EUROPEAN and COLONIAL

WINE COMPANY,

No. 122, PALL MALL, LONDON.

The above Company has been formed for the purpose of supplying the

Nobility, Gentry, and Private Families with PURE WINES of the highest

character, at a saving of at least 30 Per Cent.

| SOUTH AFRICAN SHERRY |

20s. & 24s. per doz. |

| SOUTH AFRICAN PORT |

20s. & 24s. ” |

THE FINEST EVER INTRODUCED INTO THIS COUNTRY.

| ROYAL VICTORIA SHERRY |

32s. per doz. |

| (A truly Excellent and Natural Wine) |

| SPLENDID OLD PORT |

42s. |

| (Ten years in the wood.) |

| PALE COGNAC BRANDY |

52s. and 60s. |

| SPARKLING EPERNAY CHAMPAGNE, |

38s. |

| (Equal to that usually charged 60s. per doz.) |

| ST. JULIEN CLARET |

28s. |

| (Pure and without acidity.) |

Bottles and Packages included.

Delivered free to any London Railway Station. Terms, Cash, or Reference.

Country Orders to be accompanied with a Remittance. Price Lists sent Free on application.

Cheques to be crossed Barclay & Co.; and Post Office Orders made payable to

WILLIAM REID TIPPING, Manager.

BY ROYAL COMMAND.

METALLIC PENMAKER

TO THE QUEEN.

JOSEPH GILLOTT

Respectfully invites the attention of the Public to the following Numbers of his

PATENT METALLIC PENS,

which, for Quality of Material, Easy Action, and Great Durability, will ensure

universal preference.

For General Use.—Nos. 2, 164, 166, 168, 604. In Fine Points.

For Bold Free Writing.—Nos. 8, 164, 166, 168, 604. In Medium Points.

For Gentlemen’s Use.—FOR LARGE, FREE, BOLD WRITING.—The Black Swan Quill, Large

Barrel Pen, No. 808. The Patent Magnum Bonum, No. 263. In Medium and Broad Points.

For General Writing.—No. 263. In Extra-Fine and Fine Points. No. 262. In Fine Points.

Small Barrel. No. 810. New Bank Pen. No. 840. The Autograph Pen.

For Commercial Purposes.—The celebrated Three-hole Correspondence Pen, No. 382.

The celebrated Four-hole Correspondence Pen, No. 202. The Public Pen, No. 292. The Public Pen, with

Bead, No. 404. Small Barrel Pens, fine and free, Nos. 392, 405, 603.

To be had of every respectable Stationer in the World.

WHOLESALE AND FOR EXPORTATION, AT THE

Manufactory: Victoria Works, Graham-street; and at 99, New-street,

Birmingham; 91, John-street, New York; and of

WILLIAM DAVIS, at the London Depôt, 37, Gracechurch-street, E.C.

THE

CORNHILL MAGAZINE.

MARCH, 1860.

CONTENTS.

|

PAGE |

| A Few Words on Junius and Macaulay |

257 |

| William Hogarth: Painter, Engraver, and Philosopher.

Essays on the Man, the Work, and the Time. |

264 |

| II.—Mr. Gamble’s Apprentice. (With an Illustration.) |

|

| Mabel |

282 |

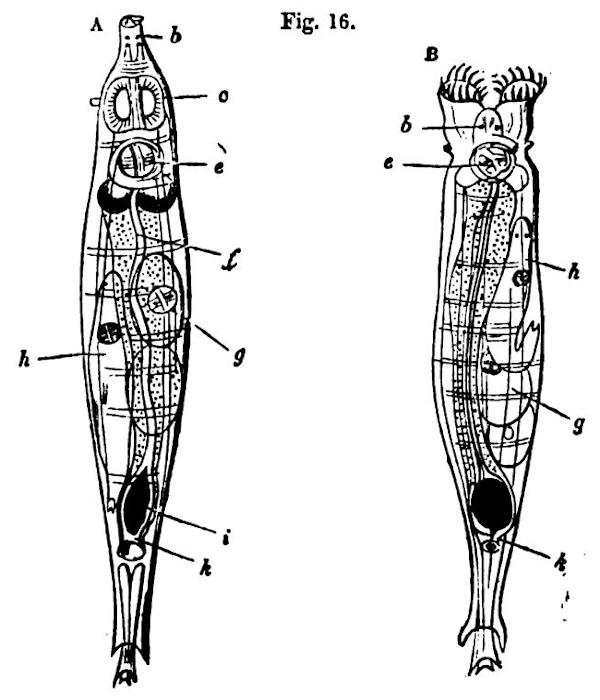

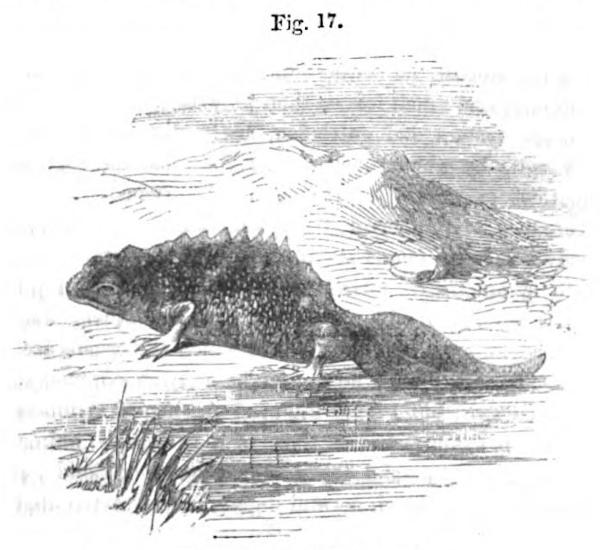

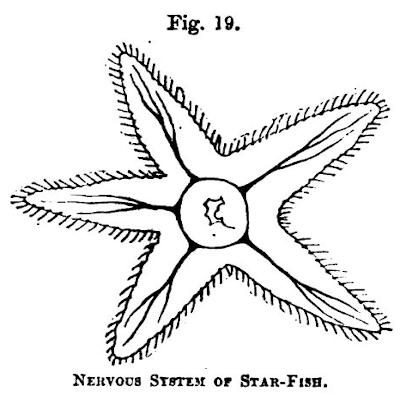

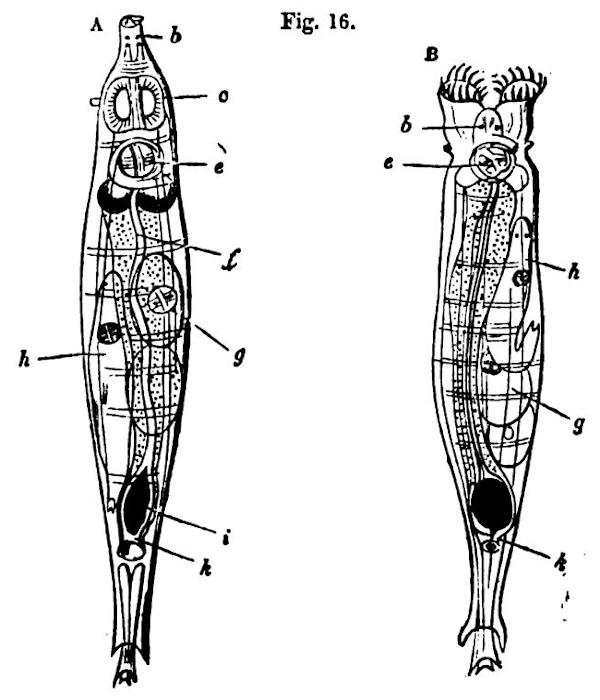

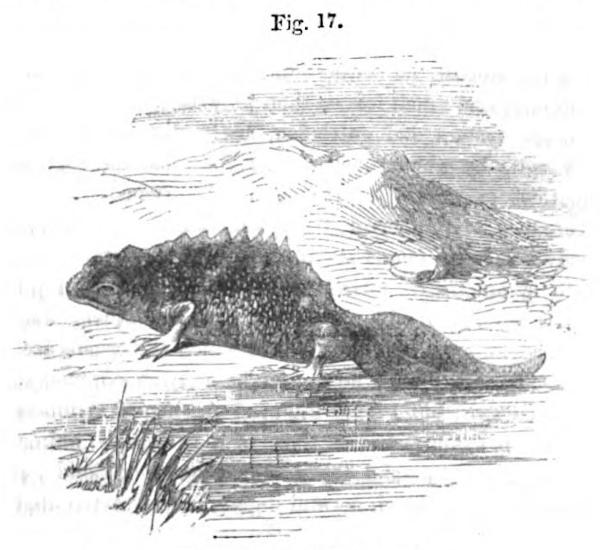

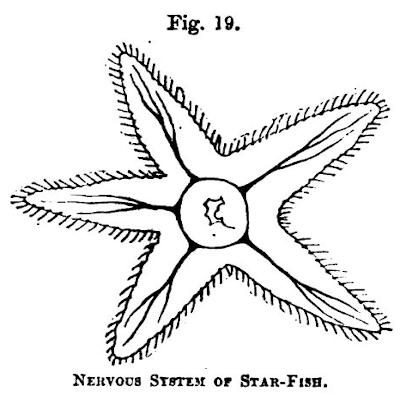

| Studies in Animal Life |

283 |

| Chapter III.—A garden wall, and

its traces of past life—Not a breath perishes—A bit of dry moss and its

inhabitants—The “Wheel-bearers”—Resuscitation of Rotifers: drowned into

life—Current belief that animals can be revived after complete

desiccation—Experiments contradicting the belief—Spallanzani’s

testimony—Value of biology as a means of culture—Classification of

animals: the five great types—Criticism of Cuvier’s arrangement. |

|

| Framley Parsonage |

296 |

| Chapter VII.—Sunday Morning. |

|

| ” VIII.—Gatherum Castle. |

|

| ” IX.—The Vicar’s Return. |

|

| Sir Joshua and Holbein |

322 |

| A Changeling |

329 |

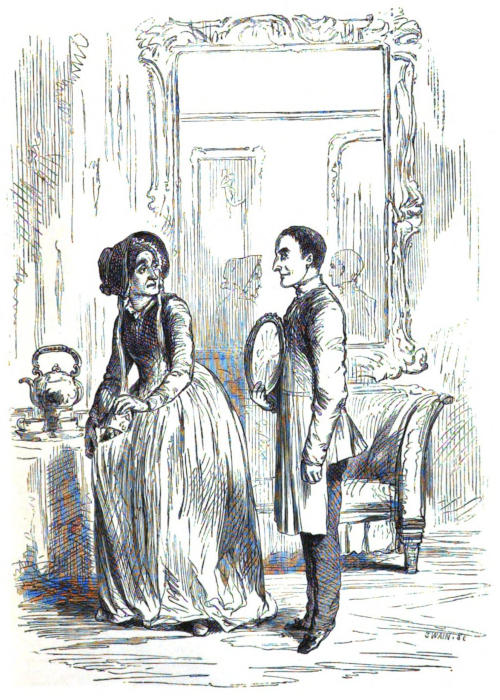

| Lovel the Widower |

330 |

| Chapter III.—In which I play

the Spy. (With an Illustration.) |

|

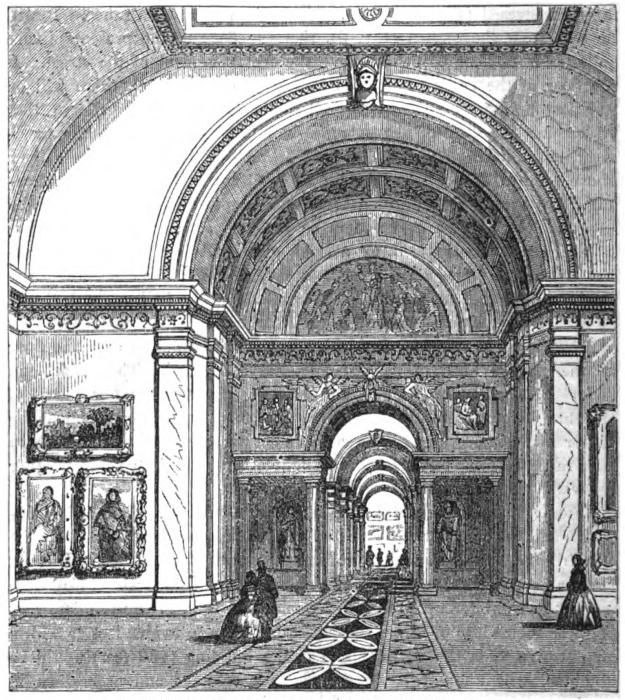

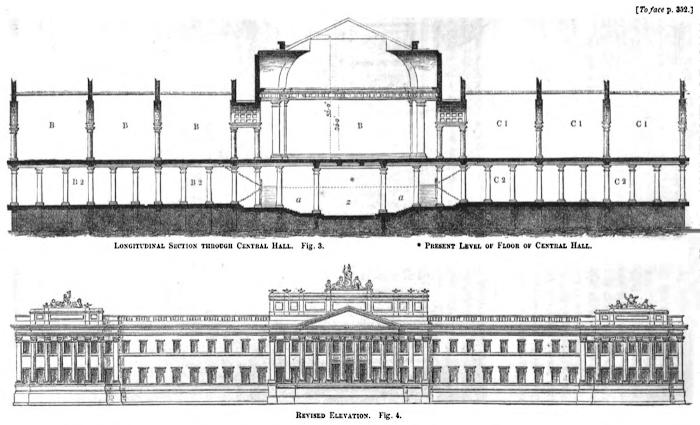

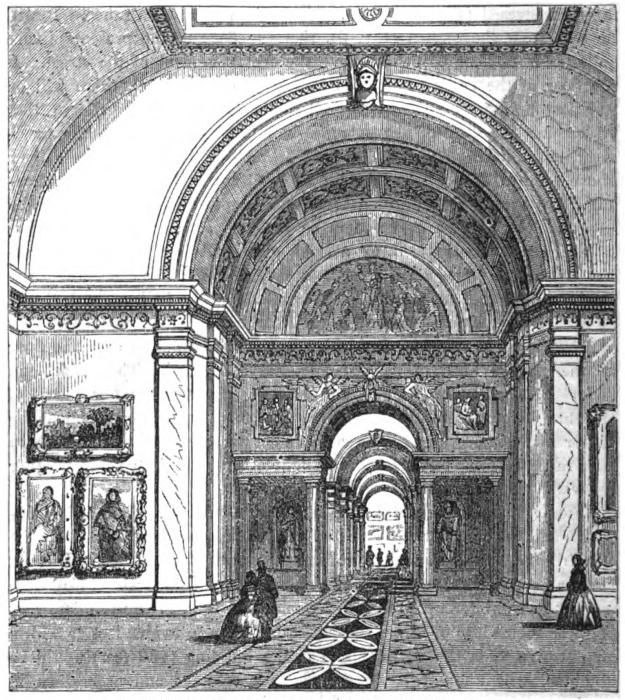

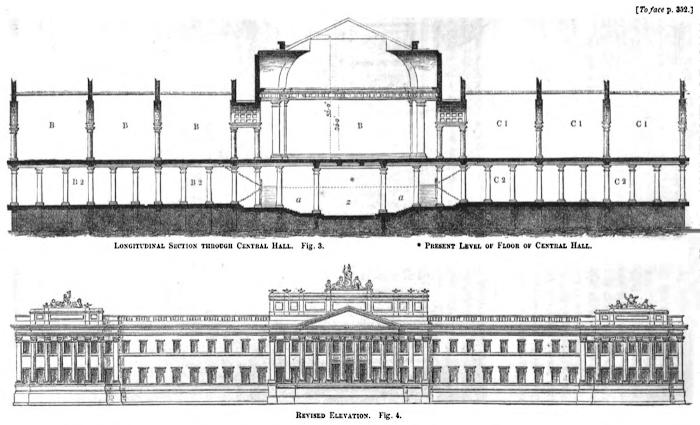

| The National Gallery Difficulty Solved |

346 |

| A Winter Wedding-party in the Wilds |

356 |

| Student Life in Scotland |

366 |

| Roundabout Papers.—No. 2 |

380 |

| On Two Children in Black. |

|

LONDON: SMITH, ELDER AND CO.,

65, CORNHILL.

THE CORNHILL MAGAZINE.

CONTENTS of No. 1.

January, 1860.

- Framley Parsonage. Chapters 1, 2 and 3.

- The Chinese and the “Outer Barbarians.”

- Lovel the Widower. Chapter 1. (With an Illustration.)

- Studies in Animal Life. Chapter 1.

- Father Prout’s Inaugurative Ode to the Author of “Vanity Fair.”

- Our Volunteers.

- A Man of Letters of the last Generation.

- The Search for Sir John Franklin (from the Private Journal of an Officer of the Fox). (With an Illustration and Map.)

- The First Morning of 1860.

- Roundabout Papers.—No. 1. On a Lazy Idle Boy.

CONTENTS of No. 2.

February, 1860.

- Nil Nisi Bonum.

- Invasion Panics.

- To Goldenhair (from Horace). By Thomas Hood.

- Framley Parsonage. Chapters 4, 5 and 6.

- Tithonus. By Alfred Tennyson.

- William Hogarth: Painter, Engraver, and Philosopher. Essays on the Man, the Work, and the Time.—I. Little Boy Hogarth.

- Unspoken Dialogue. By R. Monckton Milnes. (With an Illustration.)

- Studies in Animal Life. Chapter 2.

- Curious if True. (Extract from a Letter from Richard Whittingham, Esq.)

- Life among the Lighthouses.

- Lovel the Widower. Chapter 2. (With an Illustration.)

- As Essay without End.

NOTICE TO CORRESPONDENTS.

⁂ Communications for the Editor should be addressed to the care of Messrs. Smith, Elder and Co.,

65, Cornhill, and not to the Editor’s private residence. The Editor cannot be responsible for

the return of rejected contributions.

[257]

THE

CORNHILL MAGAZINE.

MARCH, 1860.

A Few Words on Junius and Macaulay.

The “secret of Junius” has been kept until, like over-ripe wines, the

subject has lost its flavour. Languid indeed is the disposition of mind in

which any, except a few veterans who still prefer the old post-road to

the modern railway, take up an essay or an article professing to throw

new light on that wearisome mystery, or to add some hitherto unknown

name to the ghostly crowd of candidates for that antiquated prize. And

yet there is a deep interest about the inquiry, after all, to those who, from

any special cause, are induced to overcome the feeling of satiety which it

at first excites, and plunge into the controversy with the energy of their

grandfathers. The real force and virulence of those powerful writings,

unrivalled then, and scarcely equalled since, let critics say what they may;

the strangeness of the fact that none of the quick-sighted, unscrupulous,

revengeful men who surrounded Junius at the time of his writing, who

brushed past him in the street, drank with him at dinner, sat opposite him

in the office, could ever attain to even a probable conjecture of his identity;

the irresistible character of the external evidence which fixes the authorship

on Francis, contrasted with those startling internal improbabilities which

make the Franciscan theory to this day the least popular, although the

learned regard it as all but established—the eccentric, repulsive, “dour”

character of Francis himself, and the kind of pertinacious longing which

besets us to know the interior of a man who shuts himself up against his

fellow-men in fixed disdain and silence:—these are powerful incentives,

and produce an attraction, of which we are sometimes ourselves ashamed,

towards the occupation of treading over and over again this often beaten

ground of literary curiosity.

Never have I felt this more strongly, than when accident led me, a few

years ago, into Leigh and Sotheby’s sale-room, when the library of Sir

Philip Francis was on view previous to auction. I know not whether any

reader will sympathize with me in what I am about to say: but to me

there is a solemn and rather oppressive feeling, which attends these exposures

of books for sale, where the death is recent, and where the owner and[258]

collector was a man of this world, taking an interest in the everyday

literature which occupies myself and those around me. There stands his

copy of a memoir of some one whom both he and I knew well—he had

just had time to read it, as I see by the date, and with interest, as I judge

by the pencil marks—in what mysteriously separate relation do he and I

now respectively stand towards that common acquaintance? There is his

copy of the latest volume of Travels—he had only accompanied the adventurer,

I see, as far as the First Cataract—what matters now to him the

problem of the Source of the Nile? There is his last unbound number of

the Quarterly—he had studied it for many a year: at such a page, the

paper-cutter rested from its work, the marginal notes ended, the influx of

knowledge stopped, the chain of thought was snapped, the mental perceptions

darkened. Can it be, that the active mind of our fellow-worker ceased then

and there from that continuous exertion of so many years, and became that

we wot not of—a living Intelligence, it may be, but removed into another

sphere, with which its habitual region of labour—the cycle in which it

moved and had its being—had no connection whatever? Must it be (as

Charles Lamb so quaintly expresses it) that “knowledge now comes to

him, if it comes at all, by some awkward experiment of intuition, and no

longer by this familiar process of reading?”

But I do not wish to dally, here and now, with fancies like these. I

only introduced the subject, because Sir Philip Francis’ library was a good

deal calculated to suggest this class of thoughts. He was a great marginal

note-maker. He criticized all that came under his eye, and especially

what related to political events, even to his latest hour. And—singular

enough, yet in accordance with much that we know of him, and with all

that we must suppose, if Junius he was—he had avoided keeping up, in

this way, his connection with the time in which his sinister and anonymous

fame was achieved. So far as I remember, his books of the Junian period

were little noted. He seemed to have exercised his memory and judgment

on the records of Warren Hastings’ trial, the French Revolution, the revolutionary

war—not on those of Burke and Chatham.

This, however, is all by the way, and I must crave pardon for the

digression. I lost myself, and wandered off, it seems, just when I was

reminding the reader that the subsidiary features of the Junian controversy

have now become much more interesting than the old question of authorship

itself, and that it is an admirable exercise for the intellectual faculties

to trace the way in which different lines of reasoning, wholly distinct and

yet severally complete, converge towards the “Franciscan” conclusion. It

was in this light, especially, that the subject appeared to captivate the

mind of that great historical genius whom we have lost: whom we have

just seen in the ample enjoyment of most rare faculties, the fulness of

fame, and the height of fortune, committed to the soft arms of an euthanasia

such as has rarely waited on man. The “Junian controversy” was with

Macaulay an endless subject of ingenious talk. It suited certain peculiarities

of his mind. As he was the very clearest of writers, so he was also,[259]

in a special sense and manner, the most acute of reasoners. In limited, close

historical argument—in the power to infer a third proposition from a

second, a second from a first—the power to expand a fact, either proved

or assumed as a trifling postulate, into a series of facts, with undeniable

cogency—I think we must go far to find his equal.

If you gave Cuvier a tarsal bone, he constructed you, with unerring

certainty, a humming-bird or an elephant. If you gave Macaulay a casual

passage from a letter, he would divine, with strange precision, the circumstances

of that letter: the occasion of its writing, the reason of its publication

or non-publication, the way in which the writer was connected

with some great event of the time, and in which the letter bore on that

event. But his judgment of the character of the man, or character of the

event, was another matter altogether, and tasked a different order of faculties,

with which we are not now concerned. If we were to seek a rival

to Macaulay in this peculiar province of clear and cogent reasoning from

fact A to fact X, imparting to conjecture the force of truth, we should

probably find him rather among lawyers than writers. In truth, the

historian always retained, and to his great advantage, many of the mental

habits, as well as many of the tastes and joyous recollections of the bar. He

was at once the most Paleyan and the most forensic of historical inquirers.

When he entered the arena of controversy, you might doubt whether he had

donned his armour in the Senate House of Cambridge or the Assize Court

of Lancaster. We may assume (as Coke assumed, lamentingly, of Bacon)

that had he only stuck to the law he would have made a great lawyer.

But it is open to doubt whether, as a judge, he would have done more of

service by the marvellous lucidity with which he would have drawn out

a series of circumstantial evidence before a jury, or more of harm by his

tendency to force the various considerations attending a complicated case

into conformity with his own too complete and too vivid ideal of that case.

There is no better way towards appreciating the intensity of this

peculiar faculty in Macaulay, than to study the various controversies into

which his essays and his history led him: both the few in which he

vouchsafed a reply, and the many more in which he rested contented with

his first statement—his issues with Dixon, Paget, the High Churchmen,

the Scotch, the Quakers, and the like—and to contrast his method with

that of his antagonists. They all beat the bush, more or less, and flounder

in every variety of historical fallacy. They beg the question, frame

“vicious processes” from their premisses, “pole” themselves on self-created

dilemmas, commit, in short, every error which logicians denounce in their

fantastic terminology—in Macaulay’s reasoning, simply as such, you will

never detect a flaw. His conclusion follows his premisses as surely and safely

as “the night the day.” You may agree with his antagonist, and not with

him; but you will find that what you consider to be his error lies quite in

another direction, and consists, not in misusing his own facts, but in

ignoring or neglecting true and material facts adduced by his opponents.

And beware, O young and ardent Reader, too readily pleased with seeing[260]

a hole picked in a great man’s coat, lest the triumphant crow, with which

these opponents invariably trumpet their supposed victory, seduce you into

premature acquiescence. By-and-by, when cooler and steadier, you may

be inclined to conjecture that Macaulay’s piercing instinct was right after

all, and that the facts evoked against him are in reality either doubtful or

immaterial to the argument.

It was, as I have said, this fondness and aptitude for following up with

accuracy converging lines of evidence, which gave Macaulay so great an

interest in the Junian controversy, and made him so ready to allude to it

incidentally both in writing and conversation. He contributed, himself,

two, at least, of the most remarkable collateral proofs which tend to fix the

authorship on Francis—the curious error of the English War-office clerk

about the rules of Irish pensions, in the correspondence with Sir William

Draper—the personal hostility of the Francis family towards the Luttrells,

which accounts for the savage treatment by Junius of such obscure offenders.

And now, having used the great historian’s name, somewhat

unfairly, by way of shoeing-horn, to draw on a fresh chapter on the old

controversy, let me place before you another singular instance of this class

of collateral proofs, which, I believe, has not been made public before,

but which greatly excited the curiosity of Macaulay, and which he would

have followed out—if ever he had taken up the question again—with all

the force of his inductive mind.

In one of the early letters of Woodfall’s collection, under the signature

“Bifrons” (April 23, 1768: vol. ii. p. 175, of Bohn’s Edition), the writer,

after accusing the Duke of Grafton of being a ‘casuist,’ proceeds as follows:—

“I am not deeply read in authors of that professed title: but I

remember seeing Busenbaum, Suares, Molina, and a score of other Jesuitical

books, burnt at Paris, for their sound casuistry, by the hand of the common

hangman.”

I shall assume at once that Bifrons was the same writer as Junius. The

general reasons for the assumption are familiar to those versed in the controversy.

And even were those general grounds of identity less strong

than they are, every one would allow that to prove that Francis was

Bifrons, would go a long way towards proving him Junius.

A passage so pregnant with suggestion has of course provoked abundant

comment: but all of the loosest description. No one seems to have taken

the pains to follow out for himself a hint pointing to conclusions of so much

importance, both negative and affirmative.

Mr. W. H. Smith, the recent editor of the Grenville Papers, thus

presses it into the service of his theory, attributing the authorship of

Junius to Lord Temple:

“The ceremony here alluded to probably took place in or about the

year 1732, when the disputes between the King of France and his parliaments,

relative to the Jesuits, had arrived at the highest point of acrimony.

Several burnings of obnoxious and prohibited books and writings are

described by cotemporary authorities at this time; and as Lord Temple,[261]

then Richard Grenville, was in France, and chiefly at Paris, from the

autumn of 1731 to the spring of 1733, he had, consequently, many opportunities

of witnessing the ceremonies of the burning of ‘scores of Jesuitical

books’ by the common hangman, as described by Junius.”—(Introductory

notes relating to the authorship of Junius, p. cxliv.)

Mr. Smith is scarcely so familiar with the details of French as of

English history. No doubt books were publicly burnt in Paris about the

time he mentions: but the books were Jansenist, not Jesuit: the letters

concerning the Miracles of M. de Paris, the Nouvelles Ecclésiastiques, and

the like—not the works of the Casuists. In 1732, the Jesuits were the

executioners: their turn, as victims, came a generation later.

A writer, who endeavours to establish a claim for Lord Lyttelton, is

nearer the mark: but, unluckily, just misses it:——

“We may assume,” says he, “that this burning took place in 1764,

as it was in that year that Choiseul suppressed the Jesuits. Thomas

Lyttelton was on the continent during the whole of 1764, and for part of

the time resided at Paris.”

The burning of books, so accurately described by Bifrons, took place,

beyond a doubt, as we shall presently see, on August the 7th, 1761. Now

this date raises a curious question, which is indicated, but in a very careless

manner, by Mr. Wade (in his notes to Junius, Bohn’s edition):——

“It may be doubted, indeed, whether Bifrons was an Englishman, or

even an Irishman: he certainly could not have been a British subject in

1761, unless he was a prisoner of war: for in that year we were at war

with France. But if a prisoner of war, how unlikely that he could be at

Paris to witness an auto-da-fé of heretical works: he would have been

confined in the interior of the kingdom, not left at large to indulge his

curiosity in the capital.”

Now, assuming (as all these writers do), that Bifrons-Junius actually

saw what he says he saw, how does the circumstance bear on the claims of

the several candidates?

What was Lyttelton in August, 1761? An Eton boy, enjoying his

holidays.

Where was Lord Temple? At Stowe (see the Grenville Letters) caballing

with Pitt.

Where was Burke? At Battersea, preparing to join Gerard Hamilton

in Ireland.

Where were Burke the younger, Lord George Sackville, and the rest of

the illustrious persons implicated in some people’s suspicions? Not in

Paris, we may safely answer, without pursuing our inquiry farther.

But it is undoubtedly possible that Bifrons-Junius, after all, did not

himself see the auto-da-fé in question: he may have heard of it, or read

of it, and may have described himself as a witness for effect, by way of a

flourish, or even by way of false lure to throw inquirers off the scent.

It would then only remain to inquire, in what way, by what association

of ideas, Bifrons-Junius came to give so circumstantial a description, and in[262]

so prominent a manner, of an occurrence which had passed in a time of

war, almost unmarked by the English public, and which had excited in

England but very little attention or interest since?

Now let us see how either supposition bears on the “Franciscan theory.”

Francis was a very young clerk in Mr. Pitt’s department (which

answered to the Foreign Office of these days) in 1759. In that year he

accompanied Lord Kinnoul on his special mission to Portugal. His lordship

returned in November, 1760, with all his staff, and the youthful

Francis (in all probability) returned to his desk at the same time.

He was certainly at work in the same office between October, 1761,

and August 1768; for he says of himself (Parl. Debates, xxii. 97), that he

“possessed Lord Egremont’s favour in the Secretary of State’s Office.”

That nobleman came into office in October, 1761, and died in August,

1763. In the latter year Francis was removed to the War Office, where

he remained until 1772.

Where was he in August, 1761?

According to all reasonable presumption, at work in Pitt’s department.

And yet Lady Francis, in that biographical account of her husband

which was published by Lord Campbell—an account evidently incorrect in

some details, yet authentic in striking particulars, as might be expected

from a lady’s reminiscences of what she heard from an older man—says,

“He was at the Court of France in Louis XV.’s time, when the Jesuits were

driven out by Madame de Pompadour.”

This, it will be at once allowed, is a strange instance of coincidence

between Bifrons and the lady. The more striking, because the particulars

of disagreement show that the two stories do not come from the same source.

But how can we account for either story? How came Francis to be in

Paris—if in Paris he were—in time of war?

With a view to solve this question to my own satisfaction, I once consulted

the State Paper Office. It happens that during the summer of 1761,

Mr. Hans Stanley was in Paris, on a diplomatic mission, to negotiate terms

of peace with Choiseul. He failed in that object—some folks thought Mr.

Pitt never meant he should succeed—and returned home in September of

that year. His correspondence with Pitt, as Secretary of State, is preserved

in the office aforesaid. He seems to have had the ordinary staff of

assistants from Pitt’s department: but I could not find any record of their

names. His despatches are entirely confined to the subject of the negotiation

on which he was engaged, with one exception. He seems, for some

reason or other, to have taken much interest in the affair of the Jesuits.

On August 10, he writes at length on the whole of that matter. To his

despatch is annexed a careful précis, in Downing Street language, of the

history of the Jesuits’ quarrel with the parliament: evidently drawn up by

one of his subordinates. Enclosed in this précis is the original printed

Arrêt de la Cour du Parlement, du 6 Août, 1761, condemning Molina, de

Justitiâ et Jure; Suares, Defensio Fidei Catholicæ; Busenbaum, Theologia

Moralis; and several other books of the same class, to be lacérés et[263]

brûlés en la cour du Palais. And a MS. note at the foot of the Arrêt

states that the books were burnt on the 7th accordingly.

Thus much, therefore, is all but certain; some member of Mr. Stanley’s

mission, or other confidential subordinate, was present in the Cour du

Palais when that arrêt was executed, and reported it to his principal, who

reported it to Mr. Pitt: and Francis was at that time a clerk in Pitt’s

office, which was in constant communication with Stanley’s mission. We

do not know the names of the individual clerks who were attached to that

mission, or passed backwards and forwards between Paris and London in

connection with it. But we do know that Francis had been twice employed

in a similar way (to accompany General Bligh’s expedition to Cherbourg,

and Lord Kinnoul’s mission to Portugal). Evidently, therefore, he was very

likely to be thus employed again. He may then assuredly have witnessed

with his own bodily eyes what no Englishman, unconnected with that

mission, could well have witnessed: may have stood on the steps of the

Palais de Justice, watched the absurd execution taking place in the courtyard

below, and treasured up the details as food for his sarcastic spirit;

or (to take the other supposition) he may have read at his desk in the

office that curious despatch of Mr. Stanley’s; may have retained it in his

tenacious memory; and, writing a few years afterwards, may have thought

proper, for the sake of effect, to represent himself as an eye-witness of

what he only knew by reading.

All this I once detailed to Macaulay, who, as I have said, was much

interested by the argument, and took an eager part in discussing it. But

one circumstance (I said) perplexed me, and seemed to interfere with the

probabilities of the case. How came Junius, whose excessive fear of

detection betrays itself throughout so much of his correspondence, and led

him to employ all manner of shifts and devices for the sake of concealment,

to give the public, as if in mere bravado, such a key to his identity as this

little piece of autobiography affords?

The answer is plain, replied Macaulay on the instant, with one of those

electric flashes of rapid perception which seemed in him to pass direct from

the brain to the eye. The letter of Bifrons is one of Junius’s earliest

productions—its date, half-a-year before the formidable signature of Junius

was adopted at all. The first letter so signed is dated in November, 1768.

In April, the writer had neither earned his fame, nor incurred his personal

danger. A mere unknown scatterer of abuse, he could have little or no

fear of directing inquiry towards himself.

But (he added) I much prefer your first supposition to your second.

It is not only the most picturesque, but it is really the most probable.

And unless the contrary can be shown, I shall believe in the actual

presence of the writer at the burning of the books. Remember, this fact

explains what otherwise seems inexplicable, Lady Francis’s imperfect

story, that her husband “was at the court of France when Madame de

Pompadour drove out the Jesuits.” Depend on it, you have caught Junius

in the fact. Francis was there.

[264]

William Hogarth:

PAINTER, ENGRAVER, AND PHILOSOPHER.

Essays on the Man, the Work, and the Time.

II.—Mr. Gamble’s Apprentice.

How often have I envied those who—were not my envy dead and buried—would

now be sixty years old! I mean the persons who were born at

the commencement of the present century, and who saw its glories evolved

each year with a more astonishing grandeur and brilliance, till they culminated

in that universal “transformation scene” of ’15. For the appreciation

of things began to dawn on me only in an era of internecine frays and

feuds:—theological controversies, reform agitations, corporation squabbles,

boroughmongering debates, and the like: a time of sad seditions and

unwholesome social misunderstandings; Captain Rock shooting tithe-proctors

in Ireland yonder; Captain Swing burning hayricks here; Captains

Ignorance and Starvation wandering up and down, smashing machinery,

demolishing toll-bars, screeching out “Bread or blood!” at the carriage-windows

of the nobility and gentry going to the drawing-room, and

otherwise proceeding the wretchedest of ways for the redress of their

grievances. Surely, I thought, when I began to think at all, I was born

in the worst of times. Could that stern nobleman, whom the mob hated,

and hooted, and pelted—could the detested “Nosey,” who was beset by a

furious crowd in the Minories, and would have been torn off his horse, perchance

slain, but for the timely aid of Chelsea Pensioners and City Marshalmen,—and

who was compelled to screen his palace windows with iron shutters

from onslaughts of Radical macadamites—could he be that grand Duke

Arthur, Conqueror and Captain, who had lived through so much glory, and

had been so much adored an idol? Oh, to have been born in 1800! At six,

I might just have remembered the mingled exultation and passionate grief

of Trafalgar; have seen the lying in state at Greenwich, the great procession,

and the trophied car that bore the mighty admiral’s remains to his last

home beneath the dome of Paul’s. I might have heard of the crowning

of the great usurper of Gaul: of his putting away his Creole wife, and

taking an emperor’s daughter; of his congress at Erfurt,—and Talma, his

tragedian, playing to a pit full of kings, of his triumphal march to Moscow,

and dismal melting away—he and his hosts—therefrom; of his last defeat

and spectral appearance among us—a wan, fat, captive man, in a battered

cocked hat, on the poop of an English war-ship in Plymouth Sound—just

before his transportation to the rock appointed to him to eat his heart upon.

I envied the nurse who told upon her fingers the names of the famous

victories of the British army under Wellington in Spain; Vimieira,

Talavera, Vittoria, Salamanca, Ciudad Rodrigo, Badajos, Fuentes[265]

d’Onore,—mille e tre; in fine—at last, Waterloo. Why had I not lived in that

grand time, when the very history itself was acting? Strong men there

were who lived before Agamemnon; but for the accident of a few years,

I might have seen, at least, Agamemnon in the flesh. ’Tis true, I knew

then only about the rejoicings and fireworks, the bell-ringings, and thanksgiving

sermons, the Extraordinary Gazettes, and peerages and ribbons

bestowed in reward for those deeds of valour. I do not remember that I

was told anything about Walcheren, or about New Orleans; about the

trade driven by the cutters of gravestones, or the furnishers of funeral

urns, broken columns, and extinguished torches; about the sore taxes, and

the swollen national debt. So I envied; and much disdained the piping

times of peace descended to me; and wondered if the same soldiers I

saw or heard about, with scarcely anything more to do than lounge on

Brighton Cliff, hunt up surreptitious whisky-stills, expectorate over

bridges, and now and then be lapidated at a contested election, could

be the descendants of the heroes who had swarmed into the bloody

breach at Badajos, and died, shoulder to shoulder, on the plateau of Mont

St. Jean.

MR. GAMBLE’S APPRENTICE.

Came 1848, with its revolutions, barricades, states of siege, movements

of vast armies, great battles and victories, with their multiplied hecatombs

of slain even; but they did not belong to us; victors and vanquished were

aliens; and I went on envying the people who had heard the Tower guns

fire, and joybells ring, who had seen the fireworks, and read the Extraordinary

Gazettes during the first fifteen years of the century! Was I

never to live in the history of England? Then, as you all remember, came

the great millennium or peace year ’51. Did not sages deliberate as to

whether it would not be better to exclude warlike weapons from the

congress of industry in Hyde Park? By the side of Joseph Paxton with

his crystal verge there seemed to stand a more angelic figure, waving wide

her myrtle wand, and striking universal peace through sea and land. It

was to be, we fondly imagined, as the immortal blind man of Cripplegate

sang:—

“No war or battle’s sound

Was heard the world around:

The idle spear and shield were high uphung,

The hookèd chariot stood

Unstain’d with hostile blood,

The trumpet spake not to the armèd throng;

And kings sate still with awful eye,

As if they sorely knew their Sovereign Lord was by.”

O blind man! it was but for an instant. The trodden grass had

scarcely begun to grow again where nave and transept had been, when

the wicked world was all in a blaze; and then the very minstrels of peace

began to sharpen swords and heat shot red-hot about the Holy Places; and

then the Guards went to Gallipoli, and farther on to Bulgaria, and farther

on to Old Fort; and the news of the Alma, Inkermann, Balaklava, the[266]

Redan, the Tchernaya, the Mamelon, the Malakhoff came to us, hot and

hot, and we were all living in the history of England. And lo! it was

very much like the history of any other day in the year—or in the

years that had gone before. The movements of the allied forces were

discussed at breakfast, over the sipping of coffee, the munching of

muffins, and the chipping of eggs. Newspaper-writers, parliament-men,

club-orators took official bungling or military mismanagement as their

cue for the smart leader of the morrow, the stinging query to Mr.

Secretary at the evening sitting, or the bow-window exordium in the

afternoon; and then everything went on pretty much as usual. We

had plenty of time and interest to spare for the petty police case, the

silly scandal, the sniggering joke of the day. The cut of the coat

and the roasting of the mutton, the non-adhesiveness of the postage-stamp,

or the misdemeanors of the servant-maid, were matters of as

relative importance to us as the great and gloomy news of battle and

pestilence from beyond sea. At least I lived in actual history, and my

envy was cured for ever.

I have often thought that next to Asclepiades, the comic cynic,[1]

Buonaparte Smith was the greatest philosopher that ever existed. B.

Smith was by some thought to have been the original of Jeremy

Diddler. He was an inveterate borrower of small sums. On a certain

Wednesday in 1821, un sien-ami accosted him. Says the friend:

“Smith, have you heard that Buonaparte is dead?” To which retorts

the philosopher: “Buonaparte be ——!” but I disdain to quote his

irreverent expletive—“Buonaparte be somethinged. Can you lend me

ninepence?” What was the history of Europe or its eventualities to

Buonaparte Smith? The immediate possession of three-fourths of a

shilling was of far more importance to him than the death of that

tremendous exile in his eyrie in the Atlantic Ocean, thousands of miles

away. Thus, too, I daresay it was with a certain small philosopher, who

lived through a very exciting epoch of the history of England: I mean

Little Boy Hogarth. It was his fortune to see the first famous fifteen

years of the eighteenth century, when there were victories as immense as

Salamanca or Waterloo; when there was a magnificent parallel to Arthur

Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, existent, in the person of John Churchill,

Duke of Marlborough. I once knew a man who had lived in Paris, and

throughout the Reign of Terror, in a second floor of the Rue St. Honoré.[267]

“What did you do?” I asked, almost breathlessly, thinking to hear of

tumbrils, Carmagnoles, gibbet-lanterns, conventions, poissarde-revolts, and

the like. “Eh! parbleu,” he answered, “je m’occupais d’ornithologie.”

This philosopher had been quietly birdstuffing while royalty’s head was

rolling in the gutter, and Carrier was drowning his hundreds at Nantes.

To this young Hogarth of mine, what may Marlborough and his great

victories, Anne and her “silver age” of poets, statesmen, and essayists,

have been? Would the War of the Succession assist young William in

learning his accidence? Would their High Mightinesses of the States-General

of the United Provinces supply him with that fourpence he

required for purchases of marbles or sweetmeats? What had Marshal

Tallard to do with his negotiations with the old woman who kept the apple-stall

at the corner of Ship Court? What was the Marquis de Guiscard’s

murderous penknife compared with that horn-handled, three-bladed one,

which the Hebrew youth in Duke’s Place offered him at the price of

twentypence, and which he could not purchase, faute de quoi? At most,

the rejoicings consequent on the battles of Blenheim or Ramillies, or

Oudenarde or Malplaquet, might have saved William from a whipping

promised him for the morrow; yet, even under those circumstances, it is

painful to reflect that staying out too late to see the fireworks, or singeing

his clothes at some blazing fagot, might have brought upon him on that

very morrow a castigation more unmerciful than the one from which he

had been prospectively spared.

Every biographer of Hogarth that I have consulted—and I take

this opportunity to return my warmest thanks to the courteous book

distributor at the British Museum who, so soon as he sees me enter the

Reading Room, proceeds, knowing my errand, to overwhelm me with

folios, and heap up barricades of eighteenth century lore round me—every

one of the biographers, Nichols, Steevens, Ireland, Trusler, Phillips, Cunningham,

the author of the article “Thornhill,” in the Biographia

Britannica—the rest are mainly copyists from one another, often handing

down blunders and perpetuating errors—every Hogarthian Dryasdust

makes a clean leap from the hero’s birth and little schoolboy noviciate

to the period of his apprenticeship to Ellis Gamble the silversmith.

Refined Mr. Walpole, otherwise very appreciative of Hogarth, flirting

over the papers he got from Vertue’s widow, indites some delicate manuscript

for the typographers of his private press at Strawberry Hill, and

tells us that the artist, whom he condescends to introduce into his

Anecdotes of Painting, was bound apprentice to a “mean engraver of

arms upon plate.” I see nothing mean in the calling which Benvenuto

Cellini (they say), and Marc Antonio Raimondi (it is certain), perhaps

Albert Durer, too, followed for a time. I have heard of great

artists who did not disdain to paint dinner plates, soup tureens, and

apothecary’s jars. Not quite unknown to the world is one Rafaelle

Sanzio d’Urbino, who designed tapestry for the Flemish weavers, or a

certain Flaxman, who was of great service to Mr. Wedgwood, when he[268]

began to think that platters and pipkins might be brought to serve some

very noble uses. Horace Walpole, cleverest and most refined of dilettanti—who

could, and did say the coarsest of things in the most elegant of

language—you were not fit to be an Englishman. Fribble, your place

was in France. Putative son of Orford, there seems sad ground for the

scandal that some of Lord Fanny’s blood flowed in your veins; and that

Carr, Lord Hervey, was your real papa. You might have made a collection

of the great King Louis’s shoes, the heels and soles of which

were painted by Vandermeulen with pictures of Rhenish and Palatinate

victories. Mignon of arts and letters, you should have had a petite maison

at Monçeaux or at the Roule. Surrounded by your abbés au petit collet,

teacups of pâte tendre, fans of chicken-skin painted by Leleux or Lantara,

jewelled snuff-boxes, handsome chocolate girls, gems and intaglios, the

brothers to those in the Museo Borbonico at Naples, che non si mostrano

alle donne, you might have been happy. You were good enough to admire

Hogarth, but you didn’t quite understand him. He was too vigorous,

downright, virile for you; and upon my word, Horace Walpole, I don’t

think you understood anything belonging to England—nor her customs,

nor her character, nor her constitution, nor her laws. I don’t think that

you would have been anywhere more in your element than in France, to

make epigrams and orange-flower water, and to have your head cut off in

that unsparing harvest of ’93, with many more noble heads of corn as

clever and as worthless for any purpose of human beneficence as yours,

Horace.

For you see, this poor Old Bailey schoolmaster’s son—this scion of

a line of north-country peasants and swineherds, had in him pre-eminently

that which scholiast Warton called the “ἩΘΟΣ,” the strong sledgehammer

force of Morality, not given to Walpole—not given to you,

fribbles of the present as of the past—to understand. He was scarcely

aware of the possession of this quality himself, Hogarth; and when

Warton talked pompously of the Ethos in his works, the painter went about

with a blank, bewildered face, asking his friends what the doctor meant,

and half-inclined to be angry lest the learned scholiast should be quizzing

him. It is in the probabilities, however, that William had some little Latin.

The dominie in Ship Court did manage to drum some of his grammar

disputations into him, and to the end of his life William Hogarth preserved

a seemly reverence for classical learning. Often has his etching-needle

scratched out some old Roman motto or wise saw upon the gleaming copper.

A man need not flout and sneer at the classics because he knows them not.

He need not declare Parnassus to be a molehill, because he has lost his

alpenstock and cannot pay guides to assist him in that tremendous ascent.

There is no necessity to gird at Pyrrha, and declare her to be a worthless

jade, because she has never braided her golden hair for you. Of

Greek I imagine W. H. to have been destitute; unless, with that ingenious

special pleading, which has been made use of to prove that Shakspeare was

a lawyer, apothecary, Scotchman, conjuror, poacher, scrivener, courtier—what[269]

you please—we assume that Hogarth was a Hellenist because he

once sent, as a dinner invite to a friend, a card on which he had sketched

a knife, fork, and pasty, and these words, “Come and Eta Beta Pi.” No

wonder the ἩΘΟΣ puzzled him. He was not deeply learned in anything

save human nature, and of this knowledge even he may have been half

unconscious, thinking himself to be more historical painter than philosopher.

He never was a connoisseur. He was shamefully disrespectful

to the darkened daubs which the picture-quacks palmed on the curious

of the period as genuine works of the old masters. He painted “Time

smoking a picture,” and did not think much of the collection of Sir

Luke Schaub. His knowledge of books was defective; although another

scholiast (not Warton) proved, in a most learned pamphlet, that he had

illustrated, sans le savoir, above five hundred passages in Horace, Virgil,

Juvenal, and Ovid. He had read Swift. He had illustrated and evidently

understood Hudibras. He was afraid of Pope, and only made a timid,

bird-like, solitary dash at him in one of his earliest charges; and,

curiously, Alexander the Great of Twickenham seemed to be afraid of

Hogarth, and shook not the slightest drop of his gall vial over him.

What a quarrel it might have been between the acrimonious little scorpion

of “Twitnam,” and the sturdy bluebottle of Leicester Fields! Imagine

Pope versus Hogarth, pencil against pen; not when the painter was old

and feeble, half but not quite doting indeed, as when he warred with

Wilkes and Churchill, but in the strength and pride of his swingeing

satire. Perhaps William and Alexander respected one another; but I

think there must have been some tacit “hit me and I’ll hit you” kind

of rivalry between them, as between two cocks of two different schools

who meet now and then on the public promenades—meet with a

significant half-smile and a clenching of the fist under the cuff of the

jacket.

To the end of his life Hogarth could not spell; at least, his was not

the orthography expected from educated persons in a polite age. In

almost the last plate he engraved, the famous portrait of Churchill as a

Bear, the “lies,” with which the knots of Bruin’s club are inscribed, are

all “lyes.” This may be passed over, considering how very lax and

vague were our orthographical canons not more than a century ago, and

how many ministers, divines, poets—nay, princes, and crowned heads, and

nabobs—permitted themselves greater liberties than “lye” for “lie” in the

Georgian era. At this I have elsewhere hinted, and I think the biographers

of Hogarth are somewhat harsh in accusing him of crass

ignorance, when he only wrote as My Lord Keeper, or as Lady Betty, or as

his grace the Archbishop was wont to write. Hogarth, too, was an author.

He published a book—to say nothing of the manuscript notes of his life

he left. The whole structure, soul, and strength of the Analysis of Beauty

are undoubtedly his; although he very probably profited by the assistance—grammatical

as well as critical—of some of the clerical dignitaries who

loved the good man. That he did so has been positively asserted; but it[270]

is forestalling matters to trot out an old man’s hobby, when our beardless

lad is not bound ’prentice yet. I cannot, however, defend him from the

charges of writing “militia,” “milicia,” “Prussia,” “Prusia”—why didn’t

he hazard “Prooshia” at once?[2]—“knuckles,” “nuckles”—oh, fie!—“Chalcedonians,”

“Calcidonians;” “pity,” “pitty;” and “volumes,”

“volumns.” It is somewhat strange that Hogarth himself tells us that

his first graphic exercise was to “draw the alphabet with great correctness.”

I am afraid that he never succeeded in writing it very correctly.

He hated the French too sincerely to care to learn their language; and

it is not surprising that in the first shop card he engraved for his master

there should be in the French translation of Mr. Gamble’s style and titles

a trifling pleonasm: “bijouxs,” instead of “bijoux.”

No date of the apprenticeship of Hogarth is anywhere given. We

must fix it by internal evidence. He was out of his time in the South

Sea Bubble year, 1720. On the 29th of April[3] in the same year, he

started in business for himself. The neatness and dexterity of the shop

card he executed for his master forbid us to assume that he was aught

but the most industrious of apprentices. The freedom of handling, the

bold sweep of line, the honest incisive play of the graver manifested in this

performance could have been attained by no Thomas Idle; and we must,

therefore, in justice grant him his full seven years of ’prentice servitude.

Say then that William Hogarth was bound apprentice to Mr.

Ellis Gamble,[4] at the Golden Angel, in Cranbourn Street, Leicester

Fields, in the winter of the year of our Lord, Seventeen hundred and

twelve. He began to engrave arms and cyphers on tankards, salvers,

and spoons, at just about the time that it occurred to a sapient legislature

to cause certain heraldic hieroglyphics surmounted by the Queen’s

crown, and encircled by the words “One halfpenny,” to be engraven

on a metal die, the which being the first newspaper stamp ever known

to our grateful British nation, was forthwith impressed on every single

half-sheet of printed matter issued as a newspaper or a periodical.

“Have you seen the new red stamp?” writes his reverence Doctor[271]

Swift. Grub Street is forthwith laid desolate. Down go Observators,

Examiners, Medleys, Flying Posts, and other diurnals, and the undertakers

of the Spectator are compelled to raise the price of their entertaining

miscellany.

One of the last head Assay Masters at Goldsmith Hall told one of

Hogarth’s biographers, when a very—very old man, that he himself had

been ’prentice in Cranbourn Street, and that he remembered very well

William serving his time to Mr. Gamble. The register of the boy’s indenture

should also surely be among the archives of that sumptuous structure

behind the Post Office, where the worthy goldsmiths have such a sideboard

of massy plate, and give such jovial banquets to ministers and city magnates.

And, doubt it not, Ellis Gamble was a freeman, albeit, ultimately,

a dweller at the West-end, and dined with his Company when the goldsmiths

entertained the ministers and magnates of those days. Yes, gentles;

ministers, magnates, kings, czars, and princes were their guests, and King

Charles the Second did not disdain to get tipsy with Sir Robert Viner,

Lord Mayor and Alderman, at Guildhall. The monarch’s boon companion

got so fond of him as to lend him, dit-on, enormous sums of money. More

than that, he set up a brazen statue of the royal toper in the Stocks

flower-market at the meeting of Lombard Street and the Poultry.

Although it must be confessed that the effigy had originally been cast

for John Sobieski trampling on the Turk. The Polish hero had a

Carlovingian periwig given to him, and the prostrate and miscreant

Moslem was “improved” into Oliver Cromwell. [Mem.:—A pair of

correctional stocks having given their name to the flower-market; on

the other hand, may not the market have given its name to the pretty, pale,

red flowers, very dear to Cockneys, and called “stocks?”]

How was William’s premium paid when he was bound ’prentice? Be

it remembered that silver-plate engraving, albeit Mr. Walpole of Strawberry

Hill calls it “mean,” was a great and cunning art and mystery.

These engravers claimed to descend in right line from the old ciseleurs and

workers in niello of the middle ages. Benvenuto, as I have hinted, graved

as well as modelled. Marc Antonio flourished many a cardinal’s hat and

tassels on a bicchiére before he began to cut from Rafaelle and Giulio

Romano’s pictures. The engraver of arms on plate was the same artist

who executed delightful arabesques and damascenings on suits of armour of

silver and Milan steel. They had cabalistic secrets, these workers of the

precious, these producers of the beautiful. With the smiths, “back-hammering”

and “boss-beating” were secrets;—parcel-gilding an especial

mystery; the bluish-black composition for niello a recipe only to be

imparted to adepts. With the engravers, the “cross-hatch” and the

“double cypher,” as I cursorily mentioned at the end of the last chapter,

were secrets. A certain kind of cross-hatching went out with Albert

Durer, and had since been as undiscoverable as the art of making the real

ruby tint in glass. No beggar’s brat, no parish protégé, could be apprenticed

to this delicate, artistic, and responsible calling. For in graving deep,[272]

tiny spirals of gold and silver curl away from the trenchant tool, and

there is precious ullage in chasing and burnishing—spirals and ullage

worth money in the market. Ask the Jews in Duke’s Place, who sweat

the guineas in horsehair bags, and clip the Jacobuses, and rasp the new-milled

money with tiny files, if there be not profit to be had from the

minutest surplusage of gold and silver.

Goldsmiths and silversmiths were proud folk. They pointed to George

Heriot, King James’s friend, and the great things he did. They pointed to

the peerage. Did not a Duke of Beaufort, in 1683, marry a daughter of

Sir Josiah Child, goldsmith and banker? Was not Earl Tylney, his

son, half-brother to Dame Elizabeth Howland, mother of a Duchess of

Bedford, one of whose daughters married the Duke of Bridgewater,

another, the Earl of Essex? Was not Sir William Ward, goldsmith,

father to Humble Ward, created Baron Ward by Charles I.? and from

him springs there not the present Lord Dudley and Ward?[5] O you

grand people who came over with the Conqueror, where would you be

now without your snug city marriages, your comfortable alliances with

Cornhill and Chepe? Leigh of Stoneleigh comes from a lord mayor of

Queen Bess’s time. Fulke Greville, Lord Brooke, married an alderman’s

daughter two years ere Hogarth was apprenticed. The ancestor to the

Lords Clifton was agent to the London Adventurers in Oliver’s time, and

acquired his estate in their service. George the Second’s Earl of Rockingham

married the daughter of Sir Henry Furnese, the money-lender

and stock-jobber. The great Duke of Argyll and Greenwich married a

lord mayor’s niece. The Earl of Denbigh’s ancestor married the daughter

of Basil Firebrace, the wine merchant. Brewers, money-scriveners,

Turkey merchants, Burgomasters of Utrecht’s daughters,—all these

married blithely into the haute pairie. If I am wrong in my genealogies,

’tis Daniel Defoe who is to blame, not I; for that immortal drudge of

literature is my informant. Of course such marriages never take place

now. Alliances between the sacs et parchemins are never heard of.

Mayfair never meets the Mansion House, nor Botolph Lane Belgravia,

save at a Ninth of November banquet. I question if I am not inopportune,

and impertinent even, in hinting at the dukes and belted earls who

married the rich citizens’ daughters, were it not that by and by ’prentice

Hogarth will paint some scenes from a great life drama full of Warton’s

ἩΘΟΣ, called Marriage à la Mode. Ah! those two perspectives seen

through the open windows! In the first, the courtyard of the proud

noble’s mansion; in the last, busy, mercantile London Bridge: court and

city, city and court, and which the saddest picture!

Dominie Hogarth had but a hard time of it, and must have been

pinched in a gruesome manner to make both ends meet. That dictionary

of his, painfully compiled, and at last with infinite care and labour completed,

brought no grist to the mill in Ship Court. The manuscript[273]

was placed in the hands of a bookseller, who did what booksellers often

do when one places manuscripts in their hands. He let it drop. “The

booksellers,” writes Hogarth himself, “used my father with great cruelty.”

In his loving simplicity he tells us that many of the most eminent and

learned persons in England, Ireland, and Scotland, wrote encomiastic

notices of the erudition and diligence displayed in the work, but all to

no purpose. I suppose the bookseller’s final answer was similar to that

Hogarth has scribbled in the Manager Rich’s reply to Tom Rakewell, in

the prison scene:—“Sir, I have read your play, and it will not doo.” A

dreadful, heartrending trade was average authorship, even in the “silver

age” of Anna Augusta. A lottery, if you will: the prizeholders secretaries

of state, ambassadors, hangers-on to dukes and duchesses, gentlemen

ushers to baby princesses, commissioners of hackney coaches or plantations;

but innumerable possessors of blanks. Walla Billa! they were in

evil case. For them the garret in Grub or Monmouth Street, or in Moorfields;

for them the Welshwoman dunning for the milkscore; for them the

dirty bread flung disdainfully by bookselling wretches like Curll. For

them the shrewish landlady, the broker’s man, the catchpole, the dedication

addressed to my lord, and which seldom got beyond his lacquey;—hold!

let me mind my Hogarth and his silver-plate engraving. Only a little

may I touch on literary woes when I come to the picture of the Distressed

Poet. For the rest, the calamities of authors have been food for

the commentaries of the wisest and most eloquent of their more modern

brethren, and my bald philosophizings thereupon can well be spared.

But this premium, this indenture money, this ’prentice fee for young

William: unde derivatur? In the beginning, as you should know, this

same ’prentice fee was but a sort of “sweetener,” peace-offering, or pot de

vin to the tradesman’s wife. The ’prentice’s mother slipped a few pieces

into madam’s hand when the boy put his finger on the blue seal. The

money was given that mistresses should be kind to the little lads; that

they should see that the trenchers they scraped were not quite bare, nor

the blackjacks they licked quite empty; that they should give an eye to

the due combing and soaping of those young heads, and now and then

extend a matronly ægis, lest Tommy or Billy should have somewhat more

cuffing and cudgelling than was quite good for them. By degree this

gift money grew to be demanded as a right; and by-and-by comes thrifty

Master Tradesman, and pops the broad pieces into his till, calling them

premium. Poor little shopkeepers in this “silver age” will take a ’prentice

from the parish for five pounds, or from an acquaintance that is broken,

for nothing perhaps, and will teach him the great arts and mysteries of

sweeping out the shop, sleeping under the counter, fetching his master

from the tavern or the mughouse when a customer comes in, or waiting at

table; but a rich silversmith or mercer will have as much as a thousand

pounds with an apprentice. There is value received on either side. The

master is, and generally feels, bound to teach his apprentice everything he

knows, else, as worthy Master Defoe puts it, it is “somewhat like Laban’s[274]

usage to Jacob, viz. keeping back the beloved Rachel, whom he served

seven years for, and putting him off with a blear-eyed Leah in her stead;”

and again, it is “sending him into the world like a man out of a ship set

ashore among savages, who, instead of feeding him, are indeed more ready

to eat him up and devour him.” You have little idea of the state, pomp,

and circumstance of a rich tradesman, when the eighteenth century was

young. Now-a-days, when he becomes affluent, he sells his stock and

good-will, emigrates from the shop-world, takes a palace in Tyburnia or a

villa at Florence, and denies that he has ever been in trade at all. Retired

tailors become country squires, living at “Places” and “Priories.” Enriched

ironmongers and their families saunter about Pau, and Hombourg,

and Nice, passing for British Brahmins, from whose foreheads the yellow

streak has never been absent since the earth first stood on the elephant, and

the elephant on the tortoise, and the tortoise on nothing that I am aware of,

save the primeval mud from which you and I, and the Great Mogul, and

the legless beggar trundling himself along in a gocart, and all humanity,

sprang. But then, Anna D. G., it was different. The tradesman was nothing

away from his shop. In it he was a hundred times more ostentatious.

He may have had his country box at Hampstead, Highgate, Edmonton,

Edgeware; but his home was in the city. Behind the hovel stuffed with

rich merchandise, sheltered by a huge timber bulk, and heralded to passers

by an enormous sheet of iron and painters’ work—his Sign—he built

often a stately mansion, with painted ceilings, with carved wainscoting or

rich tapestry and gilt leather-work, with cupboards full of rich plate, with

wide staircases, and furniture of velvet and brocade. To the entrance of

the noisome cul-de-sac, leading to the carved and panelled door (with its

tall flight of steps) of the rich tradesman’s mansion, came his coach—yes,

madam, his coach, with the Flanders mares, to take his wife and daughters

for an airing. In that same mansion, behind the hovel of merchandise,

uncompromising Daniel Defoe accuses the tradesman of keeping servants in

blue liveries richly laced, like unto the nobility’s. In that same mansion the

tradesman holds his Christmas and Shrovetide feasts, the anniversaries of

his birthday and his wedding-day, all with much merrymaking and junketing,

and an enormous amount of eating and drinking. In that same

mansion, in the fulness of time and trade, he dies; and in that same

mansion, upon my word, he lies in state,—yes, in state: on a lit de

parade, under a plumed tester, with flambeaux and sconces, with blacks

and weepers, with the walls hung with sable cloth, et cætera, et cætera,

et cætera.[6] ’Tis not only “Vulture Hopkins” whom a “thousand lights[275]

attend” to the tomb, but very many wealthy tradesmen are so buried, and

with such pomp and ceremony. Not till the mid-reign of George the Third

did this custom expire.

[I should properly in a footnote, but prefer in brackets, to qualify the

expression “hovel,” as applied to London tradesmen’s shops at this time,

1712-20. The majority, indeed, merit no better appellation: the windows

oft-times are not glazed, albeit the sign may be an elaborate and even

artistic performance, framed in curious scroll-work, and costing not

unfrequently a hundred pounds. The exceptions to the structural poverty

of the shops themselves are to be found in the toymen’s—mostly in Fleet

Street,—and the pastrycooks’—mainly in Leadenhall. There is a mania

for toys; and the toyshop people realize fortunes. Horace Walpole bought

his toy-villa at Strawberry Hill—which he afterwards improved into a

Gothic doll’s-house—of a retired Marchand de Joujoux. The toy-merchants

dealt in other wares besides playthings. They dealt in cogged

dice. They dealt in assignations and billet-doux. They dealt in masks and

dominos. Counsellor Silvertongue may have called at the toyshop coming

from the Temple, and have there learnt what hour the countess would

be at Heidegger’s masquerade. Woe to the wicked city! Thank Heaven

we can go and purchase Noah’s arks and flexible acrobats for our children

now, without rubbing shoulders with Counsellor Silvertongue or Lord

Fanny Sporus, on their bad errands. Frequented as they were by rank

and fashion, the toyshops threw themselves into outward decoration.

Many of these shops were kept by Frenchmen and Frenchwomen, and it

has ever been the custom of that fantastic nation to gild the outside of

pills, be the inside ever so nauseous. Next in splendour to the toyshops

were the pastrycooks. Such a bill as can be seen of the charges for fresh

furnishing one of these establishments about Twelfth Night time! “Sash

windows, all of looking-glass plates; the walls of the shop lined up with

galley-tiles in panels, finely painted in forest-work and figures; two large

branches of candlesticks; three great glass lanterns; twenty-five sconces

against the wall; fine large silver salvers to serve sweetmeats; large high

stands of rings for jellies; painting the ceiling, and gilding the lanterns,

the sashes, and the carved work!” Think of this, Master Brook! What

be your Cafés des Mille Colonnes, your Véfours, your Vérys, your

Maisons-dorées, after this magnificence? And at what sum, think you, does

the stern censor, crying out against it meanwhile as wicked luxury and

extravagance, estimate this Arabian Nights’ pastrycookery? At three

hundred pounds sterling! Grant that the sum represents six hundred of

our money. The Lorenzos the Magnificent, of Cornhill and Regent Street,

would think little of as many thousands for the building and ornamentation[276]

of their palaces of trade. Not for selling tarts or toys though. The tide

has taken a turn; yet some comfortable reminiscences of the old celebrity

of the city toy and tart shops linger between Temple Bar and Leadenhall.

Farley, you yet delight the young. Holt, Birch, Button, Purssell, at your

sober warehouses the most urbane and beautiful young ladies—how pale

the pasty exhalations make them!—yet dispense the most delightful of

indigestions.]

So he must have scraped this apprenticeship money together, Dominie

Hogarth: laid it by, by cheeseparing from his meagre school fees, borrowed

it from some rich scholar who pitied his learning and his poverty, or

perhaps become acquainted with Ellis Gamble, who may have frequented

the club held at the “Eagle and Child,” in the little Old Bailey. “A

wonderful turn for limning has my son,” I think I hear Dominie Hogarth

cry, holding up some precocious cartoon of William’s. “I doubt not, sir,

that were he to study the humanities of the Italian bustos, and the just

rules of Jesuit’s perspective, and the anatomies of the learned Albinus, that

he would paint as well as Signor Verrio, who hath lately done that noble

piece in the new hall Sir Christopher hath built for the blue-coat children

in Newgate Street.” “Plague on the Jesuits,” answers honest (and supposititious)

Mr. Ellis Gamble. “Plague on all foreigners and papists, goodman

Hogarth. If you will have your lad draw bustos and paint ceilings,

forsooth, you must get one of the great court lords to be his patron, and send

him to Italy, where he shall learn not only the cunningness of limning, but

to dance, and to dice, and to break all the commandments, and to play on the

viol-di-gamby. But if you want to make an honest man and a fair tradesman

of him, Master Hogarth, and one who will be a loyal subject to the Queen,

and hate the French, you shall e’en bind him ’prentice to me; and I will

be answerable for all his concernments, and send him to church and

catechize, and all at small charges to you.” Might not such a conversation

have taken place? I think so. Is it not very probable that the lad

Hogarth being then some fourteen years old, was forthwith combed his

straightest, and brushed his neatest, and his bundle or his box of needments

being made up by the hands of his loving mother and sisters, despatched

westward, and with all due solemnity of parchment and blue seal, bound

’prentice to Mr. Ellis Gamble? I am sure, by the way in which he

talks of the poor old Dominie and the dictionary, that he was a loving

son. I know he was a tender brother. Good Ellis Gamble—the lad

being industrious, quick, and dexterous of hand—must have allowed him

to earn some journeyman’s wages during his ’prentice-time; for that

probation being out, he set not only himself, but his two sisters, Mary

and Ann, up in business. They were in some small hosiery line, and

William engraved a shop-card for them, which did not, I am afraid,

prosper with these unsubstantial spinsters any more than did the celebrated

lollipop emporium established in The House with the Seven Gables.

One sister survived him, and to her, by his will, he left an annuity of

eighty pounds.

[277]

Already have I spoken of the Leicester Square gold and silver

smith’s style and titles. It is meet that you should peruse them in

full:—

So to Cranbourn Street, Leicester Fields, is William Hogarth bound for

seven long years. Very curious is it to mark how old trades and old types

of inhabitants linger about localities. They were obliged to pull old

Cranbourn Street and Cranbourn Alley quite down before they could get rid

of the silversmiths, and even now I see them sprouting forth again round

about the familiar haunt; the latest ensample thereof being in the shop of a

pawnbroker—of immense wealth, I presume, who, gorged and fevered by

multitudes of unredeemed pledges, has suddenly astonished New Cranbourn

Street with plate-glass windows, overflowing with plate, jewellery,

and trinkets; buhl cabinets, gilt consoles, suits of armour, antique china,

Pompadour clocks, bronze monsters, and other articles of virtù. But don’t

you remember Hamlet’s in the dear old Dædalean, bonnet-building Cranbourn

Alley days?—that long low shop whose windows seemed to have no

end, and not to have been dusted for centuries; those dim vistas of dish-covers,

coffee biggins and centre-pieces. You must think of Crœsus when

you speak of the reputed wealth of Hamlet. His stock was said to be

worth millions. Seven watchmen kept guard over it every night. Half

the aristocracy were in his debt. Royalty itself had gone credit for plate

and jewellery at Hamlet’s. Rest his bones, poor old gentleman, if he be

departed. He took to building and came to grief. His shop is no more,

and his name is but a noise.

[278]

In our time, Cranbourn Street and Cranbourn Alley were dingy

labyrinths of dish-covers, bonnets, boots, coffee-shops, and cutlers; but

what must the place have been like in Hogarth’s time? We can have no

realizable conception; for late in George the Third’s reign, or early in

George the Fourth’s, the whole pâté of lanes and courts between Leicester

Square and St. Martin’s Lane had become so shamefully rotten and

decayed, that they half tumbled, and were half pulled down. The

labyrinth was rebuilt; but, to the shame of the surveyors and architects

of the noble landlord, on the same labyrinthine principle of mean

and shabby tenements. You see, rents are rents, little fishes eat sweet,

and many a little makes a mickle. Since that period, however, better

ideas of architectural economy have prevailed; and, although part of

the labyrinth remains, there has still been erected a really handsome

thoroughfare from Leicester Square to Long Acre. As a sad and

natural consequence, the shops don’t let, while the little tenements in

the alleys that remain are crowded; but let us hope that the example of

the feverish pawnbroker who has burst out in an eruption of jewellery and

art fabrics, may be speedily followed by other professors of bricabrac.

Gay’s Trivia, in miniature, must have been manifest every hour in the

day in Hogarth’s Cranbourn Alley. Fights for the wall must have taken

place between fops. Sweeps and small coalmen must have interfered with

the “nice conduct of a clouded cane.” The beggars must have swarmed

here: the blind beggar, and the lame beggar, the stump-in-the-bowl,

and the woman bent double: the beggar who blew a trumpet—the

impudent varlet!—to announce his destitution;—the beggar with a beard

like unto Belisarius, the beggar who couldn’t eat cold meat, the beggar

who had been to Ireland and the Seven United Provinces—was this

“Philip in the tub” that W. H. afterwards drew?—the beggar in the blue

apron, the leathern cap, and the wen on his forehead, who was supposed

to be so like the late Monsieur de St. Evremonde, Governor of Duck

Island; not forgetting the beggar in the ragged red coat and the black

patch over his eye, who by his own showing had been one of the army

that swore so terribly in Flanders, and howled Tom D’Urfey’s song, “The

Queene’s old souldiers, and the ould souldiers of the Queene.” Then there

was the day watchman, who cried the hour when nobody wanted to hear

it, and to whose “half-past one,” the muddy goose that waddled after

him, cried “quack.” And then there must have been the silent mendicant,

of whom Mr. Spectator says (1712), “He has nothing to sell, but very

gravely receives the bounty of the people for no other merit than the

homage due to his manner of signifying to them that he wants a subsidy.”[7]

Said I not truly that the old types will linger in the old localities?[279]

What is this silent mendicant but the “serious poor young man”

we have all seen standing mute on the edge of the kerb, his head downcast,

his hands meekly folded before him, himself attired in speckless but

shabby black, and a spotless though frayed white neckerchief?

Mixed up among the beggars, among the costermongers and hucksters

who lounge or brawl on the pavement, undeterred by fear of barrow-impounding

policemen; among the varlets who have “young lambs to sell”—they

have sold those sweet cakes since Elizabeth’s time;—among the

descendants and progenitors of hundreds of “Tiddy Dolls,” and “Colly

Molly Puffs;” among bailiffs prowling for their prey, and ruffian cheats

and gamesters from the back-waters of Covent Garden; among the fellows

with hares-and-tabors, the matchsellers, the masksellers—for in this inconceivable

period ladies and gentlemen wanted vizors at twelve o’clock at

noon—be it admitted, nevertheless, that the real “quality” ceased to wear

them about the end of William’s reign—among the tradesmen, wigs awry,

and apron-girt, darting out from their shops to swallow their matutinal

pint of wine, or dram of strong waters; among all this tohu-bohu, this

Galimatias of small industries and small vices, chairmen come swaggering

and jolting along with the gilded sedans between poles; and lo! the periwigged,

Mechlin-laced, gold-embroidered beau hands out Belinda, radiant,

charming, powdered, patched, fanned, perfumed, who is come to Cranbourn

Alley to choose new diamonds. And more beaux’ shins are wounded by

more whalebone petticoats, and Sir Fopling Flutter treads on Aramanta’s

brocaded queue; and the heavens above are almost shut out by the great

projecting, clattering signs. Conspicuous among them is the “Golden

Angel,” kept by Ellis Gamble.

Mark, too, that Leicester Fields were then as now the favourite resort

of foreigners. Green Street, Bear Street, Castle Street, Panton Street,

formed a district called, as was a purlieu in Westminster too, by the

Sanctuary, “Petty France.” Theodore Gardelle, the murderer, lived about

Leicester Fields. Legions of high-dried Mounseers, not so criminal as he,

but peaceable, honest, industrious folk enough, peered out of the garret

windows of Petty France with their blue, bristly gills, red nightcaps, and

filthy indoor gear. They were always cooking hideous messes, and[280]

made the already unwholesome atmosphere intolerable with garlic. They

wrought at water-gilding, clock-making, sign-painting, engraving for book

illustrations—although in this department the Germans and Dutch were

dangerous rivals. A very few offshoots from the great Huguenot colony

in Spitalfields were silk-weavers. There were then as now many savoury,

tasting and unsavoury-smelling French ordinaries; and again, then as now,

some French washerwomen and clearstarchers. But the dwellers in

Leicester Fields slums and in Soho were mainly Catholics frequenting the

Sardinian ambassador’s chapel in Duke Street, Lincoln’s Inn Fields. French

hairdressers and perfumers lived mostly under Covent Garden Piazza, in

Bow Street and in Long Acre. Very few contrived to pass Temple Bar.

The citizens appeared to have as great a horror of them as of the players,

and so far as they could, by law, banished them their bounds, rigorously.

French dancing, fencing, and posture masters, and quack doctors, lived at

the court end of the town, and kept, many of them, their coaches. Not a

few of the grinning, fantastic French community were spies of the magnificent

King Louis. Sunday was the Frenchmen’s great day, and the Mall in

St. James’s park their favourite resort and fashionable promenade. It

answered for them all the purposes which the old colonnade of the Quadrant

was wont to serve, and which the flags of Regent Street serve now. On

Sunday the blue, bristly gills were clean shaven, the red nightcaps replaced

by full-bottomed wigs, superlatively curled and powdered. The filthy

indoor gear gave way to embroidered coats of gay colours, with prodigious

cuffs, and the skirts stiffened with buckram. Lacquer-hilted swords stuck

out behind them. Paste buckles glittered in their shoon. Glass rings

bedecked their lean paws. They held their tricornes beneath their arms,

flourished their canes and inhaled their snuff with the best beaux on town.

We are apt to laugh at the popular old caricatures of the French Mounseer,