Title: Engravers and Etchers

Author: Fitz Roy Carrington

Release date: November 30, 2021 [eBook #66848]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Art Institute of Chicago, 1917

Credits: Charlene Taylor, Alan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

MASTER OF THE AMSTERDAM CABINET. TWO LOVERS

Size of the original engraving, 6½ × 4⅛ inches

In the Ducal Collection, Coburg

ENGRAVERS

AND

ETCHERS

SIX LECTURES DELIVERED ON THE SCAMMON FOUNDATION

AT THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO, MARCH 1916

BY

FITZROY CARRINGTON, M. A.

CURATOR OF PRINTS AT THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS,

BOSTON; LECTURER ON THE HISTORY AND PRINCIPLES

OF ENGRAVING AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY; EDITOR OF

“THE PRINT-COLLECTOR’S QUARTERLY”

WITH 133 ILLUSTRATIONS

THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO

1917

COPYRIGHT 1917

THOMSEN-BRYAN-ELLIS COMPANY

DESIGNED AND PUBLISHED BY

THOMSEN-BRYAN-ELLIS COMPANY

WASHINGTON BALTIMORE

NEW YORK PHILADELPHIA

TO THOSE

WHO HELPED ME MAKE THIS BOOK

IN GRATEFUL RECOGNITION

NOTE

The lectures presented in this volume comprise the twelfth series delivered at the Art Institute of Chicago on the Scammon Foundation. The Scammon Lectureship is established on an ample basis by bequest of Mrs. Maria Sheldon Scammon, who died in 1901. The will prescribes that these lectures shall be upon the history, theory, and practice of the Fine Arts (meaning thereby the graphic and plastic arts), by persons of distinction or authority on the subject on which they lecture, such lectures to be primarily for the benefit of the students of the Art Institute, and secondarily for members and other persons. The lectures are known as “The Scammon Lectures.”

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

| LECTURE I | |

| German Engraving: From the Beginnings to Martin Schongauer |

13 |

| LECTURE II | |

| Italian Engraving: The Florentines | 51 |

| LECTURE III | |

| German Engraving: The Master of the Amsterdam Cabinet and Albrecht Dürer |

95 |

| LECTURE IV | |

| Italian Engraving: Mantegna to Marcantonio Raimondi |

139 |

| LECTURE V | |

| Some Masters of Portraiture | 181 |

| LECTURE VI | |

| Landscape Etching | 227 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | |

| Master of the Amsterdam Cabinet. Two Lovers | Frontispiece |

| Master of the Playing Cards. St. George | 15 |

| Man of Sorrows | 16 |

| Master of the Year 1446. Christ Nailed to the Cross | 19 |

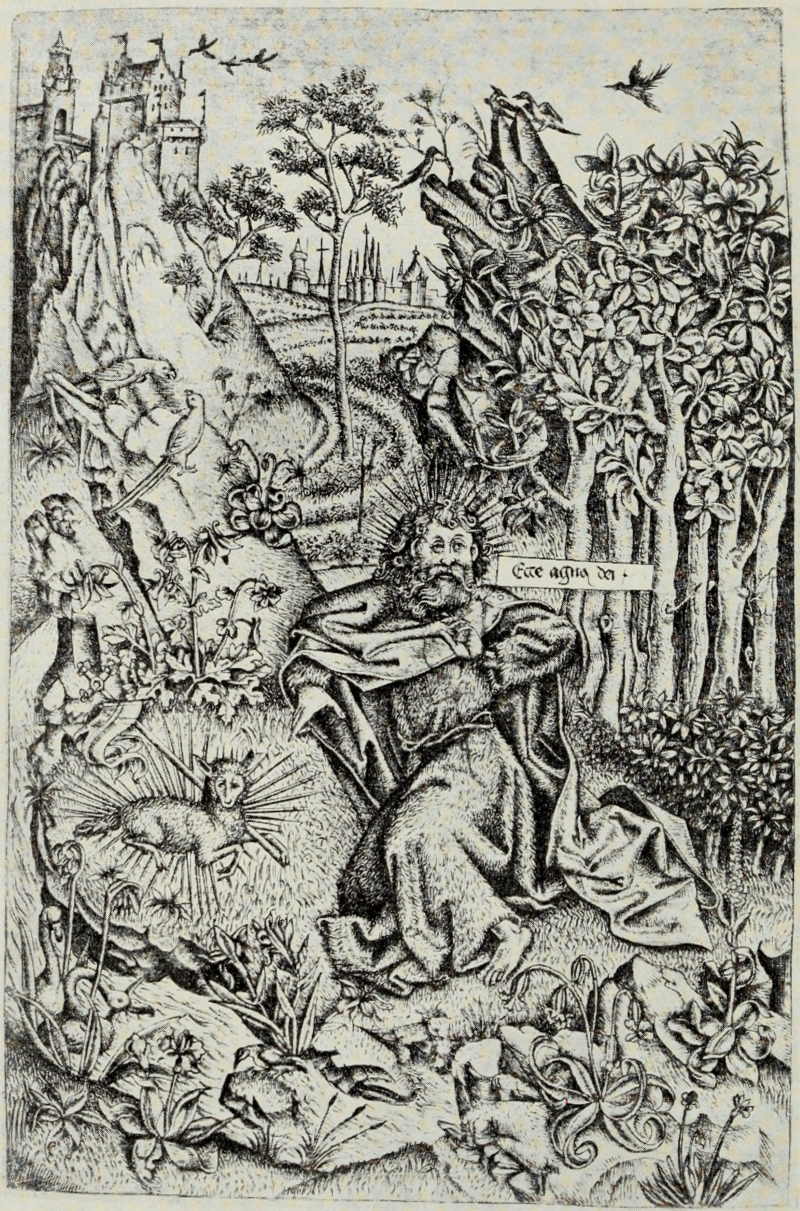

| Master of St. John the Baptist. St. John the Baptist | 20 |

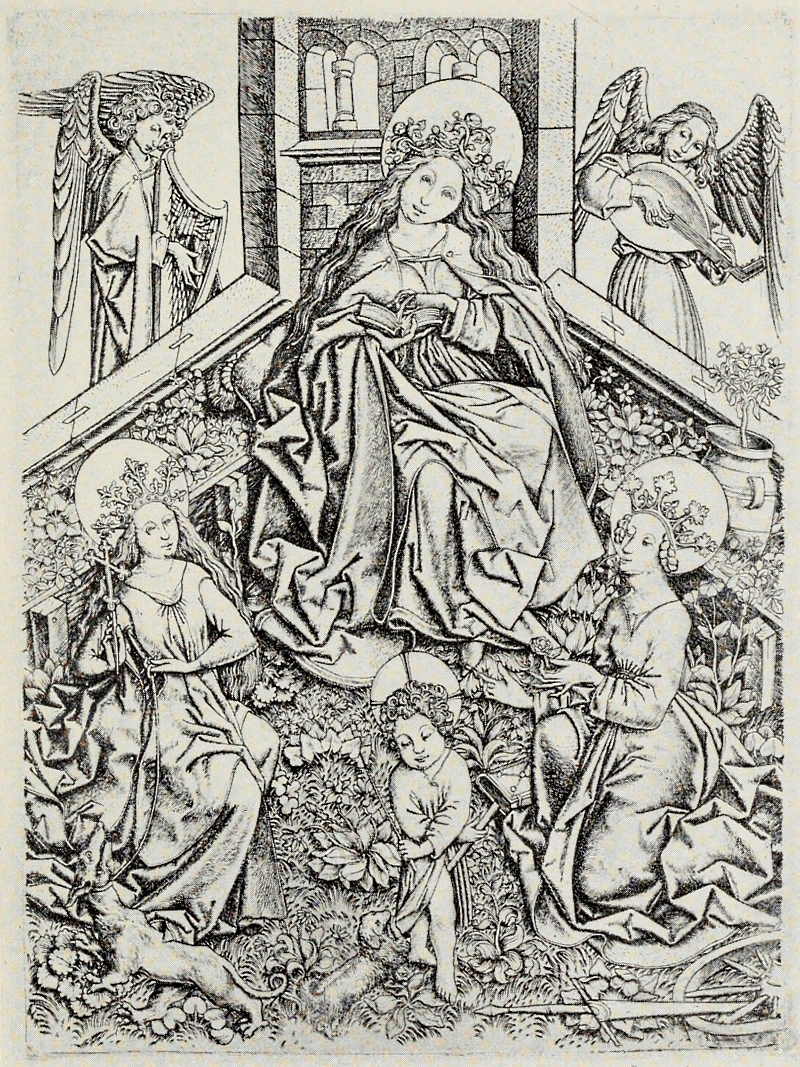

| Master E. S. of 1466. Madonna and Child with Saints Marguerite and Catherine |

23 |

| Ecstasy of St. Mary Magdalen | 24 |

| Design for a Paten | 27 |

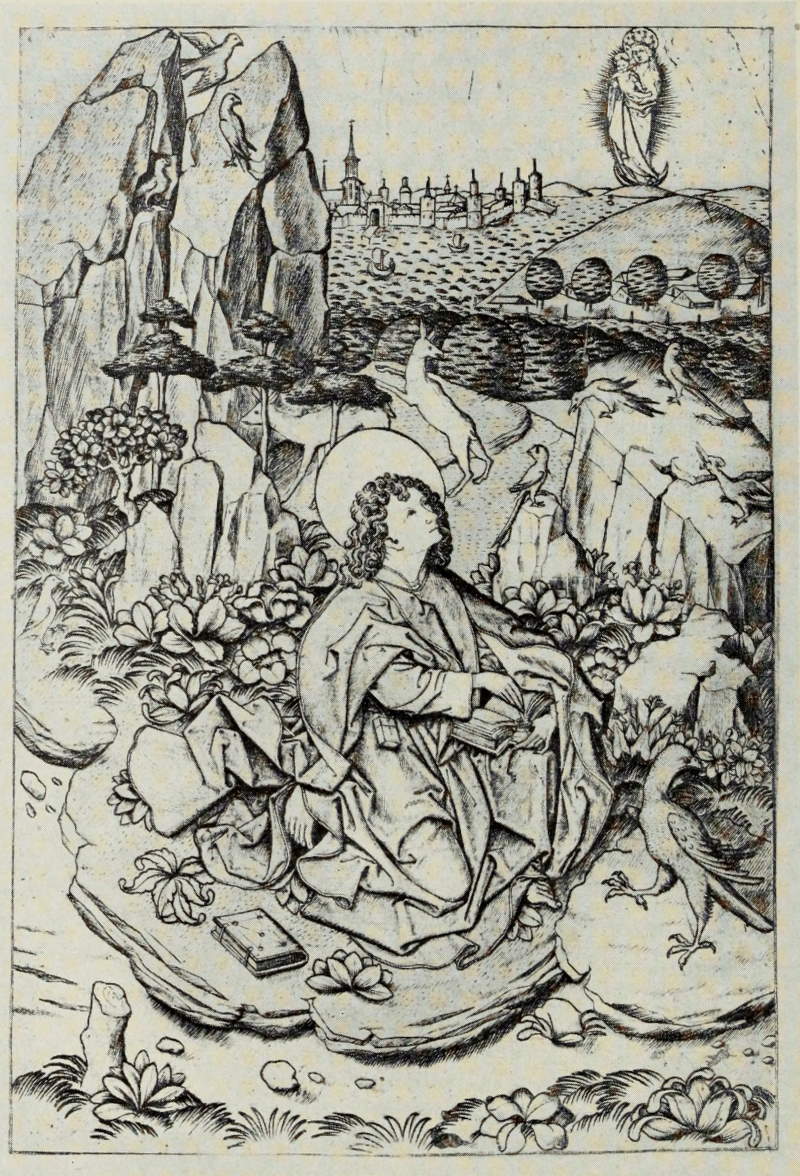

| St. John on the Island of Patmos | 28 |

| Martin Schongauer. Virgin with a Parrot | 31 |

| Temptation of St. Anthony | 32 |

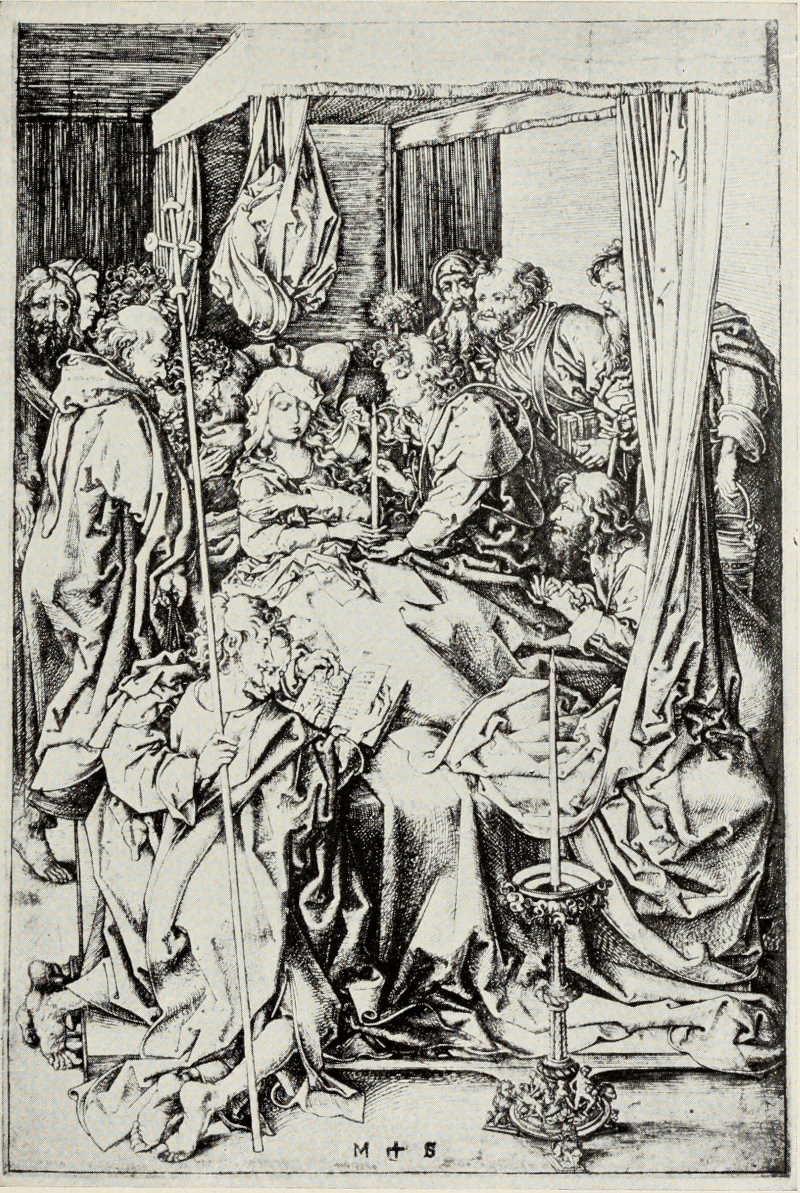

| Death of the Virgin | 33 |

| Pilate Washing His Hands | 34 |

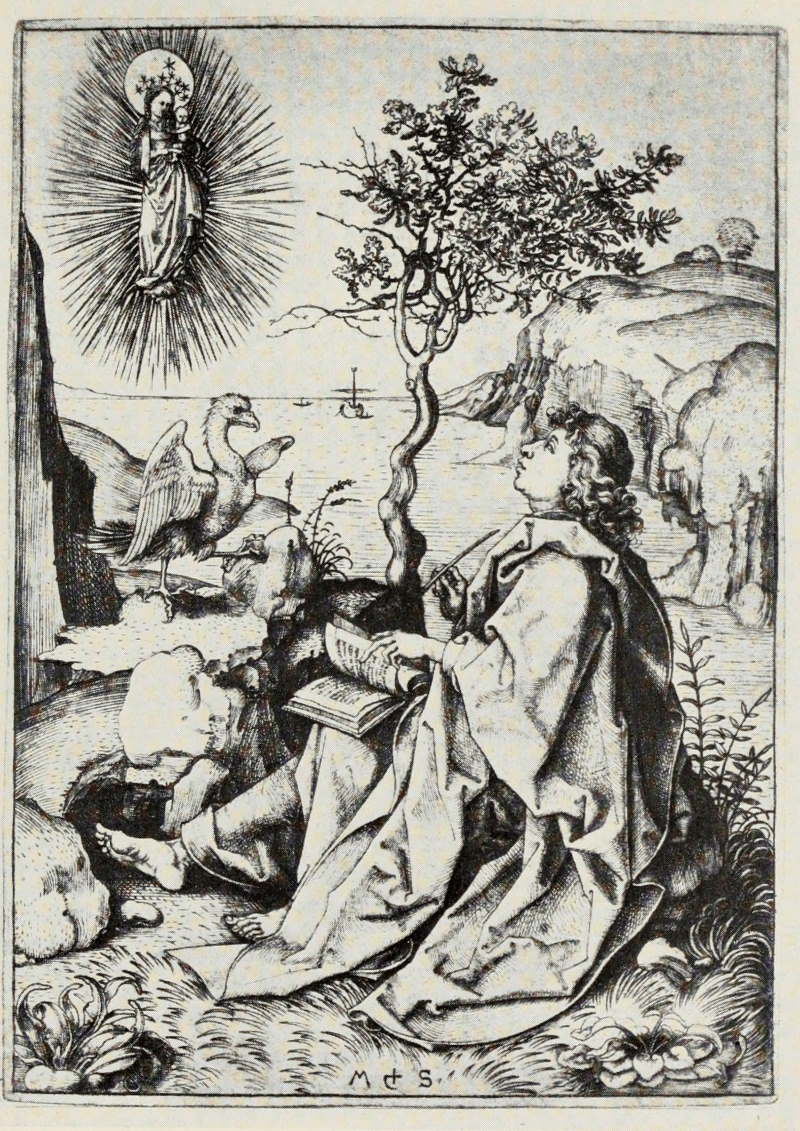

| St. John on the Island of Patmos | 37 |

| Christ Appearing to the Magdalen | 38 |

| Virgin Seated in a Courtyard | 39 |

| Angel of the Annunciation | 40 |

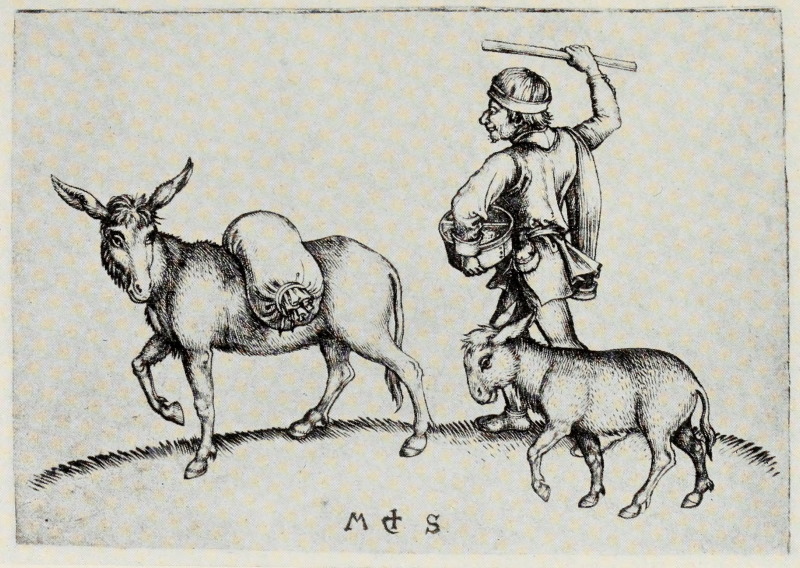

| The Miller | 43 |

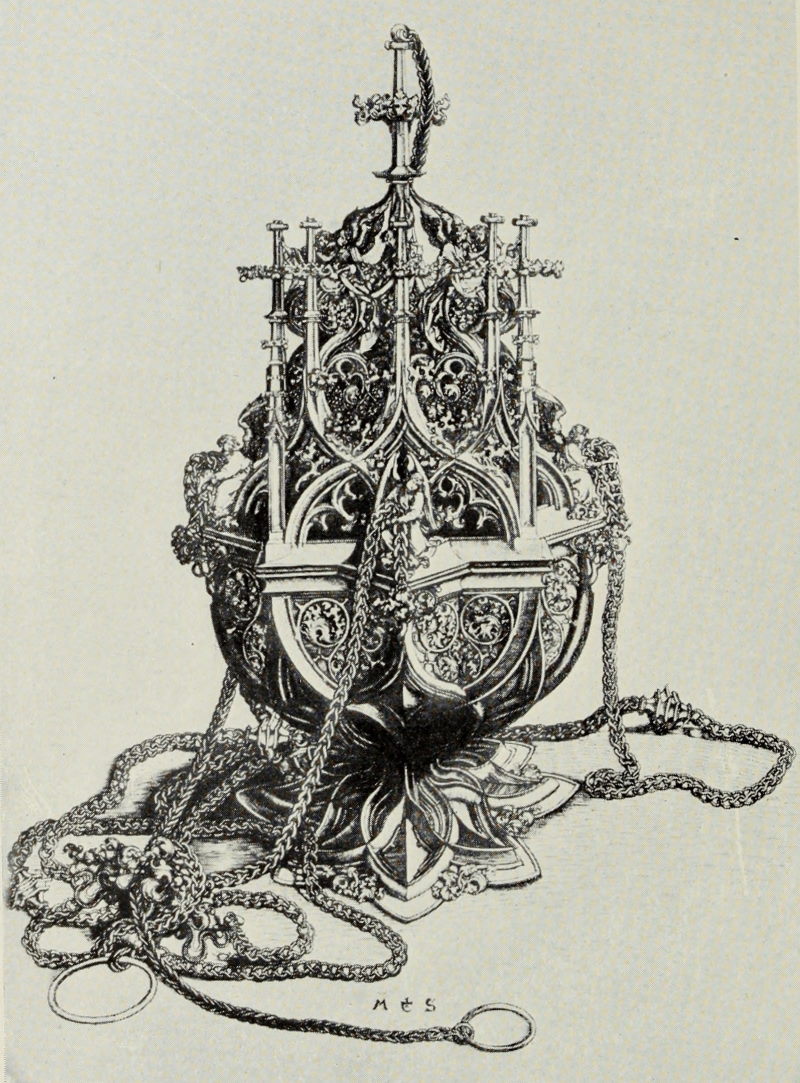

| Censer | 44 |

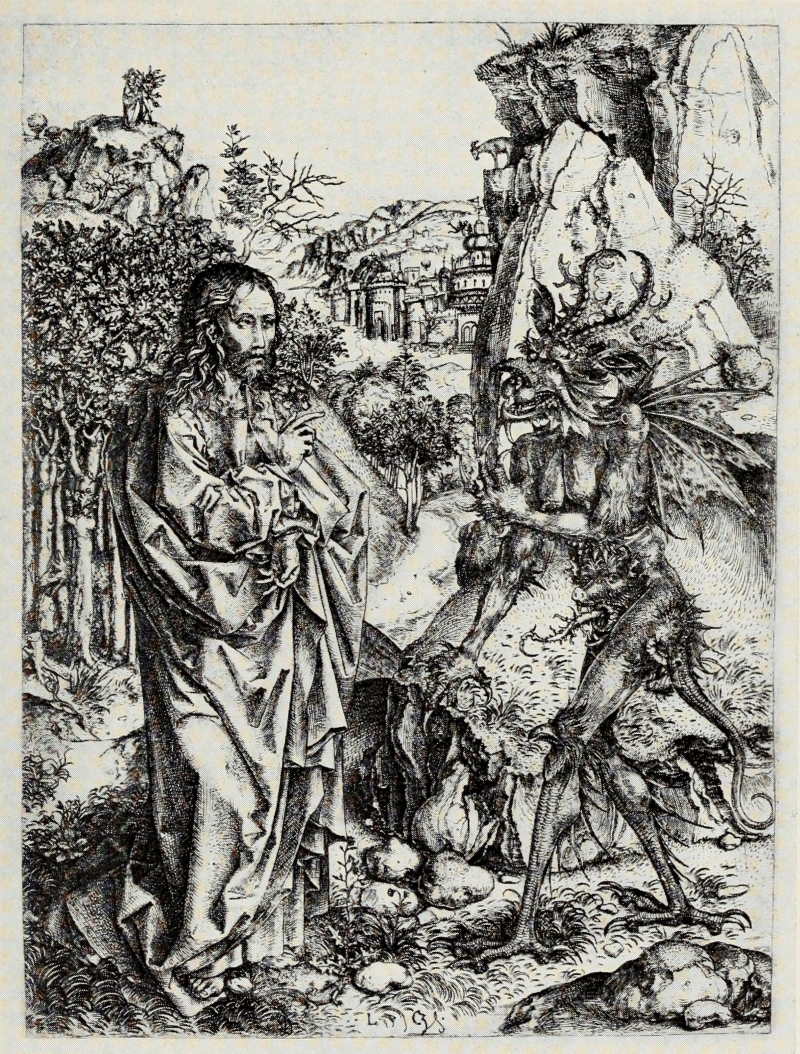

| Master L Cz. Christ Tempted | 47 |

| Christ Entering Jerusalem | 48 |

| Anonymous Florentine, XV Century. Profile Portrait of a Lady |

53 |

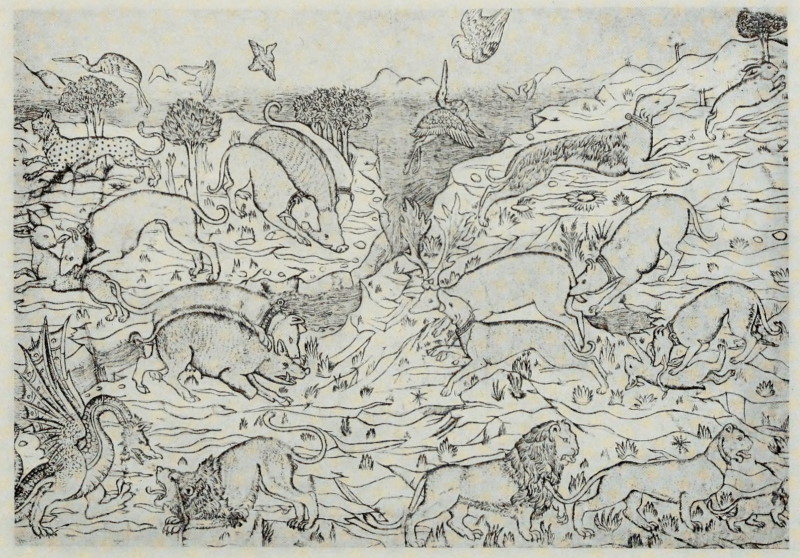

| Wild Animals Hunting and Fighting | 54 |

| Triumphal Procession of Bacchus and Ariadne | 57 |

| Jupiter | 58 |

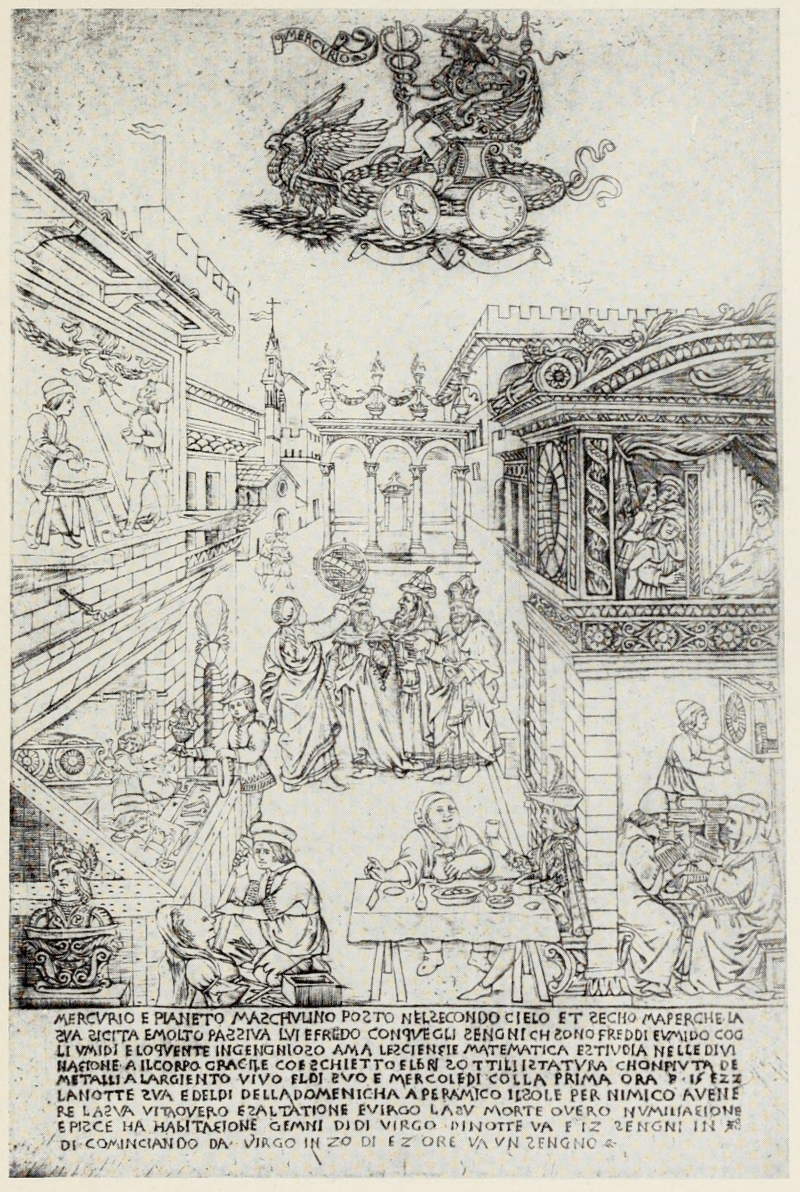

| Mercury | 63 |

| Lady with a Unicorn | 64 |

| The Christian’s Ascent to the Glory of Paradise. From “Il Monte Sancto di Dio,” Florence, 1477 |

67 |

| Dante and Virgil with the Vision of Beatrice. From the “Divina Commedia,” Florence, 1481 |

68 |

| Assumption of the Virgin (After Botticelli) | 71 |

| Triumph of Love. From the Triumphs of Petrarch | 72 |

| Triumph of Chastity. From the Triumphs of Petrarch | 75 |

| Libyan Sibyl | 76 |

| Anonymous North Italian, XV Century. The Gentleman. From the Tarocchi Prints (E Series) |

79 |

| Clio. From the Tarocchi Prints (S Series) | 80 |

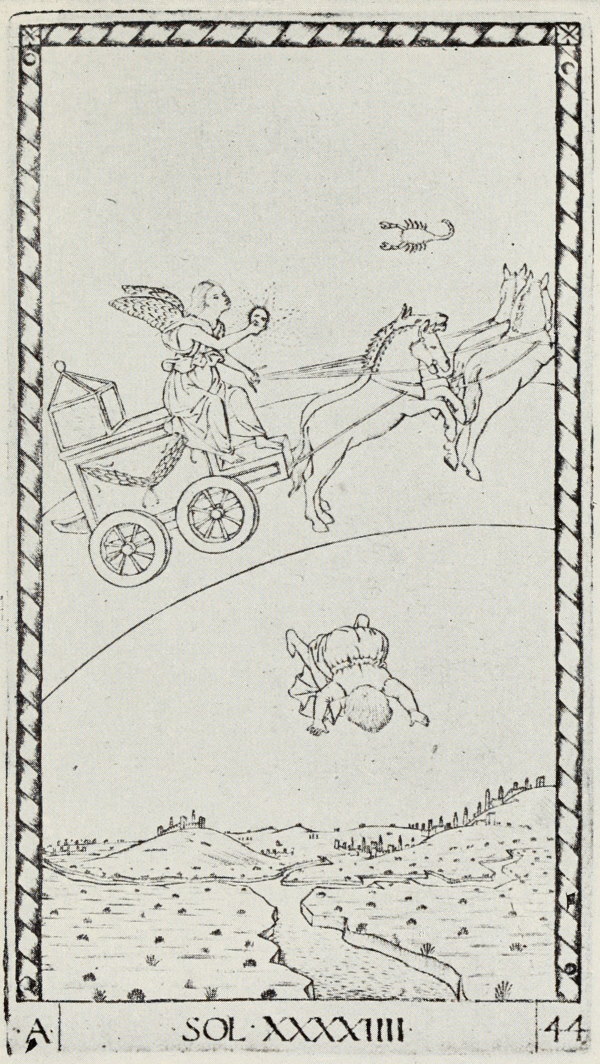

| The Sun. From the Tarocchi Prints (E Series) | 83 |

| Angel of the Eighth Sphere. From the Tarocchi Prints (E Series) |

84 |

| Cristofano Robetta. Adoration of the Magi | 87 |

| Antonio Pollaiuolo. Battle of Naked Men | 88 |

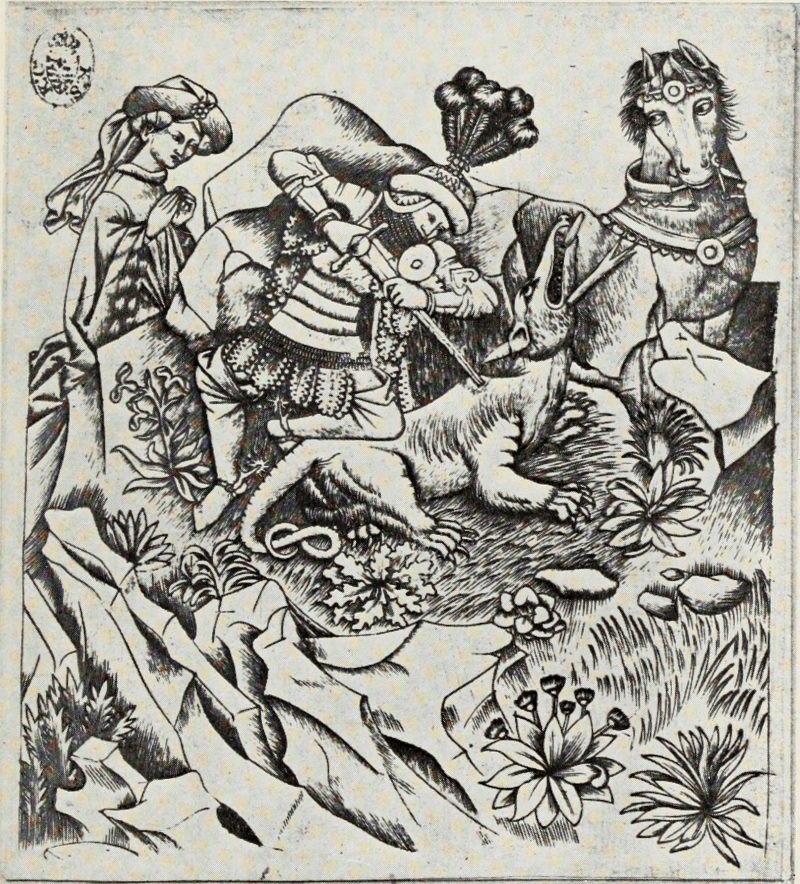

| Master of the Amsterdam Cabinet. Ecstasy of St. Mary Magdalen |

97 |

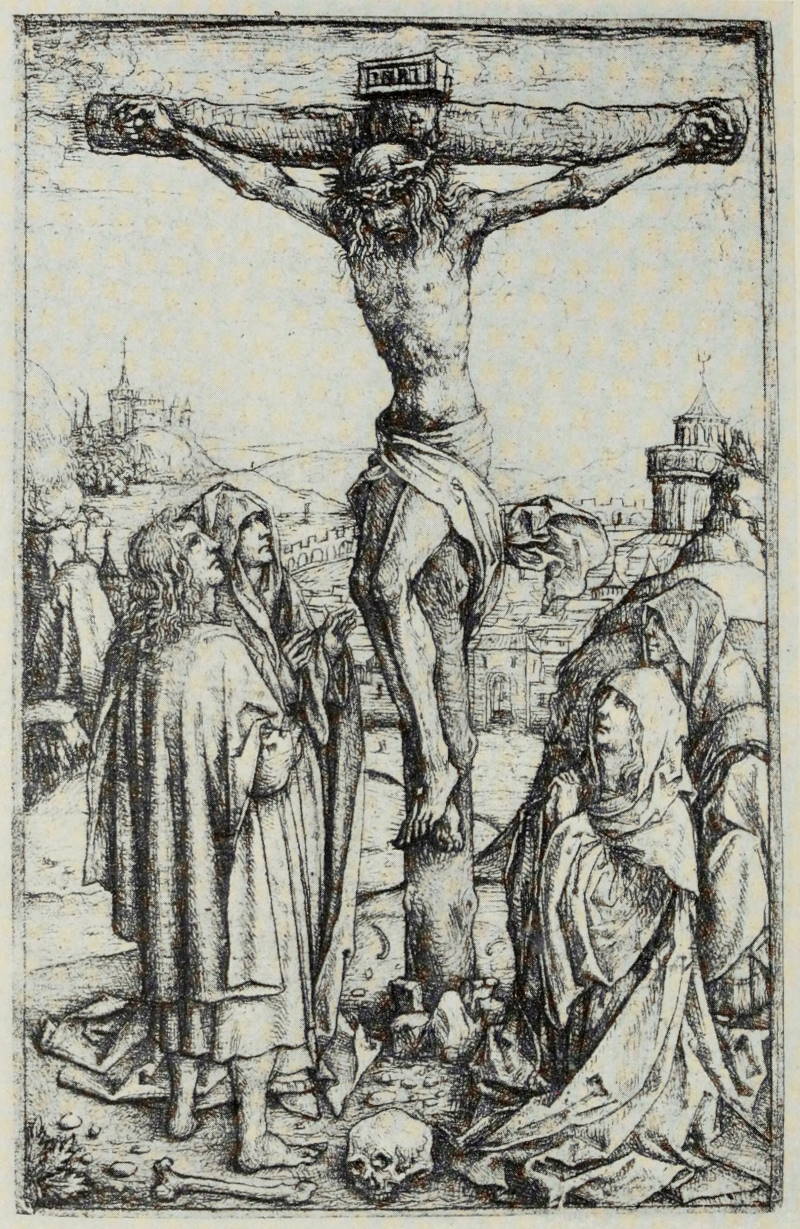

| Crucifixion | 98 |

| Stag Hunt | 101 |

| St. George | 102 |

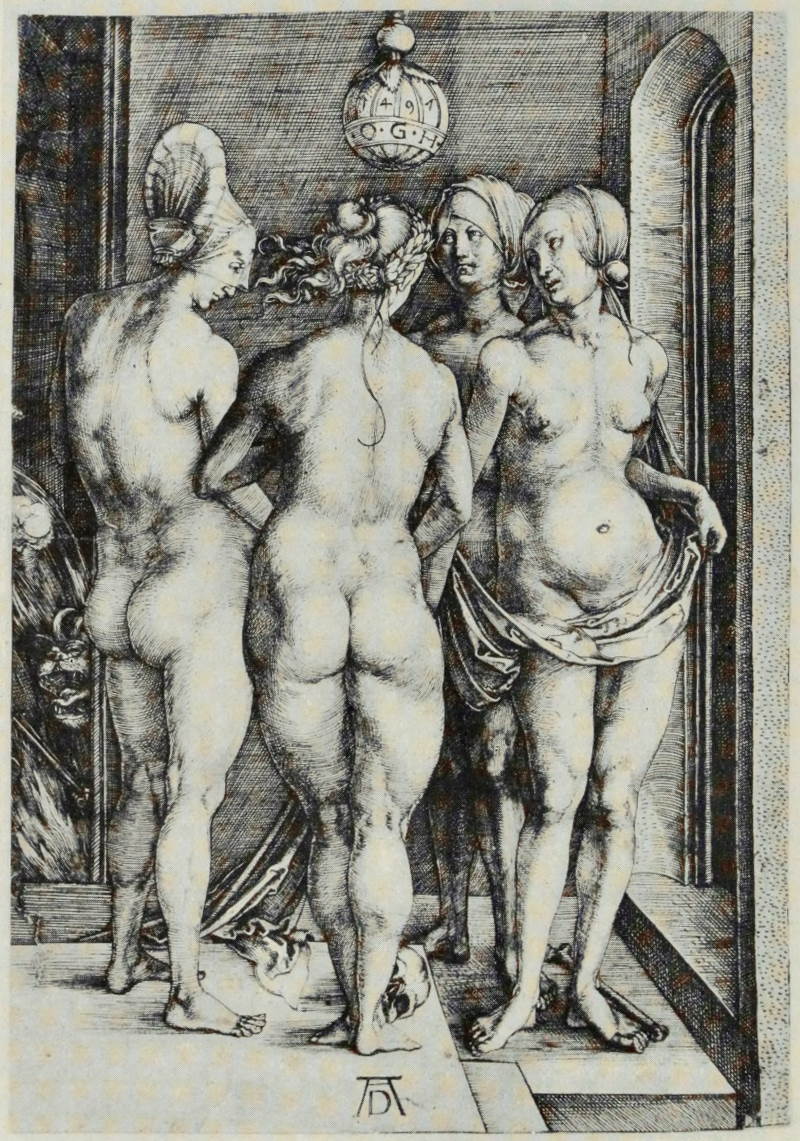

| Albrecht Dürer. Virgin and Child with the Monkey | 107 |

| Four Naked Women | 108 |

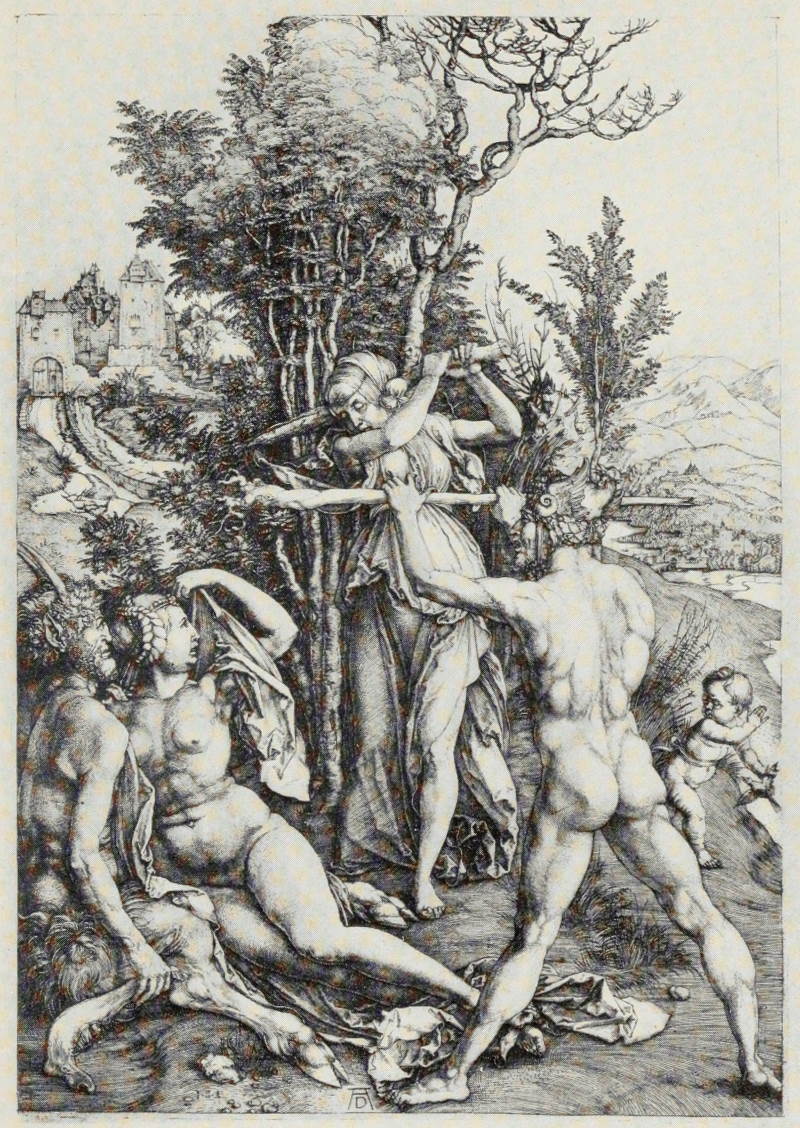

| Hercules | 111 |

| Anonymous North Italian, XV Century. Death of Orpheus |

112 |

| Albrecht Dürer. Death of Orpheus | 113 |

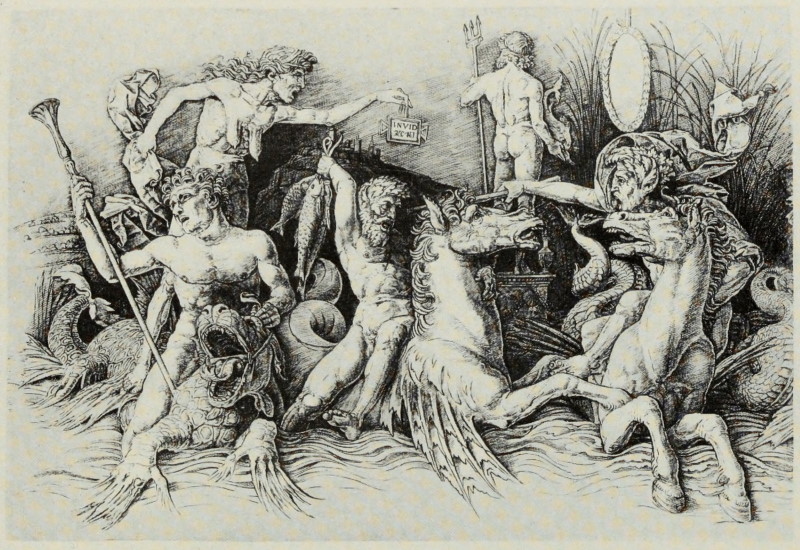

| Battle of the Sea-Gods (After Mantegna) | 114 |

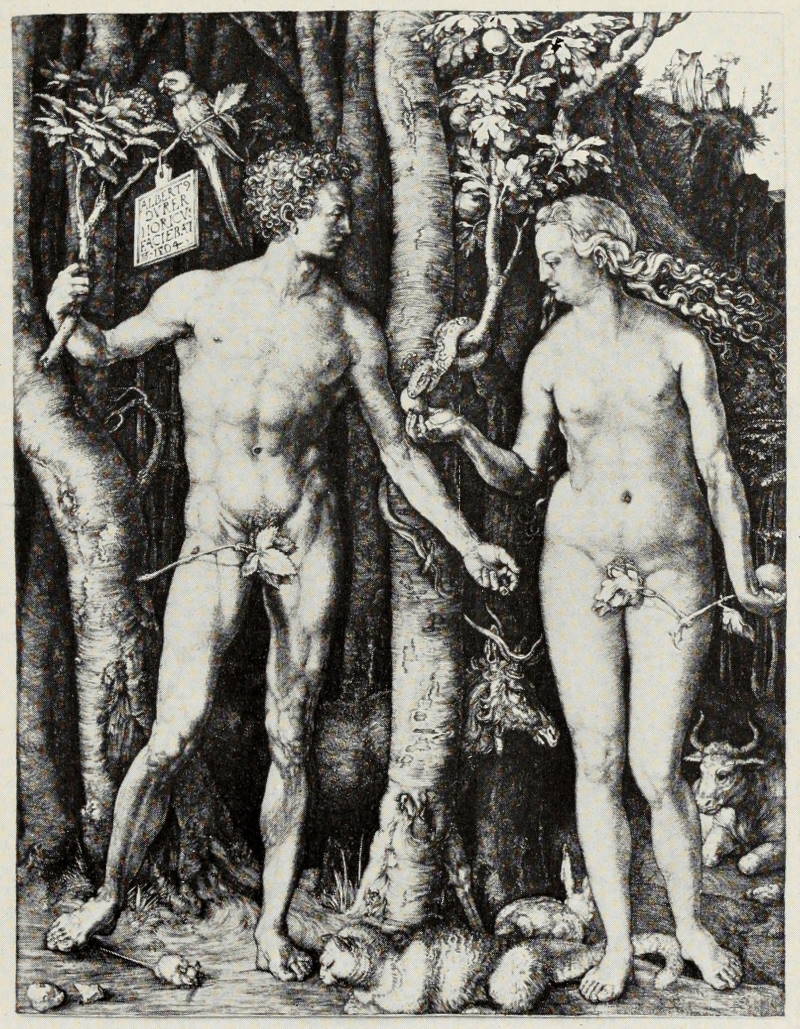

| Adam and Eve | 117 |

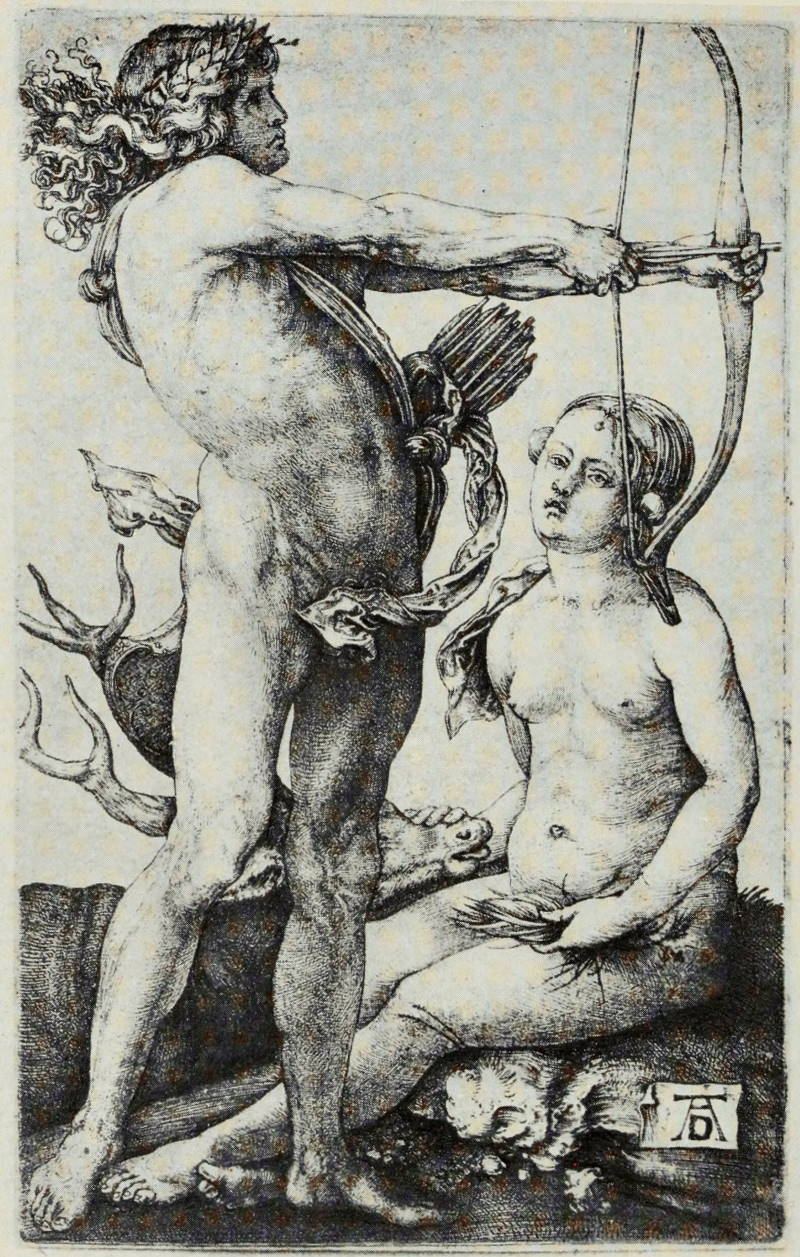

| Apollo and Diana | 118 |

| St. Jerome by the Willow Tree (First State) | 121 |

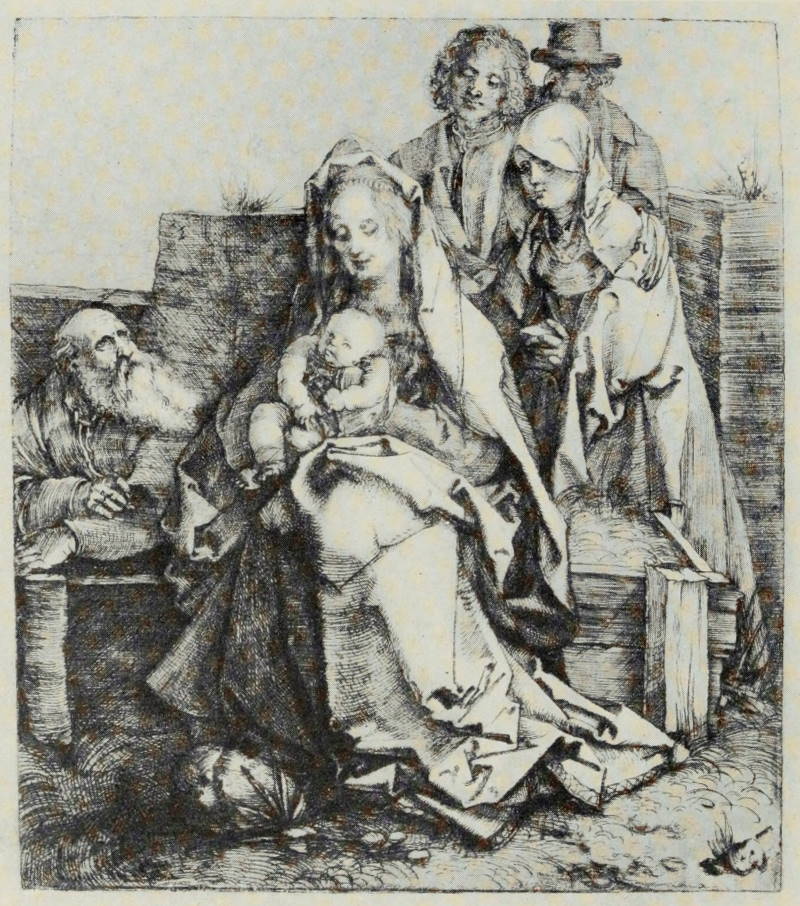

| Holy Family | 122 |

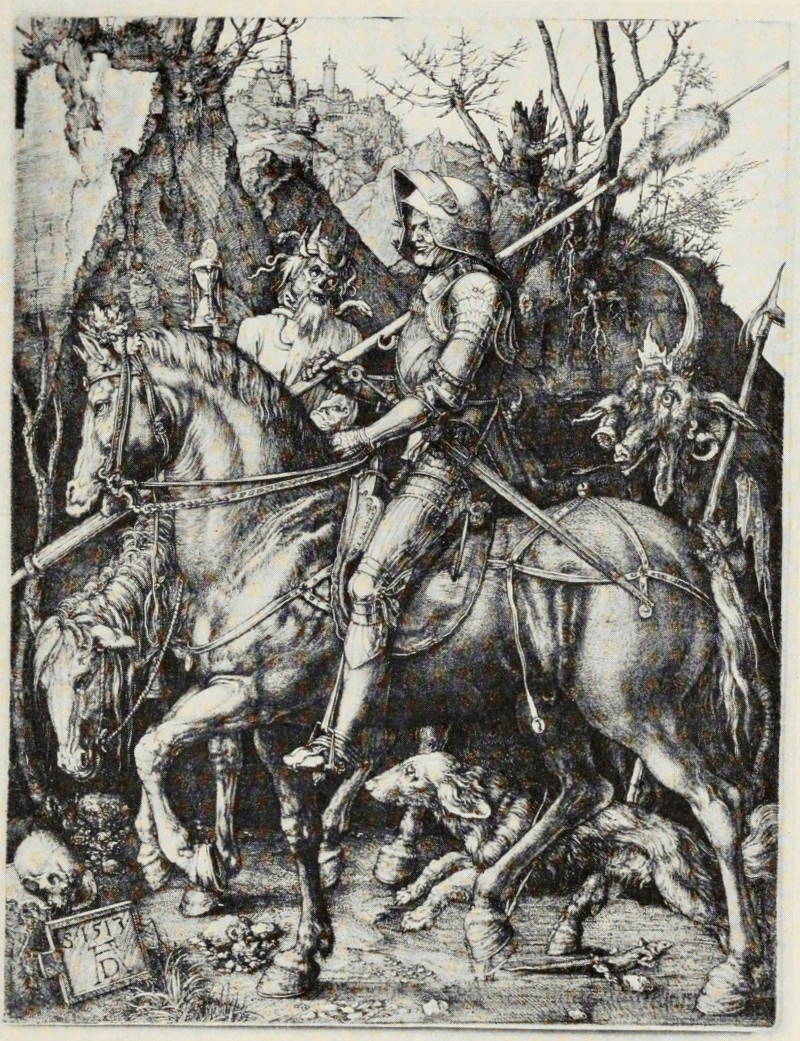

| Knight, Death and the Devil | 125 |

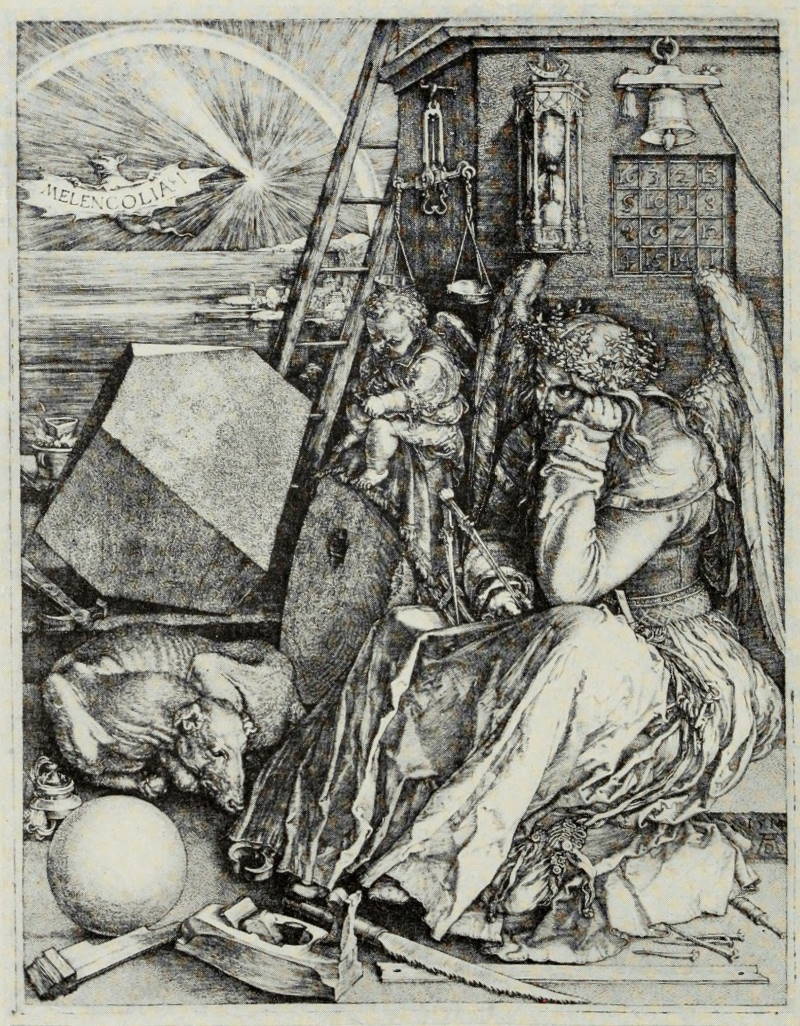

| Melancholia | 126 |

| St. Jerome in His Cell | 129 |

| Virgin Seated Beside a Wall | 130 |

| Christ in the Garden | 133 |

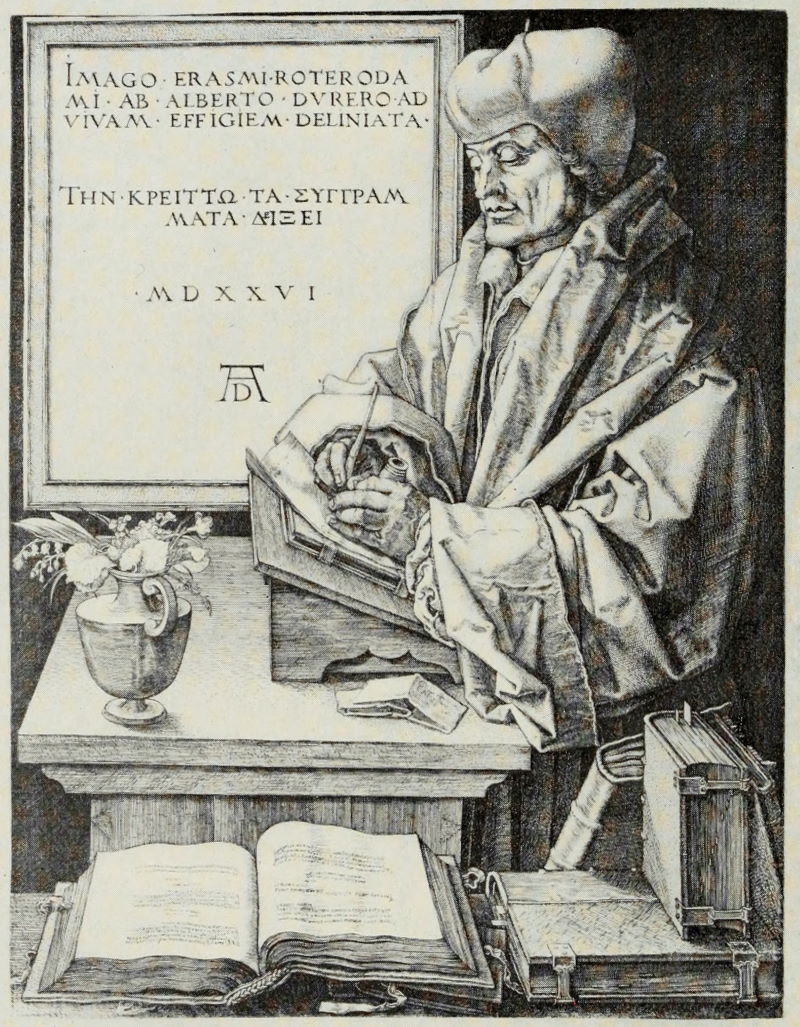

| Erasmus of Rotterdam | 134 |

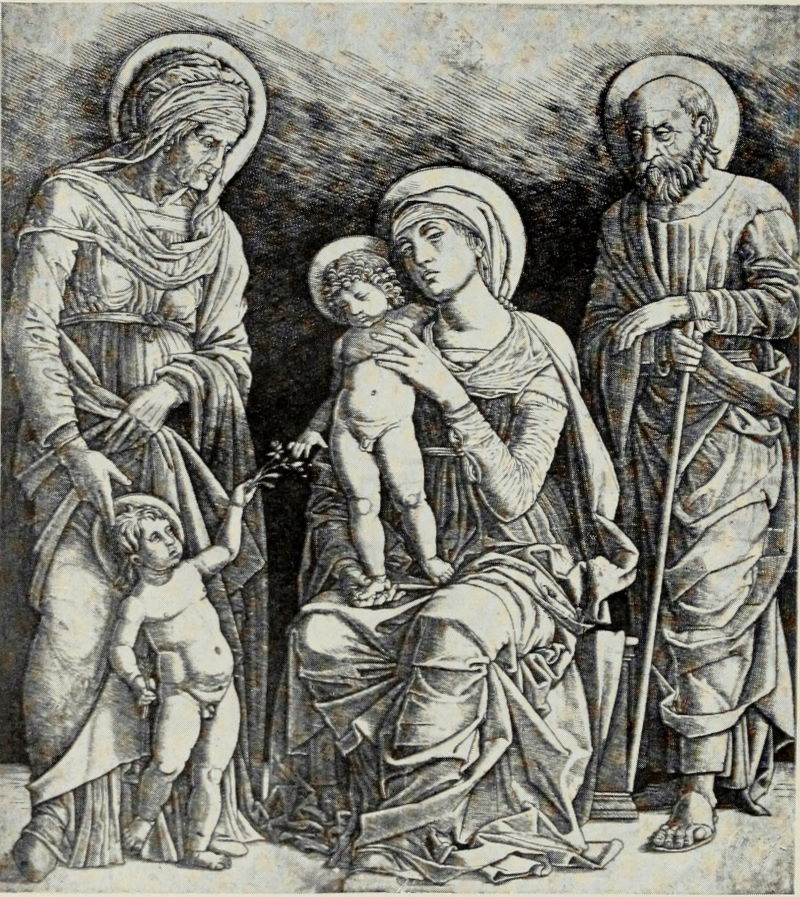

| Andrea Mantegna. Virgin and Child | 141 |

| Battle of the Sea-Gods | 142 |

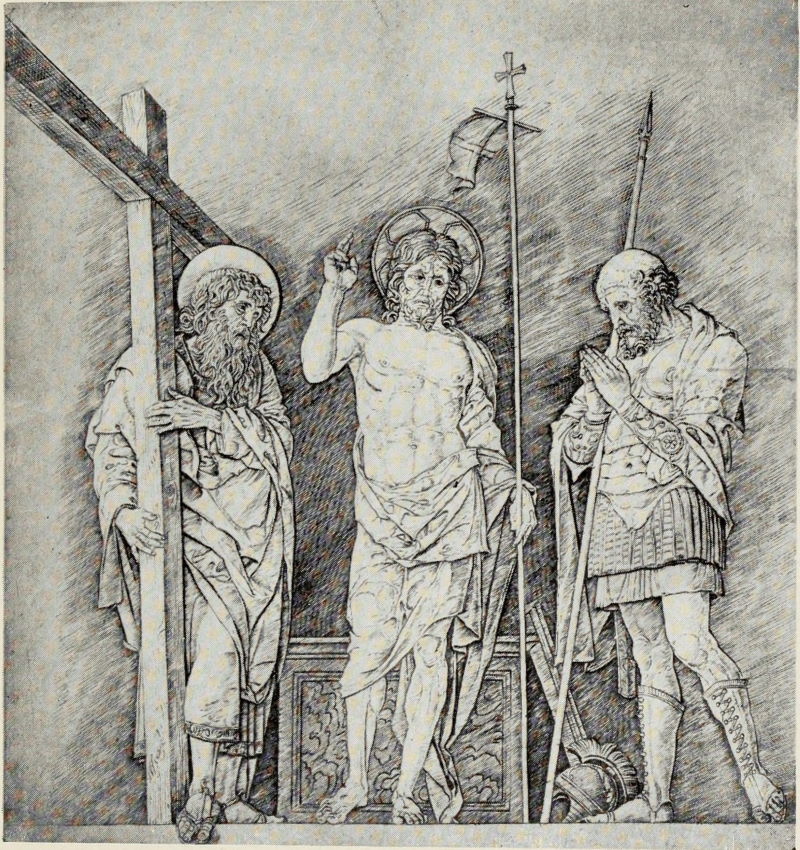

| The Risen Christ Between Saints Andrew and Longinus |

147 |

| School of Andrea Mantegna. Adoration of the Magi | 148 |

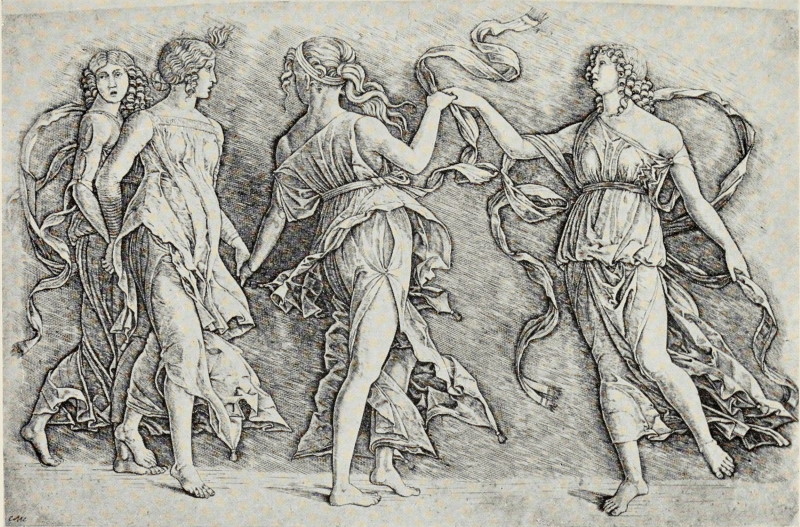

| Zoan Andrea (?). Four Women Dancing | 151 |

| Giovanni Antonio da Brescia. Holy Family with Saints Elizabeth and John |

152 |

| School of Leonardo da Vinci. Profile Bust of a Young Woman |

155 |

| Nicoletto Rosex da Modena. Orpheus | 156 |

| Jacopo de’ Barbari. Apollo and Diana | 159 |

| St. Catherine | 160 |

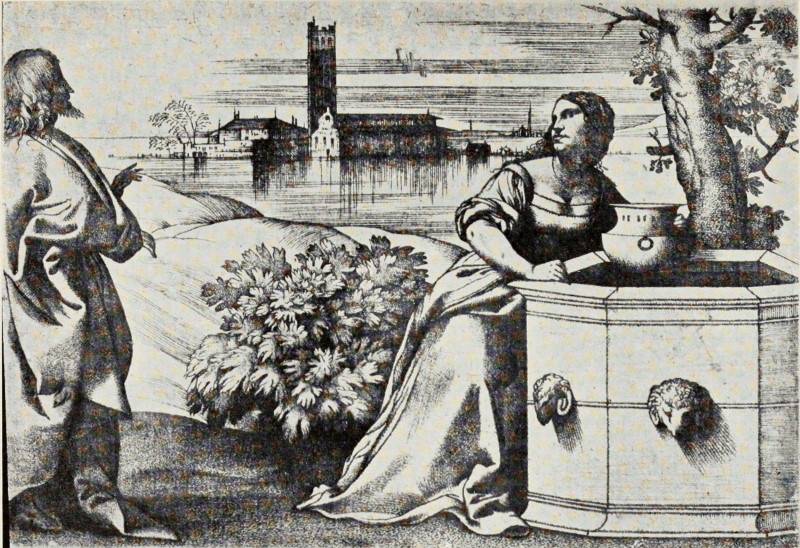

| Giulio Campagnola. Christ and the Woman of Samaria |

163 |

| Ganymede (First State) | 164 |

| St. John the Baptist | 167 |

| Giulio and Domenico Campagnola. Shepherds in a Landscape |

168 |

| Marcantonio Raimondi. St. George and the Dragon | 171 |

| Bathers | 172 |

| St. Cecelia | 173 |

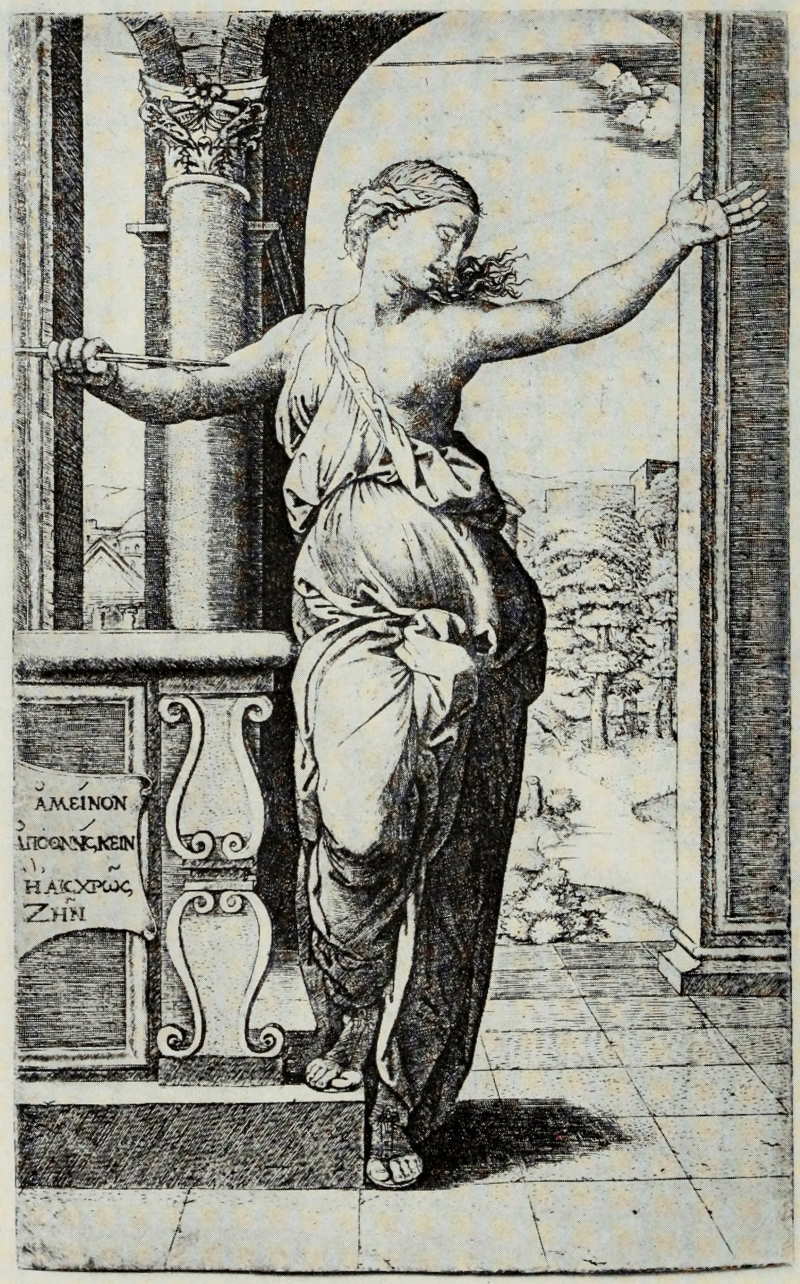

| Death of Lucretia | 174 |

| Philotheo Achillini (“The Guitar Player”) | 177 |

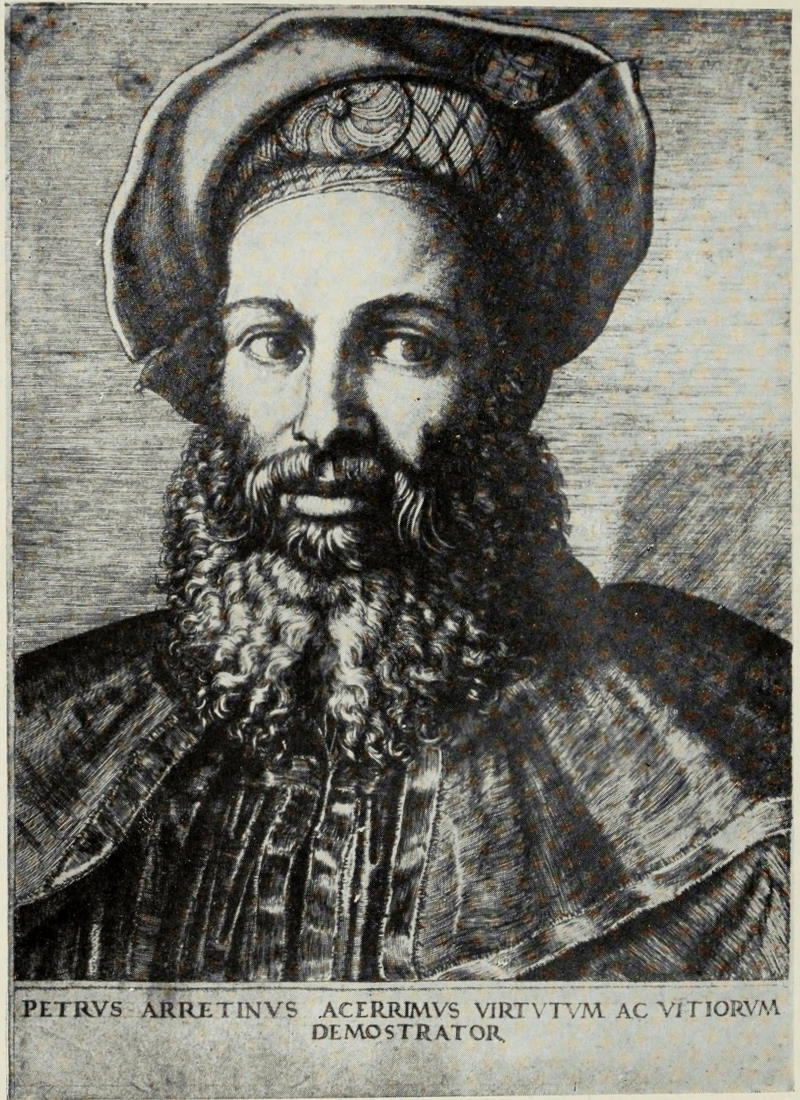

| Pietro Aretino | 178 |

Master  . Head of a Young Woman . Head of a Young Woman |

183 |

| Albrecht Dürer. Albert of Brandenburg | 184 |

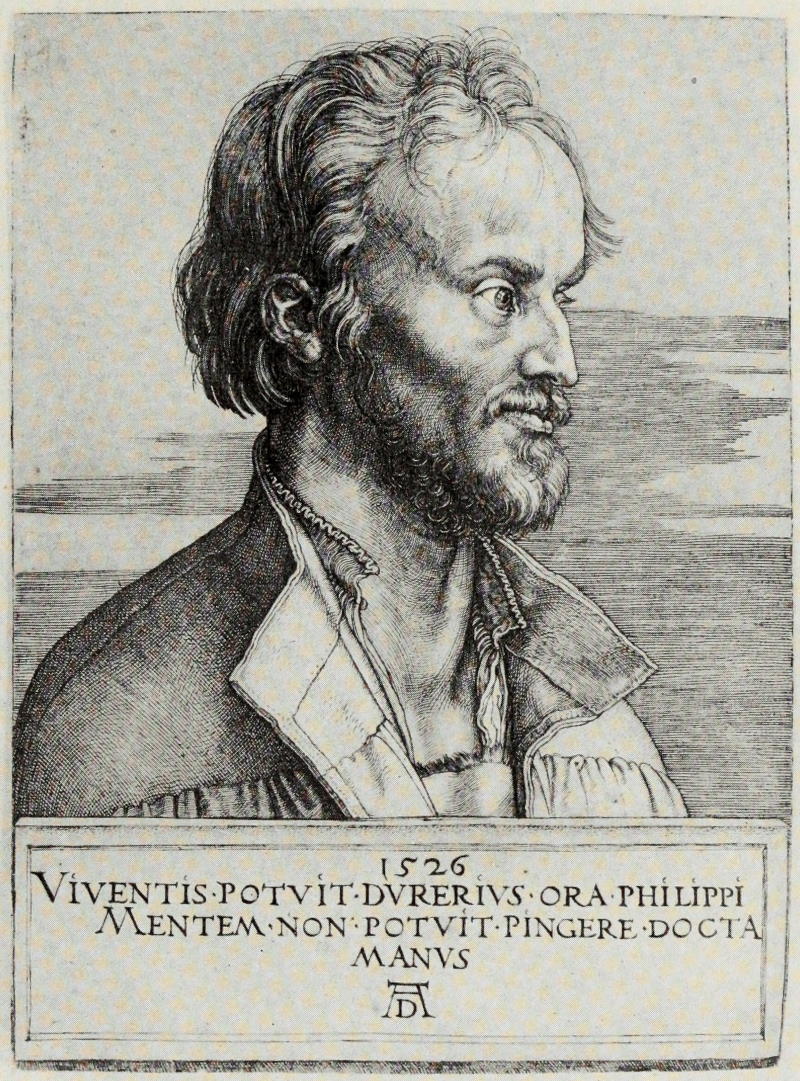

| Philip Melanchthon | 187 |

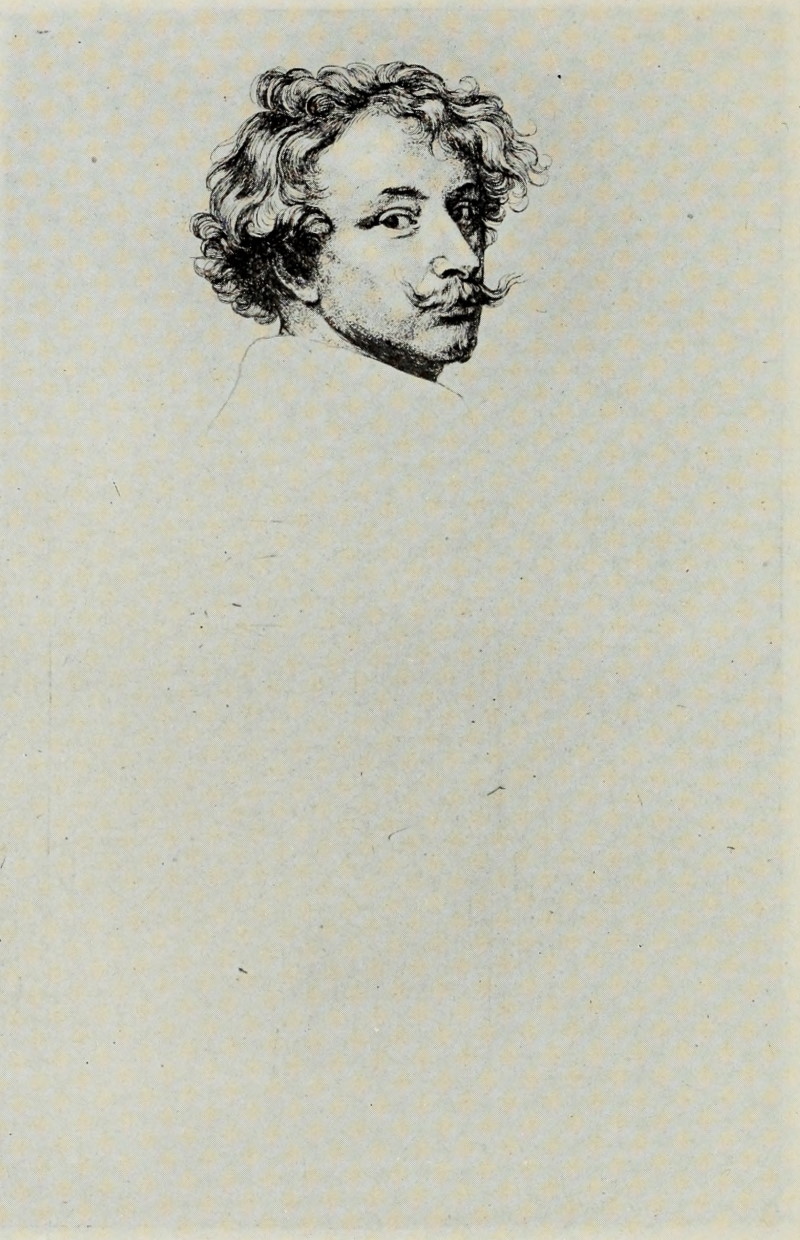

| Anthony Van Dyck. Portrait of Himself (First State) | 188 |

| Frans Snyders (First State) | 191 |

| Lucas Vorsterman (First State) | 192 |

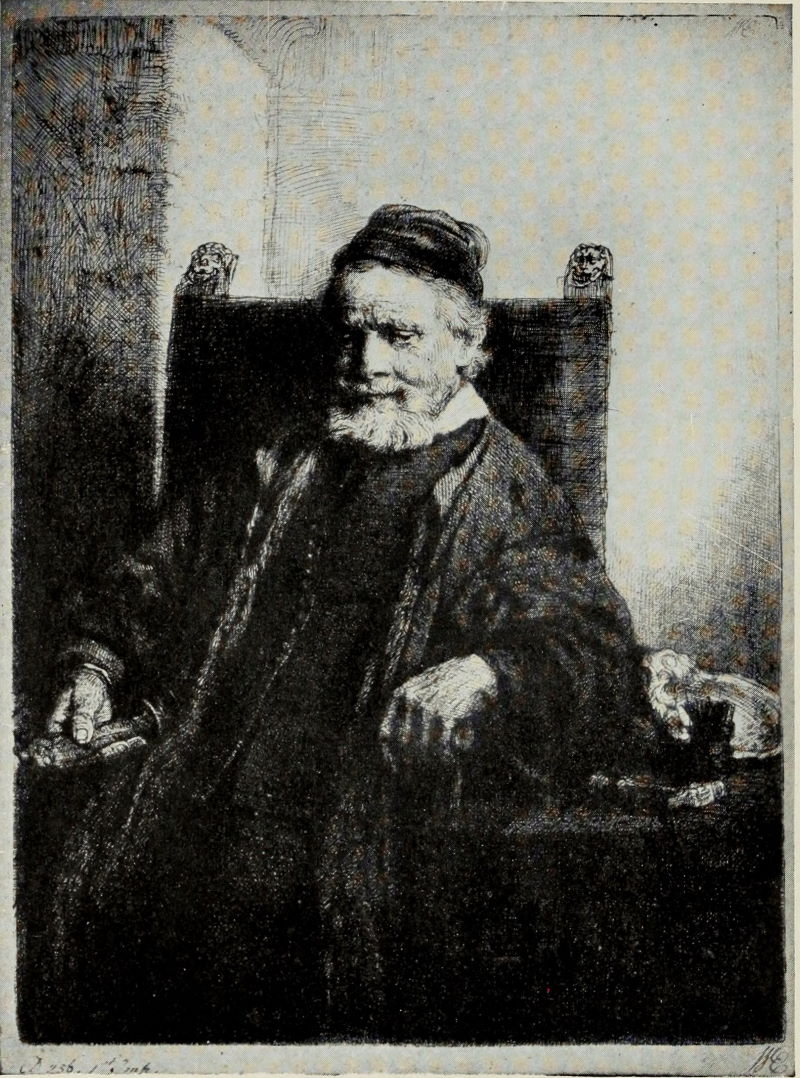

| Rembrandt. Jan Cornelis Sylvius | 195 |

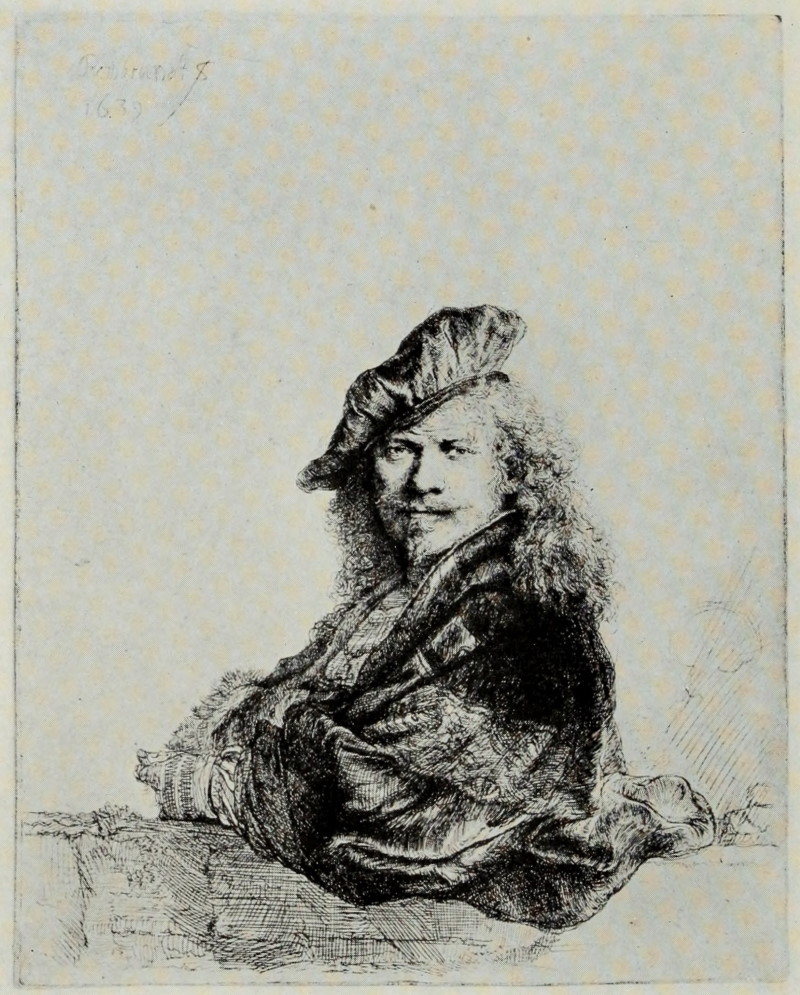

| Rembrandt Leaning on a Stone Sill | 196 |

| Clement de Jonghe (First State) | 197 |

| Jan Lutma (First State) | 198 |

| Claude Mellan. Virginia da Vezzo | 201 |

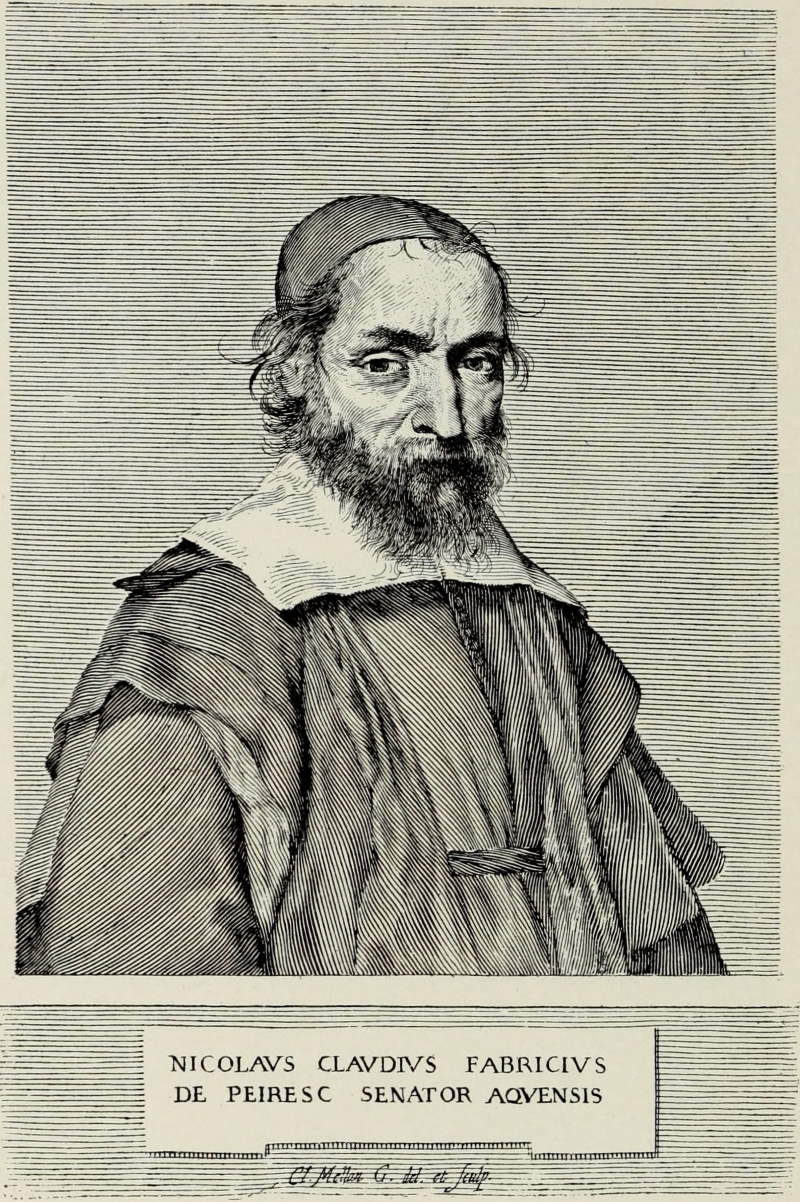

| Fabri de Peiresc | 202 |

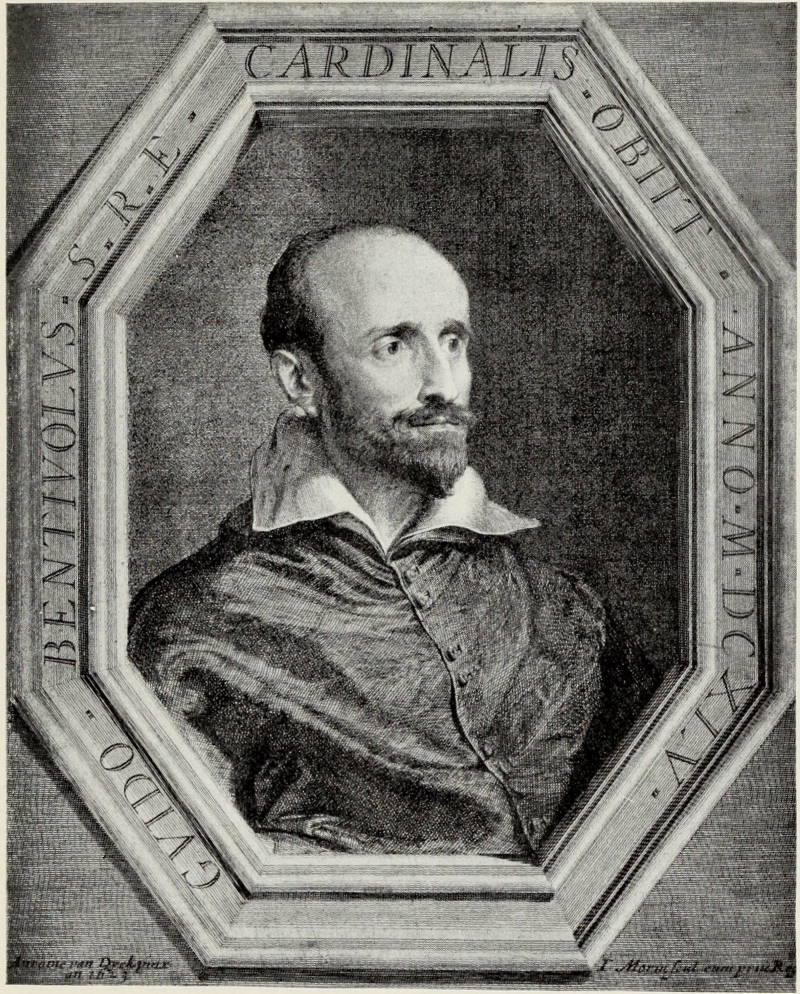

| Jean Morin. Cardinal Guido Bentivoglio | 205 |

| Robert Nanteuil. Pompone de Bellièvre | 206 |

| Basile Fouquet | 211 |

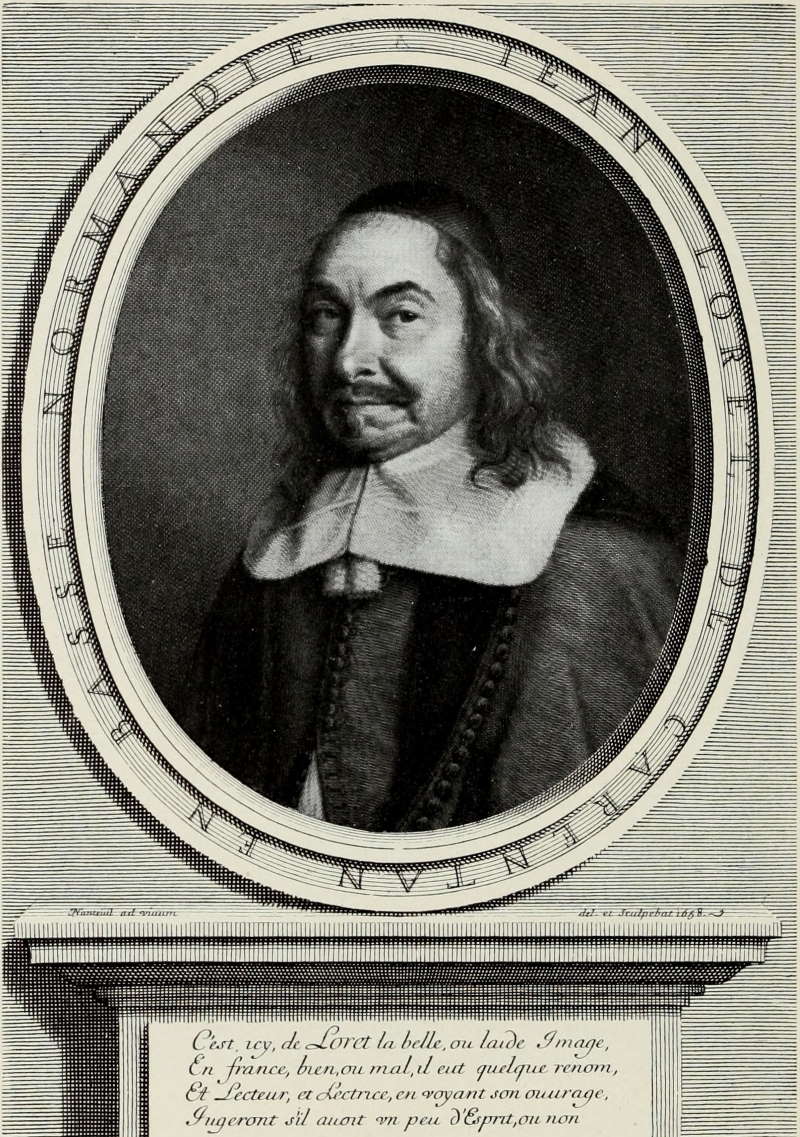

| Jean Loret | 212 |

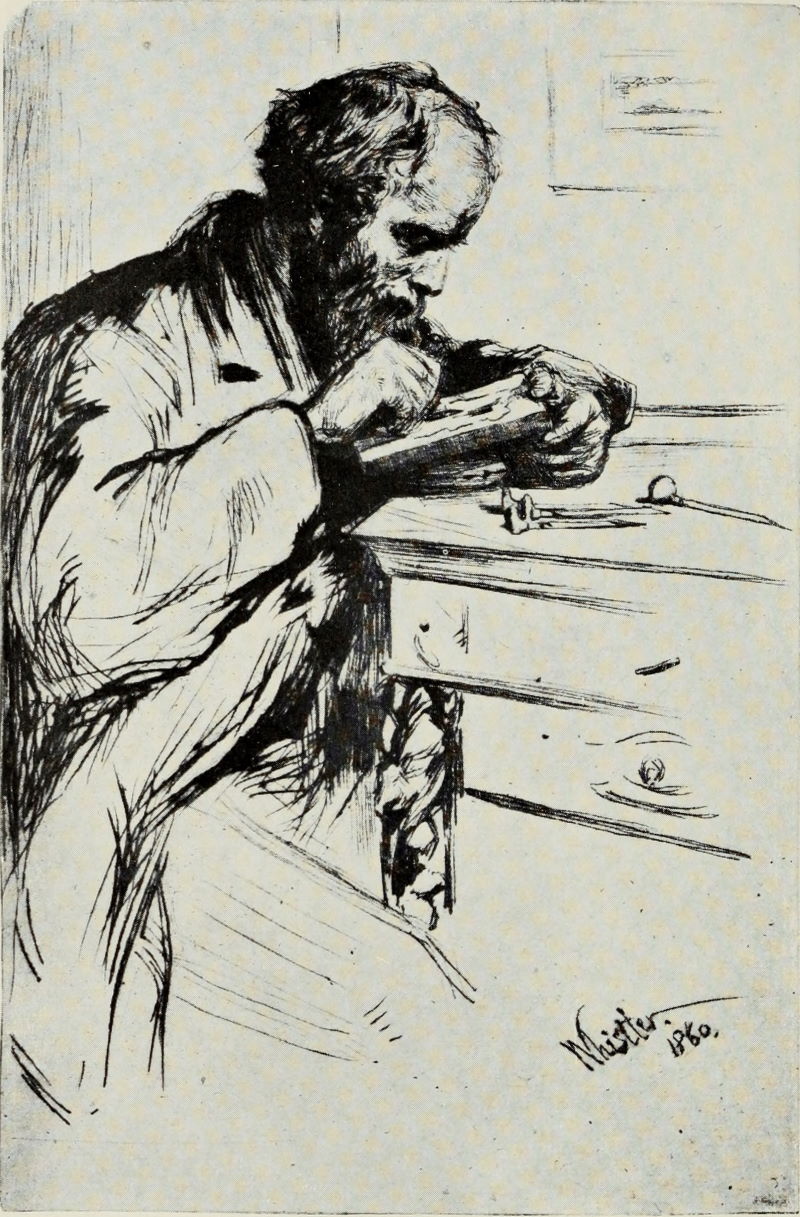

| J. A. McN. Whistler. Annie Haden | 215 |

| Riault, the Engraver | 216 |

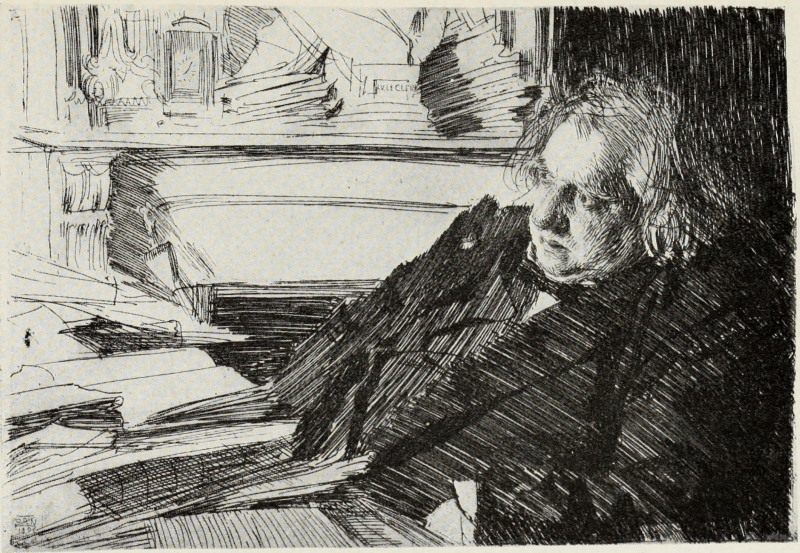

| Anders Zorn. Ernest Renan | 219 |

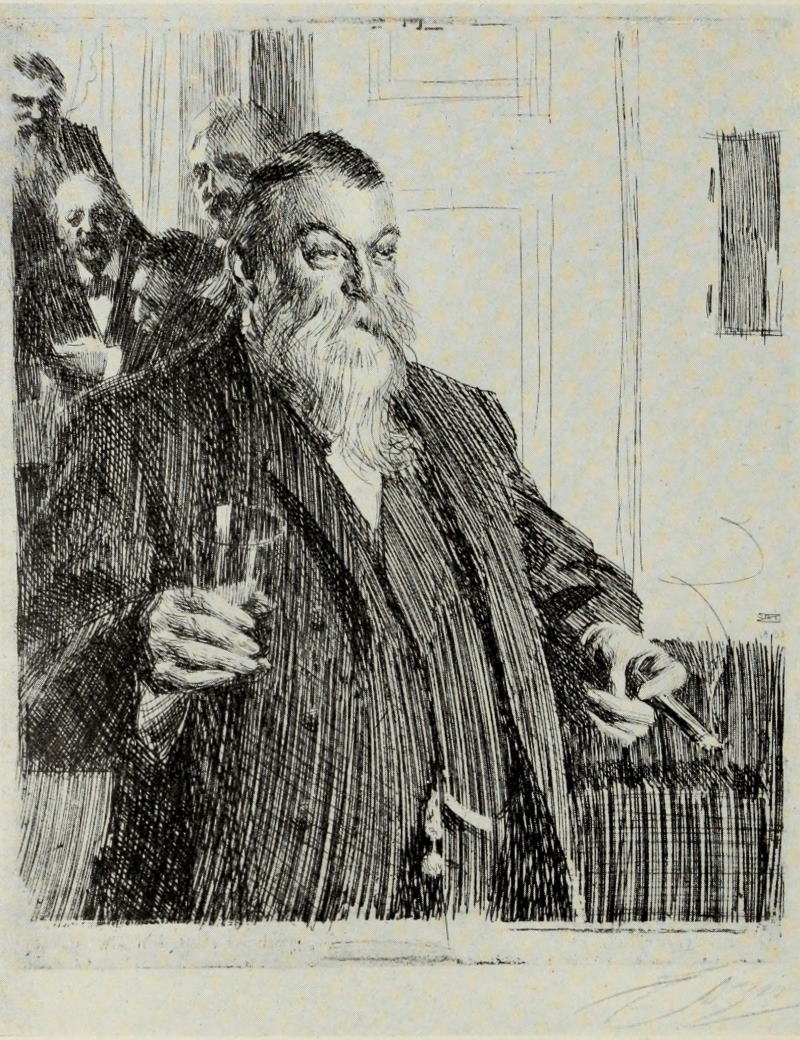

| The Toast | 220 |

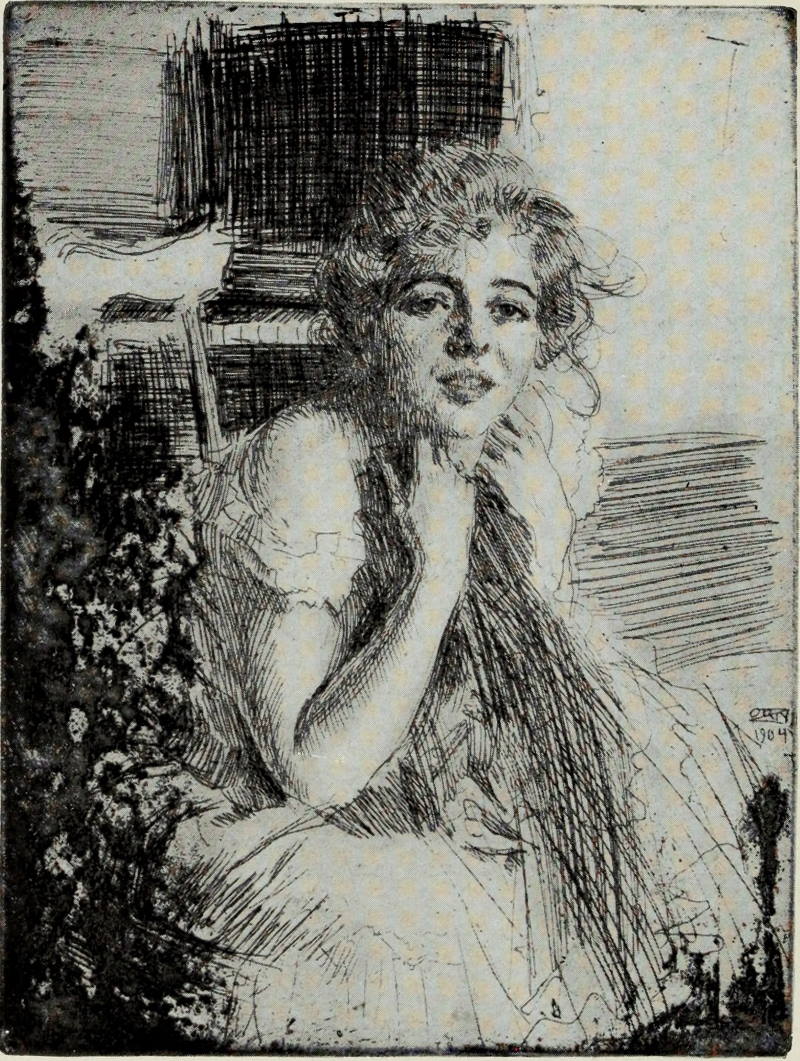

| Madame Simon | 221 |

| Miss Emma Rassmussen | 222 |

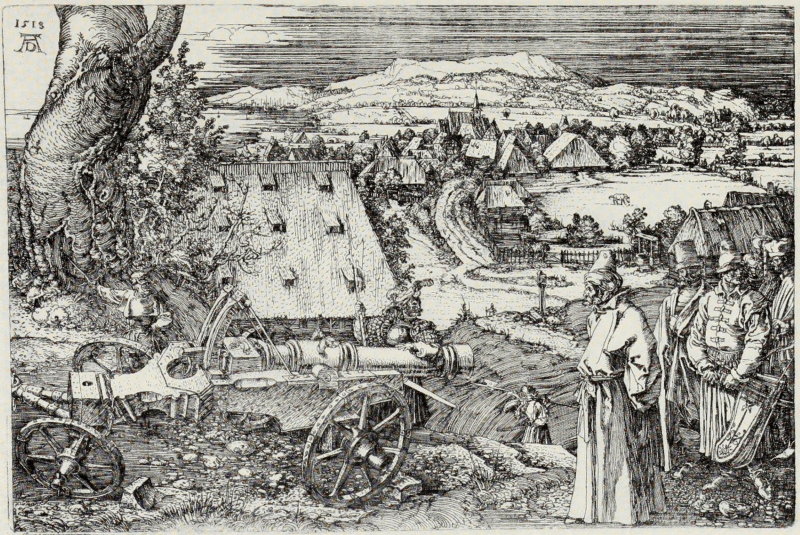

| Albrecht Dürer. The Cannon | 229 |

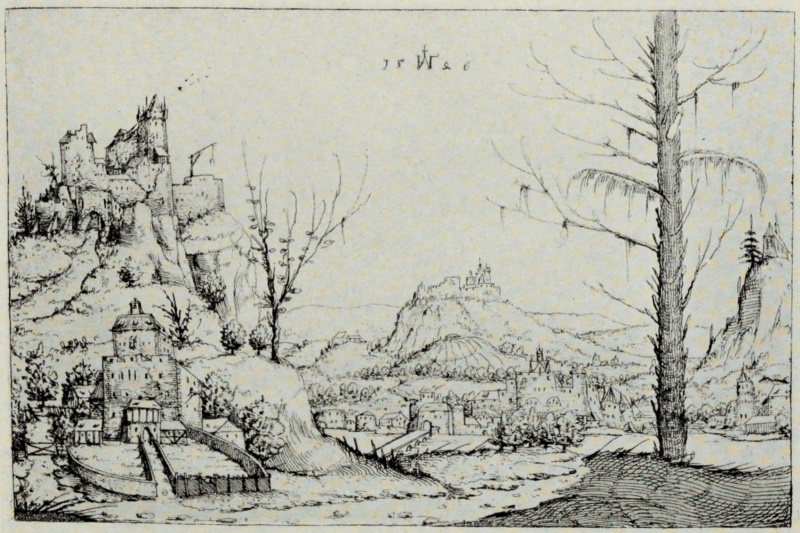

| Augustin Hirschvogel. Landscape | 230 |

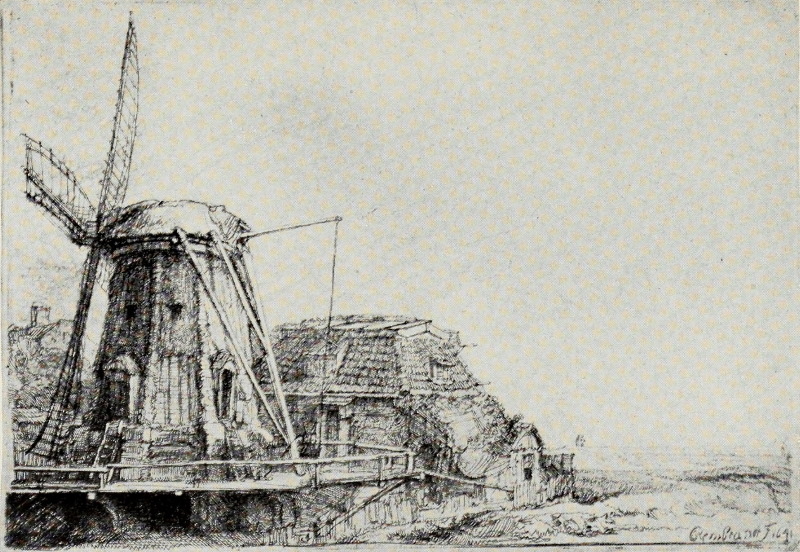

| Rembrandt. The Windmill | 233 |

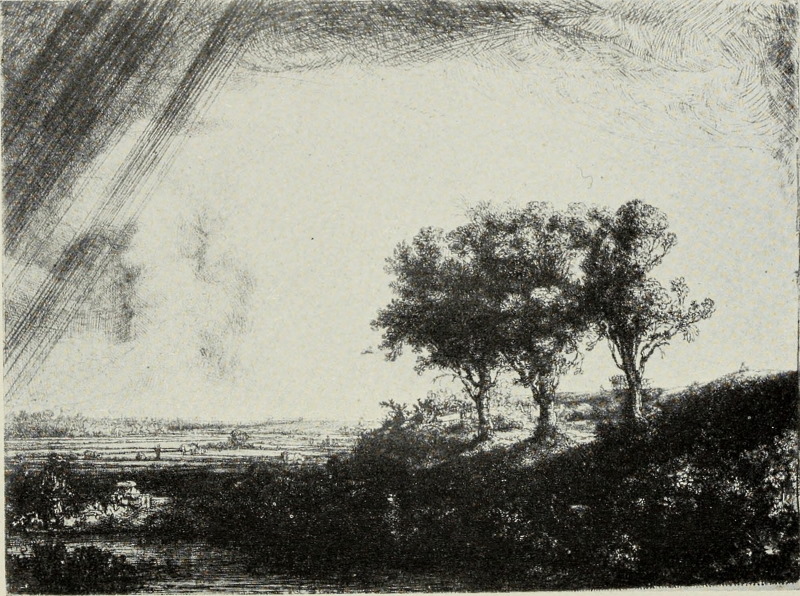

| Three Trees | 234 |

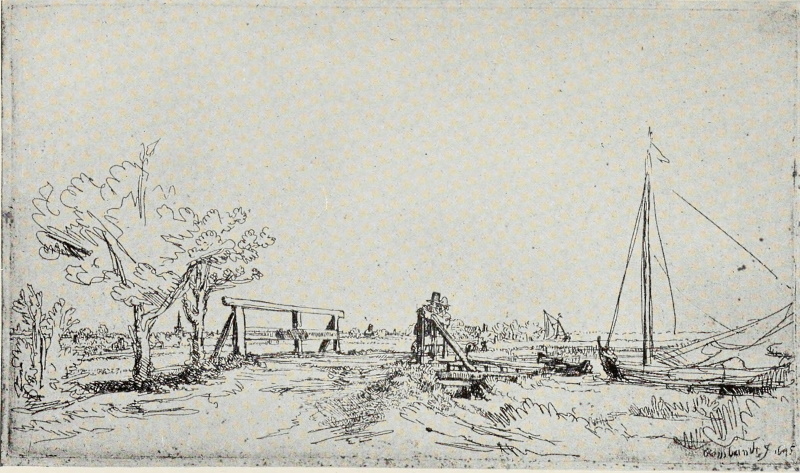

| Six’s Bridge | 237 |

| Landscape with a Ruined Tower and Clear Foreground | 238 |

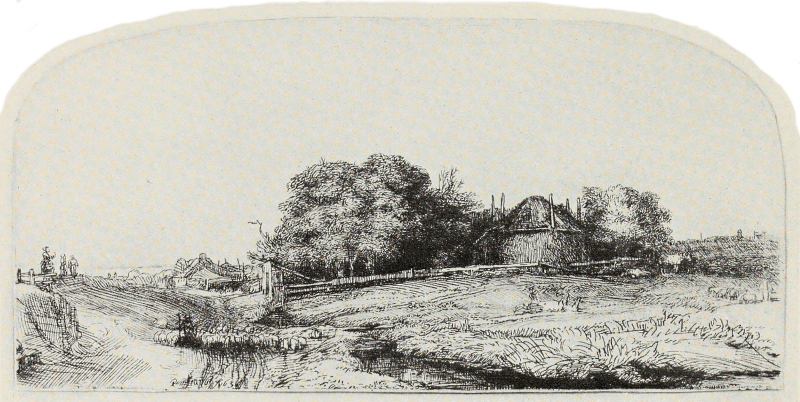

| Landscape with a Haybarn and a Flock of Sheep | 239 |

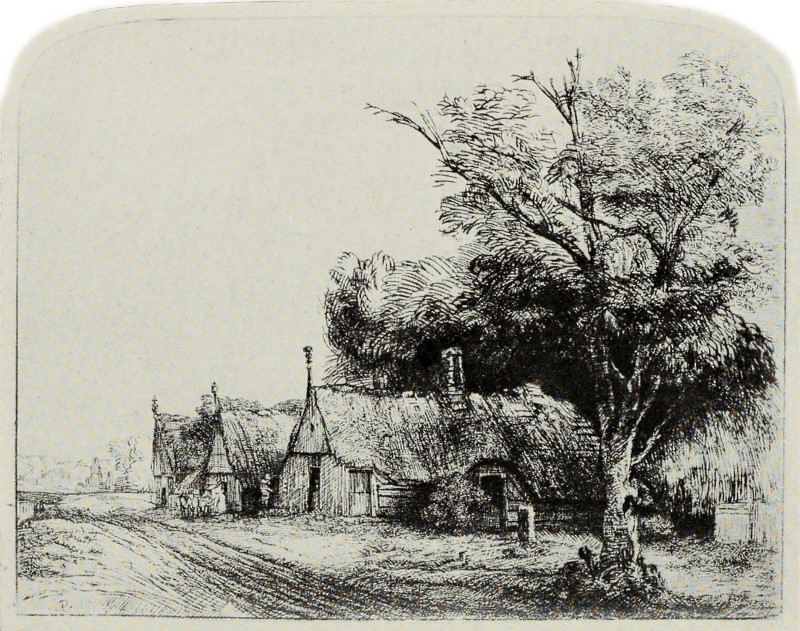

| Three Cottages | 240 |

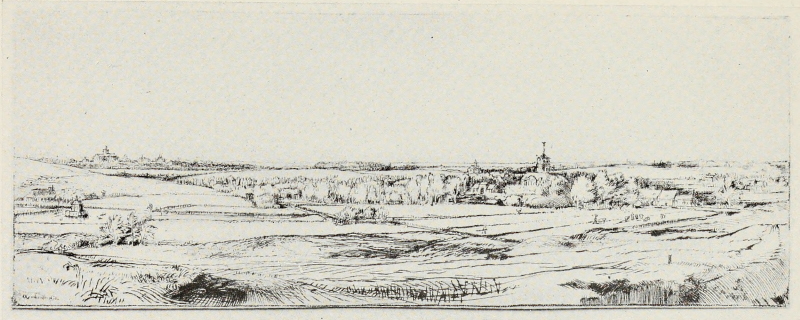

| Goldweigher’s Field | 243 |

| Jacob Ruysdael. Wheat Field | 244 |

| Claude Lorrain. Le Bouvier | 249 |

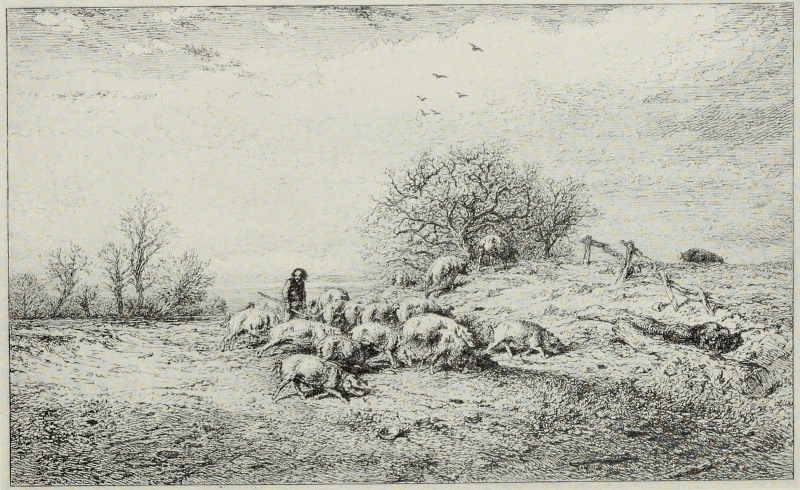

| Charles Jacque. Troupeau de Porcs | 250 |

| Storm—Landscape with a White Horse | 253 |

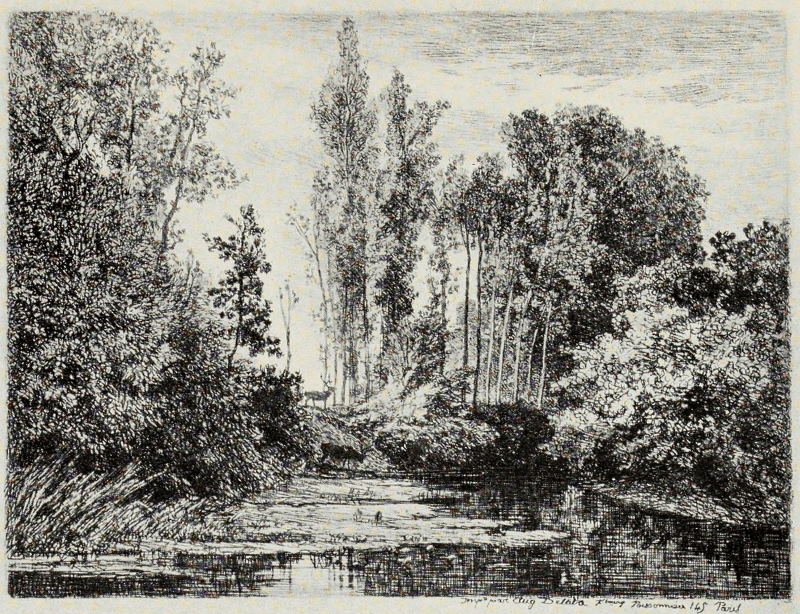

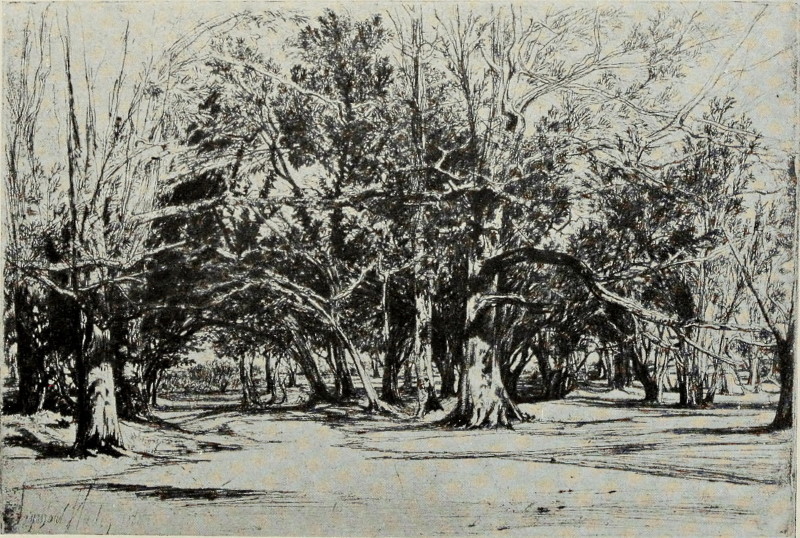

| Charles-François Daubigny. Deer in a Wood | 254 |

| Deer Coming Down to Drink | 257 |

| Moonlight on the Banks of the Oise | 258 |

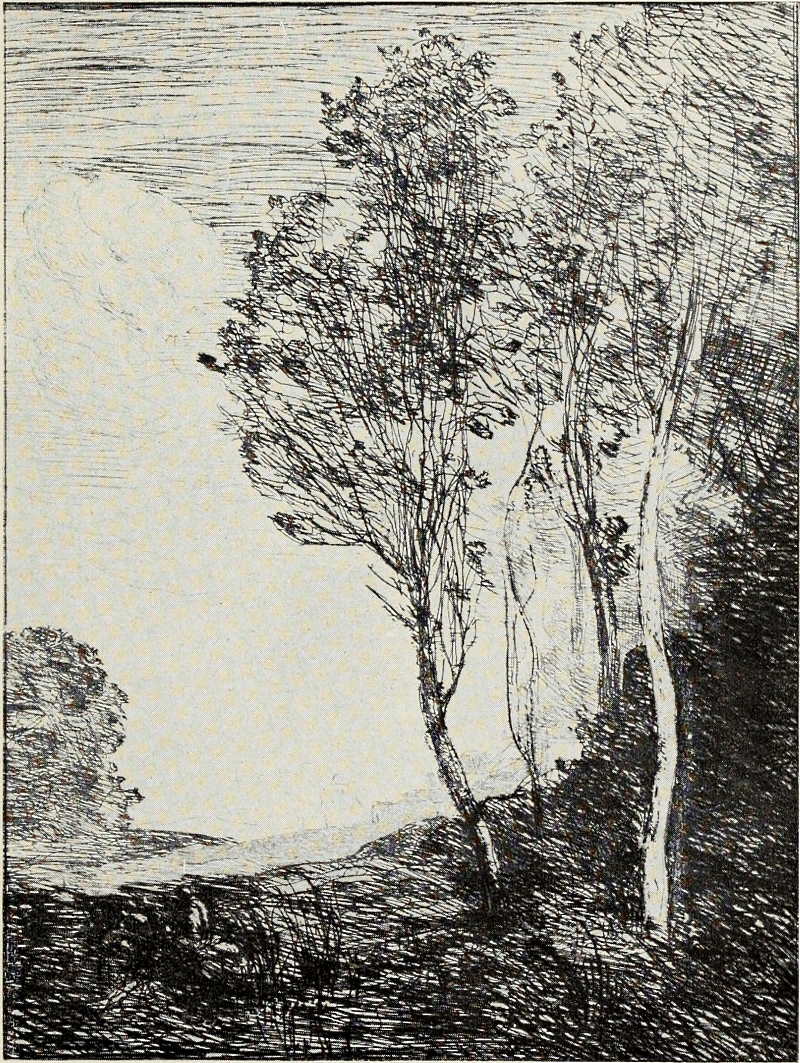

| Camille Corot. Souvenir of Italy | 261 |

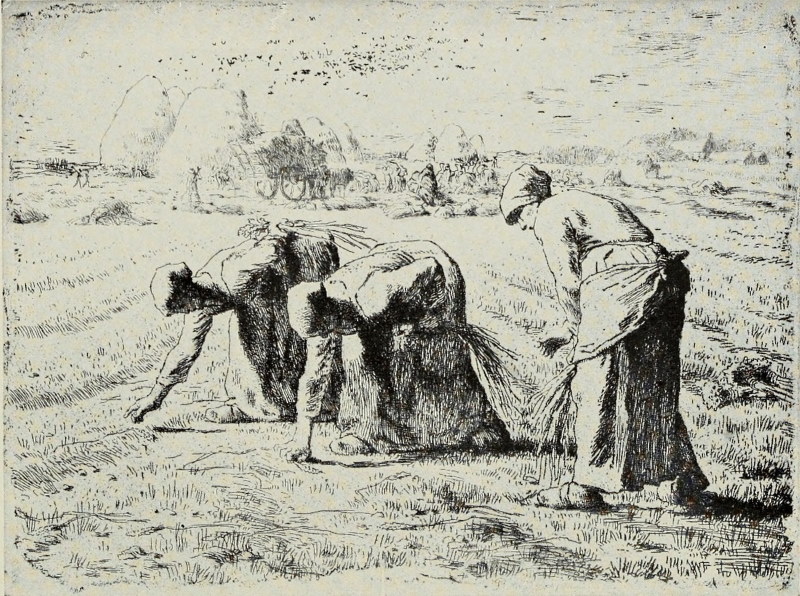

| Jean-François Millet. The Gleaners | 262 |

| Seymour Haden. Cardigan Bridge | 265 |

| By-Road in Tipperary | 266 |

| Sunset in Ireland | 267 |

| Sawley Abbey | 268 |

| J. A. McN. Whistler. Zaandam (First State) | 271 |

| Rembrandt. View of Amsterdam from the East | 272 |

When that most sensitive of American print-lovers, the late Francis Bullard, learned that I was to deliver at Harvard, each year, a course of lectures on the History and Principles of Engraving, he wrote me one of those characteristic letters which endeared him to his friends, concluding his wise counsels with these words: “Nothing original—get it all out of the books.”

In these six lectures I have endeavored to profit by his suggestion. In them there is little original: most of it is out of the books. Books, however, like Nature, are a storehouse from which we draw whatever is best suited to our immediate needs; and if in choosing that which might interest an audience, to the majority of whom engravings and etchings were an unexplored country, I have preferred the obvious to the profound, I trust that the true-blue Print Expert will forgive me. These simple lectures make no pretense of being a History of Engraving, or a manual of How to Appreciate Prints. My sole aim has been to share with my audience the stimulation and pleasure which certain prints by the great engravers and etchers have given me. If I have succeeded, even a little, I shall be happy. I would add that the lectures are printed in substantially the same form as they were delivered. Consequently they must be read in connection with the illustrations which accompany them.

The Bibliographies which follow each chapter have been prepared by Mr. Adam E. M. Paff, Assistant in the Department of Prints at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

FitzRoy Carrington

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

June 26, 1916

[Pg 13]

ENGRAVERS AND ETCHERS

WHERE were the beginnings? When were the beginnings? Germany, the Netherlands, and Italy have each claimed priority. Max Lehrs has settled these rival claims, so far as they can be settled at the present time, by locating the cradle of engraving neither in Germany, in the Netherlands, nor in Italy, but in a neutral country—Switzerland, in the vicinity of Basle—naming the Master of the Playing Cards as probably the earliest engraver whose works have come down to us. Undoubtedly this artist was not the first to engrave upon metal plates, but of his predecessors nothing is known, nor has any example of their work survived.

The technical method of the Master of the Playing Cards is that of a painter rather than of a goldsmith. There is practically no cross-hatching, and the effect is produced by a series of delicate lines, mostly vertical, laid close together. His plates are unsigned and undated, so that we can only approximate the period of his activity. That he preceded, by at least ten years, the earliest dated engraving,[Pg 14] the Flagellation, by the Master of 1446, may safely be assumed, since in the manuscript copy of Conrad von Würzburg’s “The Trojan War,” transcribed in 1441 by Heinrich von Steinfurt (an ecclesiastic of Osnabrück), there are pen drawings of figures wearing costumes which correspond exactly with those in prints by the Master of the Playing Cards in his middle period. The Master of the Playing Cards is, therefore, the first bright morning star of engraving. From him there flows a stream of influence affecting substantially all of the German masters until the time of Martin Schongauer, some of whose earlier plates show unmistakable traces of an acquaintanceship with his work.

MASTER OF THE PLAYING CARDS. ST. GEORGE

Size of the original engraving, 5⅞ × 5¼ inches

In the Royal Print Room, Dresden

MASTER OF THE PLAYING CARDS. MAN OF SORROWS

Size of the original engraving, 7¾ × 5⅛ inches

In the British Museum

St. George and the Dragon is in his early manner. Here are plainly to be seen the characteristics of this first period—the broken, stratified rocks, the isolated and conventionalized plants, and the peculiar drawing of the horse, especially its slanting and half-human eyes. The Playing Cards, from which he takes his name, may safely be assigned to his middle period. The suits are made up of Flowers (roses and cyclamen), Wild Men, Birds, and Deer, with a fifth, or alternative suit of Lions and Bears. Like all the early German designers of playing cards, he has given free rein to his fancy and inventiveness. The position of the different emblems is varied for each numeral card; and each flower, wild [Pg 17]man, bird, or beast, has an attitude and character of its own, no two being identical. No engraver has surpassed him in truthfulness and subtlety of observation and in the delineation of birds few artists have equalled him. His rendering of the growth and form of flowers would have delighted John Ruskin. In the King of Cyclamen and the Queen of Cyclamen the faces have an almost portrait-like individuality. The hands are well drawn and do not yet display that attenuation which is characteristic of nearly all fifteenth century German masters and is a noticeable feature in engravings by Martin Schongauer himself. The clothing falls in natural folds, and in the King of Cyclamen the representation of fur could hardly be bettered.

To his latest and most mature period must be assigned the Man of Sorrows—in some ways his finest, and certainly his most moving, plate. Not only has he differentiated between the textures of the linen loin-cloth and the coarser material of the cloak; but the column, the cross with its beautiful and truthful indication of the grain of the wood, and the ground itself, all are treated with a knowledge and a sensitiveness that is surprising. The engraver’s greatest triumph, however, is in the figure of Christ. There is a feeling for form and structure, sadly lacking in the work of his successors, and his suggestion of the strained and[Pg 18] pulsing veins, which throb through the Redeemer’s tortured limbs, is of a compelling truth.

Chief among the engravers who show most clearly the influence of the Master of the Playing Cards is the Master of the Year 1446, so named from the date which appears in the Flagellation. His prints present a more or less primitive appearance, and were it not for this date, one might be tempted, on internal evidence, to assign them to an earlier period. In the Passion series, in particular, many of the figures are more gnome-like than human. Such creatures as the man blowing a horn, in Christ Nailed to the Cross, and the man pulling upon a rope, in the same print, recall to our minds, by an association of ideas, the old German fairy tales.

Contemporary with the Master of 1446, and belonging to the Burgundian-Netherlands group, to which also belong the two anonymous engravers known as the Master of the Mount of Calvary and the Master of the Death of Mary, is the Master of the Gardens of Love. His figures are crude in drawing and stiff in their movements. His knowledge of tree forms is rudimentary; but his animals and birds show real observation and seem to have been studied from life.

MASTER OF THE YEAR 1446. CHRIST NAILED TO THE CROSS

Size of the original engraving, 4⅛ × 3¼ inches

In the Royal Print Room, Berlin

MASTER OF ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST. ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST

Size of the original engraving, 8½ × 5⅞ inches

In the Albertina, Vienna

In the larger of the two engravings from which he takes his name, we see reflected the pleasure-loving court of the Dukes of Burgundy. On [Pg 21]the right, a lady leads her lover to a table spread with tempting viands. She stretches forth her right hand to take the fruit. It is a fig, the sign of fertility. To their right, drinking from a stream, is a unicorn, the sign of chastity. The artist seemingly wishes the lady’s message to read that she is still unwedded, and that, were she wedded, she would be a good mother. Observe, likewise, the way in which the engraver has placed the wild hogs, deer, and bears emerging from the woods, while, in the sky, numerous birds wing their flight. In the immediate foreground a lady and a cavalier are reading poetry to each other. Another lady plays to a gallant who, in a most uncomfortable attitude, holds a sheet of music. In the right-hand corner is a fourth pair, the lady busily twining a wreath for her lover’s hat, which lies on her lap. We have here a compendium of the courtly life of the time, which is about 1448.

The Master of St. John the Baptist may fittingly be called the first realist in engraving. His plates do not display that extraordinary delicacy in cutting which is characteristic of the Master of the Playing Cards. Like that earlier engraver, he makes little use of cross-hatching, and his strokes are freely disposed—more in the manner of a painter than a goldsmith-engraver. His birds and flowers are closely observed and admirably rendered.

[Pg 22]

The mullein, the columbine, and the iris in St. John the Baptist are each given their individual character; the tree trunks to the right no longer resemble twisted columns, as in earlier work, but have real bark with knot holes and branches organically joined, though the foliage is still conventionally treated. One cannot but remark, also, the skilful way in which the engraver has differentiated between the furry undergarment and the cloak which St. John the Baptist wears.

In St. Christopher we have probably one of his latest works. His representation of the waves, of the sky and clouds, is noteworthy, while, on the beach, the sea-shells give mute testimony to his love for little things.

Of the predecessors of Martin Schongauer, none exerted a greater influence than the Master E. S. of 1466. On the technical side he was the actual creator of engraving as practised in modern times, and was a determining factor in the progress of the art. Even the Italian engravers were unable to withstand it; their Prophets and Sibyls are partly derived from his Evangelists and Apostles, the easy disposition of his draperies furnishing them with models. Over three hundred engravings by the Master E. S. have come down to us, and over a hundred more can be traced through copies by other hands, or as having formed component parts [Pg 25]of his two sets of playing cards—the smaller set made up of Wild Animals, Helmets, Escutcheons, and Flowers, while the larger set comprises Men, Dogs, Birds, and Escutcheons.

MASTER E. S. OF 1466. MADONNA AND CHILD WITH SAINTS

MARGUERITE AND CATHERINE

Size of the original engraving, 8⅝ × 6⅜ inches

In the Royal Print Room, Dresden

MASTER E. S. OF 1466. ECSTASY OF ST. MARY MAGDALEN

Size of the original engraving, 6½ × 5 inches

In the Royal Print Room, Dresden

His work shows unmistakably the influence of the Master of the Playing Cards, and we may safely place him in the region of the upper Rhine, probably in the vicinity of Freiburg or Breisach. In the Madonna and Child with Saints Marguerite and Catherine his peculiar qualities and limitations may clearly be seen. The plants and flowers, with which the ground is thickly carpeted, are engraved in firm, clear-cut lines, betokening the trained hand of the goldsmith. The figures and drapery are rendered with delicate single strokes; but in the shaded portions of the wall, back of the Madonna, cross-hatching is skilfully employed. As is the case in nearly all the works of the early German engravers, the laws of perspective are imperfectly understood, but none the less the composition has a charm all its own.

The Ecstasy of St. Mary Magdalen is of interest, not only technically and artistically, but because of its influence upon the Master of the Amsterdam Cabinet, who has twice treated the subject, and upon Albrecht Dürer, by whom we have a woodcut seemingly copied from this engraving. Martin Schongauer, likewise, may have profited by the[Pg 26] feathered forms of the angels which reappear, somewhat modified, in his engraving of the Nativity. The birds and the isolated plants in the foreground still show the influence of the Master of the Playing Cards.

St. Matthew (whom we shall meet again in our consideration of Florentine engraving, transformed into the Tiburtine Sibyl, engraved in the Fine Manner of the Finiguerra School) and St. Paul (who likewise reappears as Amos in the series of Prophets and Sibyls) show an increasing command of technical resources. The draperies are beautifully disposed; and, in St. Paul, the system of cross-hatching upon the back of the chair, in the shaded portions beneath, and upon the mantle of the saint, is fully developed.

The Madonna of Einsiedeln, dated 1466, is usually accounted the engraver’s masterpiece. Beautiful though it is in composition and in execution, it suggests a translation, into black and white, of a painting, and on technical grounds, as well as for the beauty of its component parts, one may prefer the Design for a Paten, dating from the same year [1466]. Here the central scene, representing St. John the Baptist, owes not a little, both in composition and in technique, to the Master of St. John the Baptist. The four Evangelists, arranged in alternation with their appropriate symbols, around [Pg 29]the central picture, are little masterpieces of characterization and of engraving, and there can be nothing but unmixed admiration for the way in which plant and bird forms are woven into a perfectly harmonious pattern.

MASTER E. S. OF 1466. DESIGN FOR A PATEN

Size of the original engraving, 7⅛ inches in diameter

In the Royal Print Room, Berlin

MASTER E. S. OF 1466. ST. JOHN ON THE ISLAND OF PATMOS

Size of the original engraving, 8⅛ × 5½ inches

In the Hofbibliotek, Vienna

St. John on the Island of Patmos likewise shows unmistakably the influence of the Master of St. John the Baptist and is doubly interesting inasmuch as, in its turn, it had a shaping influence upon the engraving of the same subject by Martin Schongauer. It is dated 1467, the latest date found upon any plate by the Master E. S., and it is assumed that in this year his activity came to an end.

Martin Schongauer, who was born in Colmar about 1445 and is known to have died in 1491, is not only the most eminent painter and engraver in the latter third of the fifteenth century, he is one of the very greatest masters of the graphic arts. His plates number one hundred and fifteen, and, as in the case of Albrecht Dürer, it is upon his engraved work, rather than upon his all too few paintings, that his immortality must rest.

Schongauer’s prints can be arranged in something approximating chronological order. In the earliest twelve engravings the shanks of the letter M, in his monogram, are drawn vertically, whereas in all his later prints they slant outward. This apparently minor point is really of great significance in a study[Pg 30] of his development, since it enables us to place correctly certain plates which, until recently, were assigned to his latest period, such as the Death of the Virgin, the Adoration of the Magi, and the Flight Into Egypt.

One of the richest toned plates in this first group is the Virgin with a Parrot, an engraving which, incidentally, exists in two states. In the second state, the cushion upon which the Christ Child is seated, instead of being plain, has an elaborate pattern upon the upper side, and the flowing tresses of the Virgin are extended more to the left, thereby greatly improving the composition as a whole.

For Martin Schongauer, as for nearly all the earlier German masters, the grotesque had a strange fascination. His power of welding together parts of various animals into living fantastic creatures is nowhere better seen than in the Temptation of St. Anthony. Vasari tells how the young Michelangelo, meeting with an impression of this engraving in Florence, was impelled to copy it with a pen “in such a manner as had never before been seen. He painted it in colors also, and the better to imitate the strange forms among these devils, he bought fish which had scales somewhat resembling those of the demon. In this pen copy also he displayed so much ability that his credit and reputation were greatly enhanced thereby.” [Pg 35]It would appear to be one of Schongauer’s early plates, not only from the form of the monogram, but also from the treatment of the upper portion of the sky, shaded with many horizontal graver strokes, growing stronger as the upper edge of the plate is reached—a treatment which does not occur in any other print by him.

MARTIN SCHONGAUER. VIRGIN WITH A PARROT

Size of the original engraving, 6¼ × 4¼ inches

In the Public Art Collections, Basle

MARTIN SCHONGAUER. TEMPTATION OF ST. ANTHONY

Size of the original engraving, 12⅜ × 9⅛ inches

In the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

MARTIN SCHONGAUER. DEATH OF THE VIRGIN

Size of the original engraving, 10⅛ × 6⅝ inches

In the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

MARTIN SCHONGAUER. PILATE WASHING HIS HANDS

Size of the original engraving, 6⅜ × 4½ inches

In the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Among the myriad renderings of the Death of the Virgin, by painters and engravers, it is doubtful if any version is superior, so far as dramatic intensity is concerned, to Schongauer’s. As a composition, Dürer’s woodcut from the Life of the Virgin, is simpler and more “telling,” in that certain non-essentials have been eliminated; but could we well spare so beautiful a design as that of the candelabrum which, in Schongauer’s engraving, stands at the foot of the bed?

From the twelve plates of the Passion, each of which repays study, it is not easy to select one for reproduction. The Crucifixion, a subject which Schongauer engraved no less than six times, has a poignant charm; and for sheer beauty the Resurrection is among the most significant of the series. Pilate Washing His Hands has, however, a double interest. The faces of Christ’s tormentors and of the figures standing beside and to the left of Pilate’s throne, are strongly characterized, portrait-like heads, in marked contrast with the gentleness[Pg 36] of Christ, and the weak and vacillating Pilate. The enthroned Pilate later reappears as the Prophet Daniel in the series of Prophets and Sibyls, Florentine engravings in the Fine Manner.

We have already referred to St. John on the Island of Patmos by the Master E. S. A more significant contrast between the work of the earlier engraver and that of Schongauer could hardly be found. The Master E. S. gives a multiplicity of objects, animate and inanimate, charming and interesting in themselves, but distracting from the main purpose of the composition—witness the St. Christopher crossing the river in the middle distance, the lion and the terrified horse in the wood to the right, the swan in the stream to the left, and the life-like birds perched upon the castle-crowned cliff. Schongauer eliminates all these accessories. One vessel and two small boats alone break the calm expanse of the unruffled sea. Save for the two plants in the foreground (which betray the influence of the Master of the Playing Cards) the ground is simply treated and offers little to distract our attention from the seated figure of St. John, who faces to the left and gazes upwards at the Madonna and Child in glory. The eagle bears a strong family likeness to the same bird in the Design for a Paten by the Master E. S. Schongauer has here drawn a tree, not bare, as is his wont, [Pg 41]but adorned with foliage beautifully disposed and artistically treated, in marked contrast to the conventional and decorative manner of the Master E. S. and his predecessors.

MARTIN SCHONGAUER. ST. JOHN ON THE ISLAND OF PATMOS

Size of the original engraving, 6½ × 4⅝ inches

In the Kunsthalle, Hamburg

MARTIN SCHONGAUER. CHRIST APPEARING TO THE

MAGDALEN

Size of the original engraving, 6¼ × 6⅛ inches

In the Kunsthalle, Hamburg

MARTIN SCHONGAUER. VIRGIN SEATED IN A

COURTYARD

Size of the original engraving, 6¾ × 4⅞ inches

In the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

MARTIN SCHONGAUER. ANGEL OF THE ANNUNCIATION

Size of the original engraving, 6⅝ × 4½ inches

In the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The type of the Redeemer, which Schongauer has made so peculiarly his own, is nowhere seen to better advantage than in the two beautiful plates of the Baptism of Christ and Christ Appearing to the Magdalen. Max Geisberg acclaims the last-named as Schongauer’s most beautiful engraving. “Here, the contents of the composition have received an embodiment, the fervor, depth, and delicacy of which have never been surpassed in art.”[1] It can, however, share this high praise with the Virgin Seated in a Courtyard and the Angel of the Annunciation. For sheer beauty, these plates remain to this day not only unsurpassed, but unequalled. What quietude and restraint there is in the Virgin Seated in a Courtyard, the wall back of her discreetly bare, the grass indicated by a few small but significant strokes, while the branches of one little, leafless tree form an exquisite pattern against the untouched sky! By contrast one of Dürer’s technical masterpieces—the Virgin Seated by a City Wall—seems overworked and overloaded with needless accessories.

[1] Martin Schongauer. By Dr. Max Geisberg. The Print-Collector’s Quarterly. Vol. IV. April, 1914. p. 128.

[Pg 42]

The Angel of the Annunciation marks the culmination of Schongauer’s art and belongs to his most mature period. Everything not absolutely necessary for a clear presentation has been eliminated. A slight shadow upon the ground gives solidity to the figure. All else is blank. The art of simplification can hardly go further, and were one to be restricted to the choice of a single print by any of Dürer’s predecessors, one might wisely select the Angel of the Annunciation.

That Schongauer was equally interested in things mundane is convincingly proved by Peasants Going to Market, Goldsmith’s Apprentices Fighting, or The Miller. How well he has differentiated between the mother-ass, filled with maternal solicitude, and the woolly, stocky, and somewhat foolish little donkey which follows, while the miller with upraised staff urges her onward.

The Crozier and the Censer furnish unmistakable proof, were such needed, that as a goldsmith-designer, no less than as an engraver, Schongauer is entitled to the loftiest place in German art. They are masterpieces, alike in invention and in execution. His influence was not confined to his contemporaries, but can be traced in many ways, and in many media, long after his death. His School, however, produced no engraver worthy, for a moment, of comparison with him.

[Pg 43]

MARTIN SCHONGAUER. THE MILLER

Size of the original engraving, 3½ × 4⅞ inches

In the Albertina, Vienna

[Pg 44]

MARTIN SCHONGAUER. CENSER

Size of the original engraving, 11½ × 8¼ inches

[Pg 45]

The Master L Cz alone seems to have caught something of Schongauer’s spirit while, at the same time, preserving his own individuality. The face of the Redeemer in Christ Entering Jerusalem is reminiscent of the earlier engraver; and, among the Apostles to the left, two, at least, are taken, with slight modifications, from Schongauer’s Death of the Virgin.

Christ Tempted has a singular charm. The figure of Satan, realistically treated, is an interesting example of that passion for the grotesque from which even the greatest artists in the North seemed unable to shake themselves wholly free. The wood in the middle distance, to the left of Christ, evinces a close study of natural forms, while the landscape takes its place admirably in the composition. The excessive rarity of engravings by L Cz alone has prevented them from being appreciated at their true worth. They are original in composition, full of fantasy and charm. Even so universal an artist as Albrecht Dürer did not disdain to borrow, from Christ Tempted, the motive of the mountain goat gazing downward, which reappears, slightly modified, in Adam and Eve, his masterpiece of the year 1504.

[Pg 46]

ENGRAVERS AND ETCHERS

GERMAN ENGRAVING: FROM THE BEGINNINGS

TO MARTIN SCHONGAUER

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Le Peintre Graveur. By Adam Bartsch. 21 volumes. Vienna: 1803-1821. Volumes 6 and 10, Early German Engravers.

Les deux cents Incunables xylographiques du Département des Estampes. By Henri Bouchot. Volume 1, Text. Volume 2, Atlas (191 reproductions). Paris: Librairie Centrale des Beaux-Arts. 1903.

Geschichte und kritischer Katalog des deutschen, niederländischen und französischen Kupferstichs im XV. Jahrhundert. By Max Lehrs. Vienna: Gesellschaft für vervielfältigende Kunst. Volume 1. The Primitives. With portfolio of 114 reproductions on 43 plates. 1908. Volume 2. Master E. S. With portfolio of 237 reproductions on 92 plates. 1910.

Die ältesten deutschen Spielkarten des königlichen Kupferstich-cabinets zu Dresden. By Max Lehrs. 97 reproductions on 29 plates. Dresden: W. Hoffmann. 1885.

Katalog der im germanischen Museum befindlichen deutschen Kupferstiche des XV. Jahrhunderts. By Max Lehrs. 1 original engraving and 9 reproductions. Nürnberg. 1887.

Le Peintre-Graveur. By J. D. Passavant. 6 volumes. Leipzig: Rudolph Weigel. 1860-1864. Volumes 1 and 2, Early German Engravers.

Histoire de l’origine et des progrès de la gravure dans les Pays-Bas et en Allemagne, jusqu’à la fin du quinzième siècle. By Jules Renouvier. Brussels: M. Hayez. 1860.

Die Inkunabeln des Kupferstichs im Kgl. Kabinet zu München. By Wilhelm Schmidt. 32 reproductions. Munich. 1887.

Manuel de l’amateur de la gravure sur bois et sur métal au XVᵉ SIÈCLE. By Wilhelm Ludwig Schreiber. Volumes 1-4, Text. Volumes 6-8, Reproductions. Berlin: Albert Cohn, 1891-1900. (Vol. 4 in Leipzig: O. Harrassowitz.)

A Descriptive Catalogue of Early Prints in the British Museum. By William Hughes Willshire. 2 volumes. 22 reproductions. London: The Trustees. 1879-1883.

Master of the Playing Cards (flourished 1440-1450)

Das älteste gestochene deutsche Kartenspiel vom Meister der Spielkarten (vor 1446). By Max Geisberg. 68 reproductions on 33 plates. Strassburg: J. H. Ed. Heitz (Heitz & Mündel). 1905. (Studien zur deutschen Kunstgeschichte. Part 66.)

Master of the Gardens of Love (flourished 1445-1450)

Der Meister der Liebesgärten; ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des ältesten Kupferstichs in den Niederlanden. By Max Lehrs. 28 reproductions on 10 plates. Dresden: Bruno Schulze. 1893.

[Pg 49]Master E. S. (flourished 1450-1470)

Der Meister E. S.; sein Name, seine Heimat, und sein Ende. By Peter P. Albert. 20 reproductions on 16 plates. Strassburg: J. H. Ed-Heitz (Heitz & Mündel). 1911. (Studien zur deutschen Kunstgeschichte. Part 137.)

The Master E. S. and the “Ars Moriendi”; A Chapter in the History of Engraving During the Fifteenth Century. By Lionel Cust. 46 reproductions. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1898.

Die Anfänge des deutschen Kupferstiches und der Meister E. S. By Max Geisberg. 121 reproductions on 71 plates. Leipzig: Klinkhardt & Biermann. 1909. (Meister der Graphik. Vol. 2.)

Geschichte und kritischer Katalog des deutschen, niederländischen und französischen Kupferstichs im XV. Jahrhundert. By Max Lehrs. Vienna: Gesellschaft für vervielfältigende Kunst. 1908-1910. Volume 2. Master E. S. With portfolio of 237 reproductions on 92 plates.

The Playing Cards of the Master E. S. of 1466. Edited by Max Lehrs. 45 reproductions. London: Asher & Co. 1892. (International Chalcographical Society. Extraordinary Publication. Vol. 1.)

Schongauer, Martin (1445(?)-1491)

Zwei datierte Zeichnungen Martin Schongauers. By Sidney Calvin. 2 illustrations. Jahrbuch der königlichen preussischen Kunstsammlungen, Vol. 6, pp. 69-74. Berlin. 1885.

Martin Schongauer’s Kupferstiche. By Max G. Friedländer. 5 illustrations. Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst, Vol. 26, pp. 105-112. Leipzig. 1915.

Martin Schongauer. By Max Geisberg. 14 illustrations. The Print-Collector’s Quarterly, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 102-129. Boston. 1914.

Martin Schongauer; Nachbildungen seiner Kupferstiche. Edited by Max Lehrs. 115 reproductions on 72 plates. Berlin: Bruno Cassirer. 1914. (Graphische Gesellschaft. Extraordinary Publication 5.)

Schongauerstudien. By Wilhelm Lübke. 3 illustrations. Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst, Vol. 16, pp. 74-86. Leipzig. 1881.

Schongauer und der Meister des Bartholomäus. By L. Scheibler. Repertorium für Kunstwissenschaft, Vol. 7, pp. 31-68. Berlin and Stuttgart. 1884.

Martin Schongauer als Kupferstecher. By Woldemar von Seidlitz. Repertorium für Kunstwissenschaft, Vol. 7, pp. 169-182. Berlin and Stuttgart. 1884.

Martin Schongauer als Kupferstecher. By Hans Wendland. 32 reproductions. Berlin: Edmund Meyer. 1907.

Martin Schongauer. Eine kritische Untersuchung seines Lebens und seiner Werke nebst einem chronologischen Verzeichnisse seiner Kupferstiche. By Alfred von Wurzbach. Vienna: Manz’sche K. K. Hofverlags und Universitäts Buchhandlung. 1880.

[Pg 50]

Master of the Banderoles (flourished c. 1464)

Der Meister mit den Bandrollen; ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des ältesten Kupferstichs in Deutschland. By Max Lehrs. 19 reproductions on 7 plates. Dresden: W. Hoffmann. 1886.

Meckenem, Israhel van (c. 1440-1503)

Der Meister der Berliner Passion und Israhel van Meckenem. By Max Geisberg. 6 reproductions. Strassburg: J. H. Ed. Heitz (Heitz & Mündel). 1903. (Studien zur deutschen Kunstgeschichte. Part 42.)

Verzeichnis der Kupferstiche Israhels van Meckenem. By Max Geisberg. 11 reproductions on 9 plates. Strassburg: J. H. Ed. Heitz (Heitz & Mündel). 1905. (Studien zur deutschen Kunstgeschichte. Part 58.)

Master  (flourished c. 1470)

(flourished c. 1470)

Der Meister  ; ein Kupferstecher der Zeit Karls des Kühnen.

By Max Lehrs. 77 reproductions on 31 plates. Dresden: W. Hoffmann.

1895.

; ein Kupferstecher der Zeit Karls des Kühnen.

By Max Lehrs. 77 reproductions on 31 plates. Dresden: W. Hoffmann.

1895.

Stoss, Veit (c. 1450-c. 1533)

Veit Stoss; Nachbildungen seiner Kupferstiche. Edited by Engelbert Baumeister. 13 reproductions. Berlin: Bruno Cassirer. 1913. (Graphische Gesellschaft. Publication 17.)

Olmütz, Wenzel von (flourished 1480-1500)

Wenzel von Olmütz. By Max Lehrs. 22 reproductions on 11 plates. Dresden: W. Hoffmann. 1889 (In German.)

[Pg 51]

MASTER L Cz. CHRIST TEMPTED

Size of the original engraving 8¾ × 6⅝ inches

MASTER L Cz. CHRIST ENTERING JERUSALEM

Size of the original engraving, 8⅞ × 7 inches

In the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

ENGRAVING in Italy differs, in many essentials, from the art as practised in Germany. Germany may claim priority in point of time, but it is doubtful whether the Florentines—for in Florence, and among the goldsmiths, the art took its rise in Italy—in the beginning were influenced by, or even acquainted with, the work of their northern contemporaries. In Germany the designer and the engraver were one, and some of the greatest masters embodied their finest conceptions in their prints. We may truly say that the world-wide reputation which Dürer and Schongauer have enjoyed for four centuries and more, rests almost entirely upon their engraved, rather than upon their painted, work.

In Italy it was otherwise. There, with a few signal exceptions, engraving was used merely as a convenient method of multiplying an existing design. It may be that we owe to this fact both the color of the ink used in these early Florentine prints, and the method of taking impressions. This would seem, in many cases, to be by rubbing rather than by the[Pg 52] use of the roller press, which appears to have been known and used in the North substantially from the very beginning. The Florentine, aiming to duplicate a drawing in silver-point or wash, would naturally endeavor to approximate the color of his original. Consequently we do not find the lustrous black impressions, strongly printed, which are the prize of the collector of early German engravings.

Vasari’s story of the invention of engraving by Maso Finiguerra (1426-1464) was long ago disproved, and for a time it seemed as though Finiguerra and his work were likely to be consigned to that limbo of the legendary from which Baldini—at one time accredited with many prints—is only just now emerging. Yet Finiguerra, although not the “inventor” of the art, is, beyond peradventure, the most important influence in early Italian engraving, not only on account of his own work on copper, but still more through the Picture-Chronicle, which served as an inspiration to the artists working in his School and continuing his tradition after his death. So that Vasari’s tale, though not accurate in the matter of fact, was veracious in the larger sense.

ANONYMOUS FLORENTINE, XV CENTURY. PROFILE

PORTRAIT OF A LADY

Size of the original engraving, 8⅞ × 5⅝ inches

In the Royal Print Room, Berlin

ANONYMOUS FLORENTINE, XV CENTURY. WILD ANIMALS HUNTING

AND FIGHTING

Size of the original engraving, 10⅛ × 14¾ inches

In the British Museum

The Picture-Chronicle is a book of drawings illustrating the History of the World, and evidently proceeds from the hand and workshop of a Florentine [Pg 55]goldsmith-engraver of about 1460. It was acquired by the British Museum from Mr. Ruskin in 1888. The drawings are in pen and ink and wash, often reinforced with open pen-shading like that imitated later by the Broad Manner engravers. At its best the work has the true early Renaissance combination of archaic strength with attractive naiveté—the ornamental detail carried out with a masterly power of pen, and with the patient delight of one who is by instinct and training above all things a jeweler.

Finiguerra’s fame as the leading worker in niello was firmly established by 1450; and although we cannot assign certainly any engraving by him to a date earlier than 1460, there is a group of Florentine primitives which may be placed between the years 1450 and 1460, thus antedating Finiguerra’s first plate by about ten years. The most beautiful of these early prints in conception, and the purest in execution, is the Profile Portrait of a Lady, a single impression of which has come down to us and is now in Berlin. In style it recalls the paintings of Piero della Francesca, Verrocchio, Uccello, or Pollaiuolo, and although it would be unwise to attribute it to any known master, there is a sensitive quality in the drawing, and a restraint, which differentiates it from any other print of this period.

Among the engravings which may be by Finiguerra [Pg 56]himself, one of the most interesting is the plate of Wild Animals Hunting and Fighting, wherein we see a number of motives taken directly from the Picture-Chronicle—motives which reappear again and again in works undoubtedly by other hands. This print, as also the Encounter of a Hunting Party with a Family of Wild Folk, is unique. In the last-named we see a number of motives repeated from the Wild Animals Hunting and Fighting: such as the boar being pulled down by two hounds, the hound chasing a hare, in the upper right corner; and the dog, slightly to the left, devouring the entrails of yet another hare.

The Road to Calvary and the Crucifixion is a far more elaborate and important composition, and in this engraving we see that which is especially noteworthy in the Judgment Hall of Pilate—the largest and most important of all the Fine Manner prints—the goldsmith’s love of ornament. In the Judgment Hall of Pilate the head-dresses, and especially the armor, are highly elaborate, while the architecture itself is overlaid with ornate decoration directly drawn from the Picture-Chronicle. In the only known impression the plate seems to have been re-worked, in the Broad Manner, by a later hand.

ANONYMOUS FLORENTINE, XV CENTURY. TRIUMPHAL PROCESSION OF BACCHUS

AND ARIADNE

Size of the original engraving, 8⅛ × 22 inches

In the British Museum

(If supported click figure to enlarge.)

ANONYMOUS FLORENTINE, XV CENTURY. JUPITER

Size of the original engraving, 12⅝ × 8½ inches

In the British Museum

Somewhat later in date, by an engraver of the Finiguerra School, is the Triumphal Procession of [Pg 59]Bacchus and Ariadne, the most joyous of all Florentine engravings. The original design was attributed at one time to Botticelli; and although, as Herbert P. Horne has shown, it cannot be by this master, it is similar in style to his compositions. Whatever the immediate original, it shows marked traces of classical influences, and its motive is directly derived from antique sculpture—a sarcophagus in all probability. “The splendid design has suffered not only from the feebleness of the engraving, but also from the florid manner in which the engraver has exaggerated some of the decorative details and added others.... In spite of the feebleness of its execution it remains an incomparably greater work of art than any other print in the Fine Manner.”[2]

[2] Sandro Botticelli. By Herbert P. Horne. London: George Bell & Sons. 1908. p. 84.

The Fine Manner, in which all of the engravings hitherto mentioned are executed, owes its name to the method employed. The engraver has incised his outlines upon the plate—probably unbeaten copper or some even softer metal—and for his shading has employed a system of delicate strokes, laid close to one another and overlaid with two, and, at times, three, sets of cross-hatching. Such engravings, when printed, as is usually the case, in a greenish or grayish ink, give a result similar to a[Pg 60] wash drawing. In the Broad Manner the style of engraving is based upon that of pen drawing, with open, diagonal shade strokes and without cross-hatching. The Broad Manner was finally developed by Pollaiuolo and Mantegna, who modified it by a series of delicate lines laid at an acute angle to the heavier shadings, blending the main lines into a harmonious whole.

“None of the sciences that descended from antiquity,” writes Arthur M. Hind,[3] “possessed a firmer hold on the popular imagination of the Middle Ages than that of Astrology. That science took as its foundation the ancient conception of the universe, with the earth as the centre round which all the heavenly bodies revolved in the space of a day and a night. Encircling the earth were the successive spheres of water, air, fire, the seven planets (Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn), the firmament with the constellations (the cœlum crystallinum), and the Primum Mobile. To each of the planets were ascribed attributes according to the traditional character of the deity whose name it bore, and these attributes were regarded as transmissible under certain conditions to mankind. The influence of the planets depended on their position in the heavens in respect[Pg 61] of the various constellations, with which each had different relations. Each planet had what was called its ‘house’ in one of the constellations, and according to its position relative to these was said to be in the ‘ascendant’ or ‘descendant’. In regard to individual human beings the date of birth was the decisive point, and the degree of influence transmitted from the planets depended on the respective degree of ‘ascendance’ or ‘descendance’ at the particular epoch.”

[3] Catalogue of Early Italian Engravings ... in the British Museum. By Arthur Mayger Hind. London. 1910. pp. 49-50.

The planets and their influences afforded subject matter for many artists of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and the finest and most important series is that engraved in the Fine Manner by an artist of the Finiguerra School, who has, as usual, drawn directly upon the Picture-Chronicle for his ornamental accessories. We can reproduce two only from the set of seven—Jupiter and Mercury. The inscription beneath Jupiter reads, in part, as follows: “Jupiter is a male planet in the sixth sphere, warm and moist, temperate by nature, and of gentle disposition; he is sanguine, cheerful, liberal, eloquent; he loves fine clothes, is handsome and ruddy of aspect, and looks toward the Earth. Tin is his metal; his days are Sunday and Thursday, with the first, eighth, fifteenth and twenty-fourth hours; his night is that of Wednesday; he is friendly to the Moon, hostile to Mars....”[Pg 62] In the landscape we again meet with several of the stock Finiguerra motives, the muzzled hounds, the dog chasing the hare, etc. Of especial interest is the group at the right—“wing-bearing Dante who flew through Hell, through the starry Heavens and o’er the intermediate hill of Purgatory beneath the beauteous brows of Beatrice; and Petrarch too, who tells again the tale of Cupid’s triumph; and the man who, in ten days, portrays a hundred stories (Boccaccio).”

Mercury—“eloquent and inventive ... slender of figure, tall and well grown, with delicate lips. Quicksilver is his metal”—sets forth various applications of the arts and sciences. Especially interesting is the goldsmith’s shop at the left, where we see an engraver actually at work upon a plate. The goldsmith is seated, his apprentice behind him, as a prospective purchaser examines a richly ornamented vessel. In the foreground a sculptor is chiseling his statue, while, standing above, on a scaffolding, a fresco painter is actively at work—a record of the Florence of 1460 or thereabouts, full of interest for us.

ANONYMOUS FLORENTINE, XV CENTURY. MERCURY

Size of the original engraving, 12¾ × 8½ inches

In the British Museum

ANONYMOUS FLORENTINE, XV CENTURY. LADY

WITH A UNICORN

Size of the original engraving, 6¼ inches in diameter

In the British Museum

To a slightly later date, 1465-1470, belong the group of Fine Manner prints, known as the Otto Prints, also emanating from the Finiguerra workshop. They are not a series, in any true sense, and owe their name—also their fortunate preservation—to the accidental circumstance[Pg 65] of their having belonged at one time to Peter Ernst Otto, a merchant and collector of Leipzig. The purpose served by these prints—twenty-four in all—was the decoration of box lids, either as patterns to be copied, in the case of metal caskets, or to be colored and pasted on the lids of wooden boxes. The escutcheons are usually left blank, to be filled in by hand with the device of the donor or the recipient, or with some appropriate sentiment.

In the print entitled Two Heads in Medallions and Two Hunting Scenes we again meet with the animal motives taken from the Picture-Chronicle. One of the most charming is the Lady with a Unicorn (Chastity), in its arrangement suggestive of the beautiful drawing by Leonardo da Vinci in the British Museum; and its symbolic meaning is doubtless the same. “The unicorn,” writes Leonardo in his “Bestiarius,” “is distinguished for lack of moderation and self-control. His passionate love of young women makes him entirely forget his shyness and ferocity. Oblivious of all dangers, he comes straight to the seated maiden and falling asleep in her lap is then caught by the hunter.” The ermine, likewise a sign of chastity, is to be seen at the right, gazing upward into Marietta’s face.

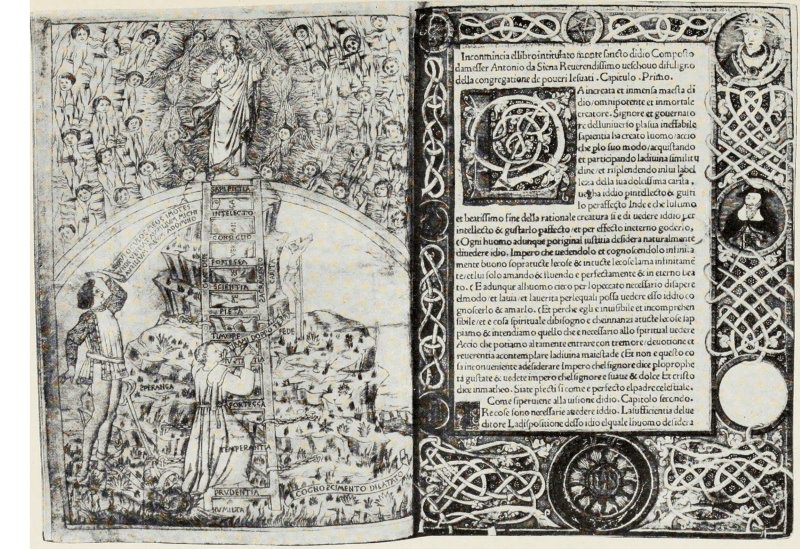

Still later than the Otto prints, and greatly inferior[Pg 66] to them in execution, are the three illustrations for Il Monte Sancto di Dio, of 1477; and the nineteen engravings for Dante’s Divina Commedia, with Landino’s Commentary, of 1481. Il Monte Sancto di Dio is the first book in Italy or in Germany in which there appear illustrations from engraved plates printed on the text page. This entailed much additional labor, and was soon discontinued in favor of the wood-block, which could be printed simultaneously with the letterpress, and was not taken up again until nearly the end of the sixteenth century.

Alike by tradition and internal evidence, Botticelli is unquestionably the author of the Dante designs; but no artist has been suggested as the probable designer of the three illustrations for Il Monte Sancto di Dio. In the first illustration the costume and general attitude of the young gallant to the left are strongly reminiscent of the Otto prints. The lower portion of the plate shows all the characteristics of the Fine Manner, but the angel heads are treated in a simpler and more open linear method. The Christian’s Ascent to the Glory of Paradise is allegorically represented by a ladder placed firmly in the ground of widespread Knowledge and Humility, and reaching up to the triple mountain of Faith, Hope, and Charity, on the summit of which stands the Saviour. This ladder is called Perseverance,[Pg 69] one of its sides being Prayer, the other Sacrament. It has eleven steps: Prudence, Temperance, Fortitude, Justice, etc.

ANONYMOUS FLORENTINE, XV CENTURY. THE CHRISTIAN’S ASCENT TO

THE GLORY OF PARADISE. FROM “IL MONTE SANCTO DI DIO,”

FLORENCE, 1477

Size of the original engraving, 9⅞ × 7 inches

In the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University

(If supported click figure to enlarge.)

ANONYMOUS FLORENTINE, XV CENTURY. DANTE AND VIRGIL WITH THE VISION

OF BEATRICE. FROM THE “DIVINA COMMEDIA,” FLORENCE, 1481

Size of the original engraving, 3½ × 6⅞ inches

In the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The second illustration depicts the glory of Paradise; the third the punishment of Hell, the main motives of the last-named being adapted from the fresco attributed to Orcagna, in the Campo Santo at Pisa.

In the illustrations to the Divina Commedia, of 1481, there is little left of the beauty which the original designs must have possessed. They are, indeed, “disguised into puerility by the feebleness of the engraver”; but, none the less, they remain, with the exception of Botticelli’s superb series of drawings on vellum, in Berlin and in the Vatican, unquestionably the best, one might say the only, satisfactory illustrations of Dante’s text. No known copy contains more than the first three engravings printed directly upon the page itself. In every other case, where a greater number of illustrations appear, they are printed separately and pasted in place, indicating the difficulty experienced by the Renaissance printer in making his plates register with the letterpress.

The first print of the series shows Dante lost in the wood, emerging therefrom, and his meeting with Virgil—three subjects on a single plate. The second represents Dante and Virgil with the Vision[Pg 70] of Beatrice. Dante and Virgil are seen twice—first to the left, where Dante doubts whether to follow the guidance of Virgil further, and again on the slope of the hill to the right, where Virgil relates how the vision of Beatrice appeared to him. Near the summit of the rocky mountain is seen the entrance to Hell.

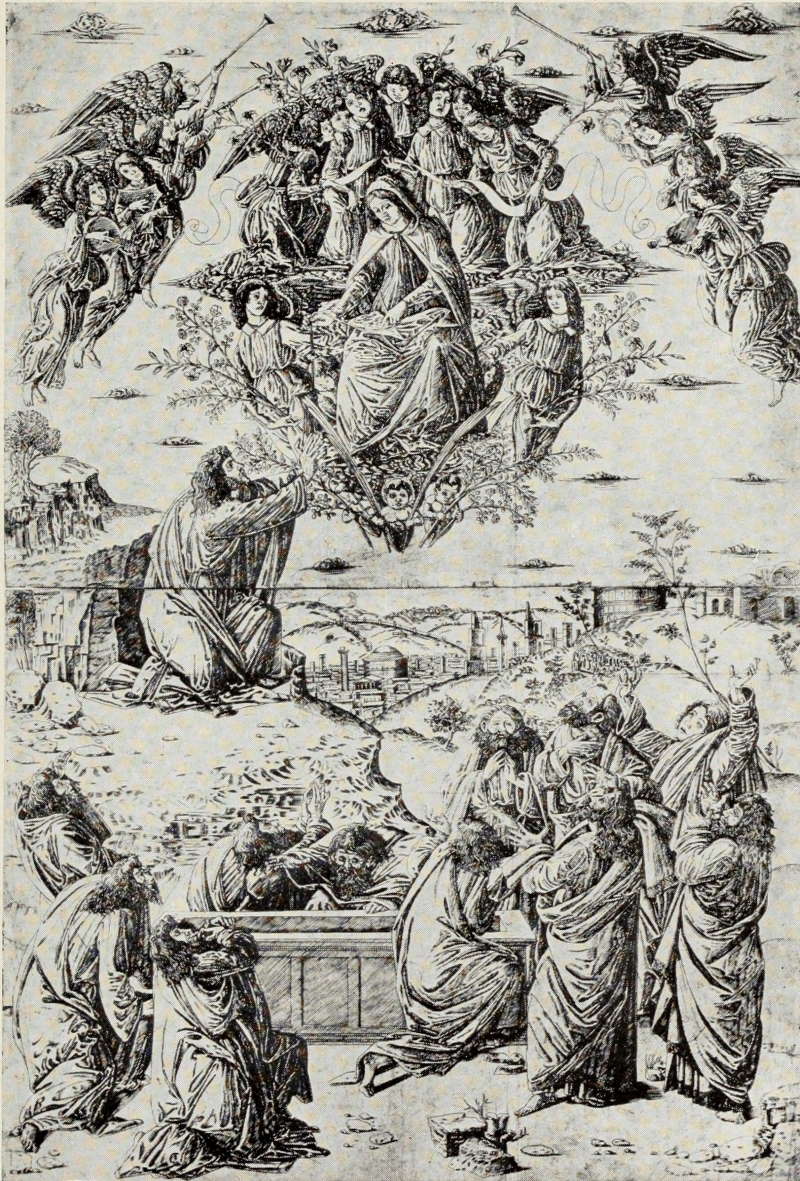

“Of the extant engravings in the Broad Manner, unquestionably the most remarkable is the large print on two sheets of the Assumption of the Virgin, after Botticelli. The original design [no longer known to exist], whether drawing or painting, from which this engraving was taken, must have been among the grandest and most vigorous works of the last period of Botticelli’s art. The large and rugged treatment of the figures of the apostles, their strange mane-like hair and beards, their fervent and agitated gestures and attitudes, lend to this part of the design a forcible and primitive character, which recalls, though largely, perhaps, in an accidental fashion, the grand and impressive art of Andrea del Castagno. Not less vigorous in conception, but of greater beauty of form and movement, is the figure of the Virgin, and the motive and arrangement of the angels who form a ‘mandorla’ around her are among the most lovely and imaginative of the many inventions of the kind[Pg 73] which Botticelli has left us.”[4] In the distant valley is a view of Rome showing the Pantheon, the Column of Trajan, the Colosseum, and other buildings.

[4] Sandro Botticelli. By Herbert P. Horne. London: George Bell & Sons. 1908. p. 289.

ANONYMOUS FLORENTINE, XV CENTURY. ASSUMPTION

OF THE VIRGIN (After Botticelli)

Size of the original engraving, 32⅝ × 22¼ inches

In the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

ANONYMOUS FLORENTINE, XV CENTURY. TRIUMPH OF

LOVE. FROM THE TRIUMPHS OF PETRARCH.

Size of the original engraving, 10⅜ × 6¾ inches

In the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

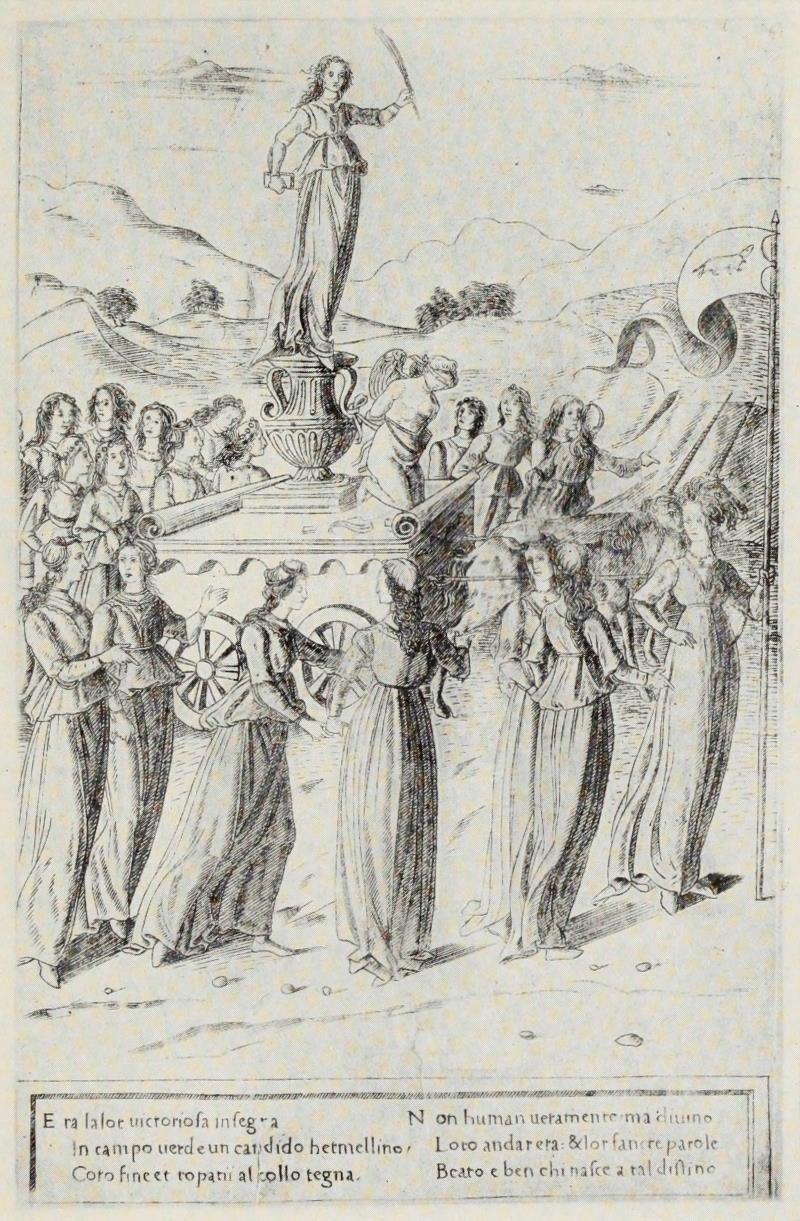

If the Assumption of the Virgin is the noblest print in the Broad Manner, the Triumphs of Petrarch—a set of six prints—may be said to possess the greatest charm, not less by its subject than by its treatment. Petrarch first saw Laura on April 6, 1327, in the Church of Santa Clara at Avignon, and “in the same city, on the same 6th day of the same month of April, in the year 1348, the bright light of her life was taken away from the light of this earth.” The poet’s aim in composing these Trionfi is the same which he proposed to himself in the Canzoniere: namely, “to return in thought, from time to time, now to the beginning, now to the progress, and now to the end of his passion, taking by the way frequent opportunities of rendering praise and honor to the single and exalted object of his love. To reach this aim he devised a description of man in his various conditions of life, wherein he might naturally find occasion to speak of himself and of his Laura.

“Man in his first stage of youth is the slave of appetites, which may all be included under the generic name of Love, or Self-Love. But as he[Pg 74] gains understanding, he sees the impropriety of such a condition, so that he strives advisedly against those appetites and overcomes them by means of Chastity, that is, by denying himself the opportunity of satisfying them. Amid these struggles and victories Death overtakes him and makes victors and vanquished equal by taking them all out of the world. Nevertheless, it has no power to destroy the memory of a man, who by illustrious and honorable deeds seeks to survive his own death. Such a man truly lives through a long course of ages by means of his Fame. But Time at length obliterates all memory of him, and he finds, in the last resort, that his only sure hope of living forever is by joy in God and by partaking with God in his blessed Eternity.

“Thus Love triumphs over man, Chastity over Love, and Death over both alike; Fame triumphs over Death, Time over Fame, and Eternity over Time.”[5]

[5] Le Rime di Francesco Petrarca con l’interpretazione di Giacomo Leopardi ... e gli argomenti di A. Marsand. Florence. 1839. p. 866. Translation in, Petrarch: His Life and Times. By H. C. Hollway-Calthrop. London. 1907. pp. 41-42.

With the exception of the first plate, The Triumph of Love, none of these engravings illustrates, in any strict sense of the word, the text of Petrarch’s poem. It is the spirit which the engraver has interpreted. Who may have been the designer [Pg 77]we know not, but they show certain affinities to the work of Pesellino and Baldovinetti.

ANONYMOUS FLORENTINE, XV CENTURY. TRIUMPH OF

CHASTITY. FROM THE TRIUMPHS OF PETRARCH

Size of the original engraving, 10 × 6⅜ inches

In the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University

ANONYMOUS FLORENTINE, XV CENTURY. LIBYAN SIBYL

Size of the original engraving, 7 × 4¼ inches

In the British Museum

In the first plate, Cupid, the blind archer, with flame-tipped arrow, is poised upon a ball rising from a flaming vase, the base of which, in its turn, rests upon flame. Jupiter(?), chained, is seated in the front of the car, while Samson, bearing a column, walks upon the further side. Four prancing steeds draw the car; behind, Love’s victims follow in endless procession. In the second plate, Chastity stands upon an urn; in front of her kneels Cupid, still blindfolded, with his broken arrow beside him. Two unicorns, symbols of chastity, draw the car, while upon the banner borne by the maiden at the extreme right there appears the symbolic ermine. Then follow in order the Triumphs of Death, of Fame, of Time, and of Eternity.

This series of illustrations reappears, somewhat modified and simplified, in the form of woodcuts, in the editions of the Trionfi published in Venice in 1488, 1490, 1492, and in Florence in 1499.

We have already referred to the Evangelists and Apostles engraved by the German, Master E. S. of 1466. It is from him that the anonymous Florentine engraver borrowed his figures, in many cases leaving the form of the drapery unchanged but enriching it with elaborate designs in the manner of Finiguerra. The Prophet Ezekiel is thus compounded[Pg 78] of St. John and St. Peter, while Amos is copied in reverse from St. Paul. The seated figure of Daniel, in its turn, is derived from Martin Schongauer’s engraving, Christ Before Pilate, but the throne upon which he is seated is strongly reminiscent of the Picture-Chronicle, and likewise recalls Botticelli’s early painting of Fortitude. The Tiburtine Sibyl is derived from St. Matthew, who, in changing his position, has likewise changed his sex. The precedent thus established has been followed by St. John, transformed into the Libyan Sibyl in the Fine Manner, with the addition of a flying veil, to the right, copied from the Woman with the Escutcheon, also by the Master E. S. In the Broad Manner print the figure of this Sibyl gains in dignity by the elimination of much superfluous ornament upon her outer garment, and from the fact that she now sits in a more upright posture, the Fine Manner print still suggesting the crouching attitude of its Northern prototype. It is to the influence, if not to the hand, of Botticelli that such improvement is most likely due.

The twenty-four Prophets and the twelve Sibyls, engraved both in the Fine and in the Broad Manner of the Finiguerra School, are individually and collectively among the most delightful productions of Italian art. It was doubtless as illustrations of mystery plays or pageants in Florence that this[Pg 81] series of engravings was designed, and we are able to reconstruct from the Triumphs of Petrarch, and from these prints, a Florentine street pageant at its loveliest.

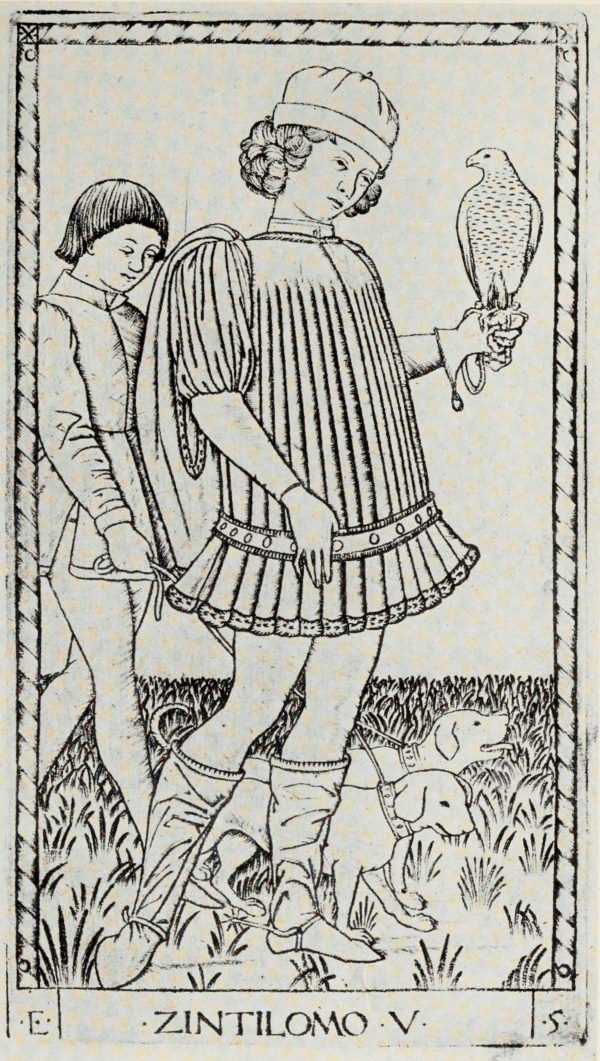

ANONYMOUS NORTH ITALIAN, XV CENTURY. THE

GENTLEMAN. FROM THE TAROCCHI PRINTS

(E Series)

Size of the original engraving, 7⅛ × 4 inches

In the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

ANONYMOUS NORTH ITALIAN, XV CENTURY. CLIO.

FROM THE TAROCCHI PRINTS (S Series)

Size of the original engraving, 7⅛ × 4 inches

In the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

However great their beauty and however strong the fascination which they exert, they have a rival in the series of fifty instructive prints, which, for many years, were miscalled the Tarocchi Cards of Mantegna. Tarocchi cards they are not, and of Mantegna’s influence, direct or indirect, there would seem to be no trace whatsoever. They are of North Italian origin and are the work, in all probability, of some anonymous Venetian engraver, working from Venetian or Ferrarese originals, about 1465—contemporary, therefore, with the Florentine engravings of the Prophets and Sibyls. Forming, apparently, a pictorial cyclopædia of the mediæval universe, with its systematic classification of the various powers of Heaven and Earth, they divide themselves into five groups of ten cards each. First we have the ranks and conditions of men from Beggar to Pope; next Apollo and the nine Muses; then the Liberal Arts, with the addition of Poetry, Philosophy, and Theology, in order to make up the ten; next the Seven Virtues, the set being brought up to the required number by the addition of Chronico, the genius of Time, Cosmico, the genius of the Universe, and Iliaco, the genius[Pg 82] of the Sun. The fifth group is based on the Seven Planets, together with the Sphere of the Fixed Stars and the Primum Mobile, which imparts its own revolving motion to all the spheres within it; and enfolding all the Empyrean Sphere, the abode of Heavenly Wisdom.

Much wisdom and many words have been expended upon the still unsolved riddle as to which of the two sets, known respectively as the E series and the S series (from the letters which appear in the lower left-hand corners of the ten cards of the Sorts and Conditions of Men) may claim priority of date. Both series are in the Fine Manner, the outlines clearly defined, the shadings and modelling indicated with delicate burin strokes, crossed and re-crossed so as to give a tonal effect. These delicate strokes soon wore out in printing, and the structural lines of the figures then emerge in all their beauty. It may seem absurd that one should admire impressions from plates obviously worn, but the critic would do well to suspend his condemnation, since the Tarocchi Prints present many and manifold forms of beauty—in the early impressions a delicate and bloom-like quality; in certain somewhat later proofs, a charm of line which recalls the art of the Far East.

ANONYMOUS NORTH ITALIAN, XV CENTURY. THE SUN.

FROM THE TAROCCHI PRINTS (E Series)

Size of the original engraving, 7⅛ × 4 inches

In the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

ANONYMOUS NORTH ITALIAN, XV CENTURY. ANGEL OF

THE EIGHTH SPHERE. FROM THE TAROCCHI PRINTS

(E Series)

Size of the original engraving, 7⅛ × 4 inches

In the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Gentleman is the fifth in order in the first group of the Sorts and Conditions of Men, and is[Pg 85] from the so-called E series (claimed by Sir Sidney Colvin and Mr. Arthur M. Hind, of the British Museum, to be the earlier of the two sets). The sequence runs: (1) The Beggar, (2) The Servant, (3) The Artisan, (4) The Merchant, (5) The Gentleman, (6) The Knight, (7) The Doge, (8) The King, (9) The Emperor, (10) The Pope.

Clio is the ninth of the Muses and is from the S series (placed first in point of time, by Kristeller, and about ten years later than the E series, by the British Museum authorities).

The Sun naturally finds his place in the group of Planets and Spheres. There is a delightful and childish touch in the way in which Phæton is pictured as a little boy falling headlong into the river Po, which conveniently flows immediately beneath him. To this group belongs likewise the Angel of the Eighth Sphere, the Sphere of the Fixed Stars, one of the loveliest prints in the entire set, both in arrangement and in execution.

Nothing could be in greater contrast to the gracefulness of such a print as the above than the Battle of Naked Men by Antonio Pollaiuolo, “the stupendous Florentine”—if one may borrow Dante’s title; but, for the moment, we will hold Pollaiuolo and his one engraving in reserve while we glance at the work of Christofano Robetta, who, born in Florence in 1462, was consequently the junior of[Pg 86] Pollaiuolo by thirty years. As an engraver, Robetta is inferior to the anonymous master to whom we owe the E series of the Tarocchi prints. His style is somewhat dry, and the individual lines are lacking in beauty; but his plates have that indefinable and indescribable fascination and charm which is the peculiar possession of Italian engraving and of the Florentine masters in particular. The shaping influences which determined his choice and treatment of subject are Botticelli, and, in a much larger measure, Filippino Lippi, though only in a few cases can he be shown to have worked directly from that painter’s designs. The Adoration of the Magi is obviously inspired by Filippino Lippi’s painting in the Uffizi, though whether Robetta actually worked from the painting itself, or, as seems more probable, translated one of Filippino’s drawings, is an interesting question. The fact that the engraving is in reverse of the painting proves nothing; but there are so many points of difference between them—notably the introduction of the charming group of three angels above the Virgin and Child—that one can hardly think Robetta would have needlessly made so many and important modifications of the painting itself, if a drawing had been available. It is interesting, though of minor importance, that the hat of the King to the right, which lies on the ground, is copied in[Pg 89] reverse from Schongauer’s Adoration, and that the Allegory of the Power of Love, one of Robetta’s most charming subjects, is engraved upon the reverse side of the plate of the Adoration of the Magi, the copper-plate itself being now in the Print Room of the British Museum. Whether the Allegory of Abundance is entirely Robetta’s, or whether the design was suggested by another master’s painting or drawing, can be only a matter of conjecture. It shows, however, so many of the characteristics which we associate with his work that we may give him the benefit of the doubt and consider him as its “onlie begetter.”

CRISTOFANO ROBETTA. ADORATION OF THE MAGI

Size of the original engraving, 11⅝ × 11 inches

In the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

ANTONIO POLLAIUOLO. BATTLE OF NAKED MEN

Size of the original engraving, 15¾ × 23½ inches

In the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

(If supported click figure to enlarge.)

Hercules and the Hydra and Hercules and Antæus show so markedly the influence of Pollaiuolo that we may conclude them to have been taken from the two small panels in the Uffizi; though, in the case of the first named, Pollaiuolo’s original sketch, now in the British Museum, may also have served Robetta.

Whether Pollaiuolo based his technical method upon that of Mantegna and his School, or whether Mantegna’s own engravings were inspired by his Florentine contemporary, is an interesting, but thus far unanswered, question. Pollaiuolo’s one print, the Battle of Naked Men, is engraved in the Broad Manner, somewhat modified by the use of a light stroke laid at an acute angle between the[Pg 90] parallels. The outlines of the figures are strongly incised; while the treatment of the background lends color to the supposition that, in his youth, Pollaiuolo engraved in niello, as well as furnished designs to be executed by Finiguerra and his School. In this masterpiece the artist has summed up his knowledge of the human form, and has expressed, in a more convincing and vigorous measure than has any other engraver in the history of the art, the strain and stress of violent motion and the fury of combat.

“What is it,” asks Bernhard Berenson, “that makes us return to this sheet with ever-renewed, ever-increased pleasure? Surely it is not the hideous faces of most of the figures and their scarcely less hideous bodies. Nor is it the pattern as decorative design, which is of great beauty indeed, but not at all in proportion to the spell exerted upon us. Least of all is it—for most of us—an interest in the technique or history of engraving. No, the pleasure we take in these savagely battling forms arises from their power to directly communicate life, to immensely heighten our sense of vitality. Look at the combatant prostrate on the ground and his assailant, bending over, each intent on stabbing the other. See how the prostrate man plants his foot on the thigh of his enemy and note the tremendous energy he exerts to keep off the[Pg 91] foe, who, turning as upon a pivot, with his grip on the other’s head, exerts no less force to keep the advantage gained. The significance of all these muscular strains and pressures is so rendered that we cannot help realizing them; we imagine ourselves imitating all the movements and exerting the force required for them—and all without the least effort on our side. If all this without moving a muscle, what should we feel if we too had exerted ourselves? And thus while under the spell of this illusion—this hyperæsthesia not bought with drugs and not paid for with cheques drawn on our vitality—we feel as if the elixir of life, not our own sluggish blood, were coursing through our veins.”[6]

[6] Florentine Painters of the Renaissance. By Bernhard Berenson. New York: Putnam’s Sons. 1899. pp. 54-55.

Pollaiuolo is the one great original engraver Florence produced, and with him we bring to a close our all too brief study of Florentine engraving.

[Pg 92]

ITALIAN ENGRAVING: THE FLORENTINES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Le Peintre Graveur. By Adam Bartsch. 21 volumes. Vienna: 1803-1821. Volume 13, Early Italian Engravers.

The Drawings of the Florentine Painters. By Bernhard Berenson. 2 volumes. 180 illustrations. New York: E. P. Dutton & Company. 1903.

Catalogue of Early Italian Engravings Preserved in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum. By Arthur Mayger Hind. Edited by Sidney Colvin. 20 illustrations. London: The Trustees. 1910.

———. Illustrations to the Catalogue ... 198 plates. London: The Trustees. 1909.

Some Early Italian Engravers Before the Time of Marcantonio. By Arthur Mayger Hind. 22 illustrations. The Print-Collector’s Quarterly, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 253-289. Boston. 1912.

Sulle origini dell’incisione in rame in Italia. By Paul Kristeller. 4 illustrations. Archivio Storico dell’Arte, Vol. 6, p. 391-400. Rome. 1893.

Le Peintre-Graveur. By J. D. Passavant. 6 volumes. Leipzig: Rudolph Weigel. 1860-1864. Volumes 1 and 5, Early Italian Engravers.

Des Types et des manières des maitres graveurs ... en Italie, en Allemagne, dans les Pays-Bas et en France. By Jules Renouvier. 2 volumes. Montpellier: Boehm, 1853-1855. Volume 1, Engravers of the Fifteenth Century.

Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. By Giorgio Vasari. Translated by Mrs. Jonathan Foster. With commentary by J. P. Richter. 6 volumes. London: George Bell & Sons. 1890-1892.

Finiguerra, Maso (1426-1464)

A Florentine Picture-Chronicle; being a Series of Ninety-nine Drawings Representing Scenes and Personages of Ancient History, Sacred and Profane; reproduced from the Originals in the British Museum. Edited by Sidney Colvin. 99 reproductions and 117 text illustrations. London: B. Quaritch. 1898.

Sandro Botticelli. By Herbert P. Horne. 43 plates. London: George Bell & Sons. 1905. pp. 77-86.

The Planets (c. 1460)

The Seven Planets. By Friedrich Lippmann. Translated by Florence Simmonds. 43 reproductions. London. 1895. (International Chalcographical Society. 1895.)

The Otto Prints (c. 1465-1470)

Florentinische Zierstücke aus dem XV. Jahrhundert. Edited by Paul Kristeller. 25 reproductions. Berlin: Bruno Cassirer. 1909. (Graphische Gesellschaft. Publication 10.)

[Pg 93]

Delle ‘Imprese amorose’ nelle più antiche incisione fiorentine. By A. Warburg. Rivista d’Arte, Vol. 3 (July-August). Florence. 1905.

Engravings in Books (1477-1481)

Works of the Italian Engravers in the Fifteenth Century; Reproduced ... with an Introduction. By George William Reid. 20 reproductions on 19 plates. First Series: Il Libro del Monte Sancto di Dio, 1477; La Divina Commedia of Dante; and the Triumphs of Petrarch.

Illustrations of the Divina Commedia, Florence, 1481

Sandro Botticelli. By Herbert P. Horne. 43 plates. London: George Bell & Sons. 1908. pp. 75-77, 190-255.

Zeichnungen von Sandro Botticelli zu Dante’s Goettlicher Komoedie nach den Originalen im K. Kupferstichkabinet zu Berlin. Edited by Friedrich Lippmann. 20 reproductions of engravings bound with text. With portfolio of 84 reproductions of the drawings.

Supplemented by—Die acht Handzeichnungen des Sandro Botticelli zu Dantes Göttlicher Komödie im Vatikan. Edited by Josef Strzygowski. With portfolio of 8 reproductions.

Triumphs of Petrarch (c. 1470-1480)

Pétrarque; ses études d’art, son influence sur les artistes, ses portraits and ceux de Laure, l’illustration de ses écrits. By Victor Masséna, Prince d’Essling, and Eugène Muntz. 21 plates and 191 text illustrations. Paris: Gazette des Beaux-Arts. 1902.

Études sur les Triomphes de Pétrarque. By Victor Masséna, Prince d’Essling. 6 illustrations. Gazette des Beaux-Arts. 2 parts. Part I. Vol. 35 (second period). pp. 311-321. Part II. Vol. 36 (second period). pp. 25-34. Paris. 1887.

Petrarch; His Life and Times. By H. C. Hollway-Calthrop. 24 illustrations. London: Methuen & Co. 1907.

Broad Manner Plates (c. 1470-1480)

Sandro Botticelli. By Herbert P. Horne. 43 plates. London: George Bell & Sons. 1908. pp. 288-291.

The Tarocchi Prints (c. 1467)

Die Tarocchi; zwei italienische Kupferstichfolgen aus dem XV. Jahrhundert. Edited by Paul Kristeller. 100 reproductions on 50 plates. Berlin: Bruno Cassirer. 1910. (Graphische Gesellschaft. Extraordinary Publication 2.)

Der venezianische Kupferstich im XV. Jahrhundert. By Paul Kristeller. 6 illustrations. Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für vervielfältigende Kunst, Vol. 30, No. 1. Vienna. 1907.

Origine des cartes à jouer. By R. Merlin. About 600 reproductions. Paris: L’auteur. 1869.

[Pg 94]

The Tarocchi Prints. By Emil H. Richter. 13 illustrations. The Print-Collector’s Quarterly, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 37-89. Boston. 1916.

Catalogue of Playing and Other Cards in the British Museum. By William Hughes Willshire. 78 reproductions on 24 plates. London: The Trustees. 1876.

Pollaiuolo, Antonio (1432-1498)

Florentine Painters of the Renaissance. By Bernhard Berenson. New York: Putnam’s Sons. 1899. pp. 47-57.

Antonio Pollaiuolo. By Maud Cruttwell. 51 illustrations. London: Duckworth and Company. 1907.

Note su Mantegna e Pollaiuolo. By Arthur Mayger Hind. 2 illustrations. L’Arte, Vol. 9, pp. 303-305. Rome. 1906.

[Pg 95]

WITH the exception of Martin Schongauer, none of Dürer’s immediate predecessors better repays a thorough study, or exerts a more potent fascination, than the Master of the Amsterdam Cabinet. The earlier writers, from Duchesne to Dutuit, were united in their opinion that this engraver was a Netherlander; but Max Lehrs, following the track opened up by Harzen, has proved conclusively that the Master of the Amsterdam Cabinet (so called because the largest collection of his engravings—eighty subjects out of the eighty-nine which are known—is preserved in the Royal Print Rooms in Amsterdam) was not a Netherlander but a South German, a native of Rhenish Suabia—the very artist, in fact, who designed the illustrations of the Planets and their influences and the various arts and occupations of men, for the so-called “Medieval House Book” in the collection of Prince von Waldburg-Wolfegg.