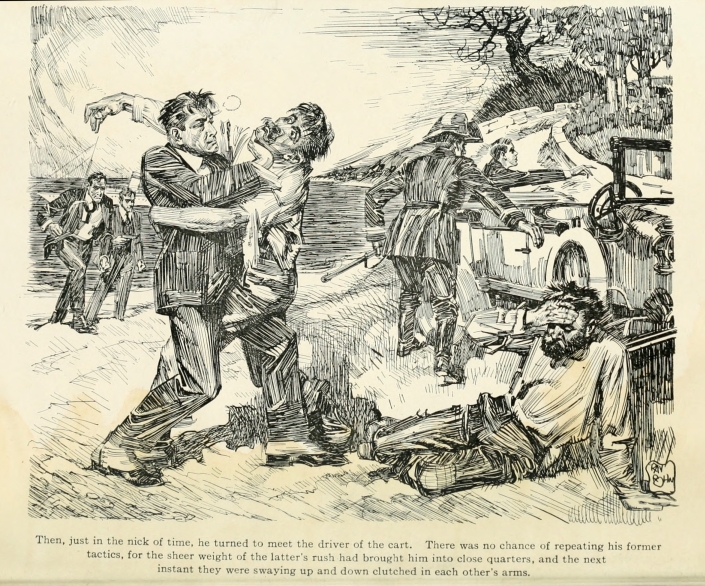

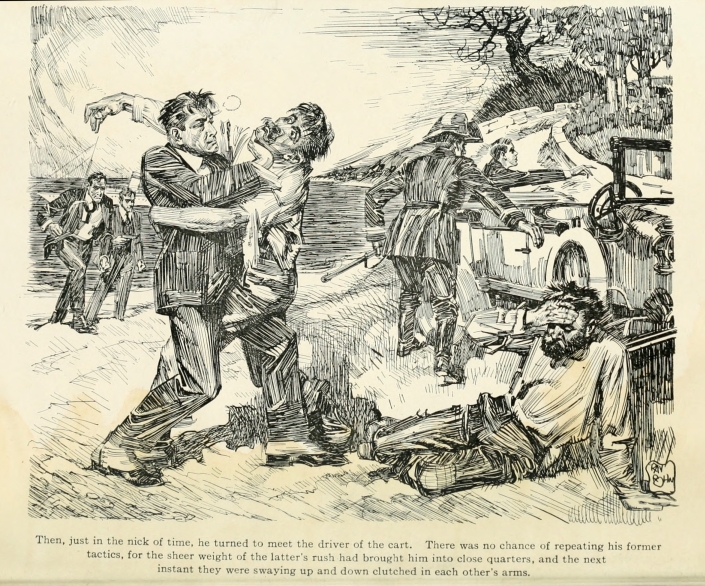

Then, just in the nick of time, he turned to meet the driver of the cart.

There was no chance of repeating his former tactics, for the sheer weight

of the latter's rush had brought him into close quarters, and the next

instant they were swaying up and down clutched in each other's arms.

The

Lady from Long Acre

By

Victor Bridges

Author of "A Rogue by Compulsion," "The Man from Nowhere,"

"Jetsam"

Illustrated by Ray Rohn

G. P. Putnam's Sons

New York and London

The Knickerbocker Press

1919

Copyright, 1919

BY

VICTOR BRIDGES

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I.—"Tiger" Bugg Versus "Lightning" Lopez

II.—The Morals of Molly

III.—Two Yellow-Faced Foreigners

IV.—Like a Fairy Story

V.—The Leniency of Justice

VI.—Pricing an Heirloom

VII.—Bugg's Strategy

VIII.—Affairs in Livadia

IX.—A Run-Away Queen

X.—The Royal Enterprise

XI.—The Baited Trap

XII.—Molly Becomes an Ally

XIII.—A Move by the Enemy

XIV.—A Disturbance in Hampstead

XV.—Impending Events

XVI.—An Artistic Forgery

XVII.—A Decoy Message

XVIII.—The Royal Pass

XIX.—Jimmy Dale

XX.—Counterplotting

XXI.—The Solution

XXII.—Getting Access to Isabel

XXIII.—Kidnapping the Bride

XXIV.—Making Sure of Isabel

ILLUSTRATIONS

Just in the Nick of Time he Turned to Meet

the Driver of the Car . . . . . . Frontispiece

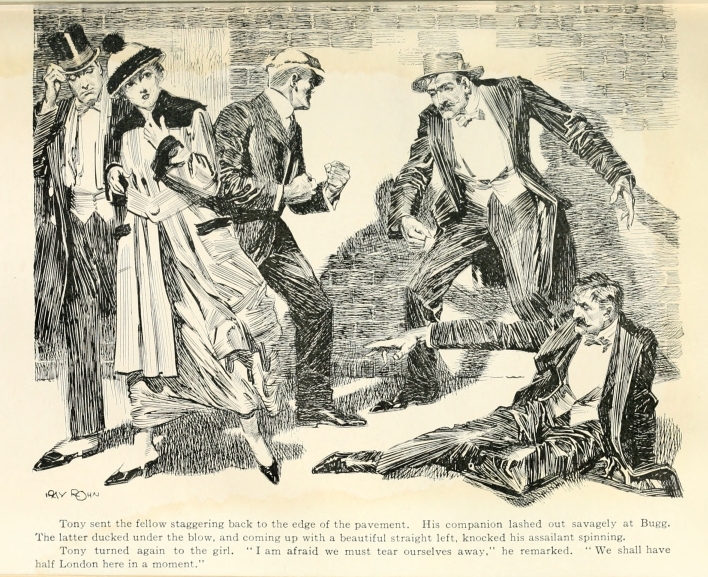

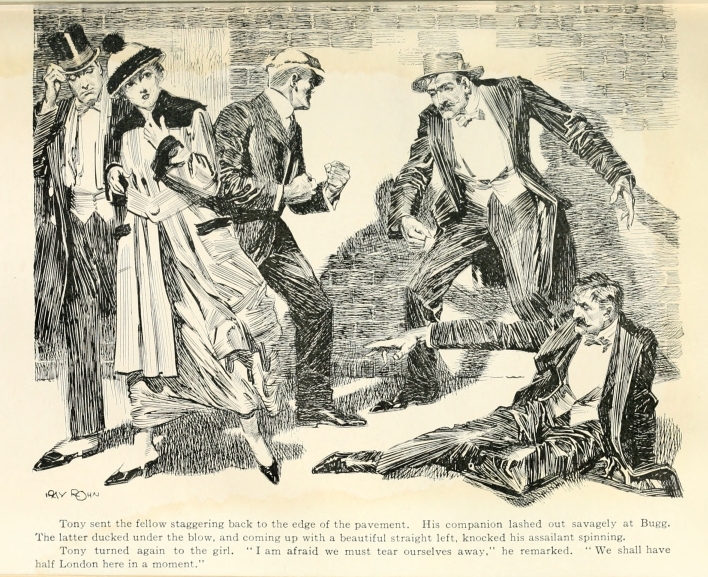

Tony Sent the Fellow Staggering Back to the

Edge of the Pavement

"I am so Sorry to have Kept you Waiting,"

Said Tony

"And do you Mean to Say," he Remarked,

"that you really Waste this on Dramatic

Critics?"

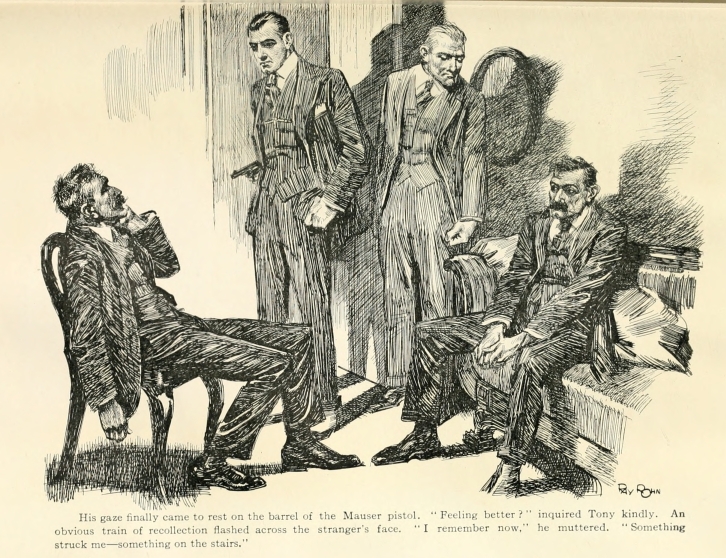

His Gaze finally Came to Rest on the Barrel

of the Mauser Pistol

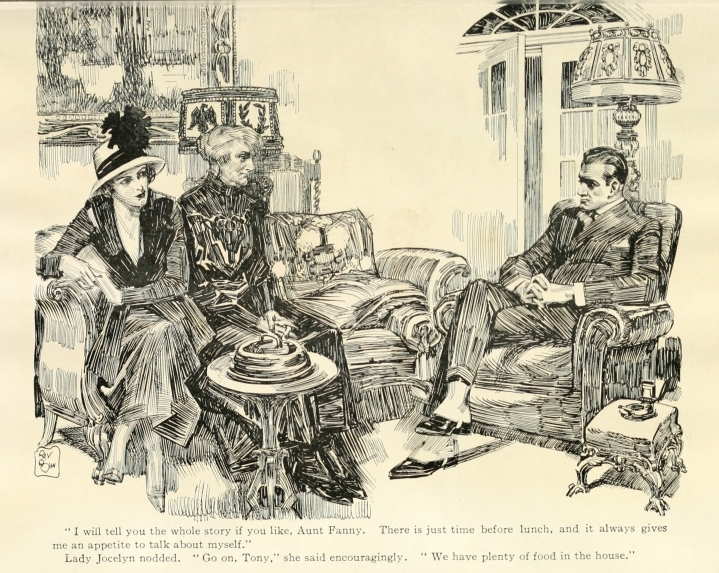

"I will Tell you the Whole Story if you Like,

Aunt Fanny"

The Lady from Long Acre

CHAPTER I

"TIGER" BUGG VERSUS "LIGHTNING" LOPEZ

Lady Jocelyn sighed gently and put down her

cup on the tea-table.

"I suppose, Tony," she said, "that when one gets

to seventy-two, one's conscience begins to decay just

as one's body does. I seem to like good people less

and immoral and useless ones more. You are the

only member of the family it gives me the faintest

pleasure to see nowadays."

Sir Antony Raymond Fulk Desmoleyn Conway—Conway

Bart., more commonly known as Tony,

nodded his head.

"They are rather a stuffy lot the others, aren't

they!" he answered cheerfully. "Who's been round

to see you?"

"Only Laura and Henry as yet." Lady Jocelyn

spoke with some thankfulness.

"Well, that's enough," observed Tony. "Ten

minutes with either of them always makes me feel

I want to do something improper."

"Allowing for age and infirmity," said Lady

Jocelyn, "they have a rather similar effect on me."

Tony laughed. "So you have heard all about my

misdeeds?"

"I would hardly go as far as that. They were

only here for two hours. You may smoke you know,

Tony, if you want to."

He lighted a cigarette. "Tell me, Aunt Fanny,"

he pleaded. "There is no pleasure in blackening

the family name unless one hears what the family

says about it."

"The family," remarked Lady Jocelyn, "has a

good deal to say about it. They consider that not

only are you wasting your own life in the most

deplorable manner, but that your methods of amusing

yourself are calculated to bring a certain amount

of discredit upon your more distinguished relatives.

Henry attributes it chiefly to the demoralizing effect

of wealth; Laura thinks that you were born with

naturally low tastes."

"They're both right," observed Tony placidly.

"I am what Guy calls 'a menace to my order.' That's

a jolly way for one's secretary to talk to one,

isn't it?"

"It's the only way dear Guy can talk, and after

all I daresay he is telling the truth."

"I am sure he is," said Tony. "Guy is quite

incapable of telling anything else." He paused.

"Was Henry referring to any recent atrocity?"

"I think your choice of friends is what distresses

him chiefly. He said that your more intimate

acquaintances appear to consist of prize-fighters and

chauffeurs."

Tony laughed good-humouredly. "I do a bit of

motor racing, you know. I suppose that's what

he meant by chauffeurs. As for prize-fighters—well,

somebody must have been telling him about

Bugg."

"About what?" inquired Lady Jocelyn mildly.

"Bugg," repeated Tony. "'Tiger' Bugg. He's a

youthful protégé of mine—a boxer. In about three

years, when he's grown a bit, he'll be champion of

England."

Lady Jocelyn's good-humoured face wrinkled up

into a whimsical smile.

"Dear Tony," she said. "Your conversation is

always so stimulating. Tell me some more about

Mr. Tiger Bugg. What a name! It sounds like

some kind of American butterfly."

"Oh, he spells it with two g's," said Tony. "It's

a very good name in the East End of London. There

have been Buggs in Whitechapel for generations."

"So I have always understood," replied Lady

Jocelyn. "How did you come across this particular

branch of the family?"

"It was at a boxing club off the Stepney High

Street. It's a blackguard sort of place run by a Jew

named Isaacs. He gets in the East End street boys,

and they fight each other for nothing in the hope that

some boxing promoter will see them and give them a

chance. Well, one night when I was there they put

up this boy Bugg against a fellow who was big

enough to eat him—a chap who knew something

about the game, too. Bugg was hammered nearly

silly in the first round, but he came up for the second

and popped in a left hook bang on the point that put

the big chap to sleep for almost ten minutes. It was

one of the prettiest things I've ever seen."

"It sounds delightful," said Lady Jocelyn. "Go

on, Tony."

"I was so pleased with his pluck," pursued the

baronet tranquilly, "that I sent for him after the

show and took him out to have some supper. I

thought he was precious hungry from the way he

wolfed his food, and when I asked him I found he'd

had nothing to eat all day except a bit of dry bread

for breakfast. In addition to that he had tramped

about ten miles looking for a job. Hardly what

one would call a good preparation for fighting a

fellow twice your size."

"It seems a most deserving case," remarked Lady

Jocelyn sympathetically.

"That's what I thought," said Tony. "I had him

up to Hampstead the next day and I gave him a good

try out with the gloves. I saw at once that I'd got

hold of something quite out of the common. He

didn't know much about the science of the game, but

he was just a born boxer—one of those boys who take

to fighting as naturally as they do to breathing. He

seemed a decent lad too in his way—a bit rough, of

course, but then you couldn't expect anything else.

Anyhow the end of it was I took him on, and he has

been with me ever since."

"How nice!" said Lady Jocelyn. "And in

what capacity does he figure in the household

returns?"

Tony indulged in a smile. "I always call him my

assistant secretary," he said, "just to fetch old Guy.

As a matter of fact Bugg is a most useful chap.

There's hardly anything he can't do. When he

isn't training for a fight, we use him as a sort of

maid-of-all-work."

"Oh, he still fights then?"

"Rather," said Tony. "He has never been

beaten yet. Backing Bugg is my only source of

income apart from the estate. I made twelve

hundred pounds out of him last year."

"Dear me!" exclaimed Lady Jocelyn. "I had no

idea you had a regular profession like that, Tony.

What sort of people does he fight with?"

"We are open to meet any one in the world up to

ten stone seven. In fact there are only about four

who really matter that he hasn't met. There will be

one less after to-morrow."

"What happens to-morrow?"

"Bugg is going to fight 'Lightning Lopez' at the

Cosmopolitan."

"What beautiful names all these people seem to

have," said Lady Jocelyn. "Who is 'Lightning

Lopez'?"

"He calls himself the champion welter-weight of

Europe," replied Tony a little contemptuously.

"He's half an American and half a Livadian. That's

why Pedro has taken him up."

"Pedro?" repeated Lady Jocelyn. "Do you mean

King Pedro?"

Tony nodded. "Yes, Lopez is being backed by

royalty or rather ex-royalty. We hope to have

five hundred of the best out of His Majesty by

to-morrow night."

"Are you a friend of Pedro's?" asked Lady

Jocelyn.

"Oh, hardly that," said Tony. "He belongs to

the Cosmo, you know, and I often meet him at

races and first nights."

Lady Jocelyn paused for a moment.

"I remember him very well as a little boy at

Portriga before the revolution," she said. "What

has he grown up like?"

"Well," observed Tony, thoughtfully brushing

some cigarette ash from his sleeve, "he's short and

fat and dark and rather spotty, and he drinks too

much."

Lady Jocelyn nodded. "Ah!" she said, "just like

his poor father. Has he inherited the family

weakness for female society?"

"He's a bit of a rip," said Tony. "Or rather he

was. Molly Monk of the Gaiety has got hold of

him now, and I think she keeps him pretty straight.

She's not the sort to stand any nonsense, you

know."

"I will take your word for it, Tony," said Lady

Jocelyn gravely.

Tony laughed. "Well, you can, Aunt Fanny," he

returned. "I've known Molly since she was a little

flapper. She is the granddaughter of old Monk who

used to look after the lodge at Holbeck."

Lady Jocelyn raised her eyebrows. "Dear me!"

she exclaimed. "Is that so, Tony! Why I remember

the old man perfectly. She must be a clever

girl to have got on like she has. What a pity she

couldn't be content with her profession."

"Oh, Molly's all right," said Tony carelessly.

"She's straight enough as girls of that sort go.

You can be quite sure she's really fond of Pedro or

she wouldn't have anything to do with him."

"He didn't sound exactly lovable from your

description of him," remarked Lady Jocelyn.

"Well, perhaps I didn't do him justice. He isn't

such a bad fellow in his way, you know. He drinks

too much and he's stupid and spoilt, but he's quite

good-natured and amiable with it. I have no doubt

Molly can twist him round her finger; and I suppose

there's a certain attraction in having a king trotting

around after you—even if he is out of a job. No

doubt it annoys the other girls."

"As a bachelor, my dear boy," said Lady Jocelyn,

"you have no right to be so well acquainted with

feminine weaknesses." She paused. "You know

you really ought to get married, Tony," she added,

"if only to circulate your income."

Tony laughed. "You have hit on my one strong

point as a capitalist," he said. "You ask Guy,

Aunt Fanny!"

"But you can't spend forty thousand a year by

yourself—surely?"

"Oh, I get a little help now and then. I don't

know that I really want it though. It's wonderful

what one can do with practice and a steam yacht."

"It's not nearly as wonderful as what you could

do with a wife," said Lady Jocelyn. "Anyhow you

ought to get married if only to please me. I shall

soon be too old for travelling about, and then I shall

want some really naughty children to give me an

interest in life. I shall never be interested in

Henry's twins: they are such dreadful little prigs."

Tony got up from his chair and taking the old

lady's slender, much beringed hand raised it to his

lips.

"If you feel like that, Aunt Fanny," he said, "I

shall certainly have to think about it. You won't

mind who she is, I suppose?"

"I only make two stipulations," said Lady Jocelyn.

"She mustn't be a German and she mustn't

wear squeaky boots."

Tony laughed. "All right, Aunt Fanny," he

said. "I can promise you that safely."

He walked to the window and glanced down into

Chester Square where a huge venomous-looking,

two-seated Peugot was filling up the roadway.

"I must toddle away now," he observed. "I

want to run up to the Club, and see that everything's

all right for to-morrow night, and then I must get

back home and change. I have promised to go to

this fancy dress dance at the Albert Hall, and it will

take me a long time to look like Charles the

Second."

Lady Jocelyn leaned forward and rang the bell.

"Come and see me again some day, Tony," she said,

"when you have nothing better to do. I shall be

home till the end of July, at all events."

Tony bent down and kissed her affectionately.

"I shall often be dropping in if I may," he said. "I

am always in scrapes you know, Aunt Fanny, and

you are about the only person I can look to for a little

sympathy and encouragement."

"If my moral support is of any use, Tony," she

said, "you can count on it to the utmost."

Outside the house a small crowd of loafers and

errand boys had gathered round the car, which with

its enormous strapped bonnet and disk wheels looked

singularly out of place in this trim, respectable

neighbourhood.

"Wotyer call that, guv'nor?" inquired one of

them. "A cycle car?"

"It's the new Baby Peugot," replied Tony gravely.

He started up the engine, and climbing into the

seat, disappeared round the corner, followed by the

admiring glances of his audience.

The Cosmopolitan Club, the headquarters of

British pugilism, is situated in Covent Garden. It is

regarded by some excellent people as a plague spot

that will eventually be wiped away by the rising flood

of a more humanized civilization, but this opinion

can hardly be said to represent the views of the porter

and carmen who frequent the vicinity. To them the

Club represents all that is best and brightest in

English civilization, and amongst its numerous and

oddly assorted members nobody could claim to be

better known or more popular than Tony.

As the big car picked its way over the cobbles,

twisting neatly in and out between unattended carts

and piles of empty baskets, a good number of the

men who were lounging about greeted the owner with

a friendly salute. When he reached the Club and

pulled up, several of them stepped forward eagerly

to open the door.

"'Ow abaht ter-morrer, sir," inquired one huge,

hoarse-voiced carter. "Sife to shove a bit on

Tiger?"

"You can shove your horse and cart on him," said

Tony, "and if it doesn't come off I'll buy you

another."

He jumped out and crossed the pavement, followed

by an approving murmur from everyone who had

heard his offer.

The carter spat decisively into the gutter. "E's

a ruddy nobleman, 'e is," he observed, looking round

the group with a bloodshot eye. "'Oo says 'e

ain't?"

No one ventured on such a rash assertion; indeed,

putting aside the carter's discouraging air, everyone

present considered Tony's offer to be the very acme

of aristocratic behaviour.

The creator of this favourable impression pushed

open the swinging door of the Club and, accepting

a couple of letters from the hotel porter, walked

through into the comfortably furnished bar lounge at

the back. Its two inhabitants, who were each in the

act of consuming a cocktail, glanced round at his

entrance. One was "Doggy" Donaldson, the manager,

a burly, genial-looking, bullet-headed individual

with close-cropped grey hair, and a permanently

unlit cigar jutting up rakishly out of the corner of

his mouth.

"Hello, Tony," he exclaimed. "You're just in

time to join us. You know the Marquis da Freitas,

of course?"

Tony nodded easily, and Donaldson's companion,

a stout, dark-complexioned, well-dressed man of

about fifty with a certain air of distinction about

him, returned the greeting with a courteous wave

of his hand.

"We meet as enemies, Sir Antony," he remarked

smilingly.

"Well, I just dropped in for a second to see that

everything was all right about to-morrow," said Tony.

"Our boy is in fine form: never been fitter. I hope

you have been equally lucky?"

The Marquis indulged in the faintest possible shrug

of his broad shoulders. "I believe so," he said. "I

am not a great authority on these matters myself, but

they amuse His Majesty."

"Everything's O.K.," observed the manager in a

satisfied voice. "We sold the last seat this morning,

and there have been several applications since. It's

going to be the best night of the season. You will

see your boy turns up in good time, won't you?"

Tony helped himself to the cocktail, which the

barman, without asking any superfluous questions,

had been quietly preparing for him.

"Right you are," he said, drinking it off. "What's

the betting, Doggy?"

"Martin-Smith told me this morning he'd got a

level hundred on Lopez."

Tony put down the empty glass. "Ah well," he

said, "he can afford to lose it."

There was a short pause.

"You seem confident, Sir Antony," remarked the

Marquis in his suave voice. "Perhaps you would

like to back your opinion a little further. I don't

know much about this sort of thing, as I said just

now, but I am prepared to support our man if only

from patriotic motives."

"Anything you care to suggest, Marquis," said

Tony indifferently.

"Shall we say a couple of hundred, then?"

Tony nodded, and booked the bet on his shirt

cuff.

"I must be off now," he said. "I suppose you and

the King will be at the Albert Hall to-night?"

The Marquis shook his head. "I do not think His

Majesty intends to be present. As for me—" he

again shrugged his shoulders—"I grow old for such

frivolities."

"Well, till to-morrow then," said Tony.

He passed out again through the hall, and jumping

into the car steered his way slowly round the corner

into Long Acre, where he branched off in the direction

of Piccadilly. He was just passing Garnett's, the

celebrated theatrical costumier, when the door of

that eminent establishment swung open, and a very

pretty and smartly dressed girl stepped out on to

the pavement. Directly Tony saw her he checked

the car and turned it gently in towards the gutter.

She came up to him with a most attractive smile.

"But how convenient, Tony," she exclaimed.

"You will be able to drive me home. I was just

going to waste my money on a taxi."

He leaned across and opened the door. "You can

give me the bob instead, Molly," he said. "Jump

in."

She stepped up alongside of him, and with a harsh

croak the big car glided forward again into the

thronging bustle of Leicester Square.

"Funny picking you up like this," he said. "I've

just been talking about you."

"I'm always being talked about," replied Molly

serenely. "I hope you weren't as nasty as most

people."

"I was saying that you were the only girl in

London with that particular shade of red hair." Tony

brought out this shameless untruth with the

utmost coolness.

"It is rather nice, isn't it?" said Molly. "All

the girls think I touch it up. As a matter of fact

it's one of the few parts of me I don't." She paused.

"What were you really saying about me, Tony?"

"Oh, quite nice things," he replied. "Can you

fancy me saying anything else?"

"No," she said. "I'll admit you're an amiable

beast as men go. But why haven't you been to see

me lately?"

Grasping his opportunity Tony darted across the

bows of an onrushing motor-bus, and gained the

comparative shelter of Regent Street.

"If it is a fact," he observed, "I can only attribute

it to idiocy."

"You know it's a fact," said Molly, "and it's

hurt me, Tony. I wouldn't mind being chucked by

any one else. But somehow you're different. I have

always looked on you as a pal."

Tony slipped his left hand off the wheel for a

second and lightly squeezed hers.

"So I am, Molly," he said. "Why on earth

should I have changed?"

"I thought you might be sick with me about—well,

about Peter."

"Good Lord, no," said Tony. "I never criticize

my friends' hobbies. If I haven't routed you out

lately, it's only because I've been really busy."

Her face brightened. "You're a nice old thing,

Tony," she said. "Come and lunch with me to-morrow

if you're not booked up. Just us two. I

really do want to have a talk with you, badly."

"Right-o," said Tony. "You'll be able to give

me the latest stable information about Lopez. It's

the fight to-morrow night, you know."

Molly nodded. "Peter thinks he's going to win

all right," she said. "He's cocksure about it."

"I gathered that," said Tony. "I ran into da

Freitas at the Club just now and he bet me a level

two hundred we were in for a whipping. I shouldn't

think he was a gentleman who chucked away his

money out of patriotic sentiment."

Molly made as near an approach to an ugly face as

nature would allow.

"You don't like him?" inquired Tony artlessly.

"He's a pig," said Molly, and then after a short

pause she added with some reluctance, "but he's a

clever pig."

"That," observed Tony, "only aggravates the

offence."

He pulled up at Basil Mansions, a big block of

luxurious flats just opposite the Langham Hotel, and

a magnificently gilded porter hastened forward to

open the door of the car.

"I'll tell you about him to-morrow," said Molly.

"Don't be later than half-past one. I'm always

starving by then, and I shan't wait for you."

"I am always punctual for meals," said Tony.

"It's the only virtue that's rewarded on the spot."

CHAPTER II

THE MORALS OF MOLLY

It was exactly eleven o'clock when Tony woke up.

He looked at his watch, yawned, stretched himself,

ran his fingers through his hair, and then reaching out

his hand pressed the electric bell beside his bed.

After a short pause it was answered by a middle-aged,

clean-shaven man, with a face like a tired

sphinx, who entered the room carrying a cup of tea

upon a tray. Tony sat up and blinked at him.

"Good-morning, Spalding," he observed.

"Good-morning, Sir Antony," returned the man;

"I trust that you slept well, sir?"

"Very well, thank you," replied Tony. "What

time did I get home?"

"I fancy it was a little after four, sir."

Tony took a long drink out of the tea-cup, and

then put it down again. "I am curiously thirsty

this morning, Spalding," he said. "Was I quite

sober when I came back?"

The man hesitated. "I should describe you as

being so, sir," he replied.

"Thank you, Spalding," said Tony gratefully.

Crossing the room the valet drew up the blinds,

and admitted a cheerful stream of sunshine.

"Mr. Oliver left a message, sir, to say that he

would not be back until the afternoon. He has

gone out on business and is lunching with

Mr. Henry Conway."

"Where's Bugg?" inquired Tony.

"At the present moment, sir, I believe he is in the

gymnasium. He informed me that he was about to

loosen his muscles with a little shadow boxing."

"Is he all right?"

"He appears to be in the most robust health, sir."

A look of relief passed across Tony's face. "You

have taken a weight off my mind, Spalding," he said.

"I dreamed that he had broken his neck."

The valet shook his head reassuringly.

"I observed no sign of it, sir, when I passed him in

the hall."

"In that case," said Tony, "I think I shall get up.

You can fill the bath, Spalding, and you can tell the

cook I shan't want any breakfast."

The impassive servant bowed and withdrew from

the room, and after finishing his tea, Tony got

luxuriously out of bed, and proceeded to drape

himself in a blue silk dressing-gown with gold dragons

embroidered round the hem. It was a handsome

garment originally intended for the President of

China, but that gentleman had unexpectedly rejected

it on the ground that it was too ornate for the elected

head of a democratic community. At least that was

how the Bond Street shopman who had sold it to

Tony had accounted for its excessive price.

Lighting a cigarette, Tony sauntered across to the

bathroom, where a shave, a cold tub, and a few

minutes of Muller's exercises were sufficient to

remove the slight trace of lassitude induced by his

impersonation of Charles the Second. Then, still

clad in his dressing-gown, he strolled down the main

staircase, and opening the front door passed out into

the garden.

The house was one of those two or three jolly

old-fashioned survivals which still stand in their own

grounds in the neighbourhood of Jack Straw's Castle.

Tony had bought up the freehold several years

previously, the quaint old Georgian residence in its

delightful surroundings appealing to him far more

than his own gloomy family mansion in Belgrave

Square. As he himself was fond of explaining, it

gave one all the charm of living in the country

without any of its temptations to virtue.

A few yards' walk along a gravel path, hedged in

on each side by thick laurel bushes, brought him to

the gymnasium. The door was slightly open, and

from the quick patter and shuffle of footsteps inside,

it sounded as if a number of ballet girls were

practising a novel and rather complicated form of step

dance.

The spectacle that actually met Tony's eyes when

he entered, however, was of a less seductive nature.

Clad only in a pair of flannel trousers, a young man

was spinning and darting about the room in the most

extraordinary fashion, indulging at the same time in

lightning-like movements with his head and arms.

To the uninitiated observer he would have appeared

to be either qualifying for a lunatic asylum or else

attempting the difficult feat of catching flies on the

wing. As a matter of fact either assumption would

have been equally inaccurate. He was engaged in

what is known amongst pugilists as "shadow boxing"

which consists of conducting an animated contest

with a vicious but imaginary opponent.

On seeing Tony the young man in question came

to an abrupt halt in the middle of the room, and

raised his forefinger to his close-cropped forehead.

"Mornin', Sir Ant'ny," he observed.

Notwithstanding his exertions he spoke without

the least trace of breathlessness, and there was

no sign of perspiration upon his clean white skin.

He looked what he was—a splendidly built lad of

about nineteen, trained to the last pitch of physical

fitness.

Tony glanced him over with an approving eye.

"Good-morning, Bugg," he answered. "I am glad

to see you looking so well. I dreamed you had

broken your neck."

The lad grinned cheerfully. "Not me, sir. Never

felt better in me life. Must 'a bin the other bloke."

"I hope not," said Tony anxiously. "I backed

you for another two-fifty yesterday, and I can't very

well claim the money unless the fight comes off. By

the way, a hundred of that goes on to the purse if you

do the trick all right."

The young prize-fighter looked a trifle embarrassed.

"There ain't no call for that, sir—thankin' ye kindly

all the saime, sir. I'd knock out 'alf a dozen blokes

like Lopez for a purse o' three 'undred."

"Your unmercenary nature is one of your chief

charms, Bugg," said Tony. "All the same you

mustn't carry it to extremes. How much money

have you got in the bank now?"

Bugg scratched his ear. "The last time I goes in,

sir, the old geezer with the whiskers says somethin'

abaht a matter of eleven 'undred quid."

"Well, by to-morrow you ought to have fifteen

hundred. In other words, Bugg, you will be a

capitalist—one of the idle rich. That money,

properly invested, will bring you in thirty shillings a

week. If you want to set up as an independent

gentleman now's the time to begin."

A sudden look of surprised dismay spread itself

across Bugg's square-jawed face.

"Meanin' I got the chuck, sir?" he inquired

dully.

Tony laughed. "Of course not," he said. "Don't

be an ass, Bugg. I was only pointing out to you that

if you like to set up on your own you can afford to do

it. I'll go on backing you as long as you want me to,

but you needn't feel bound to stop on here if you'd

rather clear out. It's not much of a job for a budding

champion of England with fifteen hundred pounds in

the bank."

Bugg gave an audible sigh of relief.

"I thought you was 'andin' me the bird, sir," he

observed. "Give me a proper turn it did, jest for

the minit."

"Then you don't want to go?"

Bugg laughed, almost contemptuously.

"Where'd I go to, sir?" he demanded. "'Ow long

would that fifteen 'undred last if I was knockin'

arahnd on me own with every flash cove in London

'avin' a cut at it? 'Sides, that, sir, I don't want

nothin' different. I wouldn't change the job I got,

not to be King of England. If it weren't for you I'd

be 'awkin' welks now, or fightin' in a booth, an'

Tiger Bugg ain't the sort to forget a thing like that.

Wen you don't want me no more, sir, jest you tip

me the orfice straight and proper and I'll 'op it,

but so long as there's any bloomin' thing I can do

for you, sir, well, 'ere I am and 'ere I means to

stop."

It was the longest speech that Tiger Bugg had

ever indulged in, and certainly the most eloquent.

Tony, who was genuinely touched by the obvious

sincerity with which it was uttered, stepped forward

and patted the lad on his shoulder.

"That's all right, Tiger," he said. "There will

always be a job for you here if it's only to annoy my

relations." He paused and lighted himself another

cigarette. "Give us a bit of your best to-night," he

added. "I should like to make Da Freitas look silly,

and if you win easily, Donaldson has practically

promised me a match for the Lonsdale Belt."

Bugg's eyes gleamed, and his hands automatically

clenched themselves.

"I'll slip one over the fust chance I get, sir," he

observed earnestly. "I don't think I'll 'ave to wait

long either."

Tony nodded, and gathering up his dressing-gown,

turned towards the door.

"Well, be ready by eight o'clock," he said, "and

we'll go down together in the car."

Leaving the gymnasium he strolled on up the path

till it curved round the corner and opened out into

an asphalt yard, where a man in blue overalls was

attending to the toilet of the big Peugot. He was

a tall, red-haired individual with an expression of

incurable melancholy on his face.

"Good-morning, Jennings," said Tony. "It's

a nice morning, isn't it?"

The chauffeur cast a resentful glance at the

unclouded blue overhead.

"It's all right at present, sir," he admitted

grudgingly, "but these here extra fine mornings have a

way of turning off sudden."

Tony sauntered up to the car, and lifting the

bonnet looked down into the gleaming network of

copper and brass which bore eloquent testimony to

the care and energy expended on it.

"I didn't think she was pulling quite at her best

yesterday," he said. "You might have a run

through and tune her up a bit, when you've got

time."

The chauffeur nodded. "Once these here big

racin' engines begin to give trouble, sir," he remarked

with a sort of gloomy relish, "they ain't never the

same again—not in a manner o' speaking. Least,

that's how it seems to me."

"That's how it would seem to you, Jennings,"

said Tony kindly. "Is the Suiza all right?"

"She'll run, sir."

"Well, have her ready about one o'clock, and I

shall want you and the Rolls-Royce at eight to-night,

to take us down to the Club." He paused. "I

suppose you have backed Bugg?" he added.

Jennings shook his head. "Not me, sir. I think

he's flying too high, sir. From all they tell me this

here Lopez is a terror. I'll be sorry to see Bugg

knocked out, but there it is; it comes to all of 'em in

time."

"I like talking to you after breakfast, Jennings,"

said Tony. "You cheer one up for the entire day."

Jennings received the compliment with an utterly

unmoved expression. "I don't take much stock in

bein' cheerful meself, sir," he observed, "not unless

there's something to be cheerful about."

He stepped forward and resumed his work on the

car, and after watching him for a moment or two with

a pleasant languid interest Tony turned round and

sauntered back to the house.

He finished his toilet in a leisurely fashion, and

then spent an agreeable half-hour over the Sportsman,

which was the only morning paper that he took

in. Current affairs of a more general nature did not

interest him much, though in times of national or

political crisis it was his habit to borrow the Daily

Mail from Spalding.

Soon after one, Jennings brought the Suiza round

to the front door, and a quarter of an hour later Tony

turned in through the gateway of Basil Mansions and

drew up alongside the rockery and fountain with

which a romantic landlord had enriched the centre

of the courtyard.

Leaving the car there, he strolled across to Molly's

flat and rang the bell. It was answered almost at

once by a neatly dressed French maid, who

conducted him into a bright and daintily furnished

room where Molly was sitting at the piano practising

a new song. She jumped up gaily directly she saw

him.

"Oh, how nice of you, Tony," she exclaimed.

"You are ten minutes early and I'm fearfully hungry.

Lunch as soon as it's ready, Claudine."

She gave Tony her hand which he raised gallantly

to his lips.

"You are looking very beautiful this morning,

Molly," he said. "You remind me of one of those

things that come out of ponds."

"What do you mean?" asked Molly. "Frogs?"

"No," said Tony, "not frogs. Those sort of jolly

wet girls with nothing on; what do you call

them—naiads, isn't it?"

Molly burst into a ripple of laughter. "I don't

think that's much of a compliment to my frock,

Tony," she said. "It was specially designed for me

by Jay's too! Don't you like it?"

Tony stepped back and inspected her critically.

"It's wonderful," he said. "I should imagine

Mr. Jay was now prostrate with nervous exhaustion."

"Oh, well," replied Molly comfortingly, "he'll

have heaps of time to recover before he's paid."

The clear note of a silver gong sounded from the

passage and she thrust her arm through Tony's.

"Come along," she said, "there are roast quails

and it would be awful if they got cold, wouldn't it?"

Tony gave a slight shudder. "There are some

tragedies," he said, "that one hardly likes to think

about."

All through lunch, which was daintily served in

Molly's pretty, sunny little dining-room, they

chatted away in the easy cheerful fashion of two

people who have no illusions about each other and

are yet the firmest of friends. The lunch itself was

excellent, and Claudine waited on them with a graceful

skill that lent an additional harmony to its

progress.

"I think I am in love with your new maid,"

observed Tony thoughtfully, when she at length left

them to their coffee and cigarettes.

"I am glad you approve of her," said Molly, "but

if you haven't seen her before it only shows how

disgustingly you must have treated me. She has been

here since Christmas."

"I like her face," pursued Tony. "It's so pure.

She looks as if she had been turned out of a convent

for being too good."

"She isn't good," said Molly. "Don't you think it."

"That only makes her all the more wonderful,"

said Tony. "To look good and to be wicked is the

ideal combination. You get the benefits of both

without any of their drawbacks."

"In that case," observed Molly, "I must be

dead out of luck. With my red hair and red lips I

look desperately wicked, while as a matter of fact

I'm quite uninterestingly good—by instinct." She

paused. "I want to talk to you about my morals,

Tony. That has been one of the chief reasons why

I asked you to lunch."

Tony poured out a glass of liqueur brandy. "The

morals of Molly," he remarked contentedly. "I

can't imagine a more perfect subject for an

after-lunch discussion."

Molly lit herself a cigarette and passed him across

the little silver box. "It's not so much a discussion

as an explanation," she said. "I want to explain

Peter." She sat back in her chair. "You see,

Tony, you're the only person in the world whose

opinion I care a hang for. If it hadn't been for you

I don't know what would have happened to me

after I ran away from home. You helped me to get

on the stage, and I don't want you to think I've

turned out an absolute rotter. Oh, I know people

have always said horrid things about me, but then

they do that about any girl in musical comedy. I

believe I'm supposed to have lived with a Rajah and

had a black baby, and Lord knows what else, but as

a matter of fact it's all lies and invention. People

talk like that just to appear more in the swim than

somebody else. Of course I don't mean to say I

haven't had lots of kind offers of that sort, but until

Peter came along I'd said 'no' to all of them."

"What made you pitch on Peter?" asked Tony.

"I don't know," said Molly frankly. "I think I

was sorry for him to start with. He's so stupid you

know—any one can take him in, and that little cat

Marie d'Estelle was getting thousands out of him

and carrying on all the time with half a dozen other

men. So I thought I'd just take him away if only to

teach her common decency."

"If rumour is correct," observed Tony, "the

lesson was not entirely successful."

Molly laughed. "Well, that was how the thing

started anyway," she said. "Peter got awfully

keen on me, and after I had seen a little bit of him

and snubbed him rather badly once or twice for being

too affectionate, I really began to get quite fond of

him. You see if he wasn't a king he'd be a jolly good

sort. There's nothing really the matter with him

except that he's been horribly spoilt. He isn't a bit

vicious naturally; he only thought he was until he

met me. He is weak and stupid, of course, but then

I like a man not to be too clever if I am going to have

much to do with him. Stupid men stick to you, and

you can make them do just what you want. You

know Peter consults me about practically everything."

"And what does Da Freitas think of the situation?"

asked Tony mildly.

"Oh, Da Freitas!" Molly's expression was an

answer in itself. "He hates me, Tony; he can't

stand any one having an influence over Peter except

himself. He didn't mind d'Estelle and people like

that, in spite of the money they cost, but he would

give anything to get rid of me. He likes Peter to

be weak and dissipated and not to bother about

things, because then he has all the power in his own

hands."

"But how is all this going to end, Molly?" asked

Tony. "Suppose there's another revolution in Livadia,

and Peter, as you call him, has to go back to be

King. It's quite on the cards according to what one

hears."

"Oh, I know," said Molly, shrugging her shoulders,

"but what's the good of worrying? If they

knew Peter as well as I do they wouldn't be so stupid.

He'd be no earthly use as a king, by himself, and

he'd look too absolutely silly for words with a crown

on his head. As far as his own private tastes go,

he's a lot happier at Richmond. He quite sees it

too, you know, when I point it out to him, but he

says he wouldn't be able to help himself if there

really was a revolution."

"No," said Tony. "I imagine Da Freitas would

see to that. It will be a precious cold day when he

gets left. He hasn't schemed and plotted and kept

in with Pedro all this time in order to let the chance

slip when it comes along. If he isn't back there one

day in his old job of Prime Minister, it won't be the

fault of the Marquis Fernando."

Molly looked pensively into the fire. "He only

makes one mistake," she said. "He's a little too apt

to think other people are more stupid than they are.

I suppose it comes from associating so much with

poor old Peter."

CHAPTER III

TWO YELLOW-FACED FOREIGNERS

Very carefully Tony sprinkled a little Bengal

pepper over the perfectly grilled sole which Spalding

had set down in front of him. Then he returned

the bottle to the cruet-stand and looked across the

table at his cousin.

"You really ought to come to-night, Guy," he

said. "It will be a beautiful fight while it lasts."

Guy Oliver shook his head. He was a tall, rather

gaunt young man with a pleasant but too serious

expression. "My dear Tony," he replied, "my

tastes may be peculiar, but as I have told you before,

it really gives me no pleasure to watch two lads

striking each other violently about the face and

body."

"You were always hard to please," complained

Tony sadly. "Fighting is one of the few natural

and healthy occupations left to humanity."

Guy adjusted his glasses. "I am not criticizing

fighting in its proper place," he said. "I think

there are times when it may be necessary and even

enjoyable. All I do object to is regarding it as a

pastime. There are some things in life that we

are not meant to make a popular spectacle out of.

What would you say if someone suggested paying

people to make love to each other on public platforms?"

"I should say it would be most exciting," said

Tony. "Especially the heavy-weight championship." He

poured himself out half a glass of sherry

and held it up to the light. "Talking of

heavy-weights," he added, "how did you find our dear

Cousin Henry?"

"Henry was very well," said Guy. "He is coming

to see you."

Tony put down his glass and surveyed his cousin

reproachfully. "And you call yourself a secretary

and a friend?" he remarked.

"I think it is very good for you to entertain Cousin

Henry occasionally," returned Guy. "He is an

excellent antidote to the Cosmopolitan Club and

Brooklands." He paused. "Besides, he has a

suggestion to make with which I am thoroughly in

sympathy."

A depressed expression flitted across Tony's face.

"I am sure it has something to do with my duty," he

said.

Guy nodded. "I wish you would try and look on

it in that light. Henry has put himself to a lot of

trouble about it, and he will be very hurt if you don't

take it seriously."

"My dear Guy!" said Tony. "A proposal of

Henry's with which you are in sympathy couldn't

possibly be taken any other way. What is it?"

"He has set his heart on your going into Parliament

as you know. Well, he told me that last week he

had spoken about you to the Chief Whip, and that

they are arranging for you to stand as Government

candidate for Balham North at the next general

election."

There was a long pause.

"For where?" inquired Tony faintly.

"For Balham North. It's a large constituency in

South London close to Upper Tooting."

"It would be," said Tony. "And may I ask

what I have done to deserve this horrible fate?"

"That's just it," said Guy. "You haven't done

anything. Henry feels—indeed we all feel that as

head of the family it is quite time you made a start."

"You don't understand," said Tony with some

dignity. "I am sowing my wild oats. It is what

every wealthy young baronet is expected to do."

"Leaving out the war," retorted Guy, "you have

been sowing them for exactly six years and nine

months."

Tony smiled contentedly. "I always think,"

he observed, "that if a thing is worth doing at all, it

is worth doing well."

There was another pause, while Guy, crumbling a

bit of bread between his fingers, regarded his cousin

with a thoughtful scrutiny.

"As far as I can see, Tony," he said, "there is

only one thing that's the least likely to do you any

good. You want a complete change in your

life—something that will wake you up to a sense of

duty and responsibility. I think you ought to get

married."

Tony, who was helping himself to a glass of champagne,

paused abruptly in the middle of that engaging

occupation.

"How remarkable!" he exclaimed. "Only yesterday

Aunt Fanny made exactly the same suggestion.

It must be something in the spring air."

"I don't always agree with Aunt Fanny," said

Guy, "but I think that for once in a way she was

giving you excellent advice. A good wife would

make a tremendous difference in your life."

"Tremendous!" assented Tony with a shudder.

"I should probably have to give up smoking

in bed and come down to breakfast every

morning."

"You would be all the better for it," said Guy

firmly. "I was thinking, however, more of your

general outlook on things. Marriage with the right

woman might make you realize that your position

carries with it certain duties that you ought to regard

both as a privilege and a pleasure."

"Is going into Parliament one of them?" asked Tony.

"Certainly. As a large landowner you are just

the type of man who is badly wanted in the House of

Commons."

"They must be devilish hard up for legislators,"

said Tony. "Still, if you and Henry have made

up your minds, I expect I shall have to do it." He

paused. "I don't think I should like to be the

member for Balham North though," he added

reflectively. "It sounds like the sort of place where

a chorus girl's mother would live."

Any defence of the constituency which Guy may

have had to offer was cut short by the re-entrance of

Spalding.

"The car is at the door, sir," he observed.

"Aren't you going to finish your dinner?" inquired

Guy, as Tony pushed back his chair.

The latter shook his head. "I never eat much

before a fight," he said. "It prevents my getting

properly excited." He got up from his seat.

"Besides," he added, "I always take Bugg round to

Shepherd's after he has knocked out his man, and we

celebrate the victory with stout and oysters. It's

Bugg's idea of Heaven."

He passed out into the hall where Spalding helped

him on with his coat. Outside the front door

stood a beautifully appointed Rolls-Royce limousine,

painted the colour of silver and upholstered in grey

Bedford cord. Jennings was at the wheel and inside

sat Tiger Bugg and a large red-faced man with

little twinkling black eyes. This latter was

Mr. "Blink" McFarland, the celebrated proprietor of the

Hampstead Heath Gymnasium, who acted as Tiger's

trainer and sparring partner. They both touched

their caps as Tony appeared.

"I wouldn't let 'im get out, sir," observed McFarland

in a gruff voice. "Might 'a took a chill hangin'

around."

"Quite right, Blink," replied Tony gravely.

"Lopez isn't to be sneezed at even by a future

champion."

He lit himself a cigarette, and stepping inside

closed the door behind him. Spalding made a signal

to Jennings and the big car slid off noiselessly down

the drive.

Tony turned to Bugg. "Feeling all right?" he

inquired.

The young prize-fighter grinned amiably. "Fine,

sir, thank ye, sir."

With an affectionate gesture, McFarland laid an

enormous mottled hand on his charge's knee. "He's

fit to jump out of 'is skin, sir; you take it from me.

If he don't knock two sorts of blue 'ell out of that

dirty faced dago I'll give up trainin' fighters and

start keepin' rabbits."

"Lopez is supposed to have a bit of a punch

himself, isn't he?" inquired Tony.

McFarland made a hoarse rumbling noise which

was presumably intended for a laugh.

"All the better for us, sir. The harder 'e hits the

more 'e'll hurt hisself. It's a forlorn jog punchin'

Tiger. You might as well kick a pavin' stone."

Bugg, who was evidently susceptible to compliments,

blushed like a schoolgirl, and then to cover

his confusion turned an embarrassed gaze out of the

window. The long descent of Haverstock Hill was

flying past at a rare pace, for whatever might be

Jenning's shortcomings as a cheerful companion he

could certainly drive a car. Indeed it could scarcely

have been more than ten minutes from the moment

they left the Heath, until, with a loud blast from

the horn, they glided round the corner of the street

into Covent Garden.

The pavement and roadway in front of the

Cosmopolitan were filled by the usual rough-looking

crowd that invariably congregates outside the Club

on the occasion of a big fight. With surprising

swiftness, however, a space was cleared for Tony's

car, and as its three occupants stepped out, a hoarse

excited buzz of "That's 'im! that's Tiger!" rose up

all round them.

Bugg and McFarland hurried through into the

Club; Tony stopping behind for a moment to give

some directions to Jennings.

"You can put the car up at the R.A.C.," he said.

"I'll telephone over when I want you."

He followed the others across the pavement, amid

encouraging observations of, "Good-luck, me lord!"

and one or two approving pats on the back from

hearty if not overclean hands.

Bugg and his trainer had of course gone direct to

their dressing-room, where Tony made no attempt

to pursue them. He knew that Tiger's preparations

were safe in McFarland's hands, so relinquishing his

coat to one of the hall porters, he walked straight

through to the big gymnasium where the Club

contests were held.

It was an animated scene that met his eyes as he

entered. A preliminary bout was in progress and

round the raised and roped dais in the centre, with

its blinding glare of light overhead, sat a thousand or

fifteen hundred of London's most eminent

"sportsmen." They were nearly all in evening dress: the

dazzling array of white shirt fronts and diamond

studs affording a vivid testimony to the interest

taken in pugilism by the most refined and educated

classes.

As soon as the round was ended, Tony made his

way slowly towards his seat by the ring-side, exchanging

innumerable greetings as he passed along. Almost

everybody seemed to know him, and he seemed to

have a smile and a cheery word for them all.

A few yards from his destination he came across

the Marquis da Freitas. That distinguished statesman

was seated in the front row of chairs enjoying

a big cigar, while beside him lounged a dark, squarely

built, rather coarse-featured youth, who greeted

Tony with an affable if slightly condescending wave

of his hand. The latter was none other than His

Majesty King Pedro the Fifth, the rightful though

temporarily discarded ruler of Livadia.

Tony pulled up at this mark of Royal recognition

and shook hands with the Marquis and his monarch.

It was understood that on such occasions as the

present the ex-king preferred to be regarded as an

ordinary member of the Club.

"Everything is good I hope," he observed to Tony.

"Your man he is up to the scratch—eh?"

He spoke English confidently, but with a marked

foreign accent.

"Rather," said Tony. "Never been fitter in his

life. No excuses if we're beaten."

Da Freitas blew out a philosophic puff of smoke.

"Ah, Sir Antony," he observed, "that is one of your

national virtues. You are good losers, you English.

Perhaps you do not feel defeat as deeply as Southerners."

"Perhaps not," admitted Tony cheerfully.

"Anyhow, it's not much good making a song

about things, is it? One's bound to strike a snag

occasionally."

The Marquis nodded. "In Livadia," he said

softly, "we do not like to be beaten. We——"

There was a loud tang from the gong and the two

boxers sprang up out of their respective corners to

resume the fight. With a gesture of apology Tony

moved along to his seat, where he found himself

next to "Doggy" Donaldson, who was discharging

his customary rôle of Master of the Ceremonies.

He welcomed Tony with a grip of the hand.

"Glad you've turned up," he said. "I never feel

really happy till both parties are in the Club. All

serene?"

"As far as we're concerned," replied Tony.

Donaldson rubbed his hands. "That's good," he

observed contentedly. "We'll have 'em in the ring

by nine-thirty at latest. That'll just give us time

to—Hullo! Look at that! Damned if Young Alf

isn't chucking it."

One of the two contesting youths had suddenly

stepped back and held out his hand to his opponent.

He had just received a severe dig in the stomach,

which had apparently convinced him for the moment

that boxing was an unfriendly and over-rated amusement.

With a grunt of disgust at such pusillanimity

Donaldson clambered up into the ring, and in a

stentorian voice announced the name of the winner.

He then introduced two more lithe-limbed

active-looking lads, who promptly set about the task of

punching each other's heads with refreshing

accuracy and vigour.

It was about a quarter-past nine when this bout

came to an end, and preparations were begun for the

principal event. Two buckets of clean water were

brought in, and a large cardboard box containing a

couple of new pairs of boxing-gloves was deposited

in the centre of the ring. Then, while a truculent

looking gentleman in flannel trousers and a sweater

strolled about crushing lumps of resin beneath his

feet, Doggy Donaldson again hoisted himself into

the roped square, and held up his hand for silence.

"Gentlemen," he said, "I have the pleasure to

announce that the Committee has decided to match

the winner of to-night's contest against Jack Rivers,

the holder of the Lonsdale Welter Weight Belt."

The applause that greeted this statement had

scarcely died away, when a louder and more enthusiastic

outburst proclaimed the appearance of the boxers.

They came on from different sides of the building

each with a small army of seconds in attendance.

Climbing up into opposite corners of the ring they

bowed their acknowledgments to the audience, and

then, after carefully rubbing their feet in the resin,

seated themselves on the small stools that had been

placed in readiness.

A number of lengthy preliminaries followed. The

bandages that each man wore on his hands were

gravely inspected by one of his rival's seconds, while

another opened the cardboard box, and selected one

of the two pairs of gloves for his principal. They

were nice-looking gloves, but to the casual observer

they would have appeared to be constructed more for

the purpose of conforming to the law than of really

deadening the effect of a blow. By dint of much

pulling and straining, however, each boxer managed

to get them on, and then sat with a dressing-gown

over his shoulders while "Doggy" Donaldson made

the inevitable introductions.

"Gentlemen! A twenty three-minute round contest

between 'Lightning' Lopez of Livadia on my

right, and 'Tiger' Bugg of Hampstead on my left.

The bout will be refereed by Mr. 'Dick' Fisher."

An elderly man in evening dress with a weather-beaten

face, hard blue eyes, and a chin like the toe

of a boot stepped up alongside the speaker and jerked

his head at the audience. He was an ex-amateur

champion of England, and one of the best judges of

boxing in the world.

The gong sounded as a signal to clear the ring, and

the cluster of seconds each side made a leisurely

exit through the ropes. For a moment the two

boxers were left sitting on their respective stools

facing each other across the brilliantly lighted arena.

Then came another clang, and with a simultaneous

movement they leaped lightly to their feet, and

advanced swiftly but cautiously towards the centre.

To any one sufficiently pagan to admire the human

form they made a pleasing and effective picture.

Both nude, except for a pair of very short blue trunks,

they moved forward with the lithe grace of a couple

of young panthers. Under the pitiless glare of the

big arc lamps the rippling muscles on their backs

and shoulders were plainly visible. Bugg's white

skin stood out in dazzling contrast to the swarthy

colour of his opponent, but as far as bodily perfection

went there seemed to be nothing to choose between

them.

For a few seconds they circled stealthily round

the ring sparring for an opening. Lopez, who had

adopted a slightly crouching pose, was the more

aggressive of the two. He was famed for the fierce

impetuousness of his methods, and on his last

appearance at the Club he had signalized the occasion by

knocking out his adversary in the second round.

In the present instance, however, he appeared to be

a little at a loss. There was nothing very unusual

to the eye about Bugg's style, but the almost

contemptuous ease with which he brushed aside a couple

of lightning-like left leads was distinctly

disconcerting to his opponent.

Realizing apparently that as far as quickness and

skill went he had met more than his match, the

Livadian evidently decided that his usual robust

tactics might be the most effective. He drew back a

pace, and then slightly dropping his head, sprang in

with the vicious fury of a wildcat, hitting out fiercely

with both hands.

The suddenness of the attack would have taken

most boxers by surprise, but that embarrassing

emotion appeared to have no place in Bugg's philosophy.

With the swiftness of light he stepped to one

side, and just as the human battering ram in front of

him hurled itself forward, he brought up his right

hand in a whizzing upper cut that caught his

adversary under the angle of the jaw. The blow was so

perfectly timed and delivered with such tremendous

force that it lifted Lopez clean off his feet. With his

arms flung out wide each side of him he made a sort

of convulsive jerk into the air, and then crashed

over backwards on to the floor, where he lay a huddled

and inert mass.

For an instant the whole house remained hushed

in a stupefied silence. Then as the time-keeper

began to count off the fateful seconds a sudden

hoarse roar broke out all over the building. Above

the din could be heard the voices of Lopez' seconds,

howling abuse and entreaty at their unconscious

principal. In vain the referee waved his arms,

entreating some sort of order for the count.

"Doggy" Donaldson clutched Tony by the wrist.

"Damn it!" he shouted excitedly, "I believe he's

broken his neck."

Even as he spoke came the clang of the time-keeper's

gong, signifying that the ten seconds had

passed. In a moment half a dozen figures were

swarming over the ropes, but before any one of them

could reach him, Bugg had picked up his limp,

unconscious adversary in his arms, and was carrying

him across the ring to his own corner. He seemed

to be by far the coolest and most collected person

present.

Almost immediately Tony became the centre of

a number of friends and acquaintances who were

wringing his hand and congratulating him on the

victory. After a minute or two he managed to free

himself, and pushing his way through to the ringside,

inquired anxiously after the health of the

unfortunate Lopez. "Doggy" Donaldson, who was

amongst the crowd surrounding that fallen warrior,

bent down with an air of considerable relief upon

his honest countenance.

"It's all right," he said, "the beggar's coming

round. I really thought for a moment he was a

goner though. Gad, what a kick that boy of yours

has got!"

"Well, I'm glad it's no worse," said Tony.

The other nodded. "Yes," he observed, "we

must all be thankful for that. It would have been

a rotten thing for the Club if he'd broken his neck."

He turned away, and following suit, Tony suddenly

found himself face to face with the Marquis

da Freitas, and his royal master, who had apparently

stepped forward in order to learn the news. The

Marquis appeared as suave as ever, but anything

more sulky looking than His Majesty it would have

been difficult to imagine.

Da Freitas bowed with the faintest ironical

exaggeration. "Permit me to congratulate you,

Sir Antony. Your victory is indeed crushing."

Tony regarded him with his usual amiable smile.

"Thanks," he said. "I am awfully glad your man

isn't seriously hurt. It was bad luck his running

into a punch like that." He turned to Pedro.

"You can have a return match you know any time,

if you care about it."

His Majesty scowled. "I will see him dead before

I back him again," he observed bitterly.

The Marquis da Freitas showed his white teeth

in a polite smile. "I fear you are rather too strong

for us in the boxing-ring, Sir Antony. Perhaps

some day we may find a more favourable battle-ground."

"I hope so," said Tony. "I rather like having

a shade of odds against me. It's so much more

interesting."

He nodded cheerfully to the pair of them, and

moving off from the ring-side began to make his way

across the hall. It was slow work, for friends kept

on pulling him up with boisterous words of congratulation,

while several of them made strenuous endeavours

to persuade him to join a party at some

neighbouring night club, to which they were going

on for supper.

Tony, however, declined the invitation on the

plea of a previous engagement. As he had told Guy

at dinner it was his invariable custom after a

successful fight to take Bugg out to Shepherd's, the

celebrated oyster bar in Coventry Street—a resort much

frequented by gentlemen of pugilistic and sporting

tastes. The simple-minded Tiger had not many

weaknesses, but on these occasions it afforded him

such extreme pleasure to be seen therewith his patron,

that Tony wouldn't have missed gratifying him for

the most festive supper party in London.

On reaching the dressing-room he found Bugg

fully clothed and in the centre of a small levee of

pressmen and fellow pugilists. McFarland,

immensely in his element, was dispensing champagne

to the visitors, and explaining how very lately his own

unrivalled training methods had contributed to the

result.

Tony stopped and chatted amiably for a few

minutes until he could manage to extract Bugg from

the centre of his admirers. When at last they

succeeded in getting away they slipped out quietly

by the side door of the Club in order to avoid the

crowd who were still hanging about the front, and

with a breath of relief found themselves in the cool

night air of Long Acre.

Tony lit a cigarette and offered one to his companion.

"You positively surpassed yourself to-night,

Bugg," he said. "The worst of it is that if you go

on improving in this way, I shall have to find a

new profession. No one will dare to bet against you."

"I 'ope I didn't shove it across 'im too sudden,

sir?" inquired Bugg anxiously. "You said you was

in a hurry."

"It was perfect," said Tony. "The only person

who had any complaint to make was King Pedro."

Bugg sniffed contemptuously. "'E ain't much of

a king, sir. I don't wonder they give 'im the chuck.

A real king wouldn't taike on abaht droppin' a few

quids."

"I daresay you're right," said Tony. "A certain

recklessness in finance——"

He suddenly pulled up and for a moment remained

where he was, staring across the street. On the

opposite pavement, in the bright circle of light

thrown by one of the big electric standards, he had

caught sight of the figure of a girl, who at that

distance reminded him curiously of Molly Monk. She

had apparently just come out of the entrance to

some flats above, and with a bag in her hand she was

standing there in an uncertain, indefinite sort of way,

as though she scarcely knew what to do next.

Realizing that it couldn't be Molly, who was of

course at the theatre, Tony was just about to move

on again, when something checked him.

Two well-dressed men in dark overcoats and soft

hats had suddenly appeared out of the shadow ahead

and advanced quickly to where the girl was standing.

For an instant they all three remained facing each

other under the light, and then taking off his hat, one

of them addressed her.

With a little frightened gesture the girl shrank

back against the wall, where she glanced wildly

round as though seeking for some means of escape.

The man who had spoken followed her forward, his

hat still in his hand, apparently making an effort

to reassure her.

Tony turned to Bugg. "We really can't allow

this sort of thing in Long Acre," he observed. "It

has always been a most respectable street."

He threw away his cigarette, and followed by

the future champion of England started off briskly

across the road.

On hearing their footsteps the two men spun

round with some abruptness. They were both

obviously foreigners, and the sight of their sallow

faces and black moustaches filled Tony with a

pleasant sense of patriotic morality.

Without paying any attention to either of them

he walked straight up to the girl, and taking off his

hat made her a slight bow.

"I beg your pardon," he said, "but from the other

side of the road it looked as if these gentlemen were

annoying you. Can I be of any assistance?"

She gazed up at him with grateful eyes. At close

quarters her resemblance to Molly, though still

remarkable, was not quite so convincing. She was a

little younger and slighter, and there was a delicate

air of distinction about her that was entirely her

own.

"Oh, if you would be so kind," she said in a

delightfully soft voice. "I do not wish to speak with

these men. If you could send them away—right

away——"

"Why, of course," replied Tony with his most

cheerful smile, "please don't distress yourself."

He turned to the two sallow-faced strangers who

seemed to have been utterly disconcerted by his

sudden appearance on the scene.

"Go away," he said, "and hurry up about it."

CHAPTER IV

LIKE A FAIRY STORY

There was a short pause, and then the shorter of

the two men stepped forward. He was an aggressive

looking person with a cast in his eye, and he spoke

with a slight foreign accent.

"Sir," he said, "you are making a mistake. We

do not intend any insult to this lady. We are indeed

her best friends. If you will be good enough to

withdraw——"

With the gleam of battle in his eye, Bugg ranged up

alongside the speaker, and tapped him on the elbow.

"'Ere!" he observed. "You 'eard wot the guv'nor

said, didn't you?" He jerked his thumb over his

left shoulder. "'Op it before you get 'urt."

Tony turned to the girl. "You mustn't be mixed

up in a street fight," he said. "If you will allow

me to see you to a taxi, my friend here will prevent

these unpleasant looking people from following us."

He offered her his arm, and after a second's

hesitation she laid a small gloved hand upon his

sleeve.

"It is very kind of you," she faltered. "I fear I

am going to give you a great deal of trouble."

"Not a bit," replied Tony. "I love interfering

in other people's affairs."

With a swift stride the cross-eyed gentleman

thrust himself across their path.

"No, no!" he exclaimed vehemently. "You must

not listen to this man. You——"

With a powerful thrust of his disengaged arm

Tony sent him staggering back to the edge of the

pavement, where he stumbled over the curb and sat

down heavily in the gutter.

His companion, seeing his fall, gave a guttural

cry of anger and lifting the light stick that he was

carrying lashed out savagely at Bugg. As coolly as

if he were in the ring the latter ducked under the

blow, and coming up with a beautiful straight left

knocked his assailant spinning against the lamp-post.

Tony sent the fellow staggering back to the edge of the pavement.

His companion lashed out savagely at Bugg. The latter ducked under

the blow, and coming up with a beautiful straight left, knocked

his assailant spinning. Tony turned again to the girl.

"I am afraid we must tear ourselves away," he remarked.

"We shall have half London here in a moment."

Tony turned again to the girl at his side. "I am

afraid we must tear ourselves away," he remarked.

"We shall have half London here in a moment."

Already from down the street came the shrill blast

of a whistle, followed a moment later by the sound

of running footsteps. Heedless of these warnings the

two strangers, now apparently reckless with fury,

were collecting themselves for a fresh attack.

"Keep them busy, Bugg," said Tony quietly;

and the next instant he and the girl were hurrying

along the pavement in the direction of Martin's Lane.

That fairly prosperous thoroughfare was only a few

yards' distant, but before they could reach it the

sounds of a magnificent tumult broke out again

behind them. The girl glanced nervously over her

shoulder, and her grip on Tony's arm tightened.

"Oh!" she gasped, "oughtn't we to go back?

Your friend will be hurt!"

Tony laughed reassuringly. "If any one's hurt,"

he observed, "it's much more likely to be one of the

other gentlemen."

They rounded the corner, and as they did so a

disengaged taxi came bowling opportunely up the

street. Tony signalled to the driver to stop.

"Here we are!" he said.

A look of frightened dismay leaped suddenly into

his companion's pretty face.

"What's the matter?" asked Tony.

"I—I forgot," she stammered. "I can't take a

taxi. I—I haven't any money with me."

There was a moment's pause, while the driver bent

forward from his box listening with interest to the

spirited echoes from Long Acre.

"That's all right," remarked Tony. "We will

talk about it in the cab." He turned to the driver.

"Take us to Verrier's," he said. It was the first

place that happened to come into his head.

The man jerked his head in the direction of the

noise. "Bit of a scrap on from the sound of it, sir!"

he observed.

Tony nodded. "Yes," he said regretfully, "it's a

quarrelsome world."

He helped his companion into the taxi, and then

following himself, shut the door. The vehicle started

off with a jerk, and as it swung round the corner into

Coventry Street, its occupants were able to catch a

momentary glimpse of the spot they had so recently

quitted. It appeared to be filled by a small but

animated crowd, in the centre of which a cluster of

whirling figures was distinctly visible. Tony heard

the girl beside him give a faint gasp of dismay.

"It's all right," he said. "Bugg's used to fighting.

He likes it."

She looked up at him anxiously. "He is a soldier?"

she asked, in that soft attractive voice of

hers.

Tony suppressed a laugh just in time. "Something

of the sort," he answered. Then with a pleasant

feeling that the whole adventure was becoming

rather interesting he added: "I say, I have told the

man to drive us to Verrier's. I hope if you aren't

in a hurry you will be charitable and join me in a

little supper—will you? I'm simply starving."

By the light of a passing street lamp he suddenly

caught sight of the troubled expression that had come

into her eyes.

"Do just what you like, of course," he added

quickly. "If you would rather I drove you straight

home——"

"As a matter of fact," said the girl with a sort of

desperate calmness. "I haven't a home to go to."

There was another brief pause. "Well, in that

case," remarked Tony cheerfully, "there is no possible

objection to our having a little supper—is there?"

For a moment she stared out of the window without

replying. It was plain that she was the prey of

several contradictory emotions, of which a vague

restless fear seemed to be the most prominent.

"I don't know what to do," she said unhappily.

"You are very kind, but——"

"There is only one possible thing to do," interrupted

Tony firmly, "and that is to come to Verrier's.

We can discuss the next step when we get there."

Even as he spoke the taxi swerved across the road,

and drew up in front of the famous underground

restaurant.

Before getting out the girl threw a quick hunted

glance from side to side of the street. "Do you

think either of those men have followed us?" she

whispered.

Tony shook his head comfortingly. "From what

I know of Bugg," he said, "I should regard it as

highly improbable."

He settled up with the driver, and then strolling

across the pavement, rejoined the girl, who was

waiting for him just outside the entrance. She had

evidently made a great effort to recover her

self-composure, for she looked up at him with a brave

if slightly forced smile.

"I must make myself tidy," she said, "if you

won't mind waiting a minute. I am simply not fit

to be seen."

The statement appeared to be exaggerated to

Tony, but he allowed it to pass unchallenged.

"Please don't hurry," he said. "I want to use

the telephone, and if I finish first I can brood over

what we'll have for supper."

She smiled again—this time more naturally, and

taking the dressing-bag that he had been carrying

for her, disappeared into the cloak-room. Tony

abandoned his hat and coat to a waiter, and then

sauntering forward, entered the restaurant.