Title: A history of Canada, 1763-1812

Author: Sir Charles Prestwood Lucas

Release date: June 17, 2022 [eBook #68336]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Clarendon Press, 1909

Credits: Sonya Schermann, hekula03, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Footnotes have been placed at the end of their respective chapters.

BY

Sir C. P. LUCAS, K.C.M.G., C.B.

OXFORD

AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

1909

HENRY FROWDE, M.A.

PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD

LONDON, EDINBURGH, NEW YORK

TORONTO AND MELBOURNE

My warm thanks are due to Mr. C. T. Atkinson, M.A., of Exeter College, Oxford, who most kindly read through the proofs of the chapter on the War of American Independence and made some valuable corrections; and also to Mr. C. Atchley, I.S.O., Librarian of the Colonial Office, who has given me constant help. Two recent and most valuable books have greatly facilitated the study of Canadian history since 1763, viz., Documents relating to the Constitutional History of Canada, 1759-91, selected and edited with notes by Messrs. Shortt and Doughty, and Canadian Constitutional Development, by Messrs. Egerton and Grant. I want to express my grateful acknowledgements of the help which these books have given to me.

C. P. LUCAS.

December, 1908.

| CHAPTER I | PAGE |

| The Proclamation of 1763, and Pontiac’s War | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Causes of the American War of Independence and the Quebec Act | 30 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The War of American Independence | 90 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The Treaty of 1783 and the United Empire Loyalists | 208 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Lord Dorchester and the Canada Act of 1791 | 236 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Sir James Craig | 298 |

| APPENDIX I | |

| Treaty of Paris, 1783 | 321 |

| APPENDIX II | |

| The Boundary Line of Canada | 327 |

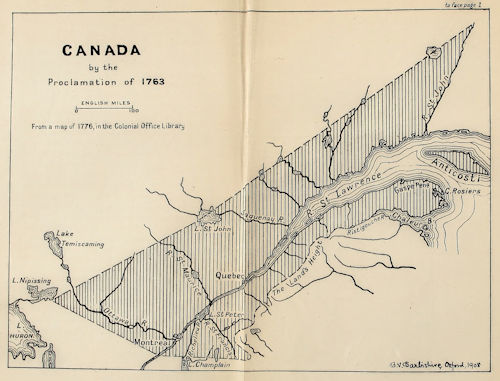

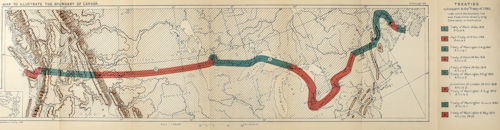

| 1. | Map to illustrate the Proclamation of 1763 | To face p. | 1 |

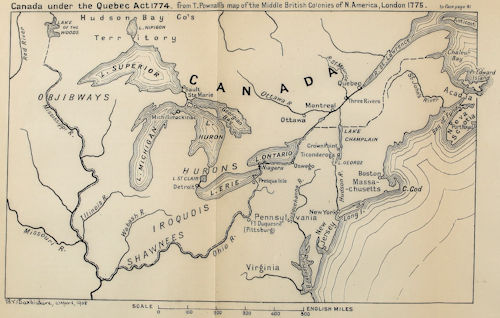

| 2. | Canada under the Quebec Act | " | 81 |

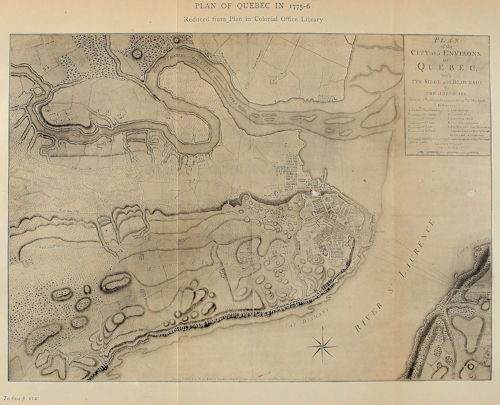

| *3. | Plan of the City and Environs of Quebec | ” | 112 |

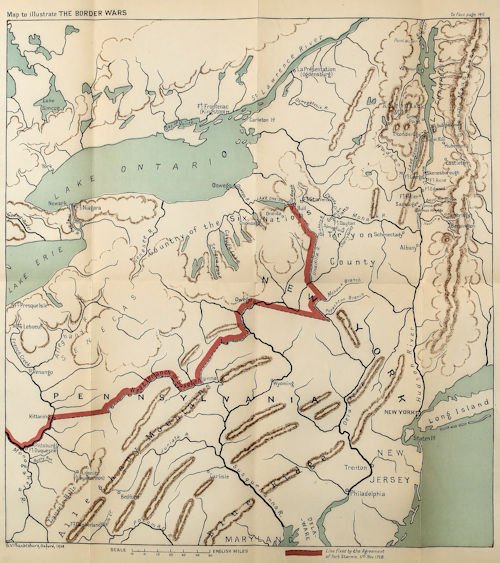

| 4. | Map to illustrate the Border Wars | ” | 145 |

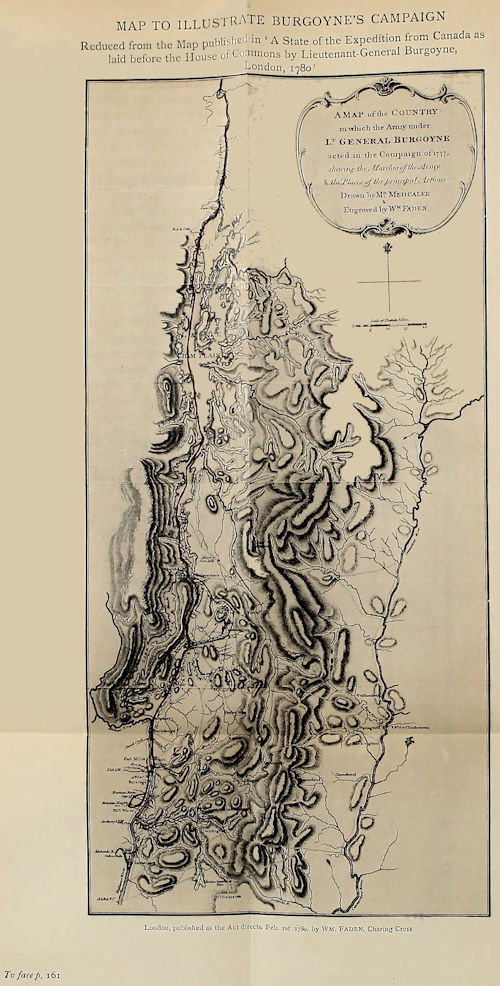

| *5. | A Map of the Country in which the army under Lieutenant-General Burgoyne acted in the campaign of 1777 | ” | 161 |

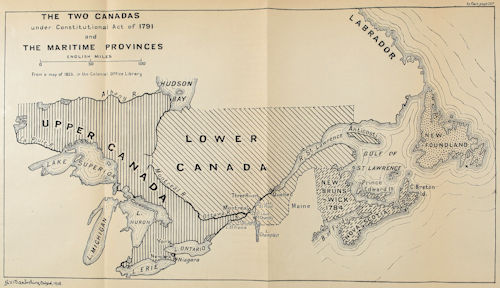

| 6. | The two Canadas under the Constitutional Act of 1791 | ” | 257 |

| 7. | Map to illustrate the Boundary of Canada | ” | 321 |

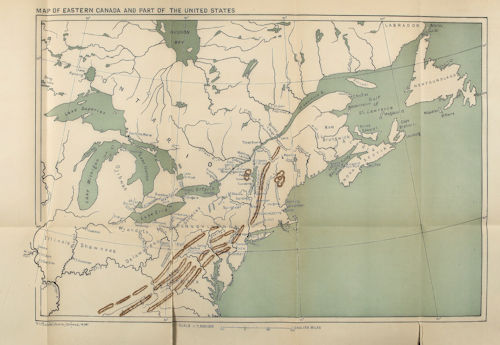

| 8. | Map of Eastern Canada and part of the United States | End of book. | |

| * Reproductions of contemporary maps. | |||

click here for larger image.

click here for larger image.

to face page 1

CANADA

by the

Proclamation of 1763

From a map of 1776, in the Colonial Office Library

B. V. Barbishire, Oxford, 1908

HISTORY OF CANADA, 1763-1812

On the 10th of February, 1763, the Peace of Paris was signed between Great Britain, France, and Spain. Under its provisions all North America, east of the Mississippi, which had been owned or claimed by France, was, with the exception of the city of New Orleans, transferred to Great Britain, the navigation of the Mississippi being thrown open to the subjects of both Powers. The English also received Florida from Spain, in return for Havana given back to its old owners. Under a treaty secretly concluded in November, 1762, when the preliminaries of the general treaty were signed, Spain took over from France New Orleans and Louisiana west of the Mississippi, the actual transfer being completed in 1769. Thus France lost all hold on the North American continent, while retaining various West Indian islands, and fishing rights on part of the Newfoundland coast, which were supplemented by possession of the two adjacent islets of St. Pierre and Miquelon.

In the autumn of the year 1763, on the 7th of October, King George III issued a proclamation constituting ‘within the countries and islands, ceded and confirmed to us by the said treaty, four distinct and separate governments, styled and called by the names of Quebec, East Florida, West Florida, and Grenada’. Of these four governments, the first alone requires special notice. The government of Grenada was in the West Indies, and the governments of East and West Florida, excluding a debatable strip of territory which was annexed to the[2] State of Georgia, were co-extensive with the new province which had been acquired from Spain.

The limits assigned by the proclamation to the government of Quebec were as follows: north of the St. Lawrence, the new province was ‘bounded on the Labrador coast by the river St. John, and from thence by a line drawn from the head of that river, through the Lake St. John, to the south end of the Lake Nipissim’. The river St. John flows into the St. Lawrence over against the western end of the island of Anticosti; Lake St. John is the lake out of which the Saguenay takes its course; Lake Nipissim or Nipissing is connected by French river with Georgian Bay and Lake Huron. The line in question, therefore, was drawn due south-west from Lake St. John parallel to the St. Lawrence.[1] From the southern end of Lake Nipissim the line, according to the terms of the proclamation, crossed the St. Lawrence and Lake Champlain in 45 degrees of north latitude. In other words, it was drawn due south-east, to the west of and parallel to the Ottawa river, until it struck the St. Lawrence, where the 45th parallel of north latitude meets that river at the foot of the Long Sault Rapids. It then followed the 45th parallel eastward across the outlet of Lake Champlain, and subsequently, diverging to the north-east, was carried ‘along the highlands which divide the rivers that empty themselves into the said river St. Lawrence from those which fall into the sea’. Further east it skirted ‘the north coast of the Baye des Chaleurs and the coast of the Gulf of St. Lawrence to Cape Rosieres’, which last named cape is at the extreme end of the Gaspé peninsula. The line then again crossed the St. Lawrence by the western end of the island of Anticosti, and joined the river St. John.

Thus, south of the St. Lawrence, the boundary of the province of Quebec was, roughly speaking, much the same as it is at the present day. Its westernmost limit was[3] also not far different, the Ottawa river being in the main the existing boundary between the provinces of Ontario and Quebec. On the north and north-east, on the other hand, the government of Quebec in 1763 covered a smaller area than is now the case. ‘To the end that the open and free fishery of our subjects may be extended to and carried on upon the coast of Labrador and the adjacent islands,’ ran the terms of the proclamation, ‘we have thought fit, with the advice of our said Privy Council, to put all that coast from the river St. John’s to Hudson’s Straits, together with the islands of Anticosti and Madelaine, and all other smaller islands lying upon the said coast, under the care and inspection of our Governor of Newfoundland.’ To the government of Nova Scotia were annexed the conquered islands of St. Jean or St. John’s, now Prince Edward Island, and Isle Royale or Cape Breton, ‘with the lesser islands adjacent thereto.’

It was greatly desired to encourage British settlement in North America, and special regard was had in this respect to the soldiers and sailors who in North American lands and waters had deserved so well of their country. Accordingly the proclamation contained a special provision for grants of land, within the old and the new colonies alike, to retired officers of the army who had served in North America during the late war; to private soldiers who had been disbanded in and were actually living in North America; and to retired officers of the navy who had served in North America ‘at the times of the reduction of Louisbourg and Quebec’. It was thought also by the Lords of Trade that confidence and encouragement would be given to intending settlers, if at the outset they were publicly notified of the form of government under which they would live. Provision for a legislature and for the administration of justice. Hence the proclamation provided, as regards the new colonies, ‘that so soon as the state and circumstances of the said colonies will admit thereof,’ the governors ‘shall, with the advice and consent of the members of our Council, summon and call General Assemblies within the said governments respectively, in such[4] manner and form as is used and directed in those colonies and provinces in America which are under our immediate government’. The governors, councils, and representatives of the people, when duly constituted, were empowered to make laws for the public peace, welfare, and good government of the colonies, provided that such laws should be ‘as near as may be agreeable to the laws of England, and under such regulations and restrictions as are used in other colonies.’ Pending the constitution of the legislatures, the inhabitants and settlers were to enjoy the benefit of the laws of England, and the governors were empowered, with the advice of their councils, to establish courts of justice, to hear and decide civil and criminal cases alike, in accordance as far as possible with the laws of England, a right of appeal being given in civil cases to the Privy Council in England. It was not stated in the proclamation, but it was embodied in the governors’ instructions, that until General Assemblies could be constituted, the governors, with the advice of their councils, were to make rules and regulations for peace, order, and good government, all matters being reserved ‘that shall any ways tend to affect the life, limb, or liberty of the subject, or to the imposing any duties or taxes’.

In June, 1762, James Murray, then military governor of the district of Quebec, and subsequently the first civil governor of the province, wrote that it was impossible to ascertain exactly what part of North America the French styled Canada. In the previous March General Gage, then military governor of Montreal, had written that he could not discover ‘that the limits betwixt Louisiana and Canada were distinctly described, so as to be publicly known’, but that from the trade which Canadians had carried on under the authority of their governors, he judged ‘not only the lakes, which are indisputable, but the whole course of the Mississippi from its heads to its junction with the Illinois, to have been comprehended by the French in the government of Canada’. In June, 1763, the Lords of Trade, when in obedience to the Royal[5] commands they were considering the terms and the scope of the coming proclamation, reported that ‘Canada, as possessed and claimed by the French, consisted of an immense tract of country including as well the whole lands to the westward indefinitely which was the subject of their Indian trade, as all that country from the southern bank of the river St. Lawrence, where they carried on their encroachments’.

After the Peace of Paris had been signed, the King, through Lord Egremont, who had succeeded Chatham as Secretary of State for the southern department, referred the whole subject of his new colonial possessions to the Lords of Trade. In doing so he called special attention to the necessity of keeping peace among the North American Indians—a subject which was shortly to be illustrated by Pontiac’s war—and to this end he laid stress upon the desirability of protecting their persons, their property, and their privileges, and ‘most cautiously guarding against any invasion or occupation of their hunting lands, the possession of which is to be acquired by fair purchase only’. The Lords of Trade recommended adoption of ‘the general proposition of leaving a large tract of country round the Great Lakes as an Indian country, open to trade, but not to grants and settlements; the limits of such territory will be sufficiently ascertained by the bounds to be given to the governors of Canada and Florida on the north and south, and the Mississippi on the west; and by the strict directions to be given to Your Majesty’s several governors of your ancient colonies for preventing their making any new grants of lands beyond certain fixed limits to be laid down in the instructions for that purpose’. Egremont answered that the King demurred to leaving so large a tract of land without a civil jurisdiction and open, as being derelict, to possible foreign intrusion; and that, in His opinion, the commission of the Governor of Canada should include ‘all the lakes, viz. Ontario, Erie, Huron, Michigan, and Superior’, and ‘all the country as far north and west as the limits of the[6] Hudson’s Bay Company and the Mississippi’. At the same time He cordially concurred in not permitting grants of lands or settlements in these regions, which should be ‘for the present left unsettled, for the Indian tribes to hunt in, but open to a free trade for all the colonies’. The Lords of Trade were not convinced. They deprecated annexing this western territory to any colony, and particularly to Canada, on three grounds: The first was that annexation to Canada might imply that the British title to these lands was the result of the late treaty and of the cession of Canada, whereas it rested on antecedent rights, and it was important not to let the Indians form a wrong impression on this head by being brought under the government of the old French province. The second ground was that, if the Indian territory was annexed to one particular province and subjected to its laws, that province would have an undue advantage over the other provinces or colonies in respect to the Indian trade, which it was the intention of the Crown to leave open as far as possible to all British subjects. The third objection to annexing the territory to Canada was that the laws of the province could not be enforced except by means of garrisons established at different posts throughout the area, which would necessitate either that the Governor of Canada should always be commander-in-chief of the forces in North America, or that there should be constant friction between the civil governor and the military commanders. This reasoning prevailed, and the lands which it was contemplated to reserve for the use of the Indians were not annexed to any particular colony or assigned to any one colonial government.

With this great area, covering the present province of Ontario and the north central states of the American Republic, the Royal proclamation dealt as follows: ‘Whereas it is just and reasonable, and essential to our interest, and the security of our colonies, that the several nations or tribes of Indians, with whom we are connected, and who live under our protection, should not be molested[7] or disturbed in the possession of such parts of our dominions and territories as, not having been ceded to or purchased by us, are reserved to them, or any of them, as their hunting grounds ... we do further declare it to be our Royal will and pleasure, for the present as aforesaid, to reserve under our sovereignty, protection, and dominion, for the use of the said Indians, all the lands and territories not included within the limits of our said three new governments, or within the limits of the territory granted to the Hudson’s Bay Company, as also all the lands and territories lying to the westward of the sources of the rivers which fall into the sea from the west and north-west as aforesaid; and we do hereby strictly forbid, on pain of our displeasure, all our loving subjects from making any purchases or settlements whatever, or taking possession of any of the lands above reserved, without our especial leave and licence for that purpose first obtained.’

Thus North America, outside the recognized limits of the old or new colonies, was for the time being constituted a great native reserve; and even within the limits of the colonies it was provided ‘that no private person do presume to make any purchase from the said Indians of any lands reserved to the said Indians within those parts of our colonies where we have thought proper to allow settlement: but that, if at any time any of the said Indians should be inclined to dispose of the said lands, the same shall be purchased only for us, in our name, at some public meeting or assembly of the said Indians, to be held for that purpose by the governor or commander-in-chief of our colony respectively within which they shall lie’. Trade with the Indians was to be free and open to all British subjects, but the traders were to take out licences, and, while no fees were to be charged for such licences, the traders were to give security that they would observe any regulations laid down for the benefit of the trade.[2]

It is impossible to study the correspondence which preceded the Proclamation of 1763, without recognizing that those who framed it were anxious to frame a just and liberal policy, but its terms bear witness to the almost Difficulties of the situation. insuperable difficulties which attend the acquisition of a great borderland of colonization, difficulties which in a few years’ time were largely responsible for the American War of Independence. How to administer a new domain with equity and sound judgement; how to give to new subjects, acquired by conquest, the privileges enjoyed by the old colonies; how to reconcile the claims of the old colonies, whose inland borders had never been demarcated, with the undoubted rights of native races; how to promote trade and settlement without depriving the Indians of their heritage;—such were the problems which the British Government was called upon to face and if possible to solve. The proclamation was in a few years’ time followed up by the Quebec Act of 1774, in connexion with which more will be said as to these thorny questions. In the meantime, even before the proclamation had been issued, the English had on their hands what was perhaps the most dangerous and widespread native rising which ever threatened their race in the New World.

The great French scheme for a North American dominion depended upon securing control of the waterways and control of the natives. Even before the dawn of the eighteenth century, Count Frontenac among governors, La Salle among pioneers, saw clearly the importance of gaining the West and the ways to the West; and they realized that, in order to attain that object, the narrows on the inland waters, and the portages from one lake or river to another, must be commanded; that the Indians who were hostile to France must be subdued, and that the larger number of red men, who liked French ways and French leadership, must be given permanent evidence of the value of French protection and the strength of French statesmanship.

Along the line of lakes and rivers in course of years[9] French forts were placed. Fort Frontenac, first founded in 1673 by the great French governor whose name it bore, guarded, on the site of the present city of Kingston, the outlet of the St. Lawrence from Lake Ontario. Fort Niagara, begun by La Salle in the winter of 1678-9, on the eastern bank of the Niagara river, near its entrance into Lake Ontario, covered the portage from that lake to Lake Erie. Fort Detroit, dating from the first years of the eighteenth century, stood by the river which carries the waters of Lake Huron and Lake St. Clair into Lake Erie. Its founder was La Mothe Cadillac. The post at Michillimackinac was at the entrance of Lake Michigan. From Lake Erie to the Ohio were two lines of forts. The main line began with Presque Isle on the southern shore of the lake, and ended with Fort Duquesne, afterwards renamed Pittsburg, the intermediate posts being Fort Le Bœuf at the head of French Creek, and Venango where that stream joins the Alleghany. Further west, past the intermediate fort of Sandusky, which stood on the southern shore of Lake Erie, there was a second series of outposts, of which we hear little in the course of the Seven Years’ War. The Maumee river flows into the south-western end of Lake Erie, and on it, at a point where there was a portage to the Wabash river, was constructed Fort Miami, on or near the site of the later American Fort Wayne. On the Wabash, which joins the Ohio not very far above the confluence of the latter river with the Mississippi, were two French posts, Fort Ouatanon and, lower down its course, Fort Vincennes. On the central Mississippi the chief nucleus of French trade and influence was Fort Chartres. It stood on the eastern bank of the river, eighty to ninety miles above the confluence of the Ohio, and but a few miles north of the point where the Kaskaskia river flows into the Mississippi. On the Kaskaskia, among the Illinois Indians, there was a French outpost, and settlement fringed the eastern side of the Mississippi northwards to Fort Chartres. Above that fort there was a road running north on the same side to[10] Cahokia, a little below and on the opposite side to the confluence of the Missouri; and in 1763 a French settler crossed the Mississippi, and opened a store on the site of the present city of St. Louis. The posts on the Mississippi were, both for trading and for political purposes, connected with Louisiana rather than with Canada; and, though the Peace of Paris had ceded to Great Britain the soil on which they stood, the French had not been disturbed by any assertion of British sovereignty prior to the war which is associated with the name of the Indian chief Pontiac.

The rising which Pontiac headed came too late for the Indians to be permanently successful. In any case it could have had, eventually, but one ending, the overthrow of the red men: but, while it lasted, it seriously delayed the consolidation of English authority over the West. After most wars of conquest there supervene minor wars or rebellions, waves of the receding tide when high-water is past, disturbances due to local mismanagement and local discontent; but the Indian war, which began in 1763, Its special characteristics. had special characteristics. In the first place, the rising was entirely a native revolt. No doubt it was fomented by malcontent French traders and settlers, disseminating tales of English iniquities and raising hopes of a French revival; but very few Frenchmen were to be found in the fighting line; the warriors were red men, not white. In the second place it was a rising of the Western Indians, of the tribes who had not known in any measure the strength of the English, and who had known, more as friends than as subjects, the guidance and the spirit of the French. Of the Six Nations, the Senecas alone, the westernmost members of the Iroquois Confederacy, joined in the struggle, and the centre of disturbance was further west. In the third place the rising was more carefully planned, the conception was more statesmanlike, the action was more organized, than has usually been the case among savage races. There was unity of plan and harmony in action, which betokened leadership of no ordinary kind. The leader was the Ottawa chief Pontiac.

‘When the Indian nations saw the French power, as it were, annihilated in North America, they began to imagine that they ought to have made greater and earlier efforts in their favour. The Indians had not been for a long time so jealous of them as they were of us. The French seemed more intent on trade than settlement. Finding themselves infinitely weaker than the English, they supplied, as well as they could, the place of strength by policy, and paid a much more flattering and systematic attention to the Indians than we had ever done. Our superiority in this war rendered our regard to this people still less, which had always been too little.’[3] The Indians were frightened too, says the same writer, by the English possession of the chains of forts: ‘they beheld in every little garrison the germ of a future colony.’ Ripe for revolt, and never yet subdued, as their countrymen further east had been, they found a strong man of their own race to lead them, and tried conclusions with the dominant white race in North America.

In the autumn of 1760, after the capitulation of Montreal, General Amherst sent Major Robert Rogers, the New Hampshire Ranger, to receive the submission of the French forts on the further lakes. On the 13th of September Rogers embarked at Montreal with two hundred of his men: he made his way up the St. Lawrence, and coasted the northern shore of Lake Ontario, noting, as he went, that Toronto, where the French had held Fort Rouillé, was ‘a most convenient place for a factory, and that from thence we may very easily settle the north side of Lake Erie’.[4] He crossed the upper end of Lake Ontario to Fort Niagara, already in British possession; and, having taken up supplies, carried his whale boats round the falls and launched them on Lake Erie. Along the southern side of that lake he went forward to Presque Isle, where Bouquet was in command of the English garrison; and, leaving his men, he went himself down by Fort[12] le Bœuf, the French Creek river, and Venango to Fort Pitt, or Pittsburg, as Fort Duquesne had been renamed by John Forbes in honour of Chatham. His instructions were to carry dispatches to General Monckton at Pittsburg, and to take orders from him for a further advance. Returning to Presque Isle at the end of October, he went westward along Lake Erie, making for Detroit. No English force had yet been in evidence so far to the West. On the 7th of November he encamped on the southern shore of Lake Erie, at a point near the site of the present city of Cleveland, and there he was met by a party of Ottawa Indians ‘just arrived from Detroit’.[5]

They came, as Rogers tells us in another book,[6] on an embassy from Pontiac, and were immediately followed by that chief himself. Pontiac’s personality seems to have impressed the white backwoodsman, though he had seen and known all sorts and conditions of North American Indians. ‘I had several conferences with him,’ he writes, ‘in which he discovered great strength of judgement and a thirst after knowledge.’ Pontiac took up the position of being ‘King and Lord of the country’, and challenged Rogers and his men as intruders into his land; but he intimated that he would be prepared to live peaceably with the English, as a subordinate not a conquered potentate; and the result of the meeting was that the Rangers were supplied with fresh provisions and were escorted in safety on their way, instead of being obstructed and attacked, as had been contemplated, at the entrance of the Detroit river. On the 12th of November Rogers set out again; on the 19th he sent on an officer in advance with a letter to Belêtre, the French commander at Detroit, informing him of the capitulation of Montreal and calling Surrender of Detroit to the English. upon him to deliver up the fort. On the 29th of November the English force landed half a mile below the fort, and on the same day the French garrison laid down their arms.[13] Seven hundred Indians were present; and, when they saw the French colours hauled down and the English flag take their place, unstable as water and ever siding at the moment with the stronger party, they shouted that ‘they would always for the future fight for a nation thus favoured by Him that made the world’.[7]

There were at the time, Rogers tells us,[8] about 2,500 French Canadians settled in the neighbourhood of Detroit. The dwelling-houses, near 300 in number, extended on both sides of the river for about eight miles. The land was good for grazing and for agriculture, and there was a ‘very large and lucrative’ trade with the Indians.

Having sent the French garrison down to Philadelphia, and established an English garrison in its place, Rogers sent a small party to take over Fort Miami on the Maumee river, and set out himself with another detachment for Michillimackinac. But it was now the middle of December; Return of Rogers. floating ice made navigation of Lake Huron dangerous; after a vain attempt to reach Michillimackinac he returned to Detroit on the 21st of December; and, marching overland to the Ohio and to Philadelphia, he Michillimackinac occupied by the English. finally reached New York on the 14th of February, 1761. In the autumn of that year a detachment of Royal Americans took possession of Michillimackinac.

Throughout 1761 and 1762 the discontent of the Indians increased; they saw the English officers and soldiers in their midst in strength and pride; they listened to the tales of the French voyageurs; they remembered French friendship and address, and contrasted it with the grasping rudeness of the English trader or colonist; a native prophet rose up to call the red men back to savagery, as the one road to salvation; and influenced at once by superstition and by the present fear of losing their lands, the tribes of the West made ready to fight.

For months the call to war had secretly been passing from tribe to tribe, and from village to village; and on[14] the 27th of April, 1763, Pontiac held a council of Indians at the little river Ecorces some miles to the south of The fort at Detroit. Detroit, at which it was determined to attack the fort. Fort Detroit stood on the western side of the Detroit river, which runs from Lake St. Clair to Lake Erie, at about five miles distance from the former lake and a little over twenty miles from Lake Erie. The river is at its narrowest point more than half a mile wide, and, as already stated, Canadian settlement fringed both banks. The fort, which stood a little back from the bank of the river, consisted of a square enclosure surrounded by a wooden palisade, with bastions and block-houses also of wood, and within the palisade was a small town with barracks, council house, and church. The garrison consisted of about 120 soldiers belonging to the 39th Regiment; and, in addition to the ordinary Canadian residents within the town, there were some 40 fur-traders present at the time, most of whom were French. The commander was Major Gladwin. a determined man, Major Gladwin, who, under Braddock on the Monongahela river, had seen the worst of Indian fighting. Before April ended Gladwin reported to Amherst that there was danger of an Indian outbreak; and, when the crisis came, warned either by Indians or by Canadians, he was prepared for it. For some, at any rate, of the Canadians at Detroit, though they had no love for the English, and though Pontiac was moving in the name of the French king, were men of substance and had something to lose. They were therefore not inclined to side with the red men against the white, or to lend themselves to extermination of the English garrison.

On the 1st of May Pontiac and forty of his men came into the fort on an outwardly friendly visit, and took stock of the ways of attack and the means of defence. Then a few days passed in preparing for the blow. A party of 60 warriors were once more to gain admittance, hiding under their blankets guns whose barrels had been filed down for the purpose of concealment: they were to hold[15] a council with the English officers, and at a given signal to shoot them down. The 7th of May was the day fixed for the deed, but Gladwin was forewarned and forearmed. The Indian chiefs were admitted to the fort, and attended the council; but they found the garrison under arms, and their plot discovered. Both sides dissembled, and the Indians were allowed to leave, disconcerted, but saved for further mischief. On the 9th of May they again applied to be admitted to the fort, but this time were refused, and open warfare began. Two or three English, The fort openly attacked. who were outside the palisade at the time, were murdered, and on the 10th, for six hours, the savages attacked the fort with no success.

There was little danger that Detroit would be taken by assault, but there was danger of the garrison being starved out. Gladwin, therefore, tried negotiation with Pontiac, and using French Canadians as intermediaries, sent two English officers with them to the Indian camp. The two Englishmen, one of them Captain Campbell, an old officer of high character and repute, were kept as captives, and Campbell was subsequently murdered. The surrender of the fort was then demanded by Pontiac, a demand which was at once refused; and against the wishes of his officers Gladwin determined to hold the post at all costs. Supplies were brought in by night by friendly Canadians, and all immediate danger of starvation passed away.

Amherst, the commander-in-chief, far away at New York, had not yet learnt of the peril of Detroit or of the nature and extent of the Indian rising, but in the ordinary course in the month of May supplies were being sent up for the western garrisons. The convoy intended for British convoy cut off. Detroit left Niagara on the 13th of that month, in charge of Lieutenant Cuyler with 96 men. Coasting along the northern shore of Lake Erie, Cuyler, towards the end of the month, reached a point near the outlet of the Detroit river, and there drew up his boats on the shore. Before an encampment could be formed the Indians broke in upon[16] the English, who fled panic-stricken to the boats; only two boats escaped, and between 50 and 60 men out of the total number of 96 were killed or taken. The survivors, Cuyler himself among them, made their way across the lake to Fort Sandusky, only to find that it had been burnt to the ground, thence to Presque Isle, which was shortly to share the fate of Sandusky, and eventually to Niagara. The prisoners were carried off by their Indian captors, up the Detroit river; two escaped to the fort to tell the tale of disaster, but the majority were butchered with all the nameless tortures which North American savages could devise.

While Detroit was being besieged, at other points in the West one disaster followed another. Isolated from each other, weakly garrisoned, commanded, in some instances, by officers of insufficient experience or wanting in determination, the forts fell fast. On the 16th of May Sandusky was blotted out; on the 25th Fort St. Joseph, at the south-eastern end of Lake Michigan, was taken; and on the 27th Fort Miami, on the Maumee river. Fort Ouatanon on the Wabash was taken on the 1st of June; and on the 4th of that month the Ojibwa Indians overpowered They take Michillimackinac. the garrison of Michillimackinac, second in importance to Detroit. Captain Etherington, the commander at Michillimackinac, knew nothing of what was passing elsewhere, though he had been warned of coming danger, and he lost the fort through an Indian stratagem. The English were invited outside the palisades to see an Indian game of ball; and, while the onlookers were off their guard, and the gates of the fort stood open, the players turned into warriors; some of the garrison and of the English traders were murdered, and the rest were made prisoners. The massacre, however, was not wholesale. Native jealousy gave protectors to the English survivors in a tribe of Ottawas who dwelt near: a French Jesuit priest used every effort to save their lives; and eventually the survivors, among whom was Etherington, were, with the garrison of a neighbouring and subordinate[17] post at Green Bay, sent down in safety to Montreal by the route of the Ottawa river.

Next came the turn of the forts which connected Lake Erie with the Ohio. On the 15th of June Presque Isle was attacked; on the 17th it surrendered. It was a strong fort, and in the opinion of Bouquet—a competent judge—its commander, Ensign Christie, showed little stubbornness in defence. Fort le Bœuf fell on the 18th, Venango about the same date, and communication between Fort Pitt isolated. the lakes and Fort Pitt was thus cut off. Fort Pitt itself was threatened by the Indians, and towards the end of July openly attacked, while on Forbes’ and Bouquet’s old route from that fort to Bedford in Pennsylvania, Fort Ligonier was also at an earlier date assailed, though fortunately without success.

Amherst now realized the gravity of the crisis, and his first care was the relief of Detroit. A force of 280 men, commanded by Captain Dalyell, one of his aides de camp, and including Robert Rogers with 20 Rangers, was sent up from Niagara, ascended on the 29th of July the Detroit river by night, and reached the fort in safety. Long experience in North American warfare had taught the lesson which Wolfe always preached, that the English should, whenever and wherever it was possible, take the offensive. Accordingly Dalyell urged Gladwin, against the latter’s better judgement, to allow him to attack Pontiac at once; and before daybreak, on the morning of the 31st, he led out about 250 men for the purpose. Less than two miles north-east of the fort, a little stream, The fight at Parents Creek. then known as Parents Creek and after the fight as Bloody Run, ran into the main river; and beyond it was Pontiac’s encampment, which Dalyell proposed to surprise. Unfortunately the Indians were fully informed of the intended movement, and there ensued one more of the many disasters which marked the onward path of the white men in North America. The night was dark: the English advance took them among enclosures and farm buildings, which gave the Indians cover. As the leading soldiers were crossing[18] the creek they were attacked by invisible foes; and, when compelled to retreat, the force was beset on all sides and ran the risk of being cut off from the fort. Death of Dalyell. Dalyell[9] was shot dead; and, before the fort was reached, the English had lost one-fourth of their whole number in killed and wounded. The survivors owed their safety to the steadiness of the officers, to the fact that Rogers and his men seized and held a farmhouse to cover the retreat, and to the co-operation of two armed boats, which moved up and down the river parallel to the advance and retreat, bringing off the dead and wounded, and pouring a fire from the flank among the Indians.

Pontiac had achieved a notable success, but Detroit remained safe, and meanwhile in another quarter the tide set against the Indian cause.

After General Forbes, in the late autumn of 1758, had taken Fort Duquesne, a new English fort, Fort Pitt, was in the following year built by General Stanwix upon the site of the French stronghold. The place was, as it had always been, the key of the Ohio valley, and on the maintenance of the fort depended at once the safety of the borderlands of Virginia and Pennsylvania, and the possibility of extending trade among the Indian tribes of the Ohio. In July, 1763, Fort Pitt was in a critical position. The posts which connected it with Lake Erie had been destroyed: the road which Forbes had cut through Pennsylvania on his memorable march was obstructed by Indians; and the outlying post along it, Fort Ligonier, about fifty-five miles east of Fort Pitt, was, like Fort Pitt itself, in a state of siege. The Indians were, as in the dark days after Braddock’s disaster, harrying the outlying homesteads and settlements, and once more the colonies were exhibiting to the full their incapacity for self-defence,[19] or rather, the indifference of the residents in the towns to the safety of their fellows who lived in the backwoods.

Forbes’ road to Fort Pitt ran for nearly 100 miles from Bedford or Raestown, as it had earlier been called, in a direction rather north of west, across the Alleghany Mountains and the Laurel Hills. The intermediate post, Fort Ligonier, stood at a place which had been known in Forbes’ time as Loyalhannon, rather nearer to Bedford than to Fort Pitt. Bedford itself was about thirty miles north of Fort Cumberland on Wills Creek, which Braddock had selected for the starting-point of his more southerly march. It marked the limit of settlement, and 100 miles separated it from the town of Carlisle, which lay due east, in the direction of the long-settled parts of Pennsylvania.

There was no security in the year 1763 for the dwellers between Bedford and Carlisle: ‘Every tree is become an Indian for the terrified inhabitants,’ wrote Bouquet to Amherst from Carlisle on the 29th of June.[10] Pennsylvania Difficulties with the Pennsylvanian legislature. raised 700 men to protect the farmers while gathering their harvest, but no representations of Amherst would induce the cross-grained Legislature to place them under his command, to allow them to be used for offensive purposes, or even for garrison duty. The very few regular troops in the country were therefore required to hold the forts, as well as to carry out any expedition which the commander-in-chief might think necessary. A letter from one of Amherst’s officers, Colonel Robertson, written to Bouquet on the 19th of April, 1763, relates how all the arguments addressed to the Quaker-ridden government had been in vain, concluding with the words ‘I never saw any man so determined in the right as these people are in their absurdly wrong resolve’;[11] and in his answer Bouquet speaks bitterly of being ‘utterly abandoned by the very people I am ordered to protect’.[20][11]

Henry Bouquet had reason to be bitter. He had rendered invaluable service to Pennsylvania and Virginia, when under Forbes he had driven the French from the Ohio valley. The colonies concerned had been backward then, they were now more wrong-headed than ever, and this at a time when the English army in America was sadly attenuated in numbers. All depended upon one or two men, principally upon Bouquet himself. Born in Canton Berne, he was one of the Swiss officers who were given commissions in the Royal American Regiment, the ancestors of the King’s Royal Rifles, another being Captain Ecuyer, who was at this time commander at Fort Pitt. Bouquet was now in his forty-fourth year, a resolute, high-minded man, a tried soldier, and second to none in knowledge of American border fighting. In the spring of 1763 he was at Philadelphia, when Amherst, still holding supreme command in North America, ordered him to march to the relief of Fort Pitt, while Dalyell was sent along the lakes to bring succour to Detroit. At the end of June Bouquet was at Carlisle, collecting troops, transport, and provisions for his expedition; on the 3rd of July he heard the bad news of the loss of the forts at Presque Isle, Le Bœuf, and Venango; on the 25th of July he reached Bedford.

He had a difficult and dangerous task before him. The rough road through the forest and over the mountains had been broken up by bad weather in the previous winter, and the temporary bridges had been swept away. His fighting men did not exceed 500, Highlanders of the 42nd and 77th Regiments, and Royal Americans. The force was far too small for the enterprise, and the commander wrote of the disadvantage which he suffered from want of men used to the woods, noting that the Highlanders invariably lost themselves when employed as scouts, and that he was therefore compelled to try and secure 30 woodsmen for scouting purposes.[12]

On the 2nd of August he reached Fort Ligonier, and[21] there, as on the former expedition, he left his heavy transport, moving forward on the 4th with his little army on a march of over fifty miles to Fort Pitt. On that day he advanced twelve miles. On the 5th of August he intended to The fight at Edgehill. reach a stream known as Bushy Creek or Bushy Run, nineteen miles distant. Seventeen miles had been passed by midday in the hot summer weather, when at one o’clock, at a place which in his dispatch he called Edgehill, the advanced guard was attacked by Indians. The attack increased in severity, the flanks of the force and the convoy in the rear were threatened, the troops were drawn back to protect the convoy, and circling round it they held the enemy at bay till nightfall, when they were forced to encamp where they stood, having lost 60 men in killed and wounded, and, worst of all, being in total want of water. Bravely Bouquet wrote to Amherst that night, but the terms of the dispatch told his anxiety for the morrow. At daybreak the Indians fell again upon the wearied, thirsty ring of troops: for some hours the fight went on, and a repetition of Braddock’s overthrow seemed inevitable. At length Bouquet tried a stratagem. Drawing back the two front companies of the circle, he pretended to cover their retreat with a scanty line, and lured the Indians on in mass, impatient of victorious butchery. Just as they were breaking the circle, the men who had been brought back and had unperceived crept round in the woods, gave a point blank fire at close quarters into the yelling crowd, and followed it with the bayonet. Falling back, the Indians came under similar fire and a similar charge from two other companies who waited them in ambush, and leaving the ground strewn with corpses the red men broke and fled. Litters were then made for the wounded: such provisions as could not be carried were destroyed; and at length the sorely tried English reached the stream of Bushy Run. Even there the enemy attempted to molest them, but were easily dispersed by the light infantry.

The victory had been won, but hardly won. The[22] casualties in the two days’ fighting numbered 115. That the whole force was not exterminated was due to the extraordinary steadiness of the troops, notably the Highlanders, and to the resolute self-possession of their leader. ‘Never found my head so clear as that day,’ wrote Bouquet to a friend some weeks later, ‘and such ready and cheerful compliance to all the necessary orders.’[13] On the 10th of August the expedition reached Fort Pitt without further fighting, and relieved the garrison, whose defence of the post had merited the efforts made for their rescue.

Bouquet’s battles at Edgehill were small in the number of troops employed, and were fought far away in the American backwoods. They attracted little notice in England—to judge from Horace Walpole’s contemptuous reference to ‘half a dozen battles in miniature with the Indians in America’;[14] but none the less they were of vital importance. Attacking with every advantage on their side, with superiority of numbers, in summer heat, among their own woods, the Indians had been signally defeated, and among the dead were some of their best fighting chiefs. In Bouquet’s words, ‘the most warlike of the savage tribes have lost their boasted claim of being invincible in the woods;’[15] and he continued to urge the necessity of reinforcements in order to follow up the blow and carry the warfare into the enemy’s country. But the colonies did not answer, the war dragged on, and at the beginning of October Bouquet had the mortification of hearing of a British reverse at Niagara.

The date was the 14th of September, and the Indians concerned were the Senecas, who alone among the Six[23] Nations took part in Pontiac’s rising. A small escort convoying empty wagons from the landing above the falls to the fort below was attacked and cut off; and two companies sent to their rescue from the lower landing were ambushed at the same spot, the ‘Devil’s Hole’, where the path ran by the precipice below the falls. Over 80 men were killed, including all the officers, and 20 men alone remained unhurt. Nor was this the end of disasters on the lakes. In November a strong force from Niagara, destined for Detroit, started along Lake Erie in a fleet of boats; a storm came on: the fleet was wrecked: many lives were lost: and the shattered remnant gave up the expedition and returned to Niagara. Detroit, however, was now safe. When October came, Ending of the siege of Detroit. various causes induced the Indians to desist from the siege. The approach of winter warned them to scatter in search of food: the news of Bouquet’s victory had due effect, and so had information of the coming expedition from Niagara, which had not yet miscarried. Most of all, Pontiac learnt by letter from the French commander at Fort Chartres that no help could be expected from France. Accordingly, in the middle of October, Pontiac’s allies made a truce with Gladwin, which enabled the latter to replenish his slender stock of supplies; at the end of the month Pontiac himself made overtures of peace: and the month of November found the long-beleaguered fort comparatively free of foes. In that same month Amherst Amherst succeeded by Gage. returned to England, being succeeded as commander-in-chief by General Gage, who had been Governor of Montreal.

Before Amherst left he had planned a campaign for the coming year. Colonel Bradstreet was to take a strong force along the line of the lakes, and harry the recalcitrant Indians to the south and west of that route, as far as they could be reached, while Bouquet was to advance from Fort Pitt into the centre of the Ohio valley, and bring to terms the Delawares and kindred tribes, who had infested the borders of the southern colonies.

Colonel John Bradstreet had gained high repute by his well-conceived and well-executed capture of Fort Frontenac in the year 1758— which earned warm commendation from Wolfe. He was regarded as among the best of the colonial officers, and as well fitted to carry war actively and aggressively into the enemy’s country. In this he conspicuously failed: he proved himself to be a vain and headstrong man, and was found wanting when left to act far from head quarters upon his own responsibility. In June, 1764, he started from Albany, and made his way by the old route of the Mohawk river and Oswego to Fort Niagara, encamping at Niagara in July. His force seems to have eventually numbered nearly 2,000 men, one half of whom consisted of levies from New York and New England, in addition to 300 Canadians. The latter were included in the expedition in order to disabuse the minds of the Indians of any idea that they were being supported by the French population of North America.

Before the troops left Niagara, a great conference of Indians was held there by Sir William Johnson, who arrived early in July. From all parts they came, except Pontiac’s own following and the Delawares and Shawanoes of the Ohio valley. Even the Senecas were induced by threats to make an appearance, delivered up a handful of prisoners, bound themselves over to keep peace with the English in future, and ceded in perpetuity to the Crown a strip of land four miles wide on both sides of the Niagara river. About a month passed in councils and speeches; on the 6th of August Johnson went back to Oswego, and on the 8th Bradstreet went on his way.

His instructions were explicit, to advance into the Indian territory, and, co-operating with Bouquet’s movements, to reduce the tribes to submission by presence in force. Those instructions he did not carry out. Near Presque Isle, on the 12th of August, he was met by Indians who purported to be delegates from the Delawares and Shawanoes: and, accepting their assurances, he[25] engaged not to attack them for twenty-five days when, on his return from Detroit, they were to meet him at Sandusky, hand over prisoners, and conclude a final peace. He went on to Sandusky a few days later, where messengers of the Wyandots met him with similar protestations, and were bidden to follow him to Detroit, and there make a treaty. He then embarked for Detroit, leaving the hostile tribes unmolested and his work unaccomplished. From Sandusky he had sent an officer, Captain Morris, with orders to ascend the Maumee river to Fort Miami, no longer garrisoned, and thence to pass on to the Illinois country. Morris started on his mission, came across Pontiac on the Maumee, found war not peace, and, barely escaping with his life, reached Detroit on the 17th of September, when Bradstreet had already come and gone.

Towards the end of August Bradstreet reached Detroit. He held a council of Indians, at which the Sandusky Wyandots were present, and, having proclaimed in some sort British supremacy, thought he had put an end to the war. The substantive effect of his expedition was that he released Gladwin and his men, placing a new garrison in the fort, and sent a detachment to re-occupy the posts at Michillimackinac, Green Bay, and Sault St. Marie. He then retraced his steps to Sandusky. Here the Delawares, with whom he had made a provisional treaty at Presque Isle, were to meet him and complete their submission; and here he realized that Indian diplomacy had been cleverer than his own. Only a few emissaries came to the meeting-place with excuses for further delay, and meanwhile he received a message from General Gage strongly disapproving his action and ordering an immediate advance against the tribes, whom he had represented as brought to submission. He made no advance, loitered a while where he was, and finally came back to Niagara at the beginning of November after a disastrous storm on Lake Erie, a discredited commander, with a disappointed following.

If Bradstreet had any excuse for failure, it was that he did not know the temper of the Western Indians, and had not before his eyes perpetual evidence of their ferocity and their guile. Bouquet knew them well, and great was his indignation at the other commander’s ignorance or folly. After the relief of Fort Pitt in the preceding Bouquet’s operations. autumn he had gone back to Philadelphia, and throughout the spring and summer of 1764 was busy with preparations for a new campaign. On the 18th of September he was back at Fort Pitt, ready for a westward advance, with a strong force suitable for the work which lay before him. He had with him 500 regulars, mostly the seasoned men who had fought at Edgehill. Pennsylvania, roused at last to the necessity of vigorous action, had sent 1,000 men to join the expedition; and, though of these last a considerable number deserted on the route to Fort Pitt, 700 remained and were supplemented by over 200 Virginians. In the first days of October the advance from Fort Pitt began, the troops crossed the Ohio, followed its banks in a north-westerly direction to the Beaver Creek, crossed that river, and, marching westward through the forests, reached in the middle of the month the valley of the Muskingum river, near a deserted Indian village known as Tuscarawa or Tuscaroras. Bouquet was now within striking distance of the Delawares and the other Indian tribes who had so long terrorized the borderlands of the southern colonies. Near Tuscarawa Indian deputies met him, and were ordered—as a preliminary to peace—to deliver up within twelve days all the prisoners in their hands.

The spot fixed for the purpose was the junction of the two main branches of the Muskingum, forty miles distant to the south-west, forty miles nearer the centre of the Indians’ homes. To that place the troops marched on, strong in their own efficiency and in the personality of their leader, although news had come that Bradstreet, who was to threaten the Indians from Sandusky, was retreating homewards to Niagara. At the Forks of the[27] Muskingum an encampment was made, and there at length, at the beginning of November, the red men brought back their captives. The work was fully done: north to Sandusky, and to the Shawano villages far to the west, Bouquet’s messengers were sent; the Indians saw the white men in their midst ready to strike hard, and they accepted the inevitable. The tribes which could not at the time make full restoration gave hostages of their chiefs, and hostages too were taken for the future consummation of peace, the exact terms of which were left to be decided and were shortly after arranged by Sir William Johnson. With these pledges of obedience, and with the restored captives, Bouquet retraced his steps, and reached Fort Pitt again on the 28th of November.

He had achieved a great victory, bloodless but complete; and at length the colonies realized what he had done. A vote of thanks to him was passed by the Pennsylvanian Assembly in no grudging terms. The Virginians, too, thanked him, but with rare meanness tried to burden him with the pay of the Virginian volunteers, who had served in the late expedition. This charge Pennsylvania took upon itself, more liberal than the sister colony; and the Imperial Government showed itself not unmindful of services rendered, for, foreigner as he was, Bouquet was promoted to be a brigadier-general in the British army. He was appointed to command the troops in Florida, and His death. died at Pensacola in September, 1765, leaving behind him the memory of a most competent soldier, and a loyal, honourable man.

Beyond the scene of Bouquet’s operations—further still to the west—lay the Illinois country and the settlements on the eastern bank of the Mississippi. Ceded to Great Britain by the Treaty of 1763, they were still without visible sign of British sovereignty; and, when the year 1764 closed, Pontiac’s name and influence was all powerful among the Indians of these regions, while the French flag still flew at Fort Chartres. By the treaty, the navigation of the Mississippi was left open to both[28] French and English; and in the spring of 1764 an English officer from Florida had been dispatched to ascend the river from New Orleans, and take over the ceded forts. The officer in question—Major Loftus—started towards the end of February, and, after making his way for some distance up-stream, was attacked by Indians and forced to retrace his steps. Whether or not the attack was instigated by the French, it is certain that Loftus received little help or encouragement from the French commander at New Orleans, and it is equally certain that trading jealousy threw every obstacle in the way of the English advance into the Mississippi valley. It was not until the British occupation of Fort Chartres. autumn of 1765 that 100 Highlanders of the 42nd Regiment made their way safely down the Ohio, and finally took Fort Chartres into British keeping.

The way had been opened earlier in the year by Croghan, one of Sir William Johnson’s officers, who in the summer months went westward down the Ohio to remind the tribes of the pledges given to Bouquet, and to quicken their fulfilment. He reached the confluence of the Wabash river, and a few miles lower down was attacked by a band of savages, who afterwards veered round to peace and conducted him, half guest, half prisoner, to Vincennes and Ouatanon, the posts on the Wabash. Near Ouatanon he met Pontiac, was followed by him to Detroit, where it was arranged that a final meeting to conclude a final peace should be held at Oswego in the coming year. The meeting took place in July, 1766, under the unrivalled guidance of Sir William Johnson, and with it came the end of the Indian war.

The one hope for the confederate Indians had been help from the French. Slowly and reluctantly they had been driven to the conclusion that such help would not be forthcoming, and that for France the sun had set in the far west of North America. Pontiac himself gave in his submission to the English; he took their King for his father, and, when he was killed in an Indian brawl on the Mississippi in 1769, the red men’s vision of independence[29] or of sovereignty in their native backwoods faded away. The two leading white races in North America, French and English, had fought it out; there followed the Indian rising against the victors; and soon was to come the almost equally inevitable struggle between the British colonists, set free from dread of Frenchman or of Indian, and the dominating motherland of their race.

[1] The Annual Register for 1763, p. 19, identified the St. John river with the Saguenay, and the mistake was long perpetuated.

[2] All the quotations made in the preceding pages are taken from the Documents relating to the Constitutional History of Canada 1759-1791, selected and edited by Messrs. Shortt and Doughty, 1907.

[3] Annual Register for 1763, p. 22.

[4] Journals of Major Robert Rogers, London, 1765, p. 207.

[5] Journals of Major Robert Rogers, London, 1765, p. 214.

[6] A Concise Account of North America, by Major Robert Rogers, London, 1765, pp. 240-4.

[7] Rogers’ Journals, p. 229.

[8] A Concise Account of North America, p. 168.

[9] Dalyell seems to have been a good officer. Bouquet on hearing of his death about two months’ later wrote, ‘The death of my good old friend Dalyell affects me sensibly. It is a public loss. There are few men like him.’ Bouquet to Rev. M. Peters, Fort Pitt, September 30, 1763. See Mr. Brymner’s Report on Canadian Archives, 1889, Note D, p. 70.

[10] Brymner’s Report on Canadian Archives, 1889, note D, p. 59.

[11] Ibid., Note D, pp. 60, 62.

[12] Bouquet to Amherst, July 26, 1763: Canadian Archives, as above, pp. 61-2.

[13] Bouquet to Rev. Mr. Peters, September 30, 1763: Canadian Archives, as above, p. 70.

[14] ‘There have been half a dozen battles in miniature with the Indians in America. It looked so odd to see a list of killed and wounded just treading on the heels of the Peace.’ Letter of October 17 and 18, 1763, to Sir Horace Mann.

[15] Bouquet to Hamilton, Governor of Pennsylvania, Fort Pitt, August 11, 1763: Canadian Archives, as above, p. 66.

It was said of the Spartans that warring was their salvation and ruling was their ruin. The saying holds true of various peoples and races in history. A militant race has often proved to be deficient in the qualities which ensure stable, just, and permanent government; and in such cases, when peace supervenes on war, an era of decline and fall begins for those whom fighting has made great. But even when a conquering race has capacity for government, there come times in its career when Aristotle’s dictum in part holds good. It applied, to some extent, to the English in North America. As long as they were faced by the French on the western continent, common danger and common effort held the mother country and the colonies together. Security against a foreign foe brought difficulties which ended in civil war, and the Peace of 1763 was the beginning of dissolution.

In the present chapter, which covers the history of Canada from the Peace of Paris to the outbreak of the War of Independence, it is proposed, from the point of view of colonization, to examine the ultimate rather than the immediate causes which led to England losing her old North American colonies, while she retained her new possession of Canada.

It had been abundantly prophesied that the outcome of British conquest of Canada would be colonial independence in British North America. In the years 1748-50 the Swedish naturalist, Peter Kalm, travelled through the British North American colonies and Canada, and left on record his impressions of the feeling towards the mother country which existed at the time in the British[31] provinces. Noting the great increase in these colonies of riches and population, and the growing coolness towards Great Britain, produced at once by commercial restrictions and by the presence among the English colonists of German, Dutch, and French settlers, he arrived at the conclusion that the proximity of a rival and hostile power in Canada was the main factor in keeping the British colonies under the British Crown. ‘The English Government,’ he wrote, ‘has therefore sufficient reason to consider the French in North America as the best means of keeping the colonies in their due submission.’[16]

Others wrote or spoke to the same effect. Montcalm was credited with having prophesied the future before he shared the fall of Canada,[17] and another prophet was the French minister Choiseul, when negotiating the Peace of Paris. To keen, though not always unprejudiced, observers the signs of the times betokened coming conflicts between Great Britain and her colonies; and to us now looking back on history, wise after the event, it is evident that the end of foreign war in North America meant the beginning of troubles within what was then the circle of the British Empire.

Until recent years most Englishmen were taught to believe that the victory of the American colonists and the defeat of the mother country was a striking instance of the power of right over might, of liberty over oppression; that the severance of the American colonies was a net gain to them, and a net loss to England; that Englishmen did right to stand in a white sheet when reflecting on these times and events, as being citizens of a country which grievously sinned and was as grievously punished. All this was pure assumption. The war was one in which[32] there were rights and wrongs on both sides, but, whereas America had in George Washington a leader of the noblest and most effective type, England was for the moment in want both of statesmen and of generals, and had her hands tied by foreign complications. We can recognize that Providence shaped the ends, without going beyond the limits of human common sense. Had Pitt been what he Great Britain failed for want of leaders. was in the years preceding the Peace of Paris, had Wolfe and the eldest of the brothers Howe not been cut off in early manhood, the war might have been averted, or its issue might have been other than it was. One of Wolfe’s best subordinates, Carleton, survived, and Carleton saved Canada; there was no human reason why men of the same stamp, had they been found, should not have kept for England her heritage. The main reason why she lost her North American colonies was not the badness of her cause, but rather want of the right men when the crisis came.

Equally fallacious with the view that England failed because wrong-doing never prospers, is, or was, the view that the independence of the United States was wholly a loss to England and wholly a gain to the colonists. What would have happened if the revolting provinces had not made good their revolt must be matter of speculation, but it is difficult to believe that, if the United States had remained under the British flag, Australia would ever have become a British colony. There is a limit to every political system and every empire, and, with the whole of North America east of the Mississippi for her own, it is not likely that England would have taken in hand the exploiting of a new continent. At any rate it is significant that, within four years of the date of the treaty which recognized the independence of the United States, the first English colonists were sent to Australia. The success or failure of a nation or a race in the field of colonization must not be measured by the number of square miles of the earth’s surface which the home government owns or claims at any given time. To judge aright, we must revert to the older and truer view of colonizing[33] as a planting process, replenishing the earth and subduing it. If the result of the severance of the United States from their mother country was to sow the English seed in other lands, then it may be argued that the defeat of England by her own children was not wholly a loss to the mother country.

Nor was it wholly a gain to the United States. Such at least must be the view of Englishmen who believe in the worth of their country, in its traditions, in the character of the nation, in its political, social, moral, and religious tendencies. The necessary result of the separation was to alienate the American colonists from what was English; to breed generations in the belief that what England did must be wrong, that the enemies of England must be right; to strengthen in English-speaking communities the elements which were opposed to the land and to the race from which they had sprung. With English errors and weaknesses there passed away, in course of years and in some measure, English sources of strength; the sober thinking, the slow broadening out, the perpetually leavening sense of responsibility. Had the American provinces remained under the British flag it is difficult to see why they should not have been in the essence as free and independent as they now are; it is at least conceivable that their commercial and industrial prosperity would have been as great; assuredly, for good or for evil, they would have been more English.

The faults and shortcomings of the English, which throughout English history have shown themselves mainly in foreign and colonial matters, seem all to have combined and culminated in the interval of twenty years between the Peace of 1763, which gave Canada to Great Britain, and the Peace of 1783, which took from her the United States; and in addition there were special causes at work in England, which at this more than at any other time militated against national success.

The shortcomings in question are, in part, the result of counterbalancing merits, fair-mindedness, and freedom[34] of thought, speech, and action. Love of liberty among the English has begotten an almost superstitious reverence for Parliamentary institutions. Parliamentary institutions have practically meant the House of Commons; and the House of Commons has for many generations past implied the party system. In regard to foreign and colonial policy the party system has worked the very serious evil that Great Britain has in the past rarely spoken or acted as one nation. The party in power at times of national crisis is constantly obliged to reckon on opposition rather than support, from the large section of Englishmen whose leaders are not in office; and ministers have to frame not so much the most effective measures, as those which can under the circumstances be carried with least friction and delay. The result has been weakness and compromise in action; among the friends of England, suspicion and want of confidence; among her foes, waiting on the event which prolongs the strife. The English have so often gone forward and then back, they have so often said one thing and done another, that their own officers, their friends and allies, their native subjects, and their open enemies, cannot be sure what will be the next move. If the Opposition in Parliament and outside, by speech and writing, attacks the Government, the natural inference to be drawn is that a turn of the electoral tide will reverse the policy.

Apart too from this more or less necessary result of party government, the element of cross-grained men and women, who, when their own country is at issue with another, invariably think that their country must be wrong and its opponent must be right, has always been rather stronger, or, at any rate, rather more tolerated in the United Kingdom than among continental nations. This is due not merely to the habit of free criticism, but also to a kind of conceit familiar enough in private as in public life. Englishmen, living apart from the continent of Europe, are, as a whole, more wrapped up in themselves than are other nations; and in this self-satisfied whole[35] there is a proportion of superior persons who sit in judgement on the rest, and who, having in reality a double dose of the national Pharisaism, think it their duty to belittle their countrymen.

Fault-finders of this kind, or political opponents of the Government for the time being, are apt, as a rule, to make light of any minority in the hostile or rival country, who may be friendly to England: they tend to misrepresent them as being untrue to their own land and people, as wanting to domineer over the majority, as seeking their own interests: and, if they have suffered losses for England’s sake, the tale of the losses is minimized. But it is not only the opponents of the Government who take this line; too often in past history it has been to a large extent the line of the Government itself. The perpetual seeking after compromise, and trying to see two sides after the choice of action has been made, has lost many friends to our country and nation, and made none: while the retracing of steps, unmindful of claims which have arisen, of property which has been acquired, and of responsibilities which have been incurred has, as the record of the past abundantly shows, brought bitterness of spirit to the friends of England, and bred distrust of the English and their works.

The element of uncertainty in British policy and action towards foreign nations or towards British colonies has been in part due to ignorance: and to ignorance and want of preparation have been due most of the disasters in war which have befallen Great Britain. Here again something must be attributed to the fact of the island home. The rulers of continental peoples have been driven by the necessities of their case to learn the conditions of their rivals, by secret service and intelligence agents to ascertain all that is to be known, and at the same time to keep their own arms up to date, and their own powder dry. They have prepared for war. England has prepared for peace. Her policy has paid in the long run, but it would not have been a possible policy for other nations; and at certain[36] times in English history it has wrought terrible mischief. England does not always muddle through, as the English fondly hope she does; notably, she did not muddle through when the United States proclaimed their independence.

In these years, 1763-83, there was the party system in England with all its mischievous bitterness; there was a weak Executive at home, and a still weaker Executive in the colonies; there was ignorance of the real conditions in America, unwise handling of the colonial Loyalists, threatening talk coupled with vacillation in action, laws made which gave offence, and, when they had given offence, not quite repealed. All the normal English weaknesses flourished and abounded at this period, and were supplemented by certain sources of danger which were the outcome of the particular time.

It was a special time, a time of reaction. England had lately gone through a great struggle, made a great effort, incurred great expense, and won great success. She was for the moment vegetating, not inclined or ready for a A time of reaction. second crisis. Second-rate politicians were handling matters, and the influence of the new King was all in favour of their being and remaining second-rate; for George the Third intended, by meddling in party politics, Partisan attitude of the Crown. and by Parliamentary intrigues, to rule Parliament. Thus the Crown became a partisan in home politics, and in colonial politics was placed in declared opposition to the colonies, instead of remaining the great bond between the colonies and the mother country.

The result was, that throughout the years of the American quarrel, and in a growing degree, the colonies found powerful support in this country, because they were, after all, not foreigners but Englishmen—Englishmen who compared favourably with Englishmen at home and whom patriotic Englishmen at home could admire and uphold; because they were apparently the weaker side, attracting the sympathy which in England the weaker side always attracts; and because, through the attitude[37] of the King, their cause was associated with the cause of political liberty at home. Add to this that the one great English statesman of world-wide reputation, Chatham, had warmly espoused the colonial side, and it may well be seen that, unless some able general, as Wellington in later days, by military success, saved his country from the results of political blunders, the position was hopeless.

But for the special purpose of determining what place the episode of the severance of the British North American colonies holds in the history of colonization we must look still further afield. The constitutional question as to whether the colonies were subject to the Parliament of the mother country or to the Crown alone may, from this particular point of view, be omitted, for the story of the troubled years abundantly shows that theories would have slept, if certain practical difficulties had not called them into waking existence, and if lawyers had not been so much to the front, holding briefs on either side. Nor is it necessary to dwell upon the specific and immediate causes of the strife, except so far as they were ultimate causes also. Among such immediate causes, some of which have been already noted, were the personal character of the English king for the time being, the corruption and jobbery of public life in England, the weakness of the Executive in the colonies, the enforcing of commercial restrictions already placed by the mother country on the colonies, the kind of new taxes which the Home Government imposed, the method of imposing them, and the object with which they were devised; the outrageous laws of 1774 for penalizing Massachusetts, the Quebec Act, and the employment of German mercenaries against the colonists, which gave justification to the colonists for calling in aid from France. All these and other causes might have been powerless to affect the issue, if England had possessed statesmen and generals, and if the growing plant of disunion had not been deeply rooted in the past.

When France lost Canada and Louisiana, two European[38] nations, other than the Portuguese in Brazil, practically shared the mainland of America. They were Spain and Great Britain. Spain won her American empire not far short of a hundred years before Great Britain had any strong footing on the American continent; she kept it for Spain held her American possessions for a longer time than Great Britain held the North American colonies. some thirty or forty years after the United States had achieved their independence. The Spanish-American empire was therefore much longer-lived than the first colonial dominion of Great Britain in North America, and the natural inference is, either that the Spaniards treated their colonies or dependencies better than the English treated theirs, or that the English colonies were in a better position than the Spanish dependencies to assert their independence, or that both causes operated simultaneously.

It is difficult to compare Spain and Great Britain as regards their respective colonial policies in America, for their possessions differed in kind. Spain owned dependencies rather than colonies, Great Britain owned colonies rather than dependencies. Spanish America was the result of conquest: English America, not including Canada, was the result of settlement. But, so far as a comparison can be instituted, it will probably not be seriously contended that the British colonies suffered more grievously at the hands of the mother country than did the colonial possessions of Spain. The main charge brought against England was that she neglected her colonies and left them to themselves. Whether the charge was true or not—as to which there is more to be said—neglect is not oppression; and within limits the kindest and wisest policy towards colonies, which are colonies in the true sense, is to leave them alone. ‘The wise neglect of Walpole and Newcastle,’ writes Mr. Lecky, ‘was eminently conducive to colonial interests.’[18]