Title: The Dead-Line

Author: W. C. Tuttle

Release date: November 26, 2021 [eBook #66821]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: The Ridgway Company, 1924

Credits: Roger Frank and Sue Clark.

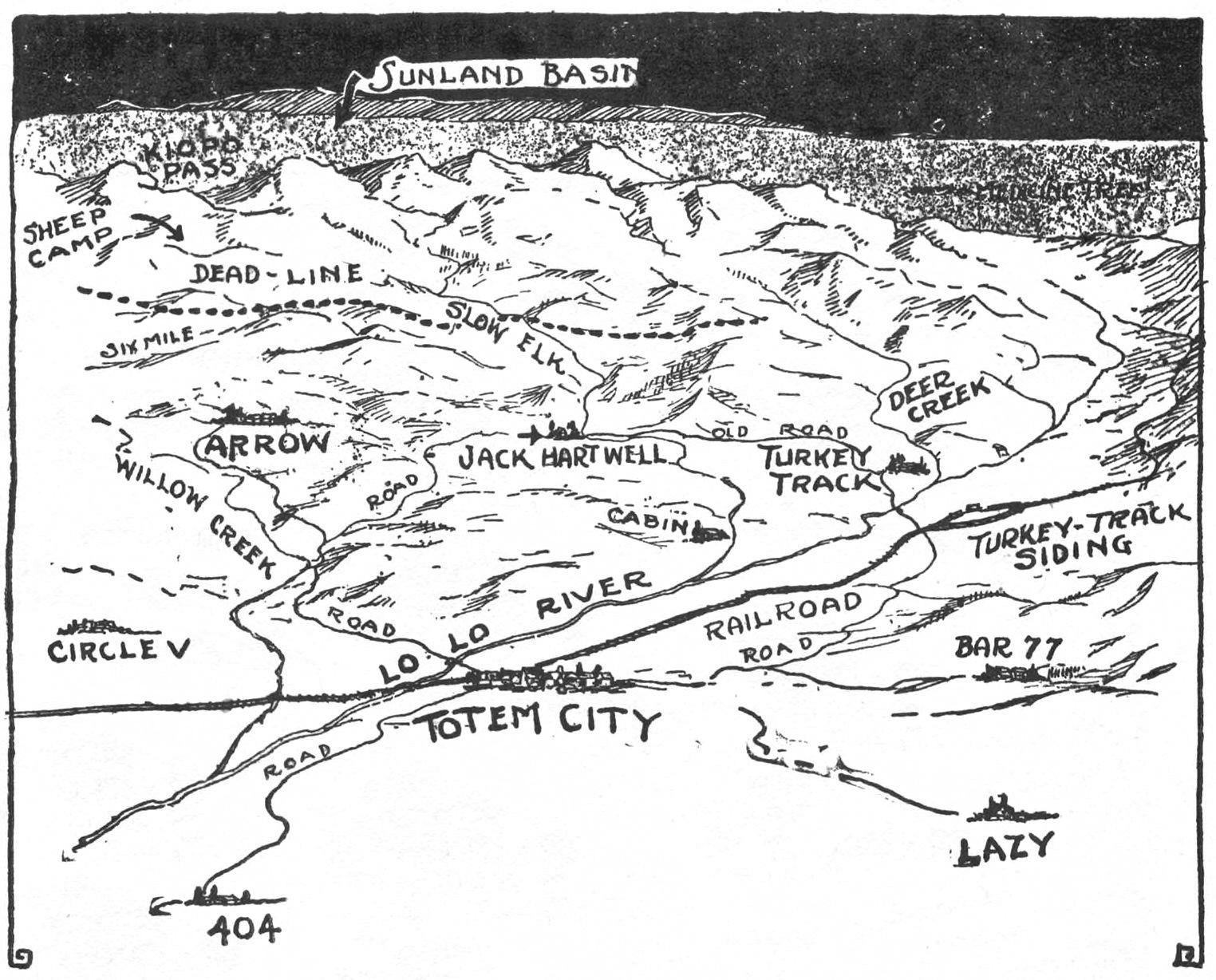

Jack Hartwell’s place was not of sufficient importance in Lo Lo Valley to be indicated by a brand name. It was a little four-room, rough-lumber and tar-paper shack, half buried in a clump of cottonwoods on the bank of Slow Elk Creek.

The house had been built several years before by a man named Morgan, who had the mistaken idea that a nester might be welcome on the Lo Lo range. He had moved in quietly, built his shack, and—then the riders from Marsh Hartwell’s Arrow outfit had seen his smoke.

Whether or not Marsh Hartwell legally owned the property made no difference; he claimed it. And few men cared to dispute Marsh Hartwell. At any rate, it was proved that a nester was not welcome on the Arrow.

It was an August afternoon. Only a slight breeze moved the dry leaves of the cottonwoods, and the air was resonant with the hum of insects. Molly Hartwell, Jack Hartwell’s wife, stood on the unshaded front steps of the house, looking down across the valley, which was hazy with the heat waves.

Mrs. Hartwell was possibly twenty years of age, tall, slender; a decided brunette of the Spanish type, although there was no Spanish blood in her ancestry. She was the kind of woman that women like to say mean things about; and try to make themselves believe them.

The married men of the Lo Lo mentally compared her with their women-folk; while the single men, most of them bashful, hard-riding cowpunchers, avoided her, and hoped she’d be at the next dance.

Jack Hartwell did not wave at her as he rode in out of the hills and dismounted at the little corral beside the creek. He unsaddled, turned his sweat-marked sorrel into the corral and hung his saddle on the fence.

Jack Hartwell was a few years older than his wife; a thin-waisted, thin-faced young man with an unruly mop of blond hair and a freckled nose. His wide, blue eyes were troubled, as he squinted toward the house and kicked off his chaps.

He could not see his wife, but he knew that she was waiting for him, waiting for the news that he was bringing to her. After a few moments of indecision he shrugged his shoulders and walked around the house to her.

She was sitting down in the doorway now, and he halted beside her, his thumbs hooked over the heavy cartridge belt around his waist.

“It’s hot,” he said wearily.

“Yes, it’s hot,” she said. “There hasn’t been much breeze today.”

“Water is gettin’ kinda low, Molly. Several of the springs ain’t runnin’ more than a trickle.”

“We need rain.”

Neither of them spoke now, as they looked down across the valley. Winged grasshoppers crackled about the duty yard, and several hornets buzzed up and down the side of the house, as if seeking an entrance. Finally the woman looked up at him and he moved uneasily.

“Yeah, it’s him—Eph King.”

There was bitterness in Jack Hartwell’s voice, which he did not try to conceal.

A flash of triumph came into the woman’s eyes, and she turned back to her contemplation of the hills. Her husband looked down at her, shaking his head slowly.

“Molly, it’s goin’ to mean —— in these hills.”

“Is it?”

She did not seem to mind.

“They’ve drawn a dead-line now,” he said slowly, “and there has been some shootin’. They’ve sent for the outfits down in the south end, and they’ll be here tonight.”

“Well, we won’t be in it,” she said flatly. “It means nothing to us.”

“Don’t it?”

Jack squinted hard at her, but she did not look up.

“No. The law has decided that a sheep has the same right as a cow. The cattlemen of the Lo Lo do not legally own all this valley.”

“Mebbe not—” Jack shook his head wearily—“but they hold it, Molly.”

“Well,” she laughed shortly, scornfully, “you are not a cattleman. You’ve got nothing to fight for.”

“No-o-o?”

She sprang to her feet, her eyes flashing.

“Well, have you?” she demanded. “Your own people have turned you down. Your own father cursed you for marrying a daughter of Eph King. You wasn’t good enough to even work for him; so he gave you this!” She flung out her arms in a gesture of contempt. “Is this worth fighting for?”

Jack Hartwell bit his lip for a moment and the ghost of a smile passed his thin lips.

“It ain’t worth much, is it, Molly? Still, it was worth so much that——”

“That they killed the man who took possession of it,” she finished angrily.

“Yeah, they killed him, Molly. Morgan was a fool. He had a chance to go away, but he would rather fight it out.”

“He was a friend of my father.”

“Yeah, I know it, Molly. But that has nothing to do with us.”

“Did you see the sheep?”

“Yeah. I went as far as the dead-line, Molly. The hills are full of sheep. They were comin’ down the draws like the gray water of a cloud-burst, spreadin’ all over the flats. As far back as yuh can see, just sheep and dust.”

“Are they on Arrow range?”

“On the upper edge. The punchers threw ’em back about half a mile, but I dunno.” Jack shook his head. “There’s so many of ’em.”

“Dad has thirty thousand head,” she said slowly. “Or he did have that many before——”

“Before yuh ran away to marry me,” finished Jack.

“I went willingly, Jack.”

“Oh, I know it, Molly.” He turned and threw an arm across her shoulder. “You’ve had a rotten deal, girl. I wish for your sake that it could be undone. I didn’t know that there was so much hate between your dad and mine. I knew that they were not friends, but—well, I know now.”

“Your father drove my father out of this valley.”

“But that was years ago, Molly.”

“And branded him a thief,” bitterly.

“Yeah, I reckon that’s right. It never was proved nor disproved, Molly. We’ve known for years that he was goin’ to try and shove sheep across the range into Lo Lo. He swore that he would sheep us out. There ain’t been a time in two years that men haven’t ridden the upper ranges, watchin’ for such a thing.

“There’s a man livin’ in Kiopo Cañon, whose job is to watch the other slope. I dunno how it was he didn’t warn us; and I dunno how your father ever found out that we were goin’ to hold the roundup two weeks ahead of time. He sure picked the right time. If we’d ’a’ known it, he’d never got his sheep up over the divide.”

“You say ‘we,’” said Molly slowly. “Are you one of them? After they have turned you out, are you still one of them?”

Jack turned away, shading his eyes with one hand, as he studied the hills.

“I’ve always been a cowman,” he said slowly. “I’ve been raised to hate sheep and yuh can’t change a man in a day.”

“What have the cattlemen done for you, Jack?”

Jack did not reply.

A man was riding out of the hills on a jaded horse. He rode slowly up to them, a bronzed, wiry cowboy, with sun-red eyes and a sweat-streaked face.

“Hello, Spiers,” said Jack.

“G’d afternoon, folks. Hotter’n ——, ain’t it.”

“Crawl off and rest your feet,” invited Jack.

“No, thank yuh. I jist rode down this-away to tell yuh that there’s a meetin’ at the Arrow t’night. The boys from the other end of the range’ll be there by evenin’.”

“Did my dad send yuh after me, Spiers?”

“No-o-o, he didn’t,” Spiers shifted in his saddle nervously. “But I’ve always liked yuh, Jack; and I kinda thought yuh might want t’ come. It’s a cattlemen’s meetin’, yuh know.”

“And he’s a cattleman,” said Molly dryly.

Spiers flushed slightly and picked up his reins.

“Well, I’ll be ridin’ on. S’long, folks.”

He swung his horse around and rode on into the hills, without looking back.

“Oh, I hate that man!” exclaimed Molly angrily.

“Spiers is all right,” defended Jack calmly.

“All right! He’s a gunman, a killer.”

“Prob’ly. He’s dad’s foreman; been his foreman for years.”

“And does your dad’s dirty work.”

Jack sighed deeply and shook his head.

“There’s no use arguin’ with yuh, Molly.”

“Spiers killed Jim Morgan.”

“Well, Morgan had an even break. He—Say, how did you know that Spiers killed Morgan?”

“I didn’t.”

Molly turned away and went into the house.

Jack went back to the corral, where he leaned on the fence and tried to decide what to do. Naturally his sympathies were with the cattleman. He had been born and raised in the Lo Lo Valley, steeped in the lore of the rangeland; a top-hand cowboy at sixteen.

He had known Molly King when they were both attending the little cow-town school at Totem City, when the fathers of both were struggling for supremacy in the valley. Then came a day, when accusations were hurled at Eph King and his outfit. He was accused of wholesale cattle stealing, but no arrests were made. The cattlemen, headed by Marsh Hartwell, bought him out at a fair price and sent him out of the country.

But whether through his ill-gotten gains or through his own ability, Eph King became the sheep king of the Sunland Basin, a vast land to the north of Lo Lo, a land that was a constant threat to Lo Lo.

But there was one thing in the cattlemen’s favor: The sheep would have to come through the pass at the head of Kiopo Cañon, where old Ed Barber kept daily watch of the slopes which led off into Sunland.

Jack Hartwell again met Molly King in Medicine Tree, which was the home town of the King family. It was circus day. The recognition had been mutual and old scores were forgotten. They spent the day together, like a couple of kids out of school, drinking pink lemonade and feeding peanuts to the one elephant. It was not a big circus.

For several months after that Jack Hartwell found excuses to go to Medicine Tree. Then one day he came back to the Arrow ranch with a wife. They had eloped. Big Marsh Hartwell listened to their explanations, his face blue with suppressed anger, while Mrs. Hartwell, a frail little, gray-haired woman, with pleading blue eyes, clutched her apron with both blue-veined hands and watched her husband anxiously.

“So that’s it, eh?” Marsh Hartwell nodded slowly, his eyes almost shut. “You went over there and married her, did yuh. You married Eph King’s daughter.”

“Father!”

Ma Hartwell put a hand on his arm, but he shook it off.

“And yuh brought her back here, eh? Now what are yuh goin’ to do?”

“Why, I thought—” began Jack.

“No, yuh didn’t think! That’s the trouble. You know —— well that a King ain’t welcome in this valley. You’ve put yourself on a level with them. The son-in-law of a shepherd! You can’t stay here. Don’t you know that for years we’ve spent money to keep the King family out of this valley? And here yuh bring one in on us.”

“All right,” Jack had replied angrily. “We’ll go back to ’em.”

“No, yuh won’t. You move your stuff over to the old Morgan place. I’ll make yuh a present of it. Mebbe yuh can live it down—I dunno; but yuh can’t stay here on the Arrow.”

Jack thought all this over as he leaned on the corral fence. They had lived there less than a year. People avoided them. Molly had no women friends. To them she was the sheep woman, although they were forced to admit that she did not contaminate the air. Jack took her to dances and tried to make her one of the crowd, but without success.

And the men were not friendly to Jack. He had been one of them; one of a crowd of wild-riding, rollicking cowboys, who drank, played poker and danced with reckless abandon. In fact, Jack had been a sort of ring-leader of the gang.

He missed all this more than any one knew. But most of all he missed the home life of the Arrow ranch.

His sister and her husband, Bill Brownlee, lived at the Arrow. Brownlee hated the sheep even worse, if such a thing were possible, than did Marsh Hartwell. There were three cowboys employed:

Three gunmen, as Molly had called them.

“Honey” Wier, a wide-mouthed, flat-faced cowboy, who hailed from “Alberty, by gosh,” “Cloudy” McKay, a dour-faced, trouble expecter from Arizona, and “Chet” Spiers, the foreman, composed the hired element of the Arrow. And Lo Lo Valley respected them for their ability. Marsh Hartwell knew cowpunchers, and in these three men he had ability plus.

And Jack Hartwell, as he leaned on the corral fence, knew down deep in his heart that he could not remain neutral. It would be impossible. He must decide quickly, too. If he did not attend that meeting, the cattlemen would take it for granted that he was against them. Spiers had given him no chance to vacillate.

Far back in the hills sounded the report of a rifle. Jack lifted his head, and as he did so he thought he caught a flash of color back on the side of a hill. For several minutes he watched the spot, but there was nothing other than the sage brush and the dancing haze.

“Seein’ things,” he told himself, but to make sure he walked back up the brush-lined stream, keeping out of sight of that certain spot. But he found nothing, and came back to the corral, where he busied himself for an hour or so, putting in a couple of new posts.

He needed physical action, and he worked swiftly in the blazing sun. Then he flung himself down in the shade and smoked innumerable cigarets, still wrestling with himself. The sun went down before he walked back to the house. Molly was putting their supper on the table, but he had no appetite.

“I heard a shot a while ago,” she told him, and he nodded grimly.

“You’ll prob’ly hear a lot more before it’s over, Molly.”

He sat down at the table, but shoved his plate aside.

“I’m not hungry,” he said slowly. “I’ve fought it all out with myself today, Molly. It’s been a —— of a fight.”

“Fought out what?”

She swallowed dryly, almost choking.

“Just what to do. I’m goin’ to that meetin’ at the Arrow tonight.”

She got to her feet, staring down at him.

“You going to that meeting? Why, you won’t be welcome. Don’t be a fool, Jack. They know you won’t be there.”

“I’ll be there,” Jack nodded slowly, but did not look at her. “Molly, you married a cowpuncher, not a sheepherder. This is my country. I—I reckon I hate sheep as bad as anybody around here, and I’ve got to help keep ’em out.”

“You have?” She sat down and stared across the table at him. “After what they’ve done to us?”

“Yeah—even after that.”

“You’d fight against—me?”

“You? Why, bless yore heart, Molly; it ain’t you.”

“It’s my father, my folks. He never did you any harm.”

“Well,” Jack smiled grimly, “he never had a good chance. Yuh must remember that I haven’t seen him since I was a kid. I had to steal yuh, girl. He’d ’a’ prob’ly killed me, if he knew.”

Molly shook her head quickly.

“I think he knew, Jack. In fact, I’m sure of it.”

“How do you know?” He squinted closely at her. “We didn’t know it was goin’ to happen until we met that day, the day we ran away to get married. And you never seen him since.”

“Oh, I don’t know.”

She got to her feet and walked to the kitchen door. He watched her for a while, and then got up from the table, picking up his hat. Quickly she turned and walked back to the table.

“Jack, I forbid you to go there tonight.”

“Well,” he smiled softly at her, “I’m sorry yuh feel that way about it, Molly, but I’m goin’, thassall.”

“Are you?” Her eyes blazed with anger.

“Well, go ahead. I may not be here when you come back.”

“Uh-huh?”

He turned his sombrero around several times, as if trying to control himself.

“Well,” he looked up at her wistfully, “I may not come back, yuh know.”

“Why—why do you say that, Jack?”

“Well, I don’t want to come back, unless I’m sure you’ll be home.”

She stared at him as he went past her and walked down to the corral, where he saddled his horse, drew on his chaps and rode away toward the Arrow. She had not told him whether or not she would be home when he returned, and he had not told her good-by.

Jack rode out over the trail that led to the Arrow ranch house three miles away. He was in no hurry, and drew up his horse after he was hidden from the house. He wondered if Molly would be foolish enough to ride back into the hills to her father. Her horse and saddle were at the corral.

He knew that it might be dangerous for her to ride across the dead-line at night. She wore men’s garb for riding purposes. He turned his horse around and rode back to where he could watch the house. It was not his nature to spy upon his wife, but he did not want her to run into danger foolishly.

He did not have long to wait. A man came through the fringe of brush along the creek, going cautiously. Once he stopped and looked intently at the spot where Jack was hidden. Then he went swiftly toward the house, coming in at the opposite side.

Jack mounted his horse and spurred back along the trail. He could not recognize this man, but his very actions stamped him as dangerous. Jack dismounted at the rear of the house and went around to the front, where he stopped. Voices were coming from the other side of the house. Silently as possible he went to the corner. Molly was standing with her back to him, looking at something in her hands, while the man stood beside her, looking down toward the corral.

“Company came, eh?” said Jack softly.

Molly and the stranger turned quickly. With a quick intake of breath, Molly flung her hands behind her. The stranger was a middle-aged man, unkempt, with a face covered with black stubble. His clothes were dirty, torn. The butt of a six-shooter stuck out of the waistband of his overalls.

He merely squinted at Jack and looked at Molly. It was evident that he did not know Jack, who came closer, holding out his hand to Molly.

“Give me that letter, Molly,” ordered Jack.

“I will not!”

Her teeth clicked angrily, as she faced him.

He walked up, ignoring the man, grasped her by the shoulder and whirled her around. The action was unlooked for and she threw out one hand to catch her balance. Quick as a flash Jack grabbed at the hand which held the letter, but all he got was a corner of the paper.

“Quit that!” snapped the stranger, grasping Jack by the arm. “Don’tcha try ——”

He whirled Jack around and got a left-hand smash full in the jaw, which sent him to his knees, spitting blood. But the blow was not heavy enough to do more than daze him, and as he straightened up he jerked the six-shooter from his waist.

But Jack was looking for this, and his bullet crashed into the stranger’s arm between elbow and wrist, leaving the man staring up at him, unable to do more than mouth a curse.

Molly had been leaning back against the side of the house, her face white with fright, but now she sped into the kitchen, slamming the door behind her. The stranger got to his feet, holding his arm with his left hand, and looked around.

“Yo’re from the sheep outfits, ain’t yuh?” asked Jack.

“That’s my business.” The stranger was not a bit meek.

“It’s a —— of a business,” observed Jack. “Who was that letter from?”

“Mebbe yuh think yuh can find out, eh?”

“All right. Now you mosey back where yuh came from, sabe? If I ever catch yuh around here again, I’ll not shoot at yore arm. Now vamoose pronto.”

The man turned and went swiftly back past the corral, where he disappeared through the brush. A few moments later he came out on to the side of a hill, where he lost no time in putting distance between himself and the ranch.

Jack watched him disappear and went to the kitchen door. It was locked. For a while he stood there, wondering what to do. He had lost the piece he had torn from the corner of the letter, but now he found it on the ground.

It had torn diagonally across the corner, and on it were only three words, written in lead-pencil:

Just the three words. For a long time he studied them, before the full import of them struck him. He walked to the front door, but found it locked. Then he went back, mounted his horse and rode back toward the Arrow. It was growing dark now, and he felt sure that the stranger would not come back. He was in need of medical attention, and Jack felt that he would lose no time in getting back to his own crowd.

Jack took the tiny piece of paper from his pocket and looked it over again.

“It’s from her father,” he told himself. “Find out what? Find out somethin’ about the cattlemen, I wonder? My ——, is my wife a spy?”

He straightened in his saddle, as past events flashed through his mind. Molly had known that there was a lookout in Kiopo Cañon. He remembered that Honey Wier had spoken in her presence of old Ed Barber, the keeper of the Kiopo Pass, who drew a salary for sitting up there, watching for sheep.

She also knew that the fall roundup was to be held at this time. Had she written this to her father, he wondered? She had plenty of chances, when she went for the mail. And she had intimated that her father knew she was going to marry him.

“Is she standin’ all this for her father?” he asked himself. “Did she marry me just to give her father a chance to get even with the Arrow?”

He tried to argue himself out of the idea, but the tiny, triangular piece of paper, with the three written words, was something that he could not deny. It was after dark when he rode in at the Arrow. There were twelve horses tied to the low fence in front of the ranch house. A yellow glow showed through the heavy window curtains of the living room.

Jack did not stop to knock on the front door, but walked right in. The room was full of men, hazy with smoke. They had been arguing angrily as he entered, but now they were still.

His father was sitting at the back of the room, in the center, while the others were facing him. There were Cliff Vane, owner of the Circle V, and his two cowboys, Bert Allen and “Skinner” Close; Sam Hodges, the crippled owner of the Bar 77, with Jimmy Healey, Paul Dazey and Gene Hill; Old Frank Hall, who owned the 404, his son Tom and three punchers.

“Slim” De Larimore, the saturnine-faced owner of the Turkey track brand, a horse outfit. Three of his punchers were scattered around the room. Seated near Marsh Hartwell was “Sudden” Smithy, the sheriff, who owned the Lazy S outfit. Near him sat “Sunshine” Gallagher, his deputy, the prize pessimist of Lo Lo Valley.

Near the dining-room door, Spiers sat hunched against the wall, and near him was Brownlee, Jack’s brother-in-law. Jack closed the door behind him and looked quickly around the room. Marsh Hartwell squinted closely at Jack. It was the first time that Jack had been in the Arrow ranch house since his father had told him he would not be welcome any longer.

De Larimore had evidently been talking, as he started in again to explain something, but Marsh Hartwell silenced him with a motion of his hand, looking intently at Jack.

“Was there somethin’ yuh wanted?”

Marsh Hartwell’s voice was cold and impersonal. He might have been speaking to a total stranger instead of to his own son.

“Somethin’ I wanted?” said Jack puzzled. “I came to the meetin’, thass all.”

“I asked him to,” said Spiers. “I didn’t think he’d come.”

“Yuh can’t never tell about some folks.” Thus Sunshine Gallagher, grinning.

“Thank yuh, Sunshine,” said Jack easily.

“Oh ——, yore welcome, I’m sure.”

“What did you expect to do at this meetin’?” queried Marsh Hartwell.

“For one thing,” said Jack coldly, “I didn’t expect to be insulted. I know I’m an outsider, but I own a few cattle.”

Some one laughed and Jack turned his head quickly, but every one was straight faced.

“Oh, ——, you fellers make me tired!” roared old Sam Hodges, hammering his cane on the floor. His white beard twitched angrily. “Why don’tcha let the kid alone. What if he did marry the daughter of a sheepherder? By ——, that ain’t so terribly awful, is it?”

He glared around as if daring any one to challenge his argument.

“Are any of you fellers pure? Ha, ha, ha, ha! By ——, I could tell a few things about most of yuh, if I wanted to. I’ve seen Jack’s wife, and I’ll rise right up and proclaim that they raise some —— sweet lookin’ females in the sheep country. Set down, Jack. Yo’re a cowman, son, and this here is a cowman’s meetin’. We need trigger fingers, too, by ——! And if m’ memory don’t fail me, you’ve got a good one.”

“But—” began the sheriff.

“But ——!” snorted the old man.

“Don’t ‘but’ me! You —— holier-than-thou! Smithy, some day you’ll make me mad and I’ll tell yuh right out what I know about yuh. Oh, I know all of yuh. I’m a ——ed old cripple, and the law protects me from violence, so hop to it. Start hornin’ into me, will yuh? I’ve lived here since Lo Lo Valley was a high peak, and I’m competent to write a biography of every ——ed one of yuh. And some of it would have to be written on asbestos paper. Set down, Jack Hartwell; yo’re interruptin’ the meetin’.”

Jack sat down near the door, hunched on his heels. Old Sam Hodges had come to his rescue at a critical time, and he inwardly blessed the old cripple. Hodges had been a cripple as long as Jack could remember, and his tongue was vitriolic. He was educated, refined, when he cared to be, which was not often. But in spite of the fact that he cursed every one, the men of Lo Lo Valley listened to his advice.

“Well, let’s get on with the meetin’,” said Vane impatiently. “You were talkin’, Slim.”

“And that’s all he was doin’,” said Sunshine. “Slim is jist like a dictionary. He talks a little about this and a little about that, and the —— stuff don’t connect. What we want is an agreement on some move, it seems to me.”

“Sunshine’s got the right idea,” agreed Hodges. “Too much talk. If anybody has a real suggestion, let ’em outline it. You ought to have one, Hartwell.”

Marsh Hartwell shook his head.

“It will be impossible to wipe them out now. The only thing to do will be to make a solid dead-line and hold ’em where they are until the feed plays out and they have to go back. The feed ain’t none too good up there now, and if it don’t rain they can’t stay long.”

“How many men will it take to hold that line, Marsh?” asked Vane.

“They’re spread over a two-mile front now. Figure it out. They’ve got about twenty-five herders, all armed with rifles. I look for ’em to spread plumb across the range, and the —— himself couldn’t stop ’em from tricklin’ in.”

“Which ruins the idea of a solid dead-line,” said Hodges dryly. “Who has a worse idea than that?”

The sheriff got to his feet, but before he could state his proposition there came a noise at the front door. Jack sprang to his feet and flung the door open, while in came Honey Wier, half-carrying, half-dragging old Ed Barber, who had been the keeper of the Kiopo Pass.

The old man was blood-stained, clothes half torn from his body, his face chalky in the light of the lamp. One of the men sprang up and let Honey place the old man in an easy chair, while the rest crowded around, questioning, wondering what had happened to him.

“I found him about a mile from Kiopo,” panted Honey. “His cabin had been burned. They shot him, but he managed to hide away in the brush. I reckon he lost his mind and came crawlin’ out on to the side hill. I got shot at, too, when I was bringin’ him in, but they missed me.”

“How bad is he hurt?” asked Hartwell.

“Kinda bad, I reckon. He talked to me a while ago.”

Vane produced a flask and gave the old man a drink. The strong liquor brought a flush to his cheeks and he tried to grin.

“Good stuff!” he whispered wheezingly. “I ain’t dead yet. Need a doctor, I reckon.”

“I’ll get one right away,” said one of the cowboys, and bolted out after his horse.

“Who shot yuh, Ed?” asked Hartwell.

“I dunno, Marsh. They sneaked up on me, roped me tight and brought in the sheep next day. I heard ’em goin’ past the cabin. They knowed what I was there for. One of ’em told me. They knowed that the roundup was on, too. I managed to fight m’self out of them ropes, but it was too late.

“The sheep had all gone past. Some of them men was comin’ back toward the cabin and they seen me makin’ my getaway. I didn’t have no gun. They hit me a couple of times, but I crawled into a mesquite and they missed findin’ me.”

“Then they burned the cabin,” said Honey angrily.

Marsh Hartwell scowled thoughtfully, as he turned away from the old man.

“What do yuh think of it, Marsh?” asked Hodges.

“I think there’s a spy in Lo Lo Valley.”

“A spy?” queried the sheriff.

“Yeah, a spy. How did they know that Ed Barber lived in Kiopo Cañon to watch for sheep? How did they know that we’d hold our fall roundup this early in the season? By ——, somebody told ’em, some sneakin’ spy!”

Marsh Hartwell turned and looked straight at Jack. It was a look filled with meaning, and nearly every man in the room interpreted it fully. Still Jack did not flinch, as their eyes met. Some one swore softly.

“There’s only one answer to that,” said De Larimore. “Show us the spy, Hartwell. This is a time of war.”

Marsh Hartwell shook his head slowly and turned back to his seat.

“Things like that must be proven,” said Hodges. “It ain’t a thing that yuh can take snap judgment on.”

“We better put Ed between the blankets,” suggested Honey Wier. “He’s got to be in shape for the doctor to work on when he comes, so I reckon we’ll take him down to the bunk house, Marsh.”

The boss of the Arrow nodded, and three men assisted the wounded man from the room. Jack turned to Gene Hill,

“Have they got any men on the dead-line now, Gene?” he asked softly.

Hill was a long-nosed, watery-eyed sort of person, generally very affable, but now he seemed to draw into his shell.

“Better ask Marsh Hartwell,” he said slowly. “I ain’t in no position to pass out information.”

There was no mistaking the inference in Hill’s reply. Jack turned and walked to the door, where he faced the crowd, his hand on the door-knob.

“I came here tonight to throw in with yuh,” he said hoarsely. “I’m as much of a cattleman as any of yuh here tonight, and —— knows I hate sheep as bad as any of yuh. I had a gun to help yuh fight against the sheep men.

“But I know how yuh feel toward me. My own father thinks I’ve done him an injury. You think I’m a spy. Well, —— yuh, go ahead and think all yuh want to! From now on I don’t have to show allegiance to either side. I’m neither a cattleman nor a sheepman. I’ll mind my own business, sabe? You’ve drawn a dead-line against the sheep; I’ll draw one against both of yuh. You know where my ranch-lines run? All right, keep off. Now, yuh can all go to ——!”

He yanked the door open and slammed it behind him. For several moments the crowd was silent. Then old Sam Hodges laughed joyfully and hammered on the floor with his cane.

“Good for the kid!” he exploded. “By ——, I’m for him! He told yuh all to go to ——, didn’t he? Told me to go with yuh. But I wouldn’t do it, nossir. Catch me with this gang? Huh! Draw a dead-line, will he? Ha, ha, ha, ha! Betcha forty dollars he’ll hold it, too. Hartwell, you are an ass!”

Marsh Hartwell flushed hotly, but did not reply. He knew better than to cross old Hodges, who chuckled joyfully over his evil-smelling pipe.

“If I had a boy like Jack, I’ll be —— if I’d turn him down because his wife’s father favored mutton instead of beef,” he continued. “Now that we’ve all agreed that Marsh Hartwell is seventeen kinds of a —— fool, let’s get back to the business at hand.”

Marsh Hartwell glared at Hodges, his jaw muscles jerking.

“If you wasn’t a cripple, Sam——”

“But I am, Marsh.” The old man chuckled throatily, as he sucked on his pipe. “I wish I wasn’t, but I am.”

“All of which don’t settle our questions,” observed Slim Larimore impatiently.

“No, and it don’t look to me like there was any use of talkin’ any further.”

Thus Frank Hall, of the 404, a dumpy, little old cowman, with an almost-round head. He got to his feet, as if the meeting was over.

“There’s only one thing to do: Shove every —— rider we’ve got along that dead-line and kill every sheep and sheepherder that crosses it.”

“That looks like the only reasonable thing to do,” nodded Marsh Hartwell, looking around the room. “Are we all agreed on that?”

Sudden Smithy, the sheriff, got to his feet.

“Gents,” he said slowly. “I can’t say yes to that. You all know that I’ve sworn to uphold the law; and the law has given the sheep the same right as cattle. Legally, we don’t own but a small portion of Lo Lo range; morally, we do. I’m as much of a cowman as you fellers, but first of all, I’m the sheriff.”

“That’s all right,” said Hartwell. “You’re not against us, Sudden?”

“O-o-oh, —— no! I’m just showin’ yuh that it won’t be my vote that turns —— loose in these hills. And she’s goin’ to be ——, boys. Eph King is a fighter. He shoved that mass of sheep over Kiopo Pass, and the —— himself ain’t goin’ to be able to stop him, until every sheepherder is put out of commission and the sheep travelin’ back down the slopes into Sunland Basin.”

“And King’s no fool,” growled Bill Brownlee. “He prob’ly ain’t got no central camp, where we might ride in and bust ’em up quick. Every sheepherder goes it alone. King is prob’ly back there somewhere, directin’ ’em.”

“I sure like to notch my sight on him,” said Cloudy McKay of the Arrow. “I got a bullet so close to my ear today that it plumb raised a blister. And any of you fellers that ride that dead-line better look out. Them shepherds lay close in the brush, and they can shoot, don’tcha forget it. Our best bet is to leave our broncs in a safe place, and play Injun.”

“There’s wisdom there,” nodded Sam Hodges. “Eph King hasn’t got ordinary sheepherders in charge of that outfit. He can hire trigger fingers and pay ’em their price. He’s got more men up there right now than we can throw against him, and he’s ready for battle.

“We better shove our men in close to that line before daylight, Hartwell. Spread ’em out, hide ’em in the brush. It looks —— nice to see a long string of mounted punchers, but a man on a horse up there will prove that he’s a cattleman, a legitimate target for a shepherd. My idea is: Fight ’em with their own medicine.”

“Suits me fine.” Old Frank Hall picked up his hat. “We’re too shy on men to make targets out of ’em. That’s the best idea we’ve had, so let’s go. How’s everybody fixed for ammunition?”

A check of the cartridge belts showed that every man had enough for his immediate needs.

“I’ll throw a chuck wagon into Six-Mile Gulch,” stated Hartwell, “and we can feed in relays. If this lasts very long, we can throw another into the head of Brush Cañon; so that we won’t have to draw the men too far away from the line.

“Smithy, when yuh go back to Totem, tell Jim Hork to wire Medicine Tree or Palm Lake for ca’tridges. Tell him to get plenty of thirty-thirties, forty-five seventies and a slough of forty-fours and forty-fives. If he can get us fifty pounds of dynamite, we’ll take that, too. That’s all, I reckon.”

The crowd of men filed out to their horses, where they mounted and rode away into the hills. Marsh Hartwell stood in the doorway of the ranch house, bulking big in the yellow light, and watched them ride away. He turned back into the smoky room and squinted at his wife, who stood just inside the room, one hand still holding the half-open dining-room door.

For several moments they looked at each other closely. Then she released the door and came toward him.

“Marsh, I heard what was said to Jack,” she said softly. “I was just outside that door.”

“Well?”

“You drove him away from here.”

“He drove himself away, Mother. When he married that——”

“He came to help you. After what you had done to him, he came to help you, Marsh. Blood is thicker than water.”

“Not his blood! Came to help me? More likely he came to see what he could hear.”

“Marsh! Do you think that Jack——?”

“Well, somebody did. I tell you, there’s a dirty spy around here.”

“Marsh Hartwell!”

The old lady came closer and put a hand on his arm, but he did not look at her.

“Perhaps there is a spy, Marsh,” she said softly. “There are many people in Lo Lo Valley. We don’t know them all as well as we know each other. And knowing each other so well, after all these years, Marsh, are we the only ones capable of raising a—a spy?”

He looked down at her. There were tears in her old eyes and her lips trembled in spite of the forced smile. Then she turned away and went back through the doorway. He stared after her for along time, before he turned and went back to the open front door, where he scowled out into the night.

There was no relaxation, no admission that he might be wrong in his estimate of Jack. But between his lips came a soft exclamation, which had something to do with “a —— fool,” but only Marsh Hartwell knew whom he meant.

A long train of cattle-cars creaked through the hills, heading for the eastern markets. Back in the rattling old caboose, a number of cowboys sat around a table under a swaying lamp and tried to kill time at poker.

They were the men in charge of the stock, and had found, to their sorrow, that a swaying, creaking, jerking caboose was no place for a cowboy to sleep. They growled at each other and swore roundly, when the caboose swayed around a sharp curve and upset their piles of poker-chips.

“I ain’t got a solid j’int in m’ body,” declared a wizen-faced cattleman seriously, holding his chips in his hands. “By ——, I jist went on this trip t’ say that I’d seen Chicago, but I’ll never see it. Nossir, I won’t. Yeah, I’ll call jist one more bet before I fall apart.”

“One more bet and ‘Hashknife’ will have all the money, anyway,” declared “Sleepy” Stevens, yawning widely.

“I spur my chair,” grinned Hashknife Hartley, a tall, thin, serious-faced cowboy. “And thataway—” he shoved in a stack of chips and leaned back in his chair—“I ride ’em steady, while you mail-order cowpunchers wobble all over and expose yore hands. Cost yuh six bits to call, ‘Stumpy’.”

“Not me.” The wizen-faced one threw down his cards. “You call him, ‘Nebrasky’.”

“F’r six bits?” Nebraska Holley shook his head. “Nawup. I’ve paid too danged many six bits to see him lay down big hands. Anyway, I’ve had enough of this kinda poker. I wish t’ —— that engineer would go easy f’r a while. I ain’t slept since night afore last, and I didn’t sleep good then.”

“He’s whistlin’ for somethin’,” observed Hashknife.

“Mebbe he’s scared of the dark, and he’s whistlin’ for company.”

“Whistlin’ for a station,” yawned Stumpy. “I asked the conductor about them whistles.”

“Must be a wild station,” observed Sleepy Stevens. “He’s sure sneakin’ up on it in the dark.”

The train had slowed to a snail’s pace, and finally stopped with a series of jolts and jerks.

“We’re at a station,” declared Stumpy, flattening his nose against a window pane. “I can see the lights of the town.”

The conductor came storming into the caboose, swearing at the top of his voice.

“Some more —— hot-boxes!” he snorted. “Half of the axles on this —— train are on fire. A fine lot of rollin’ stock to ship cows in. Be held up here a couple of hours, I reckon. Take us half an hour to cool ’em off, and then we’ll have to lay out for the regular passenger.”

“What’s the town, pardner?” asked Nebraska.

“Totem City.”

“Let’s all go over and see what she looks like,” suggested Hashknife. “I’ll spend some of my ill-gotten gains.”

“Not me,” declared Nebraska. “In two hours I can be poundin’ my ear.”

“Me, too,” said Stumpy Lee. “I’m goin’ to sleep.”

“How about you, Napoleon Bonaparte?”

Napoleon Deschamps, a fat-faced cowpuncher, who had been trying to read an old magazine, shook his head at Hashknife.

“Bimeby I go sleep too, Hartlee. De town don’ int’rest.”

“Well, Sleepy, we’ll go. And you snake-hunters won’t sleep much after we get back; sabe? C’mon, Sleepy.”

They swung down off the caboose and walked the length of the train. Toward the upper end of the train lanterns were bobbing around, and there was a sound of hammers on steel. There was a dim light in the depot, but they did not stop. About midway of the main street a brightly lighted building beckoned them to the Totem City Saloon.

“Little old cow-town,” said Hashknife as they walked down the wooden sidewalk, passing hitch racks, where saddle horses humped in the dark.

“I seen this place on the map,” offered Sleepy. “I kinda wanted to know what country we were goin’ through, so I took the trouble to look it up. This here is that Lo Lo Valley.”

“Lo Lo, eh?” grunted Hashknife. “They liked it so well that they named it twice.”

They walked into the Totem Saloon and headed for the bar. It was rather a large place for a cow-town. There were not many men in the room and business was slack, but that could be accounted for because of the late hour.

A big, sad-faced cowboy was leaning on the bar, gazing moodily at an empty glass. It was Sunshine Gallagher, the deputy sheriff. He had come to the Totem Saloon, following the meeting at the Arrow ranch, and had imbibed considerable hard liquor. Sudden Smithy was across the room, involved in a poker game.

Hashknife and Sleepy ordered their drinks. Sunshine looked them over critically, and solemnly accepted Hashknife’s invitation to partake of his hospitality.

“I never refuse,” he told them heavily. “’S nawful habit to git into.”

“Drinkin’ whisky?” asked Hashknife.

“No—o—o—refusin’. Oh, I ain’ heavy drinker, y’understand! I jist drink so-and-so. I c’n take it or leave it alone. Right now, I could jist walk away from that drink. Yesshir. Jist like anythin’, I could do that. But wha’s the use, I ask yuh? If it wasn’t made to be drank—would they make it? Now, would they? The anshwer is seven times eight is fifty shix, and twenty-five is a quarter of a dollar. Here’s how, gents.”

They drank solemnly. Sunshine looked them over with a critical eye.

“Strangers, eh?” he decided.

“Just passin’ through,” said Hashknife. “We’re goin’ East with a train load of cattle. Old cattle-cars developed hot-boxes, so we had to stop a while.”

“Thasso? Goin’ East, eh?” Sunshine grew reflective. “I ain’t never been East. Mus’ be wonnerful country out there. No cows, no sheep—nothin’. Not a thing. I wonder how folks git along out there. Lo’s of barb wire, I s’pose, eh? Whole —— country fenced in, eh? P’leecemen to fight yore battles. Nothin’ for a feller t’ do, but eat and sleep. Mus’ be wonnerful.”

“We dunno,” admitted Hashknife. “This is our first trip East.”

“Oh, my, is that so? My, my! Hones’, I wouldn’t go, ’f I was you fellers, nossir. Firs’ trip is always dangerous. Let’s have another snifter of demon rum and I’ll try to talk yuh out of it.

“I had a frien’ who went East. Oh, my gosh, it was ter’ble! Got drunk and bought him some clothes. My, my, my! Wore ’em when he got back here and got shot twice before anybody rec’nized him. Everybody thought he was a drummer.”

“Did he have a drum with him?” asked Sleepy innocently.

“Huh?” Sunshine goggled at Sleepy wonderingly. “Shay! Me and you are goin’ to git along fine. If you ever want to be arrested decently, you have me do it. Gen’lemen, I sure can do a high-toned job of arrestin’. I’m Shunshine Gallagher, the dep’ty sheriff of Lo Lo County ’f I do shay it m’self.”

Hashknife and Sleepy shook hands solemnly with Sunshine, removing their hats during the handshaking. Sunshine was just as solemn, and almost fell against the bar in trying to make an exaggerated bow. Sudden Smithy drew out of the poker game and came over to the bar.

“Better let up on it, Sunshine,” he advised.

“Oh, h’lo, Sudden,” said Sunshine owlishly. “Meet two of the mosht perfec’ gen’lemen, Sudden. Misser Hartknife Hashley and Steepy Stevens. Gen’lemen, thish is Misser Smithy, our sheriff. Hurrah for the king, queen and both one-eyed jacks!”

Sudden grinned widely and shook hands with Hashknife and Sleepy, while Sunshine tried to shake the bar with both hands to hurry the bartender. Sudden was sober. Hashknife explained about their reasons for being in Totem City.

A couple of cowboys clattered into the place and came up to the bar, where they had a drink and bought a bottle to take with them. Both men were carrying rifles in their hands, in addition to the holstered guns on their hips. Both of them spoke to Sunshine and Sudden, but went away immediately.

Hashknife and Sleepy looked inquiringly at each other, but asked no questions. They were wise to the ways of the range, and knew that, as an ordinary thing, cowboys did not carry Winchesters in their hands at midnight, drink whisky in a hurry and ride away without any explanation.

But the sheriff vouchsafed no explanation, although they felt that he knew what was afoot. They drank to each other’s good health.

“They’re goin’ Easht,” explained Sunshine owlishly to the sheriff. “Use yore influensh, Shudden. Tell ’m lotta lies, won’t yuh? No use wastin’ good cowboys on the Easht, when we need ’m sho badlee. Talk to ’m.”

“You better go to bed,” advised the sheriff. “This ain’t no condition for you to be into, Sunshine. Yo’re a disgrace to the office yuh hold.”

“Tha’s right. I’m no good, thassall. No brainsh, no balansh. Ought t’ git me a steel bill and live with the chickens. I’m jist ol’ Shunshine Gallagher, if I do shay it m’shelf. But with all my faults, I’m hungry as ——. Now, deny that if you can. I dare you to deny me the right to eat.”

“Speakin’ of eatin’,” said Hashknife seriously, “I’m all holler inside.”

“Good place to eat here,” offered the sheriff. “Up the street a little ways. I’m kinda hungry, too.”

“Count me in,” grinned Sleepy. “Let’s go git it.”

They went up to a Chinese restaurant, where they proceeded to regale themselves with ham and eggs, and plenty of coffee. Hashknife tried to draw the sheriff out in regard to conditions in that country, but the sheriff refused to offer any information. Sunshine went to sleep, with his head in a plate of ham and eggs, and the sheriff swore feelingly at him.

“He’s a danged good deputy most of the time,” he declared. “But once in a while he slops over and gits all lit up like a torchlight procession. He’s harmless thataway.”

After the meal, Hashknife and Sleepy helped the sheriff take Sunshine down to the sheriff’s office, where they put him to bed. An engine whistled as they came out of the office, and Hashknife opined that they had better go to the depot and see if their train was ready to pull out. The sheriff offered to go with them, so the three of them sauntered up there.

A passenger train was just pulling out, but there was no sign of the cattle-train.

“Well, I know danged well we left one here,” said Hashknife blankly, as they walked up to the depot and questioned the sleepy-eyed agent.

“Cattle-train? Oh, yes. Why, it left here quite a while ago. Went on to the siding at Turkey Track for the passenger.”

“Oh, so that’s where it went, eh?” Hashknife scratched his head wonderingly. “Where’s Turkey Track sidin’?”

“About six miles east. They’ve pulled on quite a while ago.”

“With all our valuables!” wailed Sleepy.

“That’s right,” agreed Hashknife. “There’s an ancient telescope valise, inside of which is three pairs of socks, seven packages of Durham, two cartridge belts and two holsters.”

“And my yaller necktie,” added Sleepy mournfully.

“Well, that’s almost frazzled out,” said Hashknife. “Yuh can’t wear ’em forever, yuh know, Sleepy.”

“Yeah, I s’pose. It’s a danged good thing that we saved our guns.”

“Wearin’ ’em à la shepherd,” laughed Hashknife, opening his coat to show the butt of a heavy Colt sticking out of the waistband of his trousers. “We was headin’ East, where it ain’t proper to wear ’em on the hip, yuh know. Feller kinda gets so used to packin’ a gun that he feels plumb nude if he ain’t got one rubbin’ his carcass.”

“And we don’t go East,” complained Sleepy. “Dang it all, I’ll never see nothin’, I don’t s’pose. That makes three times I’ve started East.”

“Yuh never got this far before,” laughed Hashknife. “Yo’re gainin’ on her every time, Sleepy. Anyway, we won’t have to fight that blamed caboose t’night, and that’s somethin’ to cheer about.”

They walked back to the Totem Saloon. The sheriff did not seem as friendly as he had been before they went to the depot. Down deep in his heart was a suspicion that these two men might be in the plot to sheep out Lo Lo Valley. They had arrived at an opportune time, and they did not seem greatly concerned over the departure of their train.

“What’ll yuh do now?” he asked, as they stood on the sidewalk in front of the Totem.

“Sleep,” said Hashknife. “No use worryin’ about that train. It’s gone, thassall.”

“Yeah, it’s gone, that’s a cinch. Where are you fellers from?”

The sheriff knew better than to ask that question, and did not expect an answer.

“From the cattle-train,” said Sleepy after a pause. It was more than the sheriff expected.

A man was coming down the sidewalk, and as he came into the lights of the saloon windows they saw that he was the depot agent. He stopped and peered at them.

“I was wonderin’ if I’d find you,” he said, a trifle out of breath. “One of them cattle-cars got derailed just out of Turkey Track sidin’, and they’re held up for a while. It ain’t more than six or seven miles out there.”

“A nice long walk,” observed Hashknife.

“I can fix that,” said the sheriff quickly. “I’ll let yuh have a couple of horses and saddles. Yuh can leave ’em tied to the loadin’ corral and I’ll get ’em tomorrow.”

“Now that’s danged nice of yuh,” agreed Hashknife. “We’ll take yuh up on that, and thank yuh kindly. Let’s go.”

The sheriff led the way to his stable, where they secured two horses and saddles.

“It’s only six or seven miles on a straight line, but yuh can’t go thataway,” explained the sheriff, leading the way back to the main street. “Yuh go straight north out of town, follerin’ the road kinda northwest. Then yuh turn at the first road runnin’ northeast. About a mile along on that road you’ll find a trail that leads due east. Foller that and it’ll take yuh straight to Turkey Track sidin’.”

“This is doggone white of yuh,” said Hashknife, holding out his hand. “We ain’t the kind that forget, Sheriff. Yore broncs will be there at the corral. And some day, we’ll try real hard to return the favor.”

“Don’t mention it,” said the sheriff. “I hope yuh catch yore train. Adios!”

They rode out into the night. It was light enough for them to follow the dusty road, but not light enough for them to distinguish the kind of country they were traveling through.

“I hope they’ve got that danged car on the track, and are headin’ East right now,” said Sleepy, peering into the night. “I like this country, Hashknife.”

“After seein’ as much of it as you have, I don’t wonder.”

“Not that,” said Sleepy seriously. “There’s punchers packin’ Winchesters, and nobody tellin’ yuh what a —— of a good country this is. I tell yuh, there’s trouble brewin’. I can smell it, Hashknife.”

“Then I hope there’s more than one car off the track, and that we can get to sleep on that caboose before the train starts. I can build up all the trouble I can use. If there’s trouble around here, leave it alone. My old dad used to say—

“‘If yuh ain’t got no business of yore own, yuh ain’t qualified to monkey with somebody else’s.’”

“That’s a fine sentiment,” laughed Sleepy. “But it don’t work in our case. We’ve been monkeyin’ with other folks’ business for several years, haven’t we?”

“Yeah, that’s true. But it don’t prove that we were qualified to do it. Mebbe somebody else could ’a’ done it better.”

“Well, I’d sure like to set on a fence and watch ’em do it,” laughed Sleepy. “It would be worth havin’ a front seat at the show. Here’s that road runnin’ northeast, Hashknife.”

And Sleepy was right when he said that he would like to have a front seat at the show. For several years, he and Hashknife had drifted up and down the wide ranges, working here and there, helping to fight range battles; a pair of men who had been ordained by fate to bring peace into troubled range-lands.

It was not for gain nor glory. They usually left as abruptly as they came; dreading the thanks of those who gained by their coming; leaving only a memory of a tall, serious-faced cowpuncher with a deductive brain and a wistful smile. And of his bow-legged partner; him of the innocent blue eyes, which did not harden even in the heat of gun-battle.

They did not want wealth, power nor glory. Either of them could have been a power in the ranges, but they were of that breed of men who can’t stay still; men who must always see what is on the other side of the hill. The lure of the unknown road called them on, and when their work was done they faded out of the picture. It was their way.

Jack Hartwell was in a white-hot rage when he rode away from the Arrow. His own father had virtually accused him of being a spy for Eph King, and his life-long friends were all thinking him guilty of giving information to the invading sheepmen.

He set his jaw tightly as he spurred across the hills toward home, vowing in his heart to make them sorry that they had spurned his assistance and added insult to injury by declaring him a traitor. Once he drew rein on the crest of a hill and looked back, his throat aching from the curses that surged within him.

It was then that he realized how powerless he was, how foolish he had been to declare a dead-line around his property. It had been a childish declaration. And with this realization came the selfish hope that the sheep men might break the dead-line and flood the valley with sheep. He wanted revenge. And why not help them, he wondered?

His own father had outlawed him among cattlemen. He had been ostracized from the cowland society. He owed them nothing. Perhaps Eph King would welcome him into Sunshine Basin. He might even make him a sheep baron. But the vision did not taste sweet to Jack. He had the cattlemen’s inborn hatred of sheep. He had heard them cursed all his life, and it was too late for him to change his attitude toward them.

He rode in at his little corral and put up his horse. There was no light in the house, but the door was unlocked. He went in and lighted the lamp. It was not late, and he wondered why Molly had gone to bed so early. He picked up the light and entered the bedroom, only to find it vacant, the bed unruffled.

He went back to the living room and placed the lamp on the little table. It was evident that Molly had left the place. He went out to the stable and found that her horse and saddle were not there.

He remembered dazedly that she had said she might not be there when he returned. Back to the house he went, searching around for a possible note, which might tell him where she had gone. But there was no note. She had left without a word.

He sat down on the edge of a chair and tried to figure out what to do. Right now he cared more for his wife than he ever had, and the other events of the night paled into insignificance before this new shock.

Suddenly he got to his feet, blew out the light and ran down to the corral. Swiftly he saddled and rode out into the yard, heading straight back toward the slopes of Slow Elk Creek.

“Get ready, you sheepherders!” he gritted aloud. “I’m comin’ after my wife, and I’d like to see any of yuh stop me.”

Jack knew every inch of the country, and was able to pick his way through the starlit hills at a fairly swift pace. He knew that the dead-line was within three miles of his place, but he did not slacken pace until up near Slow Elk Springs.

As he rode up through the upper end of a little cañon, a man arose up in front of him, the starlight glinting on the barrel of his rifle. It was Gene Hill. The recognition was mutual.

“Where yuh goin’?” asked Hill in a whisper.

He was standing at the left shoulder of Jack’s horse, as if to bar his way.

For a moment Jack hesitated, and then drove the spurs into his horse, causing the animal to knock Hill sprawling. Then he ducked low and went racing away toward the dead-line. Hill got to his feet, cursing painfully, searching for his rifle, while Bert Allen, of the Circle V, another of the watchers, came running through the sage, calling to Hill and questioning him as to what the commotion had been about.

“It was Jack Hartwell,” said Hill, trying to pump some air into his lungs. “He tried to sneak through, and when I stopped him he rode me down. The dirty pup has gone over to the sheep.”

“Gives us a good chance at him,” said Allen. “I wasn’t so sure about him before. We’ll have to pass the word. Sure yuh ain’t hurt, Gene?”

“Not bad enough to make me miss him, if he ever shows up here again.”

Once out of range of Hill’s rifle, Jack drew up, with the sudden realization that he had given them plenty of circumstantial proof that he was a spy. He knew that Hill would lose no time in spreading the report that he had forced his way through the dead-line. He laughed bitterly at the tricks of fate, but swore that somebody would pay dearly.

Then he realized that he was in a precarious position. The sheepmen would be looking for mounted men. Jack knew that they would be just as alert as the cattlemen; so he dismounted and went on slowly, leading his horse. There were plenty of sheep bedded down on the slopes of the hills, and they bleated softly at his approach.

Jack had made a guess as to the probable location of the main camp. It was a wide swale on a little tributary of Slow Elk Creek, where there was plenty of fuel and water, and also a bed ground for thousands of sheep. He led his horse out on to the rim of this swale, where he could see the lights of the camp below him.

There were several camp-fires, and as he came closer he could see the outlines of several camp-tenders’ wagons. It was a big outfit and this was their main camp. Several men were playing cards on a blanket stretched in the light of one of the fires, and behind them several tents had been pitched. The men were all wearing holstered guns, and behind them, leaning against the guy rope of a tent, were several rifles.

Jack left his horse out beyond the firelight, and walked boldly into camp, coming in behind the players. Somehow he had slipped through the sheepmen’s line of guards. He stood near the front of a tent, listening closely. The players were so engrossed in their game that they made signs instead of sounds. One of them lifted his head and looked at Jack, but made no move to indicate that he did not recognize Jack as one of them.

A few minutes later, three men came walking into camp. One of them was a big man, walking empty handed, while the other two carried rifles. As they came into the light of the fires, Jack recognized Eph King. He was head and shoulders above the other men, bulking giant-like in the firelight.

His head was massive, with a deeply lined face, looking harsh and stern in the sidelights, which accentuated the rough contour of his features. The two men sauntered over to the card game, while Eph King, after a long glance out into the night, turned toward the tent and walked past Jack, without looking at him.

Once inside the tent he lighted a lantern, and Jack heard a cot-spring creak a protest as King settled his great bulk upon it. Then Jack stepped over, threw back the flap of the tent and stepped into the presence of the sheep king.

For several moments the big man stared at him. He had not seen Jack for several years, and it took him quite a while to recall the features of his enemy’s son. Jack did not speak, but waited to see what King would have to say.

The big man knitted his brows, glanced toward the flap of the tent and back at the cowboy, facing him tensely.

“How did you get here?” he asked harshly.

“Walked right in,” said Jack evenly.

“Did yuh?” King studied him closely. “What for?”

“To take my wife back home.”

Eph King started slightly.

“To take her back home, eh? Back from where, Hartwell?”

“From here!” Jack’s jaw muscles tightened and he leaned forward slightly. “By —— she’s my wife and I want her! Now you produce her, King.”

“Oh, is that so?” The big man’s bushy brows lifted in mock surprize. “I’m not a wizard, Hartwell. In fact I don’t know what in —— you are talkin’ about.”

“That’s a lie, King! She came here tonight, and I came after her.” Jack’s hand clenched and unclenched over the butt of his gun. “Come on—tell me where she is.”

The big man sighed and motioned to a camp chair.

“Set down, Hartwell. I’m not in the habit of lettin’ men tell me that I lie, but you’ve kinda got the edge on me this time. At the risk of bein’ called a liar again, I tell you that I haven’t seen Molly. —— it, I haven’t seen her since you stole her away from me.”

“I didn’t steal her,” denied Jack hotly. “She went willingly. You knew she was goin’, too. Was it a trick, King? Did she marry me to supply you with information?”

“Eh?” King scowled at the questions. “Did she marry you to—hm-m-m! What made you think she came up here?”

“She’s gone. I just came from home. One of your men took a note to her. I reckon he came home with a smashed arm, didn’t he?”

King nodded slowly.

“We expected a few smashes. There are more to come.”

“But that don’t tell me where my wife is, King.”

“No, that’s true, Hartwell. I wish I knew. She ain’t here.”

There was a ring of truth in King’s voice. “If she was here, I wouldn’t lie to you, Hartwell. And if she didn’t want to go back with you—well, you’d have a hard time takin’ her. Didn’t you realize that you was runnin your neck into it by comin’ up here tonight? It’s war, Hartwell. I’m leadin’ one side and your father leadin’ the other. And you came into my camp.

“It was a risky thing to do, young feller. You took a big chance of bein’ shot. Do you think I ought to let you go back? You are my son-in-law, and I don’t want to have yuh get shot.”

“I reckon I’ll go back,” said Jack coldly. “I never seen the sheepherder yet that could stop me. I ——”

Jack stopped. King had lifted his hand from the blanket and Jack looked into the muzzle of a big revolver. The big man was smiling softly, and the hand holding the gun was as steady as a rock.

“Set down,” he said softly. “Keep your hands on your knees. I’d hate to kill my son-in-law, but if you make a move toward your gun, that marriage is annulled by Mr. Colt.”

“All right,” grunted Jack. “I know that kind of language. Go ahead and shoot. It’ll save yuh future trouble.”

But Eph King only smiled and rested the muzzle of the gun on his knee.

“Futures don’t bother me, Hartwell—not that kind. You come blusterin’ up here and talk big. You kinda amuse me, so I’ve a —— good notion to keep you here. Did yuh ever read about the old-time kings? They had a jester—a fool—to amuse ’em. I’m as good as they, so why not have a jester, eh?”

“A fool,” corrected Jack bitterly.

“Very likely,” dryly. “Still, I’d hate to even be amused by a Hartwell. Anyway, I’ve a notion to keep yuh here and let your father know that I’m holdin’ yuh. It might——”

“Amuse him,” finished Jack.

“Meanin’ what?” queried King quickly.

“Meanin’ that he thinks I’m a spy for you. They all think I am—except Molly. I forced my way through the cattlemen’s dead-line to get up here tonight. They recognized me. I had to knock one of ’em down to get through. And they’d be liable to care a whole lot if I didn’t come back, wouldn’t they?”

Eph King stared at Jack closely. He knew that Jack was telling the truth and it seemed to amuse him a little. With a flip of his wrist he threw the gun behind him on the cot, and got to his feet.

“Hartwell,” he spoke seriously, “do you want to throw in with us?”

“No.”

“Still loyal, eh?”

There was a sneer in the question.

“Mebbe not loyal, King.”

“Blood thicker than water, eh?”

“Probably. Anyway, I hate sheep.”

King sighed deeply and threw open the tent flap.

“Sometimes I hate ’em myself,” he said softly, as they went outside.

The men crowded around them, realizing that Jack was an outsider. His horse had just been brought in by one of the sheepmen. But none of them questioned King.

“This is one of the cattlemen,” he said to them. “He is going back now, and I’d like to have one of you go with him until he passes our lines.”

“Not with me,” declared Jack. “I’ll circle wide and come out away beyond the sheep. Much obliged, just the same.”

“And tell all yuh know to the cattlemen, eh?” growled one of the men, and then to King:

“If one of ’em can ride into our camp, what’s to stop a dozen of ’em from comin’.”

“That’s my lookout, Steen,” replied King coldly. “All he knows won’t hurt us any.”

The men stood aside and watched him ride away. As soon as he was out of earshot, King swore harshly.

“You had the right idea, Steen,” he said, “but I didn’t want him to think that his comin’ bothered us any. We’ve got to tighten the line. Next thing we know a whole horde of men will come ridin’ over the hill, and —— will be holdin’ a recess. But I don’t think that Hartwell will tell what he knows.”

“Was that young Hartwell?” asked Bill Steen, foreman for King.

“Yeah.”

King nodded shortly and went back into his tent, where he sat down on the creaking cot, leaned his elbows on his knees and stared at the ground. From beyond the immediate hills came the sound of several rifle shots. The big sheepman shook his head slowly, thoughfully. Steen lifted the flap of the tent.

“I’m sendin’ all the men down to the line for the rest of the night” he said. “We’ll likely have to draw the herd back a little early in the mornin’, ’cause they’ll prob’ly start shootin’ at ’em.”

“I s’pose,” King nodded. “Not too far, though. We’ll have our own men placed, and mebbe we can do a little shootin’, too.”

“Sure. We ought to string ’em out pretty wide tomorrow. I think we’ve got more men than they have, and by stringin’ out kinda wide, we can slip through the holes any old time yuh say. I don’t think they can stop us when we get ready to start.”

“When we get ready,” echoed King. “We’re not ready yet.”

“Yeah, this is the right road, but where is that danged trail the sheriff told us about?” complained Sleepy. “I tell yuh we’re past it, Hashknife.”

“Prob’ly,” agreed Hashknife dryly. “It’s so danged dark that yuh couldn’t see it.”

They drew rein and debated upon their next move.

“Let’s go ahead a little ways,” suggested Hashknife. “Mebbe we ain’t past it. The sheriff said we couldn’t miss it.”

“Mebbe he was educated in a night school and can see like an owl,” laughed Sleepy as they rode on.

Suddenly both horses shied from something that was in the middle of the road. Hashknife dismounted quickly and made an examination.

“An old telescope valise, busted wide open,” he remarked. “Lot of women’s plunder, looks like. Must ’a’ fell out of a wagon.”

He lighted several matches and examined it, while the two horses snuffed suspiciously at the smashed valise.

“I’ll just move it aside of the road, where the owner can find it,” said Hashknife. “Some woman is worryin’ over the loss of all them things, I’ll betcha.”

They laughed and rode on, peering into the darkness. About two hundred yards beyond the valise, the two horses jerked to a stop. Hashknife’s horse snorted and tried to whirl sidewise off the road, but the lanky cowboy swung it back and dismounted again.

“It’s a woman this time,” declared Hashknife as he leaned over the dark patch on the yellow road. “That driver must ’a’ been pretty careless to lose his load thataway. Here, hold some matches for me, Sleepy, and don’t let loose of my bronc. That danged jug-head must be a woman-hater.”

Together they examined the woman, who groaned slightly as they lifted her to a sitting position. It was Molly Hartwell. She blinked at the matches and tried to get to her feet.

“You better take it kinda easy,” advised Hashknife. “You’ve got a cut on yore head, which has bled quite a lot, ma’am.”

“I—I know,” she said painfully. “I guess I didn’t have the cinch tight enough and the saddle turned with me. I tried to go back home, but I got so dizzy I had to lie down.”

“Where do yuh live?” asked Hashknife.

Molly Hartwell peered out into the gloom and was forced to admit that she did not know.

“It is either—well, I don’t know. Anyway, it is on this road.”

“Well, it ain’t behind us—’less it’s hid,” declared Sleepy. “So it must be the way we’re travelin’.”

Hashknife assisted her on to his horse, while Sleepy went back and got the valise. It was a cumbersome object to carry, and the broken straps made it almost impossible for him to keep from spilling its contents.

It was not far back to the Hartwell place. Sleepy opened the gate, while Hashknife led his horse up to the house. It was then that the valise refused to remain intact any longer. It skidded out of Sleepy’s arms and the contents spilled all about. And as fast as he picked up one article another fell out.

Finally he tied his horse to the gate-post, so he could use both hands. The valise had evidently been packed with care, but in upsetting it had jumbled things until it was impossible for Sleepy to get them all back.

He swore feelingly, perspired copiously and finally tripped over the stack of white clothes. He came up with a handful of womanly garments, to be exact—a nightgown. It was of the voluminous kind, and its bulk forbade the shutting down of the valise cover.

Hashknife and the lady had gone into the house and lighted the lamp. Sleepy whistled to himself, as he slipped the nightgown over his head, ran his arms through the short sleeves, picked up the valise and started for the house. He had solved the transportation problem to his own satisfaction.

A man had ridden in at the rear of the house, but Sleepy had not seen him. He walked up to the open front door and stepped inside, just as Jack Hartwell came in through the rear door. Hashknife was standing near the table, looking at Mrs. Hartwell, who was sitting in a low rocker, her head held in her two hands.

Jack Hartwell’s clothes were torn and there was a smear of blood across his face, which gave him a leering expression. In his right hand he held a cocked revolver. His eyes strayed from his wife and Hashknife to Sleepy, who stood in the doorway dressed in a white gown, and holding the bulky valise in his two hands. For several moments, not a word was spoken. Then:

“Evenin’, pardner,” Sleepy spoke directly to Jack, who was staring at him wonderingly. “Ain’t you the feller I met in Cheyenne last year?”

Jack Hartwell shifted his feet nervously.

“No,” he said hoarsely, “I’ve never been in Cheyenne.”

“Neither have I,” said Sleepy innocently. “Both parties must be mistaken.”

Hartwell shoved away from the door and came closer to Hashknife.

“Who in —— are you? More sheepherders?”

Mrs. Hartwell looked up at Jack and at sight of his bloody face she started to get up. He looked at her. She was as bloody as he, and her clothes were dusty and disarranged.

“More sheepherders?” queried Hashknife.

“Yeah, —— yuh! What are yuh doin’ here, anyway?”

“Excuse me for appearin’ in this condition,” said Sleepy, starting to disrobe, “but this thing was what broke the telescope’s straps. There’s a limit to what yuh can git into ’em.”

Jack squinted at Molly.

“Where have you been?” he asked. “You’ve been hurt, Molly. Did these men ——?”

He whirled and faced Hashknife, who had moved toward him.

“They found me and brought me home, Jack. I—I was going away—going to Totem City to catch the train—home. But the cinch turned and I fell off. That valise was too heavy.”

Molly Hartwell began crying softly, and Hashknife walked over to Sleepy, who had managed to get out of the gown.

“We better go, Sleepy,” he said quietly.

“Just a minute,” said Jack. “I’d kinda like to know who you two fellers are.”

“Well—” Hashknife grinned slightly—“we’re not sheepherders, if that’ll help yuh any. We missed the place where the sheriff told us to turn off, and mebbe it was lucky that we did. We was headin’ for Turkey Track sidin’, wherever that is.”

“I can show yuh how to get there,” offered Jack. “Go out of my gate, turn to the left and foller that old road to the Turkey Track ranch. It turns and crosses the river leadin’ right to the sidin’. Yuh can’t miss it.”

“Uh-huh, thanks,” nodded Hashknife. “’Pears to me that there’s a lot of folks around here that have confidence in us. The sheriff told us we couldn’t miss that trail, too.”

They walked out abruptly, mounted their horses and turned to the left, following the old road.

“What do yuh make of that outfit?” asked Sleepy, as they gave the horses a free rein and spurred into a gallop.

“It’s got me pawin’ my chain,” said Hashknife. “Kinda looks like the little lady was goin’ home to pa, but the cinch turned, and ag’in she’s in the bosom of her family. Right pretty sort of a girl.”

“And the husband looks like he’d been kinda pawed around, too,” said Sleepy. “He had blood on his face and a gun in his hand. And he wondered if we were sheepherders, Hashknife.”

“Well, it’s none of our business, Sleepy. That hubby is a right snappy sort of a jigger, and he might be bad medicine.”

“Do yuh reckon there’s a sheep and cattle war on here?”

“There’s somethin’ wrong, Sleepy, and it feels like it might be wool versus hides. Anyway, it ain’t none of our business, bein’ as we’re just a pair of train chasers and ain’t got no interest in either side.”

“I hope the cattlemen knock —— out of ’em,” declared Sleepy.

“Same here. What’s this ahead of us?”

They slowed their horses to a walk. Ahead of them, crossing the road, was a herd of cattle. They were traveling at a fairly good rate of speed, heading toward the river. From the bulk of them Hashknife estimated that there must be at least a hundred head.

A rider came surging down through the sagebrush, silhouetted dimly against the sky, as he urged them on with a swinging rope. The cattle cleared the road, and the circling rider almost ran into them, possibly thinking that these other two objects were straggling cows.

“Runnin’ ’em early, ain’t yuh?” called Hashknife.

For a moment the rider jerked to a standstill, and Hashknife’s answer came in the form of a streak of fire, the zip of a bullet and the echoing “wham!” of a revolver. He had fired at not over fifty feet, but his bullet went over their heads.

Then he whirled his horse and went down the slope, swinging more to the east, before either of them realized that he had shot at them and escaped. The cattle were bawling, as they scattered down through the brush, evidently thinking that this loud noise was part of things designed to keep them moving.

“Well, can yuh beat that?” exclaimed Hashknife. “Shot right at us. Ain’t this a queer country, cowboy?”

“I’ll betcha that’s a bunch of rustlers!” declared Sleepy excitedly.

“By golly, you do deduct once in a while,” laughed Hashknife. “Let ’em rustle. As I said before, we’re chasin’ a train, not trouble. C’mon.”

“Yeah, and c’mon fast,” chuckled Sleepy. “That impudent son-of-a-gun headed down this road, I’ll betcha. Shake up that old bed spring yo’re ridin’, Hashknife and he’ll have to be a wing shot to hit us.”

Together they went down the old road as fast as the two horses could run, each man carrying a heavy revolver in his right hand. The old road was only a pair of unused ruts, but the horses had good footing. A quarter of a mile below where the shot had been fired at them, a rider swung across the road and faded into the tall sage, but whether he was a rustler or not they were unable to say.

They drew up at the bank of the Lo Lo River and let the horses make their own crossing. The river was shallow at this point. It was only a short distance from the river to the old loading corrals at Turkey Track siding, but there was no sign of the cattle-train.

“Empty is the cra-a-adul—baby’s gon-n-ne,” sang Hashknife in a melancholy voice as they dismounted and sat down on the corral fence.

“Who the —— told you you could sing?” asked Sleepy.

“A feller with a voice like mine don’t have to be told. It’s instinct, cowboy, instinct.”

“Extinct,” corrected Sleepy. “Like do-do-bird and muzzle-loadin’ pistols. I wonder if that jigger was a rustler, or was he just nervous. Some folks are thataway, Hashknife.”

“All rustlers are, Sleepy. The more I see of this country the more I envy Stumpy, Nebrasky and Napoleon in their nice, easy-ridin’ caboose. Right now I hanker for that good old dog house. Sleepy, I hankers for it so strong that I becomes melancholy and must sing.”

Hashknife cleared his throat delicately and began:

“Hark!” blurted Sleepy dramatically. “There came a scream of agony! The lights went out! From somewhere came the crashing report of a gun. Then everything was still. A man lighted a match and held it above his head, dimly illuminating the room. But it was enough. The singer was dead—shot through the vocal cords.”

“Didn’t yuh like the song?” asked Hashknife meekly.

“——, the song was all right; it’s the way it was bein’ abused that made me step in and stop it. Yore ears must shut up tight every time yuh try to sing, Hashknife. That must be it, ’cause you’d never do it if yuh knowed what it sounded like.”

“Uh-huh, that must be it,” agreed Hashknife sadly. “I wish that train would back up long enough for us to get our belts and holsters. This darned six-gun of mine is goin’ to give me stummick trouble, if I don’t find a new place to carry it. The barrel is too long for my pocket.”

“Carry it over yore shoulder,” advised Sleepy. “We better go back and give these horses to the sheriff. It’ll be daylight pretty soon, and I’m sleepy.”

“Might as well,” agreed Hashknife. “No tellin’ where that train is by this time, so there’s no use chasin’ it.”