Title: Toodle and Noodle Flat-tail: The Jolly Beaver Boys

Author: Howard Roger Garis

Illustrator: Louis Wisa

Release date: May 4, 2022 [eBook #67990]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: A. L. Burt Company, 1919

Credits: Charlene Taylor, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Author of "Sammie and Susie Littletail," "Johnnie and

Billie Bushytail," "Curly and Floppy Twistytail,"

"Uncle Wiggily's Airship," "Uncle Wiggily's

Adventures," "Uncle Wiggily's Journey," Etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY LOUIS WISA

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers

New York

Books intended for reading aloud to the Little Folk

each night. Each volume contains 8 colored illustrations

and 31 stories—one for each night in the month.

Handsomely bound in cloth. Size 6-1/2 by 8-1/4.

SAMMIE AND SUSIE LITTLETAIL

JOHNNIE AND BILLIE BUSHYTAIL

LULU, ALICE AND JIMMIE WIBBLEWOBBLE

JACKIE AND PEETIE BOW WOW

BUDDY AND BRIGHTEYES PIGG

JOIE, TOMMIE AND KITTIE KAT

CHARLIE AND ARABELLA CHICK

NEDDIE AND BECKIE STUBTAIL

BULLY AND BAWLY NO-TAIL

NANNIE AND BILLIE WAGTAIL

JOLLIE AND JILLIE LONGTAIL

JACKO AND JUMPO KINKYTAIL

CURLY AND FLOPPY TWISTYTAIL

TOODLE AND NOODLE FLAT-TAIL

DOTTIE AND WILLIE LAMBKIN

UNCLE WIGGILY BED TIME STORIES

UNCLE WIGGILY'S ADVENTURES

UNCLE WIGGILY'S TRAVELS

UNCLE WIGGILY'S FORTUNE

UNCLE WIGGILY'S AUTOMOBILE

UNCLE WIGGILY AT THE SEASHORE

UNCLE WIGGILY'S AIRSHIP

UNCLE WIGGILY IN THE WOODS

UNCLE WIGGILY ON THE FARM

UNCLE WIGGILY'S JOURNEY

For sale at all booksellers, or sent, prepaid,

on receipt of price by the publishers.

A. L. BURT COMPANY,

114-120 East 23 Street

New York City

Copyright, 1919, by

R. F. Fenno & Company

Once upon a time, not so very many years ago, when every one was younger than he is now, but when the sun shone just as brightly and the wind blew just as sweetly, there lived in a curious little house, built right in the middle of a pond of water, a family of animals called beavers. They looked something like Nurse Jane Fuzzy-Wuzzy, the muskrat lady who took care of Uncle Wiggily Longears, the rabbit gentleman, only these beavers were larger than Nurse Jane, and they had long, broad, flat tails, which they could fold up under themselves and sit on, just like a stool. That's why I have named them "Flat-tail," and I'm going to tell you some stories about these beavers, who are really very wonderful animals. They are covered with soft fur.

In the Flat-tail family there was, of course, Mamma and Papa Flat-tail, and there was also dear old Grandpa Whackum. Grandpa had such a funny name, not because he was fond of whacking the little beavers, but because, when there was any danger, the old gentleman beaver would whack or pound his broad, flat tail on the ground two or three times.

That made a sound like a drum, and whenever the other beavers heard it they would rush for the pond, dive down in it, swim to the front door of their house, the door being under water, and, once inside, they would be safe. So that is why the oldest beaver of them all was called Grandpa Whackum.

Well, then, to begin on the story—

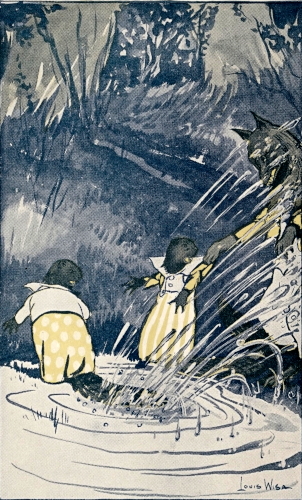

Oh, dear me! I beg your pardon. I'm forgetting the most important part. Toodle and Noodle Flat-tail, to be sure! Toodle and Noodle were the two small boy beavers of the family, and without them and the funny things they did, and dangers they got into, and out of again, there would be very few stories to tell. Toodle wore a spotted suit of clothes, and Noodle one that was striped. Now you can tell who is which.

Now, then, to start all over again.

Toodle Flat-tail, the little boy-beaver, came out of the under-water door of his home one day, dived down under the pond, holding his breath so the water would not get in his nose, and swam to shore. Then he sat up on his broad, flat tail and looked back toward his house.

"I wonder where Noodle is?" spoke Toodle, as he turned his head from side to side. "He said he'd come right out and play. What can be keeping him?"

But Noodle, the brother of Toodle, was not in sight.

There were other beaver children, and some grown-up ones, to be seen about the pond. Some were putting mud-plaster on their houses, others were cutting down trees with their four strong, orange-colored front teeth, and the nice green bark of these trees would be eaten by the beavers during the long, cold winter. But Noodle Flat-tail was not with the others.

"I guess he must be playing a trick on me," said Toodle, as he picked up a piece of a birch twig in his front paw and began chewing the soft bark. A beaver's front paw, you know, is almost like a monkey's, and he can hold things in it almost as well as you can in your hand. His hind feet, though, are made for swimming and are webbed like a duck's.

All of a sudden Toodle felt some one pushing him from behind, and before he knew what had happened he went kerflop! off the little hill on which he was sitting, into the water.

"Wow!" cried Toodle. "Who did that, I wonder? If it was a bad fox, or a lynx, or some animal that wants to eat me, I'd better stay under water, or go back home."

But Toodle Flat-tail was a brave little chap and he wanted to see who it was that had pushed him into the water. So he swam around a little, and then he carefully stuck his nose up, and then his eyes, and then, sitting in the same place where he had been sitting, he saw his brother Noodle. Noodle was laughing as hard as he could laugh.

"Oh, ho! So it was you who pushed me in, eh?" cried Toodle. "Well, I'll fix you for that!"

Out of the water he came with a rush and raced after Noodle. But Noodle waddled away and soon the two little beaver boys were having a regular game of tag.

Finally Toodle caught Noodle and pushed him into the water. But do you s'pose Noodle minded that? Not a bit of it, for he was more at home in the water than on land. In fact beavers have to go quite slowly on land, and they walk with a waddle like a duck, but in the water they can swim so fast that scarcely anything can catch them.

Toodle and Noodle splashed each other about in the pond, throwing water all over themselves, wrestling, playing tag and hide-and-go-seek, and when they were tired they climbed out on the bank and rested.

They looked at the other beavers working away. Some of the older ones were mending a hole in the dam. The beaver dam, you know, is just like a time when it rains and the gutter in front of your house fills with water. Then if your mamma lets you, you take some sticks and stones and mud, and pile it in the gutter so the water can't run down. This is called a dam, and it holds back the water, making it deeper back of the dam and shallow in front.

Beavers do the same thing. They build a dam across a little brook, so as to make a deep pond, for beavers have to have deep water to live in, and build their houses in; and in this pond, back of the dam, they also keep their food for the winter, big pieces of trees with soft bark on. The beaver dam is made of tree trunks and branches, sticks, mud, grass, stones—in fact, anything the beavers can get. When the dam breaks all the beavers work together to mend it.

So Toodle and Noodle watched their papa and mamma and the other big beaver folk mending the hole in the dam. A bad bear had clawed the hole there, hoping that all the water would run out of the pond so he could catch and eat the beavers. But the bear's plan did not work, I'm glad to say.

"I hope I didn't hurt you when I crawled up behind you and pushed you in the water," said Noodle to his brother most politely.

"Oh, no," said Toodle. "I liked it. First, though, I thought it was a fox after me."

"Ho! If it had been a fox!" exclaimed Noodle, "I guess you would have heard Grandpa Whackum pounding on the ground with his big tail to tell us there was danger."

"Yes, I guess we would," said Toodle. "Oh, Noodle!" he cried suddenly, "let's go over where those nice, juicy aspen trees grow, and get some bark off them. I'm just hungry for an aspen-bark ice cream cone."

"But papa said we weren't to go there without him," objected Noodle. "You know he said there was an old wolf not far from there, and he might get us."

"Oh, I don't believe there is any danger just now," said Toodle. "It's daylight. Besides, Grandpa Whackum can see that far and he'll bang with his tail if there's any danger. Come on!"

So the two little beaver boys went over to where some aspen and willow trees grew, though it was not just exactly right. They swam through the water and then came out and waddled over the land. Soon they were in the grove of trees.

"You take a willow tree and I'll take an aspen," said Toodle, "and after we each cut off a nice piece with the juicy bark on we'll take them home and divide them."

So, sitting up on their big tails, which were like stools to them, the little beaver boys began to gnaw away. A beaver's gnawing teeth are as good to cut with as a carpenter's chisel. There are four gnawing teeth, and the funny part of it is that they are colored yellow, like an orange.

Well, Toodle and Noodle were gnawing away, and they had almost cut down two little trees when, all of a sudden they heard:

"Whack! Whack! Thud! Thud!"

"Hark! What's that?" cried Toodle.

"It's Grandpa Whackum, telling us there's danger!" shouted Noodle. "Run, Toodle! Run!"

Away they ran for the water, and only just in time, for the bad old wolf sprang after them. But he did not get either of them, for Toodle and Noodle slipped into the water just in time and swam safely home.

From where he was working Grandpa Whackum had seen the wolf stealing up on the two little chaps and had warned them. So the wolf didn't have a beaver dinner that day, and Papa Flat-tail made Toodle and Noodle stay in the house the rest of the afternoon for not minding him.

But they were not always like that, and so in the next story, if the stove poker doesn't take the teakettle out to the moving picture show, I'll tell you about Toodle Flat-tail cutting down a tree.

"Hey, Toodle, wake up! Wake up!" called Noodle Flat-tail, the little beaver boy, to his brother one morning. "Wake up! Breakfast is ready!"

Toodle turned over on the bed of white birch chips in the beaver house that was built in the middle of the pond of water, and said, sleepily:

"Oh, please let me alone, Noodle. I don't want to open my eyes yet. Let me sleep!"

"But don't you know what we're going to do today?" asked Noodle. "Have you forgotten what papa said?"

"Oh, it is a picnic? Are we going on a picnic?" asked Toodle, and this time he sat up on his tail and rubbed the sleepy feeling out of his eyes with his handlike paws.

"No, it isn't exactly a picnic," answered Noodle, as he combed out his fur with his hind claws so as to be nice and neat for breakfast. "But papa said he'd show us how to cut down a big tree today. Don't you want to learn how to do that?"

"Indeed I do!" cried Toodle, and he rolled from his bed in such a hurry that he nearly fell out of the front door, which led into the water. In that case Toodle would have had a swim before breakfast.

Not that he would have minded that much, for, like all beavers, he loved being in the water just as much as being on land. In fact, beavers, when they wear any clothes at all, as they have to, in stories of course, wear a kind that water cannot hurt—sort of rubber garments, you know.

"Oh, goodie!" cried Toodle. "That's what I want to do—cut down a tree," and he opened his mouth and felt his four sharp, orange-colored front teeth that were purposely made for gnawing. They were always sharp, too, and made in such a way that when they grew dull they sharpened themselves. No scissors-grinder ever had to come to the beaver colony to sharpen their teeth. Nature did that for the queer animals.

"Let's see who'll be first at breakfast," cried Noodle, and then he and his brother washed their paws and faces, brushed some dirt off their broad, flat tails, combed out their fur until it shone like Grandfather Goosey Gander's silk hat, and went into the dining-room, where Mamma Flat-tail was getting breakfast for her husband and for Grandpa Whackum, the oldest beaver of them all.

"Good morning, Toodle and Noodle," said their papa, as he helped himself to some willow bark pancakes, flavored with water-lily root sauce. "You are a little late this morning, and if you are going to be working beavers, and learn how to cut down trees, you must get around earlier than this."

"I should say so!" exclaimed Grandpa Whackum, as he spread some watercress butter on his piece of birch bark bread. "Why, when I was a boy I used to get up before breakfast every morning, and cut down two or three trees. Then I'd float them down the canal to the dam we were building."

"Well, anyhow, we got up before breakfast," said Toodle, winking at his brother.

"Yes, but you haven't chopped even a tooth-pick," laughed their mamma.

"What's a canal, Grandpa?" asked Noodle, who wanted to learn all he could about beaver work.

"Oh, it's like a little stream of water, or a brook," said the old gentleman beaver, "only it's deeper, and we have to make it ourselves. We cut through the dirt and grass and take out the stones, and make a place for the water to run from one pond to another. Then we can float our logs through the canal, just as you boys play float your toy ships."

"I see," said Noodle, and he made up his mind he would soon dig a canal.

Well, the two little beaver boys ate their breakfast, and then got ready to go with their papa who was to give them their first lesson in cutting down a tree. Grandpa Whackum, who, as I told you before, used to whack on the ground with his tail to give warning of danger, went along also.

Mrs. Flat-tail stayed home to do the dishes in her kitchen. Of course, not all beaver families have a house with as many rooms in it as the Flat-tails had. But then Mr. and Mrs. Flat-tail were quite rich. Most beavers have only one room in their house.

So Mr. Flat-tail, the two boys, Toodle and Noodle, and Grandpa Whackum swam out of the front door of the water-house and across the pond to a little wood where some sweet willow trees grew. This was near the place where the wolf had nearly caught the two boy beavers the day before, as I told you in the first story. But now, with their papa and grandpa beavers to look after them, Toodle and Noodle were not afraid.

"Now, Toodle," said Mr. Flat-tail, when they had come out of the water and were all waddling along on land, "I'll give you a lesson in tree-cutting first. Then I'll show Noodle. Meanwhile, Noodle, you can go with Grandpa Whackum and get some fresh aspen bark for dinner."

So Grandpa Whackum and Noodle went off to another place, while Papa Flat-tail began to give Toodle his first lesson.

"We'll cut this tree," said Mr. Flat-tail, as he put his paw on one that was about as big around as a clothes post in your yard.

"Oh. I never can cut down such a big tree," said Toodle. "It would take me a week."

"Nonsense!" exclaimed Mr. Flat-tail. "You don't know what you can do until you try. Now get a good seat on your tail and reach up with your four sharp front teeth and bite into the tree. Pull off the slivers and chips, and soon you will have cut through the trunk and the tree will fall."

"Gracious!" cried Toodle, "I hope it doesn't fall on me. It's no fun to have a tree fall on you."

"Of course not," laughed Mr. Flat-tail. "But that is what you must look out for, Toodle. Don't let the tree fall on you, or on any one else. And when you see that it is just ready to topple over, whack on the ground with your tail, just as your grandpa does. That will tell every one else around you to get out of the way. And another thing. Always pick out a tree that won't fall on top of another and get all tangled up, so it can't be moved."

"Will this tree do that?" asked Toodle, looking up into the top of the tree his papa wanted him to cut down.

"No," said Mr. Flat-tail, "it will not. Begin now, Toodle. This tree will fall just right."

Toodle thought he could never cut down such a large tree, but then he was a brave little beaver boy, and he was not going to give up without trying. So, sitting on his big, thick, broad tail, which, as I have told you is like a stool, he began. Into the soft wood he sank his sharp orange-colored front teeth, and soon the bark and chips began to fly, just as they do when a woodman cuts a log.

Mr. Flat-tail saw that his little son was learning his lesson well, so he said:

"Now, Toodle, I'll go over here and cut down a large tree by myself. But don't forget what I told you about whacking your tail on the ground just before your tree falls."

"I won't," promised Toodle.

Well, he was cutting and cutting away with his teeth, and then he began to think what fun he and his brother would have that afternoon, playing water-tag.

And Toodle was thinking so much about the fun that he forgot all about what his papa had told him. All of a sudden he heard a sound he knew well.

"Whack! Whack! Thud! Thud!" echoed through the woods.

"That's Grandpa Whackum!" exclaimed Toodle. "Good gracious sakes alive! There must be some danger. I must run!"

Poor Toodle started to run, but alas he was not quick enough. Down crashed the tree he had been cutting, and one limb struck him on the back, pinning him fast to the ground. Poor Toodle could not move. It was just as though he had been caught in a trap.

"Oh, dear!" he cried. "Oh, dear! My tree fell on me!"

And had it not been that Grandpa Whackum and Papa Flat-tail were there in the woods Toodle might never have gotten loose. But the two old beaver gentlemen soon came up and gnawed through the tree branches so Toodle could get up. His brother Noodle helped, too.

"Why didn't you watch out to see when your tree was going to fall?" asked Papa Flat-tail when they were on their way home again.

"I—I forgot," said Toodle, sort of ashamed-like.

"Well, if I hadn't seen it falling, and whacked on the ground with my tail," said his grandpa, "you might have been killed. Be more careful after this."

Toodle said he would, and he was quite proud after all that he had cut down a tree all by himself. Then they all swam home.

And on the next page, if the shoe horn doesn't blow so loudly that it wakes up the rubber doll in the puppy dog's hammock, I'll tell you about Noodle building a dam.

Toodle Flat-tail, the little beaver boy, was so lame and sore from having been caught under the tree he was gnawing down, as I told you in the story before this, that the day afterward he could not leave the house in the pond to go out and play.

"Cutting down trees is more dangerous than I thought it was," said Toodle when Dr. Possum came to put some sassafras liniment on his sore places.

"Indeed it is," said Dr. Possum. "I can climb trees very well, and hang on by my tail, but I never tried cutting one down. I don't believe I could do it. Though often I have heard of hunters, who when they are after friends of mine, cut down trees to get them out."

"How dreadful!" exclaimed Mrs. Flat-tail who was baking some apple-bread for dinner. "But, Dr. Possum, do you think Toodle will have to stay in the house long?"

"Well, maybe two or three days more," said the old gentleman doctor.

"Oh, dear!" exclaimed Mrs. Flat-tail, the beaver lady. "Boys are so troublesome when they are in the house!"

And I guess this is so. Anyhow Noodle, who was the brother of Toodle, stayed in to play with him, and the two of them frisked around and got up all sorts of games, and nearly upset the piano and did all things like that. At least Noodle did, for Toodle was too sore and stiff to do much. But Noodle was trying to amuse his sick brother you see, and really he did not mean to make trouble.

"I'll tell you what I'll do," said Dr. Possum, as he closed up his birch bark satchel filled with all sorts of colored medicines. "On my way back home I'll stop and tell Nurse Jane Fuzzy-Wuzzy, the muskrat lady, to come over and take care of Toodle. Then Noodle can go out and play, and your house will be quiet, Mrs. Flat-tail."

"Oh, that will be fine!" exclaimed the beaver lady, and Toodle said the same thing.

Noodle said he would be very glad to go out and play, for though he did not much mind staying in the house to amuse his brother, still he would much rather have gone out, to swim around in the pond, play on top of the big dam, that made the beaver pond, or even cut down a little tree so he could gnaw the green, sweet bark.

So Nurse Jane Fuzzy-Wuzzy came from Uncle Wiggily's hollow stump bungalow, and she read stories to Toodle and told him how she could swim under water, almost as well as the beavers could, and how she could make a fiddle out of a cornstalk and play a tune on it. And she did, and it was such a nice, sleepy sort of tune, all about going to by-low land, that, before he knew it, Toodle was fast, fast asleep, and the house was quiet.

But what happened to Noodle? Ah, ha! We must find out about that before we go much further. For Noodle had made up his mind to do something, and when he did that something almost always happened.

As Noodle did not have to stay in the house any more to play with his little sick brother, he dived down through the front door, which was under water, so no bad animals could get in, and out the little beaver boy swam into the pond. This pond was made by a big dam being built across the lower end, to keep the water from running away, as I have told you, and in this pond were many beaver houses, built of sticks, mud, grass, stones and pieces of trees.

On the dam, which was wide enough on the top for several beavers to walk, there were a number of the animal folk talking, laughing and doing different things.

Some were gnawing pieces of tender bark, which they had stripped off the aspen or willow trees. Others were carrying in their front paws mud or sticks to mend holes in the roofs of their houses. Some beaver children were playing tag and pushing each other into the water.

"I wish I could make a dam," thought Noodle. "I would like to make a little one and have a pond of water all to myself. Then I'd build a house in it, and when Toodle gets well he and I can have lots of fun in it. I think that's what I'll do. I'll build a dam and have a toy beaver pond just for us boys."

The more Noodle thought of this the better he liked it, so he swam off up the big pond until he came to a place in the woods where a little brook ran along over the green stones, singing a pretty song all to itself.

"Here is where I will make my dam," said Noodle.

He remembered how his papa had told him to do it—to cut down little trees, pile them across the brook, then how to pile sticks and stones and mud and grass against the trees until the water could not trickle through. Then it would stop running and there would be a pond, just as the children make one in the gutter after a rain storm.

Noodle was soon a very busy little beaver boy. But he was careful only to gnaw down small trees, so that even if they fell on him before he could get out of the way he would not be caught or hurt, as his brother had been. Soon he had quite a pile of wood, and then, pulling it in his strong teeth or paws, he piled it across the brook. Then he carried sticks and stones and grass until he had made a fine little dam.

Of course it wasn't as large as the big dam, nor made so well, but really it was quite good for a small beaver boy, and Noodle was quite proud of it. The water back of the dam got deeper, and soon there was enough of it for Noodle to swim in. And how he could swim!

He could dive, and float on his back, and stay under water so long that it is a wonder how he could hold his breath. With his strong hind paws, and sometimes by using his tail like the propeller on a steamboat, Noodle went back and forth across the pond he had made by building the dam.

"Now I'll begin the play-house," thought the little beaver boy. "I can't finish it today, but when Toodle gets well he can help me."

So Noodle began. He gathered a lot of sticks and pushed them down in the mud of his pond. Then he got more and arranged them around in a pile, plastering them with mud he dug up from the bottom, under the water. This mud he carried in his front paws, walking on his hind ones like a bear in the circus.

Soon the play-house began to look almost like the real ones beavers make. And while Noodle was taking a rest and glancing from side to side to see that there was no danger, all of a sudden, out from the woods sprang a bad old fox. He made a run for Noodle, and almost caught him, but the little beaver boy, thudding on the ground with his tail, to warn others who might be near of the danger, gave a jump into the water and dived down under it.

"I'll fool that fox!" thought Noodle. "I'll just swim along and stay under water until he goes away."

So he stayed under, but after a while he wanted to get some air to breathe, and of course he had to come up. And, as it happened, he came up near shore where the fox was waiting for him.

"Ah ha! I have you!" cried the fox, and he made a grab for Noodle. But Noodle dived under water again. The fox didn't dare go in water, you know, for he couldn't swim as well as Noodle.

"I fooled him again," thought the little beaver boy. "I guess he must be gone by this time, and I can come out." Noodle had to come up for another breath of air, but no sooner was his nose out of the water than the fox, who had been watching, made another grab for him, and Noodle only got a sniff of air.

"No you don't get me!" cried Noodle, and down he went again. But he was getting tired, and out of breath, and I don't know what would have happened if Grandpa Whackum, the old gentleman beaver, hadn't come along just then. He saw what the trouble was, and the danger Noodle was in. So Grandpa Whackum gathered up a big ball of mud on the end of his tail, and, when that fox was making another grab for Noodle, Grandpa Whackum threw the mud in the eyes of the fox.

"Oh, wow!" cried the fox, and then he couldn't see (not even with his glasses on) to bite Noodle, so the little beaver boy got safely away, and so did Grandpa Whackum, and all the fox had to eat that day was peanut shells. But it served him right, I think.

So that's how Noodle built a dam, and what happened afterward, and next, in case the man in the moon doesn't come down and take my straw hat to play ball with, I'll tell you about Toodle and Noodle in the canal.

"Come, boys," said Mrs. Flat-tail to Toodle and Noodle, the little beaver chaps, one morning when they were swimming around the house in the pond, playing tag; "come boys, I want you to go to the store for me."

Mrs. Flat-tail, the beaver lady, had swam out of the front door of her house, and was sitting up on the roof, looking to see if there were any holes there where the snow might come in during the winter. She saw a small one, and made up her mind that her husband or Grandpa Whackum, would have to plaster that hole up with mud before cold weather set in.

"What do you want from the store, mamma?" asked Toodle, as he dived down under the water, and began swimming toward his brother, who had his back turned. Toodle was going to tickle the other little beaver boy, and make believe it was a water snake that had done it.

"Well, if you'll keep still long enough for me to tell you what I want, I'll do so, and give you the green-leaf money to get it," said Mrs. Flat-tail, laughing, for she loved to see her two boys play in the water.

Up came Toodle from the bottom of the pond, where he had dived—up he shot, right under Noodle, and he upset Noodle, who went toppling head over tail, and then the two beaver boys splashed around in the water and had a lot of fun. Oh, it's great to be a beaver, I tell you!

"Well, are you done playing?" asked Mrs. Flat-tail, after a while. "If you are I'd like to have you get me some cat-tail flour and some candied cocoanut from the store. I'm going to make a cake!"

"Oh, goodie!" cried Noodle. "I'm going to carry the cocoanut!"

"No, I am!" said his brother. "You might eat some on the way home."

"Huh! You mean you would yourself," cried Noodle.

"Well," said their mamma, "I'll give you a basket with a water-proof rubber cloth on it, so you can dive down under the water with the things in it if you have to, and then you won't get them wet. So you may each carry half the basket with the cocoanut in it."

Toodle and Noodle thought this a good plan, and soon they were swimming on toward the store, which was kept by a nice old water rat, and the store was in an old rowboat that no one wanted any more. Mr. Rat had stuffed up the holes in it with cheese, and it did very well for a grocery.

There were two troubles with it, however. One was that often Mr. Rat got hungry and then he would graw some of the cheese out of the holes. That would make the boat leak, and the grocery store got wet. The other trouble, which was almost quite as bad, was that the boat would float away all over the beaver pond, and when you started out to find it you could never tell just where it was going to be, whether at one end of the pond or the other. So going to the store was not as easy as might seem, but still no one minded much.

But this time Noodle and Toodle were quite lucky. They soon found the floating boat store, and bought what their mamma had sent them for, putting the things in the basket and covering them up with the water-proof cloth so as to keep them dry.

"Now let's see how quickly we can go home," said Noodle.

"All right," agreed Toodle. "The sooner we get home the quicker mamma can bake the cake and—" Then he stopped and laughed. So did Noodle.

"I know what you're thinking of," said Toodle, blinking his eyes.

"What?" asked Noodle.

"You're thinking that maybe we'll get some of the cake," spoke his brother, and truly, that was right. Oh, those beaver boys were just like you real children! Indeed they were.

So, carrying the basket, with the candy cocoanut for the cake, between them, Toodle and Noodle swam away from Mr. Rat's floating boat store. Then they had to get out on dry land, for this pond did not go all the way to the pond where the Flat-tail house was built.

"Now we must be very careful," said Toodle, as he and his brother crawled out on shore. "Look carefully around for danger, Noodle, for you know we can't go as fast on the land as we can in the water, and something may catch us. So if you see a fox, or a wolf, or a bear, bang your tail on the ground as Grandpa Whackum does, and we'll both run."

Of course, Noodle said he would, but for some time the two little beaver boys went on together and saw nothing to alarm them. Then, all at once, when they were almost to the pond where they lived, and were ready to plunge in it and swim home, they saw a big, savage lynx on the path ahead of them. A lynx is like a wolf, only worse, and he has sofa-cushion tassles on the tips of his ears, so you can always tell him when you see him. In a picture, I mean, not real. I wouldn't want you to meet a real lynx.

"Oh, the lynx!" whispered Noodle. "He'll get us sure if we don't look out! Let's go back to Mr. Rat's pond."

"No, wait until I bang the ground with my tail," said Toodle. "Maybe papa or Grandpa Whackum will hear it and come to help us."

"No, don't make a noise with your tail now," said Noodle, "or the lynx will hear it and come for us."

"Then let's run," suggested Toodle. "We'll go back to the other pond."

"I'm afraid if we do that the lynx will see us, and chase after us," spoke Noodle. "Oh, dear!"

"Then what can we do?" asked his brother in a whisper.

"Dig a canal," was the answer. "Listen! We are not far from our own pond. If we can dig a canal from here to there we can walk down in it, for it will be like a ditch without any water in it, and the lynx won't see us. Then we can run along and when we get to our pond we can easily swim home."

"That's what we'll do!" cried the other beaver. So keeping down low in the grass, where the lynx would not see them, they began digging a ditch. With their strong claws Toodle and Noodle could easily do this, for they had often watched the older beavers doing it. They wished there was water at the place where they had begun to dig, for that would have made it easier for them, but it could not be helped. They hid the grocery basket under a bush in the grass as they began to dig.

My! how the dirt did fly! The two little beaver boys worked very hard, for they wanted to get away from that lynx. As for that bad animal, there he lay in the sun, just wishing some fat beaver, or some other poor chap, would come along to be eaten.

Pretty soon Toodle said:

"I think we're near our pond now, Noodle."

"I think so, too," whispered Noodle. "Soon the water will rush into our canal and we will be safe. Then we can tell papa and he'll get the basket of groceries."

The beaver boys dug a little more and then, all of a sudden, with a rush, the canal filled with water, and Toodle and Noodle were swimming. This was just what they wanted.

Then something happened. All at once a lot of beavers came paddling down the new canal Toodle and Noodle had made, and among them was Grandpa Whackum.

"Oh, ho!" cried the old gentleman beaver. "Look here! What's this? Who dug this canal?"

"We did," answered Toodle proudly. "Noodle and I dug it to get away from the lynx. Isn't it a good one?"

"The canal is all right," said Grandpa Whackum, with a laugh, as he splashed water with his broad tail, "but you made your canal so low down that all the water is running out of our pond into it. We will have no water left if we don't stop up your canal, boys. Hurry, friends!" cried Grandpa Whackum to the other beavers. "Make a dam across the boys' canal and that will keep the water in our pond. It won't all run out then."

So the beavers did this, bringing mud and sticks and grass for a dam, and soon the canal was dry again, and the beaver pond stopped running out. Then the big beavers stole softly up to where that lynx was and they threw stones at him until he was glad enough to run home.

Then Grandpa Whackum got the basket of cocoanut and flour which Toodle and Noodle had hid in the grass and brought it home, so Mrs. Flat-tail could make a cake. She did, and the two beaver boys each had a large piece.

So that's all now, but in case the baker man doesn't let his cake of ice roll over our lawn and spoil the watering can, I'll tell you next about Grandpa Whackum being caught.

"Come, boys!" called Grandpa Whackum, the old gentleman beaver, to Toodle and Noodle, the little beaver boys, as they awoke one morning in their mud and stick house in the pond. "We must be off early today for we have a great deal to do."

"Oh, dear!" exclaimed Toodle. "I was going to play ball with Bully No-tail, the green frog, this morning."

"And I was going to play tag on the flat lily pad leaves with Bawly, his brother," spoke Noodle. "What do we have to do, grandpa?"

"I am going to show you how to dig a canal," answered the old gentleman beaver.

Toodle looked at Noodle, and Noodle looked at Toodle. Then they both looked sort of ashamed-like.

"Do you mean a canal like the one we dug the other day, when we wanted to get away from the bad lynx?" asked Noodle, brushing a mosquito off his ear.

"No," answered Grandpa Whackum with a laugh, as he got up from where he was sitting on his tail. "You dug that canal all right, only you didn't look where it was going to end, and you nearly let all the water from our pond run away through it. No, I'll show you how to make a canal just right."

You remember I told you how, when Toodle and Noodle went to the store for their mamma, they had to dig a canal to get away from a bad animal.

"Well, I guess then we'd better go with you," said Toodle, "for we must learn how to make canals in the right way. Sometimes we might want to get away from a bear by swimming in one of them."

"That's so," agreed Noodle. So he and his brother gave up the idea of playing ball or tag, and off they set with their grandpa, who was the oldest beaver in all the beaver colony, or city, and the wisest and strongest.

"You'll have plenty of time to play after you practice your canal-digging lesson," went on the old gentleman. "Come along, we're going over to the aspen tree grove."

"Hadn't we better take along some sandwiches, or maybe an ice cream cone to eat," suggested Toodle. "We've just had our breakfast, I know," he added as he saw his mamma looking at him, "but we may be gone a long while."

"Oh, there will be plenty to eat where we are going boys," said Grandpa Whackum, with a laugh and a whistle through his big, orange-colored front teeth. "There are sweet aspen trees there, and willows with nice, thick, juicy bark—indeed, you'll not get hungry, even though you don't have an ice cream cone. Come along."

So off the old gentleman beaver went, with Toodle and Noodle frisking on ahead. Mr. Flat-tail, their papa, stayed home to plaster with mud a hole his wife had found on the roof of the house in the pond. It would never do to have a hole there, for a bad water rat might easily scratch it larger, and some night, when Toodle and Noodle were asleep he might sneak in and bite them. No, indeed!

As Grandpa Whackum and the two boys swam along the pond, and then went out on dry land to waddle for a short distance, Toodle suddenly exclaimed:

"Why, I know where this is!"

"Where?" asked his brother Noodle.

"It's the same place where I had my first lesson in cutting down a tree!" cried the little beaver boy. "That time I was caught under it, you know."

"Oh, yes!" exclaimed Noodle. "Is that where we are going, Grandpa Whackum?"

"The very place," said the old beaver gentleman, as he kindly stopped to allow a toad that accidentally sat on his tail to hop off. "And, boys, we are going to dig a canal so we can float down through it, on the water that will run in, the very tree Toodle cut down. That tree is good to eat, Toodle, my boy," went on Grandpa Whackum, "and it will be very good this winter."

"Oh, fine!" cried Toodle, and he was very glad that he could be of some use to the other beavers, even if it was only in cutting down one tree for use as food.

"I wish I could cut down a tree!" exclaimed Noodle.

"Well, you can soon," promised his grandpa. "But now I need you both to help dig the canal. We will soon begin. Here is a little brook that runs into our pond. Now if we dig a sort of ditch from this brook to where Toodle's tree is, we can float it right to our house, and that's what we'll do."

Soon the work of digging the canal was started. The old gentleman beaver and Toodle and Noodle used their sharp claws to loosen the earth. Then they would carry it off to one side, either holding it in their front paws, which were like hands, or by taking a lot of it on their tail, and holding their tail close to their body so the dirt would not slip off. In this way they soon had quite a ditch dug, and when the water from the little brook ran in it would be a canal.

"You boys are doing very well," said Grandpa Whackum, after a bit. "I think I will leave you for a little while and go off in the wood to see if there are any more good trees to cut down for winter. If there are I'll show Noodle, tomorrow, how to cut them. While I'm gone you boys can finish the canal."

So Grandpa Whackum, washing the mud from his tail, went off in the aspen grove, and Toodle and Noodle worked harder than ever on the canal. Soon it was dug all the way to where lay the tree Toodle had cut down.

"Now let's rest," suggested Noodle. "When Grandpa comes back he'll show us how to cut down the little wall of dirt that is between the brook and our canal, and that will let in the water. Then we can float the tree home."

"And while we're waiting let's eat," suggested his brother. So they gnawed off some sweet willow bark, which is as good to them as are lollypops or popcorn candies to you children.

Toodle and Noodle were just finishing their little bark lunch, when, all of a sudden, they heard a voice calling:

"Help! Help! Help!"

"Hark! Who's that?" asked Toodle.

Then they heard a whistle and the sound:

"Whack! Whack! Thud-ud-dud!"

"That's Grandpa Whackum!" cried Noodle. "He must be in trouble!"

"Help! Oh, boys, come and help me!" they heard the old beaver gentleman calling. "I'm caught in a trap!"

Toodle and Noodle rushed as fast as they could toward where they heard the sounds. All the while the old beaver gentleman was thumping his flat tail on the ground, to tell his little grandsons how to reach him.

Pretty soon they came to where he was, and there poor Grandpa Whackum stood, caught fast by his hind leg in a wooden trap.

"Oh, boys!" he cried. "Hurry and get me out! I was walking along, looking up at the trees to make sure which were the best to cut, when I stepped into this trap. It has snapped shut on my paw, and I can't turn around to gnaw myself loose! Can you do it for me?"

"Of course we can!" cried Toodle bravely.

"Right away, quick!" cried Noodle.

Then with their orange-colored front teeth those beaver boys gnawed and gnawed on the wooden trap until they had gnawed it all to pieces and their grandpa could come out. He was not much hurt, I'm glad to say. And the hunter who set the trap, thinking to catch a beaver, was much disappointed that night, I guess.

"It was very foolish of me not to look where I was going," said Grandpa Whackum, a few days later as he rubbed some witch hazel leaves on his sore paw, which was nearly well now. "I'll never get caught again, and I hope you boys will not, either. How is the canal coming on?"

"It is all done," said Toodle.

"Good!" cried Grandpa Whackum. Then he went with the two beaver boys to where they had dug. With a few strokes of his strong claws the old gentleman soon tore down the last bit of the earth, and that let the water into the canal. It was filled very shortly, and then the three beavers rolled into it the tree which Toodle had cut down.

"Now, sit on the log," said Grandpa Whackum. "Hold up your broad, flat tails for sails and we'll ride home." And they did, as nicely as you please, and every one was glad to see them.

So that's how Toodle and Noodle dug a canal and how Grandpa Whackum was caught and got out again. And on the next page, if I don't lose all my money, so I have to walk down town instead of going on my roller skates, I'll tell you about Toodle making a house.

"Hurray!" cried Noodle Flat-tail, the little beaver boy, as he hopped out of his clean shavings bed one morning, and tickled his brother Toodle with a turkey feather. "Hurray! no school today!"

"That's so," spoke Toodle, rubbing the sleepy feeling from his eyes so he could look out of the window and see if the sun was up yet. As it was quite high in the sky, it shone, making the beaver pond sparkle like silver.

Most beaver houses have no windows, and they are all dark inside, but the one where Toodle and Noodle lived had several windows in it, for Mr. Flat-tail was a very rich beaver.

Besides there was Grandpa Whackum, the oldest beaver of them all, and he helped make the windows. So if some of you children have seen real beaver houses, and have never noticed the windows, don't say they never have any. Because this Flat-tail family of beavers was different from those you may know.

"Well, I guess we may as well get up," said Toodle, when he saw how high the sun was. "And I'm glad it's Saturday, so we don't have to go to school."

I believe I forgot to tell you that Toodle and Noodle went to school just the same as any animal children do, and later on in these stories I'm going to tell you some of the things they did there.

"Yes, we can have a lot of fun," spoke Noodle. "Bully No-tail, the frog, is going to have a ball game, with the broad lily pad leaves for bases, and you and I can play."

"Good!" cried Toodle.

So the two little beaver boys hurried down to their breakfast of willow bark oatmeal with frizzled watercress pancakes, and soon they had dived down through the water, in their rubber cloth suits, out of the front door, and across the pond they swam.

Down on the beaver dam, which was built to keep the water from running out of the pond where the animal folk lived, were a number of the grown-up beavers, and they were very busy. They were bringing mud and sticks and stones and grass in their paws, and putting it in a pile near where Grandpa Whackum stood on his hind legs sitting on his tail for a stool.

"That's right!" the old gentleman beaver was saying. "Hurry now, everybody, bring a lot of mud and plaster it over the hole. Hurry, everybody!"

"What's the matter?" asked Noodle. "Is there a fire?"

"No, but in the night a bad bear tore a hole in our dam, to let all the water out of our pond, so he could tear open our houses and get us," said a policeman beaver, who was sitting on top of the police station, looking out for danger. And when he saw any he was ready to whack his tail on the water, making a noise like a fire-cracker. When the other beavers heard this they would all run and hide.

"A bear; eh?" exclaimed Toodle. "Wow!"

"Yes, and you boys must be careful where you play today," said Grandpa Whackum, as he showed the other beavers how to mend the hole the bear had torn in the dam. "I can't be with you to look out for danger."

"Oh, we'll be careful," said Noodle, sort of easy-like, as all boys are.

They watched the mending of the dam for a little while, and then they went on to play ball with Bully, the frog, Jimmie Wibblewobble, the duck, and some other of their animal friends.

Well, this story isn't about the ball game, though I will tell you one like that some time. But now I must relate what happened when Toodle built his play-house. So I'll just say that there was lots of fun at the ball game, and that Noodle's side won.

Soon after that Noodle had to go to the store for his mamma, and as Toodle did not want to go along he stayed home.

"But I would like to have some fun," said this little beaver boy to himself, "so I guess I'll build a play-house. Then, when Noodle comes back it will be a surprise to him and he and I can stay in it, and play soldier, and Indians, and all things like that."

So Toodle began to build his house. Perhaps if Grandpa Whackum, or his papa, or some of the older beavers had seen him they might not have let Toodle do this, for he started his house away off at one end of the pond, near the wood where the bears and wolves lived.

"But if we are going to play Indian in our house," said Toodle to himself, "we don't want it too near the other houses. The people will make a fuss if we yell and holler."

So off he went by himself, while all the grown beavers were mending the hole the bear had torn in the dam. Other boy and girl beavers were playing around, some swimming, some sliding down slippery, muddy banks, that were just like coasting-hills, and some girl beavers were playing with their dolls, which were made out of pieces of wood.

Toodle had watched other beavers making houses, some of them very large, so he thought he knew how to do it. But he only wanted a small play-house. He gathered a lot of sticks, and then, diving down to the bottom of the pond, and holding his breath, he scooped up a little pile of mud and grass roots. This was the bottom part of his house. On top of this he laid sticks, and more sticks, until his house was above the water. Then he brought still more sticks and mud and grass roots up from the bottom of the pond.

Toodle then piled some long poles up slanting, just as you might take a lot of bean poles and stand them up in a circle in the garden, to make an Indian tent. Toodle did this, and then he spread mud all over the outside, and when this had partly dried in the sun, there he had a nice little house.

"Won't Noodle be surprised when he sees this!" cried the little beaver boy.

If you had been there you could not have seen any door to the queer house, but there was one just the same. The entrance to it was under water, and when he wanted to go in Toodle had to dive down below the water and swim up along a dark front hall to get into his house. It was safer that way, as no other animal dared come in.

Well, the little beaver boy finished his house, and then he began to wish for his brother to come along so they could have a good time. Toodle was sitting on the roof, putting some mud plasters on a few holes he saw, when all of a sudden, there was a swirl in the water, and along came the bad old skillery-scalery alligator with the double-jointed tail. He swam straight for Toodle, crying:

"Ah, ha! This is the time I have you! Wuff!"

"No, you haven't!" cried the little beaver boy, and with that he gave a dive off the roof of his play-house into the water, and swimming with his paws and his broad, flat tail, he soon had found his front door. The next minute he was up inside his house.

"Now you can't get me!" he cried through the sides to the skillery-scalery alligator.

"I can't, eh? You just watch me!" cried the bad old 'gator.

With that he began to scratch and claw, and to claw and to scratch at Toodle's house, scattering all over the sticks and the mud, that was not yet hard and dry.

"Oh, dear!" thought the little beaver boy. "I shouldn't have come in here. When I was in the water I should have swum home; for I can go faster in the pond than that 'gator can. Now he'll get me sure! And I don't dare go out now, or he'll grab me. Oh, dear! I wish I'd made my house nearer the dam, where Grandpa Whackum is. He'd save me."

Well, the 'gator went on clawing away at Toodle's nice little house, and he had it almost clawed apart, and was going to reach in and grab Toodle, when, all of a sudden, Noodle, who had come back from the store, came swimming along, looking for his brother.

"Help! Help! Oh, will no one help me?" cried poor Toodle in his little play-house.

"Yes, I will!" said Noodle. He had with him two ice cream cones, one for himself and one for Toodle, and they were full, and heavy with ice cream. But Noodle knew there was but one thing to do. First he threw one cone at the bad 'gator, and the sharp point stuck in one eye. Then Noodle threw the other cone, and the sharp point of that stuck in the 'gator's other eye. Then the 'gator couldn't see to scratch or claw Toodle's house any more, and he couldn't see to grab the little beaver boy, who easily swam out and got safely away with his brother.

Of course, the ice cream cones were lost, for the 'gator took them away with him, and had to go to a dentist to have them pulled out of his eyes. But, anyhow, Toodle was saved by Noodle, whom he thanked very much. And Toodle never built a house so far away from the dam again.

So this is all now, but on the page after this, if it happens that the butterfly spreads some honey on a cracker for the rag doll to eat, I'll tell you about Toodle saving Noodle.

Toodle and Noodle Flat-tail, the two little beaver boys, sat on top of the big dam, that kept the water in the pond from flowing all away, as the water does in your gutter on a rainy day, unless you make a pile of mud and sticks to hold it back. Toodle was gnawing a bit of sweet bark from an aspen tree, and Noodle was making a whistle out of a bit of willow wood.

"Well," said Noodle after a while, when he had blown on the whistle, making a noise like a toy choo-choo engine, "is this all we're going to do today, Toodle?"

"Oh, I don't know," answered Toodle as he looked at the stick to see if there was any more eating-bark on it, and, finding there was none, he threw it away. "I don't know," said Toodle again, "what would you like to do to have fun?"

"Let's go away in the woods," spoke Noodle, "and gnaw down some trees with our teeth, the way Grandpa Whackum showed us, and we can build a little cabin and play Indian."

"That would be fun," agreed Toodle, "only suppose a bad bear or an unpleasant wolf should get after us?"

"Then I would just blow on my whistle," said his brother, "and Grandpa Whackum, or maybe papa, or some of the big folks would hear it and come to save us. I say let's go off to the woods," and he blew his whistle quite loudly, so that Grandpa Whackum, the oldest beaver of them all, who was mending a hole in the dam where the water was running away, Grandpa Whackum, as I say, came running up, banging his broad, flat tail on the ground, and asking:

"What's the matter, boys? Is some one trying to catch you? Are you in a trap?"

"Neither one, thank you kindly, Grandpa Whackum," said Noodle, speaking very politely, as he had been taught to do, "we are in no danger, and I was just blowing on my whistle to show Toodle how I could call for help if we went to the woods."

"I see," spoke the old gentleman beaver. "I heard the whistle, all right, but if you boys go off to the woods I could not get to you as soon as I did this time. So you want to be very careful if you do go."

"We will," promised Noodle. "Come on, Toodle. Let's go have some fun."

So the two little beaver boys jumped down from the big dam, and began swimming toward the woods some distance off. The beavers could swim in the water much better than they could waddle, or walk, on land, even if they did stand up on their hind legs. And they were much safer in the water, but of course they could not stay in it all the while.

On and on swam Noodle and Toodle, and sometimes the little beaver boys would see gold or silver fish in the water around them, and they'd stop for a minute and talk about how warm the pond was, and whether there would be a fishball game that day, and all things like that.

And sometimes Toodle and Noodle would see some little girl beaver friends of theirs playing with their dolls, and their hair ribbons, and their sewing on top of the big beaver houses that stuck up out of the water.

"Well, here we are at the woods," said Noodle, after awhile, and he swam to the bank, and climbed out of the water.

"Yes, we're here," said Noodle, as he climbed out and sat down beside his brother, to dry off a little. Both the little beaver boys sat on their big tails, which were as good as little stools to them, as I have told you in the stories before this one.

"Now for some fun!" cried Toodle, as he turned a somersault and part of a peppersault, while Noodle blew on his whistle, not very loudly, you know, for he did not want to scare Grandpa Whackum and make him come running up, thinking there was danger.

Then the two beaver boys began to play. With their four strong orange-colored teeth they gnawed down small trees, and began to pile them on shore to make a little log cabin. They did not build a regular beaver house, which is almost always made in the water. This time Toodle and Noodle were just playing, and they wanted a cabin on shore.

"Now it's almost done!" exclaimed Toodle, as he went inside and looked out of the window.

"Yes, a few more logs and it will be ready for us to play in," spoke his brother. "Then you can be an Indian part of the time, and I'll be a soldier, and make believe chase and shoot a bang-bang gun at you, and then it will be your turn to be a soldier with a gun, and I'll be an Indian."

And just then, all of a sudden, something fell down out of the air, and came down, cracko-whacko! hitting Toodle on the head as he was looking out of the play-cabin window.

"Wow," cried Toodle. "Did you do that, Noodle?"

"Indeed, I didn't," said his brother. "Can't you see that I'm busy here gnawing down this tree to make the bang-bang gun with? I didn't hit you."

Just then Toodle heard some one laughing, and, looking up, he saw Billie Bushytail, the squirrel boy, sitting on a tree branch right over the log cabin. Billie was eating a hickory nut.

"Excuse me, Toodle," said Billie, the squirrel boy. "I hit you, but I didn't mean to. I was eating a nut and it fell out of my paws and landed on your head. Did it hurt you very much, Toodle?"

"Oh, hardly any," said the little beaver boy. "You see I have a lot of fur on top of my head, Billie, and it bounced right off—the nut did, I mean—not my head."

I guess if the nut had hurt him, Toodle wouldn't have said so. Boys are like that, you know. That's the reason they don't cry, after they get over being babies.

"Come on down and play with us," said Noodle.

"Yes, do," invited Toodle. So Billie, the squirrel boy, scrambled down from the tree, and soon he and the two beaver brothers were playing in the little log cabin.

Oh, such fun as they had! They made up all sorts of games, including the one about Indians and soldiers, and then they played a new game called "Don't bite your Paws when all alone. You try to eat An Ice Cream Cone." That is a very funny game, only you have to have ice cream cones to play it, and it was a lucky thing Uncle Wiggily Longears, the old gentleman rabbit, came along just as Toodle, Noodle and Billie were ready to start it, for he had the ice cream cones with him in his valise, and he gave them to the boy animals to use.

Well, the old rabbit gentleman watched them playing about for some time, and then he hopped off to see his friend, Grandfather Goosey Gander, and Billie, the squirrel, went with him. So that left Toodle and Noodle alone. They played some more, and then Noodle thought he would make himself a little toy boat to go sailing in.

Noodle went off by himself down to the edge of the water where a nice little tree grew, and he was cutting this tree down with his sharp teeth, while Toodle was up in the play-cabin making believe he was a soldier on guard, when all of a sudden something happened.

A great big, old, gray wolf, who hadn't had anything to eat in a long, long time—not since Fourth of July I guess—this bad, old, gray wolf sprang out of the bushes and grabbed Noodle in his paws.

"Now I've got you!" growled the wolf, and really he had. There was no mistake about that. The wolf had poor Noodle!

"Oh, dear," cried the little beaver boy. "Let me go! Oh, please let me go, and I'll give you all the money I have home in my tin bank."

"No! No!" growled the bad old wolf, and he started to take Noodle off to his den. Noodle tried to blow on his willow whistle to call for help, but it was in his pocket where he couldn't reach it. And it looked as if the wolf would take him away.

But have no fear, little ones. I have a plan to save Noodle.

Toodle, up in the cabin, saw what had happened, and he cried:

"I'm coming, Noodle! I'm coming!" Down the hill ran Toodle, and going close up to where the wolf was with his brother, Toodle stood in the water, and with his broad, flat tail, which is just like a pancake-turner, that brave little beaver boy splashed water all over that wolf. In the wolf's eyes and nose and mouth it went, making him sneeze and gasp and choke. Of course Noodle got all wet too, but he didn't mind that a bit. He liked it. And finally the wolf was so soaking wet, and he sneezed and choked so hard, that he had to let go of Noodle, who at once ran away and was safe, for Toodle had saved him, just as I said he would.

"Come on, I guess we'd better go home," said Toodle, and he and Noodle went back to the beaver dam. As for the wolf he had to go to the doctor to get something to make him stop sneezing, and it served him right, I think.

So no more now, if you please, but if the little chicken next door doesn't come in and pick a hole in the baby's red circus balloon so that it bursts, I'll tell you next about Toodle's and Noodle's little sister.

"Well, boys," said Grandpa Whackum, the old gentleman beaver, one morning, as he swam out of the house in the pond and took a seat on his tail, on top of the dam, next to where Toodle and Noodle Flat-tail were sitting; "well, boys, I think you might take a few more swimming lessons today, for after you start going to school I won't find much time to teach you."

"School!" cried Noodle, "are we going to school, grandpa?"

"Of course," said the old gentleman beaver, slowly blinking both his eyes.

"But school for the other animals began some time ago," spoke Toodle. "Johnnie and Billie Bushytail, the squirrels, have been going two weeks, and so has Sammie Littletail, the rabbit. I thought we wouldn't have to go."

"Yes," said Grandpa Whackum, "it is true you two boys will start in a little late, but that is because your papa and mamma first wanted you to have some lessons at home in tree cutting, and in house and dam making and things like that. But when you do start to school, say in a week or so, you can easily catch up to the others.

"So, as I said, I'll give you your last swimming lesson now, and then you will always be able to get away from any animals that chase after you in the water."

Now Toodle and Noodle liked the water very much, and they so enjoyed having Grandpa Whackum show them the best way to swim and dive and float, as well as stay under water without breathing for a long time—they liked this so much, I say, that they forgot about soon having to go to school.

My! how they splashed about in the pond, using their hind paws, which were something like a duck's feet. They fairly rushed through the water, and when they wanted to go very specially fast they used their broad, flat tail just like a propeller on a steamboat.

"That's the way to do it!" cried Grandpa Whackum, as he told the beaver boys what to do. "Turn around quickly in the water, and dive down when an alligator or a sea lion chases you," said the old gentleman beaver, showing them how.

So Toodle and Noodle practiced their swimming lesson, and then their grandpa said:

"Now, boys, come up on this old stump and do some diving. Jump right into the water; don't be afraid!"

Grandpa Whackum showed them how to do this, springing off his hind feet and going away down under water where no one could see him until he popped up again.

Toodle and Noodle did this after him, and, though at first they were not very good at it, soon they got so they could dive as nicely as could be.

"Now you are good swimmers," said the old gentleman beaver, "and you may have time to play. But be careful not to go too far away, over to the woods, or the bad wolf may get you."

Toodle and Noodle said they would be careful, and then they began playing tag, and hide your tail, and jump over your chewing gum, and all games like that. Finally they swam away up to one end of the beaver pond, and they were just going to climb out on land, and sit on their tails for a while, until they thought of a new game, or until some of their friends came home from school, when, all of a sudden, something happened.

No, it wasn't a rustling in the bushes, and no bad animal jumped out on them. Goodness knows that takes place often enough, as you well know. But it was something different this time.

Toodle and Noodle heard a gentle little voice somewhere off in the woods, and it kept saying:

"Oh dear! Oh dear! Oh dear! What shall I do? Who will take care of me? Oh dear!"

"Hark!" cried Noodle. "Did you hear that?"

"Indeed, I did," answered his brother. "Come on, let's go home!" and he started toward the pond.

"Go home!" exclaimed Noodle. "What for? Let's go see what that is."

"No, sir! Never!" cried Toodle. "Why most likely it's a bear or a wolf, making believe cry like that so we'll come closer, and then he can grab us. No, sir! don't you go see what it is at all. Come on home!"

"Oh, don't be a silly!" exclaimed Noodle. "That's some little boy or girl animal in trouble. A wolf or a bear couldn't cry in such a tiny, weeny voice as that. I say let's see what it is."

Toodle listened to the crying voice again. Truly it did sound like some little animal, and not like a bad bear, and finally Toodle said:

"Well, let's go take a look. But be all ready to run in case there's danger. Remember Grandpa Whackum isn't here to help us."

"Oh, I'll be careful," promised Noodle.

Slowly and carefully the two little beaver boys went toward where they heard the voice. It was still crying away like this:

"Oh, dear! Oh, dear! Will no one come and take care of me? Oh, dear!"

"It's in that old stump over there," said Toodle after a bit of looking about.

"Yes, that's where it is," agreed Noodle. "The stump is hollow and some poor chap is inside it."

So Toodle and Noodle went up to the hollow stump, and they stood up on their tippy-toes, and they looked in, and at first it was so dark they couldn't see anything, and then—and then—all of a sudden—they looked once more, and—what do you think they found?

Why, there was the dearest, sweetest, cutest little baby beaver girl you ever saw! She was all dressed in a long blue-pink-yellow dress, and she had a little bottle of milk in one paw and a rubber rattle-box in the other, but she was crying, this little baby beaver girl was, and she seemed so lonesome and afraid that Toodle and Noodle felt very sorry for her, and loved her at once.

"Oh, look!" cried Toodle. "A baby in a hollow stump!"

"Yes, and maybe we can take her home and keep her for our little sister," said Noodle. "Oh, joy!"

"Oh, dear!" said the little baby beaver.

"What's the matter?" asked Noodle.

"Oh, I'm left all alone," said the baby. "I was out in the woods with my papa and mamma, and a bear and a wolf chased us. My papa and mamma ran as fast as they could, but the bear and wolf kept after them, and finally they got so close that my papa and mamma couldn't get away. Then my mamma hid me in this stump, hoping, I guess, that some one would find me, and then she and papa ran on and—and——"

But the little baby beaver cried so hard that she couldn't talk. Toodle and Noodle felt the tears coming into their eyes also, but Toodle asked, very, very softly:

"What happened after that, baby?"

"The—the bear and wolf carried my papa and mamma away to their dens," said the baby beaver, "and—and I'm left all alone. Nobody loves me! Oh, dear!"

"Don't cry any more!" said Toodle, and with his handkerchief he wiped the eyes of the baby beaver. "We love you, and we'll take care of you, won't we, Noodle?"

"Indeed we will!" exclaimed the other beaver boy. "We'll take you home with us, and you can be our little sister."

"Will you really?" asked the baby, who was old enough to talk, you see, and she could walk a little. "That will be lovely!" she said, and she stopped crying.

So Toodle and Noodle helped her out of the hollow stump, and then they made a little boat out of a piece of tree which they gnawed down, and they rowed the baby beaver across the pond to their house. And Mrs. Flat-tail said her boys did just right to bring the poor little thing home; and she took her for her very own baby and for a sister to Noodle and Toodle.

They named her Crackie, for she used to drop the dishes and cups and crack them. But no one minded that very much, for they loved Crackie so. And one day a wolf chased her and she threw an ice cream cone at him and cracked that, but it scared the wolf so that he ran away, which was what Crackie wanted.

So that's how Toodle and Noodle got a little sister, whom they loved very much, and some day Grandpa Whackum said he might find that bad wolf and bear and make them let Crackie's papa and mamma go. But lots of things happened before that.

And in the next story, if the cocoanut pie doesn't roll off the table and break the cream pitcher's leg, I'll tell you tomorrow night about Toodle and Noodle sliding down hill.

Once upon a time Toodle and Noodle Flat-tail, the little beaver boys, went sliding down hill when there wasn't any snow on the ground, and a very strange thing happened to them. I'm going to tell you all about it, if you'd like to hear it. So, if you will kindly not wiggle too much, and not call the dog over here to rub his wet tail on my newly polished shoes and take all the shine off so I can't go to the party, I'll tell you all about it.

It began this way. Toodle said to Noodle, his brother, one day:

"Let's have some fun."

"All right," said Noodle to Toodle, "we will. What shall we do?"

"Let's go out on the dam and look around," said Toodle. "Maybe we'll see something there."

The dam, you know, was the big wall of sticks and stones, and grass and mud, that held the water of the beaver pond from running away and leaving all the beaver houses on dry land. Because the beaver animals, you know, like to have their houses in water.

"Shall we take Crackie with us?" asked Noodle. Crackie, you remember, was the new little baby sister of the beaver boys. They had found her in a hollow stump. "Shall we take Crackie?" asked Noodle.

"Why, yes, I guess so," answered Toodle. "She'd like to come and have some fun."

So they swam back to the beaver house, dived down under water where the front door was (so no bad animals could get in without at least getting wet) and then Noodle called:

"Hi there, Crackie! Want to come with us?"

"Of course I do," answered Crackie, and then something sounded "Bango!"

"My goodness! What is that?" cried Mrs. Flat-tail, mother of the beaver children. "What did you break that time, Crackie?"

"Only the looking glass. Oh, dear!" answered the little baby beaver. "It's all cracked to pieces."

"Oh, Crackie!" cried Toodle, sadly like.

That's the reason her name was "Crackie," as I told you in the story before this one. The poor little girl did not mean to do it, but she was always cracking or breaking something. Some people are like that; aren't they?

"I—I was just looking in the glass to see if my hair ribbon was on straight," said Crackie, "when the mirror just fell out of my claws and broke!"

Crackie was getting to be quite a girl, you see, to have hair ribbons and all things like that. Oh, beaver children grow very fast, you know. They are something like mushrooms that spring up over night.

"Well, never mind, Crackie, my dear," said Mrs. Flat-tail. "You couldn't help it, I know. You didn't do it on purpose. Run along out with the boys and play."

"Yes, come on, Crackie!" cried Toodle. "We're going to have some fun!"

Say, I guess, I'd better begin telling about that sliding down hill without any snow on the ground pretty soon, had I not? or else I'll get to the end of this story without putting it in.

Well, anyhow, as the telephone girl says sometimes, Toodle and Noodle and Crackie, the three beaver children, swam out of the house in the pond and began looking for something so that they might have a good time.

They looked over toward where Grandpa Whackum, the oldest beaver of them all, was showing another beaver gentleman, who had just gone to housekeeping, how to stop a leak in his roof. And the animal children saw their grandpa climb up on the roof with some plastermud in his paws to fix the hole, and then, when he had used up the plaster, they saw him slide down the roof for more, going splash! into the water.

"Say, that's what we can do to have some fun!" exclaimed Toodle.

"Do what?" asked Noodle.

"Slide down hill," answered Toodle.

"How can we slide down hill when there isn't any snow," asked Crackie, who was a very smart little beaver baby girl.

"I'll show you," said Toodle. "You know mud is very slippery, and the roofs of lots of our houses are made of mud. Grandpa Whackum just slid down one, sitting on his flat tail, and we can do the same."

"That's right," cried Noodle. "We'll find an old house, where no one lives any more, and we'll wet the roof by splashing water on it, and then we'll take turns sliding down into the pond. That will be jolly fun!"

Toodle thought so, too, and so did Crackie. She swam along with her brothers, carrying her rubber doll in one paw. The rubber doll didn't mind being wet, you know.

Well, finally the beaver children found a big house, that was rounding on top just like a hill, and no one lived in it. The roof was covered with dried mud, but with their tails Toodle and Noodle and Crackie soon splashed water on it and made it as slippery as the most slippy-ippy hill covered with snow or ice that you ever saw. For you know how sluppy-slippy wet mud is if you have ever fallen down in it when you were going to school. Or maybe your rubber has stuck in the slippery-sticky mud and come off. Mine did once, and I dropped my ice cream cone in a puddle of water, and the worst of it was I didn't have any more money to get another, either.

Well, finally the rounding, hilly top part of the roof of the beaver house was all wet and slippery mud, and Toodle and Noodle began to slide down it. They wanted to try it first before they let their little sister Crackie go on it, to be sure it was safe for her.

And it was all right, I'm glad to say, and when the beaver boys sat on their tails and gave themselves a little push away they went down the muddy hill, without any snow on it, almost as fast as a choo-choo train, or maybe even an automobile, for all I know. Think of that!

"Now may I try it?" asked Crackie.

"Yes, come along," said Toodle.

"We'll give you a good push!" said Noodle.

Crackie let her rubber doll swim in the water while she climbed up on top of the house-hill and got ready to slide down into the water. It was like shooting the chutes at Coney Island, you know.

"Splish-splash!" went Crackie into the water, and she laughed and shouted, it was such fun.

"She slides as well as we do, Noodle," said Toodle.

"Indeed she does!" said Noodle to Toodle.

Then the beaver children took more turns sliding down the muddy hill. Sometimes they slid separately, and often all three of them would go down together. Then Toodle got a long piece of birch bark for a sled, and they all sat on that, holding their tails up in the air, and down they went, whizzing along until they hit the water with a splash.

Oh, it was great fun!

Then, all of a sudden, when Toodle and Noodle had gone sliding down together, leaving Crackie standing alone on the top of the muddy hill, to come down after them, all of a sudden, up out of the water came the bad old skillery-scalery alligator, and before Toodle or Noodle knew what was happening the savage creature, with the double-jointed tail, had grabbed them both in his paws.

"Oh, let us go! Let us go!" cried Toodle.

"Yes, please let us go!" begged Noodle, and he tried to make his tail go "whack!" on the water, the way his grandpa had taught him to do to call for help. But the alligator held him too tightly, and Noodle couldn't move even his nose.

"Oh, will no one help us?" shouted Toodle.

"No, there is no one here to help you," barked the alligator, just like a dog. "I am going to take you off to my den!"

"Oh, ho! No, you're not!" cried little Crackie, up on top of the mud-hill, and with that she came sliding down so fast that she suddenly hit that alligator right on the end of his nose, and that made tears come into his eyes, and whenever that happens to a skillery-scalery alligator he has to go right away to the dentist. It was that way with this one, and, as soon as Crackie bumped him, he dropped Toodle and Noodle, letting them go, and away the bad creature swam to have a tooth pulled out, which served him right, I think.

So that's how Crackie saved Toodle and Noodle by sliding down the mud-hill and bumping the alligator. Then the beaver children had a lot more fun in the water and the alligator didn't bother them any more that day. And in the story after this, if the merry-go-round doesn't dance a jig on the roof, and wake up the little mouse in the pantry, I'll tell you about Toodle and Noodle going to school.

"Hark! What's that?" cried Toodle Flat-tail, the little beaver boy, as he rolled over in his bed of clean, white pine-splinters one morning. "Did you hear that, Noodle?"

"Indeed I did," answered the other beaver boy. "Listen, Toodle."

They both listened, and they heard a bell ringing off in the distance:

"Ding-dong! Ding-dong!"

"Fire!" cried Noodle. "It's a fire. Let's get up and—"

"Fire! That's no fire!" said Toodle. "That's the school bell that's ringing, and we have to go to school today, Noodle, my boy. Don't you remember what Grandpa Whackum said to us?"

"Indeed I do," answered Noodle. "So this is the day we have to start school? I wonder if our little sister Crackie is coming?"

"I don't believe she is old enough," answered Toodle. "It would be fun if she could, though. But did you hear anything else besides the bell, Noodle?"

Then both the little beaver boys listened again, just as the telephone girl does when you talk to her, and they heard some one calling:

"Hi there, Noodle! Hi there, Toodle! Time to get up! You have to go to school today." It was their papa.

"All right!" called the two beaver boys very politely, as all animal children do. "We're coming."

Quickly they washed their faces and paws in the water of the beaver pond, and then they were ready for breakfast. They had water-lily pancakes with birch bark syrup on, and winter-green muffins with maple sugar, and their mamma, Mrs. Flat-tail, also put them up a nice lunch of watercress bread with willow bark jam in between the slices.

"I wish I could go to school," said Crackie, the little beaver girl baby, whom the two boys had found in a hollow stump one day. "I'd like to go and learn how to make mud pies."

"Some day you may, my dear," said Mrs. Flat-tail, as she hurried about the kitchen, making some nice warm ginger-root soup for Grandpa Whackum.