Title: Alice and Beatrice

Author: Grandmamma

Illustrator: John Absolon

Release date: February 26, 2022 [eBook #67511]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: E. P. Dutton & Co, 1881

Credits: Charlene Taylor and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

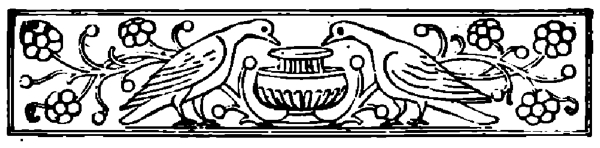

The Old Woman showing how Lace is made.—Page 19.

IIAlice

AND

Beatrice.

| PAGE |

| VISIT TO GRANDMAMMA—WALKS TO THE SEA-SHORE—BATHING IN THE SEA | 7 |

| EVENING WALK—STEAMER—LACEMAKING | 15 |

| A RAINY DAY—STORY OF PRETTY AND THE BEAR | 21 |

| RUSSIA AND THE FROZEN SEA | 29 |

| CELLAR—WALK TO THE SEA-SHORE—RAINBOW, ETC. | 35 |

| BEES SWARMING—FABLE OF THE ANT AND GRASSHOPPER | 46 |

| SAIL TO BRANSCOMBE—HORSES CARRYING COALS | 59 |

| WALK ON THE HILLSIDE—TAME AND WILD RABBITS—RETURN HOME | 73 |

| THE CHILD BURNT—A NEGRO CHILD CURED BY COTTON-WOOL | 83 |

| A WINTER’S DRIVE IN RUSSIA | 94 |

| CIDER-MAKING | 102 |

| SQUIRRELS | 113 |

| THE SHIPWRECK—THE PARROT | 117 |

| THE KITTEN | 133 |

| INSTINCT OF ANIMALS | 139 |

| LENGTH OF DAY IN RUSSIA AND FINLAND | 147 |

| PATIENCE AND PERSEVERANCE MAKE ALL THINGS EASY | 156 |

ALICE and Beatrice were two little girls of about four and six years of age. They were staying with their grandmamma. Alice and Beatrice were very glad to be with their grandmamma, for she lived in the country and near the sea. They liked to see the green fields, full of pretty flowers, and to play in the nice large garden, and to walk up and down the high hills that were on all sides of the house, and also they liked to go to the sea-shore and look on the wide sea.

Grandmamma loved Alice and Beatrice very much, and she liked to have them with her, 8and she tried to make them good and happy. Every morning they said their prayers to her, and every evening before they went to bed; and they never forgot to thank God, who had taken care of them during the night, and to beg God to bless and take care of them, and all those they loved, that day and always. Little Beatrice could not say her prayers quite so well as Alice, but she said them better and better every day.

After breakfast grandmamma had to order the dinner, and whilst she went to the kitchen to speak to the cook, she let the two little girls run up and down the long verandah which was in front of the house, and which led to the pretty garden.

Alice read to her grandmamma, learned by heart and said some verses from her hymnbook, and little Beatrice always learned one verse every day. Then Alice did some sums, and after she had shown them, and grandmamma had found them all right, Alice wrote her copy. As soon as Alice began to write, Beatrice brought her letters and tried to learn to know them. Grandmamma told her when 9she knew them all she would give her a book with large letters and words.

After the lessons were over, the little girls went out for a walk with Mary.

Mary was a kind person and very fond of the two children, and they liked Mary very much. Mary went with Alice and Beatrice down the sloping walks, till they came to a gate, which they opened; they then went across a little wooden bridge, and down a very steep path and some steps that led to the sea-shore.

Alice and Beatrice liked to go to the sea-shore very much. Mary sat on the sand and worked, whilst Alice and Beatrice played about. They had each of them a pretty wooden basket and a little wooden spade, and they dug in the sand on the sea-shore, and filled their baskets with sand or stones. Sometimes they dug large holes for the sea to come in, and they liked to see the waves come higher and higher, till the large holes were full of water. Sometimes Alice and Beatrice dug a long ditch down the sloping shore to the edge of the waves, and the water ran down it into the sea, and they called it their river. When they were tired of 10digging, they asked Mary if they might look for pretty stones, and shells, and sea-weed.

There were plenty of pretty stones and sea-weed, and even shells, to be found. Some of the shells were pretty and white and smooth, and the children took great care of them, and took them home to play with. They often found sea-weeds of all colours, red and yellow, green and brown, and some sea-weeds were small and fine, like hair or moss; and grandmamma helped them to dry them, and put them on paper. There was another kind of sea-weed that was very long and heavy, and looked like large black rushes. Mary told them not to take those home, for they were not nice, and they could not be dried.

One day Alice found a pretty stone, or pebble, as it is called: it was very clear, not quite so clear as glass; but when she held it towards the sun, she could see through it.

‘I will take the pretty stone home, Mary,’ said Alice, ‘and give it dear mamma.’

‘Perhaps,’ said Mary, ‘your mamma will have it cut and polished for a brooch.’

‘Yes, I am sure she will,’ cried Alice; ‘I am 11so glad that I have found it!’ and Alice put it into her pocket.

‘I will try and find a pretty stone too for mamma,’ said Beatrice, and she ran along the sand, close to the waves: and just when Mary called her to come away, a large wave came higher up than the others had done before, and wetted little Beatrice’s shoes and socks.

Beatrice ran back to Mary, and she was a little frightened, and she said, ‘Mary, I did not hear you call me till that big wave came up to my feet, and I could not run away quick enough, and my feet are so wet.’

‘We must go home directly, Miss Beatrice,’ said Mary, ‘and make haste and change your shoes and socks;’ and they went home.

Another day they went to the beach again, and their grandmamma went with them. As they went through the pretty garden, they stopped to look at the rose-trees that were beginning to bloom; and grandmamma gave Alice a white rose and Beatrice a dark-red one. She cut off the thorns from the stalks, and Beatrice asked her, ‘Why do you cut off those things, grandmamma?’

12‘Those things are called thorns, my dear child; they would prick your fingers, for they are very sharp.’

The children looked at the thorns, and put their fingers to them, and said, ‘They prick like needles.’ They thanked her for the roses, and smelt them, for they were very sweet.

They went on to the gate, and then grandmamma opened it, and gave Beatrice her hand across the narrow bridge, and down the steep path, and the many steps.

Alice ran on alone, jumping along, and pulling some wild flowers that grew in the grass on each side the path, and she came first to the beach, and then ran back to meet her grandmamma and little sister.

When they came to the sea-shore, they saw that Mary was there waiting for them with a large basket. They knew that the basket was full of their bathing dresses; for their grandmamma liked them to bathe in the sea whenever the weather was warm and the sun shone.

There was a tent at the foot of the cliff, for a steep cliff rose very high a little way from the sea-shore on each side of the narrow valley 13through which they had to come. In this tent the two little girls went to undress and get ready for bathing. Mary helped them; and when they had put on their bathing dresses, Mary did the same, and went into the sea with them.

Alice ran into the water alone, and jumped over the little waves that came rolling gently on to the shore. Beatrice took hold of Mary’s hand, but she was not afraid, and she dipped her face and hands into the waves, and she tried to jump about like Alice.

Then Beatrice asked Mary to let her float; and Mary held Beatrice’s head, and the little girl lay quite stiff and quiet on the water, and her feet and body floated, which she liked very much.

‘Please, Mary,’ said Alice, ‘let me try and float too.’ And Mary let Beatrice stand by her side and floated Alice backwards and forwards.

‘When I am a little older,’ said Alice, ‘grandmamma says that I must learn to swim.’

‘And I, too,’ said Beatrice.

After the children had jumped about a short time in the waves, and were quite warm, their grandmamma said—

14‘Come out now, you have been in the water long enough;’ and the little girls came out and ran into the tent, where they were soon dried and dressed, for their grandmamma helped them too, and they made haste to go home, up the many steps and steep path, and were glad to have their dinner, because they were hungry after their bath.

THE weather had been very hot—so hot that the children had had no walk, but had spent most of the day in the shade under the long verandah, and in the afternoon they had played under a large tree in the garden. When the evening came it was much cooler; and after the little girls had had their tea, grandmamma told them that she would take them over the high hill at the back of the house to visit a poor woman who had been ill. Their grandmamma’s house was half-way up the hill—you could see the sea through a narrow valley; and opposite the house on the other side of the valley was another high hill, and behind that hill was the town.

16Grandmamma walked slowly up the hill, up a zig-zag path, and rested on a bench half-way up, for it was a very steep hill. The little girls were not tired, and they ran on before and waited for their grandmamma at each turn of the path. They went higher and higher, till at last Alice called out—

‘How much I can see now, grandmamma! I can see all the town, the houses, and the church!’

‘I can see two churches,’ said Beatrice; ‘and what a lot of ships!’

‘Please, grandmamma,’ said Alice, ‘come up higher. Pray, dear grandmamma, make haste, there is a great smoke on the sea; it comes from a ship. Is the ship on fire?’ she asked a little anxiously.

Their grandmamma was soon by the children’s side.

‘That is a steamer or steamship, dear Alice; it has a fire in it that causes the smoke, but it is not on fire, and you can see that the smoke comes out of a tall black chimney. You have seen the train come and go often, and you know how much smoke it makes.’

17‘Yes, I know; but the smoke from the train is not black like that, and why is that?’

‘You are right, dear child, it is not black; but that is because they burn a different kind of coal, called coke, in trains. Trains and steamers are made to move by the same means, which is by steam. Some clever man made steam turn wheels and raise heavy beams up and down, and thus it is that ships and trains are made to move. Steam is made to grind corn, and to make biscuits, and to saw wood, and steam helps to make nearly everything we wear.’

‘Oh! grandmamma, how wonderful! I do not understand how steam can do all that. The man must have been very clever to have thought of this. Do you know his name?’

‘James Watt was his name; he made the first good and useful steam-engine, I believe, about seventy years ago; but he was not the first man who had found out that steam could be made useful, or who made the first engine.’

When they came to the top of the hill they saw several cows feeding on the grass.

‘Will these cows hurt us?’ asked Alice.

18‘No, my dear, they will not, unless you tease them.’

‘But why do people run away when they see cows?’

‘It is very foolish of any one to run away. When a poor cow or ox has been treated ill by naughty boys or cruel men, and frightened and made angry, it runs about; sometimes people have been tossed and hurt. But if you will treat a cow kindly, I am sure that it will never hurt you.’

The little girls walked through the green meadow when the cows were feeding, and the cows did them no harm. They soon came to a nice little cottage, with a few trees close by, and a little garden.

Their grandmamma spoke to an old woman who was sitting outside the cottage door, and said to her that she was glad to see her up and looking better; and the old woman replied that the warm weather had done her a great deal of good, and that she was very glad to see her and the little children.

Whilst their grandmamma was talking to the old woman, Alice and Beatrice looked about them, 19and examined with wonder a cushion that the old woman had had on her lap when they came.

They then played with a little kitten that was in the garden till their grandmamma had finished talking. Then Alice asked, ‘What is this cushion for, with all those little sticks hanging down on each side of it, and what was the old woman doing with them?’

‘Mrs. Miller is making lace, dear Alice, and these sticks are called bobbins, and there is some very fine thread which she braids and twists together into a pretty pattern.’

The kind old woman came and took her cushion, and sitting down, began to show Alice and Beatrice how she twisted the little bobbins backwards and forwards, and threw them from one side the cushion to the other. She did this at first very slowly, that the little girls might see it more easily; but when they had looked enough, she threw her bobbins backwards and forwards so quickly that the children were quite surprised. Mrs. Miller then told them that all the little girls in the village begin to learn to make lace when they are seven or eight years old, and learn soon to make it nicely.

20‘How very pretty it is!’ said Alice. ‘I should like to learn to make lace. May I, grandmamma, when I am older?’

‘Yes, you may, if you wish it; but you must first learn to sew neatly, for that is more useful than making lace.’

‘But why do all the little girls here learn to make lace, grandmamma?’

‘Because they can help to earn money for their father and mother. Among the poor people in the village, very young children begin to help to earn their own bread.’

Before the little girls went home, they ran about on the green meadow, and gathered a handful of yellow cowslips and other wild flowers; but when the sun went behind the opposite hill, and the clouds above the sun were red and bright like gold, and the sea looked nearly the same colour as the clouds, grandmamma said—

‘We will go back now, for it is time for my little girls to go to bed.’

Then they all returned down the zig-zag path, and were soon home again, and Alice and Beatrice went to bed, after telling Mary first of all that they had seen.

‘WHAT a rainy day!’ said Alice, one morning, when Mary came to call them, and to help them to dress. ‘We cannot go out at all to-day.’

‘What a pity!’ said her little sister. ‘I am so sorry.’

‘What shall we do all day, if we cannot go out?’ said Alice.

‘The rain will make all your flowers grow, miss,’ said Mary, ‘and make the weather a little cooler.’

‘But I want to go out and dig in the sand,’ said Alice.

‘And so do I,’ said Beatrice.

22Mary took no further notice of the children’s words; but when they were at breakfast, Alice said, ‘Grandmamma, is it not very tiresome that the rain is come to-day? We cannot go out. I wish that it would never rain.’

‘Nasty rain,’ said Beatrice; ‘I can’t bear the rain!’

‘You must not say that the rain is nasty, for it does a great deal of good, dear children. God sends us the rain when we want it, and we thank God for it.’

‘Why do you thank God, grandmamma,’ asked Alice, ‘for the rain? What good can the rain do?’

‘It makes the grass grow; and horses, cows, and sheep, and all other animals that eat grass, live upon it; and the rain makes the corn grow, and from corn we make our bread; and what would you or I do, or any one else, if the corn did not grow and we had no bread? The rain makes the trees and the flowers grow, and all the fruit too, and my little girls would be sorry if there were no fruit.’

‘Yes, indeed, grandmamma,’ cried both children.

23‘But I thought,’ said Alice, ‘that the sun made the fruit ripe.’

‘Yes, so it does; but the sun alone could not make the plants grow, and the rain alone could not make the flowers open their leaves, or the fruit or the corn get ripe. We want both sun and rain, and we must thank God that He gives us enough of each to do good on earth.’

After the two little girls had finished their little lessons, and done all that their grandmamma wished them to do, she said to them—

‘As you have both been good this morning, and because it rains, I will tell you a story of my two dogs, when I lived in Russia.

‘It was a hot summer’s day, a long time ago, when my little dog Pretty came to me yelling and barking. I was busy writing in a little sitting-room that opened into my bedroom, and my rooms in Russia were all downstairs, as there was but one floor.

‘When I looked at Pretty, I saw that the dog was trembling all over, and every hair was standing up, for he was so frightened; and he whined and ran about, and howled and barked in great distress; and at last he ran into my 24bedroom, and crept under the bed, and there he lay trembling and whining.

‘All the doors stand open in a house in Russia; so I went into the hall and then out of the open front door, and I soon saw what was the cause of Pretty’s fear. There was a great brown bear; and though little Pretty had never seen a bear before, yet his terror was so great.

‘The bear had a leathern strap round his mouth, a small iron chain was fixed to the strap; and when I looked nearer, I saw that a hole had been made in the bear’s upper lip, and a ring was put through the hole, and the chain was fastened to the ring as well as to the leathern strap.

‘A Russian peasant was with the bear, and he wore blue striped linen trousers, and his trousers were tucked into his boots, but he had neither stockings nor socks. He had a red and white checked shirt, which hung loose over his trousers, and funny pieces of blue linen sewed into the sleeves of his shirt. He had a fur cap on his head, and in his hand he carried a long stout pole.

‘The Russian peasant called to the bear to get 25up, for the bear seemed tired, and had laid down to rest himself. The bear growled, but did not move at first, though his master shook the chain and pulled him by it; at last the man gave him a sharp blow with a whip he had, and told him to begin dancing.

‘The poor tired bear stood up on his hind legs, and took the pole from the man’s hand, and began to jump over it, but in a very clumsy manner. The man kept calling to him in a sing-song manner, pulling often with the chain, and giving him a smart cut with his whip: and the bear jumped backwards and forwards over the pole, or, as the man called it, danced, and grumbled and growled, for he seemed very cross and angry that he was obliged to do all this when he was so very hot and tired. I looked about to see where my good old dog Lion was all this time. Lion was a splendid dog, something like an English mastiff, and something like a lioness, and therefore I had named him “Lion.” He went out daily with the herd of cattle into the fields and woods, and saved many of them from being killed by the wolves. He was a brave dog, and I was very fond of him.

26‘And where do you think I found Lion now?—not running away and hiding himself, like Pretty, in “the lady’s chamber,” but trying to make the bear afraid of him.

‘For Lion walked slowly up close to the bear, then went round him twice, looking at him well all the time, as if to say, “I am not in the least afraid of you, Mr. Bear,” and then Lion lay down on the grass in the shade, a little way off, but so that he should see him still, and went to sleep, or pretended to do so. I dare say that the bear thought he had better not go near such a brave dog, though he would have liked to give Lion a good hug, and eat him up.

‘At last the Russian peasant seemed as hot and as tired as the bear, and he asked for something to eat, and some spirits to drink. So I told a servant to bring the man some black bread and some beer and a little spirits, and I ordered some honey and some bread for the bear.’

‘Why did you give the poor man black bread, grandmamma?’ asked Alice.

‘In Russia, the servants and common people all eat black bread; the white bread which we 27eat here is only made for the rich people to eat!’

‘But why is that, grandmamma?’

‘It is because wheat, of which our white bread is made, does not grow nearly so well as rye in Russia and other cold countries: and rye makes black bread. It is not so good as wheat bread; but some people like it, and even prefer it.’

‘Please, Alice, let grandmamma tell us the story of Lion and the Bear,’ said Beatrice.

‘Well, my dear children, you would have been glad to see how the bear liked the bread dipped in honey, and how he drank the spirits and the beer; but the man did not give him much of either. Afterwards I gave the man some money, and the poor tired bear walked after his master, as well as he could, on his four feet. As soon as the bear was gone, out came Pretty from my bedroom, and began to bark very furiously, as if he had been a brave dog, and driven the bear away.’

‘Thank you, dear grandmamma,’ said both the little girls. ‘We like that story so much, pray tell us some more about your brave dog 28Lion, and about silly little Pretty, another day.’

‘But Pretty was not always silly, although he was afraid of a big bear. He was a knowing little dog, and so fond of us.’

‘I should have been afraid, I think,’ said Alice. ‘I should not like a bear to come to this house.’

‘There are no bears here, are there, grandmamma?’ asked little Beatrice.

‘And no horrid wolves?’ added Alice.

‘No, dear children, none, I am glad to say. When you read more in your history of England, you will read when the last wolves were killed in England: a very long time ago there used to be plenty of wolves here.’

The two little girls looked afraid; but they were very glad when grandmamma said—

‘That was a very, very long time ago.’

‘NOW, Alice, bring your atlas, and I will show you on the map where Russia lies.’

Alice brought her book of maps, and soon found the maps of Europe and Asia; and grandmamma showed her where the large country lay, and pointed out to her that the greatest part of Russia was in Asia, and reached across the whole of northern Asia.

‘Oh, how big it is!’ cried Alice; ‘it is much bigger than all the other countries together. Look at little England, Beatrice,—this little island is England, where we live; does it not look tiny? And now look at big Russia. Look, all that yellow is Russia!’ and Alice put her finger on the line that divided Russia from all 30the other countries, and showed her little sister how large it was.

‘Do you see, Alice,’ said grandmamma, ‘how far Russia extends? Even that smaller part that is in Europe reaches up to the Arctic or Frozen Ocean, and down to the Black Sea on the south; do you see, Alice?’

‘Why is that sea called the Frozen Ocean?’

‘Because it is frozen for many months in the year, and the greater part of it is always frozen.’

‘Can the sea really freeze, grandmamma?’ asked both the little girls. ‘How can the waves freeze, and be made quiet?’

‘The sea that lies on the north of Russia freezes every winter, but our sea here does not freeze; it is too warm.’

‘But how can it freeze, grandmamma? I cannot understand how it can,’ said the little girl.

‘It is difficult to make it clear to you, Alice; but I will try and explain it. First, from the great cold, little pieces of ice are formed; these pieces float about, for ice is lighter than water, and are tossed up and down by the restless 31waves; and they grow in size, and become bigger and bigger, till some join and stick together, and go on getting larger, till by degrees they cover the surface of the water. These pieces or masses of ice are pushed towards the shore, and there the ice first begins to make a firm covering over the sea.

‘But the ice on the sea is never smooth or even, like the ice on a pond or on a river; it is rough, and large pieces are heaped together, and large cracks are often made in the ice by the wind and the waves moving it, which makes it dangerous to drive or even walk a long distance over the Frozen Sea.’

‘Can people drive over the sea? But if it is frozen hard, why is it dangerous?’

‘Yes, dear Alice, people can and do drive on the Frozen Sea, and I have driven short distances myself on it, and I have known many people cross this gulf,’ showing Alice the Gulf of Finland. ‘You know, dear, what a gulf is?’

‘Yes,’ said Alice; ‘it is an arm of the sea that runs into the land.’

‘The peasants, or poor country people, used 32to drive across this gulf, as soon as the ice was tolerably firm and safe. They drove in small sledges drawn by little horses, and took over corn and other things to sell to the inhabitants of rocky Finland, where very little corn grows. But the getting across the large crevices or cracks was both difficult and dangerous. The people for that purpose take long boards with them on their sledges, and laying them across these open places, they drag their sledges over, walking over the planks themselves, and making their horses swim through the water; but their horses have often been lost in these large cracks, for though the horses can always swim, they cannot always get out of them, as the ice at the edges is brittle, and breaks under their efforts to scramble up.

‘I remember how some men, belonging to one of our villages, were lost in a snow-storm out at sea, and their bodies were not found till the summer, on a small, uninhabited island where they had taken refuge during the storm, lying on their faces. I believe that they had first lost their horses.’

‘How did they die, poor men? Were they 33starved or frozen to death on that desert island?’

‘I believe that they were frozen to death, and had gone to sleep from the cold, and never awoke.’

‘How very sad!’ said both the little girls.

‘But did you like Russia, grandmamma,’ asked Alice; ‘so cold and horrible, with wolves and bears?’

‘The winter in Russia is very long, and where I lived it sometimes lasted half the year, and we saw no grass all that time.’

‘How did you like to live in Russia, then?’

‘I had kind friends there; but though I liked some people very much, I did not like the country or the climate. In truth, dear children, there is no country in the whole world like our dear England; no country where people love God and pray to God so much as in England; and no country where everybody tries to do so much good as in England.’

‘Now, Alice, look for the two great capital cities of Russia. The old capital is called Moscow, and the new one is called St. Petersburg.’

34Alice looked carefully at her map, and when grandmamma had told her that St. Petersburg lies high up in the north and Moscow much lower to the east, Alice found both places.

‘Please show me, grandmamma, where you lived.’

‘Here,’ said grandmamma, ‘on the shores of the Gulf of Finland, where the sea freezes in winter.’

THE next morning it rained again, and the little girls could not go out; but they were not unhappy, because they knew that grandmamma would tell them some stories, or give them something to amuse them.

After their lessons, grandmamma said, ‘Alice and Beatrice, I am going down into the cellar, will you come with me?’

‘Yes, please, please,’ cried both the little girls; ‘we shall like to come with you so much; we have never seen the cellar.’

‘Is it quite dark, grandmamma?’ asked Beatrice.

‘Yes, to be sure,’ said Alice; ‘but Mary has a candle, and will show us light.’

36Mary walked on in front, and went slowly down a long, dark, narrow staircase. Alice ran after her, and Beatrice, holding grandmamma’s hand, followed carefully.

The little girls looked about in wonder; they did not know what a large place the cellar was. There were several rooms, all called cellars, which Mary showed them. First, to the right hand, without a door, was a very large and black-looking place, and when Mary lighted it up, the children saw that it was full of coals.

‘That is our coal cellar, miss,’ said Mary; ‘and this,’ opening a door, ‘is for the beer and cider.’

The children looked in, and saw several tubs of beer and cider placed side by side. Then grandmamma unlocked another door, and that was the wine cellar. They all went in; it was much cleaner and drier than the other cellars, and all the bottles were arranged neatly: and just when the children were going to ask some questions, grandmamma remembered that Mary had forgotten to bring down a bottle of wine to exchange for another bottle; so Mary went back with the candle, and Alice and Beatrice 37were left in the dark cellar with their grandmamma.

At first the two children were quite silent, till Beatrice, who held grandmamma’s hand, said, ‘Grandmamma, can God see us everywhere?’

‘Yes, Beatrice; everywhere and always.’

‘Can God see us in this dark cellar?’

‘Yes, dear children. God sees in the dark as in the light; by night and by day: God sees everybody and everything. In the Psalms[1] you will read, “He who planted the ear, shall he not hear? or he who made the eye, shall he not see?” which means that God who made our ears must be able to hear everything, and God who made our eyes surely can see everything.’

1. Psa. xciv. 9.

Little Beatrice thought a little while, and then she said, ‘But God cannot tell mamma when I am naughty, can He?’

‘No, my dear little girl; but you must fear God more than you fear mamma. You can never be naughty without God’s knowing it; and are you not afraid of God’s being angry with you?’

38‘Mamma says that God is very good and very great,’ said Alice, ‘and that He takes care of us always, and of the whole world; and will God be angry with such a little girl as Beatrice?’

‘If Beatrice did not know that it was wrong to be naughty, God would not be angry with her; but Beatrice knows quite well when she is good and when she is naughty.’

Little Beatrice pressed grandmamma’s hand, and as grandmamma thought she heard her sob, she took her up in her arms, and Beatrice whispered, as soon as her tears let her, that she would try and be very good.

‘You must think more about being good, both of you, when you say your prayers, and when you ask God to help you to be good children.’

Mary now came back with the candle, and grandmamma soon finished all that she wished to do, and then they all went upstairs again; and it seemed so light and bright when they were upstairs, that they could scarcely see, and the sun was shining, and the rain had ceased. The black clouds had gone away far over the hills, and the blue sky was there again.

39Alice and Beatrice clapped their hands, and were like the sunshine, gay and bright; all their black clouds had gone away too. They put on their hats and jackets to run down the steep path to the sea for their usual bath; but before they went, grandmamma told them to be careful, for it would be very slippery after the rain.

Alice and Beatrice walked slowly down to the sea-shore with Mary. When they crossed the wooden bridge they were surprised to see how much water was in the little brook. They stopped to look at it, for it was very pretty: there was quite a waterfall just above the bridge, and the water splashed and made a loud noise in falling. The grass looked more green, and the flowers smelt more sweet, and Alice said, ‘Mary, I think that grandmamma is quite right: the rain does a great deal of good. The grass looks much greener, and the flowers look much prettier, and the little brook does not murmur now, but it rushes and roars like the river Sid by the mill. I know some pretty verses about “How welcome is the rain!” but I never thought before how nice the rain was.’

40‘When it is over, Alice; but not while it rains and you cannot go out,’ said Beatrice.

‘But grandmamma tells us nice stories, or shows us something. I do not think that I mind the rain now,’ said Alice.

‘Oh! Mary, what is that over the sea?’ cried Alice. ‘How beautiful it is! Look, Beatrice, blue and red and yellow—I cannot count the colours.’

‘It is a rainbow, Miss Alice,’ said Mary.

‘But what is a rainbow, and how does it come there?’

‘You must ask your grandmamma when you go home. I only know that it comes when the rain is over.’

The sea had been very rough early in the morning. A sailor told the children that it was then much too rough for them to bathe; but the rain had come and made the sea smoother, and Alice said, ‘The rain has done good again.’

The waves, or breakers, as they are called, when they came up on the shore, were still too rough for the little girls to move about alone in the water, so Mary let them sit near the edge and held them firmly; and the white 43waves dashed over their heads and the froth covered them, and they liked it very much.

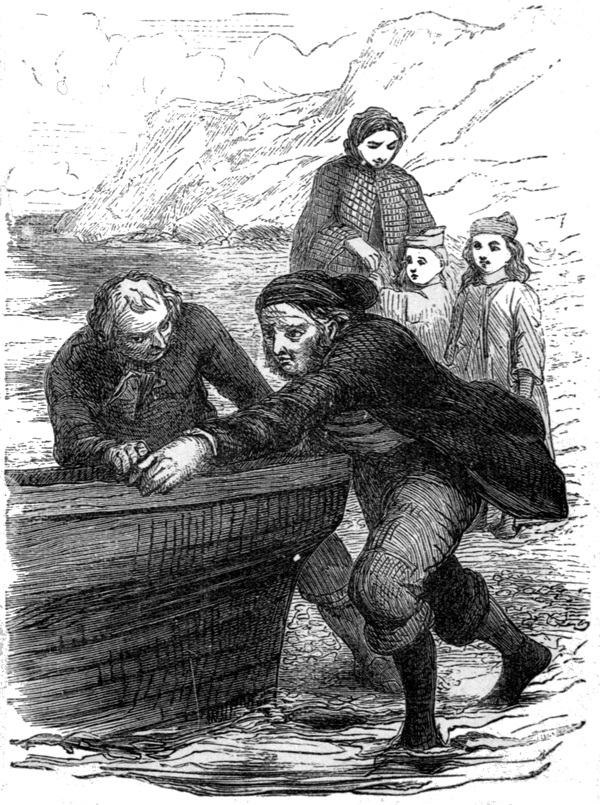

Fishermen pushing their Boat off to Sea.—Page 43.

They saw two fishermen afterwards putting a boat into the sea, and they begged Mary to let them stay and see it go off. Several times the men pushed the boat off the shore, and each time a big wave came and lifted it up and threw it back again. Then two other men came to help them, and pushed the boat with great force from the shore far into the water; and the boat rocked up and down so much among the great waves, that the two children were frightened, and Alice began to cry. But Mary told them not to be afraid, for the men were quite safe, as the sea was much smoother as soon as the boat had passed the breakers and was farther off the shore.

When Alice and Beatrice were at home they told grandmamma all that they had seen, and how high the waves were, and that there was so much white froth on the shore.

Then Alice asked grandmamma to tell them about the rainbow that they had seen. ‘It was so beautiful, grandmamma!’

‘I cannot explain to you the reason why the 44rainbow appears, but I know that it is caused or made by the sun being reflected on the moist air. You know, Alice, what “reflected” means; it is as when the light of the candle is seen again, or reflected in the looking-glass: and the sun shining on the moist air reflects those bright colours on a cloud. When you are older you will learn all about it, and why it is always in the shape of an arch or bow. Every one loves to see a rainbow, because it reminds us of the promise God made to Noah, and all people, after the flood, that He would no more destroy all flesh, which means, every living creature.’

‘I remember all about it, grandmamma,’ said Alice; ‘I have read it in my Bible stories. May I read it to Beatrice?’ and Alice fetched her book and read about the flood and the rainbow to Beatrice; and afterwards grandmamma read to them from the Bible as follows (Gen. ix. 13-15): ‘I do set my bow in the cloud, and it shall be for a token of a covenant between me and the earth. And it shall come to pass, when I bring a cloud over the earth, that the bow shall be seen in the cloud: and I will remember my covenant between me and you and every living creature of 45all flesh: and the waters shall no more become a flood to destroy all flesh.’

‘So you see, dear children, that God has made a covenant, which means an agreement or promise, never to destroy the earth again by a flood, and the rainbow is a sign of His promise, and reminds us of it.’

‘I am very glad to know about the rainbow, and I will think of God’s promise when I see one again.’

IT was just after the children’s dinner, one very hot day towards the end of May, that the gardener came to the verandah where the two little girls were sitting with their grandmamma, and said—

‘Please, ma’am, the bees are swarming.’

‘Swarming, grandmamma,’ said Alice and Beatrice, ‘what is that? May we come and see?’

Grandmamma gave leave, and they ran and put on their hats and followed their grandmamma into the garden, to that part where the bee-house was. When they came there, the gardener showed them a large black lump, that looked 47like a great bag, hanging from a rose-tree, and the rose-tree was bent down by the weight of it.

Grandmamma explained to the children that the black lump or mass was all bees; that there had been too many bees in the hive, so that there was not room enough for all of them to work, and that the hive was too hot in this very hot weather, and the queen bee wished to seek another home for herself, and had flown out accompanied by the older bees, leaving all the young ones and a young queen in the old hive with its store of honey.

When the queen bee had settled on this rose-tree, all the other bees that were flying about in the air had come to her, and collected round her, hanging one over another. Grandmamma told the children, too, that every bee had provided itself with a quantity of honey, in case they should not find a shelter that night, and were not able to provide themselves with food the next day; each bee carried a little bag of honey.

The children were very much interested in hearing this, and were not afraid, because grandmamma 48told them that the bees rarely sting people when they are swarming; so they went nearer, and liked to see the gardener take a board and place it on a flower-pot just under the rose-tree; then he took a hive and turned it up and held it under the swarm of bees, and he shook the rose-tree very sharply twice, and the lump of bees fell off into the hive, or at least the greater part of it: and the gardener turned the hive down with all the bees that were in it on to the board. A number of bees that had not fallen into the hive, began to buzz and fly about; but the gardener said—

‘If the queen bee is inside, and I think she is, the others will soon go to her.’

And he raised the hive a little on one side by putting a pebble under it, and thus made room enough for the bees to enter the hive.

Alice and Beatrice, seeing so many bees still flying about, thought that they were all coming out again; but the bees knew better; their queen was in the hive, and content with her new house, and all the bees went in by degrees, and soon but very few were seen flying about the hive.

49The gardener said that he would leave the hive where it was till the evening, when he would move it into its proper place.

Whilst the gardener was thus busied, Beatrice cried out, ‘Look! look! what are those bees doing? Oh, grandmamma, do look at them!’

Grandmamma turned to look, and so did Alice, and they saw some bees pouring out of another hive, as if they were blown out of it, or shot from a gun. Out and out they came quicker and quicker, pouring thicker and thicker; and then they rose in the air, and spread about, and whirled round and round, flying higher and higher, and it seemed as if the whole air was filled with bees, and they made quite a noise when they flew, humming so loud. Grandmamma told the two children that this was a swarm from another hive, and added, ‘Now we must try and watch where they will settle, and we must follow them. I hope that they will not fly away, else we shall lose them.’

Alice and Beatrice looked on in great astonishment, and then followed their grandmamma, who would not call the gardener or 50ask him to follow this swarm, as he was still busy with the other.

‘Are you not afraid, grandmamma, that these bees will fly away, they fly so high and so far?’

‘No, dear; I think that they will settle soon, as they begin to fly lower and more together.’ And as she spoke, the cloud of bees came lower and lower, and soon a black mass was seen on an apple tree, just between two branches. The black mass grew larger and larger, till at last the number of flying bees became less, and they grew quiet. They covered the branch all round, and it looked as if something black had been put round the branch.

‘How will John get those bees? He cannot reach them, they are so high up.’

‘John will bring a ladder, and some one must hold the board and the hive for him.’

Alice ran to call the gardener, and told him of the second swarm.

John said, ‘That is your luck to-day, miss; two swarms on one day are very lucky. The weather is hot, and our hives are so full of brood, and so heavy, that I dare say they are 51glad enough to get rid of some of their numbers and go into a new hive.’

‘But have you another hive and a board ready, John?’ asked Alice.

‘Yes, miss, to be sure I have. I made ten new hives this winter, when I had nothing else to do, and I got the carpenter to cut me a dozen boards; so we have plenty for all the swarms that may come. Perhaps, miss, your grandmamma will like me to take the new Scotch hive which came last week, so I will bring that and a straw one, and ask her which is to be used.’

Alice went with John: and Alice carried the straw hive, and John carried the Scotch hive, which was an octagon, or eight-sided, wooden one, painted red, with glass windows and shutters; and he took two boards as well, and they both hastened to the kitchen garden, where the new swarm of bees had settled.

‘What luck the little ladies have, ma’am!’ said the gardener. ‘You promised them the second swarm; and what a fine one it is, much bigger than the one I have just hived!’

‘Yes, this is the children’s swarm, and I am 52glad that it is such a large one. But how will you take it, John? it is in such an awkward place.’

‘With the ladder, quite easy, ma’am; but,’ added John, looking up at it, ‘I can’t shake them off the branch, and shall have to take them as I can.’

John ran to fetch the ladder, which was close by against the wall, where he had been pruning some fruit trees.

The little girls were very impatient, and watched the gardener mount the ladder; then their grandmamma handed him the Scotch hive; and to their great astonishment, John said—

‘I must sweep these bees into the hive.’

The gardener fixed the wooden hive between the ladder and his own knee, and then with one rapid sweep with his hands, he threw the whole lump of bees into the hive, and turned the hive down on the board.

A great number of the bees flew off and rose again high up into the air, but John said—

‘Don’t be afraid, ma’am, they never sting when they are swarming.’

53Alice and Beatrice began crying out, for the bees were flying all about their grandmamma; but John was soon down from the ladder, and taking the board with the hive upon it very gently, he placed them carefully on a garden bench close by, and raising one side of the hive a little, as he had done with the first swarm, he left the bees, and they all stood at a little distance and watched them.

The bees still rose in great numbers high into the air, and whirled about in great confusion, and John began to fear that the queen bee was not in the hive; but by degrees they began to cluster round the hive and cover it. For it seemed that one or two had found out that the queen was safely housed in the strange-looking box, and had told the news to the others, for they came lower, flying closer and closer, and crept all over it until they had found the entrance, and before a quarter of an hour had passed, there was scarcely a bee to be seen out of the hive.

‘You can leave them safely now, I think, John, till the evening, and then I shall like these two swarms to be placed in the new bee-house. 54And now you know, dear Alice and Beatrice, that the Ayrshire hive is yours, and all the honey the bees make will be yours too.’

The little girls were much pleased, and thanked their grandmamma well. Afterwards they returned slowly through the hot garden to the verandah, and they were very glad of its cool shade.

Their grandmamma told them a great deal about bees: that this immense family, of often twenty thousand bees, was obedient to one single bee, a queen bee, who was their mother and their queen, for whom they worked and gathered stores of honey, and whom they protected from all harm. Grandmamma told them how busy and industrious the bees were, how early they were up in the summer, and how many times they flew out and returned ladened with honey or with pollen which they take from the flowers, what distances they fly in search of flowers, and it has been proved that they will fly even several miles to gather honey.

She described to the children how carefully they laid up a store for the winter; and said that it was cruel of people to kill the bees to get 55the honey, instead of being content to take only what the bees can spare, which is often a great deal.

‘I never kill my bees, you know, and I have plenty of honey—indeed, much more than I want.’

‘I can say, “How doth the little busy bee!”’ said Beatrice, and her grandmamma let her repeat the whole of the little hymn, which Beatrice did very nicely, and grandmamma said, ‘You will soon see through the little windows of your new hive “how skilfully she builds her cells.” I will let you read about the cells in a nice book called “Homes without Hands.”

‘There is another insect,’ grandmamma went on, ‘which is very industrious, and lays up a large store of food for the winter, and that is the ant. There is a very pretty fable in French about the ant and the grasshopper, which, when you are older, I should like you to learn.’

‘But will you tell us about it, grandmamma?’ asked Alice.

‘Well then, my Alice, I will try, but I cannot tell it in the pretty and clever way it is told 56in French. It was thus: One cold stormy October, a grasshopper, who had skipped and chirped in the sun all through the summer time, came to an ant, and said, “Good Mrs. Ant, you have such a large store of corn and seed in your hill, will you spare me a little, for I am very hungry?”’

‘Now, though the ant was very industrious I am afraid that she was not very charitable, or perhaps she thought it was useless to feed lazy people who will not work; so she answered and said, “Pray, Mrs. Grasshopper, what did you do all the summer, while I was working hard, and laying in a store to keep my children through the winter?”’

‘“Oh, in summer I sang and chirped all the day long,” replied the grasshopper.

‘“Then I advise you,” said the ant, “to dance now;” and the ant went into her house in her hill, and left the grasshopper to die.

‘You know, both of you, what an ant-hill is, do not you?’

‘Yes, grandmamma, I remember those little mounds, which I wanted to kick to pieces to make the ants run about, and you would not let 57me, and told me that it was cruel. Now I understand that those ant-hills are the ants’ houses, where they live and lay up their food for the winter.’

‘You are quite right. Here in England the ant-hills are small, but in other countries they are as high as you are. When I first saw them in Russia, I could not believe that they were ant-hills; and the ants are very little larger than those here, and yet they can collect such quantities of earth and leaves, and can raise up such pyramids for their houses.’

‘The ants are not so good as the bees; they do not make anything for us, like those nice busy bees,’ said Alice. ‘I do not like them; and, besides, the ant was very cross to the poor grasshopper.’

‘The ant was certainly very uncharitable; but all animals act only in accordance with God’s laws. This is a fable to show the difference between industrious and idle people. God has taught all creatures who are to live through the winter, to labour and lay up stores; but the grasshopper and butterflies who flutter in the sunshine, and many other insects, by 58God’s will are made to live only for a short time, and therefore do not need to store food like the ant and the bee.

‘The industrious ant serves in the fable to show us that we ought all to work, and you know from the Bible, that God has ordained that man should earn his bread in the sweat of his brow, which means by working. The poor man works, or ought to work, with his hands, the gentleman, or the educated man, with his head; but work is ordered for all—for the queen in her palace, and for little children at school.’

‘ALICE and Beatrice,’ said grandmamma one morning, ‘make haste and eat a good breakfast, for we are going to spend the day at Branscombe.’

‘Branscombe! Oh, how nice, grandmamma! But how are we going? Are we going to walk?’

‘No, dear children, we are going in a boat. The weather is so fine to-day, and there is so little wind, and John Bartlett tells me he thinks that it will remain fine; and therefore we will go in his boat to Branscombe, and see the beautiful rocks there.’

Alice and Beatrice made haste; they were very much pleased to go in a boat, for they had 60never been before on the sea. The little girls would have eaten no breakfast, unless grandmamma had told them that the sea air would make them very hungry, and that they must try and eat their breakfast properly. They were told that they were to have their dinner at Branscombe, which pleased them much.

The cook had provided a nice dinner, and had packed it into a basket; and the gardener carried it down the steep path and steps to the sea-shore.

At last grandmamma said, ‘Now you have been very good children; run upstairs, and ask Mary to dress you.’

Alice and Beatrice ran upstairs; and whilst Mary was taking out their hats and jackets, they both sat down on the carpet and pulled off their shoes, and put on their thick boots, and stood very quiet when Mary buttoned their little white jackets and tied on their hats.

‘I will put your cloaks with your grandmamma’s,’ said Mary, ‘because it will be cold when you come back.’

‘Cold!’ cried Alice, ‘this hot day. Oh, Mary, we cannot want our cloaks!’

61‘On the sea it is often cold, Miss Alice; and it may be late when you return,’ added Mary.

The three cloaks were put together, and the children were glad to see that Mary was to come with them in the boat.

When they came to the shore, there was John Bartlett waiting for them, and a very nice large boat, half on the sand and half in the water, and there was another sailor there, and a little boy.

Little Beatrice said, ‘Grandmamma, that is Jack; I know Jack, he brings us nice shrimps for our tea; don’t you Jack?’ and the boy smiled. ‘I am so glad that Jack is going with us.’

The sea was very smooth, and the tide was neither high nor low, and there were no waves.

The children were lifted into the boat, after grandmamma and Mary had walked along a sloping plank into it, and had seated themselves at the end, where there were cushions, and Alice and Beatrice sat on the cushions on each side of their grandmamma.

Bartlett and the little boy jumped into the boat; and the other man first pushed the boat 62deeper into the sea, going into the water himself, and then climbed into the boat; and Bartlett and his boy, each with an oar, rowed a little till they were away from the shore, and the boat tossed up and down, and Alice and Beatrice came close to grandmamma and looked afraid.

Grandmamma then took Beatrice on her lap, and said—

‘A boat always rocks up and down at first; as soon as the sails are up, it will be much quieter.’

So they did not cry; but Beatrice said, ‘I should like to go back best.’

‘May we go back?’ asked Alice.

‘No, dear children, you must wait a little, and then I think that you will like the boat very much. Look at little Jack Bartlett, how he helps his father to unroll the sail and to pull the ropes.’

The children looked, and saw the sailor and his boy unroll a large piece of cloth; they knew that it was a sail, and they saw the men pull it up a high pole, which Alice told her sister was called a mast. The sail was red, and had a 63little hole in it. The wind blew upon the sail and made it straight; then the two men put up another sail, and little Jack came to sit near grandmamma, at her end of the boat.

There was so much to look at, that the children soon forgot their fear, and Alice asked—

‘What is Jack doing at our end of the boat?’

‘He is steering, miss,’ said Bartlett.

‘But what is steering?’

‘Steering means guiding the boat; and this is done by a piece of wood at the end, which Jack moves backwards and forwards in the water, and this makes the boat go to the right or to the left, as his father tells him.’

‘How funny that is! How can a bit of wood make a boat go one way or another?’ said Alice.

‘I cannot explain it to you now, dear Alice; but when you are older I will show you how it moves, and what it does. This piece of wood is called the rudder;’ and Alice watched the rudder some little time.

‘Why is there a hole in the sail, Jack?’ asked little Beatrice. ‘Is the sail old?’

‘No, little miss,’ said Bartlett, ‘it is quite a 64new sail; but a lady let her dog make that hole only last week.’

‘Why did she let her dog make that hole and spoil your new sail?’ asked Alice.

‘The lady was playing with her dog, as she sat on the beach, and threw stones for him to fetch; and at last she threw a stone on to the sail, that was lying next my boat, and the dog jumped upon the sail, and turned it over the stone, and then he bit and gnawed at the sail to get it out. The lady did not think what harm she did me in letting her dog make a hole in my new sail,’ said the boatman.

‘Did she not give you anything for the mischief her dog had done?’ asked grandmamma.

‘No, ma’am, nothing; and she did not even say that she was sorry, but took no notice, and walked away.’

‘That was naughty of her,’ said Beatrice; ‘I will not let our good dog Wolf bite any sail.’

The wind filled the sails, and the boat glided quickly through the water. The children began to enjoy the pleasant movement, and liked to watch the mark in the water that the boat left 65behind it; and asked if they might put their hands into the clear green water, which grandmamma allowed them to do.

Alice soon cried out, ‘Oh, grandmamma, how far I can see into the sea! How deep it is, and how green, and how pretty!’

‘Very pretty,’ repeated Beatrice; and both children looked long over the side of the boat.

‘What is Jack doing now?’ asked the children suddenly, when they saw the boy unwind some cord from a piece of wood, and throw the end of it into the sea; then he threw another piece of cord, and then another, till at last there were four strings in the sea, two on each side the boat.

‘He is fishing,’ said grandmamma.

‘Fishing!’ cried Alice; ‘please tell me how he is fishing.’

‘Each of these cords has a hook at the end of it,’ said grandmamma, ‘and on each hook is a little bit of fish or meat. When the fish try to catch hold of it to eat it, the hook sticks in their throats, and they cannot get away.’

Just now Bartlett called to his boy, and said, ‘Jack, you have got a fish on that line;’ so 66Jack pulled up the line—and it was a very long piece of string—and at the end hung a fish. The boy took it and put it into the other end of the boat, and threw his line in again. The fish jumped at first up and down, but it soon lay still; and soon several other fishes were caught, and all thrown together into the end of the boat.

The little girls were sorry, for they did not like seeing the fishes hurt.

‘Jack,’ said his father, ‘go back to the rudder, for we must try and land soon. There is Branscombe now, young ladies.’

The children looked and saw that they were coming quite close to the land again. The rocks were no longer red in colour, as at Salcombe, but white, and very different in shape; and there was a wide valley between these rocks and hills, and a very few houses were in the valley, not far from the sea-shore.

‘What a large ship that is! Shall we go close to it?’ asked Alice.

‘Yes, quite close, miss; it is full of coals, and the people on board are putting the coals into sacks, and then they let down the sacks into those big boats.’

67Their boat soon came quite near the large ship, which grandmamma told the children was called a collier, because it always carried coals from one place to another. The children looked hard at the ship, as they had never been so close to a ship before. Then they sailed past the collier, and soon came up to the big black boat, and saw that it was full of sacks of coals, and they soon passed that. Beatrice thought that the men who were rowing the boat looked very black and dirty.

‘The coals make the men black, Beatrice,’ aid Alice. ‘If we played with coals, our hands and our dresses would be quite black too.’

‘But do these men play with the coals?’ asked little Beatrice.

‘No; to be sure they do not. Did you not see how the men put the coals into the sacks, and how the dust flew about on the ship? That is enough to make anybody black and dirty.’

The boat now came nearer and nearer to the land, and the little girls looked eagerly, and asked how they should get on shore.

‘Quite easy, little miss,’ said Bartlett. ‘Now, please sit quite quiet, and we will run her on 68shore. But please, ma’am, will you sit in the middle of the boat?’ which grandmamma and Mary did immediately; and the two sailors let down the sails, and took the oars and rowed hard, and in a very few minutes the boat went on to the shore, the one end much higher than the other end. The men jumped on to the shore; and when the next wave came and lifted the boat, they pulled it by a rope, and brought it up much higher on the shore.

‘Please take me out, Bartlett,’ cried Beatrice. ‘And me too,’ said Alice. ‘May we go, grandmamma?’ asked the children; and as the answer was ‘Yes,’ the children went to the higher end of the boat, and were lifted on to the shore, and grandmamma and Mary and Jack followed them. The great basket that the cook had packed was taken out, and the cloaks and umbrellas.

‘Take all the things up to the farm-house, please, Bartlett,’ said grandmamma, ‘and tell Mrs. Wilmot that we shall soon come up.’

The children, in the meantime, were looking at something which amused them very much.

There were a number of horses—about twenty 69(for Alice counted them)—which all walked, one after each other, with no one to guide them, up to the big black boat that had brought the sacks of coal, and had just reached the shore. The horses, one after another, went into the water to the side of the boat; and when the men had laid a sack of coals across each horse’s back, the horses went away out of the water in a row, and up the shore, and carried the sacks in front of a large house, where some men took off the sacks, emptied each sack, and threw them over the backs of the horses, which then turned round and went back again to the boat. Thus there were always two rows of horses, one row going to the sea, and the other returning loaded with sacks of coals.

The little girls were very much pleased to see how clever the horses were—how regularly they went, never stopping behind, but on and on till they reached the right place. They liked to see each horse come up to the edge of the sea, put down its head for an instant, as if to see how deep the water was, and step in until it reached the boat, then wait till its turn came, and take the place of the last horse that was 70loaded. The horses did not seem to mind the waves that washed up against them, for the tide was high, and there were more waves than when the children landed.

After Alice and Beatrice had looked a long time, they turned away from the sea, and went up the path that led through a green field up the side of the valley, and followed their grandmamma till they came to an old farm-house.

They were very hot and tired, for the path was long and very steep, and the sun shone bright, and they found the weather much warmer on the land than on the sea.

There was a large tree in front of the house, and it was so shady and cool there, that grandmamma asked the farmer’s wife if she would let them have a table and some chairs under the tree, as they would like to sit in the shade, and eat their dinner out of doors.

Mrs. Wilmot, the farmer’s wife, then ordered a table and some chairs, and Alice and Beatrice sat down and rested a little, for they were tired; but very soon they began to run up and down the sloping side of the hill, and laughed when some sheep that were feeding there began 71to run about too; and they chased the sheep about, till at last the sheep leaped over the hedge at the end of the field, and began to jump from one rock to another.

Alice and Beatrice followed the sheep; but, on going through the gate, they saw that they were near the sea, which lay below the steep cliff; and large pieces of white rock, that sparkled in the sun, lay half-way down, as if they had fallen down.

‘You must not go so near the edge,’ said Mary, who had followed them. ‘Miss Beatrice, give me your hand, and I will let you look down into the sea.’

‘I can take care of myself,’ said Alice; ‘please let me, Mary. Oh, I never saw such beautiful rocks! I wish that grandmamma were here, she would like so much to see them. What is that large white piece further on—it goes so far into the sea?’

‘That is Portland, a sort of island; it is a long way off; only to-day the air is so clear that we can see it easily. But we must go back to your grandmamma,’ added Mary. ‘Are you not hungry?’

72‘Oh yes, so hungry, Mary! Let us go back to the nice farm-house.’ And they ran quickly back again.

Alice and Beatrice found the table spread with a white table-cloth, and some nice things on it ready for their dinner. The farmer’s wife had lent some plates, and had put some milk and some cream on the table, and some of her own brown bread; and the children drank the milk, and grandmamma gave them some fruit tart, with a little of the nice cream.

‘It is very good of the farmer’s wife to give us such nice things,’ said Alice; ‘everything tastes so much better than what we have at home, I think. But I was very hungry and thirsty; perhaps that’s why I like everything so much to-day.’

“I think that is one of the reasons, dear Alice,’ was the answer.

‘It is nice to have our dinner under this tree: do you not like it, grandmamma!’

‘Yes, very much.’

‘And so do I, grandmamma,’ said little Beatrice.

SOON after dinner grandmamma went with the children to the pretty green field which sloped down to the white rocks.

‘What is that little white thing,’ asked Beatrice, ‘up there, grandmamma? Look, please—it moves, it runs, it is alive!’

‘And there, too, and there!’ cried Alice; ‘how many little animals! What can they be?’

Grandmamma looked too, and said, ‘They are rabbits, little white rabbits.’

‘Rabbits!’ said Alice; ‘I thought that rabbits were brown.’

‘Yes, so they are, my dear, that is the wild 74rabbits are brown; but tame rabbits are of different colours, some white, some black, or grey, or spotted. I do not know how these tame rabbits came here.’

‘May we go nearer and look at them?’ both the children asked; and they went much nearer, and they saw a great number of white rabbits running about in a green field higher up the hill than the one they were walking in. The children liked to look at these rabbits running about and playing with each other.

‘Why are these white rabbits called tame?’ asked Alice.

‘Tame animals are those that are taken care of and fed. For, as these pretty white or black rabbits are not so strong as the brown ones, they are usually kept in little houses, and fed with cabbage leaves and other food, because the cold in winter might kill them. In Devonshire the winter is not very cold; so I suppose that these rabbits do not suffer from it, and that they have learnt to make themselves warm houses in the earth, as the wild rabbits do.’

‘Will you tell us, grandmamma, how the 75wild rabbits make themselves houses in the ground?’

‘They make or burrow holes in the ground, digging out the earth with their feet, as you must have seen a dog scratching and digging with his feet. But the rabbits dig long passages under the earth, and often near or under a tree. I have read that the rabbits first dig down straight till the hole is deep, and that then they make a passage, and sometimes turn upwards again, or make it crooked, to prevent dogs finding them and killing them.

‘Rabbits live together in great numbers, and it is called a warren. They like a sandy or gravelly soil to burrow in, and make the entrance to the little house often under a furze bush that it may not be seen. Sometimes they loosen the roots of trees so much that the trees fall; and where there are many rabbits in a warren, the ground is very unsafe, for if any one was riding, the horse’s foot might go through, and he would fall, and perhaps break his leg and throw his rider. Even in walking you might stumble, by getting your foot into a rabbit hole, which is not easily seen. I have 76heard, too, that rabbits have undermined walls and buildings, and made them unsafe.’

‘What is undermined, grandmamma?’

‘It means making a hole or mine under the ground; and when these holes are made in soft sand or gravel beneath a heavy wall, it will fall into the hole.’

‘Will you tell us what the wild rabbit eats?’

‘It eats nearly everything it can get; but it is very fond of all our vegetables, and would soon spoil our gardens if it came into them. The wild rabbit lives in the fields and meadows and woods, and eats the young buds of the bushes and young trees; it likes especially the tender roots of the furze bushes, and it nibbles the soft bark of the trees, and spoils a great number of them. There are also many plants and roots that it lives on.’

The children then asked to go to the end of the field, and look down on to the sea beneath; and they all went on walking till they came to the edge of the field. The two little girls called out with pleasure and surprise, for they saw beyond and below them a number of large rocks, which looked like great towers, close to 77the steep cliff, on the edge of which they were now standing.

Some of these rocks were slender and pointed, and sharp on the top, and many were strangely shaped, and lay scattered about; but one tall piece of rock stood out alone, nearly in the sea, as if it had been cut off the cliff, and on the top was perched a sea-gull.

‘Oh, grandmamma, look at that sea-gull!’ cried Alice; ‘how can it stand on the point of that high rock?’

‘The sea-gull need not be afraid of standing there,’ said grandmamma, ‘for if its foot should slip, its wings would keep it from falling; and should it even fall, which is not likely, it would not be drowned, for the sea-gull swims well on a stormy sea.’

‘How wonderful it is that it can swim and fly so well!’ said Alice. ‘It can fly much better than a goose or a duck, and they can swim and fly a little.’

‘God, in His great mercy, has made the wild bird fly and swim much better than the tame bird. The sea-gull provides its own food by diving into the waves and catching fish, and it 78flies about in stormy weather and swims on the wild waves. Man, or people, take care of the duck and goose, and feed it, so it does not want to fly far, or swim on rough seas.’

‘How very wonderful it is!’ said Alice; and little Beatrice listened attentively, although she could not understand it all.

‘God’s wisdom is always wonderful, my child, and God’s love is very great. As God provides for the sea-gull and for all animals, and gives them all their food, and takes care of them all, so God takes care of us all, and gives us food and clothes, and everything that we want. God, as you know, gives us summer and winter, sunshine and snow and rain, and all for our good. God has made the earth beautiful, the grass green, the flowers gay, the sea wide, and the heavens high; and we must never forget to thank God for everything, and for His care of us by day and by night.’

They sat down on the edge of the cliff and rested, and looked at the beautiful sight before them; and when they had seen the sea-gull spread its wide wings and fly over the sea, and they had watched it till they could see it no 79longer, they turned back to the farm-house. There they found Mary had put everything ready, and Bartlett was waiting.

Grandmamma thanked the farmer’s wife, and she and the children bade her good-bye; and after grandmamma had asked Mary if she had given the sailors a good dinner, and Mary had answered that she had, they all went down the side of the hill to the shore, where little Jack and the other sailor were waiting by the side of the boat.

They all stepped into the boat, and were pushed off, and after a little rocking to and fro, which no longer frightened the children, two sails were hoisted, and as there was more wind now, the boat went much quicker.

Soon the little girls said, ‘How cold it is!’ for the wind blew strong; and Mary put their cloaks about them, and little Beatrice crept on to her grandmamma’s lap, and soon fell asleep, for she was very tired.

Alice sat between her grandmamma and Mary, and talked the whole way. She had so many things to ask about; and she made Bartlett tell her about his little girls at home, who had no mother.

80The sailor told Alice that his eldest girl kept his house clean and neat, and cooked the dinner, and looked after the little ones.

‘Do your little boys and girls go to school, Bartlett?’ asked Alice.

‘Yes, miss, they all go; and it is a very nice school. They learn to read and write very nicely, and the little girls learn to sew.’

‘Can Jack swim, Bartlett?’ she asked again.

‘No, not yet, for I have not much time to teach him.’

‘Not yet! Why, Jack is older than I am, and grandmamma says that I must learn to swim next summer.’

‘But, dear Alice, how can Jack learn to swim if his father has not the time to teach him?’

‘Bartlett, you will teach Jack to swim when you have time, will you not? Grandmamma says that if people do not learn to swim, when they fall into the water by accident, they will be drowned.’

The sailor promised the little girl that he would make Jack swim very soon.

As the boat sailed past the high red cliffs 81before they reached home, Alice spied a man and an ass on a narrow piece of rock some way down the steep side of the high cliff, and asked the sailor how and why the man had taken his donkey to such a place.

‘It must be so dangerous. Look, Bartlett how they are going along, they must fall!’ and Alice looked quite uneasy and frightened.

But Bartlett soon explained to her that some poor people made gardens on tiny plots of ground among the ledges of the steep cliff, and planted them with potatoes; and as these little strips of ground slope towards the noon-day sun, and are protected from the cold north winds by the rising cliff, these people have potatoes earlier than any one else. He told her that by setting their potatoes in September or October, the potatoes were ready in early spring, and were often sent to London and sold for a great deal of money.

The sailor told the little girl that nothing but a donkey was sure-footed enough to carry down the baskets of manure for these little gardens, and to bring up the potatoes; that no horse could tread safe where these asses walk 82firmly and steadily, choosing their own paths. ‘As you see, Miss Alice, that donkey is going on alone with his load, and the man is following him as he best can; and the man knows that it is safest to walk where his ass has gone already.’

‘How clever donkeys must be, grandmamma!’ said Alice. ‘I thought that donkeys were always stupid. But how can it know where it is safe to walk?’

‘By instinct, dear child. Instinct is a knowledge which comes of itself, and is given to animals by God. Another time I will tell you about it.’

Bartlett began to pull down the sails, and called to Jack to steer for the land, as they were now close to their own shore. Little Beatrice woke up in time to see how some very large waves lifted the boat, and brought it up high on the shingle. The sailors jumped out, and helped first the children and then grandmamma and Mary out of the boat. Before they went up the steps from the shore, they thanked Bartlett and bade him and Jack ‘good-bye.’

THE next day, at breakfast, Alice asked when they might go in a boat again. ‘I like it so much, grandmamma. I love to be on the sea.’

‘I like it too, my Alice; but we must not go often; for yesterday you know we did nothing else but amuse ourselves, and now we will stay at home and work and do lessons.’

‘Please, ma’am,’ said Mary, entering the room rather hastily, ‘Mrs. Dunne’s little girl has been scalded with hot water. Will you please go and see the poor child? The boy says that she is screaming so much.’

‘Yes, indeed I will; but whilst I am putting on my cloak and bonnet, get me some cotton-wool; you will find some in the lowest drawer.’

84Alice and Beatrice were very sorry that the little child was hurt, for they knew the child quite well, and they sometimes went to the village to see Mrs. Dunne, who was a washer-woman.

Their grandmamma told Mary to bring the two little girls to meet her in an hour’s time, and walked very quickly to the village.

When she came near Mrs. Dunne’s cottage she heard the child’s screams; so she opened the door, and went in. Mrs. Dunne was holding the little girl on her lap; and the poor child was crying as loud as she could, and her mother was crying too.

‘Mrs. Dunne,’ said grandmamma, ‘put little Betsy on the bed, and show me where she is hurt.’

Little Betsy knew the lady, and looked up at her, and left off crying for one minute; and whilst her mother put her on the bed, grandmamma made a glass of sugar and water and held it to the child to drink, and though she still went on crying, she did not scream so loud, and Mrs. Dunne was able to show the lady where her child was hurt.

85The little leg was very red, and was covered with large blisters. The lady first took off the poor child’s shoe, and then drew off her little sock so quietly that it did not hurt her, and wrapped the whole leg and foot in the cotton-wool she had brought, and wound it round and round with some broad tape.

The little girl soon appeared to have less pain, for her cries were less; and then Mrs. Dunne told the lady how her poor little Betsy, who was but four years old, had met with this accident.

‘But I am glad that the boiling water that went on to her leg did not go into my dear child’s face or neck, for then it would have been much worse.’

‘You see, Mrs. Dunne, that in everything we have reason to thank God for His mercy.’

‘Yes, ma’am,’ said Mrs. Dunne, wiping her eyes: ‘I thank God, and you too, that you have come and helped me so kindly.’

‘I will leave Betsy some medicine,’ said the lady, ‘and I will come again in the evening and see how the poor child is; but do not move the cotton-wool on any account.’

86Whilst Betsy’s medicine was preparing, Mrs. Dunne was pleased to see that her little child was much easier; and after the lady had given her a spoonful of the medicine, she went away, and she met Alice and Beatrice not far from the cottage.

The two children had their hoops, and were running with them till they saw grandmamma in the distance; then they stopped their hoops, and came running to meet her.

‘How is poor little Betsy?’ asked Beatrice.

‘Where is she hurt, grandmamma?’ asked Alice.

Grandmamma told them all about Betsy, and what she had done for her, and said that the little girl was much easier when she left her.

‘May we take her something nice for her dinner or for her tea?’ asked Alice: to which Beatrice added, ‘Please let us, grandmamma.’

‘You may take Betsy a little basketful of strawberries, and you may gather them yourselves.’

‘Thank you, dear grandmamma,’ said the little girls; ‘may we go now for them?’

87‘No, not now, dear children,’ said grandmamma; ‘you must come in and do your lessons.’

‘Do let us go first and pull some strawberries,’ said they.

‘No; I cannot let you go till after your dinner.’ Upon which, Alice and Beatrice seemed very much inclined to cry, but they knew that their grandmamma did not like them to ask again after she had refused; so they walked on slowly, and did not speak at first.

At last Alice said, ‘Why did you wrap Betsy’s leg up in cotton-wool, grandmamma?’

‘Because it has been found that cotton-wool lessens the pain of a burn, and helps to make it get well.’

‘How did people find this out?’

‘There is a pretty story about it, and I will tell it you:—

‘In North America the cotton plant grows—for this white wool grows on a small plant—and the plant has little pods. You know what a pod is, do you not?’

‘Yes, grandmamma; a pea has a pod, and the peas are in it.’

88‘Well, the cotton plant has a pod which holds its seeds—of a different shape to the peas-pod, and not so long or so large; but the seeds are wrapped up in this soft woolly stuff, which the negroes pick and clean and wash.

‘It happened once that the little child of a poor negro woman was burnt all over—I do not know how; and as the mother had nothing to put on, she laid her little screaming child down on a heap of the picked cotton-wool, and returned to her work. After she had finished her appointed work she went to her child, and found that in its pain it had rolled about in the cotton-wool till it was covered with the wool, and was lying quiet and asleep; and the poor negro woman was very glad.

‘Some one who had seen the accident, and also seen the child asleep, examined the child, and found that the blisters had gone down, and the burnt places, which had been quite red, were nearly well.

‘After this, people tried cotton-wool for burns, and found it nearly always of the greatest service in relieving the pain and healing the injuries.’

‘Thank you, grandmamma; that is a nice story. How glad that poor woman must have been to find her little child nearly well!’

Now they were quite close to their own house, their own dog came running to them, and jumped up at them, and nearly threw little Beatrice down, which made her laugh, and she said, ‘Down, Wolf, down. Grandmamma, Wolf will kiss me, he has licked my face.’

‘And he has licked mine too,’ said her sister.

Wolf ran on in front, and then turned back to the children, and played with them and jumped round them, and they had already forgotten their disappointment about the strawberries.