Title: British Campaigns in Flanders 1690-1794

Author: Sir J. W. Fortescue

Release date: February 3, 2022 [eBook #67310]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: MacMillan & Co. Ltd, 1918

Credits: Brian Coe, David Tipple and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes:

BRITISH CAMPAIGNS IN FLANDERS

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA · MADRAS

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO

DALLAS · SAN FRANCISCO

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

BEING EXTRACTS FROM

“A HISTORY OF THE BRITISH ARMY”

BY

MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED

ST. MARTIN’S STREET, LONDON

1918

COPYRIGHT

[Pg v]

This volume consists simply of extracts reprinted from my History of the British Army. It is published in order that the troops at the front may, if they wish it, study the experiences of their forerunners in the Low Countries in a book which is fairly portable and fairly inexpensive, though neither so cheap nor so compendious as The British Soldiers’ Guide to Northern France and Flanders.

J. W. F.

[Pg vii]

| PAGE | |

| William III.’s Campaigns | 1–37 |

| Marlborough’s Campaigns— | |

| 1701–2 | 38 |

| 1705 | 51 |

| 1706 (Ramillies) | 62 |

| 1707–8 (Oudenarde) | 77 |

| 1709 (Malplaquet) | 103 |

| 1711 | 122 |

| War of The Austrian Succession— | |

| Campaigns of 1744–5 (Fontenoy) | 133 |

| Campaigns of 1746–7 (Lauffeld, Roucoux) | 158 |

| War of the French Revolution | 177 |

| Campaign of 1793 (Linselles) | 207 |

| Preparations for the Campaign of 1794 | 261 |

| Campaign of 1794 (Villers-en-Cauchies, Beaumont, Willems, Tourcoing) | 295 |

| Campaign of 1794 (Continued) | 343 |

| End of the Campaign of 1794 | 366 |

[Pg ix]

| PAGE | |

| Steenkirk, 23rd July (3rd Aug.) 1692 | 13 |

| Landen, 19th (29th) July 1693 | 27 |

| Lines of the Geete, 7th (18th) July 1705 | 55 |

| Ramillies, 12th (23rd) May 1706 | 67 |

| Oudenarde, 30th June (11th July) 1708 | 85 |

| Malplaquet, 31st Aug. (11th Sept.) 1709 | 111 |

| The Campaign of 1711 | 125 |

| Fontenoy, 30th April (11th May) 1745 | 143 |

| Roucoux, 30th Sept, (11th Oct.) 1746 | 163 |

| Lauffeld, 21st June (2nd July) 1747 | 171 |

| Attack of the Allies on the Camp of Famars, 23rd May 1793 | 217 |

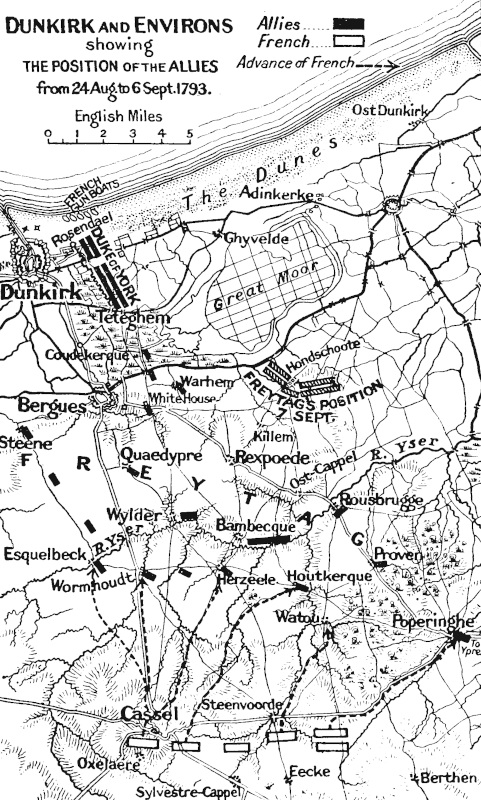

| Dunkirk and Environs, showing the Position of the Allies from 24th Aug. to 6th Sept. 1793 | 237 |

| Campaign of April 1794 | 299 |

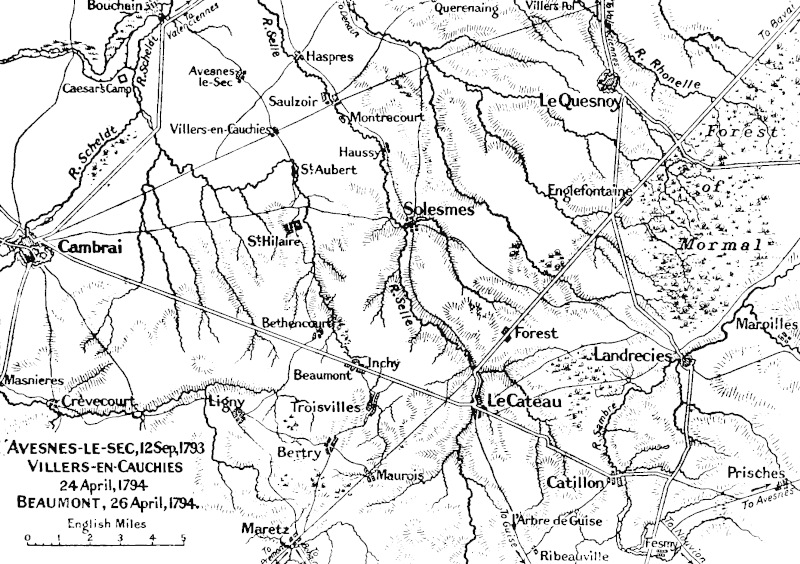

| Avesnes-le-Sec, 12th Sept. 1793; Villers-en-Cauchies, 24th April 1794; Beaumont, 26th April 1794 | 303 |

| Willems, 10th May 1794 | 319 |

| The Netherlands in the 18th Century | At end |

[Pg 1]

I pass now to Flanders, which is about to become for the second time the training ground of the British Army. The judicious help sent by Lewis the Fourteenth to Ireland had practically diverted the entire strength of William to that quarter for two whole campaigns; and though, as has been seen, there were English in Flanders in 1689 and 1690, the contingents which they furnished were too small and the operations too trifling to warrant description in detail. After the battle of the Boyne the case was somewhat altered, for, though a large force was still required in Ireland for Ginkell’s final pacification of 1691, William was none the less at liberty to take the field in Flanders in person. Moreover, Parliament with 1690. October. great good-will had voted seventy thousand men for the ensuing year, of which fully fifty thousand were British,[1] so that England was about to put forth her strength in Europe on a scale unknown since the loss of Calais.

But first a short space must be devoted to the theatre of war, where England was to meet and break down the overweening power of France. Few studies are more difficult, even to the professed student, than that of the old campaigns in Flanders, and still fewer more hopeless of simplification to the ordinary reader. Nevertheless, however desperate the task, an effort [Pg 2] must be made once for all to give a broad idea of the scene of innumerable great actions.

Taking his stand on the northern frontier of France and looking northward, the reader will note three great rivers running through the country before him in, roughly speaking, three parallel semicircles, from south-east to north-west. These are, from east to west, the Moselle, which is merged in the Rhine at Coblentz, the Meuse, and the Scheldt, all three of which discharge themselves into the great delta whereof the southern key is Antwerp. But for the present let the reader narrow the field from the Meuse in the east to the sea in the west, and let him devote his attention first to the Meuse. He will see that, a little to the north of the French frontier, it picks up a large tributary from the south-west, the Sambre, which runs past Maubeuge and Charleroi and joins the Meuse at Namur. Thence the united rivers flow on past the fortified towns of Huy, Liège, and Maestricht to the sea. But let the reader’s northern boundary on the Meuse for the present be Maestricht, and let him note another river which rises a little to the west of Maestricht and runs almost due west past Arschot and Mechlin to the sea at Antwerp. Let this river, the Demer, be his northern, and the Meuse from Maestricht to Namur his eastern, boundary.

Returning to the south, let him note a river rising immediately to the west of Charleroi, the Haine, which joins the Scheldt at Tournay, and let him draw a line from Tournay westward through Lille and Ypres to the sea at Dunkirk. Let this line from Dunkirk to Charleroi be carried eastward to Namur; and there is his southern boundary. His western boundary is, of course, the sea. Within this quadrilateral, Antwerp (or more strictly speaking the mouth of the Scheldt), [Pg 3] Dunkirk, Namur, and Maestricht, lies the most famous fighting-ground of Europe.

Glancing at it on the map, the reader will see that this quadrilateral is cut by a number of rivers running parallel to each other from south to north, and flowing into the main streams of the Demer and the Scheldt. The first of these, beginning from the east, are the Great and Little Geete, which become one before they join the main stream. It is worth while to pause for a moment over this little slip of land between the Geete and the Meuse. We shall see much of Namur, Huy, Liège, and Maestricht, which command the navigation of the greater river, but we shall see still more of the Geete, and of two smaller streams, the Jaar and the Mehaigne, which rise almost in the same table-land with it. On the Lower Jaar, close to Maestricht, stands the village of Lauffeld, which shall be better known to us fifty years hence. On the Little Geete, just above its junction with its greater namesake, are the villages of Neerwinden and Landen. In the small space between the heads of the Geete and the Mehaigne lies the village of Ramillies. For this network of streams is the protection against an enemy that would threaten the navigation of the Meuse from the north and west, and the barrier of Spanish Flanders against invasion from the east; and the ground is rich with the corpses and fat with the blood of men.

The next stream to westward is the Dyle, which flows past Louvain to the Demer, and gives its name, after the junction, to that river. The next in order is the Senne, which flows past Park and Hal and Brussels to the same main stream. At the head of the Senne stands the village of Steenkirk; midway between the Dyle and Senne are the forest of Soignies and the field of Waterloo.

[Pg 4]

Here the tributaries of the Demer come to an end, but the row of parallel streams is continued by the tributaries of another system, that of the Scheldt. Easternmost of these, and next in order to the Senne, is the Dender, which rises near Leuse and flows past Ath and Alost to the Scheldt at Dendermond. Next comes the Scheldt itself, with the Scarpe and the Haine, its tributaries, which it carries past Tournay and Oudenarde to Ghent, and to the sea at Antwerp. Westernmost of all, the Lys runs past St. Venant, where in Cromwell’s time we saw Sir Thomas Morgan and his immortal six thousand, past Menin and Courtrai, and is merged in the Scheldt at Ghent.

The whole extent of the quadrilateral is about one hundred miles long by fifty broad, with a great waterway to the west, a second to the east, and a third, whereof the key is Ghent, roughly speaking midway between them. The earth, fruitful by nature and enriched by art, bears food for man and beast; the waterways provide transport for stores and ammunition. It was a country where men could kill each other without being starved, and hence for centuries the cockpit of Europe.

A glance at any old map of Flanders shows how thickly studded was this country with walled towns of less or greater strength, and explains why a war in Flanders should generally have been a war of sieges. Every one of these little towns, of course, had its garrison; and the manœuvres of contending forces were governed very greatly by the effort, on one side, to release these garrisons for active service in the field, and, on the other, to keep them confined within their walls for as long as possible. Hence it is obvious that an invading army necessarily enjoyed a great advantage, since it menaced the fortresses of the enemy [Pg 5] while its own were unthreatened. Thus ten thousand men on the Upper Lys could paralyse thrice their number in Ghent and Bruges and the adjacent towns. On the other hand, if an invading general contemplated the siege of an important town, he manœuvred to entice the garrison into the field before he laid siege in form. Still, once set down to a great siege, an army was stationary, and the bare fact was sufficient to liberate hostile garrisons all over the country; and hence arose the necessity of a second army to cover the besieging force. The skill and subtlety manifested by great generals to compass these different ends is unfortunately only to be apprehended by closer study than can be expected of any but the military student.

A second cause contributed not a little to increase the taste for a war of sieges, namely, the example of France, then the first military nation in Europe.[2] The Court of Versailles was particularly fond of a siege, since it could attend the ceremony in state and take nominal charge of the operations with much glory and little discomfort or danger. The French passion for rule and formula also found a happy outlet in the conduct of a siege, for, while there is no nation more brilliant or more original, particularly in military affairs, there is also none that is more conceited or pedantic. The craving for sieges among the French was so great that the King took pains, by the grant of extra pay and rations, to render this species of warfare popular with his soldiers.[3]

Again, it must be remembered that the object of a campaign in those days was not necessarily to seek out [Pg 6] an enemy and beat him. There were two alternatives prescribed by the best authorities, namely, to fight at an advantage or to subsist comfortably.[4] Comfortable subsistence meant at its best subsistence at an enemy’s expense. A campaign wherein an army lived on the enemy’s country and destroyed all that it could not consume was eminently successful, even though not a shot was fired. To force an enemy to consume his own supplies was much, to compel him to supply his opponent was more, to take up winter-quarters in his territory was very much more. Thus to enter an enemy’s borders and keep him marching backwards and forwards for weeks without giving him a chance of striking a blow, was in itself no small success, and success of a kind which galled inferior generals, such as William of Orange, to desperation and so to disaster. The tendency to these negative campaigns was heightened once more by French example. The French ministry of war interfered with its generals to an extent that was always dangerous, and eventually proved calamitous. Nominally the marshal commanding-in-chief in the field was supreme; but the intendant or head of the administrative service, though he received his orders from the marshal, was instructed by the King to forward those orders at once by special messenger to Louvois, and not to execute them without the royal authority. Great commanders such as Luxemburg had the strength from time to time to kick themselves free from this bondage, but the rest, embarrassed by the surveillance of an inferior officer, preferred to live as long as possible in an enemy’s country without risking a general action. It was left to Marlborough to advance triumphant in one magnificent campaign from the Meuse to the sea.

[Pg 7]

Next, a glance must be thrown at the contending parties. The defenders of the Spanish Netherlands, for they cannot be called the assailants of France, were confederate allies from a number of independent states—England, Holland, Spain, the Empire, sundry states of Germany, and Denmark, all somewhat selfish, few very efficient, and none, except the first, very punctual. From such a heterogeneous collection swift, secret, and united action was not to be expected. King William held the command-in-chief, and, from his position as the soul of the alliance, was undoubtedly the fittest for the post. But though he had carefully studied the art of war, and though his phlegmatic temperament found its only genuine pleasure in the excitement of the battlefield, he was not a great general. He could form good plans, and up to a certain point could execute them, but up to a certain point only. It should seem that his physical weakness debarred him from steady and sustained effort. He was strangely incapable of conducting a campaign with equal ability throughout; he would manœuvre admirably for weeks, and forfeit all the advantage that he had gained by the carelessness of a single day. In a general action, of which he was fonder than most commanders of his time, he never shone except in virtue of conspicuous personal bravery. He lacked tactical instinct, and above all he lacked patience; in a word, to use a modern phrase, he was a very clever amateur.

France, on the other hand, possessed the finest and strongest army in Europe,—well equipped, well trained, well organised, and inured to work by countless campaigns. She had a single man in supreme control of affairs, King Lewis the Fourteenth; a great war-minister, Louvois; one really great general, Luxemburg; and one with flashes of genius, Boufflers. [Pg 8] Moreover, she possessed a line of posts in Spanish Flanders extending from Dunkirk to the Meuse. On the Lys she had Aire and Menin; on the Scarpe, Douay; on the Upper Scheldt, Cambray, Bouchain, Valenciennes, and Condé; on the Sambre, Maubeuge; between Sambre and Meuse, Philippeville and Marienburg; and on the Meuse, Dinant. Further, in the one space where the frontier was not covered by a friendly river, between the sea and the Scheldt, the French had constructed fortified lines from the sea to Menin and from thence to the Scheldt at Espierre. Thus with their frontier covered, with a place of arms on every river, with secrecy and with unity of purpose, the French enjoyed the approximate certainty of being able to take the field in every campaign before the Allies could be collected to oppose them.

The campaign of 1691 happily typifies the relative positions of the combatants in almost every respect. The French concentrated ten thousand men on the Lys. This was sufficient to paralyse all the garrisons of the Allies on and about the river. They posted another corps on the Moselle, which threatened the territory of Cleves. Now Cleves was the property of the Elector of Brandenburg, and it was not to be expected that he should allow his contingent of troops to join King William at the general rendezvous at Brussels, and suffer the French to play havoc among his possessions. Thus the Prussian contingent likewise was paralysed. So while William was still ordering his troops to concentrate at Brussels, Boufflers, who had been making preparations all the winter, suddenly marched up from Maubeuge and, before William was aware that he was in motion, had besieged Mons. The fortress presently surrendered after a feeble resistance, and the line of the Allies’ frontier [Pg 9] between the Scheldt and Sambre was broken. William moved down from Brussels across the Sambre in the hope of recovering the lost town, outmanœuvred Luxemburg, who was opposed to him, and for three days held the recapture of Mons in the hollow of his hand. He wasted those three days in an aimless halt; Luxemburg recovered himself by an extraordinary march; and William, finding that there was no alternative before him but to retire to Brussels and remain inactive, handed over the command to an incompetent officer and returned to England. Luxemburg then closed the campaign by a brilliant action of cavalry, which scattered the horse of the Allies to the four winds. As no British troops except the Life Guards were present, and as they at any rate did not disgrace themselves, it is unnecessary to say more of the combat of Leuse. It had, however, one remarkable effect: it increased William’s dread of the French cavalry, already morbidly strong, to such a pitch as to lead him subsequently to a disastrous military blunder.

The campaign of 1691 was therefore decidedly unfavourable to the Allies, but there was ground for hope that all might be set right in 1692. The Treasurer, Godolphin, was nervously apprehensive that Parliament might be unwilling to vote money for an English army in Flanders; but the Commons cheerfully granted a total of sixty-six thousand men, British and foreign; which, after deduction of garrisons for the safety of the British Isles, left forty thousand free to cross the German Ocean.

Of these, twenty-three thousand were British, the most important force that England had sent to the Continent since the days of King Henry the Eighth. The organisation was remarkably like that of the New Model. William was, of course, Commander-in-Chief, [Pg 10] and under him were a general of horse and a general of foot, with a due allowance of lieutenant-generals, major-generals, and brigadiers. There is, however, no sign of an officer in command of artillery or engineers, nor any of a commissary in charge of the transport.[5] The one strangely conspicuous functionary is the Secretary-at-War, who in this and the following campaigns for the last time accompanied the Commander-in-Chief on active service. But the most significant feature in the list of the staff is the omission of the name of Marlborough. Originally included among the generals for Flanders, he had been struck off the roll, and dismissed from all public employment, in disgrace, before the opening of the campaign. Though this dismissal did not want justification, it was perhaps of all William’s blunders the greatest.

As usual, the French were beforehand with the

Allies in opening the campaign. They had already

broken the line of the defending fortresses by the

capture of Mons; they now designed to make the

breach still wider. All through the winter a vast

siege-train was collecting on the Scheldt and Meuse,

with Vauban, first of living engineers, in charge of it.

May.

In May all was ready. Marshal Joyeuse, with one

corps, was on the Moselle, as in the previous year, to

hold the Brandenburgers in check. Boufflers, with

eighteen thousand men, lay on the right bank of the

Meuse, near Dinant; Luxemburg, with one hundred

and fifteen thousand more, stood in rear of the river

Haine. On the 20th of May, King Lewis in person

May 10/20.

May 13/23.

May 16/26.

reviewed the grand army; on the 23rd it marched for

[Pg 11]

Namur; and on the 26th it had wound itself round

two sides of the town, while Boufflers, moving up from

Dinant, completed the circuit on the third side. Thus

Namur was completely invested; unless William could

save it, the line of the Sambre and one of the most

important fortresses on the Meuse were lost to the

Allies.

William, to do him justice, had strained every nerve to spur his indolent allies to be first in the field. The contingents, awaked by the sudden stroke at Namur, came in fast to Brussels; but it was too late. The French had destroyed all forage and supplies on the direct route to Namur, and William’s only way to the city lay across the Mehaigne. Behind the Mehaigne lay Luxemburg, the ablest of the French generals. The best of luck was essential to William’s success, and instead of the best came the worst. Heavy rain swelled the narrow stream into a broad flood, and the building of bridges became impossible. There was beautiful fencing, skilful feint, and more skilful parry, between the two generals, but William could not get May 26./June 5. under Luxemburg’s guard. On the 5th of June, after a discreditably short defence, Namur fell, almost before William’s eyes, into the hands of the French.

Then Luxemburg thought it time to draw the enemy away from the vicinity of the captured city; so recrossing the Sambre, and keeping Boufflers always between himself and that river, he marched for the Senne as if to threaten Brussels. William followed, as in duty bound; and French and Allies pursued a parallel course to the Senne, William on the north and July 23./Aug. 2. Luxemburg on the south. The 2nd of August found both armies across the Senne, William at Hal, facing west with the river in his rear, and Luxemburg some five miles south of him with his right at Steenkirk, and [Pg 12] his centre between Hoves and Enghien, while Boufflers lay at Manny St. Jean, seven miles in his rear.

The terrible state of the roads owing to heavy rain had induced Luxemburg to leave most of his artillery at Mons; and, as he had designed merely to tempt the Allies away from Namur, the principal object left to him was to take up a strong position wherein his worn and harassed army could watch the enemy without fear of attack. Such a position he thought that he had found at Steenkirk.[6] The country at this point is more broken and rugged than is usual in Belgium. The camp lay on high ground, with its right resting on the river Sennette and its fight front covered by a ravine, which gradually fades away northward into a high plateau of about a mile in extent. Beyond the ravine was a network of wooded defiles, through which Luxemburg seems to have hoped that no enemy could fall upon him in force unawares. It so happened, however, that one of his most useful spies was detected, in his true character, in William’s camp at Hal; and this was an opportunity not to be lost. A pistol was held to the spy’s head, and he was ordered to write a letter to Luxemburg, announcing that large bodies of the enemy would be in motion next morning, but that nothing more serious was contemplated than a foraging expedition. This done, William laid his plans to surprise his enemy on the morrow.

[Pg 13]

[Pg 14]

An hour before daybreak the advanced guard of William’s army fell silently into its ranks, together with a strong force of pioneers to clear the way for a march through the woods. This force consisted of the First Guards, the Royal Scots, the Twenty-first, Fitzpatrick’s regiment of Fusiliers, and two Danish regiments of great reputation, the whole under the command of the Duke of Würtemberg. Presently they moved away, and, as the sun rose, the whole army followed them in two columns, without sound of drum or trumpet, towards Steenkirk. French patrols scouring the country in the direction of Tubise saw the two long lines of scarlet and white and blue wind away into the woods, and reported what they had witnessed at headquarters; but Luxemburg, sickly of constitution, and, in spite of his occasional energy, indolent of temperament, rejoiced to think that, as his spy had told him, it was no more than a foraging party. Another patrol presently sent in another message that a large force of cavalry was advancing towards the Sennette. Once more Luxemburg lulled himself into security with the same comfort.

Meanwhile the allied army was trailing through narrow defiles and cramped close ground, till at last it emerged from the stifling woods into an open space. Here it halted, as the straitness of the ground demanded, in dense, heavy masses. But the advanced guard moved on steadily till it reached the woods over against Steenkirk, where Würtemberg disposed it for the coming attack. On his left the Bois de Feuilly covered a spur of the same plateau as that occupied by the French right, and there he stationed the English Guards and the two battalions of Danes. To the right of these, but separated from them by a ravine, he placed the three remaining British battalions in the Bois de Zoulmont. His guns he posted, some between the two woods, and the remainder on the right of his division. These dispositions complete, the advanced party awaited orders to open the attack.

[Pg 15]

It was now eleven o’clock. Luxemburg had left his bed and had ridden out to a commanding height on his extreme right, when a third letter was brought to him that the Allies were certainly advancing in force. He read it, and looking to his front, saw the red coats of the Guards moving through the wood before him, while beyond them he caught a glimpse of the dense masses of the main body. Instantly he saw the danger, and divined that William’s attack was designed against his right. His own camp was formed, according to rule, with the cavalry on the wings; and there was nothing in position to check the Allies but a single brigade of infantry, famous under the name of Bourbonnois, which was quartered in advance of the cavalry’s camp on his extreme right. Moreover, nothing was ready, not a horse was bridled, not a man standing to his arms. He despatched a messenger to summon Boufflers to his aid, and in a few minutes was flying through the camp with his staff, energetic but perfectly self-possessed, to set his force in order of battle. The two battalions of Bourbonnois fell in hastily before their camp, with a battery of six guns before them. The dragoons of the right wing dismounted and hastened to seal up the space between Bourbonnois and the Sennette. The horse of the right was collected, and some of it sent off in hot speed to the left to bring the infantry up behind them on their horses’ croups. All along the line the alarm was given, drums were beating, men snatching hastily at their arms and falling into their ranks ready to file away to the right. Such was the haste, that there was no time to think of regimental precedence, a very serious matter in the French army, and each successive brigade hurried into the place where it was most needed, as it happened to come up.

[Pg 16]

Meanwhile Würtemberg’s batteries had opened fire, and a cunning officer of the Royal Scots was laying his guns with admirable precision. French batteries hastened into position to reply to them with as deadly an aim, and for an hour and a half the rival guns thundered against each other unceasingly. All this time the French battalions kept massing themselves thicker and thicker on Luxemburg’s right, and the front line was working with desperate haste, felling trees, making breastworks, and lining the hedges and copses while yet they might. But still Würtemberg’s division remained unsupported, and the precious minutes flew fast. William, or his staff for him, had made a serious blunder. Intent though he was on fighting a battle with his infantry only, he had put all the cavalry of one wing of his army before them on the march, so that there was no room for the infantry to pass. Fortunately six battalions had been intermixed with the squadrons of this wing, and these were now with some difficulty disentangled and sent forward. Cutts’s, Mackay’s, Lauder’s, and the Twenty-sixth formed up on Würtemberg’s right, with the Sixth and Twenty-fifth in support; and at last, at half-past twelve, Würtemberg gave the order to attack.

His little force shook itself up and pressed forward with eagerness. The Guards and Danes on the extreme left, being on the same ridge with the enemy, were the first that came into action. Pushing on under a terrible fire at point-blank range from the French batteries, they fell upon Bourbonnois and the dragoons, beat them back, captured their guns, and turned them against the enemy. On their right the Royal Scots, Twenty-first, and Fitzpatrick’s plunged down into the ravine into closer and more difficult ground, past [Pg 17] copses and hedges and thickets, until a single thick fence alone divided them from the enemy. Through this they fired at each other furiously for a time, till the Scots burst through the fence with their Colonel at their head, and swept the French before them. Still further to the right, the remaining regiments came also into action; muzzle met muzzle among the branches, and the slaughter was terrible. Young Angus, still not yet of age, dropped dead at the head of the Cameronians, and the veteran Mackay found the death which he had missed at Killiecrankie. He had before the attack sent word to General Count Solmes, that the contemplated assault could lead only to waste of life; and he had been answered with the order to advance. “God’s will be done,” he said calmly, and he was among the first that fell.

Still the British, in spite of all losses, pressed furiously on; and famous French regiments, spoiled children of victory, wavered and gave way before them. Bourbonnois, unable to face the Guards and Danes, doubled its left battalion in rear of its right; Chartres, which stood next to them, also gave way and doubled itself in rear of its neighbour Orléans. A wide gap was thus torn in the first French line, but not a regiment of the second line would step into it. The colonel of the brigade in rear of it ordered, entreated, implored his men to come forward, but they would not follow him into that terrible fire. Suddenly the wild voice ceased, and the gesticulating figure fell in a heap to the ground: the colonel had been shot dead, and the gap was still unfilled.

The first French line was broken; the second and third were dismayed and paralysed: a little more and the British would carry the French camp. Luxemburg perceived that this was a moment when only his best [Pg 18] troops could save him. In the fourth line stood the flower of his infantry, the seven battalions of French and Swiss Guards. These were now ordered forward to the gap; the princes of the blood placed themselves at their head, and without firing a shot they charged down the slope upon the British and Danes. The English Guards, thinned to half their numbers, faced the huge columns of the Swiss and stood up to them undaunted, till by sheer weight they were slowly rolled back. On their right the Royal Scots also were forced back, fighting desperately from hedge to hedge and contesting every inch of ground. Once, the French made a dash through a fence and carried off one of their colours. The Colonel, Sir Robert Douglas, instantly turned back alone through the fence, recaptured the colour, and was returning with it when he was struck by a bullet. He flung the flag over to his men and fell to the ground dead.

Slowly the twelve battalions retired, still fighting furiously at every step. So fierce had been their onslaught that five lines of infantry backed by two more of cavalry[7] had hardly sufficed to stop them, and with but a little support they might have won the day. But that support was not forthcoming. Message after message had been sent to the Dutch general, Count Solmes, for reinforcements, but there came not a man. The main body, as has been told, was all clubbed together a mile and a half from the scene of action, with the infantry in the rear; and Solmes, with almost criminal folly, instead of endeavouring to extricate the foot, had ordered forward the horse. William rectified the error as soon as he could; but the correction led to further delay and to the increased confusion [Pg 19] which is the inevitable result of contradictory orders. The English infantry in rear, mad with impatience to rescue their comrades, ran forward in disorder, probably with loud curses on the Dutchman who had kept them back so long; and some time was lost before they could be re-formed. Discipline was evidently a little at fault. Solmes lost both his head and his temper. “Damn the English,” he growled; “if they are so fond of fighting, let them have a bellyful”; and he sent forward not a man. Fortunately junior officers took matters into their own hands; and it was time, for Boufflers had now arrived on the field to throw additional weight into the French scale. The English Horse-grenadiers, the Fourth Dragoons, and a regiment of Dutch dragoons rode forward and, dismounting, covered the retreat of the Guards and Danes by a brilliant counter-attack. The Buffs and Tenth advanced farther to the right, and holding their fire till within point-blank range, poured in a volley which gave time for the rest of Würtemberg’s division to withdraw. A demonstration against the French left made a further diversion, and the shattered fragments of the attacking force, grimed with sweat and smoke, fell back to the open ground in rear of the woods, repulsed but unbeaten, and furious with rage.

William, it is said, could not repress a cry of anguish when he saw them; but there was no time for emotion. Some Dutch and Danish infantry was sent forward to check further advance of the enemy, and preparations were made for immediate retreat. Once again the hardest of the work was entrusted to the British; and when the columns were formed, the grenadiers of the British regiments brought up the rear, halting and turning about continually, until failing light put an end to what was at worst but a half-hearted pursuit. [Pg 20] The retreat was conducted with admirable order; but it was not until the chill, dead hour that precedes the dawn that the Allies regained their camp, worn out with the fatigue of the past four-and-twenty hours.

The action was set down at the time as the severest ever fought by infantry, and the losses on both sides were very heavy. The Allies lost about three thousand killed and the same number wounded, besides thirteen hundred prisoners, nearly all of whom were wounded. Ten guns were abandoned, the horses being too weary to draw them; the English battalions lost two colours, and the foreign three or four more. The British, having borne the brunt of the action, suffered most heavily of all, the Guards, Cutts’s, and the Sixth being terribly punished. The total French loss was about equal to that of the Allies, but the list of the officers that fell tells a more significant tale. On the side of the Allies four hundred and fifty officers were killed and wounded, no fewer than seventy lieutenants in the ten battalions of Churchill’s British brigade being killed outright. The French on their side lost no fewer than six hundred and twenty officers killed and wounded, a noble testimony to their self-sacrifice, but sad evidence of their difficulty in making their men stand. In truth, with proper management William must have won a brilliant victory; but he was a general by book and not by instinct. Würtemberg’s advanced guard could almost have done the work by itself but for the mistake of a long preliminary cannonade; his attack could have been supported earlier but for the pedantry that gave the horse precedence of the foot in the march to the field; the foot could have pierced the French position in a dozen different columns but for the pedantry which caused it to be first deployed. Finally, William’s knowledge [Pg 21] of the ground was imperfect, and Solmes, his general of foot, was incompetent. The plan was admirably designed and abominably executed. Nevertheless, British troops have never fought a finer action than Steenkirk. Luxemburg thought himself lucky to have escaped destruction; his troops were much shaken; and he crossed the Scheldt and marched away to his winter-quarters as quietly as possible. So ended the campaign of 1692.

[Pg 22]

In November the English Parliament met, heartened indeed by the naval victory of La Hogue, but not a little grieved over the failure of Steenkirk. Again, the financial aspect was extremely discouraging; and Sir Stephen Fox announced that there was not another day’s subsistence for the Army in the treasury. The prevailing discontent found vent in furious denunciations of Count Solmes, and a cry that English soldiers ought to be commanded by English officers. The debate waxed hot. The hardest of hard words were used about the Dutch generals, and a vast deal of nonsense was talked about military matters. There were, however, a great number of officers in the House of Commons, many of whom had been present at the action. With much modesty and good sense they refused to join in the outcry against the Dutch, and contrived so to compose matters that the House committed itself to no very foolish resolution. The votes for the Army were passed; and no difficulty was made over the preparations for the next campaign. Finally, two new regiments of cavalry were raised—Lord Macclesfield’s Horse, which was disbanded twenty years later; and Conyngham’s Irish Dragoons, which still abides with us as the Eighth, King’s Royal Irish, Hussars.

[Pg 23]

Meanwhile the French military system had suffered an irreparable loss in Louvois’s death, the source of woes unnumbered to France in the years that were soon to come. Nevertheless, the traditions of his rule were strong, and the French once more were first in the field, with, as usual, a vast siege-train massed on the Meuse and on the Scheldt. But a late spring and incessant rain delayed the opening of the campaign till the beginning of May, when Luxemburg assembled seventy thousand men in rear of the Haine by Mons, and Boufflers forty-eight thousand more on the Scheldt at Tournay. The French king was with the troops in person; and the original design was, as usual, to carry on a war of sieges on the Meuse, Boufflers reducing the fortresses while Luxemburg shielded him with a covering army. Lewis, however, finding that the towns which he had intended to invest were likely to make an inconveniently stubborn defence, presently returned home, and after detaching thirty thousand men to the war in Germany, left Luxemburg to do as he would. It had been better for William if the Grand Monarch had remained in Flanders.

The English king, on his side, assembled sixty thousand men at Brussels as soon as the French began to move, and led them with desperate haste to the Senne, where he took up an impregnable position at Park. Luxemburg marched up to a position over against him, and then came one of those deadlocks which were so common in the old campaigns. The two armies stood looking at each other for a whole month, neither venturing to move, neither daring to attack, both ill-supplied, both discontented, and as a natural consequence both losing scores, hundreds, and even thousands of men through desertion.

At last the position became insupportable, and on [Pg 24] June 6./July 6. the 6th of July Luxemburg moved eastward as if to resume the original plan of operations on the Meuse. William thereupon resolved to create a diversion by detaching a force to attack the French lines of the Scheldt and Lys, a project which was brilliantly executed by Würtemberg, thanks not a little to three British regiments—the Tenth, Argyll’s, and Castleton’s—which formed part of his division. But meanwhile Luxemburg, quite ignorant of the diversion, advanced to the Meuse and laid siege to Huy, in the hope of forcing William to come to its relief. He judged rightly. William left his impregnable camp at Park and hurried to the rescue. But he came too late, and Huy fell after a trifling resistance. Luxemburg then made great seeming preparations for the siege of Liège, and William, trembling for the safety of that city and of Maestricht, detached eight thousand men to reinforce those garrisons, and then withdrew to the line of the Geete. Luxemburg watched the whole proceeding with grim delight. Würtemberg’s success was no doubt annoying, but William had weakened his army by detaching this force to the Lys, and had been beguiled into weakening it still further by reinforcing the garrison on the Meuse. This was exactly what Luxemburg wanted. If he could bring the Allies to action forthwith, he could reasonably hope for success.

The ground occupied by William was a triangular space enclosed between the Little Geete and a stream called the Landen Beck, which joins it at Leuw. The position was not without features of strength. The camp, which faced almost due south, was pitched on a gentle ridge rising out of a vast plain.[8] This ridge [Pg 25] runs parallel to the Little Geete and has that river in its rear. The left flank was protected by marshy ground and by the Landen Beck itself, while the villages of Neerlanden and Rumsdorp, one on either side of the Beck and the latter well forward on the plain, offered the further security of advanced posts. The right rested on a little stream which runs at right angles to the Geete and joins it at Elixheim, and on the villages of Laer and Neerwinden which stand on its banks. From Neerlanden on the left to Neerwinden on the right the position measured close on four miles; and to guard this extent, besides supplying strong garrisons for the villages, William had little more than fifty thousand men. Here then was one signal defect: the front was too long to permit troops to be readily moved from flank to flank, or to be withdrawn without serious risk from the centre. But this was not all. The depth of the position was less than half of its frontage, and thus allowed no space for the action of cavalry. This William ignored: he was afraid of the French horse, and was anxious that the action should be fought by infantry only. Finally, retreat was barred by the Geete, which was unfordable and insufficiently bridged; and therefore the forcing of the allied right must inevitably drive the whole army into a pinfold, as Leslie’s had been driven at the battle of Dunbar.

Luxemburg, who knew every inch of the ground, was now anxious only lest William should retire before July 18/28. he could catch him. On the 28th of July, by a great effort and a magnificent march, he brought the whole of his army, eighty thousand strong, before William’s position. He was now sure of his game, but he need not have been anxious, for William, charmed with the notion of excluding the French cavalry from all share in the action, was resolved to stand his ground Many [Pg 26] officers urged him to cross the Geete while yet he might; but he would not listen. Fifteen hundred men were told off to entrench the open ground between Neerwinden and Neerlanden. The hedges, mud-walls, and natural defences of Neerwinden and Laer were improved to the uttermost, and the ditches surrounding them were enlarged. Till late into the night the King rode backward and forward, ordering matters under his own eyes, and after a few hours’ rest began very early in the morning to make his dispositions.

The key of the position was the village of Neerwinden with the adjoining hamlet of Laer, and here accordingly he stationed the best of his troops. The defence of Laer was entrusted to Brigadier Ramsey with the Scots Brigade, namely, the Twenty-first, Twenty-fifth, Twenty-sixth, Mackay’s and Lauder’s regiments, reinforced by the Buffs and the Fourth Foot. Between Laer and Neerwinden stood six battalions of Brandenburgers, troops already of great and deserved reputation, of whom we shall see more in the years before us. Neerwinden itself was committed to the Hanoverians, the Dutch Guards, a battalion of the First and a battalion of the Scots Guards. Immediately to the north or left of the village the entrenchment was lined by the two remaining battalions of the First and Scots Guards, the Coldstream Guards, a battalion of the Royal Scots, and the Seventh Fusiliers. On the extreme left of the position Neerlanden was held by the other battalion of the Royal Scots, the Second Queen’s, and two Danish regiments, while Rumsdorp was occupied by the Fourteenth, Sixteenth, Nineteenth, and Collingwood’s regiments. In a word, every important post was committed to the British. The remainder of the infantry, with one hundred guns, was ranged along the entrenchment, and in rear of them stood the cavalry, powerless to act outside the trench, and too much cramped for space to manœuvre within it.

[Pg 27]

[Pg 28]

Luxemburg also was early astir, and was amazed to find how far the front of the position had been strengthened during the night. His centre he formed in eight lines over against the Allies’ entrenchments between Oberwinden and Landen, every line except the second and fourth being composed of cavalry. For the attack on Neerlanden and Rumsdorp he detailed fifteen thousand foot and two thousand five hundred dismounted dragoons. For the principal assault on Neerwinden he told off eighteen thousand foot, supported by a reserve of two thousand more and by eight thousand cavalry; while seventy guns were brought into position to answer the artillery of the Allies.

Shortly after sunrise William’s cannon opened fire against the heavy masses of the French centre; and at eight o’clock Luxemburg moved the whole of his left to the attack of Neerwinden. Six battalions, backed by dragoons and cavalry, were directed against Laer, and three columns, counting in all seven brigades, were launched against Neerwinden. The centre column, under the Duke of Berwick, was the first to come into action. Withholding their fire till they reached the village, the French carried the outer defences with a rush, and then meeting the Hanoverians and the First Guards, they began the fight in earnest. It was hedge-fighting, as at Steenkirk, muzzle to muzzle and hand to hand. Every step was contested; the combat swayed backwards and forwards within the village; and the carnage was frightful. The remaining French columns came up, met with the like resistance, and made little way. Fresh regiments were poured by the French into the fight, and at last the First Guards, completely [Pg 29] broken by its losses, gave way. But it was only for a moment. They rallied on the Scots Guards; the Dutch and Hanoverians rallied behind them, and, though the enemy had been again reinforced, they resumed the unequal fight, nine battalions against twenty-six, with unshaken tenacity. At Laer, on the extreme right, the fight was equally sharp. Ramsey for a time was driven out of the village, and the French cavalry actually forced its way into the Allies’ position. There, however, it was charged in flank by the Elector of Bavaria, and driven out with great slaughter. Ramsey seized the moment to rally his brigade. The French columns, despite their success, still remained isolated and detached, and presented no united front. The King placed himself at the head of the Guards and Hanoverians, and with one charge British, Dutch, and Germans fell upon the Frenchmen and swept them out of both villages.

The first attack on Neerwinden had failed, and a similar attack on the allied left had been little more successful. At Neerlanden the First and Second Foot had successfully held their own against four French battalions until reinforcements enabled them to drive them back. At Rumsdorp the British, being but three thousand against thirteen thousand, were pushed out of the village, but being reinforced, recovered a part of it and stood successfully at bay. Luxemburg, however, was not easily discouraged. The broken troops in the left were rallied, fresh regiments were brought forward, and a second effort was made to carry Neerwinden. Again French impetuosity bore all before it, and again the British and Germans, weakened and weary though they were, rallied when all seemed lost, and hurled the enemy back, not merely repulsed, but in confused and disorderly retreat.

[Pg 30]

On the failure of the second attack the majority of the French officers urged Luxemburg to retire; but the marshal was not to be turned from his purpose. The fourteen thousand men of the Allies in Laer and Neerwinden had lost more than a third of their numbers, while he himself had still a considerable force of infantry interlined with the cavalry in the centre. Twelve thousand of them, including the French and Swiss Guards, were now drawn off to the left for a third attack. When they were clear of the cavalry, the whole six lines of horse, which had stood heroically for hours motionless under a heavy fire, moved forward at a trot to the edge of the entrenchments;[9] but the demonstration, for such it seems to have been, cost them dear, for they were very roughly handled and compelled to retire. But now the French reinforcements, supported by the defeated battalions, drew near, and a third attack was delivered on Neerwinden. British and Dutch still made a gallant fight, but the odds against their weakened battalions were too great, and ammunition began to fail. They fought on indomitably till the last cartridge was expended before they gave way, but they were forced back, and Neerwinden was lost. Five French brigades then assailed the central entrenchment at its junction with Neerwinden, where stood the Coldstream Guards and the Seventh Fusiliers. Wholly unmoved by the overwhelming numbers in their front and the fire from Neerwinden on their flank, the two regiments stood firm and drove their assailants back over the breastwork. Even when the French Household Cavalry came spurring through Neerwinden and fell upon their [Pg 31] flank, they fought on undismayed, and the Coldstreamers not only repelled the charge but captured a colour.

Such fighting, however, could not continue for long. William, on observing Luxemburg’s preparations for the final assault, had ordered nine battalions from his left to reinforce his right. These never reached their destination. The Marquis of Feuquières, an officer even more celebrated for his acuteness as a military critic than for his skill in the field, watched them as they moved, and suddenly led his cavalry forward to the weakest point of the entrenchment. The battalions hesitated, halted, and then turned about to meet this new danger, but too late to save the forcing of the entrenchment. The battle was now virtually over. Neerwinden was carried, Ramsey after a superb defence had been driven out of Laer, the Brandenburgers had perforce retreated with him, the infantry that lined the centre of the entrenchment had forsaken it, and the French cavalry was pouring in and cutting down the fugitives by scores. William, who had galloped away in desperation to the left, now returned at headlong speed with six regiments of English cavalry,[10] which delivered charge after charge with splendid gallantry, to cover the retreat of the foot. On the left Tolmach and Bellasys by great exertion brought off their infantry in good order, but on the right the confusion was terrible. The rout was complete, the few bridges were choked by a heaving mass of guns, waggons, pack-animals, and men, and thousands of fugitives were cut down, drowned, or trampled to death. William did all that a gallant man could do to save the day, but in vain. His troops had done heroic things to redeem his [Pg 32] bad generalship; and against any living man but Marlborough or Luxemburg they would probably have held their own. It was the general, not the soldiers that failed.

The losses on both sides were very severe. That of the French was about eight thousand men; that of the Allies about twelve thousand, killed, wounded, and prisoners, and among the dead was Count Solmes, the hated Solmes of Steenkirk. The nineteen British battalions present lost one hundred and thirty-five officers killed, wounded, and taken. The French captured eighty guns and a vast quantity of colours, but the Allies, although beaten, could also show fifty-six French flags. And, indeed, though Luxemburg won, and deserved to win a great victory, yet the action was not such as to make the allied troops afraid to meet the French. They had stood up, fifty thousand against eighty thousand, and if they were beaten they had at any rate dismayed ever Frenchman on the field but Luxemburg. In another ten years their turn was to come, and they were to take a part of their revenge on the very ground over which many of them had fled.

The campaign closed with the surrender of Charleroi, and the gain by the French of the whole line of the Sambre. William came home to meet the House of Commons and recommend an augmentation of the Army by eight regiments of horse, four of dragoons, and twenty-five of foot. The House reduced this list by the whole of the regiments of horse and fifteen of foot, but even so it brought the total establishment up to eighty-three thousand men. There is, however, but one new regiment of which note need be taken in the campaign of 1694, namely, the Seventh Dragoons, now known as the Seventh Hussars, which, raised in 1689–90 in Scotland, now for the first time took its place on the [Pg 33] English establishment and its turn of service in the war of Flanders.

I shall not dwell on the campaign of 1694, which is memorable only for a marvellous march by which Luxemburg upset William’s entire plan of campaign. Nor shall I speak at length of the abortive descent on Brest, which is remembered mainly for the indelible stain which it has left on the memory of Marlborough. It is only necessary to say that the French, by Marlborough’s information, though not on Marlborough’s information only, had full warning of an expedition which had been planned as a surprise, and that Tolmach,[11] who was in command, unfortunately, though most pardonably, lacked the moral courage to abandon an attack which, unless executed as a surprise, had no chance of success. He was repulsed with heavy loss, and died of wounds received in the action—a hard fate for a good soldier and a gallant man. But it is unjust to lay his death at Marlborough’s door. For the failure of the expedition Marlborough was undoubtedly responsible, and that is quite bad enough; but Tolmach alone was to blame for attempting an enterprise which he knew to be hopeless. Marlborough cannot have calculated that he would deliberately essay to do impossibilities and perish in the effort, so cannot be held guilty of poor Tolmach’s blunders.

Before the new campaign could be opened there had come changes of vital importance to France. The vast expense of the war had told heavily on the country, and the King’s ministers were at their wit’s end to raise money. Moreover, the War Department had deteriorated rapidly since the death of Louvois; and [Pg 34] January. to this misfortune was now added the death of Luxemburg, a loss which was absolutely irreparable. Lastly, with the object of maintaining the position which they had won on the Sambre, the French had extended their system of fortified lines from Namur to the sea. Works so important could not be left unguarded, so that a considerable force was locked up behind these entrenchments, and was for all offensive purposes useless. We shall see before long how a really great commander could laugh at these lines, and how, in consequence, it became an open question whether they were not rather an encumbrance than an advantage. The subject is one which is still of interest; and it is remarkable that the French still seem to cling to their old principles, if they may be judged by the works which they have constructed for defence against a German invasion.

His enemy being practically restricted to the defensive, William did not neglect the opportunity of initiating aggressive operations. Masking his design by a series of feints, he marched swiftly to the Meuse and invested Namur. This fortress, more famous through its connection with the immortal Uncle Toby even than as the masterpiece of Cohorn, carried to yet higher perfection by Vauban, stands at the junction of the Sambre and the Meuse, the citadel lying in the angle between the two rivers, and the town with its defences on the left bank of the Meuse. To the northward of the town outworks had been thrown up on the heights of Bouge by both of these famous engineers; and it was against these outworks that William directed his first attack.

Ground was broken on the 3rd of July, and three days later an assault was delivered on the lines of Bouge. As usual, the hardest of the work was given to the British, and the post of greatest danger was [Pg 35] made over, as their high reputation demanded, to June 26./July 6. the Brigade of Guards. On this occasion the Guards surpassed themselves alike by the coolness of their valour and by the ardour of their attack. They marched under a heavy fire up to the French palisades, thrust their muskets between them, poured in one terrible volley, the first shot that they had yet fired, and charged forthwith. In spite of a stout resistance they swept the French out of the first work, pursued them to the second, swept them out of that, and gathering impetus with success, drove them from stronghold to stronghold, far beyond the original design of the engineers, and actually to the gates of the town. In another quarter the Royal Scots and the Seventh Fusiliers gained not less brilliant success; and in fact it was the most creditable action that William had fought during the whole war. It cost the Allies two thousand men killed and wounded, the three battalions of Guards alone losing thirty-two officers. The British were to fight many such bloody combats during the next twenty years—combats forgotten since they were merely incidents in the history of a siege, and so frequent that they were hardly chronicled, and are not to be restored to memory now. I mention this, the first of such actions, only as a type of many more to come.

The outworks captured, the trenches were opened against the town itself, and the next assault was directed against the counterguard of St. Nicholas gate. This again was carried by the British, with a loss of eight hundred men. Then came the famous attack on the counterscarp before the gate itself, where Captain Tobias Shandy received his memorable wound. This gave William the possession of the town. Then came the siege of the citadel, wherein the British had the honour of marching to the assault over half a mile of [Pg 36] open ground, a trial which proved too much even for them. Nevertheless, it was they who eventually stormed a breach from which another of the assaulting columns had been repulsed, and ensured the surrender of the citadel a few days later. For their service on this occasion the Eighteenth Foot were made the Royal Irish; and a Latin inscription on their colours still records that this was the reward of their valour at Namur.

Thus William on his return to England could for the first time show his Parliament a solid success due to the British red-coats; and the House of Commons gladly voted once more a total force of eighty-seven thousand men. But the war need be followed no further. The campaign of 1696 was interrupted by a futile attempt of the French to invade England, and in 1697 France, reduced to utter exhaustion, gladly concluded the Peace of Ryswick. So ended, not without honour, the first stage of the great conflict with King Lewis the Fourteenth. The position of the two protagonists, England and France, was not wholly unlike that which they occupied a century later at the Peace of Amiens. The British, though they had not reaped great victories, had made their presence felt, and terribly felt, on the battlefield; and, as the French in the Peninsula remembered that the British had fought them with a tenacity which they had not found in other nations, not only in Egypt, but even earlier at Tournay and Linselles, so, too, after Blenheim and Ramillies they looked back to the furious attack at Steenkirk and the indomitable defence of Neerwinden. “Without the concurrence of the valour and power of England,” said William to the Parliament at the close of 1695, “it were impossible to put a stop to the ambition and greatness of France.” So it was [Pg 37] then, and so it was a century later, for though none know better the superlative qualities of the French as a fighting people, yet the English are the one nation that has never been afraid to meet them. With the Peace of Ryswick the ’prentice years of the standing Army are ended, and within five years the old spirit, which has carried it through the bitter schooling under King William, will break forth with overwhelming power under the guiding genius of Marlborough.

Authorities.—The leading authority for William’s campaigns on the English side is D’Auvergne, and on the French side the compilation, with its superb series of maps, by Beaurain. Supplementary on one side are Tindal’s History, Carleton’s Memoirs, and Sterne’s Tristram Shandy; and on the other the Mémoires of Berwick and St. Simon, Quincy’s Histoire Militaire de Louis XIV, and in particular the Mémoires of Feuquières. Many details as to Steenkirk, in particular, respecting the casualties, are drawn from Present State of Europe, or Monthly Mercury, August 1692, and as to Landen from the official relation of the battle, published by authority, 1693. Beautiful plans of both actions are in Beaurain, rougher plans in Quincy and Feuquières. All details as to the establishment voted are from the Journals of the House of Commons. Very elaborate details of the operations are given in Colonel Clifford Walton’s History of the British Standing Army.

[Pg 38]

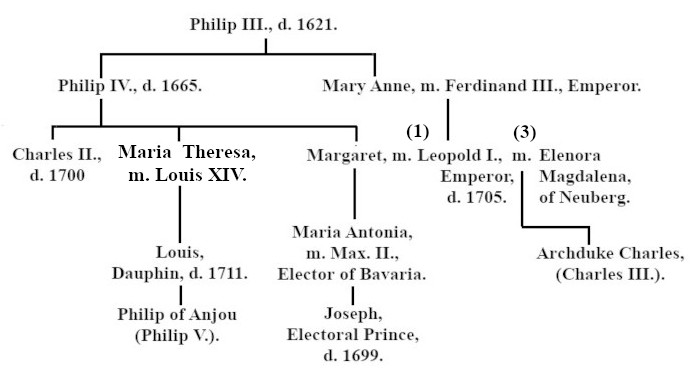

A European quarrel over the succession to the Spanish throne,[12] on the death of the imbecile King Charles the Second, had long been foreseen by William, and had been provided against, as he hoped, by a Partition Treaty in the year 1698. The arrangement then made had been upset by the death of the Electoral Prince of Bavaria, and had been superseded by a second Partition Treaty in March 1700. In November of the same year King Charles the Second died, leaving a will wherein Philip, Duke of Anjou, and second son of the Dauphin, was named heir to the whole Empire of Spain. Hereupon the second Partition Treaty went for naught. Lewis the Fourteenth, after a becoming interval of hesitation, accepted the Spanish crown for the Duke of Anjou under the title of King Philip the Fifth.

[Pg 39]

The Emperor at once entered a protest against the will, and Lewis prepared without delay for a campaign in Italy. William, however, for the present merely postponed his recognition of Philip the Fifth; and his example was followed by the United Provinces. Lewis, ever ready and prompt, at once took measures to quicken the States to a decision. Several towns[13] in Spanish Flanders were garrisoned, under previous treaties, by Dutch troops. Lewis by a swift movement surrounded the whole of them, and, having thus secured fifteen thousand of the best men in the Dutch army, could dictate what terms he pleased. William expected that the House of Commons would be roused to indignation by this aggressive step, but the House was far too busy with its own factious quarrels. When, however, the States appealed to England for the six thousand four hundred men, which under the treaty of 1668[14] she was bound to furnish, both Houses prepared faithfully to fulfil the obligation.

Then, as invariably happens in England, the work which Parliament had undone required to be done again. Twelve battalions were ordered to the Low Countries from Ireland, and directions were issued for the levying of ten thousand recruits in England to take their place. But, immediately after, came bad news from the West Indies, and it was thought necessary to despatch thither four more battalions from Ireland. Three regiments[15] were hastily brought up to a joint [Pg 40] strength of two thousand men, and shipped off. Thus, within fifteen months of the disbandment of 1699, the garrison of Ireland had been depleted by fifteen battalions out of twenty-one; and four new battalions required to be raised immediately. Of these, two, namely Brudenell’s and Mountjoy’s, were afterwards disbanded, but two more, Lord Charlemont’s and Lord Donegal’s, are still with us as the Thirty-fifth and Thirty-sixth of the Line.

In June the twelve battalions[16] were shipped off to Holland, under the command of John, Earl of Marlborough. Since 1698 he had been restored to the King’s favour and was to fill his place as head of the European coalition and General of the confederate armies in a fashion that no man had yet dreamed of. He was full fifty years of age; so long had the ablest man in Europe waited for work that was worthy of his powers; and now his time was come at last. His first duties, however, were diplomatic; and during the summer and autumn of 1701 he was engaged in negotiations with Sweden, Prussia, and the Empire for the formation of a Grand Alliance against France and Spain. Needless to say he brought all to a successful issue by his inexhaustible charm, patience, and tact.

Still the attitude of the English people towards the contest remained doubtful, until, on the death of King James the Second, Lewis made the fatal mistake of recognising and proclaiming his son as King of England. Then the smouldering animosity against France leaped instantly into flame. William seized the opportunity to dissolve Parliament, and was rewarded by the election of a House of Commons more nearly resembling [Pg 41] that which had carried him through the first war to the Peace of Ryswick. He did not fail to rouse its patriotism and self-respect by a stirring speech from the throne, and obtained the ratification of his agreement with the Allies, that England should furnish a contingent of forty thousand men, eighteen thousand of them to be British and the remainder foreigners. So the country was committed to the War of the Spanish Succession.

It was soon decided that all regiments in pay must be increased at once to war-strength, and that six more battalions, together with five regiments of horse and three of dragoons, should be sent to join the troops already in Holland. Then, as usual, there was a rush to do in a hurry what should have been done at leisure; and it is significant of the results of the late ill-treatment of the Army that, though the country was full of unemployed soldiers, it was necessary to offer three pounds, or thrice the usual amount of levy-money, to obtain recruits. The next step was to raise fifteen new regiments—Meredith’s, Coote’s, Huntingdon’s, Farrington’s, Gibson’s, Lucas’s, Mohun’s, Temple’s, and Stringer’s of foot; Fox’s, Saunderson’s, Villiers’, Shannon’s, Mordaunt’s and Holt’s of marines. Of the foot, Gibson’s and Farrington’s had been raised in 1694, but the officers of Farrington’s, if not of both regiments, had been retained on half-pay, and, returning in a body, continued the life of the regiment without interruption. Both are still with us as the Twenty-eighth and Twenty-ninth of the Line. Huntingdon’s and Lucas’s also survive as the Thirty-third and Thirty-fourth, and Meredith’s and Coote’s, which were raised in Ireland, as the Thirty-seventh and Thirty-ninth, while the remainder were disbanded at the close of the war. Of the marines, Saunderson’s had originally [Pg 42] been raised in 1694, and eventually passed into the Line as the Thirtieth Foot, followed by Fox’s and Villiers’ as the Thirty-first and Thirty-second. Nothing now remained but to pass the Mutiny Act, which was speedily done; and on the 5th of May, just two months after the death of King William, the great work of his life was continued by a formal declaration of war.

The field of operations, which will chiefly concern us, is mainly the same as that wherein we followed the campaigns of King William. The eastern boundary of the cock-pit must for a time be extended from the Meuse to the Rhine, the northern from the Demer to the Waal, and the southern limit must be carried from Dunkirk beyond Namur to Bonn. But the reader should bear in mind that, in consequence of the Spanish alliance, Spanish Flanders was no longer hostile, but friendly, to France, so that the French frontier, for all practical purposes, extended to the boundary of Dutch Brabant. Moreover, the French, besides the seizure, already related, of the barrier-towns, had contrived to occupy every stronghold on the Meuse except Maestricht, from Namur to Venloo, so that practically they were masters so far of the whole line of the river.

A few leagues below Venloo stands the fortified town of Grave, and beyond Grave, on the parallel branch of the Waal, stands the fortified city of Nimeguen. A little to the east of Nimeguen, at a point where the Rhine formerly forked into two streams, stood Fort Schenck, a stronghold famous in the wars of Morgan and of Vere. These three fortresses were the three eastern gates of the Dutch Netherlands, commanding the two great waterways, doubly important in those days of bad roads, which lead into the heart of the United Provinces.

It is here that we must watch the opening of the [Pg 43] campaign of 1702. There were detachments of the French and of the Allies opposed to each other on the Upper Rhine, on the Lower Rhine, and on the Lower Scheldt; but the French grand army of sixty thousand men was designed to operate on the Meuse, and the presence of a Prince of the blood, the Duke of Burgundy, with old Marshal Boufflers to instruct him, sufficiently showed that this was the quarter in which France designed to strike her grand blow. Marlborough being still kept from the field by other business, the command of the Allied army on the Meuse was entrusted to Lord Athlone, better known as that Ginkell who had completed the pacification of Ireland in 1691. His force consisted of twenty-five thousand men, with which he lay near Cleve, in the centre of the crescent formed by Grave, Nimeguen, and Fort Schenck, watching under shelter of these three fortresses the army of Boufflers, which was encamped some twenty miles to south-east of him at Uden and Xanten. On May 30./June 10. the 10th of June Boufflers made a sudden dash to cut off Athlone from Nimeguen and Grave, a catastrophe which Athlone barely averted by an almost discreditably precipitate retreat. Having reached Nimeguen Athlone withdrew to the north of the Waal, while all Holland trembled over the danger which had thus been so narrowly escaped.

Such was the position when Marlborough at last took the field, after long grappling at the Hague with the difficulties which were fated to dog him throughout the war. In England his position was comparatively easy, for though Prince George of Denmark, the consort of Queen Anne, was nominally generalissimo of all forces by sea and land, yet Marlborough was Captain-General of all the English forces at home and in Holland, and in addition Master-General of the [Pg 44] Ordnance. But it was only after considerable dispute that he was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Allied forces, and then not without provoking much dissatisfaction among the Dutch generals, and much jealousy in the Prince of Nassau-Saarbrück and in Athlone, both of whom aspired to the office. These obstacles overcome, there came the question of the plan of campaign. Here again endless obstruction was raised. The Dutch, after their recent fright, were nervously apprehensive for the safety of Nimeguen, the King of Prussia was much disturbed over his territory of Cleve, and all parties who had not interests of their own to put forward made it their business to thwart the Commander-in-Chief. With infinite patience Marlborough soothed them, and at last, on June 21./July 2. the 2nd of July, he left the Hague for Nimeguen, accompanied by two Dutch deputies, civilians, whose duty it was to see that he did nothing imprudent. Arrived there he concentrated sixty thousand men, of which twelve thousand were British,[17] recrossed the Waal and encamped at Ober-Hasselt over against Grave, within two leagues of the French. Then once more the obstruction of his colleagues caused delay, July 15/26. and it was not until the 26th of July that he could cross to the left bank of the Meuse. “Now,” he said to the Dutch deputies, as he pointed to the French camp, “I shall soon rid you of these troublesome neighbours.”

Five swift marches due south brought his army over the Spanish frontier by Hamont. Boufflers thereupon in alarm broke up his camp, summoned Marshal Tallard from the Rhine to his assistance, crossed the Meuse with all haste at Venloo, and pushed [Pg 45] July 22./Aug. 2. on at nervous speed for the Demer. On the 2nd of August he lay between Peer and Bray, his camping-ground ill-chosen, and his army worn out by a week of desperate marching. Within easy striking distance, a mile or two to the northward, lay Marlborough, his army fresh, ready, and confident. He held the game in his hand; for an immediate attack would have dealt the French as rude a buffet as they were to receive later at Ramillies. But the Dutch deputies interposed; these Dogberries were content to thank God that they were rid of a rogue. So Boufflers was allowed to cross the Demer safely at Diest, and a first great opportunity was lost.

Marlborough, having drawn the French away from the Meuse, was now at liberty to add the garrison of Maestricht to his field-force, and to besiege the fortresses on the river. Boufflers, however, emboldened by his escape, again advanced north in the hope of cutting off a convoy of stores that was on its way to join the Allies. Marlborough therefore perforce moved back to Hamont and picked up his convoy. Then, before Boufflers could divine his purpose, he had moved swiftly south, and thrown himself across the line of Aug. 11/22. the French retreat to the Demer. The French marshal hurried southward with all possible haste, and came blundering through the defiles before Hochtel on the road to Hasselt, only to find Marlborough waiting ready for him at Helchteren. Once again the game was in the Englishman’s hand. The French were in great disorder, their left in particular being hopelessly entangled in marshy and difficult ground. Marlborough instantly gave the order to advance, and by three o’clock the artillery of the two armies was exchanging fire. At five Marlborough directed the whole of his right to fall on the French left; but to [Pg 46] his surprise and dismay, the right did not move. A surly Dutchman, General Opdam, was in command of the troops in question and, for no greater object than to annoy the Commander-in-Chief, refused to execute his orders. So a second great opportunity was lost.

Still much might yet be won by a general attack on the next day; and for this accordingly Marlborough at once made his preparations. But, when the time came, the Dutch deputies interposed, entreating him to defer the attack till the morrow morning. “By to-morrow morning they will be gone,” answered Marlborough; but all remonstrance was unavailing. The attack was perforce deferred; the French slipped away in the night; and, though it was still possible to cut up their rearguard with cavalry, a third great opportunity was lost.

Marlborough was deeply chagrined; but although with unconquerable patience and tact he excused Opdam’s conduct in his public despatches, he could not deceive the troops, who were loud in their indignation against both deputies and generals. There was now nothing left but to reduce the fortresses on the Meuse, a part of the army being detached for the siege while the remainder covered the operations under the command of Marlborough. Even over their favourite pastime of a siege, however, the Dutch were dilatory beyond measure. “England is famous for negligence,” wrote Marlborough, “but if Englishmen were half as negligent as the people here, they would be torn to pieces by Parliament.”[18] Venloo Aug. 18/29. was at length invested on the 29th of August,[19] and[Pg 47] after a siege of eighteen days compelled to capitulate. The English distinguished themselves after their own peculiar fashion. In the assault on the principal defence General Cutts, who from his love of a hot fire was known as the Salamander, gave orders that the attacking force, if it carried the covered way, should not stop there but rush forward and carry as much more as it could. It was a mad design, criminally so in the opinion of officers who took part in it,[20] but it was madly executed, with the result that the whole fort was captured out of hand.

The reduction of Stevenswaert, Maseyck, and Ruremond quickly followed; and the French now became alarmed lest Marlborough should transfer operations to the Rhine. Tallard was therefore sent back with a large force to Cologne and Bonn, while Boufflers, much weakened by this and by other detachments, lay helpless at Tongres. But the season was now far advanced, and Marlborough had no intention of leaving Boufflers for the winter in a position from which he might at any moment move out and bombard Maestricht. No sooner, therefore, were his troops released by the capture of Ruremond than he prepared to oust Boufflers. The French, according to their usual practice, had barred the eastern entrance to Brabant by fortified lines, which followed the line of the Geete to its head-waters, and were thence carried across to that of the Mehaigne. In his position at Tongres Boufflers lay midway between these lines and Liège, in the hope of covering both; but after the fall of so many fortresses on the Meuse he became specially anxious for Liège, and resolved to post himself under its walls. He accordingly examined the defences, selected his camping-ground, and on [Pg 48] Oct. 1/12. the 12th of October marched up with his army to occupy it. Quite unconscious of any danger he arrived within cannon-shot of his chosen position; and there stood Marlborough, calmly awaiting him with a superior force. For the fourth time Marlborough held his enemy within his grasp, but the Dutch deputies, as usual, interposed to forbid an attack; and Boufflers, a fourth time delivered, hurried away in the night to his lines at Landen. Had he thrown himself into Liège Marlborough would have made him equally uncomfortable by marching on the lines; as things were, the French marshal perforce left the city to its fate.