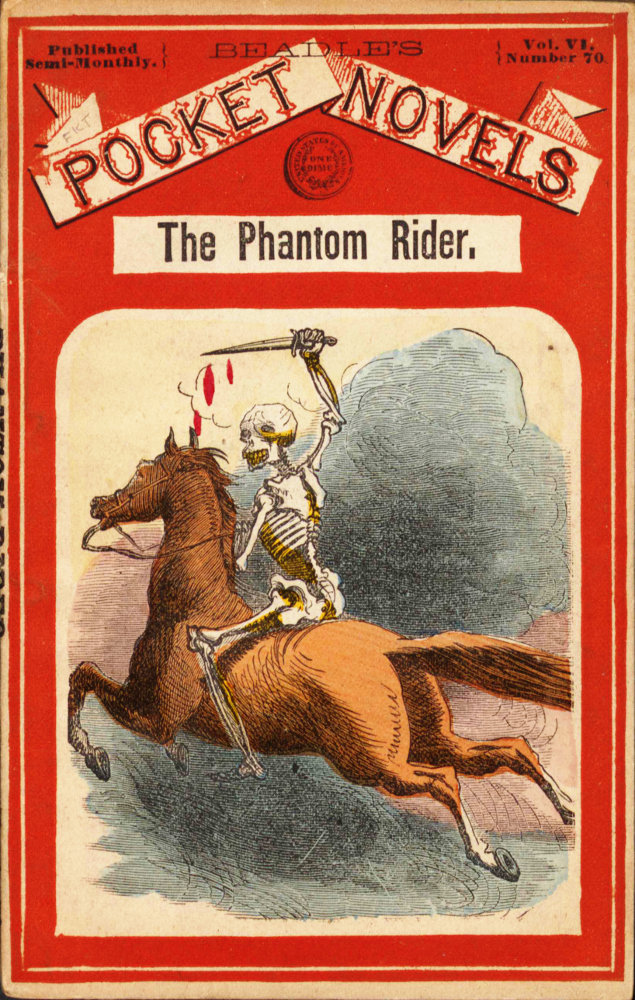

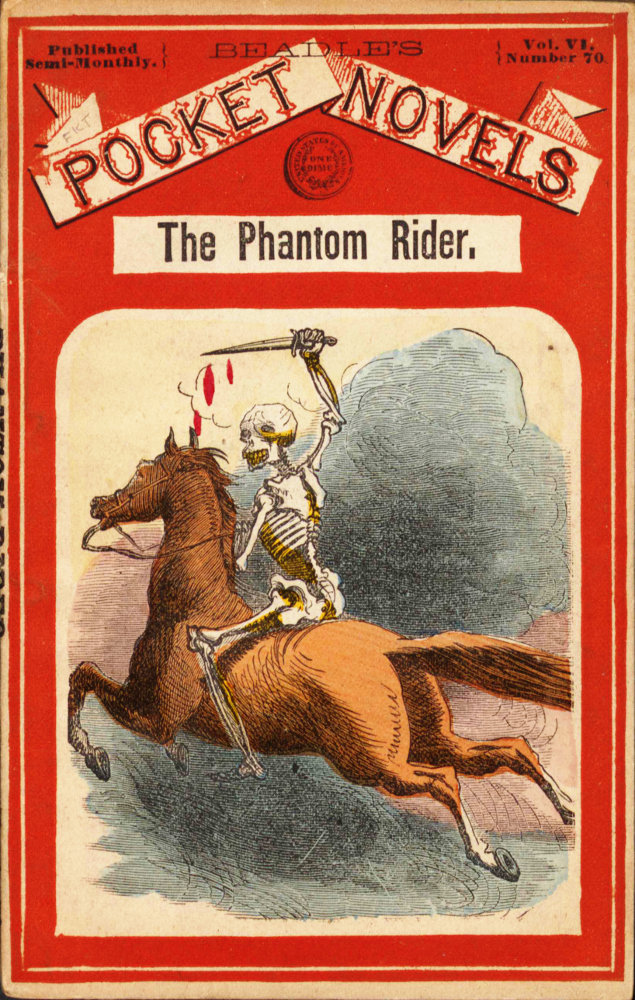

Title: The Phantom Rider; or The Giant Chief's Fate: A tale of the old Dahcotah country

Author: Maro O. Rolfe

Release date: September 1, 2021 [eBook #66193]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: David Edwards, Stephen Hutcheson, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (Northern Illinois University Digital Library)

A Tale of the Old Dahcotah Country.

BY MARO O. ROLFE,

Author of Pocket Novel No. 47, “The Man Hunter.”

NEW YORK.

BEADLE AND ADAMS, PUBLISHERS,

98 WILLIAM STREET.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1872, by

FRANK STARR & CO.,

In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

The scene of our story is laid in the great North-west.

It was a bleak, windy day in November. The shrill blasts wailed through the forest trees like the last despairing cry of a lost spirit, and gust after gust beat and roared around the little log cabin standing so silent and lonely, half buried in the midst of the Titanic oaks that spread their long branches protectingly over its low roof, and whose sturdy trunks environed it, seeming to keep silent and untiring guard over its four rough walls.

The scene within the cabin was in striking contrast with the wild aspect without.

It was a rude but homelike place, and despite the chinked walls and rough furniture, there was such an air of plain comfort as one might expect to see in the abode of the sturdy western pioneer.

A young girl sat by a table engaged in embroidering a broad strip of dressed deer-skin with fancifully colored beads and quills—a blue-eyed, slender-looking little woman with shining masses of golden-brown hair falling unconfined about her small, shapely head, and down over her shoulders until it reached the waist of her dress, which fitted her willowy form to perfection, and whose ample folds half concealed, half disclosed a small, neatly-clad foot and well-turned ankle.

Her sunny blue eyes held a soft, loving light, and a bright smile played continually upon her dainty face and around her rosy little mouth, with its ripe lips half parted from the rows of small white teeth.

But the azure eyes could flash with courage and determination, and the pretty mouth could be hard and stern with its strawberry lips tightly drawn and its tiny, gleaming teeth hard-set.

The settler’s daughter was very lovely, and she possessed a nerve and courage far beyond her sex.

A tall, powerfully-made man of fifty stood near the great wide-mouthed fire-place, in which a ruddy blaze leapt and glowed fantastically, shedding a pleasant radiance over the homely place that could not but be grateful to one who, like Emmett Darke, was preparing to leave it and go out into the wind and cold of the chill November day. But the settler, long used to the perils of border life, thought little of this.

His sharp gray eye and firm through pleasant mouth bespoke indomitable courage and strength of will; and as he stood there in the red glow of the dancing firelight, buckling on his deer-skin belt in which he thrust the borderman’s trusty companion, a long, keen-edged hunting-knife, with a brace of heavy pistols, he looked the personification of the ideal hunter of the far western wilds.

A huge blood-hound lay on the floor at his feet—a large, red-eyed creature with white, gleaming teeth—a brute that might be a true and faithful friend, but could not but be a terribly dangerous enemy.

The object in the room most likely to attract the attention of a casual observer was a small square box of polished wood, standing on the table.

Besides the tall clock ticking in a corner, this casket was the only visible thing that bore evidence of having been made by hands more skilled than those of the settler, or with tools other than those common implements ever ready at the pioneer’s grasp, the ax and the auger.

What this curious little box contained, will appear hereafter.

Soon the hunter’s preparations were completed, and slinging a long rifle, which he had taken down from its place on three pegs in the wall, across his shoulders, he turned to his daughter who had wound the soft deer-skin belt, upon which she had wrought innumerable fancy devices, gracefully about 11 her waist and shoulders, and stood regarding him with a merry light sparkling in her blue eyes.

“How do I look, papa?” she asked. “Like some dusky forest princess?”

And she finished by placing a jaunty turban in which were fastened several bright-colored plumes, which drooped down until they touched her beautiful golden hair, coquettishly on her head.

“More like a regular angel, wings and all!” he exclaimed, admiringly: for Emmett Darke loved his beautiful motherless child more than his life. “That hair and those eyes of yours don’t look very Injiny. Wouldn’t that red lover of yours go wild if he saw you now? I don’t wonder he’s half-crazy and calls you ‘Sun-Hair!’ How about that youngster, Clancy Vere, eh, Vinnie? Has he an eye to beauty?”

The maiden blushed rosy red; but the laughing eyes became thoughtful in a moment.

“Do you know, papa, that I often think of him—the Indian? Oh, if he should come some day when you are gone! He is wild and bloodthirsty and his passions are ungovernable. He has taken a solemn vow to make me his wife!”

“He shall never fulfill that vow!” cried the old man, with a dangerous light in his cold gray eyes. “I’ll have his life, first! If he comes here again I’ll give him a free pass to the happy hunting-grounds!”

Emmett Darke’s face was almost white with rage, and he brought the heavy stock of his long rifle down on the floor with a sharp bang.

“Just so sure as that red devil has the misfortune to be caught anywhere near my cabin, I will shoot him down like the coward he is! My daughter is never to become a squaw, eh, Vinnie?”

“Never, father! Never will I become the Indian’s wife! I would sooner shed my own heart’s blood!”

She spoke so calmly and yet determinedly that her father half-shuddered. He knew that she meant every word, and he breathed an inward prayer that God would watch over his lonely child and guard her from all peril during his absence.

The hunter stood silent and motionless for a few moments, 12 thinking intently. Arousing himself at length, he said, turning to the blood-hound, who was on his feet in an instant, running around him and licking his hands:

“Come, Death! We must go.”

In a few minutes they had passed out, and were walking rapidly and silently through the forest.

As Darke went away, a face appeared among the thick bushes close by the cabin—a red face, hideously daubed with black and yellow paint, with long, coarse black hair, hanging down the sunken jaws, and fierce black eyes flashing triumph and exultation as the hunter disappeared from view. Darke did not see this face, and the bushes closed over it in a moment, concealing it as suddenly as it had appeared.

After her father was gone, Vinnie went and stood before the fireplace, looking down into the red mass of leaping flames.

She was deeply buried in thought, and she heard no sound save the hissing of the fire and the wailing of the wind around the corners of the cabin, and through the bare branches of the great oaks outside.

She little thought what a lovely picture she made as she stood thus, silent and motionless—one might almost imagine breathless—with a dreamy, far-off look in her soft eyes, and the glancing blaze lighting up her fair face till she looked, in fantastic guise, like some beautified Fairy queen, some incomparable silvan goddess.

Rarely, radiantly lovely she appeared, strangely out of place in that homely room.

She was unconscious of this—unconscious, also, of another presence in the cabin until the back-log fell suddenly with a dull thud, throwing out a shower of red sparks and arousing her on the instant from the fit of abstraction into which she had fallen.

With a quick start, she turned her head and saw a tall form close behind her—so near that it might easily have touched her.

It was the form of an Indian, powerful and massive. The face was the same that had peered through the shrubbery at Emmett Darke a few minutes before.

There was a strange light glowing in the fierce eyes fixed 13 so steadily on the lovely face before him—a look of wild passion as dangerous as it was intense.

The savage did not speak nor even stir; but the hard, cruel lines on his forehead and about his mouth relaxed a little as he tried to twist his ugly visage into the semblance of a smile—a semblance that was even more loathsome than its habitual scowl—that was nearer the leer of an exultant fiend than the smile of a human being.

Vinnie’s face was deathly pale, and her heart seemed for a moment to lay still in her bosom; but she tried to meet the gaze of those devilish eyes calmly. She stood quite still, looking into the cruel face, but she dared not trust her voice.

The Indian spoke at length, in a tone harsh and rasping, like the snarl of some wild animal:

“Ku-nan-gu-no-nah has come for his squaw. Sun-Hair is very beautiful. Ku-nan-gu-no-nah is a mighty warrior. He has always loved the white maiden since he met her in the forest many moons ago. The great chief’s heart has been burning for Sun-Hair. He has prepared his wigwam. It is hung around with the scalps of his slain foes. Sun-Hair will be a queen. The Indian women will bow down their heads in shame before the beautiful Sun-Hair! Is she ready? Will she go with the great chief? His warriors are waiting to see their queen!”

For a moment Vinnie did not speak, then the words came clear and sharp from her white lips:

“No! I will never go!”

The chief’s face was fairly demoniac in an instant—the sickish leer was gone, and the savage teeth shone through the drawn lips in two white, gleaming rows. He advanced with a quick motion, and laid his hand roughly on her arm.

“Come!” said the harsh voice, “Sun-Hair must go!”

“Here I am!”

It was a young man who spoke, standing on the bank of a small stream that had its course through the forest at a point about two miles distant, as a bird flies, from Emmett Darke’s cabin.

He was tall and well-formed, with hazel eyes and dark-brown hair. His face was clear-cut and handsome, open and frank in its expression, while it indicated a goodly stock of firmness and courage.

This is Clancy Vere, the young hunter, an allusion to whom had brought the rich blood to Vinnie’s face that very afternoon.

He was clad in a complete suit of dressed deer-skin, elaborately ornamented about the shoulders with bright-colored beads and quills, his hunting-shirt being gathered about his waist with a wide belt from which protruded the stock of a heavy revolver and the silver-mounted hilt of a long bowie-knife, while a powder-horn and bullet-pouch were slung by a leathern cord under his left arm.

As he spoke, he dropped the butt of his rifle, a trim, beautifully-mounted weapon, until it rested on the turf at his feet; then he stood leaning on it for a long time, looking intently down into the depths of the eddying stream before him.

He was thinking—of a girl with blue eyes and golden brown hair—of Emmett Darke’s beautiful daughter, Vinnie.

Clancy Vere loved Vinnie devotedly, and not hopelessly, she had led him to think; though, as yet, he had never made any formal declaration of his passion.

Still, as a look is oftentimes fraught with more meaning than the most high-sounding speech, and the pioneer’s daughter had not, upon certain occasions which he could recall, 15 been chary of these looks, Vere was very far from being despondent.

He lived at a small settlement a half-dozen miles away, and had set out that morning to visit the cabin of the hunter. His errand there may be easily surmised.

He had proceeded thus far on his way without adventure worthy of note, and intended to cross the stream in a canoe that he knew Darke kept concealed in the undergrowth at a place a hundred yards below the spot where he now stood.

So intent was he upon his musings, that he heard no sound save the rippling of the water and the roar of the wind through the trees.

He did not see the bushes part close behind him and a dusky form emerge from its concealment, to be followed by another, then another, until six Indians had entered the little grassy space in which he was standing, and began stealthily to take different positions around him until his chances of escape were cut off on all sides.

He was brought to realize his situation in a moment.

A chorus of shrill, exultant yells rung out on every hand.

He turned on the instant, and his quick eye measured the strength of his savage foes. They were too near at hand for him to bring his rifle to bear; but gripping it firmly around the barrel, he brought the ponderous stock down on his nearest assailant, crushing in his skull like an egg-shell.

There was a muffled thud as the deadly weight fell a second time, and another savage sunk over on the ground without a groan.

An Indian was creeping up stealthily behind him. As Vere raised his clubbed rifle a third time, throwing it high above his head, in order that the blow might be more effective, the savage, who had been crouching down on the ground a moment close beside him, sprung high in the air, and clutching the gun-barrel near the lock, wrenched it from the young hunter’s hands just as it began to descend.

This quick, hard pull upon the weapon, which he gripped with all his strength, caused him to stagger a trifle, and before he could regain his footing and draw his bowie-knife, the three remaining Indians sprung upon him and bore him to the ground.

In a moment his elbows were pinioned behind his back, and his weapons were transferred from his belt to those of his captors.

They pulled him roughly to his feet, and an Indian took his place on either side, leading him along by the arms. The brave who had disarmed him walked behind, while the remaining savage, who was evidently a warrior of some importance, to judge from the number of eagle’s feathers which ornamented his head and the many trophies of the war-path and the chase which were hung about his neck and secured to his belt, led the way up the stream, pausing ever and anon to give some guttural command in his native dialect to his followers, who clutched their captive’s arms firmly, as if they feared that, bound and almost helpless as he was, he would attempt to escape.

They had seen evidence of his prowess, and wisely concluded that he was a safer prisoner well guarded than when allowed to walk alone.

For an hour they kept on, over fallen trees and heaps of rock, through tangled masses of undergrowth, now bearing a little to the right, then to the left; but always keeping within hearing of the stream, whose monotonous murmurings seemed to grow louder and hoarser as they proceeded, until they changed to a wild, sullen roar, like the impetuous rushing and dashing of a cataract.

At length, after a long silence, the leader of the party turned toward Vere and said, impressively:

“Does the pale-face hear the song of the waterfall? It is chanting his death-song! The black waters laugh because they will swallow up the pale-face!”

Soon the sun appeared through an opening in the leaden gray clouds that had drifted lazily through the sky until they were gathered together in a dark, lowering mass overhead, and its bright rays trembled for a moment upon the surface of the water.

“See!” continued the Indian, pointing to the falls just visible through the trees. “See the waters smile! They laugh because the red men will give them a pale-face victim! Let the white man hear them sing! ‘Ha! ha!’ they say, ‘the pale-face must die!’ It is his death chant! The great 17 Manitou is speaking through the laughing waters. He is happy with his red children when a pale-face dies. The white hunter is brave. He is not afraid to fight. But his heart will grow small within his bosom when he must go down into the black waters—the river of death! Will he be brave when he meets the unknown dangers of the dark valley? He will find it hard to die now. He is young and the world looks bright to his eyes. Perhaps a white woman will weep when he is dead. The Indian women have mourned for their husbands and brothers when they have gone out to fight the Long-knives and never returned. The laughing waters are crying aloud for their victim. The white man must die!”

“We all must die,” said Vere, calmly, not caring to show the concern he really felt. “Men have died before, why should I fear death?”

An expression of surprise flitted over the Indian’s painted face.

Few men could meet death so calmly.

The young hunter had resolved not to die without a desperate struggle; but he preferred that his captors should think him resigned to his fate—the horrible fate which seemed inevitable.

A few rods above the falls a tree grew far out over the water, rushing madly to the cataract below.

The bank at this point was rough and jagged, its steep and rocky sides jutting out full twenty feet above the black, roaring mass underneath.

The party halted here.

“The pale-face hunter’s feet must be tied,” said the Indian who had spoken before. “He must not fight with the laughing waters.”

Producing a stout leathern thong, about twelve feet in length, one of the savages advanced to coil it around the captive’s ankles.

As he stooped, Vere drew his foot back suddenly and planted it with tremendous force squarely in his face, flattening his long nose and knocking out several of his sharp white teeth.

The Indian rolled over on the ground with a wild screech.

The pain was terrible, and he lay for a moment, pressing his disfigured face and giving utterance to a series of hoarse, agonized groans.

Then he sprung up suddenly with a wild yell of rage and vengeance.

He was upon Vere in an instant, his long fingers entwined in his hair and his scalping-knife circling with lightning rapidity around his head.

The young hunter’s arms were securely pinioned.

He was utterly powerless in the red fiend’s hands.

Death—sudden and terrible—seemed certain; but he did not flinch.

His fearless eye was fixed on the Indian’s face, and his own did not change when he felt the keen knife-point pricking the skin upon the crown of his head.

He was not afraid to die.

He thought of the terrible, because unknown life beyond the grave—and of Vinnie!

Would she weep when he was gone?

He trusted so, and stood calmly awaiting the great change.

Vinnie’s face was very pale, but she did not cry out. A wild fear, an awful terror, was tugging at her heart, but she would not give way to it. She knew she would need all her native courage and coolness in the ordeal which she foresaw she must endure.

Ku-nan-gu-no-nah’s hand retained its rough grip on her arm, and his harsh voice repeated:

“Come. Sun-Hair must go!”

Resistance would, she knew, be of no avail. It would only serve to arouse the Indian’s passions to a still higher pitch of intensity—to make him, if possible, still more demoniac, and still more determined than ever to fulfill his vow, and carry out his intention to abduct and bear her away to his wigwam.

She must have recourse to stratagem.

So, to gain time, she said as calmly as possible, but with a wild throbbing at her heart which she tried in vain to still:

“So the great chief loves the pale-face maiden? He would make her a queen? He would spend his whole life to make her happy? Is it not so?”

“Yes,” he said, eagerly. “Ku-nan-gu-no-nah loves Sun-Hair as the bird loves its mate. He will always make her happy. She shall never know what it is to weep. Her life shall always be pleasant. It shall be like a day when the green grass is new on the ground, and the dancing waters, freed from their cold bonds of ice, are laughing in the bright sunlight.”

“And my life shall be like one long day in the bright spring-time?” she said, as bravely as she could, smiling through all her fear.

“Yes,” again said the chief, with a searching look in her white face.

He had expected tears and opposition, and he received instead, 20 smiles, and apparent acquiescence, and he was surprised and partially thrown off his guard.

“May be the white maiden will go with her Indian lover,” said Vinnie. “Give her time to think. It is very hard for her to leave her home and her kind old father. Does the chief think he can make Sun-Hair happier than she has been here? Can he make her forget her father and her home?”

“Did not Ku-nan-gu-no-nah tell the beautiful Sun-Hair that she should be a queen? She shall wear robes as dazzling as the light of the sun. She need not work like the Indian women. She need do nothing but sit and sing like a bird all day long. The red-women will bow their heads in shame before her bright face, and the warriors will sing songs about her beauty. They will think of their beautiful queen when they go on the war-path, and they will always return with the scalps of their dead enemies hanging in their belts. What more can Sun-Hair wish?”

“I think I will go,” said the girl, slowly. “Only give me time to think.”

“Ugh! It is well!” grunted Ku-nan-gu-no-nah, with another of his sickish smiles. Then frowning darkly, and with a significant tap on the handle of his tomahawk:

“But Sun-Hair no fool the chief! If she does he will kill her! She can’t get away. Take care!”

The Indian let her free now; and he sat down on a low stool near the door, as if half fearing some treachery on Vinnie’s part, but he was pretty well assured, after all, that she would go with him without much resistance. Vinnie stood for some time, striving to think of some plan by which she might escape the Indian, who watched her every motion from under his heavy, overhanging brows, as closely as a cat watches a mouse.

There was such a look of half-suspicious triumph on his dark face and in his cruel eyes as is sometimes seen in the eyes of the panther, as it sits quietly by, watching its prey, and suffering it to live and exult in a few moments more of life that the moment of its annihilation, when it comes suddenly and unlooked for, may be the harder to bear.

But the poor girl rejected plan after plan as impracticable. At one time she thought of making some excuse to 21 enter an adjoining apartment and secure a pistol which she knew her father kept there; but she feared that the savage would discover her intention and tomahawk her at once. Then she contemplated making a rush for the door at the cabin and escaping into the forest; but her reason told her that the chief would overtake her before she was fairly outside the door.

At last, when she had nearly given up in despair, a thought suggested itself to her brain—how, she never knew, it was so wild and strange—that made her heart leap with a newborn hope—a hope that she might yet outwit her captor and gain time until something—she know not what—should intervene to save her from the fate he had marked out for her.

She sat down by the table and opened the small box of polished wood, of which mention was made in our first chapter, the Indian watching her the while from his place near the door.

This casket, on being opened, prove to be a small galvanic battery; and Vinnie was but a moment preparing it for action.

When all was in readiness, she took a pair of electric slippers from a drawer in the table and placed them beside the battery.

Then, knowing the superstition of the Indian race, she arose, and waving her hands several times very slowly around her head, seemed to be invoking a charm. Her eyes were fixed apparently on vacancy, and she stood motionless for several minutes; then smiling sweetly, she turned to Ku-nan-gu-no-nah, who had advanced to the center of the room, and stood regarding her mystic performance with a sort of awed wonder, she said in a low, soft voice, that sounded to him like the murmuring of a distant brooklet:

“Does the chief know that the Great Manitou has given the white maiden a mysterious power, greater than is possessed by any of the Indian medicine-men? Would Ku-nan-gu-no-nah like to see evidence of the white maiden’s power?”

The Indian stood quite still while she was speaking, with a look of mingled doubt and awe on his face. At last he said in his harsh voice:

“Ugh! Let Ku-nan-gu-no-nah see what Sun-Hair can do. She is not a great medicine-woman. There is but one who has a mighty power from the Great Spirit, and that is Yon-da-do, the great conjuror of my tribe. Sun-Hair can’t get away. The chief will kill her if she tries. Let Ku-nan-gu-no-nah see!”

“Let the chief look and be convinced!”

Vinnie attached the slippers to the conductors leading from the battery, and set them side by side on the cabin floor.

Then, taking up her position behind the table, she commenced to operate the machine slowly at first, then faster, until the slippers began to skip about, dancing a sort of shuffle, which caused the Indian’s face to take on a look of still greater wonder.

“See,” she said, turning the little crank faster, causing the magic slippers to jump higher and oftener than before. “Do you longer doubt my power? You, Ku-nan-gu-no-nah, strong brave though you are, can not hold those dancing moccasins when I command them to move!”

The chief’s face lighted up in an instant with a look of scorn and contempt. No one had ever doubted his strength before. Surely he could hold those skipping bits of leather.

“Look!” he said. “Let Sun-Hair see the chief hold them so fast they can not tremble.”

He stooped down and raised them from the floor, holding one in each hand.

He clutched them firmly, and then went on:

“See the chief hold them. A pappoose could do it. See—”

His words were cut short suddenly, the slippers dropped from his hands, and with a wild shriek of terror, he ran to the further side of the room.

He stood motionless several minutes, his dusky face the picture of blank amazement, looking at the palms of his hands as if he would see what had acted upon them with such powerful effect. He could not conceal his chagrin as Vinnie said, tauntingly;

“Ku-nan-gu-no-nah is a great brave. He is very strong. He can not hold a pair of moccasins. They jump out of his hands, and he runs away like a whipped dog! The big 23 chief is very strong. What a warrior he must be!”

“It is a lie!” yelled the Indian, almost beside himself with rage and mortification. “I can hold the dancing moccasins!”

“Try it,” said the beautiful magician, sententiously. Ku-nan-gu-no-nah advanced timidly, and took the slippers up daintily between his thumbs and fore-fingers.

“Get a firm hold,” said Vinnie. “You will need all of your boasted strength. Ku-nan-gu-no-nah, a great chief and a brave warrior, has said that a pappoose could hold the dancing moccasins. Let us see if he can do what a pappoose could do. He says that Sun-Hair has no mysterious power, more terrible than that of the Indian medicine-man, Yon-da-do. He will see. Is he ready?”

The savage gripped the magic slippers with all his strength, seeming determined that this time he would give the fair conjuror no opportunity to taunt him with lack of success.

“Ugh!” he grunted, “Ku-nan-gu-no-nah is ready.”

“You have them fast now, have you?”

Vinnie could not repress a smile as he answered, clutching the electric slippers tighter than before:

“Yes; they not stir now.”

She muttered a few words in a low tone, passing her hands backward and forward before her face, and commanded the slippers to dance.

At the same instant she set the battery in action, and the chief’s hands, acted upon by the electricity, which she had made more powerful than before, seemed to clutch the slippers like a vise.

A horrible expression of mingled rage and pain crossed his distorted face, and he gave utterance to a shrill scream of fear and agony that might have been heard, so loud and resonant was it, fully a mile away.

At last Vinnie ceased to turn the machine, and Ku-nan-gu-no-nah reeled back and sunk down in a corner of the cabin almost exhausted.

His eyes rolled wildly in their sockets, his mouth twitched nervously, his long, coarse black hair stood half-erect, and he trembled with an awful, superstitious fear in every fiber of his being.

“What does the chief think now of the white maiden’s power?” asked Vinnie. “What does he think of the little box and the dancing moccasins? Where now is his vaunted strength? Can the great brave do what a pappoose can do? Does he want to try again?”

“No! No!” panted Ku-nan-gu-no-nah, with chattering teeth. “Sun-Hair is a great conjuror. She has a power from the Great Spirit! She has a devil-box, and moccasins such as are worn where the Long-knives go when they die—where there is fire always! Hell, they call it. The white maiden is a greater conjuror than Yon-da-do. She has a devil-box and hell-moccasins!”

At this moment there were sounds of footfalls outside the door. The noise came nearer, and there was a sharp, scratching sound on the door like that produced by some keen-pointed instrument.

Vinnie felt a terrible fear forcing its way to her heart.

“My God!” she thought. “What if it should be some of Ku-nan-gu-no-nah’s warriors? Would they show me any mercy after the trick I have played on their chief?”

The scratching noise was repeated, louder than before, and she could see the heavy door tremble. With a white face, she stood awaiting—she knew not what!

The Indian still cowered down in the corner, apparently heedless of what was passing around him.

But it was not fated that Clancy Vere should die by the scalping-knife.

The Indian who had acted as the leader of the party leaped forward with a sharp cry, and with a quick blow of his powerful hand, sent the knife flying from the maddened brave’s grasp into the water tossing and roaring twenty feet below.

“What would Bear-Killer do?” he said, giving the baffled savage a sudden push that sent him staggering back against the tree. “Has he forgotten the laws of our nation? Does he forget that the great chiefs have said that when a number of warriors take a captive all shall have a share in putting him to death?”

Bear-Killer was cowed; but he stood with lowering brows, glowering upon the young hunter with a look of fierce hatred that made him appear, with his dark face bruised and bleeding, absolutely diabolical.

“Wy-an-da is right,” he said, at length. “Bear-Killer forgot. The pale-face must die hard! Bear-Killer must be avenged!”

“We will give the white hunter to the laughing waters,” said Wy-an-da. “He must die!”

“He must die!”

The four Indians repeated these three ominous words in a hoarse chorus, and began to circle slowly around the captive, brandishing their tomahawks and knives furiously and screaming the wild scalp-halloo of their tribe.

Several minutes passed thus, Vere standing in the circle of screeching braves calm and unmoved; then all became suddenly silent, standing still and dropping their hands by their sides as if moved by a common impulse.

“Is the pale-face ready to die?” asked Wy-an-da.

“I have said that I do not fear death!” replied the young hunter, calmly. “I am ready!”

The last faint ray of hope was extinguished now. He was bound and helpless—they could do with him as they would; and as calmly as possible he resigned himself to his fate—the horrible fate that seemed inevitable!

“Wy-an-da will tell the pale-face hunter how he must die,” said the chief. “It is not a pleasant death. He will be afraid. His heart will grow small within his bosom and his face will be white as the snow in winter. He will not like to die so. Will he be brave at the last moment?”

“I tell you I am ready to die!” shouted Vere.

He knew that the savage was trying to torture him, and he would not let him see what pain it really gave him—the anticipation of this sudden and terrible departure from the life that had just begun to seem so happy to him.

“Why do you wait?” he added, stolidly. “I tell you I am ready!”

“It is well,” said Wy-an-da. “The white hunter is a brave man. He shall die thus: he will be hung by a lasso, head downward, from the branch of that tree there that reaches out over the laughing waters. Then the Indian that can throw his tomahawk the truest will cut the lasso, and the white man will fall down and the laughing waters will sweep him over the rocks. Then his body will be dashed to pieces on the sharp stones below! Is it pleasant to think of? Will the pale-face be brave?”

This speech was greeted by a chorus of satisfied grunts from the savages.

A shudder ran through Vere’s frame and his spirits sunk as he heard the chief pronounce his fearful doom; but it was only for a moment. Then he appeared calm and apparently unmoved.

A more diabolical torture could not well be conceived.

It was terrible—this standing face to face with death; but the young hunter showed no signs of fear.

Five minutes later he was swinging, head downward, over that black flood hastening on with a wild roar to the precipice below.

The chill autumn wind, wailing in fitful gusts through the 27 forest trees, his body gave an oscillating motion, and it seemed, as he swayed at that dizzy height, as if every vibration would precipitate him into the water below.

After the lasso was securely fastened to the protruding branch, the Indians drew back about twenty paces from their swinging victim and prepared for their trial of skill in hurling the tomahawk.

Each was anxious to have the first throw.

At length it was decided that Wy-an-da should have the precedence.

He took his place with a confident air, like one who is assured of success.

Carefully noting the distance, he drew his tomahawk back, and, taking deliberate aim, gave it a quick jerk; and it went whirling out of his hand.

They watched its flight eagerly.

It missed the lasso by six inches.

The swaying hunter was saved thus far.

He had been watching Wy-an-da as he only could look whose life hung on the issue.

He closed his eyes as he saw the weapon whizzing through the air, and awaited the end.

A tall Indian of massive frame stepped forward.

“O-wan-ton try,” he said.

He measured the space accurately with his keen eye; but his tomahawk flew wide of its mark, burying itself to the eye in the limb to which the lasso was secured.

The victim of the laughing waters was saved again.

Next came Wolf-Nail.

The young hunter watched him with a white face and a heart wild with despair.

He stepped forward slowly, and hurled his tomahawk without much care.

The swinging cord was a difficult target.

Vere felt the lasso jerk, and thought the end had come.

But he was saved again.

The handle of the tomahawk struck the lasso, and the weapon glanced off and fell with a muffled splash into the water.

Bear-Killer was the last to try.

He was yet half-wild with rage; and with the blood still streaming from his disfigured face, he made ready to hurl his tomahawk, hoping to sate his vengeance and send the young hunter to eternity.

Vere was looking at him, and his heart seemed for a moment to stop its pulsations.

This time death seemed certain.

He saw that the red demon did not intend to throw at the cord.

He was taking deliberate aim at his head!

The young hunter saw him draw back his weapon, and closed his eyes.

There was a moment of terrible agony to the man vibrating, as it were, between earth and eternity—and then all became dark!

He seemed to be shooting down—down—and he knew no more.

He had fainted.

Those few terrible moments of suspense—ages they seemed to him—had been more than he could bear. The constantly tightening noose around his ankles was excruciatingly painful, and the position in which he hung caused the blood to flow to his head. None but a man young and strong like Vere could have retained his consciousness so long as he had done.

Bear-Killer was exultant. A moment more, and his fiend-like longing for vengeance would be satisfied.

He noted the distance carefully with his practiced eye, and with a grim smile of triumph on his blood-streaked face, raised his tomahawk and prepared to make the fatal throw.

Suddenly a wild, unearthly cry, like a prolonged wail, rung out on the wind, sounding strangely ghastly above its moanings.

Bear-Killer’s tomahawk slipped from his grasp, and a sickly pallor overspread his face, and those of his companions blanched to an ashen hue.

The four Indians gave utterance to wild cries of fear and consternation.

“The Spirit Warrior! The Spirit Warrior!”

A white steed was flying across a small opening in the forest 29 directly toward them, and mounted upon its bare back, guiding it with neither bridle nor reins, rode a ghastly human skeleton of gigantic proportions.

With cries of terror, the stricken little band of savages turned to fly.

On came the terrible Phantom Rider with the speed of the wind!

As it drew near, it sprung up suddenly, and standing upright on the back of its flying steed, threw something round and black high in the air; then, with another unearthly scream, rode on and disappeared in the forest.

The thing went up with a hissing noise, a broad, brilliant streak of flame marking its course, and then fell with a terrific explosion in the very midst of the Indians.

Then there came a chorus of agonized shrieks, and three of the savages were laid dead on the ground.

Bear-Killer escaped, and fled with a loud, terrified howl into the forest.

The dead Indians were horribly mangled, and Wy-an-da’s head was blown a rod from his body.

Then all was silent save the roaring cataract and soughing wind.

Not a being was in sight, save the unconscious one who swung by a small cord between this life and the one beyond the grave!

Emmett Darke went into the forest in search of game; and he was successful, for in an hour’s time he had shot and dressed a large buck.

He only took the choicest portions of the deer, which he rolled carefully up in the skin, leaving the remainder to the wolves, panthers, and other beasts of prey that infested the forest. He bound the pelt around the meat he had selected by means of deer-skin thongs through a firmly tied loop, in which he thrust his gun-barrel; and throwing his burden across his shoulder, set out for home.

He was very anxious to reach the cabin; for he could not keep his mind from dwelling on his conversation with Vinnie that afternoon, and he did not like to leave her alone longer than was necessary.

The blood-hound, Death, who had rendered his master valuable service in securing the deer, trotted along after him, as if pleased with the idea of returning to the cabin so soon.

The hunter had proceeded but a short distance, however, when he met with an accident that nearly cost him his life.

As the afternoon advanced, the chill November wind blew harder and colder, till its moanings changed to a fierce roar, and it was evident, even to eyes less accustomed to weather signs than Darke’s, that a fearful storm was approaching—one of those cold, gusty rains peculiar to the North-west.

As he was passing a dead oak, whose barkless, decayed trunk and bare, broken branches bore marks of the storms and winds of a hundred years, he was startled by a loud crash overhead.

Looking up, he saw that a fearful gust of wind that just then swept through the wood, blowing the dried leaves and twigs hither and thither and everywhere in wild confusion, had broken off a massive limb, which was falling with lightning velocity directly toward him. Dropping his burden, he 31 sprung aside, but though the movement saved his life, he did not escape the full force of the blow.

The ponderous mass came whirling down, one end of it striking him on the back of the head.

He reeled and staggered two or three steps, and then sunk down insensible among the fallen leaves.

After surveying his fallen master a minute or two, the blood-hound advanced and lay down by his side, as if to keep guard over him. For several minutes he remained in this position, then probably not noting any signs of vitality in the unconscious man, he arose, and, after whining several times in a low key, the sagacious creature took the sleeve of his hunting-shirt between his teeth and pulled it gently. This action was repeated several times; and at last, receiving no reply from his master, the faithful dog set out as fast as his feet would carry him for the cabin.

Had he forsaken his master, or gone after assistance?

How long Darke remained unconscious, he knew not.

When consciousness returned, he found himself in a sort of cavern fitted up as a hunter’s lodge, apparently, for great piles of skins were to be seen in different parts of the place, and a couple of rifles leaned against the rocky wall at one side, while a small keg, that evidently contained powder, stood near by, half concealed by a deer-skin hunting-shirt, which was thrown carelessly over it, with a bullet-pouch and powder-horn secured to the belt.

He noticed also that the cave was divided into apartments, for a curtain made of the skins of various wild animals was suspended from a cord overhead.

A dull, hard pain in his head caused him to think of himself, and he now saw, for the first time, that it was bandaged, and he was reclining on a bed made of the pelts of the bear and the panther at one side of the place.

If any further evidence was required to satisfy the hunter that the place was inhabited, it was forthcoming in the shape of a savory odor of broiling venison that was wafted from the inner apartment.

“Where was he? Who had brought him to this place?”

These and many other questions he asked himself, but after five minutes had been consumed in vain conjecture, he was 32 as far from the solution of the mystery as at the moment when he first awoke to consciousness. He remembered the circumstance of the falling limb in the forest, and after that, all was blank. He did not know when he came, or who had brought him to this place. He was familiar with the country for miles around, he thought, and yet he did not know that there was such a cavern in the vicinity of his cabin.

Of one thing, however, he was assured.

The people who occupied the place must be friendly, else why had they brought him here and cared for him so tenderly?

Soon he heard a voice in the other part of the cave—a coarse, heavy voice, evidently that of a man. It said:

“Give us the whis’, ’Lon. I guess he’s comin’ round all correct. A good pull at this’ll fetch his idees back, I reckon.”

A corner of the curtain was raised, and a man appeared, carrying a small bottle of liquor—so Darke inferred from the words he had just heard.

“Well, stranger, how do you feel?” said he, approaching the hunter. “I reckon you got a right smart of a swat along side yer poll with that ar’ twig out yender. I shouldn’t wonder if it’d ’a’ splintered when it struck terry-firmy if you hadn’t ’a’ happened along jest in the nick o’ time to break its fall. I was a witness of the lamentationable catastofy, and see the stick when it broke off; but I obsarved that ’twas bound to fall, and knowin’ I couldn’t stop its wild career, I let it fall; and then started to go to you, but I had to stop and watch that ar’ pup o’ your’n. He’s a nation cute plant, he is, and I reckoned he was a-goin’ to snake you home; but after awhile he give up and started off for help. Then I went out and picked you up and brought you here and laid you out. Here, take a little pull at the whis’. It’ll kinder regulate yer pulse, set yer heart in stidy operation and ile up yer thinkin’ merchine. Don’t say a word. I ain’t ready for you to talk yet, and, besides, I don’t b’lieve as how you’re a nat’ral talker anyhow. Now I’m a nat’ral-born talker. When I was an infant and didn’t weigh but fourteen pounds, my uncle Peter informed my ma that he thought I’d become a preacher or an auctioneer with the proper advantages—and my uncle Peter was a physionologist and a powerful judge of live-stock!”

Darke took the flask, drank some of its contents, and handed it back to the man, whom he had been regarding attentively from head to foot all the while he had been speaking.

He was very tall—nearer seven feet than six—and his frame was massive in proportion. He was, to judge from his face, which was partially obscured by a thin growth of sandy beard, thirty-five years of age, though one might easily have called him five years older or five years younger. He had pale watery-blue eyes; a capacious mouth, from which projected the points of a few large, scraggy teeth; very high and sharp cheek-bones; enormous ears; long, sunken jaws, with hollow cheeks, and a high, sloping forehead, blowing about which, and streaming down his back, were a few long, thin locks of red hair, escaping from beneath the rim of a battered and dirty old silk hat that had once been white, though evidently a good while since.

This ancient tile was secured to the giant’s great head by means of a light strap of deer-skin, which was lost to view under his chin among his sparse, bristling whiskers.

He was dressed in a fur garment, part coat, part pantaloons, that enveloped his entire person from his chin to his feet, which were enormously large, and incased in a pair of cowhide boots that looked, so extensive were they, and at the same time so old, as if they might have seen service, in the removal of the baggage of the patriarchal Noah and his sons and daughters from the family mansion to the ark, when they were compelled to pull up stakes and emigrate at the time of the universal deluge.

“Where am I? Who are you?”

This Darke asked after the “natural talker” had stopped to take breath.

“Why, stranger, or Mr. Darke, I might say—for I’ve known you by sight this four year—you’re right here, and safe, I reckon. I’ve lived here six years, and I’ve never seen any r’al ginewine ghosts yet. I’m Leander Maybob, formerly of Maybob Center, down in old Massachusetts. If I was real up in etiquette, I s’pose I’d ’a’ introduced myself afore; but I ain’t polite. Now my uncle Peter was a master polite man. I remember once, when he went down to Bosting to sell his wool—wool was ’way down that season, he lost on that wool 34 awful—and got kinder turned ’round like. Well, he kept wanderin’ all over for a right smart of a while, but he couldn’t nohow see his way clear back to the ‘Full Bottle Inn’—he was a-puttin’ up there. My uncle Peter was a master polite man, and didn’t consider it proper to speak to folks as hadn’t been introducted to him, and so he kept right on wanderin’ about without inquirin’ the way till late in the afternoon, when he begun to experience the gnawin’ pangs of an empty stummick; and he made up his mind as ’twould be better to be guilty of a breach of politeness than to starve. But he wasn’t quite certain, and so he took out his etiquette book—he always carried one, my uncle Peter did, Deacon Checkerfield’s, I believe—and looked to see if there was any rules touchin’ this very peculiar case o’ his’n. Well, he set down on a bar’l in a shed, for ’twas a-rainin’ hard by this time, and studied his book till it got so dark he couldn’t see to read any longer, and then he concluded to break etiquette or bu’st. Etiquette was a master fine thing, he argu’d, the very foundation o’ society; but ’twasn’t hardly the thing for an empty stummick. So he got up and went into a big house right across the way. Here he see a feller as looked kinder nat’ral. ‘Pardin,’ sez he, ‘your countenance looks f’miliar.’ He made a master bow as he spoke. ‘Will you be so kind as to tell me the way to go to the Full Bottle Inn?’ ‘’Tain’t no way in p’tickler’, sez the feller. ‘Beg pardon,’ sez my uncle Peter. He was a master polite man. ‘But I want to know how fur ’tis to the Full Bottle Inn.’ ‘’Tain’t no distance at all,’ sez the feller, ‘It’s right here.’ My uncle give in and begged the feller’s pardon—he was a master polite man, my uncle Peter was. He’d been settin’ right in front of the inn for hours studyin’ his etiquette book, cause he didn’t know nobody to ask. He didn’t tell of it for five years afterward.”

At this moment the curtain which divided the cavern was pushed back at one side, and another person advanced toward Darke and his Titanic companion.

He came and stood by Leander Maybob, and the hunter looked from one to the other in astonishment.

He was scarcely four feet in hight, the top of his head barely reaching the giant’s waist.

His apparel resembled that of his more portly companion, with the exception of the covering for the head and feet.

The dwarf’s round little pate was surmounted by a grotesquely broad-brimmed wool hat, and he appeared, as his small keen eyes flashed quick, nervous glances about, not unlike the traditional “toad under a cabbage-leaf,” while his lower extremities were adorned by a pair of nicely-fitting deer-skin moccasins.

“He’s my little brother,” the giant said, by way of introduction. “We’re the Maybob twins. We ain’t much alike you see. He’s a little mite of a feller, and I’m big enough to be his daddy; he’s dumb—can’t speak a word—and I’m a nat’ral talker. Now uncle Peter said as how he thought ’twasn’t hardly fair, makin’ me so big and so complete in every way, and him so little and scarce; but says daddy, says he—and he was a univarsal smart man daddy was—says he it’s all in the family, and they’ll both together make a couple of middlin’ good-sized men—they’ll about average, and it’s all in the family. My little brother’s name’s Alonphilus. But if we’re different in sich respects, we’re alike as fur as the one great principle of our lives goes. Ain’t we, ’Lon?”

There was a scintillant glow in the dwarf’s little black eyes as he nodded assent.

Trembling herself with a fear all the more terrible because of its vagueness and uncertainty, and with her beautiful face pale as death, Vinnie stood and watched the trembling of the heavy cabin door, as the scratching noise was repeated for a third time.

The sound was louder, more imperative than before.

The chief seemed suddenly to arouse from the state of frightened inactivity into which he had fallen, and rising on his feet, walked, or rather staggered, toward the shaking door.

He seemed to have lost all his strength, for he reeled across the floor like a drunken man.

For two or three minutes the sound was not repeated, and Vinnie and the savage stood waiting with bated breath.

They had not long to wait.

Again came that harsh, grating sound, as though some one was digging the point of a knife, or some other hard, sharp instrument into the door.

Almost simultaneously with this noise, came a long, low whine, evidently that of a brute.

Vinnie started.

The look of wild fear left her face, and she advanced toward the door, while the low wail was repeated in a louder key and more prolonged than before.

She gave utterance to a glad exclamation.

“It is Death!”

It was evident in a moment that Ku-nan-gu-no-nah, also, had discovered the cause of the strange sounds.

He seemed to gain new strength.

“It is the dog!” he said harshly, laying hold of the girl’s hand, just as she was about to open the door to admit Death.

Vinnie nodded.

“He is large and strong,” continued the chief, “and his teeth are like the points of knives!”

She knew her power over his untutored, superstitious mind, and she was no longer afraid.

She nodded again and said:

“Yes, he is very strong, and his teeth are like needles. If he sets them into an Indian’s flesh he will die. Shall I let him in to you? His name is Death!”

The savage gripped her hand tighter.

“No,” he said, with evident alarm. “Sun-Hair must not let the dog in.”

Giving her a quick, sudden pull, he drew her across the room and through the other apartment to a rear door.

Her face changed color and she tried to release herself from his hold, but without avail.

Here he unhanded her, and went back and closed the door between the two rooms. Barring it securely he returned, and laying his heavy hand on her shoulder, he bent over till his dark face almost touched hers, and fairly hissed through his set teeth:

“Sun-Hair has a mighty power from the great Manitou. She has escaped Ku-nan-gu-no-nah this time, with her devil-box; but let her beware! If the dog could get at the chief he would kill him, but Ku-nan-gu-no-nah is safe. Before Sun-Hair can open both doors he will be away in the forest. Let the pale-face medicine-woman beware!”

Vinnie did not try to detain him. She could not. All the time he had been speaking, his hard, bony fingers were closed on her shoulder like an iron vise.

He let go his hold suddenly, and an instant later was running across the little open space at the rear of the cabin.

Vinnie saw him disappear among the trees, and then turned and opened the door that led into the other apartment.

In a moment she had undone the fastenings of the other one, and the blood-hound sprung into the cabin.

He stopped before Vinnie, and looking up into her face, gave utterance to a long, low whine.

She patted his head and caressed him, but he would not be satisfied.

Still whining piteously he turned, and with his red eyes fixed on her face walked toward the door.

She did not heed this mute appeal.

He turned again and going up to her, took hold of her dress with his teeth and pulled it quietly.

“Why, Death, old fellow!” she said, caressing the sagacious brute again. “What is the matter? Where is your master?”

When she mentioned her father the dog pulled harder at her dress, almost pulling her along toward the door.

A wild fear seemed suddenly to force its way to her heart. There was only one way in which she could account for the strange demeanor of the dog.

Surely something must have happened to her father!

She was sure of this when she remembered a story that he had told her once, about the blood-hound’s saving her life when she was a child of five or six.

The chill wind was blowing harder than when the hunter set out from the cabin, and the black, angry clouds, hanging low in the sky, threatened momentarily to open and shower down the cold, half-frozen November rain over the earth.

Suddenly, while Vinnie looked out, there came a fierce gust of wind tearing through the great oaks and rattling their heavy leafless branches against the walls of the cabin.

Twigs and leaves were flying in wild confusion through the air, and it was growing darker every moment.

“A wild and fearful storm is approaching,” said the girl, shudderingly; “but I must not hesitate. My father is in danger—may be he is—”

She paused a breath, as if fearful to say the word; and then went on: “Maybe he is dead!”

The dog was tugging at her dress again.

“Yes,” she said, in reply to his dumb, eager look. “Yes, I am going. Come!”

And shutting the door after her, she followed her brute guide out into the storm, which had now begun to fall, and away through the forest till they arrived at the place where the hunter had met with the accident from the falling limb a short time before.

Here the dog stopped, and after sniffing about for a moment, readily found the trail which the giant hunter had made as he carried Darke away to the cavern, where we left him at the close of our last chapter.

Then he turned, and pulling again at Vinnie’s dress, trotted slowly away on the track he had just discovered.

The storm had been steadily increasing, and it had been growing darker all the time, till the forest was indescribably somber and gloomy.

The brave girl did not shrink; but drawing a blanket she had thrown around her on leaving the cabin closer about her slender form, to shield her in a measure from the sleet that dashed against her person, cutting almost like a knife, she pushed on after the blood-hound, increasing her speed to keep up with him.

By and by Death stopped suddenly at the foot of a steep, rocky acclivity.

He seemed, all at once, to have lost the trail.

Vinnie drew her blanket closer about her face and shoulders, and crouching close up against the trunk of a large tree, watched him eagerly.

He ran back and forth several times along the base of the acclivity, searching for the lost trail; then paused at last, with a quick, glad yelp, before a large rock that, almost hidden by the thick overhanging shrubbery along the hillside, seemed to be firmly imbedded in the earth. Then for several minutes he made no sign.

Had he lost the trail again?

He whined, and began to scratch away at the earth about the bottom of the bowlder.

Vinnie, at a loss to account for his strange behavior, drew the blanket up over her head, and creeping closer up under the friendly shelter of the great tree-trunk, looked on in wonder.

It did not occur to her that the flat stone might conceal the entrance to the cavern beyond—for she was indeed at the opening that led into the place where Leander Maybob, the giant hunter, had carried her father but a little while before.

Soon the blood-hound stopped digging, and sat down, with another long, low whine, keeping his red eyes fixed immovably on the dark surface of the rock before him.

“What can it mean?” Vinnie asked herself. “He does not search for the trail any longer. Why does he stop here? What is there about that rock? I wonder if it is immovable. 40 Perhaps it covers the trail some way. I am going to attempt to move it. It looks very ponderous. It must be very heavy.”

She examined the bowlder closely, but could see nothing to indicate that it had ever been stirred from the place where it seemed so firmly imbedded into the earth.

She laid hold of a corner that appeared to project more than any other portion of the rock, and pulled with all her strength.

The stone remained immovable. Of what avail were her weak little hands?

“I can not stir it,” she said. “It is as firmly fixed as masonry. I am not strong enough.”

When the dog saw that she was trying to remove the bowlder, he recommenced scratching at the dirt at its base, giving utterance ever and anon to quick, glad yelps.

She tried once more; but her second efforts were as unavailing as her first.

“It is no use,” she said, half to herself and half to the blood-hound. “I can not stir it. But what does it mean? In what manner does it cover the trail? It does, somehow; or Death would surely pick it up and follow on. What a fearful storm! I never saw one like it before. How the sleet cuts my face and hands!”

And she shrunk back into her old shelter.

The dog kept his place before the bowlder, from which he never removed his eyes till his quick ear caught a strange sound, which even Vinnie heard plainly above the roar of the storm.

Following the direction of the brute’s gaze, the girl saw a sudden and unexpected sight.

Some one was approaching on a white horse.

She cowered down out of sight behind the tree-trunk and watched. The storm half blinded her; but she could see that it was a man, and that something, wrapped in a thick, black cloth, hung limp and helpless across the horse before him. It was like a human being. Was it alive or dead?

The minutes—ten—thirty—sixty, dragged slowly by, and Clancy Vere knew naught of them. All this time he had hung by a cord between this life and the next; but he comprehended it not. He was still insensible.

The wind increased in force until it swayed the great tree from which he was suspended, and swung him backward and forward, pendulum-like, over the turbid, roaring flood below.

Still he knew it not.

By and by a lithe, dark form, with great fiery eyes and ravenous jaws drew its dark length out of the cover of a thicket near by, and creeping stealthily along the ground, ascended the tree, and crouched menacingly on a branch directly above him.

It was a panther.

For ten minutes the terrible brute eyed him with its red, fiery eyes, and then, settling further back on its haunches, prepared to pounce upon him.

Still he knew not his peril!

Closer down on the branch of the tree crouched the panther, its great red eyes seeming fairly to blaze, while its long tail waved to and fro, lashing first one of its sleek, shining sides and then the other.

It was all ready to spring—in an instant it would dart from its perch on the limb and shoot like an arrow down upon its swaying prey; every muscle of its lithe body was contracted. One breath—and then?

There was a dull, cutting sound, as a tense-drawn bow-string was jerked straight, and a long, slender arrow came whizzing out of a copse near at hand, and, pierced to the heart, the panther rolled off of the limb and fell quivering to the ground at the very moment when its victim seemed so secure and its triumph so complete. Its powerful limbs straightened out, and the ravenous brute was dead.

In a moment a form emerged stealthily from the thicket and crept across the opening to the foot of the tree.

It was Bear-Killer!

His ugly face still bled from the effects of the kick he had received from the young hunter a couple of hours before. His purpose in returning so soon to the scene of his late discomfiture and the death of his companions, is easily surmised when the reader remembers that he was as vindictive and vengeful as a fiend.

He gave the panther a kick with the toe of his moccasin, and saw at once that it was quite dead.

“The panther would cheat the red-man out of his revenge,” he said, savagely. “It must not be so. Nothing can save him now. He must die! The revenge of Bear-Killer is near at hand. The white hunter’s time has come.”

As the Indian ceased speaking, he drew his tomahawk, and stepped back a few paces where his aim at the head of the swinging and senseless young hunter would be true and certain.

He noted the distance accurately with his practiced eye, and poised his weapon.

“How quick he will die!” he muttered. “How easy Bear-Killer will slay him!”

“Bear-Killer will not slay him!” said a deep voice, close at his side; and a heavy hand was laid on his arm, so suddenly and with such force that the tomahawk fell from his grasp and half buried itself among the leaves at his feet.

Bear-Killer turned with a sharp grunt of rage and surprise. His mutilated face expressed nothing, but his small, baleful eyes scintillated like those of a cowed and baffled wolf.

The hand on his arm tightened its hold, and the deep, stern voice repeated authoritatively:

“Bear-Killer will not slay him!”

The speaker was an Indian, tall and massive in build, and manifestly the superior of Bear-Killer in strength.

His dress and equipments indicated him to be a chief. Bear Killer seemed to recognize his superiority, either of rank or strength, or both.

It was Ku-nan-gu-no-nah, who had but just now made his escape from the cabin of Emmett Darke, and the terrible 43 power which he believed Vinnie possessed; and he was making his way back through the forest toward the Indian village, when he discovered Bear-Killer in the act of consummating his dreadful vengeance on the unconscious white man.

Ku-nan-gu-no-nah recognized this white man at a glance.

He knew it was Clancy Vere.

And he had particular reasons for not wishing Bear-Killer to become his slayer.

Perhaps his chief reason was that he wanted to put the young hunter to death himself.

He was aware that Clancy Vere was his successful rival in the affections of Vinnie Darke, or Sun-Hair, as he was wont to call her.

Jealous and vindictive as he was, this was sufficient to make him hunt his pale-faced rival to the ends of the earth, if he could not compass his death without.

Many times when he had seen Clancy go to the hunter’s cabin, had he vowed in his fierce, jealous rage to kill him, but something had heretofore always intervened to baffle him; but now he was exultant. The time for which he had so long waited had come. The young hunter was bound and insensible in his power. He asked nothing more. His triumph seemed almost complete. His discomfitures and rebuffs at Vinnie’s hands that afternoon had more than ever determined him to wreak vengeance on her lover, since he stood in too wholesome awe of the lovely magician to think for a moment of again attempting to obtain forcible possession of her person—at least not at present.

With a sudden movement, Bear-Killer wrenched himself free from the chief’s grasp, and faced him half angrily, at the same time picking up the tomahawk out of the leaves at his feet.

“Why does the chief interfere?” he asked.

“Because,” said Ku-nan-gu-no-nah, “he would slay the pale-face hunter himself. He has cause for revenge!”

“And has not Bear-Killer cause for revenge?” the Indian almost yelled. “Look at his face! Yonder white man did this. The pain is like a thousand tortures. What says the chief? Has he greater cause for revenge than Bear-Killer?”

“The chief has greater cause for revenge than Bear-Killer,” said Ku-nan-gu-no-nah.

“He has not!” said the Indian, decisively. “Bear-Killer will not be cheated out his vengeance! He saved the pale-face from the panther that he might kill him himself!”

“And the chief has saved him from the vengeance of Bear-Killer that he might have his revenge!” said Ku-nan-gu-no-nah, with a grim, devilish smile. “Let the warrior wait, and he shall see the vengeance of a chief.”

He advanced toward the tree; and, as he neared it, his gaze fell on the dead and horribly mangled bodies of the savages who had fallen before the terrible charge of the Phantom Rider.

The undergrowth had concealed them from his view until now.

He started back with a loud cry of surprise and wonder.

“Did he do it?” he asked, pointing toward the swaying white man.

“No,” said Bear-Killer, in a voice that was half a gasp. “No; it was—”

“Who then?” interrogated the chief, in an awed whisper.

“The Spirit Warrior.”

“The Spirit Warrior!”

The chief reiterated the words in a dazed sort of way, like one under some subtle spell, while for an instant a shudder seemed to convulse his massive frame, causing it to shake like an aspen.

“Yes,” said Bear-Killer, “it was the Spirit Warrior—the spirit of the outcast chief, Meno. When will Meno’s vengeance be complete?“

“When Ku-nan-gu-no-nah and all his braves are no more! When the sons of the red-men who tortured their own chief to death are all numbered with the dead! Then, and not before, will the vengeance of the outcast and murdered sachem, Meno, be complete. Every day brings it nearer the end!”

The two Indians started as though a keen-edged knife had pierced their vitals. Then they stood transfixed with fear, 45 staring into each other’s eyes as if to inquire the source of the answer that had come to Bear-Killer’s question almost before it had left his lips.

The tones of the voice that had spoken the words were hollow, and the weird and terrible menace seemed to be borne to them on the winds from afar off, in a wild, ghastly chant that thrilled every fiber of their superstitious beings with a vague horror that they could not shake off.

The dismal wailing of the wind through the forest trees, the sullen roar of the storm which had set in a little while before, and the monotonous dashing of the cataract below, all combined to inspire them with a sort of awed dread, that the spirit voice, crying out to them above the crash of the wind and storm, augmented into a wild, ungovernable fear.

For several moments, the two Indians stood silent and motionless, neither daring to speak or stir.

For a few seconds the wind was hushed and the dashing storm seemed to have spent its fury.

Then in an instant it seemed as if the storm demon had sent forth all his forces of wind and sleet. Trees were blown over, limbs were flying hither and thither, and the wind increased to a perfect tornado, wailing and shrieking like a regiment of fiends. The Indians saw that the white man was swinging to and fro at a fearful rate. It seemed as though the lasso must break at every oscillation. He vibrated backward through a space of fully twenty feet. They could not keep their footing, and were obliged to throw themselves prostrate on the ground.

High above the fearful roar, and crashing of uprooted trees and fallen limbs, loud and clear above the shrieking of the wind, was borne to them again the voice of Meno, the Spirit Warrior:

“Let Ku-nan-gu-no-nah beware! Meno’s vengeance will overtake him. He will die a more horrible death than even his devilish mind can comprehend! Let him beware!”

The two Indians remained motionless upon the earth, trembling at every joint. Although giant trees were being uprooted on every hand and massive limbs were falling all around them, they were unharmed.

Clancy Vere’s peril was imminent.

The tree, from a branch of which he was suspended, groaned and cracked under the force of the storm, threatening momentarily to break loose from its place in the bank and go crashing over the precipice.

Even if the stout roots remained firm in their hold on the earth, the cord by which he hung was liable to be jerked asunder at any oscillation of his body; and he would shoot headlong down into the seething flood underneath and be swept to destruction over the waterfall below.

A quarter of an hour passed, during which the two savages did not arise from their recumbent position and the spirit voice did not again speak.

The tree remained firm and the lasso seemed to deride all attempts on the part of the tempest to break it. It would crack, but it would not part.

Thus far, Clancy Vere had been saved; but he was still unconscious, and had not realized the terrible danger that had menaced him.

Soon the storm began to abate somewhat.

Ku-nan-gu-no-nah and Bear-Killer got upon their feet by-and-by, when the fury of the storm was in a measure spent.

Their sharp sense of bearing had been keenly alert to catch any further words from the Spirit Warrior. But they did not hear the terrible, menacing voice again.

“It has gone,” said the chief.

“Yes,” assented Bear-Killer, in a tone of relief. “We shall hear it no more to-day. It went away on the storm.”

“The vengeance of Meno is terrible!” said the chief, with a shudder. “But we are safe now. Now for my revenge!”

“Stop,” said Bear-Killer. “We will draw lots. I, too have come here for vengeance on the white hunter.”

The chief grunted a guttural and very unwilling compliance to this proposition.

“We must hurry,” he said, “or he will be dead. He is almost dead now.”

Bear-Killer made a very small mark on the trunk of the tree.

“The one that throws his tomahawk the nearest to the mark wins,” said he.

They took their places almost on the verge of the high bluff on which they were standing.

Ku-nan-gu-no-nah threw first.

His tomahawk buried itself in the tree-trunk, within half an inch of the mark.

There was a baleful glow in Bear-Killer’s wolfish eyes as he poised his weapon, a treacherous glitter that the chief did not fail to notice. Just as the handle of the tomahawk was slipping out of his grasp, the chief dealt him a powerful blow on the side of the head. He staggered a moment and his body swayed to and fro as he tried to regain his balance on the very edge of the bank. The next instant his wild death-yell came up from below!

Darke noted the angry flash in the dwarf’s little black eyes, as he nodded an eager assent to his brother’s strange question, and wondered not a little what the “one great purpose” of this queerly assorted pair’s lives was; but he forbore to question the giant, not doubting that, if it was not some secret that they did not wish to disclose, he would explain himself in good time. And this belief was not far from correct, as the giant hunter’s next words attested. He sat down on a stool near at hand; and as Alonphilus came and stood at his side, he said:

“Yes; wer’e livin’ for some purpose. We have given our lives up to revenge! Wer’e a-gittin’ revenge every day, hain’t we, ’Lon?”

The dwarf’s round little pate was bent forward again until Darke just caught the glitter of the dusky eye under the broad rim of his slouch hat; and this he interpreted to be a token of assent to the giant’s question. As his face was raised to view again, he thought he saw the dwarf’s mute lips move, as if in an attempt to speak, and he imagined that volumes of vindictive, vengeful words were struggling for utterance. But the dumb tongue was incapable of expressing even a tithe of the dark passion that was written on every lineament of the pigmy’s face.

“And we’ve anuff to be revenged for, God knows!” Leander Maybob went on. “We can’t never wipe out of our memories our old father and mother that the red devils murdered in cool blood; we can’t never forgit the awful sight our eyes rested onto, when we came home from a hunt one morning; we can’t never wipe this out of our minds. But, the just God helpin’ us, we’ll wipe every one of their murderers off o’ the earth before we die! The devil that led them shall die a more horrible death than even his own hellish mind has planned for his poor helpless victims! We’ve done 49 a deal t’ward fulfillin’ our vow in the past six years; eh, ’Lon? We’ve made many a savage bite the dust in that time!”

The dwarf’s hand darted into the bosom of his hairy vestment; it came out again in an instant, and he held up to Darke’s view a deer-skin string about four feet in length, which was knotted almost from one end to the other.

He touched each knot in succession with the forefinger of his right hand, accompanying every motion with a nod of the head.

“There’s just a hundred an’ forty-eight knots,” said the big hunter; “and every one on ’em is a red-skin’s eppytoph!”

That slender strip of deer-skin, simple and harmless as it appeared, told a ghastly story of conflict and of death and of half-sated vengeance!

“We’ll git our hands on him yet,” the big hunter went on. “We’ve had chances to kill him of’en enough; but jest a common death ain’t enough fer him. He desarves more; an’ I want to give him his jest desarts. He must die an awful death! Our vengeance’ll overhaul him yet, ’Lon. Then you may tie a double knot! We’ll give him two varses to his eppytoph; eh, ’Lon?”

The dwarf nodded, touched the hilt of his hunting-knife significantly, and made motions as if to tie a knot in the string which he still held in his hand.

“Of whom do you speak?” queried Darke, as he supported himself on his elbow.

“The red fiend that led the attack on our cabin! The devil that shot my mother and carried my old father’s white scalp away in his belt! Hain’t we got reason plenty fer vengeance? Do ye wonder that we hunt, and kill Indians as you would kill serpints? Do ye think it’s strange that we don’t want to let that red imp die a common way?”

The big hunter had arisen while he spoke, drawing his Titanic form up to its full hight. The expression on his face was terrible to look upon. As he finished, he brought his ponderous clenched fist down, striking it in the horny palm of his other hand.

Drake half shuddered.

“No—no!” he cried. “No death—no torture on earth is 50 horrible enough to be meet punishment for the atrocities of such a fiend incarnate! Is he an Indian chief?”

The giant nodded. His ungovernable rage seemed to have entirely spent itself, and he did not speak; but stood with folded arms and downcast eyes, his massive frame as motionless as though carved out of the solid rock around them.

Alonphilus seemed to partake keenly of this feeling of undying, inveterate hatred of the Indians. His face wore a hard, implacable look, and he kept drawing the record of their vengeance slowly through his fingers from one hand to the other, as if he longed to tie the short end of it that was yet unmarked by the little death register into one great hard knot, that could never be entangled, in commemoration of the passage from this life to the next of the murderer of his parents and the triumphant consummation of their terrible work of vengeance.

The spell that was on the big hunter was only momentary, and it was but a minute or two before he was himself again; and he signified his willingness to resume the conversation by saying, as he reseated himself on the stool at the side of the couch of skins on which Darke reclined:

“Well, I heerd Elder Fugwoller say onc’t—and he was college l’arnt—‘It’s a long tow-path, or cow-path, or suthin’, as hasn’t got no turns into ’em;’ and I believe it’s true as gospil.”

The dwarf turned and walked across the cavern, and, pushing aside the dividing curtain, disappeared within the inner apartment, replacing the death record in his bosom as he did so.

“The day of retribution is sure to come at last. It is not often that the guilty escape punishment,” said Darke. “It is sure to overtake them sooner or later. God’s justice is certain!”

“I’m a-thinkin’,” returned Leander Maybob, “as how Ku-nan-gu-no-nah’s tow path or cow-path’ll take a mighty unexpected turn some day!”

“Ku-nan-gu-no-nah!”

The big hunter seemed surprised at Darke’s sudden exclamation.

“Yes,” he said, “that’s the devil’s name. Do you know him? Have you got an account ag’in’ him?”

“Yes,” cried Darke, sitting bolt upright on the couch, while a hard, stern look settled on his face. “Yes; I believe I have. And I am going to present it for settlement the very first time I see him!”

“What do you mean?” the other asked, evincing no small degree of interest in the words and actions of Darke. “Has he ever—”