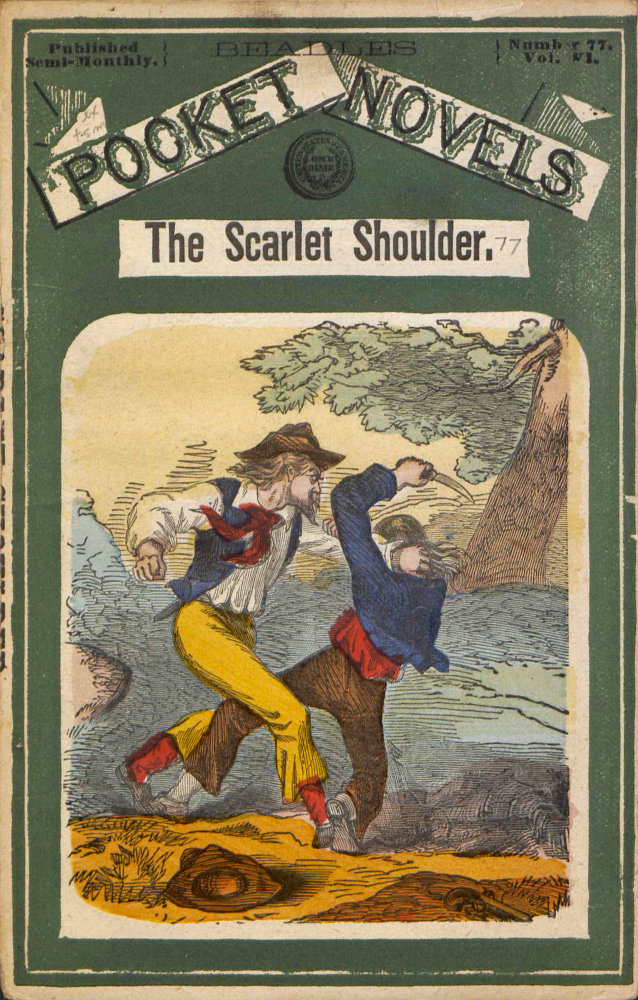

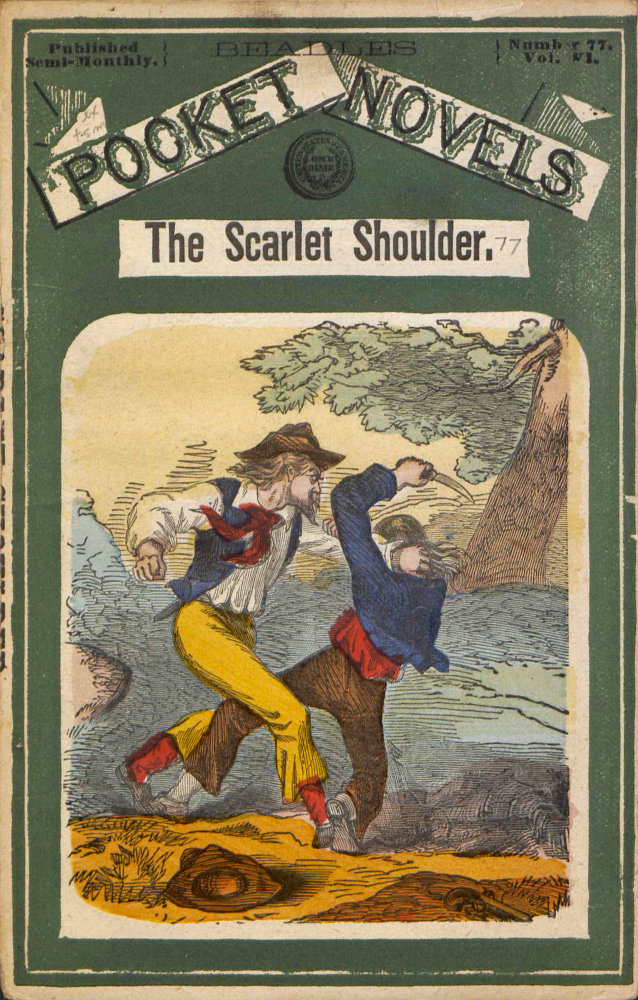

Title: The Scarlet Shoulders; or, The Miner Rangers

Author: Jos. E. Badger

Release date: September 28, 2021 [eBook #66407]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: David Edwards, Stephen Hutcheson, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (Northern Illinois University Digital Library)

BY HARRY HAZARD.

AUTHOR OF THE FOLLOWING POCKET NOVELS:

NEW YORK:

BEADLE AND ADAMS, PUBLISHERS,

98 WILLIAM STREET.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1870, by

FRANK STARR & CO.,

In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

“Indios—Indios bravos!” yelled Manuel Navaja, as he discharged his escopette full at the glowing disk of old Sol; then dropping it, he rushed through the outer gates, sounding the terrible words at every step, his affright being shared by all the peons who heard him, and, leaving their posts, one and all swarmed to the main building.

There is a spell—a fascination like that of a rattlesnake—that none but the dweller in “the land of the sun” can know. Young and old, men, women and children felt it now, and all rushed into the hacienda, only intent upon their own safety. But a clear, stern voice soared above the din, above the shouts of men, the shrieks of women and children; and, aided by his strong arm, that dealt blows upon every hand, he managed to restore order so far that the inner gates were fastened securely, the window shutters closed, and doors barred, and then blockaded with such heavy articles of the furniture as could be moved. The outer gates were left open; no person would venture there, the haciendado being held back by a beautiful woman, who twined her arms around him with strength lent by terror.

Then, with wild yells and whoops, the half nude, paint-bedaubed horde came swarming through the gateway into the patio, or outer courtyard, while others assailed the building in front. The peons within had been hastily armed, and opened a scattering fusilade, but with little damage to the enemy, for in their terror they generally fired at random, as often with both eyes shut as taking aim.

Then the shock came. The doors shook and creaked 10 under the weight hurled against them; the hinges slowly yielded, but the barricade held them in place.

If the majority of the defenders were cowardly, others were there whose courage amply supplied this deficiency. A tall, stalwart man, of a singularly handsome and noble countenance, went from post to post, reproving or encouraging the men in a few quick words, pointing out the best methods of procedure—at times aiming an escopette with a skill that spoke well for his marksmanship. This was the haciendado, Don Christobal Canelo, a man of perhaps thirty years of age.

Close behind him was a lady, who, although her face was as pale as death, betrayed no fear; on the contrary, whenever her husband fired a shot, and the wild yell of mortal agony followed, a smile of pride swept athwart her face, and her eyes flashed with an ardor equal to his own. Then the first fury of the assault was checked, the savages drawing behind the outbuildings, and, turning to note the extent of the damage inflicted upon his little band, Canelo noticed the presence of his wife.

“My God, Luzecita, you here! Where is Felipe?”

“With Josefa in the—”

“But you—this is no place for you, my wife. Think, a bullet might—”

“Pardon, Christobal; where should I be if not by my husband’s side?”

“But not now; there is danger. You should be with your child—our boy,” urged Canelo, affectionately.

“And is there no danger to you?” she added, reproachfully.

“It is my place—my duty to encourage and assist the peons. But think, if you are here, in danger, it will do no good, and only distract me. I could think of nothing else. If you should be—any thing happen to you, what would become of our Felipe? Come, let me take you to him, where you will be safe, at least for the present.”

“And leave you here to be killed?”

“Mi alma, if that is to be my fate, your presence could not avert it, but only make it the more bitter. Your prayers to the blessed Virgin will strengthen our hands and hearts. Come,” and he led her from the hall.

“See, comarados,” exclaimed Tadeo Campos, the capataz, “the red-skinned devils come again. Show yourselves men now, and true Mexicans. Fire!”

He was answered by a volley that did some execution, and then the savages hurled themselves against the shattered door, hewing it with axes, battering it with beams and logs of wood that they had procured from the caballariza (stable), while others pummeled the window screens, or fired at the loop-holes. The patio was filled with smoke, and through it gleamed the oiled bodies of the Indians, as they flitted to and fro.

A large hole was now made in the door, and through it shots were exchanged. But the besieged had the advantage of being in a darkened room, while the enemy were plainly revealed. From without the shots were fired at random, although several took effect; but Campos, with his comrades, taking deliberate aim, made fearful havoc among their assailants.

But this could not last long. One of the shutters began to give way before the force applied to it, and the grills of strong iron bars, called rega, were bending inward, and the ranks of the besieged were really thinned. Then came a loud shout from without, and, with wild yells of exultation, the savages retreated, to the great joy of the peons, for it seemed as if a few minutes more would see the foe effect an entrance.

For a few moments all was silence within the building; even the process of reloading was checked, so eager were they to learn the cause of this strange maneuver. They could hear a faint hum from without, that told them the enemy had not yet abandoned the siege. In vain they peered through the shattered door. The smoke concealed every thing, as it was a still, foggy day, and it settled heavily upon the earth.

Then came a bright flash, a loud roar, and the adobes by the side of the door crumbled, while the shock made the entire house tremble. But one thing could have that effect, and the swarthy faces turned a shade more ashen as the whisper run around of:

“Los canones!”

Where had the cannon come from? there were none belonging to the hacienda. And what were the Indians doing with 12 such a piece? These were questions that all asked, but none could answer.

If their danger had been great before, now it was increased tenfold. A few hours, at least, would end the struggle. The fog and smoke might prevent them from getting range of the doorway for a spell, but not long; and then one or two balls would open a breach for their entrance. Another barricade was formed at the other end of the hall, but that could avail little. The same power would reduce that, and then it would be hilt to hilt, breast to breast.

At this new phase, Canelo sought the chamber where his wife and child were, and hastily explained the cause of the commotion.

“And now, Luzecita, you must not remain here. We can not tell what may happen, and with you and darling Felipe in safety, I can fight with a better will.”

“And you?”

“My place is here. The peons need my influence to encourage and direct them.”

“Where you are, I stay—nay, do not interrupt me,” she hastily exclaimed. “I am your wife, and will live or die with you. The blow that kills you shall reach my heart at the same time.”

“But it can not be; think—”

“I do think—I have thought, and I will stay. What would life be without you?” the woman uttered, as she clasped him around the neck.

“My wife, you must listen, and you will see that what I say is best. Think of our Felipe—what would become of him if these fiends should overpower us? Remember that not we alone would perish—and you know but too well the fate a woman would receive at their hands—but he, our bright, beautiful boy—he, too, would die!”

“Why should he live if we are killed?” faltered the wife.

“Perhaps we may beat them off, then no harm is done. But if the worst is to be, he will have a parent’s hand—a mother’s love to show him how to live. Would you doom him to death, and he so brave and innocent? And then,” as he bent his head and whispered, “think of the one that is to come; would you—”

“My husband, do not ask me; I can not—can not leave you!” and she clung to Canelo hysterically, sobbing as though her heart would break.

“Luzecita,” he cried, assuming a stern voice, while the great tears stood in his eyes, “this is folly. You must go, and soon, or it will be too late. See, if you refuse, I will kill myself before your eyes! And then you will have my death upon your soul, as well as that of your children!” and he held her tightly to his breast as he drew a pistol, and, cocking it, placed the barrel against his temple.

“Christobal—husband, what would you do?” shrieked his wife, struggling wildly to free her arms, so that she could avert the weapon.

“I have said, if you will not flee with Felipe—our son—as I believe in the holy Virgin, I will kill myself!”

“Enough—enough, I will go—my God, I will go!” faintly murmured the lady, as she swooned from grief and terror.

“This is a deeper pain to me, my darling, than death could bring,” he murmured, as he gently placed her upon a sofa, while the scalding tears fell freely from his eyes. “My God, to speak such words to her—my heart’s darling, when perhaps an hour may part us forever. It is hard, ah, so hard; but it was for her sake and our child’s,” and then he hastened from the room, after directing the terrified maid to attend to her mistress.

As he entered the hall, the cannon was fired for the second time, and the six-pound ball crashed through the barricade, shattering the furniture and scattering the splinters in every direction. One of the peons was killed outright, and several others severely wounded. Another shot as well aimed would clear the passage so that an entrance could be effected. Canelo knew that he had no time to spare, if he would save his dear ones.

As he looked for Tadeo Campos, he heard a loud shout and then the sound of a struggle in an adjoining room, or pantry, where there was a door leading out into the garden. Thinking the enemy had effected an entrance, he rushed to the place, just in time to see the capataz master one of the peons, and hurl him to the floor.

“What’s this, Campos? Is not that Pepe Raymon?”

“Si, senor,” panted the capataz, “and a precious scoundrel he is, too. What do you think? He was unbarring the door yonder to let in the savages—the cursed dog!”

“Are you sure, Tadeo?”

“Carrai! yes. He pretended to be badly wounded, but I watched him, and when he sneaked off here, I followed after, and was just in time, as you see. The upper bolt is drawn!”

“Then he must be put beyond chance of doing us any further harm. Take this pistol, and when it is unloaded, come to me. I have work for you to do.”

He had scarcely passed the door, when the report told that the traitor had met his doom, and then Campos overtook his master. In a few, quick words, Canelo told him what he required him to do, and although the capataz looked any thing but pleased at the task, he dared not hint as much.

He was to conduct his mistress and child, with the servant, by a rear exit, from the hacienda, trusting that the besiegers would be all occupied with the cannon and preparing for the assault, in front of the building, and the dense and smoke-laden fog, to effect their escape unseen. It would be risky to attempt securing horses, as the stable was probably occupied by the savages, so they were to hasten on foot to the chapparal, where they could lay concealed until the fate of the building was settled. It was risky, but would not entail as great danger as remaining in the building, when in a few minutes more, at the furthest, a hand-to-hand combat must take place.

Tadeo Campos first reconnoitered the ground, found the way clear, and then, after a few hasty words of parting, the husband, wife, and child separated, never more to meet on this earth alive.

And not a minute too soon, either. Another ball hurtled through the barricade and completed the breach. The haciendado returned to his men, and formed them into a double rank to meet the onset that he knew was coming. Over the heads of the kneeling ones, those in the rear leveled their escopettes, nerved with despair, to meet their fate like men. Many of them were the veriest cowards that lived, but now, under their master’s eye, and knowing that, while there was no chance of fleeing, no quarter was to be expected from their red-skinned foes, they would fight desperately and well.

Then came the rush. There was only a subdued rustling, as of many feet cautiously planted, and then from the dense fog a horde of the painted demons rushed into the breach left by the shattered door. Their own impetuosity came near being fatal to themselves, for, as the crowd became jammed in the doorway, and entangled in the mass of broken furniture, the clear, strong tones of Canelo rung out the order to fire.

The double volley, delivered at such close quarters, was withering in its effects. The savages fell in piles, almost blocking up the entrance, and the others shrunk back from such a deadly reception. The besieged, led by Canelo, sprung forward to meet them, with machetes, pistols, or clubbed guns. Then came an order for the savages to rush over their dead and close hand to hand.

Christobal Canelo started, as if thunderstruck. The order had been given in pure Castilian, and, moreover, he could almost have sworn that he recognized the voice as that of one whom he had befriended, trusted, and loved!

And then where did an Indian—a Comanche upon the war-path—learn to speak that language so perfectly? And to his braves; could they comprehend him? If so, they must be strange savages.

But he had no further time to ponder over the matter. The savages had rallied, and tearing their dead comrades from the breach, they swarmed into the house, led by a tall, sinewy man, who dashed into the midst of his foes. In vain Canelo strove to meet this person, for he knew that if their chief was slain, the assailants would probably retreat. But the savage ever eluded him, ever kept a crowd between him and the haciendado. He wielded a heavy saber that, while it seemed to shed the blows rained at him, like a magic shield, dealt death or gaping wounds at every stroke.

Several savages had singled out Canelo, and were pressing him hard. Two of their number had fallen before his sword, but he was wounded, and the blood flowed freely. It required all his address and activity to keep from being clenched from behind by his enemies; but then, as he clove down the foremost, he dashed to the wall, where he could no longer be surrounded.

The savages were all around with sabers or machetes, and he 16 was fast failing. Still he met them bravely. A saber laid bare his cheek but the man who dealt the wound went down the next moment with his head cloven in twain.

The tall leader of the savages saw this, and, hissing out a fierce oath, drew his pistol, and, retreating to the wall at a space that was free from combatants, deliberately aimed at the brave Canelo. The latter saw nothing of this, as he desperately struggled with his assailants. Then the finger pressed upon the trigger, and there came a flash, a loud report, and the haciendado sunk at the feet of his foes, with the blood slowly oozing from the little discolored hole in the center of his forehead, a dead man.

His death was noted by a peon, and he raised the cry. It was like depriving a ship in a storm of its rudder, the fall of their leader, and with but one or two exceptions, the besieged threw down their weapons and begged for quarter. But the mercy they received was like that rendered famous in the revolutionary war, as “Tarleton quarter.”

One by one they were cut down, even as they kneeled and implored mercy in the Virgin’s name, and in two minutes after the death of Christobal Canelo the only survivors were they who wore the paint and trappings of Comanche warriors; even those who were dying received a finishing stroke.

The leader did not await this. As soon as he had murdered the haciendado, he left the hall, and proceeded at once, and without hesitation, to the room where Canelo had so shortly before changed his wife’s resolve of sharing his fate. He looked through this apartment as though he was seeking some person, and then ran hurriedly into the other rooms, but with the same result. What he sought was not there.

Calling to his men in a tone choked with rage and baffled vengeance, he cried to one, a huge, herculean man:

“Mil diablos, Barajo, the birds have both vanished! But they can’t be gone far, for they were here an hour since. Take you a few men and circle around the place. Scatter, and look well, for if they are lost, what we have done here is all for nothing. Find them and a thousand pesos are yours. Al monte—al monte! Capa de Dios! why do you wait?” raged the disguised Mexican or Spaniard, for surely an Indian tongue never mastered the lingua Espagnol so perfectly.

But at length the men returned from a fruitless search, and then, half wild with rage and disappointment, the leader reluctantly gave the order for marching, and they filed out from the hacienda. The building was left intact, with the exception of what injury had been done by the cannon. The outhouses were undisturbed; the stock, both horses and cloven-footed animals, were abandoned. Truly they were a strange war-party of Comanches in more ways than one.

“Madre mia, why so sad this bright and beautiful day, when all should be as gay and happy as it is out of doors?” exclaimed a young girl, as she entered the room, and, kneeling at her mother’s feet, lifted the bowed head, holding it between her two dainty palms, and pressed affectionate kisses upon the pale cheeks and lips.

“Ah, child, if you knew what anniversary this sad day is, you would not wonder at my grief,” returned the elder lady, mournfully. “Luisa, child, how old are you?” she added, half vacantly.

“Why, mother, need you ask that?” laughed her daughter. “I am nearly nineteen! Almost an old woman, aren’t I?” and her soft, gleesome laugh again rung out.

“Listen, Luisa; you have never learned the true way in which your father—my husband, died. But you are old enough now, and I think I can bear to tell it all. I have been thinking of the past this morning—of your father and brother, child, who was stolen when you were a babe.”

“Stolen!” exclaimed Luisa, eagerly. “I thought you said he was dead?”

“And so he is—he must be, or I should have found him years ago,” murmured the mother; and then she detailed at length the incidents embodied in our first chapter, so far as she was conversant with them.

“We lay concealed in the chapparal, where the undergrowth was most dense, Felipe and I, together with Tadeo Campos 18 and Josefa. How we managed to reach the place, I know not. My mind was distracted with fear for my husband and my son. And then, as we crouched there, under a thorny mezquiti, we heard the loud shouts and tramping of men, as they searched for us, and we could hear them speaking in Spanish!

“Oh, how my poor heart bounded with joy then, as I thought that my husband had been victorious, and would have cried aloud to them, if brave, prudent Tadeo had not placed his hand upon my mouth, and bade me beware; that he feared they were foes.

“He said that he had suspected the men who had attacked the hacienda were not Indians, although disguised as such, but were Mexicans. Why, he did not say, but bade me remain quiet for my child’s sake, while he would reconnoiter, and learn for certain who the voices belonged to that we had heard. Then he crawled along and was gone but a few moments before he returned. One glance at his face told me the worst, and I swooned away in my great grief.

“It was but too true. The hacienda had been taken, and my husband killed, not by Indians, but by our own countrymen, although who they were or who led them we never learned. Toward midnight we cautiously returned to the house, and there I found your father, dead! shot through the brain!

“It was a horrible sight. The mangled bodies of our brave peons lay in heaps upon the floor, where they had been slain. Not one of them had been spared, or escaped that dreadful massacre, save us four. All were dead!

“The house, as you see, was left standing, the herds were untouched; nothing, save a few articles of plate and the ready money, was taken. Surely a war-party of Indians would never act in this manner, and it further confirmed a belief that the marauders were of our own country. But what was their object? Alas, I fear it was but to murder all, although for what reason I know not.

“We mounted our horses and fled from the spot, after burying your father, and did not rest until we reached the city of Guanajuato, where we arrived nearly dead from fatigue and hunger, and told our tale to the kind friends we met there. I 19 dispatched Tadeo Campos, with a note detailing the sad tragedy, to your uncle Augustin Canelo, who was then at the city of Mexico.

“He was fearfully enraged and grieved at his brother’s murder, and vowed to search the world over but he would have revenge. But we could give him no clue to the assassins. Well, he sent a number of his own peons to the hacienda, and when it was renovated we returned to it. He remained with us at my request, and for a year all went well. He would be absent for weeks at a time on business connected with his silver mines, or searching for some trace of the murderers.

“I thought my cup of sorrow was full, even to overflowing, but I had yet to endure more; another fearful blow awaited me. You, my child, were nearly six months old, when one day our little Felipe, the darling boy, so brave and beautiful, and the image of his father, was torn from me. He had been stolen, but by whom or how, could never be discovered. The Indians were very troublesome then, and I thought that perhaps they had stolen, perhaps murdered my son for the sake of the rich clothes and costly jewels that he wore.

“For long months we searched far and wide for some traces of him, but in vain. The river and arroyos were dragged, the chapparal searched inch by inch, but there were no traces found. In my grief I thought I should die, but it was denied me. And now do you wonder at my sorrow? On this day, nineteen years ago, my husband was murdered; one year later, on the same day, your brother Felipe disappeared—perhaps met the same fate!” and she bowed her head upon her hands, while the hot, scalding tears trickled through her fingers.

The girl at her feet sat in silence, her dark eyes dimmed at the tragical tale she had just listened to. Her sorrow was less than that of her mother, for her brother she could not remember, and the father her eyes had never rested upon, seemed but in a remote degree associated with herself. It was a subject that her mother had ever avoided, and Luisa was too gay and light-hearted to press the topic; so it is not to be wondered at that she did not feel the intense grief that agitated the form of her mother.

No one who could have seen her then would have pronounced her other than beautiful. She was rather under the 20 medium size, but so perfectly proportioned that she appeared taller. Her large, lustrous black eyes were shaded by lashes of the deepest jet, and her finely-arched eyebrows were of the same sable hue. Glossy black tresses were braided like a coronet around her finely-formed head, whence a mass of fine ringlets flowed over a neck and shoulders which would have been considered fair even in our land of blonde beauties, and in her sunny clime were deemed white as the newly-fallen snow. A stranger’s eye would detect and dwell upon the faintly dark shading on her upper lip, that in a youth might have been termed an incipient mustache. But is it a blemish? Her friends thought otherwise. It but added another attraction to her piquant beauty.

Her mother was slightly taller, but the same contour of face and great resemblance, although somewhat impaired by time and sorrow, showed that Senora Luzecita Canelo lived again in her daughter Luisa.

They were aroused by a light tap at the half-opened door, and glanced around.

“Well Josefa, what is it?” said Luisa.

The old nurse entered the room on tiptoe, as if fearful of disturbing the mistress, and whispered, in a low tone:

“It is a stranger, ’na Luisa, on particular business, he says, and—”

“Well, where is Sarguela; he attends to all such, as you know, Josefa,” interrupted the maiden, a little impatiently.

“Don Garcia is with him, but he says he must see the senora; that his business is for her ear alone,” hesitated Josefa.

“Wishes to see me,” asked the lady, looking up. “What and who is he?”

“That he will not tell; but he is a handsome cavallero, and—pardon me, lady, if I say that he is a perfect image of el coronel when I first saw him.”

“Of my husband?” exclaimed the lady, as her face flushed. “And young, say you? Oh, Santissima Virgin, if it should be—ah, no, he is dead long since,” she murmured; then added: “Go, Josefa, and show him here. I will see him.”

In a few moments the old nurse, as she was still called, returned and ushered in the persistent stranger. At first he appeared somewhat abashed and ill at ease, for the ladies had 21 arisen and were facing the door in half eager expectation, and quickly doffing his hat he made a stiff, slightly awkward bow.

“My heart, the picture!” faltered Senora Canelo, pointing to a full-length portrait of her husband, hanging against the wall.

Luisa instantly checked the smile that lurked around her rosy mouth, called forth by the outre demeanor of the stranger, and she too uttered an exclamation as she glanced from the face to the picture.

“I crave your pardon, ladies, if I appear rude, but I have seen so little of society, that for a moment I was dazzled,” he apologized, in a soft, musical tone. “Am I right in thinking I address Senora Canelo?”

“That is my name, senor; and yours?”

“Alas, lady, once I would not have hesitated in replying Felipe Barana; but now, if this packet does not give me a name, I know not that I have one,” replied the youth, in a mournful tone, as he advanced and placed a small parcel, securely tied and sealed, in the trembling hand of the senora.

“Felipe—he said Felipe, and then that face,” murmured she, as she sunk heavily into the chair she had just quitted, and with trembling fingers began to untie the package.

“Be seated, senor,” said Luisa, motioning to a chair, and placing one for herself, so as to partially screen her mother, whom she saw was strangely perturbed.

Senora Canelo tore the wrapper apart, and laying upon an inner package was a note superscribed with her name, in a bold, firm hand that seemed familiar. It was unsealed, and opening its folds, she hurriedly glanced at the contents. Then, with a wild cry, she started to her feet, and advanced a step toward the stranger, but her limbs refused to do their duty, and she sunk to the floor in a swoon.

Luisa bent over her, shrieking for help, and as she loosened the throat of her mother’s dress she caught the words:

“Felipe—my son—thank God!”

Josefa came rushing in, and unceremoniously hustled the stranger out of the room, and set about restoring her mistress.

“Never fear, ’na Luisa, it is only a fainting fit; there’s no cause of alarm. In a few moments it will be over.”

“Are you sure, Josefa, are you sure?” eagerly queried the sobbing girl. “Ay de mi! She looks like dead!”

“No, no; it’s nothing—nothing at all. Why, bless you, child, she’s had thousands of them!” returned the old nurse, exaggerating a little, the better to reassure Luisa. “See, the color comes to her lips, and, praise the Virgin, her eyes open!”

“Oh, mother, mother, I thought you were dead!”

“Where—where is he—Felipe, my son?” and the lady half raised from the lounge, glancing eagerly around the room, then sinking back, she wailed, “Nuestra Madre de los Merced! it was all a dream, a cruel, bitter dream!”

“No, no, it was no dream; he is here—the stranger, I mean, who looks so much like papa’s portrait. And see, here is the letter he gave you!” exclaimed Luisa, placing the note in her mother’s hand.

“Call—but no, I must have been mistaken; he is dead long, long since! My daughter, read what it says, to me; my eyes are blurred, and I can not see.”

Luisa opened the note with intense curiosity, but then looked up in surprise.

“Why, mother, it is from Uncle Augustin!”

“Yes, go on—read, quick!”

“My deeply-wronged sister:” it began, “when you read this, I shall be no more. I am dying, and the padre tells me that, before the sun goes down, I shall be dead. How this occurred, the bearer of this, my dying confession, will tell you. I have deeply wronged you and yours, and stained my soul with a horrible crime; but now make reparation as far as lies in my power. Listen, and, in God’s mercy, do not curse me after I am dead! I hired the men who, disguised as Comanches, attacked the hacienda nineteen years ago, and by my hand, my brother—your husband—died! I was mad, crazy, but I loved you, and thought that, if he was out of the way, in time you would listen to my suit. Then I caused your son, Felipe, to be stolen, and at the time meant to kill him, for I was poor, and he stood between me and wealth. But my heart failed me, and he yet lives, a noble, brave boy, who looks at me with your eyes and his father’s face. I can not tell you all I would of my reasons for the crimes I confess, for my strength is fast failing. But I will send this by YOUR SON, although he knows not who his parents are. I inclose the jewels and a scarf that he wore when he was first abducted, so that you may have no doubt. And now listen to my prayer, the last I shall ever make. I know I have been fearfully guilty, yet I do not think I could rest in my grave if you should curse me as the murderer of your husband. I do not ask for forgiveness, but that you will strive to forget me; as though I had never been born. May the holy Virgin ever smile upon and guard you, and cause the son I return to your heart to be a joy and a blessing. As I hope for mercy hereafter, he is your only son, Felipe.

“Augustin Canelo.”

The mother did not speak while this strange letter was being read, but pressed both hands tightly upon her bosom, as if to still the painful throbbings of her heart, while the breath came in gasps from between her pallid lips. When the last word was pronounced, she essayed in vain to arise; then, as she sunk back, feebly whispered to Luisa, who was scarcely less agitated than herself:

“Go, Luisa; go bring YOUR BROTHER to me!”

The sister needed no further prompting, but sped away like a startled fawn to the room where her brother had been so unceremoniously consigned by Josefa. He was pacing rapidly to and fro, his handsome countenance expressing no small degree of wonder and perplexity.

“Felipe, my brother, don’t you know your little sister, Luisa?” she cried, and throwing her arms around his broad shoulders, stood on tip-toe to press her lips to his.

He was startled, as well he might be, but the tempting lips, pouting out like twin cherries, would have enticed far older and more sedate hearts than his, and clasping her to his breast, he pressed kiss after kiss upon her blushing face, with an ardor that half alarmed her. Truly, it would be pleasant, really pleasant, to be a big brother, if all sisters were like Luisa. But the voice of the mother was heard from within, calling him to hasten, and Luisa said:

“Come, Felipe, brother; come to mother,” and together they entered the room.

Old Josefa stole out from the apartment, and we will follow her example, for the meeting between the long-parted ones was sacred. But an hour afterward the three were seated close together, while before them lay the jewels and scarf that the mother instantly recognized, and they removed any doubt that she could have entertained as to the reality of the youth’s identity.

“Do you recollect nothing whatever of this place, Felipe?” asked his mother.

“I can not just now. Perhaps it will come back to me when I am a little less bewildered. Remember what a surprise I have had; I, who thought I was alone in the world, without even a name,” he replied, as he kissed first one and then the other.

“No; the first I can remember is being in a little village on a mountain’s side, and then it changes to a vast and gloomy cavern, with wild-looking men all around me. I know now that they were Jarochos and a sort of guerilleros, who robbed; but I never knew of their shedding blood, unless in a quarrel between themselves. And as I grew older I became one of them. Do not start, or look so terrified, for you must remember that I knew no better. It was the way I had been taught and I thought all men were like us.

“The man whom I called father—your uncle, Luisa, who went by the name of Don Serapio Barana—was the chief or leader of the band, and he taught me this, and gave me the education I have; him and padre Gayferos. He would often be gone for weeks and months at a time, and then the lieutenant, Lopez Romulo, would be left in command. He was a wicked, cruel man, and I hated him!” Felipe added, while his eyes flashed and a hand crept to the jeweled hilt of the poniard that peeped from his bosom.

“Twice he insulted me so bitterly that, if it had not have been for those around me, I would have slain him like a dog, as he is. Well, one day, perhaps two weeks since, when I returned from a hunt of several days’ duration, I found Don Barana at the point of death. How it happened I only could learn that he had been wounded in an attack upon a conducta de plata” (convoy of silver), “in which the band had been repulsed with severe loss. Then he told me that he was not my father, but that he would send me with a package, and the one who received it would tell me all concerning who and what I was. He made me promise to deliver the packet into no hands but your own, as I valued my future.

“Then padre Gayferos dismissed us all from the room or chamber in the cave, as he wished to receive his last confession. In a few minutes they told me he was dead, and then I took a last farewell of my rough but kind friends. I amused myself on the long journey with picturing what would be my reception—who I would turn out to be; but ah, mi almas, the most romantic air castle did not realize the truth!” he exclaimed, as he caressed his newly-found relatives.

“Oh, my children,” murmured the mother, “this has ever been a fearful, horrible anniversary for me, hitherto, but now 25 it will be divided with joy. On it I lost a dear husband and a son; but the one is an angel in heaven, where he is now smiling down upon us, and the other is here! Oh, my son, my Felipe, we must never more part in this world. For eighteen years I have mourned for you, and—”

“And now, for thrice that long we will rejoice together!” exclaimed Luisa joyously, as she nestled closer against her brother’s arm, looking lovingly up into his handsome face.

The venta of tia Joaquina was widely celebrated among the miners of Los Rayas for the excellence of its liquors, the fine flavor of its cigarettes, and the buxom beauty of el patrona, or “the hostess.” Situated on the outskirts of Guanajuato, it was allowed a little more license then would have been shown it, had it stood in a more respectable portion of the city. Many a night of wild revelry, drinking, carousing, quarreling, and fighting had been passed there by the hotheaded young miners of the surrounding country, without fear of being interrupted by the entrance of the alguazils, to wind up their festivities by a morning visit at the levee of the alcalde.

Many a tragic scene had those old walls witnessed, either within or without, as the miners of Los Rayas, as a general thing, are not over punctilious in regard to the shedding of blood when their veracity or honor is deemed brought in question.

A young man was slowly approaching the venta, and although he kept his hand upon the haft of his cuchillo, it was more from habit than caution, for he was evidently in a deep reverie. But when he reached the door of the posada, he threw off this feeling, and entering the room, was met by the patrona, a large, handsome woman of perhaps forty years.

“Well, ’nor Marcos, you are here at last,” she exclaimed, warmly greeting the miner, who was an especial favorite with her. “The cavalleros have given you up, and, as you can hear, are enjoying themselves hugely,” she added, as a burst of laughter came from beyond a thickly-listed door.

“Yes, tia Joaquina, I was delayed, and even now, if I must confess the truth, I own more than half inclined to give the lads a cold shoulder to-night. I am not in the humor for revelry,” said he, in a low voice, that sounded rich and deep as the tones of a flute.

“P’r Dios, that would never do! There is business to be done to-night. I believe they have heard that on the morrow the Melladios are going to try the strength of your ‘Scarlet Shoulders,’ and see if the defeat you gave them at the last—”

“By the Virgin of Atocha! but that is good news,” exclaimed Marcos, his full, black eyes sparkling with ardor. “We will teach the—”

“H’la, ’na Joaquina!” shouted a voice, as the door was opened and a head thrust through the aperture from within. “Bring some more—mira, comarados, the capitan is making love to Santa Joaquina!” he yelled, as he caught sight of the young miner.

“Treason—treason!” they shouted, as several rushed forth, and, clustering around Marcos, forced him laughingly into the room, where he was greeted with cheers and vivas, that testified to his popularity.

It was a long, low-ceiled room, the rude adobe walls white-washed, but the rough rafters overhead were black with smoke and festooned with cobwebs, the accumulations of years. A rough table ran the entire length of the room, with a narrow passage at either end. Along the sides and secured to the walls were small stands, intended for three persons each, and all equally guiltless of cloth or covering of any kind. Lights were suspended from overhead, and, with candles stuck in niches around the walls, illumined the room sufficiently for the purpose.

A thick, hazy cloud of smoke now filled every crevice, being supplied by the glowing cigarette that each man held, some forty in number. Before them were scattered various utensils that were, or had been, full of liquor. Tin and bone cups, stone jugs and leather bottles, in every possible position that such utensils could possibly assume, covered the table. The patrona was far too careful of her crockery to intrust it in such hands, even though sure of being paid for the damage done. It was too scarce a commodity.

He who was called Marcos Sayosa finally seated himself at one of the side tables, with two of his more particular friends, who quickly enlightened him as to the truth of the subject hinted at by Joaquina. To understand it more fully, the reader must know that the men who worked in Los Rayas, and those of Mellado, a neighboring mine, were bitter rivals, each party contending that their mine was the richest and best, and many were the contests, both single and en masse, that had taken place; all leaving the point in question as far from being settled as ever. It had reached such a point that regular organizations were formed on both sides, with officers chosen, signals and passwords arranged, and the office of spy was well rewarded. Of the miners from Rayas, who had gained the soubriquet, “Scarlet Shoulders,” from the knot of ribbon of that color they wore around their left shoulder, Marcos Sayosa was the chief, while a middle-aged man, Perico Fuenter by name, commanded the opposition. The two war-cries, “Rayas” or “Mellado,” were as famous and promptly answered as that of the ’prentices in London of “clubs.” When they were heard, those not belonging to the faction barred their doors, and sought such place of security as they could find.

“You see,” said Lucas Planillas, the second in command, “they swear they will go through the town on the morrow, and make every man drink to the health of their cursed hole, and vow that it is far superior to our blessed mine.”

“I wish them joy of the attempt,” sneered Marcos, “but this—this spy; who is he? I never heard of him before as I know of.”

“Sylva Cohecho is his name. But who he is I know not, save that he gave the signals and grips all correct. Look, yonder he is, at the next table. Shall I call him?”

“No, no; I wish to take a good look at the gentleman first. So, that is he?”

The man that he looked upon was one that would have attracted attention in any company, not for his beauty, either of face or person; on the contrary, he was rather under-sized, but had the head and shoulders of a giant. As he faced the captain, with one arm dangling by the side of his seat, the immense length of arm and deepness of his chest 28 was fully revealed. His cheeks and chin was covered with a stiff, bristly mass of grizzled hair of much more recent growth than his mustache, the ends of which rested upon his shoulders. He was dressed in the usual holiday garb of the mineros, and from beneath the slouched brim of his straw hat one piercing black eye glanced around the room. The bridge of his nose was wanting, the purple scar showing that it had been mutilated by the same blow that had deprived him of his eye. Altogether he was not exactly the person a traveler would be pleased to meet upon a solitary road. And so thought Marcos.

“Voto a Brios, ’nor Lucas, but he is a hang-dog looking fellow. Are you sure he is not a spy upon the wrong side?” muttered Sayosa.

“You know as much about him as I do,” returned Planillas. “But if you suspect, better end it before harm is done. Say but the word, a nod, and he will never trouble any one, unless it is his master, the devil,” significantly tapping the hilt of his knife that peeped from his shirt frill.

“No, Planillas; at least not until I have had speech with him. The mezcal he is using so freely may loosen his tongue after awhile. But have you sent messengers to the rest of the band?”

“By daylight the city will be full, and all prepared for business,” said the lieutenant, as he lighted another cigar.

They sat conversing in whispers for some time, forming their plans for the expected assault, and drinking but sparingly. Then the young captain heard a name mentioned that made him start from his chair and listen intently.

“H’la, ’nor Carlos,” shouted a young man across the table, “you know how you were foiled by that little Carlita, the one who lives with old tio Tomas? Here is a cavallero who has been smiled upon by the Virgin, ay, and the black-eyed doncella, too!”

“Who is it you mean. Not yourself, I hope,” replied the man addressed, a little sarcastically.

“Not so happy. But I referred to Senor Don Despierto here.”

“’Tis true, senores cavalleros,” added Despierto, with mock modesty. “I saw the beautiful Carlita, and as I had nothing 29 of greater importance on my hands, I laid siege to her affections, and—succeeded.”

“By Venus, the cunning little prude, and she would not so much as even look at me!” murmured Don Carlos. “But how far did you succeed?”

“How far can—”

“Hold, Senor Despierto!” shouted Marcos, as he leaped forward and grasped the speaker by the shoulder. “Por todos de Santos! if you do not retract that base calumny, and say that you foully lied of one who is as pure as the holy Virgin herself, I will tear your tongue out by the roots, and force it down your throat!” he hissed, compressing his fingers until it seemed they would meet through the yielding flesh.

“Mil demonios, if you were twice my captain, you should answer for this,” gritted Estevan Despierto. “Unloose your hand, or I’ll unloosen it with a dose of steel.”

“Bah, if you looked on a knife you’d turn pale and run like a coyote!” said Marcos, as he hurled the other from his seat, half way through the crowd that had gathered around the disputants.

“Look out, Marcos; he’s drawn his cuchillo,” cautioned Planillas, as he leaped before his captain, who was prepared for the attack of his foe. “Abojo—abojo los armas (down with your weapons). Do you think there are no bodies to carve but those of your friends? Remember the Melladios!” he added.

“Peace, ’nor Planillas. He must either retract his words, and acknowledge he was lying, or not all the saints will save him from my vengeance,” calmly, but bitterly said Sayosa.

“A Despierto is not a Sayosa. He never denies his word,” sneered Don Estevan.

“Enough. Stand aside, comarados, and let us end this,” gritted Marcos, drawing his cuchillo and wrapping a frazada (a woolen cloak) around his left arm.

“H’la, senores,” called a voice from the crowd. “Fair play! let them fight upon the great table, so we can all see the sport.”

Ready for any thing that was novel, the mineros soon cleared the table, by brushing the drinking utensils upon the floor—thus proving the patrona’s prudence in abjuring 30 crockery. A few minutes sufficed for this, and then the combatants leaped upon the table, prepared for the sport, while the spectators crowded around the arena, or stood upon the little stands by the side of the walls, eagerly staking their money upon the first wound and result of the duel.

Marcos had doffed his hat and outer jayneta, revealing a closely-fitting garment of quilted silk. A sash was tightly bound around his waist, and a handkerchief secured his long hair from falling over his face. His antagonist was prepared much like the same. They were both handsome, well-built and hardened men, but there was a peculiar look about Despierto, that could only result from dissipation and excesses, that was not visible in his adversary, and the older gamesters freely laid their money against him. They knew that in a prolonged contest he must go down before his more temperate foe.

“Andela!” (forward), shouted Lucas Planillas.

At the word both men bounded forward, and their knives met with a clash that sent showers of tiny sparks to the table. Then their thrusts and blows were made so quickly, the parries and changes of position were so rapid, that the eye could not follow them. It was like the rapid shifting of the kaleidoscope when quickly turned. The eye could catch the motion, but ere it could fix the details, another combination would obliterate its predecessor.

Despierto was slowly being forced back, or retreated from policy, when, as Marcos stood near the edge of the table, Sylva Cohecho—he who had brought the news of the intended attack by the Melladios—thrust forth a hand, and strove to catch the young miner by the foot. If he had succeeded it must have been fatal, for Estevan would have profited by the stumble, and ended the combat then and there. But Lucas’ eye caught the motion in time to frustrate it, and as he delivered a swift blow behind the spy’s ear with his clenched fist, an adroit trip of the foot sent him headlong under the table.

“Cursed crookback, you would do murder?” yelled Planillas, drawing his knife and diving under the table just as Cohecho crowded out through the crowd, who were ignorant of the cause of the disturbance.

He ran to the door, and turning, saw Lucas dart forward. Drawing a pistol from his belt, he fired at the youth, the bullet piercing his sombrero, while a faint yell and heavy fall among the spectators told that the bullet had not been entirely harmless. Cohecho saw Planillas stagger, and thinking his aim had been true, burst open the door with a strong pull, and rushed through the bar-room, gaining the open street in safety, sending back a wild, taunting laugh of triumph.

Further pursuit would be worse than useless, so the miners returned to the room where the fight was still in progress, and a little knot gathered around the dead body of a youth, who had been shot through the brain by the missile intended for Planillas. The latter only gave one glance at the victim, and then turned to view the duel.

They were both wounded, but evidently not very severely. The perspiration ran in streams from their bronzed faces. Marcos adroitly unrolled the frazada that enveloped his left arm until it nearly reached the floor. And, as the motions of his knife were thus concealed, penetrated his antagonist’s guard, and sent his long blade to the hilt in Despierto’s body.

But an attempted parry of the latter diverted the aim slightly, and instead of passing between his ribs, as was intended, the knife glanced into his back, inflicting a painful flesh wound, but not disabling the duelist. The force of the blow, however, staggered him, and he fell upon his back, as his foot slipped upon some blood. Marcos kicked the knife from his grasp, and then kneeling upon his breast, pressed the point of his knife against the man’s throat.

“Now, base liar, unsay the words, or by the Virgin of Atocha, I will kill you like a dog!”

“I am Don Estevan Despierto!” scornfully replied the defeated duelist, as though in those words were contained his answer to the threat.

“Once more I ask you. If you do not, before I count ten, you will never speak again!”

“Bah! your arm is not strong enough, nor your heart brave enough to kill a man,” sneered Despierto, vindictively struggling to free himself.

For a moment all was breathless silence in the room. Naught was heard but the half-choked breathing of the man, who, laying 32 upon his back, with a foeman’s knees pressing into his breast—the dull, red gleam of the long knife that had already drank his blood, as it was poised above his throat, glancing full in his eyes, quailed not, but glowered fiercely at his conqueror, as if daring the final blow. Then a faint murmur ran around the room, half of admiration, half of pity for the bold, strong-hearted man who was about to meet his death. But no one offered to interfere; had he done so, a score of knives would have confronted him. By the miner’s laws of the entire country, Despierto’s life was forfeited to his victor, to be taken when and how his fancy might dictate. Still, a shudder ran over the spectators as the voice of the young miner began to count; it had a hard, metallic ring to it, that appeared to fill the entire room, like the clanging of a huge bell.

“Uno, dos, tres, cuatro, cinco, seis, siete, ocho—”

But he counted no further, for the door was thrown violently open, and Joaquina rushed in from the bar-room, screaming:

“Valga me Dios, cavalleros, you are betrayed! The accursed Melladios are here. Hay mucho—muchissimos!” (they are many.)

Instantly all was confusion. Several of those nearest the door ran out to the entrance to see if it was not a false alarm, while the rest hastily possessed themselves of their firearms that were stacked in the corner of the room. Marcos Sayosa arose from the prostrate body of his foe, and said:

“We will settle this affair afterward. Now, every man is needed. Will you help your comrades?”

“I belong to the band,” haughtily replied Despierto, “and will do my duty. You will not have to search for me, if we are both alive after we chastise these beggarly hounds.”

“Good! I will trust you.”

A loud roar, as of many voices, was heard from without, closely followed by a volley of firearms, and then two of the “Scarlet Shoulders” re-entered, bearing between them the wounded body of their comrade.

“Anda, comarados,” shouted Sayosa, “push the table against the door, quick; the ladrones are here!”

This was performed, but none too soon, for, as the massive table was thrust against the closed door, a rush was heard in the outer room, and the assailants gave it a fearful shock; but thanks to its brace, the heavy puncheon did not give way, although it shook upon its hinges. A volley was fired at the door, but it was only a waste of ammunition, as the four inches of well-seasoned wood resisted all such attempts.

“Out with the lights, men, and then open the loops. Perhaps we may return the compliments of our friends outside,” added Marcos.

The shouts of the besiegers in the tap room, together with the clashing of the bar fixtures, told but too plainly the fate of the patrona’s wines and liquors. Nothing else could be expected, for the mineros were not accustomed to having such a windfall every day, and even those who usually were so chary of the exhilarating beverage when good, hard money had to be disgorged in lieu, now emptied glass after glass.

Joaquina cowered in one corner of the room, ringing her hands in despair, as she pictured her loss, praying to the Virgin that the liquor might choke the ladrones, or pouring out a torrent of vituperation that only an enraged Mexicana could invent.

“Madre de Dios, good patrona, rest your tongue for a while,” exclaimed Marcos, half impatiently, “or the padre will require a fortune before he can absolve you at next confession. Look, if you are injured by this night’s work, we will make it up to you either in money or a venta.”

“Muy bueno, then I hope the villains will drink the barrels dry, for then they would be beyond doing you any harm.”

“Ha, that is a good thought! Is there enough for that, ’na Joaquina?”

“You will—”

“Capitan, there is a large body of men out here in full view. Shall we fire?” interrupted a man who was standing at a loop-hole.

He was speedily answered, for scarcely had the words issued from his lips, than a blaze of light shone in at the loop-holes, and the loud roar of many guns told that the half-drunken Melladios had fired a volley at the building. The man who had just spoken gave a convulsive spring into the air, and fell dead at his young leader’s feet, shot through the throat. A low, thrilling rattle, a gasp, and he was dead!

“Fire, men, fire!” yelled Sayosa, as he sprung to the loop-hole thus vacated, and sent his bullet with the rest.

The stars shone brightly enough to indistinctly reveal the forms of their assailants as they surged to and fro in the open space beyond, and at the dense mass were the guns discharged with deadly effect. The reports were followed by a hideous uproar: the groans and shrieks of the wounded, mingled with the hoarse yells of rage and vengeance of their comrades; the rushing tramp hither and yon, as they retreated or advanced, according to their courage or recklessness; the clang of steel, shot and escopettes against the pavement as the weapons were reloaded; the flash and dull roar as a piece was discharged at the building—all made up a wild, weird picture.

Afar off could faintly be heard the roll of a drum and call of bugles, showing that the town was alarmed, but that afforded neither fear to the one nor hope to the other party, for well they knew that the military force available could do nothing toward quelling the riots, and, before aid could be procured, the matter would be decided in one way or the other.

Marcos Sayosa had no fear of the ultimate result being against him. He knew that his comrades of the Rayas mine would soon learn of their situation, and, until they should arrive to the rescue, he could hold the building against the Melladios. So, by his orders, the men kept up a steady fusillade from the loop-holes wherever a foe could be seen, and by dodging as quickly as their shot was delivered, the return fire, aimed at the flashes, was harmless, although several bullets passed through the apertures.

Then came a wild, ferocious yell from the besiegers, as if at 35 the arrival of some powerful auxiliary. The occupants of the posada were not long left in doubt as to the meaning of this uproar. Indeed, the truth was suspected before the cries had died away, and those nearest to the door soon heard the roaring, crackling sound that but one thing emits—fire.

It was but too true. The Melladios had splintered the shelves, outer door, and bar-room furniture, piled it in the center of the room and against the partition door, poured spirits over it, and then applied a candle. Although the side-walls were of sun-dried bricks, or adobes, there was plenty of fuel in the floors, partition, roof and ceiling, that would burn like tinder, and was a danger not to be scorned.

“Bah! the drunken fools; let them yell. We will foil them yet,” sneered Sayosa. “Here, half a dozen of you cut a hole through the adobes at the further end. You can do it easily with your machetes and cuchillos. The rest of you keep up a fire on the demons out yonder. The light will reveal them plainly now, and it will keep them from suspecting what we are doing. This bonfire will show our conpairanos where to seek us, and then we will take a dear revenge upon these rascally dogs who disgrace the name of mineros!”

While uttering these directions, the young leader was not idle, but led the party in their work upon the end wall of the building. Under the sharp points of their weapons, wielded by strong and willing hands, the hard clay began to crumble and fall to the floor. But it was thick, and required time. The fire had already began to creep along the roof of the apartment, and the massive door showed signs of rapid burning upon its inner side. The room was oppressively hot and close; perspiration dampened the clothes of the besieged, and in their eagerness to obtain a breath of fresh air, through the loop-holes, they exposed themselves to the bullets of the beleaguers, and two were instantly killed, while several others received flesh-wounds in the head, more or less dangerous.

Then a blow, better directed than the rest, pierced the wall, the wielder’s hand and arm following the knife. They could not suppress a shout of joy, and worked on with increased energy to enlarge the aperture. Foot by foot it fell outward, and then, when it was large enough for their purpose, Marcos ordered his followers to reload all their firearms, as it was 36 likely they would be needed. Then, selecting two of the most trustworthy miners, he directed them to hasten at full speed through the town, and raise assistance by sounding the motto of the Scarlet Shoulders.

Then the little band pressed through the aperture, and the messengers darted off into the darkness upon their errand. Before the last of the Scarlet Shoulders were outside of the burning building, a loud shout told both them and the main body of their foes that they were discovered. A wild rush was made toward them, and telling the terrified patrona to flee for her life, Marcos retreated rapidly from the circle of light cast by the burning venta.

The Melladios came rushing on, outnumbering their rivals three to one, and evidently thinking that the Scarlet Shoulders would not dare risk a hand-to-hand combat. Indeed, several of the miners shouted out that the cowards were running, in a derisive voice. But if this was their thoughts, they were soon undeceived. As soon as the gloom was entered, and while the enemy were in the broad light, Marcos Sayosa directed:

“Comarados, when I give the word, fire, and then drop on your faces. The man that stands up will never do so again!”

The little band stood firm with leveled carbines, and the foe approached. Half crazed with drink, they thought not of caution, but with demoniac hoots and yells, they crossed the point Sayosa had selected as the limit. Like a clarion note the young miner’s voice sounded:

“Fire, men, fire!”

As a sheet of lightning the carbines vomited their contents almost in the face of the enemy, at less than twenty paces. The front ranks went down like the weeds before a prairie fire, as many, perhaps from surprise and terror as wounds. Those in the rear discharged a random volley, but as the Scarlet Shoulders had obeyed their leader’s orders and dropped to the ground, it was perfectly harmless.

“Now, compadres, out with your steel, and teach the cowardly dogs better manners than to molest men!” yelled Marcos, as he drew his machete and sprung into the melee.

Before the Melladios recovered from the confusion the unexpected onslaught had thrown them into, their foes were upon them, slashing and thrusting, fighting with sword in one hand, 37 a knife in the other with which to deal wounds or ward off blows, as might be. Thus a fearful scene ensued.

The dense mass of swarthy, powerful men, swaying to and fro, wielding the deadly weapons they had been familiar with from childhood; yelling, cursing, cheering and blaspheming like a horde of demons fresh let loose from pandemonium; the long black hair floating around their fierce, inflamed faces with every movement; the weapons flashing around them, clashing together until tiny showers of sparks gritted from the steel, falling swiftly, to rise again, gleaming a dull red, while the ruby drops of life-blood trickled from the edge or point; the shrieks and moans of the wounded wretches as they are trampled ruthlessly under foot; the falling forms of those who are stricken unto death in their tracks, or tottering away from the melee to fall in some unoccupied spot, where they can die undisturbed, save by the terrible din; while the burning house roars in concert, casting its ruddy light over the conflict, revealing every phase in all its details, and the crash of the heavy walls, seem in keeping with the fall of man.

Oh, what pen could portray such a scene? The dreadful interest of the whole would absorb the particulars.

Foremost among the Melladios was the form of the man who had betrayed the Scarlet Shoulders—he who had enacted the part of spy to lull their suspicions—Sylva Cohecho. Sayosa recognized him, and divining the true part he had played, strove to encounter him to reward his treachery. But whether by accident or design, in this he was baffled, for sometime, as was also Lucas Planillas.

The traitor seemed to bear a charmed life, and as his long, powerful arms wielded a heavy sword, he cut down or beat off all who attacked him, until at length Marcos found himself face to face with the spy.

“Accursed dog, I have met you at last, and now you will never play the spy again!” hissed the young miner, as he aimed a heavy, downright blow at his foe, but which slid harmlessly from the machete of Cohecho.

“Bah! you crow loud for a chicken that has not yet grown his spurs,” taunted the ruffian, as he returned the compliment. “Señor Estevan Despierto will not have you for a rival with ’na Carlita, after to-night.”

“I shall live to see the coyotes poisoned by your carcass, at any rate.”

The tumult was constantly increasing in the city, and was rapidly nearing the scene of the conflict; but the combatants did not heed that. The long-smothered rage and rivalry between the partisans had now broken bounds, and it must be a strong barrier that would be able to stay its course. Although blood had been spilled upon more than one occasion by the factions, it was only in solitary instances, settled rather as a duel between enemies than a partisan affair. But now the revolt had come to a head, and nothing but the complete defeat of one party could check the riots, unless, indeed, a military force should arrive sufficiently strong to compel peace—an event that was far from likely.

At this point of the contest, a crowd of armed men arrived upon the scene, and, with loud shouts of “Los Rayas forever!” “Down with the Melladios!” they plunged into the melee, and the next minute the enemy broke, and fled in every direction, darting into the gloom that was rendered more intense by the contrast with the ruddy glow of the still burning building, closely pursued by the victorious miners.

The rescuing party of Scarlet Shoulders who had arrived so opportunely, had been closely followed by the police and military force; but these prudently awaited until the battlefield was comparatively clear, when they boldly advanced and arrested several of the victors and a few wounded. But the cry for rescue was quickly set up, and the miners promptly rallied, with wild yells, and charged the troops. These latter worthies, deeming valor the better part of discretion, abandoned their captives and fled for their lives, seeing the folly of attempting a resistance.

The rioters well knew what penalty awaited them if they should become known, and collecting their wounded, speedily vanished to place them in security. But the affair was not yet over, as they well knew. The defeated Melladios would collect reinforcements, and another effort would be made to retrieve their lost honor.

The rioting and confusion did not entirely cease, although, owing to the retreat of the Melladios, it was but in an idle and desultory way, either among themselves or the police of the town. These last worthies, after one or two rencontres, left the city to the tender mercies of the victors, and sought safety in flight. But as many of the Rayas miners had families or friends living in the place, the principal source of danger was to be dreaded from the Melladios attempting to storm the city.

So the night wore on; fresh recruits coming in from time to time to join the Scarlet Shoulders under Marcos Sayosa, until he had a body of hardy, resolute men strong enough to make him have little doubt as to his being able to hold his own against whatever force might be brought against him. So, instead of fortifying any of the buildings, he contented himself with posting sentinels around the town, with attendants to carry the news in case any enemy should appear.

The few hours that intervened before daylight he spent in searching for Despierto, but without success. Whether he was dead, a prisoner, or had fled, he could only conjecture, but for the time his vengeance must be deferred.

About the middle of the forenoon a strong body of the Melladios appeared in view at some distance from the city, and Marcos Sayosa, at the head of the majority of his men, sallied out to give them battle. As they came within gunshot, a volley was exchanged, but without material effect, and the Melladios retreated before the impetuous charge of the Scarlet Shoulders, who pressed forward at speed with wild hurrahs of victory.

But then Sayosa hurriedly ordered them to halt, turning his face anxiously toward the town. They could hear the rapid reports of firearms and faint shouting, while the thin, sulphurous smoke could be seen rising above the housetops.

Then they comprehended the trap they had fallen into: 40 that the Melladios had signally outwitted them. They knew then the reason why the enemy had so suddenly and strangely retreated without joining, hand to hand. It was their object to draw the main force, if not all of the Scarlet Shoulders, from the advantageous position they held, under cover of the houses, and keep them employed while another body took possession of the city.

The plot was well laid, and a few more minutes would have insured its success, if, indeed, it had not been already accomplished. Sayosa knew that his only hope was to gain the city before his comrades were overpowered, or, placed between two fires, he would stand a fair chance of being cut to pieces.

“Back, comarados, back to the city! Never mind those ladrones; anda—anda!” he shouted, and darted forward at the top of his speed, closely followed by his men, all fully sensible that nothing but celerity of action and desperate fighting could repair the folly they had been led into.

Then the tables were turned. The pursued became the pursuers—the chasers chased. Each man strained every nerve, and ran as he had never ran before. The one to reach the city in time to assist their beleaguered comrades, the other to overtake and force the Scarlet Shoulders into a struggle that would detain them until the other division of the Melladios should have accomplished their mission.

Two men were seen to run from the town, but when they saw the miners returning, sped back to announce the news to those who had dispatched them for assistance.

The pursuers and pursued were scattered over the plains—the swiftest of the former close upon the heels of the rearmost of the latter. Fortunately all firearms had been discharged, or a serious loss would have been inflicted. As it was, more than one of the Scarlet Shoulders were cut down before the city was reached.

As the fugitives swept down an angle in the street, Marcos Sayosa halted, and ordered his men to face the foe. This was promptly done, and the bright swords and scarcely less terrible knives flashed in the sunlight. Others hastily began reloading their escopettes.

The enemy came sweeping on, uttering their wild yells and shouts of exultation. The rearmost of the men from whose 41 left shoulders streamed the bright knot of ribbon, came up and fell promptly into the ranks.

Then the Melladios swept around the corner, and so great was their impetus that many ran headlong into the close ranks of their foes, and then the cold steel began its work. Almost without resistance a score of the leaders were cut down, and then, while the remainder faltered at the sudden and unexpected resistance, the loud, clear tones of Sayosa rung out the order to charge!

And right bravely was his call responded to. Sounding their war-cry: “Rayas forever—down with the Melladios!” the Scarlet Shoulders rushed into the confused mass of men, and for a few brief minutes the blood flowed like water.

The enemy quickly rallied and fought desperately, but the momentary surprise had been fatal to their chance of successful resistance. Outnumbered and without order, they sustained the fearful onset for a time, and then, pressed back, slowly giving way, foot by foot, at first, and then more rapidly, until at length they turned on their heels and fled in despair, closely pursued by the victorious Scarlet Shoulders. But Marcos Sayosa sounded the recall, that was obeyed, and just in time.

Their comrades who had been left in the town now appeared in view, being driven back by their assailants. Sullenly and with desperate courage they fought the overpowering force of Melladios, stubbornly contending the ground inch by inch, borne back, not by superior bravery, but by mere force of numbers. But one man turned to flee in affright, and he was promptly cut down by one of his comrades.

Then sounding their war-cry, the victorious division of the Scarlet Shoulders pressed forward to the rescue, and the tug of war commenced. The Melladios, flushed with success, would not retreat, although now outnumbered, and the street was filled with the clash of steel and the horrible din of a death struggle. But the scale was turned by the miners of Rayas, the band who had reloaded their firearms, and at close quarters poured in a withering volley, some of the victims being scorched by the burning powder.

This started the retreat, and then began a bloody running fight from one end of the city to the other. Three several times did the fugitives rally and strive nobly to retrieve their lost 42 fortunes, but in vain. They were overmatched, and finally broke in every direction, each man fleeing as choice impelled him, only intent upon escaping the avengers who stood in their footpaths.

The pursuit was continued by the main body for several miles, and when they abandoned it a few still persisted. Marcos Sayosa led his triumphant band back to the town, and retiring to the house he had selected as his quarters for the present, with his officers, they deliberated as to what should be their future course. They well knew that should their identity become known, and they were captured by the military, there could be but one ending. And some hours they argued pro and con, without coming to any definite conclusion. They knew that in a short time the fugitive military would return with reinforcements, against which they would stand but a faint chance of making a successful resistance, even were they mad enough to attempt it.

The city was gloomy enough. The main street was still scattered with the dead and wounded miners, lying as they fell. The houses were all closed and barred, the inhabitants most likely trembling lest their doors should be forced and their wealth, perhaps even life, be taken. Several posadas had been forced open, and the Scarlet Shoulders were fast becoming uproarious over the confiscated wines and liquors.

The young captain was standing with Lucas Planillas and several others upon the azotea, still in consultation, when Sayosa suddenly paused, and, shading his eyes with his hand, peered keenly toward the south-west. The form of a single horseman was riding at a break-neck speed toward the city, while on the rising ground far beyond him could faintly be distinguished the light cloud either produced by a fire or the discharging of guns.

“Voto a Dios, ’nor Lucas, but I believe there is mischief going on yonder. Surely a fight is going on; perhaps some of our comarados are in trouble. Go you and see what the cavallero is spurring so fast for, and let us know as soon as possible;” and then, as Planillas departed upon his errand, Marcos turned to his companions, and added:

“Cavalleros, we may be needed yonder. See how many horses you can find before the lieutenant returns, and one of 43 you pass the word for the men to be in readiness to march, if needs be.”

As he turned toward the point where the horseman had been seen, he found that Planillas had just met him, and, after a few moments, during which, apparently, a few explanations were given, the man dismounted, and Don Lucas, vaulting into the saddle, galloped on toward the headquarters. Descending the steps, Sayosa awaited his approach, and, when within call, exclaimed:

“Well, amigo, what is it?”

“We are needed out yonder. There is an escort guarding some ladies that have been attacked by a band of Melladios, who outnumber them two to one. They have sent to ask assistance. Will you go?”

“Cascaras, yes! Go you and start what men you can find on foot. We will follow as soon as horses can be got. In a few moments,” hastily returned Marcos.

In two minutes the majority of the Scarlet Shoulders were en route on the double-quick toward the scene of the struggle, and three more saw about a score of horsemen, including the leaders, spur out from the city, well mounted upon confiscated horses that quickly carried them past the footmen, who were ordered to push on at top speed for the rescue.

The reason for the miners being all upon foot is not fully known, when perhaps there was not a man in the band but what owned one or more horses. But partly from policy, and partly from being ignorant of the period of the intended attack by the Melladios, such was the case.

In ten minutes the horsemen had reached the scene of the surprise, and were none too soon, for the peons were fast falling before the more numerous army of the assailants, and, although fighting desperately, were being forced back. At their head fought a tall, handsome cavalier, bare-headed and blood-stained, but whose saber drank blood at every stroke, while the rearing and plunging of his snorting horse helped to keep him free from the mass of miners that swarmed around him.

With a loud cheer of encouragement, the little band of horsemen plunged into the melee, and joined the leader, who welcomed them with a cry of pleasure. Still they were greatly outnumbered, and, although encouraged by the accession, the 44 peons fought with renewed energy, it was all they could do to hold their own against the raging mass. Time and time again did the horsemen charge among the enemy, beating them back with the desperate onset, yet each time the miners closed around them, and they had to cut their way out again, gradually losing some of their number, either by death or by being unhorsed.

The work was all done with the cold steel. There was no time to reload their firearms, and perhaps it was well that such was the case. The peons were ranged around a sort of coach, or close carriage, in which were the ladies, and obstinately retained their position, although so closely pressed that it seemed a miracle they were not annihilated. The bodies of their horses, and the ones which had drawn the carriage, were lying where they had been shot at the first onset.

Then with wild yells the foremost of the Scarlet Shoulders came up and poured a withering volley of musket balls into the close ranks of the Melladios. In the excitement their approach had not been noticed, or was unheeded. In a moment the struggle was changed, and with yells of dismay, the miners broke in confusion and fled from the spot.

“Andela, comarados, andela!” shouted Marcos Sayosa. “Give the cursed ladrones no quarter; give them a lesson they will not forget soon!”

The Scarlet Shoulders pressed hotly after the fleeing Melladios, fulfilling to the letter the order given them. Marcos Sayosa alone remained behind. The cavalier already mentioned was at the side of the carriage, and opening the door, eagerly exclaimed:

“Mother—Luisa, are you safe and unhurt?”

“Yes, yes, Felipe; but you? My God, you are killed!”

“No, it is only a scratch—nothing; a little cut from a machete, that is all. Thank the Virgin you are safe! I thought it was all over with us, when this cavallero came up,” and he turned to where the young miner sat upon his horse, wrapping his scarf around a severe gash in his left arm.

“Pardon me, senor, if I neglected you for a moment. But this is my mother and sister, and they might have been injured.”

“You were perfectly right, ’nor cavallero, and no apologies are needed. But if you will be so kind as to knot this troublesome scarf, I will remain your debtor,” returned Marcos.

“No, brother; it was for us that he received it, let me fasten it,” interrupted a musical voice from the carriage, and as the speaker looked forth, Sayosa gave a start of mingled admiration and wonder that called up a deeper blush to the cheek of Luisa Canelo, that made her still more charming.

“A thousand pardons, senorita, but I am a rough, unpolished miner, and the sight of such loveliness confused me. I really thought that an angel—there, see, I have sinned again!” he added, with a slight laugh of confusion, as he saw the effect of his words.

“It is a sin then that my sister has often provoked,” said Felipe, feeling slightly annoyed. “But pardon, again. This is my mother and sister. I am Felipe Canelo.”