Title: Jackson's Gymnastics for the Fingers and Wrist

Author: Edwin Ward Jackson

Release date: February 11, 2022 [eBook #67375]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: N. Trübner & Co, 1864

Credits: Charlene Taylor, Les Galloway and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Obvious typographical errors have been silently corrected. Variations in hyphenation have been standardised but all other spelling and punctuation remains unchanged.

In preparation.

A Hand-book of Bodily Exercises, based upon A. Ravenstein’s “Volks-Turnbuch,” and edited by E. G. Ravenstein, F.R.G.S., &c., President of the German Gymnastic Society of London, and John Hulley, Director of the Athletic Club, Liverpool. In one volume, 8vo, pp. 400, and 700 woodcuts.

This will be the most complete work on Gymnastics and all descriptions of bodily exercises ever published in the English language.

Contents: History of Gymnastics—Constitutiom of Gymnastic Societies—On the manner of conducting the Exercises—Distribution into Squads—Training of Instructors—Gymnastic Festivals and Competitions—Sanitary Rules—Exercises without apparatus—(free exercises, walking, running, co-operative and facto-gymnastical exercises, wrestling, boxing, &c.)—Exercises with portable apparatus (wands, dumb-bells, clubs, bars, &c.)—Exercises at fixed apparatus (rack, parallel bars, horse, buck, climbing and escalading, leaping and vaulting, swings, &c.).

LONDON: N. TRÜBNER & CO., 60, PATERNOSTER ROW.

BEING

A SYSTEM OF GYMNASTICS,

BASED ON ANATOMICAL PRINCIPLES,—FOR DEVELOPING AND

STRENGTHENING THE MUSCLES OF THE HAND; FOR MUSICAL,

MECHANICAL, AND MEDICAL PURPOSES.

With thirty-seven Diagrams.

LONDON:

N. TRÜBNER & CO., 60, PATERNOSTER ROW.

1865.

[Right of Translation reserved.]

The whole of the Engravings contained in this work were executed for

the author by Berndt, in Berlin, July, 1864.

The apparatus referred to in this work may be had, price 3s. 6d., of Messrs

Metzler & Co., 36 to 38, Great Marlborough Street, W.

JOHN CHILDS AND SON, PRINTERS.

[Pg v]

The subject of this little work develops, on anatomical and physiological principles, a system of Gymnastics for the Fingers and Wrist, the object of which is—, to lay a solid and scientific foundation for the acquisition of technical skill in the fingers and wrist, as applied to the playing on musical instruments and to finger-work generally.

For a detailed account of the circumstances under which this system was discovered, I refer to the Introductory Remarks, wherein I have explained the process of reasoning and the series of experiments, which enabled me to arrive at the results I have now the pleasure of submitting to the consideration of my countrymen; more especially to all those among them who are[Pg vi] engaged in musical pursuits, or any other work requiring the constant use of the fingers.

I may simply state that both the scientific principles and the practical utility of this system of Gymnastics—, after having been subjected to the test of numerous experiments—, have met with the approval of the highest anatomical, musical, and gymnastic authorities of Germany; at whose special solicitation I was induced to make these discoveries known by means of public and private lectures—, delivered gratis in the German language in many German cities—, during a journey undertaken at my own expense, in the course of the summer of 1864.

I gladly avail myself of this opportunity to return my best thanks to Professors Hyrtl, Virchow, Hermann Meyer, and Griesinger; to Drs Richter, C. C. Carus, J. V. Carus, Berend, and Angerstein; to Professors Moscheles, Kullak, Stern, Geyer, Kittl, Joachim, and Lauterbach; to Capellmeister Taubert, Ferdinand Hiller, Lachner, Strauss, Abenheim, Täglichsbeck, and Meyer; to Concertmeister F. Schubert, Carl Baermann, Scholtz, Singer, Grün, and many others whom space precludes[Pg vii] me from mentioning here,—for the assistance they have given me, and for the kind and favourable reception which they, the press, and the public generally, gave to my lectures.

And I indulge the hope that this little work may meet with the same approval from the medical, musical, and gymnastic authorities in this country, and be a means of practical utility among those for whom it is more particularly intended.

In all the gymnastic establishments throughout Europe and the civilized world, gymnastic exercises have been introduced for every part of the body except for the Fingers, notwithstanding that it is these important members of the human frame—with the mental organs—which chiefly distinguish Man from the Brute creation.

Therefore I venture to dedicate to the public—, “Gymnastics for the development of the Muscles, Ligaments, and Joints of the Fingers and Hand”—, specially adapted to

Musicians of all classes,

Authors, and all who are occupied much in writing,

[Pg viii]

Artists and Draughtsmen,

Printers and Compositors,

Lithographers and Engravers on steel and copper,

Workers in ivory and wood,

Watch-makers and fine Mechanicians.

Spinners and Weavers, for

All female handiwork, for

Surgical and anatomical processes, for the treatment of rheumatism, contortions, and other diseases of the Fingers and Hand,—and for

All those who require a flexible Hand, or who earn their bread with their Fingers.

EDWIN W. JACKSON.

September, 1865.

[Pg ix]

| PAGE | ||

| PREFACE. | ||

| INTRODUCTORY REMARKS ON THE ORIGIN OF THIS SYSTEM OF GYMNASTICS FOR THE FINGERS AND WRIST | 1 | |

| CHAP. | ||

| I. | ANATOMY OF THE HAND. ON LIGAMENTS, TENDONS, ETC. | 16 |

| II. | THE MUSCLES OF THE HAND AND OF THE FINGERS | 22 |

| III. | EFFECTS OF THIS GYMNASTIC TREATMENT ON THE MUSCLES, LIGAMENTS, AND JOINTS OF THE FINGERS AND THE HAND | 29 |

| IV. | NEGLECT HITHERTO OF THE HAND AND FINGERS | 35 |

| V. | THE FINGER-JOINTS ARE THE LEAST EXERCISED, AND THE WEAKEST | 39 |

| VI. | THE PRINCIPAL DIFFICULTY DOES NOT CONSIST IN THE READING OF MUSIC, BUT IN THE WEAKNESS OF THE FINGERS | 41[Pg xi] |

| VII. | MUSIC IS THE ART WHICH MAKES THE HIGHEST DEMANDS ON THE MUSCLES OF THE FINGERS. MOVING THE FINGERS UP AND DOWN INSUFFICIENT | 44 |

| VIII. | ARTISTS AND TEACHERS OF MUSIC | 46 |

| IX. | FREE GYMNASTIC EXERCISES FOR THE FINGERS AND THUMB | 49 |

| X. | FREE GYMNASTIC EXERCISES FOR THE THUMB | 55 |

| XI. | FREE GYMNASTIC EXERCISES FOR THE WRIST | 58 |

| XII. | MECHANICAL FINGER-EXERCISES | 63 |

| XIII. | MECHANICAL FINGER-EXERCISES (CONTINUED) | 70 |

| XIV. | MECHANICAL FINGER-EXERCISES (CONTINUED) | 80 |

| XV. | BOARD FOR STRETCHING THE MUSCLES, ESPECIALLY THOSE OF THE THUMB AND THE LITTLE FINGER | 84 |

| XVI. | ON STRINGED INSTRUMENTS IN PARTICULAR. THE WRIST OF THE RIGHT HAND | 86 |

| XVII. | CONTINUATION | 89 |

| XVIII. | CONTINUATION. STACCATO | 92 |

| XIX. | CONCLUDING REMARKS | 95 |

[Pg 1]

If any one should desire to know how and in what manner I, as a private individual, came to hit upon these discoveries, I answer simply:

Six years ago I took my family, principally consisting of daughters, to Germany, to have them educated there, and especially to obtain for them good instruction in music. I soon found that the method of teaching the pianoforte then in general use was very fatiguing and trying to the nerves; at the same time, as Germany stands at the head of the musical world, that method, as a matter of course, must be considered the best which we at present[Pg 2] know. In order to investigate that system more minutely, I visited several musical schools and conservatories for music in Germany, inquiring what was the very best method known for strengthening the fingers and wrist, for bringing them into order and preparing them to play the pianoforte? The answer I everywhere received was as follows: “The chief difficulties and impediments to be overcome in teaching the piano, the violin, and almost all other musical instruments, are muscular, and lie in the joints of the fingers and wrists; and the very best method of rendering them strong and flexible is frequently and perseveringly to move the fingers up and down on the instrument, preserving the hand in the same position. This movement, together with the usual finger-exercises, if continued for five or six years, and diligently carried out, is usually sufficient to render the joints and muscles of the fingers agile and flexible, and to bring the fingers generally into order.”

I inquired further, “Are those exercises not very fatiguing?” to which I was answered,[Pg 3] “They certainly are very trying to the muscles and nerves;” and whether “the health of the students, male and female, did not suffer thereby?” to which the reply was, that it did, and that, indeed, it was sometimes necessary for them to discontinue playing for some months; but then they added, “It must be remembered that learning to play the piano was in itself at all times attended with very considerable difficulties.”

I observed that this result was really lamentable; and inquired whether there did not exist any other method for obtaining the same end and becoming proficient on the piano? To this I received a negative answer, and was again told, “After all possible experiments, it is the opinion of all artists and teachers at the present time, in all cities in Europe, that the method alluded to is the most effective of any we know for imparting quickness and flexibility to the joints of the fingers and wrist.”

Now on observing that my daughters suffered in the same manner, I said to myself,[Pg 4] “There must surely be something wrong here.” And here I would mention the fact that when I was 12 or 13 years of age I learnt the violin, and afterwards for upwards of 35 years discontinued it. But later in life, desiring to accompany my children, I was induced to take up the violin again. I then found that, although I was in all other respects exceedingly strong and healthy and capable of all athletic exercises, my fingers and hand in a few minutes became painfully fatigued. The same result followed whenever I took the violin in hand,—in fact, I found that my fingers were the only weak parts of my body. This happened a few years ago, about the same time when the above-mentioned inquiries took place, exciting in me great surprise and an earnest desire to search into the cause. I thought to myself, “There must underlie some unknown hidden cause to account for this phenomenon. I will thoroughly probe the matter.” For this purpose I now put myself in the way of those individually who earn their bread by the sweat of their brow, viz., the smith, the joiner, the[Pg 5] bricklayer, the labourer, the peasant, the gardener, the wood-cutter, the miner, &c. &c. I found that all these persons work with their arms, and thereby acquire muscle like steel and arms like giants; but that none of them work with their fingers.

After this I visited boys’ and girls’ schools, and also observed them in their families; and there I found again that nearly all of them in their work made no use of the fingers. The same observation I made with the educated classes, of every age and sex.

This discovered to me the fact that the muscles of the fingers are extremely little exercised in the ordinary occupations of life; and must, therefore, on physiological ground, be weak; a fact of much importance.

I then repaired to the most renowned gymnastic establishments of the Continent, and begged to be shown all the varied gymnastic exercises practised on the body, from the crown of the head to the sole of the foot, and when all these various movements had been exhibited before me, I inquired “But where[Pg 6] are your gymnastic exercises for the fingers?” “We have none.” “Why?” “We never thought of it.” “But they require them surely as much or more than all!” “It has never occurred to us; we did not know the fingers required gymnastics, and they have been entirely overlooked.” This disclosed to me another great fact; namely, that the fingers are the only active members of the human body to which a properly constituted system of gymnastic exercises has NOT been applied.

I thereupon visited houses and institutions where men do work with their fingers, viz., where carvers in wood and ivory, in steel, copper, and stone, painters and draughtsmen, watchmakers and fine mechanists, spinners and weavers, printers and compositors, &c., drive their trade, and after that, people who are in the habit of writing much, and even the whole day, such as authors, copyists, clerks, stenographers, lithographers, as well as sempstresses and workwomen;—in short, all those who have much finger-work, or earn their living by their fingers. And here I observed all kinds of finger diseases, such as[Pg 7] stiffness of the joints and limbs, writers’ cramp, hands and forearms debilitated in the highest degree, paralyzed limbs, nervous weakness, &c. Then I said to myself, “A light begins to dawn upon me. I find, first, that the fingers are the least exercised, in the ordinary occupations of life, of all the active members of the body; secondly, that they are on that account relatively and physiologically the weakest; and, thirdly, that they are also the only active members which are not gymnastically trained and treated. I must consider the matter now ANATOMICALLY, PHYSIOLOGICALLY, and GYMNASTICALLY.”

And I forthwith began to make all sorts of artistic and mechanical experiments, for the purpose of gymnastically exercising, stretching, and developing the muscles, the ligaments, and joints of the fingers and hands in all directions, so as to strengthen and prepare them for playing the piano and the violin, as well as other instruments, and for all kinds of finger-work and handicraft.

In doing so I studied the physiology of the muscles and ligaments, and directed especial[Pg 8] attention to the transverse metacarpal ligament. In comparing this anatomy with the difficulties experienced, I sought to discover a means more particularly of stretching the ligaments or bands which run transversely across the hands and knuckles. This I succeeded in effecting, and then I discovered, to my astonishment, that the moment I had applied my gymnastic movements to these stout and very obstinate elastic bands, the muscles became instantaneously looser, and moved with greatly increased freedom and agility. In a word, the muscles were set free.

At the same time I tried on myself various simple, natural, free movements with the joints of the fingers, in order to examine them practically and physiologically, and thus to found a system on solid principles. And I may here be permitted to state as the result, in my own case, that though at that time 54 years of age, after I had diligently practised the course of gymnastic exercises herein described, a comparatively short time, every day, my fingers and wrists became so strong and flexible that I[Pg 9] was able to play, and can now play upon the violin many hours daily in succession without fatigue.

I caused the same to be tried by many other persons also, of different ages. Then I found, to my surprise, in each case that, in the absence of proper gymnastic exercises, these most important parts of the human frame, owing to their being so unpractised in the ordinary occupations of life, and being consequently so weak, are not equal to the least work or exertion beyond the usual movements of daily life, and that whenever anything beyond the ordinary routine is required of them, they are found to be utterly incapable of fulfilling the task.

Then I said to myself, “I now see as clear as sunlight whence arise the extraordinary difficulties of learning to play the piano and violin. They arise from the very fact that an art the most difficult, from a muscular point of view, which we know of, has to be performed with the least practised and, proportionately, the weakest of muscles. The impediments and[Pg 10] difficulties in almost all cases can be referred to the muscles; and it is this weakness which must be overcome.”

Upon this I repaired to anatomical, chirurgical, and medical institutions, in order to study still further the anatomy of the hand, the fingers, and the arm. I found that the muscles, the ligaments, and the tendons of the fingers and hands consist of elastic masses, intersecting the hand, and running TRANSVERSELY as well as LONGITUDINALLY; and I especially discovered, after a number of experiments, that the TRANSVERSE LIGAMENTS, unless they be exercised, remain quiet and stiff, and impede to a certain extent the movements and activity of the muscles, when the latter are more than ordinarily exerted; that in order practically to exercise and stretch them, and particularly the TRANSVERSE ligaments and tendons, and to render them strong and supple, it is necessary not only to move the fingers up and down, but laterally also; that, in short, both muscles and ligaments ought to be practised gymnastically; and that the fatigue[Pg 11] and the danger to health, the nervous weakness and the disgust often observed in musical students, arise from the following causes:

Firstly, that the muscles, tendons, and ligaments of the hand and fingers are, proportionately, the least practised, and, consequently, as stated before, the weakest;

Secondly, that they have never been gymnastically trained or treated;

Thirdly, that the methods now in use for strengthening those weak muscles and rendering them flexible are insufficient and erroneous;

Fourthly, that the transverse ligaments have never been stretched; thus on these several grounds hampering the learning of music with unnatural difficulties, and with exertions of the muscular and nervous system injurious to health;

Fifthly, that so soon as the muscles are properly and gymnastically exercised, and the ligaments and tendons stretched, the fingers set at liberty move glibly and freely over the instrument; and,

Sixthly, that all this is readily accounted[Pg 12] for on the simplest, though till now unexplained, anatomical and physiological grounds.

And as regards the different persons and classes already mentioned, who earn their living with their fingers, it would have been easy to prevent the various diseases of the same to which they are exposed, if the joints of their fingers and hands had previously been daily practised, strengthened, and prepared by transversal and longitudinal gymnastic exercises. And more than this, those sad infirmities might, in most cases, either have been entirely cured or at any rate alleviated by the above muscular treatment. Besides, a continuance of the same diseases would be easily obviated, if such treatment were resorted to.

Then I asked myself, “Is any one to blame that the facts just mentioned have not been previously known and acted upon?” No one. It certainly is not the fault of the artist and teacher, because their task, so great in itself, did not necessarily lead them to direct their attention to this speciality of gymnastics. Nor could anatomists and physicians, nor other[Pg 13] learned men, in treating problems more nearly, and perhaps more important in themselves, be expected to have thought of it. As we are frequently indebted to chance for the most important discoveries, so it has been with this one. For my part, I lay claim to very little. The idea had taken hold of me that a hiatus and a want in the method of learning and practising music, also in finger-work of various kinds, existed, and I set to work to fill up the former and to satisfy the latter. For several years I have indefatigably pursued this work in Germany, and after multifarious trials, experiments, and exercises, I have happily achieved the following simple system of gymnastics, whose aim and object, as regards music, after full and complete proof, are; by strengthening the muscles and stretching the ligaments through careful training, to impart to them flexibility and agility, to shorten considerably the time of study, and facilitate the work of both teachers and students; whilst as regards all classes generally who work with their fingers, it is calculated to a great extent[Pg 14] to render their work more easy, and in case of disease of the fingers and hands, to prevent it, to cure it, or at the least to diminish its injurious consequences.

Having been requested by the highest anatomical and artistic authorities in Germany to give publicity to this method and to explain it personally, I undertook, in 1864, at my own expense, from love of the art, a journey through many towns of the Continent, where, as already stated, I delivered, in the German language, a number of private and public lectures on the subject. And here I desire specially to crave the forgiveness of my kind German friends, if, in delivering those lectures, I did not at all times express myself in accents of the purest German, since I only commenced the study of that difficult language,—for the first time in my life,—six years ago, after I had attained the age of 52 years. The exposition of this method having met with cordial approval, I now offer the result of my labours to artists, musical students, and to all friends of music, as well as to all those who work much with their fingers, or who suffer[Pg 15] from finger disease; also to anatomists, physiologists, surgeons, and gymnasts; indulging the hope that, if applied correctly and carefully, they will go far towards removing the evils to which I have alluded, and be of much practical usefulness and advantage.

[Pg 16]

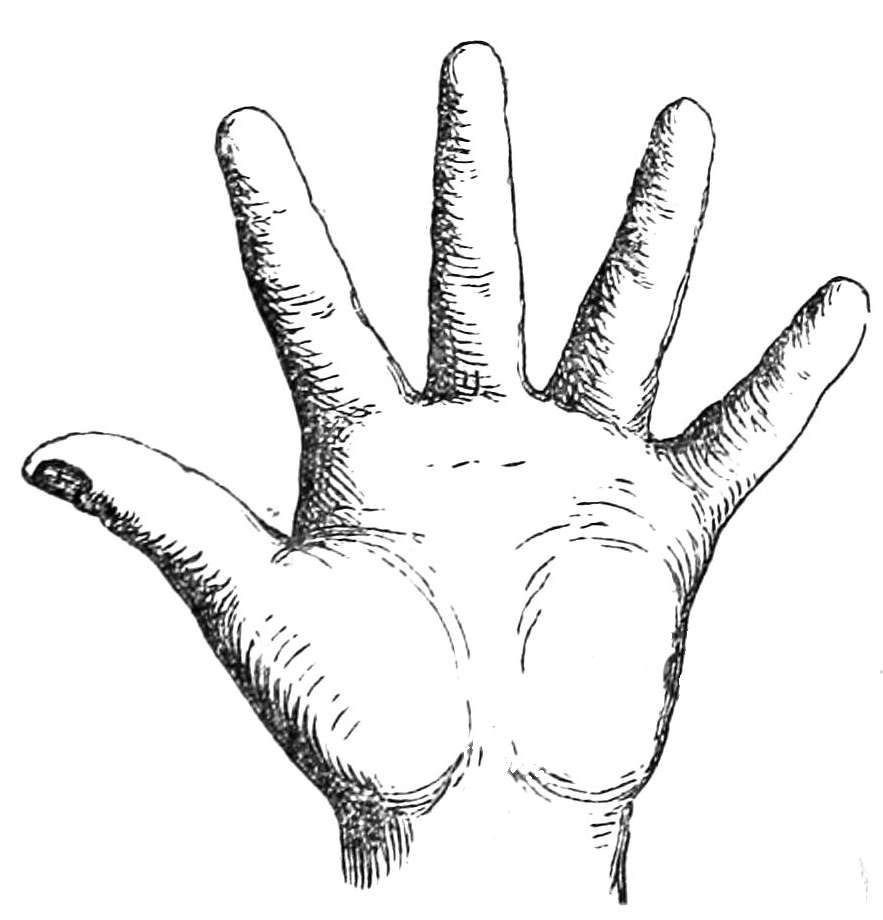

The skeleton of the hand, consisting of 27 bones and moved by 40 muscles, most ingeniously combines firmness with pliant flexibility, is equally fit for rough work and the most subtle occupation, and corresponds in its well-balanced mechanism with that mental superiority through which man, amongst all creatures the poorest in means of defence, becomes the ruler of living and inanimate nature. The hand, fixed to the end of a long articulated column of bones, and, through its skin-covering, particularly in the cavity, endowed with high sensibility, raises itself to the importance of an organ of feeling, which, moveable in all directions,[Pg 17] apprizes us of the extent of matter, and of its physical qualities.

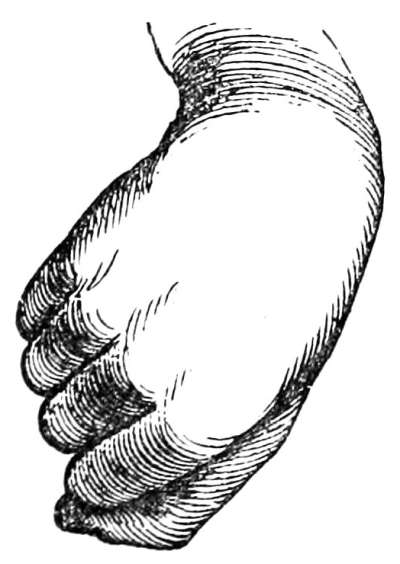

The most ancient forms of measurement have, therefore, been taken from the length of the several subdivisions of the hand. The capability of the hand of assuming the hollow shape of a spoon, and of being stretched like a shovel, determines its use for gathering and for turning up matter. The curvature of the fingers forms a strong and broad hook, which renders excellent service in climbing; and the thumb, whose position enables it to be placed opposite all the other fingers, acts in conjunction with the latter like a pair of pincers, capable of seizing and feeling smaller objects. The thumb being easily moveable and strong at the same time, is a privilege of the human hand. It powerfully opposes itself against the other fingers into the fist, for the seizing and holding of heavy objects. In doing this the thumb indeed performs almost as much as the remaining fingers taken together; it represents one half of a pair of pincers, wherefore Albin has called it Manus parva.

[Pg 18]

The unequal length of the fingers is well adapted for the taking hold of spherical forms, and the fingers being bent towards the hollow of the hand and held together, encloses an empty space, which is shut by the thumb serving as a lid. The wrist of the hand, having a circular shape, and being composed of several bones, is much less exposed to the danger of being broken, than if one single curved bone were to take its place. Its cavity, which by strong transversal ligaments is transformed into a ring, protects the bending tendons of the fingers from pressure and friction. The firm connection between the middle hand and the wrist renders possible the actions of stemming and hurling with the hands, and the longitudinal curve of the separate bones of the middle hand, as well as their lying one at the side of the other, and convexly towards the back of the hand, facilitates the forming of the cavity of the hand. The great moveability of the fingers, and the many possible combinations of their relative positions, have made them the instruments of language by signs. The deep[Pg 19] slits separating them allow of folding the hands, in order to press with double force, and the bending of the two last finger-joints, which can only take place at an angle, imparts to the clenched fist a force which once usurped the place of right. How necessary the joint action of both hands is for certain performances is proved by the old proverb: Manus manum lavat. In short, all the thousandfold occupations of the hand which necessity commands and the mind develops, and which are an exclusive prerogative of man, become practicable through the wonderful structure of this instrument.[1]

As regards the system of the gymnastic training of the fingers in particular, which I am now placing before the public, it is founded on an important fact, namely, the action of the LIGAMENTS AND TENDONS.

It has been acknowledged at all times, that if a muscle is to be made both stronger and[Pg 20] quicker in its movements, it should be exercised; that the ligaments and tendons play, in these exercises, an indispensable part, has hitherto (to use the words of a celebrated German physiologist), hardly been sufficiently acknowledged or explained. It is further known, that the principal method now in use of strengthening and rendering flexible the joints and muscles of the fingers in playing the piano, consists in alternately raising and dropping the fingers, and that this method requires very great exertion, and consumes very much time. Now, I have found, by means of many different experiments and exercises, which I have made with the hand and the fingers, that the tight ligaments and skin-folds, intersecting the hand transversely, unless they be exercised, and if they be allowed to remain firm, for this very reason, impede the movements of the muscles whenever they are more than ordinarily exerted; while, on the contrary, the stretching of the transversal ligaments produces a remarkable influence on the moveability of the fingers and the hand, facilitates the work of the muscles,[Pg 21] and imparts to them freedom, steadiness, and precision.

By placing the cylinders to be used for this purpose between the fingers for only a very short time, and thereby exercising the ligaments of the hand, both transversely and longitudinally, the movement of the fingers is at once rendered much easier and quicker. This result can only be explained by the fact that the ligaments and folds of the hand, having been stretched by the cylinders, have become loosened, and, therefore, as I said before, impede less the muscles in their fatiguing work. If, on the other hand, all the muscles, ligaments, and tendons are put into motion in both directions, longitudinally and transversely, they soon become strong and flexible.

[Pg 22]

[1] Joseph Hyrtl: Lehrbuch der Anatomie. 4te Auflage. Wien, 1855. Erasmus Wilson, F.R.S., System of Human Anatomy. 8th Edition. London, 1862.

Leaving aside the vessels and nerves unconnected with our subject, we may describe the hand as being composed of three classes of organs, 1. bones with joints, 2. ligaments, 3. muscles.

1. Bones with joints.

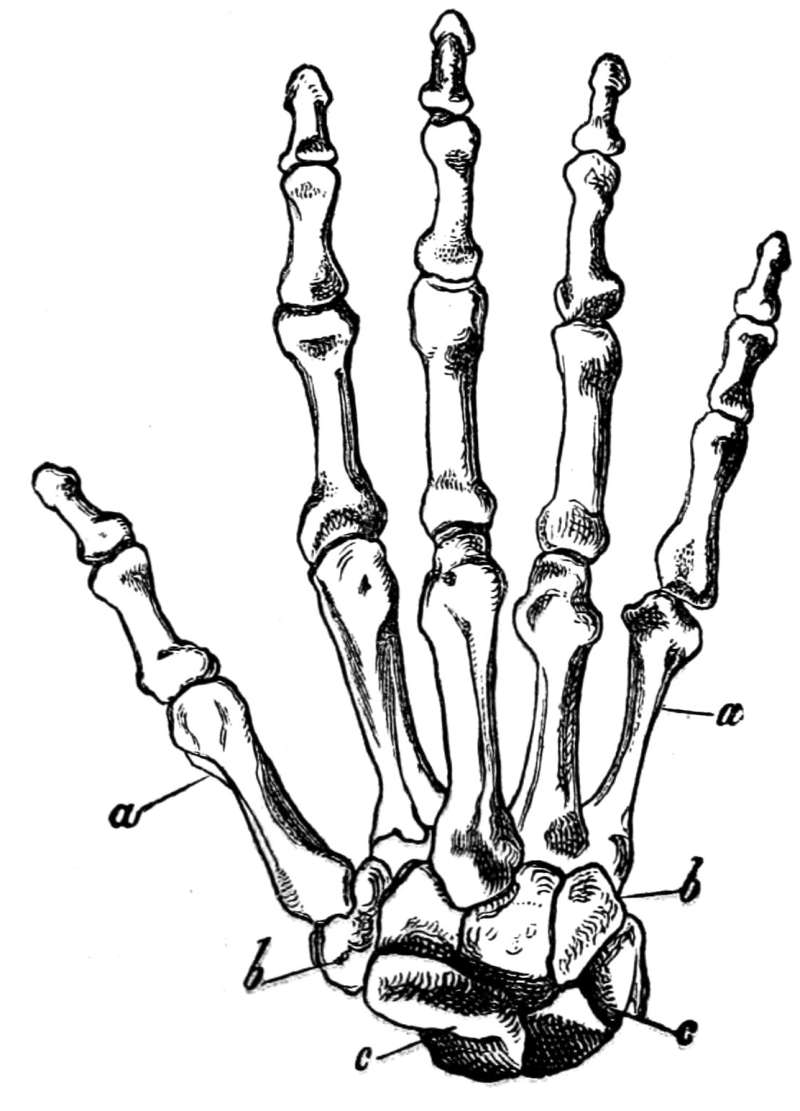

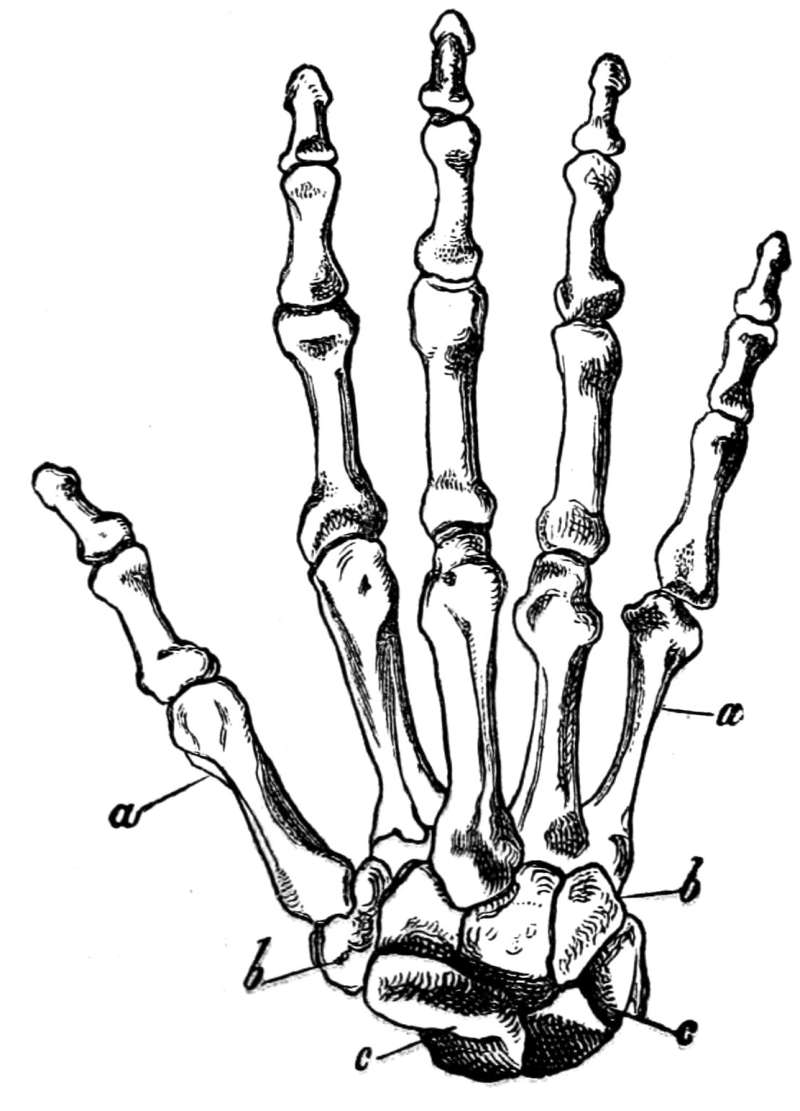

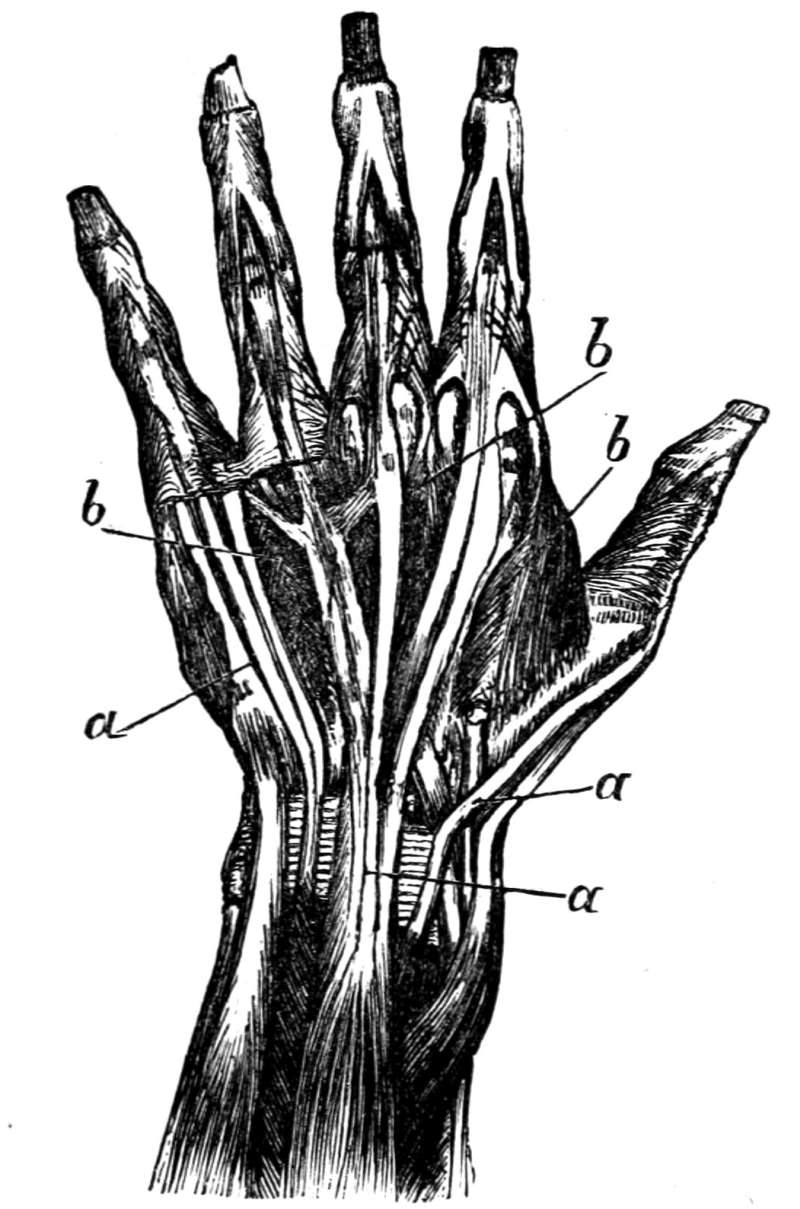

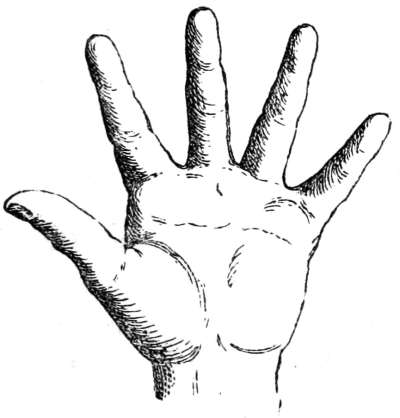

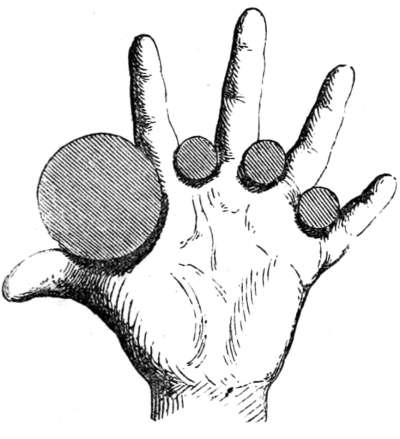

The hand is subdivided into five separate limbs (fingers), lying one at the side of the other, and being, at the lower end, firmly joined together into one whole. Each of these five limbs (fingers) is composed of a row of bones, having the nature of long bones. The first of these bones, next to the lower arm, is called the metacarpal or middle-hand bone (Fig. 1 a); the others are called finger-joints. The thumb[Pg 23] has only two finger-joints, the other fingers three each. The fourth and fifth fingers are the weakest of all.

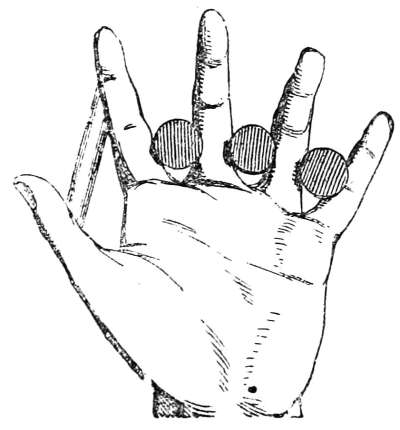

The union of the five fingers into one whole is effected by means of the extremities of the middle-hand bones, commonly known as knuckles, which are turned towards the forearm, being connected with one another by[Pg 24] very tight transversal ligaments (Fig 2 aa and Fig. 3 bb), and being thus connected, are again fixed to a row of four roundish bones, joined to one another in the same manner (Fig. 1 b). Thus, the five middle-hand bones and the four bones of the upper wrist form one firm structure. In this structure the middle-hand bone of the thumb and of the[Pg 25] little finger can be more easily moved than the others.

On account of this moveability of the two extreme middle-hand bones, it is possible to move the two edges of the hand close to one another, whereby the cavity of the hand assumes the shape of a groove.

The structure here described (the hand, in the narrower sense of the word) is joined to the lower arm by means of three muscles, the posterior row of the bones of the wrist (Fig. 1 c). The movement between these bones and the hand is hardly anything but a hinge-movement; that between them and the lower arm, however, is a movement in almost all directions. The bending and stretching of the hand is, therefore, produced with the participation of both joints, the side movement of the hand, however, almost exclusively by the joint situated between the posterior row of the bones of the wrist and the lower arm.[2]

[Pg 26]

2. Ligaments.

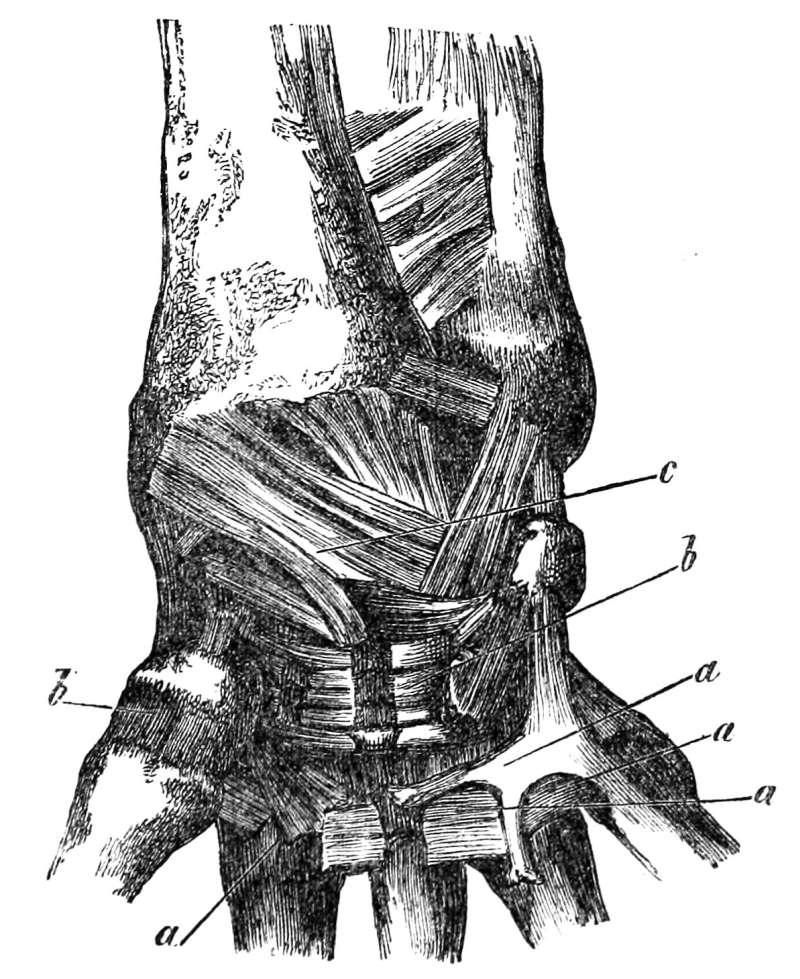

All the finger-joints are provided with capsules, which are woven out of strong transversal fibres (Fig. 3 aa). The bones of the wrist are connected between themselves and with the bones of the middle-hand by tight transversal and longitudinal ligaments, as seen in Fig. 2 aa, bb. Lastly, the two ends of the middle-hand bones, or knuckles, are connected with one another and with the first joints of the fingers by a separate strong, transversal ligament (Fig. 2 aa, Fig. 3 bb).

3. The Muscles of the Hand consist

1. Of muscles (four in number) rising from the lower arm and bending the wrist up and down, right and left (Fig. 3 c, d, e).

2. Of muscles of the fingers. These are subdivided into—

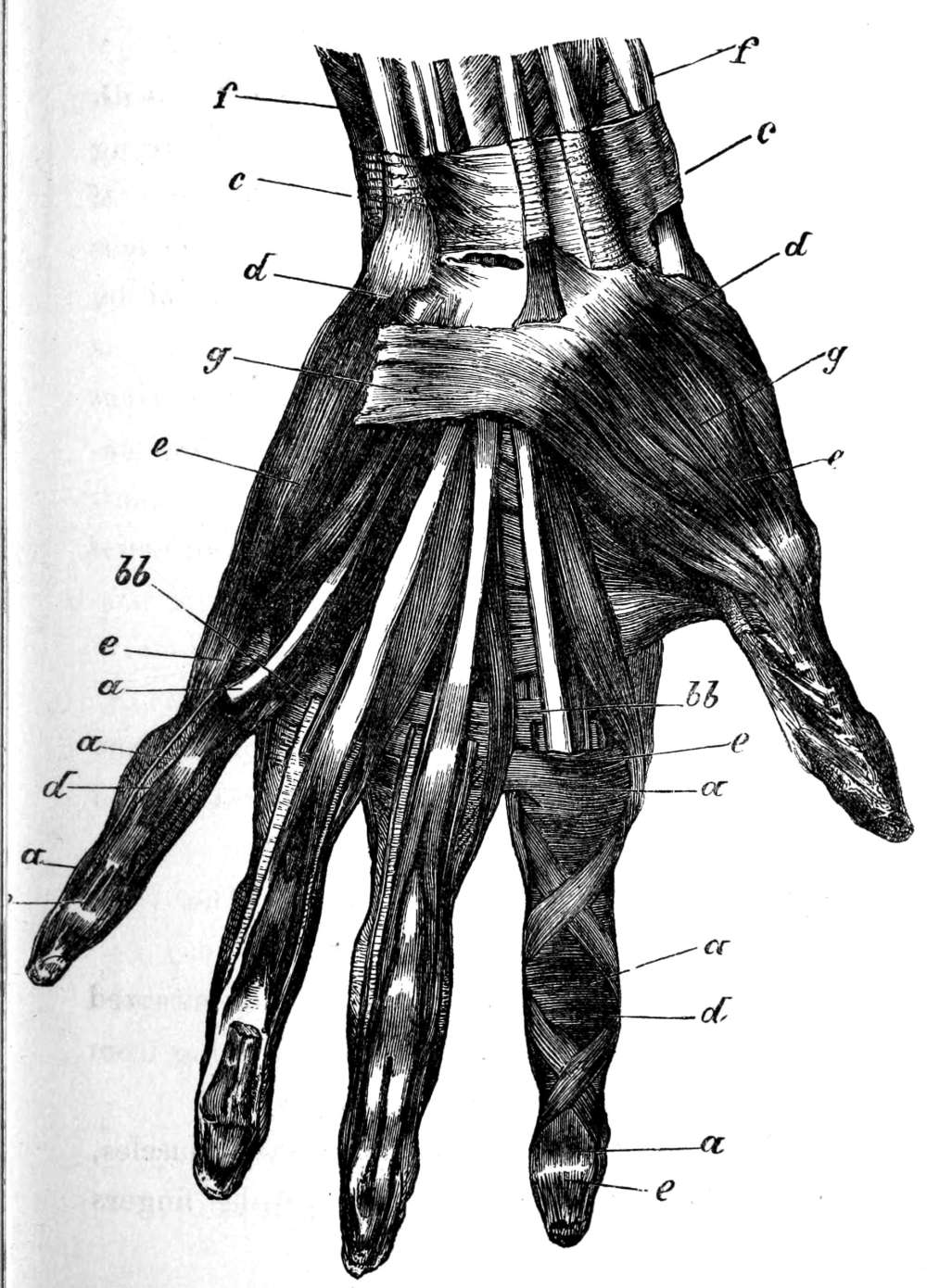

a. Extensors of the fingers, being situated in the back part of the hand and rising from the bones of the lower arm (Fig. 4 a).

b. Benders of the fingers. Two muscles, the one for the second joints of the fingers[Pg 28] (Fig. 3 d), the other for the first joints of the fingers and the joints of the nails (Fig. 3 e) also rising from the bones of the lower arm.

c. Contractors of the fingers, rising from the hand itself, between the bones of the middle-hand (Fig. 4 b), and extending as far as the first finger-joint (Fig. 4 b).

d. Two muscles, also rising from the cavity of the hand, and moving the little finger towards the thumb (Fig. 3 g).

Lumbricales, or Flexores primi Internodii Digitorum, are situated in the hollow of the hand, and pass to their tendinous implantations with the interossei at the first joint of each finger, externally and laterally, next the thumb (Fig. 4 a, b). These perform those minute motions of the fingers when the second and third internodes are curvated by the muscles, and therefore are used in playing musical instruments, whence they are named Musculi Fidicinales, or fiddle-muscles.[3]

[Pg 29]

[2] Luther Holden, Manual of Anatomy (London, 1861), Lecturer on Anatomy in Bartholomew’s Hospital. Hermann Meyer: Lehrbuch der Physiologischen Anatomie. Leipzig, 1856.

[3] William Cowper, Myotomia reformata. London, 1724. Richard Quain, Professor of Clinical Surgery, Surgeon Extraordinary to the Queen.

After the explanations just given, it may readily be conceived what effects the cylinders placed between the fingers and the gymnastic staff must produce on the joints and ligaments of the hand.

1. The ligaments connecting the bones of the middle-hand amongst themselves and with the fingers (Fig. 2 aa) are extended and stretched (Fig. 3 bb), and thus those joints, so important in playing on musical instruments, are rendered more moveable.

[Pg 30]

2. The connecting links between the bones of the middle-hand and the bones of the wrist are loosened (Fig. 2 bb).

3. Almost all the ligaments of the cavity of the hand are made flexible.

4. At the same time, all the muscles of the hand, and particularly the muscles situated between the bones (Fig. 4 b), generally so little practised, are stirred into activity by the cylinders, the stick, the staff, and the free exercises.

From the diagrams (Fig. 2 and 3) it may be plainly seen, what was mentioned before, viz., that the movement of the middle-hand and of the bones of the wrist in general, unless specially practised, is very inconsiderable; while through the cylinder gymnastics prescribed in this work, that limited movement of the bones is rendered more easy. It may also be seen from the diagrams that, if both the great and the small tight transversal ligaments remain still and firm, they impede and render more difficult the free movement of the fingers in every direction; and these ligaments will[Pg 31] always remain stiff and tight, unless they be specially trained.

For this reason the cylinder exercise, just mentioned, is particularly intended to loosen the impeding transversal ligaments, as well as to exercise and strengthen all the muscles of the hand and fingers.

[Pg 32]

To convince yourself that this opinion is correct, extend your fingers for two minutes only with the cylinders alluded to, and you will find that the fingers instantaneously move much more easily, and that the muscles, liberated from their tight, stiff neighbours, act with much greater freedom.

In the same manner as with the cylinders, the greatest advantage may be experienced from the use of the gymnastic staff or stick.

The principle on which these movements are founded is, that by them almost all the muscles of the hand and the fingers, the smallest as well as the largest, which in playing musical instruments and all the other occupations of the fingers bear the chief part, are stirred into action. At the same time, the extraordinary effect of the free exercises on the large finger-joints and on the ligaments and tendons is increased. And further—every portion of the hand and fingers, ligaments, tendons, joints, and particularly the muscles, are well practised, strengthened, and rendered flexible, by the fingers being[Pg 33] stretched and extended on, pressed and exercised against, a solid body. Finally, while imparting to the muscles of the fingers and hand far greater strength and ease than the continued quick movement on the musical instrument is calculated to affect, all these exercises affect the nerves in a lesser degree, and prepare the fingers for all kinds of work.

These results, observed and tested by me countless times, are of the greatest importance to all those who work with their fingers, but more particularly to those engaged in musical pursuits, who, instead of being overwhelmed with fatiguing work as before, will find that by these exercises their studies are facilitated and divested of much of their previous trouble and vexation.

The Wrist.

This joint, which for players on the piano and other instruments is of such great importance (Fig. 2 c), should also be exercised gymnastically; since, by means of the[Pg 34] gymnastic exercises here recommended, strength and flexibility will be gained in a very short time, and a great deal of trouble saved. Nor ought it to be overlooked that for all those who work with their fingers, a flexible, pliant wrist is a great help, and that by it all the joints of the hand are made to act harmoniously together.

[Pg 35]

[4] Anatomists and physicians of great eminence have observed to me, “Your anatomical researches have solved some important questions long held in dispute by physiologists, and are of great practical value.”

Many books have been written on gymnastics, but I am not acquainted with one which treats of the gymnastical exercise of the fingers. Why these important members of the human body should until now have been so much overlooked and neglected, it is difficult to understand. For, as Professor Richter in Dresden says, “Next to the more powerful development of the brain, it is almost exclusively the structure and skill of the fingers and hand which raises man above the brute, and has made him ruler of the earth.”

In order, therefore, to heighten the capacities of the human hand, the joints of the hand and fingers should, from early youth, be[Pg 36] exercised gymnastically, as much and in as many various ways as possible, partly by free exercises, partly by means of mechanical appliances.

Gymnastics, according to anatomists and physicians, is the stretching, extending, pressing, and training of the muscles, the ligaments, and the limbs of the body.[5]

Flexibility, agility, and strength can be[Pg 37] acquired only by means of a regular exercise of the muscles of the body.

Strength and power impart agility and quickness. This every physician and every sensible man knows.

A soldier only becomes fit for his work after the muscles of his body have been gymnastically attended to and developed. Any man, having to perform hard physical labour, must exercise his muscles gymnastically, and every one ought to exercise those particular limbs the use of which is most necessary for his profession.

And more than any one else, the teachers of music have to experience the consequences of a want of skill and strength in the hands of many learners, and they know how greatly a systematic educational training of the fingers and hands for the execution of the more delicate movements is needed at all times.

Nevertheless, there are many arts besides music for which the hand ought to be also trained from early youth, in order to be able permanently to accomplish, in later years,[Pg 38] what is excellent, e. g., many kinds of handicraft, machine-work, needle-work, anatomy, and surgery, writing and drawing, and all fine manipulations.

An untrained hand will either remain clumsy in these branches of work, or it will soon fail through over-exertion, which causes a peculiar kind of paralysis, connected with cramp, and well known to writers (the so-called writers’ cramp), but which also affects musicians, artists, shoemakers, tailors, sempstresses, and other working people. Certain it is, that if this matter had been inquired into before, and public attention directed to it, a great deal of trouble and vexation in learning music might have been saved; the labour of many working people of all classes, who chiefly have to use their fingers, have been greatly facilitated; and, moreover, many diseases of the joints of the fingers and hand might have have been prevented.

[Pg 39]

[5] The following quotations from the works of some of the leading authorities may be of interest to the reader:—

“Methodical gymnastic exercises of the hands and fingers afford the very best means of overcoming the technical difficulties.”—Schmidt’s “Annals of Medicine.”

“Technical difficulties will most safely and quickly be conquered by proper gymnastic exercises of the hand and fingers.”—Dr Dietz, Member of the Royal Council of Medicine.

“To obtain technical skill and muscular steadiness, a gymnastic education is the best means.”—P. M. Link. The gymnast exercises his limbs through preparatory exercises; how, therefore, is it possible for the player of the piano and violin to dispense with this gymnastic preparation of the joints of the hand and fingers?”—Prof. Rector v. Schmidt, President of the Royal Gymnasium. “La souplesse et l’étendue des poignets dépendent du développement gymnastique des forces. La gymnastique développe l’aisance et la grâce.”—Dr M. Bally. “For so great an art as piano or violin playing, the muscles of the fingers are weak; they ought to be prepared by proper gymnastic exercises.”—Ferguson.

To become a skilful musician is no small matter. There is no art which demands more labour, patience, and especially more time, than, for instance, piano or violin playing; and at least half of that time is for years required for the particular purpose of strengthening the muscles of the fingers, and rendering them flexible. And why so many years? Because the muscles, the ligaments, and the tendons of the finger-joints and wrists have not previously been gymnastically exercised and trained.

To prove in a practical manner that it is particularly important to prepare the muscles and ligaments of the fingers and hand, I will cite a fact which may appear startling,[Pg 40] but which, nevertheless, is true, viz., that the muscles and tendons of the fingers, in spite of their great importance, are, proportionately speaking, the least of all practised in daily life.

Take all sorts of people from amongst the labouring classes, such as the smith, the joiner, the gardener, the bricklayer, the stone-mason, the husbandman, the day-labourer, &c., &c. They are at work the whole day, and acquire arms like steel and muscle like giants; but they very rarely use the fingers, which, therefore, remain unexercised. And it is the same with the educated classes, without difference of age or sex.

This is the reason why the learning of piano and violin playing is attended with such great difficulties, and why the muscles and ligaments of the hand ought to be trained by proper gymnastic exercises. For their weakness arises, for physiological reasons, from the very fact of their inactivity.

This fact I will satisfactorily prove in the sequel, for it forms the basis and key of my discoveries.

[Pg 41]

In the opinion of many, the chief difficulty to be overcome in studying music consists in learning to read it. But this is by no means the case. The reading of music is learned in the same manner as a child learns to read letters. The first difficulties having been mastered, the task is easy; as with a printed book, so with music.

Consequently the paramount difficulty is not in the notes, but in the weakness and awkwardness of the fingers and wrists. From this, again, it may be plainly seen how necessary it is to train the fingers before commencing[Pg 42] the work of the head. In short, what is wanted is a regular gymnastic training for the muscles of the fingers, the joints, and the wrists; and it will be found that the following exercises, being as desirable as they are applicable for every age, will strengthen and render them flexible in a most surprising manner, will materially shorten the time of study, and save much labour; nevertheless, on that account the ordinary finger-practice, scales, and studies should of course NOT be omitted.

Suppose a boy from 10 to 14 years old, who is strong and healthy by means of gymnastics and other exercises, set to learn the piano or violin. His body is strong with gymnastic exercises, but his wrists and fingers are weak and awkward. How is he, with the method now in use, to succeed in playing an instrument well, without very long and wearying work? No wonder that the painful exertion almost makes him despair, and that finally he gives up the thing altogether. But if, on the contrary, his fingers and joints have been gymnastically trained and exercised beforehand,[Pg 43] he will get on easily and quickly, and continue his studies with pleasure.

Many presidents and teachers of the most celebrated gymnastic institutions have, therefore, come to the determination to introduce into their establishments these exercises in addition to the other branches of gymnastic training. Their practical utility for all those who work with their fingers, for anatomists, surgeons, sculptors, watchmakers, and many others, is as evident as their salutary effect;—from a medical point of view, in curvature and paralysis of the hand and forearm, in weakness of the muscles and nerves, writers’ cramp, and similar complaints,—is undeniable.

[Pg 44]

These exercises for persons engaged in musical pursuits can, least of all, be dispensed with, because music is the art which makes the highest demands on the muscles of the fingers and wrists.

Eminent physiologists say, “Gymnastic exercises for the fingers and joints ought to have been commenced 150 years ago; they form the real foundation of practical art.”

It is, indeed, incredible that so great an art as piano and violin playing should have arrived at so high a stage of perfection without[Pg 45] a previous training of the muscles. As a matter of course, this is only to be ascribed to the unremitting exertions and the indefatigable zeal of the teachers, and to the unwearying industry of the pupils. And how much easier might this have been attained!

The muscles, ligaments, and tendons consist of soft elastic matter, and, as has been stated, run partly longitudinally, partly transversely. This is a point to be borne in mind. It is, therefore, one-sided and erroneous to believe that the best means of strengthening the muscles consists in simply raising and dropping the fingers. All one-sided practice is hurtful; and an exercise of the fingers limited to an upward and downward movement, occasions much severe work. If, on the other hand, the muscles be moved according to physiological principles, in all directions, both laterally and up and down, and trained gymnastically, they will become within a very short time strong and flexible.

[Pg 46]

If any one should say that he has diligently studied the piano and violin after the method used at present, and in course of time has learned and taught it with the greatest success, without having found it necessary to trouble himself about any other system, my reply is, that music is one of the most beautiful, and with respect to muscular work, the most difficult of arts, and that all the arts and sciences, music not excepted, have made enormous strides in advance during the present century. But exactly because music has become a universal boon for all classes of the civilized world, one ought to be so much the less disposed to shut out new ideas respecting[Pg 47] it, from whatever side they may come. The representatives of this art, professional musicians and teachers of music, are generally the most active and often the most educated men, who devote their lives to the art, and promote it in a way which is hardly acknowledged sufficiently by the musical world. The most highly honoured, however, are those who have made the greatest progress in theory and in practice, or who have readily and generously acknowledged such progress, from whatever direction it might come.

It is, therefore, the duty of all to assist teachers of music and proficients, as much as possible, in promoting this beautiful accomplishment; for this reason, encouraged by persons of the highest distinction, and moved by the love of the art and of mankind, I venture to make known my “Gymnastics of the Fingers and Wrist,” and to offer to all who work with their fingers in general, and to musicians in particular, a means which, based on physiological principles, leads most surely to the attainment of artistic execution, and[Pg 48] which is in itself so simple, that any child may use it; a means, too, which will effect a great saving of time and facilitate the work of both teachers and students.

I have only to add that, as a matter of course, these exercises, in order to have the desired effect, should be performed gymnastically and regularly, according to the directions given, and not otherwise; whilst, on the other hand, they ought not to be carried to excess, nor are they intended to supersede the usual finger-exercises, scales, and studies.

[Pg 49]

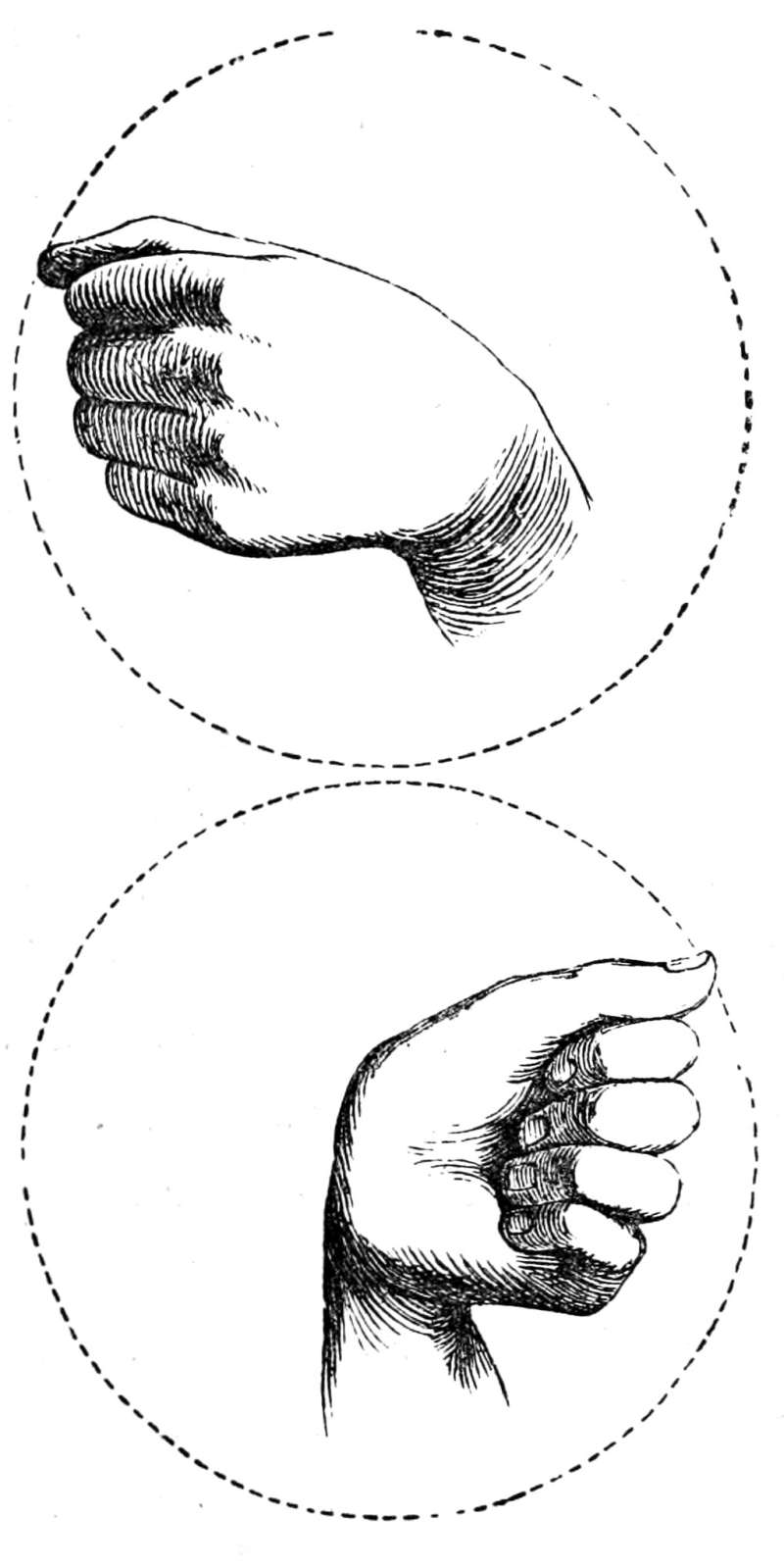

Stretch the fingers as much as possible one from the other, let them fall on the large muscle of the thumb (thumb-ball), and press[Pg 50] them firmly on it; remain for a moment in this position, and bring the thumb against the forefinger, 40 times up and down.

You will find that this exercise, as well as several others, if vigorously continued for three minutes only, is very fatiguing; a clear proof that the muscles of the fingers, although they may be quite fit for ordinary daily occupations, are, nevertheless, very weak and incapable when anything more is demanded from them, and without proper gymnastical training, they must remain so.

Stretch the fingers as before, but let the[Pg 51] finger-ends fall against the middle of the cavity of the hand, instead of against the great muscle of the thumb, and press them firmly. To be repeated 40 times.

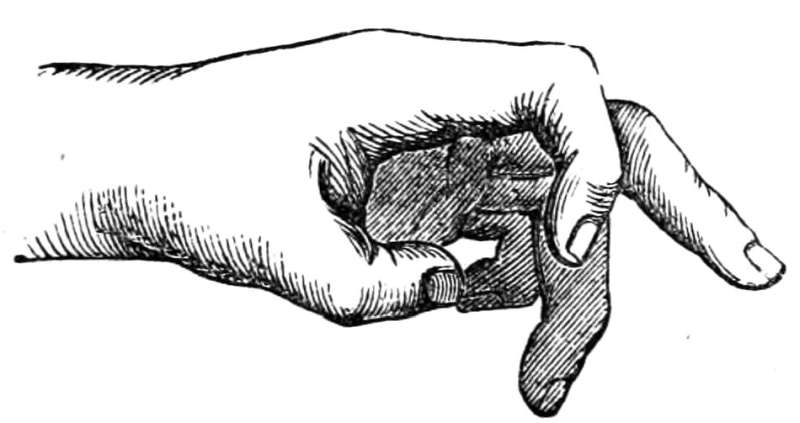

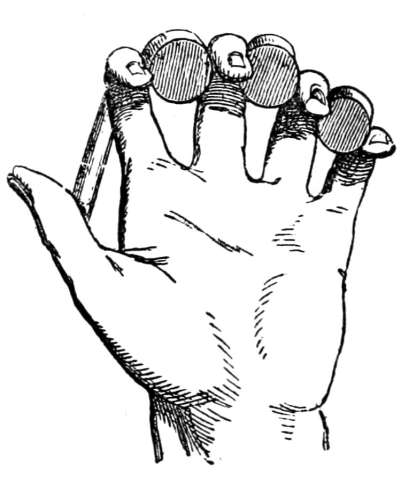

The following exercise (9 and 10) is intended particularly for the small joints of the fingers. It is effective, but difficult.

Do not stretch the fingers away from one another, but hold them firmly and close together, as this produces the effect particularly desired. Bend the two first finger-joints of the four fingers closely together; move them[Pg 52] vigorously up and down, and press them on firmly, without, however, moving the large joints. Repeat this movement until you are tired, which will not be long, thus affording another practical proof how weak the untrained finger-joints are. This is also an excellent exercise for the thumb, provided it is made slowly and vigorously. It may also be made with outstretched fingers.

I again repeat that no one who has not already tried the above or similar exercises of the fingers, will be able vigorously to continue them for even so short a time as three minutes without experiencing painful fatigue. And why? Because, as I have demonstrated before, the joints of the fingers and wrists are, in the ordinary occupations of life, the least of all exercised, and consequently the weakest, in comparison with what they have afterwards to perform.

After this experience people will, in future, hardly venture to teach and to continue the exercise of an art like music (which, from a muscular point of view, is the most difficult[Pg 53] of all), with muscles the weakest and least trained, without having previously prepared them by proper gymnastic exercises.

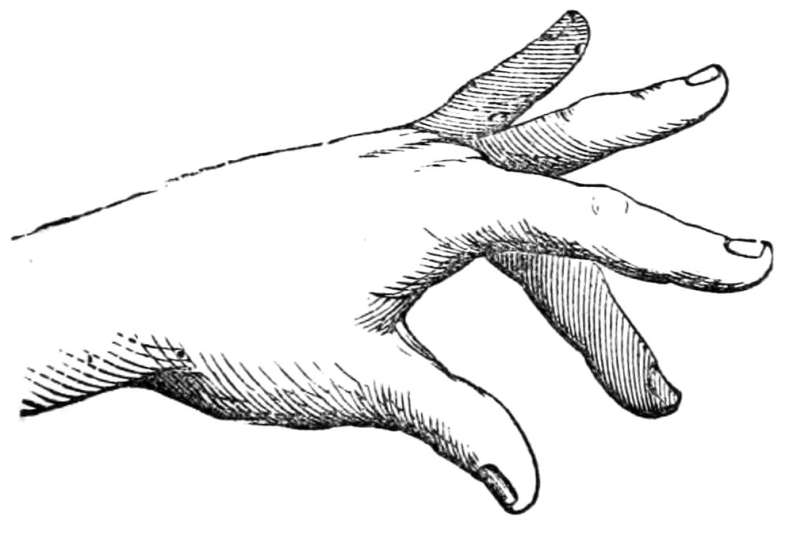

The last free exercise for the finger-joints, which I will recommend here (11 and 12), consists in moving all the fingers and the[Pg 54] thumb simultaneously together, that is to say, in stretching them far away from one another, like claws, and making all sorts of eccentric movements in whatever direction you please, and as long as you like or are able, but always vigorously.

[Pg 55]

Although it is not easy to prescribe complete gymnastic exercises for the thumb, the following, if made vigorously, will, nevertheless, be found very effective.

[Pg 56]

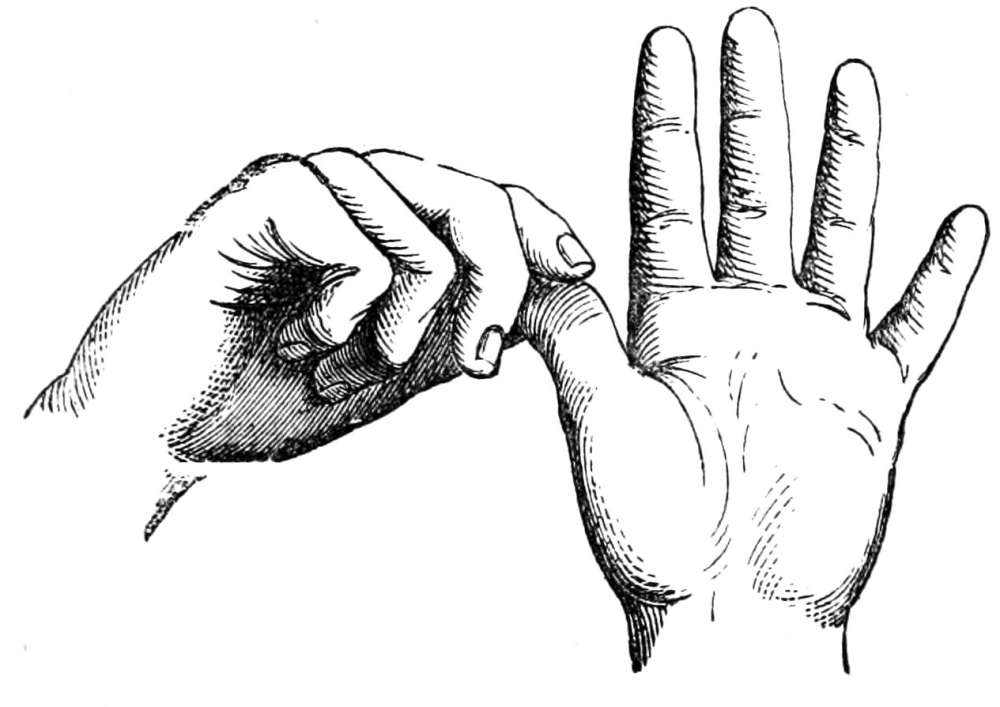

Stretch the fingers as far as possible away from one another, then press the hand firmly together, the thumb being held fast in the cavity of the hand; continue for a moment in this position, and then repeat the same movement, alternately opening and closing the hand.

Hold the fingers close together, stretch out the thumb, and then perform with the latter a circular movement inside the hand, first 20 times to the right, then 20 times to the left: to be repeated again and again.

[Pg 57]

Take hold of the thumb of the one hand with the fingers of the other, or with the whole hand, and shake it or bend it to its root, without, however, overdoing either.

In short, perform every day some exercise with the thumb, whereby it will be sufficiently brought into exercise.

[Pg 58]

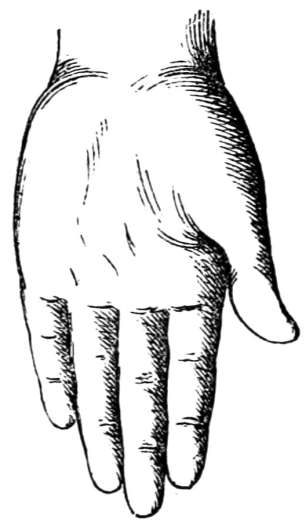

Move the wrist, without moving the arm or elbow, vigorously up and down in a perpendicular direction, from 20 to 40 times, first[Pg 59] slowly, then more quickly; finally, as quick as possible. In doing so, let the elbows rest close to the body, so as to bring both hands and wrists into the proper position. As soon as you are tired, leave off.

Move the hand horizontally or vertically without moving the arm.

To understand the practical utility of this exercise (19, 20), it ought to be borne in mind that the entire action of the wrist is effected by two principal joints, one of which, the smaller of the two, lies at the root of the hand, and is[Pg 60] called the “joint of the hand,” by means of which it becomes possible to move the hand, independently of the arm, at its root. The other joint, the larger of the two, rises from the elbow, and is called the rotatory joint of the forearm. Holding, then, all the five fingers close together, move the smaller joint perpendicularly or horizontally, as you please, without in any way moving the arm, and at the same time holding the elbow close to the body.

Move the wrist in a slanting direction right and left, as above, first slowly, then quicker and quicker. Hold the elbows as before. By[Pg 61] this movement, both the joints mentioned above will be put into action, 21, 22.

The young violinist, who generally finds the[Pg 62] sideways movement of the wrist of the right hand so difficult, will derive great advantage from all these wrist exercises.

Holding your arm quite still, move the free hand or fist vigorously round in a circle, 20 times to the right, and 20 times to the left, first slowly, then more quickly. By this exercise all the muscles of the hand and the arm will be put into motion, and though the most difficult of all, this is at the same time one of the most important exercises.

All these several free movements of the hand and fingers may be repeated many times, with advantage; still by simply performing them, short though they be, daily and regularly, the prescribed time only, the desired end of strengthening the muscles of the fingers and wrists, and rendering them vigorous and flexible, will be surely attained.

I could mention some other free exercises of the fingers; but since they are neither so practical nor so effective as those I have already described, I prefer to omit them.

[Pg 63]

[6] One or two of these exercises may possibly have been mentioned in some former work.

Take for each hand three cylinders, three quarters of an inch long, and from half to one inch in diameter, according to the size of the fingers; place them between the upper ends[Pg 64] of the fingers, and while gradually and conveniently extending the muscles, by bending the fingers, move the latter as shown by the above figures, 24 and 25.

Move the cylinders further down, to the roots of the fingers, and perform the exercises according to Figs. 26 and 27. In doing this, put a small round piece of wood between the thumb and the forefinger, at a distance sufficient to extend the former as much as possible.

Leaving the other fingers as before, put a large cylinder between the thumb and[Pg 65] forefinger (28 and 29), so as to entirely fill up the intervening space. In doing this, be careful to extend the thumb as much as possible. In case the tension of the fingers is small, take smaller cylinders: or if the latter should be too hard for tender hands, cover them with some soft substance, such as velvet, or the like.

Third movement.

Perform all these exercises vigorously, and, if possible, just before practising the musical instrument, twice or three times daily, each time for a few minutes, especially in the morning,[Pg 66] on getting up. As a matter of course, after eight or 10 hours rest, the muscles of the fingers and wrist, like those of the rest of the body, are somewhat stiff, and ought to be prepared by proper gymnastic exercises, before beginning to play. Besides, provided over-exertion be avoided, there is not, according to the best medical authorities, the least danger to be apprehended, from these exercises, for the joints and muscles of even the very smallest hands.

If players of the piano and the violin should object that, in the act of playing, the fingers need not be as much extended as prescribed here, or assert that the finger-exercises, scales, and études as at present used are perfectly sufficient, and that nothing more is wanted, I can only repeat, that the fingers must be prepared in order to render them strong and flexible; that, for this purpose, it is necessary to exercise them gymnastically, and that, as I have explained before, these preparatory exercises will save much time and trouble, and facilitate the work of both teachers and pupils;[Pg 67] further—that, by the diligent practice of these gymnastics, the fingers become elastic and independent of each other; you acquire thereby complete control over them, and when you have done this, you can move them and do with them as you will.

Another most effective mode of stretching and loosening the tendons and ligaments which encompass the large middle-hand bones, or “knuckles,” may be performed as follows:

Place the forefinger of each hand, up to the middle joint, firmly on the table, and in that position press it up and down with a certain degree of force, for a few seconds; then withdraw it, and apply the next finger in a precisely similar manner; then the two other fingers in succession, each finger remaining on the table alone, unaccompanied by any other.

Afterwards apply the 2nd and 4th together, exactly in the same way, for a few seconds; then the 3rd and 5th; lastly the thumb.

The pupil may do this many times a day with great advantage; for by this process the ligaments and tendons of the knuckles[Pg 68] are stretched and loosened, and the muscles are set free.

Of course always with due moderation.

Another very important exercise, bearing chiefly on the tendons and ligaments of the large metacarpal joints or knuckles, is the following:

With the thumb and forefinger of the one hand take hold of one finger of the other hand, and shake it up and down, for one minute, to its root. Then take the other fingers in succession in like manner. To be applied equally to both hands, and to be done, especially with the 4th and 5th fingers separately, as often as leisure permits.

To this category belongs also ANOTHER EXERCISE of the metacarpal joints or knuckles. Into the palm of one outstretched hand place the closed fingers or fist of the other: then open and close the latter as fast and as long a time as is agreeable, always continuing to press[Pg 69] upon the palm. Change hands and repeat. Ever remember that the difficulties of bringing the fingers into order lie, physiologically, almost all in the middle-hand bones or knuckles; and as the five preceding exercises,—and especially the three last,—act in a very efficient and special manner upon the ligaments, tendons, and muscles of these and the other joints of the fingers, they cannot be made too often.

[Pg 70]

It is not sufficient to play the ordinary finger-exercises and scales. As has been shown in the opening chapters, and in the anatomical representations of the hand, all the fingers are not equally strong; for instance, the 4th and 5th fingers are, by nature, much weaker than the others, and it is necessary to remedy this inequality.

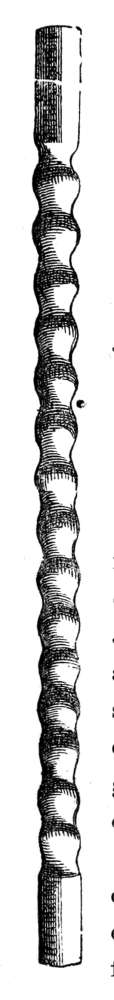

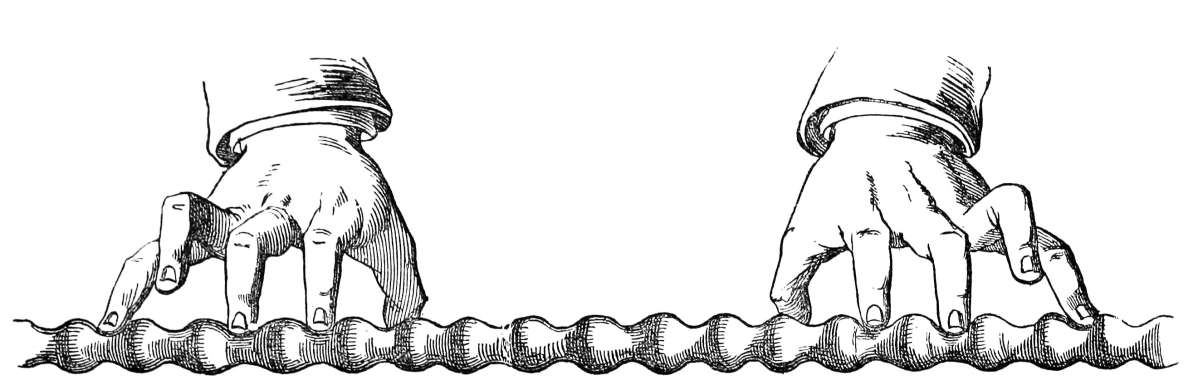

Each finger ought, therefore, to have gymnastic exercises for itself, and they ought to be performed on some solid body, which can be firmly grasped. For this purpose take a round staff, from 12 to 18 inches long, and half to three quarters of an inch thick, on which, at a proper distance from one another, round[Pg 71] indentations are made, and into which the fingers are to be placed after the manner illustrated in the adjoining and following figures.

Directions.

Place the thumb of each hand on one side, and the four fingers very firmly fixed on the other side of the staff; raise one finger as high as possible, and let it fall down vigorously, like a hammer, 20 times in succession, while the three remaining fingers, stretched out from one another, like claws, remain immoveable. In the same way exercise the other fingers; firmly, slowly, vigorously, and immediately after the cylinder exercises just described. Repeat this three times daily, each time for five minutes, altogether for 15 minutes a day, but the oftener it be done the better.

Those playing the piano need not confine themselves to one particular exercise, but may make use of all the figures at pleasure.

[Pg 72]

[Pg 73]

[Pg 74]

The fingers of the left hand may also be trained for violin playing, as seen in Fig. 35.

Further upon the same. After the cylinders, by far the most effective of all means for imparting, gymnastically, strength and flexibility to the fingers, together with evenness of vigour, individuality, and independence, is, daily, in the room, or while walking, to take the above-named staff, or, indeed, a smooth round stick of 18 inches long, and half to three quarters of an inch thick, or an ordinary walking-stick, and to perform on it as follows—With[Pg 75] the four fingers of one or both hands firmly pressed and stretched upon it, raise one finger as high as possible, and, as above stated, let it fall down upon it vigorously, like a hammer, while the other fingers remain firmly pressed on the stick, 20 to 30 times in succession, then in couplets with the 5th and 4th fingers, then with the 4th and 3rd, then with the 3rd and 2nd, 20 times each, the two fingers, in all cases, as stated, lifted as high as possible, and the others remaining, stretched at even distances, firm upon the staff; finally, with the four fingers of each hand, 12 times ascending, and 12 times descending, but always SLOWLY, energetically, with firm pressure, “and in time.” You may occasionally practise a little faster, but it must be the exception. Slow moving, pressing, and stretching should from the chief gymnastic rule.[7]

[Pg 76]

In a similar manner you may practise, slowly and with energy, with one or with both hands, all sorts of difficult, muscular movements and passages upon the staff, for example:—

First series. In couplets 20 to 30 times each in succession, with the 2nd and 4th fingers, alternating, afterwards, with the 4th and 2nd; then with the 3rd and 5th fingers, alternating with the 5th and 3rd; in each case the two fingers stretched wide apart, and the other fingers pressed upon the staff.

Second series. In couplets 20 to 30 times each in succession, with the 2nd and 3rd fingers, first close together, then wide apart, afterwards alternating in the same way, with the 3rd and 2nd. With the 3rd and 4th fingers first close together, then wide apart, afterwards alternating, in the same way, with the 4th and 3rd. With the 4th and 5th fingers, first close together, then wide apart, afterwards alternating in the same way, with the 5th and 4th. In each case slowly, the two fingers lifted as high as is convenient, 20 to 30 times in succession,[Pg 77] and the other fingers remaining firmly fixed upon the staff. Lastly, all the four fingers together, in each of these varied and different directions.

The number of times of each movement, and the duration of time, also whether all should be made at the same hour, or otherwise, is left to the discretion of the teacher and pupil. I would recommend, at first, the selection of three or four modes or exercises for persistent practice, to last over a given period of time, then to change to others.

But the regular exercise of the whole or part of them, daily, will, in a comparatively short time, most surely impart immense strength to, and render flexible, the muscles and joints of the fingers; will enable you, if the directions be duly followed, to effect for yourself perfectly equal and even fingering, and render the fingers entirely independent one of another.

But let all be done with due moderation, and not driven to excess.

This gymnastic staff, or walking-stick exercise, however simple it may appear, should, on[Pg 78] no account, any single day be omitted. It produces a most surprising effect if carefully and vigorously made; an effect which will be the more remarkable in proportion as the fingers are pressed and stretched far away from one another. By this means all the various muscles, and even the tendons, joints, and ligaments are put into motion, and both fingers and nerves are rendered strong and firm. Besides, no time need be lost; as in performing these exercises you may converse or engage in other occupations.[8]

In this manner, also, the 4th finger may have a special training, and become equally strong with the others. This finger is, on physiological grounds, the weakest of all, and after a number of vain attempts at remedying its well-known weakness, some physiologists of note in Germany, have gone so far as to suggest the idea whether it would not be well to cut the[Pg 79] ligament joining the two fingers, in order to set the 4th finger free.

But it is unnecessary to have recourse to such rude and unnatural measures; the natural weakness of the 4th finger may be effectually remedied, and may be entirely overcome, by the above exercises. The same exercises, if performed strictly according to the directions given above, are extremely useful for all the fingers, which they will render both strong and flexible.

These exercises may be partially performed on musical instruments; but they are far more effective if made gymnastically, as directed, because the fingers, in having a resting point, or lever, and having something firm to grasp, are enabled to perform them gymnastically.

[Pg 80]

[7] The late Mr Clementi was celebrated for the perfect evenness and beauty of his touch in playing rapid passages on the piano. The means by which he attained this execution he was unwilling to disclose. It is now known that he effected it by playing his scales VERY SLOWLY, and with great pressure of each individual finger (see page 96).

[8] The celebrated violinist, Bernard Molique, told me lately, in London, that when he was called on to play difficult solo pieces in public, he very often played them previously over upon a stick.

Moreover, beautiful works of art, like pianofortes, violins, and other musical instruments, ought not to be used as gymnastic implements. They are destined for play, not for gymnastic appliances. The fingers and joints ought, therefore, first to be gymnastically exercised; then play upon the instrument.

The head and the fingers ought to go together; but how is this possible if the latter remain behind? The mind strives forward, the fingers keep it back. Why should this torture be inflicted? No; let the fingers first be properly trained; then head and fingers will go harmoniously together.

[Pg 81]

Another great advantage attending the above exercises is, that so long as they last, the organs of hearing are spared. Many persons, who zealously and with endurance perform finger-exercises on musical instruments, injure their health, through the irritation of the auditory nerves, to such a degree, as either to be prevented, on medical authority, from continuing to practise, or otherwise to be subjected to serious consequences; whereas, if the exercises are preceded by the gymnastic movements given above, the hearing organs of the pupil will be greatly spared, and not injured in any way.

The greatest technical art consists in controlling alike the fingers, the joints, and the nerves. Now, if the muscles and tendons are exercised and strengthened by proper physical work, the nerves will be invigorated at the same time. This is a well-known fact, and for those engaged in musical pursuits, an advantage which it is impossible to overrate. The fingers then will not be fatigued as easily as[Pg 82] before, and you learn at the same time by habit, to acquire complete control over the joints, the muscles, and nerves.

Nor ought another advantage to be overlooked; viz., that in regard to artists and persons who play well, when these travel, or from any other cause are prevented from playing for some time on a musical instrument, they will be enabled, in the manner described above, to exercise efficiently for a short time daily their fingers and joints. Thus the fingers and joints will not get stiff, and you will always remain their master.

However, to attain this end, the exercises on the stick ought not be performed carelessly, but gymnastically, and STRICTLY according to the directions given above.

The same exercises are very useful for persons playing the violin, by promoting the proper bending of the forefinger of the left hand.

Generally speaking, the whole of the above

exercises are equally fit for all persons playing[Pg 83]

the piano, the organ, the violin, the violoncello,

and other instruments; and they will find,

after having accustomed themselves to perform

them vigorously and gymnastically for a short

time daily, that they then come to the instrument

with a strength and individuality of

finger which will exceed their utmost expectations.

[Pg 84]

Take a board, about 22 inches long, four to five inches wide, and three quarters of an inch thick, and mark out on it four or five grooves, about half an inch deep. To fix this board on the table, have a little ledge glued on to one of its sides, as in Fig. 36 and 37.

Place the outstretched hand on the board; stretch the thumb and the little finger as far as possible away from one another, into one of the grooves, place the other fingers into one of the other grooves, and set them in motion, while holding the thumb and little finger firmly in their places.

[Pg 85]

[Pg 86]

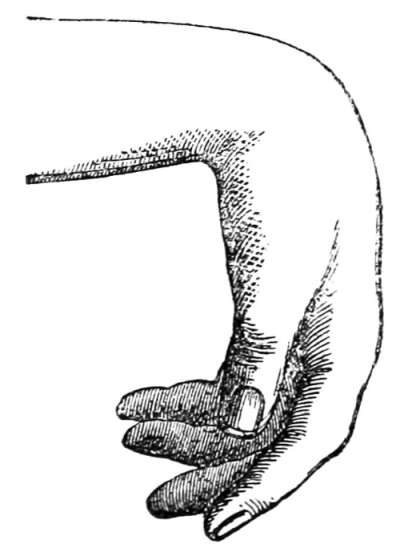

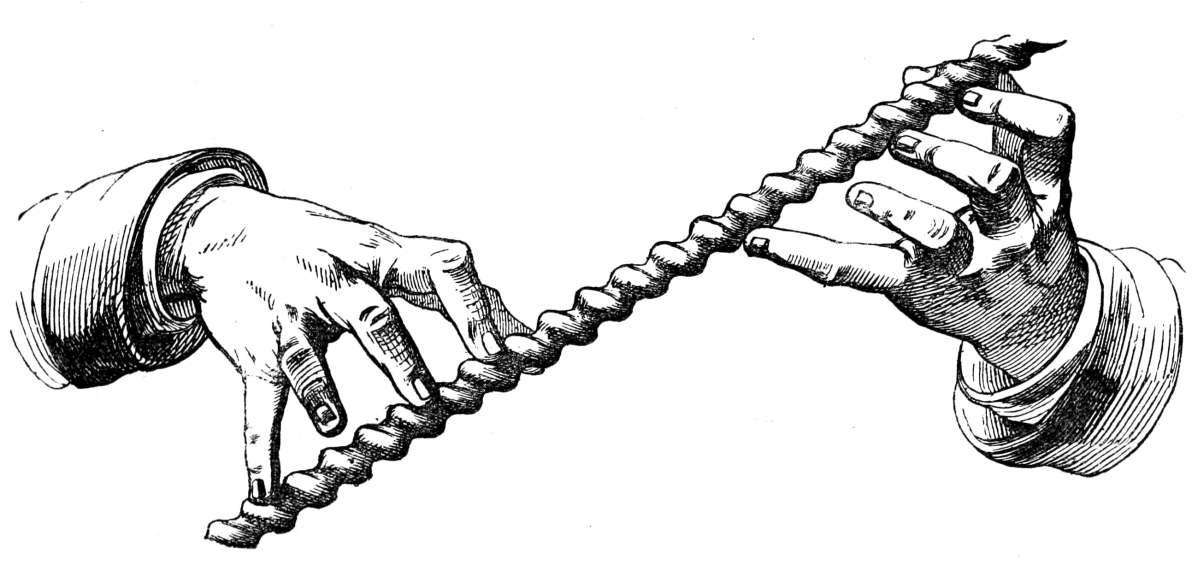

The following mechanical gymnastic exercises refer to the wrist of the right hand, and are intended for players on stringed instruments. Their chief purpose is to render the wrist of the right hand and the forearm strong and flexible. This all students find very difficult; it will soon be evident for what reason.

It is a fact acknowledged by the most celebrated musicians, that the principal bowing difficulties in playing the violin arise from the wrist. This is chiefly owing to the circumstance that, in playing the violin, the movement sideways of the wrist is a peculiar one, being, in fact, totally different from any other[Pg 87] movements taking place in the ordinary occupations of life. If, therefore, it be desired to diminish the painful work, as customary at present, it is indispensable to prepare the wrist and arm by exercises like those we are about to describe.

Take three times daily, and particularly early in the morning, a stick or cane exceeding the length of a violin bow by 8-10 inches, holding it in your right hand the same as a bow; lay it on the left hand,—which is to be raised to the same height as if playing the violin or violoncello,—and move it vigorously up and down as follows:

1. The entire length, 30 times;

2. The middle length; with the forearm and wrist only, without moving the upper arm, 30-40 times;

3. At the nutt; with the wrist alone,—and especially up-stroke,—with energy; without in the least moving the arm, 30-40 times;

4. At the extreme head-end; with the wrist alone, and with pressure; without in the least moving the arm, 30-40 times.

[Pg 88]

Move the cane alternately up and down, pressing it with the thumb and forefinger, and look at the direction of the wrist and the stick or cane. With this gymnastic cane you may exercise gymnastically, at pleasure, up and down strokes, triplets, and all sorts of bow-movements. The effect you will find surprising.

These exercises are particularly useful for the student. As a matter of course, they can also be partially made with the bow, but not with the same effect.

[Pg 89]

There is another very effective gymnastic exercise for strengthening and rendering flexible the wrist of the right hand. A movement resembling it has already been described above, but to prevent any misconception, I think it well to give explicit directions respecting it here.

Take hold with your right hand of the extreme end of a long and rather heavy Alpenstock, and while continually keeping the hand in the same place, move it upon the upheld left hand vigorously up and down:

1. With the whole arm, 30 times;

2. The middle length, 25 times;

3. As near as possible to the lower end, with the wrist alone, without in any way moving the arm, 30 times;

[Pg 90]

4. As near as possible to the upper end, with the wrist alone, and especially up-stroke, without in any way moving the arm, 30 times.

This exercise, on anatomical grounds, produces a considerable effect on the muscles and sinews of the wrist and the forearm, in imparting to them the wished-for strength and flexibility.

Besides, it is a well-known fact that, having handled a heavy object, it is more easy skilfully to handle a lighter one.

If it should be objected that the last-mentioned gymnastic exercises, being of rather a rough kind, might spoil the elegant stroke, my answer is, that those so-called rough exercises only last a very short time daily, and are undertaken for the special purpose of rendering the arm and wrist strong, easy, even, and flexible. Indeed, if these right-hand exercises are made carefully and according to the directions given, a short time every day, they will strengthen the wrist of the right hand and render it pliant and flexible to such a degree, as to enable persons, in a comparatively[Pg 91] short time, to play with the wrist almost as vigorously as with the arm.

There is, moreover, another advantage attending these exercises, viz., that, if continued for some weeks only, and for a few minutes daily, they will soon give the proper position to the student’s arm, which, consequently, will not be required to be tied to the body, as was often done in former times.

[Pg 92]

A famous German chamber violinist once remarked to me, “I find that staccato playing is the best exercise for bowing, but I can’t say why.” The reason, however, lies in the fact that, by frequently playing with the end of the bow, or with the staccato-stroke, the muscles of the wrist are put in motion, thus undergoing a gymnastic training by which strength and flexibility are acquired.

It is impossible to perform the staccato-stroke well, unless the muscles of the wrist have become strong and agile; and the reason why the student finds this stroke in most cases so difficult is, that the wrist has not been specially trained and prepared, in consequence of which it remains weak and stiff.

[Pg 93]

It ought to be remembered that in almost all kinds of handiwork in daily life, the whole arm is active and in motion, and very rarely the wrist alone. With musical instruments, on the contrary, and particularly in playing the violin, it is necessary always to use the wrist, and it is impossible to play well unless the wrist has been rendered strong and elastic. It is, therefore, absolutely indispensable that proper gymnastic exercises should be made with the wrist, in order to prepare it. The wrist, indeed, ought to be accustomed, in other words, to move of itself, and the student ought, as often as possible, to perform all kinds of movements calculated to impart to it pliancy and strength. It will then soon become free and easy, and the student will, in course of time, acquire the strongest, most elegant, and artistic stroke.

No single one of these practical gymnastic exercises ought to be despised on account of its simplicity. Only try them, and they will be found very effective. All sensible artists and teachers will do homage to every improvement,[Pg 94] and consider it their duty to welcome any assistance calculated to diminish and render lighter the arduous toil, and shorten the valuable time required for becoming a proficient in music.

[Pg 95]

I will only add in conclusion, that it would be well not to continue too long with the same gymnastic exercise, but to allow the muscles and joints some change, which will be found both agreeable and advantageous. If, therefore, the student be tired of one exercise, he should begin another. Besides, if the fingers are fatigued and hot by playing, and the nerves irritated, an exercise of some of the different free or mechanical gymnastic appliances will refresh the muscles, by imparting to them a new and an easier movement. And be it remembered, “these exercises are not irksome, but recreative.”

It may also be recommended in such cases,[Pg 96] to dip the points of the fingers for half a minute into half a glassful of cold water, and let them get dry of themselves, thus cooling by evaporation; or still better, wash the hands with soap and water.

To sum up: No student ought to begin to learn or to play the piano, violin, or other musical instrument, or even to engage in any work or occupation requiring a strong and flexible hand, before having set the joints of his fingers and hands in order, by means of preparatory gymnastic exercises; and he ought to continue the same from day to day.

Let it ever be borne in mind that much rapid playing affects injuriously the muscles and nerves; while, on the other hand, slow exercises and studies invigorate them.

To borrow an illustration from the animal world; take the race-horse, the fleetest animal which we use in this country, whose great task requires that his muscle should be brought into the highest condition of strength and flexibility. Do you suppose that, in training and preparing him for the race,—a[Pg 97] process often extending over a considerable period,—that he is, in the course of it, much galloped? By no means! Galloping forms the exception, and, during this long interval, walking, trotting, and cantering form his chief training paces; namely, four-fifths or seven-eighths of the time; galloping only one-fifth or one-eighth part! His skilful trainer knows that much rapid exertion, such as galloping long continued, weakens and wears out his muscle. So, also, in the hunting-field and on the road, it is “the pace that kills.” Even so with the player upon a musical instrument; long continued, rapid movements wear out the muscle and shake the nerves, while slow exercises, however vigorously executed, invigorate and strengthen both (see p. 75, note).

The exercises for stringed instruments will be most satisfactorily performed before a looking-glass, and I may here add that a little work by the author, entitled “Gymnastic Exercises for the Violin and Violoncello,” having for its special object the exercise of the[Pg 98] wrist of the right hand on the instrument, will be published in a short time.