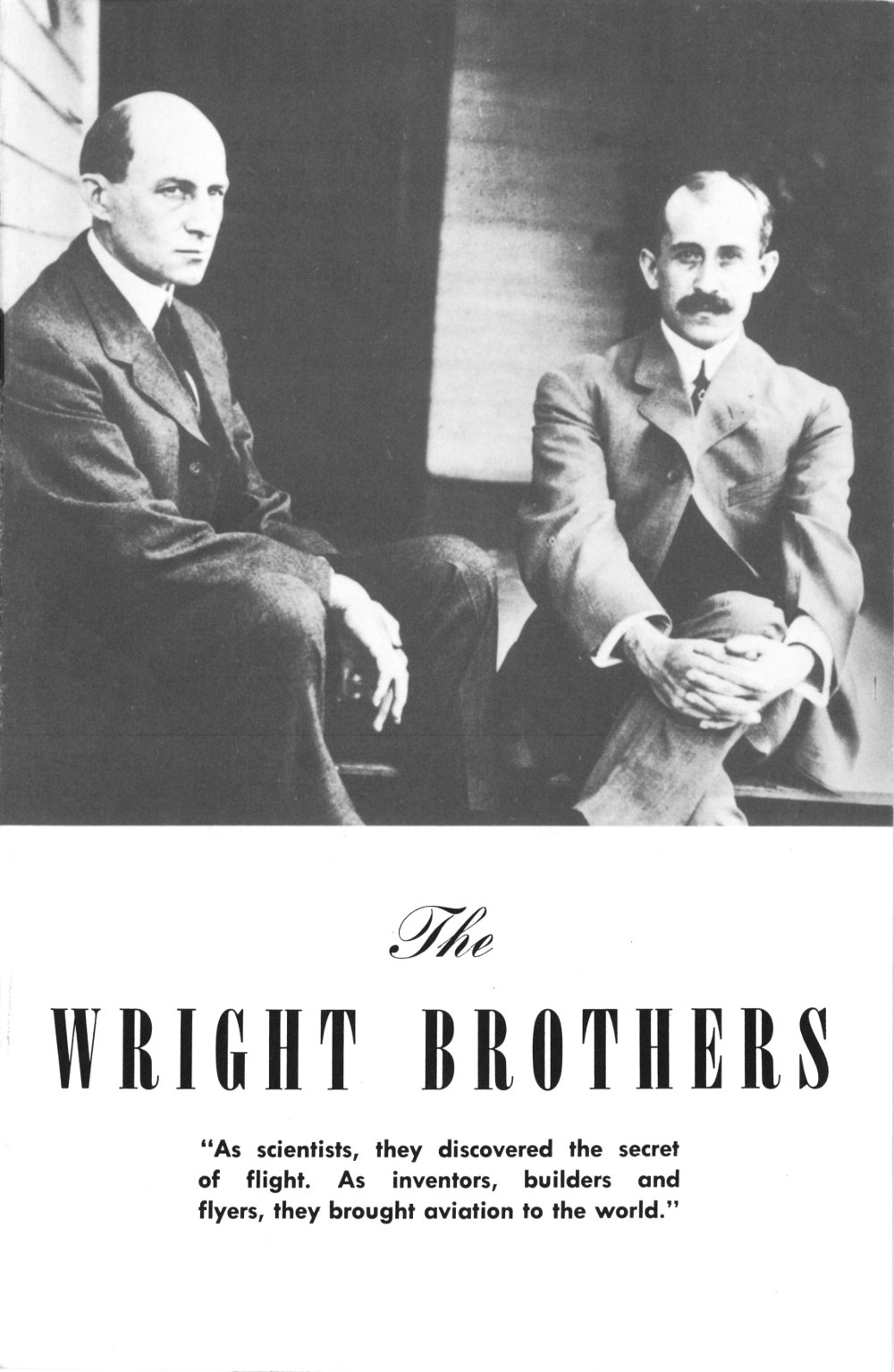

Title: The Wright Brothers

Author: Anonymous

Release date: September 1, 2021 [eBook #66194]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

“As scientists, they discovered the secret of flight. As inventors, builders and flyers, they brought aviation to the world.”

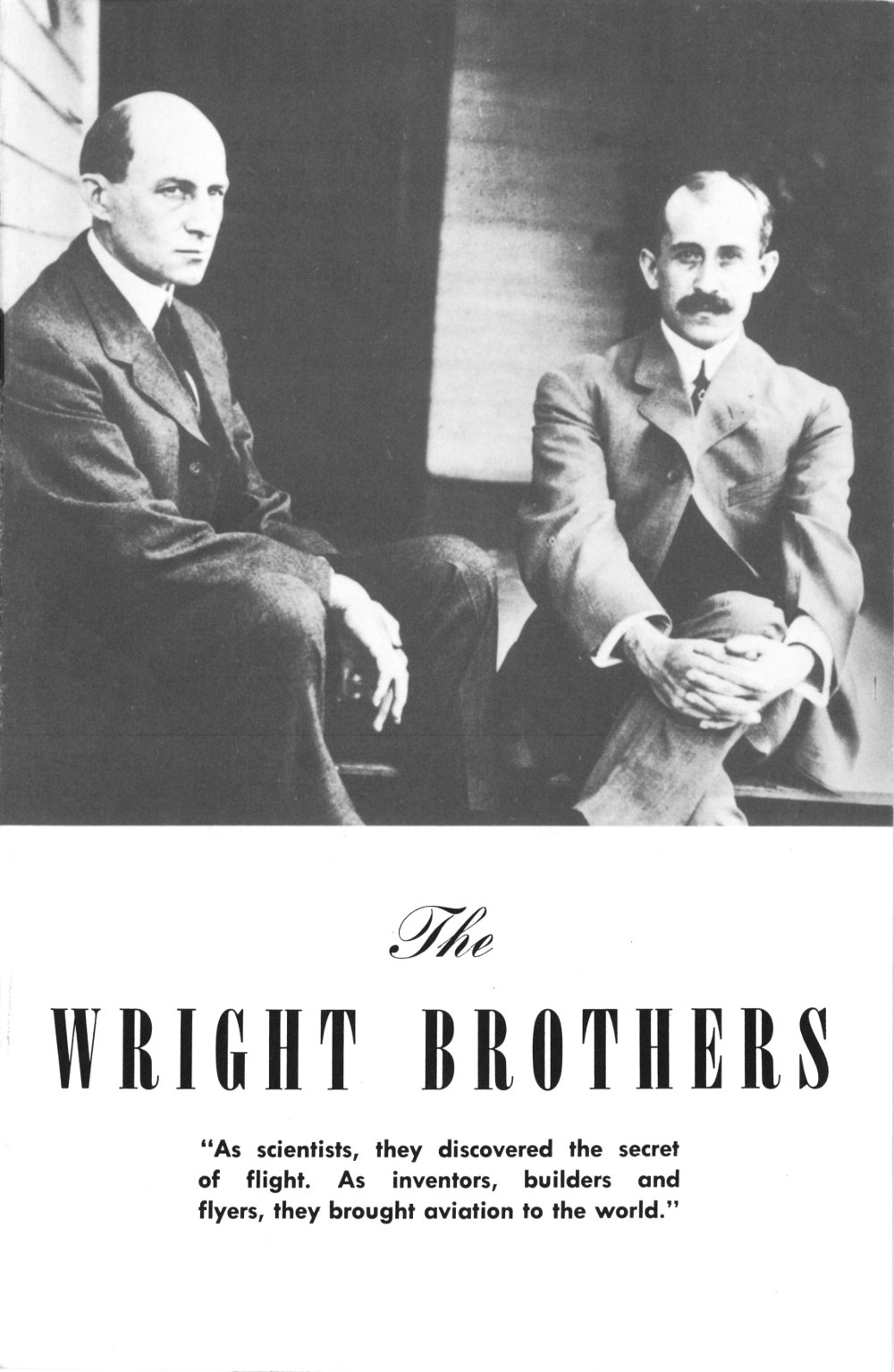

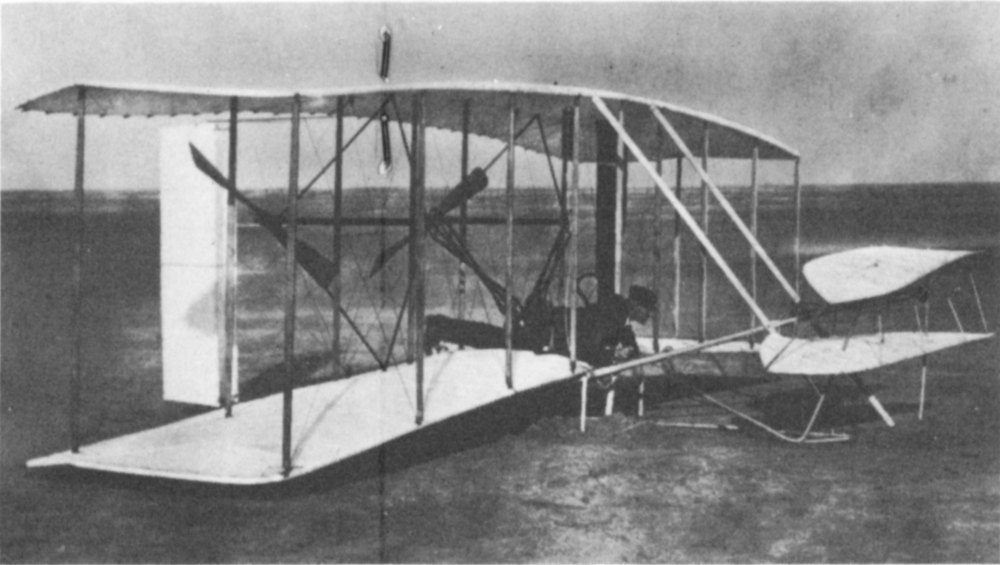

On December 17, 1903, at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, the first power-driven heavier-than-air machine ever to achieve sustained flight rose from its starting track and in 12 seconds soared through the air for a distance of 120 feet. Short as this flight was, it nevertheless marked the beginning of man’s conquest of the air. Orville Wright was at the controls; Wilbur Wright balanced the machine at the take-off. This picture records for posterity an epochal event witnessed by just seven men, the Wright brothers themselves and five others who, more than they knew, stood that day on the threshold of history.

The first flight at Kitty Hawk, N. C., December 17, 1903.

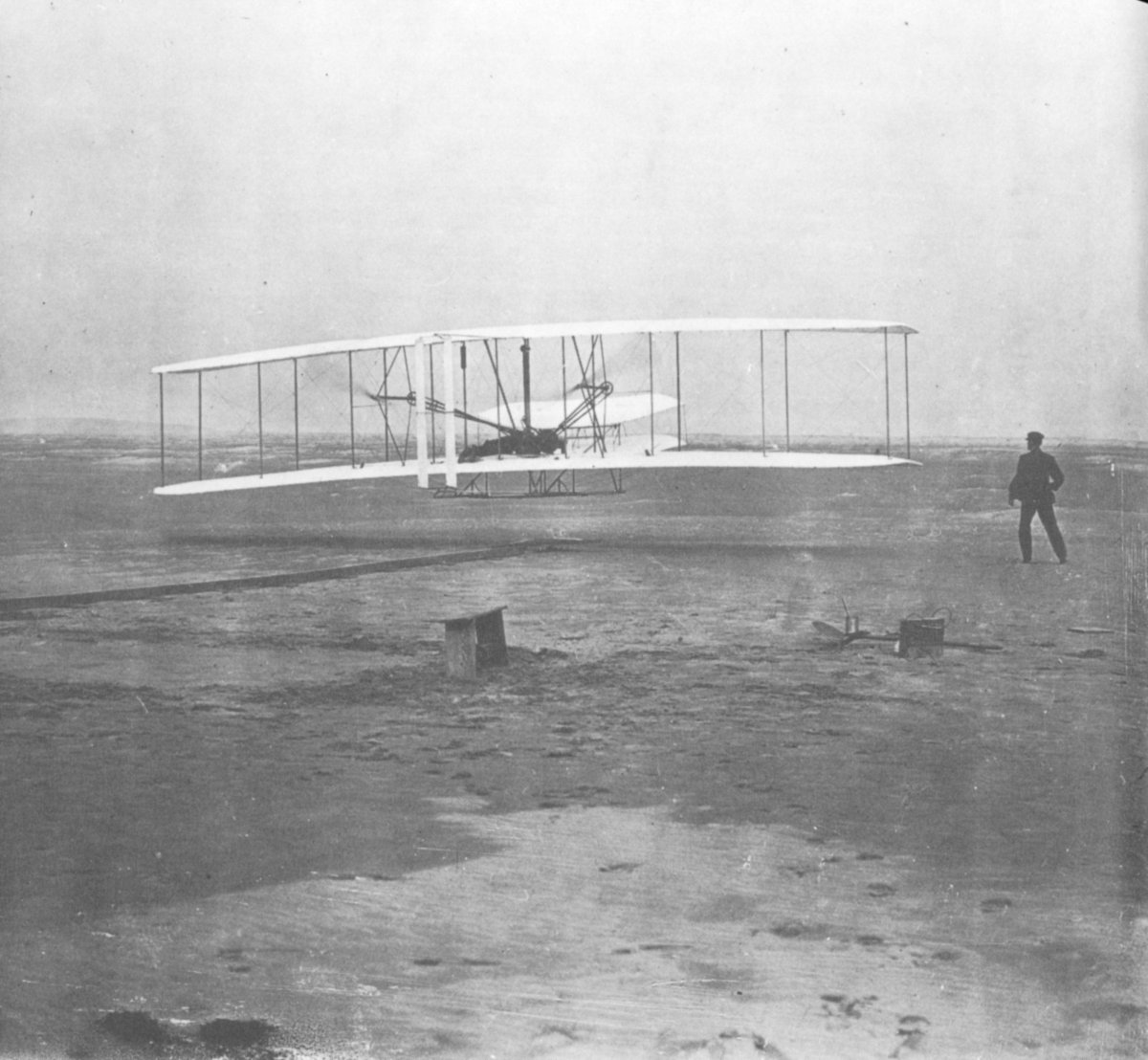

The Age of Flight, with its miracle of service, began in an obscure little bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio. Here two devoted brothers, working amid tires, wheels and air pumps, dreamed that man could fly in a heavier-than-air machine. The names of these two brothers who wrote themselves indelibly into history, were Wilbur and Orville Wright.

The story of the Wright brothers is an inspiring narrative of success. Wilbur and Orville combined to a rare degree the searching intelligence of the scientist, the ability to visualize of the inventor, and the practical craftsmanship of the builder. In addition they had great personal courage.

The Wright brothers were by no means the first who sought the secret of flight. Particularly in Europe, able men had delved deep and risked much in the effort to fly like a bird. Certain theories of aerodynamics had been developed and were generally accepted as accurate. One of the major setbacks to the hopes of the Wrights was the discovery, through their own experiments, that these previously accepted theories were incorrect.

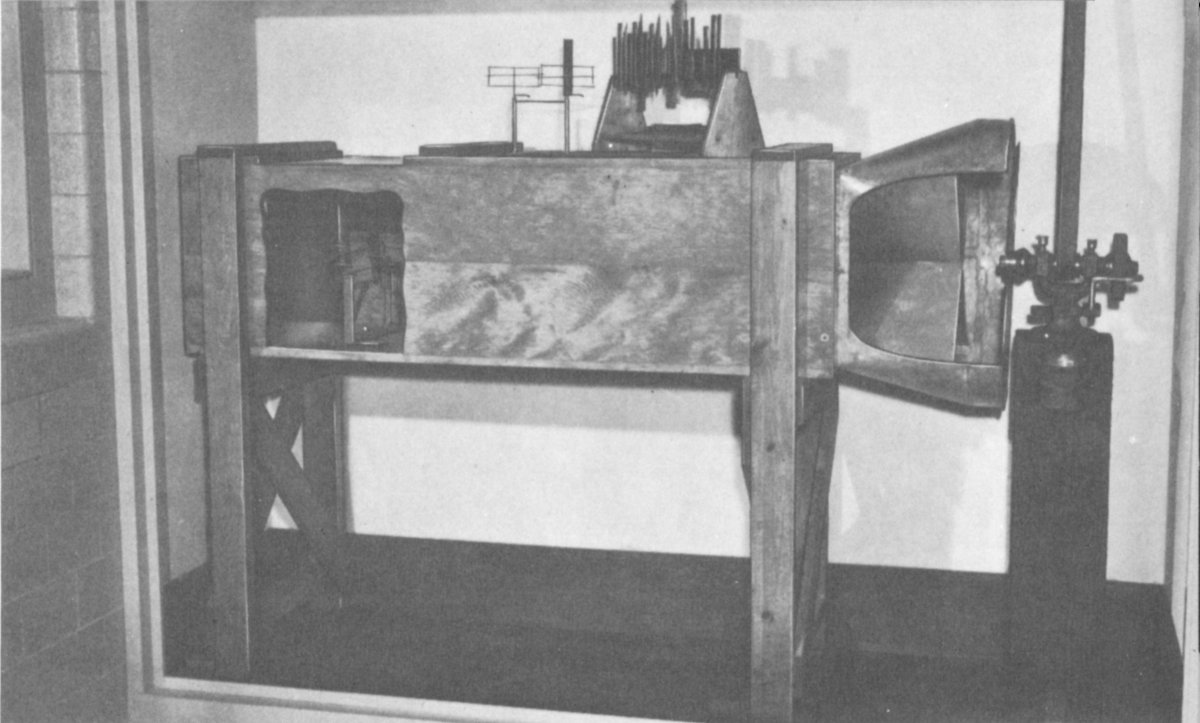

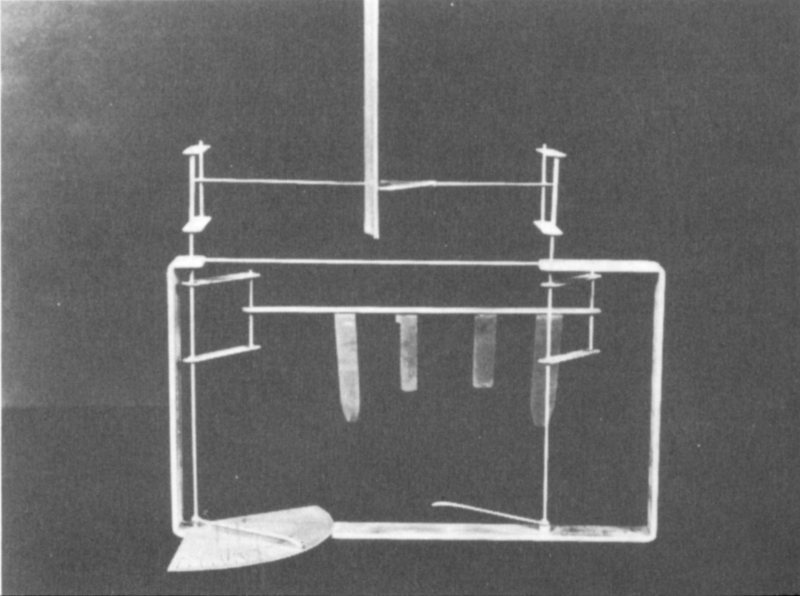

This meant that they had to start from the beginning and develop their own tables of air pressures. Two developments of the Wrights made it possible to build an aeroplane that would fly. One was a crude wind tunnel and the other was an ingenious set of balances made out of old hack saw blades and bicycle spokes. With these comparatively crude instruments, they compiled data which made flight possible.

In the months and years following their first flights, the Wrights were acclaimed by nations and by men. They knew success in the fullest measure. But probably no subsequent achievement quite equaled the thrill which must have been theirs when they were able to send to their father and sister that now famous message:

“Success four flights Thursday morning all against twenty-one-mile wind started from level with engine power alone average speed through air thirty-one miles longest 59 seconds inform press home Christmas.”

The shop of the Wright Cycle Company on West Third Street in Dayton ... birthplace of the aeroplane.

The Wright brothers sprang from pioneers who settled Dayton when the Ohio country was young. Their father, the Reverend Milton Wright, became a bishop of the United Brethren Church. His vocation necessitated frequent changes of residence. Thus it came about that Wilbur was born April 16, 1867, on a farm eight miles from Newcastle, Indiana, while Orville was born in a house at 7 Hawthorn Street in Dayton. This house was the Wright home for more than forty years.

From earliest childhood, the boys were mechanically minded. They had both the inclination and the aptitude for creative work. The pioneering urge and the gift of original thinking were theirs.

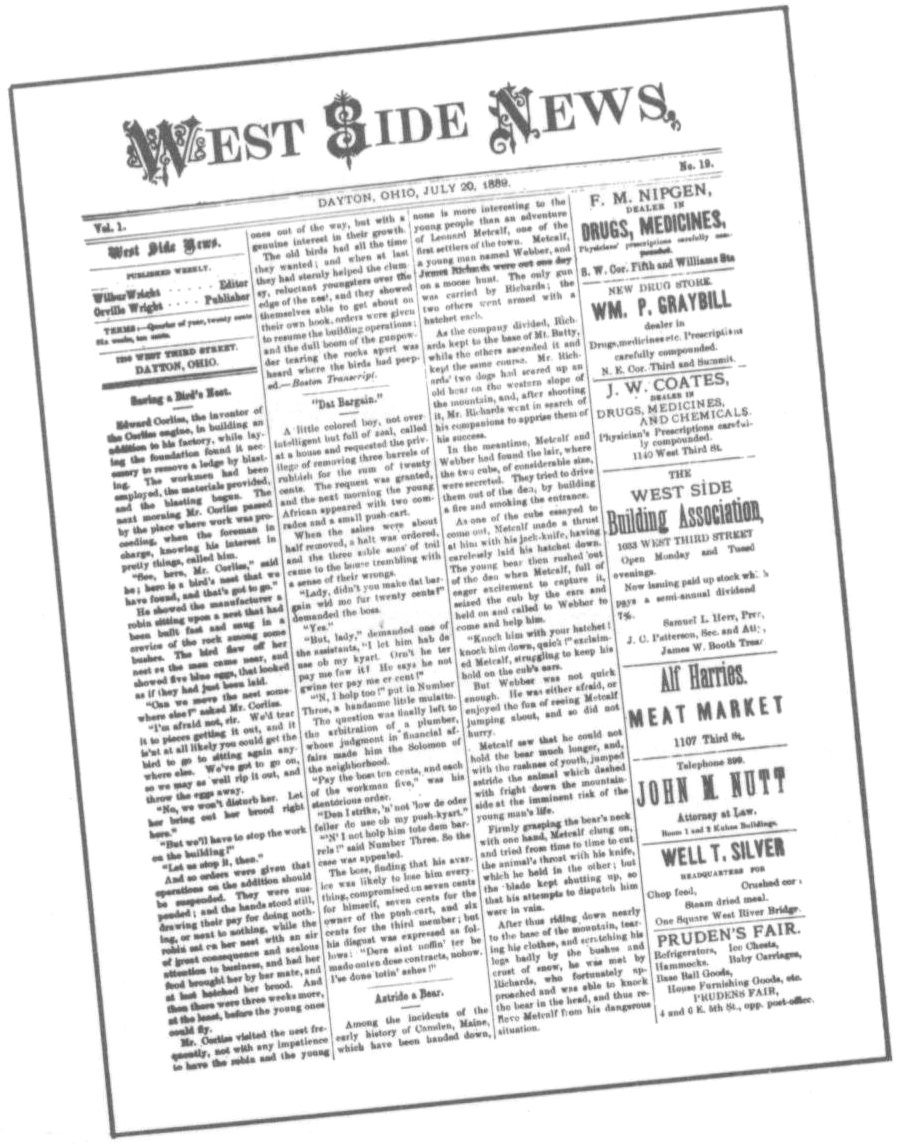

An issue of the “West Side News,” an early Wright venture.

One day the Bishop came home from a short trip, bringing the children a present. He held something in his hands and then tossed it toward them. It was a toy helicopter. Instead of flopping to the floor, it ascended to the ceiling where it 3 fluttered before it fell. That helicopter set up a milepost in the lives of the Wright boys. The idea of their future conquest of the air, in all likelihood, was born then and there.

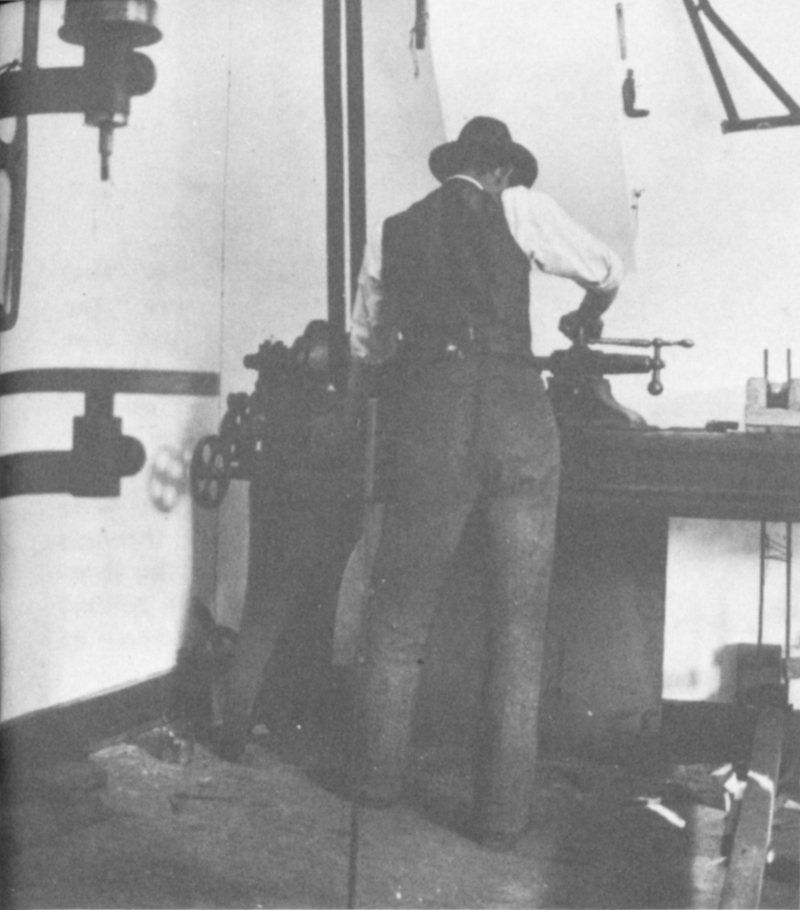

Wilbur Wright in the bicycle shop, 1897.

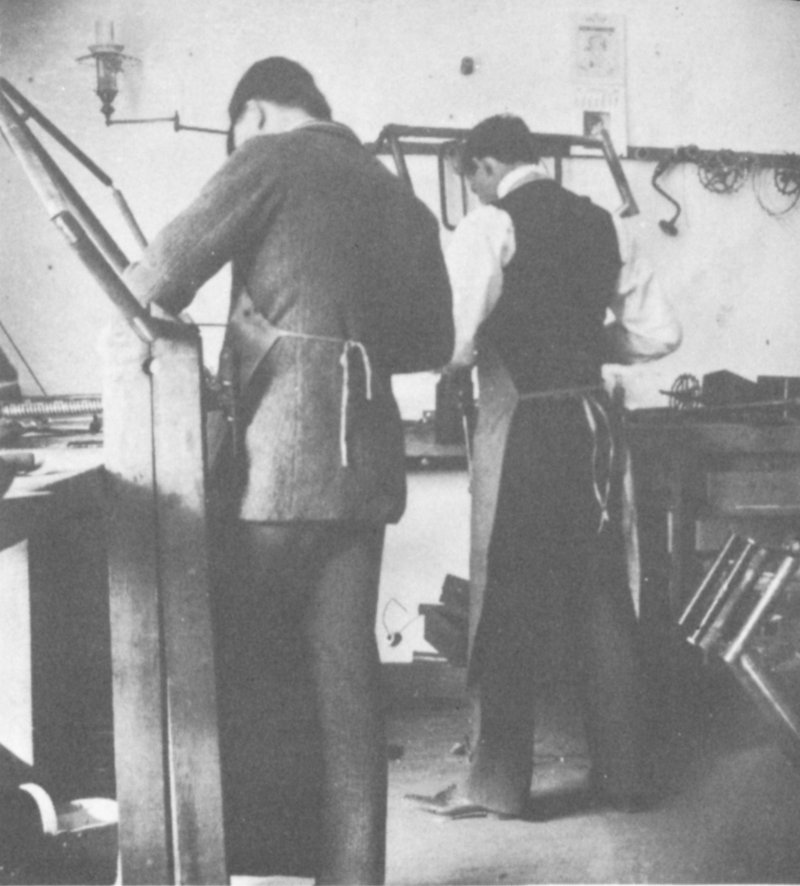

Orville Wright, in white shirt, at work in shop.

At an early age they began to fly kites. They became interested successively in wood cuts, printing and photography. The urge for invention was strong in them. Wilbur got a job folding the entire issue of an eight-page church paper. When he found the handwork tiring and tedious, he designed and built a machine that did the folding.

The house on Hawthorn Street, home of the Wrights for 40 years and now re-erected in Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan.

Orville was no less enterprising. When he was 15, he entered into a partnership with Ed Sines, a neighbor boy, and launched the printing firm of Sines and Wright. The plant was located in a corner of the 4 Sines kitchen. One of their first ventures was to print a little paper called “The Midget.”

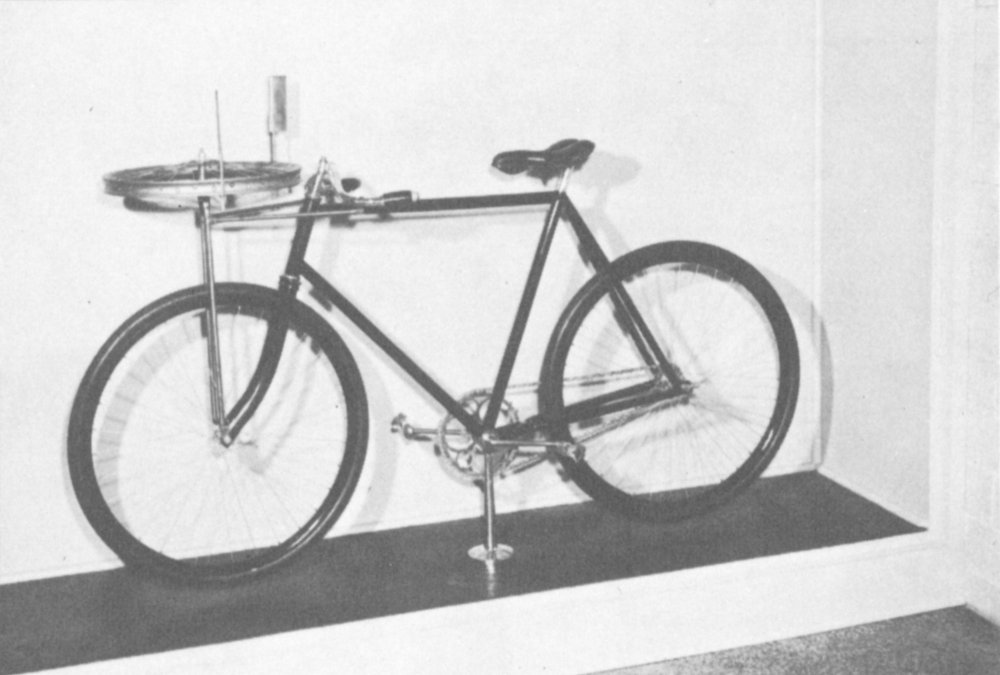

One of the Wrights’ first efforts to measure the effect of air pressure was this horizontal bicycle wheel mounted on one of their own bicycles and equipped with two metal vanes. This bicycle was placed in the Park through the co-operation of the family of the late Frank Miller, former Superintendent of Dayton Schools.

Later Orville started a weekly newspaper called the “West Side News.” Wilbur joined him as an editorial writer. These publications and others which followed were printed on a press which the Wright boys designed and built.

In 1892 came the enterprise that was to provide the setting for, and the approach to, the supreme adventure with which the names of the Wright brothers are associated. The boys became absorbed in bicycles. Orville became interested in track racing and participated in several events. In their enthusiasm the boys decided to go into the bicycle business. After embarking on bicycle selling they discovered they must have a repair shop. Punctures provided the bulk of their business, with free air as a side issue. The first shop of what became the Wright Cycle Company was at 1005 West Third Street.

Business increased to such an extent that the Wrights moved to South Williams Street. Here they began to manufacture bicycles. Their first model was called the Van Cleve, named after one of their pioneer Dayton ancestors. Continued expansion of the business necessitated a move to 1127 West Third Street. This was the shop linked with the birth and development of aviation. It was here that Wilbur and Orville not only dreamed of flying but practically built the first plane.

A hint of what the future had in store came one day when the brothers were discussing what was then the new-fangled horseless carriage. Since it was an original idea, it appealed to them. Orville suggested that they might engage in the automobile business. “No,” replied Wilbur, “you’d be tackling the impossible. Why, it would be easier to build a flying machine.”

A replica of the Wrights’ original wind tunnel which secured its pressure from a fan mounted on the shaft of an old grinding wheel.

The first active interest in flying that the Wrights displayed developed in 1895 when they read about the glider experiments being carried out by Otto Lilienthal in Germany. They now began to read everything they could lay hands on that bore on the attempts of man to fly, going back to the days of the great Leonardo da Vinci. They wrote to the Smithsonian Institution for a list of books on the subject. The germ of flying now entered their systems, never to be eradicated.

The Wrights went thoroughly into the problem of gliders. After Lilienthal had been killed while gliding, the brothers discovered that neither he nor any other man who glided had an adequate method of insuring lateral balance. In seeking the solution to this problem, Orville worked out a theory for the operation to vary the inclination of sections of the wings, thereby obtaining force for restoring balance. Thus he hit upon a fundamental principle which became a claim in the original Wright patent.

One of the most valued possessions of the Wrights, a balance made of hacksaw blades. With this balance they evolved their own tables of air pressure which eventually enabled them to fly. The original balance is in Franklin Institute, Philadelphia; this replica is in Wright Hall, Carillon Park.

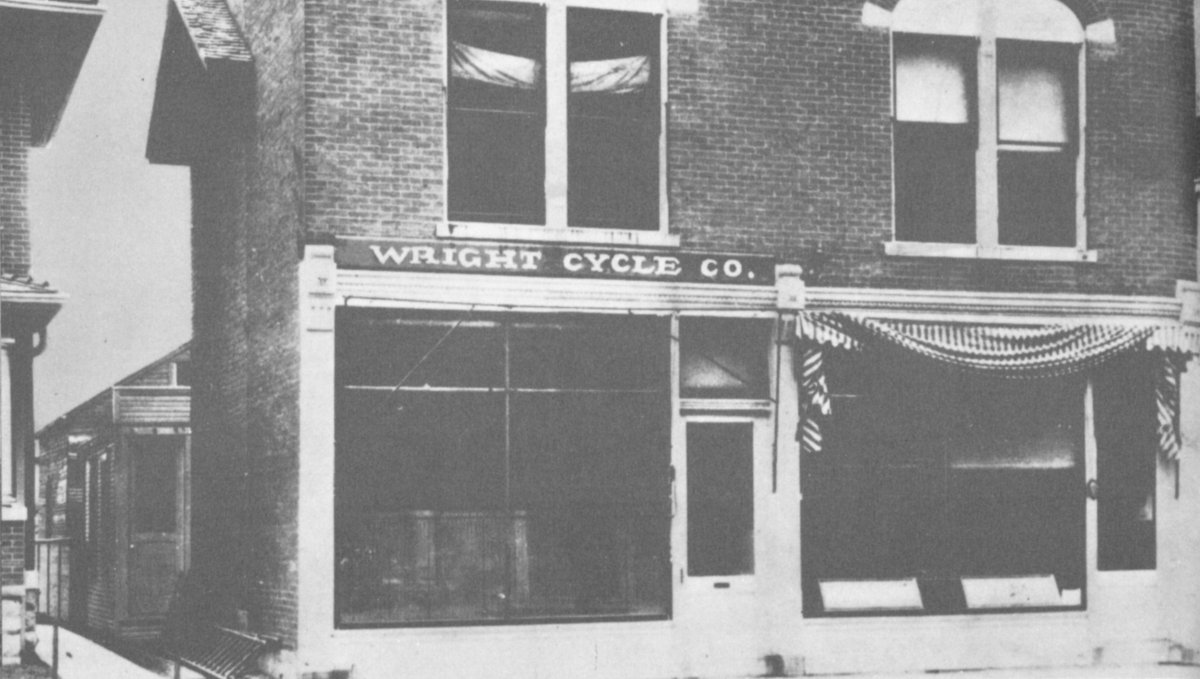

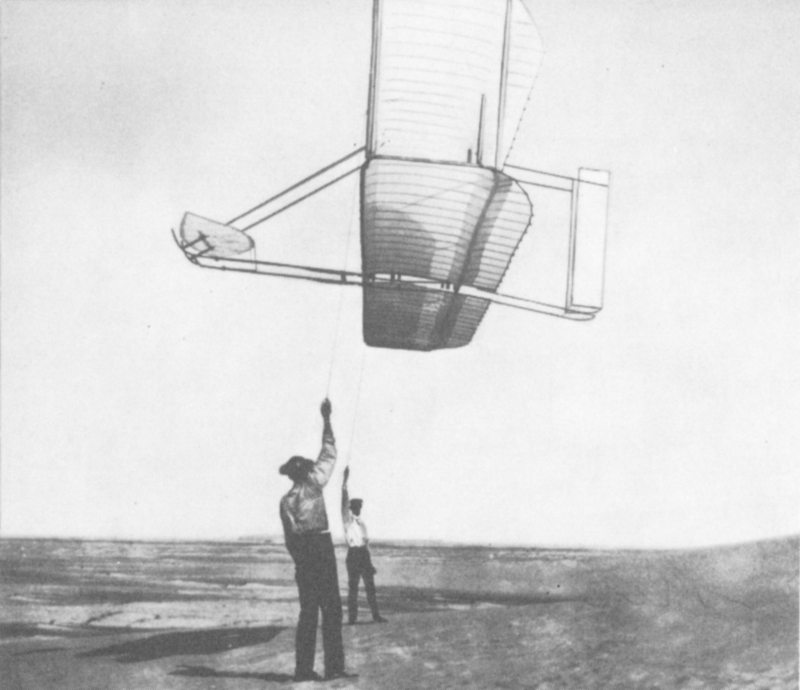

Many glider flights at Kitty Hawk preceded the first attempt to fly in a power-driven plane. Here the Wrights are flying a glider as a kite, controlling it from the ground. Later flights were made in man-carrying gliders.

The brothers now began to study wing structure, but hit upon many difficulties. A simple incident set them on the right track. In selling a customer an inner tube for a tire, Wilbur had taken the tube from the pasteboard box and was idly twisting the box back and forth as he talked to the customer. In doing so he noticed that although the vertical sides remained rigid at the ends, the top and bottom sides could be twisted so that they made different angles at the opposite ends. He immediately wondered why the wings of a gliding machine could not be warped from one end to the other in this same way. In this way the wings could be put at a greater angle at one side than the other and there would be no structural weakness. Wilbur explained the plan to Orville and it seemed so satisfactory that they adopted it for their gliders.

The Wrights were now glider-conscious. They built a bi-plane kite with a new system of controls. In 1900 the brothers constructed a man-carrying glider. In order to get practice in operation, they decided to fly it first as a kite. For kite flying they required flat, open country; and for gliding, sand hills free from trees or shrubs were necessary. Favorable winds were also needed.

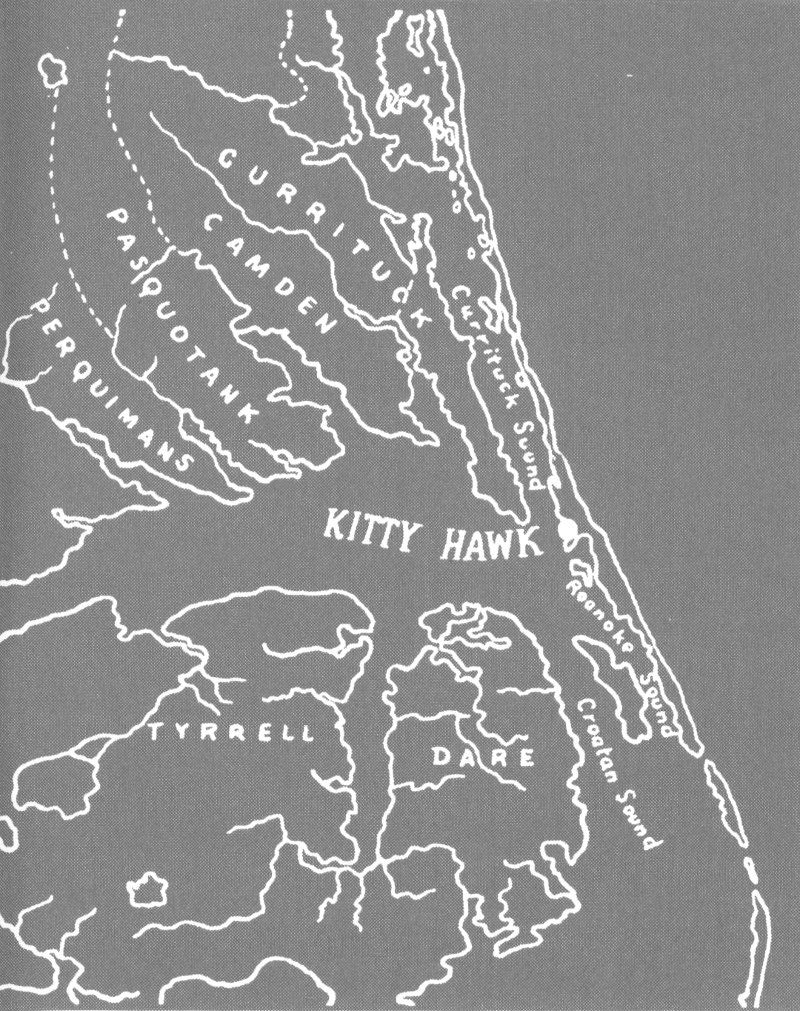

From reports received from the Weather Bureau in Washington, the Wrights learned that a place named Kitty Hawk in North Carolina seemed to meet all requirements. So they wrote to the man in charge of the weather station there for further information. On his and other data, the brothers came to the conclusion that Kitty Hawk was suitable for experiments. What was then a tiny spot on the map was to become, in time, a center of world interest.

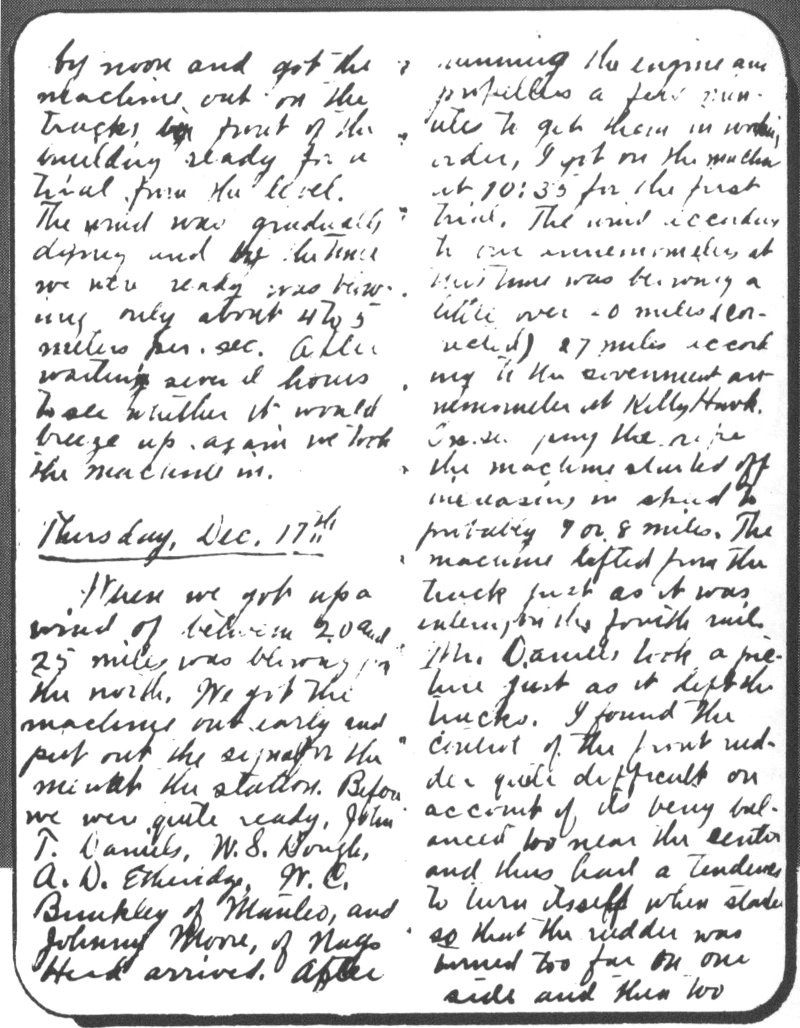

Diary of Orville Wright, showing page recording the first successful flight.

Map of Kitty Hawk area.

The spot chosen for the Wrights’ experiments was located on a long strip of sandy beach separated from the mainland of North Carolina. At one point was the Kitty Hawk Life Saving Station and alongside, a government weather station. A mile back from the ocean was the tiny village of Kitty Hawk. Four miles south was the Kill Devil Life Saving Station. Altogether, it was a dreary and uninviting area but one where history was to be made.

The Wrights’ experiments at Kitty Hawk covered two periods. In 1900 they began flying gliders. Winds proved to be unsatisfactory with the result that the experiments of this year fell far below expectations. They were back in 1901 with a much larger glider. From this model they learned that large surfaces could be controlled almost as easily as smaller ones, provided the control was by manipulation of the surfaces themselves instead of the movements of the operator’s body. In their glider experiments of 1901 they broke all records for distance in gliding.

Air lift still troubled the brothers, so Orville rigged up a small wind tunnel made out of an old starch box. Within the box was a balance, the main feature of which was a metal rod that pivoted like a weather 8 vane. The starch box experiment led to the design of the more scientific wind tunnel shown on Page 5.

Newspaper comments on the early efforts of the Wright brothers.

In the third glider trials in 1902 the brothers put all their new knowledge to the test with good results. One new feature was a “tail.” The idea of making this tail movable led to the system of control generally used today—the independent control of aileron and rudder. The third series of glider flights was highly successful.

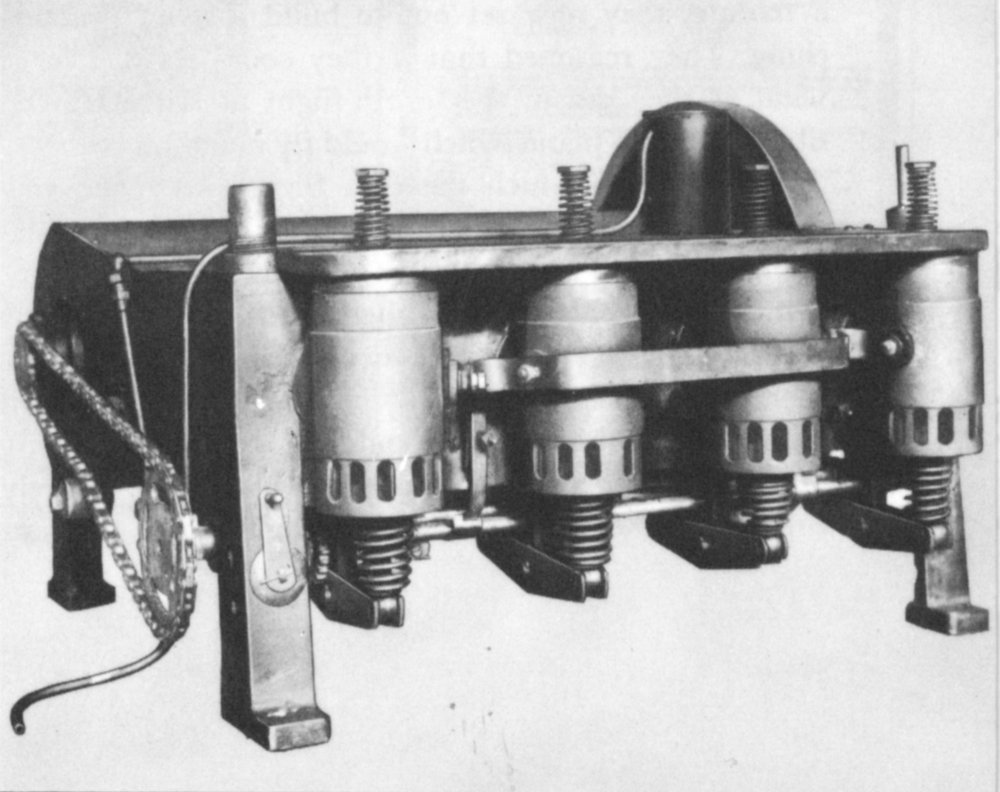

The Wright brothers were now convinced they could build a successful power flyer. One of the first requirements was an engine to produce at least eight horsepower and weigh not more than 20 pounds per horsepower. Unable to obtain such an engine, they built one themselves. The plane now took shape with wings having a total span of a little over 40 feet with the upper and lower wings six feet apart. Total weight of the plane was 750 pounds.

Although the plane was assembled in Kitty Hawk by September 23, 1903, weather and various mechanical mishaps postponed the day of trial until December 14. On the toss of a coin, Wilbur won the right to make the first trial. The machine climbed a few feet, stalled and fell. 9 Several parts were broken, requiring two days for repairs. There were other minor delays and then came the fateful day of December 17.

This time Orville was the pilot. The few spectators stood silently by, little realizing that they were participating in an event that would be “forever known.” Orville lay flat in the pilot’s place with Wilbur running alongside, a hand on a wing, until the machine left the rail. This, in the words of one of the historians of the flight, is what happened:

“Signals that all was in readiness were exchanged. The motor turned, the propellers whirled, a restraining wire was released; the machine rolled along a crude runway, then took off under its own power and flew for twelve unbelievable seconds for 120 incredible feet.

“With that brief flight, the first ever made by a heavier-than-air machine, man was freed from the bonds that held him close to Mother Earth from the beginning of time, and glimpsed the realization of his oldest, boldest dream ... the conquest of the air.”

The moment when that homemade plane rose from the ground was akin to others that heralded epochs in the progress of mankind. Crude as it was, that first plane represented an almost incredible amount of preparation. Gliders had been designed, constructed and flown to gain technical data and piloting technique; a satisfactory system of control had been discovered; a wind tunnel and balance had been built to amplify flight data; an aircraft engine sufficiently light in weight had been developed; and finally an aeroplane had been designed and built. All these things were accomplished in about three years. As one challenge followed another, the Wrights met them all and from their first flight went on to the further development of their invention.

The engines used in the first Wright planes were built by Orville and Wilbur and had four cylinders. This is the original engine from the 1903 plane.

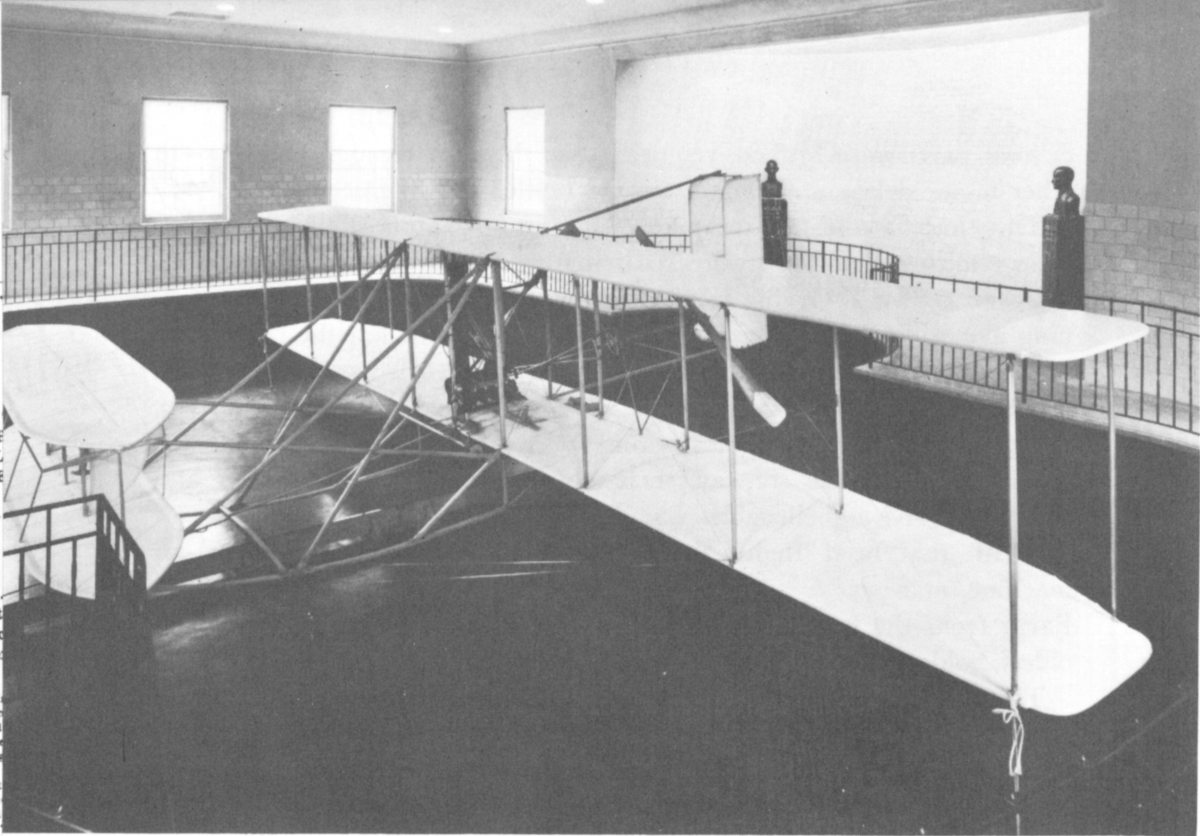

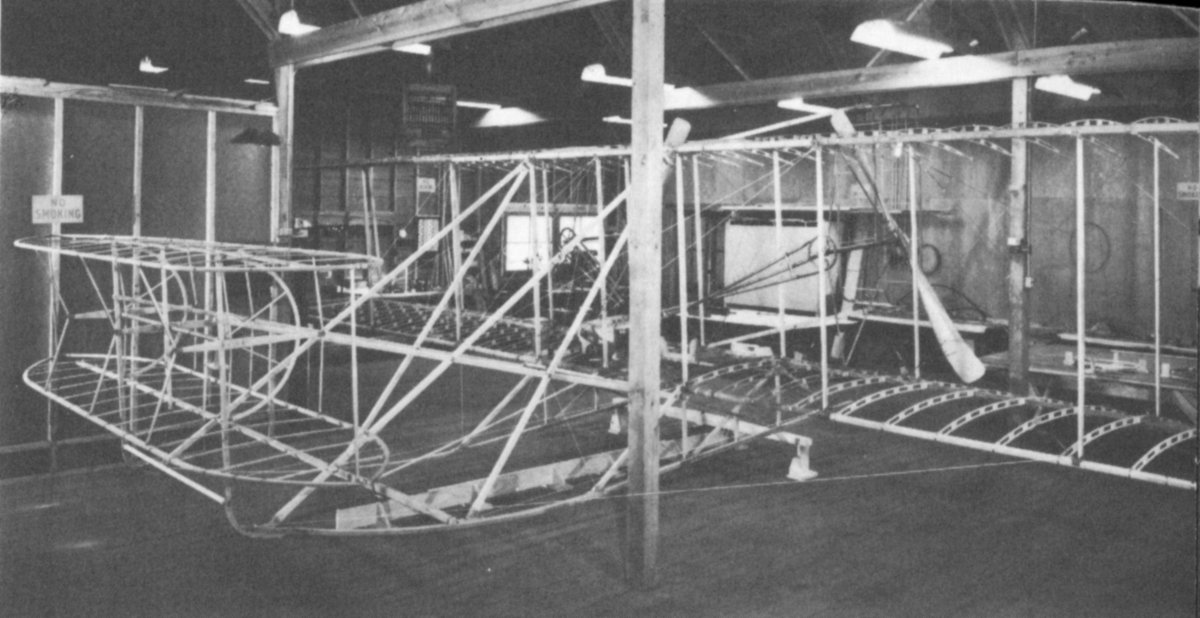

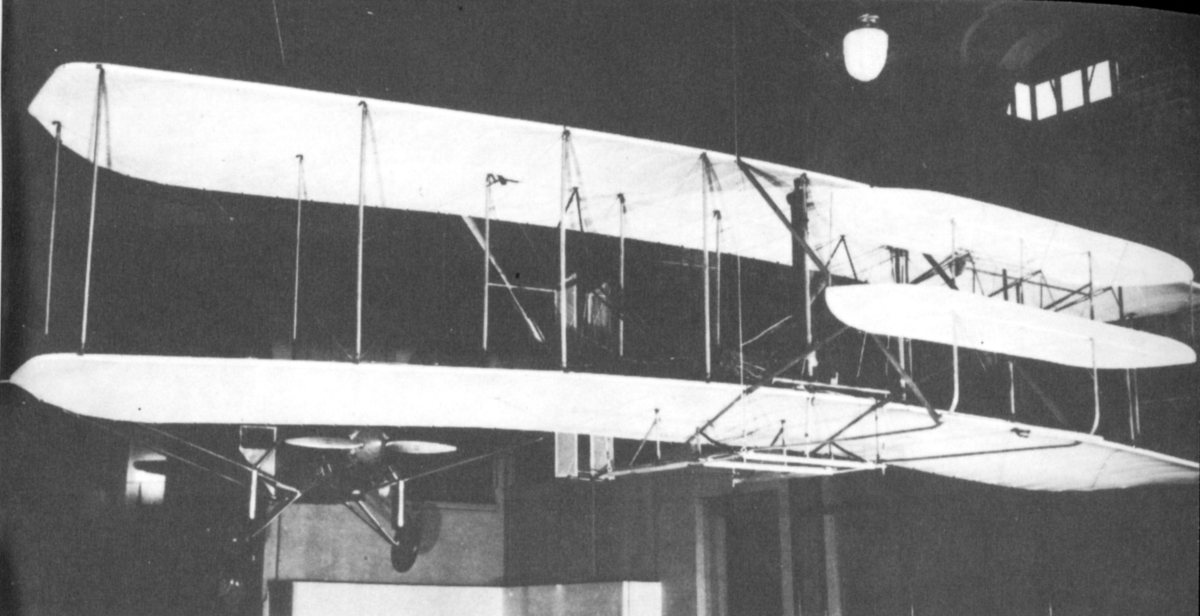

The restored 1905 Wright plane in Wright Hall.

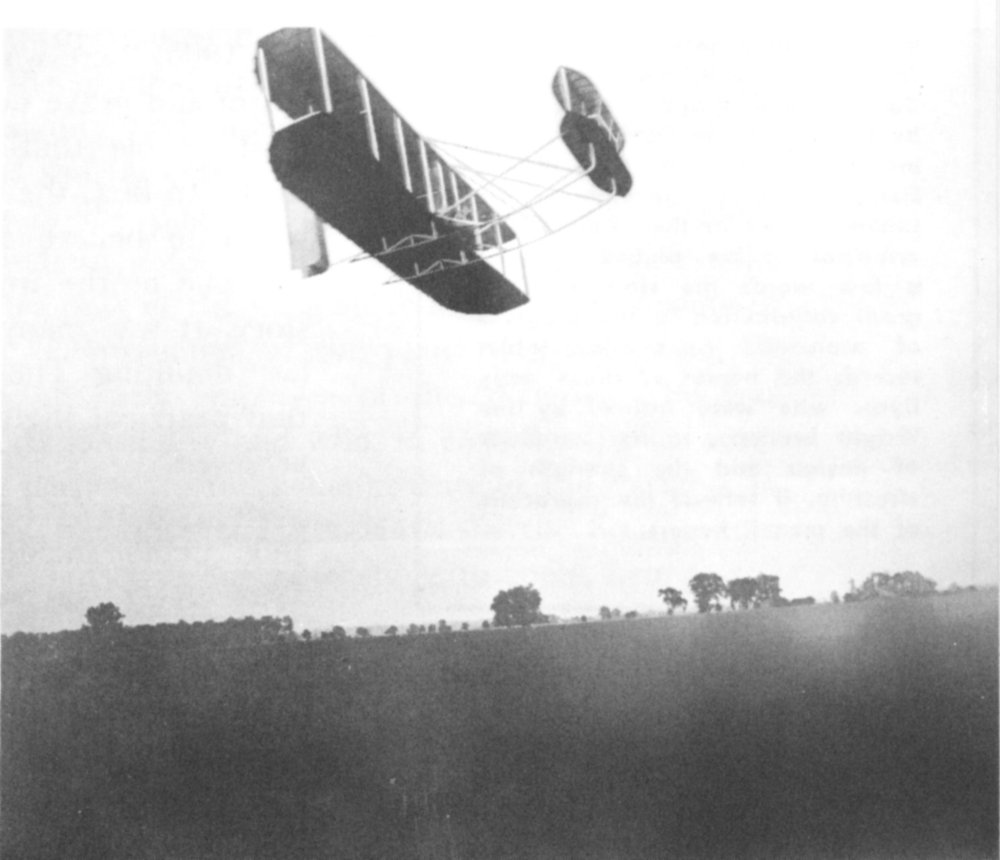

Although the first flight took place at Kitty Hawk, the Wrights themselves always said that they really learned to fly on Huffman Prairie east of Dayton on the present site of Wright-Patterson Field. Having proved that they could fly even if for a maximum of less than a minute, they now set out to build a more practical and useful machine. They reasoned that if they could fly 852 feet against a 20-mile wind as they did in the fourth flight at Kitty Hawk, it should be possible to build a plane which would fly much farther.

The plane in which the first flight was made was called the Kitty Hawk. Construction of its immediate successor began in January, 1904. It was much the same as the one flown at Kitty Hawk but there were a number of changes and the construction was more sturdy throughout. This plane was equipped with an entirely new engine. Because of a shortage of spruce in Dayton they changed to white pine for spar construction, thinking it would be equally good. However, the pine broke in actual use and the wings had to be entirely rebuilt.

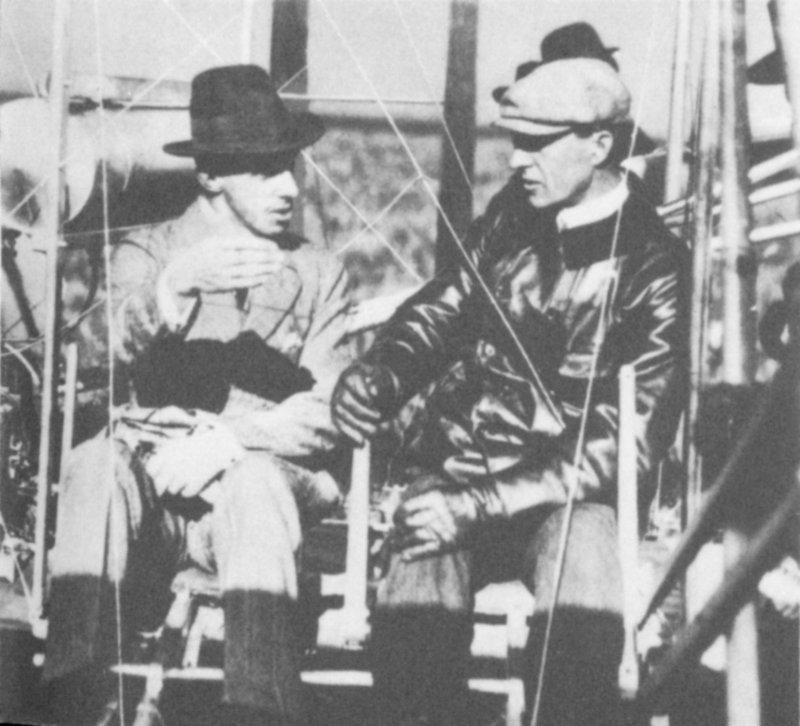

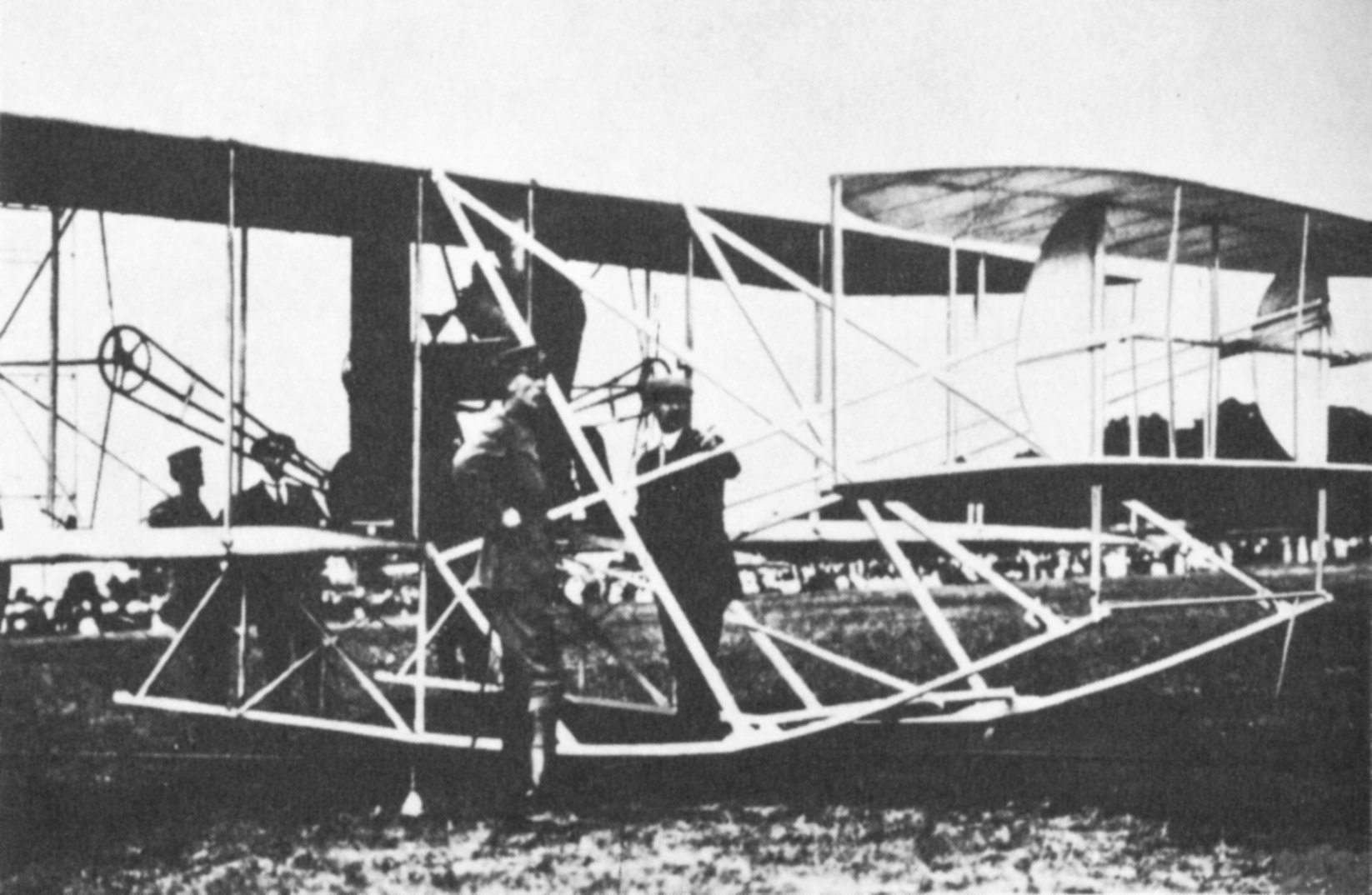

Wilbur Wright during the first demonstrations of the plane in Europe.

Wilbur at the controls during a flight in France.

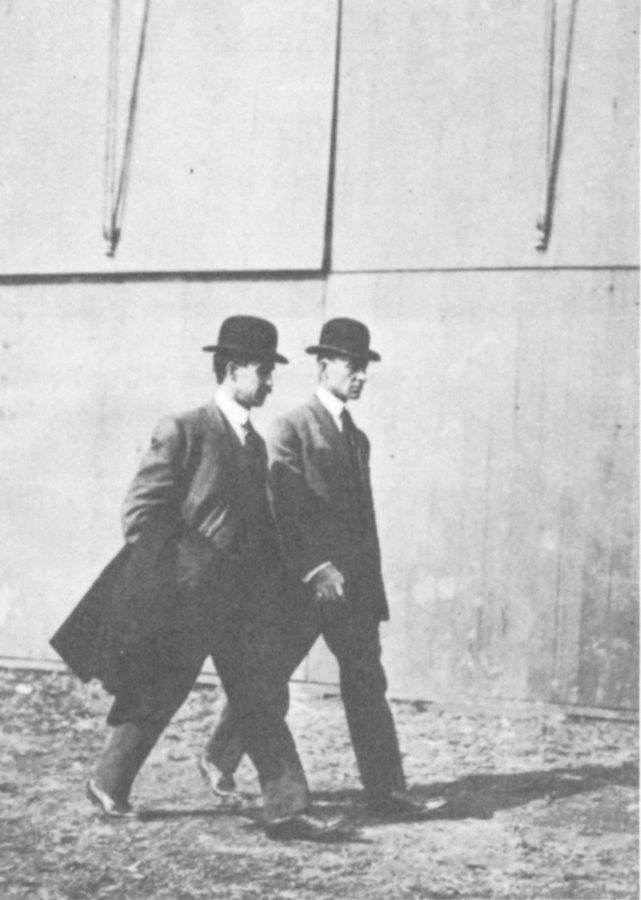

Orville and Wilbur Wright, modest men whose achievements made history.

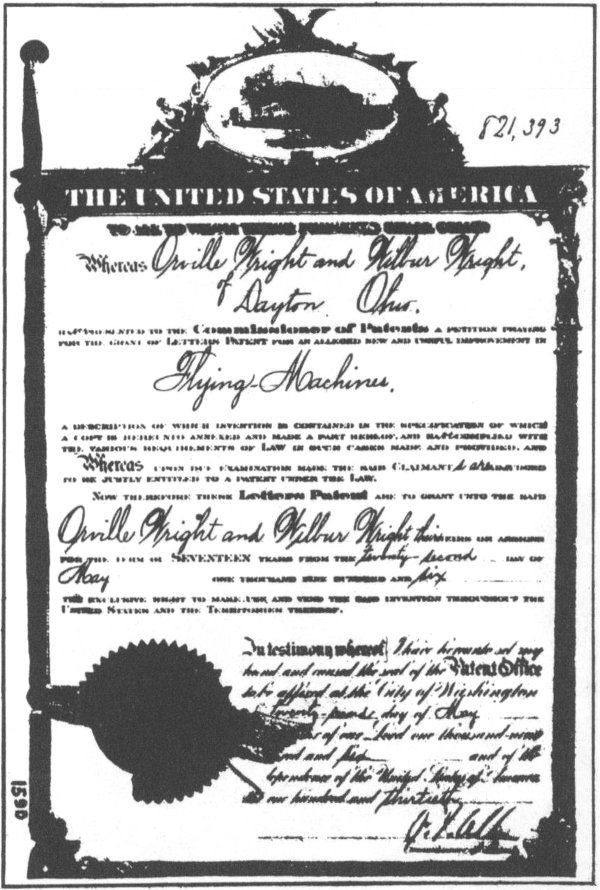

Original patent issued to the Wrights.

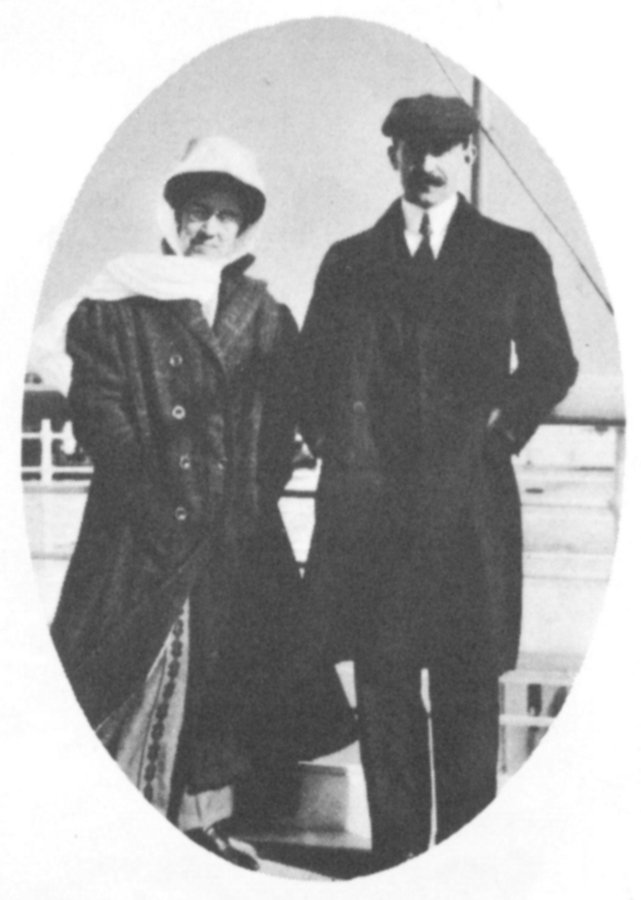

Katherine and Orville Wright aboard ship bound for Europe.

Orville Wright with Thomas A. Edison.

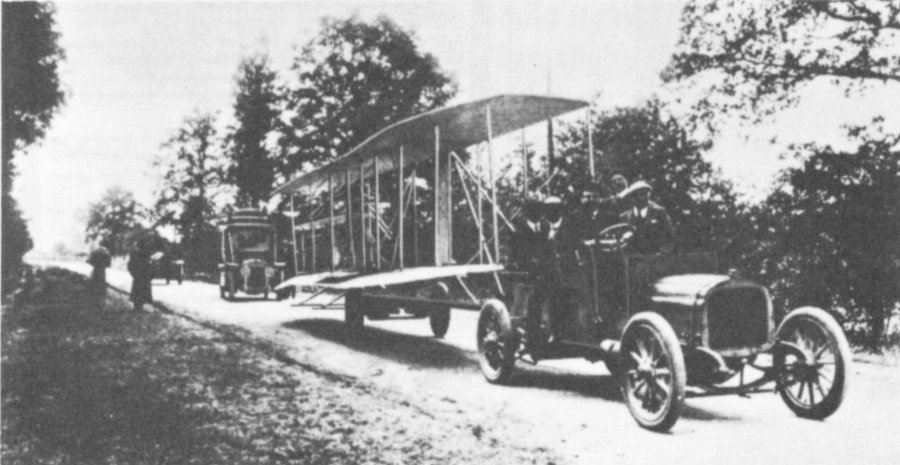

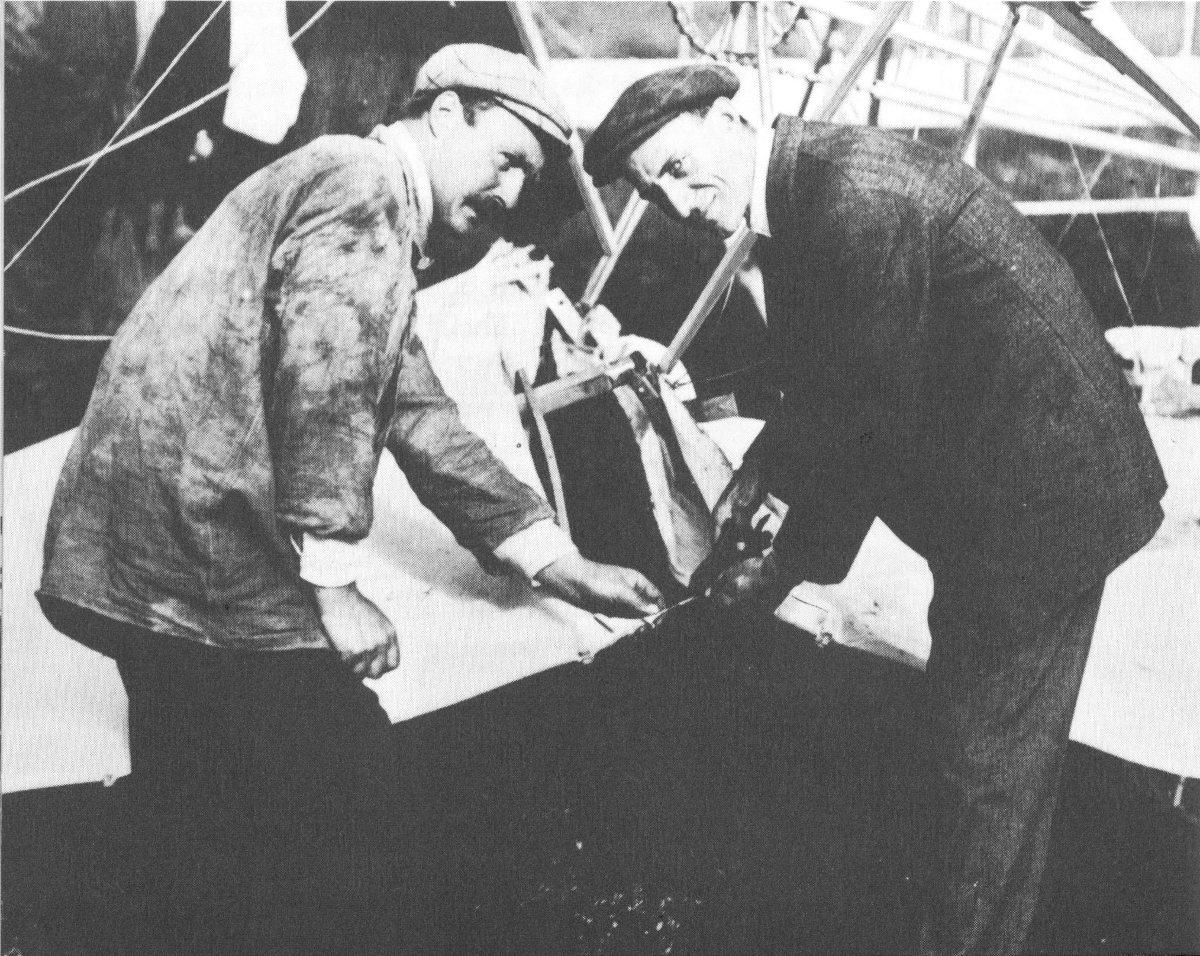

Towing the plane from one field to another at Le Mans, France.

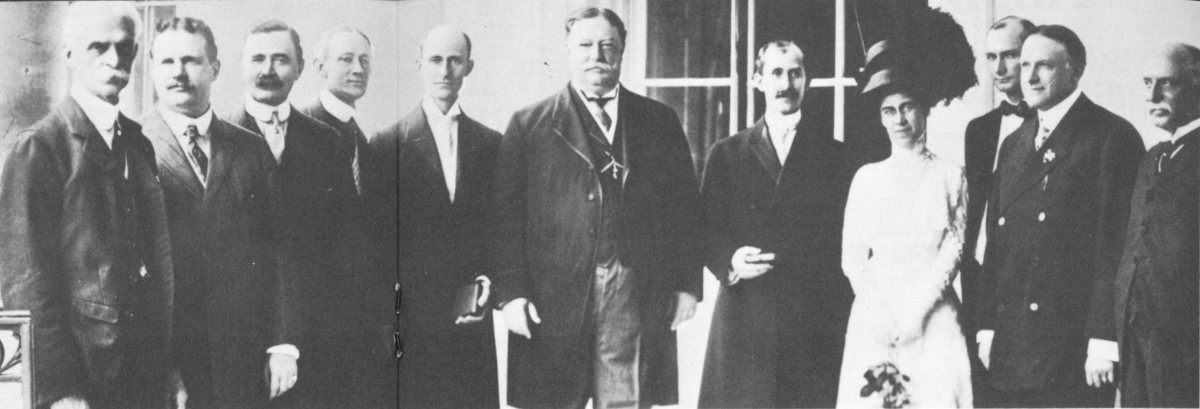

Upon their return from Europe in May 1908, the Wright brothers and their sister, Katherine, were received at the White House by President Taft.

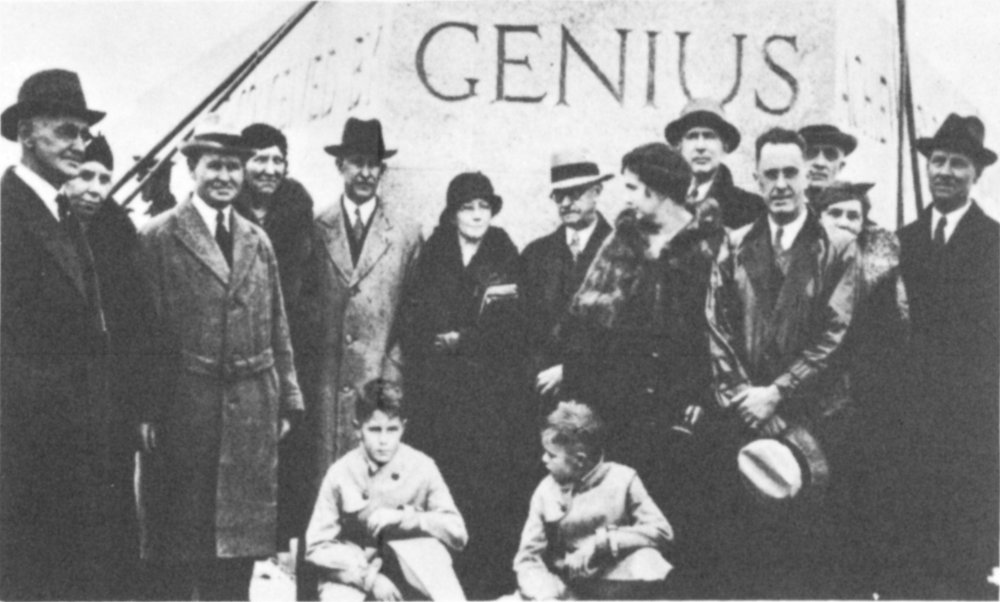

Orville Wright, members of his family and fellow Daytonians at dedication of the Kitty Hawk monument.

The pilot lay prone in early Wright planes.

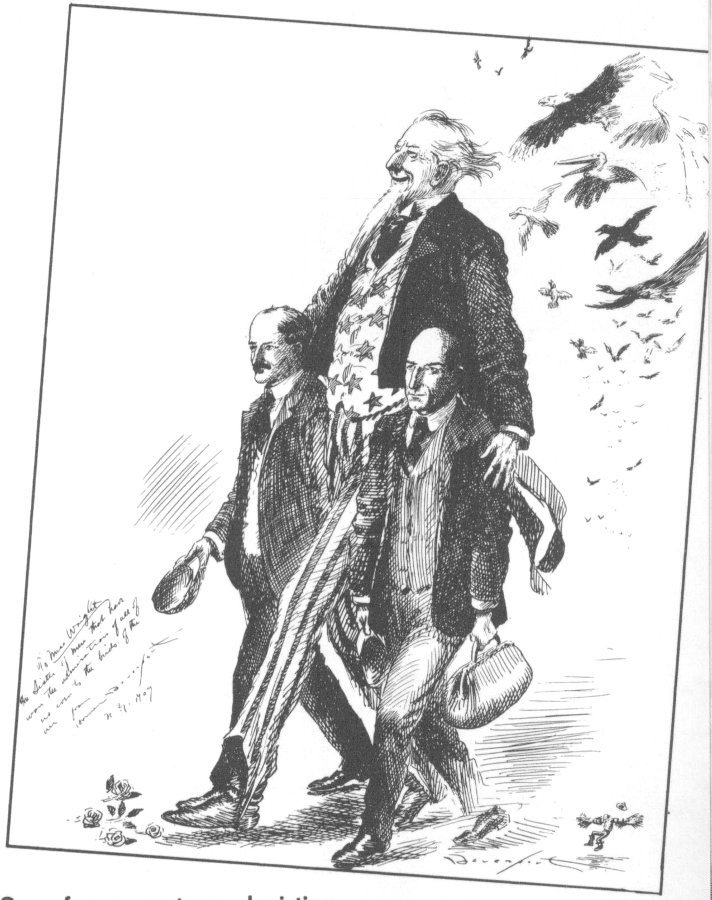

One of many cartoons depicting the honors which came to the Wright brothers.

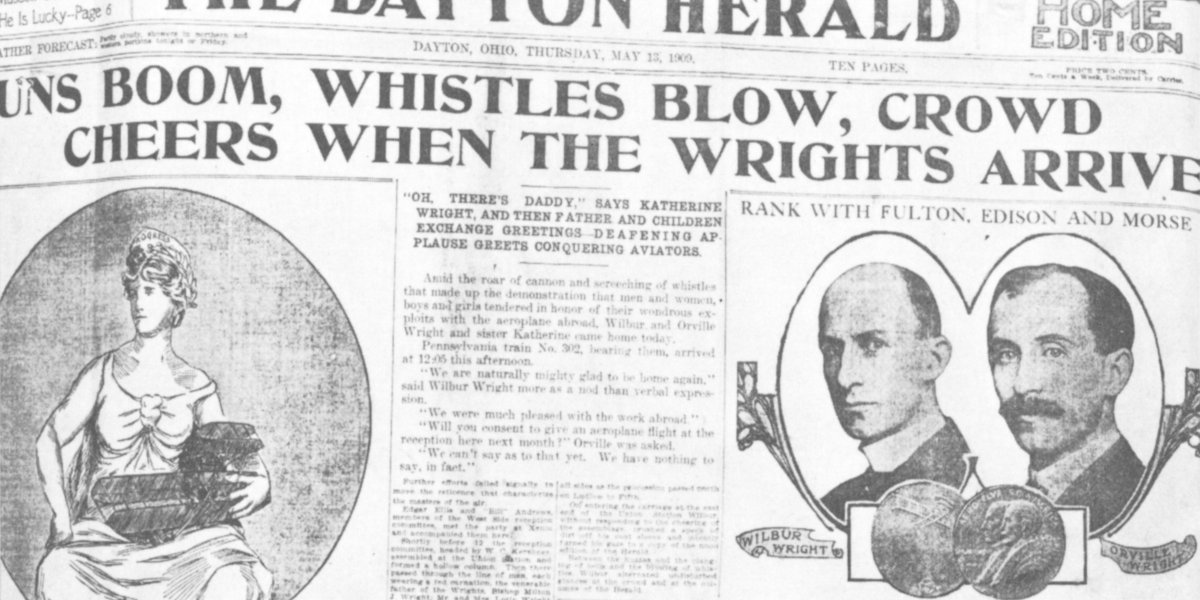

Dayton newspaper reporting the Home-coming Celebration in honor of the Wright brothers.

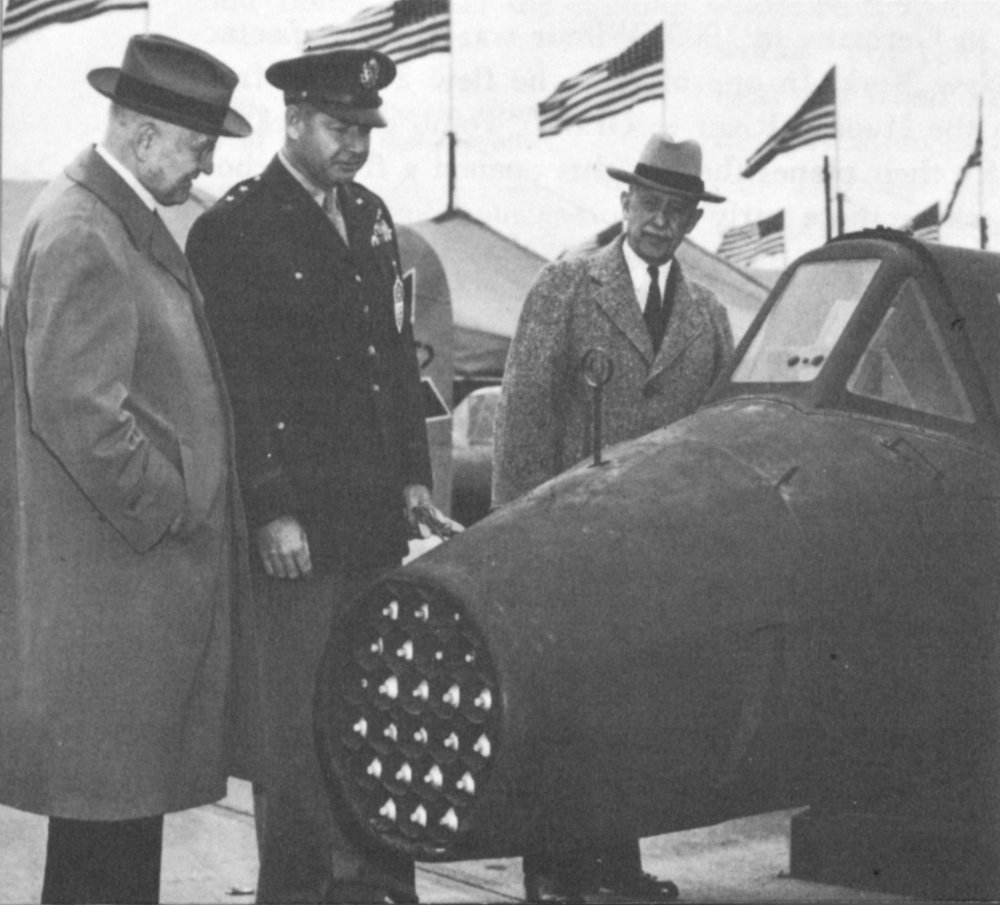

Orville Wright with Colonel E. A. Deeds on a visit to Wright Field.

Orville Wright with Henry Ford as Dayton honored 35th anniversary of flight.

The Wright home and bicycle shop as they appear today in Greenfield Village, Dearborn, Michigan.

During 1904 more than 100 flights had been made at Huffman Prairie. Of those flights, a complete circle made for the first time on the 20th of September and two flights of three miles each were the most notable. In May of 1905 the Wrights made various improvements in the machine making it much stronger at various points which had proved weak when landing in 1904 flights. The warping of the wings and operation of the tail rudder were made independent of each other and the camber of the wings was changed. The most important development was the addition of two “blinkers” between the surfaces of the front elevator. The purpose of the blinkers was to assist the rear rudder in making a turn. This device was patented and proved quite important for it removed the danger of a tail spin.

The Wright brothers considered their flights of 1905 of great importance, and the 1905 plane proved through performance that it was a greatly improved “flyer.” In a report to the Aero Club of America dated March 12, 1906, they said this:

“The object of the 1905 experiments was to determine the cause and discover remedies for several obscure and somewhat rare difficulties which had been encountered in some of the 1904 flights and which it was necessary to overcome before it would be safe to employ flyers for practical purposes. Toward the middle of September, means of correcting the obscure troubles were found and the flyer was at last brought under satisfactory control. From this time forward almost every flight established a new record.” The last flight was the longest of all, lasting for 38 minutes and 3 seconds and covering 24⅕ miles. It ended because of exhaustion of fuel. The gas tank, which held only about a gallon, had, through oversight, not been full before the take-off.

One of the many flights made over Huffman Prairie, just east of Dayton on present site of Wright-Patterson airfields.

The Wright Memorial overlooking Huffman Prairie.

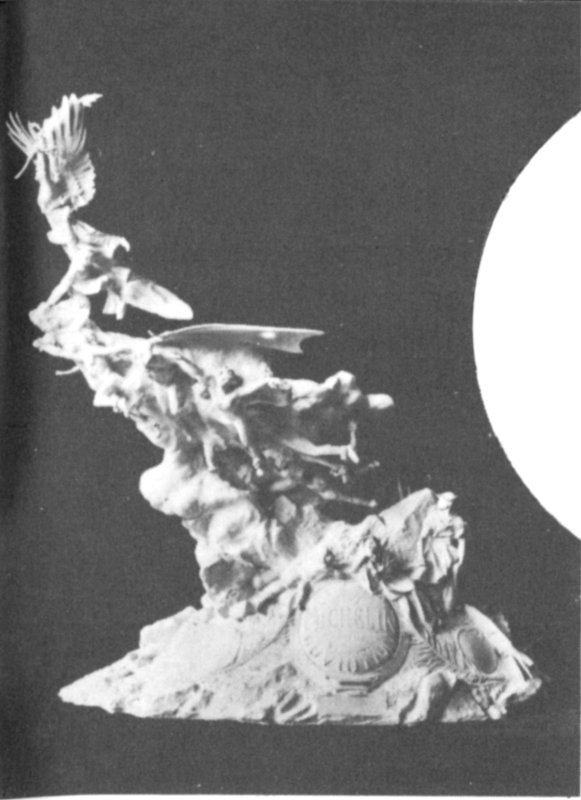

THE WRIGHT MEMORIAL

On a hilltop overlooking Huffman Prairie where the Wright brothers accomplished so much, stands this shaft, made of North Carolina pink granite and erected by the citizens of Dayton in their memory. To the east lies Wright Field, the great government air center named in their honor. The principal bronze plaque tells in a few words the story of their great contribution to the progress of mankind. A smaller tablet records the names of those early flyers who were trained by the Wright brothers. In the simplicity of design and the strength of structure, it reflects the characters of the men it honors.

The report to the Aero Club continued, “The 1905 flyer had a total weight of about 925 pounds, including the operator and was of such substantial construction as to be able to make landings at high speed without being strained or broken. From the beginning the prime object was to devise a machine of practical utility, rather than a useless and extravagant toy.... The favorable results which have been obtained have been due to improvements in flying quality resulting from more scientific design and to improved methods of balancing and steering.... The best dividends on the labor invested have invariably come from seeking more knowledge rather than more power.”

The submission of this report was followed by the adoption of a resolution by the Aero Club commending the Wrights upon their accomplishment. This, it might be said, marked official recognition on the part of the public that the Wrights really had flown. Despite numerous flights made in 1904 and 1905, there was considerable skepticism and grave doubts on the part of most people that flights were being made. In fact, the unwillingness of the world to believe that man could fly was one of the ironies of the Wright story. It was many months before the last doubting Thomas was convinced that practical flight had actually been achieved.

Improvements had been made on the 1905 plane, including the engine. In 1908 the plane was taken to Kitty 17 Hawk for further tests. After several successful flights, an accident occurred which so badly damaged the plane that it was dismantled and stored there in frame hangars. Over the years parts of the plane were given to several museums and others were acquired by residents of the area as mementoes. The engine, the propellers and other parts were shipped back to Dayton.

The restored 1905 aeroplane in process of reconstruction. Engineers and others who inspected the plane during its rebuilding, marveled at the craftsmanship reflected in its original construction.

When it was decided to reconstruct an early Wright plane for Carillon Park, the first thought was that it should be a replica of the Kitty Hawk, which of course would have been accurate in appearance but would have contained no original parts.

Orville Wright himself suggested that if the original parts of the 1905 plane could be brought together, a plane which could truly be called a restored Wright aeroplane could be built. An exhaustive search was begun and with the co-operation of the museums and the residents of Kitty Hawk, many of the original parts were secured. Orville Wright located the original drawings and supervised much of the reconstruction. His death occurred shortly before the plane was finished.

At least 60 per cent of the parts in the plane are original. These include the engine, the chain guides, control levers and pilot’s cradle, the propellers, the greater part of the wing structure as well as some of the front rudder struts. Construction of the plane was supervised by Mr. Harvey D. Geyer, an early employee of the Wrights, who was uniquely fitted for this responsibility and who, in contributing his services, has done much to perpetuate the achievements of the Wrights in their home city. As does the original Kitty Hawk in the Smithsonian Institution, this restored plane will, for generations to come, help to tell the story of the genius of the Wrights.

King Edward VII visits Wright brothers during flights at Pau, France.

A world that has convinced itself something cannot be done, yields slowly to the realization that the “impossible” has been achieved. When the Wrights approached their own government with the suggestion that their invention might be useful for scouting purposes their proposal evoked no interest. Actually, appreciation of the implications and possibilities of the new device came more quickly from Europe than America. England and France were among the first to seek information on the machine that had so thoroughly proved its ability to fly. As early as 1905 a member of the French military had at least made unofficial inquiry as to the cost of a plane, but for a time this led to nothing.

In 1907 the United States government realized that the Wrights had proved the practicability of flying. The Signal Corps drew up specifications and asked for bids. The Wrights offered to build a test plane for $25,000. Their bid was accepted in February, 1908. Three months later they signed a contract with a French syndicate to sell or license the use of the plane in France. The Wrights were now in the international picture.

King Alfonso XIII of Spain was keenly interested in flying, but promised his family that he would not make flight.

About this time the Wrights, always seeking better performance, 20 made a notable improvement in their plane. In their first historic flight and during the experiments on Huffman Prairie, they rode “belly buster” just as a boy does when coasting on a sled. They now made a different arrangement of levers which enabled them to sit up while piloting the plane. A seat for a passenger was also provided. Interestingly enough, recent experiments with high-speed planes have brought some return of the prone position for the pilot.

On May 14, 1908, newspaper men saw a history-making flight at Kitty Hawk. The remodeled 1905 machine under perfect control carried two men. Flights for the army followed in September and the last trace of skepticism disappeared. Unfortunately, on the last flight Lieutenant Selfridge, the passenger, was killed and Orville severely injured.

The year 1908 was notable in the saga of the Wrights. Wilbur made a series of flights abroad that not only won all observers but aroused wide interest and admiration throughout Europe. His quiet demeanor, his unassuming modesty and his proved skill, stirred the popular imagination. The French exalted him to the status of a hero. The great of the world flocked to meet him and see him fly. They included King Edward VII of England, King Alfonso XIII of Spain, and the Dowager Queen Margherita of Italy. Invitations to fly came from Rome and Berlin. In Rome King Victor Emmanuel watched him fly.

Wilbur, at right, in characteristic pose—making a repair in France.

Orville Wright with army officer during highly successful flights at Fort Myer, Virginia.

In December, 1908, Orville and his sister, Katherine, went to Europe to join Wilbur. The weather at Le Mans where Wilbur had been flying became unsuitable for further flights and operations were transferred to Pau in southern France. Here Orville and Katherine joined Wilbur. Many flights were made and many distinguished visitors came to see the modern miracle of human flight.

Honors were heaped upon the Wrights. They received among many other distinctions, the gold medal of the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain and the Aero Club of the United Kingdom. The French Aero Club of the Sarthe gave them a bronze trophy. Later the Aero Club of America bestowed medals on the flyers. A few weeks afterward, President Taft received the Wrights at the White House and the brothers returned to Dayton where a tumultuous welcome awaited them.

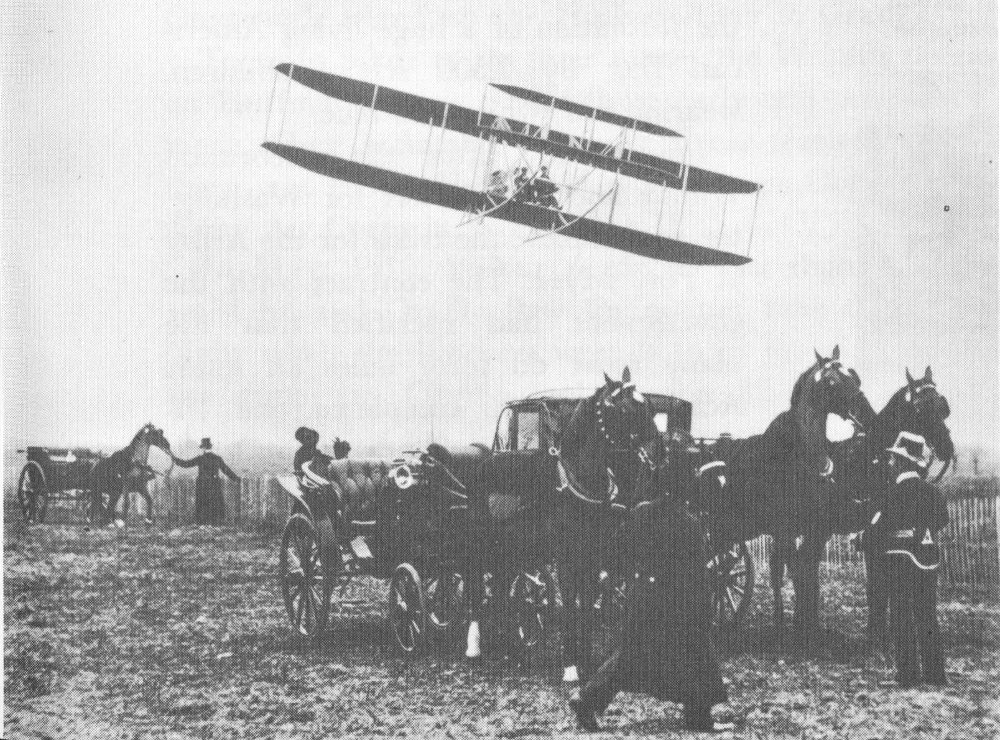

Wilbur flies low over spectators’ carriages at Pau, France.

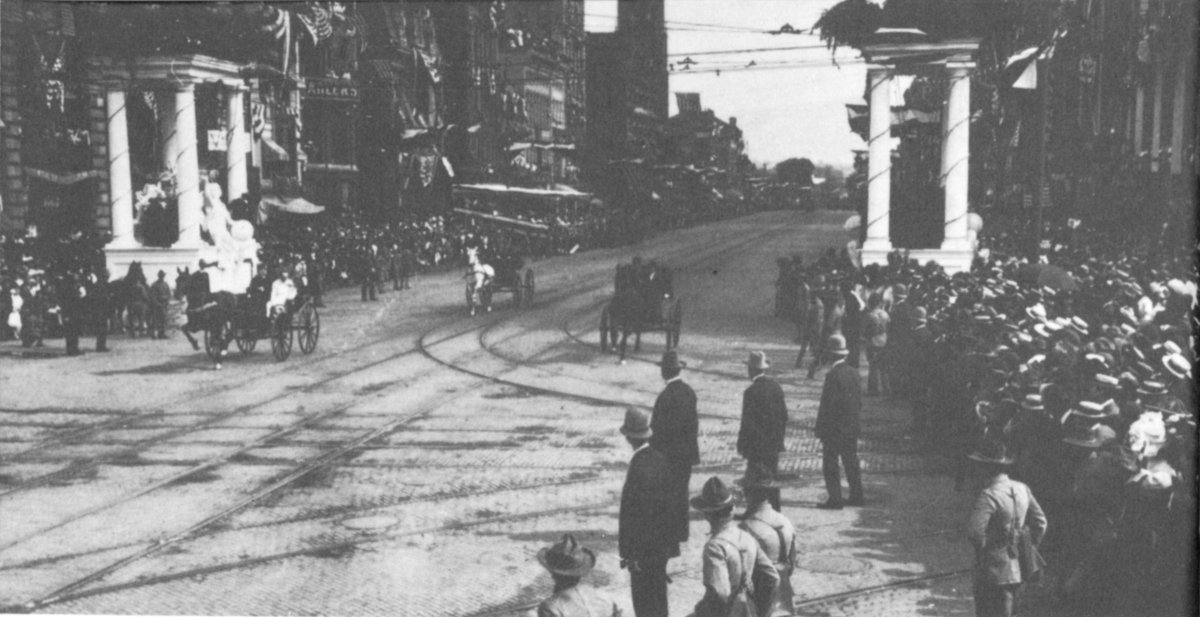

Main Street and Third on day of great Homecoming Celebration, June 17, 1909.

Probably nothing stirred the Wrights quite so deeply as their welcome when they returned to Dayton from their foreign triumphs. The “homecoming” lasted two days, June 17 and 18, 1909. Whistles blew, bands played, bells rang, men, women and children paraded. During the celebration practically all business in Dayton was suspended.

Orville and Wilbur on second day of Dayton demonstration.

Wilbur and Orville rode to the celebration in a carriage with their old friends, Ed Sines, boyhood newspaper partner of Orville, and Ed Ellis, a long-time friend of Wilbur. The Wrights reviewed a parade in their honor and in the evening witnessed a spectacular display of fireworks. The celebration continued the next day when one of the features was the formation of a huge living American flag by 2,500 school children, wearing red, white and blue. Immediately after the celebration Wilbur and Orville left for Washington to complete the trials for the Army at Fort Myer. The contract with the government had specified that the plane must do forty miles an hour. Actually, Orville completed one 10-mile flight in 14 minutes at approximately 43 miles per hour. The Wright 23 plane was accepted by the Army at the conclusion of these tests.

Michelin Trophy awarded to Wright brothers for achievements in France.

{Medal from the Aero Club of America.}

This trophy from the Aero Club of Sarthe, France, was placed in niche in Wright home.

Immediately after the flights at Fort Myer, Orville and Katherine left for Germany. His purpose was to train pilots for the German company which had been organized. He made many flights on that trip, some of them witnessed by members of the royal family and on one of which the Crown Prince was a passenger. On one he raised the world’s altitude record from 100 meters to 172 meters, roughly 550 feet. Shortly thereafter he flew for one hour, thirty-five minutes and forty-seven seconds with a passenger, thereby establishing a new world’s record for a flight with a passenger.

While Orville was in Germany in 1909, Wilbur was making spectacular flights around New York. In one of these he flew 21 miles from Governor’s Island up the Hudson River to Grant’s Tomb and back.

To train pilots to fly their planes the Wrights opened a flying school on Huffman Prairie where those early and precarious flights had been made. Here a notable group of flyers received their training. One of them was Henry H. Arnold who became Commanding General of the Army Air Corps in World War II.

In May, 1910, Wilbur made his last flight as pilot. Shortly afterward he and Orville flew for a brief time together. It was the only flight when the brothers were both in the air at the same time. Later the same day Orville took up his 82-year-old father. In the spirit of the Wrights the Bishop’s only comment was ... “Higher! Higher!” Orville’s final flight as pilot was made in 1918 from South Field near Dayton.

Orville Wright meeting with members of National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics.

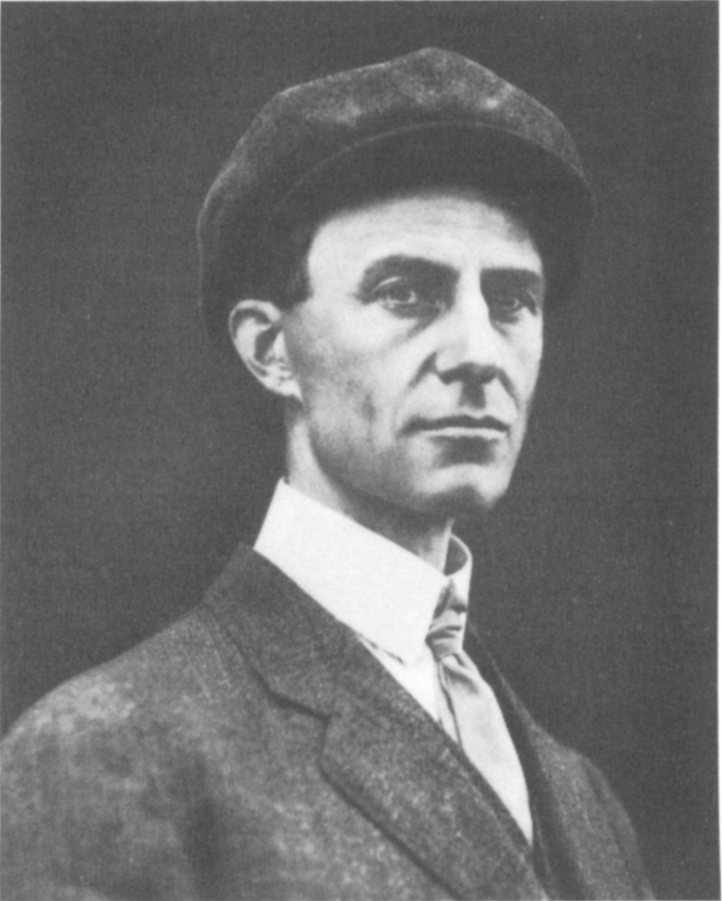

After an illness of three weeks, Wilbur Wright died on May 30, 1912, in his forty-fifth year. The whole world mourned him. Thus, in the prime of life, with a record of achievement privileged to few, passed a notable figure in American creative history. Orville Wright survived his brother for 36 years, passing away January 30, 1948. Throughout his life he maintained his active interest in aviation, was a life member of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics and a frequent and honored visitor to Wright Field, the great Air Force research center named in honor of the Wright brothers.

Always interested in new developments, Orville Wright visits Wright Field.

The “Kitty Hawk,” Smithsonian Institution, Washington.

The Wright brothers have been honored by many nations. Medals, trophies, monuments tell in part, at least, the story of their great achievement. The original Kitty Hawk aeroplane holds the place of honor in the aeronautical exhibit of Smithsonian Institution, Washington. A replica of the Kitty Hawk in the Science Museum at South Kensington, London, speaks for the British nation in honoring the Wrights. Monuments have been erected at Kitty Hawk, N. C., at Le Mans, France, and at Dayton. And now Wright Hall with its restored 1905 plane takes its place as one of the efforts of a grateful world to honor one of man’s greatest achievements.

Wright Memorial, Kitty Hawk, N. C.

Monument to Wrights, Le Mans, France.

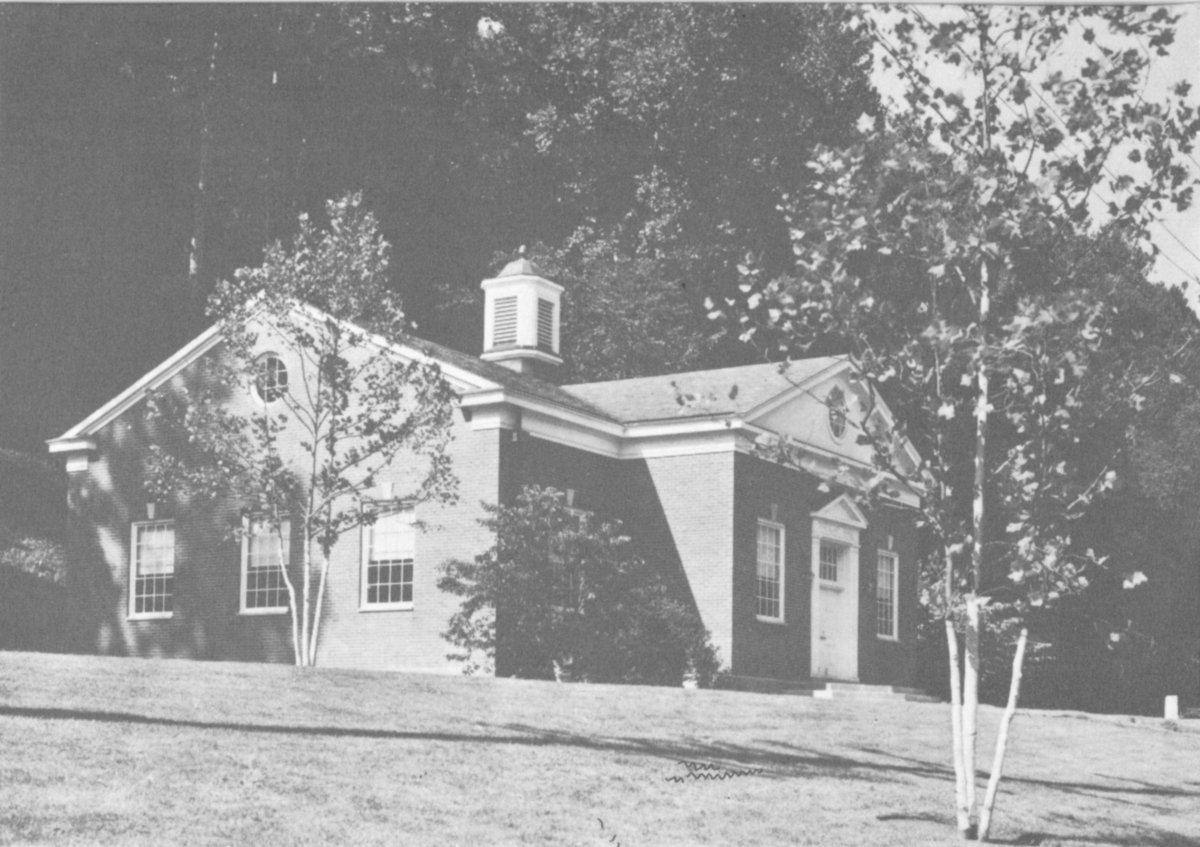

Wright Hall in Carillon Park houses restored 1905 Wright aeroplane.

On the walls of Wright Hall is inscribed this tribute to the achievements and to the personal character of two great Americans:

In honored memory of Wilbur and Orville Wright, citizens of Dayton and of the world. Through original research, the Wright brothers acquired scientific knowledge and developed theories of aerodynamics which, with their invention of aileron control, enabled them in 1903 to build and fly, at Kitty Hawk, the first power-driven, man-carrying aeroplane capable of flight.

Their further development of the aeroplane gave it a capacity for service which established aviation as one of the great forward steps in human progress.

As scientists, Wilbur and Orville Wright discovered the secret of flight. As inventors, builders and flyers, they brought aviation to the world.

Their courage, perseverance and ability are comparable only to the magnitude of their achievement. The aeroplane will stand for all time as one of those few truly great inventions which have shaped the life and destiny of man.

CARILLON PARK

DAYTON, OHIO

One of a series of Carillon Park

booklets. Price ten cents.

PRINTED IN U.S.A.