Title: With Grenfell on the Labrador

Author: Fullerton L. Waldo

Author of introduction, etc.: Sir Wilfred Thomason Grenfell

Release date: March 3, 2022 [eBook #67551]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1920

Credits: Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net from page images generously made available by the Internet Archive

WITH GRENFELL ON THE

LABRADOR

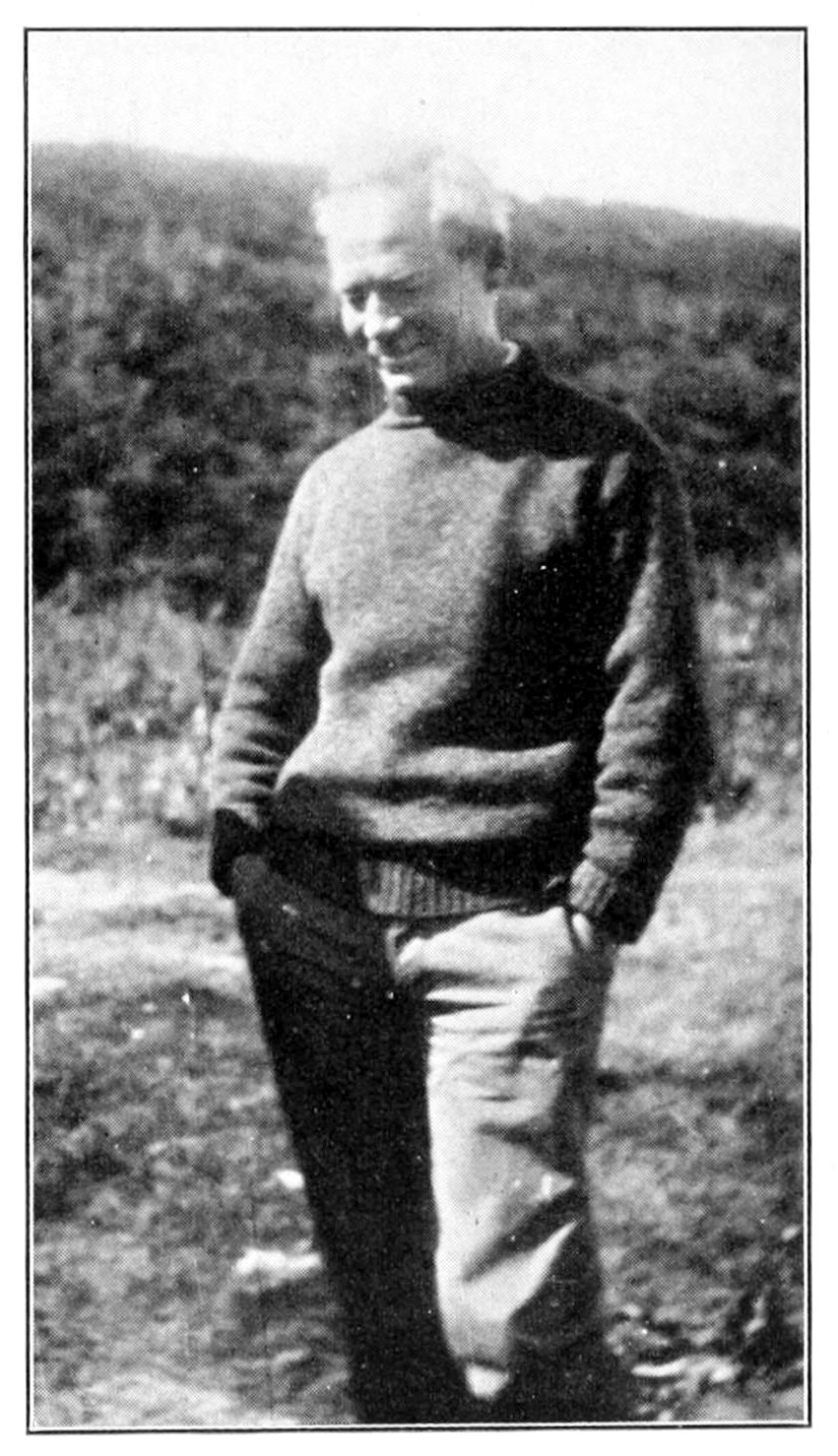

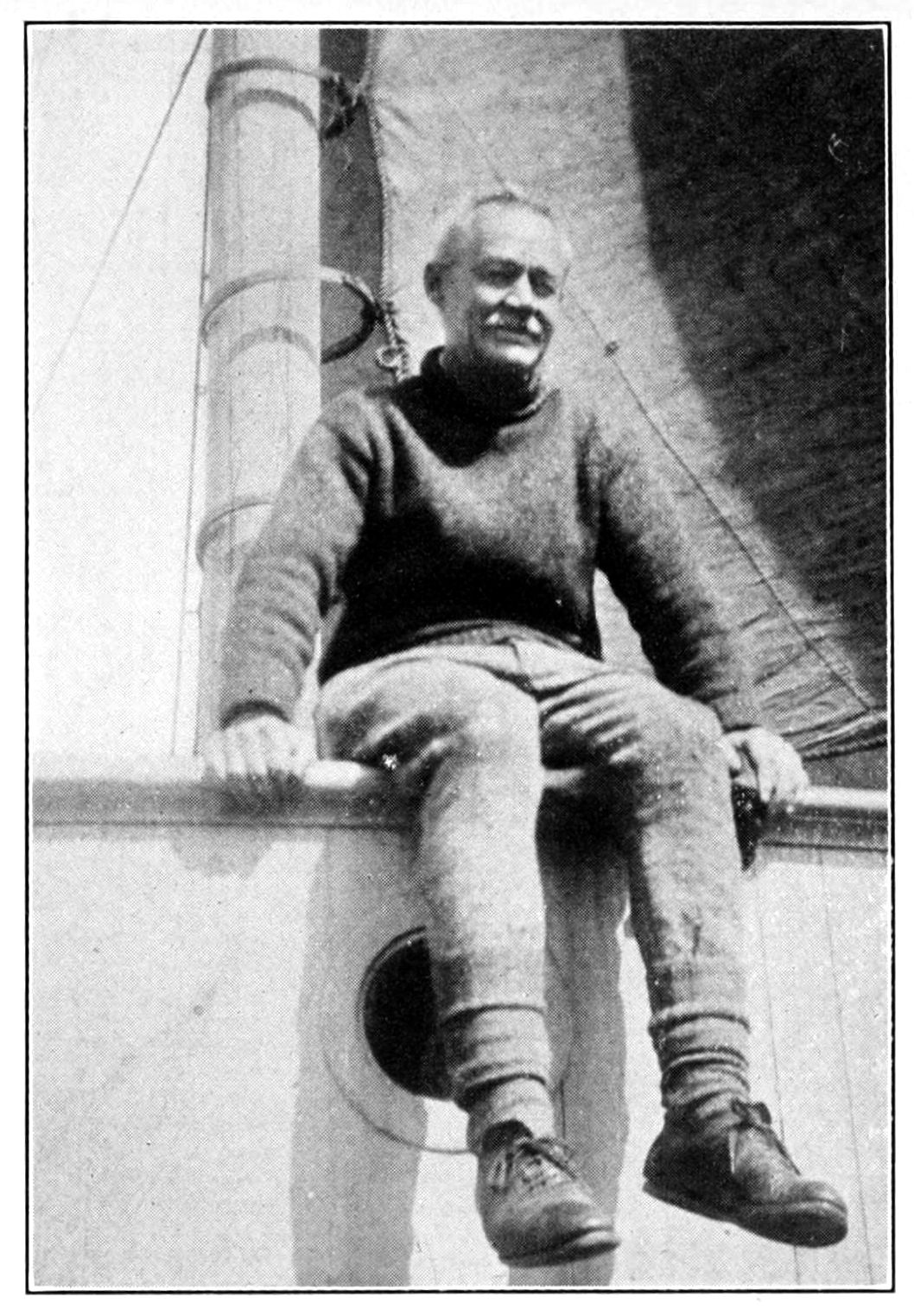

DR. GRENFELL, A.B.

(Three ratlins were broken on the ascent).

WITH GRENFELL ON

THE LABRADOR

BY

FULLERTON L. WALDO

ILLUSTRATED

New York Chicago

Fleming H. Revell Company

London and Edinburgh

Copyright, 1920, by

FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY

New York: 158 Fifth Avenue

Chicago: 17 North Wabash Ave.

London: 21 Paternoster Square

Edinburgh: 75 Princes Street

To

DORIS KENYON

OF

COMPANY L., 307th INFANTRY,

77th DIVISION;

HONORARY SERGEANT, U.S.A.

Aboard the Strathcona,

Red Bay, Labrador, Sept. 9, 1919.

Dear Waldo:

It has been great having you on board for a time. I wish you could stay and see some other sections of the work. When you joined us I hesitated at first, thinking perhaps it would be better to show you the poorer parts of our country, and not the better off—but decided to let you drop in and drop out again of the ordinary routine, and not bother to ‘show you sights.’ Still I am sorry that you did not see some other sections of the people. There is to me in life always an infinite satisfaction in accomplishing anything. I don’t care so much what it is. But if it has involved real anxiety, especially as to the possibility of success, it always returns to me a prize worth while.

Well, you have been over some parts, where things have somehow materialized. The reindeer experiment I also estimate an accomplished success, as it completely demonstrated our predictions, and as it is now in good hands and prospering. The Seamen’s Institute, in having become self-supporting and now demanding more space, has also been a real encouragement to go ahead in other lines. But there is one thing better than accomplishment, and that is opportunity; as the problem is better than the joy of writing Q. E. D.

So I would have liked to show you White Bay as far as La Scie, where our friends are fighting with few assets, and many discouragements. It certainly has left them poor, and often hungry and naked, but it has made men of them, and they have taught me many lessons; and it would do your viewpoint good to see how many debts these people place me under.

If life is the result of stimuli, believe me we ought to know what life means in a country where you are called on to create every day something, big or small. On the other hand, if life consists of the multitude of things one possesses, then Labrador should be graded far from where I place it, in its relation to Philadelphia.

A thousand thanks for coming so far to give us your good message of brotherly sympathy.

Yours sincerely,

Wilfred T. Grenfell.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | ||

| Foreword, by Doctor Grenfell | 7 | ||

| I | “Doctor” | 15 | |

| II | A Fisher of Men | 27 | |

| III | At St. Anthony | 39 | |

| IV | All in the Day’s Work | 53 | |

| V | The Captain of Industry | 78 | |

| VI | The Sportsman | 97 | |

| VII | The Man of Science | 106 | |

| VIII | The Man of Law | 114 | |

| IX | The Man of God | 119 | |

| X | Some of His Helpers | 130 | |

| XI | Four-Footed Aides: Dogs and Reindeer | 139 | |

| XII | A Wide, Wide “Parish” | 150 | |

| XIII | A Few “Parishioners” | 173 | |

| XIV | Needs, Big and Little | 183 |

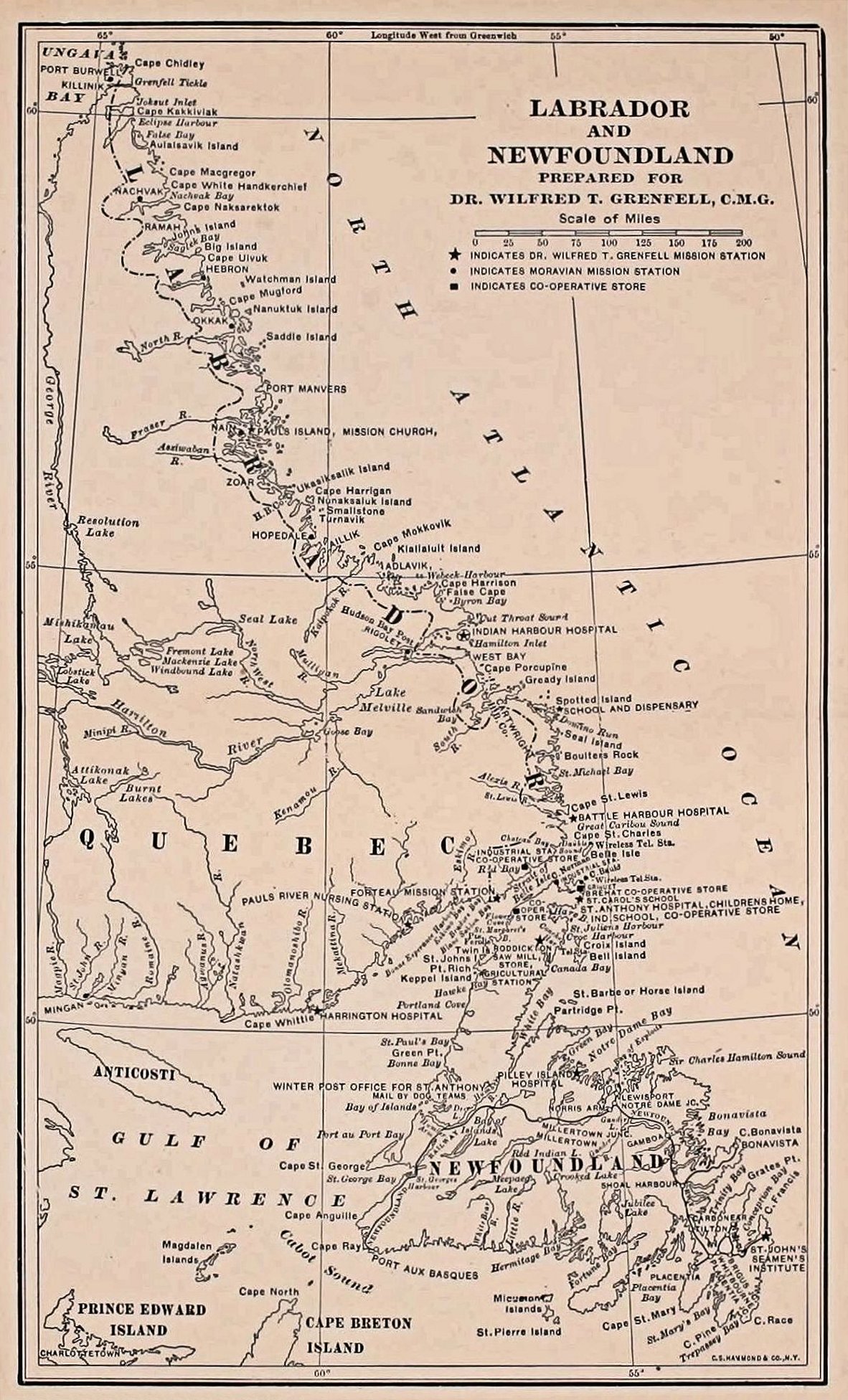

LABRADOR AND NEWFOUNDLAND

PREPARED FOR DR. WILFRED T. GRENFELL, C.M.G.

| PAGE | ||

| Dr. Grenfell, A.B. | Title | |

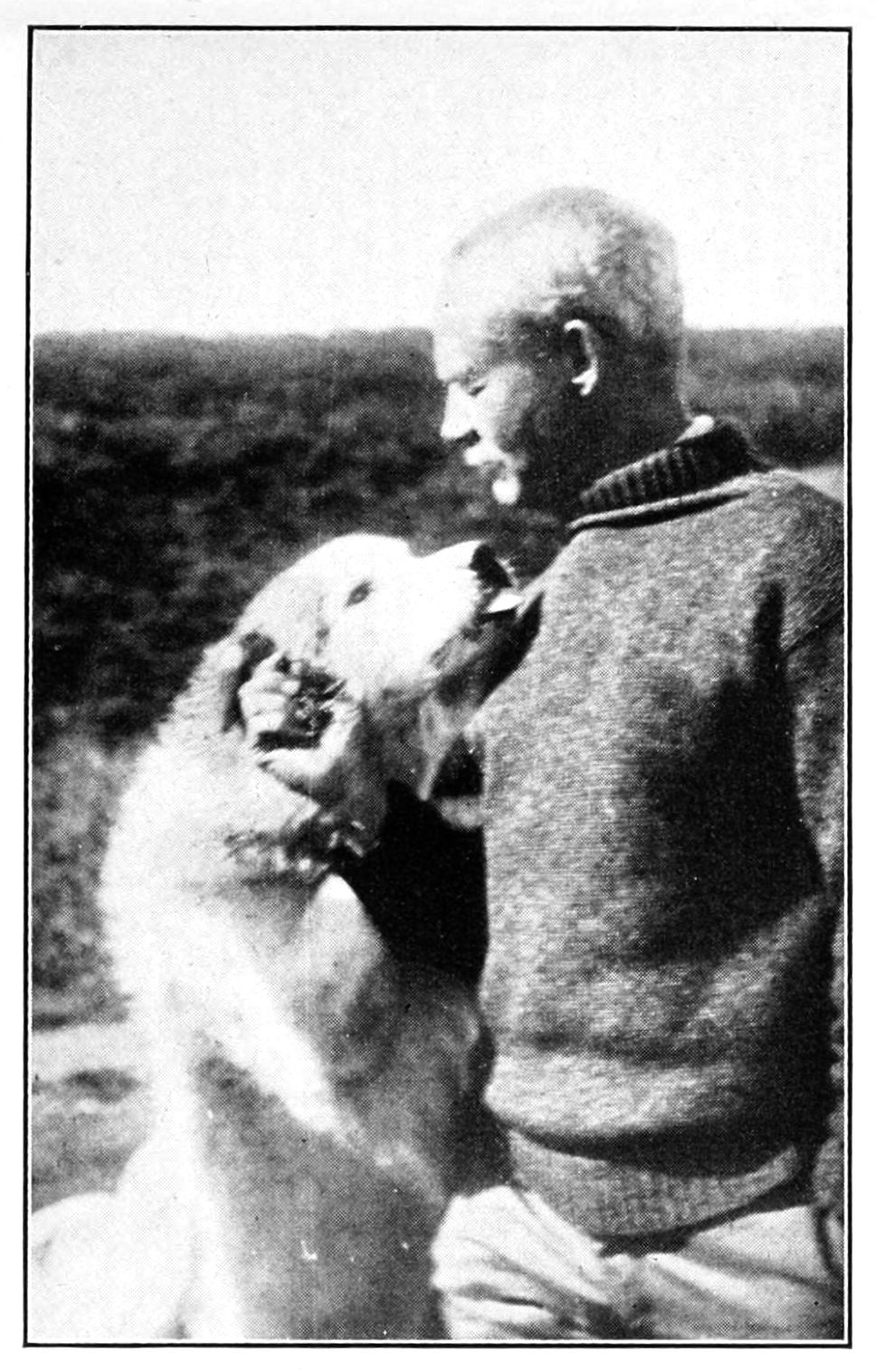

| Fritz and His Master | 38 | |

| “Doctor” | 38 | |

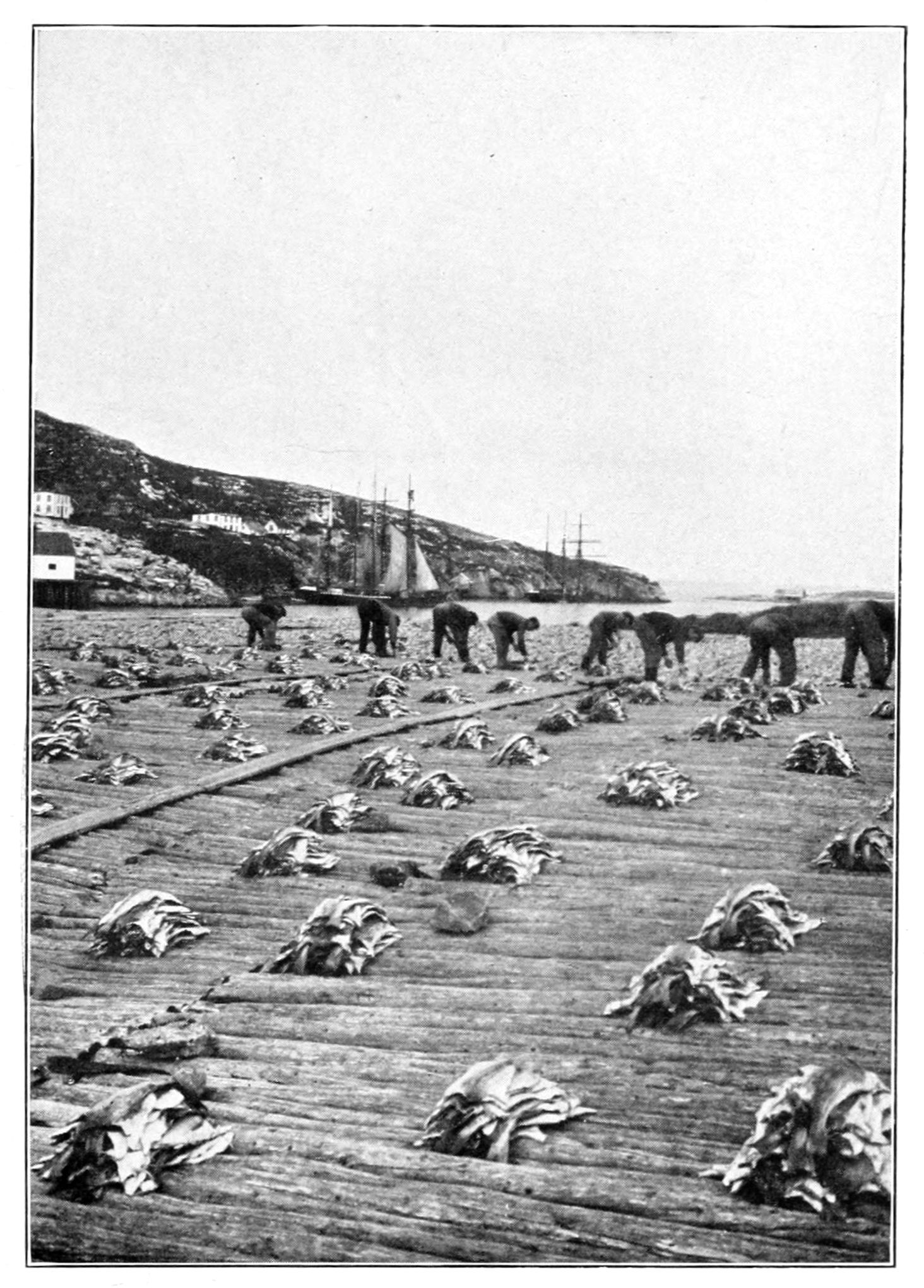

| Battle Harbour, Spreading Fish for Drying | 60 | |

| “Please Look at My Tongue, Doctor” | 98 | |

| “Next” | 98 | |

| Dr. Grenfell Leading Meeting at Battle Harbour | 120 | |

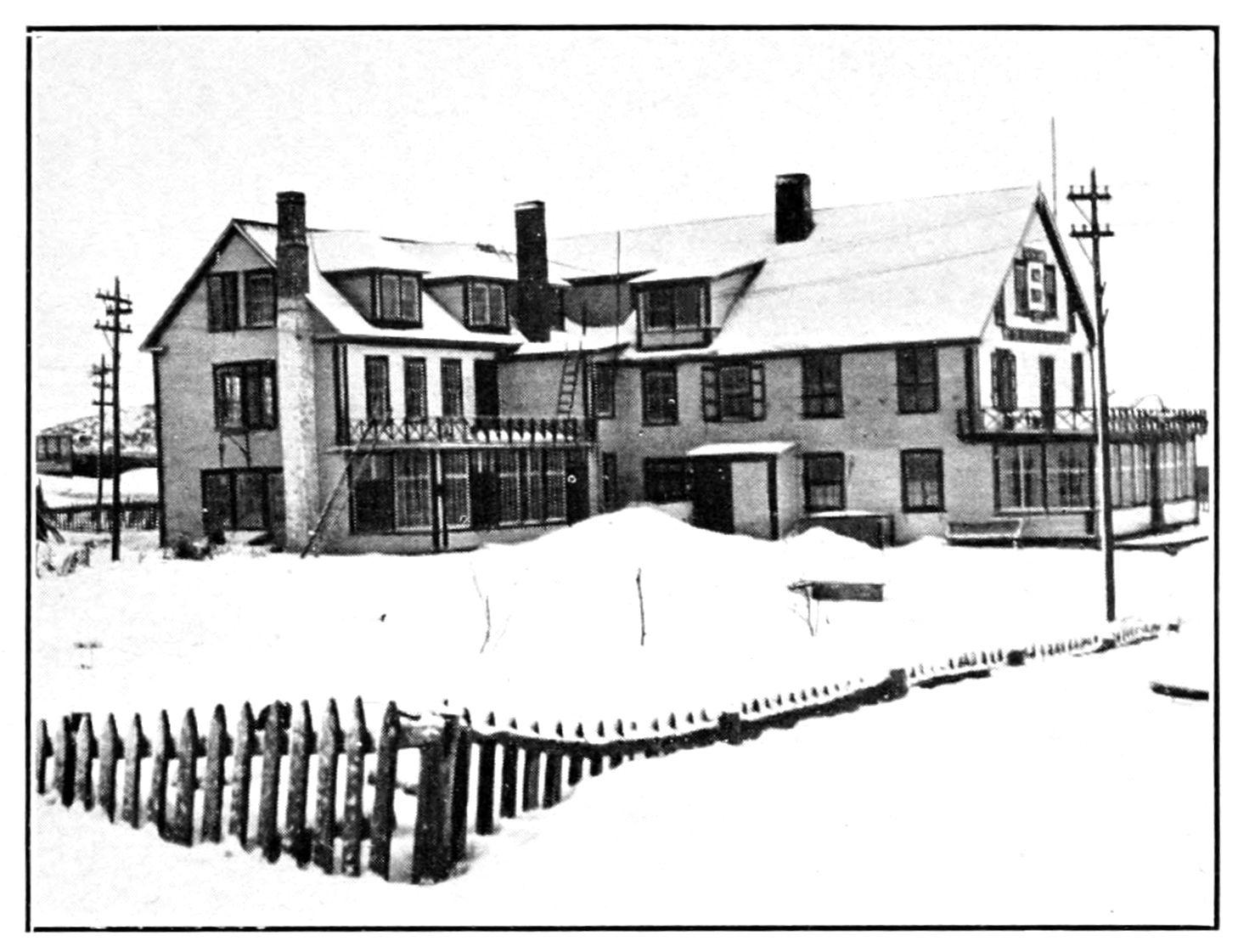

| St. Anthony Hospital in Winter | 134 | |

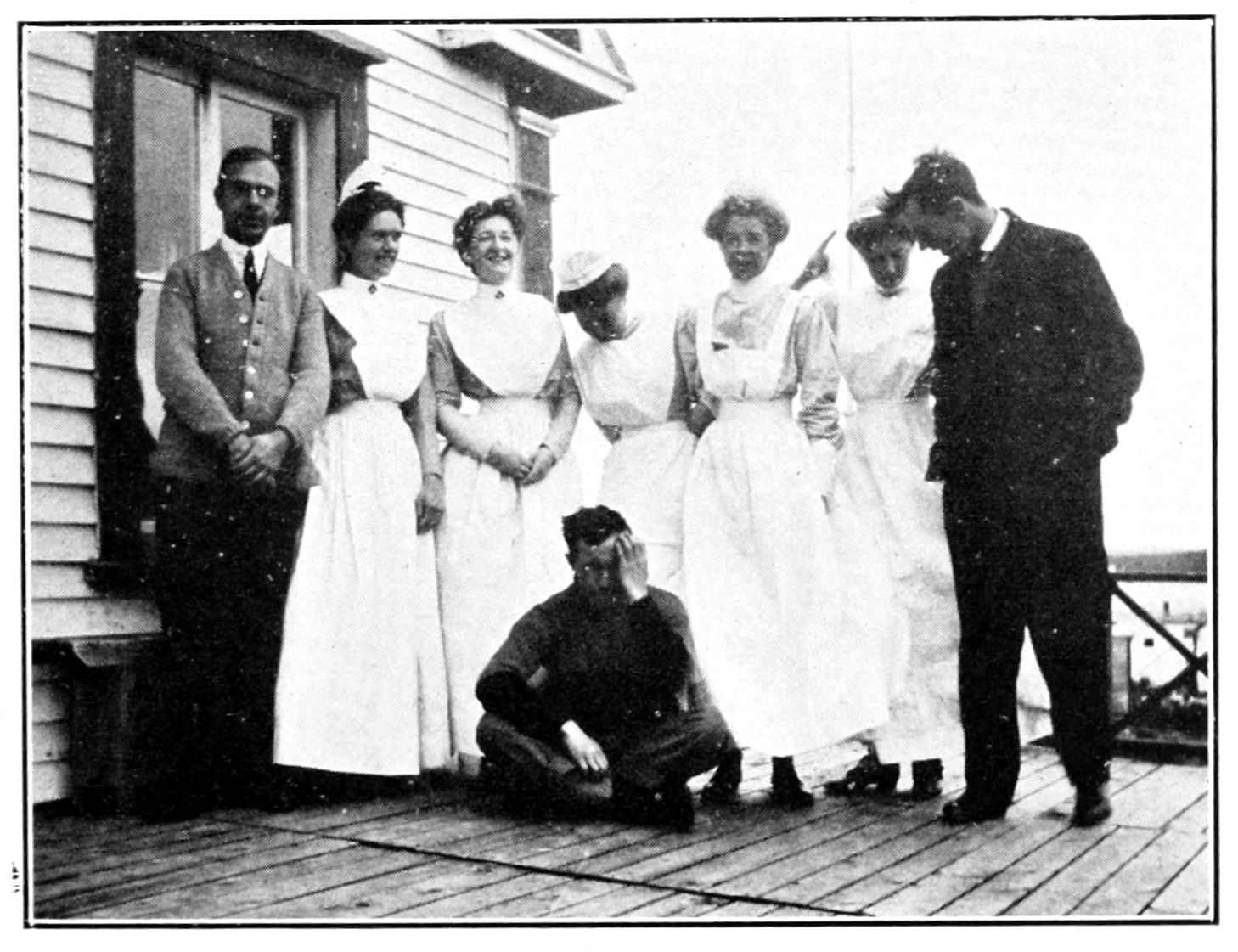

| Some of the Helpers | 134 | |

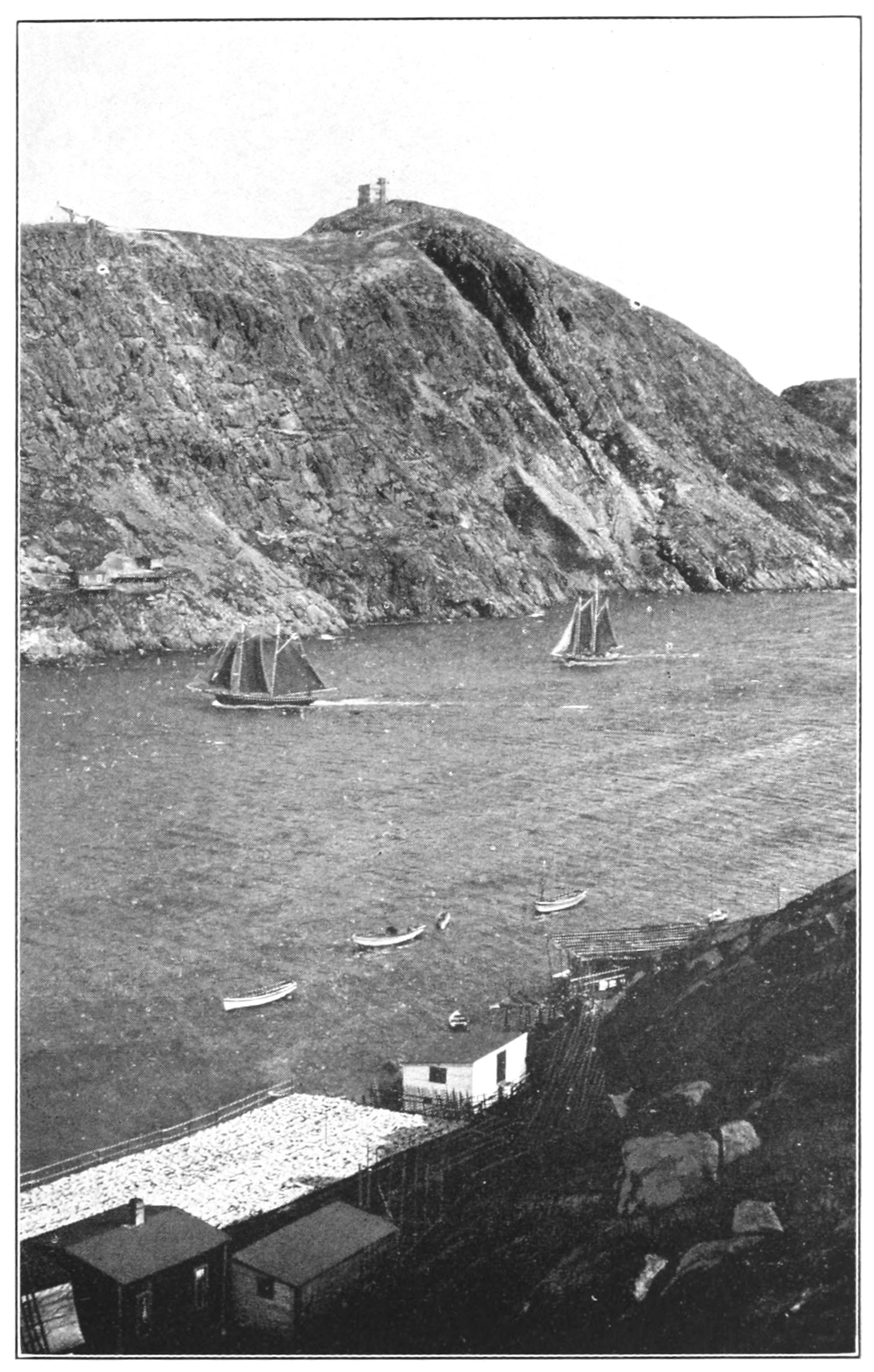

| Signal Hill, Harbour of St. Johns | 150 | |

| Happy Days at the Orphanage St. Anthony | 180 | |

Grenfell and Labrador are names that must go down in history together. Of the man and of his sea-beaten, wind-swept “parish” it will be said, as Kipling wrote of Cecil Rhodes:

“Living he was the land, and dead

His soul shall be her soul.”

Some folk may try to tell us that Wilfred Thomason Grenfell, C.M.G., gets more credit than is due him: but while they cavil and insinuate the Recording Angel smiles and writes down more golden deeds for this descendant of an Elizabethan sea-dog. Sir Richard Grenville, of the Revenge, as Tennyson tells us—stood off sixty-three ships of Spain’s Armada, and was mortally wounded in the fight, crying out as he fell upon the deck: “I have only done my duty, as a man is bound to do.” That tradition of heroic devotion to duty, and of service to mankind, is ineradicable from the Grenfell blood.

“We’ve had a hideous winter,” the Doctor said, as I clasped hands with him in June at the office of the Grenfell Association in New York. His hair was whiter and his bronzed face more serious than when I last had seen him; but the unforgettable look in his eyes of resolution and of self-command was there as of old, intensified by the added years of warfare with belligerent nature and sometimes recalcitrant mankind. For a few moments when he talks sentence may link itself to sentence very gravely, but nobody ever knew the Doctor to go long without that keen, bright flash of a smile, provoked by a ready and a constant sense of fun, that illumines his face like a pulsation of the Northern Lights, and—unless you are hard as steel at heart—must make you love him, and do what he wants you to do.

The Doctor on this occasion was a month late for his appointment with the board of directors of the Grenfell Association. His little steamer, the Strathcona, had been frozen in off his base of operations and inspirations at St. Anthony. So he started afoot for Conch to catch a launch that would take him to the railroad. He was three days covering a distance which in summer would have required but a few hours, in the direction of White Bay on the East Coast. He slept on the beach in wet clothes. Then he was caught on pans of ice and fired guns to attract the notice of any chance vessel. Once more ashore, he vainly started five times more from St. Anthony harbour. Finally he went north and walked along the coast, cutting across when he could, eighty miles to Flower’s Cove. In the meantime the Strathcona, with Mrs. Grenfell aboard, was imprisoned in the ice on the way to Seal Harbour; and it was three weeks before Mrs. Grenfell, with the aid of two motor-boats, reached the railroad by way of Shoe Cove.

At Flower’s Cove the Doctor rapped at the door of Parson Richards. That good man fairly broke into an alleluia to behold him. With beaming face he started to prepare his hero a cup of tea. But there came a cry at the door: “Abe Gould has shot himself in the leg!”

Out into the cold and the dark again the Doctor stumbled. He put his hand into the leg and took out the bone and the infected parts with such instruments as he had. Then he sat up all night, feeding his patient sleeping potions of opium. With the day came the mail-boat for the south, the Ethie, beaten back from two desperate attempts to penetrate the ice of the Strait to Labrador.

Two months later I rejoined the Doctor at Croucher’s wharf, at Battle Harbour, Labrador.

The little Strathcona, snuggling against the piles, was redolent of whalemeat for the dogs, her decks piled high with spruce and fir, white birch and juniper, for her insatiable fires. (Coal was then $24 a ton.)

“Where’ve you been all this time?” the Doctor cried, as I flung my belongings to his deck from the Ethie’s mail-boat, and he held out both hands with his radiant smile of greeting. “I’m just about to make the rounds of the hospital. This is a busy day. We pull out for St. Anthony tonight!” With that he took me straight to the bedside of his patients in the little Battle Harbour hospital that wears across its battered face the legend: “Inasmuch as ye did it unto one of the least of these my brethren ye did it unto me.”

The first man was recovering from typhoid, and the Doctor, with a smile, was satisfied with his convalescence.

The next man complained of a pain in the abdomen. Dr. Grenfell inquired about the intensity of the pain, the temperature, the appetite and the sleep of the patient.

“He has two of the four cardinal symptoms,” said the Doctor, “pain and temperature. Probably it’s an appendical attack. We had a boy who—like this man—looked all right outwardly, and yet was found to have a bad appendix.”

The Doctor has a way of thinking aloud as he goes along, and taking others into his confidence—frequently by an interrogation which is flattering in the way in which he imputes superior knowledge to the one of whom the question is asked. It is a liberal education in the healing craft to go about with him, for he is never secretive or mysterious—he is frankly human instead of oracular.

“How about your schooner?” was his next question. “Do you think that they can get along without you?”

He never forgets that these are fishermen, whose livelihood depends on getting every hour they can with their cod-traps, and the stages and the flakes where the fish is salted and spread to dry.

The third patient was a whaler. He had caught his hand in a winch. The bones of the second and third fingers of the right hand were cracked, and the tips of those fingers had been cut off. The hand lay in a hot bath.

“Dirty work, whaling,” was the Doctor’s comment, as he examined the wound. “Everything is rotten meat and a wound easily becomes infected.”

Number four was a baffling case of multiple gangrene. This Bonne Bay fisherman had a nose and an ear that looked as if they had turned to black rubber. His toes were sloughing off. The back of his right hand was like raw beef. His left leg was bent at an angle of 90 degrees, and as it could not bear the pressure of the bedclothes a scaffolding had been built over it. The teeth were gone, and when the dressings were removed even the plucking of the small hairs on the leg gave the patient agony.

“What have you been eating?”

“Potatoes, sir.”

“What else?”

“Turnips, sir.”

“You need green food. Fresh vegetable salts.”

The Doctor looked out of the window and saw a dandelion in the rank green grass. “That’s what he ought to have,” was his comment.

On the verandah were four out-of-door patients to whom fresh air was essential. One had a tubercular spine. A roll of plaster had been coming by freight all summer long and was impatiently awaited. But a delay of months on the Labrador is nothing unusual. Dr. Daly, of Harvard, presented the Strathcona with a searchlight, and it was two years on the way—most of that time stored in a warehouse at North Sydney.

Around these fresh-air cases the verandah was netted with rabbit-wire. That was to keep the dogs from breaking in and possibly eating the patients, who are in mortal terror of the dogs.

When the Doctor took a probe from the hand of a trusted assistant he was careful to ask if it was sterile ere he used it. He constantly took his juniors—in this instance, Johns Hopkins doctors—into consultation. “What do you think?” was his frequent query.

The use of unhallowed patent medicines gave him distress. “O the stuff the people put into themselves!” he exclaimed.

“Have we got a Dakin solution?” he asked presently.

“We’ve been trying to get a chloramine solution all summer,” answered one of the young physicians.

The Doctor made a careful examination of the man with the tubercular spine, who was encased in plaster from the waist up. “After all,” was his comment as he rose to his feet, “doctors don’t do anything but keep things clean.”

In the women’s ward the Harris Cot, the Torquay Cot, the Northfield Cot, the Victoria Cot, the Kingman Cot, the Exeter Cot were filled with patient souls whose faces shone as the Doctor passed. “More fresh air!” he ejaculated, and other windows were opened. Those who came from homes hermetically sealed have not always understood the Doctor’s passion for ozone. One man complained that the wind got in his teeth and a girl said that the singing on Sundays strained her stomach.

He had a remarkable memory for the history of each case. “The day after you left her heart started into fibrillation,” said an assistant. “It was there before we left,” answered the Doctor quietly.

At one bedside where an operation of a novel nature had been performed he remarked, “I simply hate leaving an opening when I don’t know how to close it.”

He never pretends to know it all: he never sits down with folded hands in the face of a difficulty or “passes the buck” to another. In his running commentary while he looks the patient over he confesses his perplexities. Yet all that he says confirms rather than shakes the patient’s confidence in him. Those whom he serves almost believe that he can all but raise the dead.

“Now this rash,” he said, “might mean the New World smallpox—but probably it doesn’t. We’ve only had two deaths from that malady on the coast. It ran synchronously with the ‘flu.’ In one household where there were three children and a man, one child and the man got it and two children escaped it.

“This woman’s ulcers are the sequel to smallpox. She needs the vegetable salts of a fresh diet. How to get green things for her is the problem. And this patient has tubercular caries of the hip. The X-ray apparatus is across the Straits at St. Anthony, sixty miles away. If we only had a portable X-ray apparatus of the kind they used in the war! Now you see, no matter what the weather, this woman must be taken across the Straits because we are entirely without the proper appliances here.”

Screens were put around the cots as the examination was made, so that the others wouldn’t be harrowed by the sight of blood or pain.

The sick seemed to find comfort merely in being able to describe their symptoms to a wise, good man. Much of the trouble seemed actually to evaporate as they talked to him. Miss Dohme and the other nurses kept the rooms spotlessly clean, and gay bowls of buttercups were about.

“I don’t feel nice, Doctor,” said the next woman. “Some mornings a kind of dead, dreary feeling seems to come out of me stummick and go right down me laigs. Sometimes it flutters; sometimes it lies down. The wind’s wonderful strong today, and it’s rising.”

Usually the diagnosis is not greatly helped by the patient, who meekly answers the questions with “Yes, Doctor,” or “No, Doctor,” or describes the symptoms with such poetic vagueness that a great deal is left to the imagination. It takes patient cross-questioning—in which the Doctor is an adept—to elicit the truth.

Here is a dear little baby, warmly muffled, on the piazza with the elixir of the sun and the pine air. The pustular eczema has been treated with ammoniate of mercury—but what will happen when the infant goes home to the old malnutrition and want of sanitation? If only the Doctor could follow the case!

Bathtubs are a mystery to some of the patients, who after they have been undressed and led to the water’s edge ask plaintively, “What do you want me to do now?”

So many times in this little hospital one was smitten by the need of green vegetables which in so many places are not to be had—“greens” (like spinach), lettuce, radishes and the rest.

As we came away the Doctor spoke of the feeling that he used to have that wherever a battle for the right was on anywhere he must take part in it. “But I have learned that they also serve who simply do their duty in their places. These dogs hereabouts seem to think they must go to every fight there is, near or far. But none of us is called upon to do all there is to do. I often read of happenings in distant parts of the earth and feel as though I ought to be there in the thick of things. Then I realize that if we all minded our own business exactly where we are we’d be doing well. And when such thoughts come to me I just make up my mind to be contented and to buckle down to my job all the harder.”

That evening Dr. Grenfell spoke in the little Church of England, taking as his text the words from the twelfth chapter of John: “The spirit that is ruling in this world shall be driven out.” Across the tickle the huskies howled at the moon, and one after another took up the challenge from either bank. But one was no longer conscious of the wailful creatures, and heard only the speaker; and the kerosene lamps lighted one by one in the gloom of the church became blurred stars, and the woman sitting behind me in a loud whisper said, “Yes! yes!” as Dr. Grenfell, in the earnest and true words of a man who speaks for the truth’s sake and not for self’s sake, interpreted the Scriptures that he has studied with such devotion.

“When I was young,” he said, “I learned that man is descended from a monkey, and I was told that there is no God.

“When I became older and did my own thinking I refused to believe that God chose one race of mankind and left the rest to be damned.

“No one has the whole truth, whether he be Church of England, Methodist or Roman Catholic.

“The simple truth of Christianity is what the world needs. How foolish seem the tinsel and trumpery distinctions for which men struggle! What is the use of being able to string the alphabet along after your name? Character is all that counts.

“Some say that religion is for the saving of your soul. But it is not a grab for the prizes of this world, and the capital prize of the life eternal.

“The things the world holds to be large, Christ tells us, are small. Jesus says the greatest things are truth and love.

“Love is so big a thing that it forgets self utterly.

“How many of us know what it is to love? It is not mere animal desire.

“If we all truly loved, what a world it would be!

“Suppose a doctor loved all his patients. He wouldn’t be satisfied then to say: ‘Your leg is better,’ or ‘Here is a pill.’

“Suppose a clergyman loved his people. He wouldn’t say: ‘I wonder how many in this congregation are Church of England.’

“God Himself is love and truth. Jesus lived the beautiful things He taught. He was them.

“Every man has something in him that forces him to love what is unselfish and true and altogether lovely and of good report.

“In the war, in the midst of all the horror and the terror and the pity of it, a noble spirit was made manifest among men—a heroic spirit of self-control and a sense of true values.

“If I couldn’t have a palace I could have a clean house; if I couldn’t speak foreign languages I needn’t speak foul language. We may be poor fishermen or poor London doctors: we can serve in our places, and we can let our lives shine before men. If I have done my duty where I am, I don’t care about the rest. I shall not care if they leave my old body on the Labrador coast or at the bottom of the Atlantic for the fishes, if I have fought the good fight and finished the course. Having lived well, I shall die contented.”

As soon as the service in the church was over a meeting was held in the upper room of the hospital. The room was filled, and Dr. Grenfell spoke again. Before his address familiar hymns were sung, and—noting that two of those present had violins and were accompanying the cabinet organ—he referred to their efforts in his opening words.

“We all have the great duty and privilege of common human friendliness,” he said. “We may show it in the little things of every day. For everybody needs help, everywhere. There is no end to the need of human sympathy. It may be shown with a fiddle—or perhaps I ought to say ‘violin’ (apologizing to a Harvard student who was officiating).

“I have always loved Kim in Kipling’s story of that name. Kim is just a waif. Nobody knows who his father is; but he is called ‘the little friend of all the world.’

“There is a book which has found wide acceptance called ‘Mrs. Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch.’ Mrs. Wiggs lived in a humble cottage with only her cabbage patch, but everybody came to her for sunshine and healing. She had plenty of troubles of her own, but just because she had them she knew how to help others. Whoever we are, whatever we are, we may wear the shining armour of the knights of God: there is work waiting for our hands to do, there is good cheer for us to spread.”

Dreamer and doer live side by side in amity in Dr. Grenfell’s make-up. At the animated dinner-table of the nurses and the doctors in the Battle Harbour hospital, after asking a blessing, he was talking eagerly about the League of Nations, the industrial situation in England and America and the future for Russia while brandishing the knife above the meat pie and letting no plate but his own go neglected.

Dr. Grenfell is happy and his soul is free at the wheel of the Strathcona. That wheel bears the words, “Jesus saith, Follow me and I will make you fishers of men.” At the peak of the mainmast is likely to be the blue pennant bearing the words, “God is Love.” The Strathcona is ketch-rigged. Her mainmast, that is to say, is in the foremast’s place; and above the mainsail is a new oblong topsail that is the Doctor’s dear delight. The other sail has above it a topsail of orthodox pattern, and there are two jibs. So that when she has her full fuel-saving complement of canvas spread, the Strathcona displays six sails at work. Could the Doctor always have his way, all the sails would be up whenever a breeze stirs. With a good wind the ship is capable of eight knots and even more an hour: five knots or so is her average speed under steam alone. In the bow, his paws on the rail, or out on the bowsprit sniffing the air and seeing things that only he can see, is the incomparable dog Fritz—Fritz of “57 varieties”—brown and black, like toast that was burned in the making. No one knows the prevailing ancestry of Fritz, but a strain of Newfoundland is suspected. He will take a chance on swimming ashore if we cast anchor within half a mile of it, though the water is near congealment, and he knows that a pack of his wolfish brethren is ready to dispute the shoreline with him when he clambers out dripping upon the stony beach with seaweed in his hair. When he swims back to the ship again his seal-like head is barely above the waves as he paddles about, a mute appeal in his brown eyes for a bight of rope to be hitched about his body to help him aboard.

Dr. Grenfell keeps unholy hours, and dawn is one of his favourite out-door sports. He may nominally have retired at twelve—which is likely to mean that he began to read a book at that hour. He may have risen at two, three and four to see how the wind lay and the sea behaved: and perhaps five o’clock will find him at the wheel, bareheaded, the wind ruffling the silver locks above his ruddy countenance, his grey-brown eyes—which are like the stone labradorite in the varying aspects they take on—watching the horizon, the swaying bowsprit, the compass, and the goodness of God in the heavens.

The Doctor is a great out-of-doors man. He scorns a hat, and in his own element abjures it utterly. He wears a brown sweater, high in the neck, and above it he smokes a briarwood pipe that is usually right side up but appears to give him just as much satisfaction when the bowl is inverted. The rest of his costume is a symphony of grey or brown, patched or threadbare but neat always, ending in boots high or low of red rubber or of leather.

You may think that the dog Fritz out on the bowsprit is enjoying all the morning there is, but the Doctor is transformed.

“I love these early mornings,” he says—and he is innocent of pose when he says it: it is not a mere literary emotion. “It’s a beautiful sight in autumn with the ice when the banks are red with the little hills clear-cut against the sky and the sea a deep, deep blue. Isn’t it a beautiful world to live in? Isn’t it fun to live?”

You have to admit that it is.

“A man can’t think just of stomachs all the time. Sometimes I have to go away for a day or two. But I can’t say when I’ve ever been tired.

“A great little ship she is. She is very human to me. She has done her bit—she has carried her load. On that small deck and down below we once took 56 Finns from the wreck of the Viking off Hamilton Inlet. We had nothing but biscuit and dry caplin on which to feed them. Once we were caught in a storm with seven schooners. We had 60 fathoms out on two chains for our anchors. Six of the other seven ships went ashore. Then the seventh overturned—ours was the only ship that stood. All of a sudden our main steampipe burst. We had to use cold sea-water. It was a hard struggle to bring our ship into shallow water at 1½ fathoms. Another time we had to tow 19 small boats at once.

“We always have something up our sleeve to get out of trouble.”

Then suddenly spying other vessels with their sails up, Dr. Grenfell proceeds to study them for a lesson as to the way his own ship is to take. He calls out to Albert Ash, his pessimistic mate, “She’s well-ballasted, that two-master. Have those others tacked?” His talk runs on easily as he swings the ship about and the sails are bellying with a favouring breeze. “This wind’ll run out three knots. I’m cheating it up into the wind. We’ll let her go by a bit. This is Chimney Tickle in here. A beautiful harbour. The tide and the polar current meet here. It’s always open water. It’s the place they’re thinking of for a transatlantic harbour. It’s only 1,625 miles from here to Galway. The jib and mainsail aren’t doing the work. That man has no idea of trimming a jib!” He rushes out to the wheelhouse and does most of the work of setting the mainsail himself.

“I’m so fond of those words ‘The sea is His,’ ” he says, coming back to the spokes again. “I think it runs in the blood. I like to think of the old sea-dogs—like Frobisher and Drake and Cabot. Shackleton told Mrs. Grenfell that the first ship that came to Labrador was named the Grenfell.”

“The comings and goings of the Strathcona mean much to these people,” said Dr. McConnell. “At Independence a woman met us on the wharf, the great tears rolling down her cheeks. She lost her husband and her son in the ‘flu’ epidemic. She told me that her son said to her: ‘Mother, if Dr. Grenfell were only here, he could save me.’ At Snack Cove the people went out on the rocks and cried bitterly when the Strathcona passed them by—as we learned when to their great relief we dropped in upon them a fortnight later.”

We cast anchor at Pleasure Harbour because of rough weather and for a few hours had one of the Doctor’s all too infrequent play-times, while waiting for the Strait to abate its fury to permit of a possible crossing.

Here a delicious trout stream tumbled and swirled from sullen, mist-hung uplands into a piratical cove where two small schooners swung at anchor. Like so many of these places the cove was a complete surprise—you came round the rock with no hint that it was there till you found it, placid as a tarn and deep and black, with big blue hills stretching to the northward beyond the fuzzy fringes of the nearer trees and the mottled barrens where the clouds were poised and the ghosts of the mist descended. (A tuneful, sailor-like name it is that the Eskimoes give to a ghost—the “Yo-ho”: and they say that the Northern Lights are the spirits of the dead at play).

An unhandy person with a rod, I was allowed by Dr. Grenfell and Dr. McConnell to go ahead and spoil the nicest trout-pools with my fly. Even though cod fishermen at the mouth of the stream had unlawfully placed a net to keep the trout from ascending, there were plenty of trout in the brook, and in the course of several hours forty-nine were good enough to attach themselves to my line. The banks were soggy under the long green grass: the water was acutely cold: and in two places there were small fields of everlasting snow in angles of the rock. It was an ideal trout-brook, for it was full of swirling black eddies, rippling rapids, and deep, still pools. The brook began at a lake which was roughened by a wind blowing steadily toward us. Dr. Grenfell cast against the wind where the lake discharged its contents into the brook, and the line was swept back to his boots. With unwearying patience he cast again and again, and while I strove in vain to land a single fish from the lake he caught one monster after another, almost at his own feet. All the way up the brook he had successfully fished in the most unpromising places, that we had given over with little effort, and here he was again getting by far the best results in the most difficult places of all. There seemed to be a parallel here with his medical and spiritual enterprise on the Labrador. He has worked for poor and humble people, when others have asked impatiently: “Why do you throw away your life upon a handful of fishermen round about a bleak and uncomfortable island where people have no business to live anyway?” He could not leave the fishermen’s stage at the mouth of the brook this time without being called upon to examine a fisherman troubled by failing eyesight. On the run of a couple of hundred yards in a rowboat to the Strathcona the thunder-clouds rolled up, with lightning, and as we set foot on board the deluge came.

FRITZ AND HIS MASTER.

“DOCTOR.”

Next evening found us at St. Anthony. Doctors and nurses were on the wharf to greet their chief after his absence of several weeks. Dr. Curtis showed the stranger through the clean and well-appointed hospital, with its piazza for a sun-bath and the bonny air for the T. B. patients, its X-ray apparatus and its operating room, its small museum of souvenirs of remarkable operations. I saw Dr. Andrews of San Francisco perform with singular deftness an operation for congenital cataract, with a docile little girl who had been blind a long time, and whose sight would probably be completely restored by the two thrusts made with a needle at the sides of the cornea. Her eyes were bandaged and she was carried away by the nurse, broadly smiling, to await the outcome. For ten years or so this noted oculist, no longer young except in the spirit, has crossed the continent to spend the summer in volunteer service at St. Anthony—a fair type of the men that are naturally drawn to the work in which the Doctor found his life.

One of the St. Anthony doctors visiting out-patients came upon a woman who was carefully wrapped in paper. This explanation was offered: “If us didn’t use he, the bugs would lodge their paws in we.” “Bugs” are flies, and the use of “he” for “it” is characteristic. A skipper will talk about a lighthouse as he, just as he feminizes a ship, and the nominative case serves also as the objective.

Another woman had been wrapped by her neighbours in burnt butter and oakum. “Now give her a bath,” was Dr. Grenfell’s advice after he had made his examination. “You can if you like, Doctor,” the volunteer nurse said. “If you do it and she dies we shan’t be blamed.”

In the hospital the Doctor was concerned with a baby twelve months old whose feet were twisted over till they were almost upside down. The mother had massaged the feet with oil for hours at a time. The baby cried constantly with pain, and neither the child nor the mother had known a satisfactory night’s rest since it was born. When the Doctor said the condition was curable, because she had brought her child in time, the look of relief in the mother’s face defied recording. It is a look often seen with his patients, and since he scarcely ever asks or receives a fee worth mentioning, it constitutes a large part of his reward.

The herd of reindeer that the Doctor imported from Lapland and installed between St. Anthony and Flower’s Cove with two Lapp herders are now flourishing under Canadian auspices in (Canadian) Labrador in the vicinity of the St. Augustine River. The Doctor himself took a hand in the difficult job of lassoing them and tying their feet, and still there were about forty of the animals that could not be found. The Doctor says it was “lots of fun” catching them—but he gives that description to many transactions that most of us would consider the hardest kind of hard work.

Next in importance after the hospital, Exhibit A is the spick-and-span orphanage, with thirty-five of the neatest and sweetest children, polite and friendly and more than willing to learn. The boys who are not named Peter, James or John are named Wilfred. “Suffer little children to come unto me” is in big letters on the front of the building. On the hospital is the inscription: “Faith, hope and love abide, but the greatest of these is love.” Over the Industrial School stands written, “Whatsoever ye do, do it heartily, as unto the Lord.” Here the beautiful rugs are made—hooked through canvas—according to lively designs of Eskimoes and seals and polar bears prepared in the main by the Doctor. Even the bird-house has its legend: “Praise the Lord, ye birds of wing.” There is a thriving co-operative store, next door to the well-kept little inn. A sign of the Doctor’s devising and painting swings in front of the store. On one side is a picture of huskies with a komatik (sled) bringing boxes to a settler’s door, and the inscription is, “Spot cash is always the leader.” On the other side of the sign a ship named Spot Cash is seen bravely ploughing through mountainous waves and towering bergs. Underneath it reads: “There’s no sinking her.” “That is a reminiscence,” smiled the Doctor, “of my fights with the traders. Do you think these signs of mine are cant? I don’t mean them that way. I want every one of them to count.”

A school, a laundry, a machine-shop and a big store are other features of the plant at St. Anthony. The dock is a double-decker, and from it a diminutive tramway with a hand-car sends “feeders” to the various buildings and even up the walk to the Doctor’s house. All the mail-boats now turn in at this harbour. The captain of a ship like the Prospero—which in the summer of 1919 brought on four successive trips 70, 70, 60 and 50 patients to overflow the hospital—appreciates the facilities offered by this modern wharfage.

As the Doctor goes about St. Anthony he does not fail to note anything that is new, or to bestow on any worthy achievement a word of praise, for which men and women work the harder.

To “The Master of the Inn” he expressed his satisfaction in the smooth-running, cleanly hostelry. “He is one of my boys,” he remarked to me after the conversation. “He was trained here at St. Anthony, and then at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn.”

Then he meets the electrician. “Did you get your ammeter?” he asks. And then: “How did you make your rheostat?”

He points with satisfaction to a little Jersey bull recently acquired, and then he critically surveys the woodland paths that lead from his dooryard to a tea-house on the hill commanding the wide vista of the harbour and the buildings of the industrial colony. “Nothing of this when we came here,” he observes. “The people seem possessed to cut down all their trees: we do our best to save ours, and we dote on these winding walks, which are an innovation.” Then he laughs. “A good woman heard me say that lambs were unknown in Labrador, and that we had to speak of seals instead when we were reading the Scriptures. She sent me a lamb and some birds, stuffed, so that the people might understand. She meant well, but in transit the lamb’s head got sadly twisted on one side, and the birds were decrepit specimens indeed with their bedraggled plumage.”

The house itself is delightful, and it is only too bad that the Doctor and his wife see so little of it.

It is a house with a distinct atmosphere. The soul of it is the living-room with a wide window at the end that opens out upon a prospect of the wild wooded hillside, with an ivy-vine growing across the middle, so that it seems as if there were no glass and one could step right out into the clear, pure air. There is a big, hearty fireplace; there is a generously receptive sofa; there is an upright Steinway piano, where a blind piano-tuner was working at the time of my visit.

Lupins, the purple monk’s hood and the pink fireweed grow along the paths and about the house. A glass-enclosed porch surrounds it on three sides, and in the porch are antlered heads of reindeer and caribou, coloured views of scenery in the British Isles and elsewhere, snowshoes and hunting and fishing paraphernalia, a great hanging pot of lobelias, and—noteworthily—a brass tablet bearing this inscription:

To the Memory of

Three Noble Dogs

Moody

Watch

Spy

whose lives were given for

mine on the ice

April 21, 1908

Wilfred Grenfell

St. Anthony

It is the kind of house that eloquently speaks of being lived in.

It is comfortable, but the note of idle luxury or useless ostentation is absent. There is no display for its own sake. The books bear signs of being fireside companions. Dr. Grenfell is fond of running a pencil down the margin as he reads. He is very fond of the books of his intimate friend Sir Frederick Treves, in whose London hospital he was house-surgeon. “The Land that is Desolate” was aboard the Strathcona. Millais’ book on Newfoundland was on the writing desk at St. Anthony, and had been much scored, as, indeed, had many of his other books.

I asked him to name to me his favourite books. Offhand he said: “The Bible first, naturally. And I’m very fond of George Borrow’s ‘The Bible in Spain.’ I admire Borrow’s persistence until he sold a Testament in Finisterre. ‘L’Avengro’ and ‘Romany Rye’ are splendid, too. I’m very fond of Kipling’s ‘Kim.’ Then I greatly care for the lives of men of action. Autobiography is my favourite form of reading. The ‘Life of Chinese Gordon’—the ‘Life of Lord Lawrence’—the ‘Life of Havelock.’ You see there is a strong strain of the Anglo-Indian in my make-up. My family have been much concerned with colonial administration in India. The story of Outram I delight in. He was everything that is unselfish and active—and a first-class sportsman. Boswell’s ‘Johnson’ is a great favourite of mine. I take keen pleasure in Froude’s ‘Seamen of the 16th Century.’ In the lighter vein I read every one of W. W. Jacob’s stories. Mark Twain is a great man. What hasn’t he added to the world!

“Then there is ‘Anson’s Voyages.’ It’s a capital book. He describes how he lugged off two hundred and ten old Greenwich pensioners to sail his ships, though they frantically fled in every direction to avoid being impressed into the service. All of them died, and he lost all of his ships but the one in which he fought and conquered a Spanish galleon after a most desperate battle.

“I used to have over my desk the words of Chinese Gordon:

‘To love myself last;

To do the will of God,’

and the rest of his creed.

“The only man whose picture is in my Bible is the Rev. Jeremiah Horrox, a farmer’s son. He was the first to observe the transit of Venus. That was in 1640. The picture shows him watching the phenomenon through the telescope. It inspired me to think what a poor lonely clergyman could accomplish. He and men like him stick to their jobs—that’s what I like.

“I have in my Bible the words of Pershing to the American Expeditionary Force in France in 1917—the passage beginning ‘Hardship will be your lot.’ ”

I was privileged to look into that Bible. It is the Twentieth Century New Testament This he likes, he says, because the vernacular is clear, and sheds light on disputed passages which are not clear in other versions.

“I care more for clearness than anything else,” he declared. “When I read to the fishermen I want them to understand every word. But I have often read from this version to sophisticated congregations in the United States and had persons afterwards ask me what it was. Many passages are positively incorrect in the King James Version. For instance, the eighth chapter of Isaiah, which is the first lesson for Christmas morning, is misleading in the Authorized Version.”

We debated the relative merits of the King James Version and the Twentieth Century Version for a long time one evening. I was holding out for the old order, in the feeling that the revised text deliberately sacrificed much of the majestic beauty and poetry of the style of the King James Version and that—despite an occasional archaism—the meaning was clear enough, and the additional accuracy did not justify putting aside the earlier beloved translation. Dr. Grenfell earnestly insisted that the most important thing is to make the meaning of the Scriptures plain to plain people—that the sense is the main consideration, and the truth is more important than a stately cadence of poetic prose.

“I don’t want the language of three hundred years ago,” he asserted. “I want the language of today.”

It is his custom to crowd the margins of his Bibles with annotations. He fills up one copy after another—one of these is in the possession of Mrs. John Markoe of Philadelphia, who prizes it greatly.

By the name of George Borrow and the picture of Jeremiah Horrox on the fly-leaf of the copy he now uses, he has written “My inspirers.”

There is much interleaving and all the inserted pages are crowded with trenchant observations and reflections on the meaning of life.

Adhering to the inner side of the front corner is a poem:

“Is thy cruse of comfort failing?

Rise and share it with another.

. . . . . .

Scanty fare for one will often

Make a royal feast for two.”

There is a clipping from the Outlook, of an article by Lyman Abbott quoting Roosevelt to American troops, June 5, 1917, on the text from Micah, “What more doth the Lord require of thee than to do justly and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God?”

Then there is a quotation from Shakespeare:

“Heaven doth with us, as we with torches do,

Nor light them for ourselves. For if our virtues

Did not go forth of us, ’twere all alike

As if we had them not.”

Pages of meditation are given to dreams—service—conversion—going to the war in 1915 with the Harvard Medical Unit—the place of religion in daily life—the will—the religion of duty.

Another clipping—in large print—bears the words: “Not to love, not to serve, is not to live.”

In the back of the book is pasted an extended description of the death of Edith Cavell.

In one place he writes: “I don’t want a squashy credulity weakening my resolution and condoning incompetency—but just a faith of optimism which is that of youth and makes me do things regardless of the consequences.”

His marginal annotations disclose the profound and the devoted student of the Bible—the man who without the slightest shred of mealy-mouthed sanctimoniousness searches the Scriptures, and lives close to the spirit of the Master. Anyone who sees even a little of Grenfell in action must realize how faithful his life is to the pattern of Christ’s life on earth. There are many passages of Christ’s experience—as when the crowd pressed in upon Him—or when learned men were supercilious—or when He perceived that virtue had gone out of Him—or when He was reproached because He let a man die in His absence—that remind one of Grenfell’s thronged and hustled life. Many believe that Grenfell can all but work a miracle of healing; and the lame, the halt and the blind are brought to him from near and far, at all times of the day or the night, even as they were brought to the Master. In his love of children, in his patience with the doer of good and his righteous wrath aflame against the evil-doer, in his candour and his sunny sweetness and his unfailing courage Grenfell translates the precepts of the Book into the action and the speech of the living way. He cannot live by empty professions of faith; he is happy only when he is putting into vivid practice the creed which guides his living.

It was hard to say where the Doctor’s day began or ended. One night he rose several times to inspect wind and weather ere deciding to make a start; and at twenty minutes before five he was at the wheel himself. Mrs. Grenfell clipped from “Life” and pinned upon his tiny stateroom mirror a picture of a caterpillar showing to a class of worms the early bird eating the worm. The legend beneath it ran: “Now remember, dear children, the lesson for today—the disobedient worm that would persist in getting up too early in the morning.”

His books and articles are usually written between the early hours of five and seven o’clock in the morning. The log of the Strathcona, religiously kept for the information of the International Grenfell Association, was likely to be pencilled on his knee while sitting on a pile of firewood on the reeling deck. Just as Roosevelt wrote his African game-hunting articles “on safari,” while so wearied with the chase that he could hardly keep his eyes open, the Doctor has schooled himself to do his work without considering his pulse-beat or his temperature or his blood pressure. After a driving day afloat and ashore, as surgeon, magistrate, minister and skipper, he rarely retires before midnight, and often he sits up till the wee small hours engrossed in the perusal of a book he likes.

When the Doctor enters a harbour unannounced and drops anchor, within a few minutes power-boats and rowboats are flocking about the Strathcona, and the deck fills with fishermen, their wives and their children, all with their major and minor troubles. Sometimes it requires the whole family to bring a patient. Often after a diagnosis it seems advisable to place a patient in the hospital at Battle Harbour or St. Anthony, and so the “Torquay Cot” or another in the diminutive hospital on the Strathcona is filled, or perhaps the passenger goes to hob-nob with the good-natured crew and consume their victuals. Many a crying baby, in the limited space, makes the narrow quarters below-decks reverberate with the heraldry of the fact that he is teething or has the tummyache.

The Doctor operates at the foot of the companion-ladder leading down into the saloon, which is dining-room, living-room and everything else. “I always have a basin of blood at the foot of the ladder,” he grimly remarks.

I told him I thought I would call what I wrote about him “From Topsails to Tonsils,” since with such versatility he passed from the former to the latter. “That reminds me,” he said with a laugh, “of the time I went ashore with Dr. John Adams, and the first thing we did was to lay three children out on the table and remove their tonsils. That was a mighty bloody job, I can tell you!”

The hatchway over his head as he operates is always filled with the heads of so many spectators—including frequently the Doctor’s dog, Fritz—that the meagre light which comes from above is nearly shut off. Often a lamp is necessary, and as electric flash-lamps are notoriously faithless in a crisis, it is usually a kerosene lamp. Often an impatient patient starts to come down before his time, or an over-eager parent or husband thinks he must accompany the one that he has brought for the doctor’s lancet. It is hard to get elbow-room for the necessary surgery, and every operation is a more or less public clinical demonstration.

Usually the description of the symptoms is of the vaguest.

“I’m chilled to the cinders,” said an anxious Irishman.

“Well, we can put on some fresh coal,” was the Doctor’s answer. “How old are you?”

“Forty-six, Doctor!”

“A mere child!” the doctor replies, and the merry twinkle in his eyes brings an answering smile to the face of the sufferer. The Doctor himself was fifty-five years old in February, 1920.

So many fishermen get what are called “water-whelps” or “water-pups,”—pustules on the forearm due to the abrasion of the skin by more or less infected clothing. Cleaning the cod and cutting up fish produces many ugly cuts and piercings and consequent sores, and there is always plenty of putrefying matter about a fishing-stage to infect them. So that a very common phenomenon is a great swelling on the forearm—and an agonizing, sleep-destroying one it may be—where pus has collected and is throbbing for the lance. It is a joy to witness the immediate relief that comes from the cutting, and as the iodine is applied and deft fingers bandage the wound the patient tries to find words to tell of his thankfulness.

One afternoon just as the Doctor thought there was a lull in the proceedings four women and a man came over the rail at once. The first woman had a “bad stummick”; the second wanted “turble bad” to have her tooth “hauled”; the third had “a sore neck, Miss” (thus addressing Mrs. Grenfell); the fourth woman had something “too turble to tell”; the man merely wanted to see the Doctor on general principles.

Here is a bit of dialogue with a woman who couldn’t sleep.

“What do you do when you don’t sleep?”

“I bide in the bed.”

“Do you do any work?”

“No, sir.”

“Do you cook?”

“No, sir.”

“Do you wash the children?”

“Scattered times, sir.”

Then the husband put in: “She couldn’t do her work and it overcast her. She overtopped her mind, sir.”

He was a fine, dignified old fellow, and it was a real pleasure to see how tender he was toward his poor fidgety, neurasthenic spouse. She hadn’t any teeth worth mentioning, and her lips were pursed together with a vise-like grip. I shall not forget how Doctor Grenfell murmured to me in a humorous aside: “Teeth certainly do add to a lady’s charm!”

When medicine is administered, it is hard to persuade the afflicted one that the prescription means just what it says.

This lady was told to take three pills, and she took two. But most of them exceed their instruction. To a woman at Trap Cove Dr. Fox gave liniment for her knee. It helped her. Then she took it internally for a stomach-ache, arguing logically enough that a pain is a pain, a medicine is a medicine, and if this liniment was good for a hurt in the knee it must be good for any bodily affliction. Luckily she lived to tell the tale.

“When I was in the North Sea the sailors if they got the chance ransacked my medicine cupboard and drank up everything they could lay their hands on.” Such autobiographic confessions are often made while the Doctor mixes a draught or concocts a lotion. “Here it is the same way. I have had my customers drain off the whole bottle of medicine at once, on the theory that if one teaspoonful did you good, a bottle would be that much better.” His questions, like his lancet, go right to the root of the trouble. Nothing phases him. He answers every question. He never tells people they are fools; his inexhaustible forebearance with the inept and the obtuse is not the least Christlike of his attributes.

It is difficult for these men to come to the hospital in summer, for their livelihood depends on their catch, and then on their salting and spreading the fish: and after the cod-fishery has fallen away to zero the herring come in October, and the cod to some extent return with them.

“When I tell them they must go to the hospital, they always say ‘I haven’t time: I want to stay and mind my traps.’ ”

The Doctor hates above all things—as I have indicated—to leave a wound open, or a malady half-treated, and hustle on. It is the great drawback and exasperation in his work that the interval before he sees the patient again must be so long. He mourns whenever he has to pull a tooth that might be saved if he could wait to fill it.

He is always working against time, against the sea, against ignorance, against a want of charity on the part of nominal Christians who ought to help him instead of carping and denouncing.

But he is working with all honest and sincere men, all who are true to the high priesthood of science, all who are on the side of the angels.

One man thus describes his affliction, letting the Doctor draw his own deductions:

“Like a little round ball the pain will start, sir; then it will full me inside; and the only rest I get is to crumple meself down.”

An unhappy woman reciting the history of her complaint declared: “The last doctor said I had an impression of the stomach and was full of glams.”

“Bless God!” exclaimed another, speaking of her children. “There’s nothing the matter with ’em. They be’s off carrying wood. They just coughs and heaves, that’s all.”

One mother, asked what treatment she was administering to her infant replied: “Oh, I give ’er nothing now. Just plenty of cold water and salts and spruce beer; ne’er drop o’ grease.”

When there is no doctor to be had the services of the seventh son of a seventh son are in demand.

BATTLE HARBOUR—SPREADING FISH FOR DRYING.

Elemental human misery made itself heard in the dolorous accents of a corpulent lady of fifty. “I works in punishment on account of my eyes. Sometimes I piles two or three fish on top of each other and I has to do it over. I cries a good deal about it.” Her gratification as she was fitted to a pair of “plus” glasses that greatly improved her sight was worth a long journey to witness. Many pairs of glasses were put on her nose en route to the discovery of the most satisfactory pair, and each time she would say “Lovely! Beautiful!” with crescendo of fervour.

I heard a fond father tell the Doctor that there was a “rale squick (real squeak) bawling on the inside of” his offspring.

A man who climbed down the companion way with an aching side, a rupture, and a hypertrophic growth on his finger, was asked what he did for his ribs.

“I rinsed them,” was the response.

The Doctor is always on the lookout for the “first flag of warning”—as he calls it—of the dreaded “T. B.” which is responsible for one death in every four in Newfoundland. Much of his talk with a patient has to do with fresh air and fresh vegetables. The Eskimoes may know better than some native Newfoundlanders. “I like air. I push my whiphandle through the roof,” said one of the Eskimoes.

Here is a typical excerpt, from a conversation with a young man who to the layman looked very robust.

“How old are you?”

“Twenty-two, sir.”

“Have any in your family had tuberculosis?”

“Father’s brother Will and Aunt Clarissa died of it, sir.”

“Are you suffering?”

“It shoots up all through my stomach, sir.”

“Do you read and write?”

“No, Doctor.”

“See clearly?”

“Yes, Doctor.”

“Are you able to get any greens?”

“Sometimes, sir.”

“Dock-leaves?”

“No, sir.”

“What greens have you?”

“Alexander greens, sir.”

“Any berries?”

“Yes, Doctor. And bake apples.”

“That’s good. You must eat plenty of them. You must have good food. As good as you can afford. I’m sorry it’s so hard where you live to get anything fresh. Do you sleep well?”

“Yes, Doctor.”

“Anybody else sleep in the same bed?”

“No, Doctor.”

“When you go to bed do you keep the windows open?”

“Yes, Doctor.”

“That’s right. That’s very important. Do people spit around you?” (The Doctor is always on the war-path against this disgusting and dangerous habit.)

“No, sir.”

“Quite sure?”

“Well, we use spit-boxes.”

“Do you burn the contents?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Do you wear warm things?”

“Yes, Doctor.”

“Sweat a lot?”

“Yes, Doctor.”

“You mustn’t get wet without changing your clothes. Now, when you eat potatoes I want you to eat them baked, with the skins on. I don’t mean eat the skins. But the part right under the skins is very important.”

“Yes, Doctor.”

As one listens to such catechizing it becomes clear that the Doctor lays great stress on fresh air and fresh food as medicines, “Cold is your friend and heat is your enemy” is his oft-reiterated dictum to consumptives.

Once he said to me, “I attach great importance to the sun-bath. I believe in exposing the naked body to all it can get of the air.” In the nipping cold of the early morning on the Strathcona I emerged from beneath four double blankets to hear the Doctor joyfully cry: “I’ve just had my bucket on deck. You could have had one too, but I lost the bucket overboard.” It has been a pastime of his to row with a boatload of doctors and nurses to an iceberg and go in swimming from the platform at the base of the berg.

Sometimes the Macedonian cry comes by letter.

Here is a pencilled missive from an old woman who evidently got a kindly neighbour to write it for her, for the signature is misspelled:

“Pleas ducker grandlield would you help me with a little clothing I am a wodow 85 yars of age.”

“Grandlield” is not further from the name than a great many have come. Here are some other common variants:

Gumpin

Grinpiel

Greenfield

Gramfull

Gremple

Gransfield

From a village in White Bay, where the fishing was woefully poor in 1919, comes this pathetic plea:

“To Dr. and Mrs. Grenfell: Dear Friends: I am writing to see if you will help me a little.—My husband got about 1 qtl of fish (1 quintal—pronounced kental—of 112 pounds, worth at most $11.20) this summer, and I have four children, 15, 13, 11, 6 years, and his Father, and we are all naked as birds with no ways or means to get anything. What can I do; if you can do anything for me I hope God will bless you. It is pretty hard to look at a house full of naked children.”

Mrs. Grenfell visited White Bay in July and in two villages found a number of people all but utterly destitute. They were living on “loaf” (bread) and tea. They had icefields instead of fish. Six of the breadwinners got a job at St. Anthony. The villagers had few pairs of shoes among them, In several instances the foot-gear was fashioned of the sides of rubber boots tied over the feet with pieces of string. The people of this neighbourhood are folk of the highest character, and richly deserving, though poverty-stricken.

Another characteristic letter:

“Dr. dear sir. please send two roals fielt (rolls of felt) one Roal Ruber Hide (rubberoid) one ten Patent for Paenting Moter Boat some glass for the bearn (barn) thanks veary mutch for the food you sent me. Glad two have James Home and his Leg so well you made a splended Cut of it this time I will all way Pray for you while I Live Potatoes growing well on the Farm Large Enough two Eaght all redey. But I loast my Cabbages Plants wit the Big falls rain and snow i the first of the summer, but I have lotes of turnips Plants I have all the Caplen (a small fish) I wants two Put on the farm this summer.

“dr—dear sir I want some nails to finesh the farm fance I farn.”

In a fisherman’s house in an interval between examinations of children for tonsils and adenoids the Doctor related this incident to a spellbound group. He never has any trouble holding an audience with stories that grow out of his work, and the fishermen delight as he does in his informal chats with them and with their families.

“We had a long hunt for a starving family of which we had been told by the Hudson Bay Company agent, on an island at Hamilton Inlet in Labrador. The father was half Eskimo. He had a single-barrelled shotgun with which he had brought down one gull. With his wife and his five naked children he was living under a sail. The children, though they had nothing on, were blue in the face with eating the blueberries, and they were fat as butter. The mate took two of the little ones, as if they were codfish, one under each arm, and carried them aboard. There were tears in his eyes, for he had seven little ones of his own, and he was very fond of children. Both were carefully brought up at our Childrens’ Home and one of them, who can now both read and write, is aboard at present as a member of the crew of the Strathcona.”

After evening prayers on Sunday, at which the Doctor has spoken, he has treated as many as forty persons.

In one place after removing a man’s tonsils it was a case of eyeglasses to be fitted, then came one who clamoured to have three teeth extracted. The teeth were “hauled” and a bad condition of ankylosis at the roots was revealed. Then a girl had a throat abscess lanced, and she was followed by a boy with a dubious rash and a tubercular inheritance. The Doctor is ever on the lookout for the “New World” smallpox: but the stethoscope detected a pleuritic attack, and strong supporting bandages were wound about the lower part of his chest.

Another group was this:

1. An operation on a child’s tonsils. A local anaesthetic was given—10 per cent. cocaine. A tooth was also removed. The total charge was $1.00.

2. A fisherman came for ointments—zinc oxide and carbolic.

3. An eight months old infant was brought in, blind in the right eye. This condition might have been obviated had boric acid been applied at the time of the baby’s birth. The mother said that only a little warm water had been used.

So many, though they may not say so, appear to believe with Mary when she said to Jesus, “Lord, if thou hadst been here my brother had not died.” They think the Doctor has something like supernatural powers.

With the utmost care he prepared to administer novocaine and treat the wound of a man who had run a splinter into his left hand between the first and second fingers, leaving an unhealed sinus. “Wonderful stuff, this novocaine!” he remarked, as he put on a pair of rubber gloves, washed them in alcohol, and then gave his knives a bath in a soup-plate of alcohol.

“In the inflamed parts none of these local anaesthetics work very well,” was his next comment.

But the patient scarcely felt it when he ran a probe through the hand till it all but protruded through the skin on the inner side.

The bad blood was spooned out, and then the deep cavity swallowed about six inches of iodoform gauze. When the wound had been carefully packed the hand was bandaged. For nearly an hour’s work requiring the exercise of rare skill and the utmost caution the charge was—a dollar. And that included a pair of canvas gloves and another pair of rubber mitts, of the Doctor’s own devising, drawn over the bandages and tied so that the man might continue at his work without getting salt-water or any contaminating substance in the wound and so infecting it badly.

These two importunate telegrams arrived while he was paying a flying visit to headquarters at St. Anthony:

“Do your best to come and operate me I have an abscess under right tonsil will give you coal for your steamer am getting pretty weak.

Capt. J. N. Coté, Long Point.”

A second telegram arriving almost simultaneously from the same man read: “Please come as fast as you can to operate me in the throat and save my life.”

Captain Coté is the keeper of the Greenly Island Lighthouse, near Blanc Sablon. It is a very important station.

The Doctor, true to form, at once made up his mind to go. Greenly Island is about 100 miles from St. Anthony, and on the opposite side of the Straits, on the Canadian side of the line that divides Canadian Labrador from Newfoundland Labrador. The short cut took us through Carpoon (Quirpon) Tickle, and there we spent the night, for much as the Doctor wanted to push ahead the wind made the Strait so rough that—having it against us—the Strathcona could not have made headway. “I remember,” said the Doctor with a smile, “that once we steamed all night in Bonavista Bay, full speed ahead, and in the morning found ourselves exactly where we were the night before. Coal is too scarce now.” On one occasion the Strathcona distinguished herself by going ashore with all sails set.

By the earliest light of morning we were under way. The tendency of a land-lubber at the wheel off this cruel coast was naturally to give the jagged and fearsome spines of rock as wide a berth as possible. In the blue distance might be seen a number of bergs, large and small, just as a reminder of what the ice can do to navigation when it chooses; and in the foreground were fishermen’s skiffs bobbing about and taking their chances of crossing the track of our doughty little steamer. But the Doctor called in at the door of the wheelhouse: “Run her so close to those rocks that you almost skin her!” He was thinking not of his ship, not of himself, but of the necessity of getting to the lonely lighthouse-keeper at the earliest possible moment, to perform that operation for a subtonsillar abscess. There was a picture in his mind of the valiant French Canadian engineer gasping for breath as the orifice dwindled, and now he was burning not the firewood but coal—a semi-precious stone in these waters in this year of grace. The Strathcona labours and staggers; Fritz the dog goes to the bowsprit and sniffs the sun by day and the moon by night; the ship is carrying all the bellying sails she has; and the Doctor mounts to the crow’s-nest to make sure that his beloved new topsail is doing its full share. He tools the Strathcona—when he is at the wheel—as if she were a taxicab. So the long diagonal across the Strait is cut down, seething mile by mile, till between Flower’s Cove and Forteau—where the Strait is at the narrowest, and the shores are nine miles and three-quarters apart—it almost seems as if an hour’s swim on either hand would take one to the eternal crags where the iris blows and the buttercup spreads her cloth of gold.

We drew near Blanc Sablon (pronounced Sablow) with Grant’s Wharf by the river. West of that river for several hundred yards it is no man’s land between the two Labradors—that is to say, between Canada and Newfoundland. A man stood up in a jouncing power-boat and waved an oar, and then—his overcoat buttoned up to his ears—our patient, Captain Coté, stood up beside him. They had come out to meet us to save every moment of precious time. It was a weak and pale and shaky man that came aboard—but he was a man every bit of him, and he did not wince when the Doctor, in the crypt-like gloom of the Strathcona’s saloon, while the tin lamp was held in front of the Captain’s mouth, reached into the throat with his attenuated tongs and scissors and made the necessary incision after giving him several doses of the novocaine solution as a local anaesthetic.

“Then the Captain sat back white and gasping on the settle, and—with a strong Canadian French flavour in his speech—told us a little of his lonely vigil of the summer.

“In eighteen days, Doctor, I never saw a ship for the fog: but I kept the light burning—two thousand gallons of kerosene she took.

“All summer long it was fog—fog—fog. I show you by the book I keep. Ever since the ice went out we have the fog. Five days we have in July when it was clear—but never such a clear day as we have now. Come ashore with me on Greenly Island and you shall have the only motor car ride it would be possible for you to have in Labrador.”

We accepted the invitation. At the head of the wharf were men spreading the fish to dry—grey-white acres of them on the flakes like a field of everlastings. In the lee of a hill they had a few potato-plants, fenced away from the dogs. In a dwelling house with “Please wipe your feet” chalked on the door we found a spotless kitchen and two fresh-cheeked, white-aproned women cooking. It was a fine thing to know that they were upholding so high a standard of cleanliness and sanitation in that lonely outpost—as faithful as the keeper of the light in his storm-defying tower.

From the fish-flakes of the ancient “room” over half a mile of cinderpath and planking we rode on the chassis of a Ford car, which the keeper uses to convey supplies.

“The first joy-ride I ever had in Labrador,” said the Doctor, and the Captain grinned and let out another link to the roaring wind that flattened the grass and threatened to lift his cabbage-plants out of their paddock under his white housewalls.

Safe in his living-room, with wife and children, two violins, a talking-machine, an ancient Underwood typewriter and even a telephone that connected him with the wharf, Captain Coté pulled out his wallet, selected three ten-dollar bills and offered them to the Doctor, saying: “I will pay you as much more as you like.”

Dr. Grenfell took one of the bills, saying, “That will be enough.”

The Captain, mindful of his promise about the coal, said, “How much coal do you want?”

“On the understanding that the Canadian Government supplies it,” answered the Doctor, “I will let you put aboard the Strathcona just the amount we used in coming here—5½ tons.”

The Captain went to the telephone and talked with a man at the wharf. Then he turned away from the transmitter and said: “He tells me that he can’t put the coal on board today, because it would blow away while they were taking it out to the Strathcona on the skiff. We have no sacks to put it in.”

“Very well,” returned the Doctor, “when it’s convenient you might store it at Forteau. They will need it there this winter at Sister Bailey’s nursing station.” Then he dismissed the subject of the fee and the fuel-supply to tell us how pleased he was to find that Mackenzie King, author of “Industry and Humanity,” had become the Liberal leader in Canada. King is a Harvard Doctor of Philosophy, a man of thought and action of the type by nature and training in sympathy with Grenfell’s work. It is a great thing for Canada that a man of his calibre and scholarly distinction has been raised to the place he holds.

From the site of the lighthouse there are observed most singular wide shelves of smooth brown rock presenting their edges to the fury of the surf, and over the broad brown expanse are scattered huge boulders that look as though the Druids who left the memorials at Stonehenge might have put them there. Captain Coté said the winter ice-pack tossed these great stones about as if it were a child’s game with marbles.

A happy man he thought himself to have his children with him. The lighthouse-keeper at Belle Isle lost six of his family on their way to join him; another at Flower’s Cove lost five. As a remorseless graveyard of the deep the region is a rival of the dreaded Sable Island off Newfoundland’s south shore.

A wire rope indicates the pathway of two hundred yards between the light and the foghorn: and in winter the way could not be found without it. The foghorn gave a solo performance for our benefit, at the instigation of either member of a pair of Fairbanks-Morse 15 horse-power gasoline engines. We were ten feet from it, but it can be heard ten miles and more.

A “keeper of the light” like Captain Coté, or Peter Bourque, who tended the Bird Rock beacon for twenty-eight years, is a man after Grenfell’s own heart. For Grenfell himself lets his light shine before men, and knows the need of keeping the flame lambent and bright, through thick and thin.

Dr. Grenfell in his battles with profiteering traders has incurred their enmity, of course—but he has been the people’s friend. The favourite charge of those who fight him is that he is amassing wealth for himself by barter on the side, and collecting big sums in other lands from which he diverts a golden stream for his own uses. The infamous accusation is too pitifully lame and silly to be worth denying. The most unselfish of men, he has sometimes worked his heart out for an ingrate who bit the hand that fed him. His enterprise, whose reach always exceeds his grasp, is money-losing rather than money-making.

The International Grenfell Association has never participated in the trading business. Dr. Grenfell, however, started several stores with his own money and took it out after a time with no interest. He delights in the success of those whose aim is no more than a just profit, who buy from the fisherman at a fair price and sell to him in equity. There is a co-operative store of his original inspiration and engineering at Flower’s Cove, and another is the one at Cape Charles, which in five years returned 100 per cent. on the investment with 5 per cent. interest.

Accusations of graft he is accustomed to face, and a commission appointed by the Newfoundland Legislature investigated him, travelled with him on the Strathcona, and completely exonerated him. Some persons had even gone so far as to accuse him of making money out of the old clothes business aboard what they were pleased to term his “yacht.” They descended to such petty false witness as to swear that he had taken a woman’s dress with $12 in it. It is wearisome to have to dignify such charges by noticing them. They are about on a par with the letter of a bishop who wrote to him: “I should like to know how you can reconcile with your conscience reading a prayer in the morning against heresy and schism, and then preaching at a dissenting meeting-house in the afternoon.”

A vestryman objected to his preaching in the church at a diminutive and forlorn settlement because “he talks about trade.”

The Doctor is never embittered by his traducers. He knows the meaning of J. L. Garvin’s saying, “He who is bitter is beaten.” Nothing beclouds for long his sunny temperament, but his unfailing good-humour never dulls the fighting edge of his courage.

“I bought a boat for a worthy soul, to set him on his feet,” the Doctor told me. “She had been driven ashore in North Labrador. I had to buy everything separately—and the total came to $500. The boat was to work out the payment. This she did—Alas! later on she went ashore on Brehat (‘Braw’) Shoals. Only her lifeboat came ashore, with the name—Pendragon—upon it.”

The Doctor put $1,000 of his money into the co-operative store at Flower’s Cove, and when the enterprise was fairly launched and the Grenfell Association decided to abstain from lending help to trade he drew it out, and asked no interest. That store in its last fiscal year sold goods to the value of more than $200,000, paying fair prices and selling at a fair profit. It had three ships in the summer of 1919 carrying fish abroad—“foreigners.” The proprietor bought for $50 a schooner that went ashore at Forteau, dressed it in a new suit of sails worth $1,250, and now has a craft worth $8,000 to him. Dr. Grenfell has personally great affection for some of the traders—it is the “truck system” he hates. “Trading in the old days,” the Doctor observes, “was like a pond at the top of a hill. It got drained right out. The money was not set in circulation here on the soil of Newfoundland. The traders in two months took away the money that should have been on the coast. 1919 was the first year in which the co-operative stores themselves sent fish to the other side. A vessel from Iceland came here to the Flower’s Cove store; another was a Norwegian; a third came from Cadiz with salt; and today a small vessel is preparing to go across.”

At Red Bay is another store to which Dr. Grenfell loaned money, which he drew out, sans interest, when it was prosperous. It has saved the people there, as every soul in the harbour will testify.

The fishermen on the West Coast in 1919 enjoyed something like affluence as compared with their brethren on the East Coast, where the fish were scarce.

Where there were lobsters, they were getting $35.50 or $35.00 per case of 48 one-pound cans. For cod, $11.20 a quintal of 112 pounds was paid. In 1918 over $15 per quintal was paid.

On the other hand, with pork at $100 a barrel, coal at $24 a ton, and gasoline at 70 cents a gallon, the big prices for fish were matched by an alarming cost of the necessaries of life.

Some fishermen make but $200 a year; a few make as much as $2,000 and even more. The merchant princes as a rule are the store-keepers who deal with the fishermen. There were two big bank failures in St. John’s years ago, and since that time many persons have hidden their money in the ground. One fisherman of whose case I heard had but $35 in cash as the result of his season’s effort, and he had eight to support besides himself. The small amount of ready money on which people can live with a house, a vegetable garden, and a supply of firewood at their backs in the timbered hillsides is unbelievable. If a man was fortunate enough to possess any grassland, he might get as much as $65 a ton for his hay in 1919, if he could spare it from his own cows and sheep. It is too bad that for the sake of the sheep the noble Newfoundland dog that chased them has had to perish. It is almost impossible today to find a pure-breed example of the dog that spread the name of the island to the ends of the earth. Such dogs as there are are remarkably intelligent and make excellent messengers between a man at work and his house.

The “Southerners” go to the Grand Banks for their fishing; the others go to the Labrador. The three classes of fishermen are the shore fishermen, the “bankers,” and the “floaters”—those of the Labrador. Ordinarily the catch is reckoned by quintals (pronounced kentals) of 112 pounds. Those who live on the Labrador coast the winter through are known as the “liveyers”—the live-heres—and those who come regularly to the fishing are “stationers” or “planters.”

During the war big prices have been realized for the fish, and unprecedented prosperity has come to the fishermen. The growth in the number of motor-boats is an index of this condition, though with gasoline at 70 cents a gallon on the Labrador (for the imperial gallon, slightly larger than ours), the question of fuel has been a disturbing one to many. Of late much of the fish has been marketed on favourable terms in the United States and Canada, but before this the preferred markets in order have been Spain and Portugal, Brazil and the West Indies. The three grades recognized, from the best to the lowest, are “merchantable,” “Madeira,” and “West Indies” (“West Injies”), the last-named for the negroes.

An industry of growing importance to the future of the Grenfell mission is the manufacture and sale of “hooked” rugs by the women trained at the industrial school at St. Anthony. Large department stores in the United States have begun to buy these rugs in considerable quantities, and the demand is lively and increasing.