“It may be truly said that the commandment of the Sea is an abridgement or a quintessence of a universal monarchy.”

Francis Bacon

Title: The Last Fight of the Revenge

Author: Walter Raleigh

Author of introduction, etc.: Sir Henry John Newbolt

Illustrator: Frank Brangwyn

Release date: December 17, 2021 [eBook #66958]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Gibbings and Company, 1908

Credits: deaurider, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

Pages in the original book were quite narrow, with large print; and most pages included a large illustration at the top or bottom. Viewing this ebook in a narrow window will approximate that original design more closely than will a wide window.

“It may be truly said that the commandment of the Sea is an abridgement or a quintessence of a universal monarchy.”

Francis Bacon

THE LAST FIGHT OF THE

REVENGE

BY Sr WALTER RALEIGH

WITH AN INTRODUCTION

BY HENRY NEWBOLT, M.A.,

AND ILLUSTRATIONS BY

FRANK BRANGWYN, A.R.A.

LONDON: GIBBINGS AND

COMPANY 1908

| Some Appreciations | page 11 |

| Introduction | 15 |

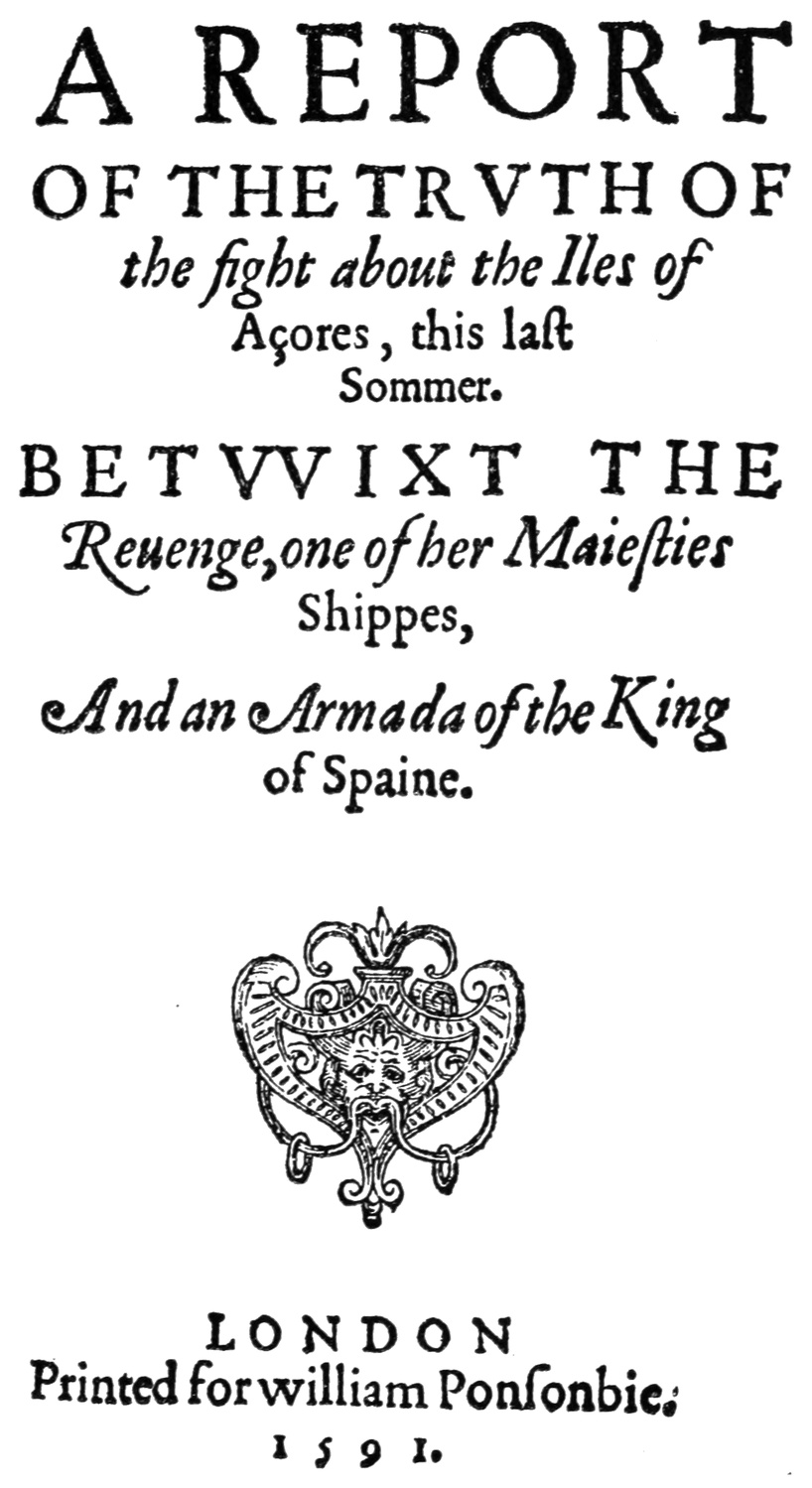

| Facsimile of original Title Page | 57 |

| The Last Fight of the Revenge | 61 |

9

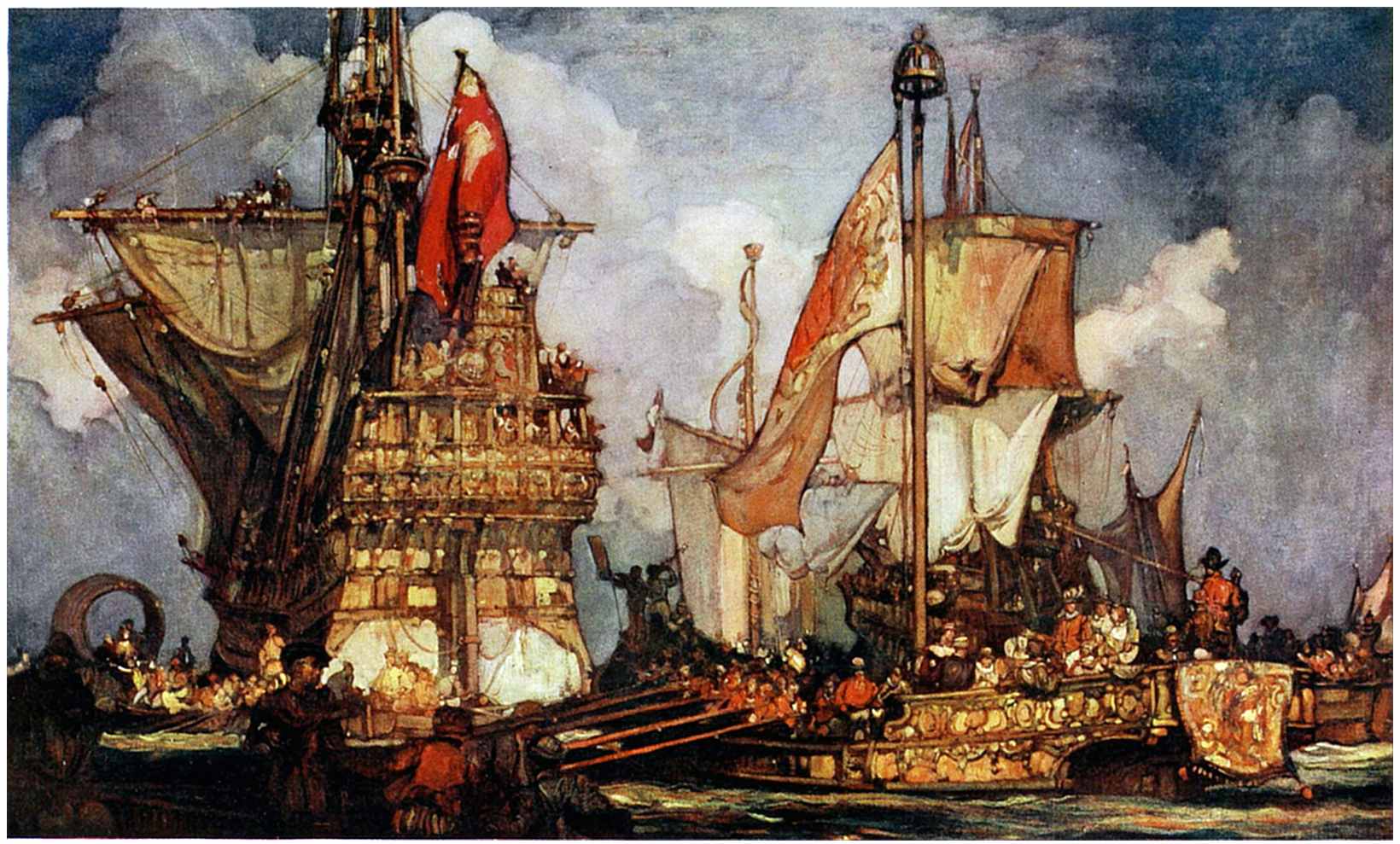

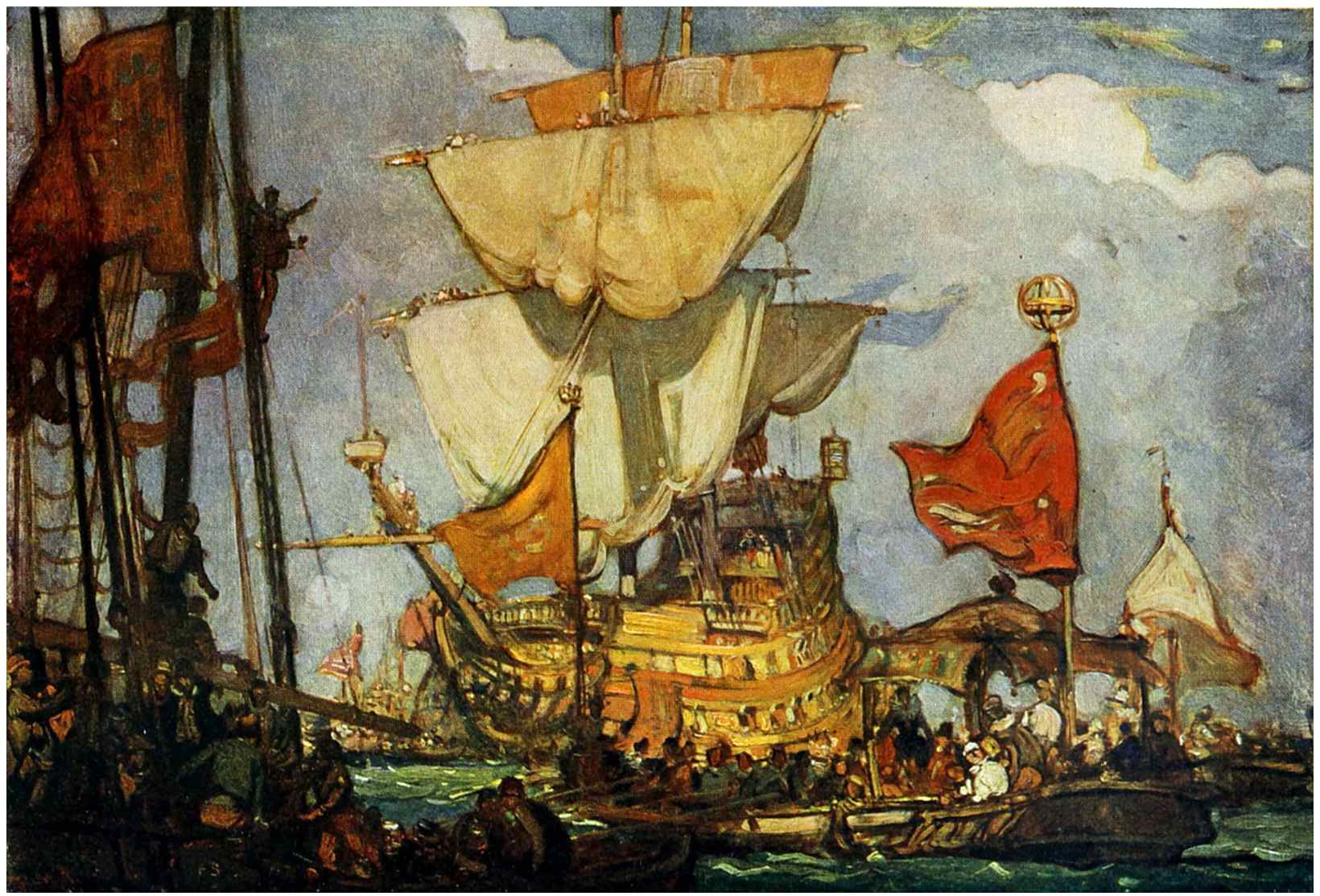

| 1. Queen Elizabeth going on board the Golden Hind (By kind permission of the Committee of Lloyd’s Register) | page 19 |

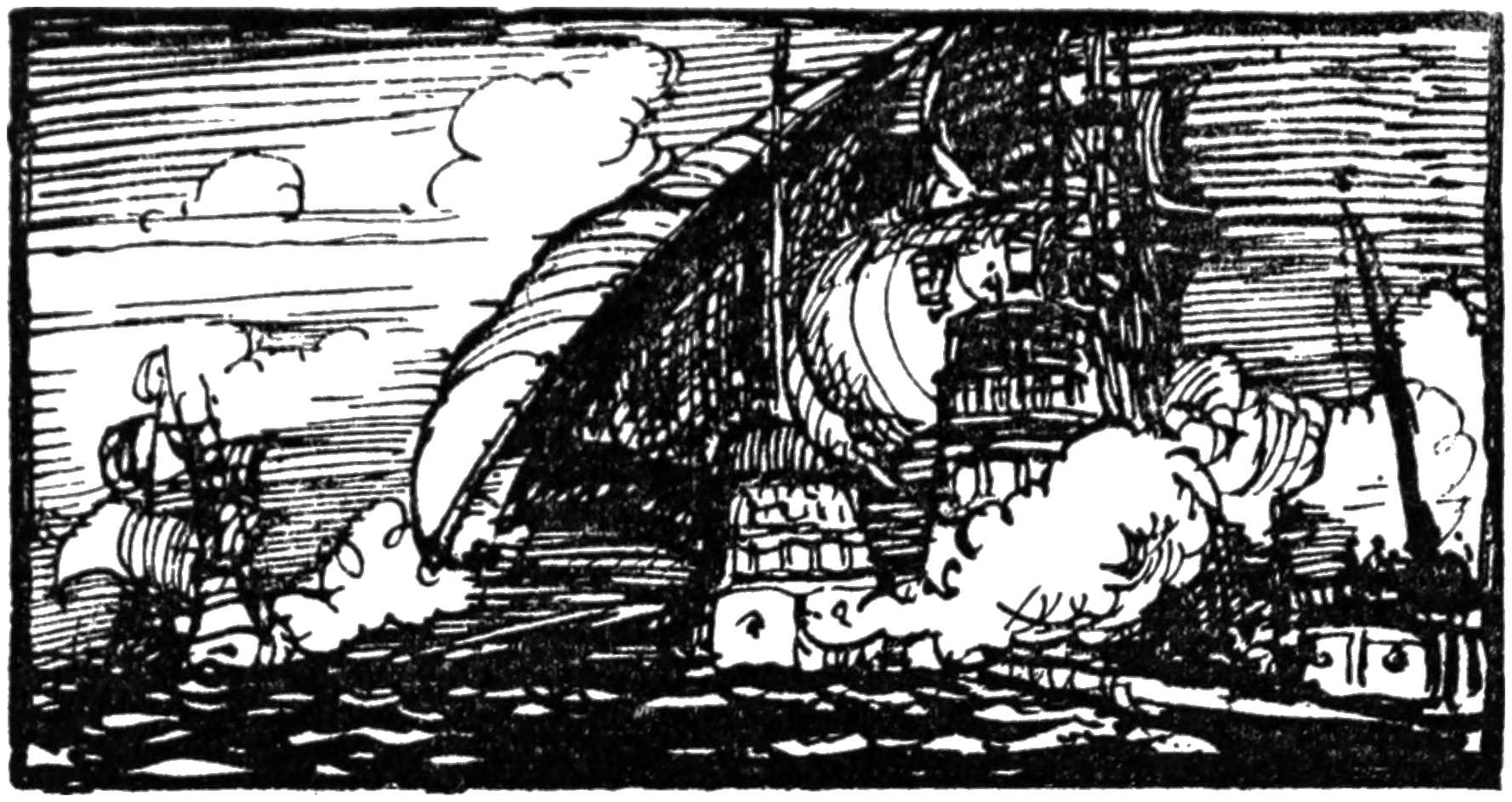

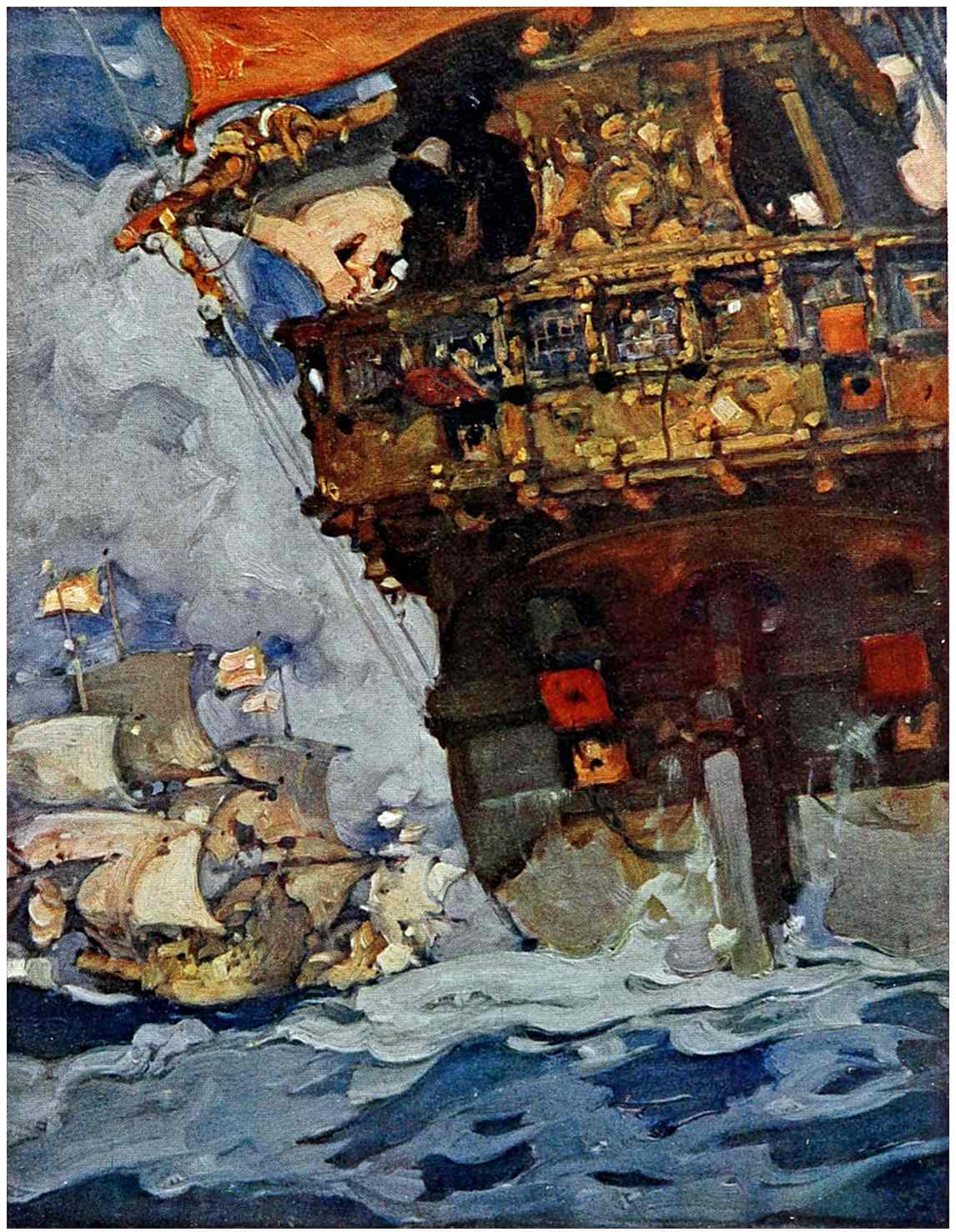

| 2. The Last Fight | 59 |

| 3. Galleons in Harbour | 73 |

| 4. Loading the Galleons | 85 |

| 5. The Galleon Fair | 97 |

| 6. A Captured Galleon (From a picture in the possession of Colonel Goff) | 105 |

11

“In the year 1591 was that memorable Fight of an English Ship called the Revenge, under the command of Sr Richard Greenvill; Memorable (I say) even beyond credit, and to the Height of some Heroicall Fable. And though it were a Defeat, yet it exceeded a Victory.”

Sir FRANCIS BACON

“Sr Richard Greenfield got eternall honour and reputation of great valour, and of a experimented Souldier, chusing rather to sacrifice his life, and to passe all danger whatsoever, then to fayle in his Obligation.... And rather we ought to imbrace an honourable death then to live with infamie and dishonour, by fayling in dutie.”

Sir RICHARD HAWKINS

“Than this what have we more! What can be greater!”

JOHN EVELYN

12

“Struck a deeper terror, though it was but the action of a ship, into the hearts of the Spanish people; it dealt a more deadly blow upon their fame and moral strength than the destruction of the Armada itself.”

J. A. FROUDE

“Perhaps in all naval history there never was a more gallant fight than that of the Revenge off the Western Isles.”

PROFESSOR ARBER

13

By permission of Messrs Macmillan & Co., Ltd, the owners of the copyright.

15

17

Which is the greatest name upon the roll of English ships? Which is the most sure of a lasting and effectual renown? There was a day when all England would have given but one answer. If you ask the Elizabethan of 1580, you will find him very positive upon the point, and not a little exalted. Drawn round the world by the Divine

18

Hand, under the Northern and Southern Pole stars, victor over a hundred enemies, ballasted with royal treasure, & steered by the captured charts of Spanish Admirals, the little ship that sailed as the Pelican, comes home again as the Golden Hind. She brings her fabulous booty and her still more fabulous romance from Plymouth Sound to Deptford, and then and there the great names of the past—the Christophers, the Great Harrys, the Dragons and the Swans—are all finally eclipsed. Drake, kneeling upon her deck, receives his knighthood from the hand of Gloriana, and the Golden Hind herself, bidding farewell for ever to wind and wave, is laid up as a national monument—“consecrated to perpetuall Memory.”

She is remembered still, but it is hardly for her own sake; her story is a part of Drake’s, and not the greatest part. Question your Elizabethan again some ten years later, and hers is no longer the name that he will give you; he will speak of things that are even nearer to his heart, and to ours; for though an Englishman will always, I suppose, lick his lips over a tale of treasure, it is the fighting and not the plunder that he is really fitted to enjoy, and in his imagination even the jewels of the Golden Hind will shine with a less bright and steady glow than the battle-lanterns of the Revenge.

The Revenge is a part of no man; she saw many captains and more triumphs than one. She had a personality, as great ships always have; she had a career, a life of her own. She has a life after death; not only a posterity but a true survival.

22

She may be said, in no merely figurative sense, to be on active service still. If the day ever comes when she no longer helps to keep the sea for us, it can only be when Time shall have paid off the British Navy.

The last of her successes is more freshly remembered by our friends than by ourselves. A neighbouring potentate, whom pride in his English descent had exhilarated to a pitch of splendid audacity worthy of an Elizabethan, challenged us by a telegram encouraging a vassal State to throw off the suzerainty of the Queen. If the message meant anything, it was a promise of armed support; but the promise had none of the Elizabethan hardihood to back it, and proved bankrupt as soon as the Flying Squadron put to

23

sea. It was not that this force was unknown, or suddenly created; the ships had long been on the Navy List, their names, guns, tonnage and complement all as familiar to the German Kaiser as to the rest of the world. But there was a sense abroad of something more than brute strength: a memory of great traditions, of inherited skill, of undaunted and indomitable tenacity. When on that January 15, 1896, the English Admiral hoisted his flag in the Revenge, and Her Majesty’s Marines marched on board under the command of Captain Drake, the enemy disappeared from the seas, and we made haste to forget another naval victory.

The lesson, we may hope, remains; this was not a triumph of physical force. The challenger’s nerve, and not his ships, failed him; he feared his

24

own destruction more than he desired ours. In an age even more materially minded, if possible, than those which went before it, we are increasingly diligent to measure our armour and our guns, to reckon up our horse-power and the number of our hits at target practice. It is not for any man to blame us; we should be wrong if we neglected these things, but we should be still more wrong if we forgot for a moment that there were years in our history when it was not we but our enemies who had the advantage of armament, and that whether by combination or otherwise, such a time may come upon us again. Build as we will, we cannot secure ourselves against it for ever; but we can forestall it by facing it with the remembrance of the past. It was by moral superiority that the

25

Elizabethans came through their trial. The Spaniards were contending to maintain their hold upon the wealth of the world, and they fought as men will fight in such a cause—courageously, but not desperately; the English fought as, at sea, they must always be fighting, for national existence, and they took care—it was a great part of their strength—to leave their enemies in no doubt that they meant in every engagement to make the affair fatal to one side or the other. This is a policy which we did not follow in the latest of our wars; we may have been justified, we had our reasons, and we paid the full price; but on the day when we abandon it upon the sea, we shall have thrown away our only sure defence and our deadliest weapon. Men and nations are never so nearly invincible and never26 half so terrible as when they are armed with contempt of death; and that such an ardent temper can defy, discourage and destroy mere bulk or numbers, “even beyond credit and to the Height of some Heroicall Fable”—this is the meaning of the last fight of the Revenge.

27

It was in 1577, the year in which the Golden Hind sailed from Plymouth on her ever-memorable voyage, that the Revenge first took the water. Probably, says Arber (but I cannot find upon what authority), she was built at Chatham by Sir John Hawkins. According to Sir John Laughton she was launched at Deptford. Ships

28

are the children of predestination, as every sailor knows: from the moment when they leave the slips they are either lucky or unlucky. In the opinion of the younger Hawkins the Revenge “was ever the unfortunatest Ship the late Queene’s Majestie had during her Raigne.” He supports this view by a list of hairbreadth escapes, which might as easily be quoted to prove her the especial care of Providence, many times miraculously preserved to be the scourge and dishonour of the Queen’s enemies. First, says Sir Richard, “Comming out of Ireland with Sir John Parrot, she was like to be [but was not] cast away upon the Kentish coast.” Then, in 1586, “in the Voyage of Sir John Hawkins, she struck aground coming into Plimouth, before her going

29

to Sea”; but to sea she went nevertheless. Upon the coast of Spain she was “readie to sinke with a great Leake,” and (though she did not sink) “at her return into the harbour of Plimouth, she beat upon Winter Stone”—again without fatality. She escaped a still greater danger when, soon after, she twice ran aground in going out of Portsmouth Haven, lay twenty-two hours beating upon the shore, and was forced off with eight feet of water in her, only to ground again “upon the Oose,” where she stuck for six months, until the following spring, testifying to the skill of those who built and the clumsiness of those who sailed her. Being at last got off and brought round into the Thames to be docked, “her old Leake breaking upon her, had like to

30

have drowned all those which were in her.” Neither then, however, nor in any of her mishaps, does she appear to have actually drowned anyone, not even when, in 1591, “with a storme of wind and weather, riding at her moorings in the river of Rochester, nothing but her bare Masts overhead, shee was turned topse-turvie, her Kele uppermost.” One might have thought that this final proof of her indestructibility would convince her detractor. Drake, at any rate, knew a good sea-boat when he saw one, for he chose her for his flagship when he sailed against the Armada as Vice-Admiral, and the Calendar of State Papers contains, under the date of November, 1588, a “Device of Lord Admiral Howard, Sir F. Drake, Sir W. Wynter, Sir John Hawkyns, Capt. Wm. Borough and others, for the construction of four new ships to be built on the

31

model of the Revenge, but exceeding her in burthen.” (She was but of 500 tons herself, and carried at most 260 men and forty guns.) To this evidence we may add the statement of a Spanish prisoner, bearing the delightful name of Gonsalo Gonsalez del Castillo, who writes in 1592 that in England “they have been much pained by the loss of one of the Queen’s galleons, called the Revenge; they say she was the best ship the Queen had, and the one in which they had the most confidence for her defence.”

Such was the Revenge, and, if she had her share of misfortune she had also her full share of prosperous service. She bore Drake’s flag as Vice-Admiral from January 3, 1588. On May 23, at the head of sixty sail, she escorted the Lord Admiral Howard into Plymouth; then, till July 12,

32

she watched and longed for the “felicisima Armada.” On Saturday the 20th, while the enemy crept up Channel in heavy rain, and the wind fell lighter and lighter, she tacked and tacked her way out painfully through a night of deadly anxiety. She had her reward. On Sunday, “conspicuous with an extravagant pennant and a banner on her mizzen, and fighting almost at grappling distance,” she battered Don Juan Martinez de Recalde in the Santa Anna. Towards evening the Admirals held Council on board her; when night fell her lantern led the fleet, until Drake, finding himself among strange sail, extinguished it and lay by for daylight. Howard and the rest went after the Spanish lights, and when dawn came the Revenge found herself alone,

33

and drifting within a few cables of the huge Nuestra Señora del Rosario, flagship of Don Pedro de Valdes, Captain-General of the Andalusian Squadron and one of Sidonia’s best officers. The Captain-General was “spoiled of his mast the day before,” and had smashed his bowsprit in collision; but he tried to stand out for conditions of surrender. The Vice-Admiral replied that he was Drake, and had no time to parley. That ended the matter; the galleon went into Dartmouth “under the conduction of the Roebuck” and the Revenge “bare with the Lord Admiral, and recovered his Lordship that night, being Monday.” Aboard of her went poor Don Pedro and forty of his officers; also their cash, to the tune of fifty thousand ducats.

34

On Tuesday the 23rd, the prisoners, or those of them who were allowed on deck, witnessed the battle off the Isle of Wight, the failure of the galleasses with their countless oars, and the rescue of the Triumph, in which our first Victory and our first Dreadnought distinguished themselves. They saw, too, in the bird-like line-ahead flights of the Revenge and her consorts, their quick concentrations and dispersals, what Mr Julian Corbett has described as “the first dawn of those modern tactics which Blake and Monk were to develop and Nelson to perfect.” By the end of the day they were probably all deaf; the unknown eyewitness who wrote the Relation of Proceedings for Howard, declares that “there was never seen a more terrible value of great shot, nor more hot fight than this was; for although the musketeers

35

and harquebusiers of crock were then infinite, yet could they not be discerned nor heard for that the great ordnance came so thick that a man would have judged it to have been a hot skirmish of small shot, being all the fight long within half musket shot of the enemy.”

On the 24th fresh ammunition arrived, and the fleet was divided into four squadrons, of which Revenge was to lead the second.

On Thursday the 25th, in a calm, the galleasses ventured again and were finally knocked out of the fight. For the next two days “the Spaniards went always before the English Army like sheep” until on Saturday evening they suddenly came to an anchor off Calais.

On the night of Sunday the 28th, the Lord Admiral “caused eight ships to be fired and let36 drive amongst the Spanish fleet; whereupon they were forced to let slip or cut cables at half and to set sail.” When day came, Howard stopped to take a prize, and it was the Revenge who led the last great chase northwards, pounding Sidonia himself in the huge San Martin, sinking, scattering and driving ashore his followers. “It was the hour,” says Mr Corbett, “for which Francis Drake had been born.” But glorious as it was, it was not yet the hour for which the Revenge had been built.

37

Drake was beyond doubt the greatest man who ever set foot in the Revenge, but it was not for him, or any like him, to sail her to the fulfilment of her unparalleled destiny. The imagination of two great peoples has made of him an almost supernatural hero, a gigantic figure of romance; but in spite of his inexhaustible courage,

38

his dazzling fortune, and the touch of extravagance which he caught from the spirit of his time, he was neither a Don Quixote nor a Prince Fortunate of mere adventures. For him there was nothing that could not be dared, but it must be dared with method and for an end in view; for him wisdom could never be “wisdom in the scorn of consequence.” Setting aside their natural bravery and the fashion of the day, there was little in common between this heroic prototype of the modern Englishman, and Sir Richard Grenville, the inheritor of a temperament which has long been practically extinct among us, and was even then the characteristic of a dwindling

39

class. The men of courage without discipline, of enthusiasm without reason, of will without science—a type of arrested development surviving from the days beyond the Renaissance—fell with the Stuart Kings and were finally buried with the rebels of the ’45. It is easy to say that they were of no use, these turbulent, insensate, self-willed children of aristocracy; at the least they added colour and vivacity to life, and these are something; now and again they had their great moments, when folly touched the height of tragedy, and left a true inspiration for those who are not too sober or too senile to receive it.

Men have always liked to think of definite characteristics as the hereditary possession of certain families—often, no doubt, without much justification, but surely not altogether so in the

40

case of the Grenvilles. Reading their records without any preconceived belief, we cannot but hear one note ringing out again & again through at least three centuries and a half. We hear Sir Richard’s grandson, Sir Bevil—it goes without saying that he was a Cavalier—swearing “to fetch those traitors out of their nest at Launceston, or fire them in it.” We see him, “after solemn prayers,” charging furiously “both down the one hill and up the other” at Bradock Down; or again dying on the brow of Lansdowne Hill, after he had stormed it in the face of cannon, “small shot from the breastworks” and “two full charges from the enemy’s horse.”

His brother, another Sir Richard, was a Cavalier, too, and a Grenville to the backbone; hated by his men for his iron discipline—“no doubt,”

41

says Clarendon, “the man had behaved himself with great pride and tyranny over them”—he was even more intolerable to his superiors; he flatly refused to act under Hopton, and drove the Prince of Wales to imprison him in despair. A more attractive, but still characteristic, member of the family was Bevil’s son, Denis, Archdeacon of Durham, whom we find, after James II had already fled the kingdom, preaching in the midst of his enemies “a seasonable loyall Sermon”; collecting a war fund from the prebendaries for his fallen sovereign; bolting to Scotland on horseback; captured, but escaping to France; coming back incognito and escaping again. Ardent Jacobite and equally ardent Protestant, he defied the Court at St Germain to convert him to Romanism, and when they would

42

not allow him to read the English Service, consoled himself by publishing at Rouen a manifesto with the exquisite title of “The Resigned and Resolved Christian and Faithful and Undaunted Royalist in two plain farewell Sermons and a loyal farewell Visitation Speech.”

It must be admitted that even so late as the eighteenth century—the Venerable Denis lived till 1703—these gentlemen were the opposite of tame; even when they were “Resigned” they were at the same time “Resolved” and “Undaunted.” This is even more true of their fourteenth-century ancestor, Sir Theobald, the first Grenville of whom I have found anything essential to relate. He, at the age of twenty-two, thought fit to rebel against the paternal despotism of John Grandison, Bishop of Exeter, who had

43

instituted a nominee of Sir John Raleigh’s to the Grenville family living of Kilkhampton, in defiance, it would appear, of the lawful patron’s rights. Sir Theobald made war at once in the best Grenville manner. At dawn on Sunday, March 24, 1347, he invaded the Manor of Bishop’s Tawton with 500 followers “armed with divers kinds of weapons, offensive and defensive, after the fashion of men going to mortal war.” They stormed the Manor-house, the Sanctuary and the Manse; killed some of the defenders, took plunder to the value of two hundred marks (the Bishop’s estimate) and otherwise “multipliciter perturbarunt pacem et tranquillitatem Domini nostri Regis.” The Bishop’s peace and tranquillity being also disturbed, he at once excommunicated the entire army. Sir Theobald

44

then brought and won an action against Raleigh in the King’s Bench; the Bishop’s man appealed to Rome, with the inevitable result; the King’s Bench judgement was annulled, with costs against Sir Theobald. Cheered by this, the Bishop sent the Abbot of Hartland and the Prior of Launceston to Kilkhampton one fine July day to put things to rights. The Grenville army, with faces masked and painted, bows bent and arrows notched, met the Church Militant in a narrow lane and routed it shamefully; the pursuit lasted for a mile, and Sir Theobald then fortified and held Kilkhampton Church for several days. After eighteen months more of contumacy, peace was made; from the terms we may judge how hard the Grenville had pressed his tremendous adversary. He knelt, it is true, and confessed his guilt—there

45

there was no denying that—but the Bishop, in return for this preservation of his dignity, had to revoke his own institution and admit a new rector upon Sir Theobald’s presentation; Raleigh got nothing but the barren pleasure of reading aloud the Act of Submission. The significant points of the story are to me, first, that this boy of twenty-two gained his end in the teeth of all Rome; second, that to gain it he cared not what he did or suffered; and last, that it was never worth the money or the crimes it cost him.

It is vain, I think, to deny that in such a family group as this, Sir Richard Grenville of the Revenge would be in every sense at home. His record is plain. In 1585, when Raleigh’s first colony for Virginia set out from Plymouth in seven ships, it was Sir Richard who took command of it,

46

though he knew little of seamanship, and still less, apparently, of government. Letters from Lane, the head of the colony, to Secretary Walsingham, and dispatches from the treasurer to Raleigh himself, set forth Grenville’s “intolerable pride” and his “insatiable ambition.” His behaviour to his subordinates was such that they desire to be freed from any place where he is to carry any authority in chief. But what an irresistible fighter he is! On the homeward voyage he falls in with “a Spanish ship of 300 tunne, richly loaden”; having no boats, he boards her with an improvised one, “made with boards of chests, which fell a sunder, and sunke at the shippes side as soone as ever he and his men were out of it.” He reached

47

home at the end of October, and was off again in the following April, when the Justices of Cornwall report to the Council, Sir Richard having evidently neglected to do so, that, “being about to depart to sea, he has left his charge of 300 men to George Greynvil.” On this voyage he sacked the Azores, took “divers Spanyardes” and performed “many other exploytes,” but he reached Virginia too late to be of any service to the colony, which had already left for England. Then came the business of the Armada, in which he had at least three ships of his own engaged, though he got little chance of distinguishing himself in his station off the coast of Devon and Cornwall. His next voyage was that in the Revenge: and here again, in the one memorable action of his life, we cannot but see the working48 of the peculiar character which is visible in all the rest.

“This Sir Richard Greenfield was a great and a rich Gentleman in England,” says a contemporary, the Dutchman Linschoten, “and had great yearly revenewes of his owne inheritance: but he was a man very unquiet in his minde, and greatly affected to warre: in so much as of his owne private motion he offered his service to the Queene: he had performed many valiant acts, and was greatly feared in these Islands [i.e., the Azores], and knowne of every man, but of nature very severe, so that his owne people hated him for his fiercenes and spake verie hardly of him: for when they first entered into the Fleete or Armado, they had their great sayle in a readinesse, and might possiblie enough have sayled

49

away: for it [i.e., the Revenge] was one of the best ships for sayle in England, and the Master perceiving that the other shippes had left them, and followed not after, commanded the great sayle to be cut, that they might make away: but Sir Richard Greenfield threatened both him, and all the rest that were in the ship, that if any man laid hand upon it, he would cause him to be hanged, and so by that occasion they were compelled to fight, and in the end were taken.”

Sir William Monson, another contemporary, has left behind him a similar account, first printed in 1682. “Upon view of the Spaniards, which were 55 sail, the Lord Thomas warily, and like a discreet General, weighed Anchor, and made

50

signs to the rest of his Fleet to do the like, with a purpose to get the wind of them: but Sir Richard Grenvile, being a stubborn man, ... would by no means be persuaded by his Master, or Company, to cut his main Sail, to follow the Admiral: nay, so headstrong and rash he was, that he offered violence to those that counselled him thereto.”

Sir Walter Raleigh, Grenville’s kinsman, friend and apologist, tells substantially the same story, but he endeavours to throw a different complexion upon it, by representing Sir Richard as being in the first instance trapped in the fulfilment of a duty. He declares that the Revenge “was the last waied, to recover the men that were upon the Island, which otherwise had been

51

lost.” Unfortunately, this contention is negatived by the numbers of the men captured in her; and, indeed, he goes on to say that Grenville afterwards “utterly refused to turn from the enemy” and boasted that he would “enforce those of Sivill to give him way.” Sir Richard Hawkins is more whole-hearted. “At the Ile of Flores, Sir Richard Greenfield got eternall honour and reputation of great valour, and of an experimented Soldier, chusing rather to sacrifice his life, and to passe all danger whatsoever, than to fayle in his Obligation, by gathering together those which had remained ashore in that place, though with the hazard of his ship and companie: and rather we ought to imbrace52 an honourable death than to live with infamie and dishonour, by fayling in dutie.”

No man would have been quicker to lay down such a principle than Grenville, but it is clear that on this occasion he did not observe it, and to maintain that he did so would be to mistake the nature of the man. He was no quiet resolute victim of duty: his stubbornness was not that of faithful endurance. If the evidence we have quoted goes for anything he was then, as ever, proud, rash, headstrong and tyrannical, and he remained true to himself even in his famous dying speech, which has been garbled by every translator for 300 years. “Here die I, Richard Greenfield, with a joyfull and quiet mind, for that I have ended my life as a true soldier53 ought to do, that hath fought for his country, Queene, religion, and honor, whereby my soule most joyfull departeth out of this bodie, and shall alwaies leave behind it an everlasting fame of a valiant and true soldier, that hath done his dutie, as he was bound to do.” So it has always run; it was not until 1897 that Mr David Hannay first translated and replaced the fierce concluding sentence: “But the others of my company have done as traitors and dogs, for which they shall be reproached all their lives and leave a shameful name for ever.” That, to my ear, is the authentic voice of the Grenville.

54

Is this a condemnation? Is Sir Richard Grenville of the Revenge, after three centuries of fame, to be summed up as a ferocious and domineering fire-eater, hateful to his subordinates and disobedient to his chief? I do not think so. It is true that we cannot look to him for an example of what a seaman should be, or what an officer55 should do, but he is none the less a beacon to all Englishmen, because he was a great fighter and above the fear of death. To breathe the inspiration of his genius, it is not necessary to tamper with the record of his character; we have but to look at him as he was, with open eyes, to think what we will of his faults, and then to turn once more to the story of his superb valour and his supreme achievement. Beyond question, he and all his company are among the Immortals.

A Austin Dobson, A Ballad of Heroes.

57

A REPORT

OF THE TRVTH OF

the fight about the Iles of

Açores, this last

Sommer.

BETWIXT THE

Reuenge, one of her Maiesties

Shippes,

And an Armada of the King

of Spaine.

LONDON

Printed for william Ponsonbie.

1591.

59

61

Because the rumours are diversely spread, as well in England as in the Low Countries and elsewhere, of this late encounter between her Majesty’s ships and the Armada of Spain; and that the Spaniards, according to their usual manner, fill the world with their vainglorious

62

vaunts, making great appearance of victories: when, on the contrary, themselves are most commonly and shamefully beaten and dishonoured; thereby hoping to possess the ignorant multitude by anticipating and forerunning false reports. It is agreeable with all good reason, for manifestation of the truth, to overcome falsehood and untruth; that the beginning, continuance and success of this late honourable encounter of Sir Richard Grenville, and other her Majesty’s Captains, with the Armada of Spain, should be truly set down and published without partiality or false imaginations.

63

And it is no marvel that the Spaniard should seek, by false and slanderous pamphlets, advices and letters, to cover their own loss, and to derogate from others their due honours, especially in this fight being performed far off; seeing they were not ashamed in the year 1588, when they purposed the invasion of this land, to publish in sundry languages in print, great victories in words, which they pleaded to have obtained against this Realm, and spread the same in a most false sort over all parts of France, Italy and elsewhere. When shortly after it was happily manifested in very deed to all nations, how their

64

Navy, which they termed invincible, consisting of 240 sail of ships, not only of their own kingdom, but strengthened with the greatest argosies, Portugal caracks, Florentines and huge hulks of other countries, were, by thirty of her Majesty’s own ships of war and a few of our own merchants, by the wise, valiant and most advantageous conduction of the Lord Charles Howard, High Admiral of England, beaten and shuffled together, even from the Lizard in Cornwall, first to Portland, where they shamefully left Don Pedro de Valdes with his mighty ship; from Portland to Calais, where they lost Hugo de Moncado with

65

the galleass of which he was captain; and from Calais, driven with squibs from their anchors, were chased out of the sight of England, round about Scotland and Ireland. Where for the sympathy of their barbarous religion, hoping to find succour and assistance, a great part of them were crushed against the rocks, and those other that landed, being very many in number, were, notwithstanding, broken, slain and taken, and so sent from village to village coupled in halters to be shipped into England. Where Her Majesty of her princely and invincible disposition, disdaining to

66

put them to death, and scorning either to retain or entertain them, [they] were all sent back again to their countries, to witness and recount the worthy achievements of their invincible and dreadful Navy. Of which the number of soldiers, the fearful burthen of their ships, the commanders names of every squadron, with all other their magazines of provision, were put in print as an Army and Navy unresistible, and disdaining prevention. With all which so great and terrible an ostentation, they did not in all their sailing round about England, so much as sink or take

67

one ship, barque, pinnace, or cockboat of ours: or ever burnt so much as one sheepcote of this land. When as on the contrary, Sir Francis Drake, with only 800 soldiers, not long before, landed in their Indies, and forced Santiago, Santo Domingo, Cartagena, and the forts of Florida.

And after that, Sir John Norris marched from Penich in Portugal, with a handful of soldiers, to the gates of Lisbon, being about forty English miles, where the Earl of Essex himself and other valiant gentlemen braved the city of Lisbon, encamped

68

at the very gates; from whence, after many days’ abode, finding neither promised party, nor provision to batter: made retreat by land, in despite of all their garrisons, both of horse and foot. In this sort I have a little digressed from my first purpose, only by the necessary comparison of theirs and our actions: the one covetous of honour without vaunt or ostentation; the other so greedy to purchase the opinion of their own affairs, and by false rumours to resist the blasts of their own dishonours, as they will not only not blush to spread all manner of untruths: but even for the least advantage, be it but for the taking

69

of one poor adventurer of the English, will celebrate the victory with bonfires in every town, always spending more in faggots, than the purchase was worth they obtained. Whereas we never yet thought it worth the consumption of two billets, when we have taken eight or ten of their Indian ships at one time, and twenty of the Brazil fleet. Such is the difference between true valour, and ostentation: and between honourable actions, and frivolous vainglorious vaunts. But now to return to my first purpose.

70

The Lord Thomas Howard, with six of Her Majesty’s ships, six victuallers of London, the barque Ralegh, and two or three pinnaces riding at anchor near unto Flores, one of the westerly islands of the Azores, the last of August in the afternoon, had intelligence by one Captain Midleton, of the approach of the Spanish Armada. Which Midleton being in a very good sailer, had kept them company three days before, of good purpose, both to discover their forces the more, as also to give advice to my Lord Thomas of their approach. He had no sooner delivered the news but the

71

fleet was in sight: many of our ship’s companies were on shore in the island; some providing ballast for their ships; others filling of water and refreshing themselves from the land with such things as they could, either for money, or by force recover. By reason whereof our ships being all pestered & rummaging every thing out of order, very light for want of ballast. And that which was most to our disadvantage, the one half part of the men of every ship sick, and utterly unserviceable. For in the Revenge there were ninety diseased; in the Bonaventure, not so many in health as could handle her mainsail. For had not

72

twenty men been taken out of a barque of Sir George Cary’s, his being commanded to be sunk, and those appointed to her, she had hardly ever recovered England. The rest for the most part, were in little better state. The names of Her Majesty’s ships were these as followeth: the Defiance, which was Admiral, the Revenge Vice-Admiral, the Bonaventure commanded by Captain Cross, the Lion by George Fenner, the Foresight by Thomas Vavasour, and the Crane by Duffield. The Foresight and the Crane being but small ships, only the other were of the middle size; the rest, besides the barque

73

75

Ralegh, commanded by Captain Thin, were victuallers, and of small force or none. The Spanish fleet having shrouded their approach by reason of the island, were now so soon at hand, as our ships had scarce time to weigh their anchors, but some of them were driven to let slip their cables and set sail. Sir Richard Grenville was the last weighed, to recover the men that were upon the island, which otherwise had been lost. The Lord Thomas with the rest very hardly recovered the wind, which Sir Richard Grenville not being able to do, was persuaded by the master and others to cut his

76

main sail and cast about, and to trust to the sailing of the ship, for the squadron of Seville were on his weather bow. But Sir Richard utterly refused to turn from the enemy, alleging that he would rather choose to die, than to dishonour himself, his country, and Her Majesty’s ship, persuading his company that he would pass through the two squadrons in despite of them, and enforce those of Seville to give him way. Which he performed upon divers of the foremost, who, as the mariners term it, sprang their luff, and fell under the lee of the Revenge. But the other course had been

77

the better, and might right well have been answered in so great an impossibility of prevailing. Notwithstanding out of the greatness of his mind, he could not be persuaded. In the meanwhile as he attended those which were nearest him, the great San Philip being in the wind of him, and coming towards him, becalmed his sails in such sort, as the ship could neither weigh nor feel the helm, so huge and high charged was the Spanish ship, being of a thousand and five hundred tons. Who after laid the Revenge aboard. When he was thus bereft of his sails, the ships that were under his lee luffing up, also laid him aboard, of which

78

the next was the Admiral of the Biscaines, a very mighty and puissant ship commanded by Brittan Dona. The said Philip carried three tier of ordinance on a side, and eleven pieces in every tier. She shot eight forthright out of her chase, besides those of her stern ports.

After the Revenge was entangled with this Philip, four others boarded her; two on her larboard and two on her starboard. The fight thus beginning at three of the clock in the afternoon, continued very terrible all that evening. But the great San Philip having received the lower tier of the Revenge, discharged with cross-bar shot,

79

shifted herself with all diligence from her sides, utterly misliking her first entertainment. Some say that the ship foundered, but we cannot report it for truth, unless we were assured. The Spanish ships were filled with companies of soldiers, in some two hundred, besides the mariners; in some five, in others eight hundred. In ours there were none at all, beside the mariners, but the servants of the commanders and some few voluntary gentlemen only. After many interchanged volleys of great ordnance and

80

small shot, the Spaniards deliberated to enter the Revenge, and made divers attempts, hoping to force her by the multitudes of their armed soldiers and musketeers, but were still repulsed again and again, and at all times beaten back into their own ships, or into the seas. In the beginning of the fight the George Noble, of London, having received some shot through her by the Armadas, fell under the lee of the Revenge, and asked Sir Richard what he would command him, being but one of the victuallers and of small force; Sir Richard bid him save himself, and leave him to his fortune.

81

After the fight had thus, without intermission, continued while the day lasted and some hours of the night, many of our men were slain and hurt, and one of the great galleons of the Armada and the Admiral of the Hulks both sunk, and in many other of the Spanish ships great slaughter was made. Some write that Sir Richard was very dangerously hurt almost in the beginning of the fight, and lay speechless for a time ere he recovered. But two of the Revenge’s own company, brought home in a ship of Lime from the Islands, examined by

82

some of the Lords and others, affirmed that he was never so wounded as that he forsook the upper deck till an hour before midnight, and then being shot into the body with a musket as he was dressing, was again shot into the head, and withal his surgeon wounded to death. This agrees also with an examination taken by Sir Francis Godolphin, of four other mariners of the same ship being returned, which examination the said Sir Francis sent unto Master William Killigrew, of Her Majesty’s Privy Chamber.

But to return to the fight, the Spanish ships which attempted to board the Revenge, as

83

they were wounded and beaten off, so always others came in their places, she having never less than two mighty galleons by her sides and aboard her. So that ere the morning from three of the clock the day before, there had fifteen several Armadas assailed her, and all so ill approved their entertainment, as they were by the break of day, far more willing to hearken to a composition, than hastily to make any more assaults or entries. But as the day increased so our men decreased; and as the light grew more and more, by so much more grew our discomforts. For none appeared in

84

sight but enemies, saving one small ship called the Pilgrim, commanded by Jacob Whiddon, who hovered all night to see the success: but in the morning bearing with the Revenge, was hunted like a hare amongst many ravenous hounds, but escaped.

All the powder of the Revenge to the last barrel was now spent, all her pikes broken, forty of her best men slain, and the most part of the rest hurt. In the beginning of the fight she had but one hundred free from sickness, and fourscore and ten sick, laid in hold upon the ballast. A small troop

85

87

to man such a ship, and a weak garrison to resist so mighty an army. By those hundred all was sustained, the volleys, boardings, and enterings of fifteen ships of war, besides those which beat her at large. On the contrary, the Spanish were always supplied with soldiers brought from every squadron: all manner of arms and powder at will. Unto ours there remained no comfort at all, no hope, no supply either of ships, men, or weapons; the masts all beaten overboard, all her tackle cut asunder, her upper work altogether razed, and in effect evened

88

she was with the water, but the very foundation or bottom of a ship, nothing being left overhead either for flight or defence. Sir Richard finding himself in this distress, and unable any longer to make resistance, having endured in this fifteen hours’ fight, the assault of fifteen several armadas, all by turns aboard him, and by estimation eight hundred shot of great artillery, besides many assaults and entries. And that himself and the ship must needs be possessed by the enemy, who were now all cast in a ring round about him; the Revenge not able to move one way or other,

89

but as she was moved with the waves and billow of the sea: commanded the master Gunner, whom he knew to be a most resolute man, to split and sink the ship; that thereby nothing might remain of glory or victory to the Spaniards: seeing in so many hours’ fight, and with so great a Navy they were not able to take her, having had fifteen hours’ time, fifteen thousand men, and fifty and three sail of men-of-war to perform it withal. And persuaded the company, or as many as he could induce, to yield themselves unto God, and to the mercy of none else; but as they had like valiant resolute men, repulsed so many

90

enemies, they should not now shorten the honour of their nation, by prolonging their own lives for a few hours, or a few days. The master Gunner readily condescended and divers others; but the Captain and the Master were of an other opinion, and besought Sir Richard to have care of them, alleging that the Spaniard would be as ready to entertain a composition, as they were willing to offer the same: and that there being divers sufficient and valiant men yet living, and whose wounds were not mortal, they might do their country and prince acceptable service hereafter. And (that where Sir Richard had alleged

91

that the Spaniards should never glory to have taken one ship of Her Majesty’s, seeing that they had so long and so notably defended themselves) they answered, that the ship had six foot water in hold, three shot under water which were so weakly stopped, as with the first working of the sea, she must needs sink, and was besides so crushed and bruised, as she could never be removed out of the place.

And as the matter was thus in dispute, and Sir Richard refusing to hearken to any of those reasons: the master of the Revenge (while the Captain won unto him the greater

92

party) was convoyed aboard the General Don Alfonso Bassan. Who, finding none over-hasty to enter the Revenge again, doubting lest Sir Richard would have blown them up and himself, and perceiving by the report of the master of the Revenge his dangerous disposition: yielded that all their lives should be saved, the company sent for England, and the better sort to pay such reasonable ransom as their estate would bear, and in the mean season to be free from galley or imprisonment. To this he so much the rather condescended as well as I have said, for fear of further93 loss and mischief to themselves, as also for the desire he had to recover Sir Richard Grenville; whom for his notable valour he seemed greatly to honour and admire.

When this answer was returned, and that safety of life was promised, the common sort being now at the end of their peril, the most drew back from Sir Richard and the master Gunner, being no hard matter to dissuade men from death to life. The master Gunner finding himself and Sir Richard thus prevented and mastered by the greater number, would have slain himself with a sword, had he not been by force withheld and locked into his cabin. Then

94

the General sent many boats aboard the Revenge, and divers of our men, fearing Sir Richard’s disposition, stole away aboard the General and other ships. Sir Richard thus overmatched, was sent unto by Alfonso Bassan to remove out of the Revenge, the ship being marvellous unsavoury, filled with blood and bodies of dead and wounded men like a slaughter-house. Sir Richard answered that he might do with his body what he list, for he esteemed it not, and as he was carried out of the ship he swooned, and reviving again desired the company to pray for him. The General used Sir Richard

95

with all humanity, and left nothing unattempted that tended to his recovery, highly commending his valour and worthiness, and greatly bewailed the danger wherein he was, being unto them a rare spectacle, and a resolution seldom approved, to see one ship turn toward so many enemies, to endure the charge and boarding of so many huge armadas, and to resist and repel the assaults and entries of so many soldiers. All which and more, is confirmed by a Spanish captain of the same armada, and96 a present actor in the fight, who being severed from the rest in a storm, was by the Lyon of London a small ship, taken and is now prisoner in London.

The general commander of the Armada, was Don Alfonso Bassan, brother to the Marquesse of Santa Cruce. The Admiral of the Biscaine squadron was Britan Dona. Of the squadron of Seville, Marques of Arumburch. The Hulkes and Flyboats were commanded by Luis Cutino. There were slain and drowned in this fight, well near two thousand of the enemies, and two especial commanders Don Luis de

97

99

St John, and Don George de Prunaria de Malaga, as the Spanish Captain confesseth, besides divers others of special account, whereof as yet report is not made.

The Admiral of the Hulks and the Ascension of Seville, were both sunk by the side of the Revenge; one other recovered the road of Saint Michael’s, and sunk also there; a fourth ran herself with the shore to save her men. Sir Richard died as it is said, the second or third day aboard the General, and was by them greatly bewailed. What became of his body, whether

100

it were buried in the sea or on the land we know not: the comfort that remaineth to his friends is, that he hath ended his life honourably in respect of the reputation won to his nation and country, and of the fame to his posterity, and that being dead, he hath not outlived his own honour.

For the rest of Her Majesty’s ships that entered not so far into the fight as the Revenge, the reasons and causes were these. There were of them but six in all, whereof two but small ships; the Revenge engaged past recovery: The Island of Flores was on the one side, 53 sail of the Spanish, divided into squadrons on the

101

other, all as full filled with soldiers as they could contain. Almost the one half of our men sick and not able to serve: the ships grown foul, unrummaged, and scarcely able to bear any sail for want of ballast, having been six months at the sea before. If all the rest had entered, all had been lost. For the very hugeness of the Spanish fleet, if no other violence had been offered, would have crushed them between them into shivers. Of which the dishonour and loss to the Queen had been far greater than the spoil or harm that the enemy

102

could any way have received. Notwithstanding it is very true, that the Lord Thomas would have entered between the squadrons, but the rest would not condescend; and the master of his own ship offered to leap into the sea, rather than to conduct that Her Majesty’s ship and the rest to be a prey to the enemy, where there was no hope nor possibility either of defence or victory. Which also in my opinion had ill sorted or answered the discretion and trust of a General, to commit himself and his charge to an assured destruction, without hope103 or any likelihood of prevailing: thereby to diminish the strength of Her Majesty’s Navy, and to enrich the pride and glory of the enemy. The Foresight of the Queen, commanded by Thomas Vavasour, performed a very great fight, and stayed two hours as near the Revenge as the weather would permit him, not forsaking the fight, till he was like to be encompassed by the squadrons, and with great difficulty cleared himself. The rest gave divers volleys of shot, and entered as far as the place permitted and their own necessities, to keep the weather gauge of the enemy, until they were parted by night.

104

105

A few days after the fight was ended, and the English prisoners dispersed into the Spanish and India ships, there arose so great a storm from the west and north-west, that all the fleet was dispersed, as well the Indian fleet which were then come unto them

107

as the rest of the Armada that attended their arrival, of which fourteen sail together with the Revenge, and in her 200 Spaniards, were cast away upon the Isle of S. Michael’s. So it pleased them to honour the burial of that renowned ship the Revenge, not suffering her to perish alone, for the great honour she achieved in her life time. On the rest of the islands there were cast away in this storm fifteen or sixteen more of the ships of war; and of a hundred and odd sail of the India fleet expected this year in Spain, what in this tempest and what before in the Bay of

108

Mexico, and about the Bermudas, there were seventy and odd consumed and lost, with those taken by our ships of London, besides one very rich Indian ship, which set herself on fire, being boarded by the Pilgrim, and five other taken by Master Wats his ships of London, between the Havana and Cape S. Antonio. The 4th of this month of November we received letters from the Tercera affirming that there are 3,000 bodies of men remaining in that island, saved out of the perished ships; and that by the Spaniards own confession there are 10,000 cast away in this storm, besides those that are perished

109

between the islands and the main. Thus it hath pleased God to fight for us, and to defend the justice of our cause against the ambitious and bloody pretences of the Spaniard, who, seeking to devour all nations, are themselves devoured. A manifest testimony how injust and displeasing their attempts are in the sight of God, who hath pleased to witness by the success of their affairs His mislike of their bloody and injurious designs, purposed and practised against all Christian princes, over whom they seek unlawful and ungodly rule and Empery.

110

One day or two before this wreck happened to the Spanish fleet, when as some of our prisoners desired to be set on shore upon the islands, hoping to be from thence transported into England, which liberty was formerly by the General promised: One Maurice Fitz John, son of old John of Desmond a notable traitor, cousin german to the late Earl of Desmond, was sent to the English from ship to ship, to persuade them to serve the King of Spain. The arguments he used to induce them were these. The increase of pay which he promised to be trebled: advancement to

111

the better sort: and the exercise of the true Catholic religion, and safety of their souls to all. For the first, even the beggarly and unnatural behaviour of those English and Irish rebels, that served the king in that present action, was sufficient to answer that first argument of rich pay. For so poor and beggarly they were, as for want of apparel they stripped their poor country men prisoners out of their ragged garments, worn to nothing by six months’ service, and spared not to despoil them even of their bloody shirts, from their wounded bodies, and the very shoes from their feet; a notable testimony of their

112

rich entertainment and great wages. The second reason was hope of advancement if they served well and would continue faithful to the king. But what man can be so blockishly ignorant ever to expect place or honour from a foreign king, having no argument or persuasion than his own disloyalty; to be unnatural to his own country that bred him; to his parents that begat him, and rebellious to his true prince, to whose obedience he is bound by oath, by nature, and by religion. No, they are only assured to be employed in all desperate enterprises, to be held in scorn and disdain ever among those whom they serve.

113

And that ever traitor was either trusted or advanced I could never yet read, neither can I at this time remember any example. And no man could have less become the place of an orator for such a purpose than this Maurice of Desmond. For the Earl his cousin being one of the greatest subjects in that kingdom of Ireland, having almost whole countries in his possession, so many goodly manors, castles and lordships; the Count Palatine of Kerry, 500 gentlemen of his own name and family to follow him, besides others. All which he possessed in peace for three or four

114

hundred years, was in less than three years after his adhering to the Spaniards and rebellion, beaten from all his holds, not so many as ten gentlemen of his name left living, himself taken and beheaded by a soldier of his own nation, and his land given by a Parliament to Her Majesty and possessed by the English. His other cousin Sir John of Desmond taken by Mr. John Zouch, and his body hanged over the gates of his native city to be devoured by ravens; the third brother Sir James hanged, drawn and quartered in the same place. If he had withall vaunted of this success

115

of his own house, no doubt the argument would have moved much and wrought great effect; which because he for that present forgot, I thought it good to remember in his behalf. For matter of religion it would require a particular volume if I should set down how irreligiously they cover their greedy and ambitious pretences with that veil of piety. But sure I am, that there is no kingdom or commonwealth in all Europe, but if they be reformed, they then invade it for religion sake; if it be as they term Catholic they pretend title, as if the Kings of Castile were the natural heirs of all the world; and so between both,

116

no kingdom is unsought. Where they dare not with their own forces to invade, they basely entertain the traitors and vagabonds of all nations, seeking by those and by their runagate Jesuits to win parties, and have by that means ruined many noble houses and others in this land, and have extinguished both their lives and families. What good, honour or fortune ever man yet by them achieved is yet unheard of or unwritten. And if our English Papists do but look into Portugal, against whom they have no pretence of religion, how the nobility are put to death, imprisoned, their rich men made a prey, and all sorts of people

117

captived, they shall find that the obedience even of the Turk is easy and a liberty, in respect of the slavery and tyranny of Spain. What they have done in Sicily, in Naples, Milan and in the Low Countries; who hath there been spared for religion at all? And it cometh to my remembrance of a certain burgher of Antwerp, whose house being entered by a company of Spanish soldiers, when they first sacked the city, he besought them to spare him and his goods, being a good Catholic and one of their own party and faction. The Spaniards

118

answered that they knew him to be of a good conscience for himself, but his money, plate, jewels and goods were all heretical, and therefore good prize. So they abused and tormented the foolish Fleming, who hoped that an Agnus Dei had been a sufficient target against all force of that holy and charitable nation. Neither have they at any time as they protest invaded the kingdoms of the Indies and Peru, and elsewhere, but only led thereunto, rather, to reduce the people to Christianity, than for either gold or empery. When as in one only island called

119

Hispaniola, they have wasted thirty hundred thousand of the natural people, besides many millions else in other places of the Indies: a poor and harmless people created of God, and might have been won to His knowledge, as many of them were, and almost as many as ever were persuaded thereunto. The story whereof is at large written by a Bishop of their own nation called Bartholome de las Casas, and translated into English and many other languages, entitled The Spanish Cruelties. Who would therefore repose trust in such a nation of ravenous strangers,

120

and especially in those Spaniards which more greedily thirst after English blood, than after the lives of any other people of Europe; for the many overthrows and dishonours they have received at our hands, whose weakness we have discovered to the world, and whose forces at home, abroad, in Europe, in India, by sea and land, we have even with handfuls of men and ships, overthrown and dishonoured. Let not therefore any Englishman of what religion soever, have other opinion of the Spaniards, but that those whom he seeketh to win of our nation,

121

he esteemeth base and traitorous, unworthy persons, or unconstant fools: and that he useth his pretence of religion for no other purpose but to bewitch us from the obedience of our natural prince; thereby hoping in time to bring us to slavery and subjection, and then none shall be unto them so odious, and disdained as the traitors themselves, who have sold their country to a stranger, and forsaken their faith and obedience contrary to nature or religion; and contrary to that human and general honour, not only of Christians, but of heathen and irreligious122 nations, who have always sustained what labour soever, and embraced even death itself, for their country, prince or commonwealth. To conclude, it hath ever to this day pleased God to prosper and defend her Majesty, to break the purposes of malicious enemies, of foresworn traitors, and of unjust practices and invasions. She hath ever been honoured of the worthiest Kings, served by faithful subjects, and shall by the favour of God, resist, repel, and confound all whatsoever attempts against her sacred person or kingdom. In the meantime, let the Spaniard and traitor vaunt of their success; and we her true and obedient vassals guided by the shining light of her virtues, shall always love her, serve her, and obey her to the end of our lives.

FINIS

123

A PARTICULAR NOTE OF THE INDIAN FLEET, EXPECTED TO HAVE COME INTO SPAIN THIS PRESENT YEAR OF 1591, WITH THE NUMBER OF SHIPS THAT PERISHED OF THE SAME; ACCORDING TO THE EXAMINATION OF CERTAIN SPANIARDS, LATELY TAKEN AND BROUGHT INTO ENGLAND BY THE SHIPS OF LONDON

125

126

The fleet of Nova Hispania, at their first gathering together and setting forth, were 52 sails. The Admiral was of 600 tons, and the Vice-Admiral of the same burden. Four or five of the ships were of 900 and 1000 tons a piece, some 500 and 400, and the least of 200 tons. Of this fleet 19 were cast away, and in them 2600 men by estimation, which was done along the coast of Nova Hispania, so that of the same fleet, there came to the Havana, but three and thirty sails.

The fleet of Terra Firma, were at their first departure from Spain, 50 sails, which were bound for Nombre de Dios, where they did discharge their lading, and thence returned to Cartagena, for their healths sake, until the time the treasure was ready they should take in, at the said Nombre de Dios. But before this fleet departed, some were gone by one or two at a time,127 so that only 23 sails of this fleet arrived in the Havana.

| At the Havana there met | { 33 sails of Nova Hispania. |

| { 23 sails of Terra Firma. | |

| { 12 sails of San Domingo. | |

| { 9 sails of Hunduras. |

In the whole 77 ships, which joined and set sail together, at the Havana, the 17th of July, according to our account, and kept together until they came into the height of 35 degrees, which was about the tenth of August, where they found the wind at south west, changed suddenly to the north, so that the sea coming out of the south128 west, and the wind very violent at north, they were put all into great extremity, and then first lost the General of their fleet, with 500 men in her; and within three or four days after another storm rising, there were five or six other of the biggest ships cast away with all their men, together with their Vice-Admiral.

And in the height of 48 degrees about the end of August, grew another great storm, in which all the fleet saving 48 sails were cast away: which 48 sails kept together, until they came in sight of the Islands of Coruo and Flores, about the 5th or 6th of129 September, at which time a great storm separated them; of which number 15 or 16 were after seen by these Spaniards to ride at anchor under the Tercera; and twelve or fourteen more to bear with the Island of S. Michael’s; what became of them after that these Spaniards were taken, cannot yet be certified; their opinion is, that very few of the fleet are escaped, but are either drowned or taken. And it is otherwise of late certified, that of this whole fleet that should have come into Spain this year, being 123 sail, there are as yet arrived but 25. This note was taken out of the examination of certain Spaniards, that were brought into England by six of the ships of London, which took seven of the above named Indian fleet, near the Islands of Azores.

FINIS

“It may be truly said that the commandment of the sea is an abridgement or a quintessence of a universal monarchy.”

Francis Bacon.

Letchworth: At the Arden Press.

Punctuation, hyphenation, and spelling were made consistent when a predominant preference was found in the original book; otherwise they were not changed.

Simple typographical errors were corrected; unbalanced quotation marks were remedied when the change was obvious, and otherwise left unbalanced.

The larger illustrations have been positioned at the tops of the pages on which they originally appeared, even when that placed them in the middle of sentences or paragraphs. This was done to simulate the appearance of the original book: every page contained at least one illustration at the top or bottom, while many paragraphs and some sentences were more than one page in length.

The black-and-white illustrations were printed with thick, coarse lines and irregular borders. That appearance has been retained in this eBook.