Title: Graham's Magazine, Vol. XX, No. 6, June 1842

Author: Various

Editor: George R. Graham

Release date: February 23, 2022 [eBook #67480]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: George R. Graham, 1842

Credits: Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net, from page images generously made available by The Internet Archive

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XX. June, 1842 No. 6.

Contents

| Fiction, Literature and Articles | |

| The Wire Suspension Bridge | |

| The Science of Kissing!! | |

| Harry Cavendish | |

| Miss Thompson | |

| Russian Revenge | |

| Mrs. Ware’s Poems | |

| Love and Pique | |

| The Two Dukes | |

| Review of New Books | |

| Poetry and Fashion | |

| Farewell | |

| The Pewee | |

| The Return Home | |

| Olden Deities | |

| Perditi | |

| The Heavenly Vision | |

| Sights From My Window—Alice | |

| The Absent Wife | |

| Song | |

| Fashion Plate | |

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

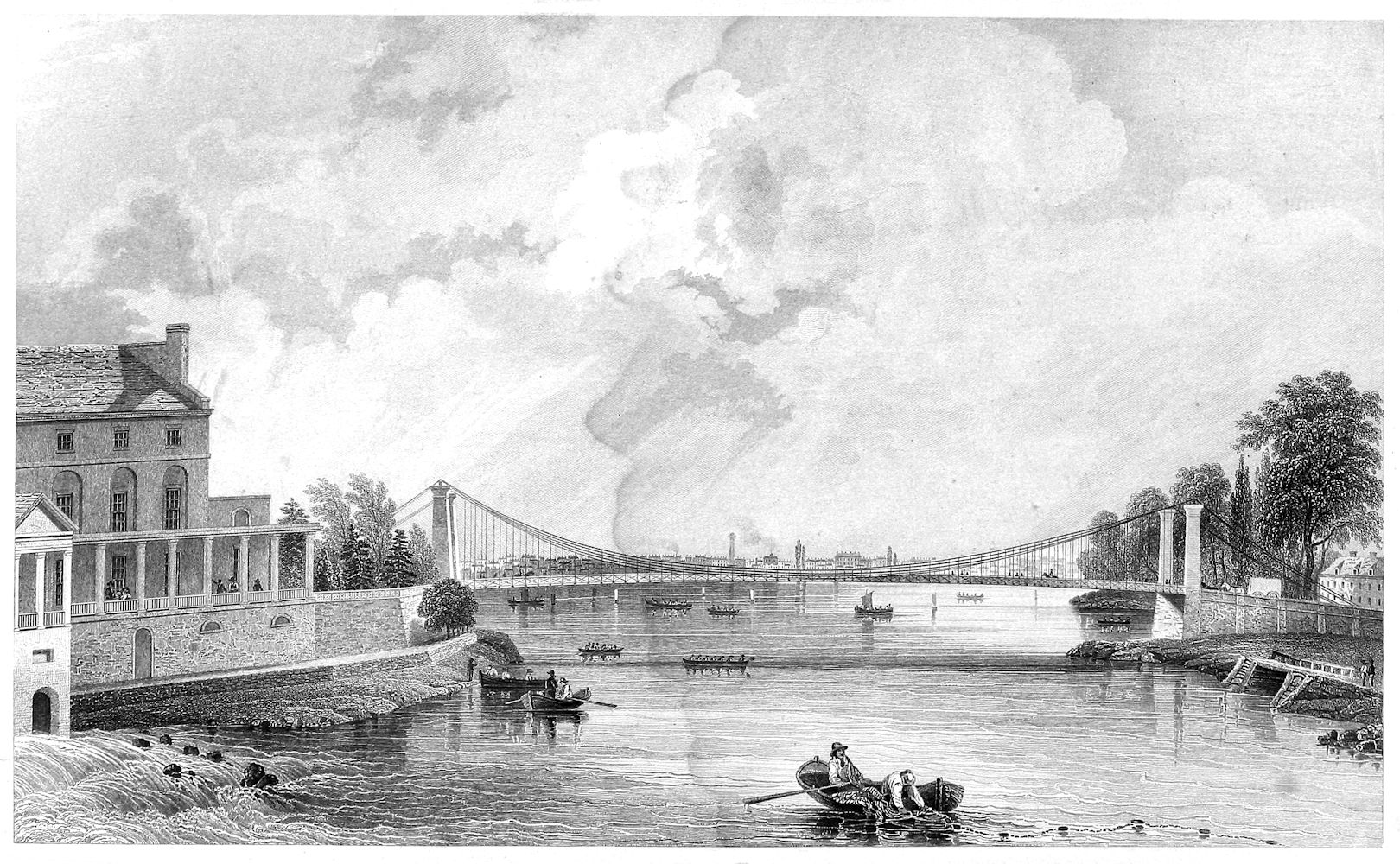

W. Croome, del. Engraved by Rawdon, Wright, Hatch & Smillie

Philadelphia.

Engraved expressly for Graham’s Magazine.

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XX. PHILADELPHIA: JUNE, 1842. No. 6.

This elegant structure is thrown across the Schuylkill, on the site once occupied by an airy and graceful wooden erection, for years the pride of our city, and celebrated as being the longest bridge of a single arch in the known world. The boldness of the architect in thus spanning a river three hundred and fifty feet wide, was the theme of universal admiration. Few will forget Fanny Kemble’s poetic comparison, when she said the bridge looked like a white scarf flung across the water. The destruction of this favorite fabric, by fire, in the fall of 1838, was regarded as an irreparable loss.

The conflagration presented a grand picture. The flames were first seen towards the western entrance of the bridge, and in a very few minutes the whole fabric was a mass of fire. The wind was down the stream, and catching the flames as they broke from the flooring of the bridge, it swept them far away under, until a fiery cataract, reaching from shore to shore, seemed pouring horizontally down the river. By this time spectators began to throng around, and before the bridge fell, thousands lined the adjacent shores and covered the side of the overhanging hill, looking down on the scene below, as from the seats in an amphitheatre.

This splendid sight continued for some time, the gazers looking on in a rapt silence, until suddenly a low murmur, followed by an involuntary shiver, ran through the crowd, as the bridge, with a graceful curtesy, descended a few feet, hesitated, and then, with a gentle, swan-like motion, sank, like a dream, down on the waters. But the moment the fabric touched the wave, a simmering, hissing sound was heard, while ten thousand sparkles shot up into the air and sailed away to leeward. The fire still, however, burned fiercely in the upper works, which had not reached the water; while volumes of smoke rolled down the river, blending the earth, the wave, and the sky into one dark, indistinct mass, so that the burning timbers, occasionally detached from the bridge, and borne along by the current, seemed, almost without the aid of fancy, to be lurid stars floating through the firmament. The moon, which was just rising, and which occasionally burst through the dense veil of smoke, appeared almost side by side with these wild meteors, and added to the illusion. The effect was picturesque; at times even sublime.

More than two years elapsed before the bridge was replaced by the present elegant structure, whose airiness and grace more than reconcile us to the loss of its predecessor.

This new fabric is, we believe, the finest, if not the only, specimen of its kind in the United States. The plan is simple. Two square towers of solid granite, thirty-two feet in height, are built on either abutment. Over each of these towers, on iron rollers, pass five wire cables, each cable being composed of two hundred and sixty strands, each strand being an eighth or an inch thick. The length of each cable is six hundred and fifty feet. These cables are secured, on each shore, in pits, distant from the towers one hundred feet, and continuing under ground fifty feet further, to a point where they are securely fastened at the depth of thirty feet. These pits are built over so as to exclude the rain, but not the air; and the cables, being painted, are thus preserved from rust. The cables, in stretching from tower to tower, form a curve, the lowest point of which is at the centre of the bridge. The causeway is of wood, and hangs, by smaller wire cables, from these larger ones. The width of the bridge is twenty-seven feet, and its length, from abutment to abutment, three hundred and forty-three feet. The strength of the bridge has been tested by a weight of seventy tons. The structure is painted white throughout, and has already won the name of the most graceful bridge in the country.

Painted by Sir T. Lawrence Eng’d by H.S. Sadd, N.Y.

Engraved Expressly for Graham’s Magazine.

———

THE AFTER-DINNER TALK OF JEREMY SHORT, ESQ.

———

What glorious times, Oliver, the old Turks must have, sitting, on a sultry day like this, listening to the cool plashing of their fountains, and smoking their chiboques—egad!—until they fall asleep, and dream of dark-eyed Houris smiling on them, amid the fragrant groves and by the cool rivers of a Musselman Paradise. What a pity we were not born in Turkey, you a Bashaw of three tails, and I the Sultaun of Stamboul! How we would have stroked our beards—and smoked our pipes—and given praise to the prophet as we drank our sherbert, spiced, you know, with a very little of the aqua vitæ, that comfort of comforts to the inner man! We could then have dressed like gentlemen, and not gone about, as we do now, breeched, coated, and swaddled in broadcloth, like a couple of Egyptian mummies. Just imagine yourself in a dashing Turkish dress, with a turban on your head, and a scimitar all studded with diamonds at your side, with which—the scimitar I mean—you are wont to slice off the heads of infidels as I slice off the top of this pyramid of ice-cream—help yourself, for it’s delicious! I think I see us now, charging at the head of our spahis against the rascally Russians, driving their half starved soldier slaves like chaff before a whirl-wind, and carrying our horse-tails and shouting “Il Allah!” into the very tents of their chieftains. What magnificent fellows we would have made! Ah!—my dear boy—you and I are out of our element. Take my word for it, a Turk is your finest gentleman, your true philosopher, the only man that understands how to live. He keeps better horses, wears richer clothes, walks with a nobler mien, smokes more luxuriously, drinks more seductive coffee, and kisses his wife or ladye-love with better grace, than any man or set of men, except you and I, “under the broad canopy of heaven” as the town-meeting orators have it. And let me tell you this last accomplishment—this kissing gracefully, “secundum artem”—is a point of education most impiously neglected amongst us. Kissing is a science by itself. Let us draw up to the window where we can drink in the perfume of the garden, and while you whiff away at your meerschaum, I will prove the truth of my assertion. One has a knack for talking after dinner—I suppose it is because good steaks and madeira lubricate the tongue.

We are born to kiss and be kissed. It comes natural to us, as marriage does to a woman. Why, sir, I can remember kissing the female babies when I was yet in my cradle, and my friend Sir Thomas Lawrence did himself the honor to paint me at my favorite pursuit, as you know by that exquisite picture in my library. The very first day I went to school I kissed all the sweet little angels there. I wasn’t fairly out of my alphabet, when I used to wait behind a pump, for my sweetheart to come out of school, and as soon as I saw her I made a point of kissing her just to see how prettily she blushed. As I grew older I loved to steal in, some summer evening, on her, and kiss her asleep on the sofa—or, if she was awake, and the old folks were by, I’d wait till they both got nodding, and then kiss her all the sweeter for the slyness of the thing. Ah! such stolen draughts are delicious. I wouldn’t give a sous to kiss a girl in company, and I always hated Copenhagen, Pawns, and your other kissing plays, as I hope I hate the devil. They had a shocking custom when I was young, that everybody at a wedding should kiss the bride, just as they all drank, in the same free and easy way, out of the one big china punch-bowl; but the practice always hurt my sensibilities, and I avoided weddings as I would avoid a ghost, a bailiff, or any other fright. No—no—get your little charmer up into a corner by yourselves—watch when everybody’s back is turned—then slip your arm around her waist, and kiss her with a long sweet kiss, as if you were a bee sucking honey from a flower. Nor can one kiss every girl. I’d as lief take ipecacuanha as kiss some of your sharp-chinned, icicle-mouthed, lignum-vitæ-faced spinsters—why one couldn’t get the taste of the bitters out of his mouth for a week! I go in for your rosy, pouting lips, that seem to challenge everybody so saucily—egad! when we kiss such at our leisure, we think we’re in a seventh heaven. I once lived on such a kiss for forty-eight hours, for it took the taste for commoner food out of my mouth “intirely,” as poor Power used to say. Oh! how I loved the wide, dark entries one finds in old mansions, where one could catch these saucy little fairies, and, before they were well aware of your presence, kiss them so deliciously. There’s kissing for you! Or, to go upon a sleigh ride, and when all, save you and your partner, are busy chatting—while the merry ringing of the bells and the whizzing motion of the vehicle cause your spirits to dance for very joy—to make believe that you wish to arrange the buffalo, or pull her shawl up closer around her, and then slyly stealing your face into her bonnet to kiss her for an instant of ecstasy, while she blushes to the very temples, lest others may catch you at your sport. And then, on a summer eve, to row out upon the bosom of a moonlit lake, and while one of the ladies sings and all the rest listen, to snatch a chance and laughingly kiss the pretty girl at your side, all unnoticed except by her. Or to sit beside a charmer on a sofa, before a cozy fire on a bitter winter night, and fill up the pauses of the conversation, you know, by drawing her to you and kissing her. But more than all,—when you have won a blushing confession of love from her you have long and tremblingly worshipped with all a boy’s devotion,—is the rapture of the kiss which you press holily to her brow, while her warm heart flutters against your side, and every pulse in your body thrills with an ecstasy that has no rival in after life. Ah! sir, that kiss is The Kiss. It is worth all the rest.

Next to being born a Turk I should choose to have been born an Englishman in the days of Harry the Eighth. Do you remember how Erasmus tells us, in one of his letters, that all the pretty women in London ran up to him and kissed him whenever they met? That’s what I call being in clover. I don’t wonder people long for the good old times, for, if all their fashions were like this, commend me to the days of the bluff monarch, when

“thus paused on the time,

With jolly ways in those brave old days,

When the world was in its prime.”

Did you ever attend a children’s party, and see the little dears play Copenhagen? The boys seem to have an instinctive knack at kissing their partners, who always show the same modest repugnance—for modesty is inborn in every woman—aye! and flings a glory about her like the halo around a Madonna’s head. The very instant one of the young scapegraces gets into the ring, he looks slyly all around it, and there be sure is one little face that blushes scarlet, and one little heart that beats faster, for well the owner knows that she is in peril. How fast her hands slide to and fro along the rope, and directly the imprisoned youngster makes a dash at her hand, and, missing it, turns away amid the uproarious laughter and clapping of hands of the rest, and essays perchance a feint to tap some other little hand, all the while, however, keeping one corner of his eye fixed on the blushing damsel who has foiled him. And lo! all at once—like an eagle shooting from the skies—he darts upon it. And now begins the struggle. What a shouting—and merry laughing—what cries of encouragement from the lookers on—what a diving under the rope, and over the rope, and among the chairs, mingled with whoopings from the boys, ensues, until the victim has escaped, or else been caught by her pursuer. Sometimes she submits quietly to the forfeit, but at other times she will fight like a young tiger. Then, indeed, comes “the tug of war.” If she covers her face in her hands, and is a sturdy little piece beside, young Master Harry will have to give up the game, and be the laughing stock of the boys, or else set all chivalry at defiance and tear away those pretty hands by force. Many a time, you old curmudgeon, have I laughed until the tears ran out of my eyes to see a young scoundrel, scarcely breeched, kissing an unwilling favorite. How sturdily he sticks up to her, one hand around her neck, and the other, perhaps, fast hold of her chin; while she, with face averted, and a frown upon her tiny brow, is all the while pushing him desperately away. But the young rascal knows that he is the strongest, and with him might makes right. With eagerness in every line of his face, he slips his arm around her waist, and, after sundry repulses, wins the kiss at last. And then what a mighty gentleman he thinks he is! In just such a scene has my old friend Lawrence taken me off, in that picture, of The Proffered Kiss, in my library, egad!

It is a great grief to me that so few understand how to kiss gracefully. Kissing is an accomplishment, I may be allowed to remark, that should form a part of every gentleman’s education. A man that is too bashful to kiss a lady when all is agreeable, as Mrs. Malaprop would say, is a poor good-for-nought, a lost sinner, without hope of mercy! He will never have the courage to pop the question—mark my words—and will remain a bachelor to his dying day, unless some lady kindly takes him in hand and asks him to have her, as my friend Mrs. Desperate did. The women have a sly way of doing these things, even if, like a spinster I once knew, they have to ask a man flatly whether his intentions are serious or not; and they are very apt to do this as soon as the kissing becomes a business on your part. But to return to the modus operandi of a kiss. Delicacy in this intellectual amusement is the chief thing. Don’t—by the bones of Johannes Secundus!—don’t bungle the matter by a five minutes torture, like a cat playing with a mouse. Kiss a girl deliberately, sir—sensible all the time of the great duty you are performing—but remember also that a kiss, to be enjoyed in its full flavor, should be taken fresh, like champaigne just from the flask. Ah! then you get it in all its airy and spirituelle raciness. If you wish a sentimental kiss—and after all they are perhaps the spicier—steal your arm around her waist, take her hand softly in your own, and then, tenderly drawing her towards you, kiss her as you might imagine a zephyr to do it! I never exactly timed the manœuvre with a stop-watch, but I’ve no doubt the affair might be managed very handsomely in ten seconds. The exact point where a lady should be kissed may be determined by the intersection of two imaginary lines, one drawn perpendicularly down the centre of the face, and the other passing at right angles through the line of the mouth. Two such old codgers as you and I may talk of these things without indiscretion; and, it is but doing our duty by the world, to give others the benefits of our experience. Some of these days, when I get leisure, I shall write a book called “Kissing Made Easy.” The title—don’t you think?—will make it sell.

Kissing, however, has its evils, for the world, you know, is made up of sweet and sour. One often gets into a way of kissing a pretty girl by way of a flirtation, and ends by tumbling head over ears into love with her. This is taking the disease in its most virulent form; but—thank the stars!—it is most apt to attend on cases where the gentleman has not been used to kissing. I would recommend, as a general rule, that every one should be inoculated to the matter, for, depend upon it, this is the only way to save them from a desperate and perhaps fatal attack. I once knew a fine fellow—talented, rich, in a profession—whose only fault, indeed, was that he had never kissed anybody but his sister. He had the most holy horror of a man who could so insult the dignity of the sex as to kiss a lady—and, I verily believe, the sight of such a thing, in his younger days, would have thrown him into a fit. At length he fell in love; and as sweet a creature was Blanche Merrion as ever trod greensward, or sang from very gaiety of heart on the morning air. Day after day her lover watched her from afar, as a worshipper would watch the countenance of a saint; but months passed by and still he dared not lift his eyes to her face, when her own were shining on him from their calm, holy depths. Other suitors appeared, and if Blanche had fancied them, she would have been lost forever to Howard, through his own timidity; but happily none of them touched her heart, and she went on her way “in maiden meditation fancy free.” Often, in her own gay style of raillery, would she torment poor Howard about his bashfulness; and during these moments, I verily believe, he would gladly have exchanged his situation for that of any heretic that ever roasted in an inquisitorial fire. A twelvemonth passed by, and yet Howard could not muster courage to express his devotion, and if, perchance, his eyes sometimes revealed his tale, the confession faded from them as soon as the liquid ones of Blanche were turned upon him. If ever one suffered, he suffered from his love. He worshipped his divinity in awe-struck humility, scarcely deeming she would deign to see his adoration. He might have said with Helena,

“thus, Indian-like,

Religious in mine error, I adore

The sun, that looks upon his worshipper,

But knows of him no more.”

At length a friend of Howard asked him to wait on him as a groomsman, and who should be his partner but Blanche! Now, of all places for kissing, commend me to a wedding. The groom kisses the bride—and the groomsmen kiss the bridemaids—and each one of the company kisses his partner, or if any one is destitute of the article he makes a dumb show of kissing somebody behind the door. But the groomsmen have the cream of the business, for it’s one of the perquisites of their office that they should kiss their partners, as a sort of recompense for shawling them, and chaperoning them, and paying them those thousand little attentions which are so exquisite to a lady, and which a gentleman can only pay, especially if the lady is grateful, at some peril to his peace of mind. Ah! sir, a bridemaid is a bachelor’s worst foe—one plays with edge tools when he waits at a wedding—and though you may dance with an angel or flirt with a Houri, I’d never—heaven bless you—recommend you to wait on a girl unless you were ready to marry. Seeing other folks married is infectious, and, before you know it, you’ll find yourself engaged. It was a lucky chance for Howard when he was asked to wait on Blanche, for I would stake my life that nothing else could have cured him of his bashfulness. Nor even then would he have succeeded but for an accident. One lovely afternoon—it was a country wedding—he happened to pass by a little sort of summer-house in a secluded spot in the grounds attached to the mansion, and who should he see within but Blanche, asleep on a garden sofa. I wish I could paint her to you as she then appeared. One arm was thrown negligently back over her head, while the other fell towards the floor, holding the book she had been reading. Her long, soft eye-lashes were drooped on her cheek. Her golden curls fell, like a shower of sunbeams scattered through the forest leaves on a secluded stream, around her brow and down her neck; and one fair tress, stealing across her face and nestling in her bosom, waved in her breath, and rose and fell with the gentle heaving of that spotless bust. A slight color was on her cheek, and her lips were parted in a smile, the smallest space imaginable disclosing the pure teeth beneath, seeming like a line of pearl set betwixt rubies, or a speck of snow within a budding rose. Howard would have retreated, but he could not, and so he stood gazing on her entranced, until, forgetting everything in that sight, he stole towards her, and falling on his knees, hung a moment enraptured over her. As he thus knelt, his eyes glanced an instant on the book. It was the poems of Campbell, and open at a passage which he had the evening before commended. Blanche had pencilled one verse which he had declared especially beautiful. His heart leapt into his mouth. His eyes stole again to that lovely countenance, and instinctively he bent down and pressed his lips softly to those of Blanche. Slight, however, as was the kiss, it broke her slumber, and she started up; but when her eyes met those of Howard the crimson blood rushed over her face, and brow, and down even to her bosom, while the lover stood, even more abashed, rooted to the spot. Poor fellow! He would have given the world if he could have recalled that moment’s indiscretion. He stammered out something for an apology, he knew not what, yet without daring to lift his eyes to her face. She made no reply. A minute of silence passed. Could he have offended past forgiveness? He was desperate with agony and terror at the thought—and, in that very desperation, resolved to face the worst, and looked up. The bosom of Blanche heaved violently, her eyes were downcast, her cheek was changing from pale to red and from red to pale. All her usual gaiety had disappeared, and she stood embarrassed and confused, yet without any marks of displeasure, such as the lover had looked for, on her countenance. A sudden light flashed on him, a sudden boldness took possession of him. He lifted the hand of Blanche—that tiny hand which now trembled in his grasp—and said,

“Blanche! dear Blanche! if you forgive me, be still more merciful, and give me a right to offend thus again. I love you, oh! how deeply and fervently!—I have loved you with an untiring devotion for years. Will you, dearest, be mine?” and in a torrent of burning eloquence—for the long pent-up emotions of years had now found vent—he poured forth the whole history of his love, its doubts and fears, its sensitiveness, its adoration, its final hope. And did Blanche turn away? No—you needn’t smile so meaningly, you old villain—she sank sobbing on her lover’s shoulder, who, when at length she was soothed, was as good as his word, and sinned by a second kiss. It turned out that Blanche had loved him all along, and it was only his bashfulness that had blinded him, else by a thousand little tokens he might have seen what, in other ways, it would have been unmaidenly for her to reveal. Now, sir, months of mutual sorrow might have been saved to both Blanche and her lover, if he had only possessed a little more assurance—he would have possessed that assurance if he had been less finical—if he had been less finical he would not have been shocked at kissing a pretty girl. Isn’t that demonstrated like a problem in the sixth book?

I might multiply instances, egad, for fifty years of experience will store one’s memory with facts, and by the aid of them I could reel off arguments for this accomplishment faster than a rocket whizzes into the sky. Kissing, sir—but there goes the supper bell, and I see your meerschaum’s out. We will rejoin the ladies, and after taking our Mocha, set the young folks to dancing, while you and I accompany them on the shovel and tongs!—Ta-ra-la-ra!

———

BY JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL.

———

Farewell! as the bee round the blossom

Doth murmur drowsily,

So murmureth round my bosom

The memory of thee;

Lingering, it seems to go,

When the wind more full doth flow,

Waving the flower to and fro,

But still returneth, Marian!

My hope no longer burneth,

Which did so fiercely burn,

My joy to sorrow turneth,

Although loath, loath to turn,—

I would forget—

And yet—and yet

My heart to thee still yearneth, Marian!

Fair as a single star thou shinest,

And white as lilies are

The slender hands wherewith thou twinest

Thy heavy auburn hair;

Thou art to me

A memory

Of all that is divinest:

Thou art so fair and tall,

Thy looks so queenly are,

Thy very shadow on the wall,

Thy step upon the stair,

The thought that thou art nigh,

The chance look of thine eye

Are more to me than all, Marian,

And will be till I die!

As the last quiver of a bell

Doth fade into the air,

With a subsiding swell

That dies we know not where,

So my hope melted and was gone:

I raised mine eyes to bless the star

That shared its light with me so far

Below its silver throne,

And gloom and chilling vacancy

Were all was left to me,

In the dark, bleak night I was alone!

Alone in the blessed Earth, Marian,

For what were all to me—

Its love, and light, and mirth, Marian,

If I were not with thee?

My heart will not forget thee

More than the moaning brine

Forgets the moon when she is set;

The gush when first I met thee

That thrilled my brain like wine,

Doth thrill as madly yet;

My heart cannot forget thee,

Though it may droop and pine,

Too deeply it had set thee

In every love of mine;

No new moon ever cometh,

No flower ever bloometh,

No twilight ever gloometh

But I’m more only thine.

Oh look not on me, Marian,

Thine eyes are wild and deep,

And they have won me, Marian,

From peacefulness and sleep;

The sunlight doth not sun me,

The meek moonshine doth shun me,

All sweetest voices stun me,—

There is no rest

Within my breast

And I can only weep, Marian!

As a landbird far at sea

Doth wander through the sleet

And drooping downward wearily

Finds no rest for her feet,

So wandereth my memory

O’er the years when we did meet:

I used to say that everything

Partook a share of thee,

That not a little bird could sing,

Or green leaf flutter on a tree,

That nothing could be beautiful

Save part of thee were there,

That from thy soul so clear and full

All bright and blessed things did cull

The charm to make them fair;

And now I know

That it was so,

Thy spirit through the earth doth flow

And face me whereso’er I go,—

What right hath perfectness to give

Such weary weight of wo

Unto the soul which cannot live

On anything more low?

Oh leave me, leave me, Marian,

There’s no fair thing I see

But doth deceive me, Marian,

Into sad dreams of thee!

A cold snake gnaws my heart

And crushes round my brain,

And I should glory but to part

So bitterly again,

Feeling the slow tears start

And fall in fiery rain:

There’s a wide ring round the moon,

The ghost-like clouds glide by,

And I hear the sad winds croon

A dirge to the lowering sky;

There’s nothing soft or mild

In the pale moon’s sickly light,

But all looks strange and wild

Through the dim, foreboding night:

I think thou must be dead

In some dark and lonely place,

With candles at thy head,

And a pall above thee spread

To hide thy dead, cold face;

But I can see thee underneath

So pale, and still, and fair,

Thine eyes closed smoothly and a wreath

Of flowers in thy hair;

I never saw thy face so clear

When thou wast with the living,

As now beneath the pall, so drear,

And stiff, and unforgiving;

I cannot flee thee, Marian,

I cannot turn away,

Mine eyes must see thee, Marian,

Through salt tears night and day.

———

BY DILL A. SMITH.

———

In hedges where the wild brier-rose,

Woos to its breast the sweets of June;

When soft the balmy south-wind blows,

The Pewee trills its simple tune.

And when on glade and upland hill

Shines out the sultrier July’s sun;

And forest shade and bubbling rill

The red-bird’s shriller notes have won,

Oh then along the dull road side—

(As if the deepening gloom to cheer)

The Pewee loves to wander wide—

There still its airy lay you hear.

Or now, when more familiar grown,

It seeks the busier haunts of men;

And to the welcome barn roof flown,

Renews its joyous song again.

And thus throughout the livelong day,

(Tho’ showery pearl-drops damp its wings;

And heedless who may pass its way,)

The modest Pewee sits and sings.

Bird of the heart—meek Virtue’s child!

Emblem of sweet simplicity;

An thou’d’st a pleasant hour have whiled,

Go list the Pewee’s minstrelsy!

The eagle’s wing it may not boast,

Nor yet his plume of golden sheen;

But not in garb of regal cost

Are Virtue’s children always seen.

Ah, no, sweet bird! in lowly guise

Her fairest child is oftenest met;

And seldom knows thy cloudless skies,

Or path with flowers so richly set.

When summer buds are bright and gay

I fly the city’s dull confines,

And love to sport the hours away

By sedgy streams and leafy shrines.

Nor least among the happy sounds

Which then salute my raptur’d ear,

I hail, from hedge and meadow grounds,

The Pewee, with its song so clear.

———

BY THE AUTHOR OF “CRUISING IN THE LAST WAR,” “THE REEFER OF ’76,” ETC. ETC.

———

When I recovered my senses, after the events narrated in the last chapter, I found that I was lying in the cabin of the schooner on board which I had been serving, while a group composed of the three surgeons and several officers of the expedition stood around me. As I opened my eyes and glanced around, scarce conscious as yet of the objects that met my gaze, one of the medical men bent over me and said that my safety depended on my quiet. Gradually I imbibed the full meaning of his words, and called to mind the events immediately preceding my fall; but, in spite of his charge, I felt an uncontrollable desire to learn the extent of my injury. In a low whisper—so low indeed that I was startled at its faintness—I asked if I was seriously wounded and whether we had conquered. But he smiled as he replied,

“Not now, at least not in full, for your weakness forbids it. But the danger is over. The ball has been extracted. Quiet is all you now require.”

“But,” said I again, “how of our expedition? Have we conquered?”

“We have, but not a word more now. To-morrow you shall hear all. Gentlemen,” he continued, turning to the group, “we had best withdraw now that our friend is past the crisis. He needs repose.”

I felt the wisdom of this advice, for my brain was already whirling from the attempt to control my thoughts, even for the mere purpose of asking the questions necessary to satisfy my curiosity; so when the group left the cabin I sank back on my couch, and closing my eyes with a sense of relief, soon lost all recollection in a deep sleep, the effect, no doubt, of the opiate which had been administered to me.

When I awoke, the morning breeze was blowing freshly through the cabin, bringing with it the odors of thousands of aromatic plants from the shores of the neighboring islands, and as it wantoned across my forehead, dallying with my hair and imparting a delicious coolness to the skin, I felt an invigorating, pleasurable sensation—a sensation of the most exquisite delight—such as no one can imagine who has not felt the cool breath of morning after an illness in the close cabin of a small schooner.

My curiosity to hear the events of the combat that occurred after my fall, would not suffer me to rest, and I gave my attendants no peace until I had learnt the whole.

It will be recollected that when I sank to the deck in a state of insensibility, we were engaged in a warm contest with the piratical hulk which had been moored across the mouth of the outlet from the lagoon. The fight was maintained for some time on board of the enemy, and at first with varying success; but the daring of our men at last overcame the desperate resistance of the pirates, and the enemy were either driven below, cut down, or forced overboard. This outwork, as it were, having thus been carried, we pushed on to the settlement itself, for the other vessels moored in the lagoon were by this time deserted, the pirates having retreated to a fortification on the shore, where their whole force could act together, and where they had entrenched themselves, as they vainly imagined, in an impregnable position. But our brave fellows were not intimidated. Flushed with success, and burning to revenge those of their comrades who had already fallen, they cried out to be led against the desperadoes. Accordingly, under cover of the guns of our little fleet, the men were landed, and, while a brisk fire was kept up from the vessels, the assault was made. At first the pirates stood manfully to their posts, pouring in a deadly and unremitting fire on the assailants. In vain did the officers lead on their men three several times to the assault, for three several times were they driven back by the rattling fire of the now desperate pirates. To increase the peril of their situation, no sign of their companions in the rear had as yet appeared. The ruffians were already cheering in anticipation of a speedy victory, and our men, although still burning for vengeance, were beginning to lose all hope of victory, when the long expected rocket, announcing the arrival of the other party, shot up from the dense thicket in the rear of the fort, and instantaneously a crashing volley burst from the same quarter, followed by a long, loud cheer in which was recognised the battle shout of our comrades. The sounds shivered to the very hearts of our almost dispirited men, and added new energy to their souls and fresh vigor to their arms. Again they demanded to be led to the assault, and, with fixed bayonets, following their leader, they dashed up to the very embrasures of the fort. Then began a slaughter so terrific that the oldest veterans assured me they had never witnessed the like. Through an impervious veil of smoke, amid plunging balls and rattling grape shot, our gallant fellows swept over the plain, through the ditch, up the embankment, and into the very heart of the fortification. At the mouths of their guns they met the pirates, bearing them bodily backwards at the point of the bayonet. But if the onslaught was determined the resistance was desperate. Every step we advanced was over the dead bodies of the foeman. Throwing away their muskets, they betook themselves to their pikes and cutlasses, and though forced to retreat by our overwhelming numbers, retreating sullenly, like a lion at bay, they marked their path with the blood of the assailants. Meanwhile the detachment of our troops in the rear, finding the defences in that quarter weaker than those in front, soon carried the entrenchments, and driving before it as well the immediate defenders of the walls, as the desperadoes who had hurried to reinforce them, it advanced with loud cheers to meet us in the centre of the fortification. Hemmed in thus on every side, the pirates saw that further resistance was useless, and were seized with a sudden panic. Some threw down their arms and cried for quarter, others cast themselves in despair on our bayonets, while a few, managing to escape by cutting their way through a part of our line, took to the swamps in the rear of the fort, whither they defied pursuit. In less than an hour from the first assault, not a pirate was left at large within the precincts of the settlement. The huts were given to the flames, and the hulk at the outlet of the lagoon scuttled and sunk. The other vessels were manned by our own forces and carried away as trophies. Thus was destroyed one of the most noted piratical haunts since the days of the Bucaneers.

We learned from the prisoners that the approach of the expedition had been detected while it was yet an hour’s sail from the settlement, and that preparations had instantly been made for our repulse. Had we not been under a misapprehension as to the strength of these desperadoes, and thus been induced to take with us more than double the force we should otherwise have employed, their efforts would no doubt have been successful, since the almost impregnable nature of their defences enabled them to withstand the assault of a force four times the number of their own. It was only the opportune arrival of our comrades, and the surprise which they effected in their quarter of attack, that gave us the victory after all. As it was, our loss was terrible. We had extirpated this curse of society, but at what a price!

The wound which I had received was at first thought to be mortal, but after the extraction of the ball my case assumed a more favorable aspect. The crisis of my fate was looked for with anxiety by my comrades in arms. My return to consciousness found them, as I have described, watching that event at my bedside.

Our voyage was soon completed, and we entered the port of —— amid the salvos of the batteries and the merry peals of the various convent bells. The governor came off to our fleet, almost before we had dropped our anchors, and bestowed rewards on the spot on those of his troops who had peculiarly distinguished themselves. He came at once to my cot, and would have carried me home to the government-house, but Mr. Neville, the uncle of the fair girl whom I had saved from the desperadoes, having attended his excellency on board, insisted that I should accept the hospitalities of his home.

“Well,” said his excellency, with a meaning smile, “I must give him up, for, as you say, mine is but a bachelor establishment, and hired nurses, however good, do not equal those who are actuated by gratitude. But I must insist that my own physician shall attend him.”

I was still too weak to take any part in this controversy, and although I made at first a feeble objection to trespassing on Mr. Neville’s kindness, he only smiled in reply, and I found myself, in less than an hour, borne to his residence, without having an opportunity to expostulate.

What a relief it is, when suffering with illness, to be transported from a close, dirty cabin to a large room and tidy accommodations! How soothing to a sick man are those thousand little conveniencies and delicacies which only the hand of woman can supply, and from which the sufferer on shipboard is debarred! The well-aired bed linen; the clean and tidy apartment; the flowers placed on the stand opposite the bed; the green jalousies left half open to admit the cooling breeze; the delicious rose-water sprinkled around the room, and giving it an aromatic fragrance; and the orange, or tamarind, or other delicacy ever ready within reach to cool the fevered mouth, and remind you of the ceaseless care which thus anticipates your every want. All these, and even more, attested the kindness of my host’s family. Yet everything was done in so unobtrusive a manner that, for a long while, I was ignorant to whom I was indebted for this care. I saw no one but the nurse, the physician, and Mr. and Mrs. Neville. But I could not help fancying that there were others who sometimes visited my sick chamber, although as yet I had never been able to detect them, except by the fresh flowers which they left every morning as evidences of their presence. More than once, on suddenly awaking from sleep, I fancied I heard a light footstep retreating behind my bed, and once I distinguished the tone of a low sweet voice which sounded on my ear, tired as it was of the grating accents of the nurse, like music from Paradise. Often, too, I heard, through the half open blinds that concealed the entrance to a neighboring room, the sounds of a harp accompanied by a female voice; and, at such times, keeping my eyes closed lest I should be thought awake and the singer thus be induced to stop, I have listened until my soul seemed fairly “lapped into Elysium.” The memory of that ample apartment, with its spotless curtains and counterpanes, and the wind blowing freshly through its open jalousies, is as vivid in my memory to-day as it was in the hour when I lay there, listening to what seemed the seraphic music of that unseen performer. I hear yet that voice, so soft and yet so silvery, now rising clear as the note of a lark, and now sinking into a melody as liquid as that of flowing water, yet ever, in all its variations, sweet, and full, and enrapturing. Such a voice I used to dream of in childhood as belonging to the angels in heaven. Our dreams are not always wrong!

At length I was sufficiently recruited in strength to be able to sit up, and I shall ever remember the delicious emotions of the hour when I first took a seat by the casement and looked out into the garden, then fragrant with the dew of the early morning. I saw the blue sky smiling overhead, I heard the low plashing of a fountain in front of my window, I inhaled the delicate perfume wafted to me by the refreshing breeze, and as I sat there my soul ran over, as it were, with its exceeding gladness, and I almost joined my voice, from very ecstasy, with that of the birds who hopped from twig to twig, carolling their morning songs. As I sat thus looking out, I heard a light footstep on the gravel walk without, and directly the light, airy form of a young girl emerged from a secluded walk of the garden, full in my view. As she came opposite my window she looked up as if inadvertently, for, catching my eye, she blushed deeply and cast her gaze on the ground. In a moment, however, she recovered herself, and advanced in the direction she had been pursuing. The first glance at the face had revealed to me the countenance of her I had been instrumental in rescuing from the pirates. My apartment, like all those on the island, was on the ground floor, and when Miss Neville appeared she was already within a few feet of me. I rose and bowed, and noticing that she held a bunch of newly gathered flowers in her hands, I said,

“It is your taste, then, Miss Neville, which has filled the vase in my room every morning with its flowers. You cannot know how thankful I am. Ah! would that all knew with what delight a sick person gazes on flowers!”

She blushed again, and extending the bouquet to me, said with something of gaiety,

“I little thought you would be up to-day, much less at so early an hour, or perhaps I might not have gathered your flowers. Since you can gaze on them from your window they will be less attractive to you when severed, like these, from their parent stem.”

“No—never,” I answered warmly, “indeed your undeserved kindness, and that of your uncle and aunt, I can never forget.”

She looked at me in silence with her large, full eye a moment ere she replied, and I could see that they grew humid as she gazed. Her voice, too, softened and sank almost to a whisper when at length she spoke.

“Undeserved kindness! And can we ever forget,” she said, “what we owe to you?”

The words, as well as the gentle tone of reproof in which they were spoken, embarrassed me for a moment, and my eyes fell beneath her gaze. As if unwilling further to trust her emotions, she turned hastily away as she finished. When I looked up she was gone.

We met daily after this. The ennui of a convalescent made me look forward to the time she spent with me as if it constituted my whole day. Certainly the room seemed less cheerful after her departure. Often would I read while she sat sewing. At other times we indulged in conversation, and I found Miss Neville’s information on general subjects so extensive as sometimes to put me to the blush. She had read not only the best authors of our own language, but also those of France, and her remarks proved that she had thought while she read. She was a passionate admirer of music, and herself a finished performer. For all that was beautiful in nature she had an eye and soul. There was a dash of gaiety in her disposition, although, perhaps, her general character was sedate, and late events had if anything increased its prominent trait. Her tendency to a gentle melancholy—if I may use the phrase—was perceptible in her choice of favorite songs. More than once, when listening to the simple ballads she delighted to sing, have I caught the tears rolling down my cheeks, so unconsciously had I been subdued by the pathos of her voice and song.

In a few days I was sufficiently convalescent to leave my room, and thenceforth I established myself in the one from which I had heard the mysterious music. This apartment proved to be a sort of boudoir appropriated to the use of Miss Neville, and it was her performance on the harp that I had heard during my sickness. Hers too had been the figure which I had seen once or twice flitting out of sight on my awaking from a fevered sleep.

It is a dangerous thing when two young persons, of different sexes, are thrown together in daily intercourse, especially when one, from his very situation, is forced to depend on the other for the amusement of hours that would otherwise hang heavily on him. The peril is increased when either party is bound to the other by any real or fancied ties of gratitude. But during the first delicious fortnight of convalescence I was unconscious of this danger, and without taking any thought of the future I gave myself wholly up to the enjoyment of the hour. For Miss Neville I soon came to entertain a warm sentiment of regard, yet my feelings for her were of a far different nature from those I entertained for Annette. I did not, however, stop to analyze them, for I saw, or thought I saw, that the pleasure I felt in Ellen’s society was mutual, and I inquired no further. Alas! it never entered into my thoughts to ask whether, while I contented myself with friendship, she might not be yielding to a warmer sentiment. Had I been more vain perhaps this thought might have occurred to me. But I never imagined—blind fool that I was—that this constant intercourse betwixt us could endanger the peace of either. If I could, I would have coined my heart’s blood sooner than have won the love which I could not return. Yet such was my destiny. My eyes were opened at length to the consequences of my indiscretion.

We had been conversing one day of the expected arrival of the Arrow, and I had spoken enthusiastically of my profession, and, perhaps, expressed some restlessness at the inactive life I was leading, when I noticed that Ellen sighed, looked more closely at her work, and remained silent for some time. At length she raised her eyes, however, and said,

“How can you explain the passion which a sea-man entertains for his ship? One would think that your hearts indulged in no other sentiment than this engrossing one.”

“You wrong us, indeed, Ellen,” I said, “for no one has a warmer heart than the sailor. But we have shared so many dangers with our ship, and it has been to us so long almost our only world, that we learn to entertain a sort of passion for it, which, I confess, seems a miracle to others, but which to us is perfectly natural. I love the old Arrow with a sentiment approaching to monomania, and yet I have many and dear friends whom I love none the less for this passion.”

I saw that her bosom heaved quicker than usual at these words, and she plied her needle with increased velocity. Had I looked more narrowly, I might have seen the color faintly coming and going in her cheek, and almost heard her heart beating in the audible silence. But I still was blind to the cause of this emotion. By some unaccountable impulse I was led to speak of a subject which I had always avoided, though not intentionally—my early intimacy with Annette, and her subsequent rescue from the brig. Secure, as I thought, of the sympathy of my listener, and carried away by my engrossing love for Annette, I dwelt on her story for some time, totally unconscious of the effect my words were producing on Ellen. My infatuation on that morning seems now incredible. As I became more earnest with my subject, I noticed still less the growing agitation of my listener, and it was not until I was in the midst of a sentence in which I paused for words to express the loveliness of Annette’s character, that I saw that Ellen was in tears. She was bending low over her work so as to conceal her agitation from my eye, but as I hesitated in my glowing description, a bright tear-drop fell on her lap. The truth broke on me like a flash of lightning. I saw it all as clear as by a noonday sun, and I wondered at my former blindness. I was stung to the heart by what I had just been saying, for what agony it must have inflicted on my hearer! I felt my situation to be deeply embarrassing, and broke short off in my sentence. After a moment, however, feeling that silence was more oppressive than anything else, I made a desperate effort and said,

“Ellen!”

It was a single word, and one which I had addressed to her a hundred times before; but perhaps there was something in the tone in which I spoke it, that revealed what was passing in my mind, for, as she heard her name, the poor girl burst into a flood of tears, and covering her face with her hands she rushed from the room. She felt that her secret was disclosed. She loved one whose heart was given to another.

That day I saw her no more. But her agony of mind could not have been greater than my own. There is no feeling more acute to a sensitive mind than the consciousness that we are beloved by one whom we esteem, but whose affection it is impossible for us to requite. Oh! the bitter torture to reflect that by this inability to return another’s love, we are inflicting on them the sharpest of all disappointments, and perhaps embittering their life. Point me out a being who is callous to such a feeling, and I will point you out a wretch who is unworthy of the name of man. He who can triumph in the petty vanity of being loved by one for whom he entertains no return of affection, is worse than a fop or a fool—he is a scoundrel of the worst stamp. He deserves that his home should be uncheered by a WOMAN’S smiles, that his dying hour should be a stranger to her tender care. God knows! to her we are indebted for all the richest blessings and holiest emotions of our life. While we remember that we drank in our life from a mother’s breast—that we owed that life a thousand times afterwards to a mother’s care—that the love of a sister or the deeper affection of a wife has cheered us through many a dark hour of despair, we can never join that flippant school which makes light of a woman’s truth, or follow those impious revilers who would sneer at a woman’s love. The green sod grows to-day over many a lovely, fragile being, who might still have been living but for the perfidy of our sex. There is no fiction in the oft-told story of a broken heart. It is, perhaps, a consumption that finally destroys the victim, but alas! the barb that infused the poison first into the frame was—a hopeless love. How many fair faces have paled, how many hearts have grown cold, how many seraphic forms have passed, like angel visitants, from the earth, and few have known the secret of the blight that so mysteriously and suddenly withered them away. Alas! there is scarcely a village churchyard in the land, in which some broken hearted one does not sleep all forgotten in her lonely bed. The grave is a melancholy home; but it has hope for the distressed: there, at least, the weary are at rest.

It is years since I have visited the grave of Ellen, and I never think of her fate without tears coming into my eyes.

I said I saw her no more that day. When I descended to the breakfast table on the following morning, I looked around, and, not beholding her, was on the point of inquiring if she was ill; but, at the instant, the door opened and one of my old mess-mates appeared, announcing to me that the Arrow was in the offing, where she awaited me—he having been despatched with a boat to bring me on board. As I had been expecting her arrival for several days, there was little preparation necessary before I was ready to set forth. My traps had been already despatched when I stood in the hall to take leave of the family. My thoughts, at this moment, recurred again to Ellen, and I was, a second time, on the point of asking for her, when she appeared. I noticed that she looked pale, and I thought seemed as if she had been weeping. Her aunt said,

“I knew Ellen had a violent headache, but when I found that you were going, Mr. Cavendish, I thought she could come down for a last adieu.”

I bowed, and taking Miss Neville’s hand raised it to my lips. None there were acquainted with our secret but ourselves, yet I felt as if every eye was on me, and from the nervous trembling of Ellen’s fingers, I knew that her agitation was greater than my own.

“God bless you, dear Miss Neville,” I said, and, in spite of my efforts, my voice quivered, “and may your days be long and happy.”

As I dropped her hand, I raised my eyes a moment to her face. That look of mute thankfulness, and yet of mournful sorrow, I never shall forget. I felt that she saw and appreciated my situation, and that even thus her love was made evident. If I had doubted, her words would have relieved me.

“Farewell!” she said, in a voice so low that no one heard it but myself. “I do not blame you. God be with you!”

The tears gushed to her eyes, and my own heart was full to overflowing. I hastily waved my hand—for I had already taken leave of the rest—sprang into the carriage, rode in silence to the quay, and throwing myself into the stern sheets of the barge, sat, wrapt in my own emotions and without speaking a word, until we reached the ship. That night I early sought my hammock; and there prayed long and earnestly for Ellen.

The memory of that long past time crowds on me to-night, and I feel it would be a relief to me to disburden my full heart of its feelings. I will finish this melancholy story.

It was a short six months after my departure from Mr. Neville’s hospitable mansion, when we came to anchor again in the port, with a couple of rich prizes, which we had taken a short time before, in the Gulf Stream. The first intelligence I heard, on landing, was that Miss Neville was said to be dying of a consumption. Need I say that a pang of keenest agony shot through my heart? A something whispered to me that I was the cause, at least partially, of all this. With a faltering tongue I inquired the particulars. They were soon told. I subsequently learned more, and shall conceal nothing.

From the day when I left ——, the health of Ellen had begun gradually to droop. At first her friends noticed only that she was less gay than usual, and once or twice they alluded jestingly to me as the secret of her loss of spirits. But when the expression of agony, which at such times would flit across her face, was noticed, her friends ceased their allusions. Meanwhile her health began sensibly to be affected. She ate little. She slept in fitful dozes. No amusement could drive away the settled depression which seemed to brood upon her spirits. Her friends resorted to everything to divert her mind, but all was in vain. With a sad, sweet smile, she shook her head at their efforts, as if she felt that they could do nothing to reach her malady.

At length she caught a slight cold. She was of a northern constitution, and when this cold was followed by a permanent cough, her friends trembled lest it foreboded the presence of that disease, which annually sweeps off its thousands of the beautiful and gay. Nor were they long in doubt. Their worst fears were realised. Consumption had fixed its iron clutch on her heart, and was already tugging at its life-strings. The worm was gnawing at the core of the flower, and the next rough blast would sweep it from the stalk. As day by day passed, she drew nearer to the grave. Her eye grew sunken, but an unnatural lustre gleamed from its depths—the hectic flush blazed on her cheek—and that dry hacking cough, which so tortures the consumptive, while it snaps chord after chord of life, hourly grew worse.

At an early period of Ellen’s illness, Mrs. Neville, who had been to the orphan girl a second mother, divined the secret of her niece’s malady. She did not, however, urge her confidence on her charge, but Ellen soon saw that her aunt knew all. There was a meaning in her studied avoidance of my name, which could not be mistaken. Ellen’s heart was won by this delicacy, until, one day, she revealed everything. Mrs. Neville pressed her to her bosom at the close of the confession, and, though nothing was said, Ellen felt that the heart of her second mother bled for her.

As death drew nearer, Ellen’s thoughts became gradually freed from this world. But she had still one earthly desire—she wished to see me before she died. Only to Mrs. Neville, however, was this desire confided, and even then without any expectation that it could be gratified. When, however, the Arrow stopped so opportunely in ——, her petitions became so urgent, that Mrs. Neville sent for me. With a sad heart I obeyed her summons.

“The dear girl,” she said, when she met me in the ante-room, “would not be denied, and, indeed, I had not the heart to refuse her. Oh! Mr. Cavendish, you will find her sadly changed. These are fearful trials which God, in his good providence, has called us to undergo,” and tears choked her further utterance. I was scarcely less affected.

It would be a fruitless task in me to attempt to describe my emotions on entering the chamber of the dying girl. I have no recollection of the furniture of the room, save that it was distinguished by the exquisite neatness and taste which always characterized Ellen. My eyes rested only on one object—the sufferer herself.

She was reclining on a couch, her head propped up with pillows, and her right hand lying listlessly on the snowy counterpane. How transparent that hand seemed, with the blue veins so distinctly seen through the skin that you could almost mark the pulsation of the blood beneath. But it was her countenance which most startled me. When I last saw her—save at that one parting interview—her mild blue orbs smiled with a sunniness that spoke the joy of a young and happy heart. Now the wild hectic of consumption blazed on her cheek, and her eyes had a brilliancy and lustre that were not of earth. Then, her rich golden tresses floated in wavy curls across her shoulders—now, that beautiful hair was gathered up under the close-fitting cap which she wore. Then her face was bright with the glow of health—alas! now it was pale and attenuated. But in place of her faded loveliness had come a more glorious beauty; and the glad smile of old had given way to one of seraphic sweetness. When she extended her wan hand toward me, and spoke in that unrivalled voice which, though feeble, was like the symphony of an Æolian harp, it seemed, to my excited fancy, as if an angel from heaven had welcomed me to her side.

“This is a sad meeting,” she said; for my emotions, at the sight of her changed aspect, would not permit me to speak—“but why grieve? It is all for the best. It might seem unmaidenly to some,” she continued, with a partial hesitation, while, if possible, a brighter glow deepened on her cheek, “for me thus to send for you; but I trust we know each other’s hearts, and this is no time to bow to the formalities of life. I feel that I am dying.”

“Say not so, dear Ellen,” I gasped, while my frame shook with agony at the ruin I had brought about—“oh! say not so. You will yet recover. God has many happy years in store for you.”

“No, no,” she said touchingly, “this world is not for me; I am but a poor bruised reed—it were better I were cast aside. But weep not, for oh! I meant not to upbraid you. No, never, even in my first agony, have I blamed you—and it was to tell you this that I prayed I might survive. Yes! dearest—for it cannot be wrong now to confess my love—I would not that you should suppose I condemned you even in thought. You saved my life—and I loved you before I knew it myself. You weep—I know you do not despise me—had we met under better auspices, the result might have been—” here her voice choked with emotion—“might have been different.” I could only press her hand. “Oh! this is bliss,” she murmured, after a pause. “But it was not so to be,” she added, in a moment, with a saddened tone, which cut me to the heart. “I should love to see her of whom you speak—she is very beautiful, is she not? In heaven the angels are all beautiful.” Her mind wandered. “I have heard their music for days, and every day it is clearer and lovelier. Hear!” and with her finger raised, her eye fixed on the air, and a rapt smile on her radiant countenance, she remained a moment silent.

Tears fell from us like rain. But by and bye, her wandering senses returned; and a look of unutterable wo passed over her face. Oh! how my heart bled. I know not what I said; I only know that I strove to soothe the dying moments of that sweet saint, so suffering, yet so forgiving. A look of happiness once more lightened up her face, and, with a sweet smile, she talked of happiness and heaven. As we thus communed, our hearts were melted. Gradually her voice assumed a different tone, becoming sweeter and more liquid at every word, while her eyes shone no longer with that fitful lustre, but beamed on me the full effulgence of her soul once more.

“Raise me up,” she said. I passed my arm around her, and gently lifted her up. Her head reposed on my shoulder, while her hand was still clasped in mine. She turned her blue eyes on me with a seraphic expression, such as only the sainted soul in its parting moment can embody, and whispered—

“Oh! to die thus is sweet! Henry, dear Henry—God bless you! In heaven there is no sorrow,” and then, in incoherent sentences, she murmured of bright faces, and strange music, and glorious visions that were in the air. The dying musician said that he then knew more of God and nature than he ever knew before, and it may be, that, as the soul leaves the body, we are gifted with a power to see things of which no mortal here can tell. Who knows? In our dying hour we shall learn.

The grave of Ellen is now forgotten by all, save me. The grass has grown over it for long years. But often, in the still watches of the night, I think I hear a celestial voice whispering in my ear; and sometimes, in my dreams, I behold a face looking, as it were, from amid the stars: and that face, all glorious in light, is as the face of that sainted girl. I cannot believe that the dead return no more.

———

BY GEORGE P. MORRIS.

———

I’m with you once again, my friends—

No more my footsteps roam—

Where it began my journey ends,

Amid the scenes of home.

No other clime has skies so blue,

Or streams so broad and clear,

And earth no hearts so warm and true,

As those that meet me here.

Since last, with spirits wild and free,

I pressed my native strand,

I’ve wandered many miles at sea,

And many miles on land;

I’ve seen all nations of the earth,

Of every hue and tongue,

Which taught me how to prize the worth

Of that from whence I sprung.

In distant countries when I heard

The music of my own,

Oh how my echoing heart was stirred!—

It bounded at the tone!

But when a brother’s hand I grasp’d

Beneath a foreign sky,

With joy convulsively I gasp’d,

Like one about to die.

My native land, I come to you

With blessings and with prayer,

Where man is brave, and woman true,

And free as mountain air.

Long may our flag in triumph wave,

Against the world combined,

And friends a welcome, foes a grave,

On land and ocean find.

A TALE OF A VILLAGE INN.

———

BY MRS. A. M. F. ANNAN.

———

It may be out of keeping with our subject to apply the homely epithet of a “fish out of water” to Mr. Bromwell Sutton in the rural village of G——, but as no periphrasis suggests itself which would express his position as well, we must fain eschew elegance for the occasion, and let it stand. It was a sultry afternoon, in the middle of summer, when he arrived at the Eagle Inn, and after changing his dress, stepped to the door to see what could be seen. He looked up the street, and down and across, and not a living thing was visible besides himself, except a few sheep dozing in the market-house, and two or three cows silently ruminating in the shade of the town hall, both of which edifices were near at hand. Then having decided that there was nothing in the architectural aspect of the straggling village worth a second look, he concentred his scrutiny upon himself.

The result of his investigation stood thus:—that he was a very charming young man, was Mr. Bromwell Sutton. He had a slender, well formed figure, which was encased in a fresh suit of the finest texture and most unexceptionable make. His features were regular, and of that accommodating order which allows the spectator to assign them any character he may choose. His complexion was fair and clear, his teeth were very white and his eyes very blue. His hair was dark, daintily glossed and perfumed with oil, and of a length, which, on so warm a day, would have made a silver arrow or a gilded bodkin a judicious application; and he had two elongated tufts on his upper lip, and a round one on his chin corresponding to the space between them. He wore a Panama hat of the most extensive circumference, and carried a pair of white gloves, either to be drawn on his hands or slapped on his knees, whichever circumstances might require; and the corner of a hem-stitched handkerchief of transparent cambrick stuck out of his pocket.

A handbill pasted on the sign-post next caught his eye, and, though it was a favorite saying with him that he “never read,” to be understood of course, not that he never had read, but that he knew enough already; he so far conquered his disdain of literature as to step forward and ascertain its purport. This, set forth in the interesting typographical variety which veteran advertisers so well comprehend, of large and small Romans, and Italics leaning some to the right and some to the left, and some standing perpendicular, was as follows:

“Mr. Azariah Chowders, celebrated throughout the Union for his eloquent, entertaining and instructive discourses on miscellaneous subjects, proposes delivering a lecture on the evening of the present instant, in the town hall of G——. The theme selected is, the Genius of the American People, one, which, from its intrinsic importance, requires no comment,” &c. &c.

He was interrupted by the rattle of a distant vehicle, and looking up the street, saw a chaise approaching which contained a single “individual,” as he mentally pronounced him. He drove a fine horse, and drew him up before the door of the inn. The chaise was a plain, common looking concern, full of travel-worn trunks and boxes, and its occupant was dressed in a light summer suit, rather neat, but entirely too coarse for gentility.

“It’s only a Yankee pedlar,” said Mr. Sutton to the landlord who was coming out, and entirely careless of being overheard by the stranger; and he walked up to his chamber, where he awakened a diminutive poodle, his travelling companion, from the siesta with which it was recruiting after its journey, and occupied himself in cracking his handkerchief at it, until an additional stir in the house indicated the approach of tea-time. He then came down, carrying Cupidon, for so was the animal appellated; and found in the bar-room a young gentleman, a law-student, to whom he had delivered a letter on his arrival, and who was a boarder in the house. The other stranger had, meanwhile, entered the room, and was cooling himself at an open window, with his short curling hair pushed back from a forehead remarkable in its whiteness and intellectual development, and crowning a face of strikingly handsome lineaments and prepossessing expression.

“How do you contrive to exist in this stupid place?” asked our dandy of his new acquaintance, whose name was Wallis; “they say there are some genteel people about,—have you any pretty girls among them to flirt with?”

“We have some pretty young ladies, but don’t use them for that purpose exactly,” replied Wallis; “we admire them, and wait on them and try to please them, and then, when we can afford it, we marry them, if they don’t object.”

“Have you seen anything of a lady vagabondising in this region,—a Miss Valeria North?”

“Miss Valeria North, the fashionable heiress of B——? the niece of the celebrated Judge North? what should she be doing here?”

“Oh, I don’t know,—it’s beginning to be genteel for people to get tired of society, and to go hunting up out-of-the-way places that one knows nothing about except from the maps; I heard in the railroad cars that she was making a tour along the river here, and was in hopes that I might fall in with her. What do you know of her?”

“I heard a great deal about her at Saratoga last summer, where I happened to stop for a few days. Every body was talking about her beauty, talents and accomplishments, and in particular about her plain and simple manners, so singular in an heiress and a belle. The young men, mostly, seemed to have been afraid of her; regarding her as a female Caligula who would have rejoiced in the power of decapitating all the silliness, stupidity and puppyism in the world with one stroke of her wit.”

“Indeed!” said Sutton, with a weak laugh that proved him not to apprehend what he was laughing at; “I hope she’ll soon come along; I’m prepared for a dead set at her. Girls of two or three hundred thousands are worth that trouble; it’s a much pleasanter way to get pocket money than to be playing the dutiful son for it.”

Wallis elevated his eyebrows, but made no other reply.

“That, I suppose, is one of your village beauties,—that one walking in the garden with the pink dress on and the black apron,” resumed Sutton.

“No; she is a stranger boarding here,—a Miss Thompson.”

“Miss Thompson!—it might as well be Miss Blank for all the idea that conveys. Who, or what is she?”

“She does not say;—there is the name in the register beside you,—‘Mrs. Thompson and daughter’—so she entered it. She and her mother stopped here a week or two ago, on account of the lady’s health.”

“Thompsons!—they oughtn’t to be found at out-of-the-way places; all the genteel Thompsons that I ever heard of go to springs and places of decided fashion; it is absolutely necessary, that they may not be confounded with the mere Thompsons,—the ten thousand of the name. But that is a pretty looking girl,—and rather ladyish.”

“She is a lady—a well-bred, sensible girl, as ever I met with, and very highly educated.”

They were interrupted by the bell for tea, and, on entering the eating-room, they found the young lady in the pink dress at the table, with an elderly, delicate looking woman (Mrs. Thompson, of course,) beside her. Mr. Sutton advanced to the place immediately opposite to her, and a nearer view suggested that she might be one of the genteel Thompsons after all. She was a spirited looking girl, rather under the middle height, with a clear and brilliant, though not very fair complexion; large black eyes, surmounted by wide and distinctly marked eyebrows, and a broad, smooth forehead; a nose, (that most difficult of features, if we may judge by the innumerable failures,) a nose beautifully straight in its outline and with the most delicately cut nostrils possible; and the most charmingly curved lips, and the whitest teeth in the world. Having made these discoveries, Mr. Sutton decided that if her station should forbid his admiring her, he would not allow it to prevent her from admiring him. To afford her the benefit of this privilege, it was necessary that he should first attract her notice, for she had bestowed but a single glance at him on his entrance, as had her mother, the latter drawing up her eyelids as if she had been very near-sighted; and to affect this, he called, in a peremptory voice to the servant attending,

“Waiter, I wish you would give my dog something to eat.”

“Your dog, sir?—where is it?” asked the colored man, looking around the room, and then giving a loud whistle to call the invisible animal forth.

“Here,” replied Sutton, sharply; “or you may bring me a plate and I’ll feed him myself;” and he pointed to the miniature specimen, lying like a little lump of floss-silk, on his foot.

“That! I-I-I—he! he! ha! ha!” exclaimed the waiter, attempting at first to restrain himself, and then bursting into a chuckling laugh; “is it—really—a dog, sir?—a live dog!”

Cupidon, as if outraged by the suspicion, hereupon sprang into the middle of the room, barking at the height of his feeble voice, and showing his tiny white teeth, while his wicked little eyes sparkled with anger. The cachinnations of the amused and astonished servant increased at every bark, and drew a laugh from Wallis, and a smile from each of the ladies. Sutton with difficulty silenced his favorite, and finding that the desired impression of his consequence had not been made, he proceeded to another essay. “Waiter,” he slowly enunciated, with a look of disgust at the steel implement in his hand; “have you no silver forks?”

“Sir?” said the attendant with a puzzled expression.

“Any silver forks?” he repeated emphatically.

“No, sir; we don’t keep the article.”

“Then you should not put fish on the table; they ought properly to be inseparable,” he returned, magisterially, and rising from his seat, he approached the stranger of the chaise, who had quietly placed himself some distance below them, and asked, “Have you any such things as silver forks among your commodities?—I believe that persons in your vocation sometimes deal in articles of that description.”

The stranger looked up in surprise, and, after scanning him from head to foot, a frown which was gathering on his face gave way to a look of humorous complacency—“I am sorry I can’t accommodate you, sir,” said he; “but I might probably suggest a substitute;—how would a tea-spoon do?”

He returned to his seat, rather dubious about the smiles he detected, and, as a third effort, addressed himself, somewhat in the following manner, to Wallis, whose interlocutions are unnecessary. “How far did you say it was to the Sutton Mills?—only four miles, isn’t it? I shall have to apply to you to show me the way. I have a curiosity to see them, as they are one of my father’s favorite hobbies. I often laugh at him for christening them with his own name. Calling a villa, a fashionable country seat, after one’s self, is well enough, but mills or manufactories—it is rather out of taste. Is the fourth finished yet? I believe it is to be the finest of all; indeed, it seems to me a little injudicious in the old gentleman to have invested so much in a country property—there are at least half a dozen farms, are there not? but I suppose he was afraid to trust his funds to stocks, and he has already more real estate in the city than he can well attend to. However, if he had handed over the amount to me, I think I could have disposed of it with a much better grace. He did offer me a title to them, some time ago, but it was on condition that I should come here and manage them myself, but I begged to be excused, and it was only on agreement that I should have a hundred per cent. of the revenue this year, that I consented to undergo the trouble of visiting them, or the sacrifice, rather—there are so many delightful places to go to in the summer,” and so forth.

Having, from these indirect explanations, made a clear case that his society was entitled to a welcome from the best Thompson in the world, and to that with thanks, if his fair neighbor was only a crockery Thompson, he arose and returned to the front of the house. The village had, by this time, awakened from its nap, and the larger proportion of its inhabitants were bending their steps to the town hall. Numerous well appointed carriages were also coming in from the surrounding neighborhood, whose passengers were all bound to the same point. “Where are all these people going?” asked Sutton.

“To the lecture announced in that handbill,” replied Wallis—and Miss Thompson presenting herself at the door, ready bonnetted, he walked with her in a neighborly sort of a way across the street. After a while the throng ceased, and from some impatient expressions of the loungers about the tavern, Sutton ascertained that the lecturer had not yet appeared.

“Why, that man I mistook for a Yankee pedlar must be he, I should judge,” said he to the landlord.

“Who?—where?” said a young man, who had not heard the last clause.

“That tall fellow, in the garden, there, drest in the brown-holland pantaloons and Kentucky jean coat.”

“Indeed!—I thought he was to stop at the other house;” and he hastened down the street, while Sutton, finding that every body was going to the hall, strolled there also.

Meanwhile, the stranger in the coarse jeans was enjoying himself in a saunter through the quiet and pretty garden of the inn, which was so hedged and enclosed as to admit of no view of the street, when a consequential personage presented himself, and saluting him stiffly, introduced himself as “Mr. Smith, the proprietor of the G—— Hotel.”

“I am happy to make your acquaintance, sir,” said the young stranger, courteously.