VOLUME I

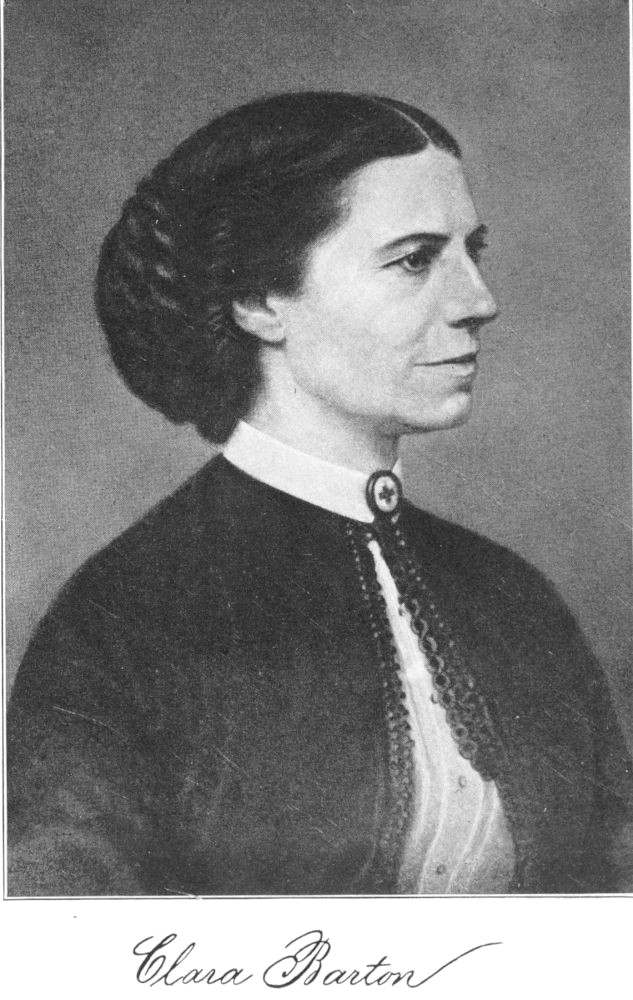

Clara Barton

Title: The Life of Clara Barton, Founder of the American Red Cross (Vol. 1 of 2)

Author: William E. Barton

Release date: February 26, 2022 [eBook #67505]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1922

Credits: MWS and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

VOLUME I

Clara Barton

FOUNDER OF

THE AMERICAN RED CROSS

BY

WILLIAM E. BARTON

AUTHOR OF “THE SOUL OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN”

“THE PATERNITY OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN,” ETC.

With Illustrations

VOLUME I

![]()

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

1922

COPYRIGHT, 1922, BY WILLIAM E. BARTON

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The Riverside Press

CAMBRIDGE · MASSACHUSETTS

PRINTED IN THE U. S. A.

TO

STEPHEN E. BARTON

HER TRUSTED NEPHEW; MY KINSMAN AND FRIEND

CONTENTS

VOLUME I

| Introduction | xi | |

| I. | Her First Attempt at Autobiography | 1 |

| II. | The Birth of Clara Barton | 6 |

| III. | Her Ancestry | 9 |

| IV. | Her Parentage and Infancy | 16 |

| V. | Her Schools and Teachers | 22 |

| VI. | The Days of Her Youth | 36 |

| VII. | Her First Experience as a Teacher | 50 |

| VIII. | Leaves from Her Unpublished Autobiography | 56 |

| IX. | The Heart of Clara Barton | 76 |

| X. | From Schoolroom to Patent Office | 89 |

| XI. | The Battle Cry of Freedom | 107 |

| XII. | Home and Country | 131 |

| XIII. | Clara Barton to the Front | 172 |

| XIV. | Harper’s Ferry to Antietam | 191 |

| XV. | Clara Barton’s Change of Base | 225 |

| XVI. | The Attempt to Recapture Sumter | 238 |

| XVII. | From the Wilderness to the James | 263 |

| XVIII. | To the End of the War | 282 |

| XIX. | Andersonville and After | 304 |

| XX. | On the Lecture Platform | 328 |

The life of Clara Barton is a story of unique and permanent interest; but it is more than an interesting story. It is an important chapter in the history of our country, and in that of the progress of philanthropy in this country and the world. Without that chapter, some events of large importance can never be adequately understood.

Hers was a long life. She lived to enter her tenth decade, and when she died was still so normal in the soundness of her bodily organs and in the clarity of her mind and memory that it seemed she might easily have lived to see her hundredth birthday. Hers was a life spent largely in the Nation’s capital. She knew personally every president from Lincoln to Roosevelt, and was acquainted with nearly every man of prominence in our national life. When she went abroad, her associates were people of high rank and wide influence in their respective countries. No American woman received more honor while she lived, either at home or abroad, and how worthily she bore these honors those know best who knew her best.

The time has come for the publication of a definitive biography of Clara Barton. Such a book could not earlier have been prepared. The “Life of Clara Barton,” by Percy H. Epler, published in 1915, was issued to meet the demand which rose immediately after her death for a comprehensive biography, and it was published with the full approval of Miss Barton’s relatives and of her literary executors, including the author of the present work. But,[Pg xii] by agreement, the two large vaults containing some tons of manuscripts which Miss Barton left, were not opened until after the publication of Mr. Epler’s book. It was the judgment of her literary executors, concurred in by Mr. Epler, that this mine of information could not be adequately explored within any period consistent with the publication of a biography such as he contemplated. For this reason, the two vaults remained unopened until his book was on the market. The contents of these vaults, containing more than forty closely packed boxes, is the chief source of the present volume, and this abundant material has been supplemented by letters and personal reminiscences from Clara Barton’s relatives and intimate friends.

Clara Barton considered often the question of writing her own biography. A friend urged this duty upon her in the spring of 1876, and she promised to consider the matter. But the incessant demands made upon her time by duties that grew more steadily imperative prevented her doing this.

In 1906 the request came to her from a number of school-children that she would tell about her childhood; and she wrote a little volume of one hundred and twenty-five pages, published in 1907 by Baker and Taylor, entitled, “The Story of my Childhood.” She was gratified by the reception of this little book, and seriously considered using it as the corner stone of her long contemplated autobiography. She wrote a second section of about fifteen thousand words, covering her girlhood and her experiences as a teacher at home and in Borden town, New Jersey. This was never published, and has been utilized in this present biography.

[Pg xiii]

Beside these two formal and valuable contributions toward her biography, she left journals covering most of the years from her girlhood until her death, besides vast quantities of letters received by her and copies of her replies. Her personal letters to her intimate friends were not copied, as a rule, but it has been possible to gather some hundreds of these. Letter-books, scrap-books, newspaper clippings, magazine articles, records of the American Red Cross, and papers, official and personal, swell the volume of material for this book to proportions not simply embarrassing, but almost overwhelming.

She appears never to have destroyed anything. Her temperament and the habits of a lifetime impelled her to save every scrap of material bearing upon her work and the subjects in which she was interested. She gathered, and with her own hand labeled, and neatly tied up her documents, and preserved them against the day when she should be able to sift and classify them and prepare them for such use as might ultimately be made of them. It troubled her that she was leaving these in such great bulk, and she hoped vainly for the time when she could go through them, box by box, and put them into shape. But they accumulated far more rapidly than she could have assorted them, and so they were left until her death, and still remained untouched, until December, 1915, when the vaults were opened and the heavy task began of examining this material, selecting from it the papers that tell the whole story of her life, and preparing the present volumes. If this book is large, it is because the material compelled it to be so. It could easily have been ten times as thick.

The will of Clara Barton named as her executor her[Pg xiv] beloved and trusted nephew, Stephen E. Barton. It also named a committee of literary executors, to whom she entrusted the use of her manuscripts for such purpose, biographical or otherwise, as they should deem best. The author of these volumes was named by her as a member of that committee. The committee elected him as its chairman, and requested him to undertake the preparation of the biography. This task was undertaken gladly, for the writer knew and loved his kinswoman and held her in honor and affection; but he knew too well the magnitude of the task ahead of him to be altogether eager to accept it. The burden, however, has been measurably lightened by the assistance of Miss Saidee F. Riccius, a grand-niece of Miss Barton, who, under the instruction of the literary executors, and the immediate direction of Stephen E. Barton and the author, has rendered invaluable service, without which the author could not have undertaken this work.

In her will, written a few days before her death, Miss Barton virtually apologized to the committee and to her biographer for the heavy task which she bequeathed to them. She said:

“I regret exceedingly that such a labor should devolve upon my friends as the overlooking of the letters of a lifetime, which should properly be done by me, and shall be, if I am so fortunate as to regain a sufficient amount of strength to enable me to do it. I have never destroyed my letters, regarding them as the surest chronological testimony of my life, whenever I could find the time to attempt to write it. That time has never come to me, and the letters still wait my call.”

They still were there, undisturbed, thousands of them,[Pg xv] when the vaults were opened, and none of them have been destroyed or mutilated. They are of every sort, personal and official; and they bear their consistent and cumulative testimony to her indefatigability, her patience, her heroic resolution, and most of all to her greatness of heart and integrity of soul.

Interesting and valuable in their record of every period and almost every day and hour of her long and eventful life, they are the indisputable record of the birth and development of the organization which almost single-handed she created, the American Red Cross.

Among those who suggested to Miss Barton the desirability of her writing the story of her own life, was Mr. Houghton, senior partner in the firm of Houghton, Mifflin and Company. He had one or more personal conferences with her relating to this matter. Had she been able to write the story of her own life, she would have expected it to be published by that firm. It is to the author a gratifying circumstance that this work, which must take the place of her autobiography, is published by the firm with whose senior member she first discussed the preparation of such a work.

The author of this biography was a relative and friend of Clara Barton, and knew her intimately. By her request he conducted her funeral services, and spoke the last words at her grave. His own knowledge of her has been supplemented and greatly enlarged by the personal reminiscences of her nearer relatives and of the friends who lived under her roof, and those who accompanied her on her many missions of mercy.

In a work where so much compression was inevitable, some incidents may well have received scant mention[Pg xvi] which deserved fuller treatment. The question of proportion is never an easy one to settle in a work of this character. If she had given any direction, it would have been that little be said about her, and much about the work she loved. That work, the founding of the American Red Cross, must receive marked emphasis in a Life of Clara Barton: for she was its mother. She conceived the American Red Cross, carried it under her heart for years before it could be brought forth, nurtured it in its cradle, and left it to her country and the world, an organization whose record in the great World War shines bright against that black cloud of horror, as the emblem of mercy and of hope.

Wherever, in America or in lands beyond, the flag of the Red Cross flies beside the Stars and Stripes, there the soul of Clara Barton marches on.

First Church Study

Oak Park, July 16, 1921

[Pg 1]

Though she had often been importuned to furnish to the public some account of her life and work, Clara Barton’s first autobiographical outline was not written until September, 1876, when Susan B. Anthony requested her to prepare a sketch of her life for an encyclopædia of noted women of America. Miss Barton labored long over her reply. She knew that the story must be short, and that she must clip conjunctions and prepositions and omit “all the sweetest and best things.” When she had finished the sketch, she was appalled at its length, and still was unwilling that any one else should make it shorter; so she sent it with stamps for its return in case it should prove too long. “It has not an adjective in it,” she said.

Her original draft is still preserved, and reads as follows:

For Susan B. Anthony

Sketch for CyclopædiaSeptember, 1876

Barton, Clara; her father, Capt. Stephen Barton, a non-commissioned officer under “Mad Anthony Wayne,” was a farmer in Oxford, Mass. Clara, youngest child,[Pg 2] finished her education at Clinton, N.Y. Teacher, popularized free schools in New Jersey.

First woman appointed to an independent clerkship by Government at Washington.

On outbreak of Civil War, went to aid suffering soldiers. Labored in advance and independent of commissions. Never in hospitals; selecting as scene of operations the battle-field from its earliest moment, ’till the wounded and dead were removed or cared for; carrying her own supplies by Government transportation.

At the battles of Cedar Mountain, Second Bull Run, Chantilly, South Mountain, Falmouth and “Old Fredericksburg,” Siege of Charleston, Morris Island, Wagner, Wilderness, Fredericksburg, The Mine, Deep Bottom, through sieges of Petersburg and Richmond under Butler and Grant.

At Annapolis on arrival of prisoners.

Established search for missing soldiers, and, aided by Dorence Atwater, enclosed cemetery, identified and marked the graves of Andersonville.

Lectured on Incidents of the War in 1866-67. In 1869 went to Europe for health. In Switzerland on outbreak of Franco-Prussian War; tendered services. Was invited by Grand Duchess of Baden, daughter of Emperor William, to aid in establishing her hospitals. On fall of Strassburg entered with German Army, remained eight months, instituted work for women which held twelve hundred persons from beggary and clothed thirty thousand.

Entered Metz on its fall. Entered Paris the day succeeding the fall of Commune; remained two months, distributing money and clothing which she carried. Met the poor of every besieged city of France, giving help.

Is representative of the “Comité International of the Red Cross” of Geneva. Honorary and only woman member of Comité de Strasbourgoes. Was decorated with the Gold Cross of Remembrance by the Grand Duke and[Pg 3] Duchess of Baden and with the “Iron Cross” by the Emperor and Empress of Germany.

Miss Anthony regarded the sketch with the horror of offended modesty.

“For Heaven’s sake, Clara,” she wrote, “put some flesh and clothes on this skeleton!”

Thus admonished, Miss Barton set to work to drape the bones of her first attempt, and was in need of some assistance from Miss Anthony and others. The work as completed was not wholly her own. The adjectives, which had been conspicuously absent from the first draft together with some characterizations of Miss Barton and her work, were supplied by Miss Anthony and her editors. It need not here be reprinted in its final form; for it is accessible in Miss Anthony’s book. As it finally appeared, it is several times as long as when Clara Barton wrote it, and is more Miss Anthony’s than Miss Barton’s.

In the foregoing account, mention is made of her being an official member of the International Committee of the Red Cross. In that capacity she did not at that time represent any American organization known as the Red Cross, for there was no such body. Although such an organization had been in existence in Europe from the time of our Civil War, and the Reverend Dr. Henry W. Bellows, late of the Christian Commission, had most earnestly endeavored to organize a branch of it in this country, and to secure official representation from America in the international body, the proposal had been met not merely by indifference, but by hostility.

Clara Barton wrote her autobiographical sketch from a sanitarium. She had not yet recovered from the strain of her service in the Franco-Prussian War. One reason[Pg 4] why she did not recover more rapidly was that she was bearing on her heart the burden of this as yet unborn organization, and as yet had found no friends of sufficient influence and faith to afford to America a share in the honor of belonging to the sisterhood of nations that marched under that banner.

The outbreak of the World War found America unprepared save only in her wealth of material resources, her high moral purpose, and her ability to adapt her forms of organized life to changed and unwelcome conditions. The rapidity with which she increased her army and her navy to a strength that made it possible for her to turn the scale, where the fate of the world hung trembling in the balance, was not more remarkable than her skill in adapting her institutions of peace to the exigencies of war. Most of the agencies, which, under the direction of civilians, ministered to men in arms had either to be created out of hand or adapted from institutions formed in time of peace and for other objects. But the American Red Cross was already organized and in active service. It was a factor in the fight from the first day of the world’s agony, through the invasion of Belgium, and the three years of our professed neutrality; and by the time of America’s own entrance into the war it had assumed such proportions that everywhere the Red Cross was seen floating beside the Stars and Stripes. Every one knew what it stood for. It was the emblem of mercy, even as the flag of our Nation was the symbol of liberty and the hope of the world.

The history of the American Red Cross cannot be written apart from the story of its founder, Clara Barton.[Pg 5] For years before it came into being, her voice almost alone pleaded for it, and to her persistent and almost sole endeavor it came at length to be established in America. For other years she was its animating spirit, its voice, its soul. Had she lived to see its work in the great World War, she would have been humbly and unselfishly grateful for her part in its beginnings, and overjoyed that it had outgrown them. The story of the founding and of the early history of the American Red Cross is the story of Clara Barton.

[Pg 6]

Clara Barton was a Christmas gift to the world. She was born December 25, 1821. Her parents named her Clarissa Harlowe. It was a name with interesting literary associations.

Novels now grow overnight and are forgotten in a day. The paper mills are glutted with the waste of yesterday’s popular works of fiction; and the perishability of paper is all that prevents the stopping of all the wheels of progress with the accumulation of obsolete “best-sellers.” But it was not so in 1821. The novels of Samuel Richardson, issued in the middle of the previous century, were still popular. He wrote “Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded,” a novel named for its heroine, a pure and simple-minded country girl, who repelled the dishonorable proposals of her employer until he came to respect her, and married her, and they lived happily ever after. The plot of this story lives again in a thousand moving-picture dramas, in which the heroine is a shop girl or an art student; but Richardson required two volumes to tell the story, and it ran through five editions in a year. He also wrote “Sir Charles Grandison,” and it required six volumes to portray that hero’s smug priggishness; but the Reverend Dr. Finney, president of Oberlin College, who was also the foremost evangelist of his time, and whose system of theology wrought in its day a revolution, was not the only distinguished man who bore the name of Charles Grandison.

[Pg 7]

But Richardson’s greatest literary triumph was “Clarissa Harlowe.” Lady Mary Wortley Montagu was not far wrong when she declared that the chambermaids of all nations wept over Pamela, and that all the ladies of quality were on their knees to Richardson imploring him to spare Clarissa. Clarissa was not a servant like Pamela: she was a lady of quality, and she had a lover socially her equal, but morally on a par with a considerable number of the gentry of his day. His name, Lovelace, became the popular designation of the gentleman profligate. Clarissa’s sorrows at his hands ran through eight volumes, and, as the lachrymose sentiment ran out to volume after volume, the gentlewomen of the English-reading world wept tears that might have made another flood. Samuel Richardson wrote the story of “Clarissa Harlowe” in 1748, but the story still was read, and the name of the heroine was loved, in 1821.

But Clarissa Harlowe Barton did not permanently bear the incubus of so long a name. Among her friends she was always Clara, and though for years she signed her name “Clara H. Barton,” the convenience and rhythm of the shorter name won over the time-honored sentiment attached to the title of the novel, and the world knows her simply as Clara Barton.

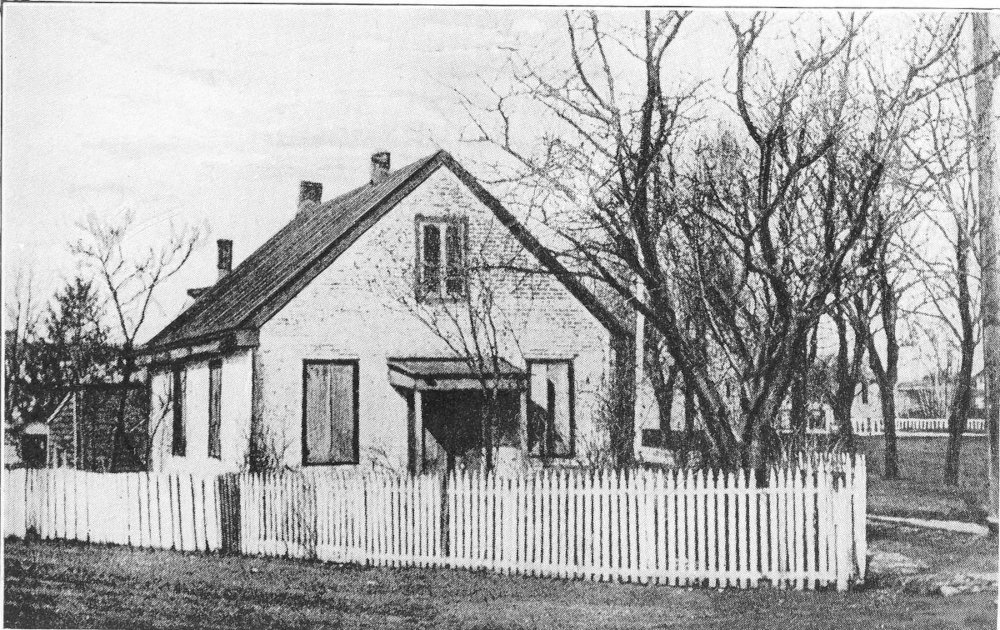

He who rides on the electric cars from Worcester to Webster will pass Bartlett’s Upper Mills, where a weather-beaten sign at the crossroads points the way “To Clara Barton’s Birthplace.” About a mile from the main street, on the summit of a rounded hill, the visitor will find the house where she was born. It stands with its side to the road, a hall dividing it through the middle. It is an unpretentious home, but comfortable,[Pg 8] one story high at the eaves, but rising with the rafters to afford elevation for chambers upstairs. In the rear room, on the left side, on the ground floor, the children of the Barton family were born. Clara was the fifth and youngest child, ten years younger than her sister next older. The eldest child, Dorothy, was born October 2, 1804, and died April 19, 1846. The next two children were sons, Stephen, the third to bear the name, born March 29, 1806, and David, born August 15, 1808. Then came another daughter, Sarah, born March 20, 1811. These four children followed each other at intervals of a little more than two years; but Clara had between her and the other children the wide gap of more than a decade. Her brothers were fifteen and thirteen, respectively, and her sister was “going on eleven” when she arrived. She came into a world that was already well grown up and fully occupied with concerns of its own. Had there been between her and the other children an ascending series of four or five graduated steps of heads, the first a little taller than her own, and the others rising in orderly sequence, the rest of the universe would not have been quite so formidable; but she was the sole representative of babyhood in the home at the time of her arrival. So she began her somewhat solitary pilgrimage, from a cradle fringed about with interested and affectionate observers, all of whom had been babies a good while before, but had forgotten about it, into that vast and vague domain inhabited by the adult portion of the human race; and while she was not unattended, her journey had its elements of solitude.

[Pg 9]

The Bartons of America are descended from a number of immigrant ancestors, who have come to this country from England, Scotland, and Ireland. The name, however, is neither Scotch nor Irish, but English. While the several families in Great Britain have not as yet traced their ancestry to a single source, there appears to have been such a source. The ancestral home of the Barton family is Lancashire. The family is of Norman stock, and came to England with William the Conqueror, deriving their English surname from Barton Manor in Lancashire. From 1086, when the name was recorded in the Doomsday Book, it is found in the records of Lancashire.

The derivation of the name is disputed. It is said that originally it was derived from the Saxon bere, barley, and tun, a field, and to mean the enclosed lands immediately adjacent to a manor; but most English names that end with “ton” are derived from “town” with a prefix, and it is claimed that bar, or defense, and ton, or town, once meant a defended or enclosed town, or one who protects a town. The name is held to mean “defender of the town.”

In the time of Henry I, Sir Leysing de Barton, Knight, was mentioned as a feudal vassal of lands between the rivers Ribbe and Mersey, under Stephen, Count of Mortagne, grandson of William the Conqueror, who later became King Stephen of England. Sir Leysing de Barton[Pg 10] was the father of Matthew de Barton, and the grandfather of several granddaughters, one of whom was Editha de Barton, Lady of Barton Manor. She inherited the great estate, and was a woman of note in her day. She married Augustine de Barton, possibly a cousin, by whom she had two children, John de Barton, who died before his mother, and a daughter Cecilly.

After the death of Augustine de Barton, his widow, Lady Editha, married Gilbert de Notton, a landed proprietor of Lincolnshire, who also had possessions in Yorkshire and Lancashire. He had three sons by a previous marriage, one of whom, William, married Cecilly de Barton, daughter of Editha and her first husband Augustine. Their son, named for his uncle, Gilbert de Notton, inherited the Barton Manor and assumed the surname Barton.

The Barton estate was large, containing several villages and settlements. The homestead was at Barton-on-Irwell, now in the municipality of Eccles, near the city of Manchester.

Other Barton families in England are quite possibly descended from younger sons of the original Barton line.

The arms of the Bartons of Barton were, Argent, three boars’ heads, armed, or.

In the Wars of the Roses the Bartons were with the house of Lancaster, and the Red Rose is the traditional flower of the Barton family. Clara Barton, when she wore flowers, habitually wore red roses; and whatever her attire there was almost invariably about it somewhere a touch of red, “her color,” she called it, as it had been the color of her ancestors for many generations.

In the seventeenth century there were several families[Pg 11] of Bartons in the American colonies. The name is found early in Virginia, in Pennsylvania, in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Jersey, and other colonies.

Salem had two families of Bartons, probably related,—those of Dr. John Barton, physician and chirurgeon, who came from Huntingdonshire, England, in 1672, and was prominent in the early life of Salem, and Edward Barton, who arrived thirty-two years earlier, but, receiving a grant of land on the Piscataqua, removed to Portsmouth, and about 1666 to Cape Porpoise, Maine. On account of Indian troubles, the homestead was deserted for some years, but Cape Porpoise continued to be the traditional home of this branch of the Barton family.

Edward’s eldest son, Matthew, returned to Salem, and lived there, at Portsmouth, and at Cape Porpoise. His eldest son, born probably at Salem in or about 1664, was Samuel Barton, founder of the Barton family of Oxford.

Not long after the pathetic witchcraft delusion of Salem, a number of enterprising families migrated from Salem to Framingham, among them the family of Samuel Barton. On July 19, 1716, as recorded in the Suffolk County Registry of Deeds in Boston, Jonathan Provender, husbandman, of Oxford, sold to Samuel Barton, Sr., husbandman, of Framingham, a tract of land including about one-thirtieth of the village of Oxford, as well as a fourth interest in two mills, a sawmill and a gristmill.

In 1720, Samuel Barton and a few of his neighbors met at the home of John Towne, where, after prayer, “they mutually considered their obligations to promote the kingdom of their Lord and Saviour, Jesus Christ,” and[Pg 12] covenanted together to seek to establish and build a church of Christ in Oxford. On January 3, 1721, the church was formally constituted, Samuel Barton and his wife bringing their letters of dismission from the church in Framingham of which both were members, and uniting as charter members of the new church in Oxford. The Reverend John Campbell was their first pastor. For over forty years he led his people, and his name lives in the history of that town as a man of learning, piety, and rare capacity for spiritual leadership. Long after his death, it was discovered that he was Colonel John Campbell, of Scotland, heir to the earldom of Loudon, who had fled from Scotland for political reasons, and who became a soldier of Christ in the new world.

Samuel Barton, son of Edward and Martha Barton, and grandson of Edward and Elizabeth Barton, died in Oxford September 12, 1732. His wife, Hannah Bridges, died there March 13, 1737. From them sprang the family of the Oxford Bartons, whose most illustrious representative was Clara Barton.

The maternal side of this line, that of Bridges, began in America with Edmund Bridges, who came to Massachusetts from England in 1635, and lived successively at Lynn, Rowley, and Ipswich. His eldest son, Edmund, Jr., was born about 1637, married Sarah Towne in 1659, lived in Topsfield and Salem, and died in 1682. The fourth of their five children was a daughter, Hannah, who, probably at Salem about 1690, married Samuel Barton, progenitor of the Bartons of Oxford, to which town he removed from Framingham in 1716.

Edmund, youngest son of Samuel and Hannah Barton, was born in Framingham, August 15, 1715. He married,[Pg 13] April 9, 1739, Anna Flint, of Salem. She was born June 9, 1718, eldest daughter of Stephen Flint and his wife, Hannah Moulton. Anna Flint was the granddaughter of John Flint, of Salem Village (Danvers), and great-granddaughter of Thomas Flint, who came to Salem before 1650.

Edmund settled in Sutton, and owned lands there and in Oxford. He and his wife became members of the First Church in Sutton, and later transferred their membership to the Second Church in Sutton, which subsequently became the First Church in Millbury. He served in the French War, and was at Fort Edward in 1753. He died December 13, 1799, and Anna, his wife, died March 20, 1795.

The eldest son of Edmund and Anna Barton was Stephen Barton, born June 10, 1740, at Sutton. He studied medicine with Dr. Green, of Leicester, and practiced his profession in Oxford and in Maine. He had unusual professional skill, as well as great sympathy and charity. He married at Oxford, May 28, 1765, Dorothy Moore, who was born at Oxford, April 12, 1747, daughter of Elijah Moore and Dorothy Learned. On her father’s side she was the granddaughter of Richard, great-granddaughter of Jacob, and great-great-granddaughter of John Moore. John Moore and his wife, Elizabeth, daughter of Philemon Whale, bought a home in Sudbury in 1642. Their son, Jacob, married Elizabeth Looker, daughter of Henry Looker, of Sudbury, and lived in Sudbury. Their son Richard, born in Sudbury in 1670, married Mary Collins, daughter of Samuel Collins, of Middletown, Connecticut, and granddaughter of Edward Collins, of Cambridge. Richard Moore was one of the[Pg 14] most capable and trusted men in early Oxford. Dorothy Learned, wife of Elijah Moore, was the daughter of Colonel Ebenezer Learned, the largest landowner in Oxford, one of the original thirty proprietors. He was a man of superior personality, for thirty-two years one of the selectmen, for many years chairman of that body, and moderator of town meetings, a justice of the peace, a representative in the Great and General Court, and an officer in the militia from 1718 to 1750, beginning as Ensign and reaching the rank of Colonel. He was active in the affairs of the town, the church, and the military organization during his long and useful life. His wife was Deborah Haynes, daughter of John Haynes, of Sudbury. He was the son of Isaac Learned, Jr., of Framingham, who had been a soldier in the Narraganset War, and his wife, Sarah Bigelow, daughter of John Bigelow, of Watertown. Isaac Learned was the son of Isaac Learned, Sr., of Woburn and Chelmsford, and his wife, Mary Stearns, daughter of Isaac Stearns, of Watertown. The parents of Isaac Learned, Sr., were William and Goditha Learned, members of the Charlestown Church in 1632, and of Woburn Church in 1642.

The Learned family shared with the Barton family in the formation of the English settlement in Oxford, and were intimately related by intermarriage and many mutual interests. Brigadier-General Ebenezer Learned, a distinguished officer in the Revolution, was a brother of Dorothy Learned Moore, the great-grandmother of Clara Barton.

Dr. Stephen Barton and his wife, Dorothy Moore, had thirteen children. Their sons were Elijah Moore, born October 12, 1765, and died June 13, 1769; Gideon, born[Pg 15] March 29, 1767, and died October 27, 1770; Stephen, born August 18, 1774; Elijah Moore, born August 10, 1784; Gideon, born June 18, 1786; and Luke, born September 3, 1791. The first two sons died at an early age; the four remaining sons lived to marry, and three of them lived in Maine. The daughters of Dr. Stephen Barton and Dorothy, his wife, were Pamela, Clarissa Harlowe, Hannah, Parthena, Polly, and Dolly.

It is interesting to note in the names of these daughters a departure from the common New England custom of seeking Bible names, and the naming of the first two daughters after the two principal heroines of Samuel Richardson.

Of this family, the third son, and the eldest to survive, was Stephen Barton, Jr., known as Captain Stephen Barton, father of Clara Barton.

[Pg 16]

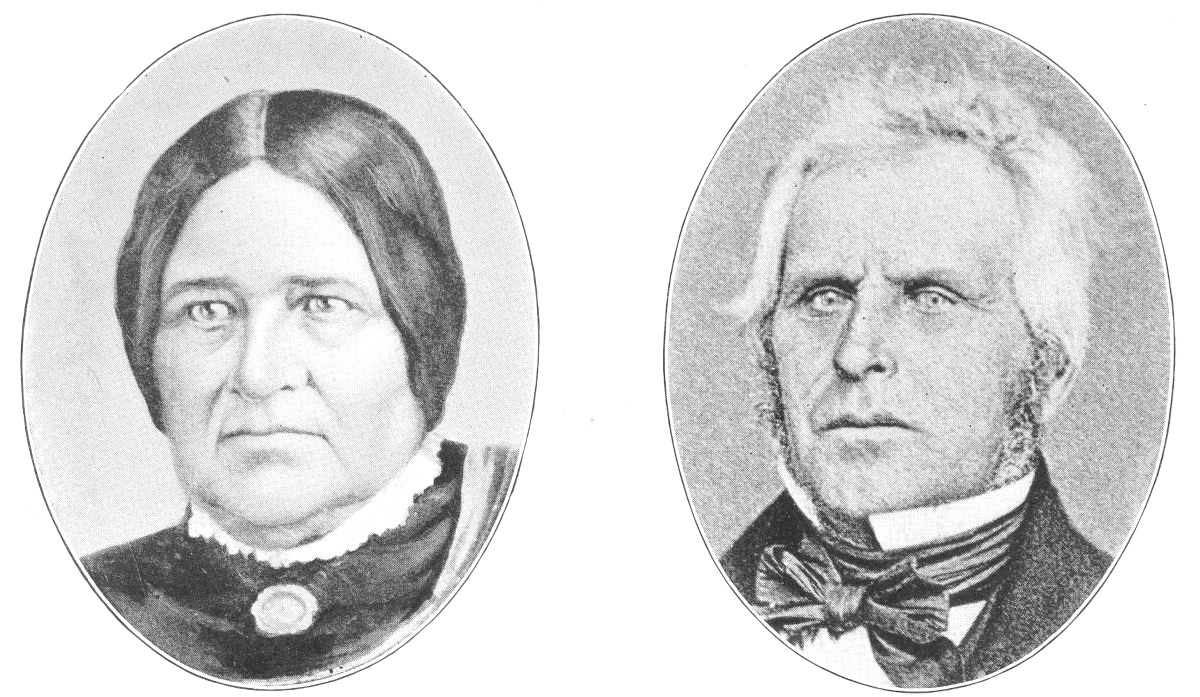

Captain Stephen Barton won his military title by that system of post-bellum promotion familiar in all American communities. He was a non-commissioned officer in the wars against the Indians. He was nineteen when he enlisted, and marched on foot with his troop from Boston to Philadelphia, which at that time was the Nation’s capital. The main army was then at Detroit under command of General Wayne, whom the soldiers lovingly knew as “Mad Anthony.” William Henry Harrison and Richard M. Johnson, later President and Vice-President of the United States, were then lieutenants, and Stephen Barton fought side by side with them. He was present when Tecumseh was slain, and at the signing of the treaty of peace which followed. His military service extended over three years. At the close of the war he marched home on foot through northern Ohio and central New York. He and the other officers were greatly charmed by the Genesee and Mohawk valleys, and he purchased land somewhere in the vicinity of Rochester. He had some thought of establishing a home in that remote region, but it was so far distant from civilization that he sold his New York land and made his home in Oxford.

In 1796, Stephen Barton returned from the Indian War. He was then twenty-two years of age. Eight years later he married Sarah Stone, who was only seventeen. They established their home west of Oxford, near Charlton,[Pg 17] and later removed to the farm where Clara Barton was born.

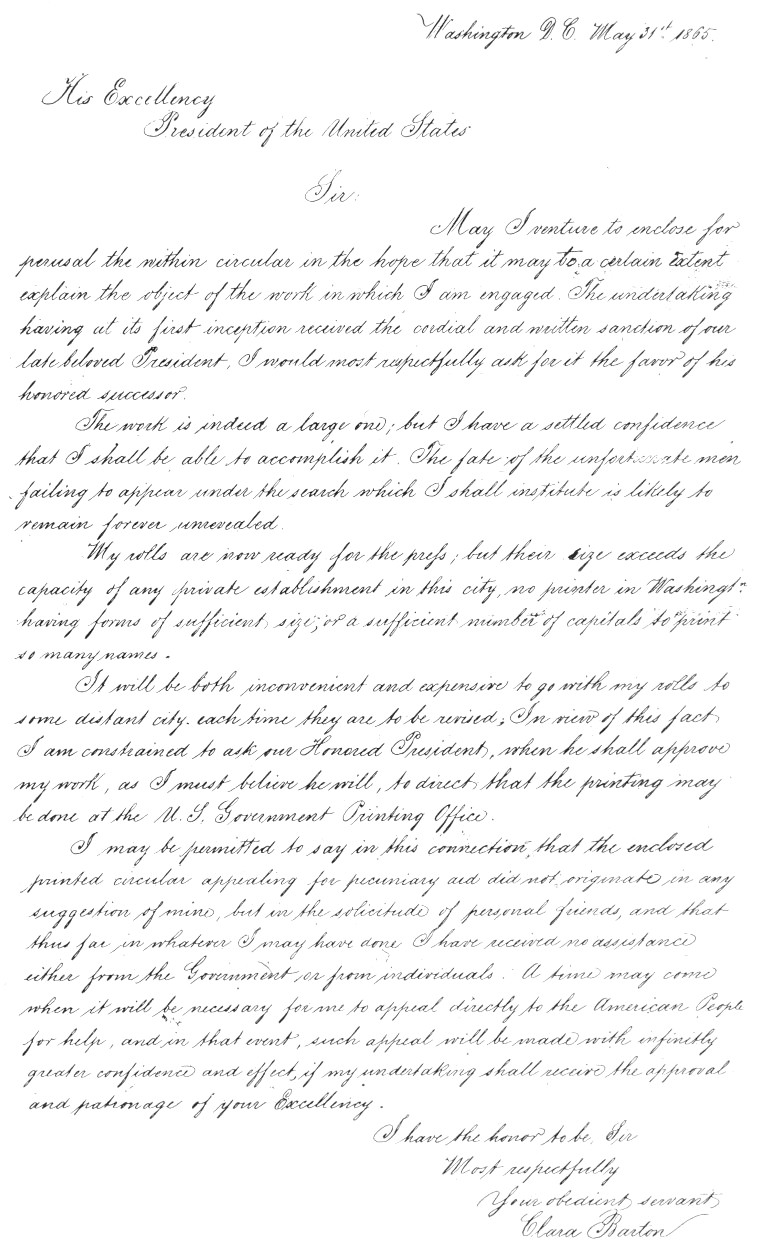

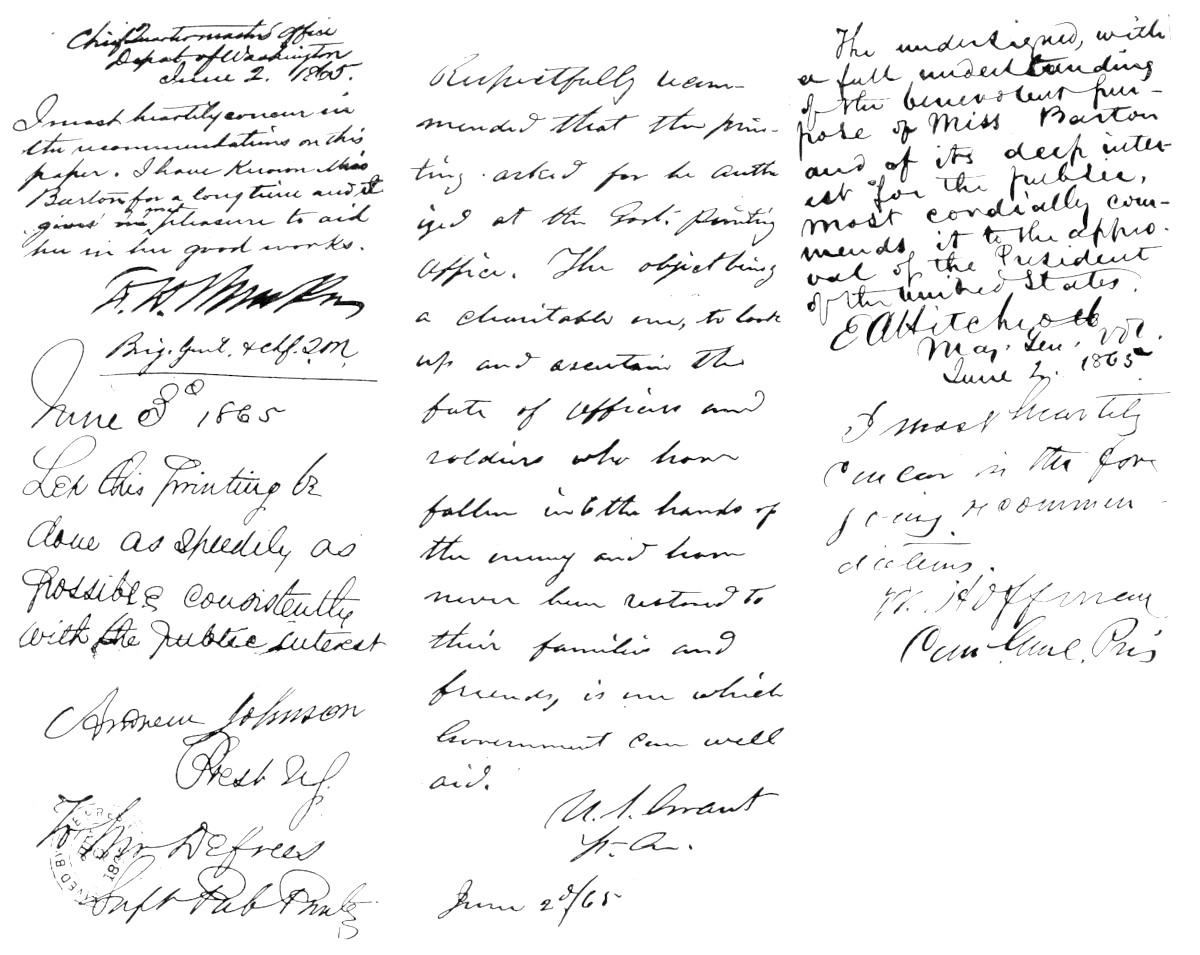

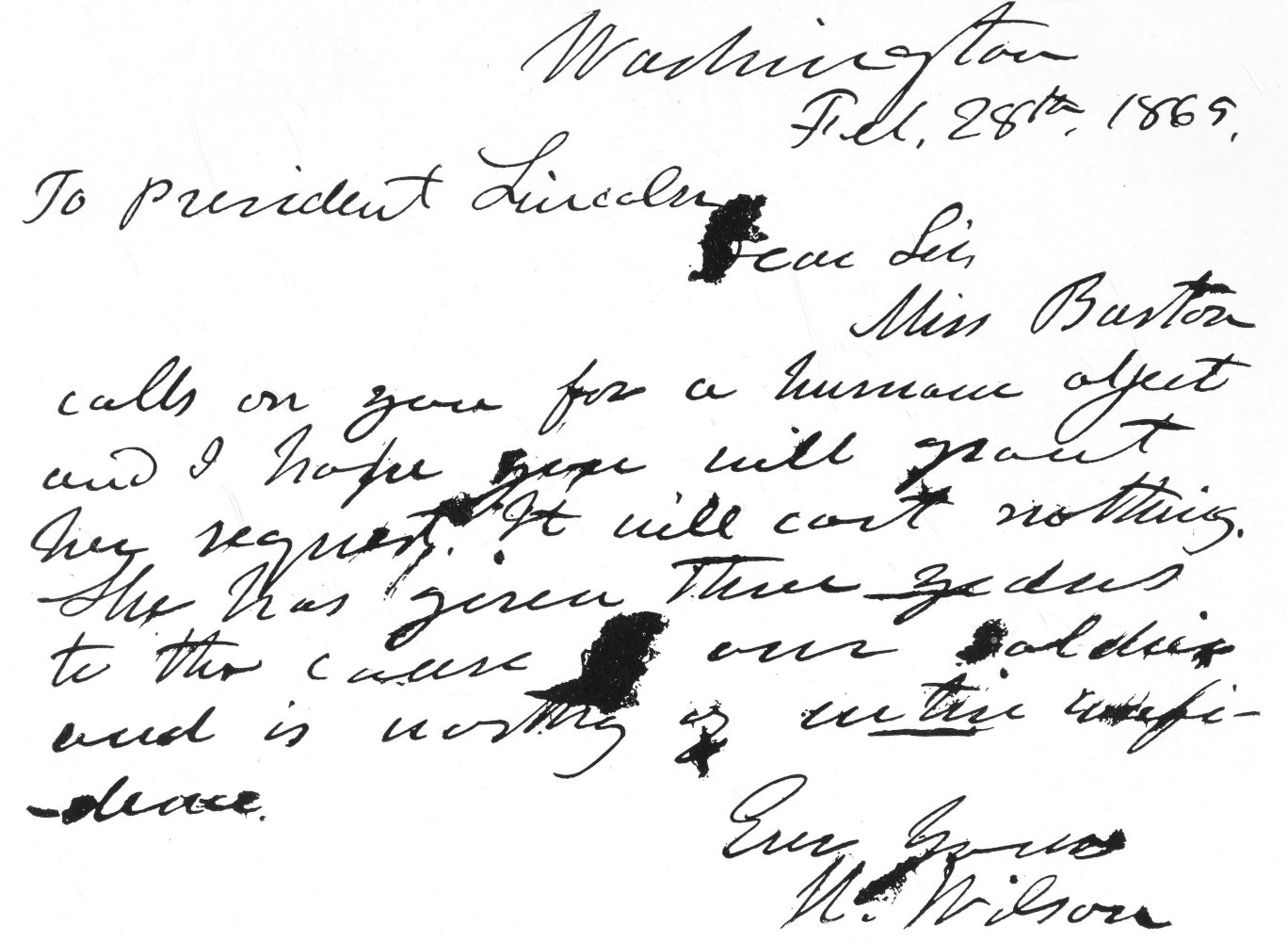

MOTHER AND FATHER OF CLARA BARTON

It was a modest home, and Stephen Barton was a hardworking man, though a man of influence in the community. He served often as moderator of town meetings and as selectman for the town. He served also as a member of the Legislature. But he wrought with his own hands in the tillage of his farm, and in the construction of most of the articles of furniture in his home, including the cradle in which his children were rocked.

BIRTHPLACE OF CLARA BARTON

Stephen Barton combined a military spirit with a gentle disposition and a broad spirit of philanthropy. Sarah Stone was a woman of great decision of character, and a quick temper. She was a housewife of the good old New England sort, looking well to the ways of her household and eating not the bread of idleness. From her father Clara Barton inherited those humanitarian tendencies which became notably characteristic, and from her mother she derived a strong will which achieved results almost regardless of opposition. Her mother’s hot temper found its restraint in her through the inherited influence of her father’s poise and benignity. Of him she wrote:

His military habits and tastes never left him. Those were also strong political days—Andrew Jackson Days—and very naturally my father became my instructor in military and political lore. I listened breathlessly to his war stories. Illustrations were called for and we made battles and fought them. Every shade of military etiquette was regarded. Colonels, captains, and sergeants were given their proper place and rank. So with the political world; the President, Cabinet, and leading officers of the government were learned by heart, and nothing gratified[Pg 18] the keen humor of my father more than the parrot-like readiness with which I lisped these difficult names. I thought the President might be as large as the meeting-house, and the Vice-President perhaps the size of the schoolhouse. And yet, when later I, like all the rest of our country’s people, was suddenly thrust into the mysteries of war, and had to find and take my place and part in it, I found myself far less a stranger to the conditions than most women, or even ordinary men for that matter. I never addressed a colonel as captain, got my cavalry on foot, or mounted my infantry!

When a little child upon his knee he told me that, as he lay helpless in the tangled marshes of Michigan the muddy water oozed up from the track of an officer’s horse and saved him from death by thirst. And that a mouthful of a lean dog that had followed the march saved him from starvation. When he told me how the feathered arrow quivered in the flesh and the tomahawk swung over the white man’s head, he told me also, with tears of honest pride, of the great and beautiful country that had sprung up from those wild scenes of suffering and danger. How he loved these new States for which he gave the strength of his youth!

Two sons and two daughters were born to Stephen and Sarah Barton in their early married life. Then for ten years no other children were born to them. On Christmas, 1821, their eldest daughter, Dorothy, was as old as her mother had been at the time of their marriage. Their eldest son, Stephen, was fifteen, the younger son, David, was thirteen, and the daughter, Sally, was ten. The family had long considered itself complete, when the household received Clara as a Christmas present. Her brothers and sisters were too old to be her playmates. They were her protectors, but not her companions. She was a little child in the midst of a household of grown-up[Pg 19] people, as they seemed to her. In her little book entitled “The Story of my Childhood,” she thus describes her brothers and sisters:

I became the seventh member of a household consisting of the father and mother, two sisters and two brothers, each of whom for his and her intrinsic merits and special characteristics deserves an individual history, which it shall be my conscientious duty to portray as far as possible as these pages progress. For the present it is enough to say that each one manifested an increasing personal interest in the newcomer, and, as soon as developments permitted, set about instructing her in the various directions most in accord with the tastes and pursuits of each.

Of the two sisters, the elder was already a teacher. The younger followed soon, and naturally my book education became their first care, and under these conditions it is little to say, that I have no knowledge of ever learning to read, or of a time that I did not do my own story reading. The other studies followed very early.

My elder brother, Stephen, was a noted mathematician. He inducted me into the mystery of figures. Multiplication, division, subtraction, halves, quarters, and wholes, soon ceased to be a mystery, and no toy equaled my little slate. But the younger brother had entirely other tastes, and would have none of these things. My father was a lover of horses, and one of the first in the vicinity to introduce blooded stock. He had large lands, for New England. He raised his own colts; and Highlanders, Virginians, and Morgans pranced the fields in idle contempt of the solid old farm-horses.

Of my brother, David, to say that he was fond of horses describes nothing; one could almost add that he was fond of nothing else. He was the Buffalo Bill of the surrounding country, and here commences his part of my education. It was his delight to take me, a little girl of five years old, to the field, seize a couple of those beautiful[Pg 20] young creatures, broken only to the halter and bit, and gathering the reins of both bridles firmly in hand, throw me upon the back of one colt, spring upon the other himself, and catching me by one foot, and bidding me “cling fast to the mane,” gallop away over field and fen, in and out among the other colts in wild glee like ourselves. They were merry rides we took. This was my riding-school. I never had any other, but it served me well. To this day my seat on a saddle or on the back of a horse is as secure and tireless as in a rocking-chair, and far more pleasurable. Sometimes, in later years, when I found myself suddenly on a strange horse in a trooper’s saddle, flying for life or liberty in front of pursuit, I blessed the baby lessons of the wild gallops among the beautiful colts.

One of the bravest of women, Clara Barton was a child of unusual timidity. Looking back upon her earliest recollections she said, “I remember nothing but fear.” Her earliest memory was of her grief in failing to catch “a pretty bird” when she was two and a half years old. She cried in disappointment, and her mother ran to learn what was the trouble. On hearing her complaint, that “Baby” had lost a pretty bird which she had almost caught, her mother asked, “Where did it go, Baby?” “Baby” indicated a small round hole under the doorstep, and her mother gave a terrified scream. That scream awoke terror in the mind of the little girl, and she never quite recovered from it. The “bird” she had almost caught was a snake.

Her next memory also was one of fear. The family had gone to a funeral, leaving her in the care of her brother David. She told of it afterward as follows:

[Pg 21]

I can picture the large family sitting-room with its four open windows, which room I was not to leave, and my guardian was to remain near me. Some outside duty called him from the house and I was left to my own observations. A sudden thunder-shower came up; massive rifts of clouds rolled up in the east, and the lightning darted among them like blazing fires. The thunder gave them language and my terrified imagination endowed them with life.

Among the animals of the farm was a huge old ram, that doubtless upon some occasion had taught me to respect him, and of which I had a mortal fear. My terrors transformed those rising, rolling clouds into a whole heaven full of angry rams, marching down upon me. Again my screams alarmed, and the poor brother, conscience-stricken that he had left his charge, rushed breathless in, to find me on the floor in hysterics, a condition of things he had never seen; and neither memory nor history relates how either of us got out of it.

In these later years I have observed that writers of sketches, in a friendly desire to compliment me, have been wont to dwell upon my courage, representing me as personally devoid of fear, not even knowing the feeling. However correct that may have become, it is evident I was not constructed that way, as in the earlier years of my life I remember nothing but fear.

[Pg 22]

Clara Barton’s education began at her cradle. She was not able to remember when she learned to read. When three years old she had acquired the art of reading, and her lessons in spelling, arithmetic, and geography began in her infancy. Both of her sisters and her eldest brother were school-teachers. Recalling their efforts, she said: “I had no playmates, but in effect six fathers and mothers. They were a family of school-teachers. All took charge of me, all educated me, each according to personal taste. My two sisters were scholars and artistic, and strove in that direction. My brothers were strong, ruddy, daring young men, full of life and business.”

Before she was four years old she entered school. By that time she was able to read easily, and could spell words of three syllables. She told the story of her first schooling in an account which must not be abridged:

My home instruction was by no means permitted to stand in the way of the “regular school,” which consisted of two terms each year, of three months each. The winter term included not only the large boys and girls, but in reality the young men and young women of the neighborhood. An exceptionally fine teacher often drew the daily attendance of advanced scholars for several miles. Our district had this good fortune. I introduce with pleasure and with reverence the name of Richard Stone; a firmly set, handsome young man of twenty-six or seven, of commanding figure and presence, combining all the elements of a teacher with a discipline never questioned.[Pg 23] His glance of disapproval was a reprimand, his frown something he never needed to go beyond. The love and respect of his pupils exceeded even their fear. It was no uncommon thing for summer teachers to come twenty miles to avail themselves of the winter term of “Colonel” Stone, for he was a high militia officer, and at that young age was a settled man with a family of four little children. He had married at eighteen.

I am thus particular in my description of him, both because of my childish worship of him, and because I shall have occasion to refer to him later. The opening of his first term was a signal for the Barton family, and seated on the strong shoulders of my stalwart brother Stephen, I was taken a mile through the tall drifts to school. I have often questioned if in this movement there might not have been a touch of mischievous curiosity on the part of these not at all dull youngsters, to see what my performance at school might be.

I was, of course, the baby of the school. I recall no introduction to the teacher, but was set down among the many pupils in the by no means spacious room, with my spelling book and the traditional slate, from which nothing could separate me. I was seated on one of the low benches and sat very still. At length the majestic school-master seated himself, and taking a primer, called the class of little ones to him. He pointed the letters to each. I named them all, and was asked to spell some little words, “dog,” “cat,” etc., whereupon I hesitatingly informed him that I did “not spell there.” “Where do you spell?” “I spell in ‘Artichoke,’” that being the leading word in the three syllable column in my speller. He good naturedly conformed to my suggestion, and I was put into the “artichoke” class to bear my part for the winter, and read and “spell for the head.” When, after a few weeks, my brother Stephen was declared by the committee to be too advanced for a common school, and was placed in charge of an important school himself, my[Pg 24] unique transportation devolved upon the other brother, David.

No colts now, but solid wading through the high New England drifts.

The Reverend Mr. Menseur of the Episcopal church of Leicester, Massachusetts, if I recollect aright, wisely comprehending the grievous inadaptability of the schoolbooks of that time, had compiled a small geography and atlas suited to young children, known as Menseur’s Geography. It was a novelty, as well as a beneficence; nothing of its kind having occurred to makers of the schoolbooks of that day. They seemed not to have recognized the existence of a state of childhood in the intellectual creation. During the winter I had become the happy possessor of a Menseur’s Geography and Atlas. It is questionable if my satisfaction was fully shared by others of the household. I required a great deal of assistance in the study of my maps, and became so interested that I could not sleep, and was not willing that others should, but persisted in waking my poor drowsy sister in the cold winter mornings to sit up in bed and by the light of a tallow candle, help me to find mountains, rivers, counties, oceans, lakes, islands, isthmuses, channels, cities, towns, and capitals.

The next May the summer school opened, taught by Miss Susan Torrey. Again, I write the name reverently, as gracing one of the most perfect of personalities. I was not alone in my childish admiration, for her memory remained a living reality in the town long years after the gentle spirit fled. My sisters were both teaching other schools, and I must make my own way, which I did, walking a mile with my one precious little schoolmate, Nancy Fitts. Nancy Fitts! The playmate of my childhood; the “chum” of laughing girlhood; the faithful, trusted companion of young womanhood, and the beloved life friend that the relentless grasp of time has neither changed, nor taken from me.

[Pg 25]

On entering the wide-open door of the inviting schoolhouse, armed with some most unsuitable reader, a spelling book, geography, atlas, and slate, I was seized with an intense fear at finding myself with no member of the family near, and my trepidation became so visible that the gentle teacher, relieving me of my burden of books, took me tenderly on her lap and did her best to reassure and calm me. At length I was given my seat, with a desk in front for my atlas and slate, my toes at least a foot from the floor, and that became my daily, happy home for the next three months.

All the members of Clara Barton’s household became her teachers, except her mother, who looked with interest, and not always with approval, on the methods of instruction practiced by the others. Captain Barton was teaching her military tactics, David was teaching her to ride horseback, Sally, and later Dorothy, established a kind of school at home and practiced on their younger sister, and Stephen contributed his share in characteristic fashion. Sarah Stone alone attempted nothing until the little daughter should be old enough to learn to do housework.

“My mother, like the sensible woman that she was, seemed to conclude that there were plenty of instructors without her,” said Miss Barton. “She attempted very little, but rather regarded the whole thing as a sort of mental conglomeration, and looked on with a kind of amused curiosity to see what they would make of it. Indeed, I heard her remark many years after that I came out of it with a more level head than she would have thought possible.”

Clara Barton’s first piece of personal property was a sprightly, medium-sized white dog, with silky ears and a[Pg 26] short tail. His name was Button. Her affection for Button continued throughout her life. Of him she said:

My first individual ownership was “Button.” In personality (if the term be admissible), Button represented a sprightly, medium-sized, very white dog, with silky ears, sparkling black eyes and a very short tail. His bark spoke for itself. Button belonged to me. No other claim was instituted, or ever had been. It was said that on my entrance into the family, Button constituted himself my guardian. He watched my first steps and tried to pick me up when I fell down. One was never seen without the other. He proved an apt and obedient pupil, obeying me precept upon precept, if not line upon line. He stood on two feet to ask for his food, and made a bow on receiving it, walked on three legs when very lame, and so on, after the manner of his crude instruction; went everywhere with me through the day, waited patiently while I said my prayers and continued his guard on the foot of the bed at night. Button shared my board as well as my bed.

After her first year’s instruction at the hands of Colonel Stone, that gentleman ceased his connection with the common schools, and established what was known as the Oxford High School, an institution of great repute in its day. This left the district school to be taught by the members of the Barton household. For the next three years Clara’s sisters were her public school-teachers in the autumn and spring, and her brother Stephen had charge of the school in the winter terms. Two things she remembered about those years. One was her preternatural shyness. She was sensitive and retiring to a degree that seemed to forbid all hope of her making much progress in study with other children. The other was that she had a fondness for writing verses, some of which[Pg 27] her brothers and sisters preserved and used to tease her with in later years. One thing she learned outside the schoolroom, and she never forgot it. That was how to handle a horse. She inherited her mother’s sidesaddle, and though she protested against having to use it, she learned at an early age to lift and buckle it, and to ride her father’s horses.

Meantime her brothers grew to be men and bought out her father’s two large farms. Her father purchased another farm of three hundred acres nearer the center of the town, a farm having upon it one of the forts used for security against the Indians by the original Huguenot settlers. She now became interested in history, and added that to her previous accomplishments.

At the age of eight, Clara Barton entered what was called high school, which involved boarding away from home. The arrangement met with only partial success on account of her extreme timidity:

During the preceding winter I began to hear talk of my going away to school, and it was decided that I be sent to Colonel Stone’s High School, to board in his family and go home occasionally. This arrangement, I learned in later years, had a double object. I was what is known as a bashful child, timid in the presence of other persons, a condition of things found impossible to correct at home. In the hope of overcoming this undesirable mauvais honte, it was decided to throw me among strangers.

How well I remember my advent. My father took me in his carriage with a little dressing-case which I dignified with the appellation of “trunk”—something I had never owned. It was April—cold and bare. The house and schoolrooms adjoined, and seemed enormously large. The household was also large. The long family table with the dignified preceptor, my loved and feared teacher[Pg 28] of three years, at its head, seemed to me something formidable. There were probably one hundred and fifty pupils daily in the ample schoolrooms, of which I was perhaps the youngest, except the colonel’s own children.

My studies were chosen with great care. I remember among them, ancient history with charts. The lessons were learned, to repeat by rote. I found difficulty both in learning the proper names and in pronouncing them, as I had not quite outgrown my lisp. One day I had studied very hard on the Ancient Kings of Egypt, and thought I had everything perfect, and when the pupil above me failed to give the name of a reigning king, I answered very promptly that it was “Potlomy.” The colonel checked with a glance the rising laugh of the older members of the class, and told me, very gently, that the P was silent in that word. I had, however, seen it all, and was so overcome by mortification for my mistake, and gratitude for the kindness of my teacher, that I burst into tears and was permitted to leave the room.

I am not sure that I was really homesick, but the days seemed very long, especially Sundays. I was in constant dread of doing something wrong, and one Sunday afternoon I was sure I had found my occasion. It was early spring. The tender leaves had put out and with them the buds and half-open blossoms of the little cinnamon roses, an unfailing ornamentation of a well-kept New England home of that day. The children of the family had gathered in the front yard, admiring the roses and daring to pick each a little bouquet. As I stood holding mine, the heavy door at my back swung open, and there was the colonel, in his long, light dressing-gown and slippers, direct from his study. A kindly spoken, “Come with me, Clara,” nearly took my last breath. I followed his strides through all the house, up the long flights of stairs, through the halls of the schoolrooms, silently wondering what I had done more than the others. I knew he was by no means wont to spare his own children.[Pg 29] I had my handful of roses—so had they. I knew it was very wrong to have picked them, but why more wrong for me than for the others? At length, and it seemed to me an hour, we reached the colonel’s study, and there, advancing to meet us, was the Reverend Mr. Chandler, the pastor of our Universalist Church, whom I knew well. He greeted me very politely and kindly, and handed the large, open school reader which he held, to the colonel, who put it into my hands, placed me a little in front of them, and pointing to a column of blank verse, very gently directed me to read it. It was an extract from Campbell’s “Pleasures of Hope,” commencing, “Unfading hope, when life’s last embers burn.” I read it to the end, a page or two. When finished, the good pastor came quickly and relieved me of the heavy book, and I wondered why there were tears in his eyes. The colonel drew me to him, gently stroked my short cropped hair, went with me down the long steps, and told me I could “go back to the children and play.” I went, much more easy in mind than I came, but it was years before I comprehended anything about it.

My studies gave me no trouble, but I grew very tired, felt hungry all the time, but dared not eat, grew thin and pale. The colonel noticed it, and watching me at table found that I was eating little or nothing, refusing everything that was offered me. Mistrusting that it was from timidity, he had food laid on my plate, but I dared not eat it, and finally at the end of the term a consultation was held between the colonel, my father, and our beloved family physician, Dr. Delano Pierce, who lived within a few doors of the school, and it was decided to take me home until a little older, and wiser, I could hope. My timid sensitiveness must have given great annoyance to my friends. If I ever could have gotten entirely over it, it would have given far less annoyance and trouble to myself all through life.

To this day, I would rather stand behind the lines of[Pg 30] artillery at Antietam, or cross the pontoon bridge under fire at Fredericksburg, than to be expected to preside at a public meeting.

Again Clara’s instruction fell to her brothers and sisters. Stephen taught her mathematics, her sisters increased her knowledge of the common branches, and David continued to give her lessons in horsemanship. Stephen Barton, her father, was the owner of a fine black stallion, whose race of colts improved the blooded stock of Oxford and vicinity. When she was ten years old she received a present of a Morgan horse named Billy. Mounted on the back of this fine animal, she ranged the hills of Oxford completely free from that fear with which she was possessed in the schoolroom.

When she was thirteen years of age, her education took a new start under the instruction of Lucian Burleigh, who taught her grammar, composition, English literature, and history. A year later Jonathan Dana became her instructor, and taught her philosophy, chemistry, and writing. These two teachers she remembered with unfaltering affection.

While Clara Barton’s brother Stephen taught school, his younger brother, David, gave himself to business. He, no less than Stephen, was remembered affectionately as having had an important share in her education. He had taught her to ride, and she had become his nurse. When he grew well and strong, he took the little girl under his instruction, and taught her how to do things directly and with expedition. If she started anywhere impulsively, and turned back, he reproved her. She was not to start until she knew where she was going, and why, and having started, she was to go ahead and accomplish[Pg 31] what she had undertaken. She was to learn the effective way of attaining results, and having learned it was to follow the method which promoted efficiency. He taught her to despise false motions, and to avoid awkward and ineffective attempts to accomplish results. He showed her how to drive a nail without splitting a board, and she never forgot how to handle the hammer and the saw. He taught her how to start a screw so it would drive straight. He taught her not to throw like a girl, but to hurl a ball or a stone with an under swing like a boy, and to hit what she threw at. He taught her to avoid “granny-knots” and how to tie square knots. All this practical instruction she learned to value as among the best features of her education.

One of her earliest experiences, in accomplishing a memorable piece of work with her own hands, came to her after her father had sold the two hill farms to his sons and removed to the farm on the highway nearer the village. It gave her her opportunity to learn the art of painting. This was more than the ability to dip a brush in a prepared mixture and spread the liquid evenly over a plane surface; it involved some knowledge of the art of preparing and mixing paints. She found joy in it at the time, and it quickened within her an aspiration to be an artist. In later years and as part of her education, she learned to draw and paint, and was able to give instruction in water-color and oil painting. It is interesting to read her own account of her first adventure into the field of art:

The hill farms—for there were two—were sold to my brothers, who, entering into partnership, constituted the well-known firm of S. & D. Barton, continuing mainly[Pg 32] through their lives. Thus I became the occupant of two homes, my sisters remaining with my brothers, none of whom were married.

The removal to the second home was a great novelty to me. I became observant of all changes made. One of the first things found necessary, on entering a house of such ancient date, was a rather extensive renovation, for those days, of painting and papering. The leading artisan in that line in the town was Mr. Sylvanus Harris, a courteous man of fine manners, good scholarly acquirements, and who, for nearly half a lifetime, filled the office of town clerk. The records of Oxford will bear his name and his beautiful handwriting as long as its records exist.

Mr. Harris was engaged to make the necessary improvements. Painting included more then than in these later days of prepared material. The painter brought his massive white marble slab, ground his own paints, mixed his colors, boiled his oil, calcined his plaster, made his putty, and did scores of things that a painter of to-day would not only never think of doing, but would often scarcely know how to do.

Coming from the newly built house where I was born, I had seen nothing of this kind done, and was intensely interested. I must have persisted in making myself very numerous, for I was constantly reminded not to “get in the gentleman’s way.” But I was not to be set aside. My combined interest and curiosity for once overcame my timidity, and, encouraged by the mild, genial face of Mr. Harris, I gathered the courage to walk up in front and address him: “Will you teach me to paint, sir?” “With pleasure, little lady; if mamma is willing, I should very much like your assistance.” The consent was forthcoming, and so was a gown suited to my new work, and I reported for duty. I question if any ordinary apprentice was ever more faithfully and intelligently instructed in his first month’s apprenticeship. I was taught how to hold my brushes, to take care of them, allowed to help[Pg 33] grind my paints, shown how to mix and blend them, how to make putty and use it, to prepare oils and dryings, and learned from experience that boiling oil was a great deal hotter than boiling water, was taught to trim paper neatly, to match and help to hang it, to make the most approved paste, and even varnished the kitchen chairs to the entire satisfaction of my mother, which was triumph enough for one little girl. So interested was I, that I never wearied of my work for a day, and at the end of a month looked on sadly as the utensils, brushes, buckets and great marble slabs were taken away. There was not a room that I had not helped to make better; there were no longer mysteries in paint and paper. I knew them all, and that work would bring calluses even on little hands.

When the work was finished and everything gone, I went to my room, lonesome in spite of myself. I found on my candle stand a box containing a pretty little locket, neatly inscribed, “To a faithful worker.” No one seemed to have any knowledge of it, and I never gained any.

One other memory of these early days must be recorded as having an immediate effect upon her, and a permanent influence upon her life. While she was still a little girl, she witnessed the killing of an ox, and it seemed so terrible a thing to her that it had much to do with her lifelong temperance in the matter of eating meat. She never became an absolute vegetarian. When she sat at a table where meat was served, and where a refusal to eat would have called for explanation, and perhaps would have embarrassed the family, she ate what was set before her as the Apostle Paul commanded, but she ate very sparingly of all animal food, and, when she was able to control her own diet, lived almost entirely on vegetables. Things that grew out of the ground, she said, were good enough for her:

[Pg 34]

A small herd of twenty-five fine milch cows came faithfully home each day with the lowering of the sun, for the milking and extra supper which they knew awaited them. With the customary greed of childhood, I had laid claim to three or four of the handsomest and tamest of them, and believing myself to be their real owner, I went faithfully every evening to the yards to receive and look after them. My little milk pail went as well, and I became proficient in an art never forgotten.

One afternoon, on going to the barn as usual, I found no cows there; all had been driven somewhere else. As I stood in the corner of the great yard alone, I saw three or four men—the farm hands—with one stranger among them wearing a long, loose shirt or gown. They were all trying to get a large red ox onto the barn floor, to which he went very reluctantly. At length they succeeded. One of the men carried an axe, and, stepping a little to the side and back, raised it high in the air and brought it down with a terrible blow. The ox fell, I fell too; and the next I knew I was in the house on a bed, and all the family about me, with the traditional camphor bottle, bathing my head to my great discomfort. As I regained consciousness, they asked me what made me fall? I said, “Some one struck me.” “Oh, no,” they said, “no one struck you.” But I was not to be convinced, and proceeded to argue the case with an impatient putting away of the hurting hands, “Then what makes my head so sore?” Happy ignorance! I had not then learned the mystery of nerves.

I have, however, a very clear recollection of the indignation of my father (my mother had already expressed herself on the subject), on his return from town and hearing what had taken place. The hired men were lined up and arraigned for “cruel carelessness.” They had “the consideration to keep the cattle away,” he said, “but allowed that little girl to stand in full view.” Of course, each protested he had not seen me. I was altogether too[Pg 35] friendly with the farm hands to hear them blamed, especially on my account, and came promptly to their side, assuring my father that they had not seen me, and that it was “no matter,” I was “all well now.” But, singularly, I lost all desire for meat, if I had ever had it—and all through life, to the present, have only eaten it when I must for the sake of appearance, or as circumstances seemed to make it the more proper thing to do. The bountiful ground has always yielded enough for all my needs and wants.

[Pg 36]

So large a part of the schooling of Clara Barton was passed under the instruction of her own sisters and her brother Stephen that she ceased to feel in school the diffidence which elsewhere characterized her, and which she never fully overcame. Not all of her education, however, was accomplished in the schoolroom. While her mother refrained from giving to her actual instruction as she received from her father and brothers and sisters, her knowledge of domestic arts was not wholly neglected. When the family removed to the new home, her two brothers remained upon the more distant farm, and the older sisters kept house for them. Into the new home came the widow of her father’s nephew, Jeremiah Larned, with her four children, whose ages varied from six to thirteen years. She now had playmates in her own household, with frequent visits to the old home where her two brothers and two sisters, none of them married, kept house together. Although her mother still had older kitchen help, she taught Clara some of the mysteries of cooking. Her mother complained somewhat that she never really had a fair chance at Clara’s instruction as a housekeeper, but Clara believed that no instruction of her youth was more lasting or valuable than that which enabled her, on the battle-field or elsewhere, to make a pie, “crinkly around the edges, with marks of finger-prints,” to remind a soldier of home.

Two notable interruptions of her schooling occurred.[Pg 37] The first was caused by an alarming illness when she was five years of age. Dysentery and convulsions came very near to robbing Captain and Mrs. Barton of their baby. Of this almost mortal illness, she preserved only one memory, that of the first meal which she ate when her convalescence set in. She was propped up in a huge cradle that had been constructed for an adult invalid, with a little low table at the side. The meal consisted of a piece of brown bread crust about two inches square, a tiny glass of homemade blackberry cordial, and a wee bit of her mother’s well-cured cheese. She dropped asleep from exhaustion as she finished this first meal, and the memory of it made her mouth water as long as she lived.

The other interruption occurred when she was eleven. Her brother David, who was a dare-devil rider and fearless climber, ascended to the ridge-pole on the occasion of a barn-raising. A board broke under his feet, and he fell to the ground. He fell upon solid timbers and sustained a serious injury, especially by a blow on the head. For two years he was an invalid. For a time he hung between life and death, and then was “a sleepless, nervous, cold dyspeptic, and a mere wreck of his former self.” After two years of suffering, he completely recovered under a new system of steam baths; but those two years did not find Clara in the schoolroom. She nursed her brother with such assiduity as almost permanently to injure her own health. In his nervous condition he clung to her, and she acquired something of that skill in the care of the sick which remained with her through life.

Clara Barton was growing normally in her twelfth year when she became her brother’s nurse. Not until that long vigil was completed was it discovered that she[Pg 38] had ceased to grow. Her height in her shoes, with moderately high heels, was five feet and three inches, and was never increased. In later life people who met her gave widely divergent reports of her stature. She was described as “of medium height,” and now and then she was declared to be tall. She had a remarkable way of appearing taller than she was. As a matter of fact in her later years, her height shrank a little, and she measured in her stocking-feet exactly sixty inches.

Clara was an ambitious child. Her two brothers owned a cloth-mill where they wove satinet. She was ambitious to learn the art of weaving. Her mother at first objected, but her brother Stephen pleaded for her, and she was permitted to enter the mill. She was not tall enough to tend the loom, so a raised platform was arranged for her between a pair of looms and she learned to manage the shuttle. To her great disappointment, the mill burned down when she had been at work only two weeks; but this brief vocational experience served as a basis of a pretty piece of fiction at which she always smiled, but which annoyed her somewhat—that she had entered a factory and earned money to pay off a mortgage on her father’s farm. The length of her service in the mill would not have paid a very large mortgage, but fortunately there was no mortgage to pay off. Her father was a prosperous man for his time, and the family was well to do, possessing not only broad acres, but adding to the family income by manufacture and trade. They were among the most enterprising, prosperous, and respected families in a thrifty and self-respecting community.

One of the enterprises on the Barton farm afforded[Pg 39] her great joy. The narrow French River ran through her father’s farm. In places it could be crossed by a foot-log, and there were few days when she did not cross and recross it for the sheer joy of finding herself on a trembling log suspended over a deep stream. This river ran the only sawmill in the neighborhood. Here she delighted to ride the carriage which conveyed the logs to the old-fashioned up-and-down saw. The carriage moved very slowly when it was going forward and the saw was eating its laborious way through the log, but it came back with violent rapidity, and the little girl, who remembered nothing but fear of her earliest childhood, was happy when she flaunted her courage in the face of her natural timidity and rode the sawmill carriage as she rode her high-stepping blooded Billy.

She went to church every Sunday, and churches in that day had no fires. Her people had been brought up in the orthodox church, but, revolting at the harsh dogmatism of the orthodox theology of that day, they withdrew and became founders of the first Universalist Church in America. The meeting-house at Oxford, built for the Universalist Society, is the oldest building in existence erected for this communion. Hosea Ballou was the first minister—a brave, strong, resolute man. Though the family liberalized their creed, they did not greatly modify the austerity of their Puritan living. They kept the Sabbath about as strictly as they had been accustomed to do before their break with the Puritan church.

Once in her childhood Clara broke the Sabbath, and it brought a painful memory:

One clear, cold, starlight Sunday morning, I heard a low whistle under my open chamber window. I realized[Pg 40] that the boys were out for a skate and wanted to communicate with me. On going to the window, they informed me that they had an extra pair of skates and if I could come out they would put them on me and “learn” me how to skate. It was Sunday morning; no one would be up till late, and the ice was so smooth and “glare.” The stars were bright; the temptation was too great. I was in my dress in a moment and out. The skates were fastened on firmly, one of the boy’s wool neck “comforters” tied about my waist, to be held by the boy in front. The other two were to stand on either side, and at a signal the cavalcade started. Swifter and swifter we went, until at length we reached a spot where the ice had been cracked and was full of sharp edges. These threw me, and the speed with which we were progressing, and the distance before we could quite come to a stop, gave terrific opportunity for cuts and wounded knees. The opportunity was not lost. There was more blood flowing than any of us had ever seen. Something must be done. Now all of the wool neck comforters came into requisition; my wounds were bound up, and I was helped into the house, with one knee of ordinary respectable cuts and bruises; the other frightful. Then the enormity of the transaction and its attendant difficulties began to present themselves, and how to surround (for there was no possibility of overcoming) them was the question.

The most feasible way seemed to be to say nothing about it, and we decided to all keep silent; but how to conceal the limp? I must have no limp, but walk well. I managed breakfast without notice. Dinner not quite so well, and I had to acknowledge that I had slipped down and hurt my knee a little. This gave my limp more latitude, but the next day it was so decided, that I was held up and searched. It happened that the best knee was inspected; the stiff wool comforter soaked off, and a suitable dressing given it. This was a great relief, as it[Pg 41] afforded pretext for my limp, no one observing that I limped with the wrong knee.

But the other knee was not a wound to heal by first intention, especially under its peculiar dressing, and finally had to be revealed. The result was a surgical dressing and my foot held up in a chair for three weeks, during which time I read the Arabian Nights from end to end. As the first dressing was finished, I heard the surgeon say to my father: “That was a hard case, Captain, but she stood it like a soldier.” But when I saw how genuinely they all pitied, and how tenderly they nursed me, even walking lightly about the house not to jar my swollen and fevered limbs, in spite of my disobedience and detestable deception (and persevered in at that), my Sabbath-breaking and unbecoming conduct, and all the trouble I had caused, conscience revived, and my mental suffering far exceeded my physical. The Arabian Nights were none too powerful a soporific to hold me in reasonable bounds. I despised myself, and failed to sleep or eat.

My mother, perceiving my remorseful condition, came to the rescue, telling me soothingly, that she did not think it the worst thing that could have been done, that other little girls had probably done as badly, and strengthened her conclusions by telling me how she once persisted in riding a high-mettled, unbroken horse in opposition to her father’s commands, and was thrown. My supposition is that she had been a worthy mother of her equestrian son.

The lesson was not lost on any of the group. It is very certain that none of us, boys or girls, indulged in further smart tricks. Twenty-five years later, when on a visit to the old home, long left, I saw my father, then a gray-haired grandsire, out on the same little pond, fitting the skates carefully to the feet of his little twin granddaughters, holding them up to make their first start in safety, I remembered my wounded knees, and blessed the great[Pg 42] Father that progress and change were among the possibilities of His people.

I never learned to skate. When it became fashionable I had neither time nor opportunity.

Another disappointment of her childhood remained with her. She wanted to learn to dance, and was not permitted to do so. It was not because her parents were wholly opposed to dancing, but chiefly because the dancing-school was organized while a revival of religion was in progress in the village, and her parents felt that her attendance at dancing-school at such a time would be unseemly. Of this she wrote: