Title: All the World Over: Interesting Stories of Travel, Thrilling Adventure and Home Life

Author: Ella Farman Pratt

Lucia Chase Bell

Frank H. Converse

Louise Stockton

Release date: March 5, 2022 [eBook #67560]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: D. Lothrop Company, 1892

Credits: Alan, Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

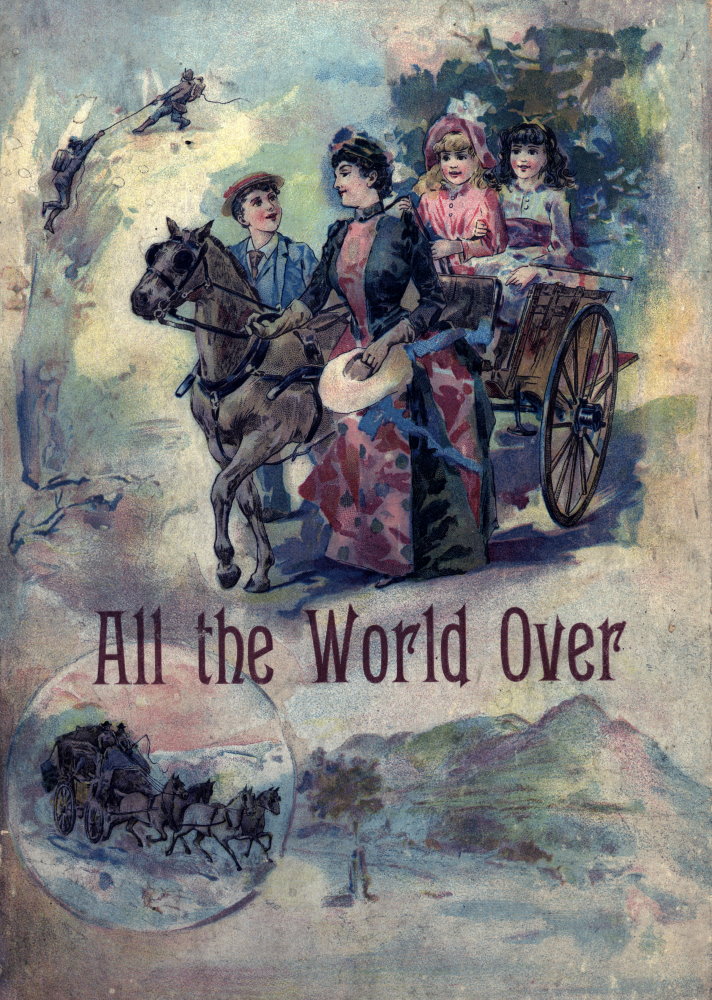

IN THE BULL-CIRCUS, MADRID.

INTERESTING STORIES OF TRAVEL, THRILLING

ADVENTURE AND HOME LIFE

BY

ELLA FARMAN, MRS. LUCIA CHASE BELL, FRANK H. CONVERSE, LOUISE STOCKTON,

AND OTHER POPULAR AUTHORS

ON A WILD GOOSE CHASE

FULLY ILLUSTRATED

BOSTON

D. LOTHROP COMPANY

1893.

Copyright, 1892,

by

D. Lothrop Company.

—————

All rights reserved.

CONTENTS

(Created by transcriber. Not present in original.)

| All the World Over | Unknown |

| Queen Louisa and the Children | Mary Stuart Smith |

| The Plaything of an Empress | M. S. P. |

| Charlie’s Week in Boston | Charles E. Hurd |

| A Wonderful Trio | Jane Howard |

| Two Fortune-seekers | Rossiter Johnson |

| The Little Christmas Pies | E. F. |

| The Strangers from the South | Ella Farman |

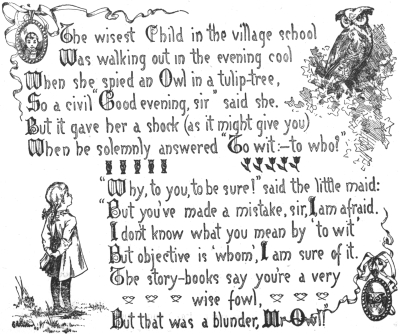

| Wi’ Wee Winkers Blinkin’ | J. E. Rankin, D. D. |

| The Childrens’ Shoes | Blanche B. Baker |

| Ethel’s Experiment | B. E. E. |

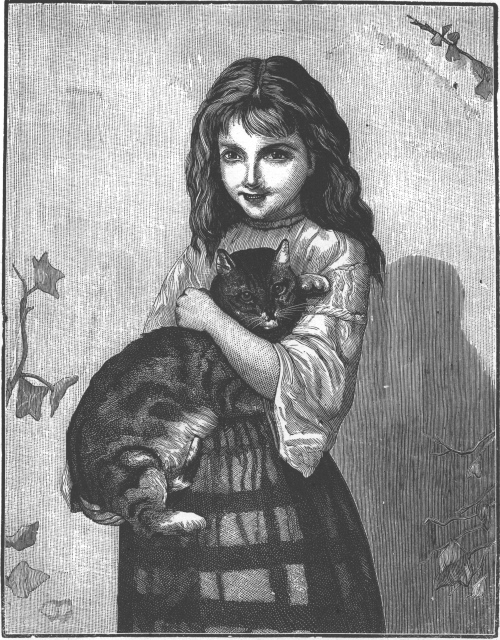

| Cinders | Madge Elliot |

| Tom’s Centennial | Margaret Eytinge |

| Little Chub and the Sky Window | Mary D. Brine |

| Little Boy Blue | C. A. Goodenow |

| Ghosts and Water-melons | J. H. Woodbury |

| Funny Little Alice | Mrs. Fanny Barrow |

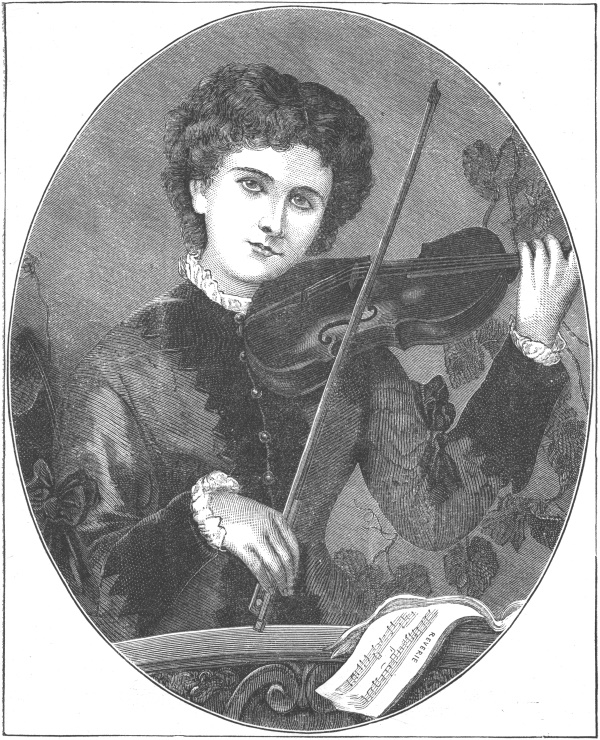

| “Pretty,” and Her Violin | Holme Maxwell |

| Dolly’s Last Night | Emily Huntington Miller |

| Nib and Meg | Ella Farman |

| The Little Parsnip-man | E. F. |

| How Dorr Fought | Salome |

| Tim’s Partner | Amanda M. Douglas |

| Unto Babes | Helen Kendrick Johnson |

| What Happened to the Baby | Magaret Eytinge |

| Mrs. White’s Party | Mrs. H. G. Rowe |

| Queer Church | Rev. S. W. Duffield |

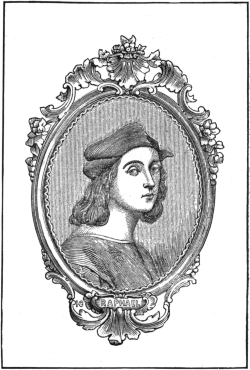

| The Fun-and-frolic Art School | Stanley Wood |

| Some Quaker Boys of 1776 | C. H. Woodman |

| What I Heard on the Street | Clara F. Guernsey |

| Kip’s Minister | Kate W. Hamilton |

| Jim’s Troubles | Grandmere Julie |

| The Christmas Thorn | Louise Stockton |

| Midget’s Baby | Mary D. Brine |

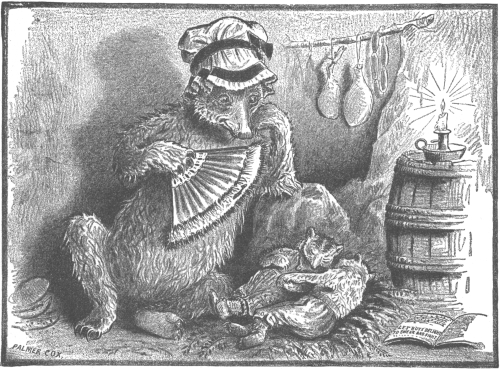

| A Nocturnal Lunch, and Its Consequences | Lily J. Chute |

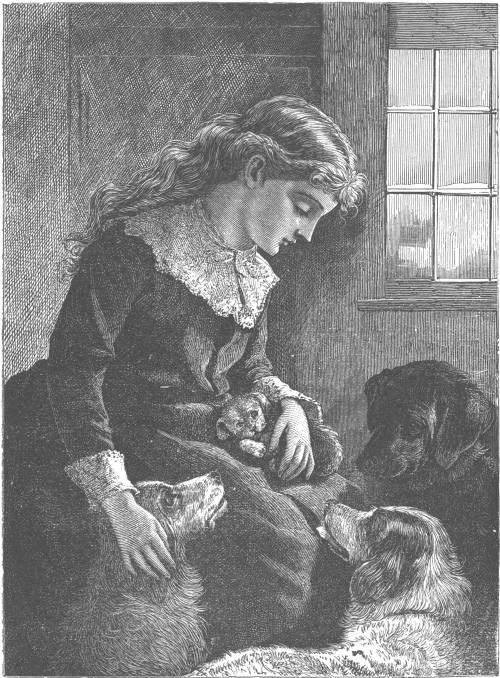

| Lulu’s Pets | Mary Standish Robinson |

| What Janet Did With Her Christmas Present | L. J. L. |

| Christmas Roast Beef | A. W. Lyman |

| Granny Luke’s Courage | M. E. W. S. |

| Billy’s Hound (PI) | Sara E. Chester |

| Billy’s Hound (PII) | Sara E. Chester |

| Pussy Willow and the South Wind | A Poem |

| Little Sister and Her Puppets | Rev. W. W. Newton |

| Spring Fun | A Poem |

| The Lost Dimple | Mary D. Brine |

| The Other Side of the Story | Kate Lawrence |

| Jack Horner | A Poem’s Meaning |

| Double Dinks | Elizabeth Stoddard |

| Learning to Swim | Edgar Fawcett |

| Sweetheart’s Surprise | Mary E. C. Wyeth |

| The Cross-patch | Mrs. Emily Shaw Farman |

| The Proud Bantam | Clara Louise Burnham |

| The True Story of Simple Simon | Harriette R. Shattuck |

| In the Tunnel of Mount Cenis | Mrs. Alfred Macy |

| A Ride on a Centaur | Hamilton W. Mabie |

| Lill’s Travels in Santa Claus Land | Ellis Towne |

| Bob’s “Breaking in” | Eleanor Putnam |

| The First Hunt | J. H. Woodbury |

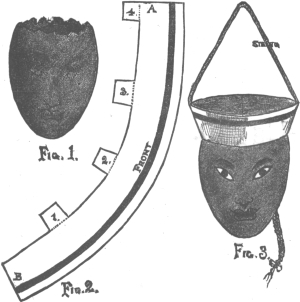

| Chinese Decoration For Easter Eggs | S. K. B. |

| Il Santissimo Bambino | Phebe F. Mᶜkeen |

| My Mother Put It on | Mrs. A. D. T. Whitney |

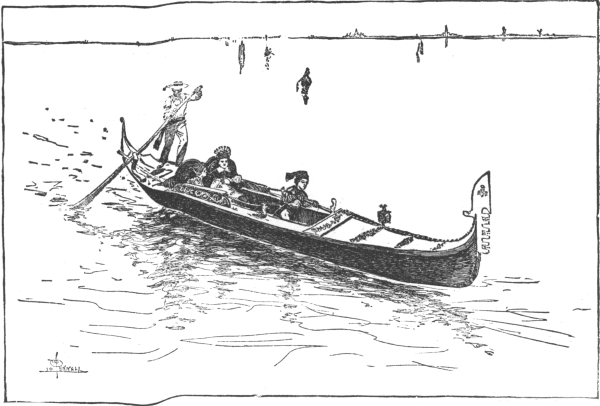

| A Child in Florence (PI) | K. R. L. |

| A Child in Florence (PII) | K. R. L. |

| A Child in Florence (PIII) | K. R. L. |

| Seeing the Pope | Mrs. Alfred Macy |

| Fayette’s Ride | Clara F. Guernsey |

| Fanny | Clara Doty Bates |

| Little Mary’s Secret | Mrs. L. C. Whiton |

| How Patty Curtis Learned to Sweep | Mrs. M. L. Evans |

| A Bird Story | M. E. B. |

| A New Lawn Game | G. B. Bartlett |

| How Philip Sullivan Did an Errand | Mary Densel |

| Winter With the Poets | The Editor |

| Bessie’s Story | Frank H. Converse |

| Difference of Opinion | The Editor |

| The Grass, the Brook, and the Dandelions | Margaret Eytinge |

| The Birds’ Harvest | Mrs. J. D. Chaplin |

| Birds’-nest Soup | Ella Rodman Church |

| The Story of Two Forgotten Kisses | Kitty Clover |

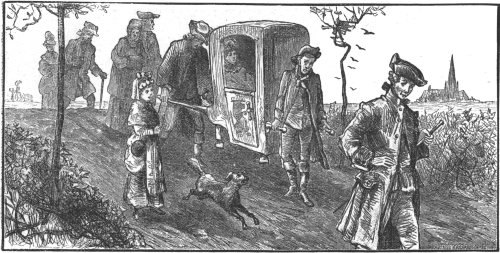

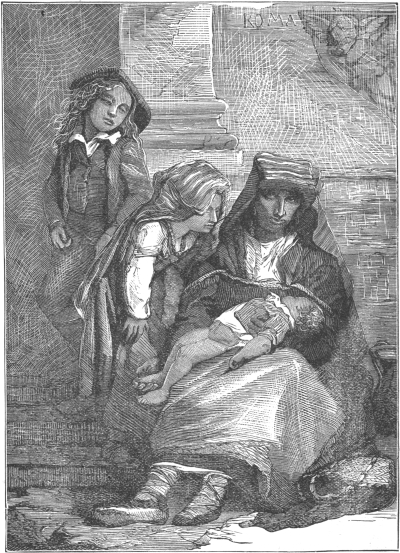

PERHAPS one of the most vivid impressions which the tourist receives upon his entrance into any Spanish city whatsoever, is of its muscular beggars—men of enormous size, with their ruffianly swaggering strength exaggerated by the national cloak. This garment is of heavy, tufted woollens, long and fringed, almost indestructable, and is frequently worn to muffle half the face; and the broad slouch hat, usually with a couple of rough feathers stuck in its band, does not tend to soften the general brigandish effect.

These beggars are licensed by the government, which must reap a goodly revenue from the disgraceful crowd, as they are numerous, and therefore they pursue their avocation in the most open manner. They will frequently follow the traveller a half-mile, especially should they find him to be ignorant of that magic formula of dismissal which is known to all Spaniards:

Pardon, for God’s sake, Brother!

This appeal is constantly on the lip of every Spanish lady. She utters it swiftly, without so much as a glance, a dozen times of a morning on her way to church, as a dozen gaunt, dirty hands are thrust in her face as she passes; and hearing it, the most persistent fellow of them all is at once silenced, and falls back.

Coming in from their kennel-homes among the ruins and the holes in the hills outside, it is the custom to make an early morning tour of the city before they take up their stations for the day at the various church and hotel doors. Each seems to be provided with “green pudding,” in his garlic pot, and he eats as he goes along, and prays as he eats, stopping in front of the great oval patio or court gates of iron lattice, which guard the mansions of the rich.

At these patio doors he makes a prodigious racket, shaking the iron rods furiously, and all the while muttering his prayers, until some one of the family appears at a gallery window. Then instantly the mutter becomes a whine, a pitiful tale is wailed forth, and alms are dolefully implored “for the love of God.” But although such mottoes as “Poverty is no Crime” are very often painted on the walls of their fine houses, the probability is that the unmoved Señorita will murmur a swift “Pardon, for God’s sake, Brother!” and retire, to soon appear again to silence another of the fraternity with the same potent formula.

However, each of the countless horde is sure to gather in centimes sufficient for the day’s cigarettes and garlic, and, in the long run, to support life to a good old age.

THE Spaniards are a nation of dancers and singers. Every Spanish child seems born with the steps, gestures, snappings and clappings of the national fandango dance, at the ends of his fingers and toes. A guitar is the universal possession, and every owner is a fine player. The solitary horseman, the traveller by rail, takes along his guitar; and in car, or at cross-roads, he is sure of dancers at the first thrilling twang. There is always a merry youth and maiden aboard ready to make acquaintance in a dance, and anywhere the whole household will troop from the cottage, the plowman will leave his team in the furrow, and the laborer drop his hoe, for a half-hour’s joyous “footing o’t.”

One of the interesting sights of Toledo is the great city fountain on Street St. Isabel, near the cathedral. It is a good place to study donkeys and their drivers, and the lower classes of the populace. The water, deliciously sweet and cool, is brought from the mountains by the old Moorish-built water-ways, and flows by faucet. There is no public system of delivery, consequently a good business falls into the hands of private water-carriers. These supply families at a franc a month. The poorer households go to and fro with their own water-jars as need calls, carrying them on their heads. They often wear a cushioned ring, fitting the head, to render the carrying of the jar an easier matter.

A picturesque article of dress among Spanish men, is the national sash, a broad woollen some four yards in length, of gay colorings. This is wound three or four times around the waist, its fringed end tucked in to hang floating, and the inevitable broad knife thrust within its folds, which also hold the daily supply of tobacco. A common sight is the sudden stop on the street, a lighting of a fresh cigarette, a loosening of the loosened sash, a twitch of the short breeches, and then a tight, snug wind-up, when the lounger moves on again.

Another amusing sight is the picturesque beggar who seems at first glance to be hanging in effigy against the cathedral walls, so motionless will some of these fellows stand, hat slouched over the face, the brass government “license” labelling the breast, a hand extended, and, in many cases, a crest worn prominently on the ragged garments, to show that the wearer is a proud descendant of some old grandee family. To address this crested beggar by any other title than Caballero (gentleman) is a deadly insult.

AMONG the many small sights of the Plaza about Christmas time, are the sellers of zambombas, or Devil’s Fiddles. This toy, which the stranger sometime takes for a receptacle of sweet drinks to be imbibed through a hollow cane, is a favorite plaything with Spanish children. A skin is stretched over a bottomless jar; into this is fastened a stout length of sugar-cane, and lo! a zambomba. Its urchin-owner spits on his palms, rubs them smartly up and down the ridgy cane, when the skin-drum reverberates delightfully.

The fruit markets are of a primitive sort. The peasant fills his donkey-panniers with grapes, garlic, melons straw-cased and straw-handled, whatever he has ripe, and starts for town. Reaching the Plaza, in the shade of the cathedral, he spreads his cloak, rolling a rim. On this huge woollen plate he arranges his fruit, weighing it out as customers demand.

From the old Moorish casements, the traveller looks down on the most rudimentary sort of life. He sees no labor-saving machinery. Instead of huge vans loaded with compact hay bales, he beholds the donkey hay-train. The farmer binds a mountain of loose hay on each of his donkeys, lashes them together, and with a neighbor to help beat the train along, starts for market. These trains may be seen any day crooking about among the steep mountain-ways.

The student of folk-life notes the shoemakers on the Plaza at work in the open air. Formerly the sandal was universally worn, with its sole of knotted hemp, and its canvas brought up over the toe, at which point was fastened a pair of ribbons about four feet long, and these ribbons each province had its own fashion of lacing and tying. But now the conventional footgear of Paris is common, and one buys boots of the fine glossy Cordovan leather for a trifle.

The proprietors of the neighboring vineyards visit the wine shops weekly to bring full wine-skins, and take such as are emptied. These skins, often with their wool unsheared, are cured by remaining several weeks filled with wine-oil, and all seams are coated with pitch to prevent leakage. The wholesale skins hold about eight gallons, being usually those of well-grown animals. They are stoutly sewn, tied at each knee, and also at the neck, whence the wine is decanted into smaller skins by means of a tunnel.

THE beggars of Spain are a most devout class. Piety is, with them, the form under which they conduct business; a shield, and a certificate of character. They walk the streets under the protection of the patron saint of the principal church in town, and they formally demand alms of you in the name of that saint. It is Religion that solicits you—the beggar’s own personality is not at all involved; and it is thus that the proud Spanish self-respect is saved from hurt.

The tourist who has not tarried in French towns, is, at first, astonished to behold women passing to and fro upon the streets with no head covering whatever. Hats and bonnets are rarely seen upon Spanish women of the lower and middle classes. Those who are street-venders sit bareheaded all day long in their chairs on the Plaza, wholly indifferent to the great heat and blinding dazzle of the Spanish sun. About Christmas, dozens of a “stands” spring up along the Plaza. It is at that season that the gypsy girls come in with their roasters and their bags of big foreign chestnuts; and they do a thriving business, for every good Spanish child expects roast chestnuts and salt at Christmas.

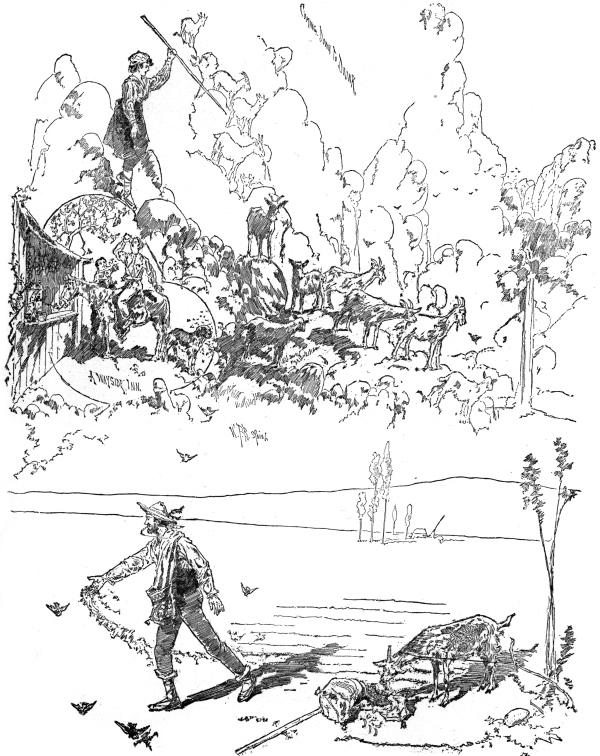

Many of the mountain families about Toledo keep small flocks of sheep—flocks that, instead of dotting a green landscape with peaceful white, as in America and Northern Europe, only darken the reddish-brown soil of Spain with a restless shading of a redder and a deeper hue. These brown sheep are herded daily down on the fenceless wastes. The shepherd-boys are usually attended by shepherd-dogs so enormous in size that the traveller often mistakes them for donkeys. They are sagacious, and do most of the herding, their masters devoting themselves to the guitar, the siesta, the cigarette, and the garlic pudding.

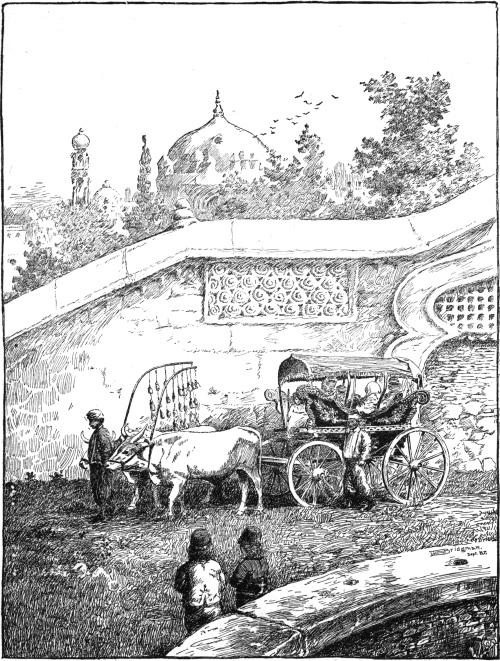

Toledo, more than any other Spanish city, abounds with interesting bits and noble examples of the old Moorish architecture, for the reason that it has not been rebuilt at all, and that few of its ruins have been restored, or even retouched. Color alone has changed. The city now is of the soft hue of a withered pomegranate. Turn where you will, your eye is delighted by an ornate façade, a carved gateway with its small reticent entrance door, a window with balcony and cross-bars, and everywhere there is the horseshoe arch with its beautiful curve. The old Alcazar is standing, though occupied as a Spanish arsenal, and on the height opposite is the ruin of a fine Moorish castle.

ONE of the best “small businesses” in a Spanish city, is that of the domestic water-supply. Those dealers who have no donkeys, convey it to their customers in long wheelbarrows constructed with a frame to receive and hold several jars securely. Stone jars, with wood stopples attached with a cord, are used, the carrying-jars, being emptied into larger jars in the water-cellars. The peasants have a poetic appellation for the soft, constant drip of the water from the old aqueducts: The sigh of the Moor.

With the Spaniard, as with the American, the turkey is a special Christmas luxury. But the tempting rows of dressed fowls common to our markets and groceries, are never to be seen. As the holiday season draws very close at hand, the mountain men come down into the city, driving before them their cackling, gobbling, lustrous-feathered flocks, bestowing upon them, of course, the usual daily allowance of blows which is meted out to the patient family donkey. These poultry dealers congregate upon the Plaza, where they smoke, and chaff, and dicker, keeping their droves in place with the whip; and the buyer shares in the capture of his flying, screaming, flapping purchase, in company with all the children on the street, for the turkey market is usually great fun for the Spanish youngster.

In the cold season, one of the morning sights of a Spanish town is the preparation of the big charcoal braziers outside the gates of the fine dwelling-houses. The coals are laid and lighted, and then the servant blows them with a large grass fan until the ashes are white, when he may consider that all deadly fumes are dissipated, and that it is safe to carry it within to the room it is to warm.

Nearly all the peasants in the near vicinity of cities are market gardeners on a small scale. They cultivate small plots, and whenever any crop is ripe, they load their donkey-panniers and go into the cities, where they sell from house to house. These vegetable-panniers have enormous pockets, and are woven of coarse, dyed grasses, in stripes and patterns of gaudy blue and red. When filled, they often cover and broaden the donkey’s back to such an extent that the lazy owner, determined to ride, must sit on the very last section of backbone. Some of the streets in Toledo are so narrow that the brick or stone walls of the buildings have been hewn and hollowed out at donkey-height, to allow the loaded panniers to pass. The buyers make their bargains from the windows, a sample vegetable being handed up for inspection.

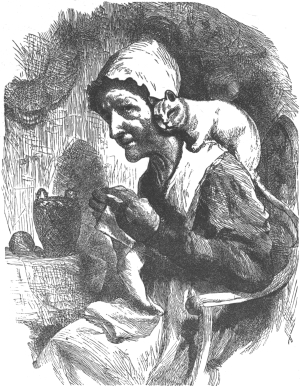

TRAVELLERS should deny themselves Spain during December, January and February. The heating apparatus of the American and the English house is unknown in Spanish dwellings—fireplace, stove, nor furnace. The peasant draws his cloak up to his nose and shivers and cowers, while the middle-class family lights a single brazier, and the household, gathering in one room, hovers over the charcoal smouldering away in its brass cage, and the cats sit and purr on the broad wooden rim. These braziers are expensive—constructed of brass and copper—and few families afford more than one, making winter comfort out of the question, as the floors, of marble or stone, never get well warmed.

With the coming of pleasant weather Spanish families usually forsake the blinded, draperied, balconied rooms of the gallery for the secluded and garden-like patio. This court is often fifty feet square, and in its enclosure there is generally a fountain; the floor is tiled with marble, there are stately tropic plants in tubs, and orange and palm-trees are growing. Should the sunshine become too fierce there are smoothly-running screens and awnings to roof the whole court in an instant. Some of the old Moorish patios contain quaint wells, dry at some seasons, but often affording water sufficient for housekeeping needs.

The water-jars come from the famous potteries of Seville, and, made of a rude red clay, are similar in hue to our plant pots. They are brought in high loads by oxen—and these pottery carts are often an enlivening feature of the dull country roads.

The water cellar is not a cellar at all, but a stone-paved room off the patio, delightfully cool and sloppy of a fiery July day, with the water-carriers unloading, and filling the array of dripping red jars with the day’s supply from the public fountain.

Every Spanish peasant wears a knife in his sash. These knives are usually about eighteen inches long, with a broad, sharp, murderous blade. The handles are of tortoise or ivory, often carved richly, or inlaid with figures of the Virgin, the Saviour, or the crucifix. The knife is kept open by a curious little wheel, between blade and handle, and is used indiscriminately, to slice a melon or lay bare a quarrelsome neighbor’s heart.

SEVILLE is celebrated for its oranges and its pottery. Nearly the whole Spanish supply of water-jars comes from this city; and the outlying country is agreeably dotted with orange orchards, as olive oases enliven the vicinity of Cordova. The export of the fruit is a considerable business. The most delicious orange in the world may be bought in the streets of Seville for a cent, and the ordinary rate for the ordinary fruit is four for a cent. In the Christmas season large and selected oranges are sold in the outdoor booths. They are carefully brought, and temptingly hung in nets, along with melons cased in straw, fine bunches of garlic, chestnuts, assorted lengths of sugar-cane, tambourines, zambombas, and such other sweet and noisy objects as delight the Spanish youngster.

The decorative plant of Spain is the aloe—truly decorative, with its base of long, dark, clear-cut, sword-like leaves, its tall slender trunk often rising twenty feet high, and its broad candelabras of crimson blooms.

A picturesque industry of Seville is the spinning of the green rope so much used by Spanish farmers. It is manufactured from the coarse pampas grass of the plains, and the operation is a very leisurely and social one, requiring three persons: one to feed the wheel, one to turn it, and a third to receive the twisted rope.

Plowing, in Spain, is still a very rude performance. The primitive plow of the Garden of Eden era is yet in use—a sharp crotch of a tree, crudely shod, however, with iron.

An indispensable article of peasants’ costume for both men and women, should an absence of even two hours be contemplated, is the alforja, or peasant’s bag. This, in idea, is similar to the donkey-pannier—a long, stout, woollen strip thickly tufted with bunches of red and blue wool, with a bag at either end, and is worn slung over the shoulder. The pockets of the alforja invariably contain, one a pot of garlic, or green pudding, the other a wine skin.

The mouths of some wine-skins are fitted with a bottomless wooden saucer, and are lifted to the lips for drinking; but the preferable and national style is to catch the stream with the skin held aloft and away at arm’s-length.

A CENTRAL point of interest for visitors to Seville is the Cathedral. Its tower, known as the Giralda, is one of the most celebrated examples of sacred Moorish architecture. It was erected in an early century, and was considered very ancient when the Spaniards, in the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, built upon it the fine Cathedral. In the interior, the Tribuna de la Puorta Mayor is much visited for its lofty and beautiful sunlight effects, and there are several precious Murillos. The ascent of the Giralda is usually made by tourists—an agreeable variety in European climbing, as there are no stairs, the whole progress being by an easy series of inclined planes of brick masonry. Queen Isabella, not long ago, made the entire ascent and return upon horseback. From the summit, one views the whole of Seville, with its dark-green rim of orange gardens, set in the great flat barrens that stretch out towards Cadiz. A comic sight usual at the foot of the tower, significant as a sign of the complete contempt in which the Catholic Spaniard holds all things Moslem and Moorish, is that of a goat belonging to one of the custodians, tethered from morning till night to a fine old Muezzin bell.

Another noted building is the Tower of Gold, on the banks of the Guadalquiver, opposite the Gypsy quarter. Tourists visit it to get the fine architectural effect of the Cathedral, also for its view of the Bull Ring. It stands on the site of the old Inquisition, where hosts of Moorish captives were tortured.

The Alcazar, always visited, is an ancient Moorish palace, and is considered, in point of elegance, second to only the Alhambra. It is now set aside by the government as the residence of the Queen-mother Isabella.

San Telmo is also much visited. It is the palace of the Duc de Montpensier, known throughout Spain as “the orange man.” He owns numerous orange orchards, and lavishes much time and money on his plantations and hothouses.

Another point of curiosity is known as the House of Pilate. It is said to be an exact reproduction of the celebrated House of Pilate in Jerusalem. It is remarkable for some exquisite tiles, and it bears many interesting inscriptions.

Seville presents an odd aspect to the stranger between the hours of three and six P. M. During this hot interval the streets and shops are deserted, everybody, even to the beggars, being under cover and asleep.

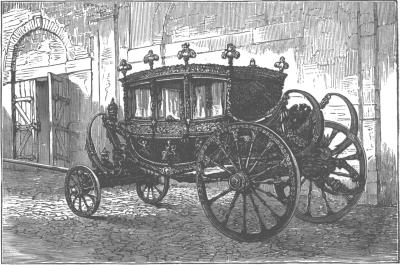

MOST of the peasant girls in the vicinity of Spanish cities contrive to keep a bit of flower-garden for their own personal purposes. She is a thriftless lass indeed, who has not at least one fragrant double red rose in tending, or some other red-flowered shrub. From Christmas on through the spring fête-days of the Church, they reap their tiny harvests. During this season every Spanish man and woman who can, wears a red flower in button-hole or over the ear, and the streets are thronged with bareheaded, black-tressed peasant and gypsy flower-venders. Flowers are a part of the daily marketing, and two or three centimos—a centimo is one fifth of a cent—suffice to buy a fresh nosegay. New Year’s is a marked fête in Seville, as then “The Old Queen” in the Alcazar rides out in state, the Alameda is thronged with carriages, and the whole populace is a-blossom with red.

A custom noticed by the tourist who lingers about cathedral doors, is one most observed, perhaps, by the poorer and more superstitious classes. Men and women dip the fingers, on entrance and departure, in holy water, and wet some one of the countless crosses which are set in the wall just above the cash-boxes—the cash-box in Spain being the inevitable accompaniment of the cross.

As in other Spanish cities, the noble Profession of Beggary considers itself under the protection of the Church, and the entrance to the cathedral is down a long vista of outstretched hands, the fortunate one at the far end, who holds aside the matting portiere for you to enter, feeling sure of a fee, however the others fare. The whole vicinity abounds with loathsome spectacles of disease and distress, those entirely helpless managing to be conveyed daily into holy precincts. It is often amusing to witness an adult beggar “giving points” to some young amateur in the art, the dignity of the national calling evidently being insisted upon.

An agreeable sight in this city of churches and beggars, is the afternoon stroll of companies of young priests and students from the convents. They are very noticeable, as part of the panorama, with their broad, silky shovel hats and black flowing gowns. Some are scholastic and intent upon their studies even in the streets, while others evidently take a most young man-of-the-world enjoyment in their cigarettes and the street-sights.

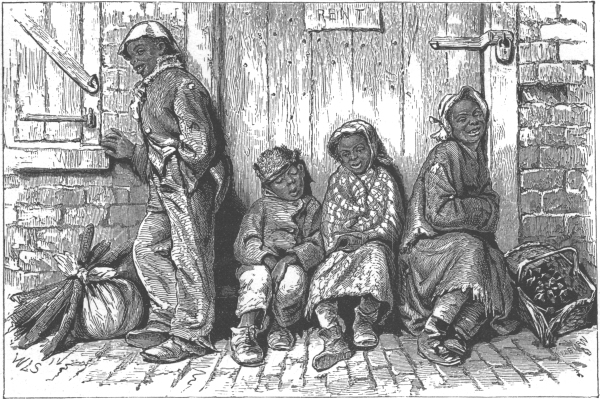

REVENUES are collected in most primitive ways by the Spanish City Fathers. As there are no important sources of public income, there are few transactions, however trifling, that do not pay tax and toll. Every man is suspected of smuggling and “false returns,” and it is a small bunch of garlic that escapes. Burly officials, often in shirt-sleeves and with club, lounge at all the entrances to the town, to levy duty upon any chance donkey-pannier or cart bringing in fruit and vegetables for sale. Frequently there are scenes of confusion, sometimes of violence. The government is determined that not a turnip, not a carrot, not a cabbage shall escape the yield of its due; and it is not to be denied that the poor farmer hopes fervently to smuggle in a wine-skin or two—a dozen of eggs, or some other article of price, among his cheaper commodities. As a rule, he fails; for, suspicious of over-much gesticulation and protestation, the official is quite likely to tumble out sacks, baskets, bundles and bales, and empty every one upon the ground, leaving the angry farmer to pick up and load again at his leisure.

Andalusia is a brown region stretching gravely between Cadiz and Granada. The effect of this landscape, all in low tones, upon natives of the green lands of America and England, is most depressing. The soil itself is red, and the grass grows so sparsely that the color of the ground crops up, giving impression of general sun-blight, broken here and there by the glimmering moonlight gray of an olive orchard, or the dark-green of an orange garden. The huts of the farmers are built of the red clay; the clothing of the population appears to be of the undyed wool of the brown sheep, while to add to the prevailing russet hue, the general occupation seems to be that of herding pigs on the plains—and the pigs are hideously brown also. It is said that they derive their color from feeding on the great brown bug, or beetle, which abounds in the soil. The traveller counts these feeding droves by the dozen, each with two lazy, smoking swineherds.

Travelling by rail over the Andalusian levels, one passes a succession of petty stations, villages of half a dozen houses each, where the only visible business appears to be in the hands of women, in the shape of one or two open-air tables, with pitchers and glasses, and a cow or goat tethered near in order to supply travellers, as the trains stop, with drinks of fresh milk.

MANY of the public buildings of Spanish cities stand as they were captured from the Moors. Sometimes, as in Cadiz, the town has received a coat of whitewash; but more frequently the only Spanish additions and improvements are a few crosses inlaid in the old cement, or a plaster Virgin niched, in rude contrast, beside some richly wrought Moorish door of horseshoe form. The town hall of Seville remains to-day as ten centuries ago.

The Spanish towns lie, for the most part, in the valley. The Moors usually chose the site for their cities with a view to the natural defences of mountain and river. The hills of course, remain, but the rivers, once full rushing tides, are now dried into stagnant shallow waters, a natural result in a country long uncultivated.

A favorite business with the young men among the mountain peasants is the breeding of poultry; not alone of fat pullets for the Christmas markets—that is a minor interest so far as enjoyment goes—but of choice young game cocks—cock-fighting being the staple, everyday national amusement, while the bullfight is to be regarded as fête and festival—“the taste of blood” is a welcome ingredient in any Spanish pleasure. All poultry is taken to market alive; the pullets, hanging head downwards, are slung in a bunch at the saddle bow, and the cocks are carried carefully in cages. Fowls are not a common article of food, as in France, but are, instead, a holiday luxury, and the costliest meat in the market.

Looking idly abroad as he crosses the Andalusian plains, the tourist on donkey-back notices the queer carts that take passengers from one station to another. These odd omnibuses are but rude carts, two-wheeled, and covered with coarse mats of pampas grass, and they are drawn by two, three, four or five donkeys harnessed tandem. On the rough, movable seats, gentlemen in broadcloth, and common folk with laced canvas shoes and peasant-bags, huddle together, all eating from the garlic-pots as they are passed, and drinking from the same wine-skin; this good fellowship of travellers is one of the unwritten laws of Spain. Meantime the sauntering boys of the roadside hop up on the cart behind with the identical vagrant joy experienced by the American urchin after a like achievement.

YOU never can be sure when a Spaniard will arrive. Due at noon, should he meet a guitar, he comes at nightfall; and as it is certain that every second Spaniard, walking or riding, will have his guitar along, it is best not to look for the return of any messenger before evening. He may have chosen to alight from his donkey and dance an hour, or he may have elected to sit still and clap and snap a dance in pantomime—either is exciting and deeply satisfactory—and a fulfilment of one of the obligations of daily life which no true Spaniard can be expected to neglect for any such simple considerations as promise given, command laid, or bargain made.

A peculiarly gloomy look is lent to the Spanish landscape by the cypress, sometimes growing in groups, sometimes towering singly in solitude. This tree, funereal in its best aspect, has a dead, dry, white trunk, and the branches begin at a height of twenty, thirty, or forty feet, and then drape themselves in a cone-like monumental mass of purplish green. These gloomy evergreens are common, and the tourist feels, even if he does not note, the absence of the lively sunny greens of American and French landscapes, with the bowery shadows that everywhere invite the wayfarer to stop and rest.

The Bergh Societies would find ample range for work in Spain, for the beating and prodding of the donkey is one of the national occupations. As a rule, poor Burro is overloaded. A whole family will frequently come down into the city on his back, and tired though he be with plodding and stumbling and holding back, the officer at the gate is sure to give him a blow and a bruise with his bludgeon of authority as he passes in; and the poor creature sometimes very justly lies down in the street and dies without warning, allowing his owners to climb homeward on foot.

Now and then one comes unexpectedly on an example of ancient enterprise put to use. There are spots in the brown waste which are green and fertile, because the old irrigating wells have been cleaned out and set in motion—a pair of wheels studded with great cups operated by means of a pair of poles, and a pair of donkeys, and a pair of drivers. The land is cut in ditches, and often the farmer can be seen hoeing his garlic and his cabbages while he stands in water ankle-deep.

GREATLY dreaded by the unmarried young Spanish woman is the Beggars’ Curse; and a goodly portion of the beggars’ revenue is ensured by this superstitious national fear. The more vicious of the fraternity keep good watch upon the wealthy young señoritas and their cavaliers when they go out for pleasure. They do not follow them, perhaps; instead they take up their stations around the doors of those restaurants—whence they never are driven—where ladies and their escorts are wont to stop for chocolate, or coffee, or aguardente, on their return from calls or the theatre, or the Bull Ring. As the pair are departing, the burly beggar approaches, half barring the way perhaps, and asks for alms. It is usually bestowed; but he begs insolently for more; and if it be not forthcoming, a bony and rosaried arm is raised, “the evil eye” is fastened upon the doomed ones, and the Beggars’ Curse—the Curse of the Unfortunate—which all Spaniards dread, is threatened; and if it be evening, it is quite probable that the group stand near some crucifix of the suffering Saviour, with the red light of the street lantern shining down upon its ghastliness, so that the feeling of pious dread is greatly heightened, and a frightened pressure on the cavalier’s arm carries the doubled alms into the outstretched hand.

The dress of Spanish people of fashion is singularly artistic and pleasing. Although Paris styles are now followed by the señoritas, they still cling to the national black satin with its lustrous foldings and flouncings, to the effective ball fringes, and to the mantilla, draping face and shoulder with its heavy black or white laces, the national red rose set just above the ear. Nor is this too remarkable under the high broad lights of the Spanish sky, though it might seen theatrical in our cold, harsh, Northern atmosphere. The dress of the Spanish gentlemen is as picturesque. The hat is usually a curious, double-brimmed silky beaver, while the cloak is most artistic in color and in drapery. This cloak, lasting a life-time, is of fine broadcloth, lined with heavy blue or crimson velvet; and it is so disposed that the folding brings this gorgeous lining in a round collar about the neck, while another broad fold is turned over upon the whole long left side of the garment. The peasant’s cloak, of the same cut, is lined with red flannel, but it is often worn as gracefully. Long trousers are becoming general, but in some districts the tight pantaloon, slashed at the knee, is still seen, with its gay garter embroidered with some fanciful motto. One just brought from Spain bears this legend: There is a girl in this town—with her love she kills me.

WHAT THEY ALL FEAR—THE BEGGAR’S CURSE.

MORE! SEÑORITA. MORE!

SOUTHERN Spain is so mountainous that herding naturally becomes the occupation of the peasantry, rather than tillage. Great flocks of goats browse and frolic among the rocky heights and along the steep ravines where it seems hardly possible for the tiny hoofs to keep foothold; and the traveller often beholds far above him dozens of these bounding creatures, leaping down the cliffs to drink at the valley streams. They are generally followed, at the same fearless pace, by a short-frocked shepherdess as sure-footed as they. Her rough, hempen-soled shoe, however, yields her excellent support, being flexible and not slippery, like boot-leather.

Along the narrow mountain highways, the traveller frequently comes upon little booths built in among the cliffy recesses, like quaint pantries hewn in the rock. Melons, and grapes, and garlic, and oranges in nets, hang against the wall, and the heavy red wine of the country is for sale by the glass, also goat’s milk.

Farming processes go on at all times of year in Spain. Subsistence is a matter comparatively independent of care and calculation. Crops may be sown at any time. The whole year round the peasant lights no fire in his earthen, bowl-like hut of one room. He cooks outside his door, in gypsy fashion. His furniture consists of some rude wool mattresses, a table, and some stools with low backs. A few bowls, plates, and knives and forks suffice to set his table. A kettle and a garlic pot comprise his cooking utensils. Frequently he and his family are to be seen at meals, leaning their elbows on the table in company, and sipping like so many cats, from the huge platter of hot garlic soup, crumbling their slices of coarse black bread, as they need. In contrast with this crude bread of the common people, are the long, fine, sweet white loaves to be had at the Seville bakeries—a bread so cake-like, so delicious, as to require no butter, even with Americans accustomed to the use of butter with every meal. The salted butter of American creameries, made to keep for months, is wholly unknown in Spain, Spanish butter being a soft mass, and always eaten unsalted. But with his strong garlic and his fine fragrant tobacco, the Spaniard hardly demands or appreciates the refinements of food, and his tobacco is of the best, coming from the Spanish plantations in Cuba, and is very cheap, as it enters the country free of duties.

Sunny Spain: Sewing and Reaping in Winter

HOUSEWORK, among the sun-basking, siesta-loving Spaniards, seems to be not the formidable, systematic matter that it is made in America. Washing, as well as cookery, is of simplest form. “Blue Monday” does not follow Sunday in Spain. A necessary garment is washed when needed; superfluous ones are allowed to accumulate until it is worth while to give a day to the task. Then, among the peasants, “the washing” is carried to a mountain torrent, and the garments are rubbed and rinsed in the swift waters, while picnic fun makes the labor agreeable, as often several families wash in company. Among townspeople, the work is done in great stone tubs in the patio, or in the water-cellar. There the goods, repeatedly wetted, are laid upon a big stone table and beaten with flat wooden paddles. The snowy array of the American clothes-line is seldom seen. The washed garments are hung upon the table edges, and held fast by stones or other weights until dried.

A frequent incident in mountain travel is the sight of some stout lazy peasant away up the heights, holding fast by his donkey’s tail to help himself along as the poor creature scrambles up the zigzag steeps. At the base and along the face of these rocks cacti grow abundantly, often presenting a beautiful cliff-side of cacti fifty feet high.

Another sight, not so agreeable, along many a Spanish roadside, is that of the ancient wooden crosses, erected on the sites where travellers have been murdered by banditti. These roads are often desolate and dreary beyond description, unfenced, seldom travelled, and set with the constantly recurring stones of the Moorish road-makers. Leading across brown, treeless wastes, with habitations far apart, both peasant and tourist would easily wander from these roads, were it not for those rude mile-stones, which are often the only guide-posts and land-marks. When a fence is required, a hedge of aloe is usually started.

Spanish children chew sugar-cane as American children munch candy. The cane is brought from Cuba and is sold everywhere; carried about by venders in big bundles of handy lengths, to capture all stray centimos.

Not so well patronized is the street dealer in soap—“old Castile” soap—for this business is recognized to be a form of beggary, and though bargains are made and money paid, the soap is seldom carried away by the purchaser.

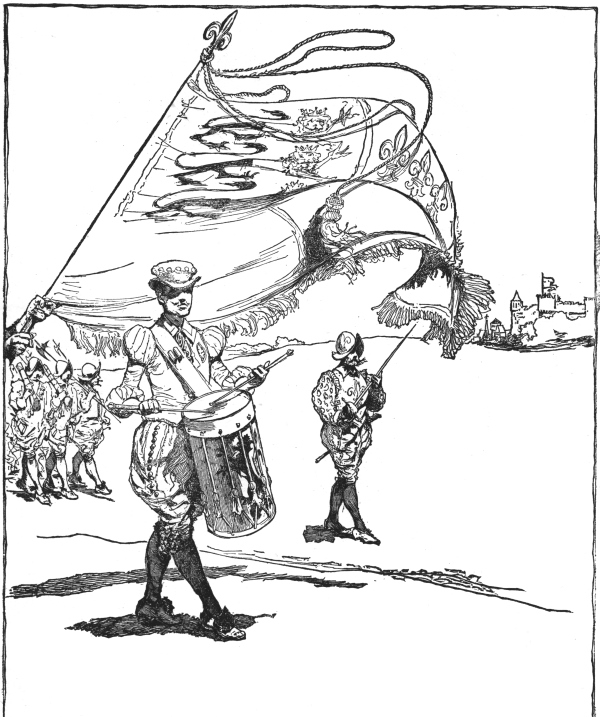

EVERY male Spaniard is obliged to render three years of military service; but usually this is no severe hardship, and loving his ease, he leaves home cheerily enough. The government is rather embarrassed than served, in the matter of stationing this soldiery, especially since the close of the Carlist War. The conscripts are set to guard the palaces, the parks, the national buildings; they are sent to Cuba and elsewhere, whenever it is possible, in fact all opportunities and pretexts are seized to set up a soldier on duty, or rather a pair of them, as two are usually to be seen together. Leave of absence is easily obtained, and but few days of actual presence and service are required during the third year. However, the military requirements by the government never relax, as “insurrections” are indigenous to the country and climate.

As the ancient Moorish doors are still frequent, so is the old form of knock and admission. The arrival raps smartly at the small door set within the great nail-studded gate. Presently an eye, a face, appears at the little wicket window to reconnoitre, to question. Should the examination reveal nothing dangerous or disagreeable, the latch-string is pulled, and entrance is permitted.

“Burro” must needs appear in all Spanish picture and story, for he is prominent in all Spanish folk-life. He is to be seen everywhere, with his rude harness tufted with gay woollens, and big brass nails, moving over the landscape in town or country—the helpless slave and abused burden-bearer, seldom petted, even by the children of the family. There are very handsome mules in Madrid and a few elsewhere; but the donkey is the national carrier. He is small, brown, brave, and always bruised. The Spaniards’ “Get up!” is a brutal blow between the eyes. He is seldom stabled, seldom decently fed. He is tethered anywhere—under the grapevine, by the door, among the rocks, but always at his master’s convenience; and his food is in matter and manner best known to himself. His harness is heavy and uncomfortable, and his hair is clipped close on his back where he needs protection most from the burning sun. This clipping is usually done at the blacksmith’s, by a professional clipper, and is a sight of interest to the lazy populace. Under the great shears Burro’s body is often decorated with half moons, eyes, monograms, garlands—whatever the fancy of his master, or the clipper, or the bystander may direct. Poor Burro! from first to last—poor Burro!

IN Cordova, a sudden stir in the street often betokens “The Return from the Chase”—not, however, the picturesque scattering of the “meet” after an English fox-hunt, but the arrival home of some solitary mule and rider, with a pack of harriers. The huntsman has been riding across country all by himself, his cigarette, and his dogs, to ferret out some luckless colony of hares in a distant olive orchard. The rabbits are very mischievous in the young olive plantations, and the huntsman and his pack are warmly welcomed by the olive-growers. These Spanish harriers are a keen-nosed race of dogs; quite as good hunters as the English fox-hounds. Nearly every breed of dog is found in Spain, except, perhaps, the Newfoundland. In most Spanish cities the dogs are one of the early morning sights as they gather in snarling, quarrelsome packs of from fifteen to twenty, before the doors of the hotels and restaurants, to devour the daily kitchen refuse—a very disagreeable spectacle; but there seems to be no other street-cleaning machinery.

The chief streets of a Spanish town are usually thronged with fruit-sellers, especially the Plaza, where the great portion of the population seems to congregate to lounge and sleep in the sun all day long, naturally waking now and then to crave an orange, a palmete, or a pomegranate—“regular meals” appearing to be a regulation of daily life quite unknown. These fruit sellers are girls, for the most part, though sometimes there may be seen some old man who has not been able to procure a beggar’s license. Oranges are always plenty. Palmetes, a tender, bulbous growth, half vegetable, half fruit, are brought into the city in January, and are consumed largely by the peasants and beggars, who strip them into sections, chewing them for their rather insipid sweetish juices.

The Spanish peasant cooks out-of-doors, like a gypsy. Often his kettle is his only “stove furniture;” in it he stews, boils, fries and bakes. Even in January, the cold month in Spain, he makes no change in his housekeeping. The peasants’ daily bread is hardly bread at all, but rather a pudding, a batter of coarse flour, water and garlic, stirred, and boiled, and half baked in his kettle, and then pressed into a jar. This “garlic pot” he always carries about with him in his shoulder bag. In the patio apartments of some of the ancient, Moorish-built houses there are quaint arches with stone ovens, which are sometimes utilized for cookery.

A DRUNKEN Spaniard is rarely seen, although the “wine-skin” keeps constant company with the “garlic pot” in the peasant’s bag. The heavy red wine of the country is used as freely as water, being sold for four cents a wine-skin; this wine-skin holds a quart or more. Not to drink with the skin held at arms-length, is to be not Spanish, but French—their generic name for a foreigner or stranger. Fine and delicate wines are made in the neighborhood of some of the great vineyards, but they are chiefly for exportation.

There is a popular saying, that Spanish ladies dress their hair but once a week. This is on Sunday, when they meet on one another’s balconies to chat and gossip while their maids arrange their coiffures, each maid taking care that she pat, and pull, and puff until her mistress be taller than her friends, for height is a Spanish requisite for beauty and style. Certain it is that the tourist sometimes looks up and beholds this leisurely out-of-doors toilet-making. The glossy black hair is universal, a fair-haired woman becoming an occasion for persistent stares, although Murillo, in his time, seems to have found plenty of red-haired Spanish blondes to paint. Happy is the gazing traveller if he also may listen; for the music of a high-bred Spanish woman’s voice is remarkable, holding in its flow, sometimes, the tones of a guitar, and the liquid sounds of dropping water.

Spanish urchins are as noted for never combing their hair as Italian boys are for never washing their faces. The change of the yellow handkerchief dotted with big white eyes, which they knot about their heads and wear day and night, seems to be the only attention they think needful ever to bestow upon their raven locks.

That Spanish peasant is very poor and unthrifty indeed, who does not contrive to own a foot or two of land upon which to grow a choice Malaga grapevine. Owning the vines, he erects an out-of-door cellar to preserve his crop—a simple arbor, upon the slats of which he suspends his clusters for winter use. Hanging all winter in the current of wind, the bunches of pale-green grapes may be taken down as late as February, and still be found as plump and delicious and as full of flavor as when hung. It is in this simple manner that they are preserved for the holiday markets.

ONE of the most picturesque features of natural scenery which the traveller comes upon in Southern Spain, is that of the olive orchards, especially those which cluster about Cordova. As the time of harvest draws near, the coloring of these orchards is particularly pleasing. The ripening fruit varies in tint, from vivid greens to gay reds and lovely purples, while the foliage, of willow-leaf shape, restless and quivering, is of a tender, shimmering, greenish gray, and the trunks often have a solemn and aged aspect. Many of these plantations are very ancient indeed, planted perhaps by the grandsires of the present owners. They are usually a source of much profit, as the best eating olives are those grown in Spain, and though the trees come into bearing late, there are orchards which have been known to yield fruit for centuries.

Each orchard has a guard, or watchman, who tends it the year round, for the pruning, the tillage, and the watch upon the ripening fruit, demand constant care. In the harvest season the watch is by night as well as by day, for a vigorous shake of the branches will dislodge almost every berry, and a thief, with his donkeys and his panniers, might easily and almost noiselessly strip an entire orchard in a few hours. The olive guard lives in a hut of thatch or grass in summer, and in a sort of cave, or burrow, in winter.

The crop is mainly harvested by girls and women, and the scene is like a picnic all day long, for Spanish girls turn all their labors into merry-making whenever it is possible to do so. The gray orchards are lighted up with the rainbowy colors of the peasant costumes, and the air is musical with the donkey bells, while the overseer, prone on the ground with his cigarette, “loafs and invites his soul,” evidently finding great delight in the double drudgery he controls—that of the donkeys and the damsels.

In regard to the great age of olive-trees, a recent writer says: “When raised from seed it rarely bears fruit under fifty years, and when propagated in other ways it requires at least from twenty to twenty-five years. But, on the other hand, it lives for centuries. The monster olive at Beaulieu, near Nice, is supposed by Risso to be a thousand years old. Its trunk at four feet from the ground has a circumference of twenty-three feet, and it is said to have yielded, five hundred pounds of oil in a single year.”

CORDOVA, lying in the beautiful valley of the Guadalquiver, surrounded with gardens and villas, is well named the city of Age, Mellowness, and Tranquility. It abounds with antiquities, and at every turn memories are awakened of old Roman emperors, and the Arabian caliphs; the gates, the sculptures, the towers, the mullioned windows and nail-studded doors, the galleried houses and their beautiful patios fitted for idle life in the soft Andalusian weather, the mosques and the great bridges are all of those times. Even the streets are named after the old Roman and Spanish scholars and poets.

The large bridge over the Guadalquiver was originally built by the Roman Emperor, Octavius Augustus; it was afterwards remodelled by the Arabs. The gate is very fine which leads into the gypsy quarter. The Moors had three thousand baths on the banks of the river, but in their day it was a full shining tide; now it is a muddy current, hardly in need of bridging at all.

The mosques of Cordova are fine, and among them is the greatest Moslem temple in the world, with its beautiful chapels, its Court of Oranges, and its wondrous grove of marbles. This mosque, now used for Christian worship, was erected on the ruins of an old cathedral, which it is said had been built upon the site of a Roman temple. The Moslem structure was erected by the Caliph Abdurrahman, in the seventh century, and was a hundred years in building. The principal entrance is through the Court of Oranges, where beautiful palms also grow, and other tropical trees. Thence one emerges among a very forest of marble pillars, where countless magnificent naves stretch away and intersect, and the shining columns and pilasters spring upward into delicate double horseshoe arches. One marble is shown where a Christian captive, chained at its base, scratched a cross upon the stone with his nails. In some sections the ceiling is dazzling with arabesques and crystals. Within the mosque, in its very centre, rises a fine Catholic church, built in the time of Charles the Fifth. It contains many illuminated missals and rare old choir books.

The Cordovans, like the people of other Spanish cities, are indebted to the Moors for the fine aqueducts which bring the cold mountain water across the valley into the public watering places. These great reservoirs are good points for observing some phases of folk-life.

GRANADA, the beautiful city, with beautiful rivers, is named for a “grenade” or pomegranate. At the time of the Conquest, King Ferdinand on being assured how valiantly the Moors would defend their last stronghold, replied, “I will pick out the seeds of this grenade one by one.”

There is a tradition among the Moors that when the hand carved over the principal entrance of the Alhambra shall reach down and grasp the key, also carved there, they shall regain their city, the ancient home of their caliphs.

The Generalife lies across the valley from the Alhambra. It was the summer palace of the Moorish sovereigns, and is built on a mountain slope by the Darro River, and its white walls gleam out from lovely terraced gardens, and groves of laurel. The grounds abound with fountains and summer houses.

The Alhambra—the great royal castle—a town in itself—is built on a lovely tree-embowered height, its many towers rising high above the mass of foliage. From these towers one looks across the vale of the Vega to the spot where Columbus is said to have turned back, recalled by Isabella, on his way to seek English aid in his discovery of a New World. From these towers, too, can be seen the valley in the distance, where Boabdil, last of the Moorish Kings, looked back on Granada for the last time; and across the river, one gazes upon the sombre region of the gypsy quarter, a swarming town of caves in the hillside.

Two relics of Alhambra housekeeping still remain; a great oven, and a fine well. Both are utilized by the custodian of the palace. The palace itself has many beautiful patios. The finest is known as the Court of Lions, named from the sculptured figures which support the fountain in the centre. Another is known sometimes as the Court of the Lake, and sometimes as the Court of the Myrtles; and still another, entered by subterranean ways, is the Hall of Divans, the special retreat of the Favorites. There are many others, and all these patios and halls are bewilderingly beautiful with arabesques, mosaics, inscriptions and wondrous arches and columns, porticos, vistas, alcoves and temples—and everywhere elegance of effect indescribable.

AT Granada, whenever it is desired, the proprietor of the Washington Irving Hotel will engage the Gypsy King to come with his daughters and dance the national dance at the house of one of the guides. This dance is a most wild and weird performance. There is an incessant clapping of hands and clatter of castañets, a sharp stamping of heels, an agonized swaying of the body and the arms; and often the castañets and guitar are accompanied by a wild and mournful wail from the dancers. The king of the Granada gypsies is said to be the best guitar player in Spain.

The climb from the city up to the vast Gypsy Quarter, known as the suburb of the Albaycin, is an adventure of a nightmare sort. The squalor and horror of the life to be witnessed on the way up along narrow streets swarming with the weirdest and dirtiest of brown beggars, may not be painted, may not be written; yet now and then one goes under a superb Arab arch, passes a door rich with arabesques, or comes upon a group of elegant columns supporting a roof of mud and rock. The long hillside seems honeycombed with the denlike habitations of the gitanos, many of whom, among the men, are blacksmiths, while others work at pottery, turning out very handsome plates and water jars, while the women weave cloth, and do a rude kind of embroidery, all selling their wares in the streets—in fact the spinning and weaving and sewing is often carried on in the street itself.

But the little ones too (las niñas) add largely to the family income, as they dance for the visitor; the traveller and his guide being always invited to enter the caves. These gypsy children dance with much spirit, and they also sing many beautiful old ballads of Spanish prowess. The most beautiful ones among the girls are early trained to practice fortune-telling.

With their dances, their songs, their fortune-telling, their importunate, imperious begging, and their rude industries, these Granada gypsies live here from century to century, in swarms of thousands, never attempting to improve their condition, but boasting, instead, of the comfort of their dismal caves as being cool in summer and warm in winter. It is plain that they consider themselves and their Quarter “a part of the show,” and hardly second in interest to the Alhambra itself.

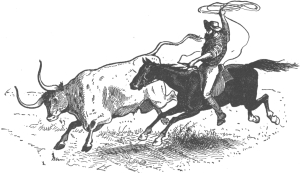

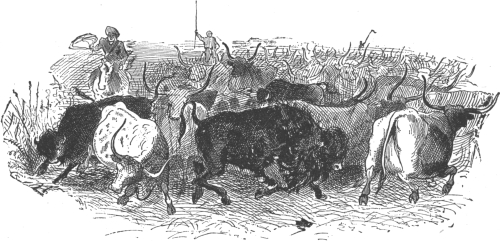

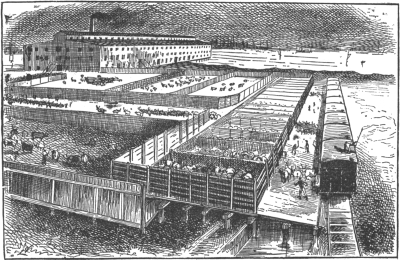

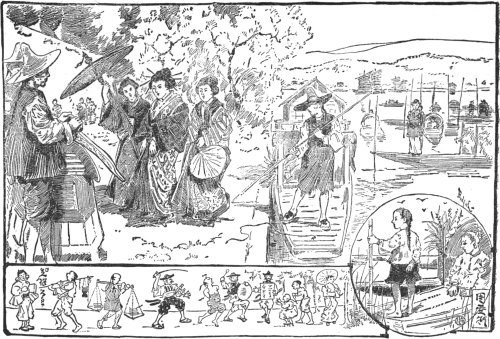

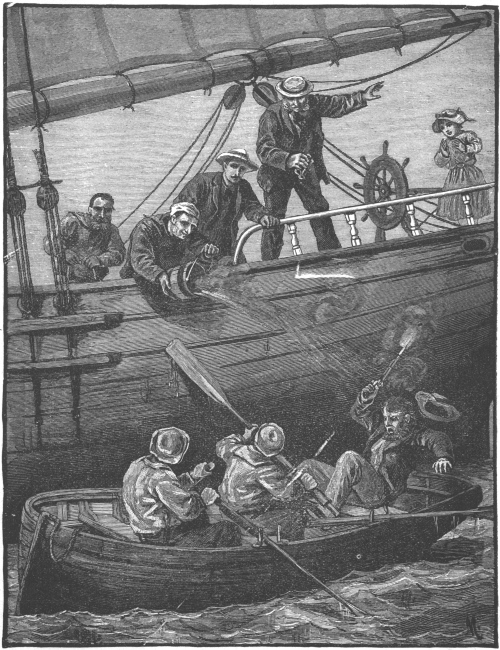

HARDLY is there a Spanish town of note, that does not possess its great Bull Ring; and there are scores of inferior Bull Circuses throughout Spain. There is but a slight public sentiment against the brutal sport which is the favorite Sunday recreation of the whole nation. Spanish kings and queens for many centuries have sat in the royal boxes to applaud, and many of the Spanish noblemen of the present time breed choice fighting bulls on their farms, and there is the same mad admiration of the agile, skilful espado or bull slayer, as a hundred years ago. To be a fine picador or banderillo, is to be sure of the praise and the presents of the entire populace. Men, women and children go; the amphitheatre is always crowded and always the crowd will sit breathless and happy to see six or eight bulls killed, and three times that count of horses—the rich and the nobles on the shady side under the awnings, the peasants sweltering and burning in the sun. It is the picador who rides on horseback to invite with his lance the attacks of the bull as he enters the arena; it is the capeador who springs into the arena with his cloak of maddening red or yellow, to distract the bull’s attention from the fallen horseman; it is the banderillo who taunts the wounded creature with metal-tipped arrows, the barbs of which cannot be extracted, or with his long pole leaps tauntingly over the back of the confused creature; but it is the gorgeous espado with his sword, entering the arena, at last, who draws all eyes. With his red flag he plays with the bull as a cat with the mouse, until the amphitheatre is mad for life blood; then with a swift, graceful stroke he ends all, his superb foe lies dead, and he turns from him to meet the wild shower of hats, cigars, flowers, fans, purses that beats upon him from all sides—it is a scene of unimaginable exultation, for there are glad cries and plaudits, and royalty itself throws the bull-slayer a golden purse and a pleased smile, and the beautiful Spanish señoritas lavish upon him the most bewildering attentions.

The Spanish boy is born with a thirst for this sport. Their favorite game is Toro. One lad mounts on his fellow’s back to take the part of the picador and his horse; another, with horns of sticks, represents the bull; and the rest are capeadors, banderillos, and escodas, while the audience of adult loungers look on with fierce excitement. It is in this fierce, popular street sport that the future champions of the Bull Ring are trained and developed—to be an escoda is usually the height of a Spanish boy’s ambition.

NOWHERE in Spain are you refreshed with the restful sound of water, sometimes soft, sometimes gay, as in Granada. You hear the flow of the Darro over its stones and rocks, you hear the splash of fountains, the gay hurry of mountain brooks, the soft sound of springs—everywhere flow, or gurgle, or drip. You hear it on the tree-bordered and bowered Alameda in your moonlit walks, and you hear it through the windows of your fonda, or hotel, when you wake. It is everywhere about the Alhambra heights, and the Generalife terraces. The Spaniards call this continuous water-sound, “The Sigh of the Moor.”

Most of the young Spanish women as well as the men, are accomplished guitar-players. The guitar belongs in story to the Señorita, along with her mantilla and her fan. It usually hangs on her casement, brave with ribbons and gay wool tufts and all manner of decorations, and by moonlight she will come out upon the balcony to answer her cavelier’s serenade with a song as sweet as his own. You feel the atmosphere of the Spanish night vibrating all about you, as you stroll along the moonlit street, with the low, soft, delicate twinkle of a hundred guitars, the players half-hidden in the dim patio balconies.

It is often the custom to drive the goats from door to door to be milked, and often an accustomed goat, tinkling its bells, will go along the street, stopping of its own will and knowledge at the doors of its customers, and knocking smartly with its horns should no one appear. The servant of the house comes out into the street and milks the desired quantity, while the “milkman” lounges near by with his cigarette.

Often it is as amusing to watch the dogs of the beggars by the churches as the men themselves. While the noble Caballeros, Don Miguel and Don Pedro, exhausted with the saying of prayers and the much asking of centimos, have fallen asleep in the shade, their respective dogs remain awake to glare at each other with true professional jealousy, and to growl and snap, should a chance stranger drop a coin in one hat and not in the other. The beggar is the last sight, as well as the first, which greets the traveler in Spain.

BY MARY STUART SMITH.

QUEEN LOUISA of Prussia was the mother of William I., Emperor of Germany, and although she has been dead over sixty years her one hundredth birthday was celebrated elaborately throughout her son’s dominions, with almost as many rejoicings as we made here over the one hundredth birthday of these United States.

When a child Louisa was very beautiful, and as she grew up did not disappoint the promise of those early days.

She was married to Frederick William, Crown Prince of Prussia, when only seventeen years of age, and brought down upon herself a sharp rebuke from the proud mistress of ceremonies for the love she showed to a little child as she was making her public entry into Berlin, preparatory to the solmnization of her marriage. It happened thus:

The streets were thronged with people who had come to catch a glimpse of the fair young bride, while every now and then select persons would step forward and present complimentary poems of welcome, or some pretty gift. A sweet little girl advanced to give the queen a bunch of flowers, and Louisa was so struck with the child’s loveliness that she stooped down and kissed her on the forehead. “Mein Gott!” exclaimed the horrified mistress of ceremonies. “What has your majesty done?” Louisa was as artless and simple as a child herself. “What?” said she, “is that wrong? Must I never do so again?”

But the prince, her husband, was no fonder of show and ceremony than herself, and asserted manfully the right of his wife and himself to act like other affectionate people, in spite of being king and queen.

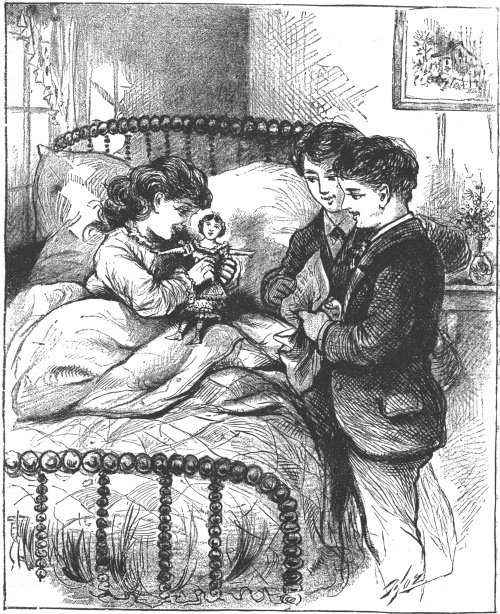

QUEEN LOUISA.

This royal pair had eight children, and upon these children was lavished every care and attention. It is said that every night the king and queen went together to visit their sleeping children after they had been put into their little beds, and many a time were they surprised by a bright pair of wide-awake eyes smiling back upon them a look of love in return. Queen Louisa used to say, “The children’s world is my world,” nor were the little creatures slow to reciprocate the love she gave.

You know Christmas is observed in Germany with peculiar reverence, and is a season set apart for mirthful recreation among all classes, but more especially for the enjoyment of children. Berlin is gay with Christmas trees and a brilliant array of toys etc., for at least a week beforehand.

Like other parents the king and queen found delight in preparing pleasant surprises for their little ones. While engaged in choosing presents for them, on one occasion they entered a top-shop where a citizen’s wife was busy making purchases, but recognizing the new-comers she bowed respectfully and retired. The queen addressed her in her peculiarly winning way and sweet voice. “Stop, dear lady, what will the stall-keeper say if we drive away his customers?” She then inquired if the lady had come to buy toys for her children, and asked how many little ones she had. Hearing there was a son about the age of the Crown Prince, the queen bought some toys and gave them to the mother, saying, “Take them, dear lady, and give them to your crown prince in the name of mine.”

But I must tell you a yet prettier story, showing the queen’s fondness for making children happy.

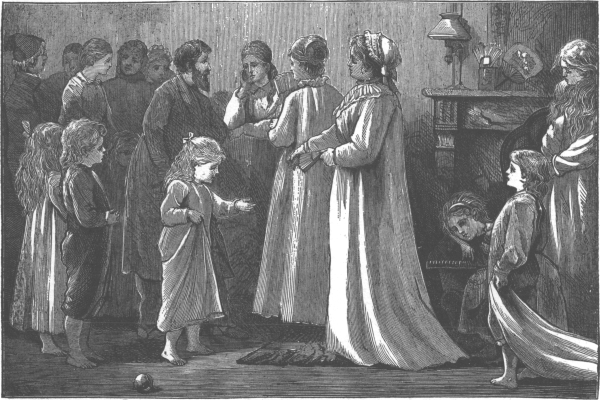

There lived in Berlin a father and mother, who from some cause were so poor, and low-spirited besides, that when the holiday came which all children love best, they quietly resigned themselves to having nothing to give their little ones. What can be more sad than a house which no Kriss Kringle visits? Just think of it! They told their children that there was to be no Christmas tree for them this year. The little boy and his sister had been led to believe that the Christ-kind or Christ-child provides the tree and the gifts which are placed on tables round it; only ornaments, sweets and tapers are hung upon the branches. Under this disappointment the children, in the innocent simplicity of their faith, sought the aid of the good Christ-kind in their own way.

Christmas Eve came, and the poor troubled parents looked on with wonder as they beheld their children hopping and skipping about with joy, although they were to be the only children for whom no Christmas tree would be lighted, nor pretty gifts provided. Still in high spirits they watched at the window, and clapped their hands when the door-bell rang, exclaiming: “Here it comes!” The door was opened and a man-servant appeared, laden with a gay tree and several packets, each addressed to some member of the family.

“There must be some mistake!” said the mother.

“No, no!” cried the boy, “it is all right. I wrote to the good Christ-kind, and told him what we wanted, and that you could not buy anything this year.”

The parents enjoyed the evening with their children and afterwards unravelled the mystery. The postmaster, astonished by a letter evidently written by a very young scribe and addressed to the Christ-kind, had sent it to the palace with a respectful inquiry as to what should be done with a letter so strangely directed. Queen Louisa read it and, as a handmaid of the Christ-kind, she answered his little children.[1]

[1] Mrs. Hudson’s Life of Queen Louisa.

Louisa’s sympathies were ever ready to flow for the sorrows of childhood, which so many grown people will not stoop to even notice.

One day as the king and queen were entering a town, a band of young girls came forward to strew flowers and to present a nosegay. Her majesty inquired how many little girls there were. “Nineteen,” replied the artless child; “there would have been twenty of us but one was sent back home because she was too ugly.”

The kind queen feeling for the child’s mortification sent for her and requested that she might by all means be allowed to join in the festivities of the day.

Nor did Louisa slight the boys.

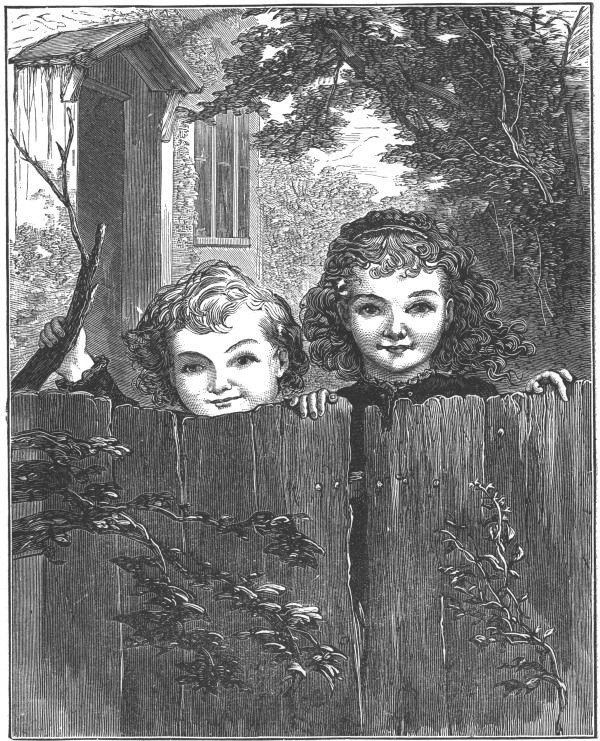

She was one day walking in the streets of Charlottenburg, attended by a lady-in-waiting; a number of boys were running and tumbling and playing somewhat rudely, and one of them ran up against the queen. Her lady reproved him sharply, and the little fellow looked frightened and abashed. The queen patted his rosy cheek, saying: “Boys will be a little wild; never mind, my dear boy, I am not angry.” She then asked his name and bade him give her compliments to his mother. The child knew who the lady was, and besides having the pleasant memory of her gracious speech and looks received a lesson in politeness which he never forgot.

Sometimes the royal children were allowed to have a party, and this indulgence young princes and princesses enjoy just as much as other juveniles. A queer anecdote is told of the only daughter of the famous Madame de Stael, in relation to one of these entertainments.

The little lady was about ten years of age, but had already imbibed many opinions and prejudices. At all events she had a high idea of her own importance, and was totally wanting in respect for her superiors in rank. She was apt to be very rude in her manners and in her remarks. On this occasion she took offence at something which the little Crown Prince said or did to her, and very coolly gave him a sharp box on the ear, upon which he ran crying to his mother and hid his face in the folds of her dress. As mademoiselle, when remonstrated with, showed not a particle of concern, and refused to say she was sorry, she was not invited again, and her learned mamma found that she must keep her daughter at home until she taught her better manners.[2]

[2] Sir George Jackson.

The annual fair at Paretz, the king’s beloved country home, took place during the merry harvest-time. A number of booths were then put up near the village, and besides buying and selling there was a great deal or dancing and singing going on, and all sorts of games and sports. It was then that the wheel of fortune was turned for the children’s lottery. Lots of cakes and fruit were set round in order, which were given away according to the movements of a pointer, turned by the wheel.

Queen Louisa encouraged the children to crowd around her on these occasions; she could not bear to see them afraid of her, and placed herself beside the wheel, in order to secure fair play and to watch carefully that she might make some amends for the unkindness of fortune. She had her own ample store of good things which she dispensed among the unlucky children, many of whom thought more of the sweet words and looks of the queen than of anything else she could give them. Moreover she was glad to have a chance of leading even one of her little subjects to be generous and self-denying. For, while she liked to see them all happy, she at the same time interested herself in giving pleasantly little hints as to conduct that might be of lasting benefit.

All her life Queen Louisa watched beside the wheel in a higher sense. She overlooked the whole circle of which she was the centre, anxiously seeking to hold out a helping hand to any whom she saw likely to be ruined by losses in the great lottery of real life.

Is it matter for wonder then that German children still cherish her memory, and delight to place flowers upon vase or tomb that bears her name?

BY M. S. P.

DOUBTLESS the readers of Grammar School have heard it said that “Men and Women are only children of a larger growth.” No matter how stately the grand ladies that we often meet with may appear, you may be very sure that they sometimes envy the pleasures of children, who have no thoughts about fine houses and servants, and a hundred other cares. Even wearing a crown does not bring happiness; the dignity it entails often becomes burdensome.

Once a young prince, who had everything that he could possibly want given him,—books, jewels, playthings of inconceivable variety, horses and dogs, in fact all the nice things that you can imagine to bring him pleasure,—was observed by his attendants to be standing by the window, crying. When asked the cause of his tears he replied that he was unhappy because he could not join the boys in the street who were making mud pies!

The Indians who use the bow and arrow say that the proper way to keep the strength of their bows is to unstring them after use and let them relax. So it is with those whose minds or bodies are engaged in one long strain of work; they must be relaxed or they become useless. The late Pope of Rome was a very dignified old man, and was also surrounded by learned and great men. He rode in a gilded coach drawn by four horses, and was in public a very grand and stately person. But I read the other day that the old gentleman and some of his cardinals were once seen playing ball in his garden, for the purpose of amusing a little boy.

More than a hundred years ago the great country east of Germany, known as Russia, was ruled by the Empress Anne. It is a very cold country and the winter is very long. The capital is St. Petersburg, and through it the river Neva runs. This river freezes in winter, and the ice is frequently so solid that it will bear up an army of several thousand men with all their heavy guns and mortars, and these be discharged without so much as cracking the ice.

At the close of the year 1739, during an extremely cold winter, the empress ordered one of her architects to build an Ice Palace. The great square in front of the royal palace was chosen for its site. Blocks of the clearest ice were selected, carefully measured and even ornamented with architectural designs. They were raised with cranes and carefully placed in position, and were cemented together by the pouring of water over them. The water soon froze and made the blocks one solid wall of ice. The palace was fifty-six feet long, seventeen and one half feet wide, and twenty-one feet high. Can you imagine anything more beautiful than such a building made of transparent ice and sparkling in the sun?

It was surrounded by a balustrade, behind which were placed six ice cannon on carriages. These cannon were exactly like real metal ones, and were so hard and solid that powder could be fired in them. The charge used was a quarter of a pound of powder and a ball of oakum. At the first trial of the cannon an iron ball was used. The empress with all her court was present, and the ball was fired. It pierced a plank two inches thick at a distance of sixty feet.

Besides these six cannon in front of the palace there were two ice mortars which carried iron balls weighing eighty pounds with a charge of one quarter of a pound of powder. Then, too, there were two ice dolphins, from whose mouths a flame of burning naptha was thrown at night with most wonderful effect. Between the cannon and dolphins, in front of the palace, there was a balustrade of ice ornamented with square pillars. Along the top of the palace there was a gallery and a balustrade which was ornamented with round balls. In the centre of this stood four beautiful ice statues.

The frames of the doors and windows were painted green to imitate marble. There were two entrances to the palace, on opposite sides, leading into a square vestibule which had four windows. All the windows were made of perfectly transparent ice, and at night they were hung with linen shades on which grotesque figures were painted, and illuminated by a great number of candles.

Before entering the palace one naturally stopped to admire the pots of flowers on the balustrade, and the orange trees on whose branches birds were perching. Think of the labor and patience required to make such perfect imitations of nature in ice!

Standing in the vestibule, facing one entrance and having another behind, one could see a door on either hand. Let us imagine ourselves in the room on the left. It is a sleeping-room apparently, but if you stop to think that every article in it is made of ice you will hardly care to spend a night there; and yet it is said that two persons actually slept on the bed there for an entire night. On one side is a toilet-table. Over it hangs a mirror, on each side of which are candelabra with ice candles. Sometimes at night these candles were lit by being dipped in naptha. On the table is a watch-pocket, and a variety of vases, boxes, and ornaments of curious and beautiful design. At the other side of the room we see the bed hung with curtains, furnished with sheets and a coverlid and two pillows, on which are placed two night-caps. By the side of the bed on a foot-stool are two pairs of slippers. Opposite the bed is the fireplace which is beautifully carved and ornamented. In the grate lie sticks of wood also made of ice, which are sometimes lighted like the candles by having naptha poured over them.

The opposite room is a dining-room. In the centre stands a table on which is a clock of most wonderful workmanship. The ice used is so transparent that all the wheels and works are visible. On each side of this table two beautifully carved sofas are placed, and in the corners of the room there are statues. On one side we see a sideboard covered with a variety of ornaments. We open the doors and find inside a tea-set, glasses and plates which contain a variety of fruits and vegetables, all made of ice but painted in imitation of nature.

Let us now go through the opposite door and notice the other curious things outside the palace. At each end of the balustrade we see a pyramid with an opening in each side like the dial of a clock. These pyramids are hollow, and at night a man stands inside of them and exhibits illuminated pictures at the grand openings.

Perhaps the greatest curiosity of all is the life-like elephant at the right of the palace. On his back sits a Persian holding a battle-axe, and by his side stand two men as large as life. The elephant, too, is hollow, and is so constructed that in the daytime a stream of water is thrown from his trunk to a height of twenty-four feet, and at night a flame of burning naptha. In addition to this, the wonderful animal is so arranged that from time to time he utters the most natural cries. This is done by means of pipes into which air is forced.

On the left of the palace stands a small house, built of round blocks of ice resembling logs, interlaced one with another. This is the bath-house, without which no Russian establishment is complete. This bath-house was actually heated and used on several occasions.

When this wonderful ice-palace was completed it was thrown open to the public, and such crowds came to see it that sentinels were stationed in the house to prevent disorder.

This beautiful palace stood from the beginning of January until the end of March. Then, as the weather became warmer, it began to melt on the south side; but even after it lost its beauty and symmetry as a palace it did not become entirely useless, for the largest blocks of ice were transferred to the ice-houses of the imperial palace, and thus afforded grateful refreshment during the summer, as well as a pleasant reminder of “The Plaything of an Empress.”

BY CHARLES E. HURD.

CHARLIE was going to Boston.