Title: The Book Collector

Author: Charles Nodier

Author of introduction, etc.: Philip Hofer

Illustrator: Honoré Daumier

Translator: Barbara F. Sessions

Release date: October 5, 2021 [eBook #66469]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Crimson Printing Company, 1951

Credits: Tim Lindell, Donald Cummings and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Cambridge, Massachusetts

1951

The accompanying essay by Charles Nodier, 1780–1844, Librarian of the Arsenal in Paris, bibliographer, bibliophile, and a literary leader of the Romantic Movement, originally appeared in French under the title “L’Amateur des Livres,” in Les Français Peints par Eux-mêmes, Paris, 1841, Vol. III, pp 201–9. It seemed to me excellent, and so agreeably of its period, that I asked my friend Barbara Sessions to translate it, which she has now done, as far as I know, for the first time. Together we have edited the few parts which seemed slightly pedantic, and have added some notes which will explain the more abstruse literary, or bibliophilic, allusions.

Book collectors, M. Nodier to the contrary notwithstanding, are still very much alive, and can again be found even in the harried ranks of capitalists. But the learned French librarian was nearer right about his own pamphlets: They have indeed faded from memory. Now I hope this one of them may survive for a few more years, despite the ephemeral form in which you receive it.

August 1951 Philip Hofer

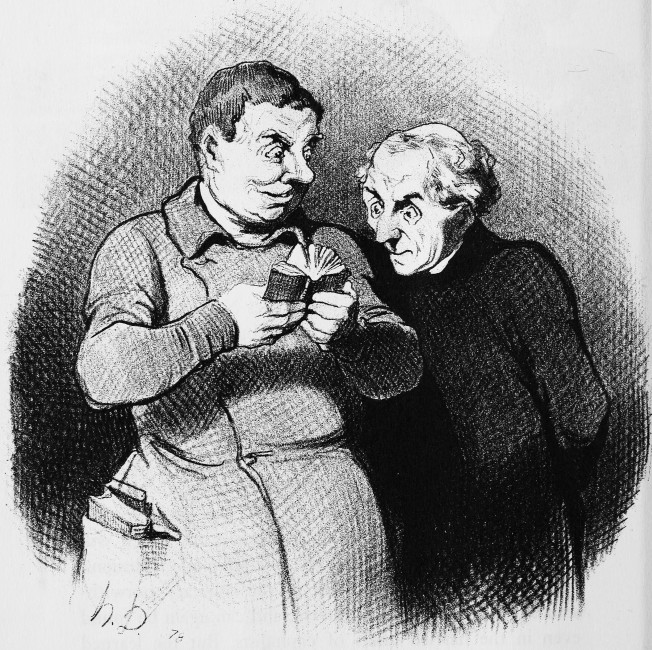

Rien n’égale ma joie ... je viens d’acheter pour cinquante écus un Horace imprimé à Amsterdam en 1780! Cette édition est excessivement précieuse: à chaque page elle est criblée de fautes!

Lithograph by Honoré Daumier, (1844)

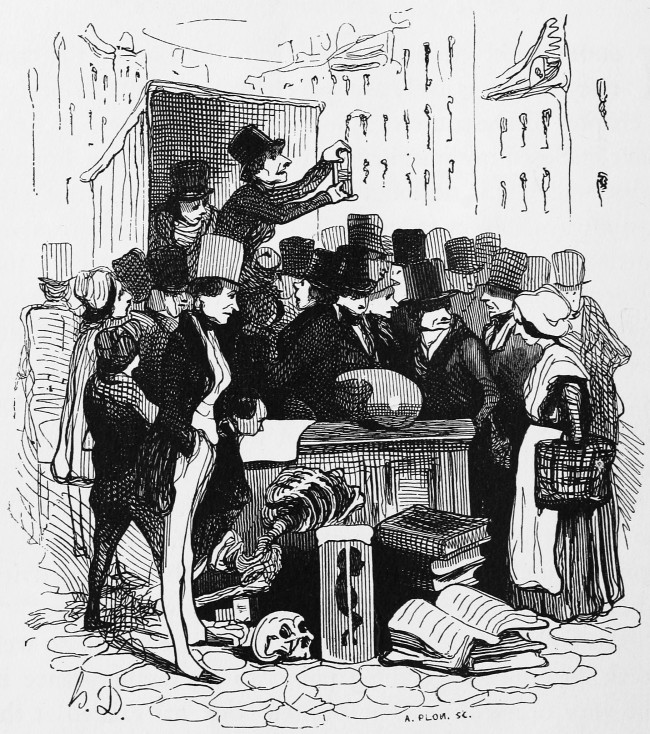

I should like to warn you, from the outset, that this essay will be as lively as a speech by Mathurin Cordier[1] or a chapter of Despautere![2] God, Nature, and the Academy have enclosed my imagination within these narrow boundaries, which it is no longer able to overstep. At least you can always refrain from reading me, and in that are more fortunate than I—who, following the dictates of a too exigent publisher, have no choice but to write. The drawings were made, the plates were ready; and the only thing needed to complete the issue was a long and unprofitable text. Well, then—here it is! But you will be disappointed if you expect to find in it one of those clever portraits to which your favorite authors have accustomed you. If what you are seeking is an original and telling sketch of the bouquiniste, the second-hand-book addict, then you need go no further. Pause here, and, following the modest advice of certain almanacs: “See illustration on opposite page.”

The collector of books is a type which we would do well to define, since everything points to his disappearance in the very near future. The printed book has existed at the most for some four hundred years, yet books are already accumulating in some countries in a manner that threatens the very equilibrium of the globe. Civilization has reached the most unexpected of its ages, the age of paper. Now that everyone writes books, no one shows any particular eagerness to buy them. Besides, our young authors are well on[8] the way to building up whole libraries for themselves out of their own works. They need only be left to their own devices.

If we were to subdivide the species book collector into its various classes, the top-most rank in the whole subtle and capricious family should without doubt be given to the bibliophile.

The bibliophile is a man endowed with a certain amount of intelligence and taste, who derives pleasure from works of genius, imagination, and feeling. He enjoys his mute[9] conversations with great minds—unilateral conversations which can be begun at will, dropped without discourtesy, and resumed without insistence; and, from this love of the absent author whose words have been made known to him through the device of writing, he comes insensibly to love the material symbol in which those words are clothed. His feeling for the book is like the love of one friend for another’s portrait, or of the lover for the portrait of his mistress; and, like the lover, he wants the loved object to look its best. He would not be happy to leave the precious volume that has so enthralled him clad in the drab habiliments of poverty, when it is in his power to clothe it luxuriously in watered silk and morocco. His library, like the gown of a favorite, is resplendent with gold lace; and his books, by their outward look alone, are worthy—as Virgil would have said—of the regard of consuls.

Alexander was a bibliophile. When victory put into his hands the rich coffers of Darius, he was able to fill them with the rarest treasures of Persia. The works of Homer were among the spoils.

Bibliophiles today are vanishing along with kings. In the past, the kings themselves were bibliophiles, and it is to their enlightened munificence that we owe the copying of so many manuscripts of inestimable value. Alcuin was the Gruthuyse[3] of Charlemagne, just as Gruthuyse was the Alcuin of the Dukes of Burgundy. The salamanders of François Ier will become as widely known through his beautiful books as through his architectural monuments. His son, Henri II, entrusted the secret of his love cipher to the magnificent bindings in his library, just as he did to the sumptuous decoration of his palaces. The volumes once[10] owned by Anne d’Autriche[4] still delight the connoisseur by their chaste and noble elegance.

Great lords and statesmen echoed the taste of their sovereigns, and there were as many rich libraries as there were families with shields and escutcheons. Almost down to our own day, the houses of Guise, d’Urfé, de Thou, Richelieu, Mazarin, Bignon, Molé, Pasquier, Séguier, Colbert, Lamoignon, d’Estrées, d’Aumont, de la Vallière, rivalled one another in their treasures of learned and serviceable books. I have named but a few of these noble bibliophiles, quite at random, in order to spare myself the tedious task of naming them all. To compile future additions to this list will be a less embarrassing task to those who come after us!

Even more remarkable—finance itself once showed a love for books. How it has since changed! King François Ier’s treasurer, Grolier, alone, did more for the progress of typography and binding than will ever be accomplished by all our paltry medals and our grudging literary budgets. A mere dealer in wood, M. Girardot de Préfond[5], bolstered his slightly insecure claim to nobility by using his money in the same worthy fashion, thus earning at least the immortality of the bibliographies and catalogues. Our bankers of today show no signs of envying him.

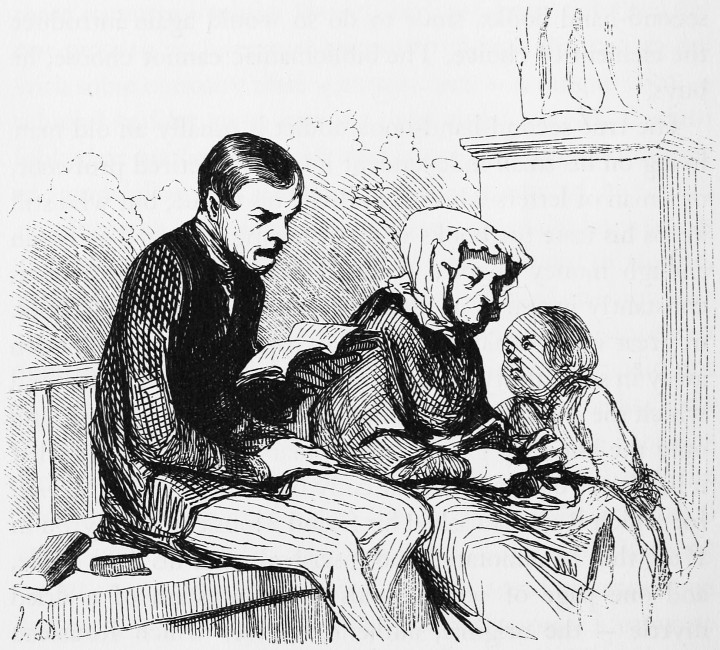

Alas, the bibliophile is no longer to be found in the upper classes of our progressive society (I ask your pardon for the adjective, but it will have to stand, by your leave, along with the verb to progress); the bibliophile of the present day is the scholar, the man of letters, the artist, the small independent proprietor or the man of moderate fortune, who finds in dealing with books some relief from the boredom and insipidity of dealing with other men, and who is, to some extent, consoled for the deceptive nature of the[11] other affections by a taste which, though perhaps misplaced, is at least innocent. But such a man will never amass important collections; it is, alas, the exception if his acquisitions are still there to meet his dying gaze or to be left as a modest legacy to his children. I know one bibliophile of this sort (and could tell you his name if I chose) who has spent fifty years of his hardworking life in building up a library, and in selling his library in order to live. There is a bibliophile for you, and I warn you that he is one of the last of the species. Today, it is love of money that prevails; books no longer offer the slightest interest.

The opposite of the bibliophile is the bibliophobe. Our great gentlemen of the political and banking worlds, our great statesmen, our great men of letters, are for the most part bibliophobes. For this imposing aristocracy which our happy advances in civilization have brought to the fore, education and human enlightenment in general date at the most from Voltaire. In their eyes, Voltaire is a myth which sums up the discovery of letters by Trismegistus and the invention of printing by Gutenberg. Since everything is to be found in Voltaire, the bibliophobe would have no more hesitation than Omar in burning the library of Alexandria. Not that the bibliophobe reads Voltaire! He takes pains not to read him; but he is grateful to have Voltaire to turn to as a specious pretext for his disdain for books. For the bibliophobe, anything that is no longer “current” is already waste paper; he lets nothing accumulate on his neglected shelves but moistening sheets and spotting pages—until such time as he unloads the whole mass of damp rags,—sterile tribute from some famished muse or other,—into the hands of the passing rubbish-collector, who pays less for them than their value by weight. The bibliophobe, in[12] other words, accepts the homage of a book and then sells it. It goes without saying that he does not read it, and never pays for it.

About ten years ago a foreigner, a man of genius, was overtaken in a Paris café where he had just finished lunching by one of those absurd predicaments in which the profoundly absorbed thinker all too often finds himself. He had forgotten his purse, and was helplessly searching his portfolio for a pound note which might accidentally have strayed there, when his eyes fell, among his papers, on the address of a certain millionaire who lived nearby. He wrote a card to this respected nouveau riche, requesting an hour’s loan of twenty francs, dispatched a waiter with his note, and after a certain interval received as his only reply a no as inflexible as that of Richelieu to Maynard![6] Providentially, a friend appeared and helped him out of his difficulty. Up to this point, the story is in no way out of the ordinary, and hardly merits being told—but it is not yet finished. The man of genius attained fame (something which does occasionally happen to genius) and then died (something which happens sooner or later to everyone). The fame of his works penetrated even the halls of the Bank, and the price paid for his autographs, though not quoted on the Bourse, made something of a sensation in the sales. I myself saw this noble appeal to French urbanity bring 150 francs at an auction sale where our bibliophobe, the man of wealth, had entered it in the hope of catching some collector’s fancy, and I have no doubt that this small capital has by now been tripled in hands so discreet and knowing. All of which goes to show that a favor withheld is no more lost than one that is granted!

There is one type of bibliophobe, however, whom I can[13] pardon for his brutish antipathy toward books. This is the good, sensible man of little cultivation, who feels a horror for books because of the ways in which they are misused and the harm which they do. Such was the attitude of my old companion in misfortune, the Commandeur de Valais, who said to me, gently turning in his hand the sole volume that remained of my library (it was, alas, a Plato!): “Away with it, in the name of God! It is rascals like this who prepared the Revolution.” “For my part,” he added, twisting somewhat coquettishly his gray moustache, “Heaven can witness that I have never read a single one of them!”

The distinguishing marks of the bibliophile are the taste, the delicate and resourceful tact, which he applies to everything, and which contribute an inexpressible charm to life. One might even be so bold as to warrant that the bibliophile is to all intents and purposes a happy man, or at least that he knows how happiness can be achieved. That good and learned book-lover, Urbain Chevreau,[7] has given us a marvelous description of this kind of happiness, as he himself experienced it. You will agree with me, if you will listen to his words for a moment instead of to mine: “I never know boredom,” he writes, “in my solitude, where I am surrounded by a large and well chosen library. Speaking in general terms, all the Greek and Latin authors are to be found there, whatever their profession: orators, poets, sophists, rhetoricians, philosophers, historians, geographers, chronologists, the Church Fathers, the theologians, and the councils. Antiquarian writings are there too, and all sorts of curious tales; many Italians, a few Spaniards, and modern authors of established reputation. I have paintings and prints; outside, a garden full of flowers and fruit trees; and, in one of the rooms, a group of house-musicians who, by their[14] warblings and chirpings, never fail to wake me in the morning and to entertain me at my meals. The house is new and well-built, the air is wholesome, and—to make sure that I do my duty—there are three churches just outside my doors.”

If Urbain Chevreau had lived in the time of Sulla, I wonder whether the Roman Senate would still have dared to proclaim Sulla the happiest man on earth; yet, on second thought, I am inclined to think that it would—for in all probability the Senate would never have known that a person like Urbain Chevreau existed. You will have noted, in fact, that this worthy man—the object and model of my favorite studies and the delight of my happiest hours of reading, praesidium et dulce decus meum—has, in the charming picture he has given us of his so enviable existence, either forgotten to mention, or himself failed to realize, the rarest and most precious ingredient of his happiness. Chevreau was happy because he knew how to be satisfied with what he had, and to do without fame and glory. He was so completely forgotten in his own time that, although he was a superb scholar, he was never made a member of the Academy! Still, envy and hatred passed him by, just as did acclaim, leaving him to die among his books and his flowers in the eighty-eighth year of his age. May the earth rest lightly on this most lovable and erudite of bibliophiles—according to the now consecrated words on his tomb.

But what has become of his books—those books so well chosen by Urbain Chevreau and so well kept, of which there has been no mention in any recent catalogue? Here is a question of vital importance, pressing, insistent; a question which will be of great concern to society once society has dropped its absorption in the absurd nonsense of humanitarian[15] philosophy and bad politics with which it is now infatuated!

The bibliophile knows how to select books; the bibliomaniac hoards and amasses them. The bibliophile puts a book in its right place on the shelf, after having explored it with all the resources of sense and imagination; the bibliomaniac stacks his books in piles without ever looking at them. The bibliophile appreciates the book; the bibliomaniac weighs or measures it. The bibliophile works with a magnifying glass, the bibliomaniac with a measuring-stick. Some who are known to me compute the growth of their libraries in square metres. The harmless, deliciously enjoyable fever of the bibliophile becomes, in the bibliomaniac, an acute malady bordering on delirium. Once it has reached that fatal stage of paroxysm it loses all contact with the intelligence and resembles any other mania. I do not know whether or not the phrenologists, who have discovered so many absurdities, have as yet localized the collector’s instinct—developed to such a high degree in some poor devils of my acquaintance—within the box of bone which houses our poor brain. Long ago in my youth I knew a man who collected corks of historic or anecdotal interest, and kept them arranged in orderly rows in his immense garret, each with its instructive label indicating on what more or less solemn occasion it had been originally drawn from the bottle. One label, for instance, read: “M. Le Maire, Champagne mousseux of first quality: Birth of His Majesty, the King of Rome.”—The skull of the bibliomaniac must have approximately the same protuberances.

Only a step separates the sublime from the ridiculous; only a crise, the bibliophile from the bibliomaniac. The one often turns into the other through mental deterioration or[16] increase of fortune—two grave afflictions to which the best of men are subject, though the first is far more common than the second. My dear and honored master, M. Boulard,[8] was once a scrupulous and fastidious bibliophile, before he amassed in his six-story house 600,000 volumes of every possible format, piled like the stones in Cyclopean walls! I remember that I was going about with him one day among these insecure obelisks (which had not been stabilized by our modern architectural science), when I chanced to ask with some curiosity after a certain item—a unique copy—which I had let go to him in a celebrated sale. M. Boulard looked at me fixedly, with that gracious and humorous air of good-fellowship which was characteristic of him, and, rapping with his gold-headed cane on one of the huge stacks (rudis indigestaque moles), then on a second and third, said, “It’s there—or there—or there.” I shuddered to think that the unfortunate booklet might perhaps have disappeared for all time beneath 18,000 folios; but my concern did not make me forget my own safety. The gigantic stacks, their uncertain equilibrium shaken by the tappings of M. Boulard’s cane, were swaying threateningly on their bases, the summits vibrating like the pinnacles of a Gothic cathedral at the sound of the bells or the impact of a storm. Dragging M. Boulard with me, I fled before Ossa could collapse upon Pelion. Even today, when I think how near I came to receiving the whole series of the Bollandist[9] publications on my head from a height of twenty feet, I cannot recall the danger I was in without pious horror. It would be an abuse of the word to apply the name “library” to menacing mountains of books which have to be attacked with a miner’s pick and held in place by stanchions!

The bibliophile ought not to be confused with the bouquiniste,[17] the second-hand-book addict, of whom I shall now have something to say, although the bibliophile is by no means too proud to visit the second-hand book-stalls from time to time. He knows that more than one pearl has been cast before swine, and more than one literary treasure found in vulgar wrappings. Unfortunately, luck of this sort is extremely rare. As for the bibliomaniac, he never looks over second-hand books, since to do so would again introduce the element of choice. The bibliomaniac cannot choose; he buys.

The true second-hand-book addict is usually an old man living on his small independent income, a retired professor, or a man of letters who has outlived his vogue, but who still keeps his taste for books without having managed to retain enough money to buy them. It is this last type who is constantly in search of that rara avis, the second-hand book of great value, which chance may capriciously have hidden away in some dusty old shop—like an unmounted diamond which the common eye would take for a piece of glass, and only the knowing gaze of the lapidary recognizes for what it is. Have you heard of that copy of the Imitation of Christ for which Rousseau asked his friend Monsieur Dupeyrou in 1765, that he annotated and inscribed with his own name, and one page of which holds the impression of a dried myrtle—the original, authentic flower which Rousseau plucked that same year under the thickets of the Charmettes? M. de Latour is the owner of this jewel of modest mien which is worth more than its weight in gold; it cost him 75 centimes. There is a prize for you! Still, I am not sure that I would not be equally glad to own the volume of Théagènes et Cariclée[10] which Racine laughingly turned over to his professor with the words: “You can burn that; I[18] know it by heart.” If that pretty little book is now no longer on the quais, with its elegant signature and the Greek notes in miniature characters which would identify it among a thousand others, I can guarantee that it once sojourned there. And what would you say to a copy of the original edition of the Pedant joué of Cyrano, in which the two famous scenes[11] are enclosed in large brackets, with this brief note by Molière jotted in the margin: “This belongs to me”? Such are the joys, and for the most part, it must be confessed, the marvelous illusions of the second-hand book. The learned M. Barbier,[12] who published so many excellent notes on the subject of anonymous writings[19] (and who also left much unsaid), promised to issue a special bibliography listing the precious books found on the Paris quais over a period of forty years. If this manuscript of his were lost, it would be a misfortune for the world of letters—but above all for the devotee of second-hand books, that skilled and adroit literary alchemist who is never without his dream of the philosopher’s stone, and who even finds chips of it from time to time, without showing any particular concern for having them mounted in the rich setting of de luxe bindings. The bouquiniste has the life-long conviction of owning something that no one else owns, and would shrug his shoulders patronizingly before the coffers of the Grand Mogul himself; but he has compelling reasons for not decking out his treasures in a meaningless display of luxury, though he disguises his real motives under a thoroughly specious excuse. “The livery of age,” he says, “adds as much to the look of early printing as patina does to bronze. The bibliophile who sends his books to be bound by Bauzonnet[13] is no better than the numismatist who has his medals gilded. Leave brass its verdigris, and the old book its worn leather.” The truth behind all this is that Bauzonnet’s bindings are expensive, while the bouquiniste is far from rich. We agree that cosmetics are a near sacrilege when applied to beauty, and that books should not be abandoned to the dangers of restoration except as a last resort; but rest assured that fine array harms a book no more than it harms a beautiful woman!

The term bouquiniste is one of those words of double meaning which unfortunately abound in all languages. It is applied both to the amateur in search of old books and to the poor open-air merchant who sells them. In times past the dealer in second-hand books lacked neither a certain[20] standing nor prospects for the future. He was occasionally known to make his way up from a modest side-walk stall, or a chilly push-cart to the dignity of a real shop measuring all of six meters square. A case in point was that of Passard, recollections of whom may still linger in the Rue du Coq. And who could forget Passard, with his close-cropped hair, his short trumpet-shaped queue, and his ill-matched eyes—the large eye tawny and prominent, the small eye blue and deep-set—which a whim of Nature had given him to bring his physical appearance into line with the eccentric originality of his character? When Passard, the right corner of his mouth raised in a slight sardonic twitch, was in the mood for talking; when his little blue eye began to sparkle with a malicious gleam which never appeared in the large, lifeless eye; then you might expect to see unrolled before you the whole chronicle of literary and political scandal of forty eventful years. Passard, who had once peddled his way from the Passage des Capucines to the Louvre and from the Louvre to the Institut, his portable book-shelf under his arm, had seen, known, and despised everything from his exalted station as bouquiniste!

I have cited this obscure book-seller whom no biographer will ever celebrate—Passard, the Brutus, the Cassius, the last of the bouquinistes. Now I move on. The present-day keeper of a book-stall on the bridges, the quais, the boulevards—poor, anomalous, battered creature, who picks up only half a living from his unwanted stock—is a mere shadow of the bouquiniste; for the bouquiniste is dead. It is a great social catastrophe, his disappearance, but one of the inevitable consequences of progress. A harmless and innocent by-product of the superabundance of good literature,[21] he could not, in the nature of things, survive its decline. In that age of ignorance from which we have now had the good fortune to emerge, the publisher was, in general, a man capable of appreciating the books he published; he printed them on good solid paper, supple and resonant, and, when they were sufficiently important, had them bound in sound moisture-proof leather, well-glued and stoutly sewn. If by chance the volume found its way to the second-hand book-stall, that did not spell its ruin. Whether of sheep-skin, calf, or parchment, the binding—blanched and hardened in the sun; moistened, stretched, and softened by passing showers—still afforded lasting protection to the visions of the philosopher or the dreams of the poet. The progressive publisher of today knows that the fame of his books, after the brief baptism of advertising, will vanish in three days along with the feuilleton. He puts a yellow or green paper jacket over his ink-spotted pages, and abandons the whole absorbent rag to the mercy of the elements. A month later, the wretched volume is lying on the stall-keeper’s shelves, a prey to a brisk morning rain. It drinks in the moisture, loses its shape, becomes mottled here and there with brown spots, gradually reverting to the pulp from which it came; with little more preparation it is ready to be stamped into cardboard. Such is the life-cycle of the book in our progressive times!

The bouquiniste of other days, presiding over his noble and venerable volumes, has nothing in common with the pitiable vendor of damp paper who offers for sale the mildewed rags which are the remains of the new books. The bouquiniste, I tell you, is no more—and as for the brochures which have replaced his bouquins, they will have[22] faded from memory in twenty years. I should know, since I am responsible for some thirty of them.

And do me the favor of telling me, if you can, what will be left of these books of mine in twenty years?

Paris, 1840 or 1841

Ch. Nodier

No book is completed until Error has crept in & affixed his sly Imprimatur

[1] Mathurin Cordier, ca. 1480–1564, French educator and austere author of numerous works for children of a moralizing nature. Calvin was among his pupils in Paris.

[2] Jan van Pauteren, ca. 1460–1524, Flemish writer whose latin grammar, however popular in its own day, was widely attacked in later times for its obscurity.

[3] Louis van der Aa, called Louis de Bruges, Seigneur de la Gruthuyse, ca. 1425–1492, a learned nobleman of Flanders who, commissioning some of the finest manuscripts which have come down to us, set an example for Charles the Bold of Burgundy.

[4] Anne of Austria, 1602–66, daughter of Philip III of Spain, wife of Louis XIII of France, a great book collector.

[5] Paul Girardot de Préfond, eighteenth-century French collector, whose fine books are now scattered in many libraries.

[6] François Maynard, 1582–1646, a French author, who, having vainly sought favor, loudly lamented his fate from the scene of his retirement in Toulouse.

[7] Urbain Chevreau, seventeenth-century French writer of some reputation in his own time, and a very discriminating bibliophile.

[8] Antoine-Marie-Henri Boulard, 1754–1825, avid collector who lived in Paris.

[9] The Bollandists are Belgian Jesuits who published the voluminous and weighty Acta Sanctorum legends of saints, arranged according to the days of the calendar.

[10] Paris, 1613 or 1623, an adaptation in verse from the Historia Ethiopica of Heliodorus.

[11] Two scenes of Cyrano used by Molière in the Fourberies de Scapin, Paris, 1671.

[12] Antoine-Aléxandre Barbier, 1765–1825, bibliophile, and author of a Dictionnaire des Anonymes.

[13] Antoine Bauzonnet, Paris bookbinder of the mid-nineteenth century.

750 Copies printed by the Crimson Printing Company

Reproductions by the Meriden Gravure Company

Transcriber’s Note:

Obvious punctuation and spelling inaccuracies were silently corrected.