Title: The Boy's Book of the Sea

Author: Eric Wood

Release date: March 13, 2022 [eBook #67614]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1915

Credits: Brian Coe, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

“Shells fell upon her like hailstones, sweeping her decks, crashing into her sides.... She was on fire”

BY

ERIC WOOD

Author of “The Boy’s Book of Heroes,” “The Boy Scouts’ Roll of Honour,”

etc., etc.

WITH FOUR COLOUR PLATES AND TWELVE

ILLUSTRATIONS IN BLACK-AND-WHITE

NEW YORK

FUNK AND WAGNALLS COMPANY

| PAGE | |

| Naval Warfare—Old and New | 1 |

| A comparison of ancient and modern naval warfare is most interesting, and here, in the stories of the Battles of Trafalgar and the Bight of Heligoland, the comparison—nay, contrast—is particularly striking. | |

| The Men who Discovered the World | 29 |

| The men who ventured forth on the unknown seas laid the foundations of nations and commerce, and opened up new worlds; and the stories of their voyages are amongst the finest in the world’s history. | |

| Some Early Buccaneers | 45 |

| The glamour of romance has been thrown around the buccaneers, and not unjustly, for anything more romantic—not to say exciting—it would be hard to imagine than the story of those men who, from being hunters of wild animals, became scourers of the seas: heroic ruffians! | |

| Morgan: Buccaneer and Governor | 57 |

| Sir Henry Morgan, most renowned of the buccaneers, was a born leader of men and a doer of mighty deeds. He would have made a capital admiral or general; as it was, he was merely a buccaneer, who later forsook that profession for the safer one of Governor of Jamaica. | |

| Under the Jolly Roger | 76 |

| Who has not read with many a thrill the imaginative stories of pirates? But no novelist can conceive anything more dramatic than the deeds of the real pirates whose tales are told here. | |

| Blockade Running | 94 |

| For peril, adventure, and courage blockade running would be difficult to beat, and the man who succeeds in slipping through earns all the money that he gets. | |

| Adventures on a Desert Island | 102 |

| The life and adventures of our old friend Robinson Crusoe have always entertained us—old and young; but we have no need to go to fiction to find adventures quite as thrilling as any poor old Robinson Crusoe experienced. Here is a tale of shipwrecked and castaway mariners. | |

| Adrift with Madmen | 113 |

| When the “Columbian” was burnt in the Atlantic one of her boats, laden with sixteen men, was adrift for thirteen days—days of terror, in which men went mad from thirst. | |

| Francis Drake’s Raid on the Spanish Main | 122 |

| Drake and Hawkins went slave-trading on the Main, and, having been played a treacherous trick by the Spaniards, a few years later Drake went back to take his revenge; and though ill-luck stepped in and kept him from doing all he would, yet he exacted good toll, and came back well pleased. | |

| A Gallant Fisherman | 140 |

| The men who garner the harvests of the seas have a perilous, adventurous life; here is a fisherman’s yarn of heroism. | |

| Fire at Sea | 145 |

| There are few things more terrible than fire at sea, where salvation depends, not on outside help, but on the resource and heroic work of the endangered sailors. | |

| Romance of Treasure-Trove | 158 |

| Scattered about the Seven Seas are islands on which tradition has it that vast hoards of treasure have been hidden; and men have fitted out expeditions to find them. Sometimes they are successful—sometimes not. | |

| Adventures Under Sea | 166 |

| Father Neptune’s kingdom down below has been invaded by presumptuous man, who not only goes upon the sea in ships, but under as well; while when the need arises he doesn’t even bother about a ship! These are stories of divers and submarines. | |

| Chasing Pirates in the China Sea | 177 |

| Some tales of modern pirating. | |

| A Voyage of Danger | 186 |

| Of all the chapters in the sea’s history few are more thrilling than those which tell of mutiny, and the affair of the “Flowery Land” is a classic. | |

| The Guardians of the Coast | 196 |

| Coastguards and lighthousemen are hardy, noble men, whose duties are manifold and arduous. Here are some stories of the men who keep watch and ward over the coasts, and in the doing of it win for themselves glory. | |

| Great Naval Disasters | 206 |

| The Loss of the “Formidable” (1915) and the “Victoria” (1893). | |

| Incidents in the Slave Trade | 219 |

| Although Britain spent millions of pounds to put down the slave trade, yet she also had to spend the lives of many gallant sailors before the work was done. | |

| A Race to Succour | 226 |

| A story of a brilliant achievement by American revenue men and lifeboatmen. | |

| A Tragedy of the South Pole | 233 |

| The quest of the South Pole lured men for years to the ice-bound regions of the earth, and at last success crowned the efforts which cost life and treasure and gave undying honour to the conquerors. | |

| Stories of the Lifeboat | 247 |

| The lifeboatmen are the saviours of men who sail the seas, and their story is one of sublime indifference to death and of glorious heroism. | |

| Tales of the Smugglers | 260 |

| Stories of smugglers have always had a fascination, and these incidents of smuggling days are full of thrill and virility. | |

| Modern Corsairs | 274 |

| When the Great War of 1914 turned the armed hosts of Europe loose, the British Navy found before it a gigantic task: the keeping open of the trade routes. German cruisers and armed liners swept hither and thither, holding up merchant vessels, as the privateers of olden days did; and the “Emden” and the “Königsberg,” etc. became the corsairs of the twentieth century. | |

| The Wreckers | 282 |

| False lights that lured the mariner astray and on to the rocks; bold, unscrupulous men who lay in wait for the ships to run to their doom; the looting of vessels rendered helpless—all these things and many others go to make up thrilling chapters in the story of the sea. | |

| The Tragedy of a Wonder Ship | 295 |

| The “Titanic” was the finest ship in the world. She was pronounced unsinkable—but, out of the night there loomed an iceberg which ripped her plates asunder like so much paper, and the safest ship in the world dived beneath the surface with hundreds of unfortunate passengers and crew. | |

| Mysteries of the Sea | 309 |

| Queer stories of ships that disappeared. | |

| COLOUR PLATES | |

| “Shells fell upon her like hailstones, sweeping her decks, crashing into her sides. She was on fire” | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| “Sword in hand, Roberts led his men to the fight, dashing through a very hail of shot” | 90 |

| “The funnels and ventilators were belching forth mighty columns of flame, every part of the ship was ablaze” | 150 |

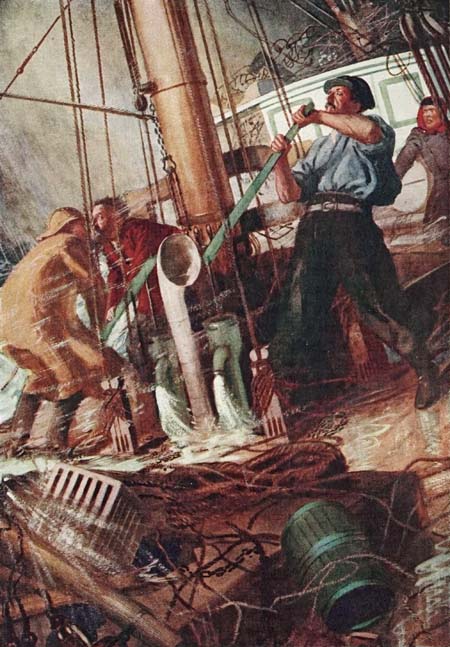

| “Though her men worked hard at the pumps, they could not save her” | 226 |

| BLACK-AND-WHITE PLATES | |

| FACING PAGE | |

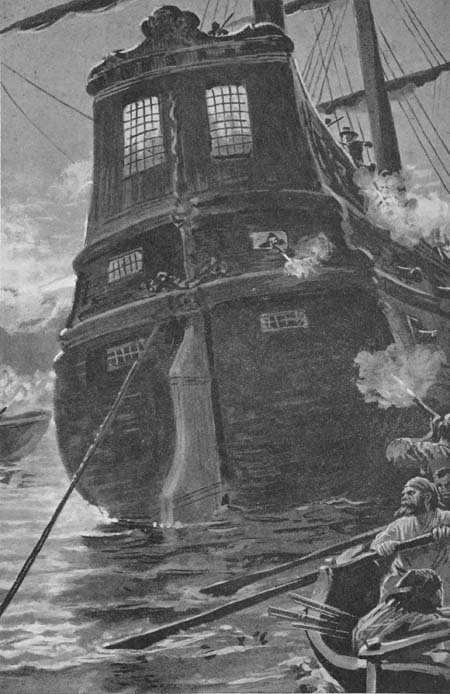

| “Kennedy, with a couple of middies and fewer than thirty men, rushed aboard” | 8 |

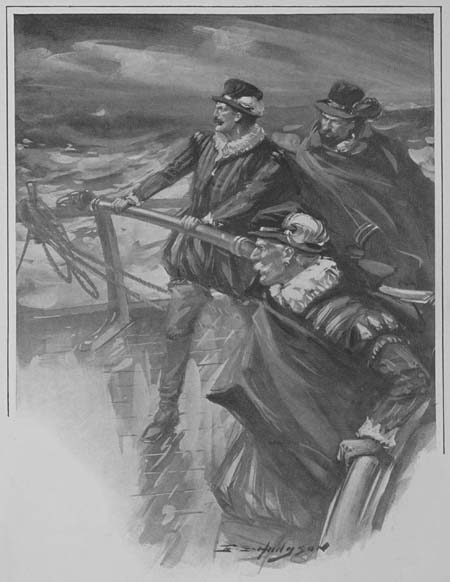

| “A mighty gale caught Diaz, and carried his frail craft before it” | 30 |

| “Promptly boarded the Vice-Admiral. ‘Surrender!’ yelled the Buccaneers” | 50 |

| “There was a whoosh! whoosh! of a rocket heavenwards—the warning to the blockading fleet” | 94 |

| “Weybhays and his men fell upon the pirates” | 108 |

| “‘For the honour of the Queen of England, I must have passage this way!’ cried Drake, and discharged his pistol” | 134 |

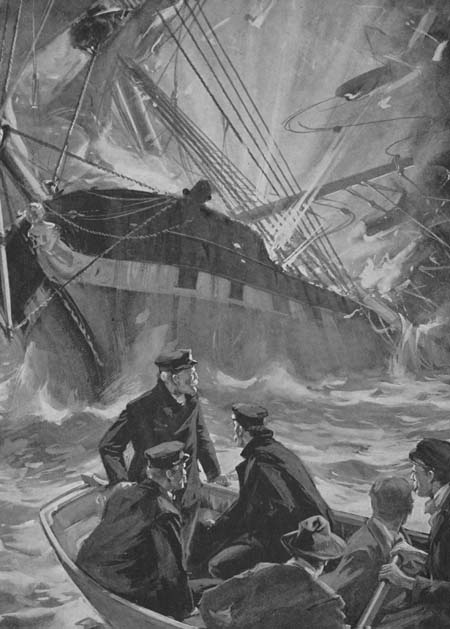

| “The ship was now in one blaze, and her masts began to fall in” | 154 |

| “Swinging from this side to that as he was attacked, the diver managed to ward off the tigers of the deep” | 176 |

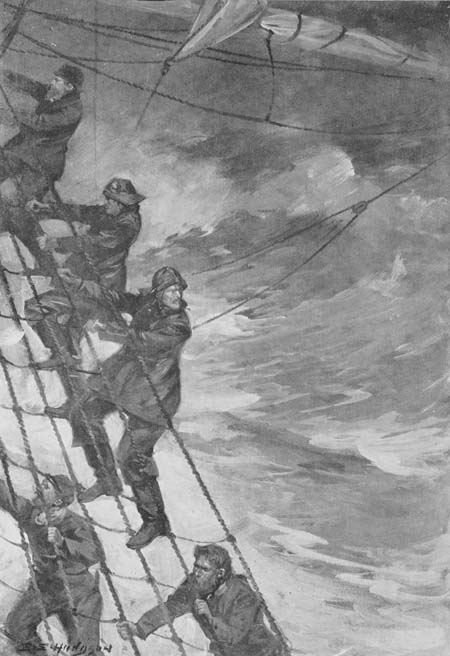

| “To the rigging they fled, scrambling up in frenzied haste” | 200 |

| “It was simply agonising to watch the wretched men struggling over the ship’s bottom in masses” | 216 |

| “She fought bravely against the tumult, but was driven back again and again” | 250 |

| “Men, strong-limbed, full-blooded, with the zest and the love of life in them, stood calmly by” | 300 |

THE BOY’S BOOK OF THE SEA

Trafalgar and Modern Fights in the North Sea

NOT the least remarkable of the changes which have taken place during the last hundred years—it is less than that, really—are those which have come to pass in the sphere of warfare; and the accounts of the battles here given show how different naval fighting is to-day from what it was in Nelson’s time. Then wooden ships, now steel leviathans; then guns that fired about 800 yards, now giant weapons that hit the mark ten miles off; then close fighting, boarding, hand-to-hand conflicts, now long-range fighting, with seldom, if ever, a chance to board. Then shots that did what would be considered little damage beside that wrought by the high-explosive shells which penetrate thick armour-plate, and which, well-placed, can send a ship to the bottom. Then none of those speeding death-tubes, the torpedoes, which work such dreadful havoc with a floating citadel; then casualties in a whole battle no more than those suffered by a single ship nowadays. And so one could go on, touching on wireless telegraphy, fire-control—that ingenious system which does man’s work of sighting the guns—aircraft and submarines, which constitute so serious a factor in present-day warfare. But the story of[2] Trafalgar, that well-fought battle against a noble foe who is now a gallant ally, and those of the North Sea, 1914 and 1915, will show the revolutions in modern naval warfare.

Nelson had determined to meet and beat Villeneuve, in command of the allied French and Spanish fleet, which left Cadiz at the end of September, 1805. The French admiral did not know how near Nelson was. To-day the means of communication are vastly different, and battleships are able to discover the proximity of their foes much more easily than in those other days. It is one of the great changes in naval warfare. So it was that the allied fleets were dogged until Nelson decided it was time to strike.

On the 21st the rival fleets met. The English fleet was in order of battle—two lines, with an advanced squadron of eight fast-sailing two-deckers. Nelson, in the Victory, led one column, Collingwood, in the Royal Sovereign, the other.

About half-past eight Villeneuve ordered his fleet to draw up in such array and position that, if necessary, they could make for Cadiz; but the manœuvre was badly executed, and the fleet assumed a crescent-shaped formation, into which the English columns were sailing.

Nelson was longing for the fight; so were his men. But, although the officers on board the Victory were eager for the fight, they would have been content to forgo the honour of opening the fight in favour of some other ship, fearing lest Nelson should be killed.

Nelson was asked: “Could not the Temeraire take the foremost place of the column?”

Nelson replied:

“Oh, yes, let her go—if she can!”

Captain Hardy hailed the Temeraire to give her instructions; but, meanwhile, Nelson was moving[3] about the decks giving orders that made the Victory leap forward and hold her place in the vanguard.

“There!” he said to Hardy, as he came back. “Let the Temeraires open the ball, if they can—which they most assuredly can’t! I think there’s nothing more to be done now, is there, till we open fire? Oh, yes, stay a minute, though. I suppose I must give the fleet something as a final fillip. Let me see. How would this do: ‘Nelson expects that every man will do his duty?’”

Hardy suggested that “England expects” would be an improvement. Nelson agreed. The order was given; and the message was soon fluttering in the breeze.

What shouts of enthusiasm greeted the signal in Trafalgar’s Bay! Every man took it as a message to himself, and forthwith vowed to do what was expected of him.

“Now,” said Nelson. “I can do no more. We must trust to the great Disposer of events and the justice of our cause. I thank God for this opportunity of doing my duty!”

For all his apparent good spirits the Admiral had a foreboding of impending ill, and when Captain Blackwood left him to take up his place on the Euryalus, the Admiral gripped him by the hand and said:

“God bless you, Blackwood! I shall never see you again.”

The battle was opened by the French ship Fougueux, which fired upon the Royal Sovereign.

“Engage the enemy more closely,” was now Nelson’s signal, and the English closed in upon the foe. Collingwood broke through the enemy’s line astern the Santa Anna. He reserved his fire until he was almost at the muzzles of their guns, then, with a roar, his port broadside was hurled at the Santa Anna, and four[4] hundred men fell killed and wounded, and fourteen of the Spaniard’s guns were put out of action.

The starboard guns spoke to the Fougueux at the same time. Owing to the dense smoke and the greater distance, the damage done was not so great.

“By Jove, Rotherham!” cried Collingwood to his flag-captain. “What would Nelson give to be here?”

“And,” says James in his Naval History, “by a singular coincidence Lord Nelson, the moment he saw his friend in his enviable position, exclaimed: ‘See how that noble fellow Collingwood carries his ship into action.’”

Collingwood now pressed still closer on the Santa Anna, and a smart battle began between the two great ships, till four other ships bore down upon the Royal Sovereign, so that she was very soon the centre of a ring of fire. So close were the ships, and so continuous was the fire, that often cannon-balls met in mid-air, though more frequently they fell on board and did much damage. Badly aimed shots often passed over the Royal Sovereign, and found their mark on the decks of French or Spanish vessels. Presently the four new-comers veered off when they noticed that other British ships were bearing down upon them.

With a roar the British Belleisle sent a broadside into the Santa Anna as she passed; and then Collingwood was alone with his foe. For over an hour the duel raged, and the Royal Sovereign, although she carried a dozen guns fewer than the Santa Anna, suffered less. Battered, mastless, with hundreds of men lying in pools of blood, the Santa Anna still fought on, refusing for a long time to strike her colours. At last, however, there was nothing for it but to give in, and the Spanish flag fluttered down the mast.

When the battle began the foe opened fire at the[5] Victory, which they knew was Nelson’s flagship. The English Admiral had made sure that he should not be lost sight of, for he had hoisted several flags lest one should be carried away. The Victory’s maintopgallant sail was shot away, and broadsides were hurled at her, but still she kept on.

Nelson wished to encounter Villeneuve, and, despite a raking fire poured in upon him by the Santissima Trinidad, he kept on his way, taking the Victory into the thick of the fight. He refused to have the hammocks slung higher lest they should interrupt his view, although they would have afforded shelter from the enemy’s fire. Men dropped all about the ship, shots ploughed up the deck or bored their way through the sides, yet the gallant Victory held on her way for the Bucentaure, which Nelson knew carried Admiral Villeneuve.

Eight ships, however, surrounded her, and made it impossible for the Victory to be brought alongside. These, belching forth their heavy fire at her, smashed her wheel, hurled her mizzen-mast overboard, shattered her sails. The wind had dropped, too; the Victory was almost at a standstill, and it was impossible to bring a gun into action.

Pacing his quarter-deck Nelson waited for his time to come. While doing so, a shot passed between him and Hardy, bruising the latter’s foot, and tearing the buckle from his shoe. Both stopped in their promenade, looking anxiously at each other.

“This is too warm work to last long, Hardy,” said Nelson.

“The enemy are closing up their line, sir,” said Hardy. “See! We can’t get through without running one of them aboard!”

“I can’t help that,” said Nelson, “and I don’t see[6] that it matters much which we tackle first. Take your choice. Go on board which you please.”

Villeneuve on the Bucentaure was therefore given a treble-shotted, close-range broadside, which disabled four hundred men and put twenty guns out of action, and left the ship almost defenceless.

Then, porting his helm, Nelson bore down on the Redoutable and the Neptune. The latter veered off, but the former could not escape the Victory, which she therefore received with a broadside. Then, fearing that a boarding party would enter her, the lower deck ports were shut. Meanwhile the Temeraire had fastened on to the Redoutable on the other side, and the most momentous episode in that great day’s work took place. In it we can see the difference between the naval fighting of a century ago and that of to-day, the latter being fought at long range, with no attempt at boarding.

The Victory’s guns were depressed so that they should not do damage to the Temeraire, and broadside after broadside was poured into the Redoutable, which made a brave show. The two ships were almost rubbing sides (now we fight at eight-mile range or more!), and men stood by the British guns with buckets of water in their hands, which, immediately the guns were fired, they emptied into the hole made in the Redoutable’s side lest she should catch fire, and so the prize be lost.

In the Redoutable’s top riflemen were posted, and throughout the fight picked off man after man—a practice which Nelson himself abhorred. It was from one of these snipers that the great Admiral received his death-wound.

While pacing the poop deck, Nelson suddenly swung round and pitched forward on his face. A ball had entered in at the left shoulder, and passed through his backbone.

[7]Hardy, turning, saw three men lifting him up.

“They have done for me at last, Hardy,” Nelson said feebly.

“Oh, I hope not!” cried Hardy.

“Yes,” was the reply; “my backbone is shot through!”

The bearers carried him down the ladders to the lower deck. On the way, despite his awful agony, Nelson had thoughts for nothing but the battle; he ordered that new tiller ropes should be rigged to replace those which had been shot away at the moment the Victory had crashed into the Redoutable. Then, that they might not recognise him, he covered his face and stars with his handkerchief.

They carried him into the cockpit. We will leave him, and return to the conflict.

The men in the Redoutable’s top still kept up their galling fire, as also did the guns of the second deck, and in less than fifteen minutes after Nelson had been shot down, no fewer than fifty of the Victory’s officers and men had met a like fate.

Then the French determined to board. As it was impossible to do this by the bulwarks, they lowered their main yard and turned it into a bridge, over which they scrambled on to the deck of the Victory.

“Repel boarders!”

It was a cry like that of a wild beast, and it brought the lion’s whelps from the lower decks. They hurled themselves at the venturesome Frenchmen. With pistol and pike, cutlass and axe, the English fought with the ferocity that had made them so dreaded in the past; when other weapons failed they fought with bare fists, hurling the trespassers overboard.

It cost the Victory thirty men to repel that attack. But it cost the Redoutable more; and very soon not[8] a Frenchman was left alive on the decks of Nelson’s ship.

As we have said, while the Victory was engaging the Redoutable on one side, the Temeraire was tackling her on the other, the three ships hugging each other with muzzles touching muzzles. Soon after the attempt to board the Victory, the Temeraire lashed her bowsprit to the gangway of the Redoutable so that she could not escape. Then she poured in a raking fire until the Frenchman was compelled to surrender, though not before she had twice been on fire, and more than five hundred of her crew had been killed or wounded.

Some of the Temeraire men then turned to deal with the Fougueux, which had attacked her during the fight with the Redoutable.

Captain Hardy was too busy with the Redoutable to do much; but Lieutenant Kennedy quickly set a party to man the starboard batteries. With these they opened fire at about one hundred yards, and crash! the Fougueux’s masts fell, her wheel was smashed, her rigging shattered, and she was so crippled that she ran foul of the Temeraire, whose crew lashed their foe to them, and Kennedy, with a couple of middies and fewer than thirty seamen and marines, rushed aboard her.

Five hundred Frenchmen were still fresh for battle on the Fougueux, but the Britishers did not hesitate. With a bound they were on the enemy’s deck, and, slashing and hacking at the crowd that came up against them, drove them back and still back. Dozens were killed and others leapt overboard to escape the whirlwind that had fallen upon them. The remainder scuttled away below, the English clapped the hatches on them, and the ship was won.

“Kennedy, with a couple of middies and fewer than thirty men, rushed aboard”

Meanwhile the Victory had been pouring a heavy[9] fire into the Santissima Trinidad on one side and the Redoutable on the other. Through and through the former was raked, her deck swept clear of men, until the Spaniards dived overboard and swam off to the Victory, whose crew helped them aboard.

The Belleisle, which had hurled her broadside into the Santa Anna early in the conflict, had been pounced upon by about half a dozen ships of the enemy, which poured in a deadly fire, battering her sides, tearing her rigging to pieces, and twisting her mizzen-mast over the aft guns, putting them out of action. Sixty men also had been sent to their account, but the rest fought on with British courage.

The Achille bore down upon her and attacked her aft, the Aigle, assisted by the Neptune, fell on her starboard, aiming at her remaining masts and bringing them down.

“Crippled, but unconquered,” masts gone by the board, nearly all the guns useless, men mostly killed or wounded, the Belleisle’s few remaining men stood to their three or four guns and hurled defiance at the foe. Pounding away for all they were worth, not a man flinched—except at the thought that the flag had been shot away. They fastened a Union Jack to a pikehead, waved it defiantly, yelled out a cheer of determination, and fought on again, keeping their ship in action throughout the battle, refusing to strike the pikehead flag.

The English Neptune assailed the Bucentaure, and brought her main- and mizzen-masts down; then the Leviathan came up, and at a range of about thirty yards gave the French flagship a full broadside which smashed the stern to splinters. The Conqueror completed the work thus begun, and brought down the flag.

A marine officer and five men put off from the[10] Conqueror to take possession. Villeneuve and two chief officers at once gave their swords to the officer, who, thinking that the honour of accepting them belonged to his captain, refused the weapons, put the Frenchmen in his boat, pocketed the key of the magazine, left two sentries to guard the cabin doors, and then pulled away to rejoin his ship. For some time the little boat searched for the Conqueror, which had gone in quest of other foes. Eventually, however, the boat was picked up by the Mars, whose acting commander, Lieutenant Hennah, accepted the surrendered swords, and ordered Villeneuve and his two captains below.

The Leviathan next tackled the Spanish San Augustino, which opened fire on her at a hundred yards. The Leviathan replied with fine effect, bringing down the Spaniard’s mizzen-mast and flag. Then she lashed herself to her foe. Clearing the way for boarders by a galling fire, the English captain sent across his boarding party. A hand-to-hand fight took place, and the Spaniards were steadily but surely forced over the side or below, and at last the ship was won.

The French Intrépide, seeing the plight of her ally, now bore down on the Leviathan, raking her with fire as she came, and getting her boarders ready for attack. They did not board, for the Africa pitted herself against the Intrépide, and smaller though she was got the best of it, and the Frenchmen were compelled to strike their flag.

Meanwhile the Prince and the Swiftsure were engaged with the Achille, into which many English ships had sent stinging shots, bringing her masts to the deck, and making the ship a blazing mass. Unable to quench the flames, the crew began cutting the masts, intending to heave them overboard.

The Prince, however, gave her a broadside which[11] did the cutting, and sent the wreckage down into the waists. The whole ship immediately took fire. The Prince and the Swiftsure, ceasing fire, sent their boats to save the Frenchmen. It was a noble but dangerous act, for the heat discharged the Achille’s guns, and many of the would-be rescuers perished as a result. Blazing hulk though she was, the Achille kept her colours flying bravely, her sole surviving senior officer, a middy, refusing to strike. The flames reached her magazine, and with colours flying she blew up, carrying all her remaining men heavenwards.

Meantime, Nelson lay dying in the cockpit of the Victory in agony, yet rejoicing that he was victorious. The rank and file were kept ignorant of his condition, though the Admiral himself knew that the end was near, and urged the surgeons to give their attention to others. “He was in great pain, and expressed much anxiety for the event of the action, which now began to declare itself. As often as a ship struck the crew of the Victory hurrahed, and at every hurrah a visible expression of joy gleamed in the eyes and marked the countenance of the dying hero.”

Every now and then Nelson asked for Hardy. “Will no one bring Hardy to me?” he cried; and when at last Hardy came, the two friends shook hands in silence.

“Well, Hardy, how goes the day with us?” asked Nelson presently.

“Very well, my lord. We have got twelve or fourteen of the enemies’ ships, but five of their van have tacked, and show an intention of bearing down on the Victory. I have therefore called two or three of our fresh ships round us, and have no doubt of giving them a drubbing.”

“I hope none of our ships have struck, Hardy?”

“No, my lord; there is no fear of that.”

[12]“Well, I am a dead man, Hardy, but I am glad of what you say. Oh, whip them now you’ve got them; whip them as they’ve never been whipped before!”

Hardy then left him for a time, returning somewhat later to report that some fourteen ships had been taken.

“That’s well,” cried Nelson, “though I bargained for twenty. Anchor, Hardy, anchor.”

Hardy suggested that Admiral Collingwood might now take over the direction of affairs.

“Not while I live, Hardy!” said Nelson. “Do you anchor.”

“Shall we make the signal, sir?”

“Yes,” answered Nelson. “For if I live, I’ll anchor.”

For a little while Hardy looked down at his admiral.

“Kiss me, Hardy,” said Nelson; and Hardy kissed him. “Don’t have my poor carcass hove overboard,” whispered Nelson, as Hardy leant over him. “Get what’s left of me sent to England, if you can manage it. Kiss me, Hardy.”

Hardy kissed him again.

“Who is that?” asked the hero.

“It is I—Hardy.”

“Good-bye. God bless you, Hardy. Thank God, I’ve done my duty.”

Then Hardy left him—for ever.

Nelson was turned on to his right side, muttered the words that he would soon be gone. Then, after a little silence, he sighed and struggled to speak, but all he could say was:

“Thank God, I have done my duty!”

Then Nelson died; and England was the poorer by her greatest sea captain.

Hardy took the news to Collingwood, who assumed command, and refused to carry out Nelson’s instructions[13] to anchor, because the fact that a gale was blowing up would make it unsafe to do so.

The battle was now over; the allied fleets had been defeated, eighteen of their ships were captured, and with these Collingwood stood out to sea. The enemy, however, recaptured four of the prizes, one escaped to Cadiz, some went down with all hands, others were stranded, and one was so unseaworthy that it was scuttled; and only four were taken into Gibraltar.

Now for a different picture!

It was the early hours of August 28, 1914. Under cover of the darkness and the fog, the first and third flotillas of our destroyers, commanded by Commodore R. Y. Tyrwhitt, under orders from the Admiralty, had crept towards Heligoland Bight, preceded by submarines E6, E7, E8, and followed by the first battle cruiser squadron and the first light cruiser squadron.

The submarines, submerged to the base of their conning-towers, swept into the Bight, and when the grey fingers of the dawn crept across the sky the Germans behind the fortress saw what they imagined was a British submarine in difficulties, with sister ships alongside, and two cruisers, Lurcher and Drake, in attendance, intent only on giving her assistance until help could reach them.

It was nothing more than a trap, into which the Germans fell.

A torpedo boat destroyer swung out of the harbour, making full steam ahead for the apparently helpless submarines, who kept their hazardous positions until they saw that the Germans had come far away from the island fortress. Then, one after the other, they sank, and simultaneously the cruisers swung about and raced madly away from the German torpedo craft.

[14]Search though they did, the Germans found no trace of the submarines; all they could see were light cruisers tearing away from them at full speed. These cruisers had acted as an additional decoy, and other destroyers slipped out, bent on making short work of the Britishers who had dared to flaunt themselves within sight of Heligoland. Then, in the distance, appeared the funnels of other British cruisers and destroyers; and it would seem that the Germans realised that they had fallen into a trap, and endeavoured to escape, for Commodore Tyrwhitt’s dispatch says: “The Arethusa and the third flotilla were engaged with numerous destroyers and torpedo boats which were making for Heligoland; course thus altered to port to cut them off.” This was from 7.20 to 7.57 A.M., when two German cruisers appeared on the scene and were engaged.

It was a gallant fight. The jolly Jack Tars of Britain had been waiting these many days for a smack at the foe, who had not dared to come out and meet them until it seemed they were in overwhelming force; and now, when the opportunity had come, they entered into the fight with a zest worthy of the Navy that rules the seas. They watched their shots; the gunlayers worked methodically, as though at target practice; and when a shot went home, men cheered lustily and rubbed their hands with glee.

And the Germans began to think they had a handful of work before them, despite numbers.

They had a bigger handful soon! Here and there, with startling suddenness, periscopes dotted the water, to be followed by the grey shells of submarines, which, getting the range for their torpedoes, as quickly disappeared, and became a menace to the German ships. It began to dawn upon the foe that they were being trapped.

[15]“Full speed ahead!” had come the command when the Germans were sighted, and on went the destroyers in the van. “We just went for them,” said one of the sailors afterwards; “and when we got within range we let them have it hot!”

Hot it was, when at last they did come to grips. But before that happened other things were to take place. The cruiser Arethusa, leader of the third destroyer flotilla—a new ship, by the way, only out of dock these forty-eight hours, of 30,000 horsepower, with a 2-inch belt of armour, and 4-inch and 6-inch guns—sped on towards the Germans, who, owing to the morning mist, could not see how many foes they were to meet, and fondly dreamed they were in the majority.

The German cruisers, like the destroyers, were successfully decoyed out to sea, and then the real fighting began.

The Arethusa tackled some of the destroyers and two cruisers, one a four-funnelled vessel. A few range-finding shots, then the aim was obtained, and a shell put the German’s bow gun out of action. The Fearless and the Arethusa were now in “Full action,” and, together with the destroyers of the flotilla, were quickly engaged in a stern piece of work.

The saucy Arethusa didn’t budge when the second cruiser (two funnels) came at her, but simply fired away for all she was worth. For over half an hour she fought the Germans at a range of 3,000 yards. What would Nelson have thought of this long-distance fighting? And “it was a fight in semi-darkness, when it was only just possible,” wrote one of her crew, “to make out the opposing grey shadow. Hammer, hammer, hammer, it was, until the eyes ached and smarted and the breath whistled through lips parched with the acrid fumes of picric acid.”

[16]It was a gallant fight. Those deadly 6-inch guns of hers did their proper work, and battered at the Germans; while, on the other hand, the Germans battered away at her; apparently misliking her entertainment, the four-funnelled German turned her attention to the Fearless, which kept her men as busy as bees for a time. About ten minutes, and the Arethusa planted a 6-inch shell on the forebridge of the German, and sent her scurrying away to Heligoland. But the Arethusa had not escaped injury in the stern fight, and once or twice, but for the gallant assistance of the Fearless and the destroyers, she seemed likely to be even more severely damaged, if not destroyed. As it was, a shell entered her engine-room, all her guns but one were put out of action, a fire broke out opposite No. 2 port gun, and was promptly handled by Chief Petty Officer Wrench.

Presently the Arethusa drew off for a while, like a gladiator getting his wind, ready to come back again.

And while the Arethusa’s crew were working like niggers putting things to rights, the Fearless standing by to help, the British destroyers were engaged in swift, destructive, rushing-about conflicts, now with opposing destroyers, now with German cruisers. Two of the British “wasps” tackled a couple of cruisers, for instance. Getting in between their larger foes, they placed the latter in such a quandary that they did not know what to do. To fire meant risking hitting each other, and, seizing the hazardous opportunity, the destroyers worked their will upon their opponents; and then, when it was not possible to do more, sped off into the haze. The Liberty and Laertes did good work during these early hours of the fighting. They opposed themselves to several German craft, roared out their thunderous welcome “to the North Sea,” and, with well-aimed[17] shots, sent one boat out of the fighting line with a hole clean through her hull, wrenched off the funnel of another, smashed up the after gun of yet a third, and blew the platform itself to pieces.

Aye, ’twas a glorious scrum! Yet not without its nasty knocks for the Britishers. Standing on his bridge, working his ship, Lieutenant-Commander Nigel Barttelot heard the crash of a shell as it struck his mast; and before he could move the whole structure had fallen with a crash upon the bridge, killing him and a signaller instantly.

The Laertes, too, received her punishment. Her for’ard gun was damaged, and its crew either killed or wounded, while the ’midship funnel was ripped from top to bottom, and a shell sang its horrific way into the dynamo-room, while another made havoc of her cabin.

Presently the Arethusa, her wreckage cleared away, her guns—some of them—working again, steamed into the battle area, and, undaunted as ever, took on another couple of German cruisers. “It looked as if she was in for a warm time,” said one of the crew; “but the fortunate arrival of our battle squadron relieved the situation.”

The first light cruiser squadron came first, and engaged the Germans.

There is much meaning in that “fortunate arrival.” It had been planned and carried out to a nicety. Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty and the two cruiser squadrons had been waiting, as arranged—waiting for the time to come when he should go to the aid of the torpedo flotillas. While waiting the squadrons were attacked by German submarines, which were not successful in wounding any of the ships. A German seaplane, scouting over the North Sea, espied the squadrons, and sped[18] back to Heligoland with the news. They brought out reinforcements, which made the flotillas signal to the vice-admiral for help. This was before noon.

The first light cruiser squadron came first, and swept the Germans with a tornado of fire. Then, when the Fearless and the first flotilla were returning, while the light cruiser squadron engaged the enemy, the battle cruiser squadron came up: the Lion, the Princess Royal, the New Zealand, and the Invincible, armed, the first two, with 13.5 guns, and the others with 12-inch. The work that the Arethusa and her smaller fry had commenced was now carried to a finish. The German cruisers Mainz and Köln shook to the impact of the rain of shells poured upon them; great holes were torn in their sides, flames spurted out, and roared their angry way about the ships. The Mainz, more badly wounded, was in a sinking condition before the arrival of the battle cruisers, and now, tortured by the horrific projectiles, began to sink rapidly by the head. With a siss! siss! as the flames met water, and a roar as the boilers exploded, the good ship Mainz, after a plucky fight, went to her last anchorage, followed later by the Köln.

Destroyers which had been battering at the unfortunate Germans now ceased their fire, and sped towards them on errands of mercy, seeking to save their foes. A large number of the crew of over 350 of the Mainz still lived, and the destroyers’ crews were horrified to see that German officers were shooting at their own men as the ship began to sink rapidly by the head. The Lurcher (Commodore Roger J. B. Keyes) rescued 220 of her crew.

British sailors helping to rescue the crew told later that the scene on deck was terrible. Steelwork had been twisted and bent as hairpins bend; the deck was a[19] shambles—grim testimony to the deadly character of the British fire.

While the destroyers were still fighting, after the sinking of the Mainz and Köln, a third German cruiser, the Ariadne, appeared on the scene, and, after the destroyers had tackled her unsuccessfully, the battle cruisers, turning from their earlier victims, spoke to her in the language of death. Shells fell all about her, battering her sides, gouging great holes in her, wrecking her so completely that within a short time she was going down to keep the Mainz and Köln company. Later it was reported that yet a fourth cruiser had been set on fire.

We must now go back to the destroyer action, which was no less sharp than the other. The small craft sped here and there, firing their 4-inch guns as rapidly as possible, and inflicting damage on one another. Out of the chaos of the fighting there shone the bright light of foes who would show mercy. The German destroyer V187 was so badly mauled that there was no hope for her or her crew, and the British destroyer Goshawk ordered the others to cease fire while she lowered her boats and sought to rescue the Germans, who, however, heeding not the humane mission of their foes, opened fire on the Goshawk at a range of about 200 yards. The German official reports eulogised this as “a glorious fight,” but the British tars saw in it something other than “glorious.” Forced to fight even when they would save, they opened fire in reply; and in double quick time the V187 was silenced, and began to settle down, her men being flung or leaping into the shell-whipped seas. British boats now endeavoured to save the lives of the men who had fired at them when they would have done so before, and several boats managed to pick up survivors.

[20]But, as if the blatant callousness of V187 were not enough, a German cruiser came swinging up, and opened a deadly fire upon the destroyers—the boats whose errand was a merciful one. The destroyers, picking up what boats they could, made away at full speed; but some boats, containing Britishers and Germans, were left behind. At that moment, Lieut.-Commodore Leir, of submarine E4, appeared on the scene, and engaged the cruiser, which altered her course before he could get the range. Down went E4 for safety’s sake.

The two boats of the Defender, left thus, were in a precarious situation, shells flying all about them and their ship far away. Then, to their amazement, there appeared on the surface the periscope of a submarine; then, presently, the conning-tower. It was E4 again. This time she hailed the boats, and, though she was a plain mark for the cruiser’s fire, she remained on the surface, bent on saving whom she could. She could not embark them all, but took a lieutenant and nine men of the Defender. There were also two of the officers and eight men of V187, unwounded, and eighteen wounded men, and, unable to take them on board, Leir left an officer and six unwounded men to navigate the British boats to Heligoland, taking steps to see that they were provided with water, biscuits, and a compass. It was the British sailor all over!

Thus it was that the Battle of the Bight was fought—and won—by the tars of Old Britain. They had hankered long after the outcoming of the Germans, who sulked in their harbours, and had had to be lured out. Boldly had the Germans issued forth when the odds had seemed all on their side, when they saw before them but a few small vessels; and, to their credit be it said, they fought well when the truth came to them. It was the first engagement in the war worthy[21] of the name of a naval battle, and the British reaped the honours, though, when the tally was taken, they had not escaped scot free. There were battered ships amongst those that put into port later. The Liberty had fourteen great holes in her port bow, her bridge was smashed, her searchlight gone, her wireless installation vanished, and nothing but a stump remained of her mast. The Laertes, hit four times, had had to be taken in tow for a while, and the Arethusa, who had started the fight in good style, had, as we have seen, received much beating about. The Fearless also had honourable wounds, receiving no fewer than nineteen hits, though none of them in a vital part.

Beginning in the early morning, with the sea-mist shrouding the sea, the battle had continued for six or seven hours; and then the Germans, knowing themselves outmatched, drew off, dropping mines as they went, while the British squadrons, finding there was nothing more to be done when the Germans had scurried to the shelter of their harbour, also drew away, without a ship lost, and with but comparatively few men hors de combat. During the return journey some of the British cruisers were attacked by submarines but escaped damage. The saucy Arethusa, wounded pretty badly, steamed away at about six knots until 7 o’clock, and then, finding it impossible to proceed farther, drew her fire in all boilers except two and called for assistance. Up came the Hogue, at 9.30, and took her in tow, while the Amethyst took in tow the Laurel, which had also suffered a fair amount of damage.

Thus, with the blood surging through their veins as they thought of the victory won, and longing for the day to come when they might once more meet their foes, the British tars steamed to port. Five months later there was another action on a large scale.

[22]What would the hero of Trafalgar have said if anyone had suggested to him the possibility of a running battle in which the opponents should never be nearer than eight miles? He would probably not have regarded it as a fight! In those good old times the guns could not carry much more than a thousand yards, and the end very often came by boarders, and the capture of the ship in a hand-to-hand fight. Nowadays sea fights are at long range; and yet another account of a battle in the North Sea (January 24, 1915) shows how greatly methods of warfare have changed. It is difficult to imagine the story of such a fight, as will be understood when the classes of ships engaged are considered: mighty battle cruisers, such as the Lion, whose guns can fire 10 miles, hurling a broadside of 10,000 lbs. twice in every minute; light cruisers, speedy destroyers, and submarines; while over all hovered the long grey shapes of airships and the darting forms of seaplanes dropping bombs. And all the time the battling ships are tearing through the seas at top speed, belching forth terrible high-explosive shells.

The battle of January 24 was the outcome of a German attempt to raid the east coast of England, as had been done before—Yarmouth first, then the Hartlepools, Scarborough, and Whitby. In the case of the last three towns a large number of defenceless women and children had been murdered by the German fire, and the War Lord proclaimed it a mighty victory for his navy. Issuing forth again, in the hope of achieving something as noble, the German admiral brought with him four battle cruisers, six light cruisers, and two flotillas of torpedo craft and submarines. When about thirty miles off the English coast they were sighted by a light cruiser, which engaged them and[23] signalled to Admiral Beatty’s squadron the news of the coming of the foe. Instantly the British vessels, which had been cleared for action for over an hour (it was now 7.30 A.M.), closed up and prepared to chase the raiders, then 14 miles away. Admiral Beatty’s force, thus once more destined to play its part in the drama of war, consisted of the battle cruiser squadron—Lion (flagship), Tiger, Princess Royal, Indomitable, New Zealand, and several light cruisers and torpedo craft. The battle cruisers were Britain’s most formidable fighting ships, outcome of what proved to be a far-sighted policy, namely, that of big guns; the first three carried twenty-four 13.5-in. guns, and the last two sixteen 12-in. guns, against which the German Derfflinger (a new ship) had eight 12-in. guns, the Moltke and Seydlitz twenty 11-in., and the Blücher twelve 8-in. guns. It will be seen, therefore, that the British ships had the superiority in weight and range.

As soon as the news was brought to the admiral he gave instructions for the destroyers to chase the enemy and report his movements, while the squadron steered south-east, “with a view to securing the lee position, and to cut off the enemy, if possible.”

The Germans, immediately they realised that they had been seen, and that they were about to be met by a large force, turned tail and ran away. It must not be thought that this was a sign of cowardice; far from it, for in all probability the German manœuvre was deliberate, and in keeping with the policy that had arranged the larger number of heavier guns in the stern of the ships, so that, in the event of a running fight, such as this was destined to be, the fleeing ships would not be at a disadvantage. The British ships have the majority of their guns fixed to fire ahead. One great disadvantage attaching to pursuers lies in the fact that[24] the ships fleeing before them may drop mines, into which the chasing ships might run.

Working at a speed of from 28 to 29 knots an hour, the British squadron raced after the Germans, gradually overhauling them, and at 20,000 yards opened fire upon the foe, keeping at it until, at 18,000 yards’ range, the shots began to tell, and the fire was returned by the Germans. The fight had begun in real earnest. The German destroyers made a plucky attack, in the hope of torpedoing the British ships, but the “M” division of British destroyers raced ahead of the cruisers and engaged the Germans and drove them off. The German destroyers belched forth great clouds of smoke, which screened the cruisers from their pursuers.

The British Lion, of course, led the way. Steering clear of the German submarines, which were to the starboard, she pounded after the great cruisers, and her great shells began to fall in a shower upon the Blücher, which, being the slowest ship, was at the tail of the German line. Not only the Lion, but practically every British ship poured in smashing salvoes. They fell upon her thick as hailstones, sweeping her decks, crashing into her sides, smashing upon her guns and wrenching them from their turrets, disabling whole gun crews. Funnels were sent toppling over, masts fell; a shell pitched in the very heart of the ship, where a large number of men were gathered, and killed them all. Her armoured sides were riddled through and through; she was on fire; but she still kept up her replies with the guns left her, and her men cheered as they fought, although they knew they were fighting a losing battle. Instructions had been given that the flag was not to be struck, and that she was to go down with it flying. Within half an hour of the opening of the battle 300 or 400 men were killed or wounded.[25] She was an unforgettable sight. She turned to port, to give her men a chance to put out the fire, but after awhile swung back and made after the other ships.

Without waiting to see the result of their attack on the Blücher, the British big ships pounded on their way after the other vessels. A devastating cyclone of shells fell upon the Derfflinger, which caught fire forward and had many guns put out of action, while the Seydlitz or the Moltke steamed on like a sheet of flame. The roar of the guns, the crash of the explosions, the thunder of the great engines of war as they romped through the seas, the flashes of fire as shells left the maws of the terrific weapons—all went to make up a scene of horror, of impressiveness. It was a battle between rival giants at giants’ distance, while simultaneously another battle was raging between the smaller cruisers and torpedo craft. There is no doubt that one reason why the Germans chose a running fight was that they hoped to be able to lure their pursuers into the minefield round about Heligoland. But, after chasing them for about a hundred miles, Admiral Beatty, realising that it was hopeless to catch them before they reached the field, turned back from the great cruisers and set his attention upon the smaller ships, seeking to turn them off, drive them down upon the British cruisers which were in hot pursuit. He did great damage amongst them, despite the difficulty of the work, there being so many ships engaged. Though many of them were very seriously mauled, they succeeded in getting to the minefield—with guns dismounted and hulls battered.

About 11 o’clock the Lion had her speed reduced very considerably, owing to a chance shot that had caught her in the bows and damaged her feed-tank, putting her port engines out of action. Admiral Beatty[26] therefore changed his flag to a destroyer, and, later, to the Princess Royal, which then took the foremost place in the fight. The Lion, whose starboard engine also got out of working order later, and had only one engine working, was shielded by the Tiger, which pluckily placed herself in the way of the enemy’s fire, and in doing so lost half a dozen of her men, though she gave the Germans a good battering in return. The Lion was then taken in tow by the Indomitable, and eventually taken into port. An eye-witness on the Tiger told of the part the Tiger played in this thrilling action between big ships:

“On the gun-deck, where I was stationed, you could hardly see one another for the smoke, but our chaps stuck it like Britons. They did work hard; but they did it with a good heart, and I believe at one time our ship was engaging three of the enemy’s ships. Four of their ships were on fire, but they could still keep on firing, and I believe one or two of our poor chaps who got on deck to have a look at them did not live long. I myself was very anxious to go on deck and have a look, but I am glad I did not. I saw the start, and then went below. We lost ten of our chaps, and several were wounded.

“A message came down from the deck, ‘All hands on deck to see the enemy’s ship sink,’ and in less than five minutes after we could see nothing of her, and our destroyers drew near to pick up survivors.

“Our ship at one time stood all the brunt of the firing, as we sheltered the leading ship in our line when she got winged. Still, thank goodness for everything, we are still alive and happy. I do not think they will want to meet us again.”

Meanwhile, the Blücher was living her last moments. Suddenly, while the Germans’ guns were[27] pounding away, there slipped from behind the bigger ships the saucy Arethusa, intent on finishing the work thus well begun. The Blücher, being wounded almost to the death, had no way upon her, and offered a fine mark to torpedo. Commodore Tyrwhitt, of the Arethusa, knowing this, gave instructions, and, as the Blücher fired her remaining guns in rapid succession, a couple of torpedoes sped through the seas towards her. The second caught her amidships, exploded, and rent a great gap in her. Listing already, she now simply heeled over “like a tin can filled with water,” as one eye-witness put it.

It was a dramatic moment, crowded with heroism. Her flag was still flying, and her men were crying, “Hoch! Hoch!” as they lined the side of the vessel, ready to jump clear. From the Arethusa there came the cry of “Jump!” and almost at the same time hundreds of men leaped into the water, most of them equipped with inflated rubber lifebelts, which kept them afloat until the boats lowered by the English picked them up. While the British tars were employed in this humane work there swung out from Heligoland an airship and a seaplane, which hovered over the rescuing boats and dropped bombs. Such methods naturally aroused the anger of the British, who promptly, for their own sakes, had to give up the work of rescue, and leave many struggling Germans to find death when they might have had life.

The Indomitable, before she took the Lion in tow, had her share of the fighting, as had the other battle cruisers. After having tackled the Seydlitz, she was attacked by a Zeppelin which dropped a bomb about forty yards away from her bridge. The Indomitable gave her a taste of shrapnel, as did the Tiger, and she cleared off. Then a torpedo was launched at the Indomitable by[28] the Blücher; but the speed of the British ship saved her.

In addition to the Blücher sunk, other ships suffered considerable damage, as we have seen. Previously one of them had been engaged by the light cruiser Aurora, which opened a terrific fire upon her. The first shot carried the midship funnel clean away, and others, poured in rapidly, swept the decks and battered her hull, so that she was soon in a deplorable condition and was fleeing at top speed for the safety of harbour. Only the proximity of the minefield and the accident to the Lion “deprived the British fleet of a greater victory.” It was not until the foremost cruiser, the Derfflinger, was within half an hour’s run of the mined area that Admiral Beatty gave up the chase, well pleased with the work that had been done.

It had been a great fight and a brilliant victory; it had shown that the British Navy was true to its traditions, that it could fight as well as exert silent pressure upon the foe; that the commanders were fearless men, and that the men behind the guns knew how to handle their great weapons. The feature that stands out most prominently is the accuracy of the British fire as contrasted with that of the German; in the latter case shots seemed to fall anywhere but on the British ships, as is clear when the only casualties were seventeen men wounded on the Lion, one officer and nine men killed, and two officers and eight men wounded on the Tiger; and four men killed and one man wounded on the Meteor, which ship was attacked by the Zeppelin, while none of the ships were at all badly damaged, and would be ready for sea again in a few days.

A fine victory, well won, and at little cost!

Stories of the Early Voyagers

IT is difficult for us who live in these days of swift travel, wireless telegraphy, palatial ships, and so forth, to realise what it meant to go a-voyaging in the Middle Ages and thereabouts. Then men set out chartless, at one time compassless, in ships which were mere cockle-boats, to traverse unknown seas (there are no unknown seas to-day!) in quest of new lands, not knowing really whether there were any new lands to discover. They went, as it were, into the darkness of the unknown, with all its terrors and dangers; and going, discovered the world.

Tradition had it that out in the Atlantic were some islands called by the ancients the Fortunate Islands; and the thirst for wider geographical knowledge came with the discovery of these, and the discovery of Madeira, in the fifteenth century; and out of the mists of the legends there shone elusive islands which, though men sought, they could not find. Then, as men grew bolder, and travelled overland to Cathay, or China, to bring back wonderful stories, with all the glamour of the East about them, Europeans cried for more and more light upon the world beyond Europe.

And the age of discovery began.

In the mind of every voyager was the one great objective—Cathay. But the way there? One school[30] said westwards; the other said that only by circumnavigating the coasts of Africa could Cathay be reached. We know now, as they discovered after many, many years, that both routes led to the East, but that in between Europe and Asia, via the West, lay a mighty continent of whose existence they had never dreamed; and which, when they did discover it, they thought was Asia.

We cannot go into details of the many voyages which were undertaken both to the south and the west; we must content ourselves with the first voyage round the Cape of Good Hope, the first sea trip to China, and the first voyage of the great Columbus.

“A mighty gale caught Diaz and carried his frail craft before it”

It fell to the lot of Bartholomew Diaz to achieve the first of these great epoch-marking events in the world’s history. Many men, under the patronage of Prince Henry the Navigator, of Portugal, had passed along the African coast, and by 1484 Diego Cam had partly explored the Congo; but two years later Diaz, heedless of the fears and warnings of his crew, sailed past the Congo, with the firm determination to get into the Indian Ocean, or at least to pass the extremity of Africa, if there were an extremity. Of that no one was sure. Diaz went round that point without knowing it; a mighty storm caught him, and carried his frail ship before it, and when the gale passed over Diaz found himself off a coast which trailed away eastwards and ever eastwards. His men, fearful of they knew not what, beseeched him to turn back, but for several days Diaz held on his way. This eastward trend of the coast meant something, though what it was he could not say. At last the crew refused to go any farther; the unknown held too many terrors for them, and they considered they had done sufficient. They had gone farther, they knew, than any mariners before them. [31]Why keep on at the risk of being lost? So Diaz had reluctantly to give way. He turned his vessel round, passed down the coast, going southward, with the land on his right—to him a significant fact. He realised its full significance later when, passing a great promontory, which, because of the storms that prevailed there, he called the Cape of Storms, he found the land still on his right, while the ship was sailing northwards. He had been round Africa!

Promptly Diaz landed, and, as was the custom, erected a pillar in the name of the King of Portugal, and thus laid claim to the new land he had discovered. Then home he went, full of joy at his achievement, to receive a mighty welcome at Court when he had told his story. The name of the southernmost cape thus discovered was renamed the Cape of Good Hope; and thus it has been known ever since.

One would have thought that this voyage would have spurred on other voyagers to follow in the track thus laid down; but for some reason or other it was ten years before an expedition was dispatched to carry it farther and try to reach Cathay by that route. Vasco da Gama was the leader of this expedition, which left the Tagus on July 7, 1497, five years after Columbus had set out for the unknown West. It consisted of three ships, which became separated soon after starting, only to meet at Cape Verde Islands. Then for four months they fought their way through storms until they reached St. Helena, where, although they were badly in need of provisions, they could get none, because the natives were so unfriendly. So southward they went, and at last came to the Cape of Good Hope, which it took them two days to sail round, owing to the terrific storm that raged. The crew, terrified at the tumultuous seas, prayed da Gama to turn back.

[32]“We cannot pass this awful cape!” they cried.

“If God preserve us,” answered da Gama boldly, “we will pass the cape and make our way to Cathay. For that honour will be given us, and we shall get much wealth.”

But, though he thus appealed to their cupidity, the crew were not to be calmed; and their dissatisfaction gave rise to conspiracy. They intended to mutiny, and force da Gama to turn back, or else kill him out of hand, and then do what they wanted to do.

Da Gama, however, received information of the plot from some of the men who were still faithful to him, and were willing to follow him where he would lead. Knowing that stern measures would be necessary now that softer ones had failed, da Gama plotted on his own account. He had each man brought into his cabin to discuss the matter, and as soon as a head showed inside the door the man was seized and put in irons. In this way every one of the dissatisfied men was taken prisoner; and da Gama found himself left with a mere handful of men to work the ship. Yet did he persist in going on; he would not be deterred, and, though all worked hard in face of what they thought was certain death, yet they weathered the cape, and presently were on the way up the east coast of Africa. Then da Gama freed his prisoners, who were shamefaced as they came on deck, to find themselves in this new sea, safely past the storm they had feared.

On Christmas Day, after having been in at various places, da Gama came to Natal, named thus in honour of the Nativity, broke up one of his ships there, as she was unseaworthy, and then went on, reaching Mozambique on March 10. Here he met trouble again. Mozambique was in the possession of the Moors, who did a fine trade with the Indies and the Red Sea, and,[33] naturally, resented the intrusion of the Portuguese. They saw their trade being taken from them. They therefore did all they could to destroy or capture the intrepid voyagers, who, however, outwitted them every time. At each place where they put in they fell foul of the Moors, until they reached Melinda, where they were received with honour, and were able to secure as many provisions as they wanted.

Da Gama, always with his eyes open to discover what commercial advantages were to be gained from his voyage, saw with delight that at Melinda there were many large ships which bore the riches of India in their holds; and, realising that that meant much to Portugal, as soon as the monsoons would allow him, hurried on his way across the Indian Ocean, having secured the services of a good native pilot. On May 20, 1498, the two ships reached Calicut—the first vessels which had arrived in India by the direct sea route.

It was an epoch-marking accomplishment, for it opened up the Far East to Europe in a way that had not been done before; trade could be carried on much more easily than by the overland route, with its many dangers. All the riches of the East—spices, peppers, and what not—were to be had by the Portuguese now. The commercial importance of the voyage was greater than that of any voyage yet undertaken, for even that of Columbus had not begun to bear the fruit it was to bear later on.

Da Gama, however, found that things were not so rosy as they had seemed; the Moors held the trade of Calicut in their hands. It was the trading centre of the merchants of Ceylon and the Moluccas—indeed, of all the Malabar coast—and the Moors there, like those at Mozambique, feared the coming of the Europeans. When they discovered that da Gama had obtained permission from the zamorin, or native chief, to trade, they[34] plotted for his destruction, inducing the zamorin to take him prisoner and capture his ships, telling him that these white men would surely come in their hundreds and take possession of his territory. Of course, the native viewed the prospect with anything but pleasure, and when da Gama, laden with rich gifts, landed, he tried to capture him. Da Gama, however, slipped through his fingers, reached his ships, and sailed away, vowing to return and to take vengeance.

Leaving Calicut in a rage, the voyager traded with another chief at Cannanore, and, having laden his vessels with rich spices and peppers, set out on the return voyage, reaching Lisbon in September, 1499; and the whole nation went wild with delight at the glorious vista opened to it.

Da Gama went back to Calicut later on to take his revenge. He allied the King of Cannanore with him, and wrought havoc with the zamorin’s trading vessels; then sailed to Cochin China, where he established a factory—the first factory in the East, and the beginning of Portuguese power in the Orient.

We must now go back a few years, and glance at the story of the first voyage of Columbus, the man who stands out as a landmark in the history of the world. He marks the beginning of the new geographical knowledge; the old world is one side of him, the new the other. For years he had been studying all the maps and charts that he could get hold of, and had imbibed the new knowledge that was being taught regarding the shape of the earth, until at last he came to believe that Asia could be reached by sailing to the west. He tried this Court and that, only to receive rebuffs and meet with delays that sickened him. He sent his brother Bartholomew to the King of England; but his messenger was captured by pirates, and when he was[35] released, and proceeded on his way to the English Court, where his proposal was accepted, it was too late; Christopher Columbus had set forth upon his venture perilous, under the patronage of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, who, after much vacillation, and not a little treachery, had agreed to father the expedition, which consisted of three small vessels. These were the Santa Maria, on which Columbus himself sailed, the Pinta, commanded by Martin Alonzo Pinzon, and the Nina, captained by Pinzon’s brother, Vincente Yanez Pinzon.

After receiving the blessing of the Church, the expedition set sail from Palos with a pressed crew, for few men could be found willing to embark on such a desperate venture. In less than a week they were compelled to put in at the Canaries to refit the ships, which had been buffeted about by adverse winds and stormy seas. When this work was done, Columbus set out again, despite the murmurings of his pressed crew, who often cast longing eyes back to the East, hardly daring to think of what might await them in the West, whither men had not ventured before. The unknown held dread terrors for them, and at every league they became more disaffected, so that Columbus found it necessary to keep two reckonings—one correct, for himself, and the other incorrect, for the satisfaction of the crews. His own showed the real distance from home; theirs showed them that they were nearer home than they had imagined themselves to be.

Two hundred leagues west of the Canaries a ship’s mast was seen floating, and the frightened crews became more scared than ever; they took it for a portent of their own fate. Then the needle of the compass showed a variation; it ceased to point to the North Star, and this was the most dreadful thing of all to these men, who knew nothing of hemispheres. Columbus did his utmost[36] to cheer and inspire them with confidence, telling them of the glory that awaited them when the voyage was over, and assuring them that they could not be a very long way from land. As if to prove him true, next day, September 14, two birds hovered round the ships; later weeds were seen floating on the surface of a kind that grow on river banks and among rocks; then, later still, more birds were seen—birds that they knew never slept on the sea. And all these things seemed to be heralds of land.

So the dissatisfied crew took heart again, and, with a steady breeze helping them, the ships sped on their unknown way, every man eagerly looking out across the vast sea in the hope of being the first to sight the land, the reward for which was to be a pension.

But as day succeeded day, and no land was seen, the spirits of the adventurers drooped, and when they ran into a vast sea of weeds, which made it difficult for the vessels to hold on their way, all hopes of ever reaching home again were dashed to the ground. Then the wind dropped, and the ships were becalmed. Never did Fate play so scurvy a trick with a mariner as it did with Columbus, who knew that the success of his voyage—the great ambition of his life—depended upon the men who sailed with him. He heard their murmurings, knew that it would not be long before they broke out into open mutiny; but still he would not swerve from his purpose.

Then one day they came to him with determination in their eyes and black murder in their hearts. They would go back, they said; they would venture no farther on this mad voyage which could lead to nowhere but death. They had, indeed, made up their minds to pitch him overboard if he would not turn the ship about and go home.

[37]Columbus, firm in his own belief that land lay to the west, and determined that he would not turn back until he had seen it, stood before the mutineers boldly. He argued with them, coaxed them, even bullied them, vowed he would hold on to the course he had mapped out. Then, seeing that he must temporise, he promised that, if they would stand by him for three more days, he would turn back if no land were discovered. He gained his point; the crew returned to their duties, and, by the greatest good luck, shortly afterwards new signs of land came to cheer the men.

Besides a quantity of fresh weeds, such as grow in rivers, they saw a green fish of a kind that keeps about rocks, then a branch of thorn with berries on it, and recently separated from the tree, floated by them. Then they picked up a reed, a small board, and, above all, a staff, artificially carved.

And where there had been mutiny and threats there was now discipline and rejoicing; and no man murmured, or thought of the distance they had come. All were eager to be the first to catch sight of the land they believed to be near. Columbus himself, overwhelmed with joy at the thought that triumph was at hand, did not sleep that night, and had the ships hove to, lest they miss the land in the night darkness. On each vessel every man was wide awake, straining his eyes through the darkness. At about one o’clock Columbus thought that he saw a light shining in the west, far away from the ships. He immediately pointed it out to; the men on his vessel; but with one exception they attached little importance to it. They thought themselves fools when, an hour later, a sailor cried:

“Land! Land!” And, pointing, showed them a dim outline on the horizon. Daylight came, and with[38] it clearer vision; and before them stretched a low, tree-covered island.

The sight of it drove them almost wild with joy. Here, after weeks of voyaging through seas unknown, they had come to land, when they had told themselves there was no land to be found, when they had harboured thoughts of murder against the man who led them. They threw themselves on deck at his feet, and implored his forgiveness; and Columbus knew that he had these men fast in his grip, that they would follow him anywhere.

As for himself, his pleasure knew no bounds; all the dreams of the years were to be fulfilled, all his hopes were to be realised, the glory of reaching Asia via the west was to be his. Had he but known! Had he but realised that something even greater than this had been achieved; that near at hand lay a vast continent undreamt of by his fellows, despite the tradition that the Norsemen had hundreds of years before found a country to the west, far north from this spot.

On October 12, 1492, Columbus, in all the glory of his official robes as representative of the majesty of Spain, landed on the island with his men and the officials sent by the King to give authority to the expedition. The Royal Standard of Spain was planted, and the adventurer fell upon his knees, kissed the ground, and declared the land to belong to the dominions of the Spanish sovereigns.

The island was inhabited, and from the natives Columbus learned that it was named Guanahani. The Spaniards renamed it San Salvador—its present name. It is one of the group known as the Bahamas, at the entrance of the Gulf of Mexico.

The natives themselves, when they saw the strange ships coming towards the island, fled, not knowing what[39] they might be, for never had they seen anything like them. As they were not pursued, however, they plucked up enough courage to come back, and very soon were making friends with the new-comers, who, thinking they were on one of the islands off the coast of India, called the natives Indians—the name still borne by the aborigines of the New World.

Almost every one of the natives was bedecked with ornaments made of gold; and the Spaniards were eager to find out whence the metal came. The natives told them by signs that it came from the south—far away; and the three vessels were presently ploughing the seas again, exploring the coast of San Salvador, by the aid of several guides. Other islands were seen in the neighbourhood, and these, too, were explored, Columbus believing that they tallied with Marco Polo’s description of certain islands lying off China. But no trace of gold was found; each time the natives pointed them to the south, and referred to a great king, whom Columbus imagined to be the Great Khan.

Then one day he gathered that near at hand was a great island called Cuba, and from the description given him believed it to be Cipango (Japan), which reports had credited with vast riches—gold and precious stones. So to Cuba the three ships sailed, reaching the island at the end of October, and taking possession of it in the name of the King of Spain.

Here the natives, after a time, received him kindly, and the answers to the sign-questions he put to them made him more convinced than ever that this was Cipango. He therefore searched it, seeking for the Great Khan; but at last gave up in despair, and sailed off to discover other islands. At this time Martin Pinzon, in the Pinta, deserted him, and, although Columbus waited many days for his return, he did not[40] come back; and when, in December, Columbus set sail, he went with only two ships. On December 6 they sighted a large island, which, because of its beauty and similarity with Spain, they named Hispaniola. Here, again the natives were friendly, and parted with many of their gold ornaments in exchange for little trinkets the mariners had brought with them. What filled them with joy that they could hardly contain was the news that the island abounded in riches. Gold, they were told, was to be obtained in plenty; and Columbus, who had taken the island in the name of Spain, resolved, when misfortune robbed him of another of his ships, to leave some of his men behind to learn the language of the natives, trade with them for gold, and explore the island for gold mines.

The disaster, which left him with only one ship, occurred through negligence. The Santa Maria was wrecked, and Columbus and his crew only escaped with great difficulty. By hard work they managed to get all the goods and guns out of her before she went to pieces, and with the latter Columbus built a fort for the security of the men he intended to leave behind, calling it La Navidad.

Then, on January 4, 1493, Columbus set sail from Hispaniola in the smallest of the vessels he had come out with, namely, the Nina, steering eastward along the coast. Presently he fell in with Pinzon, whom he reproved for his desertion. Pinzon asserted that he had been separated in a storm, but actually he had left Columbus, intending to return home and claim the honours that were due to his leader. Columbus, however, rather than have bitterness aroused, hid his anger, and the two ships sailed in company until February 1, when a terrific gale separated them again.

So dreadful was the storm that Columbus despaired[41] of ever reaching home with his wonderful news; and many were the vows taken as to what the mariners would do if Heaven spared them. Lots were cast as to who should undertake a pilgrimage to Our Lady of Guadalope, and it fell to Columbus. But the storm still held on. Then they all vowed to go in their shirts to a church of Our Lady, if she would vouchsafe them a safe voyage home.

The poor Nina, tossed about, seemed as though she would turn over at every big wave that broke upon her; all her provision casks were empty, and so she was in a poor way through lack of ballast. Columbus solved that problem by filling the casks with water, which steadied the ship, and enabled her to ride out the storm, during which Columbus had been afraid lest he should never reach Spain with the wonderful news of his discovery. He therefore wrote down an account on parchment, which he signed and sealed, wrapped in oilcloth and wax, and consigned to the deep in a cask. Another copy was packed in a similar way, and set upon the top of the poop, so that if the Nina went down the cask might float and stand a chance of carrying its precious contents to some port, or be picked up by some ship. But, fortunately, the storm eased off, and presently they reached harbour at St. Mary’s, one of the Azores.