Title: Bottoms Up: An Application of the Slapstick to Satire

Author: George Jean Nathan

Release date: November 20, 2021 [eBook #66775]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Philip Goodman Company, 1917

Credits: Charlene Taylor, SF2001, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

[Pg 1]

AN APPLICATION OF THE SLAPSTICK TO SATIRE

BY GEORGE JEAN NATHAN

NEW YORK

PHILIP GOODMAN COMPANY

1917

[Pg 2]

COPYRIGHT 1917 BY

PHILIP GOODMAN COMPANY

[Pg 3]

| I. | Continued in the Advertising Section | 5 |

| II. | We We | 8 |

| III. | The Queen of the Veronal Ring | 13 |

| IV. | Who’s Who in America | 22 |

| V. | A Little Child Shall Lead Them | 23 |

| VI. | The Letters | 27 |

| VII. | Promenades With Pantaloon | 34 |

| VIII. | Fanny’s Second Play | 50 |

| IX. | Glossaries | 59 |

| X. | Stories of the Operas | 63 |

| XI. | Three Modern Dramatists | 66 |

| XII. | Villainy | 67 |

| XIII. | A French Vest Pocket Dictionary | 69 |

| XIV. | What You Get for Your Money | 72 |

[Pg 4]

[Pg 5]

OR

MAGAZINE FICTION À LA MODE

[Page 290

Unable to contain himself longer, although he realized the vast futility of it all, Massington seized her in his arms and buried her lovely eyes and hair in the storm of a thousand kisses.

“You love me, Lolo—tell me you love me!” he choked.

“No! no!” she cried, struggling from his clasp with an adorable coquetry. “No, it must not be.”

Massington, for the moment, found himself unable to speak. Then, “Why?” he asked simply, softly.

“Because,” the girl replied, with a cunning moué—“because

[Page 291

In the finest homes and at the best-appointed tables CAMPBELL’S TOMATO SOUP is recognized as a dinner course of faultless quality and suited to the most important occasions.

[Page 292

I don’t yet know my own mind,” she finished.

Massington moved toward her. The amber glow of a small table lamp lighted up the bronze glory of Lolo’s tumbled tresses. And her eyes were as twin Chopin nocturnes dreaming out the melody of a far-off, unattainable love.

[Pg 6]

He paused before daring to lift his voice against the wonderful silence that, like midnight on southern Pacific seas, hung over her.

Presently, “When you do decide, what then?” he ventured.

“When I do decide,” she told him, “it will be forever. But ere I give you my answer, ere we take the step that must mean so much in our lives, we must both be strong enough to remember that

[Page 293

gives natural beauty to skin and hair. It is not only cleansing and softening, but its regular use imparts that natural beauty of perfect health which even the best of cosmetics can only remotely imitate. For trial cake, send four cents in stamps to Dept. 19-D, Resicura Company, Toledo, Ohio.

[Page 294

Society demands certain conventions that dare not be intruded upon.” Lolo toyed with some roses on the table at her side—roses he had sent her that same afternoon.

“But, darling,” breathed Massington, “what are mere conventions for us two now?”

Lolo tore at one of the roses with her teeth. “Oh!” she exclaimed, flinging out her arm wildly toward the ugly green wall-paper of her room that symbolized everything she so hated—“Oh, I know—I know! I do not want to think of them, but I—but we—must, Jason sweetheart, we must! And life so all-wondrous, beating vainly against their [Pg 7] iron bars and looking beyond them into paradise. We must think of them,”—a little sob crept from her throat,—“we must think of them!”

“Let us think, rather,” said Massington, “of that other world in which we might live, to which, Lolo dear, we might go, and, once there, be away from every one, all alone, we two—just you and I. Let us think of Spain, shimmering like some great topaz under the tropic sun; of the Pyrenees that, purpled against the evening heavens, watch over the peaceful valleys of Santo Dalmerigo; of the drowsy noons and silver moons of Italy; let us think, loved one, of the rippling Mediterranean and of

[Page 295

(established 1864)

for Whooping Cough, Spasmodic Croup, Asthma, Sore Throat, Coughs, Bronchitis, Colds and Catarrh. A simple, safe, and effective treatment. A boon to all sufferers. Its best recommendation is its fifty years of successful use.

For sale by All Druggists.

[Page 296

France singing like a thousand violins under summer skies.”

Lolo did not answer.

Massington waited. “Well?” he asked.

(To be continued in the next number.)

[Pg 8]

Being a pocket manual of conversation (English-French) with recognized pronunciation, and containing just and only such words and phrases as the average American needs and uses during the day in Paris.

| MORNING | ||

| Vocabulary | Vocabulaire | Pronunciation |

| Coffee (with milk) and rolls | Du café au lait et des petits pains. | Dew Coffee oh late et days petty pains. |

| The check | L’addition. | Ladditziyawn. |

| How much? | Combien? | Come-bean? |

| Overcharge! | La survente! | La servant! |

| It’s a shame! | C’est dommage! | Kest dumb-age! |

| I don’t pay! | Je ne paye pas! | Jay no pay pass! |

| You think Americans are easy marks. | Vous croyez que les Américains sont des belles poires. | Vuz croyz cue lays Americans sont days bells pores. |

| Where is the headwaiter? | Ou est le premier garçon? | Oo est lay primer garson? |

| Extortion! | L’extorsion! | Lee extortion! |

| Audacity! | L’audace! | Lowdace! |

| What impudence! | Quel effronterie! | Kwel effrontry! |

| A crime! | Un crime! | Yune cree-um! |

| Robbers! | Les voleurs! | Lays velours! |

| Call a policeman! | Appelez un gendarme! | Apple-ease yune cop! |

| One franc!! | Un franc!! | Yune frank!! |

| A shame! | L’infamie! | Linfame! [Pg 9] |

| Insolence! | L’insolence! | Linsolance! |

| Damned frog-eating Frenchmen! | Les sacrés mangeurs de grenouilles français! | Lays sackers mangers dee grenoolies frankays! |

| NOON | ||

| Vocabulary | Vocabulaire | Pronunciation |

| The bill of fare. | La carte (du jour). | La card (dee jury). |

| Roast beef and potatoes. | Un rosbif aux pommes de terre. | Yune roastbif oh poms dee tear. |

| A toothpick. | Un cure-dent. | Yune curedent. |

| The check. | L’addition. | Ladditziyawn. |

| Great Scott! | Bon Scott! | Bonnie Scot! |

| You must take Americans for boobs! | Vous croyez que les Américains sont des fous! | Vuz croyz cue lays Americans sont days simps! |

| A dirty shame! | L’infamie vilaine! | Linfame Verlaine! |

| Where’s the manager? | Ou est le maître d’hôtel? | Oo est lay mater dee hotel? |

| Two francs! | Deux francs! | Deuce franks! |

| What! | Quoi! | Quoit! |

| Incredible! | C’est incroyable! | Kest incroybul! |

| It’s awful! | C’est affreux! | Kest affrooz! |

| You can go chase yourself! | Chasse-toi! | Chase toy! |

| Why, in Chicago— | Mais à Chicago— | May in Shicawgo— |

| AFTERNOON [Pg 10] | ||

| Vocabulary | Vocabulaire | Pronunciation |

| So this is the Pré Catelan! | Eh, bien! Le Pré Catelan! | E bean! Lee Pree Cattleland! |

| It’s not up to Elitch’s Gardens. | Ce n’est pas si bon que les jardins d’Elitch. | Key nest pass so bon cue lays jardins dee Elitch. |

| Waiter, a Bronx. | Garçon, un apéritif Bronx. | Garson, yune aperteef Bronx. |

| Gee, that’s a peach of a chicken in the green hat! | Mon Dieu! Quelle jolie poulette au chapeau vert! | Mon doo! Kwel jolly pulay aw shapyou vert! |

| Waiter, my check. | Garçon, l’addition. | Garson, my ladditziyawn. |

| What! Fifty centimes? | Quoi! Cinquante centimes? | Quoit! Sinkant sentimes? |

| Do you think us Americans are rubes? | Croyez-vous que nous Américains sont des fermiers? | Croyz vuz cue news Americans sont days fermeers? |

| Too much! | Trop! | Tropp! |

| I can’t consent to it! | Je ne puis y consentir! | Jay nee pewis why consenter! |

| An awful over-charge! | Une survente terrible! | Uni servant terrible! |

| Damned French swindlers! | Les Français sont des escrocs damnables! | Lays Frankays sont days escrocks damnable! |

| EVENING | ||

| Vocabulary | Vocabulaire | Pronunciation |

| Hey there! Taxi! [Pg 11] Café de la Paix! | Hé! Arrêtez! Taxi! Café de la Paix! | Either whistle or wave arms. Caif della Pays! |

| How much, driver? | Combien, chauffeur? | Come-bean, showfer? |

| Thirty centimes! | Trente centimes! | Trenton sentimes! |

| Cursed crook! | Maudit voleur! | Maude velour! |

| It’s an absolute imposition! | C’est une véritable exploitation! | Kest uni veritable exploitation! |

| Change this five-franc piece. | Changez cette pièce de cinq francs. | Changey settee piece dee sink franks. |

| Well, anyway, I got the right change. | (Merely thought, never verbalized) | Counterfeit. |

| Waiter, bring me some roast beef and potatoes. | Garçon, apportez moi un rosbif aux pommes de terre. | Garson, apporty moey yune roastbif oh poms dee tear. |

| A toothpick. | Un cure-dent. | Yune curedent. |

| My check! | L’addition! | My ladditziyawn! |

| Two francs! | Deux francs! | Deuce franks! |

| Hell! | L’Enfer! | Loafer! |

| You take us Americans for hayseeds. | Vous croyez que nous Américains sont des graines du foin. | Vuz croyz cue news Americans sont days grains dew fun. |

| Two francs! I’m sore! | Deux francs! m’enrage! | Je Deuce franks! Jay mennyrage! |

| Here is your money and—good night! | Voici votre argent et—bon soir!! | Voce vote argent et—bon sore! |

| NIGHT | ||

| Vocabulary | Vocabulaire | Pronunciation |

| Maxim’s at last! [Pg 12] Ah there, kiddo! | Enfin, Maxim’s! Eh, bébé! | Whoop-ee! E baby! |

| Sure, I’ll buy you wine. | Certainement, j’acheterai du champagne. | Certainment, joshetarie dew wine. |

| I love you. | Je vous aime. | Jay vus Amy. |

| Oh, you’re kidding | Vous me taquinez. | Vuz me tackknees. |

| More wine? Sure, dearie! | Plus de champagne? Certainement ma chérie! | Plus dee wine? Certainment, my cherry! |

| TWO A. M. | ||

| Vocabulary | Vocabulaire | Pronunciation |

| Stung! | Une piqûre! | Uni picker! |

| BACK HOME: A MONTH LATER | ||

| Vocabulary | Vocabulaire | Pronunciation |

| Honestly, Mary, I was true to you. | Vraiment, Marie, je vous fus fidèle. | Naturally. |

FOOTNOTE.

Inasmuch as the only persons in all Paris who do not try to speak English are the Americans, it is advisable for the Americans in Paris to try speaking English and reserve their French for the United States where the only persons who do not try to speak French are the Frenchmen.

[Pg 13]

A Guaranteed Box Office Melodrama in One Act, Containing Just and Only Such Famous Melodramatic Lines as Have for Countless Years Been Successful in Evoking the Plaudits and Hisses of Melodrama Audiences.

| DICK STRONG: | A hero. |

| MARY DALLAS: | A country girl. |

| ABNER DALLAS: | Mary’s aged father. |

| JEM DALTON: | A villain. |

SCENE: Sitting room of Abner Dallas’ home.

PLACE: A small country town in New York State.

TIME: The present day.

When the curtain rises, the stage is in complete darkness. Mary enters, goes to centre table and turns up small oil lamp. Immediately the whole stage is lighted with a dazzling brilliance. Mary catches sight of Dalton standing in doorway L.U.E. A sinister smile is on his lips, a riding crop in his hand.

MARY

(shrinking back)

My God—you! What do you want here?

DALTON

(advancing with his hat on and switching his boot with riding crop)

Ha, my pretty one, we shall see—we shall see.

[Pg 14]

MARY

(in tears)

Oh, how can you, how can you? Was it not enough that you stole my youth, that you made me what I am?

DALTON

So, my proud beauty, your spirit is broken at last! And at last I have you within my power!

MARY

Oh, God, give me strength! If I were a man, I’d kill you! You are of the kind who drag women to the gutter.

DALTON

Now, now, my fine young animal! Remember—’twas you, too, who sinned!

MARY

(sobbing wildly)

Folly, yes—but not sin, no, no—not sin, not sin! It is the weakness of women and the perfidy of men that makes women sin.

DALTON

(sneering)

Sin it was—sin, I repeat it. You—you’re no better now than the women of the streets!

MARY

No, no! Don’t say that, don’t say that! Have pity!

(throwing herself before him)

See! It is a helpless woman who kneels at your feet—

[Pg 15]

DALTON

(throwing her from him)

Bah!

MARY

(pleading)

Who asks you to give back what is more precious to her than jewels and riches, than life itself—her honor!

DALTON

Enough of that! Now, you, listen to me! Do as I say and I can make a lady of you—you shall be dressed like a queen and move in society, loved, honored and famous. This I offer you if—if you will become my wife.

MARY

Your wife! Not if all the gold of the world were in your hands, and you gave it to me. Your wife—never—never—not even to become a lady! Before I’d be your wife I’d live in rags and be proud of my poverty! There is the door—go!

DALTON

Not so fast, my girl!

MARY

I’ll do what thousands of other heartbroken and despairing women have done—seek for peace in the silence of the grave!

DALTON

(sneeringly)

Well, what will you do?

MARY

Stand back! Let me pass. If you lay your hand on me, I’ll—

[Pg 16]

DALTON

Ha!

(He advances upon her and makes to seize her in his arms. She struggles, screams. Enter Dick, revolver drawn)

DICK

What’s the meaning of this? Speak!

DALTON

(to Mary, airily)

Who is this young—this young cub?

(aside)

Damnation!

DICK

(advancing)

I’ll show you soon enough, you fighter of women!

DALTON

(in a superior tone, loftily ignoring the insult)

Hm, you Americans are a peculiar lot. But I suppose your manners will improve as your country grows older.

DICK

Oh, I see! So you’re an Englishman, aren’t you? Englishmen never believe how fast we grow in this country. They won’t believe that George Washington ever made them get out of it, either, but he did!

DALTON

Ah, my dear fellow, our country has grown up of its own accord, but you have to get immigrants to help you build up your country—and what are they?

[Pg 17]

DICK

That’s so: they don’t amount to anything until they come over here and inhale the free and fresh air of liberty. Then they become American citizens and they amount to a great deal. We build up the West and feed the world!

DALTON

Feed the world! Oh, no! Certainly you don’t feed England!

DICK

Oh yes we do! We’ve fed England. We gave you a warm breakfast in 1776, a boiling dinner in 1812—and we’ve got a red-hot supper for you any time you want it!

DALTON

(insolently)

’Pon my word, you amuse me.

DICK

(sarcastically)

You don’t say so!

DALTON

And if it wasn’t for this

(he smiles sneeringly)

lady—

DICK

(stepping quickly to Dalton, raising his hand as if to strike him)

By God, if you were not so old, I’d——

MARY

(wildly)

Dick! Dick!

[Pg 18]

DICK

(to Dalton, face to face, pointing to door)

Now, then, you worthless skunk—you get straight the hell out of here!

(Dalton looks first at Dick, then at Mary. Then, with a cynical laugh, shrugs his shoulders and exits)

MARY

(throwing herself in Dick’s arms and burying her head on his breast)

Dick——

DICK

(stroking her hair fondly)

Have courage, sweetheart; do not cry. Everything will turn out for the best in the end.

MARY

You have the courage for both of us. Every blow that has fallen, every door that has been shut between me and an honest livelihood, every time that clean hands have been drawn away from mine and respectable faces turned aside as I came near them, I’ve come to you for comfort and love and hope—and have found them.

DICK

My brave little woman! My brave little woman! How you’ve suffered in silence! But brighter days are before us.

MARY

(pensively)

Brighter days. I try to see them through the clouds that stand like a dark wall between us.

DICK

You must not heed such black thoughts, my angel.

[Pg 19]

MARY

(sadly)

I’ll do my best to fight them off—for your sake, our sake.

DICK

There’s a brave dear! And now, good-bye, dearest, until to-morrow. Remember, when the clouds are thickest, the sun still shines behind them.

(exits)

MARY

(alone)

Oh, my Dick, my all, may God protect you!

(A pause. Then enter Abner, carrying a gun)

MARY

(in alarm)

Father! What are you doing? Where are you going?

ABNER

I’ve heerd all! I’m a-goin’ t’ find the varmint who wronged ye, and when I find him, I’m a-goin’ t’ kill him, kill him—that’s all!

MARY

Stop, dad! You know not what you do!

ABNER

(with a sneer)

You! A fine daughter! A fine one to speak t’ her old father who watched over her sence her poor mother died, who slaved for her with these two hands, who——

MARY

(interrupting)

Oh, father, that is cruel! Nothing that others [Pg 20] could do would hurt me like those words from you. I have suffered, father; I would rather starve than——

ABNER

(brusquely)

A fine time now fer repentance!

MARY

(in tears)

Mercy! Mercy! Have mercy!

ABNER

Mercy, eh? Well, I kalkerlate such as you’ll get no mercy from me!

MARY

(wildly)

I was young and innocent; I knew nothing of the world.

ABNER

Go! And never darken these doors again!

(he throws open the door; the storm howls)

Go! Fer you will live under my roof no longer! Thus I blot out my daughter from my life forever, like a crushed wild flower.

MARY

Oh, father, father! You don’t, you won’t, you can’t be so cruel!

(exits)

ABNER

(slams door; stands a moment at knob; then goes slowly to table and picks up Mary’s photograph. He looks at it; his eyes fill with tears)

[Pg 21]

I’ll set by that winder, and set and set, but she, my little one, ’ll never come back, never come back. Oh, my little girl, my little girl! I’ll put this here lamp in the winder to guide my darlin’ back home t’ me.

(he totters toward the window)

CURTAIN

[Pg 22]

LIPINSKI, Abraham, editor; b. Mogilef, Russia, August 16, 1869; s. Isidor and Rachel (Hipski); m. Sarah Gondorfsky, of Syschevka, Russia, 1889, Leah Ranalowski, of New York, 1897, Minna Rosensweig, of New York, 1906. Editor, the Socialist Quarterly, the Russian-Jewish Gazette. Author: “Freedom for the Poles,” “The Case for the Russian Peasants,” “The Dangers of Democracy” and sixteen children. Address: New York, New York.

O’CALLAHAN, Patrick Michael, public official; b. Dublin, Ireland, December 6, 1873; s. Seumas and Bridget (O’Shea); m. Mary Shaughnessy, of Glennamaddy, Ireland, February 12, 1890; came to New York, 1891, and was on police force 1891-2, leader 12th Assembly District, New York, 1893; 13th Assembly District 1894; 14th Assembly District 1895; commissioner of docks and ferries, New York, and treasurer of the board, 1896; Tammany Hall leader 1895.... Address: New York, New York.

DREZETTI, Pietro, charity organizer; b. Milan, Italy, October 10, 1873; s. Garibaldi and Maria (Arezzo); m. Rocca Frignano, of Giovinnazo, Italy, 1897; came to New York 1892 and began as bootblack; leader 6th District Republican Rally Club 1899-1904; organized Italian Charities League, 1906; president and treasurer Italian Charities League, 1906—, Italo-American Chowder Club, 1907—, Italian Immigrant Relief Society, 1908—, Italian Workmen of the World, 1908—. Address: New York, New York.

CHILLINGS, Algernon Ronald, playwright; b. Manchester, England, December 9, 1871; s. Hubert and Gladys (Windcourt); was actor in London, 1889-1903; came to America 1904; has written four American plays, “Lord Dethridge’s Claim,” “The Savoy at Ten,” “The Queen’s Consort,” and “Lady Cicely’s Adventure.” Has lectured on the American drama at Yale and Harvard Universities. Vice-president Society of American Dramatists. Address: New York, New York.

OBERHALZ, Gustav, ex-congressman; b. Düsseldorf, Germany, May 20, 1868; s. Ludwig and Hannah (Draushauser); m. Kunigunde Kartoffelbaum, of Teklenburg, Germany, 1884, Theresa Waxel, of Neuholdensleben, Germany, 1889; came to America in steerage 1886; joined the Deutsche Gesellschaftsverein 1886 and became its president in 1896; merged this organization in 1897 with the Vaderland Bund; presented his native city with a library in 1898. Author: “Deutschland und Der Kaiser.” Address: Brooklyn, New York.

[Pg 23]

By

—— ——

The snow swirled against the window in great gusts. Agatha Brewster sat looking into the flaming grate.

“What’s the matter, mamma dear?” asked Betty, her little daughter. “You look so sad—and this is Christmas eve.”

Agatha did not answer. She could not trust her voice. There was a mist before her eyes. She sat there thinking, thinking, thinking. It was just a year ago tonight that Dave, her husband, had parted from her in anger. Since then no word, no letter—nothing but endless conferences with that hideous lawyer, the unbearable condolences of well-meaning friends, the dull heart-ache, the thought of little Betty.... [Pg 26]

Betty crept noiselessly down the stairs.

“Papa! Oh, papa! My papa!” she cried. “You’ve come home again. Won’t Santa Claus be glad!”

Brewster, his eyes suddenly blinded with tears, grabbed the sweet child to his breast and hugged her, oh, so close! And then, bending down, he kissed the brave little woman at his side.

The End.

If you want to read the parts of this story that have been left out to save ink, you will find the whole thing in any issue of any 15 cent magazine. I say any issue, but if you want to make doubly sure, get any Christmas issue.

[Pg 27]

AN ALPHABETICAL PROBLEM PLAY AFTER THE MANNER OF PINERO, HENRY ARTHUR JONES, AND OTHER DRAMATISTS OF A BYGONE DAY.

FOREWORD: A season or so ago, Mr. Cyril Maude and Miss Laurette Taylor attracted considerable attention in a one-word play—a play in one act, each line of whose dialogue consisted of a single word. In order to meet the insistent public demand for constantly increased novelty, I submit herewith what is probably the dernier cri in dramatic literature—a play in one letter.

| ZACHERY EBBSMITH: | The usual problem play husband. |

| FELICIA EBBSMITH: | The usual problem play wife. |

| ROBERT CHARTERIS: | The usual problem play lover. |

| JENKINS: | The usual problem play butler. |

SCENE: The drawing-room of Ebbsmith’s house. Any old set will do, provided only there is a portière-hung entrance at R. 2, in which the husband may make his unexpected appearance.

TIME: An evening in May.

PLACE: New York.

When the curtain rises, Mrs. Ebbsmith (a brunette with an uncanny likeness to Mrs. Patrick Campbell), is discovered in Charteris’ arms.

[Pg 28]

MRS. E.

(in passionate ecstasy)

O!

CHARTERIS

(ditto)

O!

(Zachery Ebbsmith duly appears in doorway at R. 2. The lovers cannot see him as their backs are turned)

MRS. E.

(still in passionate ecstasy)

O!

CHARTERIS

(ditto)

O!

(Mrs. Ebbsmith frees herself reluctantly from Charteris’ embrace. She turns and catches sight of Ebbsmith)

MRS. E.

(cowering before her husband’s steady gaze)

U!

EBBSMITH

(quietly)

I.

CHARTERIS

(under his breath)

G!

MRS. E.

(sinking to her knees before Ebbsmith, seizing his hands in supplication, and looking at him appealingly)

“Z”!

EBBSMITH

(angrily withdrawing his hand)

U——

[Pg 29]

MRS. E.

(in tears, interrupting)

R?

EBBSMITH

(violently; between his teeth)

A——

MRS. E.

(in tears, again cutting in)

A?

EBBSMITH

(with a laugh)

J!

CHARTERIS

(in great surprise)

J?

EBBSMITH

(repeating, nodding his head)

J!!

CHARTERIS

(in wonder)

Y?

MRS. E.

(ditto)

Y?

EBBSMITH

(with a grim smile, displaying a bundle of letters)

C!

(Mrs. E. and Charteris look at each other in alarm, realising now what Ebbsmith’s ironic twitting means)

MRS. E.

O!

CHARTERIS

H——!

[Pg 30]

EBBSMITH

(waving the letters tauntingly under his wife’s eyes)

C!

(Mrs. E. endeavours to speak. She tries to summon courage to ask Ebbsmith how and where he got the carelessly-guarded, incriminating letters, but her lips are muffled through fear. Ebbsmith waits patiently, sneeringly. Then, seeing his wife’s hopeless struggle to phrase the question——)

EBBSMITH

(quietly taking a five dollar bill from his wallet, and holding it aloft, with a significant smile)

A——.

CHARTERIS

(puzzled)

A?

EBBSMITH

(nodding toward entrance at R. 2)

V.

MRS. E.

(beginning to comprehend)

O!

(she rushes to bell. She presses it in order to summon the bribed Jenkins and lodge her accusations against him for his deceit. There is a pause. Enter Jenkins. Mrs. Ebbsmith makes to speak. Ebbsmith interrupts her.)

EBBSMITH

(to Jenkins, quietly)

T.

(Jenkins nods and exits. There is another pause. Charteris attempts to conceal his nervousness [Pg 31] by puffing nonchalantly at a cigarette. Jenkins enters with the tea. Ebbsmith motions his wife and Charteris to take their seats at the small table. Puzzled, they obey. Jenkins pours and exits.)

EBBSMITH

(taking from his pocket two railroad tickets, one of which he hands Charteris)

U.

CHARTERIS

(perplexed)

I?

EBBSMITH

(nodding firmly)

U!

(Ebbsmith now hands the other ticket to his wife)

EBBSMITH

(as he gives it into her puzzled hands; in same tone as before)

U!

MRS. E.

(in a tone of nervous bewilderment)

I?

EBBSMITH

(nodding firmly)

U!

(Mrs. E. and Charteris look at each other. Their expressions suggest anything but a feeling of personal comfort. They look at each other’s tickets)

MRS. E.

(reading name of road on top of ticket)

“B——.”

[Pg 32]

(her eyes, still dimmed by tears, prevent her from seeing the rest. She starts to mumble the “and” which follows the “B”)

“n——.”

(but gets no further, and breaks down crying)

CHARTERIS

(finishing the name of the road)

“O.”

(Charteris and Ebbsmith look at each other fixedly across the tea-table)

CHARTERIS

(deliberately)

U——.

(Ebbsmith lifts his eyebrows)

CHARTERIS

(hotly)

B——.

(Ebbsmith lifts his eyebrows)

CHARTERIS

(choking back the “damned,” and, flinging down his hand in disgust at the whole business)

’L!

EBBSMITH

(rising, going to door and holding aside the portières, significantly)

P!

MRS. E.

(sobbing out her reawakened old love for Zachery)

“Z”!

EBBSMITH

(insisting; in even tone)

D!

[Pg 33]

MRS. E.

(sobbing wildly)

“Z”!!

EBBSMITH

(with absolute finality)

Q!!

(Charteris throws a wrap around Mrs. Ebbsmith’s shoulders and starts to lead her from the room. At the doorway, with a cry of anguish, Mrs. Ebbsmith breaks from Charteris’ arm and throws herself into the arms of her husband. A smile spreads over the latter’s features as he realises the complete effectiveness of the cure he has practised upon his wife, of the stratagem by which he has won her away from Charteris forever, of the trickery by which he has shown Charteris up to her for the insincere philanderer he is, of the device of pretending to concur in her and Charteris’ plan to elope. He clasps her close to him and presses a kiss on her brow. Charteris takes up his hat, gloves, and stick from the piano, and tip-toes from the room as there falls the

CURTAIN

[Pg 34]

Broadway playwright—one who possesses the ability to compress the most interesting episodes in several characters’ lifetimes into two uninteresting hours.

The art of emotional acting, on Broadway, consists in expressing (1) doubt or puzzlement, by scratching the head; (2) surprise, by taking a sudden step backwards; (3) grief, by turning the back to audience and bowing head; (4) determination (if standing), by thrusting handkerchief back into breast pocket, brushing hair back from fore-head with a quick sweep of hand and buttoning lower button of sack coat; (5) determination (if seated), by looking fixedly at audience for a moment and then suddenly standing up; (6) despair, by rumpling hair, sinking upon sofa, reaching over to table, pouring out stiff drink of whiskey and swallowing it at one gulp; (7) impatience, by walking quickly up stage, then down, taking cigarette from case, lighting it and throwing it immediately into grate, walking back up stage again and then down; (8) relief, by taking deep breath, exhaling quickly and mopping off face with handkerchief; and (9) fear, by having smeared face with talcum powder!

The leading elements in the Broadway humour, in the order of their popularity: (1) speculation [Pg 35] as to how the Venus de Milo lost her arms, and (2) what she was doing with them when she lost them.

Broadway actors may in the main be divided into two groups; those who pronounce it burgular and those whom one cannot hear anyway back of the second row.

The Syllogism of the Broadway Drama

1. Someone loves someone.

2. Someone interposes.

3. Someone is outwitted, someone marries someone, and someone gets two dollars.

Such critics as contend that literature is one thing and drama another, are apparently of the notion that literature is something that consists mainly of long words and allusions to Châteaubriand, and drama something that consists mainly of monosyllables and allusions to William J. Burns.

The test supreme of all acting is the coincidental presence upon the stage of a less competent actress who is twice as good-looking.

A Thumb-nail Critique—The plays which, in the last two decades, have in the United States made the most money: “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” “Way Down East,” “The Old Homestead,” “Ben Hur,” and “Peg o’ My Heart.” The plays which, in the last two decades, have, in the United States, made the least money: “The Thunderbolt,” “Strife,” [Pg 36] “The Three Daughters of M. Dupont,” “The Incubus,” and “General John Regan.”

The unities of the Belasco drama: Time, place and (legal) action.

Constructive critic: One who builds up the newspaper’s theatrical advertising revenue.

The producers of our two-dollar music shows are rapidly gobbling up all the vaudeville actors. This will immeasurably help vaudeville.

The circuses will soon go into winter quarters. They cannot compete with the Drama Leagues.

The world may be divided thus: actors and dramatic critics. The only difference between them is that the former do their acting on a platform.

Shakespeare’s plays fall into two distinct groups: Those written by Shakespeare and those acted by Beerbohm Tree.

Dramatic criticism: The theory that one is more interested in the devices with which a woman makes herself beautiful—cold creams, mascaro, false hair, eyebrow pencils, lip rouge, face powder, dental floss, whale-bone, curl papers, et cetera—than in the beautiful woman herself.

[Pg 37]

Something seemingly never remembered by dramatists when writing love scenes: the more a young woman really loves a man the less talkative, the more silent, she is in his presence.... Only women over thirty are chatty before the object of their affection.

The proficient actor is one who can completely immerse his own personality in the rôle he is playing. The star actor is one who can completely immerse the rôle he is playing in his own personality.

Although it may have absolutely nothing to do with the case, I yet believe that, in a romantic stage rôle, no actress can possibly be convincing or persuasive if she is able in private life to eat tripe, chicken livers, calves’ brains or a thick steak.

Maurice Donnay, the talented gentleman of Gallic dramatic letters, observes, “The French dramatists treat of love because it is the only subject which every member of the audience understands, and a dramatist must, of course, appeal to the masses.” Which, in another way, may account for the great appeal and success in America of crook plays.

When a critic refers to a male actor’s “authority,” the betting odds are generally thirty to one that what he has done is to mistake for that quality the aforesaid actor’s embonpoint.

[Pg 38]

Mr. George P. Goodale, a good citizen and an honest taxpayer, was lately accorded a great banquet in honor of his fifty years of continuous service as dramatic critic to the Detroit Free Press. At the banquet, it was said, repeated, and emphasized that, in all his half-century as a critic of the drama, Mr. Goodale had never made a single enemy. Where, than in this banquet and its import, a smarter satire on the American notion of what constitutes dramatic criticism?

The hero of a Broadway play may not be bald. This would seem, in the Broadway drama, to be the first rule of heroism and, with heroism, of intelligence and appeal. So, Julius Caesar, Bismarck, George Washington, Napoleon and Shakespeare would be low villains.

It is a favourite challenge of the average Broadway playwright to the dramatic critic that if the latter knows so much about plays, why doesn’t he write one himself. The same question might be asked of the average Broadway playwright.

The financial success of the Broadway play is conditioned on the proportion of theatergoers who believe that singeing keeps the hair from falling out and that the American Indians were accustomed to use the word “heap” before every adjective. The last season was the most successful Broadway has known in years.

[Pg 39]

It took Molière and Sheridan, as it now takes Shaw and Bahr, years to fashion their comedies. And yet, when all is said and done, what is funnier, what provokes a louder laughter, than the mere articulation of the name Gustav?

Literature is an art wherein one observes the effects of the thematic action upon the protagonist’s mind. Drama is an art wherein one observes the effects of the thematic action upon the protagonist’s heart. Burlesque is an art wherein one observes the effects of the thematic action upon the protagonist’s trousers-seat.

“Trying it on the dog”—a phrase referring to the trying out of a play in the provinces before bringing it into the metropolis. In other words, testing the effect of the play upon an intelligent community to predetermine, by its lack of success there, its subsequent prosperity in New York.

The so-called “laughs” in an American musical show must, if they would “get over,” be devised in such a manner and constructed of such basic materials that they shall be within the scope of the intelligence of persons who can neither read nor write. This is why nine-tenths of the persons in a Broadway audience fall out of their chairs with mirth when anybody on the stage refers to whiskers as alfalfa or when a character is named the Duc de Gorgonzola.

Royalties.—The percentage of the gross receipts [Pg 40] which playwrights get from producers, after lawsuits.

The critic who believes that such a thing as a repertory company is artistically possible believes that a dozen modern actors, assembled into one group, are sufficiently talented and skilled to interpret satisfactorily a dozen plays. The critic who does not believe that such a thing as a repertory company is artistically possible knows that a dozen modern actors, assembled into one group, are insufficiently talented and skilled to interpret satisfactorily even one play.

It is the custom in many New York theaters to ring a bell in the lobby so as to warn the persons congregated there that the curtain is about to go up on the next act and that it is time for them to go back into the theater. But it still remains for an enterprising impresario to make a fortune by ringing a bell in the theater so as to warn the persons congregated there that the curtain is about to go up on the next act and that it is time for them to go back into the lobby!

Farces fall into two classes: Those in which the leading male character implores “Let me explain!” and the leading female character tartly replies, “That’s the best thing you do,” and those in which the leading male character’s evening dress socks have white clocks on them.

Mr. Florenz Ziegfeld succeeds with his shows [Pg 41] because he addresses his chief appeal to the eye. Mr. George M. Cohan succeeds with his because he addresses his chief appeal to the ear. The impresarios of the Fourteenth Street burlesque shows succeed with theirs because they address their chief appeal to the nose.

The one big ambition of nine out of every ten American playwrights is, in the argot of the theater, to “get over the footlights.” The one big ambition of nine out of every ten audiences is exactly the same!

Most so-called optimistic comedies are based on the theory that a cup of coffee improves in proportion to the number of lumps of sugar one puts into it.

Opening Night.—The night before the play is ready to open.

The chief dramatic situation in “The Road to Happiness” consists of a hero who, with hand on hip pocket, defies the assembled villains to advance as much as an inch at peril of their lives and who, having thus held them at bay, proceeds to pull out a handkerchief, flick his nostril and make his getaway. The chief comic situation in “Arizona,” produced many years ago, consisted of the same thing, save that a whiskey flask or plug of tobacco—I forget which—was used in place of a nose-doily. Thus, little boys and girls, has our serious drama advanced.

[Pg 42]

Derivations

First-Nighter.—From Fürst (German for “prince”) and the English word nitre (KNO3: a chemical used in the manufacture of gunpowder); hence, a prince of gunpowder, or, in simpler terms, someone who makes a lot of noise.

Manager.—From the Anglo-Saxon word “manger,” the “a” having been deleted in order that the word might be shortened, and so used more aptly for purposes of swearing. Manager thus comes from “manger,” something which provides fodder for the jackasses in the stalls.

Practically speaking, it is reasonable to believe that the public doesn’t want gloom in the theater not because it is gloom, not because of the gloom itself, but for the very good reason that gloom isn’t generally interesting. Let a playwright make gloom as interesting as happiness and the public will want it theatrically. But the gloom of the drama is, more often than not, uninteresting gloom. In illustration: Take two street-corner orators. Suppose both are talking, one a block away from the other, on precisely the same topic. It is a gloom topic. For instance, the question of the large number of starving unemployed. One of the orators hammers away at his audience with melancholy statistics and all the other depressing elements of his subject. The other, equally serious, makes his points, not alone as does the first orator with blue figures, but with light comparisons and saucy illustrations. Which is the more interesting? Which gets the larger crowd? Which convinces? Take a second and correlated illustration. [Pg 43] Two weekly magazines print articles on, let us say, the work of organized charity in its attempt to relieve the community’s paupers. In itself, not particularly jocose reading matter. One of the two magazines, in its treatment of the story, has its general tone exampled by some such sentence as “Last month the charity organizations of New York supplied the poor of the city with 30,000 loaves of bread.” The other magazine, expressing the same thought and facts, has its sentence phrased thus: “Last month the charity organizations of New York supplied the poor of the city with 30,000 loaves of bread, an amount almost 8,000 in excess of all the bread eaten during the same space of time by Mr. Diamond Jim Brady in the ten leading Broadway restaurants.” Which magazine has the bigger circulation?

The conventional treatment of gloomy themes in the drama is like the ancient tale of the proud old coon who, driving a snail-paced and ramshackle horse and an even more ramshackle buggy down a Southern road used largely by automobilists, suddenly perceived a small boy hitching on behind. “Hey!” exclaimed the old brunette, “Yoh look out dar! Ef yoh ain’t careful yoh’ll be sucked under!” The mechanic of the gloomy dramatic theme, like the old dinge, too often takes his theme too pompously, too seriously. And is generally himself sucked under as a result. Clyde Fitch took a so-called gloomy theme in his play “The Climbers”—the play that started bang off with a funeral—but his play is still going with the public in the stock companies because he didn’t let the gloom of his story run away with the interest. The final curtain line in “The Shadow” is: “After all, real happiness is often to be found in tears.” Tears [Pg 44] are often provocative of a greater so-called “up-lift” feeling than mere grins and laughter. Take a couple or more of illustrations of the most popular mob plays America has known, say, “Way Down East,” “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” “The Old Homestead.” These, fundamentally, are what the mob calls “sad” plays. The yokelry would ever rather pay for the privilege of crying than laughing. What farce ever made as much money as “East Lynne”? The tears in “Cinderella” have made it the world’s most successful theatrical property.

The difference ’twixt tragedy and comedy is the difference of a hair’s breadth. Tragedy ends with the hero’s death. Comedy, with the hero’s getting married.

To be effective, acting must interpret not so much the playwright’s work as the audience’s silent criticism of that work.

... It is to be remarked that the New Movement in the theater, about which we hear so much, what with its scenery, lighting, stage architecture and what not, seems to concern everything but drama.

The moving pictures will never supplant the spoken drama, contend a thousand and one critics. Well, anyway, not so long as the drama is being spoken as it is to-day in the majority of our Broadway theaters.

[Pg 45]

Madame Karsavina of the Russian Ballet seeks in her chorographic pantomimes to interpret drama with the body. The Boston censors commanded that Madame Karsavina, who in her chorographic pantomimes seeks to interpret drama with the body, completely conceal her body in heavy draperies. The Boston censors may be expected next to command Mimi Aguglia, of the Sicilian Players, who seeks to interpret the body in terms of drama, to undress.

Comedy is but tragedy, cunningly disguised and popularized for the multitude.

Men go to the theater to forget; women, to remember.

Melodrama is that form of drama in which the characters are deliberately robbed of a sense of humor by the author. Problem drama, most often, that form in which the characters are deliberately robbed of a sense of humour by the audience.

How ashamed of themselves Galsworthy and Shaw, Molnar and Brieux, Hauptmann and Wedekind must feel when they read a book on dramatic technique by a member of the Drama League!

The error committed by the critic who, night after night, goes to the theater in an attitude of steadfast seriousness and in such attitude reviews [Pg 46] what he beholds therein lies in his confounding of the presentation with the institution. His respectful attitude toward the presentation is, therefore, under current conditions eight times in ten a direct insult to the institution.

THE AMERICAN ADAPTATION

The Plot of the Play, in the Original:

Gaston Beaubien tires of his wife, Gabrielle, and enters into a liaison with his wife’s best friend, Lucienne.

The Plot of the Play, in the Adaptation:

Gaston Beaubien tires of his wife’s best friend, Lucienne, and enters into a liaison with his wife, Gabrielle.

Brieux—Jeanne d’Arc on a mule.

WHY DRAMATIZED NOVELS OFTEN FAIL THE HEROINE

(In the book)

“As nineteen-year-old Faith Draycourt stood there, she seemed for all the world like some breathing, living young goddess come down to earth in a chariot of cloud chiffon tinted orange-pink by the setting sun. Her slender body whispered its allure from out the thin folds of silk that, like some fugitive mist, clung about her. Her hair, a tangle of spun copper, fell upon her dimpled shoulders and tumbled off them, a stormy bronze cascade, to the ground. Her eyes, like twin melodies of Saint-Saens imbedded in Bermuda’s blue woodland pools; her voice, soft as the haunt of a distant guitar——.”

[Pg 47]

(From the newspaper critique of the play made from the book)

“The role of Faith Draycourt was ably interpreted by that accomplished and experienced actress, —— ——, who is well remembered by the older generation of theater-goers for her fine performance of Juliet in 1876 at the old Bowery Theater.”

An arm-chair beside a reading lamp is the only place for worth-while drama. If you are one of those who seriously contends that such drama should be acted in the theater, that the stage is the place for such work, that it stands a fair chance there, tell me what you think would happen to Hauptmann’s “Weavers” if, in that wonderful climax to the fifth act, the child actress playing Mielchen should accidentally drop her panties, or to “Hannele” if, at a moment of its poignant pathos, a shirt-sleeved Irish scene-shifter were plainly observable in the wings.... Think of Sudermann’s “Princess Far-Away” with a bad cold in her head and an obviously tender corn!

We hear much of the difference twixt the quality of London and New York theater audiences. It may be summed up in a single sentence. In London they do not put a chain on the dime-in-the-slot opera-glasses.

A Shaw Play.—A moving-picture consisting entirely of explanatory titles.

[Pg 48]

You say it is possible for drama to reflect life? Very well, then answer me this. In the cabled dispatches from the European fighting countries, there appeared the other day an account of the astounding spectacular heroism, in the face of a death-filled fire, of a German soldier named Ludwig Dinkelblatz. If you can reconcile yourself to the notion of a man named Ludwig Dinkelblatz as the hero of a play of whatever sort, you win.

Mr. Edward Locke, who wrote “The Bubble,” “The Revolt,” and other reasons for bad theatrical seasons, observed in a recent interview that he always writes his plays by artificial light because plays are always produced by artificial light, and that, therefore, he believed that this was the logical way to go about writing plays. Mr. Locke will agree with his critics that inasmuch as people always go to bed in the dark, it is but logical that, when the lights go out in the auditorium and one of his plays gets under way, they should go to sleep.

We hear a great deal of the American drama’s failure to hold the mirror up to nature. This is nonsense, nothing more nor less. The trouble is not with the drama, but with the mirror! The American drama tries to reflect nature in one of the little mirrors women carry in their vanity-boxes. Some day it may learn—as the French drama has learned—that when there’s any reflecting of nature to be done, you’ve got to use a pier glass. We like to believe, we Anglo-Saxons, that all drama [Pg 49] lies in mortals’ faces, and that drama’s purpose is merely to reflect, as in a shaving mirror, men’s tears and smiles. The French, a wiser people, know that drama reposes alone in men’s bodies.

[Pg 50]

NOTE.—In Bernard Shaw’s “Fanny’s First Play,” there are introduced in an epilogue four characters representing as many dramatic critics of London—A. B. Walkley, Gilbert Cannan, etc. These four critics are made by Shaw to discuss the play in their four typical and familiar critical ways. When the play was produced in America it was suggested to Shaw that he come to the United States, study the peculiarities of the local critics, and alter his epilogue so that the indelible attitudes toward everything dramatic of the native criticerei might be lampooned for American audiences. Shaw was too busy. Being possessed of an hour’s spare time and considerable presumption, the present writer essays the task in Shaw’s behalf. “Fanny’s Second Play” may be any anonymously written play.

| William Summers |

| Alston Hill |

| Carlton Dixon |

| Lawrence Fenemy |

FENEMY

You ask me if I like the play. How do I know! If it’s by a foreigner, sure I like it; but if it’s by an American (particularly a young American) you can bet I’ll roast it. Why, it’s got to the point where some of these young American playwrights are getting to be better known than we are, and I’ll be darned if I’m going to do anything to help the thing along.

[Pg 51]

HILL

You’re right, Fenemy. Besides, they know how to do these things so much better abroad than our writers do. Take this play. Pretty good, to be sure. But I’ll wager it was written by some fellow who used to be a reporter—probably on my very paper. And I’m not going to be the one to give him the swelled head. No, sir!

DIXON

If Belasco had only produced this play it would have been a wonder. Belasco’s a wizard. I know it, because he has repeatedly told me so himself.

SUMMERS

Ah, gentlemen—gentlemen. Why indulge in this endless colloquy over this insignificant proscenium tidbit. Let us remember that howsoever good it may be it was still not written by Shakespeare and that however ably it may have been interpreted, Booth and Barrett and Charlotte Cushman, alas, are no longer with us.

HILL

Oh, you’re a back-number, Summers. You’re no critic—you’re a scholar! Why don’t you put a punch in your stuff and get a good job?

FENEMY

I wonder if it’s possible this play’s meant to be satirical. I’ll read what you say about it in the morning, Hill, and if you think it’s a satire, I’ll see it again and sort o’ edit my opinion of it in the Sunday edition.

DIXON

I must say again that I’m sorry Belasco didn’t produce the play. He’s a genius. Look what he [Pg 52] did for The Easiest Way. If it hadn’t been for his lighting effects the show wouldn’t have stood a chance!

FENEMY

You’re right, Dixon. Anyway, The Easiest Way was just like Iris. Our writers can’t touch the English. Besides, Pinero’s got a title and Eugene Walter, we must remember, once slept on a bench in Bryant Park.

HILL

I like the title of this piece though, fellows. Fanny’s Second Play. It’ll give me the chance to say in my review of it: “Fanny’s Second Play won’t go for a minute.” Catch it? Second—minute. Great, isn’t it? I like plays with titles you can crack jokes about.

SUMMERS

Alack-a-day, things are not in criticism as they used to be. Dignity, my friends, is what I always aimed for—dignity and dullness. Poor Daly is dead and poor Wallack sleeps in his grave. Schoolboys, mere schoolboys and shopkeepers run the drama of to-day.

HILL

Oh, cut it out. Dan Daly wasn’t half as good a comedian as Eddie Foy is! And Shakespeare—why the only time that any interest in Shakespeare has been aroused in the last ten years was when Julia Marlowe and Sothern got married. Give me Sutro.

DIXON

But as I was saying, Belasco’s the man! Shakespeare in his palmiest moments never imagined a [Pg 53] greater effect than that soft lamp-light that Belasco put over the chess table in the last act of The Concert.

FENEMY

Correct again, Dixon! Do you think Belasco would use German silver knives and forks on a dinner table in a play of his? Nix! The real stuff for him! Sterling! And you can say what you want, it’s attention to details like that that makes a play. I suppose Fanny’s Second Play may be pretty good drama, but I never had any experience like the hero in the show and by George, I don’t believe it could have happened! Besides, my sister never acted that way and consequently I must put the whole thing down as rubbish. The author doesn’t understand human nature. No, sir, he doesn’t understand human nature!

HILL

The society atmosphere, too, is perfectly ridiculous. Why, I’ve been in the Astor as many as five times and I never saw any society people act that way. Our American playwrights are not gentlemen, that’s the rub.

SUMMERS

Ah me, when Sarah Siddons and Clara Morris and Ada Rehan were in their prime—those were the days! What use longer, I ask you, gentlemen, to inscribe praise to actresses if one is no more invited to meals by them? Times have changed. This Mr. Cohan, paugh! This Miss Barrymore, fie!!

DIXON

Sure thing! Warfield’s the only one left who can act and Belasco taught him all he knows. [Pg 54] Belasco—there’s the wizard! Did you notice the way he got that amber light effect in Seven Chances? Wonderful, I say, wonderful——.

FENEMY

(interrupting)

But did you ever smoke one of George Tyler’s cigars?

HILL

About this play we saw tonight. I kind of think I’ll have to let it down a bit easy because the management’s taken out a double-sized ad. in the Sunday edition. And besides, say it should turn out next week to be by an English dramatist instead of an American! Then wouldn’t we feel foolish!

DIXON

(vehemently)

Well, we know who the producer is! Isn’t that enough? If it’s put on by Belasco, it’s great; if it’s put on by anybody else, it’s a frost—and there you are. That is, anybody but Klaw and Erlanger. No use throwing the hooks into them too hard. They pull too much influence with our bosses.

HILL

(with a self-amused grin)

I wonder what the magazine er-um-um critics, as they choose to call themselves, will think of this play?

DIXON

Humph! Magazine critics? Why they’re all young fellows. Impudent, too! They think that just because they’re educated they know more about the game than we do—than I do—and I’ve had my [Pg 55] opinions quoted on as many as two hundred garbage cans in one week!

SUMMERS

Ah, dear me, gentlemen. In my time, a critic was a person with a taste for drama; to-day a critic is largely a person with a taste for quotation in the Shubert ads.

FENEMY

(to the others, tapping his temple significantly with his forefinger)

The poor chap actually thinks Molière knew more about playwriting than Jules Eckert Goodman!

HILL and DIXON

(laughing uproariously)

Fine! Fine!! Better use that line in your review tomorrow. Of course it hasn’t anything to do with Fanny’s Second Play, but that doesn’t matter. It’s too good to lose.

HILL

By the way, the Dramatic Mirror wrote me for my picture to-day. They’re going to print it in the next number. Pretty good, eh?

FENEMY

I should say yes! I wish I could get as much advertising as you get, Hill.

HILL

(suddenly)

By Jove! An idea! What if this play we saw tonight was written by Belasco, after all?

SUMMERS

Impossible, gentlemen. Had Mr. Belasco written [Pg 56] it, we should have had an inkling of the fact through the recent lawsuit calendars.

FENEMY

Maybe it’s by Augustus Thomas. It’s got a lot of thought in it!

HILL

Yes, it certainly is full of thought!

DIXON

Sure, it’s got a pile of thought in it all right enough!

SUMMERS

(lifting his eyebrows)

What thought, gentlemen?

FENEMY

Didn’t you catch that curious new word in the second act? What was it, Dixon?

HILL

Psychothrapy.

DIXON

No, you mean psychothrupy.

FENEMY

No, no, it is psychothripy.

SUMMERS

Gentlemen, you mean psychotherapy.

ALL

Well, it doesn’t matter. It’s thought, anyway—something snappy and new. And Augustus Thomas is the only American playwright who thinks.

[Pg 57]

DIXON

Did you notice that reference to the “sweet and noble mother”? I think Roi Cooper Megrue wrote it—and I don’t like Megrue. He’s too fat looking. I think the play is punk.

HILL

But that third act attempted seduction climax sounds to me like Sheldon.

DIXON

(quickly)

Oh, then the play’s all right!

HILL

But we must remember that Sheldon is a young man and that he is a Harvard graduate. He needs taking down a little.

DIXON

But he’s a good friend of my dear friend Mrs. ——. Anyway, if only Belasco——.

FENEMY

(interrupting)

Well, I’ve got to get down to the office and write my review.

(looking at watch)

It’s got to be in at twelve o’clock and it’s ten minutes of twelve now, and I’ve got to fill a column.

(exits)

HILL

Between us, Dixon, I personally enjoyed this play [Pg 58] immensely; but professionally, I think it’s very bad.

DIXON

My idea exactly. Of course, if Belasco——.

(Exeunt)

[Pg 59]

A Vaudeville Glossary

(Embracing Translations and Explanations of Such Words and Phrases as Are Used Regularly in Vaudeville, and Necessary to a Comprehension of Vaudeville by Persons Who Do Not Wear Soft Pleated Shirts with Dinner Jackets.)

Knock-out—The designation of a performance which has succeeded in completely captivating the advertising solicitor for a weekly vaudeville paper.

Wop—A term of derision directed at an Italian who earns a difficult livelihood digging ten hours a day at subways by an American actor who earns an easy livelihood digging twenty minutes a night at Ford automobiles.

A scream—The designation of an allusion to the Prince of Denmark in Shakespeare’s celebrated tragedy as “omelet.”

Team—A term applied to two vaudeville actors who get twice as much money as they deserve.

Sure-fire—A compound word employed to describe any allusion to President Wilson or the performer’s mother.

Swell—An adjective used to describe the appearance of a gentleman performer who wears a diamond stud in his batwing tie or of a lady performer who is able to pronounce “caviar” correctly.

Artiste—A vaudeville actress who carries her own plush curtain.

[Pg 60]

Dresden-China Comedienne—Any vaudeville actress who is not a comedienne and who wears a poke bonnet fastened under the chin with pale blue ribbons.

Headliner—A performer of whom audiences in the legitimate theatres have wearied.

Society’s Pet—The designation of any young woman performer who has danced in a Broadway restaurant that was visited one evening by a slumming party from Fifth Avenue.

Mind-reader—A vaudeville performer who imagines the members of a vaudeville audience have minds to read.

A First-Night Glossary

Rotten—An adjective used to describe anything good.

Author—A noun used to designate the person who, in response to the applause, comes out upon the stage after the second act in a conspicuously new Tuxedo and talks as if he had written a play.

Laugh—A noise uttered by the audience whenever the comedian, casting an eye upon the prima donna’s hinter-décolleté, ejaculates, “I’m glad to see your back again.”

Grate—Something that is used to warm up vaudeville sketches.

Wholesome—An adjective used to describe any play which sacrifices art to morals.

Dramatic—An adjective used to describe a scene in which anything, from a vase to the seventh commandment, is broken.

[Pg 61]

Sympathy—The emotion felt by the audience for the woman character who lies, betrays, robs, deceives, steals, poisons, cheats, swindles, commits adultery, plays false, stabs, dupes or murders—in a beautiful gown.

Program—A pamphlet which assures the audience that the theatre is disinfected of germs with CN Disinfectant and that the play is disinfected of drama with actors.

A Glossary of British Slang

When George Ade’s “College Widow” was produced in London several years ago, a section of the program was devoted to a glossary of American slang. The British equivalents for the various specimens of Yankee vernacular were thus provided, so that the audience might comprehend the meaning of the words spoken by the characters in the play. By way of helping American audiences to a better understanding of the British vulgate, I append a reciprocating glossary:

Actor—A war-time patriot who shouts “God Save the King” as he hurries aboard the first steamer out of Southampton to accept an engagement in an American musical comedy adapted from the German.

Beastly—A condemnatory adjective applied by an actor (see above) to the treatment accorded an actor (see above) by Americans during his engagement in an American musical comedy adapted from the German, after the actor (see above) has returned to England following a declaration of peace.

[Pg 62]

Handkerchief—A small square of linen with which, when he has (or hasn’t) a cold, an Englishman blows his wrist.

Old Top—A term of endearment applied by an actor (see above) to an American who seems to be about to buy a drink.

A General Theatrical Glossary

| sardou (v.t.) | —1. | To lock the door and chase a reluctant lady around the room. |

| act (v.i.) | —1. | To spoil an otherwise good play. 2. To endorse a new massage cream. 3. To please William Winter. |

| Success (n.) | —1. | A bad play. 2. A d—n bad play. 3. A h—l of a d—n bad play. |

| fairbanks (v.t.) | —1. | To leap headlong out of a window. 2. To lick three men with one hand. |

| doro (v.i.) | —1. | To compel favorable critical notices by having beautiful eyes. |

| alwoods (v.t.) | —1. | To foil a villain. 2. To foil two villains. 3. To foil three villains. |

[Pg 63]

I PAGLIACCI

(ē pal-yät-chē)

Two-act drama; text and music by Leoncavallo

| CANIO | Tenor |

| TONIO | Baritone |

| BEPPO | Tenor |

| NEDDA (Canio’s wife) | Soprano |

| SILVIO (a villager) | Baritone |

At Tonio’s signal, the curtains open disclosing a cross-roads with a rude portable theatre and Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt with a party of débutantes. The distant sounds of a cracked trumpet and belabored drum call the peasants together, and they greet with joy the familiar characters in whose costumes Canio, Nedda, and Beppo enter simultaneously with Mrs. O. H. P. Belmont’s party, Mrs. Otto Kahn’s party, Mrs. Goelet, in mauve faille d’amour silk, and a party of young people chaperoned by Mrs. Douglas Robinson. Silencing the crowd (on the stage), Canio announces the play for the evening—and is heard. Canio descends and boxes the ears of Tonio, who loves Nedda. Tonio, and two old gentlemen of decided snoring proclivities who have been sitting in the eighth row, wander off. A villager invites the players to drink. Twenty-seven gentlemen in the [Pg 64] audience accept the invitation. The villager hints that Tonio lingers to flirt with Nedda, and the ladies in the boxes also get busy with recent scandal. Canio takes it as a joke, twenty-one of the twenty-seven gentlemen taking it with water. Canio says he loves his wife. And, after kissing her, he departs coincident with the arrival of the occupants of the Gould and Sloane boxes. The other peasants, and forty-two other gentlemen, leave the scene.

Nedda, left alone, broods over the fierce look which Canio and Gatti Casazza gave her. She wonders if Canio suspects her. The sunlight and the new gown and necklace on Mrs. Payne Whitney thrill her and she revels in the song and the sport of the birds (“Ballatella”). At the end of the rhapsody she finds that the hideous Tonio, if not the audience, has been listening. He makes ardent love, but she laughs him to scorn. He pursues her, however, and she, picking up Beppo’s whip, slashes him across the face. He swears revenge and stumbles away. Now her secret lover, Silvio, steals in with the twenty-seven gentlemen who have been over to Browne’s. Silvio pleads with her to go away with him. She promises in an undertone to meet him that night at Del Pezzo’s Italian Restaurant at the corner of Seventh Avenue and Thirty-fourth Street. Tonio, having seen them, hurries away. He gets the ear of Canio and returns coincidently with thirty-four of some forty-odd gentlemen who have been across the street. Silvio, however, escapes unnoticed and so do the two old gentlemen who have been sleeping in the eighth row.

Canio threatens to kill Nedda and Leoncavallo’s music. Beppo and one of the old gentlemen who [Pg 65] has forgotten his overcoat rush back. Beppo disarms Canio. Tonio hints that Nedda’s lover may appear that night in the play and some bizarre looking ladies in the third row hint a lot of other things. Left alone, Canio bewails his bitter fate, and the gentlemen whose wives won’t let them get out do the same. In wild grief, Canio finally gropes his way off. And such gentlemen as are left in the audience follow suit.

(To be continued)

[Pg 66]

| Act I ! ! ! ! ! |

} | ! ! ! ! ! |

| Act II ! ! ! ! ! |

} | |

| Act III ! ! ! ! ! |

} |

The Hampton Shops

The Edison Electrical Supplies Co.

The Tiffany Studios

Thorley

The Edison Electrical Supplies Co.

Vantine’s

The Antique Objets d’Art Exchange

The Edison Electrical Supplies Co.

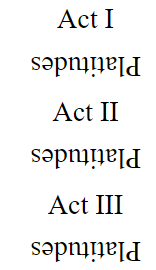

Act I

Platitudes

Act II

Platitudes

Act III

Platitudes

[1] Transcriber's Note: All three “Platitudes” printed upside down in original.

[Pg 67]

The villainy of a character in the American drama is appraised by an American audience in accordance with the following schedule of black marks:

| 1. | Black moustache | 20 points |

| 2. | Riding boots | 36 points |

| 3. | Riding boots and crop | 47 points |

| 4. | Foreign accent (save Irish) | 29 points |

| 5. | Top hat | 8 points |

| 6. | Patent-leather shoes | 8 points |

| 7. | Long cigarette holder | 4 points |

| 8. | Well fitting clothes | 52 points |

| 9. | Sexual virility | 84 points |

| 10. | Good manners | 76 points |

| 11. | Inclination to believe that a woman over twenty is perfectly able to take care of herself | 91 points |

| 12. | Inclination to believe that a woman over twenty-five is perfectly able to take care of herself | 92 points |

| 13. | Inclination to believe that a woman over thirty is perfectly able to take care of herself | 93 points |

| 14. | Inclination to believe that women between the ages of thirty-five and ninety are perfectly able to take care of themselves | 94 points |

| 15. | Inclination to believe that women between the ages of twenty and ninety are perfectly able to take care of themselves if they want to, but that they usually don’t want to | 95 points |

| 16. | One who believes that when a woman is married she does not necessarily because of this fact lose all interest [Pg 68]in the world | 82 points |

| 16a. | Or in a good time | 83 points |

| 17. | Boutonniere | 9 points |

| 18. | Suspicion on the part of the villain that the hero is a blockhead | 98 points |

| 19. | Verbal statement of the above fact by the villain | 99 points |

| 20. | [Pg 69] Common sense | 100 points |

Containing such words and phrases, together with their pronunciation and meaning, as are necessary to the proper and complete understanding of the American “society play” in which they are generally employed.

| Word or Phrase | Pronunciation | Meaning |

| beau idéal | bue idol | To smoke a cigarette in a long holder. |

| au fait | aw fête | To wear an artificial gardenia in the lapel of one’s evening coat. |

| comme il faut | comma ill faugh | Literally: “As it should be.” To appear in the drawing-room in white tennis flannels. |

| billet doux | Billie Deuce | Anything written on lavender stationery. |

| bon soir | bun sour | Greetings! |

| valet | valley | A comedy-relief Jap. |

| ennui [Pg 70] | en-wee | To glance nonchalantly through Town Topics, yawn and throw it back on the table. |

| égalité | egg-all-light | Literally: “equality.” A servant who, learning that his master is in financial straits, offers him, with tears in his eyes, his own meagre savings. |

| double entente | dub’l on-tunder | Any remark about a bed. |

| distingué | dis-tang-way | A gentleman with a goatee. |

| Céléste[2] | Seal-lest | The lady-friend of the producer. |

| coup d’état | coop de tate | Sneaking the married heroine unobserved out of the bachelor apartment by letting her wear the housekeeper’s cloak. |

| gendarme | John Domme | An English actor in a New York traffic policeman’s uniform. |

| entrée | entry | A papier-maché duck. |

| faux pas | for Pa | To wear the handkerchief in the pocket. |

| petite [Pg 71] | potate | Designation of the one hundred and seventy-two pound ingénue. |

| qui vive | key weave | To step quickly on tiptoe to the door and listen, before going on with the conversation. |

| sang froid | sang freud | Leisurely to extract a cigarette from a gold cigarette-case. |

| garçon | gar-sun | A bad actor who imitates Figman’s performance in “Divorcons.” |

| en déshabillé | N. de Shabell | Literally: “In undress.” That is, dressed up in a couple of thousand dollars’ worth of lingerie. |

| mésalliance | mess alliance | Any girl whom the son of the family desires, in the first act, to marry. |

| en règle | in riggle | A butler who waits until the visitor has entered the drawing-room before taking his hat and stick. |

| à la mode | allah mode | Tea at two o’clock in the afternoon. |

[2] The maid.

[Pg 72]

The box-office price of a theatre ticket is two dollars. The average play runs from 8.25 until 10.55—in other words, about two hours and a half. A total, that is, of one hundred and fifty minutes. The intermissions between the acts amount, at a rough estimate, to a total of about thirty-five minutes. Subtract the thirty-five minutes from the one hundred and fifty minutes, and we have left one hundred and fifteen minutes. You pay, therefore, two dollars for one hundred and fifteen minutes of entertainment, or about one and three-quarters cents a minute. Let us now see what you get for your money, and also the equivalent of what you could get for it did you spend it in other directions. A few illustrations may suffice to make one pause and reflect:

| I | ||

| “Oh, oh, what have I done that I should be made to suffer so! It was because I love you that I acted as I did! But—you don’t understand; you won’t understand!! (Buries her face in her arms. He goes to mantel and stands gazing abstractedly into the grate.) If only I could[Pg 73] make you see! Jim, oh Jim, please—for our children’s sake!” | } | 1 glass of Pilsner |

| II | ||

| “And to think, darling, that you mistrusted me! To think you did not know from the first moment I saw you, in your youth and beauty, that I loved you! Your money? BAH! It’s you I love, sweetheart, with every fibre of my being—you, you! (He strains her to him.) Come into these arms, dear, these arms that have longed to clasp you within them. They shall ever be your haven from the toil and turmoil of the world. They shall protect you from temptation. I love you; I love you!” (He kisses her passionately.) | } | 1 glass of Würzburger |

| III | ||

| “Listen, Hubert; it is but right you should know before you judge me. I wasn’t immoral; I was merely unmoral. I trusted him and he (she averts his gaze) deceived me. I was a girl, Hubert, a mere tender girl. He painted for my innocent eyes the splendor of a great career and I—I believed him. You must believe me, Hubert, you must believe me! I didn’t know—I didn’t know!! I believed him! You must believe me, Hubert, you must, you must! Look into my eyes and see for yourself it is the truth I am telling you! | } | 1 glass of Hofbräu |

A number of typographical errors were corrected silently.

Cover image is in the public domain.