Title: In the volcano's mouth; or, A boy against an army

Author: Frank Sheridan

Release date: May 24, 2022 [eBook #68164]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Street & Smith, 1890

Credits: Demian Katz, Craig Kirkwood, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (Images courtesy of the Digital Library@Villanova University.)

The Table of Contents was created by the transcriber and placed in the public domain.

Additional Transcriber’s Notes are at the end.

CONTENTS

Chapter II. Emin Bey’s Escape.

Chapter III. In a Desert Tomb.

Chapter IV. Under the Pyramid.

Chapter VII. Splendid Heroism.

Chapter VIII. Sherif El Habib.

Chapter X. The Petrified Forest.

Chapter XI. The Tribe of Klatch.

Chapter XII. “What Says Girzilla?”

Chapter XIII. Dangerous Jests.

Chapter XIV. The Subterranean River.

Chapter XV. In the Volcano’s Mouth.

Chapter XVI. Beyond Human Imagination.

Chapter XVIII. Why Our Heroes Desert.

Chapter XX. “Where Is Girzilla?”

Chapter XXII. Trick or Miracle.

Chapter XXIII. Under the Mahdi.

Chapter XXIV. Counting Chickens.

Chapter XXVI. A Plan of Campaign.

Chapter XXVII. Sowing the Seed.

Chapter XXVIII. An Unexpected Bath.

Chapter XXX. The Mahdi’s Justice.

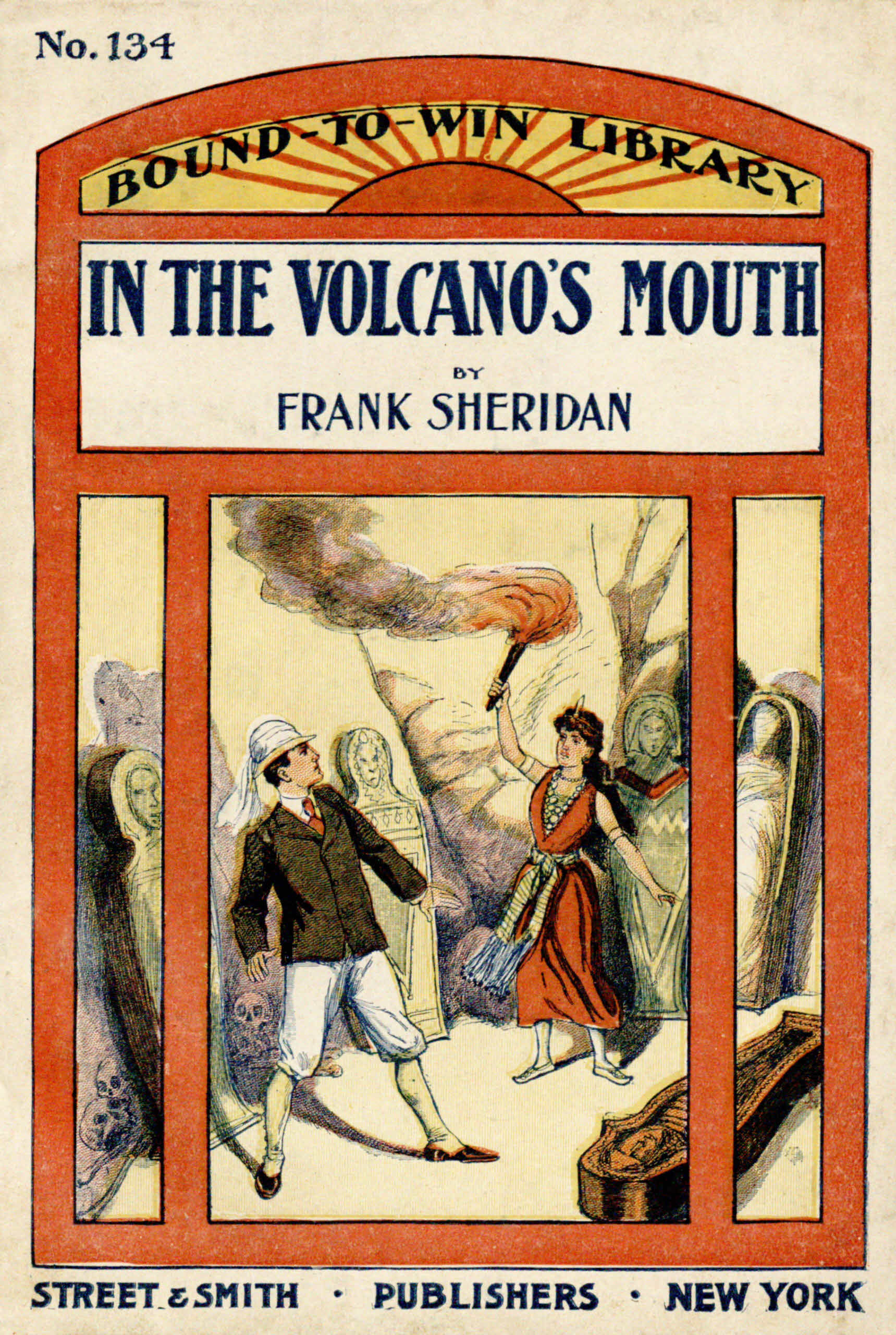

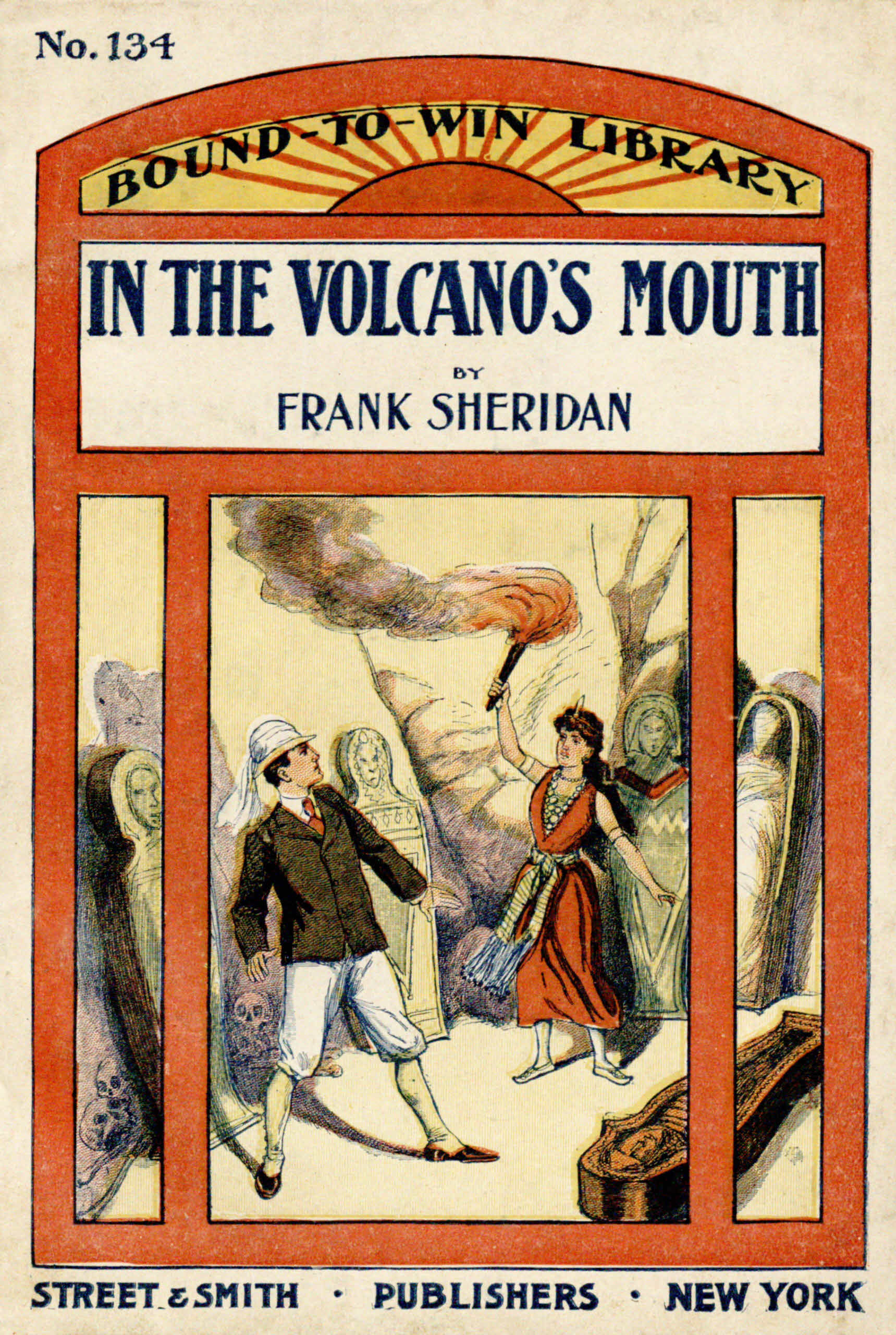

No. 134

BOUND-TO-WIN LIBRARY

IN THE VOLCANO’S MOUTH

BY

FRANK SHERIDAN

STREET & SMITH · PUBLISHERS · NEW YORK

THE BOUND TO WIN LIBRARY

We called this new line of high-class copyrighted stories of adventure for boys by this name because we felt assured that it was “bound to win” its way into the heart of every true American lad. The stories are exceptionally bright, clean and interesting. The writers had the interest of our boys at heart when they wrote the stories, and have not failed to show what a pure-minded lad with courage and mettle can do. Remember, that these stories are copyrighted and cannot be had in any other series. We give herewith a list of those already published and those scheduled for publication.

PUBLISHED EVERY WEEK

To be Published During September

| 136—Spider and Stump | By Bracebridge Hemyng |

| 135—The Creature of the Pines | By John De Morgan |

| 134—In the Volcano’s Mouth | By Frank Sheridan |

| 133—Muscles of Steel | By Weldon J. Cobb |

To be Published During August

| 132—Home Base | By Bracebridge Hemyng |

| 131—The Jewel of Florida | By Cornelius Shea |

| 130—The Boys’ Revolt | By Harrie Irving Hancock |

| 129—The Mystic Isle | By Fred Thorpe |

| 128—With the Mad Mullah | By Weldon J. Cobb |

To be Published During July

| 127—A Humble Hero | By John De Morgan |

| 126—For Big Money | By Fred Thorpe |

| 125—Too Fast to Last | By Bracebridge Hemyng |

| 124—Caught in a Trap | By Harrie Irving Hancock |

| 123—The Tattooed Boy | By Weldon J. Cobb |

| 122—The Young Horseman | By Herbert Bellwood |

| 121—Sam Sawbones | By Bracebridge Hemyng |

| 120—On His Mettle | By Fred Thorpe |

| 119—Compound Interest | By Harrie Irving Hancock |

| 118—Runaway and Rover | By Weldon J. Cobb |

| 117—Larry O’Keefe | By Bracebridge Hemyng |

| 116—The Boy Crusaders | By John De Morgan |

| 115—Double Quick Dan | By Fred Thorpe |

| 114—Money to Spend | By Harrie Irving Hancock |

| 113—Billy Barlow | By Bracebridge Hemyng |

| 112—A Battle with Fate | By Weldon J. Cobb |

| 111—Gypsy Joe | By John De Morgan |

| 110—Barred Out | By Fred Thorpe |

| 109—Will Wilding | By Bracebridge Hemyng |

| 108—Frank Bolton’s Chase | By Harrie Irving Hancock |

| 107—Lucky-Stone Dick | By Weldon J. Cobb |

| 106—Tom Scott, the American Robinson Crusoe | By Frank Sheridan |

| 105—Fatherless Bob at Sea | By Bracebridge Hemyng |

| 104—Fatherless Bob | By Bracebridge Hemyng |

| 103—Hank the Hustler | By Fred Thorpe |

| 102—Dick Stanhope Afloat | By Harrie Irving Hancock |

| 101—The Golden Harpoon | By Weldon J. Cobb |

| 100—Mischievous Matt’s Pranks | By Bracebridge Hemyng |

| 99—Mischievous Matt | By Bracebridge Hemyng |

| 98—Bert Chipley | By John De Morgan |

| 97—Down-East Dave | By Fred Thorpe |

| 96—The Young Diplomat | By Harrie Irving Hancock |

| 95—The Fool of the Family | By Bracebridge Hemyng |

| 94—Slam, Bang & Co | By Weldon J. Cobb |

| 93—On the Road | By Stanley Norris |

| 92—The Blood-Red Hand | By John De Morgan |

| 91—The Diamond King | By Cornelius Shea |

| 90—The Double-Faced Mystery | By Fred Thorpe |

| 89—The Young Theatrical Manager | By Stanley Norris |

| 88—The Young West-Pointer | By Harrie Irving Hancock |

| 87—Held for Ransom | By Weldon J. Cobb |

| 86—Boot-Black Bob | By John De Morgan |

| 85—Engineer Tom | By Cornelius Shea |

| 84—The Mascot of Hoodooville | By Fred Thorpe |

OR

A BOY AGAINST AN ARMY

By FRANK SHERIDAN, author of “Bert Fairfax,”

“Through Flame to Fame,” “Life-Line Larry,”

“Lion-Hearted

Jack,” etc.

STREET AND SMITH, PUBLISHERS

79-89 SEVENTH AVENUE, NEW YORK

Copyright, 1890

By Norman L. Munro

In the Volcano’s Mouth

IN THE VOLCANO’S MOUTH.

“All aboard!”

“All but passengers ashore.”

The loud, stentorian voices of the officers of the magnificent palace steamer L’Orient, of the Peninsular and Oriental Line, sounded all along the Southampton docks, up the streets to the old gates, and even penetrated into some of the business houses of the quaint old English town.

The shout, so commonplace to the citizens of Southampton, was one of serious import to those gathered on the deck of the steamer.

Parting is never pleasant, and when the journey is a long one, and it is known the absence is for years, the last words are always tearful.

On the deck stood two men, alone.

Not one had come to bid them good-by or a godspeed on their journey.

And yet tears filled the eyes of both.

The elder was a bronzed veteran, his face as dark as that of any mulatto, his long, white mustache standing out in startling contrast to the color of his skin.

[6]

He was sixty years of age, but his strong body, his hard muscles, and firm walk, would rather betoken a man of forty.

By his side stood his son, a youth almost effeminate in appearance, but perhaps only because of the contrast to his father; there was a brightness in his eyes which betokens an active spirit, and although so effeminate-looking, when he clinched his hand one could see the strong muscle rising beneath the sleeve.

The elder man is Maximilian Gordon, of the mercantile firm of Gordon, Welter & Maxwell, of New York.

The son is Maximilian Gordon, also, but always called Max by those who are intimate with him, and “Madcap Max” by his closest companions.

Gordon, Welter & Maxwell were interested in Egyptian produce, and for many years Maximilian Gordon had been a resident of Alexandria.

His wife, sickly and delicate at all times, had been compelled to live in England, where young Max had been educated.

The elder man paid a yearly visit to his family, and had just completed arrangements for them to return to Egypt with him when cholera broke out, and he arrived home only just in time to close his wife’s eyes in death and see her body committed to its eternal resting place.

Hence it was that, as father and son looked at the English coast, which was by this time fast receding, their eyes were filled with tears, for they were leaving a plot of earth hallowed and sacred, because it was a wife’s and mother’s grave.

[7]

Youth is ever buoyant, and before the steamer had left the English Channel, Max was the happy, light-hearted lad once again, laughing, chatting and larking with everyone he came in contact with.

His father could not hide his grief so easily, but showed by his manner how nearly broken was his heart and ruined his life.

When the troubled waters of the Bay of Biscay were reached, Max had given plentiful evidence of his love of practical joking, and showed that he fully deserved his sobriquet of Madcap.

One of the passengers had on board an African monkey.

This little, frolicsome animal became very fond of Max, and was easily induced to adapt itself to the ways of the fun-loving youth.

One night Max took Jocko and dressed him in a lady’s nightcap, which he had obtained from a stewardess, and told Jocko he must lie in a certain bed.

The stateroom was occupied by a snarling old bachelor, who declared that women and children were a nuisance.

When the old fellow entered his room he saw, to his utter astonishment, a head resting on his pillow.

Without staying to investigate, he rushed out of his room, shouting “Steward!” at the top of his voice.

“What is it, Mr. Lawrence?” asked the first officer, startled by the frantic shouting.

“Some one has placed a nigger baby in my bed.”

“Nonsense, Mr. Lawrence!”

[8]

“I say they have, and I’ll report every officer of the vessel if the offender is not punished.”

“I will see that the matter is investigated,” said Officer Tunley.

“Of course—but when? Why, in a week’s time, when everyone will have easily forgotten—no, sir, come at once.”

“I will do so; but allow me to suggest, Mr. Lawrence, that it may have been the extra bottle of Bass’ ale——”

“Do you dare, officer, to insinuate——”

“Nothing, save that Welsh rarebit, highly seasoned, and three bottles of strong ale, are likely to disturb the vision.”

“I’ll report you, sir—mark me, I’ll report you. Come, now, to my room, and if there is not a nigger baby there I’ll eat my hat.”

“Very well, sir, I will come with you.”

By the time the stateroom was reached, Jocko had fled the room, and Max had stripped the cap from its head.

The monkey sat on the table in the saloon, grinning, as if it enjoyed the joke.

The officer and Mr. Lawrence entered the stateroom.

“By Jove!” exclaimed Lawrence, as he looked at his bed.

“I was afraid you were romancing, sir,” said the officer, with proud indignation. “Take care, sir, that it does not occur again.”

The passenger was speechless.

Another day, when the steamer L’Orient was being[9] tossed about in the most fantastic manner, sometimes taking a swift pitch forward, then curving and twisting in a way which would bring joy to the heart of a baseball pitcher, Madcap Max thought the time had come for a pleasant diversion.

A drove of pigs, with other animals, was on board, to enable the company to provide fresh meat for the passengers.

Max quietly released the pigs from their quarters, and saw them, with one accord, make for the saloon.

That was just what he wanted.

A lady was tossed off her bed to the floor, but to her horror she fell on the back of a pig, who set up such a squeaking and squealing that, although the passengers were feeling sick, they were compelled to laugh.

After a voyage of fourteen days the city of Alexandria was sighted.

“Thank goodness!” exclaimed an old Indian nabob. “I am glad I have to stay at Alexandria, for L’Orient is the worst disciplined ship I was ever in.”

The verdict was concurred in by nearly everyone on board.

And yet it was not the officers’ fault, for nine-tenths of the trouble was caused by the pranks of Madcap Max.

“Do we land here?” asked Max.

“Yes, Max. We shall finish our journey overland.”

“Our journey?” repeated Max, opening his bright eyes still wider with astonishment.

“Yes, Max. We go to Cairo before we settle down at Alexandria.”

[10]

“I am so glad.”

Several scores of boats surrounded L’Orient, manned by swarthy and not too-much dressed Arabs; a dozen or so seized upon Max and his father and literally dragged them to a boat.

On the way from the steamer to the landing dock, Mr. Gordon whispered to Max:

“No jokes with these fellows, or your life is not your own.”

“All right, dad; I’ll be as sober as a judge and as full of fun as an undertaker.”

“For your own sake be careful.”

“I will, dad. That is, as careful as I can be.”

When the passengers landed, a rabble of donkey drivers met them.

No more clever, impudent little gossoons exist on the face of the earth than these same Arab donkey boys.

They hit upon the nationality of the stranger almost intuitively.

An American who had never been in Egypt before, was looking at the surging, struggling lot of donkey drivers with wonder, when one of them pushed forward and addressed him as follows:

“I’se looking for you, sah. Here he is; my donkey is[11] the one Pasha Grant rode on; him called ‘Yankee Doodle.’”

“Get away with yer. Can’t yer see the bey will only ride on Hail Columbia?”

Seated on a donkey, Max entered the city founded by Alexander three hundred and thirty-three years before the birth of Christ.

Before a strange-looking, square, flat-topped house the donkeys halted, and Mr. Gordon bade Max dismount.

“This is home.”

“Do you live here, dad?”

“Yes, Max. We will rest here to-night, and go on our journey to-morrow.”

Max was delighted, and late in the day wandered alone to that wonderful monolith of granite called “Pompey’s Pillar.”

He sat down to think.

He had always been fond of books on Egypt, and now he was actually looking on one of the wonders of that old country.

Suddenly he heard a cry.

It was like a girl’s voice.

Max was up in an instant and trying to locate the sound.

He had no difficulty in so doing, for a girl—her face half covered with a white veil—rushed past him, shrieking and crying.

“Allah! Allah!” she shouted.

Two men were in pursuit.

[12]

Max never stopped to think.

He leaped forward, and without knowing why he did so, or whether it would be wise to interfere, he struck one of the Arabs to the earth, and threw himself against the other, who was a strong, powerful fellow, with muscles like iron.

That did not worry Max, for he was lithe and strong, but he was unaccustomed to foul play.

When, therefore, he found that the man he had knocked down had risen and drawn a long, sharp dagger, with which he threatened his life, Max saw the unwisdom of his defense of the Arab girl.

A muscular Arab in front of him, and another at his back brandishing a dagger, was enough to frighten an older man than Max.

The Arabs jabbered away in a gibberish which Max did not understand.

He struck at the man in front of him and made him stagger back, then with a quick movement, he stooped as he turned and caught the armed Arab round the legs, throwing him over his shoulder.

He had not disabled his opponents, so he thought discretion better than valor. Using his legs as well as he could he ran away, only to be stopped by the girl he had—as he thought—rescued.

She flung her arms round his neck, and talking rapidly—though in an unknown tongue to Max—held him fast until his pursuers were close upon him.

With a wild shout they seized him, and would have[13] speedily rendered him insensible had not a deliverer appeared.

A man, bronzed and weather-beaten, though only in the prime of life, slowly and with deliberation took hold of one of the Arabs and flung him on one side.

Presenting a revolver at the head of the other, he commanded him and the girl to go, and that quickly.

“You have saved my life, sir,” said Max.

“Have I? Is it worth saving?”

“Perhaps not, but all the same I do not want to lose it.”

“Take care of it, then, and don’t go wandering about Alexandria without weapons.”

“What did they want with me?”

“They would have captured you, and held you until ransomed.”

“But——”

“You are not rich, you would say. What does that matter? A ten-dollar gold piece would seem a fortune to them. The girl practices that scream on hundreds of unsuspecting foreigners.”

“You speak of American money; are you from the States?”

“From them? Yes; but I am a citizen of the world, a cosmopolitan.”

“Might I ask your name?” inquired Max.

“You might; but it does not signify. If I have saved your life, prove that your life is of some value.”

The stranger left Max in one of the most frequented[14] streets of that city where Cleopatra often rode, attracting the admiration of all to the savage beauty of that

Max wondered whether the stranger spoke truly, and almost was inclined to doubt, for he was at that age when the laughing black eyes of a girl fascinate and lure, sometimes to ruin.

Anyway, he was thankful for having been saved from the Arabs.

He saw that night how much his father was respected, but he saw that which made his heart sad. His father was bowed down with grief.

And no wonder. He had loved his wife with a passion as strong as his love of life.

When they had left New York with Max, a boy of only eight summers of life, all had seemed roseate.

Leaving Max at a school in England, Mrs. Gordon accompanied her husband to Egypt; but at the end of three years the malarious climate had rendered it impossible for her to live there, and she returned to England to be near Max.

For seven years the husband had only been able to spend three months in the year with the wife he so loved.

Then came the time when once more the mother of Max was ready to brave the treacherous climate of Egypt.

How the husband had looked forward to that time, and[15] with what pleasure had he refurnished his house. Everything to please her was obtained.

Alas! her earthly eyes never saw them, and it was no wonder that Mr. Gordon should feel most wretched when he returned to his Oriental home, and knew that she would never grace it with her presence.

His only tie to life now was Max, but even with him there was anxiety, for the stern business man—the successful merchant had only seen the frivolous side of his son’s life.

To him he was the madcap.

To him the boy was the practical joker, the mischievous lad, whose thoughts were of fun and amusement.

Early next morning they took train to Cairo.

How strange it seems to the Biblical student, to think of traveling by a railroad in that country, so famous in Bible stories!

The comic rhyme of one who indulged in the ludicrous fancy of traveling by means of steam through Egypt and Palestine:

has come to be literally true, for Max heard the conductor shout out: “Gizeh—all out for Gizeh,” on the route between Alexandria and Cairo.

At the citadel of the narrow-streeted city, Mr. Gordon roused up, and told Max of the slaughter of the Mamelukes—that wonderful body of men who, from being slaves, became the rulers of Egypt.

[16]

“It was here,” said Mr. Gordon, “that when Mohammed Ali, in 1811, was organizing his expedition against the Wahhabees, he heard that the Mamelukes designed to rebel in his absence. He therefore invited their chief to be present at the investiture of his son with the command of the army.

“Above four hundred accepted the invitation. After receiving a most flattering welcome they were invited to parade in the courtyard of the citadel.”

“What for?” asked Max. “Did Mohammed want to impress them with his generosity?”

“No,” answered Mr. Gordon. “The Mamelukes defiled within its lofty walls; the portcullis fell behind the last of their glittering array; too late they perceived that their host had caught them in a trap, and they turned to effect a retreat.

“In vain.

“Wherever they looked their eyes rested on the barred windows and blank, pitiless walls.

“But they saw more.

“A thousand muskets were pointed at them, and from those muskets incessant volleys were poured.

“This sudden and terrible death was met with a courage worthy of the past history of the Mamelukes.

“Some folded their arms across their mailed bosoms, and stood waiting for death.”

“How brave!” ejaculated Max, in a low voice.

“Others bent their turbaned heads in prayer. But some, with angry brows, drew their swords and charged upon the gunners.

[17]

“It was of no avail. They were shot down, and the withering fire did its deadly work.”

“Did all perish?” asked Max, excitedly.

“Only one escaped.”

“How did he manage it?”

“Emin Bey—for that was his name—spurred his Arabian charger over a pile of his dead and dying comrades. He sprang upon the battlements; the next moment he was in the air; another and he released himself from his crushed and bleeding horse amid a shower of bullets.”

“What became of him?”

“He fled, took refuge in a sanctuary of a mosque, and finally escaped into the desert.”

“Is he dead?”

“What a question, Max! Emin was a middle-aged man at that time, and that is over seventy years ago.”

“Had he any sons?”

“I believe so. Why do you ask?”

“Because I would like to see any of his descendants. I would like to speak to them. It would be a proud honor to say, ‘I shook hands, or ate salt, with the grandson of Emin Bey.’”

“Why, Madcap, I never saw you so serious before!”

“Did you not, dad? Oh, I often get fits of that kind.”

Max laughed as he spoke, and seemed once again the merry, happy, careless boy.

“Depend upon it, Max, they are nothing better than slave hunters or pirates now.”

“I hope you are wrong, dad.”

[18]

The conversation about the last of the Mamelukes filled Max with a restless ambition.

He wanted to leave civilization behind him and go “far from the madding crowd,” into the midst of the wild residents of the Dark Continent.

Like those who believe the American Indians to be a grand race, persecuted without reason by the dominant power, so Max looked upon the residents of the Dark Continent as being a superior people.

He said nothing to his father, knowing well that his boyish ideas would be laughed at, but he spent all his waking moments dreaming dreams of the savages of the jungles.

The wonders of Cairo fascinated him, but there was something too civilized about the houses.

The lattices—which covered the windows instead of glass—pleased him, and many a time would he catch a glimpse of some white brow of a lady fair through the interstices of the lattice, and would feel like

It was to be his father’s last day in Cairo. All the wonders of the city—save the nearby pyramids and Heliopolis—had been seen, and these had to be left to a future[19] visit, for business called the merchant back to Alexandria.

Max pleaded for one more day—or at least that their journey should be deferred until the morrow.

He wanted to see that wonderful City of the Sun, where existed the university at which Moses was educated, and the daughter of one of whose professors Joseph married.

And so Mr. Gordon yielded.

Joyously the two passed by the venerable sycamore tree, hollow, gnarled and almost leafless, beneath the branches of which tradition says that Joseph and Mary rested with the infant Christ in their flight into Egypt.

The obelisk of Osertasen I., which has stood five thousand years, was gazed at by young Madcap with a certain amount of awe.

It was dark before Max was ready to return.

Instead of taking the nearest route to the city, Mr. Gordon, to please Max, dispensed with the guides who had been good for nothing save the receipt of backsheesh, and made a detour, leaving Heliopolis on their right.

They had not gone far before they came upon a number of wild-looking fellows, half Arab, half Nubian—a species of creature which is interesting as a study at long range, but whose acquaintance is not desirable.

“What shall we do, dad?” asked Max, anxiously.

“We must pass them.”

“Is it safe?”

“No, Max, far from it.”

“Then why not retrace our steps?”

[20]

“We have been seen and should be overtaken.”

“But could we not reach the men we feed so liberally?”

“We might, but they would help these fellows rather than us in order to share the backsheesh.”

While the two had been talking the Arabs had formed a circle round them, at a distance of fifty or sixty yards.

Gradually the circle diminished until the robbers closed in and stood shoulder to shoulder in firm and solid phalanx.

“What do you want?” asked Mr. Gordon.

“Money,” was the reply.

“You shall have all I have got with me.”

“Hand it over.”

Mr. Gordon was about to comply with the demand, but no sooner had he put his hand into his pocket than they suspected danger.

“No, no, by the beard of the prophet put up your hands!”

It would be just as feasible to try and sweep back ocean’s tidal waves with a broom as to oppose the demands of those robbers of the desert.

Mr. Gordon raised his hands.

“Now yours, also,” said the spokesman, whose English was intelligible.

Max raised his hands as he was commanded.

Every article of value was taken from them, and the robbers seemed to be satisfied.

“Sit down!” the chief commanded.

“What for?” asked Max.

[21]

But instead of receiving a reply he received a smart blow on the cheek which caused him to reel.

That was more than the boy could stand, and he answered the blow with another.

The chief interfered and stopped the fight.

“Sit down!”

Again Max pluckily asked:

“What for?”

“Because I order it, and I am the stronger.”

“Are you?”

“Yes; besides, I have men here who will do my bidding, even to the death.”

“Coward!” hissed Max, through his teeth, while his eyes flashed with defiance.

“Hush, Max!” whispered Mr. Gordon. “Do as we are bidden; it will be better so.”

But all the defiance of the boy’s nature was aroused, and he turned to his father almost angrily.

“You may, dad, you have lived here so long; but I am an American, and I will not obey such a command without knowing the reason.”

“You are a fool!”

It was the chief who spoke. Max could not stand such a speech, and he rushed at the strong Arab chief, aiming a blow which, had it struck the man on the temple, might have knocked him low, for Max was an expert boxer.

The blow only struck the empty air, and Max was caught round the legs and thrown to the ground.

[22]

A cord was quickly fastened round his ankles, and he was rendered powerless.

“What have you gained?” asked the chief, with a sneer.

“A knowledge of your cowardice,” answered Max, defiantly. “Frightened of a boy less than half your age. Oh! you are a brave chief, are you not?”

“Cease, you young fool, or I will gag you!”

“For my sake, hush!” whispered Mr. Gordon.

“Go on, tell us what you want,” Max said, bitterly.

“Monsieur Gordon, your wealth is well known. Send that young fool there”—pointing to Max—“with one of my men for twenty thousand piasters, and when he returns with it, both shall go free.”

Twenty thousand piasters is equal to about one thousand dollars.

“And if I refuse?” asked Mr. Gordon, nervously.

“He shall lose his tongue; it has already wagged too much,” answered the chief, pointing with his dagger at Max.

“But he cannot get the money.”

“Can’t he? Well, I can; and if you don’t send for it you shall die.”

Merchant Gordon knew not what to do.

He knew well enough that Egypt was overrun with bandits such as these, and that the authorities made but a poor pretense of suppressing the lawless bands.

He tried to temporize, but the chief was cautious. He knew he had wandered nearer to Cairo than was safe.

[23]

One of the men spoke in a low tone to the Arab, and instantly all was in commotion.

The two Americans were bound quickly and raised to the back of donkeys.

The whole gang of robbers mounted and hurried away from the vicinity of the city at a speed that Max could not believe a donkey was capable of maintaining.

But the wild tribes of the Nile have long possessed the secret of making the native donkey forget its natural laziness and go with the speed of a well-trained mule.

“Where are we going?” asked Max.

He was answered by a slap across the face, which nearly capsized him.

“Another word and the body of the American shall be but carrion.”

“Don’t speak, Max,” entreated Mr. Gordon, who was trembling with fear.

The chief led the way across a sandy desert.

The moon shone brightly, and its rays made the drifting sand look like so much dazzling silver.

It was a scene of weird grandeur.

In the distance rose the pyramids, those monuments of a past civilization, which are alike the envy and the wonder of the world.

The procession seemed to be winding round the city at an increasing distance, and nearing the pyramids.

Max forgot all fear and was oblivious to any danger.

The scene was to him one of rare beauty, and he enjoyed it.

[24]

If he could but have talked to the chief—if he could have been free, his happiness would have been complete.

But he was a prisoner, mistrusted and abused.

He dare not speak, and could not act.

Before he was aware of it the scene changed.

He could not understand in what way at first.

The sand was there, the moon was shining, although not so brightly, but he could not see the pyramids.

The shadows thrown across the desert convinced him that they had entered a broad, inclined road, and were descending below the level of the sandy desert.

Of this he was speedily assured, for now the moon’s rays were no longer seen, and in the darkness the sure-footed donkeys walked forward.

Instead of a level plain of drifting sand, the road was over and between great rocks.

Massive pieces of granite, several tons in weight, had to be passed, and it was evident that the donkeys had frequently traversed the uncertain road.

“Where are we going?” whispered Mr. Gordon.

His voice sounded like a shout, although he had spoken under his breath.

The stillness of the place was awful.

Max felt his heart beat fast and then faster.

He began to think that the road he traveled led to death.

But when his thoughts were the most gloomy, the atmosphere seemed to change.

He could breathe freely.

[25]

There was still the same oppressive silence, but it did not seem so much like that of the grave.

“Halt!”

The command was given in English, and all understood it.

Without a word of apology, and with an entire absence of ceremony, Max and his father were dragged from their donkeys and thrown with unnecessary violence on the ground.

Then again all was still.

Were they alone?

Max could not endure the silence any longer.

“Dad!” he called out.

A blow on the head reminded him that speech was forbidden.

What puzzled him was how these Arabs or Nubians—whatever nationality they might be—could see in the dark.

He could not distinguish anything in the blackness of the night.

The minutes dragged along wearily, every sixty seconds seeming like an hour, every hour as long as a day.

With an almost supernatural quickness a score of pitch torches were lighted, and Max saw that he was in a great cave.

Rocks, or rather pieces of granite, were lying in every direction.

One thing which flashed across his mind was, that the blocks of granite had been fashioned by man, and[26] brought to that cave at some period of Egypt’s greatness.

He looked round for his father, and screamed with horror when he saw the bronzed face of the only relative he had all covered with blood.

When Mr. Gordon had been thrown from the donkey, his head struck a sharp piece of granite, and was severely wounded.

The chief saw that Mr. Gordon was dying, and ordered him to be lifted tenderly into the center of the cave.

Max tried to rise, but unknown to himself his feet had been again tied together.

“My father! Oh, dad, speak to me!”

The dying man turned his eyes round and a smile was on his lips.

“Max—I—am—going—av——”

Was he going to say “Avenge me?”

Max never knew, for a cloth was stuffed into the dying man’s mouth, and the bandits commenced a wild, weird dance round the body.

Mr. Gordon turned his eyes in the direction of Max and tried to speak, but either the cloth still prevented him or his voice was hushed by the great shadow of death which was over him.

A convulsive shudder, and the American merchant’s soul had gone into the “Great Beyond” to join that of his loved wife.

Max knew he was now alone.

He could not weep.

His eyes were hot as burning coals.

[27]

If only the tear-drops would start, he felt that they would ease him; but no, his eyes were dry and his brain seemed scorched.

His tongue began to swell, and when he tried to speak it appeared to fill up his mouth.

The torches were extinguished, the place became quiet, and instinct told him that he was alone—alone with the dead.

Not a sound disturbed the silence.

A horrible thought passed through his burning brain.

“What if he were left there to starve to death beside his father’s body?”

Madcap Max was not a coward.

He had no real fear of death, but he would rather meet the great destroyer on the open field, or in any way but that slow struggle in the solitude of a big grave—a death from starvation.

The strongest soul would quake.

The hours passed along.

Time’s chariot wheels continue to revolve no matter who may wish to stay them.

Max began to think of other things besides death.

He wondered how he could escape. And if he did, how could he avenge his father’s death?

Weary and exhausted, Max at last fell asleep.

Youth had conquered.

Had he remained awake an hour longer he would have been a raving maniac.

Youth asserted itself, and “nature’s sweet restorer, balmy sleep,” came to his relief and saved his reason.

[28]

Max slept soundly, and for hours did not dream.

When the visions of the night visited his brain, they shaped themselves in pleasing form.

He saw again the massacre of the Mamelukes, but the sight seemed stripped of its hideousness, and it appeared to Max that the foul murder committed by Mohammed Ali was necessary—that from that murder would spring the regeneration of Egypt.

Max saw the flight of Emin Bey, and fancied that the brave Mameluke still lived, and was at the head of an all-conquering army, overcoming French and English and Turk, and proclaiming the freedom of Egypt from foreign rule.

And as all this passed before the mental vision of the sleeping American boy, he thought that by the side of the conqueror he rode—not as he was then, a beardless youth, but with bronzed face and flowing beard—a turban on his head, and the sacred carpet of Mohammed carried by his side.

Then his vision changed, and he saw his father, not dead, but living, and successful as a merchant. By his side was the wife whose love had been so lavishly given to her husband and her son.

The sight of his father and mother brought tears to the dreamer’s eyes, and caused him to wake.

[29]

It was some time before he could bring back to his memory the events of the preceding day.

When they recurred to him he felt most wretched.

Had the bandits removed his father’s body, or was it still in the cave?

Could he not snap the cords which bound him, and escape from that living tomb?

“Hush!”

Was that a human voice, or only the playful prank of a gust of wind?

Max, madcap as he was, had learned wisdom.

He was not going to fall into any trap, and so he did not speak.

“Son of the morning, thou wilt die.”

“Am I dreaming,” Max wondered, “or have I gone mad?”

He raised his head, but his eyes could not penetrate the darkness.

“Confound it!” he muttered, “this is Egyptian darkness with a vengeance.”

“Dost thou want to die?”

The question came out of the darkness and sounded afar off, yet Max could almost fancy that the breath of the speaker fanned his cheek.

“Who is that speaks?”

“Question not my name.”

“Where am I?”

“In the depths of the storehouse of the great Gizeh.”

The answer was given in a low voice, almost as soft as a whisper.

[30]

“Am I then under the pyramid?”

“That is how thou wouldst express it.”

“Will you aid me to escape?”

“And thou wouldst destroy those who saved thee.”

“Nay—thou art a woman.”

“Wah Illahi sahe!”

(By Allah, it is true.)

“I would not harm thee.”

“I can save thee if thou wilt swear by the beard of the prophet that thou wilt not seek revenge.”

“The price is too great.”

“And if thou refusest, death will be thy portion.”

“Better death than dishonor,” said Max, in a grandiloquent tone, which sounded almost ridiculous in the dark, but which would have been the signal for a burst of applause from the gallery of a theater had an actor so uttered the words on a stage.

All was still as the grave.

He fancied his ankles and wrists were swelling as the cord cut into the flesh.

His brain began to reel, and he almost wished for death.

“Am I to die like this? Oh, it is horrible!” he moaned, aloud, as the agony of the thought took possession of his mind.

“Help!”

He shouted and the echo of the vault answered back mockingly:

“Help!”

[31]

He shouted again, but the only reply was the faint echo of his words.

“I shall die,” he groaned.

“Die,” said the echo, with taunting emphasis.

His brain became frenzied, and he began to laugh with boisterous guffaws.

It was the laughter of delirium and not of mirth.

The echo answered back.

The whole cave seemed peopled with laughing demons.

“Fiends!” he shouted, and his head fell back with stunning force on the rock.

When he recovered consciousness, a calmly sweet breath of air was blowing on his face.

He was being fanned.

He dare not speak for fear that the delicious breeze might cease.

The fanning continued until at last he could bear the silence no longer.

“Thou art an angel!” he exclaimed.

“I know not what thou meanest. If I am thy houri, wilt thou follow me?”

“I will.”

By some means a pitch torch was lighted and in its glare Max saw the horrible cave to which he had been removed by some unknown hands.

Skeletons and mummies, rude stone sarcophagi, and blocks of red granite in endless confusion.

But in the circle of light made by the torch he saw—

A girl.

[32]

She was not what the fashionable world would call lovely.

Her skin was dark, her hair was black as a raven’s wing.

Over her dark tresses a silver band encircled her head, almost like a halo of glory.

Her limbs were bare to the knees, but round each ankle was a massive band of silver similar to those she wore on each arm above the elbow.

Her dress was of a gauzy tissue and Max could scarcely believe but that it was a phantasm of the mind which was before him, and not a living entity.

She smiled and waved her torch as a fairy queen might her wand, and in a voice of rare sweetness said:

“If thou wouldst save thy life, follow me.”

“I am bound,” answered Max.

Two rows of shiny, white teeth were shown as she pointed laughingly at the severed cords, and again she said:

“Come! Follow me!”

“To the death,” answered Max, forgetful of all danger.

“Come, and thou shalt be one of my people.”

The houri took Max by the hand, causing a strange thrill to pass through him.

“Be not afraid,” she said, as she extinguished the light.

“With you, never!” answered Max, gallantly.

And Madcap Max followed in the dark the strange[33] creature who had found him alone and suffering in the cave beneath the great pyramid.

Followed! But where?

With the greatest confidence in the strange Arab girl, Madcap Max followed her, without asking any question until she suddenly extinguished the torch.

“Why did you do that?” he inquired.

The girl did not answer in words, but dextrously placed her hand over his mouth and held it there so tightly that Max could scarcely breathe.

He struggled to release himself, but she was strong, and to add to her power, she whispered:

“Get free and I’ll kill thee!”

However disagreeable it might be it was better to have a pretty girl’s hand over his mouth than to be killed, and therefore Max made no further resistance.

A slight noise, like the dropping of water on rocks, attracted his attention.

“Do you hear that?” asked his guide.

“Yes; what is it?”

“Hush! Speak in whisper only. Thine enemies seek thee.”

“And if they find?”

“Will kill. I will save, if——”

[34]

“What?”

“Thou hast courage. Come, then, hold to my dress and follow. The least noise may seal thy fate and mine.”

“Who art thou, mysterious one? What is thy name?”

“Name, as thou wouldst say, I have several; to thee I am Girzilla. Let that be my name.”

“I will call thee Gazelle.”

“No, no, no. Girzilla, or nothing at all. Come.”

Whoever the girl with the strange name might be, she evidently knew her way, for never once did her foot slip, although Max found his ankles turning every minute, and had he not a firm hold on Girzilla’s dress, which, though of gauzy linen, seemed as strong as a hempen cord, he would have fallen frequently.

“Sit down!”

The words were uttered very abruptly, and were in the nature of a command.

Max did as ordered, and sat in silence—a silence so great that he could hear the beating of his heart, and fancied that he could also distinguish the pulsations of his guide’s organ of life at the same time. The silence was almost unbearable, and Max grew fidgety and restless.

“I have got into some queer streets before this, but I confess this is the strangest,” he mused.

“To save thee, thou must go through the place of the dead.”

The voice was that of Girzilla, but it sounded so sepulchral that Madcap Max felt a cold shiver pass over him.

[35]

“Hast thou courage?” she asked.

“I—h-have,” he stammered, his teeth chattering with nervous fear of the unknown.

“Come!”

Once more the journey was resumed, and Girzilla walked slower than before.

Suddenly Max got such a rap on the head that it made him groan with pain.

“Stoop. Better still, crawl,” said the girl, almost contemptuously.

Max felt humiliated, but he was in a quandary.

He could not go back, for he did not know the way, and he dare not go forward alone, for he was afraid.

Girzilla seemed to read his thoughts, for she laughed softly and murmured:

“Poor boy! He will have to trust his Girzilla; she will save him.”

Stooping until his head was only a few inches higher than his knees, he followed as well as he could.

Very soon the way became easier to travel, and a glimmer of light showed that the sun had risen again, and found some crevice through which it sent its heavenly rays.

Gradually the light increased, and the road became better.

The sand was so hot, however, that Max felt the shoes on his feet drying up, and even baking.

He resolved to remove them, and the hot sand blistered his tender feet.

[36]

High up above him was an opening, through which the light and heat came.

“If one of thy enemies shouldst see thee, a little stone from there”—and Girzilla pointed upward—“would make thee fit for a mummy.”

Again the spinal marrow in Max’s back seemed turned to ice, and he was almost afraid to glance upward.

“Where are we?”

“Under the temple of great Isis.”

“Under?”

“Yes, Isis had the temple high above where thou dost stand.”

“Lead on; I would know more of these mysterious passages, but I am hungry and cold.”

“Just now thou wert hot.”

“Yes, I am chilled and yet feverish.”

“Come, my gentle boy, and Girzilla will take thee where thou canst rest.”

A few yards and a sudden turn, and the narrow passageway gave place to a large plateau, on which huge bowlders were scattered promiscuously.

Scattered—apparently too large for human hands to move, and yet they bore evidence of having been transported thither.

They were of red granite, while the native rocks were of a different stone.

Max, tired and weary, sat down on one of the granite blocks, but he quickly left his seat.

He leaped away as though he had been stung by a viper.

[37]

Girzilla laughed at him, which of course added to his annoyance.

The stone was as hot as an oven bottom, and poor Max felt he would be baked or fried if he stayed there a minute.

Girzilla moved round one of the great bowlders and began scratching away the sand.

“Come and help,” she called out to Max, who was sulking since she had laughed at him.

“The way we must go is under this stone.”

“Under that stone!” repeated Max.

“Yes; there is only a small hole, but we must go through it.”

The girl was right.

The hole was so small that she could only just squeeze herself through, while the madcap declared he would not descend.

“Very well, then, you must save yourself.”

The prospect was not pleasing, and Max managed to follow the girl, though in doing so he tore his clothes and scratched his face.

But once down, he was amply repaid.

The cave, or hole, led to a large room, the atmosphere of which was charmingly cool.

Girzilla had lighted her torch, and seated herself on an open sarcophagus.

She was a happy-go-lucky kind of creature, fearing nothing, and having no superstitious dread of sitting on the stone coffin, wherein was dust, which had once been molded in human form.

[38]

“I have food here.”

“Food?”

“Yes.”

“Here?”

“Yes; art thou not hungry?”

“I am. But the place is a tomb.”

“Hush! Better men than thou lived here.”

“Have been buried here, you mean?”

“Years and years ago a brave man fled from those who would kill him, and sought refuge here.”

“Tell me of him.”

“He fought—oh, my, didn’t he fight? He cut right and left with his scimiter, and when he got tired he spurred his horse and made a run for liberty.”

“Did you know him?”

“Stupid! do I look so old, then?” and Girzilla looked coquettishly at Madcap.

“I don’t know how long it is ago; how should I?”

“Don’t get naughty again. The man was a soldier, a Mameluke——”

“What! Was it Emin Bey?”

“That was how he was called.”

“Tell me all about him. Where did he go? Had he any sons? Tell me, I am all impatience.”

“I see you are; but you must eat.”

This houri of the caves—a strange child of the desert—pushed aside the lid of another sarcophagus and took therefrom a piece of confection known as Turkish delight.

She offered it to Max, but he turned away.

[39]

Girzilla bit off a large piece and sat chewing it with all the ardor with which a Kentucky girl chews gum.

“Good!” she said, as she helped herself to another bite.

Approaching close to Max she held the confection close to his mouth, and he was tempted to take a small piece.

It was so appetizing that he asked for more.

When the gum candy was all eaten Girzilla found some bread—cakes baked in the sun, not in an oven—and some fruit, but what kind it was Max did not know.

He ate heartily and felt refreshed.

But he was thirsty.

Girzilla knew that, and produced a bottle of the most delicious sherbet he had ever tasted.

When the repast was finished Girzilla told Max that he must stay there until she came for him.

“Am I to be here alone?”

“Certainly. I must go and provide a means of escape for thee.”

“Tell me first why you have done all this for me.”

“I have my reasons.”

“And will you not tell me?”

“I heard thee speak to him who is not——”

“You mean my father?”

“Yes.”

“When?”

“When thou didst tell him that thou wouldst like to eat salt with the sons of Emin Bey.”

“And are you interested?”

[40]

“I have Mameluke blood in my veins. Find the descendant of Emin and he will restore Egypt to its greatness—I have said it, and the prophet hath spoken.”

“And will you help me?”

“If I can. I—had—another—reason——”

Girzilla hesitated, paused between her words, looked confused, and really blushed.

“And that was——” asked Max.

“Why should I not tell thee? I will save thee, even though I lose thee. I will prevent thy enemies taking thee, even if thou spurned me ever after. Oh! how shall I say it? Thou art the handsomest man I ever saw, and—I—love—thee.”

Before Max could recover from his astonishment she had fled.

Her secret had been revealed, and, modest maiden as she was, she felt she could not meet the eyes of the youth to whom she had confessed her love.

When Madcap Max felt that he was a prisoner, and that self-interest, at least, for a time, rendered it inadvisable to attempt to escape, he began to look about his strange abode.

Girzilla was more than ever a puzzle to him.

She was refined and educated—of that there could be no doubt.

[41]

She had said she had several names, but only one had she given him.

What did the word mean?

It had some special significance—of that he was sure.

Was it Arabic or Nubian? Was it of the ancient language of the Pharoahs, or the almost as ancient Syrian?

How did she overhear his conversation about the Mamelukes?

“I begin to think she is a fairy,” said Max, his head growing dizzy with puzzling over the matter.

“How long am I to remain here?”

There was no one to answer the question, so it had to remain still in the realm of doubt.

“Where am I?”

That query he could answer with a positiveness that could not be controverted. He was in a tomb.

At first the thought nearly drove him mad, but he got accustomed to the idea. After eating and drinking there, much of the superstitious fear had left him.

“Where shall I sleep?” he asked himself, “for I am tired and exhausted. The sand man has been about a long time,” he laughed; “yes, sand in my eyes, up my nostrils, down my throat, in my ears—the sand man has done his work this time. What was that?”

Max possessed a splendid amount of courage, but to be alone in a tomb and suddenly to hear a terrible noise, and to be nearly suffocated with dust, to have the torch knocked over—fortunately not extinguished—would be sufficient to set the strongest nerves quivering, and make[42] the most valiant man tremble. He dare not raise his head.

He was afraid to open his eyes.

Had he done so, he would have known that the commotion was caused by a huge bat trying to escape from the inhabited tomb.

Nearly an hour passed before Max found courage enough to lift up the torch, which had nearly burned itself out.

If his torch went out, what was he to do?

He was far from being a madcap at that time.

But youth asserted itself, and Max found his spirits rising, perhaps aided considerably by his eyes suddenly perceiving another torch.

“I’ll have a gay old time. Why shouldn’t I? Eh, old fellow?”

Was Max addressing himself or one of the mummies in the place?

He lighted the torch, and began to look round his prison house.

On the walls—which had once been smoothed by sculptor’s skill—were the remains of paintings and hieroglyphic inscriptions.

“These old fellows believed in having their tombs beautiful!” exclaimed Max, aloud.

And the words had scarcely left his lips when his hair began to rise on his head, for he heard a voice add, with sepulchral emphasis:

“Beautiful!”

[43]

“Who’s there?” asked Max, half afraid of his own voice.

“There!”

“It was only an echo,” said Max; but all the same it was startling, especially when the voice of the tomb repeated the last syllable:

“Oh!”

But the sturdy young American laughed; and the whole tomb seemed alive with demoniac mirth, as the walls beat back the loud guffaws of the youth.

“I shall go mad!” exclaimed Max.

“Mad!” repeated the echo.

With wonderful courage Madcap Max remained silent for a time, afraid of the echo, and yet not afraid to continue his search.

Close to the place where Girzilla had kept the eatables was a sarcophagus, which seemed as if it had not been opened.

Here was something to do.

He resolved to open the stone casket.

The work was easier than he anticipated, for the lid was not fastened down, and Max was able to push it on one side.

He brought over a torch so that he might the better look into the huge cavern-like coffin.

When he did so he saw a mummy; the face, outlined by the cloths, was that of a woman.

“Who can it have been?” he wondered.

And then, with a pure love of fun, he resolved to unwrap the body, which may have been hidden from[44] the world two or three thousand years, and present the mummy to his strange girl friend.

Max was now in his glory.

He had something to do, and at the same time his spirit of mischief was aroused.

He never imagined that Girzilla would be frightened if she entered and saw a mummified Egyptian looking at her.

It would be fun to watch her countenance. And that was all that Max did it for.

He managed to get the first wrapper off very easily, but when he came to the second, he found that the ancient Egyptians knew how to make a strong bandage, for every fold had to be cut with his knife.

Under this he found spices, lotos leaves and ears of corn.

The latter interested him, for while the grains looked like wheat, the general appearance was that of barley, only there were seven ears on every stalk.

“I’ll pocket some of this, and if ever I get back to America I’ll plant it and see if embalmed wheat will grow.”

As this thought passed through the mind of the daring young desecrator of the dead, he began to whistle “Yankee Doodle.”

The echo kept pace with him, and the louder he whistled the more distinct was the echo.

Suddenly stopping, his patriotic soul was stirred to its depths as the thought crossed his mind that men who had been buried there thousands of years before America[45] was known to civilization were, through the echo, joining in the chorus of “Yankee Doodle.”

“Old Pharoah was a fine old fellow,” said Max, “but I’d rather be an American citizen than——”

“A mummy.”

That was no echo.

It was a human voice.

Max could stand no more.

His eyes seemed like coals of fire, his brain was burning, his lips were parched.

“Oh, God! I am dying!” he gasped, as he fell on the floor, scattering the dust of centuries and causing the tomb to be filled with a cloud, suffocating and unpleasant.

When he recovered consciousness he was still lying on the floor, but his head rested on Girzilla’s knee, and she was fanning him with a palm leaf which she had brought in with her.

“You silly boy, did I frighten you?”

“Was it you who said ‘a mummy?’”

“Of course it was. Who else could it be?”

“I thought——”

“That these dead-and-gone people had suddenly recovered the voice which perished before Isis’ great temple was built. You silly—silly boy. But what were you doing?”

There was so much nineteenth century life about Girzilla that Max thought but little of the bygone Pharoahs.

He told her about unwrapping the mummy, and she chided him for doing it.

[46]

“I have looked on that mummy ever since I was so high,” she said, placing her hand about two feet above the floor.

“You have!”

“Of course I have, and I was going to show her to you.”

“You were?”

“Did I not say so?”

“Yes.”

“Then why ask me? What did you do with the writing you found?”

“I did not see any.”

“I placed some there.”

“When?”

“The Nile did rise and fall and rise again since I placed it there.”

“Where did you find it? What is it about?”

“I don’t know; I could not read it.”

“Get it for me.”

“You silly boy, how can I? Your head is heavy, and holds me down.”

“My head resteth on a nice pillow.”

“Osiris must have fanned thy cheeks,” she said, using an Egyptian metaphor which in more modern English would mean: “You are a flatterer,” or “You have kissed the blarney stone.”

Max was not so gallant as an American youth ought to be, so he sprang to his feet and reached over into the casket, drawing therefrom a package of papers which were decidedly modern.

[47]

The language was a strange one to him, however, and his only hope was that once away from the strange tomb he might find some one who could translate the document for him.

He had become an ardent Egyptologist.

“We will leave here at once.”

There was a sadness in Girzilla’s voice as she answered:

“And art thou tired of the houri of the cave?”

“Not tired of you, Girzilla, but I want freedom. I must search for Emin’s race.”

“Yes, yes. Fate wills it. Isis must be obeyed. Ra”—god of the sun—“ordains it. And Girzilla’s heart must be rent in twain.”

“Why so? Art thou not my guide? Shall I not restore thy family to the powerful throne?”

“I am not deceived. You of the great storehouses care not for my people.”

“But——”

“Nay, thou silly boy; the sun does not mate with darkness. Girzilla will take thee from thine enemies and will return to the tomb.”

“You are sad.”

“Did I not look upon thy face when it was sad?”

[48]

Max sat down on a broken sarcophagus, and hot, scalding tears poured from his eyes.

She had recalled to him the death of his father, nearly a week ago.

A veil of oblivion had been over his senses, and he had not been able to weep.

The tears eased his heart and soothed him more than any other thing could have done.

Girzilla, with womanly tact, withdrew and let him weep, for she knew the value of tears to the sorrow-stricken.

Truly, this girl was more than ever a mystery.

With the simple innocence of her race she looked upon herself as the consoler of the bereaved one, because she had been present when his eyes first opened to the great sorrow.

When his grief had subsided, Girzilla was transformed.

She was no longer the lively girl, but the stern guide.

“Follow me,” she said, coldly.

“Nay, stay a while.”

“Why should I? Does not the Frank desire to be free?”

“Thou knowest I do; but I have not yet explored this tomb.”

Girzilla raised herself to her full height; her eyes flashed with scorn, her little hands were clinched tightly, causing the muscles upon her arms to distend until the silver armlets must have cut into the flesh.

Her face was crimson, her body trembled with excitement.

[49]

“Explore! Yes, you Franks come to my land and carry away its images, destroy its old ruins, ransack the temples, overthrow the gods, and, not satisfied with that, dare even to desecrate the tombs!”

“You brought me here,” pleaded Max.

“I brought thee to save thy life. I brought thee, even though I knew I might die in thy place.”

“What mean you? Are you in danger?”

Girzilla laughed bitterly.

“Danger!—how silly you are!” And then, changing her manner, she added: “Have you any sense? Do you Franks ever think? I know these men who brought thee here. I know that they would take all thy gold and slit your nose—that they would slowly kill thee. Like the bird of prey looking for its victim were they. I saved thee—wilt not the vulture turn upon me? Thou knowest I shall die if I am caught.”

There was an eloquent, passionate fervor in her manner which seemed to raise her from the apathetic lazy Egyptian race and elevate her to the level of the American.

Max was about to speak, but like a queen she motioned him to be silent.

“I have been here since I was so high”—again measuring two feet from the ground. “Did I ever take the sacred bandages from the bodies of the embalmed? Never. And yet thou couldst not be alone an hour without desecrating the dead. Isis will punish thee—Osiris will return and claim his own.”

Max listened.

[50]

He was charmed.

What a splendid actress this girl would make!

What a magnificent woman she was!—and yet in years she could be only a girl.

“You speak of Isis and Osiris as though you believed in them,” Max ventured to say.

“My belief is my own. If thou wouldst escape—if thou wouldst find the son’s son of Emin, get thee ready and I will lead thee to the desert, the way that Emin traveled.”

“Lead me from here and I will ask no more.”

“Thou art a Frank! Thou askest me to risk all, and when thou art safe I may go.”

She turned away her head to hide her tears.

Going to a secluded part of the cave she took from a sarcophagus a scimiter with edge as sharp as any razor, a knife with double edge, keen as a dagger, and a small stiletto.

These she handed to Max.

“They may be useful,” she said, coldly, and prepared to leave the cave.

“Come, and quickly.”

“I have offended thee——” Max commenced, but Girzilla had scrambled through the opening, and could not hear what he was saying.

She led him across the burning sands; at every step his feet seemed to be blistering. There was no shade save from the great bowlders, and they were so hot that it was unpleasant to approach them.

[51]

On she went, keeping in advance of the American.

Not one word would she utter; and when he attempted to speak she motioned him to be silent.

It was like a new country—a land without inhabitants.

Where were they?

So near, as it seemed, to the city, and yet not a living thing to be seen.

Hour after hour they walked, blinded by the drifting sand, but never stopping.

Max would not ask Girzilla to rest, and she was too proud to suggest it.

The sun was high in the heavens.

The air seemed like the hot blast from a furnace.

Max found his tongue swelling in his mouth.

He walked along mechanically.

All control over himself appeared to be lost.

Like the fabled Wandering Jew, he continued moving, without the power to stop.

His eyes no longer saw the sand—they were hot and glassy with the glare of the sun.

Still he kept on, following that never-tiring figure in front of him.

Suddenly his foot slipped into a little hole, and he fell.

That was more eloquent than words.

Girzilla was by his side in a moment.

A little leather bottle she carried was unslung, and some water was poured down the youth’s throat.

She had resolved not to offer her aid, but now, when he was helpless and suffering, she could not resist.

[52]

She bathed his face, and fanned it so that the skin might not blister.

He was unconscious.

“He is dying,” she moaned. “And I cannot save him.”

Her bare arms and ankles seemed impervious to the heat—she was accustomed to it.

“Oh, if Jockian were but here!” she moaned; but the man she referred to was many miles away.

“I will try.”

The speech was in answer to her thoughts.

Removing the armlets from her arms, she stooped over the prostrate form of Madcap Max, and raised him as if he were a child.

Strong she undoubtedly was, but Max was heavy.

She carried him a few steps.

The perspiration ran in streams down her face.

The muscles of her arms were strained to their utmost.

She had to rest.

Again she raised him, and carried him a dozen yards or so.

It was but slow progress, but she knew he would die if she left him there.

She tightened the girdle round her waist, and again took him in her arms.

But her strength gave out.

She fell with her burden on the hot sand.

Exhausted herself, yet she would not give up the battle.

She worked like a slave, making a hole in the sand.

[53]

The blood spurted from her fingers, but she kept on until she had scraped away the sand a foot deep.

Into this hole she rolled Max.

The sun was pouring its hot rays with deadly vehemence, but Girzilla cared not, if Max were but safe.

She looked for something to shelter him.

Nothing could be seen.

With splendid devotion, she took off the loose linen blouse which was the only covering of the upper part of her body, and sprinkling it well with water, laid it over the youth’s face.

Her own skin, almost as fair as that of the American, was exposed to the torture of the heat.

The thermometer must have registered a hundred and fifty degrees, but Girzilla merely clinched her teeth and waited.

She had placed herself in a position between the sun and Max.

Hour after hour this child of the desert, this magnificent heroine, shielded the American from the rays of the Egyptian sun.

Her own shoulders were bare. The sun blistered her skin. A slight breeze, but as a furnace blast, swept across her, but it carried myriads of sand flies and atoms of sand with it.

The flies settled on her bare shoulders; they attacked the blistered flesh.

The pain must have been intense, but she never moved.

Once she shrieked with agony and resolved to rise,[54] but a look of self-denying heroism crossed her face, and she remained still.

“If I move they will attack him,” she thought, and that was enough.

He must be saved at all costs.

Her senses were leaving her, gradually her thoughts became more indistinct.

She fell forward across Max, and knew she must die.

But if it would save him, she was satisfied.

She stretched forth her hand and placed it on his forehead.

Her garment was still there, shielding his face from the sun.

“He will be saved,” she said. “Allah be praised,” she moaned.

“Allah! Allah! Great is Allah, and Mahomet is his prophet.”

The speaker had spread before him a square of carpet, and had prostrated himself, bowing before the setting sun.

“Allah be praised!”

The prayers were ended, but the man remained prostrate on the carpet.

In the distance a score of men stood, evidently waiting for their chief to rise.

[55]

When his devotions were concluded he stood up, looked in the direction of the setting sun, bowed his head once more, and sat down on the sand to put on his sandals.

The man was evidently an Arab of high rank.

Dressed in white, his face partly covered, after the manner of the chiefs of Arabia, he presented a most picturesque appearance.

Several of his escort, or guard, came forward and folded up the carpet, placing it with great care on the back of a camel, which had been brought forward.

The chief—Sherif el Habib—walked away from his servants, his companion being a youth, fair as a girl, but strong as a lion.

“Ibrahim, my heart is sad,” said Sherif el Habib to the youth.

“Sad! and why so, my uncle?”

“For all these moons have we journeyed, but mine eyes have not seen the glory of his coming.”

“Uncle, you did not expect to see the Great One at Cairo?”

“And why not?”

“Methinks the eyes of the houris as they peer through the lattices would spoil even the prophet’s mission,” answered Ibrahim, smiling, as he uttered the words.

“Those eyes were nearly thy ruin. But hath not the holy prophet spoken of the Prophet of prophets, who should come and restore the ancient glory of Egypt, and after visiting Mecca, plant the banner of the crescent and Mahomet in every land?”

[56]

“But why do you think he has come now?” asked Ibrahim.

“In a vision of the night I heard the voice of Mahomet say out to me: ‘Arise, Sherif el Habib; cross thou the sea and go as I direct thee, and thine eyes shall see the glory of the last imaum’—leader—‘the rise of the Mahdi of whom I spake.’”

“So, uncle, we made a pilgrimage to Mecca, crossed the Red Sea, wandered about these deserts for months, deserted the towns and left the pretty girls—I beg pardon—all because of a dream.”

“You young men,” said Sherif el Habib, “are material. Is there nothing better than making shawls?”

“There may be; I like to travel. I would like to go to Alexandria, to Constantinople, to Paris, London. Oh, uncle, you are rich; give up these dreams, and let us enjoy life.”

“Ibrahim, how old are you?”

“Eighteen, uncle.”

“And I am sixty-eight. Wait but a few more years and all my wealth will be thine; then thou canst journey whither thou pleasest. But I have a mission. When I go down to the grave of my fathers, my soul will have seen the light of great Mahdi’s face.”

It is believed by devout followers of Mahomet that before the end of the world there shall arise a mahdi—literally, a director who shall be of the family of Mahomet, whose name should be Mahomet Achmet, and who should fill the world with righteousness. For six[57] hundred years the Mohammedans have been expecting their messiah to appear.

“As thou wilt, uncle, but——”

Ibrahim’s speech was cut short abruptly by the hurried salaam of Effendi, the Sherif el Habib’s confidential eunuch and secretary.

“What is it, Effendi?”

“Your excellency! I know not, but a young and beautiful girl hath fainted, and with her——”

“Who is she?” asked Ibrahim. “Lead me to her!”

“Nay, nephew, it is not fit that thou——”

“Go along, uncle; when I am your age I shall do as you do. Go along, I care not for all the girls of Egypt.”

Sherif el Habib had not heard all the boy’s speech, for he had hurried away with Effendi.

The eunuch led him across the sands to the place where Madcap Max had fallen, and over him the girl, Girzilla.

Sherif el Habib looked at the youthful couple, and seemed strangely disturbed.

He stooped and placed his hand over their hearts, and found that both were alive.

“It is well,” he said, in a half-audible voice. Then, turning to Effendi, he motioned him to follow.

Going to his camel, Sherif el Habib took from the pack a small bottle.

On the side of the vial were some hieroglyphics which, if translated into good United States language, would signify that the contents were known to be that strange result of modern research, chloroform.

Giving the bottle to Effendi, Sherif el Habib said:

[58]

“It is my will that these people should go with us in a sleep as of death; do thou with this as is usual.”

Effendi took the vial, and pouring some of the contents on two pieces of linen, he returned to the Arab girl and Max and placed the linen over their mouths. When the fumes of the chloroform had done their work effectually he called some of the attendants, and ordered them to place Max and Girzilla on the backs of camels.

“It is done,” he said to Sherif el Habib, making a low salaam.

“It is well,” was the chief’s answer.

Effendi moved away, leaving his master and Ibrahim alone.

“What new fancy has taken possession of you, uncle?”

“The glory of the great Mahomet surrounds me,” was the reply.

“If I were not the most loving of nephews,” said the youth, “I should declare that you were mad.”

“My dear boy, for years I have hoped for a vision of the celestial, and now mine eyes have been directed to the approach of the great mahdi. In my dreams I heard a voice saying: ‘Go thou, and thou shalt be directed. The guides even are sleeping, but they shall awake and direct thee.’ Now did not this mean this youth and maiden? this brother and sister who were asleep and awaiting me?”

“As you like, uncle. I will go with thee, for I love adventure; but I hope we shall return alive.”

“Of that there is no doubt. Come, Effendi awaits us.”

The caravan started.

[59]

More than thirty camels were in procession; twelve of them carried baggage, tents, and provisions, the other eighteen bore upon their backs the bodyguard of Sherif el Habib.

Max and Girzilla, still unconscious, were on the same camel, being fastened to basket paniers, one on either side of the animal.

As the caravan moved across the sandy plain we will take the opportunity of more fully introducing the party to our readers.

Sherif el Habib was a Persian. In Khorassan he was known as the most prosperous shawl manufacturer of all Persia.

He gave employment to over a hundred men, and Sherif el Habib’s Persian shawls had been worn by the empresses and queens of the world.

Sherif el Habib became a widower in a peculiar way. According to the custom of his land, he had several wives.

In the palace of the Sherif—for this shawl manufacturer was ranked as a prince—every contrivance had been resorted to to render the happiness of the ladies complete.

Among other things was a large marble bath, fifty feet long by thirty feet wide, and capable of holding fifteen feet of water in depth.

By clever mechanical contrivances the supply of water was so nicely regulated that a stream to the depth of four feet was always flowing through the bath.

This water was highly perfumed with attar of roses,[60] and was so delicious to the senses that it was an intoxicating pleasure to bathe.

One day the ladies of Sherif el Habib’s household were disporting themselves in the bath, when by some accident the working gear got out of order and the water began to rise.

The ladies were not alarmed, for all were good swimmers.

Gradually the water increased in volume until it was six feet deep.

How merrily the ladies laughed!

How delighted they were at this new experience!

They could no longer touch the marble bottom of the bath.

Like children paddling in the surf, they laughed and made fun of each other.

They floated and swam about, dived and turned somersaults as though they were amphibious animals.

The entrance to the bathroom was locked. It was water-tight, so that should Sherif el Habib at any time desire the whole fifteen feet of depth to be flooded, no water could escape into the other parts of the palace.

When the ladies had grown weary they made a move to leave. But they were tired.

The water was ten feet deep, and still rising.

One, the beauteous Lola, a sweet creature made to be loved, was so exhausted that she begged one of the others to save her.

Buba, another Persian beauty, went to her assistance,[61] but Lola clung so tightly to her that both became exhausted and sank, never to rise again in life.

The others shrieked for help.

No one heard them.

They could not stand on the sides. The steps were slippery as glass, and could not be ascended.

The water gradually rose until twelve feet of water was in the bath.

When Sherif, alarmed at the long absence of the bathers, burst open the door, he was almost swept away by the overflow of the water.

His mind was unstrung, as well it might be, for floating on the surface of the water were the dead bodies of all his wives.

Almost beside himself with grief, he refused to be consoled until he thought of his sister’s orphan child, the young Ibrahim, who was living in Teheran.

From that day the love of this merchant prince’s heart was centered on Ibrahim.

European teachers were engaged, and by the time the young Persian was seventeen years old he could speak English, German and French fluently, besides having a good knowledge of Persian, Arabic and other Oriental languages and dialects.

[62]

When Ibrahim was seventeen his uncle told him that he was about to make a pilgrimage.

It was his intention to visit the shrine of the prophet at Mecca, across the Red Sea, and after exploring the wonders of Luxor, Carnac, and ancient Thebes, go up the Nile, past Cairo, to Alexandria.

It was just the kind of pilgrimage to suit Ibrahim, and his heart beat so fast with expectancy that his uncle feared he might bring on a nervous fever. When Mecca was reached Sherif was so full of religious fervor that he began to see visions and dream dreams, much to the annoyance and yet amusement of Ibrahim.

Among other things, Sherif el Habib became convinced that he was to be the discoverer of the Mahdi, or Mohammedan Messiah. When Cairo was reached he said to Ibrahim that, instead of going to Alexandria, they would cross the Libyan desert in search of the Mahdi.

As the promised route was likely to be one of wild adventure, with plenty of excitement, Ibrahim fell in with his uncle’s ideas, and with but few murmurings agreed to leave civilization behind and go into the interior of that land of mystery—the great deserts of the Dark Continent.

But we must return to our caravan.

The cavalcade had moved in silence for several hours.

The time was a most miserable one to Ibrahim, but he had learned enough of his uncle’s ways to be assured[63] that he would fall into disgrace if he dared to intrude on the silent meditations of Sherif el Habib.

The caravan stopped.

The camels were unloaded, tents were pitched, and after devotions the meal for the evening was spread.

Max and Girzilla had not yet roused from their unconsciousness.

They had been lifted with tender care from the camel, and laid down under the best and largest tent.

Girzilla was the first to awake.

She opened her eyes and closed them suddenly; she imagined she was dreaming.

Again the temptation was so great that she gently raised her eyelids, and saw that the tent was hung with Oriental silk drapery, while a thick Persian carpet had been spread upon the sand.

There was so much reality about it that she felt elated.

Where could she be?

Where was Max?

Raising her head she saw on the other side of the tent another carpet, and on it reclined the form of Max.

Should she awaken him?

A deep affection for the madcap had taken possession of her, and she was determined to do all she could to remain near him.

Cautiously she moved from the carpet and to the entrance of the tent.

She was utterly bewildered.

A score of tents surrounded the one she had just left.

[64]

Camels were lying down, chewing their cuds—others were asleep.