Title: Journal of William H. Richardson, a private soldier in the campaign of New and Old Mexico, under the command of Colonel Doniphan of Missouri

Author: William H. Richardson

Release date: July 22, 2022 [eBook #68587]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: John W. Woods, 1848

Credits: David E. Brown and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

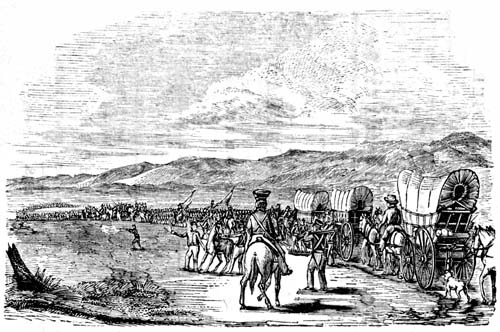

MARCHING THROUGH A JORNADA. Page 45.

SECOND EDITION.

BALTIMORE:

JOHN W. WOODS, PRINTER.

1848.

Entered, according to the Act of Congress, in the year 1848, by William H.

Richardson, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of Maryland.

I left my home on West River, Anne Arundel County, Md., the 11th November, 1845, for a southern tour, and after visiting the principal places of the south and west, inspecting the country, and meeting with adventures familiar to all who travel, I found myself, the following spring, located permanently a few miles from Carrollton, Carroll County, Missouri, boarding in the family of Judge Rea, a clever gentlemanly man. Here I formed numerous acquaintances, among them, an old Capt. Markle, who informed me of his intention to visit California, and depicted in glowing terms the pleasure of travelling in new countries, &c. In the meantime, a company of mounted volunteers was being formed in the neighborhood, under Capt. Williams, in which many young men whom I knew, had enlisted. This, together with the enthusiasm which prevailed at a public meeting on the 4th of July, (when the ladies of Carrollton presented the company a beautiful flag, and many speeches were made)—caused me to decide and join the company. I immediately set about preparing—bought my regimentals, canteen, saddlebags, also some books and a writing apparatus for convenience in noting down the occurrences of each day, thinking it probable, should I live to return, it might be a source of amusement to my friends in Maryland.

August 4th, 1846.—This morning we started for Fort Leavenworth. Many of my friends came to take breakfast with me at Squire Dorr’s. We met our Captain at Carrollton, where a public dinner was given. The company formed and marched to the table in order. In the evening we mounted our fine horses and proceeded out of town. We passed the Prairie, 30 miles wide, and rode[4] as far as the residence of Dr. Arnold. There were fifteen of us in company, separated from the rest, and all in search of quarters.

Having to water our horses, the Doctor directed us where to go. The way was plainly pointed out, but to our astonishment, we all got lost in the timber. We rode till very late, and might have been put to great inconvenience, had we not met with a servant who set us right. We returned to the Doctor’s to muse on our mishap and enjoy more hospitality. An ominous beginning for a soldier’s life.

5th.—Started this morning in company with the Doctor and his lady, who went with us eight miles to Lexington, and thence to Richmond, where we arrived at 4 o’clock. A few miles further on we encamped. I rode all this day without my dinner. Having had opportunity to become better acquainted with my Captain and other officers, I find them very clever and kind.

6th.—I discovered this morning that my horse was lame from tightness of his shoes. Went to town to a blacksmith who re-shod him. The company could not wait for me, and I travelled alone through a beautiful forest of sugar trees. Passed Elke Horn, and rode until within six miles of Liberty. Here I found our baggage team had given out. Our Captain had gone ahead with the company, and left the second Lieutenant, Mr. Smith, in charge. I discovered Lieutenant Smith to be a man of very tender feelings. Several of our company were taken with chills to-night, which is rather discouraging.

7th.—At day-light this morning our train was under way, arrived in town to breakfast, after which our Captain marched us all over the city. It is a beautiful inland place of 1000 inhabitants. Fifteen miles further on, we met our first Lieutenant, just from the Fort. He told us to hurry on and get mustered into service before the other companies should crowd in. We hurried accordingly and reached Platt City at sunset. I was fatigued and hungry, and went into the hotel to get my supper, when I came out, I found our third Lieutenant had come up with the rest of the men, and were ready to start for the[5] ferry. I went on with them. We arrived at the ferry, opposite Fort Leavenworth, about 12 o’clock at night. I went in search of something for my horse. There was a widow lady living near, to whom I applied, and she very pleasantly told me “to go to the crib and help myself.” I went, fed my horse, and spent the rest of the night on the unhusked ears in the crib, where I slept soundly.

8th.—Rose early and went in search of my Captain. Found him, with many others, between some fallen trees, wrapped up in their blankets, fast asleep on the sand. We soon prepared for crossing the river, which I felt to be the bidding adieu to friends and home, and almost civilization itself. I was the only one who had taken refreshment. It was fortunate for me that I had made a second visit to the widow and obtained a good breakfast. We were soon all safely over the ferry, 85 in number, men of all grades and dispositions, some very facetious, and others reserved and thoughtful. We were all huddled together, and ordered to form in double file, to proceed two miles from the Fort to erect our tents. We had to wait some time for the wagons which contained our provisions, consisting of mess pork, sugar, coffee, &c. The head of each mess—six in number, had to apply to the Sergeant for the necessary supplies. Having been appointed to the charge of my mess, I went up, took my share, and helped the men to theirs. The first meal I tasted in the Indian territory was supper, and such a supper! It was composed of hard water crackers and mess pork, which would cut five inches through the ribs. I boiled my pork for nearly two hours, and found it still so tough that it was harder labor than I had been at all day to eat it. Necessity is the mother of invention, and I fell upon an expedient by which to despatch it, I took it out, stewed and fried it. But it was yet spongy and stuck in my teeth. I made out, however, with the assistance of a keen appetite; and being very tired, I laid myself down on my blanket in the tent. I had not lain many minutes when our Orderly came by, calling upon the men to form a line. We had much rather slept, but to obey was our duty, and we were soon in the line. We were then drilled by a young[6] officer from the Fort. After drill, the officers commenced counting us off from right to left, and every fourth man had to stand guard.

I was taken as one of the fourth men and placed with eleven others at No. 1, where I had to walk my post two hours. It was quite long enough for a beginning, and I resigned the post with pleasure when the time expired. At 12 o’clock the relief guard put a man in my place, and I went rejoicing to my rest.

Sunday, 9th.—This morning I had to get breakfast for the first time in my life; I was perfectly green at the business, but it had to be done. I filled the kettle with water, browned my coffee, fried the pork, &c. I went on very well until by an unlucky mishap I upset the kettle, and put out the fire. Nothing daunted by the misfortune, I entered upon another trial and was more successful. We paraded immediately after breakfast, and prepared to go to the Fort, where we had the honor of being mustered into service by our Colonel. He called our names, and as each passed before him he was asked his age, and as many other questions as would afford a pretty good description of his person and history of his life. The Articles of War were then read and we formed a line and returned to camp. The roll was called soon after, and all that were not present, had to keep guard. So much for playing truant on an occasion of so much importance. I was fortunate enough to be present and escaped the infliction.

12th.—The past two or three days were employed in strict attention to the duties of a soldier, such as cooking, drilling, &c. To-day, Col. Price assembled the whole regiment at the Fort, to have an appraisement of horses, saddles, &c. In the afternoon I rode back to the encampment on a large bag of beef in the hot sun. A severe headache was my travelling companion.

14th.—Yesterday and to-day we had a terrible job, breaking mules to the wagons. It is difficult to muster these stubborn animals into service. I, with a fellow soldier, was detained from the Fort till a late hour. We were employed in the novel pursuit of pulling two[7] of the mules by main force through the hazel bushes two miles. Only think of it! Two of Uncle Sam’s worthies pulling a jackass apiece two miles through the bushes. While at the Fort I called on the minister, who was very kind and affectionate in his conversation and manners. He presented me a Testament, Prayer Book, and a bundle of Tracts—at night we threw copies into each tent, and then sung hymns until it was time to retire.

15th.—This was our washing day. I went with the rest of the b’hoys, to the branch, where we kindled three large fires, and put up our camp kettles to boil the clothes. I never boiled any before, and I felt pretty much as I did when I began to cook breakfast. I went to work awkwardly enough, as my scalded hands bore witness. But a man can even wash his clothes when he is obliged to do it, the opinions of the ladies to the contrary notwithstanding. In the evening we ceased our labors as washers of clothes and went into the branch and washed ourselves. After bathing we returned to camp quite refreshed.

Sunday, 16th.—This morning I thought I would hear the Missionary preach—and with several others, started for the purpose. Just before we got to the village, an Indian informed us there would be no preaching that day. We were greatly disappointed, and turned to wander about awhile and survey the country around. It was wild and picturesque, and the sight of it was gratifying. We met a number of Indians. Their language and gesture were very strange, and they presented a most outlandish appearance. Many of them came into our camp with a variety of things to sell. When we returned, our camp was nearly deserted. The men had gone to the Fort for equipments to commence our march. We hurried on, but only to be disappointed again. Too many companies were in before us. We went back to the camp, and spent the day quietly.

18th.—Every man was well fitted out with a musket and fifteen cartridges, a load of guns having been brought from the Fort. I have now become accustomed to implicit obedience to orders—going and returning on[8] errands to the Fort—breaking mules, looking for strayed horses, cooking breakfast, washing clothes, &c. At night it rained hard, and while I tried to compose myself to sleep, I felt the shower dripping in my face.

20th.—The important morning had now arrived. It was the morning on which we were to “strike our tents, and march away” for California. All was bustle and excitement, and we poor privates had to load the wagons with provisions for our long march. It fell to my lot as usual, to handle the bacon, pork, &c. And yet another trial awaited me: we had not travelled more than a mile, when we came to a deep slough or pond, through which I had to guide a mule. It was the first time I had the honor of leading a mule in gears. I had to dismount and wade through thick mud up to my waist. I had rather carried the mule on my back over a better road. What made the matter worse, I had my new clothes on, and they were almost ruined by the adventure. On stopping to encamp, a messmate kindly poured on water, while I washed the mud off, as well as I could, and laid down in my wet garments, very weary with my day’s journey.

21st.—We are now fairly in the Indian country. The place assigned by the Government for the future residence of the tribes who have emigrated from the States. Here we found the prairies covered with grass—a seasonable supply for our horses, and a drove of ninety-five beeves which we had brought out for present use. A strong guard was stationed around the encampment, at night, as roving bands of Indians were lurking around us, ready to seize any thing they could lay their hands on. We had travelled 12 miles when our Captain thought it best to encamp for the night, as we found a little wood. The want of timber is a great defect in this otherwise beautiful country.

22nd.—We started this morning at 8 o’clock, and travelled 15 miles through a lovely region, when we came to a settlement of the Delaware Indians. Their houses and plantations bear evident marks of civilization. In company with our first Lieutenant, I called at a house, in the[9] door of which sat two squaws making moccasons. Stretched on a bench near by, lay an Indian fast asleep. He was a man of most powerful dimensions, at least six feet four, and fat withal. By his side rested a club full of notches. We did not care to disturb his repose, for we had slight misgivings that a notch or two more in that fatal war club, might record the finale of our own history. We left him to his slumber and hastened to the river where we found several companies of our companions buying and selling among the squaws. Whiskey was the principal commodity, and a number of Indians were so much intoxicated that they could hardly tell a tree from a moccason. The ferry is kept by the Indians. The Kansas river at this place is a bold stream, it was, nevertheless, safely passed by all, using boats only for our wagons; about sunset all landed and we encamped about a mile from the river.

Sunday, 23d.—Again we started on our journey. After the first ten miles of a broken country, some high hills appeared. They were very difficult of ascent, and we had much trouble with our teams. In two places we had to put our shoulders to the wheels. Orders were given that every man should secure what wood he could find, and we commenced packing it before us, on our horses. A picturesque scene we must have presented, each man with his load of wood before him on his horse. While riding in this way we overtook Lieutenant Col. Mitchell.

24th.—After passing a few clumps of trees, an immense prairie spread out before us, extending as far as the eye could reach. At 12 o’clock we came to a branch and encamped. The water here is in standing pools, and before drinking or making coffee, we were obliged to strain it through our handkerchiefs. While thus engaged, two Indians of the Sac Tribe, made their appearance. They were elegantly mounted, but painted and tattooed in a frightful manner. They are smaller in stature than the Delawares, and at war with them. They called at our camp as a matter of curiosity. One of my mess, Levi Flowers, received a severe kick in his face[10] from a horse which nearly killed him. His face was very much swollen.

25th.—The companies are now all united—having overtaken each other at different places. Our force was 1200 strong. We travelled all day in sight of trees like little dots on the horizon. At the end of our day’s march we hoped to find water, good water, which our poor fellows needed after a long hot march, with nothing to protect their heads from the rays of the sun but small glazed caps. The goal was reached. We rested beneath the shade of a small skirt of woods.

26th.—As usual, 8 o’clock found us ready to start. After a march of 14 miles, we encamped on Beaver Creek. We killed a beef—and the soldiers busied themselves in cooking supper. Not having conveniences of home at hand, we dispensed with our dinner daily, and satisfied ourselves with eating morning and night. Our Captain is a good sort of a man and will no doubt do the best he can for us. And now while speaking of the Captain I will say a word or two about our Lieutenants. Our first Lieutenant, Mr. White, is nearly always in a good humor. He is large and somewhat corpulent—enjoys a laugh very much. He weighs 220lbs. net. Our second Lieutenant, Mr. Smith, is of the middle size, very facetious, and always ready to accommodate. Our third Lieutenant, Mr. Rock, was formerly Captain of Militia, but volunteering to go with the army to California, we elected him third Lieutenant. He is a little over the middle size, and very reserved and stately.

27th.—After travelling twelve miles we reached the encampment of the Marion company, where we found a poor fellow who was accidentally shot last night, by a revolving pistol. Two men are left to take care of him. It is thought he cannot survive. Poor fellow! His fate is a sad one. Pursuing our journey, we passed Beaver Creek, and after travelling 18 miles, came to the Big John River, where we encamped for the night.

A CAMP WASHING DAY.

28th.—The Captain told us this morning that we should stop here for a day or two to rest ourselves. And now began a most ludicrous scene. Every camp kettle and[11] other vessel that would hold water was brought in requisition, and the whole regiment commenced washing their clothes. To me it was a most singular sight. While rubbing away at our clothes a rumor reached us that we were on the route to Santa Fe, instead of California. This was news, and what with washing and what with talking we were kept pretty busy. On the route to Santa Fe, though we entered the journey for California. But alas! no matter where we are. We found our trip was not a “pleasure excursion,” as many of our imaginations had so often pictured. The two soldiers we left to-day have just come in, after digging the grave of their poor comrade.

29th.—This morning we caught some black trout and cat fish in the Big John. They were very fine. Col. Price had gone ahead, and at 12 o’clock we struck our tents, passed Council Grove, and encamped at 2 o’clock a few miles further on, where there is a blacksmith shop, established by the government. Here I left letters for my friends in Maryland, to be carried back by the return mail to Fort Leavenworth.

Sunday, 30th.—Saw near the road, one of those singular mounds, of which I have so often read. It towered beautifully to the height of 100 feet. It may have been a mount of observation; it may be filled with the bones of the red men of the forest. I have no time, however, to speculate upon subjects so foreign from my present employment. At the end of 8 miles, we came to Rock Creek, and 7 miles further we arrived at Diamond Spring, where we halted for the night.

31st.—This morning I filled my canteen with the refreshing water of Diamond Spring. At the spring I counted 45 wagons loaded with provisions for the army. Yesterday we entered upon the far-famed plains at Rock Creek. The scenery presents a dull monotony, a vast plain, almost level, bounded by the horizon and covered with a thin sward and herbage.

September 1st.—Came to a place, called the “Lost Spring,” a most singular curiosity. The stream rises suddenly out of the ground, and after rushing over the[12] sand a few yards, as suddenly sinks, and is no more seen.

2nd.—To-day we are at the Cotton Wood Fork. It takes its name from a large cluster of cotton trees, the first I had seen after leaving Diamond Spring. There is a good stream of water here, and we enjoyed the blessing of a fine shower of rain. A little misunderstanding took place among the officers about starting. Some of them were too slow in their movements and caused our Captain to collect his men and make a speech. Several of the men were disgusted and become uproarious. A march of eight miles, however, to Turkey Creek, settled the question, and all appeared in pretty good humor. Three miles further on, we came to 2nd Turkey Creek, nine miles beyond to 3rd Turkey Creek and encamped. Turkey Creeks are plenty in this vicinity. How we would have rejoiced if the turkeys had been as plenty as the titles of the streams indicated. Third Turkey Creek is a lovely stream, running through the prairie. Here we wanted wood to cook with. As yet we had not seen any game with the exception of two rabbits, caught by our men. They were of a novel species, almost white, with long black ears, and as large as a grey fox.

3rd.—About 12 o’clock to-day we came in sight of timber. Passed the 4th Turkey Creek, and after travelling 18 miles, encamped on the banks of the little Arkansas, which at some seasons is a bold stream, with tremendous cliffs that can be seen at a long distance.

4th.—We are all huddled together in our tents, in consequence of a heavy storm of wind and rain, which came on last night. Some of the tents blew down, and most of the company were in a bad fix. Fires were necessary to keep us warm. We left at 8 o’clock, and after travelling 10 miles, came to Owl Creek. Five miles from Owl Creek we reached Cow Creek, where we encamped. On the left we could see cliffs and timber at a great distance, and some small white spots like sand hills. On the right, nothing but a vast prairie. Just before we arrived at the Cow Creek an antelope was started. Our boys gave chase and fired several times, but they missed[13] him and he finally escaped. They must shoot better in fight with the enemy. We had scarcely fixed up our tents, when the news came that a buffalo was in sight. In an instant, men on horseback, fully armed, were in pursuit from every direction. He was less fortunate than the antelope. The men had improved a little and they overtook their game after a considerable chase, during which they fired fifty times. They killed him at last and brought some of the flesh to the camp. It was of very little use, for with all our cooking, it was too tough to eat. He was a bull at least 20 years old. We had better let the old patriarch run.

Arkansas Bend, Saturday, 6th.—Here we stopped last night, after a most exciting day. Herds of buffalo were seen scattered over the plains. The best hunters were picked out to secure as many as possible. The chase was a fine one, 13 were killed by the different companies. I strolled away from camp alone, to one of those mysterious mounds, which occur so frequently to the traveller among these wilds. On ascending it, I enjoyed a most magnificent prospect. It has the appearance of a Fort, but when and for what purpose erected will long remain a matter of uncertainty. I lingered so long that on my return I found that my company had gone forward, but I soon overtook them. To-day we come to Walnut Creek, 6 miles from the mound. I felt stupid and sick; as I was placed on guard last night, on the banks of the Arkansas. I was all alone in the deep midnight, and I sat three long hours, with my musket; looking up and down the stream. I could see a great distance, as the sand on the shore is very white.

7th.—We were preparing to take a buffalo chase, when word was brought that the whole command must be moving. We were much disappointed, for we expected fine sport in the chase. On our route to-day, we passed Ash Creek, and five miles on came to Pawnee Fork. We saw herds of buffalo, and surrounded one, but they made a break towards the road and crossed among the teams. They did no damage, however, nor was much damage done to them. I rode on briskly to[14] overtake a friend, when my horse trod in a hole made by prairie dogs, (a small animal and very numerous here,) and fell with me. I received no injury except a little skin rubbed off my knee. On remounting, my attention was arrested by a horse running at full speed, and dragging something on the ground. When he came closer, I discovered it to be a man whom his horse had thrown. The frightened animal stopped a little ahead of me and I rode up, expecting to see a dead man, but as soon as his foot was extricated from the stirrup, to the surprise of all, he stood up, and said that he was not much hurt. He said he regretted most of all the loss of his clothes, which were torn in shreds from his body. Another man belonging to our company, by the name of Redwine, had a severe fall. He was taken in to camp nearly dead. Chase was made again after buffalo, which appeared in thousands. Many antelopes also appeared, but it requires the fleetest horses to overtake them. Before we encamped we saw near the road side a little mound of stones, on one of which was engraved the name of R. T. Ross. It was supposed to be the grave of a man who was murdered by the Indians in 1840. He is resting in a lonely spot.

8th.—We are now on the banks of the great Arkansas river, after marching many miles through a barren and dreary looking country, almost destitute of grass or herbage. Here there is some improvement in this respect. A heavy rain caused our tents to leak, and drenched the poor soldiers, so that they passed a very uncomfortable night.

9th.—Kept up the river ten miles. A few scattered cotton trees, and cliffs, and sand banks are the only things to be seen. One of Col. Mitchell’s men was near being killed to-day by an Indian. He had chased a buffalo two miles from camp, when an arrow was shot, which pierced his clothes; the poor fellow made all the haste he could to camp with the arrow sticking in his pants. It was well it was not in his skin.

10th.—Last night as soon as we were all snugly fixed, and ready for sleep, there arose a fearful storm of wind[15] and rain, which gave our tents and ourselves a good shaking. Some of the tents were blown down, breaking in their fall the ridgepoles of others, and bringing them down also. In our tent, four of us held on with all our might, for nearly two hours, to keep it standing. To-day we continued our march, travelling 15 miles, on the banks of the river. We saw a large flock of wild geese and tried to get a shot, but without success. They were too wild for us.

11th.—The weather was quite cold this morning, and there was so dense a fog as to prevent us from seeing a hundred yards ahead. There was an antelope killed to-day. The flesh tasted like mutton. We encamped by the side of the river, and an opportunity was afforded us of catching fish, which we accomplished by the novel mode of spearing them with the bayonet. Several dozens were caught, and we found them delicious.

12th.—Resumed our journey through the same scenery 12 miles—many antelopes were seen in herds, and prairie dogs barked at us, in every direction.

Sunday, 13th.—As we proceed, the country assumes a still more dreary aspect, bare of verdure, and broken in ridges of sand. Our horses, enfeebled by their long travel, have very little to subsist on. The men too, for the past three days, have ceased to receive rations of sugar and coffee. When we could not get these articles, we did as they do in France—that is, without them. We had to fry our meat, and a few of us entered upon the funny work of making soup out of pork, buffalo flesh, and fish, boiled up together. It was a rare mess, but we pronounced it first rate.

14th.—After passing over the last 15 miles to-day, we found ourselves at a place called the crossing of the Arkansas. We were then 362 miles from Fort Leavenworth. Our course has been along the margin of the river for 75 miles. At this place are steep bluffs difficult to descend. There are multitudes of fish in the river, many of them were killed by the horses’ feet in crossing. We caught several varieties by spearing. A number of antelopes were killed here.

[16]15th.—This morning I felt very dull from loss of rest. We had to give considerable attention to the cattle, horses, &c., to prevent them from straying. I and seven others were detailed to stand sentinel. I was appointed to the second watch, and to be in readiness at the hour, I spread my blanket down in the prairie to take a nap. In two hours I was awakened, and instructed to arouse the Captain of the Watch at the expiration of three hours more; having no means to measure the time but by my own sad thoughts, and the weary hours being rather tardy, I too soon obeyed the orders, and kept the last watch on duty five hours, to the amusement of all. After breakfast I took a stroll over the sand hills, and found about a dozen of our boys, inspecting the contents of a large basket, something like a hamper in which the merchants pack earthenware. It contained the skeleton of an Indian chief in a sitting posture, wrapped in buffalo robes, with his arrows, belts, beads, cooking utensils, &c. It had fallen from the limb of a tree, on which it had been suspended. Several of the men picked up the beads, and one named Waters carried the lower jaw and skull to camp, the latter he said he intended “to make a soup gourd of.”

16th.—I took my seat quietly in the tent this morning and thought I would rest, as we were to stay a day or two at this place. I was presently surrounded by soldiers begging me to write a few lines for them “to father, mother, wives, friends and homes.” I wrote seven letters without removing from a kneeling posture, and was kept busy almost the whole day.

17th.—Our Captain told us to get ready to start at 10 o’clock to-day, and as we were to cross a sandy desert 60 miles wide, much water and provisions were to be packed. A number of us were kept busy cleaning the salt from pork barrels in order to fill them with water. Scarcely had we finished this hard job; when the news spread like electricity “that the mail from Fort Leavenworth had come in.” I cannot pretend to describe the scene that ensued. I met our Captain, who said “the Sergeant had a letter for me”—with the most peculiar[17] feelings I seized it and saw the hand-writing of my loved sister in Maryland—my home, now so many weary leagues away. The delight I experienced was not unmingled, however, with the thought that perhaps at this very spot, the entrance to a wild desert, I had bid adieu finally to all I held dear. We travelled 22 miles, and as it was late at night when we halted, we spread our blankets on the sand and slept soundly till morning.

18th.—I rose by day-light and took a slice of bread and meat. We started early and came 23 miles, where we found some water standing in pools. We tried to erect the tents, but the wind was too high—had to cook that night with buffalo chips; strange fuel even for soldiers to use.

19th.—After marching 10 miles to-day, we came to the Cimarone Springs—a sweet stream. Here we found grass enough for our poor horses. It is truly an oasis in the desert.

Sunday, 20th.—We crossed an arm of the Cimarone, but the waters were dried up—dug for water but found none. Went on 5 miles further, dug again, and procured enough for ourselves and horses. In our route of 25 miles we saw the ground encrusted with salt. A singular animal attracted our notice. It was a horned frog, a great curiosity. Every thing was involved in a thick cloud of dust.

21st.—One of the members of the Randolph Company, a gentleman by the name of Jones, died last night of consumption. He took the trip for his health, but to-day his remains were interred, not far from the camp, with the honors of war.

22nd.—We still travelled on the Cimarone, though only at certain places could we procure water. A deep sand retarded the progress of the army. On arriving where we had to encamp we found 42 wagons, laden with goods. They were the property of a Mr. Gentry, a trader who has amassed great wealth, in merchandising between Independence, Santa Fe and Chihuahua. He speaks the Spanish language, and had nearly a dozen Spaniards in the caravan.

[18]23d.—We had a considerable storm last night—and the hard rain made it rather disagreeable, especially so to me, as I had to do the duty of a sentinel in the first watch, with a wolf howling most dismally within 50 yards of me. I would have fired at him, but I had to obey orders and not arouse the camp by a false alarm. We saw to-day the bones of 91 mules, which perished in a snow-storm last winter. The bones were piled by the road side.

24th.—Overtook another caravan—still passing up the Cimarone, whose bed is through the sandy plain, at length we came to a hill from whence we descried the Rocky Mountains, rising abruptly in the distance. In our route we crossed a small spur. Mr. White our first Lieutenant, with several others ascended one, which presented the appearance of frowning rocky precipices. From its highest peaks, he brought down seashell, and petrifactions of various kinds. We had great difficulty in procuring buffalo chips. It was very amusing to see the boys in search of this indispensable article, our only resource to cook with.

25th.—We reached “Cool Spring” to-day, and found refreshing and delightful water, bursting from a solitary rock of enormous dimensions, the sides of which are covered with the names of various travellers. Our pleasant officer, Mr. White, called me up saying “he wished to see my name on a spot he pointed out,”—so taking a hearty draught from his canteen, which was just filled, I went up, and had scarcely carved my name, to remain there a monument of my folly, I suppose, when I discovered my horse making off with my accoutrements, canteen, &c. Hurried down and started after the beast. After running a great distance in the deep sand, I succeeded in capturing the runaway. Nineteen miles further on we encamped in a deep ravine, among cliffs and rocks, here a few cedar trees were found. They afforded a seasonable supply of wood to cook with. The Rocky Mountains were in sight all day.

26th.—After a slight breakfast of bread and meat, we left this inhospitable place in disgust. It did not afford[19] grass for our horses to graze on. We proceeded 12 miles through a dreary waste, and had to encamp at night in a place where there was no water.

27th.—I was awakened by the Sergeant of the Guard at 2 o’clock this morning, it being my turn to stand sentinel of the morning watch. After breakfast we went on 15 miles to Cotton Wood Creek. There we fixed up our tents, but no forage being found for our half-starved animals, we soon took them down again, and proceeded 5 miles on, to Rabbit Creek. At this place there was plenty of grass and some tolerable scenery, but we were in no condition to enjoy it; being late in the night we spread our blankets on the prairie, and composed our wearied limbs to rest.

28th.—Our journey was still continued through a dry and sterile land, where there is neither wood, water, nor grass; late in the evening we came to a pool of water. It was cool and good, and we drank of it freely. Our wagons did not come up till very late, and being tired, we wrapped ourselves in our blankets and laid down to sleep without our supper. We went supperless, not to bed—but to the sod.

October 1st.—The last two days of September we remained at a place called Whetstone Creek, to rest. This Whetstone Creek is another oasis. It was the source of great joy to ourselves and our mules and horses. Our pastime was like the boy’s holiday whose mother allowed him to stay at home from school to saw wood and bring water. Our resting spell was a spell of hard work, and most industriously did we labor in cleansing our arms for inspection by the Colonel. And we had to do a deal of marching and countermarching. Indeed the parade lasted so long and with so many manœuvres were we exercised, that the patience of officers and men was worn to its extremity. It was nearly thread-bare. And then came the orders for every man to see to his own provisions and water, as another desert was to be traversed. So we go—changing from bad to worse. To-day, after a march of ten miles, we reached the “Point of Rocks”—a significant name. Late at night we encamped in a valley between high mountains, where there was some grass, but no water.

[20]2nd.—We still moved on over barren rocks and sand hills. We labored hard all day to leave them behind us. The hope cheered us of soon finding water, we realised it at the far-famed Red River. Our whole force encamped on its banks about night-fall. The waters of this distinguished river are brackish, but refreshing. Incrustations of salt are formed upon the rocks lying above its surface. This river was named Rio Colorado by the early Santa Fe traders; who, without having followed it down to any considerable distance, believed it to be the head waters of the great river of this name, which flows into the Mississippi below Natchez. It has, however, since been followed down to its junction with the Arkansas, and found to be the Canadian fork of that river. We were now within 140 miles of Santa Fe, having marched more than 600 miles over a country destitute of timber, with but little water, and occupied only by roving bands of Indians who subsist wholly upon buffalo meat. We saw immense herds of that animal on the Arkansas and its tributaries. The whole country presents, thus far, the most gloomy and fearful appearances to the weary traveller. But rough and uninviting as it is, all who visit New Mexico via Santa Fe, are compelled to pass it.

3d.—We have journeyed well to-day, having reached St. Clair Springs. It is a beautiful spot, well watered—and glowing in delightful verdure. It is surrounded by mountains, the surface of which are covered with craggy rocks. We searched for miles around our camp for wood, with little success. The different companies killed a number of antelopes here.

Sunday, 4th.—We are still encamped, and shall remain in our position till the morning of the 5th. I took a walk, to “wagon mound,” so called from the shape of its top, being like a covered wagon when seen in the distance. This mountain top is surrounded by a cliff of craggy rocks at least 100 feet in height. A most beautiful view is presented to the beholder. To the south you see hills covered with cedar and pine, situated in the immense prairie; to the north and north-west, are seen mountains with rocks piled upon rocks, with here and[21] there groves of evergreens; far away to the east, is the desert, over which we had just passed. The sides of this mountain are covered with a hard kind of sand, and pumice stone, having the appearance of cinder. Whilst I am writing, being situated as far up as it is prudent to go, an adventurous fellow by the name of George Walton, has gained the wagon top, two others have also ascended, an achievement that few can perform. North of us there is a salt lake which we intend to visit this evening.

Sunday Afternoon.—Lieut. Smith and myself took a stroll to the lake. We found a thick crust of salt around its edge, which is several miles in circumference. We returned to camp by a mountain path, very difficult to travel.

5th.—Eighteen miles were passed over to-day, through a mountainous country. We had just erected our tents and prepared for rest, when an evidence that we were approaching some civilized country, arrived in the shape of a Frenchman, who met us here with a travelling grocery. This concern came from Moras—a barrel of whiskey was strapped on the back of a poor mule—which stuff, some of our soldiers were foolish enough to drink: it sells at $1 per pint. Such dear drinking ought to make drunkards scarce.

6th.—Saw a mud cottage on the road side to-day. The sight was most pleasant to our eyes, accustomed as they were for forty-four days to a wild waste. As we rode up, every one must have a look into the house. It was inhabited by a native of North Carolina, whose wife is a Spanish woman. After being somewhat gratified with the sight of a house, though built of mud with its flat roof, we went on 18 miles, and encamped at a town called Rio Gallenas Bagoes. On visiting this place we were struck with the singular appearance of the town and its inhabitants. The town consists of mud huts containing apartments built on the ground. The men were engaged in pounding cornstalks from which sugar is made; the women with faces tattooed and painted red, were making tortillas. We ate some, and found them excellent.

[22]7th.—The wagons which contained our provisions coming in sight, we prepared the wood, which we obtained with difficulty, for boiling the coffee, &c., when Col. Mitchell rode up and told us the wind was too high to encamp. And hungry as we were, we went ahead 17 miles through a forest of pine to Ledo Barnell, where we encamped for the night. A grisly bear was killed to-day by some members of the Randolph Company.

8th.—We passed the large village of San Miguel to-day. Col. Mitchell and his interpreter went forward in search of a good place to encamp. The weather was dry and pleasant, with a suitable temperature for travelling. The most disagreeable annoyance is the sand, which is very unpleasant when the wind is high.

9th.—Col. Mitchell had chosen a spot for our encampment, about 12 miles from our last resting place, near the foot of a mountain. There was no water to be found. Impelled by necessity we followed an Indian trail over the mountain 5 miles, and after riding through the thick pines for several hours we found the coveted treasure. As may be supposed we drank most heartily, after which we filled our canteens and returned to camp about 12 o’clock at night. We learned that Santa Fe was about 25 miles off.

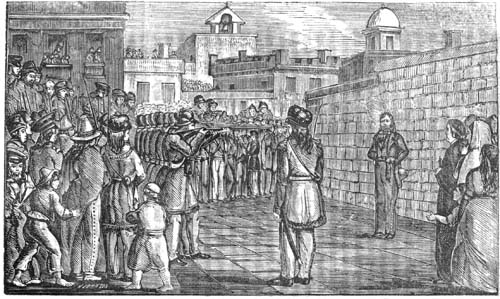

10th.—We arrived at the mountain pass at 10 o’clock, and reached Santa Fe about 3 o’clock in the afternoon. The glorious stars and stripes floating over the city was the first object that greeted our sight. We formed and marched into the town in order. We were received with martial music and several rounds of blank cartridges were fired as a welcome to us. We paraded in the square fronting the Governor’s house. After parade I took a walk through the town. The wagons did not arrive with our tents in time for us to encamp, and with our blankets around us, we laid down to rest. The blue sky was our canopy.

Sunday, 11th.—It was so cold and disagreeable last night that I found it impossible to sleep. I shivered through the night on the hard soil, and rose this morning with a severe headache. I walked about to keep myself[23] warm. After eating three small crackers for breakfast, I went to church in company with several others, to hear a Catholic priest. The music was prettily performed on various instruments. An old man in the meantime turning round before an image, and after he had bowed to the people several times the music ceased. All was over—and we returned to camp. I felt sick and sad, for the worship did not refresh my spirits. This evening I was pall-bearer to a member of the Benton Company, who died in the hospital soon after his arrival. We carried him out about a mile from the city to his final resting place. Four others were buried to-day, who died from fatigue and exhaustion. They belonged to the different companies. The muffled roll of the drum, and the firing of the farewell to the dead, did not have a tendency to cheer me.

12th.—This morning the roll was called, and various duties assigned the soldiers. Some had to work on the Fort, and others to cut and haul wood. In the latter employment I had to become teacher to some green hands. I found the task very troublesome—but performed it to the best of my ability. In the evening I wrote letters to my friends in Maryland.

15th.—The two past days have been employed in preparations for our departure from Santa Fe. We have encountered much trouble and perplexity in getting teams, &c., have to travel 80 miles up the mountains where we shall take up our winter quarters. We went out 6 miles and encamped. Having a severe headache, I tried my best to get some rest at night, but I had scarcely fallen asleep, when I was awakened by the officer to stand guard. I arose mechanically, feeling pretty much as I should suppose a fellow might feel who was on his way to execution. Taking up my gun I went to a large fire, where I sat quietly for two hours, watching my feelings more than I did the camp, for I was very unwell.

16th.—The breaking down of some wagons detained us here till late. After starting we met a number of Spaniards, mounted on mules. We passed some little patches of corn badly cultivated, which they dignify with the[24] name of farms. A messmate wishing some red pepper, I called with him at a house, but it was all “no comprenda”—“dont understand you,” so we got no red pepper. We went on to the next habitation through a broken country; here we found our third Lieutenant with the interpreter arranging for our camp. As we had to wait for the other companies to come up, I rested on some corn shucks, and very pleasantly did the bed feel. It was a bed of down in comparison with that to which I had been accustomed. I had slept on the ground for more than three months. Nothing grows spontaneously in this country but the Spanish broom.

17th.—Colds, and other complaints, are becoming common in our ranks. After the fatigue of marching on foot heavily armed, we were illy calculated to do the duties of the camp. Our horses being too much enfeebled for further use, after our arrival at Santa Fe, were sent up the mountain to recruit. Thus our hardships increase with our progress. The ground being very broken where we encamped to-night, which is in a wheat field, I gathered all the stubble I could, to make our beds soft and even—bought some wood to cook with from the natives.

18th.—I started alone, and tried to overtake two messmates who had gone on before me. I had not proceeded more than 6 miles when I found my two young gentlemen playing cards on the road side. I passed them, and came to a village where I saw a considerable number of Spaniards. An old woman invited me in her house and set before me some tortillas and cornstalk-molasses which were quite a treat. I remained there several hours, but thinking I had missed my way I was about to take leave, with many thanks for their hospitality, when, to my great surprise and embarrassment, the old lady and her daughter most affectionately embraced me. I suppose it was the custom among these simple hearted mountaineers, but of which I was quite ignorant. I was thankful for the meal my hostesses had provided for me, but the hugging was a luxury I did not anticipate, nor was I the least ambitious of having it repeated. I found[25] my company without much difficulty. We went on and crossed the Rio Grande. In the first stream I got my feet wet; the second was too deep for wading, and I was kindly invited by our Sergeant to mount behind him. We encamped there, having travelled 12 miles that day.

19th.—We were surrounded by the natives, who appeared friendly. When we came to the place where our horses were feeding, we learned from the soldiers in charge, that some of them had died, and that several had been stolen or had strayed away—mine, of course, was among the missing. While the others were preparing to mount, I shouldered my musket and walked on, in sand half a foot deep. The walk was exceedingly tiresome. I saw large quantities of wild geese on the Rio Grande. After marching 8 miles we encamped.

20th.—All on horseback this morning in fine style, except myself and a few others equally unfortunate. We made the best use of our scrapers through the sand. After walking awhile we came to a house on the road side, the inhabitants of which, men, women and children came rushing out. We were at a loss to know what it meant, till we saw them surround a colored man, (our Surgeon’s cook,) who proved a novel sight to them. The poor fellow was quite mortified at being made a show of on account of his color. We went on 8 miles and encamped among the Utah Indians. They are at war with the Navihoes, who have hunted them nearly down. After supper I asked permission of our Captain to accompany Mr. White, and several others to their encampment. Here, around a large fire sat an Indian chief with his squaws. After being introduced by our interpreter, a council was called. After some jabbering, a regular war-dance commenced. Their best warriors, equipped in full costume, and painted most hideously in twenty different ways—danced furiously around a large fire, to the music of kettles and drums. It was a horrid din, in which mingled the war-whoop. We gazed with astonishment till its conclusion, when an old chief made a long speech. We then returned to our camp to meditate upon what we had seen and heard, and to wonder at[26] the strangeness of character and habit exhibited by those poor creatures.

21st.—We were surrounded by the Indians before our breakfast was over. They came on to Abique, and encamped near us. There are several villages in this place. We arrived about two o’clock, and took up our quarters. The companies under Major Gilpin which were stationed there, and which we had been sent to relieve, were greatly worn and reduced with their long stay among the mountains. There was another dance at night in the Indian camp—being much tormented with sandburs, I did not go out. We had to eat our provisions half cooked, from the scarcity of wood. I and a messmate were forced to “hook” two small poles from a fodder crib, and when we returned to camp we found the companies on parade, and the Captain telling them the order of the next day.

22d.—The whole command, viz. two companies from Col. Price’s Regiment, consisting of about one hundred and eighty men, were obliged to remove to-day four miles further up the river, in order to obtain grass and fuel. This place being entirely destitute of either. At night, I went with our interpreter and third Lieutenant to several houses, to buy mutton. While on our errand we met with some ladies; one of them had a dough face; all the rest were smeared with red, and to my fancy, not at all beautiful. We returned to camp without our mutton, and not a little disappointed.

23d.—The country here is bare and sterile to a great degree, but there is an improvement with regard to fuel, which is so necessary at this season, in this mountainous country. I believe we are stationary at last. I was kept busy all day writing letters for the soldiers, many of whom very gladly do my washing and mending in return, for this slight service. I had rather at any time write than cook and wash and mend clothes.

24th.—I felt sick to-day. I took cold from a severe drenching, while on duty as a sentinel last night. A heavy cold rain was falling the whole time. I strove to assist in making our camp as comfortable as possible,[27] and in the evening despatched two letters to Santa Fe, for my beloved friends in Maryland.

Sunday, 25th.—At day-break this morning, a number of Mexicans came to camp; jabbering to themselves in a great rage about something. At first we could not ascertain the cause of their trouble, there being no interpreter present, and none of the soldiers knowing enough of the Spanish language to comprehend their meaning; soon, however, it was discovered that about sundown last evening, the Captain of our company had caused the embankment of their mill and irrigating pond, to be broken, a short distance above camp on the bank of the river, so as to prevent it from overflowing the bed of his tent. The water of course rushed out with great force, tearing the embankment down and washing the earth away for a considerable distance, stopping their mill and leaving many families destitute of water; all of which serious injuries, the Captain seemed disinclined to repair. This behavior of the Captain met with but little favor from his men. To their honor be it spoken.

26th.—This morning our Lieutenant went round the camp to get volunteers to repair the broken ditch. All seemed unwilling to do any thing—some had their horses to find, others to cut and haul wood. The men had no idea of laboring gratuitously for the repair of a deed wantonly done by their Captain. I with several others walked four miles up the river, with our axes, for the purpose of getting wood. We crossed the river several times in the wildest and most out-of-the-way places, between high cragged mountains which it was impossible to ascend. We returned to camp with our wagon loaded, though we encountered great difficulty in accomplishing it. We found there was a disagreeable misunderstanding among the officers respecting the embankment. The Captain wished soldiers detailed for its repair, and the Lieutenants thinking it an imposition on the poor fellows to stand in the mud to work such cold weather, without compensation.

28th.—We are now living in the midst of the greatest abundance of life’s luxuries. As an evidence of our high[28] living, I will transcribe our bill of fare for the week. It is as follows:

Monday.—Bread, beef, (tough as leather,) bean soup.

Tuesday.—Tough beef, bread, and bean soup.

Wednesday.—Bean soup, bread, and tough beef—and so on to the end of the week.

The greatest harmony prevails in camp, especially among the officers, the Captain and first Lieutenant are the greatest friends imaginable, they do every thing in their power for the good of the company. They are the bravest and most patriotic officers in the regiment. In this lovely and fertile valley, encamped on the banks of the Rio Charma, we are enjoying all the blessings of life. We are charmed by the surpassing beauty of the polished Spanish ladies, and living in so much harmony with each other that we almost imagine the “garden of Eden” to have been again raised for our enjoyment; and then, Oh! heavens, what a luxury, amid these joys, to feel the delightful sensations produced by the gentle and graceful movements of a Spanish louse as he journeys over one’s body! The very thought of it makes me poetic, and I cannot resist the temptation of dedicating a line to the memory of moments so exquisite. How appropriate are the words of Moore to such occasions of bliss?

When I took up my Journal to add a few items, I found the above had been written by some wag, in my absence. He was disposed to ridicule my description of the felicity of which I boasted. Our boys are rather mischievous, and I must confess that I felt rather waggish myself when I made the boast of our possessing Eden-like pleasures. The continuation of my narrative pleased[29] me so well that I consented to let it remain as it was written. Our mischievous feeling and manner of expression is the most innocent way in which we can relieve ourselves, for we privates are suffering many privations while some of our officers refuse to speak to each other. I am glad, however, that our troubles are so merrily turned into ridicule, the best way sometimes to treat them. We are not destitute of sport however—many amusing scenes occur among us, debating societies are formed among the soldiers in which the most absurd questions are dilated upon with a vehemence and mock seriousness truly laughable. A breakfast of coffee without sugar, some very poor beef soup, and onions sliced up with parched corn, made a better meal for us to-day than we have had for some days past. Yesterday I traded off two needles to the Spanish girls for six ears of corn and some onions, it was a trade decidedly profitable for both parties. In company with our first Lieutenant, his brother, William White, Dr. Dunlap, and a number of others, I went up on a high peak of the Rocky Mountains. We had been there but a few minutes when it commenced snowing. We kindled a large fire, and amused ourselves by listening to the reverberations of sound produced by our Lieutenant’s revolver, who fired six rounds. Becoming thirsty, we searched and found water in the crevice of the rock close to the edge of the precipice. It was too far below the surface for us to drink by stooping over, and William White proposed to throw in gravel, in order to raise the water, reminding me of one of Æsop’s fables. We followed his advice and the water was soon forced to rise high enough for our purpose. The snow increasing, we came down and made another fire in a large hollow of the rock, where all but myself sat down to cards. It was an amusement that I did not relish, and I sought my gratification in loosing the rocks and rolling them down the side of the mountain, which is at least a thousand feet above the level of our camp.

29th.—To-day, Charles Perkins and myself took our guns and proceeded down the river several miles in search[30] of game. We fired at several flocks of wild geese and ducks, but it only scared them further off. We passed several Spanish houses on our return. When we reached the camp we found the soldiers at different employments, some playing cards, and others making articles to sell to the natives. A Mr. Hatfield was engaged in the manufacture of a grindstone to trade to the Spaniards for corn and beans. These, with onions, are the only vegetables they grow.

30th.—The mountains are covered with snow, and, after raining hard all night, this morning it is clear and cold. We made the best preparations we could to send the wagons back to Santa Fe for provisions, as late last night, our second Lieutenant returned, after an absence of five days, and brought news that we are to take up our winter quarters in this dreadful region. There seems to be very little likelihood of our going south at all. The officers went in search of other quarters to-day.

31st.—We had a heavy fall of rain last night, which improved into a snow-storm before morning. I slept very uncomfortably, as a high wind from the north had full sweep in the door of our tent. We were inspected at 11 o’clock, and carried through all the evolutions of the drill. After the parade we could scarcely keep warm, though wrapped in our blankets, and crowded around the fire. Yesterday one of our beef cattle died from starvation. The Mexicans came down and took it off to their habitations. We might have made a speculation by selling it but did not think of it.

Sunday, November 1st.—Several of my mess are going up the mountains to look for their horses. I offered a friend $5 (should I ever again possess that sum) to search for mine. I read aloud in my Testament to some of the boys, while others sat apart, or pitched quoits. At night a Spaniard came in camp with a fiddle, and played a number of tunes which so exhilarated my poor half frozen companions that they united in a dance which they kept up till a late hour.

2nd.—Some Taos flour, coarsely ground in the little native mills on the Rio Grande, badly baked in the ashes,[31] and some coffee without sugar, now comprise our only sustenance. Between meals, however, we parch some corn, which we now and then procure of the natives in exchange for buttons, needles, or any little matter we can spare. At 9 o’clock, we struck our tents, and marched down the river two miles to a deserted Spanish house nearly in ruins. The inhabitants were murdered by the Navihoe Indians. This is the place where we are to take up our winter quarters. I can scarcely describe this wretched den. The soldiers have looked in and they have become very dissatisfied. They were told by the Captain to erect their tents inside the wall. All the houses in this region having that protection. We could not sleep in the house on account of the offensive odor. The tent was much more comfortable.

3d.—As soon as our breakfast of beef soup and coffee was over, some of the men were appointed to scrape and clean the house. I with several others was sent to the mountains to cut and haul wood. After walking two miles, we procured a load of green pine, which does not grow here more than half the usual size. On the return, I thought I would take a near cut to our camp alone. I turned into a foot-path, which led me to the top of a high mountain. Here I could see our quarters, though a long distance off. I took a direct course, and soon arrived at camp, where I found our boys writing down a vocabulary of Spanish words. They have become very erudite of late.

4th.—All this day we did nothing but write down words from the language spoken by the people, who, from their complexion, appear to be a mixture of the Spanish and Indian races. We made a pretty good dictionary among us.

5th.—This day is very unpleasant. It is raining hard. At 4 o’clock, our first Lieutenant, Mr. White, returned from Santa Fe. He brought bad news. He could get no provisions, except one-fourth rations of flour, and one and a half barrels of mess pork. But notwithstanding all this, our boys are still very lively.

6th.—We had great labor to-day in procuring fuel sufficient for our present purpose, and the prospect of a[32] long and severe winter before us makes our situation rather unenviable.

7th.—On short allowance yesterday and to-day, a little bread, (i. e. two pints for six men,) some fried beef, and coffee without sugar.

Sunday, 8th.—Although the morning was cloudy and cold, I walked with twenty others down to Abique to church. On arriving we went into the priest’s room. He very politely invited us to be seated, and then commenced asking all kinds of questions about the United States. He seemed to take great interest in teaching us the Spanish language. He made us repeat after him, many long and hard words. We sat two hours with him and then went in church, where a large congregation was assembled. In a few minutes our priest made his appearance, dressed in gold lace, and ascended the pulpit, while all present fell on their knees. The music of various instruments now commenced, the priest the meanwhile, drinking sundry glasses of wine. The people remained on their knees till the music ceased, when all retired.

It was noised among the soldiers that a fandango would take place in the evening. Some of us went in to inquire of the priest, who informed us that the fandango was to be at a village some miles further off. In a little while, a Mexican guide was hired to escort us. After walking a mile we came to a river, when this Spanish fellow, very quietly sat down to pull off his shoes, and told all who were in favor of wading the stream to follow his example. Eight of the boys immediately commenced stripping to cross, declaring that nothing should disappoint them from attending a fandango. As I had a bad cold, with some others, who felt no inclination to wet their feet, I returned to our quarters.

9th.—All this day in the mountains cutting wood.

10th.—I went with several others to search for lost horses. We had not gone far when to my great joy I found mine, which had not been seen since we left Santa Fe. We heard volleys of musketry in the direction of our camp, and were at a loss to understand the meaning,[33] till on our return, we learned that a dog had been buried with the honors of war. This poor dog had been a great favorite with our Captain and all the company; he was most foolishly shot by a soldier on guard last night. The man was made to dig his grave, and will be detailed on extra duty as a punishment, the Captain being much exasperated. This evening I, with four others took rations for five days, in order to drive the horses down the river to graze. Late at night, we reached a Spanish village, where we stopped. A mile from that place, a fandango was to come off, and the ladies of the place were preparing for the dance. They were nicely equipped in their best finery, and the soldiers were engaged to accompany them. Not being very desirous of attending the fandango, I preferred to remain and try to get some rest, of which I was very much in need. The party was soon prepared, and off they started, leaving me behind to cook supper and arrange matters for their comfort when they should return. I browned the coffee, fried the beef, made the bread, and having all things in readiness, I drank a cup of coffee and laid down to rest on a mattress placed on the floor. As far as the thing I laid on was concerned, I was comfortable enough; the mattress was a luxury; but I could not sleep; the reasons were various. I was lying in a house, when I was accustomed to dwell in tents;—my quarters were divided between myself several donkies and mules and two small children—the odor of the donkies was not the most agreeable, nor their noise very harmonious; the children knew their mother was out and did their best at crying. The woman had gone to the fandango, where I hope she enjoyed better music than that which she left for the lulling of my sensibilities into sweet slumbers.

11th.—Our soldiers did not return from the fandango till 3 o’clock this morning, and I was appointed to get breakfast while they slept. I had considerable trouble in accomplishing this service, as the girls crowded around the fire, and I had frequently to pass the frying pan over the naked feet of a pretty girl who was sitting near me. In company with a young Spaniard, who was exceedingly agreeable and polite, I went out after breakfast[34] to kill wild geese. We walked a long distance, and returned unsuccessful.

12th.—I find the family residing here, very agreeable. I was invited, and almost forced to accompany them to a fandango last night (for they do little else but dance.) All on horseback, the married men mounted behind their wives, we started. A little baby in its mother’s arms becoming troublesome, one of our men, who said he was a married man, most gallantly rode up, and offered to carry the little creature. The mother thankfully resigned it to his charge. There was more pleasure in the idea of enjoyment at the fandango than in taking care of a cross child. When we arrived at Abique, an old man invited us to partake of his hospitality;—an invitation we gladly accepted. We went in accordingly, and after all were seated on the floor in the posture of a tailor, a large earthen vessel was placed before us containing pepper sauce and soup; and a few tortillas, (a thin paste made of corn rubbed between flat stones.) The sauce caused my mouth to burn to a blister. The people are very fond of condiments, and become so accustomed to them that what will burn a stranger’s mouth has no effect upon theirs. After all was over, we went across the street to attend the fandango. From the crowd, I should judge it was high in favor with all classes of the community. Some of the performers were dressed in the most fantastic style, and some scarcely dressed at all. The ladies and gentlemen whirled around with a rapidity quite painful to behold, and the music pealed in deafening sounds. I took my seat near a pretty girl, and every time she leaned on my shoulder, which she did pretty often, her beau would shake his head in token of his displeasure, and showing his jealous disposition. I left the place about 10 o’clock, and returned to our quarters.

13th.—We visited our camp to-day at the Spanish ruins. The Captain and officers were glad to see us, especially as we had good news in relation to the horses. We had them in charge, and exhibited them to our comrades as the trophies of our success. On our return, we killed two wild geese and four rabbits, which we found[35] a great help to our stock of provisions which was then very low.

14th.—I was left alone with the Spaniards to-day, while our boys were attending to the horses. My Spanish friends are very courteous, but there is little to relieve the monotony of our intercourse, as from my ignorance of the language I am unable to converse with them.

15th.—This morning we had one of our wild geese stewed for breakfast, which we had without coffee, and almost without bread. After breakfast I started to camp to draw provisions of some kind. When at camp I concluded to remain there.

16th.—I was told by the Sergeant to-day, that there was no flour to issue. He referred me to the Captain, who directed young Bales and myself to a mill some distance off, where we procured 60lbs. of unsifted Taos flour very coarsely prepared. With this, we returned, and in a few minutes nearly the whole was appropriated to the use of the half-starved soldiers. A very small portion of this brown flour fell to our share. This evening we are without food, or nearly so. Martin Glaze, an old veteran, who has seen service, and belongs to my mess, got a few ears of corn and parched it in a pan, with a small piece of pork to make it greasy. When it was done, we all sat around the fire and ate our supper of parched corn greased with fat pork. The weather to-night is extremely cold.

17th.—Awoke early this morning and found it snowing very hard. At 10 o’clock I went to our first Lieutenant’s quarters. He was engaged in appraising some cattle which are pressed into our service, and for which the natives were to be paid. A bull has just been killed, and the offals are being greedily devoured by our poor fellows. At 11 o’clock to-day our third Corporal died, having been sick with camp fever and inflammation of the brain several weeks. At 3 o’clock his grave was dug and the poor fellow was wrapped in his blanket—and buried without a coffin. To-night there are several of our men sick with the measles, supposed by our Surgeon to have been brought from Santa Fe.

[36]18th.—The snow four inches deep—clear and very cold—another grave dug to-day for a member of the Livingston company, making five who have died since we have been out here. They are all buried near the mountain, where poor Johnson was laid.

20th.—The past two days have been employed in procuring wood, which is hard labor; but we do not complain as our fare is improved by the addition of bean soup and coffee.

21st.—A court martial was held this morning to try our fourth Sergeant, who has said something derogatory to the character of our Orderly. After the court adjourned, we were ordered to form a line. Our first Lieutenant then stood in front and read the proceedings of the court. The decision was that our fourth Sergeant be reduced to the ranks, for slander. It was ordered that if any man, or men should thereafter bring false charges against the officers, he or they, should be sent with a file of soldiers to Santa Fe, and tried at head quarters, &c. The company was then dismissed. Several of my mess concluded to run as candidates for the vacant place. They went among the crowd with tobacco and parched corn, electioneering. I was placed on guard at 9, and had to stand till 11 o’clock.

Sunday, 22d.—A gloomy Sabbath morning—I felt badly, but concluded to go to church at Abique. As soon as the ceremonies were ended I went in the priest’s room in company with my old friend Capt. Markle and several officers. After sitting awhile, a servant brought in a dish of refreshments, consisting of pies and wine. Placing the glass to my lips I discovered it to be Taos whiskey, as strong as alcohol. A piece of the pie, I thought might take away the unpleasant taste, so I crowded my mouth full, and found—alas! it was composed of onions, a dreadful fix indeed, for a hungry man, Taos whiskey and onion pie!—the very thought of the mess makes my mouth burn. When I returned to camp I found nearly every individual busily engaged at cards. Elias Barber, a messmate, was taken sick with the measles. The disease, is now raging among the troops.

[37]23d.—We had great trouble in procuring fuel to-day. We had to travel far up the mountain for it, and it is exceedingly difficult to cook with it out of doors in the deep snow. It fell to my lot to make the bread, and I had much ado to-night, to make the mass stick together. I felt more than usual fatigue after the parade.

24th.—Elias Barber is very sick to-day. He spent a wretched night last night in a thin cotton tent. The wind is blowing on him constantly, while the measles are out very thick. I went to the Captain this morning and informed him of the situation of the young man. He told me if I could procure a place in the house, he might be brought in. I therefore went and after making preparations to move him, I was told that no such thing should be done. I then tried to get an extra tent to place over the one we are sleeping in, and even this was denied me. The poor fellow is lying out of doors, exposed to all the inclemency of this cold climate. And last night it was so cold that the water became frozen in our canteens. The Surgeon appears interested, but it is all to no purpose—nothing further is done for the comfort of the sufferer. May the Lord deliver me from the tender mercies of such men!

25th.—I felt quite unwell all day to-day. I suffered much from a severe attack of diarrhœa. Our lodgings are very uncomfortable. I went down to the Rio Grande to get water, and found it nearly frozen over. A great mortality prevails among the troops who are dying from exposure and disease.

26th.—I was very much engaged all day, in nursing poor Barber. He is worse to-day, the measles having disappeared from the surface. I sat by him the livelong night and listened to his delirious ravings, and I felt sad to think I had no means of relief. At 4 o’clock this morning the Captain came, and finding him so ill, brought out a tent to cover the one he laid in.

27th.—Last night, my messmate Philips returned from Santa Fe, with a message from Col. Price to the different Captains, to send on ten men from each company, as an escort for Col. Mitchell, who was about to start for[38] Chihuahua. From thence he is to proceed to open a communication with General Wool. To-day an express arrived from Col. Mitchell for the same purpose. We were hastily paraded to ascertain how many would volunteer to go, when I, with five others of my company, stepped out of the ranks, and had our names enrolled. We were satisfied that we could not render our situation worse, and hoped any change might be for the better. We hastened to the grazing ground, over the mountain, for our horses, which occupied us all day. Mine was gone of course. To prevent delay, I gave my note to a young man for a horse which belonged to a deceased soldier.

28th.—A full company having been made up, this morning we gathered at our quarters, and were ready at 8 o’clock to take leave of our kind hearted comrades. They bid us “good-bye,” with many expressions of regret, and injunctions to write often. We pursued our journey 35 miles, and put up late in the evening at the house of a rich Spaniard, who accommodated us with an empty room twenty feet square, but it had so small a fireplace that we could not use it for our culinary purposes, so we were forced to do most of our cooking in the open air. It fell to my lot as usual to make the bread, and I kneaded forty pounds of Taos flour in a mass, and baked thirty-six good sized cakes, while two others prepared our camp kettles of coffee, &c.

Sunday, 29th.—At 4 o’clock we ate our breakfast, and were on the road by day-light. We travelled all day without stopping, and arrived at Santa Fe at 6 o’clock in the evening. We went immediately to the American Hotel where supper was provided for us. Nineteen men sat down to the table, none of whom had enjoyed such a privilege for nearly four months. All were hungry, and it was amusing to see how we tried to eat our landlord out of house and home. After supper we retired to our quarters in a very small room.

30th.—Word was sent from Col. Mitchell this morning for us to parade before the Governor’s house for inspection. Our horses were also examined, and all being[39] found in good order for the trip, we were dismissed and conducted to our quarters, in the court house; where we drew our rations, viz. thirty pounds of good American flour, with pork enough to last five days.

December 1st.—Paraded again soon after breakfast, and were told by our Captain, that previously to our departure, we must all march to the sutler’s store, and acknowledge our indebtedness to him, so up we rode in right order and dismounted. We had a peep at our accounts, and I found mine to be $30 75. I had purchased a few articles of clothing on my route, being forced to do so from necessity. I was therefore not surprised at the amount, especially when I read the prices of some the articles, viz. a small cotton handkerchief $1—suspenders $1—flannel shirt $3—tin coffee pot $1 50, &c. &c. Here we bade farewell to our Captains, who had accompanied us to Santa Fe to see us off. Captain Williams shook me cordially by the hand, saying, he had no expectation of seeing me again in this world. Captain Hudson now took charge, and rode with us two miles out of town—here he informed us, we had a dangerous road to travel, but would leave us to the care of Lieutenant Todd for two days, till we were joined by Col. Mitchell and himself. He returned to town, and we came on four miles and stopped at a house, whose master sold us forage for our horses and wood, it being severely cold. Sixty of us occupied two large rooms for the night.

2d.—We marched 25 miles to a place called San Domingo, and took quarters in a deserted house. This is a considerable place, with a handsome church, which was being illuminated when we arrived. In a little time the bells began to ring, and there was a firing of musketry and considerable commotion at the door of the church. Several of our soldiers were induced to go up and inquire into the meaning of the uproar. We were told that a converted Indian chief had just died, and all this was to prevent him from going down to purgatory. The roll of the drum and firing continued a long time, when the ceremonies commenced in the church, from the door of which[40] we saw many large wax candles burning, but not being permitted to enter we very quietly retired.

3d.—After travelling six miles we came to an Indian village called San Felippe, and two miles further down the Rio Grande we encamped in the midst of a good pasture for our horses. After supper, our Lieutenant told me I was honored with the appointment of Captain of the watch. In consequence of this distinction, I had to be up nearly all night. It was very cold. We were now comparatively happy, for we had plenty of good flour from the States, with coffee, sugar, &c.

4th.—We learn that we shall be obliged to stay here till Col. Mitchell comes up with the other company, so we seize the opportunity to have our horses shod. Two blacksmiths are now at work; I have just bought a set of shoes and nails from our sutler for $3.

5th.—The weather has moderated somewhat, but the face of the country presents nothing inviting at this season of the year. Every thing has a desolate and wintry appearance. There being no food for our horses, we chopped down some limbs of the cotton wood tree for them to eat. We then went to a Mexican village to buy corn. Having no money, I took some tobacco and buttons to trade for the corn. While here, I sold my greasy blanket for a Navihoe one, with a meal for my horse in the bargain. The man with whom I traded was very kind; he set before me some corn, mush and sausages, but being seasoned with onions, I declined eating. He then brought in some corn stalk molasses, which I mixed with water and drank, thanking him for his hospitality. I returned to camp, when I found that Col. Mitchell, and the baggage wagons had arrived. I was officer of the guard to-night, and up till 12 o’clock.

Sunday, 6th.—Formed in line by our Colonel in the midst of a heavy shower of rain, and marched down the Rio Grande, a long distance. Our course is due south, keeping the river constantly on our right, and ranges of mountains on our left hand. We passed many villages, and at night encamped near one.