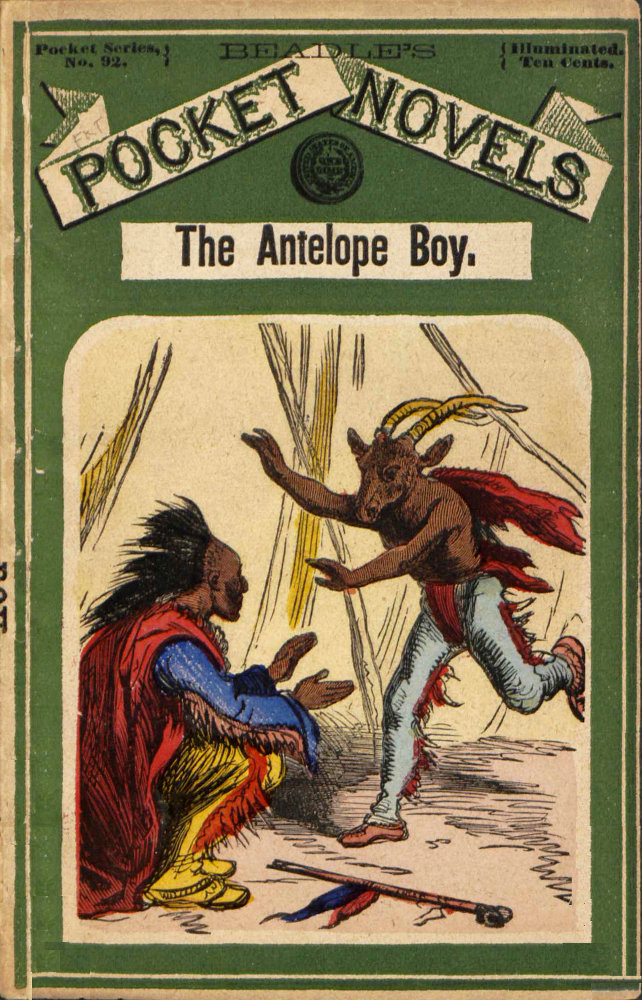

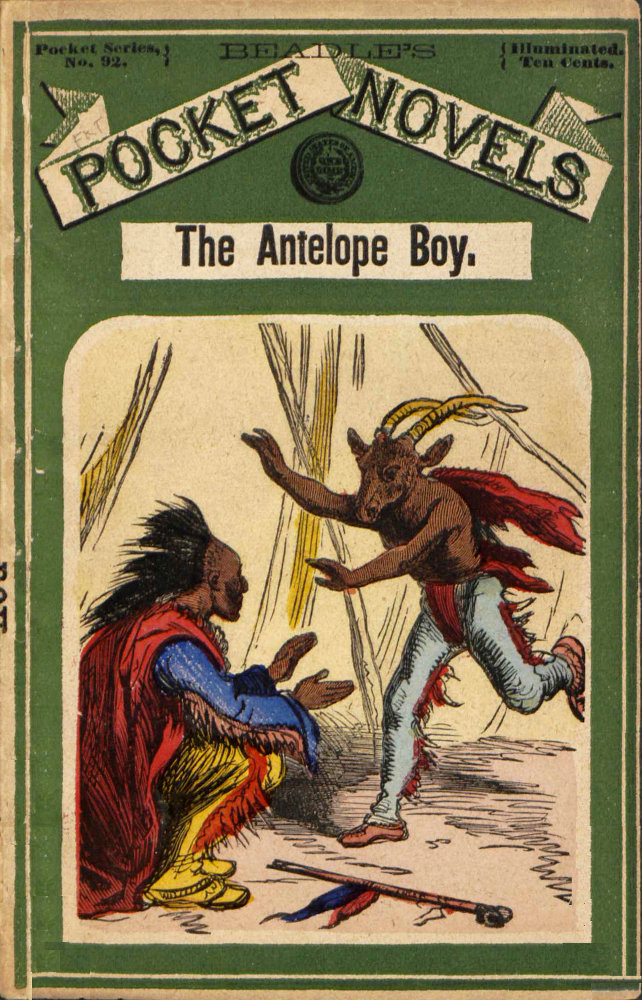

Title: The Antelope Boy; or, Smoholler the Medicine Man

Author: George L. Aiken

Release date: August 31, 2021 [eBook #66190]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: David Edwards, Stephen Hutcheson, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (Northern Illinois University Digital Library)

A TALE OF INDIAN ADVENTURE AND MYSTERY.

BY GEORGE L. AIKEN.

NEW YORK.

BEADLE AND ADAMS, PUBLISHERS,

98 WILLIAM STREET.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1873, by

FRANK STARR & CO.,

In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

The surveying party were camped upon the banks of the Columbia River, a short distance from the mouth of its confluent, the Yakima.

This party consisted of the two surveyors—Owen Blaikie, a bluff, middle-aged Scotchman, long since “naturalized” to this country, and Cyrus Robbins, a shrewd young Yankee, twelve United States soldiers under command of Lieutenant Charles Gardiner, detailed expressly from the nearest fort to protect the surveying party from predatory bands of Indians, an old hunter, generally known under the name of “Gummery Glyndon,”—his prefix of Montgomery having suffered this abbreviation at the hands of his associates—whose duty it was to act as guide, and keep the surveyors supplied with fresh meat; and two boys, the chain-bearers of the expedition.

These boys merit more than a passing notice here, as they are destined to play conspicuous parts in the events which were to follow the advance of the surveying party into the country of the Yakimas.

There was this peculiarity about them, that they were first cousins, and were both called Percy—Percy Vere and Percy Cute.

But despite their relationship and the similarity of their surnames, there was very little resemblance between the two.

Percy Vere was a slender youth, graceful and active, with a frank, honest face, and regular features, his hair being a 10 dark chestnut, thick and curly, and his eyes a clear hazel, giving evidence of courage and decision of character in their glances. He looked quite picturesque in his coarse suit, with the trowsers tucked into high-topped boots, and his crispy curls straggling from beneath his broad-leafed felt hat.

Percy Cute was full a head shorter, and his figure was decidedly dumpish. He had a fat, good-natured face, light flaxen hair, and a laughing blue eye. Indeed, a grin appeared to be the prevailing expression of his features. He was sluggish-looking, and appeared like one who would not put forth exertion unless compelled to do so. He was dressed after the fashion of his cousin and comrade, with heavy boots, coarse trowsers, a striped shirt, with a broad collar, and a kind of roundabout, which was short for a coat, and too long for a jacket; and like him, he wore a revolver in a belt buckled around his waist, the pistol resting convenient to hand, upon his right hip, while on the left side the handle of a bowie knife made itself conspicuous.

All in this party carried arms, for the service was one of danger, and at any moment the emergency for their use might arise.

The boys were quite favorites in the party, the first by his frank, manly bearing, and accommodating spirit, and the other by his unvarying good nature, and the drollery in which he was so fond of indulging. His humor appeared to be inexhaustible, and his quaint manner of giving vent to it was irresistible.

In fact, Percy Cute had, at a very early age, been forcibly impressed by the antics of a clown in a circus, and his great delight had been to play clown from that eventful moment.

The culinary department of the expedition was attended to by a colored individual who combined the two functions of cook and barber for the party. He was a jolly little darky, but terribly afraid of the Indians. The fear of his life was that he might have his “wool lifted”—as the old hunter phrased it—before he got out of the wilderness. But he had one consolation even in this apprehension: he had, like a great many other barbers, invented a HAIR RESTORATIVE, which he considered infallible.

“Never you mind, boys,” he would tell the soldiers, “if 11 de Injines does gobble us, an’ lift our ha’r, as Gummery says, I can make it grow ag’in—hi yah-yah! I jist kin!”

Whereupon he would exhibit a small bottle in a mysterious manner, adding, “Dar’s de stuff dat can do it—you bet!” And then he would consign it to his pocket again.

This assurance afforded much amusement to the “high privates” of the party, who made a standing joke of the Professor’s Hair Restorative—for Isaac Yardell had prefixed the word “Professor” to his name when he was a tonsorial artist in Chicago, before the spirit of adventure had seized upon him and led him after gold among the mountains of Montana.

Gummery Glyndon had brought in an antelope. Some of the soldiers had captured a few fish from the river, a fire had been built in the center of the camp, and preparations were going on briskly for the evening meal.

In this Isaac had four assistants, he having contrived to transfer the drudgery of his office, with true Ethiopian cunning, to others. A colored servitor will always shirk all the work he can. Thus two of the soldiers, a German named Jacob Spatz—Dutch Jake, was his camp name—and one Irishman, Cornelius Donohoe—Corney for short—were always available for services at meal-time, and the two boys—the Percys—collected the wood for the firing. By this arrangement Isaac had little to do but the cooking, which he performed to the entire satisfaction of the party.

Even the rough old hunter—Glyndon—a gaunt, grizzly man of fifty years of age, bestowed his meed of praise upon him.

“It don’t matter what I bring in,” he told Lieutenant Gardiner, “game, fish or fowl—antelope, mountain sheep, or b’ar meat, that Ike can just make it toothsome. These darkies take to cooking, ’pears to me, just as naturally as ducks do to water.”

Ike had only one grievance in the camp, Percy Cute was continually playing jokes upon him. Such little pranks as putting powder in his pipe, nipping at the calves of his legs and imitating a dog’s growl, and grasping his wool at night, and shouting a war-whoop in his ear, had a damaging effect upon Ike’s temper, and he vowed deadly vengeance. But his 12 vengeance never extended beyond a chase after Percy Cute with a ladle, with the laudable intention of administering a severe spanking; but in these onslaughts the redoubtable Isaac always came to grief; for, just as he would overtake the flying youth, Cute, with a nimbleness that his sluggish look and dumpy figure never led any one to expect, would suddenly fall upon his hands and knees, and pitch his pursuer over him. But as Isaac invariably alighted upon his head, he received no injury from these involuntary dives. A shout of laughter would herald his defeat, and he would pick himself up, and return to his camp-kettle, in a crest-fallen manner, swearing to himself until every thing got blue around him, and vowing that he would “fix him de next time, suah!”

These little episodes enlivened the camp, and nobody enjoyed them better than Gummery Glyndon. The old hunter had, generally, a morose look upon his seamed and weather-beaten countenance, and his hatred of every thing in shape of an Indian was well known.

Nor was the cause of that hatred a secret. He had been the victim of one of those forest tragedies so frequently enacted upon the frontier. It was the old story which has been told so often, and will be repeated until the extermination of the red-man—which has been going on slowly but surely for years—is completed.

While absent upon a hunting and trapping expedition, his cabin had been surprised, his wife and only child, a little girl some three years of age, cruelly murdered, and their mutilated remains consumed in the fire that destroyed his home.

A blackened ruin was all that was left of the spot that was so dear to him, and he found himself alone in the world, with only one thought in the future—vengeance upon the murderers.

In the drear solitude of that heart-sickening scene, and beside the ashes of all that he had treasured in the world, he breathed that vow of vengeance, which the lips of so many bereaved settlers in the Far West have sent up to heaven—death to the destroyers.

That was fifteen years before the time in which I introduce him here. In all those years he had pursued the Indians 13 with a deadly malignity. He had taken part in every Indian war that had broken out, and the number of his victims had been many.

As the years passed away this feeling of vengeance grew fainter, and though he never spared an Indian who came against him with hostile intent, yet he did not go out of his way to seek for them, as he had done. The Yakimas were supposed to be the destroyers of his home and family, and against that nation he cherished an undying enmity. Yet circumstances had led him away from their country, to the hunting-grounds of the Apaches, with whom he had many encounters.

He had gladly accepted the service that would take him back to the land of the Yakimas. In all these years he had gained experience as a guide, in wood-craft, and as an Indian-fighter. No hunter of the plains bore a better reputation for skill, prudence, and knowledge of the Indians than Gummery Glyndon.

His face bore a somewhat morose expression, as I have said, but he was far from being a morose man. Indeed, there was quite a fund of dry humor in his disposition, which was an agreeable surprise to those who judged the man by his saturnine countenance.

Percy Cute was a particular favorite of his, and none in the party enjoyed the boy’s drolleries more than he did. Indeed, both the boys were prime favorites with him, and often accompanied him upon his hunts. He looked upon them in the light of proteges, as he had got them their places in the expedition.

He had met them at Fort Benton, where they had come from Omaha up the Missouri river, on one of the steamboats that ply on that stream, and was rather surprised to hear what had brought them there.

Though partly led by a spirit of adventure, they had a mission, and one of some importance.

Percy Vere explained this mission to the old hunter. His father had been missing for years. He was an eccentric character, and professed spiritualism, astrology, ventriloquism, and kindred sciences, dabbling a little in magic and chemistry. In fact, he was a universal genius—a jack-of-all-trades, and not doing well with any.

Percy’s mother was a woman of ability and good sense, a first rate milliner, and her industry kept the wolf, which the father’s eccentricities brought to the door, away. In other words, she was obliged to support herself and son, and often furnish money to the genius, who could not make it for himself with all his diverse talents.

He did not appear to be able to concentrate his forces so as to produce any good from them. He was full of wild theories and startling speculations, but he failed signally whenever he attempted to put them to an application.

His wife expressed her opinion of him freely one day, and told him she could no longer expend her savings in his wild schemes. He replied that it was the fate of genius to be misunderstood, that he was destined to be a great man, and she would live to see it; and having uttered this ambiguous prophecy, left her.

He did not return the next day, or the next—a year passed away without bringing Guy Vere home. His wife became alarmed at his prolonged absence. She reproached herself with being too harsh with him and having driven him away from her. He was a handsome man, and she had cherished a warm affection for him, which his eccentricities had not destroyed. She feared that she had driven him to commit suicide. But no tidings came of his death.

She was obliged to keep her little millinery shop going for the support of herself and son, and her sister’s child, who being left an orphan, fell to her care. This was Percy Cute—who 15 was just one year younger than his cousin, his mother having been so pleased with the name of her sister’s child, that she had bestowed it upon her own.

The little shop prospered, and the boys grew in years. Mrs. Vere could not drive the image of her husband from her mind. If she could have satisfied herself that he was dead, she would have been more content, but she could not do that.

The impression among Guy’s neighbors when he was at home, was that he was not in his right mind—“Luny,” they called him.

But many years passed away before she got any tidings of the missing man, and then it came in a very vague shape.

Percy Vere got an Omaha Herald one day, which had been sent as an exchange to a St. Louis paper, and in it was the advertisement of an astrologer who called himself “Professor Guy.”

He took it home to his mother, and said to her, “That’s father!”

These words put her all in a flutter. She took the paper and scanned the advertisement eagerly.

“What makes you think so?” she asked.

“Father’s name was Guy, and he was a ‘professor’ of astrology!”

She smiled. “He was a professor of almost everything.”

“Suppose I go and see if it is my father,” he suggested.

She pondered over this.

“Would you know him, do you think?”

“Oh, yes, if the picture you have in your locket is any thing like him.”

“It was when it was taken.”

She took out the locket, which she wore constantly around her neck, sprung it open, and regarded the two portraits it contained earnestly, for it held her miniature likeness as well as his.

“I have not changed much,” she said, “and perhaps he has not, either. I should really like to know if he is alive. Suppose I was to write to this Professor Guy?”

Percy, who was a bright youth, shook his head dissentingly.

“If he is staying away of his own accord, it is no use to write to him to come back,” he replied.

She breathed a sigh. “I suppose not,” she said.

“But if I was to go after him and have a talk with him, I might prevail upon him to come back.”

Mrs. Vere was impressed by these words, but she answered: “How could I trust you so far away from home?”

He smiled, and drew himself proudly up.

“Don’t you think I am big enough to take care of myself?”

She surveyed his tall, graceful figure, with a mother’s pride, saying:

“Perhaps; but you are so young.”

“I’m seventeen, and I feel quite a man.”

“But I don’t like to trust you so far from home alone.”

“Oh! I needn’t go alone; Percy can go with me.”

Mrs. Vere laughed.

“A great protection he would be—another boy like yourself!” she cried. “There, there—let us not talk any more about it.”

But they did talk about it upon several occasions afterward, and Mrs. Vere’s desire to hear from her missing husband overcame all other considerations, and she consented to Percy’s request to go in search of him. She thought that the sight of his boy would induce him to return home.

Her business had proved prosperous, as I have said, and she was able to fit out the boys in good style. She hung the locket that contained her own and husband’s likeness around her son’s neck, and bade him a tearful “good speed.”

The boys took passage upon a steamboat bound for Omaha, and steamed up the Big Muddy, as the Missouri is called by the dwellers on its banks, and reached that ambitious city in due season.

Upon making inquiries, Percy Vere learned that Professor Guy had found Omaha dull for the exercise of his profession, and had joined a party of adventurers—a mixture of hunters and gold-seekers—and gone with them to Fort Benton.

The very eccentricity of this proceeding was a convincing proof to Percy that this Professor Guy was indeed his father 17 So he wrote to his mother, and then he and Percy Cute sailed up the river in one of the light-draught steamboats.

They reached Fort Benton without misadventure, but here, instead of being at the end of their journey, they found it was just the starting-point. The party to which the Professor had attached himself had taken the trail that led into the wilderness, and it was necessary to follow it, or abandon the search.

Percy Vere chose the former alternative, for he could never think of the latter, and Percy Cute was always of his way of thinking—in fact, thinking was irksome to his sluggish nature.

“I just tumble to any thing you say,” he told his cousin. “Follow your leader—that’s my maxim. You lead and I’ll follow. Say! we might have some high old fun among the Injuns, and bears, and things. Let’s invest in a revolver and bowie-knife, and travel on our muscle!”

So Percy Vere, filled with a true spirit of boyish adventure, wrote his intentions to his mother, and he and Cute made their preparations for a journey into the wilderness.

At this juncture of affairs they made the acquaintance of the old hunter, Gummery Glyndon. They told him their story, (or rather young Vere did, for he was the spokesman on all occasions) and he promised to aid them, and fulfilled his promise by attaching them to the surveying party, though in the capacity of chain bearers; but the boys did not mind that.

Such an opportunity to penetrate into the Indian country was not to be neglected, and the first Percy, who was treasurer, wished to husband their means, for there was no telling how long their search might last, or whither it would lead them.

They made rapid journeys at first, as a portion of the “Northern Pacific Railroad” had already been surveyed, and they were to take it up at, or near, that point, where it was to connect in a south-easterly direction with the “Union Pacific.”

As they passed the different Government forts their escort was changed, until they were joined by Lieutenant Gardiner and his squad, from Fort Walla Walla. He was to remain with them until they were through the Yakima country.

Hitherto their journey had led through the land of the Nez Perces, who were a friendly tribe, and they had been undisturbed; but when they made this new camp Gummery Glyndon told them they might now expect trouble from the Indians.

“There’s three tribes through here,” he said, “and there ain’t much choice between ’em. There’s the Cayuses, the Yakimas, and the Umatillas—a pesky set of murdering thieves the lot of ’em. They all belong to the great Snake Nation, I believe—red sarpints, every mother’s son of ’em.”

When he returned from his hunt he told them that he had seen “Indian sign.”

“There’s Injuns watching us, and we shall hear from them,” he said. “We’ll have to keep a sharp watch to-night, or they’ll stampede our animals.”

The lieutenant and the surveyors did not neglect this warning. They had great confidence in the old hunter’s judgment.

When the supper was disposed of the camp was placed in as good a condition of defense as the locality would permit. The ground had been well selected; it was a little grove on the river’s bank, a kind of oasis among the cliffs, which rose beetling upon either side, precipitously, and, apparently, inaccessible. These cliffs were some distance—a long rifle-shot—from the little grove, and a kind of rocky valley lay between them, devoid of vegetation in many places, where the hard rocks cropped up. Through this valley must the foe come, or else risk their necks, or a plunge into the river, by attempting to skirt the cliffs.

The horses belonging to the party were secured in the grove. In the center of the grove, in a kind of natural fireplace formed by the rocks, the fire had been built, and its red embers were still glowing. Two sentinels were posted at either extremity of the camp. Around the fire the hunter, the surveyors, and the lieutenant were stretched in easy attitudes, enjoying their pipes of tobacco—the great luxury of the wilderness.

A short distance from them the two boys reclined upon a mossy bowlder, listening to their conversation.

The sun had sunk, and the glorious twilight of that 19 western land was upon them. The scene was of calm tranquillity. But that tranquillity was broken in a singular manner.

There came a hurtling sound in the air, and an arrow descended, apparently from the heavens, and stuck quivering in the turf at Lieutenant Gardiner’s head.

All started and grasped their weapons, instinctively, for the trusty rifles were close at hand.

“An attack?” cried Gardiner.

“No—a message. See, there’s a scroll upon the arrow,” answered Gummery. “Read it.”

He threw some brush upon the coals which speedily burst into a flame. Lieutenant Gardiner undid the scroll of bark from the arrow, and spread it open. It contained characters which he had no difficulty in deciphering, for they were written in English.

“White men, begone! If you advance further into the land of the Yakimas, certain destruction awaits you.

“Smoholler, the Prophet.”

“What does this mean?” added Lieutenant Gardiner, having read this singular scroll aloud.

“A game of bluff!” answered the irrepressible Percy Cute. “Let’s see him, and go two better!”

“It’ll be more than a bluff game,” rejoined Gummery Glyndon, shaking his head gravely. “This means business. It’s a notice to quit, and if we don’t take it, these Injuns will do their best to put us out.”

“Rub us out entirely, I guess you mean,” cried Surveyor Robbins, laughingly. “But we won’t take the back track on such a notice as that. Who is this Smoholler?”

“Yes, that’s what I want to know,” chimed in Blaikie and Lieutenant Gardiner.

“I have heard tell of him, though I never met him,” replied Glyndon. “He’s a great gun among the Injuns hereabouts. He’s a kind of red Brigham Young—calls himself a Prophet, and has started a new religion among the red-skins.”

“What is this religion like?”

“That’s more than I can say; though, from what I’ve heard, there appears to be a deal of trickery about it. He’s a great Medicine-man, and can raise the Old Boy, generally. He has his familiar fiends, and makes ’em appear to his followers whenever he likes. He works miracles, and all that sort of thing. And when he predicts the death of any one, they just go, sure pop, at the time mentioned.”

“A singular man, this,” remarked Lieutenant Gardiner, thoughtfully.

“He’s more smart than sing’lar; he just keeps these benighted heathen right under his thumb. They don’t dare to say their souls are their own when he’s around.”

“Where did he come from?”

“He is said to be a Snake Indian of the Walla Walla tribe. He started a village on the river, above here, at a place they call Priest’s Rapids, and his followers increased like magic. He is said, by the Nez Perces, to have a couple of thousand of believers, renegades from all the other tribes in this region, and he can put three hundred fighting men in the field, and then the Cayuses, Yakimas and Umatillas all stand in dread of him, and wouldn’t dare to do any thing else but join him in a war against the whites if he called on ’em. I believe he’s got a reg’lar stronghold at Priest’s Rapids.”

“Is it named so on his account?” asked Robbins.

Glyndon shook his head dubiously.

“I s’pose so, but I couldn’t say for sure. I don’t know the place; was never up there.”

“What kind of a place is it—did you ever hear?”

“Oh, yes. It is north of the Oregon line, and is a great place for salmon-fishing. The Injuns have a great time catching ’em in the season.”

“This Smoholler, then, is a kind of independent chief among the other tribes?”

“Yes; and his tribe is a conglomeration of all the other tribes, and the pick of ’em, too. They are called Smohollers 21 by the other Injuns, but there’s Cayuses, Yakimas, Umatillas, Modocs, Snakes, and Piutes amongst them.”

“A mongrel set!”

“But tough customers to deal with.”

Lieutenant Gardiner turned to Percy Vere.

“You and your chum send the sentinels in to me, and take their places—young eyes are sharp.”

The two boys, who had been listening attentively to this conversation, obeyed at once, and the two sentinels soon appeared before the lieutenant. But they had not seen any one approach the camp, and were surprised to hear that an arrow had been shot into it.

Gummery Glyndon surveyed the nearest cliff critically. Its base was about a stone’s throw from where he sat. The rising moon threw a silvery radiance upon its peak, disclosing an irregularity near its top, that looked like a cavity in its face, though it might have been only a shadow.

“It’s my opinion the arrow came from there,” he exclaimed, giving utterance to this thought suddenly.

All eyes were turned in the direction indicated.

“But how could any one get up there? A cat couldn’t climb that. It’s as steep and as smooth as a wall.”

“Just you wait,” returned the old guide, coolly. “If this Smoholler is the kind of man he’s said to be, we ain’t done with him yet. Just keep your weather eye peeled in the direction of that cliff, and have your rifles handy. That arrow was only the commencement. I saw plenty of Injun sign to-day, and there may be a hundred of Smoholler’s braves beyond there. I opine that he is not going to let us travel much further into this country, if he can help it.”

“But, man, what harm does our surveying do him?” asked Blaikie.

“He don’t want any railroad through this country—all Injuns are down on railroads—sp’ils their hunting-grounds, and settles up the country. And the white settlers settle the Injuns. We’ve had a genteel notice to leave, and if we don’t take it, we’ll have ’em swarming round us like enraged hornets.”

“You would not advise a retrograde movement?” asked Lieutenant Gardiner.

“Who said any thing about taking the back-track?” somewhat tartly rejoined Glyndon. “Did I? I never saw Injuns enough to back me down yet.”

The lieutenant laughed, as he added:

“The suggestion of a backward movement came from me,” he said, “and by so doing I am not afraid to have my courage called into question. Discretion is said to be the better part of valor. We appear to have reached a critical position here. Our party is small—nineteen in all, counting the two boys. If the Indians oppose us in force—and from what Glyndon says it seems that this Indian Prophet Smoholler can put three hundred warriors in the field—shall we be justified in advancing against such odds?”

The surveyors looked at Glyndon, but he was silent, gazing reflectively at the cliff, upon whose summit the moonbeams now played in a fantastic manner.

“I confess I don’t like the idea of retreating,” said Blaikie. “I don’t want to be turned back by such a scarecrow as that.”

“No more do I,” added Robbins.

“I don’t say go back, and I don’t say go on,” replied Glyndon, in his deliberate manner; “but I say, just hold on for a while here, where we are, until we can see how the cat jumps.”

“How long will it be before the feline animal indulges in her gymnastic exercise, do you think?” asked Robbins.

“Before you can smoke another pipe,” answered Glyndon. “I have an idea that something is going to happen right away—kind o’ feel it in my bones. Get the men ready, leftenant—there’s no telling what is— Hello! it’s coming! Fireworks—by king!”

The amazement of the old hunter was shared by the whole camp, and the two boys came running in from their posts.

“See—see—look there!”

A strange fire issued from the face of the cliff, disclosing a little shelf or platform, backed by a cavity. From this cavity the fire came forth with crimson luster, and rose colored smoke rolled upward toward the heaven, obscuring the moon-rays.

The entire force of the whites clustered in front of the 23 grove, clutching their rifles, and gazing with wondering eyes upon this singular sight, and exclamations burst spontaneously from their lips.

“Ach Gott! what ish dat?” cried the Dutch private.

“It’s a volcayano!” explained the Irishman.

“It’s the debble’s fireplace!” mumbled Isaac, and his teeth chattered together with superstitious awe.

“It’s some of Smoholler’s deviltry!” said Glyndon.

The fire grew in intensity, and then a dark body seemed to grow up in the midst of it. A black, unearthly figure of a man, with eyes of fire, a tongue of flame, and livid horns projecting from his head, of a deep-red color.

“The devil!” was the cry that burst from the lips of the astonished whites.

He held what appeared to be a thunderbolt in his hand, and suddenly launched it like a javelin at the astonished gazers. It whizzed past Isaac’s head, singeing his wool in its passage, and exploding at his heels, and the tonsorial professor sprawled upon his back with one heart-rending yell that evinced his firm belief that he had received his quietus.

“Fiend or man, I’ll have a try at him!” cried Glyndon, and he took a rapid sight along the barrel of his rifle, and fired at the apparition on the cliff.

Two other rifles echoed his, for Blaikie and Robbins had impulsively followed his example. The three rifles sent forth their contents, and the smoke clouded their vision for a moment. But following the reports came an unearthly, soul-curdling laugh, and then something pattered down among them like heavy drops of rain.

Robbins stooped and picked up a round object that struck at his feet.

“Good heavens! here’s my bullet sent back to me!” he cried.

These words sent a thrill through every heart. Isaac, still lying curled up in a heap where he had fallen, uttered a plaintive howl.

Percy Cute went to him.

“Are you dead, Ike? If you are, say so, and tell us where you would like to be buried,” he said.

Isaac sat up on end, resenting this question.

“Glory!” he cried. “S’pose de debble had shot you, how would you like it?”

“Well, if I warn’t hurt any more than you are, I shouldn’t mind it much. Singed your wool a little, but your Hair Restorer will fix that all right, you know.”

A roar of laughter followed this remark, and in the midst of it Isaac scrambled sheepishly to his feet.

When the smoke of the rifles cleared away the fiend had vanished from the cliff, and the crimson light had died away. The silvery beams of the moon played hide and seek among the projections and depressions of the cliff’s peak.

The gazers rubbed their eyes. What they had seen appeared to them already like a fantastic dream. But a new vision awaited them, a new wonder was to be presented to their eyes.

Another light began to glow from the cliff, but this time it was of a bluish tint, and the smoke that arose from it was white and fleecy. And this light grew dense, as the other had done, and assumed a form and shape—a shape of ethereal loveliness.

As the other vision thrilled the beholders with a kind of supernatural awe, so did this one excite their wondering admiration. It bore the shape they supposed an angel would wear.

The face was that of a girl, angelic in its beauty. Her long black hair floated in wavy masses upon her neck and shoulders, and was confined upon the forehead by a golden coronet in the center of which gleamed a diamond star, which emitted scintillating rays of light. Her arms and legs were bare, revealing their faultless perfection, and the alabaster purity of her skin. Her only garment was a long white tunic, of some snowy, fleecy fabric, confined at the waist by a 25 golden cestus, which was studded with large rubies glittering with blood-red rays.

This angelic vision held in her right hand a kind of glittering dart. For a minute she transfixed their wondering gaze, then hurled the dart into their midst.

The fire around her grew more vivid, the volume of white smoke increased in density, obscured her figure from view, and then began to roll away. When the light of the fire faded and the smoke lifted from the face of the rock, the platform was vacant, the lovely vision had disappeared.

The surveying party gaze inquiringly into each other’s faces. Lieutenant Gardiner expressed the general opinion by asking the hunter, Glyndon:

“What do you think of that?”

Glyndon shook his head dubiously.

“Did you ever see a girl as pretty as that one was?” he asked.

“Well, no, I can’t say that I ever did,” the lieutenant admitted, with a smile; “and if she is a human I should like to become better acquainted with her.”

“All women have something angelic about them,” said Glyndon, reflectively, and his voice had a strange touch of pathos to it as he spoke—“particularly when they are good and true women. I knew one once—an angel couldn’t have had a better disposition, and she—” His voice broke here. “Well, well, the murdering red-skins sent her to heaven before her time!” he resumed, huskily. “And our little one went with her. Perhaps it was best so—but I’ve often thought I could have stood it better if she had been spared. Do you know, leftenant—it was an odd idea, but when I looked at that bright spirit-angel or whatever it was—up on the cliff yonder—I thought to myself, my little girl, maybe, looks just like that up in heaven.”

The hunter turned away his head and wiped his eyes with the back of his bony hand. His hearers respected his grief for they knew the story of Glyndon’s bereavement.

Percy Cute picked up the javelin and the dart, if they could be called by these names, for they were of singular construction, as we shall see anon.

“Here’s the telegrams,” he said; “they may tell us what 26 the meaning of the diorama was. A piece of birch bark is wrapped around each.”

“I must examine them,” exclaimed Gardiner, taking possession of them. “Freshen up the fire, my boy, so we can have a little more light upon the subject.”

“Better post the sentinels again,” suggested Glyndon. “This deviltry may be only the forerunner of mischief.”

“You are right. It behoves us to use every precaution.”

Two other sentinels were posted, and then the balance of the party returned to the camp-fire in the grove, which the two boys had started into a blaze again.

One of the missiles hurled from the cliff was about four feet in length, the other two. The javelin was a stout stick of wood, apparently the shoot of a tree, about an inch in diameter, and was painted a blood-red color. It was blackened at one end, as if it had been loaded with some kind of firework, on the rocket principle. Around the middle of it a strip of flexible bark was secured by a leathern string.

The dart was formed of the bone of the fore leg of an antelope, and was gilded, as if by the application of that kind of gold-leaf known to printers as “Dutch Metal.” This also had a strip of bark around it, but it was secured by a long black hair, soft and glossy, as if plucked from a woman’s head.

“Funny gim-cracks, those,” said Glyndon, as Lieutenant Gardiner unfastened the strips of bark.

“Yes; nothing very supernatural about these,” he replied. “But let us see what Smoholler has to say this time.”

He read the words upon the strip of bark taken from the javelin first:

“Begone, or fear my vengeance!”

“Good! So speaks the Fiend. Let’s hear what the Angel has to say.”

He read the second strip:

“Depart in peace, and escape the destruction that threatens you.”

Lieutenant Gardiner passed the pieces of bark to the surveyors for their inspection.

“Well, gentlemen, what do you think of this?” he asked.

Blaikie and Robbins examined the billets of bark curiously.

“There is one thing singular about this affair,” said Blaikie.

“What is that?”

“These communications, like the one sent on the arrow, are written in English, either with a red pencil or a piece of red chalk, and apparently by the same hand, for the characters appear to be alike in each.”

“There’s nothing strange in that,” said Glyndon. “Many Injuns have learned English from the numerous trappers and traders who have visited them at different times. A man as smart as this Injun Prophet must have had frequent dealings with the traders, and would be sure to get a smattering of the language.”

“The man who wrote these communications had more than a smattering,” returned Robbins. “This Smoholler is determined that we shan’t run our railroad through his country, that’s evident.”

“Yes; and he has begun by trying to frighten us away.”

“And if that don’t do it, he’ll try fighting us away next,” responded Glyndon.

“Likely; but I don’t scare worth a cent,” rejoined Robbins. “This supernatural trickery may do among the Indians, but it won’t answer with us. I’m going to survey this country in spite of Smoholler’s angels or devils—though I wouldn’t mind a closer inspection of the angel.”

“Nor I,” laughed Gardiner. “Girl or angel, she was certainly a vision of beauty. By Jove! suppose we search the cliff—we might find her there.”

He started impulsively to his feet, under the excitement of this idea.

“I will go with you!” cried Percy Vere, always ready for an adventure.

“Count me in!” added Percy Cute; the idea was firmly impressed upon his mind that wherever Percy Vere went, he must go also.

“Sit down,” said Glyndon, in his calm, deliberate manner. “You might as well attempt to find a needle in a haystack as search that cliff to-night. You’d only break your necks attempting 28 it, and not find anybody, either. If there’s a way up that cliff, they know how to get up and down it, and they won’t stop there until we come to look for ’em. Wait until morning.”

“They’ll be gone then.”

“They’re gone now. If we could surround the cliff, it might have been of some use; but it joins the range beyond, as you can see, and they probably came from the back of it, through some crevice, which we can’t see from here. I’ll take a scout up that way in the morning, and see.”

“My idea is to fortify our position here to the best of our ability, and await an attack, which is sure to come. We might repulse it here.”

“You are right every way, leftenant,” replied Glyndon. “This is a good p’int. While I take a scout to-morrow, just cut down a few of these trees, and make a breastwork. We can send to Fort Walla Walla for help if we are hard pushed; but I have an idea that if we pepper a few of Smoholler’s followers, he’ll get sick of it and let us alone. The railroad’s bound to go through, and he can’t help it. Perhaps I can get a talk with him, and convince him that we are not going within a hundred miles of his village. We’ll see to-morrow. Now just sleep, all who want to. I’m going to keep an eye on that cliff for the balance of the night.”

He took his rifle and walked to the edge of the timber; but his vigilance appeared to have been uncalled-for, as the quiet of the camp remained undisturbed through the night.

In the morning, after partaking of breakfast, Gummery Glyndon prepared for his scout. During this, he was urged by Percy Vere to allow him and his cousin to accompany him.

The hunter was inclined, at first, to refuse this request, but on reflection, he consented.

“They are smart boys, both of ’em,” he told himself, “and the surveyors always lend them their rifles when they go with me. I’d rather have them any time than the soldiers—these reg’lars ain’t worth shucks in an Injun skirmish—it would be as good as three of us, and if the Injuns are thick among the hills, and I opine so, I shall want some help along. Yes, Percy, you can go.”

These last words were uttered aloud.

The two boys were quite pleased at being permitted to join in the scout, and Blaikie and Robbins readily loaned them their rifles. The surveyors were well provided in this respect as each had a breech-loading, repeating rifle, besides the old-fashioned single-barreled, smooth bore one. The boys got the single-barreled ones, of course. But they were perfectly satisfied with them, and, by much practice, had gained considerable skill in their use.

“Do you know, Percy, I have an idea,” said the elder boy, as they equipped themselves for the adventure.

“Have you? How does it feel? Tell me, so I’ll know when I have one.”

“Oh, pshaw! you are always at your joke. My idea is that Smoholler might give me some intelligence concerning my father.”

“Very likely; but do you think it safe to trust yourself in Smoholler’s power?” suggested Cute.

“Oh, no; but we might be able to hold a parley with him. I think he would prefer to arrange matters peaceably with us if he could. He must know that he can not drive back our party without considerable loss to himself.”

“Yes, and from what I have heard old Gummery Glyndon say, I should fancy that these Indians don’t like to take any risks. Do you know, Percy, I’d like to have a scrimmage with the red-skins. I think it would beat bear-hunting all hollow—Smoholler!”

Percy Vere laughed at this pun upon the Prophet’s name.

“It might not be so funny as you imagine,” he answered; “particularly if we should happen to get the worst of it, and you should have your hair lifted.”

Percy Cute passed his fingers through his shock of flaxen hair, reflectively.

“I would not like to be obliged to experiment on Professor Ike’s Restorative in that fashion,” he said. “I’m afraid the soil is too poor for another crop, even with that help. But I’m not going to let any Indian take my top-knot if I can help it. I’ll trust to my arms, while my powder and bullets last.”

“And failing these?”

“My dependence will be in my legs.”

“You are too fat to run fast.”

“Not if a crowd of red-skins was after me. The way I could get over the ground then would be a caution to bedbugs.”

Percy Vere laughed again.

“You’ll do,” he cried.

“You bet I will! Anybody’s got to get up early to get ahead of my time.”

“Are you ready, boys?” asked Gummery Glyndon, as he approached them.

“Ready and willing,” responded Cute.

Glyndon took a critical survey of the boys, as they shouldered their rifles and joined him. Besides the rifle each was armed with a revolver—the large size called “navy”—and a bowie-knife, with a keen blade, six inches in length, and a stout horn handle. A serviceable weapon for a close encounter, and also serving the purpose of a hunting and table knife. Few travelers upon the plains and amongst the mountains of the Far West are without this useful article.

“You’ll do,” said Glyndon, shaking his head, approvingly. “Come on.”

Lieutenant Gardiner followed them to the edge of the timber.

“How long do you intend to be absent?” he asked.

“I shall try to bring you in something for dinner,” replied Glyndon. “I’ve got the boys, and so I can bring in considerable game, if we are lucky enough to find it. My idea is to go through the ravine, and skirt the cliff to the left there—where the deviltry was last night—looking for Indian sign by the way, and come back by the river’s bank, if there’s 31 footing—if not, we’ll get on some logs and let the tide float us down.”

“A good idea,” cried Gardiner, surprised by the mention of this expedient. “I should never have thought of that. You are cunning in devices.”

“So are the Injuns,” returned Glyndon, impressively. “Take care some of ’em don’t come down on you that way while I’m gone.”

“I’ll look out for them; you’ll find quite a fort here when you come back. I hardly think Smoholler will dare attack us here.”

Glyndon took a critical survey of the situation, and shook his head in the manner he had when any thing met his approval.

“It’s a good camping-ground,” he said, “and you can hold it ag’in’ a hundred Injuns, in daylight.” He laid particular stress upon this word. “An open attack is what you can beat off without any trouble, but it’s stratagem and trickery will bother you. But we can tell more about Smoholler when I come back. If he’s got a strong party near us he can’t hide the signs of them from me.”

“Can you judge of the number without seeing them?” asked Gardiner, in some surprise.

“Oh, yes.”

“How can you do that?”

“Every man to his trade; you know your tactics, and I know mine. I have learned to trail Injuns pretty well in all these years. I couldn’t very well explain to you how I do it—there’s a knack in it that some men can never pick up. But, to us old forest rangers, there’s tongues and voices in the running water, the rustling leaves, the waving grass, and the moss-grown stones. Where an Injun plants his foot he leaves a sign, and though they do their best to hide their trail, there’s always eyes keen enough to spy it out.”

“I have heard of the wonderful skill you hunters have in following a trail,” rejoined Gardiner. “You beat the Indians in their own woodcraft.”

“The white man is ahead of the red-man in every respect,” replied Glyndon, sententiously. “He can out-run him, out-hunt him, and out-fight him! It’s the intellect does it. The 32 Injun’s brain-pan wasn’t calculated for any thing but a savage—but you can’t make the Peace Commissioners believe it. Why don’t they pick up all the lazy, good-for-nothing white men in the country, put ’em on a reservation, and feed and clothe them? Waugh! Come, boys, let’s see if the ‘noble red-man’ isn’t after our ha’r.”

With this contemptuous reflection, Gummery Glyndon threw his long rifle into the hollow of his arm, and walked toward the mouth of the ravine with long strides, followed by the two boys, who kept up with him with some difficulty; but their young hearts bounded with a pleasant excitement.

The rapid strides of the old guide carried him half-way across the little valley between the cliffs: then he paused suddenly, and resting the butt of his long rifle upon the ground, and leaning his hands upon its muzzle, took a critical survey of the cliff, where the apparitions had appeared upon the previous night.

“There isn’t any way to get up there on this side,” he said; “but there may be on the other.”

“There’s something up there that looks like a hole—a kind of crack in the rock,” rejoined Cute. “There may be a cave up there.”

“It is a fissure in the cliff, and may extend through to the other side,” remarked Percy Vere.

“More’n likely,” answered the old hunter. “There’s a heap of snow lies on these hills in the winter-time, and the spring thaw sends torrents down to the river, and the water bores its way through the rocks just like a gimlet. These cliffs are a spur of the Cascade Range, and when we get upon the brow of one of them, I think we can see the white peak of Mount Rainier, looking like a big icicle turned the wrong way upwards.”

“Is it very high?”

“Thirteen thousand feet, they say. It’s the highest peak of the Cascade Mountains.”

“Why do they call them Cascade?”

“On account of the torrents I was telling you of. I’ll show you some grand sights when we get among the mountains, for the road is to run between Mount Adams and Mount Hood, Blaikie told me; that is if Smoholler lets us get any further. We can never get out of this valley with our present force, if he tries to stop us. Let’s push on and take the timber there to the right. It’s pretty thick at the skirt of the cliff.”

The trees fringed the cliff half-way to its summit, a thick growth of spruce, fir, and cedar, and through this the hunter and the boys made their way with some difficulty, as the ground was rocky and uneven, and the dwarf cedars and firs sprung from every crevice of rock and patch of earth.

After a toilsome tramp of an hour they turned the base of the cliff, and emerged upon the other side of it. During their progress they started quite a quantity of game. A huge elk galloped away within easy range, and deer crossed their path several times, while numerous wild-fowl arose from their perches and went whining away.

The temptation to shoot was very great, and it was as much as Glyndon could do to restrain the boys.

“’Tain’t safe,” he told them. “Wait until we go back. I have an idea that there’s Injuns round here, and a rifle-shot would bring ’em on us quicker’n a wink.”

“But oh, what a lovely shot that elk was!” cried Percy Vere. “And such splendid horns. I would like to have them for a trophy.”

“Wait—there’s more of ’em. We must look for Injuns first.”

“That’s my idea!” cried Cute. “I’d rather have a scalp for a trophy than a pair of horns.”

Glyndon smiled, grimly.

“I opine that there’s as many scalps around here as horns,” he said; “but we must take care we don’t lose our own in looking for ’em.”

“Have you seen any sign?” asked Percy Vere.

“Not yet; but I think we’re coming to it.”

They pressed forward, and as they skirted the cliff they bore upward toward its crest. Its aspect was entirely different upon this side, its slope being gradual, and the trees and bushes growing very near to the top.

The way was still difficult. Huge bowlders, some covered with moss and making little openings in the woods, and others thickly studded with fir trees, protruding like green spikes, continually obstructed their way.

“Great Cæsar!” cried Glyndon, pausing to wipe the perspiration from his brow. “This is tough work. I don’t see any signs of a trail yet—and there must be one to the top of the cliff, if I could only find it.”

Percy Cute, who was the last in the line of march, for he had a natural tendency for loitering, had diverged a little to one side when this halt was made and, though the hunter and Percy Vere were further up the cliff than he was, he had gone more to the right, in a forward direction, and suddenly came upon a kind of open way in the wood.

“Look here!” he called out. “Here’s better traveling; come this way.”

Glyndon and Percy Vere joined him.

“Why, it looks like a path—a path leading to the summit of the cliff!” cried Percy.

“It is the trail!” said Glyndon, with satisfaction.

He bent over it, and began to examine it attentively, and as he did so his features assumed a grave expression, and he shook his head in a dissatisfied manner.

“Boys!” he said—“I’m an old fool!”

This announcement rather surprised them.

“What’s up?” demanded Percy Cute.

“Mischief! We’ve walked into a trap, and I’ve led you into it like a consumed idiot as I am.”

“How so?” inquired both boys, eagerly.

“Why, don’t you see? When we was a looking up at the cliff there must have been one of the red-skins up there watching us. They know we are here in the wood, and they are just waiting for our return to the camp to surprise us. And there’s fifty of ’em at least.”

The boys were thrown from one surprise into another.

“How can you tell how many there are of them?” asked Percy Vere, curiously.

Glyndon pointed to the trail.

“Here’s what tells me,” he answered. “These Injuns always go single file, and tread in each other’s footsteps to blind their trail, but it would take fifty of ’em, at least, to make so plain a trail. And see there, just at one side, where her foot slipped on the stone, and she stepped out of the trail, heavily, and come near falling—see that broken branch to which she clung to save herself—that tells me there’s a squaw along.”

The boys were filled with wonder.

“And the trail is scarcely cold either,” continued Glyndon, still pursuing his examination. “They passed here less than a half an hour ago, and they’re after us.”

“After us?” repeated Percy Vere, in some consternation.

“Just so,” replied Glyndon, calmly.

“Then we had better git up and ’git,” suggested Percy Cute. “Let’s get back to camp. I wouldn’t mind a scrimmage, but I think fifty against three is a leetle too hefty.”

“We can’t go back the way we came,” answered Glyndon. “They’re between us and the camp now. We’ll have to take to the river the other side of the cliff, and get back that way.”

These words revived the boys’ spirits.

“Oh! then there is a way out of the trap?” cried Percy Vere.

“I reckon; I never got into so bad a scrape but what I could find a way out of it. Let’s travel. We’ve found out enough, and the quicker we get back to the camp now the better. We know that there is a way up to the cliff’s top here, and we’ve found out that there’s a woman in the party, so we can understand something of Smoholler’s deviltry last night.”

“Yes, but this woman is a squaw, is she not?”

“Of course.”

“But the vision that appeared upon the cliff was white, how can you account for that?” urged Percy Vere.

Glyndon shook his head in a bewildered manner.

“I can’t account for it,” he answered, reflectively. “She was white, as you say, and if she wasn’t an angel she looked enough like one to be one. The sight of her face affected me strangely—I hain’t cried for years, and yet I felt the tears coming as I looked at her. It’s witchcraft, and this Injun Prophet just knows how to play it. I don’t wonder that the savages think he’s something great. I’d like to see him once, just to see what kind of a man he is; but I don’t want to see him just now—it might not be wholesome,” he added, dryly. “He might lift my ha’r without the formality of an introduction. It’s lucky I didn’t let you shoot at that elk when you wanted to. The sound of your rifle would have brought the whole squad down upon us.”

A peculiar cry arose on the air.

“What’s that?” asked Percy Vere; a presentiment of evil entering his mind as he listened to it.

“That’s some bird calling for its mate,” said Cute.

“Nary a bird,” cried Glyndon. “That’s an Injun. They’ve struck our trail, and they’re coming for us. Come on; we must get to the river, fast as we can travel.”

“Couldn’t we make a stand here and fight them?” suggested Percy Vere.

The old hunter shook his head.

“Madness, my boy,” he replied. “I like your spunk, but it can’t be done. I’m doubtful if we can all get back to the camp, but we’ll make a try for it. Our only hope is to make for the river upon the other side of the cliff.”

Percy Cute took off his hat, and felt of his hair, while his face assumed a rueful expression.

“I wish I had a photograph of it,” he exclaimed.

“Why so?” demanded Glyndon, in some surprise.

“Because I’m afraid that I will never see it again.”

Both the hunter and Percy Vere laughed at this sally. This dry humor in the face of threatening danger pleased Glyndon greatly.

“You’ll do!” he returned. “Good grit, both of you, and 37 the Injuns shan’t get you if I can help it. Come along. We can make a stand at the river’s edge, and pepper some of ’em before we take to the water.”

They pressed rapidly forward, but their path was beset with many obstacles and obstructions. They had to clamber over huge bowlders, and force their way through thickets of cedar, and fir-trees, nor were brambles wanting in the way.

The numerous signals that now sounded behind them lent spurs to their exertions, for they told them that the Indians were following in swift pursuit.

As they approached the river’s brink the wood grew more open; there were less rocks scattered about, and the trees were taller. As they emerged into this opening, with only a fringe of trees between them and the river’s bank, the report of guns rattled in quick succession behind them, and a bullet went whistling by Glyndon’s ear.

“Great Cæsar!” he cried, “this won’t do. Turn at the trees, boys, and prepare for ’em. They’ll hit one of us next thing.”

They gained a clump of fir trees that grew close together, which afforded them a shelter, and an opportunity to fire their rifles between the trunks.

They were breathless with the exertions they had made, and were only too glad to avail themselves of this temporary rest.

“Phew! that’s what I call tall traveling,” cried Cute, panting to recover his wind. “I heard the bullets rattling around me like hailstones.”

“It’s a mercy we were none of us hit,” rejoined Percy Vere. “Well, we’re lucky so far.”

“But we ain’t out of it yet,” said Glyndon, and he looked grave. “They’ll make a rush for us, and when they come, fire your rifles, and then take your pistols. Don’t stop to load; if we can’t drive ’em back on the first fire, it’s all up with us. Give ’em every shot you’ve got, and then take the river—the current will carry us down to the camp, and we can’t be far above it. Maybe they’ll hear the firing and be ready to help us.”

“Hoop-la!” exclaimed Cute, excitedly. “Here they come. I’ll take that big fellow in front.”

A wild yell rung through the wood, and a score of painted savages bounded swiftly forward. They had determined upon a desperate charge, evidently; and this mode of attack so different from the customary warfare of the red-man provoked a cry of rage from Glyndon’s lips.

“Blast ’em!” he shouted, “somebody’s told ’em just how to beat us—but give ’em Jessie! Come on, you murdering thieves!”

The three rifles cracked simultaneously, and two of the advancing warriors went down in their tracks; but Cute missed the tall Indian, the leader of the party, and the savages came on unchecked, like a huge ocean wave. Our three scouts were instantly surrounded. The two boys fought back to back, with revolver and bowie-knife in either hand.

Glyndon clutched his long rifle by the barrel and swept the Indians from his path as he fought his way to the river. He reached the bank and plunged into its turbid tide. He was loth to leave the boys to their fate, but he knew he was powerless to help them—and self-preservation is the first law of nature.

Percy Cute received a blow from a tomahawk that stretched him upon the ground; and Percy Vere found himself clutched by the strong arm of the chief—a hideous-looking object in his war-paint. The warriors drew back, as if feeling that the boy could not cope with his formidable opponent.

Percy’s weapons were struck from his hands, and he was hurled to the ground. The hideous face of the savage glared over him, and his knee was pressed upon the boy’s chest, nearly suffocating him. Percy gave himself up for lost.

The chief clutched at his throat with his left hand, brandishing his scalping-knife in his right. His fingers came in contact with the ribbon that Percy wore around his neck, and the locket was pulled forth and sprung open.

The chief’s eyes fell upon the faces it contained, and a cry of amazement burst from his lips. He sprung to his feet.

A brawny savage was approaching Cute to give him his finishing-blow.

“Hold!” shouted the chief, in a voice that was shrill and loud, like a bugle-call. “Harm him not—harm neither—they are my captives, and their lives are sacred.”

A growl of discontent greeted these words.

“Why not kill the pale-face whelps?” cried one of the braves.

The chief stamped angrily upon the ground.

“They are mine, I tell you,” he answered, in peremptory tones. “They are the faces I have seen in my visions—and the White Spirit says they are to live.”

The savages were loth to be cheated of their prey.

“Six of our braves have fallen,” replied the warrior who had before spoken, “and the gray hunter has escaped. The blood of our brothers calls for vengeance! Death to the cubs of the pale-face!”

He raised his tomahawk to smite Percy Cute.

“Monedo! Monedo!” exclaimed the chief, in that shrill tone which contrasted strongly with the deep guttural of the Indian. “Palsy the arm that strikes against the will of Smoholler!”

The warrior’s threatening arm dropped, and he retreated apprehensively from the form of the prostrate boy.

“Smoholler, do not call up your evil-spirit!” he cried, deprecatingly.

The Prophet raised his right arm loftily. Cute recovered in a measure from the effects of the blow which had felled him, and which, fortunately for him, had been given with the blunt end of the tomahawk, and crawled to Percy Vere, who rested upon one knee beneath the Prophet’s protecting left arm.

“Are these captives mine?” demanded Smoholler.

A general murmur of affirmation was the response.

“That’s right, Smoholler; you’re a brick—just you stick to us, that’s a good fellow,” cried Cute, whose spirits were equal to any emergency. “I say, Percy, our top-knots are safe yet.”

This was whispered to his comrade. Percy said nothing; he was gazing in a bewildered manner upon the strange individual who had so unexpectedly spared his life. He was at a loss to account for this sudden clemency.

The Prophet’s face, by the aid of war-paint, was made to assume an expression frightful to look upon. He was tall in figure, and appeared to possess extraordinary activity and strength, as indeed he did. Percy thought him the best specimen he had yet seen of an Indian chief. His dress displayed his tall and sinewy form to great advantage. It seemed to have been chosen with the view of producing the greatest effect upon the eye of the beholder.

His moccasins and leggings were of buck-skin, stained black, and trimmed with red fringe. His hunting-shirt was of the same material and color, and trimmed in like manner, and upon its breast was painted in red a grinning fiend, similar to the one who had appeared upon the cliff. His head-dress was the skull of a buffalo, with the horns projecting on either side of his head, and he wore it in the fashion of a helmet.

These projecting, curved horns added to the ferocity of his face, the features of which were nearly indistinguishable beneath the paint with which it was daubed. You could see that he had deep, sunken eyes, with a wild glare to them, like the light of insanity, and a long, prominent nose, and that was all.

Upon his back he wore a mantle of deer-skin, which was curiously stained and colored, and covered with innumerable figures and characters. The prominent figures were a fiend and an angel, who appeared to be engaged in an interminable conflict.

These were representatives of his Monedos, or spirits, which his followers firmly believed he could conjure up at will to do his bidding. No wonder the boys gazed with curious eyes upon this strange leader. They could see that he was disposed to befriend them, but they could not understand why.

“The captives are mine; woe to him who seeks to harm them!” cried Smoholler, thus asserting his claim in a manner that proved he considered it settled beyond further dispute. “They shall go to the Rapids with me.”

“You’re a trump, Smoholler!” exclaimed Percy Cute, gratefully.

“There to be sacrificed to the spirits I control,” continued Smoholler.

Cute groaned.

“Oh, law! are we only going out of the frying-pan into the fire?” he muttered.

“Don’t be frightened; he does not intend to harm us,” whispered Percy Vere.

Cute shook his head in a doleful manner.

“I wish I was sure of that,” he answered.

“Well, we can only trust to his mercy.”

“Ah, yes! but if he happens to be out of it just now, and can’t get a fresh supply?” suggested Cute, lugubriously. He appeared determined to take a discouraging view of the situation. “I know the tricks of these red codgers; I’ve read about ’em in books. He has got some horrible old idol in a cave up at the Rapids, where he lives, and he makes human sacrifices to it. We shall be grilled, like a couple of innocent lambs, as we are.”

“Pshaw! don’t lose all your courage at the first reverse. You’re not goin to funk, are you?”

“Nary a funk! I’m only taking a rational view of the situation. It’s kind of tight papers now, ain’t it—you’ll allow that?”

“Perhaps; but then we can’t help it, can we?”

“No; that’s what’s the matter!”

“Besides, we can’t die but once.”

“I know it; that’s what makes it so awkward. If a chap could die two or three times he might get used to it, don’t you see?”

This reasoning provoked a smile from Percy Vere.

“Well, we must take our chances,” he answered. “Repining won’t help us. You wanted a brush with the red-skins, and you’ve had it.”

“You bet! My head sings yet where the big chap hit me. It’s lucky for me that my skull is tolerably thick. Didn’t I see stars when I went down? And I never expected to get up again. Well, we peppered some of ’em, as Gummery 42 would say, and that’s some satisfaction. I wonder if he got safe off?”

This question was answered by the return of four of the warriors, who had pursued Glyndon to the river’s edge, and who reported that the old hunter had swam down the stream, apparently uninjured by the bullets they had sent after him.

The Prophet turned to Percy Vere.

“What is the number of your party?” he demanded, in good English, and spoken with a purity that surprised the boy.

Percy Vere hesitated to answer this question.

“Speak!” cried the Prophet, in a peremptory manner.

Still Percy Vere hesitated.

“Speak!” repeated the Prophet, and the shrill tones of his voice arose in a menacing manner.

“Why don’t you go to our camp, and find out?” suggested Cute, in a sarcastical manner.

“Hush!” cautioned Percy Vere, fearing that the Prophet might become enraged.

“I intend to go,” responded the Prophet, coolly. “You see my force here, and you can tell if the surveyors will be able to withstand me.” He waved his hand complacently toward his assembled braves. “These are picked warriors. There is enough to drive away the surveyors. But, if more should be wanted, I can summon two hundred more from my village at the Rapids.”

Percy Vere glanced at the braves. There was at least forty of them, and each one carried a rifle. Among the friendly tribes through which he had passed he had never seen so fine a body of men. It appeared to him utterly impossible that the surveyors and soldiers could beat back this force.

The Prophet’s keen eyes were fixed upon his face, and he 43 read what was passing in his mind by the expression of his features.

“You see how vain it is for your party to struggle against me?” he said.

“Why do you object to the survey being made?” asked Percy. “Why harm people that have no wish to harm you?”

The Prophet drew his tall form proudly up.

“This is my land,” he replied, “and I don’t want any railroad through it.”

“It will not run within a hundred miles of your village.”

“I don’t want it within a thousand. I am forming a great nation here; already our numbers count by thousands—my followers come from every tribe. I would regenerate the red-man, make him what the Great Spirit intended him to be. These woods teem with game—the water of yonder river is alive with fish. This is the red-man’s Paradise, and the white-man is the serpent who would destroy all. Settlement follows the railroad, villages and cities spring up in the wilderness, and then there is no longer any hunting-grounds left for the Indian. The game vanishes from the forest, the fish desert the running streams, and the red-man is left to starve, or become the drudge and servant of the pale-faces.”

These words were spoken with a strange eloquence, and thrilled Percy Vere as he listened to them. There was a ring of truth in them that carried conviction to his mind.

“It does appear a hard case for the red-man, I must admit,” he rejoined; “but I don’t see how you are going to help it. Government lays out these railroads, and they must be built. You can’t stop them.”

“You will see,” replied the Prophet, darkly. “Your party dare not advance after the warning I have given them.”

“Perhaps not; but they will remain where they are.”

“I will drive them into the river!”

“I do not think you can do so, even with your force. You are not more than four to one against them, and they have fortified their position by this time, and the officer, in command of the soldiers, and the surveyors are brave and determined men. A victory will cost you dear.”

These words seemed to impress the chief. He walked moodily backward and forward, for a few moments, in deep thought.

“I must not risk my warriors’ lives,” he muttered. “I promised them an easy victory, and a defeat would shake their faith in me. Already I have lost six braves, and only those boy captives to show against their loss. I must be cautious in my future movements.”

He paused in his walk before Percy Vere, and began to interrogate him again:

“Do you think, if I was to send you back to your party with the assurance that they will not be permitted to advance another foot into this land, that they would abandon their undertaking and depart?” he demanded.

“I do not,” replied Percy, promptly.

“Ha! Then you shall go to Priest’s Rapids with me. You shall see the wonders of my subterranean temple there; you shall see the chiefs of the Cayuses, Umatillas and Yakimas subservient to my will, and ready at my bidding to make this valley swarm with a red host of painted braves. You shall behold the power of Smoholler, and return to these pale-faced leaders to tell them that at my will I can raise a red war-cloud such as this land has never witnessed, and which will annihilate them when it bursts.”

“I say, Percy, old Smo’ is a little on the blow,” whispered Percy Cute.

The quick ear of the Prophet appeared to catch these words, and he shook his head disdainfully.

“The Tow-head is incredulous,” he cried, in the sententious Indian manner; at one moment speaking like a white man and the next with the imagery of the Indian.

Percy Cute opened his mouth in wonder.

“How did he know that I was ever called ‘Tow-head?’” he cried.

“Its color is enough to lead him to that conclusion,” answered Percy Vere, laughingly.

“If I get out of this scrape, I’ll have Ike dye my hair. If I escape a die here, I’ll dye in camp,” cried Cute.

It was impossible to detect through the paint upon Smoholler’s face any indication of what was passing in his mind, for 45 it was like a hideous mask, but Percy Vere thought he was amused by his cousin’s drollery.

“Do you also doubt my power?” the Prophet demanded of Percy Vere. “Would it surprise you if I could tell you your name, and the purpose that brings you into this wilderness?”

“It would indeed,” answered the boy.

“My spirits can tell me,” rejoined the Prophet. “In my dreams the past and future are revealed to me.”

He made a few cabalistic motions with his hand, and then assumed a rigid attitude, like one in a trance, his head projected as if awaiting a message from some unseen spirit in the air.

“Whisky is said to be the most potent spirit among the Indians,” whispered the irrepressible Cute; “but I don’t see any demijohns around here.”

“Hush! you will anger him,” returned Percy Vere. “It is all a mummery, but we may as well humor it, for our lives depend upon the pleasure of this strange chief.”

Smoholler remained rigid, his eyes assuming a vacant look. His braves stood at a respectful distance, leaning upon their rifles, and watching their leader with an intent interest. These dreams of the Prophet were always fraught with singular consequences. They knew he was holding communion with his spirit, who had appeared to them, in the hideous form that was shown upon the cliff, though he generally kept himself invisible.

“Monedo! Monedo!” murmured Smoholler, in a resonant whisper.

A dead silence ensued, and the boys, despite their incredulity, were thrilled by a feeling new to them—a sort of supernatural awe.

“Master, I am here!”

These words floated above the boys’ heads in clear, distinct tones. They clutched at each other’s arms, and stared blankly around them. They stood apart with the Prophet; there was not a warrior within a hundred paces of them—not a soul from whom the voice could possibly have proceeded.

“Did you hear that?” gasped Percy Vere.

“I just did,” replied Cute, sepulchrally.

“What do you think of it?”

“It knocks me endwise. Hush! he’s going to hocus-pocus a little more.”

The boys were greatly interested now. Though they felt it was all mummery, they could not help being impressed by it.

The Prophet waved his hand in the direction of the boys.

“Reveal all you know concerning them,” he said, as if addressing an invisible spirit above his head—invisible to all other eyes but his.

Then he appeared to listen for a moment; and in this moment the boys could almost hear their hearts beat, in the intensity of their interest in the proceedings. Smoholler nodded his head.

“It is enough, good Monedo,” he said. “Depart to the Land of Shadows, from whence I summoned you.”

Then the Prophet came out of his trance, and addressed himself to the first Percy.

“Your name is Percy Vere,” he said. “The locket you wear contains the portraits of your father and your mother. Your companion is your cousin, Percy Cute; and you are here in the wilderness seeking your father.”

To say that the boys were surprised by these words would inadequately describe the emotion that seized upon them as they listened to them—they were literally dumbfounded.

“Great heavens! this is wonderful!” cried Percy Vere. “What do you think of it?” he added, appealing to his cousin.

“I take all back; old Smo’ is by no means slow!” responded Cute. “I don’t wonder that he can bamboozle the benighted Indians, for he has completely kerflummixed me.”

The warriors, who had drawn nearer when Smoholler dismissed 47 his spirit, uttered an approving grunt. It may be that the Prophet had purposely availed himself of this opportunity of displaying his divining power before them.

“Is what I have told you true?” he demanded of the boys.

“It is,” Percy Vere admitted.

“Every word of it,” added Cute. “This beats spirit-rapping all hollow; your spirit comes without a rap, and his information don’t cost a rap.”

“And having told me so much, I am led to believe you can also tell me where I can find my father?” cried Percy Vere, eagerly.

The Prophet shook his head.

“I can learn from my spirit whether he is alive or dead, perhaps,” he replied; “but Monedo does not care to seek for a pale-face; he hates the white race, as I do.”

“You have a queer way of showing it,” exclaimed Cute. “I should have been like poor uncle Ned, without any hair on the top of my head, by this time, if it had not been for you.”

“Why have you spared our lives?” asked Percy. “The Indian seldom extends mercy to a captive, I have heard.”

The Prophet laughed disdainfully.

“You have heard and read many things about the Indian,” he replied; “but they are spoken and written by the pale-faces, and there is little truth in them. I have spared your life that you may bear a message to the surveyor’s camp for me. But first you shall partake of food with me. You must feel the need of some refreshment.”

“Well, I feel peckish, and no mistake,” answered Cute. “So if you have got any fodder, just tote it along.”

“Something to eat would not come amiss,” said Percy Vere. “We intended to have been back with game to our camp before this.”

The Prophet laughed in his forbidding manner.

“Your camp will not get any game on this side of the river,” he rejoined. “A dozen of my warriors guard the mouth of the ravine, and it will be sure destruction to the pale-face who attempts to pass through it. You would have fallen into the ambush, had you not turned to the right and ascended the cliff.”

“How did you know the direction we had taken?” asked Percy, curiously.

“A sentinel posted upon the cliff gave us warning. Nothing can escape the vigilance of my scouts. They have eyes like hawks. Yonder camp is hemmed in—they must recross the river or I shall drive them into it.”

He clapped his hands and an Indian boy came bounding toward him—a boy with a graceful, lithe form, and step as bounding as that of an antelope. He was handsomely dressed, and wore the same colors as the Prophet, and was, evidently, his familiar attendant, or page.

Like the Prophet, he wore a head-dress taken from an animal, but his was the head of an antelope. The sharp horns were left, and the whole face of the animal preserved in such a manner that the boy’s face was completely covered by it, and his dark eyes glistened through the eye-holes; and so nicely was the skin fitted to his face, that he appeared to be a boy with an antelope’s head.

“Jumping ginger!” exclaimed Cute, as the boy bounded lightly forward; “what kind of a critter is that, anyway?”

“Glyndon was mistaken,” remarked Percy, thoughtfully, as he watched the Indian boy’s approach.

“In what?”

“It was his tracks we saw. There’s no squaw in the party.”

“That’s so, by king! I never thought of it before; but you are right, there isn’t.”

“Oneotah,” said the Prophet to the boy; “prepare some venison steaks for us.”

The boy made a respectful obeisance.

“Yes, master,” he replied, in tones that were singularly clear and bell-like, and then he hastened to obey.

Cute smacked his lips.

“Venison-steaks, a-la-mode de Indian!” he exclaimed. “I think I can put myself outside of some without any difficulty.”

“I must confess to being rather sharp set myself,” replied Percy. “That tramp through the thicket, and the lively fight afterward, have freshened up my appetite to a degree.”

“The food will be quickly served,” said the Prophet. “See, Nature spreads her table for us. Come.”

He led the way to a square bowlder that reared its form from the turf beside a little streamlet that went purling by on its way to the river, its clear, crystal water looking cool and refreshing. The Prophet cast himself down beside the rock, and the boys followed his example. As they glanced through the arches of the forest they saw several fires blazing in different directions, and groups of Indians clustered around them. General preparations for a meal were in progress.

The boys were impressed by the romance of the scene, and Cute conveyed his idea of it by exclaiming, rather unpoetically:

“Say, Percy, ain’t this high? You said you would like to see Smoholler, the Prophet, and here we are, invited to take an al fresco dinner with him.”

The Prophet raised himself upon his elbow, and regarded Percy Vere earnestly.

“Why did you wish to see me?” he asked.

“Because I thought you might give me some intelligence of my father,” answered Percy.

“Why should you think so?”

“Because you are a man of great intelligence. I heard so before I saw you, and I am satisfied of it now.”

The Prophet inclined his head as if pleased with the compliment.

“You possess a wonderful power over the Indians, I can see—and I think few parties of hunters could cross the river, which you watch so jealously, unknown to you.”