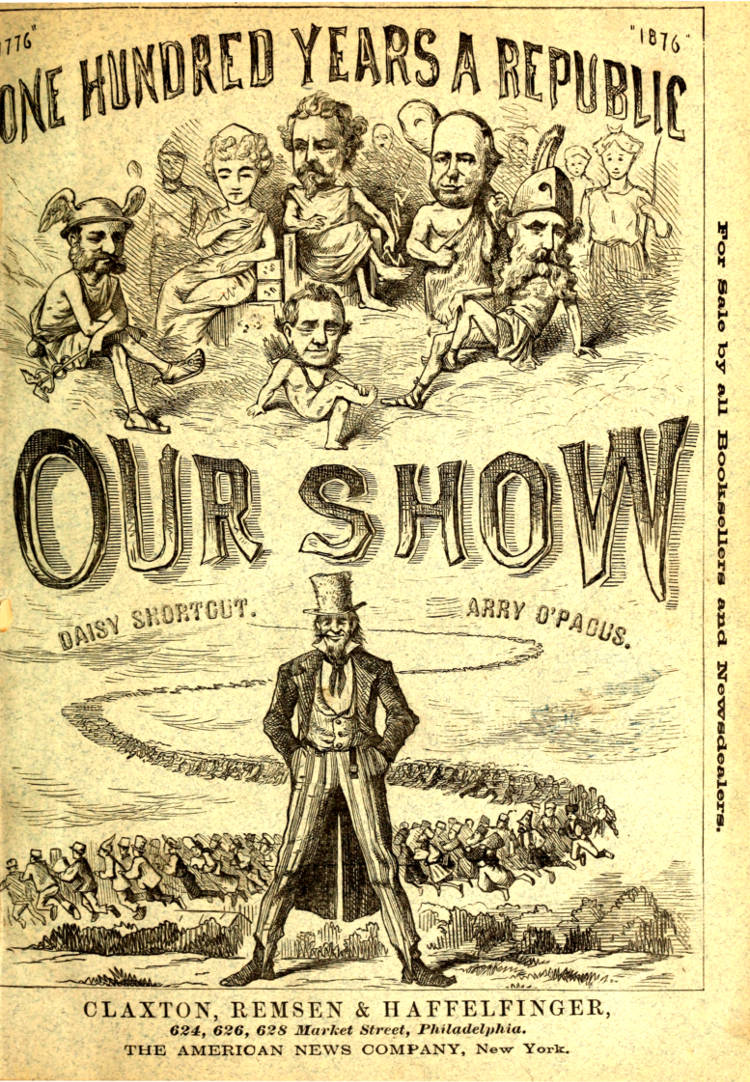

For Sale by all Booksellers and Newsdealers.

“1776”“1876”

ONE HUNDRED YEARS A REPUBLIC

OUR SHOW

DAISY SHORTCUT. ARRY O’PAGUS.

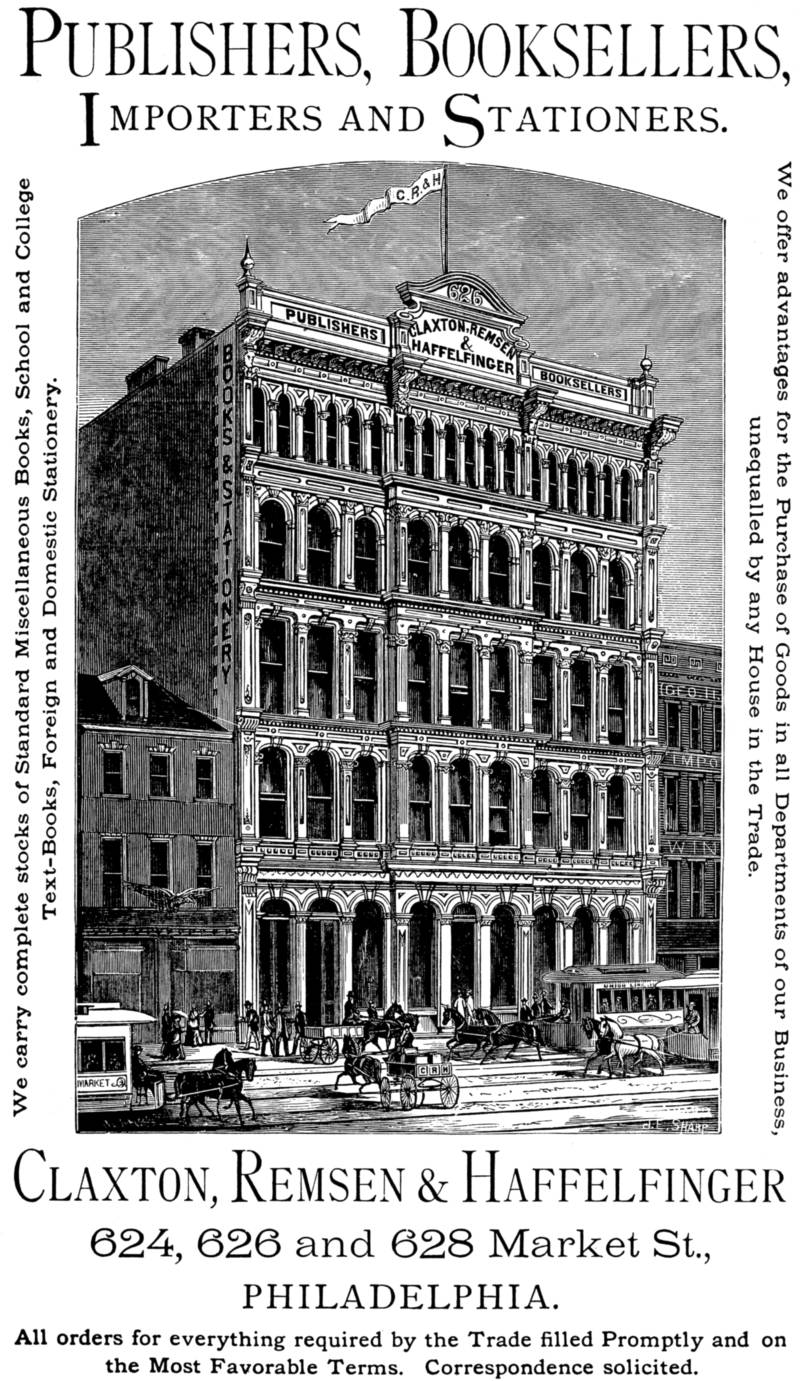

CLAXTON, REMSEN & HAFFELFINGER,

624, 626, 628 Market Street, Philadelphia.

THE AMERICAN NEWS COMPANY, New York.

Title: Our Show

Author: David Solis Cohen

H. B. Sommer

Illustrator: A. B. Frost

Release date: December 7, 2021 [eBook #66895]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Charlene Taylor, Harry Lamé and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

For Sale by all Booksellers and Newsdealers.

“1776”“1876”

ONE HUNDRED YEARS A REPUBLIC

OUR SHOW

DAISY SHORTCUT. ARRY O’PAGUS.

CLAXTON, REMSEN & HAFFELFINGER,

624, 626, 628 Market Street, Philadelphia.

THE AMERICAN NEWS COMPANY, New York.

OPINIONS OF THE PRESS

From several thousand “opinions,” carefully prepared for the use of the press, we select the following. We shall be happy to give the remainder in similar instalments in the future editions of “Our Show.”

[Special dispatch to the New York Herald.]

“Have just discovered the book on my editorial table—the fun I am still looking for; ’tis harder to find than Livingtone was. The African jungles were tame compared to the general wildness of these pages.—Stanley.”

[From the San Francisco Tribune.]

“No library is complete without it—in the waste basket.”

[From the London Times.]

“We admit that the volume puzzles us. We should be inclined to doubt some of the assertions contained within it, even to consider them preposterous, had we not long ago given up any attempt to account for events or circumstances occurring in America.”

[From Galignani’s Messenger, Paris.]

“We have not read this production in the original, but the French translation assures us that it is a work of grave import. Beneath the simple words there is a depth of meaning and a quiet, dignified tone of determination, which the friends of Liberty would do well to heed. It is a book to be pondered over. The illustrations are by Mons. Jacques Frost, an artist of warm imagination.”

[From the Berlin Freie Presse.]

“It is the only book of the kind we have ever seen—thank Heaven!”

[From the Vienna Court Journal.]

“The Emperor has not been seen in public for several days. We learn from reliable sources that he has been closeted in his study, translating, altering, and localizing an American volume called ‘Our Show,’ to make it appear the official record of our late International Exposition.”

[From the Pekin Argus.]

“The Authors are evidently insane.”

[From the St. Petersburg Daily News.]

“This, with Sherman’s ‘Memoirs,’ Motley’s ‘Dutch Republic,’ and Mrs. Lee Hentz’s ‘Wooed, not Won,’ presents a living argument against those who are in the habit of sneering at American literature. If this work fails to give America a first place in the rank of letters, it will keep her not far from the tail.”

[From the Constantinople Leader.]

“It is the joint production of two geniuses. We doubt whether one genius could have written it and survived.”

[From the Copenhagen Sentinel.]

“Copenhagen is shaken to its centre. Is Sweden dead? Is the land of the immortal Yywxtlmp sleeping? Has the American Exposition become a thing of the past whilst we are yet preparing for it? or are the authors of this book endeavoring, under the guise of an historical novel, to lay the foundation for poisoning the world in the future with the doctrines of Spiritualism? Philadelphia exchanges call it a ‘third term pamphlet.’ We have looked through its pages, and though failing to discover what this means, we found one term for which we thank the authors—the termination.”

[From the Hong Kong Examiner.]

“Americans should receive a book like this with fervor—once every hundred years.”

1776. FUN. HUMOR. BURLESQUE. 1876.

BY

DAISY SHORTCUT AND ARRY O’PAGUS.

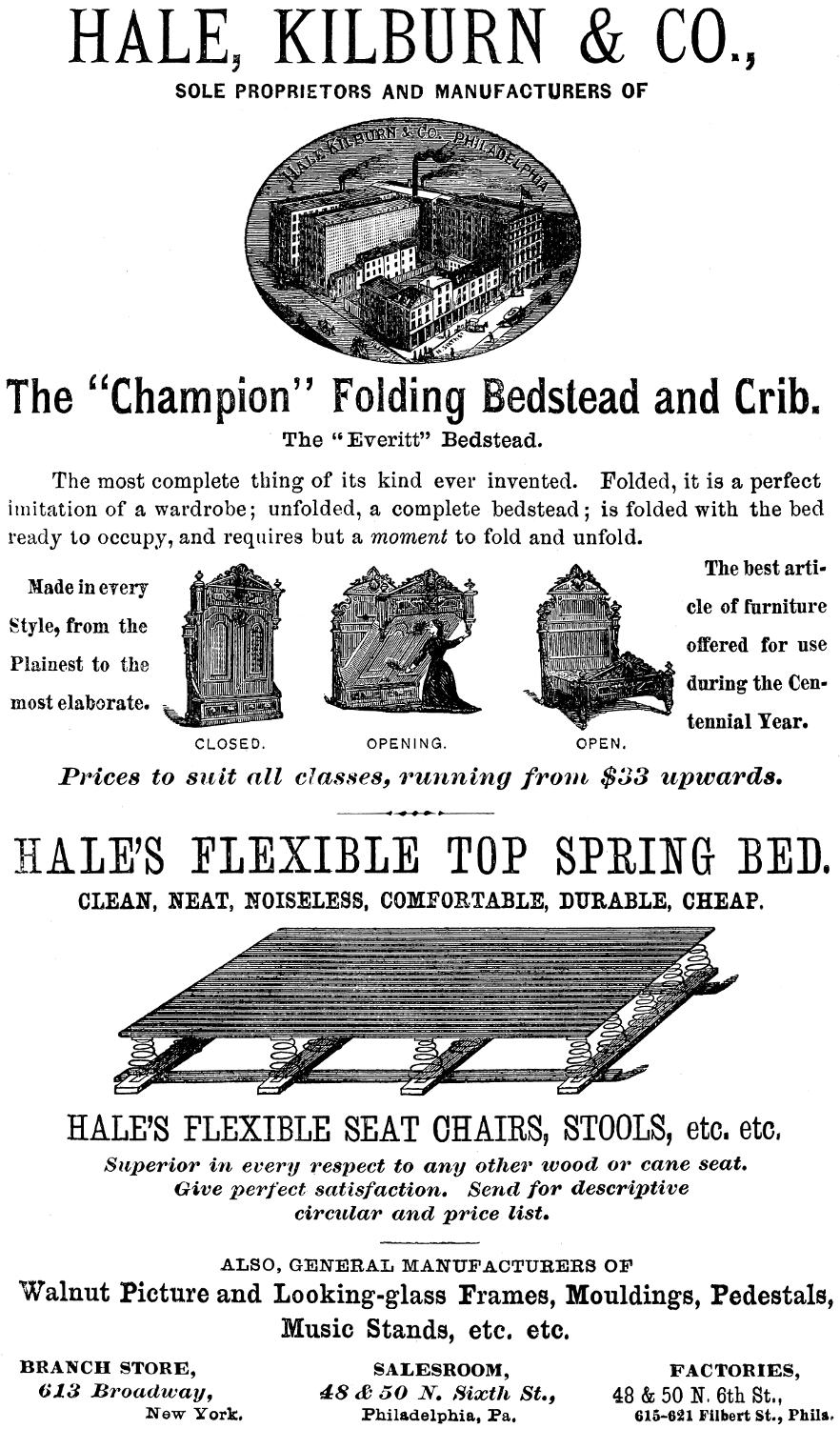

PROFUSELY ILLUSTRATED BY A. B. FROST.

PHILADELPHIA:

CLAXTON, REMSEN & HAFFELFINGER,

624, 626, and 628 Market Street.

THE AMERICAN NEWS COMPANY, NEW YORK.

1876.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1875, by

CLAXTON, REMSEN, & HAFFELFINGER,

in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. All rights reserved.

PHILADELPHIA:

COLLINS, PRINTER,

705 Jayne Street.

[5]

After forty days and forty nights of unceasing meditation, we have completed this important contribution to

AMERICAN LITERATURE.

It was especially designed for dedication to Mrs. Victoria Guelph, the representative of our mother country, as a pleasing, though tardy equivalent for the real estate confiscated by the boys who ran away

ONE HUNDRED YEARS AGO.

But, our far-sighted Secretary of State, an official of the first water, has pointed out to us the impropriety of especially distinguishing one, of the many countries interested in “Our Show;” an action likely to give birth to those bickerings and petty jealousies among the nations which are so apt to lead to grave results.

We desire, above all things, the general good. Under no circumstances would we insist upon anything apt to disturb the peace and harmony of the world; therefore, we select for the honor of a dedication, the private parties we think most deserving,

OURSELVES.

Daisy Shortcut respectfully dedicates his portion of this work to his friend and bottle-holder Arry O’Pagus, and Mr. O’Pagus returns the compliment, by dedicating the outpourings of his colossal intellect to Daisy Shortcut, and, joining hands, they sign themselves,

The Purchaser’s

Most Obedient Servants.

Parlor C, Continental Hotel,

Philadelphia, December 1st, 1875.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

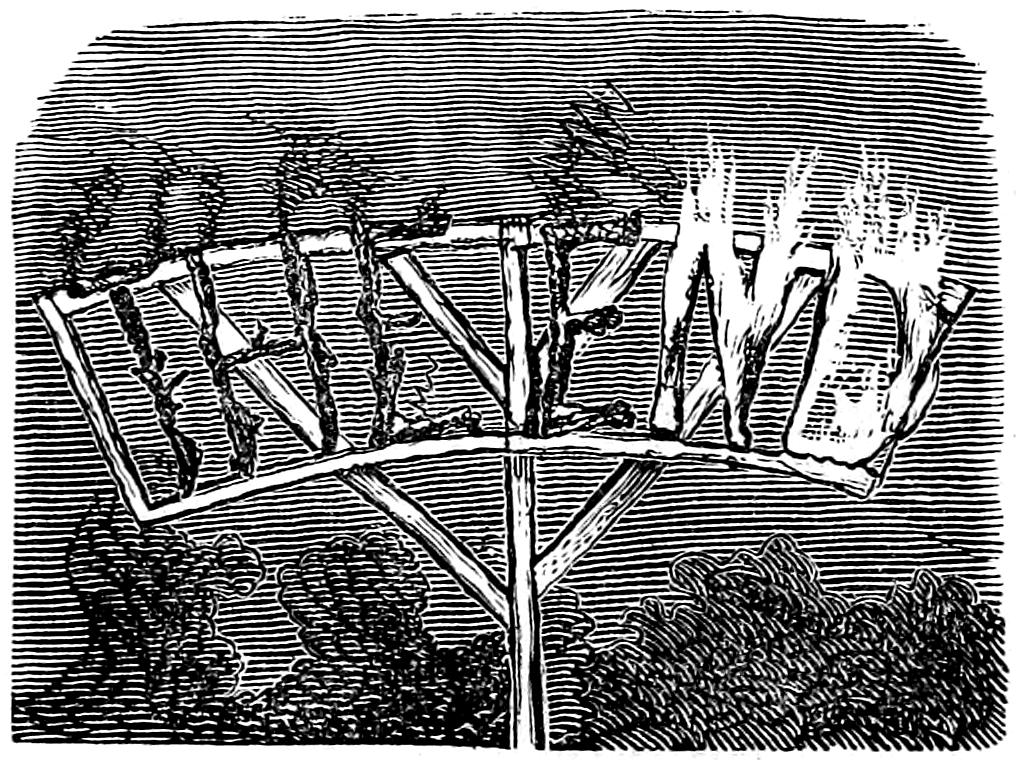

| “THE SPARK.” . . . How it all came about | 9 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| “THE FUEL.” . . . What the women did | 14 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| “THE COOKS.” . . . Who fed the flames | 21 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| “THE LOOKERS ON.” . . . Who came to be warmed | 27 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| “THE CRACKLING.” . . . Preparations for the blaze | 34 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| “THE FIRE.” . . . Who flared and how they did it | 40 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| “THE REFLECTIONS.” . . . Shadows, shapes, and those who made them | 50 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| “THE GLOW.” . . . Who helped and who enjoyed it | 58 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| “THE FLICKERING.” . . . How it dimmed and how it brightened | 66 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| “THE SMOKE.” . . . How it went up | 75 |

[8]

OUR SHOW.

[9]

OUR SHOW.

If the late Christopher Columbus, Esq., could have foreseen, as an indirect result of his little excursion in the spring of 1492, the infliction of the following pages upon posterity, Mr. Columbus, very likely, would have stayed at home. Think kindly, therefore, of the dead; let no blame attach to him. Perhaps a few remarks concerning the ancient mariner may prove instructive to the reader. Being both happy and able to impart useful and interesting information, we cheerfully devote a paragraph to the defunct navigator.

The capitalists of our country are familiar with Christopher, principally through a cut of that nautical gentleman which an artistic government has placed upon the reverse side of its five-dollar bills. The elevated cross in the hands of the piratical-looking monk kneeling beside him, has given rise to a wide-spread belief that Mr. Columbus was a bishop or a cardinal. It is our duty to dispel this grievous misconception. He was simply a Brazilian sea captain, who believed there were two sides to every question, even to such a serious question as the world. Having taught Queen Isabella of Spain, who had not then abdicated, how to make an egg stand and drink an egg-flip, she gave him, under the influence of the latter, command of the steamer “Mayflower,” with permission to row out and see what he could find. He landed at Plymouth Rock; discovered the city of Boston, first, by special request, being presented with the freedom of The Common by the [10]grateful inhabitants, and welcomed in a neat speech by Mrs. Harriet Byron Stowe.

Shortly after this, George III. of England commanded that all the male children born in the Colonies should be cast into the Atlantic ocean. He also advanced the price of postage stamps. These injustices were more than the people could stand; they met in Concord, and drove the British out of Lexington. This alarmed George, who immediately passed the famous “stamp act,” and telegraphed to Benjamin Franklin, then postmaster at Philadelphia, authorizing him to distribute free rations of postage stamps three times a day. But the wires clicked back the touching refrain—

“Too late! Too late! Of all sad words of tongue or pen, the saddest are these ‘too late.’

Yours, Ben.”

Benjamin then convened a job lot of patriots at Philadelphia, and they resolved that these United States were, and of right ought to be, free and easy. Commodore John Hancock, of the Schuylkill Navy, was chairman of the convention. On motion of Robert Morrissey (whose nephew John, late M. C. from New York, inherits his uncle’s statesmanlike and financial abilities), a bell to proclaim liberty was purchased for the State-House steeple. They practised economy in those brave days, and bought a cracked one, because they got it at half price. It is still in Independence Hall, a monument of our veracity.

The world knows well what followed, and ’tis well for the world that it does. General Cornwallis finally surrendered to General Scott at the Germantown Intersection. The “Junction” depot now marks the spot. So, dismissing our historical reminiscences, we would respectfully request both the gentle and the savage reader, to imagine, after the manner of the modern drama, the lapse of one hundred years, ere we proceed with the second act.

This century being buried in that popular mausoleum, the vast ocean of eternity, a universally expressed desire to celebrate the nation’s centennial birthday in a style befitting its present power and importance, gradually assumed the form of an International Exposition, to be held during six months of the year 1876. Philadelphia was selected as the site, partly on account of historical associations and the proprietorship of the cracked bell, but principally to gratify the inhabitants of the adjoining Dutch settlement, New York.

Congress was naturally appealed

to for countenance and assistance.

Unfortunately, however, Congress,

having bestowed all its material aid

upon railroad and steamship subsidies,

had nothing but its moral support

to offer. Having a large stock

of this commodity, it was tendered

with the usual CONGRESSIONAL

MODESTY.

modesty and circumspection

which marks the action of

that body in national affairs. The

President was authorized to invite

the world to the Exposition—without

expense to Congress. Philadelphia

was granted permission to hold

the Exposition—without expense to

Congress; each State was allowed

the privilege of appointing a commission—without

expense to Congress;[11]

and, to be brief, the economic

representatives of the people resolved

that these United States might go

in and have a good time generally—without

expense to Congress.

Jubilant with this encouragement, the State Commissioners organized an Executive Committee, which appointed a Board of Finance, and auxiliary committees upon everything and anything, including mining, manufactures, calisthenics, art, science, primogeniture, horticulture, pisciculture, agriculture, infanticulture, and hydrostatics. City committees were constituted. These were jobbed out to wards, and again sublet to precincts, through which domestic juntas were established in every household. Thus the voice of the people woke the echoes of the capitol, and reverberated to the furthermost corners of the universe.

The Building Committee immediately

contracted with GEE UP

DOBBINS!Mr. Richard

J. Dobbins (the inventor of Dobbins’

electric soap) for the construction of

He agreed to furnish the very first quality of soapstone for the masonry, and to use Castile only, for the girders. The following were the chief points of the contract:—

1st. The building to form a parallelopipedon, in order to secure the choicest location to each exhibitor.

2d. To be thoroughly waterproof. Dr. McFadden of the Aqua Fontana department, and several other eminent surgeons, to fill it up to the ceiling as a test previous to the opening. The contractors to take it back if the test proved unsatisfactory.

3d. The walls to be of gutta percha; to be distributed after the closing of the exhibition to the pupils of the public schools for chewing and erasing purposes.

4th. A transcript to meander through the centre of the building, with a knave to right and left. Cucumber pumps of the Louis Quatorze pattern on the east and west detours, alternating with eight green cellar doors, to give the same effect and finish which marked the tout ensemble of the Vienna buildings. A main curricle on the right to be flanked by iron decades, with arched approaches for bipeds, tripods, and quadrilaterals.

5th. The general appearance of the exterior to favor the Polynesian style, which is replete with architectural beauties. Fac similes of the Tower of Babel, Tower of London, Leaning Tower of Pisa, and Tower Hall, to adorn the four corners. The trusses and bandages supporting the roof, to be of purple and fine linen, with brass mountings. The roof itself to be perpetually covered with wet towels, to guard against sunstroke.

6th. The centre aisle to be covered with canton flannel matting, with the grass sloping up to the back door. Nineteen hotel candles to illuminate the ground floor, with a citrate of magnesia light in the attic window.

This extraordinary structure was completed according to agreement, and upon being weighed at the corner grocery, kicked the beam at 1234567890 pounds, 19 shillings and sixpence.

[12]

Mr. Dobbins was also entrusted with the erection of

This is a permanent building, so adapted that it may be used hereafter as an Art Gallery or a Station-house. The foundation is not only cemented with Spalding’s glue, but the iron posterns run through to China, and are tied on the other side with the back hair of coolies, detailed for the service through the courtesy of the Pekin government.

Notwithstanding Mr. Dobbins’

immense labors in completing these

two buildings, he still found time

to run over to Rome and MORITURI

SALUTAMUS.purchase

the Colosseum. He brought it home

with him for the purpose of exhibiting

Prince Bismarck and the

Pope in gladiatorial contests during

the exhibition months.

The contract for

was awarded to Mr. Philip Quigley, of Wilmington, Delaware. When it grew too big for his State, he removed it to and finished it upon the ground it occupied. The machinery exhibited was worked by forty horse-power, and a neat stable was attached to the rear for the care and accommodation of the forty horses, the contribution of the city passenger railway companies.

All the shaftings were of sandal wood, and the belting of Russia leather, supplied by the family of the Czar himself. An “hydraulic annex” was also tacked on to the building. It contained a tank 60 by 180 feet, with 10 feet depth of water for fishing and bathing purposes. A portion was fenced off for the preservation and display of “The Falls,” which the hotel keepers and hackmen of Niagara kindly loaned for the occasion. The hydraulic rams and other live stock were watered here every morning, and at stated intervals during the day hydrodynamic and hydrostatic performances were given in the tank[13] by the pupils of the “Girls’ Normal School.” The former were very unique.

The consideration for the construction of this building, as per Commissioners’ report, was $542,300, including drainage, water-pipe, plumbing, and silver-plated door knobs, but exclusive of interior white-washing. This, however, was performed gratuitously by Professor Johnson of the African Commission.

Mr. John Rice, a healthful and nutritious builder, was selected to erect the beautiful

which remains a permanent ornament to our park, and an attractive target for the shots of the young idea visiting the locality. The immense expanse of glass will doubtless provide innocent amusement to many generations of young America. May they ever appreciate the kind consideration which placed the building convenient to a line of soft rocks, supplying ready-made boulders of all sizes. We believe, however, that the building is taken in at nights; we know its visitors are taken in during the day. Some idea of its vastness may be given by stating that more than 7000 acres of land are situated around it.

being of papier maché, inlaid with mother-in-law of pearl, was cut out by steam, and work was not commenced upon it until September, 1875. The pens for live stock adjoining the building were of steel (a favorite material in public edifices), and were a part of the contract. They were fashioned after the manner of the famous floating palace, “Adelaide Neilson,” of the Noah family. The plans were furnished by the Shemitic commission from rough drafts now in possession of the descendants of Admiral Noah.

At a late date the

decided to erect a few buildings, including a hospital. They thought the latter might come handy in Washington after the exhibition, for resigning officials. When we first learned that the United States had obtained 100,000 feet for their buildings, we thought it another display of persevering frugality. We imagined they desired to save a hardware bill by using the nails accompanying the material. We discovered that the feet merely meant the ground for the buildings to stand on.

As the Grecian government had

expressed itself too poor to take part

in the Exposition, Mr. Windrim, the

architect, was instructed to design

these buildings in the shape of a

Greek cross. Through this delicate

A COMPLIMENT

TO SAPPHO.compliment, the land where Sappho

lived and sung, was represented after

all.

These, with the offices for managers, gas men, stage carpenters, etc. etc., and some national, state, and special buildings, which may claim our attention further on, complete the list of structures erected upon the Centennial grounds for exhibition purposes. Men of all nationalities vied for the privilege of taking part in the glorious work.[14] The Teuton and Celt underbid the native American; the co-patriots of Garibaldi did still better, only to be put to shame in their turn by a Chinese colony. Ignoring all natural partiality and national prejudice, the contractors, in a spirit of true republicanism, gave the most work to those who labored for the least money.

Nature always provides for

emergencies. The world required

steamboats and locomotives,

and, lo! a Fulton and

a Stephenson appeared to supply

the demand. We craved

a means of rapid intercommunication,

and Mr. Morse sat

down and invented his telegraph.

We experienced a

soaring desire to sail through

the air, and George Francis

Train stepped forward to inflate

our balloons. So, when

a lady competent to organize

and superintend the workings

of her sisters, became requisite

to the success of the Centennial

project, nature did not

desert us. Uprose, as the poet

sweetly remarks,LOVELY

WOMAN.

and grasping the banner, Mrs. Emma D.E.N. Gillespie became the special partner of the Board of Finance.

Were we about writing a work in twenty quarto volumes, the kind we have been in the habit of producing, we might faintly hope to do justice to the prodigies accomplished by the noble women of America, and especially by our own Philadelphia ladies. What we do write, however, is the result of personal observation. Blessed with female relatives in esse and in posse, who have been active members of ward committees since the first trumpet tone, we write advisedly; having been [15] snubbed, sacrificed, and made secondary to centennial enthusiasm for three long years, we write with a proper appreciation of the solemn duty in hand.

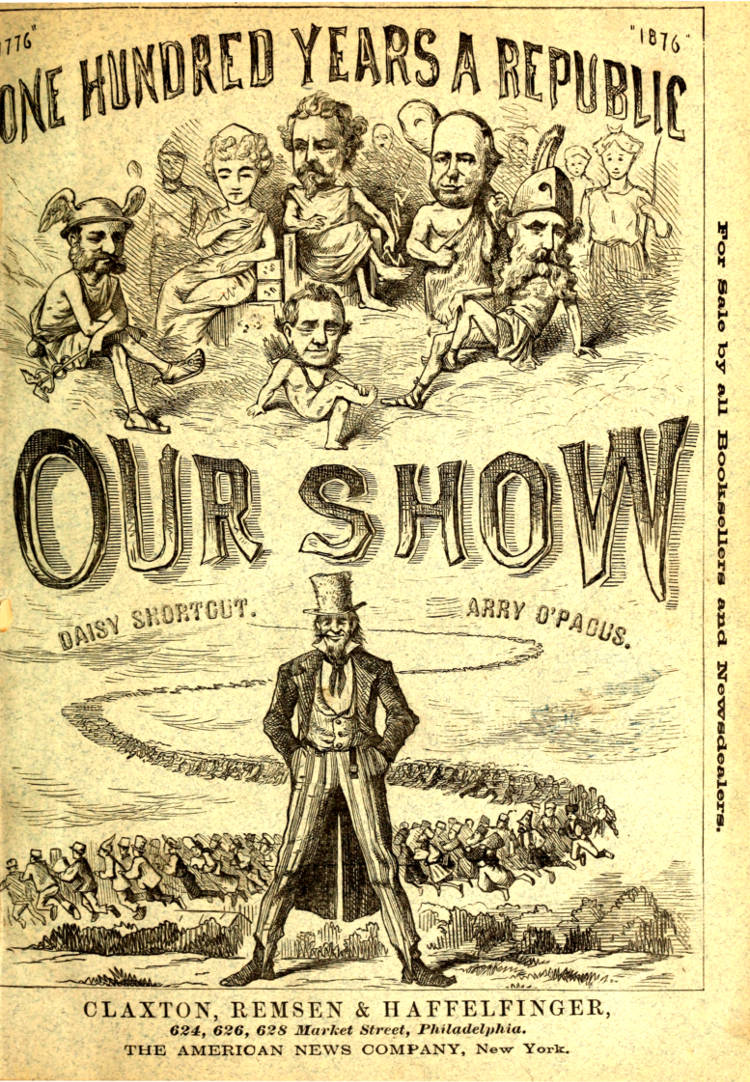

The dear creatures travelled up to the State-House steeple; they glanced around upon the situation; they rolled up their sleeves, metaphorically, and swooped down upon the city. They canvassed stores and factories from turret to foundation stone; they invaded dingy counting-houses, and sauntered like sunbeams into dusty offices, collecting subscriptions to centennial stock, peddling centennial medals, and doing irreparable damage to the peace of simpering clerks, blushing salesmen, and susceptible employers. A single case will serve for illustration. Listen to the story of

“NOT WISELY

BUT TOO WELL.”He was an innocent youth, undergoing

initiation into the mysteries

of compounding and weighing out

sugars, teas, and spices at a West-End

grocery. A Spruce Street damsel

did the cruel deed. She visited

the establishment several times in

reference to some shares of stock,

and her passing glance sank into his

soul. His deep, poetic nature demanded

an outlet for the sacred fire.

Ætna will burst; Vesuvius will explode.

Ætna and Vesuvius were

but parlor matches compared to him.

The evening succeeding the lady’s third visit to the grocery, a package, neatly done up in brown paper, was left at her residence by a youth who vanished upon the instant. The lady untied the bundle, and discovered an A. No. 1 salted codfish. The following lines, on pink initial note (slightly greased), were fastened to its tail by a blue ribbon:—

Next evening, about the same time, another package arrived, with another poetic sentiment in the same handwriting:—

The lady was somewhat puzzled, though gratified. Her father was somewhat puzzled, though not gratified. Their quandary was not lessened upon receiving a third delicate present the next evening.

[16]

“Can’t never dry up, eh?” said the old man the following evening, as he pulled on his thickest boots, and took up a commanding position on the front-door step. “Can’t never dry up, eh?—we’ll see.”

But the mysterious messenger flanked him by ringing at the back gate.

Another evening came; the old gentleman was again upon the step; the family butcher was sauntering carelessly by the back gate. Alas! in place of the youth, ’twas the grocer himself who called. The butcher did not know him; he obeyed instructions. On the day of the unfortunate man’s funeral these lines were read; they were found in his pocket, and explain the cause of his inopportune visit:—

We will dwell no longer upon this mournful episode, but return to our main subject.

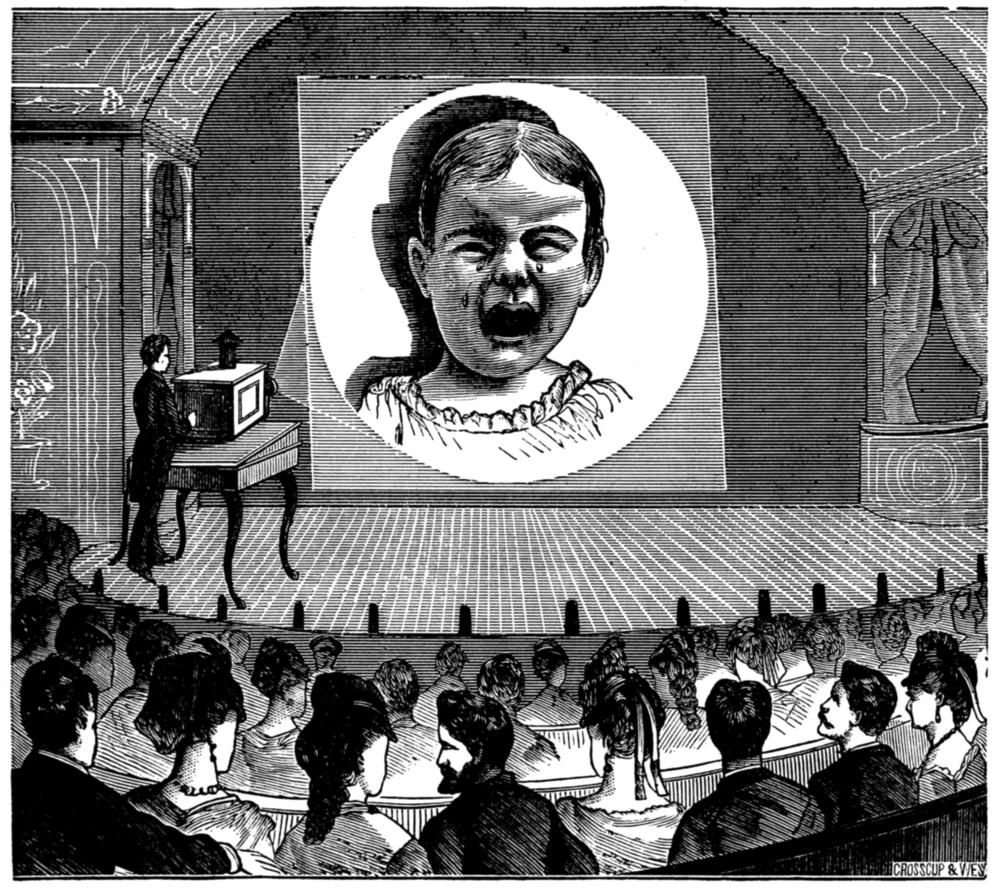

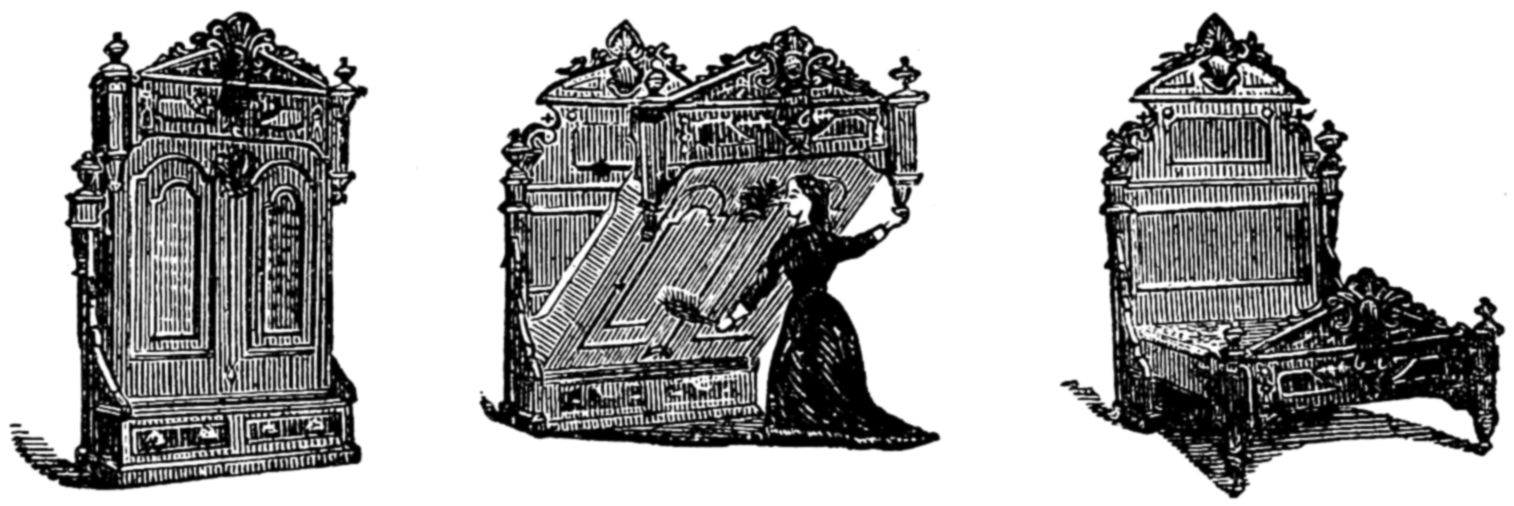

The ladies of the various ward

committees did not confine their

efforts to canvassing. They worked

afghans that nobody wanted, and

slippers that nobody could use; purchased

desks that wouldn’t open,

and pocket-books that wouldn’t

shut, and raffled them off at prices

as fancy as the goods themselves.

They appeared in amateur theatricals

and variety shows. Every ward

had its ROMEO AND

JULIET.Romeo and its Juliet; every

precinct its Lady Macbeth and Wellington

De Boots. Their acting was

wonderful and awe-inspiring. Audiences

gazed upon them in public

with dumb amaze, and wept in private,

they knew not why. People

began to look upon tickets for amateur

performances as Japanese officials

regard a polite invitation to

“Hari Kari.” Call-boys and scene-shifters

at regular theatres set up

for luminaries. The demoralization

of the drama was complete.

But all these things were mere side dishes, to be mentioned incidentally in connection with the combined efforts, viz.:—

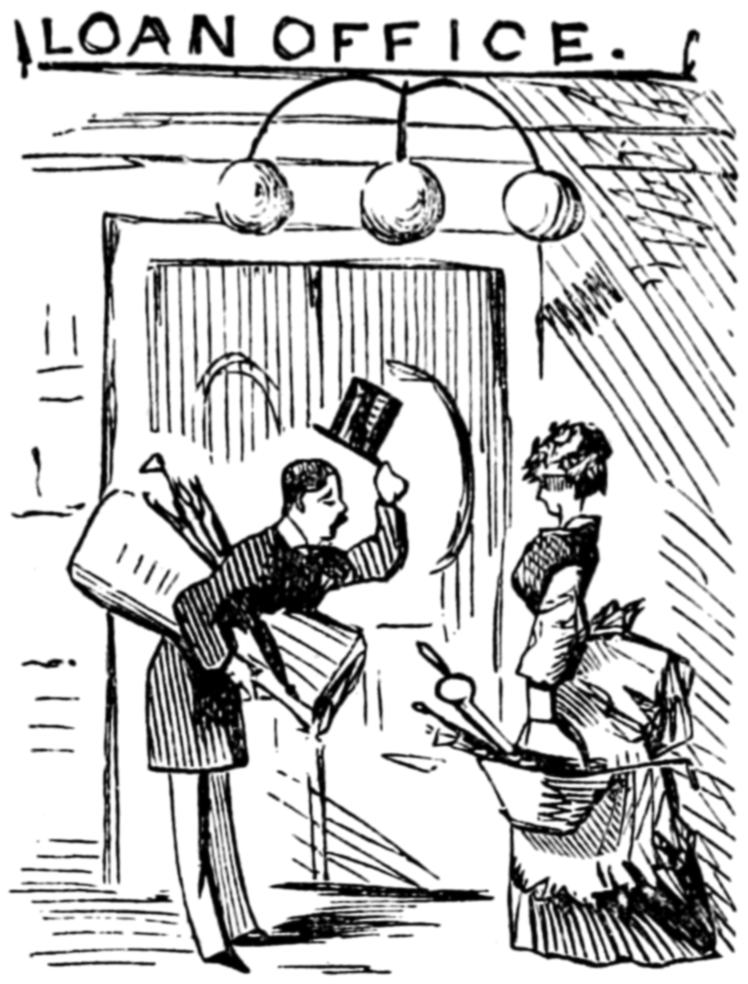

“The Great National Tea Party,”

“The Greater International Tea Party,” and

“The Greatest Patent Loan Office Exhibition.”

It is with a feeling of profound diffidence that we allude to them.

TOAST

AND TEA.Under the supervision of their revered

sovereign and her executive

star chamber cabinet, the ladies

transformed the Academy of Music

and Horticultural Hall into one

grand coffee house and sandwich

caravansary. To save the expense

of attendants, the aids themselves

dispensed tea and coffee, smiles and

gingerbread, bewitching glances and

ham sandwiches to the thousands

crowding the vast saloons. They attired

themselves in old-time fashion

to look like so many Mrs. Washingtons.

Many a family cheerfully

sacrificed its furniture covers to array

its daughters in the style of costume

made sacred by Martha. They

stuck little blotches of black court

plaster upon their chins, cheeks, and

the tips of their noses, to imitate[17]

her venerated pimples, and dipped

their heads into the family flour

barrel to make their hair look like

to hers.

Each ward represented one of the States of our Union, and the rivalry between their tables, though good-natured, was intense. At one table they sold tea made in Martha’s china tea pot; at another table they dispensed slices from a pie having its edges scalloped by her false teeth; while a third overtopped all competition and did an immense business, regaling customers with sausage manufactured from the remains of her pet poodle. The aids who dealt out this luxury seemed conscious of the sacred trust. Tears of patriotism dimmed the lustre of their lovely eyes.

They sold nosegays at the price of small conservatories, but pinned them on coat lappels without extra charge. They did more. With apparent cheerfulness, they accompanied male friends to the hall below, where the band played, and with them hopped and skipped, and glided and dipped, as if they were really enjoying themselves, and not sacrificing comfort to love of country.

The pecuniary result of this affair was most gratifying. The Finance Committee kindly acknowledged this fact to its special partner, requesting her to do so some more and keep the ball rolling. Yet still its grandeur was eclipsed, totally eclipsed, by the next great effort.

Between the two tea drinkings,

however, a Fête Champêtre was held

at Belmont, near the Centennial

grounds. We wrote to France,

Mrs. Gillespie’s native land, to find

out what a fête champêtre meant.

THIERS ON

MOONSHINE.Our respected friend Thiers replied.

“You go out,” he wrote, “to some

nice quiet spot. In the evening you

hang a few lanterns on the trees, and

leaving the other folks to dance, you

yourself wander off with some ‘nearer

and dearer one yet than all others,’

to explore the surrounding country,

its shadowed nooks and moonlit

glens.” Of course we went. But

somehow everybody else was leaving

the others to dance and seeking

moonshine. Never before was there

such a demand for nooks and glens

since nooks and glens were first invented.

The fête was a perfect success as far as moonshine was concerned, but not pecuniarily. The caterer of the evening is wearing away his days in an insane asylum. Who cares for Champagne when they can have nearer and dearer ones? Who cares for lobster salad when they can have nooks and glens?

A second tea party, to retrieve the reputation of the cabinet, was decided upon. This time, however, instead of representing only our States, all the nations of the earth were to be typified.

Emma R.”

were the suggestive lines with which “General orders 197” terminated.

The aids appeared in the costumes which long theatrical usage has established as nationally characteristic. For three successive evenings, a thing of beauty and a joy for Emma enchanted[18] and astounded throngs of visitors, and would have been continued longer had not everybody unfortunately run out of small change.

Each table was adorned by what

the ladies fondly believed to be an

unmistakable designating peculiarity.

One ward went into business

with a few yards of glazed paper

and a Noah’s Ark, and reared upYE MIGHTY

ALPS.

the mighty Alps. Shem, Ham, and

Japhet stared blankly into futurity

from the storied peaks; old Noah

and his wife looked around in a bewildered

manner as though wondering

what the genesis they were doing

in that locality, while their sheep,

goats, cows, elephants, tigers, crocodiles,

and whales jumped indiscriminately

from crag to crag.

An odor of Swiss cheese, from the sandwiches, made the illusion perfect.

The ladies of another ward had ingeniously built a polar bear with an inner structure of rags covered by variegated cat skins. He was a little lop-sided, but didn’t seem to mind it. He stood serenely upon a looking glass glacier, with tail erect, and the Russian flag between his teeth. The 8th ward (Republic of Lima) made a splendid display of Lima beans, boiled and in soup. The aids were not afraid to say “beans” to anybody.

But the 21st ward (Isle of Man) carried off the prize. This committee had secured, at enormous expense, a live specimen of the native. He was quite docile and harmless; yellow whiskers, and wore eye-glasses. This table was the Mecca to which all the aids flocked when off duty.

Talk about your heroines of revolutionary times! Bah! Do you suppose that Moll Pitcher would have donned striped leggings, a gauze flounce, and a sash around the shoulders, and wandered around like the Amazons in the “Black Crook,” as did Mrs. Vowl of the 20th ward?[19] Would Mrs. John Adams, the wife and mother of presidents, pattern of patriotism as she was—would she have put on spangled breeches and a turban of red, green, and yellow with a turkey’s feather in front, and trotted up and down the Foyer of the Academy with a bucket of lemon peel and water, calling it “sherbet,” and pretending not to notice the excruciating look which distorted the countenances of the unfortunates inveigled into investing in a glass and then feeling compelled to empty it? To these questions there can be but one response. You shall make it.

The result of this festival was also satisfactory to the Finance Committee and to all concerned. The ladies were encouraged to renewed efforts. They racked their brains searching for a novel idea, and when did women rack in vain? They invented a style of exhibition which produced an effect such as the world had not witnessed since the Israelites emptied out Egypt. The war trump sounded: “Gillespie” was the cry. Special orders 774 were promulgated, and that stupendous conception

astonished and frightened the land.

Everything was to be borrowed;A LOAN—

AND FROM HOME.

nothing bought and still less paid

for. The idea was attractive. A

wide field was opened for feminine

ingenuity. Each aid immediately

locked her own umbrella carefully

away, and called upon her friends

when the weather was cloudy.

The Franciscan Monastery, on Rittenhouse Square, was the largest article loaned to the Committee, they having declined the offer of a Frankford brickyard; and in this building the exhibition was held. Three beautiful gilded balls were extended from the attic window, and on them the neighboring residents gazed in silent rapture. A great demand was created for articles one hundred years old and upwards. Old pots, pans, and dishes were suddenly endowed with incalculable value. We ourselves worked industriously to produce relics. Our aforementioned relations in esse and in posse, acknowledged the loan of an old brick into which we had pounded a new bullet, with a fervor which more than repaid our disinterested patriotism. The sweet smile and kindly glance with which they accepted a pair of old army breeches, which we had purchased for seventy cents and riddled with augur holes, haunts us still. Nay, when we attended the exhibition, and saw an old lady reverently kiss a yellow handkerchief, which we had borrowed from an hostler of our acquaintance, and labelled “Lafayette,” we retired to a side apartment and wept tears of joy. We had afforded[20] that old lady a gratifying reminiscence for the remainder of her existence.

The Washington family came out

particularly strong. In a pavilion in

the garden, seventeen aged females

were seated. They had nursed little

George in his baby days. With

undisguised emotion they exhibitedGEORGE’S

INDIVIDUAL

CONTRIBUTION.

21 cradles, 66 gum rings, 423

hatchets, and half a bottle of soothing

syrup, all of which, they asserted,

had been the property of the

father of his country during his infantile

years. They also possessed

among them an aggregate of 34,621

buttons, which they had purloined

at different times from the dear

child’s vestment.

This was considered as George’s individual contribution.

The remainder of the family were not behindhand. They sent a few of their plates, spoons, forks, ladles, etc.; not many, only about enough to start a first-class hotel. As for family Bibles, they must have had a sufficient quantity to have allowed each member of the family a new one every day of the week and two on Sundays. There were chairs and sofas enough to seat the entire continental army, and about five wagon loads of miscellaneous furniture and chattels. Heavens, what an establishment those Washingtons must have kept!

It would be useless to attempt an enumeration of the wonders on hand and made to order for this occasion. Suffice it to say the ladies borrowed everything they could borrow, and what they couldn’t borrow they—didn’t have.

Two rooms were set apart for broken and unbroken china, which (again in compliment to Mrs. Gillespie’s native tongue) were called Bric a brac apartments.

The exhibition was open to the public for six weeks with a table à la carte in the dining-room. The net profit was close on to seventy-five dollars.

And after all this work, after obtaining from them all these ducats, what did the centennial magnates say to the ladies?

“Ladies,” said they, “we have taken your money; we have urged you to labor; we have induced you, in the person of our special partner, to travel to sister cities to persuade the daughters of our land to make a proper exhibition of their importance and standing in this home of equal rights; but, ah, unfortunately, we shall not be able to allow you any space in our buildings; the old women of China, the aged females of Timbuctoo claim it, and if you want to display that standing and importance we have mentioned, why—ah—here are plans for a building; take them, get up a side show for yourselves, pay for it yourselves, and be—happy.”

[21]

Our record would be incomplete if we failed to insert a few brief biographical sketches of some of the personages prominently connected with the conduct of the Centennial celebration. We regret being obliged to limit the list to a very few of the many deserving of the honor. The facts which we relate in regard to them, have been industriously gathered from many sources probably unknown even to the parties themselves. Should we succeed in awakening one soul to pure aspiring action—should we be the means of placing one pair of feet into those “footprints on the sands of time” which lead to honored greatness—our labor has not been in vain.

the President of the Centennial Commission, was born principally in the State of Rhode Island, but grew so rapidly that his parents soon found it necessary to have him hauled over entirely into Connecticut. Here he flourished and grew fat among the healthy wooden nutmeg groves. He early displayed unmistakable evidences of genius. At the age of seven, he invented a tin lightning rod, and a schoolboy’s improved blowpipe of the same material. For this latter, his teachers passed him a vote of thanks through the medium of a ruler, and graduated him from the scholastic establishment. Shortly afterwards he originated the business of manufacturing paper shell almonds, but sold out advantageously to a near-sighted relative and entered the Artillery school at Brienne, from whence he soon meandered to the military academy at Paris. He instituted the “legion of honor,” won the battles of Marengo, Jena, Austerlitz, Eylau, Wagram, and some few others, and then retired to the monastery at St. Helena. Here he took the veil and several other articles, and leaving, one[22] cloudy night, worked his passage to London. At this metropolis he mixed freely with the heads of the nobility, opening a hat store and being appointed “hatter extraordinary” to the Queen. He pined, however, for the breezes of his native land, and when Columbia called upon her sons to lend a hand to the Centennial structure, he returned to America and was elected President of the commission.

His bravery and prowess are equalled only by his genial nature and the style of his moustache and imperial. Of him the poet Horace (Greeley) has said,

Some of his enemies recently nominated him for Congress. Their sinister designs failed, however, and he will happily remain for some time longer an ornament to society and a credit to his country.

OH REST US.Vice President of the commission, was born, when quite an infant, in the State of Ohio. He gave such promise of future greatness that his native city was named after him.

He was the eighteenth child of his parents, and was, therefore, called Orestus. The name was suggested by the friends who had been acting as godparents for the family. He must not be confounded with the Orestes who murdered his ma and was afterwards killed by the bite of an Arcadian serpent; he is quite a different sort of an Orestes.

Through life he has been noted for his culture and refinement. These qualities he owes to his father’s care. The old gentleman made a point of polishing him off regularly twice a week during his youth.

He always displayed a remarkable fondness for school. He could often be found there an hour after all the rest of the pupils had gone home. His teacher was especially fond of him. “Frequently,” said she to us, with tears in her eyes, “frequently did I lay him across my knee to more readily display the affection with which I regarded him.”

When he was not at school he was engaged in the noble work of repairing and paying for the window panes his companions had smashed; in replacing fruit upon the trees from which they had stolen it, and in going to church and praying for their regeneration.

His manners always continued engaging. Unimpressible police officers have been known to form an attachment for him, the more remarkable as he never encouraged their sociability.

After essaying many learned professions, he finally concluded that his forte lay in the profession of being a rich man. He bought a farm near Camden, planted Kelley’s patent inflation bill, and raised money in that primitive fashion. After passing the meridian of life in honor and righteousness, the devil put evil thoughts in his mind, and he embraced the legal profession, to which he is still united.

His front elevation is very imposing. His face is somewhat in the Corregio style, with Roman nasal appendage and Grecian earwings, doing much credit to the architect who designed him. He is finished[23] with a double action expanding chest, with corrugated windpipes, and he stands on two seventeen inch pedestals cased in patent leather. He was on exhibition during the entire continuance of the exposition.

Of the early days of

but little is accurately known. Though historians agree upon essential points, there are many of those conflicting side issues which always arise from a multiplicity of traditions. We know, however, that at her birth she was taken under the especial patronage of the Fairy “Bookotheopera,” who endowed her with all the virtues in that fairy’s repertoire, and presented her with a beautiful purple pincushion with

blazing in the brass heads of the pins which it contained. It is still in her possession.

CENTENNIAL

MYTHOLOGY.She has performed many noteworthy

deeds in addition to those

connected with the Centennial. ’Tis

true, she never fooled with asps or

indulged in pearl cock-tails like

Cleopatra; nor did she act as a spy

during the war like Major Charlotte

Cushman, but her quarrel with Neptune

concerning the right of giving

a name to Cecropia (Horat. 1, od. 16),

deserves as much attention as either

of the above performances.

The inhabitants of Taurica offer upon her altars all the strangers wrecked upon their coasts as a mark of their appreciation of her efforts in establishing the American line of steamers (Apollod. 1, c. 4, etc.), and though her resentment against Paris (the son of Mr. Priam) was undoubtedly the cause of the Trojan war, yet the myrtle and the dove have ever been considered her most sacred emblems. Her ride upon the white bull is as famous as Sheridan’s ride to West Chester, and her patronage has been so extensively claimed by artists of all sorts, especially such as painters, carpenters, white-washers, and tea importers, that the poets have had occasion to say—

To her, more than to any one other individual, is the success of the celebration due. We have remarked her executive ability, and the manner in which she directed the nymphs of her train, and it is our candid opinion, that nobody could have been found or invented, to fill more perfectly a position involving so much annoyance, so much mental and physical labor, so many petty anxieties, and so comparatively little general appreciation. There are some debts which cannot be paid. We put that owing to her upon the list.

the Financial Agent of the Executive Committee, passed his early youth among the vine-clad hills of Bucks County. He was brought up a sturdy farmer’s lad. Day after day, in the hot sun of noon, he stood erect in the centre of the cornfield, the terror of the devastating crow.

He was not called “governor” at

his birth; his name is SWEET

WILLIAM.William; the

former title he acquired later in life

when he married a governess.[24]

Willie was very popular in the

country school which he attended

during the winter evenings. Upon

several occasions his master bestowed

a cane upon him, which token of desert

he received with a few powerful

and eloquent remarks and tears in

his eyes.

His nature was always affectionate. He would never visit a young lady the second time unless he could kiss her “good-bye” the first time he called.

Artless to a fault, he never knew the use of wigs until after he married, and it is said that he never acquired his second teeth until a few years back.—He couldn’t have got them then if he hadn’t paid fifty dollars for them.

Despite his gentle nature, however, his physical strength is immense. His prowess in the amphitheatre, his speech to his brother gladiators at Capua, and the able manner in which he defended the wire bridge against Mr. Porsena, of Andalusia, are favorite themes with every American school-boy.

After the revolution he had his sword cut down into a set of shoemaker’s tools, and followed the cobbler’s peaceful pursuit, until the Centennial committee demanded his time and services. For this he gave up everything. He cheerfully immured himself for a time in the St. Nicholas Hotel, New York, living on rye bread and wheat whiskey, and enduring all sorts of hardships in his endeavors to collect subscriptions from the Dutchmen of Manhattan. He came home, however, in time to tack the roof on the main building.

Should he again take to mercantile life in our midst, we cordially recommend him to our friends for “invisible patches.” His name will ever be high upon the list of the best beloved sons of the Keystone State.

As

A SECOND DANIEL

COME TO JUDGMENT.the Chairman of the Executive Committee,

was changed while an infant

in his cradle, and the child of his

nurse substituted for him in order to

obtain possession of the chateau and

estates, we were not thoroughly satisfied

that he was entitled to any

biography. We called upon him to

ascertain what he knew about himself,

and were disappointed to find

that he was not very well up upon

the subject.

We found him a man of fine appearance. He has the eye of a hawk, the nose of an eagle, the hair of a raven, and the cheek of a Colossus of Rhodes—with which he expects some day to start a museum. We informed him why we had called, and at once commenced a list of questions which we had taken the precaution to prepare.

“As a youth, sir, were you gentle, with a sweet disposition?”

“A sugar refinery, gentlemen, wasn’t a circumstance to me.”

“Were you always gay and cheerful and generous beyond measure?”

“I was.”

“Were you ever in love?”

“I decline to criminate myself.”

“Well, Schiller loved once, Goethe many times, which do you consider the most natural?”

“The latter, decidedly.”

“Were you ever jealous?”

“Once.”

[25]

“How did you act towards the cause of this feeling?”

“Smothered her with a pillow.”

“Oh, then, you could be a Othello?”

“I could be twenty Othellos; but, gentlemen, as this style of procedure is evidently fatiguing to you, suppose I relate my story without questioning, eh? James, a bottle of champagne and a box of those victorias for the gentlemen.

“Your Money or Your Life.”

“I was born,” he continued, “on the Island of Borneo. My mother was a decendant of the noble Italian family of McLaughlini; my father was also of noble birth; he never walked afoot; he always drove a carriage—for the man who owned it. Cast upon the world at a tender age, I went to England and took up my residence on Hounslow Heath—maybe you’ve heard of the place. Always of a playful disposition, I invented a pretty little game called ‘Your money or your life,’ which I taught to all the lonely travellers who passed my neighborhood, to cheer them on their way. They generally used to leave me their pocket books, watches, and whatever valuables they had about them, so gratified were they with my attention. The Royal Family soon heard of me and despatched a regiment of guards to conduct me to London. Naturally modest, I endeavored to avoid this distinction, shunning a meeting with the deputation as long as I possibly could. At last I found myself compelled, as it were, to accompany the party. I was conducted to a grand stone building of immense proportions and solidity of design, in which, apartments had been prepared for me. From thence I was introduced at Court, and, upon the suggestion of the Lord Chief Justice of England, the apartments in the granite building were placed at my disposal for six months, after which time he[26] desired me, in the name of the government, to address a public meeting of citizens and officials from a raised platform, in Newgate Yard, hinting that the address would be followed by my immediate elevation to a high position. My sensitive nature shrunk from this display. Not wishing, however, to offend the gentlemen delegated to attend me, I remained quiet as to my plans for avoiding it until the opportunity I waited for offered. Then, weaving my bed clothing into a rope, I let myself down through the chimney and hurried home to America, without saying adieu to them. They were sorry to lose me, and offered quite a large reward for my return if living, or my body, if dead, designing, no doubt, in the latter case, to give me a grand funeral. But I have ever preferred a quiet private life to the elevation they tendered me. That is all, gentlemen.”

“We are obliged to you, Daniel; good morning.”

“Good morning: but recollect, gentlemen, I am entered according to the Act of Congress, in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, and any infringement will be punished according to law; you understand? Good morning.”

Director General of the Exposition, was born in the State of New Jersey. This was, however, without collusion upon his part, and no one more sincerely regrets the circumstance than himself. His father cruised about the Spanish main, from Burlington to Gloucester. Some folks called him a free-booter; he was only this, however, when young Alfred misbehaved himself or the tide ran the wrong way. Our hero was a very promising lad. He was ever ready to promise anything. He was of a domestic turn of mind and could generally be found in the vicinity of the kitchen, especially when cakes and pies were in process of preparation. After a course of studies at Yale, Harvard, Princeton, and Cornell, his parents transferred him to a public school to acquire the arts of reading and writing and the rudiments of arithmetic.

Early in life he joined the temperance movement, but resigned when he grew too big to parade with the cadets. He adopted the profession of the law, and rose as rapidly as a schoolmaster from a tack-lined chair. He was appointed minister to the court of St. James. He preached there until the Saint moved out of the court, and he then took entire charge of the Crystal Palace Exhibition of ’44, after which he swam across the Hellespont and returned to Philadelphia.

An aunt in Cincinnati died and left him a large pork sausage manufactory. After entering into a contract with the Philadelphia dog-catchers, he moved West to take possession of, and run the mill. He assumed a leading position in the city’s trade, was made president of the Commercial Exchange, and in this capacity was selected as director of the Cincinnati Industrial Exhibition.

This double experience made him

of course THE

RIGHT MAN.the most available citizen

to take charge of the Centennial[27]

Celebration. The manner in which

he performed the arduous duties of

the office, and their effect upon his

once robust constitution, may be

conceived if the reader will but

glance at Gutekunst’s latest photograph

of Timothy, which may be

found, full length, upon the back

cover of this volume. He is going

into the sausage business again to

recuperate.

Taken altogether and without exception, we may feel justly proud of our countrymen and women who labored so faithfully for the honor of our common nationality. We trust our country may be as blessed in noble hearts, generous souls and gifted minds, at her next Centennial Anniversary, and that we may all be here to meet them.

Early in 1876 the actual hard

work of the Commissioners began.WELL DONE,

OH RARE OFFICIALS!

During the months of February,

March, and April, they were kept

busy day and night, receiving,

sorting, and arranging the goods

forwarded for exhibition. The

Adams Express Company ran its

wagons directly up to the back

door of the buildings, but as usual

left all the packages on the sidewalk.

It was a goodly, a grandly

beautiful sight, to behold the Director

General carrying huge

packing boxes upon his shoulders

while the dew of honest toil

coursed adown his noble brow, or to look upon the great Orestes heaving

bags and bundles to Willie Bigler, who stood in the doorway and caught

them on the fly. The boys of the District Telegraph Company stood

around watching the exhilarating sight, only finding tongue in their

admiring wonder to encourage the gentlemen with kind remarks and

well-meant advice. Many Foreign Commissioners were also on hand

during this time. To look upon their varied costumes was suggestive of

the grand army in a spectacular drama, with the managers short of uniforms;

to listen to their varied tongues was suggestive of the building of

Babel’s tower.

[28]

The daily travel to the Park and the vicinity of the buildings was immense. Thousands hurried thither regularly to see what they could pick up. Broken china, Japan ware, German silver, French glass, half Spanish cigars—nothing came amiss.

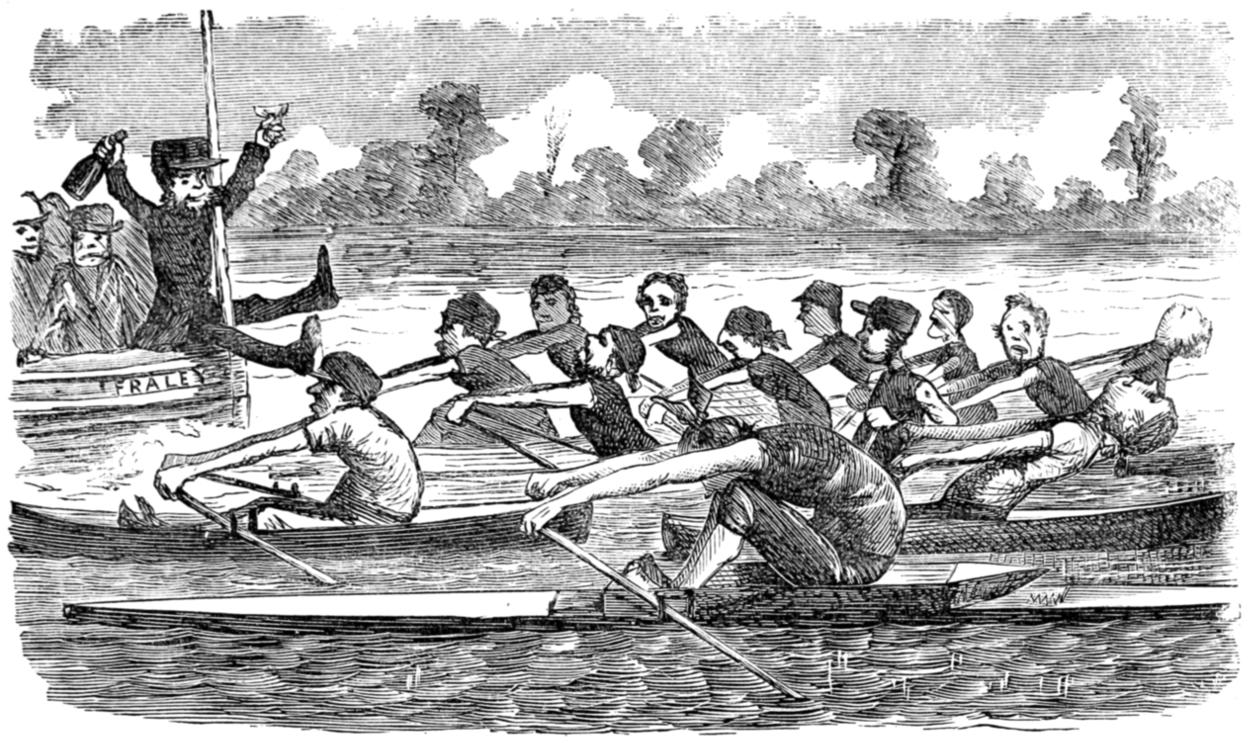

The Market Street Passenger Railway

Company reduced fares to five

cents to catch the bulk of the traffic.

Next day the Chestnut and Walnut

Street line lowered their rates to four

cents, carrying bundles free and no

questions asked. The Race and Vine

Street Company, appreciating the

situation, carried passengers for three

cents, presenting each one with a

chromo of the Bridge across the

Delaware. This was but the beginning

of the famous tramway war,

which continued with variations

during the entire Exposition. Before

its close the Market Street line

was paying passengers seven cents

apiece to ride with them, while the

newly established “People’s Line”

presented each patron with four

shares of stock LODGINGS FOR

SINGLE GENTLEMEN.and a night’s lodging

in their spacious depot.

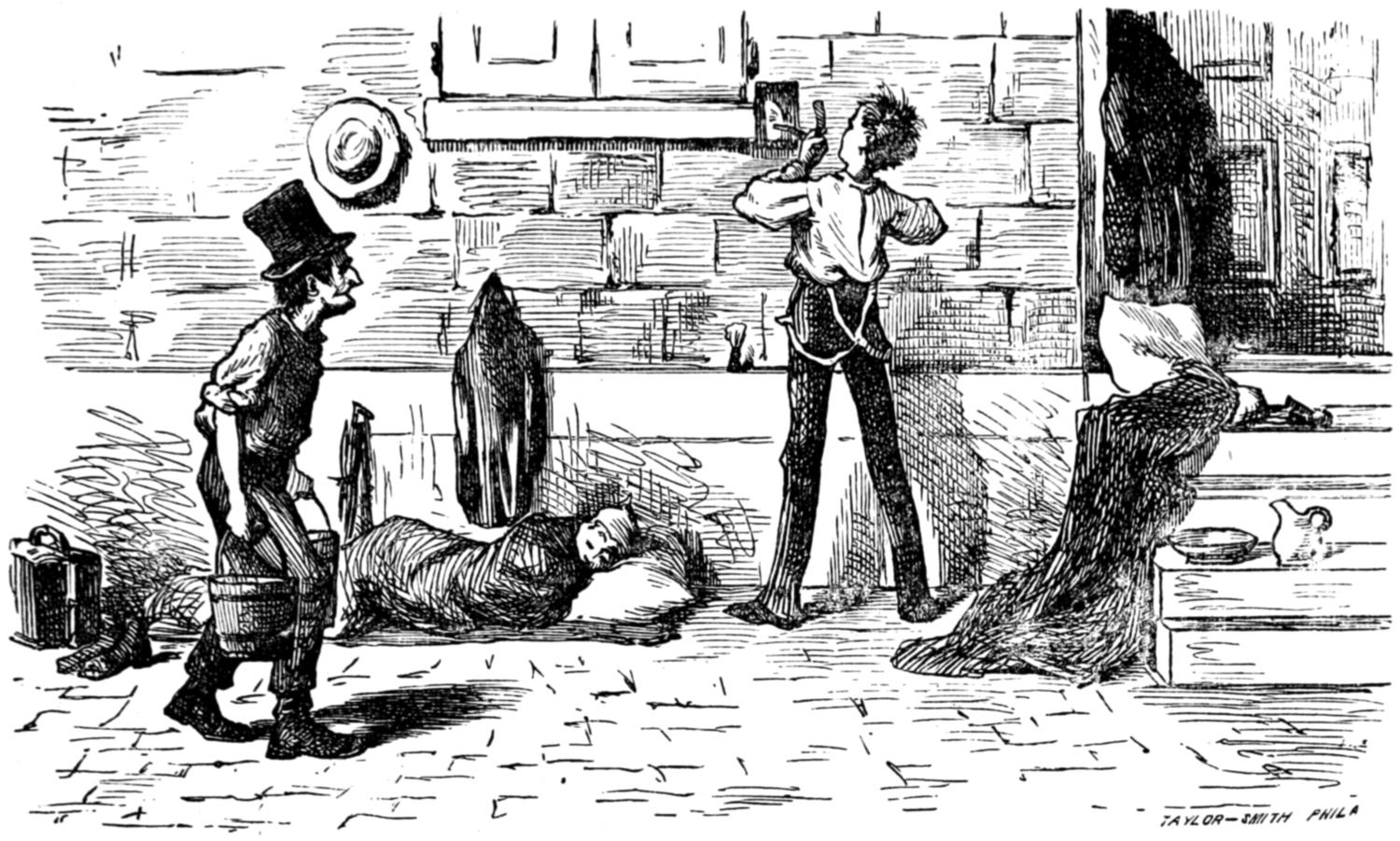

But the city, ah, the city! It really seemed as if everybody who proposed attending the Exposition had resolved to be present at its opening. Every nook and corner, highway and byway, where a tired stranger could rest his wearied head, was engaged, taken up, appropriated; and those dilatory ones who delayed securing accommodations (notably some of the most distinguished guests) were obliged to pay the penalty of their procrastination.

Imagine it to be the month of May. According to a popular fallacy this is the month of flowers and gentle zephyrs; according to Jayne’s almanac it is a first-rate time to take one of his excellent remedies for invigorating the system.

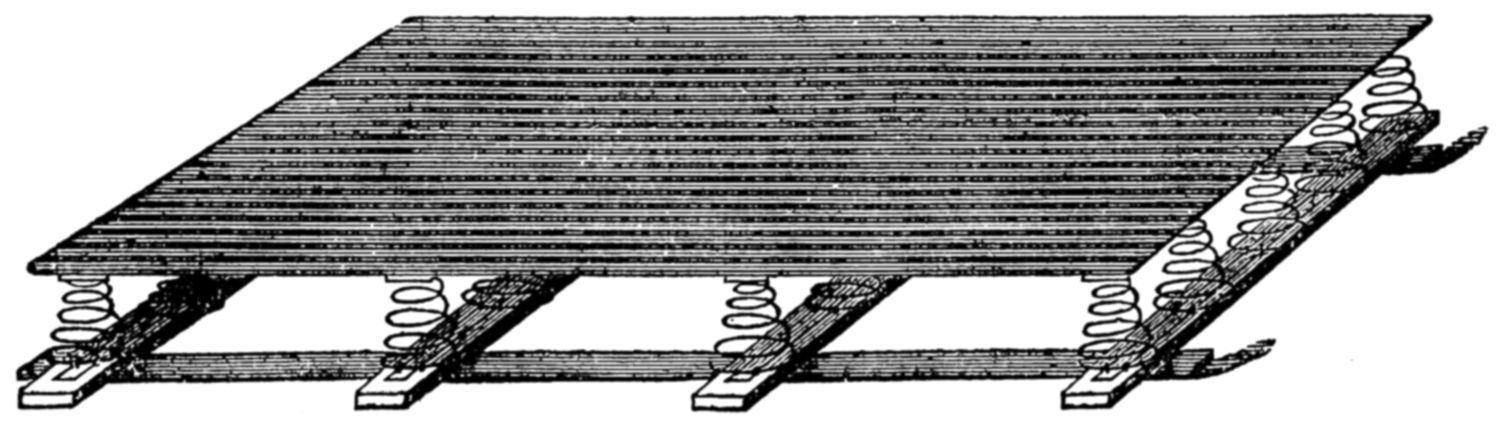

On the tenth day of this month the Exposition is to be opened. The city has cut entirely loose from its Quaker traditions. It is clad in banners, flags, garlands, arches, and emblems. Many private residences are painted to represent the American flag; numerous clothes-lines offer to the breezes various shaped streamers of red, white, blue, and orange-colored flannel. All the lamp-posts have been silver-plated; every telegraph pole has been varnished; every wire enamelled. For weeks the inhabitants have not gone to bed. An ingenious invention in the shape of an inflatable pocket-pillow enables them to take standing naps against walls, buildings, and fire-plugs.

The guns at the Navy Yard continually herald distinguished arrivals. The streets are thronged with citizens, tourists, American and foreign officers and soldiers, the advance guard of every country to be represented. ’Tis like an animated waxwork exhibition. Receptions, banquets, and serenades are of hourly occurrence.

Many side streets are converted into airy lodgings. Families have rented out their door-steps, charging double price when their door-mats are used. A new industry has arisen, and hostlers are deserting the stables to carry shaving water for, and attend to the visitors thus accommodated. It is a common thing, on the way down town in the morning, to pass an early riser making his toilette under difficulties, while a lazier companion snores away complacently with his head against the alley-gate.

[29]

The seventh day of the month was one to be remembered with pride forever. Early in the day the Chevalier De Lafayette arrived with the gentlemen of the French Commission and secured quarters at the “Guy House.” In consideration of his ancestor’s great services, the proprietor rated the Chevalier’s board at six hundred francs per diem, and as a delicate compliment to his national feelings, assigned him an apartment in the French roof. Before he departed the Chevalier ascertained to his complete satisfaction why this hotel was called the Guy House.

On the evening after their arrival, a reception was tendered the Chevalier and his companions by our citizens. Col. Fitzgerald was selected to deliver the address of welcome on account of his Parisian manners, the elegance of costume which distinguishes him from his fellows, and for his general epileptic fitness. We give a report of his speech copied from the “City Item” of the succeeding day. We are, therefore, prepared to vouch for its correctness.

LA BLESSING

DE MON PERE.“Messieurs: God bless you all;

you are noble men; we are all noble

men; a noble man’s the honest work

of God. God bless Paris; God bless

Philadelphia—they are both noble

cities! May He bless the Champs

Elysées; may He bless the Column

Vendome; may He bless the Hotel

de Ville, and, entre nous, while we

are upon this subject, God bless the

Abattoir. (Great applause.)

“Parlez vous, Messieurs (laughter), I greet you all. I stand before you a relic of the past—of a noble past—of a gigantic past—of a—a—sacre a la pain et fromage (increased laughter)—God bless the past! (Cheers.)

“Ate fif tesix five: General Grant is a great man; he is a good man; he is a noble man. In his name I bid you welcome. God bless General Grant, our noble President, our Chief Executive. (Cheers and applause of five minutes’ duration.)

[30]

“The press, Messieurs, the press! I represent that gigantic instrument of civilization. I have a family devoted to the press. Should supplies of printers’ ink give out, they would spill their dearest blood to keep it running. Je suis, pardon me, Messieurs, if I pause to bless them (cries of ‘do,’ ‘do’). God bless them all! Ate fif tesix five. (Immense applause.)

“I greet you as brothers, eau de vie. I have been to Paris. I have visited the Pont Neuf. I have stood on that bridge at midnight, I have gazed at the flowing tide, with the shining stars above me and my family by my side. (Cheers.)

“I have walked along the Champs Elysées:—

“Noble walk!

“Glorious promenade!

“I have looked upon the Column Vendome:—

“Magnificent monument!

“Sublime creation!

“I have examined the exterior of the Hotel de Ville:—

“In short, Messieurs, I have been to Paris; ’tis no more than just that you should come to Philadelphia. (Laughter and applause.)

“Philadelphia and Paris! (Cheers.)

“Paris and Philadelphia! (Cheers.)

“Noble cities!

“God bless you all. Ate fif tesix five. (Paroxysmal applause.)”

The Chevalier responded in very fair French. He was attired in his national costume. He wore a Lyons velvet coat trimmed with Valenciennes lace, a white Marseilles vest, and French papeterie knee-breeches; his hair was powdered with Paris white. Later in the evening the Commission was serenaded by the German Singing Societies. They executed the Marseillaise with great spirit and effect.

The same day the junk of Prince

Kung, the Regent of the Orphan of

the Sun, the Child Emperor of China,

arrived in the Delaware.DIE WACHT

AM DELAWARE. The vessel

was brilliantly illuminated with

Chinese lanterns, and a band of native

musicians discoursed sweet

music from the forward poop upon

their wooden accordeons and pipes

of reed. The Prince was a lantern-jawed

sort of an individual with a

candle-wicked eye. He and his suite

were met by a delegation of laundrymen

at Poplar Street wharf. Sam

Wing, Esq., extended them an invitation

to attend an opium banquet

next day at the hall of the Bedford

Street Mission.

While this reception was in progress up town, the firing of guns and ringing of bells announced the arrival of the Imperial German Commission.

Fifty thousand German citizens lined Walnut Street dock and the floating palaces in the vicinity, and no sooner had Prince Bismarck and his comrades touched land, than they were lifted bodily into several of Bergner & Engel’s beer wagons, which were in waiting. The crowd, removing the horses from the wagons and the bungs from the kegs provided, proceeded to draw both the wagons and the beer. Previous to starting, however, Alderman McMullin, who had been delegated for the pleasing duty by the German Society, spoke briefly as follows:—

“Respected Dutchmen: The proudest occasion of my eventful career is the present—to be permitted to welcome to this new world, this republic of an hundred years, the flower[31] of the great German Empire under auspices so favorable and inspiring. Not even when marshalling the once famous ‘Moya’ to do battle with the devouring element, consuming in its fury the massive storehouse, the busy factory, the domestic hearth—aye, and life, dear life itself—not even when the bullet of the assassin found a resting-place within my weakened frame, did I experience the thrill of sublime pride, the glorious impulse of friendship and common humanity, which now animates my being. For know there is between us a bond of sympathy which the boundless intervening ocean cannot sever. William is my name, and it is likewise the name of my respected friend, your honored sovereign. Like me, he is simple in his tastes; like me, he is renowned for his courage and determination.

“I desire that you should carry home with you a high opinion of our manners and institutions, and many, very many, pleasant reminiscences of your visit. I trust we shall meet frequently and become quite sociable during your stay. I invite you all to dine with me to-morrow.”

Prof. Max Müller responded, with the accent of a Latin grammar.

“Mr. Mickmullion, and gentlemen,” said he, “I thank you for this welcome in the name of the Emperor, his Highness Prince Bismarck, my colleagues, and myself. For years have I desired to visit this country for the purpose of making a geological examination. During your eloquent remarks I have taken the opportunity of analyzing a handful of the soil. To my intense gratification I find it to average a conglomeration or semi-crystalline gneissoid of dark brown hematite, or, perhaps, a combination of barytes manganese with carbonate of strontia. You will frequently notice that the debituminization of these silicious formations will degenerate in quality—at times ferruginous layers of volatile diorite form component parts. I have no doubt that you, Mr. Mucksquillion, have frequently arrived at similar conclusions.

“So, again thanking you for your kind reception, I assure you I appreciated the finish of your remarks.”

Prince Bismarck was then taken

in charge by Archbishop Wood,

who had a hammock swung for him

in the Cathedral.OUR BOYS—

FRITZ

AND WALES. “Unser Fritz,” the

Emperor, and the commissioners

were driven to the German Hospital.

They declined communication of

any kind, save an underground

communication with Bergner and

Engel’s Brewery. In the evening,

however, they were serenaded by the

Société Française. “Die Wacht am

Rhein” was sung with much feeling.

On this eventful day the Hon. Morton McMichael presided professionally at four banquets.

The day following this is also one to be looked back to with gratification. The Irish Rifle Team arrived with the dawn, and was greeted with a beautiful sunrise, very cleverly arranged by Professor Jackson. The team acted as escort to the Prince of Wales and suite. Since his return from India, the Prince had been in rather reduced circumstances. Although scrupulously clean, his coat was somewhat threadbare, and his beaver gave evidence of frequent brushing.

[32]

His Highness and suite were quartered at the house of the Spring Garden Soup Society; the team secured accommodations at a first-class livery stable.

These distinguished guests were received by General Franz Sigel, who remarked that he was glad to see them looking so fresh and green; that he liked fresh and green folks to come to this country. He advised them all to come back when they went home and get naturalized. He said that the ladder of Fame was waiting for Irishmen, and all they had to do was to come and climb. He wanted them to carry home a good opinion and leave as a remembrance the contents of their wallets. His remarks were received with hearty cheers.

Wales suffered considerably during the trip over. He says the company of the riflemen completely demoralized him. He might say he was half shot when he was half seas over.

About noon the Spanish delegation arrived in Jersey city. They landed from the ferry boat in high good humor. The commission, composed of the elite of Spanish chivalry, included the following distinguished names:—

Senor Concha Maduro.

Don Felix Estra-Maduro (cousin of the above).

Count Flor Del Fumar.

His Highness Reina De Victoria, and

Don Regalia De la Palma.

These gentlemen proceeded quietly and unostentatiously to their rooms on the seventh floor of the Colonnade Hotel. They were waited upon by the leading cigar dealers of the city, who offered their spacious establishment as headquarters.

Towards night the Duke of Gloucester and Red Bank arrived at South Street wharf. He had an apartment reserved for him on top of the Christian Street Shot Tower, to which he repaired at once.

Pere Hyacinth came on the same vessel, and was taken in charge by the Horticultural Society. They lodged him cosily in the southeast corner of the State-house steeple. He says he liked his lodgings very much, but the rarefaction of the air was such that he could hear his watch ticking all night long.

The Emperor of Brazil arrived at a very late hour and bunked temporarily back of the main chimney of the Girard House.

THE “ALMS HOUSE”

REGISTER.The following guests registered at

the Alms House.

Victor Emanuel of Italy, wife, three masters and three misses Emanuel.

Mr. Khedive, of Egypt, with seven Madames Khedive. Family left at home.

Professor Tyndale,—London.

Joseph II. of Austria, wife and mother-in-law.

General Von Moltke, Prussian Army. (He had unfortunately missed the train which had brought his copatriots, and was very warm upon his arrival.)

Mr. McMichael presided at seven banquets this day, at one of which he read a telegram from Queen Victoria, accepting with thanks the apartments kindly tendered her by Engine No. 10.

Next day, the 9th inst., the city’s pulsometer was at fever heat.

Brigham Young and family arrived[33] from Utah per Centennial R. R. special train, forty-four cars. Brigham said he wanted to give the little ones an excursion. They were located under sheds at Point Breeze Park.

On this evening, too, a most remarkable event occurred. During the day the City Solicitor of Philadelphia, who is also a military commander of renown, in addressing a meeting of some of his contemporary warriors, including Bismarck, Von Moltke, MacMahon, and others, remarked that he would meet them upon the morrow at Memorial Hall, during the opening ceremonies. Immediately a special meeting of city councils was convened, and the following preamble and resolutions presented and unanimously adopted.

“Whereas, An International Exposition was held at Vienna, in the year 1873; and WHEREAS, upon the day the City Solicitor of Philadelphia carried into effect his predeclared intention of visiting said Exposition the roof of the buildings fell in, doing great damage and causing great excitement; and WHEREAS, the same City Solicitor has announced his purpose of visiting our Centennial buildings to-morrow; and WHEREAS, it is our bounden duty to provide against the occurrence of any like disaster to our International Exposition, and especially from the same cause which affected the Vienna affair, be it hereby

“Resolved, That the interests of the Exhibition demand the incarceration of the individual above alluded to.

“Resolved, That he be immediately placed in irons and confined in the vaults of the Knickerbocker Ice CompanyON ICE. until the close of the Exposition.

“Resolved, That every attention be paid to him in his confinement, and that the Knickerbocker Ice Company be allowed $93.77 per diem for his support and the ice required to keep him cool.

“Resolved, That he be produced for one hour each Wednesday morning at the Supreme Court Rooms, to deliver opinions on municipal affairs, that the city may suffer no more than necessary from this unavoidable action.

“Resolved, That he be supplied with the ‘Times’ newspaper daily, and be allowed unlimited rations of lemons, sugar, and whatever liquid he may desire, to mix with his ice.”

At four o’clock in the morning, the subject of these resolutions was awakened from his innocent slumbers and hurried into a Knickerbocker ice wagon by detectives, with black masks over their faces. He struggled bravely, but—pro bono publico—principiis obsta.

[34]

The morning smiled bright, and the mist rose on high, and the lark whistled “Hail Columbia” in the clear sky, on the tenth day of May, 1876, the day set apart for, and consecrated to, the opening of the Centennial Exposition.

Old Probabilities himself was in the city, with his weather eye open. Early in the morning he fixed the barometer in front of McAllister’s at “set fair,” arranged the thermometer at 65°, and engaged a refreshing southern breeze to be around lively during the entire day. After this he ate his breakfast, enjoying a quiet conscience and a correspondingly good appetite.

Shortly before daylight a very curious incident occurred—fortunately it ended happily.

OH SHAH,

WHAT A FUSS!The Shah of Persia, his son John, and the Sultan of Turkey, arrived

together at Broad and Prime Street Depot. The city being weary of

receiving dignitaries, no official and but little private notice was taken

of their arrival. They jumped into a Union Line car. Unthinkingly, the

Sultan put a dollar bill into the “Slawson box,” and then demanded his

change from the conductor. Of course, the conductor was unable to open

the box, and refused to give it to him, telling him he deserved to lose it

for his stupidity. The Sultan became furious.

“My change,” he cried; “I want my change, and I’m going to have it; seven cents for me, seven cents for the Shah, and four cents for little Shah, that’s eighteen cents; give me eighty-two cents change. You can’t cheat me, you swindling Americans!”

Again the conductor refused and remonstrated; the Sultan was perfectly wild with rage; he drew his scimetar, and caught that conductor by the throat, and there would certainly have been an immediate vacancy for a conductor on the Union Line, had not Mr. McMichael been just then returning from a late banquet. Mr. McMichael, being a sportsman, was thoroughly conversant with wild turkey gobble; he smoothed matters over. He refunded the eighty-two cents from his own pocket, took the[35] Eastern monarchs home with him, and afterwards secured them a bed in the coal cellar of the House of Correction, apologizing to them because they were obliged to share it with Mr. Carlyle, the English essayist.

The Egyptian Sphynx, kindly loaned by the Khedive, also arrived in the morning, and was at once placed in position on Belmont Avenue. We regret being obliged to record the disgraceful fact, that it was entirely carried away in small bits by relic fiends before night. The Khedive immediately presented a bill of damages to the President, and levied on the Exhibition buildings in toto, the Capitol at Washington, and Mayor Stokley’s house on Broad Street. Happily the matter was amicably settled. The President promised the Khedive that Congress should have a new Sphynx made for him, a much better one than that destroyed, of bronze, and with all modern improvements. The order was subsequently given to Messrs. Robt. Wood & Co., of Philadelphia, and before the close of the Exposition they shipped to Cairo a bronze Sphynx, which will certainly add greatly to the attractions of the desert. We doubt not that the Messrs. Wood will receive orders for bronze Pyramids, provided they will take the old ones in part payment.

THE MODERN SPHYNX.

The proprietor of the Public

Ledger was so pleased with the

Sphynx which our Philadelphia firm

turned out, that he immediately

ordered a duplicate for his back

garden. He also composed the following

touching linesAND HIS RHYME,

IT WAS CHIL-DLIKE

AND BLAND. for the poet’s

corner of his journal. A copy of

them, translated into Egyptian characters,

was sent to the Eastern potentate

with the Sphynx:—

The great feature of the day was

the march from Independence Square to the Exposition grounds. We shall endeavor, in brief style, not to do justice to, but to give some slight account of the grandest pageant which any nation has yet witnessed in its midst.

The immense body, consisting of

representative military from every

nation under the sun and in the

shade, was divided into two hundred

and forty divisions, each with

a commanding general and aids.BENJAMIN’S

COAT.[36]

General Joseph E. Johnston, of

Georgia, was to have been Grand

Marshal. His uncle Andrew being

dead, unfortunately, he was obliged

to have his only military coat repaired

by a tailor who was not

punctual, and who failed to express

it to him in time. General Butler,

of Massachusetts, however, who

happened to have two coats with

him, very kindly loaned one to

Johnston, who appeared in the

afternoon. Attached to the back

of the loaned garment was a neat

show-card, bearing this inscription—

ANOTHER BRIDGE

ACROSS THE

BLOODY CHASM.

THE TRIBUTE OF

MASSACHUSETTS

TO

GEORGIA.

The General was lustily cheered wherever he went, and General Butler was the subject of more praise during this day, than during any portion of his life subsequent to his occupation of New Orleans.

The position of honor, the First Division, was given to the Philadelphia regiments by a unanimous vote of the generals of divisions.

Col. Hill and Dale Benson led off with his command, which appeared for the first time in its new uniform. The immense black fur muffs, which the members borrowed from their sisters and wore upon their heads, gave them a very ferocious appearance, though most of their noses were completely hidden from view. Company “C” attracted particular attention. It had adopted a new “hop” for marching, which was both graceful and unique, though evidently fatiguing.

The “State Fencibles” turned out in fine style. With their accustomed liberality they presented arms to all the pretty girls they met on the way. The “City Troop” brought up the rear of the division. These warriors were arrayed in all their awful panoply of war—white ties and white kid gloves, with gold vinaigrettes, containing salts and extracts, dangling from their belts. Their horses were also supplied with vinaigrettes, which they sniffed occasionally in lieu of their usual odor—the smoke of battle. The Troop carried a magnificent banner, inscribed—

First in Peace—First in War—

and

First in the Hearts of their

Countrywomen.

And, on the reverse side—

PRESENTED TO THE

CITY TROOP OF PHILADELPHIA

BY THEIR

LADY FRIENDS AND ADMIRERS,

AT THEIR

FIRST ANNUAL PICNIC,

Schuylkill Falls Park, July 1, 1872.

The Pennsylvania Veterans, G. A. R., marched in the centre of the[37] Second Division, and a moving incident occurred as they passed by the Mint near Broad Street.

The first distinguished warrior to appear was Colonel Mann, the hero of ~0007 fights, mounted upon the gallant steed which had borne him safely through them all. Along the route, his iron front proudly erect, his bronzed and battered features flushed with the nobility of a natural pride, he was greeted by the enthusiastic cheers of the assembled thousands. Maidens from beyond the seas—officers (no mean heroes themselves) from the armies of the old world, joined in the gracious tumult. One bald-headed veteran (a Marshal of the Windsor Castle Guards, who had left a leg at Balaklava, an arm at Waterloo, an eye in the Crimea, and who expected to distribute the rest of himself upon various other battle-fields before he died) turned to the Chevalier De Lafayette, who with Senator Sam Josephs occupied the barouche with him, and asked—

“Who is passing, Chevalier, that the people appear so excited?”

“Quely vous motre dio, do you really not know?” exclaimed the Chevalier, “Zat is, graciosa poverisi, zat is ze Kunel Mann, pardieu, ze great Kunel Mann.”

“What!” shouted the veteran, and

pulling from his coat the diamond

order of “St. George and the Dragon

fly” which blazed among an hundred

others upon his breast, he rose

in his coach and flung it gracefully

to the Colonel, who caught it quite

as gracefully upon the fly. At this

moment a great shout arose. The

populace imagined that a shot had

been fired at the Colonel, that an

attempt had been made to assassinate

their pet hero.THE PET OF

THE

POPULACE. The mob rushed

for the carriage which contained the

veteran, with cries of “kill him,”

etc. etc. The Colonel took in the

situation at a glance. Rising in his

stirrups he spread wide his arms to

show he was uninjured.

“Hold,” he shouted, in that same voice of loud and deep toned beauty which oft had brought the briny tears to eyes of hardened criminals in the dock, “Hold; he is my friend: he has given me this badge (‘Cape May diamonds,’ he added sotto voce); who touches a hair of his bald head, dies like a dog—march on,” he said.

The cries for vengeance changed to wild cheers of joy, and the procession moved on.