Title: Under the German shells

Author: Emmanuel Bourcier

Translator: George Nelson Holt

Mary Roxy Wilkins Holt

Release date: June 13, 2022 [eBook #68301]

Most recently updated: January 22, 2025

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1918

Credits: David E. Brown and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

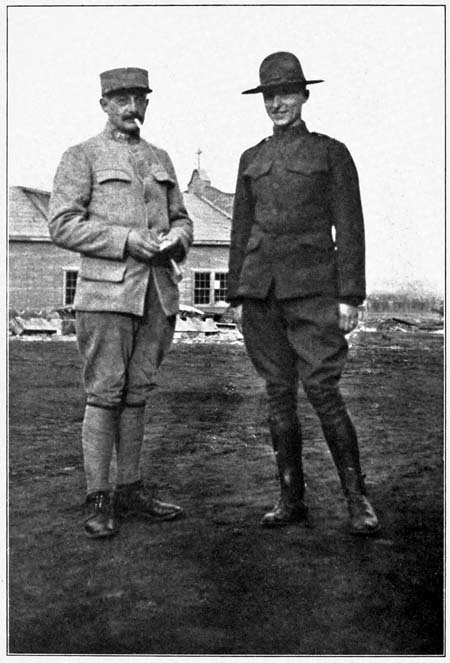

The author at Camp Grant.

The American soldier is Divisional Interpreter Umberto-Gagliasso.

UNDER THE

GERMAN SHELLS

BY

EMMANUEL BOURCIER

MEMBER OF THE FRENCH MILITARY COMMISSION TO AMERICA

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH

BY

GEORGE NELSON HOLT

AND

MARY R. HOLT

WITH PORTRAITS

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1918

Copyright, 1918, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Published May, 1918

Life is a curious thing. In time of war Life is itself the extraordinary and Death seems the only ordinary thing possible for men.

In time of war man is but a straw thrown into the wide ocean. If the tossing waves do not engulf him he can do no more than float on the surface. God alone knows his destiny.

This book, Under the German Shells, is another instance of war’s uncertainties. Sent by my government to America to join the new American army as instructor, I wrote the greater part of the book on the steamer which brought me. The reader will, perhaps, read it when I am dead; for another steamer is about to carry me back to France, where I shall again be “under the German shells,” before the book will see the light.

This is the second work which I have written during the war. The first, Gens du Front, appeared in France while I was in America. I wrote it in the trenches. The second will appear[vi] in America when I shall be in France. The father will not be present at the birth of either of his two children. “C’est la Guerre.”

My only wish is that the work may be of use. I trust it may, for every word is sincere and true. That it may render the greatest service, I wish to give you, my reader, a share in my effort: a part of the money which you pay for the book will be turned over to the French Red Cross Society, to care for the wounded and assist the widows whom misfortune has overtaken while I have been writing. Thus you will lighten the burden of those whom the scourge has stricken.

I hope that you will find in the work some instruction—you who are resolutely preparing to defend Justice and Right and to avenge the insults of the infamous Boche.

I have no other wishes than these for my work, and that victory may be with our united arms.

Emmanuel Bourcier.

Camp Grant, December 16, 1917.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | THE MOBILIZATION | 1 |

| II. | THE INVASION | 21 |

| III. | THE MARNE | 50 |

| IV. | WAITING | 93 |

| V. | LA PIOCHE | 101 |

| VI. | THE GAS | 120 |

| VII. | RHEIMS | 134 |

| VIII. | DISTRACTIONS | 148 |

| IX. | THE BATTLE OF CHAMPAGNE | 166 |

| X. | VERDUN | 177 |

| XI. | THE TOUCH OF DEATH | 200 |

[viii]

| The author at Camp Grant | Frontispiece |

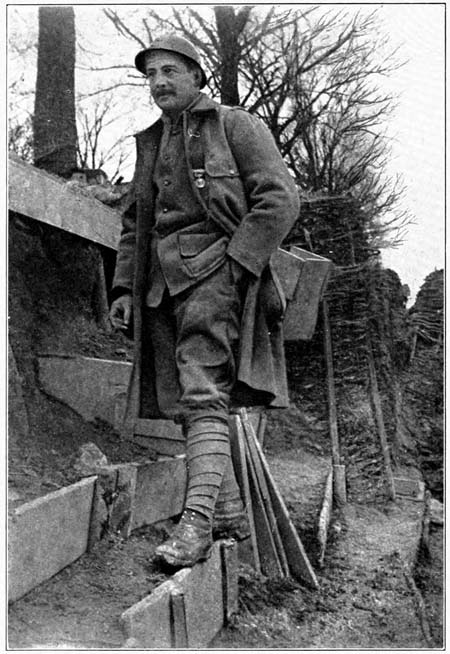

| Emmanuel Bourcier at the front in the sector of Rheims in 1915 | Facing page 118 |

[x]

Under the German Shells

ONLY those who were actors in the great drama of the mobilization of July, 1914, in France, can at this time appreciate clearly all its phases. No picture, however skilful the hand which traces it, can give in full its tragic grandeur and its impassioned beauty.

Every man who lived through this momentous hour of history regarded its development from a point of view peculiar to himself. According to his situation and environment he experienced sensations which no other could entirely share. Later there will exist as many accounts, verbal or written, of this unique event as there were witnesses. From all these recitals will grow up first the tradition, then the legend. And so our children will learn[2] a story of which we, to-day, are able to grasp but little. This will be a narrative embodying the historic reality, as the Iliad, blending verity and fable, brings down to us the glowing chronicle of the Trojan War. Nevertheless, one distinct thing will dominate the ensemble of these diverse accounts; that is, that the war originated from a German provocation, for no one of Germany’s adversaries thought of war before the ultimatum to Serbia burst like a frightful thunderclap.

At this period there existed in Europe, and perhaps more in France than elsewhere, a vague feeling that a serious crisis was approaching. A sense of uneasiness permeated the national activities and weighed heavily on mind and heart. As the gathering storm charges the air with electricity and gives a feeling of oppression, so the war, before breaking forth, alarmed men and created a sensation of fear, vague, yet terrifying.

To tell the truth, it had been felt for a long time, even in the lowest strata of the French people, that Germany was desirous of provoking war. The Moroccan affair and the incidents in Alsace, especially that of Saverne,[3] made clear to men of every political complexion the danger hanging over the heads of all. No one, however, was willing to believe what proved to be the reality. Each, as far as possible, minimized the menace, refused to accept its verity, and trusted that some happy chance would, at the last moment, discover a solution.

For myself, I must admit this was the case. Although my profession was one that called me to gather on all subjects points of information which escaped the ordinary observer, in common with the rest I allowed my optimism to conceal the danger, and tried always to convince myself that my new-found happiness need fear no attack. I had “pitched my tent.” At least, I believed I had. After having circled the globe, known three continents and breathed under the skies of twenty lands, my wanderlust was satiated and I tried to assure myself that my life henceforth was fixed; that nothing should again oblige me to resume the march or turn my face to adventure.

Alas! human calculations are of little weight before the imperious breath of destiny.

I closed my eyes, as did all my countrymen;[4] but to shut out the storm was impossible. Mingled in all the currents of public events I felt the menacing tempest and, helpless, I regarded the mounting thunder-clouds. All showed the dark path of the future and the resistless menace of 1914.

I see again the Paris of that day: that fevered Paris, swayed by a thousand passions, where the mob foresaw the storm, where clamors sprang up from every quarter of the terrible whirlpool of opinions, where clashed so many interests and individuals. Ah! that Paris of July, 1914, that Paris, tumultuous, breathless, seeing the truth but not acknowledging it; excited by a notorious trial[A] and alarmed by the assassination of Sarajevo; only half reassured by the absence of the President of the republic, then travelling in Russia; that Paris on which fell, blow after blow, so many rumors sensational and conflicting.

In the street the tension of life was at the breaking-point. In the home it was scarcely less. Events followed each other with astonishing rapidity. First came the ultimatum[5] to Serbia. On that day I went to meet a friend at the office of the newspaper edited by Clemenceau, and I recall the clairvoyant words of the great statesman:

“It means war within a month.”

Words truly prophetic, but to which at that moment I did not attach the importance they merited.

War! War in our century! It was unbelievable. It seemed impossible. It was the general opinion that again, as in so many crises, things would be arranged. One knew that in so many strained situations diplomacy and the government had found a solution. Could it be that this time civilization would fail?

However, as the days rolled on the anxiety became keener. One still clung to the hope of a final solution, but one began little by little to fear the worst. In the Chamber of Deputies the nervousness increased, and in the corridors the groups discussed only the ominous portent of the hour. In the newspapers the note of reassurance alternated with the tone of pessimism. The tempest mounted.

At night, when the dinner-hour came, I returned to my young wife. I found her calm[6] as yet, and smiling, but she insistently demanded the assurance that I would accompany her to the seaside at the beginning of the vacation. She had never before asked it with such insistence. She knew that, in spite of my desire, it was impossible for me to be absent so long a time, and other years she had resigned herself to leaving with her baby some weeks before I should lay aside my work. Generally I joined her only a fortnight before her return to Paris. This time a presentiment tortured her far more than she would admit. She made me repeat a score of times my promise to rejoin her at the earliest possible moment. In spite of my vows she could not make up her mind to go, and postponed from day to day our separation. At last I had almost to compel her to leave; to conduct her to the train with a display of gentle authority. She was warned by an instinct stronger than all my assurances. I did not see her again until thirteen months later.

Abruptly the storm broke. It came with the suddenness of a thunderclap. The happenings of this period are a part of history. It is possible, however, to review them briefly.

[7]It was announced that the President of the republic, abandoning his intended visit to the King of Denmark, would return precipitately to Paris, just as the Kaiser, terminating abruptly his cruise along the Norwegian coast, had returned to Berlin.

I went to the station curious to witness this historic return. The approaches were black with people, and an unusual force of police protected the entrance. The interior was decorated as usual with carpets and green plants, but most unusual was the throng there gathered. One noticed, in addition to the numerous officials, many notables little accustomed to going out of their way to see affairs of this sort. I still see clearly the gray-clad figure of M. Edmond Rostand, the distinguished author of Cyrano de Bergerac; the eager face of M. Maurice Barrès, and many others.

The presidential train arrived precisely at the announced hour. The engine, covered with tricolor flags, had scarcely come to a stop amid clouds of steam, when the parlor-car opened and the President appeared. He was immediately followed by M. Viviani, at that[8] time president of the Council of Ministers, who had accompanied M. Poincaré on the Russian visit. The two advanced to M. Messimy, minister of war, shook his hand and then those of the other officials. I looked with deepest interest on these men on whom fate had placed a responsibility so sudden and so heavy. They appeared calm, but it appeared to me the countenances of both were pale as if they realized the gravity of the moment and the weight of their trust. Whatever their feeling, only the most commonplace words of greeting were uttered, and the group at once proceeded to the exit.

Here something out of the ordinary occurred. Though I should live a hundred years, the scene would remain undimmed before my eyes. In my memory there is no similarly indelible picture, in spite of the fact that in the course of my ten years in the army I had witnessed a considerable number of remarkable spectacles. Even at the funeral of President Carnot, or that of President Félix Faure, even at the visit to France of Czar Nicholas II, even at the Congress of Versailles after the election of President Poincaré or any of the great public[9] events of our national life, I had not seen anything with so dramatic a note as the occurrence of this instant.

Leading the procession, the President came close to the barrier which restrained the crowd of privileged persons, who had been allowed to enter the station. Not a sound had been made, when, sudden as a lightning-flash, the silence was rent by an intense cry from thousands of throats. It swelled immediately, was taken up by the throng outside, echoing and reverberating, till it became a tonal torrent, capable, like the clamors of the Romans, of killing the birds. And this cry was:

“Vive la France!”

It was so strong, so powerful, and, in these circumstances, so poignant, that there was a wavering, a hesitation on the part of all. Even the horses attached to the carriages, and those of the cavalry guard, seemed to thrill at its fervor.

While the carriages filled and the escort, with sabres flashing, took its place, the same acclamation, the same cry, deep and powerful, continued to roar, in its fury demonstrating better than any deed the national will, and[10] expressing it in a manner so intense and precise, that any Boches in the crowd (and there certainly were many) must at this moment have felt the abyss opening beneath their feet; that the horrible adventure into which their Emperor was hurling them was destined to hasten their fall rather than assure their triumph.

Through this crashing human concert the escort moved forward. The crowd, however, was so dense that the carriages were not able to open a passage, and it was as in a living wave, with men and horses in a confused mass, that they reached Rue La Fayette, where at last they were able to disengage the presidential cortège from the still shouting throng.

In the crowd left behind, a remarkable patriotic demonstration spontaneously developed under the leadership of two noted deputies, M. Galli and Admiral Bienaimé, chanting the “Marseillaise” and acclaiming France.

Now let the war come! Unity dated from this instant.

From this hour the war imposed itself on every one. Each Frenchman resolutely prepared himself. The Miracle, that wondrous[11] French miracle which was to stupefy the world and arrest the enemy at the Marne, this sublime display of strength on the part of a France seized by the throat, was born, under German provocation, at the Gare du Nord, in this furious shout, in this cry of passionate love:

“Vive la France!”

From that evening each family felt itself warned, each man felt his heart grow stronger, and each woman lived in shuddering anticipation.

Throughout the land there gushed forth a will to battle, an admirable spirit of resolution and sacrifice, on which the enemy had not counted, that he had not foreseen, and which all his power could not conquer. France, insulted, provoked, assailed, stood erect to her foes.

This period was brief. People followed in the papers the energetic move for peace undertaken by France and England, but the day of wavering was past. War, with all its consequences, was accepted. The national sentiment was unanimous, and the mobilization found the public ready in spite of the shocks inseparable from such an event.

[12]The most serious of these which I recall, was the assassination of Jaurès, the great Socialist leader, in Rue Montmartre. Although several of the newspapers, and particularly the Italian press, printed that I was in the party of the great tribune when he was killed, the statement was inexact. I learned of the assassination shortly after it occurred, and with several of my associates hurried to the scene. The moment was tragic and the tense state of public feeling caused an immense throng to swarm the boulevard. I was able, nevertheless, to reach the office of l’Humanité and, with others, to write my name in homage to the fallen one.

Already history was on the march. The national defense was in organization, and each individual had too many personal preoccupations to give even to the most legitimate occupation more than a few brief minutes of attention. For myself it was necessary to think at once of the rôle of soldier, which I was reassuming.

I hurried to my home. In the empty apartment I assembled my military equipment with the skill of an old stager; the compact baggage[13] indispensable to the trooper, which should serve all his needs while taking up the smallest space, and add as little as possible to the weight of his burden. The experience I had had in the trade of soldiering, the expeditions in which I had taken part (the campaign in China, where, for the first time, I had as companions in arms the splendid soldiers of free America; my journeys into Indo-China and the Sahara), enabled me to know, better than most others, the essentials of the soldier’s personal provision; what must be chosen and what rejected, and the precise size limits by which a useful article should be judged indispensable or abandoned because too cumbersome.

I provided for myself accordingly without waiting for the official call. In consequence I was able to devote my last free hours to some of my less experienced neighbors. Among these, two poor fellows interested me particularly. They were brothers, one of them recently married, who, by uniting their savings, had just opened a shop not far from my home. They had watched with dismay the coming of the tempest, and questioned me incessantly, hoping to find in my answers some words of[14] reassurance. I was able to give only such answers as increased their fears, and to add advice which they would not heed.

“Imitate me,” I said to them; “the war is inevitable. Buy some heavy shoes and thick socks. Provide yourselves with needles and thread. One always needs them, and too often one hasn’t them when the need is greatest,” etc.

They wouldn’t listen. They continued to worry and do nothing, refusing to the end to accept the terrible reality, closing their eyes to the spectre as if they had a premonition that they were destined to be crushed in the torment and both killed; which, as I have since learned, was their fate within the first month of the war.

In the meantime I had to write consoling letters to my wife, abandoned at the seaside, amid a populace shocked and bewildered by the thunderbolt, and lacking definite news to satisfy the anxious need which saddened each individual.

But I was a soldier. I had to rejoin my command, and I had only enough time to pay a farewell visit to the home of my parents,[15] where my brothers, ready like myself, awaited me with their wives and children.

Such an unforgettable repast. The paternal table surrounded by the group of sons and grandchildren, each still forcing himself to smile to hearten the others, each in the bottom of his heart wondering anxiously what the morrow would unfold. Several of those who on this final evening partook of the food prepared by their mother, or touched their glasses and drank “A la France,” “A la Victoire,” will never return. They have fallen on the field of honor, battling the odious invader, breasting his blows and giving their lives that their sons may remain French and free. No one knew who would fall, who would be alive a year, even a month later, but one would have looked in vain for a quiver in any eye or a tremor in any voice. All were French. All accepted their duty, however it might present itself; each in his rank, in his assigned place; to do simply, without discussion, without hesitation, whatever the threatened country might demand of its children.

We had the courage to laugh, at this last dinner. We heard our father recall the memories[16] of the other war, that of 1870, in which he had served as a volunteer, and then we separated with words of au revoir and not good-by on our lips.

We were keenly conscious that everywhere in France, in all the homes and in all the families, an identical scene was presented at that instant. At each table the mother offered the departing ones a farewell repast; the wives repeated their vows of affection, and the children gave their tender love. Every one swore to make the Prussian pay dearly for his provocation, to chastise his insolence, to arrest him, cost what it might, and to defeat him. One entered the drama without effort and almost without hatred, because it was unavoidable, because France called and it was necessary to defend her. One was sure of the right, that the cause was just, and without discussion one obeyed. French blood—the blood which has flowed in so many wars, the blood of Bouvines, of Valmy, and of Jena, the blood of the Revolution and of 1870—surged in the veins, quickened the pulse and grimly expressed itself:

“They shall not pass!”

[17]The night of the second of August seemed short. For myself, my preparations completed, I retired early, well aware of the fatigues to come; a little shaken, it must be admitted, at the thought of leaving, for a time which might be long, an abiding-place where I had tasted so much of pure happiness and calm joy with my young wife and our pretty baby.

Adventure, the great adventure of war, of journeys, of battles, and of blood: Adventure left behind so short a time before, as I had believed, forever, had seized me again and thrown me as an insignificant atom into the path of the unknown, breaking all the bonds whose forming had given me so much joy, and whose stability had seemed so humanly sure.

When the hour arrived for my departure, I contemplated my deserted apartment, and gave a last kiss to the pictures of my absent loved ones. Then, in marching attire, my light sack on my shoulder, I descended to the street with firm step and heart beating high, to begin my journey to the front.

The animation of the streets was extraordinary. All Paris seemed to have turned out[18] to form an escort for the soldiers. These latter were easily recognized by the stern resolution of their faces, quite as much as by the accoutrement they bore. Most of them were accompanied by parents or friends; those who were alone were constantly saluted by the crowds as they passed. Many people offered their carriages to the soldiers, and others had placarded their motors with announcements that they would carry mobilized men to the stations without charge. Around these machines there was an ever-increasing crowd.

I entered this human wave. Immediately one dropped the manner of civilian life and became a soldier. By an old French habit, obligatory in the barracks, all the men replaced their formal speech by the intimate forms—le tutoyer—reserved ordinarily for one’s family and intimate friends.

Costumes of all sorts were there; the long coat of the workman, business suits, peasant blouses, bourgeois jackets with a touch of color given by the occasional red or blue uniform. Hair-cuts were in equal variety, from the tousled head of the peasant lad and the waving curls of the student to the closely cropped[19] state of those who had anticipated the military order. At the station all was well ordered. The trains, requisitioned before our coming, and with directions clearly indicated by placards, were quickly filled. Throughout the cars the men were singing and shouting, giving assurance of triumph, of prompt return, and of chastisement for the Boche. The coaches were covered with inscriptions naïve and gay.

“Excursion-train for Berlin.”

“Round trip to Germany.”

“Good fellows’ compartment-car.”

And a hundred others, many accompanied by satirical drawings, showing occasionally real talent on the part of the caricaturist. At the hour fixed all moved forward. All these men departed, singing; starting on their journey toward battle, toward glory, and toward death, while along the way, in the gardens or at the doors of the houses, the women, the children, and the old men waved their hands and their handkerchiefs, threw kisses and flowers, endlessly applauding, in a warm sentiment of love and of recognition, those who went forth to defend them.

[20]No one, perhaps, of all those who departed, of all those who saluted, believed that the war would be long, that it would involve the world and become what it now is, the battle for human freedom, the battle to death, or to the triumph of democracy over autocracy.

A SHORT time before the advent of the world catastrophe, Mr. Nicholas Murray Butler, president of Columbia University, was in France. I had the pleasure of meeting him in Paris. He gave me the first copy, in French and English, of the report of the American commission of inquiry concerning the Balkan atrocities. This report was made for the Carnegie Foundation, and he asked me to spread the knowledge of it, as far as possible, in my own country. I believed then that I was doing well in drawing from this interesting work a comparative study, which chance, rather than choice, caused to appear in the Grande Revue, in its number of July, 1914, only a few days before the outbreak of the great war itself.

I could not think, in writing this study, that it would precede by so very short a time events much worse, and that the Balkan atrocities,[22] which were already arousing the conscience of the civilized world, were about to be surpassed in number and horror at the hand of one of the nations claiming the direction of modern progress: Germany! No, I could not dream it, nor that I would be so soon a witness of it.

Let us return to my strict rôle of soldier, from which I have digressed. The digression was necessary, however, for it will make more comprehensible the amazing situation which the war created for me. At the time the mobilization took place I was accustomed to the wide liberty of action, of thought, and of speech which is usually enjoyed by the writers and artists of France. In public places as well as in certain drawing-rooms, I met the most illustrious personages, both French and foreign, whose presence gives to Paris much of its unique charm. My own signature was sufficiently well known to attract attention, and life opened before me full of attraction. Suddenly, from the fact that a demoniacal fanatic had killed the Archduke Ferdinand and his wife in the little, unknown town of Sarajevo, the conflagration flamed forth. I abandoned everything which, up to this time, had constituted[23] the essential part of my life; everything which had seemed worthy my attention and care, to become, on the morrow, an unknown, a soldier of the ranks, a number almost without a name, without volition of my own, without individual direction.

This was, it still is, a great renunciation. To really grasp its meaning, one must experience it himself. However, by reason of the importance assumed gradually by the World War, by reason of the enormous number of men called to the colors of every country of the globe, the feeling which I experienced at that time has become part of the common lot, and before the end of the tragedy, the majority of our contemporaries will have experienced it to a greater or less degree.

My order to report for duty directed me to go to Caen. It is a lovely town in Normandy, rich in superb monuments, of which one, “Abbaye aux Hommes,” is an almost unequalled marvel of twelfth-century architecture.

I arrived in the evening, after a fatiguing journey in a train packed with mobilized men, who had already dissipated all social differences by the familiarity of their conversation. Immediately[24] on our arrival we entered the barracks. As there was not nearly enough room for the throng of recruits, my company received the order to join another in a temporary camp, whither we hastened at full speed with the hope of being able to sleep. This new lodging, unfortunately, contained no conveniences whatever: it was a riding-school, where the young people of the town learned horsemanship, and which offered us for bedding nothing but the sawdust mixed with manure which had formed the riding-track. It must be confessed that one would need to have a large measure of indifference to be entirely content with this lodging. The unfortunate civilian clothing, which we were still wearing, suffered much from the experience.

Dawn found us all up and moving about, each one hunting, among the groups, those who, through mutual sympathy, would become more particularly “comrades,” or, to use a word more expressive, more characteristically French, “companions,” those with whom one breaks bread.[B]

The crowd was composed of the most diverse[25] types, but the greater number were from Normandy. Most of these Normans were farmers, many of them well-to-do; a few were dairymen and others horse-dealers. The rest of the company was Parisian. It is the custom in recruiting the French army to mix with all the contingents a certain percentage of Parisians, thus scattering over all of France, and particularly along the eastern frontier, the influence of the country’s capital. In the French army the Parisian has the reputation of being an excellent soldier; very alert, of great endurance, light-hearted, and agreeable, with a keen sense of humor which sweeps away gloom and dispels melancholy. He is also a bit hot-headed and does not yield readily to discipline. The leaders know the admirable results they can obtain by appealing to the vanity or the sentiment of the Parisian, and that he is capable of almost any effort is freely admitted. They fear, however, his caustic humor, his facile raillery and his eternal joking, which sometimes endanger their prestige. At least, these ideas existed before the war. Under the fiery tests of these three years, all differences of thought have melted as in a terrible[26] crucible; and there has been brought about a national unity so intimate and so absolute, that one would not know how to make it more perfect.

Among my new comrades the differences due to birthplace were quickly noted. By the costume, the accent, or the general manner it was easy to identify the native of the Calvados, of Havre, or of Paris. Already these affinities played their unfailing rôle, and in the general bustle the groups formed according to their origin. In the meantime every face showed that species of childish joy which always marks the French when they abandon their individualities and become merged in a crowd, as in the army. Their naturally carefree spirit comes to the surface and colors all their thought and action. They cease to feel themselves responsible for the ordering of their lives, and leave all to the authority which controls them. This enables them to throw aside all thought of their immediate needs, and permits them, at whatever age, to recover a youthfulness of spirit which is a perpetual surprise to strangers, and which constitutes one of their chief racial charms. Released from[27] all care, they jest freely on all subjects, and their spirit of quick repartee, their gifts of observation and of irony develop amazingly—perhaps to excess. They are just children, big children, full of life and gayety, who laugh at a joke and delight in a song; big children who will suffer every fatigue and every pain so long as they can retain their esprit, and whom one may lead into any danger if one knows how to provoke their good humor.

War did not in the least change all this. While perhaps most of the troop had done little more than go through the motions of slumber, and every one had missed something of his customary comfort, no one seemed tired when next morning’s reveille came. Each improvised an occupation. One built a fire between two stones that he might heat water for the soup, another prepared vegetables, a third helped the quartermasters in their accounts, and still another volunteered to help arrange the uniforms which were heaped up in a barn commandeered to serve as a store-house. In a short time the issuing of uniforms commenced. In his turn each soldier received his clothing, his equipment and all the regulation[28] baggage. And such scenes, half comic, half serious, as were enacted when the men tried on and adjusted their hurriedly assembled attire! Gradually, however, the long and short, the lean and rotund, by a series of exchanges, achieved a reasonable success in the transformation, and the variety of civilian aspect gave way to a soldierly uniformity.

At this period, in spite of all the efforts to secure a modification of the garb of the French soldier, the uniform still consisted of the celebrated red trousers and the dark-blue coat. This too gaudy attire was a grave error, soon to be corrected by stern experience. The red trousers dated from about 1830, and had acquired prestige in the conquest of Algeria and the wars in Mexico and Italy. To it also attached all the patriotic sentimentality aroused by the struggle of 1870. So strongly intrenched was it in popular fancy that it had triumphed over its most determined foes, and this in spite of the lessons regarding the visibility of the soldier, furnished by modern combats such as the Boer War and that between Russia and Japan. In consequence, the whole French army, excepting certain special troops such[29] as the Chasseurs, the Marines, and a few others, started for the front in this picturesque but dangerous costume. On its side, it cannot be doubted, it had a certain martial pride, a pride so notable that it was remarked by the Romans at the time of the conquest of Gaul. This sentiment of sublime valor makes the French prefer the hand-to-hand combat, in which they excel and where each shows the exact measure of his bravery, rather than the obscure, intrenched warfare for whose pattern the Boche has turned to the creeping beasts.

Therefore we were clothed in this glittering fashion. However, as if the visibility of our uniform had already disquieted our leaders, they concealed our red head-gear by a blue muff which completely covered the cap. It was in this attire that the company formed, that the ranks aligned and the two hundred and fifty civilians of yesterday became the two hundred and fifty soldiers of to-day; two hundred and fifty soldiers of right and justice. In like manner millions of others, scattered through all the depots and barracks where invaded France was arming herself, girded[30] their loins and burnished their arms for the sacred work of defending their homes.

Although few details are visible to the individual lost in the crowd, I feel sure that none of us even tried to see beyond the affairs of the moment. Certain things we could not help knowing: The war had already reddened our frontiers. Invaded Belgium battled desperately. Liége resisted. King Albert, his court, and the Belgian Government prepared Antwerp for a prolonged defense. Our comrades of the covering troops on one flank had invaded Alsace, and on the other had advanced to Charleroi. In the meantime, we, the soldiers of future combats, busied ourselves with preparations for our rôle with hardly a thought for the struggles already under way, or those of the future; this future so terrible which awaited us. We were more occupied in choosing our comrades than in considering the far-reaching possibilities of such incidents as the escape of the German cruisers Goeben and Breslau, and their subsequent internment at Constantinople. No, all that we learned from the newspaper dispatches interested us far less than the organization of our squads and platoons.

[31]I had the luck to find some good comrades, one the son of a celebrated novelist, the other an artist of some repute, and we three amused ourselves in observing our new surroundings and trying to foretell our next military moves. Our officers engaged our careful attention, as is natural in such circumstances. Our captain, as the chief of our company, a brave man, slightly bewildered by the astonishing rôle which had suddenly fallen to him, was the object of our special interest. We had the keenest desire for a chief who knew his trade so thoroughly that he would be able to lead us without trouble in whatever crisis. The soldier is ever thus. Without saying a word he examines his officer, measures his qualifications, and then reserves his confidence until the moment when it is made certain that this confidence is well placed and he need no longer fear the necessity of revising his judgment. This judgment which the soldier passes on his chief is definite, almost without appeal, so rare is it that circumstances will later cause a modification.

These early days, it is true, did not give our captain any opportunity to demonstrate[32] his valor. Burdened with an important physical task, that of transforming into soldiers more than two hundred men who had left the barracks years before; of clothing each according to his measure; of answering all the questions of the higher officers, and of watching at the same time a hundred little details—he was so busy that we had relatively little opportunity to study him. We were already armed, equipped and placed in the ranks before we had caught more than a glimpse of him; and then suddenly came the order to move the regiment to C——, one of the most important seaports of France.

To entrain a regiment of three thousand men with its baggage, its horses, its wagons, its stores, and its service, has become mere play for our strategists of to-day. To call it a heavy task would make one smile, for it now appears so simple. At the period of which I speak, the month of August, 1914, when our defense was hardly organized and when the enemy rushed on, driving before him the terrified populace, it was not, by long odds, the simple problem of to-day. The railroads were congested, there was a shortage of cars, and[33] orders were not always certain of prompt execution.

Nevertheless, in spite of these circumstances, the regiment entrained, departed, reached its destination without losing a minute or a man. We reached our assigned place at the scheduled time, just as if this tour de force had been planned for a long time or had been made easy by habit.

We arrived thus in our garrison without knowing each other, but none the less completely equipped and accoutred, although less than four days had elapsed since the mobilization call had been sent to these three thousand men, most of whom had forgotten all but the rudiments of their military training. This miracle of execution was reproduced throughout our territory, and after three years of war there has not arisen a single voice to claim that the French mobilization failed in any detail, or that in either plan or execution it fell short of perfection.

This was in reality a remarkable achievement. It must be here noted that France was prepared for the war neither in spirit nor in material. Most of our citizens were pacifists,[34] who refused even to acknowledge the possibility of a war. Yet, when confronted by the inevitable, each brought to the task an abundant good-will and an enthusiastic patriotism which gave speed and efficiency to each act of the mobilization. This was in truth the first step, the beginning of the “Miracle of the Marne.” It was indeed a miracle, this splendid co-ordination of good-will and eager effort into an organization, enormous but almost improvised, which worked without clash or creaking, with an almost mathematical ease that could not have been assured to a method prepared and perfected by the most careful study.

After all, we were not destined to remain long in our new post. In fact, we were hardly installed when an order came which placed us once more on the train, and sent us at last to the frontier. We were delighted.

Imagine, for the moment, these three thousand men recently armed, barely organized into squads and led by officers as yet unknown, starting on their way to meet the enemy. It was for them a veritable début. They were still unaware of the tricks and brutality of the[35] German. Very few of us had heard more than the vaguest discussion of the theories of Bernhardi and the Teuton “Kriegspiel.” We knew little of what was happening in Belgium, of the desperate efforts of the heroic defenders of Liége, or of the atrocities committed by the invaders. There was no time to study and explain the horrors of this war which threatened to submerge us; no time to instruct the soldiers; no time even to wait for munitions. Speed was necessary. We must hasten to offer our bodies, in the effort to check the black wave which advanced so ominously.

It was not a war which came. It was an inundation. The numberless German host, rolling on like a wave of mud, had already covered Belgium, submerged Luxembourg and filled the valleys of Lorraine. No one knew if there would be time to check it. The army of the front was fighting, no one knew just where. The English army was not yet ready, the Belgian army, that heroic handful was giving way, and the French mobilization was hardly finished. And here we were, rolling on at full speed along the lines of the Eastern Railway, to reach as soon as possible the frontier[36] of the Aisne, with two hundred rounds of ammunition in our pouches and two days’ rations in our sacks.

We went where we were sent, passing trains of terror-stricken refugees; speeding without stop along the sentinel-guarded way; passing Paris, then Laon, and finally arriving in the middle of the night in a darkened city; a terror-torn city, whose people gathered at the station to receive us as liberators, acclaiming our uniform as if it were the presage of victory, as if it betokened a sure defense, capable of rolling back the threatening enemy and giving deliverance from danger.

Poor people: I see them still in the touching warmth of their welcome. I see them still, as they crowded about to offer us refreshing drinks or bread and eggs, and following us clear to the fort which we were to defend, and which they believed would protect the city from all attacks.

Here we were at last, at our point of rendezvous with that grim monster: War. The men of the regiment began to look about, and especially I and my two friends, to whom I was already bound in one of those quick soldierly[37] friendships. We were ready to suffer together, to share our miseries, and to give an example to others. Because of our social position and education and our superior training, we felt capable of indicating and leading in the path of obedience. However, neither of my friends was able to follow the campaign to the end. A weakness of constitution ended the military career of one, while the other suffered from an old injury to his legs. At this early moment neither wished to think of his own sufferings. They dreamed only of France and the need she had for all they possessed of strength and courage. In spite of their good-will and stoutness of heart, neither of them was able to endure the strain of military life for any considerable period. A soldier should be a man of robust physique and unfailing morale. He should be able to withstand heat and cold, hunger and thirst, nights without sleep and the dull agony of weariness. He should have a heart of stone in a body of steel. The will alone is not enough to sustain the body when worn by fatigue, when tortured by hunger, when one must march instead of sleep, or fight instead of eat.

[38]All these things I knew well. I had served in war-time. I had marched on an empty stomach when drenched by rain or burned by the sun. I had drunk polluted water and eaten the bodies of animals. I had fought. I knew the surprises and hazards of war; hours on guard when the eyes would not stay open; hours at attention when the body groaned. I knew the bark of the cannon, the whistle of bullets, and the cries of the dying. I knew of long marches in sticky mud, and of atrocious work in the midst of pollution. I was a veteran of veterans, earning my stripes by many years of service, and therefore ready for any eventualities. My gallant comrades knew little of all this. Instinctively they looked to me for instruction, and placed on me a reliance warranted by my genuine desire to help them, as well as my long military experience.

Up to this time, however, the war had not shown us its hideous face. Our immediate task consisted of placing in a state of defense an old, dismantled fort here on the edge of French territory, and our orders were to hold it as long as possible, even to death. We were only a handful of men assigned to this heavy[39] task, of which, it is true, we did not realize the importance.

Under the orders of our commander we hurriedly cut down the trees which had overgrown the glacis, made entanglements of branches, and helped the artillerymen to furnish and protect their casemates. Oh, the folly of this moment, superhuman and heroic! We had only a dozen cannon of antiquated model to defend a defile of the first importance, and there was neither reserve nor second line to support our effort.

Before us developed the Belgian campaign. The battle of Charleroi was under way. In the evening, after supper, when we went down to visit the town and find recreation, if possible, we heard the inhabitants discuss the news in the papers as tranquilly as if these events, happening only ten leagues from their door, were taking place in the antipodes, and as if nothing could possibly endanger them and their interests.

Trains bearing the wounded passed constantly through the station. Those whose condition was so serious that they could not stand a longer journey were removed from the[40] trains and taken to the hastily improvised hospitals. This we saw daily, and so did the people of the town. We saw Zouaves, horsemen, and footsoldiers return, blood-covered, from the battle; frightfully wounded men on stretchers, who still had the spirit to smile at the onlookers, or even to raise themselves to salute.

Still, this town, so close to the battle, so warned of its horrors, remained tranquil and believed itself safe. Every day endless motor convoys passed through on the way to the front, bearing munitions and food without disturbing this calm life. Shops were open as usual, the cafés were filled, the municipal and governmental services were undisturbed in their operation, and the young women still pursued the cheerful routine of their life, without dreaming of the coming of the Uhlans and the infamy the German brutes would inflict.

Thus passed the days. We soldiers organized our habitation, placed the rifle-pits in condition, repaired the drawbridges and redressed the parades.

Ah! how little we knew of fortification, at this period, so recent and already so distant![41] How little we had foreseen the manner of war to which the Germans were introducing us. We knew so little of it that we did not even have a suspicion. We expected to fight, certainly, but we had in mind a style of combat, desperate perhaps, but straightforward, in which cannon replied to cannon, rifle to rifle, and where we bravely opposed our bodies to those of the enemy. We were confident. We reassured any timorous ones among the townspeople, saying: “Fear nothing. We are here.”

We were stupefied, civilian and soldier alike, when the French army suddenly gave way and rolled back upon us.

In the ordinary acceptation of the term this was a retreat. The regiments, conquered by numbers, by novel tactics, and by new engines of war, drew back from the plains of Charleroi. I saw them pass, still in good order, just below the fort, our fort where the work of preparation continued. Each soldier was in his rank, each carriage in its place. It was at once magnificent and surprising. We questioned these men with the utmost respect, for we envied them. They came from battle, they knew what fighting was like, and we could[42] see a new flash in their eyes. They were tired but happy. They were covered with dust and harassed by fatigue, but proud of having survived that they might once more defend their native land. Most of them could tell us but little, for they had only the most confused notion of what had happened. They were witnesses, but they had not seen clearly. A formidable artillery fire had mown down their comrades without their seeing an enemy or even knowing definitely where the Germans were. They had advanced and taken the formation of combat, when, suddenly, the storm broke upon them and forced them to retreat. They were so astonished at what had befallen them, that one could see in their faces, almost in the wrinkles of their garments, the mark of the thunderbolt.

They marched in extended formation and in excellent order, remaining soldiers in spite of the hard blows they had borne. They kept their distances, their rifles on their shoulders, their platoons at the prescribed intervals, the battalions following each other as in manœuvre and bringing their pieces of artillery.

It was an uninterrupted procession, an even[43] wave, which rolled along the road without cessation. Some stragglers entered the town and they were anxiously questioned. They could tell only of their exhaustion and of small details of the fight, describing the corner of a field, the margin of a wood, the bank of a river: the precise spot where the individual had entered the zone of fire and had seen his neighbors fall. This one had marched up a hill, but couldn’t see anything when he got there; another said his company had tramped along singing, when suddenly the machine-guns broke loose and his friends fell all about him; a third told of joining the sharpshooters, of throwing himself on the ground and, “My! how it did rain.” One tall chap recalled that in the evening his company had withdrawn to a farmhouse where they paused for a bite to eat, after which they made a détour. Such were the scraps of information they gave, minute details which told nothing.

All these stories were a jumble. None of these combatants had truly seen the war. Each knew only what had happened to himself, and even that he could not explain. These men seemed to have just awakened from a nightmare,[44] and their disjointed words told us nothing. We, who listened with such tense interest, were tortured with the desire to know if the tide of battle was bringing nearer the chance to prove our valor.

We were eager for the fray. All our forces, physical, mental, and spiritual, hungered for the combat. Our tasks of the hour were insipid. This incessant felling of trees, this clearing away of brush, this myriad of fussy efforts put forth for the refurbishing of our antiquated fortress, held us in leash until the place seemed like a suffocating tomb, whose cave-like quarters we would never leave.

In the town the people grew restless as the French armies fell back. They knew no more than we of the outcome of the battle of Charleroi, but as they saw the endless procession of convoys, of soldiers and of fugitive civilians, they began to fear the worst.

The German drive increased in power. Now, Belgian soldiers began to be mixed in the swift stream of the fleeing. Hussars, guides, infantry, and linesmen, clad in picturesque uniforms, copied from the first French empire, poured by in disorder. Some were[45] mounted on carts; others afoot, were leading their foundered horses; and these haggard, mud-covered men brought an air of defeat. Their faces, sunken from hunger and distorted from lack of sleep, told a story that sowed terror and kindled a panic.

The invasion presented itself at the gates of the town with an unforgettable cortège. Fear-stricken men deserted their fields, taking with them such of their possessions as could most quickly be gathered together. All means of transport were employed. Vehicles of all types and ages were piled high with shapeless bundles of bedding and of clothing of women and children. Some of the unfortunates were pushing perambulators, on which they had heaped such cooking-utensils as they had hurriedly gathered up. Trembling old men guided the steps of their almost helpless wives. Many had left their tranquil homes in such haste that they had not taken time even to fully clothe themselves. With weeping eyes, quivering lips, and bleeding feet they stumbled on. One heard only words of terror:

“They kill every one.”

“They have killed my mother.”

[46]“They have murdered my husband.”

“They are burning the houses and shooting the people as they try to escape.”

Can you imagine such a sight? And this never for an instant ceased. Three roads joined each other at the edge of the town, and each brought from a different direction its tales of horror. Along one came the families driven from the colliery shafts, another brought the fishermen from the Scheldt, and the third the bourgeoisie from Mons and Brussels. All marched pell-mell along with the troops, slept at the roadside, and ate when some interruption on the congested route offered the opportunity. All fled straight on, not knowing whither.

I found reproduced in this lamentable exodus certain spectacles which I had witnessed years before, but under vastly different circumstances. Yes! I had seen things just like this, but on a far-away continent where the fugitives were not men of my own race. I had seen cities taken by assault and whole populations fleeing in terror. I had seen houses in flames and corpses rotting in the fields. I had seen all the drama and horror of an invasion and had looked[47] on with infinite pity. However, nothing in all that had touched me as did the present. Those flights had not taken place in my own country. They were not my compatriots who had been harried like so many animals, and driven from their homes like frightened beasts, to be tracked in the forests or hunted across the plains. They were, nevertheless, poor, unfortunate humans. Even in their panic and distress they were still a little grotesque, owing to their strange manners and costumes. Their natural abjection had in it nothing of similarity to the fierce grief of these Europeans, surprised in a time of peace and in no way prepared to endure submission.

Once when I saw an exhausted old man fall at the roadside, near our fort, and heard him beg his companions to abandon him that they might make better speed, I recalled a scene indelibly graved on my memory. It was in China. We were moving toward Pekin in August, 1900. We pushed back before us the Boxer insurgents, whom we, with the Japanese and the Russians, had routed at Pei-Tsang. One evening when hunger tortured us, some companions and myself started out in search[48] of food. We reached a farm isolated in the midst of a rice-swamp, and we entered, just as armed men, conquerors, may enter anywhere. There was not a soul in the numerous buildings of the extensive plantation—or so it seemed at first. Finally, I went alone into one of the houses, and there came face to face with a very old woman, shrivelled and bent, with straggling wisps of hair, grimacing and repulsive. She instantly thought that her last hour had come. I had no bad intentions, but she could read my white face no better than I could have read her yellow countenance had our positions been reversed. She was overcome with fear, and her fright caused such facial contortions that I had a feeling of deepest pity for her. I tried without success to reassure her. Each of my gestures seemed to her a threat of death. She crouched before me, supplicating with most piteous cries and lamentations, until I, finding no gestures that would explain what I wanted, left the room. She followed me as I withdrew, bending to kiss each footprint as if to express her gratitude for the sparing of her life.

At that time I had thought of what my own[49] grandmother would feel were she suddenly confronted by a German soldier in her own home in France. My imagination had formed such a vivid picture that I remembered it fourteen years later when the real scene passed before my eyes.

Ah! Free men of a free country! Men whose homes are safe from invasion, men who need not dread the conflagration leaping nearer and nearer, or the lust of your neighbor—fortunate men, imagine these villages suddenly abandoned; these families in flight; these old men stumbling on the stones of the road; these young girls saving their honor; these children subjected to the hardships and dangers of such an ordeal!

Search your mind for a picture which may aid you to visualize such a spectacle. For no pen, no brush, not even a cinematograph could depict that terrified mob, that throng pushing on in the rain and the wind; the flight of a people before another people, the flight of the weak and innocent before the strong and guilty.

AS the result of tenacity and strenuous effort, our work of defense progressed. We had been able to build a smooth, sloping bank all around the fort, to place entanglements before the principal entrance, and to arrange such cannon as we had at our disposal. We put iron-bars in front of the windows to break the impact of shells, and baskets filled with sand at passage entrances. We had sufficient provision to last a month. We built a country oven that we might bake bread and not be reduced by famine.

We were tired, but confident, the enemy might come now. Each of us knew the spot he should occupy on the rampart, and we had not the least doubt of our power of resistance. The commander redoubled the exercises and drills, and each day notices were posted near the guard-house saying that we must hold the fort unto death, that surrender was absolutely[51] forbidden. As for the men, we were equally determined to offer resistance to the end.

In the meantime, we came to know each other better day by day, and genuine sympathies grew into solid friendships. In addition to my two friends of the first hour, I found myself associated with some excellent comrades. There was Yo, a splendid young Norman, strong as a giant, a carpenter by trade. He was persistently good-natured, and knew a thousand amusing stories. He had an anecdote or witticism ready for all occasions. Then there was Amelus, whom we dubbed “Angelus.” With his little, close-set eyes, small features, narrow shoulders, he was as nearly as possible the physical type of a Paris gamin. He possessed also the gamin’s quick repartee and unalterable good humor.

This man, who was killed later, deserves special mention. He was an anti-militarist. That is to say, before the war he constantly asserted, as a point of honor, in season and out of season, his hatred of the whole military business; and detested, without clearly knowing why, every one who wore an army uniform.[52] When I first met him, the war had not yet changed his habit. He indulged freely in vituperation of the officers, from the highest to the lowest; but this veneer covered a truly patriotic spirit, for whenever an officer asked a service he instantly offered himself. He volunteered for every rough job, and although he was not strong nor of robust health, he managed to accomplish the hardest kinds of labor, and would have died of the effort swearing that he “wished to know nothing about it, and no one need expect anything of him.”

This type of man was very numerous in France before 1914, and experience has proved that much could be counted on from them, whenever the occasion arose to put them to the test.

Such as he was, with his comic fury, with his perpetual tirades against the officers, and still very evident good-will, he amused us greatly. One heard often such colloquies as this:

“A man wanted to cut down trees!”

“Take me!” cried Amelus.

“A volunteer to carry rails!”

“Here I am!”

[53]Once accepted, bent under the heaviest burdens, he poured out his heart; he cursed his ill fortune, he pitied himself, he growled and groaned. That aroused the irony of Yo. There was a continual verbal tussle between the two men, the one groaning and the other responding with raillery, which spread joy among us all.

Yes, we laughed. The tragic events which were closing in upon us, which were drawing nearer irresistibly, did not yet touch us sufficiently to frighten us much. We laughed at everything and at nothing. We laughed like healthy young men without a care, men who have no dread of the morrow, and who know that, whatever may happen, the soup will be boiled and the bread will come from the oven when it is needed. We had not yet become really grave, certainly no one had suffered, when, our task of preparing the fort completed, we went to the embankment and witnessed the ghastly procession of fugitives. That froze the heart of each of us. So many old men, women, and children, thrown out at random, thrown out to the fierce hazard of flight, stripped of all their possessions! The[54] sight was distressing, and the visible horror of their situation brought tears to the eyes of the most stolid.

The hours passed rapidly. The last French troops fell back, the town was evacuated. Trains packed to the last inch carried away every one who could find room. When we went out in the evening, we found closed the shops which had been open the day before. Their owners were hastening to find shelter and safety.

The enemy was approaching. We felt it by a hundred indications, but we did not suspect how close he had come.

He arrived like a whirlwind. One evening we were told to remain in the fort, to take our places for the combat, to prepare cannon, cartridges, and shells. During the day an aeroplane had flown over the fort, and it was a German machine. Disquieting news preceded the invader. It was brought by some straggling soldiers: men panting, miserable, dying of thirst and hunger, who had been lost in the woods, and had covered twenty leagues to make their escape. They recounted things almost unbelievable. They had seen Belgian[55] villages as flaming torches, and they told their experiences little by little, with a remnant of horror in their eyes, and an expression of bravery on their faces. We gave them drink. They scarcely stopped their march, but took the bottles or glasses offered, and emptied them while continuing on their way. The fear of being taken bit at their heels. “Save yourselves!” they cried to the women, “they are coming!”

After they were gone, the people gathered in large groups, seeking further information on the highroad. The road was clouded with dust and alive with movement, where other fugitives, more hurried than the first, pushed their way, and threw out, in passing, bits of news still more alarming. Haggard peasants explained that the Germans were pillaging houses, ravaging everything. From these strange reports one would have believed himself transported into another age, carried back to the period of the great migrations of peoples.

“They have taken away my daughter,” wailed a woman in tears, “and have set fire to the farmhouse.”

[56]“They shot my husband!” cried another, “because he had no wine to give them.”

The terror of the populace increased and spread. Mothers went to their houses, gathered together some clothes and their daughters, then followed the throng of fugitives. Old men started out on foot. The threatening flail swept the country, even before it was seen, preceded by a groan of agony and of fear as the thunder-storm is preceded by the wind.

And we soldiers, with no exact knowledge of the situation, we awaited orders and completed our preparations for resistance. We lifted the drawbridges, we put in place the ladders, the tubs of water to put out fire, the tools to clear crushed roofs and arches. We never thought of flight. We had a sort of pride in remaining at the last stand, in protecting the retreat of all the others, and we strove to give encouragement to the civilians departing. But we were eager for news, and seized upon all rumors.

About four o’clock in the afternoon a rumor passed like a gust of wind. Some outposts came running: “They are here!” They told of the attack on their position five kilometres[57] away. Five of their number had been killed, six taken prisoner by the Germans. This time the invasion was rolling upon us. We almost touched it. We felt the hot breath of battle, we were going to fight, we were going to offer resistance.

This was an impression more than a certainty. Explosions could be heard in the distance: the engineers were blowing up bridges and railroads, in order to create obstacles and retard the advance of the enemy. The foe seemed to arrive everywhere at the same time. He was discerned on the right and on the left, at each cross-road, advancing in deep columns, and preceded by a guard of cavalry, the terrible Uhlans, who were plundering everything in their way.

We felt, rather than saw, the nearness of the invaders. We could do nothing but wait. In spite of the efforts exerted by the officers to quiet the men, there was among them an uncontrollable restlessness: inaction was intolerable.

It was a great relief to be able to accept, with several comrades, a piece of work outside the fort. This had to do with blowing[58] up a viaduct. We set out, much envied by those left behind. We advanced with customary precaution, following one point of light carried by an advance-guard. Naturally, this position was taken by Amelus, the habitual volunteer, followed by Yo, the giant, whose muscular force inspired confidence in every one.

We had not far to go. At the railway-station, we learned that the last train had just left, taking away the portable property of the station, and all the people who could pack themselves into the coaches. There was no longer, then, any assurance of rapid communication with the rear. The struggle was really commencing.

Our destination was scarcely two kilometres away. It was a railway-viaduct crossing a valley. We arrived quickly. The blast of powder was prepared in an arch by the engineers; our part was only to watch and protect the operation. A sharp detonation, an enormous cloud of smoke, the whole mass swaying, splitting, falling, the reverberating echo, and the route is severed. The trains of the invasion will be compelled to stop: there[59] is an abyss to cross, which will make the assailant hesitate perhaps an hour. Although our work was swiftly accomplished, it seemed that it must be effective. We had nothing to do but regain our fort and await events.

However, it is late when we arrive. Night has fallen. On our left, an immense glow stains with blood the leaden sky: it is Fourmies which is burning, fired by the enemy. It is a French town which is the prey of flames, the first one we have seen thus consumed before our eyes, in the horror of darkness; while on the highroad rolls constantly the flood of refugees, carts, wagons, carriages, all sorts of conveyances of town and country, jumbled together with bicycles and pedestrians, the turbulent throng of a province in flight, of a people driven by a horde.

In subtle ways the fort itself has changed character. It breathes war. Sand-bags are placed about the walls, sentinels watch on the ramparts, orders are given and received under the arches. Our comrades ask anxiously: “What have you seen?” We give an account of our exploit, while eating a hurried bite, then we imitate our comrades, and, following the[60] order received, we take up our sacks and prepare all our accoutrement.

There is still some joking, at this instant. Yo attempts some of his raillery, Amelus once more pours vituperation on the army, but their pleasantries fall without an echo. We are grave. The unknown oppresses us. We are attentive, and await the slightest order of our superiors. The commandant calls the officers together. The conference is prolonged, and we know nothing precise in the half-light of our fortress chambers. What is going on? Will we be attacked this evening? Will the defense be long? We exchange opinions and assurances: “There are two hundred rounds of ammunition apiece!”

Two hundred rounds! That means how many hours of fighting? Shall we be reinforced? Are there troops in the rear? And in front? No one knows. Those who affirm that there are troops in front of us meet a slight credence, which gives way immediately to doubt and then to a certainty to the contrary. Numberless contradictory pieces of information clash together, mingle, intercross:

“There is fighting at Maubeuge.”

[61]“The enemy is withdrawing on the Meuse!”

“Yes, he has lost all his cannon.”

“But he is advancing on us here!”

All these statements jostled each other in the general uncertainty. Suddenly, at the door of the chamber, I saw our lieutenant, a splendid soldier, upright and frank. He was speaking to one of my comrades. Scenting a special mission, I approach them. I am not mistaken. “Silence!” says the officer, “I need six resolute men, and no noise.”

“Take me, lieutenant,” I ask.

“If you wish.”

“And me, too,” begs Amelus.

“All right, you too, and Yo. Meet me immediately in the courtyard, with your knapsacks.”

We meet in a few minutes. My friend Berthet rushes in. “Wont you take me, too?” “Certainly. Come quickly.”

And now we are outside the fort, with knapsack and gun. We are delighted with this godsend, without knowing what it is all about: at least we are moving about, doing something, and that is the main thing.

“Be careful,” commands the lieutenant, “to the right! Forward, march!”

[62]We leave by the postern gate. We are on the embankment. The night is dark, the heavens are black except where the blood-red reflection of burning towns marks the path of the Germans. In silence we make our way down the steep slope of the fort.

“Halt! Load!”

We fill the magazines of our rifles. Ten paces farther on we meet the last sentinels. The password is given, we proceed. We go toward the town, as far as the highroad, where the flight of the distracted populace continues. Amidst a tangle of conveyances, pedestrians slip through mysteriously and hurry by. They jostle us, then make way for us in the throng. At last we stop. The town is only a hundred metres distant, without illumination, but much alive, full of the hubbub of the last departing civilians.

“Listen,” says the lieutenant, “this is your errand: a group of Uhlans has been reported about eight hundred metres from here. At this moment they must be occupying the civilian hospital. They must not be permitted to pass. Two men will hide themselves here, two others there. The others will guard the[63] cross-road. In case you sight them, give them your magazine and fall back on the fort to give the alarm. Do you understand? Go to it!”

In such moments, one’s intelligence is abnormally active: one understands instantly, and each man seems to take his own particular rôle by instinct. I advance with Berthet to take the most forward post: it is where adventure is most likely. The others leave us, to take their own positions. So there we are, he and I, alone as sentinels, at the edge of the highroad—the road which is the path of the invasion, where rolls unceasingly as a torrent the stream of fugitives.

“You tell me what to do,” says Berthet, “I will take your orders.” “It is very simple,” I respond, “one knee on the ground. In the deep grass you will not be seen. For myself, I am going onto the road itself. I will stop any one who looks suspicious. Don’t worry, and don’t let your gun go off unless you hear me fire.” “Very well.” “Oh, another thing! If we are attacked, we will fire, then run for the fort without following the road. Our companions will fire, and we must cut across the fields. Do you agree?” “Yes.”

[64]I leave him, to take my post just at the edge of the road, eyes and ears on the alert, finger on the trigger. A host of memories crowd my brain. How often in other days have I stood guard in just this manner! I recall similar hours which I experienced in China, at Tonkin, in the Sahara. I feel once more the intense poetry which is inspired by such a vigil: a poetry incomparable to any other; a poetry in which alert action is mingled with the strangeness of night, with the thousand noises of a stirring populace, with the imminence of danger, with visions crowding up from the past, with all that surrounds us and all that flees from us. Less than a fortnight ago, at this hour, I used to write my daily article. My young wife, in our dainty dining-room, was rocking the baby to sleep. Or I was correcting proof on my forthcoming book, and she came to sit near me, her fingers busy with some fine needlework. She always placed on my desk the flowers from the dinner-table, and I thanked her for being so good, so pretty, so loving and thoughtful, by a swift stolen kiss on her rosy finger-tips. I read to her the last page I had written. She smiled and approved.[65] Our confidence was complete. She had faith in my ability, I rejoiced to know that she was mine. We were so happy——

To-day, with loaded gun, with every nerve strained, I lie in wait for an advancing enemy. My wife is far away. She has shelter, at least. Without doubt she dreams of me, as I dream of her, and she trembles and she fears the future, the danger, death. My brothers—where are they?—and their wives, and our parents, and all my dear ones, like myself, like all of France, thrown into war, into danger, into suffering. And all the children, and all the helpless women, and old men, all counting on us, on our stoutness of heart, to defend and to save them.

My meditations did not in the least interfere with my watchfulness. From time to time I stopped a passer-by.

“Halt there!”

“We are French.”

“Advance slowly, one by one.”

The poor creatures were terrified and bewildered.

“We are trying to escape!”

“Pass on.”

After a bit I return to see Berthet.

[66]“Anything new?” “No, nothing.” “Supposing you look around more at the left.” “All right.”

I resume my place. All at once, I hear the clatter of horses’ hoofs. Berthet rejoins me. “Do you hear that?” “Yes. It must be they. Don’t forget. Fire, then run across fields.”

The cavalcade approaches, is clearly audible. With eyes strained, I can still see nothing in the blackness. Suddenly I catch the glitter of helmets.

“Halt, there!”

“Gendarmes!” cries a voice, “don’t shoot!” French gendarmes, in retreat!

“Advance slowly, one by one.”

The troop halts. One horseman advances, stops at ten paces from my bayonet.

“I am a brigadier of the gendarmes, brigade of Avor. I have not the password.”

The voice is indeed French. I recognize the uniform—but I still fear a possible trap.

“Command your men to pass, one by one.”

The order is executed without reply. Some ten men file by.

“Look out for yourselves,” says the last horseman, “the Uhlans are at our heels.”

[67]“Thanks for the information. Tell that to the officer whom you will meet about a hundred metres from here.” “Good luck to you.”

Ouf! Berthet and I both grow hot. The watching brings us together, we remain together. One feels stronger with company.

It begins to rain—only a mist at first, then a steady rain. The poor fugitives tramp along, miserable, driven ghosts, weird figures in the blackness of the night. Some of them give scraps of information in passing.

“They are at the chapel.”

“They are arriving at Saint Michel.”

“There are twenty Uhlans at the mairie.”

Our lieutenant makes his round. “Nothing new?” “Nothing, sir.” “Very well, I am going to look about, as far as the town. I will be back in about fifteen minutes.” “Very well, sir.”

He disappears, swallowed up in the darkness. We wait. It rains harder and harder. The water runs in rivulets on our shoulders, trickles down our necks, soaks our shirts. From time to time we shake ourselves like wet spaniels. There is nothing to do but wait. It would[68] not do to seek shelter. Besides, there is no shelter. When one is a sentinel in full campaign, one must accept the weather as it comes. If it is fine, so much the better; if it is frightful, too bad! It is impossible to provide comforts, or conveniences. If the sun burns you or the rain soaks you, if the heat roasts you or the cold freezes you, it is all the same. The strong resist it, the weak succumb: so much the worse! One is there to suffer, to endure, to hold his position. If one falls, his place is filled. So long as there are men, the barrier is raised and put in opposition to the enemy. “C’est la guerre.” That is war: a condition in which only the robust man may survive; where everything unites madly to destroy, to obliterate him, where he must fight at the same time his adversaries and the elements which seem to play with him as the breeze plays with the leaf on the tree.

However, the night was advancing. The Great Bear, intermittently visible between the clouds, had already gone down in the sky, and we were still there. The crowd still surged on, as dense as ever. The people came from every quarter. Very few were gathered into[69] groups. Here and there some worn-out soldiers were seen, who asked information and vanished in haste. In the background of the dark picture of the night were the burning villages and towns, but their flames were subsiding, their ruddy glow was waning. The fires seemed to have reached the end of their food, exhausted by a night of violence. Sudden puffs of sparks rising with the smoke already foretold their extinction.

Berthet, my comrade, was pale in the twilight dawn. “You have had enough of it?” I say to him. “Oh! no,” he responds, “it is nothing but nervousness.”

The most critical moment was approaching: the dawning of day, that troubled moment when fatigue crushes the shoulders of the most valiant, when the vision confuses distances and blurs objects, when all one’s surroundings take on a strange, uncanny appearance. Dawn, lustreless and gray, the dawn of a day of rain, rising sulkily, drippingly, coming pale and wan to meet men broken by an anxious vigil, is not a pleasing fairy, is not the divine Aurora with fingers of light; and yet, it brings solace. With its coming the vision is extended; it[70] pierces the fog, identifies the near-by hedge, the twisted birch, the neighboring knoll of ground. Day breaks. The shadows disappear, objects regain their natural aspect, and the terrors created by the night vanish.

Thus it was with us. I was pleased with Berthet. He had carried himself well, and I told him so. That pleased him. He was a boy whose self-esteem was well developed, who could impose upon a rather weak body decisions made by his will.

“I was afraid of only one thing,” he said, “and that was that I might be afraid.” I smiled and answered: “But you will be afraid. It is only fools who know not fear, or deny it. Every one knows fear. Even the bravest of the brave, Maréchal Ney himself, knew it well.”

At this moment our lieutenant returned from his hazardous expedition, without having observed anything remarkable, and there was nothing for us to do but wait for other sentries to relieve us, or for orders specifying a new mission.

Nothing of the sort came, at first. If we had been abandoned in a desert, our solitude[71] could not have been more complete. As far as the eye could see, we could not detect a living thing. There were no more fugitives. We two were guarding a bare highroad where neither man nor beast appeared.