour, any dealings with the alleged spy.

Not only so, but I myself sent for the Paris correspondent of a London newspaper of high standing, and authorised him to inform his readers that the German Emperor himself was prepared personally to exculpate the accused from the charge of selling information to Germany.

This offer, made privately to the French President,[58] was declined for the same reasons which prompted the Government to hush up the whole affair. But every thoughtful man will realise that it would not have been made unless there had been more at stake than the freedom of an obscure captain.

My own connection with the Affaire Dreyfus dates from the time of the first trial and sentence, when the theatrical spectacle of the degradation of the unfortunate officer was the theme of universal comment. At this juncture I received a visit from Colonel ——, an officer high in the Emperor’s confidence, and at that time attached to the German Embassy in Paris.

‘I have come to you,’ he announced, as soon as we found ourselves alone, ‘by command of his Imperial Majesty the Kaiser.’

I bowed respectfully as I replied—

‘I am deeply honoured by this fresh proof of his Majesty’s confidence.’

The Colonel regarded me for a moment with some curiosity.

‘You are a sort of spy, are you not?’ he inquired.

I refused to take offence at this blunt question, so natural on the part of a soldier.

‘Each of us has his own part to play,’ I explained suavely. ‘The soldier fights with the enemy in[59] the open field; the man of my profession has to encounter the foes who burrow underground.’

Colonel —— appeared satisfied.

‘The Kaiser trusts you; that is enough for me,’ he declared. ‘You will not dare to betray this confidence?’

This time I rose to my feet, stern and contemptuous.

‘You have not come here to insult me, I suppose, Colonel? If you are the bearer of instructions from the Kaiser, be good enough to deliver them without comment; if not, I will attend to my other business.’

The German’s face betrayed his astonishment at this rebuke. He hastened to mutter an apology, which I received in silence.

‘His Majesty wishes you to investigate this Affaire Dreyfus, on his behalf. There is some secret motive for the notoriety which they are conferring on this unlucky spy’—the Colonel gave me an apprehensive glance as he pronounced this word—‘and the Kaiser is determined to find out what it is. It appears that we are being made a sort of stalking-horse in the business; it is pretended that Dreyfus was an agent of ours, which is utterly untrue.’ The German smiled sardonically as he added: ‘Our information is supplied to us from higher sources than a simple captain of artillery, and we can get as much as we choose to pay for.’

[60]

‘Is it not likely that Dreyfus may be the scapegoat of others—perhaps those higher sources to which you refer?’

The Colonel shook his head.

‘That does not explain the persistence with which they are trying to connect the affair with Germany. I have information that the heads of the French Army are representing that France is in actual danger. The bitterness with which Dreyfus is assailed is due, they pretend, to a sense of the national peril.’

‘And all that is quite untrue, I understand?’

‘So untrue that I have reason to know that Wilhelm II. has a particular desire to conciliate the French——’ The Colonel stopped abruptly as if he had been on the point of saying too much.