Wemicus had a very large family. Many of his children had married the different animals

who lived in various parts of the surrounding country. By and by he had nearly all

kinds of animals for his sons-in-law, and there were still a great many children left

in his family. When winter came, Wemicus was unable to support his family, as there

were too many of them. They were all living in one wigwam.

One day Wemicus said to his wife, “We are all very hungry. I might go and see one

of our sons-in-law; he might have some [40]food.” Next morning he started out. Wemicus always tried to imitate the actions of

everybody he saw. When he reached the home of his son-in-law Ninicip (Black Duck)

he saw that he also had a large family. Ninicip was inside of his wigwam, and when

he saw Wemicus coming, he told his wife, “You had better begin to get ready for company

and boil water in the stone pail.” Then he jumped up upon the cross poles in his wigwam16 and in vas lapidum sub se17 defaecavit, telling his wife to stir up the contents of the pot. Wemicus apparently saw nothing

of this. Then one of the children of Ninicip took spoons and, dipping them in the

pot, said, “Soup, soup, soup, rice soup.” Wemicus tasted the soup, thought it tasted

good, and decided that after this he would make soup in the same manner.

The next morning, when Wemicus started for home, he was given some rice soup to take

home to his children. Before leaving the wigwam of Ninicip, however, Wemicus had purposely

left behind one of his mittens. One of the children saw the mitten and Ninicip’s wife

sent the child to return it, bidding him not to go too close to Wemicus but to throw

him the mitten. The child did the bidding of his mother and, when the mitten was thrown

to Wemicus, he said, “Ask your father to come and see me,” and he named a certain

day. On the way back home Wemicus thought, “I wonder what this soup tastes like when

it is cold. I must try it. My children don’t need any of it, so I might as well eat

it all.” So he ate all of the soup. When he reached his wigwam he said, “Ninicip and

his family are starving also. To-morrow he will come to see us and perhaps he will

bring us something. We had better fix up our wigwam.” Then they fixed up the wigwam

in the same manner as that of Ninicip. The next day Ninicip came and they gave him

the best place. Wemicus said to his wife, “We’ll get ready to eat now. Put some water

in the stone pail.” “There is no use putting any water in the pail,” answered his

wife, “we have nothing to cook.” “Well, bring the pail, anyway, and get some spoons,”

said Wemicus. When the water began boiling, Wemicus jumped up on the cross-poles,

in vas defaecavit, all over his children and the inside of the wigwam. Then Ninicip went out. His wife

[41]scolded Wemicus, saying, “You always do something like that. You must have seen someone

do that.” Then Wemicus kept quiet and everything had to be cleaned up. The wife then

invited Ninicip to come in again and he told her that he would fix up the meal. Igituo interum in vas defaecavit and they had good rice soup, and everyone, even Wemicus, had a good meal. The following

morning Ninicip made soup for the family again and then went home. Soon Wemicus and

his family were starving again and Wemicus said, “I must go and see my son-in-law,

Muskrat. He lives not far away.” “All right,” said his wife and Wemicus set out. When

he had almost reached Muskrat’s home, the little Muskrat children called out, “Our

grandfather is coming.” Wemicus told Muskrat that he was starving and Muskrat said

to his wife, “You had better make a fire in the hot sand.” So the fire was made, and

Muskrat went out with a big sack made out of hide and returned with the sack full

of ice, which he dumped into the hot ashes. Wemicus expected that it would explode

but it only cooked nicely. Wemicus wondered what it was. Soon Muskrat said, “We are

ready now,” and they took off the sand and there were a lot of nicely baked potatoes.

Wemicus thought that was an easy way in which to live—just to get ice for potatoes.

Next morning Wemicus started out for home and left his mitten behind as he had done

with Ninicip. Muskrat’s wife sent a child after him and told the child, “Don’t go

too close to Wemicus. He’s always in mischief.” Everything happened as before. The

child threw the mitten to Wemicus and Wemicus sent an invitation to Muskrat to come

to his home the next day. As Wemicus went on his way he had some potatoes which Muskrat

had given him for his family. Half way home he rested and thought he would eat the

potatoes, as they looked very good. So he ate every one. “I am the one who works hard,”

he said to himself. “My family can wait until Muskrat comes.” When he reached home

he told his wife, “Muskrat is also starving. I brought nothing. Muskrat is coming

tomorrow to see us.” Next day Muskrat came and they put him on the opposite side of

the wigwam. Wemicus said, “We have nothing much, but, wife, make a fire in the hot

sand.” The wife answered, “I suppose you saw somebody else do something. Don’t [42]you try any more mischief.” But he made his wife make the fire. He then went out and

returned with the sack full of ice, which he dumped on the fire. The sack blew up

all over everybody and put out the fire. Then his wife said, “I suppose you saw someone

do that again.” She made another fire and Muskrat said, “Give me that bag.” He went

out and brought back the sack full of ice, dumped and buried it in the fire, and,

after a while, they got the potatoes. All of them had a good meal. The next morning,

before Muskrat left, he got them another bag of potatoes.

Wemicus does not work, although his family is so large. Well, pretty soon the whole

family was starving again. Then said Wemicus, “I must go and see Meme (pileated woodpecker),

my son-in-law.” He went into the bush and when he reached Meme’s wigwam he found a

large white pine in back of it. He noticed that Meme had a sharp pointed nose. He

saw that Meme had not much to live on, but nevertheless Meme told his wife to get

the cooking pail ready. Then Meme began climbing the pine tree, which was at the back

of his wigwam, and began pecking in the trunk with his nose. Pretty soon he came down

with a raccoon.18 When Wemicus saw this, he thought, “That is a great thing; I must try it.” Meme burned

off the hair and cleaned the raccoon, and shared the meat on a stick to each one.

Wemicus received the best part, as he was the grandfather.

The next morning they had another raccoon to eat. Then everything happened as before.

Wemicus was given a raccoon to take home. He left his mitten behind, and sent an invitation

to Meme to visit him the next day. On the way home Wemicus thought to himself, “I

wonder how this raccoon tastes cold.” So he ate the entire raccoon. When he got home,

he told his wife that Meme was starving but that he was coming to visit them the following

day. They put the wigwam in order and Wemicus fixed up a big pine like that belonging

to Meme and cut two pieces of wood, which he pointed and shoved into his nose to imitate

Meme. When Meme came along he saw Wemicus sitting there with sticks in his nose. Wemicus

told his wife, as usual, to prepare for supper, and she told him that they had nothing.

When she had the water boiling in the pail, [43]Wemicus climbed up the tree and pecked upon it in imitation of Meme. He fell down,

however, and drove the sticks into his head. He fell into the fire, but after a while

he gained consciousness. Then Meme stepped out of the wigwam, climbed the tree, and

brought down a raccoon. And then the whole family had a good supper. Next morning

Meme got another raccoon and left it for the family, and then went home.

Still Wemicus did nothing and the family was again in a starving condition. Then said

Wemicus, “I have some more sons-in-law and one is close. I will go and see him; he

will help me until open water.19 I will go and see Skunk.” So he set out to visit Skunk. Wemicus was pretty hungry

and Skunk was farther off than the rest of the sons-in-law, but he finally reached

his home. Wemicus found Skunk’s water hole20 and saw a great quantity of oil in it. He knew that Skunk must have killed a great

deal of game. So he went into Skunk’s wigwam and saw a great quantity of food. Skunk

said, “We don’t have much. It is long since I hunted. But come outside.” There Wemicus

saw a piece of ground fenced in. Skunk then produced a little birch bark horn21 and said, “What will you have?” Skunk now blew on his horn and all kinds of game

came inside the enclosure. Skunk deinde pepedit and killed whatever kind Wemicus wanted. They then skinned what he killed and fried

it for supper.

In the morning Skunk said to Wemicus, “I’ll give you three shots and a horn. You can

make a fence for yourself. This horn will last forever, as long as you don’t lose

it. If you do, it will be bad.” Then Skunk gave Wemicus three shots to be used in

the future, and he did this urinando super eum to load him up three times. He did not give him any food, because he would be able

to get enough for himself. Then Wemicus thought, “Now I am going to do something.”

As Wemicus was on his way home he said to himself, “I wonder if it will go off!” So,

just as he was passing a tree stump, pepedit at the stump and blew it up. “That’s fine, but I have only two more shots left,”

said he. Later he tried the same thing and then only had one [44]left. A little while after this he saw a big pine tree, and thought he would try a

shot at this. So he blew up the pine tree, and so used up all his shots.

When he reached his wigwam, he showed his wife the horn which Skunk had given him,

saying, “Skunk gave me that.” Then he built a large fence of poles. He told his wife

to hold the horn and stay near by, while he got a club to kill the game with. Then

he blew on the horn and the fence was filled with bear, deer, and all kinds of animals.

Although he had no shots left, Wemicus managed to kill one caribou, and his wife was

very happy. He cut the fat from the breast of the caribou, made a fire, and got some

grease from it. He then spilled the caribou grease in his water hole in order to deceive

Skunk and make him believe that he had a great quantity of meat. Not long after this

Skunk started out to visit Wemicus and, on his way, he passed the three stumps which

Wemicus had blown up and knew that he had no more shots left. When he reached Wemicus’ water hole he said, “I guess he got one any way.” When he came to the wigwam, he

found that Wemicus and his family had hardly any meat left, so he said to Wemicus,

“Come out and let me see your fence.” They went out and Wemicus blew his horn, and

inside the fence it became full of game. Skunk pepedit and killed all of them, and

then Wemicus and his family had plenty. Skunk stayed over night and departed the next

morning.

Wemicus had another son-in-law who was a man. This man’s wife, the daughter of Wemicus,

had had a great many husbands, because Wemicus had put them to so many different tests

that they had been all killed off except this one. He, however, had succeeded in outwitting

Wemicus in every scheme that he tried on him. Wemicus and this man hunted beaver in

the spring of the year by driving them all day with dogs. The man’s wife warned him

before they started out to hunt, saying, “Look out for my father; he might burn your

moccasins in camp. That’s what he did to my other husbands.”22 That night in camp Wemicus said, “I didn’t tell you the name of this lake. It is

called ‘burnt moccasins lake.’ ” When the man [45]heard this, he thought that Wemicus was up to some sort of mischief and was going

to burn his moccasins. Their moccasins were hanging up before a fire to dry and, while

Wemicus was not looking, the man changed the places of Wemicus’ moccasins and his

own, and then went to sleep. Soon the man awoke and saw Wemicus get up and throw his

own moccasins into the fire. Wemicus then said, “Say! something is burning; it is

your moccasins.” Then the man answered, “No, not mine, but yours.” So Wemicus had

no moccasins, and the ground was covered with snow. After this had happened the man

slept with his moccasins on.

The next morning the man started on and left Wemicus there with no shoes. Wemicus

started to work. He got a big boulder, made a fire, and placed the boulder in it until

it became red hot. He then wrapped his feet with spruce boughs and pushed the boulder

ahead of him in order to melt the snow. In this way he managed to walk on the boughs.

Then he began to sing, “Spruce is warm, spruce is warm.” When the man reached home

he told his wife what had happened. “I hope Wemicus will die,” she said. A little

while after this, they heard Wemicus coming along singing, “Spruce is warm, spruce

is warm.” He came into the wigwam and, as he was the head man, they were obliged to

get his meal ready.

The ice was getting bad by this time, so they stayed in camp a while. Soon Wemicus

told his son-in-law, “We’d better go sliding.” He then went to a hill where there

were some very poisonous snakes. The man’s wife warned her husband of these snakes

and gave him a split stick holding a certain kind of magic tobacco, which she told

him to hold in front of him so that the snakes would not hurt him. Then the two men

went sliding. At the top of the hill Wemicus said, “Follow me,” for he intended to

pass close by the snakes’ lair. So when they slid, Wemicus passed safely and the man

held his stick with the tobacco in it in front of him, thus preventing the snakes

from biting him. The man then told Wemicus that he enjoyed the sliding.

The following day Wemicus said to his son-in-law, “We had better go to another place.”

When she heard this, the wife told her husband that, as it was getting summer, Wemicus

had in [46]his head many poisonous lizards instead of lice. She said, “He will tell you to pick

lice from his head and crack them in your teeth. But take low-bush cranberries and

crack them instead.” So the man took cranberries along with him. Wemicus took his

son-in-law to a valley with a great ravine in it. He said, “I wonder if anybody can

jump across this?” “Surely,” said the young man, “I can.” Then the young man said,

“Closer,” and the ravine narrowed and he jumped across easily. When Wemicus tried,

the young man said “Widen,” and Wemicus fell into the ravine. But it did not kill

him, and when he made his way to the top again, he said, “You have beaten me.” Then

they went on.

They came to a place of hot sand and Wemicus said, “You must look for lice in my head.”

“All right father,” replied the son-in-law. So Wemicus lay down and the man started

to pick the lice. He took the cranberries from inside his shirt and each time he pretended

to catch a louse, he cracked a cranberry and threw it on the ground, and so Wemicus

got fooled a second time that day. Then they went home and Wemicus said to his son-in-law,

“There are a whole lot of eggs on that rocky island where the gulls are. We will go

get the eggs, come back, and have an egg supper.” As Wemicus was the head man, his

son-in-law had to obey him.

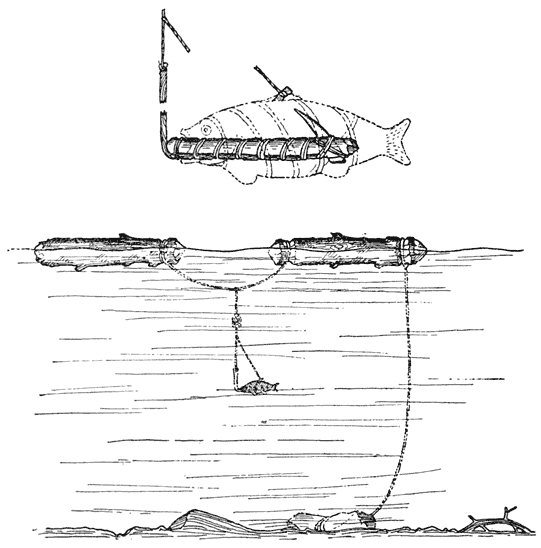

So they started out in their canoe and soon came to the rocky island. Wemicus stayed

in the canoe and told the man to go ashore and to bring the eggs back with him and

fill the canoe. When the man reached the shore, Wemicus told him to go farther back

on the island, saying, “That’s where the former husbands got their eggs, there are

their bones.” He then started the canoe off in the water by singing, without using

his paddle. Then Wemicus told the gulls to eat the man, saying to them, “I give you

him to eat.” The gulls started to fly about the man, but the man had his paddle with

him and he killed one of the gulls with it. He then took the gulls’ wings and fastened

them on himself, filled his shirt with eggs, and started flying over the lake by the

aid of the wings.

When he reached the middle of the lake, he saw Wemicus going along and singing to

himself. Wemicus, looking up, saw his son-in-law but mistook him for a gull. Then

the man flew [47]over him and defecated in his face, and Wemicus said, “Gull’s excrement always smells

like that when they have eaten a man.” The man flew back to camp and told his wife

to cook the eggs, and he told his children to play with the wings. When Wemicus reached

the camp, he saw the children playing with the wings and said, “Where did you get

those wings?” “From father,” was the reply. “Your father? Why, the gulls ate him!”

Then he went to the wigwam and there he saw the man smoking. Then Wemicus thought

it very strange how the man could have gotten home, but no one told him how it had

been done. Thought he, “I must try another scheme to do away with him.”

One day Wemicus said to his son-in-law, “We’d better make two canoes of birch-bark,

one for you and one for me. We’d better get bark.” So they started off for birch-bark.

They cut a tree almost through and Wemicus said to his son-in-law, “You sit on that

side and I’ll sit on this.” He wanted the tree to fall on him and kill him. Wemicus

said, “You say, ‘Fall on my father-in-law,’ and I’ll say, ‘Fall on my son-in-law’,

and whoever says it too slowly or makes a mistake will be the one on whom it will

fall.” But Wemicus made the first mistake, and the tree fell on him and crushed him.

However, Wemicus was a manitu23 and was not hurt. They went home with the bark and made the two canoes. After they

were made, Wemicus said to his son-in-law, “Well, we’ll have a race in our two canoes,

a sailing race.” Wemicus made a big bark sail, but the man did not make any, as he

was afraid of upsetting. They started the race. Wemicus went very fast and the man

called after him, “Oh, you are beating me.” He kept on fooling and encouraging Wemicus,

until the wind upset Wemicus’ canoe and that was the end of Wemicus. When the man

sailed over the spot where Wemicus had upset, he saw a big pike (ki·nų′je) there, into which Wemicus had been transformed when the canoe upset. This is the

origin of the pike.