Title: From North Pole to Equator: Studies of Wild Life and Scenes in Many Lands

Author: Alfred Edmund Brehm

Author of introduction, etc.: Horst Brehm

Editor: J. Arthur Thomson

Translator: Margaret R. Thomson

Release date: May 21, 2022 [eBook #68142]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Blackie & Son, Limited, 1896

Credits: Alan & The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

A E Brehm

BLACKIE & SON, LIMITED, LONDON, GLASGOW AND EDINBURGH.

FROM

NORTH POLE TO EQUATOR

STUDIES OF WILD LIFE AND SCENES

IN MANY LANDS

BY THE NATURALIST-TRAVELLER

ALFRED EDMUND BREHM

AUTHOR OF “BIRD-LIFE”, “TIERLEBEN”, ETC. ETC.

TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN BY

MARGARET R. THOMSON

EDITED BY

J. ARTHUR THOMSON, M.A., F.R.S.E.

————————————

WITH EIGHTY-THREE ILLUSTRATIONS FROM ORIGINAL DRAWINGS

————————————

LONDON

BLACKIE & SON, Limited, 50 OLD BAILEY, E.C.

GLASGOW AND DUBLIN

1896

[Pg v]

TO THE GERMAN EDITION.

Six years have passed since the grave at Renthendorf closed over the remains of my esteemed father, whose death—all too early—was as great a loss to Science as to those who loved and honoured him. It was strange that his eventful and adventurous life, in the course of which he visited and explored four quarters of the globe, should have ended at the little spot in green Thuringia where he was born. He had just reached his fifty-fifth year when his lips, so apt in speech, were silenced, and the pen which he held so masterfully dropped from his hand. He was full of great plans as to various works, and it is much to be regretted that the notes which he had collected towards the realization of these were too fragmentary for anyone but their author to utilize. But the manuscripts which he left contained many a treasure, and it seemed to me a duty, both to the author and to all friends of thoughtful observation, to make these available to the reading public.

The following pages form the first book of the kind, and contain the most valuable part of the legacy—Alfred Edmund Brehm’s lectures, once so universally popular. I believe that, in giving these pages to the world, I am offering a gift which will be warmly welcomed, and I need add no commendatory words of mine, for they speak adequately for themselves. Writing replaces spoken words very imperfectly, and my[Pg vi] father, who was never tied down to his paper, may often have delivered the same matter in different forms according to the responsiveness of his audience, abbreviating here, expanding there—yet to anyone who has heard him the following pages will recall his presence and the tones of his sonorous voice; everyone will not only recognize in them the individuality of the author of the Tierleben (Animal Life) and Bird Life, but will learn to know him in a new and attractive side of his character. For it is my father’s lectures almost more than any other of his works which show the wealth of his experiences, the many-sidedness of his knowledge, his masterly powers of observation and description, and not least his delicate kindly humour and the sympathetic interpretation of animate and inanimate nature which arose from his deeply poetic temperament.

Therefore I send these pages forth into the world with the pleasant confidence that they will add many to the author’s already numerous friends. May they also gain new and unprejudiced sympathizers for the animal world which he loved so warmly and understood so thoroughly; and may they, in every house where the love of literature, and of the beautiful is cherished, open eyes and hearts to perceive the beauty of nature, the universal mother; then will the highest and noblest aim of their author be achieved.

So may all success attend these pages, may they receive a joyful welcome, and wherever they gain an entrance may they remain as a prized possession.

HORST BREHM,

Doctor of Medicine.

Berlin, September, 1890.

[Pg vii]

TO THE ENGLISH TRANSLATION.

It has been a privilege to make available to English readers a book which shows a great naturalist at his best—a book that presents the reader with a series of vivid pictures of wild life and scenery, painted from actual observation, and with all the truth and accuracy that belong to the artist and man of science combined. It consists of a number of papers or articles that were originally read as public lectures and were afterwards collected into a volume that has met with much success in Germany. The subjects treated range over a wide and varied field. Some of them are unfamiliar to the ordinary reader, and besides their inherent interest have the added charm of novelty; others, if more familiar, are here invested with a freshness and charm that such a trained observer and practised writer as the author could alone impart.

To the translation of the German original have been added an introductory essay, showing Brehm’s position among naturalist-travellers, an extended table of contents, an appendix containing a number of editorial notes, and an index. The number of pictorial illustrations has also been increased.

For a notice of the Author and his labours see the concluding part of the Introductory Essay.

M. R. T.

J. A. T.

University Hall,

Edinburgh, December, 1895.

[Pg viii]

[Pg ix]

CONTENTS.

| Page | |

| Preface to German Edition, | v |

| Prefatory Note to the English Translation, | vii |

| INTRODUCTORY ESSAY BY THE EDITOR, | xv |

| THE BIRD-BERGS OF LAPLAND. | |

| The legend of Scandinavia’s origin—The harvest of the sea—The doves of Scandinavia—Eider-holms and bird-bergs—The nesting of the eider-duck—Razor-bills and robber-gulls—Millions of birds—(Notes, pp. 565-566), | 33 |

| THE TUNDRA AND ITS ANIMAL LIFE. | |

| High tundra and low tundra—The jewels of the tundra—The flora of the tundra—The Arctic fox—The lemming—The reindeer—The birds of the tundra—Mosquitoes—(Notes, pp. 566-568), | 63 |

| THE ASIATIC STEPPES AND THEIR FAUNA. | |

| The steppe in summer and in winter—The coming of spring—The rendezvous in the reeds—The marsh-harrier—The home of larks—Jerboa and souslik—The archar sheep—The kulan and the ancestry of the horse—(Notes, pp. 568-571), | 86 |

| THE FORESTS AND SPORT OF SIBERIA. | |

| An ice-wilderness or not—The forest zone—Axe and fire—The pines—Hunting and trapping—The elk, the wolf, and the lynx—Sable and other furred beasts—Bear-hunting and bear-stories—(Notes, pp. 571-573), | 120 |

| THE STEPPES OF INNER AFRICA. | |

| The progress of the seasons—A tropical thunderstorm—Night in the steppes—Spiders, scorpions, and snakes—Mudfish and other sleepers—Cleopatra’s asp—Geckos—The children of the air—The bateleur eagle—The ostrich—The night-jar—The mammals of the steppe—Stampede before a steppe-fire—(Notes, pp. 573-576), | 168[Pg x] |

| THE PRIMEVAL FORESTS OF CENTRAL AFRICA. | |

| Spring in the forest—The beautiful Hassanie—The baobab—Climbers and twiners—The forest birds and their voices—Sociable birds—Conjugal tenderness—Salt’s antelope—River monsters—A rain-lake—Hosanna in the highest—(Notes, pp. 576-578), | 201 |

| MIGRATIONS OF MAMMALS. | |

| Black rats and brown—Cousin man’s kindness to the monkeys—Migration of mountain animals—The restlessness of the reindeer—Wandering herds of buffaloes—The life of the kulan—Travellers by sea—Flights of bats—The march of the lemmings—(Notes, pp. 578-581), | 234 |

| LOVE AND COURTSHIP AMONG BIRDS. | |

| Are birds automata?—The battles of love—Different modes of courtship—Polygamy—Life-long devotion—(Notes, p. 581), | 259 |

| APES AND MONKEYS. | |

| Sheikh Kemal’s story—The monkey question—A general picture of monkey life—Marmosets and other New World monkeys—Dog-like and man-like Old World monkeys—Monkeys as pets—The true position of monkeys—(Notes, pp. 581-583), | 282 |

| DESERT JOURNEYS. | |

| An appreciation of the desert—The start of the caravan—The character of the camel—A day’s journey—Oases—Simoom and sand storms—Fata morgana—The peace of night—(Note, p. 583), | 318 |

| NUBIA AND THE NILE RAPIDS. | |

| Egypt and Nubia contrasted—Wady Halfa and Philæ—The three great cataracts—Journey up and down stream—The Nile boatmen—History of Nubia—(Notes, pp. 583-584), | 356 |

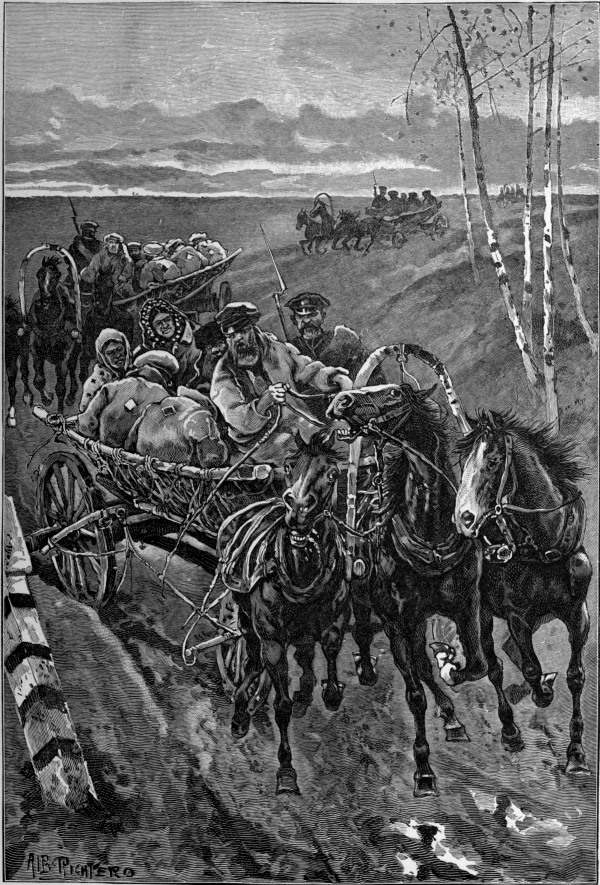

| A JOURNEY IN SIBERIA. | |

| Russian hospitality—A tedious journey—An excursion into Chinese territory—Sport among the mountains—Journeying northwards—On the track of splenic fever—(Notes, p. 584), | 390 |

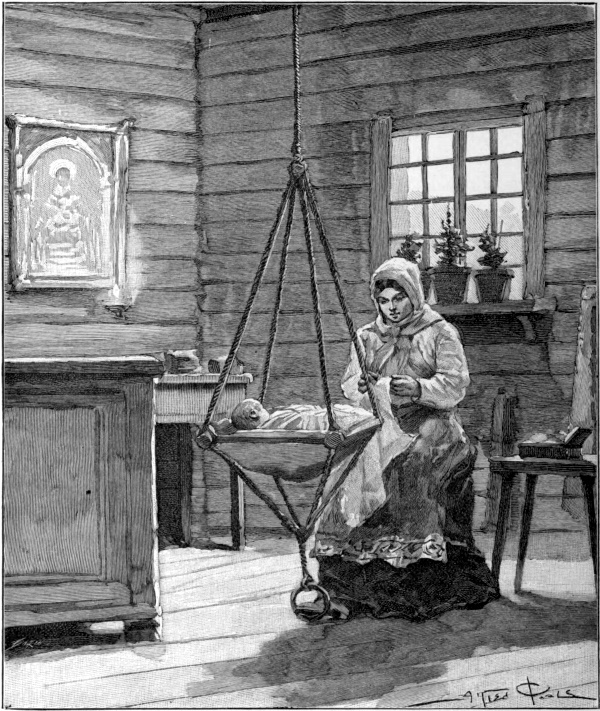

| THE HEATHEN OSTIAKS. | |

| Racial affinities—Christians and heathen—The dress of the Ostiaks—The tshum of the wandering Ostiaks—The life of the herdsmen—A fishing village—The Ostiak at the fair—An Ostiak wedding—An interview with a Shaman—Funeral rites—(Notes, pp. 584-585), | 416[Pg xi] |

| NOMAD HERDSMEN AND HERDS OF THE STEPPES. | |

| The name Kirghiz—Conditions of life on the steppe—Winter dwellings—Breaking up the camp—In praise of the yurt—The herds of the Kirghiz—The Kirghiz horse—Summer wanderings—“A sheep’s journey”—Returning flocks—Evening in the aul—(Note, p. 585), | 451 |

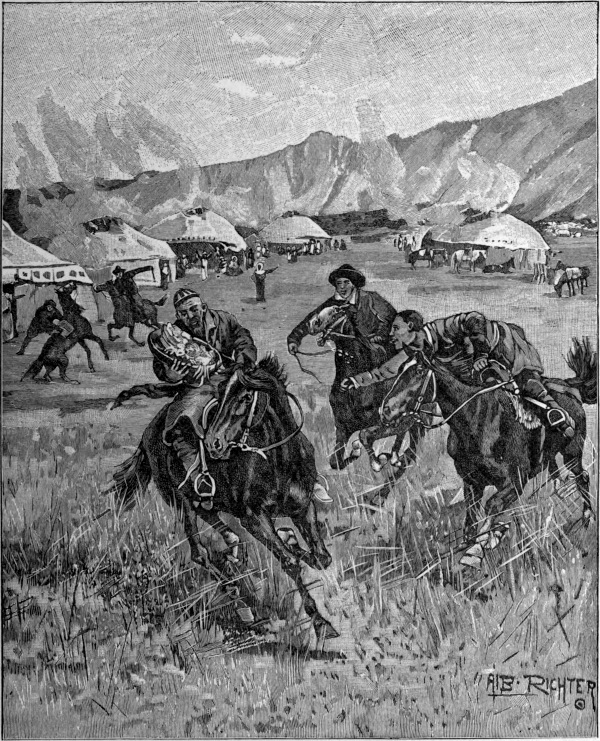

| FAMILY AND SOCIAL LIFE AMONG THE KIRGHIZ. | |

| The Kirghiz as horsemen—Racing and wrestling—Hunting with eagles and greyhounds—A sheep-drive—The “red tongue”—Kirghiz bards—Education and character—Kirghiz etiquette—The price of a bride—The children—Funeral ceremonies, | 482 |

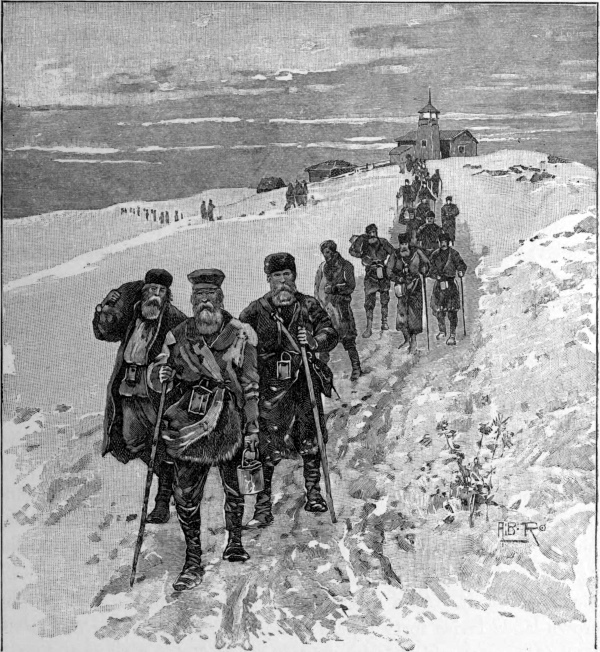

| COLONISTS AND EXILES IN SIBERIA. | |

| Mistaken impressions—Impartial observation—The emancipation of the serfs—The Altai—Compulsory service—Condition of the peasants—The superabundant harvest—Romance in Siberia—Domestic life open to the convicts—The way of sighs—General picture of Siberian life—Runaways—(Notes, pp. 585-586), | 510 |

| AN ORNITHOLOGIST ON THE DANUBE. | |

| Twenty eyries—The voyage down the river—The woods on the banks—A heronry—Sea-eagles—A paradise of birds—The marsh of Hullo—The black vultures of Fruškagora—Homeward once more—(Note, p.586), | 540 |

| Index, | 587 |

[Pg xii]

[Pg xiii]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| Fig. | Page | |

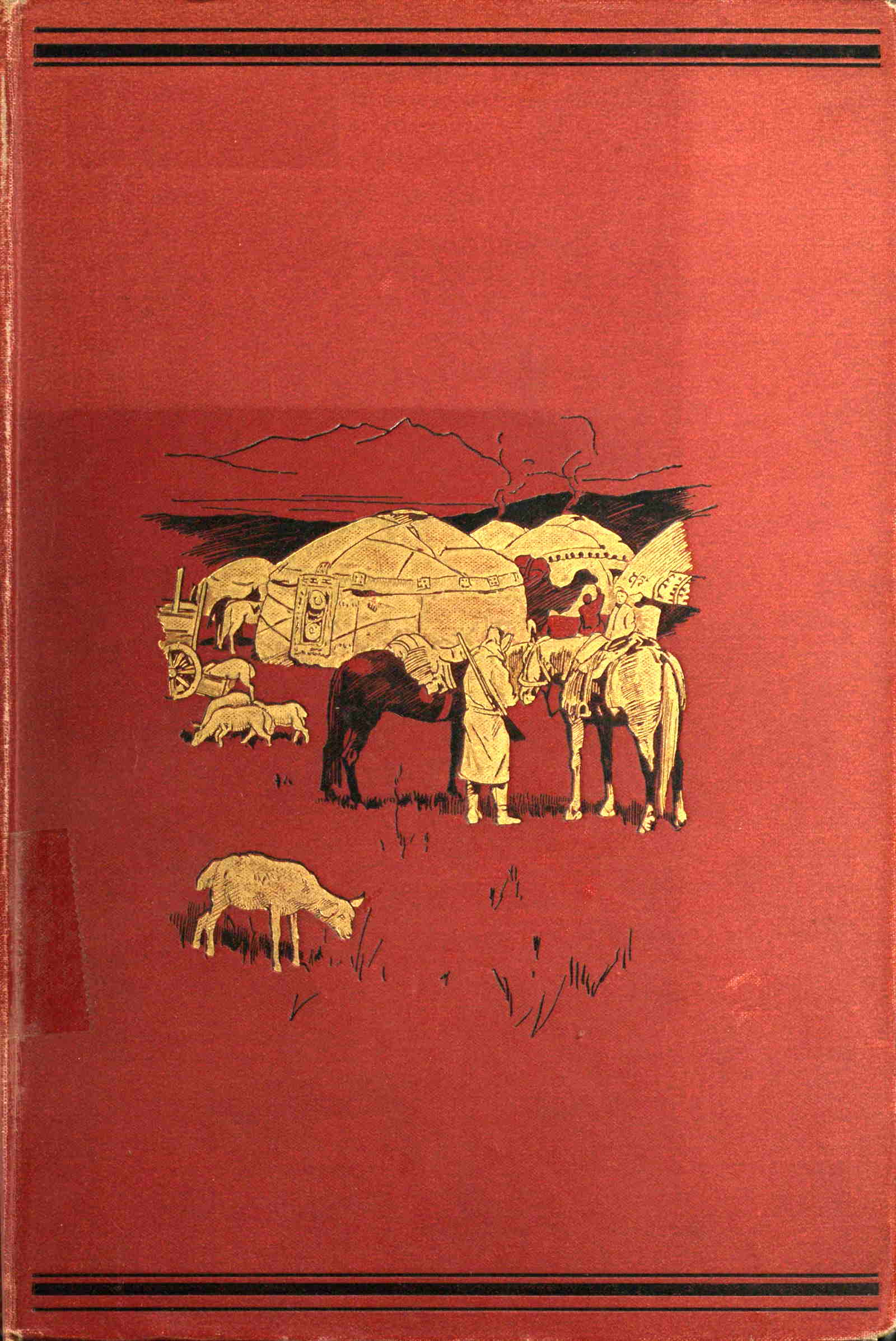

| Portrait of Alfred Edmund Brehm, | Frontispiece. | |

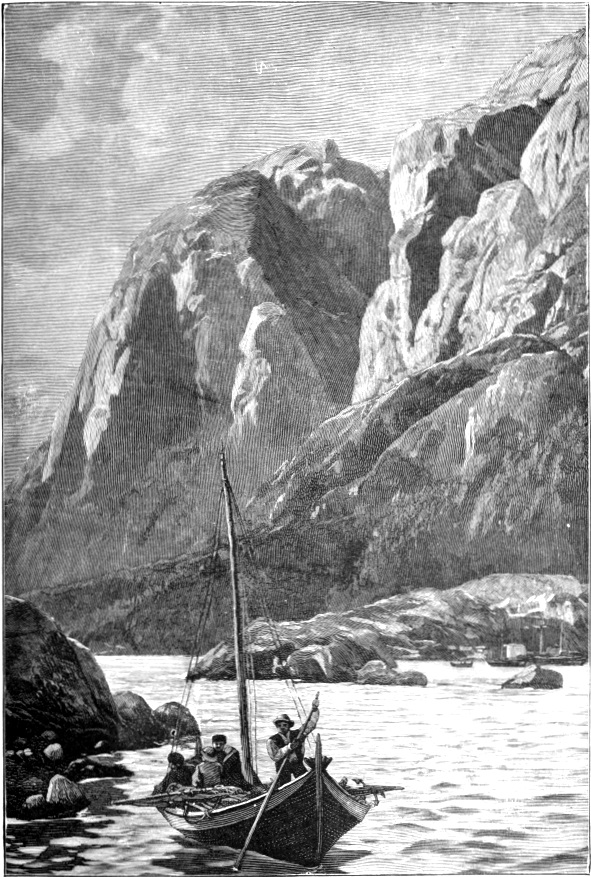

| 1. | Scene on the Sogne Fjord, Norway, | 35 |

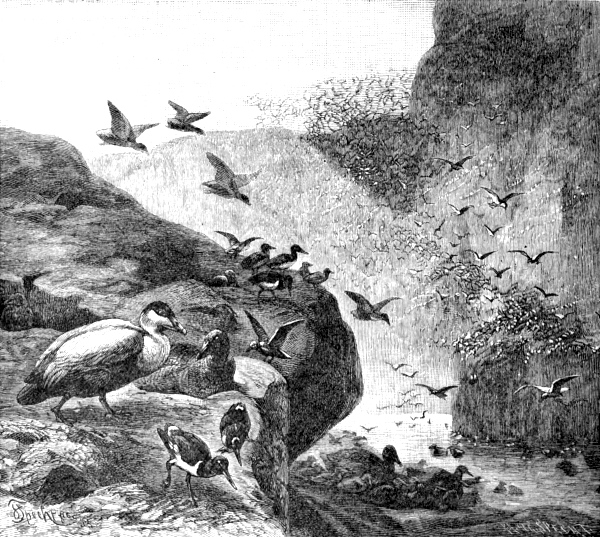

| 2. | Colony of Eider-ducks, | 44 |

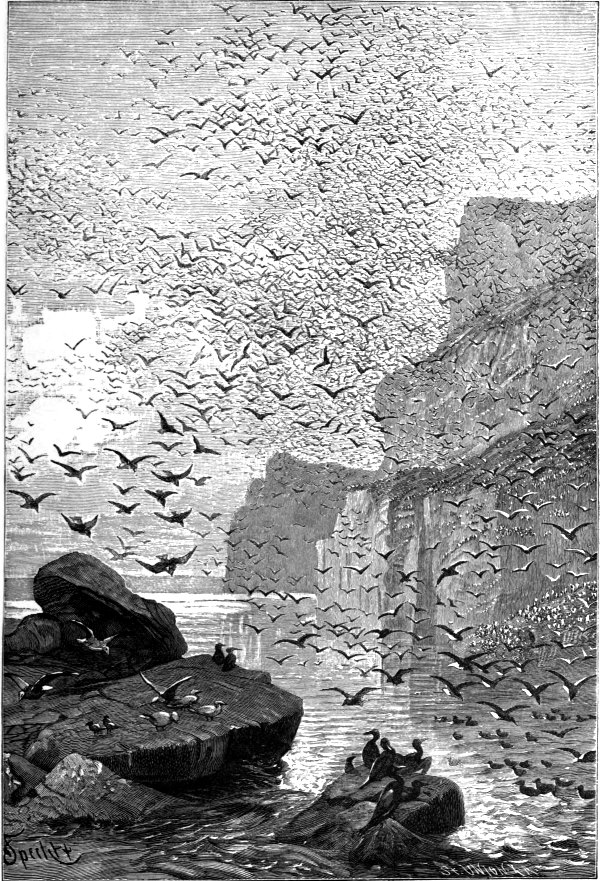

| 3. | The Bird-bergs of Lapland, | 51 |

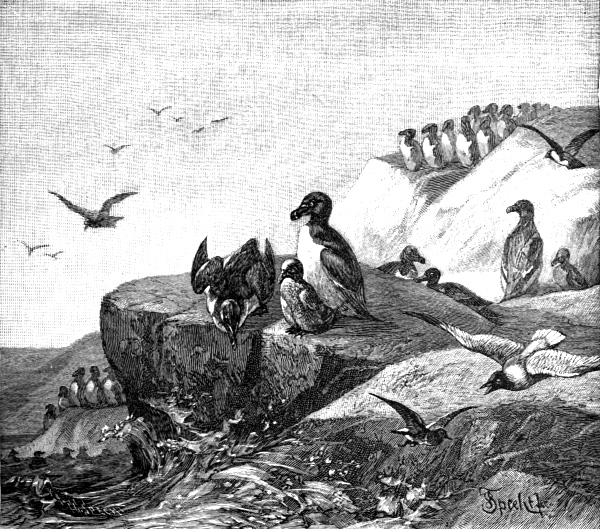

| 4. | Razor-bills, | 61 |

| 5. | The High Tundra in Northern Siberia, | 65 |

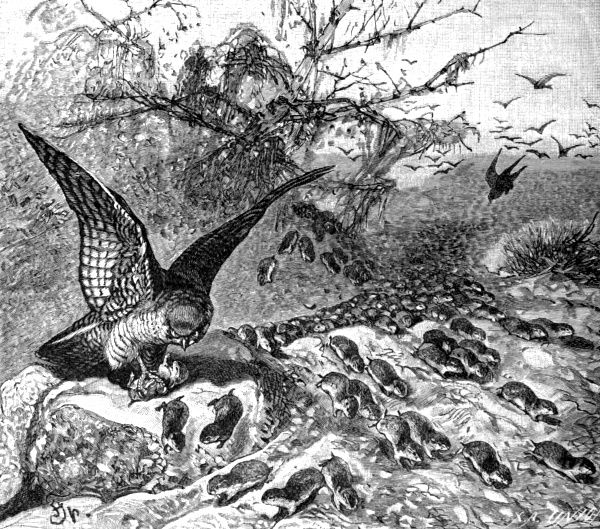

| 6. | Peregrine Falcons and Lemmings, | 70 |

| 7. | The White or Arctic Fox (Canis lagopus), | 73 |

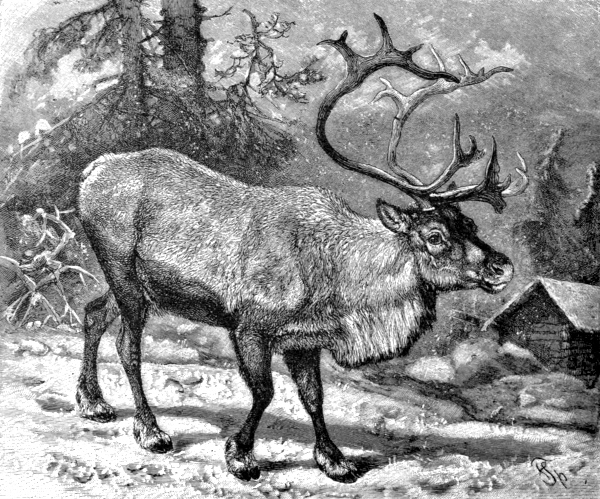

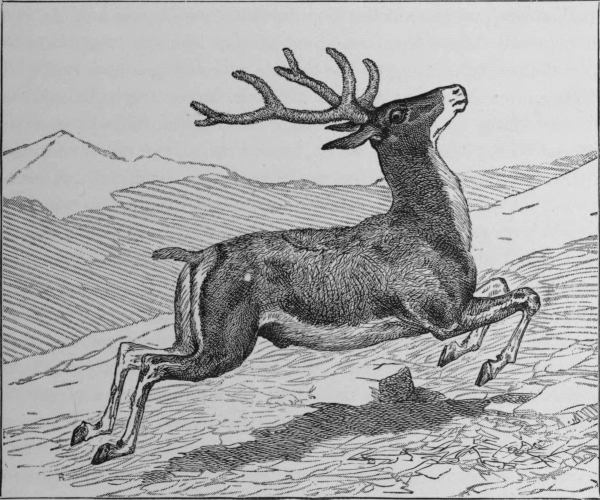

| 8. | The Reindeer (Tarandus rangifer), | 76 |

| 9. | Skuas, Phalathrope, and Golden Plovers, | 80 |

| 10. | View in the Asiatic Steppes, | 89 |

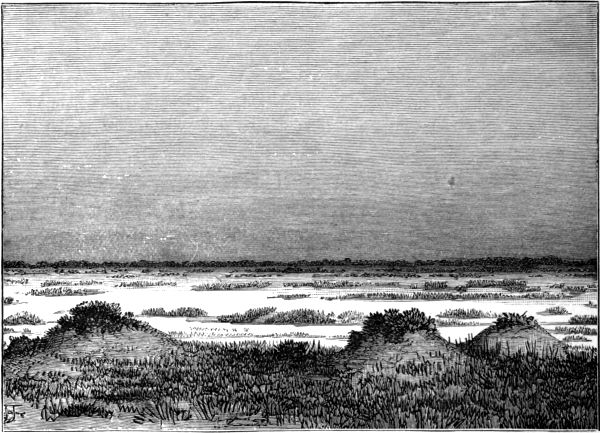

| 11. | A Salt Marsh in the Steppes, | 90 |

| 12. | A Herd of Horses during a Snowstorm on the Asiatic Steppes, | 94 |

| 13. | Lake Scene and Waterfowl in an Asiatic Steppe, | 99 |

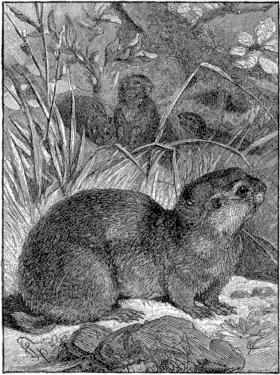

| 14. | The Souslik (Spermophilus citillus), | 108 |

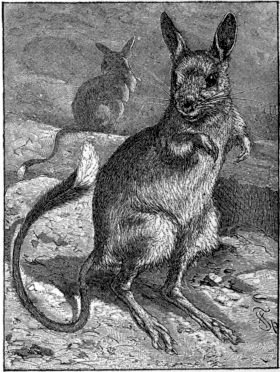

| 15. | The Jerboa (Alactaga jaculus), | 108 |

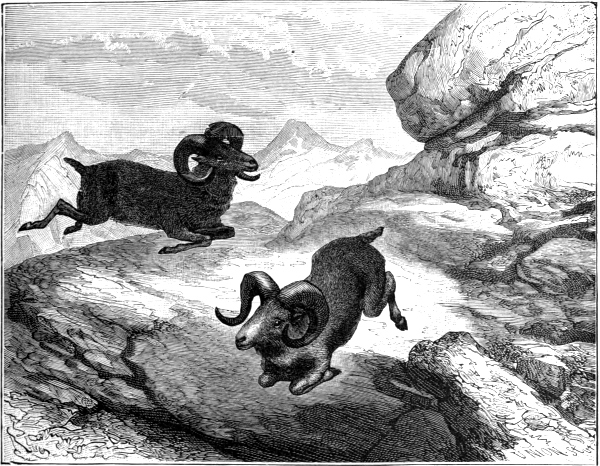

| 16. | Archar Sheep or Argali (Ovis Argali), | 111 |

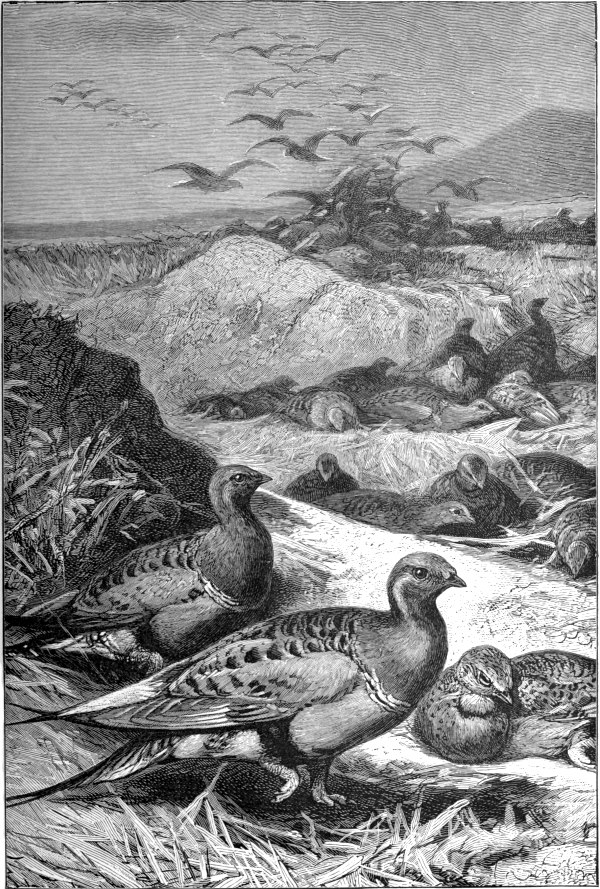

| 17. | Pallas’s Sand-grouse (Syrrhaptes paradoxus), | 113 |

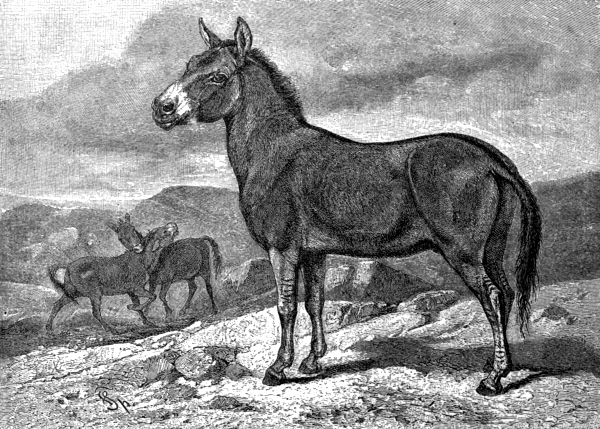

| 18. | The Kulan (Equus hemionus), | 118 |

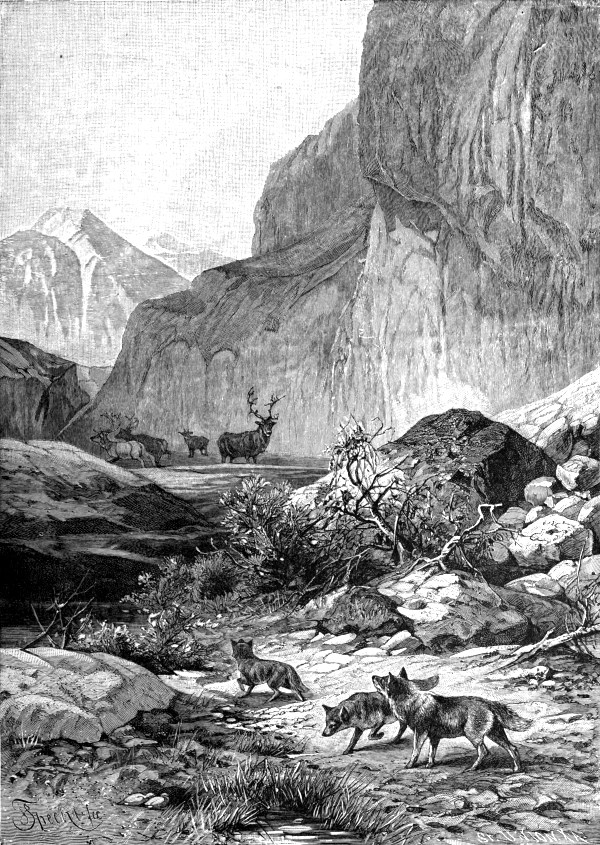

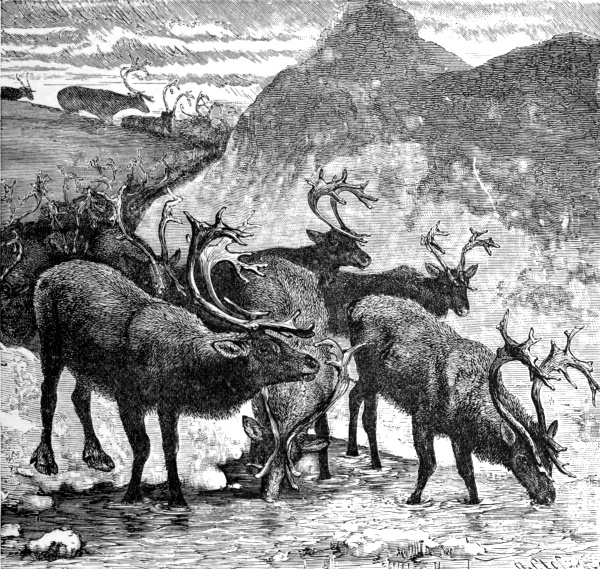

| 19. | Reindeer Flocking to Drink, | 133 |

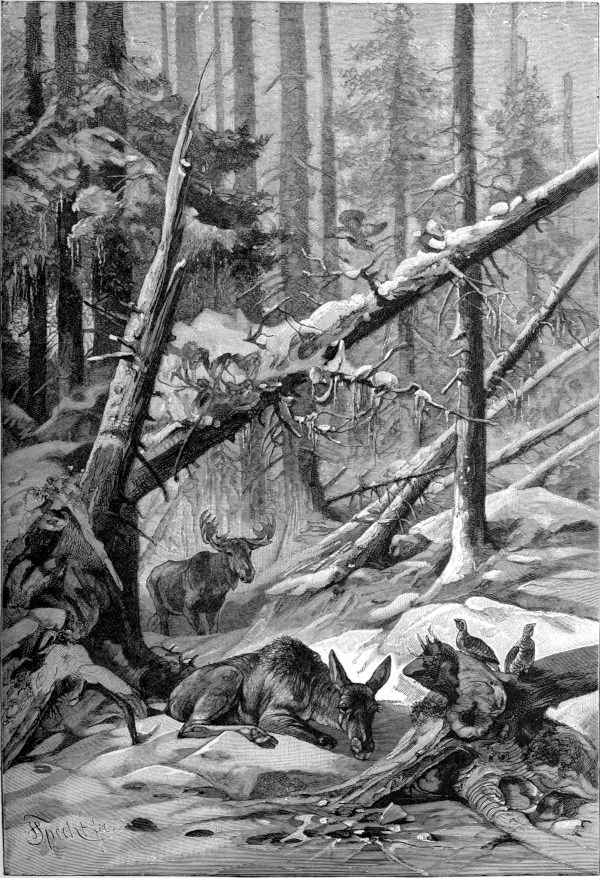

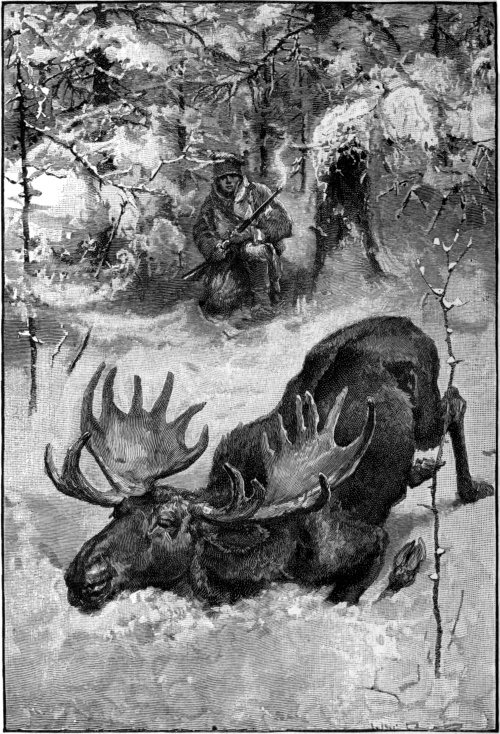

| 20. | Elk and Black-cock in a Siberian Forest, | 137 |

| 21. | The Maral Stag, | 145 |

| 22. | The Elk Hunter—A Successful Shot, | 148 |

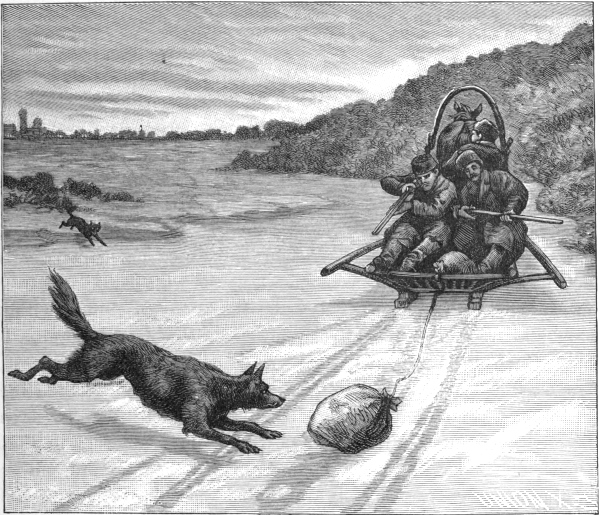

| 23. | A Siberian Method of Wolf-shooting, | 153 |

| 24. | Sable and Hazel-grouse in a Siberian Forest, | 159 |

| 25. | The Bed of an Intermittent River, Central Africa, | 175 |

| 26. | Hills of African Termites, or White Ants, | 179 |

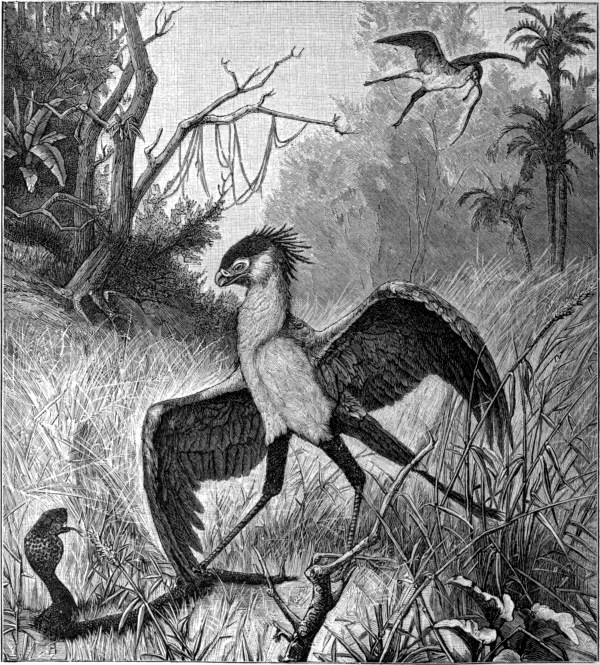

| 27. | Secretary-bird and Aspis, | 184 |

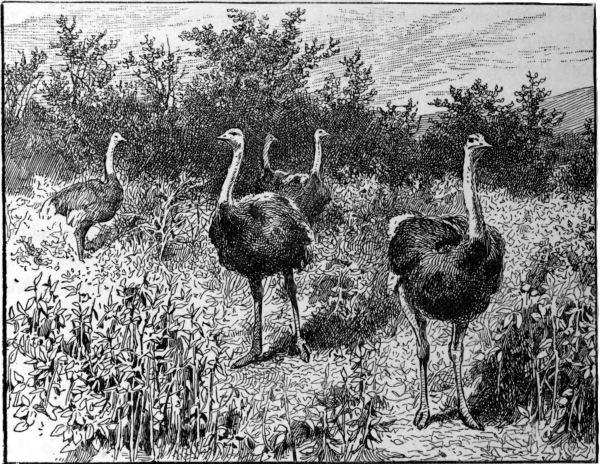

| 28. | On an Ostrich Farm in South Africa, | 190 |

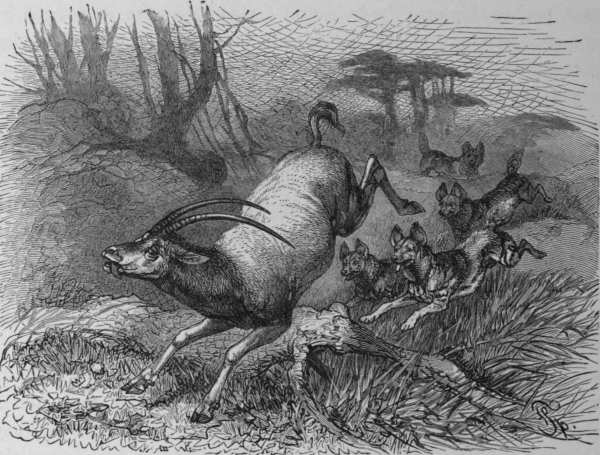

| 29. | Hyæna-dogs pursuing Antelope, | 196 |

| 30. | Zebras, Quaggas, and Ostriches flying before a Steppe Fire, | 199 |

| 31. | The Baobab Tree, Central Africa, | 211 |

| 32. | Long-tailed Monkeys, | 222 |

| 33. | Salt’s Antelope (Antilope Saltiana), | 224 |

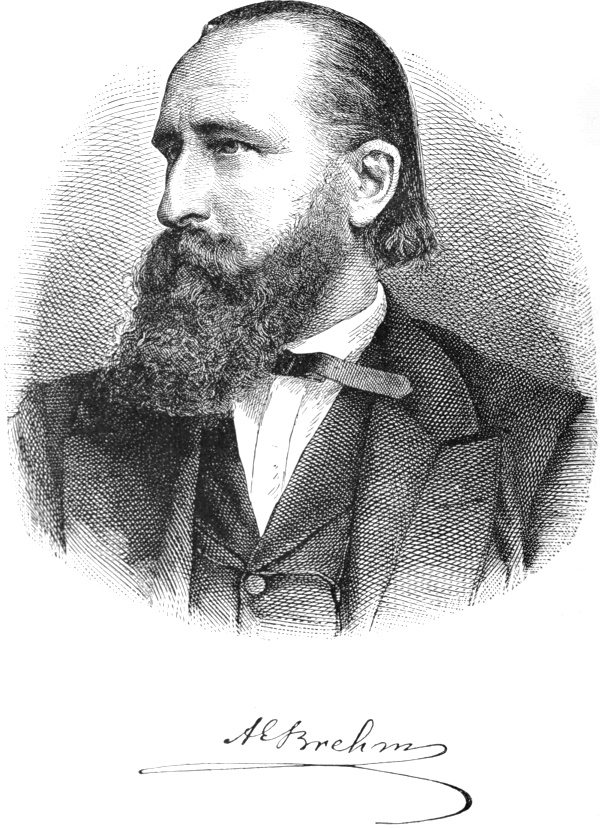

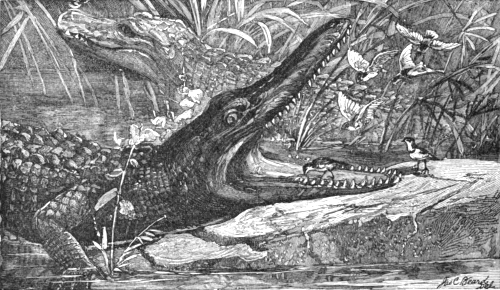

| 34. | Crocodile and Crocodile-birds (Pluxianus ægyptius), | 228 |

| 35. | A Wild Duck defending her Brood from a Brown Rat, | 236 |

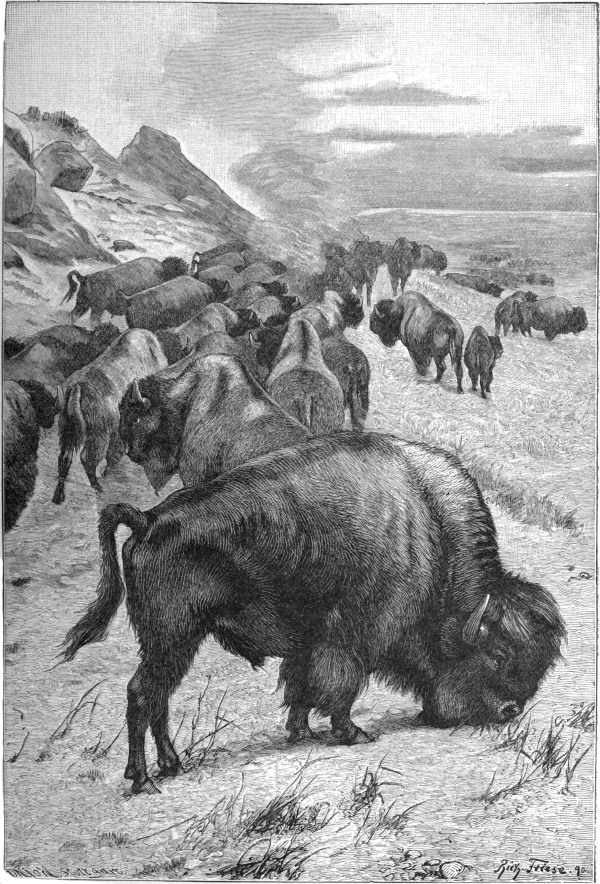

| 36. | A Herd of American Bison or Buffalo, | 243 |

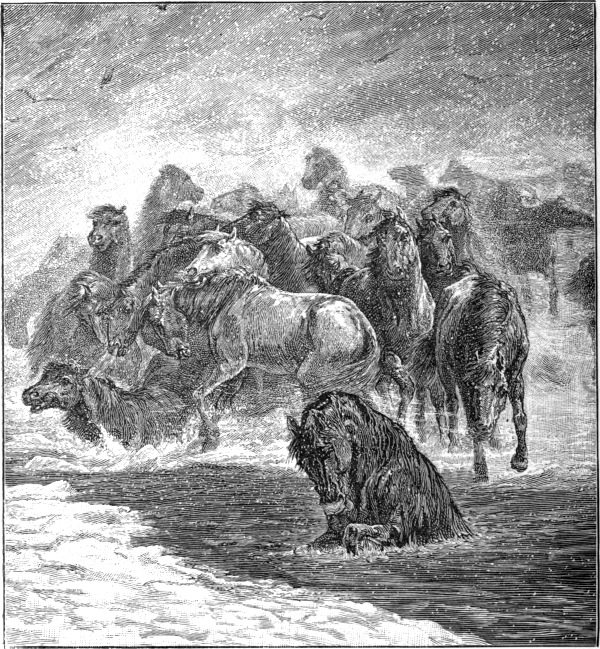

| 37. | Wild Horses crossing a River during a Storm, | 246[Pg xiv] |

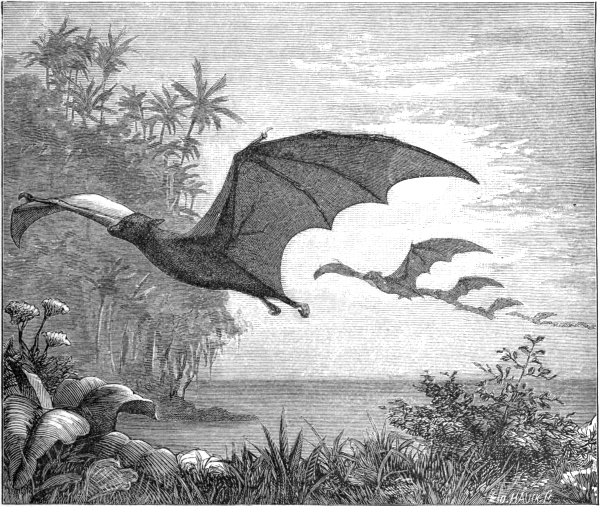

| 38. | Flying Foxes, | 251 |

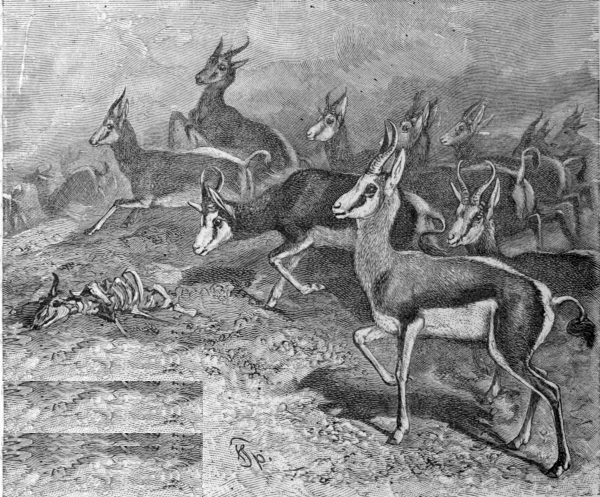

| 39. | Springbok Antelopes, | 258 |

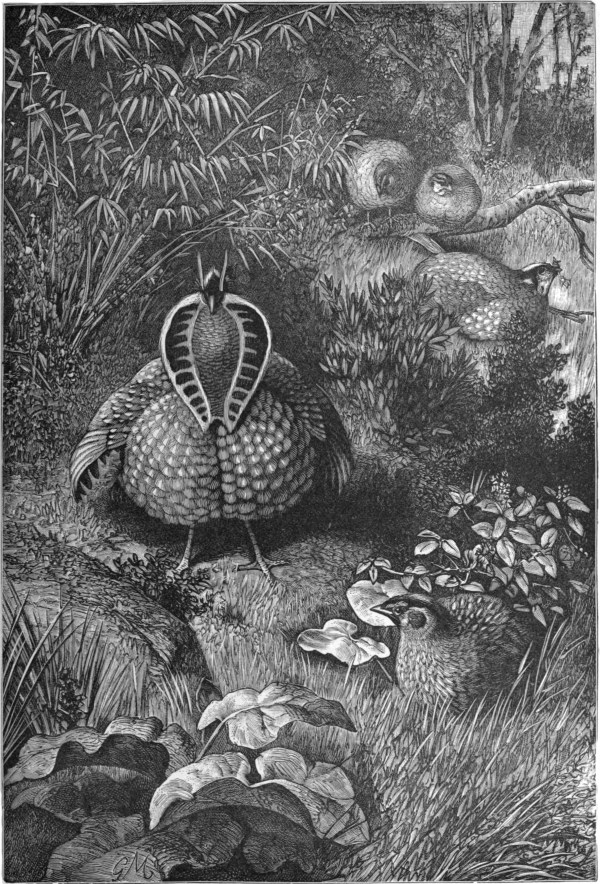

| 40. | The Strutting of the Tragopan in Pairing-time, | 269 |

| 41. | Cock Chaffinches Fighting, | 274 |

| 42. | Entellus Monkeys (Semnopithecus Entellus), | 285 |

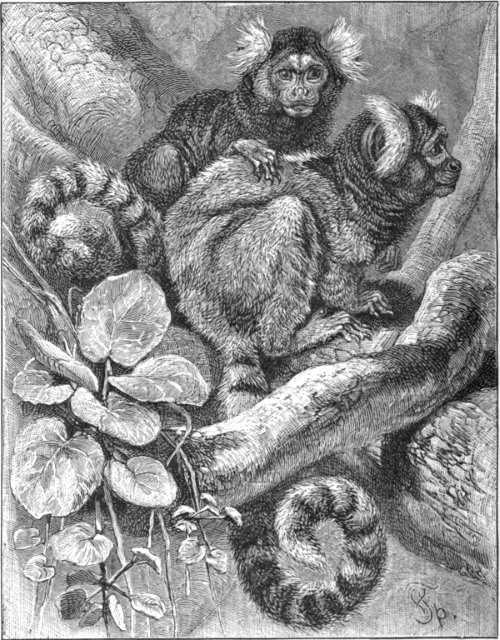

| 43. | Common Marmoset or Ouistiti (Hapale Jacchus), | 292 |

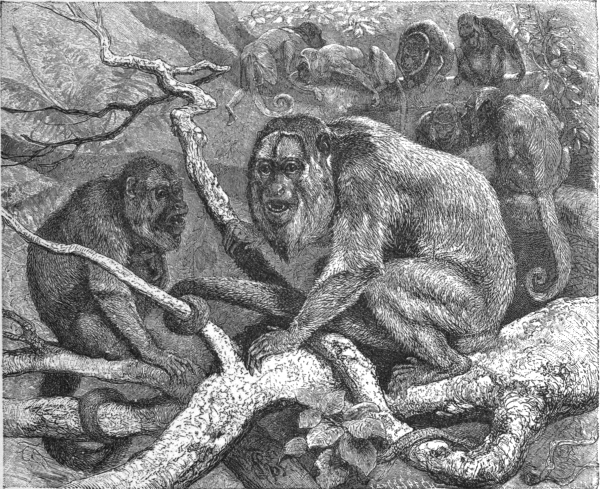

| 44. | Red Howling Monkeys (Mycetis seniculus), | 295 |

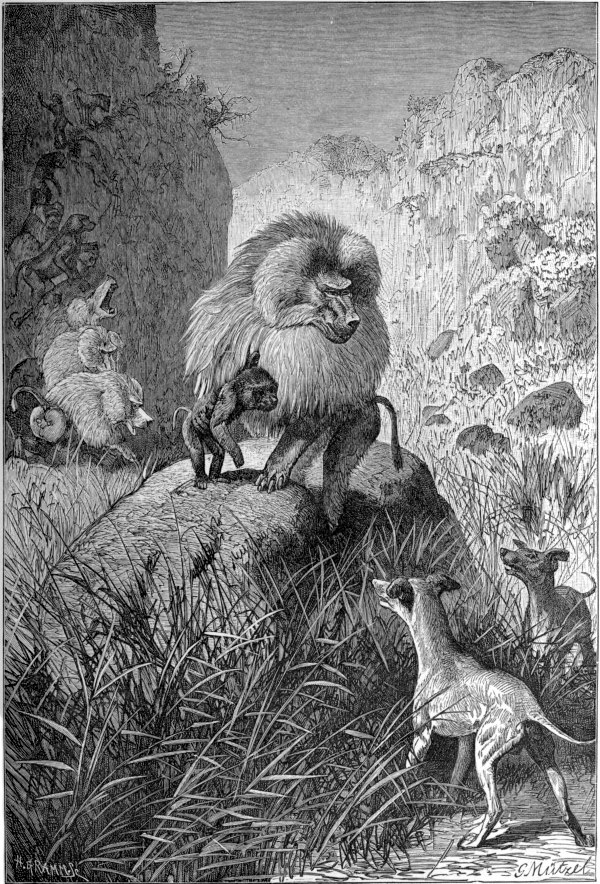

| 45. | Old Baboon Rescuing Young One, | 301 |

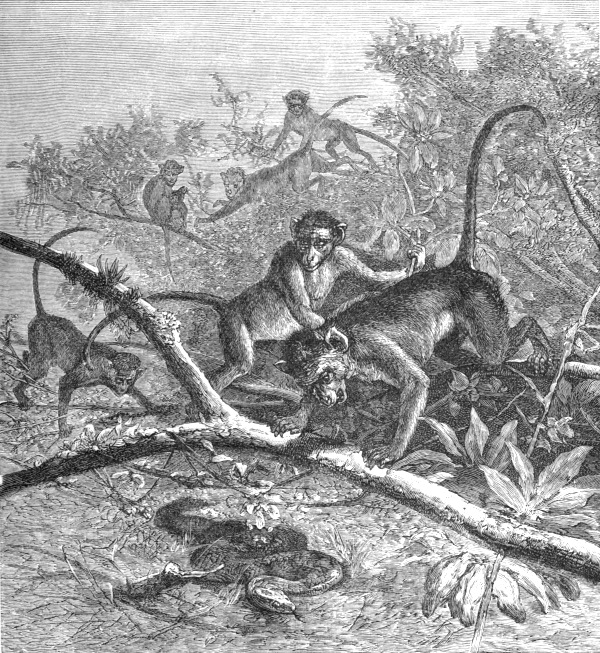

| 46. | Macaque or Bonnet-monkey (Macacus sinicus) and Snake, | 307 |

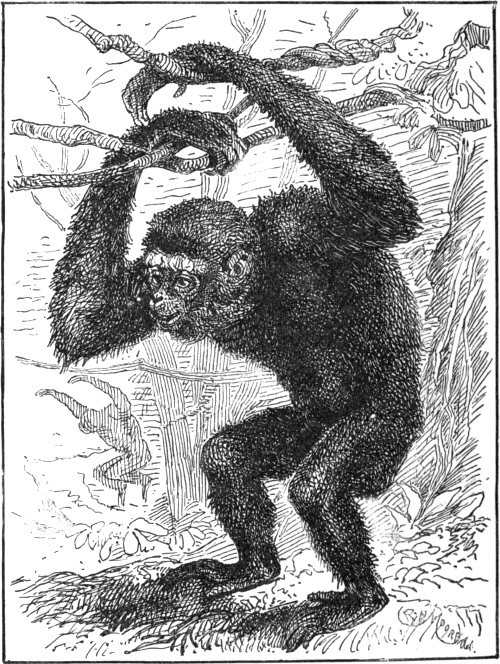

| 47. | The Hoolock (Hylobates leuciscus), one of the Gibbons, | 310 |

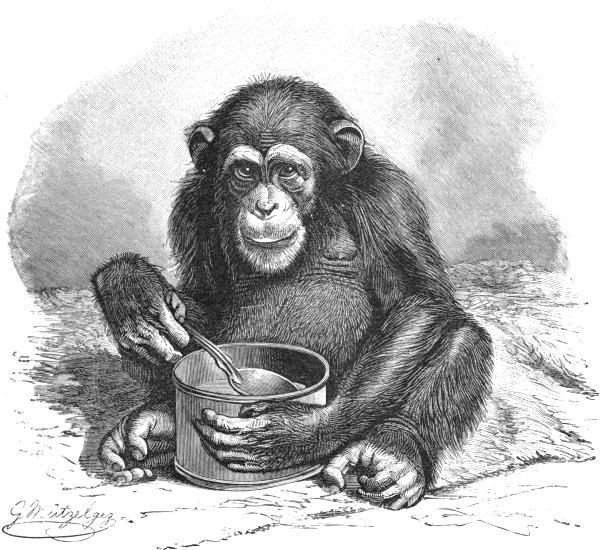

| 48. | Chimpanzee (Troglodytes niger), | 313 |

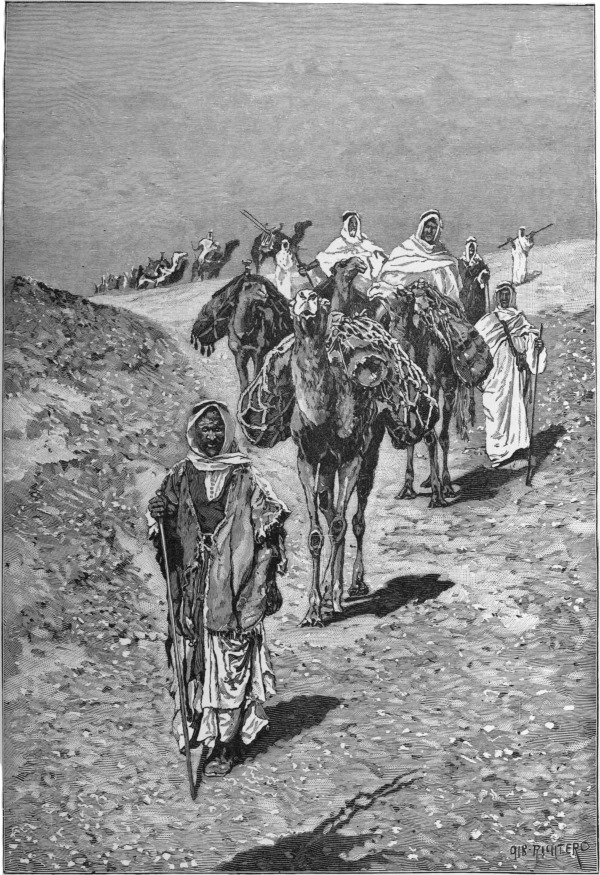

| 49. | Caravan in the African Desert, | 323 |

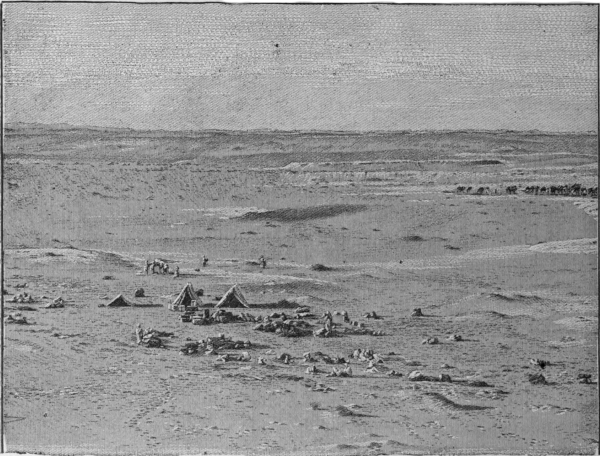

| 50. | An Encampment in the Sahara, | 328 |

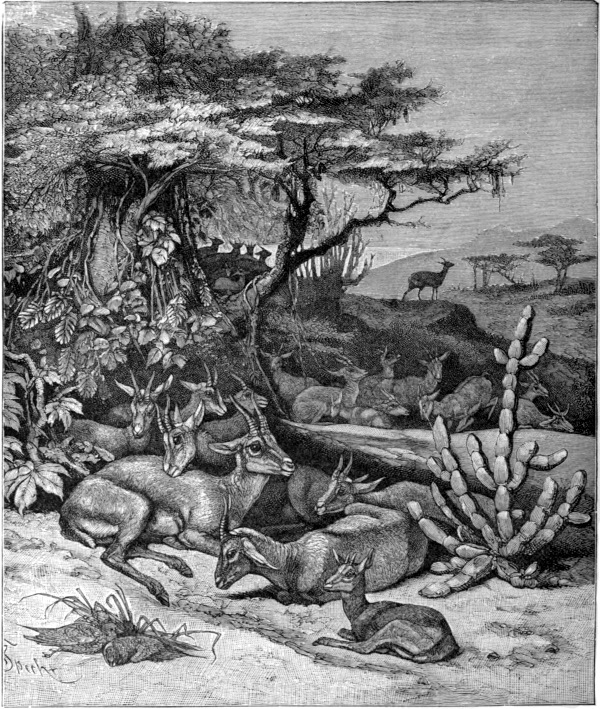

| 51. | Gazelles lying near a Mimosa, | 332 |

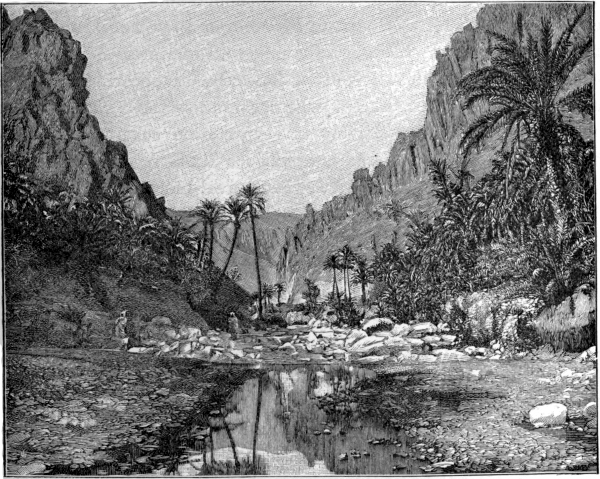

| 52. | An Oasis in the Desert of Sahara, | 343 |

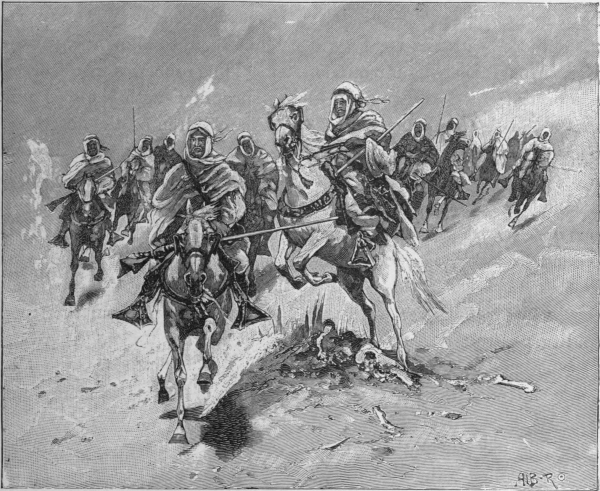

| 53. | Band of Mounted Bedouins, | 353 |

| 54. | An Egyptian Sakieh or Water-wheel, | 365 |

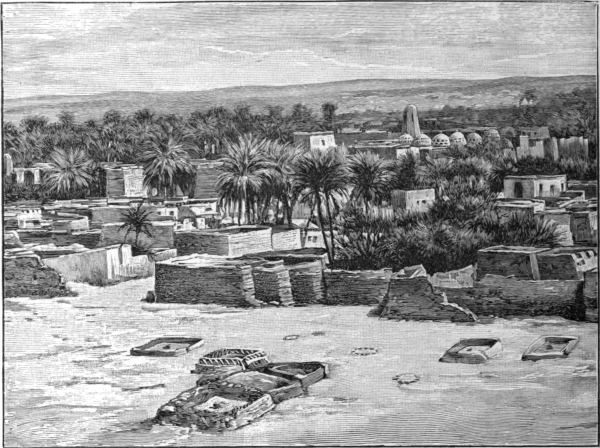

| 55. | A Nubian Village on the Nile, | 374 |

| 56. | Nubian Children at Play, | 377 |

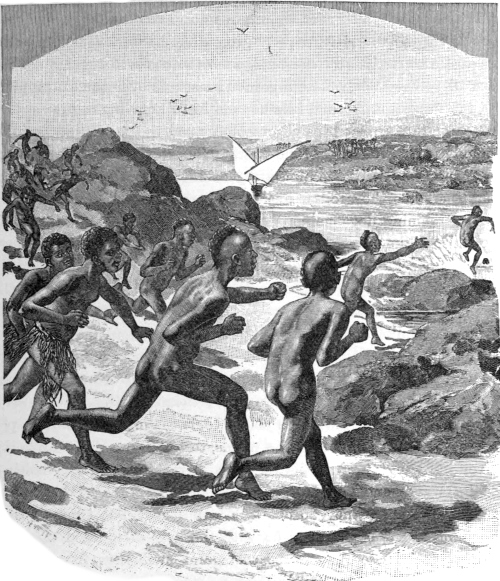

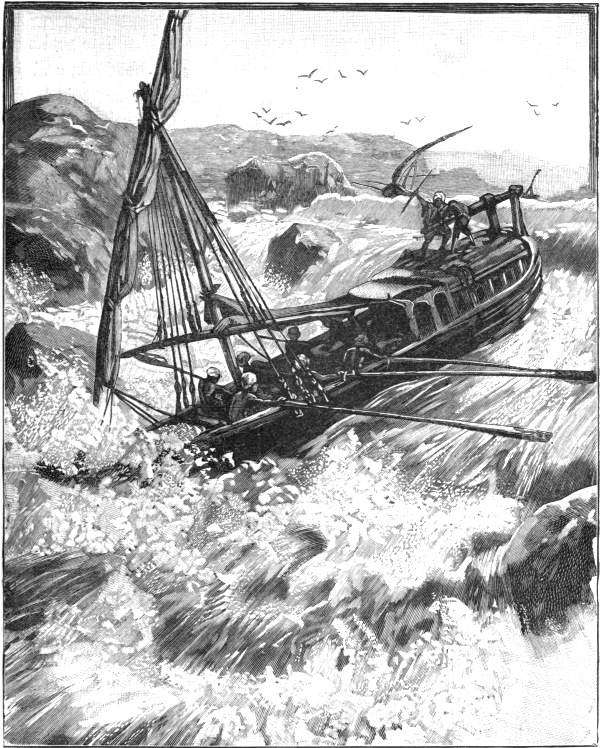

| 57. | A Passage through the Nile Rapids, | 385 |

| 58. | A Post Station in Siberia, | 395 |

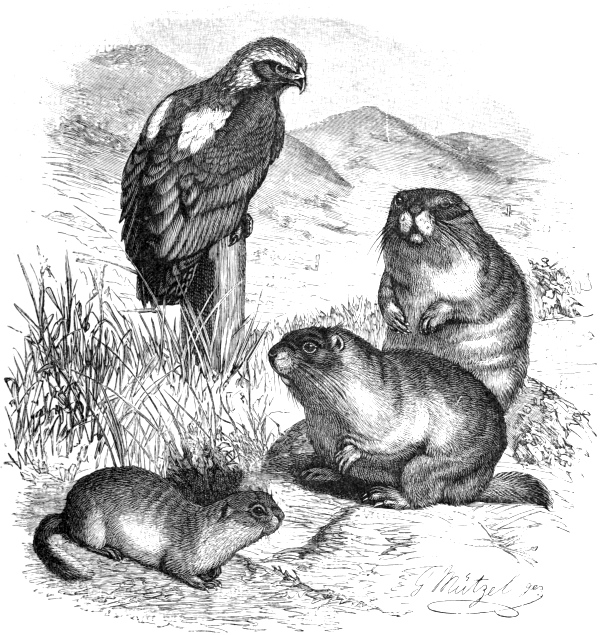

| 59. | Imperial Eagle, Marmot, and Souslik, | 407 |

| 60. | An Ostiak Settlement on the Banks of the Obi, | 409 |

| 61. | Huts and Winter Costume of the Christian Ostiaks, | 419 |

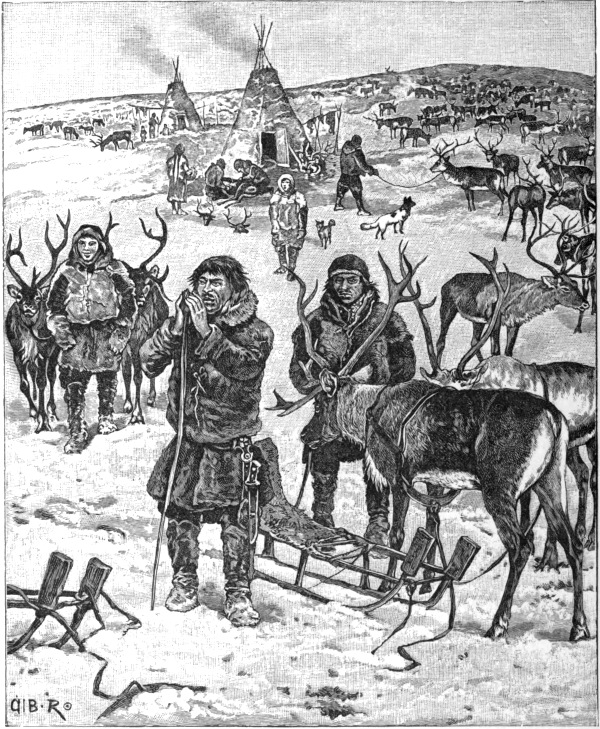

| 62. | “Heathen” Ostiaks, Reindeer, and Tshums, | 424 |

| 63. | Ostiaks with Reindeer and Sledge, | 427 |

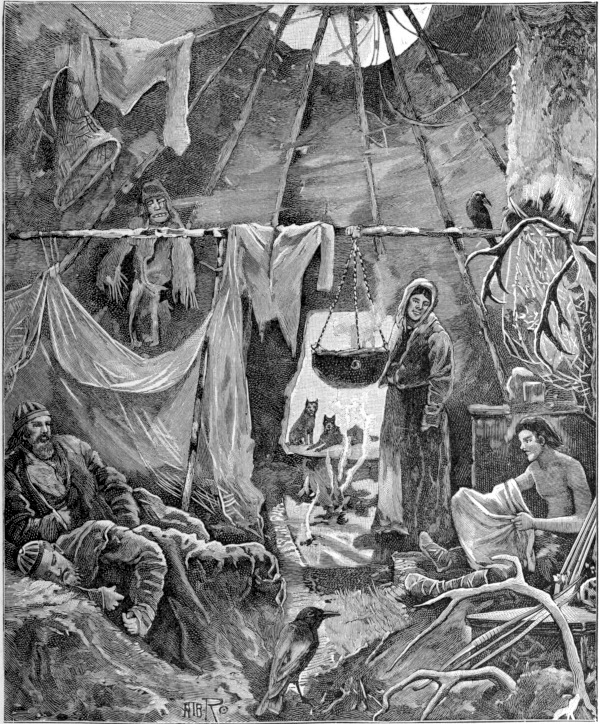

| 64. | Interior of an Ostiak Dwelling (Tshum), | 435 |

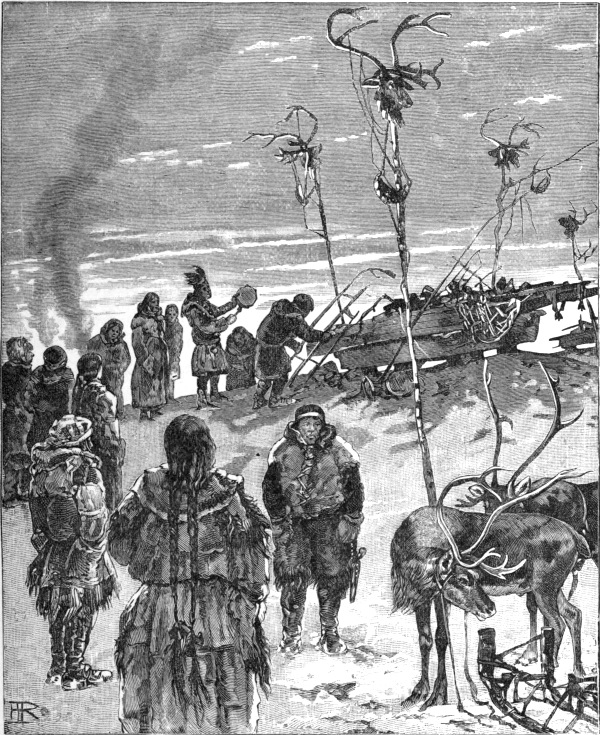

| 65. | The Burial of an Ostiak, | 449 |

| 66. | The Home of a Wealthy Kirghiz, | 455 |

| 67. | Life among the Kirghiz—the Return from the Chase, | 461 |

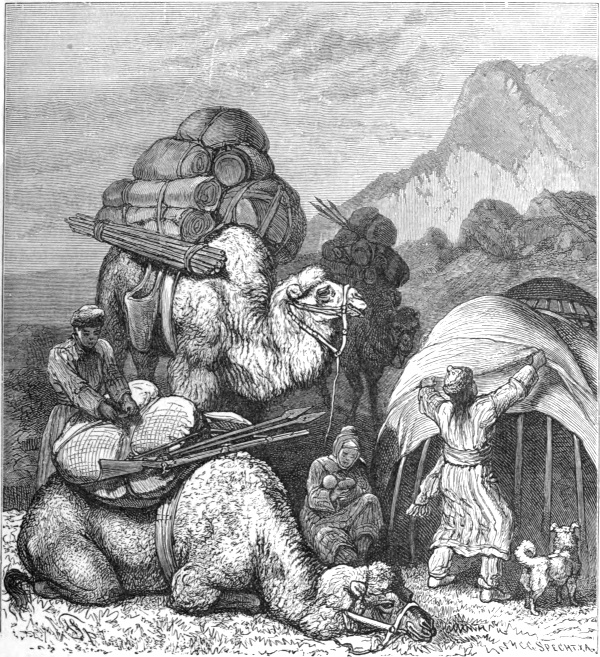

| 68. | Kirghiz with Camels, | 467 |

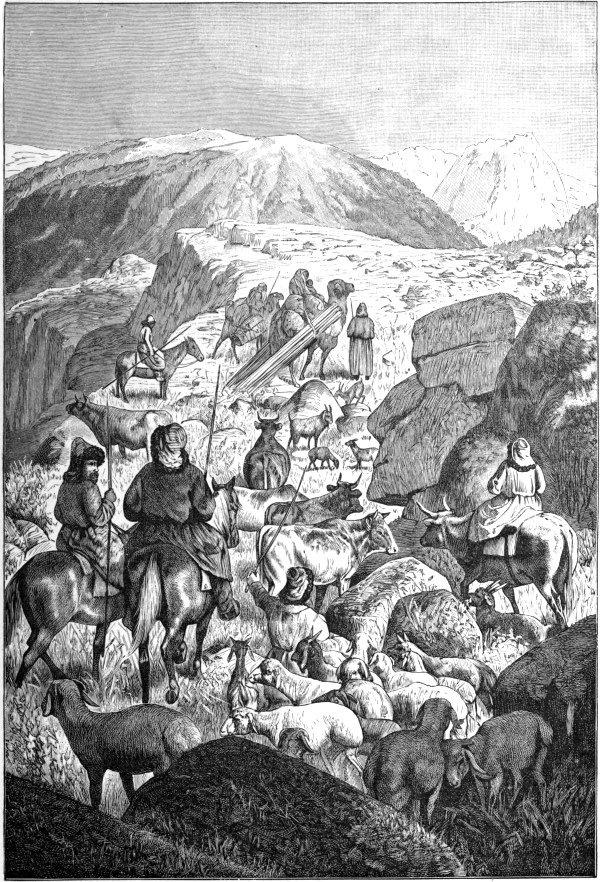

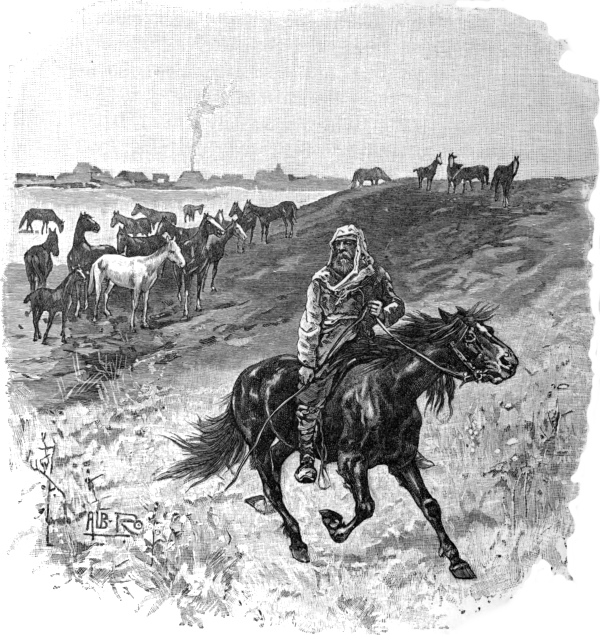

| 69. | Kirghiz and their Herds on the March in the Mountains, | 471 |

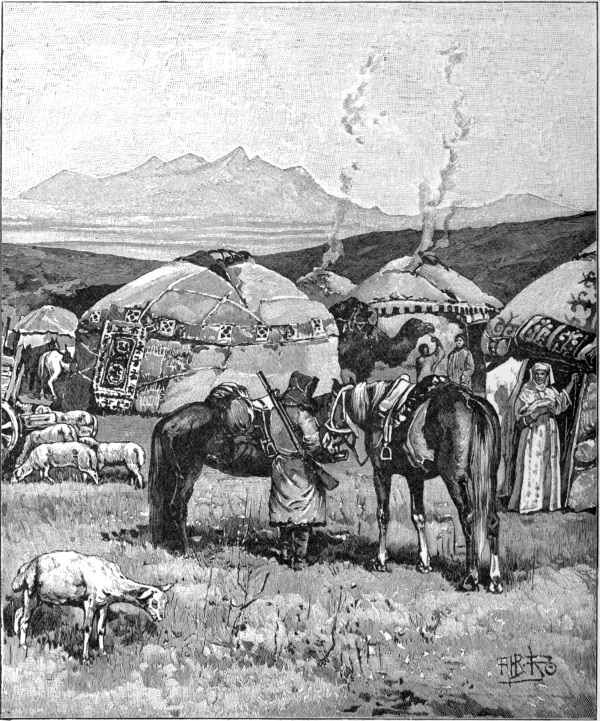

| 70. | Kirghiz Aul, or Group of Tents, | 478 |

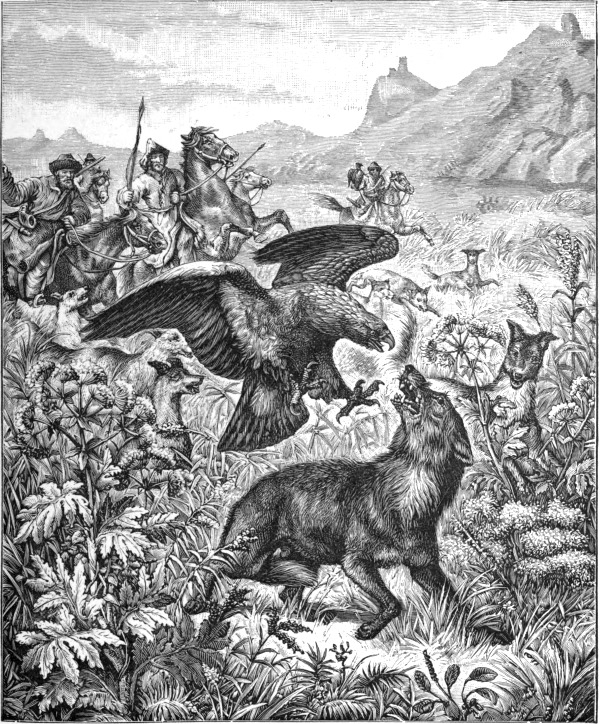

| 71. | Hunting the Wolf with the Golden Eagle, | 487 |

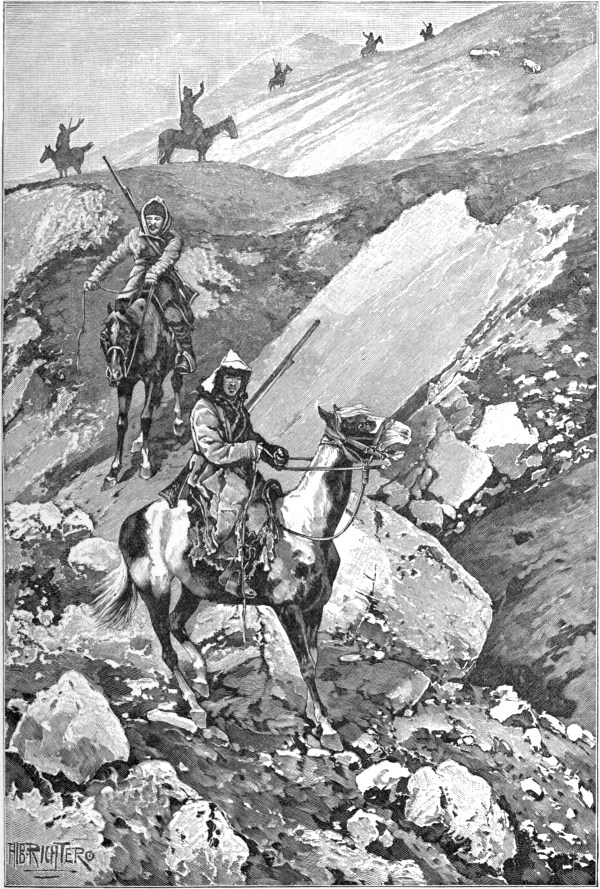

| 72. | Kirghiz in pursuit of Wild Sheep, | 489 |

| 73. | Frolic at a Kirghiz Wedding, | 505 |

| 74. | Miners in the Altai returning from Work, | 517 |

| 75. | Exiles on the Way to Siberia, | 527 |

| 76. | Interior of a Siberian Peasant’s Dwelling, | 532 |

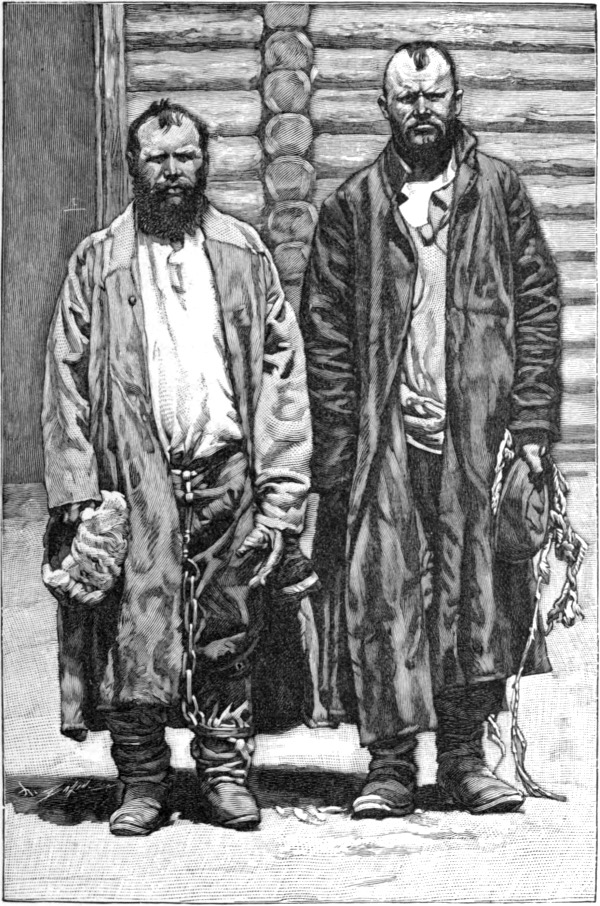

| 77. | Types of Siberian Convicts—“Condemned to the Mines”, | 535 |

| 78. | Flight of an Exile in Siberia, | 538 |

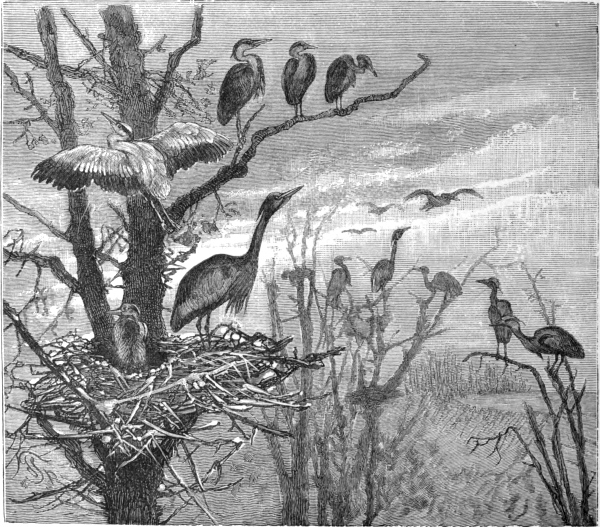

| 79. | Herons and their Nests, | 544 |

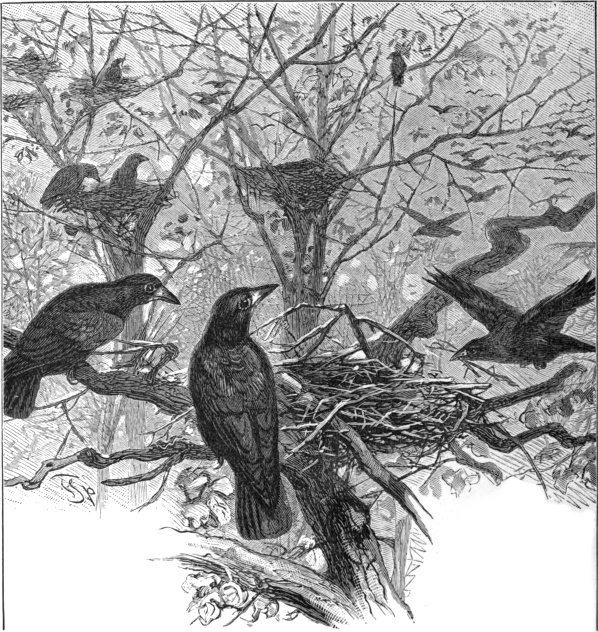

| 80. | Rooks and their Nests, | 546 |

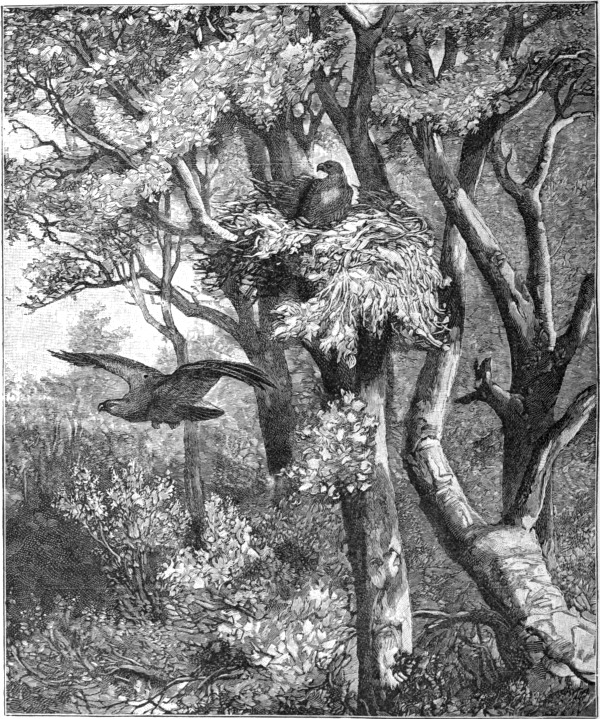

| 81. | Sea-eagles and Nest in a Danube Forest, | 550 |

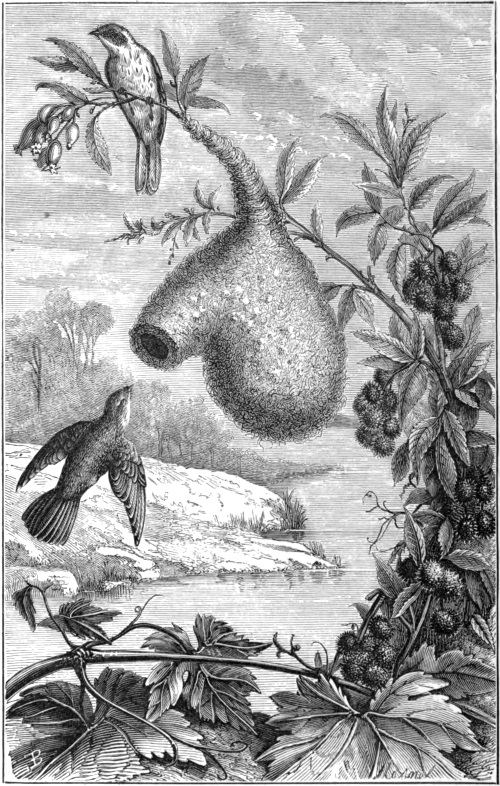

| 82. | Nest of the Penduline Titmouse (Parus Pendulinus), | 562 |

[Pg xv]

BY J. ARTHUR THOMSON.

BREHM’S PLACE AMONG NATURALIST-TRAVELLERS.

Though Brehm’s lectures might well be left, as his son has said, to speak for themselves, it seems useful to introduce them in their English dress with some notes on the evolution of the naturalist-traveller and on Brehm’s place in the honourable list; for an adequate appreciation of a book like this depends in part on a recognition of the position it occupies among analogous works, and on having some picture of the illustrious author himself.

In sketching the history of the naturalist-traveller it is not necessary to go very far back; for though it is interesting to recall how men of old followed their migrating herds, as the Lapp or Ostiak does his reindeer, and were led by them to fresh fields and new conquests, or how others followed the salmon down the rivers and became the toilers of the sea, this ancient lore is full of uncertainty, and is, besides, of more moment to the sociologist than to the naturalist. What we attempt here is merely to indicate the various types of naturalist-traveller who have in the course of time succeeded one another in the quest for the new.

I.

The foundations of zoology were laid by Aristotle some three hundred years before Christ, but they remained unbuilt on for nearly eighteen centuries. Here and there some enthusiast strove unaided, but only a fragmentary superstructure was reared. In fact, men were pre-occupied with tasks of civilization more serious than the prosecution of zoology, though that is not trivial. Gradually,[Pg xvi] however, great social movements, such as the Crusades and the collapse of Feudalism; great intellectual and emotional movements, such as those of the Renaissance; great inventions, such as that of printing, gave new life to Europe, and zoology shared in the re-awakening. Yet the natural history of the Middle Ages was in great part mystical; fancy and superstition ran riot along paths where science afterwards established order, and, for all practical purposes, the history of zoology, apart from the efforts of a few pioneers, may be said to date from the sixteenth century.

Now, one indubitable factor in the scientific renaissance of the sixteenth century was the enthusiasm of the early travellers, and this stimulus, periodically recurrent, has never failed to have a similar effect—of giving new life to science. But while science, and zoology as a branch of it, has been evolving during the last three centuries, the traveller, too, has shared in the evolution. It is this which we wish to trace.

I. The Romantic Type. Many of the old travellers, from Herodotus onwards, were observant and enthusiastic; most were credulous and garrulous. In days when the critical spirit was young, and verification hardly possible, there could not but be a strong temptation to tell extraordinary “travellers’ tales”. And they did. Nor need we scoff at them loudly, for the type dies hard; every year such tales are told.

Oderico de Pordenone and other mediæval travellers who give some substance to the mythical Sir John de Maundeville were travellers of this genial type. Oderico describes an interesting connecting link between the animal and vegetable kingdom, a literal “zoophyte”, the “vegetable lamb”, which seems to have been a woolly Scythian fern, with its counterpart in the large fungus which colonials sometimes speak of as the “vegetable sheep”. As for the pretended Sir John, he had in his power of swallowing marvels a gape hardly less than that of the great snakes which he describes. But even now do we not see his snakes in at least the picture-books on which innocent youth is nurtured? The basilisk (one of the most harmless of lizards) “sleyeth men beholding it”; the “cocodrilles also sley men”—they do indeed—“and eate[Pg xvii] them weeping, and they have no tongue”. “The griffin of Bactria hath a body greater than eight lyons and stall worthier than a hundred egles, for certainly he will beare to his nest flying, a horse and a man upon his back.” He was not readily daunted, Sir John, for when they told him of the lamb-tree which bears lambs in its pods, his British pluck did not desert him, and he gave answer that he “held it for no marvayle, for in his country are trees which bear fruit which become birds flying, and they are good to eate, and that that falleth on the water, liveth, and that that falleth on earth, dyeth; and they marvailed much thereat”. The tale of the barnacle-tree was a trump card in those days!

Another example of this type, but rising distinctly above it in trustworthiness, was the Venetian Marco Polo, who in the thirteenth century explored Asia from the Black Sea to Pekin, from the Altai to Sumatra, and doubtless saw much, though not quite so much as he describes. He will correct the fables of his predecessors, he tells us, demonstrating gravely that the unicorn or rhinoceros does not allow himself to be captured by a gentle maiden, but he proceeds to describe tailed men, yea, headless men, without, so far as can be seen, any touch of sarcasm. Of how many marvels, from porcupines throwing off their spines and snakes with clawed fore-feet, to the great Rukh, which could bear not merely a poor Sinbad but an elephant through the air, is it not written in the books of Ser Marco Polo of Venezia?

II. The Encyclopædist Type.—This unwieldy title, suggestive of an omnivorous hunger for knowledge, is conveniently, as well as technically, descriptive of a type of naturalist characteristic of the early years of the scientific renaissance. Edward Wotton (d. 1555), the Swiss Gesner (d. 1565), the Italian Aldrovandi (d. 1605), the Scotsman Johnson (d. 1675), are good examples. These encyclopædists were at least impressed with the necessity of getting close to the facts of nature, of observing for themselves, and we cannot blame them much if their critical faculties were dulled by the strength of their enthusiasm. They could not all at once forget the mediæval dreams, nor did they make any strenuous effort to rationalize the materials which they so industriously gathered.[Pg xviii] They harvested but did not thrash. Ostrich-like, their appetite was greater than their power of digesting. A hasty judgment might call them mere compilers, for they gathered all possible information from all sources, but, on closer acquaintance, the encyclopædists grow upon one. Their industry was astounding, their ambition lofty; and they prepared the way for men like Ray and Linnæus, in whom was the genius of order.

Associated with this period there were many naturalist-travellers, most of whom are hardly now remembered, save perhaps when we repeat the name of some plant or animal which commemorates its discoverer. José d’Acosta (d. 1600), a missionary in Peru, described some of the gigantic fossils of South America; Francesco Hernanded published about 1615 a book on the natural history of Mexico with 1200 illustrations; Marcgrav and Piso explored Brazil; Jacob Bontius, the East Indies; Prosper Alpinus, Egypt; Belon, the Mediterranean region; and there were many others. But it is useless to multiply what must here remain mere citations of names. The point is simply this, that, associated with the marvellous accumulative industry of the encyclopædists and with the renaissance of zoology in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, there were numerous naturalist-travellers who described what they saw, and not what they fancied might be seen.

III. The General Naturalist Type.—As Ray (d. 1705) and Linnæus (d. 1778) began to reduce to order the accumulations of the encyclopædists, and as the anatomists and physiologists began the precise study of structure and function, the naturalist-travellers became more definite in their aims and more accurate in their observations. Linnæus himself sent several of his pupils on precisely scientific journeys. Moreover, in the eighteenth century there were not a few expeditions of geographical and physical purpose which occasionally condescended to take a zoologist on board. Thus Captain Cook was accompanied on his first voyage (1768-1781) by Banks and Solander, and on his second voyage by the Forsters, father and son. On his third voyage he expressly forbade the intrusion of any naturalist, but from all that we can gather it would have been better for himself if he had not done so. In[Pg xix] these combined voyages there was nascent the idea of co-operative expeditions, of which the greatest has been that of the Challenger.

In illustration of travellers who were not specialists, but in varying degrees widely interested naturalists, it will be sufficient to cite three names—Thomas Pennant, Peter Pallas, and, greatest of all, Alexander von Humboldt.

Of Thomas Pennant (1726-1798) we may note that he was one of the early travellers in Scotland, which was then, as he says, almost as unknown as Kamchatka, and that he extorted from Dr. Johnson the admission, “He’s a Whig, sir, a sad dog; but he’s the best traveller I ever read; he observes more things than any one else does”. He knew Buffon and corresponded with Linnæus, and was the author of several works on British and North American zoology. His so-called Arctic Zoology is mainly a sketch of the fauna in the northern regions of North America, begun “when the empire of Great Britain was entire, and possessed the northern part of the New World with envied splendour”. His perspective is excellent! the botanist, the fossilist, the historian, the geographer must, he says, accompany him on his zoological tours, “to trace the gradual increase of the animal world from the scanty pittance given to the rocks of Spitzbergen to the swarms of beings which enliven the vegetating plains of Senegal; to point out the causes of the local niggardness of certain places, and the prodigious plenty in others”. It was about the same time (1777) that E. A. W. Zimmermann, Professor of Mathematics at Brunswick, published a quarto in Latin, entitled Specimen Zoologiæ Geographicæ Quadrupedum, “with a most curious map”, says Pennant, “in which is given the name of every animal in its proper climate, so that a view of the whole quadruped creation is placed before one’s eyes, in a manner perfectly new and instructive”. It was wonderful then, but the map in question looks commonplace enough nowadays.

Peter Simon Pallas (1741-1811) was a student of medicine and natural science, and did good work as a systematic and anatomical zoologist. He was the first, we believe, to express the relationships of animals in a genealogical tree, but his interest for us here lies in his zoological exploration of Russia and Siberia, the results of which[Pg xx] are embodied in a series of bulky volumes, admirable in their careful thoroughness. We rank him rather as one of the forerunners of Humboldt than as a zoologist, for his services to ethnology and geology were of great importance. He pondered over the results of his explorations, and many of his questionings in regard to geographical distribution, the influence of climate, the variation of animals, and similar problems, were prophetic of the light which was soon to dawn on biological science.

Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) was undoubtedly one of the greatest naturalists of the century which his life well nigh covered. Geologist, botanist, zoologist, and more, he was almost the last of the all-round naturalists. In this indeed lay his weakness as well as his strength, for great breadth of view is apt to imply a lack of precision as to details. In boyhood, “when life”, as he says, “appears an unlimited horizon”, he had strong desires after travel, which were in part gratified by excursions with George Forster and by Swiss explorations with the sagacious old geographer Leopold von Buch. These, however, only whetted his enthusiasm for journeys with a larger radius. At length, after many discouragements, he sailed in 1799 from Corunna, with Aimé Bonpland as companion, and spent five years in exploring the equinoctial regions of the New World. The full record of his voyage one cannot be expected to read, for there are about thirty volumes of it in the complete edition, but what we should all know is Humboldt’s Personal Narrative, in which the chief results of his explorations are charmingly set forth. Later in life (1829) he went with Ehrenberg and Rose to North Asia, and his crowning work was the publication of Cosmos (1845-58), which originated in a series of lectures delivered in the University of Berlin. In front of that building his statue now stands, along with that of his not less famous brother Wilhelm.

We think of Humboldt not so much as an early explorer of tropical America, nor because he described the habits of the condor and made observations on electric eels, nor because he furnished Cuvier and Latreille with many new specimens, but rather as a magnificent type of the naturalist-traveller, observant, widely interested,[Pg xxi] and thoughtful, who pointed forward to Darwin in the success with which he realized the complexity of inter-relations in nature. Many a traveller, even among his contemporaries, discovered more new plants and animals than the author of Cosmos, but none approached him as an all-round naturalist, able to look out on all orders of facts with keenly intelligent eyes, a man, moreover, in whom devotion to science never dulled poetic feeling. His work is of real importance in the history of geographical distribution, for he endeavoured to interpret the peculiarities of the various faunas in connection with the peculiar environment of the different regions—a consideration which is at least an element in the solution of some of the problems of distribution. It is especially important in regard to plants, and one may perhaps say that Humboldt, by his vivid pictures of the vegetable “physiognomy” of different regions, and by his observations on the relations between climate and flora, laid the foundations of the scientific study of the geographical distribution of plants. We find in some of his Charakterbilder, for example in his Views of Nature, the prototype of those synthetic pictures which give Brehm’s popular lectures their peculiar interest and value.

IV. The Specialist Type.—It would say little for scientific discipline if it were true that a man learned, let us say, in zoology, could spend years in a new country without having something fresh to tell us about matters outside of his specialism—the rocks, the plants, and the people. But it is not true. There have been few great travellers who have been narrow specialists, and one might find more than one case of a naturalist starting on his travels as a zoologist and returning an anthropologist as well. Yet it is evident enough that few men can be master of more than one craft. There have been few travellers like Humboldt, few records like Darwin’s Voyage of the Beagle (1831-6). Hence we recognize more and more as we approach our own day that naturalist-travellers have been successful either as specialists, or, on the other hand, in so far as they have furnished material for generalization (Type V.). The specialism may of course take various forms: a journey may be undertaken by one who is purely an ornithologist, or it may[Pg xxii] be undertaken with one particular problem in view, or it may be organized, like the Challenger expedition, with the co-operation of a number of specialists.

The French took the lead in organizing zoological expeditions. As early as 1800 they sent out the Géographe, Naturaliste, and Casuarina, zoologically conducted by Bury de St. Vincent, Péron, and Lesueur. Further expeditions followed with Quoy and Gaimard, Lesson, Eydoux, Souleyet, Dupetit-Thouars, and others as zoological guides. The English whaling industry gave early opportunity to not a few naturalists; and it is now a long time since Hooker went with Sir James Ross on the South Polar expedition and Huxley went on the Rattlesnake to the Australian Barrier Reef. The Russians were also active, one of the more famous travellers being Kotzebue, who was accompanied on one of his two voyages (1823-6) round the world by Chamisso and Eschscholtz. In the early part of this century the Americans were also enterprising, the work of Dana being perhaps the most noteworthy. It would require several pages to mention even the names of the naturalists who have had their years of wandering, and have added their pages and sketches to the book of the world’s fauna and flora, but such an enumeration would serve no useful purpose here.

There is, however, one form of zoological exploration which deserves a chapter to itself, that is the exploration of the Deep Sea. Several generations of marine zoologists had been at work before a zoology of the deep sea was dreamed of even as a possibility. It is true that in 1818 Sir John Ross had found a star-fish (Astrophyton) at a depth of 800-1000 fathoms, but this was forgotten; and in 1841 Edward Forbes dredged to no purpose in fairly deep water in the Ægean Sea. Indeed those who thought about the great depths at all deemed it unlikely that there could be life there, and if it had not been for the practical affair of laying the ocean cables, we might possibly have been still in ignorance of the abyssal fauna.

But the cables had to be laid—no easy task—and it became important to know at least the topography of the depths. Cables broke, too, and had to be fished up again, and when that which ran[Pg xxiii] between Sardinia and Algiers was lifted, in 1860, from a depth of 60-1000 fathoms, no less than 15 different species of animals were found on it. This was a discovery to fire enthusiasm, and Britain led the way in following it up. In 1868 Wyville Thomson began his explorations on the Lightning, and proved that most of the types of backboneless animals were represented at depths of at least 600 fathoms. Soon followed the similar cruise of the Porcupine, famous inter alia for the discovery of Bathybius, which many sceptics regard as a mare’s nest. From various quarters the quest after the deep-sea fauna began to be prosecuted.

It is now more than a score of years since the world-famous Challenger sailed from Portsmouth with Wyville Thomson, Moseley, John Murray, and Willemoes-Suhm as naturalists. During three and a half years the explorers cruised over 68,900 nautical miles, crossed the Atlantic no less than five times, reached with the long arm of the dredge to depths equal to reversed Himalayas, raised treasures of life from over 500 stations, and brought home spoils over which the savants of Europe have hardly ceased to be busy, and the records of which, now completed under Dr. Murray’s editorship, form a library of about forty huge volumes.

The Challenger expedition was important not only in itself, but in the wave of scientific enthusiasm which it raised. From Germany went forth the Gazelle; Norway sent the Vöringen to Spitzbergen; America has despatched the Tuscarora, the Blake, and the Albatross; from Sweden the Vega and the Sophia sailed to Arctic seas: Count Liechtenstein’s yacht Hertha explored Adria; the Prince of Monaco’s Hirondelle darted hither and thither; the French sent forth the Travailleur and Talisman; the Italians the Vettor Pisani and Washington; Austria and Hungary organized the Poli for work in the Mediterranean; the Germans again have recently specialized in investigating the Plankton, or surface-life of the ocean; and so, with a range even wider than we have indicated, the wave of enthusiasm has spread, one of the latest barques which it has borne being the Prince of Monaco’s, which was specially built for marine exploration.

Specialism in travelling has, of course, gone much further.[Pg xxiv] Thus to cite only three examples, we have Semper’s zoological work on the Philippines, the researches of the Sarasins in Ceylon, and the first results of Semon’s recent visit to Australasia, all of them passing far beyond records of zoological exploration into monographs on the structure and development of characteristic members of the fauna of these countries. And it is no exaggeration to say that private enterprise, Royal Society subsidies, British Association grants, and the like have sent scores of naturalists from Britain half round the world in order to solve special problems, as to the larva of a worm, for instance, or as to the bird-fauna of some little island.

V. The Biological Type. In some ways the most important scientific journey ever made was Darwin’s voyage on the Beagle. It was the Columbus-voyage of zoology. There is a great deal to be said for the Wanderjahre of the old students, for to have time to think is one of the conditions of intellectual progress. Not that the Beagle voyage was one of idleness, but it gave Darwin, at the age of twenty-two, a wealth of impressions and some measure of enforced leisure wherein to gloat intellectually over what he saw. He has said, indeed, that various sets of facts observed on his voyage, such as the aspect of the Galapagos Islands, started him on paths of pondering which eventually led to his theory of the origin of species.

We take Darwin as the type of the biological, or, we may almost say, evolutionist travellers; but he must share this position with his magnanimous colleague, Alfred Russel Wallace, whose journeyings were more prolonged and not less fruitful. Before Darwin the naturalist-travellers had been, for the most part, describers, systematists, and analysts, and it goes without saying that such work is indispensable, and must continue; but in the light of the conception of evolution all things had become new; the present world of life was henceforth seen as a stage in a process, as a passing act in a drama, not merely as a phantasmagoria to be admired and pictured, but as a growth to be understood.

It is within this group of biological travellers, which includes such men as Bates and Belt, that we must also place Brehm. For[Pg xxv] although he perhaps had not the firmness of grasp or the fineness of touch necessary for the successful handling of the more intricate biological problems, especially those which centre around the factors of evolution, he had unusual power as an observer of the habits of animals. His contributions, which must be judged, of course, from his great Tierleben,[A] as well as from his popular lectures, were rather to the old natural history than to biology in the stricter sense. His works show that he was as much interested in men as in beasts, that he was specially an ornithologist, that he was beneath the naturalist a sportsman; but so scores of other travellers have been. His particular excellence is his power of observing and picturing animal life as it is lived in nature, without taking account of which biology is a mockery and any theory of evolution a one-sided dogma.

[A] This well-known treasure-house of Natural History appeared originally in 1863-69 in six big volumes, which have since increased to ten. Even the first edition took a foremost place among similar works on the Natural History of Animals. With a wealth of personal observation on the habits of animals in their native haunts, it combined the further charm of very beautiful pictorial illustration.

Let us now bring together briefly the outstanding facts of this historical outline.

In early days men followed their wandering herds or pursued their prey from region to region, or were driven by force of competition or of hunger to new lands. Many of the most eventful journeys have been among those which had to be taken.

I. Gradually, intellectual curiosity rather than practical need became the prompter, and men travelled with all manner of mixed aims seeking what was new. When they returned they told travellers’ tales, mostly in as good faith as their hunting ancestors had done in the caves of a winter night, or as the modern traveller does after dinner still. We pass insensibly from Herodotus to Marco Polo, from “Sir John Maundeville” to Mr. X. Y. Z., whose book was published last spring. This is the type romantic.

II. But when science shared in the renaissance there ensued the extraordinary industry of the encyclopædist school, with which many naturalist-travellers were associated. Some of these were great men—perhaps Gesner was greatest of all—but all had the[Pg xxvi] defects of their qualities. They gathered into stackyards both wheat and tares, and seldom found time to thrash. The type survives afield in the mere collector, and its degenerate sedentary representatives are called compilers.

III. Just as Buffon represents the climax of the encyclopædists, and is yet something more, for he thrashed his wheat, so Humboldt, while as ambitious as any encyclopædist traveller, transcended them all by vitalizing the wealth of impressions which he gathered. He was the general naturalist-traveller, who took all nature for his province, and does not seem to have been embarrassed. Of successful representatives of this type there are few, since Darwin perhaps none.

IV. Meanwhile Linnæus had brought order, Cuvier had founded his school of anatomists, Haller had re-organized physiology, the microscope had deepened analysis, and zoology came of age as a specialism. Henceforth travellers’ tales were at a discount; even a Humboldt might be contradicted, and platitudinarian narratives of a voyage round the world ceased to find the publisher sympathetic or the public appetized. The naturalist-traveller was now a zoologist, or a botanist, or an ornithologist, or an entomologist; at any rate, a specialist. But it was sometimes found profitable to work in companies, as in the case of the Challenger expedition.

V. Lastly, we find that on the travellers, too, “evolution” cast its spell, and we have Darwin and Wallace as the types of the biological travellers, whose results go directly towards the working out of a cosmology. From Bates and Belt and Brehm there is a long list down to Dr. Hickson, The Naturalist in Celebes, and Mr. Hudson, The Naturalist in La Plata. Not, of course, that most are not specialists, but the particular interest of their work is biological or bionomical.

I have added to this essay a list of some of the most important works of the more recent naturalist-travellers with which I am directly acquainted, being convinced that it is with these that the general, and perhaps also the professional student of natural history should begin, as it is with them that his studies must also end. For, not only do they introduce us, in a manner usually full of[Pg xxvii] interest, to the nature of animal life, but they lead us to face one of the ultimate problems of biology—the evolution of faunas.

II.

Alfred Edmund Brehm (1829-1884) was born at Unter-Renthendorf in Sachsen-Weimar, where his father—an accomplished ornithologist—was pastor. Brought up among birds, learning to watch from his earliest boyhood, accompanying his father in rambles through the Thuringian forest, questioning and being questioned about all the sights and sounds of the woods, listening to the experts who came to see the famous collection in the Pfarr-haus, and to argue over questions of species with the kindly pastor, young Brehm was almost bound to become a naturalist. And while the father stuffed his birds in the evenings the mother read aloud from Goethe and Schiller, and her poetic feeling was echoed in her son. Yet, so crooked are life’s ways, the youth became an architect’s apprentice, and acted as such for four years!

But an opportunity presented itself which called him, doubtless most willing, from the desk and workshop. Baron John Wilhelm von Müller, a keen sportsman and lover of birds, sought an assistant to accompany him on an ornithological expedition to Africa, and with him the youth, not yet out of his teens, set forth in 1847. It was a great opportunity, but the price paid for it was heavy, for Brehm did not see his home again for full five years, and was forced to bear strains, to incur responsibilities, and to suffer privations, which left their mark on him for life. Only those who know the story of his African journeys, and what African travel may be with repeated fevers and inconsiderately crippled resources, can adequately appreciate the restraint which Brehm displays in those popular lectures, here translated, where there is so much of everything but himself.

After he returned, in 1852, rich in spoils and experience, if otherwise poor, he spent several sessions at the universities of Jena and Vienna. Though earnestly busy in equipping himself for further work, he was not too old to enjoy the pleasures of a student life.[Pg xxviii] When he took his doctor’s degree he published an account of his travels (Reiseskizzen aus Nordostafrica. Jena, 1855, 3 vols.).

After a zoological holiday in Spain with his like-minded brother Reinhold—a physician in Madrid—he settled for a time in Leipzig, writing for the famous “Gartenlaube”, co-operating with Rossmässler in bringing out Die Tiere des Waldes, expressing his very self in his Bird-Life (1861), and teaching in the schools. It was during this period that he visited Lapland, of whose bird-bergs the first lecture gives such a vivid description. In 1861 he married Matthilde Reiz, who proved herself the best possible helpmeet.

In 1862, Brehm went as scientific guide on an excursion to Abyssinia undertaken by the Duke of Coburg-Gotha, and subsequently published a characteristic account of his observations Ergebnisse einer Reise nach Habesch: Results of a Journey to Abyssinia (Hamburg, 1863). On his return he began his world-famous Tierleben (Animal Life), which has been a treasure-house to so many naturalists. With the collaboration of Professors Taschenberg and Oscar Schmidt, he completed the first edition of this great work, in six volumes, in 1869.

Meanwhile he had gone to Hamburg as Director of the Zoological Gardens there, but the organizing work seems to have suited him ill, and he soon resigned. With a freer hand, he then undertook the establishment of the famous Berlin Aquarium, in which he partly realized his dream of a microcosmic living museum of nature. But, apart from his actual work, the business-relations were ever irksome, and in 1874 he was forced by ill-health and social friction to abandon his position.

After recovery from serious illness he took up his rôle as popular lecturer and writer, and as such he had many years of happy success. A book on Cage Birds (1872-1876), and a second edition of the Tierleben date from this period, which was also interrupted by his Siberian journeys (1876) and by numerous ornithological expeditions, for instance to Hungary and Spain, along with the Crown Prince Rudolph of Austria. But hard work, family sorrows, and finally, perhaps, the strain of a long lecturing tour in America aged Brehm before his time, and he died in 1884.

[Pg xxix]

For these notes I am indebted to a delightful appreciation of Brehm which Ernest Krause has written in introduction to the third edition of the Tierleben, edited by Pechuel-Loesche, and as regards the naturalist’s character I can only refer to that essay. As to his published work, however, every naturalist knows at least the Tierleben, and on that a judgment may be safely based. It is a monumental work on the habits of animals, founded in great part on personal observation, which was always keen and yet sympathetic. It is a classic on the natural history of animals, and readers of Darwin will remember how the master honoured it.

Doubtless Brehm had the defects of his qualities. He was, it is said, too generous to animals, and sometimes read the man into the beast unwarrantably. But that is an anthropomorphism which easily besets the sympathetic naturalist. He was sometimes extravagant and occasionally credulous. He did not exactly grip some of the subjects he tackled, such as, if I must specify, what he calls “the monkey-question”.

It is frankly allowed that he was no modern biologist, erudite as regards evolution-factors, nor did he profess to attempt what is called zoological analysis, and what is often mere necrology, but his merit is that he had seen more than most of us, and had seen, above all, the naturalist’s supreme vision—the vibrating web of life. And he would have us see it also.

III.

The success of the pictures which Brehm has given us—of bird-bergs and tundra, of steppes and desert, of river fauna and tropical forest—raises the wish that they had been complete enough to embrace the whole world. As this ideal, so desirable both from an educational and an artistic standpoint, has not been realized by any one volume, we have ventured to insert here a list of some more or less analogous English works by naturalist-travellers, sportsmen, and others—

Adams, A. Leith. Notes of a Naturalist in the Nile Valley and Malta (Edinburgh, 1870).

Agassiz, A. Three Cruises of the “Blake” (Boston and New York, 1888).

[Pg xxx]

Baker, S. W. Wild Beasts and their Ways: Reminiscences of Europe, Asia, Africa, and America (London, 1890).

Bates, H. W. Naturalist on the Amazons (6th Ed. London, 1893).

Belt, T. Naturalist in Nicaragua (2nd Ed. London, 1888).

Bickmore, A. S. Travels in the East Indian Archipelago (1868).

Blanford, W. T. Observations on the Geology and Zoology of Abyssinia (London, 1870).

Bryden, H. A. Gun and Camera in Southern Africa (London, 1893). Kloof and Karroo (1889).

Burnaby, F. A Ride to Khiva (8th Ed. London, 1877).

Buxton, E. N. Short Stalks, or Hunting Camps, North, South, East, and West (London, 1893).

Chapman, A. and C. M. Buck. Wild Spain (London, 1892).

Cunningham, R. O. Notes on the Natural History of the Straits of Magellan (Edinburgh, 1871).

Darwin, C. Voyage of the “Beagle” (1844, New Ed. London, 1890).

Distant, W. L. A Naturalist in the Transvaal (London, 1892).

Drummond, H. Tropical Africa (London, 1888).

Du Chaillu, P. B. Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa (London, 1861). Ashango Land (1867).

Eha. A Naturalist on the Prowl, or in the Jungle (London, 1894).

Forbes, H. O. A Naturalist’s Wanderings in the Eastern Archipelago (London, 1885).

Guillemard. Cruise of the “Marchesa” (London, 1886).

Heilprin, A. The Bermuda Islands (Philadelphia, 1889).

Hickson, S. J. A Naturalist in North Celebes (London, 1889).

Holub, Emil. Seven Years in South Africa (1881).

Hudson, W. H. The Naturalist in La Plata (London, 1892). Idle Days in Patagonia (London, 1893).

Humboldt, A. von. Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America. Views of Nature (Trans. 1849). Cosmos (Trans. 1849-58).

Johnston, H. H. Kilima Ndjaro Expedition (1885).

Kingsley, C. At last! A Christmas in the West Indies (1889).

Lumholtz. Among Cannibals (London, 1889).

Moseley, H. N. Notes by a Naturalist on the “Challenger” (London, 1879. New Ed. 1892).

Nordenskiöld, A. E. Voyage of the “Vega” (London, 1881).

Oates, F., Ed. by C. G. Oates. Matabele Land, the Victoria Falls, a Naturalist’s Wanderings in the Interior of South Africa (1881).

Phillipps-Wolley. Big-Game Shooting (Badminton Libr. London, 1893).

Rodway, J. In the Guiana Forest (London, 1894). British Guiana (London, 1893).

[Pg xxxi]

Roosevelt, Th., and G. B. Grinell. American Big-Game Hunting (Edinburgh, 1893).

Schweinfurth, G. The Heart of Africa (1878).

Seebohm, H. Siberia in Europe (London, 1880), Siberia in Asia (London, 1882).

Selous, F. C. A Hunter’s Wanderings (1881). Travel and Adventure in South-East Africa (London, 1893).

Sibree, Rev. J. The Great African Island (1879).

Solymos, B. (B. E. Falkenberg). Desert Life (London, 1880).

Stanley, H. M. How I Found Livingstone (1872, New Ed. 1885). The Congo (1885). Through the Dark Continent (1890). In Darkest Africa (1890).

Swayne, H. G. C. Seventeen Trips through Somaliland (London, 1895).

Tennent, J. E. Natural History of Ceylon (London, 1861).

Thomson, Wyville. The Depths of the Sea (London, 1873). Narrative of the Voyage of the “Challenger” (1885). And, in this connection, see S. J. Hickson. Fauna of the Deep Sea (London, 1894).

Tristram, H. B. The Land of Israel (1876). The Land of Moab (1873). The Great Sahara (1860).

Wallace, A. R. Malay Archipelago (London 1869). Tropical Nature (1878). Island Life (1880). Travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro (1889).

Waterton, Ch. Wanderings in South America (Ed. by J. G. Wood, 1878).

Woodford, C. M. Naturalist among the Head-hunters (London, 1890).

[Pg 33]

FROM

NORTH POLE TO EQUATOR.

“When the Creator of the worlds had made the earth, best loved of all, and was rejoicing in His perfect work, the devil was seized with a desire to bring it all to nought. Not yet banished from heaven, he lived among the archangels in the abodes of the blessed. Up to the seventh heaven he flew, and, seizing a great stone, hurled it with might down on the earth exulting in the beauty of its youth. But the Creator saw the ruthless deed, and sent one of His archangels to avert the evil. The angel flew even more swiftly than the stone to the earth beneath, and succeeded in saving the land. The huge stone plunged thundering into the sea, and hissing waves flooded all the shores for many a mile. The fall shattered the crust of the stone, and thousands of splinters sank on either side, some disappearing into the depths, and some rising above the surface, bare and bleak like the rock itself. Then God took pity, and in His infinite goodness resolved to clothe even this naked rock with life. But the fruitful soil was all but exhausted in His hand; there remained scarce enough to lay a little here and there upon the stone.”

So runs an ancient legend still current among the Lapps. The stone which the devil threw is Scandinavia; the splinters which fell into the sea on either side are the skerries which form a richly varied wreath around the peninsula. The rents and cracks in the rock are the fjords and the valleys; the sprinkling of life-giving soil which fell from the gracious Creator’s hand forms the few fertile tracts which Scandinavia possesses. To appreciate the full depth and meaning of the childish story one must one’s self have visited[Pg 34] Scandinavia, and especially Norway, have steered a boat among the skerries, and have sailed round the country from the extreme south to the farthest north. Marvellous, indeed, is the country; marvellous are its fjords; still more marvellous is the encircling wreath of islands and reefs.

Scandinavia is an alpine country like Switzerland and the Tyrol, yet it differs in a hundred ways from both of these. Like our Alps it has lofty mountains, glaciers, torrents, clear, still alpine lakes, dark pine and fir forests low down in the gorges, bright green birch woods on the heights, far-stretching moors—or more strictly tundras—on the broad shoulders of the mountains, log-huts on the slopes, and the huts of the cowherds in the upland valleys. And yet all is very different from our Alps, as is obvious to anyone who has seen both. The reason of this difference lies in the wonderful way in which two such grand and impressive features of scenery as lofty mountains and the sea are associated and harmonized.

The general aspect of Scandinavia is at once grave and gay. Stern grandeur and soft beauty go hand in hand; gloom alternates with cheerfulness; with the dead and disquieting is linked the living and exhilarating. Black masses of rock rear themselves perpendicularly out of the sea, rise directly from the deeply-cut fjords, and, riven and cleft, tower precipitously upwards and lean threateningly over. On their heads lie masses of ice stretching for miles, covering whole districts and scaring away all life save the torrents to which they themselves have given birth. These torrents spread themselves everywhere in ribbons of silver over the dark masses, and not only give pleasure to the eye, but murmur to the ear the sublime melody of the mountains. They rush down through every cleft to the depths below, they burst forth from every gorge, or plunge in mad career from rock to rock, forming waterfall after waterfall, and awakening echoes from the farthest mountain sides. These rushing mountain-streams which hurry down to the valley through every channel, the gleaming bands of water on every wall of rock, the ascending smoke-like spray which betrays the most secluded falls—these call forth life even in the most dread wilderness, in places where otherwise nought can be seen but rocks and [Pg 37]sky—and they are most truly characteristic of the scenery of the interior.

Fig. 1.—Scene on the Sogne Fjord, Norway.

But, majestic as this beauty is, bewildering and overwhelming as are the fjords with their precipitous walls, their ravines and valleys, headlands and peaks, they are yet less characteristic than the islands and skerries lying out in the sea, stretching from the south of the country up to the far north, and forming a maze of bays, sounds, and straits such as can hardly be seen elsewhere in the wide world.

The larger islands reproduce more or less faithfully the characters of the mainland; the smaller ones and the skerries present, under all circumstances, an aspect of their own. But, as one travels towards the north, this aspect changes more or less with every degree of latitude. Like the sea, the islands lack the richness of the south, but are, nevertheless, by no means devoid of beauty. Especially in the midnight hours, when the low midsummer sun stands large and blood-red on the horizon, its veiled brilliance reflected alike from the ice-covered mountain-tops and from the sea, they have an irresistible charm. This is enhanced by the homesteads which are dotted everywhere over the landscape—dwellings built of wood and roofed with turf, glowing in a strange, blood-red colour which contrasts sharply with the green turf roof, the black darkness of the adjacent mountain-side, and the ice-blue of the glaciers in the background of the picture.

The southerner remarks, with some surprise, that these homesteads become larger, handsomer, and more roomy the farther north he travels; that, though no longer surrounded by fields, but at the most by small gardens, they far excel in size and equipment the hut-like buildings of southern Scandinavia; and that the most pretentious of all may be on comparatively small islands, where the rocks are covered only with turf, and where not even a little garden can be won from the inhospitable soil.

The seeming riddle is solved when we remember that in Norland and Finland it is not the land but the sea that is ploughed; that there men do not sow and wield the scythe in summer, but reap in midwinter without having sowed; that it is in the months[Pg 38] in which the long night holds its undisputed sway, when the light of the sun has given place to that of the moon, and the rosy flush of dawn and sunset to the glow of the Northern Lights, that the dwellers in the far north gather in the rich harvest of the sea.

About the time of the autumnal equinox strong men are preparing themselves all along the coasts of Norway to secure the harvest of the North. Every town, every village, every hamlet sends one or more well-manned ships to the islands and skerries within the Polar Circle, to anchor for months in every suitable bay. Making the ships or the homesteads on shore their head-quarters, the fishermen proceed to gather in the abundant booty. In the height of summer the whole country is still and deserted, but in winter the bays, islands, and sounds are teeming with busy men, and laborious hands are toiling night and day. Spacious as the dwelling-houses appear, they cannot contain the crowds of people who have assembled; many must remain in the ships, or even seek a rough-and-ready shelter in rudely-constructed turf-covered huts on the shore.

The bustle is at its height about the time of the winter solstice, when we celebrate our Christmas, and the Norsemen their Yule festival. For weeks the sea has been yielding its treasures. Impelled by the strongest impulse which moves living beings, guided by irresistible instinct to sow the seed of future generations, there rise from the depths of the sea innumerable shoals of fishes—cod, haddock, and the like. They ascend to the upper strata of the water, approach the coasts, and throng into the straits, sounds, and fjords in such numbers that they cover the surface of the sea for many miles. Animated, almost maddened, by one impulse, the fish swim so thickly that the boat has literally to force a way among them, that the overweighted net baffles the combined strength of the fishermen or breaks under its burden, that an oar placed upright among the densely packed crowd of swimmers remains for a few moments in its position before falling to one side.[1] Wherever the rocky islands are washed bare by the raging high tides, from the mean tide-mark to the lower edge of the turf which covers their summits, the naked rocks are covered by an unbroken ring of fish[Pg 39] split open and laid out to dry, while trestles are also erected that other fish may be exposed for the same purpose to the sharp and drying air. From time to time the rocks and frames are cleared of dried fish, which are packed in bundles and stored in sheds, but only that room may be found for others which in the meantime have been caught and prepared.

For months the bustle continues, and the traffic is uninterrupted; for months the North continues to exchange its treasures with the South. Then in the days when about noon a clear light in the south heralds the coming of the sun still hidden, or when the first rays of sunlight fall for a brief space upon the land, the rich catch comes gradually to an end. The dried cod and ling are carried from the storing sheds to the ships, all available space from keel to deck is filled up, and the fishermen prepare to journey homewards, or abroad into the wide world. One ship after another hoists its brown-edged sails and steers away.

The North becomes quieter again, more deserted the land, desolate the sea. At last, by the time of the spring equinox, all the migrant fishermen have left the fishing grounds, and all the fish have returned to the depths of the sea. But the sea is already sending forth other children to people afresh the straits and sounds, and along with them the skerries and islands; and soon from those same cliffs, at whose base there was but lately all the bustle of the winter, millions of bright bird eyes look down upon the waves.

It is a deeply-affecting trait in the life of all true sea-birds that only two causes can move them to visit the land: the joyous spring-time sense of new-awakening love, and the mournful foreboding of approaching death. Not even Winter with its long night, its cold, and its storms can drive them to the land; they are proof against all the terrors of the North, and seek their food upon or under the waves; not even the threatening jaws of voracious fish scare them ashore. They may alight occasionally, but only for a short time, often on a solitary island in the sea, to oil their feathers more thoroughly than can be done in the water. But when, with the sun’s first brightness, love stirs in their breasts, all, old and young alike, though they may have to swim and fly thousands of[Pg 40] miles, strive to reach the place where they themselves first saw the light of day. And if, in mid-winter, months after the breeding-places have been left desolate, a sea-bird feels death in his heart, he hastens as long as his strength holds out, that he may, if possible, die in the place where he was cradled.

The annual assembling of innumerable birds at the breeding-places fills these for several months with a most marvellous life. The communities differ like the sea-birds themselves, and the places, or bergs (as the Norsemen call them), which they people vary also. While some choose only those reefs which rise just above the high-tide mark, and bear no more vegetation than is enough to provide scanty material for the nest hollowed out in the sea-weed heaps, others select islands which rear themselves straight and steep for several hundred feet above the sea, and are either rich in shelves, ledges, cavities, fissures, and other hiding-places, or are covered by a thick layer of peat-like plant remains. The Norseman calls the lower islets ‘eider-holms’ (or eider bird-hills, as the German would say), for they are the favourite brooding-places of what is to him the most valuable, and, what is the same thing, the most useful of all sea-birds. The higher islands which rise precipitously from the sea, and are chiefly peopled by auks and gulls, are included under the general name of bird-bergs.

The observant naturalist is of course tempted to study and describe in detail each individual brooding bird of the sea, but the rich variety of the inhabitants of the bird-bergs of the far north and the variety of their habits impose certain limits. Similarly, lest I exceed the time allowed to me, I must refrain from giving detailed pictures of the habits of all the berg birds, though I think it well at least to outline those of a few in order to bring into prominence some of the chief characteristics of sea-bird life. Selection is difficult, but one, at any rate—the eider-duck, which returns every spring to these islands, and helps to beautify them and their surroundings so marvellously—must not be left undescribed.

Three species of these beautiful ducks inhabit or visit European shores; one of these, the true eider-bird, is to be found every summer, even on the north-western islands of Germany, especially[Pg 41] Sylt. Its plumage is a faithful mirror of the northern sea. Black and red, ash-gray, ice-green, white, brown, and yellow are the colours harmoniously blended in it. The eider-duck proper is the least beautiful species, but it is nevertheless a handsome bird. The neck and back, a band over the wings, and a spot on the sides of the body are white as the crests of the waves; throat and crop have a white ground faintly flushed with rose-colour as though the glow of the midnight sun had been caught there; a belt on the cheeks is delicate green like the ice of the glacier; breast and belly, wings and tail, the lower part of the back and the rump are black as the depths of the sea itself. This splendour belongs only to the male; the female, like all ducks, wears a more modest yet not less pleasing garb, which I may call a house-dress. The prevailing rust-coloured ground, shading more or less into brown, is marked with longitudinal and transverse spots, lines and spirals, with a beauty and variety that words cannot adequately describe.

No other species of duck is so thoroughly a child of the sea as the eider-duck; no species waddles more clumsily on land, or flies less gracefully, but none swims more rapidly or dives more deftly and deeply. In search of food it sinks fully fifty yards below the surface of the sea, and is said to be able to remain five minutes—an extraordinarily long time—under water. Before the beginning of the brooding season it does not leave the open sea at all, or does so very rarely; following a whim rather than driven by necessity. Towards the end of winter the flocks in which they congregate break up into pairs, and only those males who have not succeeded in securing mates swim about in little groups. Between two mates the most perfect unanimity reigns. One will, undoubtedly that of the duck, determines the actions of both. If she rises from the surface of the water to fly for a hundred yards through the air, the drake follows her; if she dives into the sea, he disappears directly afterwards; wherever she turns he follows faithfully; whatever she does seems to express his wishes. The pair still live out on the sea, though only where the depth is not greater than twenty-five fathoms, and where edible mussels and other bivalves are found in rich abundance on the rocks and the sea-bottom. [Pg 42]These molluscs often form the sole food of eider-ducks, and to procure them they may have to dive to considerable depths. But it is the abundance of this food which preserves the eiders from the scarcity from which so many other species of duck often suffer severely.

In April, or at the latest in the beginning of May, the pairs approach nearer and nearer the fringe of reefs and the shores of the mainland. Maternal cares are stirring in the breast of the duck, and to these everything else is subordinated. Out at sea the pair were so shy that they never allowed a ship or boat to get near them, and feared man, if he ever happened to approach them, more than any other living creature; now in the neighbourhood of the islands their behaviour changes entirely. Obeying her maternal instincts, and these only, the duck swims to one of the brooding-places, and paying no attention to the human inhabitants, waddles on to the land. Anxiously the drake follows her, not without uttering his warning “Ahua, ahua”, not without visible hesitation, for every now and then he remains behind as if reflecting for a while, and then swims forward once more. The duck, however, pays no heed to all this. Careless of the whole world around her, she wanders over the island seeking a suitable brooding-place. Being somewhat fastidious, she is not satisfied with the first good heap of sea-weed cast up by the tide, with the low juniper-bush whose branches straggling on the ground offer safe concealment, with the half-broken box which the owner of the island has placed as a shelter for her, or with the heaps of twigs and brushwood which he has gathered to entice her, but approaches the owner’s dwelling as fearlessly as if she were a domestic bird. She enters it, walks about the floor, follows the housewife through rooms and kitchen, and capriciously selects, it may be, the inside of the oven as her resting-place, thereby forcing the housewife to have her bread baked for weeks on another island. With manifest alarm the faithful drake follows her as far as he dares; but when she, in his opinion, so far neglects all considerations of safety as to dwell under the same roof with human beings, he no longer tries to struggle against her wayward whim, but leaves her to follow it alone, and[Pg 43] flies out to the safety of the sea, there longingly to await her daily visit. His mate is in no wise distracted by his departure, but proceeds to collect twigs and brushwood—a task in which she willingly accepts the Norseman’s help—and to pile up into a heap her nest materials, which include sea-weed as well as twigs. She hollows out a trough with her wings and makes it circular by turning round and round in it with her smooth breast. Then she sets about procuring the lining and incorporating it with the nest. Thinking only of her brood, she plucks the incomparably soft down from her breast and makes with it a sort of felt, which not only lines the whole hollow but forms such a thick border at its upper edge that it serves as a cover to protect the eggs from cold when the mother leaves the nest. Before the work of lining is quite completed, the duck begins laying her comparatively small, smooth-shelled, clouded-green or grayish-green eggs. The clutch consists of from six to eight, seldom more or fewer.

This is the time for which the Norseman has been waiting, for it was self-interest that prompted all his hospitality to the bird. The host now becomes the robber. Ruthlessly he takes the eggs and the nest with its inner lining of costly down. From twenty-four to thirty nests yield about two pounds of down, worth at least thirty shillings on the spot. This price is sufficient explanation of the Norseman’s way of acting.

Fig. 2.—Colony of Eider-ducks.

With a heavy heart the duck sees the downfall of her hopes for that year. Perturbed and frightened, she flies out to sea, where her mate awaits her. Whether he takes the opportunity of repeating his warnings more urgently I cannot say, but I can testify that he very soon succeeds in consoling her. The joy and spirit of the spring-time still live in the hearts of both; and in a very few days our duck waddles on land again as though nothing had happened, to build a second nest! This time she probably avoids her former position and contents herself with the first available heap of tangle which is not fully taken up by other birds. Again she digs and rounds a hollow; again she begins to probe among her plumage in order to procure the lining of down which seems to her indispensable. But, however much she exert herself, [Pg 44]stretching her neck and twisting it in intricate snake-like curves, she can find no more. Yet when was a mother, even a duck mother, at a loss when her children had to be provided for? Our duck is certainly at none. She herself has no more down, but her mate bears it untouched on his breast and back. Now it is his turn. And though he may perhaps rebel, having a lively recollection of former years, he is the husband and she the wife, therefore he must obey. Without compunction the anxious mother rifles his plumage, and in a few hours, or at most within two days, she has plucked him as bare as herself. That the drake, after such treatment, should fly out to the open sea as soon as possible, and associate for some months only with his fellows, troubling himself not in the least about his mate and her coming brood, seems to me[Pg 45] quite comprehensible. And when, as happens on every nesting island, a drake is to be seen standing by the brooding duck, I think he must be one who has not yet been plucked![2]

Our duck broods once more assiduously. And now her house-dress is seen to be the only suitable, I might say the only possible, garment which she could wear. Among the tangle which surrounds the nest she is completely hidden even from the sharp eyes of the falcon or the sea-eagle. Not only the general colouring, but every point and every line is so harmonious with the dried sea-weed, that the brooding-bird, when she has drawn down her neck and slightly spread out her wings, seems to become almost a part of her surroundings. Many a time it has happened that I, searching with the practised eye of a sportsman and naturalist, have walked across eider-holms and only become aware of the brooding duck at my feet, when she warned me off by pecking at my shoes. No one who knows the self-forgetting devotion with which the birds brood will be surprised that it is possible to come so near an eider-duck sitting in her nest, but it may well excite the astonishment of even an experienced naturalist to learn that the duck suffers one to handle the eggs under her breast without flying away, and that she does not even allow herself to be diverted from her brooding when one lifts her from the nest and places her upon it again, or lays her on the ground at some little distance in order to see the charmingly quaint way in which she waddles back to her brood.

The eider-duck’s maternal self-surrender and desire for offspring show themselves in another way. Every female eider-duck, perhaps every duck of whatever species, desires not only the bliss of bearing children, but wishes to have as many nestlings as possible under her motherly eye. Prompted by this desire, she has no scruples in robbing, whenever possible, other eiders brooding near her. Devoted as she is in her brooding, she must nevertheless forsake her nest once a day to procure her own food, and to cleanse, oil, and smooth her plumage, which suffers considerably from the heat developed in brooding. Throwing a suspicious glance at her neighbours to right and left, she rises early in the forenoon, after having perhaps suffered the pangs of hunger for some hours, stands[Pg 46] beside her nest and carefully spreads the surrounding fringe of down with her bill, so that it forms a concealing and protecting cover for the eggs. Then she flies quickly out to the sea, dives repeatedly, and hastily fills crop and gullet to the full with mussels, bathes, cleans, and oils herself, and returns to land, drying and smoothing her feathers continuously as she walks towards her nest. Both her neighbours sit seemingly as innocent as before, but in the interval a theft has been perpetrated by at least one of them. As soon as the first had flown away, one of them rose from her nest, and lifting the cover of her neighbour’s nest, quickly rolled one, two, three, or four eggs with her feet into her own nest, then carefully replaced the cover, and resumed her place, rejoicing over her unrighteously-increased clutch. The returning duck probably notices the trick that has been played, but she makes not the slightest sign, and calmly settles down to brood again as though she thought, “Just wait, neighbour, you must go to the sea, too, and then I’ll do to you what you have done to me”. As a matter of fact, the eggs of several nests standing close together are shifted continuously from one to another. Whether it is her own or another’s children that come to life under her motherly breast seems to matter very little to the eider-duck—they are children, at any rate!

The duck sits about twenty-six days before the eggs are hatched. The Norseman, who goes to work intelligently, lets her do as she pleases this time, and not only refrains from disturbing her, but assists her as far as possible by keeping away from the island all enemies who might harass the bird. He knows his ducks, if not personally, at least to this extent, that he can tell about what time this or that one will have finished brooding, and will set out with her ducklings to seek the safety of the sea. The journey thither brings sudden destruction to many unwatched young eider-ducks. Not only the falcons breeding on or visiting the island, but even more the ravens, the skuas, and the larger gulls watch for the first appearance of the ducklings, attack them on the way, and carry off one or more of them. The owner of the island seeks to prevent this in a manner which enables one to appreciate how thoroughly[Pg 47] the duck, ordinarily so wild and shy, has become a domestic bird during the breeding season. Every morning towards the end of the brooding-time he inspects the island in order to help the mothers and to gather in a second harvest of down. On his back hangs a hamper, and on one arm a wide hand-basket. Going from nest to nest he lifts each duck, and looks to see whether the young are hatched and are sufficiently dry. If this be the case, he packs the whole waddling company in his hand-basket, and with adroit grasp divests the nest of its downy lining, which he throws into his hamper, and proceeds to another nest. Trustfully the duck waddles after him or rather after her piping offspring, and a second, third, tenth nest is thus emptied, in fact the work goes on as long as the basket will accommodate more nestlings, and one mother after another joins the procession, exchanging opinions with her companions in suffering on the way. Arrived at the sea, the man turns the basket upside down and simply shakes the whole crowd of ducklings into the water. Immediately all the ducks throw themselves after their piping young ones; coaxing, calling, displaying all manner of maternal tenderness, they swim about among the flock, each trying to collect as many ducklings as possible behind herself. With obvious pride one swims about with a long train behind her, but soon a second, less favoured, crosses the procession and seeks to detach as many of the ducklings as she can, and again a third endeavours to divert a few in her own favour. So all the mothers swim about, quacking and calling, cackling and coaxing, till at length each one has behind her a troop of young ones, whether her own or another’s who can tell? The duck in question certainly does not know, but her mother-love does not suffer on that account—they are in any case ducklings who are swimming behind her!