Title: A United States Midshipman in the Philippines

Author: Yates Stirling

Illustrator: Ralph L. Boyer

Release date: February 19, 2022 [eBook #67438]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Penn Publishing Company, 1910

Credits: D A Alexander, David E. Brown, University of Michigan for the original scans and the color image of the cover, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by the Library of Congress.)

SOME ONE TURNED ON THE

CURRENT

by

Lt. Com. Yates Stirling Jr. U.S.N.

Author of

“A U.S. Midshipman Afloat”

“A U.S. Midshipman in China”

“A U.S. Midshipman in Japan”

“A U.S. Midshipman in the South Seas”

Illustrated by Ralph L. Boyer

THE PENN PUBLISHING

COMPANY PHILADELPHIA

MCMXIII

COPYRIGHT

1910 BY

THE PENN

PUBLISHING

COMPANY

The writer has attempted to describe in this volume the life of two young midshipmen of the United States Navy, serving in a small gunboat in Philippine waters.

The fighting between the United States troops and the lawless bands of Filipino bandits (for they were bandits, more or less, after Aguinaldo’s army had been dispersed) was in most cases “hand to hand” and to the death. The navy had but small share in this war, but in some instances the helpful coöperation of their web-footed brothers saved the soldiers from embarrassing situations.

Midshipman Philip Perry and his classmate at Annapolis, Sydney Monroe, first made their appearance in “A United States Midshipman Afloat.” They had a part in stirring adventures during one of the frequent South American revolutions. Here they became involved in diplomatic intrigue, and had some success; but unfortunately diplomatic successes cannot always be proclaimed to the world.

[4]“A United States Midshipman in China” told of the adventures of the same boys in China during a threatened uprising of fanatical Chinese against the foreigners. Here again diplomacy counseled silence, and their reward for saving the day was a mild rebuke from their admiral. One of the principal characters in all three books is Jack O’Neil, a typical modern man-of-war’s man.

These books are written in an endeavor to portray the life led by young officers in the naval service. The writer’s own experiences warrant the belief that the incidents are not unusual. The midshipmen are not merely automatons. To one of Napoleon’s pawns an order was an order, to be obeyed, right or wrong. But the doctrine, “their’s not to reason why” when “some one has blundered” is no longer accepted as an excuse for poor results. In these days of progress we court-martial an officer who stubbornly obeys an order, when he knows that to do so will injure the cause he has sworn to uphold.

Further account of the boys’ stirring adventures will be found in “A U. S. Midshipman in Japan” and “A U. S. Midshipman in the South Seas.”

| I. | The Start for Palilo | 9 |

| II. | A Polite Captor | 25 |

| III. | A Leak of Military Information | 41 |

| IV. | Landed in Captivity | 54 |

| V. | Captain Blynn Marches | 71 |

| VI. | The “Mindinao” | 83 |

| VII. | The Gunboat Coöperates | 101 |

| VIII. | The Privileges of Rank | 119 |

| IX. | The Katipunan Society | 138 |

| X. | In the Shadow of a Suspicion | 158 |

| XI. | A Traitor Unmasked | 175 |

| XII. | The Midshipmen Reconnoitre | 189 |

| XIII. | Unwelcome Companions | 212 |

| XIV. | Cleverly Outwitted | 225 |

| XV. | A Night of Alarm | 241 |

| XVI. | A Filipino Martyr | 259 |

| XVII. | A Daring Plan | 277 |

| XVIII. | A River Expedition | 292 |

| XIX. | A Willing Captive | 308 |

| XX. | The Struggle for the Stronghold | 324 |

| XXI. | The Gunboat Takes a Hand | 336 |

| XXII. | The Escaped Outlaw | 346 |

| XXIII. | Colonel Martinez | 355 |

| XXIV. | The Gunboat on Guard | 366 |

| XXV. | Conclusion | 377 |

[6]

| PAGE | |

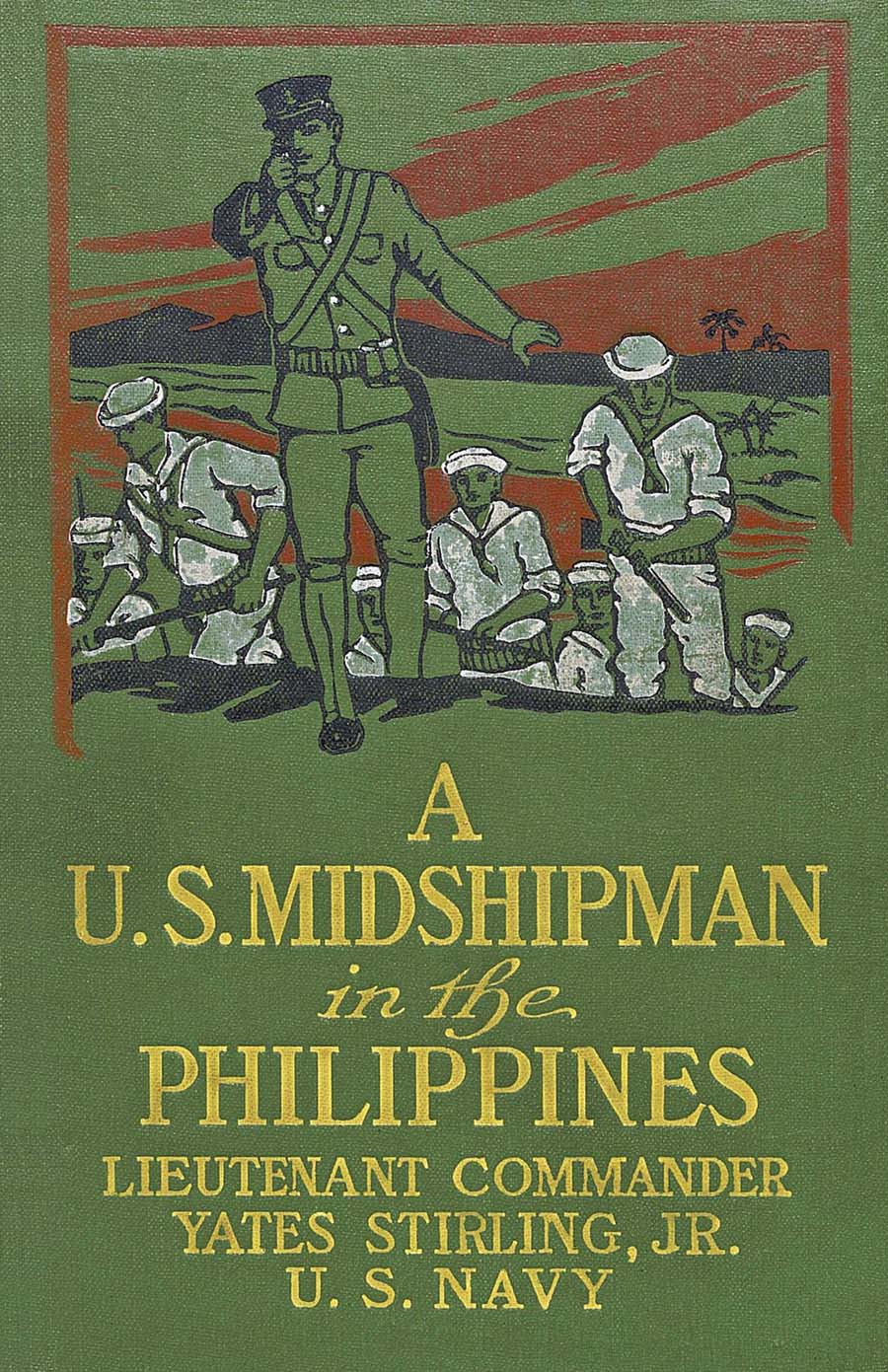

| Some One Turned On the Current | Frontispiece |

| Here was Freedom Within His Grasp | 69 |

| “I Am In Command Here!” | 126 |

| “Hello, Here Are Some Canoes!” | 205 |

| Up the Face of the Cliff | 288 |

| He Gazed Down Into the Still Face | 333 |

| A Man Stepped Silently From Behind a Tree | 356 |

[8]

A United States Midshipman

In the Philippines

The “Isla de Negros,” a small inter-island steamer, lay moored alongside the dock in the turbulent waters of the Pasig River, the commercial artery of the city of Manila. As the last of its cargo was noisily carried on board by a swarm of half-naked stevedores, the slender lines which held the steamer to the stone quay were cast off, and with many shrill screeches from its high treble whistle the steamer swung its blunt bow out into the strength of the current.

On the upper deck of the vessel, clad in white naval uniforms, two United States midshipmen stood in silent contemplation of the activity about them. They watched with undisguised interest the hundreds of toiling[10] orientals; resembling many ant swarms, traveling and retraveling incessantly between the countless hulls of steamers and lorchas and the long rows of hastily constructed storehouses facing the river frontage. Here and there stood a khaki-clad sentry, rifle in hand and belt filled with ball cartridges, America’s guardian of the precious stores now being idly collected. Into these spacious storehouses the sinews of war for the army of occupation were being hoarded to be afterward redistributed among the small steamers plying between the metropolis, Manila, and the outlying islands of the archipelago.

The American army in the Philippines, always too small for the stupendous task before it, was at last, owing to the added disaffection of the tribes in the Southern islands, receiving the attention from home which had long been withheld, and its numbers were being increased by the arrival of every transport from the far-away homeland.

“We are here at last, Syd,” Midshipman Philip Perry exclaimed, a ring of triumph in his voice as he turned toward his fellow midshipman, Sydney Monroe. Friends of long[11] standing were these two; for four years at the Naval Academy at Annapolis they had been companions and classmates, and during the past year they had together witnessed stirring service in South America and in China.

“We’ve missed nearly six months of the war,” Sydney replied querulously; “from the last accounts, Aguinaldo is on the run. Why,” he ended mirthlessly, “the war may be over before we even see the ‘Mindinao.’”

“Pessimistic as usual,” Phil laughingly retorted; “where we are going, in the words of the immortal John Paul Jones, they ‘haven’t begun to fight.’”

The steamer had now swung her bow down river, and the chug of the engines told the lads that they were fairly started on their voyage to Palilo, the capital of the island of Kapay, where the gunboat “Mindinao” was awaiting them.

“Hello, what’s this?” Phil exclaimed, while the engine bell rang with throaty clanks, and the chugging of the engines ceased. The two lads leaning inquiringly over the rail, saw a small navy launch steam alongside the moving steamer; then a tightly[12] lashed bag and hammock were thrown on deck, and finally from the depths of the white canopied awning there appeared the familiar form of a sailor, who sprang nimbly on board, waving a parting good-bye to his mates, while the launch swung away; and again the “Negros’” engines chugged noisily.

“Jack O’Neil!” the two lads cried, their faces beaming with surprised pleasure as they grasped the newcomer’s hand.

“It’s me, sir,” the sailor declared ungrammatically though heartily, highly delighted at his enthusiastic reception. “Telegraphic orders from the admiral to report to Midshipman Perry, commanding the gunboat ‘Mindinao.’”

“But where’s your old ship, the ‘Monadnock’?” Sydney questioned blankly. “We looked for her this morning as we came in on the cattle boat from Hongkong. Is she in the bay?”

“Sure, sir, she is,” returned O’Neil, “over there at Paranaque keeping the ladrones out of the navy-yard with her ten-inch guns. They made a rush for it once, about six months ago, then the gugus had an army[13] and we were kept guessing; but a few brace of hot ten-inch birds, exploding near them from our coffee kettle of a monitor soon made ’em change their minds. They decided they hadn’t lost nothing at the navy-yard after all. But,” he ended, the enthusiasm dying out of his voice, “that, I said, was six months ago; we’ve been bailing out there ever since, awnings furled, guns loaded, expecting to be boarded every night.” He made a gesture of utter disgust as he stopped.

“They don’t know anything, these gugus,” he began again, seeing that his friends didn’t understand his disjointed explanation; “they won’t try to board a man-of-war. They’ll attack you on shore; but as for paddling out in their canoes to capture a steel monitor, it’s too absurd. Yet we stood watch on and watch off every night waiting for ’em to board. Do you blame me, sir, for feeling happy when I got these orders?” tapping his telegram against an awning stanchion. “This means life again; like we had in the dago country and up with them pigtailed chinks.”

The midshipmen slapped the loquacious sailor joyfully on the back.

[14]“You’re not half as glad to be with us as we are to have you,” Phil exclaimed frankly. “We’re just aching for something worth while—we’ve been roasting up on the Yangtse River since you left us, doing nothing except watch the grass burn up and the water in the river fall. I never felt such heat.”

While the Americans were talking the little steamer slipped noisily down the busy river and out on the bay made famous by Admiral Dewey on that memorable May morning.

Corregidor Island lifted itself slowly out of a molten sea to the westward. The “Negros’” bow was pointed out through the southern channel, passing close to the precipitous island, standing like an unbending sentinel on guard between the wide portals of the Bay of Manila.

“A few guns over there on Corregidor would soon stop this talk of our waking up some morning and finding Manila at the mercy of an enemy,” Phil declared after studying the landscape earnestly. “But these islands are too far away for our people at home to take much interest. Half of them would be glad to see another nation[15] wrest them from us.—Hello! there’s one of those native lorchas,”[1] he added as his keen eye discovered a sail some miles away almost ahead of their steamer; “we passed one coming in this morning on the ‘Rubi.’ I looked at her through the captain’s spy-glass; her crew were the ugliest looking cutthroats I’ve ever seen. They reminded me of that picture ‘Revenge.’ Do you know it?” he asked suddenly turning to Sydney, and then describing the picture in mock tragic tones: “A half score of scowling Malays, in the bow of their ‘Vinta’; their curved swords in their mouths and their evil faces lustful with passion and hope of blood, approaching their defenseless victims. I hope the captain gives them a wide berth, for I haven’t even a revolver.”

The Americans had so far discovered but few people on board the steamer; the captain and pilot were on the bridge while on the lower decks there were scarcely a dozen lazy natives, listlessly cleaning the soiled decks and coiling up the confused roping.

[16]“Do you think we are the only passengers?” Sydney asked as they entered their stateroom to make ready for the evening meal.

Phil shook his head.

“No, there must be others, for I heard a woman’s voice in a cabin near ours.”

As they again emerged on deck and walked aft to where their steamer chairs had been placed, a young Filipino girl rose from her seat and bowed courteously to the two young officers. Phil noticed as he saluted that she was a remarkably pretty girl of the higher class dressed in becoming native costume, and from her dark eyes there shone intelligence and knowledge.

“Have I one of the señor’s chairs?” she asked in excellent Spanish. “It was very stupid of me to have forgotten mine.”

Both lads remarked at once the air of good breeding and the pleasing voice; the guttural lisp so common in the Malay was lacking. She could not have appeared more at her ease and yet they saw by her dark skin and straight black hair that no other blood than the native flowed in her veins.

“This is my small brother,” she explained[17] as a slight lad of about seven came toward them from behind a small boat, resting on the skids of the upper deck. “He is my only companion,” she added half shyly.

The midshipmen were at a loss how to talk to this girl of an alien race. If her skin had been fair they would have welcomed her gladly, seeing before them a pleasant two days of companionship before they would arrive at their destination; but she belonged to a race whose color they had been taught to believe placed her on a social footing far beneath their own.

The girl seemed to divine the hesitancy in the midshipmen’s manner, and for a second a slight flush spread over her dark cheeks.

Phil was the first to recover and break the embarrassing silence, heartily ashamed of himself for his boorish manner.

“We are glad, señorita,” he commenced haltingly in Spanish which had become rusty through lack of practice, “to have you use our chairs, and also,” he ended lamely, “to have you with us. I fear we are the only passengers.”

A few moments later a servant announced[18] dinner, and the four took their seats at a table spread on the upper deck after the custom of the tropics.

“The captain will not be with us,” the girl explained as Phil’s eyes rested inquiringly on the seat at the head of the table; “he begs that we will excuse him, for he is navigating the ship through the entrance to the bay.”

They sat down in silence; Phil’s seat was next to this remarkable girl.

In a few moments both lads had quite forgotten that her skin was dark, so skilfully did she preside over the plentiful board, attentive to their wants with the natural grace of one accustomed to dispense hospitality.

“Juan and I are on our way to Palilo to join our father,” she explained after the meal had fairly started. “I am very much concerned over the bad news I have heard. Oh! I hope we shall not have war in our beautiful island,” she added appealingly, “but the Filipinos are so ignorant; they will follow blindly where they are led, and so many of our educated men are at heart bad.”

“There has been some fighting there already?” Phil questioned.

[19]“Yes,” she answered, “but it has been only guerilla warfare so far. My father fears that reinforcements may come from the north. The natives in Luzon are of the Tagalo race, and if they come after being driven from their island by the American troops, we shall have the horrors of war on Kapay.”

The midshipmen’s eyes sparkled; they were just about to express their delight at this possibility when they suddenly realized that she was of the same blood as those they were wishing to fight.

Phil was the first to see the reproving look in the girl’s eyes.

“You must not blame us, señorita,” he hastened to say apologetically. “You see fighting is our business; we look for it the same as a merchant looks for trade or a fisherman for fish.”

“I think your ideas are wrong, señor,” she replied quickly, but in a caressing tone, to soften the sting. “Your duty is not necessarily to fight, but to prevent fighting. The sisters in the convent taught us that a soldier’s duty was to uphold the honor of his country. If fighting only will accomplish this duty, then it is just[20] to fight, but in this case no honor is at stake. How can our people hurt the honor of a great nation like yours?”

Phil blushed half angrily, half in shame. This girl of a dark race had the temerity to tell him what was his duty, and he was defenseless, for she was in the right.

“It is true, señorita, what you say,” Sydney came to the rescue, “but peace for us is very monotonous, always the same eternal grind. War is exciting; it stirs the blood and makes men of us.”

“Yes, señor,” the girl answered in a low, hard voice, “and it arouses all the evil passions in us. We forget all our training, all our ideals, all our instincts for good, and give way to the instincts of the beasts. My people in war are not men, señor, they are demons.”

While the girl was talking the steamer had drawn closer to the lorcha which Phil had sighted earlier in the afternoon. The night was not bright; a crescent moon cast a dim light on the hull scarcely a hundred yards on the weather bow. The breeze had freshened, and with wind free the lorcha’s sails bellied[21] out, giving it a speed almost equal to that of the steamer.

“Why doesn’t he give that sail a wider berth?” Phil exclaimed suddenly as the girl’s voice died away. “If she should yaw now, she’d be into us.”

“Look out!” Sydney cried in alarm as the lorcha suddenly sheered to leeward and the great mass of tautening canvas careened toward the unsuspecting steamer.

The midshipmen were on their feet in an instant, while O’Neil came running up from the deck below.

The Spanish captain, calling loudly to all his saints to witness that it was not his fault, jammed the helm to starboard, throwing the steamer’s bow away from the rapidly approaching lorcha. The engine bell clanked riotously, as the excited Spanish captain rang for more speed. Then the Americans’ blood froze in their veins, for the chugging of the noisy engines had ceased in a wheezy wail, and the “Negros” lay helpless, almost motionless in the path of the strange sail to windward.

The lads looked at each other in consternation.[22] The suddenness of the emergency had rendered them powerless to act.

“Was it only a stupid blunder? Or was it by design that the silent lorcha had shifted its helm and stood down upon the demoralized steamer?” were the questions that came into their minds.

A guttural hail from the lorcha accompanied by a fusillade of rifle-shots put an end to all doubt.

“Pirates!” O’Neil gasped as he dislodged an iron crowbar from a boat skid. “And there isn’t a gun among us.”

A bright glare suddenly darted from the bridge of the steamer as some one turned on the current for the search-light, and the Americans saw in the bright beam a motley crew of natives lining the lorcha’s rail, their eager bodies crouched ready to spring upon the deck of their helpless victim.

“Tagalos,” the girl cried out in sudden alarm as she instinctively put her small brother behind her, shielding him from the flying bullets.

“Don’t do it, sir,” O’Neil commanded hoarsely as Phil started precipitously forward.[23] “We can’t stand them off, we’re too few. Here we can make a stand if they attack us. We can’t save the ship.”

The lads saw at once the wisdom in O’Neil’s advice. No power could save the ship from the terrible onslaught of that savage horde. The two vessels came together with a mighty crash, and the air was rent with harsh cries of triumph as the captors leaped on board, firing their guns and slashing with their sharp bolos. The cries for mercy from the cringing crew were soon swallowed up in the shrieks of pain and anger as the vengeful victors satisfied their inherent love for blood.

The triumphant natives scaled the bridge deck, and in the bright glow from the search-light, the Americans were horrified to see those on the bridge, in spite of their hands held aloft in supplication, cruelly butchered where they stood.

The Americans in mortal dread pressed their bodies close within the deep shadow of the boats. The blinding glare from the search-light aided them in their attempt to hide from the searching eyes of their assailants. Phil and Sydney had manfully lifted[24] the native girl and her brother into the boat behind them and stood their ground ready to protect them with their lives. So this was to be the end of their hopes for adventure?—to be butchered, unarmed and in cold blood by a band of lawless murderers.

The Americans were not kept long in suspense, although to the anxious boys, huddled helplessly in the shadow of the boat, the time seemed hours until the victorious and jubilant natives moved aft, bent on annihilating those whom they believed were hiding from their search.

O’Neil grasped his weapon firmly, while the lads made a mental resolve to seize the arms of the first natives within reach and sacrifice their own lives as dearly as possible.

Suddenly the beam of the search-light swung directly aft, revealing to the pirates the defenseless band of spectators to the recent tragedy.

The helpless passengers were confident now that all was over. As if in broad daylight, they were visible to the outlaws. A volley from their rifles would send them all to death.

Blinded by the bright light, they could but[26] speculate as to the movement of their enemies, but they well knew that they must surely be advancing slowly, only awaiting the word to throw themselves on their helpless victims.

What could be done? Phil realized only too vividly that something must be done and quickly. A false move would condemn them all. Once those wild men, steeped in the blood of the innocent, had commenced, even the power of their leader could not stop them.

Then a girl’s voice, clear and commanding from behind them, made the Americans gasp in wonder. O’Neil with his great club raised to strike the misty figures just beyond his reach stiffened. The girl’s words were unintelligible to the Americans, but to the advancing natives they were like a flash of lightning from out of a clear sky. They stopped short, and for a few seconds a deep silence reigned. The girl was speaking in her native tongue. Phil cast a swift glance behind him; she stood boldly upright in the bow of the boat, like a beautiful bronze statue. The light threw her face in high relief against the[27] black background of sky. He saw the flashing eyes, the quivering straight nostrils, and the scornful curve of her mouth. She finished speaking, and still the silence was unbroken. From the gathered crowd the leader advanced, his hand held above his head in mute sign of peace. Phil could scarcely believe his eyes, but the girl’s low voice in his ear caused his heart to beat tumultuously.

“He has accepted your surrender.” She spoke in Spanish. Then, with her hands placed lightly on Phil’s shoulder she jumped down to the deck and advanced to meet the native leader. At a few paces from her he halted, and the Americans held their breath in wonder to see the bandit bow low before her, raising her hand to his lips. Then he turned and gave several harsh commands to his followers, who quietly dispersed.

Inside of but a few minutes the lorcha had disappeared in the night and the “Negros” resumed its journey, the noisy engines chugging away just as faithfully under their new masters.

[28]The Americans, as they gathered about the table to finish the meal long forgotten in the excitement of the attack, marveled at the outcome of the affair.

“Who can she be?” Sydney whispered. “Why, she orders the ladrone leader around as if she were a princess.”

Phil was about to reply when the girl herself appeared from the shadows, followed by the native chief.

The lads regarded him with a mixture of feelings, admiration for his soldierly bearing and disgust at the thought of the wilful butchery they had seen him permit on the bridge of the steamer.

They recognized at once that these two were of the highest caste among their people. The man’s face, almost perfect in contour, except in the cruel lines of the mouth, beamed hospitably upon them.

The girl spoke quickly, breathlessly.

“Colonel Martinez wishes to meet the brave Americans who would have fought unarmed against overwhelming odds and who had no thoughts of asking for quarter.”

The Americans bowed, but the Filipino advanced,[29] his hand outstretched. Phil took it with almost a shudder. Why had this hand been withheld while the Spanish captain and his officers were asking for mercy scarcely five minutes before? Yet he knew that he had no choice but to take the proffered fingers; he and his companions were in the power of this man, the lines of whose mouth told what might happen if the native leader’s pride was offended.

After shaking hands, Colonel Martinez went straight to the point. “You belong to the country of our enemy, and being such you must remain prisoners of war. We shall land at Dumaguete to-morrow, and if you will give me your solemn parole not to bear arms against us, I shall send you with an escort and safe conduct to Palilo. If not, I must send you to the headquarters of my superior, General Diocno.”

Phil as spokesman bowed.

“We shall not give you our parole, colonel,” he said emphatically. “We prefer to remain prisoners of war.”

“As you will,” the insurgent answered coldly, but his swarthy face betrayed his admiration.[30] “I shall assure you of my good offices with our general. And now, I shall leave you, but I warn you that your lives will be in danger if you leave this deck, or if you make the slightest attempt to thwart my plans. I shall have your belongings brought back here. You see I can take no chances, and I appreciate that you three Americans are no mean antagonists.” He cast a look of admiration at O’Neil, who had been listening in silence, his muscular fingers still clasping the stout crowbar with which he would like to have brained this pompous little Filipino.

“Beggars can’t be choosers, Mr. Perry,” O’Neil exclaimed with a wry smile after the officer had departed, “and I guess it was a good thing the girl knew how to get the ear of that there little bantam rooster. In another minute, I’d have brained one of them, and then those words she spoke would have had as much chance to be heard as the chairman’s voice in a state convention.”

The Americans’ belongings were brought to them from their cabin by several evil-looking natives, and very soon all were comfortable under the awning, protected from the wind by[31] the boat against which an hour ago they had been about to make their last stand.

The sun awakened the Americans at an early hour the next morning. While they were sipping their morning coffee, the lads gazed in admiration at the beautiful scenery about them. The little steamer had during the night wound its way past myriads of small islands, now but black smudges astern. The high mountains of Kapay Island rose boldly from the sea on their starboard hand. Ahead, becoming more distinct, was the shore line toward which the steamer was now traveling at an increased speed as told by the more rapid chugging of her engines.

“Hello,” Phil exclaimed as he cast a glance toward the bridge, “something’s happening.”

Sydney and O’Neil followed his gaze. There on the bridge were Martinez and the native pilot, who had apparently been spared in the attack of the night before. Martinez was walking up and down excitedly, casting an anxious glance ever and again off on the port quarter.

It was O’Neil who was the first to discover[32] the reason for the evident excitement of their captors.

“Smoke,” he exclaimed laconically, characteristically jerking his thumb toward the islands astern fast being swallowed up in the glassy sea. “They ain’t taking no chances. That stretch of shore yonder,” he added, his gaze on the shore line ahead, “must be the mouth of the Davao River.”

The lads gazed eagerly at the faint curl of smoke astern, but it gave them but scant encouragement, for it was only too evident that before the stranger, if it were one of the many small gunboats patrolling the islands, could hope to get within gunshot of the “Negros,” the steamer would have crossed the shallow bar of the Davao River and be safe from the pursuit of the deeper vessel.

“If we could only stop her,” Phil lamented. “Smash those rickety engines or haul fires in the boiler.”

O’Neil in answer cast a comprehensive glance at the sentries on guard on the upper deck. The evil-looking natives were squatted in plain sight, their loaded rifles held tightly in their brown fingers.

[33]“Oh! for three good Krag rifles,” Sydney cried petulantly; “we could clear this deck and then jam the steering gear there, and by the time they could overpower us the gunboat, if it is one, would make them heave to.”

In a short time the girl and her brother joined them, and the native guards arose and moved farther away.

“It is one of your gunboats,” she announced smiling mischievously at the evident pleasure of the midshipmen; “Colonel Martinez has recognized her through his telescope. She is giving chase, but Dumaguete is now scarcely twenty-five miles ahead, so I fear there will not be a rescue.”

Phil calculated quickly. If Martinez could see the gunboat with his glass to recognize her she could not be over ten to twelve miles astern. The “Negros’” best speed was ten knots, which meant two and a half hours before she could reach the river bar. He knew that several of the gunboats were good for fifteen knots. If this were one of the fast ones, which he earnestly prayed it was, in two hours and a half the gunboat would be up to the[34] “Negros.” His face brightened as these figures awakened his hopes.

While the Americans went through the pretense of breakfast the “Negros” steamed swiftly toward the shore, and they saw with rising hopes the white hull of a large vessel raise itself slowly out of the deep blue of the tropical sea.

Phil eyed the Filipino girl questioningly. He could tell nothing from her sphynx-like face. Would she be glad to be rescued from this band of outlaws or was she at home and safe among them? The respect shown her by the leader and his men seemed to point to the conclusion that she was of importance among her people. He knew not what were those crisp words spoken the night before to prevent the fierce onslaught of the natives, but they had calmed the storm. She had saved their lives, that much was certain; and for that, even though she was at heart in sympathy with this band of pirates, he owed her his gratitude.

His whole heart rebelled against the thought of captivity among the insurgents. He knew it would be a living death. Poorly nourished and without the necessities of life; exposed to[35] the savage temper of a people whose spirits fluctuated more rapidly than a tropical barometer, there seemed but little to live for. Perhaps death would be happier! His thoughts dwelt upon the stories he had heard of the atrocities committed by this same Diocno upon American soldiers who had been captured. Some of them he had buried alive in an ant-hill all but their heads, with their mouths propped open and a train of sugar leading to their swollen tongues. A cold shiver ran down his spine as his imagination pictured the agony of these men as they slowly died.

“It’s the ‘Albany,’” O’Neil cried joyfully a minute later, “and do you see the bone in her teeth? She’s making nearly twenty knots. Why, it’s all over but the shouting. These little yellow runts will look well when they are lined up against the wall at Cavite and shot for piracy.”

Phil held up his hand to demand silence from the excited sailor. He did not know how much English the girl might know, and the ladrone leader might learn the dire wish of the sailorman for him and his followers. Then if the “Negros” escaped, his anger could[36] be vented upon the Americans. But the girl’s face did not betray that she had understood the meaning of O’Neil’s words. The “Albany” was fast approaching, but Phil knew that O’Neil must be overestimating the cruiser’s speed; the most she could make, without special preparation, would be fifteen knots, but, and his joy welled up into his eyes,—her six-inch guns! He had seen them fired with accuracy at four miles.

The shore line ahead had now become distinct. The deep cut in the surrounding hills betrayed the presence of the Davao River as it flowed through them to the sea. Groves of high-topped palm trees appeared, a deeper green against the emerald background, while the water stretching toward them from the land polluted the sea with a dull brown stain—the muddy water of the river. The town of Dumaguete could not be seen, but from the curls of rising smoke, Phil knew it must be beyond the first bend of the river and screened from view by the spur-like hill stretching its length from the mountains behind to the water’s edge.

The girl sat between the two midshipmen,[37] her small brother innocently unconscious of the tragedy being enacted about him, playing joyfully about the decks. Phil watched the child as a relief to his overanxious mind. He had dislodged a wedge-shaped block of wood from under the quarter boat, and was using it to frighten a large monkey which was eying him grotesquely from on top of the tattered awning. The monkey apparently did not enjoy the game, for he suddenly flew screeching at the boy, his mouth opened viciously. The boy in his haste to escape dropped the block of wood almost on Phil’s foot and the midshipman determinedly placed his foot upon it. In that instant an idea had occurred to him. His pulse beat faster, as the thought flashed into his mind. He would use it as a last resort, even though it would bring the howling mob of natives vengefully about their heads.

“Now she’s talking,” O’Neil exclaimed grimly, as a flash and a puff of brownish smoke belched from the bow of the distant cruiser. The Americans arose to their feet, their eyes held fascinatingly on the cruiser. They knew that a hundred-pound shell was speeding[38] toward them at a speed of a mile in three seconds. The Filipino girl sat unconcernedly sipping her coffee. She was as yet ignorant of the meaning of that flash from a vessel nearly five miles away.

Far astern a column of water arose in the air and the distant shock of the discharge came to their expectant ears.

Phil saw with sinking heart that the “Negros” had entered the discolored water from the river. Ahead less than two miles the ever-present bamboo fish weirs showed the commencement of the shallows of the Davao River. His hopes died within him. The cruiser was not making the speed he had hoped. She would hardly be in range before the “Negros” had put the high spur of land between her and the enemy. The cruiser, apparently seeing the quarry was about to escape, opened a rapid fire in hopes of intimidating or crippling its prey; but the range was too great. The shells hissed close to the stern of the fleeing vessel; the boasted accuracy of American gunners was lacking.

“If she was only a thousand yards closer,” O’Neil cried in bitter disappointment. “It’s[39] only a matter of luck at this distance. Look out,” he yelled as a shell struck the water with the noise of an express train, within fifty feet of the fleeing “Negros.”

The Filipino girl’s face blanched, while the boy ran cowering to his sister’s side. The danger to them seemed almost supernatural. The girl’s lips moved, and Phil saw that she was praying. For a moment a fear seized him. The thought of their danger was certainly unnerving. A single shell exploding near them would send them all to eternity. The fish weirs were now abreast the ship and the “Negros’” bow was being guided into the narrow, tortuous channel of the delta. The Filipino pilot on the bridge spun his steering wheel from side to side, following the twisting channel. The quadrant with its rusty chain, connecting the wheel and the rudder, clanked loudly at Phil’s feet. Now was the time to put his daring plan in operation. He saw that the four guards had taken refuge behind the boats, from which they peered out with frightened eyes at the oncoming cruiser, dodging out of sight at each screech of a shell. They had apparently forgotten the prisoners whom[40] they were guarding, for their rifles and belts were resting on the hatch several yards away.

“When I give the word, you jump for those rifles and belts,” Phil said in a low, intense voice, glancing covertly at the terrified girl at his side. “I am going to jam the steering quadrant. When you get the guns,” he continued, “take cover behind the boats. It may cost us our lives, but anything is better than imprisonment among these people.”

O’Neil and Sydney breathed a gasping assent to the bold plan. Phil watched carefully the quadrant; he saw it move slowly over until it was hard astarboard. He reached down, grasping the boy’s block of wood under his foot, then slid it slowly, amid the terrific noise of a passing shell, toward the quadrant. He knew the wedge would hold the rudder over and the “Negros,” unable to steer, would ground on the edge of the channel, thus leaving her helpless to be captured by the cruiser. He opened his mouth to give the signal for his companions to act, when a shrill warning cry sounded in his ears and he was roughly drawn back into his chair and the wedge dropped from his hands a foot from its goal.

Brigadier-General Wilson sat at his desk in the headquarters building at Palilo. In the spacious corridors outside orderlies hurried to and fro, carrying messages from the several officers of the staff whose offices joined that of the general.

Before him was a chart of his military district, and while he pondered he juggled a score or more of different colored pins with little tags attached to them. Those pins with blue heads represented soldiers of his command in the field against the enemy while the ones with the green heads were the ladrones or insurrectos, whom he had been fighting without success for nearly six months.

“They jump about as if they were mounted in balloons,” he exclaimed testily as he drew out several green-headed pins and replaced them in accordance with recent information[42] in other localities on the map. The big headquarters clock ticked away in silence, while the gray-haired veteran again lapsed into thought over his problem.

“Here are two regiments in the field,” he complained querulously; “Gordon with two companies at San Juan, Baker with a company at Binalbagan, Anderson and a battalion at Barotoc, Huse and a company at Estancia, Pollard with two companies at Kapiz, Shanks with three companies at Carles, Stewart with his rough-riders at Dumangas and Bane with his two battalions as a flying column. That ought to give us some results, and yet what have we to show for it?”

The general raised his thoughtful eyes, as his orderly’s step sounded on the soft matting at his side.

“A telegram,” he exclaimed with a show of interest. “Tell Major Marble I wish to see him,” he added, tearing open the yellow envelope.

“Whew!” he whistled in sudden consternation as he read the unwelcome message. “They not only avoided Gordon but attacked San Juan in his absence, cutting up ten of his[43] men left to guard the town. This thing has got to be stopped. There is a leak somewhere and I am going to put my hand on it before I send out another expedition.”

He pushed the chart back on his desk and rose suddenly to his feet.

“Major,” he cried as the adjutant-general’s active figure entered the office, “we are all a set of ninnies. Don’t start and look indignant, sir,” he added in mock severity. “You are as bad as the rest, but Blynn there is the worst of us all, for he can’t do what he’s employed to do—you and I are only plain, blunt soldiers, while he is supposed,” with fine scorn, “to be in addition lawyer and detective; a regular secret service sleuth and all that.

“Here, read that,” he ended throwing the telegram on the desk. “You see it’s the same old story, and ten more men butchered through our stupidity.”

The general paced up and down his office with quick, energetic steps.

“I’ve a good mind to go out in the field myself,” he exclaimed, half to himself. “I am tired of these silly, costly blunders.” Then[44] he glanced through the open door into the next office to his own. “Come here, Blynn!” he hailed.

A stout, dark-visaged officer arose from a desk littered with countless papers and came energetically toward him.

The older officer’s eyes roamed searchingly over his judge-advocate general’s strong, massive frame; he gazed with kindling eyes at the bronzed cheeks, the unbending directness of his black eyes, the firm set to the bulldog jaws. Here surely was no weakling. He waved his hand toward the adjutant-general, standing in stunned silence, the telegram crumpled in his hand.

“That may interest you,” the general exclaimed as he turned away.

“The information was first hand, sir,” Captain Blynn’s bass voice insisted after he had straightened the paper and read the unwelcome message. “There’s been a leak.”

“Of course there’s been a leak,” the general announced hotly, “any idiot would see that, but where? Where? that’s the question!”

Captain Blynn returned to his desk and drew out a bundle of papers from a locked[45] drawer. He glanced over them hurriedly. Every word was familiar to him. Could he have made a mistake? Every witness whom he had examined had given the same information. These natives had not been coerced; they had come to him of their own volition. Espinosa had vouched for each. Then he stopped, the papers fell from his hand to the desk. No! it could not be possible! Espinosa was surely loyal. That much was sure. For the space of a minute he was lost in thought. “I shall test him,” he muttered, while he pressed a bell at his side.

“Tell Señor Espinosa over the telephone that I shall call on him in an hour on important business,” he instructed the orderly who answered his summons.

An hour later Captain Blynn mounted the high stairs of the wealthy Filipino’s dwelling.

“Buenos Dias, El Capitan,” Señor Manuel Espinosa cried delightedly as he pushed a chair forward for his visitor. But the smile died quickly on the native’s face as Captain Blynn waved away the chair impatiently, almost rudely, and in his typical way jumped into the very midst of the matter in hand.

[46]“Señor,” he exclaimed angrily, “I’ve been betrayed! Do you understand?” he cried menacingly, his flashing eyes fixed on the crafty face opposite him, while he shook his big, strong fist before the eyes of the startled Presidente of Palilo. “Betrayed, that’s the word, and if I can lay my hand on the hound, I’ll swing him to the eaves of his own house-top.”

Señor Espinosa was silent, his crafty, bead-like eyes regarding closely the angry, excited face of the judge-advocate.

“Captain Gordon went on a wild-goose chase, and when he returned he found the insurgents had been in San Juan in his absence. Ten soldiers, American men, were caught, trapped, and butchered. The natives who brought me the information were vouched for by you and now you’ve got to prove to me that you’re not a sneaking traitor!”

The captain’s words tumbled one after another so fast that the little Filipino could grasp only half their meaning, but the last could not be misunderstood. His brown face turned a sickly yellow, while his frightened eyes sought instinctively for some weapon of defense from[47] this terrible American, who was strong enough to tear his frail body limb from limb.

“Ah, señor capitan, is this your much-boasted American justice?” he gasped in a weak voice. “Am I then judged guilty without hearing my defense?” His voice became stronger as he proceeded. “Let us look over this calmly,” he begged. “I, myself, have been betrayed. In embracing the American cause, I have made many enemies among my people. I live constantly in fear of assassination.” He stopped abruptly, his voice choking and his eyes filled with tears of self-pity.

Captain Blynn had dealt with many different classes of men in his twenty odd years of service. He had been a terror to the ruffians on the Western frontier where he had been stationed during the several Indian wars. The “bad men” had said when they had found Blynn against them, “We might as well own up—we can’t fool Blynn.”

But here was a case that baffled him. In the hour before going to this house he had after deep thought believed that after all Espinosa was a traitor, and he had avowedly intended to force him to confess his treason; but[48] now in spite of these resolves, the captain was weakening. After all might not the Filipino be innocent? At all events he would listen to his defense.

Captain Blynn dropped his muscular hands, which had been creeping menacingly toward the thin yellow throat of the Presidente, and sat down suddenly in the chair which the native had previously offered him.

“Go on!” he ordered harshly. “I’ll suspend judgment, but remember, if you can’t prove your innocence, I’ll give you water. Do you understand, water! I’ve never given it, and I don’t believe in it, but if you can’t show me how these men were butchered, I’ll fill you up to the neck with it.”

Espinosa wetted his lips with his tongue and swallowed hard, but the captain by taking the proffered chair had removed the native from the terrifying influence of those powerful twitching fingers which he had seen ready to throttle him, and he, in proportion to the distance away of the cause of his fear, grew bolder.

“The señor capitan must know of my sincerity,” he pleaded in a weak voice.[49] “Have I not taken the oath of allegiance to the United States? Do I not know the punishment for breaking that oath?”

Captain Blynn nodded his head. “Go ahead,” he commanded impatiently; “cut that out, give me the unvarnished story.”

“The information which I gave you and which was sworn to by three witnesses came from Juan Rodriguez,” Espinosa continued, dropping his voice to a whisper and approaching closer to the American. Then he stopped and glanced covertly at his listener’s startled face.

“Juan Rodriguez!” the judge-advocate general exclaimed half rising in his excitement. “Then you believe that he has deliberately furnished false information of the insurgents’ movements?”

While the two were talking a servant brought refreshments, which the army man waved impatiently aside. Espinosa helped himself and as he did so he followed his servant’s eye to a tightly rolled piece of paper inside the salva. He drew it out hastily, unrolling it in silence, feeling rather than seeing the captain’s eyes upon him, then he read the[50] few lines written therein. Here was a chance to redeem his good name or at least save himself for this time from the fierce American. He asked a question in the native language and received a monosyllabic answer.

“This is very important,” he exclaimed suddenly turning to the American officer. His voice was now joyful, full of confidence. “Two hundred riflemen have landed at Dumaguete from Luzon. To-night they will be encamped on a hill near Banate. You can attack them there before they can join Diocno.”

Captain Blynn jumped to his feet, reaching out for the paper; he took it, scrutinizing it closely—then stuck it quietly into his pocket. Espinosa held out a trembling hand, bent upon regaining the note, but Captain Blynn had turned away, picking up his hat and whip from the table behind him.

“I shall myself go in command of this expedition,” he announced gruffly as he moved toward the stairs, “and I shall expect you to accompany me, señor. We shall start at sunset.”

Señor Espinosa feebly murmured his willingness, and after waiting to see the burly[51] figure of his visitor pass out through the wide entrance, he turned and called for his servant.

“Tell the messenger I will speak to him,” he said as the muchacho noiselessly entered.

A moment later a ragged native stood tremblingly before him, twisting his dirty head-covering in his nervous hands.

Espinosa seated himself luxuriously in the chair recently vacated by Captain Blynn. He had now regained his old confidence and cruel arrogance, while he fired question after question at the uncomfortable native.

The Presidente sat motionless in his chair long after his messenger had gone. His servant came noiselessly into the room several times but tiptoed away, believing his master was asleep. But Espinosa was far from sleep, his brain was actively at work. How could he hold his position and yet remain undiscovered to this terrible Captain Blynn? He shuddered as he remembered those big hands as they worked longingly to grasp his slender neck. He was not a fighting man; the inheritance of his father’s Chinese blood mixed with the cruelty in the native strain qualified[52] him only for plotting. Others could do the fighting. His brain and cunning would furnish them the means and opportunity. But Rodriguez—he was too honest, and knew too much; he stood a menacing figure in his path as the leader of his people. He had, however, set the train of powder on fire, and now he would watch it burn. Once Rodriguez was removed there were no others strong enough to thwart him. Even Diocno bowed to his superior sagacity. Then he could cast off this halter that he felt tightening about his neck. With Diocno and Rodriguez out of the way, he could make terms with these childlike Americans, and then with his fortune made shake the dust of the islands forever from his feet.

An hour before sunset he arose and dressed himself for his ride, ordering his servant to have his horse ready. The messenger had three hours’ start; that would insure the escape of the Tagalos. Captain Blynn would find that his information was true. He could not blame him if the enemy had taken alarm and fled. As for the other matter, if the Americans would only arrest Rodriguez he[53] would see that he did not interfere with his cherished plans for power. As he buckled on his English made leggings, he whistled gaily an old Spanish air, one he had heard in Spain; in his mind he saw the brightly lighted theatre, the richly dressed people in the boxes. Some day he would be rich and he would then be able to recline in a gilded box and cast disdainful glances at an admiring crowd.

His joy would have been indeed short-lived and his castles in Spain would have fallen as flat as the surface of the sea on a calm day if he could have known that at that moment his messenger was lying dead in the trail but half-way to his destination, suddenly overcome by the terrible scourge of the camp, cholera.

Phil was too angry and humiliated to do more than glare at the girl who had so cleverly thwarted him in his daring plan to strand the steamer. His companions had started to spring toward the coveted rifles of their enemy, but now they sank back into their seats and hopelessly looked into the menacing muzzles of these same rifles in the hands of the four aroused sentries. The girl had risen to her feet, her face flushed with excitement; she raised her hand to the natives, motioning them to put up their weapons.

Phil scrambled to his feet and sheepishly dropped again into his chair. His breathing was quick and his eyes dilated with suppressed rage and mortification. At that moment he could have quite forgotten his natural instinct of gallantry and would have taken pleasure in throttling this slight girl who had come between them and freedom.

[55]“They would have all been shot,” she said in quick accents of excitement. “You see I can understand a little English. I could not be a traitor to my own blood as long as I had power to prevent it.”

For answer Phil gave her a look of loathing.

The girl recoiled under his menacing glance.

“I am sorry for you,” she hastened to add, “for now Colonel Martinez will have to keep you closer prisoners, unless you give me your word that you will not again try to prevent the escape of the steamer.”

Phil shook his head savagely, his eyes on the steering quadrant within easy reach of his hand. The girl waited breathlessly for an answer, then finding none was forthcoming she gave a sharp command in her own language and immediately the four sentries closed in around the Americans, their rifles pointed toward their prisoners.

“For goodness’ sake, Phil,” Sydney exclaimed in an agony of doubt, “don’t be foolhardy. We are absolutely in their power. See,” he cried desperately, “the ‘Albany’ has stopped and sheered away. She has given up the chase.”

[56]Phil realized that Sydney was right—nothing could be gained by giving in to his rash anger. He saw that O’Neil had dropped the crowbar and had been led away by two of the natives, going as peacefully as a lamb. However his pride stood in the way of an outward surrender, and instead of agreeing to make no attempts to disable the steamer he arose and moved away from the tempting steering quadrant.

The “Negros” had meanwhile threaded her way among the dangerous shoals and was now in the river; the cruiser had disappeared behind the land.

A great crowd of natives ashore had witnessed the escape of the steamer from the war-ship and these lined the banks of the river shouting joyfully as the “Negros” steamed quietly to the bamboo pier in front of the village.

As soon as the dock had been reached, the girl dismissed the guards and the Americans once more gathered about the breakfast table.

A few moments later Colonel Martinez, his face wreathed in smiles, left the bridge and joined them.

[57]“You are to be given the freedom of the town,” he said as he took a cup of coffee from the servant’s hands and sipped it gratefully, “but I warn you if you attempt to escape you will be shot, and even if you escaped, without guides you would be lost in the jungle and be killed by ladrones.”

Phil bowed his head in sign of submission. They were certainly prisoners, without hope of rescue.

“To-morrow morning,” Colonel Martinez added, “we shall leave the village and march inland. I have already sent to notify our leader that I have successfully arrived. I think for your own good it would be wiser for you to remain on board here until we start. I do not trust the temper of the people. Americans are not just now in favor.” He finished with an amused smile on his face.

After their captors had left them, the three terribly disappointed men sat bemoaning their fate.

“We might just as well make the best of it,” Sydney philosophically assured the others. “There certainly isn’t any way to[58] escape that I can see. After all, we’ve been in just as tight places and have come out of them; we don’t make matters any better by crying over spilled milk.”

“If that girl hadn’t betrayed us,” Phil moaned, “we would have been on board the ‘Albany’ this minute.”

“Mr. Perry,” O’Neil broke in apologetically, “it ain’t like you to be unfair to anybody, most of all a woman. These are her own people—Colonel Martinez must be a friend of hers, or otherwise we wouldn’t have been living to see the ‘Albany.’ If she had only been an ordinary native girl, these ladrones wouldn’t have stopped and bowed and scraped and then given us the freedom of the after deck of the ship. No, sir, she’s a person of consequence. She saved our lives and then afterward she saved the lives of Colonel Martinez and his band of cutthroats, for if they had fallen into the hands of the crew of the ‘Albany’ they would have all been shot or swung at her yard-arm. Seizing this merchant ship and killing her captain is piracy.”

“I think O’Neil is right,” Sydney exclaimed patting the sailor on the back enthusiastically.[59] “The girl’s all right—I’ll take my hat off to her every time.”

“It was my own stupidity, I suppose,” Phil declared, his face sobering slightly. “I thought she was too frightened to know what was happening; in fact I really didn’t believe she would understand what I intended doing.”

“Who do you suppose she is?” Sydney asked eagerly. “Isn’t it queer she has never told us her name?”

“It probably wouldn’t aid us if she had,” Phil replied; “she’s probably the daughter of some rich Filipino, who holds a fat position under our civil government. By the way she talked when we first met her I thought she was dead against war, yet she appears to know and welcome these cutthroat Tagalos with open arms.”

“There you go, Phil,” Sydney admonished, “unfair again. She has so far shown herself willing to help both sides. In your heart, when you’ve recovered from your disappointment and humiliation at being handled so roughly by a girl, you’ll see that she acted in a way that was just to both the insurgents and ourselves.”

[60]The next morning at daylight the Americans were up and dressed, ready for the march with their captors.

“Colonel Martinez has secured enough horses for you and your companions to ride,” the girl told them as a half dozen small Filipino ponies were led down to the end of the wharf. “Your belongings will be carried by natives whom he has secured, so I hope you will not be put to too great hardships. The soldiers are used to marching, but for those unaccustomed to the country it is very tedious.”

Phil thanked her not ungraciously. He had during many hours of a sleepless night brooded over the situation and had awakened with much kindlier thoughts for this girl than he had held the night before.

The Americans, with Colonel Martinez, the girl and her brother rode at the head of the long file of armed insurgent soldiers. As the procession passed through the streets of the town the natives gathered and gave excited and enthusiastic yells of pleasure. Great curiosity was shown as to the white captives, but Colonel Martinez took precautions that[61] they should not be disturbed by the evident dislike of the people. Phil read hatred in many eyes as they wended their way through the curious crowds, and he quite believed the insurgent colonel’s words that they would not be safe among them.

The trail which they were following led steadily inland, and constantly climbed above the level of the sea. After a few miles had been covered all signs of habitation disappeared, the country was bleak and barren of cultivation. At first they had passed through groves of cocoanut, banana and many varieties of tropical fruit trees and afterward the velvety green of rice fields lay on either hand, but now the earth was scorched and brown, the high jungle bush lay thick on either side of the trail. The Americans realized the hardships of a campaign in such a country against a wild and determined foe. They had marched for about four hours without a rest when a signal of warning was given from scouts in front. The leader stopped, giving a low order to a soldier at his elbow.

“What is it?” Phil breathed, forcing his pony forward eagerly.

[62]“They’ve seen something,” O’Neil whispered; “probably a company of our soldiers on a ‘hike.’”

The Americans were ordered to dismount, and a dozen riflemen quietly surrounded them. Colonel Martinez spurred ahead while the entire band dissolved in the jungle, leaving the trail clear. Scarcely twenty feet from the trail the Americans were roughly seized, their hands secured tightly behind their backs and gags were forced into their mouths. They submitted peaceably. Suddenly, scarcely fifty yards away, a column of khaki-clad soldiers appeared marching down the trail. Phil caught a glimpse through a vista in the dense brush of these men, swinging lightly along, ignorant of the presence, so near them, of over two hundred armed enemies. His pulse beat fast and his heart seemed ready to burst within him. Were these Americans walking innocently into an ambush? He tried to scream a warning, but he emitted no sound save a faint gurgle, which his guards heard, and for his pains struck him down with their knees until he lay with his face pressed close to the prickly[63] earth. He could hear the tramp of shod feet and an occasional snatch of a song. Once he heard a sharp command in English and at another time a jest which called forth local laughter. It seemed an age since he had seen the head of this column appear, and yet the earth trembled under the tread of a multitude of feet. Finally the sounds died away. The soldiers had passed, and no attack had been made. After a long hour of waiting their guards brought out the Americans and unbound their hands, taking out the cruel gags from their mouths. Colonel Martinez appeared, still mounted upon his small gray pony.

“I am very sorry,” he said politely, “but I could not run the risk of detection. That was Colonel Bane with two battalions of the Seventy-eighth Infantry. I had been warned that he was in the neighborhood. I was not strong enough to attack him.”

Phil could have cried aloud at the utter uselessness of this warfare. Their movements heralded far and wide whenever a column moved, in a country well-nigh impenetrable, how were the Americans ever to put down this ugly rebellion?

[64]At sunset the band halted and went into camp. Phil saw that the site selected was a strong one and one that could be easily defended from attack if the attackers came by trail, and there seemed no other way through the impenetrable brush.

“We shall remain here until my messenger returns,” Phil overheard Colonel Martinez say to the girl. “Will you wait until your father sends for you, or will you accept an escort from me?”

“I shall remain here,” she said; “the morning should bring my own people.”

Shortly afterward the girl took her brother’s hand and led him away to the part of the camp that had been set aside for her own use, and Colonel Martinez joined the disconsolate Americans.

“The señorita,” he said as he sat down on the ground near Phil, “has told me of the brave conduct of my prisoners, and I wish it were in my power to set you free. I have known many American navy men before this war began and my treatment by them has always been courteous and considerate. I have the power to take your parole, and knowing[65] the hardships which you must undergo as prisoners among our soldiers I advise you to give it. To-morrow morning you can be on your way to Palilo.”

It was certainly a grave temptation, but the midshipmen knew that in giving their parole all hopes of taking part in the war would vanish; and then, the insurgents not being recognized as belligerents, the Navy Department might even see fit to order them to break their parole.

“Thank you, señor,” Phil finally replied. “We shall take our chances as your prisoners. We shall always remember your considerate treatment of us, and if by the chances of war the situation is reversed you can count on us to repay our obligations to a chivalrous enemy.”

“If you and your companions were to remain in my keeping,” the Filipino answered, a pleased smile on his face at Phil’s subtle compliment, “I should have no concern, but I must give you over to the mercies of General Diocno; he is a Tagalo, and has known nothing but war since his youth; he would never surrender to the Spaniards, and for years[66] a price has been upon his head; he is said to be cruel to those who fall into his hands.”

Phil shuddered at the frank words of his captor. He saw in the earnestness of his face that this gruesome information was being given for the Americans’ own good.

“Your friends,” the colonel continued, “will doubtless attempt a rescue, and that will only add to your danger.”

After Colonel Martinez had said good-night Phil told his companions of the unpleasant and disquieting reports concerning their future captor, but nothing could shake O’Neil’s good spirits.

“It’s all in the game, Mr. Perry,” he said philosophically. “They can’t do more than kill us, and as we’ve got to die some day, it might just as well be in Kapay as any other place. But as long as we’ve got our senses and our strong arms, there are going to be some little brown men hurt before I give up my mess number.

“What I’ve been trying to study out,” the sailor continued, seeing the two lads still silent, “is how all those American soldiers could pass along that trail and not find out[67] that this band of natives had just left it. Where are all the old Indian fighters we used to have in the army?”

Phil and Sydney both raised their heads, a look of surprise in their faces.

“I hadn’t thought of that,” Sydney exclaimed. “Our trail must have been there; the native soldiers all go barefooted and leave but indistinct tracks on this hard soil, but our pony tracks must have been in plain sight.”

“The solution is,” Phil broke in sadly, “those men were volunteers, the Seventy-eighth Infantry, the colonel said; there probably wasn’t an old soldier among them. They fight like demons when they see the enemy, but are as helpless as children against a savage foe skilled in woodcraft. If that had been a battalion of regulars there’d have been a fight and we would now be free, or,” he added with an unconscious shiver, “dead there in the jungle, for the native guarding me would have been only too happy to stick his bolo into me.”

O’Neil had already rolled himself in his blanket, apparently resigned to the tricks of fate, and the midshipmen, realizing, after their[68] long day’s ride in spite of their troubled minds, that they were in need of rest, were soon comfortably settled on the bundles of dry grass given them to lie upon. As Phil dropped into a troubled sleep, he was conscious of the four native guards, pacing to and fro just outside of ear-shot. These four men were all that stood between them and liberty; for once they had escaped, he felt confident that O’Neil could be depended upon to follow the track of those half a thousand soldiers who had marched past so carelessly only a few hours before.

After what seemed an incredibly short time, although he had slept for hours, he awakened with a start; sitting bolt upright, he gazed quickly about him. A faint streak of light in the eastern sky told him the night had nearly passed. His brain, keenly alive, grasped for a reason; what had stirred him to wakefulness? All was quiet about the camp. The guards were no longer on their feet, but he could see their shadowy forms squatting on the ground, their rifles in their hands. With a disappointed sigh, for what he did not know, he dropped back upon his bundle of straw,[69] but he soon found he was too wide awake for more sleep. He finally arose, stretching himself as though just awakened, and by an impulse which he was powerless to disobey, walked slowly toward the guards. As he advanced he saw with surprise that they did not move. Stealthily he went on until he stood over the nearest one, squatting naturally, the butt of his rifle between his bare feet. The guard was sound asleep. Farther on he saw in the dim mysterious light of early dawn that the other three were also silently sleeping, their bodies propped up against the trunks of the dwarf pine-trees. Phil’s heart beat fast. Here was freedom within his grasp. He leaned forward, seizing the rifle barrel of an unconscious guard, drawing it slowly from his relaxed fingers. The butt still rested between his feet and as he slowly, steadily drew the rifle toward him, the sleeping native’s body settled itself inch by inch upon the ground.

HERE WAS FREEDOM WITHIN

HIS GRASP

A twig snapped close by, sending the blood coursing through his veins while his hand shook from the sudden start. Terrified he cast his startled eyes into the jungle behind him. The dim shadow of a man stood scarcely a[70] hundred yards away, silently watching him. In the dim light the figure seemed of heroic size. He retreated toward it and back to his sleeping companions, the rifle clasped in his hand. Then suddenly the silence was broken by a volley of rifle-shots and the hiss of bullets sounded everywhere about him. Stunned, unable to explain the meaning of this, he dropped to the ground and lay silent, his face in the straw of his bed. The next second a line of shouting, excited khaki-clad men streamed past, firing their rifles as they charged upon their hidden native foes.

As night fell, Captain Blynn led his battalion of regulars from their barracks, across the bridge and on to the trail leading to the northward of Palilo. The American officer rode in the lead, the Filipino Presidente at his side. The soldiers behind him, eight full companies, each under its own officer, swung along with the long, untiring step of the American soldier. They each knew that before the night was over and the sun had lifted its fiery head above the misty mountains to the eastward twenty miles of rough trail must be covered, and then they had been promised to be brought face to face with an enemy whose shadows they had chased during these many long, tiresome months.

Espinosa, as he rode in silence by the side of the big American, chuckled inwardly at the fruitlessness of this expedition. “These childlike[72] American dogs,” he thought, “they will arrive in time to see the smouldering fires where our men have cooked their morning rice, while they will be high in the hills, looking down on them derisively, and possibly will fire a few shots at long range to show their contempt.”

Captain Blynn’s restless gaze contemplated his companion from time to time as the native signaled the right trail. They were now in a narrow defile between two hills that rose precipitously to a height of over a thousand feet. Captain Blynn, as he contemplated his surroundings with a soldier’s eyes, drew his revolver from its holster and laid it gently across the pommel of his saddle.

“A nice place for an ambush,” he said in a low, insinuating voice. “I suppose, señor, you are prepared to stand before your Maker.”

The native shuddered. He saw only too clearly the accusation and threat in this terrible American’s words. If there was to be an ambush, he knew nothing of it, but if a single hostile shot was fired, he would pay the penalty with his life.

The Filipino forced an uneasy laugh. “As[73] far as I know, señor capitan, there are no insurgents this side of Banate.”

“For your sake, I hope you are right,” the American replied. “As you see, I am taking no chances. You are our guide; if you get us into trouble, you pay, that’s all.”

Captain Blynn ordered a halt and called a lieutenant from the leading company.

“Take ten men, Simpson,” he said, “and act as the point. If you are attacked, retreat and fall back on the main body.”

Lieutenant Simpson picked his men quickly and disappeared quietly down the trail. Captain Blynn watched them until swallowed up in the darkness, and then set the long line in motion again. Every soldier took, instinctively, a tighter grip upon his musket, and loosened the sharp sword bayonet from its scabbard. Each knew that when “Black Jack” Blynn took precautions there was reason to scent trouble.

Half-way through the defile a guarded whistle of warning came to Blynn’s ears from the point. As one man the long column halted; the soldiers’ heavy breathing was distinctly audible above the tremor of the metallic[74] rattling of accoutrements. Each soldier sought his neighbor’s face for a key to the solution of the problem. Blynn, motioning Espinosa to follow, rode silently forward. In the trail a hundred paces ahead he saw Lieutenant Simpson bending over a dark object.

“What is it?” Blynn asked in a harsh whisper.

“A dead native,” Simpson answered shortly. Espinosa was off his horse instantly; bending down quickly he struck a match, illuminating the native’s dead face. He started, turning a sickly yellow. His heart stopped beating, and his knees shook under him, but Captain Blynn was too much occupied with the silent figure to notice the peculiar behavior of his guide. They turned the dead man over, revealing the terrible havoc accomplished in but a few hours by the tropical scourge.

“Poor chap!” Blynn exclaimed. “Only a common ‘Tao’ stricken by cholera and dead before he knew what had hit him.”

They moved the body off the trail, and again the command was set in motion.

In the flash of the match Espinosa had[75] recognized his messenger although his face was horribly disfigured by his last mortal suffering. He shuddered at the consequences of this man’s death—Martinez would not get his warning message and would fall into the trap set for him. He, Espinosa, could never explain his actions. He would doubtless pay for this treachery with his life. But his cruel mind was instantly made up as to his future actions. He feared this American too thoroughly not to take them to the place where the Tagalos under Martinez were encamped; above all else Captain Blynn must be made to believe that he was sincere; all depended upon that. Everything must be sacrificed for his final great ambition. Martinez would not be taken alive. That was a necessity, he would see to that. Once he was killed his part in the night’s expedition must remain a secret among the Americans.

Casting from him his first fears he straightened his slight frame and rode boldly, with head erect, beside the American leader.

One hour before sunrise Captain Blynn disposed his command in a single circular line about the base of a high hill; its sides[76] were covered with a dense jungle while a single trail led to the top.

Under the guardianship of Espinosa the command moved forward, straight up through the high clutching brush; the men were so close to each other that their neighbors on each side were always in sight. Captain Blynn and one company marched fearlessly up the trail. A few feet from where the round top hill had been cleared he halted and waited for the remainder of his men to join him. His enemy’s camp was silent, but his keen eyes could discern shadowy forms lying prone on the ground. He searched for a sentry, but no movement could be seen. Were they all asleep, believing themselves secure in their surroundings? No! there directly in front of him he saw a white figure standing upright beside a dark form on the ground. This must be an officer, for the native soldiers do not wear white—something familiar in the pose and cut of the uniform struck him. Could it be possible, was it a navy uniform? At that instant the soldiers on both sides reached the edge of the clearing. As yet the enemy were unaware of their[77] presence. Not a moment must be lost; they must attack at once. Firing his revolver, Captain Blynn plunged forward, straight toward the white-clad figure. Several of his men passed him while he stopped to find why the figure had thrown itself face downward in the grass at the discharge of his revolver.

The next moment he was shaking hands with three almost tearfully joyful fellow countrymen.

As soon as Phil realized that they were again free his thoughts were for the Filipino girl and her little brother. Was she in danger? With the rifle he had taken from the sentry in his hands, he rushed anxiously in the direction that he believed she might be found. He recognized some of her belongings on the ground at his feet, but the girl had vanished. Fearful at the thought of finding them killed by his own people, he sought her everywhere, repeatedly risking his life as the terrified natives, finding themselves trapped, flung at him with their long, sharp knives or discharged their weapons almost in his face. He gave them but little[78] heed, not giving a thought to the reason why he had not been killed, although a faithful sailor at his elbow was the only tangible cause. A score of times O’Neil had saved his young officer at the risk of his own life.

A small group of struggling men on the right near the edge of the jungle suddenly caught his restless eye and desperately he plunged downward toward them. On the ground two men struggled in a death embrace, while the girl and her brother stood wild-eyed with fright, unwilling spectators to the fierce duel. Phil gave a gasp of relief as he stood beside the girl. The two combatants uttered no sound save their sharp gasps for breath while they struggled for supremacy. Phil saw with wonder that the men were both natives and then for the first time realized that they were alone; no soldier was within a hundred yards of them. Behind them the soldiers were relentlessly, stubbornly herding the natives into a mass of flashing, frenzied humanity at the top of the hill.

“It is Colonel Martinez,” the girl gasped seizing Phil’s arm. “Oh, save him, señor,[79] he will be murdered.” Phil saw the other native, by an effort almost superhuman, free his right arm, and in it a bright blade flashed in the dim light. The girl’s appealing face looked into his for an instant, and the next moment the lad had thrown himself between the two men; seizing the hand with the knife he bent it slowly backward, finally wrenching it from its firm grasp. O’Neil was beside him. The sailor caught the two natives as if they had been fighting dogs and held them for a second in his powerful arms clear of the ground. Espinosa fell limply as the sailor released his hold, and lay breathing heavily, too exhausted for speech. Colonel Martinez quickly regained his revolver, and was immediately the man of action. He gazed boldly at the Americans, his revolver held menacingly, and the while edging slowly away from his captors. Phil turned his eyes to the figure on the ground and the angry glare he received disconcerted him; the next second as he looked about him he saw that Colonel Martinez had gone; from the gloom of the jungle he heard the rustle of brush and caught a glimpse of misty forms. He[80] raised his rifle half-way and then lowered it. In his heart he rejoiced that he had not taken him prisoner.

In the next second Espinosa leaped toward him. Phil was stunned by a stinging blow; but before it could be repeated O’Neil interposed and Espinosa had measured his length on the ground.

“Where did Colonel Martinez go?” Phil asked quietly.

“I didn’t see,” O’Neil answered, his face as solemn as that of a judge.

Phil smiled and put out his hand. The two men exchanged clasps. “I believe he would have done as much for us,” Phil said.

Before the sun had risen above the sea to the eastward, the fight was over. But few of the enemy had escaped. Asking no quarter, fighting to the last man, they had died as they had lived. Two hundred rifles were the spoils of the fight.

Captain Blynn and the midshipmen were seated after their victory on the bloody battle-field, while the lads gave a hurried account of their capture.

Suddenly from the grass a horribly disfigured[81] face confronted them. It was Espinosa. His cunning gave him counsel that he must control his ungovernable temper. He could gain nothing by accusing these Americans of wilfully aiding Martinez in his escape. “I am sorry to inform you, señor captain, that Colonel Martinez escaped. These gentlemen can tell you the details. I was about to kill him. They doubtless had good reasons for permitting him to escape.”