Title: Historical Record of the Thirty-sixth, or the Herefordshire Regiment of Foot: containing an account of the formation of the regiment in 1701, and of its subsequent services to 1852

Author: Richard Cannon

Release date: October 22, 2021 [eBook #66598]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Parker, Furnivall & Parker, 1853

Credits: Brian Coe, John Campbell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of each major section.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book. These are indicated by a dotted gray underline.

HORSE-GUARDS,

1st January, 1836.

His Majesty has been pleased to command that, with the view of doing the fullest justice to Regiments, as well as to Individuals who have distinguished themselves by their Bravery in Action with the Enemy, an Account of the Services of every Regiment in the British Army shall be published under the superintendence and direction of the Adjutant-General; and that this Account shall contain the following particulars, viz.:—

—— The Period and Circumstances of the Original Formation of the Regiment; The Stations at which it has been from time to time employed; The Battles, Sieges, and other Military Operations in which it has been engaged, particularly specifying any Achievement it may have performed, and the Colours, Trophies, &c., it may have captured from the Enemy.

—— The Names of the Officers, and the number of Non-Commissioned Officers and Privates Killed or Wounded by the Enemy, specifying the place and Date of the Action.

—— The Names of those Officers who, in consideration of their Gallant Services and Meritorious Conduct in Engagements with the Enemy, have been distinguished with Titles, Medals, or other Marks of His Majesty’s gracious favour.

—— The Names of all such Officers, Non-Commissioned Officers, and Privates, as may have specially signalized themselves in Action.

And,

—— The Badges and Devices which the Regiment may have been permitted to bear, and the Causes on account of which such Badges or Devices, or any other Marks of Distinction, have been granted.

By Command of the Right Honorable

GENERAL LORD HILL,

Commanding-in-Chief.

John Macdonald,

Adjutant-General.

The character and credit of the British Army must chiefly depend upon the zeal and ardour by which all who enter into its service are animated, and consequently it is of the highest importance that any measure calculated to excite the spirit of emulation, by which alone great and gallant actions are achieved, should be adopted.

Nothing can more fully tend to the accomplishment of this desirable object than a full display of the noble deeds with which the Military History of our country abounds. To hold forth these bright examples to the imitation of the youthful soldier, and thus to incite him to emulate the meritorious conduct of those who have preceded him in their honorable career, are among the motives that have given rise to the present publication.

The operations of the British Troops are, indeed, announced in the “London Gazette,” from whence they are transferred into the public prints: the achievements of our armies are thus made known at the time of their occurrence, and receive the tribute[iv] of praise and admiration to which they are entitled. On extraordinary occasions, the Houses of Parliament have been in the habit of conferring on the Commanders, and the Officers and Troops acting under their orders, expressions of approbation and of thanks for their skill and bravery; and these testimonials, confirmed by the high honour of their Sovereign’s approbation, constitute the reward which the soldier most highly prizes.

It has not, however, until late years, been the practice (which appears to have long prevailed in some of the Continental armies) for British Regiments to keep regular records of their services and achievements. Hence some difficulty has been experienced in obtaining, particularly from the old Regiments, an authentic account of their origin and subsequent services.

This defect will now be remedied, in consequence of His Majesty having been pleased to command that every Regiment shall, in future, keep a full and ample record of its services at home and abroad.

From the materials thus collected, the country will henceforth derive information as to the difficulties and privations which chequer the career of those who embrace the military profession. In Great Britain, where so large a number of persons are devoted to the active concerns of agriculture, manufactures, and commerce, and where these pursuits have, for so[v] long a period, been undisturbed by the presence of war, which few other countries have escaped, comparatively little is known of the vicissitudes of active service and of the casualties of climate, to which, even during peace, the British Troops are exposed in every part of the globe, with little or no interval of repose.

In their tranquil enjoyment of the blessings which the country derives from the industry and the enterprise of the agriculturist and the trader, its happy inhabitants may be supposed not often to reflect on the perilous duties of the soldier and the sailor,—on their sufferings,—and on the sacrifice of valuable life, by which so many national benefits are obtained and preserved.

The conduct of the British Troops, their valour, and endurance, have shone conspicuously under great and trying difficulties; and their character has been established in Continental warfare by the irresistible spirit with which they have effected debarkations in spite of the most formidable opposition, and by the gallantry and steadiness with which they have maintained their advantages against superior numbers.

In the Official Reports made by the respective Commanders, ample justice has generally been done to the gallant exertions of the Corps employed; but the details of their services and of acts of individual[vi] bravery can only be fully given in the Annals of the various Regiments.

These Records are now preparing for publication, under His Majesty’s special authority, by Mr. Richard Cannon, Principal Clerk of the Adjutant General’s Office; and while the perusal of them cannot fail to be useful and interesting to military men of every rank, it is considered that they will also afford entertainment and information to the general reader, particularly to those who may have served in the Army, or who have relatives in the Service.

There exists in the breasts of most of those who have served, or are serving, in the Army, an Esprit de Corps—an attachment to everything belonging to their Regiment; to such persons a narrative of the services of their own Corps cannot fail to prove interesting. Authentic accounts of the actions of the great, the valiant, the loyal, have always been of paramount interest with a brave and civilized people. Great Britain has produced a race of heroes who, in moments of danger and terror, have stood “firm as the rocks of their native shore:” and when half the world has been arrayed against them, they have fought the battles of their Country with unshaken fortitude. It is presumed that a record of achievements in war,—victories so complete and surprising, gained by our countrymen, our brothers,[vii] our fellow-citizens in arms,—a record which revives the memory of the brave, and brings their gallant deeds before us,—will certainly prove acceptable to the public.

Biographical Memoirs of the Colonels and other distinguished Officers will be introduced in the Records of their respective Regiments, and the Honorary Distinctions which have, from time to time, been conferred upon each Regiment, as testifying the value and importance of its services, will be faithfully set forth.

As a convenient mode of Publication, the Record of each Regiment will be printed in a distinct number, so that when the whole shall be completed the Parts may be bound up in numerical succession.

The natives of Britain have, at all periods, been celebrated for innate courage and unshaken firmness, and the national superiority of the British troops over those of other countries has been evinced in the midst of the most imminent perils. History contains so many proofs of extraordinary acts of bravery, that no doubts can be raised upon the facts which are recorded. It must therefore be admitted, that the distinguishing feature of the British soldier is Intrepidity. This quality was evinced by the inhabitants of England when their country was invaded by Julius Cæsar with a Roman army, on which occasion the undaunted Britons rushed into the sea to attack the Roman soldiers as they descended from their ships; and, although their discipline and arms were inferior to those of their adversaries, yet their fierce and dauntless bearing intimidated the flower of the Roman troops, including Cæsar’s favourite tenth legion. Their arms consisted of spears, short swords, and other weapons of rude construction. They had chariots, to the[x] axles of which were fastened sharp pieces of iron resembling scythe-blades, and infantry in long chariots resembling waggons, who alighted and fought on foot, and for change of ground, pursuit or retreat, sprang into the chariot and drove off with the speed of cavalry. These inventions were, however, unavailing against Cæsar’s legions: in the course of time a military system, with discipline and subordination, was introduced, and British courage, being thus regulated, was exerted to the greatest advantage; a full development of the national character followed, and it shone forth in all its native brilliancy.

The military force of the Anglo-Saxons consisted principally of infantry: Thanes, and other men of property, however, fought on horseback. The infantry were of two classes, heavy and light. The former carried large shields armed with spikes, long broad swords and spears; and the latter were armed with swords or spears only. They had also men armed with clubs, others with battle-axes and javelins.

The feudal troops established by William the Conqueror consisted (as already stated in the Introduction to the Cavalry) almost entirely of horse; but when the warlike barons and knights, with their trains of tenants and vassals, took the field, a proportion of men appeared on foot, and, although these were of inferior degree, they proved stout-hearted Britons of stanch fidelity. When stipendiary troops were employed, infantry always constituted a considerable portion of the military force;[xi] and this arme has since acquired, in every quarter of the globe, a celebrity never exceeded by the armies of any nation at any period.

The weapons carried by the infantry, during the several reigns succeeding the Conquest, were bows and arrows, half-pikes, lances, halberds, various kinds of battle-axes, swords, and daggers. Armour was worn on the head and body, and in course of time the practice became general for military men to be so completely cased in steel, that it was almost impossible to slay them.

The introduction of the use of gunpowder in the destructive purposes of war, in the early part of the fourteenth century, produced a change in the arms and equipment of the infantry-soldier. Bows and arrows gave place to various kinds of fire-arms, but British archers continued formidable adversaries; and, owing to the inconvenient construction and imperfect bore of the fire-arms when first introduced, a body of men, well trained in the use of the bow from their youth, was considered a valuable acquisition to every army, even as late as the sixteenth century.

During a great part of the reign of Queen Elizabeth each company of infantry usually consisted of men armed five different ways; in every hundred men forty were “men-at-arms,” and sixty “shot;” the “men-at-arms” were ten halberdiers, or battle-axe men, and thirty pikemen; and the “shot” were twenty archers, twenty musketeers, and twenty harquebusiers, and each man carried, besides his principal weapon, a sword and dagger.

Companies of infantry varied at this period in numbers from 150 to 300 men; each company had a colour or ensign, and the mode of formation recommended by an English military writer (Sir John Smithe) in 1590 was:—the colour in the centre of the company guarded by the halberdiers; the pikemen in equal proportions, on each flank of the halberdiers: half the musketeers on each flank of the pikes; half the archers on each flank of the musketeers, and the harquebusiers (whose arms were much lighter than the muskets then in use) in equal proportions on each flank of the company for skirmishing.[1] It was customary to unite a number of companies into one body, called a Regiment, which frequently amounted to three thousand men: but each company continued to carry a colour. Numerous improvements were eventually introduced in the construction of fire-arms, and, it having been found impossible to make armour proof against the muskets then in use (which carried a very heavy ball) without its being too weighty for the soldier, armour was gradually laid aside by the infantry in the seventeenth century: bows and arrows also fell into disuse, and the infantry were reduced to two classes, viz.: musketeers, armed with matchlock muskets,[xiii] swords, and daggers; and pikemen, armed with pikes from fourteen to eighteen feet long, and swords.

In the early part of the seventeenth century Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden, reduced the strength of regiments to 1000 men. He caused the gunpowder, which had heretofore been carried in flasks, or in small wooden bandoliers, each containing a charge, to be made up into cartridges, and carried in pouches; and he formed each regiment into two wings of musketeers, and a centre division of pikemen. He also adopted the practice of forming four regiments into a brigade; and the number of colours was afterwards reduced to three in each regiment. He formed his columns so compactly that his infantry could resist the charge of the celebrated Polish horsemen and Austrian cuirassiers; and his armies became the admiration of other nations. His mode of formation was copied by the English, French, and other European states; but so great was the prejudice in favour of ancient customs, that all his improvements were not adopted until near a century afterwards.

In 1664 King Charles II. raised a corps for sea-service, styled the Admiral’s regiment. In 1678 each company of 100 men usually consisted of 30 pikemen, 60 musketeers, and 10 men armed with light firelocks. In this year the King added a company of men armed with hand grenades to each of the old British regiments, which was designated the “grenadier company.” Daggers were so contrived as to fit in the muzzles of the muskets, and bayonets[xiv] similar to those at present in use were adopted about twenty years afterwards.

An Ordnance regiment was raised in 1685, by order of King James II., to guard the artillery, and was designated the Royal Fusiliers (now 7th Foot). This corps, and the companies of grenadiers, did not carry pikes.

King William III. incorporated the Admiral’s regiment in the second Foot Guards, and raised two Marine regiments for sea-service. During the war in this reign, each company of infantry (excepting the fusiliers and grenadiers) consisted of 14 pikemen and 46 musketeers; the captains carried pikes; lieutenants, partisans; ensigns, half-pikes; and serjeants, halberds. After the peace in 1697 the Marine regiments were disbanded, but were again formed on the breaking out of the war in 1702.[2]

During the reign of Queen Anne the pikes were laid aside, and every infantry soldier was armed with a musket, bayonet, and sword; the grenadiers ceased, about the same period, to carry hand grenades; and the regiments were directed to lay aside their third colour: the corps of Royal Artillery was first added to the Army in this reign.

About the year 1745, the men of the battalion companies of infantry ceased to carry swords; during[xv] the reign of George II. light companies were added to infantry regiments; and in 1764 a Board of General Officers recommended that the grenadiers should lay aside their swords, as that weapon had never been used during the Seven Years’ War. Since that period the arms of the infantry soldier have been limited to the musket and bayonet.

The arms and equipment of the British Troops have seldom differed materially, since the Conquest, from those of other European states; and in some respects the arming has, at certain periods, been allowed to be inferior to that of the nations with whom they have had to contend; yet, under this disadvantage, the bravery and superiority of the British infantry have been evinced on very many and most trying occasions, and splendid victories have been gained over very superior numbers.

Great Britain has produced a race of lion-like champions who have dared to confront a host of foes, and have proved themselves valiant with any arms. At Crecy, King Edward III., at the head of about 30,000 men, defeated, on the 26th of August, 1346, Philip King of France, whose army is said to have amounted to 100,000 men; here British valour encountered veterans of renown:—the King of Bohemia, the King of Majorca, and many princes and nobles were slain, and the French army was routed and cut to pieces. Ten years afterwards, Edward Prince of Wales, who was designated the Black Prince, defeated, at Poictiers, with 14,000 men, a French army of 60,000 horse, besides infantry, and took John I., King of France, and his son[xvi] Philip, prisoners. On the 25th of October, 1415, King Henry V., with an army of about 13,000 men, although greatly exhausted by marches, privations, and sickness, defeated, at Agincourt, the Constable of France, at the head of the flower of the French nobility and an army said to amount to 60,000 men, and gained a complete victory.

During the seventy years’ war between the United Provinces of the Netherlands and the Spanish monarchy, which commenced in 1578 and terminated in 1648, the British infantry in the service of the States General were celebrated for their unconquerable spirit and firmness;[3] and in the thirty years’ war between the Protestant Princes and the Emperor of Germany, the British Troops in the service of Sweden and other states were celebrated for deeds of heroism.[4] In the wars of Queen Anne, the fame of the British army under the great Marlborough was spread throughout the world; and if we glance at the achievements performed within the memory of persons now living, there is abundant proof that the Britons of the present age are not inferior to their ancestors in the qualities[xvii] which constitute good soldiers. Witness the deeds of the brave men, of whom there are many now surviving, who fought in Egypt in 1801, under the brave Abercromby, and compelled the French army, which had been vainly styled Invincible, to evacuate that country; also the services of the gallant Troops during the arduous campaigns in the Peninsula, under the immortal Wellington; and the determined stand made by the British Army at Waterloo, where Napoleon Bonaparte, who had long been the inveterate enemy of Great Britain, and had sought and planned her destruction by every means he could devise, was compelled to leave his vanquished legions to their fate, and to place himself at the disposal of the British Government. These achievements, with others of recent dates, in the distant climes of India, prove that the same valour and constancy which glowed in the breasts of the heroes of Crecy, Poictiers, Agincourt, Blenheim, and Ramilies, continue to animate the Britons of the nineteenth century.

The British Soldier is distinguished for a robust and muscular frame,—intrepidity which no danger can appal,—unconquerable spirit and resolution,—patience in fatigue and privation, and cheerful obedience to his superiors. These qualities, united with an excellent system of order and discipline to regulate and give a skilful direction to the energies and adventurous spirit of the hero, and a wise selection of officers of superior talent to command, whose presence inspires confidence,—have been the leading causes of the splendid victories gained by the British[xviii] arms.[5] The fame of the deeds of the past and present generations in the various battle fields where the robust sons of Albion have fought and conquered, surrounds the British arms with a halo of glory; these achievements will live in the page of history to the end of time.

The records of the several regiments will be found to contain a detail of facts of an interesting character, connected with the hardships, sufferings, and gallant exploits of British soldiers in the various parts of the world, where the calls of their Country and the commands of their Sovereign have required them to proceed in the execution of their duty, whether in[xix] active continental operations, or in maintaining colonial territories in distant and unfavourable climes.

The superiority of the British infantry has been pre-eminently set forth in the wars of six centuries, and admitted by the greatest commanders which Europe has produced. The formations and movements of this arme, as at present practised, while they are adapted to every species of warfare, and to all probable situations and circumstances of service, are calculated to show forth the brilliancy of military tactics calculated upon mathematical and scientific principles. Although the movements and evolutions have been copied from the continental armies, yet various improvements have from time to time been introduced, to ensure that simplicity and celerity by which the superiority of the national military character is maintained. The rank and influence which Great Britain has attained among the nations of the world, have in a great measure been purchased by the valour of the Army, and to persons who have the welfare of their country at heart, the records of the several regiments cannot fail to prove interesting.

[1] A company of 200 men would appear thus:—

| | |||||||||

| 20 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 20 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| Harquebuses. | Muskets. | Halberds. | Muskets. | Harquebuses. | |||||

| Archers. | Pikes. | Pikes. | Archers. | ||||||

The musket carried a ball which weighed 1/10th of a pound; and the harquebus a ball which weighed 1/25th of a pound.

[2] The 30th, 31st, and 32nd Regiments were formed as Marine corps in 1702, and were employed as such during the wars in the reign of Queen Anne. The Marine corps were embarked in the Fleet under Admiral Sir George Rooke, and were at the taking of Gibraltar, and in its subsequent defence in 1704; they were afterwards employed at the siege of Barcelona in 1705.

[3] The brave Sir Roger Williams, in his Discourse on War, printed in 1590, observes:—“I persuade myself ten thousand of our nation would beat thirty thousand of theirs (the Spaniards) out of the field, let them be chosen where they list.” Yet at this time the Spanish infantry was allowed to be the best disciplined in Europe. For instances of valour displayed by the British Infantry during the Seventy Years’ War, see the Historical Record of the Third Foot, or Buffs.

[4] Vide the Historical Record of the First, or Royal Regiment of Foot.

[5] “Under the blessing of Divine Providence, His Majesty ascribes the successes which have attended the exertions of his troops in Egypt to that determined bravery which is inherent in Britons; but His Majesty desires it may be most solemnly and forcibly impressed on the consideration of every part of the army, that it has been a strict observance of order, discipline, and military system, which has given the full energy to the native valour of the troops, and has enabled them proudly to assert the superiority of the national military character, in situations uncommonly arduous, and under circumstances of peculiar difficulty.”—General Orders in 1801.

In the General Orders issued by Lieut.-General Sir John Hope (afterwards Lord Hopetoun), congratulating the army upon the successful result of the Battle of Corunna, on the 16th of January, 1809, it is stated:—“On no occasion has the undaunted valour of British troops ever been more manifest. At the termination of a severe and harassing march, rendered necessary by the superiority which the enemy had acquired, and which had materially impaired the efficiency of the troops, many disadvantages were to be encountered. These have all been surmounted by the conduct of the troops themselves; and the enemy has been taught, that whatever advantages of position or of numbers he may possess, there is inherent in the British officers and soldiers a bravery that knows not how to yield,—that no circumstances can appal,—and that will ensure victory, when it is to be obtained by the exertion of any human means.”

CONTAINING

AN ACCOUNT OF THE FORMATION OF THE REGIMENT

In 1701,

AND OF ITS SUBSEQUENT SERVICES

To 1852.

COMPILED BY

RICHARD CANNON, ESQ.,

ADJUTANT GENERAL’S OFFICE, HORSE GUARDS.

Illustrated with Plates.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY GEORGE E. EYRE AND WILLIAM SPOTTISWOODE,

PRINTERS TO THE QUEEN’S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY.

FOR HER MAJESTY’S STATIONARY OFFICE.

PUBLISHED BY PARKER, FURNIVALL, AND PARKER,

30, CHARING CROSS.

1853.

THE

THIRTY-SIXTH,

OR

HEREFORDSHIRE REGIMENT OF FOOT.

OF THE

| Year. | Page. | ||

| 1700. | Introduction | 1 | |

| 1701. | Formation of the regiment | 2 | |

| ” | William Viscount Charlemont appointed Colonel of the regiment | ib. | |

| 1702. | War of the Spanish succession | 3 | |

| ” | Expedition to Cadiz | 4 | |

| ” | The regiment embarked for Cadiz | 5 | |

| ” | Embarkation return of the regiment | 6 | |

| ” | Detached to the West Indies | 7 | |

| 1704. | Returned to Ireland | ib. | |

| 1705. | Embarked for Spain | 8 | |

| ” | Siege of Barcelona | 9 | |

| ” | Capture of Montjuich | 11 | |

| ” | Surrender of Barcelona | ib. | |

| 1706. | Barcelona invested by the French and Spaniards | 13 | |

| ” | Successful defence of the place by the Allies | ib. | |

| ” | Withdrawal of the enemy from Barcelona | 13 | |

| ” | Lieut.-Colonel Thomas Alnutt appointed Colonel of the regiment | ib. | |

| ” | The regiment embarked for Valencia | 14 | |

| ” | Capture of Requena and Cuenza | ib. | |

| 1707. | Battle of Almanza | 15 | |

| ” | Casualties of the regiment | 16 | |

| 1708. | Recruiting of the regiment | 17 | |

| 1709. | Colonel Archibald Earl of Ilay appointed Colonel of the regiment | 18 | |

| 1710. | Colonel Desney appointed Colonel of the regiment | ib. | |

| 1711. | Expedition against Quebec [vi] | 19 | |

| ” | The regiment selected to form part thereof | ib. | |

| ” | Returned to England | 20 | |

| 1712. | Embarked for Dunkirk | ib. | |

| 1713. | Treaty of Utrecht signed | ib. | |

| 1714. | The regiment returned to England | 21 | |

| ” | Proceeded to Ireland | ib. | |

| 1715. | Colonel William Egerton appointed Colonel of the regiment | ib. | |

| ” | The regiment embarked for Scotland | ib. | |

| ” | Battle of Sheriffmuir | ib. | |

| ” | Arrival of the Pretender in Scotland | 22 | |

| 1716. | The Pretender returned to France | ib. | |

| ” | Termination of the Rebellion | ib. | |

| 1718. | The regiment proceeded to Ireland | ib. | |

| 1719. | Embarked for Great Britain | ib. | |

| ” | Brigadier-General Sir Charles Hotham, Bart., appointed Colonel of the regiment | 23 | |

| 1720. | The regiment returned to Ireland | ib. | |

| ” | Colonel John Pocock appointed Colonel of the regiment | ib. | |

| 1721. | Lieut.-Colonel Charles Lenoe appointed Colonel of the regiment | ib. | |

| 1732. | Brigadier-General John Moyle appointed Colonel of the | ||

| regiment | ib. | ||

| 1737. | Lieut.-Colonel Humphrey Bland appointed Colonel of the regiment | ib. | |

| 1739. | The regiment removed from Ireland to Great Britain | 24 | |

| 1740. | Part of the regiment embarked for the West Indies | ib. | |

| 1741. | Lieut.-Colonel James Fleming appointed Colonel of the regiment | ib. | |

| ” | Operations against Carthagena | 25 | |

| ” | Siege of Bocca-Chica and of the Castle of Lazar | ib. | |

| ” | Return of the expedition to Jamaica | 26 | |

| ” | The portion of the regiment which had been employed on this service returned to England | ib. | |

| 1743. | The regiment stationed in Great Britain | ib. | |

| 1744. | War of the Austrian Succession | ib. | |

| ” | The regiment embarked for Flanders | 27 | |

| 1745. | Rebellion in Scotland | ib. | |

| ” | The regiment returned to England | ib. | |

| 1746. | Battle of Falkirk | 28 | |

| ” | Battle of Culloden | 29 | |

| ” | Suppression of the Rebellion | 30 | |

| 1747. | The regiment returned to Flanders | ib. | |

| ” | Battle of Laffeld, or Val | ib. | |

| 1748. | Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle | 31 | |

| ” | The regiment returned to England | ib. | |

| 1749. | Embarked for Gibraltar | ib. | |

| 1751. | Colonel Lord Robert Manners appointed Colonel of the regiment [vii] | 31 | |

| ” | Royal Warrant of the 1st of July 1751 for ensuring uniformity in the clothing, standards, and colours of the army, and regulating the number and rank of regiments | ib. | |

| 1754. | The regiment embarked at Gibraltar for England | ib. | |

| ” | Stationed in North Britain | 32 | |

| 1755. | The regiment removed to South Britain | ib. | |

| 1756. | Augmented to two battalions | ib. | |

| ” | Encamped at Chatham | ib. | |

| 1757. | Encamped at Barham Downs | ib. | |

| 1758. | The second battalion of the Thirty-sixth formed into a distinct corps, and numbered the Seventy-fourth regiment | 33 | |

| ” | The Thirty-sixth regiment formed part of the expedition against St. Maloes | ib. | |

| ” | Returned to England | 34 | |

| ” | Second expedition to the coast of France | ib. | |

| ” | Capture of Cherbourg | ib. | |

| ” | Destruction of the batteries in the bay of St. Lunaire | ib. | |

| ” | Return of the regiment to England | ib. | |

| 1759. | Encamped at Chatham | ib. | |

| 1760. | Encamped at Sandheath | ib. | |

| 1761. | Proceeded with the expedition against Belle-Isle | 35 | |

| ” | Capture of the island | 36 | |

| ” | The regiment returned to England | ib. | |

| 1762. | Encamped at Sandheath | ib. | |

| 1763. | Treaty of Fontainebleau concluded | ib. | |

| 1764. | The regiment embarked for Jamaica | ib. | |

| 1765. | Major-General Richard Pierson appointed Colonel of the | ||

| regiment | ib. | ||

| 1773. | Return of the regiment to England from Jamaica | 37 | |

| 1774. | The light company reviewed in Richmond-park by King George III. | ib. | |

| 1775. | Embarkation of the regiment for Ireland | ib. | |

| 1778. | Colonel the Hon. Henry St. John appointed Colonel of the regiment | ib. | |

| 1782. | The Thirty-sixth designated the Herefordshire regiment | ib. | |

| ” | Removed from Ireland to England | ib. | |

| 1783. | Embarked for the East Indies | 38 | |

| ” | Employed against the forces of Tippoo Saib, the Sultan of Mysore | ib. | |

| ” | Proceeded to Mangalore | ib. | |

| ” | Capture of Cannanore | 39 | |

| 1784. | Peace concluded with Tippoo Saib | ib. | |

| 1785 | } | ||

| to | } The regiment stationed in the Madras presidency | ib. | |

| 1788. | } | ||

| 1789. | Renewal of hostilities with Tippoo Saib [viii] | 39 | |

| 1790. | The regiment selected to form part of the force under Major-General Medows | 40 | |

| ” | Advance of the troops towards the Coimbatore country | ib. | |

| ” | The regiment detached to the relief of Colonel Floyd | 41 | |

| ” | Battle of Sattimungulum | ib. | |

| ” | Battle of Shawoor | 46 | |

| ” | Subsequent operations against Tippoo Saib | 49 | |

| 1791. | The army reviewed by General Charles Earl Cornwallis | 50 | |

| ” | Siege of Bangalore | 51 | |

| ” | Capture of that fortress | 53 | |

| ” | Advance of troops towards Seringapatam | 54 | |

| ” | Returned to Bangalore | 55 | |

| ” | Capture of Nundydroog | 57 | |

| 1792. | March of the troops towards Seringapatam | 58 | |

| ” | Assault of the fortified camp of Tippoo Saib | 61 | |

| ” | Siege of Seringapatam | 62 | |

| ” | Treaty of peace concluded with Tippoo Saib | ib. | |

| 1793. | War with France | 63 | |

| ” | The regiment ordered to the Coromandel coast | ib. | |

| ” | Capture of the French settlement of Pondicherry | 64 | |

| ” | The regiment returned to Madras | ib. | |

| 1794. | Stationed at Trichinopoly | ib. | |

| 1795. | Proceeded to Negapatam | ib. | |

| 1796 | } | ||

| and | } Stationed at Warriore | ib. | |

| 1797. | } | ||

| 1798. | Embarked at Madras for England | ib. | |

| 1799. | Arrived at Greenhithe, and afterwards proceeded to Winchester | ib. | |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Hindoostan” on the regimental colour and appointments | ib. | |

| 1800. | Embarked for Ireland | 65 | |

| ” | Proceeded with an expedition against the coast of France | ib. | |

| ” | Landed at Quiberon | ib. | |

| ” | Embarked at Minorca | ib. | |

| 1801. | Stationed in that island | ib. | |

| 1802. | Peace of Amiens | ib. | |

| ” | The regiment returned to Ireland | ib. | |

| 1803. | Renewal of the war with France | ib. | |

| 1804. | A second battalion added to the regiment | 66 | |

| 1805. | The first battalion embarked for Germany | ib. | |

| 1806. | Returned to England | 67 | |

| ” | The first battalion embarked for Buenos Ayres | ib. | |

| 1807. | Operations against Buenos Ayres | 68 | |

| ” | Return of the battalion to Europe | 69 | |

| ” | Stationed in Ireland | ib. | |

| 1808. | Embarked for Portugal with the troops under Lieut.-General the Hon. Sir Arthur Wellesley | ib. | |

| ” | Battle of Roleia | 70 | |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Roleia” on the regimental colour and appointments | ib. | |

| 1808. | Battle of Vimiera [ix] | 70 | |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Vimiera” on the regimental colour and appointments | 71 | |

| ” | Advance into Spain | 72 | |

| ” | Joined the army under Lieut.-General Sir John Moore | ib. | |

| ” | Retreat on Corunna | 73 | |

| 1809. | Battle of Corunna | 74 | |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Corunna” on the regimental colour and appointments | 75 | |

| ” | Embarkation of the battalion for England | ib. | |

| ” | Proceeded with the expedition to the Scheldt | 75 | |

| ” | Arrived at Walcheren | ib. | |

| ” | Siege and capture of Flushing | ib. | |

| ” | Casualties of the battalion | ib. | |

| ” | Returned to England | 77 | |

| 1810. | Stationed at Battle | ib. | |

| 1811. | Embarked for the Peninsula | ib. | |

| ” | Actions at Fuentes d’Onor | ib. | |

| ” | Affair of Barba del Puerco | ib. | |

| ” | Affairs of Especha and Ronda | 78 | |

| 1812. | Siege and capture of Ciudad Rodrigo | 79 | |

| ” | Siege and capture of Badajoz | ib. | |

| ” | Battle of Salamanca | 80 | |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Salamanca” on the regimental colour and appointments | 82 | |

| ” | Siege of Burgos | ib. | |

| ” | Retreat from Burgos | ib. | |

| 1813. | Battle of Vittoria | 83 | |

| ” | Crossing of the Pyrenees | ib. | |

| ” | Operations near Pampeluna | ib. | |

| ” | Action at Sorauren | ib. | |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Pyrenees” on the regimental colour and appointments | 84 | |

| ” | Affairs of Urdax | ib. | |

| ” | Battle of the Nivelle | 85 | |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Nivelle” on the regimental colour and appointments | ib. | |

| ” | Passage of the Nive | 86 | |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Nive” on the regimental colour and appointments | ib. | |

| ” | Blockade of Bayonne | ib. | |

| 1814. | Battle of Orthes | 87 | |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Orthes” on the regimental colour and appointments | 88 | |

| ” | Affairs of Vic Bigorre and Tarbes | ib. | |

| ” | Battle of Toulouse | 89 | |

| ” | Authorized to bear the words “Toulouse” and “Peninsula” on the regimental colour and appointments | 91 | |

| ” | Sortie from Bayonne | 92 | |

| ” | Termination of the Peninsular war | ib. | |

| ” | The second battalion disbanded | ib. | |

| 1815. | Return of Napoleon to France | ib. | |

| ” | Battle of Waterloo | 93 | |

| ” | The regiment embarked for Ostend | ib. | |

| ” | Marched to Paris | ib. | |

| 1815. | Returned to England [x] | 93 | |

| 1816. | Stationed at Portsmouth | ib. | |

| ” | Permitted to resume the word “Firm” on the regimental colour and appointments | 94 | |

| 1817. | Embarked for Malta | ib. | |

| 1818. | General George Don appointed Colonel of the regiment | ib. | |

| 1820. | Embarked for the Ionian Islands | 95 | |

| 1821. | Casualties from sickness | ib. | |

| 1825. | Augmentation of establishment | 97 | |

| ” | Formed into six service and four depôt companies | ib. | |

| ” | Returned from the Ionian Islands to England | ib. | |

| 1827. | Embarked for Ireland | ib. | |

| 1829. | Lieut.-General Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe, Bart., appointed Colonel of the regiment | 98 | |

| 1830. | Formed into six service and four depôt companies | ib. | |

| ” | Service companies, embarked for the West Indies | ib. | |

| 1833. | Removed from Barbadoes to Antigua | ib. | |

| 1835. | Proceeded to St. Lucia | 99 | |

| ” | Depôt companies removed from Ireland to England | ib. | |

| 1837. | Service companies returned to Barbadoes | ib. | |

| 1838. | Depôt companies returned to Ireland | ib. | |

| ” | Service companies embarked for Nova Scotia | ib. | |

| ” | Complimentary Order prior to embarkation | 100 | |

| 1839. | Service companies stationed at Fredericton, New Brunswick | ib. | |

| 1841. | Removed to St. John’s, New Brunswick | 101 | |

| 1842. | Embarked for Ireland | ib. | |

| 1845. | Removed from Ireland to Great Britain | ib. | |

| 1846. | Formed into two battalions | ib. | |

| ” | Presentation of new colours | 102 | |

| 1847. | The first and reserve battalion embarked for the Ionian Islands | ib. | |

| 1848. | The reserve battalion employed in suppressing an insurrection in Cephalonia | 103 | |

| 1849. | Part of the first battalion employed on a similar service | 104 | |

| ” | The reserve battalion again employed in operations connected with the outbreak | 105 | |

| 1850. | The establishment of the regiment reduced | ib. | |

| ” | The reserve consolidated with the first battalion | ib. | |

| 1851. | The four depôt companies embarked at Cephalonia for England | ib. | |

| ” | The service companies proceeded from Corfu to Barbadoes | ib. | |

| ” | Major-General the Lord Frederick FitzClarence, G.C.H., appointed Colonel of the regiment | ib. | |

| 1852. | The service companies removed from Barbadoes to Trinidad | ib. | |

| ” | The depôt companies proceeded from Parkhurst to Fort Pembroke Dock | ib. | |

| ” | Conclusion | ib. |

OF

THE THIRTY-SIXTH REGIMENT.

| Year. | Page. | ||

| 1701. | William Viscount Charlemont | 107 | |

| 1706. | Thomas Alnutt | 110 | |

| 1709. | Archibald Earl of Ilay | 110 | |

| 1710. | Henry Desney | 112 | |

| 1715. | William Egerton | ib. | |

| 1719. | Sir Charles Hotham, Bart. | 113 | |

| 1720. | John Pocock | ib. | |

| 1721. | Charles Lenoe | 114 | |

| 1732. | John Moyle | ib. | |

| 1737. | Humphrey Bland | 115 | |

| 1741. | James Fleming | ib. | |

| 1751. | Lord Robert Manners | 116 | |

| 1765. | Sir Richard Pierson, K.B. | ib. | |

| 1778. | The Honorable Henry St. John | ib. | |

| 1818. | Sir George Don, G.C.B. | 117 | |

| 1829. | Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe, Bart. | 118 | |

| 1851. | Lord Frederick FitzClarence, G.C.H. | 119 |

| Page. | |

| Copy of the General Orders issued by the Commander-in-chief of Madras, upon the regiment being ordered to return to Great Britain | 121 |

| Copy of an Order issued by the Governor in Council upon the regiment quitting Madras | ib. |

| Copy of a Letter from Lieut.-General the Honorable Sir Arthur Wellesley, K.B., to Viscount Castlereagh, Secretary of State, respecting the exemplary conduct of the regiment at the battle of Vimiera | 122 |

| General orders of the 18th of January and 1st of February 1809, relating to the battle of Corunna and the death of Lieut.-General Sir John Moore | 124 |

| List of regiments which composed the army under Lieut.-General Sir John Moore | 128 |

| Documents relating to the word “Firm” borne by the regiment | 129 |

| Memoir of Lieut.-General Robert Burne, formerly Lieut.-Colonel of the regiment | 133 |

| Page. | ||

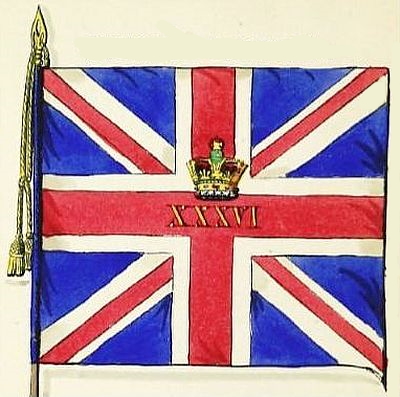

| Colours of the regiment | to face 1 | |

| Battle of Vimiera | 71 | |

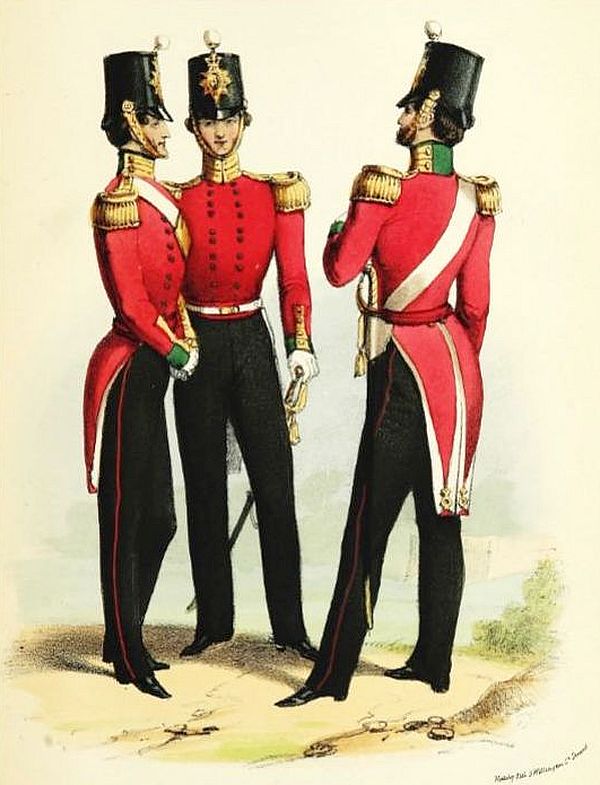

| Costume of the regiment | 106 |

THIRTY SIXTH REGIMENT

Madeley Lith., 3 Wellington St., Strand

OF

THE THIRTY-SIXTH,

OR THE

HEREFORDSHIRE REGIMENT OF FOOT.

Charles II., King of Spain, being affected with a dangerous indisposition, the European powers, in order to prevent the contention which was expected to arise on the decease of that monarch, determined to divide the Spanish territories among the several competitors. The first “Partition Treaty” was concluded between France, England, and Holland, on the 29th of August 1698; but a second Treaty was rendered necessary, in consequence of the death of the Electoral Prince of Bavaria, who had been declared heir to the Spanish Crown; accordingly, on the 15th of March 1700, a second Treaty was entered into between the same contracting powers, by which it was arranged that Charles Archduke of Austria, the second son of Leopold Emperor of Germany, should succeed to the throne of Spain, a certain portion of the territories of that Kingdom being, as before, allotted to the Dauphin of France;[2] and the Duke of Lorrain was to receive Milan in exchange for his own country, which was to be given to the French nation.

The long expected demise of the King of Spain occurred on the 1st of November 1700; and that Sovereign, incensed at the dismemberment of his dominions, bequeathed the Spanish monarchy to Philip Duke of Anjou, second son of the Dauphin of France; and Louis XIV., disregarding the treaties to which he had been a party, determined to support his grandson’s accession to the throne of Spain.

The French at this period overran the Spanish Netherlands and seized several strong towns, partly garrisoned by the Dutch, which compelled the States of Holland to acknowledge the Duke of Anjou’s title, with a view of obtaining their soldiers, who were not permitted to return, without difficulty.

It is a singular circumstance of the time, that King William, seeing the unwillingness of the nation to engage in a fresh war, actually acknowledged the Duke of Anjou as King of Spain, and sent him a letter of congratulation. In May 1701, however, the House of Commons unanimously resolved to assist the Dutch, and provide succours for the States General, in order to maintain the liberties of Europe. Several regiments were in the following month embarked for Holland; and additions were also made to the army and navy.

On the 28th of June 1701 a Royal Warrant was issued authorizing William Viscount Charlemont to raise a regiment in Ireland, which was afterwards numbered the Thirty-sixth.

England might have abstained from open hostilities with France had it not been for the following circumstance:—In the midst of these preparations the decease of James II. occurred at St. Germains on the[3] 16th of September 1701, and his son, the titular Prince of Wales, was immediately proclaimed, by order of Louis XIV., as King of England, Scotland, and Ireland, by the title of King James III. This indignity to the British Sovereign and Nation, added to the contemplated union of the crowns of France and Spain, made war inevitable; and King William, with the Emperor of Austria and the States General, concluded “the Grand Alliance,” the principal objects of which were to procure the Spanish Netherlands as a barrier for the Dutch, and to prevent France and Spain becoming eventually under the sway of the same Prince.

War was thus on the eve of being proclaimed, when King William met with the accident which terminated in his decease on the 8th of March 1702; the accession of Queen Anne, however, caused no alteration in the policy of her predecessor; and war was declared against France and Spain on the 4th of May following; additional forces were sent to Flanders, and the Earl of Marlborough was appointed to command the British, Dutch, and auxiliary troops, with the rank of Captain-General. The contest which ensued is known as “the war of the Spanish succession.”

Six regiments had been added to the regular army in the year 1702 as marine corps, and six other of the regular regiments of infantry (the Thirty-sixth being among the number) were appointed for sea service; as shown in the following list:—

The six regiments of marines were,—

The six regiments of foot for sea service were,—

The following is a copy of the Royal Warrant for levying this body of men, which was dated the 1st of June 1702.

“Anne R.

“Our pleasure is, that this establishment of six regiments of marines and six other regiments for sea service do commence and take place from the respective times of raising.

“And our further pleasure is, that the order given by our dearest brother, the late King deceased, and such orders as are, or shall be, given by us, touching the pay or entertainment of our said forces, or any of them, or any charges thereunto belonging, shall be duly complied with; and that no new charge be added to this establishment without being communicated to our High Treasurer or Commissioners of our Treasury for the time being.

“Given at our Court at St. James’s, on the first day

“of June, in the first year of our reign.

“By Her Majesty’s command,

“Godolphin.”

Prior to the decease of King William the reduction of Cadiz had been contemplated, after which it was resolved to embark an expedition against the possessions of Spain in the West Indies. Queen Anne following out this policy, it was arranged that a combined fleet of English and Dutch ships, consisting of fifty sail of the line, besides frigates, under Admiral Sir George Rooke,[5] and a land force, amounting to nearly fourteen thousand men, under the command of the Duke of Ormond, should proceed to the coast of Spain. The following corps were selected for this service, namely,—

| Officers and Men. |

||

| Lloyd’s dragoons, now Third light dragoons (detachment) | 275 | |

| Foot guards, the Grenadier and Coldstream | 755 | |

| Sir H. Bellasis, now Second foot | 834 | |

| Churchill’s, now Third foot | 834 | |

| Seymour’s, now Fourth foot | 834 | |

| Columbine’s, now Sixth foot | 724 | |

| O’Hara’s, three companies, now Seventh Royal fusiliers | 313 | |

| Erle’s, now Nineteenth foot | 724 | |

| Gustavus Hamilton’s, now Twentieth foot | 724 | |

| Villiere’s marines, five companies, now Thirty-first foot | 520 | |

| Fox’s marines, now Thirty-second foot | 834 | |

| Donegal’s, now Thirty-fifth foot | 724 | |

| Charlemont’s, now Thirty-sixth foot | 724 | |

| Shannon’s marines | 834 | |

| —— | ||

| 9,653 | ||

| Dutch regiments commanded by Major-General Baron Sparre and Brigadier Pallandt | 3,924 | |

| 13,577 |

The Thirty-sixth regiment, having been selected as part of the force to share in this enterprise, was withdrawn from Ireland, and proceeded to the Isle of Wight in June 1702, and embarked for Cadiz in July.

In the Harleian Manuscripts at the British Museum, the embarkation return of the regiment is preserved, of which the following is a copy:—

| The Right Honble ye Lord Viscount Charlemont’s Regt. | ||

| Captains. | Lieutenants. | |

| On board the Grey. |

┌ Wm Lord Charlemont, Colonel. | James Crofton |

| │ Charles Wills, Lieut.-Colonel. | Wm Whitaker | |

| │ Arthur Moore, Major | Jas. Bamber | |

| │ Thos. Alnutt | Alex. Foster | |

| └ Henry Frankland | James Brough | |

| Ensigns. | Serjts. | Corpls. | Drs. | Centinels. | |

| Thos Caulfeild | 2 | 3 | 2 | 43 | |

| Michl Merritt | 2 | 3 | 2 | 42 | |

| Rogr Mosten | 2 | 3 | 2 | 44 | |

| Wm King | 2 | 3 | 2 | 43 | |

| —— | 2 | 3 | 2 | 40 |

| Captains. | Lieutenants. | |

| On board the Ruth. |

┌ Hen. Fulvile | Hen. Fitzhugh |

| │ Jno. Hutchinson | Andw Dunbar | |

| │ Medburn Smith | Robt Ennis | |

| └ Jno. Dentilly | Anth. Callion |

| Ensigns. | Serjts. | Corpls. | Drs. | Centinels. | |

| Wm. Cuffe | 2 | 3 | 2 | 43 | |

| Wm. Musgrave | 2 | 3 | 2 | 42 | |

| Wm. Airs | 2 | 3 | 2 | 42 | |

| —— | 2 | 3 | 2 | 44 |

| Captains. | Lieutenants. | |

| On board the Friendship. |

┌ James Brathwait | Alex. Crage |

| │ Josias Campbell | —— | |

| └ Wm. Edwards | Jno. Mabbott |

| Ensigns. | Serjts. | Corpls. | Drs. | Centinels. | |

| Wm. Levinston | 2 | 3 | 2 | 43 | |

| Jno. Lloyd | 2 | 3 | 2 | 44 | |

| Wm. Hargrave | 2 | 3 | 2 | 44 | |

| 12 11 | 10 | 24 | 36 | 24 | 514 |

| On board the Grey. |

Tobias Caulfeild, Chaplain. | On board the Ruth. |

Laur. Bondelt, Surgeon. |

| Robt. Wilson, Adjt. & Quarter Master. |

Jno. Robins, Surgeon’s Mate. |

||

| Detached of ye Regt., and put on board ye Vulture Fireshipp, one Lieutenant, one Sergt, one Corpll., and twenty-six men. | |||

| (Signed) Ar. Moore. | |||

The difference in the number embarked, as shown in the foregoing document, and that specified against the Thirty-sixth in the list of regiments ordered to proceed to Cadiz, arises from the establishment being given in the first instance, while the embarkation return has reference only to effectives.

The armament appeared off Cadiz on the 12th of August, and the Duke of Ormond summoned the place; his terms being refused, a landing was effected between Rota and Fort St. Catherine on the 15th of that month, where the troops encountered and repulsed some Spanish cavalry. St. Catherine’s fort was compelled to surrender, and Port St. Mary’s was occupied by the British troops; the expedition, however, proved not of sufficient force to capture Cadiz, which was found much stronger and better garrisoned than was expected from the information which had been received in England prior to the fitting out of the armament, and the soldiers returned on board the fleet. The Thirty-sixth regiment was afterwards detached from Cadiz to the West Indies with a division of the royal navy under Commodore Walker, and sailed on this service on the 24th of September.

A powerful armament was prepared for the attack of the French and Spanish settlements in the West Indies in 1703, but this enterprise was subsequently abandoned.

After losing several men from the effects of the climate, the regiment was withdrawn from the West Indies, and was stationed in Ireland in the year 1704.

The successes obtained by the Duke of Marlborough in Flanders and Germany led to an attempt to place the Archduke Charles of Austria on the throne of Spain by force of arms. In the former year Gibraltar had been captured by the combined English and Dutch fleets, and in connexion with these events the Thirty-sixth regiment was embarked from Ireland in April[8] 1705, in order to proceed with the force under the Earl of Peterborough.

The design of this expedition was either to aid the Duke of Savoy in driving the French out of Italy, to make an attempt on Naples and Sicily, or to further the progress of the Archduke in Spain. The fleet arrived at Lisbon in June, and additional forces were embarked; at the same time the Archduke Charles went on board the fleet to share in the toils and dangers inseparable from the enterprise. From Lisbon the expedition proceeded to Gibraltar, where it was joined by the Prince of Hesse Darmstadt and a reinforcement from the garrison.

The fleet next proceeded to the bay of Altea, in Valencia, and there the officers and soldiers had opportunities of observing the attachment of the inhabitants of that part of Spain to the Austrian Prince. A thousand Catalonians and Valentians who had thrown off their allegiance to the house of Bourbon, and had acknowledged the Archduke Charles as the Sovereign of Spain, seized on the town of Denia, while others made demonstrations of giving effectual aid to the expedition; such a spirit of enterprise was evinced by King Charles, the Earl of Peterborough, the Prince of Hesse Darmstadt, and others, that both officers and men became imbued with the ardent zeal of their superiors, and resolved to effect something great and remarkable.

Under these feelings, the celebrated city of Barcelona, the capital of Catalonia, and one of the most ancient towns in Spain, was selected as the scene of the first attempt. Its situation on a plain near the sea, with a mole capable of containing only galleys and small ships, defended by ten bastions, several old towers, and other works, with a strong castle and citadel named Montjuich, on a hill on the west side, and commanding the town; the garrison consisting of between five and[9] six thousand men under the Viceroy of Catalonia, Don Francisco de Velasco, while the besieging army was unable to bring more than seven thousand men into the lines; these circumstances, with the fact that in 1697 this fortress resisted the Duke of Vendôme, with a French army of thirty thousand men, eight weeks with open trenches, and cost the French monarch twelve thousand men, gave an interesting and romantic character to the enterprise, in which the Thirty-Sixth, and other regiments employed, gained much honour. It is also to be noticed, that it was the same Prince of Hesse Darmstadt who was now engaged in capturing what he had before so nobly defended; for it was a question whether the Duke of Vendôme gained more glory by the taking, than the Prince of Darmstadt by defending Barcelona, when employed in the Spanish service.

The Earl of Peterborough landed his troops on the 23d and 24th of August near the river Bassoz, about three miles east of Barcelona. On the 28th of that month, King Charles came on shore, and several of the inhabitants of the neighbouring towns and villages greeted his landing with great acclamations. The progress of the siege was, however, retarded by opposite opinions and views entertained by the superior officers. It was at length determined to surprise the detached fortress of Montjuich, as proposed by the Prince of Hesse Darmstadt. The storming party of four hundred grenadiers, selected from the various corps employed in the siege, with a support of six hundred musketeers, commenced its march in the night of Sunday the 13th of September, round the mountains, and were followed by another detachment and a party of dragoons. The greater part of the way not being passable for above one man abreast, and the night very dark, the first detachment was nearly twelve hours on the march, and did not arrive at the foot of the mountain until break of day of the 14th of September; some Miquelets, in[10] the service of the enemy, gave the alarm to the troops in the castle and in the town, so that the Prince of Hesse, on his arrival, found the garrison in arms, with guards in the outworks, who received the Confederates with a general discharge of artillery and small arms. Upon this the Prince of Hesse, and the Viscount Charlemont, Colonel of the Thirty-sixth regiment, (who commanded on the 14th of September as Brigadier, in consequence of the indisposition of the Dutch Brigadier Schonenberg,) ordered Lieut.-Colonel Southwell, of the Sixth foot, to commence the attack with the grenadiers; this service was performed with signal intrepidity and resolution. Upon this success the Prince of Hesse Darmstadt advanced to possess himself of a post which would prevent the enemy’s communication with the town, and in the attempt was mortally wounded. The loss of this officer damped the spirits of the soldiers;—the enemy, perceiving some disorder amongst the Confederates, called out, “Long live King Charles!” and invited the assailants to come to them; upon Colonel Allen’s advance to the fort, with about two hundred and fifty men, the Spaniards opened the gate the better to conceal their stratagem, but immediately fired upon the men, and compelled this detachment to surrender; at the same time, a large reinforcement was seen advancing from the town to aid the garrison in the castle, whereupon the troops were seized with a panic, and Lord Charlemont, with other officers, endeavoured to counteract the disorder which ensued.

Upon the Earl of Peterborough receiving this intelligence, his lordship placed himself at the head of the detachments that were retreating,—rallied them, and ultimately regained the posts they had before so nobly acquired; the Spaniards who were advancing from the town retired, and the outworks of Montjuich were gained. Batteries were then constructed, and the inner works were assailed with cannon balls, bombs, and[11] grenades. After the action was over, the Earl of Peterborough introduced Lord Charlemont and Lieut.-Colonel Southwell to the King of Spain, as officers that had done His Majesty signal service on this occasion; for which they both received the thanks of that Prince.[6]

On the 17th of September, Lieut.-Colonel Southwell, of the Sixth regiment of foot, being on duty in the trenches, observed that the bombs thrown by a Dutch bombardier from a small mortar fell to the left of the fort, and concluding that there was a magazine in the place, he traversed the mortar himself more to the right, and fired it; the bomb fell into a small chapel where the garrison had stored their powder, which exploded, and buried a number of officers and men in the ruins. Lieut.-Colonel Southwell advanced at the head of his men, and was met by the surviving officers and men of the garrison, who immediately surrendered the fortress. The Lieut.-Colonel was made Governor of the place, in consideration of his services.

The capture of Montjuich facilitated the siege of the city of Barcelona, which was prosecuted with vigour; and on the 4th of October the garrison agreed to capitulate. The Viceroy made several extravagant demands, which occupied some days in debating, so that the capitulation was not signed until the evening of the 9th of October; it was agreed that the Angel-gate and bastion should be immediately delivered up to the Allies, and the whole city four days after, when the garrison should march out with all the honours of war. The capture of Barcelona was accompanied by the submission to King Charles of all Catalonia, with the exception of Roses.

King Charles commenced forming a Spanish army for his service; he soon had five hundred dragoons for a guard, and six regiments of infantry. He was joined by Colonel Nebot, who forsook the service of King Philip with a regiment of horse, and in a short time the province of Valencia submitted to the Austrian Prince.

The regiment continued under the immediate directions of the Earl of Peterborough, with whose achievements its services are connected; his raising the siege of San Matteo, the capture of Monviedro, his exploits in Valencia, and the relief of the capital of that province,—successes gained with a small body of soldiers over a numerous army,—carry with them the appearance of fiction and romance more than of sober reality; but being supported by abundance of collateral and direct evidence, the truth of these achievements is unquestionable. Unfortunately, no documents have been discovered to prove what particular corps his lordship left in garrison, and what he took with him in his daring enterprise in Valencia; the part taken by the First and Eighth dragoons, the Thirteenth, Thirtieth, and Thirty-fourth foot, and a few other corps, can be clearly made out from history; but whether the Thirty-sixth remained in garrison in Catalonia, or was employed in the enterprise in Valencia, has not been ascertained.

King Charles and his counsellors, instead of exerting themselves to provide for the security of the towns which had been acquired, and collecting the means for future conquests, wasted their time and money in balls and public diversions. The breaches in Barcelona and the detached fortress of Montjuich were left unrepaired, and the garrison unprovided for a siege. Meanwhile King Philip was obtaining reinforcements from the frontiers of Portugal, from Italy, Provence, Flanders, and the Rhine; and he soon appeared at the head of above twenty thousand men to recapture the provinces[13] he had lost. A powerful French and Spanish force approached Barcelona by land, a French fleet appeared before the place, and the enemy encamped before the north side of the city on the 2nd of April 1706.

The Earl of Peterborough hastened from Valencia with a body of select troops, but found the town so closely beset that he was unable to force his way into it, when he took to the mountains, and harassed the enemy with skirmishes and night alarms. When the garrison was nearly exhausted, its numbers decreased from deaths, wounds, sickness, and other causes to about a thousand effective men, and a practicable breach was ready for the enemy to attack the place by storm, the English and Dutch fleet arrived with five regiments of foot; the French fleet withdrew from before the town, and the reinforcements were landed. Barcelona being thus relieved, the enemy, having lost six thousand men before the town, made a precipitate retreat on the 12th of May, leaving two hundred brass cannon, thirty mortars, and vast quantities of ammunition and provision behind him, together with the sick and wounded of his army, whom Marshal de Tessé recommended to the humanity of the British commander.

Barcelona was thus preserved by British skill and valour; and the Thirty-sixth, with the other regiments in garrison, received the thanks of King Charles for this important service.

On the 10th of May 1706, Lieut.-Colonel Thomas Alnutt was promoted to the colonelcy of the Thirty-sixth regiment, in succession to the Viscount Charlemont, who had been removed by the Earl of Peterborough. A complaint on this subject was subsequently preferred by Lord Charlemont; and the reports made by the council of general officers, after a patient investigation, are inserted in the memoir of that nobleman, as Colonel of the Thirty-sixth regiment, at page 109. These documents are highly flattering to Viscount[14] Charlemont, and bear ample testimony to his gallant conduct at Barcelona.

An immediate advance upon Madrid having been resolved upon, the Marquis das Minas and the Earl of Galway, who commanded a British, Portuguese, and Dutch force on the frontiers of Portugal, were requested to penetrate boldly to the capital of Spain. To engage in this service the Thirty-sixth embarked from Barcelona, and proceeded by sea to Valencia, where King Charles was expected to arrive with the cavalry by land. While in Valencia the regiment furnished a detachment of non-commissioned officers and soldiers, which, with similar detachments from other corps of infantry, were formed into a regiment of dragoons, named the Earl of Peterborough’s regiment.

Requena and Cuenza, which places lie on the line of march from Valencia to Madrid, were captured after a short resistance by the troops detached under Major-General Wyndham. Meanwhile the army from Portugal had penetrated to Madrid, and was anxiously awaiting the arrival of King Charles, who, following the pernicious advice of his Italian counsellors, delayed his journey, and eventually proceeded by way of Arragon. This afforded time for the French and Spanish troops under King Philip to re-enter Spain; and uniting with the forces under the Duke of Berwick, the enemy had a great superiority of numbers. The allies were forced to retire from their forward position, and being joined on the 17th of September at Veles, by the troops which had been detached under Major-General Wyndham, they continued their route towards the frontiers of Valencia and Murcia, where they remained during the winter.

The Thirty-sixth, in the year 1707, joined part of the Allied army, which was composed of English, Spaniards, Portuguese, and Dutch, commanded by the Marquis das Minas and the Earl of Galway, and took[15] the field for offensive operations in the early part of April. After destroying several of the enemy’s magazines, the siege of the castle of Villena was undertaken, and while this was in progress, a French and Spanish force, of very superior numbers, commanded by the Duke of Berwick, advanced to the plains of Almanza. As the enemy expected the arrival of reinforcements under the Duke of Orleans, the allied generals, though much inferior in numbers, resolved to attack their adversaries without delay.

The following regiments were present at the battle of Almanza, and their effective strength is taken from the weekly return dated 22nd of April, three days prior to the battle:—

| Men. | ||

| Harvey’s horse, now Second dragoon guards | 227 | |

| Carpenter’s dragoons, now Third light dragoons | ┐ | 292 |

| Essex’s dragoons, now Fourth light dragoons | ┘ | |

| Killegrew’s dragoons, now Eighth hussars | 51 | |

| Pearce’s dragoons, disbanded | 273 | |

| Peterborough’s dragoons, disbanded | 303 | |

| Guiscard’s dragoons, disbanded | 228 | |

| Foot guards | 400 | |

| Portmore’s, now Second foot | 462 | |

| Southwell’s, now Sixth foot | 505 | |

| Stewart’s, now Ninth foot | 467 | |

| Hill’s, now Eleventh foot | 472 | |

| Blood’s, now Seventeenth foot | 461 | |

| Mordaunt’s, now Twenty-eighth foot | 532 | |

| Wade’s, now Thirty-third foot | 458 | |

| Gorges’s, now Thirty-fifth foot | 616 | |

| Alnutt’s, now Thirty-sixth foot | 412 | |

| Montjoy’s, disbanded | 508 | |

| Mackartney’s, disbanded | 494 | |

| Bretton’s, disbanded | 428 | |

| John Caulfeild’s, disbanded | 470 | |

| Lord Mark Kerr’s, disbanded | 429 | |

| Count Nassau’s, disbanded | 422 | |

| Total | 8,910 |

After a march of several hours along the rugged tracts of Murcia under a burning sun, the soldiers arrived in the presence of the enemy, at Almanza, about noon on the 25th of April. It was nearly three o’clock in the afternoon when the battle commenced. The Thirty-sixth were formed in brigade with the Ninth, Eleventh, and Lord Mark Kerr’s regiments under Colonel Hill, and Mino’s Portuguese dragoons were posted in the centre of the brigade, which was stationed in the second line; but nine of the enemy’s battalions having attacked Major-General Wade’s brigade, consisting of the Sixth, Seventeenth, Thirty-third, and Lord Montjoy’s regiments, the Ninth moved forward to their support. Great valour was displayed, but in vain, for the flight of the Portuguese squadrons had left the British and Dutch exposed to the weight and power of the enemy’s superior numbers, and no hope of victory remained. The Earl of Galway effected his retreat with the dragoons; several general officers collected the broken remains of the English infantry, which fought in the centre, into a body, and uniting them with some Dutch and Portuguese, formed a column of nearly four thousand men, which retreated two leagues, repulsing the pursuing enemy from time to time. On arriving at the woody hills of Caudete, the men were so exhausted with fatigue that they were unable to proceed further: they passed the night in the wood without food, and on the following morning they were surrounded by the enemy. Being without ammunition, ignorant of the country, and having no prospect of obtaining food, they surrendered prisoners of war.

Thus ended a battle in which the Thirty-sixth regiment behaved with great gallantry, but was nearly annihilated. Captains Musgrave and Parsons, Lieutenants Ayriss and Ballance, and Ensign Wells were killed; the following officers of the regiment were taken prisoners:—

The number of non-commissioned officers and soldiers killed, wounded, and taken prisoners at the battle of Almanza has not been ascertained; those who escaped, and were found serviceable, were afterwards transferred to other corps in Spain, and certain of the officers returned to England to recruit the regiment.

On the 15th of September 1707, orders were addressed to Colonel Alnutt to recruit and fill up the respective companies of the regiment; and the recruits were to assemble at Chester and Namptwich, which places were appointed for the rendezvous of the corps.

In the Annals of Queen Anne for the year 1708, it is stated, “Some time before, orders and commissions were delivered for new raising the regiments of—

which suffered most at the battle of Almanza, and the officers whereof, who were prisoners in France, were supplied by others.”

Colonel Archibald Earl of Ilay, afterwards Duke of Argyle, was appointed to the colonelcy of the Thirty-sixth regiment on the 23d of March 1709, in succession to Colonel Thomas Alnutt, deceased.

On the 23d of October 1710, Colonel Henry Desaulnais (afterwards spelt Desney) from the Coldstream foot guards, was appointed to the colonelcy of the Thirty-sixth regiment, in succession to Colonel the Earl of Ilay, resigned.

During the nine years which this war had been raging in Europe, British blood and treasure had been expended in making conquests for the house of Austria. The only advantage which had accrued to Great Britain was, that the power of the House of Bourbon had been diminished, and that of Austria augmented; the new Ministry chosen by Queen Anne, in 1710, resolved to act upon a different principle. Colonel Nicholson having made a successful attack on Port Royal, in Nova Scotia, on his return to England he submitted to the Government a plan for the reduction of Placentia and Quebec, as a preparatory measure for acquiring Canada for the British crown, and for expelling the French from Newfoundland, in order to regain the fishery.

Canada is stated to have been discovered by the famous Italian adventurer, Sebastian Cabot, who sailed under a commission from Henry VII.; and as the English monarch did not make any use of the discovery, the French soon attempted to derive advantage from it. Several small settlements were established, and in the early part of the seventeenth century the city of Quebec was founded for the capital of the French possessions in this part of the world. Although the colony continued in a very depressed state for some time, and the settlers were frequently in danger of being exterminated by the Indians, yet, in the beginning of the eighteenth century, it had become of such importance that its[19] capture was considered one of the best means of weakening the power of Louis XIV.

An expedition, consisting of about five thousand men, was accordingly ordered to proceed to North America under Brigadier-General Hill, for the purpose of making an attempt on Quebec. A large fleet formed part of the armament under Commodore Sir Hovenden Walker, and the force was to be further strengthened by troops from the North American colonies. The following regiments were employed on the expedition:—

On arriving at North America the fleet called at Boston for a supply of provisions, and the troops landed and encamped a short time on Rhode Island; but on the 20th of July they re-embarked, and having been joined by two regiments of provincial troops commanded by Colonels Walton and Vetch, sailed on the 30th of July from Boston for the river St. Lawrence. The expedition did not reach the river St. Lawrence until the 21st of August, when it encountered storms, and being furnished with bad pilots, eight transports, a store-ship, and a sloop were lost by shipwreck, and twenty-nine officers, six hundred and seventy-six soldiers, and thirty-five women of the Fourth, Thirty-seventh, Colonel Kane’s, and Colonel Clayton’s regiments, perished. There was also a scarcity of provisions. It[20] was, therefore, determined in a council of war, that further operations should be abandoned. Some of the regiments engaged in the expedition proceeded to Annapolis Royal, in Nova Scotia, but the Thirty-sixth returned to England, and arrived at Portsmouth on the 9th of October.

On the 12th of October 1711, Charles III., the claimant to the throne of Spain, was elected Emperor of Germany by the title of Charles VI., his brother Joseph having died at Vienna in the preceding April. This circumstance materially affected the war, and inclined Great Britain to agree to peace; for the consolidation of Spain with the Empire of Germany would have perilled the balance of power in Europe as much as the anticipated union of the crowns of France and Spain. The course of events had also shown, that a French and not an Austrian Prince was the choice of the Spanish nation.

Louis XIV. finding his armies defeated and dispirited, by the victorious troops under the celebrated Duke of Marlborough, at length sued for peace, negociations for which were shortly afterwards commenced.

The conditions of a Treaty of Peace having been agreed upon between Queen Anne and the French monarch, Dunkirk was delivered up to the British by Louis XIV., as a security for the performance of the stipulations, and the Thirty-sixth formed part of the force embarked under Brigadier-General Hill, to occupy that fortress. The regiment sailed from the Downs on the 7th of July 1712, with the fleet under Admiral Sir John Leake; on the following day the troops landed at Dunkirk, relieving the French guards at the citadel.

While the regiment was stationed at Dunkirk the Treaty of Utrecht was signed on the 11th of April 1713, which terminated the “War of the Spanish Succession.”

In the spring of 1714, the Thirty-sixth regiment returned to England; on the 1st of August of that year Queen Anne died, and was succeeded by King George I. The new sovereign having been quietly seated on the throne, the regiment proceeded to Ireland, and was placed on the establishment of that country.

On the 11th of July 1715, Colonel William Egerton was appointed by His Majesty King George I. to be Colonel of the Thirty-sixth regiment, in succession to Colonel H. Desney, upon whom was subsequently conferred the colonelcy of the Twenty-ninth regiment.

While the regiment was in Ireland, an insurrection was organized in England, by the partizans of the house of Stuart; at the same time the Earl of Mar summoned the Highland clans to arms, and proclaimed the Pretender King of Great Britain. On the breaking out of the rebellion, the regiment was withdrawn from Ireland, in the autumn of 1715; and it joined the troops encamped near Stirling under the Duke of Argyle.

In the early part of November, the rebel army advanced towards the Forth, with the view of penetrating to England, and the Duke of Argyle marched from Stirling to Dumblaine, near Sheriffmuir, for the purpose of opposing the progress of the insurgents. On the morning of Sunday, the 13th of November, the enemy, ten thousand strong, was seen advancing in order of battle; and the King’s troops, not mustering four thousand men, moved forward to engage their opponents. The Thirty-sixth regiment was in the left wing of the royal army. At a critical moment it was ordered to make a change of position, and, while in the act of re-forming, it was attacked by an immense body of Highlanders, the élite of the insurgent host. The soldiers were unable to withstand the very superior numbers of their opponents, and the left wing became separated from the main body of the army, and retired[22] beyond Dumblaine, to gain possession of the passes leading to Stirling. In the meantime, the right wing of the royal army had overpowered the left wing of the rebels, and chased it from the field. Thus both generals had one wing victorious, and one wing defeated: both in consequence claimed the victory. The insurgents were, however, prevented penetrating southward, and were defeated in their object. The Thirty-sixth had one serjeant and twenty-one rank and file killed; Captain Danoer, and fourteen rank and file, were wounded. From the field of battle the troops proceeded to Stirling, where they again encamped.

Towards the end of December the Pretender arrived in Scotland, and assumed all the ensigns of royalty. He held his court at Scone, and his head-quarters were at Perth: but the Highland chieftains finding it impossible to resist the royal forces, resolved to abandon the enterprize. They, however, burnt several villages, to distress the Duke of Argyle in his march, who, in January 1716, obliged them to abandon Perth, whence they retired to Montrose, where the Pretender escaped on board a French ship, together with the Earl of Mar and other adherents. After this the rebels dispersed to the Highlands.

The Thirty-sixth regiment was subsequently stationed at Dumbarton.

In the year 1718 the Thirty-sixth regiment proceeded to Ireland. In July 1718, the King of Spain having taken Sardinia and invaded Sicily, the “Quadruple Alliance” was formed between Great Britain, France, Germany, and Holland. War was declared against Spain in December by England and France.

The King of Spain afterwards made preparations in favour of the Pretender, and the Thirty-sixth regiment embarked, in March 1719, at Cork for Great Britain.

Brigadier-General Sir Charles Hotham, Bart., was appointed Colonel of the Thirty-sixth regiment on the 7th of July 1719, in succession to Colonel Egerton, removed to the Twentieth regiment.