Title: A boy's-eye view of the Arctic

Author: Kennett Longley Rawson

Author of introduction, etc.: Donald Baxter MacMillan

Release date: April 28, 2022 [eBook #67944]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: The MacMillan Company, 1926

Credits: Steve Mattern, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO · DALLAS

ATLANTA · SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

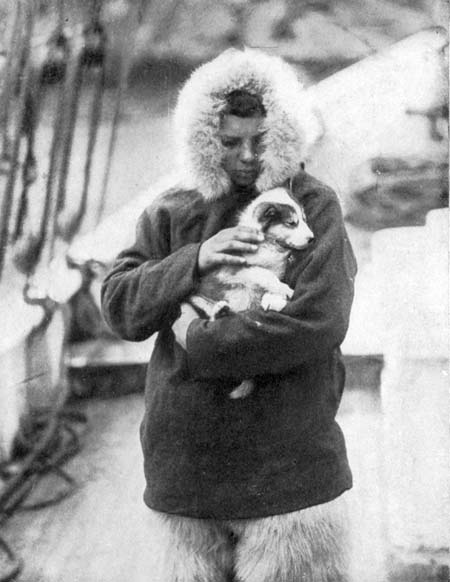

Kennett L. Rawson, June, 1925.

A BOY’S-EYE VIEW

OF

THE ARCTIC

BY

KENNETT LONGLEY RAWSON

CABIN-BOY OF THE BOWDOIN

Introduction by

Commander Donald B. MacMillan

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1926

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1926,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY,

Set up and electrotyped.

Published October, 1926.

Printed in the United States of America by

THE FERRIS PRINTING COMPANY, NEW YORK

To My Mother

Bravest of them all.

Illustrated with photographs taken by the author, and others loaned through the courtesy of Commander Donald B. MacMillan; National Geographic Society, taken by Maynard Owen Williams, photographer of the Expedition; Ralph P. Robinson, Mate of the Bowdoin; Onnig D. Melkon, moving picture photographer of the Expedition; Alfred Brust, Staff Photographer of the Boston Herald, and George Warren Lord, Staff Photographer of the Boston Post.

TO the lecturer the introduction is the most interesting part of his lecture, in that it is generally so complimentary that his feeling of guilt and a sense of his own inferiority mars somewhat his whole discourse. My cabin boy, Kennett Rawson, suffers no handicap in this respect. His work is finished. Whatever I may write will not affect its status. His narrative stands as a testimonial of the influence of good and much reading. Very few will believe that such language is natural for a fourteen-year-old boy. But we knew “Ken” in the forecastle of the little Bowdoin, and teachers at Hill School who have watched his progress for two years can assure you that the book is his own.

How fortunate that a boy in his early teens could visit the scenes of our early explorers, the headquarters of the great Peary, who, by his work, has placed before American youth the finest example of persistency, determination, and clean grit in all Arctic history. What a privilege for young Rawson to stand where the immortal Elisha Kent Kane stood with lifted ramrod[x] and fluttering cap lining, the first to step foot on historical Littleton Island, and to enter the Basin which bears his name!

From the heights about Etah he has looked across to the ice-covered hills of Ellesmere Land and Cape Sabine where Greely and his men lay dying in 1884 and where Peary fought a losing fight in 1900-1902. He has seen the last of the S. S. Polaris, which steamed farther north than ship ever steamed, now strewn about the beach rusting, rotting away. But memories of her Commander, the most enthusiastic of all Arctic explorers, will always live.

Something more than pure sentiment. No boy can look upon such things, can dwell upon the deeds of such men as Kane, Hayes, Hall, Greely and Peary, without standing a little more erect, without visualizing his own future and determining to have that future count for something beyond material gain.

With mingled feelings of apprehension, doubt as to the wisdom of my decision, I signed Kennett Rawson on the ship’s papers as “Cabin boy, Chicago, age 14,” the youngest white lad ever to go into the Far North.

Under starlit skies and unruffled sea; in the semi-darkness of his 10-11 watch, I watched him[xi] as he stood at the wheel “giving her a spoke” now and then to keep her on her course, his small sheepskin-covered form outlined against the black of the ocean. In howling winds and with the Bowdoin plunging and bucking head seas, decks awash and life lines stretched, the same huddled form, eyes on the compass card, doing his best, with never trace of quit, I, a shipmate for four months, knew him. Young Rawson made good. For that reason he goes back again with me in the Northland one week from to-day, back to the big grey hills of Labrador with their outlying, breaking reefs, to the inner reaches of its green bays, to its simple, sincere people; to Greenland, once the home of the Norsemen, now the land of the Dane and smiling half-breed; to Baffin Island, the Meta Incognita of Martin Frobisher, the objective of many an old New England whaling ship.

May he enjoy this fourth cruise of the Bowdoin as he did her third. “The thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts,” and when those thoughts or dreams are realized, doubly fortunate is youth.

Donald B. MacMillan.

Freeport, Maine.

June 12, 1926.

[xii]

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction | ix | |

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | Here Endeth the Lesson | 1 |

| II. | Under Weigh | 14 |

| III. | In the Land of Adventure | 22 |

| IV. | A Truly Glorious Fourth and Some Very Real Fishing | 32 |

| V. | Through the Pack to Disaster | 41 |

| VI. | The Heroes of Hopedale | 49 |

| VII. | In Eskimo Land and in Trouble | 56 |

| VIII. | Greenland! | 66 |

| IX. | Ice and More Ice | 76 |

| X. | We Take the Air | 89 |

| XI. | My Farthest North | 107 |

| XII. | We Break Into Society | 115 |

| XIII. | Storm and Stress and—Home! | 130 |

[xiv]

| Kennett L. Rawson, June, 1925 | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

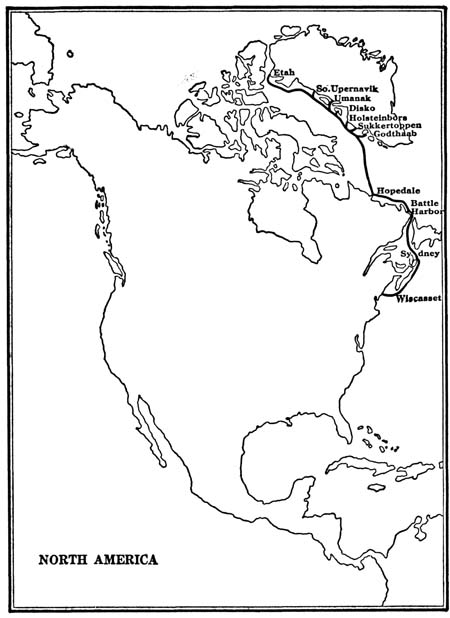

| The journey of the Bowdoin, 1925 (map) | 1 |

| The Bowdoin and her crew, Wiscasset, Maine, June 20, 1925. John Jaynes, Engineer; Commander Donald B. MacMillan; Ralph P. Robinson, Mate; Kennett L. Rawson, Cabin Boy; John Reinartz, short wave radio expert; Martin Vorce, Cook; Lieutenant Benjamin Rigg, U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey; Onnig D. Melkon, moving picture photographer | 12 |

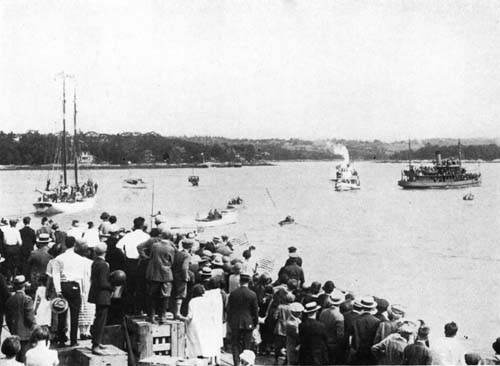

| Outward Bound, June, 1925 | 20 |

| The Bowdoin leaving the dock at Wiscasset | 20 |

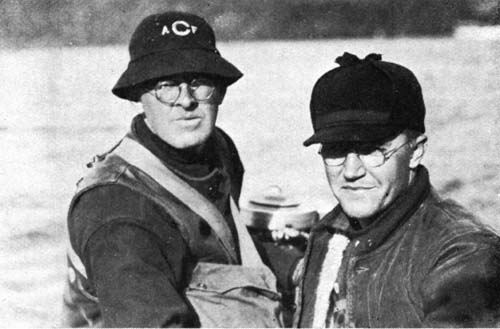

| Rawson, MacMillan at the wheel, and Dr. Grosvenor. On way to Sydney | 27 |

| “Yonder beneath the North Star lies our destination, Lad.” | 27 |

| Commander MacMillan, Dr. Grosvenor and Dr. Grenfell, Battle Harbor | 27 |

| Maynard Williams (left), photographer, National Geographic Society; Lieutenant Benjamin Rigg (right), U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey | 61 |

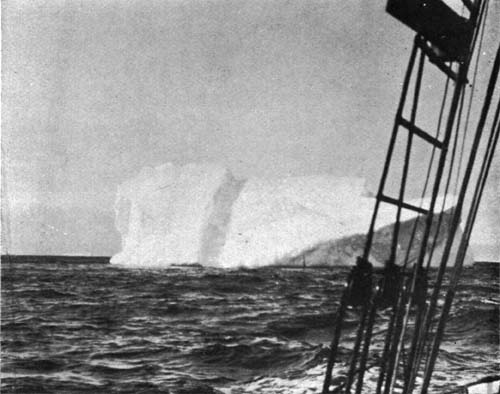

| The Bowdoin passing an iceberg off west coast of Greenland | 63 |

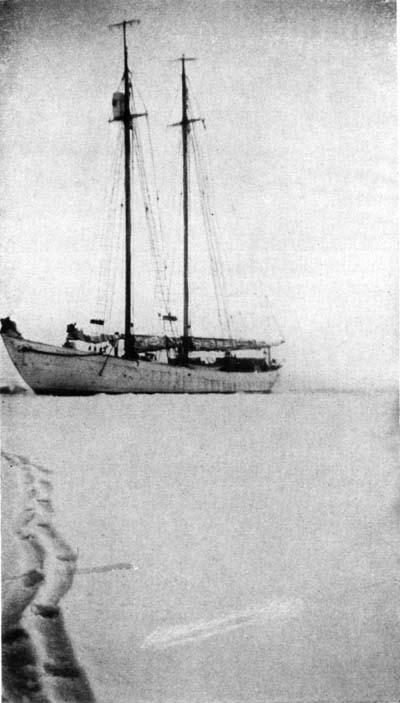

| The Bowdoin caught in a nip, at Melville Bay | 63 |

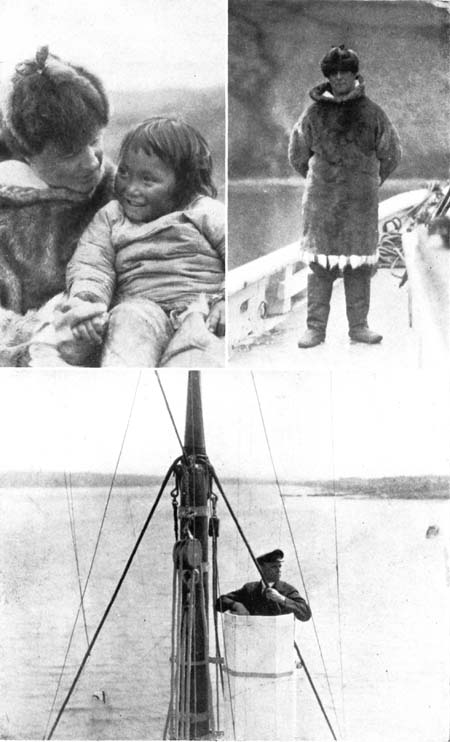

| Commander MacMillan with an Eskimo child; in flying costume; in the ice barrel | 90 |

| Brother John’s Glacier and Alida Lake, Etah, North Greenland | 90 |

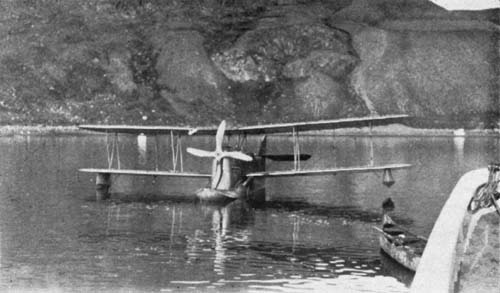

| The Peary | 94 |

| Expedition plane at stern of Bowdoin | 94 |

| Launching first plane at Etah | 95 |

| Eskimo kiddie with mother’s coat on | 104 |

| Even Eskimo boys of Ig-loo-da-houny have a sweet tooth | 104[xvi] |

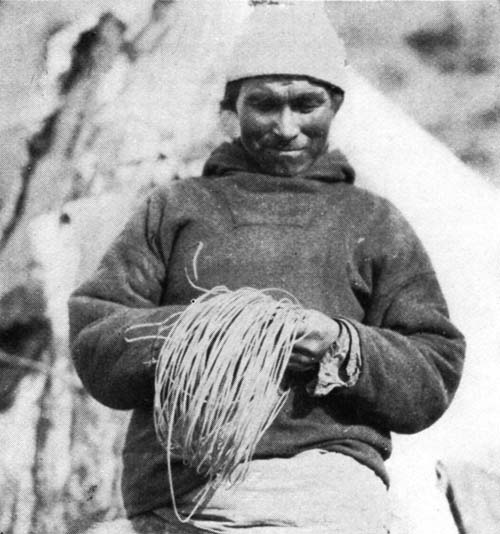

| In-you-gee-to makes a coil of rawhide line out of skin of which he is justly proud | 105 |

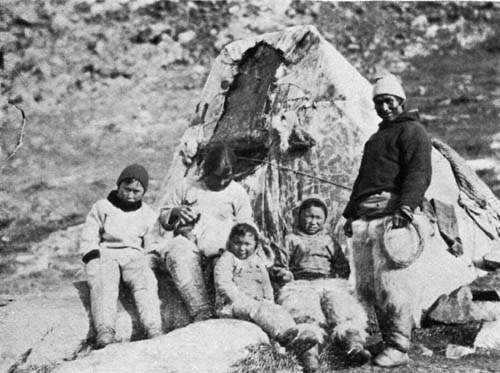

| The only Eskimo family in Etah | 105 |

| The Bowdoin on the rocks in North Greenland | 118 |

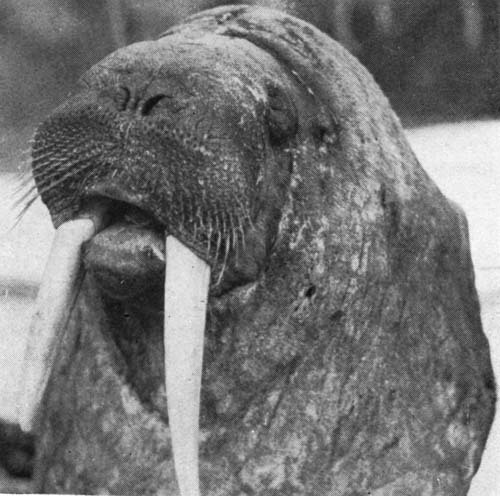

| Head of 2000-pound walrus killed at Etah, North Greenland | 118 |

| Oomiak: Eskimo women’s boat, made of sealskins | 119 |

| South Greenland kayak | 119 |

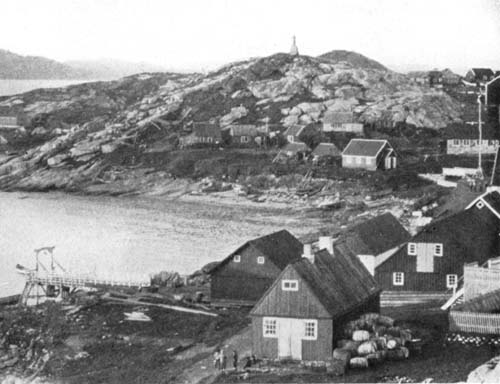

| At Sukkertoppen | 122 |

| Dick Salmon with large cod jigged while stormbound in Godthaab Fiord | 123 |

| A good Eskimo puppy | 126 |

| Typical winter home of South Greenland Eskimo | 126 |

| Eskimo girls of Holsteinborg, mixture of Danish, Spanish, English and Eskimo | 126 |

| View of Godthaab with statue of Hans Egede, first missionary to the Eskimos of Greenland | 130 |

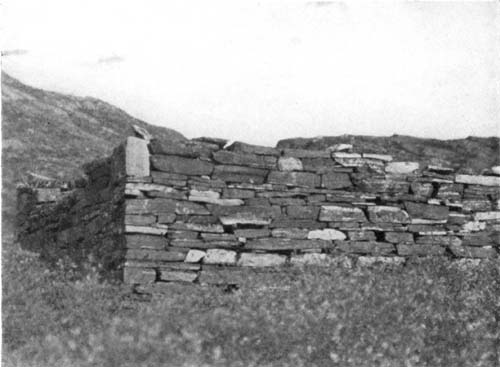

| Norse Church at head of Godthaab Fiord, probably built about 1100 A. D. | 130 |

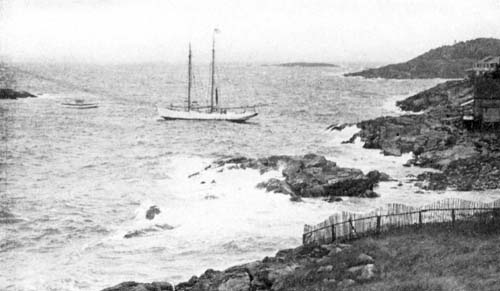

| In rough weather off Nova Scotia, homeward bound | 131 |

| The Bowdoin delayed by the storm at Monhegan | 131 |

A BOY’S-EYE VIEW OF THE ARCTIC

The journey of the Bowdoin, 1925.

[1]

A BOY’S-EYE VIEW OF THE

ARCTIC

ONE warm June evening I was sitting up in my room supposedly studying, but actually all thoughts of study had long since gone where most good resolutions go. Who can study on a mild June evening anyway? I can study almost any other time, but on such occasions my thoughts go fluie, and I am off to Treasure Island or with Jules Verne. I was somewhere in those latitudes when a rap sounded on my door. I thought just retribution had overtaken me in the form of a master; so I opened a text book, scattered a few papers about for realistic effect and then went to the door.

“Long distance for you at the exchange,” said the messenger, who after all was not a master.

I slipped into my bathrobe and reported to the master on the hall.

“Sir, long distance wants me at the exchange,” I said.

[2]“All right, here’s your permission slip. Get it signed when you are through. And Rawson—don’t loaf on your way back.”

“No, sir,” I said, and with this parting injunction I was off.

I took down the receiver, got my connection and yelled “hello.”

“Hello, Ken, that you?” It was Dad, and there was a note of excitement in his voice. “Do you want to go to the Arctic with MacMillan this summer?”

I leaned against the panel. Was I still with Jules Verne?

“What, Dad? Say it again.”

Dad laughed. “Do you want to go to the Arctic with MacMillan this summer?”

“With MacMillan? With MacMillan?” I gasped! What was he trying to put over? Well, at last it got across, and it didn’t take me long to say yes. He then told me how it all happened, and my surprise and wonderment increased at every word. At last he had to hang up, and I went back to my room in a haze. I could hardly grasp the significance of what I had just heard. A few minutes before I was merely a student at The Hill; now I was an explorer. Well of course not quite that, but something[3] along that line, and anyway I was going on an Arctic expedition and that’s all that mattered.

I returned to my hall and reported to the master in charge.

“Where is your slip?” he said rather shortly.

“My slip? I forgot to have it signed. Oh, sir, MacMillan and I are going exploring in the Arctic regions!”

The master looked incredulous, but as I still retained the air of being partly sane, he began to show real interest.

“How did you happen to choose MacMillan?” he queried.

“Oh, sir, I didn’t mean that, I meant that Commander MacMillan is going to take me with him this summer,” I replied, rather embarrassed by my outbreak.

“Well, just how did you get in on a thing like this?” he asked.

“For several summers I have sailed,” I said, “and I like the sea. Last summer I was engaged in the scientific work of the Bureau of Fisheries on a little schooner. We made a number of trips off shore, and I gained quite a bit of experience. I liked the work so well that I told father that I thought I should like to be an[4] explorer instead of a banker—father’s business. A friend of father’s, Mr. Joseph MacDonald, being acquainted with these facts and also with Commander MacMillan, conceived the idea that I ought to go on the forthcoming expedition with the Commander. I fear he must have strained a point in telling of my qualifications for a berth on the ship, but he finally persuaded the Commander to take me. After this he broke the good news to father. Then the two of them had the difficult task of convincing Mother that I ought to go. My mother is like most mothers, only a little more so, and it was quite a job to show her that the undertaking was not too dangerous and that it would be a valuable experience. She was finally won over, and so that’s how I am going.”

“Well,” said the master, “some people do seem to have all the luck. Go to your room quietly, and remember that we’re still keeping school around here.”

“Yes, sir,” I said, and I went out. He had forgotten all about the slip!

If I worked hard, I had a chance of getting exempt from my examinations at the end of the term. That meant I could go home seven days earlier than otherwise. When I had calmed[5] down, I made up my mind that no dust was going to collect on my books from then on. Too much depended on my plugging; so I tried to put away the thoughts of nice arctic coolness on a hot June night and bury myself in my books.

The days went quickly by. They were happy days filled with hard work between which came rosy dreams of the future—the prelude to the great adventure. But at last came the important day—the day on which the list of exemptions from examinations was to be posted. I parked myself outside the Dean’s office anxiously awaiting that list. No vacation ever had seemed so far away, and the minutes were ninety seconds long. At last a figure appeared from within, armed with the list and a handful of thumbtacks. There was a wild mob there by that time, but I was in the front row. I ran my eye down the alphabet. My fate was before me. It was there—my name. Exempt in everything! With a yelp of joy I rushed for my room feeling for my trunk key on the way. Somehow I got my trunk packed, did the things that had to be done before leaving, and that night at dinner I had everything ready for an early departure in the morning.

The next day, amid the good wishes of my[6] somewhat envious school friends, I bade farewell to The Hill and started for home. There I would have a few days with my family and plenty of time to select my outfit before going on to Wiscasset, Maine, to join the expedition. On the train I did not buy any magazines. I just sat there and shot polar bears and dodged icebergs; and what a grand and glorious feeling it was!

The family were at the train to meet me, and we all had so much to say that nobody could wait for the other person to finish. Mother was so happy that I could go and so unhappy because I would not be home for the vacation, that she didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. Father was so enthusiastic that he wanted to go himself.

I had about a week before joining the expedition; this time I employed in getting my equipment ready. I needed all manner of things, and without a list which the Commander had furnished, we should not have known what to get. Oilskins and rubber boots for wet weather were very necessary, as were all sorts of warm things such as knit socks, heavy underwear, flannel shirts, woolen trousers and a sheepskin coat, to name but a few of the items. I also laid in a big[7] stock of five-and-ten-cent-store trinkets for trading with the Eskimos. The Commander had suggested rings, necklaces, beads, perfume, soap and various novelties, most of which certainly went like hot cakes with the Eskimos.

At last the day arrived on which I must leave home for the last time until my return from the north, probably in a few months, but very possibly not for several years, maybe never. The Arctic keeps one guessing if it does nothing else. One never can tell what successes or disasters the next day holds.

The family were not coming east with me now, as it was necessary for me to go on a few days early to help in the work of preparation. The family, however, were coming on for the official farewell which was not to be until a week later. On my way to Wiscasset, where the Bowdoin was being outfitted, I stopped in New York and joined forces with Dick Salmon, another member of the expedition. We continued our journey by steamer to Portland and there we caught a local to Wiscasset. The afternoon of the fifteenth, the day on which we were supposed to arrive, found us bumping along and wishing that the train would make more speed. But after what seemed years, the[8] end of our trip hove in sight as we suddenly rounded a curve. With beating hearts we gathered our luggage and prepared to disembark. The train halted just opposite where the Bowdoin was anchored, and we stared with interest and admiration at our new home, for such she proved to be for the next four months. We hailed a passing launch and her skipper put us aboard our ship. We at once reported for duty to the mate, Mr. Robinson, who was in charge of the loading. He seemed rather surprised when he saw me, and he said, “Why, I was told you were a great, big fellow weighing a hundred and sixty pounds.” As I fell some pounds short of his expectation, I told him that somebody must have been kidding him. I think we both knew who it was. I had strong suspicions, anyway. He at last decided that if I could work, that would help matters quite a bit. So he told me to be ready for work early next morning and meanwhile to make myself at home and get acquainted with the members of the expedition who already had arrived.

I took a look around. The deck was piled high with boxes and barrels; the running rigging was all askew on the deck—in short, chaos reigned everywhere. This was far different[9] from what I had pictured, and I decided right then and there that when it comes to actual work, getting the ship north was no more of a job than loading it. I also saw several dishevelled workmen busily engaged in stowing the cargo in various parts of the ship. I inquired from the mate who they were, and my disillusionment was complete when he told me they were two scientific experts with national reputations. I had always thought of scientists as not quite human, people who sat around looking into instruments and writing elaborate reports. But seeing them pitch in and work like normal human beings did much to restore my confidence that they were real he-men.

I looked the ship over from stem to stern. She certainly is a beauty with lines almost as clean-cut as a yacht. But her timbering would make a yacht’s look like a melon crate. She has the most massive timbers of any ship I ever saw, and I think I may safely say that she is the strongest small vessel in existence. Another very excellent feature for Arctic work is the way the hull is shaped. It is so rounded that the ship rises when squeezed by the ice. This is the only way that an Arctic vessel should be built; as no matter how strong the vessel may be, she cannot[10] withstand the pressure of heavy ice unless she is made to rise. The bow also is sloping, so that she may rise a short way on a cake of ice and crush it with her weight. At the point of impact it is armored with a heavy iron plate to give additional strength. A rather unusual feature for Arctic vessels is also incorporated in the Bowdoin, namely, having the vessel reach its full beam a short way abaft the mainmast which, in a schooner, is quite near the stern. This serves to shunt the ice away from the propeller, and anything to protect the propeller is very helpful, as the breaking of a propeller in the ice is a disaster second only to having the ship crushed; without strong means of propulsion one cannot get very far, and sails are a poor substitute for a propeller. She has a semi-Diesel engine which will run on anything from whale oil to kerosene. If we ran out of fuel in the north, we would literally “harpoon our way home,” to quote the Commander. In spite of all these features, she is only a small vessel, eighty-eight feet over all, fifteen tons net. She is, I believe, the smallest vessel ever to enter the Arctic.

By the time we had finished our inspection, it was quitting time, and our scientist-stevedores knocked off work and began to prepare to go[11] ashore. Dick and I soon became acquainted with them. They were Lieutenant Benjamin Rigg, of the Coast and Geodetic Survey, and John Reinartz, famous short wave radio expert; our hydrographer and radio operator, respectively, both fine fellows, and we made a congenial crowd at the inn that evening. We four were the first ones to arrive, with the exception of the mate, the cook and the engineer. John Jaynes, the engineer, was another very fine fellow, and we all liked John, as we soon came to call him. In a few days we were all calling each other by our first names and felt as if we had known each other all our lives. John certainly could make an engine behave when it didn’t want to, and he also could render valuable aid and advice on nearly everything.

The cook had gone home for a couple of days to wind up his affairs, and he did not return until the day following. The mate, “Robbie,” as we soon called him, was a real mate. His job was to get things done in a hurry, and he did it. But in addition to his capability as a mate, he was a real fellow, and no one had more of the respect and friendship of the expedition than Robbie. The Commander was still in Boston supervising the preparation of the Peary, the[12] ship that was to carry the naval airplanes and aviators. He was not scheduled to arrive in Wiscasset till Wednesday night; so we had several days before his arrival. The rest of the personnel were coming up with the Peary from Boston.

Photo Brust.

The Bowdoin and her crew, Wiscasset, Maine, June 20, 1925.

Left to right: John Jaynes, Engineer; Commander Donald B. MacMillan; Ralph

P. Robinson, Mate; Kennett L. Rawson, Cabin Boy; John Reinartz, short wave radio

expert; Martin Vorce, Cook; Lieutenant Benjamin Rigg, U. S. Coast and Geodetic

Survey; Onnig D. Melkon, moving picture photographer.

After a pleasant evening and a good sleep at the local inn, the sleeping accommodations on the vessel not yet being arranged, Dick and I repaired to the Bowdoin early the next morning. My illusions about life on the bounding billow had undergone a change since I had seen scientists acting as stevedores. But it was still somewhat of a surprise when the mate ordered Dick and me to go ashore and sort and remove the sprouts from thirty bushels of potatoes that were lying in a neighboring storehouse. We spread the potatoes on the dock under a broiling sun and set to work. How good an iceberg would have looked at that moment! Some ten bushels and five blisters later, as I attempted to straighten up to see if my back had assumed a permanent wave, the thought struck me that Gareth scrubbing pots in King Arthur’s kitchen had nothing on me except that he gained immortality while I was getting an awful pain in the back. But the joke was on him; he had no[13] Arctic expedition as a reward for his pains. At last, however, the potatoes were divorced from their sprouts and carefully resacked. We both decided that our shipmates should never know how much unbargained-for sweat they were consuming with their tubers. The mate, who later appeared, seemed to be satisfied with our labors, and this fact greatly reassured me. Thus, as the old ship’s log might read: “This day came in with bliss and worked around into blisters. So ends this day.” This, with the exception of a very pleasant dance which the delightfully hospitable Sewalls gave that evening. Bliss again!

THE next day was to be a very interesting one. In the first place the Commander was coming in the evening, and secondly the cook was arriving. The time-honored tradition on shipboard is that next in importance to the captain comes the cook. My stomach was in full accord with this theory, and I was anxious to see the arbiter of its destiny. As soon as I got to know him I knew my trust had not been misplaced. Martin Vorce was the best cook and had the finest disposition I ever saw wrapped up in human form. There is no theory either about the cook’s having the hardest work on the ship; it is straight fact. Mart was always on the job, “blow high, blow low.” He had several bouts with refractory dishes in rough weather, but he always came out on top.

After the excitement incident to his arrival had died down, we were aware of the approach of a vessel. At first we thought it was the Peary, but as she was not due till the next day[15] we decided it could not be she. In a short time we saw that it was a navy tug loaded to the gunwales with gasolene. She drew alongside the dock and began discharging her cargo. First a mound of gasolene cases that seemed as big as the great pyramid of Cheops was hoisted out; this was followed by a fleet of barrels, and to cap the climax three Liberty engines made their appearance. I thought if all that was stowed aboard the Bowdoin there would be no room for the rest of us. But beyond doubt, enough of those cases would go aboard to keep me on the move for some time. My prophecy was true. The remainder of that day and all the next I walked back and forth across a narrow plank accompanied by the inevitable case. Sometimes the case and I teetered dangerously near the edge; at others we made an uneventful voyage. I almost hoped I might slip, for in my reeking condition I felt a good swim would have been worth ten years of my life. But I avoided this longed for disgrace through gyrations worthy of a gymnast, and while there was no crowd to cheer me on, I had the satisfaction of seeing the mound slowly diminish.

After work was over for the day I became painfully aware that loading gasolene had discovered[16] a number of tender muscles of which school athletics had never made me aware. But this condition did not prevent my looking forward with zest to a dance that was to be given in honor of the High School Graduation. This was to be held that evening, and the outstanding feature of the graduation was that the graduates were to receive their diplomas from the hand of the Commander, who had especially cut short his stay in Boston in order to be present.

With the big event of the evening in mind, we went below and holy-stoned our gasolene-soaked hides religiously. Then we turned to and attacked our first meal on shipboard, and we vowed that if all the other meals were as good, we should never have cause to complain.

After we had waded through our food, we started for the High School. A short walk landed us there, and we nosed our way through the mob gathered about the entrance. As we entered, the exercises were just beginning, and the Commander was on the point of entering into his presentation speech. We listened to his speech and the ones following with interest mingled with impatience. Finally the graduates were graduated, and the dance was on. Then came our long awaited opportunity to meet the[17] Commander. The mate led us over and presented us. I had never before seen the Commander, but I had heard enough about him to whet my curiosity to a degree where I wanted to know the man from the myth. From the moment I met him I knew that I was serving under a Commander who was a real leader and a man among men. This impression has never left me, but has since been constantly strengthened.

After we had chatted together for a few minutes, with characteristic good humor, the Commander told the mate to see that we met all of the sweet young things and had plenty of dancing, for it would be some time before we danced again. We accepted the Commander’s suggestion as a sacred duty, and obeyed it to the letter.

“The morning after the night before” was rather a painful period, as dancing until the midnight oil is low and then arising at the crack of dawn does not incline one to rhapsodize over the sunrise. But that morning, without the aid of our usual battery of alarm clocks, we were awakened by the shrill blast of a steamer’s siren. We all tumbled into our clothes as fast as our sleep-numbed bodies could make the grade. The first person on deck yelled, “Here comes the[18] Peary!” True enough, in another moment we could make out the white lettering against the black bow. We gave a lusty cheer as she sidled up to the dock, and then stood by to make fast her lines. In a few moments she was safely moored, and we were swarming aboard to examine our companion of the long cruise.

The first objects to attract our attention were the three navy airplanes on the after deck. On these three canvas-swathed forms hung all our hopes. If they failed, it would mean sure death for their intrepid occupants. In their undress condition they did not look very imposing, but in my imagination I already heard the roar of the mighty engines tuning up in the lee of some sheltering icepan. I visioned the flash of the white foam as they skimmed along for the take-off, and I saw them recede into the western sky with an ever-diminishing whirr of engines, outward bound on those flights from which we hoped so much. Again I saw these proud argosies of the air, this time returning triumphant with the secret of the ages disclosed. However, the cook’s sudden cry for breakfast, mingled with the savory odors of bacon and coffee effectually dissipated all this sort of dreaming.

After breakfast we got acquainted with our[19] shipmates on board the Peary. There were eight naval aviators under the leadership of Commander Richard E. Byrd, who has since distinguished himself in his daring flight over the Polar Sea, and there were also several scientists and photographers. The ship was under the general direction of Commander E. F. McDonald, who was second in command of the expedition and in charge of radio communication. Captain George Steele was master of the ship and in direct charge of the navigating and safety of the vessel.

At this time arrived the remaining members of the Bowdoin’s crew, namely, Maynard Owen Williams, author and photographer, known to many by his fine articles and pictures in the National Geographic Magazine; and Onnig D. Melkon, motion picture expert, whose job was to preserve a motion picture record of the expedition for later use in the Commander’s lectures. These two completed the ship’s crew, and now with our full complement we were counting the minutes till sailing time.

At last the great day came. The departure was an event of national importance. Town, state and nation were all officially represented. In addition to these were thousands of interested[20] citizens and visitors come to wish us bon voyage. Among the latter were most of the families of the crew, including my own. Two o’clock was the zero hour, and after short exercises at the town hall, the Commander came aboard and gave the long awaited order: “Cast off.”

Photo Geo. W. Lord.

Outward bound, June, 1925.

The Bowdoin leaving the dock at Wiscasset.

Eager hands freed the lines and amid the roar of steam whistles and cheers from the crowd we slowly headed seaward. Governor Brewster of Maine had furnished a band and a tug to transport them, and as we steamed outward they poured forth a brazen blare of melody. Alumni and students of Bowdoin College, the Commander’s alma mater, had chartered a steamer, and the enthusiastic, leather-lunged collegians raked us fore and aft with a series of vocal salvos that would have driven any team on to victory. The procession was headed by two naval vessels especially designated by the Navy Department to do honor to the occasion. In addition to this official recognition, a large number of yachts from far and near had gathered to join in the celebration. But as we reeled off the miles, our escorts gradually turned back one by one, until by the time we neared the open sea, only a persistent few remained. Even these[21] had returned by the time we were fairly launched forth on the long ocean roll, and the Peary, too, had deserted us, as she was going to Boothbay to take on a final supply of water, while we set our course in solitary state for Monhegan Island. Just as the great lighthouse began to blink, we dropped anchor under the lee of the island. Here the guests who had thus far accompanied us, soon followed the anchor over the side and went up to the village inn where we shortly joined them. There, in accordance with custom, the hospitable islanders had prepared a delicious banquet for the members of the expedition and their guests. There we ate well indeed but not too wisely for mariners who were about to slip their cable in the morning.

AT noon the next day, Sunday, June 21st, we put to sea from the last outpost of the United States that we should see until our return. As we circled the islands, a fishing boat filled with enthusiastic members of the Civitan Club, who had come all the way from Minneapolis to see us off, came alongside and throwing huge codfish aboard shouted the last farewells we heard in home waters from fellow citizens.

In a few moments a Bay of Fundy fog had swallowed us up, and the curtain had dropped on the last home setting. The day was fairly calm, but there was a long, oily swell which rolled the boat like a lazy pendulum. Moreover, the smoke from the exhaust was carried forward across the deck by a light, following breeze. In a few hours I began to notice a greenish pallor overspreading the faces of my shipmates, and, guided by my own feelings amidships, I had an intuition that my face was experiencing the same change. Soon a disheveled[23] figure sprang from the forecastle companionway and made a dash for the rail. In a few moments another appeared bound for the same destination. I thought this was very funny, when suddenly the ship fetched a great roll, and I meditated with melancholy on my liberal indulgence at the dinner of the night before. Without stopping for further speculations I too joined in the mad scramble for the rail. Under the suasion of an unstable equilibrium the gastric organs have certain generous periods when they won’t keep a thing, and when they are in this mood they follow the example of time and tide and wait for no man. This lack of a sense of expediency on the part of these unfortunate organs caused several similar embarrassing situations from time to time. After completing my first session at the rail, I felt relieved—much relieved, and decided I was all through with such foolishness; so I sat down to await my trick at the wheel and to enjoy the adventures in mal de mer of the other unfortunates. But again my mirth ended in another dash for the rail. These upsets, however, did not permit of any laying off from regular duties, since the work had to be done and there were none too many of us to do it. Thus I stood my regular trick at[24] the wheel, a task with which I was familiar from previous voyages, kept my regular watch and did whatever duties were assigned me despite a few protests on the part of my stomach. This state of affairs continued for the next three days until we reached Sydney, Nova Scotia.

Early on the morning of the second day out we rounded Cape Sable, the southernmost point in Nova Scotia, and laid a northerly course parallel to the coast heading for Cape Breton Island where Sydney is located. Here we were to take on water and fuel oil before squaring away for “The Labrador.”

Three days later on Wednesday morning, we reached Cape Breton Island and made our way into the spacious harbor of Sydney. The Peary, having preceded us, was lying at North Sydney loading coal and placing iron plates over the lower portholes, that they might not be broken by the ice.

We made our way to a supply dock in the lower end of Sydney harbor and began loading fuel and other supplies. Inasmuch as Sydney was the most outlying stop on our journey to offer tonsorial and other luxurious civilized conveniences, we availed ourselves of all the[25] facilities that the town afforded. For awhile the barber shop was the center of interest, with the soda counter at the drug store running a close second. It was while we were in a drug store that an unprecedented thing happened. Mr. Raycroft, a friend of the Commander’s, who had accompanied us up to Sydney, entered the store, started to make a purchase, when suddenly he bolted into the street without a word of explanation. In a few moments he returned looking a few shades paler, and in reply to our anxious queries he told us that the unaccustomed steadiness of the building had made him feel sick, and he felt an urgent need of fresh air. That was the only case of “land sickness” in the memory of the oldest inhabitant.

After a voyage of general exploration about the town, we discovered the product for which Sydney is famous, and that is lobsters. Under the leadership of Ben Rigg, an ardent enthusiast on the subject of shellfish, we raided every lobster joint in town. One may easily imagine after our hollow days at sea that there was plenty of room for food. After visiting about five places and exhausting their limited supplies, we ended up about eleven o’clock in a Chinaman’s, where we gorged on more of these luscious crustaceans[26] and on chop suey. None of us had nightmare, strange to say.

After three days of the strenuous life in Sydney, our preparations were complete, and we pulled out for the bleak and desolate Labrador, leaving instructions with the Peary to join us at Battle Harbor after completing her coaling.

We set sail for the Labrador with a feeling that we were at last entering the great unknown. From what we had heard and read concerning this region, none of us knew what to expect. But we had the best possible person on board to enlighten us; namely, Doctor Wilfred Grenfell, the famous Labrador missionary doctor. He was just returning from a trip around the world and had arrived in Sydney preparatory to going on to Battle Harbor. Being acquainted with the Commander, he came down, and as the Doctor was planning to leave on the next steamer, the Commander invited him to accompany us instead. In addition to Doctor Grenfell we were accompanied by another distinguished guest, Dr. Gilbert Grosvenor, President of the National Geographic Society, under whose auspices we sailed. Having voyaged with us to Sydney, he was so charmed with the life aboard ship that he continued with us to Battle Harbor. Thus we[27] were well equipped with celebrities, come what might.

Copyright, National Geographic Society.

Rawson, MacMillan at the wheel, and Dr. Grosvenor.

On way to Sydney.

“Yonder beneath the North Star lies our destination, Lad.”

Commander MacMillan, Dr. Grosvenor and Dr. Grenfell.

Battle Harbor.

After sailing for several days through the placid waters of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, we found ourselves at the entrance of the Straits of Belle Isle. Here we realized for the first time that we were really getting north, when the word was passed around to look out for bergs. I had heard much of the danger of icebergs, and an apprehensive shudder spread over my frame as I imagined what would happen if we should run on one unawares, for we were shrouded in one of the usual Straits fogs. In a short while our straining eyes discerned a dark object loom out of the fog on the starboard bow. At the time, I was at the wheel, and Dick Salmon was on the lookout. I gripped the spokes at the thought of how close this chill apparition was, but we were well to port, and in a few moments it melted into the mist.

A short time later after the excitement fomented by the berg had subsided, we began to notice signs of the proximity of land. Robbie clambered aloft into the crow’s nest to watch for shoal water, and the rest of us clustered into the bow for the same purpose. Suddenly out of the fog appeared a white line. It was breakers rolling[28] across a long point. A hasty chorus of shouts to the helmsman resulted in an immediate altering of the course to parallel the land, instead of heading straight at it as we were when we first sighted it. It was in this dramatic manner that we made our acquaintance with The Labrador, and it was in a setting typical of this rugged country. One usually becomes acquainted with The Labrador by nearly running on it every time one approaches it during the early summer months, for at that time the land is almost perpetually shrouded in fog. Not long afterwards another line of breakers indicated the presence of a new exponent of terra firma. This disturber of the mariners’ peace was named Blanc Sablon, a reminder of the old days of the French domination. This entire south coast is sprinkled with French names and with French speaking people.

As the fog was still too thick for safe navigating along this treacherous coast, we put into the little settlement of Forteau. This is one of Doctor Grenfell’s stations, and he made us very welcome there. He also recommended the splendid trout fishing and issued us honorary fishing licenses for the neighboring creeks, since he was an honorary magistrate. Armed with this legal[29] protection and also with rods and gear, we sallied forth to a likely looking brook to try conclusions with the wily denizens of the stream. It certainly seemed good to get our sea legs straightened out as we strolled up and down whipping the stream. After a few casts I felt a sudden tightening on my line, and the reel began to sing. For a minute I let it run; then I checked it abruptly in order to drive the hook well home. Then the fight was on. The fish threshed wildly in a vain endeavor to free himself, but I had him fast. There was about five minutes of play, and then I reeled him in. He was a fine specimen, weighing very nearly two pounds, and my hopes were high that we might obtain enough for all hands. In a moment I heard a yell from Mart, and looking in his direction I saw that he was holding aloft a trout fully as large as my own. Then we went at it with all our might, but the God of Fortune smiled no further, and at last tired and discomfited, we returned to the ship.

Early the next morning we were under weigh again for Battle Harbor. On our way out as we rounded Cape Point Amour we sighted what seemed to be a great cruiser sailing close to the Cape. As we drew nearer we saw that she was[30] too far in for a large ship, and still closer inspection showed that she was hard and fast on the rocks. We then learned from the Commander that this was the British cruiser Raleigh which had run aground in a fog some years previous while endeavoring to make Forteau. We felt a twinge of pity that such a fine ship should rust out her heart on the bleak rocks of Labrador.

Continuing on up the coast, sometimes in fog and sometimes in beautiful clear weather, we were encompassed by a magnificent vista. On one hand the bleak and rugged hills of the shore-line, and on the seaward side a matchless panorama of schooners, dancing waves and icebergs. The schooners tacking in and out under full sail among the glistening bergs; the tall, majestic spires and turrets of the larger bergs dwarfing the tallest mast into insignificance; the dancing wavelets curtsying to the graceful schooners whose black hulls contrasted sharply against the whiteness and marvellous shades of ultramarine blue of the glacial ice, all combined to make an unforgettable picture.

Just as the shadows of evening had begun to creep up from the west and merge the glories of a perfect day into a matchless sunset, the rugged[31] outline of Battle Island appeared bathed in a purple glow that made the hard unyielding rock look like rich dyed velvet. It was not long before we dropped anchor between the sheer rock walls of Battle Harbor.

DR. GRENFELL’S staff were down at the dock to welcome us, and they soon made us realize that American hospitality is the same the world around. Although Labrador is English territory, the hospital is manned and, to improvise an expression, “womanned” by Americans. A doctor, three nurses and three college men, all of whom had volunteered to serve for the summer, made up the staff of the hospital. In every way possible they strove to make our stay in Battle Harbor an enjoyable one, and they certainly succeeded.

While in this port we celebrated the glorious Fourth of July. The day previous we had remembered with a start that the following day was the Fourth! Dick Salmon suggested that we inaugurate the festivities with a snowball fight, since there was a large deposit on the opposite side of the tickle, so-called by the Newfoundlanders in speaking of a narrow channel[33] which indicates ticklish navigating. Dick’s cool suggestion did not meet with a warm reception for obvious reasons, and we turned in with our plans for the observance of the day somewhat nebulous.

The next morning at an early hour I was awakened from a sound sleep by the explosion of a firecracker uncomfortably close to my ear. I made a nose dive for the floor muttering imprecations against the authors of the outrage. Then realizing that the great day had come, I hurriedly dressed and made my way to the deck where the celebrants greeted me with such a penitent air that I did not engage in the retaliations I had determined to employ.

After clearing away the breakfast wreckage, the cook began making the pots fly in a business-like manner, and soon savory odors ascending from the galleys gave notice that a culinary masterpiece was in the process of preparation. To the accompaniment of these welcome sounds and odors, we swabbed down the deck and coiled down the lines with despatch, and then sat back in the crisp sunlight in languid anticipation of the approaching feast. At twelve-thirty the cook’s warcry resounded through the vessel, and we tumbled down the companionway to make[34] the first table. Since there was not room for us all at one sitting, our meals were served in two shifts. As “first come, first served” was the order of the day, the competition was keen indeed for the coveted places. I was fortunate enough to slide into the last remaining seat much to the disgust of Melkon who had been keeping his eye on the food all morning. Then came on the grub, and what grub it was! Fish chowder flavored with onions, a magnificent roast of beef—the last domestic meat we were to taste until our return—a profusion of vegetables, plum duff and candy, with coffee and fruit punch to wash it all down. Then there were cigars for those who desired them; a pleasure in which several of us did not indulge.

After this repast we repaired to the deck where we basked in the mellow sunlight like a herd of well-fed walrus. At last one of our more ambitious shipmates suggested that we have an outboard motor race with a boat from the Peary. This suggestion was hailed with acclaim, and we immediately set to work tuning up our engine. At this moment arrived Chief Aerographer Francis in the Peary’s cutter. Immediately we hurled at him our challenge which he at once accepted and it was not long before[35] both boats were at the line ready for the starting gun. Our interest was keen, and suggestions and advice poured over our bulwarks like a Bay of Fundy tide. Soon they were off neck and neck. For a time all progressed beautifully. Then the regular cadence of our boat’s exhaust became faltering. The Peary’s craft forged ahead. We yelled like mad as our crew of two desperately spun the needle valve, and tinkered with every other gadget on the craft. But to no avail. Off went our opponent and with him our hopes of victory. When he crossed the finish line, our crew was still wrestling with the refractory engine, and we reluctantly presented Francis with the first prize, a leaky rubber boot. He hove the boot at our heads and went off in high dudgeon over our lack of appreciation of his superior prowess.

All along the Commander had held forth on the delicacy of the Labrador trout and salmon, and therefore great was our delight when one day the mission people proposed a trip to the head of St. Louis Bay, where was located a fine trout stream not far from the winter hospital. It is necessary to maintain a winter station in addition to the summer station at Battle Harbor, as the outer islands are untenable in winter owing[36] to their exposed position. The heavy pack ice comes in from the sea, and savage winter gales lash the bleak and desolate islands, rendering them impracticable for winter habitation. Every one moves inland to the head of the great bays and settles down in a well sheltered log cabin in close proximity to a forest of good firewood. The hospital is no exception to this rule, and by the time the last schooner has winged its way southward, the Battle Harbor station is closed, and the winter hospital is put into service. We were all very anxious to see the back country and looked forward to the trip with keen expectancy, whetted by what we had heard from the Commander.

Early the next day with the Commander’s permission, all hands, with the exception of one or two who unfortunately had to keep the ship, gaily sallied forth in the capacious mission boat. After traversing a space of rough water, which caused embarrassment to several of the ladies, hospital nurses who accompanied us, we entered the great bay and sailed past shores at first barren of vegetation but growing progressively greener as we penetrated inland. It was interesting to observe this increase in plant life as we drew away from the blighting influence of[37] the frigid Labrador current, which makes this coast the bleak and barren land it is.

We arrived at the winter station a short time before noon and gave it a thorough inspection. It seemed so nice and cosy tucked away in the midst of a beautiful grove of pines on a picturesque arm of the bay, that I almost wished I was a patient there.

As the sun mounted higher and higher towards the zenith, I began to wonder where lunch fitted into the program. This also seemed to be in the minds of our hosts and Doctor Grenfell soon suggested that we have lunch on the banks of St. Mary’s Creek and do our fishing afterwards. The lunch was to be cooked “on location,” as they say in the movies, and the pièce de résistance was to be a real old New England fish chowder. To one who has never experienced a fish chowder—for it is an experience—words are inadequate to describe it; and to one who has experienced it any attempt at description is superfluous. Suffice it to say we gorged ourselves to repletion.

Even this heavy cargo of chowder did not hinder our getting under weigh for the trout basin, and we were soon off with rod and gear. Williams, however, who looked down on fishing[38] with sophisticated contempt, remained behind to amuse the ladies. As we moved off we last saw him feverishly tossing dishes aloft, and only on our return did we learn much to our relief that his brain had not been affected by the heavy meal and that he was merely giving an exhibition of Bagdad juggling.

A short distance up the stream we found a small series of rapids between which were dark, enticing pools. Mart, our mentor in such matters, declared the location favorable, and we were soon casting our flies into the swirling eddies. Every now and then we could see the silver flash of a fish break the white water of the rapids, but for a considerable time no welcome tug at the line ensued. We were on the point of moving farther upstream when suddenly I felt a violent jerk, my reel sang and my rod assumed an excessive arc. I stood my ground and watched the line pay out until I could see the nickel core of the reel. I was on the point of dashing into the stream to relieve the danger of having the line unreeve, when slowly the rod came straight and the reel ceased to revolve. One of father’s old fishing axioms came to me: “A slack line spells disaster.” I began reeling furiously, and for a minute I felt that my fish[39] was off. I was on the point of giving up when again came a taut jerk. Away sped the fish with another thirty feet of my line. I played him with all the cunning I could command, until at last his silver scales sparkled in the shallow pool at my feet. Just as I was about to draw him to shore, he flipped his tail and was gone again. Once more I gave him his head. This time he dashed towards a jagged clump of rocks, and I realized with dismay that unless I took extreme measures I should soon have my line inextricably tangled around the rocks. Taking a desperate chance I added a few more pounds tension to the reel. The rod bent dangerously, and my breath came hard with the suspense, but the rod held. He came short of the rocks by several inches; then, exhausted by this desperate sally, he slackened his efforts, and I began to reel him in. This time the struggle was short, and in a few minutes he was gasping on the rocks at my feet, as fine a specimen of brook trout as I ever saw!

In my excitement I had not noticed that success had crowned the efforts of my companions, and there were three or four other speckled beauties divided among them. For a while longer we fished with signal good fortune, but[40] at last the dipping sun warned us that it was time to think of returning to the ship. Gathering up our trophies we hastened down to the shore where we rejoined the others, and in a short time we were chugging along towards the ship, at the close of one of the finest days we ever had in Labrador.

IT was with regret that at dawn on the day following we bade farewell to Battle Harbor and the hospitable Grenfell workers and squared away for Hopedale whence we would make the long leg to Greenland. While on the way to Hopedale we crossed the mouth of Hamilton Inlet, a great fiord or arm of the sea that penetrates the land for a hundred miles. From this fiord extends a river containing one of the largest waterfalls in the world, the Grand Falls of the Hamilton River.

Early the next morning we were off Cape Harrison at the northern end of the inlet. Here we began to notice scattered cakes of ice drifting out to sea—“Gone abroad,” as the Newfoundlanders say. Soon the scattered fragments became thicker, and a full-fledged field of pack ice presented itself to our vision.

The Commander ascended to the crow’s nest to survey the situation and con the ship through[42] the ice. As this pack barred the entrance to Hopedale it was necessary to go through it, and the Commander seeing a likely lead—a lane of open water between the ice cakes—ordered the wheel put hard aport. The vessel rapidly swung around until her bow was directed down the lead. “Steady!” was the next command from aloft, and the helmsman spun the wheel in the opposite direction as hard as he could until she checked in her swing. She rapidly traversed the lead which soon terminated in a solid cake of ice. Straight on continued the Bowdoin like a hunter for a jump. Soon her rounded bow was almost in contact with the ice, and in another second she had struck it fair and square. Her prow leaped up on the pan, and I leaned over the prow thinking that surely she would never be able to force her way through such a large cake of ice. But driven by her powerful engine, her bow glided straight up. Then she slowly came to a halt with her bow well up on the ice. With breathless interest we watched to see whether she had the weight to crush it. Just as we were preparing to back out and hit it again, a thin line of black broke the even white. She had made it! The great cake was rent asunder by our sturdy little vessel,[43] and she slowly gained way until she leaped forward with increasing rapidity at the next obstacle which dared to bar her way. Thus we continued weaving in and out, now to port and now to starboard, wherever a lead opened, and where there was none smashing our way. Good judgment and a knowledge of ice conditions are required in ice navigation on the part of the man aloft, and the helmsman must possess the ability to follow orders rapidly and efficiently and be able to keep the ship from brushing the sides of narrow passages. Spinning that wheel frequently and for all one is worth is no joke, and even in that cold, stripped down to my underwear, I sweated like a pack mule before I had been at it for long.

All day we ploughed through the pack with the Peary near by. She was under a disadvantage in having a straight bow and in not maneuvering as readily as we did, but her superior engine power in a large measure compensated for this. As darkness slowly fell I was struck by the absence of any friendly light twinkling a welcome through the dusk, such as one sees in friendlier climes. Nothing but rocks, ice, sky and water—not even a tree or fisherman’s hut to vary the monotony of those barren cliffs. What[44] a contrast to the ceaseless activity of The Hill with its life and action, its cheering bleachers at the games and its humming classrooms—never a moment there when one feels that sense of utter detachment from one’s fellow man which oppressed me in viewing the bleak Labrador. The utter desolation of it all brought thoughts of School and Home with their warmth and life and cheer. Suddenly I found myself shivering violently, and with a start I returned to the immediate present. Turning away from the fading landscape I hastened to the companionship of my mates in the warm, well-lighted forecastle.

The following morning we were away early and were soon clear of the last of the ice and were bound up Flagstaff Tickle on the way to Hopedale, the southernmost settlement of the Eskimos. Despite the fact that these waters are poorly charted, we experienced no difficulty in keeping the channel until we were almost in Hopedale. Then out of a clear sky, grim disaster descended upon us. We were skirting a small reef which jutted a considerable way into the Sound when suddenly the bow of the Peary made an abrupt ascent; then she slowly assumed[45] a list. Immediately the Commander ordered the Bowdoin’s helm put hard down. In a moment more we were flying down wind to the aid of our stricken companion. She had struck on a sunken ledge of rock which gave no indication of its presence until the vessel’s keel had touched. At once we came alongside, which our comparatively shallow draft rendered safe, and after rigging a masthead line we steamed slowly away to see if we could pull her off. Calm and cool as always, Captain Steele ordered the lowering of a small boat in order to run out a kedge anchor.

Meanwhile we ran out the slack in the line and gradually took up a strain. But owing to a strong wind assisting the efforts of our engine, no sooner had the line come taut than it snapped. Captain Steele was now manfully striving to work his boat to windward. Seeing his plight we steamed over to give the lifeboat a tow. In a few moments we had it in the proper position, and let go the anchor. Then we ran down and placed a line over the Peary’s stern to try to haul her off in that manner. During this time the lifeboat had returned and was hauled up on a short bight astern while her crew disembarked.[46] In the stern of the small boat stood Commander McDonald awaiting his turn to get aboard the Peary. In some unaccountable manner the lifeboat caught under the counter of the ship, and a sea suddenly jammed her against the plates. As she could rise no farther, the waves poured over her gunwales and swamped her. McDonald shouted to those on deck to drop the boat aft, but she had become so waterlogged that they could do nothing with her, and each succeeding wave forced her farther and farther down. All yelled for him to jump while the jumping was good, but he still maintained his position in a manner reminiscent of the boy who stood on the burning deck. In spite of the Commander’s heroic pose, the boat gradually sank, and in a second more it began to roll over. With one wild leap he left his sinking craft to its fate, caught a hold on the bulwarks and was pulled aboard the Peary.

In the meantime, the deck of the Peary became a scene of wild excitement. Everyone stood around on the deck with their bags packed, apparently convinced that the boat was going down. But their fears were vain. Under the combined influence of a rising tide, our pulling and the kedge anchor, she began slowly to slide[47] off the ledge, and in a few moments she was once more safe afloat.

We then went in search of the submerged lifeboat which had slowly drifted away during the intervening time. We soon came upon her drifting bottom upwards. To rescue the boat was somewhat of a problem, since there was nothing visible to which we could make fast. By skillful maneuvering, however, Captain MacMillan brought us alongside, and we strove desperately to get a line on her. But the winds and the waves unfortunately separated us, and we had the whole operation to do over again. The next time we approached her a sudden gust of wind swerved our bow just enough to hit her a crashing blow, seriously damaging her.

That misfortune, however, was not the worst that befell us that afternoon, for, as we strove to clear the boat, our propeller struck one of her spare fittings thereby stripping her internal gears. At the time we were unaware of the damage, and the propellor continued turning, seemingly uninjured. We at last managed to corral the unruly lifeboat and then set our course for Hopedale. It had been a harrowing afternoon, but all in all we had much to be thankful for. Our misfortunes were nothing compared[48] to what they would have been if the tide had been falling, and the Peary had been unable to float off. For being a steel ship, she would have filled and become a total loss when the tide began to flow.

HOPEDALE, with the exception of Makkovik, which harbors only two families, is the southernmost settlement of the Eskimos and one of the principal posts of the Moravian missions. Unknown to the world at large, the Moravians have been carrying on a wonderful missionary work on this desolate coast and great have been their services. In the first place they have formed the one barrier between the primitive Eskimo and the ruin which has been the inevitable accompaniment of contact with the white race. Had it not been for these good Samaritans there would not be a single Eskimo in Labrador to-day! For when all the rest of the people who have dealings with the natives have striven to encourage their destruction, these brave missionaries, and they alone, have held firm for the right, have waged a never-ceasing fight against all who threatened the welfare of their wards. No obstacle has proved too great;[50] no effort has been too tiring; not even a lack of funds has deterred these indomitable evangelists from doing their duty where they found it. They have converted the Eskimos to Christianity and endowed them with the priceless gift of the true Christian spirit of brotherly love. Aside from their religious work, they are the only agency for carrying on education in Northern Labrador, both among Eskimos and whites. Owing to their untiring efforts the Eskimos have been uplifted from a state of complete ignorance and savagery to a status of civilization and education.

At their Makkovik station the Moravians maintain a boarding school for boys, up there education being considered the heritage of the male alone. At this school the children are given board and lodging and as much education as their untrained minds can assimilate. This board, lodging and education they receive for fifty cents a week! Yet such is the poverty of these people that most of the families find it well-nigh impossible to pay even this modest sum.

The school consisted of one bare classroom furnished with a few rough desks and chairs, while across the hall a room comprised the dormitory.[51] I could not help comparing it to the elaborately equipped plant which I had so recently left. At this primitive school there were no spacious athletic fields, no huge, airy dormitories, no stately towers, no gymnasium of any description. We, in this country, can hardly conceive of a crack school, for that is what this one is considered, not having at least a gymnasium. The children came to learn and for no other reason. There were no dances, no gay parties or entertainments and no competitive sports—in short, education was reduced to terms of severest simplicity. None the less it is, I dare say, more appreciated and more highly respected than it is in many other places.

The fearless regard of these missionaries for justice and impartiality has been the shield and buckler of the simple aborigine against the unscrupulous avarice of the trader and the demoralizing influence of the depraved white. Much also have they done for the poverty-stricken white settler, educating the children, bringing relief to the bereaved, and keeping alive in the breasts of all the spirit of honesty and idealism. In addition to their care for the things of the spirit, they were the first to introduce medical aid to The Labrador. Truly have they carried[52] out in the broadest sense the words of the Master when he said, “Go ye into all the world, and preach the Gospel unto every creature.”

What a glorious epic of Christian service has been their ministry on this coast! Clear and strong as to the apostles of old came the call of duty—that inspiring lodestone which has drawn forth the noblest and best from the men of all ages. Home and kindred, material rewards, ease and luxury were as naught before it. The stern dictates of conscience to them comprised the sole path to joy and happiness. But how little we realize the trials and deprivations that their self-imposed exile necessitates; how many of the little things that to us seem so necessary they must perforce do without. A prized possession of one of the missionaries was an old camera dating back to 1870. This he displayed with great pride one afternoon while we were taking tea at the mission. It consisted of a cumbersome old box on a tripod, of which the only method of regulating the diaphragm opening was by inserting brass plugs with a proper sized hole bored in them. He handled this venerable machine with the affection born of long years of[53] association. While we were examining it, his kindly wife brought forth with pride several bulky albums filled with the results of her husband’s efforts. We opened these and great was our surprise to see the beautiful quality and real artistry of these pictures. He was an artist to the soul, and with proper equipment what pictures he might have taken!

No one better realized the strict economy under which these people perforce must labor, than did the Commander, and it was at his suggestion that the Zenith Radio Corporation, which had supplied us with our radio equipment, donated several receiving sets for distribution among the worthy missionaries. One of these we presented to Mr. Perrit, the minister at Hopedale, and when he heard the music, his gratitude and delight were so touching that we wished we might do infinitely more for him and his cause.

Never a strong sect, the Moravians have made up in zeal and quality of service what they lack in money and numbers. With no prospect of reward from the world, they have carried on year in and year out. Many an opportunity for improvement have they seen slip for lack of[54] funds, but undaunted they have kept their faith and courage in spite of the most disheartening discouragements. When one brother succumbed another was always ready to fill the gap. Their service to humanity cannot be over-rated. Theirs is the true understanding.

But it seems that their long ministry soon may end. Never a strong sect, in the last few years they have suffered from many ill-advised attacks. During the war many of them were interned by the Newfoundland government, and their bishop was deported—acts not unlike those earlier perpetrated against the simple Acadian farmers. The great fur-trading companies have been making every effort to crowd them out. Last year unfortunately they were obliged to abandon their northernmost station to the Hudson’s Bay Company, and it is not unlikely that unless aid is soon forthcoming from some source, their remaining stations will suffer a like fate.

All true friends of Labrador who know of the labors of this noble group will view with regret the passing of this earnest organization which has accomplished so much for these simple children of the north. My strong personal hope is that the necessary funds for the perpetuation of[55] this fine work may be realized. A few thousand dollars will mean worlds of help to them, and when one sees, he realizes the worth-whileness of giving to such a cause as is supported by these apostles of the outposts of civilization.

NO sooner were we at anchor in Hopedale Harbor than I noticed the approach of several large boats filled with strange-looking, brown folk, different from any I had ever before seen. For a moment I was at a loss to explain them; then suddenly I remembered that we had arrived in Eskimo Land. I stared with interest and surprise. These were not the kind of people I had seen in pictures! These were not the grotesque, fur-swathed barbarians that my mind had conceived. With the exception of dark skin and rather high cheek-bones, they looked not so very different from ourselves, and they lacked that ferocious look I had seen stamped on their countenances in the Sunday supplements. As they came alongside they greeted us with expansive grins and a babble of good-natured banter which displayed their white teeth and black flashing eyes.

“Ochshinai! Taku oomiak-swa!” came from the boats, and I later learned that this meant, “Hello, look at the big ship.”

[57]The Commander came on deck at this juncture and was greeted with an enthusiastic outburst, for his generosity and kindliness are remembered by more than one denizen of this isolated land. Immediately he entered into conversation with them, as he is well acquainted with the language. While he was thus engaged, Robbie appeared on deck and took in the situation at one glance. He then descended into the cabin with an inscrutable smile on his face. We did not realize what he was about until he reappeared laden with tobacco and candy. At once he was surrounded by a laughing, chattering mob striving to wheedle from him some of the coveted articles. With a deliberate air, born of long experience at this game, he began distributing these much-desired treasures. To each one he presented one article, and saw that none was slighted or obtained an undue share of the spoils, in spite of many ingenious and good-natured attempts to defraud him. Each attempt was regarded as a sporting proposition, and loud were the laughs among the natives when one of their number was detected trying to “gyp the system.”

Soon Mr. Perrit, the head missionary, arrived and officially welcomed us to Hopedale. Mr.[58] Perrit is a strapping six footer with curly blonde hair—a regular Viking. He is one of the most earnest missionaries on the coast, and none has a greater and more well-deserved popularity than he. He remained aboard for some time, and after his departure we went ashore to consummate the purpose for which we had come to Hopedale—namely, to obtain warm Eskimo clothing for the colder weather to be encountered farther north.

We soon had the storekeeper booked up with orders, and he immediately set the entire female population to work chewing skins. The Eskimo tailor differs considerably from the Broadway type. In the first place it is a she instead of a he, and in lieu of shrinking the material she chews it. Since the material consists of sealskin or other heavy hides, it requires a thorough chewing to render it pliable. After the chewing is completed, she cuts the skin to the proper size and shape by means of an ooloo, or woman’s knife—a knife shaped like an old-fashioned chopping knife. Then she takes the material and sews it together with sinew from the back of a deer. This sinew has the useful property of swelling when wet, and once it has been wet, it never again contracts. This swelling completely[59] closes the needle hole and renders the garment water-tight. It is no easy task to wield a needle in this tough hide, but these strong-fingered women turn out a very finished product. The fit may leave something to be desired as the measurements are taken by eye and the garment constructed accordingly, but they are warm and comfortable.

In addition to the clothes, we also laid in a supply of sealskin boots, as the Labrador product is far superior to the Greenland variety. The workmanship is more thorough, and the water-resisting qualities are better. These boots are made of harp seal and are the best things going for Arctic work. With a handful of grass in the sole to form insulation against the cold and to act as a pad against pebbles or sharp ice, they are as comfortable an article of footwear as one can desire.

Another reason for our coming to Hopedale was to secure our old interpreter, Abram Bromfield, who had been with the Commander on numerous previous trips. Abie lived about thirty miles from Hopedale at the head of a large bay known as Jack Lane’s Bay. Therefore, after we had obtained our clothing, we set our course for his home. While on the way we[60] noticed that the vessel was not turning up her customary speed, but as the engine was functioning perfectly we decided that it must have been an illusion created by the effects of tide or wind.

On our arrival at Jack Lane’s Bay, the Commander and McDonald took one of the small boats and started up the Bay for Abie’s house. Early the next morning they returned accompanied by the whole Bromfield family who brought us several thick, tender, juicy venison steaks and a large mess of fresh-caught trout. Old Sam Bromfield, Abie’s father, aged seventy, also brought his accordion and gave us a rare treat by dancing the good old folk dances and playing some of the songs of yesteryear.

The following morning at two o’clock sharp, the mate slid back the forecastle hatch and uttered the familiar cry, “All hands on deck!” In spite of sleep-numbed brains and the well-nigh irresistible desire to return to the alluring arms of Morpheus, we snapped back, “Yes, sir,” and hit the deck with despatch.

In getting under weigh my particular job was to stow the chain in the chain locker, and in a few moments my ears were greeted with: “Stand by the chain!” I made a dash over Dick’s bunk[61] and dived into the locker just in time to grab the chain as the great electric winch by my ear was beginning its raucous clatter, and the muddy chain was commencing its rapid descent. A few minutes later there lay at my feet a huge mound of rusted links, and I heard the creak of the tackle with which the anchor is brought to the cat-head. The engine-room telegraph jangled; a sudden vibration indicated the throwing in of the clutch, and I prepared to go on deck. Suddenly I noticed the absence of the customary ripple which can be heard from the chain locker when the vessel is under weigh. I listened intently, but no murmur of gurgling water greeted my straining ears. Could the engineer have mistaken the signal? No, the engine was running as usual. I dashed on deck wondering what could be the trouble. The Commander stood by the wheel, on his face a puzzled expression. The rest of the crew were bending over the stern, vainly endeavoring to fathom the trouble.

Maynard Williams (left), photographer, National Geographic

Society, Lieut. Benjamin Rigg (right), U. S. Coast and Geodetic

Survey.

It was still nearly as dark as midnight; just a faint touch of red in the east. In a moment more the Peary came sliding along through the morning vapors like a great, grey ghost, her black smoke flickering across the face of the[62] waning moon like a dark forerunner of disaster. Shortly our ears were assailed by a shrill blast from her siren. The Commander realizing that there was something radically wrong with our propulsive apparatus, ordered a boat lowered to take him over to the Peary that he might acquaint them with our predicament. In a few moments he had spanned the intervening stretch of water, and we saw the vessel stop as she came down on the boat. The Commander then told Commander McDonald of our trouble and instructed him to continue the voyage to Greenland and await our arrival at Disko Island, where we would rejoin him as soon as our trouble had been adjusted. In the meanwhile we had again let go the anchor to keep the Bowdoin from drifting; then we pulled a small boat under the stern for a closer inspection. There the Commander joined us and took part in the investigation. As we had surmised, the propeller was sadly damaged. There was no other recourse but to beach the vessel and change the propeller. With this end in view, the Commander despatched Dick Salmon with one of our motor boats to enlist the aid of the Bromfields and their staunch motor boat. It was decided that it would be advisable to[63] return to Hopedale where there were better facilities.

The Bowdoin passing an iceberg off west coast of Greenland.

The Bowdoin caught in a nip, at Melville Bay.

The day being calm, our sails were not of much assistance, and we had to depend in the main on the Bromfield motor boat. How that little motor ever stood the strain is more than I can understand, but stand it she did, and after ten hours of slow progress we limped into Hopedale. There, since the tide was right, we immediately beached the vessel on an adjacent sand-spit and waited for the low tide to lay bare the propeller. Unfortunately we had arrived at the period of neap or small tides. The rise and fall was so small that the propeller was scarcely more accessible at low tide than at high. Luckily, however, the tides were increasing daily, and in about a week they would enter on the period of spring, or large tides. Therefore, all we could do was to wait philosophically for the much-needed higher water and pull the vessel a little farther in on each high tide.