Title: The Cat

Author: Violet Hunt

Illustrator: Adolphe Birkenruth

Release date: April 6, 2022 [eBook #67785]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Adam & Charles Black, 1905

Credits: Charlene Taylor, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

ANIMAL AUTOBIOGRAPHIES

LONDON

ADAM & CHARLES BLACK

1905

'I had rather be a kitten and cry—Mew!'

Shakespeare.

AGENTS IN AMERICA

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, New York

UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME.

PRICE 6s. EACH.

THE DOG.

By G. E. MITTON.

THE BLACK BEAR.

By PERRY ROBINSON.

THE RAT.

By G. M. A. HEWETT.

TO

ANNE CHILD

LOKI.

A cat is of all animals the most difficult to know; it is so intimate, but so detached; so dependent on human beings for its comfort, so loftily indifferent to their wishes. It requires one who has lived with cats and seen their idiosyncrasies, their whims and their strong individuality, to write about them, and in the present author they have found a spokeswoman who knows them through and through. A sense of humour is necessary in dealing with the subject—and the humour is not lacking. Loki is a real cat in more senses than one, and those who follow his life story will find themselves better able to understand their own cats than they have ever been before.

THE EDITOR.

| I. | The Nursery |

| II. | One Less than Five |

| III. | To Lap or Not to Lap |

| IV. | The Schoolroom |

| V. | One Less than Four |

| VI. | The First Journey |

| VII. | An Invalid |

| VIII. | A Man who hated Me |

| IX. | My First Mouse |

| X. | The Children's Hour |

| XI. | The Surprise that fell Flat |

| XII. | From Top to Bottom |

| XIII. | Catapuk |

| XIV. | 'Poosh!' |

| XV. | The Black Common Cat |

| XVI. | The Black Cat brings Measles |

| XVII. | A Wedding in the House |

I first saw the light—at least I did not exactly see the light, for I was blind, so they tell me, for about a week after I was born—on the twenty-third of April 19—. There were five of us, three boys and two girls. Our mother was a pure-blooded Persian; so was our father, and it was, I believe, considered by Them a very good match. They arrange all our matches for us in this country, and indeed manage most of our affairs, but then it must be remembered that we are strangers, as the title Persian denotes. Moreover, we belong to that division of the race that is called 'Blue Smokes,' which means, not that our fur is blue, for that would be ugly and loud, but that if you part it and look carefully at the roots you will see that it is exactly the shade of blue that smoke is when you get a lot of it together. Papa's name is 'Blue Boy II.,' and he is excessively handsome, and has taken prizes at cat-shows all over the country. His mistress, Miss Goddard, who lives at West Dulwich, is always travelling about with him to show him, and mother is very proud of that.

The first sound that I heard—for I wasn't born deaf as well as blind—was the voice of Rosamond, a little girl who lives in our house sometimes, screeching at the top of her voice, 'Oh, Auntie, Auntie May! Petronilla has got her kittens! Hooray! Hooray!'

My mistress came running upstairs two steps at a time, and put her foot through her dress—I heard it rip. Then she leaned over us, for I felt her breath on my face, and said in a voice quite gurgly with pleasure, 'Brava, Petronilla!'

Then another voice—I learnt afterwards that it was the voice of the parlour-maid, a good soul and as fond of cats as Auntie May—said, 'They look just like so many grey boiled rags, don't they, Miss?'

'Oh, p-p-please, Auntie May,' began Rosamond, stuttering in her eagerness, 'mayn't I take one out to look at it?'

'Certainly not. How dare you propose such a thing! Go and do your health exercises. Petronilla is to be left entirely alone and not bothered.'

'Quite right, Miss Rosamond!' said Mary; 'I've heard say that if you watch her she'll do them a mischief. I knew a cat what ate all her kittens—'

'Ssh, Mary, I am sure Petronilla would not do such a thing. She isn't a common cat. But I tell you what she will certainly do if she thinks we are going to touch them or take them away from her—she will hide them. She knows it isn't good for them to be handled. You have no idea of the amount cats know, and though Petronilla is only four years old, she knows as much as the best nurse ever did. Now be off, all of you, and leave her alone!'

All very well, but Mary the maid simply couldn't keep away, and about three days after this she came in to dust the room (although she had been forbidden to do that just yet, for fear of blowing the germy dust into our eyes and down our throats); and when she had done dusting, she bent down and took us all out one by one, and examined us till she was sure to know us again. Mother looked at her reproachfully, but did not lift a paw to her, for she knew Mary was a dear good creature, and, though silly, would sacrifice her life for a single grey hair off mother's head, or indeed a hair of anywhere off her, and she once said so. But when Mary had gone she took a decided line, and said that she was determined to make an end of all this fingering and pawing of young limbs, which would certainly prevent them from growing and developing properly.

There was a large press with low flat shelves in a corner of the room, full of Auntie May's clothes, that just suited her purpose. She took us all up, one by one, carefully, in her mouth, keeping her teeth back somehow or other not to hurt us, though she could not help making us most disagreeably wet, and carried us along to the cupboard, bumping us as little as she could help on the floor, but still she did bump us. Then with one of us in her mouth, she jumped up to the shelf she had chosen—having first opened the folding doors of the cupboard with her paws—and laid him or her carefully down in the corner, and so with us all.

When Auntie May came up to find her clothes for going out, she discovered us. Mother purred at once to disarm her, for it was known that Auntie May could not manage to be really cross with dear Pet for long, IF she purred.

'Oh, you beast—darling, I mean! Right on the top of my best white wuffy hat! Come out of it at once, angel—pet! And here is another on my ermine boa! And another on my best painted crèpe de chine blouse! Oh, this is too much, Petronilla, my lamb—'

And she took us all out quite gently, not hurting us half so much as mother did in bumping us along the floor, and put us back into our bed of fresh hay, that we have to lie in so as to make us smell sweet. Auntie May always says that very young infant kittens are like babies, and need beautiful accessories, such as blue bows, and green hay, and white powder puffs.

They fastened the wardrobe door very tight and strictly forbade Mary to touch us, and for many days after this we just lay still and ate—ate—ate! Mother, however greedy we were, never pushed us away. She was like a soft hill of wool that we had leave to lie up against and browse upon. Every now and then she spread out her paws, which were like silver streaks, wide and square, all over us, not heavily, so as to weigh us down, but lightly, like a sort of lattice that kept the cold draughts off us, and that we might fancy to be a wall or a hedge between us and the world if we liked.

It was the great advantage of mother's being a pet cat that she and her family lived in the house, not in a cattery, as they are called. Mother knew very well what a cattery was like—she had been in one before a man bought her and gave her to Auntie May as a present. She cost three guineas, she said. It was a very nice cattery, as catteries go—she admits that—and she will always look upon it with affection as being her first home, but still there was a lot of difference between it and Auntie May's house. A cattery has generally hard trodden-in earth for a floor, without a carpet, except for a few unhemmed bits spread here and there. There's generally an old chair—wooden—to scrape your claws on: now velvet, such as is kept here, mother says, is much more interesting and efficacious. The bed is inside, under cover—I grant you that—but only made out of a few old packing cases, and there is generally a horrid smelly oil-lamp to warm the whole place. Now Auntie May had us in her own bedroom for the first week of our lives, and when she did move us, it was only into her study. She was an authoress and had to have a study; at least her father, who was a distinguished painter and R.A., and adores his daughter, thought she had as much right as he to have a studio—same word as study. 'She sells her books, and I don't sell my pictures!' he said. (I call her Auntie May because Rosamond does, and because it sounds more respectful, and mother said I ought.) Her study was quite nicely furnished and full of bureaus and manuscript cupboards and high things to perch on. Mother says it is advisable when choosing a perch to get as high as possible, because of the draughts that run along the floors of even the best rooms.

Mother told us many things as we lay there, but I can't say I took much notice of them till my eyes opened. It was just a nice sleepy sound she made that sent us off to bye-bye one after another. I suppose she slept herself, but I never remember being awake when she wasn't. She was a very good mother; she hardly ever left us. Of course she got out of the bed to eat her meals; she detested crumbs in the bed, and so on. If she went away she always came back with a kind sort of speech—Rosamond called it a mew—something like 'Here we are again!' or 'Well, how goes it, infants?' and then lay down right on the top of us. Rosamond used to scold her and pull her off us, thinking she would hurt us; she didn't know that we were always able to ooze away from under mother quite easily when once she had turned round three times and got settled.

Till my eyes opened I did not know how many brothers and sisters I had, except for mother's telling me. I fought them all without having the slightest idea of the sort of thing I was fighting. I knew it had claws, though. I knew that Fred B. Nicholson, as they called him afterwards, after Auntie May's American cousin, was a regular bully from the beginning, always putting himself forward, and shoving us away from the best places. After all, eating is everything in those first days, and mother was singularly weak where Fred was concerned, and let him batter us as much as he liked, and never took our side against him. She only said 'First come, first served!' and 'Heaven helps those that help themselves!' and certainly he did grow a great strong boy.

Perhaps that was the reason why his eyes opened first!

Rosamond gave us a great deal of attention when her own lessons were over, and before, and hung over us till she got all the blood to her head, she said. She called herself cat-maid. One day when she was leaning over our bed, she suddenly jumped up and screamed:

'Oh, Auntie May, one of them—I don't even know which, but I think it is Fred B. Nicholson—has got a tiny, tiny slit where his eyes ought to be! Do you suppose he can see?'

I felt the first grief of my life. I knew there was no slit where my eyes ought to be, and I felt sure it was, as Rosamond guessed, that horrid boy Fred, who always got first in everything. Next day the slit in his face was bigger. That evening they said with certainty, 'Yes, Fred can see!' In the daylight Rosamond discovered that his eyes were blue. By that time I saw what looked like a streak of light, and guessed that my eyes were going to open soon, and wondered if they would be blue too! I asked mother, and she laughed at Rosamond and at me, saying that all kittens' eyes are blue at first. Even Rosamond ought to have known that. The question was, would they be green or orange afterwards?

'I should be very sorry,' mother said, 'if any of you turned out to have green eyes. That would defeat all poor Auntie May's plans. I have green eyes myself, alas! and she is most good to overlook it in me, but your father has the most beautiful golden eyes in the world, or in any cat-show, and let us hope that you will have the luck to take after him!'

Fred began, the others followed. My eyes were the last to open. I suppose I had caught cold; I am sure I was not delicate. They took warm milk and mopped the place where the eyes ought to be. Mother licked me. They raced to cure me. Mother always said that she backed her licking, but I fancy the warm milk did it, myself. And pretty soon I saw. We all saw, and so when we quarrelled we managed to aim better.

I really saw very little besides untidy spiky bits of hay sticking up all round me, and beyond that, a wall of wicker. I sometimes saw great moonfaces bending over me, and Rosamond's long golden fur tickled me as she put her head right into the basket. She had blue eyes, but then she was still a child. I wondered if they would be green or orange when she grew up? Auntie May's were brown, shot with green; she had quite dark fur too, and tied up, not hanging down like Rosamond's.

If I chose to keep my eyes inside the basket, I saw my mother's green eyes, and they were so pretty and mournful. Auntie May used to call them Burne-Jones eyes. She meant it as a compliment, and mother always purred. She loved being praised.

Though Freddy's eyes were open, he could not scratch himself with his hind leg without falling over, and I could. Then I found that I could do something else Freddy could not, that is, make a queer rolling, rumbling, useless sound in my throat. I don't see much good in it myself, but it gives Them pleasure. They take it as if we were saying 'Thank you' when we are given food or stroked. But no one, not even the vet,—that is the cat doctor—know how it is done. I heard him say so. I have not the slightest idea how I do it. I just listened to mother, and brooded over the thought for days, and all of a sudden I woke up, as Rosamond was tickling my stomach, and found myself r-r-ring away somewhere inside me like anything! Mother even started when she heard me; I am not sure she was altogether glad.

'Poor child!' she said, 'he is taking up his burden early. They mostly don't expect recognition from us until we are older. Don't, don't purr too easily, my son; be chary of your gift: it is wiser.' But Rosamond buried her face in me and mother, so as to hear better, and presently she raised it and called out to Auntie May, who was sitting writing at her little table:

'Oh, Auntie May'—(all her sentences began like that)—'this kitten, who was so late with his eyes, is at any rate the first to purr! Purr, darling, purr!'

I purred till my throat was sore, and she stroked my back and tickled my stomach till I had to curl up and bring my hind legs and my head together. They think you do it because you like being tickled, not because you can't help it. I purred so much that day that I had to take a rest the next, and then They said I was sulky!

And Freddy was jealous. He could not purr, though he could spit. Mother reproves him, for she says that spitting, though a useful weapon and a protection against intrusive aliens, is not to be used in private life between cat and cat. It is good for dogs, if I ever see one. Mother uses it but rarely for Them. I asked her why she didn't spit at the people in the house, who, though well-meaning, irritated her by coming and lifting us out and looking us all over, and talking about our points, and preventing us from growing? She said, 'I don't do it to Them, however annoying they are, because, when all is said and done, I am well bred and Persian.'

I knew mother never said a thing like that without being able to prove it, so I was a little surprised one day at what one of Auntie May's friends said. This man took Fred up and handled him as if he didn't know much about kittens. I watched him. His moonface had a queer little smile much too small for it—a sly smile.

'Touch of Persian about this cat, I should say!' he observed quietly.

'Why, they are Persian, Mr. Blake!' Rosamond cried out; but Auntie May said nothing, but simply hoofed him out of her room and ours. His little smile had grown bigger.

After he had gone, mother boiled with rage.

'I won't stand this!' she exclaimed. 'Come along, my traduced darlings, with me, and we will hide you, lest you be again exposed to insolent criticism of that kind. Touch of Persian indeed! Perhaps he thinks Persians haven't claws! Perhaps he thinks we cannot resent injuries adequately! Come, my pure-bred doves! Come, my prize darlings, my pedigree'd angels!'

The door into Auntie May's bedroom next door was left open. Mother carried us in one by one and laid us on the ground under the famous cupboard we had been in before, while she leaned up and, with her paw, turned the handle of the cupboard door. Then she seized me and jumped with me on to the bottom shelf and stowed me in one corner, pulling the clothes and what not that was there all over me, so as to hide me completely. She then left me, recommending me to silence, or I should get 'what for' with her hind feet, and fetched the others one by one. She placed them all on different shelves—I saw her leap past me each time—and stayed herself with Fred, for I did not see her go past again. That was a long jump, for it took her right up to the fifth shelf.

All the afternoon we lay there, mother visiting us all in turn. Unfortunately, she had not been able to succeed in closing the wardrobe door after her. It yawned in the most suspicious manner, and so Auntie May thought when she came back from Pinner, where she had gone to dine and sleep, as soon as Mr. Blake had departed. About eleven o'clock the next morning she came bouncing in in her hat and jacket, and the moment her eye fell on the open door she cried out:

'Oh, my prophetic soul! Come here at once, Rosamond, or you will be sorry!'

She opened the door wider and looked in, but, naturally, could see nothing.

'It looks all right!' she said to Rosamond. 'But all the same I feel sure that Petronilla is somewhere inside. Isn't my crèpe de chine blouse in that corner rucked up rather suspiciously? Gently! Don't let us spoil poor Petronilla's game of "Hide-and-Seek." We mustn't find them too soon.'

Fred was under the crèpe de chine blouse, and they found him. Then they found the other boy, with some artificial violets she wears pinned on to the front of her dress in the evening on top of him. On the top story one of the girls was curled into the crown of a hat, and mother was in the lowest shelf with the other, mixed up with an ermine boa. The play lasted quite ten minutes, and Rosamond was delighted. Very little damage was done; in fact, as mother said, a clean, well-licked-every-day cat, if you don't frighten him and drive him to desperation, rarely spoils clothes, or breaks ornaments, or leaves any trace of his presence. But if you chivy him or make him nervous, he doesn't choose to hold himself accountable for any harm he may happen to do, naturally!

There were five of us, and, so far, only Fred B. Nicholson had been christened. Rosamond, who is a child who loves putting things into their right places and calling them by their proper names, pointed this out to her Aunt.

'There are certain royalties,' said Auntie May, 'whose religion cannot be chosen till they have grown up and it is decided whom they are to marry. The same with kittens' names. The naming ought to be left to the people with whom they are eventually going to live. I can't keep more than one of them, you know. We should be what they call cat-ridden.'

This was the first I heard of it. From that day the thought hung over me that our pleasant little party would have to be broken up. I wondered if I could possibly contrive to be the one They kept. I could not bear the idea of moving to a new home. But mother said it was the law of nature. Her motto was from a poem of Miss Jean Ingelow that Auntie May had once quoted—

She never worried—much, though she confessed at first it was rather trying, and that she caught herself wandering about looking into corners, searching for what she knew went away in a basket the day before. It was just a habit mothers got into, and when a few weeks had elapsed she just shook herself and thought no more of the kitten that had gone to make its mark on some one else's chair cushions. 'Dear me!' she used to say, 'I have on an average five kittens a year. What should I do with them all hanging about, getting in my way at every turn? I should become irritable, I should snap at them, I should positively hate them as soon as they became independent and I could do nothing for them. It is best as it is.'

After that speech of mother's, I was not so sure that I wanted to be the kitten They chose to keep, that is, if mother meant to turn round and bully me as soon as I could stand up for myself. It seemed strange to hear her talk like that, and yet one likes to be forewarned.

Rosamond gave us temporary names—reach-me-down names, she called them. Fred B. Nicholson was allowed to stand; the boy Auntie May called Admiral Togo, a Japanese name, I understand. The two girls were Zobeide and Blanch. I was called Loki, after the devil.

They did not know, but we all had one name already, a traditional one in our family. It was Pasht. Our ancestors lived at a place called Bubastis. For convenience' sake, however, we stuck to the names They gave us. They seemed to have an idea that we should answer to them and come when we were called, but mother told us on no account ever to do so, it would be false to every tradition of our class. We might go as far as to twitch an ear when we heard our name spoken pleasantly, but only on the very rarest occasions were we to stir a paw. Then, if we decided to go to Them, it was at least manners to stop half-way and scratch. If the name was spoken in an unfriendly tone, the thing to do was just to stare the impertinent creature down. At Bubastis, in the olden time, our ancestors had been worshipped and prayed to. In the studio downstairs, where mother had been a constant visitor in the days when she was free of domestic cares, there is one of our ancestors under a glass case just as he was buried when he died thousands of years ago. He is all wrapped in a sort of brown greased cloth, so mother says, many hundred folds of it, but still you can perfectly well see the original shape of our many-hundreds-of-times-over great-uncle. Nobody has ever unwrapped him; it would be very wicked to do it, and might bring misfortune on the house. Altogether he is treated with the greatest respect, and mother is quite content to have it so. We are taught to look on that room not as the studio as They do, but as the Family Tomb, and mother says that when we grow up and are permitted to sit there sometimes, we must all keep very quiet and behave seriously and do no romping.

One morning we woke up, and found mother had left us. The window was open, and mother had suddenly felt tired of nursing and as if she must have a breath of fresh air. She was outside on a kind of coping there was all round the house. Nobody was worrying at all when in came Mary and Rosamond. They called to mother to come in at once, for it was blowing a cold east wind, and then suddenly they discovered that she was in difficulties. She had jumped off the coping to another piece that stuck out at the side, and now, though she wanted to come back, her resolution had deserted her, and she thought she should never be able to do it. She told us all this, but Mary and Rosamond only thought she was crying out piteously.

'She can do it quite easily, Miss, if she will only face it,' said Mary. 'It stands to reason that if she could jump there, she can jump back!'

'Of course, Mary,' said Rosamond. 'What you can do once you can do again. Come, you silly-billy! Jump! Don't be a coward!'

Mother explained that the more she thought about it, the more she couldn't do it, and that perhaps if they would go away and leave her to herself, she would feel differently, but of course they couldn't understand her. They took a small chair and held it out of the window with one hand. Mother knew that if she were to leap upon that, her weight would make them drop it, and, sure enough, they did drop it all the same, and it went clattering down into the garden below. Then they said 'Ow! Whatever'll Miss May say?' and shut the window. Mother was glad of that, for the wind was really too cold for us as we lay inside, and as a matter of fact she was not in the slightest danger if only they would go away, go downstairs and pick up the pieces of the chair in the garden. She mildly suggested it to them, but they did not even begin to understand.

'Aw, poor thing, don't her mew come faint-like through the window!' said that silly Mary. 'You and me can't both leave her, Miss. Shall one of us go and fetch Miss May?'

'Do, do go away!' implored mother, 'and then I shall be able to make my jump!'

'I have an idea!' said Rosamond, and she came to our basket and picked up Zobeide, and carried her to the window and held her out to mother. Of course Zobeide screamed, and poor mother couldn't stand that and her legs obeyed her unconsciously and brought her in at once. She said 'Thank you' to Rosamond as she crossed the sill and walloped back into her bed and begged them to shut the window, which of course they didn't do, and it was open half-an-hour later when Auntie May came up from her singing lesson and Rosamond told her with pride what she had done. Auntie May knows a great deal about cats. She said at once that it wasn't necessary, that Petronilla would have known quite enough to come in of her own accord, and that it was too cold a day to hold a young kitten out in the raw air; still, as far as she could see, we were all perfectly well, and feeding away busily, so probably no harm was done.

Mother said to us that she wasn't quite so sure of that, for the wind was very cold, and she took particular care of Zobeide, and gave her the best place, and cuddled her till Zobeide squealed and said she didn't like affection if it meant being held so tight.

Next morning, when Auntie May came and stood over the basket, she seemed very grave.

'Rosamond, come here,' she said. 'Which kitten did you hold out of the window?'

'I am afraid I don't quite know which,' Rosamond said, very much puzzled and upset, as I could tell by her voice. 'It was one of the girls, Blanch or Zobeide, but I am sure I could not say which of them. Why? What is the matter?'

'Come and look!' said Auntie May.

Then I myself noticed for the first time that Blanch was lying a little way off mother, and breathing very funnily. Her body seemed to break in half under the skin with every breath she took, and she gave a great shake right across her. She was flattened out and her legs parted wide so that her chest was spread along the floor of the basket. She made a rushing noise with her breathing like what one hears when the bath is filling.

'She looks just like a frog!' said Rosamond. 'Oh, Auntie May, is she ill, and is it my fault?'

'Do you think it was Blanch you held over the window?'

'I said before I don't know, but perhaps it was.'

'It looks rather like it,' said Auntie May sadly, and put on her hat and jacket and fetched the doctor.

'Lor', for a kitten!' said Mary.

'It's worth three guineas if it lives, Mary,' said Rosamond through her tears. 'But it won't, and it will be my fault. I have murdered it!'

'Don't cry, pretty child!' mother said to her. 'It was Zobeide you held out of the window, and look at her sleeping so sweetly here under my paw! This is Blanch who is dying, and it is the will of Providence.'

Poor Rosamond couldn't understand her, and began to abuse her for her calmness.

'You are a heartless old thing, Petronilla, you are! Look at you, calmly nursing four kittens, while one of them is too ill even to eat!'

'Of course it will not eat. It will die,' said mother gently, and as usual Rosamond didn't understand.

'Oh yes, you may mew, and try to palaver me, but that won't stop me thinking you a heartless beast!'

'I am a beast,' answered mother sweetly.

'Oh, please, please, make it eat! or else it will starve!'

'It will starve,' said mother, but she made no opposition when Rosamond tried to make the poor little Blanch feed like the rest of us. We had never stopped eating; we knew we couldn't do anything for poor Blanch, and we knew, too, that it was Zobeide who had been held out of the window, and longed to tell May she was mistaken and put her out of her misery. When Dr. Hobday came twenty minutes later, we had to listen to Auntie May telling him the story, and asking him if that was what had made Blanch ill?

'It is very unlikely,' said he. 'This kitten was probably unhealthy from the first. It has pneumonia now, and I am afraid in such a young kitten the case is pretty well hopeless; but we will try to save it, if you think it worth while?'

'It is not worth while,' said mother loudly and clearly, but, of course, no one took any notice of her—she was called the Talking Cat, but they didn't really think it was talking, only general friendliness—and Auntie May said she meant to try and save Blanch's life.

First of all Blanch was put into a separate basket, lined with flannel; a piece of flannel was to be sewn round her with little holes for her front paws to go out of. She had to lie on a hot bottle. The temperature of the room had to be kept up to sixty-three degrees. She was to be fed every two hours, on a mixture of milk and sugar and hot water, about equal parts, so as to make something as like mother's milk as possible.

'I shall have to sit up with her,' said Auntie May, 'or buy an alarm clock to wake me up every two hours.'

'Oh, Auntie May, do let me sit up!' cried Rosamond.

'Why, you are but a kitten yourself!'

'Ah, but I'm over three years old,' said Rosamond. 'I am twelve years old. I suppose that represents a kitten's twelve weeks, doesn't it? So this kitten is three weeks, that is to say three years old.'

'It is a baby in arms,' said Auntie May, 'and is going to be fed with a bottle, like other babies.'

She had got a doll's feeding-bottle she had bought once at a bazaar, and she tried that, but it was defective and would not let the milk run through. Then she got her stylographic pen-filler and dipped that in the milk she had arranged and sucked some up, and squirted it out into Blanch's mouth, and really got some in that way; but it was a slow business, and poor Blanch used to hate being disturbed dreadfully. She was too young to talk, but she used to get into a regular temper sometimes and turn away her body with a scraping noise in her throat that meant how disgusted she was with life and people trying to cure her.

She was an awfully pretty kitten. 'Oh, you are a beauty,' Auntie May used to say, 'and I wish I could save you.'

Blanch had been much more forward in some ways than the rest of us; she had climbed all over Auntie May, and had a strong little back, and could sit up and look grown up, though she was only three. Her fur was nice too, a very much lighter grey than Zobeide's or mine, and her head very broad, and the distance between her small ears very great.

Her sick-basket was in a different part of the room from ours; we could not, of course, get out to look at her, and I don't believe mother ever did. Auntie May did not seem to expect her to. She always told her how Blanch was, and mother used to say that Blanch was in good hands, and that Auntie May could do what she could not do for Blanch, feed her through stylographic pens, for instance. But she always said that though it was very good of Auntie May to devote herself so, she could not alter the result of Blanch's illness; no sick kitten as young as that could possibly recover. If only it had learned to feed itself, there would be a chance for it, and not much even then. She was glad for our sakes that Auntie May had parted us; she believed in the segregation of invalids. She had learned that hard long word in the cattery.

After two days the doctor came and looked at Blanch. He didn't take her up.

'This kitten is better!' he said in a surprised tone. 'It breathes more freely. You may save it yet. If you want to apply for the post of nurse for animals I'll recommend you, Miss Graham.'

The day after that Blanch was so much better that Auntie May went to a party which was given in a house near by. She was to be only two hours away. She fed Blanch at nine, after she was dressed, kneeling down beside her in her new pink dress. Having left Blanch quite comfortable, and pretty well, hardly coughing at all, she went away singing down the stairs. Rosamond was, of course, in bed. She went to bed at half-past eight, and made a great fuss about it every night. We four went to sleep. Mother liked the temperature kept at sixty degrees; à quelque chose malheur est bon, she said, which means bad-luck is good for something, and sent us to sleep with her soft purring.

Punctually at eleven I was awakened by the swish of Auntie May's dress on the stairs, and she came up followed by Mary, and the electric light was turned full on.

'Bring me my traps, Mary,' said Auntie May, and she sat down just as she was and began to mix the water and sweetened hot milk. When she had got it ready she leaned over the patient, and then called out.

'Come here, Mary,' she said in a queer voice. 'This kitten is dying!'

'The doctor said it was better, Miss.'

'So it is better—its breathing is better—but it is dying all the same. Look at its eyes!'

'Just like my old aunt's died last June! Well, Miss, it's only a kitten after all!'

Auntie May held Blanch up in her two hands and looked at her. She gave her her medicine and a little drop—a real drop, not what the cook here calls a drop—of brandy, but Blanch let it all roll out of her mouth and on to the pink gown. I knew that from what Mary said: 'Lor', Miss, your nice gown!'

'It's no good, Mary. Its eyes are glazing already. They look tormented. We mustn't plague her any more. Bring Petronilla!'

'How absurd!' said mother, as Mary lifted her out.

Auntie May showed her Blanch, whom she had laid back in her bed. Blanch's head had rolled quite uncomfortably back, and her eyes saw nothing. She was almost gone.

Mother didn't do at all what they expected, though; indeed, I don't know whether they expected her to bring Blanch back from the grave in some mysterious way that mothers ought to know of. Mother had no way. She knew it was no good. To satisfy them she did something. She licked and rolled Blanch over in her bed with her tongue—roughly, I suppose, from the way they spoke.

'She's killed it!' said Auntie May. 'Look, it's dead!'

She took Blanch up, and Blanch's head fell back over her hand and a film came over her eyes—so Auntie May said afterwards.

Poor Auntie May put Blanch down again, and cried as if her heart would break.

'I nursed it—I took such care—and he said I had saved it, and no, it's dead—oh!—oh!—'

'Don't cry, Miss May, don't cry so,' Mary begged. 'It's only a kitten at that. We'll bury it in the garden. It will be our first funeral; there's a nice little place back of them trees, I've often thought of it for that. Here, let me get you out of your dress. I'll put the corpse in the bathroom till the morning. What'll ever your father think if he hears you crying like this over a kitten, and wake Miss Rosamond, too!'

Then Auntie May stopped, because she wasn't selfish, and let Mary put her to bed, and went to sleep very soon after. I asked mother if she wouldn't mind telling me why she had licked Blanch so hard.

'My dear child,' mother said, 'I daresay you and Auntie May consider me very unfeeling, and think it very odd that she should do all the crying instead of me; but then you must realise that I was never in favour of nursing Blanch and trying to keep her alive. She was delicate and bound to die sooner or later. It is a great mistake to try to preserve the lives of kittens that are weak and feeble from the very beginning, and no sensible cat would ever countenance such a proceeding. They do as they choose with theirs, and a nice lot of invalids, cripples, and criminals They raise up to make difficulties afterwards for them! As a matter of fact, Blanch was cured of her illness, and I don't deny any of the credit to Auntie May of having done it—I couldn't have done it myself—but, as the doctor will tell her to-morrow, the child died of heart-failure. I knew it would go like that. When they called me in I had to do something for form's sake, and I licked her. Poor little dear, we must forget about this closing scene of her very short career, and try to grow up healthy ourselves. That I look upon as a cat's first duty. You ask why? In the battle of life the weaklings must go under. Now feed properly and don't choke, as you are sure to do if you are greedy and in too much of a hurry.'

Rosamond was told about Blanch next day, and she cried too. Fresh from my mother's lecture I looked upon her almost with disgust. The silly child talked of going into mourning, and, sure enough, she found an old bit of black crape somewhere and sewed it on the arm of her frock. I had no patience with her. We relations were, on the contrary, forbidden to make any difference, and mother was even gay, though I noticed a tear in her eyes sometimes when nobody was looking. I heard Rosamond propose to bring poor Blanch, who by now, she said, had grown quite stiff, to show to her mother for a last look before she was buried; but, to mother's great relief, Mary had taken Blanch and buried her before breakfast by Auntie May's orders.

'Don't be morbid, my dear child!' Auntie May said, when Rosamond complained of what Mary had done. 'I don't like any one to gloat over funerals, much less children. You must forget Blanch, poor dear Blanch, who made such a brave fight for her life, and remember that there are four left.'

So you see in the main she said the same thing as mother, which convinces me, as I said before, that she knew a good deal about cats.

'It is time they were taught to lap!' said Auntie May.

'Oh, Auntie May,' cried Rosamond, 'how dreadfully exciting! I was wondering when you were going to begin that! It will be dreadfully exciting, won't it?'

'It will be dreadfully messy,' answered Auntie May. 'I must do it in an old frock and my art pinafore.'

'Oh, Auntie May, I shall love to see you in a pinafore! You will look like a big French doll—that one of mine that Kitty spoiled.'

'Hush, don't speak ill of the absent. I daresay Kitty enjoyed the destruction of Wilhelmina very much, as much as Petronilla liked mumbling my white satin shoes last year. I forgave her. One must pay for one's pets.'

'And I forgave Kitty,' said Rosamond; 'besides, I am twelve now and past dolls. When shall we begin to feed the kittens?'

'Wait a bit!' mother said; but, of course, once having got the idea into Their heads, they took no notice. Auntie May got the big pinafore she had when she was an art student, out of a box, and put it on. Then she fetched a tiny china spoon with forget-me-nots all over it, and sent Rosamond down for some milk and some hot water. Then Rosamond and she squatted down on the floor beside our bed, and mother eyed them scornfully over the edge of it.

'Now, you silly old Petronilla, we are going to relieve you of some of your work. Four kittens are too much for you. You are beginning to look rather fagged in spite of Beef-tea and Kreochyle and Hovis food. Children, dear, you cost a pretty penny.'

These were the names of some of the messes They were continually bringing up in saucers and planting out by mother's bedside, and which she hopped out and licked up and came back again saying that Auntie May had a feeling heart and that she adored her, since, as every one ought to know, the way to a cat's heart is through its stomach, whatever may be the cause of affection afterwards. And mother did love Auntie May quite desperately much, and Auntie May could always see it in her eyes, though mother was not otherwise demonstrative.

Well, as I was saying, they managed to unhitch Fred's claws and mouth, and laid him in Auntie May's lap, and put the point of the little china spoon in between his teeth. He sputtered and choked, and he seemed to have a white beard when they let him alone again.

'He isn't taking any this time!' said Auntie May. There were white streams wandering through the rucks of her pinafore.

'Of course he is not taking any of your extraordinary preparation,' said mother. 'You are in too great a hurry to have him lap. He won't do it a moment before he is ready, and that will be when I decide to begin to wean him. You can try every day and you won't do him any harm, but you will only wet your pinafore.'

It was quite true. We none of us felt as if we could touch Auntie May's mixture, we so very much preferred mother's. Auntie May put us all back again, and stood up and shook herself, and the milk we hadn't taken ran down the creases of her pinafore on to the floor. They both went away, and Rosamond, as she went out of the door, recommended mother to tidy it by licking it up, partly in joke—at least mother took it that way, for, as she said, she was not a common cat, to eat up slops, and they would have to send Mary to wash it away with a cloth.

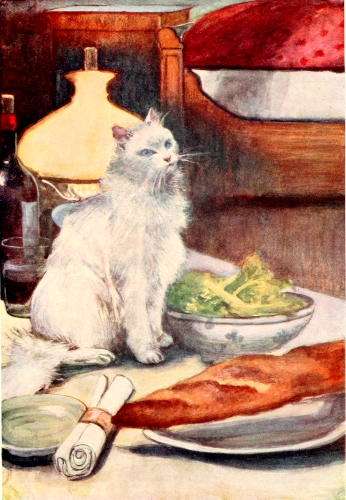

THE MILK RAN DOWN THE CREASES TO THE FLOOR.

Next morning They tried us again, but still we couldn't, and Rosamond seemed so terribly disappointed that we asked mother to tell us how it was done.

'You have to put your tongue over the milk and catch some of it up in the curve of it, and flick it into your throat in the same movement. That's all there is!'

'And quite enough,' sighed lazy Freddy.

'Dogs do it differently,' mother continued. 'They put their tongue under the milk or water, or whatever it is they want to drink, but they toss it into their mouths in precisely the same way.'

'I shall never do it,' poor Zobeide complained. 'You will have to nurse me all my days, mother.'

'You great fat podge!' I said. (Zobeide was very roundabout.) 'Mother can't nurse you when you are taken away from her and sold, as you are sure to be. Then you will get thinner and thinner, till you starve, unless they feed you with a stylographic penholder, like poor Blanch; but she was an invalid.'

'Don't jar, children,' mother said, 'but give your minds to business. To-morrow, when they begin teaching you again, don't sputter so much, but try and make a start. It comes all at once, and once gained you never lose the art. You try and you seem no nearer, and suddenly—you find you can do it! Now I will tell you as a fact that I shan't be able to feed you exclusively for much longer. I don't know about looking fagged, but I certainly begin to feel it. I can't, for all the trouble I take, keep my coat as nice as I should like to, and that is a sure sign that the fatigue is beginning to tell on me. Four great kittens! They ought to have got a foster-mother—and I should not have liked that altogether! But I tell you that the time has come when you must all try to reinforce me and supplement what I can give you from extraneous sources.' Mother did use nice long words.

So next day, when they brought the whole set-out, I thought I would really have a good try, and I swallowed down the spoonful of milk without sputtering. But that wasn't lapping, mother called loudly from the bed. I was stung by that, so when Auntie May put a little milk in a very flat saucer and ducked my head in it, I stayed in a minute and worked my tongue about. When I could positively bear it no longer, I came up again spitting and sputtering, not a drop of milk having gone down my throat. But I found that if she didn't roughly shove my head in, but let me bend over the saucer myself, and not go deep in, but skim about on the top, I could manage to flick up a little; though perhaps I only fancied I had done that, from the milk that got on to the fur about my mouth. It really was not at all bad stuff. Auntie May still went on putting the point of the little spoon down my throat, and I got a certain amount of milk into me that way, and wasn't so hungry afterwards. Fred, I must say, had no perseverance. He sulked and tossed his head, jibbed, as Auntie May called it, and would have nothing to say to the spoon; while as for the saucer, he walked straight across that and out on the other side. I couldn't do the things Freddy does; he has a 'cheek,' Auntie May says, and Rosamond says he is like Kitty, whom I have never seen, but, judging from all they say of her, she must be the naughtiest kitten in Yorkshire. When Freddy has walked right through the saucer and is all whitened, he sits down and drinks the milk off his toes, showing that he knows quite well it is meant to eat, not to bathe in, and, as Auntie May says, simply defies her.

The bad example of my brother made me somehow determine I would accomplish lapping, and, sure enough, next day I did. You should have heard the noise They all made!

'Loki can do it! Loki has done it! He's lapped three laps! He is getting some into his mouth! He has lapped first! Hooray! Bravo, Loki!'

I heard Them, but I did not look round till I had lapped right down to the pattern on the saucer. Then I raised my head proudly. Everything looked quite different now somehow. I felt another kitten. Yet nothing really was changed. Rosamond's moonface was as round as ever, Auntie May was still sitting there with her apron full of great pools where Fred and Zobeide and Admiral Togo had let it run down out of the corners of their mouths, mother was purring away and looking at us all with her great big mournful eyes.

In less than a week I was no better or cleverer than everybody else. The others could do it too, but they hated the bother of it. The other way is really so much more convenient. And mother prefers it; she says that it brings us together. She says:

'As long as I nurse you children, I shall be devoted to you. I shall cosset you and shield you and watch over you, and get miserable if you are in a draught or let people handle you or tease you, and so on; but once you can look after yourselves, it will be a very different pair of paws, I warn you! That is cat rule all the world over. I shall not, I hope, be actually unkind, but I shall take the very slightest notice of you. Out of the nursery, out of mind. Lost to sight, to memory you will not be dear, for if I allowed myself to become unduly fond of any one of my children, how could I bear to have that child taken from me? One has to steel oneself. They under whom we live are responsible, though, perhaps, in a state of nature, in that jungle of which I have visions and of which I dream at night as if it were my kingdom, it would be the same—I cannot tell.'

We all said politely, 'Oh, mother, I am sure you would never be unkind,' but indeed afterwards we found she spoke quite truly. She could not help it; it was the way she was made. Cats have the softest outsides, but the hardest hearts of all animals. Later on, nobody would have known that she was my mother from the way she bullied me, and let out with her paws when I passed her sometimes, without the slightest warning, and didn't seem to care when I hurt myself at all. There was the time when I was ill and fed out of that very forget-me-not spoon that ought to have stirred up tender recollections. I bit a piece out of that spoon in a fit of temper one day when I felt particularly bad, and was in a blue rage in consequence. I damaged the spoon, of course, as mother pointed out, but I hurt myself far more. I bled, and the spoon did not. It had a rivet put in it and was as well as ever again.

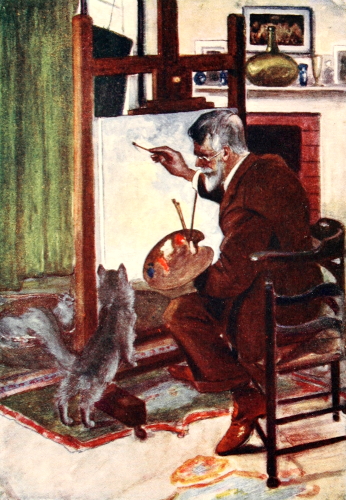

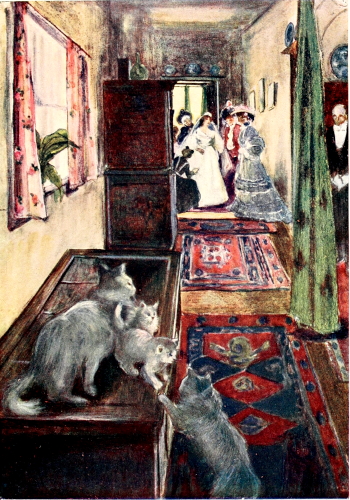

I felt mother's unkindness very much, and it was of a piece with many other bits of her conduct. I have got over it now; indeed, I have had my revenge if I had wanted it, when I saw her making a slave of herself over another lot of kittens just as she had done over us. She began to be grateful to me then, for I made myself useful taking her place in the basket sometimes, and keeping the little wretches warm while she took a turn and stretched her legs, and went to look if Auntie May had been given or had bought anything new. Mother always took notice of that sort of thing; nothing new that came into the house ever escaped her for long. She even knew when Mr. Graham was engaged on a different picture, at least he said she did. She used to stand on her hind legs and plant her fore paws on the ledge of the easel and look at the painting he was doing quite gravely. The artist himself was certain that she knew, and he used to tickle her neck with his brush or his mahl-stick and say, 'Well, Petronilla, do you approve of my new subject?' That is how mother ascertained that it was new, for if he had covered all the canvas up, without leaving one little weeny corner white, how on earth could a poor cat tell? While she was away on these voyages of discovery, I curled round the kittens, and they liked me for about ten minutes till they found I was not their mother. I could not feed them, only wash them, and that I did very nicely and thoroughly, so that mother said when she came back that she could not have done it better herself.

SHE USED TO STAND ON HER HIND LEGS AND LOOK AT THE PAINTING.

But this state of things was not until much later; for the present we four were the kittens of the hour, and she petted us, and was the dearest, sweetest little mother in the world.

We soon could do more than lap, we could eat things. Auntie May and Rosamond had a chafing-dish, and they used to cook all sorts of messes in it for us and for mother, who was very fussy about her food, and took dislikes to the most ordinary things. For instance, porridge she would not touch, or cod-liver oil biscuits, while Hovis food, or Horlick's, or a sardine put her out of her mind with delight. They say that a sardine will sometimes bring a dying cat back to life. They burnt methylated spirit in the chafing-dish, and the first time I saw the sly curling flame winding up among Auntie May's new novel, I confess I was frightened. But mother reassured us; she said if I looked attentively I would see that it was a very obedient flame, and would go straight up into the air and do no harm unless they interrupted it. She gave it a wide berth herself, and hoped we would do the same when we began to be able to get out of our basket and walk about. Auntie May and Rosamond were not so very careful, for once when they thought the spirit was getting low, Rosamond took the whole bottle and poured some more on. Huh! it took fire, and she dropped it pretty quick, and it broke, and there were three separate burning pools on the floor. Mother put a paw over us all, though we could not have got out of the bed even if we had wanted to, and gripped Freddy by the neck, ready to lift him out if it should be necessary. Luckily Auntie May was there, and there was a large flowerpot full of earth in the room. She tilted out the flower, head over roots, and poured the earth on the burning pools, instead of the water which Rosamond had torn off to the bathroom to get. It was soon out, and the poor child got a scolding and a lesson in chemistry from her grandpapa.

They had not got proper things to work with, mother said. They had no spoon, but used to stir up the mixture with the butt-end of one of Auntie May's pens. When it was ready, they would pour it out into any piece of china that was handy—Japanese pots and plates that cost a fortune, so I was told. Then they washed them up in the bath, and we used to hear this sort of thing: 'Mind that cloisonné, Rosamond!' or, 'That is a bit of Persian four-mark you have chipped, I do believe!' But it was no matter, they got a new bit out of the studio. Mr. Graham was a collector, and nothing was too good for the cats.

Up to now, none of us had ever succeeded in getting out of the bed by ourselves. We were lifted out by them to walk about a little, keeping our stomachs off the ground with great difficulty. Our legs had a strange tendency to slip away beyond us, 'doing splits' as they do in the pantomime—so Auntie May called our way of getting ourselves along. When at last we did succeed in keeping our legs at right angles to our bodies, we wobbled sadly, and longed to be put back again among the hay. But at times, when we weren't eating or sleeping, but thoroughly awake, and there wasn't much doing in the old dull bed, we used to try to get out of it. We three boys used to make a ladder of Zobeide, and, propping ourselves up on her, get over the edge in a jerk, but at first we could only one of us look over, and then Zobeide would meanly crumble away under us, and pitch us all head-over-heels into the bed again. She took an unfair advantage, too, and bit our hind legs.

One day, however, I managed to climb up without the help of Zobeide, till my paws rested on the top of the basket, and I was screwing up my hind legs till they came nearly up to join the front ones, when somebody—I believe it was Rosamond—gave the after-part of me a push and I came over on to the floor on my nose, which, luckily, is flat, not Roman. I rose unsteadily, and walked away like one in a dream. I think I must have walked right out of the door and into the bathroom. Rosamond was behind me, and I had a sort of feeling that I would like to run away from her—a feeling that I have had many a time since with nearly all of Them. It was because she was behind me. Now if she had been in front I should have longed to pass her, and then turn round and jeer at her. But as it was, Run! Run! was my motto, and into a corner for preference. I chose a corner, and squeezed myself in behind some old boxes in the bathroom. They must have been very full of dust, for I sneezed twice and so told Rosamond where I was, and she put a great hand like a house in and caught hold of me.

'Naughty little thing!' she said. That was the first hint I had that They expect us to stay beside them and not run away. I took the hint; at least, I was good enough to stop running away sometimes, when she said my name very decidedly. You never know what They may have in their hands to make it worth your while to stop; as often as not it is something to eat. Rosamond put me back in the box, and mother cleaned me for half-an-hour quite unnecessarily, saying, 'My children shall be kept unspotted from the world as far as I can manage it, for the world is very dirty.'

She is indeed most particular. She washed off the marks of people's hands carefully wherever they had touched us. It looks rude, I think, to see a cat, the moment it has been kindly stroked, turn round and begin to lick the stain away. Rosamond said it is just as if she took out her pocket-handkerchief after grandpapa had kissed her, and wiped her cheek with it.

We could all get out of our bed now. In fact, we would not stay in, except for sleeping and eating (mother still fed us a little, so as to let us down easy). We were all over the place, and the door of the study had to be always kept shut. Rosamond said that being cat-maid was much harder than lessons at home, for she could keep Fraülein in order, but she could not keep us.

'I can't keep them in,' she complained to her grandpapa. 'I collect them all in my pinafore and drop them all into bed, and out they ooze in a moment like so many india-rubber balls! Fred especially is a fiend. He is in to everything. He is outside everything. He touches everything—licks it mostly. I am glad to say that he burnt his nose badly the other day on the electric radiator. He won't touch that again in a hurry!'

No, that he won't! He singed off a bit of his whiskers, and we all laughed at him awfully. He was a queer little cat, not a bit like Zobeide or Togo. We never wanted to fight, but he lay down in a corner of the bed and said, 'Come on, you!' Then Zobeide or I took a hand, and he knocked us down and drove the straws into our eyes. Mother punished him by taking him in her arms and kicking him with her hind legs, but he bit her face and she had to leave off. When we packed ourselves to go to sleep, mother happening to be away, we always made a sort of cross, lying over each other for warmth, and Freddy always took the top, out of his turn, and having so much the biggest head, always managed to get his own way. We three others hoped that the first one of us Auntie May sold or gave away would be Fred, but nothing was said about that. Auntie May bought a ball with a jingle in it for us all, she distinctly said so, but Fred always assumed that it was his ball, and he went so far as to claw the jingle out of it, saying that it amused him quite as much without. We never got a chance of playing with that ball unless Auntie May happened to leave her house shoes in the room, and then Fred said we might take the ball, for he didn't get a chance of real leather to gnaw every day.

Altogether he was a terror, and Mary used to say she would like to wring his neck. That didn't frighten Fred; he knew she wouldn't do anything of the kind, and he went on jumping on to the back of her neck, and getting among the ashes when she was lighting the fire and being swept up by mistake, and plopping on to paper parcels, and eating coals, and needles, and buttons, and corks, and working off a hundred wicked tricks he had invented.

You see, Fred never would attend to mother's lectures when we were left quite alone in the room, and she told us all the little catly rules that we should have to guide our conduct by when we left her. Some of them, she said, were traditional, going back to the days beyond the dawn of history, when cats were worshipped. She said we must never forget that great fact, never allow ourselves to lose sight of it, but let it regulate all our conduct and our relations towards Them. They no longer worship us, though they are kind to us. They have perhaps forgotten, but we need not. Therefore we must be gentle, obedient, subservient to Them, but with a reservation. We should, if we thought proper, come to their call, but never with vulgar alacrity. She thought it the highest possible praise of a cat to have said of him, as Auntie May had once said of a friend's cat, 'The more he is called, the more he doesn't come.' We should find time to sit down on the way and make pretence to attend to our personal appearance, or what not. We might suffer Them to hold us in their arms, but not in inconvenient or indecorous positions, such as upside down, or round their necks like a boa, or pretending we are wheelbarrows, and so on. She said They—the more punctilious of Them—have a way of holding a cat up by the loose skin of its neck, that being considered the least uncomfortable one to us personally. Quite a mistake, she said; they only think so because we do not usually protest—how can we, when the skin is strained so tightly over our throats as to preclude all attempt at conversation? The only proper way to hold a cat is to take both hands to it and support the lower limbs, instead of letting the whole weight of the body depend from the shoulders or the paws. She told us how to open a door, if it was left ever so little ajar. That is to walk up it—about two good steps will do. If it is shut, the handle should be turned; but that needs special aptitudes. Then if we mew passionately before a closed door and it is opened for us, we should not go in, as would naturally occur to an undisciplined cat to do, but sit down at a distance and lick our face, so as to show we do not really care about it.

She told us the proper way to lie down—never at once, but after having described two or three circles. The right thing to do is to turn round and round, brushing our fur the right way till we are more or less in the form of a ball. Then, and not till then, we may definitely lie down with an expression of contentment if we feel like it. We are to imagine ourselves making a nest in some very high grass, beating it down all round us to form a bed before we can settle in for the night. Then we must tuck our heads in symmetrically, and safely too, taking care to keep one eye free, ready to open and see what is going on, and an ear cocked to hear strange or unusual sounds. That kind of high long grass was, she said, called jungle grass, and our ancestors long ago, in the time before they were worshipped, lived in the jungle and ran wild there. The worshipping came afterwards.

She taught us humility, too. When we heard the strays howling outside in the square garden, too weak to catch birds for their food perhaps, and begging a morsel or a cup of milk from door to door, we were to pause in our own feeding and think, 'This cat's ancestors were probably kings, like mine. I must not be stuck-up.'

Sometimes even Fred would leave off roaming and sitting away by himself, thinking over and planning some new bit of mischief to do, and come back to bed and take the warm place that Zobeide had made, and beg mother to tell us about 'Dirty Whitey' of the underground. We had all heard it many a time, but it was a nice story.

Mother had seen her once the time she was in the underground at Notting Hill Gate with Auntie May, and Auntie May had said:

'Oh, bother, there's that wretched cat again! It makes me quite sick to see it playing about between the rails.'

She was waiting for her train, and a nice porter was standing near her, and he said:

'Bless you, Miss, she knows her way better nor any of us. She takes a little walk to High Street, Kensington, now and again, and comes back quite safe and sound. She bringed up a family of kittens there in the tunnel and never a one was hurt. But I don't doubt myself she'll get copped some day!'

Auntie May said she thought so too, and she walked along to the other end of the platform to avoid seeing the white cat crossing the line just out of bravado as the train was coming in. When her own train came along, she said she felt as if that cat would be under it and be cut in bits. But it wasn't, for she saw it again a week later, and told mother. Then quite a month later she came in and told mother that 'Dirty Whitey' had been 'copped' at last.

'Whitey' had been chasing a rat across the metals when a train was just coming in, and professional pride had forbidden her to let go. So the train had cut off her head with the tail of that rat in her mouth—at least, so the porter had told Auntie May. We loved that story, and, as I have said, even Freddy used to come and listen when mother began to tell it to us.

Zobeide liked the story of the cat that walked all the way to London after its master, who was very meanly moving house and had intended not to take the family cat. Instinct, mother said. It seemed to work both ways, for another cat was brought in a covered basket away from the house it had been born in to one a hundred miles away in quite another part of the country. It never saw anything, for it had been packed up in the room in the first house, and the basket was not undone till they had got into a room in the other and shut the door. No matter, for that cat was not to be beaten. It just went straight up the chimney and home again. It evidently loved places better than people, Zobeide remarked.

'It is generally the way,' mother would answer, 'but I happen to love Auntie May, and where she is, is home to me. I'm not sure I even believe those stories. I know that I should be puzzled to find my way back to Egerton Gardens, even if I wanted to! Probably if I once started, the gods of my ancestors would endow me with a sixth sense and show me the way.'

Admiral Togo always asked for the Whittington story and got it, but I didn't care for it. I liked the story of the cat that told the people of the house that the basement was on fire, by running into their bedroom with her coat all smouldering where a hot splinter had fallen on it, and the Pied Piper of Hamelin. That was all about rats, as it happened, but no matter, it made my mouth water.

We all had a most terrible shock. Waking up from our afternoon sleep, we found that instead of being four, we were only three. Admiral Togo had gone. Mother had been asleep too, but she missed Togo first, and went routing about among us to make quite sure.

'I can't surely have mislaid him,' we heard her muttering. 'Or is it what I fear?'

'Perhaps he has got over the edge of the bed into the great world,' said Zobeide, 'and is hiding somewhere to tease us.'

'Possibly,' mother said gently. She jumped out of bed, and looked all over the room and into every corner. She called gently to Togo once or twice, using a special pet name of her own, and she was still wandering about when Rosamond came up with mother's dinner. She saw the state of affairs at once.

'Aha, old girl, looking for your kitten?' she said. 'Can't find Togo, eh?'

It struck me as suspicious that she knew which of us mother was seeking without looking into the basket. Mother answered quite crossly, 'No, nothing in particular.' She didn't want Rosamond to know that she valued Togo, or any kitten that ever was born.

'Well, then, dear Pet, I must tell you. Togo was getting too old to run about with women and children, and he has had his curls cut off, and been packed off to a preparatory school!'

'Tsha!' mother spat angrily. She didn't choose to be chaffed by a child. 'School! I am not going to be put off with a cock-and-bull story like that.'

But she couldn't keep it up for very long. She did really care what had become of Admiral Togo, and she hung her head and dropped her tail and tried to get behind the door.

'Poor Petronilla! You seem very much distressed!' observed Auntie May, coming in just then, and kindly lifting mother up, and putting her back with us. 'But you are a sensible cat—I never knew a sensibler—and you have been through this kind of thing before. Cheer up! You have three left.'

'And I wonder how long I shall have them?' mother muttered. 'You are making pretty quick work with them. You have killed one, and now you have sold the other—'

Her bitterness made her unjust, because Auntie May didn't kill Blanch, though she certainly had sold Admiral Togo, for what Rosamond said next showed it.

'May I go and see Togo?'

'You may. I am sure Mrs. Dillon will have no objection, but don't imagine for a moment that Togo will be glad to see you. Cats have hardly any memories, and kittens none at all. And a good thing too, for treated as chattels as they are they would have wretched lives of it. They don't listen to the rain upon the roof and think of other days, or have tears come into their eyes when they look at sunsets because they feel so ancient—'

'Why, Auntie May, you are talking like an old cat, while you are only a young woman. You aren't very old—not more than thirty, are you?'

'That is just the most miserable age,' said Auntie May; 'when I am forty I shall be as cheerful as—old boots!' She actually wiped a tear away as she spoke. 'Good gracious me, Pet is simply murdering Freddy! Drop it—drop it!'

'Please don't interfere!' mother said, as well as she could speak with her mouth full of Freddy. 'If you only knew what he had been up to this afternoon you would be obliged to me, I can tell you! You will miss It presently, and wonder where it has got to. But I'll make the boy tell me where it is, and put it back too, before I have done with him!'

She gave it to Fred well, but she spared his pride and never told us where he had put Auntie May's opera-glasses. She hit very hard herself, but she never allowed us to lay a paw on each other, except in kindness. She was so afraid of our hurting each other, like Uncle Tomyris, who pulled out Uncle Ra's left eye once in a cattery brawl.

'They got Professor Hobday to come and fit him with an artificial one. They really did, word of an honest cat!' mother said. She told us some other things that the Professor did, such as bandaging a cat's broken arm and putting it in splints, also false teeth, but that was a dog, I think, and it was worth about three hundred pounds. No cat that ever was born was worth that, mother says, but it is They who settle what we are all to cost, and They might be mistaken. They have agreed that cats are inferior to dogs; you may be as silly as you like about a dog, and even believe he has got a soul if you like, but a cat!—'My dear, it's too absurd!'

I hear this kind of thing in the drawing-room on Auntie May's at-home day, when we are often carried downstairs in a basket and allowed to play about and amuse the people. One hears a good deal. People who don't like cats think that Auntie May makes a perfect fool of herself about us. Once when Auntie May was persuaded to bring us down, to please a Mrs. Wheeler, I heard, with my own big ears, Mrs. Wheeler begin her sentence one way and finish it another.

'Lovely creatures, so beautiful in the firelight, when the light catches their outside fur and makes it shine like silver—' (Then Auntie May moved off and she went on) 'Poor, dear May! She is a bit of a bore with her cats, don't you think so? Do you notice how she always brings the conversation round to them in the end? It is a great mistake. She will be an old maid, it's a sure sign! Look at her now with a saucer on the floor and those three cats making a Manx penny all round it, and a nice man wanting to talk to her, and can't get a word from her! He looks disgusted, and no wonder!'

Auntie May didn't really keep us downstairs very long, and the nice man, as it happened, carried us up for her to her study, and put us all back in our basket, and stayed up talking with her quite a long time, and talking about Mrs. Wheeler, the very woman who had been abusing Auntie May for loving us so.

'She's a cat, that's what she is!' the nice man said, and Auntie May agreed, which was rather insulting to us. I am, however, not quite sure whether he didn't say a d instead of a t, which with them makes quite a different word.

Presently they said it was June, and the weather got beautiful. Auntie May thought we ought to take the air in the garden, and be allowed to run about on the grass. Rosamond was overjoyed, and so were we, at first. Then we began to get frightened. There was absolutely nothing on the top of us except the sky and the sun. I missed the nice sheltering bed and the cosy walls of the room we had lived in always. I felt as if the top of my skull had been taken off. I saw nothing to hide under either, except black poles that simply ran up straight into the blue. The sun was very hot, too, and I suppose I looked wretched, for suddenly Rosamond said:

'I do believe Loki has got a sunstroke, like Kitty had last year. His poor little head is so hot—feel!'

Auntie May was in such a fright that she bundled us all into the house.

Next day, when the sun was not quite so hot, she took us out again and we soon got used to it. Sometimes she chose me alone and took me on a lead and held the loop of it while she worked. She wrote on great white sheets of paper that the wind got under and tried to blow away. She told me to make myself useful and be a paperweight, but then when I sat on the freshly-written sheets it spread the ink all about and she did not seem to like that. At last the wind went down and she got interested and forgot me entirely. Rosamond sneaked the end of the lead out of her hand when she was not looking and held it; it seemed to give her the greatest pleasure to hold me in. It is odd how that child likes managing people, and positively begs for responsibility. Well, she took it this time, and a nice mess she made of it!

She opened her hand as she got interested in her book, and I simply walked away with the lead bobbling after me. I liked responsibility too.

Suddenly I saw a dog coming towards me—I knew it was a dog from the one that was embroidered on the child's crawler we had to lie on at home. He was black, coarse-furred, with small mean eyes, and a fringe that kept tumbling into them. He approached me. I did not like to turn, or cringe, or look afraid, but I felt my tail stiffening and my claws sliding out all ready, by no will of my own. There was an odd feeling in my back too. I knew as well as if you had told me that I should be rude and spit at him if he came nearer.

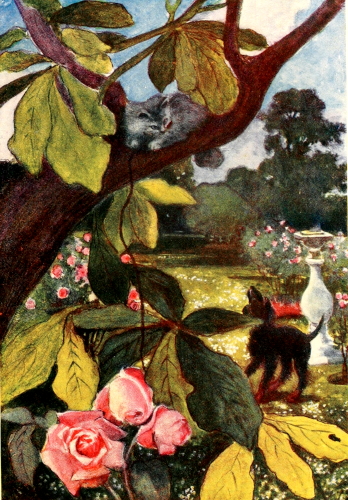

He did. I spat. He barked. Still Auntie May didn't leave off putting her pencil in her mouth and writing with it. Then my mood changed. I felt I should like to leave that dog—I wanted not to be where it was. After all I was only a kitten, and I turned round slowly and walked in the direction of Auntie May.

He came prancing after me. I ran. He ran. The lead was most awfully in my way. I went straight past Auntie May in my nervousness, and up one of the straight black poles that seemed to lead up to Heaven—out of that dog's way, at any rate. It was a tree, so I heard after. Perhaps he could climb too—I didn't know! It was an instinct. The loop of the lead lay along the ground, and the idiotic puppy, as he must have been, hadn't the sense to hang on to it and drag me down. I think it was pretty clever of me to climb my first tree handicapped and shackled like that. Auntie May heard his short, sharp, cross barks, and came running and caught hold of the end of the lead to prevent me from going any higher up. Some people called off the puppy, and then, and not till then, did I allow myself to come down on to her shoulder, which she obligingly held under the exact bit of tree I was on.

OUT OF THAT DOG'S WAY AT ANY RATE.

It was much easier to go up than to come down. Perhaps I was excited then and made light of difficulties, but still mother told me that it was always the same way with her. Cats should look before they climb.

I scratched Auntie May's nose terribly for her as I came down, and it bled and had to be bathed. She was most kind about it.

'Never mind, darling, it won't matter. I am an ugly thing anyway, and I have only got to be presented at Court to-morrow! Just a little unimportant occasion of that kind.'

'Can't you explain to the Queen,' said Rosamond, 'that your cat scratched you? I have always heard she is so very kind.'

'No, I shan't worry her with explanations,' said Auntie May; 'only soldiers' scratches are worth talking about. Let us go in.'

Mother lectured me when she heard of my adventure. 'You should not have run,' she said, 'with that great heavy lead and all. If he had had the spirit of a flea he would have broken your back for you. You should not have shown it him; you should have stopped still and gone for his nose. That hurts, and he knows it. He would have run away from you the moment you raised your paw. Remember!'

At the end of July Rosamond was taken home by somebody who was travelling up to Yorkshire. Her mother was not very well and wanted her. In fact, for the whole of August Auntie May was always worrying about Beatrice, Rosamond's mother, who was her twin-sister. She said she couldn't quite make out from Beatrice's letters what was the matter with her, or if it was serious or no, and though she paid several visits to big country houses in August she did not enjoy them. We were left to the care of Mary, who was becoming a very excellent cat's-maid, and so mother told Auntie May whenever she came home, and that, although she never could love Mary as much as she loved Auntie May, she had not wanted for anything during her absence.

At last Beatrice's letters got so scanty and muddly that Auntie May said she must go and see her and find out for herself. So she telegraphed to Tom, her brother-in-law, that she was going down to Crook Hall on Thursday, whether they wanted her or not.

The answer came back, and puzzled Auntie May very much:

'Do—want—you—bring—kitten.'

'Bring kitten? Why should I? Beatrice doesn't want to keep kittens because she has so many dogs. What can it mean? This is some game of Rosamond's, I'll be bound. I'll not take a kitten.'

But the more she thought over it, the more she felt that Tom wouldn't have put Bring Kitten unless he wanted one. He is a man who doesn't talk any more than he need, and it was he who had sent the telegram off himself. Beatrice wanted the kitten for some reason or other, there was not a doubt of it, or Tom wanted Beatrice to have a kitten. She began to think she would take a kitten.

'I will take the strongest,' she said. 'Petronilla, which do you consider your strongest kitten?'

Mother answered, 'Frederick B. Nicholson, as you call him,' but of course Auntie May couldn't understand her. She sat down by the basket, where we still spent most of our time, and talked to us about ourselves.

'Freddy's nose is too long—makes him rather snipe-faced—but his paws are broad and magnificent, and his eyes golden. Zobeide, your tail is a weeny-weeny bit too thin and drawn out at the tip, and your ears too pointed and long. You, Loki, have got a tolerably neat little chubby face of your own, but your ears are not tufted, and your nose, if you were human, would be an impertinent snub. Still, you are going to be a fluffy cat, one can see that, and invalids—if poor Beatrice really is an invalid—prefer fluffiness. I think I'll take you, Loki. No, Fred, not you, indeed, you pertinacious darling, for you always go for one's eyes, you are such a dangerous cat, without a single atom of self-control. So, Loki, you may as well say goodbye to your mother and make the most of her, for she just won't know you when you come back. Get him ready for me, Petronilla, by to-morrow morning, will you?'