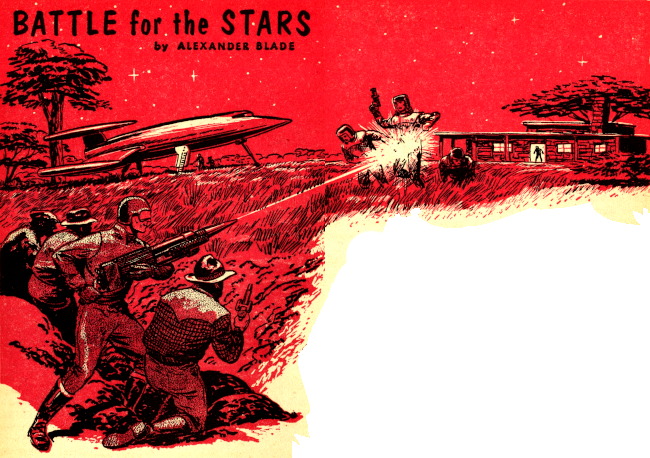

Title: Battle for the Stars

Author: Edmond Hamilton

Release date: November 29, 2021 [eBook #66843]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Kirk had never seen the distant planet

called Earth, yet his squadron was now ordered

there—to stem the outbreak of a galactic war!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Imagination Stories of Science and Fantasy

June 1956

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

It was well called the Dragon's Throat, thought Kirk. Throat of fire, of burning suns, a cosmic blind-alley into danger!

You made your decision. You threw a ship, a hundred men, your officers, your friends, your own Commander's badge you threw them all down on the gamble. But when the stakes were stars....

He said to himself, "The hell with it, we're committed."

He said aloud, "Radar?"

Joe Garstang, standing on the bridge beside him, answered without turning. "Nothing has been monitored yet. Not yet."

Kirk's palms itched. If they were running into an ambush, if Orion heavy cruisers were waiting for them, they'd soon know it. There could be ships all around them. Radar wasn't too dependable, in the howling vortices of force-field energy flung out around this jungle of stars.

Through the broad bridge-windows—the "windows" that were really scanners cunningly translating faster-than-light probe rays into visual images—there beat upon his face the light of a thousand suns.

It was Cluster N-356-44, in the Standard Atlas. It was also hellfire made manifest, to starmen. It was a hive of swarming suns, pale green and violet, white and yellow-gold and smoky red, blazing so fiercely that the eye was robbed of perspective and these stars seemed to crowd and jostle and rub each other. Up against the black backdrop of the firmament they burned, pouring forth the torrents of their life-energy to whirl in terrific cosmic maelstroms. The merchant ships that boldly drove the great darks between ordinary star-worlds would recoil aghast from the navigational perils here. Only a fool—or a cruiser—would go in here.

There was a narrow cleft between cliffs of stars, with the flame-shot glow of an immense nebula roofing it. The only possible way into the heart of the cluster, this Dragon's Throat of starman legend. But others had gone in this way. At least, so said the rumors, rumors that had reached the squadron as far away as the Pleiades. Rumors too factual, too alarming, to be ignored.

Rumors of cruisers from the squadrons of Orion Sector, that had gone into this cluster. Rumors of a secret base, on a hidden world. The ships of Orion Sector had no business here. Neither, for that matter, did the ships of Kirk's own Lyra Sector. This cluster was no-man's land, part of the buffer zones that were supposed to reduce friction between the five great Sectors of the galaxy. Actually, these stellar wildernesses were the scenes of constant, nameless little wars.

The five governors of the five great Sectors were, all of them, ambitious men. Solleremos of Orion, Vorn of Cepheus, Gianea of Leo, Strowe of Perseus, Ferdias of Lyra—they watched each other jealously. Five great barons of the galaxy, paying only a lip-service allegiance to the shadowy Central Council far away on a half-forgotten world called Earth, in reality independent satraps of the stars, hungry for space, hungry for power. Yes, even Ferdias, thought Kirk. Ferdias was the man he served, respected, and even loved in a craggy sort of way. But Ferdias, like the others, played a massive game of chess with men and suns, moving his squadrons here and his undercover operatives there, laboring ceaselessly to hold on to what he had and perhaps enlarge his domain, just a little, a solar system here and a minor cluster there....

And the game went on. Right now, Kirk thought he was probably heading into a trap. But if Orion cruisers were in here, he had to know it. A hostile base here, if left to grow, could dominate all the star-lanes from Capella to Arcturus. It was up to him as a squadron-commander, to go in and find out.

Kirk looked at the looming, overtopping cliffs of stars that went up to the glowing nebula above and down to the black pit of absolutely nothing below.

He thought of Lyllin, waiting for him back at Vega. A starman had no business with a wife.

He said again, "Radar?"

"Still nothing," said Garstang. His square face was no less grim than Kirk's. He was captain of this flagship Starsong, and what happened to her was important to him. "If there is a base here," he said, "we should have come in with the whole squadron."

Kirk shook his head. He had made his decision and he was not going to start doubting it now, no matter how lonely and exposed he felt.

"That could be exactly what Solleremos wants. With the right kind of ambush, a whole squadron could be clobbered in this mess. Then Lyra would be wide open. No. One ship is enough to risk."

"Yes, sir," said Garstang.

"The hell with you, Joe," said Kirk. "Say what you're thinking."

"I am thinking that the rumor mentioned cruisers, plural, indefinite. We'd better catch them while they're all asleep."

The Starsong forged her way onward toward the two red suns at the end of the Dragon's Throat. And Kirk thought that if he had made the wrong decision, if the Starsong never came back again, Ferdias would be very angry. But that would not then make any difference to him.

Looking up at the flaring, tumbling waves of the nebula, like the underside of a burning ocean, Kirk said to Garstang:

"Does it seem to you the pace is speeding up? I mean, this jockeying for power between the Sectors has gone on a long time, ever since Earth lost real authority. But it seems different lately, somehow. More incidents, more feeling of something driving ahead toward a definite goal, a plan and a pattern you can't quite see. You know what I mean?"

Garstang nodded "I know."

The computer banks clicked and chattered. Relays kicked, compensating power, compensating course, compensating tides of gravitic force quite capable of breaking a ship apart like a piece of flawed glass. The two red binaries gave them a final glare of malice and were gone. They were clear of the Throat.

A star the color of a peacock's breast lay dead ahead.

"Ready for approach," said Garstang.

"Stand by," said Kirk. "We'll wait until the last possible minute to shift. If they haven't picked us up already, maybe they won't."

Garstang gave his orders. Kirk watched the blaze of peacock-blue grow swiftly. No ambush in the Throat, so now what? Ambush on the world of the blue star? Or nothing? A wild-goose chase, time and money wasted? Or maybe Solleremos had planted those rumors to draw Kirk's attention while a strike was made somewhere else.

Suddenly Kirk felt very old and very tired. He had been in the squadron for twenty years, ever since he was sixteen, and in all these twenty years the great game of stars, the strain, the worry, had never let up.

It must have been nice in a way, Kirk thought, in the old days a couple of centuries ago when Earth still governed in fact, and all the star-squadrons were part of the Galactic Navy, and the great battle was with the galaxy itself and not with one another.

"We're getting close," said Garstang.

Kirk shook himself and got down to business. There followed a few minutes of split-second activity, and then the Starsong had shuddered out of overdrive and was plunging toward a bright world almost dangerously close to her. There was still no sign of any enemy, and the communicators remained silent.

An hour later by ship's chrono they had located the one port of entry listed for the planet and they had set the Starsong down in the middle of a large piece of natural desert that served well enough for what space traffic ever came here.

It was night on this side of the planet. There was no moon, but on a cluster world a moon is a useless luxury. The sky blazes with a million stars, so that day is replaced not by darkness but by the light of another sort, soft and many-colored, full of strange glimmers and flitting shadows. In this eery star-glow a town was visible about a mile away. Otherwise there was nothing. No ships.... No legions of Orion Sector.

"The ships could be hidden somewhere," Garstang said. "Maybe halfway around the planet, but waiting to jump us as soon as they get word."

Kirk admitted that was possible. He put on his best dress uniform of blue-and-silver, and strapped a portable communicator between his shoulders. It rather spoiled the effect, but there was no help for that. Garstang watched him.

"How many men will you want?" he asked.

"None. I'm going in alone."

Garstang's eyes widened. "I won't come right out and say you're crazy."

"I was here once before," said Kirk. "When old Volland was commander and I was an ensign. These people are poor but proud. They have traditions of long-ago splendor, claim their kings ruled the whole cluster and so on. They dislike strangers, and won't let many in."

"But if Solleremos' men are already here—"

"That's the reason for the porto." Kirk frowned, trying to plan ahead. "Exactly twenty minutes after I enter the town I'll contact you, and I'll continue to do so at twenty-minute intervals. If I'm so much as a minute late, take off and buzz hell out of the place. It'll give me a bargaining point, anyway."

Garstang said dourly, "A lot can happen in twenty minutes. Suppose you're not able to bargain?"

"Then you're on your own."

In the airlock, open now and filled with a dry, stinging wind, Kirk paused, looking toward the distant town, a lonely blot of darkness between the star-blazing sky and the gleaming sand. Here and there in it lights burned, but they were few and somehow not welcoming.

"She's all yours," he said to Garstang. "If anything looks wrong to you, don't wait for me. Take her away."

"Yes, sir," said Garstang.

Kirk smiled. He climbed down into the sand and began to walk.

The town took shape as he approached it. The stone-built houses, mostly round or octagonal, were scattered out with no particular plan. Under the red and gold and diamond-colored stars that burned above them as bright as moons, they looked curiously remote and evil, like old wizards in peaked hats, peering with little winking eyes. The dry wind blew, laden with alien scents. Apart from the wind there was no sound.

Three men met him at the edge of the town. They wore pale cloaks and carried long staffs tipped with horn. They were all of seven feet tall. They wore their hair high on their heads to accentuate this height, and they were slender and graceful as reeds, walking along with a light dancing step as though the wind blew them. But their faces in the star-glow were smooth and secret, their eyes as expressionless as bits of shiny glass.

"What does the man from outside desire?" asked one of them, in the universal speech.

Kirk said, "He desires to speak with those others from outside who enjoy your hospitality."

But they were not going to make it that easy for him. Their faces remained impassive, and the one who had just spoken said coolly, "Our lord has wisdom in all matters. Perhaps he will understand your words. I do not."

They fell in around Kirk and moved with him into the wide sandy space that went between the wandering houses. The nerves tightened up in Kirk's belly, and his back felt cold. He looked at his wrist chrono, carefully. There was no sound but the whispering of sand under their feet. Garstang would be watching with the 'scope, but once he was in among the houses he could no longer be seen.

That was almost at once. The tall men walked on with their light swaying stride, so that he had to move at an undignified trot to keep up. The stone houses with their high roofs closed in behind him. This dark and brooding town ill accorded with old tales of cluster-kings, he thought. Yet the past held many things.

When they were close to the center of the town, the leader stopped beside a round structure from whose open door came light.

"Will the man from outside enter the dwelling of our lord?"

Kirk breathed a little easier as he went through the door. Apparently there was no truth to the rumors that....

A chopping blow took him on the back of the head. He fell forward. He was stunned but not unconscious, and he tried to roll over, thrashing out blindly with his fists and feet. But at once there were men on top of him, heavy solid men grinding his face into the gritty carpet, pounding the wind out of him, holding him down.

In a minute his hands were tied tight behind him and his ankles lashed together. They cut the straps of the porto and pulled it off him. Then, like a sack of meal, he was dragged to the wall and propped upright.

In an absolute fury of rage, he spat blood out of his mouth and looked up dizzily into the light.

There were three or four men here, obviously not natives of this planet, but he did not pay much attention to them. The one he looked at stood apart, directly in front of Kirk, a lean dark iron-faced man with very alert eyes, and the easy, dangerous manner of one who enjoys his work because he is so admirably well fitted for it, as a cat enjoys hunting.

He said to Kirk, "My name is Tauncer."

Kirk nodded. He looked with feral interest at this most famous of Solleremos' agents. "I should be flattered, shouldn't I?"

Tauncer shrugged. "We all do what we can, Commander. Each in his own way."

"Well," said Kirk. "What do you want?"

"The answer to one simple question."

His face came closer to Kirk's, very tense, very keen, searching for any sign of evasion.

He asked his question.

"What is Ferdias planning to do about Earth?"

CHAPTER II

There was a long moment of complete silence, during which Kirk stared wide-eyed at Tauncer, and Tauncer probed him with a gaze like a scalpel.

On Kirk's part, it was a silence of sheer astonishment. No question could have taken him so unexpectedly. He'd been prepared to be grilled on squadron dispositions, forces in being, bases, all the things that the men of Orion Sector would like to know about Lyra. But this—

It didn't make sense. Earth was not part of the present-day star struggle. That old planet, so far back in the galaxy that Kirk had never been within parsecs of it—it was history, nothing more. It had had its day, its sons long ago had spread out to the stars and their blood ran in the veins of men on many worlds, in Kirk himself. But its great day had long been done, and the Sector governors who played the cosmic chess-game for suns paid it no heed at all.

"I'll repeat," said Tauncer softly. "What's Ferdias planning to do about Earth?"

"I haven't," said Kirk, "the faintest idea what you're talking about."

Tauncer sighed. "Possibly." He straightened up. "Even probably. But I've been sent here to make the inquiry, and I'll need more than your word and an expression of innocence. Brix!"

One of the other men came forward. Tauncer spoke to him in a low voice, and he nodded, and went into the shadows across the room. Kirk's heart pounded in alarm. He tried to get up, but he had been too well bound. He could not see his chrono, but he did not think that more than seven or eight minutes had elapsed since he had entered the town. Plenty of time for mischief. He said to Tauncer,

"I didn't walk into this with my eyes completely shut. My men have instructions."

"I'm sure they have. And don't feel too badly about this, Commander. The details of the trap were based on a minute study of your psychology and past record. It would have been almost impossible for you to avoid falling into it. Can't you hurry that up Brix?"

"All ready." Brix came back carrying a light tripod with a projector mounted on it. And now Kirk's heart sank coldly into the pit of his stomach. He had seen that particular type of projector before. It was called a vera-ray, and it beamed electric impulses in a carefully-controlled range that absolutely stunned and demoralized a man's brain, making him temporarily incapable of lying or resisting questioning.

Kirk had no information about Earth to give away. But there were plenty of other things in his mind, things of military importance to Lyra Sector that Solleremos would be only too glad to get hold of.

How long now? Ten minutes more? Too long. Even five minutes would be too long, with that projector pounding his skull.

He couldn't get up, but he could roll. He rolled, acting on a split-second reflex that caught even Tauncer by surprise. The projector was only four or five feet away. Brix and the other men were on top of him again almost at once but not quite in time. He fetched the tripod a thrashing kick, with both his feet bound together. It fell over. He could not hope that it was broken, not on this soft carpeted floor, but it would take them time to set it up again.

He tried to keep them busy as long as he could, but Tauncer understood perfectly well what he was up to. He pulled his men off and set Brix to adjusting the projector again, and turned to Kirk.

"You may as well spare yourself, Commander. I have my mission, and the military have theirs. There are three cruisers standing off and on, just out of radar range—they got word the moment you landed, and they're already on their way."

He smiled briefly. "The price you pay for fame, Commander. The Fifth is Ferdias' elite squadron, and nobody gets command of it unless he's in Ferdias' special favor."

"Friendship is one thing," said Kirk hotly, "and favor is another. I don't like your choice of words."

He was just talking, words, sounds with no meaning. Inside he was thinking of Garstang and the Starsong, and all the lives of all the men in her. He had led them here.

He looked at Tauncer, and he began now to hate him, with a hate as deep and cold as space.

"Ferdias will tear your heart out," he said.

"Perhaps," said Tauncer. "But he may have other things to occupy his mind."

"Earth? He's never been there. None of us have. It's only a name, and a half-forgotten one at that. Why should Earth occupy his mind? Why, Tauncer?"

How long is twenty minutes? How long does it take three cruisers to come from Point X beyond radar range to Target Zero? How long does it take a man to realize he's through at last?

Brix said again, "All ready."

Tauncer nodded.

Brix touched a stud on the projector.

As though that touch had done it, a dull and mighty roaring echoed from the desert—the full-throated cry of a heavy cruiser taking off.

The men looked, startled, toward the door. Desperately, Kirk rolled sideways, out of the force that was already battering at the edges of his mind.

"You out there!" he shouted at the doorway. "The men from outside avenge treachery! Call your lord—"

One of Tauncer's men kicked him alongside the jaw. Kirk shut up, hanging with blind determination to his consciousness. Fore-thought had provided this one chance. He would not get another. He did not dare to miss it.

The cruiser came low over the town. Dust sifted out of the cracks of the stone walls. The men fell to their knees, covering their heads with their arms. The floor rocked under them, beaten by the rolling hammers of concussion.

The ripped sky closed upon itself with a stunning, thundering crash. After a minute or two the noise and the shock wave ebbed away.

Silence.

The men began to get up again. But Kirk did not move.

The cruiser came back. This time it was even lower. Garstang must have tickled her belly on the peaked roofs. Christ, thought Kirk, he's overdoing it. This time the stones were shaking loose. When it was over, a long thin shape came in through the doorway. It was the leader of the tall men who had brought Kirk here.

His face was a mask of fear and rage as he spoke to Tauncer. "You said that if we helped you, you would keep all other outsiders away!"

"We will," said Tauncer. "Listen—"

"Yes, listen," mocked Kirk. "Listen to it coming back. It'll keep coming back, unless I walk out of here—until your town is flattened."

The tall man stood hesitating. Then the Starsong roared back over. When it was gone, he picked himself up and with a knife cut the cords around Kirk's wrists and ankles.

"Oh, no," said Tauncer, starting forward. "You can't—"

The tall man turned on him a face livid with frustrated anger. "Shall the children of cluster-kings be destroyed to serve you? Shall I call my people in?"

Kirk, scrambling to his feet, saw outside the door the crowd of tall, pale-cloaked men who had gathered. Tauncer saw them too, and stopped.

As Kirk picked up the porto and started for the door, the man Brix cried violently, "Are we just going to stand here?"

Tauncer said levelly, "Why, yes, there are times when you do just that. But I think we'll see the Commander again."

Kirk went out through the door and through the crowd outside it. No one followed him. He got the porto working and talked fast to Garstang, then dropped the porto and sprinted out of the town toward the desert.

The cruiser dropped down ahead of him, as black and big against the stars as a falling world. The lock yawned open, and Garstang was inside it to meet him. He started to ask what had happened, but Kirk pushed him bodily away down the corridor, heading for the bridge.

"Get in there and do your stuff, Joe. We've got three Orion cruisers on our tail, as of the time we landed."

At that moment they heard the voice of the radarman crying out in sudden anguish, "Sir!"

Garstang said in mild reproval, "You ought to give a man more time, Commander. Radar, what's the bearing? All right, stand by—"

Orders crackled over the intercoms. Men moved swiftly at the control-banks. The last thing Kirk heard before the howling roar of take-off drowned everything was Garstang complaining that this sort of thing was hard on a ship. Then there was a dull crash from somewhere outside. The Starsong was shaken as though by a great wind. Both Kirk and Garstang had weathered enough fire to know that she had taken no hurt. But the Orion cruisers were in range now, bearing down on them in normal space at planetary speeds. The next shell would likely be a good deal closer. They dared not wait for star-room to go into overdrive.

"Hit it!" yelled Kirk. Garstang threw the relays open. Sirens shrilled and the lights went dim. The Starsong shuddered vertiginously.

And then they were in overdrive and racing out toward the twin red suns that guarded the entrance to the Dragon's Throat.

The scanners and ultra-speed radar came into play, replacing normal instruments, making an illusion of sight. And the voice of the radarman said dismally,

"They're still with us, sir. F-Type cruisers, heavy-armed and plenty fast."

For the next quarter of an hour the Starsong gained velocity at a suicidal rate, but the Orion cruisers would not be left behind. The radarman called their coordinates in a steady sing-song and Garstang ordered more power and more power, keeping one eye on the stress indicators and the other on the overhanging star-cliffs of the Throat that seemed to be leaping toward the ship.

There was a limit. You could not take the Throat too fast. In that swarm of suns a ship's fabric could be torn apart in some swift tide of gravity, or vaporized in collision. Garstang had already passed the limit. But the Orionids were refusing to be bluffed.

Kirk said nothing. This was Garstang's job, and he let him do it. But he watched the indicators as closely as the captain. Under his feet and all around him he could feel the Starsong quiver, wincing and flinching like a live thing now and again as some wild current wrenched at her. His gaze flicked upward to the nebula, like a fiery thundercloud above the Dragon's Throat, and then to the shoaling suns below, with the narrow pass between them. The twin red stars of the binary flashed by and were gone.

Suddenly, in the screen that mirrored space astern, a tiny nova flared and winked away. The Starsong trembled, like a running deer that hears the hunter's gun.

"Wide astern," said Garstang. He looked at the cleft of the Throat and shook his head. "But we'll have to slow down for that, and they know it. They'll have time to range us before they come in themselves. They won't," he added grimly, "have to come in."

Kirk nodded. "So we'll fool them. We won't go into the Throat either."

Garstang stood silent for a moment. Then he said, "I was hoping you wouldn't think of that."

"Have you a better idea? Or even a worse one?"

"No." Garstang took a deep breath and spoke into the communicator. "New course, north and zenith, forty degrees. We're running the nebula. On full autopilot. If anyone wants to pray, go ahead."

The Starsong shot upward, plunging high into an area so choked with stellar radiance that it made the Dragon's Throat seem like empty space. The manual control-banks were dark and dead. From the calc-room back of the bridge a new sound came, different from the normal occasional outbursts of chattering. This was a steady sound, a sound of authority, the voice of the Starsong speaking. She was flying herself now. The men aboard, Captain and Commander, able spaceman and ensign, were her charges, dependent on her wisdom and her radar vision and her strength. There was nothing they could do but wait.

The Starsong spiralled higher, her radar system guiding her on a twisting path between the clotted stars. Then Kirk saw a great glowing edge slide onto the screen and grow into a vastness of dust and cosmic drift illumined by the half-smothered stars it webbed.

The Orionid cruisers had altered course and were coming after them. But the Starsong was already skimming through glowing arms that reached like misty tentacles searching for other stars to trap and feed upon. Once in the cloud, she would be screened from the cruiser's radar beams by the most effective scrambling device in space, the nebula itself.

Effective. Yes. But potentially as deadly as Orionid warheads. The only difference was that with the nebula you had a chance. Against three cruisers you had none.

Kirk strapped himself into the recoil chair beside Garstang. Nothing moved now within the ship. The frail, breakable organism of breath and heart and bone were encased in protective webs. This was the hour of the ship, the hour of steel and flame and the racing electron, faster than thought.

The Starsong spoke to herself in the calc-room, and plunged headlong into the cloud.

CHAPTER III

The universe was swallowed up in golden light, in racing, streaming tides of luminous dust. Like an undersea ship of old the Starsong raced with the gleaming currents and burst through denser, darker deeps where the stars were faint and far away, to leap once more into a glory of wild light where the drowned suns burned like torches in a mist. And the voice in the calc-room rose to an unhuman crying as the computers strained to take in the overwhelming surge of data from defensive radar, analyze it, and send imperative commands to the control-relays.

It had almost a sound of insane music in it, that voice, and the Starsong danced to it, whirling and swaying between the fragments of the drift that threatened her with instant destruction if she faltered for a fraction of a second. Kirk, half-dazed, clung to his padded chair and gasped for breath, and felt, and listened.

The same illusion gripped him now that had mastered him before when forced to run a cloud—the feeling that the suns and star-worlds were all gone, that he was enwrapped in the primal fire-mists of creation. Mighty tides seemed to bear the ship forward, everything was a boil and whirl of light, millrace currents seemed to rush them endlessly through infinity, with all space and time cancelled out. He wondered briefly, once, how the Orionids were doing, and then forgot them. The agony, the intoxication, the godlike joy and the terror were far too great to admit any petty worries about anything human.

Then, with almost shocking abruptness, they broke into clear space, and the cloud was behind them. Like men enchanted waking from a dream, Kirk and Garstang shook themselves and stood erect again, and the voice of the Starsong was stilled, and human voices spoke once more.

And human problems were still with them. Somewhat farther astern now, but still doggedly following, three tiny flecks of darkness came after them out of the cloud.

Kirk went into the com-room and made contact with his squadron far ahead. He gave crisp orders, and then rejoined Garstang on the bridge.

"Larned's on his way," he said. "Can you keep clear?"

"I can," said Garstang, and ordered full power. He had nothing between him and the Pleiades now but light-years of elbow room, and he took full advantage of it. The Orion cruisers apparently had intercepted Kirk's message, and made a frantic last attempt to overhaul him.

When that proved impossible, and their trial shots fell so far short that it was obvious the range could not be made before the Starsong reached the point of convergence with the squadron, they turned tail and ran back for the cluster. When the squadron did arrive, space was empty of everything but themselves and the distant stars.

The hard, excited voice of Larned, Kirk's Vice-Commander, came rapidly as they joined the squadron.

"So there is an Orionid base in there! By God, we'll soon—"

"No," Kirk cut in. "There was no base in there. There was a trap, for me—only I still don't know just why they set it."

He went to the com-room and set up a message on the coding machine. Top secret, to Ferdias at Vega, briefly detailing his encounter with Tauncer.

"—am unable to explain interest in Earth, and your plans concerning. Suggest attempt to distract from some other objective? Await instructions. Kirk."

In a remarkably short time the answer came back.

"Report Vega at once with full squadron." And it added, "Unfortunately, no distraction. Ferdias."

Looking at the cryptic tape, Kirk had an uneasy feeling that he had all unknowingly stepped over one of those thresholds into a new phase of existence, where nothing was going to be quite the same as it had been ever again. He had once more that premonition that the pace, the tempo of the great game for suns, was about to step up still faster.

He said nothing of that to Garstang or the others. To them, the unexpected recall to home base meant an unlooked-for leave. And to him, it would mean returning to Lyllin sooner than he had hoped. But even that could not quite banish his uneasiness.

The squadron wheeled in tight formation and set its course toward the great blue-white sun that burned in Lyra, capital of a mighty Sector that was in everything but name an empire of stars.

When they made their world-fall, when the squadron swept down through the bluish glare over Vega Town and landed on the spaceport, Larned came at once from his own ship. The Vice-Commander, a blocky, brusque and competent young man, bristled with questions.

"What the devil is all this about, Kirk? Pulling us in like this—"

"I haven't an idea," Kirk said. "But I'm about to find out. Call Lyllin for me and tell her I'll be along soon."

An air-car with a uniformed driver took him across the great city. It was really two cities. The older city of graceful white towers had been built long ago by the native Vegans, Lyllin's people. But then, more than a century ago, the starships had come to Vega, the first wave of explorers and colonizers from the inner galaxy. They had not been all Earthmen, even though that wave had first started from Earth. By the time they reached here, Earthmen had already mixed and mated with many other human star-folk. It was these newcomers who had built the new part of Vega Town.

It was to the newer city that the air-car took him, to the looming, dominating mass of Government house. A lift took him down from the roof, and he went through the corridors, a tall man with a faintly worried look on his copper-bronzed face. Efficient secretaries shunted him smoothly and quickly into a room few people ever entered.

It seemed a small room, to be the center of government of so many stars. For this was the center—the Sectors each had their elected legislatures but it was the Governors who wielded the power.

"Stop saluting, Kirk," said Ferdias. "You know you're at ease when you step in here."

Ferdias came around the desk. He limped, from the crash of a Class Twenty long ago. But you never remembered his limp, or how small a man he was. You saw only his face, and when you saw it you knew why, at the age of forty, he was one of the five great Governors.

"Now let's have it," he said.

Kirk let him have it, the full story of the trap in the cluster. And Ferdias' face got just a trifle longer.

He said, finally, "You had no business going in alone. But since you got out, I'm glad you did it. For I'm sure now of what I only suspected before. In his eagerness to find out how much I know, Solleremos has told me what I wanted to know."

Kirk, frankly puzzled, said, "I just don't get it. What is Ferdias planning to do about Earth? What plans would you have about it?"

Ferdias limped back to his chair, and sat down, and then looked up keenly. "Kirk, you're at least half Earth blood. Tell me, how do you feel about Earth?"

Kirk said, "But I've never been there. You know that—I was born in a transport off Arcturus, and have never been farther back in than Procyon."

"I know. But what do you think about Earth?"

Kirk made a gesture. "What's there to think about? It's a third-rate planet, from what I hear, important only because star-flight began there. Its Galactic Council tried to hold all the galaxy together in one government, but of course that proved impossible. Hell, it's hard enough to hold a Sector together, let alone the whole galaxy."

"But Earth isn't any of the Sectors, of course," said Ferdias.

Kirk looked at him keenly. "Of course not. Sector Governors don't touch Earth's small federal district...." He stopped. He said, after a moment, "Or do they? Do they, Ferdias?"

"Solleremos would like to," said Ferdias.

Kirk was astonished. "You mean, he wants to take Earth into Orion Sector?"

"He wants to very much indeed," said the other. "Listen, Kirk. Solleremos' pressure on our borders lately has been only cover-up. It's Earth he's after."

"But why? That unimportant little star system—"

"Is it so unimportant?" Ferdias' blue eyes, hot and flaring now, fascinated Kirk. "Materially, maybe it is—a worn-out, third-rate world. But psychologically, it's a very important world indeed. Think of the Earth blood mingled in all the galaxy races now—in you and in me, in half the civilized peoples! Think of the feelings they have, perhaps without altogether realizing it, toward that old planet they've never seen! They know it no longer directs things, they know its Council and Navy are a shadowy sham—but still it's Earth, it's the old center of things, the old heart-world. Suppose one of the other Governors gets Earth into his Sector, and speaks from it thereafter?"

Kirk saw it now. He realized, not for the first time, that when it came to galactic intrigue he was a babe in arms.

It would give any of the rival Governors a colossal psychological advantage, to make the old center of the galaxy his seat of government. Commands that came from Earth would have a psychological potency hard to withstand.

"But you're not going to let Solleremos get away with it?" he exclaimed.

"No Kirk. I don't want Earth. But I'm not going to let Orion Sector grab it, either!"

He went on. "Solleremos knows I'll try to stop him. That's why he had Tauncer, his right-hand man, set that little trap for you. They know I trust you. They hoped I'd have told you how I plan to block them."

Kirk looked at him, and then said, "How are you going to stop them?"

Ferdias said, "There's a big celebration coming up on Earth soon. The two-hundredth anniversary of the first space-flight from Earth. It means a lot to them. Their Council invited me to send an official delegation to represent Lyra Sector. So I'm sending you."

Kirk stared. "Me—to Earth? But what can I do if—"

Ferdias interrupted. "The Fifth Squadron will go with you. To take part in the commemoration pageant, the fly-over."

Now Kirk began to understand. "Then if Solleremos tries anything, the Fifth will be there waiting for him?"

"Exactly." Ferdias spoke the word like a wolf-snap. "I know Solleremos' intentions. I know about when he plans his grab for Earth. Earth can't stop him, not with their small forces. But the Fifth can!"

Kirk felt a bit stunned. Fighting the hidden border wars of the rival Governors was one thing. But a full-fledged struggle between Sectors, back there at old Earth, was quite another. It could rock the galaxy....

Ferdias went on matter-of-factly, "You'll take off five days from now. You may be there a while, so you'll take full supply auxiliaries and transports."

Kirk looked up. Transports meant the families of all personnel would accompany the squadron—and that meant Lyllin would go with him. He was glad of that.

"But when we get there," he said. "Besides taking part in that celebration, what do we do?"

Ferdias said, "Go and look up your ancestral home."

"My—what?"

"Ancestral home. Place where the Kirks came from, on Earth. I had it hunted out, and it's still standing. It's in Orville, a place near the city New York. You go and look it up first thing."

Kirk began to get it. "You'll send me orders there?"

"You'll hear from me. And you'll get warning if Solleremos moves on Earth. But Kirk—one more thing."

"Yes?"

"You're not to talk of this to anyone. Anyone."

Kirk, as the air-car took him homeward across the city, hardly saw the brilliant Vegan capital flashing by beneath. He was badly worried. A deadly, secret galactic struggle was moving toward crisis, and he was not the man to combat conspiracies, he was no good at plots and plans. But—and his jaw set hard—if Solleremos did try to grab Earth by force, there was one thing the Fifth was very good at, and that was fighting.

He couldn't tell Lyllin about any of this, not against Ferdias' strict injunction. But at least she would be going with him this time, and that would be good news to her. He strode eagerly into the metalloy cottage that was home to him. Its familiar rooms were cool and silent. He found Lyllin waiting for him on the terrace.

The blue sun was touching the hills, and the sky was flooded with a purple dusk. Lyllin came toward him. She was all Vegan and looked it, her flesh showed pale as new gold, with the darker masses of her hair picking up the same tint and turning it to copper. She was dressed in the fashion of her own people, in a chiton so mistily transparent that her fine slender body seemed to be draped in a bit of the oncoming dusk itself.

He held her, and then told her his news, and was surprised that it did not seem to make her happy. "To Earth?" she murmured. "Just for the space-flight anniversary? It's strange—"

"But this time you'll be with me," he said. "Not on the voyage—you'll ride transport, of course—but on Earth, all the time I'm there."

"How long will that be, Kirk?"

He didn't know, and said so. Lyllin's face shadowed subtly. But she had a way of silence, and it was not until later that night that she spoke of it.

She said, suddenly, "I shall hate it at Earth."

Kirk was shocked. "But why in the world? That's ridiculous. A place you've never seen, and hardly know about—"

"It's your place, your people. Not mine." She was not looking at him. "You'll be going home. But what will they think of me there? What will you think of me there, among your own people?"

Kirk turned her around with rough and angry hands. "I'm ashamed of you. If you could even think a thing like that—" He shook her. "Listen to me. Earth is no more to me than it is to you. It's a name, a place where my grandfather five times removed happened to be born. I've as much blood of other worlds in me as Earth blood. And as for you—"

Her eyes had tears in the corners of them, now. Her mouth was soft and uncertain, like a child's. He said, in a different tone, "No matter where we go, you'll be Lyllin. And I'll love you."

She came close in the circle of his arms, and she kissed him with a wild possessiveness. And her lips were bitter with those sudden tears.

But Kirk felt that she was not convinced. She had the Vegan pride, and if they treated her at Earth like a freak, an alien....

In the depth of his soul, he cursed Solleremos and his ambitious schemes. For the worry that was in him had deepened. The danger that the Fifth was going into, the danger that would explode if that unscrupulous grab for the old planet was attempted, was not the only one. He felt now that beside that there was another, subtler danger waiting for Lyllin and himself at Earth.

CHAPTER IV

The squadron was out of overdrive, cruising at normal approach velocity. There was a sun ahead in space. Compared to the blazing giants of deep space, it was not much, merely a small yellow star looking rather lonely in the midst of a great emptiness. Kirk studied it. The Sun. Not just any sun, the Sun. How should he feel about it? Like a child seeing its father for the first time, or like a man returning to an ancient hearth that has long ago lost any meaning for him? Kirk searched his heart, and nothing came. It was only another star.

Garstang touched his arm and pointed, to where far off a little green planet swung to meet them.

"Earth."

The squadron rushed toward it, the cruisers and supply-ships and transports, the men and women and children, strangers from the far reaches of the galaxy. And yet not quite strangers either, for the names that had come from this world were still among them, and the traditions, and even some of the blood. Two hundred years ago, their forefathers had left it. And now they were coming back.

A quiet had settled on the bridge. Kirk supposed it was the same with the whole squadron, everybody staring and thinking his or her own thoughts. He wondered what Lyllin was thinking, and wished she were with him instead of back there in one of the transports.

Earth came closer. He could see clouds, and the white splash of a polar cap. Closer still, and there were seas, and the outlines of continents. Colors began to show more clearly, and the land became ridged with mountain chains. Great lakes took form, and dark-green areas of forest, and winding rivers. A nice world. A pretty world. Kirk hated it. Its other name was Trouble.

"Why did Ferdias have to pick us for this job?"

Unconsciously he had spoken aloud, or loud enough for Garstang to hear. "It's only for a visit," said Garstang. "Just a celebration. What's wrong with that?" His tone was mild, without mockery.

But Kirk looked at him sharply. He knew that Garstang and Larned and all his other officers and men must have been talking and wondering. Wondering why they'd been pulled out of their needful place for this rather meaningless celebration.

They came down past the shoreline of a blue-green ocean, past a city that sprawled over islands and peninsulas and up inland river valleys, and then beneath them was a big spaceport. The squadron roared in to its appointed landing, bristling on its best behavior, every ship set down with masterly precision, and there was a crowd assembled there to meet it. Flags whipped in the wind. The brassy music of a band blared out, immensely stirring with a solemn throb of drums beneath it.

The men of the Fifth debarked and formed in marching order, every boot polished and every uniform immaculate, a solid line of blue and silver glittering in the soft blaze of this golden sun. Kirk felt the heat of it in his face. His heels struck solidly on the ground, and the wind touched him, balmily, laden with fragrances strange to him. And he thought, "This is Earth." He looked around at it.

He could see only the spaceport, and that was old and worn and poor. The tarmac was cracked and blackened, the ancient buildings weathered. Opposite the squadron were drawn up twelve cruisers with the old insigne of the Galactic Navy on their bows, and with their crews standing at attention in front of them. Those old, small ships—why, they were Class Fourteens, obsolete for years! He supposed they were all Earth had.

Two men walked toward him. One was a middle-aged civilian, the other an arrow-straight, elderly man in black uniform that also bore the old Navy insigne. He stiffly returned Kirk's salute.

"Nice landing, Commander," he said. "I'm First Admiral Laney, and I welcome your squadron."

Incredulously, Kirk realized that the old admiral was keeping up the pretense that the Fifth Squadron was still part of the Navy.

It was so preposterous it was funny! Not for a century had the old Galactic Navy had any real existence. Its staff never sent any orders out to the squadrons of the five Governors, any more than Central Council dared send orders to the Governors themselves. Yet this old Earth officer was trying hard, in front of the crowd, to act as though he really were Kirk's superior officer....

Then, seeing the faintly desperate look in Laney's eyes, Kirk softened. After all, what difference did it make—it was only a pretense and he felt sorry for the old chap trying to play this part.

He saluted again and said, "Fifth Squadron, Kirk commanding, reporting for orders, sir!"

A look of grateful relief crossed Laney's face. He said uncertainly, "At ease, Commander. Let me present Council Chairman John Charteris."

Charteris, a graying, eager, anxious man, shook hands warmly. He began a little speech, into the tele-cameras close by. "We welcome back one of the gallant squadrons of the Galactic Navy to take part in our commemoration of—"

When the speeches and handshaking and bandplaying were over, Kirk gave an order, and his men broke ranks. Larned came up to him.

"Shall we debark our people now?"

The old admiral told Kirk, "Quarters are all ready for them."

Charteris said, "But you and your wife, Commander, must be my guests."

They walked back between the lofty, looming ships. The women and children and babies of the men of the Fifth started coming out of the transports, and efficient Earth officers began smoothly shuttling them into cars to take them to their quarters. From around the fences, a big crowd of Earth folk watched interestedly.

Of a sudden, for the first time his men's families seemed a little outlandish to Kirk. The women and children were of so many different star-peoples, so many different ways of speech and dress. He looked resentfully for amusement in the Earth faces, but could not detect any.

At the transport he excused himself and went in to Lyllin's cabin. He stopped short when he saw her. He had never seen her like this. She wore an Earth-style dress of impeccable lines, was perfect in a smart, sophisticated way. She still didn't look like an Earthwoman, not with that skin and eyes and hair. But she looked stunning, and he said so.

"I'm glad I look civilized enough for your people," Lyllin said sweetly.

"My people?" Kirk drew back stiffly. "So you're still brooding on that? That's fine. I'm not in a tough enough spot here, my wife has to get super-sensitive and make it tougher."

Lyllin's expression changed. "What kind of spot?" He was silent. She looked at him steadily. "It's something dangerous, isn't it?"

"I'd have told you if it were something I could tell you," he said. "You know that. Will you forget it? And forget about these people being my people!"

He went out with her, and Lyllin went through the introductions, cool and proud. Kirk told Larned aside, "Two-day leaves for all personnel in regular rotation. Port facilities will take care of refitting and fueling."

Larned grunted. "I've seen better facilities on fifth-rate planets. Plenty old! But we'll make out."

Charteris' car swept them along a broad highway to New York. It had a stiff, strange look to Kirk, its vertical towers huddled together bold and black against the setting sun. He thought it a cramped and crowded place, though Charteris' terrace apartment high above the myriad lights was pleasant.

There was a dinner there that night, and drinks, and more speeches, and much talk about the Commemoration. Sector politics were unobtrusively avoided. Kirk fretted and worried through it all. What was Solleremos doing, where were his squadrons? Ferdias had said he'd get warning if they moved, but would that warning come in time?

In the morning, he found Charteris oddly changed. He looked at Kirk with a queerly doubtful expression.

Kirk said, "Before we make arrangements about the Commemoration, I—"

"Oh, there's no hurry about that," Charteris said hastily. Then suddenly he asked, "Do you know if Orion Sector will send a token squadron too?"

Alarm rang a bell in Kirk's brain instantly. What was behind the question? Had Charteris heard something that he hadn't?

He answered, "Why, no, I don't. But surely you would know—"

Charteris continued to eye him with that dubious expression as he said, "We sent an invitation to Governor Solleremos to take part, of course. But doubtless we'll soon hear from him."

Kirk thought swiftly, he has heard something—something that he doesn't want me to know! But what? Was Orion already moving, were Orionid forces coming to Earth on the excuse of the celebration, just as he had?

He'd get no information from Charteris. He'd better contact Ferdias, as quickly as possible. He was only a naval commander, and he felt an enormous desire for definite orders in this crisis. He could only get such orders at the rendezvous Ferdias had told him to go to.

Kirk said casually, "While I'm here on Earth I want to look up my ancestors' old home here, and now would be a good time. It's in a village not too far away, I understand. If we could borrow a ground-car—"

Charteris seemed glad to comply. "Of course. A sentimental pilgrimage, in a way? Very understandable—"

Kirk refused the offer of a driver. But by the time he and Lyllin got out of New York and were rolling northward, he almost regretted that decision. It seemed ridiculous for a man who could pilot a squadron half across the galaxy in full overdrive, but the traffic frightened him. He hadn't done much driving, and certainly none on highways like this big northern boulevard. On this crowded Earth, people apparently still used ground-cars in great numbers for short distances, and it was not until they branched off on a subsidiary highway that Kirk felt easy.

He said then, "I want to explain about this ancestral home business."

Lyllin, looking straight ahead, said, "You don't have to explain. It's perfectly natural that you should want to see where your people came from."

"Will you stop behaving like a woman and listen?" he said angrily. "My people, again. What the devil would I care where my seventh great-grandfather lived. I'm doing what Ferdias ordered." He added, "I wasn't supposed to tell you even that, but I couldn't very well go off on this supposed sentimental pilgrimage without you."

Lyllin's expression changed. "Then there'll be someone from Ferdias to meet you there secretly, is that it? And I'm not to know about what?"

"That's it," he said. "Ferdias' orders were not to tell anyone."

He thought that Lyllin looked somehow relieved. "I don't mind. I'm worried, I wish I knew, but it's all right if you can't tell me."

It came to him that she was relieved to learn he didn't really care about his Earth ancestors, that that had only been an excuse.

Kirk felt a sharp relief himself, to be on his way to Orville, to the old house there where Ferdias' agent would be waiting to tell him what to do. In this gathering crisis he couldn't act blindly! It was vital to get directive information as soon as possible.

They turned off the big boulevard onto quiet, tree-lined back roads. These roads were old and rambling, accomodatingly twisting around hills and ponds and even houses. Some of the houses were modern chromaloy villas, but there were antique stone houses also, and once he and Lyllin both exclaimed when they saw a very old house that was built all of wood.

Out here away from the city, everything looked ancient. Stone fences that had the moss of centuries on them, a steepled church mantled thick with ivy, worn fields that had been tilled for ages. In the fields, driverless automatic tractors were lumbering about their work, but there seemed little bustle or activity. Kirk thought that this was an old, worn world....

A brilliant bird flashed across the road and he and Lyllin argued what it was. "A robin, I think," Kirk said doubtfully. "In school, when I was little, we had an old Earth poem about Robin Redbreast. I didn't know then what it was."

"Not nearly so splendid as a flame-bird," Lyllin said. "But the red of it, and the green trees, and the blue sky.... It's a pretty world, in its way."

They rolled finally down a little hill and over a bridged stream into the town of Orville. It was only a village, with shops around a big open square. There was a corroded statue of a soldier at the center of the park, and benches on which old men sat in the sun.

Kirk asked directions of a merchant standing in front of his shop, a chubby man who stared open-mouthed at the two visitors. And Kirk suddenly realized how strange indeed they must look in this sleepy little Earth village—he in his blue-and-silver starman's uniform, his face dark from foreign suns, and Lyllin whose beauty was a breath of the alien.

He was glad to drive on out of the village, on the designated road. It was an even more rambling road, looping casually along the side of a shallow valley whose neat farms and fields and woods lay silent in the blaze of the soft golden sun. They met no other ground-cars, though an occasional air-car hummed across the blue sky. Kirk kept counting houses, and when he had counted five he turned in at a lane, and stopped.

The house was of field-stone, an ancient, brown dumpy structure that had a faintly forlorn, deserted look. Under the big, stiff, dark-green trees in its front yard—were they the trees called "pines?"—the grass was high and ragged. The lane went on past the house, past an orchard of gnarled trees heavy with green fruit, to a big old barn. There was no one in sight, and no sign that anyone was here.

"Are you sure it's the place?" asked Lyllin.

He nodded, moving toward the porch. "It's the place. Ferdias had his agent here buy it, weeks ago, so we'd have this quiet place for contacts. There should be someone here."

There was a bell-push at the door, but no one answered it. Kirk tried the door. It swung open, and they went in.

They went into a room such as they had never seen before. The walls were of painted wood, instead of plastic. The furniture was wooden too, and of archaic design. The room, the house, were very silent.

"Look at this," said Lyllin, in tones of surprise.

She was touching a chair, and the chair rocked back and forth on its bottom. "I thought it was a child's toy but it's not made for a child."

He shook his head. "Beyond me. And it's beyond me too why Ferdias' man isn't here!"

He called, but there was no answer. He went through all the rooms, and there was no one.

Kirk felt a mounting alarm. Had something gone wrong with Ferdias' careful plans? Where was Ferdias' agent, where was the man who should have met him in this secret rendezvous with the information and orders he must have?

Suppose that man didn't come—who then could give him warning of Solleremos' strike, if Orion did strike?

CHAPTER V

Kirk stood, his dismay and anxiety increasing by the minute. What was he going to do?

He said, finally, "We'll have to wait. Ferdias' man is bound to be along soon."

"You mean—perhaps stay here all night?" said Lyllin. "But food, and beds—"

"We'd better look around," he said unhappily.

They found fairly new blankets on the beds. And in the old kitchen cupboards was food in the self-heating plastipacks.

"We can make out," he said. "But it's a hell of a thing."

While Lyllin prepared their supper, he went out and restlessly walked around the place. The weedy yard ran into brushy fields and nearby woods. The old barn was empty, and the outbuildings were shabby and forlorn.

He did not think much of Earth, if this was a sample. He went back inside, and helped Lyllin solve the puzzle of an ancient sink. Even the reddening sunset light pouring through the windows could not make the old wooden walls and worn cupboards look less dingy.

He said so, and Lyllin smiled. "It's not so bad. We'll eat out on that back porch—it's less musty there."

The porch was not screened, and friendly insects dropped in upon them as they ate. The whole western sky was a flare of red, great bastions of crimson cloud building ever higher. Under the sunset, beyond the fields, the ragged woods brooded darkly.

A small animal came soundlessly out of the high grass and stared at them with greenish eyes.

"What is it, Kirk—a wild creature?"

He looked. "It's a cat, that's what it is. An Earthman in the Stardream had one for a pet, kept it at Base. He called it Tom." He tossed a bit of food onto the step. "Here, Tom."

The cat stalked carefully forward, eyed them coldly, then bent to the food. After a moment it turned its back on them and departed.

Darkness fell. Kirk began to feel a little desperation. Ferdias' man hadn't come. What if he didn't come at all? How long could they wait in this forgotten backwater, not knowing what was going on out there in deep space?

Lyllin said, "Isn't it possible your man is waiting in Orville, that village—and doesn't know you're here?"

"It could be, I suppose." Kirk grasped at the straw. "I'll go down to the village. If he's there, he'll see me. Mind waiting—just in case someone does come here?"

She said she didn't mind. But he took the compact shocker from his coat-pocket and left it for her before he went out.

Kirk drove rapidly down the lonely, dark road to the village. But the little town looked dark and lonely too, when he got there. The shops were almost all closed. He saw only a few people. It was very quiet. In the shadows of the square, the old iron soldier stood stiffly.

The lights of a tavern caught Kirk's eye, and he went toward it. It seemed about the only place where his man might be, and he needed a drink anyway. He shouldered in, and instantly a small buzz of talk fell silent. Kirk went to the bar, and the men at the farther end of it followed him with their eyes. The tavern-keeper, a bustling, skinny man, hurried up and tried to act as though a deep-space naval Commander was no unusual visitor at all.

"Yes, sir, what'll it be?"

Kirk's eyes searched the rack of unfamiliar bottles. He shook his head. "You pick it. Something strong and short."

"Yes, sir, some fine old whisky right here." Whisky—well, he'd heard of that. He drank it, and didn't like it. He let his eyes rest on the other man. Could one of them be Ferdias' agent?

He didn't think so. Most of these men looked like farmers or mechanics, hearty-looking, sunburned men, the younger ones tall and gangling. One was a very old man with a straggling beard who shamelessly stared at Kirk with bright, beady eyes. They weren't unfriendly, but they were aloof. Kirk had an idea he'd get little out of this insular bunch. He might as well go—none of these could be Ferdias' man.

But as he set his glass down, the bearded old man limped forward, peering bright-eyed and inquisitive at him.

"You're the fellow who was asking directions to the old Kirk place today," he said, almost accusingly.

Kirk nodded. "That's right."

The old Earthman was obviously waiting for an explanation. It occurred to Kirk that he'd better give one, if he didn't want this whole countryside wondering audibly why a starman had come here.

He said, "Kirk's my name. My great-great something grandfather, a long time ago, came from here. I'm just looking up the old place, that's all."

He turned to go then, feeling that he was wasting time here. But one of the middle-aged Earthmen came forward to him with hand outstretched.

"Why, if your folks came from here, that makes you sort of an Orville boy, doesn't it? What do you know about that! Vinson's my name, Captain."

"Commander," Kirk corrected, as he shook hands. "Glad to know you. I guess I'll be on my way."

"Say, now, not without me buying you a drink," boomed Vinson. "Not every day one of our own boys comes back from way out there."

There was a chorus of agreement, and more outstretched hands, and hearty introductions. Kirk stared at them in wonder. What in the world—Then he got it.

All over space, the pride of Earthmen was proverbial, and their clannishness. He'd met it and he didn't like it. He was therefore all the more astonished now, that they should suddenly accept him as one of their own. Seven generations, and the whole width of the galaxy between him and this place, yet they claimed him as "one of our own boys"!

He wanted to get out now, he'd found no trace of Ferdias' agent here and time was passing, but it wasn't easy to get out. More men kept coming into the tavern, as word got around, to shake hands with and buy a drink for the "Orville boy" from far-off space. Vinson, a jovial master of ceremonies, rattled on with introductions Kirk only half-heard—"Jim Barnes, whose farm's up beyond your folks' old place", "here's old Pete Marly, he can remember when there were still Kirks living there," on and on until in desperation, Kirk thanked them and shouldered toward the door.

"Have to go, my wife's waiting," he said, and a friendly chorus of voices bade him good-night, "I'll ride with you far as my own house," said Vinson.

Kirk was sweating as he drove out of the village. A hell of a way to conduct a secret job, with the whole village bawling his name! And it had got him nowhere—

Vinson's house was the second on the same road. As he got out of the car, he said, "Sure does beat all, your coming back from so far. Shows it's a small world."

"It's a small galaxy," Kirk said, and Vinson nodded. "Sure is. Well, I'll be seeing you. Drop over. Good-night."

As Kirk drove on, he was faintly startled by an upgush of yellow light that silhouetted the bending trees ahead. A great segment of silver was rising in the sky. Then he realized—it was that moon that they'd passed on their way in.

The moon of Earth, the "Moon" of the old Earth poems people still read. Not too impressive, but pretty. But how the threads of all you'd read and heard kept subtly running back to this old planet! He supposed some of these flowers whose fragrance he could smell on the warm night air were "roses". Funny, how much you knew about Earth that you didn't realize you knew.

The old road gleamed beneath the rising moon. He glanced up at the star-pricked sky. Had the Kirk who was his seventh grandfather, all those years ago, looked at the starry sky as he walked this same road? He must have. He'd looked too long, and finally he'd gone out to that sky and not come back.

The house was dark when he turned in at the lane, but he saw Lyllin's dim figure sitting on the front porch.

"No. No one came," she said, as he sat down beside her.

"And no sign of any agent of Ferdias in the village," Kirk said. "A fine thing. We'll have to wait."

They sat a while in the soft warm darkness. Kirk's thoughts were more and more gloomy. They couldn't wait here forever, yet he had to make contact as Ferdias had ordered—

Strange, glowing little sparks of light drifted across his vision, and now he became aware that the whole dark yard and woods were swarming with such floating sparks. They winked on and off, in a fashion he had never seen, dancing and whirling under the dark trees.

"What are they?" asked Lyllin, fascinated.

"Fireflies?" Kirk said doubtfully. "I remember that word, from somewhere...."

Then he suddenly started and exclaimed, "Hell, what—"

A small sinuous body had suddenly plopped into his lap. Two green eyes looked insolently up at him. It was the cat.

"It's very tame," said Lyllin. "It must have been somebody's pet."

"Probably belonged to the last people who lived here," Kirk said. "It's tame, all right."

He stroked its furry back. The cat half-closed its eyes and emitted a rusty purring sound. "Like that, eh, Tom?"

Tom settled down cozily, in answer. Lyllin reached to stroke its head.

With startling swiftness, the cat recoiled from her and leaped off Kirk's lap. It stared green-eyed back at them, then started across the lawn.

Kirk turned, laughing. "Crazy little critter—" He stopped suddenly. "Lyllin, what's the matter?"

She was crying and he had rarely seen her cry. "Did it scratch you?"

"No. But it feared me, and hated me," she said. "Because it knew I'm alien."

Kirk said, "Oh, rot. The wretched beast is just afraid of strangers."

"It wasn't afraid of you. It sensed that I'm different—"

He put his arm around her, mentally cursing Tom. Then, as he wrathfully looked after the cat, Kirk stiffened.

Tom had started across the lawn toward the dark brush nearby. But the cat had stopped. And, as Kirk looked, Tom suddenly emitted a hiss and recoiled. It went away from the dark clumps, in long swift leaps.

Kirk's thoughts raced. The cat had recoiled from that brush, exactly as it had recoiled from Lyllin. For the same reason? Because someone alien, not of Earth, was in those shadows? He thought he could hear a slight sound, and his muscles suddenly strung tight. Ferdias' agent wouldn't approach so secretly. Non-Earthmen skulking in those shadows meant only one thing.

He said, "Come on in the house and forget it, Lyllin. I could stand another drink—"

But instantly, when inside the house, Kirk made a lunge toward the nearest bedroom and grabbed for the blankets there. He tossed one of the blankets to Lyllin with frantic speed.

"Wrap it around your head—quick!"

She was intelligent. But she was not used to obeying orders instantly and without question "Kirk, what—"

He grabbed the blanket out of her hands and started wrapping it many times around her head, speaking in a whisper as he did so.

"Out there. Someone. If they want to be quiet about it, they're sure to use a sonic knockout-beam. Hurry—"

He pulled her to the floor. The blanket swathed her head. He wrapped the other one around his own head, fold after fold. They lay, tense, waiting.

Nothing happened.

He thought how foolish they would look, lying on the floor with their heads swathed, if nothing at all did happen.

He still did not move. He waited.

A series of small sounds began in the back of the house, just vaguely audible through the blanket-folds. A chattering of windows, creaking and rattling of beams, clink of dishes.

The sounds came slowly through the house toward them. Chatter, rattle—leisurely advancing. He knew then he'd guessed right. The sonic beam itself was pitched too low to hear. But it was sweeping the house.

It hit them. Lyllin stirred suddenly with a small sound, and Kirk gripped her arm, holding her down. He knew what she was feeling. He felt it himself, the sudden shocking dizziness, the keening inside his head. Even through the swathings of thick blanket, the beam made itself felt. Without protection they'd already be unconscious.

The shock passed. The beam was sweeping on to the front of the house. Kirk remained on the floor, his hand still holding Lyllin's arm. He'd used sonics himself. He had a pretty good idea of how this one would be used.

He was right. The small, half-audible sounds of the house and its shuddering contents came walking back toward them.

Chatter—clink. Rattle—clink—

It hit him again, and he set his teeth and endured it. And again it passed them, and once more the kitchen dishes started talking.

Kirk suddenly thought of the unsuspecting Earth folk in the nearby farms, sleeping peacefully in their old houses, without ever a dream that in their quiet countryside, alien folk from the stars were pitted in a secret struggle that had this whole ancient planet as its prize.

The sounds shut off abruptly. Kirk unwrapped his head, and twitched at Lyllin till she did the same. He made a warning motion to her, to keep down, and he himself crawled forward to the old living-room. He had the little shocker in his hand now.

In a corner of the living-room, behind a grotesque old table, he waited. There was no sound at all.

Then there was one. Footsteps, on the porch outside—coming fast and confidently to the door.

A man came into the room. He wore a dark space-jacket and slacks, he carried a shocker, and he walked like a dancing panther.

Kirk knew him.

His name was Tauncer.

CHAPTER VI

Behind Tauncer came an older man, as gray and solid and rough at the edges as an old brick. He could have been an Earthman, and probably was. He was loaded down with a porto, and some other piece of equipment in a carrying case slung over his shoulders.

Taking no chances at all, but allowing himself to feel a deep and vicious pleasure, Kirk fired from behind the table.

Even so, warned by some faint sound or perhaps only by the instinct of the hunter, Tauncer swung toward him in the instant before the burst of energy hit. He did not quite have time to fire. The impetus of the turn made him hurtle halfway across the room to hit the floor headlong.

The brick-like man was slower. He had only managed to open his mouth and lift his hand halfway toward his armpit when Kirk's second blast dropped him quietly where he stood.

Kirk got up. He found that he was shaking. He looked down at Tauncer, thinking how easily a man could die, flexing his fingers in a hungry way. Lyllin came into the open doorway, and he said angrily,

"You were to stay back there."

Her eyes did not leave his face. She murmured, "Yes. I did wrong." Then, looking at the sprawled bodies, "Are they dead?"

"We're not out on the Sector frontier," Kirk growled. "I wish we were. But here on these old planets they take violence seriously. No, I just used stunning bursts on them."

He rummaged the house until he found wire, and bound the hands of the two men very securely behind them. Then he searched them. He did not find any documents, which was no surprise. He removed a shocker from the brick-like man, and took it and the porto and the heavy carrying case far out of reach.

The carrying case contained a vera-ray projector with its tripod collapsed. Possibly the same one Tauncer had tried to use on him in the cluster world. Tauncer seemed extremely fond of the vera-ray. Probably, in his business, he never traveled without one.

He gave Lyllin the shocker that Tauncer had dropped. "Watch them. Back in a moment."

He went out and rapidly, carefully, searched the grounds of the old farmhouse. He found the sonic device squatting heavily behind a bush. He stood by it for some moments, perfectly still, listening, but there was no sound except the faint stirring of the breeze. There did not seem to be anyone else around. Tauncer and the Earthman must have come alone. Kirk frowned. He picked up the sonic device and stood for a second longer, uneasy but baffled. There was no sign of an air-car. They must have landed far back in the woods to avoid betraying themselves by the noise of the motors. But he could not search the whole woods, not tonight.

He went back to the house.

"They're coming around," said Lyllin. She was sitting in a chair in front of the two bound men, watching them. She rocked back and forth in a rhythmic motion, making the old floorboards squeak. "Look," she said, in a voice just a little too high, "I found out what this queer chair is for. It's rather pleasant."

"I don't find it so," said Tauncer suddenly. "The creaking irritates me." He opened his eyes, and Kirk had the feeling that he had been keeping them closed for some time, shamming, while he took stock of the situation.

"Well," he said to Kirk. "I'm an acknowledged expert with the sono-beam. Would you mind telling me how you did it?"

Kirk said, "We had warning—a friend of mine named Tom." He motioned Lyllin to get up. "Go on in the other room, dear. I don't think you'd enjoy this."

She looked at him as though he was someone she had just met and was not sure she liked.

"Try to understand," he said. "I don't do this sort of thing every day. It's hardly ever necessary."

"Of course," she said. She went into the next room, and he shut the door behind her. Then he sat down in the rocking chair, with the shocker held ready in his hand.

Kirk looked at Tauncer. "I'm a peaceful man," he said, "visiting my ancestral home. What did you want with me?"

Tauncer smiled. There was something about him that made Kirk more and more uneasy—a lack of concern, a deep-based confidence that didn't fit a man in his position.

Tauncer said gently, "You are the Commander of the Fifth Squadron, Lyra Sector, awaiting orders from your Governor. You are wasting your time."

Kirk's nerves tightened painfully, but he kept his face impassive. "Go on," he said. "I'm listening."

"Ferdias' agent was supposed to meet you here secretly with certain—information." Tauncer spoke with deliberate clarity, as one who explains some problem to a child. "He is not coming. We've known who he is, for some time. And I got to him, before he ever left New York." He nodded to the vera-ray projector across the room. "I used that extremely useful invention on him, and of course he told me all about this place and how he was supposed to meet you here. So I came instead."

Kirk looked at the vera-ray himself, but Tauncer shook his head. "It wouldn't do you any good. The particular piece of information you need—namely, when and where to move—is not known to me, and your contact man had not received it yet either. When it does come through, one of our men will get it—probably already have."

Tauncer's eyes looked up brightly at Kirk, the eyes of the adroit and wily man measuring the honest clod for another defeat.

"You might just as well free me, Kirk. It was a good try, but your cause is hopeless now."

"Not as long as I'm on my feet," said Kirk, getting up. He was a very angry man. "Not as long as the Fifth will follow me. If I don't get orders, I'll make my own."

"No," said a familiar voice behind him. "The Fifth isn't going anywhere, Commander."

Kirk whirled around.

Joe Garstang was standing in the front door. He had a shocker in his hand, pointing with rocklike steadiness at Kirk's breast.

"Drop your weapon," said Garstang.

A red haze swept over Kirk's vision. Through it he saw Garstang, wavering and distorted. Blood hammered in his temples. "You," he said, so choked with rage at this enormity that he could hardly form the words. "My own captain. My friend. Traitor. Working for him—"

Distant and strange in the red mist, Garstang's face became twisted as though with pain.

"I'm sorry," he said, and fired.

Kirk fell onto the floor. Garstang must have pressed the stud back to a light charge, because Kirk was still conscious and only partly paralyzed. His own weapon dropped out of his nerveless fingers.

Garstang came and kicked it away. Kirk flopped around like a gaffed fish, trying to get his reflexes working again. He heard the inner door open, and then Lyllin screamed, partly in fear but mostly in fury, a purely animal sound. She went for Garstang, ignoring his shocker, with a single-minded intent to kill. Her own hands were empty. She was content with them.

Garstang dropped his weapon in his pocket and caught her, holding her hands away from his face and eyes.

"Please," he said. "Please, Lyllin. He's not dead, he's not even hurt." He turned to Kirk. "You should have dropped your shocker. I told you." There was a fresh onslaught, and a red line sprang out on Garstang's cheek. It began to drip slowly, small bright drops against the leathery brown. "Kirk, for God's sake call her off," he said.

Kirk managed to sit up. He mumbled, shook his head two or three times, and finally the words were intelligible. "I'm all right. Come here, Lyllin. Help me up."

She relaxed then, dropping her hands. Garstang let her go. She hissed at him in furious Vegan and then ran to Kirk. "I should have used that weapon," she said. "I should have killed him. I forgot it. I'm sorry." She began to struggle, trying to lift him.

Garstang went immediately into the next room. Through the open door Kirk saw him look around and then pocket the shocker that Lyllin had laid down and forgotten. Lyllin didn't notice, and he said nothing. What was the use?

"Push that chair over here," Kirk said. "Now don't worry, this'll wear off. I'll be all right in just a few minutes. Yes. That's it."

He sat in the rocker, rubbing his numb right arm with his left, trying to stamp his foot, but he couldn't move it yet. He glared up at Garstang, who had come and was standing near Tauncer, looking from him to Kirk with a faint frown.

Tauncer had not spoken, and he did not speak now. He sat where he was and waited, and watched them.

"Well," said Kirk, "what are you waiting for, Joe? Go ahead and untie him."

"No," said Garstang, shaking his head slowly. "No, I'm not going to untie him."

"Why not?" demanded Kirk bitterly. "Or have you decided to double-cross him, too?"

"I don't think you understand," said Garstang. "I'm not working with Tauncer. I'm not working for Solleremos at all."

Kirk stared, for a moment surprised out of his rage. "But then who—"

"My loyalty," said Garstang, "is to Earth."