Title: In the Name of the People

Author: Arthur W. Marchmont

Illustrator: A. Forestier

Release date: April 9, 2022 [eBook #67801]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Ward, Locke and Co., Limited, 1911

Credits: D A Alexander, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

WHEN I WAS CZAR.

The Court Circular says:—“There is always something supremely audacious about Mr. Marchmont’s books. This, however, I will say, that for a long evening’s solid enjoyment ‘When I was Czar’ would be hard to beat.”

The Nottingham Guardian says:—“The best story of political intrigue which has been written since ‘The Prisoner of Zenda,’ with which it compares for the irresistible buoyancy by which it is told and the skill in which expectation is maintained on tiptoe till the last move.”

The Freeman’s Journal says:—“A very brilliant work, every page in it displays the dramatic talent of the author and his capacity for writing smart dialogue.”

AN IMPERIAL MARRIAGE.

The Sporting Life says:—“Every page is full of incident and bright dialogue. The characters are strongly and vividly drawn, and the development of the whole story shows the author to be a thorough master of his craft.”

The Scotsman says:—“The action never flags, the romantic element is always paramount, so that the production is bound to appeal successfully to all lovers of spirited fiction.”

The Notts Guardian says:—“The interest is absorbing and cumulative through every chapter, and yet the tale is never overloaded with incident. The vigour and reality of the story does not flag to the last page.”

The Court Journal says:—“One of those intricate webs of intrigue and incident in the weaving of which the author has no equal.”

BY SNARE OF LOVE.

The Dundee Courier says:—“To say that the clever author of ‘When I was Czar’ has eclipsed that stirring romance is to bring one within the sphere of the incredible. But it is true. The present novel is full to overflowing of boundless resource and enterprise, which cannot but rouse even the most blasé of readers.”

The Daily Mail says:—“The story is undoubtedly clever. Mr. Marchmont contrives to invest his most improbable episodes with an air of plausibility, and the net result is an exciting and entertaining tale.”

The Birmingham Post says:—“Mr. Marchmont creates numerous thrilling situations which are worked out with dramatic power, his description of the interior of a Turkish prison, with all its horrors, being a realistic piece of work.”

IN THE CAUSE OF FREEDOM.

The Times:—“Mr. Marchmont’s tales always have plenty of go. He is well up to his standard in this busy and exciting narrative.”

The Globe:—“Mr. A. W. Marchmont can always write an exciting story bristling with adventures and hazard, and incidents of all sorts. ‘In the Cause of Freedom’ furnishes a good example of his talent. Vivid, packed with drama, with action that never flags, this novel ought to appeal successfully to all lovers of romantic and spirited fiction.”

The People’s Saturday Journal:—“It is an admirable example of the type of exciting fiction for which Mr. Marchmont is justly famous, and lacks nothing in the way of plot and incident.”

THE QUEEN’S ADVOCATE.

The Daily News says:—“Written in a vigorous and lively manner, adventures throng the pages, and the interest is maintained throughout.”

The Belfast Northern Whig says:—“As one book follows another from Mr. Marchmont’s pen we have increased breadth of treatment, more cleverly constructed plots and a closer study of human life and character. His present work affords ample evidence of this.”

Madam says:—“A thrilling story, the scene of which takes us to the heart of the terrible Servian tragedy. We are taken through a veritable maze of adventure, even to that dreadful night of the assassination of the Royal couple. A very readable story.”

A COURIER OF FORTUNE.

The Daily Telegraph says:—“An exciting romance of the ‘cloak and rapier.’ The fun is fast and furious; plot and counterplot, ambushes and fightings, imprisonment and escapes follow each other with a rapidity that holds the reader with a taste for adventure in a state of more or less breathless excitement to the close. Mr. Marchmont has a spirited manner in describing adventure, allowing no pause in the doings for overdescription either of his characters or their surroundings.”

The Bristol Mercury says:—“A very striking picture of France at a period of absolute social and political insecurity. The author’s characters are drawn with such art as to make each a distinct personality. ‘A Courier of Fortune’ is quite one of the liveliest books we have read.”

BY WIT OF WOMAN.

The Morning Leader says:—“A stirring tale of dramatic intensity, and full of movement and exciting adventure. The author has evolved a character worthy to be the wife of Sherlock Holmes. She is the heroine; and what she did not know or could not find out about the Hungarian Patriot Party was not worth knowing.”

The Standard says:—“Mr. Marchmont is one of that small band of authors who can always be depended upon for a distinct note, a novel plot, an original outlook. ‘By Wit of Woman’ is marked by all the characteristic signs of Mr. Marchmont’s work.”

THE LITTLE ANARCHIST.

The Sheffield Telegraph says:—“The reader once inveigled into starting the first chapter is unable to put the book down until he has turned over the last page.”

Manchester City News says:—“It is no whit behind its predecessors in stirring episode, thrilling situation and dramatic power. The story grips in the first few lines and holds the reader’s interest until ‘finis’ is written.”

The Scotsman says:—“A romance, brimful of incident and arousing in the reader a healthy interest that carries him along with never a pause—a vigorous story with elements that fascinate. In invention and workmanship the novel shows no falling off from the high standard of Mr. Marchmont’s earlier books.”

“‘To whom are you going to give the papers you have

just received from M. Dagara?’” (Page 193.)

IN THE NAME OF

THE PEOPLE

By

ARTHUR W. MARCHMONT

Author of “When I was Czar,” “The

Queen’s Advocate,” etc., etc.

ILLUSTRATED

WARD, LOCK & CO., LIMITED

LONDON, MELBOURNE AND TORONTO

1911

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I | An Unpropitious Start | 9 |

| II | Developments | 18 |

| III | The Reception | 28 |

| IV | Miralda | 38 |

| V | Inez | 49 |

| VI | Dr. Barosa | 59 |

| VII | Sampayo is Uneasy | 70 |

| VIII | Miralda’s Mask | 79 |

| IX | The Interrogation | 90 |

| X | A Drastic Test | 100 |

| XI | Police Methods | 110 |

| XII | The Real “M.D.” | 121 |

| XIII | Miralda’s Confidence | 132 |

| XIV | Alone with Sampayo | 143 |

| XV | In the Flush of Success | 151 |

| XVI | Barosa’s Secret | 161 |

| XVII | A Little Chess Problem | 172 |

| XVIII | Dagara’s Story | 180 |

| XIX | Spy Work | 190[8] |

| XX | A Night Adventure on the River | 199 |

| XXI | Plot and Counterplot | 207 |

| XXII | Ready | 216 |

| XXIII | On the Rampallo | 226 |

| XXIV | A Tight Corner | 235 |

| XXV | Ill News | 244 |

| XXVI | In Sight of Victory | 253 |

| XXVII | Dr. Barosa Scores | 263 |

| XXVIII | “You Shall Die” | 272 |

| XXIX | Miralda’s Appeal | 280 |

| XXX | Jealousy | 289 |

| XXXI | A Night of Torment | 299 |

| XXXII | A Hundred Lashes | 309 |

| XXXIII | The Luck Turns | 318 |

| XXXIV | On the Track | 327 |

| XXXV | The Problem of an Empty House | 335 |

| XXXVI | Until Life’s End | 343 |

“318, Rua de Palma,

“Lisbon,

“September 20, 1907.

“MY DEAR MURIEL,—

“I’m here at last, and the above is my address. The Stella dropped her anchor in the Tagus yesterday afternoon, and within half an hour I was at the Visconte de Linto’s house. That will show you I mean my campaign to be vigorous. But the Visconte and his wife are at Coimbra, and Miralda is with them. I should have been off in pursuit of her by the first train; but I managed to find out that they are with friends there and will be back to-morrow for a big reception. As that is just the sort of place I should choose before all others for the meeting with Miralda, I promptly set to work to get an invitation. I have done it all right. I got it through that M. Volheno whom you and Stefan brought on a visit to us at Tapworth, just after I got home from South Africa. Tell Stefan, by the way, that Volheno is quite a big pot and high in the confidence of the Dictator. I told him, of course, that I had come here about the mining concessions in East Africa; and I shall rub that in to every one. I think his mouth watered a bit at the prospect of getting something for himself; anyway, he was awfully decent and promised me all sorts of a good time here. Among the introductions he mentioned was one to the de Lintos! I kept my face[10] as stiff as a judge’s; but I could have shrieked. Imagine a formal introduction to Miralda! ‘Mademoiselle Dominguez. Mr. Donnington,’ and those eyes of hers wide with astonishment, and her lips struggling to suppress her laughter! I really think I must let him do it, just to see her face at the moment. Anyway, I shall see her to-morrow night. Ye gods! It’s over four months since I fell before her beauty as intuitively as a pagan falls before the shrine of the little tin god he worships. I hope no one has got in the way meanwhile; if there is any one—well, I’ll do my best to give him a bad time. I’m not here for my health, as the Yanks say; nor for the health of any other fellow. By all of which you will see I am in good spirits, and dead set on winning.

“By the way, I hear that things are in the very devil of a mess in the city; and Volheno told me—unofficially of course—that the streets are positively unsafe after dark. But I was out for a couple of hours last night, renewing my acquaintance with the city, and saw no ripple of trouble. After his warning I shoved a revolver in my pocket; but a cigar-holder would have been just as much good. I should rather like a scrap with some of the Lisbon ragamuffins.

“I’ve taken a furnished flat here; yacht too awkward to get to and from; and a hotel impossible—too many old women gossips.

“Love to your hub and the kiddies.

“Your affect. brother,

“Ralph.

“PS. Think of it. To-morrow night by this time I shall have met her again. Don’t grin. You married a Spaniard; and for love too. And you’re not ashamed of being beastly happy. R. D.

“PPS. Mind. I hold you to your promise. If there is any real trouble about M. and I need you, you are to come the moment I wire. Be a good pal,[11] and don’t back down. But I think I shall worry through on my own.”

I have given this letter because it explains the circumstances of my presence in Lisbon. A love quest. In the previous March, my sister’s husband, Stefan Madrillo, who is on the staff of the Spanish Embassy in Paris, had introduced me to Miralda Dominguez—the most beautiful girl in Paris as she was generally acknowledged; and although up to that moment I had never cared for any woman, except my sister, and the thought of marriage had never entered my head, the whole perspective of life was changed on the instant.

The one desire that possessed me was to win her love; the one possible prospect which was not utterly barren and empty of everything but wretchedness, was that she would give herself to me for life.

I had one advantage over the crowd of men whom the lodestone of her beauty drew round her. I had lived in her country, spoke her language as readily as my own, and could find many interests in common. Naturally I played that for all it was worth.

From the first moment of meeting I was enslaved by her stately grace, her ravishing smile, her soft, liquid, sympathetic voice, the subtle but ineffable charm of her presence, and the dark lustrous eyes into which I loved to bring the changing lights of surprise, curiosity, interest and pleasure.

I was miserable when away from her; and should have been wholly happy in her presence if it had not been for the despairing sense of unworthiness which plagued and depressed me. She was a goddess to me, and I a mere clod.

For three weeks—three crazily happy and yet crazily miserable weeks for me—this had continued; and then I had been wired for at a moment’s notice, owing to my dear father’s sudden illness.

[12]I had to leave within an hour of the receipt of the telegram, without a chance of putting the question on which my whole happiness depended, without even a word of personal leave-taking. And for the whole of the four months since that night I had had to remain in England.

During nearly all the time my father lay hovering between life and death. At intervals, uncertain and transitory, he regained consciousness; and at such moments his first question was for me. I could not think of leaving him, of course; and even when the end came, the settlement of the many affairs connected with the large fortune he left delayed me a further two or three weeks.

My sister assured me that, through some friend or other, she had contrived to let Miralda know something of the facts; but this was no more than a cold comfort. When at length I turned the Stella’s head toward Lisbon, steaming at the top speed of her powerful engines, I felt how feeble such a written explanation, dribbling through two or three hands and watered down in the dribbling process, might appear to Miralda, even assuming that she had given me a second thought as the result of those three weeks in Paris.

But I was in Lisbon at last; and although I could not help realizing that a hundred and fifty obstacles might have had time to grow up between us during the long interval, I gritted my teeth in the resolve to overcome them.

Anyway, the following night would show me how the land lay; and, as anything was better than suspense, I gave a sigh of relief at the thought, and having posted the letter to my sister, set off for another prowl round the city.

I had not been there for several years—before I went out with the Yeomanry for a fling at the Boers—and it interested me to note the changes which had taken place. But I thought much more of Miralda[13] than of any changes and not at all of any possible trouble in the streets. After a man has had a few moonlights rides reconnoitring kopjes which are likely to be full of Boer snipers, he isn’t going to worry himself grey about a few Portuguese rag-and-bobtail with an itch for his purse.

Besides, I felt well able to take care of myself in any street row. I was lithe and strong and in the pink of condition, and knew fairly well “how to stop ’em,” as Jem Whiteway, the old boxer, used to say, with a shake of his bullet head when he tried to get through my guard and I landed him.

But my contempt for the dangers of the streets was a little premature. My experiences that night were destined to change my opinion entirely, and to change a good many other things too. Before the night was many hours older, I had every reason to be thankful that I had taken a revolver out with me.

It came about in this way. I was skirting that district of the city which is still frequently called the Mouraria—a nest of little, narrow, tortuous by-ways into which I deemed it prudent not to venture too far—and was going down a steep street toward the river front, when the stillness was broken by the hoarse murmur of many voices. I guessed that some sort of a row was in the making, and hurried on to see the fun. And as I reached a turning a little farther down, I found myself in the thick of it.

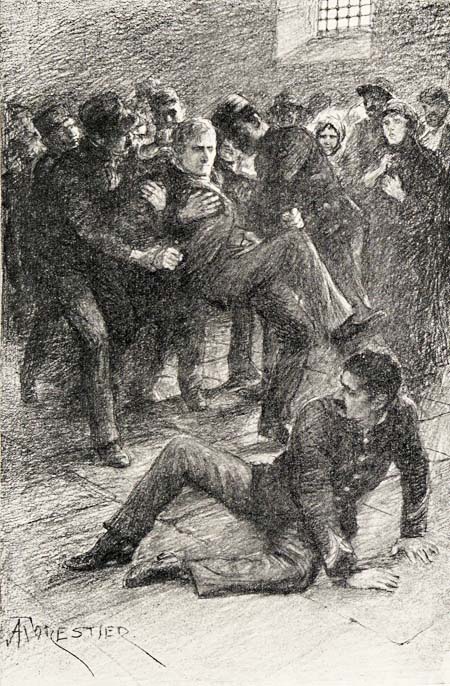

A small body of police came tearing round the corner running for their lives with a crowd of men at their heels, whooping and yelling like a pack of hounds in full sight of the fox.

As the police passed, one of them struck a vicious blow at me with a club, and I only just managed to jump back and escape the blow. I drew into the shelter of a doorway as the mob followed. The street was very narrow and steep at this point, and the police, seeing the advantage it gave them, rallied to make a[14] stand some forty or fifty yards up the hill above me.

The foremost pursuers paused a few moments to let a good number come up; and then they went for the police for all they were worth. The fight was very hot; but discipline told, as it will; and although the police were tremendously outnumbered, they held their ground well enough at first.

Meanwhile the racket kept bringing up reinforcements for the mob, and some of them began to get disagreeably curious about me. Here was a glorious struggle going on against the common foe, and I was standing idly by instead of taking a hand in it.

One or two of them questioned me in a jeering tone, and presently some fool yelled out that I was a spy. From taunts and gibing insults, those near me proceeded to threats, fists and sticks were shaken at me, and matters looked decidedly unpleasant.

I kept on explaining that I was a foreigner; but that was no more than a waste of breath; and I looked about for a chance to get away.

I was very awkwardly placed, however. If I went up the street, I should only run into the thick of the fight with the police; while the constant arrival of freshcomers below me made escape in that direction impossible.

Then came a crisis. One excited idiot struck at me with a stick, and of course I had to defend myself; and for a time I was far too busy to heed what was going on in the big row higher up the street. I tried fists at first and, putting my back to the wall, managed to keep the beggars at bay. Then a chance came to seize a big heavy club with which a little brute was trying to break my head; and with that I soon cleared quite a respectable space by laying about me indiscriminately.

But suddenly the club was knocked out of my hands, and a howl of delight hailed my discomfiture. Then I[15] remembered my revolver. I whipped it out and a rather happy thought occurred to me. Shouting at the top of my lungs that I was an Englishman and had nothing to do with either the mob or the police, I grabbed hold of the ringleader of my assailants, and used him as a sort of hostage. Keeping him between myself and the rest, I shoved the barrel of the revolver against his head and sung out that I would blow out his brains if any other man attempted to harm me.

The ruse served me well. The crowd hung back; and my prisoner, in a holy scare for his life, yelled at his friends to leave me alone.

Whether the trick would have really got me out of the mess I don’t know. There was not time to tell, for another development followed almost immediately. Some fresh arrivals came up yelling that the soldiers were close at hand; and we soon heard them.

The mob were now caught between two fires. The police were still holding their own above us, and the troops were hurrying up from the other direction. Some one had the wit to see that the crowd’s only chance was to carry the street against the police and clear that way for flight. A fierce attack was made upon them, therefore, and they were driven back to one side, leaving half the roadway clear.

The throng about me melted away, and I let my prisoner go, intending to wait for the troops. But I soon abandoned that idea; for I saw they had clubbed their muskets and were knocking down everybody they saw.

I had already had a blow aimed at me by the police, and had been threatened by the mob; and being in about equal danger from both sides, I was certain to get my head cracked if I remained. Their tactics were to hit first and inquire afterwards, and I therefore adopted the only alternative and took to my heels.

Being among the last to fly I was seen. A tally-ho[16] was raised and four or five of the police came dashing after me. Not knowing the district well, I ran at top speed and bolted round corner after corner, haphazard, keeping a sharp look-out as I ran for some place in which I could take cover.

I had succeeded in shaking off all but two or three when, on turning into one street, I spied the window of a house standing partly open. To dart to it, throw it wide, clamber in, and close it after me took only a few seconds; and as I squatted on the floor, breathing hard from the chase and the effects of my former tussle, I had the intense satisfaction of hearing my pursuers go clattering past the house.

That I might be taken for a burglar and handed over to the police by the occupants of the house, did not bother me in the least. I could very easily explain matters. It was the virtual certainty of a cracked pate, not the fear of arrest from which I had bolted; and that I had escaped with a sound skull was enough for me for the present.

But no one came near me; so I stopped where I was until the row outside had died down. It seemed to die a hard death; and I must have sat there in the dark for over an hour before I thought of venturing out to return to my rooms.

Naturally unwilling to leave by the window, I groped my way out into the passage and struck a match to look for the front door. Close to me was a staircase leading to the upper rooms; and at the end of the passage a second flight down to the basement.

Like so many houses in Lisbon this was built on a steep hill, and guessing that I should find a way out downstairs at the back, I decided to use that means of leaving, as it offered less chance of my being observed.

I had just reached the head of the stairway, when a door below was unlocked and several people entered the house. A confused murmur of voices followed, and among them I heard that of a woman speaking in a tone[17] of angry protest against some mistake which those with her were making.

The answering voices were those of men—strident, stern, distinctly threatening, and mingled with oaths.

Then the woman spoke again; repeating her protest in angry tones; but her voice was now vibrant with rising alarm.

“Silence!”

The command broke her sentence in two, and her words died away in muffled indistinctness, suggesting that force had been used to secure obedience.

Then a light was kindled; there was some scuffling along the passage; and they all appeared to enter a room.

I paused, undecided what to do. The thing had a very ugly look; but I had had quite enough trouble to satisfy me for one night. I didn’t want to go blundering into an affair which might be no more than a family quarrel; especially as I was trespassing in the house.

A few seconds later, however, came the sound of trouble; a blow, a groan, and the thud of a fall.

I caught my breath in fear that the woman had been struck down.

But the next instant a shrill piercing cry for help rang out in her voice, and this also was stifled as if a hand had been clapped on her mouth.

That decided things for me.

Whatever the consequences, I could not stop to think of them while a woman was in such danger as that cry for help had signalled.

MY view of the trouble was that it was a case of robbery. The disordered condition of the city was sure to be used by the roughs as a cover for their operations; and I jumped to the conclusion that the woman whose cry I was answering had been decoyed to the house to be robbed.

But as I ran down the stairs I heard enough to show me that it was in reality a sort of by-product of the riot in the streets. The woman was a prisoner in the hands of some of the mob, and they were threatening her with violence because she was, in their jargon, an enemy of the cause of the people.

To my surprise it was against this that she was protesting so vehemently. Her speech, in strong contrast to that of the men, was proof of refinement and culture, while the little note of authority which I had observed at first suggested rank. It was almost inconceivable, therefore, that she could have anything in common with such fellows as her captors.

The door of the room in which they all were stood slightly ajar, and as I reached it she reiterated her protest with passionate vehemence.

“You are mad. I am your friend, not your enemy. I swear that. One of you must know Dr. Barosa. Find him and bring him here and he will bear out every word I have said.”

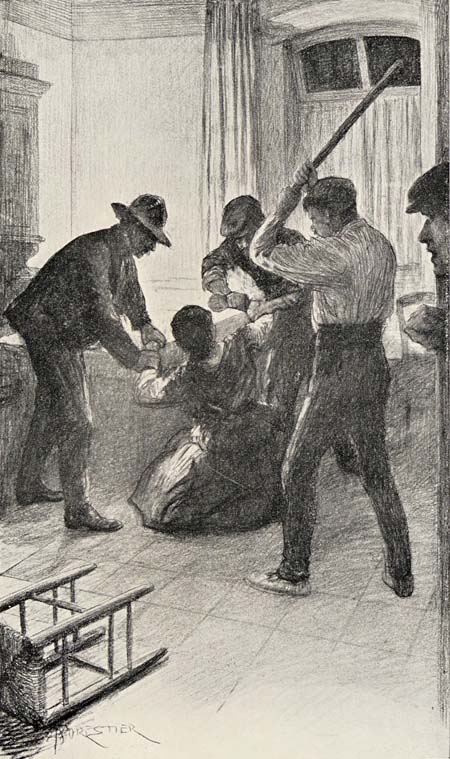

“Holding my revolver in readiness, I entered.”

“That’s enough of that. Lies won’t help you,” came the reply in the same gruff bullying tone I had[19] heard before. “Now, Henriques,” he added, as if ordering a comrade to finish the grim work.

Holding my revolver in readiness, I entered. There were three of the rascals. Two had hold of the woman who knelt between them with her back to me, while the third, also with his back to me, was just raising a club to strike her.

They were so intent upon their job and probably so certain that no one was in the house, that they did not notice me until I had had time to give the fellow with the club a blow on the side of the head which sent him staggering into a corner with an oath of surprise and rage. The others released their hold of the woman, and as I stepped in front of her, they fell away in healthy fear of my levelled weapon.

They were the reverse of formidable antagonists; rascals from the gutter apparently; venomous enough in looks, but undersized, feeble specimens; ready to attack an unarmed man or a defenceless woman, but utterly cowed by the sight of the business end of my revolver.

They slunk back toward the door, rage, baulked malice and fear on their ugly dirty faces.

“A spy! A spy!” exclaimed the brute who had the stick; and at the word they felt for their knives.

“Put your hands up, you dogs,” I cried. “The man who draws a knife will get a bullet in his head.”

Meanwhile the woman had scrambled to her feet, with a murmured word of thanks to the Virgin for my opportune intervention, and then to my intense surprise she put her hand on my arm and said in a tone of entreaty: “Do not fire, monsieur. They have only acted in ignorance.”

“You hear that, you cowardly brutes,” I said, without turning to look at her, for I couldn’t take my eyes off the men. “Clear out, or——” and I stepped toward them as if I meant to fire.

[20]In that I made a stupid blunder as it turned out. They hung together a second and then at a whisper from the fellow who appeared to be the leader, they suddenly bolted out of the room, and locked the door behind them.

Not at all relishing the idea of being made a prisoner in this way, I shouted to them to unlock the door, threatening to break it down and shoot them on sight if they refused. As they did not answer I picked up a heavy chair to smash in one of the panels, when my companion again interposed.

But this time it was on my and her own account. “They have firearms in the house, monsieur. If you show yourself, they will shoot you; and I shall be again at their mercy.”

She spoke in a tone of genuine concern and, as I recognized the wisdom of the caution, I put the chair down again and turned to her.

It was the first good square look I had had at her, and I was surprised to find that she was both young and surpassingly handsome—an aristocrat to her finger tips, although plainly dressed like one of the people. Her features were finely chiselled, she had an air of unmistakable refinement, she carried herself with the dignity of a person of rank, and her eyes, large and of a singular greenish brown hue, were bent upon me with the expression of one accustomed to expect ready compliance with her wishes. She had entirely recovered her self-possession and in some way had braided up the mass of golden auburn hair, the dishevelled condition of which I had noticed in the moment of my entrance.

“You are probably right, madame,” I said; “but I don’t care for the idea of being locked in here while those rascals fetch some companions.”

I addressed her as madame; but she couldn’t be more than four or five and twenty, and might be much younger.

[21]“There will be no danger, monsieur,” she replied in a tone of complete confidence.

“There appeared to be plenty of it just now; and the sooner we are out of this place, the better I shall be pleased.” And with that I turned to the window to see if we could get out that way. It was, however, closely barred.

“You may accept my assurance. These men have been acting under a complete misunderstanding. They will bring some one who will explain everything to them.”

“Dr. Barosa, you mean?”

“What do you know of him?” The question came sharply and with a touch of suspicion, as it seemed to me.

“Nothing, except that I heard you mention him just as I entered.”

She paused a moment, keeping her eyes on my face, and then, with a little shrug, she turned away. “I will see if my ser—my companion is much hurt,” she said, and bent over the man who was lying against the wall.

I noticed the slip; but it was nothing to me if she wished to make me think he was a companion instead of a servant.

She knew little or nothing about how to examine the man’s hurt, so I offered to do it for her. “Will you allow me to examine him, madame? I have been a soldier and know a little about first aid.”

She made way for me and went to the other end of the room while I looked him over. He had had just such a crack on the head as I feared for myself when bolting from the troops. It had knocked the senses out of him; but that was all. He was in no danger; so I made him as comfortable as I could and told her my opinion.

“He will be all right, no doubt,” was her reply, with about as much feeling as I should have shown[22] for somebody else’s dog; and despite her handsome face and air of position, I began to doubt whether he would not have been better worth saving than she.

“How did all this happen?”

She gave a little impatient start at the question, as if resenting it. “He was brought here with me, monsieur, and the men struck him,” she replied after a pause.

“Yes. But why were you brought here?”

“I have not yet thanked you for coming to my assistance, monsieur,” she replied irrelevantly. “Believe me, I do thank you most earnestly. I owe you my life, perhaps.”

It was an easy guess that she found the question distasteful and had parried it intentionally; so I followed the fresh lead. “I did no more than I hope any other man would have done, madame,” I said.

“That is the sort of reply I should look for from an Englishman, monsieur.” Her strange eyes were fixed shrewdly upon me as she made this guess at my nationality.

“I am English,” I replied with a smile.

“I am glad. I would rather be under an obligation to an Englishman than to any one except a countryman of my own.” She smiled very graciously, almost coquettishly, as if anxious to convince me of her absolute sincerity. But she spoilt the effect directly. Lifting her eyes to heaven and with a little toss of the hands, she exclaimed. “What a mercy of the Virgin that you chanced to be in the house—this house of all others in the city.”

I understood. She wished to cross-examine me. “You are glad that I arrived in time to interrupt things just now?” I asked quietly.

“Monsieur!” Eyes, hands, lithe body, everything backed up the tone of surprise that I should question it. “Do I not owe you my life?” I came to the conclusion that she was as false as woman of[23] her colour can be. But she was an excellent actress.

“Then let me suggest that we speak quite frankly. Let me lead the way. I am an Englishman, here in Lisbon on some important business, and not, as the doubt underneath your question, implies—a spy. I——”

“Monsieur!” she cried again as if in almost horrified protest.

“I was caught in the thick of a street fight,” I continued, observing that for all her energetic protest she was weighing my explanation very closely. “And had to run for it with the police at my heels. I saw a window of this house standing partly open and scrambled through it for shelter.”

“What a blessed coincidence for me!”

“It would be simpler to say, madame, that you do not believe me,” I said bluntly.

“Ah, but on my faith——”

“Let me put it to you another way,” I cut in. “I don’t know much of the ways of spies, but if I were one I should have contented myself with listening at that door, instead of entering, and have locked you all in instead of letting myself be caught in this silly fashion.” Then I saw the absurdity of losing my temper and burst out laughing.

She drew herself up. “You are amused, monsieur.”

“One may as well laugh while one can. If my laugh offends you, I beg your pardon for it, but I am laughing at my own conversion. An hour or two back I was ridiculing the idea of there being anything to bother about in the condition of the Lisbon streets. Since then I have been attacked by the police, nearly torn to pieces by the mob, had to bolt from the troops, and now you thank me for having saved your life and in the same breath take me for a spy. Don’t you think that is enough cause for laughter? If you have any sense of humour you surely will.”

[24]“I did not take you for a spy, monsieur,” she replied untruthfully. “But you have learnt things while here. We are obliged to be cautious.”

“My good lady, how on earth can it matter? We have met by the merest accident; there is not the slightest probability that we shall ever meet again; and if we did—well, you suggested just now that you know something of the ways of us English, and in that case you will feel perfectly certain that anything I have seen or heard here to-night will never pass my lips.”

“You have not mentioned your name, monsieur?”

“Ralph Donnington. I arrived yesterday and stayed at the Avenida. Would you like some confirmation? My card case is here, and this cigar case has my initials outside and my full name inside.”

“I do not need anything of that sort,” she cried quickly, waving her hands. But she read both the name and the initials.

“What have you inferred from what you have seen here to-night?”

“That the rascals who brought you here are some of the same sort of riff-raff I saw attacking the police and got hold of you as an enemy of the people. I heard that bit of cant from one of them. That you are of the class they are accustomed to regard as their oppressors was probably as evident to them as to me; and when you expressed sympathy with them——”

“You heard that?” she broke in earnestly.

“Certainly, when I heard you tell them to fetch this Dr. Barosa. But it is nothing to me; nor, thank Heaven, are your Portuguese politics or plots. But what is a good deal to me is how we are going to get out of this.”

“And for what do you take me, monsieur?”

“For one of the most beautiful enthusiasts I ever had the pleasure of meeting, madame,” I replied[25] with a bow. “And a leader whom any one should be glad indeed to follow.”

She was woman enough to relish the compliment and she smiled. “You think I am a leader of these people, then?”

“It is my regret that I am not one of them.”

“I am afraid that is not true, Mr. Donnington.”

“At any rate I shall be delighted to follow your lead out of this house.”

“You will not be in any danger, I assure you of that.”

As she spoke we heard the sounds of some little commotion outside the room and I guessed that the scoundrels had brought up some more of their kind.

“I hope so, but I think we shall soon know.”

“I have your word of honour that you will not breathe a word of anything you have witnessed here to-night.”

“Certainly. I pledge my word of honour.”

The men outside appeared to have a good deal to chatter about and seemed none too ready to enter. They were probably discussing who should have the privilege of being the first to face my revolver. I did not like the look of the thing at all.

“If they are your friends, why don’t they come in?” I asked my companion. “Hadn’t you better speak to them?”

She crossed to the door and it occurred to me to place the head of a chair under the handle and make it a little more difficult for them to get in.

“You need have no fear, Mr. Donnington,” she said with a touch of contempt as I took this precaution.

“It’s only a slight test of the mood they are in.”

As she reached the door the injured man began to show signs of recovering his senses; and I stooped over him while she spoke to the men.

“Is Dr. Barosa there?” she called.

Getting no reply, she repeated the question and knocked on the panel.

[26]There was an answer this time, but not at all what she had expected. One of the fellows fired a pistol and the bullet pierced the thin panel and went dangerously near her head.

I pulled her across to a spot where she would be safe from a chance shot. Only just in time, for half a dozen shots were fired in quick succession.

She was going to speak again, but I stopped her with a gesture; and then extinguished one of the two candles by which the room was lighted.

A long pause followed the shots, as if the scoundrels were listening to learn the effect of the firing.

In the silence the man in the corner groaned, and I heard the key turned in the lock as some one tried to push the door open.

I drew out my weapon.

“You will not shoot them, Mr. Donnington?” exclaimed my companion under her breath.

“Doesn’t this man Barosa know your voice?” I whispered.

“Of course.”

“Then he isn’t there,” I said grimly.

I raised my voice and called loudly: “Don’t you dare to enter. I’ll shoot the first man that tries to.” Then to my companion: “You’d better crouch down in the corner here. There’ll be trouble the instant they are inside.”

But she had no lack of pluck and shook her head disdainfully. “You must not fire. If you shoot one of these men you will not be safe for an hour in the city.”

“I don’t appear to be particularly safe as it is,” I answered drily.

There was another pause; then a vigorous shove broke the chair I had placed to the door and half a dozen men rushed in.

As I raised my arm to fire, my companion caught it and stopped me.

[27]For the space of a few seconds the scoundrels stared at us, their eyes gleaming in vicious malice and triumph. I read murder in them.

“Throw your weapon on the table there,” ordered one of them.

Then a thought occurred to me.

I made as if to obey; but, instead of doing anything of the sort, I extinguished the remaining candle, grabbed my companion’s arm, drew her to the opposite side of the room and, pushing her into a corner, stood in front of her.

And in the pitchy darkness we waited for the ruffians to make the first move in their attack.

THE effect of my impulse to extinguish the light in the room was much greater than I had anticipated. It proved to be the happiest thought I had ever had; for I am convinced that it saved my life, and probably that of my companion.

The average Portuguese of the lower class is too plugged with superstition ever to feel very happy in the dark. He is quick to people it with all sorts of impalpable terrors. And these fellows were soon in a bad scare.

For a few moments the wildest confusion prevailed. Execrations, threats, cries of anger, and prayers were mingled in about equal proportions; and every man who had a pistol fired it off. At least, that appeared to be the case, judging by the number of shots.

As they aimed at the corner where they had seen us, however, nothing resulted except a waste of ammunition.

The darkness was all in my favour. I knew that any man who touched me in the dark must be an enemy; while they could not tell, when they ran against any one, whether it was friend or foe. More than one struggle among them told me this, and showed me further what was of at least equal importance—that they were afraid to advance farther into the room.

When a lull came in the racket, therefore, I adopted another ruse. I crept toward the corner where they[29] had seen us, and, stamping heavily, cried out that I would shoot the first man I touched.

Another volley of shots followed; but I was back out of range again, and soon had very welcome proof that the trick was successful. Each man appeared to mistake his neighbour for me, and some of them were pretty roughly handled by their friends before the blunders were discovered.

Some one shouted for a light; and in the lull that succeeded we had a great stroke of luck. The wounded man, who lay in a corner near to them, began to move his feet restlessly, and they immediately jumped to the conclusion that I was going to attack them from there.

I backed this idea promptly. Letting out a fierce yell of rage, I fired a shot at random. This filled to overflowing the cup of their cowardice, and in another moment they had bolted like rabbits out of the room and locked the door again.

I lost no time in relighting the candles, and set to work to pile the furniture against the door to prevent them taking us again by surprise, and to give me time to see if we couldn’t get away by the window.

Opening it as quietly as possible I had a good look at the bars, and saw that it would be possible to force them sufficiently apart with wedges for us to squeeze through.

“We can reach the street this way, madame?” I asked my companion, who was now very badly scared.

“It is useless,” she replied despairingly.

“Not so useless as stopping here. We can’t expect such luck a second time as we have just had.” I spoke sharply, wishing to rouse her.

But she only shook her head and tossed up her hands. So I began to break up some of the furniture to make some wedges, when she jumped to her feet with a cry of surprise and delight.

“It is his voice,” she exclaimed, her eyes shining[30] and her face radiant with delight. Whoever “he” might be, it was easy to see what she felt about him.

Then the key was turned once more and an attempt made to force away my impromptu barricade.

I closed the window instantly and blew out one of the candles.

“Open the door. It is I, Barosa,” called a voice.

“Let him in, monsieur. Let him in at once. We are safe now.”

“Are you sure?” I asked, suspecting a trick.

Again the rich colour flooded her face. “Do you think I do not know his voice, or that he would harm me? Let him in. Let him in, I say,” she cried excitedly.

I pulled away enough of the barricade to admit one man at a time. I reckoned that no one man of the crowd I had seen would have the pluck to come in alone.

A dark, handsome, well-dressed man squeezed his way through the opening with an impatient exclamation on the score of my precaution. And the instant she saw his face, my companion sprang toward him uttering his name impetuously.

“Manoel! Manoel! Thank the Holy Virgin you have come.”

His appearance excited me also, for I recognized him at a glance. He had been pointed out to me in Paris some time before by my brother-in-law as one of the chief agents of Dom Miguel, the Pretender to the Portuguese Throne. His real name was Luis Beriardos. His presence in Lisbon at such a time and his connexion with a section of the revolutionaries gave me a clue to the whole business.

The two stood speaking together for a time in whispers, and then he went out to the others. I heard him explain that they had made a blunder in regard to madame and that he was ready to vouch for her as[31] one of their best friends and a leader of their movements.

Some further murmur of talk followed, and when he returned, one or two of the rest tried to follow. But I stopped that move. One man was all I meant to have in the room at a time; and when I told the others to get out they went. I had managed to make them understand that it was safer to obey.

“What does this mean, sir?” asked Barosa, indignantly.

“You need have no fear now, Mr. Donnington,” added madame.

I replied to Barosa. “Those men have been telling you that I am a spy and you have come in to question me. This lady has assured me that I have nothing to fear from you. You will therefore have the goodness to get the key of that door and lock it on this side. Then we can talk, but not till then.”

“I shall not do anything of the sort,” he replied hotly.

“Then I shall shove these things back in position;” and I began.

“Dr. Barosa will get the key, Mr. Donnington,” put in madame; and she appealed to him with a look. “He has saved my life, doctor,” she said in an undertone.

I noticed that she did not now call him by his Christian name as in the first flush of her relief.

He hesitated a second or two and then with an angry shrug of the shoulders complied.

“I’ll take the key, doctor,” I said quietly; and when he stood irresolute, I pushed past him and drew it out of the lock. “Now we can talk, and I’m ready to answer any questions, in reason, which you like to ask.”

“Your conduct is very extraordinary, sir.”

“Not a bit of it. These friends of yours take me for a spy. You may come to the same conclusion.[32] They tried to take my life; and you may wish to do the same. I am simply taking precautions. I have told this lady enough about myself to satisfy her that I am no spy; but if you are not equally satisfied, I prefer to remain here with no other company than ourselves until a chance of getting away offers.”

He was going to reply when madame interposed. To do her justice she took up my cause with a right good will. She repeated all I had previously told her, gave him a graphic account of what had passed, lauded me to the skies, and ended by declaring her absolute conviction that every word I had spoken was the truth.

Feeling that my case was in safe hands, I let them have it out together. He was suspicious, and at every proof of this, her anger and indignation increased.

“I have accepted Mr. Donnington’s word, Dr. Barosa,” she said hotly, when he declared that I ought not to be allowed to leave the house; “and I have given him a pledge for his safety. You know me, and that I will keep my word. Very well, I declare to you on my honour that if any harm comes to him now, I will abandon the cause and reveal everything I know about it and all concerned in it.”

That shook all the opposition out of him on the spot.

“You are at liberty to go, Mr. Donnington,” he said at once.

“Thank you; but what about your friends out there?”

“I will leave the house with you,” declared madame. “And we will see if any one will dare to try and stop you.”

“It might be simpler if they were to go first,” I suggested.

“I will answer for them,” said Barosa. “We have your word that you will not speak of anything you have learned here to-night?”

“Yes, I pledge my word,” I replied.

[33]“Let me thank you once more, Mr. Donnington——” began madame.

But I stopped her. “We can call the account between us squared, madame. If I helped you out of one mess you have got me out of this. And for the rest, silence for silence. We shall not meet again.”

“Are you staying long in the city, sir?” asked Barosa with a suggestion of eagerness in his tone.

“Not an hour longer than my business here renders necessary. I am not so delighted with my experiences so far as to wish to remain.”

He left the room then and after a hurried conference with the fellows outside he called to us and we left the house.

With what relief I drew the first breath of the fresh night air will be readily understood; but I do not think I fully realized how narrow an escape I had had until I was safe in my rooms and sat recalling the incidents of the strange adventure.

Who was the woman I had helped? Not a hint had been dropped of her name; but that she was a person of as much importance in the world outside as in the ranks of the revolutionary party of which she was a leader, I could not doubt. That the conspiracy was being carried on in the interest of the Pretender was fairly certain, seeing that this Beriardos, or Barosa, as he now called himself, was mixed up in it; and I resolved to write at once to Madrillo to send me everything he knew about him.

What had he meant, too, by that eager question as to the length of my stay in the city? He was certainly not satisfied that I was not a spy. Should I have to be on the look-out for further trouble from him and the scum of the city joined with him? It was a more probable than pleasant prospect.

As that exceedingly handsome creature had reminded me, I had gained some information which made me dangerous to these people; and however willing she[34] might be to accept my promise of secrecy, it was all Portugal to a bunch of grapes that the others would not be so content.

And the irritating part of it was that I had got into the mess through my own blundering stupidity. If I hadn’t been ass enough to go wandering about the city when I had been warned to stop indoors, I shouldn’t have had this bother. But the world is full of asses; and many of them with a heap more brains than I. And with a chuckle, as if that silly cynicism were both an excuse and a consolation, I tossed away my cigar and went to bed.

A night’s sound sleep put me on much better terms with myself, and I scouted the thought of troublesome personal consequences following my adventure. The thing was over and done with and I was well out of the mess.

Instead of bothering to write to Madrillo for details about this Dr. Barosa, therefore, I went off to the Stella for a cruise to blow the cobwebs away and think about Miralda and the meeting with her that evening.

We were to meet at the house of the Marquis de Pinsara, and my friend, Volheno, had impressed upon me the importance of the gathering.

“Affairs are in a somewhat delicate condition just at present,” he had said; “and as there is a great deal of surface discontent here and in Oporto—although the bulk of the country is solid in our favour—we have to exercise some care in organizing our followers. The Marquis de Pinsara is one of M. Franco’s firmest adherents, and this reception will really be political in character. You may have heard of the ‘National League of Portugal?’ No? Well, it is a powerful loyalist association, and we are doing our utmost to make the movement fully representative and powerful;” and being a politician and proportionately verbose, he had first inflicted upon me a long account of the League and its merits, and from that had launched[35] into the reasons why he meant to take me to the reception. Put shortly these were simply that he wished to interest the Marquis de Pinsara and many of his loyalist friends in the concessions at Beira which I had put forward as the object of my visit.

What this process of “interesting” the Marquis meant, I learnt within a few minutes of my entering his house.

As Volheno sent me a line at the last moment saying he was detained, I had to go alone and I was very glad. Not being quite certain how Miralda would receive me, I did not wish to have any lookers-on when me met. Moreover, I certainly did not want to fool away the evening, a good deal of which I hoped to spend with her, in talking a lot of rot about these concessions which I had only used as a stalking-horse for my visit to Lisbon.

But I soon found that in choosing them, I had invested myself with a most inconvenient amount of importance.

The Marquis received me with as much cordiality as if I were an old friend and benefactor of his family. He grasped my hand warmly, expressed his delight at making my acquaintance, could not find words to describe his admiration of England and the English, and then started upon the concessions.

I thought he would never stop, but he came to the point. Volheno had taken as gospel all the rubbish I had talked about the prospects of wealth offered by the concessions, and had passed it on to the marquis through a magnifying glass until the latter, being a comparatively poor man, was under the impression that I could make his fortune. He was more than willing to be “interested” in the scheme; and took great pains to convince me that without his influence I could not succeed. And that influence was mine for a consideration.

In the desire to get free from his button-holing I[36] gave him promises lavish enough to send him off to his other guests with eyes positively glittering with greed.

Unfortunately for me, however, he began to use his influence at once, and while I was hanging about near the entrance, waiting to catch Miralda the moment she arrived, he kept bringing up a number of his friends—mostly titled and all tiresome bores—whom he was also “interesting” in the scheme.

They all said the same thing. Theirs was the only influence which could secure the concessions for me, and they all made it plain about the consideration. I began at length to listen for the phrase and occasionally to anticipate it; and thus in half an hour or so I had promised enough backsheesh to have crippled the scheme ten times over.

One of these old fellows—a marquis or visconte or something of the sort, the biggest bore of the lot anyway—was in possession of me in a corner when Miralda arrived, and for the life of me I couldn’t shake him off. I was worrying how to get away when the marquis came sailing up with another of them in tow, a tall, stiff, hawk-faced, avaricious-looking old man, with a pompous air, and more orders on his breast than I could count.

I groaned and wished the concessions at the bottom of the Tagus, but the next moment had to shut down a smile. It was the Visconte de Linto, Miralda’s stepfather.

The marquis had evidently filled him up with exaggerated stories of my wealth and the riches I had come to pour into the pockets of those who assisted me, and his first tactic was to get rid of the bore in possession. He did this by carrying me off to present me to his wife and daughter.

It was the reverse of such a meeting as I had pictured or desired; for at that moment Miralda was besieged by a crowd of men clamouring for dances. But I[37] could not think of an excuse, and I had barely time to explain that I had met Miralda and her mother in Paris, when the old man pushed his way unceremoniously through the little throng and introduced me, stumbling over my name which he had obviously forgotten, and adding that Miralda must save two or three dances for me.

As he garbled my name she was just taking her dance card back from a man who had scribbled his initials on it and she turned to me with a little impatient movement of the shoulders which I knew well.

Our eyes met, and my fear that she might have forgotten me was dissipated on the instant.

ALTHOUGH it was easy to read the look of recognition in Miralda’s eyes, it was the reverse of easy to gather the thoughts which that recognition prompted. After the first momentary widening of the lids, the start of surprise, and the involuntary tightening of the fingers on her fan, she was quick to force a smile, as she bowed to me, and the smile served as an impenetrable mask to her real feelings.

The viscontesse gave me a very different welcome. She was pleased to see me again and frankly expressed her pleasure. I had done my best to ingratiate myself in her favour during those three weeks in Paris, and had evidently been successful. She was a kind-hearted garrulous soul, and before I could get a word in about the dances, she plunged into a hundred and one questions about Paris and England and the beauties of Lisbon, and why I had not let them know of my coming and so on, and without giving me time to reply she turned to Miralda.

“You surely remember Mr. Donnington, child? We met him in Paris, last spring.”

“Oh yes, mother. His sister is M. Madrillo’s wife,” said Miralda indifferently.

This was not exactly how I wished to be remembered. “I am glad you have not forgotten my sister, at any rate, mademoiselle,” I replied, intending this to be very pointed.

“M. Madrillo showed us many kindnesses, monsieur,[39] and did much to make our stay in Paris pleasant; and it is not a Portuguese failing to forget.”

This was better, for there was a distinct note of resentment in her voice instead of mere indifference. But before I could reply, the viscontesse interposed a very natural but extremely inconvenient question. “And what brings you here, Mr. Donnington?”

The visconte answered this, making matters worse than ever; and there followed a little by-play of cross purposes.

“Mr. Donnaheen is here on some very important business, my dear—very important business indeed.”

“If I remember, Donnington is the proper pronunciation, father,” interposed Miralda, very quietly, as if courtesy required the correction—the courtesy that was due to a stranger, however.

“I wish you wouldn’t interrupt me, Miralda,” he replied testily. “This gentleman will understand how difficult some English names are to pronounce and will excuse my slip, I am sure.”

“Certainly, visconte.”

“I am only sorry I do not speak English.”

“Donnington is quite easy to pronounce, Affonso,” his wife broke in.

He gave a sigh of impatience. “Of course it is, I know that well enough.”

“You were speaking of the reason for Mr. Donnington’s visit,” Miralda reminded him demurely; and as she turned to him her eyes swept impassively across my face. As if a stranger’s presence in Lisbon were a legitimate reason for the polite assumption of curiosity.

“It is in a way Government business; Mr. Donnington”—he got the name right this time and smiled—“is seeking some concessions in our East African colony and he needs my influence.”

“Oh, business in East Africa?” she repeated, with a lift of the eyebrows. “How very interesting;”[40] and with that she turned away and handed her programme to one of the men pestering her for a dance.

No words she could have spoken and nothing she could have done would have been so eloquent of her appreciation of my conduct in absenting myself for four months and then coming to Lisbon on business. Once more I wished those infernal concessions at the bottom of the Tagus.

“I hope to be of considerable use and you may depend upon my doing my utmost,” said the visconte, self-complacently.

“I cannot say how highly I shall value your influence, sir, not only in that but in everything,” I replied, putting an emphasis on the “everything” in the hope that Miralda would understand.

But she paid no heed and went on chatting with the man next her.

“And how long are you staying, Mr. Donnington?” asked her mother.

“Rather a superfluous question that, Maria,” said her husband. “Of course it will depend upon how your business goes, eh, Mr. Donnington?”

I saw a chance there and took it. “I am afraid my object will take longer to accomplish than I hoped,” I replied; for Miralda’s benefit again of course.

“At any rate you will have time for some pleasure-making, I trust,” said the viscontesse.

“Englishmen don’t let pleasure interfere with business, my dear, they are far too strenuous,” replied her husband, who appeared to think he was flattering me and doing me a service by insisting that I could have no possible object beyond business. “I presume that you are only here to-night for the one purpose. The Marquis de Pinsara told me as much.”

At that moment a partner came up to claim Miralda for a dance, and as she rose she said: “Mr. Donnington is fortunate in finding so many to help him in his business.”

[41]“Wait a moment, Miralda,” exclaimed her father as she was turning away. “Have you kept the dances for Mr. Donnington?”

Again her eyes flashed across mine with the same half-disdainful smile of indifference. “Mr. Donnington has been so occupied discussing the serious purpose of his visit that he has had no time to think of such frivolity and ask for them;” and with that parting shot she went off to the ball-room without waiting to hear my protest.

The visconte smiled and gestured. “I suppose you don’t dance, Mr. Donnington,” he said, “I have heard that many Englishmen do not.”

“Indeed he does, Affonso,” declared his wife quickly. “I remember that well in Paris. He and Miralda often danced together. And now, sit down here in Miralda’s place till she comes back and let us have a chat about Paris,” she added to me.

But the old visconte had not quite done with me. Drawing me aside—“I want you to feel that I shall do all in my power, Mr. Donnington,” he began.

I knew what was coming so I anticipated him. “I am sure of that, and I have been given to understand that you can do more for me than any one else in Portugal. And of course you’ll understand that those who assist me in the early stages will naturally share in the after advantages and gains. I make a strong point of that.”

“Of course that was not in my mind at all,” he protested.

“Naturally. But I should insist upon it,” I said gravely.

“I suppose it will be a very big thing?”

“Millions in it, visconte. Millions;” and I threw out my hands as if half the riches of the earth would soon be in their grasp. “And of course I know that without you I should be powerless.”

He appreciated this thoroughly and went off on excellent terms with himself and with a high opinion[42] of me as a potential source of wealth, while I sat down by the viscontesse to explain why four months had passed since we met.

But these miserable concessions gave me no peace. I was only beginning my explanation when up came the marquis and dragged me off for the first of another batch of introductions, followed by a long conference in another room with him and Volheno who had meanwhile arrived. And just as the marquis took my arm to lead me away, and thus prevented my escape, Miralda returned from the dance.

A single glance showed her that I was fully occupied in the business which I had been forced to admit in her presence was the object of my visit to Lisbon, and the expression of her eyes and the shrug of her shoulders were a sufficient indication of her feeling.

I was properly punished for the silly lie which I had merely intended to conceal my real purpose, and when I saw Miralda welcome a fresh partner with a smile which I would have given the whole of Portuguese Africa to have won from her, I could scarcely keep my temper.

I was kept at this fool talk for an hour or more when I ought to have been making my peace with her, and I resolved on the spot to invent a telegram from London the next day reporting a hitch in the negotiations.

When at length I got free, Miralda was not anywhere to be seen; and I wandered about the rooms and in and out of the conservatories looking for her, putting up no end of couples in odd corners and getting deservedly scowled at for my pains.

I saw her at last among the dancers; and I stood and watched her, gritting my teeth in the resolve that no titled old bores nor even wild horses should prevent my speaking to her as soon as the waltz was over.

I stalked her into a palm house which I had missed in my former search and, giving her and her partner[43] just enough time to find seats, I followed and walked straight up to them.

She knew I was coming. I could tell that by the way she squared her shoulders and affected the deepest interest in her partner’s conventional nothings.

“I think the next is our dance, mademoiselle,” I said unblushingly, as I affected to consult my card. She gave a start as if entirely surprised by and rather indignant at the interruption; while her partner had the decency to rise. But she glanced at her card and then looked up with a bland smile and shook her head. “I am afraid you are mistaken, monsieur.”

The man was going to resume his place by her side, but I stopped that. “I have the honour of your initials here, and if to my intense misfortune you have given the dance to two of us, perhaps this gentleman will allow me, as an old acquaintance of yours, to enjoy the few minutes of interval to deliver an important message entrusted to me.”

I was under the fire of her eyes all the time I was delivering this flowery and untruthful rigmarole; but I was as voluble and as grave as a judge. I took the man in all right. I made him feel that under the circumstances he was in the way and with a courteous bow to us both, he excused himself.

Miralda was going to request him to remain, I think, so I took possession of the vacant chair; and then of course she could not bring him back without making too much of the incident and possibly causing a little scene.

That I had offended her I could not fail to see; her hostility and resentment were obvious, but whether the cause was my present effrontery or my long neglect of her, I had yet to find out.

She did not quite know what to do. After sitting a few moments in rather frowning indecision, she half rose as if she were going to leave me, but with a little[44] toss of the head she decided against that and turned to me.

“You have a message for me, monsieur?” Her tone was one of studied indifference and her look distinctly chilling.

“For one thing, my sister desired to be most kindly remembered to you.”

Up went the deep fringed lids and the dark eyebrows, as a comment upon the message which I had described as important. “Please to tell Madame Madrillo that I am obliged by her good wishes and reciprocate them.” This ridiculously stilted phrase made it difficult for me to resist a smile. But I played up to it.

“I feel myself deeply honoured, mademoiselle, by being made the bearer of any communication from you. I will employ my most earnest efforts to convey to my sister your wishes and the auspicious circumstances under which they are so graciously expressed.”

She had to turn away before I finished, but she would not smile. There was, however, less real chill and more effort at formality when she replied—

“As you have delivered your message, monsieur——” she finished with a wave of the hands, as if dismissing me.

But I was not going of course, and then I made a very gratifying little discovery. Her dance card was turned over by her gesture and I saw that for the next dance she had no partner.

“That is only one of the messages, mademoiselle,” I replied after a pause in the same stilted tone. “Have I your permission to report the second?”

I guessed she was beginning to see the absurdity of it, for she turned slightly away from me and bowed, not trusting herself to speak.

“My brother-in-law, M. Stefan Madrillo, desired me to bring you an assurance of his best wishes.”

“Have you any messages from the children also,[45] monsieur?” she asked quickly, with a swift flash of her glorious eyes.

I kept it up for another round. “I am honoured by being able to assure you that their boy appreciated to the full the bon-bons which were the outcome of your distinguished generosity when in Paris, and retains his appetite for delicacies; but the little girl, not yet being able to speak, has entrusted me with no more than some gurgles and coos. To my profound regret I cannot reproduce them verbatim. May I have the honour of conveying your reply?”

She kept her face turned right away from me and did not answer.

“I have yet another message, mademoiselle, if your patience is not exhausted,” I said after a pause.

“Still another, monsieur?”

“Still another, mademoiselle.”

“From whom, monsieur?”

“From a man you knew in Paris, mademoiselle, Mr. Ralph Donnington. He has charged me to explain——”

“I don’t wish to hear that one, thank you,” she broke in.

“But he is absolutely determined that you shall hear it.”

“Shall?” she cried warmly, throwing back her head with a lovely poise of indignation and looking straight into my eyes.

“Yes, shall,” I replied firmly. “I have travelled over a thousand miles to deliver it.”

“I am not interested in mining concessions, Mr. Donnington,” she cried scornfully, thinking to wither me.

“Nor am I.”

Her intense surprise at this put all her indignation to flight, and left nothing in her eyes but bewildered curiosity.

“Nor am I,” I repeated with a smile.

“But——”

[46]“I know,” I said when she paused. “I had to have a pretext.”

She knew what I meant then and lowered her eyes.

“I still do not wish to hear Mr. Donnington’s message,” she said after a pause and in a very different tone.

“I do not wish to force it upon you now, and certainly not against your wish. I may be some months in Lisbon, and——”

“There is the band for the next dance, I must go,” she interposed.

“I have seen by your card that you have no partner; but if you wish me to leave you I will do so, or take you back to the viscontesse—unless you will give it to me.”

She leant back in her chair, her head bent, her brows gathered in a frown of perplexity and her fingers playing nervously with her fan.

“I do not wish to dance, Mr. Donnington, thank you,” she murmured.

“Just as you will.”

A long silence followed. She was agitated and I perplexed.

After perhaps a minute of this silence, I rose.

“You wish to be alone, mademoiselle?”

She did not reply and I was turning to leave when she looked up quickly. “I do not wish you to go, Mr. Donnington.” Then putting aside the thoughts, whatever they were, which had been troubling her, she laughed and added: “Why should I? It is pleasant to meet an old acquaintance. You have come through Paris on your way here, of course. Were you there long?”

I was more perplexed by the change of tone and manner than by her former silent preoccupation.

“I did not come through Paris,” I replied, as I resumed my seat. “I came from England in the Stella—my yacht.”

[47]“You have had delightful weather for your cruise.”

“I was not cruising in that sense. The Stella is a very fast boat and I came in her because I could get here more quickly.”

“Our Portuguese railways are very slow, of course, and the Spanish trains no better. It is a very tedious journey from Paris.”

“Very,” I agreed. Whether she wished to make small talk in order to avoid my explanation, I did not know; but I fell in with her wish and then tried to lead round to the old time in Paris.

She turned my references to it very skilfully however, and after my third unsuccessful attempt, she herself referred to it in a way that forced me to regard it as a sealed page.

“It has been very pleasant to meet you again, Mr. Donnington, and have such a delightful chat, and I am so much obliged to you for not having pressed me to dance. I hope we shall see a good deal of you while you are here. You quite captured my dear mother during that time in Paris. Of course you’ll call.”

“I ventured to leave cards immediately on my arrival.”

Then she rose. “I must really go now. Major Sampayo will be looking for me for the next dance. Have you met the major yet?”

“I don’t think so; but I have had so many introductions this evening that I don’t remember all the names.”

“Ah, the result of your supposed purpose in Lisbon, probably. Of course I shall keep your secret,” she replied with a smile. Then a sudden change came over her. She paused, the hand which held her fan trembled, the effort to maintain the light indifference of voice and manner became apparent, and her voice was a trifle unsteady as she added: “You will meet Major Sampayo at our house. Ah, here he comes with[48] my friend the Contesse Inglesia. I suppose my mother has told you I am betrothed to him.”

The news gripped me like a cramp in the heart, and I caught my breath and gritted my teeth as I stared at her.

But the next instant I rallied. The pain and concern in her eyes seemed to explain what had so perplexed me in her manner. Her agitation when I told her the real purpose of my presence; her quick assumption of indifference, of mere acquaintanceship, her studious evasion of my references to our time in Paris, and her light surface talk on things of no concern to either of us. If my new wild hope was right, all this had been merely intended to school herself to refer lightly to the matter of her betrothal.

I forced a smile. “Permit me to congratulate——” I began; but the words died on my lips as I turned and saw the two people whom she had mentioned.

The man, Major Sampayo, I knew to be one of the vilest scoundrels who ever escaped the gallows.

And his companion was the woman whose life I had saved from her revolutionary associates on the previous night.

WITH a big effort I managed to pull myself together, and much to Miralda’s surprise I covered my momentary confusion with a hearty laugh and a sentence spoken for the benefit of the other two who were now within earshot.

“I’m afraid I’ve bored you frightfully, but I couldn’t resist sparing a few minutes from this concession-mongering business. And after your saying that the viscontesse remembers our chats in Paris, I shall certainly ask her to allow me to call.”

I succeeded in speaking in the tone of a quite casual acquaintance, and I turned to find two pairs of eyes fixed intently upon me.

Whether the fellow who now called himself Major Sampayo recognized me I could not tell, but his companion did, and I waited for her to decide whether we were to acknowledge that we had met.

She made no sign and I made my bow to Miralda and was moving off when the major intervened.

“Will you present me to your friend, Miralda?”

I could have kicked him for the glib use of her name. I paused and turned with a smile, as if highly pleased by the request. If I knew myself, the kicking would come later.

“Mr. Donnington, may I introduce Major Sampayo?” said Miralda, a little nervously.

I bowed and smirked, but behind the entrenchment of English reserve I made no offer to take his hand.

[50]“I am glad to meet you, Mr. Donnington.”

“I consider myself equally fortunate, Major Sampayo.”

I saw then that he had an uneasy feeling that we had met somewhere before, and his eyes moved from side to side as he searched his memory to place my voice or face or name.

“Is that really Mr. Donnington?” exclaimed his companion, with a delightful assumption of interested surprise. “My dear Miralda, please don’t leave me out.”

“My friend the Contesse Inez Inglesia,” said Miralda.

She held out her hand and as I took it she looked straight into my eyes with a most cordial smile. “I have heard so much about you, Mr. Donnington, that I have been questioning every one I know to find a mutual friend, and wandering all over the rooms to find you.”

Which meant that she knew I had been a long time with Miralda.

“I have such an implicit faith in Portuguese sincerity, contesse, that you will turn my head if you flatter me so. The fact is I have been making an unconscionable bore of myself with Mademoiselle Dominguez. I met her and the viscontesse in Paris last spring, and I was so glad to find a face I knew to-night, that I could not resist the temptation for a chat.”

“Have you been long in Lisbon, sir?” asked Sampayo, still worrying himself about me.

“Two days, major, that’s all. I came in my yacht.”

“Surely you’ve heard about Mr. Donnington, major,” said the contesse. “He’s the millionaire who has come about the mining concessions in Beira, or somewhere.”

“No, I had not heard that,” he replied, with a little start, as if this might have suggested a clue to his problem. “Have you been in Beira, sir?”

[51]I smiled and shrugged my shoulders. “I suppose I ought not to own it, but I was never there in my life.”

“Major Sampayo knows every inch of South Africa, Mr. Donnington,” said the contesse. “He was out there at the time your country was at war with the Boers.”

“Oh, indeed,” said I, as if in great surprise. I knew that well enough. “Then I shall hope to get some wrinkles from him.”

“You served in that war, didn’t you, Mr. Donnington?” asked Miralda, evidently feeling she ought to say something.

“For a few months. I was in Bloemfontein and Mafeking.” I purposely named places as distant as possible from the spot where I had seen him. I did not wish him to recognize me yet.

“Were you out at the finish of the campaign?” he asked at the prompting of his uneasy fears.

“About the middle. I was sent down country after the relief of Mafeking.” This was half truth but also half lie. I had gone up again almost immediately. But it appeared to ease his unrest.

“I have a curious feeling that we have met somewhere,” he said; “and was wondering whether it could have been out in South Africa. That was the reason for my rather inquisitive questions.”

I laughed. “Oh, I should have recognized you in a moment if that had been the case. I never forget a face.”

This made him uneasy again, but, as the band struck up, he gave his arm to Miralda.

“Thanks for a delightful chat, mademoiselle,” I said lightly to Miralda. “May I take you to your partner, madame?” I asked, offering my arm to the Contesse.

Instead of accepting it she said to Miralda. “If you see Vasco tell him I’ll give him another waltz[52] for this. I am going to sit this out with Mr. Donnington—that is, of course, if he is willing.”

“I’ll tell him, Inez,” replied Miralda over her shoulder as she walked away.

Inez was silent until they were out of hearing, and then she said very meaningly: “What an excellent actor you are, Mr. Donnington.”

“May I return the compliment? I saw that you wished it to appear that we were complete strangers. And with your permission that is just what we have been up to the moment of this introduction.”

Another pause followed by a surprise for me.

“So you are Miralda’s Englishman!”

But I was too well on my guard to betray myself. “Am I really?” I asked with an easy laugh. “We had a jolly time for a week or two, but—that’s four months ago.”

“You are fond of camelias, Mr. Donnington.”

“I am wearing one, as you see,” I replied pointing to my buttonhole. But I had often given camelias to Miralda in those three weeks; and this handsome, dangerous, stately creature with hazel eyes, which were open and frank or diabolically sly at will, knew it.

Again she paused once more as the preface to a shot.